Introduction

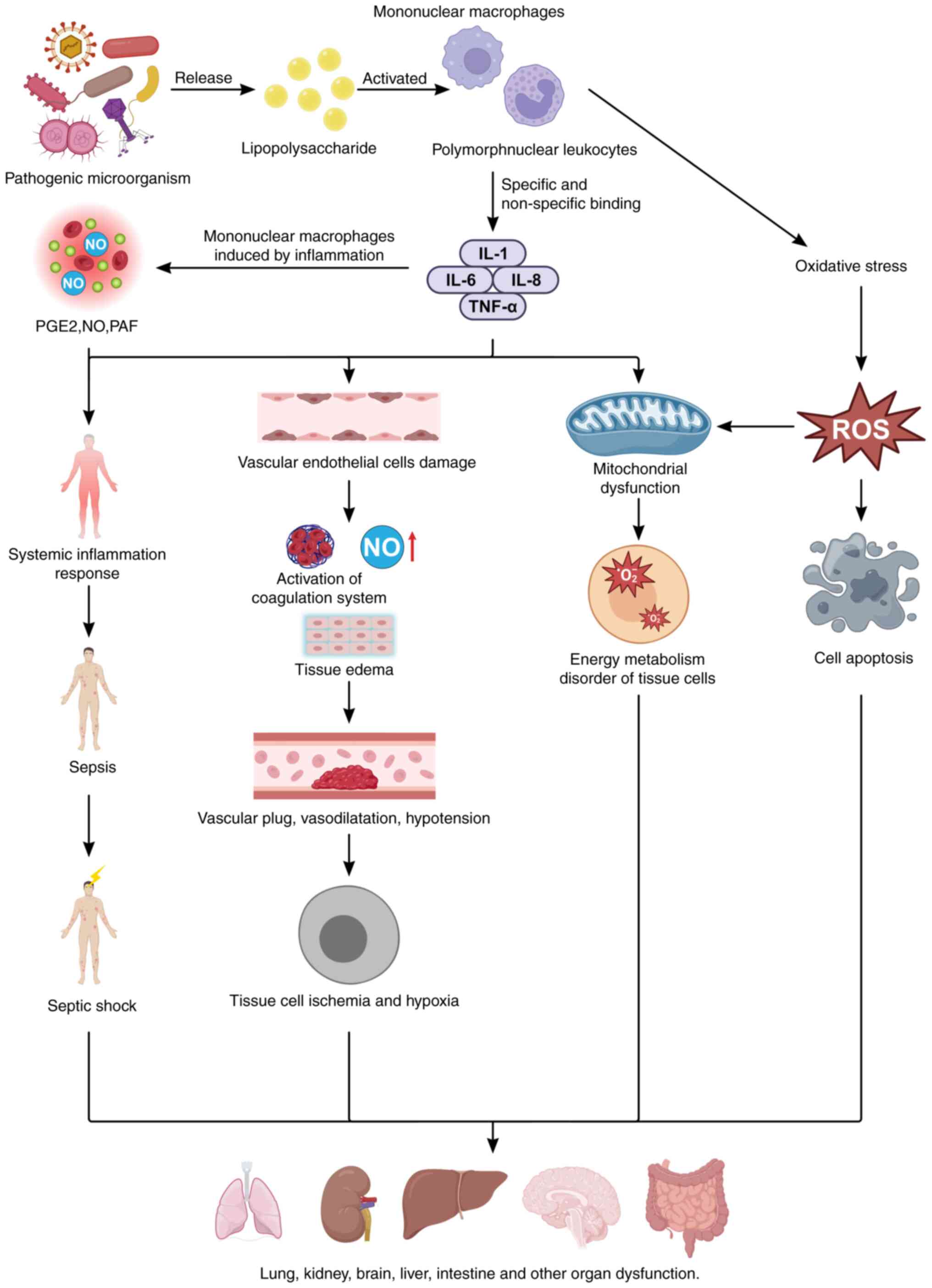

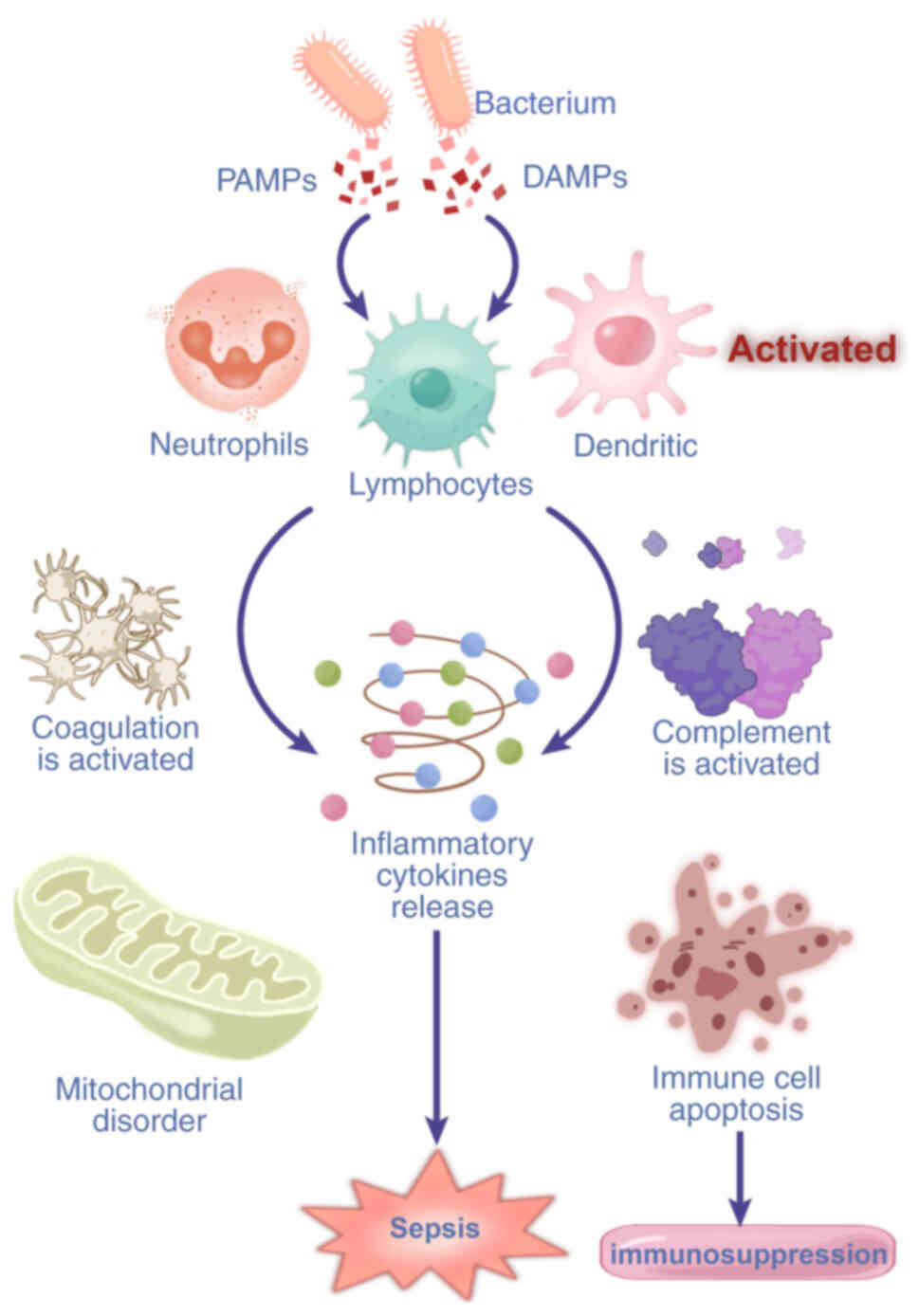

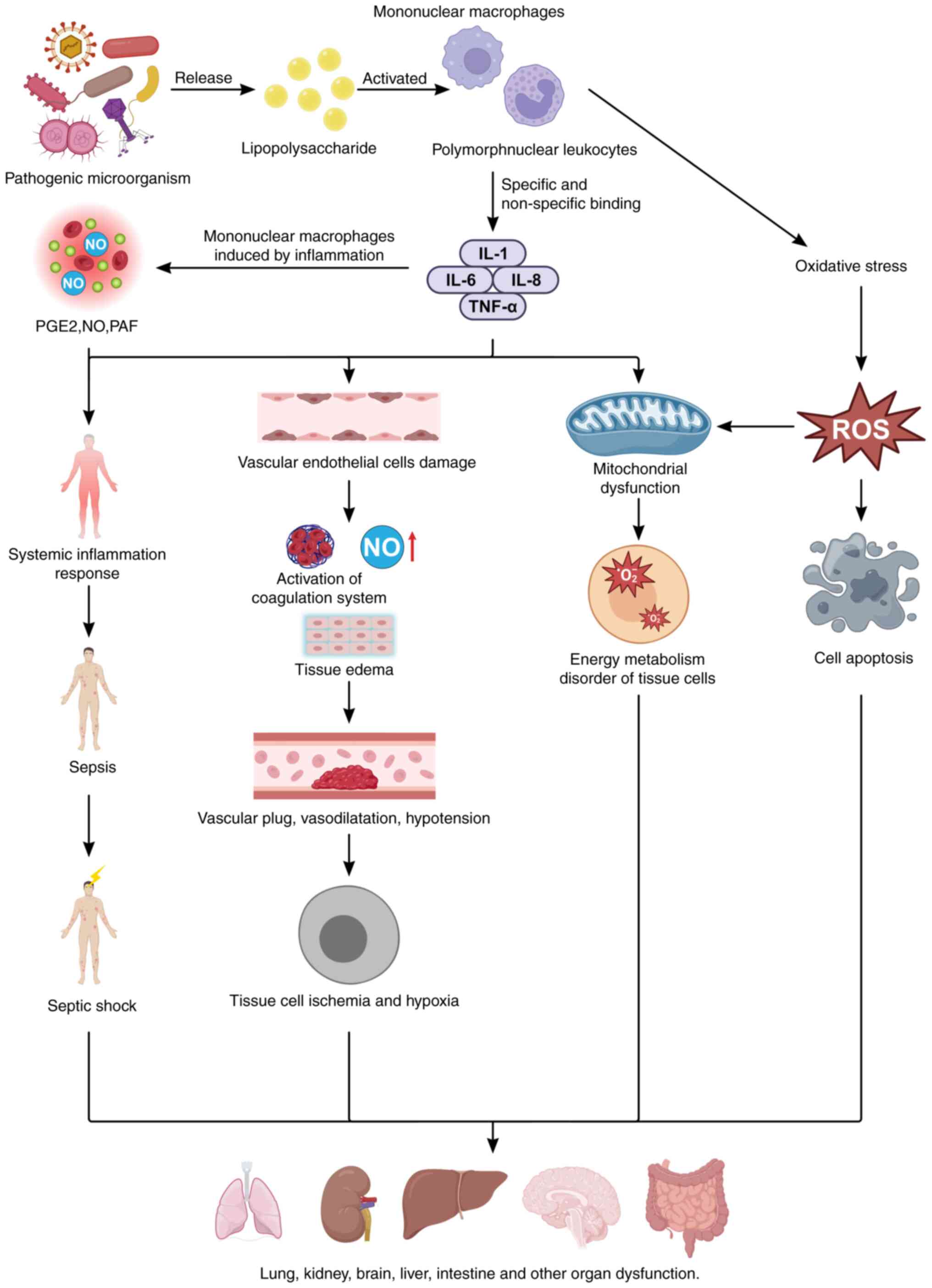

Sepsis-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

(MODS) involves dysfunction of two or more organs triggered by a

dysregulated response to infection and is characterized by a series

of physiological, pathological and biochemical abnormalities caused

by infection (1) (Fig. 1). During the early stage of

sepsis, inflammation is activated, leading to the release of

numerous proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α

(TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6, and inflammatory mediators,

such as high-mobility group protein B1 and prostaglandins,

resulting in immune overactivation. Additionally, immune cells,

including T lymphocytes, release various cytokines, accompanied by

redox imbalance. These mechanisms collectively activate endothelial

cells, increasing the release of cytokines, nitric oxide (NO),

platelet-activating factor and coagulation factors, thereby

exacerbating sepsis and advancing to MODS, ultimately resulting in

patient mortality (2) (Fig. 1). Despite extensive research on

the pathogenesis and therapeutic targets of MODS, the incidence and

mortality rates have improved little.

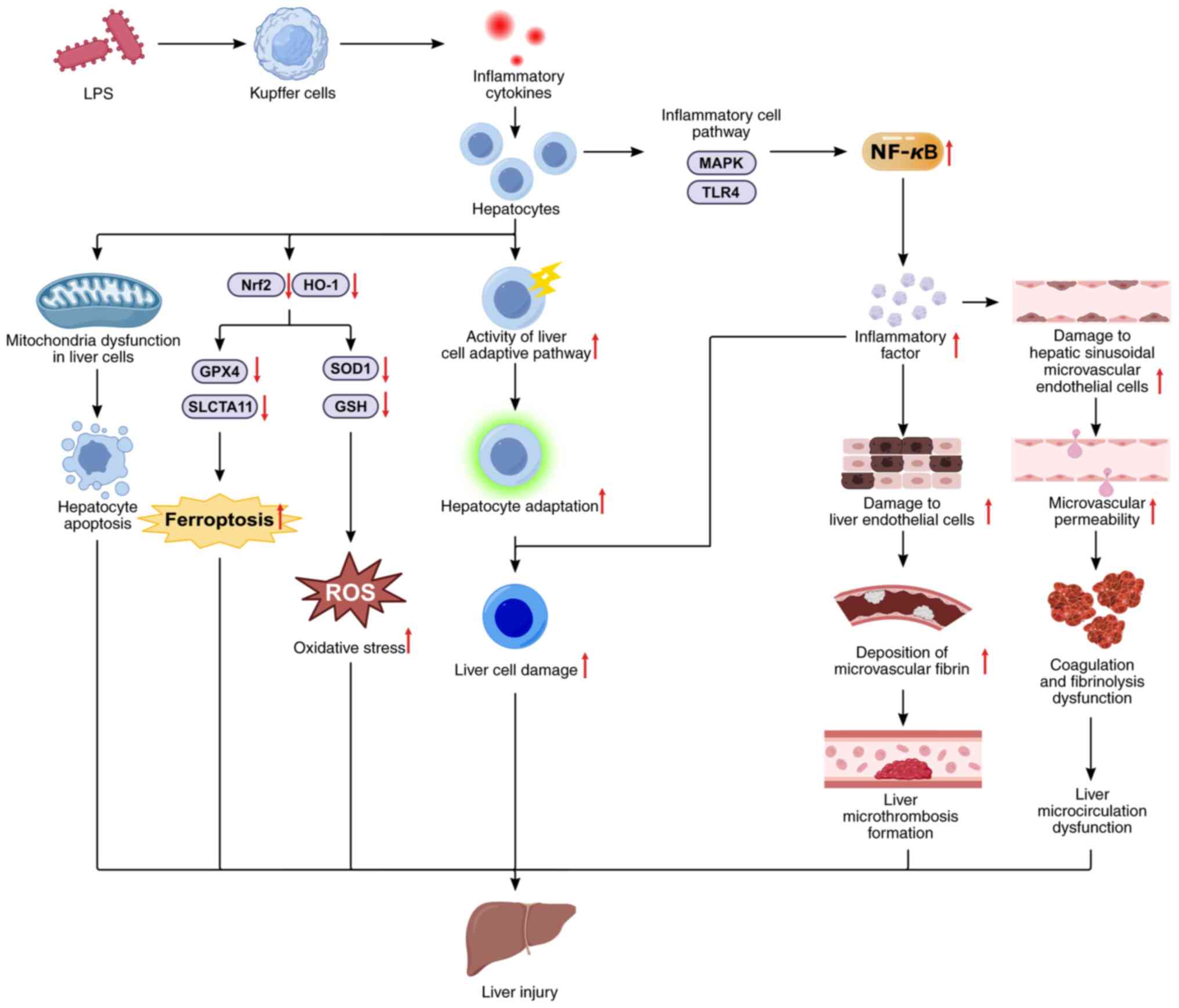

| Figure 1Mechanism of multiple organ

dysfunction caused by sepsis. The endotoxins produced by pathogenic

microorganisms stimulate inflammatory cells, which produce a large

concentration of inflammatory mediators, leading to sepsis, septic

shock and multiple organ dysfunction. Moreover, inflammatory

mediators can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, an oxidative

stress response, coagulation dysfunction and microvascular blockage

and exacerbate damage to multiple organs, such as the liver, brain

and lungs. PGE2, prostaglandin E2; NO, nitric oxide; PAF,

platelet-activating factor; ROS, reactive oxygen species. |

Dexmedetomidine (DEX), a potent selective

α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, functions as a sympathetic blockade

within the nervous system and provides anxiolytic, sedative,

analgesic and hemodynamic stabilizing effects (3). It induces sedation without causing

respiratory depression, which is significant in clinical treatment.

DEX is commonly used for preanesthetic induction and as a sedative

in intensive care units (ICUs) (3,4).

Previous studies have indicated that DEX has protective effects on

various disease models: i) DEX enhances the 2-year survival of

elderly patients in ICUs and improves cognitive function and

quality of life in 3-year survivors (5); ii) DEX mitigates apoptosis,

necrosis and autophagy in the brain and surrounding tissues in both

in vitro and in vivo models (6); iii) DEX promotes cell survival by

inhibiting apoptosis and protecting against bilirubin-related lung

injury (7); iv) DEX protects

against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting

autophagy (7); and v) DEX

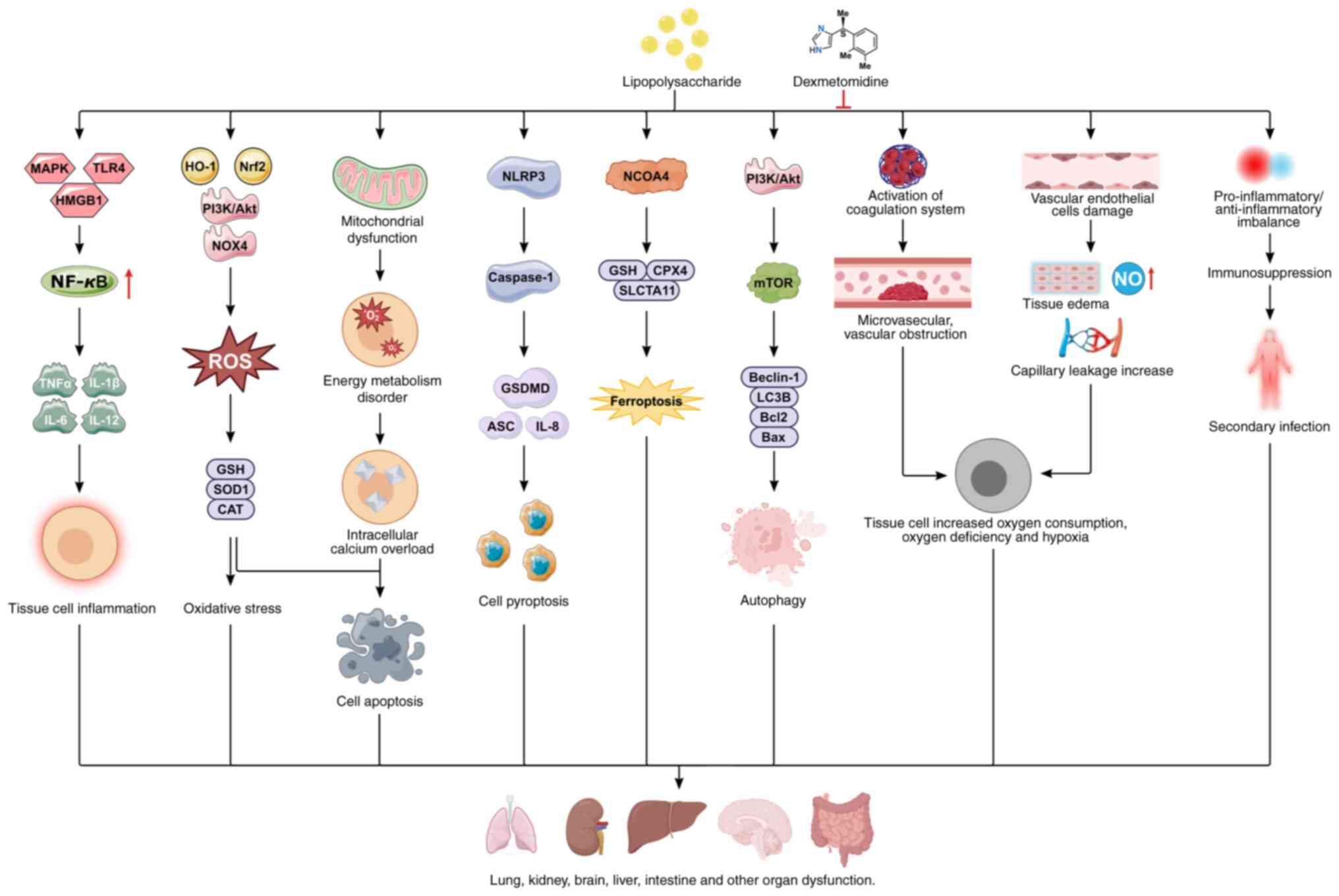

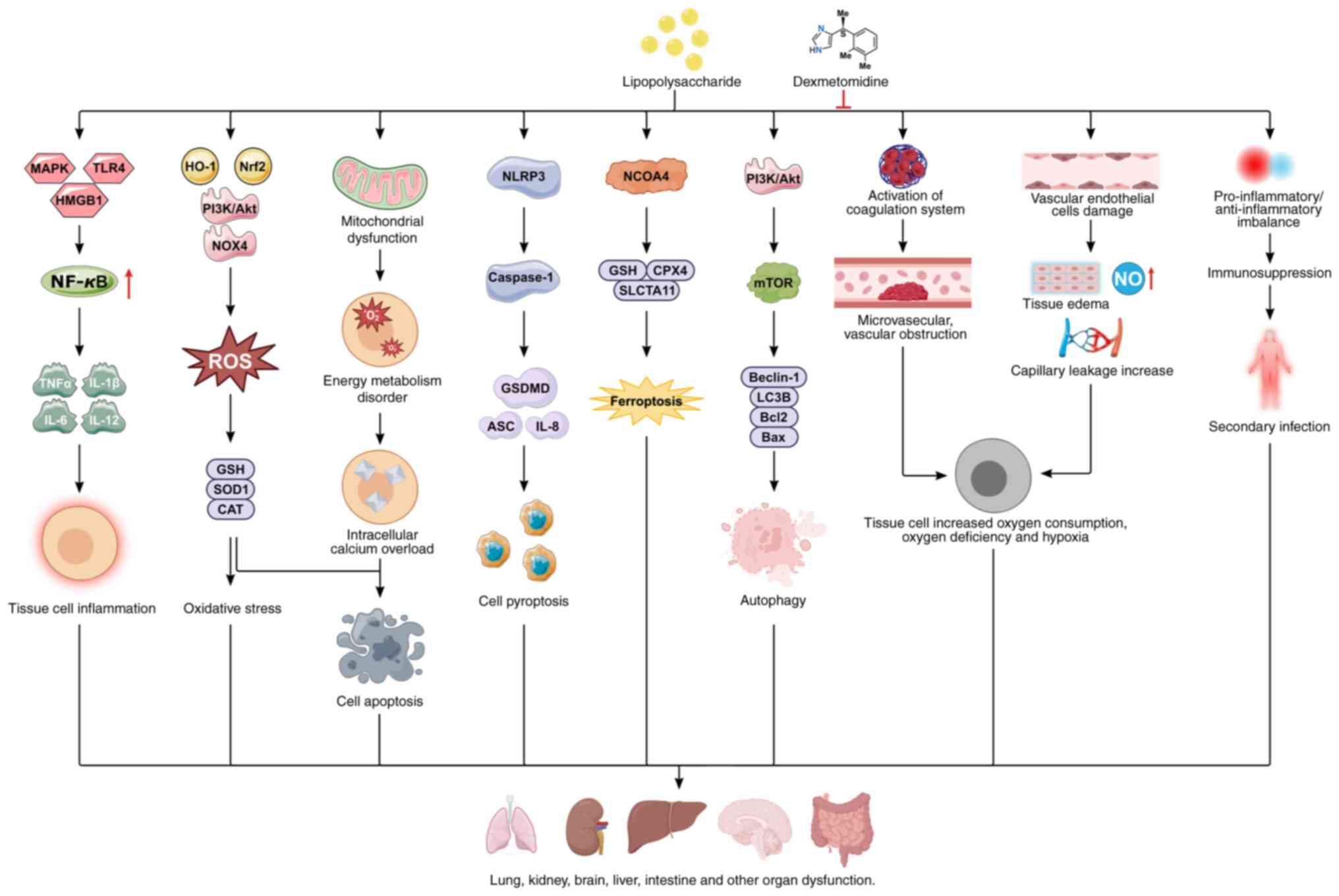

shields against sepsis-related organ injury (8-11). The roles of DEX in mitigating

lung, kidney, liver, brain and immune dysfunctions by regulating

signaling pathways related to inflammation, apoptosis, pyroptosis,

autophagy, and ferroptosis in sepsis treatment are summarized in

Fig. 2.

| Figure 2Protective mechanism of

dexmedetomidine against multiorgan dysfunction. LPS regulate tissue

cell inflammation by modulating the MAPK, TLR4, or HMGB1/NF-κB

signaling pathways; regulate tissue cell oxidative stress by

modulating Nrf2/HO-1, P13K/Akt and NOX4 signaling pathways; and

regulate cellular autophagy by modulating the P13K/Akt/mTOR

signaling pathways. In addition, lipolysis can lead to endothelial

damage, abnormal coagulation function and immune imbalance.

Lipopolysaccharides induce multiple organ dysfunction through these

mechanisms; however, dexmedetomidine alleviates

lipopolysaccharide-induced multiple organ dysfunction by regulating

these pathways. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAPK, mitogen-activated

protein kinase; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; HMGB1, high mobility

group protein box-1; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain

containing 3; NF-κB, Nuclear factor κB; CAT, catalase; HO-1, heme

oxygenase 1; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein; NCOA4,

nuclear receptor coactivator 4; GSH, glutathione; GPX4, glutathione

peroxidase 4; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide

dismutase; GSDMD, gasdermin D. |

Epidemiology of sepsis and multiple organ

dysfunction

Sepsis, a severe disease that threatens human

health, is not only a medical issue but also a public health

problem. A search of the World Health Organization website revealed

that, according to data released in 2020 (12), there are 48.9 million cases and

11 million sepsis-related deaths globally, accounting for nearly

20% of all global deaths. Of these, nearly half of the sepsis cases

occur in children, with an estimated 20 million child cases and 2.9

million deaths among children under the age of 5. The incidence and

mortality rates of sepsis vary by region, with ~85% of sepsis cases

and sepsis-related deaths occurring in low- and middle-income

countries. Sepsis treatment is costly, and in high-income

countries, the average hospital cost for sepsis exceeds $32,000 per

patient (13). The incidence of

sepsis in mainland China is similar to that in developed countries.

However, owing to the large population base and relatively low ICU

bed-to-population ratio, more patients with sepsis are not admitted

to the ICU because of insufficient bed availability. A

population-based epidemiological study of hospitalized sepsis

patients conducted by Zhou et al (14) revealed that only 20% of patients

with severe sepsis and 59% of patients with septic shock were

admitted to the ICU. The burden of sepsis in mainland China may

thus be underestimated. The study also revealed that the

standardized incidence rate of sepsis is 461/10 million, with a

mortality rate of 79/10 million. The high incidence and mortality

of sepsis, as well as the annual medical burden it causes,

highlight the need to improve the diagnosis and treatment of sepsis

and, at the macrolevel, strengthen the management of sepsis

prevention and treatment.

Sepsis-related organ injury or dysfunction is a

common complication of sepsis, and in severe cases, it can lead to

multiple organ dysfunction or failure, resulting in a poor

prognosis (15). According to

the American Society of Critical Care Medicine, the incidence of

MODS in the United States is ~240-300/100,000 people, with ~54% of

ICU-admitted patients developing MODS (16). The pathophysiology of MODS is

complex, with an unclear pathogenesis and rapid disease

progression, and the mortality rate is as high as ~30-40% (14). Studies have reported that the

average mortality rate for individuals with two organ dysfunctions

is 59%; for those with three organ dysfunctions, the average

mortality rate is 75%; and for those with four or more organ

dysfunctions, the average mortality rate is 100% (17). In terms of the frequency of organ

dysfunctions occurring in MODS, the highest incidence is

respiratory dysfunction, followed by gastrointestinal and renal

dysfunction. Among them, renal dysfunction has the highest

mortality rate, with an average of 79%, followed by respiratory

dysfunction at 68%, gastrointestinal dysfunction at 59%, hepatic

dysfunction at 55% and coagulation dysfunction at 44% (18). If severe infection is present,

the mortality rate increases significantly. In recent years, the

mortality rate of MODS has significantly increased with the number

of organ failures and the age of patients, making MODS a major

clinical challenge that urgently needs to be addressed in

medicine.

Pharmacokinetics of DEX

The chemical molecular formula of DEX is C13H16N2,

and its chemical name is

(+)-4-(2,3-dimethylphenyl)-ethyl-1H-imidazole (19). DEX shares a similar chemical

structure with clonidine, including an imidazole ring and a benzene

ring, indicating that both can act as agonists on α-adrenergic

receptors. As a highly selective α2-adrenergic receptor agonist,

DEX has a binding affinity ratio of 1,620:1 for α2-adrenergic

receptors compared with α1 receptors. Its affinity for

α2-adrenergic receptors is 8-fold greater than that of clonidine.

Studies have shown that the pharmacokinetics of DEX are strongly

predictable (20). For example,

during absorption, owing to the first-pass effect, the oral

bioavailability of DEX is extremely low. The bioavailability is

only 16% for sublingual administration, whereas intranasal

administration achieves a bioavailability of 84%. For intramuscular

and subcutaneous injections, the bioavailabilities are 73 and 51%,

respectively. Therefore, intranasal, intravenous and intramuscular

routes of administration are all applicable. However, considering

the storage and usage of DEX, along with its physicochemical

property of being fully soluble in water at a pH of 7.4, clinical

formulations are commonly provided as colorless, clear liquid

hydrochloride injection solutions. Intranasal administration is

particularly beneficial for special populations, such as children

and elderly individuals (21).

DEX is a highly plasma protein-bound drug, with a binding rate of

94% to plasma albumin and α1-glycoprotein. Studies have shown that

the plasma protein binding rate of DEX is not significantly

influenced by sex or age (22).

Additionally, DEX has a shorter half-life than does clonidine. Its

distribution half-life is ~6 min, allowing it to be distributed

rapidly in the body following intravenous injection. The

elimination half-life (t1/2) is ~2 h, with intravenous infusion

lasting up to 24 h. The linear pharmacokinetic range of DEX in the

body is 0.2-0.7 µg/kg·h. It is metabolized primarily in the

liver, with the metabolites being excreted mainly through urine

(95%) and feces (5%) (21).

Pharmacodynamics of DEX

DEX is a potent and highly selective α2-adrenergic

receptor agonist that exerts various effects by stimulating three

subtypes of α2 receptors in the body (α2A, α2B and α2C). For

example, the activation of α2A receptors, which are located

primarily in the locus coeruleus of the brain, can produce effects

such as sedation, analgesia, hypnosis and neuroprotection; the

activation of α2B receptors, which are distributed mainly in the

thalamus, heart, liver, spleen and aorta, can lead to analgesia,

peripheral arterial vasoconstriction, and the suppression of

centrally mediated shivering; and the activation of α2C receptors,

which are found in the heart, spleen and aorta, can result in

cognitive and emotional changes (3). Therefore, by stimulating α2

receptors in these organs and tissues, DEX can exert multiple

biological effects, including sedation, analgesia, hypnosis,

maintenance of normal respiration, and a reduction in organ

damage.

DEX induces a unique sedative response characterized

by a smooth transition from sleep to wakefulness, allowing patients

to communicate and interact when stimulated by external factors. It

mimics the effects of 'natural sleep', enabling patients to remain

in a sleep-like state during surgery while being easily arousable.

DEX has minimal toxic side effects on the body and, regardless of

the dosage, does not cause respiratory depression (23). Sleigh et al (24) suggested that the sedative and

hypnotic effects of DEX are mediated by the activation of pre- and

postsynaptic α2 receptors in the central nucleus of the brainstem

locus coeruleus, which function through endogenous physiological

sleep pathways to exert sedative and hypnotic effects. Clinical

studies have shown that DEX has dose-dependent sedative effects,

with doses of 0.2-0.6 µg/kg·h inducing significant yet

easily reversible sedation. At sufficiently high doses, DEX can

produce deep sedation and even general anesthesia, indicating its

potential role as part of total intravenous anesthesia. Although

the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved DEX for

short-term sedation (<24 h), multiple clinical studies have

confirmed that continuous use of DEX for several days can mitigate

adverse effects in patients with ICU (3,23). Ding et al (25) reported that, compared with

traditional sedatives, long-term ICU sedation with DEX reduced

mechanical ventilation time of patients by 22%, shortened hospital

stays by 14%, and did not significantly affect mortality. When the

sedative effects of midazolam, propofol and DEX in mechanically

ventilated ICU sepsis patients were compared, DEX demonstrated

comparable sedation efficacy while better stabilizing blood

pressure and cardiac function. Kawazoe et al (26), in a study of 201

mechanically-ventilated patients with sepsis, reported that the

sedation control rate during mechanical ventilation was

significantly greater in the DEX group than in the non-DEX group.

Furthermore, DEX significantly reduced the levels of inflammatory

markers such as C-reactive protein and procalcitonin, alleviating

systemic inflammatory responses.

Pharmacokinetic study of DEX in special

populations

Inside the child's body

DEX can be administered via intramuscular injection,

intravenous injection, nasal drops, or oral administration inside

the child's body. The use of nasal drops or oral administration can

prevent high peak plasma levels that may cause respiratory and

circulatory depression after intravenous injection. It also helps

avoid the irritation caused by intravenous administration,

rendering it more suitable for children. The nasal mucosa has a

rich distribution of aqueous channels, providing high drug

permeability and rapid absorption. It also bypasses the hepatic

first-pass effect. Research by Miller et al (27) indicates that nasal administration

of DEX for pediatric sedation can provide adequate blood drug

concentrations, with a bioavailability >80%, whereas oral

administration has a bioavailability of only 16% owing to the

first-pass effect (20). Yadav

and Ramdas (28) conducted a

randomized controlled trial of intranasal DEX for preoperative

pediatric anesthesia. The results showed that, compared with

midazolam, it offered more stable hemodynamics, a shorter time to

achieve sedation, and lower anxiety scores. It is an excellent

sedative and anxiolytic and can be safely used in children. DEX is

a drug with a strong binding ability to proteins, with a protein

binding rate of 94%. It is distributed quickly and extensively in

the human body and is also a highly lipophilic drug that easily

crosses the blood-brain barrier (29). Non-compartmental analysis has

shown that the distribution half-life in healthy volunteers is ~6

min (30). Studies have

indicated that in critically ill patients with hypoalbuminemia,

long-term administration of DEX significantly increases its

apparent Vd (31). In pediatric

pharmacokinetics for children <11 years old, the results

revealed that the steady-state Vd (Vss) is negatively correlated

with the age of the subjects (32), indicating that younger children

require a larger initial dose of DEX to reach a certain blood

concentration. DEX is metabolized primarily in the liver, with most

of its metabolites excreted through the kidneys and a small portion

through feces (33,34). Research on the pharmacokinetics

of DEX in neonates and infants shows that the drug clearance (CL)

rate increases with age, particularly within the first 2 weeks

after birth, whereas after 1 month of age, the impact of age on the

CL rate is minimal (33). The

metabolic enzyme system of newborns and infants is not fully

mature, resulting in low CL rates. Research has shown that the

expression and activity of cytochrome P450 enzymes approach adult

levels by the age of 1 (35).

The CL rate of full-term newborns is ~42.2% of that of adults,

reaching 84.5% at 1 year of age (29). Premature infants have even lower

CL rates [0.3 l/(h x kg) than 0.9 l/(h x kg)] and longer

elimination half-lives (7.6 compared with 3.2 h) (33). The CL rate of DEX is only mildly

affected by hypoproteinemia, but since the liver is the primary

metabolic organ, the CL rate decreases as the severity of liver

damage increases (32).

Among the elderly group

With increasing age, the body fat content also

increases in the elderly group (36). For males, from the ages of 20 to

30, the fat content increases from 8% to 20%, whereas for females,

it increases from 30 to 50% (37). First, lipophilic drugs (such as

DEX) have a relatively large volume of distribution (Vd) (38). Second, the plasma protein

concentration decreases with age, which in turn increases the free

fraction of drugs with a high protein binding rate (39), thus increasing the Vd of DEX.

Changes in liver and kidney function in elderly individuals can

affect plasma protein binding rates. Additionally, an increase in

fat content affects organ blood flow and the activity of

mixed-function oxidases (40).

Studies on the population pharmacokinetics of ICU patients

receiving long-term DEX infusion have revealed that age and plasma

protein concentration can influence the pharmacokinetic

characteristics of DEX. In the elderly population, CL decreases,

and the t1/2 increases. Moreover, patients with low plasma ALB

concentrations have an increased Vd and a prolonged t1/2. The CL of

the elderly population, with an average age of 80 years, is 25%

lower than that of those aged 60 years (41). This finding is consistent with

the report by Venn et al (42). CL is related primarily to liver

blood flow and is less affected by the protein binding rate

(43). As various bodily

functions decline in elderly individuals, the CL of DEX decreases,

leading to an extended t1/2. Lin et al (44) conducted a population

pharmacokinetic study on post-operative ICU patients, and the

results revealed that factors such as age and sex had no impact on

their pharmacokinetics. This may be due to the small sample size

and the high variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters of DEX

(45). Moreover, the

aforementioned study did not provide standard errors or confidence

intervals, indicating insufficient model stability and

reliability.

In individuals with liver

dysfunction

Individuals with liver dysfunction, the CL of DEX

decreases, with significant individual variability (46). According to the Child-Pugh

classification, liver dysfunction patients are divided into three

groups: mild (n=5), moderate (n=6), and severe (n=5). Compared with

those in the three control groups, the average CL rates of DEX were

41, 49 and 68% lower in patients with mild, moderate and severe

liver dysfunction, respectively. Compared with those in both the

mild group and the control group, the Vss and t1/2 were

significantly greater in severe liver dysfunction patients

(P<0.05) (47), indicating

that when DEX is used in patients with liver dysfunction, dose

adjustments should be considered.

In individuals with renal

insufficiency

There was no statistically significant difference in

the pharmacokinetic parameters of DEX in patients with renal

insufficiency compared with healthy subjects. A comparative study

was conducted between 6 patients with renal insufficiency

(creatinine CL <30 ml/min) and 6 healthy volunteers, and the

results revealed that there were no statistically significant

differences in maximal plasma/serum concentration, time to maximal

plasma/serum concentration, area-under-the-curve plasma/serum

concentrations, CL, or Vss (48). However, in patients with renal

insufficiency, the elimination-phase concentration was lower, and

elimination was faster, with a 17% decrease at t1/2 (P<0.05). In

patients with renal insufficiency, the protein binding rate of

alfentanil, which has a high plasma protein binding rate, decreases

from 19 to 11% (49). Therefore,

the decrease in the t1/2 of DEX may also be due to the reduced

plasma protein binding rate in patients with renal insufficiency,

leading to an increase in the amount of drug entering the

elimination phase.

Others

There have been few studies on the pharmacokinetics

of DEX in other special populations (including pregnant women,

parturient women and lactating patients). In one case, a pregnant

woman with spinal muscular atrophy who underwent routine cesarean

section had DEX infusion stopped, and 68 min later, the fetus was

delivered. DEX was detected in the umbilical blood, suggesting that

DEX can cross the placental barrier (50). DEX can cause a significant

increase in blood glucose levels in both the mother and the fetus

(51).

Organ protection mechanisms of DEX

In recent years, an increasing number of basic and

clinical studies have shown that DEX may exert organ-protective

effects through anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, antioxidative

stress, and autophagy-regulating mechanisms involving the heart,

brain, lungs, kidneys, liver and gastrointestinal tract. Despite

its common effects, the biological mechanisms of DEX vary across

different organs. Studies have shown that perioperative infusion of

DEX can reduce the levels of inflammatory factors such as

interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and TNF-α, with the effect being more

significant during continuous intraoperative infusion than during

single-dose administration (52). The anti-inflammatory mechanism of

DEX is closely related to the inhibition of the nuclear factor κB

(NF-κB) pathway and Toll-like receptors via α2 receptors (53). The vagus nerve and nicotinic

acetylcholine receptors are key components of the cholinergic

anti-inflammatory pathway. In addition to acting directly on α2

receptors, DEX can activate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory

pathway to exert its anti-inflammatory effects (54,55). DEX also has antiapoptotic effects

on various cell types, potentially through activation of the

α2AR/PI3K/Akt and p38MAPK/ERK signaling pathways (56-58). Additionally, DEX may inhibit

mitochondrial apoptosis by activating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling

pathway via the long non-coding RNA HCP5 (59). However, some studies have shown

that high concentrations of DEX can induce hippocampal neuronal

apoptosis. In vitro experiments suggest that DEX

concentrations ≥100 µmol/l significantly reduce cell

viability and induce neuronal apoptosis (60). In different cell injury models,

such as vascular smooth muscle cells, renal tubular epithelial

cells and hepatocytes, DEX can alleviate oxidative stress by

inhibiting the production of malondialdehyde (MDA) and reactive

oxygen species (ROS) and increasing the activity of superoxide

dismutase (SOD) (61-63). DEX also inhibits the decrease in

the mitochondrial membrane potential and reduces respiratory chain

enzyme complex damage, thereby suppressing the mitochondrial

oxidative stress induced by general anesthesia (64). Autophagy is an adaptive catabolic

process that maintains intracellular homeostasis by engulfing

intracellular substances, including damaged organelles, unfolded

proteins and pathogens. In cases of damage to critical organs such

as the heart, lungs, brain and kidneys, DEX treatment can increase

autophagy levels (65,66). However, studies have also shown

that DEX can suppress excessive autophagy in cardiomyocytes and

neurons to protect organs (67,68). Therefore, under different

pathological conditions in various organs, DEX has distinct

regulatory effects on autophagy.

Mechanism of MODS induced by sepsis

Currently, MODS caused by sepsis is considered to be

associated with factors such as uncontrollable infection, the

systemic inflammatory response, immune paralysis, coagulation

activation, microcirculatory failure and hypoxia (69). Studies have shown that

immune-metabolic reprogramming occurs at various stages of sepsis,

making it a key regulatory factor in the pathogenesis of this

disease (70). Polymorphonuclear

neutrophils (PMNs) are innate immune cells that respond first to

infectious pathogens and play a crucial role in host defense.

During infection, the body reacts rapidly to local inflammatory

stimuli, recruiting numerous PMNs efficiently from the bloodstream

to the site of inflammation. PMNs eliminate pathogens through

phagocytosis, degranulation, respiratory bursts, the generation and

release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and the

production of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and

IL-8, thus controlling infection (71). Under normal conditions,

inflammatory responses are tightly regulated and confined to the

infection site. After infection is resolved, inflammation subsides,

and PMNs undergo apoptosis and are cleared. However, during sepsis,

systemic inflammation causes PMN polarization. The chemotaxis and

migration functions of PMNs are impaired, leading to a reduced

number of PMNs at the infection site (source site) and increased

PMN infiltration in distant vital organs (72). Activated PMNs in organs release

proinflammatory cytokines, ROS, lysosomal enzymes, NETs and other

active substances, resulting in cell, tissue and organ damage and

ultimately leading to MODS (73). A previous study has reported that

ROS produced by polarized PMNs during sepsis can damage various

organs, including the heart, kidneys, liver and lungs, through

multiple mechanisms, contributing to the development of MODS

(74). Moreover, activated PMNs

are significant sources of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs),

particularly MMP-9, which can degrade extracellular matrix proteins

such as elastin and collagen. This degradation can stimulate the

immune system and create a positive feedback loop of tissue

degradation and immune cell infiltration, further exacerbating

organ damage at infiltration sites (75). Substances released by PMNs also

stimulate the production of NO by various cells, leading to blood

pressure reduction and the generation of peroxynitrite, which

causes cellular damage. In sepsis-induced myocardial injury,

peroxynitrite can alter protein structure and function, causing

PMNs to adhere to and accumulate in the endothelium and myocardium,

ultimately resulting in cardiovascular dysfunction (76). Additionally, ROS, NETs and

lysosomal enzymes released by polarized PMNs can act as

damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), causing endothelial

injury and increased vascular permeability. DAMPs can also activate

immune cells, including macrophages, triggering uncontrolled

inflammatory responses. The release of inflammatory factors results

in the recruitment of more PMNs, further stimulating the excessive

production of NETs and ROS and creating a positive feedback loop

that exacerbates organ damage. These harmful substances contribute

to vascular injury and death in organs, eventually leading to organ

failure. During the development of sepsis-induced lung injury,

increased PMN infiltration promotes bacterial translocation in the

lungs, exacerbating ROS production and worsening lung damage

(77). The progression of MODS

in sepsis significantly increases patient mortality, making the

protection of organ function a critical strategy for improving

sepsis outcomes, with the regulation of immune cell function being

a key factor.

Protective mechanism of DEX on important

organs

Current research indicates that DEX has a protective

effect on sepsis-induced multiorgan dysfunction, as follows:

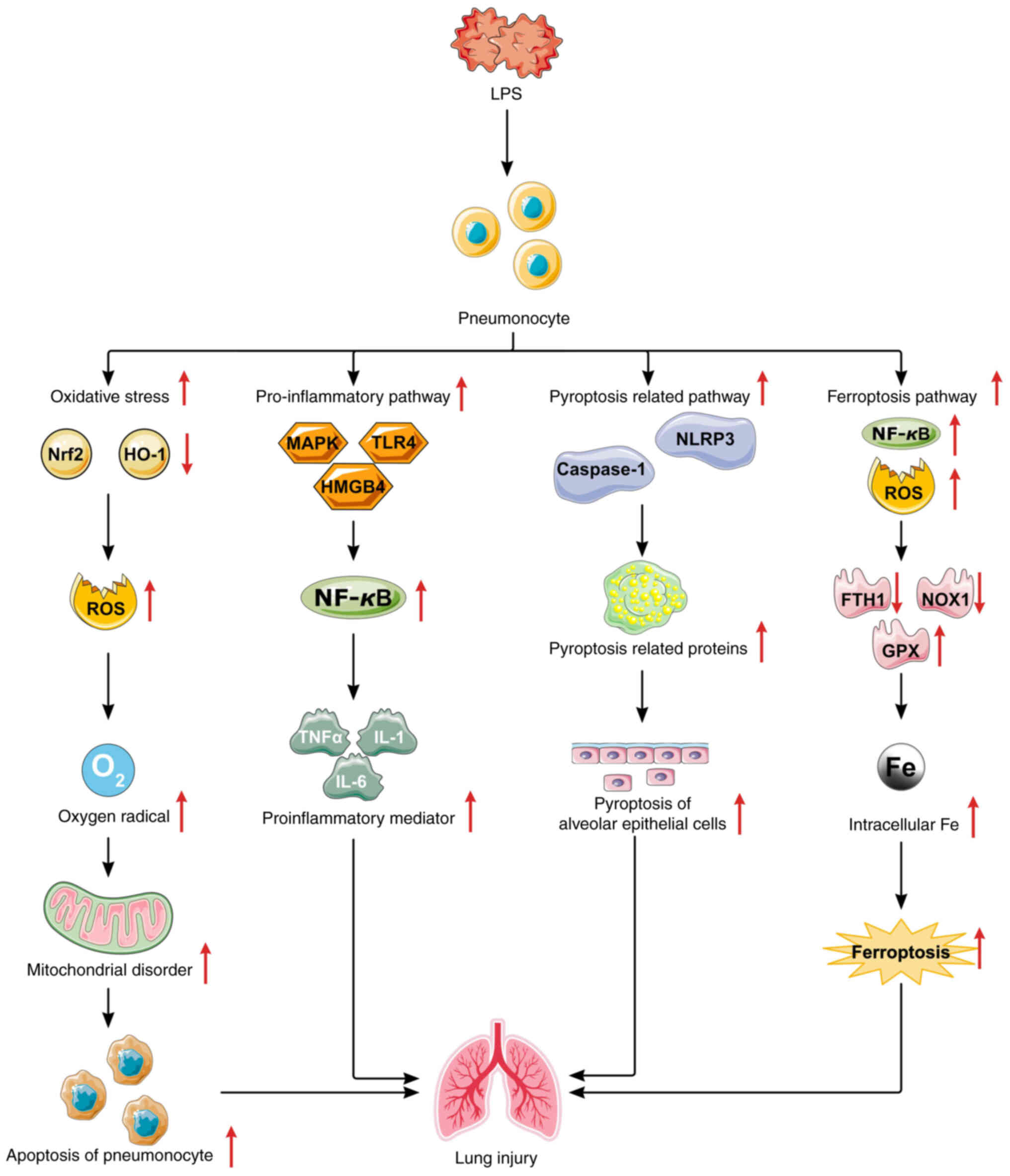

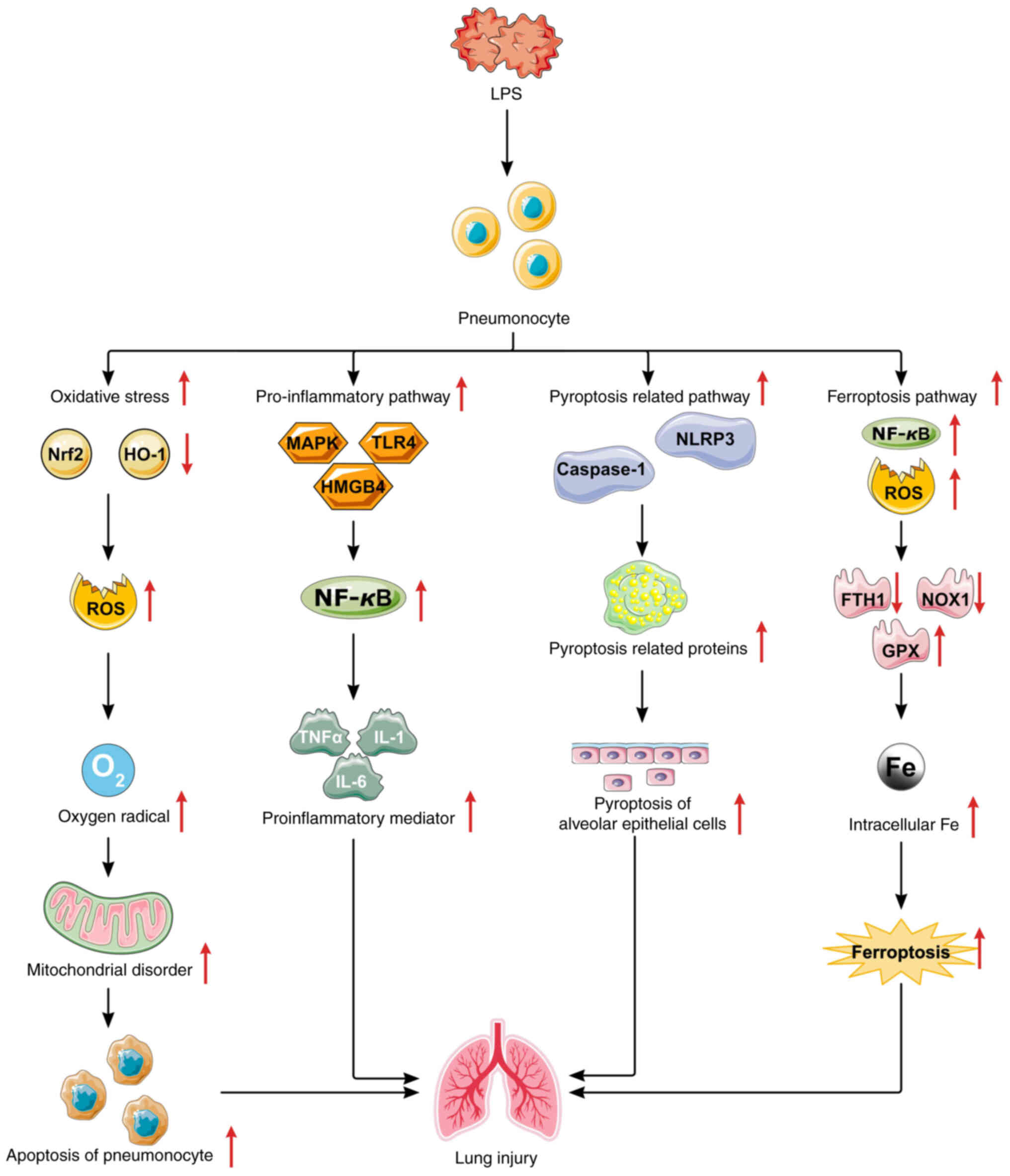

Lung injury

Sepsis often leads to multiple organ injuries, with

lung injury being particularly prevalent, occurring in 83-100% of

cases (78). The

lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory response and

oxidative stress through the regulation of inflammatory pathways

such as MAPK and TLR4, as well as the oxidative stress pathway

Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), are the primary causes of lung

injury, and sepsis-induced alveolar cell pyroptosis and ferroptosis

through the regulation of pyroptosis pathways such as the NLRP3

pathway, as well as the ferroptosis pathway SLC7A11/glutathione

peroxidase 4 (GPX4), are also involved in acute lung injury

(Fig. 3) (78). Research has shown that inhibiting

the high mobility group protein box-1 (HMGB1)/myeloid

differentiation factor-88 (MyD88)/NF-κB pathway and NLRP

inflammasome activation induced by cecal ligation and puncture

(CLP) can reduce CLP-induced lung inflammation and alveolar cell

pyroptosis and ameliorate sepsis-induced acute lung injury

(79), and increasing the

activity of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway can reduce LPS-induced oxidative

stress and inflammation in alveolar cells and ameliorate

sepsis-induced acute lung injury (80,81). Therefore, inhibitors of

sepsis-induced alveolar cell inflammation, oxidative stress,

pyroptosis and ferroptosis may help improve sepsis-induced lung

injury. Wu et al (82)

demonstrated that DEX inhibits the expression of Toll-like receptor

4 (TLR4), a molecule associated with endotoxin recognition, and the

activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB. This

inhibition reduces TNF-α and IL-6 levels in alveolar lavage fluid

and plasma, significantly decreasing the fatality rate in

CLP-induced septic rats within 24 h. Additionally, DEX attenuates

LPS-induced acute lung injury in rats by inhibiting the

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B

(Akt)/forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) signaling pathway and mitigating

oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis (83). DEX also reduces oxidative stress

and inflammation in alveolar cells and maintains the balance of

mitochondrial dynamics through the HIF-1α/HO-1 signaling pathway,

thereby ameliorating endotoxin-induced acute lung injury both in

vivo and in vitro (84). Furthermore, DEX inhibits the

secretion of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and

NO by alveolar cells via the HMGB1-mediated TLR4/NF-κB and

PI3K/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, increases

the production of the antioxidant stress markers SOD and

glutathione peroxidase, and alleviates LPS-induced lung injury by

reducing inflammation and oxidative stress (85). A previous study indicated that

DEX maintains endothelial barrier integrity by reducing

angiopoietin 2 (ANG2) levels and increasing endothelial VE-cadherin

in rats with CLP-induced sepsis, thereby mitigating lung

inflammation (86,87). The Ang-tyrosine kinase receptor 2

(Tie2) axis is a well-studied pathway that regulates endothelial

barrier function. Ang1 binds to and activates angiopoietin Tie2

receptors, upregulating VE-cadherin to stabilize the cell barrier.

Conversely, ANG2 competes with Tie2 receptors, antagonizing the

anti-inflammatory effects of Ang1, leading to barrier damage and

endothelial cell activation, which induces inflammation (87). DEX reduces the wet/dry weight

ratio of lung tissue, leukocyte infiltration, plasma ANG2 levels

and ANG2/ANG1 ratios and decreases VE-cadherin phosphorylation

through the ANG1-Tie2-VE-cadherin signaling pathway, thereby

alleviating endothelial barrier damage and lung injury in septic

rats (87). Additionally, DEX

ameliorates sepsis-induced acute lung injury by modulating the

adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/silent

information regulator 1 (SIRT1) pathway (88). These data suggest that DEX

improves sepsis-induced lung injury by inhibiting multiple

proinflammatory and oxidative stress pathways. However, these

studies remain in the animal experimentation stage, and further

research is needed to explore their clinical applications.

| Figure 3Mechanisms of sepsis-induced lung

injury. LPS regulates oxidative stress and mitochondrial

dysfunction by modulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways;

regulates lung inflammation by modulating the MAPK, TLR4 or

HMGB1/NF-κB signaling pathways; regulates lung inflammation by

modulating the MAPK or TLR4 or HMGB1/NF-κB signaling pathways; and

regulates alveolar cell pyroptosis by modulating the

NLRP3/caspase-1 signaling pathway and regulates alveolar cell

ferroptosis by modulating the NF-κB/ROS/GPX4 signaling pathway.

LPS, lipopolysaccharide; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4;

HMGB1, high mobility group protein box-1; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor

family pyrin domain containing 3; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB. |

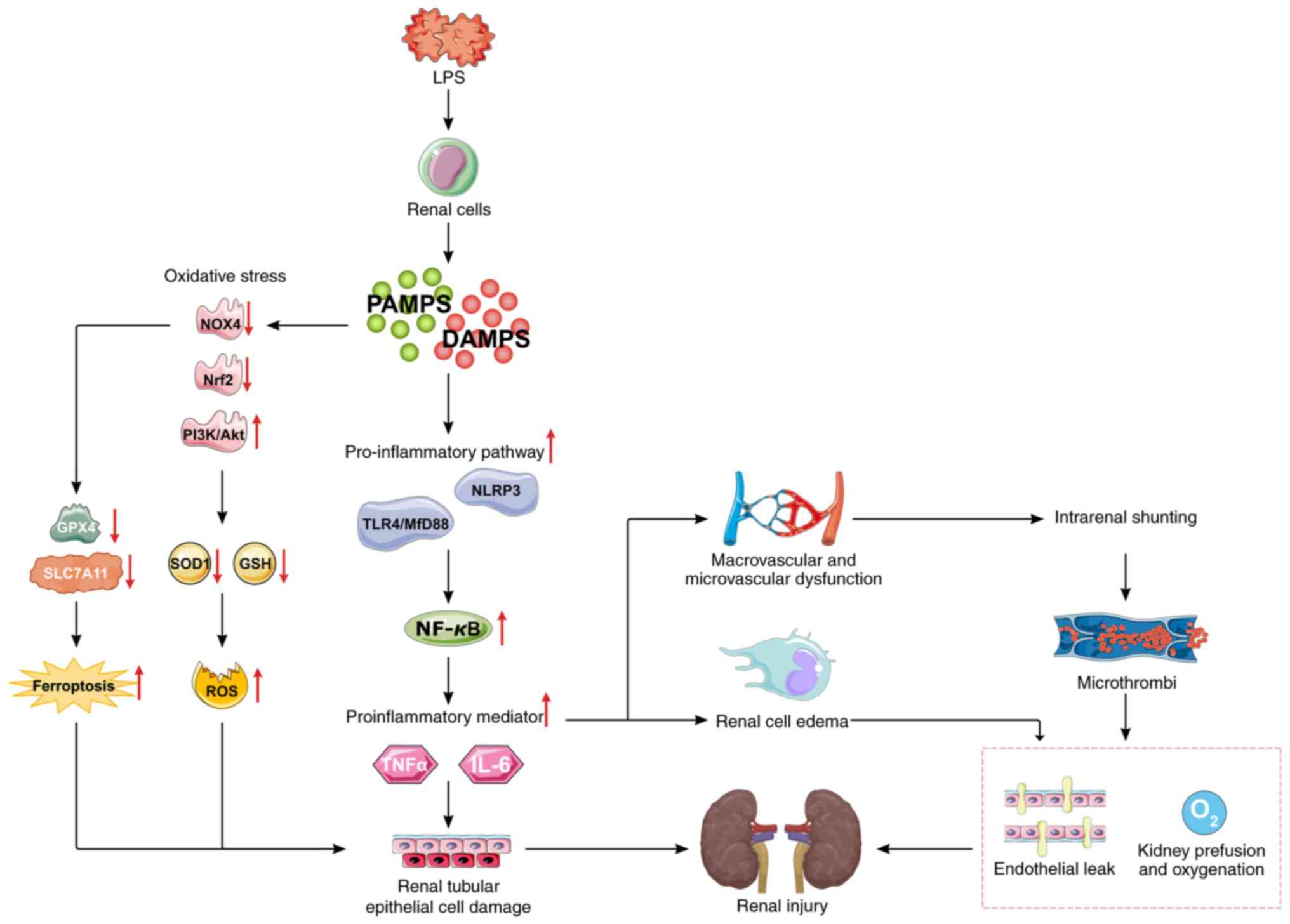

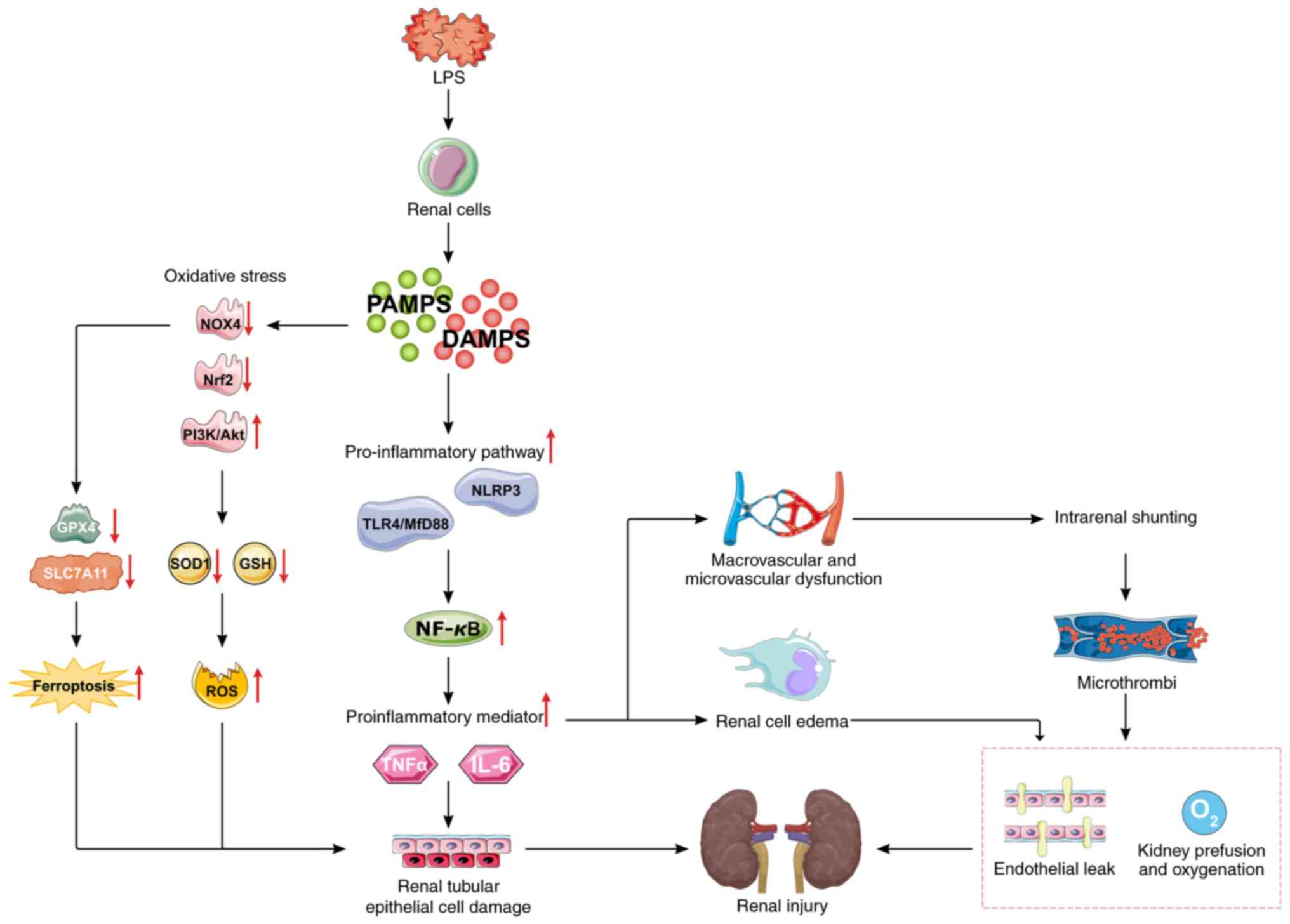

Kidney injury

The kidney is a primary target organ in sepsis

(89). Acute kidney injury (AKI)

manifests as progressively worsening renal function, severe

oliguria and fluid overload, often necessitating renal replacement

therapy. This condition not only increases hospitalization and

treatment costs but also severely impacts patient prognosis. The

pathophysiological process of sepsis-induced AKI remains poorly

understood, and effective prevention and treatment measures are

lacking in clinical settings. Studies have revealed that the

pathogenic mechanisms of sepsis-induced AKI are complex, involving

LPS-induced inflammation, microcirculatory disorders and oxidative

stress by regulating inflammatory pathways, such as TLR4 and MAPK,

as well as oxidative stress-related pathways, such as Nrf2, NADPH

oxidase 4 (NOX4) and P13k/Akt, with inflammation being a pivotal

factor (Fig. 4) (89,90). Research has shown that inhibiting

the activity of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway can inhibit

LPS-induced kidney inflammation and improve sepsis-induced AKI in

mice (91) and that decreasing

NLRP3 inflammasome activation can alleviate LPS-induced tubular

cell inflammation and pyroptosis and ameliorate LPS-induced kidney

injury (92). The inhibition of

NOX4 protects against sepsis-induced AKI by reducing the generation

of ROS and the activation of NF-κB signaling, which suppresses

mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation and

apoptosis (93). Therefore,

inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress and improving renal

microcirculation may help alleviate sepsis-induced AKI. Liu et

al (94) investigated the

immunomodulatory effects of DEX on sepsis-related AKI induced by

tail vein injection of LPS in rats at doses of 3, 5, 10 and 20

µg/kg iv. DEX was found to reduce inflammatory cytokine

levels in a dose-dependent manner. The addition of the α2

adrenergic receptor antagonist yohimbine negated the regulatory

effect of DEX on cytokine production, confirming its

anti-inflammatory role as an α2 adrenergic receptor agonist. Jin

et al (95) established a

sepsis-related AKI model in rats via LPS induction. The DEX group

received 80 mg/kg DEX daily starting 4 days before modeling. The

results indicated that DEX downregulates TLR4 protein expression,

inhibits MyD88 and NF-κB activation, and causes expression of

inducible NO synthase (iNOS), thereby suppressing inflammatory

factor production. These findings indicate that DEX may reduce

inflammation by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB/iNOS signaling

pathway and attenuating LPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation

through the TLR4/NOX4/NF-κB pathway, thereby mitigating oxidative

stress (96). Wang et al

(97) investigated an

inflammatory proximal tubular epithelial cell model and an

LPS-induced sepsis-related AKI model in mice. The results revealed

that DEX significantly increased SOD activity in renal tissue,

decreased the production of the lipid peroxidation product MDA,

inhibited ROS production in renal tubular epithelial cells, and

ameliorated sepsis-induced AKI. Zhao et al (98) pretreated an LPS-induced

sepsis-related AKI model in rats with ip DEX at 30 µg/kg and

discovered that DEX enhanced autophagy through α2 adrenergic

receptors and inhibited the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, leading to the

CL of damaged mitochondria and a reduction in oxidative stress and

apoptosis in LPS-induced AKI. The use of autophagy inhibitors, such

as AT2 receptor-interacting proteins and 3-methyladenine, blocked

the reno-protective effect of DEX, suggesting that regulating

autophagy is crucial in the pathogenesis of LPS-induced AKI. By

modulating renal autophagy, DEX improved oxidative stress and cell

apoptosis. These studies demonstrate the protective effects of DEX

on the kidney through various signaling pathways. However, since

most experiments are based on animal models and the mechanisms of

action have not yet been fully elucidated, further research is

necessary.

| Figure 4Mechanisms of sepsis-induced kidney

injury. LPS regulate kidney inflammation by modulating the

NLRP3/NF-κB or TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB signaling pathways; regulate

oxidative stress and ferroptosis by modulating the NOX4, Nrf2 or

P13K/Akt signaling pathways; and LPS-induced inflammatory mediators

can lead to renal microcirculation disorders, renal hypoperfusion,

ischemia and hypoxia and exacerbate sepsis-induced kidney injury.

LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PAMPS, pathogen-associated molecular

patterns; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; NLRP3,

NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; TLR4, Toll-like

receptor 4; MyD88, myeloid differentiation factor 88; PI3K,

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; Akt, protein kinase B; NOX4, NADPH

oxidase 4; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase;

GSH, glutathione; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4. |

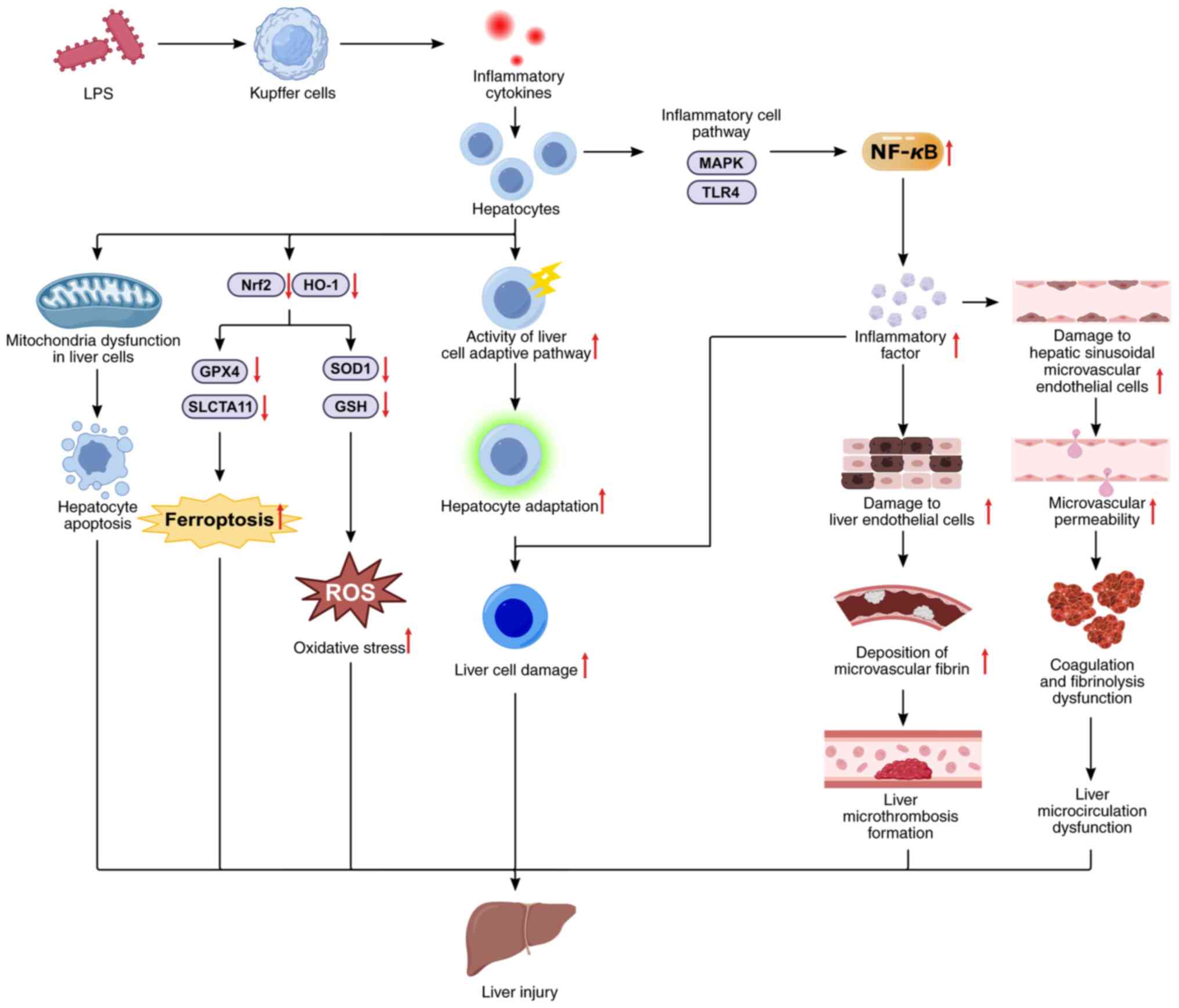

Liver injury

Endotoxin-induced liver failure is the second

leading cause of multiple organ failure (99). Sepsis-induced hepatic injury

resulting from endotoxin induces inflammation, hepatic blood flow

alterations, microcirculatory disturbances and mitochondrial

dysfunction by regulating inflammatory pathways, such as the MAPK

and TLR4 pathways, and oxidative stress- and ferroptosis-related

pathways, such as the Nrf2/HO-1 pathways (Fig. 5) (99,100). Hepatic sinusoidal cells are the

initial sites of liver injury. The macrophages (KCs) within these

sinusoids are pivotal in the inflammatory process and

endotoxin-mediated hepatic injury (101). High doses of LPS provoked KC

overactivation and reduced phagocytic capacity while increasing

CD14 expression on KC surfaces. The LPS receptor/signaling complex,

which is composed of TLR4, CD14 and MD2, further activates KCs,

releasing a cascade of proinflammatory mediators that exacerbate

endotoxin-induced hepatic damage (102). Thus, inflammation is central to

sepsis-induced liver injury. Suppressing this inflammation may

mitigate acute hepatic injury in sepsis. Studies on septic murine

liver tissue revealed that DEX mitigates portal venous and

sinusoidal congestion, reduces hepatic sinusoidal swelling, and

decreases lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration in the liver

hilum, effectively curbing hepatic inflammation (103). DEX has been demonstrated to

prevent acute hepatic injury in LPS-induced septic rats by

inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-KB pathway. Additionally, DEX

modulates caveolin-1, inhibits the TLR4/NLRP3 pathway, and curtails

proinflammatory cytokine release, thus alleviating sepsis-induced

hepatic injury (104,105). Furthermore, autophagy in the

liver is crucial for maintaining cellular energy and nutrient

balance, clearing damaged hepatic proteins, and counteracting

oxidative stress (106).

Research conducted by Yu et al (106) indicated that DEX potentially

enhances autophagy via the SIRT1/AMPK pathway, mitigating

inflammation in CLP-induced liver injury and increasing the

survival rate of model mice by 20% within 24 h. LPS induces liver

damage through apoptosis mediated by ROS. DEX activates the

GSK-3β/MKP-1/Nrf2 pathway via the α2-adrenergic receptor,

diminishing LPS-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in the rat

liver and thereby ameliorating sepsis-induced liver injury

(107). DEX pretreatment

facilitates M2 macrophage activation through PPARγ/STAT3 signaling,

reducing liver inflammation and alleviating ischemia-reperfusion

injury in mice (108). This

evidence indicates that DEX confers protection against

sepsis-induced liver injury by modulating inflammation, apoptosis,

autophagy, and ferroptosis-related pathways and proteins. However,

these findings are confined to animal research, and clinical

validation is needed.

| Figure 5Mechanism of sepsis-induced liver

injury. LPS regulate liver cell inflammation by modulating the

MAPK/NF-κB and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathways; regulate liver cell

oxidative stress and ferroptosis by modulating the Nrf2/HO-1

signaling pathways; and LPS-induced inflammatory mediators can lead

to endothelial cell damage, microcirculation disorders, adaptive

pathway activity in liver cells, and exacerbated sepsis-induced

liver injury. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4;

MyD88, myeloid differentiation factor 88; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor

family pyrin domain containing 3; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase; Akt, protein kinase B; NOX4, NADPH oxidase 4; PPARγ,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; GPX4,

glutathione peroxidase 4; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B. |

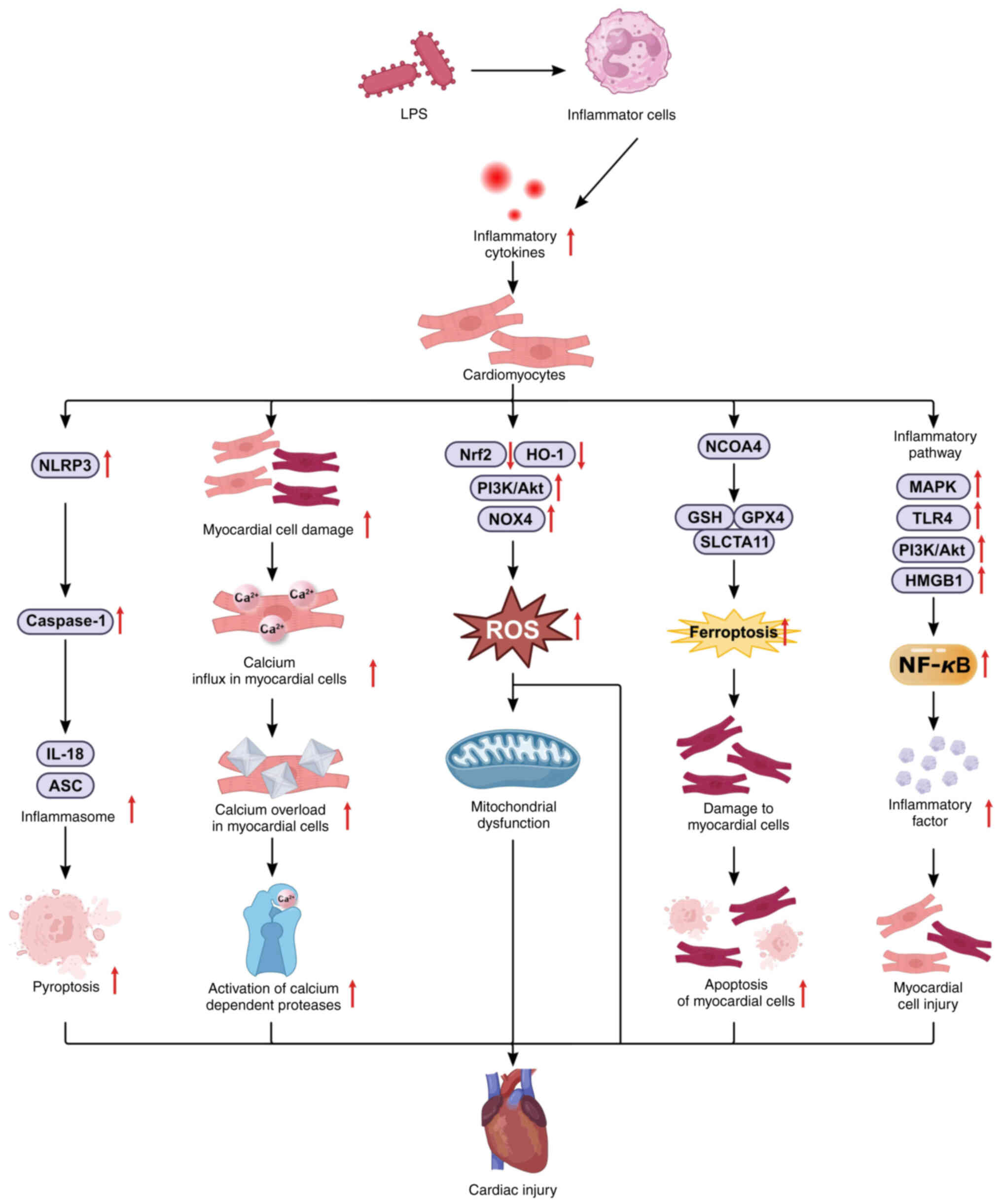

Myocardial injury

Epidemiological studies indicate that the global

mortality rate of sepsis remains high and is gradually increasing

(109). The heart is the organ

most frequently affected during sepsis. It has been revealed that

40-60% of septic patients suffer from myocardial injury, with a

fatality rate of 70-90%, which correlates positively with the

severity of the injury (110).

The extensive inflammation and 'cytokine storm' associated with

sepsis lead to ischemia, oxidative stress, pyroptosis, ferroptosis,

and hypoxic damage to myocardial cells by regulating pathways

related to pyroptosis and inflammation, such as NLRP3 and MAPK, as

well as pathways related to oxidative stress and iron death, such

as Nrf2/HO-1 and NCOA4/GPX4 (Fig.

6), resulting in a significantly higher mortality rate than

that in septic patients without myocardial injury. Long-term

prognosis studies have also shown that survivors of sepsis-induced

myocardial injury experience markedly reduced quality of life

(111). Previous studies have

identified that the activation of Nrf2/HO-1 and the inhibition of

the NLRP3 signaling pathway can inhibit LPS-induced inflammation

and oxidative stress; protect cardiomyocytes against LPS-induced

injury (112); suppress

NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis via the upregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1

signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro; decrease

oxidative stress, inflammatory responses and NLRP3-mediated

pyroptosis; and reduce LPS-induced myocardial injury (113,114). Thus, mitigating sepsis-related

inflammation may alleviate myocardial injury and reduce mortality

(115). In experimental mice

treated with DEX, the incidence of septic shock was lower, and the

plasma levels of the inflammatory factors TNF-a, IL-1β and IL-6

were significantly lower. Additionally, NF-кB binding activity was

downregulated, increasing survival rates (116,117). In LPS-induced septic heart

injury in rats, DEX appears to confer cardioprotective effects by

diminishing the expression of NF-κB p65 and phosphorylated STAT3,

thereby inhibiting the expression of the apoptotic proteins

Caspase-3, Caspase-8, Bax and p53 and the inflammatory factors

IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α (118).

DEX also inhibits GPX4 expression, upregulates HO-1, and reduces

sepsis-induced cardiomyocyte ferroptosis and myocardial injury in

mice (119). Compared with

pre-surgery, the administration of varying doses of DEX to septic

patients significantly decreased the levels of inflammatory factors

such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α within 24 h post-surgery. Moreover,

high, medium, and low doses of DEX maintain and enhance cardiac

function, significantly mitigating the adverse effects of

inflammatory mediators on the heart (120). Despite substantial progress in

understanding the myocardial protective effects of DEX, the

underlying mechanisms remain incompletely elucidated, necessitating

further research.

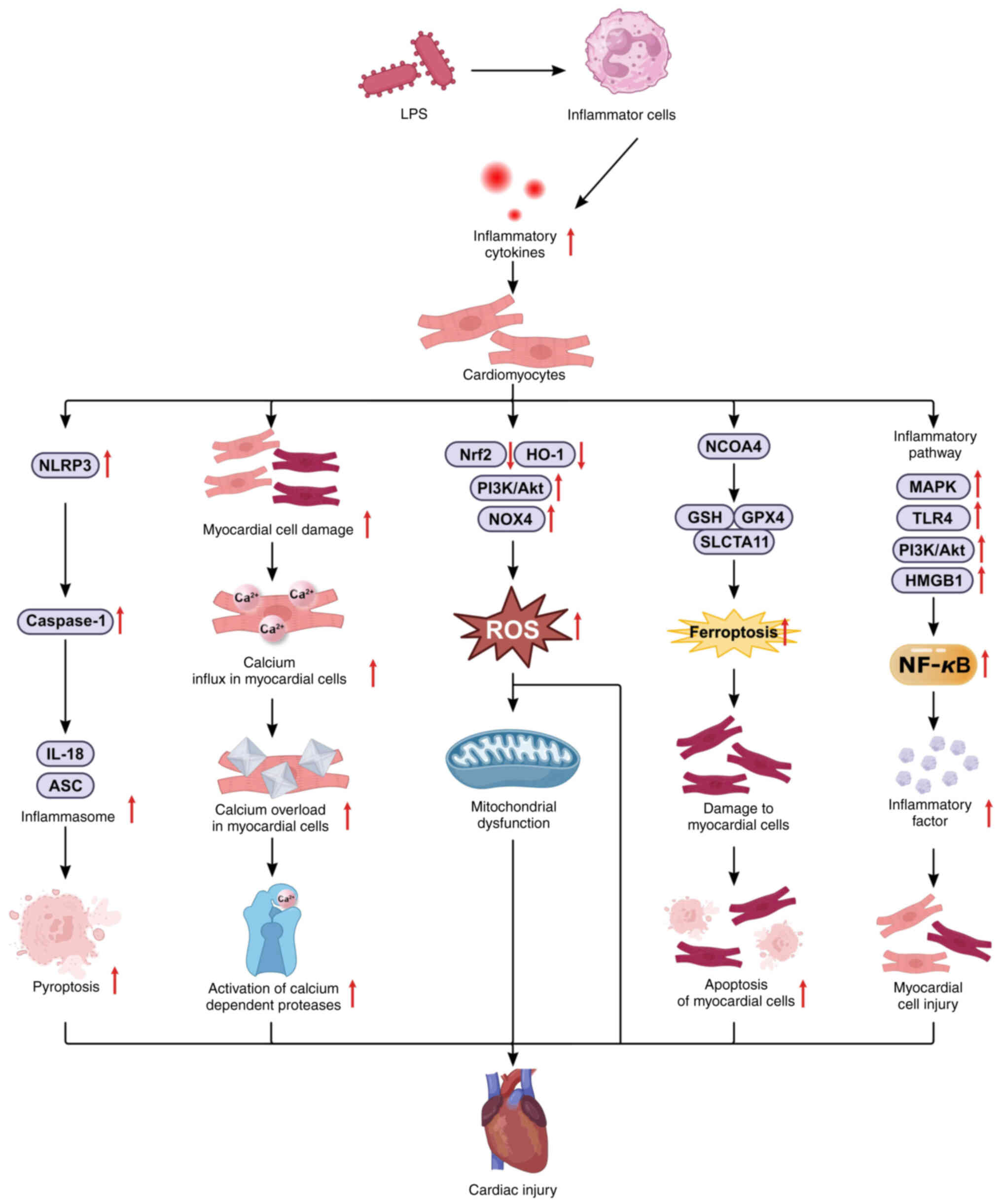

| Figure 6Mechanisms of sepsis-induced

myocardial injury. LPS regulate cardiomyocyte inflammation by

modulating the MAPK/NF-κB, MGB1/TLR4/NF-κB, and P13K/Akt/NF-κB

signaling pathways; regulate liver cell oxidative stress and

ferroptosis by modulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways;

regulate cardiomyocyte pyroptosis by modulating the NLRP3/caspase-1

signaling pathways; and regulate cardiomyocyte oxidative stress by

modulating the Nrf2/HO-1, P13K/Akt, and NOX4 signaling pathways. In

addition, LPS-induced inflammatory mediators can lead to calcium

influx, and calcium overload in myocardial cells exacerbates

sepsis-induced cardiac injury. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TLR4,

Toll-like receptor 4; MyD88, Myeloid differentiation factor 88;

NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; PI3K,

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; Akt, protein kinase B; NOX4, NADPH

oxidase 4; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; ASC, apoptosis-associated

speck-like protein; NCOA4, nuclear receptor coactivator 4; GSH,

glutathione; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; MAPK,

mitogen-activated protein kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species. |

Gastrointestinal injury

Late-stage sepsis often progresses to MODS, a

primary cause of mortality in ICU patients (121). As the body's largest 'bacteria

reservoir' and 'endotoxin reservoir', the gastrointestinal tract is

among the first and most severely impacted organs in the

pathophysiological progression of sepsis (122). Sepsis results in the generation

of substantial amounts of endotoxins and inflammatory mediators

that compromise the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier, increase

mucosal permeability, and promote intestinal bacterial

translocation. Consequently, numerous bacteria and endotoxins

infiltrate the bloodstream via lymphatic and capillary pathways,

instigating a 'secondary infection' and triggering entheogenic

endotoxemia. This can elicit unrestrained inflammatory responses,

exacerbate intestinal damage, create a vicious cycle, and

potentially advance to MODS, resulting in fatality (122,123). Hence, prompt evaluation of

gastrointestinal function and early intervention in sepsis patients

are essential to mitigate damage and improve patient prognosis. As

shown in Table I (124-131), DEX ameliorates

ischemia/reperfusion, LPS and CLP-induced intestinal injury in rats

by suppressing TLR4, p38 MAPK/NF-κB SIRT3-dependent

PINK1/HDAC3/p53, and alpha2AR/caveolin-1/p38MAPK/NF-κB signaling

pathways in intestinal tissue; increasing ZO-1 and occludin

expression; decreasing inflammatory cytokine levels and MLCK

protein expression; and increasing intestinal permeability

resulting from burns with concurrent histological damage. However,

deep sedation with DEX, unlike propofol, significantly suppresses

gastrointestinal motility in endotoxemic mice, an effect that

dissipates after 24 h of sedation (131). These results indicate that

while DEX has protective effects against intestinal barrier

dysfunction, its administration in sepsis and intestinal paralysis

requires careful consideration.

| Table IStudy on the protective mechanism of

DEX against intestinal injury caused by sepsis. |

Table I

Study on the protective mechanism of

DEX against intestinal injury caused by sepsis.

| First author,

year | Object of

study | Dosage of DEX | Effect | Regulatory

mechanism of the intestine injury | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Chen et al,

2015 | CLP-ICLP-induced

intestinal injury | 5 µg ×

kg−1 × h−1 | Reducing systemic

inflammation and alleviating CLP-induced intestinal tissue

damage | Suppressing TLR4

expression in intestinal tissue, curtailing inflammatory

mediators | (124) |

| Qin et al,

2021 | Burn-induced

intestinal barrier damage | 5 µg ×

kg−1 × h−1 | Decrease in

intestinal permeability and histological damage to the

intestine | Anti-inflammatory

effect and protected tight junction complexes by inhibiting the

MLCK/ p-MLC signaling pathways | (125) |

| Yang et al,

2021 | Intestinal

ischemia/ reperfusion injury | 5 µg ×

kg−1 × h−1 | Reduce intestinal

I/R injury in rats and OGD/R damage in Caco-2 cells | Attributed to

anti-inflammatory effects and inhibition of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB

signaling pathway | (126) |

| Ye et al,

2022 | DSS-induced colitis

mice | 5 µg ×

kg−1 × h−1 | Improve weight

loss, shortening of the colon, increased DAI score, histological

abnormalities | Reduces colonic

inflammation and intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis by inhibiting

the p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway | (127) |

| Zhang et al,

2021 | Rat model of

intestinal I/R injury | 2.5 µg ×

kg−1 × h−1 and 5 µg × kg−1

× h−1 | Protection against

experimentally induced intestinal I/R injury | Suppresses

apoptosis of EGCs through SIRT3-mediated PINK1/HDAC3/p53

pathway | (128) |

| Dong et al,

2022 | Mice model of

intestinal I/R injury | 5

µg·kg−1 × h−1 | Alleviate

intestinal I/R injury | Reverses

I/R-induced bacterial abnormalities | (129) |

| Xu et al,

2021 | Rat model of

intestinal I/R injury | 5 µg ×

kg−1 × h−1 | Protection against

lung injury following intestinal ischemia-reperfusion |

Ca2+-regulating alpha

2AR/Caveolin-1/ p38MAPK/NF-kappa-B axis | (130) |

| Chang et al,

2020 | LPS-induced

intestinal injury in mice | 80 µg ×

kg−1 | Inhibits

gastrointestinal motility disorder | Markedly inhibits

gastric emptying, small intestinal transit, colonic transit,

gastrointestinal transit and the whole gut transit | (131) |

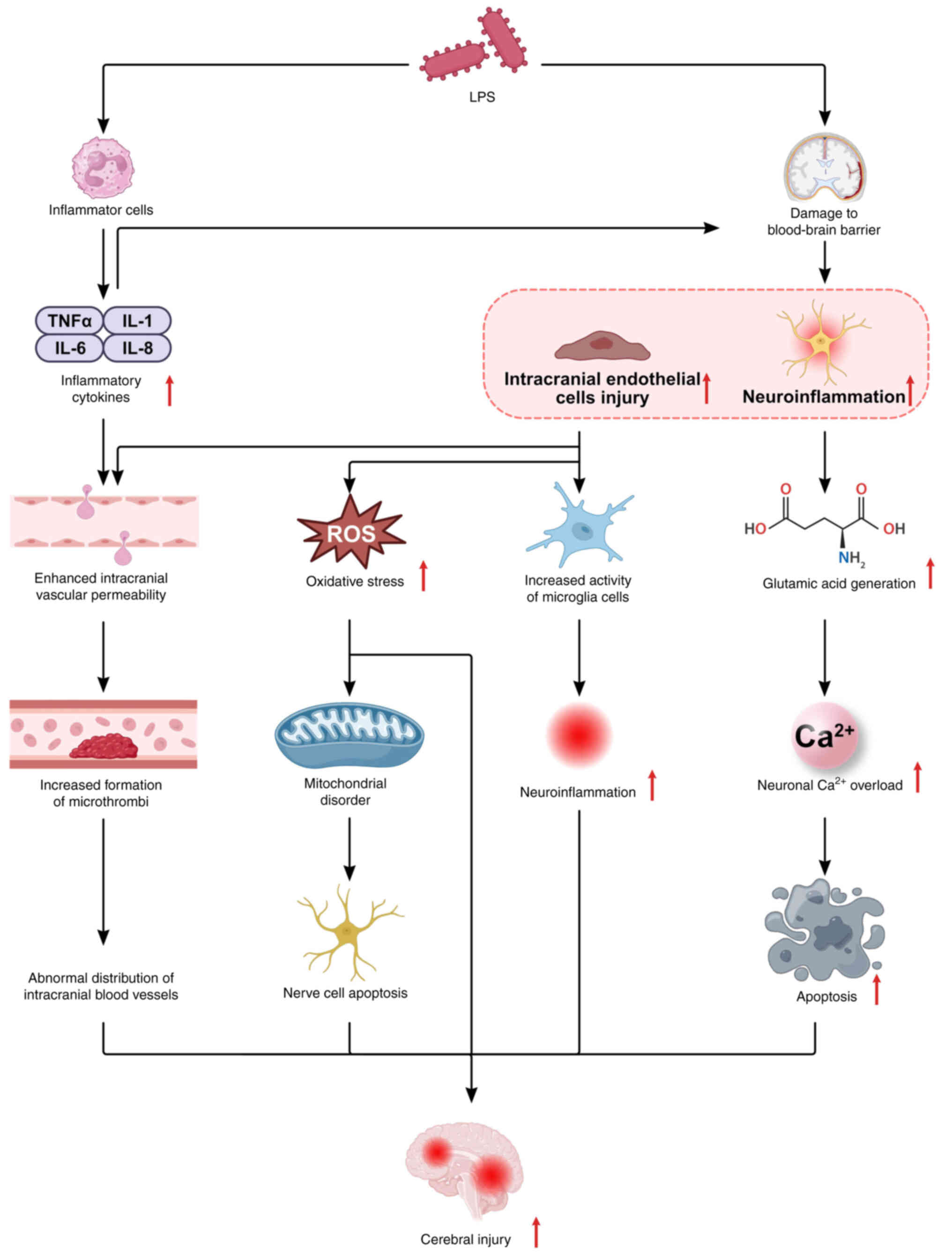

Brain injury

During sepsis, various inflammatory mediators and

endotoxins damage capillary endothelial cells, resulting in

leakage, inflammatory damage and tight junction dysfunction. This

compromises the blood-brain barrier, permitting systemic

inflammation and neurotoxic mediators to infiltrate the brain,

leading to sepsis-associated brain injury (Fig. 7) (132). Following central nervous system

damage, microglia are activated, proliferate rapidly, polarize,

migrate to the injury site, and secrete proinflammatory factors

such as IL-1β and TNF-α (133),

which further degrade the blood-brain barrier, perpetuating

microglial activation in a vicious cycle that exacerbates neuronal

damage (Fig. 7). Mitigation of

microglial activation is crucial for ameliorating sepsis-induced

brain injury. Research indicates that DEX attenuates

neuroinflammation in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia by upregulating

miR-340 (134) and modulates

neuroinflammation and microglial activation through the

circ-Shank3/miR-140-3p/TLR4 axis (135). Additionally, DEX inhibits the

TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, reducing the expression of

inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, thereby protecting against

ischemia-reperfusion injury (126). By inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB

activation, DEX decreases TNF-α and IL-1β levels, shielding brain

tissue from inflammatory damage (136). It also enhances microglial M2

polarization by inhibiting ERK1/2 phosphorylation, exerting

anti-inflammatory effects in BV2 cells (137). Consequently, DEX mitigates

sepsis-induced brain injury through multiple mechanisms. Current

research on the protective mechanisms of DEX against sepsis-induced

injury has focused primarily on animal and cell studies. Extensive

clinical research is necessary to validate these findings and

establish a theoretical foundation for the clinical treatment of

sepsis-induced injury.

Modulating the

proinflammatory/anti-inflammatory imbalance

Sepsis involves hyperinflammation and acquired

immunosuppression (Fig. 8).

Multiple studies (138-140) have indicated immune

dysregulation during sepsis. Initially, infection triggers an

immune response, leading to the extensive production of

inflammatory factors and consequent immune stress, exacerbating

organ injury. As sepsis progresses, there is a decline in

lymphocyte subsets, further intensifying inflammation. This period

is characterized by concurrent immunosuppression and inflammation,

which mutually exacerbate sepsis. Thus, immune regulation is

pivotal in sepsis treatment. Research on DEX, a novel sedative in

sepsis, is expanding, although studies on its impact on immune

dysfunction are limited. Wang et al's meta-analysis

(52) demonstrated that

intraoperative DEX infusion is correlated with i) reduced plasma

levels of epinephrine, norepinephrine and cortisol; ii) increased

NK cells, B cells and CD4 cells; decreased CD8+ T cells;

iii) elevated CD4+CD8+ and Th1:Th2 ratios;

iv) reduced TNF-α and IL-6; and increased IL-10. The Th1/Th2 helper

T-cell 2 (Th2) and helper T-cell 17 Th17/regulatory T-cell (Treg)

ratios reflect immune response dynamics. In patients under surgical

and anesthesia stress, DEX elevates the IFN-γ to IL-4 and IL-17 to

IL-10 ratios, shifting the Th1/Th2 and Th17/Treg cytokine balance

toward Th1 and Th17 in an alcohol-dependent manner and resulting in

immunomodulatory effects (141). DEX effectively increases

CD3+, CD4+ and NK cells and

CD4+/CD8+ levels in patients undergoing

radical mastectomy for breast cancer, maintaining cellular immune

function homeostasis (142).

These studies reveal that DEX possesses anti-inflammatory

properties and enhances cellular immunity, making it suitable for

septic patients with immunosuppression.

Maintaining hemodynamics

DEX inhibits norepinephrine neuron activity in the

locus coeruleus through negative feedback, suppresses sympathetic

nerve excitation, and lowers blood catecholamine levels. This

stabilizes the intraoperative circulatory status and minimizes the

hemodynamic fluctuations induced by surgical trauma and painful

stimulation (143,144). Norepinephrine is the preferred

vasopressor for restoring mean arterial pressure in septic

patients. Refractory septic shock often necessitates higher doses

of norepinephrine to maintain blood pressure. However, in

sepsis-related AKI, norepinephrine-induced blood pressure

restoration exacerbates renal medullary hypoperfusion and hypoxia

(145). DEX enhances

responsiveness to exogenous vasopressors (146). The results of the present study

are shown in Table II (11,117,147-151). DEX significantly reduced

catecholamine requirements, halved the required norepinephrine

dose, prevented further renal medullary hypoperfusion and hypoxia,

and progressively improved creatinine CL, potentially through an

enhanced vascular response to catecholamines and angiotensin II.

Thus, DEX reduces the norepinephrine dosage in septic patients and

is suitable for anesthesia and sedation in severe sepsis and septic

shock patients. Nonetheless, large, randomized trials are needed to

confirm whether DEX consistently reduces the norepinephrine dosage

in septic patients.

| Table IIStudies on the effects of DEX on

sepsis-induced hemodynamics. |

Table II

Studies on the effects of DEX on

sepsis-induced hemodynamics.

| First author,

year | Object of

study | Dosage of DEX | Effect | Regulatory

mechanism of the hemodynamics | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Morelli et

al, 2019 | Patients with

septic shock | 0.7 µg/kg x

h | Significantly

reducing catecholamine. requirements | Inhibits

norepinephrine neuron activity in the locus coeruleus. | (147) |

| Lankadeva et

al, 2019 | Sheep model of

sepsis-related acute kidney injury | 0.5 µg/kg x

h | Restore mean

arterial pressure to pre-illness levels, halved the required

norepinephrine dose. | Enhanced vascular

response to catecholamines and angiotensin II. | (148) |

| Taniguchi et

al, 2004 | Endotoxemic

rats | 0.5 µg/kg x

h | Improving endotoxin

induced. hypotension | Inhibitory effect

on inflammatory response during endotoxemia. | (117) |

| Yao et al,

2021 | Patients with

septic shock | 0.7 µg/kg x

h | Has a smaller

effect on hemodynamics in patients with septic shock than

midazolam. | Reduce plasma

catecholamine levels in patients with septic shock. | (149) |

| Carnicelli et

al, 2022 | Model of septic

shock pigs | 0.5 µg/kg x

h | Maintain

hemodynamic stability. | Not affecting the

early metabolic, and inflammatory disorders induced by septic

shock. | (11) |

| Moore et al,

2022 | Patients who

underwent rhytidectomy | 0.7 µg/kg x

h | Resulted in a

significant reduction and maintenance of blood pressure from onset

of anesthesia. | Suppresses

sympathetic nerve excitation and lowers blood catecholamine

levels. | (150) |

| Hazrati et

al, 2022 | Patients with hip

fracture surgery. | 0.7 µg/kg x

h | Maintain

hemodynamic stability. | Reduces the amount

of intraoperative bleeding without causing any significant

hemodynamic disturbances. | (151) |

Regulating endothelial cells

During sepsis, the activation and dysfunction of

vascular endothelial cells result in leukocyte chemotaxis,

inflammatory outbreaks, microcirculatory disturbances and altered

vascular permeability (Fig. 9)

(152). Endothelial cell damage

leads to intermittent or complete cessation of capillary blood

flow, reducing capillary density and causing nonuniform organ

perfusion (153). This

endothelial damage-induced microcirculatory disorder results in

tissue hypoxia and abnormal cellular oxygenation despite adequate

organ blood supply, precipitating organ dysfunction (154). The results of the present study

are shown in Table III

(87,155-160). Dex pretreatment effectively

decreased EC inflammation, apoptosis and hypoxia/reoxygenation

injury by inhibiting the DUSP1/MAPK/NF-κB, HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB, MAPK

and angiopoietin II signaling pathways. These studies indicate that

DEX protects endothelial barrier function; mitigates sepsis-induced

inflammation, microcirculatory disturbances and vascular

permeability; and exerts protective effects on vital organs such as

the brain, lungs, heart and kidneys during sepsis.

| Table IIIStudy of the protective mechanism of

DEX against sepsis-induced injury to endothelial cells. |

Table III

Study of the protective mechanism of

DEX against sepsis-induced injury to endothelial cells.

| First author,

year | Object of

study | Dosage of Dex | Effect | Regulatory

mechanism of the alleviating endothelial cells injury | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Dai et al,

2023 | Angiotensin

II-induced endothelial cell | 100 ng/ml | Attenuates Ang

II-induced EC dysfunction | Inactivating

HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling. pathway | (155) |

| Newton et

al, 2002 |

Statin-statin-induced apoptosis of

vascular endothelial cells | 1 µM | Blocks apoptosis of

vascular endothelial cells | Inhibit serum

deprivation, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, oxidants, DNA damage and

mitochondrial disruption. | (156) |

| Chai et al,

2020 | Monocyte-vascular

endothelial cells | 0.1 and 1 nM | Reduce

monocyte-endothelial adherence | Inhibit Cx43

alternation regulating the activation of MAPK signaling

pathways. | (157) |

| Dong et al,

2020 | H/R induced mouse

pulmonary vascular endothelial cells | 0.1 nM | Reduce mouse

pulmonary vascular endothelial cells apoptosis | Increased cell

viability, reduced apoptotic ratio and downregulated expression

levels of Cleaved Caspase-3 and Cleaved Caspase-9 in H/R induced

MPVECs | (158) |

| Han et al,

2022 | LPS induced

MPMVECs | 0.1 nM | Alleviate

LPS-induced MPMVECs injury | Regulate

DUSP1/MAPK/NF-κB axis by inhibiting miR-152-3p | (159) |

| Zhao et al,

2021 |

Hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced brain

endothelial cells | 0.1 nM | Alleviated

hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced brain endothelial cells injury | OGD/alleviated

Hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced inflammatory injury and permeability

in brain endothelial cells mediated by sigma-1 receptor | (160) |

| Zhang et al,

2021 | CLP-induced rat

model of sepsis | 10

µg/kg | Protective effect

against CLP-induced endothelial injury | Decreasing

angiopoietin 2 and increasing vascular endothelial cadherin

levels | (87) |

Reducing postoperative arrhythmias

DEX mitigates postoperative arrhythmias through its

antisympathetic effects. Perioperative administration of DEX [with

or without a loading dose of 0.2-1.5 µg/kg or an

intraoperative maintenance dose of 0.2-1.5 µg/(kg x h)] has

been shown to decrease the incidence of atrial fibrillation

following cardiac surgery (161), although it may increase the

risk of bradycardia (162). A

previous large multicenter randomized controlled trial indicated

that a lower dose of DEX [0.1-0.4 µg/(kg x h)] as a

continuous infusion for 24 h from the induction of anesthesia did

not reduce atrial arrhythmias post-cardiac surgery (163). The efficacy of DEX in managing

postoperative atrial arrhythmias in septic patients remains

controversial and warrants further investigation.

Alleviating brain injury related to

general anesthetics

Neurotoxicity associated with general anesthetic

drugs is a significant concern. Animal studies have demonstrated

that exposure to general anesthetics can induce structural and

functional changes in the developing brain, leading to the

apoptosis of neurons and glial cells (164,165). The results of the present study

are shown in Table IV (166-176). DEX reduced the serum levels of

IL-6, TNF-α, MDA and S100β neuron-specific enolase, whereas SOD

levels significantly increased 24 h post-surgery, decreased the

incidence of postoperative delirium from 23-9%, reduced

postoperative agitation within 3 days, inhibited caspase-3

expression in certain cortical and subcortical regions, and

exhibited notable neuroprotective effects. However, higher doses of

DEX (5 µg/kg) increased mortality rates in rats. Thus, the

use of DEX during anesthesia in septic patients may mitigate brain

injury caused by sepsis and anesthetic drugs.

| Table IVStudy on the protective mechanism of

DEX against brain injury related to general anesthetics. |

Table IV

Study on the protective mechanism of

DEX against brain injury related to general anesthetics.

| First author,

year | Object of

study | Dosage of DEX | Brain protective

effect | Regulatory

mechanism of the alleviating brain injury | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Luo et al,

2016 | Patients undergoing

craniotomy | 1 µg/kg

before anesthesia induction, maintenance dose of 0.4 µg/kg x

h | Alleviating brain

injury by inhibiting inflammation | Reduces serum

levels of IL-6, TNF-α, malondialdehyde, and S100β neuron-specific

enolase, while superoxide dismutase levels significantly

increased | (166) |

| Sanches et

al, 2022 | Cats subjected to

ovariohysterectomy | 1-5 µg/kg x

h | Alleviating brain

injury by reducing propofol consumption and quicker recovery from

anesthesia | Reduces propofol

consumption and improves cardiorespiratory stability and

intraoperative analgesia, while promoting a improved and quicker

recovery from anesthesia | (167) |

| Liu et al,

2022 | Mice undergoing

Intracerebral hemorrhage | 25-100

µg/kg | Alleviating brain

injury by reducing the neuro-logical damage, brain edema, the

lesion volume and pathological damage | Reducing damage

induced by ferroptosis after ICH by regulating iron metabolism,

amino acid metabolism and lipid peroxidation processes | (168) |

| Perez-Zoghbi et

al, 2017 | sevoflurane-induced

neonatal rats | 1-50

µg/kg | Affording the

highest protection in the thalamus (84% reduction) and lowest in

the hippocampus and cortical areas (50% reduction) | Decreases

sevoflurane anesthesia-induced widespread apoptosis | (169) |

| Goyagi, 2019 | Sevoflurane-induced

neonatal rats | 6.6-50

µg/kg | Improving long-term

cognitive function and ameliorate the neuronal degeneration | Suppresses neuronal

apoptosis | (170) |

| Sun et al,

2021 | Sevoflurane-induced

mice | 10

µg/kg | Improved

sevoflurane-induced cognitive impairment | Inhibits the

sevoflurane-induced Tau phosphorylation via activation of alpha-2

adrenergic receptor | (171) |

| Chai et al,

2024 | Ketamine-induced

mice | 0.1 µM | Improved

ketamine-anesthesia-induced the neurotoxicity (reduced motor

coordination in mice) | Mitigated

ketamine-induced apoptosis in hippocampal neurons. | (172) |

| Lv et al,

2020 | Ethanol-neonatal

mice | | Protects against

EtOH-mediated inhibition of hippocampal neurogenesis | Reverses

EtOH-induced neuroinflammation via repressing microglia activation

and the expression of inflammatory cytokines | (173) |

| Lee et al,

2021 | Sevoflurane-induced

neonatal rats | 2.5-50

µg/kg/h | Reduce the

anesthetic dosage of Sevofluran and improve the neurotoxicity

induced by Sevofluran. | Inhibit programmed

cell death in several developing brain regions. | (174) |

| Fu et al,

2024 | Patients undergoing

craniocerebral surgery | 0.5

µg/kg/h | enhance

postoperative cognitive function | Mitigates oxidative

stress | (175) |

| Shan et al,

2018 | Sevoflurane-induced

rats | 20

µg/kg | Improved

sevoflurane-anesthesia-induced the neurotoxicity (including

apoptosis and axonal injury, long-term learning and memory

dysfunction in the offspring rats) | Inhibits neuronal

apoptosis by activating the BMP/SMAD signaling pathway | (176) |

Improving coagulation disorders

Pathogenic microorganisms invade the body,

triggering immune cells to release proinflammatory mediators that

induce tissue factor expression (177). Concurrently, activated

coagulation factors engage protein-activated receptors on cell

membranes, activating NF-κB and exacerbating inflammation, leading

to systemic inflammatory response syndrome, organ damage and

potentially MODS (178). The

antisympathetic effects of DEX mitigate inflammation, alleviating

the hypercoagulable state. Additionally, DEX promotes vasodilation,

accelerates blood circulation, reduces red blood cell aggregation,

reverses thrombosis, and mitigates organ damage caused by

coagulation. Thus, DEX diminishes sepsis-induced inflammation,

enhances coagulation function in septic patients, dilates blood

vessels, and inhibits the progression of multiple organ failure

induced by sepsis.

Future expectations

Although DEX shows promise in reducing organ

damage, randomized controlled trials on its efficacy and safety in

sepsis are limited. Future research should further assess the

therapeutic potential of DEX in sepsis. At present, the protective

mechanism of DEX against sepsis-induced damage to organs such as

the brain, lungs, liver and heart remains unclear and requires

further research. With further research, new targets and clear

mechanisms of DEX in the treatment of sepsis may be discovered,

expanding its clinical indications beyond perioperative sedatives

and providing evidence-based support for promoting patient recovery

and improving prognosis. Although numerous studies have reported

the organ-protective effects of DEX, numerous aspects of this

effect remain controversial. For example, the clinical evidence on

whether DEX can reduce postoperative atrial fibrillation and

long-term postoperative neurocognitive disorders is not yet unified

and still needs to be validated through multicenter large-scale

randomized controlled trials.

Conclusions

Sepsis-induced MODS is a leading cause of mortality

among critically ill patients and those outside ICUs, with

infections primarily originating from the respiratory, digestive

and urinary systems. Respiratory infections constitute ~50% of

these cases. Sepsis impairs the respiratory and circulatory systems

to varying extents, initially presenting as decreased systemic

vascular resistance and increased cardiac workload. The severity of

sepsis progression is correlated with the characteristics of the

infecting bacteria and the patient's immune status. Effective

treatment of sepsis-induced MODS hinges on early administration of

broad-spectrum antibiotics, stabilization of blood pressure and

organ perfusion, timely surgical intervention at the primary

infection site and restoration of organ function. Despite these

measures, the incidence and mortality rates of sepsis-related MODS

remain high (179).

DEX, a highly selective α2-adrenergic receptor

agonist initially used for surgical sedation in intensive care

units, exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antiapoptotic

properties both in vivo and in vitro. Research

indicates that DEX modulates immune dysfunction, enhances the

immune response, lowers cytokine levels, and mitigates organ

inflammation during sepsis. It protects against lung and kidney

injury, reduces astrocyte inflammatory necrosis in the nervous

system, decreases hepatocyte oxidative stress, and inhibits

apoptosis pathways, thereby improving circulatory function and

reducing mortality in septic rats.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MWL conceptualized the study, acquired funding, and

wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. SXD curated data. XYZ

conducted investigation and design. QFW provided resources,

analyzed and interpretated the data. SLY performed software

analysis and validation. XL supervised the study and interpretation

of data. NM performed visualization and interpretation of data. All

authors read and approved the final the version of the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Union Foundation of

Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department and Kunming

Medical University (grant no. 202201AY070001-091) and the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81960350).

References

|

1

|

Kumar S, Srivastava VK, Kaushik S, Saxena

J and Jyoti A: Free radicals, mitochondrial dysfunction and

sepsis-induced organ dysfunction: A mechanistic insight. Curr Pharm

Des. 30:161–168. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lelubre C and Vincent JL: Mechanisms and

treatment of organ failure in sepsis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 14:417–427.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Keating GM: Dexmedetomidine: A review of

its use for sedation in the intensive care setting. Drugs.

75:1119–1130. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Poon WH, Ling RR, Yang IX, Luo H, Kofidis

T, MacLaren G, Tham C, Teoh KLK and Ramanathan K: Dexmedetomidine

for adult cardiac surgery: A systematic review, meta-analysis and

trial sequential analysis. Anesthesia. 78:371–380. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang DF, Su X, Meng ZT, Li HL, Wang DX,

Xue-Ying Li, Maze M and Ma D: Impact of dexmedetomidine on

long-term outcomes after noncardiac surgery in elderly: 3-Year

follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 270:356–363.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Sun YB, Zhao H, Mu DL, Zhang W, Cui J, Wu

L, Alam A, Wang DX and Ma D: Dexmedetomidine inhibits astrocyte

pyroptosis and subsequently protects the brain in in vitro and in

vivo models of sepsis. Cell Death Dis. 10:1672019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Cui J, Zhao H, Yi B, Zeng J, Lu K and Ma

D: Dexmedetomidine attenuates bilirubin-induced lung alveolar

epithelial cell death in vitro and in vivo. Crit Care Med.

43:e356–e368. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mei B, Li J and Zuo Z: Dexmedetomidine

attenuates sepsis-associated inflammation and encephalopathy via

central α2A adrenoceptor. Brain Behav Immun. 91:296–314. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Bo JH, Wang JX, Wang XL, Jiao Y, Jiang M,

Chen JL, Hao WY, Chen Q, Li YH, Ma ZL and Zhu GQ: Dexmedetomidine

attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced sympathetic activation and

sepsis via suppressing superoxide signaling in paraventricular

nucleus. Antioxidants (Basel). 11:23952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ma S, Evans RG, Iguchi N, Tare M,

Parkington HC, Bellomo R, May CN and Lankadeva YR: Sepsis-induced

acute kidney injury: A disease of the microcirculation.

Microcirculation. 26:e124832019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Carnicelli P, Otsuki DA, Filho AM,

Kahvegian MAP, Ida KK, Auler JOC Jr, Rouby JJ and Fantoni DT:

Effects of dexmedetomidine on hemodynamic, oxygenation,

microcirculation, and inflammatory markers in a porcine model of

sepsis. Acta Cir Bras. 37:e3707032022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford

KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer

S, et al: Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and

mortality, 1990-2017: Analysis for the global burden of disease

study. Lancet. 395:200–211. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Arefian H, Heublein S, Scherag A,

Brunkhorst FM, Younis MZ, Moerer O, Fischer D and Hartmann M:

Hospital-related cost of sepsis: A systematic review. J Infect.

74:107–117. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|