Ovarian cancer (OC) ranks third among all

gynecologic malignancies, is one of the three most diagnosed

malignancies in the female reproductive system and has the highest

mortality rate among gynecologic tumors (1). Due to the insidious nature of its

onset during the early stages, the majority of patients are

diagnosed with advanced-stage OC in the first instance, and at this

stage, the primary treatment methods, such as surgery,

radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy, have well-established

side effects, including recurrence, metastasis and chemotherapy

resistance, and thus, OC is characterized by a high mortality rate

(2). As the incidence of OC is

increasing annually, with an increasing number of younger

individuals developing OC (3,4),

the need for methods and biomarkers to allow earlier detection and

more effective treatment options after diagnosis is becoming ever

more pertinent (5-8).

Ferroptosis, distinct from apoptosis, necrosis and

autophagy, is an iron-dependent form of programmed cell death

triggered by lipid peroxide (LPO) accumulation (9). While conventional cancer therapies

usually eliminate tumor cells by inducing cell death to generate

drug resistance, ferroptosis has become an increasingly researched

topic in cancer therapy given its role in regulating cell death

(10-12). Several studies have shown that

ferroptosis is associated with resistance to cancer treatment,

potentially allowing for the reversal of cancer treatment

resistance (13-15). Current research has shown that

neurological disorders, kidney damage, breast cancer, pancreatic

cancer and several other diseases are associated with ferroptosis

(16-19). Among these, ferroptosis is most

closely related to malignant tumors, and tumor cells may be notably

sensitive to ferroptosis (20).

Ferroptosis can regulate the development of OC through different

mechanisms or factors, thereby increasing the sensitivity of OC

cells to ferroptosis-targeting therapeutics, and thus, combatting

resistance to chemotherapy (21,22) and improving the efficacy of

chemotherapeutic drugs in the management of OC (23). Additionally, a related study has

demonstrated the pattern of immune infiltration and associated

genetic features of ferroptosis, which can hopefully be applied to

predict the prognosis of patients with OC (24). The combination of ferroptosis

with chemotherapy, nanotechnology, X-ray therapy and photodynamic

therapy has been demonstrated to improve therapeutic efficacy

(25), providing potential

targets and novel therapeutic directions for ferroptosis in the

treatment of OC.

Several studies have found that ferroptosis and ERS

share a common regulatory pathway and that the two can alter the

development of several diseases by interacting with each other

(33-36). However, to the best of our

knowledge, the link between them has not been investigated in

detail in studies on the pathogenesis of OC or related therapies.

Therefore, the present review discusses the mechanisms of

ferroptosis and ERS in OC and the potential relevance of both to

highlight novel strategies and potential targets for the treatment

of OC.

Ferroptosis is a mode of programmed cell death

characterized by excessive accumulation of iron, lipid

antioxidation and lipid peroxidation (37). Patients with OC frequently

exhibit resistance to chemotherapy, and a study has shown that this

is closely related to ferroptosis (38).

Iron is one of the essential trace elements in the

human body and serves an important role in human growth and

development, energy metabolism, and immune system functions

(39). Abnormalities in iron

metabolism affect redox reactions, gene regulation, enzymatic

reactions and DNA synthesis or repair (40). In the human body, iron has a

complex and elaborate circulatory mechanism to ensure its proper

distribution, utilization and storage to maintain appropriate and

non-toxic cellular iron levels (41). Iron in the body exists in two

forms, Fe2+ and Fe3+, and there are transport

carriers and modes for the different forms of iron. Daily intake of

dietary iron includes heme iron and non-heme iron (42). They arrive in the intestinal

lumen as Fe3+ and are reduced to Fe2+ by

duodenal cytochrome B to be absorbed; non-heme iron in the

intestine is absorbed via divalent metal transporter protein 1

(43). Heme iron is then

transported into the duodenal epithelium via heme carrier protein 1

and is absorbed, internalized, and broken down into Fe2+

and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (44). Thereafter, iron can remain in the

enterocytes or enter the bloodstream from the basolateral membrane

of intestinal epithelial cells via membrane iron transport protein

1, while being oxidized by ferrous oxidase or ceruloplasmin to

produce Fe3+ (45).

Upon entering the bloodstream, plasma transferrin (TF) spreads the

captured Fe3+ throughout the cells of the body and is

used by various organs to synthesize specific iron-containing

components through TF receptor (TFR)-mediated holo-TF endocytosis

(46). For example, the liver

synthesizes hemosiderin, muscle tissue produces myoglobin and the

bone marrow produces red blood cells containing hemoglobin. Cells

promote iron uptake primarily through the TF and TFR systems, and

Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+ by ferric oxide

reductase, most of which binds to ferritin to form storage iron,

and a small portion enters the cytoplasm to collectively form the

labile iron pool (47). Due to

the instability and high oxidizability of Fe2+, excess

iron ions catalyze the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS),

which promotes lipid peroxidation through the Fenton reaction

(48), thereby causing oxidative

damage to lipid membranes, proteins and DNA, and ultimately leading

to cell death (49). Among the

three main mechanisms of ferroptosis, excessive accumulation of

Fe2+ in the labile iron pool increases the sensitivity

of cells to ferroptosis and is the initial component responsible

for ferroptosis (47).

To the best of our knowledge, the initial signal for

ferroptosis has not yet been identified, but ferroptosis is closely

related to the levels of intracellular free iron content (50). Iron metabolism serves a key role

in the pathophysiology of OC, and the degree of intracellular iron

accumulation serves a decisive role in the course of OC (51). Concurrently, abnormalities in

iron metabolism, especially the acquisition and retention of excess

iron, contribute to tumorigenesis and tumor growth (52,53). Iron accumulation increases the

risk of diseases such as cancer and damage to tissues (54). Therefore, maintaining homeostasis

of intracellular iron ions is critical. According to Basuli et

al (55), OC-initiating

cells show high iron dependence. Increased iron efflux also

decreases the proliferation and invasion of OC-initiating cells,

and conversely increased iron uptake increases OC cell

proliferation and invasion. High-grade serous OC (HGSOC) typically

originates from the fallopian tube and is diagnosed at a later

stage, and it has been observed that the iron content of HGSOC is

higher than that of normal ovarian tissues and low-grade serous OC,

suggesting that there is a strong association between HGSOC and

iron metabolism (56). In

addition, the malignant transformation and metastasis of cancer

cells are closely associated with changes in cellular redox status

(57). The molecular damage

caused by the excessive and harmful ROS catalyzed by free iron is

often referred to as 'oxidative damage', and Bauckman et al

(58) reported that ROS can

transform normal ovarian tissue into cancerous tissue by promoting

the MAPK pathway. In addition, ROS can hydroxylate DNA residues to

generate the highly mutagenic 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, elevated

levels of which have been found to be associated with a poor

prognosis in patients with HGSOC (59,60). Iron polyporphyrin heme binds to

p53, interfering with p53-DNA interactions, leading to nuclear

export and cellular degradation of p53, and increased

susceptibility to HGSOC (61,62). Basuli et al (55) demonstrated that excess iron

simultaneously affects tumor cell proliferation, metabolism and

metastasis. Increasing the expression of ferroportin on cell

membranes (63), decreasing iron

intake (64), or decreasing the

concentration of TF (65) and

TFR in vivo (66) can

inhibit tumor growth. In addition, iron metabolism can contribute

to the development of OC by regulating hypoxia-inducible factor

(HIF). HIF-1α induces OC progression by inhibiting p53 function,

promoting IL-6 expression or being regulated by long non-coding

RNAs (67,68). Iron metabolism is also closely

related to resistance to chemotherapy, and solute carrier family 40

member 1 (SLC40A1), an iron metabolism-related gene, which is the

only known iron-exporting gene (69), serves a crucial role in

transporting iron from the intracellular environment to the

extracellular environment, and thus, the physiological expression

of SLC40A serves a vital role in the regulation of iron

homeostasis. SLC40A1-induced iron overload leads to cisplatin

resistance in OC (70).

Upregulation of SLC40A1 reduces cisplatin resistance by exporting

iron, decreasing the intracellular iron concentration and oxidative

stress. By contrast, an increase in the intracellular iron

concentration and enhanced oxidative stress induced by the

downregulation of SLC40A1 increase cisplatin resistance (70). Thus, modulating iron levels to

influence the redox system may be a potential strategy to reverse

drug resistance in OC therapy.

The iron-dependent nature of OC tumor-initiating

cells also makes them sensitive to drugs that induce ferroptosis,

as well as to iron chelators, providing a potential therapeutic

approach for the management of OC (71). Desferrioxamine (72), a natural iron chelator used in

the treatment of iron overload, has shown promising results in the

treatment of OC. Wang et al (72) assessed the effects of

desferrioxamine on OC cell lines and found that it not only

inhibited OC stem cells but also enhanced cisplatin efficacy,

improved resistance to chemotherapy and increased the length of

survival. There are also drugs that regulate iron metabolism in

several ways and may have effects on other biological processes.

For example, artemisinin is known for its anti-malarial,

anti-inflammatory and antitumor effects, and its compounds

(artesunate) can reduce cell proliferation and induce ROS

production in OC cells (73). In

addition, artesunate can activate the function of lysosomes,

promote the degradation of ferritin and lead to the release of iron

in lysosomes, and thereby mediate cell death (74). Regulators, including iron

uptake-related regulators (75),

iron storage-related regulators (76) and iron transport-related

regulators (77), influence the

pathological process of OC through the regulation of iron

metabolism levels.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent non-apoptotic cell

death mechanism caused by iron-dependent membrane lipid

peroxidation and massive accumulation of cellular ROS (78). Membrane lipids serve an important

role in the regulation of cell fate and lipid metabolism, which is

fundamental in determining the fate of ferroptosis (79), and is similarly critical for

ferroptosis execution.

Among various lipids, polyunsaturated fatty acids

(PUFAs) associated with several phospholipids such as

phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine are responsible

for inducing lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. Phospholipids

containing PUFAs are susceptible to oxidation, but less oxidizable

saturated/monounsaturated fatty acids protect cells from

ferroptosis (80). Thus, the

enzymes and pathways that regulate the metabolism of PUFAs and

monounsaturated fatty acids, as well as the balance of PUFAs and

monounsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids, can

influence cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis (81). The findings of the aforementioned

study provide a novel strategy for lipid peroxidation treatment of

OC ferroptosis. Since the membrane phospholipids of PUFAs that

drive ROS production catalyzed by iron ions interacting with PUFAs

are responsible for triggering lipid peroxidation leading to

cellular ferroptosis, and not free PUFA itself, the enzymes that

bind free PUFA to phospholipids serve a crucial role in ferroptosis

(81). Acyl-CoA synthetase

long-chain family member 4 is an essential component of ferroptosis

execution as shown by microarray analysis of ferroptosis-resistant

cell lines and using a genome-wide CRISPR-based genetic screening

system (82). Under the

catalytic action of Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4,

free long-chain fatty acids are converted to acyl-CoA by linking

with CoA. Acyl-CoA inserts into membrane phospholipids and binds to

phosphatidylethanolamine to form PUFA phospholipids catalyzed by

lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (83). Lipid peroxidation, via two

primary mechanisms, non-enzymatic spontaneous oxidation and

enzyme-mediated lipid peroxidation (84), results in the production of

phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOHs), and if antioxidants do not

convert PLOOH to phospholipid hydroxides (PLOHs) in a timely

manner, the resulting accumulation of PLOOH leads to extensive

lipid peroxidation and activation of the antioxidant system,

directly inducing damage to cell membranes and ultimately leading

to cell dysfunction and ferroptosis (85). Non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation

(also known as lipid autoxidation) is a free radical-driven chain

reaction. Hydroxyl radicals (OH·) are generated through the

reaction of H2O2 with Fe2+, which

reacts with PUFAs in the plasma membrane in a Fenton reaction to

generate LPO, leading to ferroptosis (86,87). Enhanced accumulation of LPO is

therefore necessary to increase the efficiency of ferroptosis

(88), and OH· is the most

active ROS (89), and thus, it

also serves as an emerging cancer treatment target for the

management of OC via chemodynamic therapy.

H2O2 nano-enzymes developed by Sun et

al (90) using CoNi alloys

encapsulated with nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes exhibited glucose

oxidase and lactate oxidase activities to effectively disrupt the

antioxidant defense system by catalyzing the formation of OH·,

increasing ROS content in the tumor microenvironment and damaging

the tumor cells, while depleting glutathione (GSH) to induce

ferroptosis of the cells. Liang et al (91) demonstrated that

polydopamine-mediated Michael addition combined with

Fe2+ depletion of GSH enhanced OH· accumulation and

ultimately resulted in the intracellular release of the

chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin, thus inducing ferroptosis. In

addition, lipid peroxidation is tightly regulated by various

metabolic and signaling pathways, such as the cytochrome P450

oxidoreductase pathway, and iron-containing enzymes, including

lipoxygenase, also contribute to the process of lipid peroxidation

(92). Enzymatic lipid

peroxidation, conversely, is a process of direct oxidation of free

PUFAs into various types of lipid hydroperoxides catalyzed by

lipoxygenase (93,94). Among them, the arachidonic acid

lipoxygenase family regulates lipid peroxidation. It has been shown

that the binding of 5-lipoxygenase to microsomal GSH S-transferase

1 led to a decrease in lipid peroxidation and mediated ferroptosis

in cancer cells (95).

12-lipoxygenase, conversely, has been identified as a key factor in

p53-mediated ferroptosis under conditions of ROS-induced stress

(96), while the expression

levels of 15-lipoxygenase are associated with the spermine/spermine

N1-acetyltransferase 1 gene, a transcriptional target of p53

(97). Zhang et al

(98) demonstrated that

chemotherapeutic drugs for OC induced excessive lipid peroxidation

through ROS and initiated ovarian cell ferroptosis, thus leading to

ovarian cell death. A study (99) has demonstrated that p53 serves an

important role in the ferroptosis process. p53 exhibits a

bidirectional regulatory effect based on specific environmental

conditions. When lipid peroxidation levels are low, p53 inhibits

the occurrence of ferroptosis, promoting cell survival. However,

when excess lipid peroxidation persists, ferroptosis is induced

(99).

In summary, further studies on the effects of

various lipid metabolic pathways on lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis from the perspective of chemotherapy-induced oxidative

stress and ferroptosis may help control ovarian damage and improve

the quality of life of patients with OC. All of them will provide a

deeper understanding of ferroptosis and therapeutic strategies for

OC.

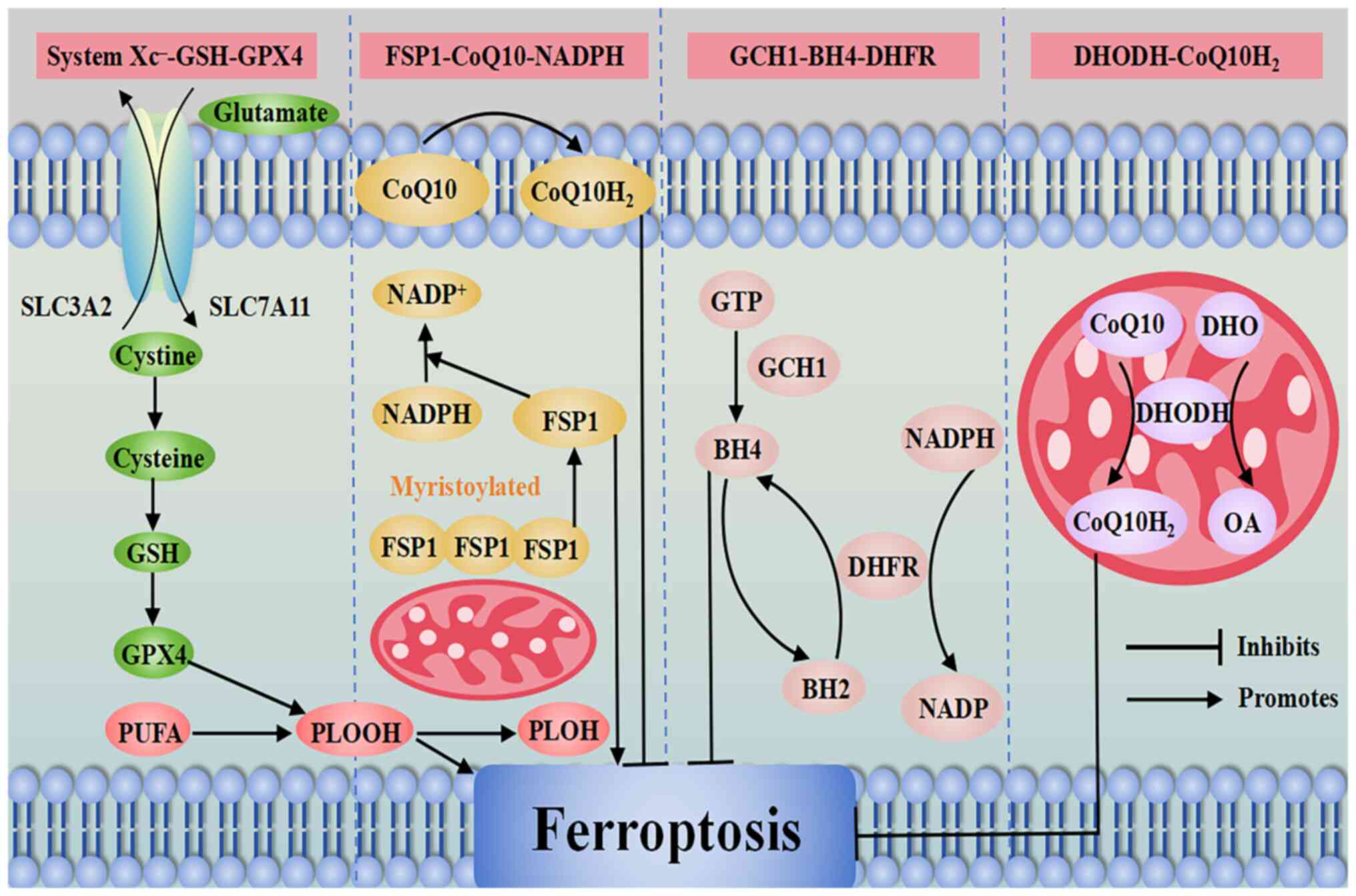

Oxidative damage occurs due to an imbalance between

the cellular antioxidant system with the production of free

radicals and/or the neutralization or elimination of their

deleterious effects. ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation is a key step

to drive cellular ferroptosis, and inactivation of the antioxidant

system is the primary cause of ferroptosis (100). At present, it has been shown

that the primary antioxidant systems regulating ferroptosis include

the System Xc−-GSH-GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4) pathway, the

ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)-coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

pathway, the guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase 1

(GCH1)-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) pathway and the dihydroorotate

dehydrogenase (DHODH)-CoQ10H2 pathway. Among these, the

System Xc−-GSH-GPX4 pathway is the most fundamental

antioxidant system, which serves a key role in protecting cells

from ferroptosis (101). An

overview of the primary antioxidant systems regulating ferroptosis

is shown in Fig. 1.

Therefore, the FSP1-CoQ10-NADPH pathway may

complement and work with the System Xc−-GSH-GPX4 pathway

to inhibit lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis, providing a potential

therapeutic strategy for the treatment of OC.

A previous study has identified the GCH1-BH4-DHFR

pathway as an alternative compensatory mechanism for the System

Xc−-GSH-GPX4 pathway (120). GCH1 is the rate-limiting enzyme

for BH4 biosynthesis, which promotes ferroptosis via the

metabolites BH4 and dihydrobiopterin (BH2). BH4 acts as a free

radical trapping antioxidant that can be recycled by DHFR for redox

cycling, and BH4 has antioxidant degradation effects on

phospholipids containing two PUFA tails and prevents lipid

peroxidation and thus ferroptosis by inhibiting the production of

specific LPOs (120,121).

Through the direct trapping of antioxidant free

radicals and the production of CoQ10 (120), when GCH1 is upregulated, it

promotes BH4 production and abrogates the deleterious effects of

RSL3-induced cellular ferroptosis. Additionally, overexpression of

GCH1 has been shown to decrease the sensitivity of drug-resistant

cancer cells to ferroptosis, which in turn further ameliorated the

progression of ferroptosis in cancer cells through the regulation

of CoQ10 (122).

In addition, relevant studies have shown that BH4 is

involved in the synthesis of dopamine, nitric oxide synthase and

melatonin (123), whereas

exogenous dopamine or melatonin can inhibit ferroptosis (124). Several studies have shown that

nitric oxide can induce or inhibit ferroptosis in tumor cells

depending on environmental conditions (125-127). DHFR reduces BH2 through the

involvement of NADPH, thereby promoting BH4 synthesis. If DHFR is

inhibited, ferroptosis of tumor cells is promoted via the

synergistic action of GPX4 inhibitors (87).

Therefore, the GCH1-BH4-DHFR pathway serves a role

in regulating the balance between oxidative damage and antioxidant

defense during ferroptosis and interacts with the System

Xc−-GSH-GPX4 pathway and the FSP1-CoQ10-NADPH pathway in

a synergistic or complementary manner. Although other specific

mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets remain to be

determined, the identified pathways may serve as potential

therapeutic targets for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy in

OC.

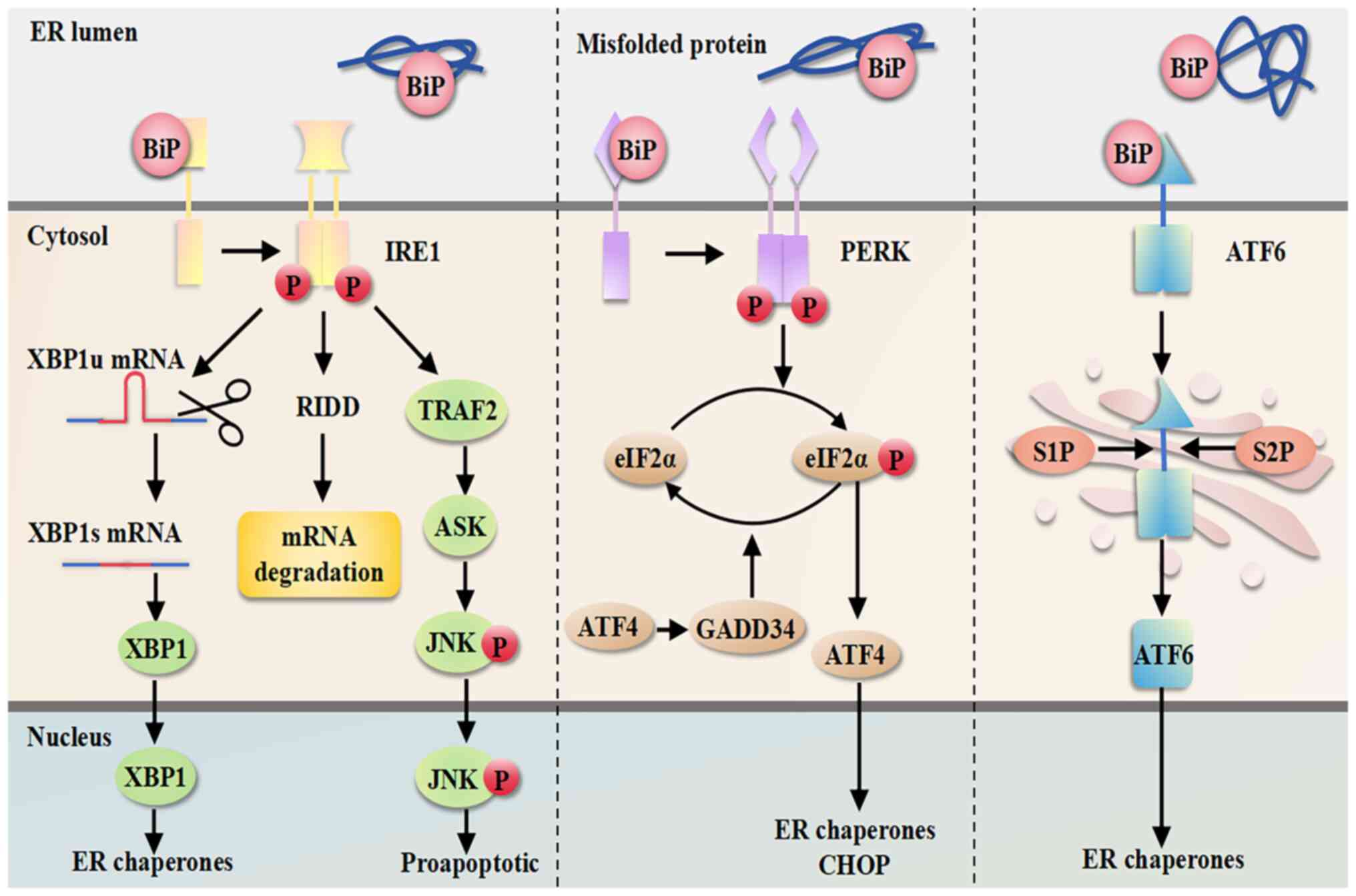

When tumor cells are challenged by intrinsic factors

such as oncogenic activation, altered chromosome numbers or

enhanced secretory capacity, as well as by extrinsic factors such

as hypoxia, nutrient deprivation and acidosis, protein homeostasis

is altered, resulting in the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded

proteins in the lumen of the ER, activating the ERS and the UPR,

thus restoring homeostasis to the cell (32). However, when ERS is prolonged or

the stimulus is too strong, exceeding the tolerance threshold of

the UPR leads to cell death, which in turn causes the development

of cancer (130).

UPR is initiated by three major ERS sensors located

in the ER membrane, including inositol-requiring protein 1α

(IRE1α), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) and activating

transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (131). The ER-resident chaperone

binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) acts as a master regulator of

the UPR by binding to and inactivating three ERS sensors, IRE1α,

PERK and ATF6, negatively regulating them and keeping them in an

inactive state. When misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, they

bind to the inhibitory chaperone BiP and sequester it, which

activates the ERS sensors to initiate UPR signaling (132). An overview of the mechanisms of

ERS is shown in Fig. 2.

IRE1 consists of two isoforms, IRE1α and IRE1β;

IRE1β is primarily expressed in the respiratory and

gastrointestinal tracts, whereas IRE1α is more widely expressed

(133). The cytoplasmic tail of

IRE1α has two domains, a serine/threonine kinase structural domain

and a ribonuclease (RNase) structural domain, which work together

(134). The kinase of IRE1α is

activated upon binding to misfolded proteins and undergoes

dimerization/coupling and trans-autophosphorylation, leading to

ectopic activation of the structural domain of RNase (135). Under the catalysis of active

RNase, the intron containing 26 nucleotides is excised from the

mRNA encoding the homeostasis transcription factor X-box protein 1

(XBP1). Then, two mRNA fragments are cleaved by RNA splicing ligase

RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate and 5′-OH ligase, thereby generating the

stable active transcription factor XBP1s (spliced form) (136,137). XBP1s (spliced form) is involved

in the expression of genes encoding ER membrane biogenesis, ER

protein folding, ER-associated degradation and multiple UPR targets

(138). C/EBP homologous

protein (CHOP), a major regulator of ERS-induced apoptosis, is

activated by activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) through the

PERK-ATF4-CHOP pathway (139).

In addition, IRE1α promotes apoptosis by activating the apoptosis

signal-regulating kinase 1/JNK pathway, and by binding to tumor

necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 (140). In addition, regulated

IRE1-dependent decay is a novel UPR-regulated pathway that has been

identified to control cell fate under ERS. Activated RNase can

target other mRNAs and microRNAs (miRs) by regulating this pathway

(141).

PERK is a type I transmembrane protein with

similarities to IRE1, which has an ER lumenal dimerization

structural domain and a cytoplasmic kinase structural domain. The

tubulin dimerization structural domain of PERK has less sequence

similarity to IRE1 but is structurally and functionally similar to

the structural domain of IRE1. The cytoplasmic kinase structural

domain of PERK also undergoes trans-autophosphorylation in response

to ERS, but it differs from IRE1 in that PERK also phosphorylates

the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) at serine

51, and phosphorylated eIF2α inhibits overall translation of

proteins, and thus, reduces the amount of proteins entering the

lumen of the ER (147,148). In addition, phosphorylation of

eIF2α alters the utilization efficiency of the AUG start codon

(149), which results in

preferential translation of the ATF4 mRNA (148).

ATF4 is a transcription factor that activates

downstream UPR target genes, such as the expression of growth

arrest DNA-damage 34 (GADD34), which induces CHOP expression

(148,150). CHOP promotes DNA damage,

inhibits cell proliferation and activates apoptosis by upregulating

the pro-apoptotic members of the B-cell lymphoma-2 family of

proteins (151). Therefore,

ATF4 serves an important role in ER-functional gene expression,

ERS-mediated ROS production and ERS-induced apoptosis. ATF4 can

also regulate the dephosphorylation of eIF2α through GADD34 to form

an inhibitory feedback loop to reverse PERK-mediated translational

decay (152). In addition, PERK

phosphorylates nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2),

thereby upregulating antioxidants to promote cellular antioxidation

(153). Overall, the PERK-eIF2α

pathway first mediates the promotion of cell survival during ERS

but shifts to the promotion of apoptosis when ERS is sustained and

maintains cellular homeostatic balance by activating ATF4 and NRF2.

Therefore, the PERK pathway is an attractive therapeutic target in

OC therapy.

ATF6 is a type II transmembrane protein with a

carboxy-terminal stress-sensing lumenal structural domain and an

amino-terminal bZip transcription factor structural domain

(154). ATF6 is transported to

the Golgi under conditions of ERS, where it is sequentially

hydrolyzed by serine protease site 1 and metalloprotease site 2

(S2P) proteins to release its amino-terminal transcription factor

structural domain, which, synergistically with XBP1, upregulates

genes involved in protein folding and ER amplification, as well as

genes involved in ER-associated degradation pathway components

(155). It has been shown that

ATF6 expression in OC tumor tissues is higher than that in normal

ovarian tissues (156), and

under irreversible ERS, it downregulates the levels of

anti-apoptotic proteins (157).

In addition, by regulating ATF6, the sensitivity of OC cells to

chemotherapeutic agents can be altered (158). However, the role of ATF6 in

ER-induced cell death and co-targeting of chemotherapeutic agents

to improve survival in OC still needs to be explored further.

With the gradual increase in interest in ferroptosis

and ERS, an increasing number of studies have shown that

ferroptosis and ERS have an important impact on OC and that there

is a close relationship between the two (35,159-161).

ERS also serves a crucial role in the development

and prognosis of OC. Studies have shown that activation of UPR

sensors, and thus, induction of ERS can lead to apoptosis of OC

cells (169), and regulation of

ERS-associated targets influences drug resistance in OC treatment

(170,171), highlighting potentially novel

targets for the management of OC. Zhang et al (172) developed promising medical aids

for the prognostic assessment of patients with epithelial OC by

establishing a risk classifier for differentially expressed genes

associated with ERS. Ma et al (173) utilized nanotechnology to

accurately and durably induce ERS through photodynamic responses,

thus inducing an antitumor effect in a mouse model of OC.

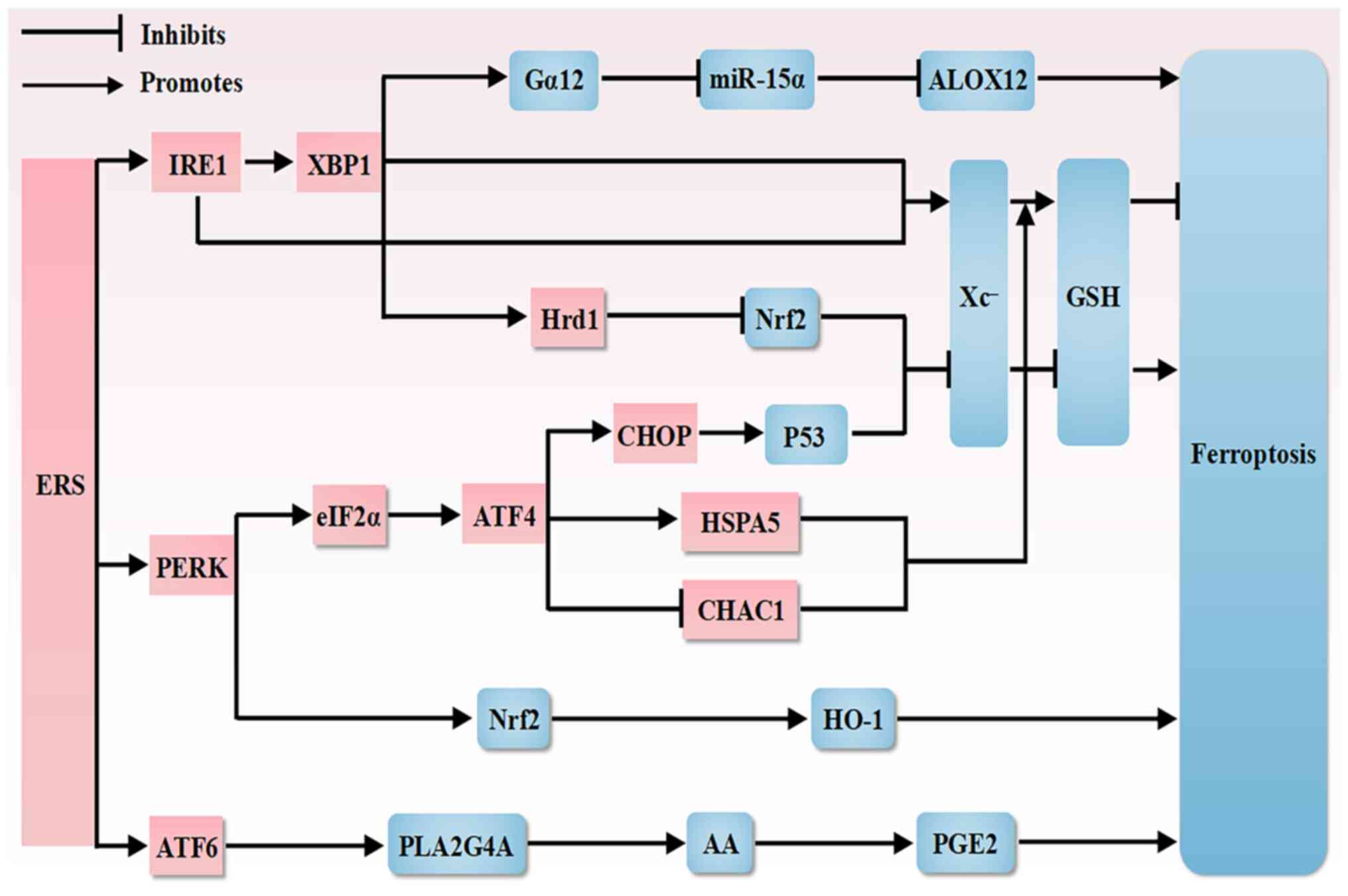

A growing body of research has shown a link between

ferroptosis and ERS, which share common pathways (174-176), and that ROS, a byproduct of

ERS, may exacerbate ferroptosis, while the ER is a key site for

lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis, and conversely ROS produced

during ferroptosis further exacerbate ERS. However, ferroptosis and

ERS have been discussed separately regarding OC, and, to the best

of our knowledge, there are no studies assessing their interactions

in OC. In the present review, the potential therapeutic targets for

OC treatment are examined based on a potential association between

ERS and ferroptosis in OC using the existing literature. An

overview of interactions between ferroptosis and ERS is shown in

Fig. 3 and an overview of

mechanisms associated with ferroptosis and ERS is shown in Table I.

Colorectal cancer is a common digestive malignancy

in which both surgery and chemotherapy exhibit limited therapeutic

efficacy (187). Tagitinin C, a

natural product, induces ERS production, which results in nuclear

translocation of Nrf2 and upregulation of HO-1. HO-1 is a

downstream effector of Nrf2, which leads to an increase in the pool

of unstable iron, and thus, promotes lipid peroxidation. This

increase in the pool of unstable iron together with erastin exerts

synergistic antitumor effects in inducing ferroptosis in colorectal

cancer cells. Thus, tagitinin C has been identified as a novel

ferroptosis inducer and potent sensitizer (188). Furthermore, in a prostate

cancer study, the mediation of arachidonic acid release and

prostaglandin E2 production via ATF6α-phospholipase A2 group IVA

was found to protect prostate cancer cells from ferroptosis

(189). Upregulation of Gα12

through the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway after ERS in hepatocytes thereby

promotes hepatic ferroptosis and exacerbates acute liver injury

through Rho associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase

1-mediated dysregulation of 12-lipoxygenase and miR-15α (190). Furthermore, in a study related

to diabetic nephropathy, ERS downregulated SLC7A11 expression

through the XBP1-E3 ligase-Nrf2 pathway, which decreased GSH

antioxidant levels and enhanced cellular sensitivity to

ferroptosis, thereby inducing ferroptosis, providing insights into

the potential mechanism of delaying epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in renal tubular epithelial cells (35).

In addition, several studies have demonstrated that

herbal components can also improve cellular ferroptosis by

modulating ERS. Esculin, a compound extracted from the cortex of

the willow bark, inhibits the development and progression of colon

cancer by activating the ERS PERK signaling pathway, and inducing

apoptosis and ferroptosis through the Nrf2/HO-1 and eIF2α/CHOP

pathways (191). Tanshinone

IIA, the primary active ingredient of the traditional Chinese

medicine Danshen, has been shown to exert antitumor effects

primarily in the ER-mediated ferroptosis signaling pathway,

downregulating the ferroptosis of tumor cells through the

PERK-ATF4-heat shock 70 kDa protein 5 pathway (192). Acetaminophen overdose is a

major cause of drug-induced liver injury. Salidroside inhibits ER

stress-mediated ferroptosis via the ATF4-cation transport regulator

homolog 1 axis by activating AMPK-SIRT1 signaling, and serves an

important role in alleviating acetaminophen-induced acute liver

injury (193). In a study on

glioma, DHA-induced ERS upregulated ATF4 via PERK, thereby

increasing the expression and activity of GPX4, thus inhibiting

DHA-induced lipid peroxidation and protecting glioma cells from

ferroptosis, highlighting a novel anticancer mechanism in glioma

(194).

It has been shown that ERS and ferroptosis are also

related in terms of tumor angiogenesis. In a glioma-related study,

elevated expression of ATF4, a transcription factor that activates

downstream UPR target genes, promoted angiogenesis by facilitating

tumor shaping of vascular structures in a System

Xc−-dependent manner, and erastin, a ferroptosis

inducer, and RSL3, a GPX4 inhibitor, could reduce ATF4-induced

angiogenesis (197).

Drug development research on natural compounds and

their derivatives is a popular research topic for cancer treatment.

Research on novel drugs also takes into consideration the side

effects and off-target effects, which can negatively affect the

quality of life of patients. Drugs with high specificity and

selectivity need to be developed to minimize off-target effects and

their potential toxicities (198). In OC, reducing off-target

effects during treatment can help improve patient outcomes and

prognosis (199). Studies have

shown that off-target effects are strongly linked to ferroptosis

and ERS. Dahlmanns et al (200) found that adjusting the

mechanism of ferroptosis improved tumor therapy, but that

interfering with the induction of ferroptosis produced an

off-target effect, and thus, a reduction in therapeutic efficacy.

Similarly, it has been shown that ERS may modulate off-target

effects in glioblastoma multiforme (201). Inhibitors of ROS, which are

closely related to ferroptosis and ERS, likewise have some degree

of influence on off-target effects (202). Recent advances in research on

coupled drug delivery systems (203), liposomes (204) and nanotechnology (205) in combination with bioactive

agents for the treatment of a wide range of diseases, including

cancer, may lead to improved efficacy through the localized and

precise delivery of drugs, thereby reducing off-target effects.

In summary, ERS interacts with ferroptosis in

several diseases through various pathways, regulatory proteins and

related factors to regulate disease development, highlighting

potential therapeutic targets and strategies for disease treatment

and prevention. However, the specific mechanisms by which ERS

interacts with ferroptosis in the development, treatment and

prevention of OC remain to be investigated.

Ferroptosis and ERS are both increasingly popular

topics in relation to cancer research, and studies have shown that

ferroptosis and ERS are related to the development and potential

treatment of gynecological tumors (13,20,32,206,207). OC, as the gynecological

malignant tumor with the highest mortality rate, has attracted

attention; however, there is no relevant research on the potential

mechanism of the interaction between ERS and ferroptosis in OC. In

the present review, the pathogenesis of ERS and ferroptosis in OC,

and the common pathways and related links between the two in liver,

lung and colorectal cancer, are discussed, with the aim of

providing novel strategies for the prevention, treatment and

prognosis of OC in the future.

There is also an association between the two, with

ERS inducing ferroptosis by causing Fe2+ accumulation

and lipid peroxidation through related pathways (195), and the ER, which contains more

than half of all the lipid bilayers in any given cell, being the

source of lipids for the majority of the cytosolic membranes, thus

being critical for the initiation of ferroptosis (216). Ferroptosis can maintain ER

homeostasis by signaling and regulating the degree of ERS.

Ferroptosis can also be positively regulated by inducing ERS

through various pathways.

However, ferroptosis and ERS have different and

complex mechanistic pathways, and several novel mechanisms,

pathways and potential targets are gradually being identified,

although it is likely that more remain to be uncovered. For

example, the detailed mechanisms of the four pathways associated

with lipid antioxidation, particularly the GCH1-BH4-DHFR pathway

and the DHODH-CoQ10H2 pathway in OC, still remain to be

explored. Oxidative stress in mitochondria is closely associated

with related processes in ferroptosis and ERS, and the mechanisms

involved in mitochondria are not fully understood at present.

Furthermore, the early onset of OC is insidious, and regarding

diagnostic accuracy, there is still a lack of research on the

difference in iron content between OC tissues of different stages

and normal ovarian tissues (55). Interfering with iron metabolism

during early OC may inhibit the further development of OC (104). The occurrence, progression and

treatment of OC is a complex process, and there is a complex

connection between ERS and ferroptosis. Whether the relevant

pathways present in other diseases have the same role in OC,

whether there are obvious differences in the roles in different

cells at different stages of OC, and whether they have the same

regulatory role in the different stages of OC occurrence,

development, and recurrence remain to be determined. Furthermore,

the prognostic prediction of OC still has major deficiencies and

lacks the support of clinical data. Although current studies on

various diseases have shown that the crosstalk between ferroptosis

and ERS has a related improvement effect on the diseases (34,217-219), there is still a lack of

relevant research regarding mechanisms for the crosstalk between

ERS and ferroptosis in terms of OC.

Based on the clearer understanding of potential

targets of ERS and ferroptosis, the role of the mechanistic

pathways in the process of OC, the impact of the crosstalk between

the two, and how to translate the results of research and

experiments into clinical practice is an important and challenging

aspect. In terms of clinical index detection, the aforementioned

mechanism and modern scientific technologies such as nano-molecular

materials, MRI and X-ray may be combined to detect the pathological

factors of OC before the onset of the disease, and analyze the

efficacy or assess prognosis during and following treatment of the

disease. Assessment of iron metabolism levels during relevant

clinical testing may allow for earlier detection of OC, potentially

improving treatment options and patient outcomes. The direction of

these studies, which await further translation to the clinic, may

serve as a means of assessing patients to improve prevention, and

assess efficacy and recurrence. In terms of drug development, for

the commonly used chemotherapeutic regimens, there are obvious side

effects alongside drug resistance. Thus, additional screening of

safe and effective therapeutic drugs is required. Whether

ferroptosis inhibitors and inducers of ERS can be used clinically

or as references for future drug development remains to be

explored. In addition, several studies (14,80,192,220) have found that traditional

Chinese herbs are effective in regulating the crosstalk between

ferroptosis and ERS-related mechanisms in relation to OC, thus the

dosage and clinical safety of these options should be investigated.

Whether the combination of various drugs, chemotherapeutic

treatments and modern technologies will have a synergistic effect

or inhibit resistance to chemotherapy and side effects also needs

to be tested.

The present review highlights the potential

therapeutic promise of crosstalk between ferroptosis and ERS in OC,

suggesting that the intricate interactions merit deeper

exploration. In addition, several potential treatments have shown

therapeutic potential and efficacy in combination with conventional

chemotherapy for the treatment of OC in preclinical testing, and

future studies are required to determine the detailed molecular

mechanisms of these compounds and to assess their efficacy in the

clinic. To address these unknown challenges, it is necessary to

draw on the results of existing research to help understand the

focus and direction of the research. After clarifying the mechanism

of each target and pathway, it is necessary to screen for important

links or representative factors and more precise biomarkers. For

drug development, a large amount of clinical data is required.

Overall, understanding ferroptosis and ERS, and the

potential crosstalk between them, may provide novel therapeutic

approaches for the management of OC.

Not applicable.

JY wrote and revised the manuscript. YW revised the

manuscript. FL revised the manuscript. YZ and FH conceived the

topic of study. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present review was supported by funding from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82274566).

|

1

|

Jiang C, Shen C, Ni M, Huang L, Hu H, Dai

Q, Zhao H and Zhu Z: Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance

in ovarian cancer. Genes Dis. 11:1010632023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Maioru OV, Radoi VE, Coman MC, Hotinceanu

IA, Dan A, Eftenoiu AE, Burtavel LM, Bohiltea LC and Severin EM:

Developments in genetics: better management of ovarian cancer

patients. Int J Mol Sci. 24:159872023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ekmann-Gade AW, Høgdall CK, Seibæk L, Noer

MC, Fagö-Olsen CL and Schnack TH: Incidence, treatment, and

survival trends in older versus younger women with epithelial

ovarian cancer from 2005 to 2018: A nationwide Danish study.

Gynecol Oncol. 164:120–128. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Mallen A, Todd S, Robertson SE, Kim J,

Sehovic M, Wenham RM, Extermann M and Chon HS: Impact of age,

comorbidity, and treatment characteristics on survival in older

women with advanced high grade epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol

Oncol. 161:693–699. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lumish MA, Kohn EC and Tew WP: Top

advances of the year: Ovarian cancer. Cancer. 130:837–845. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wang A, Wang Y, Du C, Yang H, Wang Z, Jin

C and Hamblin MR: Pyroptosis and the tumor immune microenvironment:

A new battlefield in ovarian cancer treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta

Rev Cancer. 1879:1890582024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wong RW and Cheung ANY: Predictive and

prognostic biomarkers in female genital tract tumours: An update

highlighting their clinical relevance and practical issues.

Pathology. 56:214–227. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wang Y, Liu L, Jin X and Yu Y: Efficacy

and safety of mirvetuximab soravtansine in recurrent ovarian cancer

with FRa positive expression: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 194:1042302024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y and Guo R:

Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: A novel approach to reversing drug

resistance. Mol Cancer. 21:472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Wang N, Chen M, Wu M, Liao Y, Xia Q, Cai

Z, He C, Tang Q, Zhou Y, Zhao L, et al: High-adhesion ovarian

cancer cell resistance to ferroptosis: The activation of NRF2/FSP1

pathway by junctional adhesion molecule JAM3. Free Radic Biol Med.

228:1–13. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Teng K, Ma H, Gai P, Zhao X and Qi G:

SPHK1 enhances olaparib resistance in ovarian cancer through the

NFκB/NRF2/ferroptosis pathway. Cell Death Discov. 11:292025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yao Y, Wang B, Jiang Y, Guo H and Li Y:

The mechanisms crosstalk and therapeutic opportunities between

ferroptosis and ovary diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14:11940892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kapper C, Oppelt P, Arbeithuber B, Gyunesh

AA, Vilusic I, Stelzl P and Rezk-Füreder M: Targeting ferroptosis

in ovarian cancer: Novel strategies to overcome chemotherapy

resistance. Life Sci. 349:1227202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Guo W, Wang W, Lei F, Zheng R, Zhao X, Gu

Y, Yang M, Tong Y and Wang Y: Angelica sinensis polysaccharide

combined with cisplatin reverses cisplatin resistance of ovarian

cancer by inducing ferroptosis via regulating GPX4. Biomed

Pharmacother. 175:1166802024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ni M, Zhou J, Zhu Z, Xu Q, Yin Z, Wang Y,

Zheng Z and Zhao H: Shikonin and cisplatin synergistically overcome

cisplatin resistance of ovarian cancer by inducing ferroptosis via

upregulation of HMOX1 to promote Fe2+ accumulation.

Phytomedicine. 112:1547012023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Li J, Cao F, Yin HL, Huang ZJ, Lin ZT, Mao

N, Sun B and Wang G: Ferroptosis: Past, present and future. Cell

Death Dis. 11:882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li Y, Liu J, Wu S, Xiao J and Zhang Z:

Ferroptosis: Opening up potential targets for gastric cancer

treatment. Mol Cell Biochem. 479:2863–2874. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Tang D, Kroemer G and Kang R: Ferroptosis

in hepatocellular carcinoma: From bench to bedside. Hepatology.

80:721–739. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Qiu X, Bi Q, Wu J, Sun Z and Wang W: Role

of ferroptosis in fibrosis: From mechanism to potential therapy.

Chin Med J (Engl). 137:806–817. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Hushmandi K, Klionsky DJ, Aref AR, Bonyadi

M, Reiter RJ, Nabavi N, Salimimoghadam S and Saadat SH: Ferroptosis

contributes to the progression of female-specific neoplasms, from

breast cancer to gynecological malignancies in a manner regulated

by non-coding RNAs: Mechanistic implications. Noncoding RNA Res.

9:1159–1177. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wu Y, Jia C, Liu W, Zhan W, Chen Y, Lu J,

Bao Y, Wang S, Yu C, Zheng L, et al: Sodium citrate targeting

Ca2+/CAMKK2 pathway exhibits anti-tumor activity through

inducing apoptosis and ferroptosis in ovarian cancer. J Adv Res.

65:89–104. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhao L, Yang H, Wang Y, Yang S, Jiang Q,

Tan J, Zhao X and Zi D: STUB1 suppresses paclitaxel resistance in

ovarian cancer through mediating HOXB3 ubiquitination to inhibit

PARK7 expression. Commun Biol. 7:14392024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li J, Chen M, Huang D, Li Z, Chen Y, Huang

J, Chen Y, Zhou Z and Yu Z: Inhibition of Selenoprotein I promotes

ferroptosis and reverses resistance to platinum chemotherapy by

impairing Akt phosphorylation in ovarian cancer. MedComm (2020).

5:e700332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang B, Guo B, Kong H, Yang L, Yan H, Liu

J, Zhou Y, An R and Wang F: Decoding the ferroptosis-related gene

signatures and immune infiltration patterns in ovarian cancer:

Bioinformatic prediction integrated with experimental validation. J

Inflamm Res. 17:10333–10346. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li G, Shi S, Tan J, He L, Liu Q, Fang F,

Fu H, Zhong M, Mai Z, Sun R, et al: Highly efficient synergistic

chemotherapy and magnetic resonance imaging for targeted ovarian

cancer therapy using hyaluronic acid-coated coordination polymer

nanoparticles. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e23094642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hetz C, Chevet E and Oakes SA:

Proteostasis control by the unfolded protein response. Nat Cell

Biol. 17:829–838. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sims SG, Cisney RN, Lipscomb MM and Meares

GP: The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in astrocytes. Glia.

70:5–19. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

28

|

Hu H, Tian M, Ding C and Yu S: The C/EBP

homologous protein (CHOP) transcription factor functions in

endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and microbial

infection. Front Immunol. 9:30832019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ren J, Bi Y, Sowers JR, Hetz C and Zhang

Y: Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in

cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 18:499–521. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Oakes SA and Papa FR: The role of

endoplasmic reticulum stress in human pathology. Annu Rev Pathol.

10:173–194. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Song M and Cubillos-Ruiz JR: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress responses in intratumoral immune cells:

Implications for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 40:128–141.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yan T, Ma X, Guo L and Lu R: Targeting

endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in ovarian cancer therapy.

Cancer Biol Med. 20:748–764. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang L, Ma X, Zhou L, Luo M, Lu Y, Wang Y,

Zheng P, Liu H, Liu X, Liu W and Wei S: Dual-targeting TrxR-EGFR

Alkynyl-Au(I) gefitinib complex induces ferroptosis in

gefitinib-resistant lung cancer via degradation of GPX4. J Med

Chem. 68:5275–5291. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhong P, Li L, Feng X, Teng C, Cai W,

Zheng W, Wei J, Li X, He Y, Chen B, et al: Neuronal ferroptosis and

ferroptosismediated endoplasmic reticulum stress: Implications in

cognitive dysfunction induced by chronic intermittent hypoxia in

mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 138:1125792024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Liu Z, Nan P, Gong Y, Tian L, Zheng Y and

Wu Z: Endoplasmic reticulum stress-triggered ferroptosis via the

XBP1-Hrd1-Nrf2 pathway induces EMT progression in diabetic

nephropathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 164:1148972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Song W, Zhang W, Yue L and Lin W:

Revealing the effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress on

ferroptosis by two-channel real-time imaging of pH and viscosity.

Anal Chem. 94:6557–6565. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ye R, Mao YM, Fei YR, Shang Y, Zhang T,

Zhang ZZ, Liu YL, Li JY, Chen SL and He YB: Targeting ferroptosis

for the treatment of female reproductive system disorders. J Mol

Med (Berl). 103:381–402. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Muckenthaler MU, Rivella S, Hentze MW and

Galy B: A red carpet for iron metabolism. Cell. 168:344–361. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Galy B, Conrad M and Muckenthaler M:

Mechanisms controlling cellular and systemic iron homeostasis. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25:133–155. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Anderson GJ and Frazer DM: Current

understanding of iron homeostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 106(Suppl 6):

1559S–1566S. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gulec S, Anderson GJ and Collins JF:

Mechanistic and regulatory aspects of intestinal iron absorption.

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 307:G397–G409. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Montalbetti N, Simonin A, Kovacs G and

Hediger MA: Mammalian iron transporters: Families SLC11 and SLC40.

Mol Aspects Med. 34:270–287. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Li H, Wang D, Wu H, Shen H, Lv D, Zhang Y,

Lu H, Yang J, Tang Y and Li M: SLC46A1 contributes to hepatic iron

metabolism by importing heme in hepatocytes. Metabolism.

110:1543062020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Mayneris-Perxachs J, Moreno-Navarrete JM

and Fernández Real JM: The role of iron in host-microbiota

crosstalk and its effects on systemic glucose metabolism. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 18:683–698. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Seyoum Y, Baye K and Humblot C: Iron

homeostasis in host and gut bacteria-a complex interrelationship.

Gut Microbes. 13:1–19. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhao H, Tang C, Wang M, Zhao H and Zhu Y:

Ferroptosis as an emerging target in rheumatoid arthritis. Front

Immunol. 14:12608392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M,

Shchepinov MS and Stockwell BR: Peroxidation of polyunsaturated

fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E4966–E4975. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kajarabille N and Latunde-Dada GO:

Programmed cell-death by ferroptosis: Antioxidants as mitigators.

Int J Mol Sci. 20:49682019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang L, Rao J, Liu X, Wang X, Wang C, Fu

S and Xiao J: Attenuation of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by

exogenous H2S via inhibition of ferroptosis. Molecules.

28:47702023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Deng M, Tang F, Chang X, Zhang Y, Liu P,

Ji X, Zhang Y, Yang R, Jiang J, He J and Miao J: A targetable

OSGIN1-AMPK-SLC2A3 axis controls the vulnerability of ovarian

cancer to ferroptosis. NPJ Precis Oncol. 9:152025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Torti SV and Torti FM: Iron and cancer:

more ore to be mined. Nat Rev Cancer. 13:342–355. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Torti SV and Torti FM: Ironing out cancer.

Cancer Res. 71:1511–1514. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Toyokuni S: The origin and future of

oxidative stress pathology: From the recognition of carcinogenesis

as an iron addiction with ferroptosis-resistance to non-thermal

plasma therapy. Pathol Int. 66:245–259. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Basuli D, Tesfay L, Deng Z, Paul B,

Yamamoto Y, Ning G, Xian W, McKeon F, Lynch M, Crum CP, et al: Iron

addiction: A novel therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Oncogene.

36:4089–4099. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Chen Y, Liao X, Jing P, Hu L, Yang Z, Yao

Y, Liao C and Zhang S: Linoleic acid-glucosamine hybrid for

endogenous iron-activated ferroptosis therapy in high-grade serous

ovarian cancer. Mol Pharm. 19:3187–3198. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Piskounova E, Agathocleous M, Murphy MM,

Hu Z, Huddlestun SE, Zhao Z, Leitch AM, Johnson TM, DeBerardinis RJ

and Morrison SJ: Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by

human melanoma cells. Nature. 527:186–191. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Bauckman K, Haller E, Taran N, Rockfield

S, Ruiz-Rivera A and Nanjundan M: Iron alters cell survival in a

mitochondria-dependent pathway in ovarian cancer cells. Biochem J.

466:401–413. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Xu X, Wang Y, Guo W, Zhou Y, Lv C, Chen X

and Liu K: The significance of the alteration of 8-OHdG in serous

ovarian carcinoma. J Ovarian Res. 6:742013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Valavanidis A, Vlachogianni T and Fiotakis

C: 8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG): A critical biomarker of

oxidative stress and carcinogenesis. J Environ Sci Health C Environ

Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 27:120–139. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Prat J, D'Angelo E and Espinosa I: Ovarian

carcinomas: At least five different diseases with distinct

histological features and molecular genetics. Hum Pathol. 80:11–27.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Shen J, Sheng X, Chang Z, Wu Q, Wang S,

Xuan Z, Li D, Wu Y, Shang Y, Kong X, et al: Iron metabolism

regulates p53 signaling through direct heme-p53 interaction and

modulation of p53 localization, stability, and function. Cell Rep.

7:180–193. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Deng Z, Manz DH, Torti SV and Torti FM:

Effects of ferroportin-mediated iron depletion in cells

representative of different histological subtypes of prostate

cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal. 30:1043–1061. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

64

|

Hann HW, Stahlhut MW and Blumberg BS: Iron

nutrition and tumor growth: Decreased tumor growth in

iron-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 48:4168–4170. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

White S, Taetle R, Seligman PA, Rutherford

M and Trowbridge IS: Combinations of anti-transferrin receptor

monoclonal antibodies inhibit human tumor cell growth in vitro and

in vivo: Evidence for synergistic antiproliferative effects. Cancer

Res. 50:6295–6301. 1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sandoval-Acuña C, Torrealba N, Tomkova V,

Jadhav SB, Blazkova K, Merta L, Lettlova S, Adamcová MK, Rosel D,

Brábek J, et al: Targeting mitochondrial iron metabolism suppresses

tumor growth and metastasis by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction

and mitophagy. Cancer Res. 81:2289–2303. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Moon EJ, Mello SS, Li CG, Chi JT, Thakkar

K, Kirkland JG, Lagory EL, Lee IJ, Diep AN, Miao Y, et al: The HIF

target MAFF promotes tumor invasion and metastasis through IL11 and

STAT3 signaling. Nat Commun. 12:43082021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Wang X, Du ZW, Xu TM, Wang XJ, Li W, Gao

JL, Li J and Zhu H: HIF-1α is a rational target for future ovarian

cancer therapies. Front Oncol. 11:7851112021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Benyamin B, Esko T, Ried JS, Radhakrishnan

A, Vermeulen SH, Traglia M, Gögele M, Anderson D, Broer L, Podmore

C, et al: Novel loci affecting iron homeostasis and their effects

in individuals at risk for hemochromatosis. Nat Commun. 5:49262014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wu J, Bao L, Zhang Z and Yi X: Nrf2

induces cisplatin resistance via suppressing the iron export

related gene SLC40A1 in ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget.

8:93502–93515. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Szymonik J, Wala K, Górnicki T, Saczko J,

Pencakowski B and Kulbacka J: The impact of iron chelators on the

biology of cancer stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 23:892021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Wang L, Li X, Mu Y, Lu C, Tang S, Lu K,

Qiu X, Wei A, Cheng Y and Wei W: The iron chelator desferrioxamine

synergizes with chemotherapy for cancer treatment. J Trace Elem Med

Biol. 56:131–138. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Greenshields AL, Shepherd TG and Hoskin

DW: Contribution of reactive oxygen species to ovarian cancer cell

growth arrest and killing by the anti-malarial drug artesunate. Mol

Carcinog. 56:75–93. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Yang ND, Tan SH, Ng S, Shi Y, Zhou J, Tan

KS, Wong WS and Shen HM: Artesunate induces cell death in human

cancer cells via enhancing lysosomal function and lysosomal

degradation of ferritin. J Biol Chem. 289:33425–33441. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Cheng Y, Qu W, Li J, Jia B, Song Y, Wang

L, Rui T, Li Q and Luo C: Ferristatin II, an iron uptake inhibitor,

exerts neuroprotection against traumatic brain injury via

suppressing ferroptosis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 13:664–675. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Zhang Y, He F, Hu W, Sun J, Zhao H, Cheng

Y, Tang Z, He J, Wang X, Liu T, et al: Bortezomib elevates

intracellular free Fe2+ by enhancing NCOA4-mediated

ferritinophagy and synergizes with RSL-3 to inhibit multiple

myeloma cells. Ann Hematol. 103:3627–3637. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Ma S, Henson ES, Chen Y and Gibson SB:

Ferroptosis is induced following siramesine and lapatinib treatment

of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 7:e23072016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Mortensen MS, Ruiz J and Watts JL:

Polyunsaturated fatty acids drive lipid peroxidation during

ferroptosis. Cells. 12:8042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Liu S, Yang X, Zheng S, Chen C, Qi L, Xu X

and Zhang D: Research progress on the use of traditional Chinese

medicine to treat diseases by regulating ferroptosis. Genes Dis.

12:1014512024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Rodencal J and Dixon SJ: A tale of two

lipids: Lipid unsaturation commands ferroptosis sensitivity.

Proteomics. 23:e21003082023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S,

Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, et al: Oxidized

arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem

Biol. 13:81–90. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Forcina GC and Dixon SJ: GPX4 at the

crossroads of lipid homeostasis and ferroptosis. Proteomics.

19:e18003112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Yin H, Xu L and Porter NA: Free radical

lipid peroxidation: Mechanisms and analysis. Chem Rev.

111:5944–5972. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Murphy MP: How mitochondria produce

reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 417:1–13. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Zheng J and Conrad M: The metabolic

underpinnings of ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 32:920–937. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Chen J, Duan Z, Deng L, Li L, Li Q, Qu J,

Li X and Liu R: Cell membrane-targeting type I/II photodynamic

therapy combination with FSP1 inhibition for ferroptosis-enhanced

photodynamic immunotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 13:e23044362024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wang Q, Ji H, Hao Y, Jia D, Ma H, Song C,

Qi H, Li Z and Zhang C: Illumination of hydroxyl radical generated

in cells during ferroptosis, Arabidopsis thaliana, and mice using a

new turn-on near-infrared fluorescence probe. Anal Chem.

96:20189–20196. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Sun M, Chen Q, Ren Y, Zhuo Y, Xu S, Rao H,

Wu D, Feng B and Wang Y: CoNiCoNC tumor therapy by two-ways

producing H2O2 ferroptosis. J to aggravate

energy metabolism, chemokinetics, and Colloid Interface Sci.

678:925–937. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Liang KA, Chih HY, Liu IJ, Yeh NT, Hsu TC,

Chin HY, Tzang BS and Chiang WH: Tumor-targeted delivery of

hyaluronic acid/polydopamine-coated Fe2+-doped

nano-scaled metal-organic frameworks with doxorubicin payload for

glutathione depletion-amplified chemodynamic-chemo cancer therapy.

J Colloid Interface Sci. 677:400–415. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Stockwell BR: Ferroptosis turns 10:

Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic

applications. Cell. 185:2401–2421. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Foret MK, Lincoln R, Do Carmo S, Cuello AC

and Cosa G: Connecting the 'Dots': From free radical lipid

autoxidation to cell pathology and disease. Chem Rev.

120:12757–12787. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Stoyanovsky DA, Tyurina YY, Shrivastava I,

Bahar I, Tyurin VA, Protchenko O, Jadhav S, Bolevich SB, Kozlov AV,

Vladimirov YA, et al: Iron catalysis of lipid peroxidation in

ferroptosis: Regulated enzymatic or random free radical reaction?

Free Radic Biol Med. 133:153–161. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

95

|

Kuang F, Liu J, Xie Y, Tang D and Kang R:

MGST1 is a redox-sensitive repressor of ferroptosis in pancreatic

cancer cells. Cell Chem Biol. 28:765–775.e5. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Chu B, Kon N, Chen D, Li T, Liu T, Jiang

L, Song S, Tavana O and Gu W: ALOX12 is required for p53-mediated

tumour suppression through a distinct ferroptosis pathway. Nat Cell

Biol. 21:579–591. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Ou Y, Wang SJ, Li D, Chu B and Gu W:

Activation of SAT1 engages polyamine metabolism with p53-mediated

ferroptotic responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113:E6806–E6812.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Zhang S, Liu Q, Chang M, Pan Y, Yahaya BH,

Liu Y and Lin J: Chemotherapy impairs ovarian function through

excessive ROS-induced ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 14:3402023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Xu R, Wang W and Zhang W: Ferroptosis and

the bidirectional regulatory factor p53. Cell Death Discov.

9:1972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Kuang F, Liu J, Tang D and Kang R:

Oxidative damage and antioxidant defense in ferroptosis. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 8:5865782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Liu Y, Lu S, Wu LL, Yang L, Yang L and

Wang J: The diversified role of mitochondria in ferroptosis in

cancer. Cell Death Dis. 14:5192023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, Lambros M,

Gout PW, Kalivas PW, Massie A, Smolders I, Methner A, Pergande M,

et al: The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(-) in health

and disease: From molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic

opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 18:522–555. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

103

|

Hu S, Chu Y, Zhou X and Wang X: Recent

advances of ferroptosis in tumor: From biological function to

clinical application. Biomed Pharmacother. 166:1154192023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME,

Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji

AF, Clish CB, et al: Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by

GPX4. Cell. 156:317–331. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Li D, Zhang M and Chao H: Significance of

glutathione peroxidase 4 and intracellular iron level in ovarian

cancer cells-'utilization' of ferroptosis mechanism. Inflamm Res.

70:1177–1189. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Sun X, Niu X, Chen R, He W, Chen D, Kang R

and Tang D: Metallothionein-1G facilitates sorafenib resistance

through inhibition of ferroptosis. Hepatology. 64:488–500. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Guan J, Lo M, Dockery P, Mahon S, Karp CM,

Buckley AR, Lam S, Gout PW and Wang YZ: The xc-cystine/glutamate

antiporter as a potential therapeutic target for small-cell lung

cancer: Use of sulfasalazine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

64:463–472. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T,

Hibshoosh H, Baer R and Gu W: Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated

activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 520:57–62. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Yuan J, Wang J, Song M, Zhao Y, Shi Y and

Zhao L: Brain-targeting biomimetic disguised manganese dioxide

nanoparticles via hybridization of tumor cell membrane and bacteria

vesicles for synergistic chemotherapy/chemodynamic therapy of

glioma. J Colloid Interface Sci. 676:378–395. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Luo Y, Liu X, Chen Y, Tang Q, He C, Ding

X, Hu J, Cai Z, Li X, Qiao H and Zou Z: Targeting PAX8 sensitizes

ovarian cancer cells to ferroptosis by inhibiting glutathione

synthesis. Apoptosis. 29:1499–1514. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Li FJ, Long HZ, Zhou ZW, Luo HY, Xu SG and

Gao LC: System Xc -/GSH/GPX4 axis: An important

antioxidant system for the ferroptosis in drug-resistant solid

tumor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 13:9102922022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Okuno S, Sato H, Kuriyama-Matsumura K,

Tamba M, Wang H, Sohda S, Hamada H, Yoshikawa H, Kondo T and Bannai

S: Role of cystine transport in intracellular glutathione level and

cisplatin resistance in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Br J

Cancer. 88:951–956. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Wang W, Kryczek I, Dostál L, Lin H, Tan L,

Zhao L, Lu F, Wei S, Maj T, Peng D, et al: Effector T cells

abrogate stroma-mediated chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Cell.

165:1092–1105. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong

L, Ford B, Tang PH, Roberts MA, Tong B, Maimone TJ, Zoncu R, et al:

The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit

ferroptosis. Nature. 575:688–692. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M,

da Silva MC, Ingold I, Goya Grocin A, Xavier da Silva TN, Panzilius

E, Scheel CH, et al: FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis

suppressor. Nature. 575:693–698. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Tesfay L, Paul BT, Konstorum A, Deng Z,

Cox AO, Lee J, Furdui CM, Hegde P, Torti FM and Torti SV:

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 protects ovarian cancer cells from

ferroptotic cell death. Cancer Res. 79:5355–5366. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Shimada K, Skouta R, Kaplan A, Yang WS,

Hayano M, Dixon SJ, Brown LM, Valenzuela CA, Wolpaw AJ and

Stockwell BR: Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals

metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 12:497–503.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Yang N, Pan X, Zhou X, Liu Z, Yang J,

Zhang J, Jia Z and Shen Q: Biomimetic nanoarchitectonics with

chitosan nanogels for collaborative induction of ferroptosis and

anticancer immunity for cancer therapy. Adv Healthc Mater.

13:e23027522024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Liu MR, Shi C, Song QY, Kang MJ, Jiang X,

Liu H and Pei DS: Sorafenib induces ferroptosis by promoting

TRIM54-mediated FSP1 ubiquitination and degradation in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 7:e02462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Kraft VAN, Bezjian CT, Pfeiffer S,

Ringelstetter L, Müller C, Zandkarimi F, Merl-Pham J, Bao X,

Anastasov N, Kössl J, et al: GTP cyclohydrolase

1/tetrahydrobiopterin counteract ferroptosis through lipid

remodeling. ACS Cent Sci. 6:41–53. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Ge A, Xiang W, Li Y, Zhao D, Chen J, Daga

P, Dai CC, Yang K, Yan Y, Hao M, et al: Broadening horizons: The

multifaceted role of ferroptosis in breast cancer. Front Immunol.

15:14557412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Wang M, Liu J, Yu W, Shao J, Bao Y, Jin M,

Huang Q and Huang G: Gambogenic acid suppresses malignant

progression of non-small cell lung cancer via GCH1-mediated

ferroptosis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 18:3742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Werner ER, Blau N and Thöny B:

Tetrahydrobiopterin: Biochemistry and pathophysiology. Biochem J.

438:397–414. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

NaveenKumar SK, Hemshekhar M, Kemparaju K

and Girish KS: Hemin-induced platelet activation and ferroptosis is

mediated through ROS-driven proteasomal activity and inflammasome

activation: Protection by melatonin. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis

Dis. 1865:2303–2316. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Homma T, Kobayashi S, Conrad M, Konno H,

Yokoyama C and Fujii J: Nitric oxide protects against ferroptosis

by aborting the lipid peroxidation chain reaction. Nitric Oxide.

115:34–43. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Jiang L, Zheng H, Lyu Q, Hayashi S, Sato

K, Sekido Y, Nakamura K, Tanaka H, Ishikawa K, Kajiyama H, et al:

Lysosomal nitric oxide determines transition from autophagy to

ferroptosis after exposure to plasma-activated Ringer's lactate.

Redox Biol. 43:1019892021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|