Ion channels are a major class of membrane proteins

that are sensitive to a variety of stimuli, including changes in

membrane potential, ligand binding, temperature fluctuations and

mechanical forces (1). These

stimuli trigger conformational changes in the protein, leading to

the formation of gated ion-permeable pores in biological membranes,

which facilitate the passive diffusion of ions along their

respective electrochemical gradients both across the cell membrane

and between intracellular compartments. Ion channels contribute to

the regulation of various processes, such as the maintenance of

cellular osmotic pressure and membrane potential, motility (through

interactions with the cytoskeleton), invasion, signal transduction,

transcriptional activity and cell cycle progression, all of which

can lead to tumor progression and metastasis (2). Their central role in intracellular

and intercellular signaling also facilitates the coupling of

extracellular events to cellular responses (3).

Over the past decade, interest in the study of ion

channels in digestive disorders has increased. The literature

suggests that dysregulated ion channel activity plays a pathogenic

role in various digestive diseases, including cancer. For instance,

dysfunction of ion channels and transporter proteins can lead to

gastrointestinal mucosal damage, such as disruption of the

bicarbonate and mucosal layers (4-7),

loss of epithelial cells (8,9),

atrophy of glandular mucosa (10), loss of tight junction (TJ)

proteins (11-13), imbalances in the gut flora

(14) and changes in mucosal

blood flow (15). These

alterations contribute to gastrointestinal mucosal diseases,

including gastritis, ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease and

gastrointestinal cancers (16).

Ion channels and transporter proteins have been

reported to be crucial for maintaining both the exocrine and

endocrine functions of the pancreas. They facilitate enzymatic

reactions necessary for the digestion of fats and proteins in the

intestines, while also facilitating the secretion of

bicarbonate-rich fluids (17,18). Pancreatic islet β-cells express a

variety of ion channels located in lipid membranes or subcellular

organelles, which are collectively involved in glucose-dependent

insulin secretion. Consequently, dysfunction of these ion channels

and transporter proteins can result in pancreatic injury,

potentially leading to conditions such as pancreatitis, diabetes

mellitus, pancreatic cystic fibrosis (CF) and an increased risk of

pancreatic cancer (19,20).

In addition, the role of ion channels and

transporter proteins in liver diseases has garnered considerable

attention. For instance, dysfunction of various calcium channels

can disrupt intraand extracellular calcium homeostasis, leading to

endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and the

inhibition of autophagy in hepatocytes, all of which contribute to

the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

(21). Ion channels intersect

with multiple signaling pathways, promoting hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) cell invasion and metastasis by modulating gene

expression, regulating cell proliferation and triggering

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (22). In addition, ion channels and

transporter proteins also regulate the growth and invasion of

esophageal cancer (EC) (23-25).

As mentioned above, ion channels and transporter

proteins play critical roles in regulating pathophysiological

processes in various organs of the digestive system. While numerous

studies have extensively investigated the role of cation channels,

particularly calcium channels (26-32), sodium channels (33-36) and potassium channels (37-39), anion channels have received

comparatively less attention. Anion channels (40,41) have been identified as important

molecules with aberrant expression, activity and localization in

various pathological conditions, including cardiovascular diseases,

neurological disorders, metabolic diseases and cancer.

As the primary anion in the human body,

intracellular chloride concentrations are dynamically regulated

(42) and play a crucial role in

maintaining intracellular and osmotic homeostasis, primarily

through transmembrane transport and ion channels (43). Chloride channels have been

implicated in a variety of pathological diseases (44). These channels and transport

proteins are located both in the plasma membrane and intracellular

membranes, with functions ranging from ion homeostasis and cell

volume regulation to transepithelial transport and electrical

excitability regulation (45).

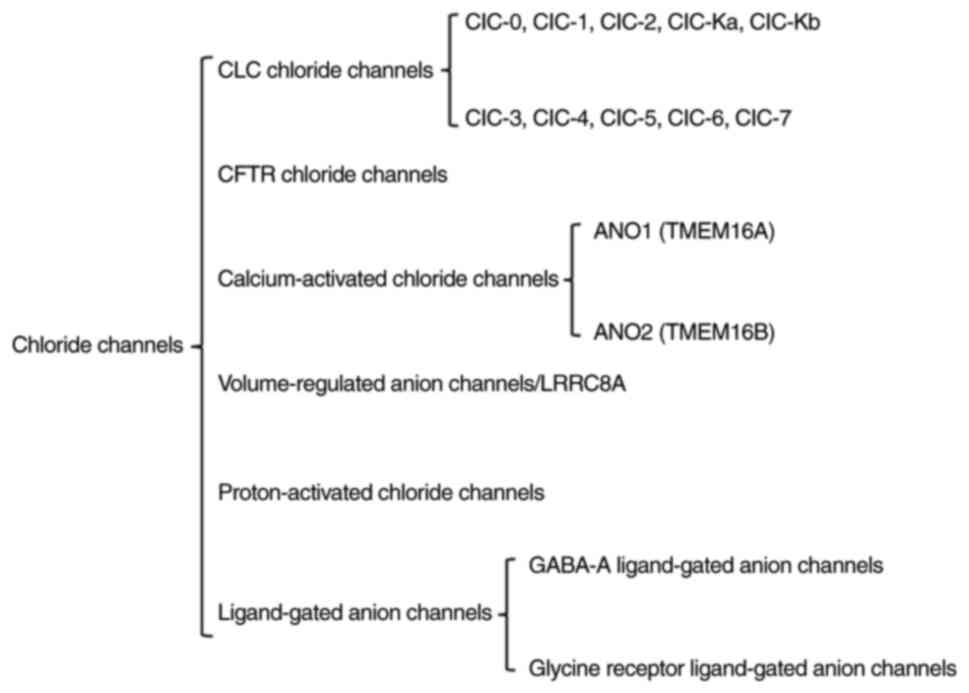

Chloride ions are regulated by chloride channels for their intra-

and extracellular distribution and transport. Chloride channels are

currently classified into several groups (Fig. 1), including the chloride channel

(ClC) family, CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR),

calcium-activated chloride channels (CaCCs), volume-regulated anion

channels (VRACs), proton-activated chloride channels (PACs)

(46) and ligand-gated anion

channels (47). Chloride

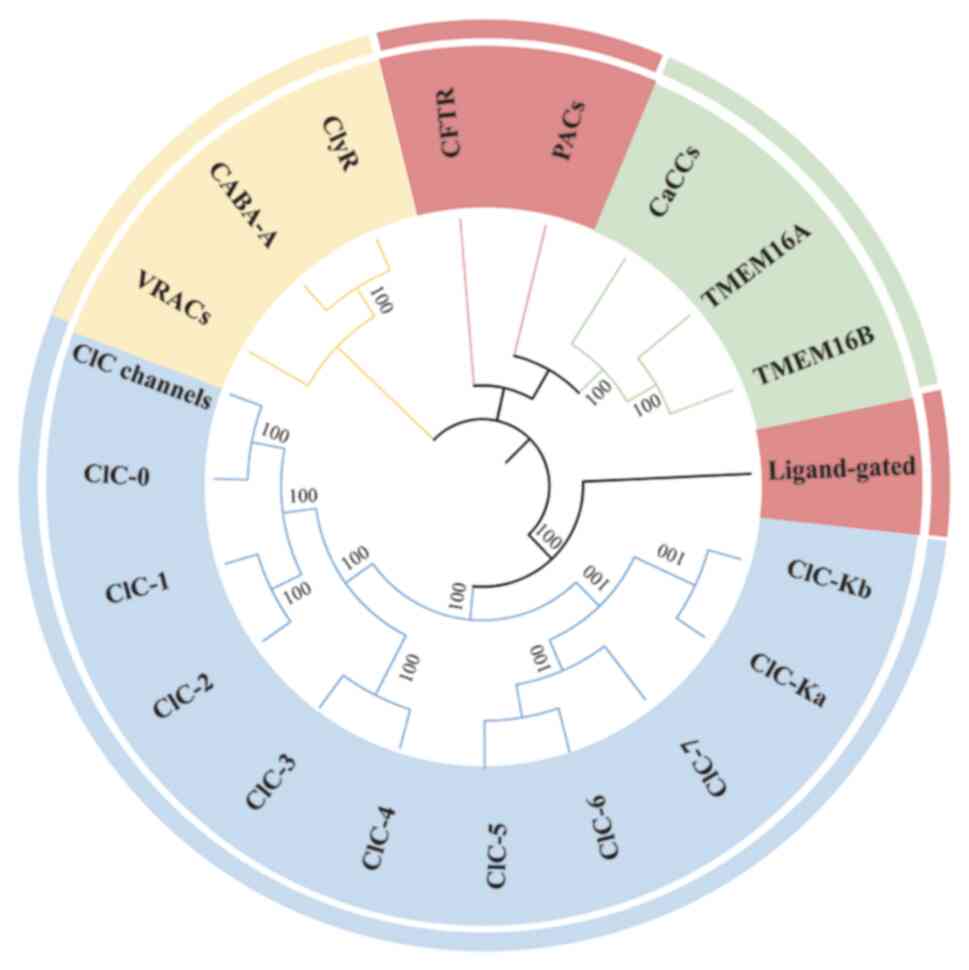

channels have undergone significant functional differentiation and

diversification during evolution and are distributed from

prokaryotes to higher vertebrates (Fig. 2). The ClC family is one of the

evolutionarily oldest classes of chloride channels and is

widespread in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (48). During evolution, the ClC family

differentiated into voltage-gated chloride channels and

chloride/proton exchangers. In vertebrates, the ClC family has

further differentiated into several isoforms (e.g., ClC-1 to -7),

which are involved in the regulation of cell membrane potential or

chloride homeostasis of intracellular organelles (49). Among CaCCs, anoctamin (ANO)1 has

been extensively studied. ANO1 [transmembrane protein (TMEM)16A]

belongs to the anoctamin family and is found in both invertebrates

and vertebrates (50). ANO1 may

have initially evolved as a lipid scramblase, and subsequently

gained calcium-activated chloride channel function. In mammals,

ANO1 is expressed in a variety of tissues and is involved in

secretion, smooth muscle contraction and signaling (51). CFTR belongs to the ATP-binding

cassette (ABC) superfamily of transporter proteins and is a

vertebrate-specific chloride channel (52). CFTR has evolved to acquire a

unique regulatory domain (R-domain) that allows it to be activated

by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation (53). PACs/TMEM206 belongs to a family

of transmembrane proteins, TMEM, that are highly conserved in

vertebrates. No direct homologs have been identified in

invertebrates, but functionally similar channels may exist in some

lower organisms. In mammals, PACs are expressed in a variety of

tissues, particularly in the brain, lungs and kidneys, and may be

associated with pathological processes related to acidosis. PACs

may have evolved as an adaptive mechanism for cells to cope with

acidic environments, and are involved in maintaining intracellular

pH homeostasis (54).

Ligand-gated anion channels belong to the Cys-loop ligand-gated ion

channel superfamily and share a common ancestor with related

channels in invertebrates, such as glutamate-gated chloride

channels (55). In vertebrates,

gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABA-A) and glycine

receptor (GlyR) mediate inhibitory neurotransmission (56) (Fig. 2). Of note, in a study

investigating chloride channels in an in vivo porcine model

of esophageal acid damage, ClC-2 was found to localize to the basal

epithelium of the porcine esophageal mucosa and esophageal

submucosal glands. Chloride intracellular channel protein 1

recruited phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinases to lipid

membranes, which, in turn, regulate cell-matrix adhesion and

membrane protrusion, contributing to tumor aggressiveness,

metastasis and a poor prognosis (57).

To date, there has been no comprehensive review of

the role of chloride ion channels in digestive system diseases.

Therefore, the aim of this review was to compile and summarize the

physiopathological roles of chloride channels and transporter

proteins in digestive system diseases, with the goal of providing a

solid theoretical foundation for future research and offering new

perspectives for the treatment of these diseases.

The ClC channel exists as a dimer, with each monomer

forming a separate ion-conducting pore, and each monomer contains

18 alpha helices, some of which form ion-conducting pores (49). The ClC family comprises ClC-0,

ClC-1, ClC-2, ClC-Ka, ClC-Kb, ClC-3, ClC-4, ClC-5, ClC-6 and ClC-7.

On the basis of their distribution, ClC-0, ClC-1, ClC-2, ClC-Ka and

ClC-Kb are plasma membrane channels, whereas the others are

intracellular membrane channels. Functionally, ClC-1, ClC-2, ClC-Ka

and ClC-Kb are voltage-gated chloride channels, whereas the

remaining members act as Cl−/H+ exchangers.

The ClC family is involved in several key functions, including

volume regulation, ion dynamic homeostasis, transepithelial

transport and the regulation of electrical excitability. ClC-2, a

voltage-gated chloride channel composed of 907 amino acids with a

molecular weight of 99 kDa, features a two-pore homodimeric

structure (58,59). Its activity is regulated by

changes in the extracellular pH, displaying a biphasic response.

ClC-2 is activated by moderate acidification but abruptly shuts

down when the pH drops below ~7.

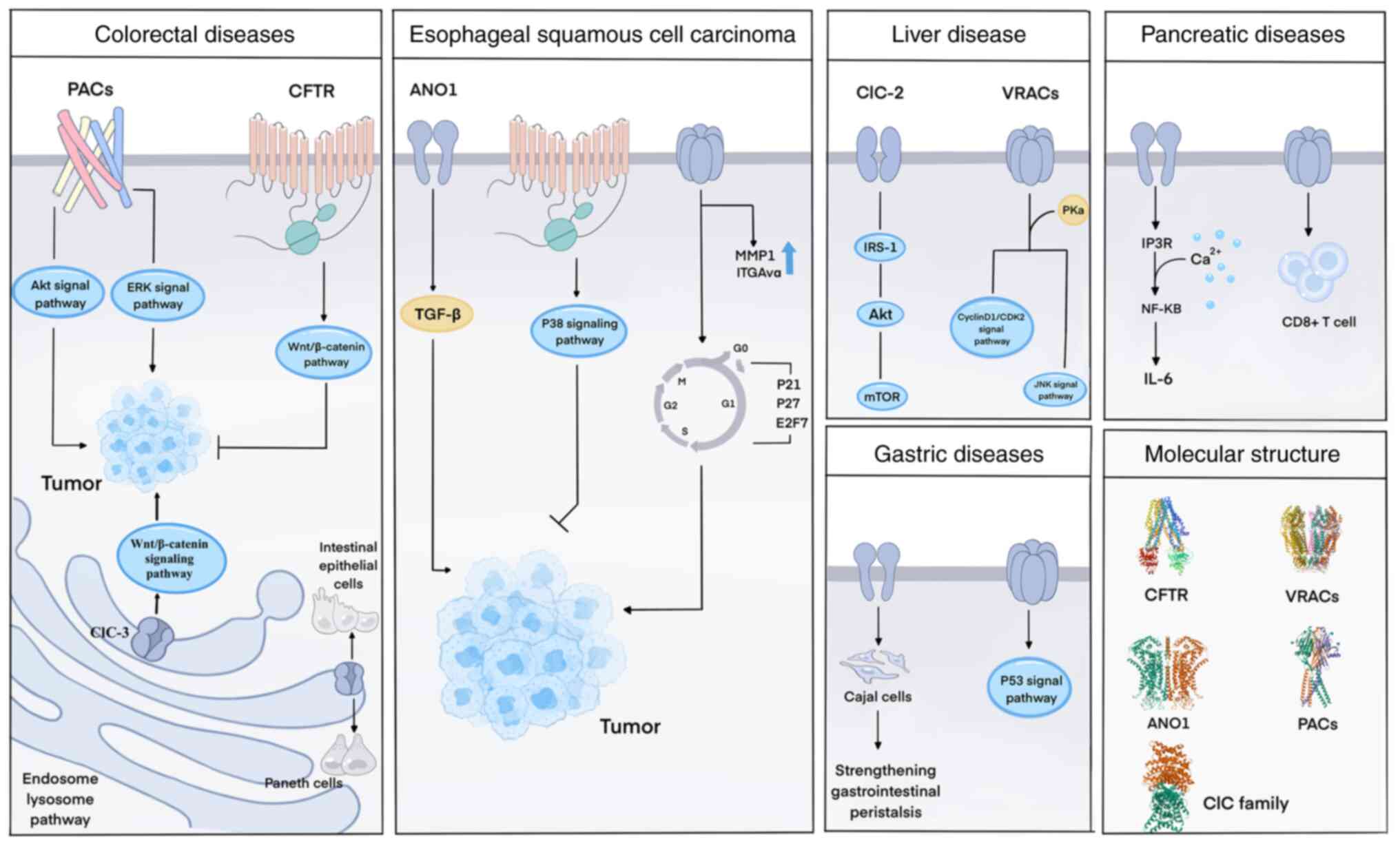

ClC-2 mRNA levels are significantly elevated in

patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and mice lacking ClC-2

exhibit a beneficial metabolic phenotype, suggesting that reducing

or knocking down ClC-2 may be a potential strategy for treating

NAFLD and further research revealed that ClC-2 downregulated the

activation of IRS-1/Akt/mTOR signaling (60) (Fig. 3).

Chloride channels also play a critical role in

intestinal diseases. The intestinal barrier, which is essential for

nutrient absorption and preventing the entry of harmful substances,

consists of epithelial cells connected by apical junction

complexes, comprising TJs and adherens junctions (AJs) (61,62). In a ClC-2 knockout mouse model,

the absence of ClC-2 delayed recovery of intestinal barrier

function after ischemic injury, possibly because ClC-2 anchors the

TJ structure following injury (63). Additionally, disruption of AJs

affected colon homeostasis and differentiation, promoting

tumorigenicity through the regulation of β-catenin signaling

(64). Furthermore, genetic

inactivation variants in the ClC-Ka and ClC-Kb genes have been

associated with renal salt-losing nephropathies, with or without

deafness, including the rare Bartter's syndrome (BS) (65), highlighting the crucial role of

the ClC-Ka and ClC-Kb genes in renal and inner ear chloride

processing (66); however, to

the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have explored the

role of these chloride channels in digestive diseases.

ClC-3 plays an important role in cancer regulation

as a volume-regulated anion channel that also controls the cell

cycle and is overexpressed in various cancers. ClC-3 can promote

the development and metastasis of colorectal cancer (CRC) through

the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (67) (Fig. 3). In a study on prognostic

biomarkers in gastric cancer (GC), high expression of ClC-3 was

associated with deeper tumor invasion and increased lymph node

metastasis, with overexpression of ClC-3 being regulated by x-ray

repair cross complementing 5 (68). ClC-3 is also significantly

overexpressed in HCC, and its upregulation is associated with tumor

size and overall prognosis, suggesting that ClC-3 expression may

serve as a predictor of tumor size and overall prognosis in HCC

(69). Furthermore, ClC-3 has

been reported to be expressed in intestinal tissues and to be

involved in the regulation of intestinal inflammation (70). ClC-3 deficiency may exacerbate

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) by promoting the apoptosis of

intestinal epithelial cells and causing Paneth cell deficiency

(Fig. 3), indicating that

modulating ClC-3 expression could be a novel therapeutic strategy

for treating IBD (71).

ClC-3 to ClC-7 are located primarily in

intracellular organelles, particularly along the endosome-lysosome

pathway, and are distributed differentially across compartments

(43,72-74). ClC-4 localizes to various

endosomal clusters, whereas ClC-5 is predominantly expressed in the

kidney, where it localizes to early endosomes and participates in

endocytic uptake in the proximal tubule. Both ClC-3 and ClC-4 are

widely expressed and found in various endosomal populations. ClC-6

is expressed primarily in neurons and localizes to late endosomes,

whereas ClC-7, along with its β-subunit osteopetrosis-associated

transmembrane protein 1, localizes to lysosomes in all cell types

and is also found at the ruffled borders of bone-resorbing

osteoclasts. Dysfunction of ClC-3, ClC-4, ClC-6 and ClC-7 has been

linked to intellectual disability, epilepsy, lysosomal storage

disorders and neurodegeneration, respectively (75-77). However, to the best of our

knowledge, their roles in digestive disorders have not yet been

reported.

Mutations in the CFTR gene lead to CF due to CFTR

dysfunction. This gene encodes an anion channel that mediates the

transport of chloride (Cl−) and bicarbonate

(HCO3−) across epithelial surfaces, which is

crucial for osmotic homeostasis and the maintenance of normal

electrolyte transport in the lungs, upper respiratory tract,

pancreas, liver, gallbladder, intestine and other exocrine glands

on the apical surface of epithelial cells (80). While the CFTR protein is located

primarily in the plasma membrane, increasing evidence suggests its

presence in intracellular organelles such as endosomes, lysosomes,

phagosomes and mitochondria. Dysfunction of CFTR not only impairs

ion transport across epithelial tissues but also disrupts the

normal functioning of these organelles (81).

Following CFTR dysfunction, bicarbonate ion

transport is inhibited, disrupting the pH balance of the esophageal

epithelium. This imbalance can result in cellular stress, DNA

damage and increased susceptibility to carcinogenesis. In

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), overexpression of CFTR

was found to activate the p38 signaling pathway, which inhibits

cell proliferation, migration and invasion; induces apoptosis; and

is associated with a favorable patient prognosis (82). In esophageal cancer,

gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit pi(GABRP) promoted CFTR

expression, and CFTR knockdown significantly counteracted the

inhibitory effects of GABRP overexpression on EC cell

proliferation, migration and invasion. These findings suggest that

GABRP overexpression inhibits EC progression by increasing CFTR

expression (83). Therefore,

CFTR may act as a mediator and/or biomarker for ESCC (82). In addition, CFTR has been shown

to inhibit the growth and migration of ESCC by downregulating NF-κB

protein expression (23). CFTR

modulators improve gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms in

patients with advanced CF (84).

One of the specific reasons for this is that CFTR modulators

improve gastroduodenal pH (85),

in addition, CFTR is expressed in esophageal tissues and CFTR

modulators may have a direct effect on esophageal motility and

gastric emptying (82).

Pancreatitis is a common cause of hospitalization

for digestive diseases, with high morbidity and mortality rates

(86). It is a complex

inflammatory disease of the acinar and ductal epithelium that is

often caused by the premature activation of digestive enzymes

(87). There is substantial

evidence that CFTR plays a critical role as an anion transporter in

maintaining normal pancreatic exocrine function. Dysfunction of

CFTR triggers pancreatic disorders, including impaired insulin

regulation, pancreatic ductal obstruction, acute and chronic

inflammation and carcinogenesis (88,89). However, the specific

pathophysiological mechanisms remain to be fully understood.

In the pancreas, digestive enzymes play a well-known

role; however, electrolytes are equally important as carriers,

helping to transport enzymes to the small intestine, neutralize

gastric acid and increase the duodenal pH to the optimal level for

enzyme activity (90). In

particular, bicarbonate (HCO3−) secretion is

essential, as it regulates the pH of the ductal epithelium,

increases mucin secretion (which acts as an antimicrobial) and

prevents the premature activation of pancreatic enzymes (91). CFTR is a key player in

HCO3− secretion in pancreatic fluid. This

secretion involves the coordinated action of ion-transporting

proteins located on the basolateral and luminal membranes of

pancreatic ductal cells (PDCs). HCO3− can

accumulate via electrogenic sodium-bicarbonate cotransporter

1 (NBCe1), the solute carrier family 4 member 4 (SLC4A4)

cotransporter protein, which is produced intracellularly through

the carbonic anhydrase-catalyzed reaction of CO2 and

water. It is then secreted into the ductal lumen via the

coordinated action of CFTR and SLC26A6 (91,92). CFTR not only functions in

conjunction with SLC26A6 but its R domain also binds to the spread

through air spaces domain of SLC26A6, further regulating

HCO3− secretion (93,94). CFTR channels directly mediate

epithelial HCO3− transport and selectively

secrete HCO3− when intracellular

Cl− levels are low and HCO3−

levels are relatively high (95). The dynamic regulation of CFTR

anion conductance is thought to be mediated by With No Lysine

Kinase (WNK) (18). WNK1, for

example, has been shown to activate oxidative stress-responsive

kinase 1 and STE20/SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK)

at low extracellular Cl− concentrations, significantly

increasing HCO3− secretion in

CFTR-transfected 293 cells and guinea pig PDCs (96). However, WNK1 and WNK4 can also

inhibit CFTR by reducing its level at the cell surface, thus

inhibiting CFTR-mediated anion efflux (97). This inhibition is counteracted by

the binding of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor,

with released IP3 antagonizing the WNK/SPAK pathway (98). IRBIT, through its PDZ domain,

binds to CFTR and NBCe1 at the apical and basolateral membranes,

recruiting protein phosphatase 1 to counteract SPAK-mediated

phosphorylation of CFTR and NBCe1 (99).

In addition, patients with CF are at increased risk

of developing various types of cancer, particularly

gastrointestinal cancers (104). A study involving 1,468

heterozygous germline carriers of the CFTR F508del mutation

revealed an increased risk of GC in this population. Another report

showed that serum CFTR levels in patients with GC correlated with

the expression of the tumor biomarker CA199 (105). A study by Yamada et al

(106) further highlighted that

patients with CF have a significantly increased risk of

gastrointestinal cancers, including small bowel cancer, and

recommended the development of individualized screening protocols

for site-specific gastrointestinal cancers in this population.

CFTR is expressed throughout the intestine, with a

decreasing gradient of expression from the proximal (duodenum) to

the distal (ileum) small intestine. In both the small and large

intestines, CFTR is most strongly expressed at the base of the

crypts and can influence intestinal stem cell function. Studies

have demonstrated that CFTR is expressed by intestinal stem cells

(107). The transmembrane

domains of CFTR form water channels that allow Cl− and

HCO3− ions to be secreted from epithelial

cells into the intestinal lumen, particularly within the crypts,

while simultaneously increasing water secretion in the same

direction. This regulates the water homeostasis and pH of the

intestine (108). CFTR also

influences the composition of the intestinal flora (109,110), the maintenance of the

epithelial barrier (111,112), and the balance of innate and

adaptive immune responses (113,114). Clinical manifestations of

gastrointestinal issues in patients with CF, such as inflammation,

chronic abdominal pain and complications such as Crohn's disease

and gastroesophageal reflux disease (115,116), are associated with

dysregulation of these processes, increasing the risk of cancer. A

20-year epidemiologic study reported that patients with CF have an

elevated risk of gastrointestinal cancers with age, particularly a

sixfold increase in the risk of Colorectal Cancer (CRC), the most

common gastrointestinal malignancy in patients with CF (117).

CFTR deficiency has also been linked to CRC in the

general population, with disease-free survival being lower in

patients with CRC with reduced CFTR expression in the tumor

(118). CFTR-depleted CRC cell

lines exhibit enhanced oncogenic features, including increased

colony formation, migration and invasion (119). Increased β-catenin activity,

associated with increased proliferation, has been observed in CFTR

knockout crypt cells and organoids. Although studies on CRC without

CF are limited, Palma et al (120) reported that CFTR may play a

nontumor suppressive role in CRC initiation and progression by

enhancing a set of genes associated with cancer stemness in

patients without CFTR mutations. Mechanistic studies have shown

that CFTR knockdown or transient inhibition by CFTR (inh)-172 leads

to an increase in the intracellular pH of leucine-rich

repeat-containing g-protein coupled receptor 5+ stem cells,

promoting the binding of dishevelled segment polarity protein 2 (a

member of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway) to plasma membrane

phospholipids and thereby enhancing Wnt/β-catenin signaling

(121).

CFTR expression is downregulated in CRC, potentially

due to promoter methylation. Overexpression of CFTR has been shown

to inhibit CRC tumor growth by suppressing cell proliferation,

migration and invasion. Furthermore, CFTR promoter methylation is

significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis, suggesting

that CFTR may serve as a potential marker for lymph node metastasis

in patients with CRC (122).

CaCCs are chloride channels that can be

synergistically activated by intracellular calcium and voltage.

ANO1/TMEM16A contains 8 transmembrane structural domains (TM1-TM8),

of which TM3-TM7 form the ion-conducting pore. The calcium binding

site is located on the cytoplasmic side and contains multiple

acidic residues responsible for calcium ion binding and channel

activation. ANO1 exists as a dimer, with each monomer having a

separate ion-conducting pore (123,124). CaCCs are expressed in both

invertebrates and mammals, suggesting that they play crucial

physiological roles, including regulating epithelial Cl−

secretion, neuronal and cardiomyocyte excitability, smooth muscle

contraction and injury perception (125). The main CaCCs identified so far

are ANO1, also known as TMEM16A, and ANO2, also known as TMEM16B

(126). ANO1 is widely

expressed in various cancers, where it controls cancer cell

proliferation, survival and migration (127). It also regulates the secretory

function of epithelial cells (128) and the electrical pacing

activity of interstitial cells of Cajal in gastrointestinal smooth

muscle (129). By contrast,

ANO2 (TMEM16B), although functioning as a CaCC, is expressed

primarily in olfactory sensory neurons (130), hippocampal pyramidal neurons

(131) and thalamocortical

neurons in the brain (132).

In research on acute pancreatitis (AP), IL-6 was

found to promote TMEM16A (ANO1) expression via IL-6R/STAT3

signaling activation, and overexpression of TMEM16A further

increased IL-6 secretion through the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

receptor/Ca2+/NF-κB signaling pathway (143). Therefore, inhibiting TMEM16A

could represent a novel therapeutic strategy for treating AP. In

addition, studies have identified ANO1 as a prognostic factor after

radical resection of pancreatic carcinoma, where ANO1 may induce an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in a paracrine manner

(144), suggesting that ANO1

could be a potential therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer.

Ion channels have been extensively studied in liver

diseases in recent years, but chloride channels, including TMEM16A

(ANO1), have been less frequently explored. Studies have shown that

TMEM16A expression is elevated in the liver tissues of both mice

and patients with NAFLD. Hepatocyte-specific knockdown of TMEM16A

in mice improved hepatic glucose metabolism disorders and

steatosis. TMEM16A in hepatocytes interacts with vesicle-associated

membrane protein 3 (VAMP3), inducing its degradation and inhibiting

the formation of VAMP3/synaptobrevin complexes, such as

VAMP3/synaptosome-associated protein 23 and VAMP3/syntaxin 4. This

interaction disrupts the translocation of hepatic glucose

transporter protein 2 (GLUT2), leading to impaired glucose uptake.

Notably, VAMP3 overexpression counteracts the inhibitory effect of

TMEM16A on GLUT2 translocation and helps reduce lipid deposition,

insulin resistance and inflammation (145). These findings suggest that

inhibiting hepatic TMEM16A or disrupting the TMEM16A/VAMP3

interaction could offer new therapeutic strategies for NAFLD. Guo

et al (146) reported

that the TMEM16A-glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) interaction and

GPX4 ubiquitination are essential for TMEM16A-regulated hepatic

ischemia/reperfusion injury, suggesting that blockade of the

TMEM16A-GPX4 interaction or inhibition of TMEM16A in hepatocytes

may represent promising therapeutic strategies for acute liver

injury. Kondo et al (147) reported that downregulation of

TMEM16A expression in cirrhotic portal hypertension-associated

portal vein smooth muscle cells reduces Ca2+-activated

Cl− channel activity; it is mediated by the increase in

angiotensin II in cirrhosis. In addition, while ANO1 plays a

regulatory role in various cancers, its role in HCC has been less

studied. TMEM16A is overexpressed in HCC, and the inhibition of

TMEM16A suppresses the MAPK signaling pathway (Fig. 3), reducing HCC growth. These

findings indicate that TMEM16A may serve as a promising therapeutic

target for HCC (148).

VRACs, also known as volume-sensitive outwardly

rectifying channels, regulate vertebrate cell volume by mediating

the extrusion of chloride ions and organic osmolytes. VRACs are

composed of a heterodimer of leucine-rich repeat-containing 8

(LRRC8) proteins, where LRRC8A (also known as SWELL1) serves as an

essential subunit. LRRC8A binds to any of its homologs, such as

LRRC8B-E, to form the hexameric VRACs complex, which functions as

an anion-selective channel. VRACs are activated either by cellular

swelling or by reactive oxygen species, a process dependent on

intracellular ATP (149-151).

VRACs play a crucial role in various physiological processes,

including cell volume regulation, proliferation, migration and

apoptosis (152).

LRRC8A has been shown to influence the growth of GC

cells, and high expression of LRRC8A was identified as an

independent prognostic factor for 5-year survival in patients with

GC on the basis of multivariate analysis of clinical samples.

Further research revealed that knockdown of LRRC8A inhibited cell

proliferation and migration, enhanced apoptosis and affected the

expression of genes associated with the p53 signaling pathway,

including JNK, p53, p21, Bcl-2 and FAS (154).

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD) is a highly

malignant tumor of the digestive system with increasing morbidity

and mortality rates. LRRC8A has been shown to influence the

prognosis of PAAD and to be associated with cell proliferation,

migration, drug resistance and immune infiltration. Notably, LRRC8A

plays a role in the progression and prognosis of patients with PAAD

by regulating the immune infiltration of CD8+ T cells

(155).

SWELL1, an integral component of the VRACs, is

highly expressed in HCC tissues and is associated with poor

prognosis. An in vitro study showed that the overexpression

of SWELL1 significantly promoted cell proliferation and migration

while inhibiting apoptosis. Mechanistically, SWELL1 interacts with

protein kinase Cα, activates the cyclin D1/cyclin-dependent kinase

2 pathway to induce cell growth, and regulates cell migration

through the JNK pathway (156).

LRRC8A was found to be elevated in 60% of CRC

patient tissues, and patients with high LRRC8A expression had

shorter survival times, suggesting that LRRC8A may serve as a novel

prognostic biomarker for CRC. Elevated expression of LRRC8A has

been linked to enhanced cancer cell growth and metastasis (157), whereas downregulation of VRACs

has been shown to inhibit colon cancer cell proliferation (158). Furthermore, one study reported

that LRRC8A contributed to oxaliplatin resistance in colon cancer

cells (159). Of note,

exosomes, which are crucial mediators of intercellular

communication in the tumor microenvironment and accelerate colon

cancer progression, contain LRRC8A. This protein, which is one of

the components of exosomes released from colon cancer HCT116 cells,

is responsible for exosome production and is involved in volume

regulation (160).

Research has reported elevated TMEM206 expression in

CRC tissues compared with adjacent noncancer tissues. TMEM206

promotes CRC cell proliferation, invasion and migration by

increasing the levels of phosphorylated AKT and downstream

signaling components, as well as the level of phosphorylated

extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), facilitating

interactions between the AKT and ERK pathways (163). Bioinformatics analysis revealed

that TMEM206 expression is significantly elevated in CRC, breast

cancer, HCC and lymphoma tissues compared with corresponding normal

tissues, identifying TMEM206 as a potential prognostic biomarker

for HCC (164).

Ligand-gated chloride channels, such as GABA-A and

glycine receptor channels, consist of five subunits that form the

central ionotropic pore. Each subunit contains a characteristic

Cys-loop structural domain involved in ligand binding and channel

gating (165). They primarily

play roles in the development and function of the nervous system

(166). Channelopathies

involving these channels have been linked to neurological disorders

such as Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease and Alzheimer's

disease (167-169). However, to the best of our

knowledge, no studies have explored the role of these channels in

digestive disorders.

Ion channels and transport proteins play crucial

roles in regulating pathophysiological processes across various

organs of the digestive system. In recent years, sodium, calcium

and potassium ion channels have been extensively studied, whereas

chloride channels have received comparatively less attention.

Chloride, the most abundant anion in the body, is regulated

primarily by chloride channels or transporters. Existing studies on

chloride channels have demonstrated their significant role in the

development of numerous digestive system diseases (Table I), including esophagitis,

esophageal cancer, gastrointestinal dyskinesia, gastritis, GC,

colonic diverticulitis, diverticulosis, congenital megacolon, colon

cancer, pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, hepatic lipid metabolism

disorders and HCC. Although the involvement of chloride channels in

the digestive system has been explored, the underlying

physiological and pathological mechanisms within various organs

have not been thoroughly investigated. Most research to date has

focused on verifying the high or low expression of chloride

channels in digestive diseases or their involvement in relevant

signaling pathways, whereas fewer studies have delved into deeper

mechanisms such as transcriptional regulation or posttranslational

modifications. Therefore, further investigations into chloride

channels constitute an important and promising research area that

remains to be fully explored.

Not applicable.

YH wrote the original manuscript and performed the

literature review. BT was responsible for the conceptualization and

review of the study and provided supervision. Both authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

The authors thank Professor Hui Dong (Department of

Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego

University, San Diego, USA) for providing guidance in the writing

of the paper.

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81960507),

the Basic Research Projects of Science and Technology Department of

Guizhou Province (grant code, Qian Ke He-zk[2022]-646) and the 2023

Graduate Research Fund Program B (grant no. ZYK248).

|

1

|

Nguyen HX and Bursac N: Ion channel

engineering for modulation and de novo generation of electrical

excitability. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 58:100–107. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Capatina AL, Lagos D and Brackenbury WJ:

Targeting ion channels for cancer treatment: Current progress and

future challenges. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 183:1–43.

2022.

|

|

3

|

Bulk E, Todesca LM and Schwab A: Ion

channels in lung cancer. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 181:57–79.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Xiao F, Yu Q, Li J, Johansson ME, Singh

AK, Xia W, Riederer B, Engelhardt R, Montrose M, Soleimani M, et

al: Slc26a3 deficiency is associated with loss of colonic HCO3 (-)

secretion, absence of a firm mucus layer and barrier impairment in

mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 211:161–175. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zahn A, Moehle C, Langmann T, Ehehalt R,

Autschbach F, Stremmel W and Schmitz G: Aquaporin-8 expression is

reduced in ileum and induced in colon of patients with ulcerative

colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 13:1687–1695. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Xu H, Zhang B, Li J, Wang C, Chen H and

Ghishan FK: Impaired mucin synthesis and bicarbonate secretion in

the colon of NHE8 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver

Physiol. 303:G335–G343. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Singh AK, Sjöblom M, Zheng W, Krabbenhöft

A, Riederer B, Rausch B, Manns MP, Soleimani M and Seidler U: CFTR

and its key role in in vivo resting and luminal acid-induced

duodenal HCO3-secretion. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 193:357–365. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Schultheis PJ, Clarke LL, Meneton P,

Harline M, Boivin GP, Stemmermann G, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Miller

ML and Shull GE: Targeted disruption of the murine Na+/H+ exchanger

isoform 2 gene causes reduced viability of gastric parietal cells

and loss of net acid secretion. J Clin Invest. 101:1243–1253. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang A, Li J, Zhao Y, Johansson ME, Xu H

and Ghishan FK: Loss of NHE8 expression impairs intestinal mucosal

integrity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 309:G855–G864.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Boivin GP, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE and

Stemmermann GN: Variant form of diffuse corporal gastritis in NHE2

knockout mice. Comp Med. 50:511–515. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ding X, Li D, Li M, Wang H, He Q, Wang Y,

Yu H, Tian D and Yu Q: SLC26A3 (DRA) prevents TNF-alpha-induced

barrier dysfunction and dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute

colitis. Lab Invest. 98:462–476. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang W, Xu Y, Chen Z, Xu Z and Xu H:

Knockdown of aquaporin 3 is involved in intestinal barrier

integrity impairment. FEBS Lett. 585:3113–3119. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Moeser AJ, Nighot PK, Ryan KA, Simpson JE,

Clarke LL and Blikslager AT: Mice lacking the Na+/H+ exchanger 2

have impaired recovery of intestinal barrier function. Am J Physiol

Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 295:G791–G797. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kumar A, Priyamvada S, Ge Y, Jayawardena

D, Singhal M, Anbazhagan AN, Chatterjee I, Dayal A, Patel M, Zadeh

K, et al: A novel role of SLC26A3 in the maintenance of intestinal

epithelial barrier integrity. Gastroenterology. 160:1240–1255.e3.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Doi K, Nagao T, Kawakubo K, Ibayashi S,

Aoyagi K, Yano Y, Yamamoto C, Kanamoto K, Iida M, Sadoshima S and

Fujishima M: Calcitonin gene-related peptide affords gastric

mucosal protection by activating potassium channel in Wistar rat.

Gastroenterology. 114:71–76. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Deng Z, Zhao Y, Ma Z, Zhang M, Wang H, Yi

Z, Tuo B, Li T and Liu X: Pathophysiological role of ion channels

and transporters in gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Cell Mol

Life Sci. 78:8109–8125. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Pallagi P, Hegyi P and Rakonczay Z Jr: The

physiology and pathophysiology of pancreatic ductal secretion: The

background for clinicians. Pancreas. 44:1211–1233. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ishiguro H, Yamamoto A, Nakakuki M, Yi L,

Ishiguro M, Yamaguchi M, Kondo S and Mochimaru Y: Physiology and

pathophysiology of bicarbonate secretion by pancreatic duct

epithelium. Nagoya J Med Sci. 74:1–18. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Novak I, Haanes KA and Wang J: Acid-base

transport in pancreas-new challenges. Front Physiol. 4:3802013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Schnipper J, Dhennin-Duthille I, Ahidouch

A and Ouadid-Ahidouch H: Ion channel signature in healthy pancreas

and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Front Pharmacol.

11:5689932020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen X, Zhang L, Zheng L and Tuo B: Role

of Ca(2+) channels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and their

implications for therapeutic strategies (Review). Int J Mol Med.

50:1132022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stock C: How dysregulated ion channels and

transporters take a hand in esophageal, liver, and colorectal

cancer. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 181:129–222. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Li W, Wang C, Peng X, Zhang H, Huang H and

Liu H: CFTR inhibits the invasion and growth of esophageal cancer

cells by inhibiting the expression of NF-κB. Cell Biol Int.

42:1680–1687. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Goldman A, Chen H, Khan MR, Roesly H, Hill

KA, Shahidullah M, Mandal A, Delamere NA and Dvorak K: The

Na+/H+ exchanger controls deoxycholic

acid-induced apoptosis by a H+-activated,

Na+-dependent ionic shift in esophageal cells. PLoS One.

6:e238352011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Boult J, Roberts K, Brookes MJ, Hughes S,

Bury JP, Cross SS, Anderson GJ, Spychal R, Iqbal T and Tselepis C:

Overexpression of cellular iron import proteins is associated with

malignant progression of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer

Res. 14:379–387. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gao N, Yang F, Chen S, Wan H, Zhao X and

Dong H: The role of TRPV1 ion channels in the suppression of

gastric cancer development. Exp Clin Cancer Res. 39:2062020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chang Y, Roy S and Pan Z: Store-operated

calcium channels as drug target in gastroesophageal cancers. Front

Pharmacol. 12:6687302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Csekő K, Pécsi D, Kajtár B, Hegedűs I,

Bollenbach A, Tsikas D, Szabó IL, Szabó S and Helyes Z:

Upregulation of the TRPA1 Ion channel in the gastric mucosa after

iodoacetamide-induced gastritis in rats: A potential new

therapeutic target. Int J Mol Sci. 21:55912020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Capurro MI, Greenfield LK, Prashar A, Xia

S, Abdullah M, Wong H, Zhong XZ, Bertaux-Skeirik N, Chakrabarti J,

Siddiqui I, et al: VacA generates a protective intracellular

reservoir for Helicobacter pylori that is eliminated by activation

of the lysosomal calcium channel TRPML1. Nat Microbiol.

4:1411–1423. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang L, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Dou X, Li S,

Chai H, Qian Q and Wang M: Upregulated SOCC and IP3R calcium

channels and subsequent elevated cytoplasmic calcium signaling

promote nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by inhibiting autophagy.

Mol Cell Biochem. 476:3163–3175. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Swain SM, Romac JM, Shahid RA, Pandol SJ,

Liedtke W, Vigna SR and Liddle RA: TRPV4 channel opening mediates

pressure-induced pancreatitis initiated by Piezo1 activation. J

Clin Invest. 130:2527–2541. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin R, Bao X, Wang H, Zhu S, Liu Z, Chen

Q, Ai K and Shi B: TRPM2 promotes pancreatic cancer by PKC/MAPK

pathway. Cell Death Dis. 12:5852021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li S, Han J, Guo G, Sun Y, Zhang T, Zhao

M, Xu Y, Cui Y, Liu Y and Zhang J: Voltage-gated sodium channels β3

subunit promotes tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by

facilitating p53 degradation. FEBS Lett. 594:497–508. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Nattramilarasu PK, Bücker R, Lobo de Sá

FD, Fromm A, Nagel O, Lee IM, Butkevych E, Mousavi S, Genger C,

Kløve S, et al: Campylobacter concisus impairs sodium absorption in

colonic epithelium via ENaC dysfunction and claudin-8 disruption.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:3732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gao F, Wang D, Liu X, Wu YH, Wang HT and

Sun SL: Sodium channel 1 subunit alpha SCNN1A exerts oncogenic

function in pancreatic cancer via accelerating cellular growth and

metastasis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 727:1093232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang H, Li C, Peng M, Wang L, Zhao D, Wu

T, Yi D, Hou Y and Wu G: N-Acetylcysteine improves intestinal

function and attenuates intestinal autophagy in piglets challenged

with β-conglycinin. Sci Rep. 11:12612021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Goswami S: Interplay of potassium channel,

gastric parietal cell and proton pump in gastrointestinal

physiology, pathology and pharmacology. Minerva Gastroenterol

(Torino). 68:289–305. 2022.

|

|

38

|

Patel SH, Edwards MJ and Ahmad SA:

Intracellular ion channels in pancreas cancer. Cell Physiol

Biochem. 53:44–51. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Schroeder BC, Waldegger S, Fehr S, Bleich

M, Warth R, Greger R and Jentsch TJ: A constitutively open

potassium channel formed by KCNQ1 and KCNE3. Nature. 403:196–199.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ponnalagu D and Singh H: Anion channels of

mitochondria. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 240:71–101. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Gururaja Rao S, Ponnalagu D, Patel NJ and

Singh H: Three decades of chloride intracellular channel proteins:

From organelle to organ physiology. Curr Protoc Pharmacol.

80:11.21.1–11.21.17. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kouyoumdzian NM, Kim G, Rudi MJ, Rukavina

Mikusic NL, Fernández BE and Choi MR: Clues and new evidences in

arterial hypertension: Unmasking the role of the chloride anion.

Pflugers Arch. 474:155–176. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Jentsch TJ and Pusch M: CLC chloride

channels and transporters: Structure, function, physiology, and

disease. Physiol Rev. 98:1493–1590. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Shi J, Shi S, Yuan G, Jia Q, Shi S, Zhu X,

Zhou Y, Chen T and Hu Y: Bibliometric analysis of chloride channel

research (2004-2019). Channels (Austin). 14:393–402. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F and

Zdebik AA: Molecular structure and physiological function of

chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 82:503–568. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Peng F, Wu Y, Dong X and Huang P:

Proton-activated chloride channel: Physiology and disease. Front

Biosci (Landmark Ed). 28:112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Patil VM and Gupta SP: Studies on chloride

channels and their modulators. Curr Top Med Chem. 16:1862–1876.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Accardi A and Miller C: Secondary active

transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of ClC Cl- hannels.

Nature. 427:803–807. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Jentsch TJ: CLC chloride channels and

transporters: From genes to protein structure, pathology and

physiology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 43:3–36. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y,

Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, et al: TMEM16A confers

receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature.

455:1210–1215. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N,

Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O and

Galietta LJ: TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with

calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 322:590–594.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gadsby DC, Vergani P and Csanády L: The

ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic

fibrosis. Nature. 440:477–483. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N,

Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et

al: Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: Cloning and

characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 245:1066–1073.

1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Ullrich F, Blin S, Lazarow K, Daubitz T,

von Kries JP and Jentsch TJ: Identification of TMEM206 proteins as

pore of PAORAC/ASOR acid-sensitive chloride channels. Elife.

8:e491872019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Olsen RW and Sieghart W: International

Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A)

receptors: Classification on the basis of subunit composition,

pharmacology, and function. Update. Pharmacol Rev. 60:243–260.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Lynch JW: Molecular structure and function

of the glycine receptor chloride channel. Physiol Rev.

84:1051–1095. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Peng JM, Lin SH, Yu MC and Hsieh SY: CLIC1

recruits PIP5K1A/C to induce cell-matrix adhesions for tumor

metastasis. J Clin Invest. 131:e1335252021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

58

|

Bi MM, Hong S, Zhou HY, Wang HW, Wang LN

and Zheng YJ: Chloride channelopathies of ClC-2. Int J Mol Sci.

15:218–249. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Okada Y, Okada T, Sato-Numata K, Islam MR,

Ando-Akatsuka Y, Numata T, Kubo M, Shimizu T, Kurbannazarova RS,

Marunaka Y and Sabirov RZ: Cell volume-activated and

volume-correlated anion channels in mammalian cells: Their

biophysical, molecular, and pharmacological properties. Pharmacol

Rev. 71:49–88. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Fu D, Cui H and Zhang Y: Lack of ClC-2

alleviates high fat diet-induced insulin resistance and

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Physiol Biochem.

45:2187–2198. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Blikslager AT, Moeser AJ, Gookin JL, Jones

SL and Odle J: Restoration of barrier function in injured

intestinal mucosa. Physiol Rev. 87:545–564. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Gehren AS, Rocha MR, de Souza WF and

Morgado-Díaz JA: Alterations of the apical junctional complex and

actin cytoskeleton and their role in colorectal cancer progression.

Tissue Barriers. 3:e10176882015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Nighot PK, Moeser AJ, Ryan KA, Ghashghaei

T and Blikslager AT: ClC-2 is required for rapid restoration of

epithelial tight junctions in ischemic-injured murine jejunum. Exp

Cell Res. 315:110–118. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Jin Y, Ibrahim D, Magness ST and

Blikslager AT: Knockout of ClC-2 reveals critical functions of

adherens junctions in colonic homeostasis and tumorigenicity. Am J

Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 315:G966–G979. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Mrad FCC, Soares SBM, de Menezes Silva

LAW, Dos Anjos Menezes PV and Simões-E-Silva AC: Bartter's

syndrome: Clinical findings, genetic causes and therapeutic

approach. World J Pediatr. 17:31–39. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Andrini O, Eladari D and Picard N: ClC-K

kidney chloride channels: From structure to pathology. Handb Exp

Pharmacol. 283:35–58. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Mu H, Mu L and Gao J: Suppression of CLC-3

reduces the proliferation, invasion and migration of colorectal

cancer through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 533:1240–1246. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Gu Z, Li Y, Yang X, Yu M, Chen Z, Zhao C,

Chen L and Wang L: Overexpression of CLC-3 is regulated by XRCC5

and is a poor prognostic biomarker for gastric cancer. J Hematol

Oncol. 11:1152018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Cheng W, Zheng S, Li L, Zhou Q, Zhu H, Hu

J and Luo H: Chloride channel 3 (CIC-3) predicts the tumor size in

hepatocarcinoma. Acta Histochem. 121:284–288. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Huang LY, Li YJ, Li PP, Li HC and Ma P:

Aggravated intestinal apoptosis by ClC-3 deletion is lethal to mice

endotoxemia. Cell Biol Int. 42:1445–1453. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Huang LY, He Q, Liang SJ, Su YX, Xiong LX,

Wu QQ, Wu QY, Tao J, Wang JP, Tang YB, et al: ClC-3 chloride

channel/antiporter defect contributes to inflammatory bowel disease

in humans and mice. Gut. 63:1587–1595. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Stauber T, Weinert S and Jentsch TJ: Cell

biology and physiology of CLC chloride channels and transporters.

Compr Physiol. 2:1701–1744. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Stauber T and Jentsch TJ: Chloride in

vesicular trafficking and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 75:453–477.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Wartosch L, Fuhrmann JC, Schweizer M,

Stauber T and Jentsch TJ: Lysosomal degradation of endocytosed

proteins depends on the chloride transport protein ClC-7. FASEB J.

23:4056–4068. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Nicoli ER, Weston MR, Hackbarth M,

Becerril A, Larson A, Zein WM, Baker PR II, Burke JD, Dorward H,

Davids M, et al: Lysosomal storage and albinism due to effects of a

de novo CLCN7 variant on lysosomal acidification. Am J Hum Genet.

104:1127–1138. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Polovitskaya MM, Barbini C, Martinelli D,

Harms FL, Cole FS, Calligari P, Bocchinfuso G, Stella L, Ciolfi A,

Niceta M, et al: A recurrent gain-of-function mutation in CLCN6,

encoding the ClC-6 Cl(-)/H(+)-exchanger, causes early-onset

neurodegeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 107:1062–1077. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Bose S, He H and Stauber T:

Neurodegeneration upon dysfunction of endosomal/lysosomal CLC

chloride transporters. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6392312021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Locher KP: Mechanistic diversity in

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

23:487–493. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Csanády L, Vergani P and Gadsby DC:

Structure, gating, and regulation of the CFTR anion channel.

Physiol Rev. 99:707–738. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Fonseca C, Bicker J, Alves G, Falcão A and

Fortuna A: Cystic fibrosis: Physiopathology and the latest

pharmacological treatments. Pharmacol Res. 162:1052672020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Lukasiak A and Zajac M: The distribution

and role of the CFTR protein in the intracellular compartments.

Membranes (Basel). 11:8042021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Matsumoto Y, Shiozaki A, Kosuga T, Kudou

M, Shimizu H, Arita T, Konishi H, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Fujiwara H,

et al: Expression and role of CFTR in human esophageal squamous

cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 28:6424–6436. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Zhang J, Liu X, Zeng L and Hu Y: GABRP

inhibits the progression of oesophageal cancer by regulating CFTR:

Integrating bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation.

Int J Exp Pathol. 105:118–132. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Shakir S, Echevarria C, Doe S, Brodlie M,

Ward C and Bourke SJ: Elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor improve

gastro-oesophageal reflux and sinonasal symptoms in advanced cystic

fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 21:807–810. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Rowe SM, Heltshe SL, Gonska T, Donaldson

SH, Borowitz D, Gelfond D, Sagel SD, Khan U, Mayer-Hamblett N, Van

Dalfsen JM, et al: Clinical mechanism of the cystic fibrosis

transmembrane conductance regulator potentiator ivacaftor in

G551D-mediated cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

190:175–184. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Petrov MS and Yadav D: Global epidemiology

and holistic prevention of pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 16:175–184. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

87

|

Mayerle J, Sendler M, Hegyi E, Beyer G,

Lerch MM and Sahin-Tóth M: Genetics, cell biology, and

pathophysiology of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology.

156:1951–1968.e1. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Hou Y, Guan X, Yang Z and Li C: Emerging

role of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-an

epithelial chloride channel in gastrointestinal cancers. World J

Gastrointest Oncol. 8:282–288. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Fűr G, Bálint ER, Orján EM, Balla Z,

Kormányos ES, Czira B, Szűcs A, Kovács DP, Pallagi P, Maléth J, et

al: Mislocalization of CFTR expression in acute pancreatitis and

the beneficial effect of VX-661 + VX-770 treatment on disease

severity. J Physiol. 599:4955–4971. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Kim Y, Jun I, Shin DH, Yoon JG, Piao H,

Jung J, Park HW, Cheng MH, Bahar I, Whitcomb DC and Lee MG:

Regulation of CFTR bicarbonate channel activity by WNK1:

Implications for pancreatitis and CFTR-Related disorders. Cell Mol

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9:79–103. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Lee MG, Ohana E, Park HW, Yang D and

Muallem S: Molecular mechanism of pancreatic and salivary gland

fluid and HCO3 secretion. Physiol Rev. 92:39–74. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Fong P: CFTR-SLC26 transporter

interactions in epithelia. Biophys Rev. 4:107–116. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Ko SB, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Luo X, Kim KH,

Millen L, Goto H, Naruse S, Soyombo A, Thomas PJ and Muallem S:

Gating of CFTR by the STAS domain of SLC26 transporters. Nat Cell

Biol. 6:343–350. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Berg P, Svendsen SL, Sorensen MV, Larsen

CK, Andersen JF, Jensen-Fangel S, Jeppesen M, Schreiber R, Cabrita

I, Kunzelmann K and Leipziger J: Impaired renal HCO(3)(-) excretion

in cystic fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 31:1711–1727. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Ishiguro H, Steward MC, Naruse S, Ko SB,

Goto H, Case RM, Kondo T and Yamamoto A: CFTR functions as a

bicarbonate channel in pancreatic duct cells. J Gen Physiol.

133:315–326. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Park HW, Nam JH, Kim JY, Namkung W, Yoon

JS, Lee JS, Kim KS, Venglovecz V, Gray MA, Kim KH and Lee MG:

Dynamic regulation of CFTR bicarbonate permeability by [Cl-]i and

its role in pancreatic bicarbonate secretion. Gastroenterology.

139:620–631. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Yang CL, Liu X, Paliege A, Zhu X, Bachmann

S, Dawson DC and Ellison DH: WNK1 and WNK4 modulate CFTR activity.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 353:535–540. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Yang D, Li Q, So I, Huang CL, Ando H,

Mizutani A, Seki G, Mikoshiba K, Thomas PJ and Muallem S: IRBIT

governs epithelial secretion in mice by antagonizing the WNK/SPAK

kinase pathway. J Clin Invest. 121:956–965. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Shirakabe K, Priori G, Yamada H, Ando H,

Horita S, Fujita T, Fujimoto I, Mizutani A, Seki G and Mikoshiba K:

IRBIT, an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-binding protein,

specifically binds to and activates pancreas-type

Na+/HCO3-cotransporter 1 (pNBC1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

103:9542–9547. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Park S, Shcheynikov N, Hong JH, Zheng C,

Suh SH, Kawaai K, Ando H, Mizutani A, Abe T, Kiyonari H, et al:

Irbit mediates synergy between ca(2+) and cAMP signaling pathways

during epithelial transport in mice. Gastroenterology. 145:232–241.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Pankonien I, Quaresma MC, Rodrigues CS and

Amaral MD: CFTR, cell junctions and the cytoskeleton. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Wen G, Jin H, Deng S, Xu J, Liu X, Xie R

and Tuo B: Effects of helicobacter pylori infection on the

expressions and functional activities of human duodenal mucosal

bicarbonate transport proteins. Helicobacter. 21:536–547. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Reyes EA, Castillo-Azofeifa D, Rispal J,

Wald T, Zwick RK, Palikuqi B, Mujukian A, Rabizadeh S, Gupta AR,

Gardner JM, et al: Epithelial TNF controls cell differentiation and

CFTR activity to maintain intestinal mucin homeostasis. J Clin

Invest. 133:e1635912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Bhattacharya R, Blankenheim Z, Scott PM

and Cormier RT: CFTR and gastrointestinal cancers: An update. J

Pers Med. 12:8682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Liu H, Wu W, Liu Y, Zhang C and Zhou Z:

Predictive value of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance

regulator (CFTR) in the diagnosis of gastric cancer. Clinical and

investigative medicine. Clin Invest Med. 37:E226–E232. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Yamada A, Komaki Y, Komaki F, Micic D,

Zullow S and Sakuraba A: Risk of gastrointestinal cancers in

patients with cystic fibrosis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 19:758–767. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Jakab RL, Collaco AM and Ameen NA:

Physiological relevance of cell-specific distribution patterns of

CFTR, NKCC1, NBCe1, and NHE3 along the crypt-villus axis in the

intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 300:G82–G98.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

108

|

Tse CM, Yin J, Singh V, Sarker R, Lin R,

Verkman AS, Turner JR and Donowitz M: cAMP stimulates SLC26A3

activity in human colon by a CFTR-dependent mechanism that does not

require CFTR activity. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7:641–653.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

109

|

Vernocchi P, Del Chierico F, Russo A, Majo

F, Rossitto M, Valerio M, Casadei L, La Storia A, De Filippis F,

Rizzo C, et al: Gut microbiota signatures in cystic fibrosis: Loss

of host CFTR function drives the microbiota enterophenotype. PLoS

One. 13:e02081712018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Burke DG, Fouhy F, Harrison MJ, Rea MC,

Cotter PD, O'Sullivan O, Stanton C, Hill C, Shanahan F, Plant BJ

and Ross RP: The altered gut microbiota in adults with cystic

fibrosis. BMC Microbiol. 17:582017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

De Lisle RC: Disrupted tight junctions in

the small intestine of cystic fibrosis mice. Cell Tissue Res.

355:131–142. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

112

|

Broadbent D, Ahmadzai MM, Kammala AK, Yang

C, Occhiuto C, Das R and Subramanian H: Roles of NHERF family of

PDZ-binding proteins in regulating GPCR functions. Adv Immunol.

136:353–385. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Meeker SM, Mears KS, Sangwan N,

Brittnacher MJ, Weiss EJ, Treuting PM, Tolley N, Pope CE, Hager KR,

Vo AT, et al: CFTR dysregulation drives active selection of the gut

microbiome. PLoS Pathog. 16:e10082512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Mulcahy EM, Cooley MA, McGuire H, Asad S,

Fazekas de St Groth B, Beggs SA and Roddam LF: Widespread

alterations in the peripheral blood innate immune cell profile in

cystic fibrosis reflect lung pathology. Immunol Cell Biol.

97:416–426. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Trigo Salado C, Leo Carnerero E and de la

Cruz Ramírez MD: Crohn's disease and cystic fibrosis: There is

still a lot to learn. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 110:835–836. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Gabel ME, Galante GJ and Freedman SD:

Gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary disease in cystic fibrosis.

Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 40:825–841. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Maisonneuve P, Marshall BC, Knapp EA and

Lowenfels AB: Cancer risk in cystic fibrosis: A 20-year nationwide

study from the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 105:122–129.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Than BL, Linnekamp JF, Starr TK,

Largaespada DA, Rod A, Zhang Y, Bruner V, Abrahante J, Schumann A,

Luczak T, et al: CFTR is a tumor suppressor gene in murine and

human intestinal cancer. Oncogene. 35:4179–4187. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Sun TT, Wang Y, Cheng H, Xiao HZ, Xiang

JJ, Zhang JT, Yu SB, Martin TA, Ye L, Tsang LL, et al: Disrupted

interaction between CFTR and AF-6/afadin aggravates malignant

phenotypes of colon cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1843:618–628.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Palma AG, Soares Machado M, Lira MC, Rosa

F, Rubio MF, Marino G, Kotsias BA and Costas MA: Functional

relationship between CFTR and RAC3 expression for maintaining

cancer cell stemness in human colorectal cancer. Cell Oncol

(Dordr). 44:627–641. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Strubberg AM, Liu J, Walker NM, Stefanski

CD, MacLeod RJ, Magness ST and Clarke LL: Cftr modulates

Wnt/β-catenin signaling and stem cell proliferation in murine

intestine. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5:253–271. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Liu C, Song C, Li J and Sun Q: CFTR

functions as a tumor suppressor and is regulated by DNA methylation

in colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 12:4261–4270. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Paulino C, Neldner Y, Lam AK, Kalienkova

V, Brunner JD, Schenck S and Dutzler R: Structural basis for anion

conduction in the calcium-activated chloride channel TMEM16A.

Elife. 6:e262322017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Dang S, Feng S, Tien J, Peters CJ, Bulkley

D, Lolicato M, Zhao J, Zuberbühler K, Ye W, Qi L, et al: Cryo-EM

structures of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel.

Nature. 552:426–429. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Ji Q, Guo S, Wang X, Pang C, Zhan Y, Chen

Y and An H: Recent advances in TMEM16A: Structure, function, and

disease. J Cell Physiol. 234:7856–7873. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

126

|

Liu Y, Liu Z and Wang K: The

Ca(2+)-activated chloride channel ANO1/TMEM16A: An emerging

therapeutic target for epithelium-originated diseases? Acta Pharm

Sin B. 11:1412–1433. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Crottès D and Jan LY: The multifaceted

role of TMEM16A in cancer. Cell Calcium. 82:1020502019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Jang Y and Oh U: Anoctamin 1 in secretory

epithelia. Cell Calcium. 55:355–361. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Ji Q, Shi S, Guo S, Zhan Y, Zhang H, Chen

Y and An H: Activation of TMEM16A by natural product canthaxanthin

promotes gastrointestinal contraction. FASEB J. 34:13430–13444.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Stephan AB, Shum EY, Hirsh S, Cygnar KD,

Reisert J and Zhao H: ANO2 is the cilial calcium-activated chloride

channel that may mediate olfactory amplification. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 106:11776–11781. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Huang WC, Xiao S, Huang F, Harfe BD, Jan

YN and Jan LY: Calcium-activated chloride channels (CaCCs) regulate

action potential and synaptic response in hippocampal neurons.

Neuron. 74:179–192. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Ha GE, Lee J, Kwak H, Song K, Kwon J, Jung

SY, Hong J, Chang GE, Hwang EM, Shin HS, et al: The

Ca(2+)-activated chloride channel anoctamin-2 mediates

spike-frequency adaptation and regulates sensory transmission in

thalamocortical neurons. Nat Commun. 7:137912016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Vanoni S, Zeng C, Marella S, Uddin J, Wu

D, Arora K, Ptaschinski C, Que J, Noah T, Waggoner L, et al:

Identification of anoctamin 1 (ANO1) as a key driver of esophageal

epithelial proliferation in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy

Clin Immunol. 145:239–254.e2. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

134

|

Yu Y, Cao J, Wu W, Zhu Q, Tang Y, Zhu C,

Dai J, Li Z, Wang J, Xue L, et al: Genome-wide copy number

variation analysis identified ANO1 as a novel oncogene and

prognostic biomarker in esophageal squamous cell cancer.

Carcinogenesis. 40:1198–1208. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Le SC, Jia Z, Chen J and Yang H: Molecular

basis of PIP(2)-dependent regulation of the Ca(2+)-activated

chloride channel TMEM16A. Nat Commun. 10:37692019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Fairfield CJ, Drake TM, Pius R, Bretherick

AD, Campbell A, Clark DW, Fallowfield JA, Hayward C, Henderson NC,

Iakovliev A, et al: Genome-wide analysis identifies

gallstone-susceptibility loci including genes regulating

gastrointestinal motility. Hepatology. 75:1081–1094. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

137

|

Camilleri M, Sandler RS and Peery AF:

Etiopathogenetic mechanisms in diverticular disease of the colon.

Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9:15–32. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

138

|

Schafmayer C, Harrison JW, Buch S, Lange

C, Reichert MC, Hofer P, Cossais F, Kupcinskas J, von Schönfels W,

Schniewind B, et al: Genome-wide association analysis of

diverticular disease points towards neuromuscular, connective

tissue and epithelial pathomechanisms. Gut. 68:854–865. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Zeng X, Pan D, Wu H, Chen H, Yuan W, Zhou

J, Shen Z and Chen S: Transcriptional activation of ANO1 promotes

gastric cancer progression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

512:131–136. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Xie R, Liu L, Lu X and Hu Y: LncRNA

OIP5-AS1 facilitates gastric cancer cell growth by targeting the

miR-422a/ANO1 axis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai).

52:430–438. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Lu G, Shi W and Zheng H: Inhibition of

STAT6/Anoctamin-1 activation suppresses proliferation and invasion

of gastric cancer cells. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 33:3–7.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Yan Y, Ding X, Han C, Gao J, Liu Z, Liu Y

and Wang K: Involvement of TMEM16A/ANO1 upregulation in the

oncogenesis of colorectal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis

Dis. 1868:1663702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Wang Q, Bai L, Luo S, Wang T, Yang F, Xia

J, Wang H, Ma K, Liu M, Wu S, et al: TMEM16A Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-)

channel inhibition ameliorates acute pancreatitis via the IP(3)

R/Ca(2+)/NFκB/IL-6 signaling pathway. J Adv Res. 23:25–35. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Zhang G, Shu Z, Yu J, Li J, Yi P, Wu B,

Deng D, Yan S, Li Y, Ren D, et al: High ANO1 expression is a

prognostic factor and correlated with an immunosuppressive tumor

microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. Front Immunol.

15:13412092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Guo JW, Liu X, Zhang TT, Lin XC, Hong Y,

Yu J, Wu QY, Zhang FR, Wu QQ, Shang JY, et al: Hepatocyte TMEM16A

deletion retards NAFLD progression by ameliorating hepatic glucose

metabolic disorder. Adv Sci (Weinh). 7:19036572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Guo J, Song Z, Yu J, Li C, Jin C, Duan W,

Liu X, Liu Y, Huang S, Tuo Y, et al: Hepatocyte-specific TMEM16A

deficiency alleviates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury via

suppressing GPX4-mediated ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 13:10722022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Kondo R, Furukawa N, Deguchi A, Kawata N,

Suzuki Y, Imaizumi Y and Yamamura H: Downregulation of

Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channel TMEM16A mediated by angiotensin II

in cirrhotic portal hypertensive mice. Front Pharmacol.

13:8313112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Deng L, Yang J, Chen H, Ma B, Pan K, Su C,

Xu F and Zhang J: Knockdown of TMEM16A suppressed MAPK and

inhibited cell proliferation and migration in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 9:325–333. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

König B and Stauber T: Biophysics and

structure-function relationships of LRRC8-formed volume-regulated

anion channels. Biophys J. 116:1185–1193. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Sawicka M and Dutzler R: Regulators of