Introduction

Schizophrenia affects ~1% of the global population,

typically emerging in late adolescence or early adulthood and

significantly impairing cognitive and emotional functions (1). It is characterized by positive

symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions, negative symptoms

including reduced emotional expression and social withdrawal and

cognitive impairments affecting attention, memory and executive

functions (2). Neuroimaging

studies demonstrate substantial brain alterations in patients,

including reduced gray matter in the medial temporal and prefrontal

regions, pronounced ventricular enlargement, extensive cortical

thinning and white matter abnormalities (3,4).

Emerging evidence highlights blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction

as a critical factor in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia,

potentially triggering neuroinflammatory cascades, aberrant

neurotransmission and structural remodeling that contribute to

symptom onset and progression (5,6).

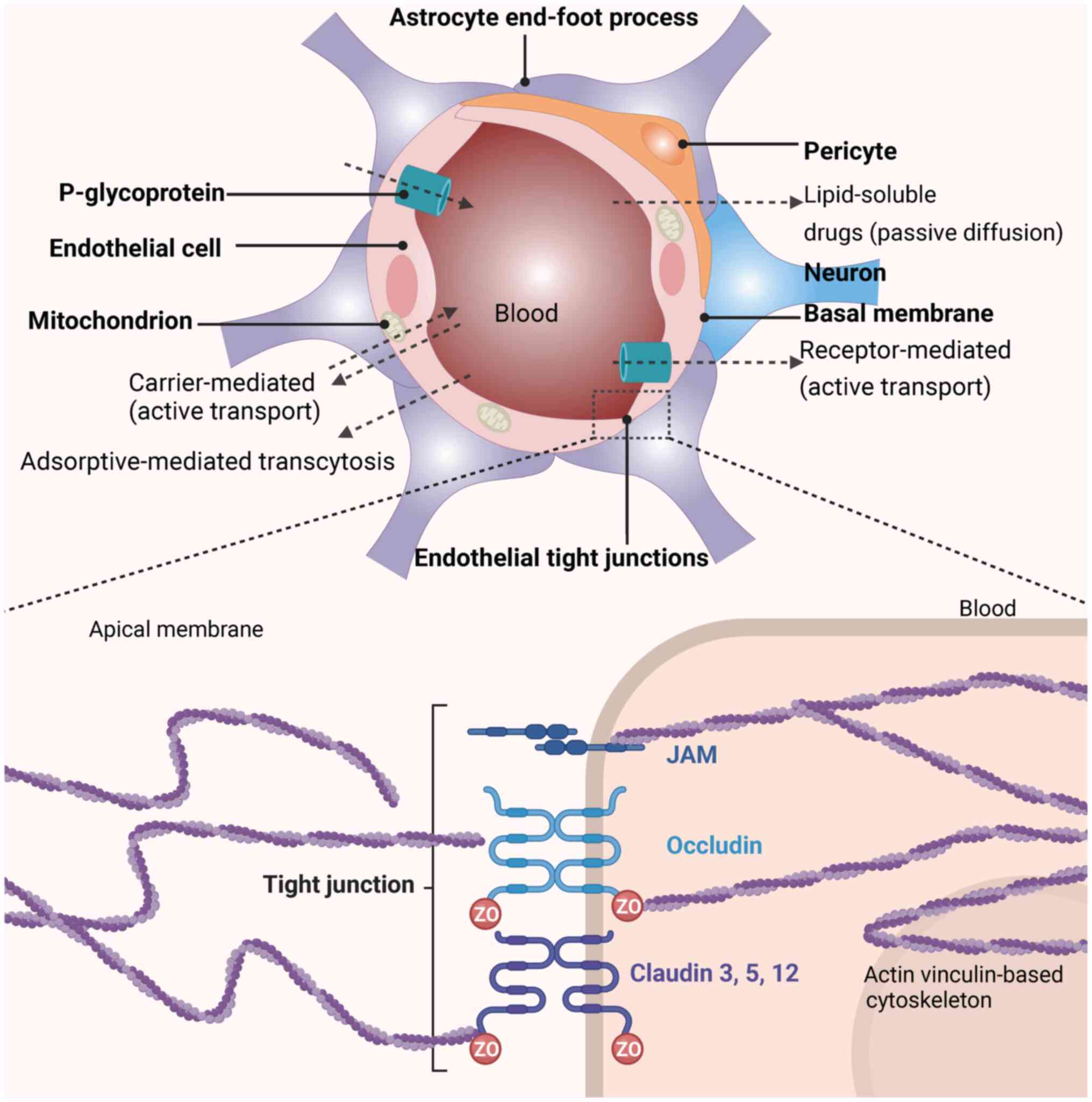

The BBB, a dynamic interface composed of tightly

joined endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes (Fig. 1) regulates the molecular exchange

between the bloodstream and the central nervous system (CNS). The

selective permeability of the BBB depends on tight junction

proteins such as claudin-5 (CLDN5) and occludin (OCLN), limited

endothelial pinocytosis and efflux transporters (7,8).

Beyond its barrier function, the BBB serves an active role in

modulating neuroimmune signaling and maintaining neuronal

homeostasis, making its integrity critical for brain health

(9).

In schizophrenia, BBB disruption has emerged as a

key pathological feature. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

albumin levels and altered expression of tight junction proteins,

particularly hippocampal claudin-5 deficits, indicate compromised

barrier selectivity (10,11).

Dysregulation of permeability regulators, including zonulin and

matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), further suggests active BBB

breakdown (12). Such

disruptions allow the infiltration of neurotoxic substances,

inflammatory cytokines and potentially pathogenic autoantibodies

into the brain parenchyma. These infiltrating molecules may

initiate or exacerbate pathological processes in schizophrenia,

including synaptic dysfunction, glial activation and oxidative

stress, all consistently observed in patients with schizophrenia

(13). Notably, evidence

suggests that BBB leakage may precede the clinical onset of

schizophrenia, indicating its potential role as an initiating

factor rather than merely a secondary consequence of disease

pathology (14).

The present review synthesized current evidence

linking BBB dysfunction to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia,

emphasizing structural and molecular alterations in the BBB, their

contribution to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, and the

implications for therapeutic strategies targeting barrier

integrity.

Schizophrenia overview

Introduction to schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a debilitating neuropsychiatric

disorder that profoundly alters mental processes, including

thought, perception and emotional regulation (15). Schizophrenia typically manifests

in late adolescence or early adulthood, with rare diagnoses in

childhood or later stages of life. Although the prevalence is

similar across men and women, the progression and severity of

symptoms exhibit notable differences; men generally experience more

severe symptoms at an earlier age, while women often present with

more depressive symptoms and a later onset (16,17).

Clinically, schizophrenia is categorized into three

primary symptom types: Positive, negative and cognitive (1). Positive symptoms include

hallucinations (commonly auditory), delusions and disorganized

speech, which represent distortions or exaggerations of normal

perceptions and beliefs. For instance, patients may hear

non-existent voices or believe they are being persecuted without

basis (18). Negative symptoms

are characterized by reduced emotional expression, infrequent

speech and a lack of motivation, often resulting in withdrawal and

inactivity (19). Cognitive

symptoms involve impairments in executive functions, such as

processing complex information, maintaining focus and managing

working memory, skills essential for decision-making and daily

functioning (2). The Positive

and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is key for assessing

schizophrenia, evaluating both positive and negative symptoms

(20). This scale serves a vital

role in diagnosis, treatment guidance and symptom monitoring

(21). Neuroimaging studies have

highlighted both structural and functional brain abnormalities in

schizophrenia (22). Structural

imaging demonstrates decreased gray matter volume and cortical

thinning, especially in regions such as the hippocampus, amygdala,

thalamus and frontal cortex, areas critical for memory, emotion

regulation, sensory gating and decision-making (22). Functional imaging demonstrates

altered activation patterns during cognitive tasks and atypical

resting-state brain activity (23). Furthermore, diffusion tensor

imaging has identified white matter tract abnormalities, suggesting

disrupted connectivity between brain regions (24,25).

Genetics strongly influence the development of

schizophrenia, with heritability estimates ranging from 60-85%

(26). The disorder is

polygenic, involving complex interactions across multiple genetic

loci that increase susceptibility. Genome-wide association studies

(GWAS) have pinpointed several genomic regions linked to

schizophrenia, highlighting the significance of synaptic

organization and neurotransmission in its pathogenesis (27). Environmental factors also serve a

substantial role in the onset of schizophrenia. Prenatal and

perinatal exposures to infections or malnutrition, psychosocial

stress, trauma, substance use during adolescence, urban living and

migration all contribute to the schizophrenia development. These

factors emphasize the developmental vulnerability of the brain to

environmental stressors (28).

Together, these findings illustrate the multifaceted nature of

schizophrenia, underscoring the need for an integrated approach

that considers both biological and environmental influences in its

management and treatment.

Pathophysiology of schizophrenia

The pathophysiology of schizophrenia is

multifaceted, involving genetic factors, neurodevelopmental

disruptions, neurotransmitter imbalances and neuroimmune

alterations (Table I) (15,28-56). Each of these components

contributes to the complexity of schizophrenia, emphasizing the

need for comprehensive therapeutic approaches that target these

diverse mechanisms.

| Table IPathophysiological factors in

mechanisms of schizophrenia. |

Table I

Pathophysiological factors in

mechanisms of schizophrenia.

| Mechanism | Related

factors | Results | (Refs.) |

|---|

|

Neurodevelopment | NRG1 gene

variations | Altered neuronal

development and synaptic plasticity; disturbed cognitive

function. | (29) |

| C4-A gene

activation | Pruned and lost

synapses | (30,31) |

| Microglial

overactivity | Disturbed synaptic

maintenance and stability | (32) |

| Mutation or

dysfunction of DISC1 gene | Compromised

neurogenesis; destabilized neuronal networks. | (33,34) |

| Malnutrition | Compromised

neurogenesis; disrupted fetal brain development. | (35,36) |

| Early-life

stress | Compromised

neurogenesis; destabilized neuronal networks. | (37-39) |

| Neurotransmitter

dysregulation | COMT gene

variations | Disturbed

neurotransmitter regulation | (40) |

| Variations in MAO-B

gene | Disturbed

astrocytic enzyme levels; affected neurotransmitter dynamics. | (41,42) |

| Increased dopamine

receptor sensitivity | Elevated dopamine

activity; destabilized neuronal networks. | (38,43,44) |

| Increased dopamine

synthesis and release | Elevated dopamine

activity. | (43,45) |

| NMDAR

dysfunction | Dysregulated

glutamate; imbalanced neurotransmitters. | (45-47) |

| Norepinephrine

dysregulation | Disrupted synaptic

transmission; distorted stress response mechanisms. | (48) |

| Neuroimmune

interactions | MHC genes | Dysregulated

immunity; exacerbated neuroinflammation. | (49,50) |

| Elevated cytokines

(TNF-α, IL-4, IL-6, IgM, PON1) | Exacerbated

neuroinflammation; disturbed neurotransmitter function. | (51,52) |

| Prenatal infections

(influenza, Toxoplasma gondii) | Activated maternal

immune responses. | (53,54) |

| p75 neurotrophin

receptor | Compromised

neuroprotection; neurotoxicity. | (55) |

Neurodevelopmental factors

Schizophrenia is increasingly recognized as a

neurodevelopmental disorder, characterized by disruptions during

critical stages of brain maturation that significantly influence

its onset and progression. These disruptions are often compounded

by genetic vulnerabilities and environmental factors such as

prenatal exposure to toxins or infections (31). The neurodevelopmental hypothesis

asserts that key developmental phases, particularly early gestation

and adolescence, involve crucial processes such as cell

proliferation and synaptic pruning, which are essential for normal

cognitive and emotional development (32).

During adolescence, synaptic pruning serves a vital

role in enhancing neuronal network efficiency by eliminating

redundant synapses; however, in schizophrenia, this process may

become excessive. For instance, the immune response of the brain

which is mediated by microglia that clear pathogens and prune

synapses, may become overactive. The activation of the complement

system, particularly the complement C4-A (C4-A) gene during late

adolescence, has been implicated in driving the excessive synaptic

pruning observed in schizophrenia (33). C4-A is essential for synaptic

pruning, marking synapses for removal by microglia, thereby

establishing a direct genetic-neuropathological connection to the

disorder. This excessive pruning leads to significant synaptic

loss, disrupting the balance between excitatory and inhibitory

signals in the brain (34,56).

Key genes such as neuregulin-1 and

disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 (DISC1) also serve pivotal roles in

brain development and are functionally interconnected (35,36). For example, DISC1 influences

neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus and is involved in synaptic

transmission and astrocyte development (57). Furthermore, environmental factors

such as prenatal infections, malnutrition and early-life stress

exacerbate genetic predispositions, increasing the complexity and

susceptibility of schizophrenia (39). This pathological synaptic loss

significantly affects gray matter volume in critical brain regions,

such as the prefrontal cortex, which is essential for higher

cognitive functions (38,44).

Neurotransmitter dysregulation

The initial model of schizophrenia attributed

positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, to

hyperdopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway, while

negative symptoms, such as social withdrawal and apathy, were

linked to dopaminergic hypoactivity in the mesocortical pathway

(58). Consistently, elevated

dopamine synthesis and release capacity have been observed in the

striatum of individuals with schizophrenia (59). Recent research, however, presents

a more nuanced perspective, emphasizing that the timing, specific

sites of dopamine release and receptor sensitivities are critical

factors in understanding the variability of symptoms among patients

(60-62). This approach moves beyond

dopamine dysregulation, offering further insights into the

neurochemical dynamics underlying the disorder (46).

There is increasing recognition of the complex

interactions between dopamine and other neurotransmitter systems,

particularly glutamate, in schizophrenia (46,56). Glutamate, the primary excitatory

neurotransmitter, has been implicated in both cognitive deficits

and negative symptoms, underscoring its pivotal role in the

pathology of schizophrenia (45,47). Variations in glutamate levels

across brain regions highlight the potential role of

region-specific glutamatergic dysfunction in the development and

symptom heterogeneity of schizophrenia (47). Dopaminergic activity in the

midbrain is heavily influenced by glutamatergic inputs from the

frontal cortex. This interaction forms a complex neural circuit,

where cortical pyramidal glutamatergic neurons activate GABAergic

interneurons, which, in turn, inhibit further glutamate release

from cortical neurons projecting to midbrain dopamine neurons. This

regulatory mechanism helps control the excitatory inputs received

by dopamine-producing neurons (50,63). γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the

principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS, is critical for

maintaining neural circuit balance. In schizophrenia, disrupted

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) activity on GABA interneurons

impairs inhibitory control, contributing to the cognitive deficits

associated with the disorder (59). Imbalances in this system can lead

to either increased or decreased dopaminergic output, significantly

affecting the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (64). These disturbances highlight the

need to elucidate the complex interplay between neurotransmitter

systems, as this may reveal novel therapeutic targets, such as

glutamatergic modulators or GABAergic enhancers, offering more

effective interventions for schizophrenia.

Neuroimmune interactions

The etiology of schizophrenia is increasingly viewed

in terms of neuroimmune interactions, highlighting the complex

interplay between genetic predispositions, environmental triggers

and immune system dysregulation (65,66). This perspective shifts the

traditional understanding of neuroinflammation from a consequence

to a potential contributing factor in schizophrenia development

(67).

The major histocompatibility complex on chromosome

6, essential for immune regulation, is associated with

schizophrenia (68,69). Dysregulation of genes within this

locus, related to innate immunity, may induce a pro-inflammatory

state in the CNS, exacerbating synaptic and neurotransmitter

disturbances (27,49). Increased levels of inflammatory

markers in both blood and CSF have been consistently observed in

patients with schizophrenia (70-72). Specifically, IL-6 levels are

significantly higher in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia

compared with that of healthy controls (73). IL-6 levels remain elevated in

both acute and chronic phases of psychosis, reinforcing the complex

relationship between neuroinflammatory processes and schizophrenia

pathology (71,74). This inflammation, marked by

increased levels of cytokines such as IL-6, influences

neurotransmitter systems, including dopaminergic and glutamatergic

pathways, which may exacerbate schizophrenia symptoms (51,75). Furthermore, increased IL-6 levels

correlate with cognitive decline and greater severity of both

positive and negative symptoms. Elevated C-reactive protein, a

systemic inflammation marker, has also been associated with

worsened cognitive function during acute psychosis (76). The entry of pro-inflammatory

cytokines and neurotoxic compounds into the CNS triggers an

inflammatory cascade linked to reactive oxygen species (ROS)

production. While ROS are normally byproducts of cellular

metabolism, excessive production leads to substantial cellular

damage. This inflammatory response, in conjunction with elevated

ROS, activates microglia and astrocytes, critical immune cells in

the brain, further promoting cytokine release and ROS production.

The resulting cycle of increased oxidative stress damages cellular

components, including membranes, proteins and DNA, contributing to

neuronal injury and dysfunction (77,78).

Additionally, maternal immune activation during

pregnancy due to infections such as influenza or Toxoplasma

gondii can disrupt immune regulation in the developing fetus.

The associated increase in cytokines such as IL-6 may impair normal

brain development, elevating the risk of schizophrenia in offspring

(79). This emerging

understanding underscores the significant role immune system

interactions serve in shaping the neuropsychiatric outcomes of

individuals predisposed to schizophrenia.

Treatment of schizophrenia

Antipsychotics remain the primary treatment for

schizophrenia, targeting dopamine receptors to alleviate core

symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations. These medications

are broadly classified into two categories: Typical

(first-generation) and atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics.

Typical antipsychotics, such as haloperidol and chlorpromazine,

exert their effects mainly through dopamine D2 receptor antagonism

and are often associated with significant adverse effects,

including extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), tardive dyskinesia and

neuroleptic malignant syndrome (80,81). By contrast, atypical

antipsychotics, including risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine and

aripiprazole, target both dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A

receptors. While these agents carry a reduced risk of motor side

effects, they are more frequently linked to metabolic

complications, such as weight gain, insulin resistance and

increased cardiovascular risk (82,83). Current treatment guidelines, such

as those from the American Psychiatric Association and the National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence, recommend

second-generation antipsychotics as first-line therapy, with drug

selection tailored to individual symptom profiles, side effect

tolerance and comorbid conditions. Despite their efficacy, ~33% of

patients with schizophrenia exhibit resistance to standard

antipsychotic treatments (84,85).

Targeting the BBB has demonstrated new therapeutic

avenues for treating schizophrenia. Although no FDA-approved drugs

currently regulate tight junction proteins, existing

anti-inflammatory therapies have demonstrated promise in improving

schizophrenia symptoms. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors, minocycline,

neurosteroids, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), statins and estrogens have

all shown consistent benefits (86). Minocycline inhibits microglial

activation and TNF-α production, indirectly stabilizing BBB

integrity (87). NAC boosts

glutathione levels and inhibits IL-6 and IL-1β, reducing oxidative

stress (88). A 6-month course

of NAC at 2 g/day has been shown to reduce overall symptom severity

significantly (PANSS effect size=0.45) (89).

Among novel therapies, lumateperone

(Caplyta®) has shown potential as a treatment option.

Lumateperone modulates dopaminergic, serotonergic and glutamatergic

neurotransmission, while its anti-inflammatory properties reduce

cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. By restoring BBB

integrity, lumateperone improves barrier function and mitigates

inflammation triggered by immune challenges or stress (90). Clinical trials, including

ITI-007-301 and ITI-007-005, have shown significant efficacy in

managing schizophrenia and bipolar depression symptoms (91). The favorable side effect profile

of lumateperone, lower rates of EPS and minimal metabolic impact,

makes it an attractive treatment option. Lumateperone also reduced

relapse risk by 63% over 26 weeks (hazard ratio=0.37), with relapse

rates of 16.4% compared with 38.6% for placebo. The drug

demonstrated a favorable safety profile, with low akathisia rates

(2.1 vs. 6.9% placebo), minimal sedation [24%; number needed to

harm (NNH)=8] and few treatment discontinuations. Serious adverse

events, such as seizures (0.2%) and orthostatic hypotension (0.3%),

were rare (92). However,

variability in clinical trial outcomes underscores the need for

further studies to further understand the long-term benefits and

limitations, particularly in diverse patient subgroups (93,94).

BBB

Structure and function

The BBB serves a critical role in maintaining CNS

homeostasis by regulating the exchange of substances between the

blood and the brain. Comprised of endothelial cells lining the

capillaries of the brain, the BBB is specifically structured to

protect the brain from potential harm while facilitating the

efficient transport of essential nutrients into the environment of

the brain (95).

The BBB is reinforced by endothelial cells connected

by tight junctions formed by transmembrane proteins, including OCLN

and CLDNs, particularly CLDN5 (96). These proteins are essential for

maintaining the selective permeability of the barrier, permitting

the passage of essential nutrients while blocking harmful

substances. Scaffolding proteins such as zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1)

and junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs) provide structural support

and facilitate cellular signaling critical for regulating barrier

function and integrity. Surrounding the endothelial cells, the

basal lamina offers additional reinforcement, incorporating

proteins such as collagen type IV, laminin and fibronectin

(95). Collagen type IV forms a

scaffold supporting endothelial cells and pericytes, laminin

enhances cell adhesion and influences differentiation and

migration, while fibronectin facilitates cell adhesion and

modulates growth and migration (97). These interactions are pivotal for

the organization and stability of the BBB (98). Embedded in this extracellular

matrix, pericytes regulate blood flow and contribute to BBB

integrity, serving a pivotal role in processes such as angiogenesis

and barrier repair. Astrocytic end-feet closely envelop the

endothelium, augmenting tight junction functionality and supporting

the overall operations of the barrier. This intricate structure

ensures that the BBB effectively controls the entry and exit of

substances, maintaining the protected environment of the brain

(98).

The tight junctions of the BBB limit the diffusion

of hydrophilic molecules, allowing only selective substances to

penetrate. This selective permeability is essential for preventing

harmful substances from entering the brain while enabling the

passage of necessary nutrients. Nutrient transport across the BBB

is mediated by specialized transporter proteins, such as GLUT1 for

glucose and LAT1 for amino acids, which are essential for supplying

neuronal cells with the substrates required for energy production

and neurotransmitter synthesis (99). In addition to nutrient transport,

the BBB employs efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp)

to actively expel potentially harmful substances, such as

neurotoxins and excess neurotransmitters, that may have crossed

into the brain. This protective mechanism helps maintain chemical

stability and safeguards the brain against toxic threats, ensuring

optimal function (100,101). Transport across the BBB occurs

via several mechanisms: Passive diffusion for small lipophilic

molecules, carrier-mediated transport for essential nutrients,

receptor-mediated transcytosis for larger molecules and efflux

pumps for removing potentially harmful substances (7). Furthermore, the BBB serves a

critical role in maintaining ion balance, preventing electrolyte

disturbances that could disrupt neuronal function. It also

dynamically adjusts its permeability in response to both

physiological and pathological stimuli, such as inflammation, to

meet the needs of the CNS (3).

Evidence of BBB dysfunction in

schizophrenia

Clinical studies and case reports (76,102) provide compelling evidence of

BBB abnormalities in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia,

suggesting that BBB dysfunction may serve a significant role in the

pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Table II) (13,18,71,103-111). A meta-analysis demonstrated

that ~16% of patients with first-episode psychosis exhibit

increased BBB permeability (18), indicating that BBB dysfunction

may manifest early in the illness and potentially serve as a

biomarker. However, it is essential to consider potential

confounding factors such as medication use, concurrent medical

conditions and lifestyle factors, all of which may impact BBB

integrity (112-114). Furthermore, the heterogeneity

among patients with schizophrenia, including variations in

symptomatology, disease progression and treatment response,

presents challenges in generalizing these findings across the

broader patient population (115). Future studies should address

these confounders and explore subgroup analyses to refine the

current understanding of BBB dysfunction in specific cohorts.

| Table IIBBB-associated molecules in

schizophrenia. |

Table II

BBB-associated molecules in

schizophrenia.

| Marker | Normal

function | Change observed in

schizophrenia | Implication | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Q-Alb | Maintains blood

environment | Elevated in

CSF | Increased BBB

permeability | (103) |

| Total protein | - | Elevated in

CSF | Increased BBB

permeability | (18,71) |

| S100B | Supports astrocyte

function and CNS homeostasis | Elevated in

blood | Increased CNS

leakage due to compromised BBB | (104) |

| MMP9 | Regulates

extracellular matrix integrity and tight junction stability in the

BBB | Elevated in

blood | Compromised

BBB | (105,106) |

| Claudin-5 | Key component in

maintaining tight junctions that seal the BBB | Decreased in

postmortem hippocampus | Damaged BBB | (13,107) |

| Zonulin | Regulates tight

junctions and intestinal barrier function, extrapolated to BBB | Elevated in

blood | Damaged BBB | (108-110) |

| Soluble

P-selectin | Serves a role in

vascular health and regulating inflammation | Elevated in

blood | May facilitate

worsening of neuroinflammation, cognitive deficits and psychotic

symptoms | (111) |

Biochemical indicators

BBB dysfunction in schizophrenia is evident in both

the CSF and systemic biomarkers. For example, studies have shown

that ~29.4% of patients with schizophrenia display elevated

CSF/serum albumin quotient (Q-Alb) levels, indicating impaired

barrier selectivity that allows blood-derived proteins to

infiltrate the CNS (103,116). In addition to increased Q-Alb,

elevated total protein levels in CSF further underscore the extent

of BBB disruption, reflecting a loss of selective permeability.

This indicates that the BBB is no longer effectively restricting

the passage of large plasma-derived proteins, allowing non-specific

leakage into the central nervous system (18,71).

Serum biomarkers also support the evidence of BBB

compromise. S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B), an

astrocyte-derived protein, leaks into the bloodstream when the BBB

is disrupted, correlating with neuroinflammatory activity (104). Similarly, elevated MMP9 levels

in schizophrenia contribute to the degradation of tight junction

proteins and extracellular matrix components, perpetuating BBB

leakage and neurovascular remodeling (105,106). Increased zonulin levels, a

regulator of paracellular permeability, in the serum of patients

with schizophrenia further indicate compromised BBB integrity

(108).

Neuroimaging insights

Neuroimaging studies, particularly dynamic

contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI), have

notably advanced the current understanding of BBB dysfunction in

schizophrenia (14,23,102). These studies demonstrate

substantial BBB leakage in patients at their first episode of

psychosis, suggesting that such disruptions may be foundational to

disease onset rather than secondary manifestations and could

potentially serve as early biomarkers (117). DCE-MRI findings demonstrate

that increased BBB permeability, quantified by the volume transfer

constant (Ktrans), correlates with increased symptom severity and

longer disease duration (118).

Advancements in positron emission tomography (PET)

imaging have also enhanced the current understanding by enabling

non-invasive assessments of BBB permeability using specialized

radiotracers. Advancements in positron emission tomography (PET)

imaging have also enhanced the current understanding by enabling

non-invasive assessments of BBB permeability using specialized

radiotracers. In schizophrenia, PET studies utilizing tracers such

as [¹¹C]-verapamil and [¹¹C]-L-dopa have demonstrated

region-specific reductions in P-glycoprotein function and altered

dopamine synthesis capacity, particularly in the striatum and

prefrontal cortex (10,119). Additionally, functional MRI

(fMRI) can assess cerebral blood flow (CBF) and neuronal activity,

offering insights into how BBB dysfunction affects the clinical

symptoms of schizophrenia (12,120).

Evidence of genetic and developmental

correlation

Genetic and developmental factors serve a pivotal

role in the pathogenesis of BBB dysfunction in schizophrenia

(12). The genetic basis of BBB

disruption is exemplified by 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22qDS), a

disorder caused by a deletion of a small DNA segment on chromosome

22, which not only elevates schizophrenia risk but also impairs key

genes essential for BBB integrity (120). Notably, CLDN5, encoding

claudin-5, a protein critical for maintaining BBB tight junctions,

is significantly affected in this context and implicated in the

pathophysiology of schizophrenia (107). Induced pluripotent stem cell

models derived from patients with 22qDS exhibit a 'leaky' BBB

phenotype, marked by disorganized claudin-5 and enhanced

permeability (120,121).

Additionally, GWAS have identified loci linked to

both schizophrenia susceptibility and vascular health, highlighting

genes such as slit guidance ligand (SLIT)1, SLIT3 and roundabout

guidance receptor 1, which regulate endothelial signaling and

angiogenesis (13,122). The Frizzled Class Receptor 1

(FZD1) gene, integral to the Wnt signaling pathway that governs

endothelial function and BBB integrity, shows a notable independent

genetic association with schizophrenia, as identified in GWAS and

supported by transcriptomic analyses of patient-derived brain

tissue (123). In particular,

reduced FZD1 expression has been observed in the prefrontal cortex

of individuals with schizophrenia, suggesting impaired Wnt

signaling may contribute to BBB dysfunction and heightened

neuroinflammatory susceptibility (124).

These findings underscore the direct impact of

genetic predispositions on BBB integrity in schizophrenia,

increasing susceptibility to environmental factors and potentially

accelerating disease progression.

Mechanisms linking BBB dysfunction to

schizophrenia

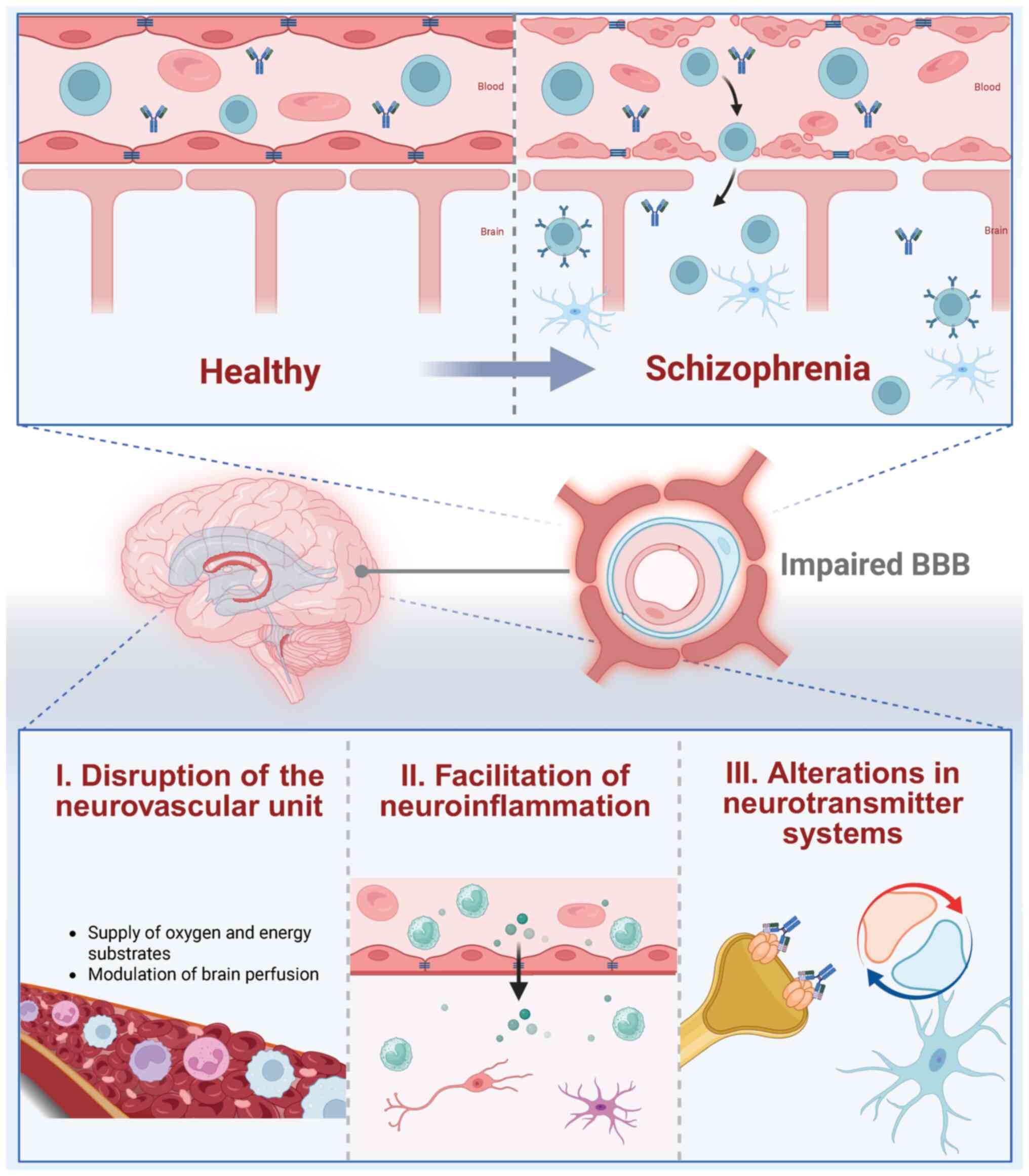

The breakdown of the BBB in schizophrenia

contributes to disease progression through multiple mechanisms

(Fig. 2), facilitating the entry

of inflammatory mediators and immune cells into the CNS. This

disruption exacerbates neuroinflammation, further affecting key

neurotransmitter systems and CBF, which are critical for the

development of cognitive and psychotic symptoms (10,14).

Dysregulating CBF

CBF quantifies the volume of blood flow through

brain tissue over time, increasing in response to neuronal activity

to ensure adequate oxygen and glucose supply for metabolic demands

(125). However, in

schizophrenia, reduced CBF impairs this process, exacerbating

neuronal damage and cognitive deficits, including auditory verbal

hallucinations (AVHs) (126). A

failure in neurovascular coupling has been identified, correlating

with specific symptoms such as AVHs (127), as well as a broader reduction

in CBF associated with cognitive decline and dementia progression

(128).

The BBB is integral in regulating CBF and

maintaining brain health by stabilizing the microenvironment and

facilitating the clearance of metabolic waste (40,129). BBB dysfunction disrupts CBF

regulation, leading to the accumulation of neurotoxic substances

and the amplification of neuroinflammatory processes that impair

synaptic function (130). This

relationship underscores the critical role of BBB integrity in

mitigating the progression and symptom severity of schizophrenia

(131).

Neuroinflammation promotion

In schizophrenia, BBB disruption permits the entry

of peripheral immune components into the CNS, exacerbating deficits

in synaptic pruning and neurotransmitter imbalances central to the

pathology of schizophrenia (10).

Elevated levels of soluble P-selectin (sP-selectin)

and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule in patients indicate a

pro-inflammatory state that promotes immune cell migration across

the compromised BBB (111).

This infiltration activates glial cells, including microglia and

astrocytes, which release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6

and TNF-α (132), exacerbating

cognitive and psychotic symptoms by disrupting neurotransmitter

systems, particularly glutamatergic and dopaminergic pathways

(73,132). Additionally, inflammation can

further disrupt GABAergic signaling, disrupting the delicate

balance between excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory

(GABAergic) neurotransmission, essential for cognitive function

(10,133). Inflammation related to BBB

dysfunction may also affect serotonin transporter activity and

receptor function, influencing these symptoms (10). Furthermore, the neuroinflammatory

process may damage the BBB further, creating a harmful feedback

loop that exacerbates the symptoms and progression of schizophrenia

(134,135). The increased vulnerability of

the brain to immune mediators following BBB compromise highlights

the need for longitudinal studies on BBB function in individuals at

high risk for psychosis to further understand and address these

complex interactions (133,136).

Alteration of neurotransmitter

systems

BBB disruption in schizophrenia leads to

neurochemical imbalances, significantly impacting neurotransmitter

systems essential for CNS homeostasis, and contributing to a wide

range of symptoms including hallucinations, delusions, social

withdrawal, apathy and cognitive deficits. Hammer et al

(137) suggested that although

NMDAR autoantibody prevalence is similar between patients with

schizophrenia and controls, these autoantibodies correlate with

more severe neurological and affective symptoms in patients

exhibiting markers of BBB disruption, such as a history of head

trauma or the presence of the apolipoprotein E4 allele. Animal

models further support these findings by demonstrating that the

pathogenic effects of neuronal autoantibodies manifest only when

BBB integrity is compromised (10). In one study, mice passively

infused with human-derived anti-NMDAR IgG displayed no behavioral

abnormalities under normal BBB conditions; however, when BBB

permeability was transiently increased, via systemic

lipopolysaccharide injection or mannitol-induced osmotic opening,

mice developed anxiety-like behaviors, memory impairments and

reduced exploratory activity (138). Molecular analyses revealed

decreased synaptic NMDAR density and altered glutamatergic

signaling in the hippocampus. These findings highlight that

circulating autoantibodies require BBB disruption to access

neuronal targets and exert neurotoxic effects, underscoring the

pivotal role of BBB integrity in modulating autoimmune

contributions to schizophrenia-like phenotypes.

The BBB also regulates the transport of essential

nutrients and precursors required for neurotransmitter synthesis.

For instance, dopamine synthesis depends on the availability of

tyrosine, an amino acid that must cross the BBB. When BBB

permeability is compromised, the transport of key precursors such

as tyrosine is hindered, resulting in reduced dopamine synthesis

and potentially affecting other neurotransmitters (9,46,139,140). Increased BBB permeability

allows neurotoxic substances and bioactive molecules, such as

glutamate, norepinephrine, epinephrine and glycine, to infiltrate

the brain, disrupting neurotransmitter balance. This dysregulation

further impairs neuronal communication, intensifying cognitive

dysfunction, emotional instability and psychotic symptoms in

schizophrenia (141).

Limitations and future directions

Limitations and novel techniques of

current studies

Research on BBB permeability in schizophrenia has

become a pivotal area of investigation, providing insight on the

neurobiological mechanisms underlying of the disorder. Given the

heterogeneity of schizophrenia, with distinct subtypes potentially

exhibiting different pathophysiological mechanisms, variability in

BBB dysfunction may arise and should be considered a potential

source of bias (142).

Demographic factors such as age, sex and

comorbidities such as depression may also influence BBB

permeability. Furthermore, the impact of medications, particularly

antipsychotics, on BBB integrity represents a significant

confounding factor. For instance, clozapine may stabilize BBB

function in certain patients, complicating causal interpretations

(143). Environmental factors,

including stress and trauma, commonly experienced by individuals

with psychosis, can further impact BBB function (144).

From a methodological perspective, imaging

techniques used to assess BBB permeability, such as DCE-MRI and

ASL, could undergo further rigorous evaluation in improve

reliability and standardization across participants. The

generalizability of current findings is constrained by relatively

small sample sizes (schizophrenia, n=29; controls, n=18) (14). Larger and more diverse cohorts

are essential to determine the applicability of these findings to a

broader schizophrenia population. Furthermore, inconsistencies

across studies may arise from heterogeneity in imaging parameters,

contrast agent administration protocols, region-of-interest

definitions and permeability quantification models. For instance,

while some DCE-MRI studies have reported increased BBB leakage in

regions such as the hippocampus and temporal cortex, others have

not detected significant changes, likely due to variations in

acquisition timing, contrast dosage or differences in permeability

metrics (e.g., Ktrans vs. Vp) (14). ASL, although non-invasive and

contrast-free, measures cerebral perfusion rather than direct

barrier permeability, making it difficult to disentangle BBB

disruption from secondary vascular changes (129). Addressing these gaps will

deepen the current understanding of BBB permeability changes in

schizophrenia and guide future research directions.

Recent technological advancements have provided new

avenues for molecular, physiological, neurophysiological and

genomic insights. Dynamic in vitro BBB models, microfluidic

BBB and BBB-on-a-chip platforms offer sophisticated systems for

studying BBB permeability (145-147). Additionally, new cell culture

scaffolds containing essential anchoring or adhesion molecules

allow more precise control over cell differentiation, interactions

and responses (148).

Patient-derived brain organoids have emerged as

invaluable models for investigating BBB dysfunction in

schizophrenia. Organoids derived from patients with schizophrenia

exhibit a 30-50% increase in paracellular permeability and display

elongated microvascular networks, associated with the dysregulated

expression of tight junction proteins CLDN5 and OCLN. Differential

gene expression analysis of endothelial cells isolated from

schizophrenia patient-derived brain organoids reveals significant

enrichment of genes related to angiogenesis, vascular regulation

and inflammatory responses when compared with controls (149,150).

Using primary cultures derived from human cells

could mitigate species-specific differences; however, their

availability is limited due to ethical considerations. The

olfactory system, closely associated with significant olfactory

deficits in patients with schizophrenia, has become a key model in

schizophrenia research (151,152). The olfactory epithelium (OE)

offers a 'unique' window into the brain, providing an opportunity

to assess various hypotheses related to the neurodevelopmental

models of schizophrenia (153).

Recent single-cell RNA sequencing of cultured nasal turbinate cells

derived from patients with schizophrenia has shown that these cells

closely resemble neural progenitors and mesenchymal cells found in

the olfactory neuroepithelium and the developing brain (154). The OE presents a minimally

invasive source of neurons and precursor cells, sharing

developmental origins with CNS cells, facilitating the study of

gene-genomic interactions and neurophysiological processes relevant

to both schizophrenia and BBB pathology (155).

These innovations enable researchers to further

simulate the complex interactions underlying BBB dysfunction and

explore potential therapeutic interventions for conditions such as

schizophrenia.

Biomarkers and advanced imaging

techniques

Current research on BBB dysfunction in schizophrenia

highlights the critical role of biomarkers and imaging techniques

in understanding and diagnosing the disorder. However, the reliable

assessment of BBB integrity remains challenging due to the indirect

nature of numerous existing biomarkers and imaging methods. For

instance, plasma S100β levels have been shown to correlate with

negative symptoms and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia (156). Meta-analyses further indicate a

positive association between S100β levels, positive symptoms and

disease progression, suggesting that BBB permeability may increase

as the disease advances (157).

However, it remains unclear whether elevated S100β directly

reflects increased BBB permeability or merely signifies enhanced

glial cell production/secretion or degeneration.

The integration of blood-based biomarkers with

advanced neuroimaging techniques has potential for more

comprehensive and patient-specific diagnostic approach. For

example, while DCE-MRI Ktrans values provide valuable insights into

BBB dysfunction, they lack the molecular specificity needed to

fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying BBB impairment (14). To overcome this limitation,

combining DCE-MRI with PET imaging could enable molecular-level

visualization. PET could employ radiolabeled probes targeting

specific BBB markers such as CLDN5 or OCLN, which are vital for

tight junction formation and permeability regulation. However,

these PET tracers are still in early developmental stages, and

conclusive evidence supporting their clinical application for BBB

visualization, particularly in schizophrenia, remains lacking

(158,159).

By integrating these biomarkers with advanced

imaging techniques, diagnostic accuracy can be significantly

improved, enabling longitudinal tracking of BBB dysfunction. This

combined approach would facilitate more targeted, personalized

diagnostics, enhancing the monitoring of disease progression and

therapeutic responses in individual patients with

schizophrenia.

BBB-targeted therapies in

schizophrenia

Future directions regarding

BBB-targeted therapies

The development of drugs targeting BBB tight

junctions represents an emerging and promising avenue for

schizophrenia treatment. Preclinical studies have shown that

restoration of the endothelial glycocalyx can reduce oxidative

stress by up to 40% and enhance the expression of tight junction

proteins (160). Combination

strategies, such as pairing BBB stabilizers (e.g., mucin-domain

glycoproteins) with conventional antipsychotics, may not only

improve therapeutic efficacy but also allow dose reduction and

minimize systemic side effects (161).

Molecular modulators that reinforce tight junction

architecture, including CLDNs and OCLNs, are central to BBB

stabilization. Experimental evidence indicates that specific

peptides can promote the assembly of these proteins and restore

barrier integrity (162).

Epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor with an established

safety profile, has been shown to improve BBB function and enhance

neurobehavioral outcomes in animal models (163). Gene therapy approaches, such as

adeno-associated virus-mediated overexpression of mucin

biosynthesis enzymes (e.g., C1galt1), have successfully

reversed BBB dysfunction and cognitive deficits in preclinical

models (164). In addition,

small molecules targeting frizzled receptors have demonstrated the

ability to upregulate CLDN5 and OCLN, further supporting their

potential in preserving tight junction integrity (165).

Innovative dual-action strategies are also gaining

attention. For instance, co-administration of the LRP1-targeting

peptide KS-487 with the VIPR2 antagonist KS-133 has been shown to

enhance BBB penetration, reduce neuroinflammation and improve

cognitive performance in murine models, reflected by a ~30%

increase in novel object recognition (166). Such approaches, which

simultaneously target psychiatric symptoms and BBB dysfunction,

exemplify a new generation of therapeutics that extend beyond

neurotransmitter modulation. Ultimately, integrating BBB

stabilization strategies with standard pharmacological treatments

may lead to more effective, biologically grounded interventions for

schizophrenia and related neuropsychiatric disorders (85,160,161).

Impact of improving drug efficacy and

side effects

BBB variability serves a critical role in

influencing the therapeutic efficacy and side effects of

antipsychotic drugs. P-gp, a key efflux transporter at the BBB,

directly regulates the CNS concentration of these medications

(167). P-gp actively exports

numerous antipsychotics from the brain, creating variability in

patient responses and increasing the risk of side effects due to

suboptimal drug levels in the brain (167). Genetic polymorphisms or drug

interactions can alter P-gp activity (168). Among the most studied variants,

the ABCB1 C3435T single nucleotide polymorphism has been associated

with reduced P-gp expression and activity. Individuals carrying the

T allele often exhibit higher plasma and CNS concentrations of P-gp

substrates, including antipsychotics such as olanzapine and

risperidone (169). This

increased CNS exposure has been linked to both enhanced therapeutic

effects and a higher incidence of adverse reactions, such as

sedation and extrapyramidal symptoms. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic

interactions involving P-gp inhibitors, such as verapamil and

ketoconazole, can also lead to elevated brain-to-plasma

concentration ratios of co-administered P-gp substrates in both

preclinical and clinical settings, raising concerns about potential

neurotoxicity and altered efficacy (170). Chronic exposure to

antipsychotics in patients with compromised BBB function may also

lead to cumulative side effects or long-term neurovascular changes

(171,172). Ongoing research suggests that

prolonged medication use can deteriorate neurovascular integrity,

potentially worsening BBB dysfunction and exacerbating psychiatric

symptoms (133). Addressing the

increased activity of P-gp at the BBB, a significant contributor to

pharmacoresistance, is a key focus of current research, which

serves to advance treatment models and improve outcomes for

patients with schizophrenia (173). Various strategies have been

developed to enhance drug delivery to the CNS, such as intranasal

administration, incorporation of nanomaterials, RNA interference

and extracellular vesicles (174-177). Advanced delivery platforms,

including ligand-conjugated nanoparticles targeting receptors such

as LRP1, offer the potential for more efficient BBB crossing and

improved therapeutic outcomes (178). Combining anti-inflammatory

agents, such as minocycline, with nanoparticle-based delivery

systems presents a promising approach to stabilizing BBB function

and alleviating schizophrenia symptoms (166). However, most of these methods

assume a functional BBB in patients, often overlooking the dynamic

nature of the BBB and the potential dysfunction in psychiatric

populations.

Patients with impaired P-gp functionality may

experience higher drug concentrations in the brain, potentially

exacerbating side effects such as EPS due to enhanced dopamine

receptor blockade (179,180).

By contrast, robust P-gp activity could lower brain drug levels,

potentially reducing efficacy and decreasing side effect risks.

This dynamic is supported by research using Mdr1a/b knockout mice,

which lack functional P-gp and show increased brain concentrations

of drugs such as risperidone (167), highlighting critical role of

P-gp in modulating CNS drug access. Emerging strategies aim to

optimize BBB penetration without provoking unwanted side effects.

For instance, the novel TAAR1 agonist compound 50B demonstrates

favorable BBB permeability and does not induce EPS, suggesting that

strategic drug design can enhance efficacy while minimizing adverse

effects (181). Furthermore,

individual variability in BBB integrity underscores the importance

of personalized treatment approaches. While some patients maintain

intact BBB function, others exhibit significant permeability

changes, necessitating tailored therapeutic strategies that account

for individual differences in BBB dysfunction.

Conclusion

The present review synthesized key findings on the

role of BBB dysfunction in schizophrenia, emphasizing its

association with the neuropathological features of schizophrenia.

Notable insights include increased BBB permeability, reduced

expression of tight junction proteins, and elevated inflammatory

markers. These alterations not only exacerbate neuroinflammation

but also disrupt neurotransmitter systems, thereby influencing

symptom severity and treatment response (100). Thus, maintaining BBB integrity

is critical for the comprehensive management of schizophrenia,

underscoring its importance in both disease strategy and patient

care.

Future research focused on the BBB could

revolutionize diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in

schizophrenia by facilitating early detection and improving

treatment outcomes (4).

Non-invasive imaging techniques, such as DCE-MRI, and biomarker

discovery could enable earlier identification of BBB dysfunction,

leading to timely interventions (23,182). Furthermore, integrating DCE-MRI

with PET tracers may enhance diagnostic accuracy, facilitating the

detection of early BBB changes. Additionally, the development of

BBB-targeted therapies, including pharmacological agents that

promote BBB repair and nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems,

holds the potential to significantly improve treatment efficacy by

enhancing drug penetration into the brain (75,183). However, challenges remain,

particularly regarding the safe delivery of therapeutics across the

BBB and minimizing potential toxicity to non-target brain regions.

Personalized medicine approaches, incorporating genetic profiling

related to BBB integrity, could enable the development of tailored

treatment plans that address both symptom management and the

underlying neurobiological mechanisms of schizophrenia (184). Monitoring biomarkers of BBB

integrity, such as changes in the levels of tight junction proteins

and inflammatory markers, could offer valuable insights into the

effectiveness of treatment and inform the refinement of disease

management strategies (185).

Tailored treatment strategies, informed by genetic factors

affecting BBB function, may further enhance antipsychotic efficacy

by targeting both the symptoms and the underlying neurobiological

mechanisms of the disorder (133,186). Thus, future research into

diagnostic tools such as DCE-MRI and BBB-targeting therapies have

potential to improve the management and treatment of

schizophrenia.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

SL contributed to the writing and editing of this

review. CL collected the data. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

|

1

|

Hany M, Rehman B, Rizvi A and Chapman J:

Schizophrenia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island,

FL: 2024

|

|

2

|

Jauhar S, Johnstone M and McKenna PJ:

Schizophrenia. Lancet. 399:473–486. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Keshavan MS, Collin G, Guimond S, Kelly S,

Prasad KM and Lizano P: Neuroimaging in schizophrenia. Neuroimaging

Clin N Am. 30:73–83. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

4

|

DeLisi LE, Szulc KU, Bertisch HC, Majcher

M and Brown K: Understanding structural brain changes in

schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 8:71–78. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Goldwaser EL, Swanson RL II, Arroyo EJ,

Venkataraman V, Kosciuk MC, Nagele RG, Hong LE and Acharya NK: A

preliminary report: The hippocampus and surrounding temporal cortex

of patients with schizophrenia have impaired blood-brain barrier.

Front Hum Neurosci. 16:8369802022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Goldwaser EL, Wang DJJ, Adhikari BM,

Chiappelli J, Shao X, Yu J, Lu T, Chen S, Marshall W, Yuen A, et

al: Evidence of neurovascular water exchange and endothelial

vascular dysfunction in schizophrenia: An exploratory study.

Schizophr Bull. 49:1325–1335. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pardridge WM: Drug transport across the

blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 32:1959–1972. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Daneman R and Prat A: The blood-brain

barrier. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 7:a0204122015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Knox EG, Aburto MR, Clarke G, Cryan JF and

O'Driscoll CM: The blood-brain barrier in aging and

neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry. 27:2659–2673. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Najjar S, Pahlajani S, De Sanctis V, Stern

JNH, Najjar A and Chong D: Neurovascular unit dysfunction and

blood-brain barrier hyperpermeability contribute to schizophrenia

neurobiology: A theoretical integration of clinical and

experimental evidence. Front Psychiatry. 8:832017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Puvogel S, Palma V and Sommer IEC: Brain

vasculature disturbance in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry.

35:146–156. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Greene C, Kealy J, Humphries MM, Gong Y,

Hou J, Hudson N, Cassidy LM, Martiniano R, Shashi V, Hooper SR, et

al: Dose-dependent expression of claudin-5 is a modifying factor in

schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 23:2156–2166. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

13

|

Greene C, Hanley N and Campbell M:

Blood-brain barrier associated tight junction disruption is a

hallmark feature of major psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry.

10:3732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Moussiopoulou J, Yakimov V, Roell L,

Rauchmann BS, Toth H, Melcher J, Jäger I, Lutz I, Kallweit MS,

Papazov B, et al: Higher blood-brain barrier leakage in

schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: A comparative dynamic

contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging study with healthy

controls. Brain Behav Immun. 128:256–265. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Murray AJ, Rogers JC, Katshu MZUH, Liddle

PF and Upthegrove R: Oxidative stress and the pathophysiology and

symptom profile of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Front

Psychiatry. 12:7034522021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Su G, Chen Y, Li X and Shao JW: Virus

versus host: Influenza A virus circumvents the immune responses.

Front Microbiol. 15:13945102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Giordano GM, Bucci P, Mucci A, Pezzella P

and Galderisi S: Gender differences in clinical and psychosocial

features among persons with schizophrenia: A mini review. Front

Psychiatry. 12:7891792021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Maurus I, Wagner S, Campana M, Roell L,

Strauss J, Fernando P, Muenz S, Eichhorn P, Schmitt A, Karch S, et

al: The relationship between blood-brain barrier dysfunction and

neurocognitive impairments in first-episode psychosis: Findings

from a retrospective chart analysis. BJPsych Open. 9:e602023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

McCutcheon RA, Reis Marques T and Howes

OD: schizophrenia-an overview. JAMA Psychiatry. 77:201–210. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kay SR, Fiszbein A and Opler LA: The

positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia.

Schizophr Bull. 13:261–276. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lim K, Peh OH, Yang Z, Rekhi G, Rapisarda

A, See YM, Rashid NAA, Ang MS, Lee SA, Sim K, et al: Large-scale

evaluation of the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS)

symptom architecture in schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr.

62:1027322021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Karlsgodt KH, Sun D and Cannon TD:

Structural and functional brain abnormalities in schizophrenia.

Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 19:226–231. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dabiri M, Dehghani Firouzabadi F, Yang K,

Barker PB, Lee RR and Yousem DM: Neuroimaging in schizophrenia: A

review article. Front Neurosci. 16:10428142022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Tønnesen S, Kaufmann T, Doan NT, Alnæs D,

Córdova-Palomera A, Meer DV, Rokicki J, Moberget T, Gurholt TP,

Haukvik UK, et al: White matter aberrations and age-related

trajectories in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

revealed by diffusion tensor imaging. Sci Rep. 8:141292018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kubicki M, McCarley R, Westin CF, Park HJ,

Maier S, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA and Shenton ME: A review of diffusion

tensor imaging studies in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 41:15–30.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Trifu SC, Kohn B, Vlasie A and Patrichi

BE: Genetics of schizophrenia (review). Exp Ther Med. 20:3462–3468.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

V'Kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder

H and Thiel V: Coronavirus biology and replication: Implications

for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 19:155–170. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Georgiades A, Almuqrin A, Rubinic P,

Mouhitzadeh K, Tognin S and Mechelli A: Psychosocial stress,

interpersonal sensitivity, and social withdrawal in clinical high

risk for psychosis: A systematic review. Schizophrenia (Heidelb).

9:382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Nisha Aji K, Lalang N, Ramos-Jiménez C,

Rahimian R, Mechawar N, Turecki G, Chartrand D, Boileau I, Meyer

JH, Rusjan PM and Mizrahi R: Evidence of altered monoamine oxidase

B, an astroglia marker, in early psychosis and high-risk state. Mol

Psychiatry. 30:2049–2058. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Schmitt A, Falkai P and Papiol S:

Neurodevelopmental disturbances in schizophrenia: Evidence from

genetic and environmental factors. J Neural Transm (Vienna).

130:195–205. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Kotsiri I, Resta P, Spyrantis A,

Panotopoulos C, Chaniotis D, Beloukas A and Magiorkinis E: Viral

infections and schizophrenia: A comprehensive review. Viruses.

15:13452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Selemon LD and Zecevic N: Schizophrenia: A

tale of two critical periods for prefrontal cortical development.

Transl Psychiatry. 5:e6232015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, Davis A,

Hammond TR, Kamitaki N, Tooley K, Presumey J, Baum M, Van Doren V,

et al: Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement

component 4. Nature. 530:177–183. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Uliana DL, Zhu X, Gomes FV and Grace AA:

Using animal models for the studies of schizophrenia and

depression: The value of translational models for treatment and

prevention. Front Behav Neurosci. 16:9353202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mei L and Xiong WC: Neuregulin 1 in neural

development, synaptic plasticity and schizophrenia. Nat Rev

Neurosci. 9:437–452. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Soares DC, Carlyle BC, Bradshaw NJ and

Porteous DJ: DISC1: Structure, function, and therapeutic potential

for major mental illness. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2:609–632. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen L, Xu J, Zhu L, Xu P, Chang L, Han Y

and Wu Q: Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 reverse ectopic migration of

neural precursors in mouse hilus after pilocarpine-induced status

epilepticus. Mol Neurobiol. 60:6689–6703. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Breitmeyer R, Vogel S, Heider J, Hartmann

SM, Wüst R, Keller AL, Binner A, Fitzgerald JC, Fallgatter AJ and

Volkmer H: Regulation of synaptic connectivity in schizophrenia

spectrum by mutual neuron-microglia interaction. Commun Biol.

6:4722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

McGrath J, Saari K, Hakko H, Jokelainen J,

Jones P, Järvelin MR, Chant D and Isohanni M: Vitamin D

supplementation during the first year of life and risk of

schizophrenia: A Finnish birth cohort study. Schizophr Res.

67:237–245. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Duan L, Li S, Chen D, Shi Y, Zhou X and

Feng Y: Causality between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia: A

bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. BMC Psychiatry.

24:8172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Bondrescu M, Dehelean L, Farcas SS, Papava

I, Nicoras V, Podaru CA, Sava M, Bilavu ES, Putnoky S and Andreescu

NI: Cognitive impairments related to COMT and neuregulin 1

phenotypes as transdiagnostic markers in schizophrenia spectrum

patients. J Clin Med. 13:64052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bergen SE, Fanous AH, Walsh D, O'Neill FA

and Kendler KS: Polymorphisms in SLC6A4, PAH, GABRB3, and MAOB and

modification of psychotic disorder features. Schizophr Res.

109:94–97. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yang AC and Tsai SJ: New targets for

schizophrenia treatment beyond the dopamine hypothesis. Int J Mol

Sci. 18:16892017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Luvsannyam E, Jain MS, Pormento MKL,

Siddiqui H, Balagtas ARA, Emuze BO and Poprawski T: Neurobiology of

schizophrenia: A comprehensive review. Cureus.

14:e239592022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wu Q, Huang J and Wu R: Drugs based on

NMDAR hypofunction hypothesis in schizophrenia. Front Neurosci.

15:6410472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

McCutcheon RA, Krystal JH and Howes OD:

Dopamine and glutamate in schizophrenia: Biology, symptoms and

treatment. World Psychiatry. 19:15–33. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kruse AO and Bustillo JR: Glutamatergic

dysfunction in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 12:5002022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Jain R, Chepke C, Davis LL, McIntyre RS

and Raskind MA: Dysregulation of noradrenergic activity: Its role

in conceptualizing and treating major depressive disorder,

schizophrenia, agitation in Alzheimer's disease, and posttraumatic

stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 85:plunaro2417ah2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Murphy CE, Walker AK and Weickert CS:

Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia: The role of nuclear factor

kappa B. Transl Psychiatry. 11:5282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Hughes H, Brady LJ and Schoonover KE:

GABAergic dysfunction in postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex:

Implications for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and affective

disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 18:14408342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Müller N, Weidinger E, Leitner B and

Schwarz MJ: The role of inflammation in schizophrenia. Front

Neurosci. 9:3722015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Borovcanin MM, Jovanovic I, Radosavljevic

G, Pantic J, Minic Janicijevic S, Arsenijevic N and Lukic ML:

Interleukin-6 in schizophrenia-is there a therapeutic relevance?

Front Psychiatry. 8:2212017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Brown AS: Exposure to prenatal infection

and risk of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2:632011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Jenkins TA: Perinatal complications and

schizophrenia: Involvement of the immune system. Front Neurosci.

7:1102013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chandra J: The potential role of the p75

receptor in schizophrenia: Neuroimmunomodulation and making life or

death decisions. Brain Behav Immun Health. 38:1007962024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Hu W, MacDonald ML, Elswick DE and Sweet

RA: The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia: Evidence from human

brain tissue studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1338:38–57. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

57

|

Chen L, Zhu L, Xu J, Xu P, Han Y, Chang L

and Wu Q: Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates ectopic

neurogenesis in the mouse hilus after pilocarpine-induced status

epilepticus. Neuroscience. 494:69–81. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Winship IR, Dursun SM, Baker GB, Balista

PA, Kandratavicius L, Maia-de-Oliveira JP, Hallak J and Howland JG:

An overview of animal models related to schizophrenia. Can J

Psychiatry. 64:5–17. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

59

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Deserno L, Schlagenhauf F and Heinz A:

Striatal dopamine, reward, and decision making in schizophrenia.

Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 18:77–89. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Eisenberg DP, Yankowitz L, Ianni AM,

Rubinstein DY, Kohn PD, Hegarty CE, Gregory MD, Apud JA and Berman

KF: Presynaptic dopamine synthesis capacity in schizophrenia and

striatal blood flow change during antipsychotic treatment and

medication-free conditions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 42:2232–2241.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Bulumulla C, Walpita D, Iyer N, Eddison M,

Patel R, Alcor D, Ackerman D and Beyene AG: Synaptic

specializations at dopamine release sites orchestrate efficient and

precise neuromodulatory signaling. bioRxiv: 2024.09.16.613338.

2024.

|

|

63

|

Jahangir M, Zhou JS, Lang B and Wang XP:

GABAergic system dysfunction and challenges in schizophrenia

research. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6638542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Cohen SM, Tsien RW, Goff DC and Halassa

MM: The impact of NMDA receptor hypofunction on GABAergic neurons

in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 167:98–107.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Khandaker GM, Cousins L, Deakin J, Lennox

BR, Yolken R and Jones PB: Inflammation and immunity in

schizophrenia: Implications for pathophysiology and treatment.

Lancet Psychiatry. 2:258–270. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Müller N and Schwarz MJ: Immune system and

Schizophrenia. Curr Immunol Rev. 6:213–220. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Vallée A: Neuroinflammation in

schizophrenia: The key role of the WNT/β-catenin pathway. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:28102022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Ebrahimi M, Teymouri K, Chen CC, Mohiuddin

AG, Pouget JG, Goncalves VF, Tiwari AK, Zai CC and Kennedy JL:

Association study of the complement component C4 gene and suicide

risk in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia (Heidelb). 10:142024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Mokhtari R and Lachman HM: The major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) in schizophrenia: A review. J Clin

Cell Immunol. 7:4792016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Jeppesen R, Orlovska-Waast S, Sørensen NV,

Christensen RHB and Benros ME: Cerebrospinal fluid and blood

biomarkers of neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier in

psychotic disorders and individually matched healthy controls.

Schizophr Bull. 48:1206–1216. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix

SW, Nordentoft M, Kondziella D, Krogh J and Benros ME:

Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in

schizophrenia and affective disorders: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 24:869–887. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

72

|

Chaves C, Dursun SM, Tusconi M and Hallak

JEC: Neuroinflammation and schizophrenia-is there a link? Front

Psychiatry. 15:13569752024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Garver DL, Tamas RL and Holcomb JA:

Elevated interleukin-6 in the cerebrospinal fluid of a previously

delineated schizophrenia subtype. Neuropsychopharmacology.

28:1515–1520. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Zhilyaeva TV, Rukavishnikov GV, Manakova

EA and Mazo GE: Serum interleukin-6 in schizophrenia: Associations

with clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. Consort

Psychiatr. 4:5–16. 2023.

|

|

75

|

Fond G, Lançon C, Korchia T, Auquier P and

Boyer L: The role of inflammation in the treatment of

schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 11:1602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Miller BJ, Buckley P, Seabolt W, Mellor A

and Kirkpatrick B: Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in

schizophrenia: Clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol

Psychiatry. 70:663–671. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Li Y, Li YJ and Zhu ZQ: To re-examine the

intersection of microglial activation and neuroinflammation in

neurodegenerative diseases from the perspective of pyroptosis.

Front Aging Neurosci. 15:12842142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Salim S: Oxidative stress and the central

nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 360:201–205. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

79

|

Choudhury Z and Lennox B: Maternal immune

activation and schizophrenia-evidence for an immune priming

disorder. Front Psychiatry. 12:5857422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Siafis S, Wu H, Wang D, Burschinski A,

Nomura N, Takeuchi H, Schneider-Thoma J, Davis JM and Leucht S:

Antipsychotic dose, dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and

extrapyramidal side-effects: A systematic review and dose-response

meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 28:3267–3277. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, Remington G

and Houle S: Relationship between dopamine D(2) occupancy, clinical

response, and side effects: A double-blind PET study of

first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 157:514–520. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Grinchii D and Dremencov E: Mechanism of

action of atypical antipsychotic drugs in mood disorders. Int J Mol