Introduction

Glioma, the most common malignant tumor of the

central nervous system, poses a significant challenge in the field

of neuro-oncology due to its high invasiveness and poor response to

conventional treatments (1).

Despite advancements in surgical interventions, radiotherapy and

pharmacotherapy, the prognosis of glioma remains unfavorable, with

a short survival period (2). In

recent years, researchers have explored targeted therapies and

immunotherapies in hopes of improving treatment outcomes and

survival rates for these patients (3). However, despite progress in

existing treatment modalities, the high recurrence rate and

therapeutic resistance of gliomas significantly complicate their

clinical management (4). Hence,

investigating these molecular mechanisms not only aids in

elucidating the biological characteristics of gliomas but also

provides a theoretical basis for the development of new targeted

therapeutic strategies.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a continuous

network of membrane-bound tubular structures within the cytoplasm

that is primarily responsible for the folding, modification,

transport and degradation of proteins (5). ER-associated degradation (ERAD) is

a highly conserved quality control mechanism that plays a crucial

role in identifying and disposing of misfolded proteins by

retro-translocating them into the cytoplasm for proteasomal

degradation (6). This process

involves several key steps, including substrate recognition,

extraction, polyubiquitination, and subsequent degradation via

ERAD, in which molecular chaperones and lectins recognize unfolded

or misfolded nascent polypeptides (7). These misfolded proteins bind to

chaperones and are then delivered to ERAD ligands (7,8).

Ultimately, the polyubiquitinated substrates are translocated

through the retro-translocation channel into the cytoplasm, where

they are degraded by the 26S proteasome (8,9).

Glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78, Bip), a prominent ER

chaperone, not only assists in protein folding but also plays a

pivotal role in the ERAD pathway by recognizing misfolded proteins

and facilitating their retro-translocation, highlighting its

importance in maintaining ER homeostasis and cellular health

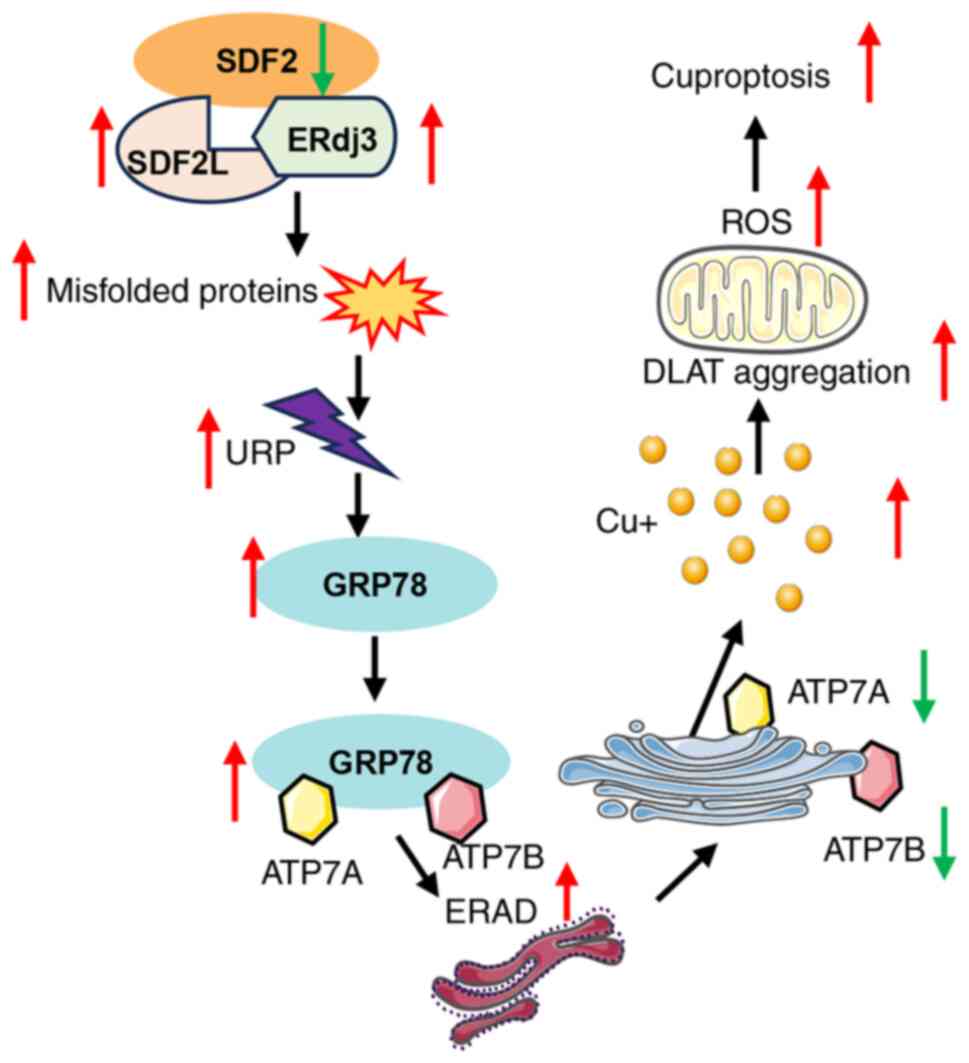

(Fig. 1) (10). Cuproptosis is a recently

identified form of programmed cell death characterized by the

accumulation of copper ions, which bind to lipoylated proteins in

the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 2). This interaction leads to

protein aggregation, loss of iron-sulfur cluster proteins,

proteotoxic stress, and ultimately, cell death. Emerging evidence

indicates a significant interplay between cuproptosis and ER stress

pathways (11,12). In cervical cancer, the

curcuminoid analog PBPD

(1-propyl-3,5-bis(2-bromobenzylidene)-4-piperidinone) has been

shown to induce cuproptosis by modulating the

Notch1/RBP-J/NRF2/FDX1 signaling axis (11). Specifically, PBPD suppresses

Notch1 and RBP-J expression, leading to decreased NRF2 activity and

subsequent upregulation of FDX1. This cascade results in increased

oxidative stress, activation of ER stress responses, and induction

of cuproptosis in cervical cancer cells. In lung adenocarcinoma, it

has been demonstrated that copper accumulation activates the

unfolded protein response (UPR), particularly through the spliced

form of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1s) (12). Hence, targeting the molecular

crosstalk between ER stress and copper-induced cell death pathways

may offer novel therapeutic strategies for cancers characterized by

disrupted copper homeostasis and ER stress responses.

Stromal cell-derived factor 2 (SDF2) acts as an ER

chaperone protein, primarily facilitating protein folding,

enhancing chaperone activity, maintaining ER functionality, and

regulating stress responses (13). SDF2 forms a complex with ER DnaJ

heat shock protein 3 (ERdj3), helping to maintain the folded state

of newly synthesized proteins and preventing misfolding and

aggregation (14). Its presence

enhances the chaperone activity of ERdj3, making it more effective

at inhibiting protein aggregation under normal physiological

conditions. By associating with ERdj3 and SDF2-like protein 1, SDF2

contributes to the maintenance of ER quality control mechanisms,

ensuring the proper function of intracellular proteins (14). Under ER stress conditions, the

role of SDF2 may be linked to the secretion of ERdj3 and its

extracellular functions, aiding cells in addressing the challenges

of protein folding (15).

Therefore, the primary function of SDF2 in the ER is to serve as a

molecular chaperone that promotes and maintains the correct folding

of proteins, thereby ensuring normal physiological activities and

stress responses in cells (Fig.

1) (15). However, its role

in glioma remains unexplored. The objective of the present study

was to investigate the specific functions and mechanisms of SDF2 in

glioma development and progression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The glial cell lines U87 (cat. no. CL-0238), U251

(cat. no. CL-0237) and HMC3 (cat. no. CL-0620; all from Procell

Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) were cultured in complete

MEM (HyClone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS), 1% non-essential amino acids, sodium pyruvate and

penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were maintained in a humidified

incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. When the cells reached

~85% confluence, they were passaged using trypsinization. All cell

lines were authenticated using STR profiling.

MG132 treatment

To investigate the involvement of the proteasome

degradation pathway in the downregulation of ATP7A and ATP7B, U87

and U251 glioma cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor

MG132. Specifically, cells were incubated with MG132 (cat. no.

HY-13259; MedChemExpress) at a final concentration of 10 μM

for 24 h.

Western blotting

Protein extraction was performed from cells or

tissue samples using RIPA lysis buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.). The lysates were centrifuged at 10,000

× g for 15 min to remove cellular debris, and the supernatant

containing the total protein was collected. Protein concentrations

were quantified using a BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein samples

(15 μg/lane) were then subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. Following

electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane

(MilliporeSigma). The membrane was then blocked with 5% non-fat

milk or BSA (cat. no. A8010; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) in TBST (TBS with 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at

room temperature. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies specific to the target proteins SDF2 (cat. no.

PK47764), SDF2L1 (cat. no. PK17377), ERdj3 (cat. no. PA2683), GRP78

(cat. no. T55166), ATP7A (cat. no. PA7106), ATP7B (cat. no.

TA0410), dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (DLAT; cat. no.

T58125) and GAPDH (cat. no. M20006; 1:1,000; all purchased from

Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.). Lipoic acid (cat. no.

437695) was purchased from MilliporeSigma. After washing with TBST

to remove unbound primary antibodies, the membrane was incubated

with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat. no. ZB-2301 for

rabbit; cat. no. ZB-2305 for mouse) Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature. Following

several washes with TBST, the bound antibodies were visualized

using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The intensity of each

protein band was quantified using ImageJ analysis software (version

10; Media Cybernetics, Inc.). GAPDH was used as an internal

control.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol

reagent, and cDNA was synthesized following the instructions

provided with the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time)

(Takara Bio, Inc.). The reverse transcription conditions were set

at 37°C for 15 min, followed by 85°C for 5 sec and then 4°C

indefinitely. For qPCR, a 20-μl reaction mixture consisting

of 10 μl of Applied Biosystems™ SYBR Green Master Mix

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1 μl each of forward and

reverse primers, 2 μl of cDNA, and 6 μl of

ddH2O was prepared. The PCR protocol included initial

denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of

amplification with denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec, annealing at

60°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 30 sec. qPCR was

conducted on a LightCycler 480 system (Roche Diagnostics) to

quantify gene expression. The primers used in the present study

were listed as follows: SDF2 forward, 5′-GGAGCTTGGCATCATGGACT-3′

and reverse, 5′-GGAGCTTCATAGCGTCTCCA-3′; CHOP forward,

5′-ATGAACGGCTCAAGCAGGAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGAAAGGTGGGTAGTGTGG;

GRP78 forward, 5′-TCAGGCCAAGCCCAATACAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCCACGGTAGTGAGAGCCTT-3′; XBP1s forward,

5′-TGCTGAGTCCGCAGCAGGTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCTGGCAGGCTCTGGGGAAG-3′;

XBP1u forward, 5′-ACGGGACCCCTAAAGTTCTG-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGCACGTAGTCTGAGTGCTG-3′; and GAPDH forward,

5′-CCAGCAAGAGCACAAGAGGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGGAGATTCAGTGTGGTGG-3′.

The 2−ΔΔCq method was used for quantification assay

(16).

Human samples

Human tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissue samples

were obtained from patients with glioma during surgical procedures,

with informed consent obtained from all participants. A total of 10

patients were enrolled in the present study, including 4 females

and 6 males. The median age was 66 years (range, 53-67 years).

Ethical approval for sample collection and study was granted by the

institutional review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of

Xi'an Jiaotong University (approval no. 2024SF-FAHX-212; Xi'an,

China).

Additionally, the GEPIA database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) was used to analyze SDF2

mRNA expression levels across various tissue types and pathological

conditions. Statistical significance was assessed using GEPIA's

integrated analytical tools, providing insights into the potential

role of SDF2 in disease pathology.

Detection of malondialdehyde (MDA),

reduced glutathione (GSH) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

Cells from each group were collected, and the levels

of MDA, reduced GSH and ATP were measured using the appropriate

assay kits in strict accordance with the manufacturers' protocols.

The lipid peroxidation level was assessed using an MDA Assay kit

(cat. no. S0131S), ATP levels were quantified using an ATP Assay

kit (cat. no. S0026), and GSH and oxidized glutathione (GSSG)

levels were measured using a GSH and GSSG Assay kit (cat. no.

S0053) (all from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

EdU (5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine)

detection

The procedure was conducted using a BeyoClick EdU

Cell Proliferation Kit (DAB method) (cat. no. C0085S; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, cells were incubated in

medium containing 10 μM EdU for 2 h. After EdU labeling, the

medium was removed, and 1 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; cat. no.

P0099; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was added to each well

before incubation at room temperature for 15 min. The fixative was

then removed, and the cells were washed three times with 1 ml of

wash solution per well, with each wash lasting 5 min. Following the

wash steps, 1 ml of PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 was added to

each well, and the cells were incubated at room temperature for 15

min to permeabilize the cells. Next, 0.5 ml of Click reaction

solution was added to each well, and the cells were incubated in

the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The Click reaction

solution was then aspirated, and the cells were washed three times

with wash solution, with each wash lasting 5 min. Finally, the

cells were mounted with antifade mounting medium containing DAPI (a

final concentration of 1 μg/ml) and observed under a

fluorescence microscope.

Transwell assay

The bottom membrane of the Transwell insert

(Corning, Inc.) was coated with Matrigel matrix (Corning, Inc.) at

37°C for 1 h. U87 and U251 glioma cells, which were cultured to

~85% confluence, were harvested using trypsinization and

centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min. The cell density was adjusted

to 5×103 cells/100 μl, and the cells were

resuspended in serum-free medium to create a single-cell

suspension. Transwell inserts (8 μm pore size) were placed

in a 24-well plate, 600 μl of serum-containing medium was

added to the lower chamber to act as a chemoattractant, and 200

μl of the treated cell suspension was added to the upper

chamber. After 24 h of incubation, the inserts were removed, and

the remaining medium was aspirated. The inserts were washed with

PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min at room temperature, followed

by staining with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min. The cells that had

migrated through the membrane were visualized and images were

captured under an inverted light microscope (Keyence Corporation).

The number of invasive cells was quantified using ImageJ

software.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis

using Annexin V-PE/7-AAD staining

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were harvested

by trypsinization, collected in centrifuge tubes, and resuspended

in PBS. After the cells were counted, 5×105 cells were

collected and washed with PBS. The cells were then resuspended in

binding buffer from an Annexin V-PE/7-AAD Apoptosis Detection Kit

(cat. no. E-CK-A216; Elabscience Biotechnology, Inc.) and incubated

in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. Following incubation,

the cells were washed, resuspended and analyzed for apoptosis by

flow cytometry (CytoFLEX; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The data were

analyzed using FlowJo 10 (FlowJo LLC). The experiment was performed

in triplicate for statistical reliability.

Quantification of intracellular reactive

oxygen species (ROS) levels by flow cytometry

Intracellular ROS levels were measured by flow

cytometry using a fluorescent probe-based ROS detection kit (Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). Briefly, the cells were washed

twice with PBS, centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min to remove the

supernatant at room temperature, and collected. DCFH-DA working

solution was then added to each sample at a density of

1×105 cells/ml, and the cells were incubated at 37°C in

a CO2 incubator protected from light for 30 min. After

incubation, the cells were centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min to

remove the DCFH-DA solution, followed by washing with PBS 3 times

to ensure the removal of excess probe. The cells were finally

resuspended in PBS and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry for

ROS detection.

siRNA transfection

For transfection, cells were seeded in 6-well plates

at a density of 4×105 cells per well 24 h prior to

transfection to achieve optimal confluency. Small interfering RNA

(siRNA, 5′-AAAUAGAACAUUUUGAAGGUG-3′) targeting the gene of interest

and a non-targeting control siRNA (NC, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′)

were obtained from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. Transfection was

performed using HiPerFect Transfection Reagent (cat. no. 301705;

Qiagen, Inc.) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 150

ng of siRNA (final concentration of 10 nM) was diluted in 100

μl of serum-free DMEM. Subsequently, 6 μl of

HiPerFect Transfection Reagent was added to the diluted siRNA

solution, mixed gently, and incubated at room temperature for 10

min to allow complex formation. The siRNA-lipid complexes were then

added dropwise to each well containing cells in 2 ml of complete

growth medium. Cells were assessed 48 h post-transfection.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

U87 and U251 cells were adjusted to a density of

1,000 cells/μl and seeded into a 96-well plate. The cells

were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 h.

After incubation, the medium was removed, and the wells were washed

with PBS. Fresh medium (100 μl) was added to each well,

followed by 10 μl of CCK-8 solution (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The plate was then incubated

for an additional 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a

microplate reader to assess cell viability. The experiments

included the following groups: Ad-NC and Ad-shSDF2. To investigate

the mechanisms underlying the reduction in cell viability induced

by Ad-shSDF2, several inhibitors were added to the Ad-shSDF2 group:

z-VAD (20 μM), Nec-1 (10 μM), VX-765 (10 μM),

Fer-1 (1 μM), and TTM (10 μM). Cell viability was

calculated based on absorbance (A450) values, allowing for the

assessment of each inhibitor's effect on Ad-shSDF2-induced cell

viability reduction and identification of the specific cell death

pathways involved.

Detection of copper ion content

The intracellular copper ion content was quantified

using a Copper (Cu2+) Colorimetric Assay kit

(Elabscience Biotechnology, Inc.). For the assay, 15 μl of

each of the eight copper standards at different concentrations, as

well as 15 μl of each test sample, were added to individual

wells. Then, 230 μl of chromogenic working solution was

added to each well. The plates were covered with sealing film and

incubated at 37°C for 5 min. The optical density (OD) of each well

was measured at 580 nm using a microplate reader.

Detection of intracellular copper

ions

The intracellular copper ion distribution was

visualized using the fluorescent probe Coppersensor 1

(MedChemExpress). Cells were incubated with the probe at a final

concentration of 5 μM in each well, protected from light, at

37°C for 30 min. After incubation, the cells were observed under a

fluorescence microscope to assess the localization and intensity of

copper ion fluorescence.

Detection of mitochondrial ROS

Mitochondrial ROS levels were detected using the

specific fluorescent probe MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Once the cells reached the desired

density, the culture medium was removed and replaced with

MitoTracker Red CMXRos working solution at a final concentration of

1 μM. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After

incubation, the working solution was removed, and prewarmed fresh

culture medium was added. Fluorescence was observed using a

fluorescence microscope to assess the mitochondrial ROS levels.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

U87 and U251 cells were seeded in six-well plates at

a density of 5×105 cells per well and incubated at 37°C

with 5% CO2 until adherence. After 24 h, the cells were

fixed with 500 μl of 4% PFA for 30 min, followed by

permeabilization with 500 μl of 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30

min. The cells were then blocked with IF blocking buffer for 1 h.

After the blocking solution was removed, a mixture of primary

antibodies against TOM20 and DLAT (Abcam) was added (50 μl

per well), and the cells were incubated overnight at 4°C. The next

day, the primary antibodies were removed, and the cells were

incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies (500 μl

per well) at room temperature, protected from light, for 1 h. DAPI

staining solution (a final concentration of 1 μg/ml) was

then applied for 5 min to stain the nuclei. Images were captured

and stored using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

For these experiments, a co-IP kit (cat. no. P0401;

GENESEED; https://www.geneseed.com.cn/web/lxwm.html) was used.

Briefly, protein extracts were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). A specific

antibody against GRP78 was added to the protein samples to allow

binding with the target protein, and the samples were incubated at

4°C for several hours or overnight. 30 μl of protein A or G

magnetic beads (50% concentration) were then added to bind the

antibody-protein complexes, which were collected using magnetic

separation. The beads were washed multiple times with lysis buffer

to remove non-specifically bound proteins. The immunoprecipitated

proteins were then eluted from the beads by heating or by adding an

elution buffer. Finally, the eluted proteins were separated by

SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting to detect

co-immunoprecipitated proteins. By normalizing the Co-IP results to

GAPDH levels, any potential discrepancies in protein loading were

accounted for and it was ensured that the observed decrease in

ATP7A and ATP7B co-precipitation was specifically attributable to

the reduced availability of GRP78 for interaction, rather than

other experimental variations.

Construction of adenoviral vectors

Adenoviral vectors were constructed by Vigene

Biosciences for the overexpression and knockdown of the SDF2 or

GRP78 proteins. Adenoviral vectors carrying negative control genes

(Ad-NC, UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT) or shRNA sequences (Ad-sh-SDF2,

UCUUUUUGCCCACUGAUAGGU) targeting SDF2 were designed to infect

cells. Adenoviral vectors were added at a concentration of

109 PFU/ml, with 20 μl viral suspension per well

in six-well plates. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the

viral-containing medium was removed, cells were washed with PBS,

and fresh medium was added.

Xenograft tumor model in mice

A total of 15 SPF-grade BALB/c nude male mice (6-8

weeks old, 18-22 g, Cyagen Biosciences; https://www.lascn.net/SupplyDemand/Site/Index.aspx?id=30)

were randomly assigned into three experimental groups (Ad-NC,

Ad-SDF2, and Ad-SDF2 + Ad-GRP78), with five mice per group, using a

computer-generated randomization schedule. This sample size was

selected based on precedent studies and accepted practices in

glioma xenograft models, where comparable group sizes have been

sufficient to detect statistically significant effects (17-19). Investigators responsible for data

collection and outcome assessment were blinded to group allocation

to minimize potential bias. All animals were acclimatized to the

laboratory environment for one week prior to experimentation and

housed under standard specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions

[22±2°C, 55±10% humidity, 12/12-h light/dark cycle (7:00-19:00),

with ad libitum access to diet and sterile water].

Logarithmically growing U251 cells were collected from each

treatment group. Cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of

ice-cold PBS to maintain viability and kept on ice until injection.

Each mouse was subcutaneously injected with 1×106 cells

into the inguinal region. Tumor implantation was designated as day

0. Tumor growth and general health were monitored every two days.

Tumor volume (mm3) was measured using calipers and

calculated according to the formula: volume=1/2 × longest diameter

(mm) × [shortest diameter (mm)]2. At the experimental

endpoint, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation.

Subcutaneous tumors were excised, weighed, and processed for

further analysis. The maximum tumor diameter observed was 8.2 mm,

corresponding to a volume of 106.64 mm3. All animal

procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee of the Animal Experimentation Center, Xi'an Jiaotong

University (approval no. XJTUAE2023-1944; Xi'an, China).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tumor tissue sections were subjected to Ki-67 IHC.

In brief, the tissues (5 μm) were deparaffinized in xylene,

rehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and treated with 3% hydrogen

peroxide to inactivate endogenous peroxidase activity. Antigen

retrieval was performed, followed by blocking with goat serum (cat.

no. C0625; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Ki-67 primary

antibody (1:200; cat. no. AB2008; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was applied, and the samples were incubated

overnight at 4°C. The sections were then incubated with

HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. A0208; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) at 37°C for 30 min, followed by the

application of DAB substrate for color development (30 sec).

Hematoxylin counterstaining was performed for 1 min, and

differentiation was achieved in 1% hydrochloric acid ethanol. The

sections were then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series,

cleared in xylene, and mounted with neutral resin. Images were

captured using a light microscope. In each field, the number of

Ki-67-positive tumor cell nuclei and the total number of tumor cell

nuclei were manually counted. The proliferation index was then

calculated as the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells among the

total tumor cells in each field, and the average of these five

fields was taken as the final proliferation index for the

sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad

Prism software (version 10.0; Dotmatics). The data are presented as

the mean ± standard deviations (SDs). For relative expression

graphs, the control group was normalized to a fixed value (for

example, 1 or 100%). For comparisons between two groups, an

unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was employed. For comparisons

among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance was conducted,

followed by Tukey's post hoc test to assess pairwise differences

between group means. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Increased expression of SDF2 in glioma

tissues

Bioinformatic predictions revealed an increase in

SDF2 mRNA expression in glioma tissues compared with control

tissues (Fig. 3A and B).

Consistently, RT-qPCR analysis revealed significantly elevated SDF2

mRNA levels in tumor tissues relative to adjacent normal tissues

(Fig. 3C). IF staining further

demonstrated an increase in SDF2 fluorescence intensity in glioma

tissues compared with control tissues (Fig. 3D). Western blot analysis

confirmed higher SDF2 protein expression in glioma samples than in

adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig.

3E). These findings collectively suggest that SDF2 expression

is upregulated in glioma, potentially implicating it in glioma

pathogenesis.

SDF2 promotes malignant proliferation in

glioma cells

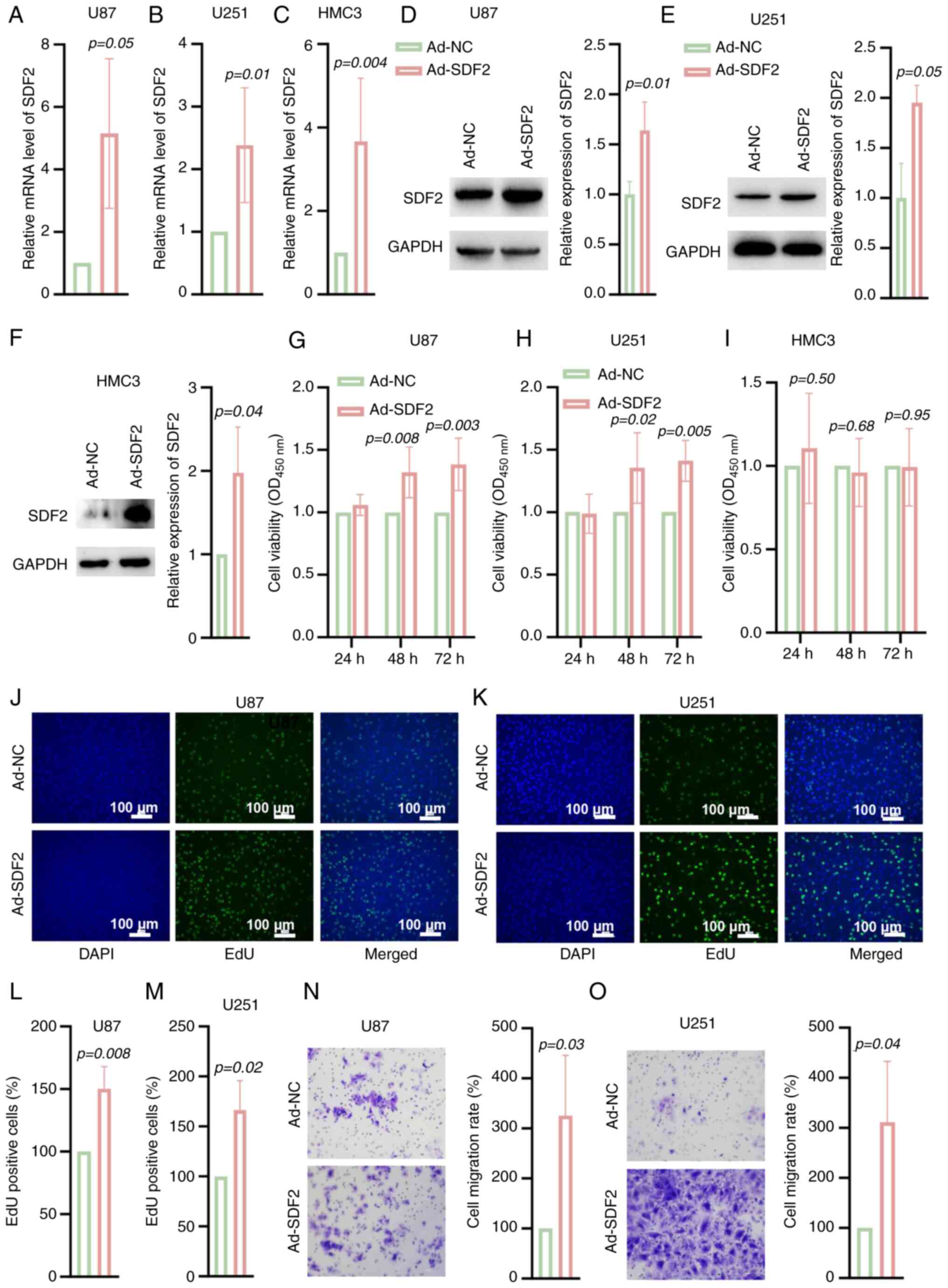

U87 and U251 cells were transfected with Ad-SDF2 to

overexpress SDF2. Following SDF2 overexpression, both the mRNA and

protein levels of SDF2 were significantly elevated in U87, U251 and

HMC3 cells (Fig. 4A-F).

Additionally, cell viability assays demonstrated that, compared

with the control, SDF2 overexpression enhanced the viability of U87

and U251 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4G and H), but the viability of

HMC3 cells did not change (Fig.

4I). The EdU staining results further confirmed that SDF2

overexpression increased the proliferative capacity of U87 and U251

cells relative to that of the controls (Fig. 4J-M). Moreover, Transwell assays

indicated that SDF2 overexpression promoted the migratory ability

of U87 and U251 cells (Fig. 4N and

O). These findings suggest that SDF2 plays a role in promoting

the malignant proliferation and migration of glioma cells.

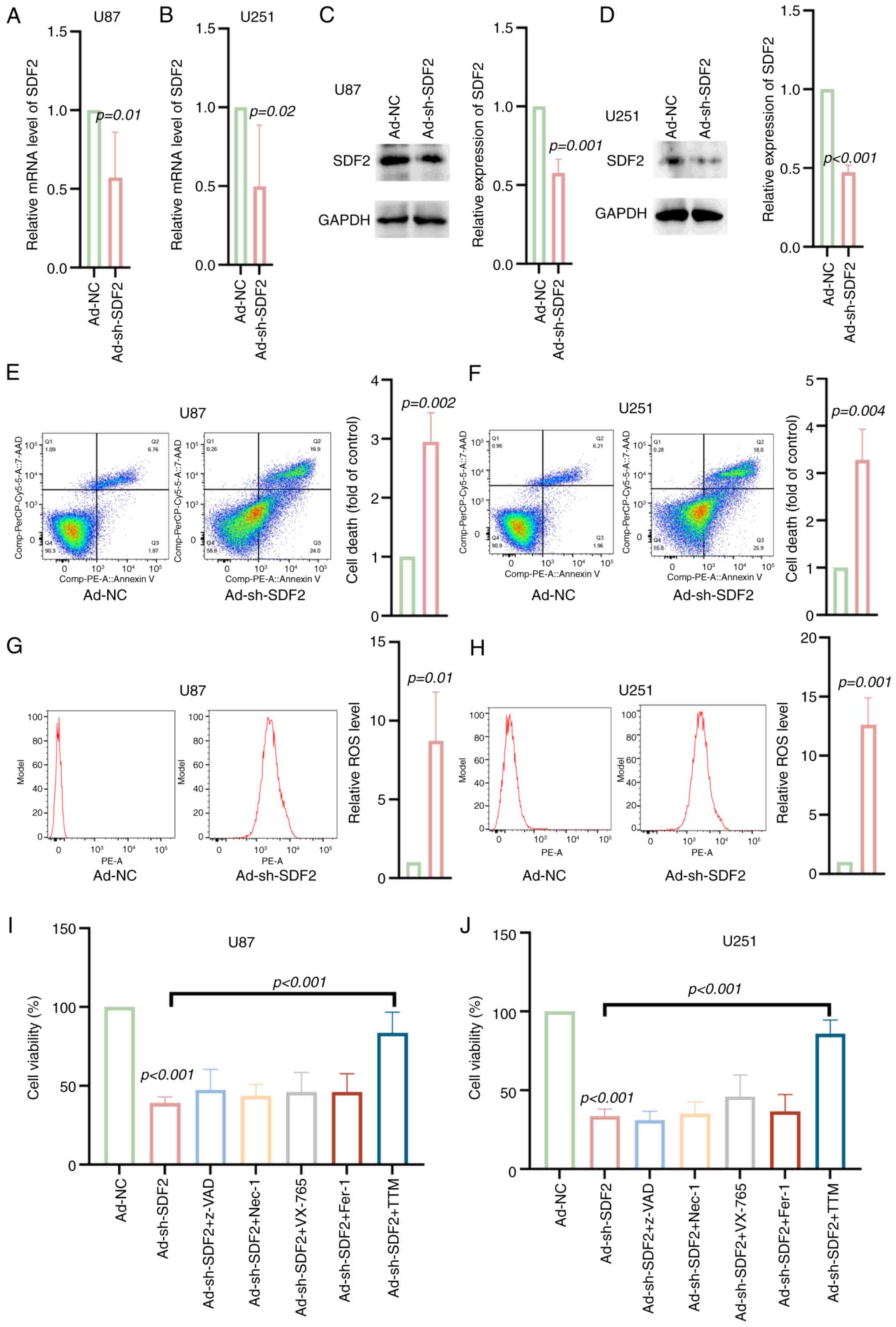

Knockdown of SDF2 increases ROS levels

and cuproptosis in glioma cells

U87 and U251 cells were transfected with Ad-shSDF2

to achieve SDF2 knockdown. The mRNA and protein levels were

decreased in U87 and U251 cells transfected with Ad-shSDF2

(Fig. 5A-D). Compared with the

control, Ad-shSDF2 transfection resulted in a significant increase

in the proportion of late apoptotic and necrotic cells in both the

U87 and U251 lines (Fig. 5E and

F). Additionally, ROS levels were significantly elevated

following SDF2 knockdown in U87 and U251 cells, indicating

increased oxidative stress (Fig. 5G

and H). Interestingly, only the cuproptosis inhibitor TTM

reversed the decrease in viability induced by Ad-shSDF2 in U87 and

U251 cells (Fig. 5I and J).

These results suggest that SDF2 knockdown induces oxidative stress,

increases apoptosis, and may involve copper-dependent cell death

pathways in glioma cells.

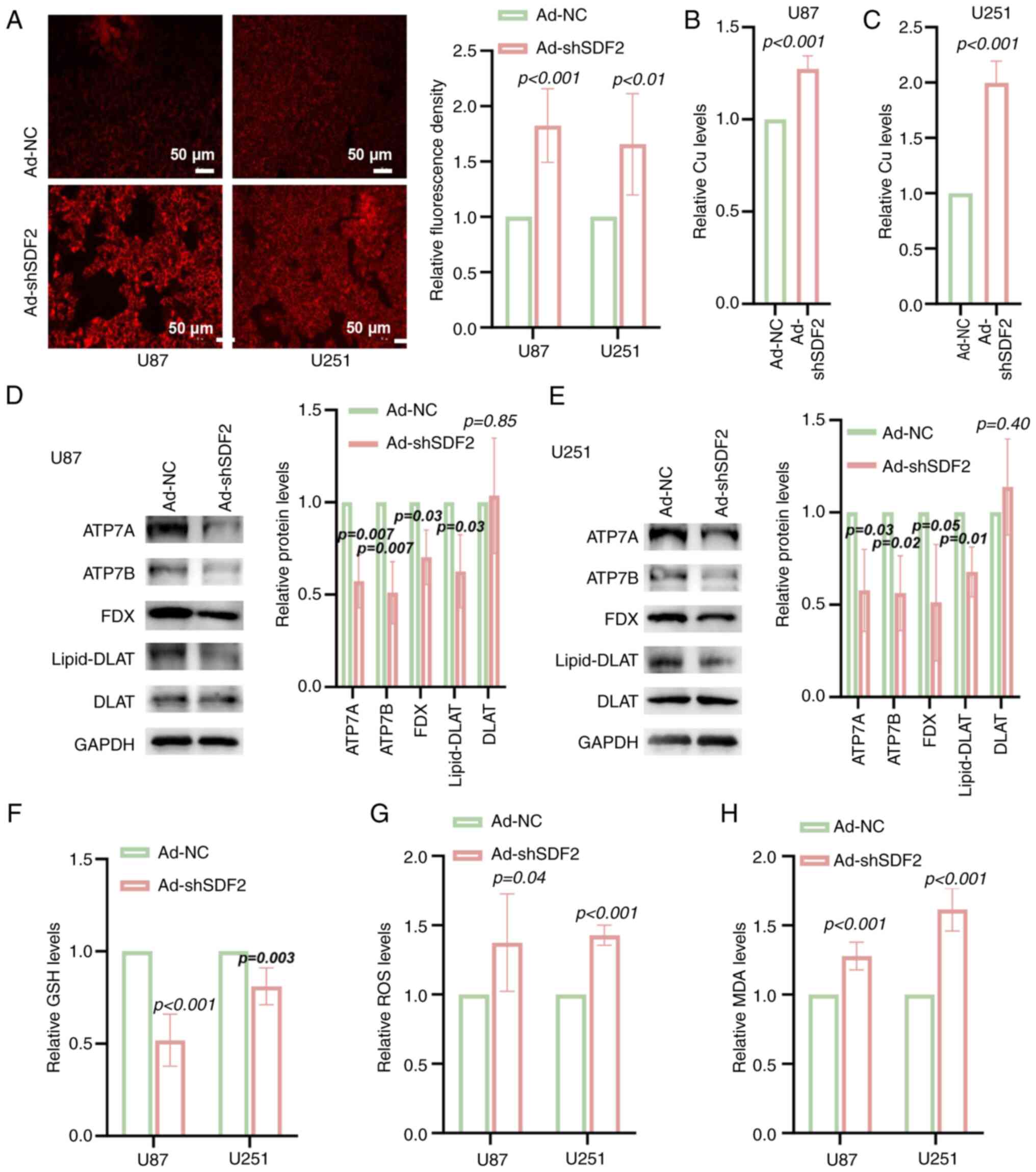

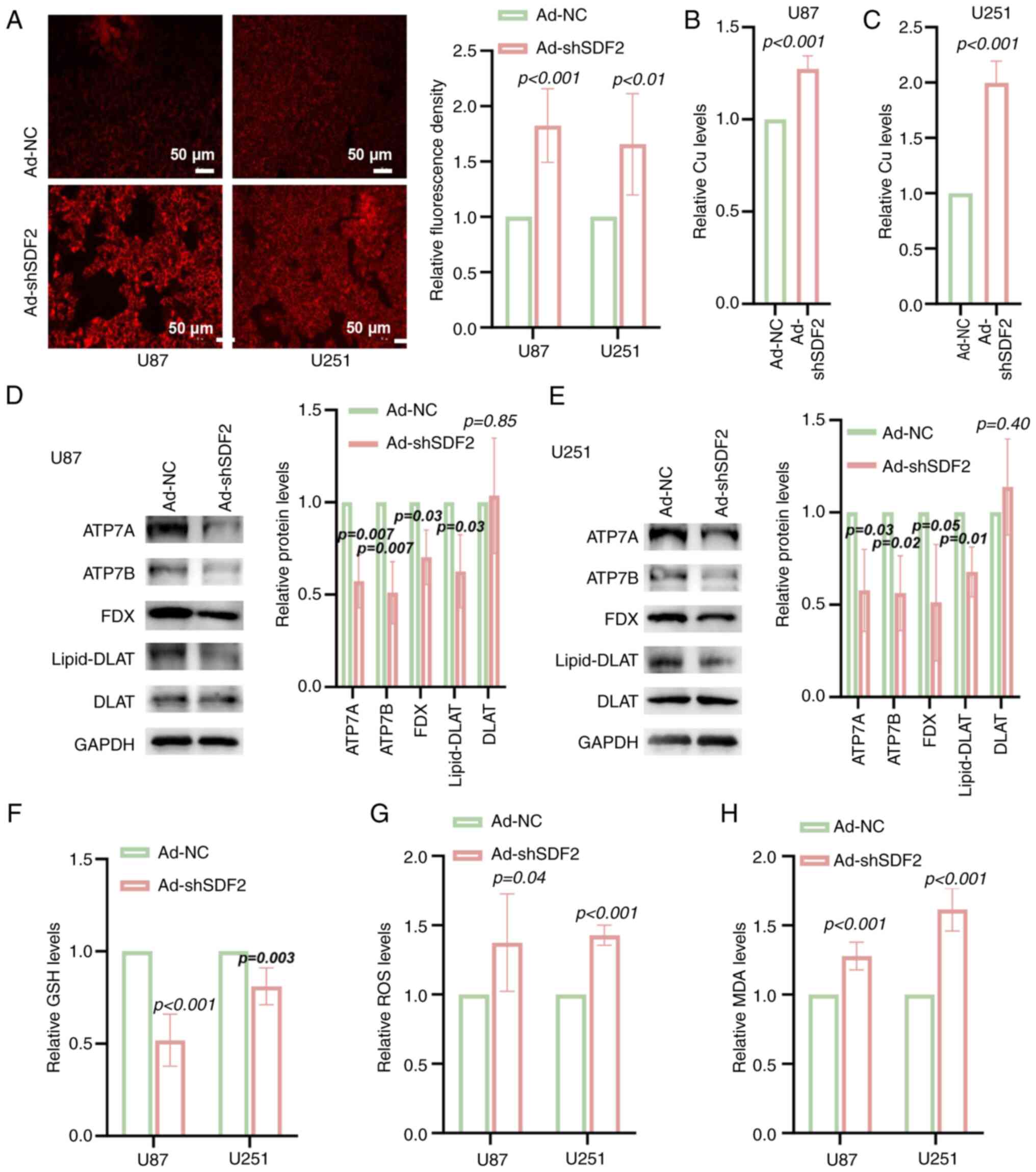

Knockdown of SDF2 induces copper ion

accumulation in glioma cells

In both the U87 and U251 cell lines, SDF2 knockdown

led to a significant increase in the intracellular copper ion

concentration compared with that in the controls. This finding was

confirmed through fluorescence staining (Fig. 6A) and further quantified using

colorimetric assays (Fig. 6B and

C). Additionally, the expression of the copper-exporting

proteins ATP7A and ATP7B, as well as FDX and lipid-DLAT, was

reduced in U87 and U251 cells following SDF2 knockdown, whereas

DLAT protein levels remained unchanged (Fig. 6D and E). Furthermore, SDF2

knockdown resulted in decreased intracellular GSH levels (Fig. 6F) and increased ROS and MDA

levels, indicating elevated oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation

within the cells (Fig. 6G and

H). These results suggest that SDF2 plays a role in maintaining

copper homeostasis, antioxidant capacity, and oxidative stress

regulation in glioma cells.

| Figure 6Knockdown of SDF2 increases

intracellular copper ion accumulation and oxidative stress in

glioma cells. (A) Fluorescence staining suggested that

intracellular copper ion levels were elevated in U87 and U251 cells

following SDF2 knockdown compared with those in control cells (n=3,

scale bar, 50 μm). (B and C) Quantitative assessment of

intracellular copper ion levels revealed significant copper

accumulation in U87 and U251 cells upon SDF2 knockdown (n=5). (D

and E) Western blot analysis revealed that ATP7A, ATP7B, FDX and

lipid-DLAT expression was reduced, whereas DLAT protein expression

did not significantly change (n=3). (F) A decrease in GSH was

identified following SDF2 knockdown in U87 and U251 cells (n=5). (G

and H) Increased ROS and MDA levels were detected in U87 and U251

cells upon SDF2 knockdown (n=3 for each group). SDF2, stromal

cell-derived factor 2; DLAT, dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase;

GSH, reduced glutathione; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MDA,

malondialdehyde; sh-, short hairpin; NC, negative control. |

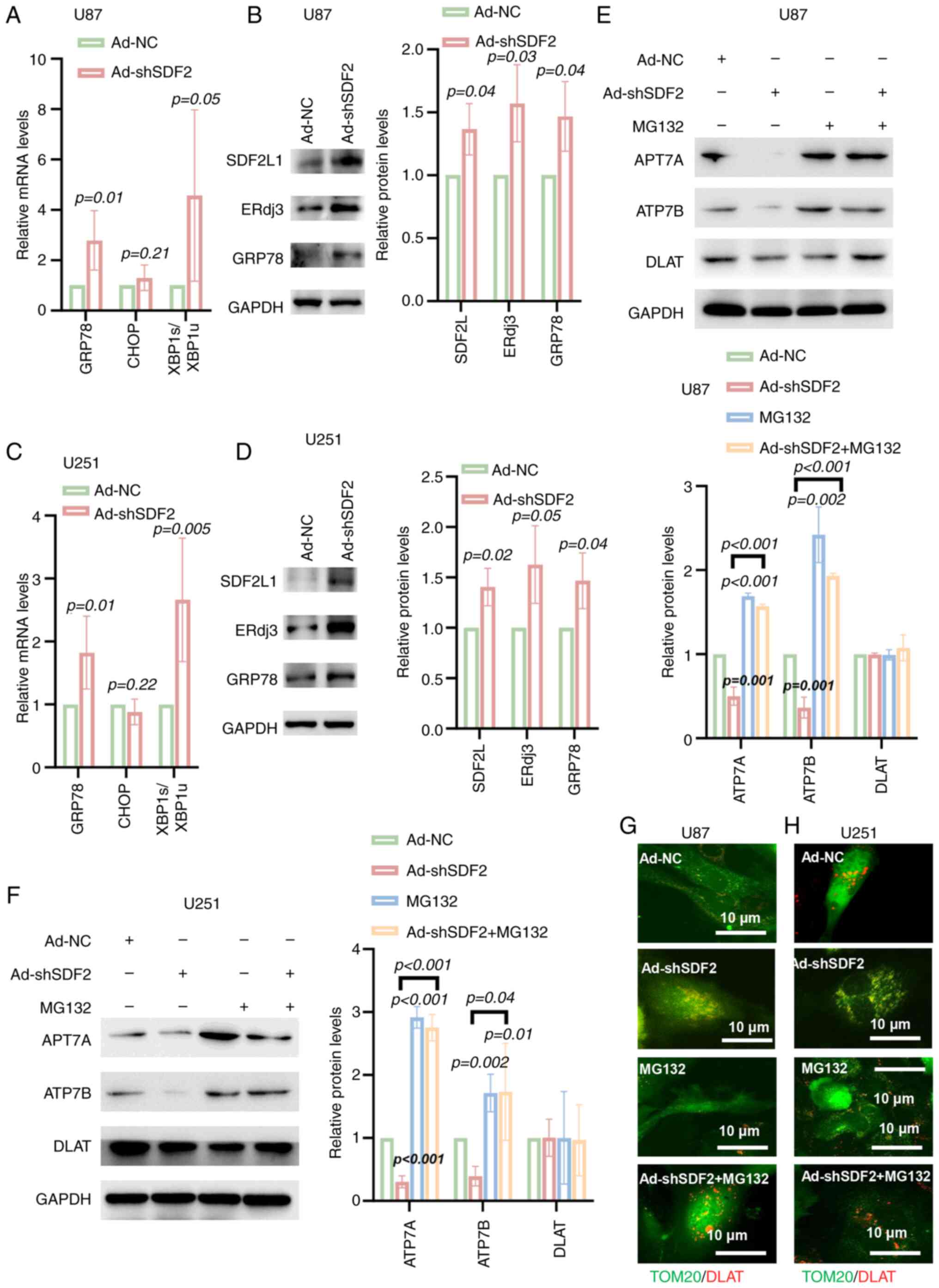

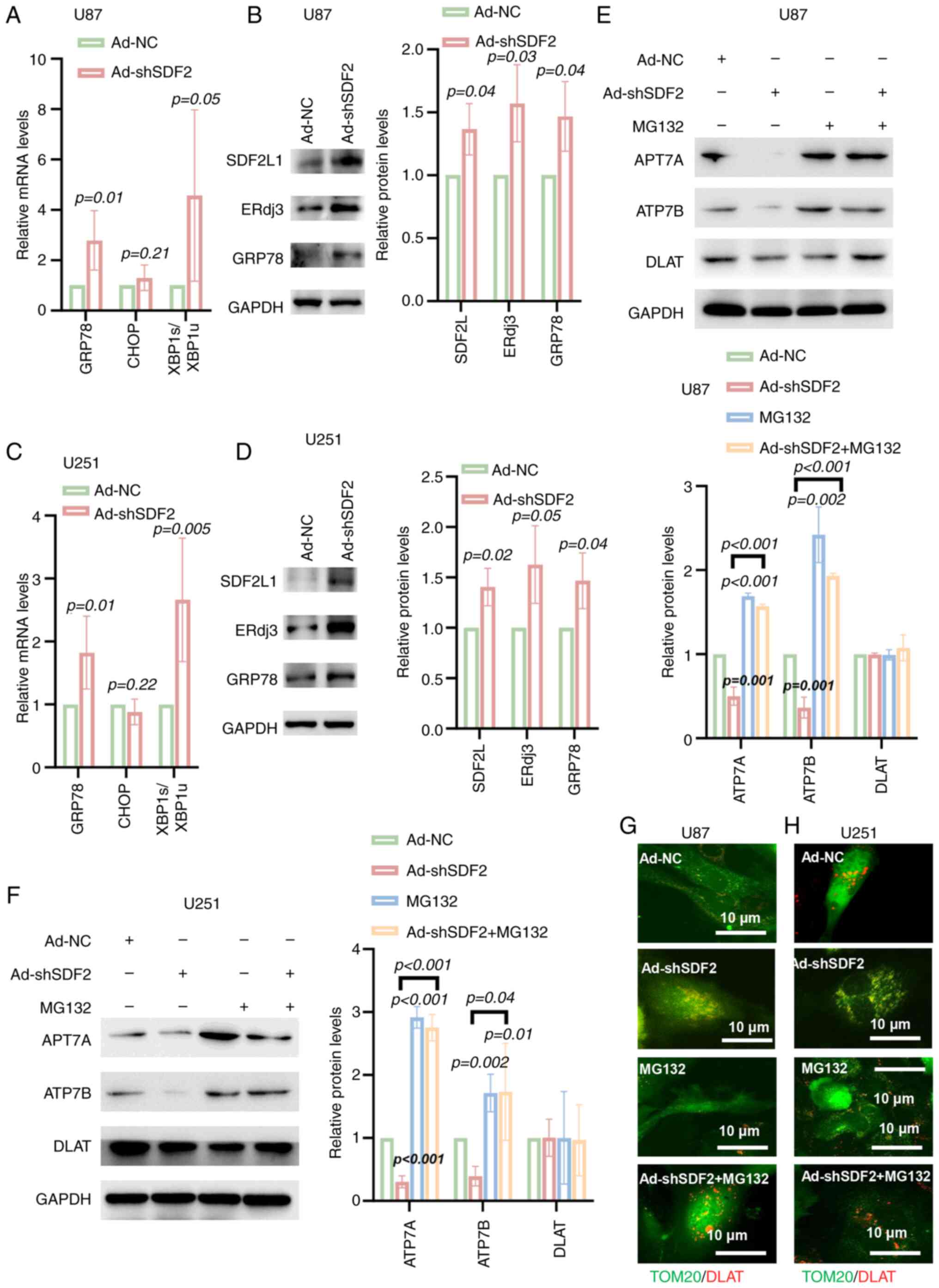

SDF2 mediates the downregulation of ATP7A

and ATP7B through the ERAD pathway

The effects of SDF2 on key proteins in the ER stress

pathway were investigated. Compared with Ad-NC, Ad-shSDF2 increased

GRP78 mRNA levels and the ratio of XBP1s/XBP1u in U87 and U251

cells, whereas CHOP mRNA levels remained unchanged (Fig. 7A and C). Additionally, Ad-shSDF2

increased GRP78 protein expression in both cell lines (Fig. 7B and D). To confirm the

involvement of the proteasome degradation pathway in ATP7A and

ATP7B downregulation, U87 and U251 cells were co-incubated with the

proteasome inhibitor MG132. Compared with the control treatment,

SDF2 knockdown reduced ATP7A and ATP7B expression, whereas MG132

treatment increased ATP7A and ATP7B expression (Fig. 7E-H). Notably, pretreatment with

MG132 significantly reversed the Ad-shSDF2-induced reduction in

ATP7A and ATP7B levels (Fig. 7E and

F). Furthermore, compared with Ad-NC, Ad-shSDF2 increased DLAT

aggregation within mitochondria; however, MG132 pretreatment

reduced DLAT aggregation (Fig. 7G

and H). These findings indicate that SDF2 knockdown promotes

ATP7A and ATP7B degradation through a GRP78-mediated ER-associated

degradation pathway, with potential downstream effects on

mitochondrial DLAT accumulation.

| Figure 7SDF2 knockdown mediates the

downregulation of ATP7A and ATP7B via the endoplasmic

reticulum-associated degradation pathway. (A and C) Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR analysis revealed that GRP78 mRNA

levels and the XBP1s/XBP1u ratio were increased in U87 and U251

cells following Ad-shSDF2 transfection (n=5). (B and D) Western

blot analysis demonstrated that the protein expression of GRP78,

SDF2L and ERdj3 was increased in U87 and U251 cells after SDF2

knockdown (n=3). (E and F) Western blot analysis revealed that in

U87 and U251 cells, SDF2 knockdown reduced ATP7A and ATP7B

expression compared with that in control cells, whereas

pretreatment with MG132 significantly reversed the

Ad-shSDF2-induced reduction in ATP7A and ATP7B levels (n=3). (G and

H) Immunofluorescent analysis revealed that DLAT aggregation was

increased following Ad-shSDF2 transfection in U87 and U251 cells

(n=3; scale bar, 10 μm). SDF2, stromal cell-derived factor

2; GRP78, glucose-related protein 78; XBP1, X-box binding protein

1; sh-, short hairpin; DLAT, dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase;

ERdj3, endoplasmic reticulum DnaJ heat shock protein 3; NC,

negative control. |

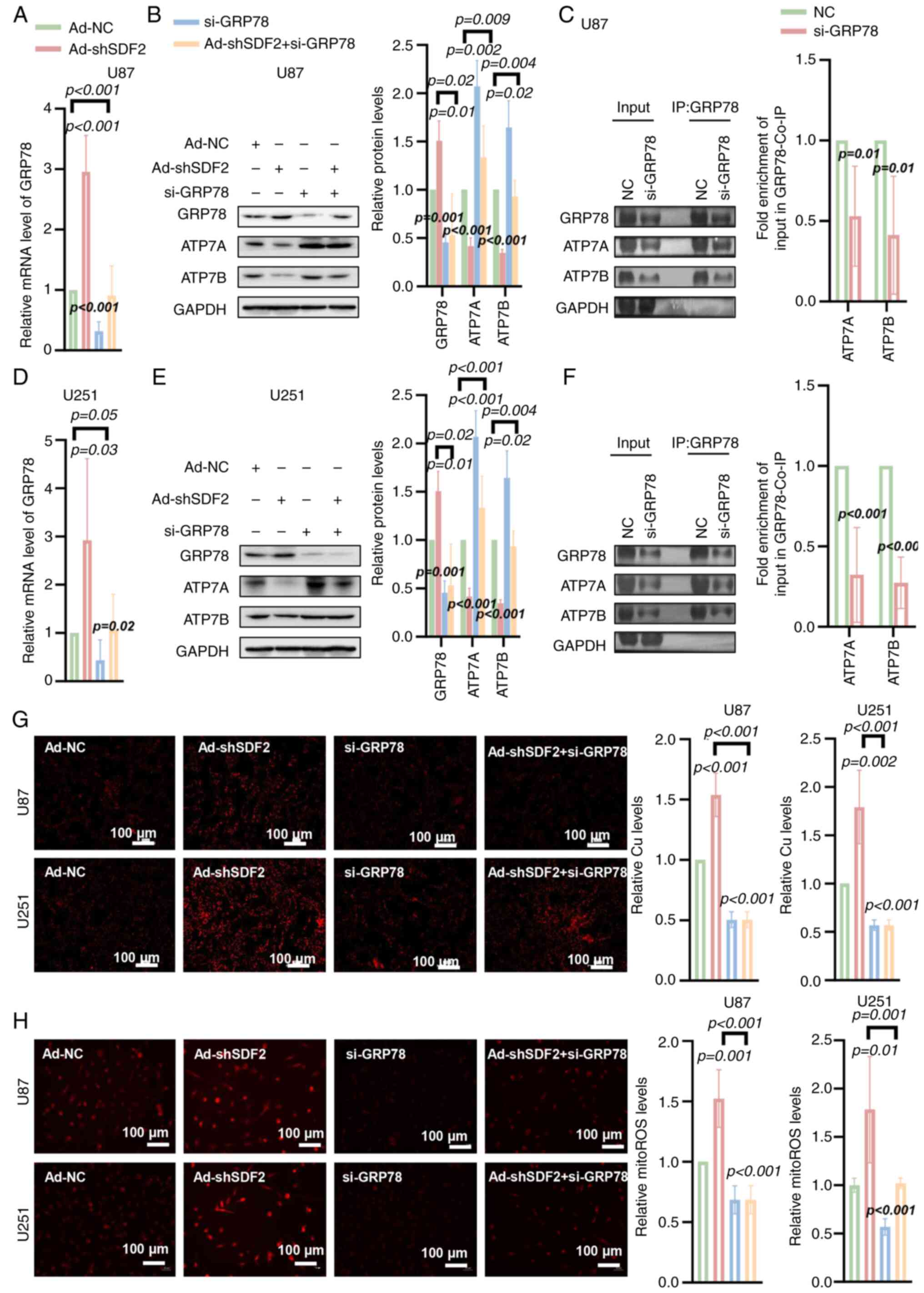

SDF2 suppresses ATP7A and ATP7B

expression via a GRP78-mediated mechanism

To investigate the role of GRP78 in this process,

si-GRP78 was utilized to specifically knock down GRP78 expression.

RT-qPCR analysis confirmed a significant reduction in GRP78 mRNA

levels in U87 and U251 cells following si-GRP78 transfection

(Fig. 8A and D). Western blot

analysis further verified that si-GRP78 effectively suppressed

GRP78 protein expression in both glioma cell lines (Fig. 8B and E). Importantly, GRP78

silencing also blocked the Ad-shSDF2-induced downregulation of

ATP7A and ATP7B in U87 and U251 cells (Fig. 8B and E). Co-IP results

demonstrated that knockdown of GRP78 led to a reduction in the

amount of ATP7A and ATP7B co-precipitated with GRP78. This decrease

was observed after normalizing the Co-IP signals to GAPDH levels in

the corresponding Input samples (Fig. 8C and F). These findings suggest

that GRP78 may play a role in regulating ATP7A and ATP7B stability

in glioma cells. Additionally, GRP78 silencing partially reversed

the Ad-shSDF2-induced increase in the intracellular Cu2+

and mito-ROS levels in U87 and U251 cells (Fig. 8G and H). These findings indicate

that SDF2 suppresses ATP7A and ATP7B expression through a

GRP78-dependent mechanism, impacting copper ion homeostasis and

mitochondrial oxidative stress in glioma cells.

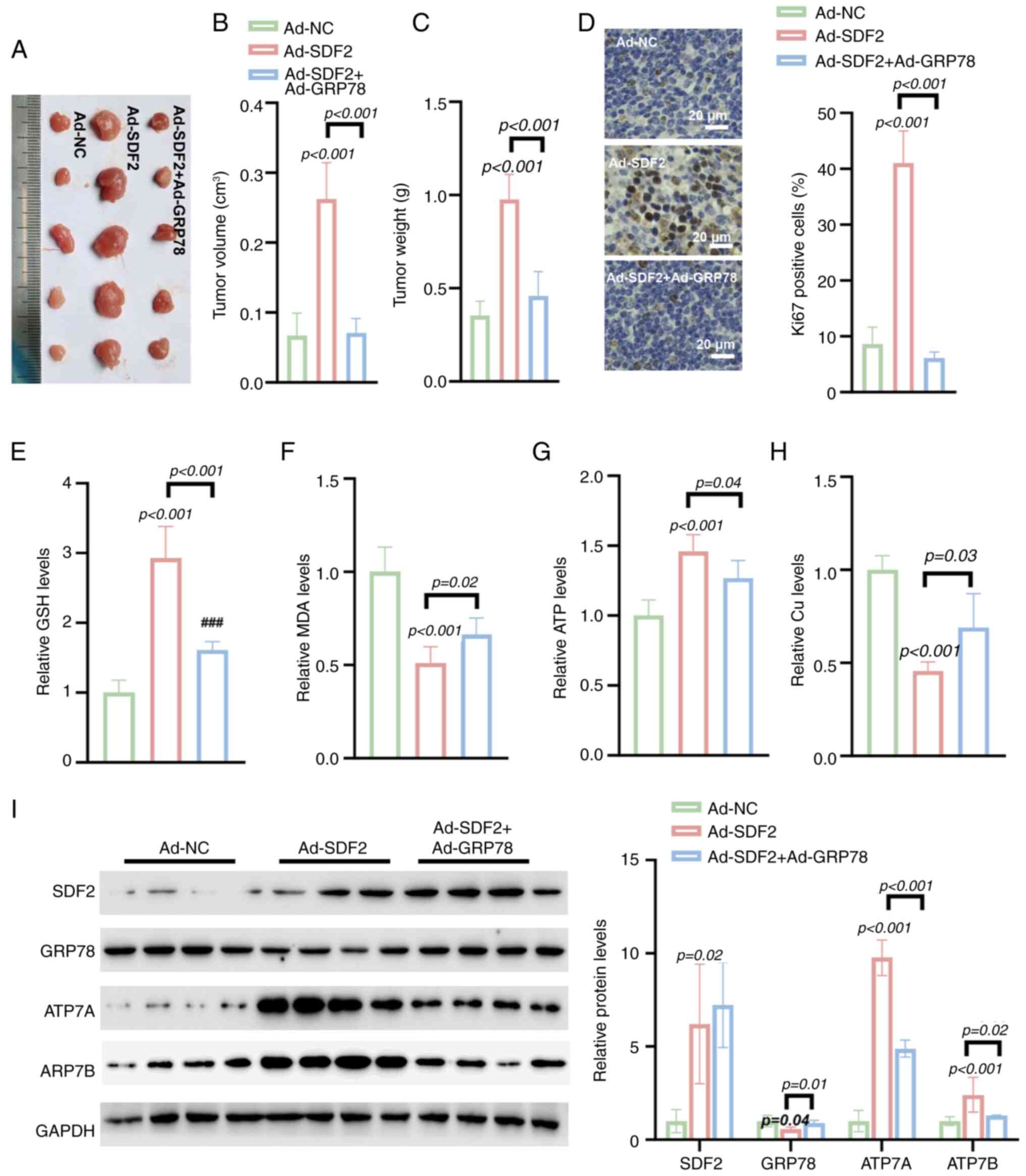

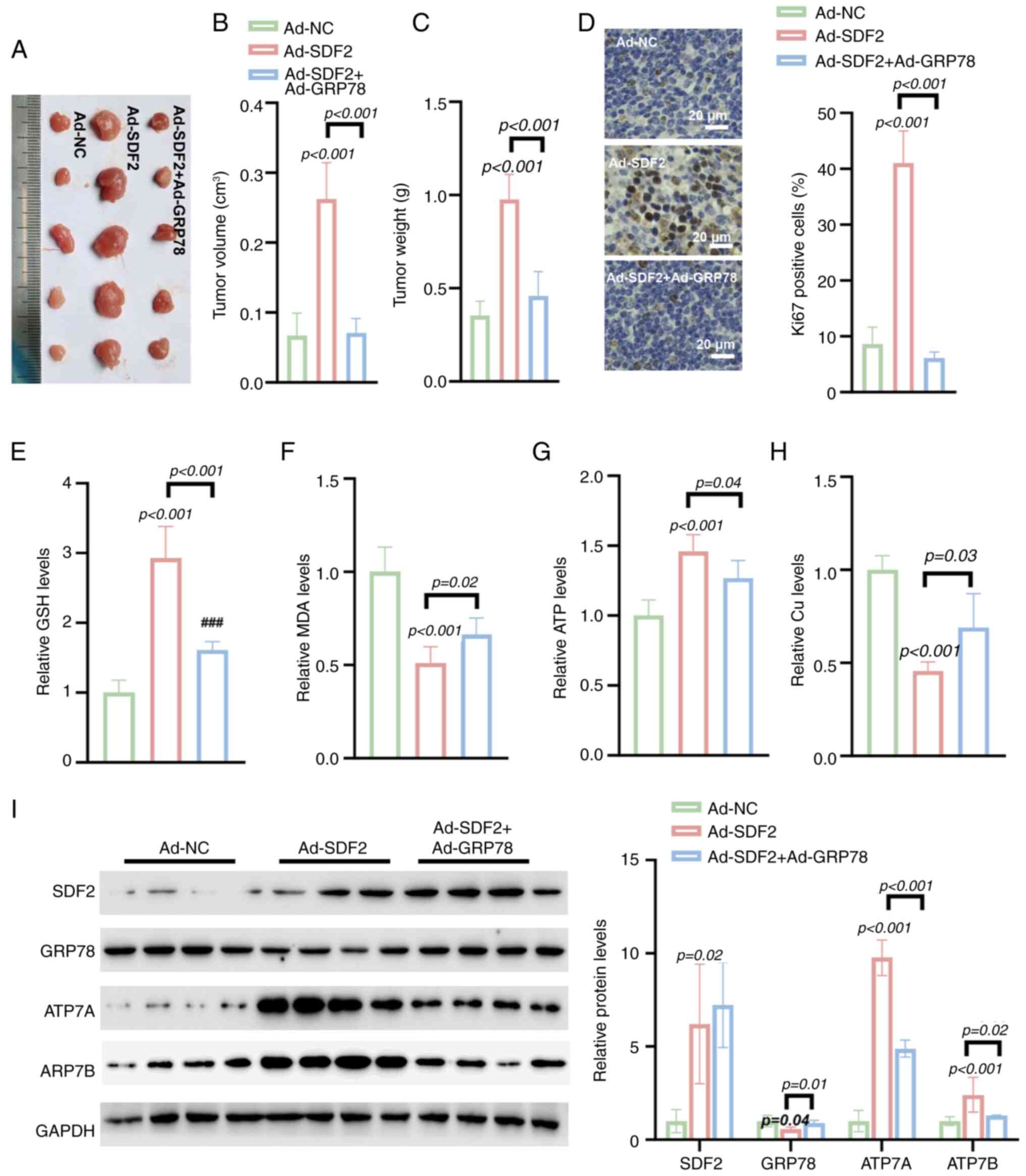

Ad-GRP78 reverses Ad-SDF2-induced tumor

growth in vivo

Compared with Ad-NC, Ad-SDF2 significantly increased

tumor volume, and weight in a nude mouse model (Fig. 9A-C). IHC analysis revealed that

Ad-SDF2 increased the Ki-67 positivity rate in tumors, whereas the

co-expression of Ad-GRP78 reversed this increase, suggesting an

impact on cell proliferation (Fig.

9D). Further analysis revealed that Ad-SDF2 increased the GSH

level in tumor tissues, which was effectively reversed by Ad-GRP78

(Fig. 9E). Similarly, Ad-SDF2

overexpression led to decreased MDA levels, whereas co-expression

of Ad-GRP78 partially restored MDA levels (Fig. 9F). Moreover, Ad-SDF2 increased

ATP levels and reduced Cu2+ concentrations in tumor

tissues, while co-expression with Ad-GRP78 restored both parameters

(Fig. 9G and H). Additionally,

Ad-SDF2 overexpression suppressed GRP78 expression while increasing

the expression of copper transporters ATP7A and ATP7B.

Co-expression of Ad-GRP78 significantly reversed these changes

(Fig. 9I). These findings

indicate that GRP78 overexpression can counteract the effects of

SDF2-induced changes in tumor growth and metabolism, highlighting

the regulatory role of GRP78 in modulating SDF2-mediated changes in

glioma growth and oxidative stress.

| Figure 9Ad-GRP78 reverses Ad-SDF2-induced

tumor growth and metabolic changes in a nude mouse model. (A-C)

Tumor size, volume and weight in nude mice injected with Ad-SDF2 or

Ad-NC (n=5). (D) Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that

Ad-GRP78 co-expression reversed the Ad-SDF2-induced increase in

Ki-67 positivity (n=5; scale bar, 20 μm). (E) Ad-SDF2

increased GSH levels, whereas Ad-GRP78 restored GSH levels in tumor

tissues (n=5). (F) Ad-SDF2 reduced MDA levels, while Ad-GRP78

partially restored them (n=5). (G and H) Ad-SDF2 increased ATP and

decreased Cu2+ levels, which were restored by Ad-GRP78

co-expression (n=5). (I) Western blot analysis showing that

co-expressing Ad-GRP78 counteracted the Ad-SDF2-induced increases

in ATP7A and ATP7B levels in tumor tissues (n=5). GRP78,

glucose-related protein 78; SDF2, stromal cell-derived factor 2;

GSH, reduced glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; NC, negative

control. |

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that the expression of

SDF2 is closely related to the development of breast and gastric

cancers, highlighting its importance in tumor biology (20,21). Additionally, changes in SDF2

expression are associated with the occurrence of gestational

diabetes and preeclampsia, further enhancing its potential as a

biomarker (13). However,

research on the role of SDF2 in glioma remains limited. The present

study is the first to confirm the elevated expression of SDF2 in

glioma samples. In vitro experiments demonstrated that SDF2

promotes the malignant proliferation and migration of glioma cells.

These findings suggest that SDF2 may play a crucial role in the

pathogenesis and progression of glioma. Further investigations are

warranted to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms and

explore the potential clinical applications of targeting SDF2 in

glioma therapy.

In the present study, it was observed that the

knockdown of SDF2 significantly increased the levels of ROS and

enhanced the death of glioma cells. Transfection of U87 and U251

cells with Ad-shSDF2 resulted in a notable increase in the

proportion of late apoptotic and necrotic cells, indicating that

SDF2 depletion leads to increased cellular stress and compromised

cell viability. Further analysis revealed that ROS levels were

markedly elevated following SDF2 knockdown, suggesting a state of

heightened oxidative stress. This finding is consistent with

previous findings that link ROS accumulation to tumor progression

and cell death in various cancer types, where oxidative stress has

been shown to promote apoptotic pathways and influence tumor

behavior (22,23). Interestingly, when the mechanisms

underlying the observed decrease in cell viability were assessed,

only the cuproptosis inhibitor TTM effectively reversed the effects

of Ad-shSDF2. This finding highlights the specific involvement of

copper-dependent cell death pathways in glioma cells, aligning with

recent studies that highlight cuproptosis as a novel form of

regulated cell death distinct from apoptosis and other forms of

cell death, such as autophagy and ferroptosis (24,25). The selective reversal of cell

viability impairment by the cuproptosis inhibitor suggested that

SDF2 may play a role in modulating copper metabolism and its

downstream effects on glioma cell survival.

SDF2-L1 is a close homologue of SDF2, thus, the

expression of SDF2-L1 was detected in SDF2 knockdown cells. The

present data showed that knockdown of SDF2 elevated the expression

of SDF2-L1. These data indicated that SDF2-L1 may compensate the

deficiency of SDF2. ERdj3, an abundant and soluble ER co-chaperone

within the regulatory network of the Hsp70 family member BiP,

stimulates BiP's ATPase activity to enhance its affinity for

substrate proteins (26). Our

findings confirmed that knockdown of SDF2 upregulated ERdj3

expression. It was hypothesized that SDF2 knockdown leads to

dissociation of the SDF2-ERdj3 complex, resulting in accumulation

of unfolded proteins, which triggers ER stress and subsequently

induces the upregulation of both ERdj3 and GRP78 expression. Under

homeostatic conditions, the SDF2-ERdj3 complex maintains ER

homeostasis by suppressing the aggregation of unfolded proteins,

thereby restraining the activation of UPR signaling pathways such

as PERK and IRE1 (15). It is

proposed that knockdown of SDF2 disrupts this complex, leading to

the accumulation of unfolded proteins, which triggers ER stress and

subsequently activates the UPR. This activation drives the

transcriptional upregulation of GRP78 (27,28). In the present study, it was found

that knockdown of SDF2 elevated XBPs/XBPu, indicating the

activation of unfolded protein response (URP). Following activation

of URP in glioma cells, the expression of GRP78 was increased. As a

multifunctional chaperone, GRP78 recruits core ERAD components (for

example, Sec61, Derlin-1 and ubiquitin ligases) under stress

conditions to retro-translocate misfolded protein to the cytoplasm

for proteasomal degradation (29). Notably, GRP78 may facilitate the

maturation of ATP7A/7B through its chaperone activity under

non-stressed conditions but shifts toward a pro-degradative role

during persistent ER stress. In the present study, it was observed

that SDF2 knockdown in glioma cells led to increased levels of

spliced XBP1, indicating activation of the UPR, which in turn

upregulated GRP78 expression. This upregulation may shift GRP78's

role from promoting the maturation of ATP7A and ATP7B to

facilitating their degradation via ERAD, thereby impacting their

expression levels.

The expression of FDX and Lipid-DLAT was also

detected. The current data showed that the expression of FDX and

Lipid-DLAT was reduced in U251 and U87 cells transfected with

Ad-sh-SDF2 compared with that of Ad-NC. These data strengthened the

cuproptosis link. In the process of cuproptosis, the aggregation of

DLAT is a key feature. Studies have shown that during cuproptosis,

DLAT aggregation results from the binding of copper ions to its

lipoylated sites, forming insoluble aggregates, while the levels of

DLAT are not changed (30-32). In the present study, it was

observed that although DLAT aggregation increased in the Ad-SDF2

group, the total protein expression level of DLAT did not change

significantly. This phenomenon may be due to the binding of copper

ions to lipoylated DLAT, inducing the formation of

high-molecular-weight aggregates, leading to loss of protein

function, but these aggregates are not necessarily rapidly

degraded, thus maintaining the total protein level unchanged. This

suggests that DLAT aggregation is not due to protein degradation

pathways reducing its expression level.

The in vivo experiments demonstrated that

SDF2 overexpression led to increased tumor size, volume and weight

in a nude mouse model, suggesting a significant role in promoting

tumor proliferation, as indicated by increased Ki-67 positivity.

This effect, however, was counteracted by co-expressing Ad-GRP78,

which reversed the SDF2-induced increase in tumor growth and

proliferation. These findings suggest that GRP78 plays a key

regulatory role in modulating SDF2-mediated effects on glioma

progression. GRP78, a well-established ER chaperone protein,

facilitates protein folding and guides misfolded proteins to the

ERAD pathway for subsequent degradation (33). In the context of cellular stress,

GRP78 binds to misfolded proteins and initiates their transport to

the ERAD system, where they are ubiquitinated and targeted for

proteasomal degradation (34).

In the present study, SDF2 overexpression downregulated GRP78,

suggesting that reduced GRP78 expression impairs its ability to

guide ATP7A and ATP7B to the ERAD pathway. Consequently, this leads

to decreased degradation of these copper transport proteins,

resulting in their increased expression (Fig. 10).

However, it is accepted that ATP7A and ATP7B are key

copper-exporting transporters, and their downregulation may lead to

intracellular copper accumulation, thereby triggering cuproptosis.

The importance of rescue experiments was also acknowledged to

validate this mechanism. While such experiments were not included

in the current study, the authors plan to perform overexpression of

ATP7A/B in future studies to further investigate their role in

copper accumulation and cell death.

In summary, these findings collectively indicate

that GRP78 overexpression counters SDF2-driven tumor growth and

oxidative stress by enhancing the degradation of ATP7A and ATP7B

through the ERAD pathway. These findings highlight the potential

therapeutic value of modulating GRP78 to control SDF2-mediated

effects in glioma, suggesting a novel approach to mitigate tumor

growth and associated metabolic disruptions.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TW and JS designed the experiments and revised the

manuscript. AL and XL performed the experiments. AL analyzed the

data and wrote the manuscript. TW and JS confirmed the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Human tumor and adjacent nontumor tissue samples

were obtained from patients during surgical procedures, with

informed consent obtained from all participants. Ethical approval

for the collection and use of human samples was granted by the

Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of

Xi'an Jiaotong University (approval no. 2024SF-FAHX-212; Xi'an,

China), in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the

Declaration of Helsinki. All animal experiments were conducted in

compliance with institutional, national, and international

guidelines, specifically adhering to the revised Animals

(Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (UK) and Directive 2010/63/EU

(Europe). Approval for all animal experiments was granted by the

Institutional Ethics Committee of the Animal Experimentation

Center, Xi'an Jiaotong University (approval no. XJTUAE2023-1944;

Xi'an, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Shaanxi Key Research and

Development Plan Project (grant no. 2024SF-YBXM-215).

References

|

1

|

Wang LM, Englander ZK, Miller ML and Bruce

JN: Malignant glioma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1405:1–30. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Weller M, Wen PY, Chang SM, Dirven L, Lim

M, Monje M and Reifenberger G: Glioma. Nat Rev Dis Primers.

10:332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hakar MH and Wood MD: Updates in pediatric

glioma pathology. Surg Pathol Clin. 13:801–816. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wei R, Zhou J, Bui B and Liu X: Glioma

actively orchestrate a self-advantageous extracellular matrix to

promote recurrence and progression. BMC Cancer. 24:9742024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Krshnan L, van de Weijer ML and Carvalho

P: Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. Cold

Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 14:a0412472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhou Z, Torres M, Sha H, Halbrook CJ, Van

den Bergh F, Reinert RB, Yamada T, Wang S, Luo Y, Hunter AH, et al:

Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation regulates

mitochondrial dynamics in brown adipocytes. Science. 368:54–60.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Turk SM, Indovina CJ, Miller JM, Overton

DL, Runnebohm AM, Orchard CJ, Tragesser-Tiña ME, Gosser SK, Doss

EM, Richards KA, et al: Lipid biosynthesis perturbation impairs

endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J Biol Chem.

299:1049392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Stevenson J, Huang EY and Olzmann JA:

Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation and lipid homeostasis.

Annu Rev Nutr. 36:511–542. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xu Y and Fang D: Endoplasmic

reticulum-associated degradation and beyond: The multitasking roles

for HRD1 in immune regulation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun.

109:1024232020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Sun S, Shi G, Sha H, Ji Y, Han X, Shu X,

Ma H, Inoue T, Gao B, Kim H, et al: IRE1α is an endogenous

substrate of endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation. Nat Cell

Biol. 17:1546–1555. 2015. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang MJ, Shi M, Yu Y, Ou R, Ge RS and

Duan P: Curcuminoid PBPD induces cuproptosis and endoplasmic

reticulum stress in cervical cancer via the Notch1/RBP-J/NRF2/FDX1

pathway. Mol Carcinog. 63:1449–1466. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gu Y, Wang H, Xue W, Zhu L, Fu C, Zhang W,

Mu G, Xia Y, Wei K and Wang J: Endoplasmic reticulum stress related

super-enhancers suppress cuproptosis via glycolysis reprogramming

in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 16:3162025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lorenzon-Ojea AR, Yung HW, Burton GJ and

Bevilacqua E: The potential contribution of stromal cell-derived

factor 2 (SDF2) in endoplasmic reticulum stress response in severe

preeclampsia and labor-onset. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1866:1653862020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hanafusa K, Wada I and Hosokawa N:

SDF2-like protein 1 (SDF2L1) regulates the endoplasmic reticulum

localization and chaperone activity of ERdj3 protein. J Biol Chem.

294:19335–19348. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fujimori T, Suno R, Iemura SI, Natsume T,

Wada I and Hosokawa N: Endoplasmic reticulum proteins SDF2 and

SDF2L1 act as components of the BiP chaperone cycle to prevent

protein aggregation. Genes Cells. 22:684–698. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

DiVita Dean B, Wildes T, Dean J, Yegorov

O, Yang C, Shin D, Francis C, Figg JW, Sebastian M, Font LF, et al:

Immunotherapy reverses glioma-driven dysfunction of immune system

homeostasis. J Immunother Cancer. 11:e0048052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang Y, Xiang Z, Chen L, Deng X, Liu H

and Peng X: PSMA2 promotes glioma proliferation and migration via

EMT. Pathol Res Pract. 256:1552782024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zamler DB, Shingu T, Kahn LM, Huntoon K,

Kassab C, Ott M, Tomczak K, Liu J, Li Y, Lai I, et al: Immune

landscape of a genetically engineered murine model of glioma

compared with human glioma. JCI Insight. 7:e1489902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gong W, Martin TA, Sanders AJ, Jiang A,

Sun P and Jiang WG: Location, function and role of stromal

cell-derived factors and possible implications in cancer (Review).

Int J Mol Med. 47:435–443. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang Y, Zheng M, Du S, Wang P, Zhang T,

Zhang X and Zu G: Clinicopathological and prognostic significance

of stromal cell derived factor 2 in the patients with gastric

cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 24:3252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Slika H, Mansour H, Wehbe N, Nasser SA,

Iratni R, Nasrallah G, Shaito A, Ghaddar T, Kobeissy F and Eid AH:

Therapeutic potential of flavonoids in cancer: ROS-mediated

mechanisms. Biomed Pharmacother. 146:1124422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Jelic MD, Mandic AD, Maricic SM and

Srdjenovic BU: Oxidative stress and its role in cancer. J Cancer

Res Ther. 17:22–28. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang J, Li S, Guo Y, Zhao C, Chen Y, Ning

W, Yang J and Zhang H: Cuproptosis-related gene SLC31A1 expression

correlates with the prognosis and tumor immune microenvironment in

glioma. Funct Integr Genomics. 23:2792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang B, Xie L, Liu J, Liu A and He M:

Construction and validation of a cuproptosis-related prognostic

model for glioblastoma. Front Immunol. 14:10829742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Guo F and Snapp EL: ERdj3 regulates BiP

occupancy in living cells. J Cell Sci. 126:1429–1439.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lorenzon-Ojea AR, Guzzo CR, Kapidzic M,

Fisher SJ and Bevilacqua E: Stromal cell-derived factor 2: A novel

protein that interferes in endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway in

human placental cells. Biol Reprod. 95:412016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ibrahim IM, Abdelmalek DH and Elfiky AA:

GRP78: A cell's response to stress. Life Sci. 226:156–163. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Cesaratto F, Sasset L, Myers MP, Re A,

Petris G and Burrone OR: BiP/GRP78 mediates ERAD targeting of

proteins produced by membrane-bound ribosomes stalled at the

STOP-Codon. J Mol Biol. 431:123–141. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hu F, Huang J, Bing T, Mou W, Li D, Zhang

H, Chen Y, Jin Q, Yu Y and Yang Z: Stimulus-responsive copper

complex nanoparticles induce cuproptosis for augmented cancer

immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e23093882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Qi RQ, Chen YF, Cheng J, Song JW, Chen YH,

Wang SY, Liu Y, Yan KX, Liu XY, Li J and Zhong JC: Elabela

alleviates cuproptosis and vascular calcification in

vitaminD3-overloaded mice via regulation of the PPAR-γ/FDX1

signaling. Mol Med. 30:2232024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Xiao Y, Yin J, Liu P, Zhang X, Lin Y and

Guo J: Triptolide-induced cuproptosis is a novel antitumor strategy

for the treatment of cervical cancer. Cell Mol Biol Lett.

29:1132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cai X, Ito S, Noi K, Inoue M, Ushioda R,

Kato Y, Nagata K and Inaba K: Mechanistic characterization of

disulfide bond reduction of an ERAD substrate mediated by

cooperation between ERdj5 and BiP. J Biol Chem. 299:1052742023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Akinyemi AO, Simpson KE, Oyelere SF, Nur

M, Ngule CM, Owoyemi BCD, Ayarick VA, Oyelami FF, Obaleye O, Esoe

DP, et al: Unveiling the dark side of glucose-regulated protein 78

(GRP78) in cancers and other human pathology: A systematic review.

Mol Med. 29:1122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|