Introduction

Ischemic brain injury (IBI) is a leading cause of

disability and death worldwide. In China, it has been categorized

as one of the important causes of disease-related deaths (1). The condition is primarily caused by

the narrowing or blockage of blood vessels, which leads to

insufficient blood and oxygen supply to the brain tissue; this, in

turn, causes necrosis or apoptosis of neurons in the brain tissue,

resulting in irreversible neurological damage. A number of patients

who survive may experience long-term neurological sequelae, such as

cerebral palsy, paraplegia and other lifelong disabilities.

Currently, clinical treatment for IBI entails symptomatic support,

cerebrovascular circulation improvement, neuroprotective medication

or interventional therapy, such as endovascular stenting and

percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. However, the administration

of therapy is impeded by the blood-brain barrier, and recurrence of

the intervention is possible, with incomplete repair of the

infarcted area (2,3). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are

adult stem cells with the capacity for self-renewal and

multidirectional differentiation, and under certain conditions they

can be differentiated into various neural cells across the

embryonic layer (4,5). Research has shown that MSCs possess

the ability to repair tissue damage when locally transplanted,

intravenously or intra-arterially administered after an injury

(6,7). Furthermore, MSCs have been shown to

possess the capacity to survive, migrate, integrate and

differentiate into neuronal cells within living organisms. The

utilization of MSCs to address neurological disorders through the

replacement of defective or damaged neural tissues represents a

promising therapeutic strategy that circumvents various challenges.

These challenges include the scarcity of adult neural stem cells

(NSCs), the difficulties involved in their isolation and culture,

and the ethical and immunological problems that are associated with

them (8).

Notably, obstacles to the clinical application of

MSCs persist. MSCs necessitate hundreds of millions of cells in

vitro, and although MSCs can be harvested from a range of

organs, the number of isolated cells is inadequate (9) and long-term expansion in

vitro is required to obtain enough stem cells. However, as the

number of passages increase, MSCs display senescence

characteristics, including changes in cell morphology, reduced

proliferation and diminished directed differentiation ability

(10-12). The loss of stemness in MSCs

during in vitro culture, their low survival rates following

transplantation, and compromised self-renewal and differentiation

capacities collectively pose major obstacles to the clinical

translation of MSC-based therapies. Therefore, enhancing the

regulatory mechanisms that sustain MSC proliferation, migration and

differentiation in vivo is critical for optimizing MSC

transplantation efficacy in treating neurological disorders and

promoting the recovery of neurological function.

The neural differentiation of adult stem cells is

regulated by various factors, with epigenetic mechanisms serving a

crucial role in precisely controlling gene expression (13). Polycomb family proteins are

notable epigenetic regulators of adult stem cells, comprising

mainly of two protein complexes: PRC1 and PRC2. B lymphoma Mo-MLV

insertion region 1 homolog (Bmi1), discovered in 1991, is localized

on human chromosome 10p12.2 locus, and consists of nine exons and

nine introns, mainly encoding poly sparse histones (components of

PRC1-like complexes) (14). PRC1

complexes containing Bmi1 proteins can act through chromatin

remodeling and histone modifications to cause epigenetic

alterations (15). Numerous

studies have confirmed that Bmi1 is crucial for neurogenesis in

vivo (16). Notably,

knocking down the Bmi1 gene has been shown to disrupt the stable

development of NSCs, hamper NSC proliferation and leads to an

increase in glial cells (17).

Previous studies (18,19) demonstrated that, through Bmi1

knockdown experiments, Bmi1 serves a crucial role in the

proliferation and survival of cortical bone-derived stem cells.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Bmi1 can

regulate the expansion capacity of mammary epithelial cells and

fibroblasts in vitro and in vivo through the Wnt

signaling pathway (20). The Wnt

signaling pathway is one of the major signaling pathways that

regulate cell proliferation and differentiation, including the

classical Wnt/β-catenin pathway and the non-classical Wnt pathway.

Our prior research has shown that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway notably impacts the neural differentiation process of MSCs

(21,22). The non-classical Wnt pathway is

less explored and more complex than the classical Wnt/β-catenin

pathway. The planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling pathway is a

specific type of non-classical Wnt pathway that controls cell

motility and cellular differentiation; this pathway triggers

signaling cascades via cytoplasmic cytoskeletal proteins, RhoA,

Rac-activated c-Jun amino-terminal kinases and Rho-associated

kinases (23). Wnt3a is the

primary ligand responsible for Wnt signaling pathways, as research

has indicated that when Wnt3a binds to the cell membrane receptor,

it extracellularly activates both the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway and the nonclassical Wnt signaling pathway (24). RhoA is present in the cell as a

bound form in the signaling pathway and serves as a downstream

element of the PCP pathway. RhoA, along with its regulatory

proteins, has crucial roles in neural differentiation (25). Nonetheless, it remains unclear

whether Bmi1 has the ability to regulate neural differentiation in

MSCs through the Wnt3a-RhoA pathway.

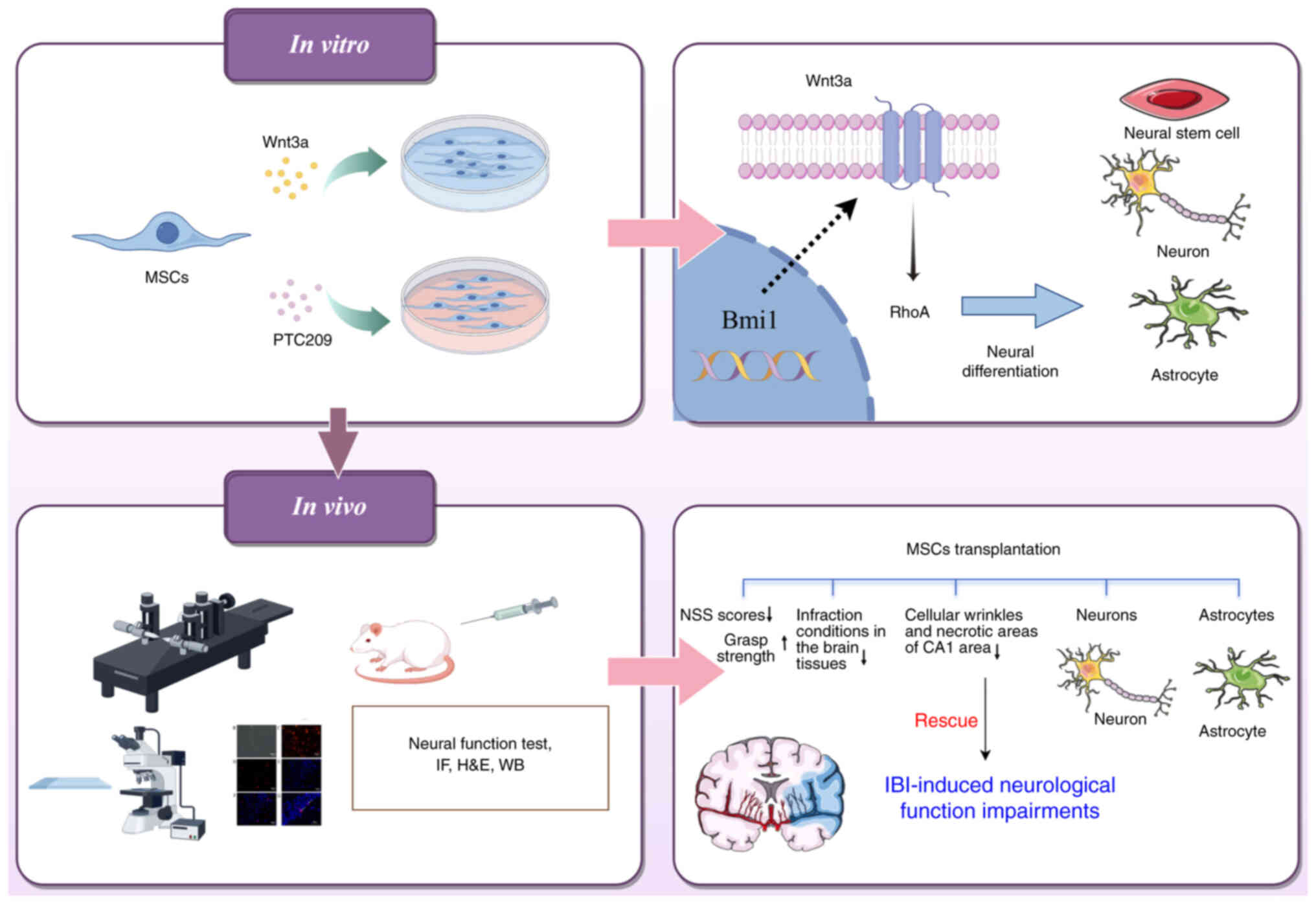

The present study therefore investigated the role of

Bmi1 in regulating the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway and promoting

neural differentiation of MSCs in vitro. In addition, a

middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model was established in

vivo to evaluate the therapeutic potential of MSC

transplantation in IBI. To assess this, recombinant Wnt3a cytokine

was administered to upregulate the Wnt3a-RhoA pathway, whereas the

small-molecule inhibitor PTC209 was utilized to suppress Bmi1

expression.

Materials and methods

Animals

In the present study, male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats

(weight, 80-120 g; age, 2-4 weeks) were used for MSC isolation and

culture. One rat was required for each T25 cell culture flask of

primary MSCs collected, and 33 male SD rats were used for MSC

isolation. The MCAO model was established using 45 male SD rats

(weight, 260-300 g; age, 6-8 weeks). All rats were provided by

Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Animal Center (Laboratory

Animal Certificate: SCXK 2018-0006; Hangzhou, China). The rats were

maintained at a temperature of 20±2°C, a humidity of 55±5%, under a

12-h light/dark cycle, and were given free access to food and

water. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethical

and Welfare Committee of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University

(approval no. 20210524-05, review no. IACUC-202108-05). All SD rats

in all experiments were euthanized by intravenous injection of an

overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg), which was confirmed by

observing their vital signs 10 min after administration.

Chemicals

Wnt3a recombinant cytokine (cat. no. 96-315-20-10)

was purchased from PeproTech; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. and

the small molecule inhibitor PTC209 (cat. n. S7372) was purchased

from Selleck Chemicals. Before use, Wnt3a powder was dissolved in

sterile water, and PTC209 powder was dissolved in dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO). A quantity of 10 mg PTC209 powder was dissolved

in 1.14 ml DMSO to create a 2 mmol/l master mix.

Isolation and culture of rat MSCs

MSCs were obtained from rat bone marrow by flushing

the contents of the tibia and femur with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS) in a sterile environment, and were then transferred to a

centrifuge tube to be centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at room

temperature. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded,

and the cells were resuspended in MSC medium prepared with

DMEM/F-12 (cat. no. TBD10565; Tianjin Haoyang Biological Products

Technology Co., Ltd.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat.

no. 10091-148; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin solution, and were inoculated in T25 cell

culture flasks at a temperature of 37°C in a 5% CO2

incubator. Cell morphology was observed under an inverted

fluorescence microscope (ECLIPSE TE2000-U; Nikon Corporation).

Cell proliferation assay

MSCs were cultured in 96-well plates with varying

concentrations of recombinant cytokine Wnt3a (0, 10, 50 and 100

ng/ml) and a small molecule inhibitor PTC209 (0, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10

μmol/l). Each group was subjected to a 24-h stimulation

period within a 37°C incubator, comprising five replicate wells at

varying concentrations. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to 5

mg/ml MTT for 4 h, the blue-violet formazan crystals were dissolved

in DMSO and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an

enzyme-linked instrument. The MTT kit was purchased from Abcam

(cat. no. ab211091).

In vitro induction of neural

differentiation in MSCs

The 3rd-5th generation MSCs in logarithmic growth

phase were collected and inoculated in two 6-well plates at a cell

density of 1×105 cells/ml. The cells were randomly

divided into four groups (n=3 wells each): Normal control (NC)

group, β-mercaptoethanol (BME) group, Wnt3a group and PTC209 group.

The NC group comprised normal cultured cells without induction of

neural differentiation; the BME group was pre-induced with neural

differentiation pre-induction medium for 24 h, followed by

induction with neural differentiation medium for 3-6 h. The Wnt3a

group and the PTC209 group were treated with neural differentiation

medium containing 10 ng/ml Wnt3a and 1 μmol/ml PTC209,

respectively, and the incubation steps were the same as that of the

BME group. The neural differentiation pre-induction medium

consisted of DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 20% FBS, 1 mmol/l BME and

1% penicillin-streptomycin solution. The neural differentiation

induction medium was prepared by adding 5 mmol/l BME and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin solution to DMEM/F-12.

Immunofluorescence staining of MSCs

The culture medium in the cell plates was aspirated

and discarded, and the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. The cells were

washed again with PBS and cell membranes were ruptured with a

permeabilizing solution of 0.5% TritonX-100 (cat. no. V900502;

MilliporeSigma) at room temperature for 10 min. After further

washing with PBS, the cells were blocked in PBS containing 2% BSA

(cat. no. 9048-46-8; Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd.) and

0.1% Tween-20 (cat. no. 9005-64-5; Shanghai Macklin Biochemical

Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature. The appropriate primary

antibody dilutions were then added and incubated overnight at 4°C.

Subsequently, the primary antibody was removed, the cells were

washed three times with PBS (8 min each) and the corresponding

secondary antibody dilution was added and incubated in the dark for

1 h at room temperature. Both primary and secondary antibodies were

prepared at a ratio of 1:200. Finally, DAPI staining solution was

added in the dark, and the cells were observed and images were

captured under an inverted phase contrast fluorescence microscope

to detect neuronal cell markers. The intermediate filament protein

nestin is a common specific marker for NSCs, which is mainly

expressed in the cytoplasm; NeuN is a neuron-specific nuclear

protein; Olig2 is an oligodendrocyte-specific marker; glial

fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is primarily found in astrocytes

within the central nervous system and is a commonly used cellular

marker. The primary antibodies anti-GFAP (cat. no. ab7260),

anti-NeuN (cat. no. ab177487), anti-nestin (cat. no. ab254048) and

anti-Olig2 (cat. no. ab254043), and the Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG

H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) secondary antibody (cat. no.

ab150077) were obtained from Abcam. The antibodies were diluted

with 5% BSA solution according to the instructions.

Modeling of rat MCAO

The rats were deprived of food for 12 h prior to

surgery and administered an intraperitoneal injection of 3% sodium

pentobarbital (45 mg/kg, provided by the Animal Experiment Center

of Zhejiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine) for

anesthesia. The rat MCAO model was created using the modified Zea

Longa wire bolus method. The rats were immobilized in the supine

position, and an incision was made in the midline of the neck. The

right common carotid artery (CCA), external carotid artery (ECA)

and internal carotid artery (ICA) were sequentially isolated, and

threads (4-0 sutures) were placed distal and proximal to the CCA

and at the ECA. The ICA was temporarily clamped with a

microarterial clip, and then the CCA and ECA were ligated

proximally. Subsequently, a small opening was cut with scissors 4

mm from the bifurcation of the CCA, the prepared suture was

inserted into the ICA, and the suture was tied securely with a thin

wire wrapped around the distal end of the CCA when the marked point

on the suture reached the bifurcation. The wound was covered with a

saline-soaked cotton ball to keep it moist, and after 1.5 h of

embolization, the suture was removed, the vessels were ligated, and

the wound was sutured and disinfected. Rats were scored according

to the Longa 5-point scale (26)

on day 3 after modeling, and modeling was considered successful in

rats with ≥1 point.

CM-Dil labeling of MSCs

The 3rd-5th generation MSCs in logarithmic growth

phase were collected, and after discarding the original medium,

they were rinsed twice with PBS. Staining solution was prepared by

adding the labeling solution to the medium in a ratio of 1 ml MSC

medium: 1 μl CM-Dil labeling solution (cat. no. C7000;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were

incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 10-20 min after

the addition of the staining solution. At the end of the

incubation, the cells were rinsed twice with PBS and then incubated

again at 4°C for 15 min to avoid staining of the nuclei. The MSCs

that had been labeled with CM-Dil were cultured for a further 24 h,

and were then observed and images were captured under an inverted

fluorescence microscope, which was used to detect the survival of

MSCs in brain tissues after subsequent cell transplantation.

Brain stereotactic transplantation of

MSCs and animal grouping

On day 3 after modeling, the rats were anesthetized

by inhalation of 4% isoflurane through a mask, fixed into a brain

stereotaxic apparatus, sterilized and a 10 μl suspension of

MSCs (107 cells/ml) was injected into the injection

sites of the hippocampus at a rate of 1 μl/min. The rats

were observed for infection and mortality.

A total of 45 SD rats were randomly assigned to five

groups: Sham, MCAO, MSCs, Wnt3a-MSCs and PTC209-MSCs (n=9

rats/group). The Sham and MCAO groups were transplanted with 10

μl PBS on the postoperative day 3, the MSCs group was

transplanted with MSCs on postoperative day 3, the Wnt3a-MSCs group

was transplanted with 10 ng/ml Wnt3a-treated MSCs on day 3 after

modeling, and the PTC209-MSCs group was transplanted with 1

μmol/l PTC209-treated MSCs on postoperative day 3. MSCs in

each group were pretreated for 48 h.

Neurological function tests

The neurological injury severity in rats was

assessed using the Neurological Severity Score (NSS) on days 1, 3,

5 and 7 after MSC transplantation. The rat tail was lifted 30 cm

off the ground and the forelimbs were observed. Rats with both

forelimbs symmetrically extended to the ground, with the left

shoulder internally rotated and the left forelimb internally

retracted were considered normal and rated 4 points, otherwise they

were rated 0 points. In addition, the rat was placed on a smooth

floor and resistance to movement was examined by pushing the left

(or right) shoulder to the opposite side, respectively. Rats with

resistance that was clearly symmetrical on both sides were

considered normal (0 points); when the resistance was decreased,

this was rated 1-3 points according to the degree of decrease.

Furthermore, the two forelimbs of the rats were placed on a metal

net and the tension of the two forelimbs was observed. When the

tension of the two forelimbs was obviously symmetrical, this was

considered normal (0 points); when the muscle tension of the left

forelimb decreased, this was rated 1-3 points according to the

degree of decrease. Based on the aforementioned scores out of 10,

the higher the score, the more severe the behavioral disorder.

Grip assays were also performed on days 1, 3, 5 and

7 after transplantation of MSCs. In order to measure grip force,

the grip force measuring instrument was placed on a horizontal

table and levelled so that the grip force plate was in a horizontal

direction. The rat was then gently placed on the grip plate and the

tail was pulled back horizontally to record the maximum grip force

of the rat.

Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)

staining

On day 7 after MSC transplantation, intact brain

tissues were obtained from three randomly selected rats in each

group after euthanasia.; the animals were euthanized as

aforementioned. These tissues were placed in a pre-cooled tank

(4°C), rapidly frozen at −20°C for 20 min, and 2-mm coronal

sections were cut and placed in 2% TTC dye at 37°C away from light

for 15 min. After staining, images were captured, and were

processed using the Image-Pro Plus 6.0 image analysis system

software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.) to calculate the infarction rate

of the rat brain tissue.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining

On day 14 after the transplantation of MSCs, three

rats in each group were randomly selected for the removal of intact

brain tissues, which were subjected to H&E staining to observe

the pathological changes in the CA1 area of the hippocampus in each

group. The animals were euthanized as aforementioned. Brain tissues

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h, embedded in

paraffin and were cut into 5-10 μm slices on a sectioning

machine at 4°C. Tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene two

times (10 min each), hydrated with a descending series of ethanol

concentrations, washed with water and distilled water, and stained

with hematoxylin for 5 min. Subsequently, the sections were washed

with water, incubated with 1% hydrochloric acid and 70% ethanol for

3 sec, washed with water for 10 min and stained with 1% eosin for 1

min. Finally, the sections were washed with water, dehydrated in an

ascending series of ethanol concentrations, permeabilized twice

with xylene (1 min each) and sealed with neutral gum. Finally, the

sections were observed and images were captured under a light

microscope.

Immunofluorescence staining

On day 14 after transplantation of MSCs, three brain

tissue sections were randomly collected from each group. Rat brain

tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 8 h at room

temperature., dehydrated in 30% sucrose solution, and embedded in

OCT embedding agent, before being frozen at −80°C. Subsequently,

the tissues were sectioned into 5-10 μm slices.

Subsequently, 3% H2O2 was added dropwise to

the sections and incubated at 37°C for 10 min to block endogenous

peroxidase, after which, the sections were rinsed with distilled

water three times (5 min each). The sections were then placed in

boiling sodium citrate buffer solution and reacted at 92-98°C for

20 min for antigen retrieval. After cooling, the slices were washed

three times with PBS solution (2 min each). Immunofluorescence was

then performed as aforementioned for MSCs, using the same

antibodies.

Western blotting

The MSCs of each group, as well as the ischemic

penumbra tissues and hippocampal tissues on the damaged side of the

rat brain of each group, were lysed with protein lysis solution

(cat. no. 89900; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on ice. The

supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15

min at 4°C after lysis. Following the extraction of total proteins

from the cells and tissues, the protein concentration was detected

according to the instructions in the BCA kit (cat. no.AR0146;

Boster Biological Technology). Depending on the molecular weight of

the protein, a 10 or 12% separation gel was prepared, and 20

μg proteins underwent SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then

transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, which were

blocked with a ready-to-use 5% skimmed milk powder sealer. The

membranes were then incubated at 4°C overnight with the following

primary antibodies: Anti-Bmi1 (cat. no. ab38295), anti-RhoA (cat.

no. ab187027), anti-Wnt3a (cat. no. ab219412) (all from Abcam) and

anti-β-actin (cat. no. BK7018; Bioker), anti-GFAP (cat. no.

ab7260), anti-NeuN (cat. no. ab177487) and anti-nestin (cat. no.

ab254048) (all from Abcam). Primary antibodies were diluted and

prepared in 5% BSA solution at a ratio of 1:1,000 according to the

antibody instructions. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated

for 2 h at room temperature with a Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L

(Alexa Fluor® 488) secondary antibody (cat. no.

ab150077; Abcam), which was diluted and prepared according to the

antibody instructions. Images of membranes were captured using an

ultrasensitive chemiluminescent substrate kit (cat. no. AR1111;

Boster Biological Technology) utilizing a chemiluminescent imaging

system (cat. no. 6000; Clinx Science Instruments Co., Ltd.) was

used to capture images of the membranes, which were subsequently

analyzed via ImageJ v1.8.0 analysis software (National Institutes

of Health) for semi-quantification.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated more than three times.

The experimental data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 25.0

(IBM Corp.). Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation and bar graphs were constructed using GraphPad Prism 9

(Dotmatics). A χ2 test for variance was performed on the

experimental data to assess distribution of data. One-way analysis

of variance was used to compare the differences between groups and

the data were analyzed by Tukey's post-hoc test for multiple

comparisons between groups. The analysis of NSS scores was

performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc

test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

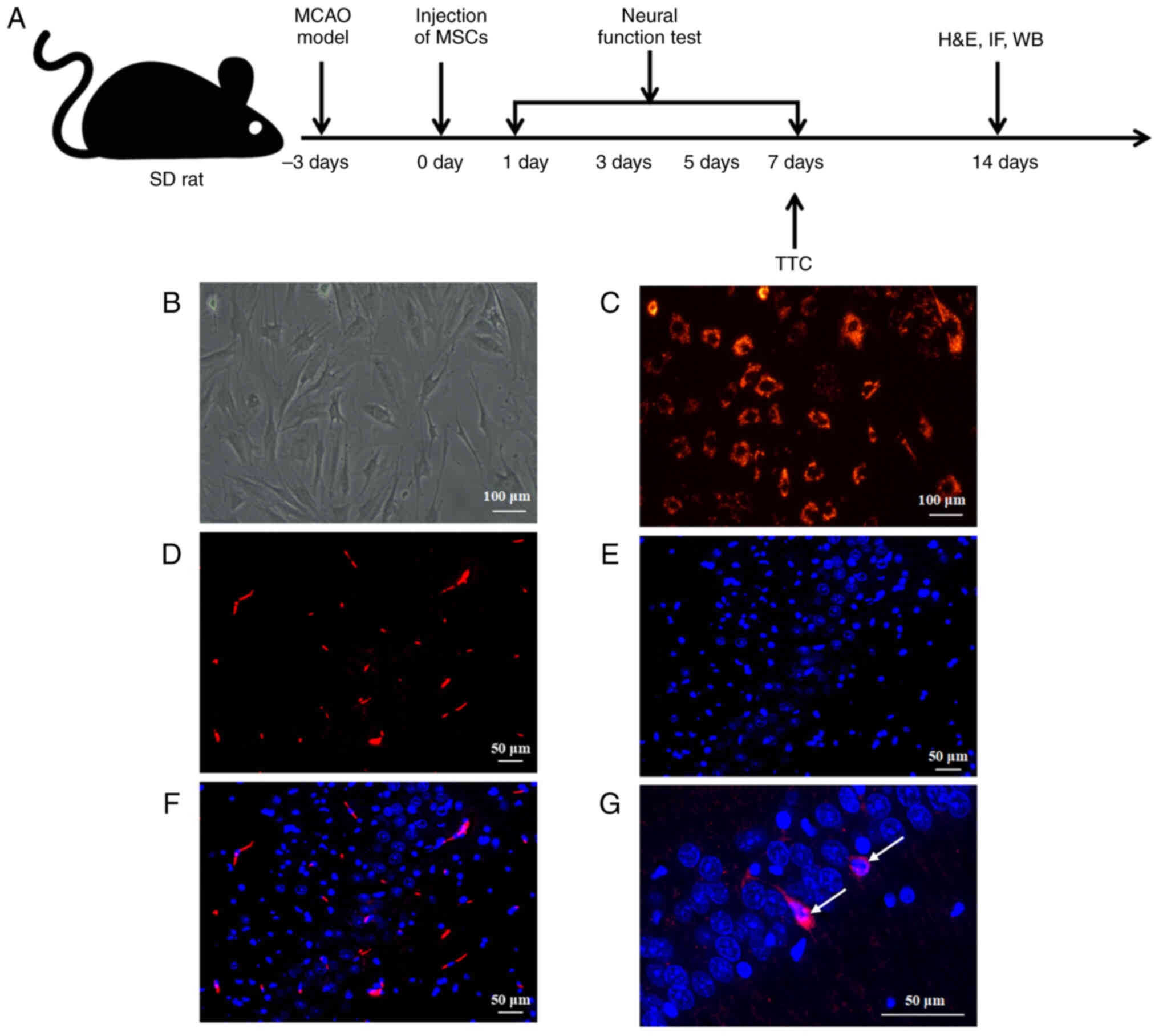

MSC isolation culture and proliferative

activity

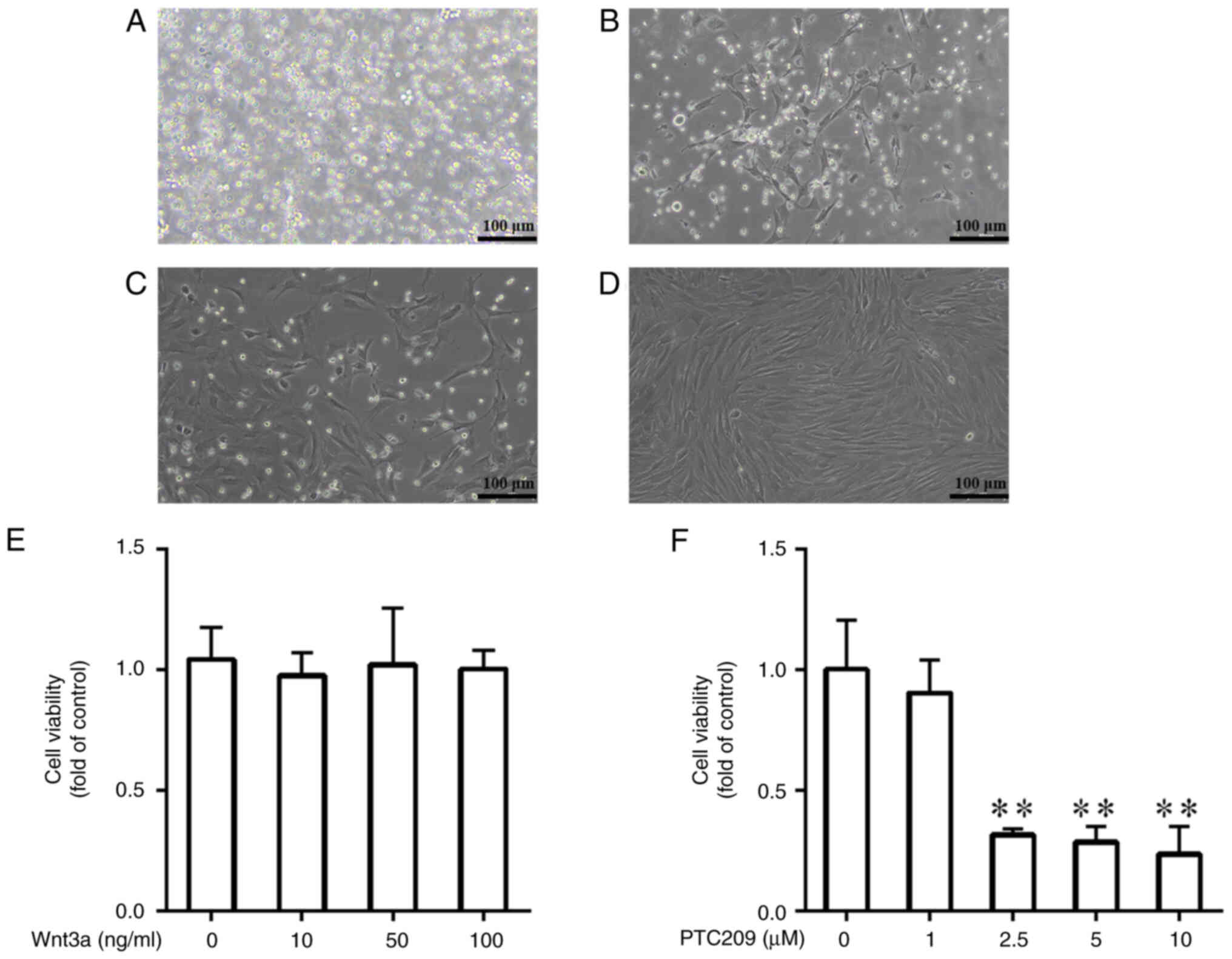

Primary MSCs were cultured in T25 cell culture

flasks and allowed to adhere to the wall and aggregate for 3 days.

By day 7, the cells had formed colonies and were vigorously

proliferating and dividing. Under a microscope, the cells were

found to be either polygonal or irregularly shuttle-shaped

(Fig. 1A-C). When the primary

cultured MSCs reached 80-90% fusion, passaging culture was

performed. Subsequently, MSCs experienced an increase in

proliferative activity, as well as a continuous improvement in

purity. Furthermore, their cell morphology gradually changed from

an irregular polygonal shape to a shuttle or spindle shape

(Fig. 1D). Different

concentrations of Wnt3a (0, 10, 50 and 100 ng/ml) and Bmi1 small

molecule inhibitor PTC209 (0, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 μmol/l) were

utilized to treat MSCs for 24 h, and the impact of both on cell

viability was measured through MTT analysis. The results indicated

that the viability of MSCs was normal in all groups of

Wnt3a-treated cells, and there was no significant difference in the

proliferative activity of MSCs between the different concentration

groups, thus indicating that Wnt3a treatment did not affect the

activity of MSCs (Fig. 1E). By

contrast, in the cell groups treated with PTC209, that 1

μmol/l PTC209 had no significant effect on cell viability,

whereas 2.5, 5 and 10 μmol/l PTC209 had a toxic effect on

cells (Fig. 1F). Combining the

findings of previous studies (27,28) and the present experimental

results, 10 ng/ml Wnt3a and 1 μmol/l PTC209 were selected

for subsequent experiments in the current study.

Wnt3a promotes and PTC209 inhibits

differentiation of MSCs toward neurons

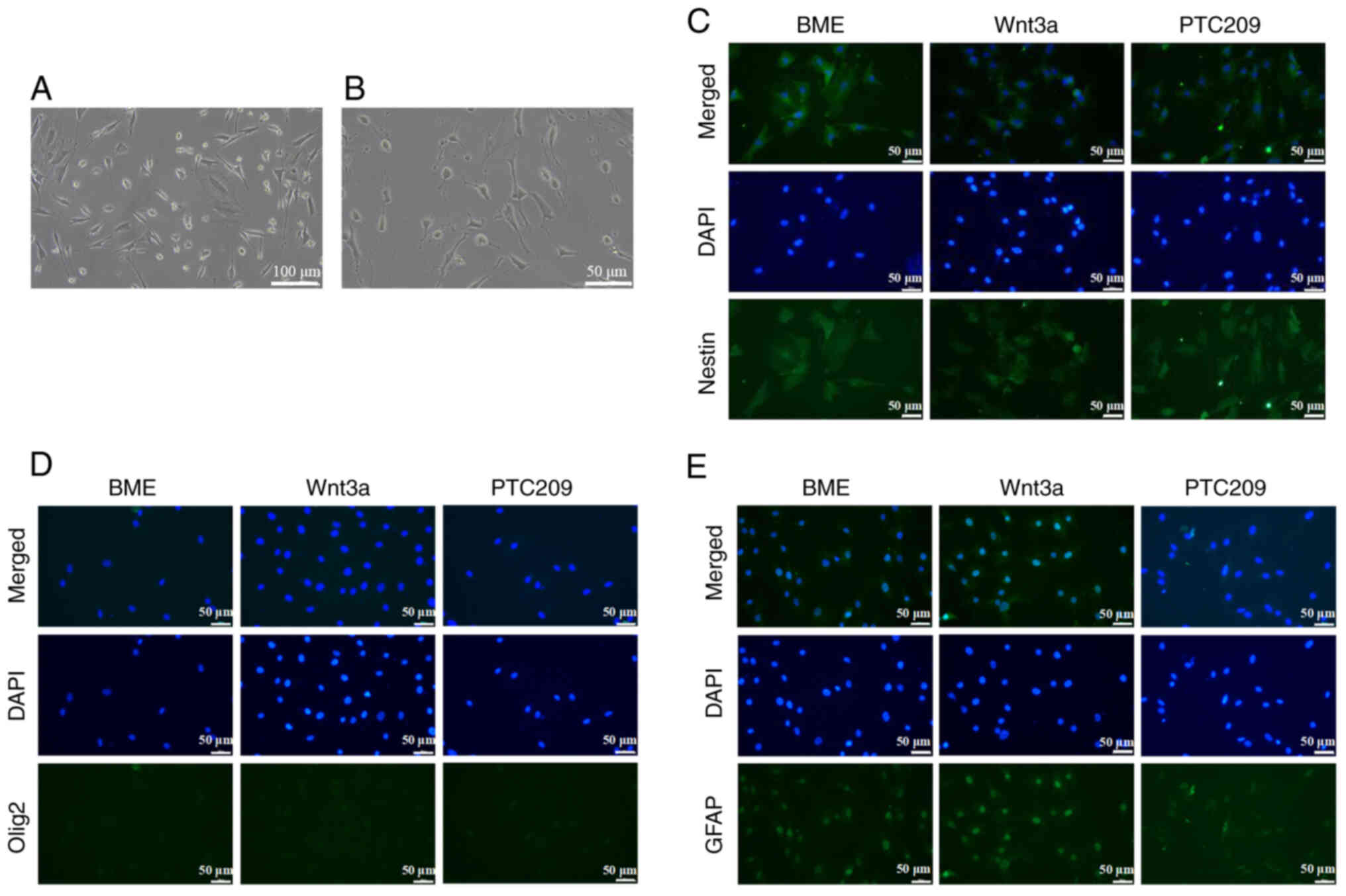

Compared with untreated MSCs, after 3 h of neural

differentiation, the cytoplasm of MSCs contracted, longer synapses

were formed, tiny branches appeared to converge into a meshwork,

the cells grew well and a neuronal cell-like appearance was

presented (Fig. 2A and B). MSCs

induced by neural differentiation for 3 h could therefore be used

for subsequent experiments. The BME, Wnt3a and PTC209 groups

demonstrated specific green fluorescence of Nestin, indicating

Nestin positive expression (Fig.

2C). In addition, the immunofluorescence results indicated the

absence of marked green fluorescence in both the nucleus and

cytoplasm following Olig2 staining; double-color staining of the

nucleus and cytoplasm was not observed under a microscope, thus

establishing that the expression of Olig2 was negative in all cell

groups (Fig. 2D). Furthermore,

after inducing neural differentiation of MSCs in vitro, the

cytoplasm and nucleus emitted green fluorescence following GFAP

staining; GFAP-positive cells could be clearly seen under the

microscope in the BME and Wnt3a groups, whereas GFAP-positive cells

were almost unobservable in the PTC209 group (Fig. 2E).

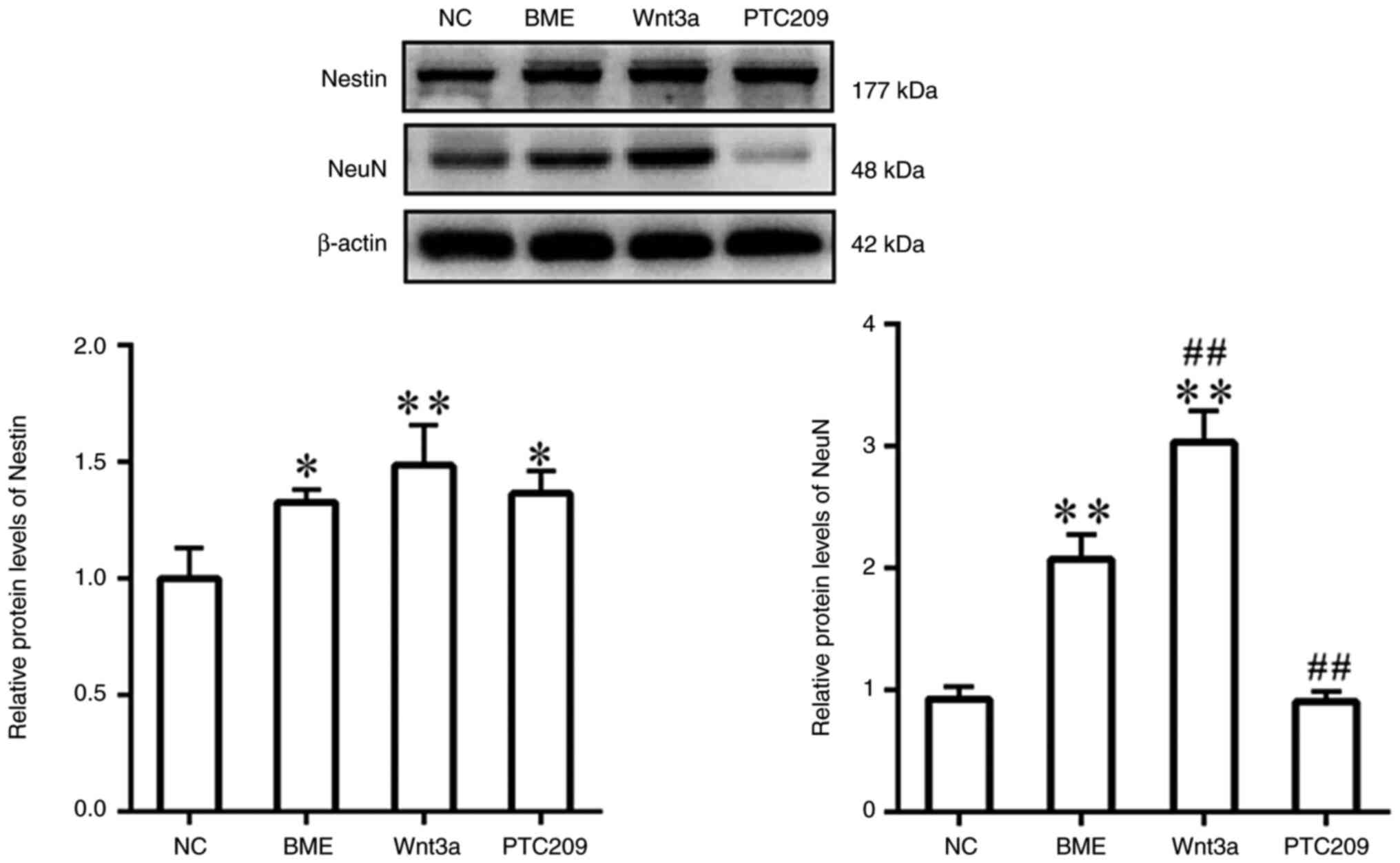

As determined by western blotting, the protein

expression levels of Nestin were enhanced in the BME, Wnt3a and

PTC209 groups compared with those in the NC group; however, no

significant difference emerged between the three groups (Fig. 3). In addition, the protein levels

of NeuN were significantly increased in the BME group compared with

those in the NC group, and were significantly higher in the Wnt3a

group compared with in the BME group. By contrast, NeuN protein

expression levels were significantly lower in the PTC209 group

compared with those in the BME group.

These findings indicated that BME stimulated MSCs to

differentiate into NSCs in vitro, but not towards downstream

oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Furthermore, Wnt3a treatment

enhanced the differentiation of MSCs towards neurons, whereas

PTC209 treatment impeded the differentiation of MSCs into

astrocytes and neurons.

Bmi1 regulates the protein expression of

Wnt3a and RhoA in vitro

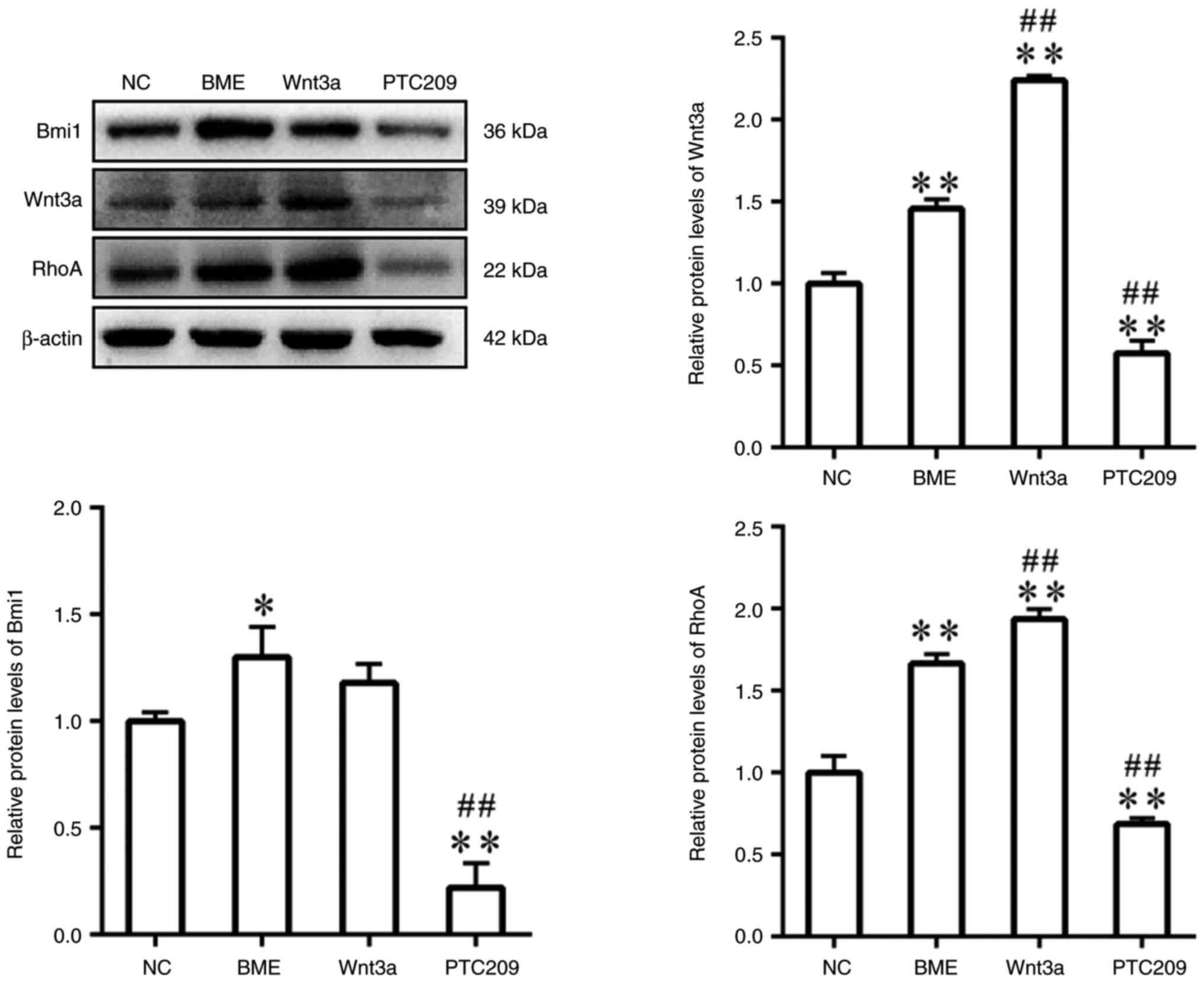

The protein expression levels of Bmi1, Wnt3a and

RhoA were significantly increased in the BME group compared with

those in the NC group (Fig. 4).

In comparison with the BME group, the protein expression levels of

Wnt3a and RhoA were increased in the Wnt3a group; however, there

was no significant difference in Bmi1 protein expression. By

contrast, the protein expression levels of Bmi1, Wnt3a and RhoA

were significantly decreased in the PTC209 group compared with

those in the BME group. These findings indicated that Bmi1 may be

implicated in the neural differentiation process of MSCs by

controlling the expression of Wnt3a and RhoA.

Engraftment and survival of MSCs in

ischemically injured brain tissue

In the present study, SD rats were subjected to the

experiment shown in Fig. 5A.

When cultured in vitro to the third generation, MSCs

displayed spindle-shaped morphology with high homogeneity (Fig. 5B), and CM-Dil-labeled MSCs

exhibited strong red fluorescence with an uncolored nucleus and

high labeling efficiency (Fig.

5C). A total of 7 days after MSCs transplantation the rats were

sacrificed and their brain tissues were analyzed using fluorescence

detection. The transplanted cells were visibly labeled with red

fluorescence after CM-Dil labeling (Fig. 5D), and blue cell fluorescence was

observed following DAPI staining (Fig. 5E). The cells that displayed

co-localization of red and blue fluorescence were considered MSCs

that had been implanted in the brain tissue (Fig. 5F and G). These findings indicated

that the MSCs were successfully transplanted into the brain tissues

of rats that had IBI and were viable.

Bmi1 downregulation inhibits repair of

IBI by MSC transplantation

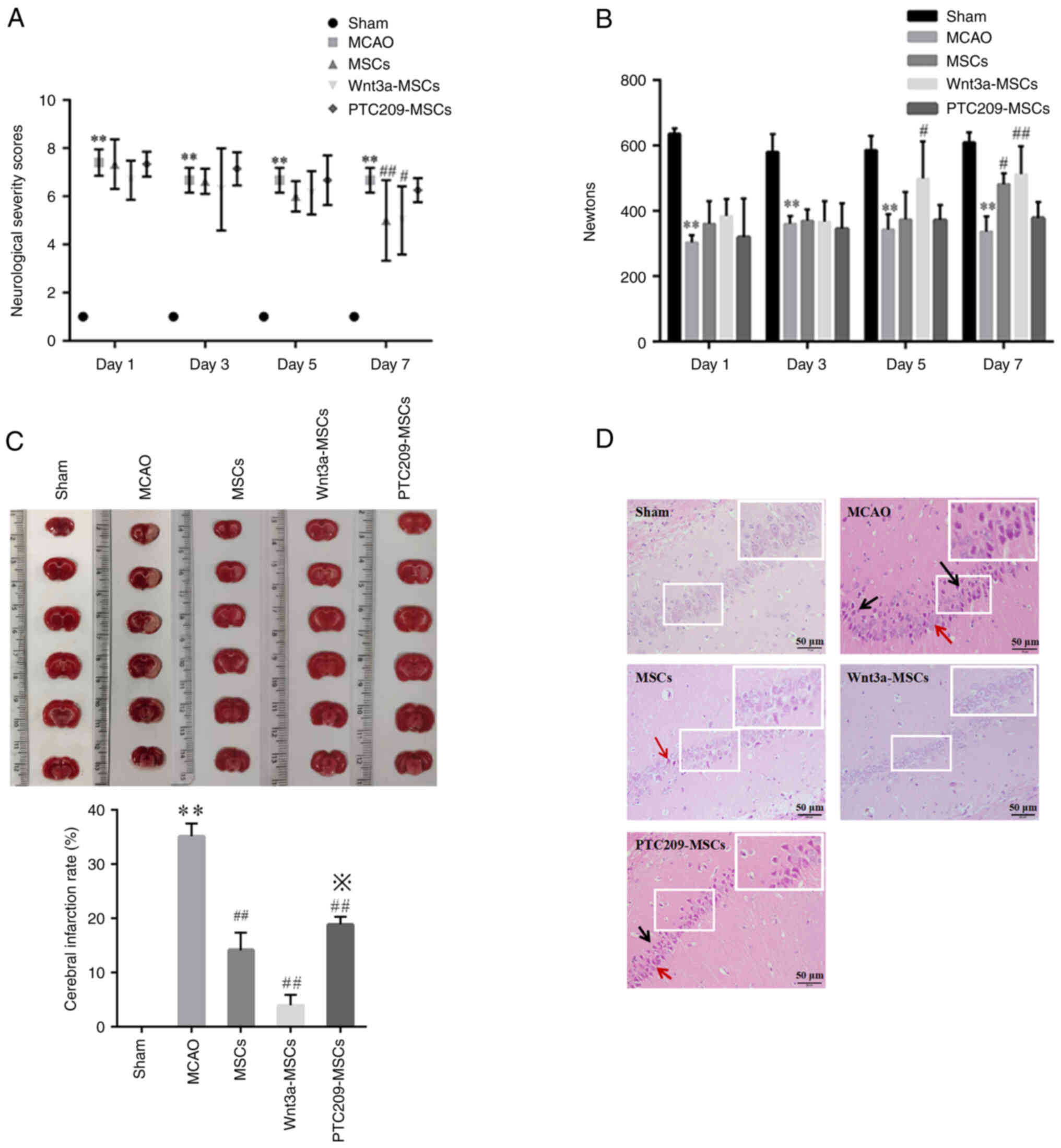

The NSS scores demonstrated that rats in the Sham

group obtained a score of 1 on days 1, 3, 5 and 7, and displayed no

observable behavioral abnormalities (Fig. 6A). Conversely, rats in the MCAO

group exhibited substantial behavioral deficits, including left

shoulder internal rotation, decreased unilateral resistance to

countermovement, and grip strength reduction on the left side due

to IBI. There were no significant differences between the three

groups receiving MSC transplantation on days 1, 3 and 5 when

compared with the MCAO group; however, on day 7, rats in the MSC

and Wnt3a-MSC groups had lower scores compared with in the MCAO

group, whereas the PTC209-MSC group showed no significant change

compared with the MCAO group. Furthermore, the results suggested

that rats in the MCAO group had significantly weaker grasping

strength than those in the Sham group on days 1, 3, 5 and 7

(Fig. 6B). On day 7, the MSCs

group showed an improvement in grasping strength compared with the

MCAO group. Furthermore, the Wnt3a-MSCs group exhibited an

improvement in grasp strength on days 5 and 7, whereas the

PTC209-MSCs group did not show any significant improvement at all

time points. The TTC staining results indicated uniformly symmetric

brain tissue coloring without infarction in the Sham group rats,

whereas different degrees of infarction conditions were observed in

the brain tissues of the MCAO group and the three MSC

transplantation groups (Fig.

6C). The infarction rate in brain tissue was significantly

decreased in all three groups receiving MSC transplantation

compared with that in the MCAO group. Moreover, the Wnt3a-MSCs

group had a lower infarction rate than the MSCs group, whereas the

PTC209-MSCs group had an increased infarction rate compared with

that in the MSCs group. After performing H&E staining on brain

tissue sections, a normal and clear cell structure was observed in

the Sham group; by contrast, the MCAO group exhibited more deeply

stained, degenerated and atrophied neuronal cells, as well as a

markedly enlarged tissue gap (Fig.

6D). The three groups that underwent MSC transplantation

exhibited fewer cellular wrinkles and necrotic areas compared with

the MCAO group, with varying degrees of improvement in tissue

damage. However, among these three groups, there were still more

wrinkled and deeply stained cells in the PTC209-MSCs group. This

suggests that Wnt3a may enhance the neural repair function of MSCs

and PTC209 could attenuate the neural repair function of MSCs.

All of the aforementioned findings indicated that

the MCAO model rats developed notable behavioral disturbances

following ischemic brain damage, whereas neurological function and

localized brain infarction symptoms improved following

transplantation of MSCs into MCAO model rats. Treatment of MSCs

with Wnt3a further improved infarction symptoms in damaged brain

tissues, whereas downregulation of Bmi1 using PTC209 hindered the

reduction of the cerebral infarction rate, thus suggesting that

Bmi1 serves a role in repairing IBI through MSC

transplantation.

Downregulation of Bmi1 inhibits recovery

of neurological function in MCAO rats

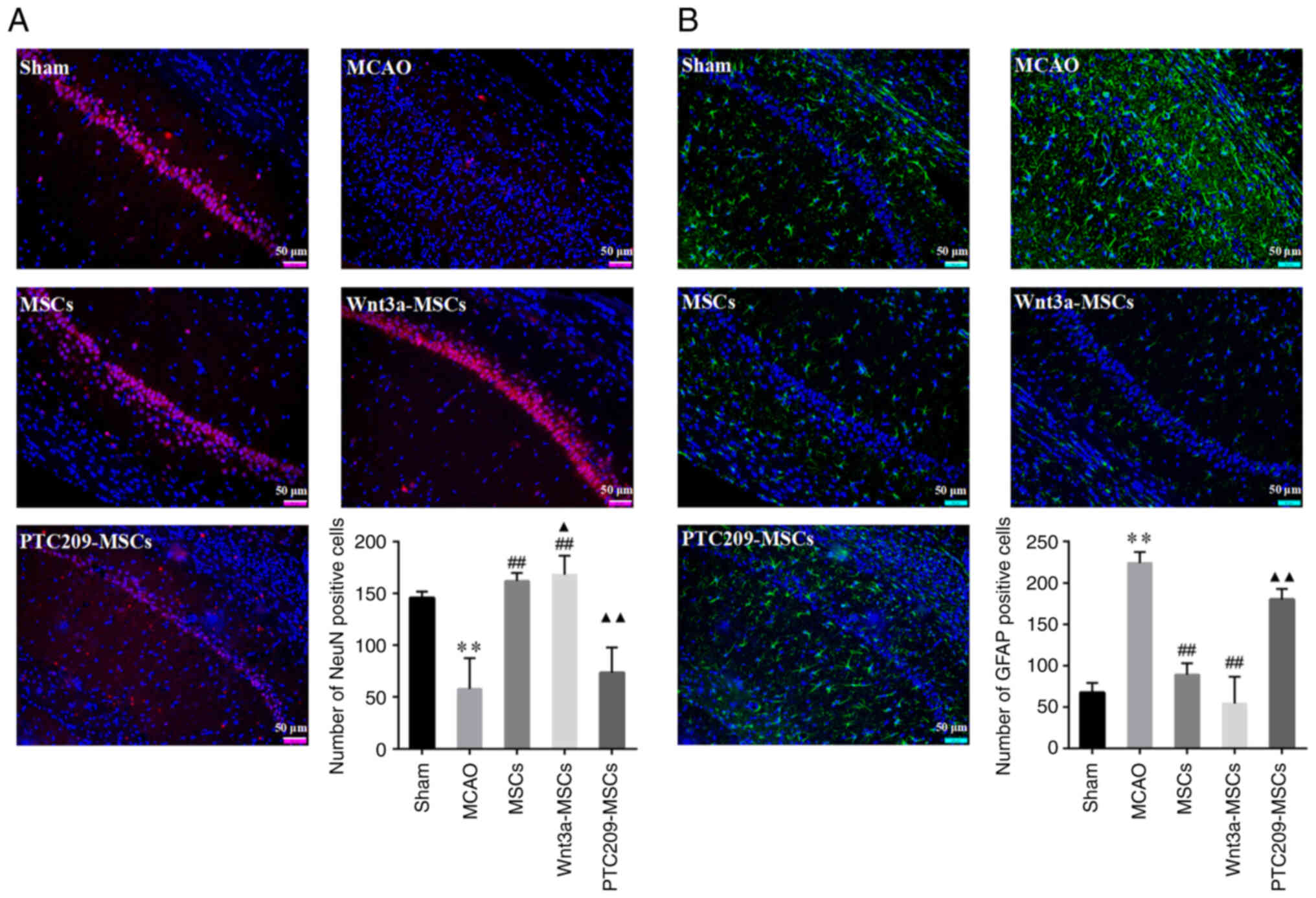

Sections of the rat hippocampal CA1 area were

stained with red fluorescence for NeuN-positive cells and green

fluorescence for GFAP-positive cells. The NeuN immunofluorescence

results indicated a significant decrease in the number of

NeuN-positive cells in the MCAO group as compared with in the Sham

group (Fig. 7A). By contrast,

the MSCs and Wnt3a-MSCs groups exhibited a significant increase in

NeuN-positive cells compared with those in the MCAO group, whereas

the PTC209-MSCs group showed no significant difference. When

compared with the MSCs group, the Wnt3a-MSCs group showed a

significant increase in NeuN staining while the PTC209-MSCs group

showed a significant decrease. By contrast, the GFAP

immunofluorescence results revealed a notable increase in

GFAP-positive cells in the MCAO group when compared with the Sham

group (Fig. 7B). Furthermore,

the MSCs and Wnt3a-MSCs groups exhibited a significant reduction in

the number of GFAP-positive cells compared with in the MCAO group,

whereas there was no statistically significant difference in GFAP

staining between the PTC209-MSCs group and the MCAO group. The

number of GFAP-positive cells was significantly increased in the

PTC209-MSCs group compared with the MSCs group.

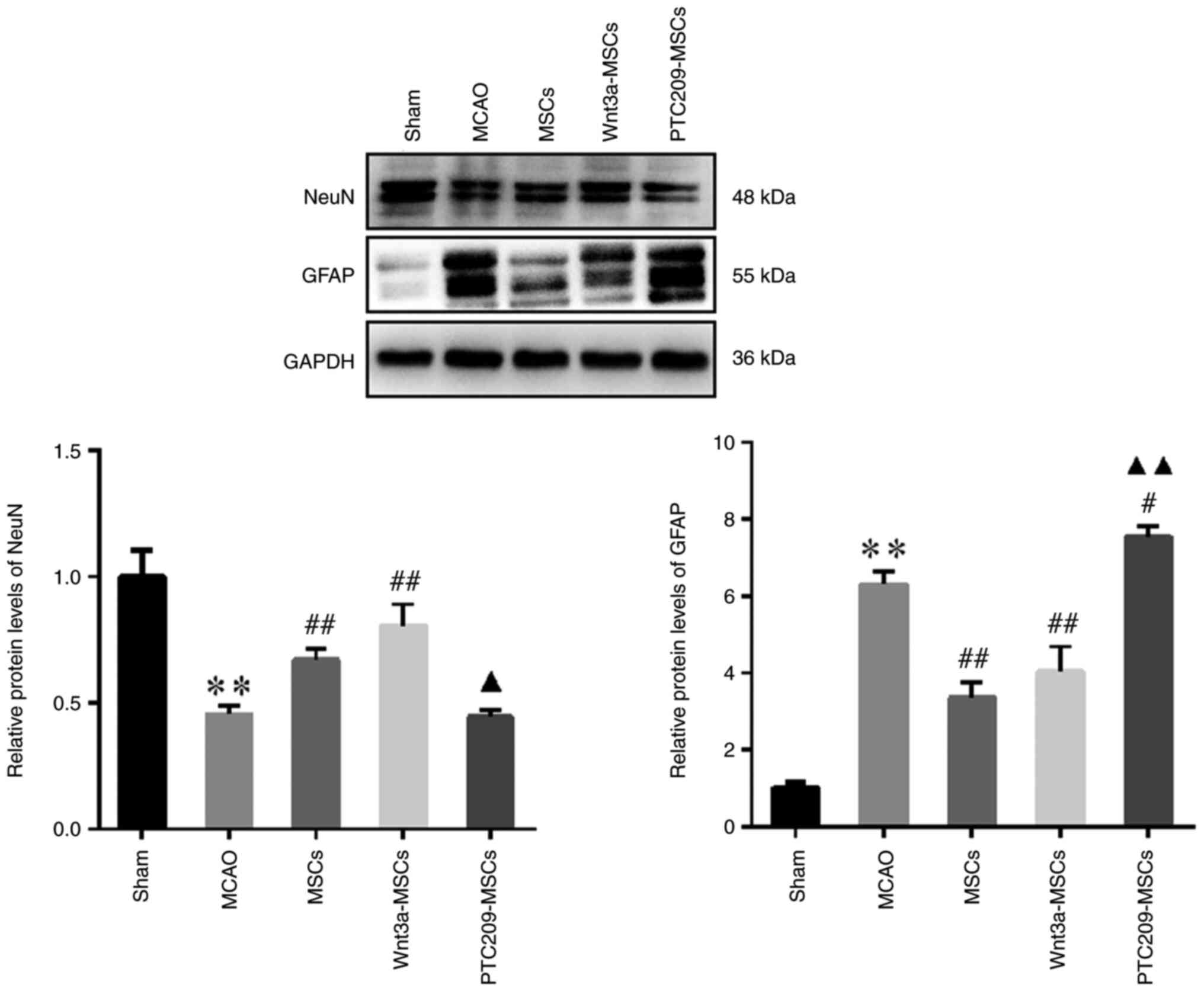

The results of western blotting indicated that in

the MCAO group, NeuN protein expression was lower and GFAP

expression was higher compared with that in the Sham group

(Fig. 8). Conversely, in the

MSCs and Wnt3a-MSCs groups, NeuN protein expression was higher

whereas GFAP protein expression was lower than that in the MCAO

group. Notably, neither NeuN or GFAP expression was significantly

altered in the Wnt3a-MSCs group compared with in the MSCs group.

NeuN expression was decreased and GFAP expression was elevated in

the PTC209-MSCs group compared with the MSCs group.

The present findings suggested that Wnt3a may

promote an increase in the number of neurons in the CA1 region of

the rat hippocampus and enhance the neural repair function of MSCs,

whereas downregulation of Bmi1 could inhibit the increased neuronal

number and the decrease of astrocyte number in the CA1 region of

the hippocampus of MSC-transplanted rats, and may thus suppress

neural repair.

Discussion

IBIs are associated with high morbidity, disability

and mortality due to their complex pathogenesis, with MCAO being a

prevalent cause. Cerebral ischemia results in restored blood supply

after a certain period of time; however, brain function is not

restored and is accompanied by severe delayed neuronal apoptosis

and necrosis, leading to brain dysfunction. Notably, stem cell

therapy utilizing MSCs has become a promising approach for treating

neurological disorders (29).

However, the altered homeostasis of the internal brain tissue

environment in IBI adversely affects the survival, proliferation

and effective differentiation rate of transplanted stem cells;

these factors notably impede the efficacy of MSC transplantation

(30,31). To address this issue, the present

study showed that Wnt3a can promote MSC neural differentiation by

upregulating the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway. Investigations have

shown that Wnt3a treatment or Wnt3a overexpression in MSCs

activates both classical and non-classical Wnt signaling pathways

(32). Several cytokines and

chemokines, such as stromal cell-derived factor-1α, a CXC-type

chemokine produced by bone marrow stromal cells, can induce the

chemotactic migration of MSCs toward the injured part of the nerve

and contribute to the repair of structure and function at the site

of injury (33). In our previous

study, it was found that upregulation of the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling

pathway using Wnt3a could promote the migration of MSCs in

vitro (27). Therefore, 10

ng/ml Wnt3a was used in the present study.

MSCs have the potential to differentiate into neural

cells, offering a promising option for treating IBI. The present

study confirmed that BME induced the differentiation of MSCs to the

neuronal lineage, as indicated by positive staining of Nestin, a

marker for tumor stem cells, NSCs and astrocytes and GFAP, an

astrocyte surface marker.

Cerebral ischemia instigates neuronal necrosis,

apoptosis and progressive neuronal depletion, particularly in the

CA1 section of the hippocampus, culminating in notable debilitation

in cognitive ability, spatial perception and behavior (34). The CA1 region of the hippocampus

in the brain is particularly vulnerable to IBI, and the neuronal

cells within this area are susceptible to necrosis and apoptosis

following such an injury (35).

This region of the hippocampus is comprised of dense, large

neurons, and these vertebral neurons are the principal output

neurons of the hippocampus (36), which have the capacity to

selectively transmit different behavioral information to various

target areas (37).

Consequently, the CA1 region of the hippocampus was selected as the

primary assessment target in the present study. In the present

study, rats that underwent MCAO showed notable behavioral deficits

after IBI episodes. CM-Dil-labeled cells were visible in the

hippocampal region of rat brain tissue sections after MSCs

transplantation, and the NSS and grasping ability of rats gradually

improved. Transplanting MSCs promoted neurogenesis, which aligns

with the results indicating that MSCs have the ability to nourish

cells, promote cell proliferation and differentiation, inhibit cell

death and regulate homeostasis in the injured area (38-41). The current study indicated that

upregulation of the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway in MSCs led to an

increase in the number of neurons in the CA1 region of the rat

hippocampus by immunofluorescence staining and H&E staining,

thus improving the neural repair ability of MSCs.

The Bmi1 protein belongs to the multi-comb

inhibitory complex 1 family, and contributes to various biological

processes, including embryonic development, organogenesis,

tumorigenesis, and stem cell stabilization and differentiation

(42). The results of the

current study demonstrated an increase in Bmi1 protein expression

during the induction of neural differentiation of MSCs in

vitro, suggesting its potential involvement in this process.

However, the effects of Bmi1 on the neural differentiation of MSCs

and the underlying mechanism remain unclear. Notably, Bmi1 acts as

an oncogene, and its anomalous expression is associated with the

progression and drug resistance of various types of cancer,

including bladder cancer and B-cell lymphoma (43,44). Therefore, the present study

implemented targeted small molecule inhibition of Bmi1 to

specifically restrict Bmi1 levels, enabling the investigation of

its association with and function in stem cell self-renewal and

differentiation. The Bmi1-selective inhibitor PTC209 was initially

screened by Kreso et al (45) through small-molecule gene

expression modulation technology. As demonstrated in a preceding

study, a concentration of 1 μM of the small molecule

compound PTC-209 was shown to inhibit the expression of Bmi1 during

the process of induced pluripotent stem cell differentiation

(46). The findings of the

present study demonstrated that 1 μmol/l PTC209 exerted no

effect on the proliferation of MSCs. Furthermore, the inhibition of

Bmi1 expression by PTC209 impeded the differentiation of MSCs

towards astrocytes and neurons during BME-induced neural

differentiation of MSCs in vitro.

NeuN is a neuronal protein the expression of which

directly reflects the maturity of neurons, whereas GFAP acts as a

marker for astrocyte activation. GFAP upregulation leads to a low

percentage of NeuN protein phosphorylation and the formation of

glial scarring, which hinders axon regeneration and thus negatively

affects the repair of neural tissue structures. Changes in the

expression of these two proteins may indicate the extent of nerve

cell injury caused by cerebral ischemia (47). In the current study, the quantity

of neurons and astrocytes were analyzed in brain tissues following

MSC transplantation. The outcomes revealed that downregulation of

Bmi1 by PTC209 inhibited the increase in neuron number and the

decrease in astrocytes in the CA1 region of the hippocampus of

MSC-transplanted rats and attenuated the frontal neural repair

ability of MSCs. It may be hypothesized that the upregulation of

GFAP resulting from reduced Bmi1 expression following IBI in rats

may hinder CA1 hippocampal neuron repair and compromise the neural

repair capacity of MSCs. It is important to note that the

experimental results differed slightly due to the different

experimental conditions employed in the present study between in

vitro and in vivo experiments. For example, the results

of in vitro experiments demonstrated that after inducing

neural differentiation of MSCs, GFAP-positive cells could be

observed under a microscope in the BME and Wnt3a groups, whereas

GFAP-positive cells were almost unobservable in the PTC209 group.

Conversely, the in vivo experiments demonstrated that the

MCAO group exhibited significantly higher levels of GFAP-positive

cells compared with the Sham group, whereas the MSCs and Wnt3a-MSCs

groups exhibited a decrease in GFAP-positive cells compared with

the MCAO group. A comprehensive review of the literature on GFAP

revealed its expression in the intermediate filaments of the

astrocyte lineage, thus serving as a marker for astrocytes.

Astrocytes can form physical barriers to isolate damaged tissues,

regulate blood flow after ischemia, promote the blood-brain

barrier, support myelin formation and provide mechanical strength;

however, it is important to note that prolonged upregulation of

GFAP and proliferation of astrocytes can result in neurological

damage, as well as the inhibition of the proliferation of mature

brain neurons and protrusion extension (48-50). It is possible that the results of

the in vitro and in vivo experiments are not

completely uniform because of the different time and conditions for

inducing neural differentiation in vitro and nerve injury

in vivo.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that Bmi1 can

regulate Wnt signaling in various types of cells (51-54). To further explore the

relationship between Bmi1 and the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway, the

present study examined the effects of Wnt3a-induced upregulation of

the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway and PTC209-induced inhibition of

Bmi1 on the expression of proteins related to Bmi1 and the

Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway. No significant difference in Bmi1

protein expression was observed after upregulating Wnt3a-RhoA in

MSCs; however, downregulation of Bmi1 in MSCs resulted in a

significant decrease in the protein expression levels of both Wnt3a

and RhoA. These findings suggested that Bmi1 might serve a role in

the neural differentiation process of MSCs by regulating the

expression of Wnt3a and RhoA.

In summary, the repair of IBI by MSC transplantation

is a multifaceted process that is affected by numerous factors. The

utilization of MSCs in the replacement of damaged or functionally

deficient neural tissue for the treatment of IBI represents a

highly promising therapeutic modality. It has been reported that

Bmi1 is essential for the maintenance of stemness in a variety of

stem cells (55,56); however, studies on Bmi1 in MSCs

are still scarce. The present study aimed to explore the mechanism

of Bmi1 and the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway on the in vitro

neural differentiation of MSCs and on in vivo IBI repair.

Through the findings of the in vivo and in vitro

experiments, it was indicated that Bmi1 may regulate neural

differentiation of MSCs through the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway to

repair ischemic brain injury in rats (Fig. 9). In the current study, the role

of Bmi1 in the repair of IBI by MSC transplantation was

investigated. With the continuous development of translational and

neuroregenerative medicine, these findings may provide novel

insights and targets for the treatment of IBI. Furthermore, Bmi1

could serve as a new therapeutic target for the treatment of

neurological diseases. Nevertheless, the present study is not

without limitations. Firstly, only the Wnt3a and RhoA components of

the Wnt signaling pathway were analyzed. Secondly, the antagonistic

effect of Wnt3a, an agonist of Wnt3a-RhoA, on PTC209, a Bmi1

inhibitor, requires further investigation. It is evident that

further exploration is required to gain a more comprehensive

understanding of the subject; this necessitates the conduction of

additional in-depth studies. Finally, following extensive

consultation of the literature, normal MSC culture conditions were

employed in the in vitro experiments to explore the

mechanism. The paucity of studies based on ischemic cell conditions

was noted and it was acknowledged that this area should be a focus

of future research.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

provide conclusive evidence that suggests Bmi1 may serve a crucial

role in the process of neural differentiation of MSCs by regulating

the expression of Wnt3a and RhoA. Furthermore, the findings

indicated that elevating the Wnt3a-RhoA signaling pathway in MSCs

may foster the restoration of neural function in rats with brain

injuries. Conversely, downregulation of Bmi1 in MSCs may impede the

recovery of neural function in brain-damaged rats.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KC performed all relevant experiments and prepared

the drafts. HZ performed the in vitro experiments. JZ and YZ

performed the in vivo experiments. XD prepared the drafts,

revised the manuscript, and analyzed and interpreted the data. QY

and LZ designed and directed the project. All authors confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal

Ethical and Welfare Committee of Zhejiang Chinese Medical

University (approval no. 20210524-05; review no.

IACUC-202108-05).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

MSC

|

mesenchymal stem cell

|

|

Bmi1

|

B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1

homolog

|

|

IBI

|

ischemic brain injury

|

|

BME

|

β-mercaptoethanol

|

|

NSC

|

neural stem cell

|

|

PCP

|

planar cell polarity

|

|

SDF-1α

|

stromal cell-derived factor-1α

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethyl sulfoxide

|

|

TTC

|

triphenyltetrazolium chloride

|

|

NSS

|

Neurological Severity Score

|

|

MCAO

|

middle cerebral artery occlusion

|

|

H&E

|

hematoxylin and eosin

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Project of Zhejiang

Chinese Medical University (grant no. 2022JKZKTS21) and the

Research Project on Laboratory Work in Universities of Zhejiang

Province (grant no. YB202268).

References

|

1

|

Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries

in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis

for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 396:1204–1222.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

McIntyre CW and Goldsmith DJ: Ischemic

brain injury in hemodialysis patients: Which is more dangerous,

hypertension or intradialytic hypotension? Kidney Int.

87:1109–1115. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Liu X and Jia X: Neuroprotection of stem

cells against ischemic brain injury: From bench to clinic. Transl

Stroke Res. 15:691–713. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

4

|

Sakai S and Shichita T: Inflammation and

neural repair after ischemic brain injury. Neurochem Int.

130:1043162019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Nie X, Leng X, Miao Z, Fisher M and Liu L:

Clinically ineffective reperfusion after endovascular therapy in

acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 54:873–881. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Guo Y, Peng Y, Zeng H and Chen G: Progress

in mesenchymal stem cell therapy for ischemic stroke. Stem Cells

Int. 2021:99235662021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chrostek MR, Fellows EG, Crane AT, Grande

AW and Low WC: Efficacy of stem Cell-based therapies for stroke.

Brain Res. 1722:1463622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li C, Sun T and Jiang C: Recent advances

in nanomedicines for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Acta Pharm

Sin B. 11:1767–1788. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Leveque X, Hochane M, Geraldo F, Dumont S,

Gratas C, Oliver L, Gaignier C, Trichet V, Layrolle P, Heymann D,

et al: Low-dose pesticide mixture induces accelerated mesenchymal

stem cell aging in vitro. Stem Cells. 37:1083–1094. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cao Z, Xie Y, Yu L, Li Y and Wang Y:

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and stem cell factor (SCF)

maintained the stemness of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

(hBMSCs) during long-term expansion by preserving mitochondrial

function via the PI3K/AKT, ERK1/2, and STAT3 signaling pathways.

Stem Cell Res Ther. 11:3292020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang L, Xiong N, Liu Y and Gan L:

Biomimetic cell-adhesive ligand-functionalized peptide composite

hydrogels maintain stemness of human amniotic mesenchymal stem

cells. Regen Biomater. 8:rbaa0572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhou T, Yang Y, Chen Q and Xie L:

Glutamine metabolism is essential for stemness of bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells and bone homeostasis. Stem Cells Int.

2019:89289342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

de Morree A and Rando TA: Regulation of

adult stem cell quiescence and its functions in the maintenance of

tissue integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:334–354. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sahasrabuddhe AA: BMI1: A biomarker of

hematologic malignancies. Biomark Cancer. 8:65–75. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang J, Xue J, Hu W, Zhang L, Xu R, Wu S,

Wang J, Ma J, Wei J, Wang Y, et al: Human embryonic stem

cell-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretome reverts silica-induced

airway epithelial cell injury by regulating Bmi1 signaling. Environ

Toxicol. 38:2084–2099. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zheng X, Wang Q, Xie Z and Li J: The

elevated level of IL-1α in the bone marrow of aged mice leads to

MSC senescence partly by down-regulating Bmi-1. Exp Gerontol.

148:1113132021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Mich JK, Signer RA, Nakada D, Pineda A,

Burgess RJ, Vue TY, Johnson JE and Morrison SJ: Prospective

identification of functionally distinct stem cells and

neurosphere-initiating cells in adult mouse forebrain. Elife.

3:e026692014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kraus L, Bryan C, Wagner M, Kino T,

Gunchenko M, Jalal W, Khan M and Mohsin S: Bmi1 augments

proliferation and survival of cortical Bone-derived stem cells

after injury through novel epigenetic signaling via histone 3

Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 22:78132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang D, Huang J, Wang F, Ding H, Cui Y,

Yang Y, Xu J, Luo H, Gao Y, Pan L, et al: BMI1 regulates multiple

myeloma-associated macrophage's pro-myeloma functions. Cell Death

Dis. 12:4952021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Russell JO and Monga SP: Wnt/β-Catenin

signaling in liver development, homeostasis, and pathobiology. Annu

Rev Pathol. 13:351–378. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yu Q, Liu L, Duan Y, Wang Y, Xuan X, Zhou

L and Liu W: Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates neuronal

differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 439:297–302. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Schunk SJ, Floege J, Fliser D and Speer T:

WNT-β-catenin signalling-a versatile player in kidney injury and

repair. Nat Rev Nephrol. 17:172–184. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Torban E and Sokol SY: Planar cell

polarity pathway in kidney development, function and disease. Nat

Rev Nephrol. 17:369–385. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bengoa-Vergniory N, Gorroño-Etxebarria I,

González-Salazar I and Kypta RM: A switch from canonical to

noncanonical Wnt signaling mediates early differentiation of human

neural stem cells. Stem Cells. 32:3196–208. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Govek EE, Newey SE and Van Aelst L: The

role of the Rho GTPases in neuronal development. Genes Dev.

19:1–49. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhou Y, Li HQ, Lu L, Fu DL, Liu AJ, Li JH

and Zheng GQ: Ginsenoside Rg1 provides neuroprotection against

blood brain barrier disruption and neurological injury in a rat

model of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion through downregulation of

aquaporin 4 expression. Phytomedicine. 21:998–1003. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yao P, Yu Q, Zhu L, Li J, Zhou X, Wu L,

Cai Y, Shen H and Zhou L: Wnt/PCP pathway regulates the migration

and neural differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro.

Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 60:44–54. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zaghloul RA, Elsherbiny NM, Kenawy HI,

El-Karef A, Eissa LA and El-Shishtawy MM: Hepatoprotective effect

of hesperidin in hepatocellular carcinoma: Involvement of Wnt

signaling pathways. Life Sci. 185:114–125. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Liu D, Ye Y, Xu L, Yuan W and Zhang Q:

Icariin and mesenchymal stem cells synergistically promote

angiogenesis and neurogenesis after cerebral ischemia via PI3K and

ERK1/2 pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 108:663–669. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Goldman SA: Stem and Progenitor Cell-based

therapy of the central nervous system: Hopes, hype, and wishful

thinking. Cell Stem Cell. 18:174–188. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li Q, Guo Y, Chen F, Liu J and Jin P:

Stromal cell-derived factor-1 promotes human adipose tissue-derived

stem cell survival and chronic wound healing. Exp Ther Med.

12:45–50. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Meng Z, Feng G, Hu X, Yang L, Yang X and

Jin Q: SDF Factor-1α promotes the migration, proliferation, and

osteogenic differentiation of mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Stem Cells Dev.

30:106–117. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Marquez-Curtis LA and Janowska-Wieczorek

A: Enhancing the migration ability of mesenchymal stromal cells by

targeting the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Biomed Res Int. 2013:5610982013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Liu P, Xu J, Chen Y, Xu Q, Zhang W, Hu B,

Li A and Zhu Q: Electrophysiological signatures in global cerebral

ischemia: Neuroprotection via chemogenetic inhibition of CA1

pyramidal neurons in rats. J Am Heart Assoc. 13:e0361462024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Fu HY, Cui Y, Li Q, Wang D, Li H, Yang L,

Wang DJ and Zhou JW: LAMP-2A ablation in hippocampal CA1 astrocytes

confers cerebroprotection and ameliorates neuronal injury after

global brain ischemia. Brain Pathol. 33:e131142023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Lalkovičová M, Bonová P, Burda J and

Danielisová V: Effect of bradykinin postconditioning on ischemic

and toxic brain damage. Neurochem Res. 40:1728–1738. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Mao M, Xu Y, Zhang XY, Yang L, An XB, Qu

Y, Chai YN, Wang YR, Li TT and Ai J: MicroRNA-195 prevents

hippocampal microglial/macrophage polarization towards the M1

phenotype induced by chronic brain hypoperfusion through regulating

CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling. J Neuroinflammation. 17:2442020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chang CY, Liang MZ, Wu CC, Huang PY, Chen

HI, Yet SF, Tsai JW, Kao CF and Chen L: WNT3A promotes neuronal

regeneration upon traumatic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci.

21:14632020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

He M, Shi X, Yang M, Yang T, Li T and Chen

J: Mesenchymal stem cells-derived IL-6 activates AMPK/mTOR

signaling to inhibit the proliferation of reactive astrocytes

induced by hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Exp Neurol. 311:15–32.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Pourheydar B, Soleimani Asl S, Azimzadeh

M, Rezaei Moghadam A, Marzban A and Mehdizadeh M: Neuroprotective

effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on bilateral common

carotid arteries occlusion model of cerebral ischemia in rat. Behav

Neurol. 2016:29647122016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Xin H, Katakowski M, Wang F, Qian JY, Liu

XS, Ali MM, Buller B, Zhang ZG and Chopp M: MicroRNA cluster

miR-17-92 cluster in exosomes enhance neuroplasticity and

functional recovery after stroke in rats. Stroke. 48:747–753. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Park IK, Qian D, Kiel M, Becker MW,

Pihalja M, Weissman IL, Morrison SJ and Clarke MF: Bmi-1 is

required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem

cells. Nature. 423:635–642. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wen T, Zhang X, Gao Y, Tian H, Fan L and

Yang P: SOX4-BMI1 axis promotes non-small cell lung cancer

progression and facilitates angiogenesis by suppressing ZNF24. Cell

Death Dis. 15:6982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhao Y, Yang W, Zheng K, Chen J and Jin X:

The role of BMI1 in endometrial cancer and other cancers. Gene.

856:1471292023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kreso A, van Galen P, Pedley NM,

Lima-Fernandes E, Frelin C, Davis T, Cao L, Baiazitov R, Du W,

Sydorenko N, et al: Self-renewal as a therapeutic target in human

colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 20:29–36. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Shan W, Zhou L, Liu L, Lin D and Yu Q:

Polycomb group protein Bmi1 is required for the neuronal

differentiation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Exp Ther

Med. 21:6192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Okoh OS, Akintunde JK, Akamo AJ and Akpan

U: Thymoquinone inhibits Neuroinflammatory mediators and

vasoconstriction injury via NF-κB dependent NeuN/GFAP/Ki-67 in

hypertensive Dams and F1 male pups on exposure to a mixture of

Bisphenol-A analogues. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 494:1171622025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Li M, Li Z, Yao Y, Jin WN, Wood K, Liu Q,

Shi FD and Hao J: Astrocyte-derived interleukin-15 exacerbates

ischemic brain injury via propagation of cellular immunity. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E396–E405. 2017.

|

|

49

|

Duan CL, Liu CW, Shen SW, Yu Z, Mo JL,

Chen XH and Sun FY: Striatal astrocytes transdifferentiate into

functional mature neurons following ischemic brain injury. Glia.

63:1660–1670. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Sullivan SM, Sullivan RK, Miller SM,

Ireland Z, Björkman ST, Pow DV and Colditz PB: Phosphorylation of

GFAP is associated with injury in the neonatal pig hypoxic-ischemic

brain. Neurochem Res. 282:29414–29423. 2012.

|

|

51

|

Hosoya A, Takebe H, Seki-Kishimoto Y,

Noguchi Y, Ninomiya T, Yukita A, Yoshiba N, Washio A, Iijima M,

Morotomi T, et al: Polycomb protein Bmi1 promotes odontoblast

differentiation by accelerating Wnt and BMP signaling pathways.

Histochem Cell Biol. 163:112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yu J, Shen C, Lin M, Chen X, Dai X, Li Z,

Wu Y, Fu Y, Lv J, Huang X, et al: BMI1 promotes spermatogonial stem

cell maintenance by epigenetically repressing Wnt10b/β-catenin

signaling. Int J Biol Sci. 18:2807–2820. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

53

|

Chen MH, Fu LS, Zhang F, Yang Y and Wu XZ:

LncAY controls BMI1 expression and activates BMI1/Wnt/β-catenin

signaling axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Life Sci.

280:1197482021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Yu H, Gao R, Chen S, Liu X, Wang Q, Cai W,

Vemula S, Fahey AC, Henley D, Kobayashi M, et al: Bmi1 regulates

wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cell

Rev Rep. 17:2304–2313. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Bartucci M, Hussein MS, Huselid E,

Flaherty K, Patrizii M, Laddha SV, Kui C, Bigos RA, Gilleran JA, El

Ansary MMS, et al: Synthesis and characterization of novel BMI1

Inhibitors Targeting Cellular Self-renewal in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Target Oncol. 12:449–462. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhu D, Wan X, Huang H, Chen X, Liang W,

Zhao F, Lin T, Han J and Xie W: Knockdown of Bmi1 inhibits the

stemness properties and tumorigenicity of human bladder cancer stem

cell-like side population cells. Oncol Rep. 31:727–736. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|