Introduction

The maintenance of redox homeostasis is dependent

upon the levels of pro-oxidant active molecules and antioxidants

(1). The disruption of this

equilibrium plays a crucial role in the development and progression

of numerous diseases (2). The

accumulation of pro-oxidative reactive factors, including reactive

oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive

lipids (RLS), leads to the oxidation of DNA, proteins and lipids,

altering their structure, activity and physical properties, and

resulting in oxidative stress and cellular dysfunction (3). ROS are among the most ubiquitous

oxidants in cells and are capable of reacting with numerous

substances to form superoxide (4). The reaction between ROS and

polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in plasma, cell membranes and

organelle membranes is critical, leading to the production of lipid

peroxides (5). RLS produced by

lipid peroxidation, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and

malondialdehyde (MDA), are closely associated with the onset and

progression of numerous diseases, including cancer, diabetes,

neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases and

ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Redox homeostasis therefore

plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of multiple diseases.

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a

transcription factor intricately linked to redox homeostasis in a

variety of inflammatory diseases (6). AhR is activated by a diverse array

of exogenous and endogenous ligands and transcriptional regulates

downstream target genes. This process consequently modulates the

oxidative and antioxidant balance and a variety of cellular

functions. AhR target genes, including the NAD(P)H dehydrogenase

[quinone] 1 (NQO1), glutathione S-transferase (GST),

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1-1 (UGT1A1), CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 genes,

play a crucial role in regulating cellular redox homeostasis

(7). Moreover, AhR plays a

crucial role in the metabolism of exogenous substances and drugs,

iron and heme metabolism, glutathione synthesis, and lipid

metabolism (8,9). The dysregulation of AhR is observed

in numerous disease processes, highlighting its essential role in

cell survival, particularly under conditions of redox homeostasis

imbalance.

AhR plays a multifaceted role in maintaining cell

survival, and both AhR agonists and inhibitors have been shown to

modulate cell survival or death, particularly in the context of

tumor therapy (10-14). In 2003, Dixon et al

(15) identified a novel form of

cell death termed ferroptosis, characterized as an iron-dependent

process triggered by lipid peroxidation. This pathway was initially

discovered through the high-throughput screening of anti-neoplastic

drugs (15). The

ferroptosis-inducing drug, erastin, induces ferroptosis through the

inhibition of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system xC-/xCT,

which is essential for the synthesis of reduced glutathione,

ultimately leading to the accumulation of toxic lipid peroxides

(16). Transcriptome analysis

conducted by Kwon et al (17) on pan-cancer cell lines revealed

that the activity of transcription factors, including Nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NFE2L2/NRF2) and AhR, serves

as a critical marker of erastin resistance. AhR plays a

context-dependent role in modulating ferroptosis sensitivity across

tumor cell lines (18,19). For instance, the siRNA-mediated

knockdown of AhR increases erastin sensitivity in

erastin-insensitive A549 cells, while reducing sensitivity in

erastin-sensitive Calu1 cells, highlighting its dual role in

ferroptosis resistance (17).

Supporting this, Kou et al (19) and Peng et al (20) demonstrated that AhR expression

levels were closely associated with erastin sensitivity in both

A549 and BEAS-2B (human normal bronchial epithelial cells). Their

research further identified the solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11) antioxidant system as a key downstream effector of AhR

(19,20). Despite these advancements, the

precise molecular mechanisms underlying the involvement of AhR in

ferroptosis remain to be fully elucidated.

AhR plays a pivotal role in modulating disease

progression through the regulation of lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis across diverse pathological contexts (17,18). Beyond its established functions

in tumors, AhR activation has been implicated in other diseases.

For example, in I/R injury (liver, myocardium and kidneys), it

exacerbates tissue damage by promoting lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis (21-24); AhR-mediated lipid peroxidation

and ferroptosis have been implicated in neurodegenerative

disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease (25); in intestinal inflammation, AhR

induces ferroptosis in intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes

(natural TCRαβ+ CD8αα+ T-cells and

TCRγδ+ CD8αα+ T-cells, as well as induced

TCRαβ+ CD4+ and TCRαβ+

CD8αβ+ T-cells) (26); and in asthma pathogenesis, AhR

modulates ferroptosis in lung epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) (27). Notably, AhR exhibits

context-dependent roles in these processes. In I/R injury, AhR

activation uniformly aggravates tissue damage. By contrast, its

role in tumors is more intricate, displaying dual effects that vary

by cell type and ligand specificity. While the AhR-ferroptosis axis

has been extensively studied in tumors and I/R injury, its

implications in inflammatory bowel disease, neurodegenerative

diseases and lung diseases remain underexplored, representing

critical gaps in current research.

Early studies have identified several key mechanisms

underlying the context-dependent roles of AhR in response to

diverse ligands or cellular environments (28). The differential effects of AhR

activation may be attributed to the following factors: i)

Ligand-specific receptor conformation. Distinct ligands, such as

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and the tryptophan

metabolite, 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ), induce unique

conformational changes in AhR, affecting its interaction with the

exenobiotic response element (XRE), the core DNA sequence

regulating gene transcription in the AhR signaling pathway. ii)

Ligand affinity and chemical properties: The binding stability and

nuclear retention of AhR are determined by ligand characteristics

(e.g., hydrophobicity, molecular size). High-affinity ligands

prolong nuclear localization and sustained signaling, while

low-affinity ligands (e.g., plant-derived metabolites) typically

trigger transient activation. iii) Cofactor recruitment

specificity: The AhR-AhR nuclear translocator (ARNT) complex

recruits ligand-dependent cofactors, such as inflammation-related

cofactors (e.g., NF-κB and STAT), metabolic regulators (e.g.,

glypican 1α and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1), to

direct the downstream responses. iv) Cell type and microenvironment

dependency: Tissue-specific expression of cofactors results in the

activation of different genes by the same ligand in different

cells. For example, AhR may preferentially bind to IL-6 or IL-22

promoters in immune cells, while promoting CYP450 transcriptione in

hepatocytes. Furthermore, ligands may remodel the chromatin

accessibility of AhR, and at the same time, change the epigenetic

state through metabolites. v) Species/tissues-specific AhR

isoforms: AhR subtype expression (e.g., AhR1 and AhR2) induces

differential responses across tissues or species.

Given that AhR target genes critically regulate

redox homeostasis, its role in lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis

varies by ligand context and disease setting, suggesting that

targeted AhR modulation may have potential for use in various

pathological conditions (Table

I). Ferroptosis has emerged as a crucial pathological mechanism

in diverse diseases, particularly in cancer and I/R injury, where

its initiation is intricately linked to disruptions in redox

homeostasis and excessive lipid peroxidation (29). This review specifically examines

the therapeutic implications of targeting AhR-mediated lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis in these two clinically significant

conditions. The present review focuses on the fundamental

association between lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, summarizing

and critically analyzing the role and potential mechanisms of AhR

in these processes. The present review aimed to enhance the

understanding of AhR signaling in diseases pathogenesis and to

explore novel therapeutic avenues targeting this pathway for

disease intervention.

| Table ISummary of AhR ligands and

antagonists regulating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis

pathways. |

Table I

Summary of AhR ligands and

antagonists regulating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis

pathways.

| Ligands or

antagonists | Promotes/inhibits

the AhR signaling pathway | Cell line/animal

model | Target gene and

signaling pathway | Influence of

ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CH223191 | Inhibits | Mesenchymal stem

cells (MSCS) in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury models | STAT3-HO-1/COX-2

pathway | Inhibits | (67) |

| CH223191 | Inhibits | Hepatocytes of the

mouse model of Metabolic Disaster-associated steatohepatitis

(MASH) | Pten/Akt/β-catenin

pathway | Inhibits | (24) |

| CH223191 | Inhibits | Primary murine

renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (RPTECs) | The cytochrome P450

superfamily | Inhibits | (21) |

| TCDD | Promotes | Prostate cancer

(LNCap, 22Rv1) | NR4A1/SCD1

axis | Promotes | (18) |

| IDA | Promotes | Colorectal cancer

cell lines and mouse models of colorectal cancer (HT29) | ALDH1A3-FSP1

axis | Inhibits | (91) |

| indirubin | Promotes | Mouse embryonic

fibroblast (MEF) cell line induced by cysteine deprivation for

ferroptosis | ATF4-SLC7A11

axis | Inhibits | (84) |

| SR1 | Inhibits | Mouse embryonic

fibroblast (MEF) cell line induced by cysteine deprivation for

ferroptosis | ATF4-SLC7A11

axis | Promotes | (84) |

| DIM | Inhibits | Non-small cell lung

cancer cell lines (A549, H1299) | NRF2-GPX4 axis | Promotes | (112) |

| I3P | Promotes | BEAS-2B | SLC7A11 axis | Inhibits | (20) |

| Benzopyrene | Promotes | Airway epithelial

cells (AEC) of the mouse asthma model | cPLA2-ACSL4

axis | Promotes | (27) |

| Kyn | Promotes | Human lung cancer

cell lines A549 and H1299 and mouse lung cancer cell lines | NRF2 pathway | Inhibits | (76) |

| Kyn | Promotes | Glioblastoma

multiforme (GBM) cell line | FTO-SLC7A11

axis | Inhibits | (108) |

| NBP | Inhibits | In vitro

ferroptosis models (HT22 cells, hippocampal sections and primary

neurons) and in vivo controlled cortical shock mouse

models | CYP1B1-ROS

axis | Inhibits | (53) |

| IS | Promotes | MC3T3-E1 cell line

and mouse models of chronic kidney disease | SLC7A11/GPX4

axis | Promotes | (81) |

| ILA | Promotes | Cardiotoxic (DIC)

mice and DOX-treated H9C2 cells | NRF2 pathway | Inhibits | (107) |

| YH439 | Promotes | Mouse hepatic

stellate cells (mHSCs) | Mrp1 | Promotes | (111) |

| Ethanol extract of

Hibiscus (HS) calyx | Inhibits | Human keratinocytes

HaCaT cells | FTH1, GPX4 and

SLC7A11 pathway | Promotes | (113) |

Association between lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis

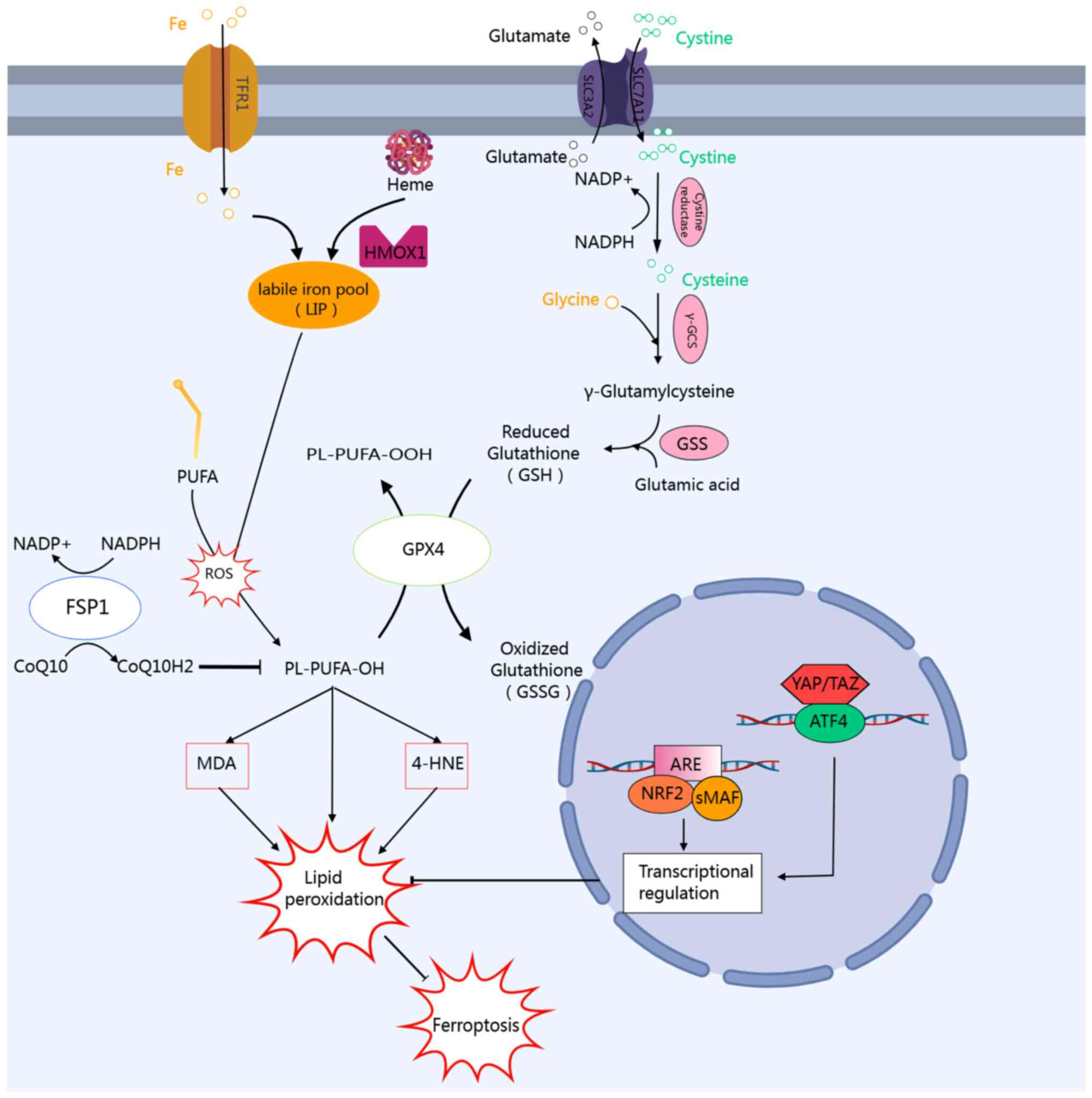

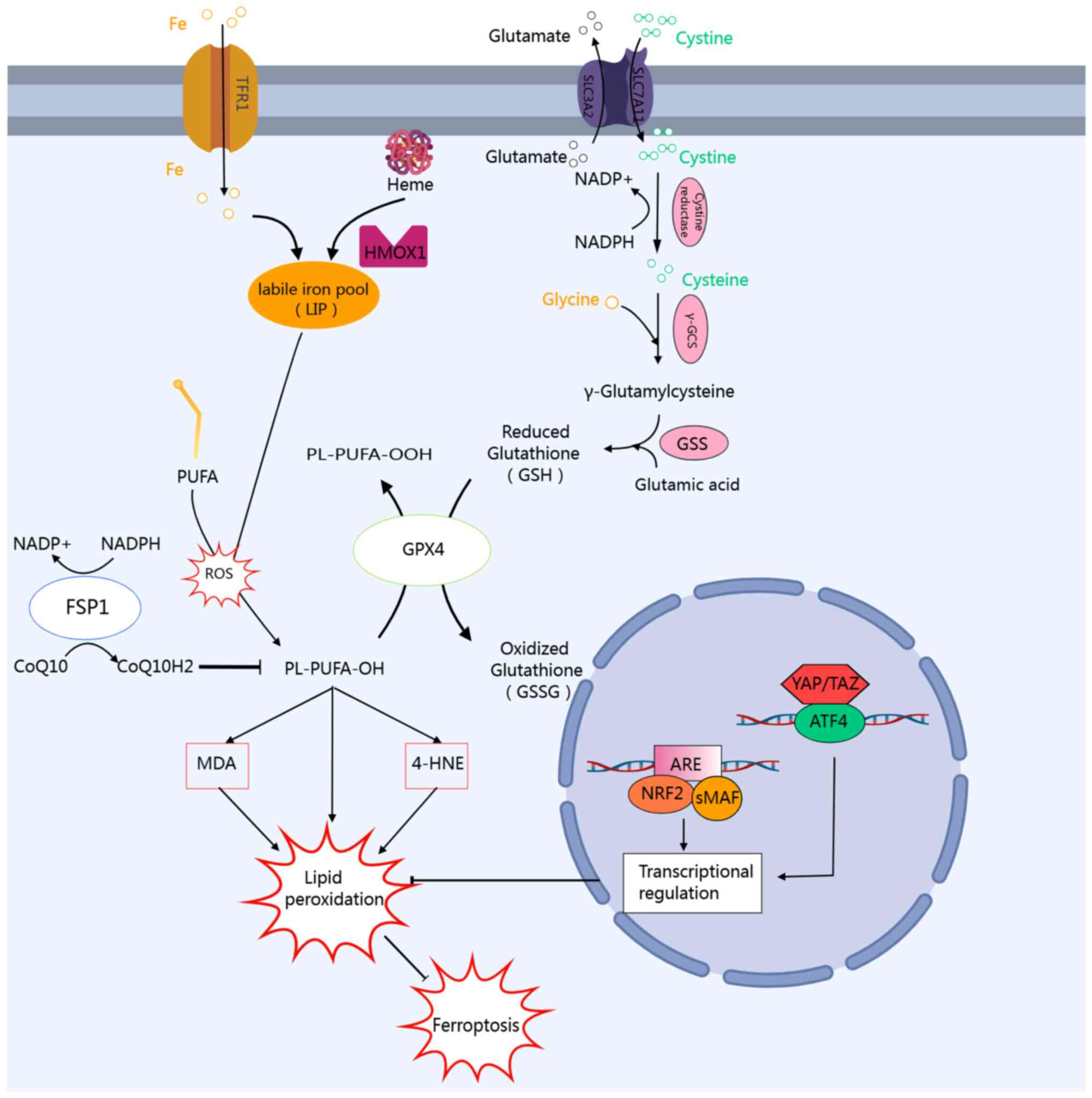

Lipid peroxidation is an ubiquitous phenomenon

observed in a wide array of disease conditions and serves as a

critical triggering factor for ferroptosis. This process typically

manifests as a free radical chain reaction, characterized by an

overabundance of reactive species, such as ROS, RNS and RLS, along

with the excessive accumulation of labile iron pools in cells

(30). The primary event in

lipid peroxidation involves the generation of labile hydroperoxides

(LOOH) through the interaction of ROS with membrane PUFAs. LOOH

compounds are highly susceptible to decomposition, leading to the

formation of metabolically toxic by-products, MDA and 4-HNE, which

are closely associated with iron-induced cell death (31). Furthermore, ferrous iron plays a

crucial role as an initiator of ferroptosis (32). Ferrous iron can catalyze the

conversion of hydrogen peroxide into hydroxyl radicals, which

subsequently react with PUFAs to produce lipid peroxides, leading

to cellular membrane damage and the onset of ferroptosis.

Lipid peroxides and their degradation products are

controlled by intracellular antioxidant mechanisms (33). It has been found that the defense

systems against ferroptosis primarily consist of glutathione

(GSH)-dependent and GSH-independent antioxidant pathways. Reduced

glutathione serves as a substrate for glutathione peroxidase 4

(GPX4), which catalyzes the reduction of lipid peroxides to

non-toxic alcohol forms, thereby detoxifying these harmful

compounds. Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) utilizes NADPH

to generate reduced coenzyme Q10, thereby shielding the cell

membrane from damage induced by lipid peroxides. These two

independent antioxidant defense systems exert stringent control

over lipid peroxidation levels. Erastin and icFSP1 are specific

inhibitors of both ferroptosis defense systems and have been used

in the treatment of various diseases (34,35).

The induction of lipid peroxidation-mediated

ferroptosis is critically influenced by three pivotal factors: The

generation of reactive species, the concentration of the

intracellular labile iron pool and the modulation of the

antioxidant defense system (Fig.

1). These pathways are governed by multiple factors, many of

which are transcriptionally regulated by AhR. For instance,

stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 regulates the metabolism of unsaturated

fatty acids and reduces the oxidative vulnerability of PUFAs,

thereby promoting lipid peroxide formation (36). Heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) regulates

heme catabolism, releasing free iron that upregulates the levels of

labile iron pools within cells (37). Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)

facilitates ROS production via multiple metabolic pathways,

inducing lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis (38). The SLC7A1/GPX4 system, a

GSH-dependent antioxidant mechanism, maintains intracellular redox

homeostasis by promoting the synthesis of reduced GSH (39). FSP1, an antioxidant system

independent of GSH, inhibits lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by

consuming NADPH and promoting the reduction of ubiquinone Q10

(34). NFE2L2/NRF2 is a master

regulator of the cellular antioxidant response, promoting the

transcription of numerous downstream antioxidant-related genes

through binding to their antioxidant response elements (ARE)

(40). CYP1B1, a member of the

cytochrome P450 enzyme family, mediates metabolic processes that

generate ROS, contributing to lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis

(41). Other members of the

cytochrome P450 enzyme family, including CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, have

also been implicated in lipid peroxidation, although to the best of

our knowledge, no studies to date have demonstrated a direct link

between these enzymes and ferroptosis. Notably, the key factors

regulating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis are either target

genes of AhR or are regulated by AhR target genes. This suggests

that AhR may serve as a crucial regulatory node for lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis. Investigating the mechanisms by which

AhR modulates ferroptosis and identifying the potential targets of

AhR in this process holds significant promise for the development

of novel therapeutic agents and the treatment of associated

diseases.

| Figure 1Molecular mechanisms and key

regulators of lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. The initiation of

ferroptosis is primarily driven by the accumulation of labile iron

pools within cells, which originates from two main sources: Iron

uptake mediated by transferrin receptor 1 and free iron release

during heme metabolism catalyzed by heme oxygenase 1. In normal

cells, free iron, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and ROS generate

lipid hydroperoxides via the Fenton reaction. This process is

predominantly modulated by GSH-dependent and non-GSH-dependent

intracellular antioxidant systems. The GSH-dependent system

facilitates the uptake of cystine, an essential precursor for

reduced glutathione, through the SLC7A11/SLC3A2 isodimer, and

subsequently consumes reduced GSH via GPX to detoxify lipid

peroxides. FSP1, also known as AIFM2 or AMID, represents a recently

identified core inhibitor of ferroptosis. It regulates the redox

cycle of coenzyme Q10 through pathways independent of GSH and GPX4,

thereby forming a secondary defense mechanism against lipid

peroxidation. ATF4 and NRF2 function as the core transcription

factors enabling cells to respond to oxidative stress and metabolic

imbalance. Both ATF4 and NRF2 inhibit lipid peroxidation and confer

resistance to ferroptosis by regulating distinct target gene

networks. ROS, reactive oxygen species; GSH, glutathione; SLC7A11,

solute carrier family 7 member 11; GPX, glutathione peroxidase;

FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; ATF4, activating

transcription factor 4; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2; CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; NADP+, nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide phosphate; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid;

MDA, malondialdehyde; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; ARE, antioxidant

response element. |

AhR-mediated regulation of lipid

peroxidation and ferroptosis

AhR orchestrates lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis

through diverse molecular mechanisms, thereby critically

influencing the pathogenesis of multiple diseases. The AhR-mediated

regulation of lipoferroptosis includes the following: The

regulation of the gene expression levels of pro-oxidant and

antioxidant enzymes; the regulation of iron, heme and arachidonic

acid metabolism; and the regulation of the ferroptosis defense

system and synthesis of antioxidant compounds. Notably, AhR

activation plays a dual role in lipid peroxidation-ferroptosis

axis, with distinct regulatory effects depending on the specific

ligands (42). This mechanistic

plasticity, evidenced by ChIP-seq and microarray analyses across

different cell lineages and developmental stage (43-46), positions AhR as both a potential

therapeutic target and a challenge for precise pharmacological

intervention.

AhR mediates lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis by regulating the transcription of pro-oxidant and

antioxidant enzymes AhR activation by pro-oxidative ligands induces

pro-oxidative enzymes expression, mediating lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis

AhR is a ligand-dependent transcription factor that

can mediate both protective and pathological responses. Initially

identified due to its involvement in the toxicity of dioxins such

as TCDD, AhR predominantly resides in the cytoplasm in an inactive

state, complexed with chaperone proteins, including HSP90, AIP and

p23. Upon binding to TCDD, AhR translocates to the nucleus,

dimerizes with ARNT, and binds to XRE in target gene enhancer

regions (47). This classical

AhR/ARNT pathway upregulates the expression of CYP1 family members,

such as CYP1A1, CYP1A2 and CYP1B1 (48). These enzymes represent the most

extensively studied target genes of the AhR/ARNT complex of the

activation of the classic pathway of AhR. CYP450 enzymes, including

CYP1, CYP2 and CYP3, catalyze metabolic reactions that facilitate

the production of ROS (49). The

upregulation of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 promote lipid peroxidation and

trigger ferroptosis, and both TCDD and benzo(a)pyrene promote lipid

peroxidation via this pathway (50), while the AhR antagonist,

CH223191, reverses this effect (51). Similarly, decabromodiphenyl ether

(BDE-209) induces lipid peroxidation via the AhR-CYP1A1-ROS pathway

(52).

Notably, AhR activation by natural ligands, such as

dietary indole and sulforaphane, as well as other low-affinity AhR

ligands, supports intestinal homeostasis and immune regulation.

However, in chronic inflammatory bowel disease, dysregulated AhR

signaling, driven by gut microbiota imbalances, exacerbates

oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and iron deficiency in

intestinal epithelial lymphocytes, and this can potentially be

mitigated by specific AhR inhibitors (26). Moreover, in neurological and

hepatic contexts, butylphthalide mitigates traumatic brain

injury-induced ferroptosis by inhibiting the AhR-CYP1B1-ROS pathway

(53), while CYP1B1 drives

ferroptosis in hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma (41). Collectively, these findings

underscore the pivotal role of AhR in modulating lipid peroxidation

and ferroptosis through pro-oxidant enzyme regulation.

Antioxidant AhR ligands induce

antioxidant enzyme expression to regulate lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis

While pro-oxidative ligands, such as TCDD and

benzo(a) pyrene induce lipid peroxidation via AhR activation,

emerging evidence highlights the dual role of AhR in redox

regulation. Natural exogenous AhR agonists, such as extracts from

artichoke (Cynara scolymus), soybean, fig tree and

Houttuynia cordata, mitigate ROS production, oxidative

stress and lipid peroxidation by regulation of antioxidant enzyme

target genes, such as NQO1, GST and UGT1A1 genes by AhR (54-56) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the key

antioxidant stress transcription factor NRF2 serves as a direct

target for AhR signaling transduction. Notably, its promoter region

containing multiple XRE (57),

antioxidant enzymes such as NQO1, GST and UGT1A1 are also direct

target genes of NRF2. This indicates that AhR regulates the NRF2

gene and thereby promotes the transcription of antioxidant enzymes.

In summary, the activation or inhibition of AhR classic signaling

using appropriate AhR ligands under various disease conditions can

influence lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis levels by regulating

the synthesis of pro-oxidant and antioxidant enzymes.

![Oxidative and antioxidant AhR ligands

regulate lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis via an

oxidative-antioxidant bidirectional regulatory network. Exogenous

pro-oxidative AhR ligands, such as the toxins TCDD and

benzo[a]pyrene, bind to AhR, forming the AhR-ARNT complex that

translocates into the nucleus. This complex subsequently binds to

the XRE, initiating the transcription of various progenitor

enzymes, including CYP1A1, CYP1B1, CYP1A2, COX-2 and NOX, then

mediating ROS production, which in turn induces lipid peroxidation

and ferroptosis. Conversely, natural AhR ligands derived from plant

sources, such as snake tail grass, soybean, fig tree, and fish tail

grass, activate the transcription of antioxidant enzymes (e.g.,

NQO1, GST and UGT1A1) through AhR signaling. This activation

suppresses ROS production, thereby mitigating lipid peroxidation

and inhibiting ferroptosis. AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; TCDD,

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; ARNT, AhR nuclear

translocator; NOX, nitrogen oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

NQO1, NAD(P) H dehydrogenase [quinone] 1; GST, glutathione

S-transferase; UGT1A1, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1-1; HMOX1, heme

oxygenase 1; IDO1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; SLC7A11, solute

carrier family 7 member 11; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; ALDH1A3,

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3.](/article_images/ijmm/56/4/ijmm-56-04-05597-g01.jpg) | Figure 2Oxidative and antioxidant AhR ligands

regulate lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis via an

oxidative-antioxidant bidirectional regulatory network. Exogenous

pro-oxidative AhR ligands, such as the toxins TCDD and

benzo[a]pyrene, bind to AhR, forming the AhR-ARNT complex that

translocates into the nucleus. This complex subsequently binds to

the XRE, initiating the transcription of various progenitor

enzymes, including CYP1A1, CYP1B1, CYP1A2, COX-2 and NOX, then

mediating ROS production, which in turn induces lipid peroxidation

and ferroptosis. Conversely, natural AhR ligands derived from plant

sources, such as snake tail grass, soybean, fig tree, and fish tail

grass, activate the transcription of antioxidant enzymes (e.g.,

NQO1, GST and UGT1A1) through AhR signaling. This activation

suppresses ROS production, thereby mitigating lipid peroxidation

and inhibiting ferroptosis. AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; TCDD,

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; ARNT, AhR nuclear

translocator; NOX, nitrogen oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

NQO1, NAD(P) H dehydrogenase [quinone] 1; GST, glutathione

S-transferase; UGT1A1, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1-1; HMOX1, heme

oxygenase 1; IDO1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; SLC7A11, solute

carrier family 7 member 11; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; ALDH1A3,

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A3. |

AhR regulates lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis by modulating a range of metabolic pathways

Targeted lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis affect the pathogenesis of I/R injury

I/R injury represents a condition wherein tissue

cells, following a period of ischemia, experience reperfusion,

leading to an accelerated exacerbation of tissue damage. This

pathological process, observed in multiple organs and diseases,

results in massive ROS production in I/R injury (58). During I/R injury, various

endogenous ligands of AhR, such as the tryptophan metabolite

kynurenine (Kyn), are generated to sustain AhR activation, leading

to CYP450-mediated ROS overproduction and exacerbating oxidative

stress (59). The restoration of

blood flow and subsequent reoxygenation during reperfusion

frequently result in reperfusion injury, a condition increasingly

recognized as being mediated by ferroptosis (60). Previous studies have indicated

that ferroptosis is more likely to occur during the reperfusion

phase rather than the ischemic phase in I/R injury (61). The endogenous mechanisms

responsible for scavenging ROS are compromised following I/R,

leading to ineffective ROS neutralization. I/R injury is

characterized by a series of intracellular events, including

excessive ROS production during reperfusion, lipid peroxidation and

elevated intracellular iron levels (62). Lipid peroxidation and oxidative

damage induced by ROS can result in cellular damage and death,

which aligns with the hallmarks of ferroptosis. Ferroptosis

inhibitors, such as Fer-1 and deferoxamine (DFO), can effectively

prevent or mitigate the progression of I/R injury when administered

prior to or during the I/R event. DFO is applied in coronary artery

bypass grafting procedures. The intravenous administration of DFO

has been shown to protect the myocardium from reperfusion injury

and mitigate lipid peroxidation (63).

Targeting AhR-mediated arachidonic

acid and heme metabolism to mitigate I/R injury

Emerging evidence highlights AhR as a crucial

regulator in I/R injury affecting the liver, kidneys and myocardium

(21-23,64). During the early phase of I/R

injury, oxidative stress stimulates the production of oxyindole, a

compound that has been demonstrated to be an effective AhR agonist

and significantly activates AhR (65). Moreover, under the oxidative

stress conditions associated with I/R injury, there is an increased

presence of endogenous pro-oxidative ligands for AhR (66). These multiple pro-oxidative

endogenous ligands may constitute a critical component in the

pathophysiology of I/R injury. In a previous study, in two distinct

mouse models of liver I/R injury, both the conventional ferroptosis

inhibitor DFO and the AhR antagonist CH223191 were found to be

effective in reversing ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation.

Moreover, CH223191 demonstrated superior efficacy compared with DFO

(67), suggesting that AhR

activation is closely related to I/R injury. HMOX1 and COX-2 are

pivotal enzymes in heme and arachidonic acid metabolism,

respectively. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that the

STAT3-HMOX1/COX-2 signaling pathway was inhibited following the

administration of CH223191 (67). The activation of HMOX1

facilitates the release of free iron ions from heme, consequently

elevating intracellular free iron levels (68). COX-2 also catalyzes the

production of ROS, leading to oxidative stress and lipid

peroxidation (38). Both HMOX1

and COX-2 genes play crucial roles in the induction of ferroptosis.

Previous studies have demonstrated that AhR signaling exerts direct

or indirect effects on the HMOX1/COX-2 signaling pathway via

multiple mechanisms (69-72),

and the AhR signaling pathway is intricately associated with the

metabolism of arachidonic acid and heme (73).

A previous study demonstrated that targeting

ferroptosis is a promising therapeutic approach to mitigate renal

tubular cell injury in acute tubular necrosis induced by I/R

(74). The administration of the

AhR antagonist, CH223191, or the ferroptosis inhibitor, α-col,

prior to the onset of reperfusion and reoxygenation injury has the

potential to prevent the production of ROS, reduce lipid

peroxidation and mitigate cellular iron toxicity. The underlying

mechanism may involve the transcriptional regulation of AhR through

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)-mediated Kyn metabolism (21,66). The inhibition of AhR signaling

has been shown to mitigate reperfusion injury in a rat model of

cardiac I/R (23). Arachidonate

12/15-lipoxygenase-mediated arachidonic acid metabolism

significantly contributes to myocardial I/R injury (75). Therefore, arachidonic acid

metabolism mediated by AhR signaling may be a potential target for

alleviating myocardial I/R injury.

These studies demonstrate that AhR plays a crucial

role in I/R injury across various parenchymal organs. The

underlying mechanisms may be associated with the metabolism of

hemin and arachidonic acid. Oxidative stress induced by I/R injury

results in the activation of AhR through endogenous pro-oxidative

ligands, such as Kyn and oxyindole. IDO, as a key enzyme in

tryptophan metabolism, can produce many endogenous ligands of AhR.

IDO also serves as the target gene of AhR. Due to this particular

cyclic activation characteristic, it will easily cause the

continuous activation of AhR (76). Moreover, studies have shown that

IDO plays a key role in I/R injury. The pharmacological inhibition

of IDO by using 1-MT (IDO inhibitor) limits the production of Kyn,

inhibits the activation of AhR, and subsequently the production of

ROS. This effect can also be achieved by using the AhR antagonist,

CH223191 (66,77). This indicates that it is of

utmost importance to reduce the production of ROS induced by

arachidonic acid and heme metabolism mediated by the continuous

activation of AhR through targeting this circular pathway. The

overproduction of these pro-oxidant ligands during I/R injury may

contribute to continuous activation of AhR signaling. This

activation subsequently mediates oxidative stress and lipid

peroxidation, indicating that targeting AhR signaling may be a

promising therapeutic strategy for mitigating reperfusion

injury.

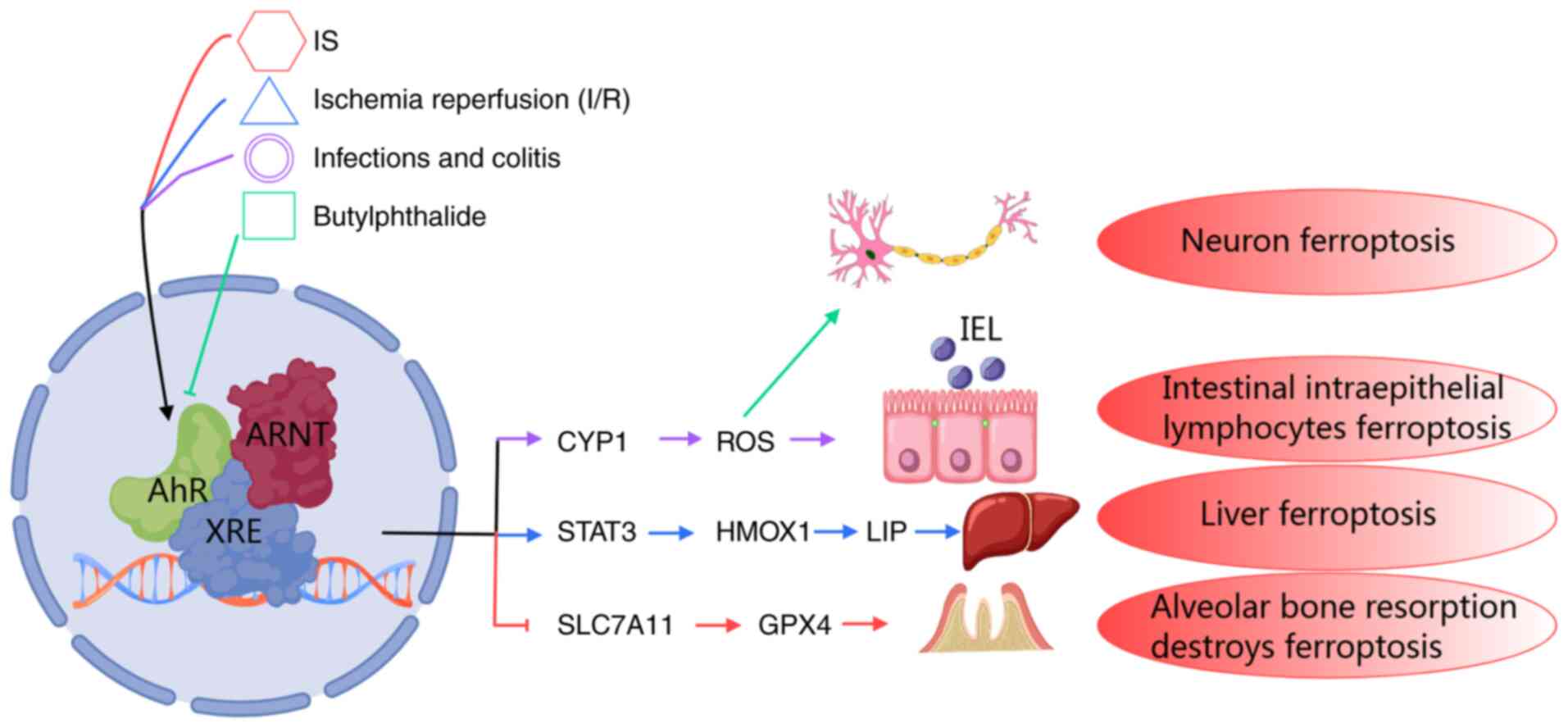

AhR affects lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis by regulating the levels of antioxidant active

substances and ferroptosis defense system

In chronic kidney disease (CKD), AhR

activation by indoxyl sulfate (IS) suppresses the antioxidant

system via SLC7A11, and subsequently promotes lipid peroxidation

and induces ferroptosis

SLC7A11 is a critical component of the

cystine/glutamate antiporter, which is crucial for glutathione

synthesis, and it exerts a significant negative regulatory

influence on ferroptosis (78).

The SLC7A11-GPX4-GSH-cysteine axis serves as the pivotal hub in the

ferroptosis cascade (79). In

patients with CKD, the accumulation of IS, a metabolite of

tryptophan, as a result of impaired renal excretion, can result in

various health-related complications (80). In a previous study, in a mouse

model of CKD, IS induced ferroptosis in MC3T3-E1 cells by

activating the AhR signaling pathway and mediating the inhibition

of the SLC7A11-GPX4 antioxidant signaling pathway. This process

inhibited the osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells and

contributed to alveolar bone resorption in mice with CKD via

ferroptosis (81). The

inhibition of AhR activity can mitigate the osteotoxic effects

induced by IS. However, the exact mechanisms through which AhR

influences SLC7A11-GPX4 signaling to trigger ferroptosis in the

context of IS activation remain elusive. A plausible explanation

for this phenomenon is the interaction between AhR signaling and

HIF-1α signaling. In patients with CKD, HIF-1α signaling is

upregulated as a result of tissue hypoxia, which is caused by

diminished erythropoietin synthesis (82). Research has demonstrated that the

activation of HIF-1α signaling leads to the increased expression of

SLC7A11 (83,84). AhR competes with HIF-1α for

binding to ARNT, thereby competitively inhibiting the HIF-1α

signaling pathway. This inhibition of SLC7A11 expression, mediated

by the HIF-1α signaling pathway, may promote lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis.

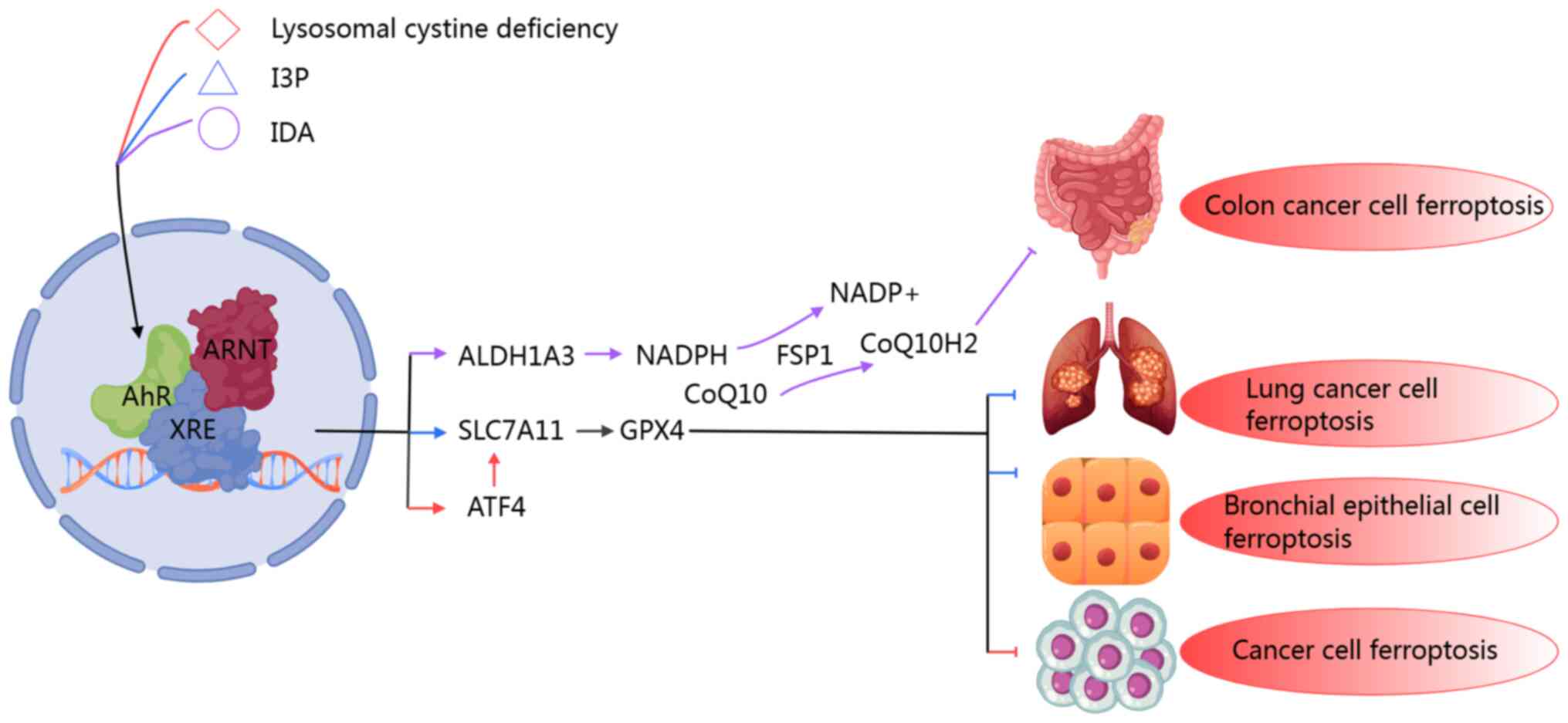

Indole-3-pyruvate (I3P)-activated AhR

upregulates SLC7A11 to suppress lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis

in both BEAS-2B and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells

In contrast to the previously described induction of

ferroptosis by IS through the activation of the AhR-mediated

inhibition of the SLC7A11-GPX4 antioxidant signaling pathway, the

knockdown of AhR influences lipid peroxidation levels in both

BEAS-2B and NSCLC cells. AhR affects the transcriptional regulation

of SLC7A11. Notably, the pharmacological inhibition and genetic

knockdown of AhR in BEAS-2B cells markedly increases

erastin-induced ferroptosis. In PC9 cells, the promoter region of

SLC7A11 harbors an AhR binding site. Furthermore, a comprehensive

database search and analysis using JASPAR indicated that the

promoter region of SLC7A11 contains specific XREs. The study also

highlighted the role of I3P, an endogenous AhR agonist ligand and a

tryptophan analog, in the development of a novel AhR receptor. The

AhR-SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis protects cells against ferroptosis via an

AhR-dependent mechanism (19,20). These findings demonstrate that

the activation of AhR signaling directly modulates the

transcriptional expression of the antioxidant defense system,

SLC7A11, thereby conferring resistance to ferroptosis in both

BEAS-2B and NSCLC cells.

The AhR signaling pathway indirectly

activates the SLC7A11 antioxidant system via activating

transcription factor 4 (ATF4), thereby enhancing ferroptosis

resistance in tumors

In addition to its direct influence on the

transcriptional expression of SLC7A11, AhR signaling also

indirectly transcriptionally regulates SLC7A11 by detecting

lysosomal cysteine levels and inducing the adaptive expression of

ATF4. ATF4 is crucial for cells adapting to adverse conditions of

amino acid deprivation and mediates a variety of cellular

phenotypic changes (85). The

study by Swanda et al (86) revealed that lysosomal cysteine

deficiency, sensed through the Kyn pathway of AhR, leads to

adaptive ATF4 expression, which subsequently enhances SLC7A11

transcription and renders cells less susceptible to ferroptosis.

The synthetic mRNA reagent, CysRx, was designed to convert

cytosolic cysteine into lysosomal cysteine, thereby sensitizing

tumor cells to ferroptosis by downregulating ATF4 expression. The

AhR inhibitor stemregenin (SR1) was used to induce ferroptosis in

cysteine-deficient cells, while the AhR activator indirubin fully

rescued these cells from ferroptosis (86). Notably, this pathway regulates

the transcriptional activity of ATF4 in the nucleus independently

of the conventional integrated stress response and oxidative stress

effects. These findings demonstrate that, apart from modulating

cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis through the regulation of

lysosomal cysteine levels, manipulating the AhR signaling pathway

to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells is a promising therapeutic

target.

Intestinal microbiota metabolites

activate AhR to confer ferroptosis resistance in intestinal tumors

through non-GSH antioxidant pathways

Gut commensal microbiota metabolites serve as a

significant source of AhR agonists (87). FICZ, Kyn, indirubin, indole and

I3P are endogenous ligands of AhR. Metabolites produced by the gut

microbiota can be categorized into two main groups:

Immunosuppressive metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids,

tryptophan metabolites and bile acid metabolites; inflammatory

metabolites, such as those activating the stimulator of interferon

genes pathway and lipopolysaccharides (88). Immunosuppressive metabolites

derived from the gut microbiota are inclined to inhibit ferroptosis

(89), whereas inflammatory

metabolites facilitate ferroptosis (90). Studies have shown that the

anaerobic gut bacterium Streptococcus gastro metabolizes

tryptophan to produce trans-3-indoleacrylic acid (IDA), which, upon

activating AhR, regulates the expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase

1 family, member A3 (ALDH1A3) by binding with a high affinity

region approximately 100 base pairs upstream of the ALDH1A3

transcription start site. This regulation occurs through

ARNT-mediated nuclear translocation, indicating that when AhR is

activated by IDA, it is recruited to the ALDH1A3 promoter (91). ALDH1A3, an aldehyde dehydrogenase

which uses retinaldehyde as its substrate, is predominantly

overexpressed in tumor cells (92), potentially due to the elevated

levels of redox metabolism observed in tumor cells. ALDH1A3 plays a

crucial role in the production of NADPH, which serves as the

primary electron donor essential for reduction reactions and

activates the classical FSP1, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis

(34). This indicates that the

intestinal microbiota metabolite IDA can enhance FSP1-mediated

synthesis of reduced coenzyme Q10 via the AhR-ALDH1A3 pathway,

leading to NADPH production, ferroptosis inhibition, and ultimately

promoting the progression of colorectal cancer (91).

Previously, transcriptomic analysis revealed a

significant association between AhR levels and erastin sensitivity

(17). Given the influence of

AhR activity on the sensitivity of various tumor cell lines to

erastin, and the role of erastin as a specific inhibitor of

SLC7A11, it was hypothesized that the bidirectional effect of AhR

signaling on SLC7A11 may be attributed to context-dependent

variations in AhR function. Investigating the association between

AhR and erastin across diverse tumor cell lines and precisely

modulating AhR activity to influence erastin-induced ferroptosis

sensitivity is an area worth further exploration. Pharmacologically

regulating AhR activity in conjunction with erastin to eradicate

tumor cells and delay tumor progression represents a promising

therapeutic strategy.

Potential applications of targeting

AhR-mediated lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in cancer and I/R

injury therapy

Pharmacological modulation by inducing or inhibiting

ferroptosis is a key potential approach for addressing

drug-resistant cancers, ischemic organ damage, and a range of other

diseases characterized by extensive lipid peroxidation (29). Previous studies have indicated

that drug-resistant cancer cells, particularly those exhibiting a

mesenchymal phenotype and propensity for metastasis, are highly

vulnerable to ferroptosis (17,93). AhR modulates ferroptosis via

multiple pathways, functioning as a promoter in specific conditions

such as I/R injury and certain tumors (Fig. 3), while serving as a suppressor

in bronchial epithelial cells and other tumor types (Fig. 4). This dual regulatory role of

AhR in ferroptosis reflects its complex function. However, the role

of AhR as either a promoter or inhibitor of ferroptosis in numerous

diseases remains underexplored. A more comprehensive understanding

of the regulatory mechanisms of AhR in ferroptosis could pave the

way for novel therapeutic approaches and may provide profound

insight into the fundamental mechanisms underlying ferroptosis.

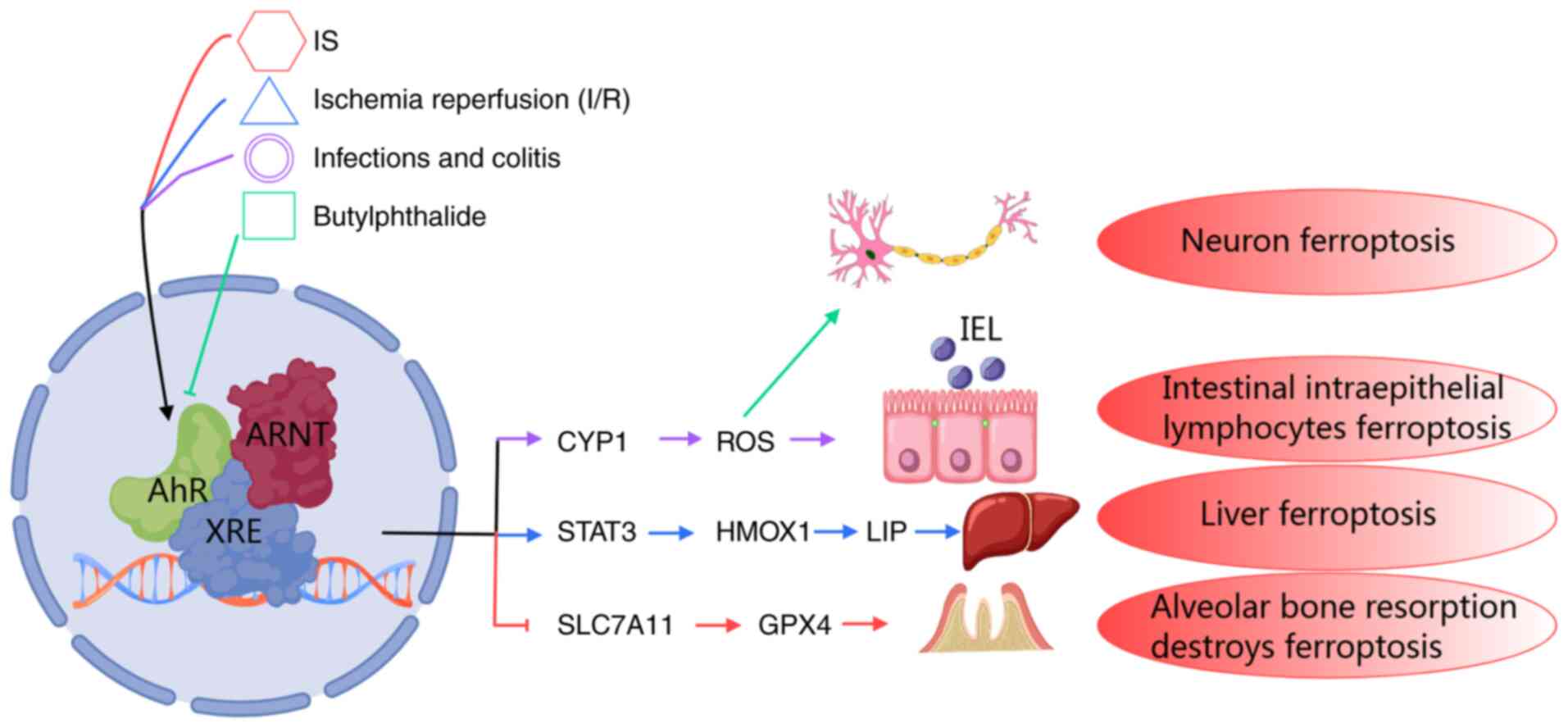

| Figure 3The mechanism of AhR mediating lipid

peroxidation-ferroptosis via CYP1, SLC7A11/GPX4 axis, or HMOX1 heme

metabolism by different ligands in different disease states. AhR

modulates the expression of diverse target genes across various

contexts, consequently influences ferroptosis in distinct disease

processes. IS triggers ferroptosis in MC3T3-E1 cells by activating

the SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway via AhR. In renal tubular

epithelial cells and liver I/R injury, suppression of the AhR

signaling pathway mitigates the extent of damage. Under the

condition of oxidative stress of intestinal epithelial lymphocytes,

inhibition of AhR signaling can alleviate intestinal epithelial

lymphocytes ferroptosis by reducing ROS production. Butylphthalide

exerts an inhibit effect on neuronal ferroptosis in traumatic brain

injury by inhibiting the AhR-CYP1A-ROS axis. AhR, aryl hydrocarbon

receptor; SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7 member 11; GPX,

glutathione peroxidase; HMOX1, heme oxygenase 1; I/R,

ischemia/reperfusion; ROS, reactive oxygen species. |

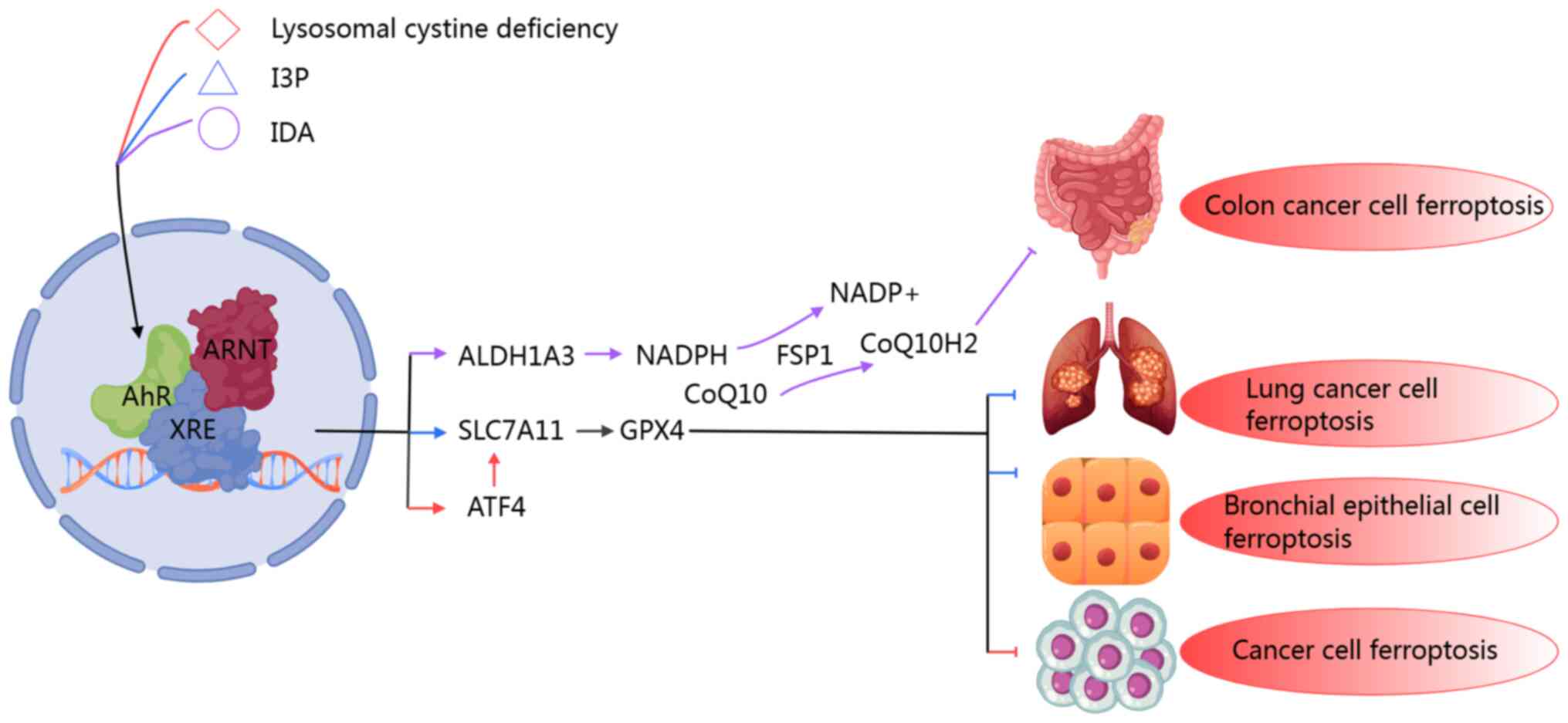

| Figure 4The mechanism of AhR mediating lipid

peroxidation-ferroptosis through the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis or the

ALDH1A3/FSP1 axis under different ligand binding or cytosolic

lysosomal cystine deficiency states. AhR modulates the expression

of diverse target genes across different contexts, thereby

influencing ferroptosis in various disease states. Specifically,

lysosomal cystine deficiency triggers ATF4 expression via the AhR

signaling pathway, leading to the activation of the SLC7A11/GPX4

antioxidant system, which in turn inhibits ferroptosis in tumors.

I3P inhibits ferroptosis by activating the AhR-mediated

SLC7A11/GPX4 axis antioxidant system in bronchial epithelial cells

and non-small cell lung cancer. In colorectal cancer, intestinal

metabolites regulate the IDA-AhR-ALDH1A3 pathway and affect the

level of NADPH to promote the production of FSP1-mediated reduced

ubiquinone, thereby inhibiting tumor cell ferroptosis and promoting

tumor progression. AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; SLC7A11, solute

carrier family 7 member 11; ALDH1A3, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1

family, member A3; FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; GPX,

glutathione peroxidase; IDA, trans-3-indoleacrylic acid; ATF4,

activating transcription factor 4; CoQ10, coenzyme Q10;

NADP+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. |

Potential to mitigate hepatic, renal and

myocardial I/R injury by targeting the AhR-mediated metabolism of

arachidonic acid and heme

In models of I/R injury, ferroptosis is

predominantly observed during the reperfusion phase, rather than

the ischemic phase (94).

Consistent with these observations, AhR is reactivated during the

reperfusion phase of I/R injury, leading to an increase in

intracellular ROS production and lipid peroxidation (21). Following I/R, the antioxidant

system is significantly impaired, leading to the inefficient

scavenging of ROS. The reperfusion of ischemic tissue results in an

overproduction of ROS, which mediates I/R injury. Evidence suggests

that I/R injury is associated with multiple cellular events,

including excessive ROS production (62), lipid peroxidation, and increased

intracellular iron concentrations (95). Lipid peroxidation and the

generation of ROS contribute to cellular damage and mortality

(21). These phenomena align

with the characteristics of iron-dependent ferroptosis, and studies

in both experimental models and clinical settings have demonstrated

that iron chelators can mitigate I/R injury by inhibiting the

initiation and progression of ferroptosis (21,63,66).

DFO, a widely used non-toxic iron chelator, has been

shown to suppress lipid peroxidation-induced ferroptosis across

diverse conditions. Beyond its role in inhibiting AhR, as detailed

in the preceding section, the AhR antagonist, CH223191, has proven

effective in reducing I/R injury in multiple organ systems,

including the liver, kidneys and myocardium, as evidenced in

various animal models (21,66,77). Previous studies have demonstrated

that AhR is closely related to arachidonic acid metabolism, and

various AhR ligands can regulate arachidonic acid metabolism in

endothelial cells, hepatocytes, and cardiomyocytes (96-98). Moreover, the COX-2 pathway,

lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway and CYP450 pathway in arachidonic acid

metabolism play key roles in I/R injury (99) and are potential targets for the

AhR-mediated relief of I/R injury. Additionally, heme metabolism is

closely related to AhR, such as in I/R injury, atherosclerosis, and

liver poisoning, and AhR can affect their occurrence and

development through iron and heme metabolism (72,100). As a transcriptional regulator,

AhR may also modulate ferroptosis via multiple potential pathways.

AhR may alleviate I/R injury through ROS production mediated by

CYP450 and COX-2 arachidonic acid metabolism, iron/heme metabolism

mediated by STAT3/6 and HMOX1 and Kyn metabolism mediated by AhR.

Notably, some studies have demonstrated that the application of

CH223191 in hepatic I/R injury is more effective than DFO in

alleviating hepatocyte I/R injury and ferroptosis (21,66,67). These findings suggest the

feasibility of targeting the AhR signaling pathway with specific

inhibitors to ameliorate I/R injury in parenchymal organs.

Inhibiting tumor progression by targeting

the AhR-mediated CYP450/ROS axis, ferroptosis antioxidant defense

system, heme metabolism and epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT)

Ferroptosis exerts a dual effect on tumor biology;

targeting ferroptosis is a promising direct strategy for cancer

cell eradication, while ferroptosis simultaneously contributes to

tumor progression and immune response suppression (101). Similarly, AhR exhibits

intricate roles in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy, exhibiting

both pro-tumor and anti-tumor effects (102). The activation of AhR is also

closely associated with tumor immunity (103), and these effects are contingent

upon the specific tumor type and the involved ligand (18,91). In ferroptosis in cancer cells,

AhR exhibits various effects, potentially associated with varying

activation levels of the downstream transcription of AhR in

distinct cell lines. For example, it was demonstrated that the

activation level of CYP1A1 in the H358 lung cancer cell line was

markedly higher compared with that in the Calu1 cell line. The

disparity in the downstream transcriptional response of AhR to the

same ligand across different tumor cell lines is likely a critical

factor of the differential roles of AhR in ferroptosis within these

cells (17). The mechanisms by

which AhR inhibits tumor ferroptosis include the modulation of the

SLC7A11/GPX4 axis and the enhancement of reduced NADPH

production.

It has been shown that AhR-mediated CYP450

influences the extent of ferroptosis in neurons following traumatic

brain injury (53). The

stabilization of CYP1B1 protein may also play a crucial role in

regulating ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and

cholangiocarcinoma (41).

However, to the best of our knowledge, there is currently no direct

evidence demonstrating that AhR promotes ferroptosis in tumor cells

via the transcriptional regulation of CYP450. Moreover, AhR

activation in certain tumor cells has been hypothesized to be

associated with a metastatic mesenchymal state, characterized by

both metastatic and immunosuppressive properties (104). Mesenchyma-like tumor cells

exhibit heightened sensitivity to ferroptosis inducers, which

aligns with the dual role of ferroptosis in tumor biology. The AhR

signaling pathway is intricately linked to heme and iron metabolism

mediated by HMOX1. Previous research has demonstrated that tumor

cells overexpressing AhR exhibit elevated basal levels of HMOX1

compared with wild-type cells (59), and a high HMOX1-mediated increase

in the free iron pool level is a key mediator for the triggering of

ferroptosis. A reasonable explanation for the close association

between AhR and heme metabolism is that AhR signaling may

indirectly mediate heme metabolism through the NRF2 signaling

pathway. CYP450, EMT and heme metabolism may serve as key

mechanisms underlying AhR-mediated ferroptosis in tumor cells.

The majority of drugs known to induce ferroptosis,

such as sorafenib, sulfadiazine, FIN and 3-phenylquinazolinone, are

systemic inhibitors of xCT, GPX4 and FSP1, which are regulated by

AhR (19,81,88). Therefore, the modulation of AhR

levels is anticipated to substantially enhance the efficacy of

ferroptosis-inducing drugs. Both AhR gene silencing and stimulation

with the exogenous ligand TCDD can induce ferroptosis and increase

the sensitivity of tumor cells to erastin (17,18). Consequently, the strategic use of

efficient AhR ligands, either alone or in combination with

ferroptosis inducers, is a viable strategy for triggering

ferroptosis in tumor cells.

The AhR agonists and inhibitors currently used in in

cancer therapy include aminoflavone, ITE and SR1 (10,11,14,105). These compounds exhibit notable

tumor-suppressive effects. The antitumor mechanism of ITE involves

restoring tumor cell sensitivity to sorafenib. The antitumor

effects of SR1 and aminoflavonone are partially mediated by ROS.

These mechanisms may be facilitated through various potential

pathways, such as those involving AhR-mediated CYP450, SLC7A11 and

EMT. The application of these highly potent AhR ligands to modulate

AhR signaling in conjunction with ferroptosis-inducing drugs is

anticipated to yield enhanced antitumor efficacy.

Synopsis

AhR modulation combined with ferroptosis

inducers triggers lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in tumor

cells

AhR-mediated lipid peroxidation-ferroptosis plays a

critical role in various diseases, particularly in tumors and I/R

injury. Silencing the AhR gene in NSCLC A549 cells was previously

shown to enhance the antitumor efficacy of erastin (17). Another study elucidated the

underlying mechanism, revealing that the activation of AhR in A549

cells mediates the transcription of SLC7A11, a well-established

target of the antitumor activity of erastin (20). It is notable that the lung cancer

cell line, A549, with the silencing of the AhR gene, promotes the

antitumor effect of erastin (19). Conversely, in the lung cancer

cell line, Calu1, the silencing of the AhR gene inhibited the

antitumor effect of erastin (17). The underlying mechanisms for

these discrepancies may resemble those observed in immune cells,

where AhR preferentially binds to the IL-6 or IL-22 promoter. In

hepatocytes, AhR is more inclined to promote the transcription of

the CYP450 enzyme system. These divergent outcomes may be

attributed to variations in AhR reactivity towards target genes

across different cell lines and within different states of the same

cell line. Such differences may involve multiple factors, including

unsaturated fatty acid anabolism, EMT, heme/iron metabolism,

transcriptional regulation of oxidative antioxidant enzymes and

GSH-dependent/independent ferroptosis defense mechanisms. Moreover,

the application of specific AhR agonists and inhibitors, including

aminoflavone, ITE, SR1 and CH223191, in conjunction with

ferroptosis inducers, is anticipated to augment the antitumor

efficacy against targeted tumor cells.

Targeting AhR signaling via specific AhR

ligands to control lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in oxidative

stress-driven diseases

While AhR plays a dual role in mediating ferroptosis

in cancer cells, it mainly acts as a pro-oxidant to promote

ferroptosis induced by lipid peroxidation in disease models, such

as I/R injury, CKD and colitis. This phenomenon may be attributed

to the pro-oxidative nature of the predominant AhR ligands in these

contexts, including oxyindole, IS, TCDD and dioxins. Conversely,

the antioxidant AhR ligand I3P maintains redox homeostasis by

activating the AhR-mediated GSH-dependent ferroptosis defense

system in BEAS-2B cells (20).

I3P also exhibits antioxidant properties across various disease

types (106). Similarly, ILA,

another antioxidant AhR agonist ligand, has also been shown to

exert an inhibitory effect on ferroptosis (107). These observations suggest that

AhR-mediated lipid peroxidation-ferroptosis in non-neoplastic

conditions may primarily depend on the specific ligand involved.

During I/R injury, oxidative stress activates the tryptophan

metabolic pathway, generating numerous endogenous AhR ligands, such

as Kyn and FICZ. Kyn has been shown to promote tumor progression by

inhibiting ferroptosis in an AhR-dependent manner in glioblastoma

multiforme and lung cancer A549 cell lines (20,108). However, Kyn also demonstrates

context-dependent effects: It induces ferroptosis in natural killer

cells within the gastric cancer microenvironment independently of

AhR, while inhibiting ferroptosis in Hela cells also via an

AhR-independent mechanism (89,109). Notably, the key enzyme IDO

produced by Kyn is the target gene of AhR, indicating that AhR is a

central molecule mediating oxidative stress and affecting

ferroptosis pathways (76). This

highlights the complex and multifaceted association between AhR and

ferroptosis, requiring the consideration of multiple factors.

Targeting AhR signaling with specific ligands presents a potential

therapeutic strategy across various diseases. A comprehensive

ligand-AhR-disease database could guide this approach.

Therapeutic potential of novel AhR

ligands: Mitigating toxicity through natural derivatives and

engineered synthetics

Numerous ligands have demonstrated antitumor

efficacy in cellular experiments or therapeutic effects in animal

models. However, well-known AhR ligands, such as TCDD and

benzo[a]pyrene may induce adverse effects. At present, a number of

low-toxicity or non-toxic AhR ligands are under investigation and

development, including indoles and flavonoids derived from natural

plant metabolites, which are characterized by their favorable

safety profiles. For instance, indole-3-carbinol exhibits both low

toxicity and anti-cancer properties. As previously mentioned, a

number of tryptophan derivatives/metabolites serve as endogenous

AhR ligands (87). Recent

findings indicate their potential in treating various inflammatory

bowel diseases, although excessive levels may concurrently promote

intestinal tumor progression (91).

Given the potent toxicity of traditional AhR ligands

such as TCDD and the potential limitations of low-affinity natural

ligands, synthesis AhR ligands represent a promising avenue.

Compounds such as 6,2′,4′-trimethoxyflavone (TMF) retain AhR

activation capabilities, but eliminate the chlorine atoms present

in TCDD, reducing abnormal signaling. TMF also mimics structural

features of endogenous ligands, such as the indole/carbazole

scaffold of tryptophan metabolites, to enhance compatibility and

incorporates formyl groups to facilitate metabolism and prevent

long-term cellular accumulation. TMF has been shown to exert

antitumor effects in liver cancer models (110). Similarly, YH439, a synthetic

low-toxicity AhR ligand, demonstrated efficacy in alleviating

hepatic fibrosis (111).

3,3′-diindolylmethane, a low-toxicity phytochemical from

cruciferous vegetables, exhibits anti-hepatocellular carcinoma

properties and can induce ferroptosis in hepatocytes (112). These findings underscore the

substantial potential of both synthetic AhR ligands and natural

plant-derived alternatives (113). Systematic investigations to

discover or synthesize clinically applicable AhR ligands are highly

promising. Furthermore, in diseases such as intestinal disorders,

modulating the gut microbiota to regulate the production of

endogenous AhR ligands provides an alternative therapeutic strategy

worthy of attention.

In conclusion, the present review underscores the

pivotal role of AhR in mediating disease onset and progression

through ferroptosis across various diseases. Pharmacological

inhibition of AhR signaling, particularly in I/R injury, can

mitigate tissue damage. The pharmacological modulation of AhR

signaling in specific tumor cell lines, either through activation

or inhibition, can induce lipid peroxidation-ferroptosis directly

or in combination with ferroptosis inducers, which provides a

biological foundation for a promising therapeutic strategy against

tumor progression (Fig. 5).

Currently, research on AhR-regulated lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis in diseases is limited, with the majority of studies

focusing on I/R injury in tumors or various organs. Exploring the

role of AhR in lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis across different

diseases and tissues, and implementing targeted regulation using

natural low-toxicity or synthetic AhR ligands, holds substantial

clinical potential.

![Pharmacological targeting of AhR to

modulate ferroptosis in cancer and I/R injury. AhR ligands regulate

lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis through different molecular

axes, demonstrating environment-dependent therapeutic potential. In

parenchymal organs, such as the heart, liver and kidneys, AhR

antagonists CH223191 and SR1 alleviate I/R injury by inhibiting the

iron-stimulating pathway: CH223191 downregulates CYP1A-driven ROS

amplification and COX-2-mediated inflammatory signals, while SR1

inhibits HMOX1-dependent iron release and IDO1-induced oxidative

stress, jointly maintaining the redox balance of cells. In tumors,

AhR is pharmacologically regulated through AhR ligands, such as

aminoflavone, ITE, SR1 and CH223191, thereby influencing key

molecules in various lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis processes,

and further inducing ferroptosis in tumor cells or enhancing their

sensitivity to erastin. This is expected to eliminate tumor cells,

alleviate tumor progression and enhance the anti-tumor efficacy of

iron deposition inducers. AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; HMOX1,

heme oxygenase 1; IDO1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; TCDD,

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; NQO1, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase

[quinone] 1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; UGT1A1,

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1-1.](/article_images/ijmm/56/4/ijmm-56-04-05597-g04.jpg) | Figure 5Pharmacological targeting of AhR to

modulate ferroptosis in cancer and I/R injury. AhR ligands regulate

lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis through different molecular

axes, demonstrating environment-dependent therapeutic potential. In

parenchymal organs, such as the heart, liver and kidneys, AhR

antagonists CH223191 and SR1 alleviate I/R injury by inhibiting the

iron-stimulating pathway: CH223191 downregulates CYP1A-driven ROS

amplification and COX-2-mediated inflammatory signals, while SR1

inhibits HMOX1-dependent iron release and IDO1-induced oxidative

stress, jointly maintaining the redox balance of cells. In tumors,

AhR is pharmacologically regulated through AhR ligands, such as

aminoflavone, ITE, SR1 and CH223191, thereby influencing key

molecules in various lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis processes,

and further inducing ferroptosis in tumor cells or enhancing their

sensitivity to erastin. This is expected to eliminate tumor cells,

alleviate tumor progression and enhance the anti-tumor efficacy of

iron deposition inducers. AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; HMOX1,

heme oxygenase 1; IDO1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; TCDD,

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; NQO1, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase

[quinone] 1; GST, glutathione S-transferase; UGT1A1,

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1-1. |

Conclusion and future perspectives

Current research demonstrates that AhR target genes

regulate numerous key genes and mediators involved in ferroptosis,

encompassing cellular antioxidant systems, oxidative/antioxidant

enzymes, heme/iron metabolism and the arachidonic acid pathway.

Notably, AhR can regulate the SLC7A11-GPX4 axis, a pivotal

suppressor of ferroptosis. Moreover, AhR modulates ferroptosis

through the GSH-independent FSP1 pathway. Consequently, targeting

AhR represents a promising therapeutic strategy for diseases driven

by lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, such as cancer and I/R

injury.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZL, WL and XS designed the study. ZL completed the

first draft of this manuscript. ZL, MH, SH and YZ collected the

data from the literature and revised the manuscript. XS, WL and ZL

designed the figures. YZ, WL and XS obtained funding. All authors

have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the high-level talents

scientific research start-up funds of the Affliated Hospital of

Guangdong Medical University (grant no. GCC2022023) and the

Zhanjiang Science and Technology Project (grant no.

2023A20709).

References

|

1

|

Ferreira MJ, Rodrigues TA, Pedrosa AG,

Gales L, Salvador A, Francisco T and Azevedo JE: The mammalian

peroxisomal membrane is permeable to both GSH and GSSG-Implications

for intraperoxisomal redox homeostasis. Redox Biol. 63:1027642023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Fujiki Y, Abe Y, Imoto Y, Tanaka AJ,

Okumoto K, Honsho M, Tamura S, Miyata N, Yamashita T, Chung WK and

Kuroiwa T: Recent insights into peroxisome biogenesis and

associated diseases. J Cell Sci. 133:jcs2369432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Agmon E, Solon J, Bassereau P and

Stockwell BR: Modeling the effects of lipid peroxidation during

ferroptosis on membrane properties. Sci Rep. 8:51552018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Jambunathan N: Determination and detection

of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, and

electrolyte leakage in plants. Methods Mol Biol. 639:292–298.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M,

Shchepinov MS and Stockwell BR: Peroxidation of polyunsaturated

fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 113:E4966–E4975. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Grishanova AY and Perepechaeva ML: Aryl

hydrocarbon receptor in oxidative stress as a double agent and its

biological and therapeutic significance. Int J Mol Sci.

23:67192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Sondermann NC, Faßbender S, Hartung F,

Hätälä AM, Rolfes KM, Vogel CFA and Haarmann-Stemmann T: Functions

of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) beyond the canonical

AHR/ARNT signaling pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 208:1153712023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

8

|

Hu DG, Marri S, McKinnon RA, Mackenzie PI

and Meech R: Deregulation of the genes that are involved in drug

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion in

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 368:363–381. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Martins M, Santos JM, Diniz MS, Ferreira

AM, Costa MH and Costa PM: Effects of carcinogenic versus

non-carcinogenic AHR-active PAHs and their mixtures: Lessons from

ecological relevance. Environ Res. 138:101–111. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Brantley E, Callero MA, Berardi DE,

Campbell P, Rowland L, Zylstra D, Amis L, Yee M, Simian M, Todaro

L, et al: AhR ligand Aminoflavone inhibits α6-integrin expression

and breast cancer sphere-initiating capacity. Cancer Lett.

376:53–61. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

McLean L, Soto U, Agama K, Francis J,

Jimenez R, Sowers L and Brantley E: Aminoflavone induces oxidative

DNA damage and reactive oxidative species-mediated apoptosis in

breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 122:1665–1674. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Elson DJ, Nguyen BD, Korjeff NA, Wilferd

SF, Sanvicens VP, Jang HS, Bernales S, Chakravarty S, Belmar S,

Ureta G, et al: Suppression of Ah Receptor (AhR) increases the

aggressiveness of TNBC cells and 11-Cl-BBQ-activated AhR inhibits

their growth. Biochem Pharmacol. 215:1157062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kober C, Roewe J, Schmees N, Roese L,

Roehn U, Bader B, Stoeckigt D, Prinz F, Gorjánácz M, Roider HG, et

al: Targeting the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) with BAY 2416964:

A selective small molecule inhibitor for cancer immunotherapy. J

Immunother Cancer. 11:e0074952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang X, He B, Chen E, Lu J, Wang J, Cao H

and Li L: The aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand ITE inhibits cell

proliferation and migration and enhances sensitivity to

drug-resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Physiol.

236:178–192. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang L, Liu Y, Du T, Yang H, Lei L, Guo M,

Ding HF, Zhang J, Wang H, Chen X and Yan C: ATF3 promotes

erastin-induced ferroptosis by suppressing system Xc. Cell Death

Differ. 27:662–675. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kwon OS, Kwon EJ, Kong HJ, Choi JY, Kim

YJ, Lee EW, Kim W, Lee H and Cha HJ: Systematic identification of a

nuclear receptor-enriched predictive signature for erastin-induced

ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 37:1017192020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chen X, Yao Y, Gong G, He T, Ma C and Yu

J: The potential role of AhR/NR4A1 in androgen-dependent prostate

cancer: Focus on TCDD-induced ferroptosis. Biochem Cell Biol.

103:1–11. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kou Z, Tran F, Colon T, Shteynfeld Y, Noh

S, Chen F, Choi BH and Dai W: AhR signaling modulates ferroptosis

by regulating SLC7A11 expression. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol.

486:1169362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Peng Y, Ouyang L, Zhou Y, Lai W, Chen Y,

Wang Z, Yan B, Zhang Z, Zhou Y, Peng X, et al: AhR promotes the

development of non-small cell lung cancer by inducing

SLC7A11-dependent antioxidant function. J Cancer. 14:821–834. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Eleftheriadis T, Pissas G, Filippidis G,

Liakopoulos V and Stefanidis I: Reoxygenation induces reactive

oxygen species production and ferroptosis in renal tubular

epithelial ; cells by activating aryl hydrocarbon

receptor. Mol Med Rep. 23:412021.

|

|

22

|

Kwon JI, Heo H, Chae YJ, Min J, Lee DW,

Kim ST, Choi MY, Sung YS, Kim KW, Choi Y, et al: Is aryl

hydrocarbon receptor antagonism after ischemia effective in

alleviating acute hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats?

Heliyon. 9:e155962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang J, Wang B, Yuan S, Xue K, Zhang J and

Xu A: Blocking the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor alleviates myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Curr Med Sci. 42:966–973.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ma C, Han L, Zhao W, Chen F, Huang R, Pang

CH, Zhu Z and Pan G: Targeting AhR suppresses hepatocyte

ferroptosis in MASH by regulating the Pten/Akt/β catenin axis.

Biochem Pharmacol. 232:1167112025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Qian C, Yang C, Lu M, Bao J, Shen H, Deng

B, Li S, Li W, Zhang M and Cao C: Activating AhR alleviates

cognitive deficits of Alzheimer's disease model mice by

upregulating endogenous Aβ catabolic enzyme Neprilysin.

Theranostics. 11:8797–8812. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

26

|

Panda SK, Peng V, Sudan R, Ulezko Antonova

A, Di Luccia B, Ohara TE, Fachi JL, Grajales-Reyes GE, Jaeger N,

Trsan T, et al: Repression of the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor

prevents oxidative stress and ferroptosis of intestinal

intraepithelial lymphocytes. Immunity. 56:797–812.e4. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yu H, Zhang C, Pan H, Gao X, Wang X, Xiao

W, Yan S, Gao Y, Fu J and Zhou Y: Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene enhances

the sensitivity of airway epithelial cells to ferroptosis and

aggravates asthma. Chemosphere. 363:1428852024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Avilla MN, Malecki KMC, Hahn ME, Wilson RH

and Bradfield CA: The Ah receptor: Adaptive metabolism, ligand

diversity, and the xenokine model. Chem Res Toxicol. 33:860–879.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yan HF, Zou T, Tuo QZ, Xu S, Li H, Belaidi

AA and Lei P: Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rochette L, Dogon G, Rigal E, Zeller M,

Cottin Y and Vergely C: Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: Two

corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:4492022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ramana KV, Srivastava S and Singhal SS:

Lipid peroxidation products in human health and disease 2016. Oxid

Med Cell Longev. 2017:21632852017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wu Y, Ran L, Yang Y, Gao X, Peng M, Liu S,

Sun L, Wan J, Wang Y, Yang K, et al: Deferasirox alleviates

DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by inhibiting ferroptosis

and improving intestinal microbiota. Life Sci. 314:1213122023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Liu J, Kang R and Tang D: Signaling

pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J.

289:7038–7050. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Nakamura T, Hipp C, Santos Dias Mourão A,

Borggräfe J, Aldrovandi M, Henkelmann B, Wanninger J, Mishima E,

Lytton E, Emler D, et al: Phase separation of FSP1 promotes

ferroptosis. Nature. 619:371–377. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhang Y, Tan H, Daniels JD, Zandkarimi F,

Liu H, Brown LM, Uchida K, O'Connor OA and Stockwell BR: Imidazole

ketone erastin induces ferroptosis and slows tumor growth in a

mouse lymphoma model. Cell Chem Biol. 26:623–633.e9. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Xuan Y, Wang H, Yung MM, Chen F, Chan WS,

Chan YS, Tsui SK, Ngan HY, Chan KK and Chan DW: SCD1/FADS2 fatty

acid desaturases equipoise lipid metabolic activity and

redox-driven ferroptosis in ascites-derived ovarian cancer cells.

Theranostics. 12:3534–3552. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu D, Hu Q, Wang Y, Jin M, Tao Z and Wan

J: Identification of HMOX1 as a critical ferroptosis-related gene

in atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 9:8336422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Adham AN, Abdelfatah S, Naqishbandi AM,

Mahmoud N and Efferth T: Cytotoxicity of apigenin toward multiple

myeloma cell lines and suppression of iNOS and COX-2 expression in

STAT1-transfected HEK293 cells. Phytomedicine. 80:1533712021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

He F, Zhang P, Liu J, Wang R, Kaufman RJ,

Yaden BC and Karin M: ATF4 suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis by

inducing SLC7A11 (xCT) to block stress-related ferroptosis. J

Hepatol. 79:362–377. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R and Zhang DD:

NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 23:1011072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu C, Zhang C, Wu H, Zhao Z, Wang Z,

Zhang X, Yang J, Yu W, Lian Z, Gao M and Zhou L: The

AKR1C1-CYP1B1-cAMP signaling axis controls tumorigenicity and

ferroptosis susceptibility of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cell

Death Differ. 32:506–520. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Apetoh L, Quintana FJ, Pot C, Joller N,

Xiao S, Kumar D, Burns EJ, Sherr DH and Weiner HL: The aryl

hydrocarbon receptor interacts with c-Maf to promote the

differentiation of type 1 regulatory T cells induced by IL-27. Nat

Immunol. 11:854–861. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Adachi J, Mori Y, Matsui S and Matsuda T:

Comparison of gene expression patterns between

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and a natural arylhydrocarbon

receptor ligand, indirubin. Toxicol Sci. 80:161–169. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Murray IA, Morales JL, Flaveny CA,