Introduction

The threat of radiation exposure from nuclear

terrorism and warfare, amplified by ongoing global conflicts and

events such as the occupation of Ukraine's Zaporizhzhia nuclear

power plant in 2022 (1), the

Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011 (2,3)

and the Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine in 1986 (4), has become a significant concern.

Exposure to high-dose radiation causes acute radiation syndrome

(ARS), characterized by various clinical complications, including

hematopoietic, gastrointestinal and neurovascular syndrome

(5). Damage to radiosensitive

hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells leads to anemia,

neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (6). Neutrophils are crucial to host

defense against pathogens. Following radiation exposure,

neutropenia increases susceptibility to life-threatening infections

and risk of mortality (7).

Furthermore, severe ARS typically includes multiple organ

dysfunction (8,9). Radiation-induced inflammation has

been shown to contribute to organ dysfunction in several systems,

including hematopoiesis, the gastrointestinal tract and lungs, and

is associated with an increased risk of mortality (5,10-13). Medical management of ARS focuses

on the targeted treatment of the subsyndromes. Treatment of

hematopoietic syndrome involves the administration of granulocyte

colony stimulating factor, granulocyte macrophage stimulating

factor, erythropoiesis-stimulating factor and platelet-stimulating

thrombopoietin mimetic (14).

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be considered in cases

of persistent aplasia (8).

Management of gastrointestinal syndrome is currently limited to

symptomatic treatment, including antiemetics, antidiarrheals and

antibiotics (5,8). Neurovascular syndrome is primarily

addressed with supportive care (14).

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are critical

for host defense against infection, trapping and eliminating

pathogens such as bacteria, fungi and viruses (15). NET formation is initiated by

peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4)-mediated citrullination of

histones, leading to decondensation of chromatin (16). Expanded chromatin is released

into the cytoplasm, causing the rupture of the plasma membrane and

the release of NETs, which form web-like structures (17). Released NETs include histones,

myeloperoxidase (MPO) and other antimicrobial proteins such as

neutrophil elastase (NE) (18).

Conversely, excessive NETs can exacerbate inflammation and

contribute to organ dysfunction in sepsis (19-21). Furthermore, NETosis is a form of

regulated cell death of neutrophils, which can potentially

contribute to neutropenia (22,23). NET formation is also implicated

in sterile inflammatory conditions such as autoimmune disorders,

vasculitis and thrombosis (19).

However, the impact of high-dose ionizing radiation on NET

formation in healthy tissue and the underlying mechanisms involved

remains largely unexplored. Current research on radiation-induced

NETs primarily focuses in the context of cancer radiotherapy

(24).

Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRP) is an 18

kDa RNA chaperone that regulates the translation of stress response

genes (25,26). Extracellular CIRP (eCIRP), which

is released actively from stressed cells and passively from dying

cells (27), acts as a

damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP). eCIRP exacerbates

inflammation and worsens survival in conditions such as sepsis,

hemorrhagic shock, ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and radiation

injury (28-30). Triggering receptor expressed on

myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) is an immune receptor expressed on the

cell surface, primarily on neutrophils and macrophages, that

initiates intracellular signaling cascades via phosphorylation of

DNAX-activation protein 12 (DAP12) and spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk)

(31). TREM-1 is known to induce

pro-inflammatory responses and amplify the severity of inflammatory

diseases (32,33). Our previous studies have

identified eCIRP as a novel ligand for TREM-1 and eCIRP-mediated

activation of TREM-1 as a key trigger for NET formation in sepsis

(34,35). Notably, it was demonstrated that

radiation-induced eCIRP upregulates TREM-1 surface expression on

macrophages, and that TREM-1 deficiency improves survival after

total body irradiation (TBI) (36). The present study aimed to

investigate NET formation after exposure to high-dose ionizing

radiation and the role of eCIRP and TREM-1 in radiation-induced NET

formation.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

A total of 84 adult C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) male mice

(age, 8-12 weeks; weight, 20-25 g) were purchased from Jackson

Laboratory. CIRP knockout mice (CIRP−/−) were obtained

from Professor Jun Fujita (Kyoto University; Kyoto, Japan). TREM-1

knockout mice (TREM-1−/−;

Trem1tm1(KOMP)Vlcg) were generated by the

trans-National Institutes of Health Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP)

and obtained from the KOMP repository (University of California)

(37). Six each of

CIRP−/− and TREM-1−/− mice were used for the

assessment of NET formation in vivo by flow cytometry. Mice

were maintained in a temperature-controlled room ranging between 20

and 26°C, with a humidity level of 30-70%, under a 12-h light/dark

cycle and were fed a standard rodent diet and water ad

libitum. All animal experiments were performed in accordance

with the guidelines for using experimental animals by the National

Institutes of Health. All study procedures were approved by

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Feinstein

Institutes for Medical Research (approval no. 2023-007; Manhasset,

NY, USA).

TBI and isolation of bone marrow

cells

A total of 54 WT mice were randomly assigned to

experimental and control groups, with 24 sham and 30 TBI mice. Mice

were exposed to a single dose of 10 Gy TBI at a dose rate of 1

Gy/min (320 kV, 12.5 mA and 50 cm source-to-skin distance) using an

X-Rad320 X-ray irradiation system (Precision X-Ray, Inc.). The 10

Gy model is considered to be high-dose irradiation in mice based on

prior studies (38-40). Mice were restrained and placed in

a fitted container without shielding during irradiation. The

container was continuously rotated for even exposure. Mice were

returned to their cages after completion. Sham (control) mice were

not irradiated. After 24 h of TBI, mice were euthanized by

exsanguination under isoflurane anesthesia (induction, 3%;

maintenance, 2%). The femurs and tibias were then dissected for

analysis. The bone marrow was flushed with PBS supplemented with 2%

FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc), and suspensions of

cells were filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer. Red blood

cells in the bone marrow were lysed with RBC lysis buffer

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Bone marrow cells

were collected by centrifugation at 300 × g and suspended with FACS

buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS). The humane criteria established for

the present study were as follows: minimal or no response to

stimuli, hunched or recumbent posture, grimace score of =2, body

condition score ≤2, weight loss of ≥20% or bleeding. All animals

fulfilling ≥2 humane criteria were subjected to euthanasia.

Isolation and irradiation of bone

marrow-derived neutrophils (BMDNs)

A total of 30 naïve WT mice were euthanized by

CO2 asphyxiation at a fill rate of 50% displacement of

the chamber volume per min followed by cervical dislocation, and

the femurs and tibias were subsequently dissected. The bone marrow

was flushed with ice-cold PBS supplemented with 2% FBS, and

suspensions of cells were filtered through a 70-μm cell

strainer and placed on ice. BMDNs were purified by negative

selection using the EasySep mouse neutrophil enrichment kit

(Stemcell Technologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions and cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a cell culture plate at 37°C in

5% CO2 for in vitro experiments. BMDNs were

either exposed to radiation at a dose rate of 3 Gy/min using the

X-ray Precision X-Rad320 (Precision X-Ray, Inc.) or not irradiated

(control). After irradiation, cells were incubated at 37°C in 5%

CO2. For the experiment of additional stimulation of

eCIRP, BMDNs were treated with 1 μg/ml eCIRP, prepared

in-house using a bacterial expression system (28), immediately after irradiation for

24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Assessment of NETs and TREM-1 expression

on neutrophils by flow cytometry

The purity of the sorted neutrophils was assessed by

labeling the cells with APC-rat anti-mouse Ly6G antibody (cat. no.

127614; BioLegend, Inc.) using a LSRFortessa™ flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences). NETs were assessed using flow cytometry for both

in vivo and in vitro experiments (35). Single-cell suspensions of

neutrophils after irradiation were blocked with TruStain FcX™ PLUS

(anti-mouse CD16/32) antibody (cat. no. 156604; BioLegend, Inc.)

for 15 min at 4°C and surface-stained with APC-Ly6G, FITC anti-MPO

(cat. no. ab90812; Abcam) and rabbit anti-histone H3 (citrulline

R2+ R8+ R17) antibodies (cat. no. ab5103; Abcam) for 30 min at 4°C,

followed by staining with PE-donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (cat.

no. 406421, BioLegend, Inc.) as a secondary antibody for 30 min at

4°C. For the assessment of TREM-1 expression, neutrophils were also

stained with BV421-rat anti-mouse TREM-1 antibody (cat. no. 747899;

BD Biosciences) or BV 421-rat IgG2a κ isotype control (cat. no.

562602; BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. Unstained cells were

used to establish control voltage setting and single-color

compensation was performed using UltraComp eBeads™ (Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Data were obtained using the

LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using the

FlowJo software (version 10.10.0; BD Biosciences). The population

of MPO and citrullinated H3 double-positive neutrophils were

identified as NET-forming neutrophils. Mean fluorescence intensity

(MFI) was used to evaluate the levels of TREM-1 expression.

Assessment of NETs via fluorescence

microscopy

NET formation by BMDNs after radiation exposure was

assessed by fluorescence microscopy in vitro (41). At 24 h after irradiation, BMDNs

were incubated with 250 nM SYTOX Green (cat. no. S7020; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30 min at 37°C in 5%

CO2. The cells were visualized as live-cell images

without fixation using fluorescence microscopy (EVOS FL Auto

Imaging System; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Western blotting

PAD4 protein expression levels were assessed by

western blotting. BMDNs were collected by centrifugation at 300 × g

at 20 h after irradiation and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer [10 mM

Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.5), 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1

mM EGTA, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl

fluoride] containing protease inhibitors (Pierce; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Protein concentrations in the cell lysates were

measured using DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

The cell lysates of BMDNs (20 μg/lane) were dissolved in 4X

SDS sample buffer and resolved on NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gels

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), after which, they

were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After blocking with 0.1% casein in TBS

for 1 h at room temperature, each membrane was incubated overnight

at 4°C with primary antibodies of rabbit anti-PAD4 antibody

(1:1,000; cat. no. 17373-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and mouse

anti-β-actin antibody (1:5,000; cat. no. A5441; MilliporeSigma).

The membranes were washed with TBS and then incubated with the

corresponding fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 h at room

temperature. The secondary antibodies IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit

IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. 926-32211; LI-COR Biosciences) and IRDye

680RD goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. 926-68070; LI-COR

Biosciences) were used. Detection was performed using the Odyssey

Clx (LI-COR Biosciences) imaging system and quantification with the

Image Studio software (version 5.2; LI-COR Biosciences).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

BMDNs were collected by centrifugation at 300 × g at

4°C for 10 min a total of 4 h after irradiation. Illustra™ RNAspin

Mini RNA Isolation kit (Cytiva) was utilized to extract total RNA

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, 1

μg RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA

(cDNA). Briefly, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using oligo(dT)

primers (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) via incubation

at 70°C for 10 min, followed by cooling to 4°C. RT was performed by

adding a reaction mixture containing PCR buffer with

MgCl2 (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), dNTP mix (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), RNase

inhibitor (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and by incubation at 42°C for 60 min, heating to 95°C for 5 min and

cooling to 4°C. PCR was performed using a final volume of 20

μl containing forward and reverse primers (final

concentration, 0.06 mM each), cDNA and SYBR Green master mix

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using a Step

One Plus real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The following program was run: 95°C for 10 min

as an initial denaturation step, followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, and annealing and extension at

60°C for 1 min. Mouse β-actin mRNA served as a reference gene for

normalization. Relative gene expression levels were calculated

using the comparative 2−ΔΔCq method (42). Relative expression levels of mRNA

were represented as fold-change relative to the control group. The

primer sequences used were as follows: PAD4 forward (F),

5′-GCAGGACATGTCTCCAATGA-3′ and reverse (R),

5′-AGCTCCAGGCAATACGAGAA-3′; TREM-1 F, 5′-CTACAACCCGATCCCTACCC-3′

and R, 5′-AAACCAGGCTCTTGCTGAGA-3′; and β-actin F,

5′-CGTGAAAAGATGACCCAGATCA-3′ and R,

5′-TGGTACGACCAGAGGCATACAG-3′.

Statistical analysis

Data represented in the figures are expressed as

mean and SEM. An unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used for

comparisons of two groups and one-way analysis of variance followed

by Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test were used for

comparisons of multiple groups. Data were analyzed using the

GraphPad Prism software (version 10.3.1; Dotmatics). P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

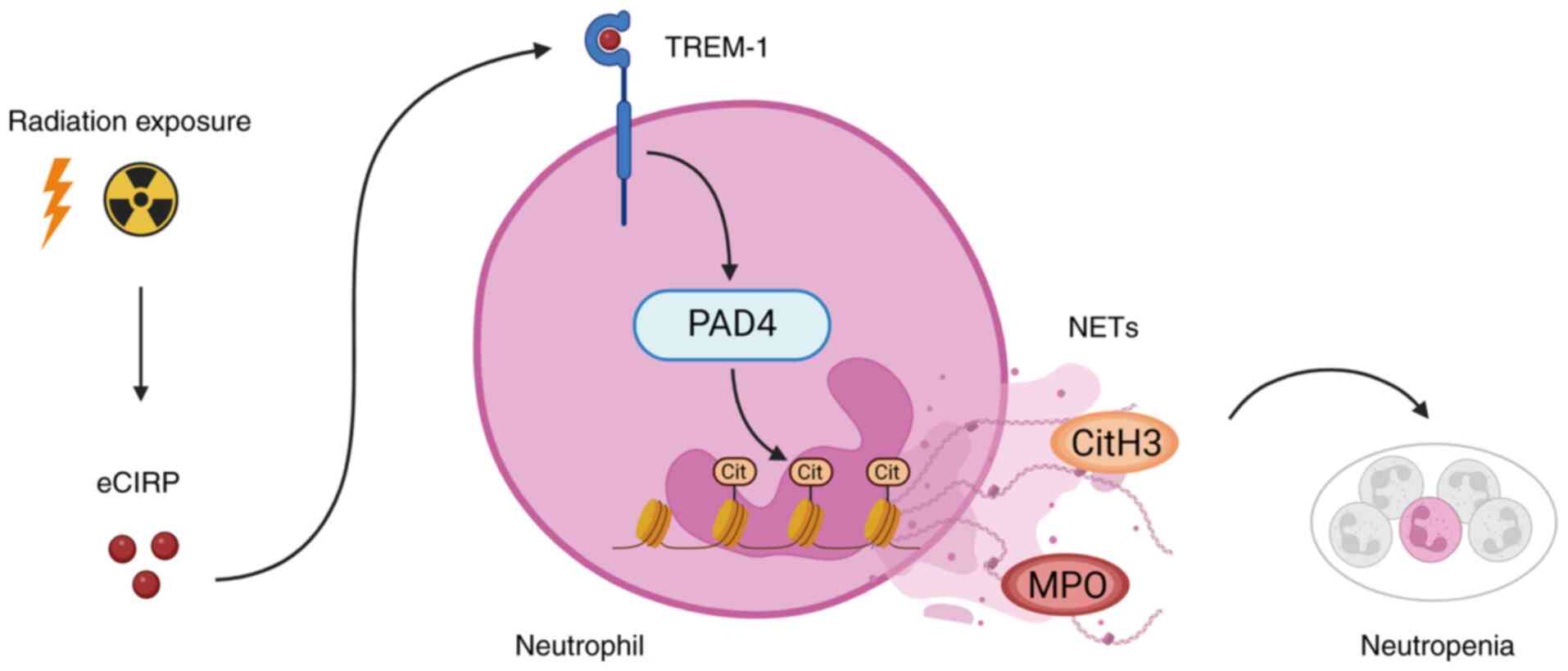

Exposure to ionizing radiation induces

NET formation

To determine whether exposure to ionizing radiation

induces NETs, BMDNs were exposed to 5 to 15 Gy radiation and NET

formation was assessed 24 h after irradiation via flow cytometry.

Citrullinated histone H3 and MPO double-positive cells were

considered as neutrophils with NETs. The number of NET-forming

neutrophils were significantly increased following 5 to 10 Gy

irradiation in a dose-dependent manner and reached a plateau at 10

Gy (Fig. 1A and B). NET

formation was further confirmed as extracellular DNA using

microscopy with SYTOX Green labelling, a nucleic acid stain that

fluoresces green when bound to DNA. Notably, SYTOX Green does not

cross intact membranes but penetrates compromised membranes. The

number of neutrophils with expanded nuclear area stained by SYTOX

Green were increased after irradiation compared with that of the

control cells, and a number of irradiated neutrophils showed long

stretches of extracellular DNA, which indicated NET formation

(Fig. 1C). NET formation was

also evaluated in vivo. Bone marrow from irradiated WT mice

24 h after 10 Gy TBI were isolated and NETs evaluated using flow

cytometry. Consistent with the in vitro experiments,

NET-forming neutrophils were significantly increased after TBI

compared with that of sham mice (Fig. 1D and E). Thus, these results

demonstrated that exposure to ionizing radiation induced NET

formation.

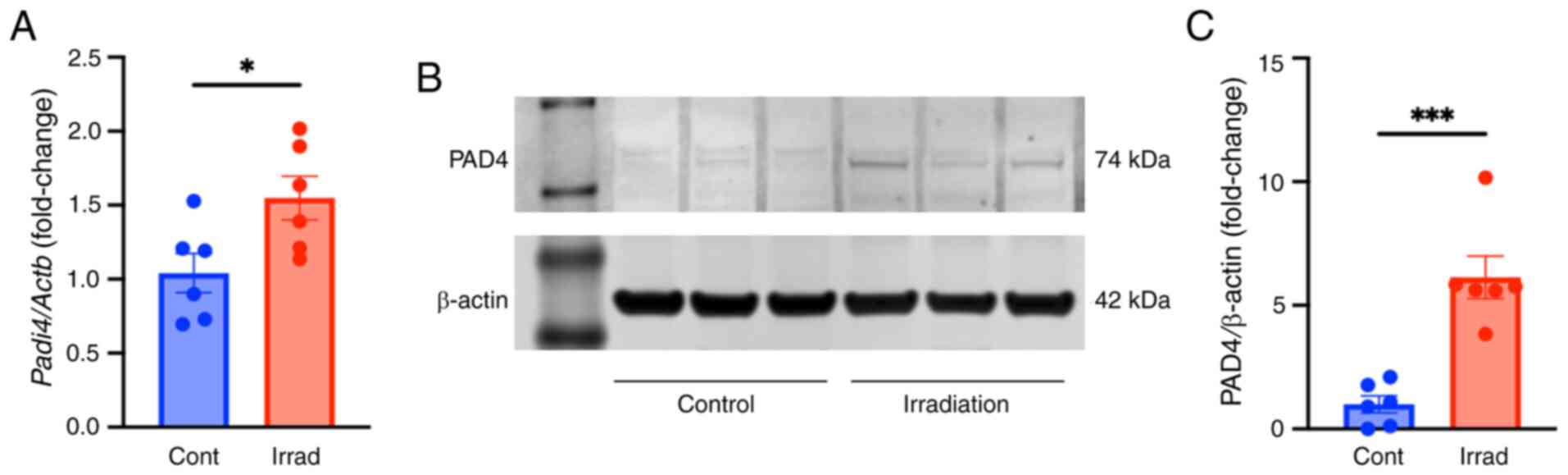

Radiation upregulates PAD4 expression

levels in neutrophils

PAD4 catalyzes histone citrullination, leading to

chromatin decondensation and NETosis (15). PAD4 mRNA and protein expression

levels in BMDNs after irradiation were investigated. BMDNs were

exposed to 10 Gy radiation and mRNA and protein expression levels

of PAD4 were evaluated 4 or 20 h after irradiation, respectively.

The mRNA levels of PAD4 were significantly upregulated after

irradiation compared with that of control cells (Fig. 2A). Similarly, PAD4 protein

expression levels were also significantly upregulated after

irradiation compared with that of control cells (Fig. 2B and C). These findings further

evidenced the induction of NET formation after irradiation.

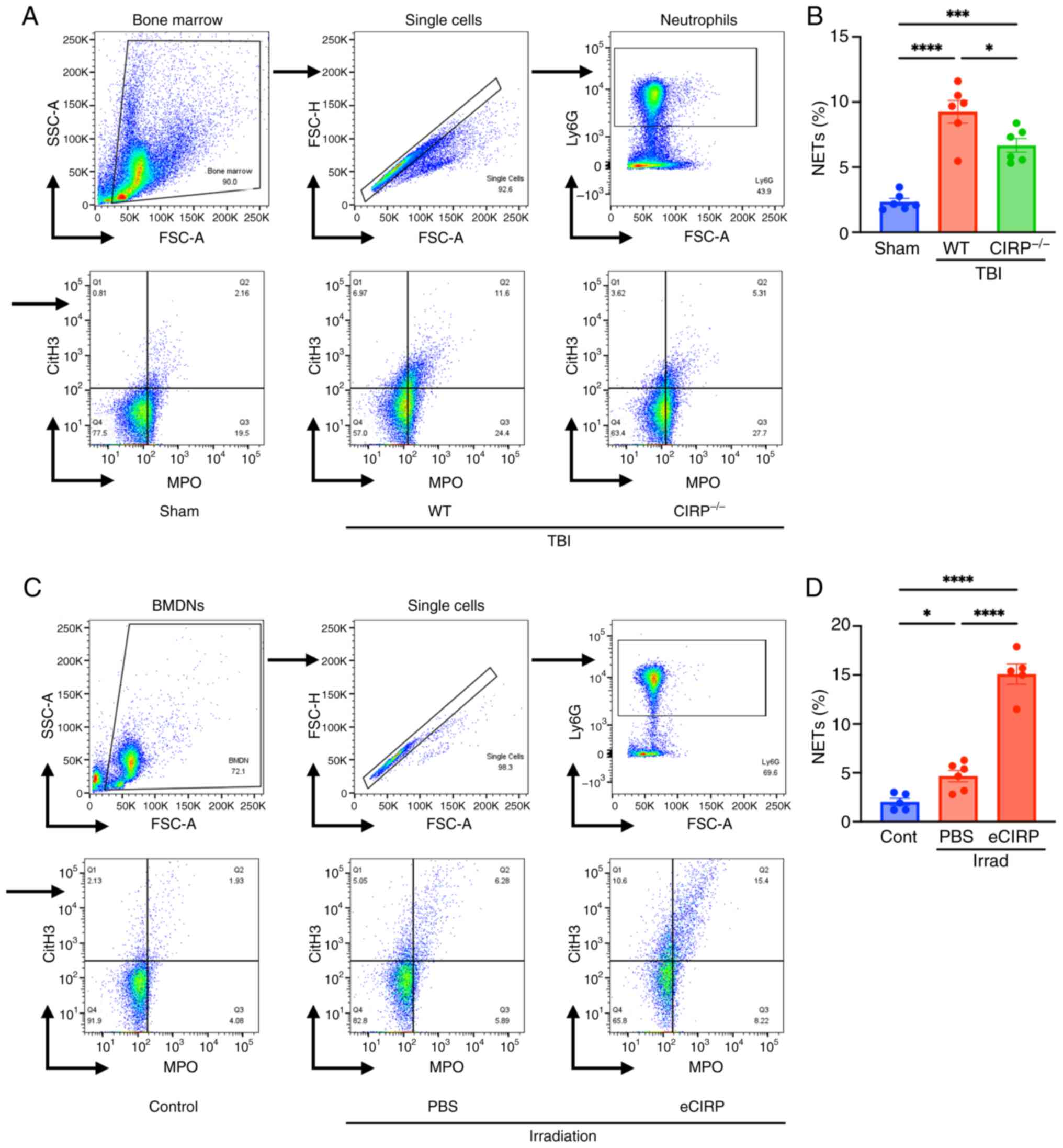

eCIRP induces NET formation after

irradiation

To determine the role of eCIRP on radiation-induced

NET formation, NET formation in bone marrow isolated from WT and

CIRP−/− mice 24 h after 10 Gy TBI was assessed.

NET-forming neutrophils were significantly increased in WT TBI mice

compared with that in sham mice. CIRP knockout ameliorated NET

formation compared with that of WT TBI mice (Fig. 3A and B). Additional effects of

eCIRP on radiation-induced NETs were assessed as a gain-of-function

experiment. The addition of eCIRP to BMDNs in culture significantly

increased NET formation after irradiation (Fig. 3C and D). These loss- and

gain-of-functional experiments indicated that eCIRP promotes

radiation-induced NET formation.

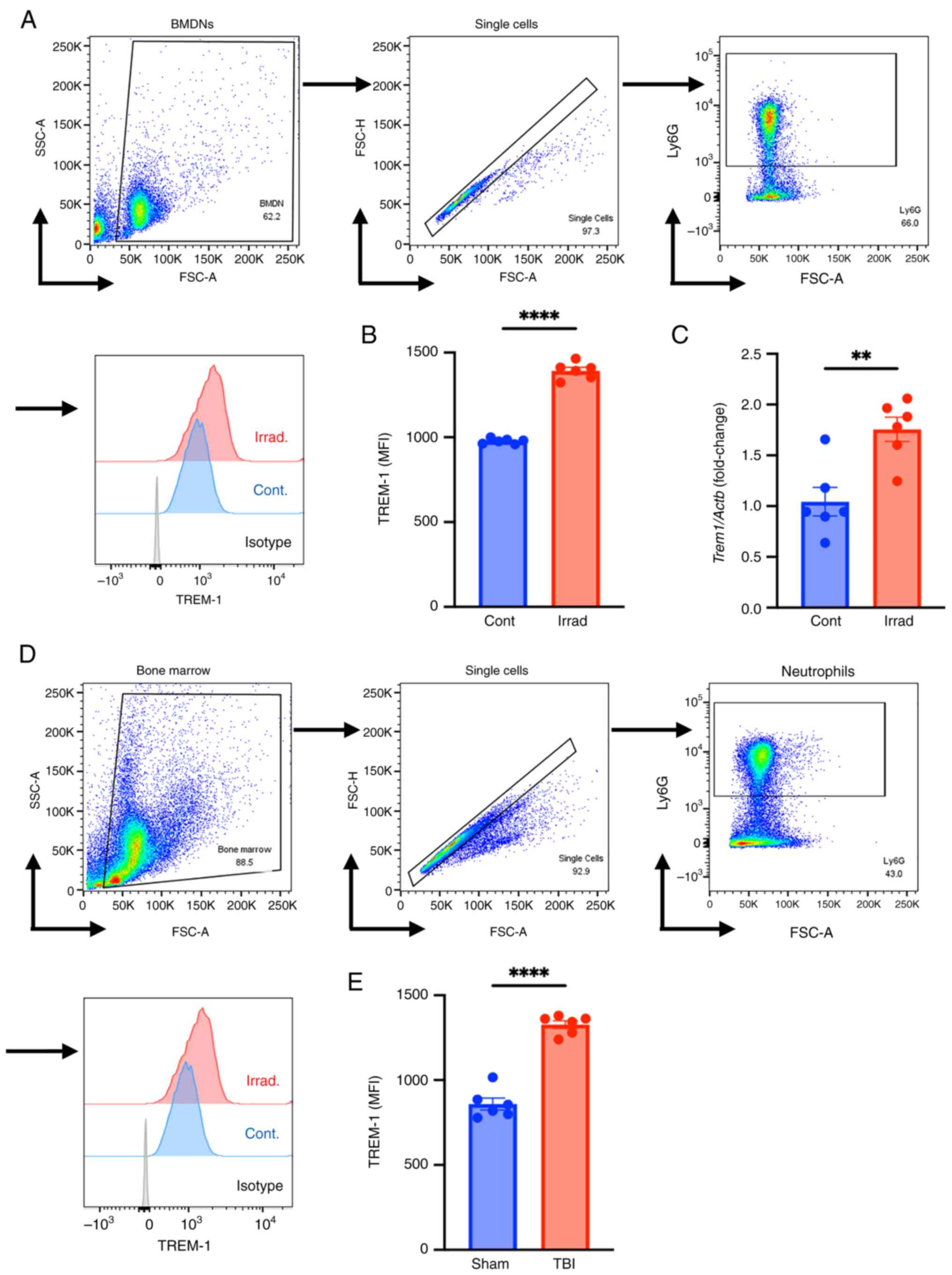

Radiation upregulates neutrophil

TREM-1

TREM-1 has been identified as a key receptor of

eCIRP and has been shown to initiate NETosis (35). Therefore, the effect of radiation

on TREM-1 expression on BMDNs after irradiation was investigated.

BMDNs isolated from WT mice were exposed to 10 Gy irradiation and

TREM-1 cell surface protein expression levels were evaluated 24 h

after irradiation using flow cytometry. Exposure to ionizing

radiation significantly upregulated TREM-1 expression levels in

BMDNs compared with that in control cells (Fig. 4A and B). A total of 4 h after

irradiation, the mRNA level of TREM-1 was significantly upregulated

compared with that of control cells (Fig. 4C). TREM-1 expression levels in WT

mice were also significantly upregulated after TBI compared with

those in the sham group (Fig. 4D and

E). Thus, radiation exposure increases mRNA and surface protein

expression of TREM-1 in neutrophils.

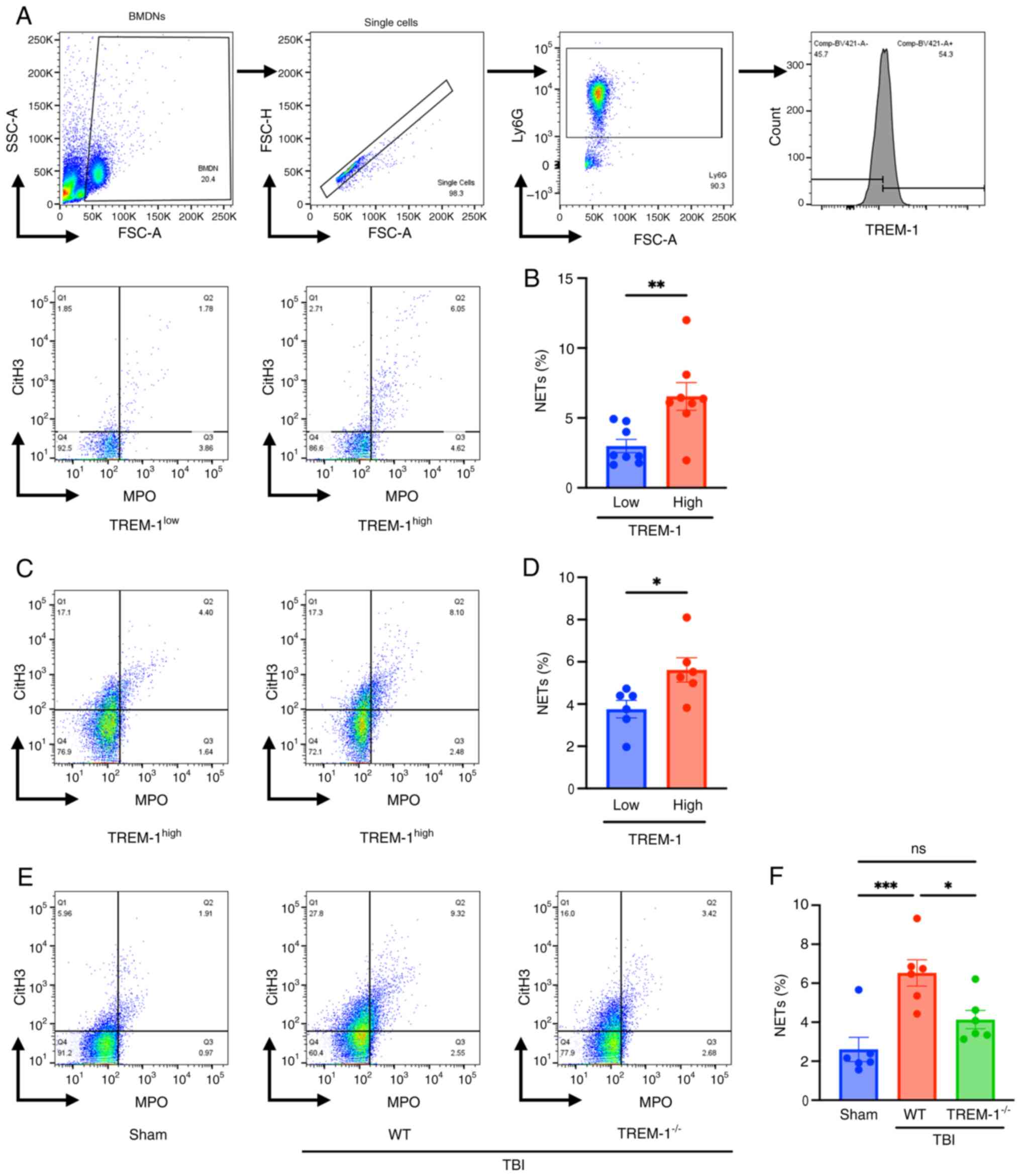

TREM-1 positively regulates

radiation-induced NETs

Next, the association between radiation-induced NETs

and the intensity of TREM-1 expression was investigated in BMDNs

in vitro. Irradiated BMDNs were classified into two

populations, neutrophils with high and low TREM-1 expression based

on the median TREM-1 expression as the cut-off value, and NET

formation was evaluated (Fig.

5A). There was a positive association between the intensity of

TREM-1 expression and the number of NET-forming neutrophils

(Fig. 5B). The association in

the bone marrow neutrophils isolated from WT TBI mice was

determined; neutrophils with high TREM-1 expression demonstrated a

significant increase in NETs after irradiation compared with that

in the low TREM-1 expression group (Fig. 5C and D). The effect of TREM-1

knockout on NET formation after irradiation was evaluated. Bone

marrow cells were isolated from irradiated WT and

TREM-1−/− mice 24 h after 10 Gy TBI and NET formation

assessed via flow cytometry. NET-forming neutrophils were

significantly increased in WT TBI mice compared with that in sham

mice, whereas NET-forming neutrophils were significantly decreased

in TREM-1−/− TBI mice compared with that in WT TBI mice

(Fig. 5E and F). These data

indicated that TREM-1 was associated with NET formation after

exposure to ionizing radiation.

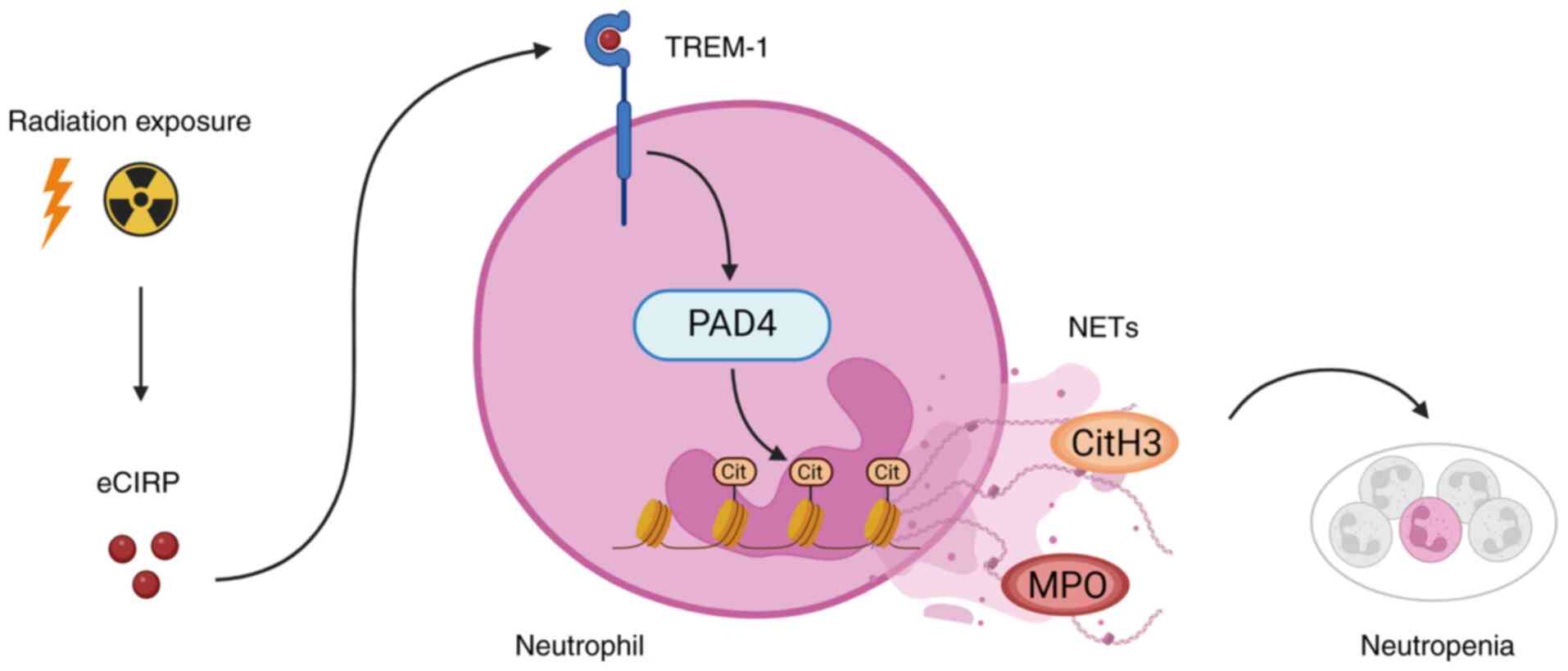

Discussion

Clinical experiences from nuclear accidents and war

have shown that ARS exhibits a variety of clinical manifestations

with lethal consequences (8).

The initial treatment of patients exposed to high doses of

radiation focuses on hematopoietic dysfunction. Bacterial

translocation due to gastrointestinal injury, combined with

neutropenia, can lead to severe infections and sepsis (43). In addition, uncontrolled

inflammatory responses worsen multi-organ dysfunction in severe ARS

(8,9). NETosis is a form of regulated cell

death that could contribute to the initiation and duration of

neutropenia (23). Furthermore,

excessive NET formation has been shown to induce pro-inflammatory

responses and exacerbate organ damage (19). The present study demonstrated

that exposure to 5-15 Gy of ionizing radiation induces NET

formation, and identified the eCIRP/TREM-1 pathway as the mechanism

that mediates NET formation after radiation exposure (Fig. 6). Therefore, focusing on

radiation-induced NET formation by targeting eCIRP/TREM-1 axis can

provide novel therapeutic strategies for acute neutropenia in the

future.

| Figure 6Exposure to ionizing radiation

induces NETs via eCIRP/TREM-1 axis. Radiation-induced eCIRP

upregulates and activates TREM-1 on neutrophils, resulting in

increased expression of PAD4 and NET formation, causing

neutropenia. NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; PAD4, peptidyl

arginine deiminase 4; eCIRP, extracellular cold-inducible

RNA-binding protein; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on

myeloid cells-1; MPO, myeloperoxidase; cit, citrulline; CitH3,

citrullinated H3. The schema was created in BioRender. Murao, A.

(2025) https://BioRender.com/qhaiby0 |

To the best of our knowledge, only two studies of

ionizing radiation-induced NETosis and NET formation have been

conducted, and they were confined to the context of tumor

microenvironment (24,44). Radiation therapy targeting cancer

tissues has been shown to activate peritumoral neutrophils and

induce NET formation, which promotes angiogenesis, enhances tumor

cell adhesion and increases the risk of radiation resistance and

metastasis (19). Teijeira et

al (44) recently showed

that exposure of neutrophils isolated from healthy human blood to

low-dose γ-radiation (0.5-1 Gy) induces NET formation. It was also

shown that oxidative stress, NADPH oxidase activity and IL-8

triggers NET formation (44).

Additionally, ultraviolet irradiation has been reported to induce

NET formation via oxidative stress (45,46). However, the formation of NETs

induced by high-dose ionizing radiation and the underlying

mechanisms have not yet been studied. The present study first

demonstrated radiation-induced NET formation by the quantitative

evaluation of NETs using flow cytometry, along with direct

observation through fluorescence microscopy. The increased mRNA and

protein expression levels of PAD4 upon exposure to ionizing

radiation further supports the radiation-induced NET formation.

Subsequently, the mechanisms that regulate radiation-induced NET

formation were investigated. Several types of receptors, such as

Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2, TLR4, G protein-coupled receptor and Fc

receptors, have been reported to be involved in NET formation

(47-50). Neutrophils can be activated via

these receptors by pathogens, lipopolysaccharide, cytokines and

DAMPs to induce NET formation (15). Our previous studies reported

TREM-1 as a key receptor responsible for NET formation in a sepsis

model (35) and demonstrated the

strong binding affinity between eCIRP and TREM-1 using surface

plasmon resonance (37). The

interaction of eCIRP with TREM-1 on mouse macrophages using a

fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay was also demonstrated

(37). In addition, our previous

studies have shown that exposure to high-dose radiation induces

release of eCIRP in mice (36,51). The present study demonstrated

that the eCIRP/TREM-1 axis serves a critical role in NET induction

after radiation exposure. Currently, it has not yet been

established how TREM-1 activation promotes NET formation. However,

in a sepsis model, eCIRP-mediated activation of TREM-1 induces the

surface expression of ICAM-1, leading to NET formation via Rho

activation (35). Furthermore,

eCIRP activates the downstream signaling pathway of TREM-1, as

evaluated by DAP12 and Syk phosphorylation (35). Syk activation mediates the

phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) (52). Activated PLCγ degrades

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate in the plasma membrane to

inositol 1,4,5-triophosphate, triggering the release of calcium

from endoplasmic reticulum (52). Elevated intracellular calcium

levels induce PAD4 activation and extracellular calcium chelation

has been shown to inhibit NETosis induced by IL-8 and

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (53,54). Furthermore, activation of Syk

following TREM-1 stimulation has been shown to induce reactive

oxygen species (ROS) production via the PIK3/AKT pathway (55). ROS are also critical in NETosis

signaling, as demonstrated by the inhibition of NETosis upon

treatment of neutrophils with ROS scavengers (53,54). A previous study has reported that

low-dose γ-radiation induces NET formation depending on oxidative

stress and ROS inhibition significantly attenuates

radiation-induced NETosis (44).

Since TREM-1 is associated with ROS production, the aforementioned

findings with low-dose irradiation could potentially also be

mediated, at least in part, via the TREM-1 pathway. Nevertheless,

whether the induction of NETs triggered by the eCIRP/TREM-1 axis is

concurrent after low-dose irradiation may require further

investigation.

Bone marrow damage from radiation exposure leads to

less recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the systemic

circulation (56). Furthermore,

the half-life of circulating neutrophils is short, ranging from 18

to 19 h. (23). Consequently,

induction of neutrophil cell death after radiation exposure

inevitably exacerbates neutropenia, resulting in high

susceptibility to infection (7).

Furthermore, organ dysfunction caused by NETs has been demonstrated

in a variety of diseases, including sepsis, I/R injury, and renal

and hepatic injuries (57-65). In sepsis and I/R injury, NETs

have been shown to cause systemic inflammation and epithelial

barrier disruption, resulting in intestinal and lung injury

(57-63). Inflammation and organ damage by

NETs have also been demonstrated in liver and renal injuries

(64,65). Histones, a key component of NETs,

have been shown to induce inflammatory responses via the

TLR2/TLR4-MyD88 signaling or the NLPR3 inflammasome pathway

(66). Histones also bind to

phospholipids in the plasma membrane of epithelial and endothelial

tissues, altering their permeability and causing cell death and

tissue damage (67). NET

components such as MPO and NE impair junctional integrity and

promote vascular permeability (68,69). MPO has been shown to bind to the

endothelial glycocalyx via heparan sulfate side chains, disrupting

the endothelial glycocalyx structure and causing endothelial injury

(68). Considering that

excessive inflammatory responses accompanied by disruption of

vascular homeostasis contribute to multi-organ dysfunction after

severe ARS, radiation-induced NET formation may potentially be an

exacerbating factor in radiation injury.

The detrimental role of DAMPs has been addressed in

a number of inflammatory conditions such as sepsis, hemorrhage and

I/R injury (27). Although

evidence for DAMPs in radiation injury is limited, targeting DAMPs

presents a promising potential strategy for mitigating

radiation-induced organ damage (30). High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)

is a nuclear protein, which can be translocated to cytoplasm in

response to cellular stress and act as a DAMP (70). Glycyrrhizin, an HMGB1 inhibitor,

suppresses the HMGB1/TLR4 signaling, including NF-κB, JNK and

ERJ1/2, and reduces the production of inflammatory cytokines,

resulting in mitigating radiation-induced lung injury (71). Our previous study has shown that

pharmacological inhibition of eCIRP/TREM-1 binding using an

eCIRP-derived decoy peptide improves systemic inflammation, tissue

injury and survival in sepsis and intestinal I/R injury (37,72). Additionally, the TREM-1 inhibitor

LP17 was shown to reduce eCIRP-induced NET formation (35). Furthermore, another TREM-1

inhibitor LR12 is currently in clinical trials for sepsis (73,74). In radiation injury, knockout of

TREM-1 improves survival after TBI, and that treatment with a

monoclonal neutralizing antibody against eCIRP improves macrophage

phagocytic function following high-dose radiation exposure

(36,51). The present study provides novel

insights into the role of eCIRP and TREM-1 in radiation-induced

immune dysfunction.

Several limitations of the present study existed.

First, the impact of radiation-induced NETosis on neutropenia was

not assessed. Studies evaluating the impact of NETosis inhibition

on neutropenia and susceptibility to infection may provide valuable

insights into the role of NETosis in radiation injury. Second,

whether the formation of NETs contributes to the progression of

organ injuries after radiation exposure was not investigated;

elucidating the possible involvement of NETs in radiation-induced

organ injuries may be important for the development of therapeutic

strategies. Third, NET formation in the tissues by

histopathological evaluation was not directly observed. Detection

of NETs in the tissues including bone marrow and intestines may

clarify the relevance of radiation-induced NET formation and organ

injuries.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

exposure to ionizing radiation induces NET formation. NETosis

resulted in neutrophil death to exacerbate neutropenia, which

contributed to increased susceptibility to infection. The

eCIRP/TREM-1 axis served a key role in radiation-induced NET

formation. Therefore, targeting the eCIRP/TREM-1 axis to regulate

NETs may potentially offer a novel therapeutic strategy for

alleviating neutropenia and preventing infection after radiation

exposure in the future.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MA, MB and PW conceived the study. SY performed the

experiments. SY and AM analyzed the data and drafted the

manuscript. MA, MB and PW reviewed and revised the manuscript. MB

and PW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All study procedures were approved by Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committees of the Feinstein Institutes for

Medical Research (approval no. 2023-007; Manhasset, NY, USA).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

ARS

|

acute radiation syndrome

|

|

BMDNs

|

bone marrow-derived neutrophils

|

|

CIRP

|

cold-inducible RNA-binding protein

|

|

DAMP

|

damage-associated molecular

pattern

|

|

eCIRP

|

extracellular CIRP

|

|

HMGB1

|

high mobility group box 1

|

|

IL

|

interleukin

|

|

I/R

|

ischemia/reperfusion

|

|

MFI

|

mean fluorescence intensity

|

|

MPO

|

myeloperoxidase

|

|

NE

|

neutrophil elastase

|

|

NETs

|

neutrophil extracellular traps

|

|

PAD4

|

peptidyl arginine deiminase 4

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

Syk

|

spleen tyrosine kinase

|

|

TBI

|

total body irradiation

|

|

TLR

|

toll-like receptor

|

|

TREM-1

|

triggering receptor expressed on

myeloid cells-1

|

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Yongchan Lee and Dr Dmitriy

Lapin of the Center for Immunology and Inflammation at the

Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research (Manhasset, NY, USA) for

their technical support and thoughtful discussion.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Institutes of

Health (grant nos. U01AI170018, U01AI133655, U01AI186997 and

R35GM118337).

References

|

1

|

Harada KH, Soleman SR, Ang JSM and

Trzcinski AP: Conflict-related environmental damages on health:

Lessons learned from the past wars and ongoing Russian invasion of

Ukraine. Environ Health Prev Med. 27:352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hasegawa A, Tanigawa K, Ohtsuru A, Yabe H,

Maeda M, Shigemura J, Ohira T, Tominaga T, Akashi M, Hirohashi N,

et al: Health effects of radiation and other health problems in the

aftermath of nuclear accidents, with an emphasis on Fukushima.

Lancet. 386:479–488. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hirohashi N, Shime N and Fujii T: Beyond

the unthinkable: Are we prepared for rare disasters? Anaesth Crit

Care Pain Med. 42:1012662023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Baranov A, Gale RP, Guskova A, Piatkin E,

Selidovkin G, Muravyova L, Champlin RE, Danilova N, Yevseeva L and

Petrosyan L: Bone marrow transplantation after the Chernobyl

nuclear accident. N Engl J Med. 321:205–212. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Macià I, Garau M, Lucas Calduch A and

López EC: Radiobiology of the acute radiation syndrome. Rep Pract

Oncol Radiother. 16:123–130. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

McCart EA, Lee YH, Jha J, Mungunsukh O,

Rittase WB, Summers TA Jr, Muir J and Day RM: Delayed captopril

administration mitigates hematopoietic injury in a murine model of

total body irradiation. Sci Rep. 9:21982019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wong K, Chang PY, Fielden M, Downey AM,

Bunin D, Bakke J, Gahagen J, Iyer L, Doshi S, Wierzbicki W and

Authier S: Pharmacodynamics of romiplostim alone and in combination

with pegfilgrastim on acute radiation-induced thrombocytopenia and

neutropenia in Non-human primates. Int J Radiat Biol. 96:155–166.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tanigawa K: Case review of severe acute

radiation syndrome from whole body exposure: Concepts of

radiation-induced multi-organ dysfunction and failure. J Radiat

Res. 62:i15–i20. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Williams JP and McBride WH: After the bomb

drops: A new look at Radiation-induced multiple organ dysfunction

syndrome (MODS). Int J Radiat Biol. 87:851–868. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kim YJ, Jeong J, Park K, Sohn KY, Yoon SY

and Kim JW: Mitigation of hematopoietic syndrome of acute radiation

syndrome by 1-Palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-3-acetyl-rac-glycerol (PLAG) is

associated with regulation of systemic inflammation in a murine

model of Total-Body Irradiation. Radiat Res. 196:55–65. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gerassy-Vainberg S, Blatt A, Danin-Poleg

Y, Gershovich K, Sabo E, Nevelsky A, Daniel S, Dahan A, Ziv O,

Dheer R, et al: Radiation induces proinflammatory dysbiosis:

Transmission of inflammatory susceptibility by host cytokine

induction. Gut. 67:97–107. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

English J, Dhanikonda S, Tanaka KE, Koba

W, Eichenbaum G, Yang WL and Guha C: Thrombopoietin mimetic reduces

mouse lung inflammation and fibrosis after radiation by attenuating

activated endothelial phenotypes. JCI Insight. 9:e1813302024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Schaue D, Micewicz ED, Ratikan JA, Xie MW,

Cheng G and McBride WH: Radiation and inflammation. Semin Radiat

Oncol. 25:4–10. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

14

|

Dainiak N and Albanese J: Medical

management of acute radiation syndrome. J Radiol Prot. 42:2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Thiam HR, Wong SL, Wagner DD and Waterman

CM: Cellular mechanisms of NETosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol.

36:191–218. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Christophorou MA, Castelo-Branco G,

Halley-Stott RP, Oliveira CS, Loos R, Radzisheuskaya A, Mowen KA,

Bertone P, Silva JC, Zernicka-Goetz M, et al: Citrullination

regulates pluripotency and histone H1 binding to chromatin. Nature.

507:104–108. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Thiam HR, Wong SL, Qiu R, Kittisopikul M,

Vahabikashi A, Goldman AE, Goldman RD, Wagner DD and Waterman CM:

NETosis proceeds by cytoskeleton and endomembrane disassembly and

PAD4-mediated chromatin decondensation and nuclear envelope

rupture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:7326–7337. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Chapman EA, Lyon M, Simpson D, Mason D,

Beynon RJ, Moots RJ and Wright HL: Caught in a trap? Proteomic

analysis of neutrophil extracellular traps in rheumatoid arthritis

and systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 10:4232019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang H, Kim SJ, Lei Y, Wang S, Wang H,

Huang H, Zhang H and Tsung A: Neutrophil extracellular traps in

homeostasis and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9:2352024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Silva CMS, Wanderley CWS, Veras FP, Sonego

F, Nascimento DC, Goncalves AV, Martins TV, Colon DF, Borges VF,

Brauer VS, et al: Gasdermin D inhibition prevents multiple organ

dysfunction during sepsis by blocking NET formation. Blood.

138:2702–2713. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tan C, Aziz M and Wang P: The vitals of

NETs. J Leukoc Biol. 110:797–808. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Stephenson HN, Herzig A and Zychlinsky A:

Beyond the grave: When is cell death critical for immunity to

infection? Curr Opin Immunol. 38:59–66. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lawrence SM, Corriden R and Nizet V: How

neutrophils meet their end. Trends Immunol. 41:531–544. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Shinde-Jadhav S, Mansure JJ, Rayes RF,

Marcq G, Ayoub M, Skowronski R, Kool R, Bourdeau F, Brimo F, Spicer

J and Kassouf W: Role of neutrophil extracellular traps in

radiation resistance of invasive bladder cancer. Nat Commun.

12:27762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Aziz M, Brenner M and Wang P:

Extracellular CIRP (eCIRP) and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol.

106:133–146. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhou M, Aziz M, Li J, Jha A, Ma G, Murao A

and Wang P: BMAL2 promotes eCIRP-induced macrophage endotoxin

tolerance. Front Immunol. 15:14266822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Murao A, Aziz M, Wang H, Brenner M and

Wang P: Release mechanisms of major DAMPs. Apoptosis. 26:152–162.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Qiang X, Yang WL, Wu R, Zhou M, Jacob A,

Dong W, Kuncewitch M, Ji Y, Yang H, Wang H, et al: Cold-inducible

RNA-binding protein (CIRP) triggers inflammatory responses in

hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. Nat Med. 19:1489–1495. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hollis R, Li J, Lee Y, Jin H, Zhou M, Nofi

CP, Sfakianos M, Coppa G, Aziz M and Wang P: A novel opsonic

extracellular cirp inhibitor Mop3 alleviates gut

Ischemia/reperfusion injury. Shock. 63:101–109. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yamaga S, Aziz M, Murao A, Brenner M and

Wang P: DAMPs and radiation injury. Front Immunol. 15:13539902024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Carrasco K, Boufenzer A, Jolly L, Le

Cordier H, Wang G, Heck AJ, Cerwenka A, Vinolo E, Nazabal A,

Kriznik A, et al: TREM-1 multimerization is essential for its

activation on monocytes and neutrophils. Cell Mol Immunol.

16:460–472. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

32

|

Siskind S, Brenner M and Wang P: TREM-1

modulation strategies for sepsis. Front Immunol. 13:9073872022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Borjas T, Jacob A, Yen H, Patel V, Coppa

GF, Aziz M and Wang P: Inhibition of the Interaction of TREM-1 and

eCIRP attenuates inflammation and improves survival in hepatic

Ischemia/reperfusion. Shock. 57:246–255. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

34

|

Denning NL, Aziz M, Diao L, Prince JM and

Wang P: Targeting the eCIRP/TREM-1 interaction with a small

molecule inhibitor improves cardiac dysfunction in neonatal sepsis.

Mol Med. 26:1212020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Murao A, Arif A, Brenner M, Denning NL,

Jin H, Takizawa S, Nicastro B, Wang P and Aziz M: Extracellular

CIRP and TREM-1 axis promotes ICAM-1-Rho-mediated NETosis in

sepsis. FASEB J. 34:9771–9786. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yamaga S, Murao A, Ma G, Brenner M, Aziz M

and Wang P: Radiation upregulates macrophage TREM-1 expression to

exacerbate injury in mice. Front Immunol. 14:11512502023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Denning NL, Aziz M, Murao A, Gurien SD,

Ochani M, Prince JM and Wang P: Extracellular CIRP as an endogenous

TREM-1 ligand to fuel inflammation in sepsis. JCI Insight.

5:e1341722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Knops K, Boldt S, Wolkenhauer O and

Kriehuber R: Gene expression in low- and high-dose-irradiated human

peripheral blood lymphocytes: Possible applications for

biodosimetry. Radiat Res. 178:304–312. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yoshida K, Misumi M, Hamasaki K, Kyoizumi

S, Satoh Y, Tsuruyama T, Uchimura A and Kusunoki Y: High-dose

radiation preferentially induces the clonal expansion of

hematopoietic progenitor cells over mature T and B cells in mouse

bone marrow. Stem Cell Reports. 20:1024232025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Albrecht H, Durbin-Johnson B, Yunis R,

Kalanetra KM, Wu S, Chen R, Stevenson TR and Rocke DM:

Transcriptional response of ex vivo human skin to ionizing

radiation: Comparison between low- and high-dose effects. Radiat

Res. 177:69–83. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ode Y, Aziz M and Wang P: CIRP increases

ICAM-1+ phenotype of neutrophils exhibiting elevated iNOS and NETs

in sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 103:693–707. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using Real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Dainiak N: Medical management of acute

radiation syndrome and associated infections in a High-casualty

incident. J Radiat Res. 59(Suppl_2): ii54–ii64. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Teijeira A, Garasa S, Ochoa MC,

Sanchez-Gregorio S, Gomis G, Luri-Rey C, Martinez-Monge R, Pinci B,

Valencia K, Palencia B, et al: Low-dose ionizing gamma-radiation

elicits the extrusion of neutrophil extracellular traps. Clin

Cancer Res. 30:4131–4142. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Arzumanyan G, Mamatkulov K, Arynbek Y,

Zakrytnaya D, Jevremovic A and Vorobjeva N: Radiation from UV-A to

red light induces ROS-Dependent release of neutrophil extracellular

traps. Int J Mol Sci. 24:57702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zawrotniak M, Bartnicka D and Rapala-Kozik

M: UVA and UVB radiation induce the formation of neutrophil

extracellular traps by human polymorphonuclear cells. J Photochem

Photobiol B. 196:1115112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yipp BG, Petri B, Salina D, Jenne CN,

Scott BN, Zbytnuik LD, Pittman K, Asaduzzaman M, Wu K, Meijndert

HC, et al: Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving

neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nat Med. 18:1386–1393. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Rossaint J, Herter JM, Van Aken H, Napirei

M, Doring Y, Weber C, Soehnlein O and Zarbock A: Synchronized

integrin engagement and chemokine activation is crucial in

neutrophil extracellular Trap-mediated sterile inflammation. Blood.

123:2573–2584. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Aleyd E, van Hout MW, Ganzevles SH, Hoeben

KA, Everts V, Bakema JE and van Egmond M: IgA enhances NETosis and

release of neutrophil extracellular traps by polymorphonuclear

cells via Fcα receptor I. J Immunol. 192:2374–2383. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Keshari RS, Jyoti A, Dubey M, Kothari N,

Kohli M, Bogra J, Barthwal MK and Dikshit M: Cytokines induced

neutrophil extracellular traps formation: Implication for the

inflammatory disease condition. PLoS One. 7:e481112012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yamaga S, Murao A, Zhou M, Aziz M, Brenner

M and Wang P: Radiation-induced eCIRP impairs macrophage bacterial

phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 116:1072–1079. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Arts RJ, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW and

Netea MG: TREM-1: Intracellular signaling pathways and interaction

with pattern recognition receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 93:209–215.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Parker H, Dragunow M, Hampton MB, Kettle

AJ and Winterbourn CC: Requirements for NADPH oxidase and

myeloperoxidase in neutrophil extracellular trap formation differ

depending on the stimulus. J Leukoc Biol. 92:841–849. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Kenny EF, Herzig A, Kruger R, Muth A,

Mondal S, Thompson PR, Brinkmann V, Bernuth HV and Zychlinsky A:

Diverse stimuli engage different neutrophil extracellular trap

pathways. Elife. 6:e244372017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Baruah S, Murthy S, Keck K, Galvan I,

Prichard A, Allen LH, Farrelly M and Klesney-Tait J: TREM-1

regulates neutrophil chemotaxis by promoting NOX-dependent

superoxide production. J Leukoc Biol. 105:1195–1207. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Cassatt DR, Winters TA and PrabhuDas M:

Immune dysfunction from radiation exposure. Radiat Res.

200:389–395. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Sun S, Duan Z, Wang X, Chu C, Yang C, Chen

F, Wang D, Wang C, Li Q and Ding W: Neutrophil extracellular traps

impair intestinal barrier functions in sepsis by regulating

TLR9-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Cell Death Dis.

12:6062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhao J, Zhen N, Zhou Q, Lou J, Cui W,

Zhang G and Tian B: NETs promote inflammatory injury by activating

cGAS-STING pathway in acute lung injury. Int J Mol Sci.

24:51252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Hawez A, Taha D, Algaber A, Madhi R,

Rahman M and Thorlacius H: MiR-155 regulates neutrophil

extracellular trap formation and lung injury in abdominal sepsis. J

Leukoc Biol. 111:391–400. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Gao X, Hao S, Yan H, Ding W, Li K and Li

J: Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to the intestine

damage in endotoxemic rats. J Surg Res. 195:211–218. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Luo L, Zhang S, Wang Y, Rahman M, Syk I,

Zhang E and Thorlacius H: Proinflammatory role of neutrophil

extracellular traps in abdominal sepsis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol

Physiol. 307:L586–596. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Chu C, Wang X, Chen F, Yang C, Shi L, Xu

W, Wang K, Liu B, Wang C, Sun D, et al: Neutrophil extracellular

traps aggravate intestinal epithelial necroptosis in

ischaemia-reperfusion by regulating TLR4/RIPK3/FUNDC1-required

mitophagy. Cell Prolif. 57:e135382024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Zhan Y, Ling Y, Deng Q, Qiu Y, Shen J, Lai

H, Chen Z, Huang C, Liang L, Li X, et al: HMGB1-Mediated neutrophil

extracellular trap formation exacerbates intestinal

Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced acute lung injury. J Immunol.

208:968–978. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Jansen MP, Emal D, Teske GJ, Dessing MC,

Florquin S and Roelofs JJ: Release of extracellular DNA influences

renal ischemia reperfusion injury by platelet activation and

formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Kidney Int.

91:352–364. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Ye D, Yao J, Du W, Chen C, Yang Y, Yan K,

Li J, Xu Y, Zang S, Zhang Y, et al: Neutrophil extracellular traps

mediate acute liver failure in regulation of miR-223/Neutrophil

elastase signaling in mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.

14:587–607. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Allam R, Scherbaum CR, Darisipudi MN,

Mulay SR, Hagele H, Lichtnekert J, Hagemann JH, Rupanagudi KV, Ryu

M, Schwarzenberger C, et al: Histones from dying renal cells

aggravate kidney injury via TLR2 and TLR4. J Am Soc Nephrol.

23:1375–1388. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Silk E, Zhao H, Weng H and Ma D: The role

of extracellular histone in organ injury. Cell Death Dis.

8:e28122017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Manchanda K, Kolarova H, Kerkenpass C,

Mollenhauer M, Vitecek J, Rudolph V, Kubala L, Baldus S, Adam M and

Klinke A: MPO (Myeloperoxidase) reduces endothelial glycocalyx

thickness dependent on its cationic charge. Arterioscler Thromb

Vasc Biol. 38:1859–1867. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ushakumari CJ, Zhou QL, Wang YH, Na S,

Rigor MC, Zhou CY, Kroll MK, Lin BD and Jiang ZY: Neutrophil

elastase increases vascular permeability and leukocyte

transmigration in cultured endothelial cells and obese mice. Cells.

11:22882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Chen R, Kang R and Tang D: The mechanism

of HMGB1 secretion and release. Exp Mol Med. 54:91–102. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zheng L, Zhu Q, Xu C, Li M, Li H, Yi PQ,

Xu FF, Cao L and Chen JY: Glycyrrhizin mitigates radiation-induced

acute lung injury by inhibiting the HMGB1/TLR4 signalling pathway.

J Cell Mol Med. 24:214–226. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Denning NL, Aziz M, Ochani M, Prince JM

and Wang P: Inhibition of a triggering receptor expressed on

myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) with an extracellular cold-inducible

RNA-binding protein (eCIRP)-derived peptide protects mice from

intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Surgery. 168:478–485. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Francois B, Lambden S, Fivez T, Gibot S,

Derive M, Grouin JM, Salcedo-Magguilli M, Lemarie J, De Schryver N,

Jalkanen V, et al: Prospective evaluation of the efficacy, safety,

and optimal biomarker enrichment strategy for nangibotide, a TREM-1

inhibitor, in patients with septic shock (ASTONISH): A

double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir

Med. 11:894–904. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Francois B, Levy M, Ferrer R, Laterre PF

and Angus DC: A mechanism-based prognostic enrichment strategy for

the development of the TREM-1 inhibitor nangibotide in septic

shock. Intensive Care Med. 51:965–967. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Exposure to ionizing radiation

induces NETs. (A) BMDNs were exposed to 5, 10 and 15 Gy radiation.

NETs were assessed via flow cytometry 24 h after irradiation. (B)

The frequencies of NET positive neutrophils are shown. Groups were

compared using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison

test. (C) Representative images of BMDNs that were exposed to 10 Gy

radiation. NET formation was assessed by fluorescence microscopy

using SYTOX Green 24 h after irradiation. White arrows indicate the

NET structures. Scale bar, 200 μm (Bright field and SYTOX

Green); scale bar, 100 μm [SYTOX Green (enlarged)]. (D)

Wild-type adult mice were exposed to 10 Gy TBI. Bone marrow cells

were isolated 24 h after TBI and NETs were assessed using flow

cytometry. (E) The frequencies of NET positive neutrophils. Groups

were compared using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. Data

are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n=6/group). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001. ns, not

significant; cont, control; NET, neutrophil extracellular traps;

BMDNs, bone marrow-derived neutrophils; TBI, total body

irradiation.](/article_images/ijmm/56/4/ijmm-56-04-05598-g00.jpg)