Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are enzymes that

regulate gene expression by deacetylating histones, thereby

modulating their interaction with chromatin (1). HDACs play critical roles in

controlling cell proliferation, differentiation and development

(2). Among them, HDAC4 belongs

to class IIa HDACs and is exclusively expressed in

non-proliferating cells (3,4).

Studies have shown that HDAC4 is highly expressed in the heart,

brain, skeletal muscle and thymus (5,6).

CVD, a group of disorders affecting the heart or

blood vessels, poses a significant threat to human health. Common

types of CVD include heart failure (HF), myocardial infarction (MI)

and coronary artery disease (CAD) (7). Multiple studies have demonstrated

altered HDAC4 expression in CVD, suggesting its potential as a

biomarker for patients with cardiovascular conditions (8-10). Moreover, previous findings

indicate that HDAC4 contributes to the progression of CVD by

regulating processes such as cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation,

fibrosis and apoptosis (11-13).

In the present review, the biochemical properties of

HDAC4 were analyzed and an in-depth discussion of its roles and

mechanisms in CVD was provided. Additionally, factors that

influence HDAC4 expression were summarized. Finally, a summary and

outlook were added as a conclusion, aiming to provide new insights

into the potential application of HDAC4 in the treatment of

CVD.

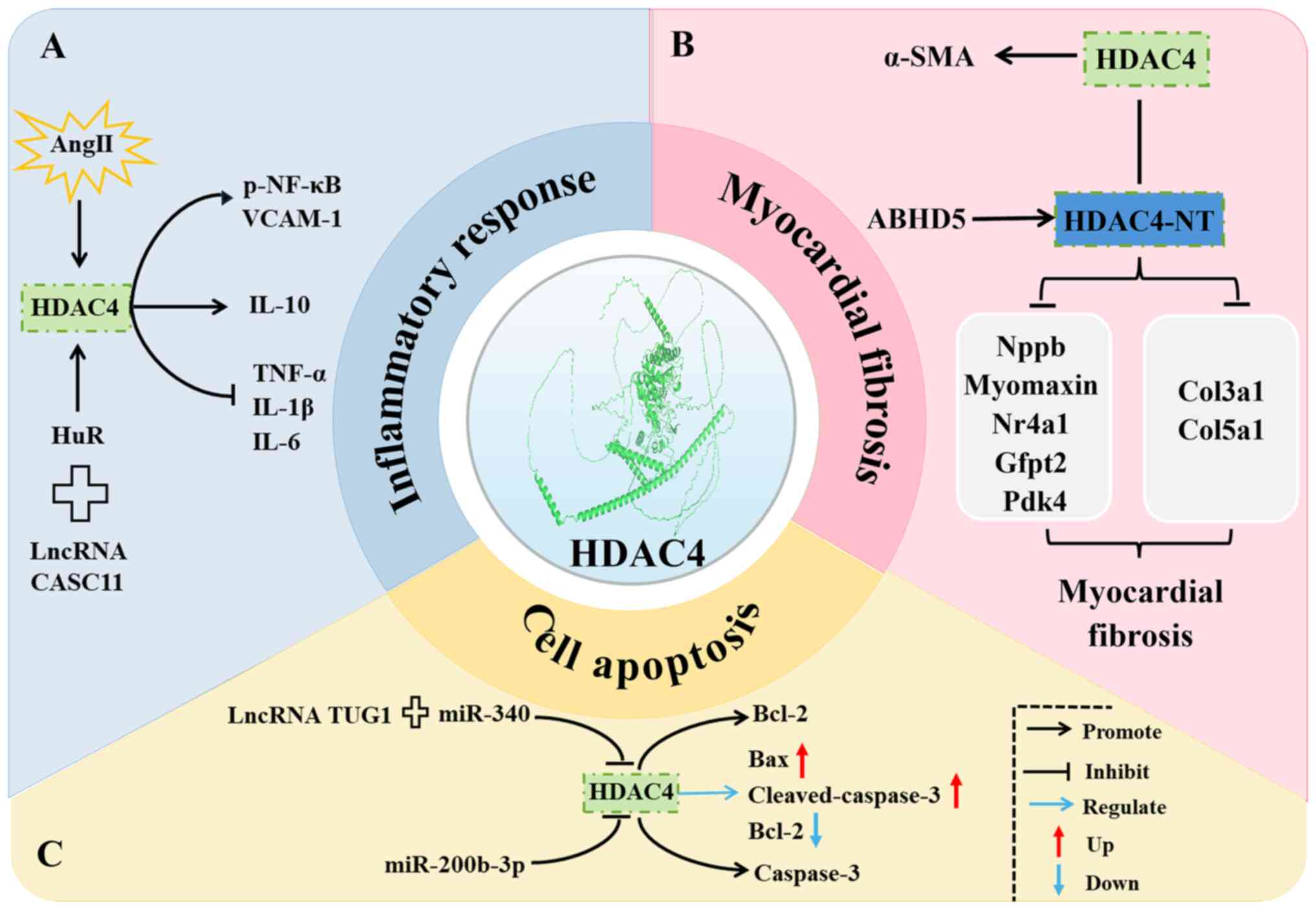

Inflammation is a response initiated by the immune

system in reaction to infections or non-infectious tissue injury

(18). Extensive research has

confirmed that inflammation is a key contributor to the development

of CVD (19-21). Emerging evidence indicates that

HDAC4 plays a critical role in mediating inflammatory responses

associated with CVD. In vitro experiments have shown that

the inhibition of HDAC4 alleviates Ang II-induced inflammatory

responses in rat aortic endothelial cells (RAECs) (22). Another study has reported that

silencing HDAC4 reverses the TNF-α-induced expression of

inflammatory markers vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and

phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in smooth muscle

cells (SMCs) (23). Furthermore,

HDAC4 knockout suppresses the effect of long non-coding RNA cancer

susceptibility candidate 11 (lncRNA CASC11) in downregulating the

expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β and

promoting the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in

human cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMECs) (24). Interestingly, a clinical study

has shown that HDAC4 expression is reduced in patients with

coronary heart disease (CHD), and it is negatively correlated with

the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and

IL-6 (13) (Fig. 2A). This alteration may result

from the influence of the inflammatory microenvironment on HDAC4

expression in vivo, or it may represent a compensatory

response to the disease state in patients with CHD. Therefore,

further studies are warranted to elucidate the context-dependent

roles and underlying mechanisms of HDAC4 under different

pathological conditions.

Following myocardial injury, cardiac fibroblasts are

activated and differentiate into myofibroblasts. These

myofibroblasts exhibit proliferative and secretory properties that

promote extracellular matrix remodeling and collagen deposition,

ultimately leading to fibrotic scarring and HF (25). One study demonstrated that

inhibition of HDAC4 expression downregulates the Ang II-induced

expression of the cardiac pericyte fibrosis marker α-smooth muscle

actin (α-SMA) (26). Another

study showed that HDAC4 knockout suppresses myocardial fibrosis in

mice with MI (27). By contrast,

HDAC4 overexpression promotes myocardial fibrosis in MI mouse

models (27,28). HDAC4-NT, the N-terminal fragment

of HDAC4, has also been investigated for its potential protective

role. A study has shown that HDAC4-NT overexpression ameliorates

cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis caused by abhydrolase

domain-containing 5 (ABHD5) deficiency. Mechanistically, this

effect may be associated with the downregulation of genes such as

natriuretic peptide B (Nppb), Myomaxin, nuclear receptor subfamily

4 group A member 1 (Nr4a1), glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate

transaminase 2 (Gfpt2), and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (Pdk4)

(29). Similarly, another study

confirmed that HDAC4-NT suppresses the expression of

fibrosis-related genes collagen type III alpha 1 chain (Col3a1) and

Col5a1 in transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced models

(30) (Fig. 2B).

Apoptosis, also known as programmed cell death, is

an active process regulated by specific genes (31). It plays a crucial role in

maintaining cellular homeostasis and in the prevention and

treatment of CVD (32). Studies

have shown that HDAC4 overexpression can induce apoptosis in

cardiomyocytes (33,34). Mechanistically, this may be

related to elevated expression of the pro-apoptotic protein,

caspase-3 (33). Evidence

indicates that HDAC4 is involved in the anti-apoptotic effects of

the lncRNA CASC11 in human CMECs (24). Similarly, Wu et al

(35) reported that silencing

lncRNA taurine-upregulated gene 1 (TUG1) suppresses the expression

of pro-apoptotic markers Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) and

cleaved caspase-3 but enhances the expression of the anti-apoptotic

protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2); this effect is associated with

increased HDAC4 expression. In addition, another study has revealed

the regulatory role of HDAC4 in apoptosis; specifically, HDAC4 can

inhibit cell death induced by the overexpression of microRNA

(miR)-200b-3p (36) (Fig. 2C).

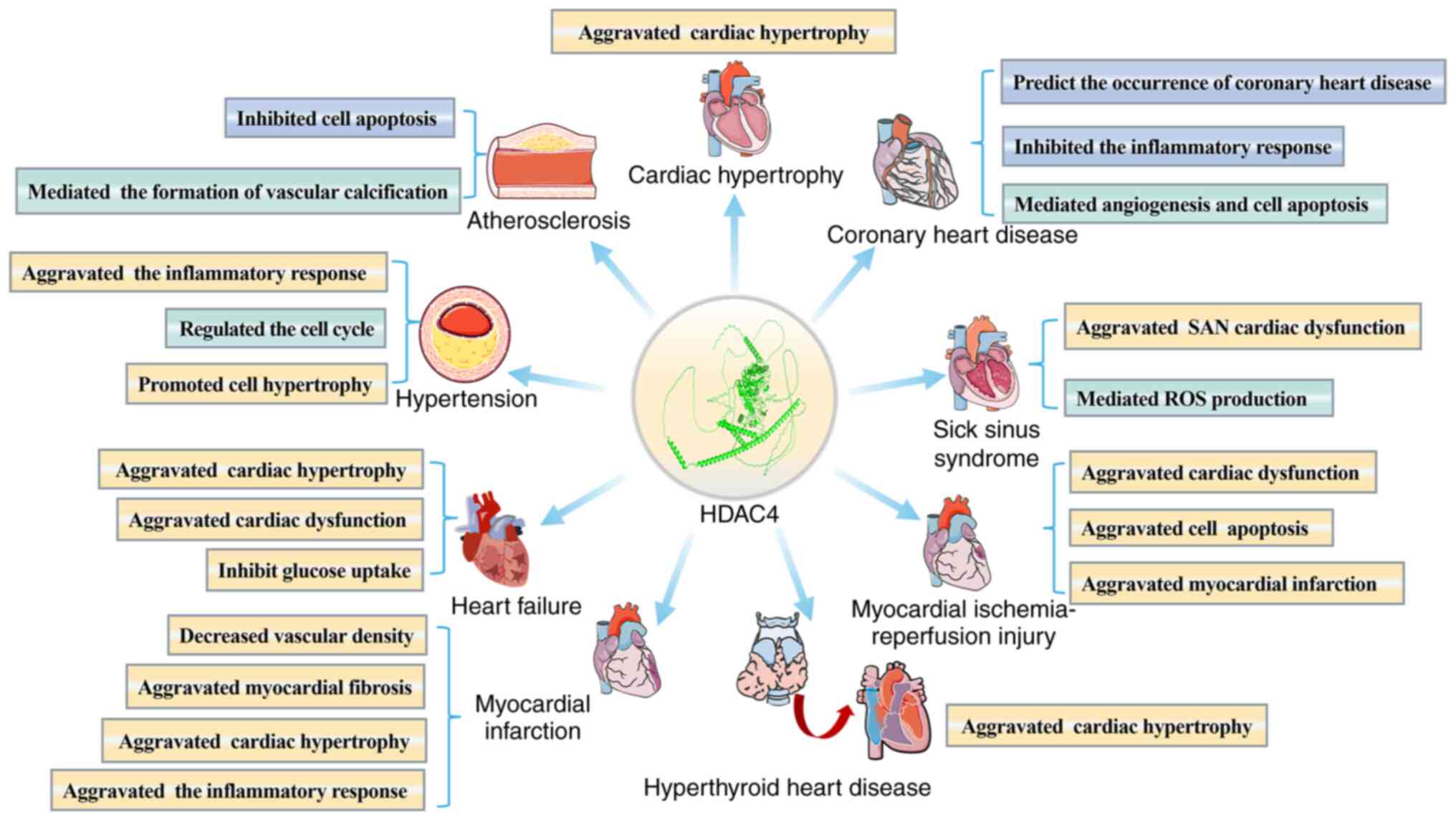

HDAC4 plays a regulatory role in inflammation,

myocardial fibrosis and apoptosis in the context of CVD (Fig. 2). These findings highlight the

significance of HDAC4 in the onset and progression of CVD. In the

following sections, the specific mechanisms by which HDAC4

functions in various types of CVD, particularly its

pathophysiological roles in common conditions such as cardiac

hypertrophy and CHD, will be further explored. A thorough

understanding of these mechanisms may offer new targets for the

treatment of these diseases.

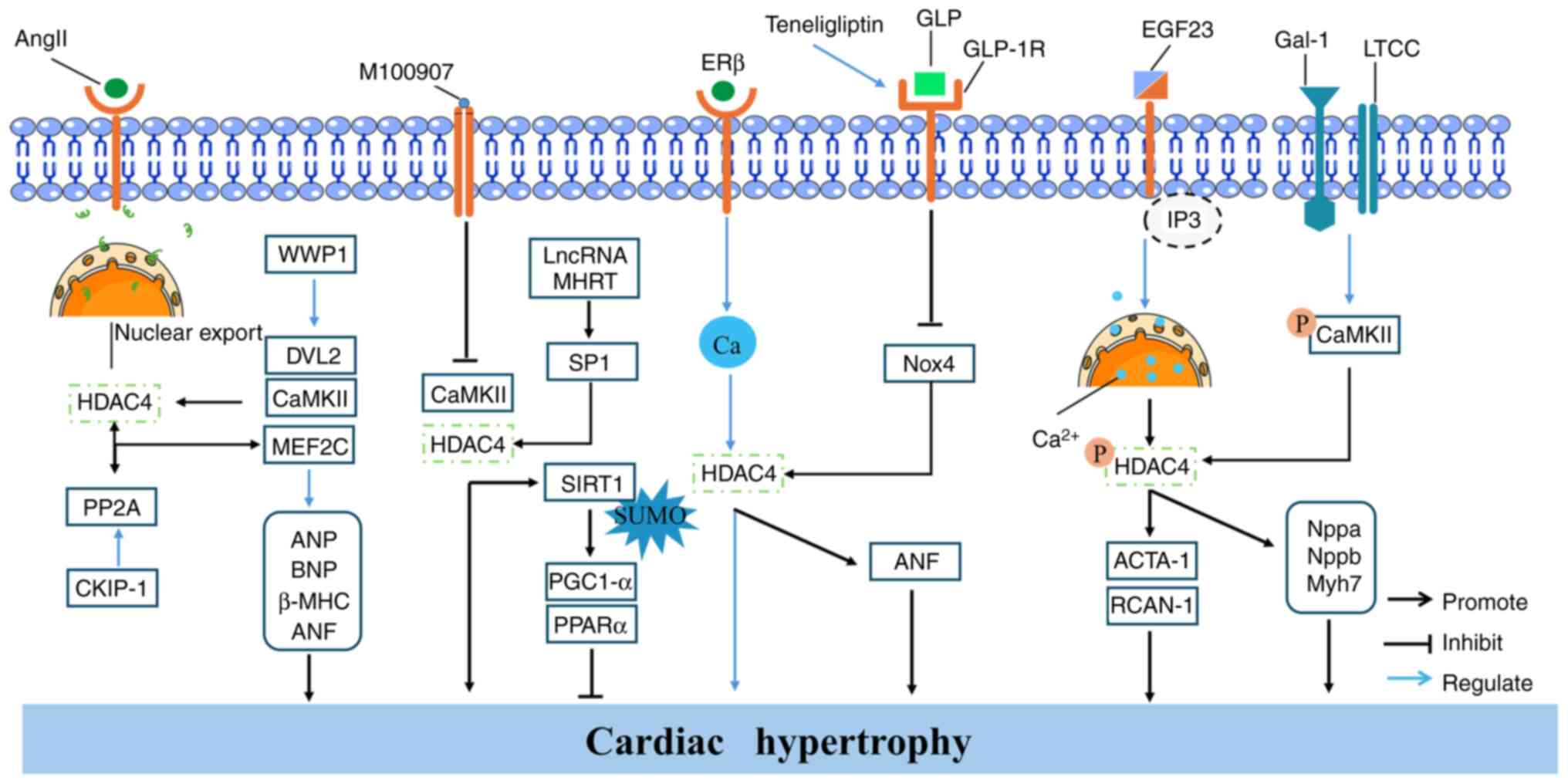

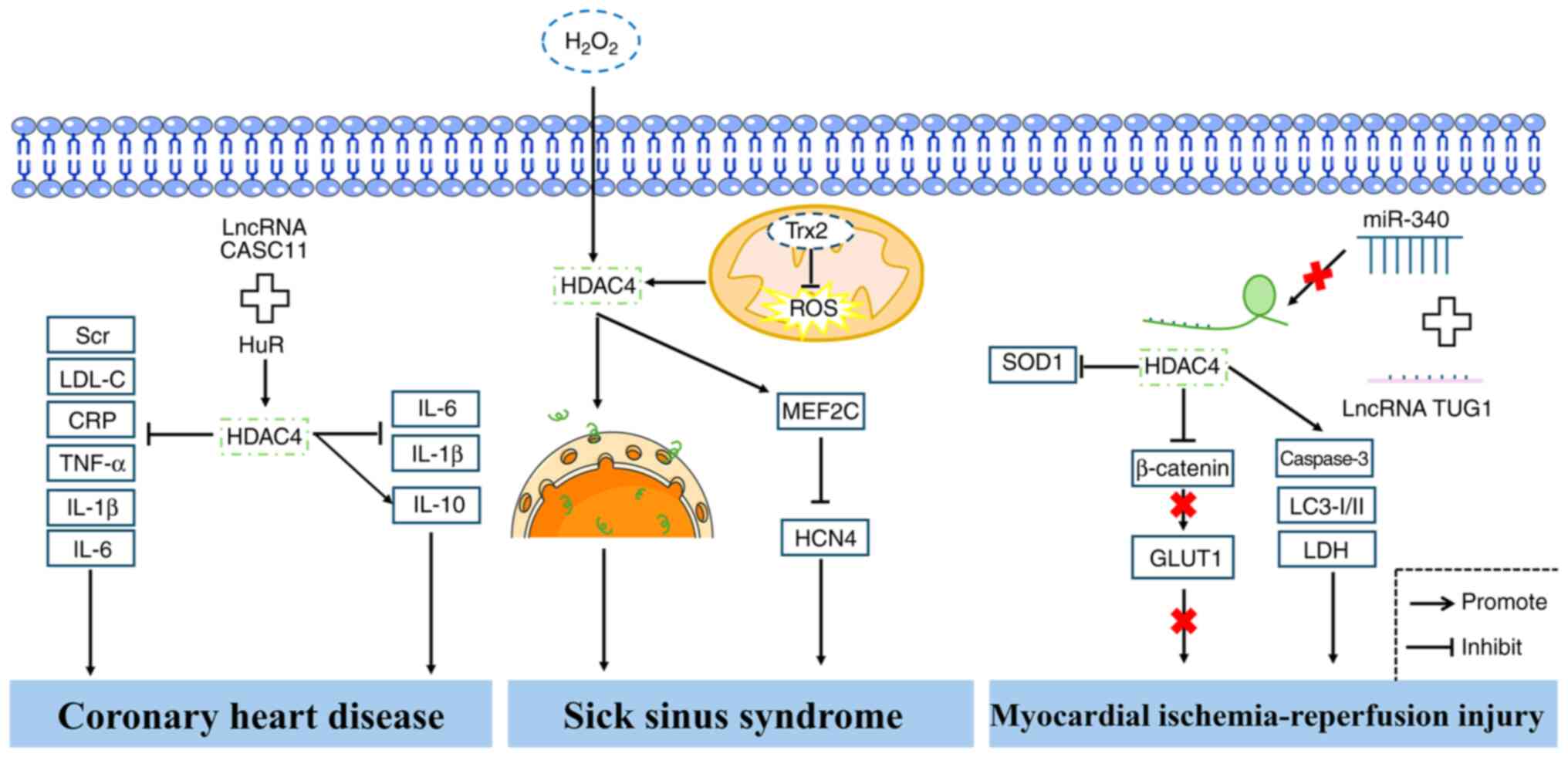

CHD, a myocardial condition caused by

atherosclerosis (AS) of the coronary arteries, remains the leading

cause of mortality worldwide (51,52). Despite advancements in medical

interventions, current treatment options for CHD are limited and

often associated with complications. A recent study has proposed

that HDAC4 expression levels may serve as a potential predictive

biomarker for CHD (13). This

hypothesis is supported by findings showing significantly reduced

HDAC4 expression in the serum of patients diagnosed with CHD.

Moreover, HDAC4 expression has been shown to correlate with several

clinical indicators, including serum creatinine (Scr), low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), C-reactive protein (CRP), and

blood glucose levels. In addition, correlation analysis revealed a

negative association between HDAC4 and inflammatory markers such as

TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 (13).

CMECs, which are among the most abundant cell types in the heart,

play a crucial role in regulating coronary blood flow (53-55). A study has shown that lncRNA

CASC11 can upregulate HDAC4 expression, thereby suppressing the

secretion of IL-6 and IL-1β and enhancing IL-10 expression in human

CMECs under ox-LDL stimulation (24). Knockdown of HDAC4 reverses these

effects, suggesting that HDAC4 plays a key regulatory role in the

anti-inflammatory process mediated by CASC11. Furthermore, HDAC4

was found to mediate the effects of CASC11 in suppressing apoptosis

and promoting angiogenesis (24). Bioinformatic analyses predicted

that CASC11 interacts with the RNA-binding protein human antigen R

(HuR), which binds to HDAC4, suggesting that CASC11 regulates HDAC4

expression through HuR-mediated stabilization. This mechanism

likely contributes to the protective effects of CASC11 against

ox-LDL-induced injury in CMECs (24). Collectively, these findings

suggested that HDAC4 may serve as a promising biomarker for the

prediction and potential therapeutic targeting of CHD (Fig. 4). However, further studies are

warranted to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms by which

HDAC4 contributes to the pathogenesis of CHD.

Preliminary studies have identified a correlation

between the development of SSS and advancing age, with the

condition primarily characterized by dysfunction of the sinoatrial

node (SAN) (56,57). Currently, treatment options for

SSS remain limited, highlighting the urgent need to explore novel

therapeutic targets. In a recent study, Zhang et al

(58) treated mouse atrial

myocytes (HL-1 cells) with hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) to mimic oxidative stress conditions

affecting SAN pace-making function. Their results demonstrated that

H2O2 treatment leads to increased HDAC4

expression and its subsequent nuclear translocation, which in turn

contribute to impaired SAN function (58). As the central organelle for

maintaining energy metabolic homeostasis in sinoatrial node cells,

mitochondria play a critical role in regulating their

electrophysiological excitability and rhythm stability (59,60). HDAC4 has been shown to play a

crucial role in mediating the protective effects of thioredoxin-2

(Trx2) against sinus bradycardia by inhibiting mitochondrial

reactive oxygen species (ROS) production within the SAN.

Mechanistically, Trx2 deficiency can suppress the expression of

hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated potassium

channel 4 via the mitochondrial ROS-HDAC4-MEF2C signaling axis,

resulting in SSS (61) (Fig. 4). These findings collectively

suggested that HDAC4 may represent a key therapeutic target for the

treatment of SSS.

MI-reperfusion injury refers to the damage inflicted

on cardiomyocytes upon the restoration of blood flow following MI,

and it has been shown to significantly affect patient prognosis

(62). An in vitro and

in vivo study demonstrated that the expression of the lncRNA

TUG1 is elevated in the hearts of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) mice

and in cardiomyocytes subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R).

Bioinformatic analysis predicted a direct interaction between TUG1

and miR-340, which in turn targets HDAC4. Subsequent experiments

confirmed that miR-340 overexpression reverses the upregulation of

HDAC4 induced by TUG1. Moreover, TUG1 knockdown suppresses the

H/R-induced expression of pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and cleaved

caspase-3 while enhancing the expression of the anti-apoptotic

protein Bcl-2 in cardiomyocytes. Conversely, HDAC4 overexpression

promotes apoptosis under these conditions (35). Interestingly, silencing β-catenin

reverses the upregulation of glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1)

induced by HDAC4 knockdown, suggesting that HDAC4 negatively

regulates β-catenin, thereby promoting GLUT1 expression, as further

supported by correlation analyses. In vivo experiments

demonstrated that TUG1 knockdown improves cardiac function, reduces

infarct size, and inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis in I/R mice.

However, these protective effects were partially abrogated by the

additional knockdown of miR-340 or GLUT1. These findings indicated

that targeting the TUG1/miR-340/HDAC4/β-catenin/GLUT1 regulatory

axis may offer a novel therapeutic approach for MI-reperfusion

injury (35). Mitochondrial

quality control (including mitophagy, mitochondrial dynamics and

mitochondrial biogenesis) has been recognized as a critical

regulatory mechanism in the pathological progression of MI injury

(63-66). A previous study found that HDAC4

overexpression increases H9c2 cell death, enhances mitochondrial

membrane permeability transition pore activity, elevates lactate

dehydrogenase release, and upregulates cleaved caspase-3 expression

under H/R conditions (67). In

line with these observations, Zhang et al (34) reported that HDAC4 overexpression

in I/R mice exacerbates myocardial injury, as evidenced by

increased infarct size, upregulation of autophagy-related proteins

microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3-I/II) and

apoptosis marker caspase-3, and downregulation of the antioxidant

protein superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), all of which contributed to

worsened ventricular dysfunction. Notably, treatment with the HDAC

inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA, 0.1 mg/kg) reversed these

pathological changes, suggesting that HDAC4 overexpression

aggravates I/R injury, whereas its inhibition may confer

cardioprotective effects (34)

(Fig. 4).

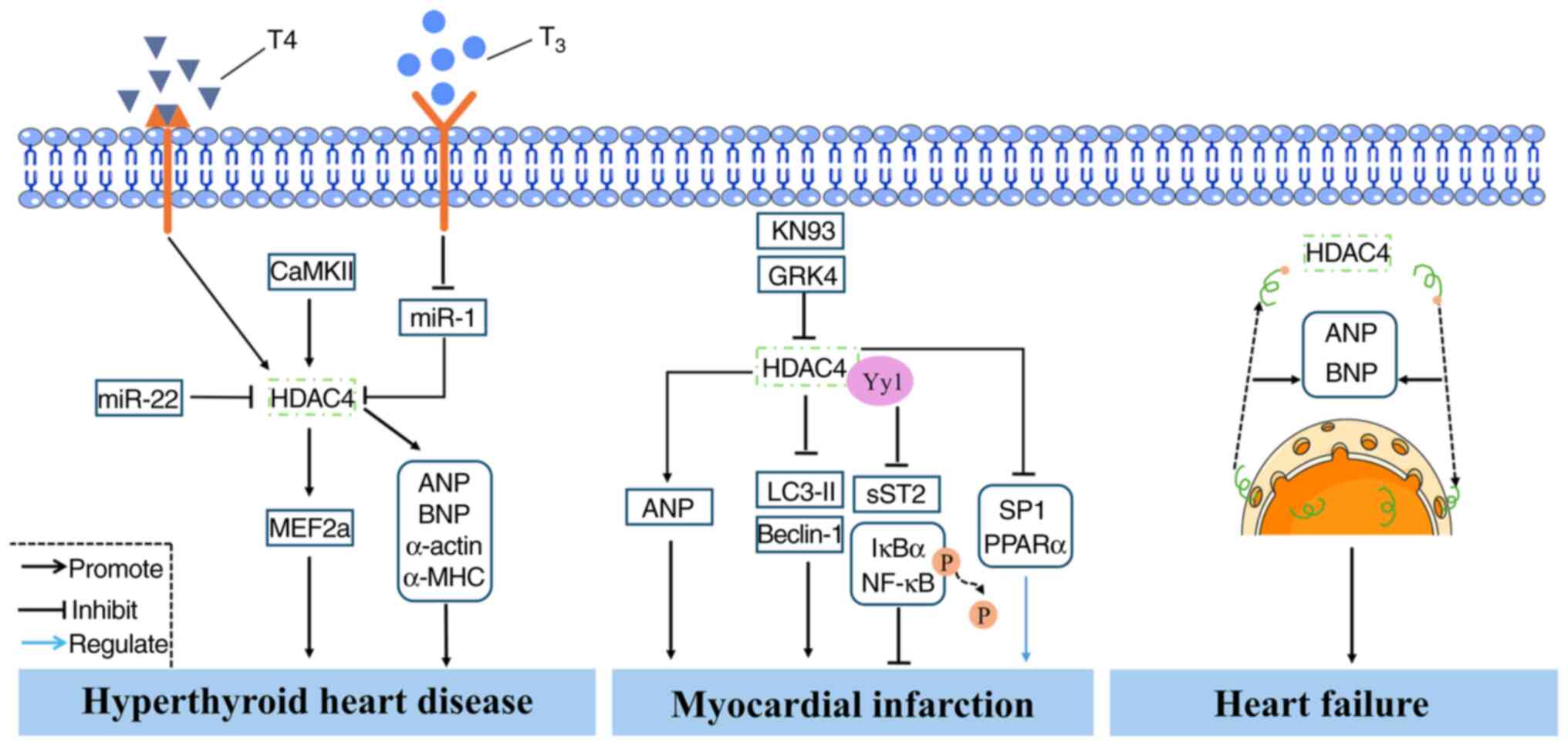

MI is a CVD with high lethality due to MI caused by

insufficient coronary blood supply (73). However, current treatment options

for MI remain limited, highlighting the urgent need to identify

novel therapeutic targets (74).

In vivo and in vitro studies have revealed that HDAC4

expression is elevated in MI (75,76). Overexpression of HDAC4 in MI

mouse models has been shown to result in impaired cardiac function,

enlarged cardiomyocytes, reduced vascular density, myocardial

fibrosis, and increased expression of the hypertrophic marker ANP

(28). Conversely,

transplantation of cardiac stem cells (CSCs) transfected with siRNA

targeting HDAC4 improves cardiac function in MI mice, suppresses

myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis, and promotes CSC-derived

neovascularization and cardiomyocyte proliferation (27). A study has also shown that HDAC4

interferes with the inhibitory effect of G protein-coupled receptor

kinase 4 on the autophagy-related genes LC3-II and Beclin-1 in the

myocardium of MI mice (77). In

another study, treatment with the HDAC4 inhibitor LMK235 was found

to rescue the upregulation of SP1 and the fatty acid oxidation

marker PPARα induced by KN93, suggesting a novel therapeutic

approach for MI (78).

Additionally, Asensio-Lopez et al (75) reported that HDAC4 specifically

interacts with yin-yang1 (Yy1) to suppress the expression of sST2,

thereby inhibiting cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and the activation of

phosphorylated inhibitor of nuclear factor κB α(IκBα)/NF-κB

signaling and ultimately ameliorating MI pathology (75). Current evidence indicates that

HDAC4 is upregulated in patients with MI, suggesting its potential

role as a key biomarker. Inhibition of HDAC4 expression has been

shown to improve MI outcomes by suppressing myocardial hypertrophy,

inflammation and fibrosis but promoting cardiomyocyte autophagy

(Fig. 5). Hypoxia contributes to

the development of MI (79).

However, a study has shown that hypoxia does not significantly

alter HDAC4 expression in H9c2 cells. Instead, HDAC1 expression is

increased under hypoxic conditions, indicating that relying solely

on HDAC4 expression levels as a predictive biomarker for MI may

have certain limitations (80).

HF is widely recognized as the end stage of numerous

CVDs and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates

(81). Therefore, the prevention

and treatment of HF are of particular clinical importance. To date,

numerous studies have demonstrated that HDAC4 plays a critical role

in the pathogenesis of HF (29,82,83). Clinical evidence indicates that,

compared with non-failing hearts, the nuclear expression of HDAC4

is reduced in the cardiomyocytes of patients with HF (5,84). Notably, HDAC4 nucleocytoplasmic

shuttling has been found to be positively correlated with the

expression of ANP and BNP (5).

An animal study has reported that HDAC4 expression is elevated in

the left ventricle of rat models of HF (83). Further research has shown that

inhibition of HDAC4 expression improves cardiac function in HF mice

and enhances myocardial glucose uptake (85) (Fig. 5). Collectively, these findings

suggested that targeting HDAC4 may provide therapeutic benefits in

the treatment of HF.

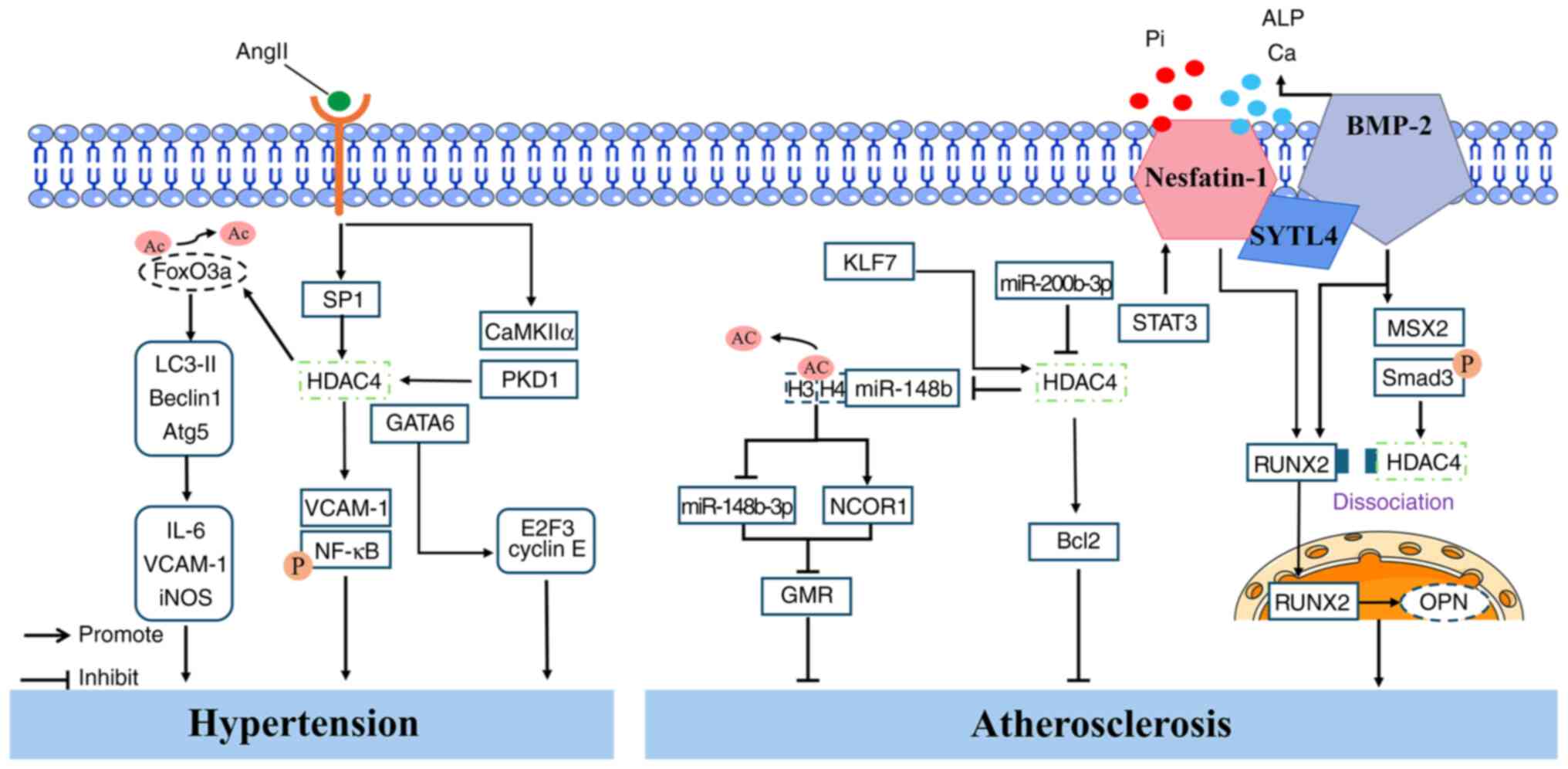

A recent study indicated that hypertension affects

over one billion people worldwide (86). Although various approaches have

been developed for the management of hypertension with advances in

medical science, a definitive cure has yet to be achieved (87). A characteristic feature of

hypertension is increased vascular stiffness (88). A study has shown that AngII

treatment upregulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines

(IL-6, VCAM-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase), autophagy

markers (LC3-II, Beclin1 and Atg5), and HDAC4 in primary RAECs and

in vivo in mice (22).

Further investigation revealed that AngII-induced autophagy

requires the involvement of endogenous forkhead box protein O3a

(FoxO3a). Treatment of RAECs with autophagy inhibitors LY294002 or

3-MA suppresses the AngII-induced expression of inflammatory

cytokines. Downregulation of HDAC4 inhibits AngII-induced vascular

inflammation and reverses the AngII-mediated reduction in FoxO3a

acetylation. These findings suggested that HDAC4 mediates the

acetylation of FoxO3a and regulates AngII-induced excessive

autophagy, thereby contributing to vascular inflammation (22). Similarly, Usui et al

(89) also demonstrated that

HDAC4 plays a key role in mediating vascular inflammation. In

animal experiments, HDAC4 expression was found to be elevated in

the mesenteric arteries of spontaneously hypertensive rats compared

with Wistar Kyoto rats. In vitro, treatment of rat

mesenteric artery SMCs with TNF-α upregulates the expression of

inflammatory markers VCAM-1 and p-NF-κB, as well as HDAC4. Notably,

silencing HDAC4 with siRNA reverses the TNF-α-induced expression of

these inflammatory markers in SMCs (23). Interestingly, HDAC4 protein

levels were found to be decreased in the aorta of hypertensive rats

but elevated in the mesenteric arteries, suggesting region-specific

differences in HDAC4 expression. This highlights the limitation of

evaluating disease progression based solely on HDAC4 levels in a

single vascular bed (23). One

study reported that MC1568, a class II HDAC inhibitor, suppresses

the AngII-induced expression of p-HDAC4S632 and

GATA-binding factor 6 (GATA6) in the kidneys and aortas of mice. An

in vitro study further showed that HDAC4 promotes the

expression of cell cycle regulatory genes E2F3 and cyclin E in

vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Notably, an endogenous

association between HDAC4 and GATA6 was confirmed in VSMCs. An

additional study demonstrated interactions among HDAC4, CaMKIIα and

PKD1 in 293T cells, which were disrupted by MC1568 treatment; thus,

MC1568 attenuates VSMC hypertrophy and proliferation by

downregulating the CaMKIIα/PKD1/HDAC4/GATA6 signaling pathway and

alleviating hypertension (90).

In summary, HDAC4 expression is elevated in multiple models of

hypertension and contributes to disease progression by promoting

vascular inflammation, VSMC hypertrophy and VSMC proliferation.

These findings underscore the potential of targeting HDAC4 as a

therapeutic strategy to delay the progression of hypertension

(Fig. 6).

AS is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized

by the accumulation of atherosclerotic plaques within the arterial

wall, resulting in reduced blood flow (91). Chen et al (92) demonstrated that HDAC4 mediates

the role of Krüppel-like factor 7 (KLF7) in AS. Specifically, KLF7

binds to the HDAC4 promoter to activate HDAC4 transcription, which

subsequently suppresses miR-148b-3p expression by reducing the

acetylation of histones H3 and H4 at the miR-148b promoter. This

suppression promotes the transcription of nuclear receptor

corepressor 1 (NCOR1), thereby inhibiting GMR in macrophages and

alleviating AS (92). AS is a

major underlying cause of CAD. A clinical study revealed that

miR-200b-3p is significantly upregulated in the epicardial adipose

tissue of patients with CAD (36). Further in vitro

experiments showed that the overexpression of miR-200b-3p

downregulates HDAC4 expression in HUVECs and reduces the expression

of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. Notably, the overexpression of

HDAC4 reverses miR-200b-3p-induced apoptosis, suggesting that HDAC4

plays a protective role against miR-200b-3p-mediated endothelial

apoptosis in AS (36). Vascular

calcification (VC) contributes to the progression of AS plaques. A

recent study reported that HDAC4 is involved in VC (93). The researchers found that

nesfatin-1 expression is elevated in patients with VS, in a vitamin

D3-induced VC mouse model, and in sodium phosphate (Pi)-treated

VSMCs. Moreover, nesfatin-1 expression was positively correlated

with the severity of VC in patients (93). In vivo experiments showed

that nesfatin-1 knockout reduces the expression of osteogenic

markers RUNX2 and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) in the

aortas of VC mice but enhances the expression of contractile

proteins α-SMA and SM22α. A further study revealed that BMP-2

promotes the expression of p-Smad3, HDAC4, RUNX2 and MSX2 in VSMCs;

enhances the binding of RUNX2 to the OPN promoter; increases

calcium content and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity; and

inhibits the formation of the HDAC4/RUNX2 complex. These effects

were reversed by nesfatin-1 knockout. Additionally, the proteasome

inhibitor MG-132 was shown to prevent BMP-2 degradation induced by

nesfatin-1 knockout. Bioinformatic analysis identified an

interaction between SYTL4 and BMP-2, and knockdown of SYTL4 also

inhibited BMP-2 ubiquitination and degradation triggered by

nesfatin-1 knockout. This reduced calcium deposition and ALP

activity under high-Pi conditions. Notably, the overexpression of

STAT3 was found to upregulate the expression of nesfatin-1, BMP-2

and RUNX2, indicating that the

STAT3/nesfatin-1/BMP-2/HDAC4/RUNX2/OPN signaling axis contributes

to VC progression (93)

(Fig. 6). In summary, these

findings highlight the potential of HDAC4 as a promising

therapeutic target in the treatment of AS.

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DC) refers to myocardial

structural and functional impairments caused by diabetes,

independent of other traditional confounding factors (94). DC has emerged as a significant

threat to human health (95).

Catalpol, one of the major active components of Rehmannia

glutinosa, has been shown to exert cardioprotective effects. A

study has found that knockdown of HDAC4 enhances the inhibitory

effects of catalpol on the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins

caspase-3 and Bax under high-glucose conditions, while promoting

the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. By contrast,

upregulation of HDAC4 expression facilitates apoptosis (33). However, another study reported

that cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of HDAC4 exacerbates cardiac

dysfunction in diabetic mice (96). These contradictory findings

suggested that the precise role of HDAC4 in DC remains

controversial and warrants further investigation.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a cardiac disorder

characterized by ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction in

the absence of abnormal loading conditions (97). A clinical study reported the

elevated expression of p-HDAC4 in the hearts of patients with

end-stage DCM (98). Similarly,

increased p-HDAC4 levels have also been observed in the hearts of

cTnTR141W familial DCM mouse models (99). Notably, HDAC4 is involved in

mediating the protective effects of Dickkopf 3, which suppresses

the expression of hypertrophic marker ANF and myocardial fibrosis

in DCM mice (99).

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a clinical

condition characterized by the sudden onset of acute ischemia or

necrosis of the myocardium. ACS encompasses ST-segment elevation MI

(STEMI), non-STEMI and unstable angina (104). A recent clinical study reported

the decreased expression of HDAC4 in patients with ACS, with the

lowest levels observed in those with STEMI. Furthermore, the study

found that HDAC4 expression was negatively correlated with total

cholesterol, LDL-C, CRP, cardiac troponin I, and a history of

hyperlipidemia (105). These

findings suggested that HDAC4 may serve as a predictive marker for

adverse cardiovascular events.

The peptide ligand apelin and its receptor APJ play

a critical role in regulating cardiovascular function. Homozygous

APJ knockout mice exhibit partial embryonic lethality, and

surviving embryos display cardiac and vascular defects. A further

study has shown that the apelin-APJ pathway regulates

cardiovascular function by modulating MEF2 activity through

Gα13-mediated phosphorylation of HDAC4 and HDAC5. Targeted

inhibition of HDAC4 phosphorylation and its cytoplasmic

translocation may potentially address cardiovascular defects and

embryonic lethality (106). A

study involving ventricular cardiomyocytes from mice, rabbits and

humans revealed that HDAC4 is regulated not only by CaMKII but also

by protein kinase A (PKA). Specifically, PKA was shown to regulate

the nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 through phosphorylation at the

S265/266 sites (107). This

novel finding provides new insights for the development of

therapeutic drugs or genetic interventions for CVD.

In summary, HDAC4 plays a crucial role in various

CVDs. Studies have shown that HDAC4 is directly or indirectly

involved in the onset and progression of CVD by modulating multiple

biological processes, including cell proliferation, inflammatory

responses and apoptosis. Moreover, an increasing number of studies

suggested that the regulatory role of HDAC4 in CVD may be closely

associated with mitochondrial function. As the central organelle

responsible for maintaining energy homeostasis in cardiomyocytes,

mitochondrial dysfunction is considered a major contributor to cell

death and the progression of CVD (108-111). Recent evidence has shown that

HDAC4 can modulate cardiomyocyte homeostasis by regulating the

mitochondrial permeability transition pore. These findings suggest

the existence of an as-yet undefined regulatory network between

HDAC4 and mitochondrial function, and further elucidation of this

interaction may deepen our understanding of CVD pathogenesis and

provide a theoretical basis for targeted therapeutic strategies.

However, despite numerous studies highlighting the potential role

of HDAC4 in cardiovascular pathology, research on its specific

molecular mechanisms and clinical applications remains in the

exploratory stage. Therefore, further elucidation of the factors

influencing HDAC4 expression is essential for the development of

targeted therapeutic strategies.

TSA is a commonly used hydroxamic acid-based HDAC

inhibitor. A study has shown that 20 nmol/l TSA can promote the

degradation of HDAC4 via the proteasome pathway, thereby inhibiting

H/R-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and LDH release (112). Yang et al (22) reported that treatment of RAECs

with 10 μM HDAC4 inhibitor tasquinimod can alleviate

AngII-induced vascular inflammation. LMK235, another hydroxamic

acid-based HDAC inhibitor, has been reported to exhibit high

selectivity for HDAC4 (113).

Chen et al (114) found

that the intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg/kg LMK235 can abolish

the protective effects of Huangqi Guizhi Wuwu decoction on

microvascular and endothelial dysfunction in diabetic mice.

However, another study has shown that LMK235 inhibits the

expression of HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, HDAC4, HDAC5 and HDAC7 induced

by CaMKIIα overexpression. Thus, LMK235 may act as a broad-spectrum

HDAC inhibitor, and its specificity for HDAC4 remains uncertain

(115). MC-1568 is a commonly

used inhibitor of HDAC4 and HDAC6. Research indicates that 1

μM MC-1568 can reduce the beating rate of cardiomyocytes in

rabbit pulmonary veins, indicating its potential application in the

regulation of arrhythmias (116).

An increasing body of research indicates that

various drugs can modulate HDAC4 expression, thereby influencing

the progression of CVD. A study has shown that 1 μM

lercanidipine or 0.1 μM tacrolimus can reverse the

AngII-induced expression of cardiac hypertrophy markers ANP and

BNP, possibly by inhibiting the CaMKII-HDAC4 signaling pathway

(117). Similarly, Wang et

al (118) found that 5

μM autocamtide-2-related inhibitory peptide suppresses

ISO-induced cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting CaMKII and HDAC4

expression. Panax quinquefolium saponin was shown to downregulate

CaMKII and HDAC4 expression in cardiomyocytes of rats subjected to

hindlimb unloading, thereby improving cardiac function (119). Liu et al (120) reported that ISO induces

hypertrophy in H9c2 cells and inhibits nuclear HDAC4 expression,

whereas 5 μmol/l isosteviol sodium (STVNa) reverses these

effects. Moreover, the addition of the Trx1 inhibitor PX-12

attenuates the effects of STVNa (120). Leucine is considered an

essential amino acid (121).

The administration of 3% leucine to HFpEF female rats has been

shown to inhibit the expression of HDAC4 in the heart, thereby

improving diastolic dysfunction (8). Quercetin, which has been

extensively studied for its cardiovascular benefits (122,123), was shown in an animal study to

alleviate cardiac hypertrophy by downregulating HDAC4 and p-HDAC4

Ser246 (123).

Additionally, 20 nM insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) analogue

Leu27IGF-II was found to increase the expression of CaMKIIδ,

p-HDAC4, p-HDAC5 and BNP in H9c2 cells. However, co-treatment with

Carthamus tinctorius extract inhibits the expression of

these proteins, suggesting that targeting HDAC4 holds therapeutic

potential for cardiac hypertrophy (124). An earlier study identified that

VSMCs contribute to increased vascular stiffness in hypertension

(125). Choi et al

(126) demonstrated that TMP269

inhibits class IIa HDACs (HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9) in VSMCs in a

dose-dependent manner. Similarly, panobinostat (LBH589) was found

to suppress class IIa HDAC activity. Notably, 10 μM TMP269

or LBH589 showed stronger inhibitory effects on HDAC4, HDAC5 and

HDAC9 in VSMCs compared with TSA (126). Gallic acid, a dietary phenolic

acid commonly found in edible plants (127,128), was also shown to inhibit class

IIa HDAC activity in VSMCs. Interestingly, 100 μM

sulforaphane inhibited the enzymatic activity of HDAC4, HDAC5 and

HDAC7, whereas a low concentration (1 μM) increased their

activity (126). A previous

study reported that 50 μM nifedipine downregulates

PE-induced p-HDAC4Ser632 expression and inhibits the

nuclear export of HDAC4, thereby alleviating pathological cardiac

hypertrophy (129). In

addition, Guo et al (130) discovered that aconitine (AC), a

key compound in Aconitum species, induces cardiotoxicity.

Transcriptomic sequencing and molecular docking experiments

demonstrated that AC promotes the interaction of HBB with ABHD5 and

AMPK, thereby regulating the ABHD5/AMPK/HDAC4 axis and contributing

to cardiotoxic effects (130).

Exercise, as a safe and effective multi-system

intervention, has shown beneficial effects in the prevention and

treatment of CVD (131). An

animal study demonstrated that 2 weeks of exercise increased the

expression of HDAC4-NT in the hearts of wild-type mice, whereas

mice with cardiomyocyte-specific knockout of HDAC4 exhibited

reduced exercise capacity (30).

By contrast, suppression of HDAC4 expression was found to enhance

exercise tolerance in mice with HF (85). Moreover, a recent study reported

that high-intensity interval training improves cardiac function in

HF by promoting skeletal muscle-derived meteorin-like, which

activates the AMPK-HDAC4 signaling pathway (132). These findings suggested that

exercise may regulate cardiac function via modulation of HDAC4,

offering new insights into personalized interventions for CVD.

The present review examined the role and underlying

mechanisms of HDAC4 in CVD, highlighting its regulatory potential

in key pathophysiological processes such as inflammation, fibrosis,

apoptosis and mitochondrial function. To date, an increasing body

of evidence has demonstrated the involvement of HDAC4 in the

progression of CVD, strongly suggesting that it may serve as a

promising molecular target for early intervention or personalized

therapy in the future (Fig. 7).

In cardiac pathologies such as myocardial hypertrophy, CHD, SSS,

MI-reperfusion injury, HHD, MI and HF, most studies have shown that

HDAC4 inhibition can alleviate cardiac damage by negatively

regulating cardiac function, suppressing myocardial inflammation

and fibrosis, and reducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis. In

hypertension, HDAC4 promotes vascular inflammation and hypertrophy

of VSMCs. By contrast, HDAC4 appears to play a protective role in

AS; for example, it can ameliorate AS by inhibiting

miR-200b-3p-induced apoptosis. In DC, HDAC4 exhibits dual

functions: On the one hand, its overexpression induces

cardiomyocyte apoptosis. On the other hand, HDAC4 deletion

exacerbates cardiac dysfunction in DC mice. These findings provide

a theoretical foundation for the development of HDAC4-centered

precision intervention strategies, which may facilitate a shift in

CVD treatment from late-stage symptom management to early-stage

molecular mechanism-based interventions.

However, there are still certain limitations in the

reports on HDAC4 in CVD. First, the expression patterns and

functional roles of HDAC4 in CVD induced by different pathological

stimuli remain controversial. There is a lack of comprehensive

analysis regarding its correlation with disease severity and

clinical prognosis, which warrants further investigation. Notably,

a previous study has revealed that HDAC4 inhibition can enhance

exercise capacity in mice with HF (85). Second, current research on the

safety, specificity and long-term efficacy of HDAC4-targeted

interventions remains in its early stages, limiting the feasibility

of clinical translation. Therefore, future studies should integrate

multi-omics approaches such as transcriptomics, proteomics and

metabolomics, combined with validation in large animal models and

analyses of patient-derived samples, to comprehensively assess the

mechanistic integrity and clinical translational potential of the

HDAC4 signaling pathway. Lastly, the potential role of HDAC4 in

diseases beyond the cardiovascular system warrants consideration.

In pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), stromal-derived factor 1

has been shown to activate the CaMKII/HDAC4 signaling pathway,

which stabilizes runt-related transcription factor 2, subsequently

promoting osteopontin expression and contributing to pulmonary

artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and vascular remodeling

(133). Simultaneously, ongoing

discussions surrounding the revised diagnostic threshold for mean

pulmonary arterial pressure have underscored the urgent need for

early molecular biomarkers in PAH (134). Thus, HDAC4 may serve as a

promising regulatory target, offering new opportunities for

mechanistic investigations and therapeutic interventions.

In summary, HDAC4 demonstrates potential as a

biomarker for monitoring CVD. Despite existing controversies,

ongoing research may confirm HDAC4 as a highly promising

therapeutic target in cardiovascular medicine.

Not applicable.

XM was responsible for conceptualization,

investigation, writing the original draft and illustration. RW was

responsible for conceptualization, investigation, illustration,

reviewing and editing the manuscript. AS was responsible for

conceptualization, reviewing and editing the manuscript. XZ was

responsible for illustration, reviewing and editing the manuscript.

JZ was responsible for investigation, reviewing and editing the

manuscript. SH was responsible for funding, supervision, reviewing

and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Scientific Research Fund

Program of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine

(grant no. KYZK2024Q18) and the Undergraduate Research Training

Program of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine

(grant no. 2025054).

|

1

|

Li P, Ge J and Li H: Lysine

acetyltransferases and lysine deacetylases as targets for

cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 17:96–115. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Haberland M, Montgomery RL and Olson EN:

The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and

physiology: Implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet.

10:32–42. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhang D, Hu X, Henning RH and Brundel BJ:

Keeping up the balance: Role of HDACs in cardiac proteostasis and

therapeutic implications for atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res.

109:519–526. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Backs J and Olson EN: Control of cardiac

growth by histone acetylation/deacetylation. Circ Res. 98:15–24.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hohl M, Wagner M, Reil JC, Müller SA,

Tauchnitz M, Zimmer AM, Lehmann LH, Thiel G, Böhm M, Backs J and

Maack C: HDAC4 controls histone methylation in response to elevated

cardiac load. J Clin Invest. 123:1359–1370. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang Z, Qin G and Zhao TC: HDAC4:

Mechanism of regulation and biological functions. Epigenomics.

6:139–150. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ouyang J, Wang H and Huang J: The role of

lactate in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 21:3172023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Alves PKN, Schauer A, Augstein A, Männel

A, Barthel P, Joachim D, Friedrich J, Prieto ME, Moriscot AS, Linke

A and Adams V: Leucine Supplementation improves diastolic function

in HFpEF by HDAC4 inhibition. Cells. 12:25612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ling S, Sun Q, Li Y, Zhang L, Zhang P,

Wang X, Tian C, Li Q, Song J, Liu H, et al: CKIP-1 inhibits cardiac

hypertrophy by regulating class II histone deacetylase

phosphorylation through recruiting PP2A. Circulation.

126:3028–3040. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li J, Gao Q, Wang S, Kang Z, Li Z, Lei S,

Sun X, Zhao M, Chen X, Jiao G, et al: Sustained increased CaMKII

phosphorylation is involved in the impaired regression of

isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats. J Pharmacol Sci.

144:30–42. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ginnan R, Sun LY, Schwarz JJ and Singer

HA: MEF2 is regulated by CaMKIIdelta2 and a HDAC4-HDAC5 heterodimer

in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem J. 444:105–114. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Berthouze-Duquesnes M, Lucas A, Sauliere

A, Sin YY, Laurent AC, Galés C, Baillie G and Lezoualc'h F:

Specific interactions between Epac1, β-arrestin2 and PDE4D5

regulate β-adrenergic receptor subtype differential effects on

cardiac hypertrophic signaling. Cell Signal. 25:970–980. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Guo Z, Wu Y, Feng Q, Wang C, Wang Z, Zhu

Y, Lu X, Chen W, Yang Q and Huo Y: Circulating HDAC4 reflects lipid

profile, coronary stenosis and inflammation in coronary heart

disease patients. Biomark Med. 17:41–49. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kong Q, Hao Y, Li X, Wang X, Ji B and Wu

Y: HDAC4 in ischemic stroke: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential.

Clin Epigenetics. 10:1172018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen Z, Zhang Z, Guo L, Wei X, Zhang Y,

Wang X and Wei L: The role of histone deacetylase 4 during

chondrocyte hypertrophy and endochondral bone development. Bone

Joint Res. 9:82–89. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mathias RA, Guise AJ and Cristea IM:

Post-translational modifications regulate class IIa histone

deacetylase (HDAC) function in health and disease. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 14:456–470. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cuttini E, Goi C, Pellarin E, Vida R and

Brancolini C: HDAC4 in cancer: A multitasking platform to drive not

only epigenetic modifications. Front Mol Biosci. 10:11166602023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Duarte LRF, Pinho V, Rezende BM and

Teixeira MM: Resolution of inflammation in acute

graft-versus-host-disease: Advances and perspectives. Biomolecules.

12:752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Liberale L, Badimon L, Montecucco F,

Luscher TF, Libby P and Camici GG: Inflammation, aging, and

cardiovascular disease: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 79:837–847. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cui C, Liu L, Qi Y, Han N, Xu H, Wang Z,

Shang X, Han T, Zha Y, Wei X and Wu Z: Joint association of TyG

index and high sensitivity C-reactive protein with cardiovascular

disease: A national cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 23:1562024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fredman G and Serhan CN: Specialized

pro-resolving mediators in vascular inflammation and

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol.

21:808–823. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang D, Xiao C, Long F, Su Z, Jia W, Qin

M, Huang M, Wu W, Suguro R, Liu X and Zhu Y: HDAC4 regulates

vascular inflammation via activation of autophagy. Cardiovasc Res.

114:1016–1028. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Usui T, Okada M, Hara Y and Yamawaki H:

Exploring calmodulin-related proteins, which mediate development of

hypertension, in vascular tissues of spontaneous hypertensive rats.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 405:47–51. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Hu K, Huang MJ, Ling S, Li YX, Cao XY,

Chen YF, Lei JM, Fu WZ and Tan BF: LncRNA CASC11 upregulation

promotes HDAC4 to alleviate oxidized low-density

lipoprotein-induced injury of cardiac microvascular endothelial

cells. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 39:758–768. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ravassa S, Lopez B, Treibel TA, José GS,

Losada-Fuentenebro B, Tapia L, Bayés-Genís A, Díez J and González

A: Cardiac Fibrosis in heart failure: Focus on non-invasive

diagnosis and emerging therapeutic strategies. Mol Aspects Med.

93:1011942023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang Y, Gao F, Tang Y, Xiao J, Li C,

Ouyang Y and Hou Y: Valproic acid regulates Ang II-induced

pericyte-myofibroblast trans-differentiation via MAPK/ERK pathway.

Am J Transl Res. 10:1976–1989. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhang LX, DeNicola M, Qin X, Du J, Ma J,

Zhao YT, Zhuang S, Liu PY, Wei L, Qin G, et al: Specific inhibition

of HDAC4 in cardiac progenitor cells enhances myocardial repairs.

Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 307:C358–C372. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang LX, Du J, Zhao YT, Wang J, Zhang S,

Dubielecka PM, Wei L, Zhuang S, Qin G, Chin YE and Zhao TC:

Transgenic overexpression of active HDAC4 in the heart attenuates

cardiac function and exacerbates remodeling in infarcted

myocardium. J Appl Physiol (1985). 125:1968–1978. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jebessa ZH, Shanmukha KD, Dewenter M,

Lehmann LH, Xu C, Schreiter F, Siede D, Gong XM, Worst BC, Federico

G, et al: The lipid droplet-associated protein ABHD5 protects the

heart through proteolysis of HDAC4. Nat Metab. 1:1157–1167. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lehmann LH, Jebessa ZH, Kreusser MM,

Horsch A, He T, Kronlage M, Dewenter M, Sramek V, Oehl U,

Krebs-Haupenthal J, et al: A proteolytic fragment of histone

deacetylase 4 protects the heart from failure by regulating the

hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Nat Med. 24:62–72. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhan J, Wang J, Liang Y, Wang L, Huang L,

Liu S, Zeng X, Zeng E and Wang H: Apoptosis dysfunction:

Unravelling the interplay between ZBP1 activation and viral

invasion in innate immune responses. Cell Commun Signal.

22:1492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Emdad L, Bhoopathi P, Talukdar S, Pradhan

AK, Sarkar D, Wang XY, Das SK and Fisher PB: Recent insights into

apoptosis and toxic autophagy: The roles of MDA-7/IL-24, a

multidimensional anti-cancer therapeutic. Semin Cancer Biol.

66:140–154. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

33

|

Zou G, Zhong W, Wu F, Wang X and Liu L:

Catalpol attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetic

cardiomyopathy via Neat1/miR-140-5p/HDAC4 axis. Biochimie.

165:90–99. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhang L, Wang H, Zhao Y, Wang J,

Dubielecka PM, Zhuang S, Qin G, Chin YE, Kao RL and Zhao TC:

Myocyte-specific overexpressing HDAC4 promotes myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Mol Med. 24:372018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wu X, Liu Y, Mo S, Wei W, Ye Z and Su Q:

LncRNA TUG1 competitively binds to miR-340 to accelerate myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 35:e211632021.

|

|

36

|

Zhang F, Cheng N, Du J, Zhang H and Zhang

C: MicroRNA-200b-3p promotes endothelial cell apoptosis by

targeting HDAC4 in atherosclerosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord.

21:1722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bazgir F, Nau J, Nakhaei-Rad S, Amin E,

Wolf MJ, Saucerman JJ, Lorenz K and Ahmadian MR: The

microenvironment of the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy. Cells.

12:17802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ago T, Liu T, Zhai P, Chen W, Li H,

Molkentin JD, Vatner SF and Sadoshima J: A redox-dependent pathway

for regulating class II HDACs and cardiac hypertrophy. Cell.

133:978–993. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Backs J, Song K, Bezprozvannaya S, Chang S

and Olson EN: CaM kinase II selectively signals to histone

deacetylase 4 during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest.

116:1853–1864. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fujioka R, Yamamoto T, Maruta A, Nakamura

Y, Tominaga N, Inamitsu M, Oda T, Kobayashi S and Yano M: Herpud1

modulates hypertrophic signals independently of calmodulin nuclear

translocation in rat myocardium-derived H9C2 cells. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 652:61–67. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zheng L, Wang J, Zhang R, Zhang Y, Geng J,

Cao L, Zhao X, Geng J, Du X, Hu Y and Cong H: Angiotensin II

mediates cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in atrial cardiomyopathy via

epigenetic transcriptional regulation. Comput Math Methods Med.

2022:63121002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhao D, Zhong G, Li J, Pan J, Zhao Y, Song

H, Sun W, Jin X, Li Y, Du R, et al: Targeting E3 ubiquitin ligase

WWP1 prevents cardiac hypertrophy through destabilizing DVL2 via

inhibition of K27-linked ubiquitination. Circulation. 144:694–711.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li C, Cai X, Sun H, Bai T, Zheng X, Zhou

XW, Chen X, Gill DL, Li J and Tang XD: The deltaA isoform of

calmodulin kinase II mediates pathological cardiac hypertrophy by

interfering with the HDAC4-MEF2 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 409:125–130. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lairez O, Cognet T, Schaak S, Calise D,

Guilbeau-Frugier C, Parini A and Mialet-Perez J: Role of serotonin

5-HT2A receptors in the development of cardiac hypertrophy in

response to aortic constriction in mice. J Neural Transm (Vienna).

120:927–935. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Liu MY, Yue LJ, Luo YC, Lu J, Wu GD, Sheng

SQ, Shi YQ and Dong ZX: SUMOylation of SIRT1 activating

PGC-1alpha/PPARalpha pathway mediates the protective effect of

LncRNA-MHRT in cardiac hypertrophy. Eur J Pharmacol.

930:1751552022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Pedram A, Razandi M, Narayanan R, Dalton

JT, McKinsey TA and Levin ER: Estrogen regulates histone

deacetylases to prevent cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Biol Cell.

24:3805–3818. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Okabe K, Matsushima S, Ikeda S, Ikeda M,

Ishikita A, Tadokoro T, Enzan N, Yamamoto T, Sada M, Deguchi H, et

al: DPP (Dipeptidyl Peptidase)-4 inhibitor attenuates Ang II

(Angiotensin II)-induced cardiac hypertrophy via GLP (Glucagon-Like

Peptide)-1-dependent suppression of Nox (Nicotinamide Adenine

Dinucleotide Phosphate Oxidase) 4-HDAC (Histone Deacetylase) 4

pathway. Hypertension. 75:991–1001. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Mhatre KN, Wakula P, Klein O, Bisping E,

Völkl J, Pieske B and Heinzel FR: Crosstalk between FGF23- and

angiotensin II-mediated Ca(2+) signaling in pathological cardiac

hypertrophy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 75:4403–4416. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Fan J, Fan W, Lei J, Zhou Y, Xu H, Kapoor

I, Zhu G and Wang J: Galectin-1 attenuates cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy through splice-variant specific modulation of

CaV1.2 calcium channel. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis

Dis. 1865:218–229. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Matsushima S, Kuroda J, Ago T, Zhai P,

Park JY, Xie LH, Tian B and Sadoshima J: Increased oxidative stress

in the nucleus caused by Nox4 mediates oxidation of HDAC4 and

cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 112:651–663. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

51

|

Zhou P, Zhao XN, Ma YY, Tang TJ, Wang SS,

Wang L and Huang J: Virtual screening analysis of natural

flavonoids as trimethylamine (TMA)-lyase inhibitors for coronary

heart disease. J Food Biochem. 46:e143762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shaya GE, Leucker TM, Jones SR, Martin SS

and Toth PP: Coronary heart disease risk: Low-density lipoprotein

and beyond. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 32:181–194. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Wang C and Ma D:

Endothelial-cell-mediated mechanism of coronary microvascular

dysfunction leading to heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction. Heart Fail Rev. 28:169–178. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

54

|

Yan P, Sun C, Ma J, Jin Z, Guo R and Yang

B: MicroRNA-128 confers protection against cardiac microvascular

endothelial cell injury in coronary heart disease via negative

regulation of IRS1. J Cell Physiol. 234:13452–13463. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhang X, Zhou H and Chang X: Involvement

of mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy in diabetic endothelial

dysfunction and cardiac microvascular injury. Arch Toxicol.

97:3023–3035. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Haqqani HM and Kalman JM: Aging and

sinoatrial node dysfunction: Musings on the not-so-funny side.

Circulation. 115:1178–1179. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mesquita T, Miguel-Dos-Santos R and

Cingolani E: Aging and sinus node dysfunction: Mechanisms and

future directions. Clin Sci (Lond). 139:577–593. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang H, Li L, Hao M, Chen K, Lu Y, Qi J,

Chen W, Ren L, Cai X, Chen C, et al: Yixin-Fumai granules improve

sick sinus syndrome in aging mice through Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway: A new

target for sick sinus syndrome. J Ethnopharmacol. 277:1142542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Chang X, Zhou S, Liu J, Wang Y, Guan X, Wu

Q, Zhang Q, Liu Z and Liu R: Zishen Tongyang Huoxue decoction

(TYHX) alleviates sinoatrial node cell ischemia/reperfusion injury

by directing mitochondrial quality control via the VDAC1-β-tubulin

signaling axis. J Ethnopharmacol. 320:1173712024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Chang X, Li Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Guan X, Wu

Q, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Chen Y, Huang Y and Liu R: β-tubulin

contributes to Tongyang Huoxue decoction-induced protection against

hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury of sinoatrial node cells

through SIRT1-mediated regulation of mitochondrial quality

surveillance. Phytomedicine. 108:1545022023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Yang B, Huang Y, Zhang H, Huang Y, Zhou

HJ, Young L, Xiao H and Min W: Mitochondrial thioredoxin-2

maintains HCN4 expression and prevents oxidative stress-mediated

sick sinus syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 138:291–303. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Chen L, Mao LS, Xue JY, Jian YH, Deng ZW,

Mazhar M, Zou Y, Liu P, Chen MT, Luo G and Liu MN: Myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury: The balance mechanism between

mitophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome. Life Sci. 355:1229982024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Chang X, Zhou S, Liu J, Wang Y, Guan X, Wu

Q, Liu Z and Liu R: Zishenhuoxue decoction-induced myocardial

protection against ischemic injury through TMBIM6-VDAC1-mediated

regulation of calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial quality

surveillance. Phytomedicine. 132:1553312024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Chang X, Liu R, Li R, Peng Y, Zhu P and

Zhou H: Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial quality control in

ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int J Biol Sci. 19:426–448. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wang J, Zhuang H, Jia L, He X, Zheng S, Ji

K, Xie K, Ying T, Zhang Y, Li C and Chang X: Nuclear receptor

subfamily 4 group A member 1 promotes myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury through inducing mitochondrial fission

factor-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation and inhibiting FUN14

domain containing 1-depedent mitophagy. Int J Biol Sci.

20:4458–4475. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Pu X, Zhang Q, Liu J, Wang Y, Guan X, Wu

Q, Liu Z, Liu R and Chang X: Ginsenoside Rb1 ameliorates heart

failure through DUSP-1-TMBIM-6-mediated mitochondrial quality

control and gut flora interactions. Phytomedicine. 132:1558802024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Zhao YT, Wang H, Zhang S, Du J, Zhuang S

and Zhao TC: Irisin ameliorates hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced

injury through modulation of histone deacetylase 4. PLoS One.

11:e01661822016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Lee SY and Pearce EN: Hyperthyroidism: A

review. JAMA. 330:1472–1483. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Kim HJ and McLeod DSA: Subclinical

hyperthyroidism and cardiovascular disease. Thyroid. 34:1335–1345.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Nie D, Xia C, Wang Z, Ding P, Meng Y, Liu

J, Li T, Gan T, Xuan B, Huang Y, et al: CaMKII inhibition protects

against hyperthyroid arrhythmias and adverse myocardial remodeling.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 615:136–142. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Diniz GP, Lino CA, Moreno CR, Senger N and

Barreto-Chaves MLM: MicroRNA-1 overexpression blunts cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy elicited by thyroid hormone. J Cell Physiol.

232:3360–3368. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Huang ZP, Chen J, Seok HY, Zhang Z,

Kataoka M, Hu X and Wang DZ: MicroRNA-22 regulates cardiac

hypertrophy and remodeling in response to stress. Circ Res.

112:1234–1243. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Yang W, Lin J, Zhou J, Zheng Y, Jiang S,

He S and Li D: Innate lymphoid cells and myocardial infarction.

Front Immunol. 12:7582722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Turkieh A, El Masri Y, Pinet F and

Dubois-Deruy E: Mitophagy regulation following myocardial

infarction. Cells. 11:1992022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Asensio-Lopez MC, Lax A, Del Palacio MJ,

Sassi Y, Hajjar RJ, Januzzi JL, Bayes-Genis A and Pascual-Figal DA:

Yin-Yang 1 transcription factor modulates ST2 expression during

adverse cardiac remodeling post-myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell

Cardiol. 130:216–233. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Lv F, Xie L, Li L and Lin J: LMK235

ameliorates inflammation and fibrosis after myocardial infarction

by inhibiting LSD1-related pathway. Sci Rep. 14:234502024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Li L, Fu W, Gong X, Chen Z, Tang L, Yang

D, Liao Q, Xia X, Wu H, Liu C, et al: The role of G protein-coupled

receptor kinase 4 in cardiomyocyte injury after myocardial

infarction. Eur Heart J. 42:1415–1430. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

78

|

Zhao J, Li L, Wang X and Shen J: KN-93

promotes HDAC4 nucleus translocation to promote fatty acid

oxidation in myocardial infarction. Exp Cell Res. 438:1140502024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Hermann DM, Xin W, Bahr M, Giebel B and

Doeppner TR: Emerging roles of extracellular vesicle-associated

non-coding RNAs in hypoxia: Insights from cancer, myocardial

infarction and ischemic stroke. Theranostics. 12:5776–5802. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Li Y, Zhang Z, Zhou X, Li R, Cheng Y,

Shang B, Han Y, Liu B and Xie X: Histone deacetylase 1 inhibition

protects against hypoxia-induced swelling in H9c2 cardiomyocytes

through regulating cell stiffness. Circ J. 82:192–202. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic

P, Rosano GMC and Coats AJS: Global burden of heart failure: A

comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res.

118:3272–3287. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Ljubojevic-Holzer S, Herren AW, Djalinac

N, Voglhuber J, Morotti S, Holzer M, Wood BM, Abdellatif M, Matzer

I, Sacherer M, et al: CaMKIIdeltaC drives early adaptive

Ca2+ change and late eccentric cardiac hypertrophy. Circ

Res. 127:1159–1178. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Lkhagva B, Lin YK, Kao YH, Chazo TF, Chung

CC, Chen SA and Chen YJ: Novel histone deacetylase inhibitor

modulates cardiac peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and

inflammatory cytokines in heart failure. Pharmacology. 96:184–191.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Calalb MB, McKinsey TA, Newkirk S, Huynh

K, Sucharov CC and Bristow MR: Increased phosphorylation-dependent

nuclear export of class II histone deacetylases in failing human

heart. Clin Transl Sci. 2:325–332. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Jiang H, Jia D, Zhang B, Yang W, Dong Z,

Sun X, Cui X, Ma L, Wu J, Hu K, et al: Exercise improves cardiac

function and glucose metabolism in mice with experimental

myocardial infarction through inhibiting HDAC4 and upregulating

GLUT1 expression. Basic Res Cardiol. 115:282020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Dzau VJ and Hodgkinson CP: Precision

hypertension. Hypertension. 81:702–708. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Kanbay M, Copur S, Tanriover C, Ucku D and

Laffin L: Future treatments in hypertension: Can we meet the unmet

needs of patients? Eur J Intern Med. 115:18–28. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Laurent S, Alivon M, Beaussier H and

Boutouyrie P: Aortic stiffness as a tissue biomarker for predicting

future cardiovascular events in asymptomatic hypertensive subjects.

Ann Med. 44(Suppl 1): S93–S97. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Usui T, Okada M, Mizuno W, Oda M, Ide N,

Morita T, Hara Y and Yamawaki H: HDAC4 mediates development of

hypertension via vascular inflammation in spontaneous hypertensive

rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 302:H1894–H1904. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Kim GR, Cho SN, Kim HS, Yu SY, Choi SY,

Ryu Y, Lin MQ, Jin L, Kee HJ and Jeong MH: Histone deacetylase and

GATA-binding factor 6 regulate arterial remodeling in angiotensin

II-induced hypertension. J Hypertens. 34:2206–2219. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Saigusa R, Winkels H and Ley K: T cell

subsets and functions in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol.

17:387–401. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Chen F, Li J, Zheng T, Chen T and Yuan Z:

KLF7 alleviates atherosclerotic lesions and inhibits glucose

metabolic reprogramming in macrophages by regulating

HDAC4/miR-148b-3p/NCOR1. Gerontology. 68:1291–1310. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Zhu XX, Meng XY, Chen G, Sru JB, Fu X, Xu

AJ, Liu Y, Hou XH, Qiu HB, Sun QY, et al: Nesfatin-1 enhances

vascular smooth muscle calcification through facilitating BMP-2

osteogenic signaling. Cell Commun Signal. 22:4882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Zhao X, Liu S, Wang X, Chen Y, Pang P,

Yang Q, Lin J, Deng S, Wu S, Fan G and Wang B: Diabetic

cardiomyopathy: Clinical phenotype and practice. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:10322682022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Ma X, Mei S, Wuyun Q, Zhou L, Sun D and

Yan J: Epigenetics in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Clin Epigenetics.

16:522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Kronlage M, Dewenter M, Grosso J, Fleming

T, Oehl U, Lehmann LH, Falcão-Pires I, Leite-Moreira AF, Volk N,

Gröne HJ, et al: O-GlcNAcylation of histone deacetylase 4 protects

the diabetic heart from failure. Circulation. 140:580–594. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Heymans S, Lakdawala NK, Tschope C and

Klingel K: Dilated cardiomyopathy: Causes, mechanisms, and current

and future treatment approaches. Lancet. 402:998–1011. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Castillero E, Ali ZA, Akashi H, Giangreco

N, Wang C, Stöhr EJ, Ji R, Zhang X, Kheysin N, Park JS, et al:

Structural and functional cardiac profile after prolonged duration

of mechanical unloading: Potential implications for myocardial

recovery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 315:H1463–H1476. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Lu D, Bao D, Dong W, Liu N, Zhang X, Gao

S, Ge W, Gao X and Zhang L: Dkk3 prevents familial dilated

cardiomyopathy development through Wnt pathway. Lab Invest.

96:239–248. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Li T, Mu N, Yin Y, Yu L and Ma H:

Targeting AMP-activated protein kinase in aging-related

cardiovascular diseases. Aging Dis. 11:967–977. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Tyrrell DJ and Goldstein DR: Ageing and

atherosclerosis: Vascular intrinsic and extrinsic factors and

potential role of IL-6. Nat Rev Cardiol. 18:58–68. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Saravi SS and Feinberg MW: Can removal of

zombie cells revitalize the aging cardiovascular system? Eur Heart

J. 45:867–869. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Shabanian K, Shabanian T, Karsai G,

Pontiggia L, Paneni F, Ruschitzka F, Beer JH and Saravi SS: AQP1

differentially orchestrates endothelial cell senescence. Redox

Biol. 76:1033172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Bhatt DL, Lopes RD and Harrington RA:

Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes: A review.

JAMA. 327:662–675. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Xu H, Zhang J, Jia H, Xing F and Cong H:

Serum histone deacetylase 4 longitudinal change for estimating

major adverse cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome

patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention. Ir J Med

Sci. 192:2689–2696. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Kang Y, Kim J, Anderson JP, Wu J, Gleim

SR, Kundu RK, McLean DL, Kim JD, Park H, Jin S, et al: Apelin-APJ

signaling is a critical regulator of endothelial MEF2 activation in

cardiovascular development. Circ Res. 113:22–31. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Helmstadter KG, Ljubojevic-Holzer S, Wood

BM, Taheri KD, Sedej S, Erickson JR, Bossuyt J and Bers DM: CaMKII

and PKA-dependent phosphorylation co-regulate nuclear localization

of HDAC4 in adult cardiomyocytes. Basic Res Cardiol. 116:112021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Li Y, Yu J, Li R, Zhou H and Chang X: New

insights into the role of mitochondrial metabolic dysregulation and

immune infiltration in septic cardiomyopathy by integrated

bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Cell Mol Biol

Lett. 29:212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Chang X, Zhang Q, Huang Y, Liu J, Wang Y,

Guan X, Wu Q, Liu Z and Liu R: Quercetin inhibits necroptosis in

cardiomyocytes after ischemia-reperfusion via

DNA-PKcs-SIRT5-orchestrated mitochondrial quality control.

Phytother Res. 38:2496–2517. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Wang J, Zhuang H, Yang X, Guo Z, Zhou K,

Liu N, An Y, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Wang M, et al: Exploring the

mechanism of ferroptosis induction by sappanone A in cancer:

Insights into the mitochondrial dysfunction mediated by

NRF2/xCT/GPX4 axis. Int J Biol Sci. 20:5145–5161. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Pang B, Dong G, Pang T, Sun X, Liu X, Nie

Y and Chang X: Emerging insights into the pathogenesis and

therapeutic strategies for vascular endothelial injury-associated

diseases: Focus on mitochondrial dysfunction. Angiogenesis.

27:623–639. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Du J, Zhang L, Zhuang S, Qin GJ and Zhao

TC: HDAC4 degradation mediates HDAC inhibition-induced protective

effects against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. J Cell Physiol.

230:1321–1331. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

113

|

Marek L, Hamacher A, Hansen FK, Kuna K,

Gohlke H, Kassack MU and Kurz T: Histone deacetylase (HDAC)

inhibitors with a novel connecting unit linker region reveal a

selectivity profile for HDAC4 and HDAC5 with improved activity

against chemoresistant cancer cells. J Med Chem. 56:427–436. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Chen M, Cheng H, Chen X, Gu J, Su W, Cai

G, Yan Y, Wang C, Xia X, Zhang K, et al: The activation of histone

deacetylases 4 prevented endothelial dysfunction: A crucial

mechanism of HuangqiGuizhiWuwu decoction in improving

microcirculation dysfunction in diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol.

307:1162402023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Choi SY, Kee HJ, Sun S, Seok YM, Ryu Y,

Kim GR, Kee SJ, Pflieger M, Kurz T, Kassack MU and Jeong MH:

Histone deacetylase inhibitor LMK235 attenuates vascular

constriction and aortic remodelling in hypertension. J Cell Mol

Med. 23:2801–2812. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Lkhagva B, Chang SL, Chen YC, Kao YH, Lin

YK, Chiu CT, Chen SA and Chen YJ: Histone deacetylase inhibition

reduces pulmonary vein arrhythmogenesis through calcium regulation.

Int J Cardiol. 177:982–989. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Chen Y, Yuan J, Jiang G, Zhu J, Zou Y and

Lv Q: Lercanidipine attenuates angiotensin II-induced cardiomyocyte

hypertrophy by blocking calcineurin-NFAT3 and CaMKII-HDAC4

signaling. Mol Med Rep. 16:4545–4552. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Wang S, Li J, Liu Y, Zhang J, Zheng X, Sun

X, Lei S, Kang Z, Chen X, Lei M, et al: Distinct roles of

calmodulin and Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in

isopreterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 526:960–966. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Sun H, Ling S, Zhao D, Li Y, Zhong G, Guo

M, Li Y, Yang L, Du J, Zhou Y, et al: Panax quinquefolium saponin

attenuates cardiac remodeling induced by simulated microgravity.

Phytomedicine. 56:83–93. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Liu F, Su H, Liu B, Mei Y, Ke Q, Sun X and

Tan W: STVNa attenuates isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy

response through the HDAC4 and Prdx2/ROS/Trx1 pathways. Int J Mol

Sci. 21:6822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Akbay B, Omarova Z, Trofimov A, Sailike B,

Karapina O, Molnár F and Tokay T: Double-Edge effects of leucine on

cancer cells. Biomolecules. 14:14012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Dulf PL, Coada CA, Florea A, Moldovan R,

Baldea I, Dulf DV, Blendea D and Filip AG: Mitigating

doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through quercetin intervention:

An experimental study in rats. Antioxidants (Basel). 13:10682024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Zhang W, Zheng Y, Yan F, Dong M and Ren Y:

Research progress of quercetin in cardiovascular disease. Front

Cardiovasc Med. 10:12037132023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Lin CY, Shibu MA, Wen R, Day CH, Chen RJ,

Kuo CH, Ho TJ, Viswanadha VP, Kuo WW and Huang CY: Leu(27)

IGF-II-induced hypertrophy in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts is ameliorated

by saffron by regulation of calcineurin/NFAT and CaMKIIδ signaling.

Environ Toxicol. 36:2475–2483. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Sehgel NL, Zhu Y, Sun Z, Trzeciakowski JP,

Hong Z, Hunter WC, Vatner DE, Meininger GA and Vatner SF: Increased

vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness: A novel mechanism for aortic

stiffness in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

305:H1281–H1287. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Choi SY, Kee HJ, Jin L, Ryu Y, Sun S, Kim

GR and Jeong MH: Inhibition of class IIa histone deacetylase

activity by gallic acid, sulforaphane, TMP269, and panobinostat.

Biomed Pharmacother. 101:145–154. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Xiang Z, Guan H, Zhao X, Xie Q, Xie Z, Cai

F, Dang R, Li M and Wang C: Dietary gallic acid as an antioxidant:

A review of its food industry applications, health benefits,

bioavailability, nano-delivery systems, and drug interactions. Food

Res Int. 180:1140682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Hadidi M, Linan-Atero R, Tarahi M,

Christodoulou MC and Aghababaei F: The potential health benefits of

gallic acid: Therapeutic and food applications. Antioxidants

(Basel). 13:10012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Ago T, Yang Y, Zhai P and Sadoshima J:

Nifedipine inhibits cardiac hypertrophy and left ventricular

dysfunction in response to pressure overload. J Cardiovasc Transl

Res. 3:304–313. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Guo YJ, Yao JJ, Guo ZZ, Ding M, Zhang KL,

Shen QH, Li Y, Yu SF, Wan T, Xu FP, et al: HBB contributes to

individualized aconitine-induced cardiotoxicity in mice via

interfering with ABHD5/AMPK/HDAC4 axis. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

45:1224–1236. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|