Introduction

Osteoblastic cells (OBCs) in bone marrow (BM)

produce the bone matrix, participate in bone mineralization and

regulate the balance of calcium and phosphate ions in developing

bone (1,2). Furthermore, radiosensitive

hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) form a niche with OBCs

to maintain the immature state and self-renewal of the BM

microenvironment. This tissue is susceptible to the formation of

cancerous bone metastases that originate from circulating cells of

a primary tumor, represent the terminal stage of cancer and are

associated with a reduction in quality of life (3,4).

One of the applied treatment modalities is radiation therapy, which

is noninvasive. In patients with castration-resistant prostate

cancer, bone metastases are curatively treated with radium-223

dichloride (223RaCl2). This therapeutic drug

went through a clinical trial called ALSYMPCA and is the world's

first internal therapy drug that uses α-radiation. The mechanism of

action of this agent is that it accumulates in bone, concentrates

on the tumor and has a very large biological effect (5,6).

However, a major problem is that the efficacy and

side effects of this therapeutic technique have a high degree of

individual variability and patient response is difficult to

predict. Hematological adverse events, such as anemia,

thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, occur in at least 5% of patients

receiving radium-223 therapy (5). The mechanisms underlying the

development of these adverse events are unknown; however,

α-radiation-induced modulation of OBC activity may be a

contributing factor. The self-renewal and differentiation of HSPCs

in BM are maintained by cytokines secreted from surrounding cells,

including OBCs (7,8). However, unpredictable BM toxicity

remains a challenge and it is currently difficult to predict which

patients will experience hematologic adverse effects. As OBCs play

a central role in maintaining the BM microenvironment through

cytokine and metabolite secretion, The present study hypothesized

that α-radiation induced specific molecular alterations in the OBC

secretome and regulatory RNAs, which could affect hematopoietic

cell behavior or serve as biomarkers of radiation-induced OBC

damage. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to characterize

the proteomic, lipidomic and miRNA expression profiles of OBCs

exposed to α-radiation and to explore the potential of these

molecules as indicators of radiosensitivity or predictors of BM

toxicity in the context of α-emitting radionuclide therapy.

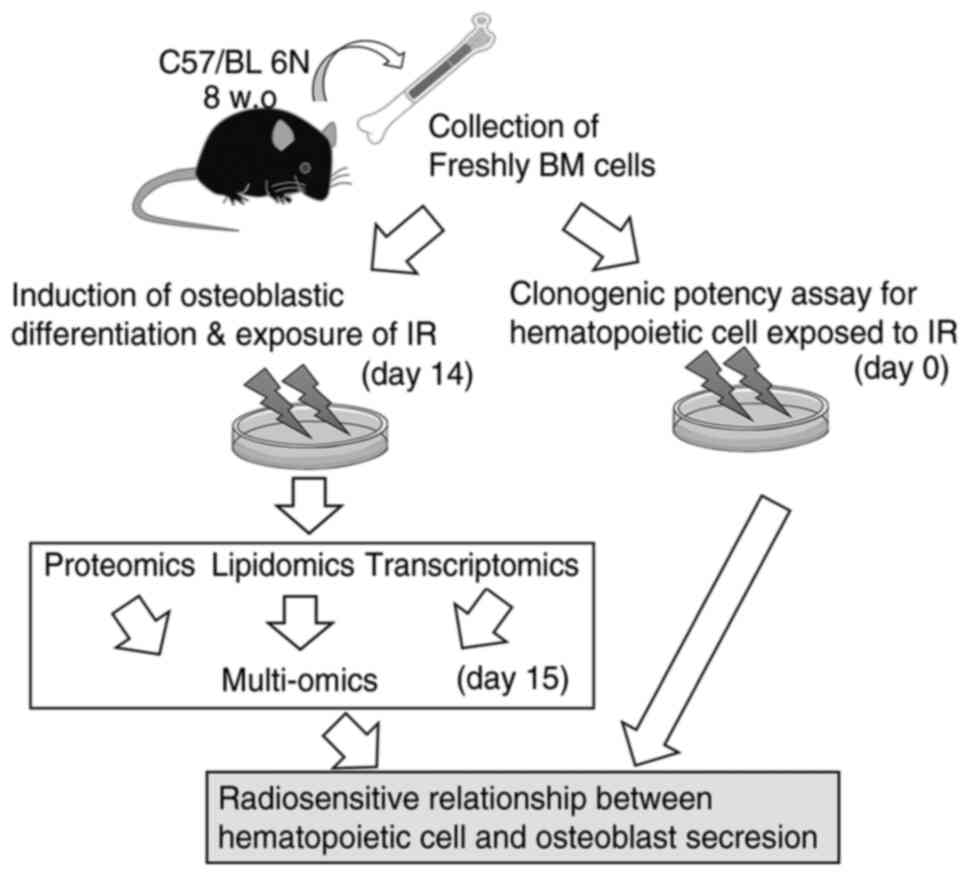

The present study analyzed the role of OBCs in the

regulation of HSPC radiosensitivity. It created an in vitro

osteoblast metabolic model from mouse primary BM and analyzed the

proteins and lipids metabolized by OBCs exposed to α-radiation.

Furthermore, The present study focused on the proteomics,

lipidomics and transcriptomics of these cells and investigated

whether there is a radioresistant component of the hematopoietic

system in OBC response to α-radiation.

Materials and methods

Mouse BM cells

The mice study was approved by the Animal Welfare

Body in Stockholm University (Djurskyddsorgan; approval number

64-2019) and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in

Hirosaki University (approval number AE05-2024-004). All animal

experiments were performed in accordance with national animal

welfare guidelines and the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of

In Vivo Experiments) guidelines (9). Mice were

anesthetized using the inhalation anesthetic isoflurane (Pfizer,

Inc.). Anesthesia was induced with 4-5% isoflurane and maintained

at 2-3% using a small animal anesthesia system. Euthanasia was

performed by cervical dislocation under deep anesthesia and death

was confirmed by the absence of respiration and heartbeat.

Immediately after euthanasia, fresh BM cells were collected from

the femurs. C57BL/6N male mice (20-25 g) were delivered at seven

weeks of age from a breeding facility, Charles River Laboratories.

Upon arrival, the mice were housed under specific pathogen-free

conditions with a controlled environment: Room temperature

(20°C), 12-h light/dark cycle and 40-60% relative humidity.

At eight weeks of age, mice were anesthetized and euthanized to

collect the fresh BM cells. The femurs were excised and cut at both

ends using sterile scissors and BM cells were isolated by flushing

the marrow cavity with phosphate-buffered saline containing

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. In total, 30 male C57BL/6N mice

were used in the present study. Three groups were based on the

α-particle doses: 0 Gy (non-irradiated), 0.5 and 1.0 Gy (n=10 per

group). For each mouse, a portion of the collected BM cells was

used for the clonogenic cell-forming capacity (CFC) assay and the

remaining cells were cultured under osteoblastic differentiation

conditions. After differentiation, the cultured cells were used for

transcriptomic analysis, while the culture supernatants were

analyzed for proteomic and lipidomic profiles.

Differentiation of osteoblastic cells and

exposure to α-radiation

The isolated BM cells were seeded in 100-mm round

dishes filled with 5 ml of RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 20%

fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

incubated for 7 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2

atmosphere (1×107 cells/dish). On day 7, the cells were

checked for viability and the differentiation of OBCs was initiated

by adding a differentiation medium (20-mM β-glycerol phosphate

disodium salt pentahydrate, 100-nM dexamethasone and 50-μM

L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate sesquimagnesium salt hydrate) for 7

days (10). On day 14, cells

were exposed to 0.5- or 1-Gy α-radiation (0.22 Gy/min). The

radiation exposure was performed on a custom-made dish covered with

2.5 μm thick Mylar foil that allowed the exposure of the

cell monolayer to α-radiation from a 241Am source (cat.

no. AP1 s/n 101; Eckert and Ziegler) (11). The cells exposed to radiation

were incubated for 15 days and the cells were harvested and stored

at −80°C as cell pellets until analysis. For proteomics and

lipidomics analyses, a cell pellet was suspended in 7-M urea and 2%

sodium dodecyl sulfate and the protein fraction was precipitated by

adding acetone. For transcriptomics analyses, total RNAs were

extracted using an RNA extraction kit (Qiagen GmbH).

Flow cytometry

The number of BM cells and OBCs expressing the CD45

cell surface antigen was analyzed by flow cytometry system (Moxi GO

II; Orflo Technologies) and the results were analyzed by Kaluza

software (v.2.2.1; Beckman Coulter Inc.). For this, samples

containing 2×105 cells were incubated with the relevant

phycoerythrin-cyanin-5-forochrome tandem conjugated anti-mouse CD45

monoclonal antibody (mAb) for 30 min at 4°C (cat. no.

103109; Biolegend Inc.). Then, erythrocytes including sample cells,

were washed using RBC lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The intracellular proteins RUNX2 (cat. no. NBP1-77462AF488)

and BAP (cat. no. NB110-3638AF488) polyclonal antibody (pAb)

(Bio-Techne) were also analyzed using a cell membrane permeation

reagent kit (BD Biosciences). Isotype-matched mAb (PE/Cyanine5 Rat

IgG2b,κ (cat. no. 400609; Biolegend Inc.) for CD45) or pAb (IgG2a

Kappa-FITC (cat. no. 400207; Biolegend Inc.) for BAP and Mouse

IgG-FITC (#NBP1-96789, bio-techne Inc.) for RUNX2) was used as

negative controls for flow cytometry.

Clonogenic potency assay of hematopoietic

BM cells

The clonogenic potency of hematopoietic cells was

analyzed using a colony-forming cell (CFC) assay. CFCs, including

colony-forming unit-granulocyte and macrophage (CFU-G/GM),

burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E) and colony-forming

unit-granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage and megakaryocyte

(CFU-GEMM), were assayed using the methylcellulose culture kit

(MethoCult; Stemcell Technologies, Inc.). The extracted cells from

BM or cultured cells were seeded into each well of a 24-well cell

culture plate with 300 μl of methylcellulose medium

containing recombinant IL-3 (100 ng/ml), recombinant SCF (100

ng/ml), IL-6 (100 ng/ml), G-CSF (10 ng/ml), EPO (4 U/ml),

penicillin (100 U/ml; Stemcell Technologies, Inc.) and streptomycin

(100 μg/ml) (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation). The

cell culture plate was incubated at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2/95% air for 7 days.

Colonies containing >50 cells were counted under 4×

magnification using an inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation).

After benzidine staining, the blue and colorless colonies were

scored as BFU-E and CFU-G/GM, respectively. Statistical analyses

were performed using the Origin software package (OriginLab Pro

ver. 9.1; OriginLab Corporation). Radiation dose-survival curves

were fitted using the algorithm of Levenberg-Marquardt, which

combines Gauss-Newton and steepest-descent methods, nonlinear

models based on the equation

y=1-[1-exp(-x/D0)]n, where x indicates the

dose in Gy. The values for D0 (the mean lethal radiation

dose) and n (the number of targets) were determined by a single-hit

multitarget equation.

Proteomics and lipidomics

The proteins in the harvested cells were

precipitated by acetone and lysed with 50% TFE. Reduction and

alkylation of proteins were conducted using 10 mM DTT and 20 mM

iodoacetamide, respectively. The protein samples were then

incubated with trypsin (AB Sciex) overnight at 37°C. The

tryptic peptides were desalted and purified using MonoSpin C18 (GL

Sciences). The resulting samples were analyzed using liquid

chromatography (LC)-MS/MS with a nanoLC Eksigent 400 system (AB

Sciex) coupled with a TripleTOF6600 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex).

Peptides were separated using a nano C18 reverse-phase capillary

tip column (75 μm × 125 mm, 3 μm; Nikkyo Technos,

Co., Ltd.). Peptide separation was performed at 300 nl/min with a

90 min linear gradient of 8-30% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid,

and then, with a 10 min linear gradient of 30-40% acetonitrile in

0.1% formic acid. Spectra acquired with data-dependent acquisition

in positive ion mode were searched using ProteinPilot software

(5.0.1; AB Sciex) with the UniProt-reviewed database (https://www.uniprot.org/). The peak areas of

individual peptides were extracted using Peakview software (v2.2.0;

AB Sciex) with the resulting group files and data-independent

acquisition sequential window acquisition of all theoretical

fragment-ion spectra (SWATH) spectral data. The peak area values

for individual proteins, consisting of the sum of the peak areas of

peptides, were normalized to the sum of all proteins detected.

Comparisons between sample groups were analyzed using SIMCA

software (version 15.0.2; InfoCom Corporation) with multivariate

analysis by orthogonal partial least squares discriminant

analysis.

Secreted lipids in the culture medium were measured

using QTRAP6500+ (AB Sciex) with multiple reaction monitoring

methods in the positive ion mode. The transition channels of

lysophosphatidylcholine (lysoPC) with acyl residues, acyl-acyl

phosphatidylcholine (PC aa), phosphatidylcholine with acyl-alkyl

residue sum (PC ae) and sphingomyelin are shown in Table I (10). Lipids were extracted at room

temperature using liquid-liquid extraction. The cell-cultured

medium was added to 50% methanol and 25% dichloromethane in a glass

screw-cap tube. The samples were mixed with internal standards of

15:0-18:1-d7-PC and 18:1-d7 Lyso PC (Merck KGaA). After inverting

the tubes 10 times, they were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min

at room temperature. The lower layer was collected and evaporated.

The residues were resuspended in methanol containing 0.1% formic

acid. The samples were analyzed in the flow injection analysis

using a high-performance liquid chromatography system (ExionLC AD;

AB SCIEX). The flow injection analysis (FIA) was done by injecting

20 μl of the sample into the flow of the FIA program,

lasting for 5 min and pumping the FIA mobile phase (methanol

containing 0.1% formic acid). QTRAP6500+ settings for FIA mode are

as follows: Curtain gas, 30; ion spray voltage, 4,500 V;

temperature, 300°C; ion source gas 1, 50 psi; ion source gas

2, 60 psi; CAD gas, 8 psi; entrance potential, 10 V; collision cell

exit potential, 15 V. Flow rate settings for FIA are as follows:

0.03 ml/min in 1.6 min; 0.03 to 0.2 ml/min in 0.8 min; 0.2 ml/min

in 0.4 min; 0.2 to 0.03 ml/min in 0.2 min. Multiple reaction

monitoring (MRM) settings are shown in Table SI. PCs and lysoPCs were

normalized to the internal standards. For semi-quantitation of all

lipids, the peak areas of individual lipids were normalized to the

sum of the peak areas of all lipids detected.

| Table ITargeted lipids. |

Table I

Targeted lipids.

| Lipid class | Number of

analyses | Analyte

abbreviation |

|---|

| Sphingomyeline,

Hydroxysphingomyelins | 15 | SM (OH) C14:1, SM

(OH) C16:1, SM (OH) C22:1, SM (OH) C22:2, SM (OH) C24:1, SM C16:0,

SM C16:1, SM C18:0, SM C18:1, SM C20:2, SM C22:3, SM C24:0, SM

C24:1, SM C26:0, SM C26:1 |

| Diacyl

phosphatidylcholine | 38 | PC aa C24:0, PC aa

C26:0, PC aa C28:1, PC aa C30:0, PC aa C30:2, PC aa C32:0, PC aa

C32:1, PC aa C32:2, PC aa C32:3, PC aa C34:1, PC aa C34:2, PC aa

C34:3, PC aa C34:4, PC aa C36:0, PC aa C36:1, PC aa C36:2, PC aa

C36:3, PC aa C36:4, PC aa C36:5, PC aa C36:6, PC aa C38:0, PC aa

C38:1, PC aa C38:3, PC aa C38:4, PC aa C38:5, PC aa C38:6, PC aa

C40:1, PC aa C40:2, PC aa C40:3, PC aa C40:4, PC aa C40:5, PC aa

C40:6, PC aa C42:0, PC aa C42:1, PC aa C42:2, PC aa C42:4, PC aa

C42:5, PC aa C42:6 |

| Acyl-alkyl

phosphatidylcholine | 38 | PC ae C30:0, PC ae

C30:1, PC ae C30:2, PC ae C32:1, PC ae C32:2, PC ae C34:0, PC ae

C34:1, PC ae C34:2, PC ae C34:3, PC ae C36:0, PC ae C36:1, PC ae

C36:2, PC ae C36:3, PC ae C36:4, PC ae C36:5, PC ae C38:0, PC ae

C38:1, PC ae C38:2, PC ae C38:3, PC ae C38:4, PC ae C38:5, PC ae

C38:6, PC ae C40:1, PC ae C40:2, PC ae C40:3, PC ae C40:4, PC ae

C40:5, PC ae C40:6, PC ae C42:0, PC ae C42:1, PC ae C42:2, PC ae

C42:3, PC ae C42:4, PC ae C42:5, PC ae C44:3, PC ae C44:4, PC ae

C44:5, PC ae C44:6 |

|

Lysophosphatidylcholine | 14 | lysoPC a C14:0,

lysoPC a C16:0, lysoPC a C16:1, lysoPC a C17:0, lysoPC a C18:0,

lysoPC a C18:1, lysoPC a C18:2, lysoPC a C20:3, lysoPC a C20:4,

lysoPC a C24:0, lysoPC a C26:0, lysoPC a C26:1, lysoPC a C28:0,

lysoPC a C28:1 |

| Total targeted

lipids | 105 | |

For pathway enrichment analysis, markedly altered

proteins and lipid species were subjected to Kyoto Encyclopedia of

Genes and Genomes (KEGG)-based annotation and analyzed using

OmicsNet 2.0 (https://www.omicsnet.ca/) (12). Functional enrichment analyses

were performed to identify affected biological pathways and

metabolic processes. The input data consisted of proteins and lipid

metabolites that showed statistically significant differences

following α-radiation exposure. The six proteins [ITIH3

(Q61704), ATPB (P56480), PDIA3 (P27773), ANT3 (P32261), PDIA6

(Q922R8) and RPL4 (Q9D8E6)] and seven lipid species (PC aa C24:0,

PC aa C26:0, PC aa C34:4, PC ae C42:3, PC ae C42:2, PC ae C44:4 and

lysoPC a C26:0) selected for KEGG enrichment were identified based

on statistically significant fold changes (adjusted P<0.05)

observed in α-irradiated OBCs compared to controls.

Prior to pathway enrichment and integrated network

analyses, all raw proteomics and lipidomics data were deposited in

the public database MetaboBank under the accession number MTBKS262

(https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/public/metabobank/study/MTBKS262/).

Integrated network analysis

To investigate the potential associations among the

identified microRNAs, proteomics and lipidomics datasets, The

present study performed an integrated network analysis using

OmicsNet 2.0. The analysis incorporated markedly downregulated

miRNAs (adjusted P<0.05) obtained from the microarray results,

alongside radiation-responsive proteins and lipids identified in

the omics datasets. Protein-protein interaction data were sourced

from the STRING database ver. 12 (https://string-db.org/), and miRNA-target

relationships were collected from TargetScan ver.8.0 (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/) and

miRTarBase ver. 9.0 (https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn/~miRTarBase/miRTarBase_2025/php/index.php).

Special attention was given to two microRNA target genes, ELF4 and

LARS2, which were selected based on their expression patterns and

biological relevance in the transcriptome data. The interaction

networks were constructed to identify potential indirect

connections between these genes and the proteins detected in the

dataset of the present study. Network visualizations were used to

highlight subnetworks suggesting functional interactions related to

stress response, mitochondrial activity and transcriptional

regulation.

MicroRNA microarray analysis

Total RNAs from cultured BM cells were extracted

using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen GmbH) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Furthermore, the concentration of total RNAs

extracted from cells or tissues was assessed using a NanoDrop

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). All RNA samples

had 260/280-nm absorbance ratios of 1.8-2.0. The quality of small

RNAs included in the total RNAs was confirmed by an RNA 6000 Pico

kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and a system of Agilent 2100

Bioanalyzer according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cy3-labeled miRNA was synthesized from 30 ng total RNAs using a

miRNA Complete Labeling Reagent and Hyb kit (Agilent Technologies,

Inc.). A SurePrint G3 miRNA microarray slide (8×60 K, ver. 21.0)

for the mouse was hybridized with the Cy3-labeled miRNA in a

hybridization solution prepared with a Gene Expression

Hybridization Kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Fluorescence signal

images of Cy3 on the slide were obtained by a microarray scanner

(SureScan; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and processed by

Feature Extraction (version 10.7; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The

raw data of microRNA microarray that was analyzed in the present

study was uploaded onto the Gene Expression Omnibus database

(GSE286553; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE286553).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical

analyses were performed using Origin software package (OriginLab

Pro ver. 9.1; OriginLab). For comparisons involving more than two

groups, one-way analysis of variance was conducted followed by

Tukey-Kramer's multiple comparisons test to control for familywise

error. All tests were two-tailed unless otherwise specified.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

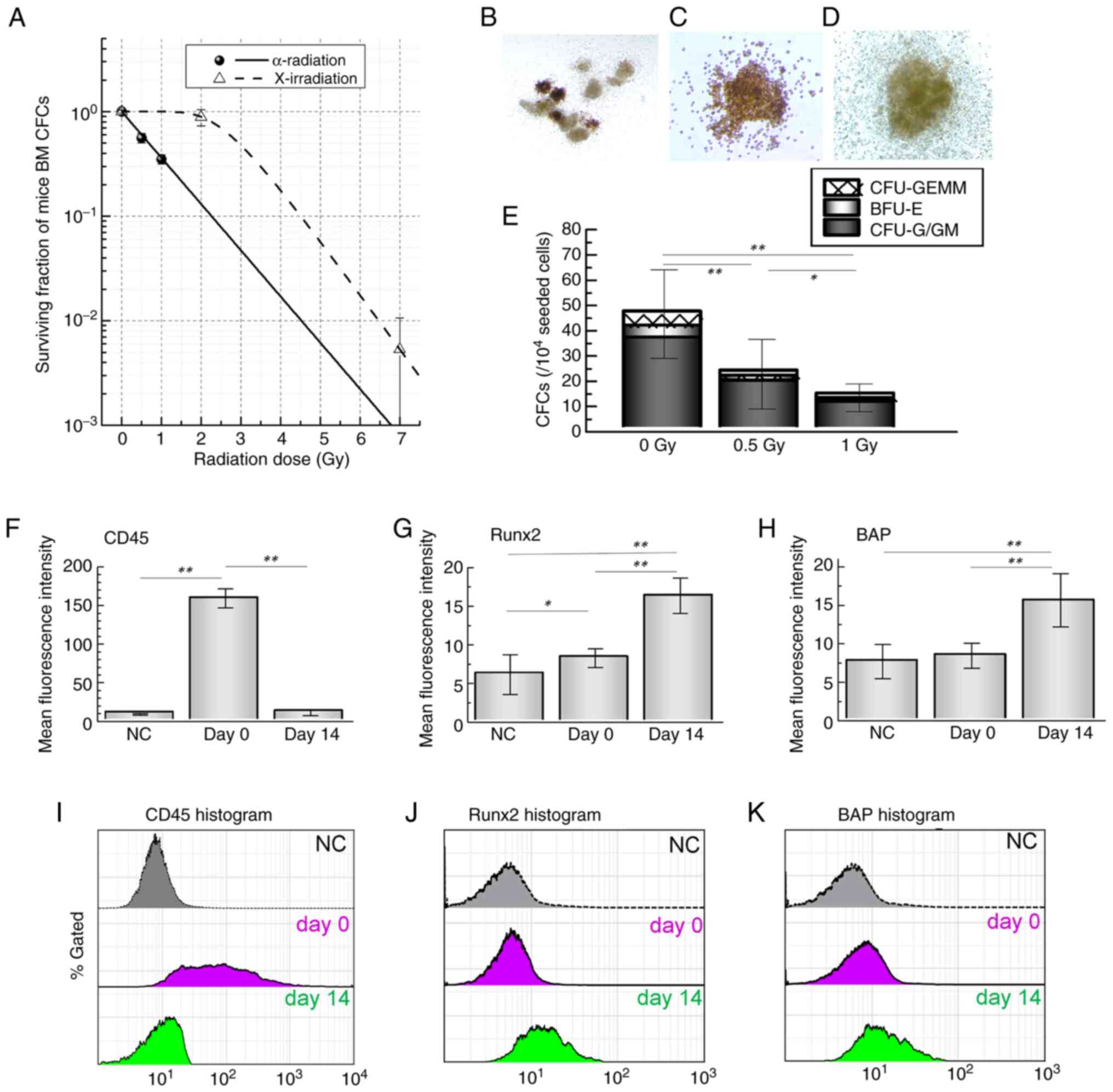

Clonal growth of BM cells exposed to

α-radiation

Freshly isolated BM cells were exposed to 0.5- or

1-Gy α-radiation and plated in methylcellulose-based

semisolid culture supplemented with an optimal cytokine combination

(Fig. 1). Fig. 2A presents the radiation

dose-response curves of hematopoietic progenitors (CFCs). The

surviving fractions of CFCs were markedly lower after α-radiation

compared with X-irradiation, indicating a higher radiosensitivity.

The D0 and n values are summarized in

Table II, confirming this

greater sensitivity (D0: 0.98±0.42 Gy for

α-radiation vs. 0.84±0.00 Gy for X-irradiation; n: 1±0.44 vs.

23±0.01, respectively). The relative biological effectiveness (RBE)

of α-radiation was calculated to be 2.96 at 30% survival and 2.0 at

10%. Representative images of CFU-GEMM, BFU-E and CFU-G/GM colonies

are shown in Fig. 2B-D, with

their quantified colony numbers displayed in Fig. 2E. To assess the effects of

radiation on hematopoietic and osteoblastic markers, The present

study performed flow cytometry analysis. The corresponding

quantitative data are shown in Fig.

2F-H. α-radiation markedly modulated both hematopoietic and

osteoblastic differentiation markers in BM-derived cells. Fig. 2I-K shows representative

histograms of CD45, RUNX2 and BAP expression, respectively.

| Figure 2Radiation dose-response of HSPCs and

osteoblastic differentiation in mouse BM cells. (A) BM cells were

irradiated with α-radiation or X-irradiation and dose-response

curves of total CFCs were plotted. Representative images of

colony-forming cells (B) CFU-GEMM, (C) BFU-E and (D) CFU-G/GM from

BM cultures are shown. (E) Quantification of each colony type is

presented. (F-J) Flow cytometric analysis of BM cultures was

performed. Quantitative values (F-H) and representative histograms

(I-K) are shown for (F and I) CD45 expression and osteoblastic

differentiation markers (G and J) RUNX2 and (H and K) BAP. Each

value represents the mean ± SD of 8-10 mice per group. Statistical

analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey-Kramer's multiple comparisons test. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 vs. undifferentiated BM-MNCs. HSPCs,

hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells; BM, bone marrow; CFCs,

colony-forming cells; CFU-GEMM, colony-forming unit-granulocyte,

erythroid, macrophage and megakaryocyte; BFU-E, burst-forming

unit-erythroid; CFU-G/GM, colony-forming unit-granulocyte and

macrophage; MNCs, mononuclear cells ; NC, negative control. |

| Table IIRadiosensitivity of hematopoietic

stem/progenitor cells in murine bone marrow. |

Table II

Radiosensitivity of hematopoietic

stem/progenitor cells in murine bone marrow.

| Radiation type | Radiosensitive

parameter | Total CFCs |

|---|

| α-radiation | D0 | 0.98±0.42 |

| n | 1.00±0.44 |

| X-radiation | D0 | 0.84±0.00 |

| n | 23.01±0.00 |

| RBE | 30% survival | 2.96±0.23 |

| 10% survival | 2.00±0.09 |

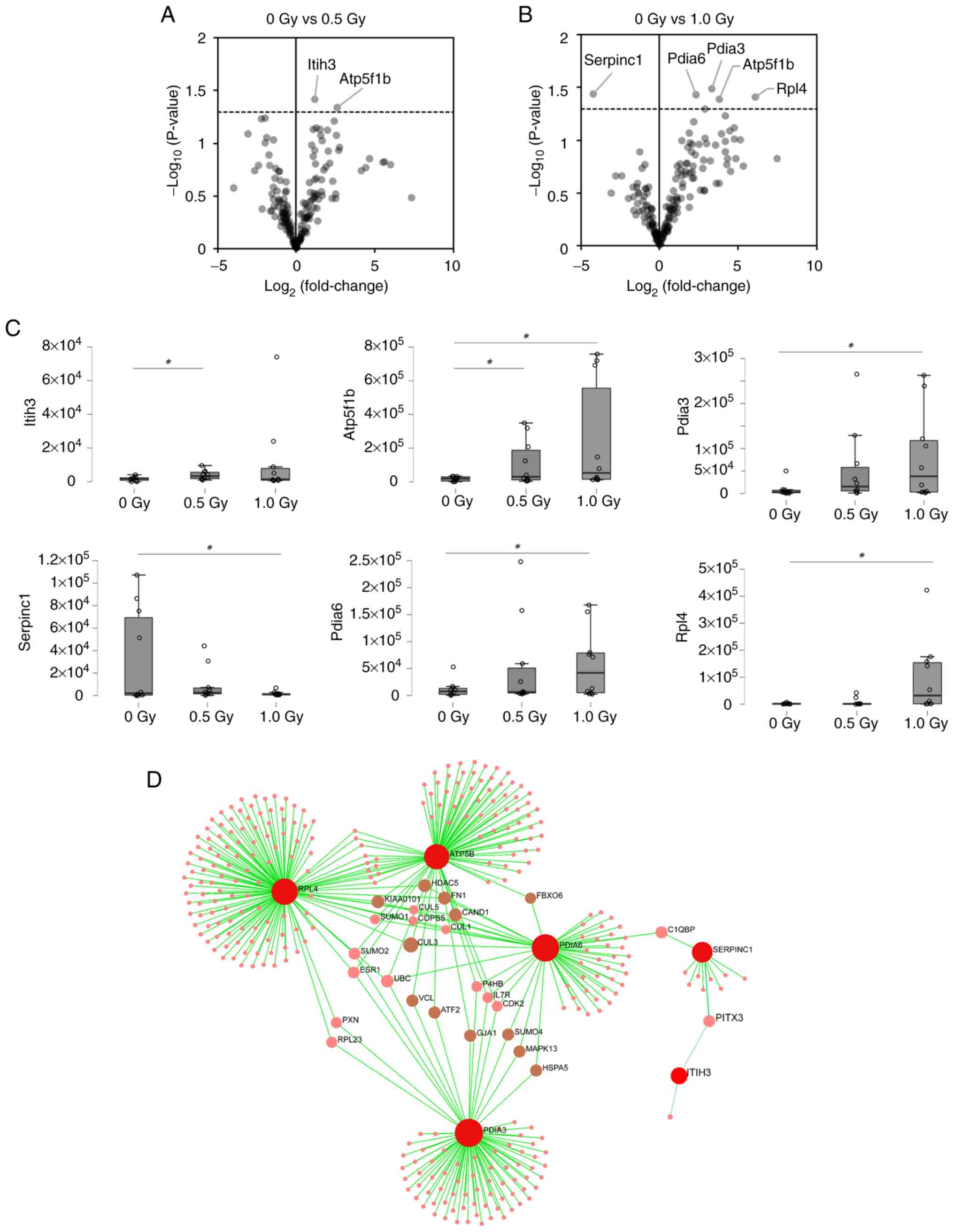

Proteomics and lipidomics analysis

The differentiation of BM stromal cells into OBCs

was confirmed by the osteoblastic differentiation markers CD45,

RUNX2 and BAP (Fig. 2F-K).

Proteins extracted from OBCs were measured in the data-dependent

acquisition mode and 171 proteins were identified with 95%

confidence, satisfying the criteria for SWATH measurement. Of

these, two and five proteins were markedly changed in OBCs exposed

to 0.5 and 1 Gy of α-radiation, respectively, compared to

nonirradiated controls (Fig. 3).

The proteins 'protein disulfide-isomerase A3', 'antithrombin-III',

'protein disulfide-isomerase A6', '60S ribosomal protein L4', 'ATP

synthase subunit β, mitochondrial', and 'inter-α-trypsin inhibitor

heavy chain H3' were detected as specific responses to α-radiation.

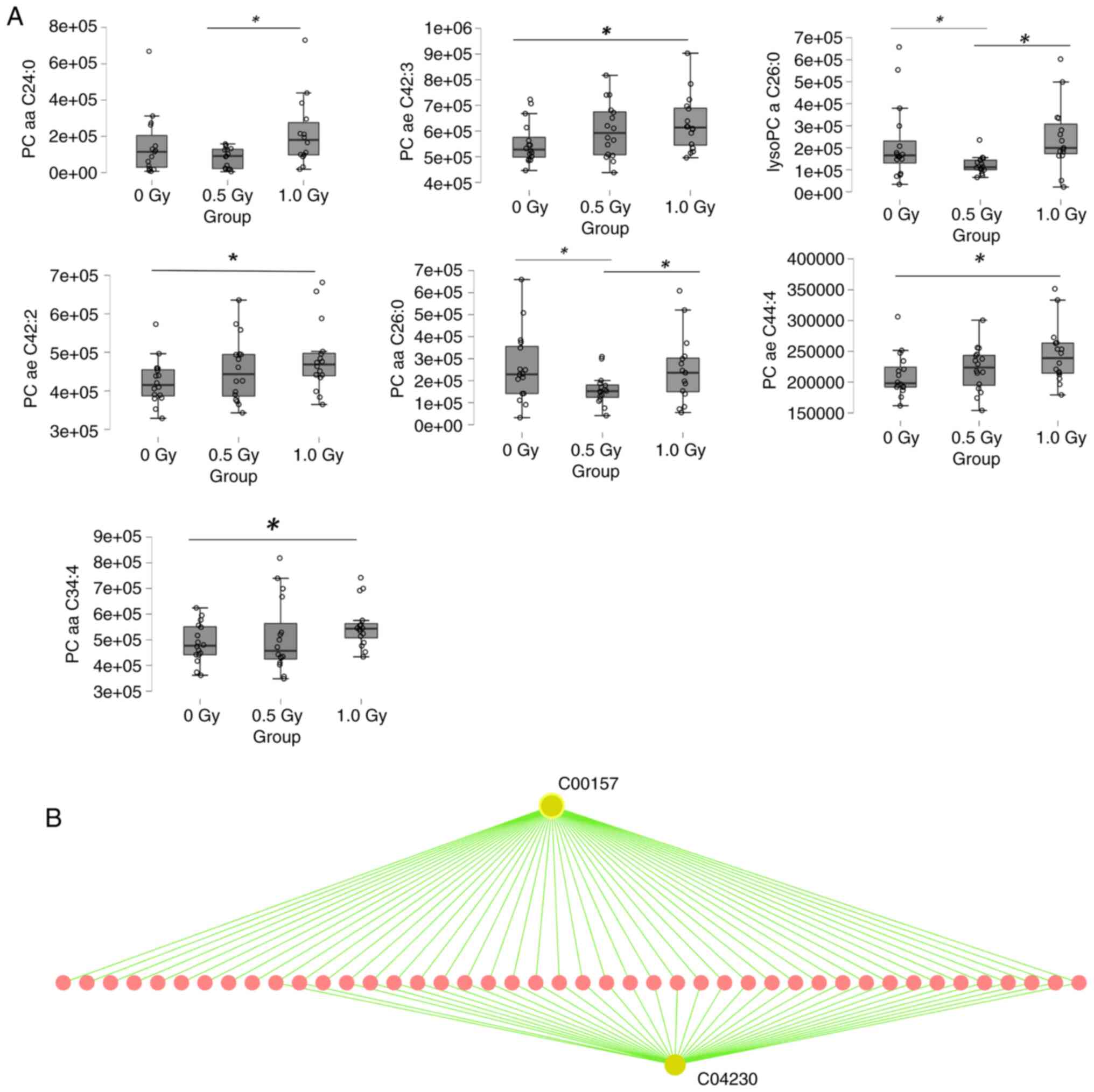

In the lipidomic analysis, several phosphatidylcholine (PC) and

lysophpsphatidylcholine (lysoPC) species were markedly changed

following α-radiation (Fig. 4A).

These specific proteins and lipids, showing consistent and

statistically significant alterations across biological replicates

in response to 0.5 or 1.0 Gy α-radiation, were selected to ensure

robust input for pathway enrichment. KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis using OmicsNet revealed that the differentially expressed

proteins were involved in pathways such as Basal transcription

factors, Apoptosis-multiple species and MicroRNAs in cancer

(Fig. 3D; Table SII). Similarly, enrichment

analysis of the altered lipid species predicted associations with

pathways including Glycerophospholipid metabolism, EGFR tyrosine

kinase inhibitor resistance, Ether lipid metabolism and

Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (Fig. 4B, Table SIII).

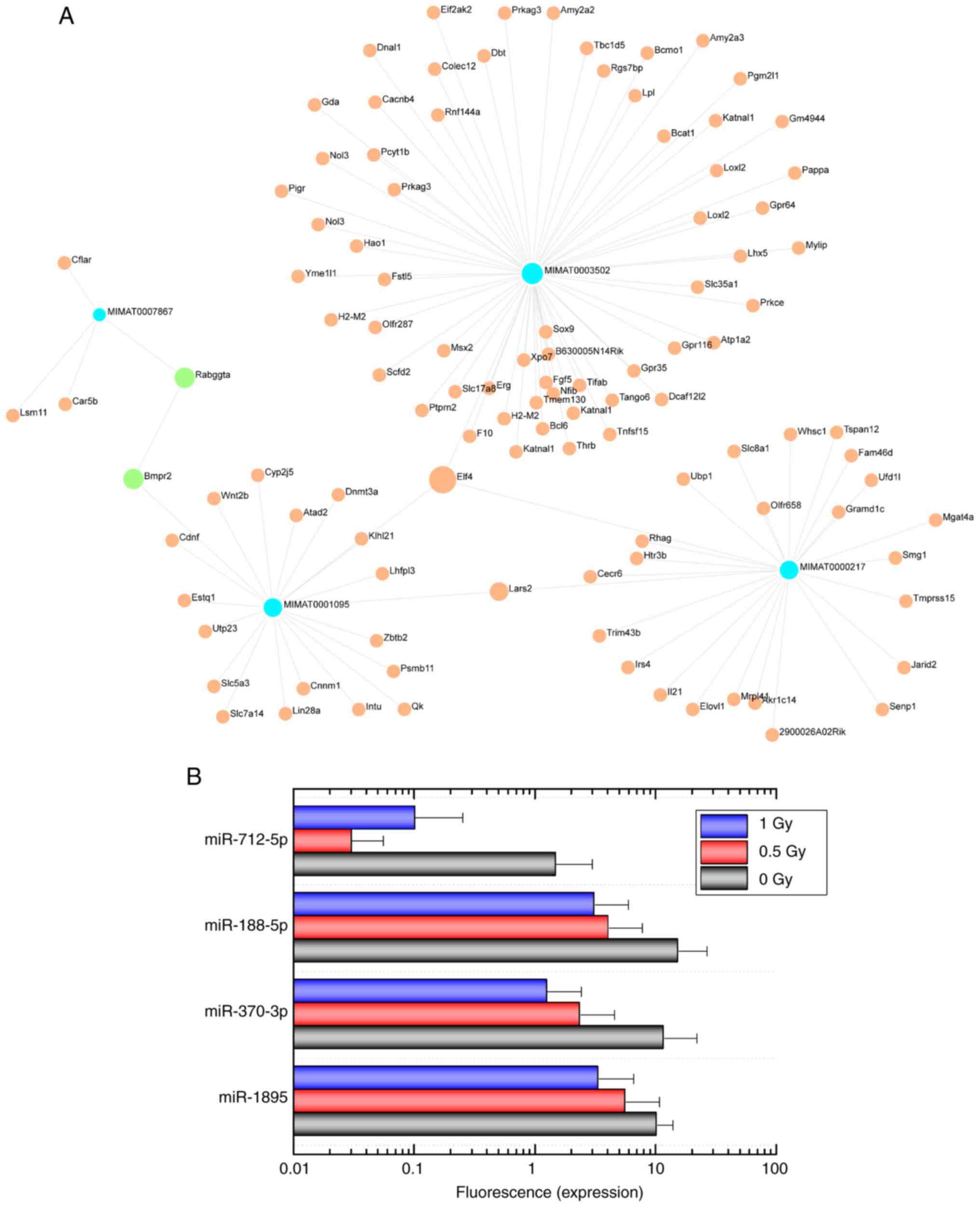

miRNA expression

RNA microarray analysis of OBCs exposed to

α-radiation revealed that 24 miRNAs were markedly downregulated.

The data has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO:

GSE286553). The following miRNAs were identified: miR-1894-3p,

miR-1895, miR-3072-5p, miR-370-3p, miR-5107-5p, miR-652-5p,

miR-6984-5p, miR-7011-5p, miR-7040-5p, miR-7226-5p, miR-8094,

miR-8102, miR-188-5p, miR-3081-5p, miR-3098-5p, miR-6538,

miR-6969-5p, miR-7020-5p, miR-7044-5p, miR-7048-5p, miR-7082-5p,

miR-712-5p, miR-721 and miR-8101. The functions of the genes

targeted by these miRNAs were identified using the database

OmicsNet 2.0 and included 'negative regulation of metabolic

process, endothelial cell proliferation' and 'regulation of protein

metabolic process' (Table

III). Furthermore, the cellular components 'organelle membrane'

and 'Golgi membrane' were identified as targets of these miRNAs

(Table SIV). Most target genes

were regulated by miR-1895, miR-370-3p, miR-188-5p and miR-712-5p

(Fig. 5).

| Table IIIFunctional of predictive targeted

genes from 24 miRNAs by Gene Ontology (Biological process). |

Table III

Functional of predictive targeted

genes from 24 miRNAs by Gene Ontology (Biological process).

| Function name | Number of

predictive genes | P-value |

|---|

| Negative regulation

of metabolic process | 12 | 0.0455 |

| Endothelial cell

proliferation | 10 | 0.038 |

| Macromolecule

catabolic process | 6 | 0.0337 |

| Cytokinesis | 6 | 0.0337 |

| Regulation of

protein metabolic process | 5 | 0.0369 |

| Sexual

reproduction | 5 | 0.042 |

| RNA catabolic

process | 5 | 0.0425 |

| Regulation of

translation | 4 | 0.00728 |

| Negative regulation

of growth | 3 | 0.0314 |

| Translation | 3 | 0.0418 |

| Positive regulation

of translation | 2 | 0.0111 |

| RNA 3′-end

processing | 2 | 0.0153 |

| Regulation of

endothelial cell proliferation | 2 | 0.0309 |

| Regulation of Rho

GTPase activity | 2 | 0.0336 |

| Pattern

specification process | 2 | 0.0364 |

| Cell projection

assembly | 2 | 0.0385 |

| Regulation of

signal transduction | 2 | 0.0445 |

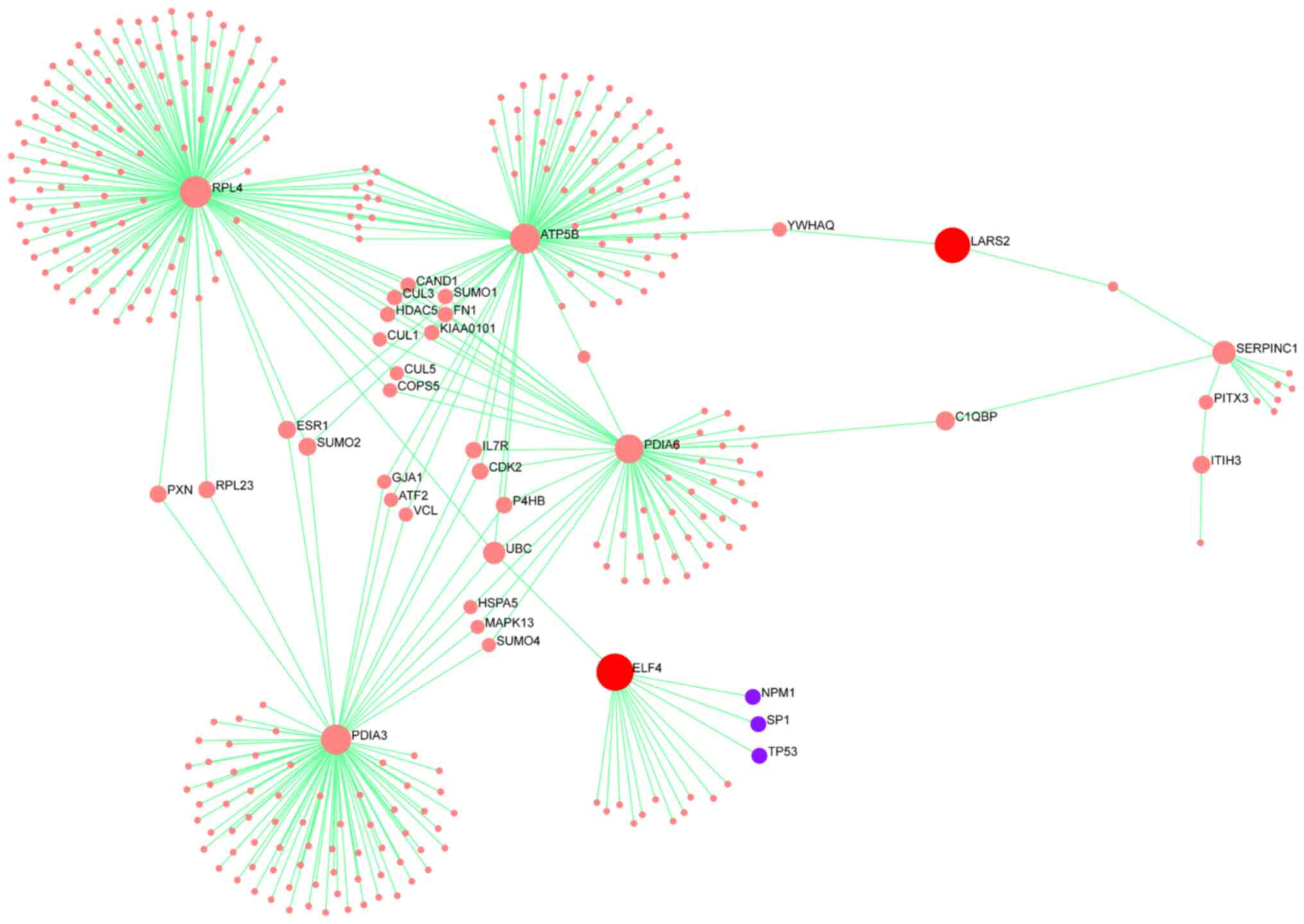

Integrated network analysis of

multi-omics data

To investigate potential mechanistic links between

the miRNA, proteomics and lipidomics datasets, an integrated

network analysis was performed using OmicsNet 2.0. Two

representative miRNA target genes, ELF4 and LARS2, were selected

based on their biological relevance and expression changes

following α-radiation. Although these genes were not directly

identified in the proteomic dataset, the analysis revealed that

ELF4 was indirectly connected to radiation-responsive proteins such

as RPL4, PDIA3, ATP5B and PDIA6 through interaction networks.

Similarly, LARS2 was associated with a subnetwork including ATP5B

and SERPINC1 (ANT3). These findings suggested indirect regulatory

relationships linking α-radiation-induced protein expression

changes to downstream gene regulation via miRNA targets. The

resulting interaction networks are visualized in Fig. 6, showing the predicted

interconnectivity between altered proteins and target genes of

radiation-responsive miRNAs.

Discussion

The present study investigated how α-radiation

alters the molecular phenotype of BM-derived OBCs, focusing on

secreted metabolites and regulatory RNAs. As OBCs play a key role

in maintaining the hematopoietic niche through cytokine and

metabolite secretion, their radiation-induced dysfunction may

influence HSPC radiosensitivity and contribute to BM toxicity

observed during α-emitting radionuclide therapies such as

223Ra. To test this hypothesis, the present study

applied an integrated omics approach combining proteomic, lipidomic

and transcriptomic analyses in murine OBCs irradiated in

vitro. This multi-layered dataset enabled the examination not

only of the direct biochemical effects of α-radiation on OBCs, but

also potential signaling pathways involved in hematopoietic

dysregulation. It is well established that HSPCs are highly

radiosensitive and that cytokine-mediated signaling can modulate

this sensitivity (13-15). A-radiation, characterized as high

linear energy transfer (LET) radiation, exerts greater biological

damage per unit dose than low-LET radiation such as X-rays

(16). The findings of the

present study were consistent with this notion.

Internal radioactive nuclide therapy using

223Ra, an α-emitting nuclide, markedly enhanced the

level of BM toxicity, particularly neutropenia and

thrombocytopenia. It is not possible to predict which patients are

at increased risk of toxicities (17,18). The self-renewal and

differentiation of HSPCs in BM are maintained by various cytokines

secreted from surrounding cells, including OBCs (7,8).

As OBCs secrete numerous growth factors, differentiation factors

and other regulatory cytokines, their secretome may affect the BM

response to α-radiation.

The present study accurately quantified the

metabolites secreted by OBCs exposed to α-radiation. The

concentrations of five proteins [protein disulfide-isomerase A3

(P27773), protein disulfide-isomerase A6 (Q922R8), 60S ribosomal

protein L4 (Q9D8E6), inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3

(Q61704) and ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial (P56480)]

were markedly upregulated following exposure to α-radiation

compared with the nonirradiated control. By contrast,

antithrombin-III (P32261) levels were markedly decreased. In the

lipidomics analysis, the concentrations of four lipids (PC ae

C42:3, PC ae C42:2, PC ae C44:4 and PC aa C34:4) exhibited a

significant upregulation following exposure to 1-Gy α-radiation

compared with the nonirradiated controls.

The reason why the secretion of the aforementioned

metabolites is modulated by α-radiation is unclear; however, they

may act directly or indirectly on cell surface receptors. Another

possibility is that they are released due to cell death caused by

radiation stress. The cell membrane is a lipid bilayer structure

containing phospholipids rich in PC and lysoPC. When apoptosis is

induced, cellular tissues are degraded and membrane lipids are

released (19).

Although these metabolites are secreted, the

expression of small RNAs also changes. In particular, the

expression of miR-1895, miR-370-3p, miR-188-5p and miR-712-5p was

markedly downregulated by exposure to α-radiation. miRNAs regulate

gene expression by binding to the 3′-untranslated regions of target

mRNAs, which modulate protein synthesis by increasing mRNA

degradation or inhibiting translation (20).

Based on the obtained results, The present study

predicted the expression of related mRNAs using OmicsNet and their

functions, inferred from Gene Ontology analysis, included 'negative

regulation of the metabolic process', 'endothelial cell

proliferation', 'macromolecule catabolic process', 'cytokinesis',

and 'regulation of protein metabolic process'. Endothelial cells

and BM microvascular cells support BM hematopoiesis (21). Furthermore, changes in gene

expression related to cell membranes are expected to be related to

the disruption of membrane formation induced by apoptosis.

To explore the interplay among different omics

layers, the present study conducted an integrated network analysis

using OmicsNet 2.0. Although ELF4 and LARS2 were not directly

identified in the proteomic dataset, the network analysis revealed

biologically plausible associations between these miRNA target

genes and radiation-responsive proteins. Specifically, ELF4 was

indirectly linked to RPL4, PDIA3, ATP5B and PDIA6; proteins

involved in ribosome biogenesis, endoplasmic reticulum stress

response and mitochondrial energy production. LARS2 was associated

with a subnetwork involving ATP5B and SERPINC1 (ANT3), suggesting

its potential involvement in mitochondrial translation and

coagulation-related stress pathways. These indirect associations

suggest that the downregulation of miRNAs regulating ELF4 and LARS2

may contribute to radiation-induced cellular responses through

downstream proteomic alterations. The integrated network, presented

in Fig. 6, underscores the

potential cross-talk between transcriptional and

post-transcriptional regulation in the α-radiation response. The

present systems-level view not only strengthened the mechanistic

understanding of OBC damage, but also offered potential molecular

targets for evaluating or mitigating radiation-induced bone marrow

toxicity.

The enrichment analysis was based on a subset of

proteins and lipids that were markedly altered following radiation

exposure, chosen for their reproducibility and magnitude of change.

This targeted approach enhanced the reliability of functional

pathway predictions. Furthermore, KEGG-based enrichment analysis

was conducted to explore the functional relevance of

radiation-induced changes at the proteomic and lipidomic levels.

The six proteins showing altered expression following α-radiation

were associated with key pathways such as 'Basal transcription

factors', 'Apoptosis-multiple species', and 'MicroRNAs in cancer',

implying involvement in transcriptional regulation and cell death

processes. Similarly, the altered lipid species were predicted to

affect 'Glycerophospholipid metabolism', 'EGFR tyrosine kinase

inhibitor resistance', and 'Cytokine-cytokine receptor

interaction', all of which are functionally linked to membrane

remodeling, inflammatory signaling and cell survival under

radiation-induced stress. These enrichment results provided

mechanistic insight into how OBCs respond to α-radiation at the

molecular level and support their potential utility as

biodosimetric markers. Currently, no publicly available omics

datasets exist for α-radiation-exposed osteoblastic or stromal

cells. Unlike prior studies focusing on hematopoietic cells, the

present study uniquely applied integrated multi-omics to bone

marrow OBCs exposed to α-radiation, revealing novel molecular

signatures that may underlie radiation-induced bone marrow

toxicity. Thus, the present study served as a foundational in

vitro model to identify candidate radiation-responsive markers.

Future studies involving clinical samples from patients treated

with α-emitting radionuclides (for example, 223Ra) are

warranted to validate the translational potential of these

findings. Although the present study provided novel insights into

the molecular responses of OBCs to α-radiation in vitro,

further validation using in vivo models or clinical BM

samples from patients treated with α-emitting radionuclide

therapies is necessary to confirm the relevance of these candidate

biomarkers in physiological settings. The present study used a

limited number of biological replicates (8-10 mice per dose group)

due to the technical challenges and resource demands of primary OBC

culture and comprehensive multi-omics analyses. While consistent

and statistically significant trends were observed, the present

study acknowledged that a larger sample size would enhance the

robustness and generalizability of these findings. Future studies

with increased biological replicates and independent validations

are warranted to confirm and extend these results. In addition,

although the present study identified radiation-responsive

metabolites and miRNAs in OBCs, The present study did not perform

functional assays (such as gene knockdown or overexpression) to

directly establish causal relationships. Such mechanistic

validations were beyond the scope of this initial exploratory study

but remain essential future directions to clarify the biological

roles of these candidate molecules.

In summary, the results indicate that exposure of

OBCs to α-radiation leads to altered secretion of metabolites and

changes in the expression of related miRNAs. The metabolites may be

OBC damage markers in α-radiation therapy to predict individual

therapy responses.

In conclusion, the present study presents a

comprehensive multi-omics characterization of osteoblastic bone

marrow cells exposed to α-radiation, providing new insights into

their molecular responses. While the findings highlight key

biological alterations associated with high-LET exposure, several

limitations remain. Notably, the present study did not include

comparisons with other types of radiation, such as γ or β rays.

Although the present study focused on α-radiation due to its

clinical relevance in 223Ra-targeted therapy, future

work should include comparative analyses with other radiation types

(such as X-rays, γ rays, or β radiation) to delineate the

specificity of the observed omics responses to high-LET radiation.

Such comparisons would provide a more comprehensive understanding

of radiation-induced molecular changes across different LET

contexts.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the

current study are available as follows. The raw microRNA microarray

data have been deposited in the NCBI GEO under accession number

GSE286553 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE286553).

The raw proteomic and lipidomic data have been deposited in

MetaboBank under accession number MTBKS262 (https://ddbj.nig.ac.jp/public/metabobank/study/MTBKS262/).

All datasets are publicly available and can be accessed through the

respective databases.

Authors' contributions

SM, YM and AW designed the study, drafted the

manuscript and actively participated in its revision. SM, MC and YT

examined and analyzed the experimental data. SM and AW oversaw the

manuscript and provided the final approval of the version submitted

and published. SM and AW confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mrs. Miyu Miyazaki of

the Scientific Research Facility Center of Hirosaki University

Graduate School of Medicine for the mass spectrometry

assistance.

Funding

The present study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grants-in-Aid

for Scientific Research (B) (Project No. 21H028 61/23K21419, Satoru

Monzen) and JSPS KAKENHI, Fund for the Promotion of Joint

International Research (Fostering Joint International Research;

project no. 17KK0181, Satoru Monzen).

References

|

1

|

Amarasekara DS, Kim S and Rho J:

Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by cytokine networks. Int

J Mol Sci. 22:28512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mizoguchi T and Ono N: The diverse origin

of bone-forming osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 36:1432–1447. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Clézardin P, Coleman R, Puppo M, Ottewell

P, Bonnelye E, Paycha F, Confavreux CB and Holen I: Bone

metastasis: Mechanisms, therapies and biomarkers. Physiol Rev.

101:797–855. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hofbauer LC, Bozec A, Rauner M, Jakob F,

Perner S and Pantel K: Novel approaches to target the

microenvironment of bone metastasis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

18:488–505. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI,

O'Sullivan JM, Fosså SD, Chodacki A, Wiechno P, Logue J, Seke M, et

al: Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate

cancer. N Engl J Med. 369:213–223. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hoskin P, Sartor O, O'Sullivan JM,

Johannessen DC, Helle SI, Logue J, Bottomley D, Nilsson S,

Vogelzang NJ, Fang F, et al: Efficacy and safety of radium-223

dichloride in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer

and symptomatic bone metastases, with or without previous docetaxel

use: A prespecified subgroup analysis from the randomised,

double-blind, phase 3 ALSYMPCA trial. Lancet Oncol. 15:1397–1406.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wilson A and Trumpp A: Bone-marrow

haematopoietic-stem-cell niches. Nat Rev Immunol. 6:93–106. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Morrison SJ and Scadden DT: The bone

marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 505:327–334.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson

M and Altman DG: Improving bioscience research reporting: The

ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. J Pharmacol

Pharmacother. 1:94–99. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Tatara Y and Monzen S: Proteomics and

secreted lipidomics of mouse-derived bone marrow cells exposed to a

lethal level of ionizing radiation. Sci Rep. 13:88022023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Staaf E, Brehwens K, Haghdoost S,

Pachnerová-Brabcová K, Czub J, Braziewicz J, Nievaart S and Wojcik

A: Characterisation of a setup for mixed beam exposures of cells to

241Am alpha particles and X-rays. Radiat Prot Dosimetry.

151:570–579. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhou G, Pang Z, Lu Y, Ewald J and Xia J:

OmicsNet 2.0: A web-based platform for multi-omics integration and

network visual analytics. Nucleic Acids Res. 50:W527–W533. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hérodin F and Drouet M: Cytokine-based

treatment of accidentally irradiated victims and new approaches.

Exp Hematol. 33:1071–1080. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Takahashi K, Monzen S, Yoshino H, Abe Y,

Eguchi-Kasai K and Kashiwakura I: Effects of a 2-step culture with

cytokine combinations on megakaryocytopoiesis and thrombopoiesis

from carbon-ion beam-irradiated human hematopoietic stem/progenitor

cells. J Radiat Res. 49:417–424. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Patterson AM, Wu T, Chua HL, Sampson CH,

Fisher A, Singh P, Guise TA, Feng H, Muldoon J, Wright L, et al:

Optimizing and profiling prostaglandin E2 as a medical

countermeasure for the hematopoietic acute radiation syndrome.

Radiat Res. 195:115–127. 2021.

|

|

16

|

Goodhead DT: Mechanisms for the biological

effectiveness of high-LET radiations. J Radiat Res. 40(Suppl):

S1–S13. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Parlani M, Boccalatte F, Yeaton A, Wang F,

Zhang J, Aifantis I and Dondossola E: 223Ra induces

transient functional bone marrow toxicity. J Nucl Med.

63:1544–1550. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Heidegger I, Pichler R, Heidenreich A,

Horninger W and Pircher A: Radium-223 for metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer: Results and remaining open

issues after the ALSYMPCA trial. Transl Androl Urol. 7:S132–S134.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nagata S: Apoptosis and clearance of

apoptotic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 36:489–517. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand

M, Lee JJ and Lötvall JO: Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and

microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells.

Nat Cell Biol. 9:654–659. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rafii S, Shapiro F, Pettengell R, Ferris

B, Nachman RL, Moore MA and Asch AS: Human bone marrow

microvascular endothelial cells support long-term proliferation and

differentiation of myeloid and megakaryocytic progenitors. Blood.

86:3353–3363. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|