Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), the leading cause of

death worldwide, claims ~18 million lives each year and has high

morbidity rates (1-4). Atherosclerosis is the main

pathologic mechanism of most CVDs (5). These chronic plaques in vessel,

composed mainly of cholesterol, fat, calcium and blood cells,

gradually harden over time, leading to arterial stenosis and

thereby restricting the flow of oxygen-rich blood to various parts

of the body (6). Atherosclerosis

has been found to be the central mechanism of this pathological

process and the leading cause of CVDs worldwide (7).

In recent years, atherosclerosis has been recognized

as a chronic inflammatory disease and leads to arterial stenosis

and plaque formation due to the accumulation of lipids and

inflammatory cells within the arterial wall (8-11). The role of adaptive immunity in

atherosclerosis has increasingly attracted attention (12). The adaptive immune system

participates in the development of atherosclerosis through various

cellular and molecular mechanisms, including the interactions of T

cells (13), B cells (14), antigen-presenting cells (15) and cytokines (16). Inflammation plays a key role in

the progression of atherosclerosis, and adaptive immune responses

influence plaque formation and stability by modulating the activity

of inflammatory cells and the secretion of cytokines. These studies

further confirm the key role of inflammation and immunity in

atherosclerosis and provide a theoretical basis for

immune-modulating therapies.

Epigenetics focuses on heritable changes in gene

expression that are not derived from alterations in the nucleotide

sequence, such as DNA or RNA methylation modifications, as well as

post-translational modifications of proteins (17). Lactylation, an emerging

post-translational modification, has garnered widespread attention

in biological and medical research (18-20). Lactylation plays a crucial role

in various biological processes, including the regulation of

macrophage function, modulation of glycolytic activity and the

promotion of tumorigenesis (21). As a key regulatory factor in

numerous biological processes and disease mechanisms, lactylation

modification has become a hot topic in molecular biology studies

(22,23).

Although the potential role of lactylation

modification in CVD has been demonstrated (24), its role in regulating immunity in

the context of atherosclerosis remains largely elusive. During the

pathological process of atherosclerosis, the accumulation of

lactate in local tissues obviously impacts this process. Therefore,

vast research efforts have explored the interaction between

lactylation modifications and adaptive immunity within the

atherosclerotic microenvironment. This review aims to clarify the

role of lactylation in immunity in the context of atherosclerosis

and summarize the driving mechanisms. This article not only

explores the roles of lactate and lactylation in atherosclerosis

but also systematically analyzes their impacts on various

components of the immune system, such as macrophages, T cells and B

cells. To the best of our knowledge, this multidimensional

perspective is relatively rare in previous reviews (12,25-27), as most studies have focused

solely on a single cell type or mechanism. By closely integrating

the metabolic characteristics of lactate with the regulation of

immune responses, the article highlights the crucial role of

metabolic reprogramming in atherosclerosis. This integrative

approach provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding

the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. These innovative aspects not

only enrich our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of

atherosclerosis but also offer new directions for future

therapeutic strategies.

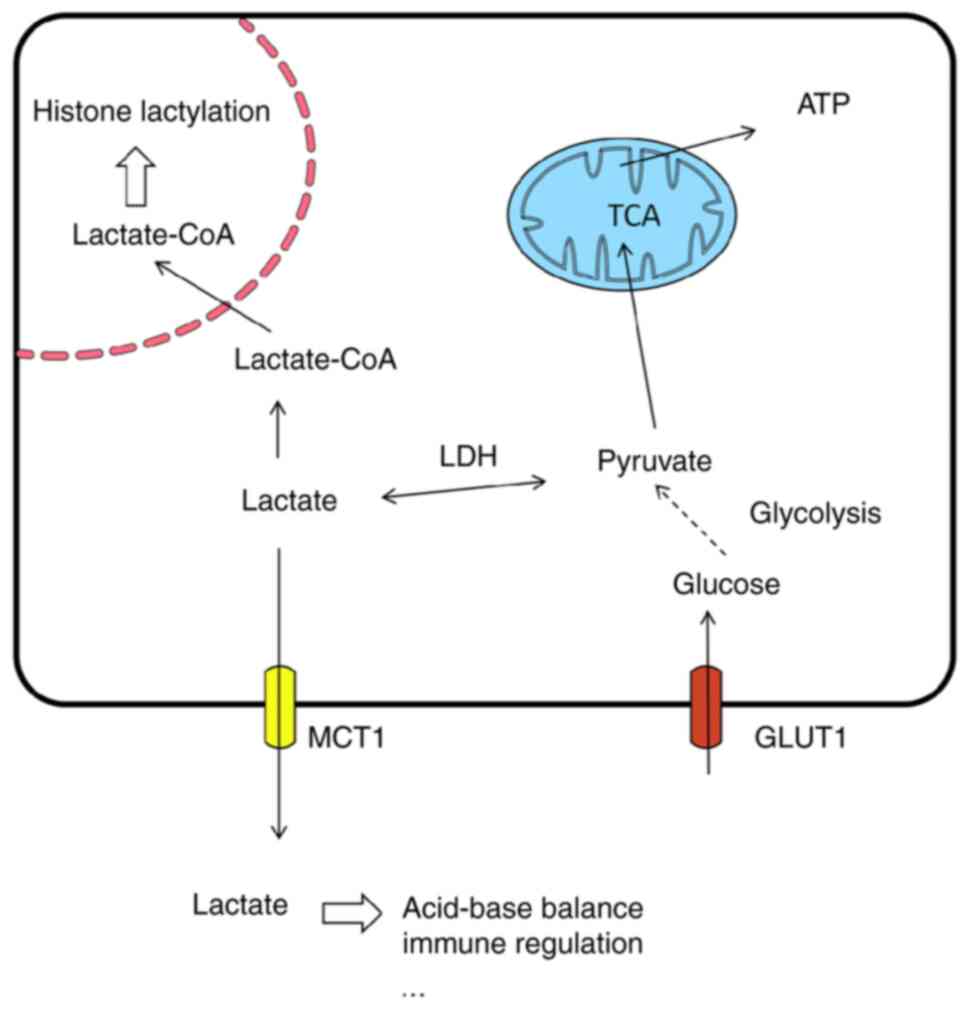

Lactate exists in two isomeric forms: D-lactate and

L-lactate, with L-lactate being the most common form in living

organisms (28). Lactate

transport mainly relies on monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs)

(29,30). In organisms, glucose is

metabolized to lactate via the glycolytic pathway under a short

supply of oxygen. Although only 2 ATP molecules are generated per

glucose molecule during this process, the energy output is

relatively low and the rapid production of lactate quickly provides

energy under hypoxic conditions to maintain normal cellular

functions (31). As an acidic

substance, lactate plays an important role in the acid-base balance

of the body. Furthermore, tumor cells often exhibit aerobic

glycolysis, producing large amounts of lactate even in the presence

of oxygen (32,33). This metabolic phenomenon is known

as the 'Warburg effect' and the accumulation of lactate facilitates

the growth and invasion of tumor cells (34,35).

Under normal physiological conditions, the

production and clearance of lactate are in a dynamic equilibrium.

It has been found that lactate is a metabolic byproduct of

glycolysis and an important signaling molecule (36-39). The metabolic pathways of lactate

vary with the cell type and environment. Lactate can be produced

through anaerobic glycolysis, leading to its accumulation, or it

can be oxidized to acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) and enter the

tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle during aerobic respiration

(40). Additionally, lactate can

be generated from pyruvate via the Warburg effect (41). These distinct metabolic fates

highlight the versatile roles of lactate in different physiological

contexts. For instance, in the immune system, lactate modulates the

activity of immune cells, inhibiting the overactivation of certain

immune cells while promoting the proliferation and differentiation

of others (42-44). In addition, lactate is involved

in various physiological and pathological processes as an energy

source and a signaling molecule and participate in epigenetic

modifications (e.g., lactylation) (19).

In the heart, lactate is a byproduct of glycolysis

and a key energy source for cardiomyocytes. Under normal

physiological conditions, lactate oxidation provides >50% of the

energy demands of cardiomyocytes. Even at rest, the proportion of

energy supplied by lactate oxidation can reach 10%, and during

exercise, this proportion can exceed 50% (45-47). Lactate enters the mitochondria

through the lactate oxidation complex, is converted into pyruvate,

and then enters the TCA cycle to ultimately generate ATP.

Furthermore, lactate activates a series of transcriptional

networks, affecting the expression and subcellular localization of

metabolism-related proteins in cardiomyocytes, such as

hexokinase-2, pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) and lactate dehydrogenase

A/B, thereby regulating metabolic homeostasis in cardiomyocytes

(48-52). Lactate and pyruvate can also

scavenge free radicals, protecting cardiomyocytes from oxidative

stress damage (53-55). A cross-sectional study involving

1,496 participants reported that blood lactate levels were

independently associated with carotid atherosclerosis, suggesting

that lactate is involved in atherosclerosis development (56). During the progression of

atherosclerosis, lactic acid accumulates in the microenvironment of

atherosclerotic plaques as an end product of glycolysis and leads

to local acidification. This acidic microenvironment facilitates

the binding of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) to aortic

proteoglycans, triggers local immune responses and recruits immune

cells, thereby exacerbating inflammatory reactions (57). Furthermore, lactic acid

stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and N-myc

downstream regulated gene 3. This further promotes the expression

of pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth

factor and forms a positive feedback loop that promotes

atherosclerosis development (58) (Fig. 1).

Lactate participates in cellular metabolism to

provide energy, serves as a donor for lactylation modification and

contribute to the regulation of the local tissue

microenvironment.

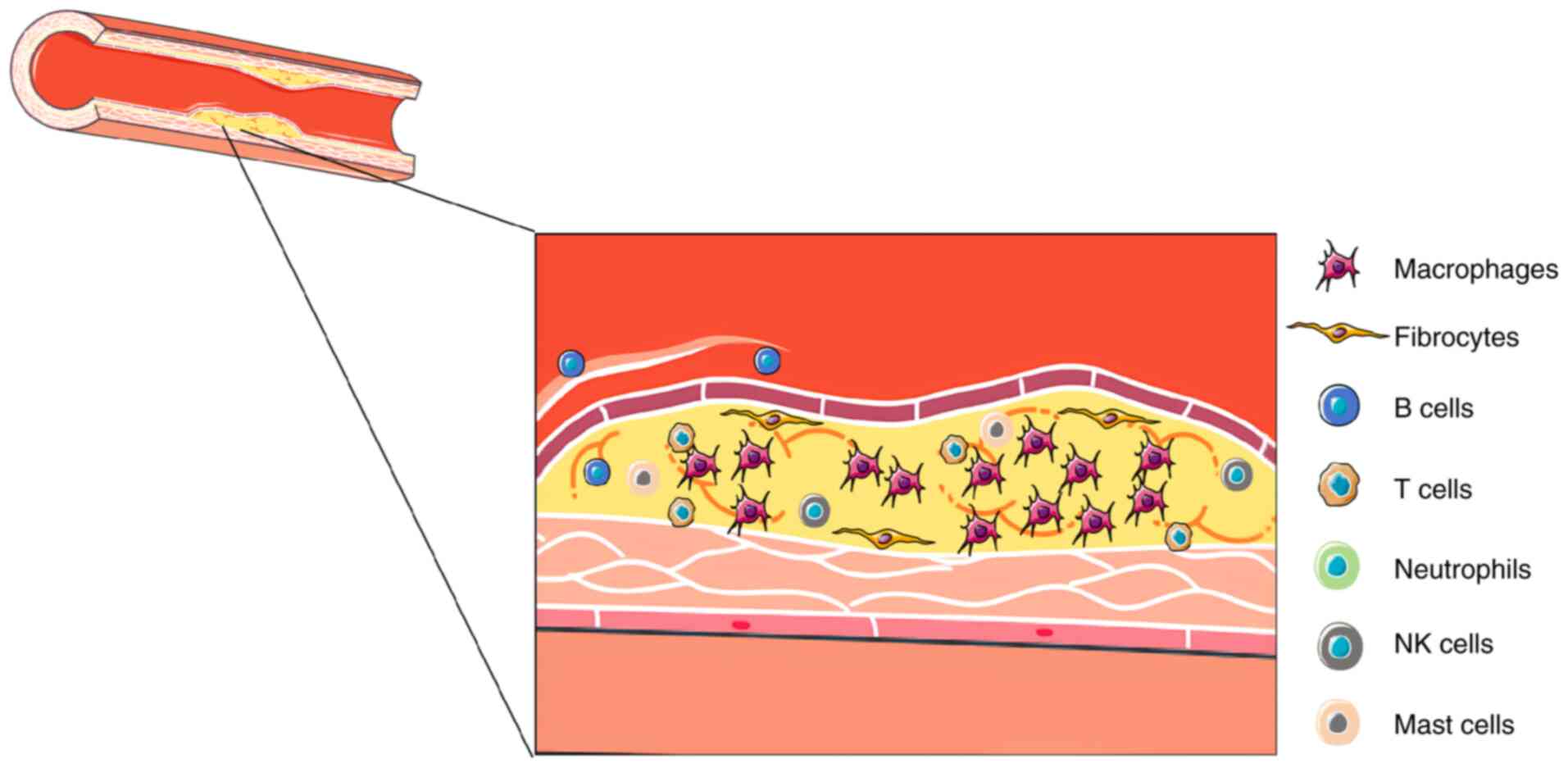

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease

triggered by lipid metabolism disorders and characterized by the

formation of atherosclerotic plaques beneath the intima of large

and medium-sized arteries (5,11,12). During the progression of

atherosclerosis, the glycolysis levels of cells within the plaque

significantly increase, leading to excessive production and release

of lactic acid, which in turn acidifies the extracellular

environment (59-61). This metabolic change further

influences the development of atherosclerosis through multiple

mechanisms.

There is a close and complex interrelationship

between atherosclerosis and the immune system (25,62,63). As a chronic inflammatory disease,

the inflammatory process in atherosclerosis is typically initiated

by the deposition of oxLDL and damage to endothelial cells. After

endothelial injury, cytokines and chemokines are released as

inflammatory mediators and then attract monocytes and other

inflammatory cells into the vascular wall, thereby initiating the

inflammatory response (Fig. 2)

(64). The immune system plays a

critical role in atherosclerosis through the interplay of innate

and adaptive immune responses, immune cell metabolism and cytokine

networks, driving inflammation and plaque progression.

The involvement of various immune cells plays a

crucial role in atherosclerosis. Macrophages engulf oxLDL to form

foam cells that accumulate within the vascular wall and serve as

the foundation for plaque formation (65-67). Lipidomics and transcriptomics

analyses have shown that foam cells themselves do not possess

pro-inflammatory properties. However, the increased oxidative

stress in the arterial wall and the accumulation of modified

lipoproteins reprogram the metabolic processes of macrophages,

thereby triggering inflammatory responses that promote

atherosclerosis (68,69). After cell death, lipid-overloaded

macrophages are usually phagocytized by other macrophages (70). However, when phagocytic cells

become overwhelmed, they release pro-inflammatory components. The

retention of macrophages in the arterial wall is promoted by

adhesion molecules (e.g., vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) and

neuroguidance factors (such as netrin 1), while high-density

lipoprotein facilitates the egress of macrophages from plaques

through a C-C motif chemokine receptor (CCR)7-mediated mechanism

(71-74). Macrophages in atherosclerotic

plaques exhibit pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory

characteristics but do not follow the classical M1/M2

classification (25,75). Single-cell studies have

identified at least five distinct macrophage subpopulations in the

mouse aorta, including inflammatory macrophages, type I

interferon-inducible cells, foam cells with high expression of

triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2, aortic

intima-resident macrophages and embryonic-derived resident

macrophages (68,69,76,77). These subpopulations play diverse

roles in atherosclerosis. These cells exert both pro-inflammatory

and anti-inflammatory effects during disease progression and their

functions are regulated by multiple factors, such as cholesterol

metabolism, oxidative stress and cell-to-cell interactions. Efforts

should be invested to further characterize the functions of these

macrophage subpopulations and explore their specific mechanisms of

action in atherosclerosis.

Adaptive immunity is a key modulator of

atherosclerosis. T cells play a complex role in atherosclerosis and

different subsets influence disease progression through numerous

mechanisms. Type 1 T-helper (Th1) cells are the most prominent

CD4+T-cell subset in atherosclerotic plaques, promoting

lesion development and plaque instability by secreting IFNγ and

expressing T-bet (78,79). The mechanisms include inducing

the uptake of oxLDL, foam cell formation, polarization of

macrophages to a pro-inflammatory phenotype and proliferation of

vascular smooth muscle cells (13,80,81).

The role of Th17 cells in atherosclerosis remains

controversial. In mouse models, the number of T cells expressing

IL-17 is positively correlated with atherosclerosis. Depletion of

Th17 cells inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines

and chemokines, as well as leukocyte infiltration and plaque

formation (92). In addition to

its pro-inflammatory effects, IL-17A has a plaque-stabilizing role

in atherosclerosis (93).

Neutrophils are mainly associated with events

following plaque rupture or erosion, releasing various enzymes and

cytokines that participate in the inflammatory response and tissue

repair process (105-107). NK cells modulate the activity

of other immune cells by releasing cytokines and cytotoxic

granules, thereby influencing the immune response within

atherosclerotic plaques (108).

Mast cells, primarily located in the adventitia of arteries,

release histamine, enzymes and cytokines, degrade the extracellular

matrix, promote the further recruitment of inflammatory cells and

enhance local inflammation, increasing the complexity and potential

rupture risk of atherosclerotic plaques (109,110) (Table I).

During the progression of atherosclerosis, the

persistent inflammatory response significantly impacts the immune

system. Chronic inflammation can lead to overactivation or

dysfunction of the immune system, thus increasing the risk of

autoimmune diseases. Furthermore, vascular changes caused by

atherosclerosis can affect the transport and distribution of immune

cells, thereby influencing the normal function of the immune system

(111-113). Considering the close

relationship between atherosclerosis and the immune system, immune

regulation strategies have potential in treating atherosclerosis.

By modulating the function of immune cells, inhibiting the

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines or enhancing the effects

of anti-inflammatory cytokines, it is possible to reduce the

inflammatory response, stabilize atherosclerotic plaques and

thereby reduce the risk of cardiovascular events, offering new

potential therapeutic options for atherosclerosis.

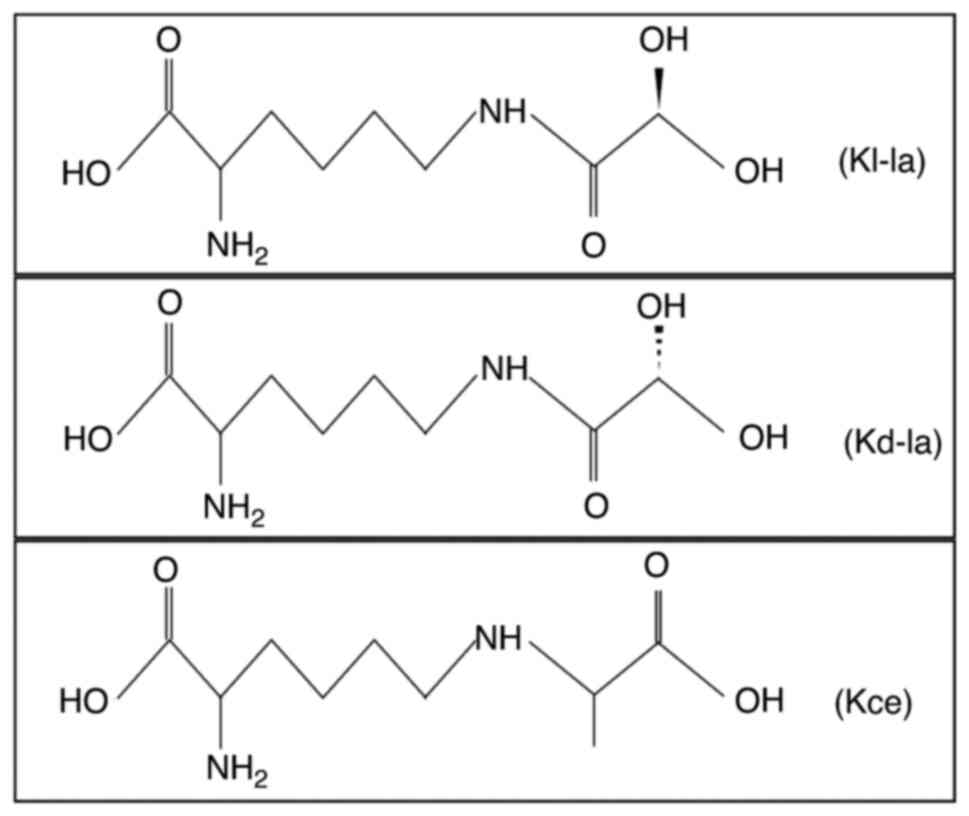

Lactylation is an epigenetic modification that

involves post-translational modifications of both histone and

non-histone proteins and plays a key role in the regulation of gene

transcription and protein function (114). There are three isomers

generated in this process: Lysine L-lactylation (Kl-la),

N-ε-(carboxyethyl) lysine and D-lactyl lysine. It has been shown

that Kl-la is the primary form of lactylation within cells and

significantly contributes to glycolysis and the Warburg effect

(115). Lactylation tends to

occur at nucleophilic sites, such as amino groups

(-NH2), interacting with corresponding functional

groups, and this high level of selectivity allows lactylation to

precisely target specific proteins, causing significant changes in

their properties and functions (114) (Fig. 3).

Induced by the accumulation of lactate, lactylation

modifies proteins and alters the spatial conformation of histones,

thereby affecting gene transcription and the regulation of gene

expression. Similarly, it affects the function of non-histone

proteins by altering their spatial conformation. Lactylation

involves a series of enzyme-catalyzed, reversible chemical

reactions, rather than spontaneous chemical activity (116). The 'writers' of lactylation

refer to enzymes or proteins capable of catalyzing lactylation

reactions, transferring lactoyl groups to target proteins after

lactate is converted into lactoyl-CoA. The known lactylation

'writers' proteins mainly include histone acetyltransferases

Sirtuin (SIRT)1 (117), P300

(117), lysine

acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A) (118), Tat-interactive protein 60 kDa

(119,120) and KAT8 (121,122). 'Erasers' include enzymes or

proteins that remove or erase lactoyl groups through hydrolysis,

restoring the target molecule to its original state, with histone

deacetylases (123) and SIRTs

(124,125) being known 'erasers' that remove

lactylation modifications. In biology, 'readers' are defined as

proteins or domains capable of recognizing and interacting with

lactoyl groups. Although no specific lactylation readers have been

discovered, this may be related to the recent discovery of

lactylation and an incomplete understanding of its underlying

molecular mechanisms. Lactylation, a post-translational

modification first reported in 2019 by Professor Yingming Zhao's

group at the University of Chicago, has a shorter research history

compared to classical modifications like acetylation and

phosphorylation (19). Although

the identification of specific 'reader' proteins for lactylation is

still in progress, their functional roles have been confirmed

through various studies. For instance, histone H3K18 lactylation

influences macrophage polarization and tumor microenvironment

regulation (126), lactylation

of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase inhibits its immune activity, and

lactylation in NK cells causes mitochondrial dysfunction (127). The lack of identified 'readers'

does not diminish lactylation's biological significance but rather

highlights the field's rapid development. Current evidence

underscores its crucial roles in gene regulation, immune responses

and disease. Future technological advancements and in-depth

research are expected to uncover lactylation-specific 'readers',

further clarifying its molecular mechanisms. As research

progresses, more information about lactylation readers will be

revealed in the future, leading to a more comprehensive

understanding of the molecular mechanisms of lactylation.

Lactylation is an important epigenetic modification

mechanism that plays a key role in various physiological and

pathological processes by affecting protein stability, enzyme

activity, protein-protein interactions, protein distribution,

structure and function (128).

Specifically, lactylation involves a series of complex

physiological activities, including somatic cell reprogramming

(129,130), embryonic development (131-133), neural excitation (134), osteoblast differentiation

(135,136), pyroptosis (137,138), macroautophagy (139), decidualization (140), homologous recombination

(119,141), cuproptosis (142), myogenesis (143) and oxidative phosphorylation

(52,144). In addition, lactylation is

closely related to the occurrence and development of various

diseases, including but not limited to malignant tumors (22,119), inflammation-related diseases

(145-147), fibrosis-related diseases

(148,149), Alzheimer's disease (150), heart disease (60,117,151), insulin resistance (152), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

(153), cerebral infarction

(154,155), viral infections (156,157) and endometriosis (158).

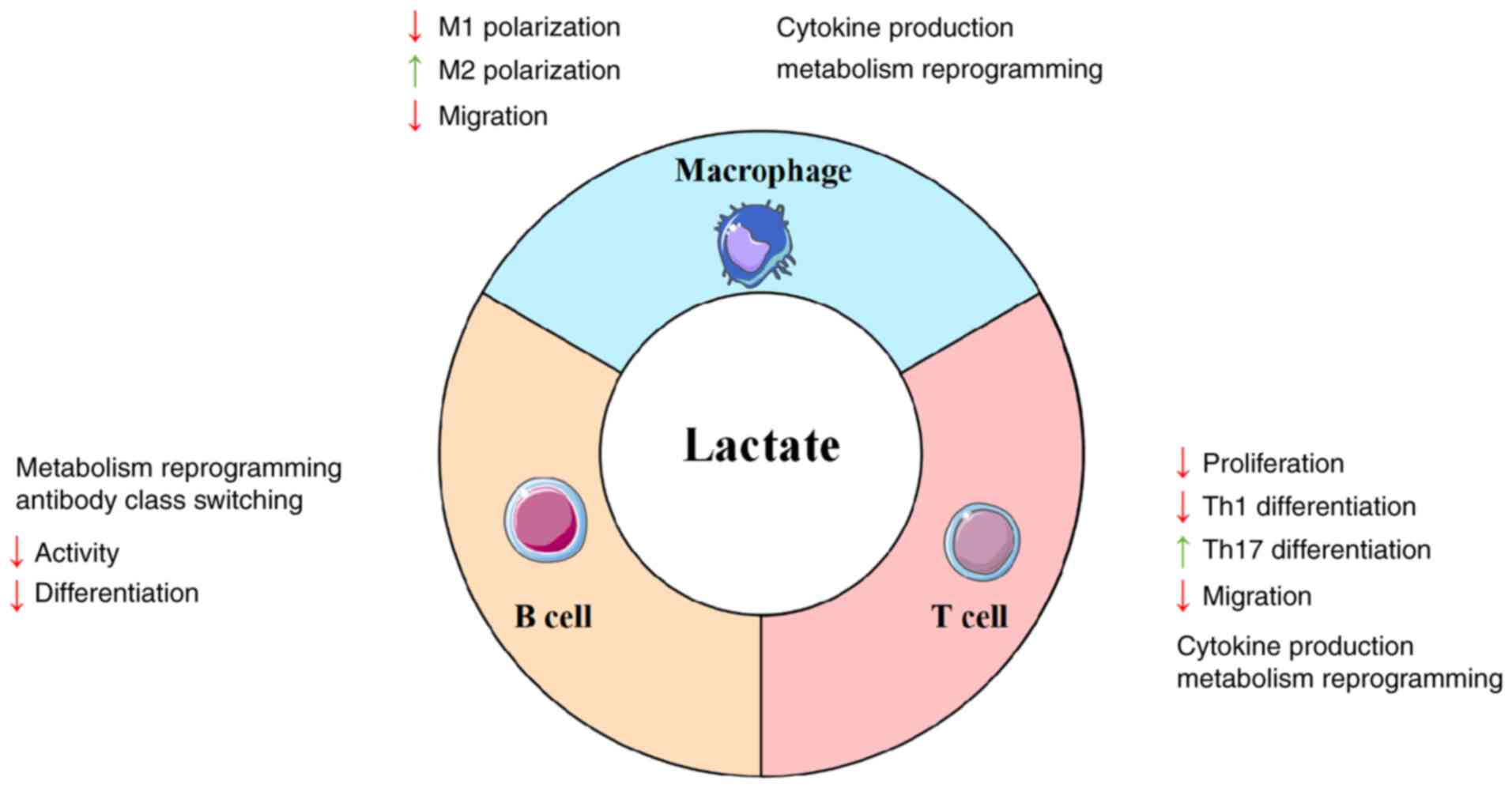

In atherosclerotic plaques, high concentrations of

lactate induce metabolic reprogramming in macrophages, shifting

their metabolism from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation

(159-161). This metabolic remodeling

significantly impacts the functional status of macrophages: The

accumulation of lactate inhibits mitochondrial function, reduces

ATP production and consequently diminishes the activity and

functional performance of macrophages (111,162,163). Furthermore, lactate induces the

polarization of macrophages towards the M2 phenotype while

inhibiting M1 polarization, thereby promoting their

anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive functions (164,165). Besides, lactate attenuates

inflammatory responses by reducing the phosphorylation levels of

NF-κB, thereby suppressing the transcription of

inflammation-related genes (166).

More critically, lactate can induce histone

lactylation, a modification that regulates macrophage metabolism

and phenotypic transformation by acting on both histones (such as

H3K18la) and non-histone proteins (such as PKM2) (167-169). For instance, H3K18la

modification activates the expression of M2-related genes and

drives the transformation of M1 macrophages towards the M2

phenotype. Macrophage activation is one of the key features of

atherosclerosis, typically accompanied by a shift in core

metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis (19). It has been found that histone

lactylation mediated by MCT4, which is associated with lactate

efflux, is closely related to atherosclerosis. In the absence of

MCT4, histone lactylation at lysine 18 of histone H3 activates the

transcription of anti-inflammatory and TCA cycle genes, thereby

initiating local repair and homeostasis (170). This finding indicates that

lactylation plays an important role in regulating macrophage

function and the progression of atherosclerosis.

Lactate is a byproduct of glycolysis and usually

accumulates in large amounts in the tumor microenvironment,

creating an acidic ecological niche. In the acute inflammatory

phase, lactate primarily exerts anti-inflammatory effects by

activating the G protein-coupled receptor 81 receptor, thereby

inhibiting the production of inflammatory mediators and alleviating

the inflammatory response (171,172). However, the acidic environment

caused by lactate accumulation exacerbates the persistence of

inflammation and promotes tissue damage in the chronic inflammatory

phase. Nevertheless, lactate also induces the polarization of

immune cells and modulates metabolic pathways to facilitate the

resolution of inflammation and exert certain anti-inflammatory

effects (173,174).

The activation and differentiation of T cells are

accompanied by metabolic reprogramming, one of the metabolic

hallmarks being aerobic glycolysis, which refers to the conversion

of glucose to lactate in the presence of oxygen (175). T cells undergo metabolic

reprogramming in different states of differentiation (176). For instance, effector T cells

primarily rely on glycolysis, whereas regulatory T cells and memory

T cells mainly depend on oxidative phosphorylation (177,178). T cells sense lactate through

the expression of specific transporters, which leads to the

inhibition of their migratory capacity. This 'stop signal' for

migration depends on the interference of lactate with intracellular

metabolic pathways, particularly glycolysis. Lactate promotes the

differentiation of CD4+ T cells into the IL-17+ subset while

reducing the cytotoxic capacity of CD8+ T cells. These phenomena

lead to the formation of ectopic lymphoid structures at sites of

inflammation and the production of autoantibodies (43,179). Lactate triggers the nuclear

translocation of the PKM2 via an active transmembrane influx

mediated by the sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporter 2 (also

known as solute carrier family 5 member 12). Within the nucleus,

PKM2 forms a complex with phosphorylated signal transducer and

activator of transcription 3, synergistically enhancing the

transcriptional activity of the IL-17 gene, thereby markedly

promoting IL-17 secretion by Th17 cells (180-182). The activity of Tregs relies on

the metabolic reprogramming from glycolysis to oxidative

phosphorylation, a process strictly regulated by the transcription

factor forkhead box P3. Lactate promotes the accumulation of Tregs

at inflammatory sites and activates the HIF-1α-dependent CCL20/CCR6

signaling axis, facilitating Treg migration to the lesion area. In

addition, Tregs utilize lactate as a substrate for the TCA cycle,

further enhancing their immunosuppressive function (164,183,184). Nevertheless, in chronic

inflammatory responses, the persistent accumulation of lactate

causes local tissue damage and drives the progression of chronic

inflammation, which significantly exacerbates the pathological

impact on atherosclerotic lesions and accelerates disease

progression (173,179). Lactate plays a complex dual

role in inflammation and immune responses. It exerts

anti-inflammatory effects by regulating metabolism and immune cell

functions, but it exacerbates tissue damage and disease progression

in chronic inflammation.

Lactylation promotes Th17 differentiation and

participates in the development of autoimmune diseases and

inflammatory responses by regulating site-specific modifications of

key proteins such as IKAROS family zinc finger 1, which directly

modulates the expression of Th17-related genes (185). In the tumor microenvironment,

lactate regulates the generation of Treg cells through lactylation

modification at lysine 72 of the MOESIN protein. This process

enhances the interaction between MOESIN and transforming growth

factor-β receptor I, activates the downstream SMAD3 signaling

pathway and significantly improves the stability and function of

Treg cells (186). This

discovery provides an important reference for understanding the

regulatory mechanisms of lactate accumulation on Treg cells in the

context of atherosclerotic tissue environments.

Lactate significantly inhibits the proliferation

capacity and antibody production of B cells by reducing the

extracellular pH (159,187). Additionally, lactate modulates

the metabolic pathways of B cells, particularly by enhancing the

glycolytic process, which provides rapid energy supply to support

their proliferation and differentiation. At the same time, lactate

suppresses oxidative phosphorylation and results in significant

alterations in the metabolic state of B cells (28,188). At the molecular level, lactate

promotes the growth and metabolic activities of B cells by

activating the mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway

(189,190). Under hypoxic conditions,

lactate enhances the adaptability of B cells to low oxygen

environments by stabilizing HIF-1α (191-193). Furthermore, lactate activates

the NF-κB signaling pathway, promoting the secretion of

pro-inflammatory cytokines by B cells, thereby participating in the

regulation of inflammatory responses (194,195). These findings demonstrate that

lactate plays a multifaceted role in the functional regulation of B

cells, influencing metabolic reprogramming, signaling pathway

activation and environmental adaptability, among other aspects.

Lactylation modulates the antibody class switch recombination (CSR)

in B cells by influencing metabolic pathways. For instance, the

MCT1-mediated lactate transport and pyruvate metabolism regulates

the acetylation modification of histone H3K27, thereby affecting

the transcriptional efficiency of activation-induced cytidine

deaminase, which ultimately impacts the CSR in B cells (196) (Fig. 4).

Lactate and its mediated lactylation modifications

play a complex dual role in atherosclerosis by regulating metabolic

reprogramming, functional polarization and epigenetic modifications

of macrophages, T cells and B cells.

In summary, this review comprehensively analyzes the

multifaceted roles of lactate and lactylation in shaping the immune

system within the context of atherosclerosis. As a chronic

inflammatory disease, atherosclerosis is characterized by the

complex interplay between lipid metabolism, immune cell

infiltration and the local microenvironment. The results highlight

the critical roles of lactate and lactylation in modulating immune

cell functions, metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic regulation,

thereby influencing the progression and stability of

atherosclerotic plaques.

The involvement of lactate and lactylation in the

regulation of macrophage polarization, T cell differentiation and B

cell metabolism underscores their potential as therapeutic targets.

Specifically, lactate-induced metabolic reprogramming and

lactylation modifications have been shown to significantly impact

the phenotypes and functions of immune cells and contribute to

pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses. These insights

provide a deeper understanding of the immune metabolic mechanisms

underlying atherosclerosis and pave the way for novel therapeutic

strategies targeting lactate metabolism and lactylation

pathways.

However, despite the progress made in elucidating

the roles of lactate and lactylation in atherosclerosis, several

gaps remain in our knowledge. The complex microenvironment of

atherosclerotic plaques, characterized by hypoxia, nutrient

deprivation and acidosis, is likely to influence the behavior of

immune cells and the efficacy of potential treatments. Yet, the

precise mechanisms through which these microenvironmental factors

interact with lactate and lactylation to modulate immune responses

are still not fully understood. Additionally, the diverse metabolic

profiles and functional states of immune cells within plaques

suggest that a more detailed characterization of immune cell

subsets and their specific roles is needed.

Furthermore, the dynamic changes in the

atherosclerotic microenvironment over time, from plaque initiation

to rupture, add another layer of complexity to the study of immune

regulation. The impact of these temporal changes on lactate

production, lactylation modifications and immune cell function

remains elusive. Furthermore, the potential compensatory mechanisms

and feedback loops involving other metabolic pathways and

epigenetic modifications in response to lactate accumulation and

lactylation need further investigation.

In conclusion, although significant advancements

have been made in understanding the roles of lactate and

lactylation in atherosclerosis, the intricate interplay between the

microenvironment, metabolic changes and immune regulation remains

an area of considerable research need. Future studies should focus

on unraveling the detailed mechanisms through which the

atherosclerotic microenvironment influences lactate metabolism and

lactylation, as well as their downstream effects on immune cell

function. These will enhance our understanding of the

pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and provide new avenues for

developing targeted therapies aimed at modulating immune responses

and improving clinical outcomes.

Not applicable.

YX was involved in the conceptualization of the

review, data curation, investigation, methodology and

writing-original draft. JZ was responsible for data curation and

project administration. JW contributed to the conceptualization,

data curation and methodology. HH was involved in

conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology and

writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is

not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

No funding was received.

|

1

|

Luengo-Fernandez R, Walli-Attaei M, Gray

A, Torbica A, Maggioni AP, Huculeci R, Bairami F, Aboyans V, Timmis

AD, Vardas P and Leal J: Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases

in the European Union: A population-based cost study. Eur Heart J.

44:4752–4767. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Weintraub WS: High costs of cardiovascular

disease in the European Union. Eur Heart J. 44:4768–4770. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Goldsborough E III, Osuji N and Blaha MJ:

Assessment of cardiovascular disease risk: A 2022 update.

Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 51:483–509. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Raleigh V and Colombo F: Cardiovascular

disease should be a priority for health systems globally. BMJ.

382:e0765762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Falk E: Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J

Am Coll Cardiol. 47(Suppl 8): C7–C12. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fan J and Watanabe T: Atherosclerosis:

Known and unknown. Pathol Int. 72:151–160. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Libby P: The changing landscape of

atherosclerosis. Nature. 592:524–533. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rocha VZ and Libby P: Obesity,

inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 6:399–409.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shoaran M and Maffia P: Tackling

inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 21:4422024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bäck M, Yurdagul A Jr, Tabas I, Öörni K

and Kovanen PT: Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis:

Mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol.

16:389–406. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kong P, Cui ZY, Huang XF, Zhang DD, Guo RJ

and Han M: Inflammation and atherosclerosis: Signaling pathways and

therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1312022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wolf D and Ley K: Immunity and

inflammation in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 124:315–327. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Saigusa R, Winkels H and Ley K: T cell

subsets and functions in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol.

17:387–401. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Srikakulapu P and McNamara CA: B cells and

atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 312:H1060–H1067.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Taghavie-Moghadam PL, Butcher MJ and

Galkina EV: The dynamic lives of macrophage and dendritic cell

subsets in atherosclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1319:19–37. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tedgui A and Mallat Z: Cytokines in

atherosclerosis: Pathogenic and regulatory pathways. Physiol Rev.

86:515–581. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kzhyshkowska J, Shen J and Larionova I:

Targeting of TAMs: Can we be more clever than cancer cells? Cell

Mol Immunol. 21:1376–1409. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sun P, Ma L and Lu Z: Lactylation: Linking

the Warburg effect to DNA damage repair. Cell Metab. 36:1637–1639.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C,

Weng Y, Liu W, Kim S, Lee S, Perez-Neut M, et al: Metabolic

regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature.

574:575–580. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li F, Si W, Xia L, Yin D, Wei T, Tao M,

Cui X, Yang J, Hong T and Wei R: Positive feedback regulation

between glycolysis and histone lactylation drives oncogenesis in

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 23:902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang Z, Zheng Y and Gao Q: Lysine

lactylation in the regulation of tumor biology. Trends Endocrinol

Metab. 35:720–731. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li H, Sun L, Gao P and Hu H: Lactylation

in cancer: Current understanding and challenges. Cancer Cell.

42:1803–1807. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y,

Zou Y, Wang JX, Wang Z and Yu T: Lactate metabolism in human health

and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:3052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhu W, Guo S, Sun J, Zhao Y and Liu C:

Lactate and lactylation in cardiovascular diseases: Current

progress and future perspectives. Metabolism. 158:1559572024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Roy P, Orecchioni M and Ley K: How the

immune system shapes atherosclerosis: Roles of innate and adaptive

immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 22:251–265. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ouyang J, Wang H and Huang J: The role of

lactate in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 21:3172023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li X, Cai P, Tang X, Wu Y, Zhang Y and

Rong X: Lactylation modification in cardiometabolic disorders:

Function and mechanism. Metabolites. 14:2172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Rabinowitz JD and Enerbäck S: Lactate: The

ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat Metab. 2:566–571. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bonen A: Lactate transporters (MCT

proteins) in heart and skeletal muscles. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

32:778–789. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Singh M, Afonso J, Sharma D, Gupta R and

Kumar V, Rani R, Baltazar F and Kumar V: Targeting monocarboxylate

transporters (MCTs) in cancer: How close are we to the clinics?

Semin Cancer Biol. 90:1–14. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Certo M, Llibre A, Lee W and Mauro C:

Understanding lactate sensing and signalling. Trends Endocrinol

Metab. 33:722–735. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Apostolova P and Pearce EL: Lactic acid

and lactate: Revisiting the physiological roles in the tumor

microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 43:969–977. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Goenka A, Khan F, Verma B, Sinha P, Dmello

CC, Jogalekar MP, Gangadaran P and Ahn BC: Tumor microenvironment

signaling and therapeutics in cancer progression. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 43:525–561. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liao M, Yao D, Wu L, Luo C, Wang Z, Zhang

J and Liu B: Targeting the Warburg effect: A revisited perspective

from molecular mechanisms to traditional and innovative therapeutic

strategies in cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 14:953–1008. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wang Y and Patti GJ: The Warburg effect: A

signature of mitochondrial overload. Trends Cell Biol.

33:1014–1020. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Magistretti PJ and Allaman I: Lactate in

the brain: From metabolic end-product to signalling molecule. Nat

Rev Neurosci. 19:235–249. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang W, Wang G, Xu ZG, Tu H, Hu F, Dai J,

Chang Y, Chen Y, Lu Y, Zeng H, et al: Lactate is a natural

suppressor of RLR signaling by targeting MAVS. Cell.

178:176–189.e15. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Brown TP and Ganapathy V: Lactate/GPR81

signaling and proton motive force in cancer: Role in angiogenesis,

immune escape, nutrition, and Warburg phenomenon. Pharmacol Ther.

206:1074512020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Li H, Liu C, Li R, Zhou L, Ran Y, Yang Q,

Huang H, Lu H, Song H, Yang B, et al: AARS1 and AARS2 sense

L-lactate to regulate cGAS as global lysine lactyltransferases.

Nature. 634:1229–1237. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lee WD, Weilandt DR, Liang L, MacArthur

MR, Jaiswal N, Ong O, Mann CG, Chu Q, Hunter CJ, Ryseck RP, et al:

Lactate homeostasis is maintained through regulation of glycolysis

and lipolysis. Cell Metab. 37:758–771.e8. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Feron O: Pyruvate into lactate and back:

from the Warburg effect to symbiotic energy fuel exchange in cancer

cells. Radiother Oncol. 92:329–333. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang K, Zhang Y and Chen ZN: Metabolic

interaction: Tumor-derived lactate inhibiting CD8+ T

cell cytotoxicity in a novel route. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

8:522023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S,

Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M, Gottfried E, Schwarz S, Rothe G,

Hoves S, et al: Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid

on human T cells. Blood. 109:3812–3819. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Feng Q, Liu Z, Yu X, Huang T, Chen J, Wang

J, Wilhelm J, Li S, Song J, Li W, et al: Lactate increases stemness

of CD8+ T cells to augment anti-tumor immunity. Nat

Commun. 13:49812022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Mohazzab-H KM, Kaminski PM and Wolin MS:

Lactate and PO2 modulate superoxide anion production in bovine

cardiac myocytes: Potential role of NADH oxidase. Circulation.

96:614–620. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Gaspar JA, Doss MX, Hengstler JG, Cadenas

C, Hescheler J and Sachinidis A: Unique metabolic features of stem

cells, cardiomyocytes, and their progenitors. Circ Res.

114:1346–1360. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chen X, Wu H, Liu Y, Liu L, Houser SR and

Wang WE: Metabolic reprogramming: A byproduct or a driver of

cardiomyocyte proliferation? Circulation. 149:1598–1610. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chung S, Arrell DK, Faustino RS, Terzic A

and Dzeja PP: Glycolytic network restructuring integral to the

energetics of embryonic stem cell cardiac differentiation. J Mol

Cell Cardiol. 48:725–734. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Dziegala M, Kobak KA, Kasztura M, Bania J,

Josiak K, Banasiak W, Ponikowski P and Jankowska EA: Iron depletion

affects genes encoding mitochondrial electron transport chain and

genes of non-oxidative metabolism, pyruvate kinase and lactate

dehydrogenase, in primary human cardiac myocytes cultured upon

mechanical stretch. Cells. 7:1752018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Li X, Zhao L, Chen Z, Lin Y, Yu P and Mao

L: Continuous electrochemical monitoring of extracellular lactate

production from neonatal rat cardiomyocytes following myocardial

hypoxia. Anal Chem. 84:5285–5291. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hammond GL, Nadal-Ginard B, Talner NS and

Markert CL: Myocardial LDH isozyme distribution in the ischemic and

hypoxic heart. Circulation. 53:637–643. 1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Pan RY, He L, Zhang J, Liu X, Liao Y, Gao

J, Liao Y, Yan Y, Li Q, Zhou X, et al: Positive feedback regulation

of microglial glucose metabolism by histone H4 lysine 12

lactylation in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Metab. 34:634–648.e6.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Liu M, Yu W, Fang Y, Zhou H, Liang Y,

Huang C, Liu H and Zhao G: Pyruvate and lactate based hydrogel film

inhibits UV radiation-induced skin inflammation and oxidative

stress. Int J Pharm. 634:1226972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Huang YF, Wang G, Ding L, Bai ZR, Leng Y,

Tian JW, Zhang JZ, Li YQ, Ahmad, Qin YH, et al: Lactate-upregulated

NADPH-dependent NOX4 expression via HCAR1/PI3K pathway contributes

to ROS-induced osteoarthritis chondrocyte damage. Redox Biol.

67:1028672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Groussard C, Morel I, Chevanne M, Monnier

M, Cillard J and Delamarche A: Free radical scavenging and

antioxidant effects of lactate ion: An in vitro study. J Appl

Physiol (1985). 89:169–175. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Shantha GPS, Wasserman B, Astor BC, Coresh

J, Brancati F, Sharrett AR and Young JH: Association of blood

lactate with carotid atherosclerosis: The atherosclerosis risk in

communities (ARIC) carotid MRI study. Atherosclerosis. 228:249–255.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Perrotta P, Van der Veken B, Van Der Veken

P, Pintelon I, Roosens L, Adriaenssens E, Timmerman V, Guns PJ, De

Meyer GRY and Martinet W: Partial Inhibition of glycolysis reduces

atherogenesis independent of intraplaque neovascularization in

mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 40:1168–1181. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Sneck M, Kovanen PT and Oörni K: Decrease

in pH strongly enhances binding of native, proteolyzed, lipolyzed,

and oxidized low density lipoprotein particles to human aortic

proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 280:37449–37454. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Li L, Wang M, Ma Q, Ye J and Sun G: Role

of glycolysis in the development of atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol

Cell Physiol. 323:C617–C629. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Li X, Chen M, Chen X, He X, Li X, Wei H,

Tan Y, Min J, Azam T, Xue M, et al: TRAP1 drives smooth muscle cell

senescence and promotes atherosclerosis via HDAC3-primed histone H4

lysine 12 lactylation. Eur Heart J. 45:4219–4235. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhou LJ, Lin WZ, Meng XQ, Zhu H, Liu T, Du

LJ, Bai XB, Chen BY, Liu Y, Xu Y, et al: Periodontitis exacerbates

atherosclerosis through Fusobacterium nucleatum-promoted hepatic

glycolysis and lipogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 119:1706–1717. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Nilsson J and Hansson GK: Vaccination

strategies and immune modulation of atherosclerosis. Circ Res.

126:1281–1296. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Xue S, Su Z and Liu D: Immunometabolism

and immune response regulate macrophage function in

atherosclerosis. Ageing Res Rev. 90:1019932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kim KW, Ivanov S and Williams JW: Monocyte

recruitment, specification, and function in atherosclerosis. Cells.

10:152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wang B, Tang X, Yao L, Wang Y, Chen Z, Li

M, Wu N, Wu D, Dai X, Jiang H and Ai D: Disruption of USP9X in

macrophages promotes foam cell formation and atherosclerosis. J

Clin Invest. 132:e1542172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Tabas I and Bornfeldt KE: Macrophage

phenotype and function in different stages of atherosclerosis. Circ

Res. 118:653–667. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Luo Y, Duan H, Qian Y, Feng L, Wu Z, Wang

F, Feng J, Yang D, Qin Z and Yan X: Macrophagic CD146 promotes foam

cell formation and retention during atherosclerosis. Cell Res.

27:352–372. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Kim K, Shim D, Lee JS, Zaitsev K, Williams

JW, Kim KW, Jang MY, Seok Jang H, Yun TJ, Lee SH, et al:

Transcriptome analysis reveals nonfoamy rather than foamy plaque

macrophages are proinflammatory in atherosclerotic murine models.

Circ Res. 123:1127–1142. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Spann NJ, Garmire LX, McDonald JG, Myers

DS, Milne SB, Shibata N, Reichart D, Fox JN, Shaked I, Heudobler D,

et al: Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage

lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 151:138–152.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Kojima Y, Weissman IL and Leeper NJ: The

role of efferocytosis in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 135:476–489.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wanschel A, Seibert T, Hewing B,

Ramkhelawon B, Ray TD, van Gils JM, Rayner KJ, Feig JE, O'Brien ER,

Fisher EA, et al: Neuroimmune guidance cue Semaphorin 3E is

expressed in atherosclerotic plaques and regulates macrophage

retention. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 33:886–893. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

van Gils JM, Derby MC, Fernandes LR,

Ramkhelawon B, Ray TD, Rayner KJ, Parathath S, Distel E, Feig JL,

Alvarez-Leite JI, et al: The neuroimmune guidance cue netrin-1

promotes atherosclerosis by inhibiting the emigration of

macrophages from plaques. Nat Immunol. 13:136–143. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Trogan E, Feig JE, Dogan S, Rothblat GH,

Angeli V, Tacke F, Randolph GJ and Fisher EA: Gene expression

changes in foam cells and the role of chemokine receptor CCR7

during atherosclerosis regression in ApoE-deficient mice. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 103:3781–3786. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Feig JE, Parathath S, Rong JX, Mick SL,

Vengrenyuk Y, Grauer L, Young SG and Fisher EA: Reversal of

hyperlipidemia with a genetic switch favorably affects the content

and inflammatory state of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques.

Circulation. 123:989–998. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Colin S, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G and Staels B:

Macrophage phenotypes in atherosclerosis. Immunol Rev. 262:153–166.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Zernecke A, Winkels H, Cochain C, Williams

JW, Wolf D, Soehnlein O, Robbins CS, Monaco C, Park I, McNamara CA,

et al: Meta-analysis of leukocyte diversity in atherosclerotic

mouse aortas. Circ Res. 127:402–426. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Williams JW, Zaitsev K, Kim KW, Ivanov S,

Saunders BT, Schrank PR, Kim K, Elvington A, Kim SH, Tucker CG, et

al: Limited proliferation capacity of aortic intima resident

macrophages requires monocyte recruitment for atherosclerotic

plaque progression. Nat Immunol. 21:1194–1204. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Ait-Oufella H, Taleb S, Mallat Z and

Tedgui A: Recent advances on the role of cytokines in

atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 31:969–979. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI and

Nourshargh S: Getting to the site of inflammation: The leukocyte

adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 7:678–689. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Ait-Oufella H, Sage AP, Mallat Z and

Tedgui A: Adaptive (T and B cells) immunity and control by

dendritic cells in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 114:1640–1660. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Chen J, Xiang X, Nie L, Guo X, Zhang F,

Wen C, Xia Y and Mao L: The emerging role of Th1 cells in

atherosclerosis and its implications for therapy. Front Immunol.

13:10796682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Kuan R, Agrawal DK and Thankam FG: Treg

cells in atherosclerosis. Mol Biol Rep. 48:4897–4910. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Shao Y, Yang WY, Saaoud F, Drummer C IV,

Sun Y, Xu K, Lu Y, Shan H, Shevach EM, Jiang X, et al: IL-35

promotes CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs and inhibits atherosclerosis via

maintaining CCR5-amplified Treg-suppressive mechanisms. JCI

Insight. 6:e1525112021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Klingenberg R, Gerdes N, Badeau RM,

Gisterå A, Strodthoff D, Ketelhuth DFJ, Lundberg AM, Rudling M,

Nilsson SK, Olivecrona G, et al: Depletion of FOXP3+ regulatory T

cells promotes hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. J Clin

Invest. 123:1323–1334. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Sharma M, Schlegel MP, Afonso MS, Brown

EJ, Rahman K, Weinstock A, Sansbury BE, Corr EM, van Solingen C,

Koelwyn GJ, et al: Regulatory T cells license macrophage

pro-resolving functions during atherosclerosis regression. Circ

Res. 127:335–353. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Fernández-Gallego N, Castillo-González R,

Méndez-Barbero N, López-Sanz C, Obeso D, Villaseñor A, Escribese

MM, López-Melgar B, Salamanca J, Benedicto-Buendía A, et al: The

impact of type 2 immunity and allergic diseases in atherosclerosis.

Allergy. 77:3249–3266. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Vinson A, Curran JE, Johnson MP, Dyer TD,

Moses EK, Blangero J, Cox LA, Rogers J, Havill LM, Vandeberg JL and

Mahaney MC: Genetical genomics of Th1 and Th2 immune response in a

baboon model of atherosclerosis risk factors. Atherosclerosis.

217:387–394. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Weinstock A, Rahman K, Yaacov O, Nishi H,

Menon P, Nikain CA, Garabedian ML, Pena S, Akbar N, Sansbury BE, et

al: Wnt signaling enhances macrophage responses to IL-4 and

promotes resolution of atherosclerosis. Elife. 10:e679322021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Engelbertsen D, Andersson L, Ljungcrantz

I, Wigren M, Hedblad B, Nilsson J and Björkbacka H: T-helper 2

immunity is associated with reduced risk of myocardial infarction

and stroke. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 33:637–644. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Knutsson A, Björkbacka H, Dunér P,

Engström G, Binder CJ, Nilsson AH and Nilsson J: Associations of

interleukin-5 with plaque development and cardiovascular events.

JACC Basic Transl Sci. 4:891–902. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Cardilo-Reis L, Gruber S, Schreier SM,

Drechsler M, Papac-Milicevic N, Weber C, Wagner O, Stangl H,

Soehnlein O and Binder CJ: Interleukin-13 protects from

atherosclerosis and modulates plaque composition by skewing the

macrophage phenotype. EMBO Mol Med. 4:1072–1086. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Gao Q, Jiang Y, Ma T, Zhu F, Gao F, Zhang

P, Guo C, Wang Q, Wang X, Ma C, et al: A critical function of Th17

proinflammatory cells in the development of atherosclerotic plaque

in mice. J Immunol. 185:5820–5827. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Gisterå A, Robertson AK, Andersson J,

Ketelhuth DFJ, Ovchinnikova O, Nilsson SK, Lundberg AM, Li MO,

Flavell RA and Hansson GK: Transforming growth factor-β signaling

in T cells promotes stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques

through an interleukin-17-dependent pathway. Sci Transl Med.

5:196ra1002013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Lu H and Daugherty A: Regulatory B cells,

interleukin-10, and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 26:470–471.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Bu T, Li Z, Hou Y, Sun W, Zhang R, Zhao L,

Wei M, Yang G and Yuan L: Exosome-mediated delivery of

inflammation-responsive Il-10 mRNA for controlled atherosclerosis

treatment. Theranostics. 11:9988–10000. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Guo S, Mao X and Liu J: Multi-faceted

roles of C1q/TNF-related proteins family in atherosclerosis. Front

Immunol. 14:12534332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Fanola CL, Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jarolim

P, Lukas MA, Bode C, Hochman JS, Goodrich EL, Braunwald E and

O'Donoghue ML: Interleukin-6 and the risk of adverse outcomes in

patients after an acute coronary syndrome: Observations from the

SOLID-TIMI 52 (stabilization of plaque using

darapladib-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 52) trial. J Am

Heart Assoc. 6:e0056372017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Schieffer B, Schieffer E, Hilfiker-Kleiner

D, Hilfiker A, Kovanen PT, Kaartinen M, Nussberger J, Harringer W

and Drexler H: Expression of angiotensin II and interleukin 6 in

human coronary atherosclerotic plaques: Potential implications for

inflammation and plaque instability. Circulation. 101:1372–1378.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Rosenfeld SM, Perry HM, Gonen A, Prohaska

TA, Srikakulapu P, Grewal S, Das D, McSkimming C, Taylor AM,

Tsimikas S, et al: B-1b cells secrete atheroprotective IgM and

attenuate atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 117:e28–e39. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Ravandi A, Boekholdt SM, Mallat Z, Talmud

PJ, Kastelein JJP, Wareham NJ, Miller ER, Benessiano J, Tedgui A,

Witztum JL, et al: Relationship of IgG and IgM autoantibodies and

immune complexes to oxidized LDL with markers of oxidation and

inflammation and cardiovascular events: Results from the

EPIC-norfolk study. J Lipid Res. 52:1829–1836. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Lappalainen J, Lindstedt KA, Oksjoki R and

Kovanen PT: OxLDL-IgG immune complexes induce expression and

secretion of proatherogenic cytokines by cultured human mast cells.

Atherosclerosis. 214:357–363. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Tew JG, El Shikh ME, El Sayed RM and

Schenkein HA: Dendritic cells, antibodies reactive with oxLDL, and

inflammation. J Dent Res. 91:8–16. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

103

|

Yang H, Chen J, Liu S, Xue Y, Li Z, Wang

T, Jiao L, An Q, Liu B, Wang J and Zhao H: Exosomes from

IgE-stimulated mast cells aggravate asthma-mediated atherosclerosis

through circRNA CDR1as-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction in

mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 44:e99–e115. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhang X, Li J, Luo S, Wang M, Huang Q,

Deng Z, de Febbo C, Daoui A, Liew PX, Sukhova GK, et al: IgE

contributes to atherosclerosis and obesity by affecting macrophage

polarization, macrophage protein network, and foam cell formation.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 40:597–610. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Silvestre-Roig C, Braster Q, Ortega-Gomez

A and Soehnlein O: Neutrophils as regulators of cardiovascular

inflammation. Nat Rev Cardiol. 17:327–340. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Franck G: Role of mechanical stress and

neutrophils in the pathogenesis of plaque erosion. Atherosclerosis.

318:60–69. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Ionita MG, van den Borne P, Catanzariti

LM, Moll FL, de Vries JPPM, Pasterkamp G, Vink A and de Kleijn DPV:

High neutrophil numbers in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques

are associated with characteristics of rupture-prone lesions.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 30:1842–1848. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Palano MT, Cucchiara M, Gallazzi M, Riccio

F, Mortara L, Gensini GF, Spinetti G, Ambrosio G and Bruno A: When

a friend becomes your enemy: Natural killer cells in

atherosclerosis and atherosclerosis-associated risk factors. Front

Immunol. 12:7981552021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Kovanen PT and Bot I: Mast cells in

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease-activators and actions. Eur

J Pharmacol. 816:37–46. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Spinas E, Kritas SK, Saggini A, Mobili A,

Caraffa A, Antinolfi P, Pantalone A, Tei M, Speziali A, Saggini R

and Conti P: Role of mast cells in atherosclerosis: A classical

inflammatory disease. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 27:517–521.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Lin A, Miano JM, Fisher EA and Misra A:

Chronic inflammation and vascular cell plasticity in

atherosclerosis. Nat Cardiovasc Res. 3:1408–1423. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Moriya J: Critical roles of inflammation

in atherosclerosis. J Cardiol. 73:22–27. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Song B, Bie Y, Feng H, Xie B, Liu M and

Zhao F: Inflammatory factors driving atherosclerotic plaque

progression new insights. J Transl Int Med. 10:36–47. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Jing F, Zhang J, Zhang H and Li T:

Unlocking the multifaceted molecular functions and diverse disease

implications of lactylation. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 100:172–189.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Zhang D, Gao J, Zhu Z, Mao Q, Xu Z, Singh

PK, Rimayi CC, Moreno-Yruela C, Xu S, Li G, et al: Lysine

L-lactylation is the dominant lactylation isomer induced by

glycolysis. Nat Chem Biol. 21:91–99. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Hu XT, Wu XF, Xu JY and Xu X:

Lactate-mediated lactylation in human health and diseases: Progress

and remaining challenges. J Adv Res. S2090-1232(24)00529-02024.Epub

ahead of print. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Zhang N, Zhang Y, Xu J, Wang P, Wu B, Lu

S, Lu X, You S, Huang X, Li M, et al: α-myosin heavy chain

lactylation maintains sarcomeric structure and function and

alleviates the development of heart failure. Cell Res. 33:679–698.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Zhu R, Ye X, Lu X, Xiao L, Yuan M, Zhao H,

Guo D, Meng Y, Han H, Luo S, et al: ACSS2 acts as a lactyl-CoA

synthetase and couples KAT2A to function as a lactyltransferase for

histone lactylation and tumor immune evasion. Cell Metab.

37:361–376.e7. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Chen H, Li Y, Li H, Chen X, Fu H, Mao D,

Chen W, Lan L, Wang C, Hu K, et al: NBS1 lactylation is required

for efficient DNA repair and chemotherapy resistance. Nature.

631:663–669. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Jia M, Yue X, Sun W, Zhou Q, Chang C, Gong

W, Feng J, Li X, Zhan R, Mo K, et al: ULK1-mediated metabolic

reprogramming regulates Vps34 lipid kinase activity by its

lactylation. Sci Adv. 9:eadg49932023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Xie B, Zhang M, Li J, Cui J, Zhang P, Liu

F, Wu Y, Deng W, Ma J, Li X, et al: KAT8-catalyzed lactylation

promotes eEF1A2-mediated protein synthesis and colorectal

carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 121:e23141281212024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Zou Y, Cao M, Tao L, Wu S, Zhou H, Zhang

Y, Chen Y, Ge Y, Ju Z and Luo S: Lactate triggers KAT8-mediated

LTBP1 lactylation at lysine 752 to promote skin rejuvenation by

inducing collagen synthesis in fibroblasts. Int J Biol Macromol.

277:1344822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Moreno-Yruela C, Zhang D, Wei W, Bæk M,

Liu W, Gao J, Danková D, Nielsen AL, Bolding JE, Yang L, et al:

Class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1-3) are histone lysine

delactylases. Sci Adv. 8:eabi66962022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Jin J, Bai L, Wang D, Ding W, Cao Z, Yan

P, Li Y, Xi L, Wang Y, Zheng X, et al: SIRT3-dependent

delactylation of cyclin E2 prevents hepatocellular carcinoma

growth. EMBO Rep. 24:e560522023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Fan Z, Liu Z, Zhang N, Wei W, Cheng K, Sun

H and Hao Q: Identification of SIRT3 as an eraser of H4K16la.

iScience. 26:1077572023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Li XM, Yang Y, Jiang FQ, Hu G, Wan S, Yan

WY, He XS, Xiao F, Yang XM, Guo X, et al: Histone lactylation

inhibits RARγ expression in macrophages to promote colorectal

tumorigenesis through activation of TRAF6-IL-6-STAT3 signaling.

Cell Rep. 43:1136882024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

127

|

Dai J, Huang YJ, He X, Zhao M, Wang X, Liu

ZS, Xue W, Cai H, Zhan XY, Huang SY, et al: Acetylation blocks cGAS

activity and inhibits self-DNA-induced autoimmunity. Cell.

176:1447–1460.e14. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Wang T, Ye Z, Li Z, Jing DS, Fan GX, Liu

MQ, Zhuo QF, Ji SR, Yu XJ, Xu XW and Qin Y: Lactate-induced protein

lactylation: A bridge between epigenetics and metabolic

reprogramming in cancer. Cell Prolif. 56:e134782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Tian Q and Zhou LQ: Lactate activates

germline and cleavage embryo genes in mouse embryonic stem cells.

Cells. 11:5482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Li L, Chen K, Wang T, Wu Y, Xing G, Chen

M, Hao Z, Zhang C, Zhang J, Ma B, et al: Glis1 facilitates

induction of pluripotency via an epigenome-metabolome-epigenome

signalling cascade. Nat Metab. 2:882–892. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Yang W, Wang P, Cao P, Wang S, Yang Y, Su

H and Nashun B: Hypoxic in vitro culture reduces histone

lactylation and impairs pre-implantation embryonic development in

mice. Epigenetics Chromatin. 14:572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Yang D, Zheng H, Lu W, Tian X, Sun Y and

Peng H: Histone lactylation is involved in mouse oocyte maturation

and embryo development. Int J Mol Sci. 25:48212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Merkuri F, Rothstein M and Simoes-Costa M:

Histone lactylation couples cellular metabolism with developmental

gene regulatory networks. Nat Commun. 15:902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Hagihara H, Shoji H, Otabi H, Toyoda A,

Katoh K, Namihira M and Miyakawa T: Protein lactylation induced by

neural excitation. Cell Rep. 37:1098202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Ma W, Jia K, Cheng H, Xu H, Li Z, Zhang H,

Xie H, Sun H, Yi L, Chen Z, et al: Orphan nuclear receptor NR4A3

promotes vascular calcification via histone lactylation. Circ Res.

134:1427–1447. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Wu J, Hu M, Jiang H, Ma J, Xie C, Zhang Z,

Zhou X, Zhao J, Tao Z, Meng Y, et al: Endothelial cell-derived

lactate triggers bone mesenchymal stem cell histone lactylation to

attenuate osteoporosis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e23013002023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Li Q, Zhang F, Wang H, Tong Y, Fu Y, Wu K,

Li J, Wang C, Wang Z, Jia Y, et al: NEDD4 lactylation promotes APAP

induced liver injury through caspase11 dependent non-canonical

pyroptosis. Int J Biol Sci. 20:1413–1435. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

You X, Xie Y, Tan Q, Zhou C, Gu P, Zhang

Y, Yang S, Yin H, Shang B, Yao Y, et al: Glycolytic reprogramming

governs crystalline silica-induced pyroptosis and inflammation

through promoting lactylation modification. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

283:1169522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Sun W, Jia M, Feng Y and Cheng X: Lactate

is a bridge linking glycolysis and autophagy through lactylation.

Autophagy. 19:3240–3241. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

140

|

Zhao W, Wang Y, Liu J, Yang Q, Zhang S, Hu

X, Shi Z, Zhang Z, Tian J, Chu D and An L: Progesterone activates

the histone lactylation-Hif1α-glycolysis feedback loop to promote

decidualization. Endocrinology. 165:bqad1692023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

141

|

Chen Y, Wu J, Zhai L, Zhang T, Yin H, Gao

H, Zhao F, Wang Z, Yang X, Jin M, et al: Metabolic regulation of

homologous recombination repair by MRE11 lactylation. Cell.

187:294–311.e21. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

142

|

Sun L, Zhang Y, Yang B, Sun S, Zhang P,

Luo Z, Feng T, Cui Z, Zhu T, Li Y, et al: Lactylation of METTL16

promotes cuproptosis via m6A-modification on FDX1 mRNA

in gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 14:65232023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

143

|

Dai W, Wu G, Liu K, Chen Q, Tao J, Liu H

and Shen M: Lactate promotes myogenesis via activating H3K9

lactylation-dependent up-regulation of Neu2 expression. J Cachexia

Sarcopenia Muscle. 14:2851–2865. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Mao Y, Zhang J, Zhou Q, He X, Zheng Z, Wei

Y, Zhou K, Lin Y, Yu H, Zhang H, et al: Hypoxia induces

mitochondrial protein lactylation to limit oxidative

phosphorylation. Cell Res. 34:13–30. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Wu J, Lv Y, Hao P, Zhang Z, Zheng Y, Chen

E and Fan Y: Immunological profile of lactylation-related genes in

Crohn's disease: A comprehensive analysis based on bulk and

single-cell RNA sequencing data. J Transl Med. 22:3002024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Zhang Y, Gao Y, Wang Y, Jiang Y, Xiang Y,

Wang X, Wang Z, Ding Y, Chen H, Rui B, et al: RBM25 is required to

restrain inflammation via ACLY RNA splicing-dependent metabolism

rewiring. Cell Mol Immunol. 21:1231–1250. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

Sun Z, Gao Z, Xiang M, Feng Y, Wang J, Xu

J, Wang Y and Liang J: Comprehensive analysis of lactate-related

gene profiles and immune characteristics in lupus nephritis. Front

Immunol. 15:13290092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Rho H, Terry AR, Chronis C and Hay N:

Hexokinase 2-mediated gene expression via histone lactylation is

required for hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis.

Cell Metab. 35:1406–1423.e8. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Wang Y, Li H, Jiang S, Fu D, Lu X, Lu M,

Li Y, Luo D, Wu K, Xu Y, et al: The glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 drives

kidney fibrosis through promoting histone lactylation-mediated

NF-κB family activation. Kidney Int. 106:226–240. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Wei L, Yang X, Wang J, Wang Z, Wang Q,

Ding Y and Yu A: H3K18 lactylation of senescent microglia

potentiates brain aging and Alzheimer's disease through the NFκB

signaling pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 20:2082023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

151

|

Huang Y, Wang C, Zhou T, Xie F, Liu Z, Xu

H, Liu M, Wang S, Li L, Chi Q, et al: Lumican promotes calcific

aortic valve disease through H3 histone lactylation. Eur Heart J.

45:3871–3885. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

152

|

Maschari D, Saxena G, Law TD, Walsh E,

Campbell MC and Consitt LA: Lactate-induced lactylation in skeletal

muscle is associated with insulin resistance in humans. Front

Physiol. 13:9513902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Gao R, Li Y, Xu Z, Zhang F, Xu J, Hu Y,

Yin J, Yang K, Sun L, Wang Q, et al: Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier

1 regulates fatty acid synthase lactylation and mediates treatment

of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 78:1800–1815.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

154

|

Si WY, Yang CL, Wei SL, Du T, Li LK, Dong

J, Zhou Y, Li H, Zhang P, Liu QJ, et al: Therapeutic potential of

microglial SMEK1 in regulating H3K9 lactylation in cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion. Commun Biol. 7:17012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

155

|

Liao Z, Chen B, Yang T, Zhang W and Mei Z:

Lactylation modification in cardio-cerebral diseases: A

state-of-the-art review. Ageing Res Rev. 104:1026312025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

156

|

Li W, Zhou J, Gu Y, Chen Y, Huang Y, Yang

J, Zhu X, Zhao K, Yan Q, Zhao Z, et al: Lactylation of RNA

m6A demethylase ALKBH5 promotes innate immune response

to DNA herpesviruses and mpox virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

121:e24091321212024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

157

|

Yan Q, Zhou J, Gu Y, Huang W, Ruan M,

Zhang H, Wang T, Wei P, Chen G, Li W and Lu C: Lactylation of NAT10

promotes N4-acetylcytidine modification on

tRNASer-CGA-1-1 to boost oncogenic DNA virus KSHV

reactivation. Cell Death Differ. 31:1362–1374. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

158

|

Wang Z, Mao Y, Wang Z, Li S, Hong Z, Zhou

R, Xu S, Xiong Y and Zhang Y: Histone lactylation-mediated

overexpression of RASD2 promotes endometriosis progression via

upregulating the SUMOylation of CTPS1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol.

328:C500–C513. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

159

|

Ye L, Jiang Y and Zhang M: Crosstalk