Introduction

Under physiological conditions, the immune system of

the gastric mucosa interacts with gastric epithelial cells, immune

cells and signaling molecules to form a protective barrier

(1). Innate and adaptive

immunity maintain the homeostasis of the gastric mucosal immune

microenvironment (2-8), whereas a disruption of the balance

of the immune microenvironment results in gastric mucosal diseases,

such as autoimmune gastritis and gastric neoplasia (5,8,9).

Chronic and persistent inflammatory microenvironment stimulation

can lead to cellular differentiation disorders and tumor-related

lesions; for example, the occurrence and progression of spasmolytic

polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) (9-11).

Pyroptosis is a type of inflammatory programmed cell

death (12,13), which can regulate the balance

between innate and adaptive immunity by identifying injury factors,

and participating in the maturation and release of inflammatory

factors (12,14-16). As an important target of immune

regulation, pyroptosis is involved in almost all processes related

to the resistance of the gastric mucosa to microbial infections and

endogenous damage. In addition, pyroptosis manipulates immune

remodeling in the gastric mucosa by releasing inflammatory factors,

further affecting the repair process and cell differentiation

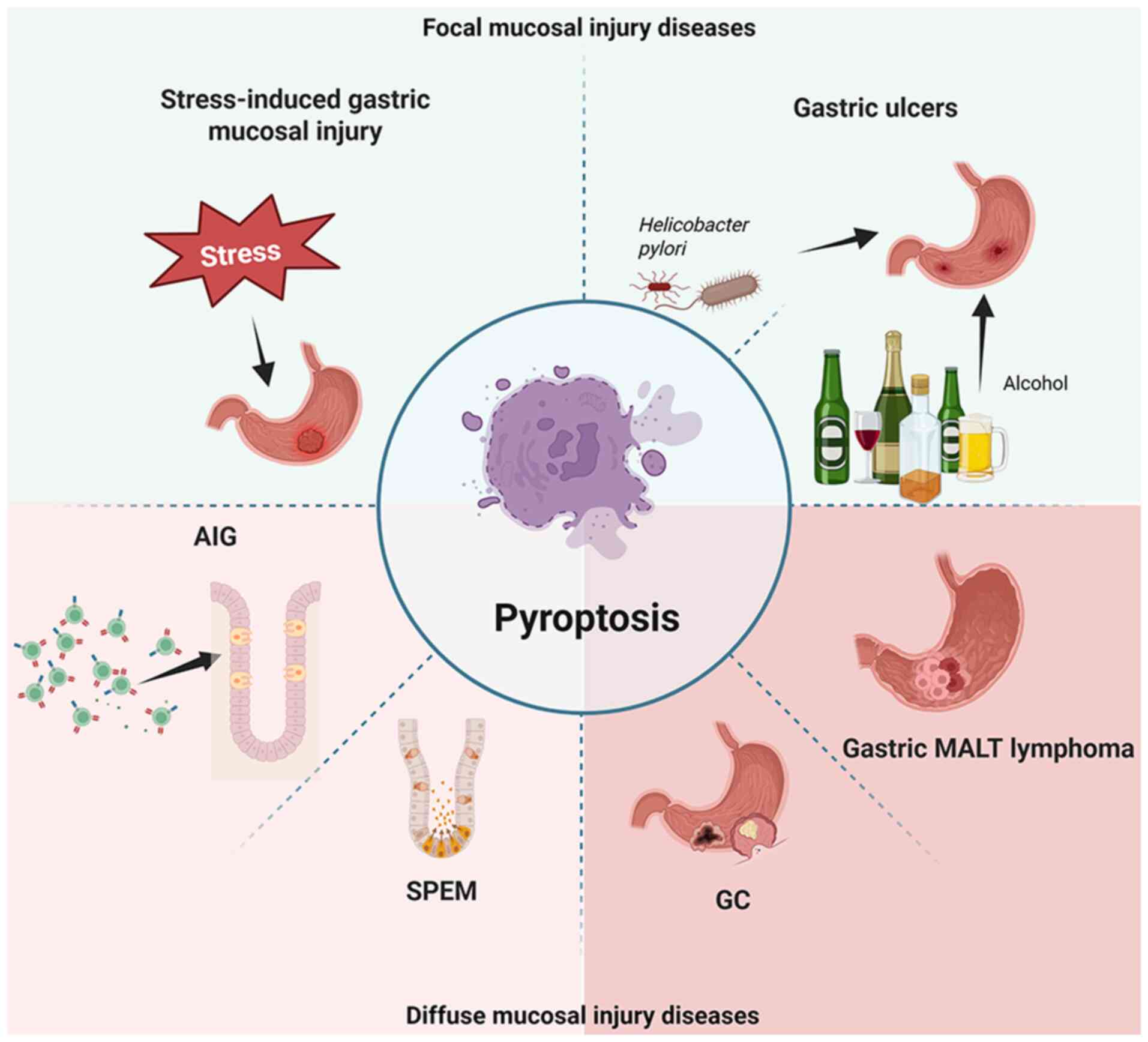

direction (17-21). The present review summarizes the

role of pyroptosis in gastric mucosal diseases, including focal and

diffuse gastric mucosal injury. The aim of the current review is to

provide a novel theoretical basis for the optimization of

prevention strategies and treatment plans for current gastric

mucosal diseases, proposing a new perspective for disease

management (Fig. 1).

Functional role of pyroptosis

Pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of programmed

cell death characterized by plasma membrane pore formation and the

release of inflammatory contents (12,22-24).

Triggering of pyroptosis

Inflammasomes, which include pattern recognition

receptors (PRRs), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing a CARD (ASC) proteins and caspase-1, recognize damage

signals such as damage-associated molecular patterns or

pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (16,25,26). PRRs are representative of immune

receptors involved in innate immunity, and the mutual recognition

and interaction between PRRs and PAMPs are key to initiating innate

immune responses (27). In cases

of microbial infection or tissue damage, PRRs rapidly activate

innate immunity and inflammasomes, promote pyroptosis and recruit

inflammatory cells to guide the initiation of adaptive immune

responses (28).

Activation of pyroptosis

Classical caspase-1-dependent activation occurs as

follows: PRR signals activate caspase-1 via ASC, and activated

caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin (GSDM) D causing membrane rupture and

activation of IL-1β/IL-18, thus amplifying inflammation (29). Non-classical activation occurs as

follows: Human caspase-4/5 or murine caspase-11 directly recognize

cytosolic lipopolysaccharide, cleave GSDMD and may indirectly

activate caspase-1, exacerbating inflammation (30).

Effector phase of pyroptosis

Cell rupture releases inflammatory mediators [such

as IL-1β, IL-18, IL-33 and high mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1)],

which recruit and activate immune cells [such as dendritic cells

(DCs) and macrophages] to promote antigen presentation and initiate

adaptive immunity (16,24,21-33).

Therefore, pyroptosis acts as a bridge between

innate and adaptive immunity, clearing infected/damaged cells and

remodeling the immune microenvironment for antimicrobial defense

and tissue repair (34,35). However, excessive inflammation

exacerbates damage, remodels the microenvironment, and can promote

autoimmune diseases or tumorigenesis (6,9,12,14). Research regarding

pyroptosis-mediated microenvironment remodeling is crucial for

understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic

strategies (34,36-38).

Pyroptosis in gastric mucosal diseases

Gastric mucosal diseases can be divided into focal

mucosal injury and diffuse mucosal injury (2,39). Focal mucosal injury is a

repairable injury that does not alter cell differentiation patterns

(4,40). When injury and chronic

inflammation persist, cells undergo changes in differentiation

patterns and develop diffuse mucosal injury (4,41). Notably, damage to the gastric

mucosa (via factors such as stress, Helicobacter pylori

infection and alcohol) is recognized by inflammasomes, and

pyroptosis activates the rapid response of the innate immune

response, initiates adaptive immunity, reshapes the immune

microenvironment, affects cell differentiation, and participates in

the occurrence and development of various gastric mucosal

diseases.

Role of pyroptosis in focal mucosal

injury diseases

Pyroptosis may serve a bidirectional

regulatory role in stress-induced gastric mucosal injury

Stress-induced gastric mucosal injury refers to

ulcers or erosions that occur due to strong and persistent stress

stimuli, such as trauma, shock, burns or surgery, causing an

imbalance between the protective and injury mechanisms of the

gastric mucosa (42,43). Stress-induced gastric mucosal

injury is a serious complication of physical and mental stress

caused by factors such as neuroendocrine imbalance (44), disruption of the gastric mucosal

protective barrier (45) and

enhancement of gastric mucosal injury factors (46).

Stress activates pro-IL-18 in the adrenal cortex via

the adrenocorticotropic hormone/superoxide-mediated caspase-1

activation pathway, converting it into mature IL-18 for release

into the bloodstream (17).

IL-18 has been reported to mediate water immersion restraint stress

(WIRS)-induced gastric injury in an animal model by increasing

gastric histidine decarboxylase activity and histamine production,

and synergizes with sympathetic overexcitation to exacerbate

gastric hemorrhage following WIRS (47).

Local reactive oxygen species (ROS) serve as

initiating factors in stress-induced gastric mucosal injury

(48). ROS promote gastrokine 2

expression, activate NF-κB, increase nucleotide-binding domain and

leucine-rich repeat protein 3 (NLRP3) activation and ultimately

exacerbate WIRS-induced inflammation (49). This process triggers

neutrophil-dominated inflammation, in which elevated NLRP3/IL-1β

levels are positively associated with neutrophil infiltration and

ulcer severity (49). Zhang et

al (50) demonstrated that

cold-induced stress increases IL-1β/IL-18 expression, whereas the

caspase-1 inhibitor AC-YVAD-CMK protects the gastric mucosa by

suppressing the NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby mitigating inflammation

and pyroptosis. However, Higashimori et al (51) reported opposing conclusions.

NLRP3/IL-1β levels in the gastric mucosa were revealed to be

transiently increased at 0.5 h post-stress (returning to baseline

by 3 h) without a concurrent elevation in IL-18. The NLRP3

inflammasome-derived IL-1β exerted gastric protective effects by

activating NF-κB, inducing the cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2

(PGE2) axis, and upregulating PGE2 production. The notable

discrepancy with the observations of Zhang et al (50) of elevated IL-1β/IL-18 at 8 h

post-stress may stem from distinct observational timepoints (0.5-3

h vs. 8 h). Therefore, a phase-dependent bidirectional regulatory

role for the NLRP3 inflammasome may be hypothesized in

stress-induced gastric injury: In the early phase (≤3 h), IL-1β

secretion may mediate mucosal protection, whereas in the late phase

(≥8 h), IL-18 release could contribute to mucosal damage. The

dynamic equilibrium between IL-1β and IL-18 dictates pathological

progression.

Collectively, pyroptosis-associated mediators serve

key regulatory roles, although their precise mechanisms require

further elucidation to establish novel therapeutic targets.

Role of pyroptosis in gastric

ulcers

The occurrence of gastric ulcers is the

comprehensive result of one or more invasive and damaging factors.

When the action of mucosal injury factors exceeds that of mucosal

protective factors, causing an imbalance between resistance to

injury and self-repair ability, the injury can penetrate the muscle

layer of the mucosa, leading to the occurrence of gastric ulcers

(52). The present review

discusses the role of pyroptosis in gastric ulcers from two

perspectives: Mucosal injury and mucosal protection.

Pyroptosis serves an important

proinflammatory role in the formation of gastric ulcers

In gastric ulcers caused by Helicobacter

pylori infection, macrophages simultaneously activate the

classical caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis pathway and the

non-classical pyroptosis pathway mediated by caspase-11 (a direct

murine homolog of human caspase-4), activating the NLRP3

inflammasome, triggering pyroptosis, and promoting the maturation

and secretion of IL-1β (18,53,54). IL-1β can inhibit gastric acid

secretion and contraction of the stomach muscles, and further drive

the expression of adhesion molecules on immune cells; regulate

neutrophil recruitment, macrophage activation, circulating monocyte

infiltration and T-cell expansion; amplify inflammatory responses;

and reshape the microenvironment of gastric mucosal tissue

(55).

In ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury, the

expression of NLRP3 and GSDMD has been shown to be increased in

gastric tissue. Further research revealed that ethanol can directly

induce pyroptosis in GES-1 cells, leading to the activation of

caspase-1, and the release of IL-1β and IL-18, causing tissue

inflammatory damage (19).

Moreover, ethanol can activate NF-κB p65 and the NLRP3

inflammasome, leading to an increase in HMGB1 expression in the

gastric mucosa (56). HMGB1 can

stimulate cytokine production through receptor for advanced

glycation end products or Toll-like receptor 4, trigger

inflammatory responses, attract immune cells to the site of injury

and further shape the immune microenvironment (57-60). The increased expression of HMGB1

in gastric ulcers can accelerate and maintain inflammatory damage,

delay tissue healing and increase the risk of tumor formation

(60). The inhibition of the

HMGB1/NLRP3/NF-κB pathway results in notable anti-inflammatory and

anti-ulcer effects in ethanol-induced gastric ulcers (55). In addition, the caspase-1

inhibitor AC-YVAD-CMK can protect mice from ethanol-induced acute

gastric injury by reducing pyroptosis and the inflammatory

response, further confirming the important proinflammatory role of

pyroptosis in ethanol-induced acute gastric ulcers (50).

Furthermore, research regarding treatment strategies

for gastric ulcers has shown that various drugs, such as

rabeprazole (61), fucoidan

(62), ALDH2 (63), saxagliptin (64), C-phycocyanin (56) and irbesartan (65), inhibit the activation of NLRP3

and pyroptosis, reduce IL-1β release, notably alleviate

inflammation and promote ulcer healing. Therefore, in the complex

pathological process of gastric ulcers, pyroptosis has been

identified as a key proinflammatory factor, and exploring

pyroptosis as a potential therapeutic target may provide new

effective avenues for the treatment of gastric ulcers.

Pyroptosis may lead to an increase in

the release of the gastric mucosal protective factor PGE2, which is

beneficial for promoting wound repair

PGE2 is an important mucosal protective factor for

gastric ulcers (66). PGE2 can

inhibit caspase-11-driven pyroptosis in macrophages, limiting the

activation of typical and atypical inflammasomes, and effectively

blocking the inflammatory cascade (54). Notably, a recent study (67) confirmed the protective role of

pyroptosis in epithelial injury repair from a new perspective. This

previous study used a system (denoted Pyro-1) that was shown to

induce macrophage pyroptosis without the release of IL-1β or IL-1α,

and reported that Pyro-1 supernatant can promote the migration of

primary fibroblasts and macrophages, facilitate faster wound

closure in vitro and improve tissue repair in vivo.

The presence of oxidized lipids and metabolites in the supernatant

of Pyro-1 was identified through lipidomics and metabolomics. The

mechanism of action of Pyro-1 was shown to involve the synthesis of

PGE2 during the late stage of pyroptosis and PGE2 release through

pores opened by GSDMD during pyroptosis to promote tissue

regeneration. These findings suggest that the occurrence of

pyroptosis may balance tissue damage and regeneration, and that

pyroptotic secretion may promote wound repair. Although it is

unknown whether pyroptosis also participates in tissue repair

through the same mechanism in gastric ulcer injury repair, these

results highlight the 'double-edged sword' of pyroptosis in immune

microenvironment regulation. Therefore, extensive research is

needed to further clarify whether pyroptosis serves a dual role in

promoting inflammation and repair in gastric mucosal injury and

repair.

Overall, pyroptosis has an important regulatory role

in damage to and repair of the gastric mucosa in gastric ulcers by

reshaping the gastric mucosal tissue microenvironment. Elucidating

the specific related mechanisms of pyroptosis may enrich the

understanding of gastric mucosal injury and repair, and provide new

targets for the treatment of gastric ulcers.

Functional role of pyroptosis in

diffuse mucosal injury diseases

Diffuse gastric mucosal injury alters cell

differentiation patterns, and is typically associated with gastric

tumors and precancerous lesions (4,40,41). Pyroptosis affects immune

remodeling of the gastric mucosa by releasing inflammatory factors,

further affecting cell differentiation, determining cell fate and

causing diffuse damage to the gastric mucosa, leading to

disease.

Role of pyroptosis in autoimmune

gastritis (AIG) (Fig. 2)

AIG is type of chronic progressive inflammation

mediated by organ-specific immunity, which characterized by

anti-parietal cell antibodies that target the

H+/K+ ATPases of parietal cells, leading to

CD4+ T cell-mediated parietal cell death and progressive

atrophy of the secretory gland (68). AIG can lead to hypergastrinemia,

resulting in enhanced lymphocyte proliferation and an increased

risk of type 1 gastric neuroendocrine tumor development (69). In addition, immune cell-cytokine

interactions further disrupt chief/mucous neck cell

differentiation, triggering cellular phenotype transformation,

SPEM, intestinal metaplasia and intestinal-type gastric

carcinogenesis (70). Therefore,

AIG is considered the basis for the occurrence of diffuse damage to

the gastric mucosa.

The type 1 immune response, which is characterized

by T helper (Th)1 CD4+ cells and the appearance of

interferon-γ (IFN-γ), is a key driving factor in the pathology of

AIG (71,72). This pathological cascade is

initiates when CD4+ T cells specifically recognize

H+/K+ ATPase (73,74), activating the NLRP3

inflammasome/ROS pathway (75)

to induce pyroptosis and exacerbate gastric inflammation (76,77). Pyroptosis further fuels disease

progression by regulating CD4+ T-cell differentiation.

Complement-driven assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome in

CD4+ T cells triggers pyroptosis-dependent IL-1β

secretion, which promotes Th1 differentiation and IFN-γ production

via autocrine signaling (78).

Upon binding with IFN-γ receptor on gastric epithelial cells, IFN-γ

not only directly induces epithelial death but also upregulates

GSDMB expression to accelerate pyroptotic cell death (79), collectively reshaping the gastric

mucosal immune microenvironment.

Additionally, CD4+ T cells differentiate

into Th17 cells (79) that

secrete IL-17 to recognize H+/K+-ATPase and

activate the NLRP3 inflammasome/ROS pathway, driving parietal cell

death and AIG pathogenesis (80-82). Notably the Th17 immune response

is regulated by the nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich

repeat containing family CARD domain-containing protein (NLRC)4

inflammasome (83,84). Several studies (84-88) have confirmed that mutations in

NLRC4 and NLR family apoptosis inhibitory proteins are involved in

the occurrence of various autoinflammatory diseases in humans by

affecting pyroptosis and inflammatory responses. Therefore, it may

be hypothesized that NLRC4-mediated pyroptosis further regulates

the immune microenvironment of the gastric mucosa by modulating the

Th17 immune response, and may thus be a novel target for the

treatment of AIG.

In summary, pyroptosis critically regulates

CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of AIG, although its

precise mechanisms require further validation. Elucidating

pyroptosis-mediated remodeling of the gastric mucosal immune

microenvironment is essential for discovering novel therapeutic

targets.

Pyroptosis is involved in regulating

SPEM (Fig. 3)

SPEM cells express mucin 6 and trefoil factor 2, and

have a morphology similar to that of deep pyloric gland cells or

duodenal Brunner gland cells. SPEM cells can be seen as a repair

lineage, and under continuous stimulation by chronic inflammation,

SPEM can develop into intestinal metaplasia, which is an important

precancerous lesion in gastric cancer (GC) (40,41,89).

Recent research has suggested that the absence of

parietal cells is the initiating factor for the occurrence of SPEM

(90). Parietal cells are

regulated by gene associated with retinoid-IFN-induced mortality

19, which activates the NLRP3 inflammasome through the ROS/nuclear

factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2/heme oxygenase-1/NF-κB axis,

initiating the classical pyroptosis pathway (20). After pyroptosis in parietal

cells, intracellular activated GSDMD mediates the transport of the

inflammatory factor IL-33 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm under

the synergistic effect of Ca2+ (91). The cell membrane of parietal

cells ruptures, and IL-33 in the cytoplasm is passively released

into the extracellular space (92,93). The release of IL-33 promotes the

secretion of Th2 cytokines (mainly IL-13) and the polarization of

M2 macrophages through the IL-33/ST2 signaling pathway, reshapes

the immune microenvironment of the gastric mucosal region,

initiates epithelial cell reprogramming and promotes the occurrence

of SPEM (94,95).

In the absence of parietal cells, the immune

microenvironment is reshaped, and epithelial cells are

reprogrammed, leading to the transdifferentiation of mature host

cells, mucinous neck cells or isthmus stem cells into SPEM cells.

SRY-box transcription factor 9 (Sox9) is the main regulatory factor

for the differentiation of mucinous neck cells during gastric

development (89) and is also an

essential mediator of chief cell recruitment to promote SPEM after

acute gastric injury. Under inflammatory conditions, macrophage

Sox9 directly targets the transcription of S100A9 in the nucleus.

Macrophage S100A9 is involved in regulating the inflammatory

response and pyroptosis driven by macrophage NIMA-related kinase

7/NLRP3 (96). However, the role

of pyroptosis in the process of gastric mucosal epithelial cell

differentiation remains unclear, and its specific regulatory role

requires extensive research. In summary, exploring the mechanisms

by which pyroptosis reshapes the immune microenvironment and

initiates epithelial cell reprogramming can help identify

therapeutic targets for SPEM, and prevent the development of more

severe phenotypes of gastric mucosal damage.

Role of pyroptosis in the development of

gastric neoplasia

Accurately locating and identifying

the cell types that undergo pyroptosis will help achieve precise

treatment of GC

GC is a common malignant tumor of the digestive

system. A number of reviews have summarized pyroptosis as an

inflammatory cell death mechanism that reshapes the tumor

microenvironment, and affects the occurrence and development of GC.

However, due to the high heterogeneity of GC, the role of

pyroptosis among different cells in tumor tissue is not consistent,

and pyroptosis also dynamically changes as a tumor progresses,

making targeted interventions for GC more challenging (97-100).

As an example, the pyroptosis inflammasome NLRP3

serves a dual role in the pathological and physiological processes

of GC. First, H. pylori infection and its virulence factor

CagA promote the upregulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in GC by

enhancing the microRNA (miR)-1290/NKD1/NLRP3 axis (21). NLRP3 upregulation not only drives

cancer cell pyroptosis, invasion, migration (via inflammasome

activation) and malignant progression, but also induces M2

macrophage polarization through the IL-6/IL-10/JAK2/STAT3 signaling

pathway, and modulates the infiltration of CD4+ T cells

and M2 macrophages within the tumor microenvironment (21). NLRP3 upregulation ultimately

accelerates GC progression and is a predictor of poor prognosis

(21). In addition, miR-22 has

been confirmed to directly target and suppress NLRP3 expression,

inhibiting its pro-tumorigenic effects. H. pylori infection

suppresses miR-22, leading to NLRP3 upregulation, disruption of

gastric mucosal homeostasis and initiation of carcinogenesis

(38). By inhibiting NLRP3

activity, the carcinogenic potential of NLRP3 has been shown to be

effectively suppressed in in vitro experiments and animal

models, further confirming the core role of NLRP3 in the

progression of GC (101).

However, the functional complexity of NLRP3 is not

limited to its carcinogenic potential. The occurrence of pyroptosis

may increase the sensitivity of GC to chemotherapy. Specifically,

activation strategies targeting lengsin (a crystalline lens protein

highly expressed in cancer stem cells that is associated with

malignant progression in patients with GC) can induce pyroptosis in

GC stem cells, thereby restoring the responsiveness of GC to

chemotherapy drugs (102). In

addition, low-dose diosbulbin-B activates the endogenous programmed

death ligand 1/NLRP3 signaling pathway in tumors, triggering

pyroptosis and notably increasing the sensitivity of GC cells to

cisplatin chemotherapy (103).

Furthermore, West et al (104) suggested that NLRP3 has no

notable prognostic value in predicting patient survival outcomes

and that it does not serve a dominant role in the inflammatory

environment-driven development of gastric tumors. These findings

challenge the traditional understanding of the comprehensive role

of NLRP3 in promoting cancer, emphasizing the diversity and

complexity of pyroptosis functions under specific pathological

conditions. Therefore, only by mechanistically elucidating the

bidirectional regulation of pyroptosis and its critical molecular

switches can human trials of pyroptosis inhibitors be rationally

guided, ultimately achieving the precise therapeutic goal of

selectively inducing pyroptosis in target cells, enhancing

treatment sensitivity while circumventing tumor-promoting

microenvironments.

However, a relative lack of precise identification

and related evidence for the phenomenon of pyroptosis in specific

single-cell populations in GC tissues remains. How different cell

subpopulations in the GC microenvironment trigger complex

interactions between cells through pyroptotic mechanisms and

further reshape the specific mechanisms of the tumor

microenvironment remains unclear; this directly leads to notable

differences in the conclusions of the aforementioned studies.

Therefore, the scientific validity and effectiveness of solely

adopting strategies to inhibit or promote pyroptosis as a cancer

treatment method are questionable. Furthermore, considering that

the role of pyroptosis is regulated by complex factors, such as the

tumor microenvironment and cell type, its biological effects

exhibit marked bidirectionality and can affect the development

trajectory and treatment response of tumors through diverse

mechanisms. This complexity requires the use of a more

comprehensive and detailed strategy when designing experiments. In

summary, future research regarding pyroptosis in GC should focus on

specific analyses of cell types and occurrence periods, in order to

achieve a comprehensive evaluation and precise regulation of the

effects of pyroptosis. The findings of these studies may provide a

solid theoretical basis for optimizing treatment strategies for

patients with cancer, and novel ideas for improving patient

prognosis and survival status.

Pyroptosis serves a role in the immune

regulation of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

(MALT lymphoma)

Gastric MALT lymphoma is one of the most common

types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (105). The proliferation and

differentiation of gastric mucosal-associated lymphoma cells are

regulated by antigen-specific intratumoral T cells (via

CD40-mediated signaling, Th2-type cytokines, chemokines,

costimulatory molecules and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells)

and their communication with B cells (106).

There is a strong causal relationship between MALT

lymphoma and chronic H. pylori-associated gastritis

(107,108). NLRC5 expression is upregulated

in the macrophages and gastric tissues of mice and humans after

H. pylori infection (109). Mice with bone marrow-specific

deletion of NLPC5 develop precursor B-cell lesions of MALT lymphoma

3 months after H. pylori infection (109). The absence of NLRC5 inhibits

GSDMD cleavage and the activation of IL-1β and caspase-3, leading

to the upregulation of IFNγ expression and the activation of

lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory responses in macrophages

(110), as well as increased

IL-1β and CD40 (111).

Anti-CD40L antibodies can prevent gastric B-cell damage in

NLRC5-deficient mice, reduce the number of DCs, and CD8+

and FOXP3+ T cells, and decrease B-cell lymphoma gene

expression in the stomach (109,111). Therefore, the involvement of

NLRC5 in pyroptosis affects antigen-specific T cells and their

communication with B cells in tumors, and further regulates the

occurrence of MALT lymphoma. However, further research and

exploration regarding the specific intercellular dialog and

mechanisms involved are needed.

Conclusion

As scientific research progresses, the understanding

of the mechanisms by which pyroptosis contributes to gastric

mucosal injury and repair has become increasingly refined. However,

key questions remain unanswered. In stress-induced injury,

elucidating the phase transition mechanism whereby the NLRP3

inflammasome shifts from early protection to late damage requires

the definition of precise neural signaling controls. Furthermore,

gastric ulcer healing hinges on cellular sources of pyroptosis,

inflammatory mediator (such as IL-1β and IL-18) and

microenvironmental integration, particularly regarding how PGE2

spatiotemporally coordinates anti-inflammatory and pro-repair

functions. For SPEM, the molecular mechanisms underlying

GSDMD-mediated IL-33 release (especially Ca2+-dependent

regulation) and whether additional factors from pyroptotic parietal

cells directly drive mucous neck/stem cell reprogramming must be

resolved. Furthermore, it remains unknown as to whether pyroptosis

or its effectors directly modulate key transcription factors to

initiate SPEM, or whether targeting pyroptosis can halt/reverse

SPEM progression. In heterogeneous GC microenvironments,

identifying which cellular subpopulations undergo pyroptosis at

specific stages (with cell type-dependent triggers) and defining

their stage-dependent roles (early tumor suppression vs. late

metastasis) are essential for developing strategies for selectively

inducing cancer cell pyroptosis to enhance chemosensitization while

avoiding tumor-promoting microenvironments. These focused efforts

will provide more precise targets for elucidating disease

pathogenesis, and hold promise for facilitating innovative and

highly effective interventions for gastric mucosal disorders.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

XL and TL conceived and designed the paper. BJ

drafted the manuscript. ZM and BT edited and revised the

manuscript. SL, SY, KM and ST participated in the literature search

and analysis of the data to be included in the review. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

PRRs

|

pattern recognition receptors

|

|

ASC

|

apoptosis associated speck-like

protein containing a CARD

|

|

PAMP

|

pathogen-associated molecular

pattern

|

|

GSDM

|

gasdermin

|

|

HMGB1

|

high mobility group protein B1

|

|

DCs

|

dendritic cells

|

|

WIRS

|

water immersion restraint stress

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

NLRP3

|

nucleotide-binding domain and

leucine-rich repeat protein 3

|

|

PGE2

|

prostaglandin E2

|

|

AIG

|

autoimmune gastritis

|

|

IFN-γ

|

interferon-γ

|

|

NLRC

|

nucleotide-binding domain and

leucine-rich repeat containing family CARD domain-containing

protein 4

|

|

SPEM

|

spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing

metaplasia

|

|

GC

|

gastric cancer

|

|

MALT lymphoma

|

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

lymphoma

|

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ms. Guorong Wen,

Professor Hai Jin and Professor Jiaxing An (Department of

Gastroenterology, Digestive Disease Hospital, Affiliated Hospital

of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China), who provided

suggestions for the article.

Funding

The present review was funded by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (National Science Foundation of China) (grant

nos. 82070536, 82073087, 82470540, 32460215 and 82160505), the

Guizhou Province International Science and Technology Cooperation

(Gastroenterology) Base [grant no. Qian Ke He Platform Talents-HZJD

(2021) 001], the Major Project of Guizhou Province Basic Research

Program [grant no. Qian Ke He basic research-ZK (2023) major

project 059], the Guizhou Province Science Plan Program [grant no.

Qian Ke He Foundation-ZK (2021) General 461], the Guizhou Province

High-level Innovative Talent Selection and Training Plan (100

level) [grant no. Qian Ke He Platform Talents-GCC (2023) 043] and

the Guizhou Innovative Talent Team on Ion Channels and Malignant

Tumors of Epithelial Origin [grant no. Qian Ke He Platform

Talents-CXTD (2023) 001].

References

|

1

|

Liu S, Deng Z, Zhu J, Ma Z, Tuo B, Li T

and Liu X: Gastric immune homeostasis imbalance: An important

factor in the development of gastric mucosal diseases. Biomed

Pharmacother. 161:1143382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mills JC and Shivdasani RA: Gastric

epithelial stem cells. Gastroenterology. 140:412–424. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Goldenring JR and Nam KT: Oxyntic atrophy,

metaplasia, and gastric cancer. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci.

96:117–131. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Goldenring JR and Mills JC: Cellular

plasticity, reprogramming, and regeneration: metaplasia in the

stomach and beyond. Gastroenterology. 162:415–430. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhou CB and Fang JY: The role of

pyroptosis in gastrointestinal cancer and immune responses to

intestinal microbial infection. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer.

1872:1–10. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang W, Niu L, Zhao X, Duan L, Wang X, Li

Y, Chen J, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Fan D and Hong L: Pyroptosis impacts

the prognosis and treatment response in gastric cancer via immune

system modulation. Am J Cancer Res. 12:1511–1534. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Villarroel-Espindola F, Ejsmentewicz T,

Gonzalez-Stegmaier R, Jorquera RA and Salinas E: Intersections

between innate immune response and gastric cancer development.

World J Gastroenterol. 29:2222–2240. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gobert AP and Wilson KT: Induction and

regulation of the innate immune response in Helicobacter pylori

infection. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 13:1347–1363. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jiao Y, Yan Z and Yang A: The roles of

innate lymphoid cells in the gastric mucosal immunology and

oncogenesis of gastric cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24:66522023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ianiro G, Molina-Infante J and Gasbarrini

A: Gastric microbiota. Helicobacter. 20(Suppl 1): S68–S71. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Goldenring JR: Pyloric metaplasia,

pseudopyloric metaplasia, ulcer-associated cell lineage and

spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia: Reparative lineages

in the gastrointestinal mucosa. J Pathol. 245:132–137. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Barnett KC, Li S, Liang K and Ting JPY: A

360° view of the inflammasome: Mechanisms of activation, cell

death, and diseases. Cell. 186:2288–2312. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li Z, Guo J and Bi L: Role of the NLRP3

inflammasome in autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacother.

130:1105422020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mridha AR, Wree A, Robertson AAB, Yeh MM,

Johnson CD, Van Rooyen DM, Haczeyni F, Teoh NC, Savard C, Ioannou

GN, et al: NLRP3 inflammasome blockade reduces liver inflammation

and fibrosis in experimental NASH in mice. J Hepatol. 66:1037–1046.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kayagaki N, Kornfeld OS, Lee BL, Stowe IB,

O'Rourke K, Li Q, Sandoval W, Yan D, Kang J, Xu M, et al: NINJ1

mediates plasma membrane rupture during lytic cell death. Nature.

591:131–136. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fu J and Wu H: Structural mechanisms of

NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation. Annu Rev Immunol.

41:301–316. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sekiyama A, Ueda H, Kashiwamura SI,

Sekiyama R, Takeda M, Rokutan K and Okamura H: A stress-induced,

superoxide-mediated caspase-1 activation pathway causes plasma

IL-18 upregulation. Immunity. 22:669–677. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tran LS, Ying L, D'Costa K, Wray-McCann G,

Kerr G, Le L, Allison CC, Ferrand J, Chaudhry H, Emery J, et al:

NOD1 mediates interleukin-18 processing in epithelial cells

responding to Helicobacter pylori infection in mice. Nat Commun.

14:38042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li G, Zhu L, Cao Z, Wang J, Zhou F, Wang

X, Li X and Nie G: A new participant in the pathogenesis of

alcoholic gastritis: Pyroptosis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 49:406–418.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zeng X, Yang M, Ye T, Feng J, Xu X, Yang

H, Wang X, Bao L, Li R, Xue B, et al: Mitochondrial GRIM-19 loss in

parietal cells promotes spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing

metaplasia through NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3

(NLRP3)-mediated IL-33 activation via a reactive oxygen species

(ROS)-NRF2-Heme oxygenase-1(HO-1)-NF-кB axis. Free Radic Biol Med.

202:46–61. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wan C, Wang P, Xu Y, Zhu Y, Chen H, Cao X

and Gu Y: Mechanism and role of H. pylori CagA-induced NLRP3

inflammasome in gastric cancer immune cell infiltration. Sci Rep.

15:143352025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cookson BT and Brennan MA:

Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol.

9:113–114. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ketelut-Carneiro N and Fitzgerald KA:

Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis-Oh My! The many ways a cell

can die. J Mol Biol. 434:1673782022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y,

Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F and Shao F: Cleavage of GSDMD by

inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature.

526:660–665. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Van Opdenbosch N, Gurung P, Vande Walle L,

Fossoul A, Kanneganti TD and Lamkanfi M: Activation of the NLRP1b

inflammasome independently of ASC-mediated caspase-1

autoproteolysis and speck formation. Nat Commun. 5:32092014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Man SM, Hopkins LJ, Nugent E, Cox S, Glück

IM, Tourlomousis P, Wright JA, Cicuta P, Monie TP and Bryant CE:

Inflammasome activation causes dual recruitment of NLRC4 and NLRP3

to the same macromolecular complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

111:7403–7408. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Berry R and Call ME: Modular activating

receptors in innate and adaptive immunity. Biochemistry.

56:1383–1402. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Que X, Zheng S, Song Q, Pei H and Zhang P:

Fantastic voyage: The journey of NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Genes Dis. 11:819–829. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Rathinam VAK and Fitzgerald KA:

Inflammasome complexes: Emerging mechanisms and effector functions.

Cell. 165:792–800. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Viganò E and Mortellaro A: Caspase-11: The

driving factor for noncanonical inflammasomes. Eur J Immunol.

43:2240–2245. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Pérez-Figueroa E, Torres J, Sánchez-Zauco

N, Contreras-Ramos A, Alvarez-Arellano L and Maldonado-Bernal C:

Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in human neutrophils by

Helicobacter pylori infection. Innate Immun. 22:103–112. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kumar S and Dhiman M: Inflammasome

activation and regulation during Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis.

Microb Pathog. 125:468–474. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yang J, Liu Z, Wang C, Yang R, Rathkey JK,

Pinkard OW, Shi W, Chen Y, Dubyak GR, Abbott DW and Xiao TS:

Mechanism of gasdermin D recognition by inflammatory caspases and

their inhibition by a gasdermin D-derived peptide inhibitor. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:6792–6797. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Fink SL and Cookson BT: Pyroptosis and

host cell death responses during Salmonella infection. Cell

Microbiol. 9:2562–2570. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Man SM: Inflammasomes in the

gastrointestinal tract: Infection, cancer and gut microbiota

homeostasis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15:721–737. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Toldo S, Mezzaroma E, Buckley LF, Potere

N, Di Nisio M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Van Tassell BW and Abbate A:

Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiovascular diseases.

Pharmacol Ther. 236:1080532022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

37

|

Wen J, Xuan B, Liu Y, Wang L, He L, Meng

X, Zhou T and Wang Y: NLRP3 inflammasome-induced pyroptosis in

digestive system tumors. Front Immunol. 14:10746062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li S, Liang X, Ma L, Shen L, Li T, Zheng

L, Sun A, Shang W, Chen C, Zhao W and Jia J: MiR-22 sustains NLRP3

expression and attenuates H. pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis.

Oncogene. 37:884–896. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhao Y, Deng Z, Ma Z, Zhang M, Wang H, Tuo

B, Li T and Liu X: Expression alteration and dysfunction of ion

channels/transporters in the parietal cells induces gastric

diffused mucosal injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 148:1126602022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu X, Ma Z, Deng Z, Yi Z, Tuo B, Li T and

Liu X: Role of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia in

gastric mucosal diseases. Am J Cancer Res. 13:1667–1681.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Meyer AR and Goldenring JR: Injury,

repair, inflammation and metaplasia in the stomach. J Physiol.

596:3861–3867. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Brzozowski T, Zwirska-Korczala K, Konturek

PC, Konturek SJ, Sliwowski Z, Pawlik M, Kwiecien S, Drozdowicz D,

Mazurkiewicz-Janik M, Bielanski W and Pawlik WW: Role of circadian

rhythm and endogenous melatonin in pathogenesis of acute gastric

bleeding erosions induced by stress. J Physiol Pharmacol. 58(Suppl

6): S53–S64. 2007.

|

|

43

|

Nithiwathanapong C, Reungrongrat S and

Ukarapol N: Prevalence and risk factors of stress-induced

gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill children. World J

Gastroenterol. 11:6839–6842. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Kromin AA and Zenina OI: Hypothalamic

control of the myoelectric activity of the gastric antrum in

rabbits during acute emotional stress. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol.

71-76:1652007.In Russian.

|

|

45

|

Bregonzio C, Armando I, Ando H, Jezova M,

Baiardi G and Saavedra JM: Anti-inflammatory effects of angiotensin

II AT1 receptor antagonism prevent stress-induced gastric injury.

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 285:G414–G423. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Olaleye SB, Adaramoye OA, Erigbali PP and

Adeniyi OS: Lead exposure increases oxidative stress in the gastric

mucosa of HCl/ethanol-exposed rats. World J Gastroenterol.

13:5121–5126. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Seino H, Ueda H, Kokai M, Tsuji NM,

Kashiwamura S, Morita Y and Okamura H: IL-18 mediates the formation

of stress-induced, histamine-dependent gastric lesions. Am J

Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 292:G262–G267. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Das D, Bandyopadhyay D, Bhattacharjee M

and Banerjee RK: Hydroxyl radical is the major causative factor in

stress-induced gastric ulceration. Free Radic Biol Med. 23:8–18.

1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Zhang Z, Xue H, Dong Y, Hu J, Jiang T, Shi

L and Du J: Inhibition of GKN2 attenuates acute gastric lesions

through the NLRP3 inflammasome. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle).

9:219–232. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang F, Wang L, Wang JJ, Luo PF, Wang XT

and Xia ZF: The caspase-1 inhibitor AC-YVAD-CMK attenuates acute

gastric injury in mice: Involvement of silencing NLRP3 inflammasome

activities. Sci Rep. 6:241662016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Higashimori A, Watanabe T, Nadatani Y,

Nakata A, Otani K, Hosomi S, Tanaka F, Kamata N, Taira K, Nagami Y,

et al: Role of nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-like

receptor protein 3 inflammasome in stress-induced gastric injury. J

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 36:740–750. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Bojanowicz K, Zubowski A, Durasiewicz Z

and Szeszenia N: Gastric or duodenal ulcer location and the more

important internal and environmental factors. Przegl Lek.

28:457–460. 1971.In Polish.

|

|

53

|

Yu Q, Shi H, Ding Z, Wang Z, Yao H and Lin

R: The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM31 attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome

activation in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis by

regulating ROS and autophagy. Cell Commun Signal. 21:12023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zaslona Z, Flis E, Nulty C, Kearney J,

Fitzgerald R, Douglas AR, McNamara D, Smith S, O'Neill LAJ and

Creagh EM: Caspase-4: A therapeutic target for peptic ulcer

disease. Immunohorizons. 4:627–633. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yuan XY, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Chen A and Liu

P: IL-1β, an important cytokine affecting Helicobacter

pylori-mediated gastric carcinogenesis. Microb Pathog.

174:1059332023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Alzokaky AA, Abdelkader EM, El-Dessouki

AM, Khaleel SA and Raslan NA: C-phycocyanin protects against

ethanol-induced gastric ulcers in rats: Role of HMGB1/NLRP3/NF-κB

pathway. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 127:265–277. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Sims GP, Rowe DC, Rietdijk ST, Herbst R

and Coyle AJ: HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer. Annu Rev

Immunol. 28:367–388. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yang H, Wang H and Andersson U: Targeting

inflammation Driven by HMGB1. Front Immunol. 11:4842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

El-Gendy ZA, Taher RF, Elgamal AM, Serag

A, Hassan A, Jaleel GAA, Farag MA and Elshamy AI: Metabolites

profiling and bioassays reveal bassia indica ethanol extract

protective effect against stomach ulcers development via

HMGB1/TLR-4/NF-κB pathway. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:12632023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Elbaz EM, Abdel Rahman AAS, El-Gazar AA

and Ali BM: Protective effect of dimethyl fumarate against

ethanol-provoked gastric ulcers in rats via regulation of

HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB, and PPARγ/SIRT1/Nrf2 pathways: Involvement of

miR-34a-5p. Arch Biochem Biophys. 759:1101032024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Xie J, Fan L, Xiong L, Chen P, Wang H,

Chen H, Zhao J, Xu Z, Geng L, Xu W and Gong S: Rabeprazole inhibits

inflammatory reaction by inhibition of cell pyroptosis in gastric

epithelial cells. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 22:442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Selim HM, Negm WA, Hawwal MF, Hussein IA,

Elekhnawy E, Ulber R and Zayed A: Fucoidan mitigates gastric ulcer

injury through managing inflammation, oxidative stress, and

NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 120:1103352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang Y, Yuan Z, Chai J, Zhu D, Miao X,

Zhou J and Gu X: ALDH2 ameliorates ethanol-induced gastric ulcer

through suppressing NLPR3 inflammasome activation and ferroptosis.

Arch Biochem Biophys. 743:1096212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Arab HH, Ashour AM, Gad AM, Mahmoud AM and

Kabel AM: Activation of AMPK/mTOR-driven autophagy and inhibition

of NLRP3 inflammasome by saxagliptin ameliorate ethanol-induced

gastric mucosal damage. Life Sci. 280:1197432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Arab HH, Eid AH, El-Sheikh AAK, Arafa EA

and Ashour AM: Irbesartan reprofiling for the amelioration of

ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats: Role of

inflammation, apoptosis, and autophagy. Life Sci. 308:1209392022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Suleyman H, Albayrak A, Bilici M, Cadirci

E and Halici Z: Different mechanisms in formation and prevention of

indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers. Inflammation. 33:224–234.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Mehrotra P, Maschalidi S, Boeckaerts L,

Maueröder C, Tixeira R, Pinney J, Burgoa Cardás J, Sukhov V, Incik

Y, Anderson CJ, et al: Oxylipins and metabolites from pyroptotic

cells act as promoters of tissue repair. Nature. 631:207–215. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Soykan İ, Er RE, Baykara Y and Kalkan C:

Unraveling the mysteries of autoimmune gastritis. Turk J

Gastroenterol. 36:135–144. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Jove A, Lin C, Hwang JH, Balasubramanian

V, Fernandez-Becker NQ and Huang RJ: Serum gastrin levels are

associated with prevalent neuroendocrine tumors in autoimmune

metaplastic atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 120:1140–1143.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Huang J, Fang M, Wu C and Qiao Z:

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis complicated with oxyntic gland

adenoma and low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Asian J Surg. Sep

12–2024.Epub ahead of print.

|

|

71

|

Park JY, Lam-Himlin D and Vemulapalli R:

Review of autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest

Endosc. 77:284–292. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M and Genta RM:

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis-pathogenesis, pathology and

management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10:529–541. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

D'Elios MM, Bergman MP, Azzurri A, Amedei

A, Benagiano M, De Pont JJ, Cianchi F, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM,

Romagnani S, Appelmelk BJ and Del Prete G: H(+),K(+)-atpase (proton

pump) is the target autoantigen of Th1-type cytotoxic T cells in

autoimmune gastritis. Gastroenterology. 120:377–386. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Toh BH, Sentry JW and Alderuccio F: The

causative H+/K+ ATPase antigen in the pathogenesis of autoimmune

gastritis. Immunol Today. 21:348–354. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Hu Z and Chai J: Structural mechanisms in

NLR inflammasome assembly and signaling. Curr Top Microbiol

Immunol. 397:23–42. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

van Driel IR, Baxter AG, Laurie KL, Zwar

TD, La Gruta NL, Judd LM, Scarff KL, Silveira PA and Gleeson PA:

Immunopathogenesis, loss of T cell tolerance and genetics of

autoimmune gastritis. Autoimmun Rev. 1:290–297. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Benítez J, Marra R, Reyes J and Calvete O:

A genetic origin for acid-base imbalance triggers the mitochondrial

damage that explains the autoimmune response and drives to gastric

neuroendocrine tumours. Gastric Cancer. 23:52–63. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Arbore G, West EE, Spolski R, Robertson

AAB, Klos A, Rheinheimer C, Dutow P, Woodruff TM, Yu ZX, O'Neill

LA, et al: T helper 1 immunity requires complement-driven NLRP3

inflammasome activity in CD4+ T cells. Science.

352:aad12102016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Lee GR: The balance of Th17 versus Treg

cells in autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci. 19:7302018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Lei L, Sun J, Han J, Jiang X, Wang Z and

Chen L: Interleukin-17 induces pyroptosis in osteoblasts through

the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol.

96:1077812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Stummvoll GH, DiPaolo RJ, Huter EN,

Davidson TS, Glass D, Ward JM and Shevach EM: Th1, Th2, and Th17

effector T cell-induced autoimmune gastritis differs in

pathological pattern and in susceptibility to suppression by

regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 181:1908–1916. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Feng WQ, Zhang YC, Xu ZQ, Yu SY, Huo JT,

Tuersun A, Zheng MH, Zhao JK, Zong YP and Lu AG: IL-17A-mediated

mitochondrial dysfunction induces pyroptosis in colorectal cancer

cells and promotes CD8+ T-cell tumour infiltration. J

Transl Med. 21:3352023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Faure E, Mear JB, Faure K, Normand S,

Couturier-Maillard A, Grandjean T, Balloy V, Ryffel B, Dessein R,

Chignard M, et al: Pseudomonas aeruginosa type-3 secretion system

dampens host defense by exploiting the NLRC4-coupled inflammasome.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 189:799–811. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Kitamura A, Sasaki Y, Abe T, Kano H and

Yasutomo K: An inherited mutation in NLRC4 causes autoinflammation

in human and mice. J Exp Med. 211:2385–2396. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kay C, Wang R, Kirkby M and Man SM:

Molecular mechanisms activating the NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome:

Implications in infectious disease, autoinflammation, and cancer.

Immunol Rev. 297:67–82. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Triantafilou K, Ward CJK, Czubala M,

Ferris RG, Koppe E, Haffner C, Piguet V, Patel VK, Amrine-Madsen H,

Modis LK, et al: Differential recognition of HIV-stimulated IL-1β

and IL-18 secretion through NLR and NAIP signalling in

monocyte-derived macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 17:e10094172021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Zhao Y and Shao F: The NAIP-NLRC4

inflammasome in innate immune detection of bacterial flagellin and

type III secretion apparatus. Immunol Rev. 265:85–102. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Romberg N, Al Moussawi K, Nelson-Williams

C, Stiegler AL, Loring E, Choi M, Overton J, Meffre E, Khokha MK,

Huttner AJ, et al: Mutation of NLRC4 causes a syndrome of

enterocolitis and autoinflammation. Nat Genet. 46:1135–1139. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Willet SG, Thanintorn N, McNeill H, Huh

SH, Ornitz DM, Huh WJ, Hoft SG, DiPaolo RJ and Mills JC: SOX9

governs gastric mucous neck cell identity and is required for

injury-induced metaplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.

16:325–339. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Petersen CP, Weis VG, Nam KT, Sousa JF,

Fingleton B and Goldenring JR: Macrophages promote progression of

spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia after acute loss of

parietal cells. Gastroenterology. 146:1727–1738.e8. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Chen W, Chen S, Yan C, Zhang Y, Zhang R,

Chen M, Zhong S, Fan W, Zhu S, Zhang D, et al: Allergen

protease-activated stress granule assembly and gasdermin D

fragmentation control interleukin-33 secretion. Nat Immunol.

23:1021–1030. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Kita H: Gasdermin D pores for IL-33

release. Nat Immunol. 23:989–991. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Chauvin C, Retnakumar SV and Bayry J:

Gasdermin D as a cellular switch to orientate immune responses via

IL-33 or IL-1β. Cell Mol Immunol. 20:8–10. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Bernink JH, Germar K and Spits H: The role

of ILC2 in pathology of type 2 inflammatory diseases. Curr Opin

Immunol. 31:115–120. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Meyer AR, Engevik AC, Madorsky T, Belmont

E, Stier MT, Norlander AE, Pilkinton MA, McDonnell WJ, Weis JA,

Jang B, et al: Group 2 innate lymphoid cells coordinate damage

response in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 159:2077–2091.e8. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Sheng M, Weng Y, Cao Y, Zhang C, Lin Y and

Yu W: Caspase 6/NR4A1/SOX9 signaling axis regulates hepatic

inflammation and pyroptosis in ischemia-stressed fatty liver. Cell

Death Discov. 9:1062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Qiang R, Li Y, Dai X and Lv W: NLRP3

inflammasome in digestive diseases: From mechanism to therapy.

Front Immunol. 13:9781902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Shadab A, Mahjoor M, Abbasi-Kolli M,

Afkhami H, Moeinian P and Safdarian AR: Divergent functions of

NLRP3 inflammasomes in cancer: A review. Cell Commun Signal.

21:2322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Si Y, Liu L and Fan Z: Mechanisms and

effects of NLRP3 in digestive cancers. Cell Death Discov.

10:102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Liu W, Peng J, Xiao M, Cai Y, Peng B,

Zhang W, Li J, Kang F, Hong Q, Liang Q, et al: The implication of

pyroptosis in cancer immunology: Current advances and prospects.

Genes Dis. 10:2339–2350. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

101

|

Zhang X, Li C, Chen D, He X, Zhao Y, Bao

L, Wang Q, Zhou J and Xie Y: H. pylori CagA activates the NLRP3

inflammasome to promote gastric cancer cell migration and invasion.

Inflamm Res. 71:141–155. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Li YT, Tan XY, Ma LX, Li HH, Zhang SH,

Zeng CM, Huang LN, Xiong JX and Fu L: Targeting LGSN restores

sensitivity to chemotherapy in gastric cancer stem cells by

triggering pyroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 14:5452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Li C, Qiu J and Xue Y: Low-dose

Diosbulbin-B (DB) activates tumor-intrinsic PD-L1/NLRP3 signaling

pathway mediated pyroptotic cell death to increase

cisplatin-sensitivity in gastric cancer (GC). Cell Biosci.

11:382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

West AJ, Deswaerte V, West AC, Gearing LJ,

Tan P and Jenkins BJ: Inflammasome-associated gastric tumorigenesis

is independent of the NLRP3 pattern recognition receptor. Front

Oncol. 12:8303502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Raderer M, Kiesewetter B and Ferreri AJ:

Clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment of marginal zone

lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). CA

Cancer J Clin. 66:153–171. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Kuo SH, Wu MS, Yeh KH, Lin CW, Hsu PN,

Chen LT and Cheng AL: Novel insights of lymphomagenesis of

Helicobacter pylori-dependent gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid

tissue lymphoma. Cancers (Basel). 11:5472019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Kiesewetter B and Raderer M:

Immunomodulatory treatment for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

lymphoma (MALT lymphoma). Hematol Oncol. 38:417–424. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Della Bella C, Soluri MF, Puccio S,

Benagiano M, Grassi A, Bitetti J, Cianchi F, Sblattero D, Peano C

and D'Elios MM: The Helicobacter pylori CagY protein drives gastric

Th1 and Th17 inflammation and B cell proliferation in gastric MALT

lymphoma. Int J Mol Sci. 22:94592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Chonwerawong M, Ferrand J, Chaudhry HM,

Higgins C, Tran LS, Lim SS, Walker MM, Bhathal PS, Dev A, Moore GT,

et al: Innate immune molecule NLRC5 protects mice from

helicobacter-induced formation of gastric lymphoid tissue.

Gastroenterology. 159:169–182.e8. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Deng Y, Fu Y, Sheng L, Hu Y, Su L, Luo J,

Yan C and Chi W: The regulatory NOD-like receptor NLRC5 promotes

ganglion cell death in ischemic retinopathy by inducing microglial

pyroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6696962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Ying L, Liu P, Ding Z, Wray-McCann G,

Emery J, Colon N, Le LH, Tran LS, Xu P, Yu L, et al: Anti-CD40L

therapy prevents the formation of precursor lesions to gastric

B-cell MALT lymphoma in a mouse model. J Pathol. 259:402–414. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|