Introduction

Functional constipation (FC) is a common,

multifactorial, nonorganic disease characterized by infrequent,

difficult, or incomplete bowel movements (1). FC considerably impairs the quality

of life of patients and imposes a substantial burden on global

healthcare systems (2,3). Epidemiological studies have

estimated that the global prevalence of FC ranges from 14-20%

(4,5). Despite its widespread occurrence,

the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of FC remain

incompletely understood, which further complicates its effective

clinical management and development of appropriate treatment

strategies.

Recent advances in gastrointestinal (GI) research

have identified the crucial role of enterochromaffin (EC) cells in

the pathophysiology of FC (6).

EC cells respond to various environmental and endogenous stimuli,

including microbial metabolites, inflammatory factors, mechanical

distension and stress-related hormones, by releasing serotonin

[5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] (7-10). Of 5-HT in the body, >90% is

synthesized from tryptophan through the catalytic activity of the

enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (TPH-1) in EC cells (11,12). Once synthesized, 5-HT is released

into the extracellular space, where it binds to various serotonin

receptors to regulate intestinal functions, including motility,

secretion and sensory perception (13-15). The activity of 5-HT is terminated

predominantly through its reuptake by serotonin transporter (SERT)

(16). Aberrant 5-HT release

from EC cells is associated with dysregulated intestinal motility

and abnormal gut sensation, which are the key contributors to the

pathophysiology of FC (17,18). Notably, therapeutic agents

targeting 5-HT receptors have shown substantial efficacy in

alleviating constipation-related symptoms (19).

Piezo ion channels, including Piezo1 and Piezo2, are

critical mechanosensors in various tissues and play a crucial role

in the functional regulation of mechanosensitive cells such as EC

cells (20,21). Following various mechanical

stimuli, Piezo ion channels open and convert mechanical forces into

cellular signals through calcium influx (22). This process regulates various

cellular activities, including cell proliferation, differentiation,

secretion, metabolism and signaling (23-25). Although Piezo1 and Piezo2 belong

to the same Piezo family, they exhibit distinct distribution

patterns in the digestive system, respond differently to mechanical

signals and regulate target organs uniquely (26,27). These differences suggest that

Piezo1 and Piezo2 may have complementary roles in regulating GI

function.

Current research has revealed that both Piezo1 and

Piezo2 individually promote the release of 5-HT from EC cells, thus

highlighting their key roles in GI function (21,28). However, it remains unclear

whether Piezo1 or Piezo2 independently promote the

pathophysiological changes associated with FC through this

mechanism. Moreover, the specific contributions of Piezo1 and

Piezo2 to 5-HT release and whether they interact cooperatively or

independently in EC cells remain to be elucidated. Hence, the

present study aimed to investigate the distinct and combined

effects of Piezo1 and Piezo2 on the regulation of 5-HT release from

EC cells and their involvement in the pathophysiology of FC.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male C57BL/6 mice 6-8 weeks old and weighing 20±2 g

(SPF grade) were obtained from Chengdu Dashuo Experimental Animal

Co., Ltd. [cat. no. SCXK (Chuan) 2020-0030 and cat. no. SCXK

(Chuan) 2024-0031]. A total of 54 mice were used in the present

study. Animals were acclimatized in an environment-controlled room

with a temperature of 20±2°C, humidity of 50±5% and a 12-h

light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum

throughout the experiment. All animal experiments were conducted in

accordance with ethical guidelines and were approved by the Animal

Experiment Ethics Committee of Chengdu University of Traditional

Chinese Medicine (approval no. 2024012).

Adeno-associated virus construction and

transduction

Technical support for the adeno-associated virus

(AAV) vector construction, packaging and purification was provided

by Shandong Weizhen Biosciences Co., Ltd.

AAV vectors were constructed using the pAV-U6-shRNA

plasmids, designed to specifically target the Piezo1 and Piezo2

genes. The plasmids were constructed with three different short

hairpin (sh)RNA sequences (Table

SI) targeting Piezo1 or Piezo2, each inserted into the vector

under the control of the U6 promoter. The plasmids were then

amplified in bacterial cultures with appropriate antibiotic

selection (Amp; 100 μg/ml) and extracted using standard

plasmid purification techniques. Following plasmid extraction, the

AAV vectors were packaged in 293 cells (Shandong Weizhen

Biosciences Co., Ltd.) using a third-generation packaging system

with a triple plasmid transfection system, according to the

manufacturer's instructions. For each transfection, 10 μg of

transfer plasmid, 6 μg of packaging plasmid, and 3 μg

of envelope plasmid were used, at a ratio of 10:6:3. Viral

particles were harvested at 72 h post-transfection. The packaged

AAV particles were subsequently purified and titers were determined

using reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR.

Two weeks prior to model induction, AAV transduction

was performed on colonic epithelial cells via enema, following the

protocol described below. Mice were fasted for 24 h before the

procedure and anesthetized using isoflurane (2% for induction and

1-1.5% for maintenance). A stainless steel round-tip needle was

gently inserted approximately 2.5 cm into the colon via the anus.

Subsequently, 300 μl of 20 mM N-acetylcysteine solution was

slowly infused into the colon to cleanse the area, with the

solution retained for 30 min. After re-anesthesia, 600 μl of

AAV (total dose: 5×1010 vg per mouse) was administered

into the colon via the same route. To facilitate uniform

distribution of the viral vector along the colonic mucosa, several

standardized procedures were employed: i) deep catheter insertion,

ii) a relatively large infusion volume (600 μl), iii)

temporary anal closure and iv) inversion of the mice into a

vertical position for at least one min. After full recovery from

anesthesia, mice were returned to their cages with free access to

food and water. The time interval between AAV transduction and

subsequent experimentation (model induction) was 2 weeks.

Animal model

A loperamide-induced mouse model was used to

establish functional constipation, given its well-established

reliability and reproducibility in gastrointestinal research. This

model closely mimics the core pathophysiological features of human

slow-transit constipation, including delayed colonic transit,

decreased fecal water content and altered serotonergic signaling.

Its technical simplicity and consistency also make it suitable for

evaluating gut motility and related molecular mechanisms in

experimental settings (29).

Male mice in the FC group were administered

loperamide (10 mg/kg) twice daily by gavage for 14 days, while

control mice received an equivalent volume of physiological saline

by gavage. After one week of adaptive feeding, 54 mice were divided

randomly into 6 groups: Control group, FC group, Control AAV group,

AAV Piezo1-knockdown (KD) group, AAV Piezo2-KD group and AAV

Piezo1/2-KD group. At the end of the modeling period, the

defecation status of the mice was recorded over a 6-h period

according to previously published methods (30), including the number of fecal

pellets, the Bristol stool form scale score (BSFS) (31) and the fecal moisture content.

Fecal pellets were collected immediately after

expulsion and placed in sealed 2-ml tubes to avoid evaporation. The

fecal pellets were weighed (wet weight, in mg), dried at 60°C

overnight, and weighed again (dry weight, in mg). Fecal water

content was calculated using the equation: water content (%)=100×

(wet weight-dry weight)/wet weight. Additionally, the total fecal

output, BSFS and wet weight were assessed every 2 h.

At the end of the experiments, all mice were

sacrificed by cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane

anesthesia, in accordance with institutional ethical

guidelines.

Assessment of functional GI motility

To measure total gastrointestinal transit time

(TGITT), overnight-fasted mice were orally gavaged with 0.2 ml of

Evans blue solution (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.). TGITT was assessed as the time from gavage until the

appearance of the first blue fecal pellet. Colonic transit time was

measured by recording the time from gavage to the expulsion of the

first blue fecal pellet.

To assess the small intestinal propulsive rate and

gastric emptying rate, mice were sacrificed 20 min after oral

gavage with the Evans blue solution. The gastric emptying rate was

calculated by the total stomach weight and the net stomach weight,

while the intestinal propulsion rate was calculated based on the

distance the blue solution travels in the small intestine. The

abdominal cavity was opened using sterile forceps and surgical

scissors, and the stomach was quickly removed after ligating the

gastric cardia and pylorus. The stomach was placed on filter paper,

opened along the greater curvature, and rinsed with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 (HyClone; Cytiva). Excess

tissue fluids and PBS were absorbed with filter paper. The net

weight of the stomachs was recorded after washing away the

contents. Simultaneously, the small intestine was quickly removed

and spread gently onto a piece of white paper to measure its total

length and the distance traveled by the Evans blue solution. The

small intestinal propulsive rate and gastric emptying rates were

calculated using the following formulas:

Small intestinal propulsive rate (%)=(distance

traveled by Evans blue/total length of the small intestine) ×100.

Gastric emptying rate (%)=[1‑(total stomach weight‑net stomach

weight)/total stomach weight] ×100.

Colonic sensitivity assessment

Behavioral responses to Colorectal Distension (CRD)

were assessed by measuring the Abdominal Withdrawal Reflex (AWR)

using a semi-quantitative score in conscious animals. Mice were

initially anesthetized with isoflurane and a lubricated latex

balloon attached to polyethylene tubing, connected to a 1 ml

syringe, was inserted into the rectum and descending colon through

the anus. The tubing was secured to the tail to keep the balloon in

place. After allowing the mice to recover from anesthesia for 30

min, AWR measurements were performed. Observers, blinded to the

experimental conditions, visually assessed the mice's responses to

graded CRD volumes (0.25, 0.35, 0.5 and 0.65 ml) and assigned AWR

scores based on the following criteria: 0, no behavioral response;

1, immobility during CRD with occasional head clinching at stimulus

onset; 2, mild contraction of the abdominal muscles without

abdominal lifting; 3, strong contraction of the abdominal muscles

and lifting of the abdomen off the platform; 4, arching of the body

with lifting of the pelvic structures and scrotum.

Cell culture

QGP-1 cells were purchased from Procell Life Science

& Technology Co., Ltd. (cat. no. CL-0977). The cells were

divided into the following five groups: Negative control (NC),

vector control (VC), LV-Piezo1 KD (Piezo1 knockdown), LV-Piezo2 KD

(Piezo2 knockdown) and LV-Piezo1/2 KD (combined Piezo1 and Piezo2

knockdown) groups. Cells were cultured in OPTI-MEM medium (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 51985-034) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.; cat. no. 16000-044) and penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. P1400-100).

Lentivirus construction and cell

infection

RNA interference (RNAi) construction and lentivirus

particle collection were conducted according to previously

described methods (32).

Lentiviral vectors were packaged in 293T cells (Shanghai GeneChem

Co., Ltd., China), using a third-generation packaging system. For

each transfection, 20 μg of transfer plasmid, 15 μg

of packaging plasmid, and 10 μg of envelope plasmid were

used, at a ratio of 4:3:2. Viral particles were harvested at 72 h

post-transfection. QGP-1 cells were infected with lentivirus

harboring RNAi targeting Piezo1 (LV-RNAi-Piezo1), Piezo2

(LV-RNAi-Piezo2) and a control (LV-RNAi-NC) at a multiplicity of

infection of 10 for 72 h. The efficiency of interference was

examined by RT-qPCR and western blotting. Cells were then used for

subsequent experiments 72 h post-infection (transient transduction,

no antibiotic selection), including functional assays and imaging

studies. The target sequences used to design the RNAi constructs

are listed in Table SI.

Histological examination of colonic

tissue

Distal colon tissues were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h, processed in an automatic tissue

processor and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4 μm

thickness were cut using a rotary microtome. Deparaffinization was

performed by immersing the sections in xylene (2×30 min), followed

by rehydration in 100% ethanol (2×5 min), 95% ethanol (5 min), 85%

ethanol (5 min) and 75% ethanol (5 min). The sections were rinsed

for 5 min, stained with hematoxylin at 22-25°C for 5-10 min,

followed by differentiation in 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol for 3

sec and bluing in alkaline water. Eosin staining was performed at

22-25°C for 3 min, followed by dehydration in graded ethanol,

clearing in xylene and mounting with neutral resin.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to detect

the co-localization and expression levels of Piezo1, Piezo2 and EC

cells in distal colon. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at

4°C for 24 h, processed and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 3

μm thickness were washed with PBS (cat. no. ZLI-9062;

Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) three

times at 22-25°C for 5 min each and blocked with 3% bovine serum

albumin (cat. no. GC305010; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

at 22-25°C for 30 min. Primary antibodies used were anti-Piezo1

(cat. no. DF12083; Affinity Biosciences, Ltd.; 1:100), anti-Piezo2

(cat. no. NBP1-78624SS; Novus Biologicals; 1:200),

anti-Chromogranin A (cat. no. 10529-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.;

1:200) and anti-5-HT (cat. no. 20080; ImmunoStar Inc.; 1:100), the

latter two of which were used to identify EC cells. Sections were

incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed with

PBS, and then incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

secondary antibodies (cat. no. GB23303; Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd.; 1:100) or CY5-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary

antibodies (cat. no. GB27303; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.; 1:100) for 50 min at 22-25°C. TSA reagents CY3-Tyramide (cat.

no. G1223; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.; 1:500) and

FITC-Tyramide (cat. no. G1222; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.; 1:500) were used for signal amplification for 10 min at

22-25°C in the dark followed by PBS washes. DAPI (cat. no. G1012;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was used for nuclear

staining for 10 min at 22-25°C in the dark followed by PBS washes.

DAPI and fluorescent signals were observed under a fluorescence

microscope at ×200 and ×400 magnifications.

Negative controls were included by omitting the

primary antibodies and replacing them with equal volumes of PBS.

These control sections were processed in parallel with experimental

samples, including incubation with the same secondary antibodies

and DAPI. No fluorescent signals were observed under these

conditions, confirming the specificity of the staining.

The analyses were carried out under an Olympus VS200

digital slide scanning system (Olympus Corporation) and images were

analyzed with ImageJ software (version 1.54f; National Institutes

of Health) to assess the co-localization and quantify the positive

expression of Piezo1, Piezo2 and EC (ChgA+) cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for

24 h, processed and embedded in paraffin. Antigen retrieval was

performed by heating sections in citrate buffer (pH 6.0, cat. no.

GA2307051; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) using a microwave

for 20 min. After cooling to 22-25°C, distal colon sections were

washed three times with PBS (cat. no. G0002-2L; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 5 min each. Endogenous peroxidase

activity was quenched by incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide (cat.

no. G1204; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 22-25°C in the

dark for 25 min, followed by three PBS washes. Nonspecific binding

was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (cat. no. GC305010; Wuhan

Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20 min at 22-25°C. Sections

were incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber with the

following primary antibodies: Anti-5-HT3 (cat. no.

120185; Zen Bioscience; 1:100) and anti-SERT (cat. no. 19559-1-AP;

Proteintech Group; 1:400) diluted in PBS. After PBS washes,

sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit

secondary antibody (cat. no. GB23303; Wuhan Servicebio Technology

Co., Ltd., 1:100) for 30 min at 37°C. Immunoreactivity was

visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (cat. no.

ZLI-9018; Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd.),

with color development monitored under a light microscope and

stopped by rinsing in distilled water. Sections were counterstained

with hematoxylin (cat. no. LM10N13; J&K Scientific) for 3 min

at 22-25°C, blued in running water, dehydrated, cleared in xylene

and mounted with neutral resin. IHC images for 5-HT3 and

SERT were acquired at ×400 magnification using a digital trinocular

microscope imaging system (cat. no. BA400Digital; Motic China Group

Co., Ltd.), including both the mucosal and muscular layers of the

distal colon. For each mouse, three non-overlapping fields were

selected and analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.54f;

National Institutes of Health). Positive immunoreactivity was

quantified as the percentage of DAB-stained area relative to the

total tissue area (positive area fraction). Color deconvolution and

thresholding were standardized across all images to ensure

consistent measurement.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Colonic tissues were lysed in IP lysis buffer (cat.

no. G2038; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) supplemented with

PMSF (cat. no. G2008; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and

phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. G2007; Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.). Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for

10 min at 4°C and supernatants were collected. Protein

concentrations were determined using a BCA Protein Assay kit (cat.

no. BL521A; Biosharp Life Sciences). For each IP reaction, 400

μl of lysate was used. Protein A magnetic beads (cat. no.

HY-K0203, MedChemExpress) were pre-washed three times with

binding/wash buffer provided in the kit and incubated with 10

μg of anti-Piezo1 antibody (rabbit polyclonal; cat. no.

15939-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at 4°C for 2 h to form

antibody-bead complexes. Then, 400 μl of lysate was added to

the complexes and incubated for an additional 2 h at 4°C with

rotation. After four washes with binding/wash buffer, beads were

collected magnetically at each wash step. Bound proteins were

eluted by boiling the beads in SDS-PAGE loading buffer (cat. no.

BL502B; Biosharp Life Sciences) at 95°C for 5 min. Eluted proteins

were resolved on 7% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membranes

(cat. no. IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma) and probed with anti-Piezo2

monoclonal antibody (mouse; cat. no. HA723342; HuaAn Biotechnology)

at 1:1,000. After washing, membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (cat. no. GB23301;

Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 1:10,000 for 1 h at

22-25°C. Signal was detected using ECL reagents (cat. no. BL520B;

Biosharp Life Sciences) and imaged using a ChemiScope 6100 system

(Clinx). No epitope tag was used.

Western blotting

To measure the expression levels of Piezo1 and

Piezo2 proteins in distal colon, proteins were extracted using RIPA

lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology),

supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails,

fractionated by SDS-PAGE (10% gels; 30 μg total protein per

lane) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was

blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 30 min at room temperature.

Primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4°C: anti-Piezo1 (cat.

no. DF12083; Affinity Biosciences; 1:1,000), anti-Piezo2 (cat. no.

NBP1-78624, Novusbio, 1:1,000) and anti-β-actin (cat. no. AC026;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.; 1:50,000)/anti-GAPDH (cat. no. ab9485;

Abcam; 1:2,500). The membrane was then washed three times with TBST

(0.1% Tween-20) and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary

antibodies (cat. no. S0001; Affinity Biosciences; 1:5,000) for 2 h

at 22-25°C. After washing three times with TBST (0.1% Tween-20),

immunoblots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence

substrate (cat. no. 17046; Chengdu Zen-Bioscience Co., Ltd.) and

imaged with a UVP imaging system (Ultra-Violet Products Ltd.).

Densitometric analysis of protein bands was performed using Gel-Pro

Analyzer (version 4; Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Detection of ERK and protein kinase C

(PKC) pathway proteins

Mouse colonic tissues were rinsed with ice-cold PBS

to remove residual blood and then homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer

(cat. no. P0013; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented

with 1Xprotease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. BL612A; Biosharp Life

Sciences) and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; cat. no.

BL507A; Biosharp Life Sciences). Homogenization was performed using

a tissue grinder (Model KZ-III-Fl; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 2-5 min until tissues were completely homogenized. Tissue

lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min, vortexing every 10 min,

followed by centrifugation at 15,805 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein

concentrations (30 μg per lane) were determined using a BCA

protein assay kit (cat. no. BL521C; Biosharp Life Sciences).

Protein samples were mixed with loading buffer (cat. no. BL502A;

Biosharp Life Sciences), denatured at 95°C for 10 min, and stored

at −80°C until use. Protein separation was performed by SDS-PAGE

(10% gels) at a constant voltage of 100 V. The proteins were then

transferred onto PVDF membranes (Immobilon-PSQ; MilliporeSigma) at

200 mA for 1-2 h. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk

diluted in TBST buffer (0.1% Tween-20) for 2 h at 22-25°C and then

incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: anti-ERK1/2

(cat. no. A4782; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.; 1:2,000),

anti-phosphorylated (p-)ERK1/2 (cat. no. 28733-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.; 1:2,000), anti-PKC (cat. no. ET1608-15; HuaAn

Biotechnology; 1:5,000), and anti-p-PKC (cat. no. ET1702-17; HuaAn

Biotechnology; 1:2,000). After washing with TBST buffer (0.1%

Tween-20) three times, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibody (cat. no. AS014; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.;

1:8,000) for 2 h at 22-25°C. Protein bands were visualized using

enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (cat. no. BL520B; Biosharp

Life Sciences) and imaged using the Tanon 5200 Multi

Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon Science and Technology Co.,

Ltd.). Densitometric analysis of protein bands was performed using

Gel-Pro Analyzer (version 4; Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Due to antibody compatibility and differences in

molecular weight, target proteins and internal controls were

detected on separate membranes. However, all blots were prepared

from the same set of samples and processed in parallel under

identical electrophoresis, transfer and exposure conditions.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from distal colon tissue

using the Molpure Cell/Tissue Total RNA kit (Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Genomic DNA was removed with a gDNA

Eraser kit. cDNA was synthesized from RNA using the PrimeScript RT

reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). RT-qPCR was performed with TB Green

Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio, Inc.) on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time

PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Thermocycling

conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 30

sec, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec,

annealing at 55°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 30 sec,

during which fluorescence signals were acquired. All primer

sequences used in the present study are listed in Table SII. Relative mRNA expression

levels of Piezo1, Piezo2 and SERT were calculated using the

2-ΔΔCq method (33),

with β-actin as the internal control. Data analysis was performed

using QuantStudio Design & Analysis Software (version 1.6;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All RNA extraction, cDNA

synthesis, and RT-qPCR procedures were carried out according to the

manufacturers' protocols.

Calcium ion imaging

The intracellular Ca2+ concentration was

measured using the Ca2+ fluorescent probe Fluo-4 AM

(cat. no. S1061S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Cells were

incubated with 2.5 μmol/l Fluo-4 AM diluted in HBSS solution

for 40 min in an incubator. After incubation, cells were washed

three times with HBSS solution. HBSS solution was added to cover

the cells and they were incubated at 37°C for 25 min. The HBSS

solution was then discarded. Cells were excited at 488 nm using an

inverted fluorescence microscope. Images were analyzed using ImageJ

software (version 1.54f; National Institutes of Health).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

The concentrations of 5-HT in the serum and colon,

vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and substance P (SP) levels in

the serum were examined using ELISA kits (cat. nos. ZC-37715,

ZC-38836 and ZC-37822; Shanghai Zhuocai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Colonic calcium ion

concentrations and tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (TPH-1) were determined

using a colorimetric calcium assay kit (cat. no. C004-2-1; Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Inc.; cat. no. ZC-57264; Shanghai Zhuocai

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad

Prism version 9.0 (Dotmatics). Data normality was assessed using

the Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene's test was used to verify

homogeneity of variances. For group comparisons, unpaired Student's

t-tests were used for two-group comparisons and one-way ANOVA

followed by Tukey correction was applied for multiple group

comparisons. Non-parametric tests, including the Mann-Whitney U

test and Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post hoc analysis, were

applied to analyze data not conforming to normal distribution.

Effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were calculated where

applicable. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Attenuated co-localization and expression

of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in enterochromaffin cells of FC mice

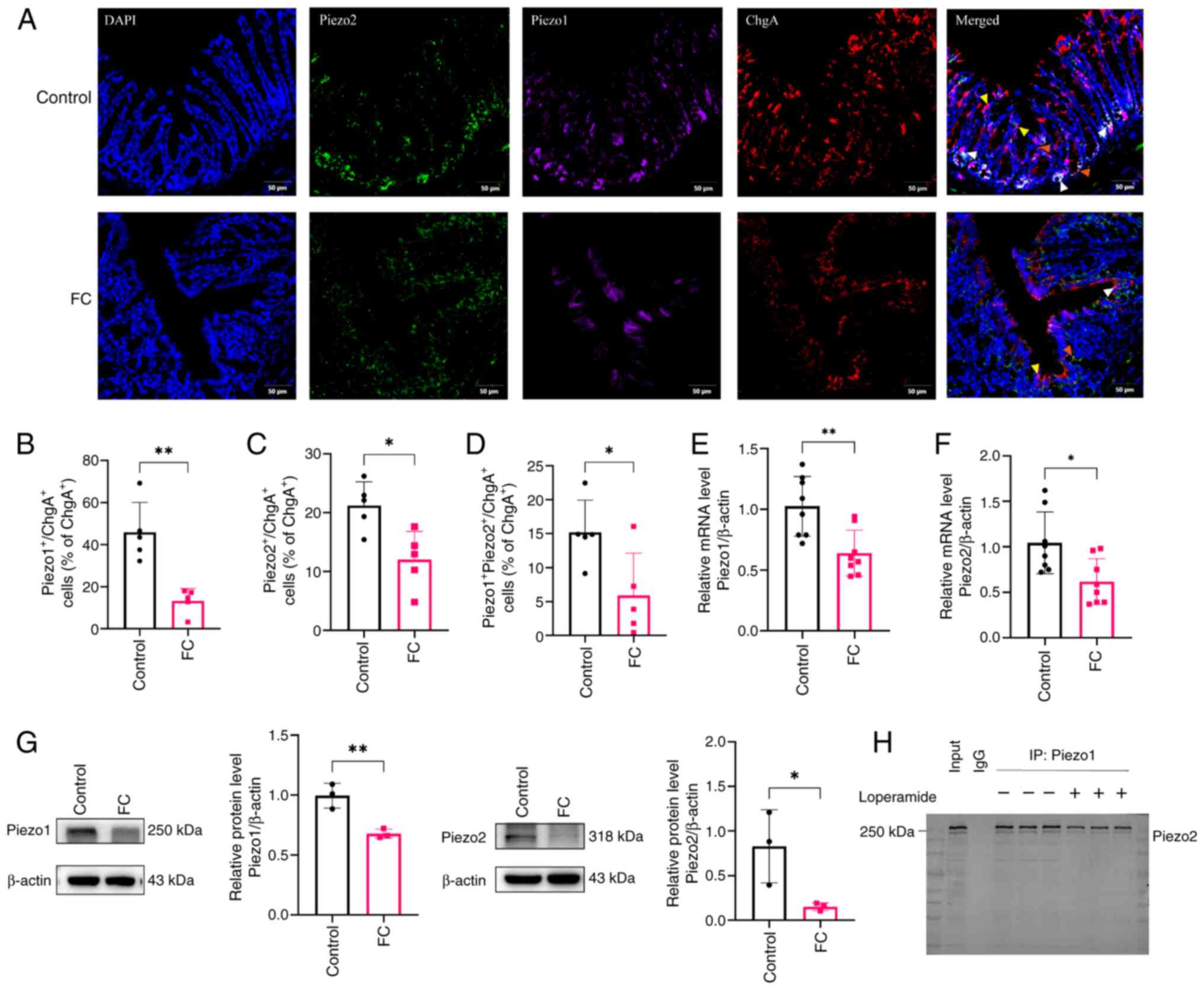

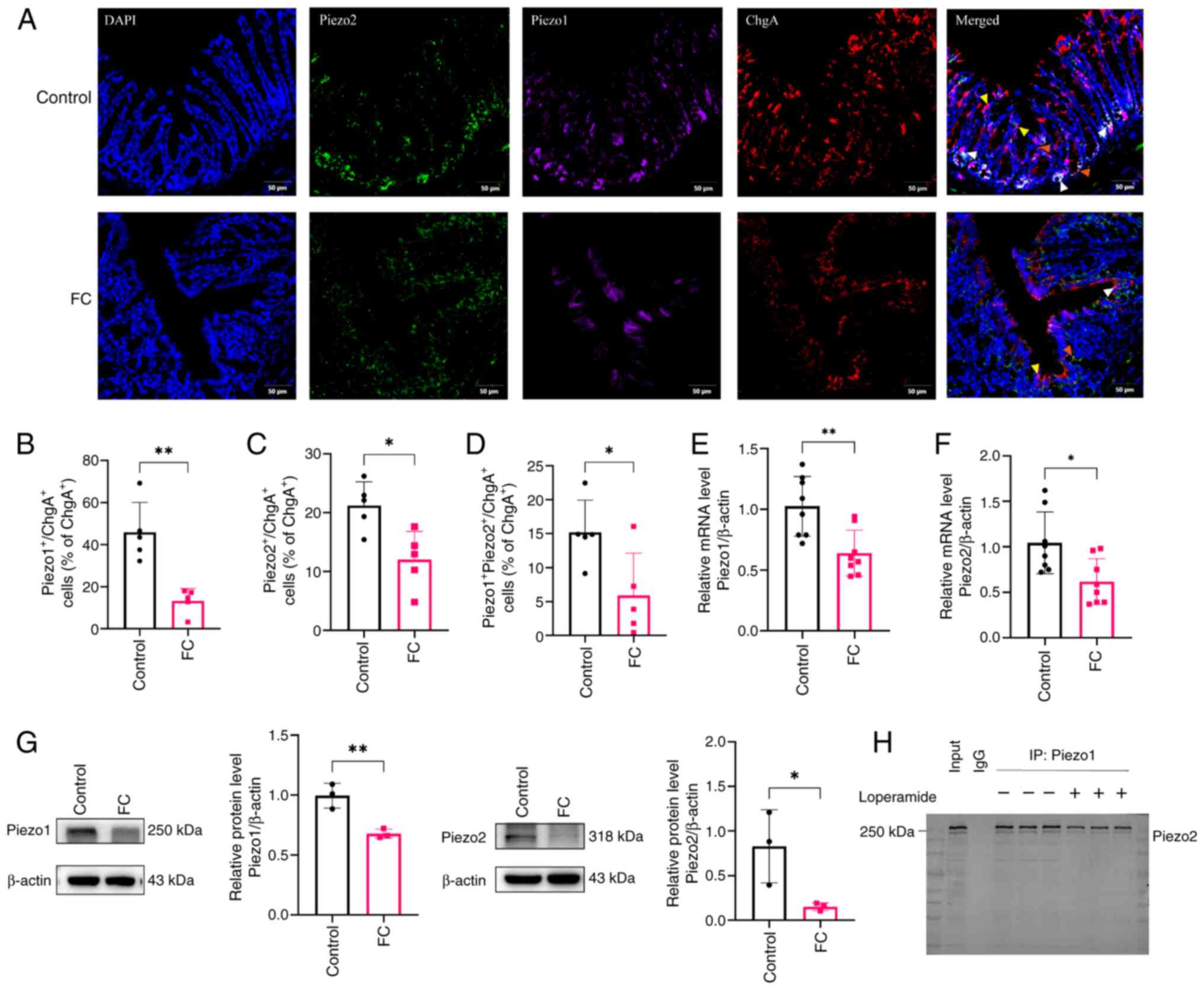

To investigate the expression of Piezo1 and Piezo2

within EC cells, immunofluorescence staining was performed in

control and FC mouse distal colons. ChgA was primarily localized at

the crypt base, exhibiting a distribution pattern similar to that

of 5-HT. (Figs. 1A and S1A). In control tissues, both Piezo1

and Piezo2 were clearly expressed in the colonic epithelium and

showed substantial co-localization with ChgA+ cells

(Fig. 1A). In FC mice,

fluorescence signals for Piezo1, Piezo2 and ChgA were visibly

reduced and the overlap among these markers appeared diminished.

Quantification confirmed a significant decrease in the proportion

of Piezo1+ ChgA+ cells, Piezo2+

ChgA+ cells and triple-positive cells among total

ChgA+ cells in FC mice compared with controls (Fig. 1B-D; P<0.01, P<0.05 and

P<0.05, respectively), suggesting that Piezo expression in EC

cells is downregulated under constipated conditions. Western blot

and RT-qPCR analyses confirmed these findings, showing decreased

protein and mRNA levels for both Piezo1 and Piezo2 in the FC group

(Fig. 1E-G; P<0.05,

P<0.01). Collectively, these results indicated that Piezos

expression and Piezo1/2-EC, Piezo1-Piezo2 colocalization are

significantly attenuated in FC mice.

| Figure 1Colocalization and expression of

Piezo1 and Piezo2 in EC cells of FC Mice. (A) Immunofluorescence

staining of Piezo1, Piezo2 and EC cells in colonic sections from

each group. DAPI (blue) indicates nuclei, Piezo2 (green), Piezo1

(purple) and EC cell (red). Scale bar, 50 μm (magnification,

×200). Yellow arrows indicate co-localization of Piezo1 and ChgA;

orange arrows indicate co-localization of Piezo2 and ChgA; white

arrows indicate triple co-localization of Piezo1, Piezo2 and ChgA.

Percentage of (B) Piezo1+ChgA+, (C)

Piezo2+ChgA+ and (D)

Piezo1+Piezo2+ChgA+ cells as a

percentage of total ChgA+ cells in control and FC

groups; n=5 mice per group. (E) Quantification of Piezo1 and (F)

Piezo2 mRNA levels relative to β-actin in the control and FC group;

n=8 mice per group. (G) Western blot analysis of Piezo1 and Piezo2

protein expression in the control and FC groups; n=3 mice per group

Target proteins and internal controls were detected on separate

membranes processed in parallel. The vertical line indicates

membrane separation. (H) Co-immunoprecipitation of Piezo1 and

Piezo2 in colonic tissues from control and FC model mice, with

Piezo1 immunoprecipitated and Piezo2 detected by western blotting.

Data are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed using an unpaired

two-tailed Student's t-test. Statistical significance indicated as

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. EC, enterochromaffin

cell; FC, functional constipation. |

To determine whether Piezo1 and Piezo2 physically

interact under physiological and pathological conditions, Co-IP was

performed using colonic tissue lysates from control and FC model

mice. Piezo1 was immunoprecipitated with a specific antibody and

western blotting was performed to detect Piezo2. As shown in

Fig. 1H, Piezo2 was strongly

detected in the immunoprecipitated fraction of control samples,

confirming a specific interaction between Piezo1 and Piezo2.

Notably, the intensity of the Piezo2 signal was markedly reduced in

the FC group, suggesting that the pathological condition impairs

the association between these two mechanosensitive ion channels. No

signal was observed in the IgG control, validating the specificity

of the assay.

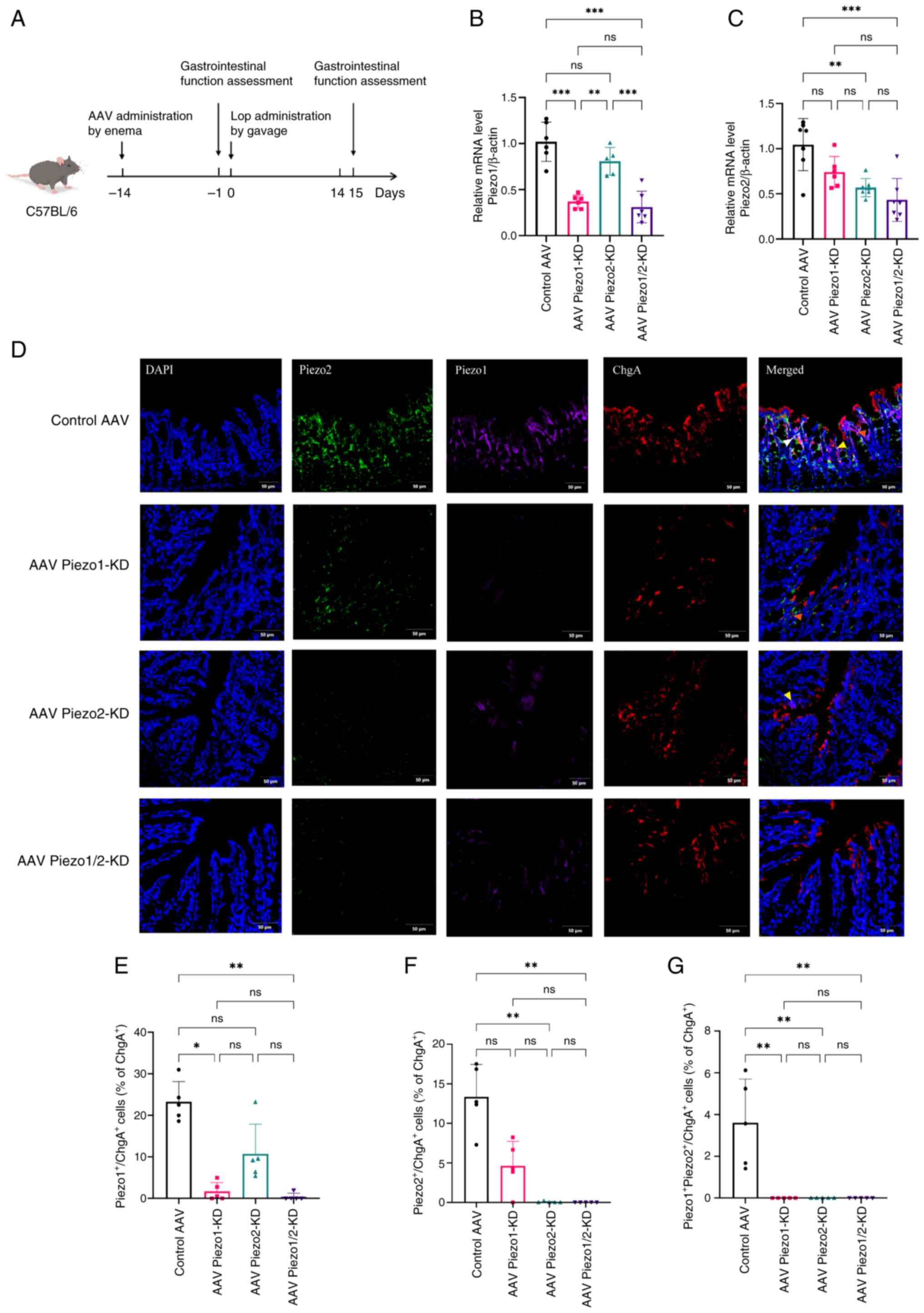

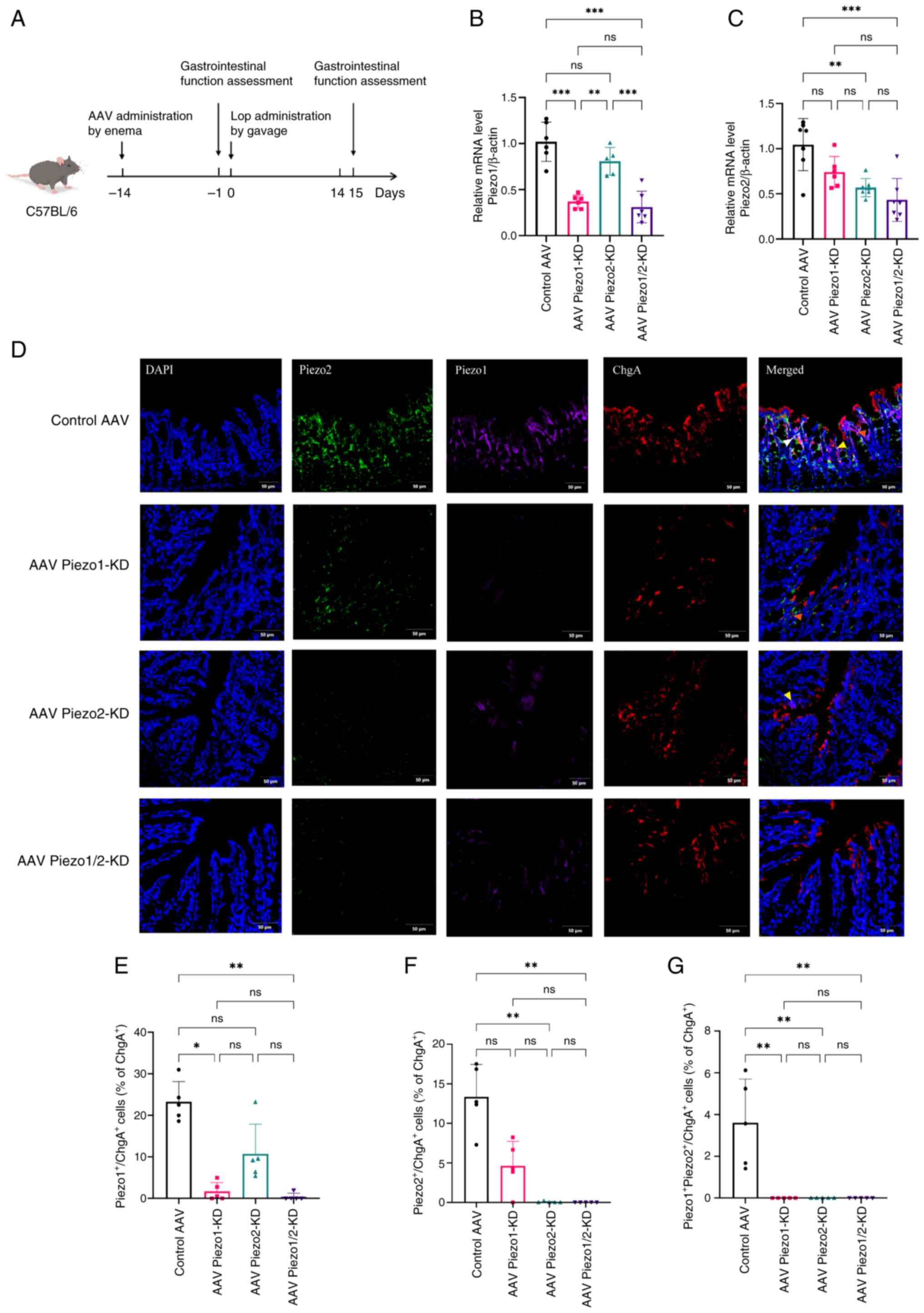

To elucidate the roles of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in FC

mice, AAV-mediated knockdown of each ion channel individually and

in combination was employed (Fig.

2A). To examine the tissue distribution of AAV transduction,

GFP fluorescence in colonic sections following rectal enema

administration of AAV vectors was evaluated. GFP signals were

mainly detectable in the mucosal layer, whereas comparatively less

fluorescence was observed in the muscularis layer (Fig. S1B). In alignment with this

distribution pattern, quantitative analysis of Piezo1+

and Piezo2+ cells showed significant decreases in the

mucosa of knockdown groups compared with controls, whereas no

obvious changes were observed in the muscular layer (Fig. S2). These results suggested that

AAV-mediated gene modulation was predominantly associated with the

mucosal region under the current delivery protocol. RT-qPCR

confirmed specific and effective knockdown: Piezo1-KD significantly

reduced Piezo1 mRNA (P<0.001), Piezo2-KD markedly decreased

Piezo2 mRNA (P<0.01) and dual KD further diminished both mRNAs

(Fig. 2B and C).

Immunofluorescence-based quantification showed that the proportion

of Piezo1+ ChgA+ cells among total

ChgA+ cells was significantly decreased in the Piezo1-KD

and Piezo1/2-KD groups (P<0.05, P<0.01), whereas

Piezo2+ ChgA+ cells were markedly reduced in

both the Piezo2-KD and Piezo1/2-KD groups (P<0.01) (Fig. 2D-F). Furthermore, the proportion

of triple-positive cells (Piezo1+ Piezo2+

ChgA+) was markedly reduced and fell below detectable

levels in all knockdown groups (P<0.01) (Fig. 2G), suggesting a near-complete

loss of co-localized expression of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in EC cells

upon knockdown.

| Figure 2Piezo1/Piezo2 knockdown attenuates

expression of Piezos in EC cells of FC mice. (A) Schematic of the

experimental timeline for AAV-mediated knockdown. RT-qPCR analysis

of (B) Piezo1 and (C) Piezo2 mRNA levels in the control AAV, AAV

Piezo1-KD, AAV Piezo2-KD and AAV Piezo1/2-KD groups; n=5-7 mice per

group. Data analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

(D) Immunofluorescence staining of Piezo1, Piezo2 and EC cells in

colonic sections from each group. DAPI (blue) indicates nuclei,

Piezo2 (green), Piezo1 (purple) and EC cell (red). Scale bar, 50

μm (magnification, ×200). Yellow arrows indicate

co-localization of Piezo1 and ChgA; orange arrows indicate

co-localization of Piezo2 and ChgA; white arrows indicate triple

co-localization of Piezo1, Piezo2 and ChgA. Percentage of (E)

Piezo1+ChgA+, (F)

Piezo2+ChgA+ and (G)

Piezo1+Piezo2+ChgA+ cells as a

percentage of total ChgA+ cells in control and knockdown

groups; n=5 mice per group. Data represent mean ± SD and were

analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical significance is

indicated as *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. ns, not significant; EC, enterochromaffin

cell; FC, functional constipation; AAV, adeno-associated virus; KD,

knockdown. |

These findings indicated that knockdown of Piezo1 or

Piezo2 effectively reduced their respective mRNAs. Furthermore,

dual knockdown markedly diminished the population of

Piezo1+ Piezo2+ ChgA+ cells to

undetectable levels, indicating that Piezo1 and Piezo2 are

co-expressed in a subset of EC cells.

Piezo1 and Piezo2 knockdown exacerbates

impaired gastrointestinal motility and colonic sensitivity in FC

mice

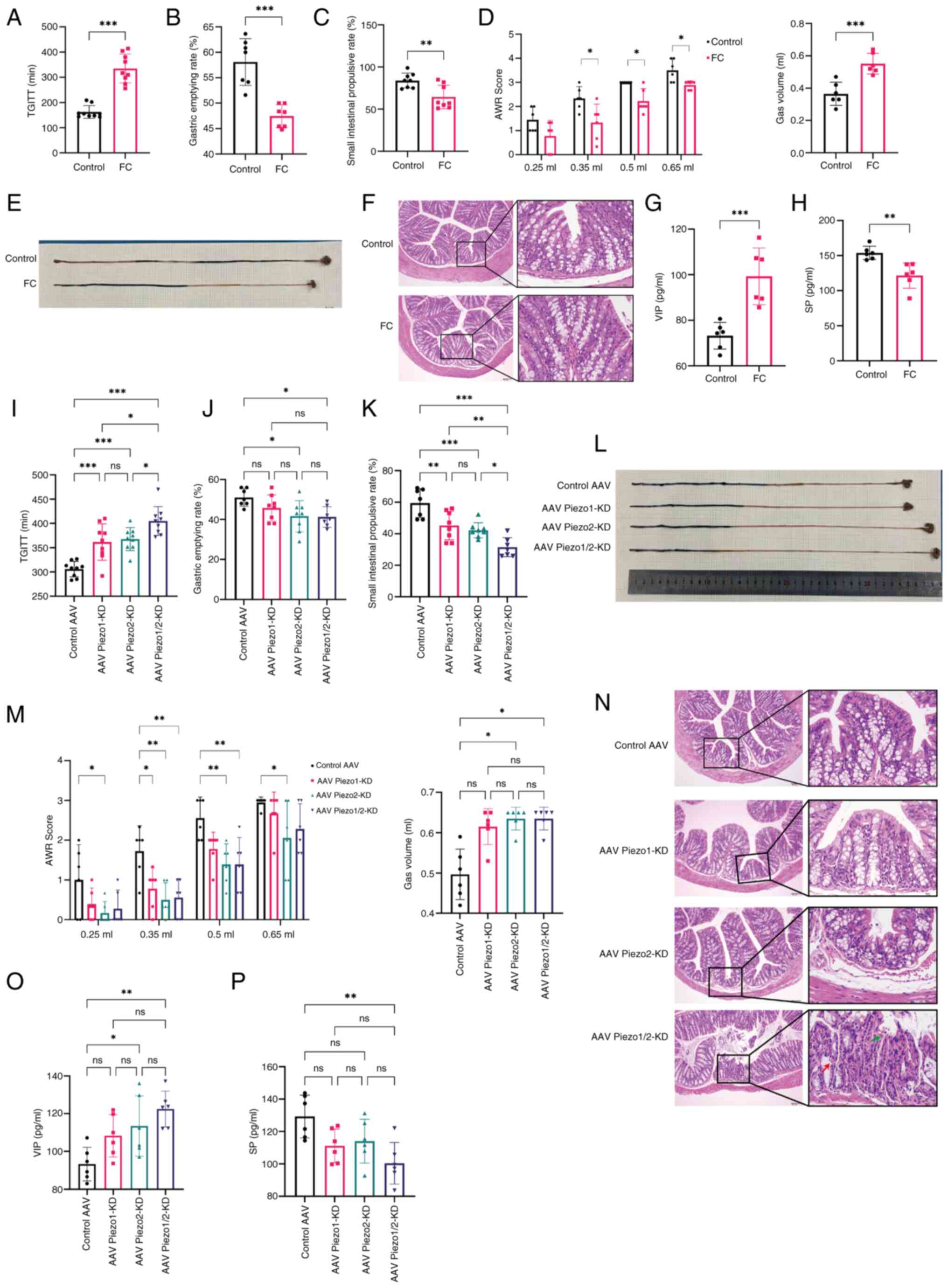

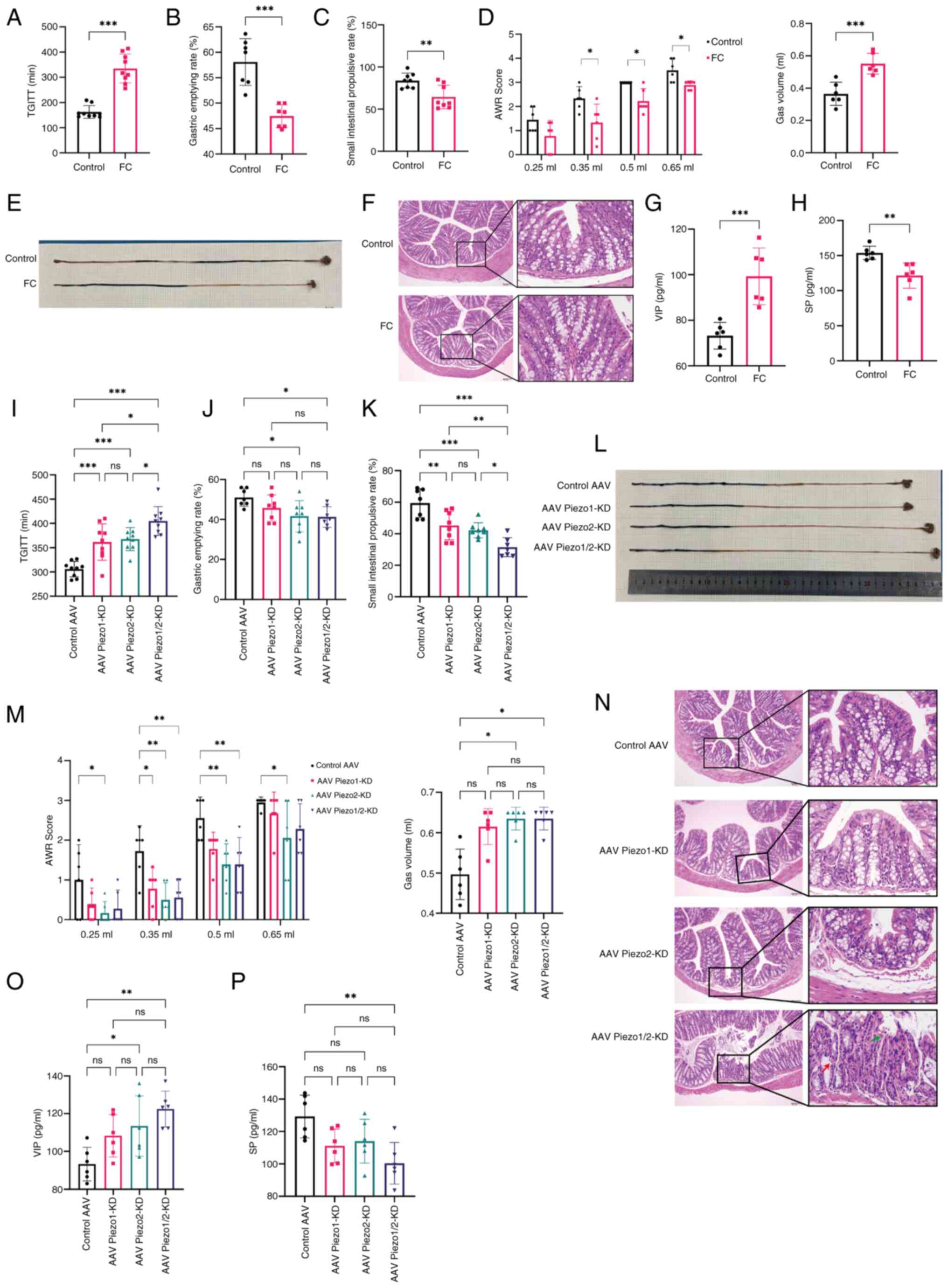

The FC group displayed significantly reduced total

fecal output, lower BSFS scores, decreased stool water content

(Fig. S3) and prolonged TGITT

compared with the control group (all P<0.001), collectively

indicating impaired overall gastrointestinal motility.

Specifically, significant delays in small intestinal transit

(P<0.01) and gastric emptying rates (P<0.001) were observed,

further confirming the reduction in gut motility. Regarding colonic

sensitivity, the FC group required a higher gas volume to reach an

AWR score of 3 (P<0.001) and showed significantly decreased AWR

scores at gas volumes of 0.35, 0.50 and 0.65 ml (all P<0.05),

indicating visceral hyposensitivity (Fig. 3A-E). Histological analysis

revealed normal colonic architecture in the control and FC,

characterized by well-organized crypt structures with no mucosal

damage or inflammatory infiltration (Figs. 3F and S4A). Serum levels of VIP and SP were

assessed as indirect biomarkers of altered gut contractile

function, given their well-established roles in regulating

intestinal smooth muscle activity (34,35). As shown in Fig. 3G and H, VIP levels were

significantly elevated and SP levels were significantly reduced in

the FC group compared with the control group (P<0.01).

| Figure 3Effects of Piezo1 and Piezo2

knockdown on gastrointestinal motility and colonic sensitivity in

FC Mice. (A-H) General effects of the FC model compared with

control mice. Data were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed

Student's t-test. (I-P) Effects of individual or simultaneous

Piezo1 and Piezo2 knockdown on gastrointestinal motility and

sensitivity in FC mice. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's post hoc test or Kruskal-Wallis test. (A and I) TGITT, (B

and J) Gastric emptying rate, (C, K, E and L) Small intestinal

transit rate, (D and M) Gas volume required to reach an AWR score

of 3 and AWR scores at gas volumes of 0.25, 0.35, 0.50 and 0.65 ml.

(F and N) Histological analysis of colonic tissue in each group;

n=3 mice per group. Red arrows highlight regions of glandular

necrosis with structural disorganization and green arrows indicate

nuclear pyknosis and cytoplasmic dissolution. Scale bar, 100

μm (left, magnification, ×100) and 10 μm (right,

magnification, ×400). (G and O) Serum levels of VIP in each group,

(H and P) Serum levels of SP in each group. Data were analyzed

using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's post hoc test. n=6-9 mice per group. Data represent mean ±

SD. Statistical significance is indicated as *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. FC, functional

constipation; TGITT, total gastrointestinal transit time; AWR,

abdominal withdrawal reflex VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide; SP,

substance P. |

To investigate the functional involvement of Piezo1

and Piezo2 in gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity, Piezo1 or

Piezo2 were independently knocked down in FC mice and their effects

on gastrointestinal parameters assessed. Piezo1 and Piezo2

knockdown both led to significantly reduced total fecal output,

delayed TGITT and increased small intestinal transit rate compared

with the control AAV group (all P<0.01) (Figs. S3 and 3I, K and L). Specifically, Piezo1

knockdown decreased fecal water content, while Piezo2 knockdown

reduced gastric emptying rate (both P<0.05) (Figs. S3 and 3J). In terms of colonic sensitivity,

Piezo2 knockdown required a higher gas volume to achieve an AWR

score of 3 compared with the control group, indicating reduced

sensitivity (P<0.05). The Piezo2 knockdown group displayed

significantly elevated AWR scores at each gas volume. (P<0.05),

while Piezo1 knockdown showed increased AWR scores only at 0.35 ml

(P<0.01) (Fig. 3M). These

findings suggested that both Piezo1 and Piezo2 contribute to the

regulation of gastrointestinal motility, jointly influencing total

fecal output and transit times. Furthermore, Piezo1 modulates fecal

water content, while Piezo2 plays a role in gastric emptying rate

and colonic sensitivity.

To determine whether Piezo1 and Piezo2 exert

cooperative effects on gastrointestinal function, a dual knockdown

of both proteins was conducted. Simultaneous knockdown of Piezo1

and Piezo2 significantly impaired gut motility and reduced colonic

sensitivity compared with the control group. Notably, dual

knockdown further prolonged TGITT and increased small intestinal

transit rate compared with the individual knockdown of either

Piezo1 or Piezo2 (both P<0.05; Fig. 3I, K and M). Additionally, dual

knockdown significantly reduced total fecal output compared with

Piezo1 knockdown alone (P<0.05) and decreased fecal water

content compared with Piezo2 knockdown alone (P<0.05) (Fig. S3). These findings indicated that

Piezo1 and Piezo2 work in cooperation to maintain optimal

gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity, jointly influencing

fecal output and transit time, with Piezo1 predominantly affecting

fecal water content and colonic sensitivity, while Piezo2 primarily

modulates gastric emptying. This cooperation underscores the

complex regulatory mechanisms involving Piezo channels in

gastrointestinal homeostasis and suggests potential therapeutic

targets for disorders related to impaired gut motility and

sensitivity.

In the Piezo1 or Piezo2 knockdown groups, mild crypt

disorganization was observed compared with the control vector

group. The dual Piezo1/2 knockdown group exhibited pronounced

mucosal atrophy and marked crypt architectural disarray, suggesting

aggravated structural damage (Fig.

3N). Quantitative analysis further confirmed that colonic crypt

depth was significantly reduced in the dual knockdown group

compared with both the control vector group (P<0.001) and the

single knockdown groups (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively)

(Fig. S4B).

The Piezo1 knockdown group showed no significant

changes in SP or VIP levels relative to the control vector group,

indicating minimal effect of Piezo1 knockdown alone. By contrast,

the Piezo2 knockdown group exhibited a significant increase in VIP

levels compared with the control vector group (P<0.05), while SP

levels remained unchanged. Notably, in the dual Piezo1/2 knockdown

group, SP levels were significantly reduced (P<0.01) and VIP

levels were further elevated (P<0.01) compared with the control

vector group (Fig. 3O and P).

These results indicated that changes in neuropeptide expression

became more pronounced under combined Piezo1 and Piezo2 knockdown

compared with single-gene knockdown.

Piezo1 and Piezo2 knockdown reduces

colonic 5-HT synthesis, release and increases serotonin transporter

(SERT) in FC mice

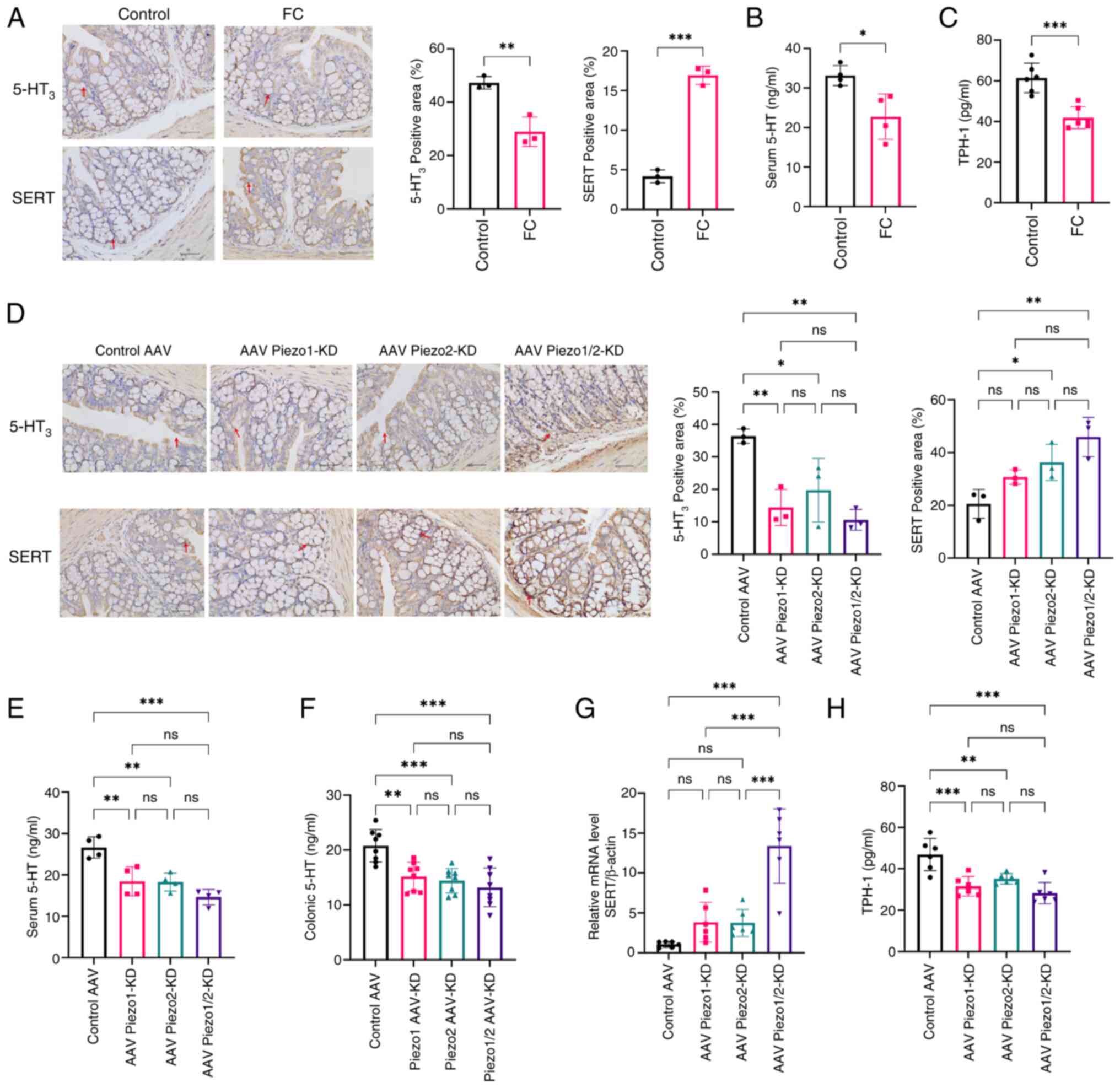

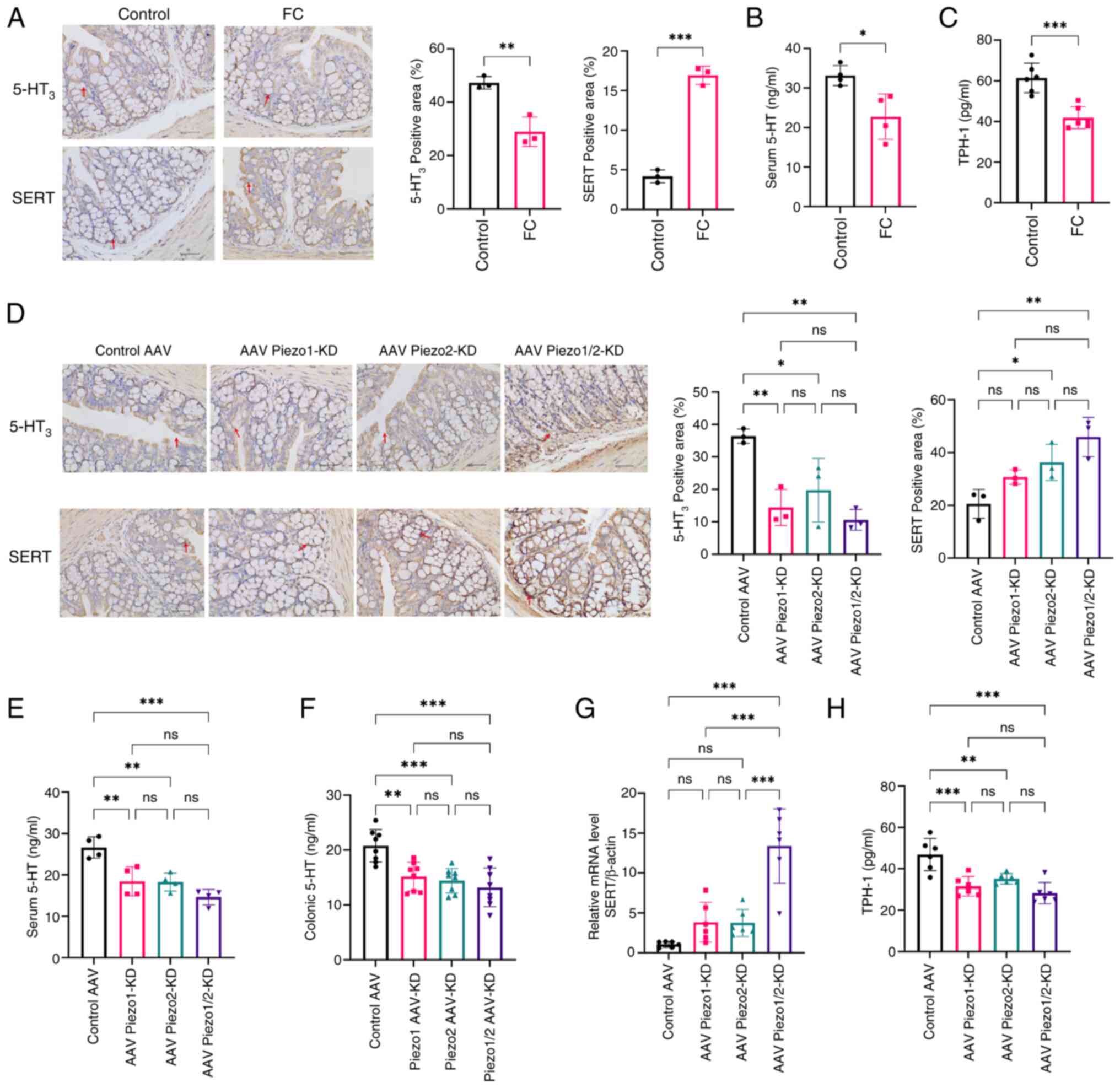

To examine the effect of Piezo1 and Piezo2 knockdown

on 5-HT synthesis, release and SERT expression in the colons of FC

mice, we performed immunohistochemical analysis, ELISA and RT-qPCR

for related genes. Immunohistochemical staining showed a

significant reduction in the percentage of 5-hydroxytryptamine

receptor 3 (5-HT3)-positive and a significant increase

in the percentage of SERT-positive areas in the FC group compared

with controls (P<0.01, P<0.001), indicating impaired

serotonergic function in FC mice (Fig. 4A). Consistent with these

findings, serum 5-HT levels were also significantly lower in the FC

group compared with the control (P<0.05; Fig. 4B), while colonic TPH-1 levels, a

key enzyme in 5-HT synthesis, were significantly reduced as well

(P<0.001; Fig. 4C).

| Figure 4Effects of Piezo1 and Piezo2

knockdown on 5-HT synthesis, release and SERT expression in FC

Mice. (A) Representative immunohistochemical staining of

5-HT3 and SERT in colonic sections from control and FC

mice. Scale bar, 40 μm (magnification, ×400). Quantification

of (B) serum 5-HT and (C) colonic TPH-1 levels in control and FC

mice. Data were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed Student's

t-test; n=4-6 mice per group. (D) Immunohistochemical staining of

5-HT3 and SERT in colonic sections from control AAV, AAV

Piezo1-KD, AAV Piezo2-KD and AAV Piezo1/2-KD groups. n=3 mice per

group. Scale bar, 40 μm (magnification, ×400). (E and F)

Serum and colonic 5-HT levels in each group, comparing knockdown

groups to the control AAV group. (G and H) Relative mRNA levels of

SERT and colonic TPH-1 levels in each group, comparing knockdown

groups to the control AAV. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with

Tukey's post hoc test. n=4-6 mice per group. Data are presented as

mean ± SD, with statistical significance indicated as

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; SERT,

serotonin transporter; FC, functional constipation; TPH-1,

tryptophan hydroxylase-1; AAV, adeno-associated virus; KD,

knockdown. |

In the knockdown groups (Fig. 4D), 5-HT3 and SERT

expression levels varied based on the specific knockdown of Piezo1,

Piezo2, or both. Quantitative analysis showed that the

5-HT3-positive area was significantly lower in the

Piezo1-KD, Piezo2-KD and combined Piezo1/2-KD groups compared with

the control AAV group (all P<0.05), while no significant

differences were observed between the knockdown groups. Similarly,

SERT-positive area was significantly increased in Piezo2-KD and

Piezo1/2-KD compared with the control AAV group (both P<0.05),

with no significant differences between the individual knockdown

and combined knockdown groups.

As serum 5-HT levels reflect both free and

platelet-stored serotonin and may not accurately represent local

biosynthesis or signaling activity, serotonergic activity in

colonic tissues was further evaluated by measuring tissue 5-HT

levels using ELISA. As shown in Fig.

4E and F, both serum and colonic 5-HT levels were significantly

reduced in all knockdown groups compared with the control AAV group

(P<0.01), with no significant differences between the knockdown

groups. The mRNA levels of SERT were significantly increased only

in combined Piezo1/2-KD group, compared with both the control AAV

group and the individual knockdown groups (Fig. 4G, P<0.001). Furthermore, TPH-1

was reduced in all knockdown groups (Fig. 4H, P<0.01), suggesting that

Piezo1 and Piezo2 are involved in maintaining 5-HT synthesis and

secretion in the colonic tissue of FC mice.

Additionally, calcium levels and ERK/PKC

phosphorylation in colonic tissue were assessed to explore the

downstream signaling events that may be involved in Piezo-regulated

5-HT synthesis (Fig. S5).

Colonic Ca2+ levels were significantly reduced in FC

mice and further decreased in the Piezo1 and Piezo1/2 knockdown

groups, with the lowest levels observed in the double knockdown

group. Western blotting showed that p-ERK/total ERK and p-PKC/total

PKC ratios were decreased in FC mice (Fig. S5C and D, P<0.001) and further

suppressed in Piezo knockdown groups (Fig. S5E and F, P<0.001, P<0.01,

P<0.05). Notably, the reduction in p-PKC/total PKC was more

pronounced in the Piezo1/2-KD group compared with either single

knockdown group (P<0.05). By contrast, total ERK1/2 and PKC

remained unchanged.

These results collectively indicated that knockdown

of Piezo1 and Piezo2 disrupted the synthesis and release of 5-HT in

the colon, potentially via ERK/PKC signaling pathways associated

with altered calcium levels.

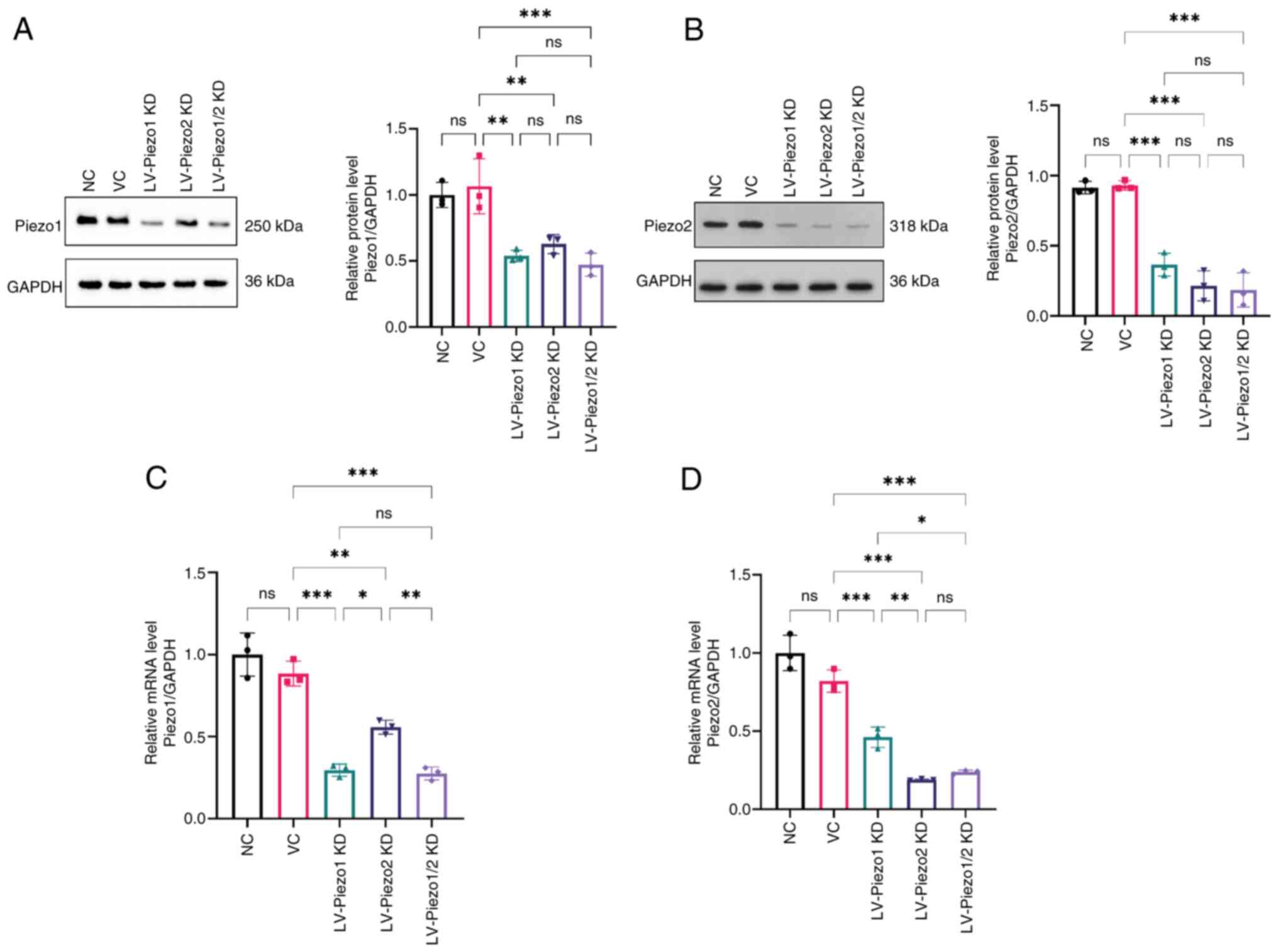

Piezo1/2 expression of Piezo1 and Piezo2

knockdown in EC-like cells

To more directly investigate how Piezo channels

affect 5-HT release from EC cells, in vitro experiments were

conducted. Lentivirus-mediated knockdown targeting each protein was

used (Fig. 5A-D). In the

LV-Piezo1 KD group, Piezo1 protein and mRNA levels were

significantly reduced compared with the control (P<0.01 and

P<0.001), confirming successful knockdown. Similarly, Piezo2

protein and mRNA levels were significantly reduced in the LV-Piezo2

KD group (P<0.001).

Notably, Piezo2 expression was also significantly

reduced in the LV-Piezo1 KD group and Piezo1 expression was reduced

in the LV-Piezo2 KD group (P<0.001 and P<0.01), suggesting a

regulatory relationship where knockdown of one Piezo protein

affects the expression of the other. In the combined LV-Piezo1/2 KD

group, Piezo1 and Piezo2 levels were comparable to those in their

respective single knockdown groups, indicating that simultaneous

knockdown is as effective as individual knockdowns in reducing each

protein's expression.

These findings confirmed the efficacy of

lentivirus-mediated knockdown for both Piezo1 and Piezo2 and

suggest a potential interaction between Piezo1 and Piezo2

expression in EC-like cells.

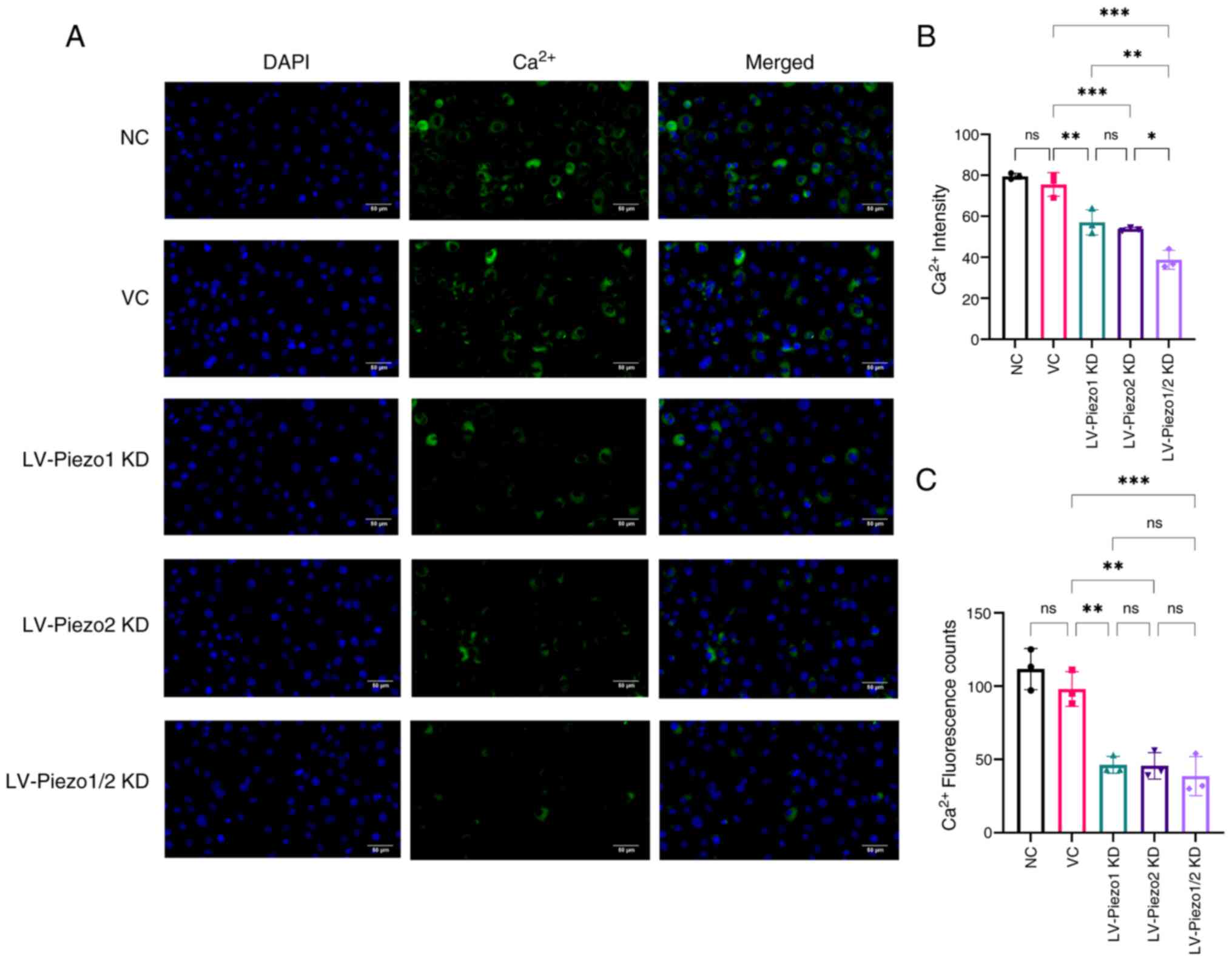

Calcium imaging of Piezo1 and Piezo2

knockdown in EC-like cells

Calcium ions play a crucial role in various cellular

processes and Piezo channels are known to be mechanosensitive ion

channels that regulate calcium influx in response to mechanical

stimuli in cells. To evaluate the effect of Piezo protein knockdown

on channel activity, intracellular calcium concentration in EC

cells was measured via immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 6A-C). The results demonstrated no

significant decrease in total fluorescence intensity in the VC

group compared with the NC group.

In EC-like cells with Piezo1 knockdown, a

significant decrease in average fluorescence intensity and cell

counts (P<0.01) was observed compared with the VC group.

Similarly, Piezo2 knockdown resulted in a marked reduction in these

parameters (P<0.01). These results suggested that knockdown of

either Piezo1 or Piezo2 significantly reduces intracellular calcium

concentration.

Notably, the simultaneous knockdown of both Piezo1

and Piezo2 led to an even more pronounced decrease in average

fluorescence intensity compared with either Piezo1 or Piezo2 single

knockdown groups (P<0.05). This indicated a cooperative effect,

where the combined reduction of Piezo1 and Piezo2 resulted in a

significantly greater decrease in intracellular calcium levels than

the reduction observed with individual gene knockdowns.

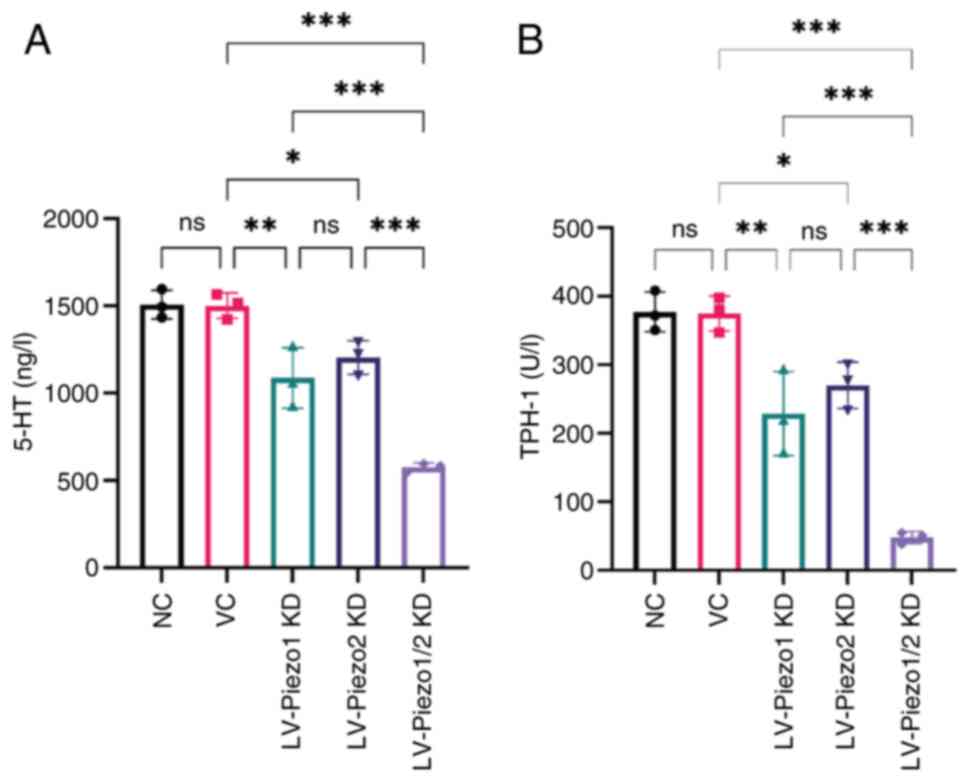

Piezo1 and Piezo2 knockdown downregulates 5-HT and

TPH-1 expression in EC-like cells. To further elucidate the effect

of Piezo1 and Piezo2 on 5-HT synthesis and release from EC-like

cells, lentiviral-mediated knockdown of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in these

cells were employed. The findings showed no significant difference

in 5-HT levels between the VC group and NC group. However,

knockdown of either Piezo1 or Piezo2 alone resulted in a marked

decrease in both 5-HT and TPH-1 expression relative to the VC group

(P<0.05). Notably, there was no significant difference in both

5-HT and TPH-1 levels between the Piezo1 and Piezo2 knockdown

groups, suggesting that both proteins play similar roles in

regulating 5-HT synthesis and release. Dual knockdown of Piezo1 and

Piezo2 led to a further reduction in 5-HT and TPH-1 expression

compared with individual knockdowns (P<0.001; Fig. 7A and B). These results suggested

that Piezo1 and Piezo2 have a cooperative effect on the regulation

of 5-HT and TPH-1 expression.

Discussion

Piezo channels are large trimeric mechanosensitive

ion channels that transduce physical forces such as luminal

distension, shear stress and peristaltic pressure into

intracellular calcium signals, thereby regulating key

gastrointestinal functions (36-38). They are known to influence

serotonin secretion, gut motility and epithelial dynamics and have

been implicated in both physiological and pathological processes

including intestinal inflammation and barrier dysfunction (39-41). The present study provided both

in vivo and in vitro evidence suggesting that Piezo1

and Piezo2 may act in a coordinated manner in EC cells. Their

knockdown was associated with reduced intracellular calcium levels

and diminished 5-HT production, along with impaired intestinal

transit and reduced visceral sensitivity. These findings suggested

that Piezo1 and Piezo2 contributed to gut homeostasis through

EC-mediated serotonergic signaling and that their dysregulation may

be involved in the pathogenesis of FC. Accordingly, targeting Piezo

channels may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for restoring

serotonin balance and improving GI motility in FC.

Piezo1 and Piezo2 are distributed across various

cell types in the gastrointestinal tract, reflecting their

involvement in multiple aspects of gut physiology. Piezo1 has been

reported in epithelial cells, endothelial cells, goblet cells and

smooth muscle cells (21,42,43).

In the enteric nervous system, it is also expressed in cholinergic

neurons along the small intestine, cecum and colon, suggesting a

role in efferent neuromuscular regulation. Piezo2, by contrast, has

a more selective distribution; primarily found in intrinsic primary

afferent neurons and enteroendocrine cells such as ECs (44), supporting its function in

mechanosensory signal input. These distinct patterns suggest that

Piezo1 and Piezo2 may coordinate to regulate gut motility and

sensitivity through both epithelial and neural pathways. In

addition to their individual roles, Piezo channels may functionally

interact with other mechanosensitive channels. Piezo1 activation

facilitates TRPV4 opening via PLA2 signaling, suggesting a

synergistic effect in amplifying mechanical responses (26,45), whereas TRPV1 activation inhibits

Piezo activity by depleting membrane phosphoinositides, indicating

an antagonistic interaction (46). Moreover, Piezo2 and TRPV1 also

co-localize in colonic sensory neurons and contribute to mechanical

hypersensitivity (47), implying

broader crosstalk beyond epithelial pathways. The present study

focused specifically on the expression and function of Piezo1 and

Piezo2 in EC cells under both physiological and pathological

conditions. While previous scRNA-seq studies have not reported

Piezo1 expression in ECs (48),

the findings of the present study supported its presence in the

colonic epithelium. It was observed that Piezo1 protein

co-localized with EC markers by immunofluorescence and Piezo1 mRNA

expression in colonic tissue confirmed by RT-qPCR. These

discrepancies may be attributed to methodological differences, as

Piezo1 expression might be relatively low or confined to a small

subset of ECs, making it difficult to detect in single-cell

transcriptomic datasets (49).

Discrepancies between transcriptomic profiling and experimental

validation have also been reported for Piezo2. Although undetected

in certain scRNA-seq studies beyond the distal colon, Piezo2

expression in the small intestine and EC cells has been confirmed

by RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry (50). To the best of the authors'

knowledge, this is the first in vivo demonstration of Piezo1

expression in colonic EC cells, providing new evidence that both

Piezo1 and Piezo2 may participate in epithelial mechanotransduction

and serotonin-mediated gut regulation.

The present study observed a significant reduction

in Piezo1 and Piezo2 expression in EC cells of FC mice, suggesting

that impaired epithelial mechanotransduction contributes to the

pathophysiology of functional constipation. In vitro,

knockdown of either Piezo1 or Piezo2 reduced the expression of the

other channel, indicating a potential regulatory association,

although this effect was not seen in vivo, probably due to

differences in cellular context or compensatory mechanisms. Despite

their shared mechanosensory roles, Piezo1 and Piezo2 exhibited

distinct physiological effects. Piezo2 knockdown selectively

impaired gastric emptying and colonic sensitivity, consistent with

its involvement in 5-HT-mediated visceral afferent signaling and

intersegmental reflex regulation (41). By contrast, Piezo1 knockdown

mainly reduced fecal water content, possibly reflecting its role in

epithelial ion transport and contractile regulation (51-53). These results suggested a

functional divergence: Piezo2 is more associated with sensory

signaling, while Piezo1 contributes to fluid homeostasis and

motility. Dual knockdown led to exacerbated gastrointestinal

dysfunction, with delayed total transit, reduced fecal hydration

and structural abnormalities. Although knockdown was confined to

the colon, changes in gastric and small intestinal transit were

observed, probably mediated by gut-brain-gut reflexes initiated by

altered colonic 5-HT signaling. While colonic transit time was not

directly assessed, the significant delay in total gastrointestinal

transit, accompanied by reduced fecal output and water content,

strongly suggested impaired colonic transport. Previous studies

have directly demonstrated the critical role of Piezo channels in

colonic propulsion: Piezo2 deletion in sensory neurons

significantly delays colonic transit (41) and enteric Piezo1 ablation impairs

colonic propulsion via disruption of neuroimmune homeostasis

(44).

In the present study, serum SP levels were

significantly decreased only following simultaneous knockdown of

Piezo1 and Piezo2, whereas VIP levels increased with Piezo2

knockdown and were further elevated in the dual knockdown group.

These results suggested that disruption of both Piezo channels may

be required to perturb specific neuropeptide regulatory pathways. A

similar cooperative interaction between Piezo1 and Piezo2 has been

reported in other mechanotransduction contexts, such as bladder

urothelium (54), supporting the

plausibility of such cooperative regulation in the gut. Given the

established roles of SP in promoting smooth muscle contraction and

visceral sensitivity and VIP in facilitating smooth muscle

relaxation and intestinal secretion (55-57), these neuropeptide changes are

consistent with impaired motility and dysregulated autonomic

signaling in FC.

EC cells, the main source of 5-HT in the gut, serve

as mechanosensors that convert physical stimuli into chemical

signals (58). Previous studies

have established Piezo2 as a key transducer of mechanical forces in

EC cells, promoting calcium influx and stimulating 5-HT synthesis

and release via TPH-1 activation (21,59). By contrast, the role of Piezo1 in

EC cells has remained unclear. Prior evidence largely limited to

epithelial responses under inflammatory or immune conditions

(28), with no direct data

confirming its expression or function in EC cells. The present

study filled this gap by providing the first direct in vivo

and in vitro evidence that both Piezo1 and Piezo2 are

expressed in colonic EC cells and act in a coordinated manner to

regulate 5-HT signaling. Notably, genetic knockdown of either

channel impaired calcium responses and reduced 5-HT synthesis and

secretion, but dual knockdown led to more pronounced suppression of

calcium levels, TPH-1 expression and 5-HT production, suggesting a

cooperative interaction between Piezo1 and Piezo2 in regulating EC

cell mechanotransduction. While previous pharmacological studies

using GsMTx4 supported a role for mechanosensitive channels in 5-HT

release, they lacked specificity between Piezo isoforms (59). To overcome this limitation, our

subtype-specific knockdown under both physiological and

pathological conditions enabled a more precise dissection of the

roles of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in regulating serotonergic signaling.

Specifically, Piezo knockdown led to a reduction in 5-HT synthesis

and downregulation of SERT expression, indicating disrupted

serotonergic signaling. Given that serotonin exerts its effects

through multiple receptor subtypes (such as 5-HT3 and

5-HT4) to coordinate intestinal motility and visceral

sensitivity, these disruptions may contribute to the observed

dysmotility and hyposensitivity in functional constipation.

Moreover, the present study examined the phosphorylation status of

ERK1/2 and PKC. ERK1/2 and PKC are both well-established

calcium-sensitive kinases that have been reported in previous

studies to be activated by Piezo1-mediated Ca2+ influx

under mechanical or chemical stimulation (23,60). The present study showed that

Piezo1 or Piezo2 knockdown significantly reduced ERK1/2 and PKC

phosphorylation in colonic tissues, suggesting that Piezo channels

may regulate serotonergic output via calcium-dependent kinase

pathways. Nonetheless, without CaMKII data, the downstream

signaling cascade remains incompletely characterized and additional

studies are needed to dissect the specific contributions of

distinct calcium-dependent kinases.

Current therapies for functional constipation, such

as the 5-HT4 receptor agonist prucalopride, offer

symptomatic relief by enhancing colonic motility through enteric

neuronal activation (61).

However, their clinical efficacy remains modest, with a substantial

proportion of patients exhibiting limited response (62). In addition, prucalopride is

associated with systemic adverse effects (63), including headache, abdominal

pain, nausea and diarrhea, which may lead to treatment

discontinuation in some cases. More importantly, these agents act

downstream of the serotonergic pathway and do not target upstream

mechanisms such as impaired serotonin synthesis or release from

enterochromaffin cells, which may underlie persistent symptoms in

certain patients. By contrast, Piezo channels, serve as

mechanosensitive regulators that directly influence both 5-HT

production and secretion. Their rapid activation kinetics,

cell-type-specific expression and dual roles in modulating

gastrointestinal motility and visceral sensation support their

potential as more physiologically relevant and precisely targeted

therapeutic candidates (64).

These features make Piezo-targeted strategies a promising

complement or alternative to existing serotonergic therapies,

particularly in patients who fail to respond adequately to current

treatment.

Although the present study revealed the

complementary roles of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in regulating the dynamics

of 5-HT release and in maintaining GI homeostasis, it has some

limitations. First, only the loperamide-induced constipation model

was used. While this model reliably reproduces core features of

functional constipation, including delayed transit and serotonergic

dysregulation, it does not fully capture the multifactorial nature

of the disease. Complementary models, such as those induced by

low-fiber diet or aging, may enhance translational relevance in

future studies. Second, the QGP-1 cell line, though widely adopted

as an EC cell model (65), is

derived from pancreatic endocrine tumors and may not fully reflect

the characteristics of native colonic EC cells. Primary EC cells or

intestinal organoids could offer greater physiological relevance.

Third, while calcium imaging showed reduced intracellular calcium

levels after Piezo knockdown, direct mechanical stimulation was not

applied. This limits the ability to directly confirm

mechanosensitive properties. Incorporating real-time mechanical

stimulation would help validate Piezo channel function more

conclusively. Finally, although AAV-mediated knockdown via enema

allows for efficient gene delivery to the colonic epithelium, it

does not offer cell-type specificity. Therefore, off-target effects

on other epithelial cell types cannot be entirely ruled out. Future

work employing EC cell-specific promoters or conditional knockout

models will help to refine the cellular specificity of

Piezo-related mechanisms.

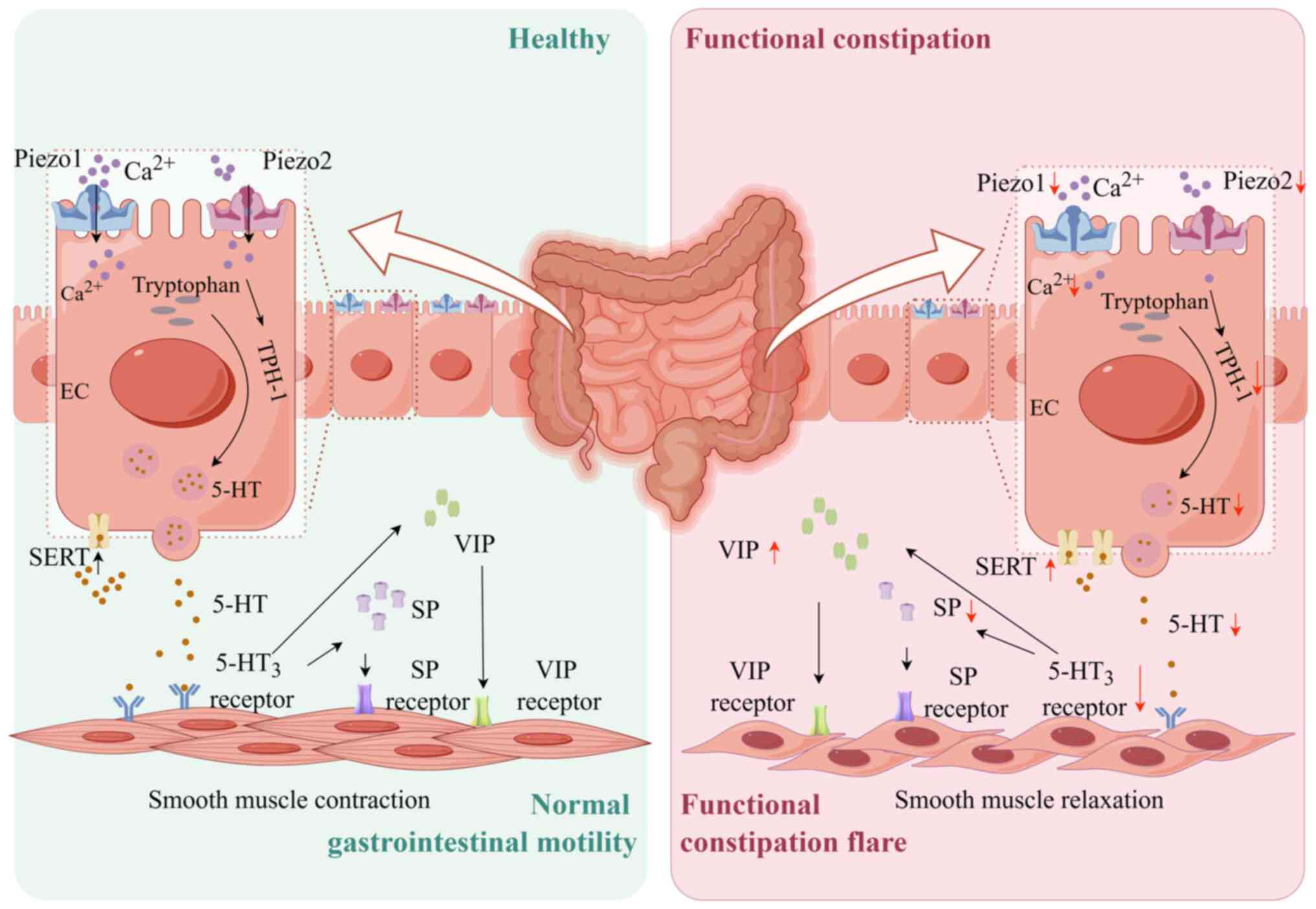

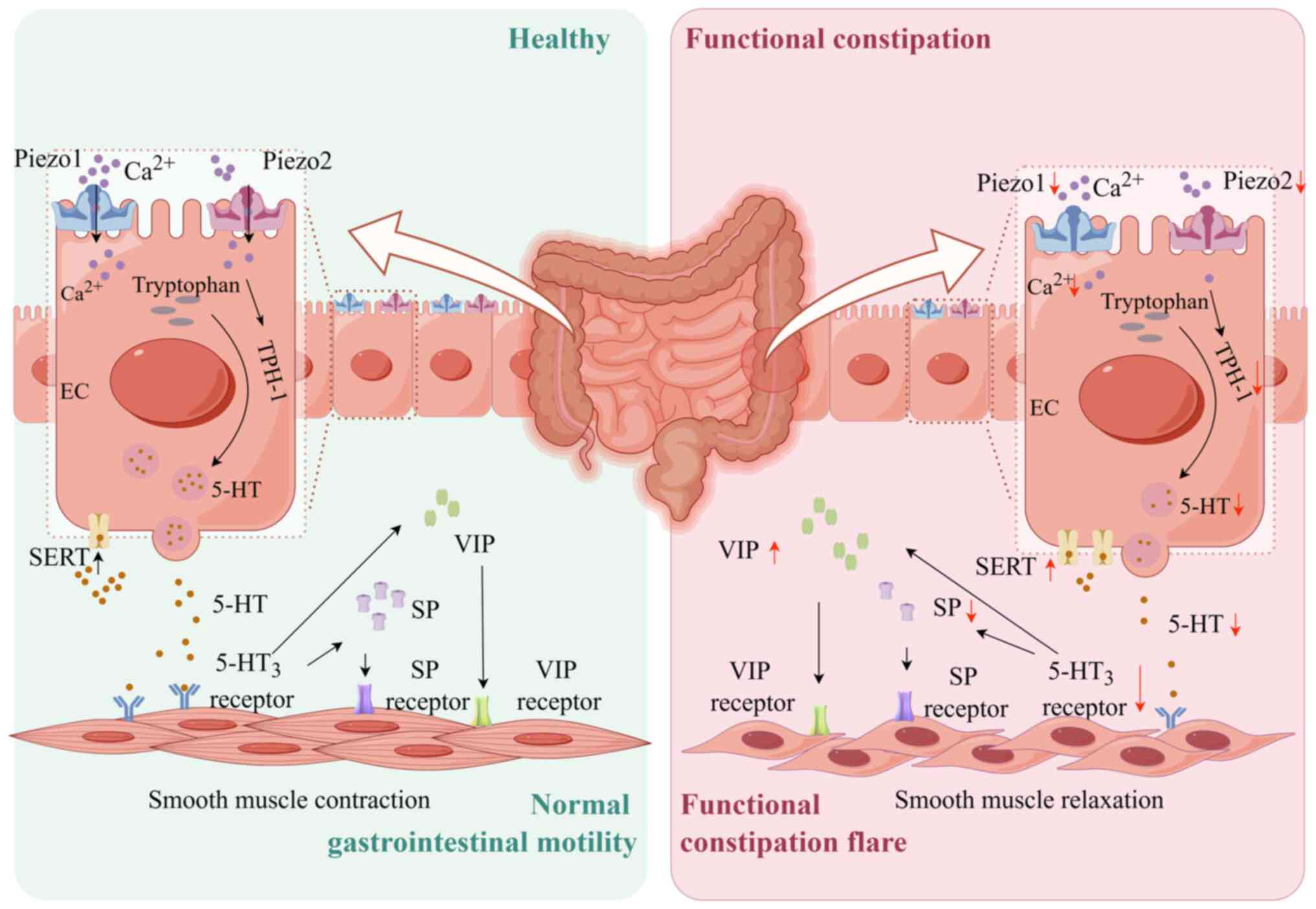

To visually summarize the mechanistic insights

derived from our findings, a schematic diagram is presented in

Fig. 8. It illustrates how

downregulation of Piezo1 and Piezo2 in EC cells reduces

Ca2+ influx and 5-HT synthesis, disrupts serotonergic

and neuropeptide signaling (increased VIP, decreased SP and

enhanced SERT) and ultimately leads to impaired intestinal motility

characteristic of functional constipation.

| Figure 8Mechanism diagram of the study. In

functional constipation, Piezo1 and Piezo2 expression is

downregulated, reducing Ca2+ influx and impairing 5-HT

synthesis. Consequently, diminished 5-HT release reduces activation

of 5-HT3 receptors, SP levels decrease and VIP levels

increase, leading to smooth muscle relaxation. Additionally,

heightened SERT activity, exacerbating the deficiency in 5-HT

signaling. These disruptions collectively induce pathological

alterations in intestinal structure and impaired motility, leading

to functional constipation symptoms. (created by figdraw.com). 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; SP,

substance P; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide; SERT, serotonin

transporter; EC, enterochromaffin cell. |

In conclusion, the present study revealed that

Piezo1 and Piezo2 play critical and cooperative roles in

maintaining GI homeostasis and regulating 5-HT signaling in the

context of FC. In vivo, knockdown of Piezo1 or Piezo2

reduced 5-HT synthesis and release, leading to impaired intestinal

motility, while in vitro experiments demonstrated that both

channels contribute to calcium influx and 5-HT secretion. Moreover,

Piezo knockdown suppressed ERK and PKC phosphorylation, indicating

their involvement in calcium-activated downstream signaling

pathways. These results suggested that Piezo1 and Piezo2 may

represent promising therapeutic targets in intestinal motility

disorders such as FC. Future research should investigate the

underlying molecular mechanisms of the interactions between Piezo1

and Piezo2 and evaluate their therapeutic potential in clinical

settings.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YL was responsible for conceptualization, funding

acquisition, writing, reviewing and editing. JYe was responsible

for methodology and project administration. XY and PM were

responsible for writing the original draft, investigation, formal

analysis and data curation. WW, WZ, YL and YH were responsible for

investigation and formal analysis. JYao, QZ and WZ were responsible

for visualization and validation. XY and JYao confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance

with ethical guidelines and were approved by the Animal Experiment

Ethics Committee of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese

Medicine (approval no. 2024012).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

5-HT

|

5-hydroxytryptamine

|

|

EC

|

enterochromaffin cell

|

|

FC

|

functional constipation

|

|

AAV

|

adeno-associated virus

|

|

TGITT

|

total gastrointestinal transit

time

|

|

BSFS

|

Bristol stool form scale score

|

|

GI

|

gastrointestinal

|

|

CRD

|

colon-rectal distension

|

|

AWR

|

abdominal withdrawal reflex

|

|

KD

|

knockdown

|

|

RNAi

|

RNA interference

|

|

SERT

|

serotonin transporter

|

|

ELISA

|

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

|

|

VIP

|

vasoactive intestinal peptide

|

|

SP

|

substance P

|

|

TPH-1

|

tryptophan hydroxylase-1

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82274652).

References

|

1

|

Black CJ, Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Ruddy J

and Ford AC: Functional gastrointestinal disorders: Advances in

understanding and management. Lancet. 396:1664–1674. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ma C, Congly SE, Novak KL, Belletrutti PJ,

Raman M, Woo M, Andrews CN and Nasser Y: Epidemiologic burden and

treatment of chronic symptomatic functional bowel disorders in the

United States: A nationwide analysis. Gastroenterology.

160:88–98.e4. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rao SSC, Rattanakovit K and Patcharatrakul

T: Diagnosis and management of chronic constipation in adults. Nat

Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 13:295–305. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Barberio B, Judge C, Savarino EV and Ford

AC: Global prevalence of functional constipation according to the

Rome criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6:638–648. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Törnblom H,

Sperber AD and Simren M: Prevalence of Rome IV functional bowel

disorders among adults in the United States, Canada, and the United

Kingdom. Gastroenterology. 158:1262–1273.e3. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rossen ND, Touhara KK, Castro J,

Harrington AM, Caraballo SG, Deng F, Li Y, Brierley SM and Julius

D: Population imaging of enterochromaffin cell activity reveals

regulation by somatostatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

122:e25015251222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bellono NW, Bayrer JR, Leitch DB, Castro

J, Zhang C, O'Donnell TA, Brierley SM, Ingraham HA and Julius D:

Enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory

neural pathways. Cell. 170:185–198.e16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen Z, Luo J, Li J, Kim G, Stewart A,

Urban JF Jr, Huang Y, Chen S, Wu LG, Chesler A, et al:

Interleukin-33 promotes serotonin release from enterochromaffin

cells for intestinal homeostasis. Immunity. 54:151–163.e6. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

9

|

Kieslich B, Weiße RH, Brendler J, Ricken

A, Schöneberg T and Sträter N: The dimerized pentraxin-like domain

of the adhesion G protein-coupled receptor 112 (ADGRG4) suggests

function in sensing mechanical forces. J Biol Chem. 299:1053562023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bayrer JR, Castro J, Venkataraman A,

Touhara KK, Rossen ND, Morrie RD, Maddern J, Hendry A, Braverman

KN, Garcia-Caraballo S, et al: Gut enterochromaffin cells drive

visceral pain and anxiety. Nature. 616:137–142. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Strege PR, Knutson K, Eggers SJ, Li JH,

Wang F, Linden D, Szurszewski JH, Milescu L, Leiter AB, Farrugia G

and Beyder A: Sodium channel NaV1.3 is important for

enterochromaffin cell excitability and serotonin release. Sci Rep.

7:156502017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Leiser SF, Miller H, Rossner R, Fletcher

M, Leonard A, Primitivo M, Rintala N, Ramos FJ, Miller DL and

Kaeberlein M: Cell nonautonomous activation of flavin-containing

monooxygenase promotes longevity and health span. Science.

350:1375–1378. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Raouf Z, Steinway SN, Scheese D, Lopez CM,

Duess JW, Tsuboi K, Sampah M, Klerk D, El Baassiri M, Moore H, et

al: Colitis-induced small intestinal hypomotility is dependent on

enteroendocrine cell loss in mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.

18:53–70. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bhattarai Y, Williams BB, Battaglioli EJ,

Whitaker WR, Till L, Grover M, Linden DR, Akiba Y, Kandimalla KK,

Zachos NC, et al: Gut microbiota-produced tryptamine activates an

epithelial G-protein-coupled receptor to increase colonic

secretion. Cell Host Microbe. 23:775–785.e5. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhao J, Zhao L, Zhang S and Zhu C:

Modified Liu-Jun-Zi decoction alleviates visceral hypersensitivity

in functional dyspepsia by regulating EC cell-5HT3r signaling in

duodenum. J Ethnopharmacol. 250:1124682020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Nygaard A, Zachariassen LG, Larsen KS,

Kristensen AS and Loland CJ: Fluorescent non-canonical amino acid

provides insight into the human serotonin transporter. Nat Commun.

15:92672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wei L, Singh R, Ha SE, Martin AM, Jones

LA, Jin B, Jorgensen BG, Zogg H, Chervo T, Gottfried-Blackmore A,

et al: Serotonin deficiency is associated with delayed gastric

emptying. Gastroenterology. 160:2451–2466.e19. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cremon C, Carini G, Wang B, Vasina V,

Cogliandro RF, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Grundy D, Tonini M, De

Ponti F, et al: Intestinal serotonin release, sensory neuron

activation, and abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J

Gastroenterol. 106:1290–1298. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jin B, Ha SE, Wei L, Singh R, Zogg H,

Clemmensen B, Heredia DJ, Gould TW, Sanders KM and Ro S: Colonic

motility is improved by the activation of 5-HT2B

receptors on interstitial cells of cajal in diabetic mice.

Gastroenterology. 161:608–622.e7. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Nan N, Gong MX, Wang Q, Li MJ, Xu R, Ma Z,

Wang SH, Zhao H and Xu YS: Wuzhuyu decoction relieves hyperalgesia

by regulating central and peripheral 5-HT in chronic migraine model

rats. Phytomedicine. 96:1539052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Alcaino C, Knutson KR, Treichel AJ, Yildiz

G, Strege PR, Linden DR, Li JH, Leiter AB, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia

G and Beyder A: A population of gut epithelial enterochromaffin

cells is mechanosensitive and requires Piezo2 to convert force into

serotonin release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 115:E7632–E7641. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kefauver JM, Ward AB and Patapoutian A:

Discoveries in structure and physiology of mechanically activated

ion channels. Nature. 587:567–576. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gudipaty SA, Lindblom J, Loftus PD, Redd

MJ, Edes K, Davey CF, Krishnegowda V and Rosenblatt J: Mechanical

stretch triggers rapid epithelial cell division through Piezo1.

Nature. 543:118–121. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Baghdadi MB, Houtekamer RM, Perrin L,

Rao-Bhatia A, Whelen M, Decker L, Bergert M, Pérez-Gonzàlez C,

Bouras R, Gropplero G, et al: PIEZO-dependent mechanosensing is

essential for intestinal stem cell fate decision and maintenance.

Science. 386:eadj76152024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ma S, Dubin AE, Zhang Y, Mousavi SAR, Wang

Y, Coombs AM, Loud M, Andolfo I and Patapoutian A: A role of PIEZO1

in iron metabolism in mice and humans. Cell. 184:969–982.e13. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|