Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a prevalent

malignant tumor globally, characterized by intricate survival

mechanisms, elevated morbidity, unfavorable prognosis and

significant cancer-related mortality (1,2).

HCC commonly originates from conditions such as chronic hepatitis B

and C infections, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, heavy alcohol

use and other causes that drive ongoing liver inflammation and the

development of cirrhosis (3).

Early diagnosis is essential to improving treatment options and

reducing disease-related mortality (4). Of these patients ~30% are diagnosed

with early-stage disease and are receiving potentially curative

treatments, such as surgical resection, liver transplantation or

local ablation, which result in a median overall survival of >60

months (5). However, the

treatment of HCC, particularly advanced HCC, has been a serious

challenge (6). Hence, it is

crucial to delve into the pathogenesis of HCC and uncover effective

treatment approaches.

Cell division cycle 5-like (CDC5L) is a key

constituent of E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which includes pre-mRNA

processing factor 19 (PRP19), pleiotropic regulator 1 and BCAS2

pre-mRNA processing factor (7).

This complex acts as a regulator of cell cycle, particularly during

G2/M phase transition and is involved in the catalytic

processes of pre-mRNA splicing and DNA damage repair (8). CDC5L has been shown to be markedly

upregulated in HCC (9) and acts

as an independent prognostic marker for unfavorable survival

outcomes in patients with HCC (10). In addition, the phosphorylation

of the CDC5L protein is involved in the metastasis of HCC (11). This indicates that CDC5L may play

a significant role in HCC tumorigenesis and could serve as a

promising therapeutic target to impede HCC progression. Predictive

analysis based on the BioGRID 4.4 database (https://thebiogrid.org/107424/summary/homo-sapiens/cdc5l.html)

showed that CDC5L interacts with the embryonic lethal abnormal

visual-like protein (ELAVL1). ELAVL1 is a widely expressed in

vivo protein that affects the target mRNA stability and

participates in post-transcriptional regulation as an RNA-binding

protein (12). The importance of

ELAVL1-mediated cell signaling, inflammation, fibrosis and cancer

development in the liver has attracted much attention (13). ELAVL1 has been shown to be

upregulated in HCC and implicated in post-transcriptional

regulation of multiple genes linked to the malignant transformation

of the liver (14). However, the

mechanism regarding the role of CDC5L and ELAVL1 in HCC is

unclear.

Pyroptosis is an innate immune response

characterized by its pro-inflammatory nature, driven by the

accumulation of large plasma membrane pores composed of subunits of

Gasdermin (GSDM) family proteins (15,16). When pathogens or other danger

signals are detected, cytokine activity and the formation of

inflammatory vesicles (cytoplasmic multiprotein complexes) trigger

pyroptosis (17). Ultimately,

this inflammatory cell death pathway results in cell lysis and

inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-18 release (18). There is growing evidence that,

depending on the type of tumor, pyroptosis could either prevent or

promote tumor progression (19).

Pyroptosis has been shown to be crucial in various tissues and

organs, including the liver (20) and it has potential as an

effective target for treating HCC (21). Caspase 3 is a key protein that is

shared between apoptosis and pyroptosis pathways (22). An elevated Caspase 3 activity in

the liver has been observed in patients with various liver diseases

(23). Research has shown that

Caspase 3 deficiency markedly increased diethylnitrosamine-induced

HCC (24). The effect of natural

killer cells on pyroptosis in HepG2 cells treated with Schisandrin

B is primarily due to their activation of the Caspase 3-gasdermin E

(GSDME) pathway (25).

Furthermore, both the small interfering (si)RNA-mediated knockdown

of Caspase 3 and application of Caspase 3 inhibitor

Z-Asp(OMe)-Glu(OMe)-Val-Asp(OMe)-ForwardMK reduced the induction of

GSDME-dependent pyroptosis by Miltirone (26). An Encyclopedia of RNA

Interactomes 3.0 database (https://rnasysu.com/encori/rbpClipRNA.php?source=mRNA&flag=target&clade=mammal&genome=human&assembly=hg38&RBP=ELAVL1&clipNum=1®ionType=None&pval=0.05&clipType=None&panNum=0&target=CASP3)-based

analysis showed that ELAVL1 binds with Caspase 3. Therefore, the

aim of the present study was to investigate whether the mechanisms

underlying the effect of CDC5L and ELAVL1 in HCC pyroptosis

involves Caspase 3. The core hypothesis was that CDC5L and ELAVL1

interact in the pyroptosis of HCC and this interaction may

influence the expression of pyroptosis-related genes by regulating

Caspase 3, thereby affecting the progression of HCC. Previous

studies on CDC5L have mainly focused on its overexpression in HCC

and its role as a prognostic factor for patient survival (9,10), as well as the role of its protein

phosphorylation in HCC metastasis (11), while the mechanism of action of

CDC5L in HCC pyroptosis remains unclear. Similarly, although it has

been reported that ELAVL1 was overexpressed in HCC and was involved

in the post-transcriptional regulation of genes related to hepatic

malignant transformation (14),

the specific role of ELAVL1 in HCC pyroptosis and its interaction

mechanism with CDC5L are also not well understood. The present

study focused on exploring the mechanism of action of CDC5L and

ELAVL1 in HCC pyroptosis and whether they affect the pyroptosis

process by regulating Caspase 3, which is a significant departure

from previous studies that have only focused on the individual

roles of CDC5L or ELAVL1.

Building upon the aforementioned, the high

expression of CDC5L in HCC predicts poor prognosis (9,10). Therefore, the present study was

designed to explore the function of CDC5L in HCC pyroptosis via

both in vivo and in vitro experimental approaches.

CDC5L may be a therapeutic target for HCC in the future. These

results may offer novel perspectives and guidance for the treatment

of HCC.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

HCC tissues and paracancerous tissues were collected

from 10 participants diagnosed with HCC at Xiangya Hospital,

Central South University (Hunan, China), through imaging,

serological, or histopathological examinations. The sex ratio was 5

males to 5 females, with an age range of 43-76 years. Patients were

recruited between January 1, 2024, and December 31, 2024. HCC and

paracancerous tissues were collected and divided into the Tumor and

Normal groups. Exclusion criteria were pathologically confirmed

diagnosis of non-HCC and patients with incomplete clinical

features. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and

approval was obtained from the medical ethics committee of Xiangya

Hospital, Central South University (Hunan, China; approval no.

2024052119).

Cell culture and treatment

The transformed human liver epithelial-2 (THLE-2)

cells (CL-0833) were purchased from Procell Life Science &

Technology Co., Ltd. SK-HEP-1 (AW-CCH036) and MHCC-97H (AW-CCH088)

human liver cancer cells Huh7 (AW-CCH237), were purchased from

Changsha Abiowell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. THLE-2 cells were

cultured in THLE-2 Cell Complete Medium (CM-0833; Procell Life

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Huh7, SK-HEP-1 or MHCC-97H

cells were cultured in DMEM (containing NaHCO3 1.5 g/l),

minimum essential medium or DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum

and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Logarithmically grown SK-HEP-1 and

MHCC-97H cells were collected and spread inside a six-well plate

and cells were processed following wall attachment. First,

CDC5L was knocked down and divided into the Control, si-NC

(negative control siRNA), si-CDC5L-1 (CDC5L-specific

siRNA-1) and si-CDC5L-2 (CDC5L-specific siRNA-2)

groups. CDC5L was overexpressed and divided into the si-NC,

si-CDC5L, oe-NC (Negative control overexpression vector) and

oe-CDC5L (CDC5L overexpression vector) groups. Caspase

3 was knocked down and divided into the si-NC, si-CDC5L,

si-CDC5L+si-NC and si-CDC5L+si-Caspase 3

(Caspase 3-specific siRNA) groups. ELAVL1 was knocked

down and divided into the Control, si-NC, si-ELAVL1#1

(ELAVL1-specific siRNA#1) and si-ELAVL1#2

(ELAVL1-specific siRNA#2) groups. ELAVL1 was

overexpressed and divided into the si-NC, si-ELAVL1, oe-NC

and oe-ELAVL1 (ELAVL1 overexpression vector) groups.

Furthermore, groups were divided as follows: si-NC,

si-CDC5L, si-CDC5L+oe-NC and

si-CDC5L+oe-ELAVL1. Finally, GSDME was knocked

down and divided into the Control, si-NC, si-GSDME#1

(GSDME-specific siRNA#1) and si-GSDME#2

(GSDME-specific siRNA#2) groups. SK-HEP-1 and MHCC-97H cells

were treated with 1 μM CDC5L inhibitor CVT-313 (HY-15339;

MedChemExpress) for 48 h (27)

and divided into the following groups: Control, CVT-313, CVT-313 +

si-NC and CVT-313 + si-GSDME (GSDME-specific siRNA).

The transfection of all siRNA and overexpression vectors was

carried out using Lipofectamine® 2000 (cat. no.

11668019; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to

the manufacturer's instructions. The siRNA was used at a

concentration of 50 nM. Transfection was performed at 37°C for 48

h. The time interval between transfection and subsequent

experimentation was 48 h. si-CDC5L (HG-SH001253),

oe-CDC5L (HG-HO001253), si-ELAVL1-1 (HG-SH001419),

oe-ELAVL1 (HG-HO001419), si-Caspase 3 (HG-SH032991),

si-GSDME and (HG-SH004403) were obtained from HonorGene. The

interference sequences are as follows: si-NC:

TTAACGGCGAGAGTTTAGGCC, si-CDC5L-1: GGACAGAATTCTGCAGGAAGC,

si-CDC5L-2: GCATAAAGCTGTCCAGAAAGA, si-ELAVL1-1:

GGTTTGGGCGGATCATCAACT, si-ELAVL1-2: GAGGCAATTACCAGTTTCAAT,

si-Caspase 3: GACAACAGTTATAAAATGGAT, si-GSDME:

GAGAGGAATTTCCATCCATTT.

Tumor formation in nude mice

Male nude mice aged 4 weeks were supplied by Hunan

SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. A total of 80 mice were used in

this study. The mice were housed in a controlled environment with a

temperature of 22±2°C, a 12-h light/dark cycle and humidity of

50±10%. The average weight of the mice was approximately 18-20 g at

the start of the experiment. The tumor formation model of

subcutaneous MHCC-97H cells in nude mice was established. Following

a week of acclimatization and rearing, MHCC-97H cells were injected

subcutaneously, with different treatment groups receiving

corresponding cell types: si-NC, si-CDC5L, oe-NC and

oe-CDC5L; si-NC, si-CDC5L, si-CDC5L+si-NC,

si-CDC5L+si-Caspase 3; si-NC, si-CDC5L,

si-CDC5L+oe-NC and si-CDC5L+oe-ELAVL1. Each

nude mouse received an injection of 1×107 cells in a

volume of 100 μl, administered into the left axillary region

(28). In the si-NC group, mice

were subcutaneously injected with si-NC-treated MHCC-97H cells. In

the si-CDC5L group, mice were subcutaneously injected with

si-CDC5L-treated MHCC-97H cells. In the oe-NC group, mice

were subcutaneously injected with oe-NC-treated MHCC-97H cells. In

the oe-CDC5L group, mice were subcutaneously injected with

oe-CDC5L-treated MHCC-97H cells. In the

si-CDC5L+si-NC group, mice were subcutaneously injected with

si-CDC5L and si-NC-treated MHCC-97H cells. In the

si-CDC5L+si-Caspase 3 group, mice were subcutaneously

injected with si-CDC5L and si-Caspase 3-treated

MHCC-97H cells. In the si-CDC5L+oe-NC group, mice were

subcutaneously injected with si-CDC5L and oe-NC-treated

MHCC-97H cells. In the si-CDC5L+oe-ELAVL1 group, mice

were subcutaneously injected with si-CDC5L and

oe-ELAVL1-treated MHCC-97H cells. Tumor dimensions were

assessed twice weekly following implantation. When tumors grew to a

diameter of 150-200 mm3, tumor volume and tumor weight

were weighted and measured. Tumor volume was tracked and calculated

using the formula: V (mm3)=LxW2/2, with L and

W denoting the longest and shortest diameters, respectively. The

study was terminated 28 days' post-implantation and the tumors were

prepared for image capture. To perform sacrifice of mice using

cervical dislocation, one hand used a rigid rod to firmly press

down on the head and neck area, while the other hand grasped the

tail or hind limbs. Then, quickly and forcefully the hindquarters

were pulled backwards and upwards to dislocate the cervical

vertebrae. Following cervical dislocation, the mice were observed

for a ≤5 min to ensure that life was extinct. To determine whether

life was extinct, its breathing and heartbeat were observed, while

simultaneously checking the pupils and limb reflexes. If the mouse

had stopped breathing and its heart had stopped beating following

cervical dislocation, the pupils did not react to light and the

limbs showed no reflex actions, it was more accurately confirmed

that life was extinct.

In addition, following a week of acclimatization,

4-week-old male nude mice were injected subcutaneously with

MHCC-97H cells and differently treated cells were injected into

corresponding groups: Control, CVT-313, CVT-313 + si-NC and CVT-313

+ si-GSDME. The amount of cells injected per nude mouse was

1×107 and a 100-μl volume was injected into the

left axilla. Following tumor implantation, tumor measurements were

conducted twice a week for observation. When the tumor grew to a

suitable size (10 days after planting), the drug was administered

in groups according to the tumor volume. Among them, mice in the

Control group were subcutaneously injected with normal MHCC-97H

cells. Nude mice in the CVT-313 group were subjected to CVT-313

drug intervention. Nude mice in the CVT-313 + si-NC group were

injected subcutaneously with transfected si-NC-treated MHCC-97H

cells and to CVT-313 drug intervention. Nude mice in the CVT-313 +

si-GSDME group were subcutaneously injected with

si-GSDME-treated MHCC-97H cells and underwent CVT-313 drug

intervention. CVT-313 drug intervention was performed by

intraperitoneal injection of CVT-313, administered every other day

at a dose of 0.625 mg/Kg in an injection volume of 10 ml/100 g

(29). The experiments were

terminated after 28 days of tumor seeding and tumors were arranged

to be sampled and images captured. All animal experiments were

carried out with the approval of the Animal Ethics Committee of

Xiangya Medical School, Central South University (approval no.

2024051707) and in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki

(30).

Bioinformatics analysis

Clinical specimens were categorized into HCC tissues

and adjacent non-tumor tissues. Data were obtained from The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Pan-Cancer%20(PANCAN)&removeHub=https%3A%2F%2Fxena.treehouse.gi.ucsc.edu%3A443)

data (369 tumor/50 normal). Box plots of differentially expressed

CDC5L were drawn. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was applied to

assess the survival outcomes of patients with HCC in the high- and

low-CDC5L groups. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) was

applied to explore Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway regulation. Bioinformatics analysis was conducted to the

expression of evaluate Caspases 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 in HCC.

Venn diagrams displayed the intersection of CDC5L binding proteins

and Caspase 3 interacting RNA-binding proteins (RBPs).

Bioinformatics analysis was conducted to measure 22 RBPs levels in

HCC. The binding of ELAVL1 with Caspase 3 was shown based on the

University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser

(http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTracks?db=hg38&lastVirtModeType=default&lastVirtModeExtraState=&virtModeType=default&virtMode=0&nonVirtPosition=&position=chr4%3A184627598%2D184627850&hgsid=2947477028_2O6buwujau0adLCDAGdFsuwkAUi0).

Cell function assays

Based on previous studies, the viability of SK-HEP-1

and MHCC-97H cells was evaluated using the Cell Counting Kit-8

(CCK-8) assay. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a

density of 5,000 cells per well and incubated. The CCK-8 reagent

(10 μl) was added to each well, and the plates were

incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using

a microplate reader. A clone formation assay was performed to

assess the proliferative capacity of SK-HEP-1 and MHCC-97H cells

(31). The migration and

invasion of SK-HEP-1 and MHCC-97H cells was assessed through

Transwell assays (32). For

migration and invasion assays, 2×104 cells were seeded

in the upper chamber of Transwell inserts with or without Matrigel

coating. Transwell inserts were precoated with Matrigel and

incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After 24 h, cells that migrated or

invaded through the membrane were fixed with methanol and stained

with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 5 min. The number

of cells was counted in five random fields under a light

microscope.

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)

PCR

CDC5L, Caspase 7, Caspase 9,

Caspase 6, Caspase 8, Caspase 1, Caspase

3, Caspase 10, GSDME and CDC5L mRNA levels were

quantified with RT-qPCR. Total RNA was isolated from cells at a

density of 80-90% confluence using the TRIzol® Total RNA

Extraction Kit (cat. no. 15596026; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

and its concentration and purity were evaluated. Subsequently, mRNA

was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using mRNA Reverse Transcription

Kit (cat. no. CW2569; CWBIO) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Target genes levels were determined on ABI 7900 system

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using Ultra

SYBR Mixture (CW2601; CWBIO) and calculated by 2−ΔΔCq

method (33), with β-actin

serving as internal reference gene. The PCR cycling conditions were

as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec.

The experiments were replicated three times. The primer sequences

used are listed in Table I.

| Table IPrimers used in this study. |

Table I

Primers used in this study.

| Name | Sequences |

|---|

| H-Caspase

1-Forward |

AGGACAACCCAGCTATGCC |

| H-Caspase

1-Reverse |

TGGATAAATCTCTGCCGACT |

| H-Caspase

3-Forward |

TGGCAACAGAATTTGAGTCCT |

| H-Caspase

3-Reverse |

ACCATCTTCTCACTTGGCAT |

| H-Caspase

6-Forward |

AGGTTCTTTTGGCACTTAACAC |

| H-Caspase

6-Reverse |

AATGTGATTGCCTTCGCCATG |

| H-Caspase

7-Forward |

ACTTCCTCTTCGCCTATTCCAC |

|

H-Caspase-7-Reverse |

TTCCAGGTCTTTTCCGTGCTC |

| H-Caspase

8-Forward C |

TGGTCTGAAGGCTGGTTGT |

| H-Caspase

8-Reverse |

GTGACCAACTCAAGGGCTCA |

| H-Caspase

9-Forward |

AAGCCAACCCTAGAAAACCTTACCC |

| H-Caspase

9-Reverse |

AGCACCGACATCACCAAATCCTC |

| H-Caspase

10-Forward |

TGCAGGTAGTAATGAGATCCTGAG |

| H-Caspase

10-Reverse |

ATGGGCTGGATTGCACTTCT |

|

H-GSDME-Forward C |

GGGCGCGCGGATAAT |

|

H-GSDME-Reverse |

GTCTCTGCCAGCACCAGAAT |

|

H-CDC5L-Forward |

GTGGCCCAATCGCTGTTACT |

|

H-CDC5L-Reverse |

CGGTATTCCTCCATACGCCC |

| M-Caspase

3-Forward |

TCTGACTGGAAAGCCGAAACTCT |

| M-Caspase

3-Reverse |

AGCCATCTCCTCATCAGTCCCA |

|

M-β-actin-Forward |

ACATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCC |

|

M-β-actin-Reverse |

TACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCAC |

|

H-β-actin-Forward |

ACCCTGAAGTACCCCATCGAG |

|

H-β-actin-Reverse |

AGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAAC |

Western blotting

Western blotting was applied to assess CDC5L, GSDME,

Gasdermin E N-terminal fragment (GSDME-N), Caspase 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9

and 10, KH RNA binding domain containing, signal transduction

associated 1 (KHDRBS1), nudix hydrolase 21 (NUDT21), heterogeneous

nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (HNRNPA2B1), RNA binding motif

protein X-linked (RBMX), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C

(HNRNPC) and ELAVL1 expressions. Total proteins were extracted

using RIPA buffer (cat. no. AWB0136; Changsha Abiowell

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The protein concentration was determined

using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. 23225; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). A total of 30 μg of protein was loaded

per lane. The proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE using a 10% gel

and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were

blocked with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1.5 h,

followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C.

The primary antibodies used were: CDC5L (cat. no. 12974-1-AP;

1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.), GSDME (cat. no. ab215191;

1:1,000; Abcam), GSDME-N (cat. no. ab222408; 1:1,000; Abcam),

Caspase-7 (cat. no. ab25900; 1:1,000; Abcam), Caspase-9 (cat. no.

ab2013; 1:2,000; Abcam), Caspase-6 (cat. no. ab52951; 1:20,000;

Abcam Plc), Caspase-8 (cat. no. ab227430; 1:1,000; Abcam),

Caspase-1 (cat. no. ab286125; 1:1,000; Abcam), Caspase 3 (cat. no.

19677-1-AP; 1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.), Caspase-10 (cat. no.

ab2012; 1:2,000; Abcam), KHDRBS1 (cat. no. 10222-1-AP; 1:3,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), NUDT21 (cat. no. 10322-1-AP; 1:5,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), HNRNPA2B1 (cat. no. 67445-1-Ig; 1:8,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), RBMX (cat. no. ab250272; 1:1,000; Abcam),

HNRNPC (cat. no. ab133607; 1:20,000; Abcam), ELAVL1 (cat. no.

ab238528; dilution, 1:1,000; Abcam) and β-actin (cat. no. AWA80002;

1:5,000; Changsha Abiowell Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Membranes were

incubated with HRP goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG (cat. no.

SA00001-1/SA00001-2; 1:5,000/1:6,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at

room temperature for 1.5 h. Next, membranes were treated with an

ECL reagent (cat. no. AWB0005, Changsha Abiowell Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) for 1 min and then subjected to analysis using an imaging

system (Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The

protein levels were quantified by Quantity One 4.6.6 software

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), with β-actin serving as internal

control.

Biochemical detection

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), IL-1β and IL-18 levels

were assessed using LDH Assay Kit (cat. no. A020-2; Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), IL-1β Assay Kit (human; cat.

no. KE00021; Proteintech Group, Inc.; mouse; cat. no. KE10003;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and IL-18 Assay Kit (human: cat. no.

KE00193; Proteintech Group, Inc.; mouse; cat. no. CSB-E04609m;

Wuhan Huamei Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the instructions.

Half-life of Caspase 3 mRNA

In cells with overexpression/knockdown of ELAVL1,

the half-life of Caspase 3 mRNA was assessed using RT-qPCR

following treatment with 5 μg/ml Act D for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and

10 h. In addition, in cells where CDC5L was knocked down and ELAVL1

was overexpressed, RT-qPCR was employed to measure Caspase 3

mRNA expression following treatment with 5 μg/ml Act D for

0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h, in order to determine the half-life of

Caspase 3 mRNA.

Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide (PI)

staining

Hoechst 33342 and PI staining was performed to

observe pyroptosis. Following the corresponding time of the

aforementioned treatments, cells in each group were washed once

with PBS, followed by the addition of 1 ml of cell staining buffer.

Subsequently, 5 μl of Hoechst 33342 staining solution and 5

μl of PI staining solution were added to the cells. Cells

were then gently mixed and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The

staining status of each group of cells was viewed under a

microscope and then the fluorescence status of each group was

viewed under a microscope and images captured.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

In order to investigate interaction between CDC5L

and ELAVL1, Co-IP experiments were conducted. SK-HEP-1 and MHCC-97H

cells were collected for protein extraction. The cells were lysed

in a lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors at 4°C for 30 min.

The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min

at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined using the BCA

protein assay kit (cat. no. 23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

For each immunoprecipitation reaction, 500 μg of protein

lysate was incubated with 2 μg of CDC5L antibody (cat. no.

12974-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) in a total volume of 500

μl of lysis buffer at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, 30

μl of Protein A/G agarose beads (cat. no. sc-2003; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) added to IP mixture and allowed to

incubate for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with 1

ml of lysis buffer to remove nonspecific binding. The entire

immunoprecipitate was eluted by boiling in 50 μl of 2X

SDS-PAGE loading buffer for 10 min at 95°C. The eluted proteins

were separated by SDS-PAGE using a 10% polyacrylamide gel and

transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked

with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 1.5 h. The membrane

was probed with primary antibodies against CDC5L (cat. no.

12974-1-AP; dilution, 1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and ELAVL1

(cat. no. AWA48828; dilution, 1:1,000; Changsha Abiowell

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were incubated

with HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no. SA00001-2; 1:6,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 1.5 h. Next, membranes were treated

with an ECL reagent (cat. no. AWB0005, Changsha Abiowell

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 1 min and then subjected to analysis

using an imaging system (Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP, Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). The protein levels were quantified by Quantity One 4.6.6

software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay

Cell RNA-binding proteins were immunoprecipitated

and fluorescence quantification was performed to detect whether

CDC5L (cat. no. 12974-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or ELAVL1

(cat. no. 11910-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) binds to Caspase

3. Briefly, cells were lysed using RIP lysis buffer at 4°C for

30 min. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for

10 min at 4°C. For each immunoprecipitation reaction, 100 μl

of cell lysate was incubated with 50 μl of magnetic beads

coated with Protein A (according to the manufacturer's protocol) in

RIP buffer for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with

RIP buffer. The isolated RNA was subjected to RT-qPCR analysis,

with total RNA used as input controls. Primer sequences were

H-Caspase 3, TGG CAACAGAATTTGAGTCCT forward and H-Caspase

3, ACCATCTTCTCACTTGGCAT reverse.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 8.0

software (Dotmatics). Results are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. For comparisons between two groups, Student's unpaired

t-test was used, whereas for multiple group comparisons, one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was applied. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

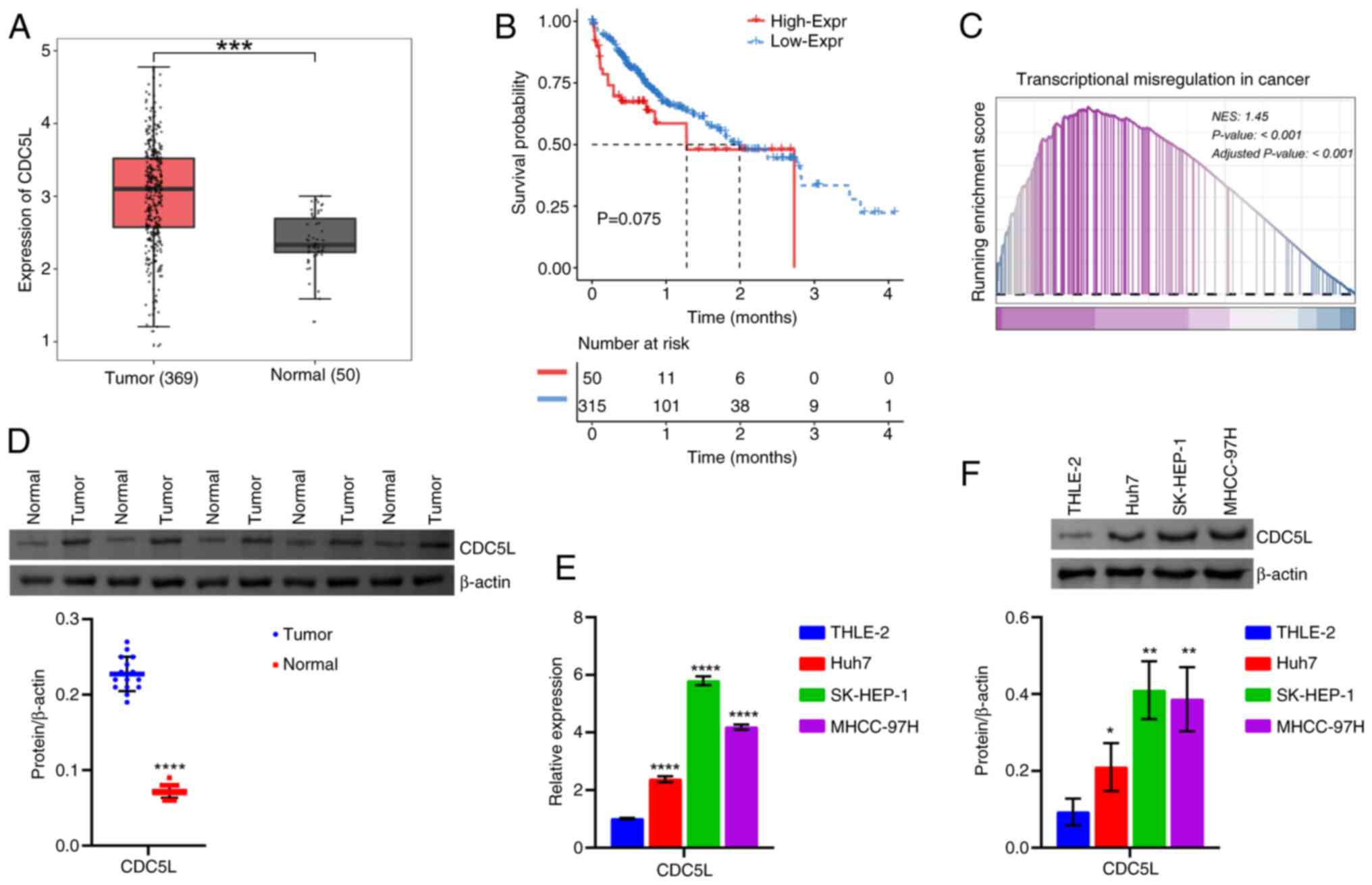

CDC5L expression is elevated in HCC

First, CDC5L expression was analyzed in HCC

based on the TCGA database. CDC5L exhibited high expression

levels in the Tumor group compared with the Normal group (Fig. 1A). In addition, Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis demonstrated that the overall survival time of

patients with HCC in the high-CDC5L group was shorter, as compared

with the low-CDC5L group (Fig.

1B). GSEA analysis showed that CDC5L was mainly enriched in

Transcriptional Misregulation In Cancer [Normalized Enrichment

Score (NES)=1.45; P<0.001; Fig.

1C]. Moreover, the functional pathways of highly expressed

CDC5L involved the MAPK signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway and others (Table SI). Next, western blot analysis

further revealed CDC5L expression in clinical tissues. CDC5L

expression was elevated in the HCC group compared with the

paracancerous tissue group (Fig.

1D). In addition, CDC5L expression was further validated at the

cellular level. CDC5L expression was elevated in human liver cancer

cells (Huh7, SK-HEP-1 and MHCC-97H cells) compared with THLE-2

cells. Among them, CDC5L expression was most markedly elevated in

SK-HEP-1 and MHCC-97H cells (Fig. 1E

and F) and was therefore selected for subsequent experimental

studies. The present results indicated that CDC5L expression was

upregulated in HCC.

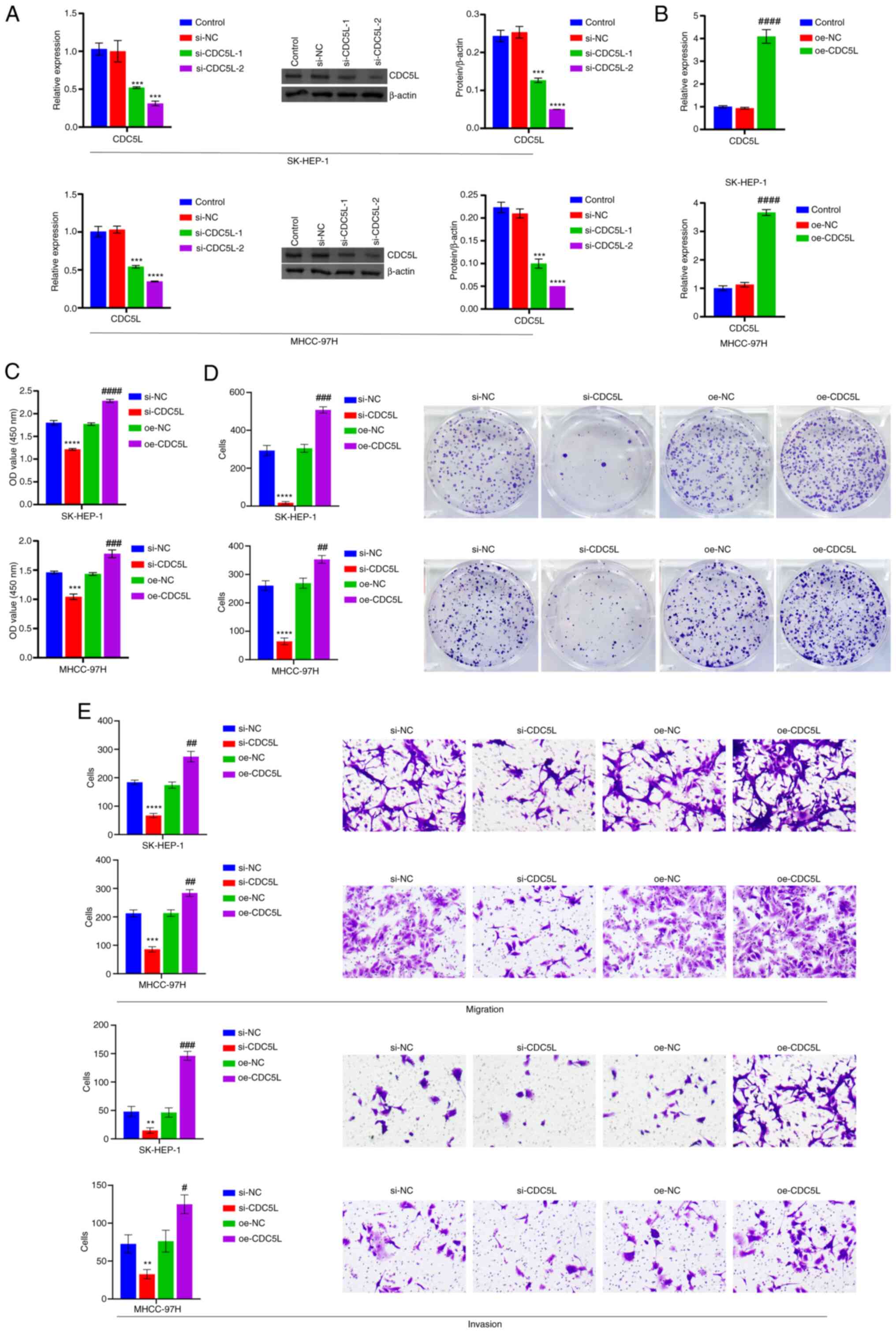

CDC5L regulates HCC pyroptosis

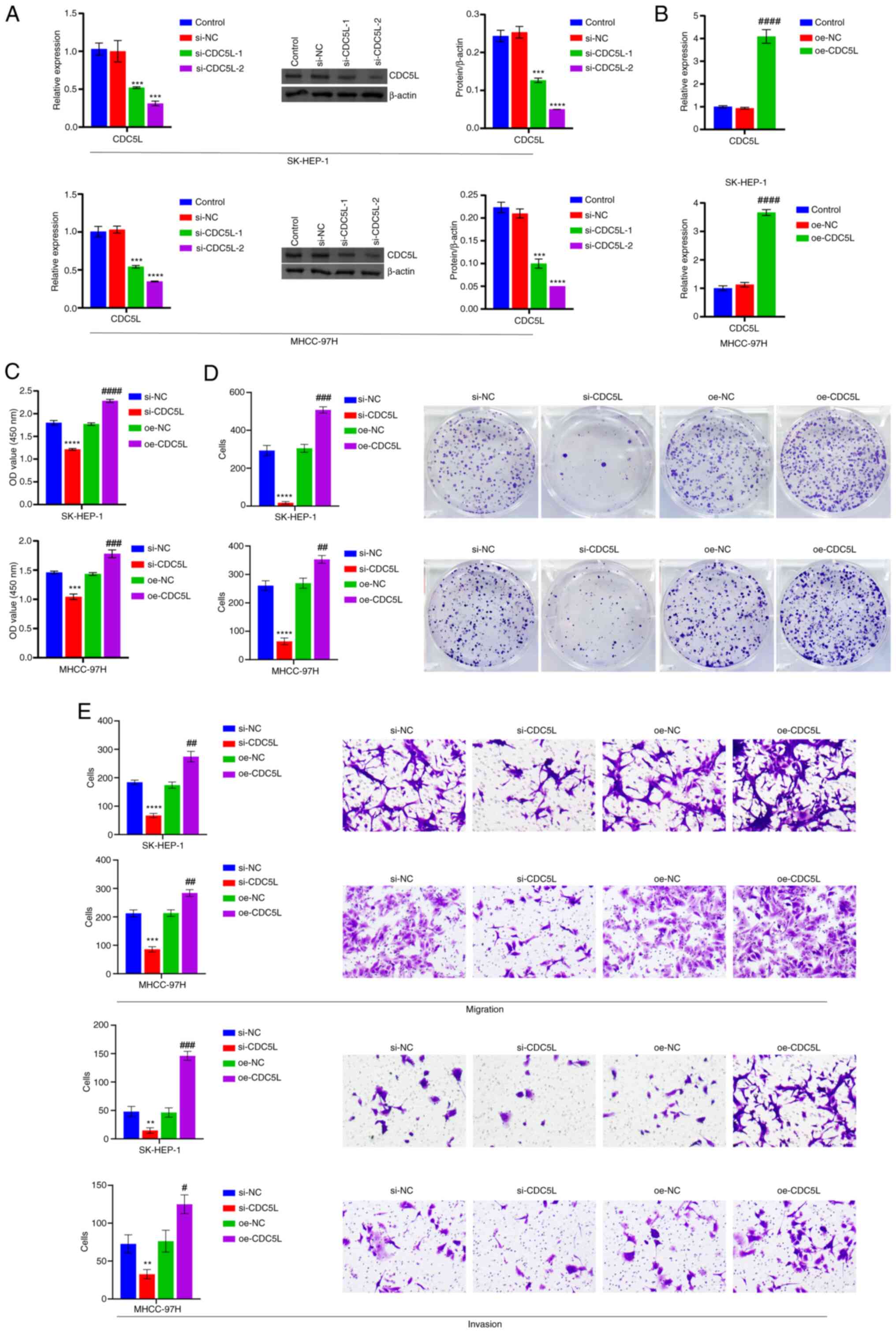

Next, CDC5L was knocked down. Compared with

the si-NC group, CDC5L levels were reduced in the si-CDC5L-1

and si-CDC5L-2 groups. Among them, the si-CDC5L-2

group exhibited the most obvious reduction in CDC5L expression

(Fig. 2A) and was therefore

selected for subsequent experimental studies. Furthermore,

CDC5L was overexpressed. For cells transfected with

oe-CDC5L alone, RT-qPCR results showed a significant

increase in CDC5L mRNA expression, indicating that

oe-CDC5L transfection successfully achieved overexpression

of CDC5L (Fig. 2B).

CDC5L knockdown repressed cell viability, proliferation,

migration and invasion, but CDC5L overexpression facilitated

cell viability, proliferation, migration and invasion (Fig. 2C-E). In addition, CDC5L

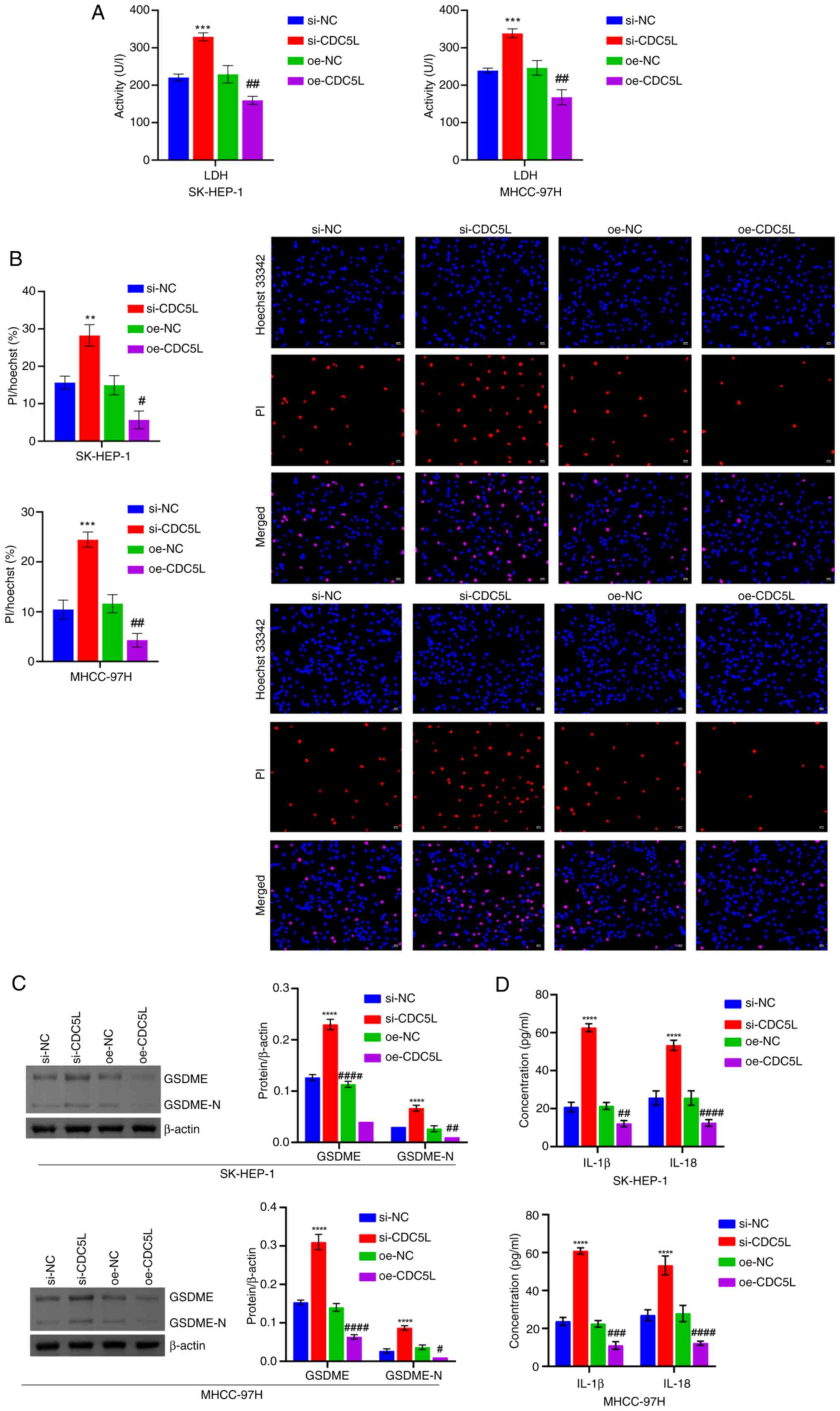

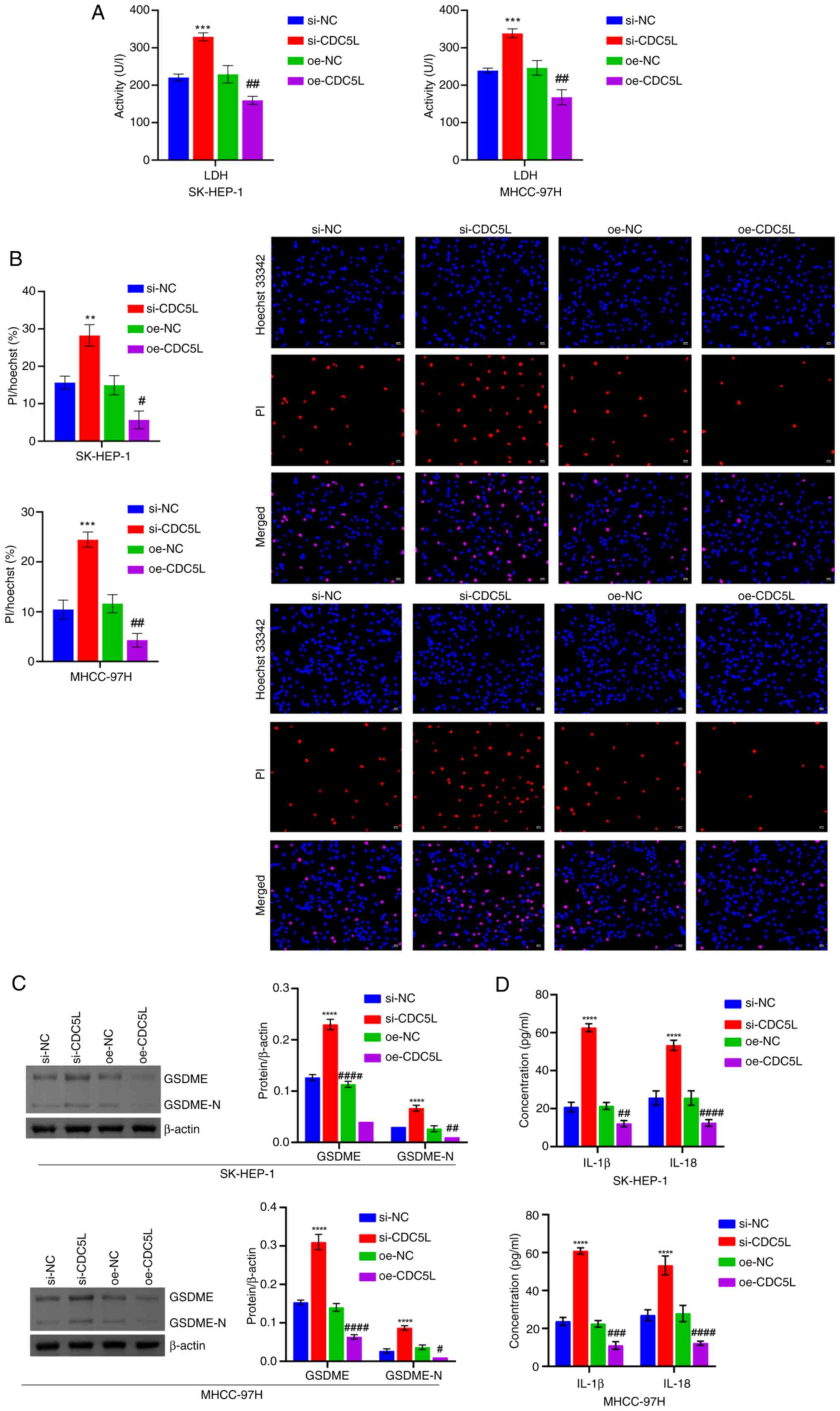

knockdown promoted LDH levels, PI positive rate, GSDME and GSDME-N

levels and IL-18 and IL-1β levels. CDC5L overexpression

suppressed LDH levels, PI positive rate, GSDME and GSDME-N levels

and IL-18 and IL-1β levels (Fig.

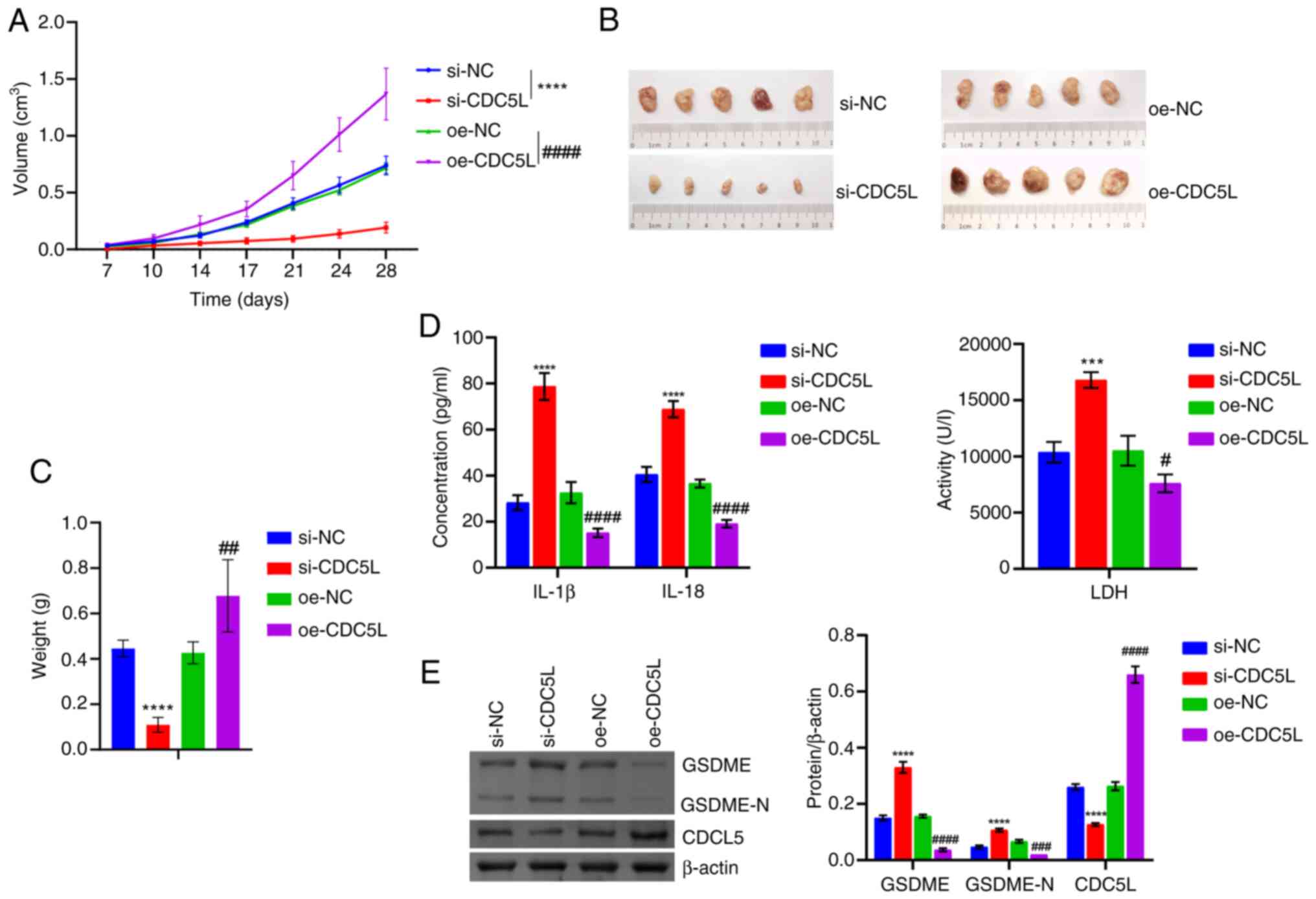

3A-D). Moreover, the effects of low and high CDC5L

expression was verified in HCC in vivo. It was found that,

following CDC5L knockdown, the tumor volume was gradually

reduced, along with reductions in tumor size and weight.

Conversely, following CDC5L overexpression, the tumor volume

gradually increased and both tumor size and weight grew larger

(Fig. 4A-C). In addition, IL-18

and IL-1β levels were elevated following CDC5L knockdown. By

contrast, these cytokine levels were diminished following

CDC5L overexpression (Fig.

4D). CDC5L knockdown promoted GSDME and GSDME-N levels

but repressed CDC5L levels. CDC5L overexpression suppressed

GSDME and GSDME-N levels but elevated CDC5L levels (Fig. 4E). These results indicated that

CDC5L regulated HCC pyroptosis.

| Figure 2CDC5L regulates HCC pyroptosis. (A)

RT-qPCR and western blot analysis of CDC5L expression.

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC.

(B) Detection of CDC5L mRNA expression after oe-CDC5L

transfection by RT-qPCR. (C) Measurement of cell viability by CCK-8

assay. (D) Evaluation of cell proliferation via clone formation

assays. (E) Analysis of cell migration and invasion through

Transwell assays. Scale bar, 100 μm, magnification, ×100.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 and

####P<0.0001 vs. oe-NC. CDC5L, cell division cycle 5

like; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription

quantitative PCR; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; si, short

interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA; si-CDC5L,

CDC5L-specific siRNA; oe-NC, negative control overexpression

vector; oe-CDC5L, CDC5L overexpression vector. |

| Figure 3Detection of pyroptosis-related

levels. (A) LDH level in cell supernatant. (B) Hoechst 33342 and PI

staining of pyroptosis. Scale bar, 50 μm, magnification,

×200. (C) Western blot analysis of GSDME and GSDME-N levels. (D)

IL-18 and IL-1β levels were assessed. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 and ####P<0.0001 vs. oe-NC.

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PI, propidium iodide; GSDME, Caspase

3/Caspase 3-gasdermin E; GSDME-N, Gasdermin E N-terminal fragment;

si, short interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA;

si-CDC5L, CDC5L-specific siRNA; oe-NC, negative

control overexpression vector; oe-CDC5L, CDC5L

overexpression vector. |

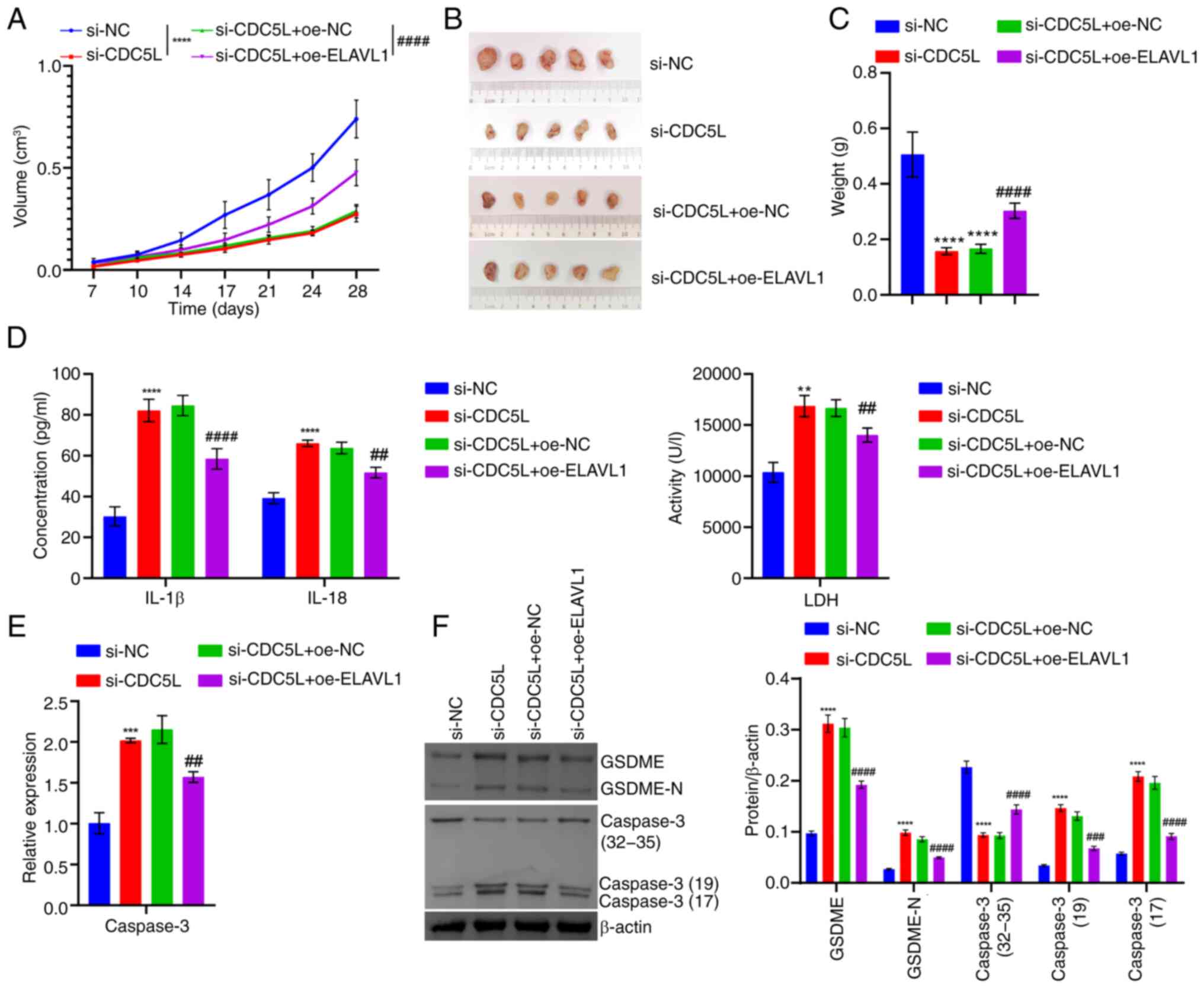

| Figure 4Validation at the animal level that

CDC5L regulates pyroptosis in HCC. (A) Tumor volume. (B) Tumor

images. (C) Tumor weight. (D) IL-18, IL-1β and LDH levels in tissue

supernatants. (E) Western blot analysis of CDC5L, GSDME and GSDME-N

levels in the tumor tissue. ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 and

####P<0.0001 vs. oe-NC. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

CDC5L, cell division cycle 5 like; GSDME, Caspase 3/Caspase

3-gasdermin E; GSDME-N, Gasdermin E N-terminal fragment; si, short

interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA; si-CDC5L,

CDC5L-specific siRNA; oe-NC, negative control overexpression

vector; oe-CDC5L, CDC5L overexpression vector. |

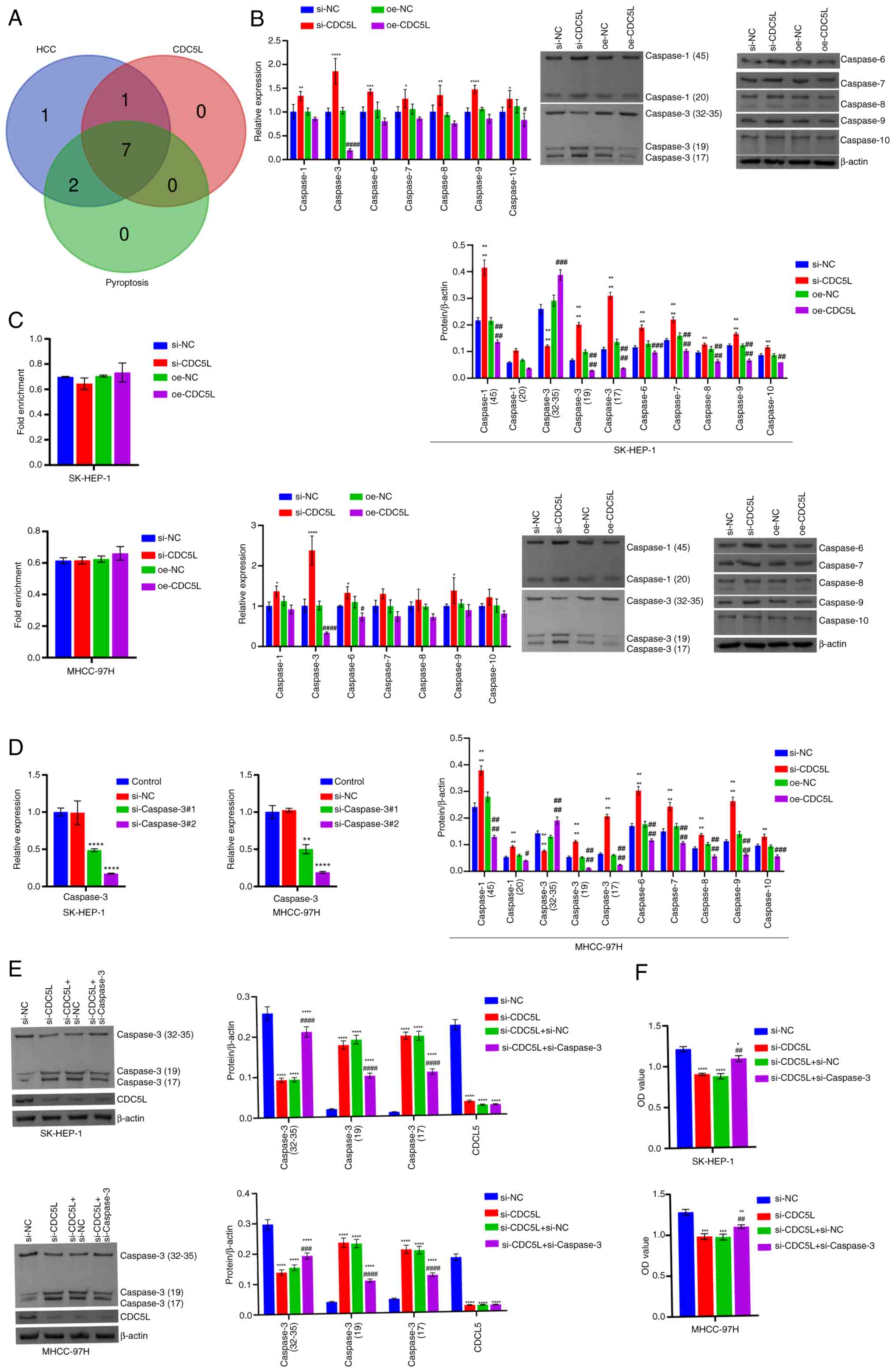

The regulation of CDC5L on pyroptosis of

HCC depends on the Caspase family

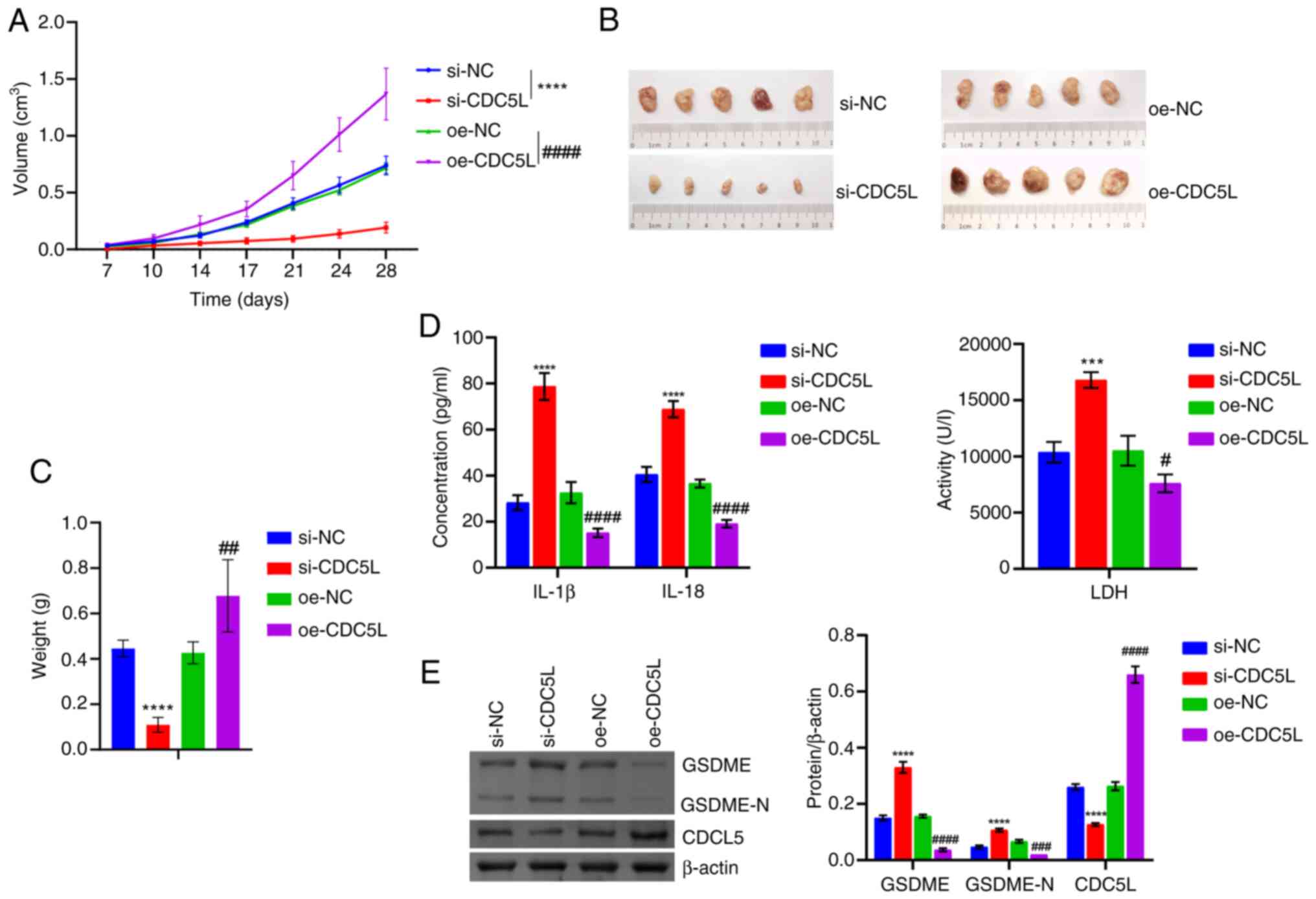

Based on GeneCards search results, Caspases 1-10

were seen to be involved in the progression of HCC. The Caspase

family genes common to both the high and low expression groups of

CDC5L were Caspases 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. According to

GeneCards search results, among them, Caspases 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and

10 mediated the process of pyroptosis (Fig. 5A). The expression of Caspases 1,

3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 was validated using RT-qPCR and western

blotting. Caspase 3, a key protein involved in both pyroptosis and

apoptosis, exerted tumor cytotoxicity via GSDME upon activation

(34). Combining the results of

mRNA and protein, it was observed CDC5L knockdown substantially

elevated Caspase 3 expression, but CDC5L overexpression result in a

markedly reduction in Caspase 3 expression (Fig. 5B). Therefore, Caspase 3 was

selected for subsequent experiments. RIP was further used to detect

the binding of CDC5L to Caspase 3 mRNA. The results showed

that CDC5L did not bind to Caspase 3 mRNA (Fig. 5C). Next, Caspase 3 was

used to interfere. For cells transfected with si-Caspase 3

alone, RT-qPCR results showed that compared with the si-NC group,

the expression of Caspase 3 mRNA was markedly reduced in

both the si-Caspase 3#1 and si-Caspase 3#2 groups.

Among them, the si-Caspase 3#2 group exhibited the most

pronounced reduction in Caspase 3 mRNA expression and was

used for subsequent experiments. This indicated that si-Caspase

3 transfection successfully achieved knockdown of Caspase

3 (Fig. 5D). Compared with

the si-NC group, si-CDC5L group exhibited a reduced the expression

of CDC5L and increased the expression of Caspase 3. Upon the

additional knockdown of Caspase 3, its expression decreased, while

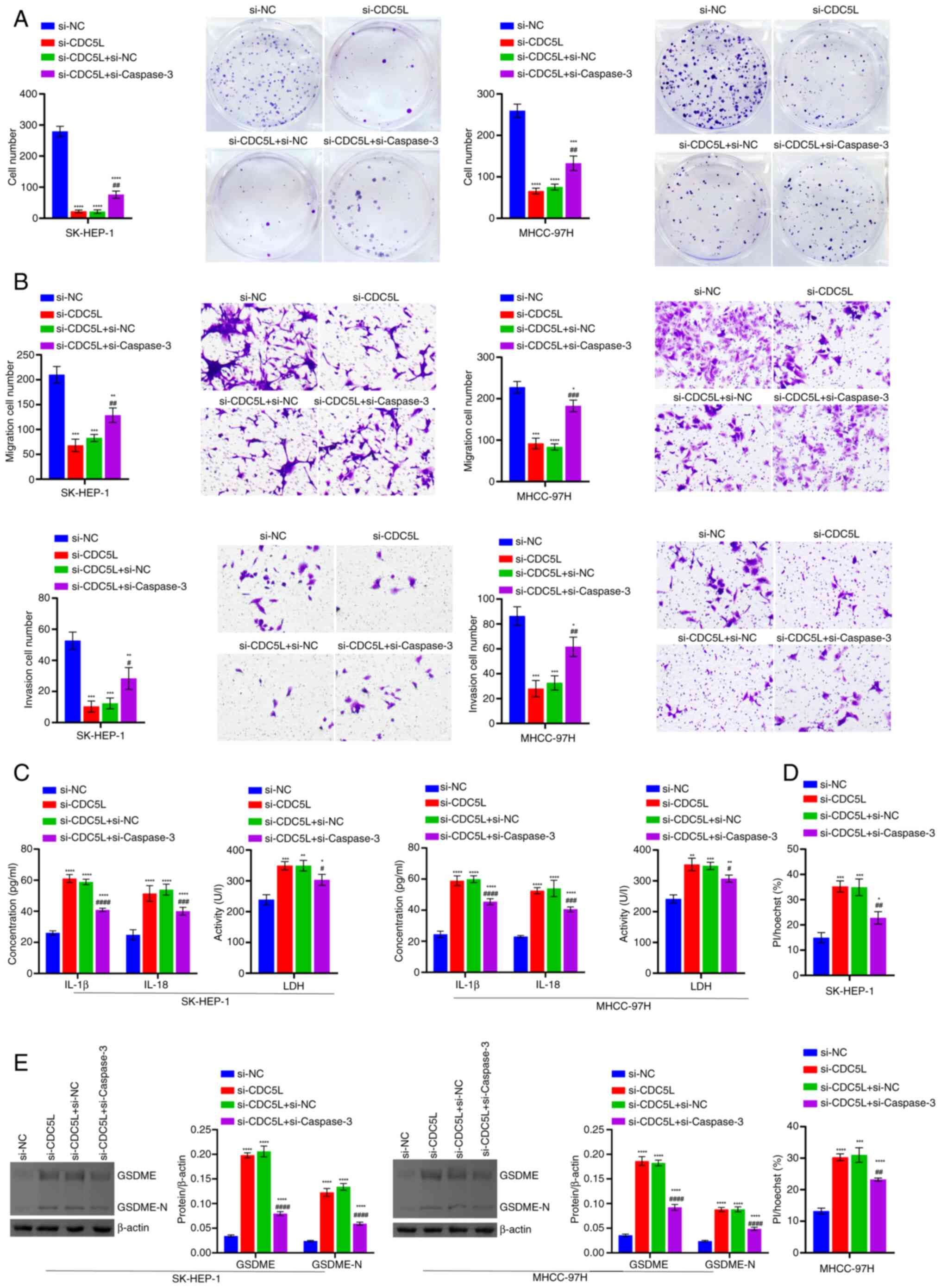

CDC5L expression remained largely unchanged (Fig. 5E). Cellular function experiments

showed that, compared with si-NC group, cell viability,

proliferation, migration and invasion capabilities in the si-CDC5L

group were diminished. Following the further knockdown of Caspase

3, cell viability, proliferation, migration and invasion

capabilities increased (Figs. 5F

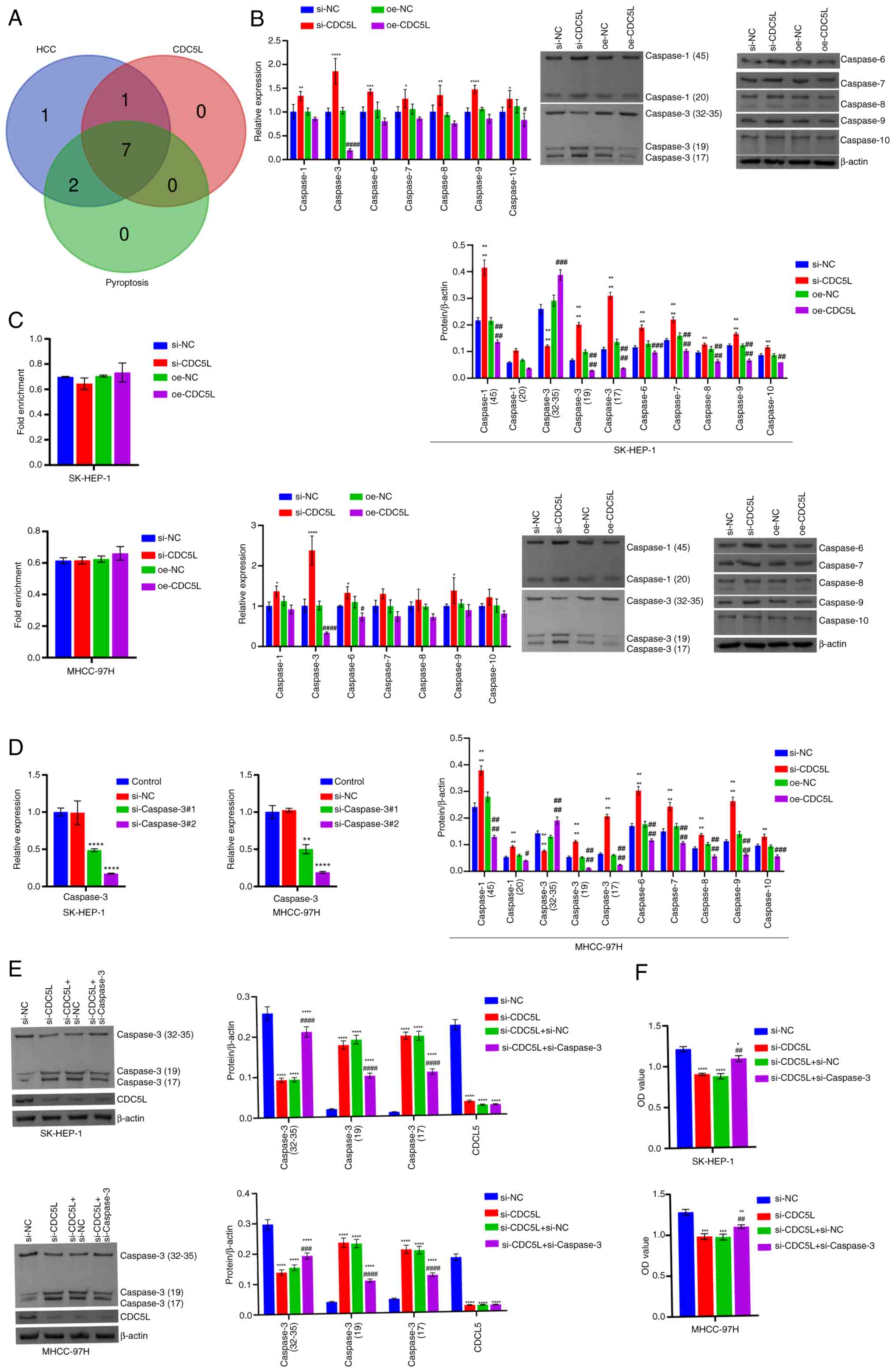

and 6A-B). In addition, compared

with the si-NC group, LDH, IL-18 and IL-1β levels, PI positive rate

and GSDME and GSDME-N protein levels in the si-CDC5L group

increased. Following the further knockdown of Caspase 3, LDH, IL-18

and IL-1β levels decreased, PI positive rate decreased and GSDME

and GSDME-N protein levels decreased (Figs. 6C-E and S1). Furthermore, the effects of

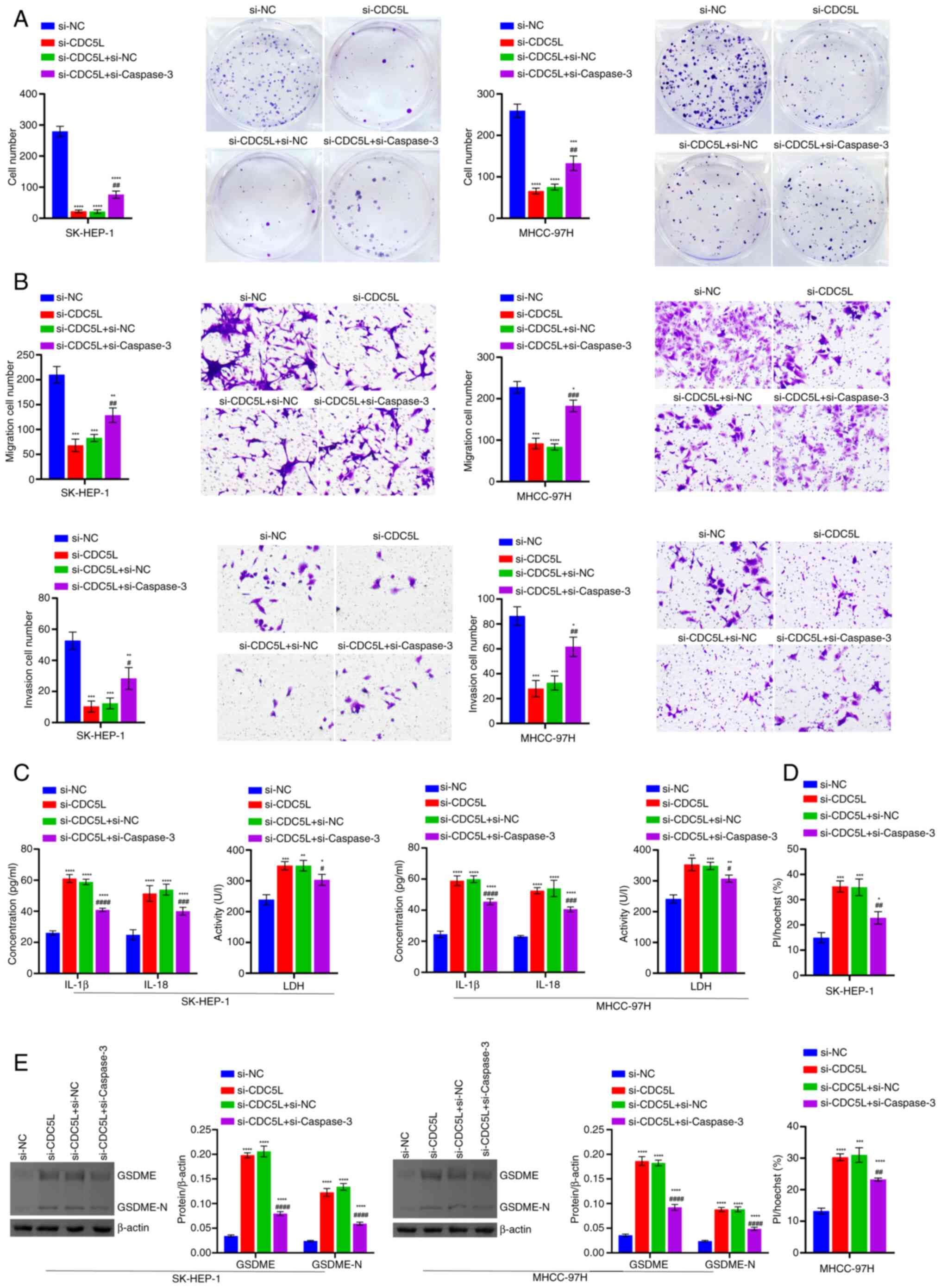

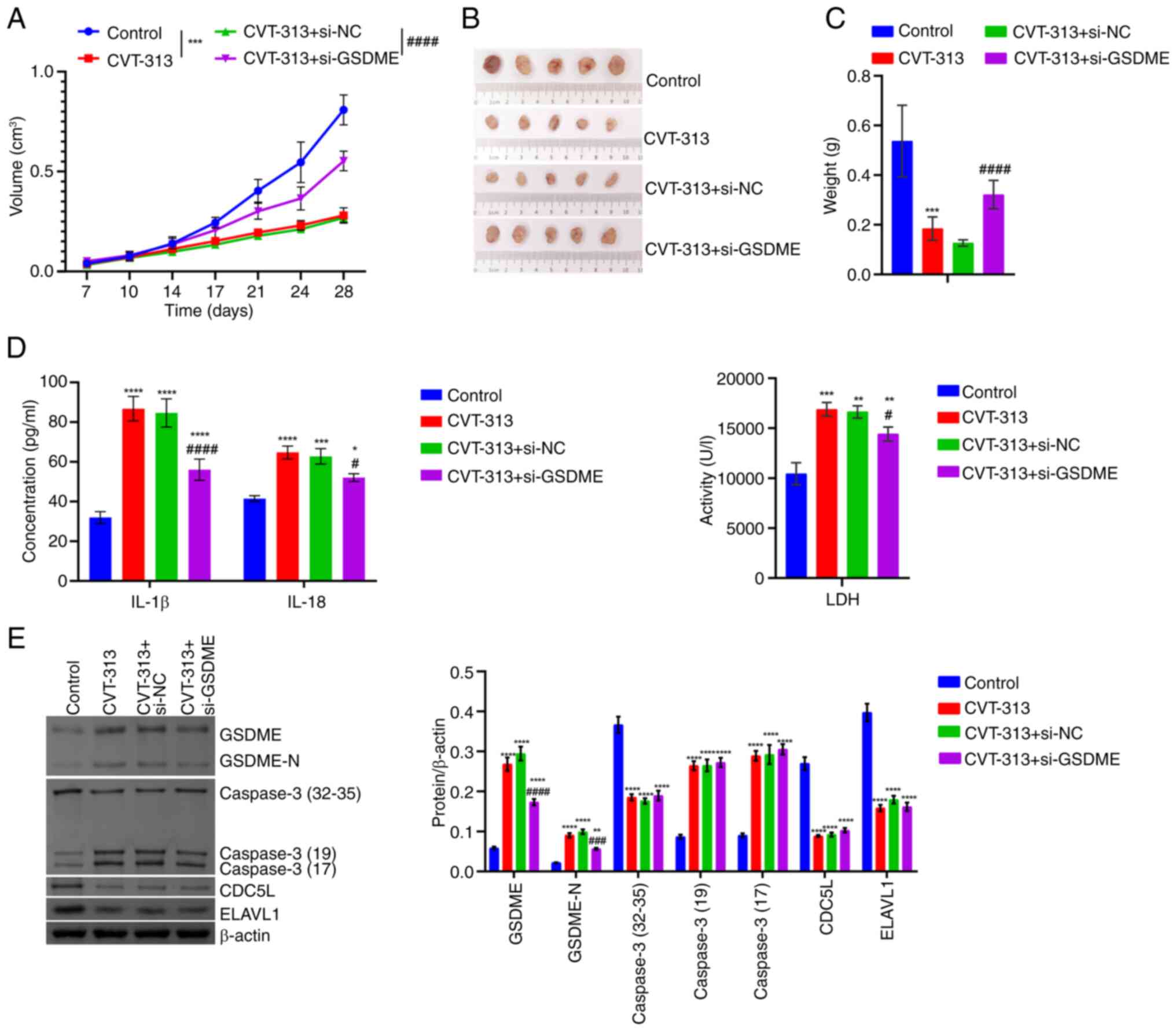

interfering with CDC5L and Caspase 3 were verified on HCC in

vivo. It was found that, following the knockdown of histone

deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), tumor volume gradually decreased and tumor

size and tumor weight also decreased. Following the further

knockdown of Caspase 3, tumor volume gradually increased and tumor

size weight also increased (Fig.

7A-C). In addition, following the knockdown of HDAC6, LDH,

IL-18 and IL-1β levels in the tissue supernatant increased.

Following the further knockdown of Caspase 3, LDH, IL-18 and IL-1β

levels decreased (Fig. 7D).

Following the knockdown of HDAC6, CDC5L expressions in the tumor

tissue decreased and Caspase 3, GSDME and GSDME-N expression

increased. Following the further knockdown of Caspase 3, there was

no significant change in CDC5L expression and Caspase 3, GSDME and

GSDME-N expression decreased (Fig.

7E). These results indicated that CDC5L regulated pyroptosis in

HCC in a Caspase 3-dependent manner.

| Figure 5The regulation of CDC5L on pyroptosis

of HCC depends on the Caspase family. (A) Bioinformatics analysis

of the expression of Caspases 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 levels in

HCC. (B) RT-qPCR and western blot analysis of Caspases 1, 3, 6, 7,

8, 9 and 10 levels. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 and ####P<0.0001 vs. oe-NC.

(C) Detection of the binding of CDC5L to Caspase 3 mRNA by

RIP. (D) Detection of Caspase 3 mRNA expression after si-Caspase

3 transfection by RT-qPCR. (E) Western blot analysis of CDC5L

and Caspase 3 levels. (F) Assessment of cell viability using the

CCK-8 assay. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC;

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 and

####P<0.0001 vs. si-CDC5L+si-NC. CDC5L, cell

division cycle 5 like; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RIP, RNA

immunoprecipitation; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription

quantitative PCR; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; si, short

interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA; si-CDC5L,

CDC5L-specific siRNA; oe-NC, negative control overexpression

vector; oe-CDC5L, CDC5L overexpression vector. |

| Figure 6Detection of cell function and

pyroptosis-related levels. (A) Evaluation of cell proliferation

through clone formation assays. (B) Analysis of cell migration and

invasion through Transwell assays. Scale bar, 100 μm,

magnification, ×100. (C) LDH, IL-18 and IL-1β levels in the cell

supernatant. (D) Results of Hoechst 33342 and PI staining of

pyroptosis. Scale bar, 50 μm, ×200. (E) Western blot

analysis of GSDME and GSDME-N levels. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 and

####P<0.0001 vs. si-CDC5L+si-NC. LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase; PI, propidium iodide; GSDME, Caspase 3/Caspase

3-gasdermin E; GSDME-N, Gasdermin E N-terminal fragment; si, short

interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA; si-CDC5L,

CDC5L-specific siRNA; si-Caspase 3, Caspase

3-specific siRNA. |

| Figure 7Validation at the animal level that

the regulation of pyroptosis in HCC by CDC5L depends on the Caspase

family. (A) Tumor volume. (B) Tumor images. (C) Tumor weight. (D)

IL-18, IL-1β and LDH levels in the tissue supernatants. (E) Western

blot analysis of CDC5L, GSDME, Caspase 3 and GSDME-N levels in the

tumor tissue. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and

####P<0.0001 vs. si-CDC5L+si-NC. LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase; CDC5L, cell division cycle 5 like; GSDME, Caspase

3/Caspase 3-gasdermin E; GSDME-N, Gasdermin E N-terminal fragment;

si, short interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA;

si-CDC5L, CDC5L-specific siRNA; si-Caspase 3,

Caspase 3-specific siRNA. |

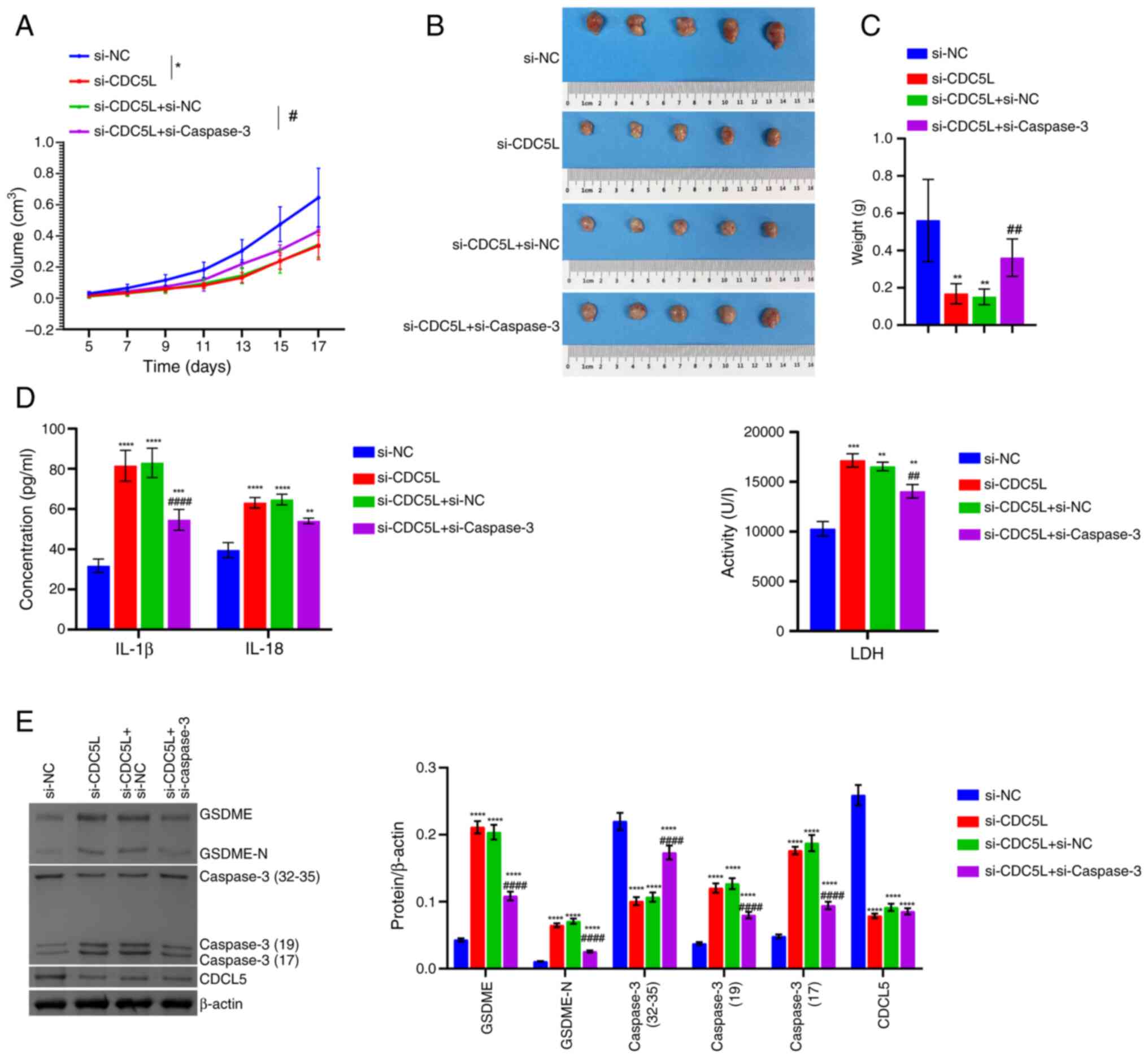

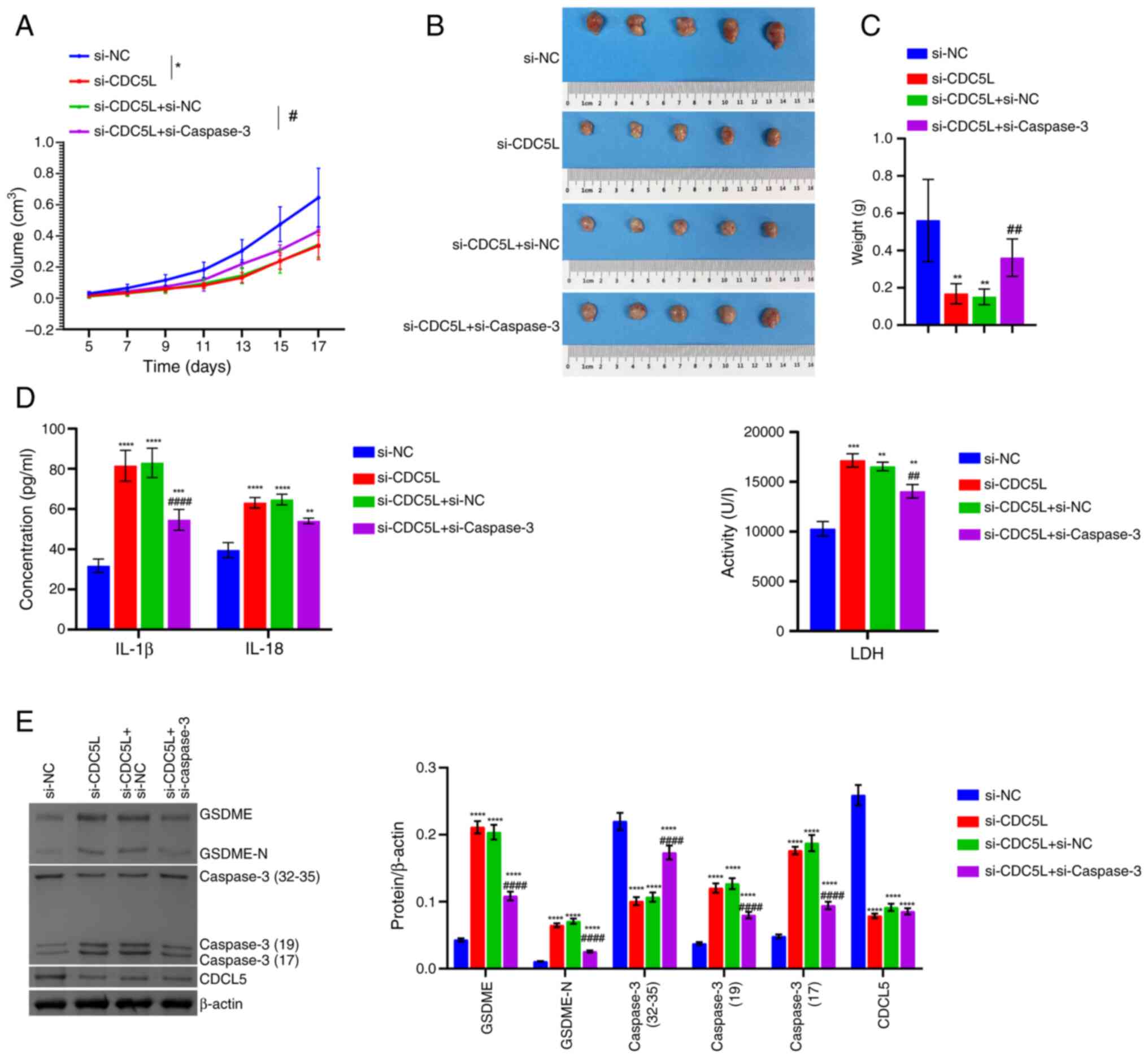

CDC5L competitively binds to ELAVL1 to

inhibit the binding of ELAVL1 and Caspase 3 mRNA to regulate the

pyroptosis of HCC

The earlier results in the present study indicated

that CDC5L downregulated Caspase 3 and reduced the stability of

Caspase 3 mRNA. It was proposed in the present study that

CDC5L might influence the stability of Caspase 3 mRNA

through specific RBPs. Therefore, starting from CDC5L, a search for

interacting proteins was performed and starting from Caspase

3 mRNA a search for interacting RBPs was performed; the RBPs

were determined by finding the intersection of these two ways.

First, the Venn diagram revealed the intersection between CDC5L

binding proteins and Caspase 3 interacting RBPs, with a total of 22

(Fig. 8A). Bioinformatics

analysis of the expression of these 22 RBPs in HCC was conducted to

screen significant RBPs (Fig.

8B). Next, the expression of markedly altered RBP proteins

KHDRBS1, NUDT21, HNRNPA2B1, RBMX, HNRNPC and ELAVL1 was validated

in clinical tissues. As compared with the Normal group, KHDRBS1,

NUDT21, HNRNPA2B1, RBMX, HNRNPC and ELAVL1 levels were elevated in

the Tumor group. Among them, the expression of ELAVL1 was the most

prominently increased, so it was selected for further analysis

(Fig. 8C). Subsequently,

ELAVL1 was knocked down and overexpressed. Compared with the

si-NC group, ELAVL1 levels in the si-ELAVL1#1 and

si-ELAVL1#2 groups were repressed, with the most significant

decrease observed in the si-ELAVL1#2 group. As compared with

the oe-NC group, ELAVL1 expression in the oe-ELAVL1 group

was markedly elevated (Fig. 8D).

The present study confirmed that si-ELAVL1 and

oe-ELAVL1 were successfully transfected. Based on the UCSC

Genome Browser, it was shown that ELAVL1 bound with Caspase

3 (Fig. 8E). RIP further

confirmed the binding of ELAVL1 to Caspase 3 mRNA. Following

the knockdown of ELAVL1, the binding of ELAVL1 to Caspase 3

mRNA was weakened. Following the overexpression of ELAVL1,

the binding of ELAVL1 to Caspase 3 mRNA was enhanced

(Fig. 8F). Furthermore,

ELAVL1 knockdown inhibited the half-life of Caspase 3

mRNA following treatment with 5 μg/ml Act D for 0, 2, 4, 6,

8 and 10 h. ELAVL1 overexpression extended the half-life of

Caspase 3 mRNA following treatment with 5 μg/ml Act D

for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h (Fig.

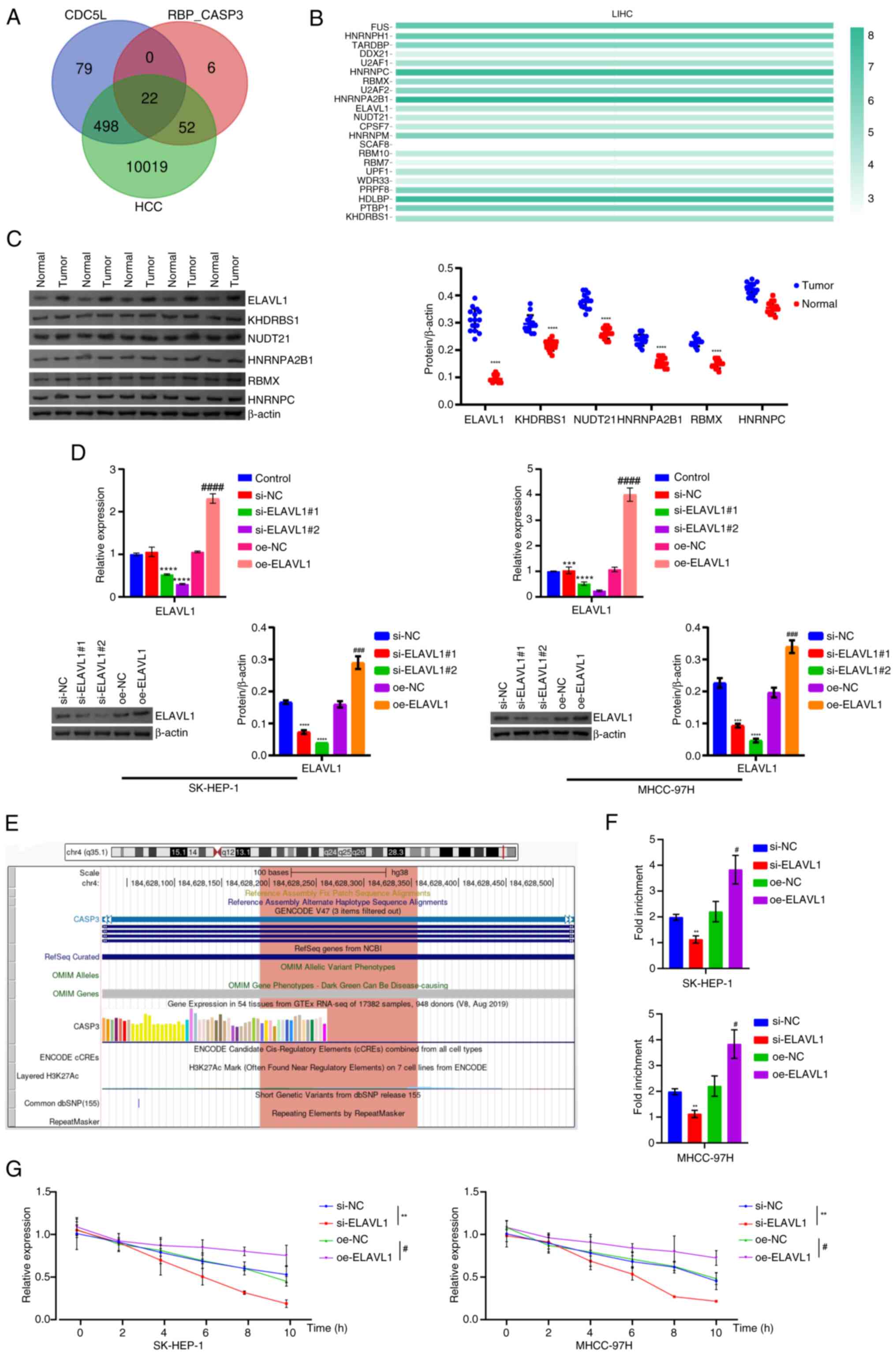

8G). In addition, ELAVL1 knockdown promoted Caspase 3,

LDH, IL-1β, IL-18, GSDME and GSDME-N levels. ELAVL1

overexpression repressed Caspase 3, LDH, IL-1β, IL-18, GSDME and

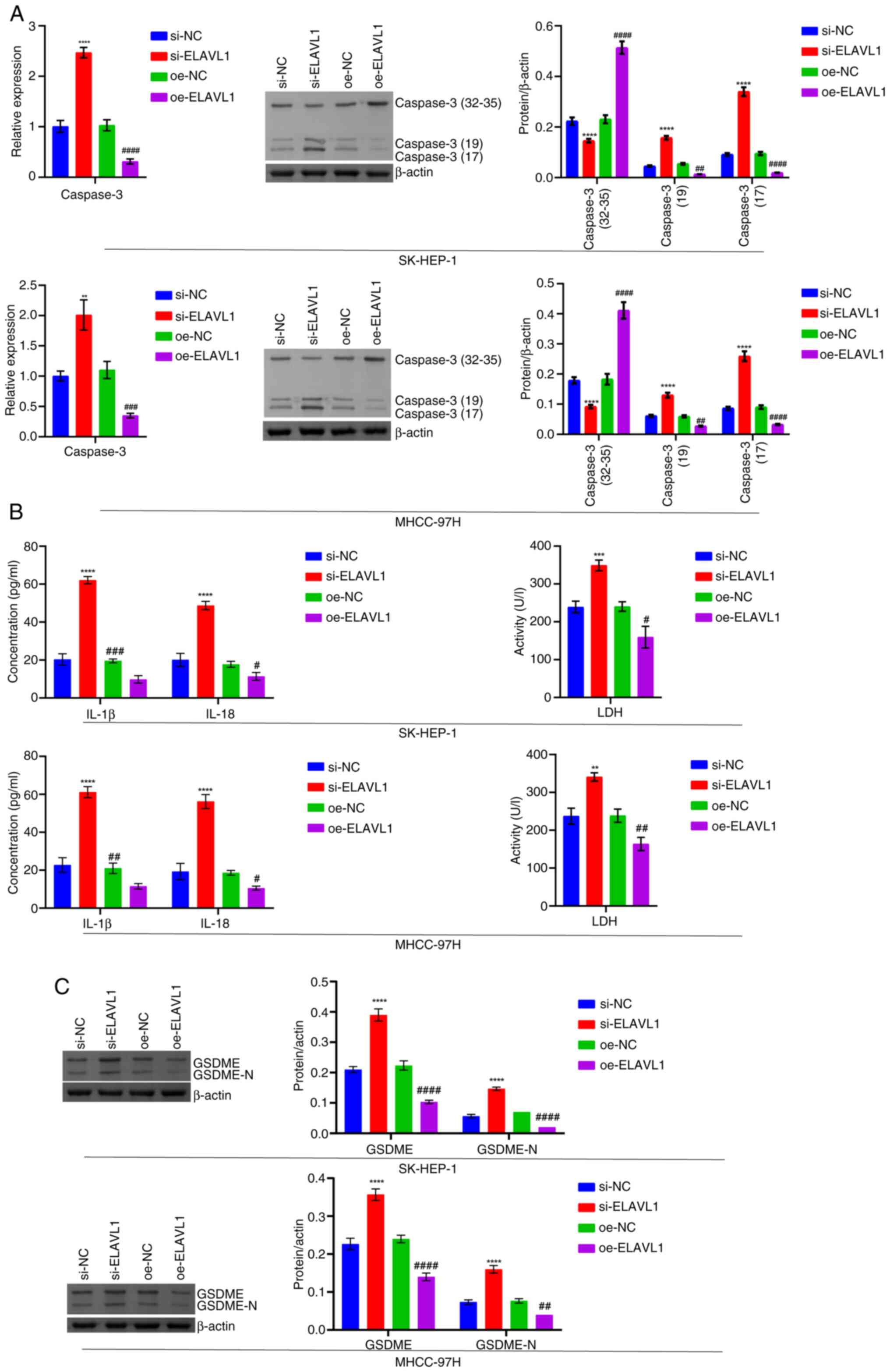

GSDME-N levels (Fig. 9A-C). In

addition, ELAVL1 knockdown promoted cell pyroptosis, while

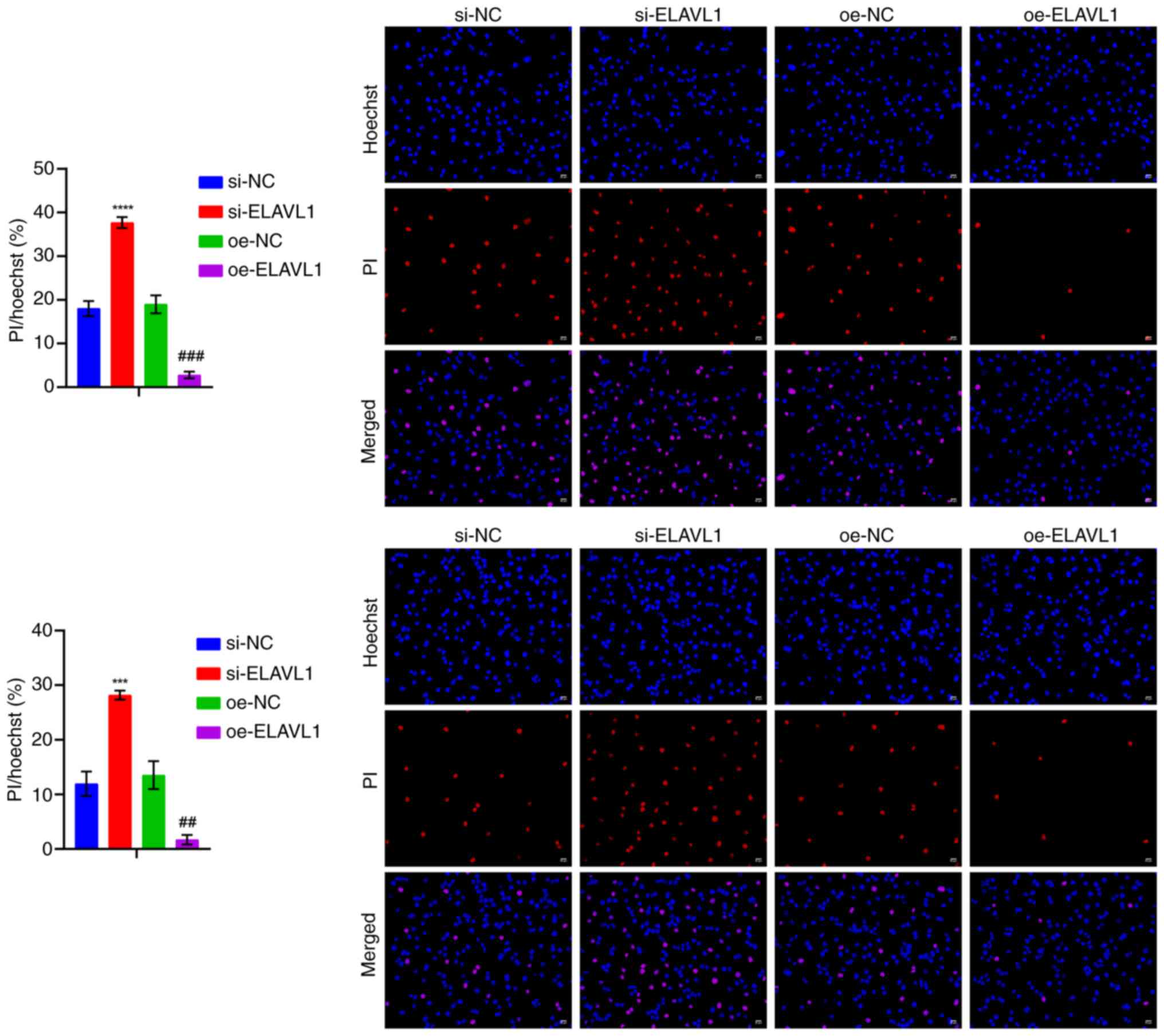

ELAVL1 overexpression inhibited cell pyroptosis (Fig. 10).

| Figure 8Mechanism of knockdown and

overexpression of ELAVL1 in pyroptosis in HCC. (A) Venn diagram

showing the intersection of CDC5L binding proteins and Caspase 3

interacting RBPs, with a total of 22. (B) Bioinformatics analysis

of the expression of these 22 RBPs in HCC was conducted to screen

significant RBPs. (C) Western blot analysis of RBP protein levels.

(D) Western blot analysis of ELAVL1 levels. (E) UCSC Genome Browser

showed that ELAVL1 binds with Caspase 3. (F) RIP detection

of the binding of ELAVL1 to Caspase 3 mRNA in cells. (G) RT-qPCR

detection of the half-life of Caspase 3 mRNA in cells

overexpressing/silencing ELAVL1 following treatment with 5

μg/ml Act D for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h.

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC; #P<0.05,

###P<0.001 and ####P<0.0001 vs. oe-NC.

ELAVL1, ELAV like RNA binding protein 1; HCC, hepatocellular

carcinoma; CDC5L, cell division cycle 5 like; RBPs, RNA-binding

proteins; UCSC, University of California, Santa Cruz; RIP, RNA

immunoprecipitation; si, short interfering; si-NC, negative control

siRNA; si-ELAVL1, ELAVL1-specific siRNA; oe-NC,

negative control overexpression vector; oe-ELAVL1,

ELAVL1 overexpression vector. |

| Figure 9Detection of pyroptosis-related

levels following knockdown and overexpression of ELAVL1. (A)

RT-qPCR and western blot analysis of Caspase 3 levels. (B) LDH,

IL-1β and IL-18 levels in the cell supernatant. (C) Western blot

analysis of GSDME and GSDME-N levels. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 and ####P<0.0001 vs. oe-NC.

RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase; GSDME, Caspase 3/Caspase 3-gasdermin E; GSDME-N,

Gasdermin E N-terminal fragment; si, short interfering; si-NC,

negative control siRNA; si-ELAVL1, ELAVL1-specific

siRNA; oe-NC, negative control overexpression vector;

oe-ELAVL1, ELAVL1 overexpression vector. |

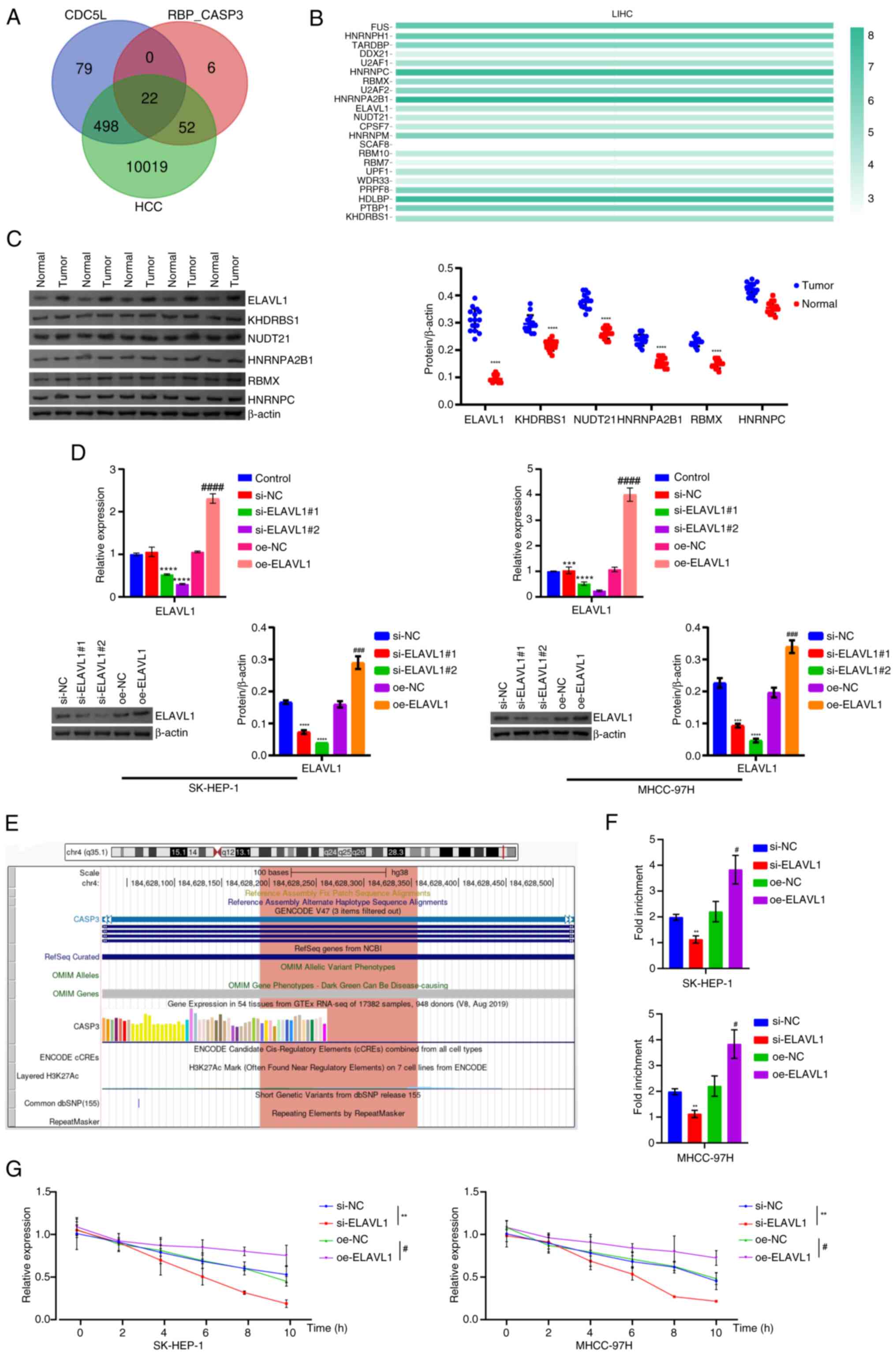

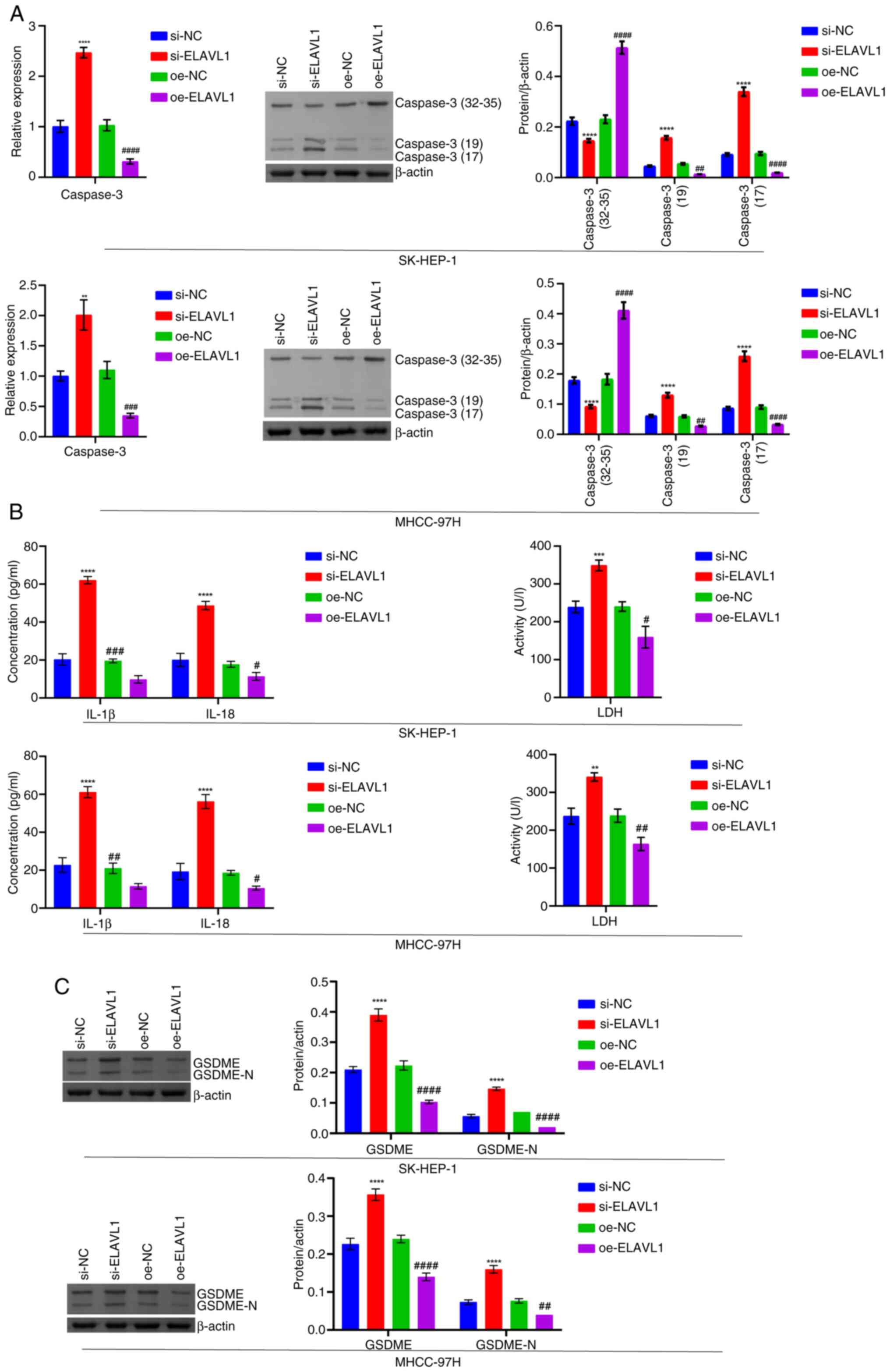

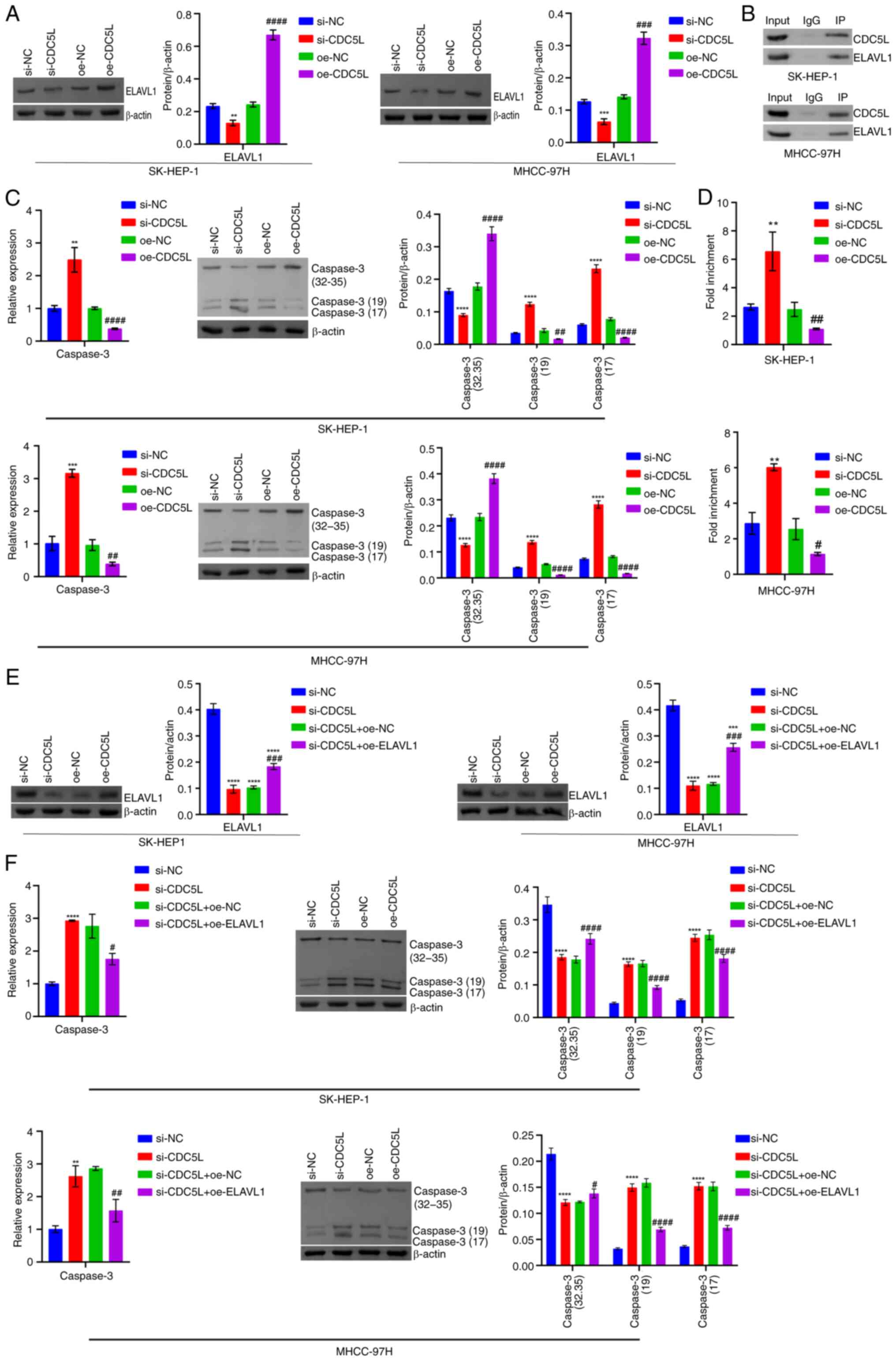

Furthermore, compared with the si-NC group, ELAVL1

expression in the si-CDC5L group was decreased. Compared

with the oe-NC group, ELAVL1 expression in the oe-CDC5L

group was markedly elevated (Fig.

11A). Co-IP verified the binding of CDC5L to ELAVL1 protein

(Fig. 11B). In addition,

following CDC5L knockdown, Caspase 3 expression increased.

Following CDC5L overexpression, Caspase 3 expression

decreased (Fig. 11C). RIP

further verified the binding of ELAVL1 to Caspase 3 mRNA.

Following CDC5L knockdown, the binding of ELAVL1 to

Caspase 3 mRNA was enhanced. Following CDC5L overexpression,

the binding of ELAVL1 to Caspase 3 mRNA was weakened

(Fig. 11D). Next, the effects

of interfering with CDC5L and overexpressing ELAVL1

on HCC pyroptosis was explored in vitro and in vivo.

In vitro, CDC5L knockdown suppressed ELAVL1

expression. Upon further overexpression of ELAVL1, its

expression increased (Fig.

11E). CDC5L knockdown promoted Caspase 3 expression.

Upon further overexpression of ELAVL1, Caspase 3 expression

decreased (Fig. 11F). RIP

verified the binding stability of ELAVL1 protein with Caspase

3 mRNA. CDC5L knockdown enhanced the binding stability

of ELAVL1 protein with Caspase 3 mRNA. Upon further

overexpression of ELAVL1, it inhibited the binding stability

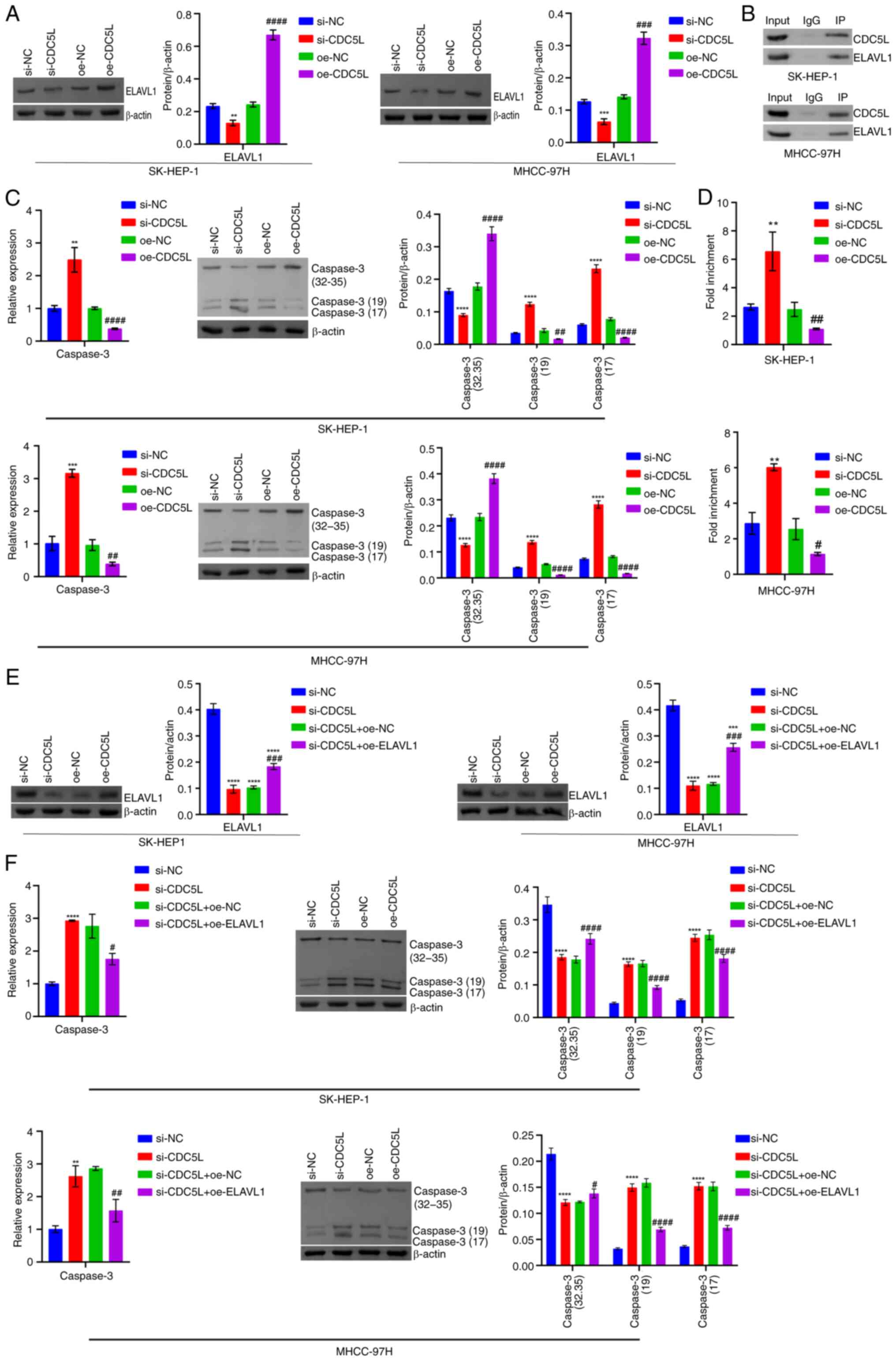

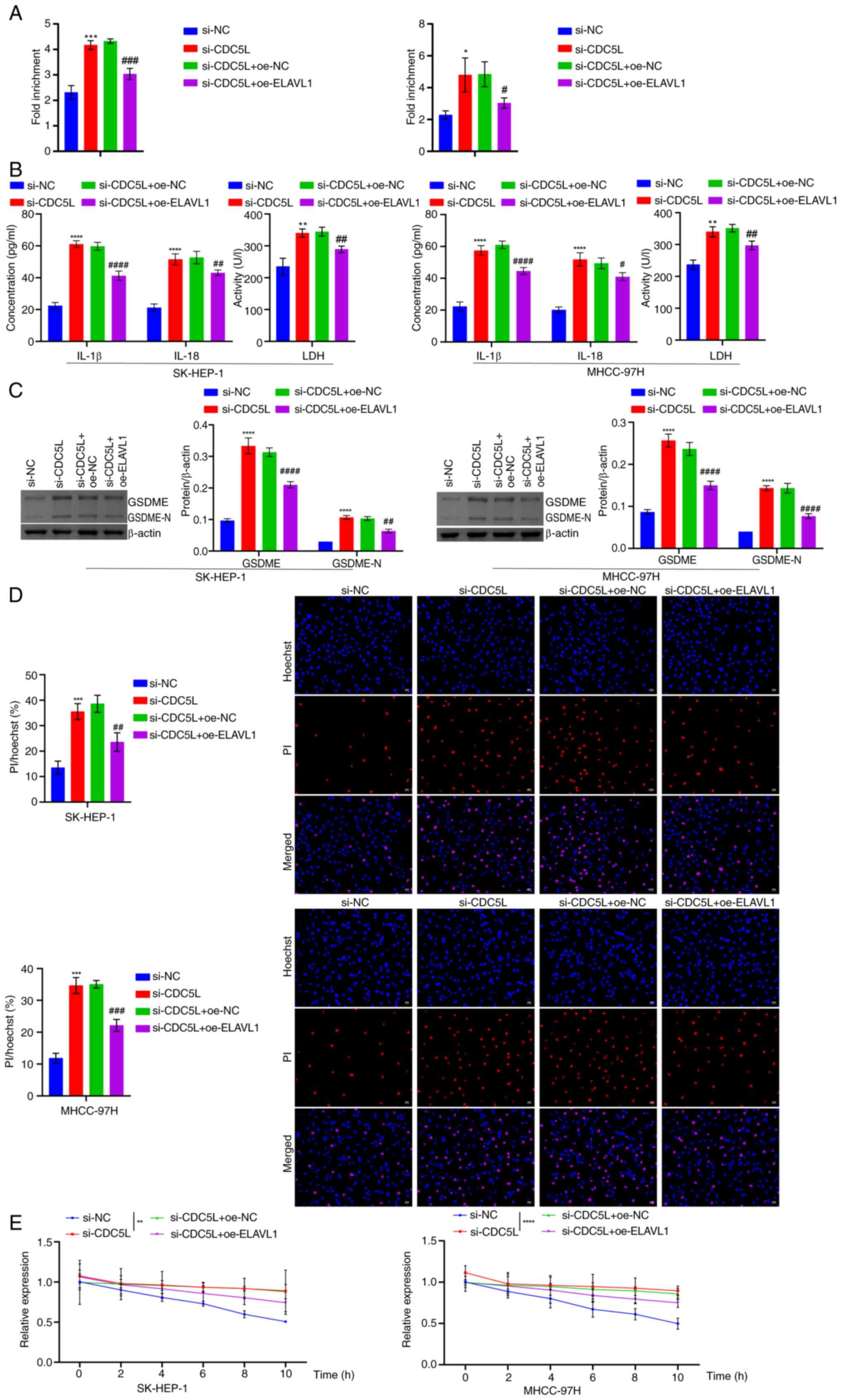

of ELAVL1 protein with Caspase 3 mRNA (Fig. 12A). In addition, CDC5L

knockdown promoted an increase in LDH, IL-1β, IL-18, GSDME and

GSDME-N levels. Upon further overexpression of ELAVL1, it

suppressed LDH, IL-1β, IL-18, GSDME and GSDME-N levels (Fig. 12B-C). Furthermore, CDC5L

knockdown promoted cell pyroptosis. Upon further overexpression of

ELAVL1, it inhibited cell pyroptosis (Fig. 12D). In addition, CDC5L

knockdown extended the half-life of Caspase 3 mRNA following

treatment with 5 μg/ml Act D for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 h.

Overexpression of ELAVL1 inhibited the half-life of

Caspase 3 mRNA following treatment with 5 μg/ml Act D

for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 h (Fig.

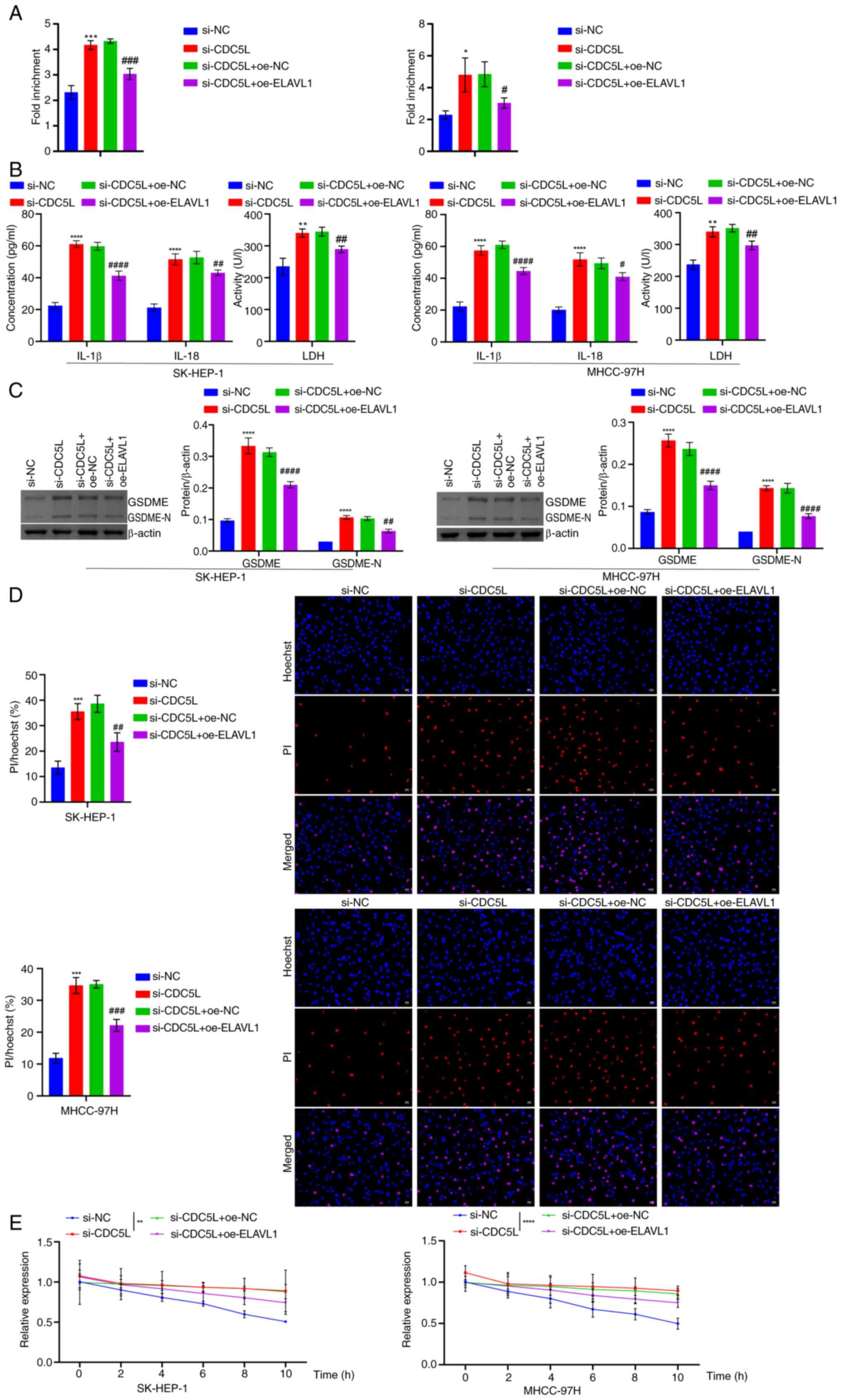

12E). In vivo, it was found that following CDC5L

knockdown, tumor volume gradually decreased and tumor size and

weight were also reduced. Following further overexpression of

ELAVL1, the tumor volume gradually increased and the tumor

size and weight also increased (Fig. 13A-C). In addition, CDC5L

knockdown promoted an increase in LDH, IL-1β, IL-18, CAPS3, GSDME

and GSDME-N levels. Following further overexpression of

ELAVL1, it suppressed CAPS3, LDH, IL-1β, IL-18, GSDME and

GSDME-N levels (Fig. 13D -

Forward). These results indicated that CDC5L competitively bound to

ELAVL1 to inhibit the binding of ELAVL1 with Caspase 3 mRNA,

thereby regulating pyroptosis in HCC.

| Figure 11Mechanism of CDC5L knockdown and

overexpression of ELAVL1 in pyroptosis in HCC. (A) Western blot

analysis of ELAVL1 levels. (B) Co-IP validation of interaction

between CDC5L and ELAVL1 protein. (C) RT-qPCR and western blot

analysis of Caspase 3 levels. (D) RIP verification of the binding

of ELAVL1 to Caspase 3 mRNA in cells. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 and ####P<0.0001 vs. oe-NC.

(E) Western blot analysis of ELAVL1 levels. (F) RT-qPCR and western

blot analysis of Caspase 3 levels. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 and ####P<0.0001 vs.

si-CDC5L+oe-NC. CDC5L, cell division cycle 5 like; ELAVL1,

ELAV like RNA binding protein 1; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma;

Co-IP, Co-immunoprecipitation; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; RIP, RNA immunoprecipitation; si,

short interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA; si-CDC5L,

CDC5L-specific siRNA; oe-NC, negative control overexpression

vector; oe-CDC5L, CDC5L overexpression vector;

oe-ELAVL1, ELAVL1 overexpression vector. |

| Figure 12Detection of pyroptosis-related

levels following CDC5L knockdown and overexpression of ELAVL1. (A)

RIP detection of the binding stability of ELAVL1 protein to Caspase

3 mRNA. (B) LDH, IL-1β and IL-18 levels in the cell supernatant.

(C) Western blot analysis of GSDME and GSDME-N levels. (D) Hoechst

33342 and PI staining of pyroptosis. Scale bar, 50 μm,

magnification, ×200. (E) Following treatment with 5 μg/ml

Act D for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h, the expression of Caspase

3 mRNA was measured using RT-qPCR and the half-life of

Caspase 3 mRNA was assessed. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 and

####P<0.0001 vs. si-CDC5L+oe-NC. CDC5L, cell

division cycle 5 like; ELAVL1, ELAV like RNA binding protein 1;

RIP, RNA immunoprecipitation; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GSDME,

Caspase 3/Caspase 3-gasdermin E; GSDME-N, Gasdermin E N-terminal

fragment; PI, propidium iodide; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; si, short interfering; si-NC,

negative control siRNA; si-CDC5L, CDC5L-specific

siRNA; oe-NC, negative control overexpression vector;

oe-CDC5L, CDC5L overexpression vector;

oe-ELAVL1, ELAVL1 overexpression vector. |

| Figure 13Validation of the mechanism of CDC5L

knockdown and overexpression of ELAVL1 in pyroptosis in HCC at the

animal level. (A) Tumor volume. (B) Tumor images. (C) Tumor weight.

(D) IL-18, IL-1β and LDH levels in tissue supernatants. (E) RT-qPCR

determination of Caspase 3 levels in tumor tissue. (F)

Western blot analysis of Caspase 3, GSDME and GSDME-N levels in the

tumor tissue. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. si-NC; ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 and ####P<0.0001 vs.

si-CDC5L+oe-NC. CDC5L, cell division cycle 5 like; ELAVL1,

ELAV like RNA binding protein 1; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; GSDME, Caspase

3/Caspase 3-gasdermin E; GSDME-N, Gasdermin E N-terminal fragment;

si, short interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA;

si-CDC5L, CDC5L-specific siRNA; oe-NC, negative

control overexpression vector; oe-CDC5L, CDC5L

overexpression vector; oe-ELAVL1, ELAVL1

overexpression vector. |

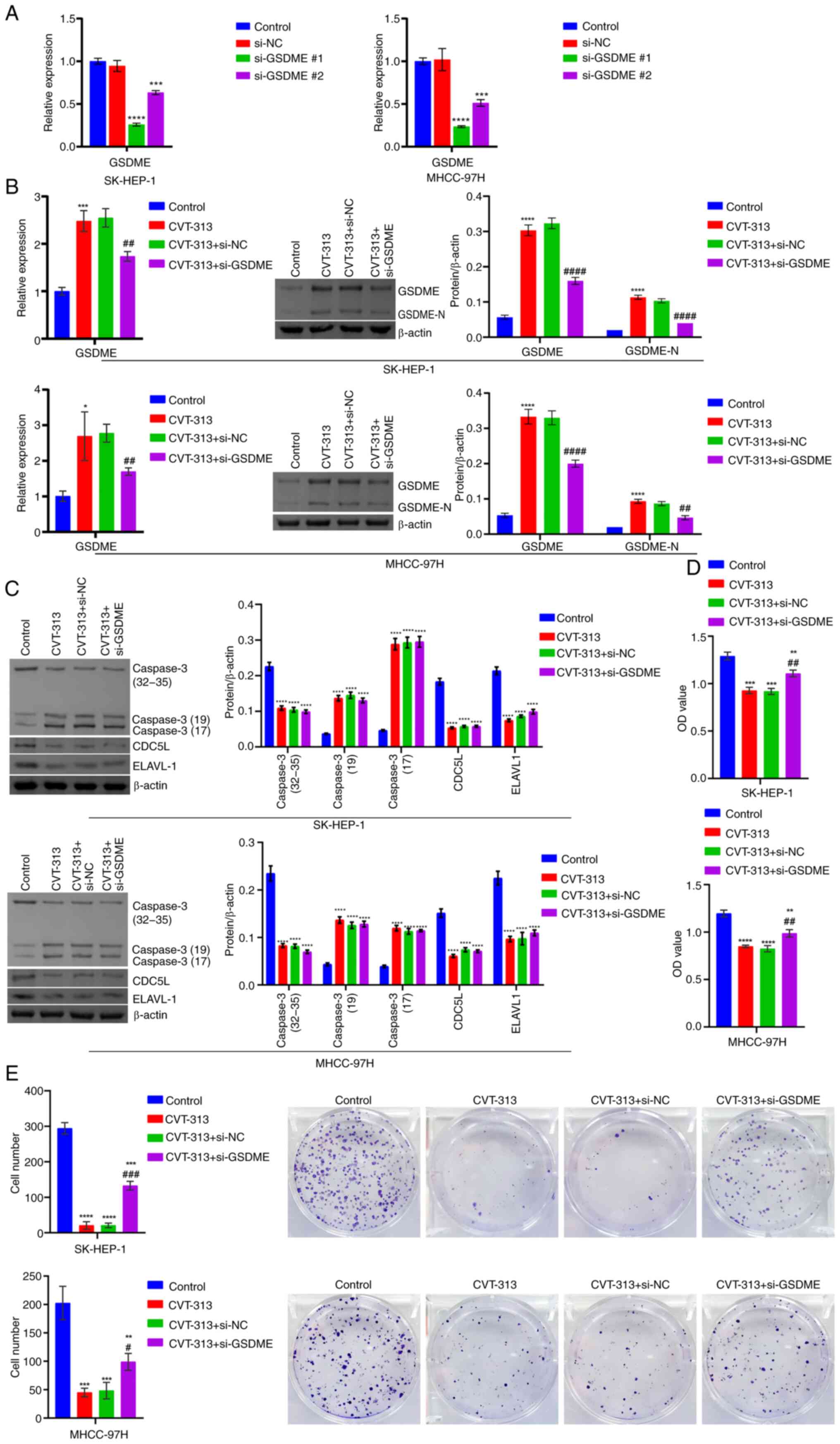

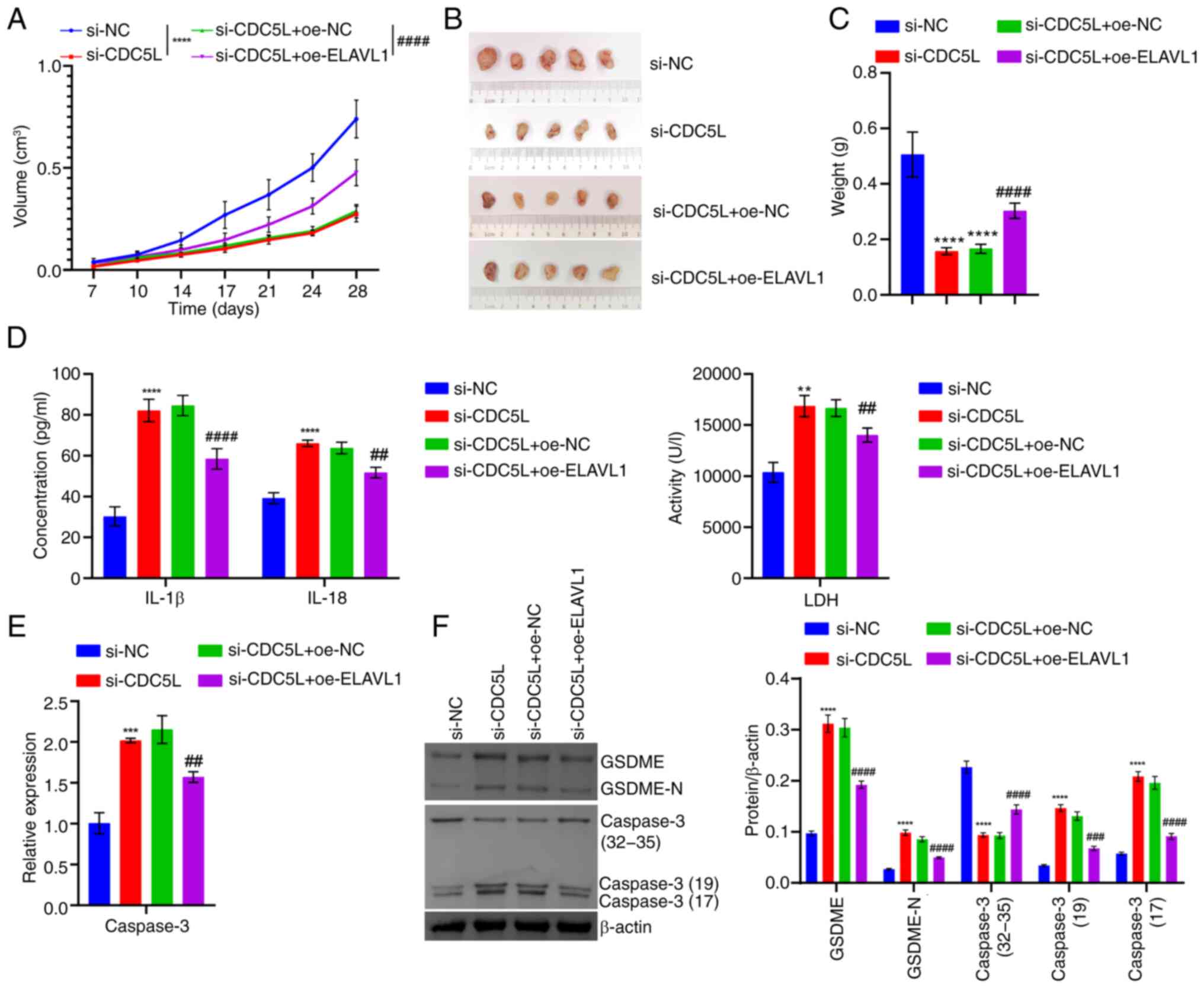

CDC5L/ELAVL1 silencing regulates Caspase

3/GSDME to promote pyroptosis and inhibit tumor progression in

HCC

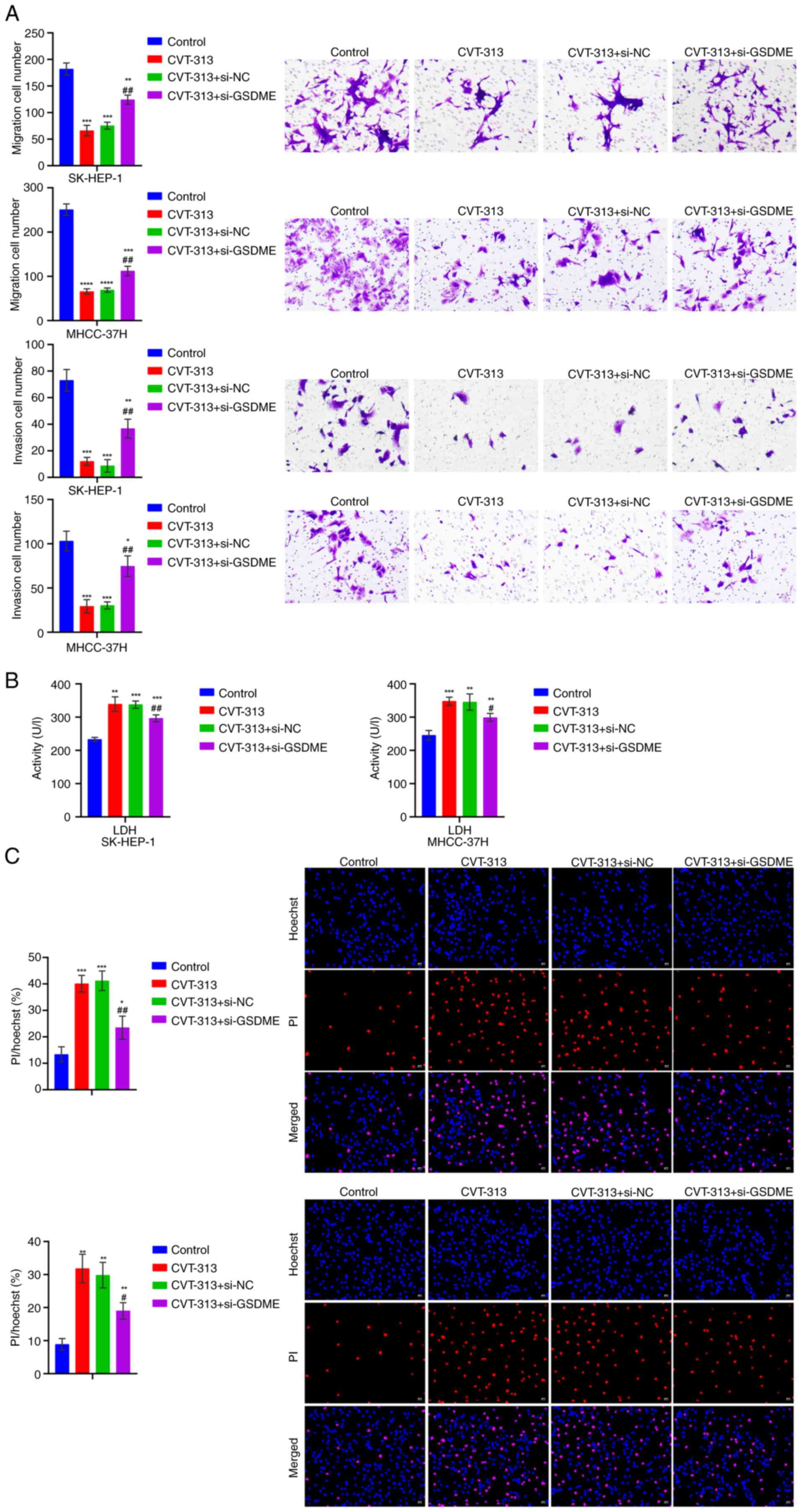

Finally, the effect of CDC5L inhibitor CVT-313 and

GSDME interference on HCC pyroptosis and tumor progression

was investigated the in vitro and in vivo. RT-qPCR

was performed on cells transfected with si-GSDME alone and

the results showed that compared with the si-NC group, the

expression of GSDME mRNA was markedly reduced in both the

si-GSDME#1 and si-GSDME#2 groups. Among them, the

si-GSDME#1 group exhibited the most pronounced reduction in

GSDME mRNA expression and was used for subsequent

experiments. This indicated that si-GSDME transfection

successfully achieved knockdown of GSDME (Fig. 14A). At the cellular level,

compared with the Control group, GSDME, GSDME-N and Caspase 3

levels were elevated, while those of CDC5L and ELAVL1 were reduced

in the CVT-313 group. Following the additional knockdown of

GSDME, GSDME and GSDME-N levels decreased, whereas Caspase

3, CDC5L and ELAVL1 levels remained largely unchanged (Fig. 14B-C). Cellular function

experiments revealed that, as compared with the Control group, cell

viability decreased and proliferation, migration and invasion

capabilities were reduced in the CVT-313 group. Upon further

knockdown of GSDME, cell viability increased and

proliferation, migration and invasion capabilities increased

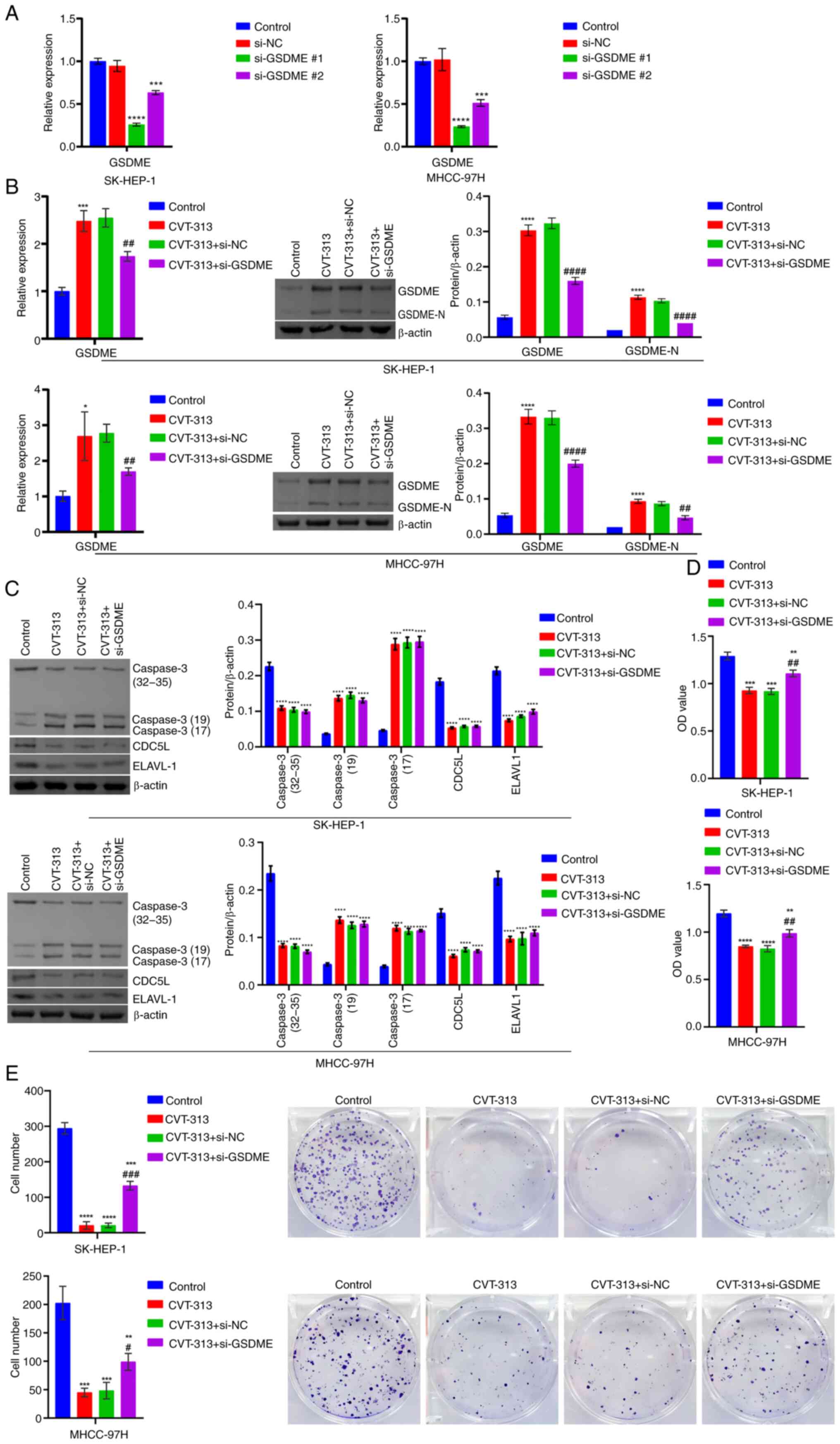

(Figs. 14D-E and 15A). In addition, as compared with the

Control group, LDH levels in the cell supernatant and pyroptosis

increased in the CVT-313 group. Upon further knockdown of GSDME,

LDH levels in the cell supernatant decreased and pyroptosis reduced

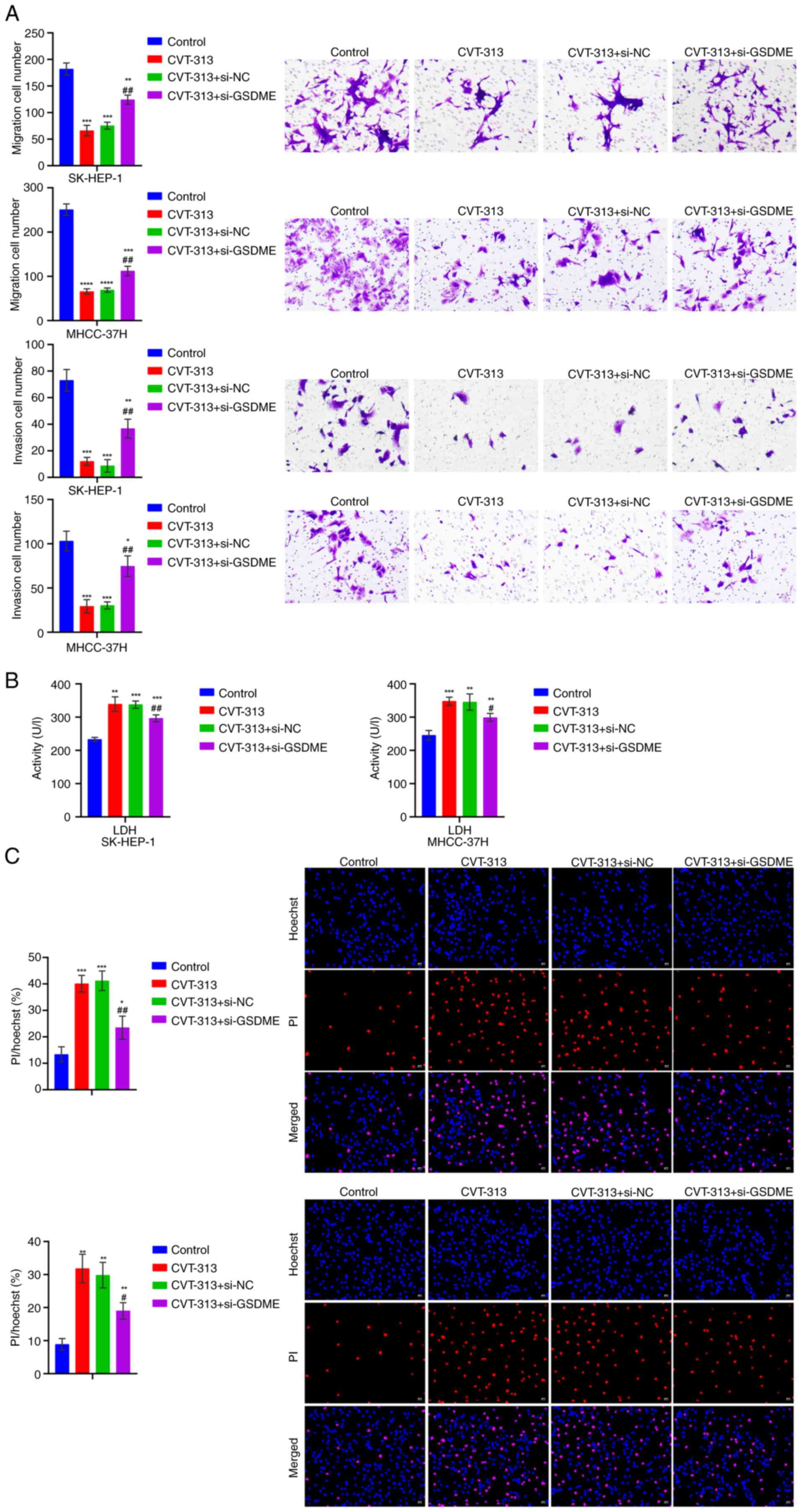

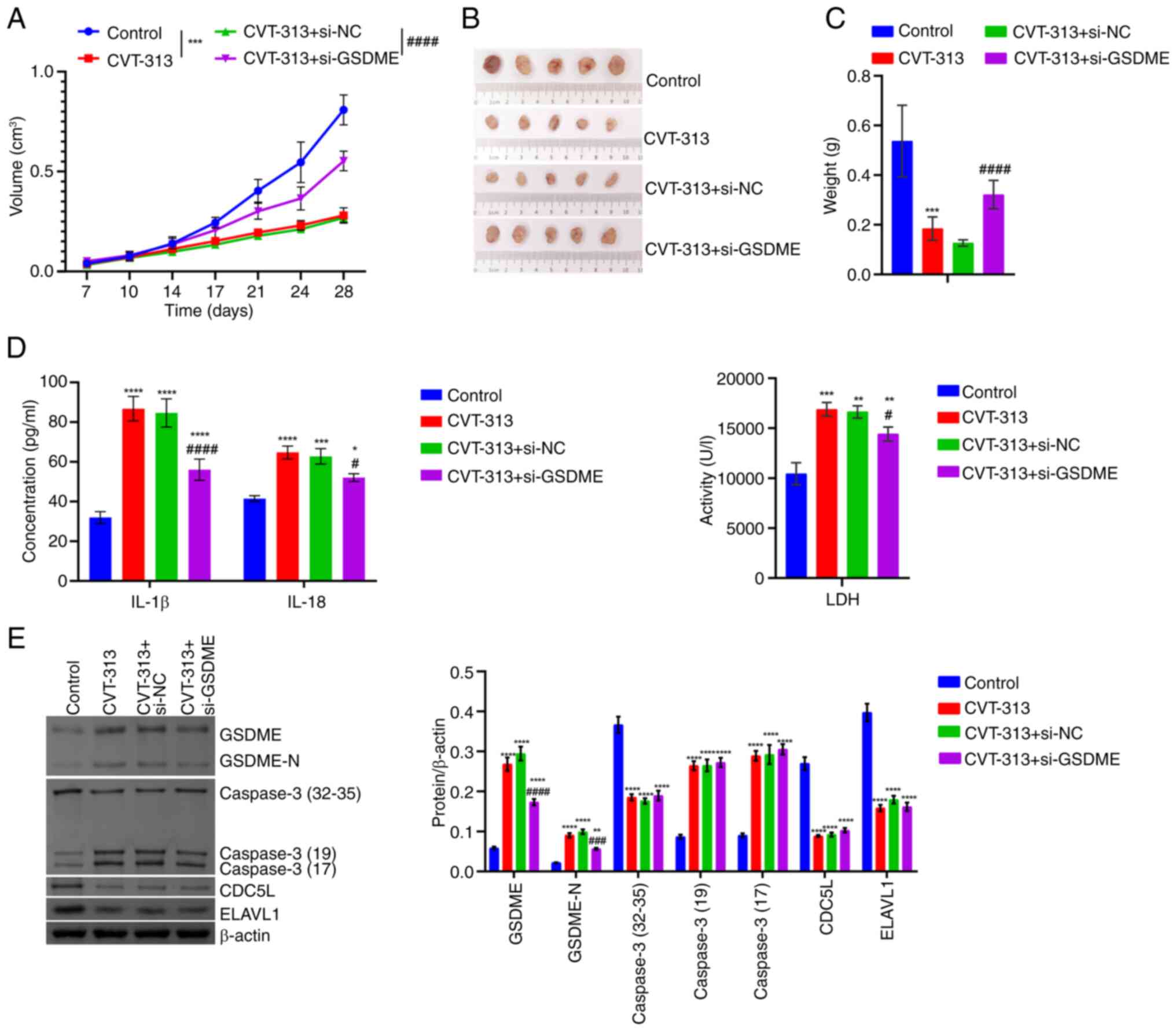

(Fig. 15B-C). At the animal

level, relative to the Control group, tumor volume decreased, tumor

size reduced and tumor weight was alleviated in the CVT-313 group.

Upon further knockdown of GSDME, tumor volume gradually increased

and tumor size and weight also increased (Fig. 16A-C). In addition, as compared

with the Control group, IL-1β, IL-18, LDH, Caspase 3, GSDME and

GSDME-N levels increased, while CDC5L and ELAVL1 levels decreased

in the CVT-313 group. upon further knockdown of GSDME,

IL-1β, IL-18, LDH, GSDME and GSDME-N levels decreased, with no

significant changes in CDC5L, ELAVL1 and Caspase 3 levels (Fig. 16D-E). These results indicated

that CDC5L/ELAVL1 silencing regulated Caspase 3/GSDME to promote

HCC pyroptosis and repress tumor progression.

| Figure 14The silencing of CDC5L/ELAVL1

regulated Caspase 3/GSDME. (A) Detection of GSDME mRNA

expression after si-GSDME transfection by RT-qPCR. (B)

RT-qPCR and western blot analysis of GSDME levels. (C) Western blot

analysis of CDC5L, ELAVL1 and Caspase 3 levels. (D) Evaluation of

cell viability by CCK-8 assay. (E) Assessment of cell proliferation

through clone formation experiments. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. Control; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 and

####P<0.0001 vs. CVT-313 + si-NC. CDC5L, cell

division cycle 5 like; ELAVL1, ELAV like RNA binding protein 1;

GSDME, Caspase 3/Caspase 3-gasdermin E; si, short interfering; HCC,

hepatocellular carcinoma; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; si,

short interfering; si-NC, Negative control siRNA; si-GSDME,

GSDME-specific siRNA. |

| Figure 15The silencing of CDC5L/ELAVL1

regulated Caspase 3/GSDME to promote pyroptosis in HCC. (A)

Examination of cell migration and invasion using Transwell assays.

Scale bar, 100 μm, magnification, ×100. (B) LDH level in

cell supernatant. (C) Hoechst 33342 and PI staining for the

detection of pyroptosis. Scale bar, 50 μm, magnification,

×200. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs.

Control; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 vs.

CVT-313 + si-NC. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PI, propidium iodide;

si, short interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA;

si-GSDME, GSDME-specific siRNA. |

| Figure 16The silencing of CDC5L/ELAVL1

regulated Caspase 3/GSDME to inhibit tumor progression in HCC. (A)

Tumor volume. (B) Tumor images. (C) Tumor weight. (D) IL-1β, IL-18

and LDH levels in tissue supernatants. (E) Western blot analysis of

CDC5L, ELAVL1, Caspase 3 and GSDME levels in tumor tissue.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs.

Control; #P<0.05, ###P<0.001 and

####P<0.0001 vs. CVT-313 + si-NC. CDC5L, cell

division cycle 5 like; ELAVL1, ELAV like RNA binding protein 1;

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; GSDME, Caspase 3/Caspase 3-gasdermin E;

si, short interfering; si-NC, negative control siRNA;

si-GSDME, GSDME-specific siRNA. |

Discussion

HCC is highly heterogeneous disease with distinct

etiologies, which leads to different driver mutations that enhance

a unique tumor immune microenvironment (35). Despite substantial advancements

in cancer treatment, HCC, the most common form of liver cancer,

remains a significant global public health challenge (36). In the present study, the role of

CDC5L on HCC tumorigenesis and pyroptosis was explored both in

vivo and in vitro. It was found that CDC5L bound to

ELAVL1 to inhibit pyroptosis in HCC through the Caspase 3/GSDME

signaling pathway. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is

the first study to report a CDC5L-induced regulation of ELAVL1 in

HCC pyroptosis. It was also the first to demonstrate that CDC5L

mediated the expression of Caspase 3 mRNA by binding to

ELAVL1.

HCC is highly malignant and prone to metastasis,

due to the heterogeneity and immunosuppressive nature of the tumor

microenvironment (37). HCC

development is a complex process involving the aberrant activation

or inactivation of multiple signaling pathways (38). CDC5L is a novel human telomerase

reverse transcriptase promoter binding protein (39). Mechanistic studies have shown

that silencing PRP19 suppresses CDC5L expression in HCC cells by

inhibiting CDC5L mRNA translation and promoting lysosome-mediated

CDC5L degradation (9). CDC5L

phosphorylation might contribute to HCC metastasis through the

regulation of mRNA processing and RNA splicing (11). Furthermore, the high expression

of methylated CDC5L-cg05671347 has been linked to improved overall

survival in patients with HCC (40). In the present study, high CDC5L

levels were found to be associated with poor HCC prognosis.

Therefore, the mechanism of CDC5L in HCC was further explored.

Evidence has indicated that tumor cells undergoing

regulated death might modulate immunogenicity in the tumor

microenvironment to a certain degree, potentially rendering it more

conducive to inhibiting cancer progression and metastasis (41). The induction of pyroptosis is

considered an anticancer therapy, due to its ability to unleash an

anticancer immune response (42). Upon detecting exogenous or

endogenous signals, cells initiate processes such as the assembly

of inflammatory vesicles, cleavage of GSDMs and release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately resulting in inflammatory

cell death (43). Recent studies

have highlighted that pyroptosis is a crucial factor in HCC

development (44,45). In the present study, CDC5L

knockdown repressed cell viability, proliferation, migration and

invasion, at the cellular level but promoted pyroptosis. Also, at

the animal level, CDC5L knockdown led to a gradual decrease in

tumor volume and a reduction in tumor size and weight. CDC5L

overexpression exerted the opposite effect. The results of the

present study revealed that CDC5L acting in HCC could affect

pyroptosis.

Pyroptosis and apoptosis are both forms of

Caspase-mediated programmed cell death. Caspase 3 is an important

protein in pyroptosis and apoptosis, controlling tumor cell

toxicity when activated, while the expression of GSDME modulates

this process (34). The Caspase

3/GSDME signaling pathway functions as a regulatory 'switch' that

determines the balance between apoptosis and pyroptosis in cancer

cells. When GSDME expression is high, Caspase 3 cleaves GSDME to

induce pyroptosis; by contrast, when GSDME expression is low,

Caspase 3 triggers apoptosis (22). Research has shown that cisplatin

induced acute liver injury through triggering Caspase

3/GSDME-mediated cellular pyroptosis (46). Furthermore, Germacrone induced

GSDME-dependent pyroptosis by activating the Caspase 3/GSDME

pathway, at least in part by damaging mitochondria and enhancing

ROS production, thus supporting the possibility of Germacrone as a

candidate drug for the prevention and treatment of liver cancer

(47). These studies suggest

that the Caspase 3/GSDME pathway is highly significant in liver

cancer, not only participating in the processes of apoptosis and

pyroptosis but also potentially serving as a target for liver

cancer treatment. In the present study, it was further discovered

the regulation of HCC pyroptosis by CDC5L depends on the Caspase

family. Therefore, the mechanisms of CDC5L and Caspase 3 in HCC

pyroptosis will be further explored.

As an RNA-binding protein, the distribution and

function of ELAVL1 within cells may be regulated by multiple

signaling pathways (48). ELAVL1

functions as a crucial post-transcriptional regulator of specific

RNAs in both normal and disease states, including cancer (49). ELAVL1 stabilizes target mRNAs

involved in cellular de-differentiation, proliferation and survival

(50). ELAVL1 is a gatekeeper of

liver homeostasis and can prevent HCC (51). ELAVL1 has been reported to

regulate hepatitis B virus replication and growth in HCC cells

(52). In the nucleus, CCAT2

binds to ELAVL1 to promote HCC progression (53). In addition, cisplatin triggered

acute kidney injury and pyroptosis in mice through exosomal

miR-122/ELAVL1 regulatory pathway (54). However, the mechanism regarding

the role of ELAVL1 and CDC5L in HCC pyroptosis is unclear. Research

has shown that ELAVL1 regulates post-transcriptional gene

expression in cancer cells and is subject to cleavage by

stress-activated Caspase 3 (55). Qiu et al (56) confirmed that pre-mRNA processing

factor 19 upregulated CDC5L expression, which bound to MAPK1,

thereby promoting gastric cancer progression via the MAPK

pathway-mediated homologous recombination. Additionally, IGF2BP1

acted as a post-transcriptional enhancer of CDC5L in an

m6A-dependent manner to promote the proliferation of multiple

myeloma cells with chromosome 1q gain (57). Jokoji et al (58) revealed that CDC5L promoted early

chondrocyte differentiation and proliferation by modulating

pre-mRNA splicing of SOX9, COL2A1 and WEE1. The KEGG analysis in

the present study revealed that the functional pathways of highly

expressed CDC5L involved the MAPK signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway and others. In gastric

cancer, high expression of CDC5L promoted homologous recombination

by activating the MAPK signaling pathway, thereby driving the

progression of gastric cancer (56). Research has shown that CDC5L mRNA

was upregulated in the exosomes of osteosarcoma patients with poor

chemotherapeutic responses. Moreover, bioinformatics analysis has

found that miRNA patterns associated with poor chemotherapeutic

responses were enriched in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (59). Therefore, high expression of

CDC5L may affect the chemotherapeutic response in osteosarcoma by

influencing the activity of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Lan

et al (60) reported that

TRIP13 was primarily enriched in the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling

pathway, suggesting that TRIP13 may promote the progression of

breast cancer by influencing the activity of the PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway. Since CDC5L is one of the hub genes highly associated with

TRIP13, it can be inferred that CDC5L may indirectly influence the

activity of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway through its interaction

with TRIP13. A study on lung adenocarcinoma demonstrated that CDC5L

promoted the progression of lung adenocarcinoma by

transcriptionally regulating WNT7B to activate the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway (61).

Additionally, the ELAVL1/PI3K/NF-κB pathway regulated by

lactoferrin was verified to participate in the protection of

infantile intestinal immune barrier damage in the study by Li et

al (62). These studies

indicated that CDC5L and ELAVL1 play important roles in various

cancers and related pathological processes through interactions

with multiple key signaling pathways. CDC5L promotes cancer

progression by activating the MAPK, PI3K-Akt and Wnt signaling

pathways, while ELAVL1, as an RNA-binding protein, regulates the

stability of specific mRNAs, affecting cell dedifferentiation,

proliferation and survival. Although their roles in different

cancers have been revealed in existing studies, the specific

mechanisms of action of CDC5L and ELAVL1 in HCC pyroptosis still

need further exploration. In the present study, at the cellular

level, CDC5L was found to competitively bind to ELAVL1 to inhibit

the binding of ELAVL1 with Caspase 3 mRNA, thereby regulating HCC

pyroptosis. This discovery is significant for understanding the

role of pyroptosis in tumor suppression. Finally, it was confirmed

through cellular and animal experiments that silencing CDC5L/ELAVL1

regulated Caspase 3/GSDME to promote HCC pyroptosis and inhibit

tumor progression. Therefore, targeting the CDC5L/ELAVL1 axis could

pave the way for new therapeutic methods that increase the

chemosensitivity of live cancer cells, thereby inhibiting tumor

progression. Notably, the present study is the first to reveal the

mechanism by which CDC5L interacts with ELAVL1 and regulates

Caspase 3/GSDME signaling pathway in the pyroptosis of HCC. This

finding not only provides a new potential therapeutic target for

HCC, but also offers a new perspective for understanding the tumor

microenvironment and immune regulation in HCC.

While the present study has made significant

progress in exploring the mechanisms of CDC5L and ELAVL1 in HCC,

there are still some limitations that need to be further improved

in future research. First, the relatively small cohort size of the

present study, which was limited by available resources and initial

research design, may affect the universality and reliability of the

results despite the significant statistical findings. Future

research should expand the sample size to further validate the

findings and reduce potential bias. Second, potential selection

bias in TCGA analysis is also a concern. Although strict screening

criteria were applied and data were validated multidimensionally,

public database analyses are generally subject to factors such as

sample sources and data quality and potential bias cannot be

completely ruled out. Therefore, future research needs to combine

more independent datasets for validation to improve the reliability

and universality of the results. In addition, the present study

relied on only two HCC cell lines, which may limit the generality

of the results. Although these two cell lines are widely used and

representative in HCC research, significant biological differences

may exist between different cell lines. To more comprehensively

evaluate the mechanisms of CDC5L and ELAVL1, future research plans

to introduce more HCC cell lines and explore the differences and

commonalities between them. Finally, the lack of in situ or

immunologically active in vivo models in the present study

somewhat limits our comprehensive understanding of the HCC

pathological process. In vitro experiments and animal models

have limitations in simulating human diseases. For an improved

simulation of the HCC pathological process, future research plans

to develop in situ HCC models and explore immunologically

active models to more comprehensively assess the mechanisms of

CDC5L and ELAVL1.

In conclusion, in the present study, a preliminary

investigation into the mechanism of CDC5L in HCC was conducted and

its potential mode was found to be associated with its interaction

with ELAVL1 and pyroptosis. These findings suggested a new way of

considering the treatment of HCC. Furthermore, gaining a deeper

understanding of the involvement of pyroptosis in HCC may provide a

basis for exploring and developing new therapeutic approaches to

combat HCC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SL and KY conceived the design, ZZ, SL, SZ, YT, MX

and XG carried out the experiments, KY carried out data

visualization, SL and KY confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data, SL wrote the first draft and ZZ, SZ, YT, MX, XG and KY

directed the revision. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The clinical study was approved by Medical Ethics

Committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (Hunan,

China; approval no. 2024052119) and all patients afforded informed

consent. The animal experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics

Committee of Xiangya Medical School, Central South University

(approval no. 2024051707) and all animal experiments were conducted

in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee.

Patient consent for publication

All patients gave informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

the present study was funded by the Enterprise Joint Fund of

Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant no.

2025JJ90293) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province

(grant no. 2023JJ30910).

References

|

1

|

Wang W, Zhou Y, Li W, Quan C and Li Y:

Claudins and hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother.

171:1161092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mo Y, Zou Z and Chen E: Targeting

ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 18:32–49.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sankar K, Gong J, Osipov A, Miles SA,

Kosari K, Nissen NN, Hendifar AE, Koltsova EK and Yang JD: Recent

advances in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol

Hepatol. 30:1–15. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

4

|

Butaye E, Somers N, Grossar L, Pauwels N,

Lefere S, Devisscher L, Raevens S, Geerts A, Meuris L, Callewaert

N, et al: Systematic review: Glycomics as diagnostic markers for

hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 59:23–38. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Llovet JM, Pinyol R, Yarchoan M, Singal

AG, Marron TU, Schwartz M, Pikarsky E, Kudo M and Finn RS: Adjuvant

and neoadjuvant immunotherapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat

Rev Clin Oncol. 21:294–311. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chen X, Kou L, Xie X, Su S, Li J and Li Y:

Prognostic biomarkers associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunology. 172:21–45. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang N, Kaur R, Akhter S and Legerski RJ:

Cdc5L interacts with ATR and is required for the S-phase cell-cycle

checkpoint. EMBO Rep. 10:1029–1035. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang Z, Mao W, Wang L, Liu M, Zhang W, Wu

Y, Zhang J, Mao S, Geng J and Yao X: Depletion of CDC5L inhibits

bladder cancer tumorigenesis. J Cancer. 11:353–363. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Huang R, Xue R, Qu D, Yin J and Shen XZ:

Prp19 arrests cell cycle via Cdc5L in hepatocellular carcinoma

cells. Int J Mol Sci. 18:7782017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Qiu H, Zhang X, Ni W, Shi W, Fan H, Xu J,

Chen Y, Ni R and Tao T: Expression and clinical role of Cdc5L as a

novel cell cycle protein in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci.

61:795–805. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Tian M, Cheng H, Wang Z, Su N, Liu Z, Sun

C, Zhen B, Hong X, Xue Y and Xu P: Phosphoproteomic analysis of the

highly-metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, MHCC97-H. Int

J Mol Sci. 16:4209–4225. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ma Q, Lu Q, Lei X, Zhao J, Sun W, Huang D,

Zhu Q and Xu Q: Relationship between HuR and tumor drug resistance.

Clin Transl Oncol. 25:1999–2014. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu R, Wu K, Li Y, Sun R and Li X: Human

antigen R: A potential therapeutic target for liver diseases.

Pharmacol Res. 155:1046842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Papatheofani V, Levidou G, Sarantis P,

Koustas E, Karamouzis MV, Pergaris A, Kouraklis G and Theocharis S:

HuR protein in hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications in

development, prognosis and treatment. Biomedicines. 9:1192021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Imre G: Pyroptosis in health and disease.

Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 326:C784–C794. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chao L, Zhang W, Feng Y, Gao P and Ma J:

Pyroptosis: A new insight into intestinal inflammation and cancer.

Front Immunol. 15:13649112024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wen J, Xuan B, Liu Y, Wang L, He L, Meng

X, Zhou T and Wang Y: NLRP3 inflammasome-induced pyroptosis in

digestive system tumors. Front Immunol. 14:10746062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wallace HL and Russell RS: Inflammatory

consequences: Hepatitis C virus-induced inflammasome activation and

pyroptosis. Viral Immunol. 37:126–138. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zou Z, Zhao M, Yang Y, Xie Y, Li Z, Zhou

L, Shang R and Zhou P: The role of pyroptosis in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 46:811–823. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhao H, Liu H, Yang Y and Wang H: The role

of autophagy and pyroptosis in liver disorders. Int J Mol Sci.

23:62082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cheng C, Hsu SK, Chen YC, Liu W, Shu ED,

Chien CM, Chiu CC and Chang WT: Burning down the house: Pyroptosis

in the tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Life

Sci. 347:1226272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jiang M, Qi L, Li L and Li Y: The

caspase-3/GSDME signal pathway as a switch between apoptosis and

pyroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 6:1122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lorente L, Rodriguez ST, Sanz P,

González-Rivero AF, Pérez-Cejas A, Padilla J, Díaz D, González A,

Martín MM, Jiménez A, et al: High serum caspase-3 levels in

hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation and high

mortality risk during the first year after liver transplantation.

Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 19:635–640. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Shang N, Bank T, Ding X, Breslin P, Li J,

Shi B and Qiu W: Caspase-3 suppresses diethylnitrosamine-induced

hepatocyte death, compensatory proliferation and

hepatocarcinogenesis through inhibiting p38 activation. Cell Death

Dis. 9:5582018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Song A, Ding T, Wei N, Yang J, Ma M, Zheng

S and Jin H: Schisandrin B induces HepG2 cells pyroptosis by

activating NK cells mediated anti-tumor immunity. Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 472:1165742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang X, Zhang P, An L, Sun N, Peng L,

Tang W, Ma D and Chen J: Miltirone induces cell death in

hepatocellular carcinoma cell through GSDME-dependent pyroptosis.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 10:1397–1413. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27