Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease (MASLD) has emerged as a global public health concern and

is characterized by the accumulation of fat in the liver in the

context of metabolic dysfunction. The pathophysiology of MASLD is

complex, with oxidative stress and insulin resistance (IR) playing

central roles in its development and progression (1). The increasing prevalence of MASLD

is closely linked to increasing rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes,

and other metabolic disorders, making it a significant health issue

worldwide. In the search for effective management strategies,

intermittent fasting (IF), also known as time-restricted feeding,

has garnered attention as a potential therapeutic approach. IF

involves alternating between periods of normal eating and fasting,

with variations such as alternate-day fasting and periodic fasting

(2). The relatively simple

structure of IF has contributed to its widespread popularity as a

dietary regimen among the general population. Studies have

suggested that IF may be beneficial in alleviating liver fat

accumulation by increasing insulin sensitivity, reducing fat

deposition, and modulating inflammatory responses, which are

crucial factors in the pathogenesis of MASLD (3). However, while IF shows promise in

managing MASLD, it has some challenges. Certain individuals,

particularly those with hypoglycemia, diabetes, or gastrointestinal

disorders, may face health risks associated with IF (4). Furthermore, although short-term IF

has demonstrated beneficial effects on liver fat reduction and

liver enzyme levels in MASLD, the long-term impact remains

inadequately studied. Some research has indicated that the

sustainability of IF may be limited, especially after periods of

refeeding, when hepatic steatosis may relapse (5). Therefore, while IF presents a

potential strategy for MASLD management, the effects of IF are

likely to vary depending on individual health conditions and

dietary habits.

Studies have shown that peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α)

plays a critical role in the onset and progression of IR (6). In the liver, PGC-1α activates key

enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis, promoting hepatic glucose

production, which results in increased hepatic glucose output

(7). Unrestrained hepatic

glucose output is a hallmark of IR. In addition, mitochondrial

dysfunction is implicated in the development of MASH (8). Mitochondrial ultrastructural damage

has been observed in the livers of patients with non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis, with a decrease in the quantity and activity of

respiratory chain complexes and impaired ATP synthesis (8). PGC-1α influences mitochondrial

function by enhancing mitochondrial respiration, a process in which

PGC-1α strongly induces the mRNA expression of nuclear respiratory

factor (NRF)-1 and NRF-2α (9).

NRF-1 and NRF-2α are key regulators of genes involved in the

mitochondrial respiratory chain, including cytochrome c oxidase IV

(COX IV), β-ATP synthase, and mitochondrial transcription factor A

(mtTFA) (9). Furthermore,

dysregulated lipid metabolism generates large amounts of reactive

oxygen species (ROS), disturbing the dynamic balance between

pro-oxidants and antioxidants, which leads to oxidative stress and

lipid peroxidation (7,10,11). PGC-1α is involved in hepatic

lipid metabolism and plays a crucial role in reducing hepatic fat

accumulation (12). Recent

studies have highlighted the important role of the PPARα nuclear

receptor transcription factor in the transcriptional regulation of

intracellular lipid metabolism (12,13). PPARα controls the transcriptional

activity of genes such as long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase,

medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and carnitine

palmitoyltransferase-1. PGC-1α synergistically stimulates PPARα to

increase the transcriptional activity of fatty acid oxidases

(13). Overall, PGC-1α plays a

protective role in the mechanisms currently recognized in MASLD,

such as IR, mitochondrial damage, and lipid metabolism

dysregulation, by increasing insulin sensitivity, promoting

mitochondrial respiration, and facilitating fatty acid β-oxidation,

thus alleviating hepatic triglyceride accumulation.

Heterophyllin B (HP-B) is a cyclopeptide compound

derived from plants that has shown significant progress in research

on blood glucose regulation and anti-inflammatory effects in recent

years (14-16). HP-B interacts with the

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R), mimicking the actions of

GLP-1 analogs, promoting insulin secretion, and improving insulin

sensitivity, thereby modulating metabolic disturbances (14). These actions are particularly

relevant in the context of MASLD, the pathogenesis of which is

closely linked to IR, fat deposition, oxidative stress and chronic

inflammation (17). Given the

potential of HP-B to regulate metabolic disturbances and reduce

oxidative stress, it was hypothesized that the combination of HP-B

with IF may have a synergistic effect on MASLD. More importantly,

the integration of a natural GLP-1R activator with a dietary

intervention strategy may provide a more effective and tolerable

therapeutic option for patients with MASLD, particularly those

unable to adhere to strict fasting protocols. By elucidating the

molecular mechanisms underlying this combinatorial approach, the

present findings may contribute to the optimization of MASLD

treatment strategies and advance the development of personalized

metabolic therapies.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cell lines were

purchased from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. STR

profiling was used for authentication. The cells were cultured in

DMEM (MedChemExpress) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; HyClone; Cytiva) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) in an incubator at

37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were divided into the

following groups: Control (Con) group, in which the cells were

treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO in PBS) for 24 h; OA/PA model

group, in which HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were treated with 750

μM oleic acid + 750 μM palmitic acid (2:1 ratio) for

24 h (18), followed by

treatment with vehicle (0.1% DMSO in PBS) for 24 h; OA/PA + HP-B

group, in which the cells were treated with OA/PA for 24 h,

followed by treatment with 50 μM HP-B (prepared from 10 mM

DMSO stock diluted in PBS) for 24 h; OA/PA + Fasting group, in

which the cells were treated with OA/PA for 24 h, followed by

culture in low-glucose DMEM + 2% FBS + vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 24

h; and OA/PA + Fasting + HP-B group, in which the cells were

treated with OA/PA for 24 h, followed by cultured in fasting medium

(low-glucose DMEM + 2% FBS) containing 50 μM HP-B for 24

h.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells were seeded at a

density of 5×103 cells/well in 96-well plates and

allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C. Following treatment with 5,

10, 25, 50, 75, 100, or 200 μM HP-B for 24 h, cell viability

was then determined according to the instructions of the CCK-8

assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). In

brief, 10 μl CCk-8 solution was added to each well

containing 100 μl culture medium and incubated at 37°C for 2

h in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Optical density

was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Oil Red O staining

Following treatment of the HepG2 and Huh-7 liver

cancer cells, the media was removed, and the cells were washed

twice with PBS. The cells in each well were fixed for 10 min at

room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.). The cells were subsequently stained

with 0.5% Oil Red O solution at room temperature for 10 min. After

staining, the excess dye was removed by washing with 60%

isopropanol, followed by three washes with distilled water (5 min

each wash) to prevent non-specific binding of the dye. Under an

inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation), the cells were examined,

and images of representative fields were acquired.

Determination of total cholesterol (TC)

and triglyceride (TG) levels

Following the treatment of HepG2 and Huh-7 liver

cancer cells, the supernatants were collected. For the liver tissue

samples, a homogenizer was used to homogenize the liver tissue. The

samples were subsequently centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C and 12,000

× g, after which the supernatants were collected. The TG and TC

levels were measured by TG (cat. no. A110-1-1) and mouse total

cholesterol ELISA kit (cat. no. A111-1-1; both from Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) according to the manufacturer's

protocols.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Following the manufacturer's instructions, TRIzol

reagent (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was

used to extract total RNA from HepG2 and Huh-7 human liver cancer

cells. The concentration and purity (2.0> OD260/280 >1.8) of

the RNA were determined using a Multiskan SkyHigh nanodrop (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Following the instructions supplied by

the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc.), 1 μg of

total RNA was used for reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA.

qPCR was then performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Takara

Bio, Inc.). The qPCR program was as follows: Pre-denaturation at

95°C for 5 min; and 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec

and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec. Relative quantification

analysis was performed using the 2−ΔΔCq method with

GAPDH used as the reference gene, and the relative expression

levels of the target genes were calculated and expressed as

2−ΔΔCq (19). The

primers used in the present study were listed as follows: SREBP1

forward, 5'-TGCTTAGCCTCCTGACCTGA-3' and reverse,

5'-GAGGCCCTAAGGGTTGACAC-3'; FAS forward, 5'-CAGTGTACACGTCTGGACCC-3'

and reverse, 5'-AATTGTGGGAGGCTGAGAGC-3'; CD36 forward,

5'-ACATGCTAGCCACTGATCATTTT-3' and reverse,

5'-ACAACTTTGGCACAAGTGCTTT-3'; GLP-1R forward,

5'-TTGGGTGGTGCAACCTTTCT-3' and reverse, 5'-GATGCTGGAGTTGGTCTGCT;

PGC1α forward, 5'-ATTGCCTTCATGCCGTGGTA-3' and reverse,

5'-GCAAGGGCTCAACTAATCGC-3'; and GAPDH forward,

5'-AATGGGCAGCCGTTAGGAAA-3' and reverse,

5'-GCGCCCAATACGACCAAATC-3'.

Detection of ROS levels

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells were plated at a

density of 3×105 cells/well in 6-well plates. After

overnight incubation, the medium was discarded, and the cells were

gently washed twice with PBS. Then, 2 ml of 10 μM DCFH-DA

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) working

solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C in the dark

for 30 min. After incubation, the DCFH-DA working solution was

discarded, and the cells were gently washed twice with PBS. The

medium was replaced with serum-free medium. Fluorescent images were

acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Detection of mitochondrial ROS (mitoROS)

levels

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells were seeded in

6-well plates at a density of 3×105 cells/well.

Following an overnight incubation period, the medium was discarded,

and the cells were gently washed twice with PBS. Then, 2 ml of 5

μM MitoSOX Red (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) working solution was added to each well, followed by

incubation at 37°C in the dark for 30 min. Following incubation,

the cells were gently washed twice with PBS, and the medium was

replaced with 2 ml of serum-free media after the MitoSOX Red

working solution was removed. Fluorescent images were acquired

using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Detection of the mitochondrial membrane

potential (MMP)

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells were seeded in

6-well plates at a density of 3×105 cells/well.

Following an overnight incubation period, the medium was discarded,

and the cells were gently washed twice with PBS. Next, 2 ml of 5

μg/ml JC-1 working solution (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to each well, followed by

incubation for 20 min at 37°C in the dark. After incubation, the

JC-1 working solution was discarded, and the medium was replaced

with serum-free medium. The fluorescent JC-1 signals in the cells

were detected using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus

Corporation).

Western blot analysis

The HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells or liver

tissues were collected and lysed using a RIPA lysis solution

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) on ice for 30

min. The samples were subsequently centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C

and 12,000 × g. The protein concentration was measured using a BCA

kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Protein

samples (20 μg/lane) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. After

being transferred, the PVDF membrane was blocked for 1 h at room

temperature in 5% non-fat milk. After blocking, the membrane was

washed three times with TBST (0.1% Tween-20, 5 min each wash). The

membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with specific primary

antibodies: anti-PGC1α (cat. no. ab176328; 1:1,000), anti-GLP1R

(cat. no. ab218532; 1:1,000) and anti-GAPDH (cat. no. ab8245;

1:5,000; all purchased from Abcam). The membrane was then incubated

at room temperature for 1 h in antibody dilution buffer containing

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (SE205; cat. no. K21001M-HRP;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The membrane

was then washed three times with TBST (10 min each wash). The

proteins in the membrane were detected via ECL reagent (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). ImageJ version 2

(National Institutes of Health) was used to assess the band

intensity, and GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Establishment of animal model

In this experiment, a total of 45 8-week-old male

C57BL/6J mice [weight, 20-22 g; SiPeiFu, (Beijing) Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.] were randomly assigned to 9 experimental groups, with 5

mice per group. The first phase of the experiment included the

following groups: i) control group (Con), in which the mice were

fed a standard chow diet with daily oral vehicle (10% DMSO/corn

oil, 200 μl) for 8 weeks; ii) HFD group, in which the mice

were fed a high-fat diet (HFD; 45% fat, D12451, Research Diets,

Inc.) for 8 weeks to induce MASLD and then subsequently fed a daily

oral vehicle (10% DMSO/corn oil, 200 μl) for 8 weeks; iii)

HFD + HP-B group, in which the mice were fed a HFD for 8 weeks,

followed by oral administration of HP-B (20 mg/kg/day; total volume

of 200 μl) for 8 weeks (20); iv) HFD + IF group, in which the

mice were fed a HFD for 8 weeks, followed by IF for 8 weeks (two

24-h fasts/week: Wed 9AM→Thu 9AM and Fri 9AM→Sat 9AM) with daily

oral administration of vehicle (10% DMSO/corn oil, 200 μl);

and v) HFD + IF + HP-B group, in which the mice were fed a HFD for

8 weeks, followed by combined HP-B administration (20 mg/kg/day)

and IF for 8 weeks.

In the second phase (initiated after 8 weeks of HFD

induction), the mice received a single tail vein injection of

adenovirus (Day 0), followed by 8 weeks of intervention. To ensure

sustained GLP-1R knockdown, Ad-sh-GLP-1R [5'-AGT

GTCTGAAGCCAACAAGGA-3', designed against the mouse GLP-1R mRNA

(NM_021332)] and an adenoviral vector expressing a non-targeting

scrambled shRNA sequence (Ad-NC, 5'-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3') were

readministered at Week 4. The second phases consisted of the

following groups: i) HFD + Ad-NC group, in which the mice were

injected with Ad-NC (100 μl, 1011 pfu/ml) on Day

0 and Week 4, followed by daily oral administration of vehicle (10%

DMSO/corn oil, 200 μl) for 8 weeks; ii) HFD + IF + HP-B +

Ad-NC group, in which the mice were injected with Ad-NC on Day 0

and Week 4, followed by continued IF + HP-B treatment (20

mg/kg/day) for 8 weeks; iii) HFD + sh-GLP-1R group, in which the

mice were injected with Ad-sh-GLP-1R (100 μl,

1011 pfu/ml) on Day 0 and Week 4, followed by daily oral

administration of vehicle for 8 weeks; and iv) HFD + IF + HP-B +

Ad-GLP-1R group, in which the mice were injected with Ad-shPGC1α on

Day 0 and Week 4, followed by IF + HP-B treatment for 8 weeks.

The mice were housed under standard laboratory

conditions with free access to water at a temperature of 24°C and a

humidity of 45%, with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. Anesthesia was

induced with 3-5% isoflurane, and deep anesthesia was confirmed by

the absence of a response to pain stimuli; 2% isoflurane was used

to maintain anesthesia during the procedures. At the end of the

experimental period, all mice were euthanized under deep anesthesia

with isoflurane (5% in oxygen), followed by cervical dislocation to

ensure death. Death was confirmed by the cessation of heartbeat and

respiratory movement, as well as the loss of reflexes.

In the first phase of the experiment, all the mice

were sacrificed at the end of the 8-week HFD treatment, and blood

and liver tissue samples were collected for analysis. For the IF

group all the mice were sacrificed within 48 h after the last

fasting cycle. The mice from all the groups were sacrificed at the

end of the experiment (after 8 weeks). Blood samples were collected

from the heart, and liver samples were obtained. In addition, liver

weights were recorded. The body weights were measured regularly,

and the liver index (liver weight/body weight) was calculated.

Additionally, liver histology, serum marker assessment of liver

function, and gene/protein expression analysis were performed to

assess the effects of the treatments. The present study was

conducted in strict accordance with ethical guidelines for animal

research and all applicable national regulations. The experimental

protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care

and Use Committee (IACUC) of Beijing University of Aeronautics and

Astronautics (approval no. 2023-KY-064-1; Beijing, China). All

procedures were designed to minimize animal suffering, and humane

care was provided throughout the study. In addition, all the animal

experiments complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and the NIH Guide

for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Insulin tolerance test (ITT)

ITT was conducted by first administering an

intraperitoneal (IP) injection of insulin at a dose of 1 U/kg body

weight to induce insulin action. Blood samples were then collected

from the tail tip at 0, 15-, 30-, 45-, 60- and 90-min

post-injection to measure blood glucose levels using a portable

glucometer.

Glucose tolerance test (GTT)

Prior to the GTT, the mice were fasted for 6 h (with

free access to water) to standardize the baseline blood glucose

levels. The baseline blood glucose value was measured at 0 min

(pre-injection) via tail-tip blood sampling. A sterile glucose

solution (20% w/v) was then administered via IP injection at a dose

of 2 g/kg body weight. Blood samples were subsequently collected

from the tail tip at 15-, 30-, 45, 60- and 120-min post-glucose

loading, and blood glucose levels were analyzed at each time point

using a portable glucometer.

H&E staining

The liver tissues were collected and fixed for 24 h

in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). The fixed liver tissues were then

dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 6-μm

thick sections. The sections were sequentially immersed in xylene

and a gradient of ethanol solutions for deparaffinization and

rehydration. The sections were then washed with tap water after

being stained for 5 min in a solution of hematoxylin (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The sections were

then stained with an eosin solution (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 1 min and rinsed with tap water. After

staining, the sections were dehydrated by sequential immersion in

70% ethanol (2 min), 80% ethanol (2 min), 95% ethanol (2 min), 100%

ethanol (twice, 2 min each), and xylene (twice, 5 min each).

Finally, the dehydrated sections were mounted with neutral balsam

and covered with coverslips. The stained sections were observed

under a light microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Determination of aspartate

aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

levels

The serum levels of AST and ALT were measured in

accordance with the guidelines provided by the AST Assay Kit (cat.

no. C010-2-1) and ALT activity assay kit (cat. no. C009-2-1; both

from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). The absorbance

was measured at 510 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

Detection of malondialdehyde (MDA)

levels

MDA levels in liver tissues were measured using MDA

assay kit (cat. no. A003-1-2; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Small interfering (siRNA)

transfection

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells were plated at a

density of 3×105 cells/well in 6-well plates and

cultured overnight. For siRNA transfection, 100 μl of

serum-free culture medium was first added to sterile centrifuge

tubes. Subsequently, 12 μl of a specific siRNA targeting

GLP-1R (si-GLP-1R, 5'-UAUUGGAAAACAAUUAUGCUU-3') or negative control

(NC, 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUAA-3') was added to achieve a final

concentration of 20 nM siRNA. In another tube, 12 μl of

HiPerFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen China Co., Ltd.) was added

to 100 μl of serum-free culture medium. The contents of

these two tubes were gently mixed and incubated at room temperature

for 20 min to form the transfection complex. Next, the mixture was

added to the wells containing the cells at 37°C for 6 h. The

transfection mixture was then removed, and fresh DMEM containing

10% FBS was added, followed by incubation for 24 h.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviations (SDs). Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests were used

to compare two groups, and one-way analysis of variance followed by

Tukey's post hoc test was used to compare three or more groups.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

HP-B and fasting work together to

counteract OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation in liver cells

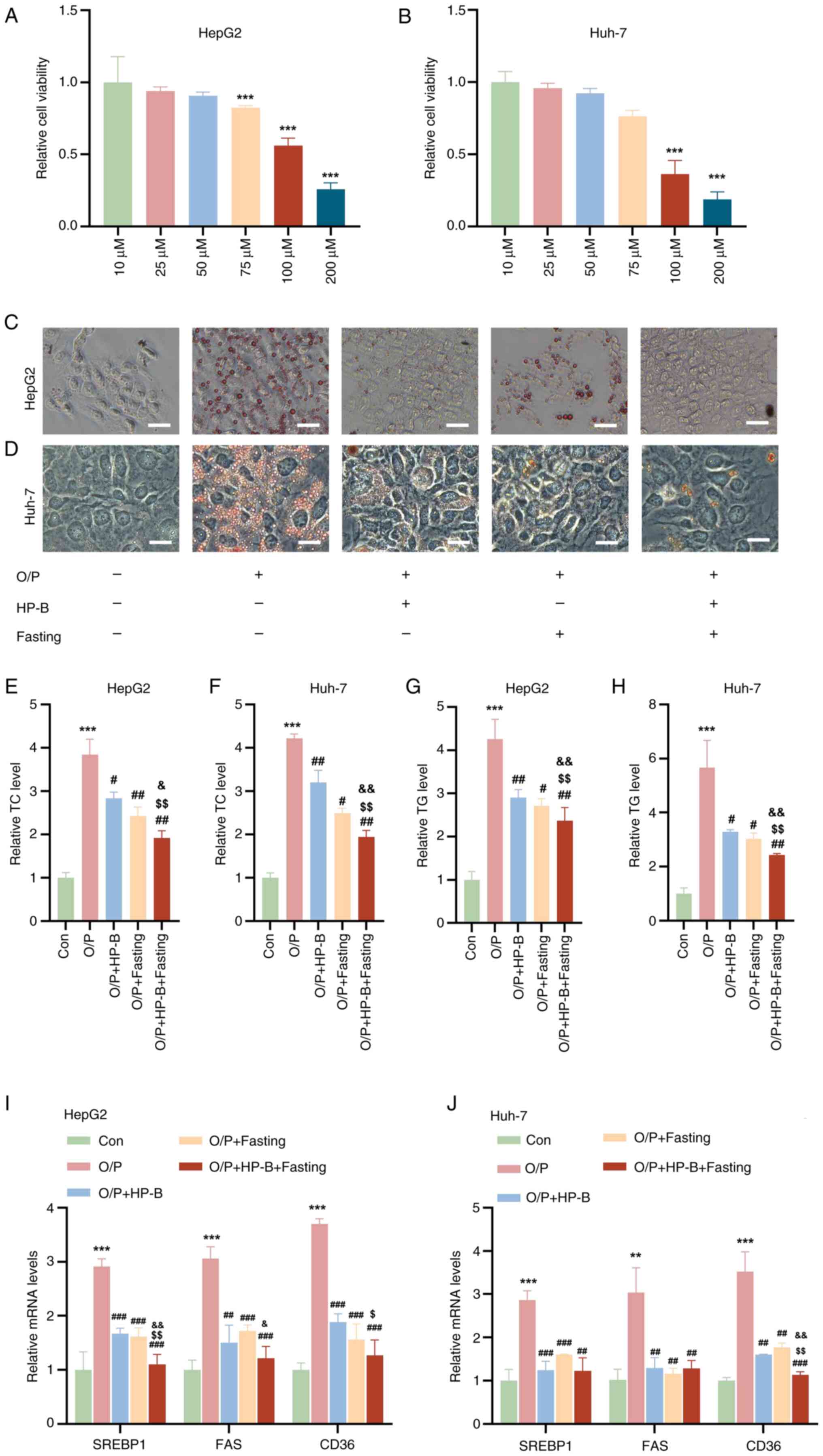

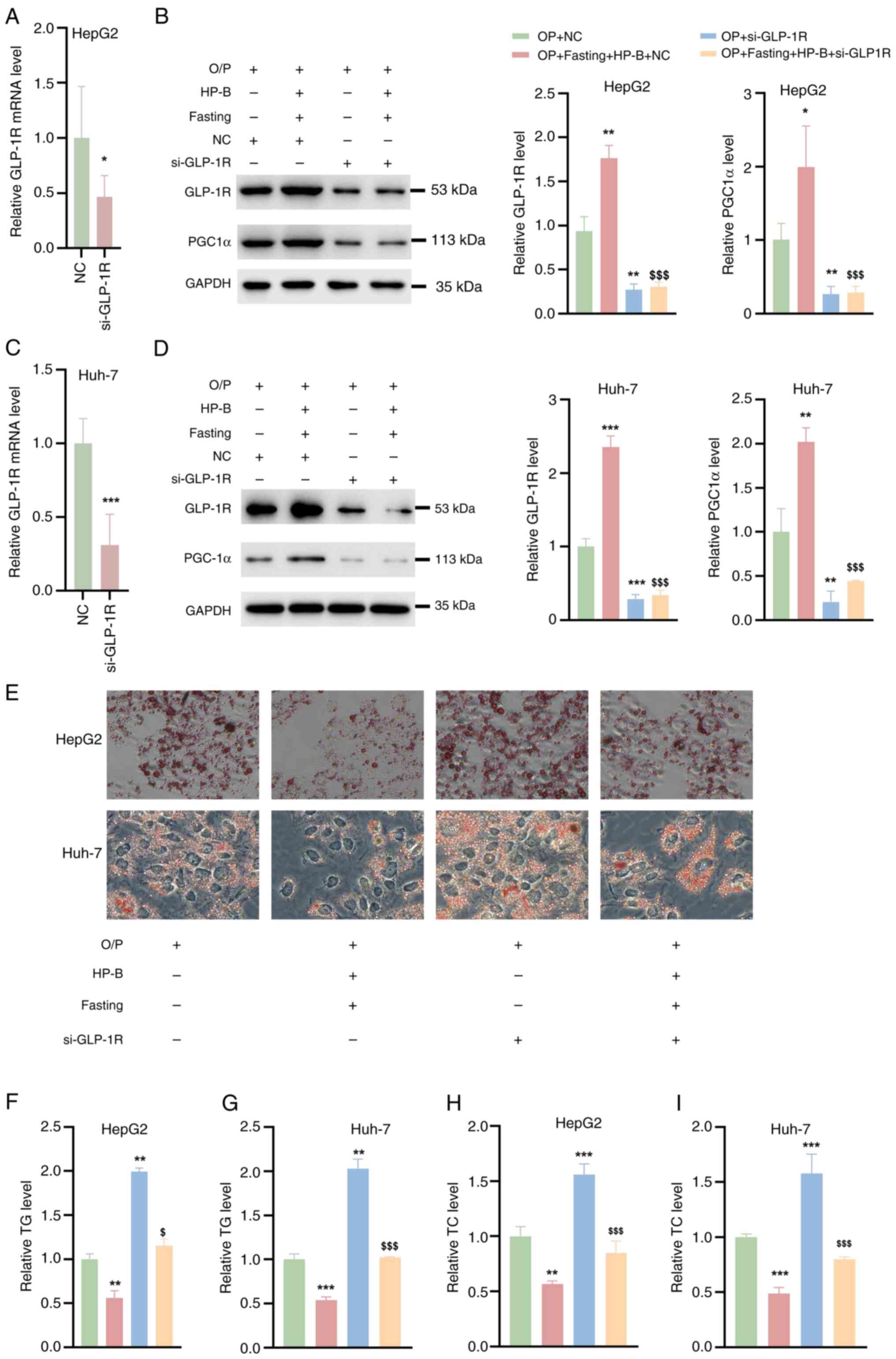

CCK-8 analysis revealed that treatment with 10, 25

and 50 μM HP-B did not affect the viability of HepG2 or

Huh-7 liver cancer cells, whereas treatment with 75, 100 and 200

μM HP-B reduced the viability of both cell types (Fig. 1A and B). Therefore, 50 μM

HP-B was used in subsequent experiments. Oil Red O staining

revealed that OA/PA treatment markedly increased lipid accumulation

in both cell types (Fig. 1C and

D). However, HP-B treatment effectively attenuated

OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation. Similarly, in HepG2 and Huh-7

liver cancer cells, fasting alone restored OA/PA-induced lipid

accumulation, but HP-B treatment in addition to fasting

significantly decreased lipid accumulation (Fig. 1C and D). After OA/PA treatment,

quantitative analysis revealed that HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer

cells had higher TC and TG levels than the control cells (Fig. 1E-H). Moreover, the increased TC

and TG levels caused by OA/PA were reversed by HP-B treatment and

fasting, and the combined treatment had a greater effect (Fig. 1E-H). Additionally, the mRNA

levels of genes associated with lipid production and absorption

(SREBP1, FAS and CD36) in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells were

quantitatively examined. OA/PA treatment significantly increased

the mRNA levels of these genes compared with the control group

(Fig. 1I and J). However, the

OA/PA-induced increase in the mRNA levels of these genes was

reduced by HP-B treatment and fasting, and the combination

treatment had a more significant effect (Fig. 1I and J). In conclusion,

OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation and related gene upregulation in

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells are successfully reversed by

both HP-B treatment and fasting, with their combined use showing

increased efficiency.

| Figure 1Effects of HP-B treatment and fasting

on OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation and gene expression in HepG2

and Huh-7 liver cancer cells. (A and B) Cell Counting Kit-8

analysis revealed that 10, 25 and 50 μM HP-B did not

significantly alter cell viability, whereas 75, 100 and 200

μM HP-B reduced cell viability in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells. (C

and D) Oil Red O staining of HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells

treated with OA/PA revealed significant lipid accumulation compared

with the Con group. Both HP-B treatment and fasting reversed

OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation, and the combined HP-B and fasting

treatment further reduced lipid accumulation (Scale bar, 10

μm). (E-H) Quantitative analysis of TC and TG levels in

HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells. (I and J) Quantitative analysis

of the mRNA levels of lipid synthesis- and uptake-related genes

(SREBP1, FAS and CD36) in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells.

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. Con;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and

###P<0.001 vs. OA/PA; $P<0.05 and

$$P<0.01 vs. OA/PA + HP-B; &P<0.05

and &&P<0.01 vs. OA/PA + Fasting. HP-B,

heterophyllin B; OA/PA, oleic acid/palmitic acid; TC, total

cholesterol; TG, triglycerides. |

Combined HP-B and fasting treatment

reverses the OA/PA-induced decrease in the MMP

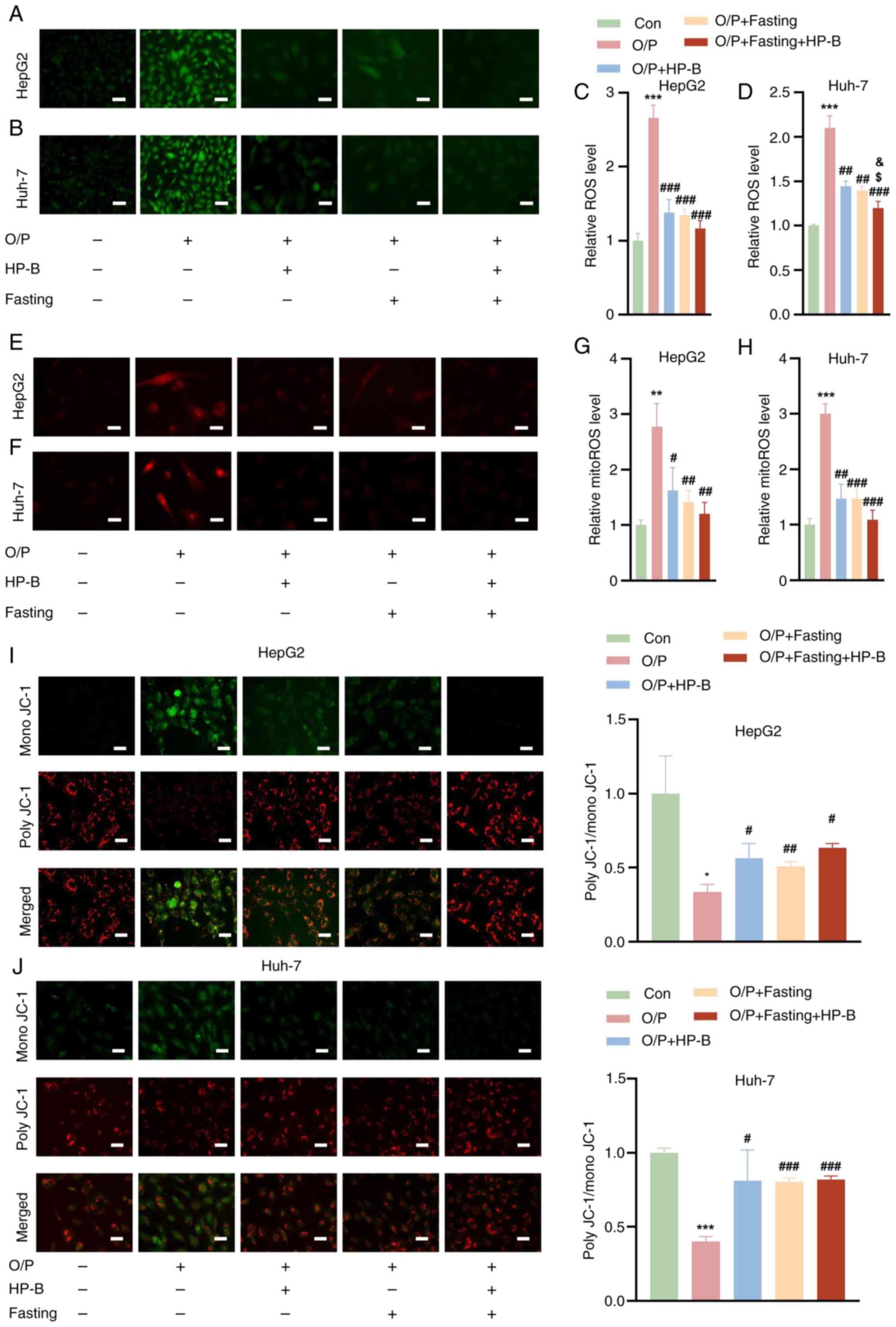

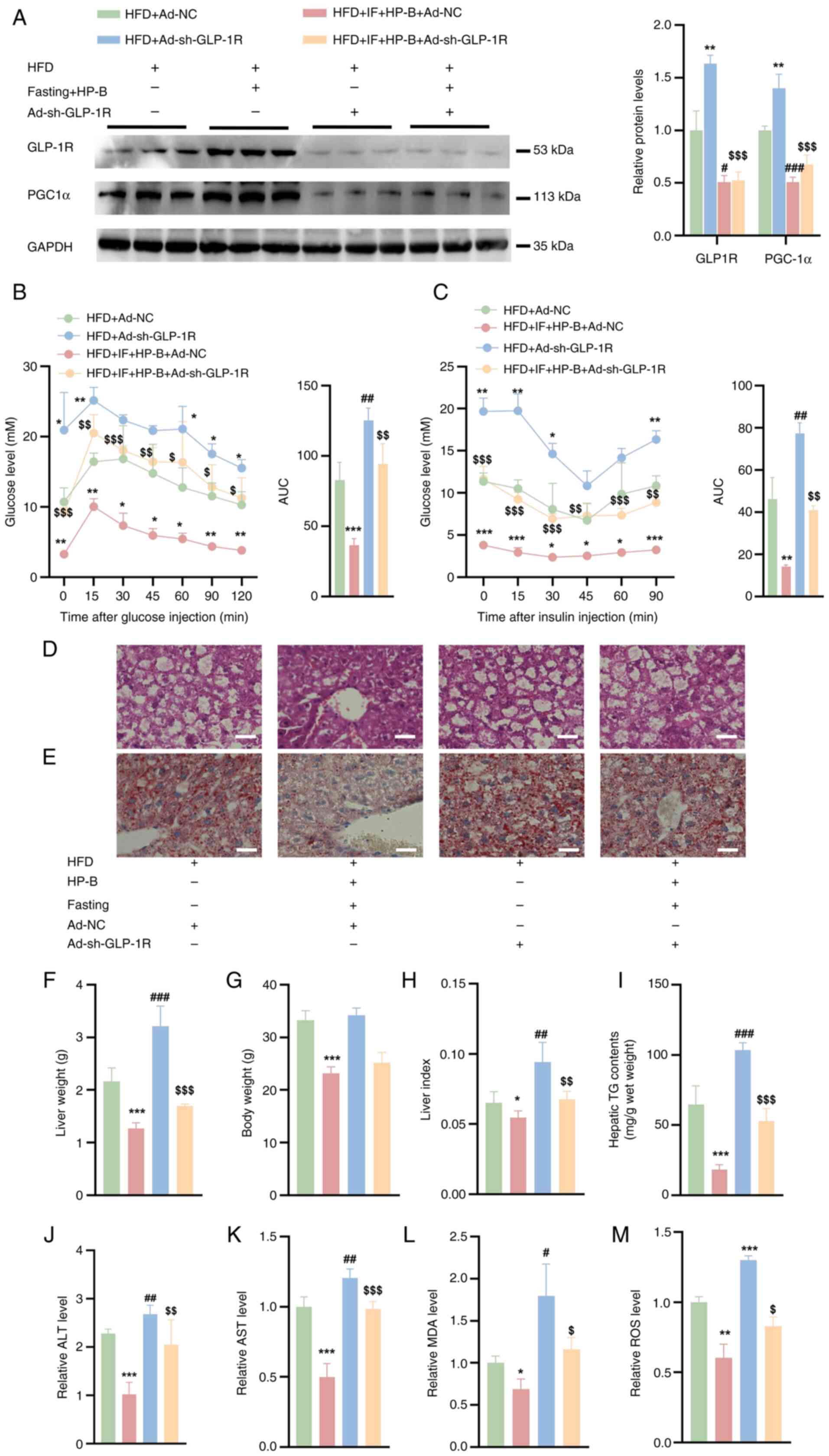

Assessment of the ROS levels in HepG2 and Huh-7

liver cancer cells revealed that OA/PA treatment increased the ROS

levels compared with those in the Con group. However, HP-B

treatment and fasting substantially reduced this increase in ROS

levels in both the HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells (Fig. 2A-D). Notably, the combined

treatment of HP-B and fasting further reduced the ROS levels

(Fig. 2A-D). Compared with the

controls, OA/PA treatment significantly increased the levels of

mitoROS in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells. Both HP-B treatment

and fasting reduced the increase in mitoROS levels caused by OA/PA,

and the combined treatment resulted in a more significant reduction

(Fig. 2E-H). Additionally, OA/PA

treatment significantly decreased the MMP in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver

cancer cells. Both HP-B treatment and fasting reversed the

OA/PA-induced reduction in the MMP, and the combined treatment

further ameliorated this decrease (Fig. 2I and J).

| Figure 2Effects of HP-B treatment and fasting

on OA/PA-induced changes in ROS, mitoROS, and the MMP in HepG2 and

Huh-7 liver cancer cells. (A and B) Representative images of the

ROS levels in (A) HepG2 and (B) Huh-7 cells are shown. (C and D)

Quantitative analysis of ROS levels in (C) HepG2 and (D) Huh-7

cells. (E and F) Representative images and quantification of

mitoROS levels in (E) HepG2 and (F) Huh-7 cells are shown. (G and

H) Quantitative analysis of mitoROS levels in (G) HepG2 and (H)

Huh-7 cells. (I and J) Representative images and quantification of

the MMP in (I) HepG2 and (J) Huh-7 cells are shown. Scale bar, 10

μm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. Con; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. OA/PA;

$P<0.05 vs. OA/PA + HP-B; &P<0.05

vs. OA/PA + Fasting. HP-B, heterophyllin B; OA/PA, oleic

acid/palmitic acid; ROS, reactive oxygen species; mitoROS,

mitochondrial ROS; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential. |

Combined HP-B and fasting treatment

reverses the OA/PA-induced decrease in GLP-1R and PGC1α

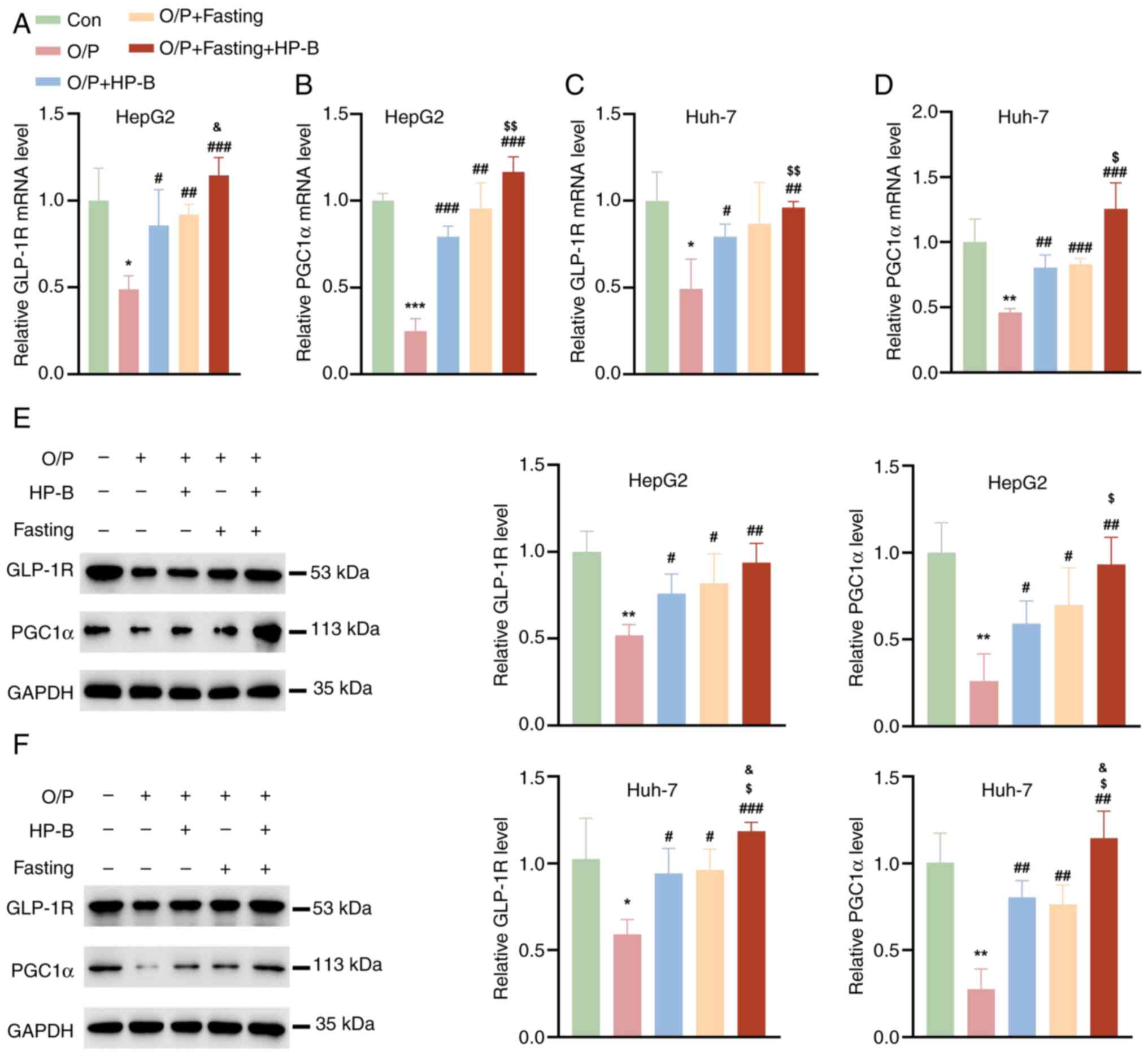

To evaluate the effects of HP-B and fasting on the

expression of GLP-1R and PGC1α, the mRNA levels of GLP-1R and PGC1α

were examined in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells. Compared with

the Con group, OA/PA significantly decreased the mRNA levels of

GLP-1R and PGC1α, whereas HP-B treatment and fasting reversed the

OA/PA-induced reduction in the mRNA levels of GLP-1R and PGC1α

(Fig. 3A-D). More importantly,

the combination of HP-B treatment and fasting further increased the

mRNA levels of GLP-1R and PGC1α (Fig. 3A-D). Evaluation of the GLP-1R and

PGC1α protein expression levels in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer

cells revealed that OA/PA treatment significantly decreased the

protein expression of GLP-1R and PGC1α (Fig. 3E and F). However, HP-B treatment

or fasting reversed the OA/PA-induced decrease in the protein

expression of GLP-1R and PGC1α, and the combined treatment of HP-B

and fasting was more effective (Fig.

3E and F).

Combined HP-B and fasting treatment

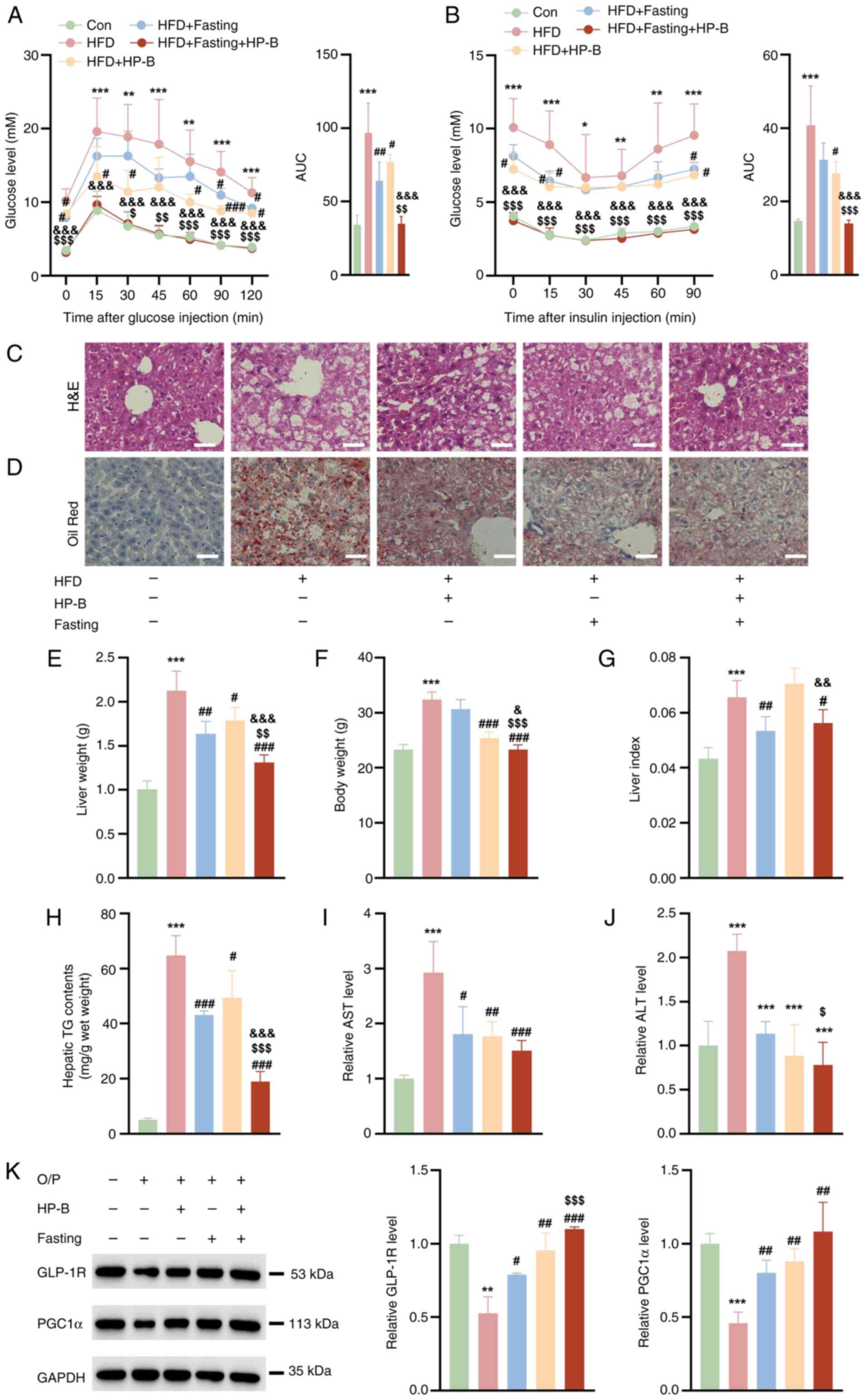

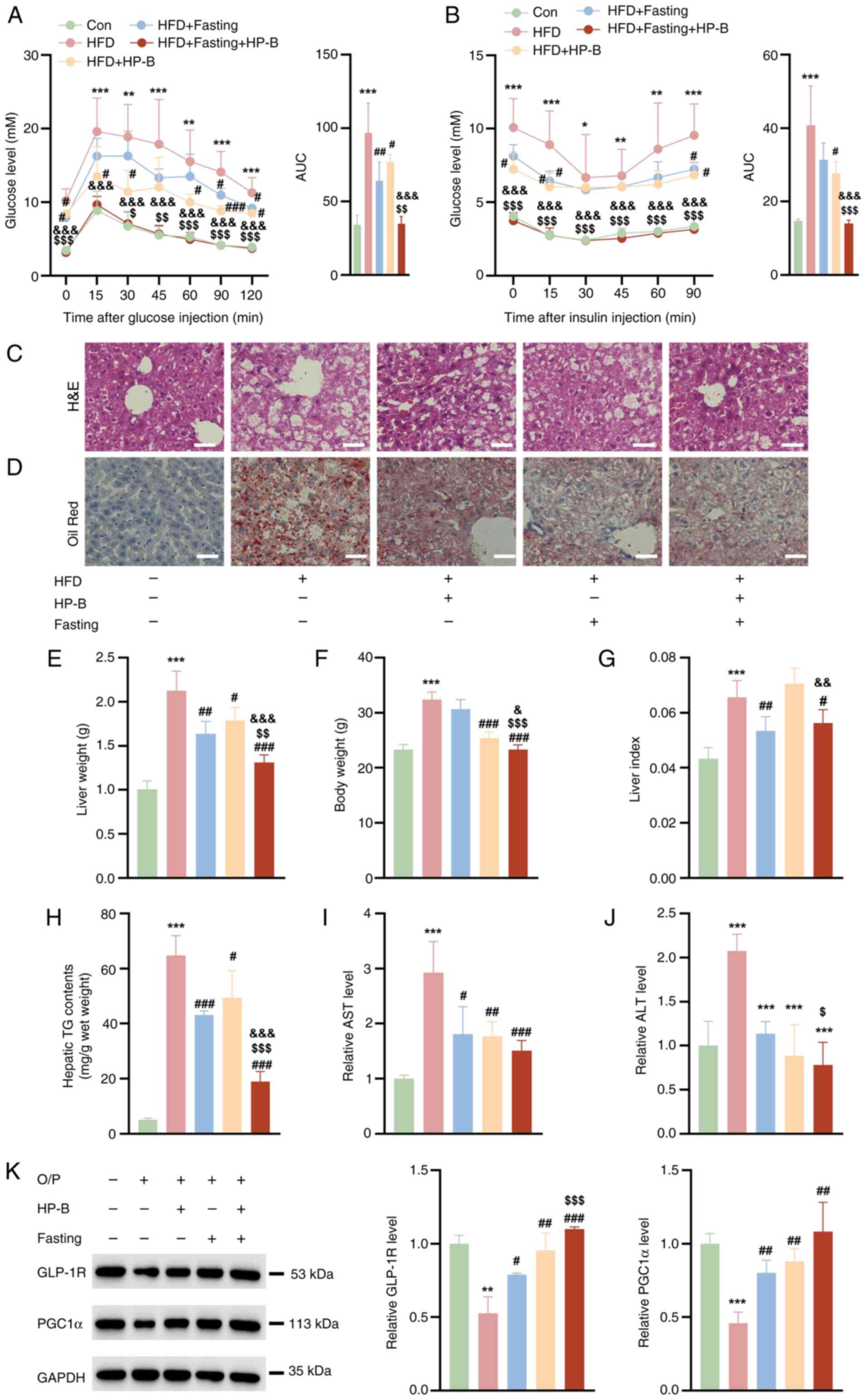

reverses lipid accumulation in the livers of HFD-fed mice

Compared with the Con group, the HFD group presented

significantly impaired glucose tolerance and decreased insulin

sensitivity, indicating HFD-induced IR (Fig. 4A and B). Both interventions

improved glucose metabolism: Fasting monotherapy reduced GTT area

under the curve (AUC) by 19.96 (vs. HFD: 96.84-76.88). HP-B

monotherapy reduced GTT AUC by 32.69 (vs. HFD: 96.84-64.15).

Similarly, ITT AUC decreased by 13.10 with fasting and 9.47 with

HP-B alone (vs. HFD: 40.84) (Fig.

4B). Critically, combination therapy reduced GTT AUC by 61.91

(vs. HFD: 96.84-34.93) and decreased ITT AUC by 26.81 (vs. HFD:

40.84-14.03). This exceeded the sum of individual effects,

specifically, GTT: 61.91> (32.69+19.96)=52.65, and ITT:

26.81> (9.47+13.10)=22.57, demonstrating synergistic reversal of

IR (Fig. 4A and B). Furthermore,

the combined HP-B and fasting treatment had a more pronounced

effect, as evidenced by enhanced glucose clearance in the GTT and

greater improvement in insulin sensitivity in the ITT, which

suggested a synergistic effect of HP-B and fasting in mitigating IR

and metabolic dysfunction (Fig. 4A

and B). Compared with those of the control group, the livers of

HFD-fed mice presented a substantial increase in lipid accumulation

(Fig. 4C and D). HP-B treatment

or fasting reduced hepatic lipid accumulation, and the combined

HP-B and fasting further reduced lipid levels (Fig. 4C and D). Compared with those in

the control group, the mice in the HFD group had significantly

greater liver weights, body weights and liver indices (Fig. 4E-G). Fasting effectively reduced

the liver weight, body weight and liver index in HFD-fed mice,

whereas HP-B treatment specifically reduced the liver weight and

liver index (Fig. 4E-G). Hepatic

steatosis was profoundly induced by HFD, with TG content surging to

64.74±7.23 mg/g wet weight vs. 5.127±0.62 mg/g in controls

(Fig. 4H). Monotherapies

partially attenuated this accumulation: HP-B alone reduced TG by

21.65 mg/g (HFD + HP-B: 43.09±1.54 mg/g), while fasting alone

reduced TG by 15.30 mg/g (HFD + Fasting: 49.44±6.113 mg/g).

Critically, the combination therapy achieved a TG reduction of

45.79 mg/g (HFD + Fasting + HP-B: 18.95±3.70 mg/g), significantly

exceeding the additive effect of monotherapies (21.65+15.30=36.95

mg/g) (Fig. 4H). This

enhancement beyond additivity demonstrates synergistic amelioration

of hepatic lipidosis. Additionally, the HFD group presented

significantly elevated levels of AST and ALT compared with those in

the control group. The HP-B and fasting treatments clearly reduced

these indices (Fig. 4I and J).

The protein expression levels of GLP-1R and PGC1α in the livers of

HFD-fed mice were significantly lower than those in the control

group (Fig. 4K). HP-B treatment

or fasting increased the expression of these proteins, and the

combined treatment exerted a more significant effect on PGC1α

protein expression (Fig. 4K).

These findings suggested that the combination of HP-B treatment and

fasting may exert a synergistic effect on hepatic lipid metabolism

and overall liver function.

| Figure 4Effects of HP-B treatment and fasting

on lipid accumulation and related parameters in the livers of

HFD-fed mice. (A) Glucose tolerance test and AUC quantification.

(B) Insulin tolerance test and AUC quantification. (C and D)

Representative H&E and Oil Red O images showing that HP-B

treatment or fasting treatment reduced liver lipid accumulation to

some extent, whereas the combined HP-B and fasting treatment

further significantly reduced lipid accumulation (Scale bar, 25

μm). (E-G) HP-B treatment or fasting reduced the liver

weight, body weight and liver index. The combined treatment

resulted in a more pronounced reduction in liver weight and body

weight, but the liver index did not obviously change. (H-J) HP-B

treatment and fasting lowered these levels, and the combined

treatment resulted in a more significant reduction in TG and ALT

levels than HP-B treatment alone, as well as a more significant

reduction in TG levels than fasting alone. (K) HP-B treatment or

fasting increased the protein levels of GLP-1R and PGC1α, and the

combined treatment further increased PGC1α protein expression

compared with HP-B treatment alone. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. Con;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and

###P<0.001 vs. HFD; $P<0.05,

$$P<0.01 and $$$P<0.001 vs. HFD + HP-B;

&P<0.05, &&P<0.01 and

&&&P<0.001 vs. HFD + Fasting. HP-B,

heterophyllin B; HFD, high-fat diet; AUC, area under the curve; TG,

triglycerides; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST aspartate

aminotransferase; GLP-1R, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor; PGC1α,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator

1-alpha. |

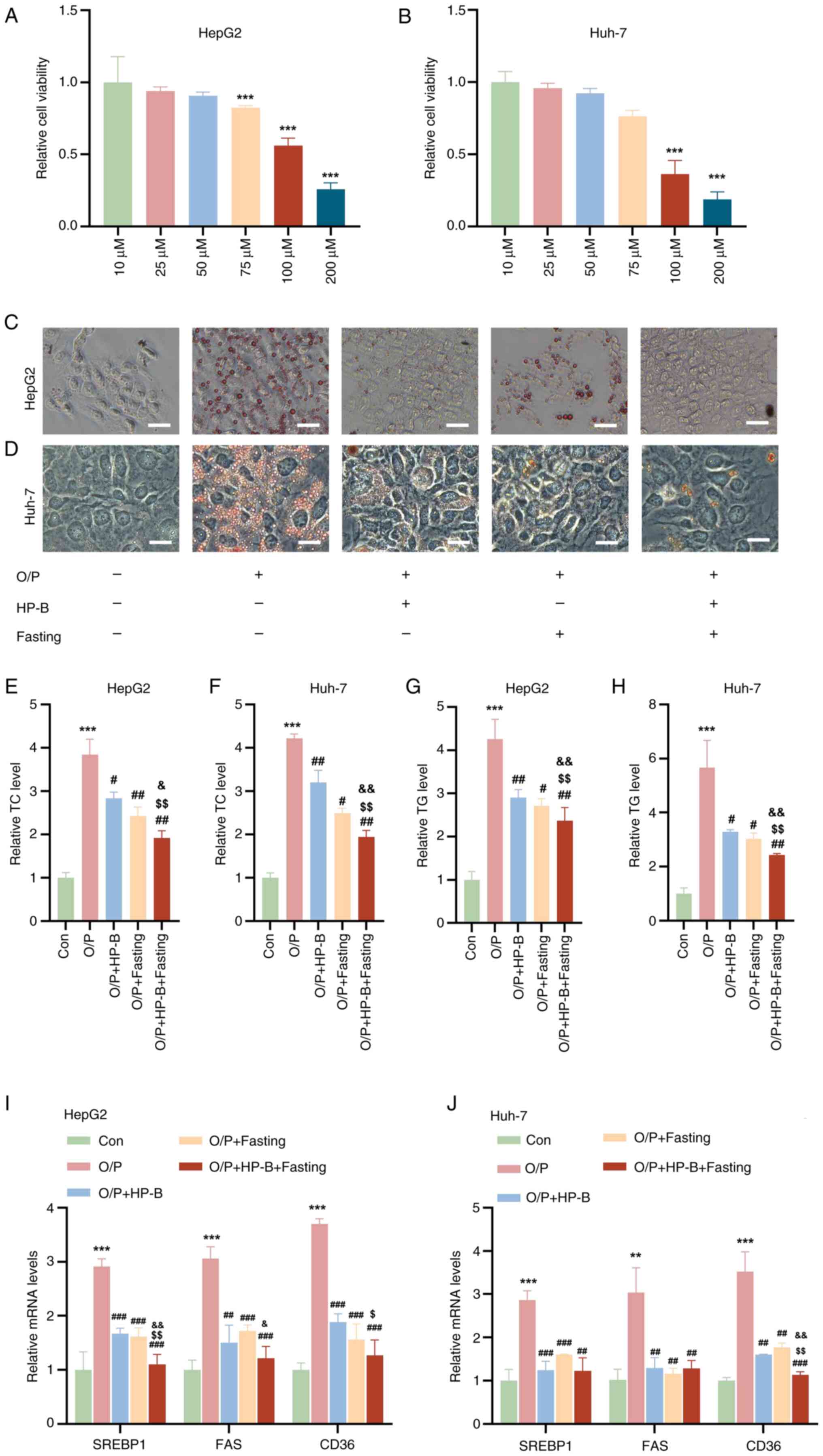

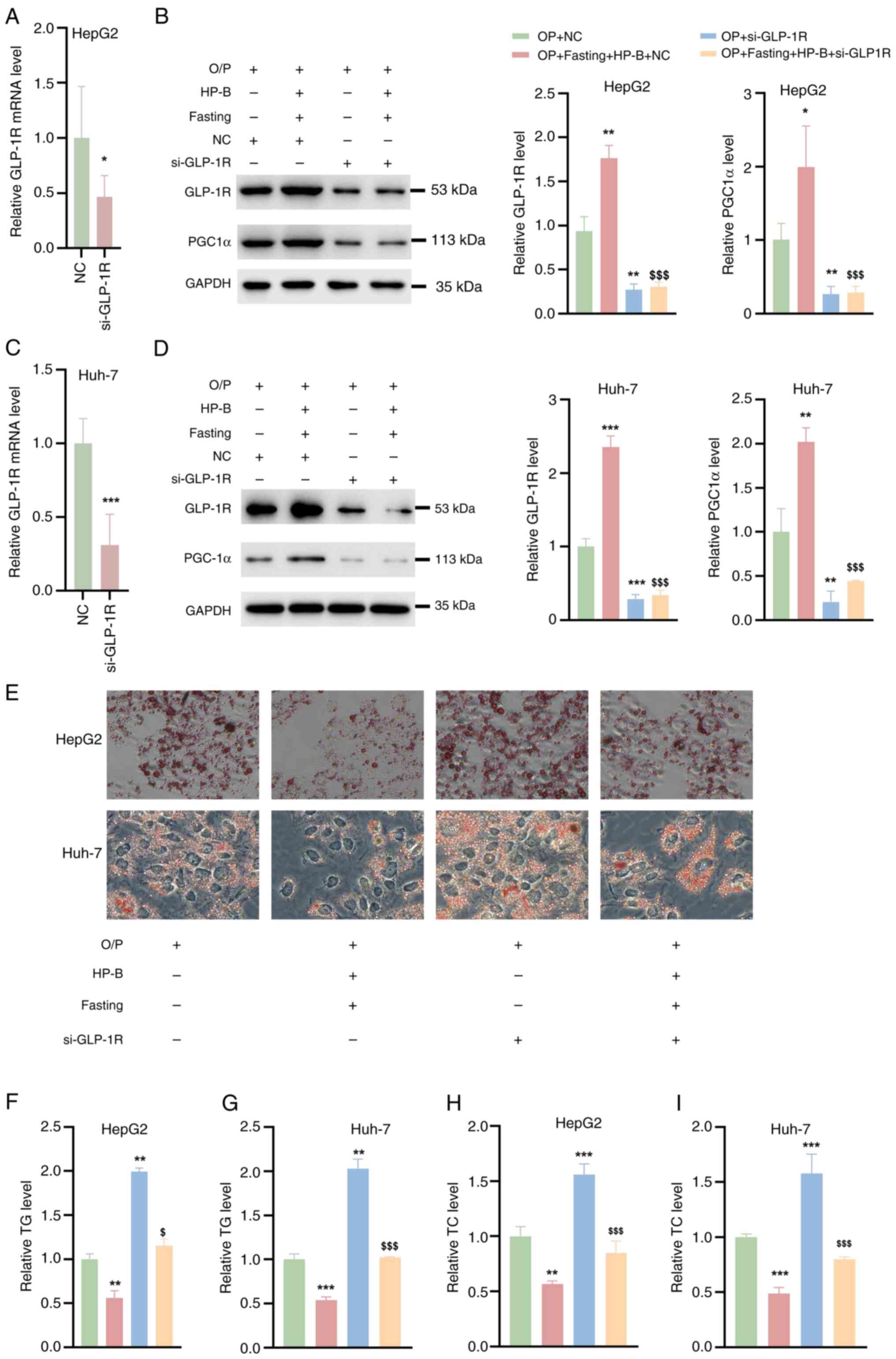

GLP-1R silencing reverses OA/PA-induced

lipid accumulation in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells

si-GLP-1R or NC were then transfected into HepG2 and

Huh-7 cells which were not combined with any other treatments.

RT-qPCR analysis showed that the mRNA level of GLP-1R was decreased

in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells compared with those of NC (Fig. 5A and C). To examine whether the

combination of HP-B treatment and fasting ameliorates OA/PA-induced

lipid accumulation in hepatocytes via GLP-1R, siRNAs specifically

targeting SLP-1R were used. Compared with the Con group, si-GLP-1R

significantly reduced GLP-1R expression in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver

cancer cells (Fig. 5B and D).

Moreover, GLP-1R silencing reduced downstream PGC1α protein

expression (Fig. 5B and D).

GLP-1R silencing significantly decreased the protein level of

GLP-1R and suppressed PGC1α expression in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver

cancer cells pretreated with OA/PA (Fig. 5B and D). Oil red O staining

revealed that while OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation was mitigated

by fasting and HP-B treatments, this ameliorative effect was

prevented by PGC1α silencing (Fig.

5E). Furthermore, in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer cells, HP-B

treatment and fasting decreased the TG and TC levels, but GLP-1R

silencing further increased the TG and TC levels in these cells

(Fig. 5F-I). Hence, GLP-1R

silencing restores OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation, suggesting a

possible mechanism by which hepatocyte lipid metabolism is improved

by a combination of HP-B treatment and fasting via GLP-1R.

| Figure 5Effects of GLP-1R silencing on

OA/PA-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 and Huh-7 liver cancer

cells. (A and C) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis

showed that the mRNA levels of GLP-1R in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells were

reduced after siGLP-1R transfection. (B and D) Western blot

analysis revealed that siGLP-1R silenced GLP-1R expression in OA/PA

pre-treated HepG2 and Huh-7 cells and reversed the OA/PA-induced

increase in PGC1α protein levels. (E) Oil Red O staining

demonstrated that fasting and HP-B treatment reduced lipid

accumulation induced by OA/PA, but this effect was blocked by

GLP-1R silencing. (F-I) GLP-1R silencing further elevated (F and G)

TG and (H and I) TC levels in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells, counteracting

the reductions achieved by fasting and HP-B treatment.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. OA/PA; $P<0.05 and

$$$P<0.01 vs. OA/PA + HP-B + Fasting. HP-B,

heterophyllin B; GLP-1R, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor; OA/PA,

oleic acid/palmitic acid; si-, small interfering; TG,

triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; NC, negative control. |

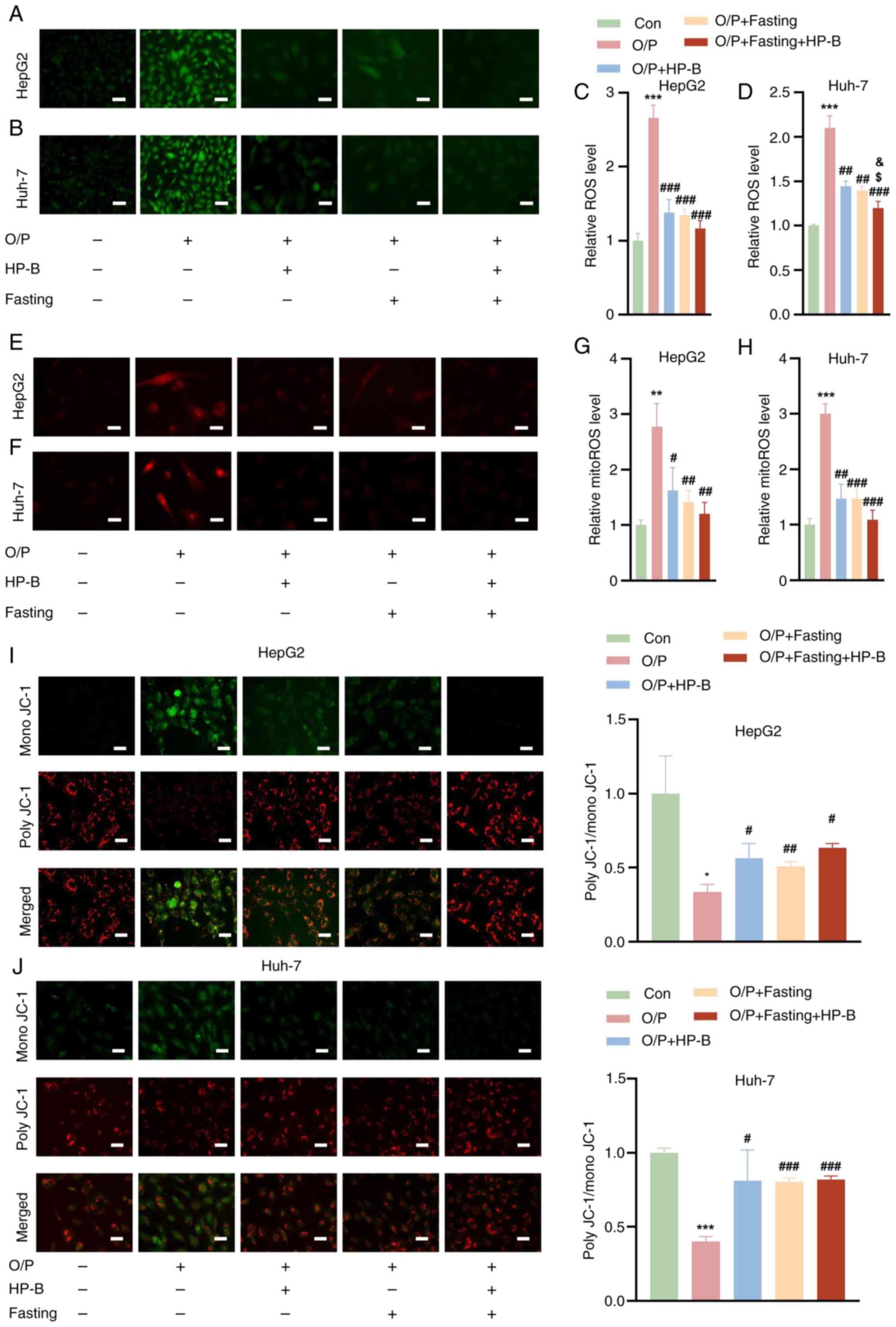

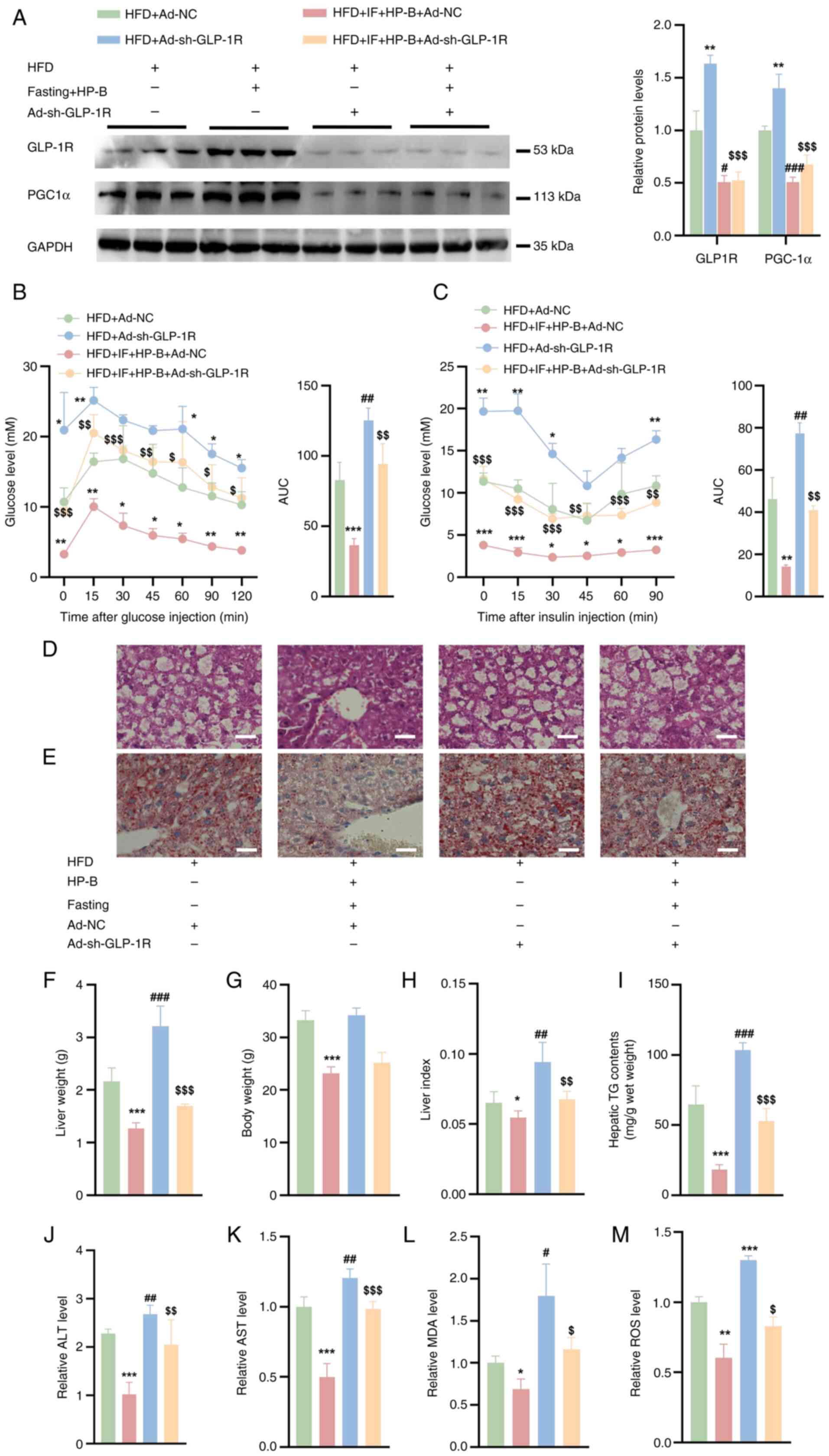

GLP-1R knockdown reverses the

hepatoprotective effects of fasting and HP-B treatment in HFD-fed

mice

As shown in Fig.

6A, GLP-1R was effectively silenced in the livers of HFD +

Ad-NC and HFD + Fasting + HP-B + Ad-NC mice. GLP-1R silencing

abolished the beneficial effects of HP-B treatment and fasting on

glucose metabolism, as evidenced by impaired GTT and reduced ITT,

with curves approaching those of the HFD group (Fig. 6B and C). Knocking down GLP-1R

abolished the protective benefits of HP-B and fasting in HFD-fed

mice. Compared with HFD + Ad-NC mice alone, Ad-short hairpin

(sh)GLP-1R exacerbated lipid accumulation in the livers of HFD-fed

mice (Fig. 6D and E). Silencing

GLP-1R prevented the combined effect of HP-B treatment and fasting

from reducing lipid droplet deposition, even in HFD-fed animals

subjected to these interventions (Fig. 6D and E). While GLP-1R knockdown

did not significantly affect the body weight of HFD-fed mice, it

increased their liver weight (Fig.

6F and G). Similarly, compared with those in the fasting and

HP-B treatment groups, the liver weights of the GLP-1R-deficient

mice were greater, but their body weights did not appreciably

change (Fig. 6F and G). Compared

with the HFD + Ad-NC group, the hepatic indices of HFD-fed mice

after fasting and HP-B treatment were lower, but these effects were

reversed when GLP-1R was silenced (Fig. 6H). Compared with that in the HFD

+ Ad-NC group, the mouse liver TG content was lower after GLP-1R

knockdown, but this effect was minimized with fasting and HP-B

treatment after silencing GLP-1R (Fig. 6I). Additionally, GLP-1R silencing

reversed the reductions in ALT and AST levels induced by fasting

and HP-B treatment (Fig. 6J and

K). Compared with those in the HFD + Ad-NC group, the MDA and

ROS levels in the livers of HFD-fed mice were lower after fasting

and HP-B treatment (Fig. 6L and

M). Conversely, Ad-shGLP-1R injections into the tail vein of

HFD-fed mice resulted in elevated levels of MDA and ROS in their

livers (Fig. 6L and M). These

findings indicated that GLP-1R is essential for the metabolic

improvements mediated by HP-B treatment and fasting.

| Figure 6GLP-1R knockdown impacts fasting and

HP-B treatment in HFD + Ad-NC mice. (A) Western blot analysis

showed that the expression of GLP-1R was decreased in the livers of

HFD mice. (B and C) Glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance

test. (D and E) H&E staining and Oil Red O staining of liver

sections from HFD-fed mice (Scale bar, 25 μm). (F and G)

Liver weights and body weights of HFD-fed mice. (H) Compared with

the oil/control treatment, fasting and HP-B treatment reduced the

liver index, whereas GLP-1R knockdown reversed this effect. (I)

GLP-1R knockdown reduced the TG content compared with that in

HFD-fed mice, and this effect was counteracted by fasting and HP-B

treatment. (J and K) Fasting and HP-B treatment decreased the ALT

and AST levels, and these reductions were reversed by GLP-1R

knockdown. (L and M) Fasting and HP-B treatment reduced the MDA and

ROS levels, whereas Ad-shGLP-1R injection increased these levels.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. HFD + Ad-NC; #P<0.05,

##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs. HFD +

Ad-sh-GLP-1R; $P<0.05, $$P<0.01 and

$$$P<0.001 vs. HFD + HP-B + IF. GLP-1R, glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor; HP-B, heterophyllin B; HFD, high-fat diet; NC,

negative control; TG, triglycerides; ALT, alanine aminotransferase;

AST aspartate aminotransferase; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; sh-, short hairpin. |

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that IF

effectively improves MASLD by modulating metabolism, reducing fat

accumulation, and mitigating inflammatory responses (5,21). However, prolonged fasting may

lead to potential side effects, such as hypoglycemia and

nutritional deficiencies, and the long-term efficacy remains to be

further validated (22).

Therefore, the inclusion of natural compounds with hepatoprotective

properties, such as HP-B, may enhance the therapeutic effects of IF

while mitigating its adverse outcomes. HP-B has significant

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities, and

antitumor effects, making it a promising candidate for improving

liver function and providing additional benefits in the management

of MASLD (14-16). Further investigation into the

synergistic effects of HP-B treatment combined with IF is warranted

to optimize treatment strategies for MASLD.

In the context of metabolic disease therapeutics,

GLP-1R agonists have emerged as key pharmacologic agents because of

their multifaceted benefits in glycemic control, weight reduction

and cardiovascular risk mitigation (23,24). These strategies offer distinct

advantages as follows: i) multitarget synergy enables greater

weight loss and comprehensive metabolic restoration, and ii)

potential to delay or reverse multiorgan pathologies such as MASLD.

Nevertheless, co-agonists present several challenges. Tolerability

remains a concern, as effective doses in animal models frequently

induce gastrointestinal adverse events (for example, nausea and

vomiting) in humans, which are particularly problematic for

GLP-1-based therapies. Additionally, the energy expenditure

mechanisms mediated via sympathetic nervous system activation and

brown adipose tissue thermogenesis are robust in rodents but often

fail to translate clinically (23,24). Further complexities include

intricate mechanism-of-action profiles, difficulties in optimizing

receptor activation ratios, and undefined cardiovascular safety

risks.

Previous research on HP-B has focused primarily on

its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities,

with applications largely confined to tumor suppression,

neurodegenerative diseases and cognitive disorders (16,20,25). However, the potential therapeutic

value of HP-B in MASLD has received limited attention. The present

study provides several novel contributions. First, the present

study provides the first experimental evidence supporting the

synergistic efficacy of HP-B treatment combined with IF in

alleviating MASLD-related metabolic disturbances. Second, the

present findings revealed a previously uncharacterized mechanism by

which HP-B exerts its metabolic benefits. Specifically,

GLP-1R-knockdown models confirmed the central role of the

GLP-1R/PGC1α signaling axis in mediating the protective effects of

HP-B. These findings significantly broaden the pharmacological

profile of HP-B and suggest a new conceptual and therapeutic

framework for MASLD intervention.

Previous studies have shown that the activation of

GLP-1R regulates lipid metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis via

the AMPK/PGC1α signaling axis (26,27). For example, in a spinal cord

injury model, the exendin9-39 GLP-1R antagonist and the SR18292

PGC1α inhibitor have been used to functionally validate the

GLP-1R/AMPK/PGC1α signaling pathway (26). Similarly, in obesity-related

chronic kidney disease models, the liraglutide GLP-1R agonist

reduces renal lipid deposition and restores mitochondrial function

through the Sirt1/AMPK/PGC1α axis (27). These studies collectively suggest

that AMPK may act as a critical intermediary linking GLP-1R

activation to PGC1α-mediated metabolic protection. To further

validate this hypothesis in the context of HP-B and IF, the authors

plan to employ pharmacologic inhibitors of AMPK (for example,

Compound C) and generate conditional AMPK knockout models. These

strategies will help elucidate the downstream signaling network of

GLP-1R and clarify the mechanistic basis of HP-B-mediated metabolic

regulation.

To ensure the reproducibility and physiological

relevance of the present results, a well-structured and widely

accepted 5:2 IF protocol was adopted. Prior studies have shown that

this regimen activates glucocorticoid (GC) signaling, which

contributes to metabolic reprogramming by upregulating Pck1

expression and enhancing fatty acid oxidation and gluconeogenesis

(4). Importantly, this GC

activation is considered an adaptive physiological response rather

than a marker of stress pathology. In support of this notion, 5:2

IF has been reported to have minimal effects on anxiety-like

behaviors or adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice (28), suggesting that it is behaviorally

and neurologically well tolerated. Although the present study did

not include direct measurements of serum corticosterone levels at

fasting endpoints due to logistical limitations, the authors plan

to incorporate such assessments in future experiments to

systematically evaluate stress-related responses and control for

their potential confounding impact.

Despite these promising findings, the present study

has certain limitations. Although reproducible, the OA/PA-induced

in vitro model of hepatic lipid accumulation may not fully

capture the complexity of MASLD pathogenesis. In future studies, it

is intended to incorporate additional proinflammatory stimuli, such

as TNF-α or lipopolysaccharide, to better mimic the inflammatory

milieu of the disease and increase the robustness of the findings.

Although GLP-1R knockdown significantly attenuated the beneficial

effects of HP-B treatment and IF, it did not completely abolish

them, which suggests the existence of GLP-1R-independent pathways,

potentially involving direct AMPK activation or the modulation of

oxidative stress responses. Thus, further investigation is

warranted. In addition, the present study did not assess the

pharmacokinetic properties of HP-B, such as its bioavailability,

half-life and tissue distribution. These parameters are crucial for

understanding the in vivo efficacy and safety profile of

HP-B. Without specific data, it is challenging to predict its

behavior in biological systems accurately. Future studies should

aim to characterize the pharmacokinetic parameters of HP-B to

better understand its therapeutic potential and optimize dosing

regimens. Moreover, while our data demonstrate functional

interaction between HP-B and the GLP-1R pathway, it is acknowledged

that direct molecular binding remains uncharacterized. To address

this mechanistic gap, molecular docking or receptor binding assays

will be carried out as future directions.

In summary, the present study elucidates the

mechanism by which HP-B treatment improves lipid metabolism,

protects mitochondrial function, and alleviates oxidative stress

through activation of the GLP-1R/PGC1α axis. The combination of

HP-B treatment and IF has significant synergistic effects and

offers a low-toxicity, mechanistically grounded intervention

strategy for the treatment of MASLD.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KL performed the experiments and wrote the

manuscript. LD and LX performed the experiments and interpreted the

data. SY supervised the project, interpreted the data, and wrote

the manuscript. KL and SY confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved

by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of

Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (approval no.

2023-KY-064-1; Beijing, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript or to generate images, and subsequently,

the authors revised and edited the content produced by the

artificial intelligence tools as necessary, taking full

responsibility for the ultimate content of the present

manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Beijing University of

Chemical Technology-China-Japan Friendship Hospital Biomedical

Transformation Engineering Research Center Joint Fund Project

(grant no. XK2022-07).

References

|

1

|

Marjot T, Tomlinson JW, Hodson L and Ray

DW: Timing of energy intake and the therapeutic potential of

intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating in NAFLD. Gut.

72:1607–1619. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Vasim I, Majeed CN and DeBoer MD:

Intermittent fasting and metabolic health. Nutrients. 14:6312022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Patikorn C, Roubal K, Veettil SK, Chandran

V, Pham T, Lee YY, Giovannucci EL, Varady KA and Chaiyakunapruk N:

Intermittent fasting and obesity-related health outcomes: An

umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials.

JAMA Netw Open. 4:e21395582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gallage S, Ali A, Barragan Avila JE,

Seymen N, Ramadori P, Joerke V, Zizmare L, Aicher D, Gopalsamy IK,

Fong W, et al: A 5:2 intermittent fasting regimen ameliorates NASH

and fibrosis and blunts HCC development via hepatic PPARα and PCK1.

Cell Metab. 36:1371–1393.e7. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Ezpeleta M, Gabel K, Cienfuegos S, Kalam

F, Lin S, Pavlou V, Song Z, Haus JM, Koppe S, Alexandria SJ, et al:

Effect of alternate day fasting combined with aerobic exercise on

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial.

Cell Metab. 35:56–70.e3. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Wang X, Wang J, Ying C, Xing Y, Su X and

Men K: Fenofibrate alleviates NAFLD by enhancing the PPARα/PGC-1α

signaling pathway coupling mitochondrial function. BMC Pharmacol

Toxicol. 25:72024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wu L, Mo W, Feng J, Li J, Yu Q, Li S,

Zhang J, Chen K, Ji J, Dai W, et al: Astaxanthin attenuates hepatic

damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease by up-regulating the FGF21/PGC-1α pathway. Br J Pharmacol.

177:3760–3777. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Quan Y, Shou D, Yang S, Cheng J, Li Y,

Huang C, Chen H and Zhou Y: Mdivi1 ameliorates mitochondrial

dysfunction in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting JNK/MFF

signaling. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 38:2215–2227. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cheng D, Zhang M, Zheng Y, Wang M, Gao Y,

Wang X, Liu X, Lv W, Zeng X, Belosludtsev KN, et al:

α-Ketoglutarate prevents hyperlipidemia-induced fatty liver

mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress by activating the

AMPK-pgc-1α/Nrf2 pathway. Redox Biol. 74:1032302024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhao Q, Liu J, Deng H, Ma R, Liao JY,

Liang H, Hu J, Li J, Guo Z, Cai J, et al: Targeting

mitochondria-located circRNA SCAR alleviates NASH via reducing mROS

output. Cell. 183:76–93.e22. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang T, Xu Q, Cao Y, Zhang C, Chen S,

Zhang Y and Liang T: Luteolin ameliorates hepatic steatosis and

enhances mitochondrial biogenesis via AMPK/PGC-1α pathway in

western diet-fed mice. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 69:259–267.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yang Y, Qiu W, Xiao J, Sun J, Ren X and

Jiang L: Dihydromyricetin ameliorates hepatic steatosis and insulin

resistance via AMPK/PGC-1α and PPARα-mediated autophagy pathway. J

Transl Med. 22:3092024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Meng D, Yin G, Chen S, Zhang X, Yu W, Wang

L, Liu H, Jiang W, Sun Y and Zhang F: Diosgenin attenuates

nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis through the hepatic SIRT1/PGC-1α

pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 977:1767372024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Liao HJ and Tzen JTC: Investigating

potential GLP-1 receptor agonists in cyclopeptides from

Pseudostellaria heterophylla, Linum usitatissimum, and Drymaria

diandra, and peptides derived from heterophyllin B for the

treatment of type 2 diabetes: An in silico study. Metabolites.

12:5492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang Z, Zhang C, Li X, Ma Z, Ge Y, Qian Z

and Song C: Heterophyllin B, a cyclopeptide from Pseudostellaria

heterophylla, enhances cognitive function via neurite outgrowth and

synaptic plasticity. Phytother Res. 35:5318–5329. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Deng J, Feng X, Zhou L, He C, Li H, Xia J,

Ge Y, Zhao Y, Song C, Chen L and Yang Z: Heterophyllin B, a

cyclopeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla, improves memory via

immunomodulation and neurite regeneration in i.c.v.Aβ-induced mice.

Food Res Int. 158:1115762022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Hutchison AL, Tavaglione F, Romeo S and

Charlton M: Endocrine aspects of metabolic dysfunction-associated

steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Beyond insulin resistance. J

Hepatol. 79:1524–1541. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xia M, Wu Z, Wang J, Buist-Homan M and

Moshage H: The coumarin-derivative esculetin protects against

lipotoxicity in primary rat hepatocytes via attenuating

JNK-mediated oxidative stress and attenuates free fatty

acid-induced lipid accumulation. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:19222023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhang H, Wang W, Hu X, Wang Z, Lou J, Cui

P, Zhao X, Wang Y, Chen X and Lu S: Heterophyllin B enhances

transcription factor EB-mediated autophagy and alleviates

pyroptosis and oxidative stress after spinal cord injury. Int J

Biol Sci. 20:5415–5435. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Holmer M, Lindqvist C, Petersson S,

Moshtaghi-Svensson J, Tillander V, Brismar TB, Hagström H and Stål

P: Treatment of NAFLD with intermittent calorie restriction or

low-carb high-fat diet-a randomised controlled trial. JHEP Rep.

3:1002562021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Mao T, Sun Y, Xu X and He K: Overview and

prospect of NAFLD: Significant roles of nutrients and dietary

patterns in its progression or prevention. Hepatol Commun.

7:e02342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Baggio LL and Drucker DJ: Glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor co-agonists for treating metabolic disease. Mol

Metab. 46:1010902021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Boland ML, Laker RC, Mather K, Nawrocki A,

Oldham S, Boland BB, Lewis H, Conway J, Naylor J, Guionaud S, et

al: Resolution of NASH and hepatic fibrosis by the GLP-1R/GcgR

dual-agonist Cotadutide via modulating mitochondrial function and

lipogenesis. Nat Metab. 2:413–431. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wei Y, Yin L, Zhang J, Tang J, Yu X, Wu Z

and Gao Y: Heterophyllin B inhibits the malignant phenotypes of

gastric cancer cells via CXCR4. Hum Cell. 36:676–688. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Han W, Li Y, Cheng J, Zhang J, Chen D,

Fang M, Xiang G, Wu Y, Zhang H, Xu K, et al: Sitagliptin improves

functional recovery via GLP-1R-induced anti-apoptosis and

facilitation of axonal regeneration after spinal cord injury. J

Cell Mol Med. 24:8687–8702. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Amorim M, Martins B and Fernandes R:

Immune fingerprint in diabetes: Ocular surface and retinal

inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 24:98212023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Roberts LD, Hornsby AK, Thomas A, Sassi M,

Kinzett A, Hsiao N, David BR, Good M, Wells T and Davies JS: The

5:2 diet does not increase adult hippocampal neurogenesis or

enhance spatial memory in mice. EMBO Rep. 24:e572692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|