Preterm birth (PTB) is a global maternal and

neonatal health problem, with ~15 million infants born preterm each

year, 11% of all live births (1). PTB contributes to 15% of under-five

childhood mortality and 35% of neonatal mortality worldwide

(2). It is associated with a

range of serious complications, including bronchopulmonary

dysplasia, respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular

hemorrhage, neurodevelopmental impairment, and necrotizing

enterocolitis (2), which rank

among the leading direct causes of mortality in children under

five. Roughly 40-45% of PTB cases occur spontaneously, 25-30%

result from preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM), and

the remaining 30-35% are due to medically indicated or elective

early deliveries (3).

Intra-amniotic infection is estimated to underlie ~35% of

spontaneous PTB and 50% of PPROM cases (3,4).

Studies have isolated specific bacterial species from the amniotic

fluid of PTB patients and confirmed that these organisms are common

vaginal colonizers, supporting ascending vaginal infection as the

primary route of microbial invasion into the amniotic cavity

(4,5).

Vaginal microbiota (VMB) plays a critical role in

maintaining maternal and fetal health (6). For example, Tabatabaei et al

(7) reported that

Lactobacillus spp. may reduce the risk of PTB, whereas

community state types (CSTs) associated with bacterial vaginosis

(BV) may increase PTB risk. Moreover, a

Lactobacillus-depleted CST, accompanied by elevated

abundances of Gardnerella or Mycoplasma, is linked to

higher PTB incidence (8).

Compared with early gestation, the VMB becomes increasingly stable

and Lactobacillus-dominated in late pregnancy (9,10), which may represent an

evolutionary mechanism to ensure successful pregnancy. By contrast,

VMBs dominated by other genera, particularly those associated with

BV, are generally considered suboptimal and correlate with greater

adverse outcomes (11,12).

PubMed and Web of Science were searched from

database inception through 31 May 2025. Medical Subject Headings

and free text terms 'preterm birth,' 'vaginal microbiota,'

'microbiota,' and 'probiotic' were combined in the search

strategy.

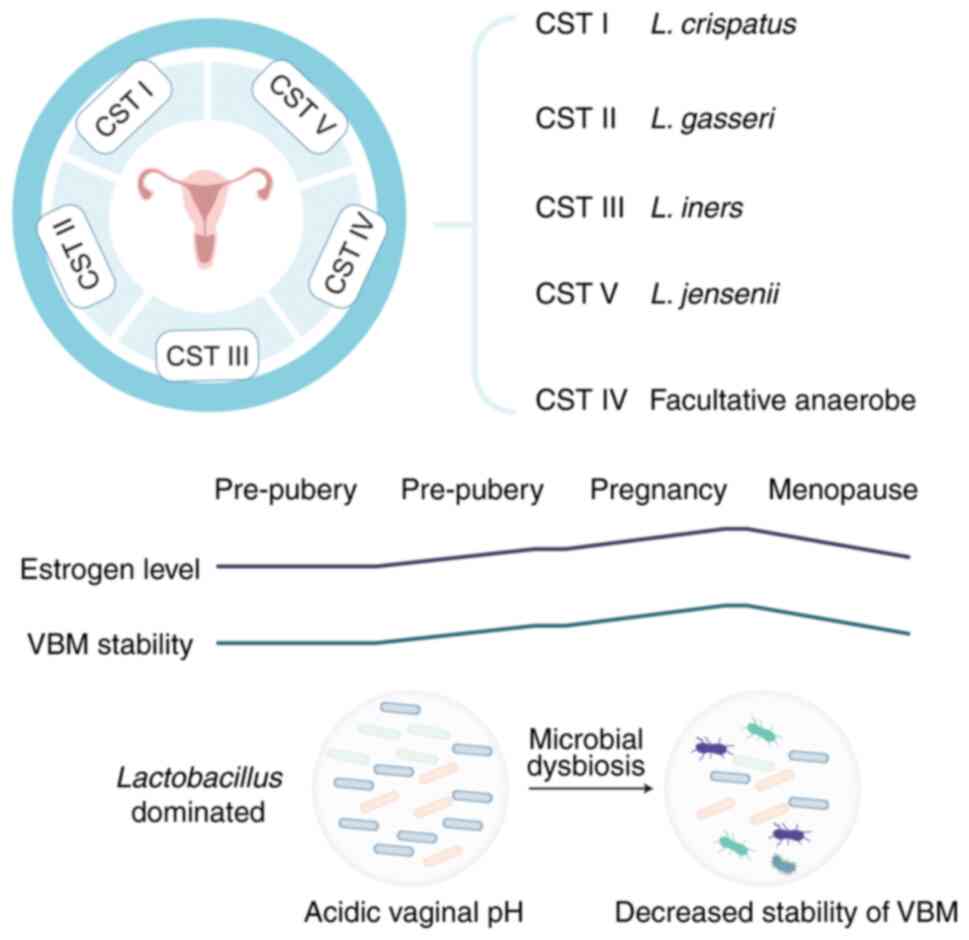

Throughout a woman's life span, both intrinsic and

extrinsic factors modulate VMB composition. Prior to menarche, low

estrogen levels correlate with a high-diversity microbiota

comprising aerobic, anaerobic and enteric bacteria (20). Although some women maintain VMB

stability across the menstrual cycle, the endocrine withdrawal of

estrogen and progesterone during menses, alongside endometrial

shedding and vaginal bleeding, induces transient shifts marked by

decreased Lactobacillus abundance that typically rebounds in

the follicular phase (21).

During pregnancy, hormonal stability, markedly elevated estrogen

concentrations and the absence of menses favor a

Lactobacillus dominated (LDOM) VMB (22). Estrogen is the principal host

factor sustaining the VMB, promoting epithelial thickening and

intracellular glycogen synthesis (23). Glycogen is hydrolyzed by host

α-amylase into glucose and maltose, substrates fermented by

Lactobacillus spp. into lactic acid, thereby reducing local

pH (24). Moreover, various

vaginal bacteria encode amylase-like enzymes capable of glycogen

metabolism (25,26). Glycogen may also originate from

epithelial-cell lysis induced by high lactate concentrations and

cytolysins secreted by Lactobacilli, a process potentially

mediated by hyaluronidase-1 and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-8

(27). With the onset of puberty

and rising estrogen, vaginal pH acidifies and meta-analyses have

demonstrated enhanced VMB stability and Lactobacillus

predominance (28,29). Similarly, cyclical and

pregnancy-related fluctuations in VMB stability parallel estrogen

levels; elevated estrogen is consistently associated with increased

VMB stability, which is beneficial for vaginal health. Conversely,

decreased estrogen post-pregnancy and in menopause is linked to

reduced VMB stability; however, estrogen therapy in postmenopausal

women restores a pronounced LDOM state (30,31). Notably, estrogen-containing

contraceptives increase Lactobacillus abundance in

reproductive-aged women and decrease BV incidence (32,33), further supporting a causal role

for estrogen in VMB regulation.

During pregnancy, the VMB is characterized by

decreased richness and diversity, with Lactobacillus spp.

emerging as the dominant genus. This maintenance of microbial

homeostasis is closely linked to rising estrogen levels (as shown

in Fig. 2), which not only

stimulate glycogen synthesis but also promote increased lactic acid

production by Lactobacillus. As gestation advances into the

late trimester, Lactobacillus proliferation is often

accompanied by a marked decline in dysbiosis-associated taxa such

as G. vaginalis, A. vaginae and P. bivia

(34). Studies show that during

pregnancy, vaginal microbiota communities dominated by

Lactobacillus usually remain stable or slowly change into

other community types still dominated by Lactobacillus

(8,35,36). Communities showing dysbiosis in

mid-gestation often become dominated by Lactobacillus. When

Gardnerella vaginalis dominates, its communities are

relatively unstable and usually shift to a Lactobacillus

iners community (35,36).

These dynamic shifts align with the overall trend toward an

optimized vaginal microenvironment during pregnancy. As white women

generally possess higher baseline Lactobacillus levels prior

to conception (36), black women

demonstrate a more pronounced transition toward

Lactobacillus dominance and enhanced VMB stability

throughout pregnancy (35,36), suggesting a stronger modulatory

effect of gestation on the VMB in this population. At parturition,

the precipitous decline in estrogen precipitates a significant

destabilization of the VMB (37,38), leading to community

restructuring: Lactobacillus proportions decrease while

anaerobic genera such as Peptoniphilus, Prevotella

and Anaerococcus proliferate; taxa whose overgrowth is often

linked to adverse outcomes (8,37). Moreover, short interpregnancy

intervals (<1 year) have been shown to markedly increase the

risk of PTB and other obstetric complications (39-41).

Abnormal VMB is recognized as a potential risk

factor for PTB. Clinical studies show that bacteria isolated from

the placenta and fetal membranes of preterm deliveries closely

match those in the vagina, supporting the idea that ascending

vaginal colonization by pathogens frequently leads to

intra-amniotic infection and PTB (71) and can be reproduced in various

animal models of ascending infection (72,73). Romero et al (74) compared the VMB of 18 women who

delivered preterm with 70 term controls and found no significant

differences in bacterial taxa, relative abundances, or CST

distributions when stratified by gestational age. A Peruvian cohort

likewise reported no association between vaginal CST and PTB

(5). These discrepancies may

reflect differences in maternal ethnicity, geographic location, and

gestational age at sampling. Fettweis et al (35) profiled the VMB and cytokine

milieu of 45 African-American women with PTB vs. 90 term-matched

controls. Multi-omics analyses showed markedly lower levels of

L. crispatus and higher abundances of BVAB1, Sneathia

amnii, TM7-H1 and a subset of Prevotella in the PTB

group. Term deliveries were more likely to harbor L.

crispatus and exhibit reduced prevalence of A. vaginae

and G. vaginalis. A small study of nulliparous

African-American women noted a nonsignificant trend toward reduced

diversity in spontaneous PTB (75), and another black cohort found

that although specific Lactobacillus abundances were not

linked to PTB risk, lower overall diversity associated with PTB

among African-American women (76). In a UK study, L. iners

dominance at 16 weeks was markedly associated with cervical

shortening and PTB before 34 weeks, whereas L. crispatus

dominance strongly predicted term birth; high-diversity communities

were not linked to cervical shortening or PTB, but

Lactobacillus depletion was relatively uncommon in that

cohort (77). The role of L.

iners remains ambiguous, as it appears in both healthy and

dysbiotic VMBs. Unlike the exclusionary L. crispatus, L.

iners has a reduced genome lacking key metabolic functions

(78), suggesting that L.

iners has evolved to tolerate other vaginal microbes, including

pathogens, and is often found in transitional microbiota states.

Consequently, L. iners may be unable to prevent pathogen

overgrowth during pregnancy, indirectly fostering high-risk VMB

profiles. Srinivasan et al (79) reported that high levels of L.

iners can be detected in women who are BV positive or BV

negative and across a broad range of vaginal pH values. Although

this phenomenon has been extensively documented under BV conditions

(80), it does not provide

direct evidence that the species is pathogenic during dysbiosis. Of

women ~50% are thought to harbor L. iners (23), so its persistent detection during

BV is unsurprising. Another study showed that the detection rate of

L. iners is similar among women with normal, intermediate

and BV Nugent scores (81);

however, relative abundance may be more decisive and further work

is required to quantify both relative and absolute levels under

diverse conditions. Shipitsyna et al (82) observed a decline in L.

iners during active BV and therefore suggested that it is

unlikely to be a primary pathogen; by contrast, other investigators

argue that communities dominated by L. iners are more prone

to shift toward dysbiosis, whereas those dominated by L.

crispatus appear more stable (83). A semi-quantitative qPCR study

that sampled Belgian women (predominantly Caucasian) throughout the

menstrual cycle found that during active BV, menstruation and after

intercourse, the previously dominant L. crispatus sharply

decreased, while L. iners became predominant, often

accompanied by a concomitant rise in Gardnerella vaginalis

(84), indicating greater

adaptability of L. iners to fluctuations in the vaginal

environment such as BV. Macklaim et al (85) further demonstrated that genes

involved in mannose and maltose uptake and glycogen degradation are

markedly upregulated in L. iners under BV. Additional

studies show that both the abundance and gene expression of L.

iners vary with the phase of the menstrual cycle (86); it is also possible that host

physiological changes first trigger BV and that L. iners

subsequently adapts. Clarifying this temporal sequence will be

critical for determining whether, and to what extent, L.

iners is harmful to the host.

Multiple studies have demonstrated significant

population specific differences in vaginal microbiome composition

and their associations with PTB risk. DiGiulio et al

(91) identified ethnicity as a

strong determinant of VMB composition and PTB risk. In a

predominantly white cohort, CSTs characterized by

Lactobacillus depletion, especially those enriched for

Gardnerella or Ureaplasma, were associated with

shorter gestational duration and higher PTB risk. A subsequent

comparison of Californian white and Alabaman black women revealed

more frequent Lactobacillus depletion and Gardnerella

enrichment among black women, yet these features predicted PTB only

in white women; in both groups, L. crispatus dominance

conferred protection against early delivery (92). Hyman et al (93) reported greater bacterial

diversity among white women who delivered preterm, while overall

species diversity was higher in African-American women. A more

recent investigation comparing black and non-black American women

confirmed that Lactobacillus depletion was more prevalent in

black women but increased PTB risk only in white women; it also

identified distinct taxa markedly associated with spontaneous PTB,

with stronger effects in the black cohort (94). The protective role of L.

crispatus has also been validated in European, Middle Eastern

and Asian populations, where L. iners dominance associated

with higher PTB risk and L. crispatus dominance with term

delivery (87). Sun et al

(95) showed in stratified

analyses that African-American women have increased abundance of

Lactobacillus iners and decreased abundance of

Lactobacillus crispatus and that lower levels of L.

crispatus are associated with increased risk of spontaneous

PTB. Another study of Asian and Myanmar/Karen minority women

combined microbiome profiling with cytokine analysis and found that

signatures composed of specific taxa and inflammatory cytokines

predict PTB more accurately than single markers, thus providing a

framework for biomarker development in resource limited settings

(96). Fettweis et al

(35) employed multi omics

approaches to identify a marked reduction in L. crispatus

and increases in pathogenic taxa such as BVAB1 and Sneathia

amnii alongside elevated levels of pro inflammatory cytokines

in cases of PTB, highlighting these features as candidate

biomarkers across populations. These findings indicate that

intervention strategies should prioritize probiotic strains that

enhance or maintain protective Lactobacilli colonization in

specific populations and that biomarker discovery should integrate

microbial and host inflammatory multi omics signatures to achieve

precise cross population applicability.

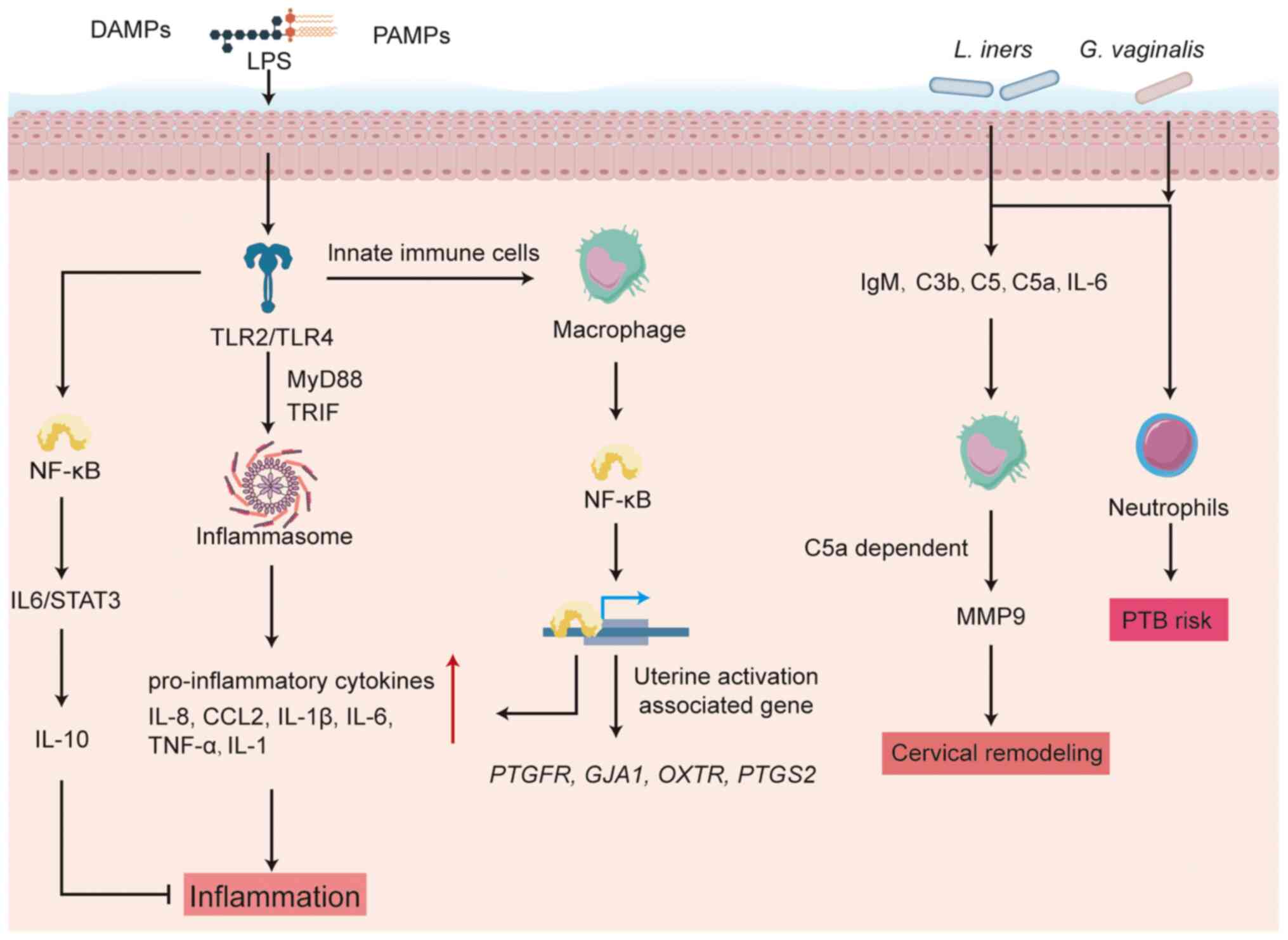

Elevated diversity within vaginal microbial

communities and the presence of bacterial vaginosis-associated

taxa, including Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium

vaginae and representatives of the Veillonellaceae family,

demonstrate a robust association with heightened risk of PTB prior

to 34 gestational weeks (7). A

study (97) indicates that one

pathway by which a diverse VMB elevates PTB risk is through

premature activation of parturition-associated inflammatory

cascades. In one early clinical investigation, women undergoing

cervical cerclage with braided sutures exhibited persistent VMB

dysbiosis and local inflammation, accompanied by ultrasound

evidence of premature cervical remodeling (97). A UK multicenter retrospective

analysis further showed that braided-suture cerclage was associated

with a threefold increase in intra-amniotic fetal death and a

twofold rise in PTB, whereas monofilament cerclage had no

significant impact on the VMB, cytokine concentrations or cervical

anatomy. These findings suggest that microbiota-triggered

inflammation may act directly on the cervix as pregnancy advances

(14). Activation of TLRs is

regarded as a critical initiating event for inflammation in both

term and preterm labor (PTL). TLRs are evolutionarily conserved

pattern recognition receptors that orchestrate innate immune

responses by sensing pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)

and damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), then triggering

downstream signaling to induce cytokine and chemokine release (as

illustrated in Fig. 3) (98). Among TLR family members, the

functional role of TLR4 is best characterized. TLR4 binds

lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other PAMP/DAMP ligands and its

activation state in the uterus correlates with both term and PTL.

In mice, TLR4 knockout delays parturition and markedly reduces

neonatal survival (99).

Pharmacologic blockade of TLR4 signaling with the antagonist

(+)-naloxone inhibits Escherichia coli induced inflammatory

cascades and prevents PTB (100). More recently, decidual

endothelial cell specific TLR4 expression has been shown to be

essential: Mice lacking endothelial TLR4 resist LPS-induced PTB,

indicating a non-immune-cell locus of the action of TLR4 (101). Clinically, maternal TLR4

single-nucleotide polymorphisms are markedly associated with

extreme preterm delivery (<32 weeks) (102). TLR4 and its co-receptor CD14

signal via both MyD88-dependent and TRIF-dependent pathways to

regulate distinct inflammatory gene programs. MyD88-deficient mice

are completely protected against E. coli induced PTB,

underscoring the dominant role of the MyD88 axis in preterm

parturition (103). Other TLRs,

such as TLR2, also contribute to labor timing (104,105), and fetal TLR4/TLR2

polymorphisms further modulate PTB risk (106,107).

TLR activation can subsequently drive inflammasome

assembly, sustaining secretion of IL-8, CCL2, IL-1β and IL-6 by

placental and decidual tissues (108). These mediators recruit immune

cells and induce prostaglandin and MMP production, collectively

promoting cervical ripening and uterine contractility. Amniotic

cavity macrophage infiltration constitutes a critical

pathophysiological mechanism for spontaneous labor initiation,

functionally mediated through NF-κB-driven transcriptional

activation of uterine activation-associated gene networks (such as

PTGFR, GJA1, OXTR and PTGS2) and

pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 (109). Thus, pattern-recognition

receptors and downstream effectors orchestrate both physiological

and pathological labor initiation.

Various approaches are used to induce PTL and

parturition in mice, including immunological, hormonal and

environmental triggers. Immunomodulators activate or amplify

physiological inflammatory pathways that drive labor onset,

recapitulating clinical features of infection and

inflammation-associated parturition. The most common murine PTL

models involve intrauterine or intraperitoneal administration of

LPS or heat-killed whole Escherichia coli cells (110). Although LPS is widely employed

to induce PTB via pro-inflammatory responses in mice (72), its role in the human female

reproductive tract remains unclear. Clinical studies (35,96,111) report elevated concentrations of

pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6,

IL-8, IL-10, IL-18, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating

factor (GM-CSF), macrophage inflammatory protein-1β (MIP-1β) and

eosinophil chemotactic factor, in the amniotic fluid,

cervicovaginal fluid and plasma of women who subsequently

experienced spontaneous PTB. Moreover, cervical levels of IL-1β,

IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, eotaxin, MIP-1β and GM-CSF are associated with

VMB composition (112). Animal

models demonstrate a central role for macrophages in both term and

PTL. Macrophage depletion via anti-F4/80 antibody markedly reduces

susceptibility to LPS-induced PTB in mice (113). Mechanistically, macrophages

contribute to PTB pathogenesis by secreting TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8

and by regulating expression of contraction-associated genes such

as MMPs (109). Specifically,

IL-1 is critical in inflammatory PTB; exogenous IL-1 induces PTL in

mice, whereas blockade of the IL-1 receptor inhibits labor

initiation (114), probably

through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (115). Research indicates that IL-6

deficient mice exhibit delays parturition and resistance to

LPS-induced PTB (116).

Dominance of L. iners is associated with elevated levels of

immunoglobulin M, complement components C3b, C5, C5a, and IL-6,

collectively leading to cervical shortening, reduced endometrial

receptivity, decreased implantation rates and increased PTB risk

(117,118). Complement activation also plays

a pivotal role: Clinical data show raised terminal complement

fragments C3a, C4a and C5a in women undergoing infection-associated

spontaneous PTB (113). In

mouse models, C5a receptor (C5aR)-deficient animals are protected

from both LPS- and RU486-induced PTB; this protection involves

aberrant complement deposition in the cervical epithelium and

C5a-dependent macrophage MMP-9 release that drives cervical

remodeling (119). IL-10 has a

protective effect against PTB. IL-10 knockout or neutralization

markedly increases susceptibility to PTB in mice (120). IL-10 deficiency leads to

downregulation of inflammatory cytokine gene expression in uterine

and placental tissues, suggesting its role in tempering excessive

inflammation during labor. Decidual endothelial cell TLR4 signaling

at term may activate the IL-6/STAT3 axis via NF-κB, promoting

perivascular stromal cell production of IL-10 (101). This mechanism probably

maintains immune homeostasis under inflammatory conditions, a

balance that is disrupted in PTB. Neutrophils, which contribute to

cervical remodeling, may infiltrate the myometrium and facilitate

cervical shortening during labor, thereby increasing PTB risk

(121,122). Limited data suggest that

neutrophil numbers in cervicovaginal fluid decline as gestation

advances (123). Notably, women

with a low-diversity VMB (CST III, dominated by L. iners)

often exhibit elevated vaginal neutrophil counts during pregnancy

(123). One study reported a

positive association between G. vaginalis (CST IV) abundance

and neutrophil levels in samples from women who subsequently

delivered preterm (123).

In vaginal epithelial-cell models, both D-lactic

and L-lactic acid, alone or in combination with a spectrum of

VMB-associated metabolites, induce the anti-inflammatory cytokine

interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) while suppressing

pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, RANTES and

macrophage inflammatory protein-3α (130,131). Organotypic models of the female

reproductive-tract epithelium confirm that L-lactic acid

upregulates IL-1RA and downregulates IL-8 (130). Although certain in vitro

studies have reported pro-inflammatory responses to specific

Lactobacillus strains (132,133), these strains are not dominant

members of the VMB. In vivo experiments and

cervical-epithelial models both demonstrate that lactate production

by Lactobacillus spp. and the resulting acidic vaginal pH

reinforce epithelial-barrier integrity, thereby inhibiting

colonization by anaerobes and pathogens (134,135). Thus, dominance of protective

lactobacilli is associated with reduced risk of suboptimal

vaginal health. However, excessive lactobacilli

proliferation can give rise to cytolytic vaginosis, a condition

marked by epithelial-cell lysis, dissolution and shedding

attributed to overproduction of lactic acid (136). Although cytolytic vaginosis is

less prevalent than BV, its occurrence underscores the clinical

importance of quantitatively assessing the VMB.

Beyond the presence or absence of key taxa, the VMB

influences immune responses and pregnancy outcomes via production

of SCFAs. While SCFAs enhance intestinal-barrier integrity

(137), their effects in the

vaginal milieu appear deleterious. SCFAs are organic fatty acids

typically containing fewer than six carbon atoms; common examples

include acetate, propionate and butyrate (138). Elevated levels of SCFAs, such

as propionate, succinate, acetate and butyrate, are associated with

increased concentrations of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α,

IFN-γ and RANTES (139). For

instance, in early gestation, elevated acetate is associated with

PTB under conditions of weakened L. crispatus dominance

(139,140). High SCFA concentrations also

inhibit expression of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin,

an innate-antimicrobial factor, potentially facilitating overgrowth

of BV-associated communities and further contributing to PTB

(141). In BV settings, high

concentrations of acetate (100 mM) and butyrate (20 mM) selectively

activate TLR1/2/3 in cervicovaginal epithelial cells, resulting in

increased TNF-α secretion and concomitant suppression of IL-6,

RANTES and IP-10 production (131).

Metabolomic analyses of PTB patients reveal

upregulation of glycerophospholipid-metabolism-related metabolites.

Glycerophospholipids are fundamental membrane constituents and

precursors for bioactive lipids such as arachidonic acid (AA) and

lysobisphosphatidic acid (LPA). These bioactive lipids are

generated by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and, in the case of AA,

further converted by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) into prostaglandins

(PGs) (142,143). LPA3, a G protein-coupled

receptor expressed in uterine epithelium, modulates COX-2 activity

and PG levels (144).

Collectively, these molecules serve as key regulators of

inflammation. Increased phosphoinositol, a glycerophospholipid

metabolite, depletes glycerophospholipid pools and downstream

mediators (LPA and PG), potentially impairing implantation;

additionally, elevated phosphoinositol promotes Ca2+

influx and uterine contractility, which may precipitate premature

labor (145).

Enhanced primary bile-acid and steroid-hormone

metabolism pathways have also been observed in PTB cohorts,

consistent with findings by Menon et al (146) and Lizewska et al

(147). Bile acids, synthesized

from cholesterol in the liver, are modified by the gut microbiota

and facilitate dietary-fat absorption (148). Pregnancy-related hormonal

changes (such as cholestasis) can disrupt bile acid clearance,

leading to elevated circulating levels that induce fetal stress

(148). Steroid hormones, also

derived from cholesterol, govern development, osmoregulation,

metabolism and stress responses. Maturation of the fetal

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and increased fetal adrenal

production of C19 steroids (dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate) and

cortisol are pivotal for labor initiation, whereas placental

progesterone maintains uterine quiescence during gestation

(149). Perturbations in

steroid synthesis, metabolism or transport may likewise trigger

labor onset.

The VMB can be modulated by various interventions,

including probiotics, prebiotics, antibiotics and pH modulators

(153). When treating

infectious diseases related to BV, the most commonly used and

fastest-acting method is antibiotic therapy. Although antibiotics

are effective against infection, they also disrupt the overall

microbial balance, including beneficial lactobacilli, leading to

high recurrence rates (154)

and increased risk of spontaneous PTB (12). As an alternative or adjunct to

antibiotics, several approaches have been proposed to restore a

Lactobacillus-dominated vaginal community. Oral probiotics,

leveraging cross-talk between the gut and vaginal microbiomes, are

considered a promising method. Probiotics are live, beneficial

strains capable of colonizing the vagina and improving its

microbial composition, such as Lactobacillus crispatus,

L. jensenii and L. gasseri (12,155). These probiotics can be

administered orally or vaginally, in formulations including

capsules, suppositories or creams (156,157). Most intervention studies have

focused on using Lactobacilli to alleviate BV and aerobic

vaginitis, both of which are dysbiotic states associated with

increased risk of spontaneous PTB. Results have been mixed: some

studies report efficacy, while others find no significant effect.

Probiotic studies are summarized in Table I. For example, one study

(158) showed that oral

capsules containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and L.

fermentum RC-14 reduced vaginal yeast and E. coli

counts, increased lactobacilli levels and restored an asymptomatic

BV microbiota to a healthy Lactobacilli-dominated state. Ho

et al's (159) study of

group B Streptococcus (GBS)-positive pregnant women at 35-37

weeks demonstrated that daily oral GR-1 + RC-14 until delivery

markedly lowered GBS positivity compared with placebo. In 40

BV-afflicted black women, GR-1 + RC-14 achieved higher cure rates

than metronidazole (160).

Maternal oral supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus

GR-1 and Lactobacillus fermentum RC-14 probiotic capsules

markedly reduced vaginal microbial α diversity and species

richness, while concurrently suppressing Gardnerella

vaginalis colonization. The probiotic cohort exhibited

enrichment of Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus

iners and the gut-associated species Prevotella copri,

taxa positively associated with VMB stability (157). Other studies have shown that

probiotic intervention reduces expression of inflammatory factors,

a known risk factor for PTB. In a double-blind trial of 159

volunteers, vaginal tablets containing Lactobacillus brevis

CD2, L. salivarius subsp. salicinius and L.

plantarum achieved clinical cure in nearly 80% of BV patients,

with 32% restoring a normal VMB (161). Post-treatment vaginal lavage

fluids showed significant decreases in IL-1β and IL-6, whereas the

control group showed no change in local pro-inflammatory cytokines

(161). Bayar et al

(155) reported that

administering LACTIN-V to high-risk pregnant women markedly reduced

early PTB incidence. The protective effect of LACTIN-V may be

attributed to its inhibition of pro-inflammatory responses to

uropathogens. However, in a randomized, double-blind trial, Husain

et al (162)

demonstrated that daily oral administration of a probiotic

preparation comprising Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and

Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 from early pregnancy did not

modify the vaginal microbiota of pregnant women nor prevent

bacterial vaginosis. In a similar study, Gille et al

observed that eight weeks of daily oral administration of L.

rhamnosus GR-1 or L. reuteri RC-14, compared with

placebo, yielded no significant difference in the incidence of BV

as assessed by Nugent score before and after intervention (163). These divergent findings may

reflect limitations in study design. In particular, the proportion

of women with abnormal vaginal microbiota in Gille et al's

(163) intervention arm was

substantially lower than that reported in general populations,

warranting validation in larger and more representative cohorts.

Moreover, an unexpectedly high loss to follow up may have reduced

the statistical power to detect intergroup differences. The two

trials employed oral delivery, which may not ensure sufficient

vaginal colonization or confer protection against spontaneous PTB.

Consequently, the investigators recommend that future research

prioritize the identification of probiotic strains and delivery

modalities capable of beneficially modulating the vaginal

microbiota during pregnancy before assessing their efficacy in

preventing PTB (162). VMB

transplantation (VMT) is another strategy under consideration. A

recent case series reported successful engraftment of healthy

vaginal communities into patients with refractory BV, with four out

of five cases achieving sustained remission for up to 21 months

(164). Although limited by

sample size, these findings underscore the need to assess the

long-term efficacy of both probiotic and VMT approaches in pregnant

populations.

PTB remains a major global health challenge, with

35-50% of spontaneous PTB and PPROM cases attributed to ascending

vaginal infections. A growing body of evidence indicates that

dynamic shifts in the VMB critically influence pregnancy outcomes.

Vaginal microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus species,

particularly L. crispatus, confer protective effects through

three synergistic mechanisms: Lactic acid-driven pH homeostasis,

bacteriocin-mediated pathogen suppression, and immunoregulatory

pathways that attenuate proinflammatory cytokine signaling,

including IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α. By contrast, high-diversity,

Lactobacillus-depleted (CST IV) vaginal microbiota enriched

with opportunistic pathogens such as Gardnerella vaginalis,

Atopobium vaginae, and Prevotella spp. demonstrate a

strong association with increased PTB risk. These pathogens

compromise epithelial integrity through biofilm formation, protease

secretion and production of SCFAs, exacerbating local inflammation

and activating TLR/NF-κB signaling cascades.

The field continues to confront several persistent

challenges despite recent advancements. While observational studies

have reproducibly linked vaginal microbial dysbiosis to PTB risk,

establishing definitive causal relationships requires longitudinal

investigations capable of tracing microbial community trajectories

across pregnancy trimesters. Such studies would clarify whether

specific pathogen colonization patterns precede cervical remodeling

events and identify predictive microbial signatures. A parallel

knowledge gap exists in understanding functional differences

between Lactobacillus species, particularly the clinically

relevant dichotomy between L. crispatus' protective mucosal

interactions and L. iners' ambiguous ecological role, which

demands comparative multi-omic analyses spanning genomic, proteomic

and metabolomic dimensions. Current microbiome profiling techniques

have limitations; for example, 16S rRNA sequencing lacks resolution

at the species level and does not capture functional information.

Future studies should integrate metagenomic and multi-omics

approaches to achieve a more comprehensive characterization of both

microbial communities and their metabolite profiles. Current

therapeutic development efforts face dual limitations:

heterogeneous probiotic formulations lacking strain-specific

rationale and clinical trials inadequately powered to detect

ethnic-geographic variations in microbial-host interactions.

Progress necessitates standardized intervention protocols paired

with mechanistic studies decoding how microbial metabolites

interface with cervical tissue immune networks at single-cell

resolution. Addressing these interconnected biological and

methodological complexities could enable microbiota-informed risk

stratification systems and next-generation therapeutic strategies

tailored to individual microbial ecologies.

Although the present review was based on a

comprehensive search and synthesis of PubMed and Web of Science

from inception to May 2025, it still has several limitations.

First, by restricting its analysis to English-language

publications, it may have overlooked important studies in other

languages. Second, the included studies vary in their definitions

of bacterial vaginosis, sampling time points and sequencing

platforms, making direct comparisons difficult. Third, as a

narrative review, it did not conduct a formal risk of bias

assessment or quantitative meta-analysis, so it cannot rule out the

influence of publication bias. Future research would benefit from

standardized protocols, broader inclusion criteria, and multicenter

collaboration to validate and build upon these findings.

Not applicable.

DC, FG and KW reviewed literature and wrote the

manuscript. NL and QS collected data and prepared figures. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors reviewed and approved

the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The present review was supported by the Science and Technology

Development Program of Jinan Municipal Health Commission (grant no.

2024203001).

|

1

|

Ohuma EO, Moller AB, Bradley E, Chakwera

S, Hussain-Alkhateeb L, Lewin A, Okwaraji YB, Mahanani WR,

Johansson EW, Lavin T, et al: National, regional, and global

estimates of preterm birth in 2020, with trends from 2010: A

systematic analysis. Lancet. 402:1261–1271. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Saigal S and Doyle LW: An overview of

mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood.

Lancet. 371:261–269. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD and

Romero R: Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet.

371:75–84. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Romero R, Gomez-Lopez N, Winters AD, Jung

E, Shaman M, Bieda J, Panaitescu B, Pacora P, Erez O, Greenberg JM,

et al: Evidence that intra-amniotic infections are often the result

of an ascending invasion-a molecular microbiological study. J

Perinat Med. 47:915–931. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Witkin SS: The vaginal microbiome, vaginal

anti-microbial defence mechanisms and the clinical challenge of

reducing infection-related preterm birth. BJOG. 122:213–218. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Fox C and Eichelberger K: Maternal

microbiome and pregnancy outcomes. Fertil Steril. 104:1358–1363.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tabatabaei N, Eren AM, Barreiro LB, Yotova

V, Dumaine A, Allard C and Fraser WD: Vaginal microbiome in early

pregnancy and subsequent risk of spontaneous preterm birth: A

case-control study. BJOG. 126:349–358. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu L, Yin T, Zhang X, Sun L and Yin Y:

Temporal and spatial variation of the human placental microbiota

during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 92:e700232024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Conde-Agudelo A, Papageorghiou AT, Kennedy

SH and Villar J: Novel biomarkers for the prediction of the

spontaneous preterm birth phenotype: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. BJOG. 118:1042–1054. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Meertens LJE, van Montfort P, Scheepers

HCJ, van Kuijk SMJ, Aardenburg R, Langenveld J, van Dooren IMA,

Zwaan IM, Spaanderman MEA and Smits LJM: Prediction models for the

risk of spontaneous preterm birth based on maternal

characteristics: A systematic review and independent external

validation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 97:907–920. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hickey RJ, Zhou X, Pierson JD, Ravel J and

Forney LJ: Understanding vaginal microbiome complexity from an

ecological perspective. Transl Res. 160:267–282. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Happel AU, Kullin B, Gamieldien H, Wentzel

N, Zauchenberger CZ, Jaspan HB, Dabee S, Barnabas SL, Jaumdally SZ,

Dietrich J, et al: Exploring potential of vaginal Lactobacillus

isolates from South African women for enhancing treatment for

bacterial vaginosis. PLoS Pathog. 16:e10085592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Giannella L, Grelloni C, Quintili D,

Fiorelli A, Montironi R, Alia S, Delli Carpini G, Di Giuseppe J,

Vignini A and Ciavattini A: Microbiome changes in pregnancy

disorders. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:4632023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Bayar E, Bennett PR, Chan D, Sykes L and

MacIntyre DA: The pregnancy microbiome and preterm birth. Semin

Immunopathol. 42:487–499. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bachmann NL, Rockett RJ, Timms VJ and

Sintchenko V: Advances in clinical sample preparation for

identification and characterization of bacterial pathogens using

metagenomics. Front Public Health. 6:3632018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sroka-Oleksiak A, Gosiewski T, Pabian W,

Gurgul A, Kapusta P, Ludwig-Słomczyńska AH, Wołkow PP and

Brzychczy-Włoch M: Next-generation sequencing as a tool to detect

vaginal microbiota disturbances during pregnancy. Microorganisms.

8:18132020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Linhares IM, Summers PR, Larsen B, Giraldo

PC and Witkin SS: Contemporary perspectives on vaginal pH and

lactobacilli. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 204:120.e1–e5. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM,

Koenig SS, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, Gorle R, Russell J, Tacket CO,

et al: Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 108(Suppl 1): S4680–S4687. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Blostein F, Gelaye B, Sanchez SE, Williams

MA and Foxman B: Vaginal microbiome diversity and preterm birth:

Results of a nested case-control study in Peru. Ann Epidemiol.

41:28–34. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Stennett CA, Dyer TV, He X, Robinson CK,

Ravel J, Ghanem KG and Brotman RM: A cross-sectional pilot study of

birth mode and vaginal microbiota in reproductive-age women. PLoS

One. 15:e02285742020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chaban B, Links MG, Jayaprakash TP, Wagner

EC, Bourque DK, Lohn Z, Albert AY, van Schalkwyk J, Reid G,

Hemmingsen SM, et al: Characterization of the vaginal microbiota of

healthy Canadian women through the menstrual cycle. Microbiome.

2:232014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Roy EJ and Mackay R: The concentration of

oestrogens in blood during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp.

69:13–17. 1962. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ma B, Forney LJ and Ravel J: Vaginal

microbiome: Rethinking health and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol.

66:371–389. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

van de Wijgert J and Verwijs MC:

Lactobacilli-containing vaginal probiotics to cure or prevent

bacterial or fungal vaginal dysbiosis: A systematic review and

recommendations for future trial designs. BJOG. 127:287–299. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bhandari P, Tingley JP, Palmer DRJ, Abbott

DW and Hill JE: Characterization of an α-Glucosidase enzyme

conserved in gardnerella spp. isolated from the human vaginal

microbiome. J Bacteriol. 203:e00213212021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Rosca AS, Castro J, Sousa LGV and Cerca N:

Gardnerella and vaginal health: The truth is out there. FEMS

Microbiol Rev. 44:73–105. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Tachedjian G, Aldunate M, Bradshaw CS and

Cone RA: The role of lactic acid production by probiotic

Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res Microbiol.

168:782–792. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kaur H, Merchant M, Haque MM and Mande SS:

Crosstalk between female gonadal hormones and vaginal microbiota

across various phases of women's gynecological lifecycle. Front

Microbiol. 11:5512020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Anderson DJ, Marathe J and Pudney J: The

structure of the human vaginal stratum corneum and its role in

immune defense. Am J Reprod Immunol. 71:618–623. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Shen J, Song N, Williams CJ, Brown CJ, Yan

Z, Xu C and Forney LJ: Effects of low dose estrogen therapy on the

vaginal microbiomes of women with atrophic vaginitis. Sci Rep.

6:243802016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cauci S, Driussi S, De Santo D,

Penacchioni P, Iannicelli T, Lanzafame P, De Seta F, Quadrifoglio

F, de Aloysio D and Guaschino S: Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis

and vaginal flora changes in peri- and postmenopausal women. J Clin

Microbiol. 40:2147–2152. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Brooks JP, Edwards DJ, Blithe DL, Fettweis

JM, Serrano MG, Sheth NU, Strauss JF III, Buck GA and Jefferson KK:

Effects of combined oral contraceptives, depot medroxyprogesterone

acetate and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on the

vaginal microbiome. Contraception. 95:405–413. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, Law

M, Pirotta M, Garland SM, De Guingand D, Morton AN and Fairley CK:

Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with

posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use.

Clin Infect Dis. 56:777–786. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Garcia-Garcia RM, Arias-Álvarez M,

Jordán-Rodríguez D, Rebollar PG, Lorenzo PL, Herranz C and

Rodríguez JM: Female reproduction and the microbiota in mammals:

Where are we? Theriogenology. 194:144–153. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Brooks JP,

Edwards DJ, Girerd PH, Parikh HI, Huang B, Arodz TJ, Edupuganti L,

Glascock AL, et al: The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat

Med. 25:1012–1021. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Serrano MG, Parikh HI, Brooks JP, Edwards

DJ, Arodz TJ, Edupuganti L, Huang B, Girerd PH, Bokhari YA, Bradley

SP, et al: Racioethnic diversity in the dynamics of the vaginal

microbiome during pregnancy. Nat Med. 25:1001–1011. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

MacIntyre DA, Chandiramani M, Lee YS,

Kindinger L, Smith A, Angelopoulos N, Lehne B, Arulkumaran S, Brown

R, Teoh TG, et al: The vaginal microbiome during pregnancy and the

postpartum period in a European population. Sci Rep. 5:89882015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang X, Zhai Q, Wang J, Ma X, Xing B, Fan

H, Gao Z, Zhao F and Liu W: Variation of the vaginal microbiome

during and after pregnancy in Chinese women. Genomics Proteomics

Bioinformatics. 20:322–333. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shachar BZ, Mayo JA, Lyell DJ, Baer RJ,

Jeliffe-Pawlowski LL, Stevenson DK and Shaw GM: Interpregnancy

interval after live birth or pregnancy termination and estimated

risk of preterm birth: A retrospective cohort study. BJOG.

123:2009–2017. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

McKinney D, House M, Chen A, Muglia L and

DeFranco E: The influence of interpregnancy interval on infant

mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 216:316.e1–316.e9. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kangatharan C, Labram S and Bhattacharya

S: Interpregnancy interval following miscarriage and adverse

pregnancy outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod

Update. 23:221–231. 2017.

|

|

42

|

Bobitt JR and Ledger WJ: Unrecognized

amnionitis and prematurity: A preliminary report. J Reprod Med.

19:8–12. 1977.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Andrews WW, Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL, Gomez

R, Romero R and Cassell GH: Amniotic fluid interleukin-6:

Correlation with upper genital tract microbial colonization and

gestational age in women delivered after spontaneous labor versus

indicated delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 173:606–612. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC,

Cliver SP, Conner M and Goepfert AR: Endometrial microbial

colonization and plasma cell endometritis after spontaneous or

indicated preterm versus term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

193:739–745. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Cassen E, Easterling

TR, Rabe LK and Eschenbach DA: The role of bacterial vaginosis and

vaginal bacteria in amniotic fluid infection in women in preterm

labor with intact fetal membranes. Clin Infect Dis. 20(Suppl 2):

S276–S278. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Leitich H and Kiss H: Asymptomatic

bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for

adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.

21:375–390. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson D,

Morgan DJ, Ison C and Pearson J: Abnormal bacterial colonisation of

the genital tract and subsequent preterm delivery and late

miscarriage. BMJ. 308:295–298. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, Brunbauer M,

Kaider A, Egarter C and Husslein P: Bacterial vaginosis as a risk

factor for preterm delivery: A meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

189:139–147. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Carey JC, Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, Hillier

SL, Thom EA, Ernest JM, Heine RP, Nugent RP, Fischer ML, Leveno KJ,

et al: Metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery in pregnant women

with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. National institute of child

health and human development network of maternal-fetal medicine

units. N Engl J Med. 342:534–540. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Klebanoff MA, Carey JC, Hauth JC, Hillier

SL, Nugent RP, Thom EA, Ernest JM, Heine RP, Wapner RJ, Trout W, et

al: Failure of metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery among

pregnant women with asymptomatic Trichomonas vaginalis infection. N

Engl J Med. 345:487–493. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Brocklehurst P, Hannah M and McDonald H:

Interventions for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jan 20–2000.Epub ahead of print.

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Guise JM, Mahon SM, Aickin M, Helfand M,

Peipert JF and Westhoff C: Screening for bacterial vaginosis in

pregnancy. Am J Prev Med. 20(Suppl 3): S62–S72. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Koumans EH, Markowitz LE and Hogan V; CDC

BV Working Group: Indications for therapy and treatment

recommendations for bacterial vaginosis in nonpregnant and pregnant

women: A synthesis of data. Clin Infect Dis. 35(Suppl 2):

S152–S172. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Petrova MI, van den Broek M, Balzarini J,

Vanderleyden J and Lebeer S: Vaginal microbiota and its role in HIV

transmission and infection. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 37:762–792. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Peebles K, Velloza J, Balkus JE,

McClelland RS and Barnabas RV: High global burden and costs of

bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex

Transm Dis. 46:304–311. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Onderdonk AB, Delaney ML and Fichorova RN:

The human microbiome during bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol

Rev. 29:223–238. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ling Z, Kong J, Liu F, Zhu H, Chen X, Wang

Y, Li L, Nelson KE, Xia Y and Xiang C: Molecular analysis of the

diversity of vaginal microbiota associated with bacterial

vaginosis. BMC Genomics. 11:4882010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Muzny CA and Schwebke JR: Gardnerella

vaginalis: Still a prime suspect in the pathogenesis of bacterial

vaginosis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 15:130–135. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Garcia EM, Serrano MG, Edupuganti L,

Edwards DJ, Buck GA and Jefferson KK: Sequence comparison of

vaginolysin from different gardnerella species. Pathogens.

10:862021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Vaneechoutte M, Guschin A, Van Simaey L,

Gansemans Y, Van Nieuwerburgh F and Cools P: Emended description of

Gardnerella vaginalis and description of Gardnerella leopoldii sp.

nov., Gardnerella piotii sp. nov. and Gardnerella swidsinskii sp.

nov., with delineation of 13 genomic species within the genus

Gardnerella. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 69:679–687. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Ahmed A, Earl J, Retchless A, Hillier SL,

Rabe LK, Cherpes TL, Powell E, Janto B, Eutsey R, Hiller NL, et al:

Comparative genomic analyses of 17 clinical isolates of Gardnerella

vaginalis provide evidence of multiple genetically isolated clades

consistent with subspeciation into genovars. J Bacteriol.

194:3922–3937. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Balashov SV, Mordechai E, Adelson ME and

Gygax SE: Identification, quantification and subtyping of

Gardnerella vaginalis in noncultured clinical vaginal samples by

quantitative PCR. J Med Microbiol. 63:162–175. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Georgijević A, Cjukić-Ivancević S and

Bujko M: Bacterial vaginosis. Epidemiology and risk factors. Srp

Arh Celok Lek. 128:29–33. 2000.In Serbian.

|

|

64

|

van de Wijgert JH, Borgdorff H, Verhelst

R, Crucitti T, Francis S, Verstraelen H and Jespers V: The vaginal

microbiota: what have we learned after a decade of molecular

characterization? PLoS One. 9:e1059982014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

France MT, Fu L, Rutt L, Yang H, Humphrys

MS, Narina S, Gajer PM, Ma B, Forney LJ and Ravel J: Insight into

the ecology of vaginal bacteria through integrative analyses of

metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data. Genome Biol. 23:662022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Garcia EM, Kraskauskiene V, Koblinski JE

and Jefferson KK: Interaction of gardnerella vaginalis and

vaginolysin with the apical versus basolateral face of a

three-dimensional model of vaginal epithelium. Infect Immun.

87:e00646–18. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ragaliauskas T, Plečkaitytė M, Jankunec M,

Labanauskas L, Baranauskiene L and Valincius G: Inerolysin and

vaginolysin, the cytolysins implicated in vaginal dysbiosis,

differently impair molecular integrity of phospholipid membranes.

Sci Rep. 9:106062019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Jung HS, Ehlers MM, Lombaard H,

Redelinghuys MJ and Kock MM: Etiology of bacterial vaginosis and

polymicrobial biofilm formation. Crit Rev Microbiol. 43:651–667.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Swidsinski A, Dörffel Y, Loening-Baucke V,

Schilling J and Mendling W: Response of Gardnerella vaginalis

biofilm to 5 days of moxifloxacin treatment. FEMS Immunol Med

Microbiol. 61:41–46. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Castro J, Machado D and Cerca N: Unveiling

the role of Gardnerella vaginalis in polymicrobial Bacterial

Vaginosis biofilms: The impact of other vaginal pathogens living as

neighbors. ISME J. 13:1306–1317. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jones HE, Harris KA, Azizia M, Bank L,

Carpenter B, Hartley JC, Klein N and Peebles D: Differing

prevalence and diversity of bacterial species in fetal membranes

from very preterm and term labor. PLoS One. 4:e82052009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Suff N, Karda R, Diaz JA, Ng J, Baruteau

J, Perocheau D, Tangney M, Taylor PW, Peebles D, Buckley SMK and

Waddington SN: Ascending vaginal infection using bioluminescent

bacteria evokes intrauterine inflammation, preterm birth, and

neonatal brain injury in pregnant mice. Am J Pathol. 188:2164–2176.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Randis TM, Gelber SE, Hooven TA, Abellar

RG, Akabas LH, Lewis EL, Walker LB, Byland LM, Nizet V and Ratner

AJ: Group B Streptococcus β-hemolysin/cytolysin breaches

maternal-fetal barriers to cause preterm birth and intrauterine

fetal demise in vivo. J Infect Dis. 210:265–273. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, Tarca AL,

Fadrosh DW, Bieda J, Chaemsaithong P, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T

and Ravel J: The vaginal microbiota of pregnant women who

subsequently have spontaneous preterm labor and delivery and those

with a normal delivery at term. Microbiome. 2:182014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Nelson DB, Shin H, Wu J and

Dominguez-Bello MG: The gestational vaginal microbiome and

spontaneous preterm birth among Nulliparous African American Women.

Am J Perinatol. 33:887–893. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Stout MJ, Zhou Y, Wylie KM, Tarr PI,

Macones GA and Tuuli MG: Early pregnancy vaginal microbiome trends

and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 217:356.e1–356.e18. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Kindinger LM, Bennett PR, Lee YS, Marchesi

JR, Smith A, Cacciatore S, Holmes E, Nicholson JK, Teoh TG and

MacIntyre DA: The interaction between vaginal microbiota, cervical

length, and vaginal progesterone treatment for preterm birth risk.

Microbiome. 5:62017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Petrova MI, Reid G, Vaneechoutte M and

Lebeer S: Lactobacillus iners: Friend or Foe? Trends Microbiol.

25:182–191. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Srinivasan S, Hoffman NG, Morgan MT,

Matsen FA, Fiedler TL, Hall RW, Ross FJ, McCoy CO, Bumgarner R,

Marrazzo JM and Fredricks DN: Bacterial communities in women with

bacterial vaginosis: High resolution phylogenetic analyses reveal

relationships of microbiota to clinical criteria. PLoS One.

7:e378182012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Santiago GL, Cools P, Verstraelen H, Trog

M, Missine G, El Aila N, Verhelst R, Tency I, Claeys G, Temmerman M

and Vaneechoutte M: Longitudinal study of the dynamics of vaginal

microflora during two consecutive menstrual cycles. PLoS One.

6:e281802011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Tamrakar R, Yamada T, Furuta I, Cho K,

Morikawa M, Yamada H, Sakuragi N and Minakami H: Association

between Lactobacillus species and bacterial vaginosis-related

bacteria, and bacterial vaginosis scores in pregnant Japanese

women. BMC Infect Dis. 7:1282007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Shipitsyna E, Roos A, Datcu R, Hallén A,

Fredlund H, Jensen JS, Engstrand L and Unemo M: Composition of the

vaginal microbiota in women of reproductive age-sensitive and

specific molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is possible?

PLoS One. 8:e606702013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, Claeys G, De

Backer E, Temmerman M and Vaneechoutte M: Longitudinal analysis of

the vaginal microflora in pregnancy suggests that L. crispatus

promotes the stability of the normal vaginal microflora and that L.

gasseri and/or L. iners are more conducive to the occurrence of

abnormal vaginal microflora. BMC Microbiol. 9:1162009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Santiago GL, Tency I, Verstraelen H,

Verhelst R, Trog M, Temmerman M, Vancoillie L, Decat E, Cools P and

Vaneechoutte M: Longitudinal qPCR study of the dynamics of L.

crispatus, L. iners, A. vaginae, (sialidase positive) G. vaginalis,

and P. bivia in the vagina. PLoS One. 7:e452812012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Macklaim JM, Fernandes AD, Di Bella JM,

Hammond JA, Reid G and Gloor GB: Comparative meta-RNA-seq of the

vaginal microbiota and differential expression by Lactobacillus

iners in health and dysbiosis. Microbiome. 1:122013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, Sakamoto J,

Schütte UM, Zhong X, Koenig SS, Fu L, Ma ZS, Zhou X, et al:

Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med.

4:132ra522012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Petricevic L, Domig KJ, Nierscher FJ,

Sandhofer MJ, Fidesser M, Krondorfer I, Husslein P, Kneifel W and

Kiss H: Characterisation of the vaginal Lactobacillus microbiota

associated with preterm delivery. Sci Rep. 4:51362014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Baldwin EA, Walther-Antonio M, MacLean AM,

Gohl DM, Beckman KB, Chen J, White B, Creedon DJ and Chia N:

Persistent microbial dysbiosis in preterm premature rupture of

membranes from onset until delivery. PeerJ. 3:e13982015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Brown RG, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, Smith A,

Lehne B, Kindinger LM, Terzidou V, Holmes E, Nicholson JK, Bennett

PR and MacIntyre DA: Vaginal dysbiosis increases risk of preterm

fetal membrane rupture, neonatal sepsis and is exacerbated by

erythromycin. BMC Med. 16:92018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Brown RG, Al-Memar M, Marchesi JR, Lee YS,

Smith A, Chan D, Lewis H, Kindinger L, Terzidou V, Bourne T, et al:

Establishment of vaginal microbiota composition in early pregnancy

and its association with subsequent preterm prelabor rupture of the

fetal membranes. Transl Res. 207:30–43. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ,

Costello EK, Lyell DJ, Robaczewska A, Sun CL, Goltsman DS, Wong RJ,

Shaw G, et al: Temporal and spatial variation of the human

microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

112:11060–11065. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Callahan BJ, DiGiulio DB, Goltsman DSA,

Sun CL, Costello EK, Jeganathan P, Biggio JR, Wong RJ, Druzin ML,

Shaw GM, et al: Replication and refinement of a vaginal microbial

signature of preterm birth in two racially distinct cohorts of US

women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:9966–9971. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Hyman RW, Fukushima M, Jiang H, Fung E,

Rand L, Johnson B, Vo KC, Caughey AB, Hilton JF, Davis RW and

Giudice LC: Diversity of the vaginal microbiome correlates with

preterm birth. Reprod Sci. 21:32–40. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

94

|

Elovitz MA, Gajer P, Riis V, Brown AG,

Humphrys MS, Holm JB and Ravel J: Cervicovaginal microbiota and

local immune response modulate the risk of spontaneous preterm

delivery. Nat Commun. 10:13052019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Sun S, Serrano MG, Fettweis JM, Basta P,

Rosen E, Ludwig K, Sorgen AA, Blakley IC, Wu MC, Dole N, et al:

Race, the vaginal microbiome, and spontaneous preterm birth.

mSystems. 7:e00017222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Kumar M, Murugesan S, Singh P, Saadaoui M,

Elhag DA, Terranegra A, Kabeer BSA, Marr AK, Kino T, Brummaier T,

et al: Vaginal microbiota and cytokine levels predict preterm

delivery in Asian women. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

11:6396652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Kindinger LM, MacIntyre DA, Lee YS,

Marchesi JR, Smith A, McDonald JA, Terzidou V, Cook JR, Lees C,

Israfil-Bayli F, et al: Relationship between vaginal microbial

dysbiosis, inflammation, and pregnancy outcomes in cervical

cerclage. Sci Transl Med. 8:350ra1022016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Green ES and Arck PC: Pathogenesis of

preterm birth: Bidirectional inflammation in mother and fetus.

Semin Immunopathol. 42:413–429. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Wahid HH, Dorian CL, Chin PY, Hutchinson

MR, Rice KC, Olson DM, Moldenhauer LM and Robertson SA: Toll-Like

receptor 4 is an essential upstream regulator of on-time

parturition and perinatal viability in mice. Endocrinology.

156:3828–3841. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Chin PY, Dorian CL, Hutchinson MR, Olson

DM, Rice KC, Moldenhauer LM and Robertson SA: Novel Toll-like

receptor-4 antagonist (+)-naloxone protects mice from

inflammation-induced preterm birth. Sci Rep. 6:361122016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Deng W, Yuan J, Cha J, Sun X, Bartos A,

Yagita H, Hirota Y and Dey SK: Endothelial cells in the decidual

bed are potential therapeutic targets for preterm birth prevention.

Cell Rep. 27:1755–1768.e4. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Liassides C, Papadopoulos A, Siristatidis

C, Damoraki G, Liassidou A, Chrelias C, Kassanos D and

Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ: Single nucleotide polymorphisms of

Toll-like receptor-4 and of autophagy-related gene 16 like-1 gene

for predisposition of premature delivery: A prospective study.

Medicine (Baltimore). 98:e173132019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Filipovich Y, Lu SJ, Akira S and Hirsch E:

The adaptor protein MyD88 is essential for E coli-induced preterm

delivery in mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 200:93.e1–8. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Montalbano AP, Hawgood S and Mendelson CR:

Mice deficient in surfactant protein A (SP-A) and SP-D or in TLR2

manifest delayed parturition and decreased expression of

inflammatory and contractile genes. Endocrinology. 154:483–498.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

105

|

Patni S, Wynen LP, Seager AL, Morgan G,

White JO and Thornton CA: Expression and activity of Toll-like

receptors 1-9 in the human term placenta and changes associated

with labor at term. Biol Reprod. 80:243–248. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Krediet TG, Wiertsema SP, Vossers MJ,

Hoeks SB, Fleer A, Ruven HJ and Rijkers GT: Toll-like receptor 2

polymorphism is associated with preterm birth. Pediatr Res.

62:474–476. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Lorenz E, Hallman M, Marttila R, Haataja R

and Schwartz DA: Association between the Asp299Gly polymorphisms in

the Toll-like receptor 4 and premature births in the Finnish

population. Pediatr Res. 52:373–376. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Romero R, Xu Y, Plazyo O, Chaemsaithong P,

Chaiworapongsa T, Unkel R, Than NG, Chiang PJ, Dong Z, Xu Z, et al:

A role for the inflammasome in spontaneous labor at term. Am J

Reprod Immunol. 79:e124402018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Lindström TM and Bennett PR: The role of

nuclear factor kappa B in human labour. Reproduction. 130:569–581.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

McCarthy R, Martin-Fairey C, Sojka DK,

Herzog ED, Jungheim ES, Stout MJ, Fay JC, Mahendroo M, Reese J,

Herington JL, et al: Mouse models of preterm birth: Suggested

assessment and reporting guidelines. Biol Reprod. 99:922–937.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Zhu B, Tao Z, Edupuganti L, Serrano MG and

Buck GA: Roles of the microbiota of the female reproductive tract

in gynecological and reproductive health. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev.

86:e00181212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Yudin MH, Landers DV, Meyn L and Hillier

SL: Clinical and cervical cytokine response to treatment with oral

or vaginal metronidazole for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy:

A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 102:527–534. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Soto E, Romero R, Richani K, Yoon BH,

Chaiworapongsa T, Vaisbuch E, Mittal P, Erez O, Gotsch F, Mazor M

and Kusanovic JP: Evidence for complement activation in the

amniotic fluid of women with spontaneous preterm labor and

intra-amniotic infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 22:983–992.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Romero R and Tartakovsky B: The natural

interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents interleukin-1-induced

preterm delivery in mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 167:1041–1045. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Nadeau-Vallée M, Quiniou C, Palacios J,

Hou X, Erfani A, Madaan A, Sanchez M, Leimert K, Boudreault A,

Duhamel F, et al: Novel noncompetitive IL-1 receptor-biased ligand

prevents infection- and inflammation-induced preterm birth. J

Immunol. 195:3402–3415. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Robertson SA, Christiaens I, Dorian CL,

Zaragoza DB, Care AS, Banks AM and Olson DM: Interleukin-6 is an

essential determinant of on-time parturition in the mouse.

Endocrinology. 151:3996–4006. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Di Simone N, Santamaria Ortiz A, Specchia

M, Tersigni C, Villa P, Gasbarrini A, Scambia G and D'Ippolito S:

Recent insights on the maternal microbiota: Impact on pregnancy

outcomes. Front Immunol. 11:5282022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Chan D, Bennett PR, Lee YS, Kundu S, Teoh

TG, Adan M, Ahmed S, Brown RG, David AL, Lewis HV, et al:

Microbial-driven preterm labour involves crosstalk between the

innate and adaptive immune response. Nat Commun. 13:9752022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Gonzalez JM, Franzke CW, Yang F, Romero R

and Girardi G: Complement activation triggers metalloproteinases

release inducing cervical remodeling and preterm birth in mice. Am

J Pathol. 179:838–849. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Robertson SA, Skinner RJ and Care AS:

Essential role for IL-10 in resistance to

lipopolysaccharide-induced preterm labor in mice. J Immunol.

177:4888–4896. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Osman I, Young A, Ledingham MA, Thomson

AJ, Jordan F, Greer IA and Norman JE: Leukocyte density and

pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes,

decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term.

Mol Hum Reprod. 9:41–45. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Rinaldi SF, Catalano RD, Wade J, Rossi AG

and Norman JE: Decidual neutrophil infiltration is not required for

preterm birth in a mouse model of infection-induced preterm labor.

J Immunol. 192:2315–2325. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Mohd Zaki A, Hadingham A, Flaviani F,

Haque Y, Mi JD, Finucane D, Dalla Valle G, Mason AJ, Saqi M,

Gibbons DL and Tribe RM: Neutrophils dominate the cervical immune

cell population in pregnancy and their transcriptome correlates

with the microbial vaginal environment. Front Microbiol.

13:9044512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Cezar-de-Mello PFT, Ryan S and Fichorova

RN: The microRNA cargo of human vaginal extracellular vesicles

differentiates parasitic and pathobiont infections from

colonization by homeostatic bacteria. Microorganisms. 11:5512023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Zen M, Canova M, Campana C, Bettio S,

Nalotto L, Rampudda M, Ramonda R, Iaccarino L and Doria A: The

kaleidoscope of glucorticoid effects on immune system. Autoimmun

Rev. 10:305–310. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Busillo JM, Azzam KM and Cidlowski JA:

Glucocorticoids sensitize the innate immune system through

regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Biol Chem. 286:38703–38713.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Hermoso MA, Matsuguchi T, Smoak K and

Cidlowski JA: Glucocorticoids and tumor necrosis factor alpha

cooperatively regulate toll-like receptor 2 gene expression. Mol

Cell Biol. 24:4743–4756. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Baschant U and Tuckermann J: The role of

the glucocorticoid receptor in inflammation and immunity. J Steroid

Biochem Mol Biol. 120:69–75. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Franchimont D: Overview of the actions of

glucocorticoids on the immune response: A good model to

characterize new pathways of immunosuppression for new treatment

strategies. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1024:124–137. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Hearps AC, Tyssen D, Srbinovski D, Bayigga

L, Diaz DJD, Aldunate M, Cone RA, Gugasyan R, Anderson DJ and

Tachedjian G: Vaginal lactic acid elicits an anti-inflammatory

response from human cervicovaginal epithelial cells and inhibits

production of pro-inflammatory mediators associated with HIV

acquisition. Mucosal Immunol. 10:1480–1490. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Delgado-Diaz DJ, Tyssen D, Hayward JA,

Gugasyan R, Hearps AC and Tachedjian G: Distinct immune responses

elicited from cervicovaginal epithelial cells by lactic acid and

short chain fatty acids associated with optimal and non-optimal

vaginal microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 9:4462020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Galdeano CM and Perdigón G: The probiotic

bacterium Lactobacillus casei induces activation of the gut mucosal