Introduction

Obesity, defined by an excessive accumulation of

body fat resulting from chronic nutrient overconsumption, has

become a significant global public health issue, not only due to

its high prevalence, but also due to its associated comorbidities

and the resulting disruption of adipocyte-immune cell interactions

within adipose tissue (1,2).

As of 2016, ~650 million adults worldwide were classified as obese,

with projections estimating that this number could reach four

billion by the year 2035. In many developed nations, it is

anticipated that nearly one-third of individuals will be affected

in the coming years (3).

Obesity profoundly affects multiple organ systems

through mechanisms involving oxidative stress, inflammation and

metabolic dysregulation (4,5).

Excessive nutrient intake leads to adipose tissue expansion and

ectopic lipid accumulation, particularly in the liver, where it

contributes to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease, characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction and the

increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (6-10). Oxidative stress promotes

hepatocellular injury and inflammation, thereby advancing disease

progression (11,12). In skeletal muscle, obesity

promotes the accumulation of intermuscular and intramyocellular

lipids, which impairs muscle regeneration and increases the risk of

atrophy and sarcopenia through mechanisms of lipotoxicity (13,14). The brain is not spared; obesity

leads to hypothalamic inflammation and gliosis, disrupting appetite

regulation and energy homeostasis by impairing neuronal integrity

in this critical region (15).

Moreover, obesity-induced chronic low-grade

inflammation, mediated by adipose tissue macrophages and cytokines,

exacerbates oxidative damage and disrupts metabolic homeostasis.

These interconnected processes underlie the pathogenesis of

metabolic syndrome, increasing cardiovascular risk and organ

dysfunction. Thus, oxidative stress is a central mediator linking

obesity to multisystemic metabolic disturbances (4,16,17).

Despite extensive research into the metabolic and

cardiovascular complications of obesity, its effects on the

reproductive system, particularly at the molecular and cellular

levels, have received comparatively less attention. Recent evidence

underscores that obesity profoundly disrupts reproductive health in

both males and females, impairing gametogenesis, hormonal balance,

fertilization, and subsequent embryonic and postnatal development

(16,18,19). The mechanisms of these effects

are multifactorial and include oxidative stress, altered

steroidogenesis, disrupted endocrine signaling along the

hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, mitochondrial dysfunction,

epigenetic modifications and chronic inflammation (5,20-23). In females, obesity is associated

with impaired oocyte quality, abnormal follicular environments,

ovulatory dysfunction, and reduced implantation and live birth

rates (18). In males, excess

adiposity is associated with reduced sperm quality, altered hormone

profiles, and increased sperm DNA damage, with evidence of

intergenerational transmission of metabolic dysfunction mediated by

epigenetic changes (24,25). Furthermore, obesity during

pregnancy increases the risk of gestational complications,

adversely affects placental function, and programs offspring for

metabolic and reproductive disorders later in life (26). However, the field lacks

comprehensive mechanistic frameworks that distinguish

obesity-specific effects from those mediated by associated

metabolic disorders or nutritional factors.

Despite these insights, a comprehensive review that

synthesizes currently available knowledge on the mechanisms through

which obesity affects the reproductive system from fertilization

through post-uterine development remains lacking, at least to the

best of our knowledge. The present review thus aimed to fill this

gap by providing an integrative overview of the molecular

mechanisms by which obesity impairs reproductive function, focusing

on oxidative stress and its downstream effects at each stage, from

gamete quality and fertilization to embryonic development and

postnatal outcomes. By elucidating these pathways, it is hoped that

the present review will inform future research and clinical

strategies to mitigate the reproductive and developmental

consequences of obesity.

Obesity as a driver of testicular

inflammation

The male reproductive tract consists of multiple

organs, including the testes, epididymis and prostate gland, which

collectively enable sperm development and androgen production

(27). Within the testes,

spermatogenesis takes place inside seminiferous tubules lined by

Sertoli cells. These cells support sperm maturation, uphold

structural integrity, and establish the blood-testis barrier to

protect developing germ cells from toxins and immune responses

(28). Spermatogenesis

progresses from spermatogonia through several developmental stages

tightly regulated by testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone

(29-31). To study male reproduction,

rodents that share comparable reproductive features and are

frequently employed in reproductive studies (32,33) are used.

Obesity may compromise both sperm development and

the blood-testis barrier through systemic inflammation, although

exact pathways involved remain unclear. The present comprehensive

overview discusses the complex association between obesity,

particularly the accumulation of excess fatty acids and sugar, and

signaling pathways involved in testicular development, as well as

sperm maturation, motility, morphology and DNA integrity.

Diet-induced obesity and its impact on

testicular function and hormonal regulation

Research utilizing high-fat diet (HFD) models to

induce obesity has revealed significant effects of obesity on

testicular function. A previous study which was performed as early

as 2001 demonstrated that HFD-induced obesity increased the weight

of the ventral prostate in Sprague-Dawley rats (34). It was the first-ever study to

demonstrate a direct effect of obesity caused by saturated fat

consumption on the reproductive tract, laying the groundwork for

future research into how excess fat intake induced by obesity

affects testicular function. Another notable study on Wistar rats

aimed to evaluate the adaptive responses in the testes of adult

rats treated with a non-toxic dose of the environmental chemical

dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), either alone or in

association with a HFD (35).

That study concluded that HFD and DDE induce cellular stress,

leading to antioxidant impairment, apoptosis and decreased levels

of the androgen receptor (AR) and serum testosterone, all of which

are associated with tissue damage. However, notable cellular

proliferation was observed, considered an adaptive response to

counterbalance tissue damage. Critical gaps exist in understanding

how HFD-induced obesity specifically affects key regulatory

pathways. Notably, a subsequent study examined the effect of both a

HFD and exercise on the 'controller' of gonadal development, the

KISS-1/G/G protein-coupled receptor 54 (GPR54) system, in the

testes of growing rats (36).

The increase of KISS-1/GPR54 during the testicular growing period,

as measured using RT-qPCR and western blot analysis, was abolished

by HFD feeding (36). Notably,

that study also revealed that the regular testicular growing

pattern, as well as normal KISS-1/GPR54 expression, can be restored

through moderate-intensity aerobic exercise at 60-70%

VO2 max (36). An

interesting finding was reported in the study by Ma et al

(37) regarding how zinc

improves semen parameters in HFD-fed male rats by regulating the

expression of long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) in testicular

tissue.

Diet-induced reproductive dysfunction in

males

While studies above focused on long-term HFD

feeding, which induces obesity, the study by Falvo et al

(38) examined the effects of

short-term HFD feeding. They proved that HFD implementation as

short as 5 weeks can reduce steroidogenesis, increase the apoptosis

of spermatogenic cells, alter spermatogenesis with reduced protein

levels of meiotic and post-meiotic markers, and notably compromise

blood-testis barrier integrity through sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)/nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)/mitogen-activated

protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways (38). Moreover, a high-fat, vitamin

D-deficient diet in Sprague-Dawley rats has been shown to reduce

sperm motility, mitochondrial function and fertilizing capacity

(39).

Obesity, characterized by the excess accumulation of

free fatty acids and glucose in blood and cells, is known to

elevate ROS production (40).

Multiple animal studies have confirmed that, for instance, HFD

triggers the accumulation of ROS in sperm and testicular tissue,

thereby leading to reproductive impairment. For example, a study

using an animal model of HFD demonstrated that HFD-fed mice

displayed a decline in the levels of antioxidant enzymes, such as

glutathione peroxidase (GPX), catalase and superoxide dismutase

(SOD), in testicular and epididymal tissues compared to mice fed a

control diet (41). In line with

this finding, mature sperm in HFD-fed mice exhibited higher ROS

levels and decreased levels of GPX1 protein, resulting in impaired

mitochondrial structural integrity and reduced mitochondrial

membrane potential, as well as decreased ATP production. Notably,

considering the significant impairment of mitochondrial function,

sperm motility was found to be reduced. Additionally, the same

conclusions were found to be true for obese males in the scope of

the study (41).

Another study examined the obesity-related increase

in intestinal permeability, which allows the passage of intestinal

bacteria into the circulation, known as metabolic endotoxemia (ME)

(42). That study on 37

infertile males revealed an association between obesity-related ME,

measured as serum zonulin, and impaired sperm DNA integrity. The

association was found to be persistent even after adjusting for

confounding factors, such as age and duration of abstinence.

However, the exact molecular mechanisms involved were not discussed

(42). The key findings of the

study by Bakos et al (43) on C57/Bl6 male mice fed a HFD were

that obesity significantly decreased the percentage of motile

spermatozoa (36 vs. 44% in controls) and that this reduction in

motility was associated with altered energy metabolism and

increased redox imbalance in sperm cells. The study by Han et

al (44) reached the same

conclusions by observing abnormal testicular structures on a larger

scale and detecting excessive oxidative stress, as well as enhanced

apoptosis and impaired glucose metabolism markers, on a molecular

scale.

The impact of obesity on the male reproductive

system has been observed from another perspective through the use

of high-sugar mouse models, thereby mimicking metabolic syndrome

(MetS). The key finding of the study by Rahali et al

(45) was that MetS induces

severe testicular toxicity in male rats, as measured by BAX

downregulation, BCL2 upregulation and a decreased

testosterone level, which was associated with the downregulation of

cytochrome P450 family (CYP)11A1, CYP17A1 and 17β HSD

testicular markers. In another study, hypercholesterolemic rabbits,

fed a diet supplemented with 0.05% cholesterol, concluded that

excess cholesterol leads to a reduced semen volume and sperm

motility, as well as changes in sperm morphology (head and

flagellum) (46). The additional

impact of obesity on the human and rodent male reproductive systems

is presented in Table I.

| Table IEffects of obesity on the human and

rodent male reproductive systems. |

Table I

Effects of obesity on the human and

rodent male reproductive systems.

| Model | Treatment | Effect | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Sprague-Dawley

rats | 16-week HFD | ↓ Testosterone

synthesis

↑ Spermatogenic cell apoptosis | (57) |

| Ldlr−/−

Leiden | 24-week HFD + BA

administration | ↑ Plasma leptin

abnormal testosterone levels aberrant ITO

↑ Level of tubules in stages VII/VIII | (58) |

| Rats with

STz-NA-induced diabetes | HFD until 12 weeks

of age | ↓ Epididymal sperm

motility

↓ Histone-protamine transition

↓ Plasma testosterone

↓ Sperm count | (59) |

| Wistar rats | 4-week HFD | ↓ Epididymal sperm

maturationas

↓ Testosterone levels

↓ Sperm viability

↓ Capacitation | (60) |

| C57BL/6 mice | 8-week HFD + diet

reversal | disrupted

testicular BTB integrity

↑ levels of oxidative stress abnormal expression of BTB-related

proteins | (61) |

| C57Bl/6 mice

AdipoR1 KO mice Akita mice | 28-week HFD

(C57Bl/6) and standard chow (AdipoR1 KO, Akita) | ↓ Sperm count,

motility fertilizing ability and AdipoR1 gene and protein

(in HFD)

↑ Pro-apoptotic genes and poteins (in HFD)

↓ Testes weight, sperm count, motility, and fertilizing ability,

phosphorylation of AMPK (in AdipoR1 KO)

↑ Pro-apoptotic proteins, CASP6 activity and pathologically

apoptotic seminiferous tubules (in AdipoR1 KO) | (62) |

| C57BL/6J mice | 10-week HFD +

exercise | ↓ LEP-JAK-STAT

pathway

↓ Expression of SF-1, StAR, CYP11A1

↓ Sserum testosterone-to-estradiol ratio, sperm quality effect can

be reversed by exercise | (63) |

| Wistar rats | 16-week HFD | ↓ Male fertility,

fertilization, cell adhesion genes

↑ Obesity, lipid metabolism-related, immune response-related and

CYP genes

↑ Aromatase activity | (64) |

| Wistar rats | 38-week

hyperglycidic diet | 15 Proteins with

differential abundance | (65) |

On the other hand, the relation of obesity to

testicular cancer (TC) appears to be heterogeneous. For instance,

tentative evidence of an inverse association between body mass

index (BMI) and testicular germ-cell tumors (TGCT) was provided in

a previous meta-analysis (47).

Additionally, a Norwegian study found that the risk of developing

TC decreased with adult BMI (48). On the other hand, a high BMI was

more prevalent in TGCT cases than in the control group, according

to Dieckmann et al (49).

In a study on Canadian males, it was demonstrated that a high

dairy, particularly cheese, intake was associated with an elevated

risk of developing TC (50).

Considering that body fat composition serves as a more effective

indicator of obesity than BMI, in another study, computed

tomography was used to determine visceral adipose tissue (VAT),

subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and skeletal muscle area ratios,

as well as TC stage (51). That

study determined a statistically significant moderate positive

association between testicular tumor stage and the VAT/SAT ratio.

While this topic requires further assessment, an interesting

finding was reported in the study by Puri et al (52), who stated that the connection

between TC and obesity was bidirectional. More specifically, it

appears that TC survivors are at an increased risk of metabolic

syndrome and obesity development.

While several studies have assessed the impact of

obesity on testicular tissue and sperm, only a small number of

studies have examined the potential for reversing its effects. A

recent study claimed that micronutrient-based antioxidant

intervention, containing added folate, vitamin B6, choline, betaine

and zinc in rats can ameliorate the effects of a HFD on testicular

tissue (53). Briefly, at 30.5

weeks of post-weaning HFD, sperm was harvested and analyzed for

sperm count and 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) content and

testes were analyzed for 8-OhdG, malondialdehyde, folate and

glutathione content, the activity of SOD, catalase and GPX,

susceptibility index of pro-oxidative damage and mRNA the

expression of Nrf2, NFκB-p65, interleukin

(IL)-6 and IL-10, and Tnfa. Notably,

micronutrient-based antioxidant intervention in HFD significantly

mitigated HFD-induced sperm and testicular oxidative damage by

enhancing testicular antioxidant capacity through the regulation of

the parameters above (53).

Subsequently, Suleiman et al (54) demonstrated the therapeutic

potential of bee bread, the outcome of the fermentation from the

combination of pollen, digestive enzymes found in saliva and

nectar, on obesity-induced testicular-derived oxidative stress,

inflammation and apoptosis in rats fed a HFD (54). They demonstrated that

administering bee bread in combination with a HFD diminished the

detrimental effects of a HFD, including a decrease in antioxidant

enzymes and proliferating cell nuclear antigen immunostaining, as

well as an increase in inflammation and apoptosis markers (e.g.,

cleaved caspase-3) in the testes (54). Additional research has

demonstrated the ameliorative effects of Myrtus communis L.

extract on HFD-induced damage to the testes in rats, through the

inhibition of oxidative stress (55). In another study, to assess

whether physical exercise can effectively ameliorate

obesity-induced abnormalities in male fertility, the sperm

parameters (motility, concentration, the ability to undergo

capacitation and the acrosome reaction) of HFD-fed mice that

underwent physical labor were evaluated (56). That study provided evidence that

the adverse effects of obesity can be mitigated through physical

exercise. Additionally, that study identified several small

non-coding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs; miR-6538,

miR-129-1, miR-7b, miR-196a-1, miR-872, miR-21a, miR-143 and

miR-200a), in germ cells that may play a crucial role in the

effects of obesity and physical exercise on spermatozoa (56).

In summary, data unequivocally suggest that

excessive fat and sugar intake exert disruptive effects on all

aspects of male reproduction, including sperm maturation,

mitochondrial structure and function, oxidative stress levels, and

sperm motility in both humans and rodent obesity models. However,

several reports claim that normal testicular function can be

restored through physical exercise and therapeutic

intervention.

Metabolic syndrome: Molecular pathways

linking MetS to male infertility

MetS is characterized by a group of conditions,

including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension and

chronic low-grade inflammation. Beyond obesity alone, MetS exerts

significant detrimental effects on male fertility. Insulin

resistance disrupts insulin signaling pathways that are critical

for testosterone biosynthesis in Leydig cells. This leads to

hypogonadism and decreased support for spermatogenesis (66). Dyslipidemia promotes lipid

peroxidation in sperm membranes, compromising motility and

acrosomal function. Moreover, hypertension-induced endothelial

dysfunction reduces testicular perfusion, exacerbating oxidative

stress and hypoxia (67).

Chronic inflammation, driven by cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6

secreted from adipose tissue, disrupts the blood-testis barrier.

This occurs through the activation of the MAPK and NF-κB signaling

pathways, enabling immune cell infiltration. Subsequently, germ

cell apoptosis also becomes increased (66,67).

Metabolic syndrome also alters adipokine profiles.

Elevated leptin (hyperleptinemia) and reduced adiponectin levels

negatively affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. This

impairment further decreases testosterone production and

spermatogenesis (68). Emerging

evidence also implicates epigenetic modifications in sperm from

males with MetS, including aberrant DNA methylation and histone

acetylation patterns, which may contribute to the transgenerational

transmission of metabolic and reproductive dysfunction (66). Collectively, these metabolic and

molecular alterations underscore the critical role of MetS in male

infertility and highlight the need for integrated clinical

approaches targeting metabolic health to improve reproductive

outcomes.

Obesity as a driver of ovarian dysfunction

and female reproductive impairment

Located within the pelvis and supported by

ligaments, the female reproductive system consists of internal

organs (the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and vagina),

as well as external genitalia (69,70). The ovaries lie adjacent to the

uterus and fimbriae and act as the site of oocyte development and

maturation (70). Apart from

producing eggs, they release estrogen and progesterone to regulate

the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. The fallopian tubes carry the

oocyte to the uterus and typically serve as the site of

fertilization; these tubes are segmented into fimbria,

infundibulum, ampulla, and isthmus (71). The muscular uterus supports

implantation and fetal growth (72).

Obesity has been proven to have marked effect on

female reproduction; it has been reported that obesity promotes

lipid accumulation and morphological changes across the uterus,

ovary and oviduct, with increased NF-κB and MAPK signaling

(73). Additionally, obesity

alters the immune cell profile in reproductive tissues, as detailed

by St-Germain et al (74).

The present comprehensive overview discusses the

mechanistic links between obesity, particularly the accumulation of

excess fatty acids and glucose, and the disruption of signaling

pathways in ovarian folliculogenesis, steroidogenesis and oocyte

quality.

Metabolic stress and follicular

development disruption induced by a high-fat diet

A pivotal study from 2014 demonstrated that

progressive obesity in female mice altered ovarian steroidogenic

enzymes and inflammatory pathways, with NF-κB signaling elevated by

12 weeks of age and STAR protein levels reduced by 50% after 24

weeks of exposure to a HFD (75). That foundational study revealed

temporal shifts in CYP11A1 and CYP19A1 expression,

impairing estrogen synthesis and follicular survival (75). Building on this, a study in 2015

demonstrated that hyperglycemic conditions during oocyte maturation

increase ROS by 40% and reduce developmental competence in antral

follicle-derived oocytes, despite normal growth during earlier

follicular stages (76). A

landmark study in 2016 established that a HFD directly reduces

primordial follicle reserves by 32% in mice through ovarian

macrophage infiltration and systemic inflammation, independent of

obesity phenotype, while compromising long-term fertility outcomes

(77).

Lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and

mitochondrial dysfunction in ovarian cells

Exposure to a HFD induces lipotoxic stress in

ovarian cells, disrupting the follicular microenvironment and

compromising oocyte developmental competence. Wu et al

(78) demonstrated that HFD-fed

mice exhibited lipid accumulation in cumulus-oocyte complexes,

leading to oxidative stress (elevated ROS levels) and endoplasmic

reticulum stress markers (BiP/GRP78), which impaired fertilization

rates by 35% compared to the controls. Single-cell RNA sequencing

by Zhu et al (79)

revealed that HFD altered mitochondrial respiration pathways in

oocytes, resulting in the downregulation of Ppargc1a (a key

regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis) and disrupted metabolic

coupling between granulosa cells and oocytes, which led to delayed

embryo cleavage and reduced blastocyst formation. These defects

were associated with aberrant lipid metabolism in granulosa cells,

including the upregulation of fatty acid-binding protein 4 and the

dysregulation of cholesterol homeostasis (79).

Interventional studies have highlighted potential

therapeutic strategies. Choi et al (80) demonstrated that

high-molecular-weight chitosan supplementation in HFD-fed mice

reduced ovarian lipid droplets by 40% and restored ovulation rates

through improved insulin sensitivity and AMPK activation.

Similarly, Morimoto et al (81) identified HFD-induced glycolytic

disruptions in granulosa cells, characterized by reduced Hk2

and Pfkfb3 expression, which impairs pyruvate provision to

oocytes, a critical energy substrate for maturation. This metabolic

uncoupling was exacerbated in aged obese mice, where oocytes

displayed 50% lower ATP levels and increased aneuploidy rates.

These findings underscore that HFD-induced lipotoxicity in ovarian

cells disrupts structural and functional integrity at multiple

levels, from follicular communication to embryonic viability, with

redox imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction as central mechanisms

(81).

Hormonal imbalance, inflammation and

fertility outcomes in obese females

Recent evidence suggests that HFD-induced oxidative

stress disrupts the ovarian microenvironment by impairing oocyte

mitochondrial function, thereby accelerating follicular atresia

through ROS-mediated DNA damage (82). These effects are compounded by

hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis dysregulation, in which obese

women exhibit a 25% lower luteinizing hormone (LH) pulse amplitude

and elevated insulin levels that disrupt gonadotropin signaling

(83). Notably, interventions

show promise: A study published in 2024 identified that

antioxidant-rich diets containing phytonutrients and organosulfur

compounds can mitigate 68% of HFD-induced ovulation irregularities

by restoring hormonal balance (82). Concurrently, lifestyle

modifications combining Mediterranean-style diets with

moderate-intensity exercise (45-60% VO2max) improve

pregnancy rates in obese women by enhancing insulin sensitivity and

reducing inflammatory cytokines (84).

Studies on animals have demonstrated that female

rodents fed a HFD exhibit reduced ovarian antioxidant enzyme

activity, resulting in oocyte mitochondrial dysfunction. This

oxidative damage disrupts ATP production and induces lipid

peroxidation in granulosa cells, impairing follicular development.

Studies on humans corroborate these findings, demonstrating

elevated ROS levels in the follicular fluid of obese women

undergoing fertility treatments, which are associated with reduced

oocyte maturation rates and embryo quality (85-87).

The inflammatory milieu in obesity further

exacerbates redox imbalance through adipose-derived cytokines, such

as TNF-α and IL-6, which activate signaling pathways promoting

granulosa cell apoptosis (87).

A previous systematic review demonstrated that obese women with

elevated chemerin levels faced a 2.3-fold higher risk of

anovulatory cycles. Structural analyses of ovarian tissue from

HFD-fed mice exhibit a reduction in primordial follicle reserves

and stromal lipid accumulation, paralleled by downregulation of

enzymes essential for estrogen synthesis. Additionally,

dysregulated adipokines, such as leptin and adiponectin, alter GnRH

pulsatility, reducing LH and FSH secretion and further compromising

ovulation. This hormonal imbalance contributes to menstrual

irregularities, anovulation, and infertility (87). Moreover, obesity-related

alterations in adipokine levels exacerbate insulin resistance and

promote systemic inflammation, further disrupting ovarian function

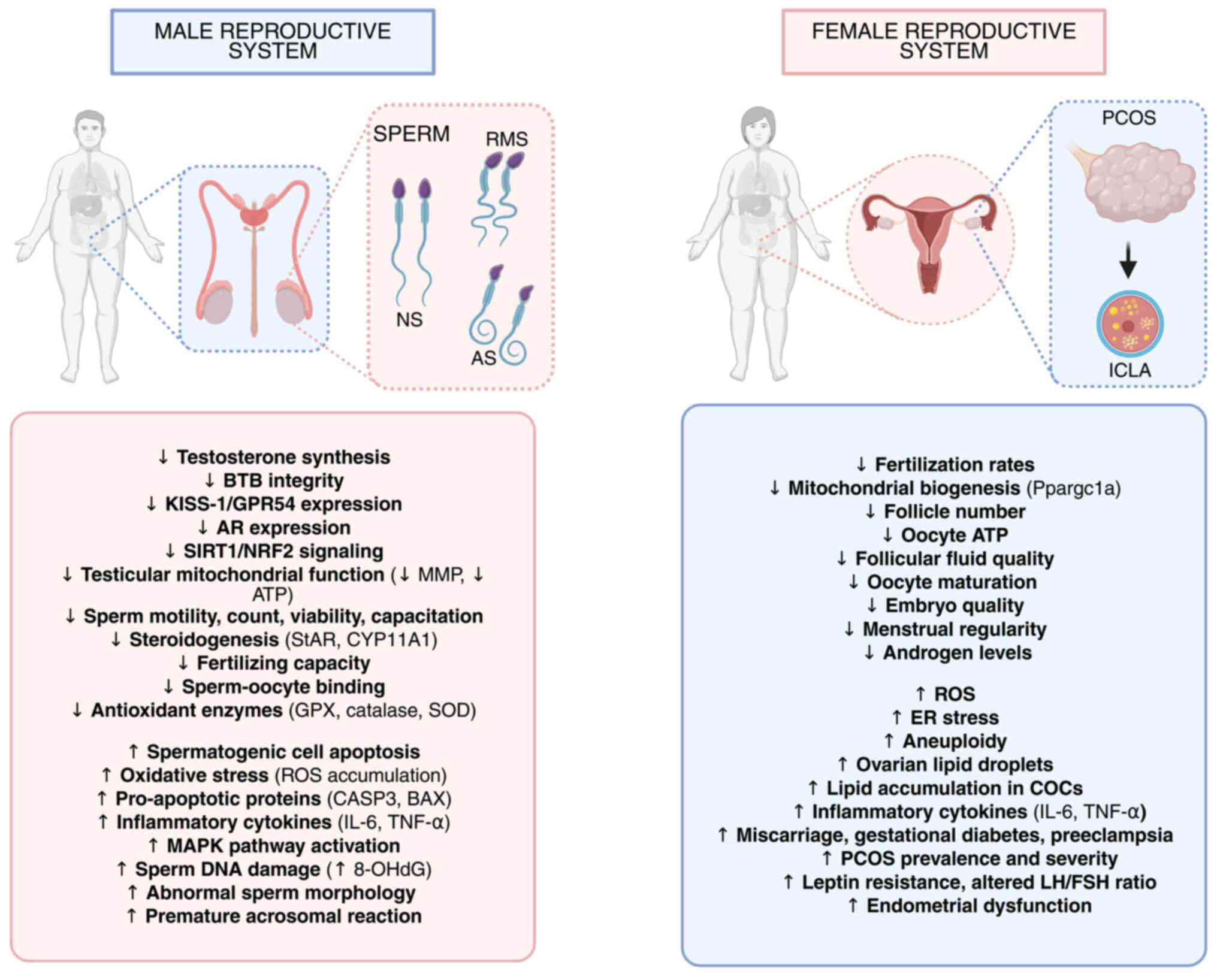

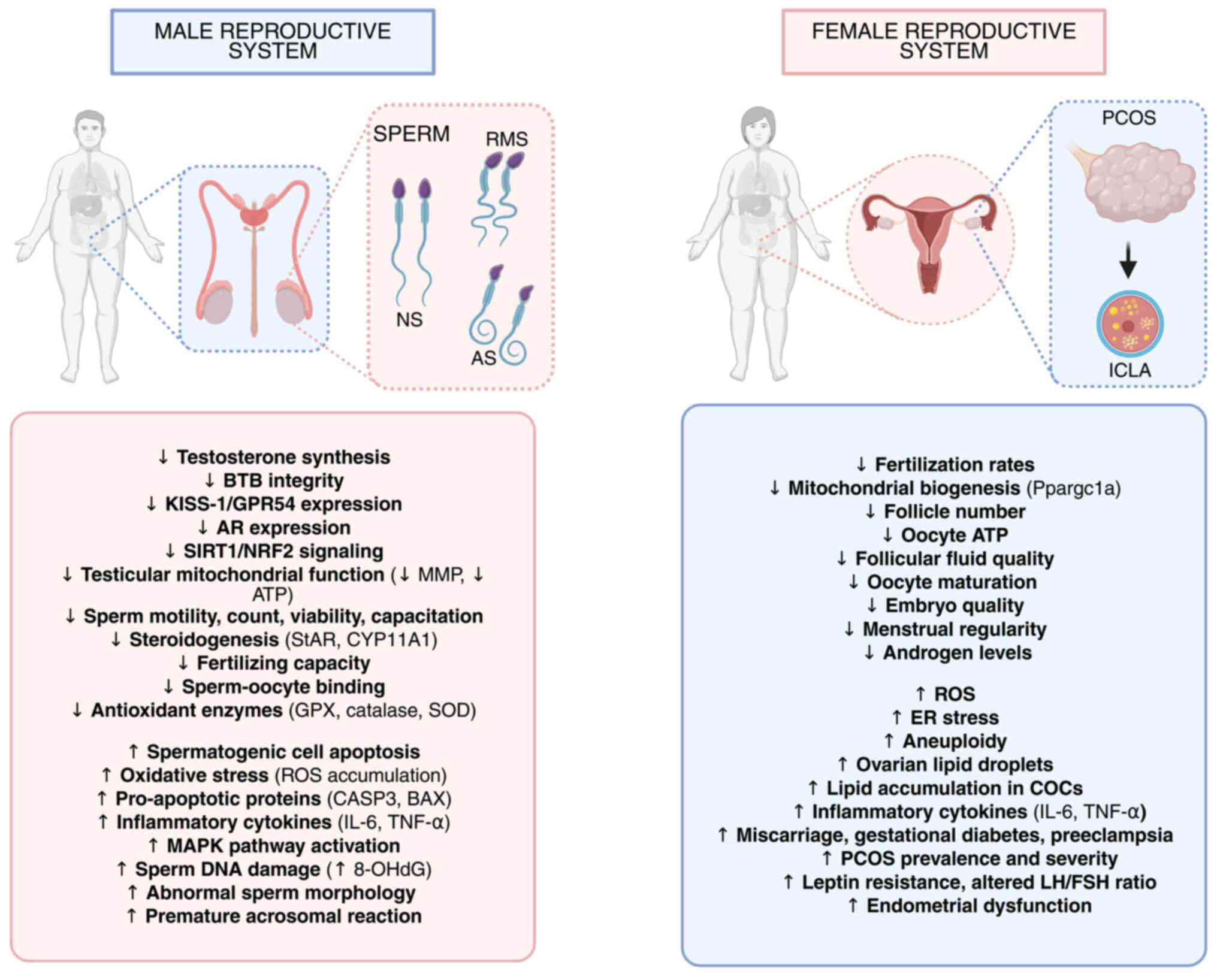

and impairing folliculogenesis (88). A summary of molecular mechanisms

caused by obesity in both females and males is illustrated in

Fig. 1.

| Figure 1Schematic illustration of the effects

of obesity on male and female reproductive systems. On the left

panel, male obesity is proven to have a significant impact on the

development of normal sperm, thereby causing reduced motility sperm

and atypical sperm production. On the right panel, female obesity

is proven to cause altered ovarian morphology and increased

cytoplasmic lipid accumulation in oocytes. Further effects of

obesity in both female and male reproductive system physiology and

development are indicated as a downward-looking arrow (decrease)

and an upward-looking arrow (increase). NS, normal sperm; RMS,

reduced motility sperm; atypical sperm; ILCA, increased cytoplasmic

lipid accumulation; BTB, blood-testis barrier; KISS-1, KiSS-1

metastasis suppressor; GPR54, G protein-coupled receptor 54; AR,

androgen receptor; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; ATP,

adenosine triphosphate; StAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory

protein; CYP11A1, cytochrome P450 family 11 subfamily A member 1;

GPX, glutathione peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; CASP3, caspase 3; BAX, BCL2-associated X

protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha;

MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; 8-OHdG,

8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; ICLA,

in vitro cultured large antral follicle; Ppargc1a,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator

1-alpha; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; COCs, cumulus-oocyte complexes;

LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone. |

Epidemiological research has reported that women

with obesity have a 2.7-fold increased risk of infertility and a

25-37% higher risk of miscarriage compared to women of normal

weight (89). Obesity also

worsens the clinical and metabolic manifestations of polycystic

ovary syndrome (PCOS), a leading cause of female infertility, by

promoting hyperinsulinemia and hyperandrogenism, which impair

follicular development and ovulatory function. Additionally,

obesity negatively affects assisted reproductive technology (ART),

reducing pregnancy and live birth rates, and increasing the

likelihood of ART failure (90,91). The additional impact of obesity

on the human and rodent female reproductive systems is presented in

Table II.

| Table IIEffects of obesity on the human and

rodent female reproductive systems. |

Table II

Effects of obesity on the human and

rodent female reproductive systems.

| Model |

Treatment/intervention | Effect | (Refs.) |

|---|

| CBA mice | 4-week HFD | Lipid accumulation

in COCs

↑ ROS,

↑ ER stress

↓ Fertilization rates (35%) | (78) |

| C57BL/6 mice | Single-cell RNA-seq

+ HFD | ↓ Ppargc1a

(mitochondrial biogenesis) impaired glucolipid metabolism delayed

embryo cleavage

↓ Follicle number | (96) |

| B6C3F1 mice | 4-week HFD +

WSC | ↓ Ovarian lipid

droplets (40%) restored ovulation via AMPK activation | (80) |

| C57BL/6J mice | HFD + aged

cohorts | ↓ Granulosa cell

Hk2/Pfkfb3

↓ Oocyte ATP (50%)

↑ Aneuploidy | (60) |

| Women

(clinical) | Obesity (BMI

≥30) | ↓ Follicular fluid

quality

↑ ROS

↓ Oocyte maturation

↓ Embryo quality | (78) |

| C57BL/6J mice | Maternal HFD

(preconception) | Altered

mitochondrial membrane potential (↓ΔΨm) in

oocytes/zygotes

↑ ROS | (97) |

| Women (PCOS) | Obesity | ↓ Menstrual

regularity

↑ Androgen levels

Suppressed ovulation

Effect can be reversed by metformin | (98) |

Apart from the physiological impact on the uterus

and ovaries, obesity increases the risk of developing endometrial

cancer, which can be decreased through weight loss by recruiting

protective immune cell types to the endometrium (92). Additionally, obesity influences

DNA methylation in pre-symptomatic endometrial epithelial cells,

and the persistent dysregulation of DNA methylation in obese women

may contribute to the development of endometrial cancer (93).

Weight loss through lifestyle modifications,

pharmacological intervention, or bariatric surgery has been shown

to improve menstrual regularity, reduce androgen levels, enhance

ovulation and increase spontaneous pregnancy rates in obese women.

These improvements underscore the importance of addressing obesity

as a modifiable risk factor to restore reproductive potential

(94,95).

In summary, substantial evidence suggests that the

excessive consumption of fats and sugars has a detrimental effect

on various aspects of female reproductive health. This includes

ovarian folliculogenesis, steroid hormone production, oxidative

balance and oocyte quality. These disruptions are consistently

observed in both human studies and animal models of obesity,

emphasizing the significant effects of metabolic dysregulation on

female fertility. Recent research suggests that lifestyle changes,

such as moderate-intensity exercise and targeted therapeutic

interventions like antioxidant supplementation, may help reduce

these harmful effects and restore normal ovarian function. These

findings highlight the importance of comprehensive strategies to

address obesity-related reproductive dysfunction in women.

Fertilization capacity as an indicator of

metabolic health

Placental development and physiology. Fertilization

is initiated when a sperm penetrates the zona pellucida of an egg,

forming a zygote. This process requires viable gametes, accurate

sperm transport, capacitation, hyperactivation, acrosome reaction

and membrane fusion (99-104).

Precise pH, calcium signaling, hormones, enzymatic activity and

molecular recognition all coordinate fertilization (104-106).

Initial connections between obesity and

fertilization emerged through the introduction and development of

in vitro fertilization (IVF). In 2011, researchers noted

that both PCOS and maternal obesity affected oocyte size in

IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles, thereby establishing

the direct impact of metabolic health on gamete quality (100). Considering that the

mitochondria play vital roles in oocyte function, it is evident

that mitochondrial functionality is a direct indicator of oocyte

quality, which in turn affects fertilization potential and

development into viable offspring (107). In this context, a previous

retrospective study explored the effects of overweight and obesity

on the IVF outcomes of poor ovarian responders (PORs) (108). A total of 188 PORs undergoing

IVF cycles were stratified into three groups (normal weight PORs,

overweight PORs and obese PORs), where it was concluded that obese

PORs had decreased fertilization and clinical pregnancy rates. In

another study, the proteomic assessment of follicular fluid from

women undergoing IVF using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

analysis found 25 proteins to be significantly altered in the

follicular fluid from women with obesity (109).

Molecular and cellular mechanisms linking

obesity to impaired fertilization

From a molecular perspective, obesity impairs sperm

function. HFD-fed male mice demonstrate reduced sperm-oocyte

binding ability, indicating impaired sperm recognition (43). In another study, HFD exposure was

shown to decrease testicular estradiol, the E2-to-testosterone

ratio and the levels of critical fatty acids, such as

docosahexaenoic acid, leading to premature acrosomal exocytosis and

diminished fertilization capacity (110). In the context of fatty

acid-related sperm modulation, Cooray et al (111) extrapolated that polyunsaturated

FAs (PUFAs), more specifically ω-3 unsaturated fatty acids, have

the highest potency in modulating sperm ion channels to increase

sperm motility, which might indicate higher fertilization potential

(111). In another study, to

identify a molecular marker for reduced fertilization rates caused

by obesity, screening for changes in gene expression in the male

reproductive tract revealed a decreased cysteine-rich secretory

protein 4 (CRISP4) expression in the testis and epididymis of obese

mice (112). The importance of

CRISPR was confirmed when the same study successfully improved the

fertilization rate through CRISPR treatment of sperm from HFD mice

prior to in vitro fertilization. Another potential player in

obesity-related fertilization issues appears to be an inflammatory

marker named lipocalin 2, which remains to be explored in the

reproductive tracts of both females and males (113). Research on other species

supports these findings: Bulls on high-gain diets produce semen

with reduced blastocyst formation capacity following IVF, linked to

increased necrosis and acrosome damage (114). Similarly, rats on high-fat,

vitamin D-deficient diets have been shown to exhibit decreased

sperm motility and mitochondrial dysfunction, impairing fertilizing

ability (39). In females,

obesity-associated implantation failure is associated with an

altered uterine DNA methylation and a reduced Dnmt gene

expression (115).

By contrast, an intergenerational murine model

combining regular chow with a high-energy supplement indicated that

an overweight status was associated with higher ovulation rates and

the increased development of fertilized oocytes, although embryo

quality was poor (113,116).

Dependence of in utero development on

parental obesity

Impact of maternal obesity on placental function and

fetal organ development. The placenta is an essential organ for

normal in utero development in mammals, functioning as the

critical exchange site for nutrients, gases, and waste products

between mother and fetus (117). This transitory organ also

serves endocrine functions by producing hormones necessary for

maintaining pregnancy and regulating fetal growth. Considering the

established connection with the maternal blood supply, it is no

wonder that maternal obesity influences the in utero

development of fetal organ systems through the placenta (118).

The placenta itself is affected by maternal obesity,

with its effects being observable through changes in placental

morphology, metabolism, inflammation, oxidative state, endothelial

function and altered angiogenesis (119,120). Moreover, a previous study

concluded that human placentas exhibit sex-specific adaptive

changes in response to maternal obesity (121). Placental development and

function in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity were proven to be

impaired through the altered transcriptome of placenta progenitor

cells in the preimplantation (trophectoderm) and early

post-implantation (ectoplacental cone) placenta precursors

(121). Crucially, the

differential expression of major upstream transcriptional

regulators in developmental pathways, such as Wingless-related

integration site (Wnt) signaling, p38 MAPK, ERK and Toll-like

receptor 2 signaling, was found to be impaired (121). In line with this, uterine

natural killer cells, which play essential roles in coordinating

uterine angiogenesis and promoting maternal tolerance to fetal

tissue, were found to display an altered repertoire of natural

killer receptors (inhibitory KIR2DL1 and activating KIR2DS1

receptors), thereby impacting early developmental processes

(122). Similarly, a study

using a cohort of obese or lean women found that obesity leads to a

significant reduction in natural killer cell numbers, accompanied

by impaired uterine artery remodeling, potentially influencing

further fetal development (123). A murine study found that

obesity alters the mouse endometrial transcriptome, potentially

affecting the endometrium's ability to function during pregnancy

(124).

To assess the impact of placental and endometrial

changes identified in the aforementioned studies on fetal

development, several studies were conducted. Ford et al

(125) followed fetal

pancreatic development in a sheep model of obesity. They noted

that, although all organs were heavier in fetuses from obesogenic

(OB) ewes, only the pancreatic weight increased as a percentage of

fetal weight (125). This was

accompanied by 50% more insulin-positive cells per unit of

pancreatic area in fetuses from OB ewes, as well as the notion that

obesity accelerates fetal pancreatic beta-cell, but not alpha-cell,

development (122).

The muscular system has also been found to be

affected by maternal obesity and exposure to excessive

glucocorticoids (126).

Specifically, glucocorticoid exposure in embryonic and fetal

developmental stages has emerged as a cause of cardiovascular

disease and muscle atrophy in adulthood. Previous studies even

mention obesity-related epigenetic dysregulation in Prader-Willi

syndrome and the agouti gene (127,128). An interesting study examining

gut intestinal structure and placental vascularization found that

diet-induced obesity decreased the maternal intestinal levels of

short-chain fatty acids and their receptors, impaired gut barrier

integrity, and was associated with fetal intestinal inflammation

(129). Moreover, maternal

obesity during pregnancy has been shown to upregulate the insulin

signaling genes, IRS2, PIK3CB and SREBP1c, in

skeletal muscle and perirenal fat, thereby favoring insulin

sensitivity (130).

Notably, the results of a study performed on baboon

fetuses of obese baboon mothers who consumed a high-sugar, HFD

during pregnancy demonstrated that the fetuses developed a fatty

liver along with significant metabolic disruption in the liver

(131). Most notably, fetal

livers exhibited the dysregulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle,

proteasome, oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis and the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, one of the most critical

developmental signaling pathways, accompanied by marked lipid

accumulation (131). Another

study on baboons proved how maternal obesity affects fetal liver

androgen signaling through reduced CYP2b6 and CYP3A activity in

conjunction with decreased nuclear AR-45 expression. Notably, the

effect was proven to be sex-specific, affecting only males

(132).

Several studies have provided evidence of maternal

obesity-related impairment of kidney development (133,134). For instance, Zhou et al

(133) found a decreased number

of peroxisomes and an increase in inflammasomes, resulting in

pyroptosis and apoptosis in the fetal kidney of obese mothers.

Additionally, the Gomeroi Gaaynggal study discovered that children

born to obese mothers had a reduced kidney size relative to

estimated fetal weight, suggesting a degree of glomerular

hyperfiltration in utero (134). The study by Tain et al

(135) demonstrated that

maternal high-fructose intake causes programmed hypertension in

offspring through changes in the renal transcriptome.

Epigenetic and molecular mechanisms

linking maternal obesity to long-term offspring health

Emerging evidence also highlights the disruption of

fetal oocyte development by maternal obesity. The recent stud by

Tang et al (136)

demonstrated that obesity induced meiotic defects in fetal oocytes,

including synapsis abnormalities and increased aneuploidy rates,

alongside the epigenetic dysregulation of DNA methylation and

histone modifications at critical developmental genes, such as

Stra8 and Sycp3. These alterations were linked to

oxidative stress and impaired DNA repair mechanisms, suggesting a

direct intergenerational transmission of metabolic risks to

reproductive health (136).

Currently, there is limited research available

investigating whether maternal or paternal obesity directly

contributes to the occurrence of chromosomal abnormalities in

offspring, highlighting a significant gap in understanding the

parental origins of such genetic risks.

A previous study on obesity has brought epigenetic

mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications and

miRNAs into focus during pregnancy as a significant indicator of

disease susceptibility in later stages of human life (137). To combat the effects of obesity

on in utero development, the assessment of alternate-day

fasting (ADF) and time-restricted feeding (TRF) in obese pregnant

mice found contrasting effects on placental function and fetal

development. TRF was proven to be superior to ADF, as it enhanced

placental nutrient transport and fetal development by reducing

endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammatory responses (138).

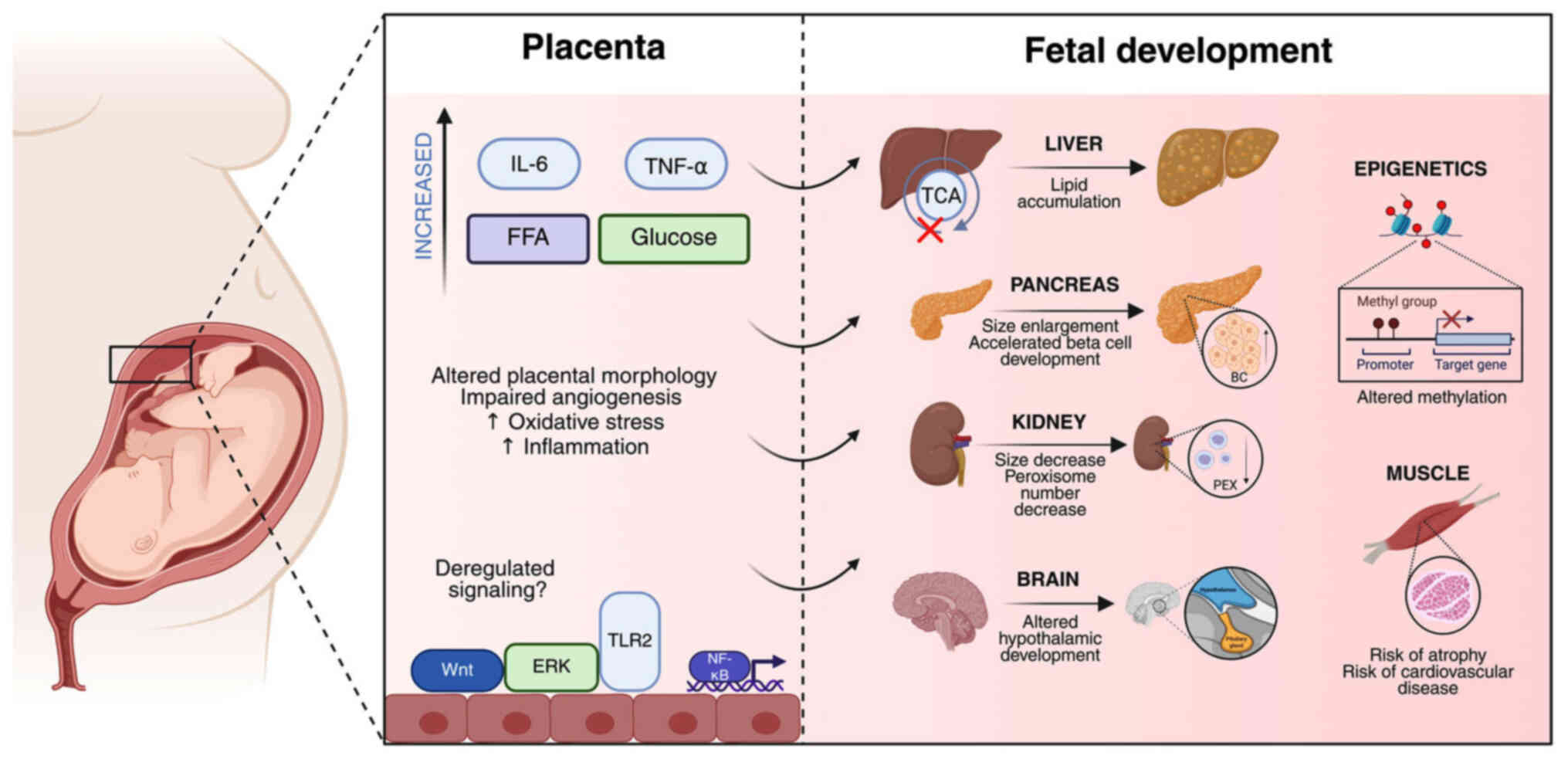

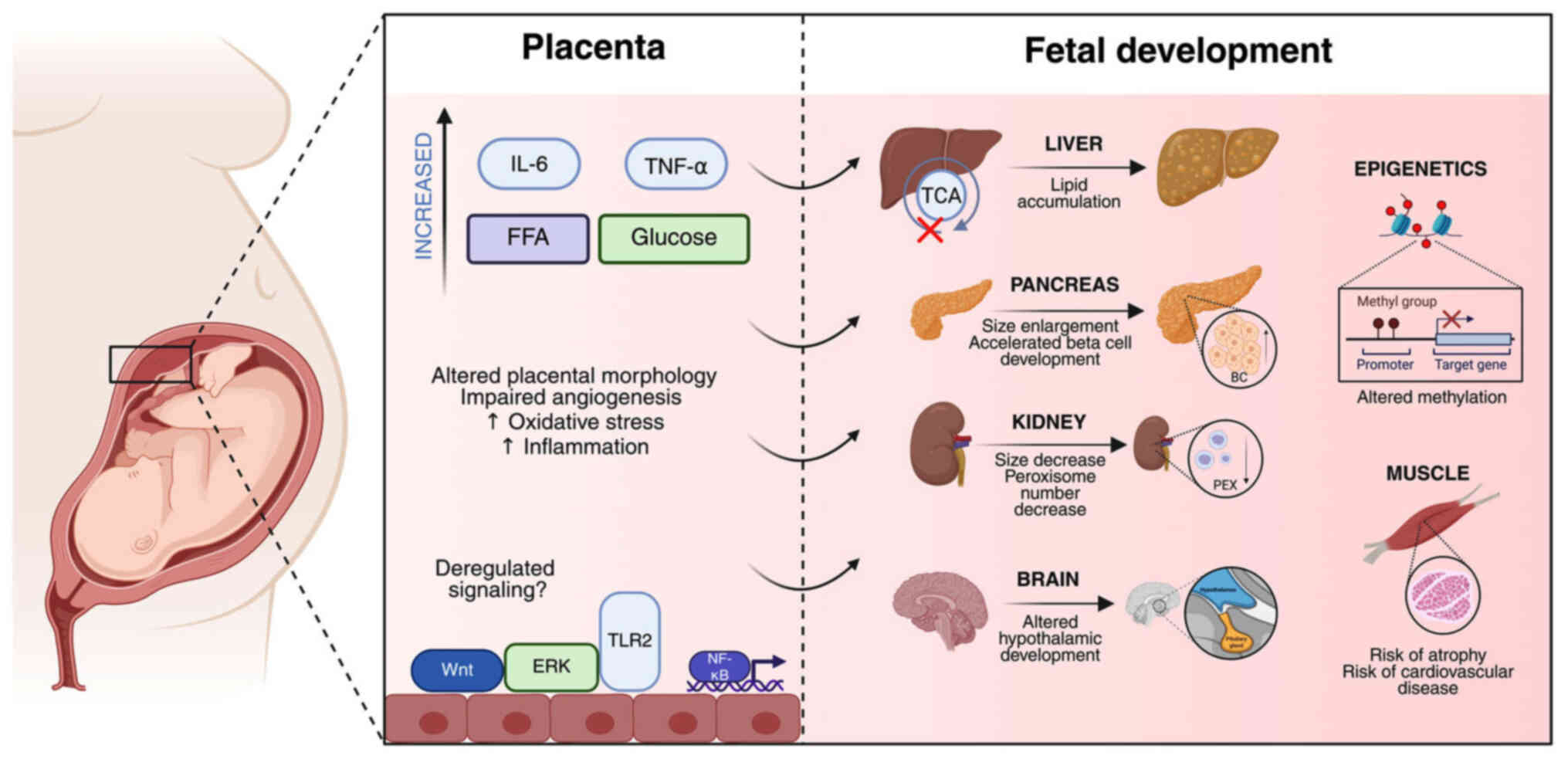

There is no doubt that parental obesity is a

critical indicator of impaired fetal development. The current

findings are summarized in Fig.

2. However, there is still room to further explore the

molecular effects of either paternal or maternal obesity on

specific organic systems.

| Figure 2Schematic illustration of the

mechanistic pathways by which maternal obesity influences fetal

development via placental alterations. On the left panel, maternal

obesity is associated with increased circulating levels of

pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α), FFAs and glucose. Apart

from the increase in pro-inflammatory markers, altered placental

morphology, impaired angiogenesis, and increased oxidative stress

can also be observed. Importantly, deregulated placental signaling

pathways, including Wnt, ERK, and TLR2, as well as the activation

of NF-κB, collectively disrupt placental function. On the right

panel, these placental changes adversely impact multiple fetal

organ system development processes. The fetal liver exhibits lipid

accumulation and impaired TCA cycle activity. The pancreas shows

enlargement and accelerated BC development. The kidney exhibits a

reduced size and a decreased number of peroxisomes. The brain is

affected through altered hypothalamic and hippocampal development.

In addition, epigenetic modifications, such as altered methylation

patterns, which may program long-term disease susceptibility, are

caused by parental obesity. Fetal muscle is shown to have an

increased risk of atrophy and predisposition to cardiovascular

disease. Together, these pathways underscore the multifaceted

effects of maternal obesity on in utero development and

future offspring health. IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis

factor-alpha; FFA, free fatty acids; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; Wnt,

wingless-related integration site; ERK, extracellular

signal-regulated kinase; TLR2, Toll-like receptor 2; NF-κB, nuclear

factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; BC, beta cell;

PEX, peroxisome. |

Obesity and offspring

Research and mechanisms linking parental obesity to

offspring health. The association between maternal or paternal

obesity and health outcomes of the offspring has emerged as a

critical area of research over the past several decades.

In the early 90s, research focused on the outcomes

of pregnancy. For instance, a previous study in 1990 reported that

the perinatal mortality rate increased from 37 to 121 per 1,000 in

obese women, indicating that even since then, it was proven that

obese women were more likely to undergo premature labor with a

negative outcome (139).

Nevertheless, mechanistic insight as to what causes specific

pregnancy outcomes and further offspring development did not lack

behind. A study on amniotic fluid at 32 to 38 weeks of gestation

revealed that insulin levels at that time account for a

longitudinal correlation with relative obesity in children at the

age of 6 (140). That study

suggested that premature and excessive exposure to insulin during

gestation may predispose to obesity in childhood. In line withthis

finding, another study in 2005 provided evidence that children who

are large for gestational age at birth and exposed to an

intrauterine environment of either diabetes or maternal obesity are

at an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome (141).

Recent studies have focused on the signaling

pathways involved in the effects of maternal obesity on the

offspring. The study by Moeckli et al (142) discovered that pathways involved

in metabolism (e.g., liver-related genes such as Egfr, Vegfb, Wnt2

and Pparg), the innate immune system, the clotting cascade and the

cell cycle were consistently dysregulated in the offspring of obese

mothers. Notably, female offspring exhibited higher non-alcoholic

liver disease prevalence, while males exhibited increased fibrosis,

indicating the different effects of the obese mother based on

offspring sex (142).

Furthermore, a review article provided a detailed explanation of

how maternal obesity affects hypothalamic development and later

function (143). Accordingly,

another review article in addressed the emerging role of the

hypothalamus in metabolic regulation in offspring of mothers with

maternal obesity (144). The

analysis of data from two French birth cohorts, EDEN (encompassing

all gestational ages) and EPIPAGE-2 (preterm children born between

24 and 34 weeks of gestation), revealed the impact of maternal

obesity on the cognitive development of children. In both cohorts,

pre-pregnancy obesity was associated with lower verbal intelligence

quotient (IQ) domains, resulting in lower IQ scores at 5 years

(145).

Sertorio et al (146) provided further knowledge on the

topic of the health implications of parental high-fat, high-sugar

diet intake on male offspring. Their study conducted on rats

evaluated multiple markers, including serum levels of testosterone

and FSH, testicular gene expression of steroidogenic enzymes,

epigenetic and inflammatory markers, as well as daily sperm

production, sperm transit time and sperm morphology (146). Of note, several factors were

influenced only by one parent: Maternal diet affected cytokine

production, testicular epigenetic parameters, inflammatory

response, oxidative balance and daily sperm production, while serum

testosterone levels were affected by the paternal diet (146). Furthermore, another study found

that cognitive deficits and impaired sphingolipid metabolism were

induced in offspring through both the maternal and paternal

lineages (147).

Epigenetic, cognitive and metabolic

impacts of parental obesity

Notably, a subsequent study of methylation profiles

of genome-wide CpG sites in blood samples from a pediatric

longitudinal cohort revealed the influence of the weight of mothers

on the methylome of offspring (148). Briefly, abundant DNA

methylation changes during child development from birth to 6 months

were detected in addition to DNA methylation biomarkers that could

discriminate children born to mothers who suffered from obesity or

obesity with gestational diabetes (148). Furthermore, another study aimed

to elucidate the effects of maternal obesity on offspring in

Kawasaki disease-like vasculitis and the underlying mechanisms

(149). The data of that study

demonstrated that maternal obesity led to more severe vasculitis

and induces altered cardiac structure in the offspring, and also

promoted the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines through the

activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (149). Maternal obesity during

pregnancy was recently connected to reduced hippocampal

ephrin-A3/EphA4 signaling in adult mouse offspring, thereby

impairing synaptic plasticity and gliovascular unit integrity, with

microglial activation indicating neuroinflammation (150). In 2024, Nelson and Friedman

(151) summarized the immense

impact of a maternal Western-style diet on the programming of the

fetal immune system.

Conversely, paternal obesity has been shown to have

a significant effect on the cognitive functions of offspring in

murine models. The underlying mechanism involves sperm-derived

methylation of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene

promoter, which disrupts BDNF/tyrosine receptor kinase B signaling

(132). Another study

demonstrated that offspring fertility appeared to be influenced by

paternal obesity, indicating that paternal obesity can span

multiple generations (152).

Evidence from that study demonstrated a transgenerational increase

in methyltransferase 3, N6-adenosine-methyltransferase complex

catalytic subunit and Wilms tumor protein N6-methyladenosine levels

in the testes of offspring mice, indicating an epigenetic

mechanism. Previous studies have addressed the significant impact

of paternal obesity on offspring metabolism (153,154). Notably, female offspring of an

obese father display impaired gluconeogenesis clues caused by

sperm-transmitted methylation of the insulin-like growth factor

(IGF)2/H19 imprinting control region in the liver of offspring,

inducing enhanced gluconeogenesis and an elevated expression of key

gluconeogenesis enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (154). Another mechanism of

transgenerational metabolic dysfunction induction was found to be

sperm H3K27me3-dependent epigenetic regulation of glucose

metabolism and apoptosis (155). Of note, only mild, transient

metabolic changes were observed in the early life of offspring in a

sperm chromatin accessibility study, indicating that the

developmental compensatory mechanisms of the offspring can

counteract epigenetic inheritance (156). To establish the role of

paternal caloric restriction (CR) preconception, researchers

discovered that the offspring display attenuated AMPK/SIRT1 pathway

(associated with inflammation and oxidative stress), indicating

beneficial effects of paternal CR (157). Furthermore, another

case-control study found that the risk of congenital urogenital

anomalies increased with paternal BMI during the preconception

period (158). Parental obesity

is associated with decreased mitochondrial functional capacity, as

evidenced by lower intact cell respiration, oxidative

phosphorylation and electron transport system capacity (159).

Effects of maternal obesity on breast

milk composition and infant development

In addition to gamete-related influences, maternal

obesity has been found to affect postnatal development through

alterations in breast milk composition. Its normal composition

includes macronutrients such as lactose, fats and proteins, as well

as micronutrients, immune modulatory proteins (such as

immunoglobulins and cytokines), growth factors, vitamins and a

diverse microbiota (160). A

mother's milk, as the primary source of micro- and macronutrients,

as well as bioactive molecules, plays a central role in the early

stages of infant development. A previous study examined the

scientific evidence on how maternal obesity alters breast milk

composition and its potential effects on infant growth and

development (161).

As demonstrated in a previous study, maternal

obesity appears to significantly alter the composition of breast

milk, particularly the lipid profile. Obese women display increased

breast milk fat and caloric content from foremilk to hindmilk, with

the average milk caloric value being 11% greater (162). In addition, protein content

also appears to be affected. Similarly, the same group of authors

investigated the association between maternal BMI, serum lipids and

insulin, as well as the fat and calorie content of breast milk,

from foremilk to hindmilk (163). They concluded that, among all

women, maternal serum triglycerides, insulin and the homeostatic

model assessment for insulin resistance were significantly

associated with the foremilk triglyceride concentration, suggesting

that maternal serum triglyceride and insulin action contribute to

human milk fat content. Maternal obesity significantly alters the

hormonal composition of milk, as assessed by Enstad et al

(164). The most significant

alteration was observed in n-6:n-3 PUFA and leptin concentrations,

which were later confirmed to be associated with accelerated weight

gain in infancy (164).

However, unlike the study by Enstad et al (164), a Chinese study found that the

emaciated group had a significantly lower level of leptin in breast

milk (165). Of note,

correlation analysis showed that the level of ghrelin in breast

milk was positively correlated with the Z score of current body

weight (165). Another

case-control study aimed to compare the levels of leptin, ghrelin,

adiponectin and IGF-1 in pre-feed and post-feed breast milk from

mothers with obesity and normal weight (166). The pre-feed breast milk of

mothers with obesity had significantly higher levels of ghrelin

than that of mothers with a normal weight. At the same time,

adiponectin, an insulin-sensitizing hormone, appeared to be reduced

in the post-fed milk of mothers with obesity compared to mothers

with normal weight (166).

Obesity appears to alter the expression of leptin, adiponectin, and

miRNA, which typically decrease over time during lactation in

normal-weight mothers (167).

Additionally, miRNAs (miR-103, miR-17, miR-181a, miR-222, miR-let7c

and miR-146b) are negatively associated with infant BMI only in

normal-weight mothers (167).

Other components of human milk, named human milk

oligosaccharides (HMOs), which serve as a source of energy for

commensal intestinal microorganisms, have been studied in the

context of obesity. These complex carbohydrates, unique to human

milk, have been studied in a research project involving Mexican

women (168). Specifically, six

HMOs (LNFPI, 2'-FL, LNT, LNnT, 3'-SL and 6'-SL) were found to be

significantly lower in overweight women compared to those of normal

weight. One review article even mentions that maternal lifestyle

affects the microbial composition of breast milk (169). Most notably, it appears that

milk obtained from obese mothers contains lower microbial

diversity, which may result in reduced amounts of

Bifidobacteria in infants (169).

An overwhelming body of evidence suggests that

maternal obesity, as well as other metabolic disorders such as

diabetes, is the leading cause of divergent offspring development.

However, paternal obesity has become a focus of research due to the

emerging evidence of sperm-transmitted epigenetic changes that have

a significant effect on offspring.

Current controversies and unresolved

debates

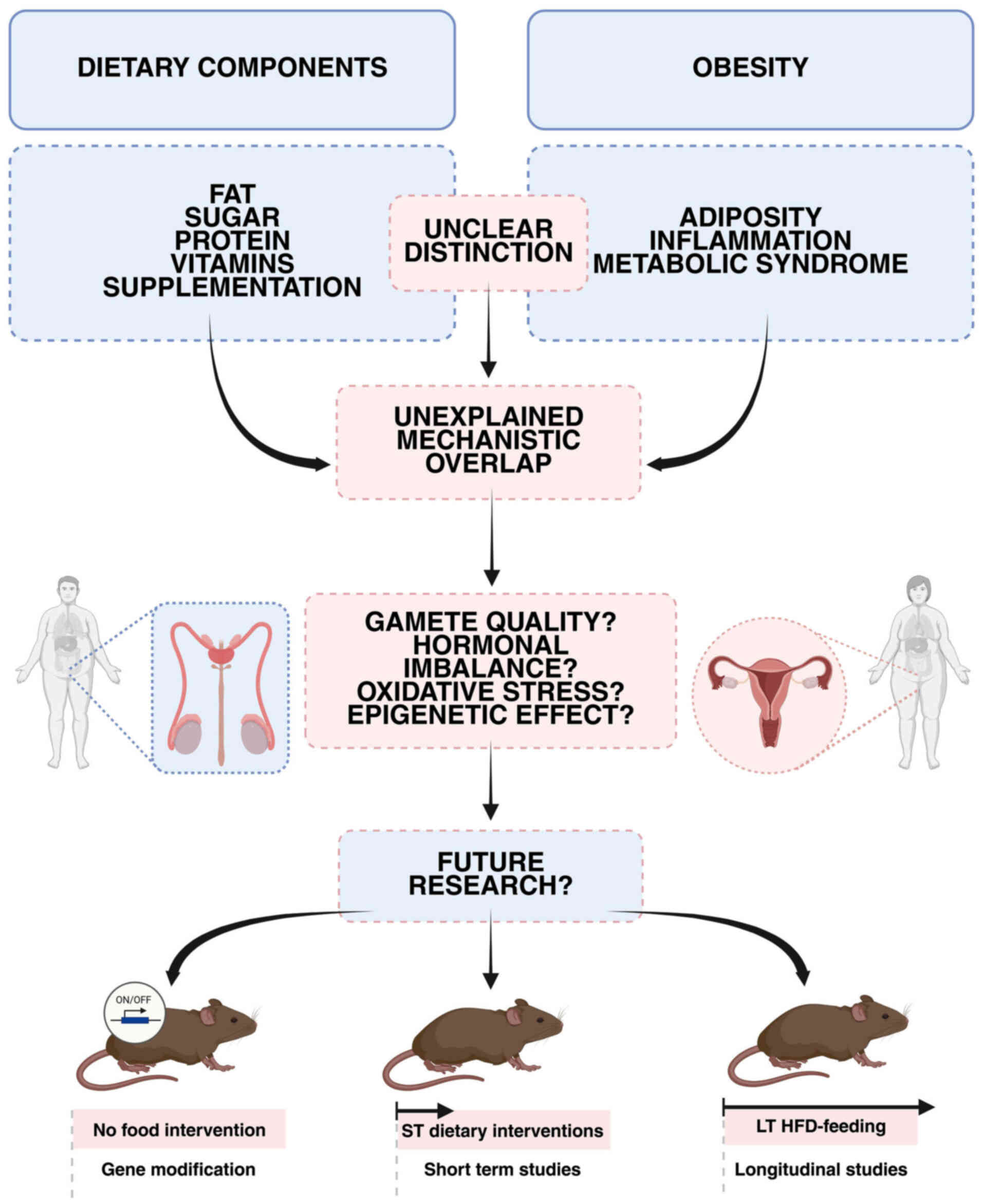

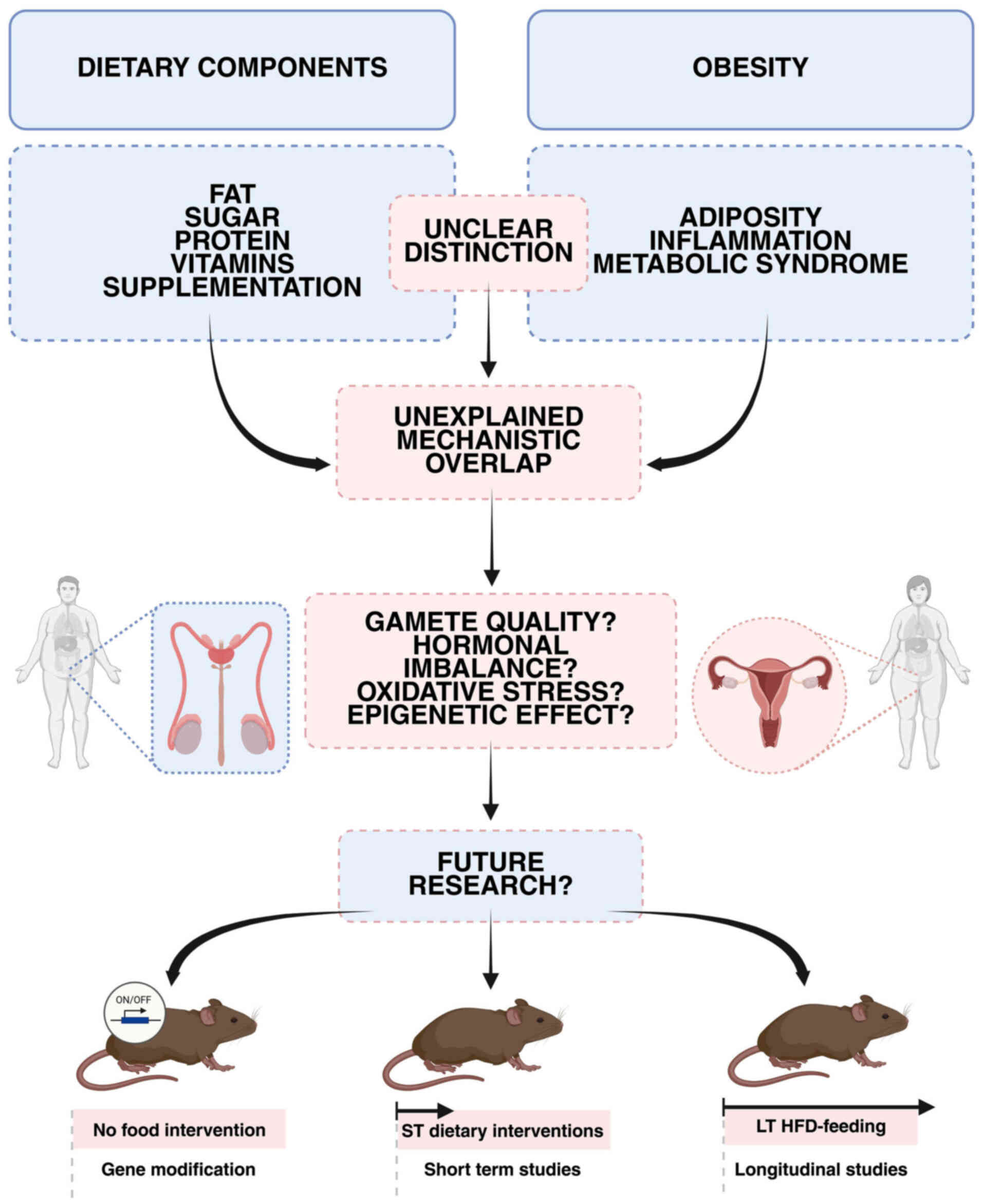

Despite notable advances made in the understanding

of the association between obesity and reproductive health,

fundamental gaps and critical controversies remain that limit the

ability of researchers to develop effective therapeutic

interventions. A major ongoing challenge is to disentangle the

direct effects of obesity itself from those attributable to dietary

components, metabolic syndrome, and associated comorbidities. While

a number of experimental models induce obesity using high-fat or

high-sugar diets, the independent contributions of excess adiposity

vs. specific nutritional factors on reproductive dysfunction have

not yet been fully clarified. Molecular pathways, such as oxidative

stress, chronic inflammation and epigenetic modifications

potentially mediate these distinct influences; however, these

require rigorous investigations using carefully controlled

experimental designs that isolate obesity from dietary variables

(Fig. 3).

| Figure 3Schematic illustration of the

unresolved distinction between dietary components and obesity

effects on reproductive mechanisms. On the left panel, major

dietary components, including fat, sugar, protein, vitamins and

supplementation, are shown as potential direct influencers on

reproductive health. On the right panel, obesity-related factors,

including adiposity, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome, are

depicted as established contributors to reproductive dysfunction.

However, it remains unclear which reproductive mechanisms are

affected explicitly by dietary factors alone and which are driven

by obesity itself, resulting in an unexplained mechanistic overlap.

Therefore, distinct mechanisms of either diet or obesity on

reproductive parameters such as gamete quality, hormonal imbalance,

oxidative stress, and epigenetic effects remain to be elucidated.

To distinguish the dietary impact from obesity's impact on

reproduction, three approaches can be proposed: murine models of

obesity caused by gene manipulation without dietary interventions

(obesity's impact); short-term special diet feeding (impact of

dietary components without causing obesity); long-term special diet

feeding (obesity's impact). ST, short-term; LT, long-term; HFD,

high-fat diet. |

The direct effects of metabolism on gametes,

fertilization and offspring health are incompletely understood. New

evidence indicates that parental obesity alters DNA methylation,

histone marks and non-coding RNA profiles in germ cells,

potentially transmitting metabolic risks across generations.

However, it remains controversial whether these epigenetic changes

are causally linked to unfavorable reproductive outcomes or

represent biomarkers for broader metabolic dysregulation. The

relative contributions of maternal and paternal obesity to

programming the development and disease susceptibility of offspring

are also not yet clear.

The intrauterine microenvironment, a crucial factor

for fetal development and long-term health, remains an

under-researched, yet therapeutically promising area. A

comprehensive characterization of the effects of obesity on uterine

physiology, including pH, oxygenation, immune cell populations and

molecular signaling networks is required. Cutting-edge

technologies, such as single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial

transcriptomics and metabolomics provide opportunities to map the

molecular landscape of the obese reproductive tract with

unprecedented resolution.

Another area of debate concerns the reversibility

and treatment of obesity-induced reproductive impairments. Although

preclinical studies have shown promise for antioxidant therapy,

pharmacological agents and lifestyle interventions, including

exercise and food modification, further research is required to

confirm their effectiveness and durability across a range of human

populations. Identifying precise molecular targets amenable to

therapeutic modulation remains an urgent priority to translate

mechanistic findings into clinical applications.

Key signaling pathways, including insulin/IGF

signaling, AMPK, mTOR and inflammatory mediators, appear to be

differentially regulated in obesity, affecting gametogenesis,

steroidogenesis and embryo development. A more in-depthy

understanding of their crosstalk, as well as the roles of

epigenetic regulators and non-coding RNAs, will be critical for

developing personalized interventions. To address these

controversies and gaps, further research is required to integrate

sophisticated molecular approaches with longitudinal cohort studies

and experimentally rigorous models. Longitudinal tracking of

metabolic and reproductive changes will clarify temporal

relationships and causal mechanisms. Ultimately, this integrated

effort is essential to improve diagnostic precision, guide the

development of targeted interventions and optimize reproductive

outcomes, thereby advancing clinical care and enhancing

multigenerational health.

Conclusions

The present comprehensive review indicates that

obesity exerts profound and multifaceted effects on reproductive

health through complex molecular mechanisms that remain

incompletely understood. While substantial progress has been made

in documenting obesity-reproduction associations, the field now

requires a fundamental shift toward mechanistic investigations that

can guide therapeutic development.

The available evidence clearly demonstrates that

obesity affects reproductive function through multiple pathways,

including oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, hormonal

disruption and epigenetic modifications. However, critical gaps

remain in the understanding of the relative importance of these

mechanisms, their temporal associations and their therapeutic

targetability. The distinction between obesity-specific effects and

those attributable to dietary factors or metabolic syndrome is a

particularly important area that requires systematic

investigation.

The identification of specific molecular pathways,

such as mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammatory signaling and

epigenetic modifications, provides a foundation for developing

targeted interventions. However, the translation of these

mechanistic insights into effective clinical therapies requires

substantial additional research, including well-designed clinical

trials with mechanistic endpoints.

Future research is warranted to prioritize

mechanistic studies that can distinguish reversible from

irreversible changes in obesity-induced reproductive dysfunction,

identify specific therapeutic targets, and develop personalized

interventions based on individual metabolic and reproductive

profiles. Only through such systematic, mechanistic investigation

can we hope to develop effective strategies for preventing and

treating obesity-induced reproductive dysfunction.

The integration of advanced molecular techniques

with carefully designed clinical studies offers unprecedented

opportunities to understand and address the reproductive

consequences of obesity. This represents both a scientific

challenge and a clinical imperative, given the global prevalence of

obesity and its impact on reproductive health across

generations.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

NP, MKr, MKu, KV and JB conceptualized the study.

NP and MKr were involved in the literature search. NP, MKr, KV, DR

and JB were involved in verifying the accuracy of the data

extracted from the literature. NP, MKr, MKu, KV, DR and JB were

involved in the writing and preparation of the original draft of

the manuscript, and in the writing, reviewing and editing of the

manuscript. NP and MKr were involved in the preparation of the

figures. KV and JB supervised the study. JB was involved in project

administration. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

ADF

|

alternate-day fasting

|

|

AR

|

androgen receptor

|

|

ART

|

assisted reproductive technology

|

|

BDNF

|

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

|

|

BMI

|

body mass index

|

|

CR

|

caloric restriction

|

|

CRISP4

|

cysteine-rich secretory protein 4

|

|

DDE

|

dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene

|

|

GPR54

|

G protein-coupled receptor 54

|

|

GPX

|

glutathione peroxidase

|

|

HFD

|

high-fat diet

|

|

HMOs

|

human milk oligosaccharides

|

|

IGF

|

insulin-like growth factor

|

|

IVF

|

in vitro fertilization

|

|

LH

|

luteinizing hormone

|

|

MAPKs

|

mitogen-activated protein kinases

|

|

ME

|

metabolic endotoxemia

|

|

NRF2

|

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2

|

|

OB

|

obesogenic

|

|

PCOS

|

polycystic ovary syndrome

|

|

PORs

|

poor ovarian responders

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

SAT

|

subcutaneous adipose tissue

|

|

SIRT1

|

sirtuin 1

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

|

TC

|

testicular cancer

|

|

TGCT

|

testicular germ-cell tumor

|

|

TRF

|

time-restricted feeding

|

|

VAT

|

visceral adipose tissue

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

|

1

|

Aida XMU, Ivan TV and Juan G JR: Adipose

tissue immunometabolism: unveiling the intersection of metabolic

and immune regulation. Rev Invest Clin. 76:65–79. 2024.

|

|

2

|

Puljiz Z, Kumric M, Vrdoljak J, Martinovic

D, Ticinovic Kurir T, Krnic MO, Urlic H, Puljiz Z, Zucko J, Dumanic

P, et al: Obesity, gut microbiota, and metabolome: From

pathophysiology to nutritional interventions. Nutrients.

15:22362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gallo G, Desideri G and Savoia C: Update

on obesity and cardiovascular risk: From pathophysiology to

clinical management. Nutrients. 16:27812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki

M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M and

Shimomura I: Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact

on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 114:1752–1761. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Gregor MF and Hotamisligil GS:

Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 29:415–445.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

White U: Adipose tissue expansion in

obesity, health, and disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 11:11888442023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Virtue S and Vidal-Puig A: Adipose tissue

expandability, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome-an

allostatic perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1801:338–349. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fabbrini E, Sullivan S and Klein S:

Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Biochemical,

metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology. 51:679–689. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Palacios-Marin I, Serra D,

Jimenez-Chillarón J, Herrero L and Todorčević M: Adipose tissue

dynamics: Cellular and lipid turnover in health and disease.

Nutrients. 15:39682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pessayre D and Fromenty B: NASH: A

mitochondrial disease. J Hepatol. 42:928–940. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ramachandran A and Jaeschke H: Oxidative

stress and acute hepatic injury. Curr Opin Toxicol. 7:17–21. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Allameh A, Niayesh-Mehr R, Aliarab A,

Sebastiani G and Pantopoulos K: Oxidative stress in liver

pathophysiology and disease. Antioxidants. 12:16532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Goodpaster BH, He J, Watkins S and Kelley

DE: Skeletal muscle lipid content and insulin resistance: Evidence

for a paradox in endurance-trained athletes. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 86:5755–5761. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Akhmedov D and Berdeaux R: The effects of

obesity on skeletal muscle regeneration. Front Physiol. 4:3712013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Thaler JP, Yi CX, Schur EA, Guyenet SJ,

Hwang BH, Dietrich MO, Zhao X, Sarruf DA, Izgur V, Maravilla KR, et

al: Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and

humans. J Clin Invest. 122:153–162. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL and Saltiel AR:

Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage

polarization. J Clin Invest. 117:175–184. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D,

Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA and Chen H:

Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development

of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest.

112:1821–1830. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Broughton DE and Moley KH: Obesity and

female infertility: Potential mediators of obesity's impact. Fertil

Steril. 107:840–847. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Agarwal A, Mulgund A, Hamada A and Chyatte

MR: A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reprod Biol

Endocrinol. 13:372015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yu X, Xu J, Song B, Zhu R, Liu J, Liu YF

and Ma YJ: The role of epigenetics in women's reproductive health:

The impact of environmental factors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

15:13997572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cecchino GN, Seli E, Alves da Motta EL and

García-Velasco JA: The role of mitochondrial activity in female

fertility and assisted reproductive technologies: Overview and

current insights. Reprod Biomed Online. 36:686–697. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pasquali R, Vicennati V, Cacciari M and

Pagotto U: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in

obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1083:111–128.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Agarwal A, Gupta S and Sharma RK: Role of

oxidative stress in female reproduction. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.

3:282005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Soubry A: Epigenetic inheritance and

evolution: A paternal perspective on dietary influences. Prog

Biophys Mol Biol. 118:79–85. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

MacDonald AA, Herbison GP, Showell M and

Farquhar CM: The impact of body mass index on semen parameters and

reproductive hormones in human males: A systematic review with