Introduction

Quinazolinone and its derivatives are important

heterocyclic compounds commonly found in various bioactive

molecules (1). They represent a

major class of biologically active compounds, with the

quinazolinone nucleus attracting substantial attention due to its

broad pharmacological activities (2). Studies have shown that

quinazolinone and its derivatives possess diverse biological

effects, including anti-HIV (3),

anti-tumor (4), anti-bacterial

(5), anti-inflammatory (6), anti-malarial (7), anti-convulsant (8), anti-diabetic (9), anti-oxidant (10), dihydrofolate reductase inhibition

(11) and kinase inhibitory

activity (12).

Chemical scaffold of quinazolinone

compounds

Heterocyclic compounds represent an important class

of organic chemicals. These compounds contain one or more

heteroatoms, such as nitrogen, oxygen or sulfur, along with carbon

atoms, forming a ring structure. Their properties are largely

influenced by the number and type of heteroatoms within the ring

(13). The cyclic structure

strongly affects the compound's characteristics, which are

primarily determined by the heteroatoms present.

The term 'cyclic' refers to the presence of at least

one ring, whereas 'hetero' indicates that non-carbon atoms, or

heteroatoms, are part of that ring (14). In general, heterocyclic compounds

resemble cyclic organic compounds composed only of carbon atoms.

However, the inclusion of heteroatoms imparts distinct physical and

chemical properties, differentiating them from their all-carbon

counterparts (15). These

compounds are highly versatile in organic chemistry and play a key

role in medicinal chemistry. They are widely used in developing

bioactive synthetic compounds, pharmaceutical agents and synthetic

intermediates (16). In the

pharmaceutical industry, heterocyclic structures are particularly

common, with >60% of top-selling drugs containing at least one

heterocyclic ring (17).

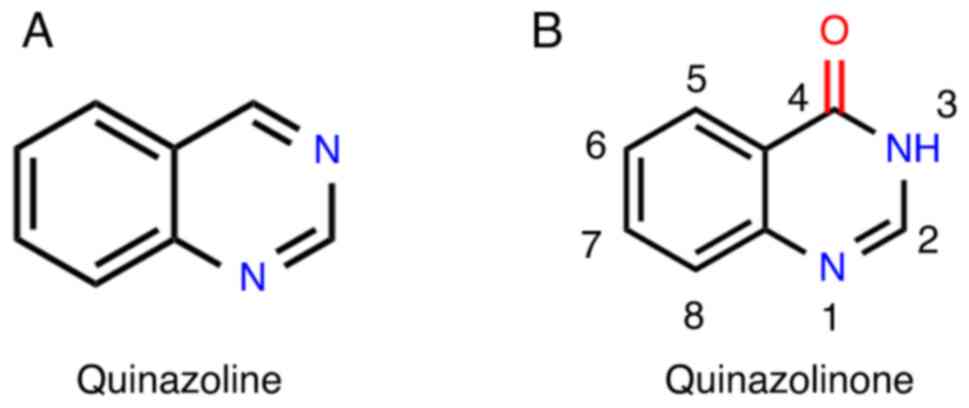

The basic structure of quinazolinone consists of a

quinazoline ring and a ketone group. This bicyclic compound

contains a pyrimidine ring fused with a benzene ring at the 4 and 8

positions (18). The quinazoline

ring comprises six carbon atoms and two nitrogen atoms located at

the 1 and 4 positions (19)

(Fig. 1). As an oxidized form of

quinazoline, quinazolinone retains the nitrogen atoms and is

categorized as a nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compound.

Quinazolinone forms the core structure of nearly 150 naturally

occurring alkaloids found in various plant families, as well as in

animals and microorganisms (20), including compounds such as

glycyrrhizin, quinazolinone, deoxycannabinoid ketone and

rutaecarpine (21). The first

quinazoline alkaloid, vasicine, was isolated in 1888 from the

Indian medicinal plant Adhatoda vasica and continues to

demonstrate significant pharmacological value (22). In recent years, studies have

shown that vasicine and its derivatives have potential

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-Alzheimer's disease

effects (23). For instance,

vasicine has been shown to alleviate atopic dermatitis induced by

2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene in BALB/c mice by inhibiting pro-Th 2 and

Th 2 cytokines in both serum and skin tissues (24). Additionally, vasicine inhibits

acetylcholinesterase (AChE) by specifically binding to the AChE

catalytic site, such as Trp 84 and Ser 200, positioning it as a

promising lead compound for Alzheimer's disease treatment (25). Furthermore, in a rat model of

lung injury, in vitro assays of lung tissue homogenates

revealed that vasicine inhibits lipid peroxidation triggered by

excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), while simultaneously

restoring the activity of the endogenous antioxidant enzyme system

(26). Thus, it is both a

historical milestone in drug development and a starting point for

research on new drugs. Later, vasicine and related quinazolinone

alkaloids such as vasicinone and deoxyvasicinone were also

identified in plants within the Acanthaceae family (27). Numerous additional natural

products containing quinazoline or quinazolinone structures have

since been isolated, analyzed and synthesized. The first

quinazolinone compound was synthesized in the late 1860s by

reacting anthranilic acid with cyanogen to produce

2-cyanoquinazolinone (28). This

compound is a key precursor in quinazolinone chemistry, with its

cyano group providing synthetic flexibility, making it a central

molecule for constructing structurally diverse and complex

quinazolinone derivatives. Systematic modification of its cyano

group and the quinazolinone ring-particularly at the N-3 and

C-6/C-7 positions-can efficiently generate a large library of

structurally diverse compounds for high-throughput screening and

structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies, supporting the

discovery of new lead compounds and optimization of drug activity

(29,30). It plays a pivotal role as a

synthetic building block in drug discovery, particularly in the

development of kinase inhibitors and related compounds. The unique

structural features of quinazolinone, particularly its fused

benzene and pyrimidine rings, increase the possibility and

flexibility of structural modification (31). In addition, the carbonyl group at

the 4-position is a strong electron-withdrawing group, markedly

reducing the electron density of the quinazolinone ring and

facilitating nucleophilic substitution reactions (32). A molecular docking study revealed

that certain quinazolinone derivatives can form strong hydrogen

bonds with LYS 630 and HIS 775 in topoisomerase II and stack π-π

interactions with DT15, supporting the compound's ability to

inhibit DNA replication and repair (33). Furthermore, the quinazolinone

core adapts to the hydrophobic channel of cyclooxygenase-2, where

the carbonyl group can form hydrogen bonds with Arg 121 and Tyr

356, thereby inhibiting enzyme activity (34). These properties enhance

selectivity and biological activity during interactions with

biomolecules, making quinazolinone a key scaffold in drug

development (35).

Quinazolinones can be classified by structural

features into six main groups: Those substituted at the 2- and/or

3-positions, simple 2-substituted quinazolin-4-ones and

quinazolinones fused with pyrrole, pyrroloquinoline, piperidine or

piperazine ring systems (36).

They can also be categorized by the position of the keto or oxo

group into 2(1H)-quinazolinones, 4(3H)-quinazolinones and

2,4(1H,3H)-quinazolinediones (37). Among these, 4(3H)-quinazolinones

are the most common and often serve as intermediates or natural

products in proposed biosynthetic pathways (38).

The pharmacological properties of

quinazolinone-based compounds can be optimized by modifying their

central structure with various functional groups. For instance,

introducing alkyl (39),

hydrazone (40,41) or other substituents at different

positions on the ring can significantly influence target

interactions and therapeutic efficacy. This structural adaptability

has made quinazolinones and their derivatives a central focus in

research on anti-tumor, anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory drug

development.

Biological activities of quinazolinone

compounds

In synthetic and medicinal chemistry, the

quinazoline scaffold has attracted considerable interest due to its

simple synthesis, versatile reactivity and broad pharmacological

potential (42). Several

quinazolinone-derived drugs, such as Idelalisib and Canertinib,

demonstrate the therapeutic potential of this class in treating

hematological malignancies and other cancers. In addition, prazosin

is used to treat hypertension, Albaconazole for fungal infections,

Balaglitazone for diabetes and Dictyoquinazol A as both a

neuroprotective agent and a glutamate receptor antagonist (43). Over the past two decades, >20

drugs containing a quinazoline or quinazolinone core structure have

been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for

anti-tumor use. A prominent example is Dacomitinib, approved in

2018 for the treatment of non-small-cell lung carcinoma. These

agents act through various mechanisms to inhibit cancer cell

growth, mainly by targeting kinases, tubulin, kinesin spindle

proteins and other related molecules (44).

Natural quinazolinone compounds, derived from

plants, animals and microorganisms and widely used in traditional

medicine, often have complex structures that have been refined

through natural selection and evolutionary processes to produce

unique biological activities (45). Quinazolinone alkaloids are

present in the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Dichroae Radix,

forming the core structure of febrifugine and isofebrifugine. These

compounds have been used as antimalarial agents in China for

>2,000 years (46). In recent

years, increasing evidence has confirmed the significant anti-tumor

activity of natural quinazolinone compounds, including their

ability to overcome tumor resistance (47). Several derivatives based on the

quinazolinone core nucleus, such as Bouchardatine, Luotonin F and

Isofebrifugine, have been widely used in cancer treatment,

underscoring the broad distribution and biological importance of

this class of compounds in nature (43,48).

By contrast, the structural design of chemically

synthesized quinazolinone-based drugs often involves modifications

to the natural structure, with researchers selectively altering

specific molecular sites (such as positions 2, 4, 6, 7 and 8)

through chemical functionalization (49). These modifications can markedly

influence pharmacological activity by introducing various

functional groups, thereby optimizing drug efficacy, selectivity,

pharmacological properties, toxicity, stability and

pharmacokinetics. The choice between natural and synthetic

quinazolinone drugs in therapy depends on their origins,

pharmacodynamics and development strategies. Natural quinazolinones

are better suited for chronic diseases that require multi-target

synergy and low toxicity, such as asthma and chronic inflammation.

By contrast, synthetic derivatives are more appropriate for

conditions requiring targeted precision, adjustable structure and

large-scale production, such as cancer therapy, anti-diabetic

treatments and central nervous system disorders (50-52).

Although quinazolinones display a wide range of

biological activities, this review focuses specifically on their

anti-tumor properties, particularly the mechanisms through which

they induce tumor cell death. It summarizes key quinazolinone

derivatives known to induce cell death and aims to provide insights

for designing structures that help elucidate the mechanisms

involved in tumor cell death.

Quinazolinone and its derivatives in

inducing cell death

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is a gene-regulated, self-controlled and

orderly form of cell death that maintains internal homeostasis

(53). It is regulated by

multiple genes, many of which are highly conserved across species.

Apoptosis enables multicellular organisms to remove damaged or

unnecessary cells, playing a critical role in tissue remodeling

during embryonic development and in maintaining tissue stability

throughout life (54). There are

two major apoptotic pathways: Intrinsic and extrinsic (55).

The intrinsic pathway is mainly triggered by

internal signals such as cellular stress, DNA damage or oxidative

stress. It involves the release of pro-apoptotic factors, including

cytochrome c, from mitochondria, which activate caspases that

execute cell death. Proteins of the Bcl-2 family are central

regulators of this pathway, controlling mitochondrial membrane

permeability (56). The

extrinsic pathway is activated by external stimuli through

membrane-bound death receptors, the most well-known being Fas and

tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors. Ligand binding to these

receptors activates a signaling cascade, including caspases, that

leads to apoptosis (57).

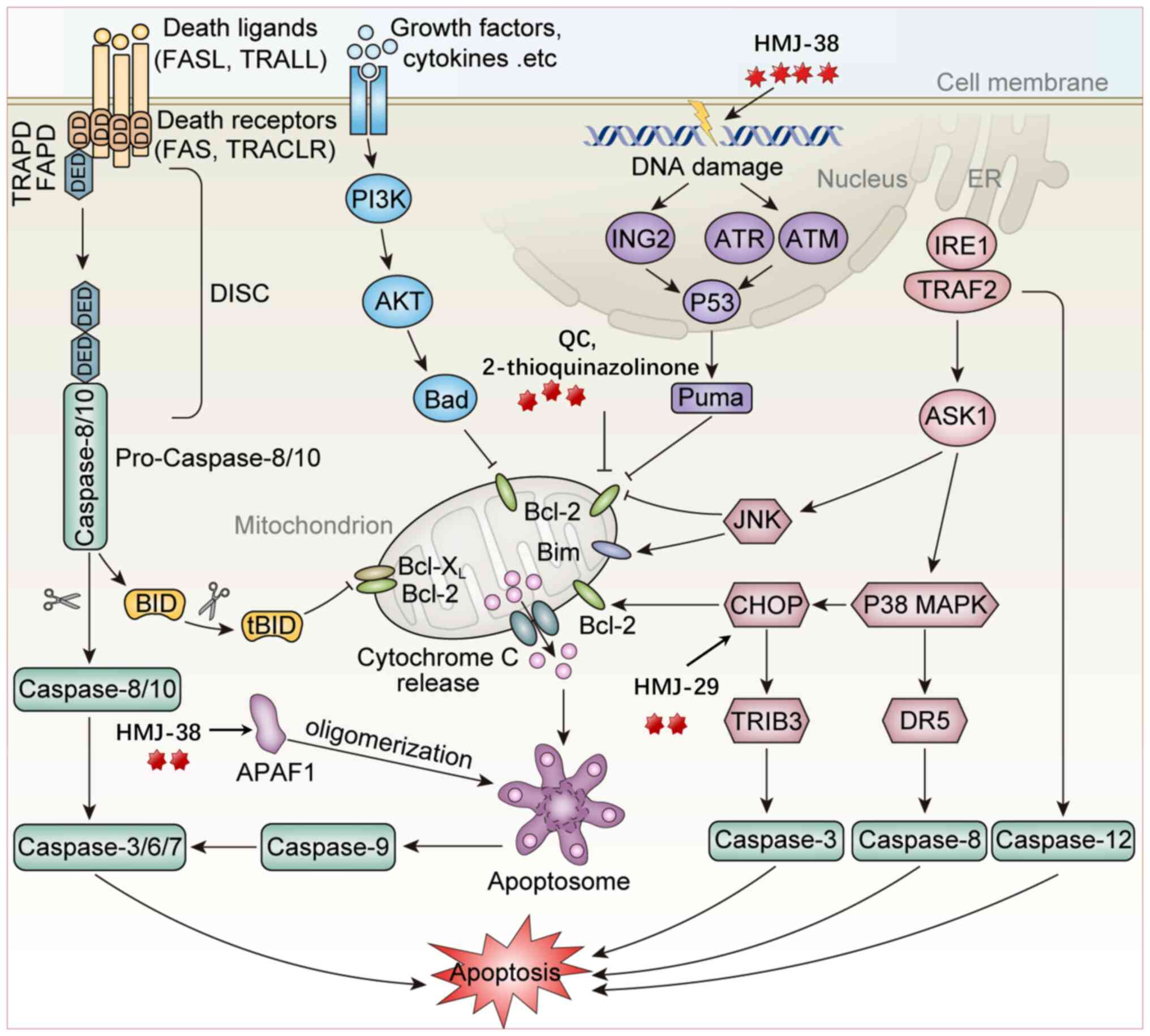

Over the past decade, most quinazolinone derivatives

have been shown to induce apoptosis through intrinsic pathways,

including mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress

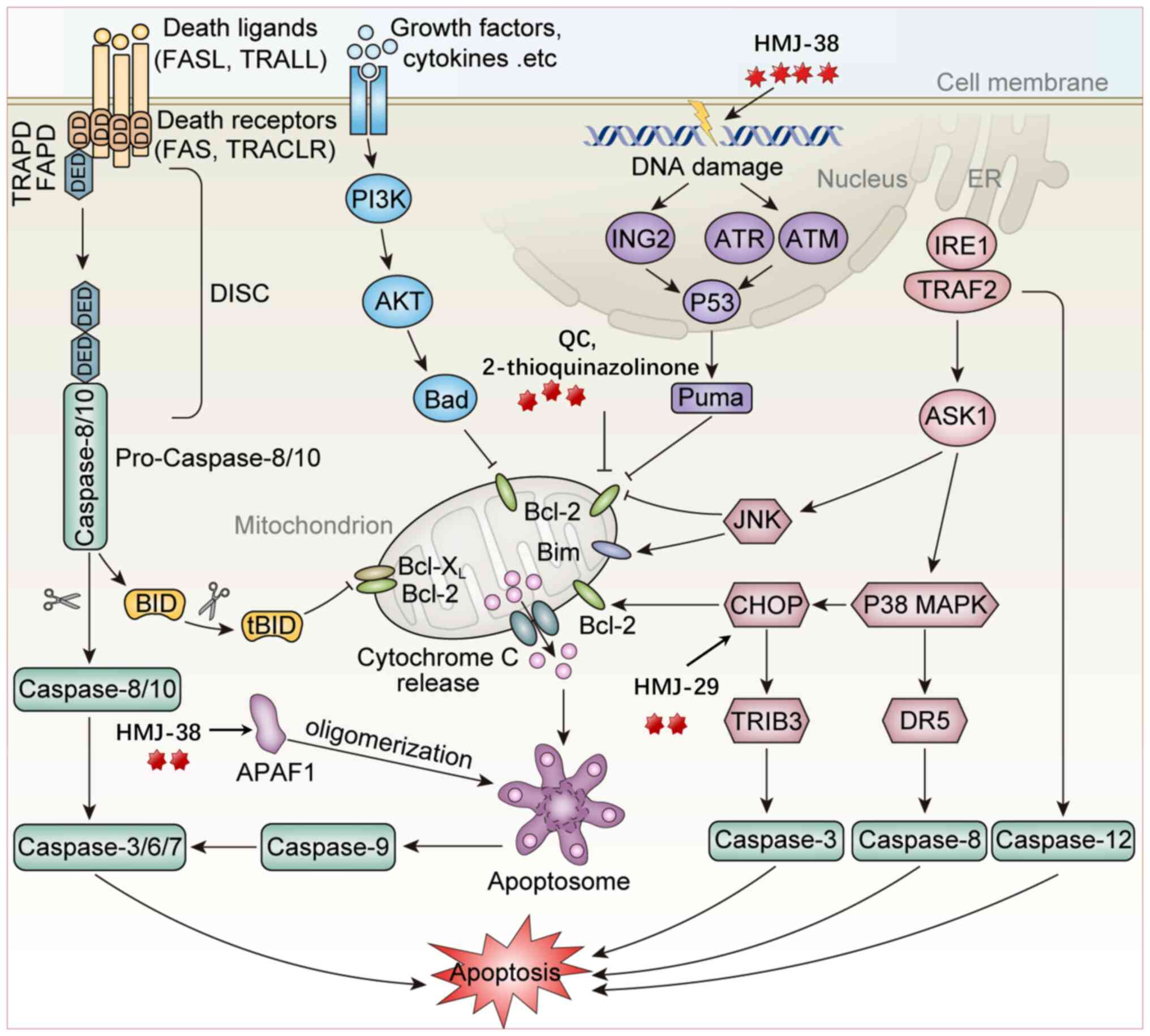

pathways (Table I, Fig. 2). Regarding targeting the

intrinsic pathway, Liang et al (58) synthesized four novel series of

quinazolinone-based compounds by adding alkynyl functional groups

at the C8 position. Among them, compound 9b showed the highest

affinity for PI3Kγ and induced apoptosis in leukemic cells by

simultaneously modulating the PI3K-AKT and MAPK signaling pathways.

Similarly, Kim et al (59) modified substituents at the C-5/6

positions and optimized side-chain positioning within a hydrophobic

binding region to develop a selective PI3Kδ inhibitor. This

compound suppressed the PI3K pathway in SUDHL-5 and MOLT-4 cell

models, reduced phosphorylation of AKT, S6 and eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1, and triggered

apoptosis in malignant cells.

| Figure 2Mechanism of quazolinone compounds

inducing cell death through apoptosis. i) In the extrinsic pathway,

the death ligand-receptor interaction triggers apoptotic signaling

and forms the DISC complex, activating the Caspase-8/-3 cascade,

leading to cell apoptosis (HMJ-38 induces apoptosis through the

Fas/Death receptor-Caspase-8 pathway and is regulated by p53/ATM

signaling). ii) In the intrinsic pathway, quinazolinones

downregulate Bcl-2/Bcl-xL and upregulate Bax/Bad, thereby promoting

cytochrome c release, Apaf-1 apoptosome formation and

Caspase-9/Caspase-3 cascade activation (QC suppresses Bcl-2,

promotes the translocation of Bax into the mitochondria, releases

Cyt C and activates Caspase-9. MITC-12 upregulates the Bax/Bcl-2

ratio and increases Caspase-3 expression. The analogs synthesized

by Madbouly et al (61)

induce apoptosis by promoting Caspase-3 and PARP-1 cleavage

(compound 5k increases Bad and Bax, reduces Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL and

enhances pro-apoptotic signals). iii) In the DNA damage pathway,

ATM/ATR/p53 signaling induces Puma expression to enhance

mitochondrial apoptosis (one of the mechanisms of HMJ-38 is to

induce the p53/ATM signaling pathway through DNA damage, thereby

activating the death receptor pathway Caspase-8). iv) ER stress

activates the IRE1-TRAF2-ASK1 signaling pathway, which in turn

activates the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways, induces CHOP expression,

promotes the upregulation of TRIB3 and DR5 and subsequently

activates Caspase-3, Caspase-8 and Caspase-12, thereby inducing

apoptosis (MJ-29 activates key markers of ER stress by increasing

the protein levels of calpain 1 and CHOP). ER, endoplasmic

reticulum; DISC, death-inducing signaling complex; DED, death

effector domain; BID, BH3 interacting domain death agonist; APAF1,

apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1; ING2, inhibitor of growth

family member 2; Puma, P53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis; Bim,

Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death; Bad, BCL2-associated

agonist of cell death; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; IRE1,

immunoglobulin-regulated enhancer 1; TRAF2, TNF receptor associated

factor 2; ASK1, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; CHOP, C/EBP

homologous protein; TRIB3, Tribbles pseudokinase 3; DR5, death

receptor 5; ATM, Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated proteins; ATR,

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3 related; caspase, cysteinyl

aspartate specific proteinase. |

| Table IApoptosis pathway changes following

quinazolinone derivative treatment. |

Table I

Apoptosis pathway changes following

quinazolinone derivative treatment.

| Authors, year | Cancer type | Chemical name | Affected molecule

or pathway | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Liang et al,

2023 | Leukemia |

3-(1-((9H-purin-6-yl)amino)ethyl)-8-((4-methoxyphenyl)

ethynyl)-2-phenylisoquinolin-1(2H)-one | PI3K-AKT↓

p-p38, p-ERK↑ | (58) |

| Kim et al,

2021 | Hematologic

malignancies |

(S)-2-(((7H-Purin-6-yl)amino)

(cyclopropyl)methyl)-5-fluoro-3-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-one | p-AKT,

p-S6↓

4EBP1↓ | (59) |

| Wani et al,

2016 | Colon cancer |

3-(3-((E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2propenoyl)phenyl)-2-methyl-3,4-dihydro-4-quinazolinone | PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway; Bcl-2/Bax↓, Caspase-9,3↑, PARP-1↑ | (60) |

| Madbouly et

al, 2022 | Epidermoid

carcinoma, fibrosarcoma |

(E)-2-((4-Cinnamoylphenoxy)methyl)-3-(4-fluorophenyl)-quinazolin-4(3H)-one |

Caspase-3↑

PARP↓ | (61) |

| Xie et al,

2023 | Glioma |

6,8-Dibromo-2-thio-3-(4-rhamnosylphenylmethyl)-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4-one |

Caspase-3↑

Bax/Bcl-2↑ | (62) |

| Qiu et al,

2020 | Lung cancer |

2-(Benzylthio)-6-(3-(dimethylamino)propoxy)-3-(furan-2ylmethyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one | Bad, Bax↑

Bcl-2, Bcl-xl↓ | (63) |

| El-shafey et

al, 2020 | Breast cancer |

3-(4-(((3-Benzyl-6-methyl-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)thio)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)benzoic

acid | ROS accumulation,

Bax/Bcl-2↑

Caspase-6,7,9↑ | (64) |

| Hour et al,

2023 and Chiang et al, 2013 | Pancreatic

cancer |

2-(3'-Methoxyphenyl)-6-pyrrolidinyl-4-quinazolinone | p53/ATM signaling

pathway; Fas/CD95 and death receptor-modulated extrinsic caspase

signaling | (65,66) |

| Lu et al,

2012 | Murine

leukemia |

6-Pyrrolidinyl-2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-4-quinazolinone | Calpain 1, CHOP and

p-eIF2α↑ | (67) |

Wani et al (60) developed a new

quinazolinonechalcone derivative,

3-(3-((E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-propenoyl)phenyl)-2-methyl-3,4

dihydro-4-quinazolinone (QC). QC suppressed the mitochondrial

anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. At the same time, it promoted the

translocation of Bax from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. Bax

forms oligomers on the mitochondria, leading to an increase in

mitochondrial membrane permeability. This results in the release of

cytochrome C from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm. Cytochrome C

binds to apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) to form an

apoptosome, which recruits and activates caspase-9. Activated

caspase-9 then further activates downstream caspases, including

caspase-3, caspase-6 and caspase-7, ultimately triggering cell

apoptosis (60). Similarly,

Madbouly et al (61)

synthesized a related quinazolinone-chalcone compound

[(E)-2-((4-acetylphenoxy) methyl)-3-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-one],

which induced apoptosis by promoting caspase-3 and poly(ADP-ribose)

polymerase 1 (PARP-1) cleavage in A431 carcinoma cells. Some

quinazolinone derivatives regulate apoptosis by modulating Bcl-2

family proteins. Xie et al (62) synthesized a series of MITC

[4-((α-L-rhamnose oxy)benzyl)] quinazolinone derivatives. Among

them, MITC-12 induced apoptosis in U251 cells by increasing

caspase-3 expression and elevating the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio. Qiu et

al (63) introduced alkoxy

substituents and showed that compound 5k induced

concentration-dependent apoptosis in HepG2 cells by increasing

pro-apoptotic proteins Bad and Bax and decreasing anti-apoptotic

proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl. El-Shafey et al (64) demonstrated that novel compounds

with a 2-thioquinazolinone scaffold triggered mitochondrial

apoptosis by increasing ROS accumulation, elevating the Bax/Bcl-2

ratio and activating caspases 6, 7 and 9.

A smaller group of quinazolinone derivatives induce

apoptosis via the extrinsic pathway. HMJ-38 [2-(3'-methoxy

phenyl)-6-pyrrolidinyl-4-quinazolinone], a quinazolinone

derivative, inhibits tubulin polymerization. Hour et al

(65) showed that HMJ-38 induces

both autophagy and apoptosis in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic

cancer cells, with the recruitment of pro-caspase-9 to the

apoptosome by the Apaf-1 complex activating caspase-9

auto-catalytically, thereby enhancing apoptosis through subsequent

activation of caspase-3, caspase-6 and caspase-7. Chiang et

al (66) reported that

HMJ-38 induces apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

through ROS generation and activation of the Fas/death

receptor-mediated caspase-8 pathway, regulated by p53/ATM

signaling. In WEHI-3 cells, MJ-29 activates key markers of ER

stress by increasing the protein levels of calpain 1 and C/EBP

homologous protein (CHOP), playing an important role in regulating

cell apoptosis (67).

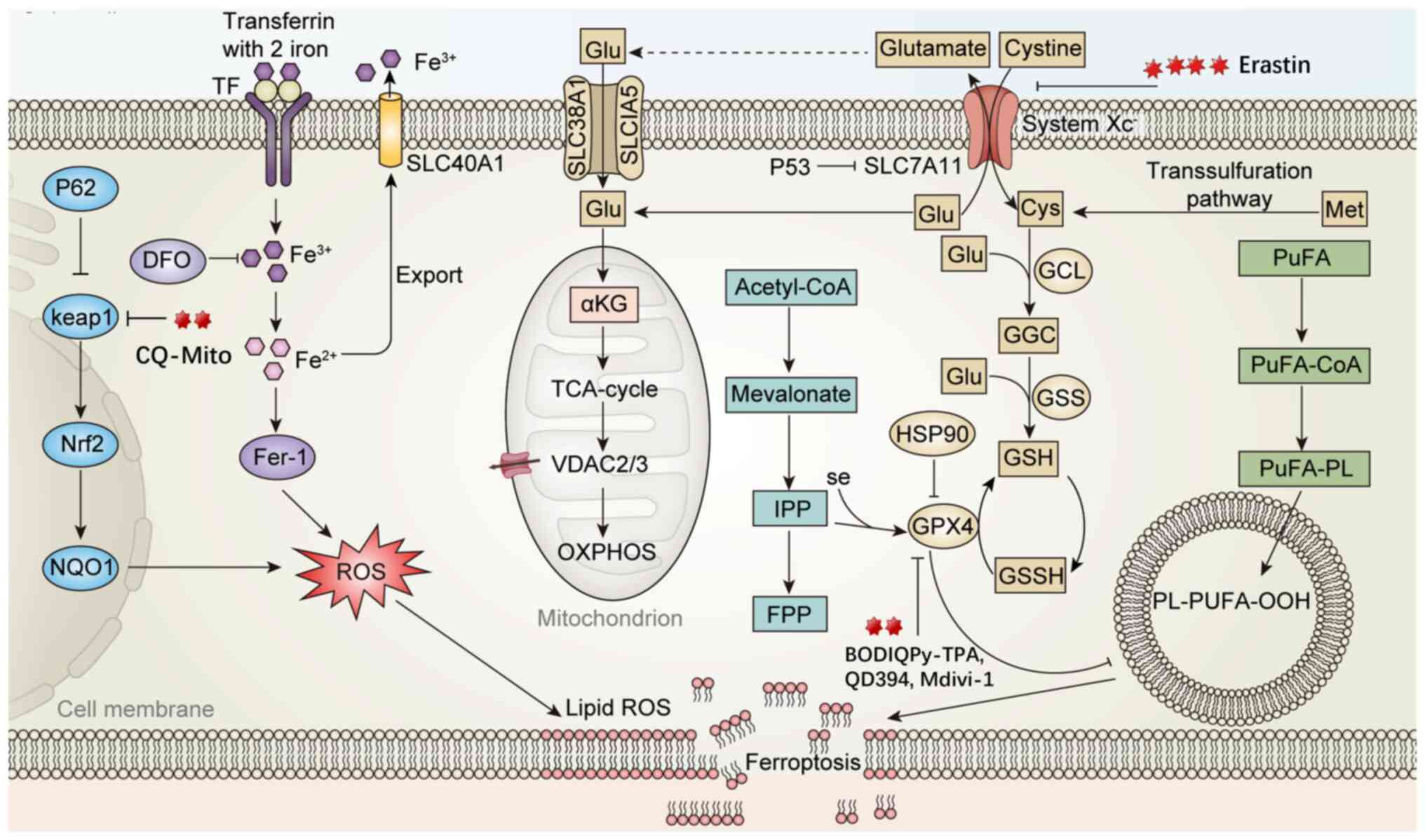

Ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death first

identified in cancer cells with oncogenic Ras mutations. It is

characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation (68,69). Unlike classical forms of cell

death such as apoptosis and necrosis, ferroptosis involves

intracellular iron accumulation and ROS generation. These processes

lead to polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation in cell membranes,

resulting in membrane damage and cell death (70). Ferroptosis is regulated by

multiple metabolic pathways, including those involved in redox

balance, iron metabolism, mitochondrial function, and amino acid,

lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Several disease-related

signaling pathways also contribute to its regulation (71). The three primary pathways that

control ferroptosis are the system Xc−/glutathione (GSH)

peroxidase 4 (GPX4) axis, lipid metabolism and iron metabolism

(72). In addition to small

molecules and drugs, external stressors such as heat, cold, hypoxia

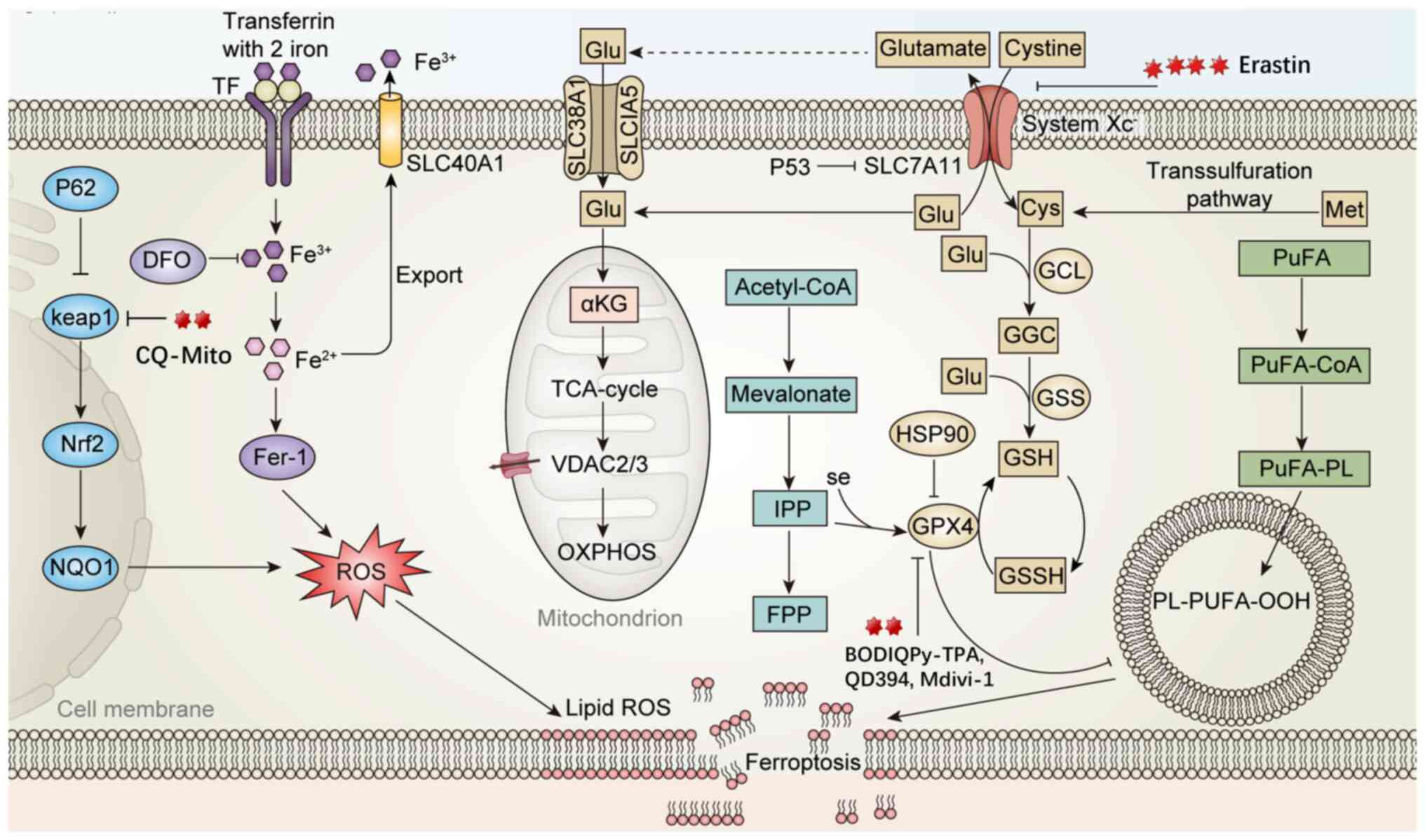

and radiation can also induce ferroptosis (73) (Table II, Fig. 3).

| Figure 3Mechanism of quazolinone compounds

inducing cell death through ferroptosis. i) System Xc−

is responsible for importing extracellular cysteine into cells for

GSH synthesis, maintaining GPX4 activity to clear lipid peroxides

PL-PUFA-OOH. When cysteine uptake is blocked or GSH is depleted,

GPX4 becomes inactive, leading to the accumulation of lipid

peroxides and triggering ferroptosis (Erastin inhibits SLC7A11,

prevents Cys entry, reduces GSH synthesis, weakens GPX4 activity

and enhances lipid peroxidation, thereby inducing ferroptosis;

BODIQPy-TPA directly acts on the GPX4/GSH axis, inhibits GPX4,

depletes GSH, blocks lipid peroxide clearance and promotes

ferroptosis). ii) After transferrin-bound Fe3+ enters

the cell, it is reduced to Fe2+, promoting ROS

generation and inducing lipid peroxidation. The Keap1-Nrf2

signaling axis regulates the downstream antioxidant gene NQO1,

which helps buffer ferroptosis stress to a certain extent (CQ-Mito

generates ROS under light, inhibits GPX4, reduces Keap1 and

activates the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway). iii) PUFA is acylated to

form PuFA-CoA, and under the influence of iron and ROS, lipid

peroxides PL-PUFA-OOH are generated, which are direct molecular

effectors of ferroptosis. ROS, reactive oxygen species; GSH,

glutathione; TF, transcription factors; GCL, glutamate cysteine

ligase; GGC, gamma-glutamylcysteine; GSS, glutathione synthetase;

SLC40A1, solute carrier family 40 member 1; system Xc−,

cystine/glutamate antiporter system; αKG, α-ketoglutaric acid;

TCA-cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion

channel; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PuFA, polyunsaturated

fatty acid; CoA, coenzyme A; Cys, cysteine; Met, methionine;

PuFA-PL, polyunsaturated-fatty-acid-containing phospholipids; IPP,

Isopentenyl pyrophosphate; FPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate; HSP90, heat

shock protein 90; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; DFO,

deferoxamine; Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; Nrf2,

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; NQO1, quinone

oxidoreductase. |

| Table IIFerroptosis pathway changes following

quinazolinone derivative treatment. |

Table II

Ferroptosis pathway changes following

quinazolinone derivative treatment.

| Authors, year | Cancer type | Chemical name | Affected molecule

or pathway | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Yang et al,

2020 | Melanoma |

2-(1-(4-(2-(4-chlorophenoxy)acetyl)

piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)-3-(2-ethoxyphenyl) quinazolin-4(3H)-one | FOXM1-Nedd4-VDAC2/3

negative feedback loop | (76) |

| Sun et al,

2020 | Gastric cancer |

2-(1-(4-(2-(4-chlorophenoxy)acetyl)

piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)-3-(2-ethoxyphenyl) quinazolin-4(3H)-one | System

Xc−↓

Block of the uptake of cystine, resulting in the accumulation of

ROS | (77) |

| Li et al,

2021 | Endometrial

cancer |

2-(1-(4-(2-(4-chlorophenoxy)acetyl)

piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)-3-(2-ethoxyphenyl) quinazolin-4(3H)-one | ROS↑, FPN↓ | (78) |

| Huang et al,

2018 | Lung cancer |

2-(1-(4-(2-(4-chlorophenoxy)acetyl)

piperazin-1-yl)ethyl)-3-(2-ethoxyphenyl) quinazolin-4(3H)-one | ROS↑, p53↑, p-p53↑,

p21, Bax↑, SLC7A11↓ | (79) |

| Zhao et al,

2024 | Liver cancer |

N-(2-(4-(((2-(7-(diethylamino)-2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl)-4-oxo-3,4-dihydroquinazolin-6-yl)oxy)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethyl)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide | Gpx4↓, Nrf2↑,

Keap1↓ | (83) |

| Xing et al,

2024 | Melanoma |

(E)-2-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)-6-fluoro-6-methyl-5λ4,6λ4-pyrido(1',2':1,5)

(1,3,2)

diazaborolo(4,3-b)quinazolin-8(6H)-one | GPX4-GSH-cysteine

axis | (84) |

| Huang et al,

2023 | Liver damage |

3-(2,4-Dichloro-5-methoxyphenyl)-2,

3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1H)-quinazolinone | p-Drp1↓, MDA↓, GSH,

GPX4↑ | (85) |

| Nakamura et

al, 2023 | Liver disease |

N-(4-(2-methyl-4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)

phenyl)-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)acetamide | FSP1↑, combination

with iron death inducers promotes apoptosis | (87) |

| Hu et al,

2020 | Pancreatic

cancer |

6-(4-(4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl)phenylamino)

quinazoline-5,8-dione | ROS↑,

GSH/GSSG↓

lipid peroxidation↑ | (90) |

Erastin, a piperazinyl-quinazolinone compound, is a

well-known ferroptosis inducer (74). It inhibits the system

Xc−, leading to reduced intracellular GSH levels and

impaired GPX4 function. This results in increased lipid

peroxidation, mitochondrial damage and other ferroptotic features

(75). Erastin remains in the

preclinical stage and is not yet marketed. Although it induces

ferroptosis in various tumor cells, its therapeutic effect is

limited by a feedback mechanism involving degradation of

voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC)2 and VDAC3. In melanoma

cells, Erastin activates forkhead box M1, which transcriptionally

upregulates NEDD4 E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, leading to VDAC2/3

ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This reduces

intracellular ROS levels and modulates ferroptosis. Silencing Nedd4

restores VDAC2/3 levels and enhances cancer cell sensitivity to

Erastin (76). Furthermore,

Erastin induces mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS accumulation in

HGC-27 gastric cancer and endometrial stromal cells, thereby

promoting ferroptosis and suppressing malignancy (77,78). This process is also marked by

iron accumulation and decreased ferroportin expression. Huang et

al (79) found that Erastin

induces both ferroptosis and apoptosis in A549 lung cancer cells by

increasing ROS and activating p53. Erastin may also enhance the

therapeutic effects of programmed cell death 1/programmed cell

death ligand 1 inhibitors by influencing tumor-associated

macrophage polarization (80).

In another study, aspirin induced ferroptosis in HepG2 and Huh7

cells, and its effect was enhanced by Erastin co-treatment

(81,82).

Organelle-targeted photosensitizers (PSs) are

promising in enhancing photodynamic therapy, as they generate ROS

under light exposure in the presence of oxygen. Zhao et al

(83) developed a series of PSs

based on the coumarin-quinazolinone (CQ) structure. The

mitochondria-targeted CQ-Mito compound inhibits GPX4 upon light

exposure, induces lipid peroxidation and activates Nrf2 while

reducing Keap1 expression, which normally deubiquitinates Nrf2.

Treatment with the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 restores

ferroptosis-related protein expression, confirming the

light-induced ferroptotic effect of CQ-Mito (83). Additionally,

BODIQPy-triphenylamine (BODIQPy-TPA), a lipophilic

quinazolinone-based probe, can directly induce lipid peroxidation

upon light exposure. In B16 and HepG2 cells, BODIQPy-TPA triggers

ferroptosis by inhibiting GPX4, depleting GSH, and promoting

cystine starvation, thereby activating the GPX4-GSH-cysteine axis

(84). It also emits strong

near-infrared fluorescence in live cells, making it useful for

real-time imaging of the ferroptosis process.

3-(2,4-Dichloro-5-methoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1H)-quinazolinone

(Mdivi-1) is a quinazolinone derivative and a selective inhibitor

of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1). In cold stress-induced liver

injury, Mdivi-1 reduces malondialdehyde levels, increases GSH and

GPX4 levels, inhibits mitochondrial fission and effectively

mitigates ferroptosis (85). It

also decreases ferrous ion and lipid peroxide levels. In models of

PM2.5 exposure, Mdivi-1 significantly reduces the expression of

acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4, ferritin, ferritin

heavy chain 1 and ferritin light chain 1, while increasing GPX4

protein levels, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis (86).

Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1), in

conjunction with mitochondrial-derived ubiquinone, exogenous

vitamin K and NAD(P)H/H+ as electron donors, has been

identified as a second ferroptosis-suppressing system (87). A recent study indicated that

3-phenyl-quinazolinone, an FSP1 inhibitor, promotes FSP1

aggregation in tumors. This aggregation synergizes with ferroptosis

inducers to enhance iron-dependent cell death and suppress tumor

progression in vivo (88).

In the search for new therapies for uveal melanoma,

coumarin-quinazolinone-phenylboronic acid has been developed as a

prodrug to induce ferroptosis by targeting elevated ROS and

tyrosinase levels in melanoma cells (89). QD394, a quinazolinone-dione

compound, promotes lipid peroxidation and destabilizes GPX4

protein, thereby triggering GPX4-mediated ferroptosis (90).

Autophagy

Autophagy is a conserved cellular process that plays

an essential role in maintaining homeostasis by degrading damaged

or unnecessary organelles and proteins (91). It begins with the formation of

autophagosomes, which enclose the targeted materials and deliver

them to lysosomes for degradation. The term 'autophagy-dependent

cell death (ADCD)' was introduced in 2018 by the Nomenclature

Committee on Cell Death (92).

ADCD is a regulated form of cell death characterized by the

activation of autophagy markers, such as enhanced degradation of

autophagosomal substrates and lipidation of

microtubule-associated-proteinlight-chain-3 (LC3) (93). During autophagy, LC3 is converted

from the cytoplasmic form LC3-I to the membrane-associated form

LC3-II, and the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio is widely used as a marker of

autophagy activity (94).

Autophagy and apoptosis may act interchangeably under certain

conditions. Excessive autophagy, referred to as 'autophagic death',

can lead to cell death resembling apoptosis. These two processes

are regulated by overlapping signaling pathways, including mTOR,

Bcl-2 and Beclin-1 (95).

Quinazolinone compounds modulate the initiation and progression of

cell autophagy (Table III,

Fig. 4).

![Mechanism of action of Quinazolinone

compounds in pyroptosis, autophagy and cellular senescence

pathways. i) In the senescence pathway, telomere shortening and

limited telomerase function activate the p53/p21/p16 pathway,

causing G1 phase arrest and cellular senescence

3-(2-(hydroxymethyl) phenyl)-2-methylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones

upregulate the expression of TRF1, POT1 and p53/p21/p16, and

inhibit telomerase, inducing cells to enter a senescence

phenotype]. ii) In the pyroptosis pathway, NLRP3 assembles with ASC

and procaspase-1 to form the inflammasome, activating caspase-1,

which mediates the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, and induces

pyroptosis through GSDMD, forming membrane pores. Quinazolinone

derivatives can inhibit this process by blocking NLRP3 inflammasome

activation and the release of inflammatory factors (Mdivi-1

inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation, reduces the activation of

NLRP3, ASC, Caspase-1 and the level of GSDMD-NT, and decreases the

release of IL-1β and IL-18). iii) In the autophagy pathway, ATG

family proteins mediate phagophore nucleation and extension. LC3 is

modified by ATG4 and ATG7, transforming into LC3-II, which promotes

autophagosome formation and fusion with lysosomes for substrate

degradation (DQQ and HF promote LC3-II generation, enhance

ATG5-ATG12 complex formation and promote autophagy. MJ-33 initiates

autophagy by activating ATG proteins during vesicle nucleation but

reduces the LC3/LC3-II ratio and increases p62 levels, inhibiting

autophagy). NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain

associated protein 3; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing a CARD; GSDMD, gasdermin D; ATG, autophagy related gene;

LC3, microtubule-associated-proteinlight-chain-3; NIX, NIP3-like

protein X; TIN2, Terf1 interacting nuclear factor 2; RAP1,

Ras-proximate-1; TRF1, telomeric repeat binding factor 2; POT1,

protection of telomeres 1.](/article_images/ijmm/56/6/ijmm-56-06-05646-g03.jpg) | Figure 4Mechanism of action of Quinazolinone

compounds in pyroptosis, autophagy and cellular senescence

pathways. i) In the senescence pathway, telomere shortening and

limited telomerase function activate the p53/p21/p16 pathway,

causing G1 phase arrest and cellular senescence

3-(2-(hydroxymethyl) phenyl)-2-methylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones

upregulate the expression of TRF1, POT1 and p53/p21/p16, and

inhibit telomerase, inducing cells to enter a senescence

phenotype]. ii) In the pyroptosis pathway, NLRP3 assembles with ASC

and procaspase-1 to form the inflammasome, activating caspase-1,

which mediates the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, and induces

pyroptosis through GSDMD, forming membrane pores. Quinazolinone

derivatives can inhibit this process by blocking NLRP3 inflammasome

activation and the release of inflammatory factors (Mdivi-1

inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation, reduces the activation of

NLRP3, ASC, Caspase-1 and the level of GSDMD-NT, and decreases the

release of IL-1β and IL-18). iii) In the autophagy pathway, ATG

family proteins mediate phagophore nucleation and extension. LC3 is

modified by ATG4 and ATG7, transforming into LC3-II, which promotes

autophagosome formation and fusion with lysosomes for substrate

degradation (DQQ and HF promote LC3-II generation, enhance

ATG5-ATG12 complex formation and promote autophagy. MJ-33 initiates

autophagy by activating ATG proteins during vesicle nucleation but

reduces the LC3/LC3-II ratio and increases p62 levels, inhibiting

autophagy). NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain

associated protein 3; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein

containing a CARD; GSDMD, gasdermin D; ATG, autophagy related gene;

LC3, microtubule-associated-proteinlight-chain-3; NIX, NIP3-like

protein X; TIN2, Terf1 interacting nuclear factor 2; RAP1,

Ras-proximate-1; TRF1, telomeric repeat binding factor 2; POT1,

protection of telomeres 1. |

| Table IIIAutophagy pathway changes following

quinazolinone derivative treatment. |

Table III

Autophagy pathway changes following

quinazolinone derivative treatment.

| Authors, year | Cancer type | Chemical name | Affected molecule

or pathway | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kumar et al,

2014 | Leukemia |

2,3-Dihydro-2-(quinoline-5-yl)

quinazolin-4(1H)-one | AVOs↑, beclin1↑,

ATG7↑, ATG5↑, LC3-II↑ | (96) |

| Sharma et

al, 2022 | Lung cancer |

7,8,9,10-Tetrahydroazepino (2,1-b)

quinazolin-12 (6H)-one | AVOs↑ | (97) |

| Xia et al,

2017 | Breast cancer |

7-bromo-6-chloro-3-(3-(3-hydroxypiperidin-2-yl)propyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one | LC3↑, ATG5-ATG12

complex↑, SQSTM1↓, STMN1↓, p53↓ | (98) |

| Ha et al,

2021 | Colorectal

cancer |

2-(3-Ethoxyphenyl)-6-pyrrolidinylquinazolinone | ATG5, ATG7, ATG12,

ATG16↑

p62↑, LC3/LC3-II↓ | (99) |

| ElZahabi et

al, 2021 | Breast cancer |

3-Amino-6,8-dibromo-2-methylquinazolin-4(3H)-one | EGFR↓, PI3K, AKT,

mTOR↓ | (100) |

Kumar et al (96) investigated a novel quinazolinone

derivative, 2,3-dihydro-2-(quinoline-5-yl)quinazolin-4(1H)-one

(DQQ). DQQ induced the formation of acidic vacuolar organelles

(AVOs) in MOLT-4 cells and significantly increased the expression

of autophagy-related proteins, including LC3-II, autophagy-related

7 (ATG7), ATG5 and Beclin-1 (96). Another study showed that a fused

quinazolinone compound [compound 6, based on

7,8,9,10-tetrahydroazepino (2,1-b) quinazolin-12(6H)-one] increased

AVO formation, as detected by acridine orange staining, indicating

enhanced autophagic flux (97).

Halofuginone (HF), a quinazolinone alkaloid derived from Dichroa

febrifuga, promoted autophagy while inhibiting stathmin 1 and

p53 expression and activity. HF increased LC3 expression, promoted

ATG5-ATG12 complex formation and reduced sequestosome 1 expression

in MCF-7 cells (98).

Certain quinazolinone derivatives can also inhibit

autophagy. For instance, MJ-33 initiates autophagy at the vesicle

nucleation stage by activating ATG proteins but decreases the

LC3/LC3-II ratio and increases p62 levels, suggesting suppression

of autophagic flux. In HT-29/5FUR cells, this suppression enhances

MJ-33-induced apoptosis (99).

ElZahabi et al (100)

designed a series of quinazolin-4-one derivatives, among which

compound 7 reduced autophagy, leading to increased apoptosis and

cancer cell death.

Senescence

Cellular senescence is generally an irreversible

arrest of cell proliferation in damaged normal cells that have

exited the cell cycle. It is associated with widespread

macromolecular alterations and a secretory phenotype linked to

chronic inflammation (101).

Senescent cells show characteristic morphological changes,

including flattened cell shape, vacuolization, cytoplasmic

granularity and organelle abnormalities (102). Key features of senescence

include persistent cell cycle arrest, altered transcriptional

activity, a pro-inflammatory secretome, accumulated macromolecular

damage and metabolic dysregulation (103). Increasing evidence indicates a

complex relationship between aging and cancer (Table IV, Fig. 4). Initially, senescence functions

as a protective mechanism by limiting abnormal cell proliferation

and reducing cancer risk. However, with aging, immune decline and

accumulated DNA damage may contribute to cancer development

(104,105).

| Table IVSenescence, necrosis and pyroptosis

pathway changes following quinazolinone derivative treatment. |

Table IV

Senescence, necrosis and pyroptosis

pathway changes following quinazolinone derivative treatment.

| Authors, year | Cancer type | Chemical name | Affected molecule

or pathway | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Kamal et al,

2013 | Breast cancer,

non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, colorectal

cancer | A series of

3-diarylethyne quinazolinone compounds | p53, p21,

p16↑

TRF1, POT1↑

SKP2, TRF2 and tankyrase protein levels↓ | (106) |

| Venkatesh et

al, 2015 | Cervical

cancer |

2-Methyl-3-(2-((4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-Triazol-1-yl)methyl)phenyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one | p53, p21↑

HDAC-1,2,3,4↓ | (107) |

| Shams et

al,2011 | Kidney damage |

4(3H)-Quinazolinone-2-propyl-2-phenylethyl

and 4(3H)quinazolinone-2-ethyl-2-phenylethyl | By metabolization

and production of active metabolites and free oxygen radicals, cell

membrane and organelles such as mitochondria and peroxisome are

damaged and necrosis appears in renal tubule cells | (112) |

| Piamsiri et

al, 2024 | Acute myocardial

infarction |

3-(2,4-Dichloro-5-methoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1H)-quinazolinone | NLRP3,

GSDMD-NT↑ | (113) |

| Li et al,

2021 | Atopic

dermatitis |

3-(2,4-Dichloro-5-methoxyphenyl)-2,3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1H)-quinazolinone | NLRP3,

ASC↓

Cleavage of Caspase-1↓

GSDMD-NT↓

IL-1β, IL-18↓ | (114) |

| Liu et al,

2020 | Acute kidney

injury |

3-(2,4-Dichloro-5-methoxyphenyl)-2,

3-dihydro-2-thioxo-4(1H)-quinazolinone | NLRP3↓

IL-1β, IL-18↓ | (116) |

Kamal et al (106) developed a series of

3-diarylacetylene quinazolinone compounds that activate p53, p21,

p16, telomeric repeat binding factor 1 (TRF1) and protection of

telomeres 1 (POT1) proteins. These compounds exhibited significant

telomerase inhibitory activity, suggesting their potential as

senescence inducers. Similarly, certain 3-(2-(hydroxymethyl)

phenyl)-2-methylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones induced a senescence

phenotype in HeLa cells (107).

The application of quinazolinone and its derivatives in aging and

cancer therapy remains an area of active investigation.

Necrosis and pyroptosis

Necrosis is an abnormal form of cell or tissue death

caused by external factors such as trauma, hypoxia, infection or

injury. Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 has been identified

as a key regulator of necroptosis, a programmed form of necrosis

activated by stimuli such as TNF, TNF superfamily member 10 (also

known as TRAIL), lipopolysaccharide, oxidative stress or DNA damage

(108). During necrosis,

membrane breakdown leads to the release of cytoplasmic contents

into the extracellular environment (109).

Pyroptosis is a regulated form of cell death

mediated by gasdermins and characterized by continuous cell

swelling, plasma membrane rupture and the release of intracellular

contents that trigger inflammatory and immune responses (110). It is initiated by inflammasome

activation in response to various triggers (111). Pyroptosis is involved in

cancer, neurodegenerative diseases and ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Research on the effects of quinazolinone derivatives in necrosis

and pyroptosis is still at an early stage and the specific

mechanisms remain elusive. The available literature is limited.

Quinazolinone compounds can induce cell death through necrosis and

pyroptosis (Table IV, Fig. 4).

In BALB/c mice, administration of two new

quinazolinone compounds, 4(3H)-quinazolinone-2-propyl-2-phenylethyl

and 4(3H)-quinazolinone-2-ethyl-2-phenylethyl, caused abnormal

kidney function. Quinazolinones can affect sulfhydryl groups,

disrupt protein structures, generate reactive metabolites and free

radicals, and damage organelles such as tubular membranes,

mitochondria and peroxisomes, ultimately leading to cell necrosis

(112).

Mdivi-1, a quinazolinone-derived compound, has been

shown to reduce necroptosis- and pyroptosis-related protein

expression, including NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3)

and gasdermin D N-terminus (GSDMD-NT), in cardiomyocytes of rats

with myocardial infarction, thereby improving cardiac function in

post-MI rats (113). Li et

al (114) were the first to

study the effect of Mdivi-1 on primary human keratinocytes in an

in vitro model of atopic dermatitis-related inflammation

induced by an inflammatory cocktail. Their results showed that

Mdivi-1 inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis, as

indicated by reduced levels of NLRP3, apoptosis-associated

speck-like protein containing a CARD, cleaved caspase-1, GSDMD-NT,

and mature interleukins IL-1β and IL-18 in keratinocytes. In

cellular and animal models of septic acute kidney injury, Mdivi-1

suppressed NLRP3-driven pyroptosis and improved mitochondrial

function (115,116). Further research is needed to

fully understand the roles and mechanisms of quinazolinone and its

derivatives in necrosis and pyroptosis.

Application of quinazolinone derivatives in

cancer therapy

Quinazolinone and its derivatives have attracted

considerable attention in recent years for their ability to induce

cell death in various cancer types, representing a promising

therapeutic approach. As single agents, these compounds act through

multiple mechanisms, including apoptosis, autophagy and

ferroptosis. To enhance therapeutic efficacy and address challenges

such as drug resistance and toxicity, increasing efforts have

focused on combining quinazolinone derivatives with other

pharmacological agents. This strategy not only amplifies their

anti-tumor effects but also enables more targeted interventions,

potentially reducing adverse effects. The following section

discusses the clinical prospectssss of quinazolinone and its

derivatives in combination therapy, emphasizing their synergistic

effects when used with conventional chemotherapeutic agents and

molecular targeted therapies.

Combination with platinum-based

drugs

Studies have shown that co-treatment with cisplatin

and Mdivi-1 synergistically enhances apoptotic cell death in both

intrinsically and acquired cisplatin-resistant tumor cells,

including MDA-MB-231 breast cancer, H1299 non-small cell lung

cancer, glioblastoma, melanoma, cholangiocarcinoma and A2780cis

cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells (117,118). In A2780cis cells, Mdivi-1

enhances cisplatin sensitivity through a Drp1-independent pathway.

The combination increases DNA damage, upregulates

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 and disrupts

mitochondrial function, ultimately triggering Bax- and

Bak-independent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and

activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (117). Tusskorn et al (118) demonstrated that Mdivi-1

increases the sensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells to cisplatin

by promoting oxidative stress and autophagosome formation, thereby

inducing cell death through mitochondrial pathways. Furthermore,

Mdivi-1 protects against cisplatin-induced hair cell death in

zebrafish by modulating mitochondrial dynamics, suggesting its

potential for reducing ototoxicity. Further studies in mammalian

models are required to clarify the underlying protective mechanisms

(119).

Combination with 5-fluorouracil

(5-FU)

MJ-33, a quinazolinone derivative, exhibits

anti-tumor activity by reducing the viability of 5-FU-resistant

HT-29 colon cancer cells. It induces apoptosis and autophagy

through the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, offering potential

therapeutic value in 5-FU-resistant colorectal cancer (CRC)

(76).

Lai et al (120) reported that

2-(3-fluorophenyl)-6-morpholinoquinazolin-4(3H)-one induces mitotic

arrest, subsequently leading to apoptosis. This compound also

synergizes with 5-FU to enhance cytotoxic effects against oral

squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC).

Combination with gemcitabine

HMJ-38 promotes both autophagy and apoptosis in

MIA-RG100 pancreatic cancer cells and demonstrates cytotoxic

effects against gemcitabine-resistant cells. The mechanism involves

activation of the EGFR-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway, which induces

autophagy, and the mitochondrial pathway, which facilitates

apoptosis (65). These findings

provide new perspectives for overcoming gemcitabine resistance in

pancreatic cancer. Another quinazolinone derivative, QD232,

suppresses the growth of gemcitabine-resistant MIA PaCa-2 cells by

inhibiting STAT3 and Src phosphorylation, offering a potential

strategy for treating drug-resistant pancreatic cancer associated

with STAT3 activation (121).

Combination with temozolomide

Targeting the catalytic domain of PARP-1, a series

of quinazolin-2,4(1H,3H)-dione derivatives have been synthesized as

PARP-1 inhibitors. Zhou et al (122) developed novel compounds

containing a 3-amino-pyrrolidine group, which enhanced the

cytotoxic effects of temozolomide in the MX-1 xenograft breast

cancer model. Similarly, 1-substituted benzyl

quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione derivatives demonstrated comparable

efficacy (123). Another study

confirmed that the 2-propionyl-3H-quinazoline-4-one scaffold acts

as a novel PARP-1 inhibitor, exhibiting synergistic effects with

temozolomide in MX1 cells (124).

Combination with paclitaxel

Ucleotide binding oligomerization domain containing

1 (NOD1) and NOD2 receptors, which contain nucleotide-binding

oligomerization domains, are emerging as potential immune

checkpoints. In a study by Ma et al (125), a quinazolinone derivative

[6-(3-chlorophenyl)-3-(2-(3,3-difluoropiperidin-1-yl)-2-oxoethyl)-4-oxo-N-(3-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy)propyl)-3,4-dihydro

quinazoline-7-carboxamide] was designed as a dual antagonist of

NOD1/2. By inhibiting NOD1/2-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling

pathways, this compound enhanced the response of B16

melanoma-bearing mice to paclitaxel therapy (125).

Quinazolinone derivatives approved by the

FDA or under clinical investigation

Idelalisib

Idelalisib (Zydelig™; CAL-101; Gilead Sciences),

with the chemical name

5-fluoro-3-phenyl-2-((1S)-1-(9H-purin-6-yl-amino)propyl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one,

has the molecular formula

C22H18FN7O and functions as a

lipid kinase inhibitor, specifically targeting the p110δ isoform of

class I phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3Kδ) (126). Idelalisib inhibits PI3Kδ by

competitively binding to the ATP-binding site of the p110δ subunit.

This inhibition disrupts key PI3Kδ signaling functions, including

chemokine secretion, cell migration and receptor-driven kinase

phosphorylation, ultimately reducing cell survival and promoting

apoptosis (127,128).

Idelalisib has shown clinical efficacy in indolent

B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and was approved by the FDA in 2014 for

monotherapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),

follicular lymphoma and small lymphocytic lymphoma. It is also

approved in combination with rituximab for the treatment of CLL

(129,130). In patients with previously

treated indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, idelalisib as monotherapy

achieved an objective response rate (ORR) of 57%, with a median

duration of response (mDOR) of 12.5 months and a median

progression-free survival (PFS) of 20.3 months (131,132). When combined with rituximab,

idelalisib further improved overall response rates and 12-month

overall survival (OS) in patients with CLL (133).

Despite its clinical benefits, idelalisib carries a

black box warning from the FDA due to the risk of severe or fatal

adverse events, including hepatotoxicity, diarrhea, colitis,

pneumonia and intestinal perforation (134). Patients who developed colitis

or transaminitis after idelalisib treatment exhibited elevated

plasma chemokine levels and reduced T-regulatory cell (Treg)

populations, suggesting that Treg depletion may contribute to the

adverse effects of p110δ inhibition by releasing the suppression of

cytotoxic T cells (135). In a

Phase III clinical trial, the combination of idelalisib and

rituximab improved PFS in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL

from 11.1 to 20.8 months; however, long-term follow-up revealed a

5-year overall survival rate of only 40%, indicating disease

progression in certain patients and suggesting the development of

resistance (136,137). In CLL, resistance to idelalisib

is closely associated with the activation of insulin-like growth

factor 1 receptor (IGF1R). Specifically, the upregulation of IGF1R

enhances the MAPK signaling pathway, bypassing PI3Kδ inhibition and

thereby promoting tumor cell survival (138). To overcome Idelalisib

resistance, researchers have explored various combination therapy

strategies. For instance, idelalisib combined with bortezomib

blocks drug resistance properties of Epstein-Barr virus-related

B-cell origin cancer cells via regulation of NF-κB (139). Nevertheless, further

investigation into the molecular mechanisms of resistance is

necessary to develop more precise therapeutic strategies.

Ispinesib

Ispinesib, a quinazolinone-derived compound, is a

selective inhibitor of kinesin spindle protein (KSP) and functions

as an allosteric modulator of KSP motor ATPase activity. By

inhibiting KSP, ispinesib disrupts mitotic spindle formation,

leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (140). Developed by Cytokinetics,

ispinesib entered clinical trials in 2004 for multiple indications,

becoming the first potent and selective KSP inhibitor to undergo

clinical testing in human diseases (20). According to data from the

National Institutes of Health, ispinesib has been evaluated as

monotherapy in 13 Phase I/II clinical trials for various cancer

types, including relapsed renal cell cancer (RCC), breast cancer,

recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(HNSCC), ovarian cancer (OC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and

CRC, with the best responses observed in breast cancer and OC

(141,142). As a combination therapy,

ispinesib has been tested in three clinical trials: With docetaxel

for HCC, with capecitabine for HNSCC and with carboplatin for

metastatic or recurrent malignant melanoma (142,143).

In clinical studies of breast cancer, Ispinesib has

shown some antitumor activity, with an ORR of 9% (144). However, its ORR was relatively

poor in other tumor types. In a phase II clinical trial for

advanced RCC, no complete responses or partial responses were

observed, and only 6 patients had stable disease (145). A phase II trial of Ispinesib

was conducted in patients with advanced HCC who had not undergone

chemotherapy. At the 8-week evaluation, 46% of patients had stable

disease as the best response, with an mDOR of 3.9 months and a

median time to tumor progression of 1.61 months (146). No significant objective

response was achieved. The most common adverse reactions associated

with ispinesib treatment include neutropenia, anemia, elevated

alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, and

diarrhea, while no neuropathy, mucositis or alopecia have been

observed (147).

In glioblastoma, resistance to ispinesib is closely

associated with the activation of STAT3. STAT3 mediates

anti-apoptotic and metabolic effects through dual phosphorylation

by Src and EGFR, thereby promoting drug resistance that can be

reversed by simultaneously inhibiting Src and EGFR (148). In addition, drug efflux

mediated by P-glycoprotein (P-gp) can pump ispinesib out of the

cells, reducing its intracellular concentration and leading to drug

resistance, which can be overcome by inhibiting P-gp activity to

enhance the cytotoxicity of ispinesib (149). Clinical trials have reported a

favorable safety profile, with no significant neurotoxicity,

alopecia or gastrointestinal toxicity. The most common adverse

event was reversible neutropenia (150). Ispinesib is currently in Phase

I/II clinical development and further studies on its mechanisms and

optimized clinical protocols may establish it as an effective

anti-tumor therapy.

Nolatrexed

Nolatrexed

[2-amino-6-methyl-5-(4-pyridylthio)-4(3H)-quinazolinone] is a

thymidylate synthase inhibitor primarily developed for the

treatment of HCC. In patients with unresectable HCC, nolatrexed

achieved a median overall survival of 22.3 weeks, with an ORR of

1.4% and a median PFS of 12 weeks (151). Initially developed by Agouron

Pharmaceuticals in the US, nolatrexed advanced to Phase II/III

trials for liver cancer and head and neck tumors through a

partnership with Roche. In 1999, Agouron transferred global

oncology rights for nolatrexed to Eximias Pharmaceutical Company,

which currently leads global development of nolatrexed. Ongoing

Phase II clinical trials are being conducted for CRC, HNSCC,

prostate cancer (PCA), pancreatic cancer and lung cancer in

countries including the US, UK, Canada, Italy and South Africa.

Phase III trials for liver cancer are also in progress (152,153).

Nolatrexed, a 4(3H)-quinazolinone derivative, has

shown promising efficacy in clinical trials, exhibiting typical

antimetabolite-related side effects such as short duration of

action and low toxicity, along with mucositis, vomiting, diarrhea

and thrombocytopenia (151).

Thymidylate synthase (TS) is the primary target of nolatrexed and

its overexpression is one of the key mechanisms of resistance. In

CRC cells with p53 mutations, both TS mRNA and protein expression

levels are significantly elevated, thereby increasing the cells'

resistance to nolatrexed (154). Furthermore, being lipophilic,

nolatrexed passively diffuses into cells without the need for

specific membrane transport proteins. Since inhibition of

transporter-mediated uptake is a mechanism of tumor cell

resistance, this property may allow nolatrexed to be effective

against drug-resistant tumors and reduce the likelihood of

resistance development (155).

Although granted orphan drug status by the European Medicines

Agency, it was not approved by the FDA in 2005 (20).

Halofuginone

Halofuginone is a synthetic derivative of a

quinazolinone alkaloid with the chemical name

7-bromo-6-chloro-3-(3-(3-hydroxy-2-piperidinyl)-2-oxopropyl)-4(3H)-quinazolinone

(156). It was developed by

Collgard Biopharmaceuticals and received FDA approval in 2000 as an

orphan drug for the treatment of scleroderma (20). Halofuginone inhibits

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in tumor cells, reducing

migration and invasiveness. It also selectively suppresses Th17

cell differentiation and inhibits Smad3 phosphorylation, a key

downstream mediator of the TGF-β pathway. These effects reduce

tumor-associated fibrosis and enhance immune surveillance (157,158). As a broad-spectrum anti-tumor

agent, it has demonstrated efficacy against Pancreatic

adenocarcinoma, CRC, breast cancer and lung cancer (159). Halofuginone has demonstrated

promising results in a Phase II study for recurrent superficial

transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. In addition, a

sustained-release formulation of fluorofebrin is under Phase II

evaluation for safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics in

patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (20).

Up to date, clinical investigations of halofuginone

have primarily focused on exploring its safety and tolerability

rather than establishing overall therapeutic efficacy, and no

specific data on ORR, PFS or DOR have yet been reported.

Nonetheless, its antitumor potential has been demonstrated in

several experimental models. For instance, in anaplastic thyroid

carcinoma (ATC), halofuginone significantly suppresses ATC cell

proliferation and tumor growth by inhibiting the enzyme-prolyl-tRNA

synthetase-activating transcription factor 4-collagen type I

signaling axis (160). In OSCC,

halofuginone suppressed collagen synthesis and myofibroblast

activation, thereby attenuating tumor invasiveness and growth

(161). Common adverse effects

include nausea, vomiting, a possible increased risk of bleeding,

and decreased red and white blood cell counts (162). A study suggested that

halofuginone can overcome drug resistance in cancer therapy with a

relatively low risk of inducing resistance. For instance, it

restores sensitivity to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors by

targeting phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 downregulation (163), reverses paclitaxel resistance

in basal-like breast cancer by modulating the BRCA1/TGF-β signaling

axis (164) and serves as a

potential therapeutic agent for 5-FU-resistant CRC by targeting

microRNA-132-3p in vitro (165).

Febrifugine

Febrifugine is the active antimalarial compound

isolated from the traditional Chinese herb Chang Shan, which has

been used for centuries to treat malaria-induced fevers (166). Febrifugine also demonstrates

anti-tumor activity and has shown potential therapeutic effects of

PCA and bladder cancer (BLCA), likely through inhibition of focal

adhesion kinase (167-169). It also suppresses

steroidogenesis and promotes apoptosis, contributing to its

anti-tumor effects by inhibiting DNA synthesis (170). The effectiveness of febrifugine

in clinical treatment is currently focused on basic research and

animal models, with no specific data reported directly on clinical

patients. A related study revealed its anticancer efficacy. In the

BLCA model, febrifugine effectively inhibited the proliferation of

T24 and SW780 BLCA cells, with IC50 values of 0.02 and

0.018 μM, respectively, and demonstrated good anticancer

effects by reducing steroidogenesis and promoting apoptosis

(168). It was also shown to

enhance the anticancer effects of cisplatin in vivo

(171). Due to significant side

effects, there has been no further research on febrifugine for a

long period of time and there is limited literature or clinical

data that discuss its resistance in different cancer types in

detail. Some potential mechanisms of resistance may include cancer

cells rejecting febrifugine, mutations in target genes or cancer

cells altering their sensitivity to the drug through metabolic

pathways. The specific mechanisms of resistance may be gradually

revealed in future studies. Common adverse effects include

dizziness, dry mouth and persistent vomiting (172,173). A summary of the aforementioned

quinazolinone derivatives is presented in Table V.

| Table VQuinazolinone derivatives approved or

under clinical investigation in cancer therapy. |

Table V

Quinazolinone derivatives approved or

under clinical investigation in cancer therapy.

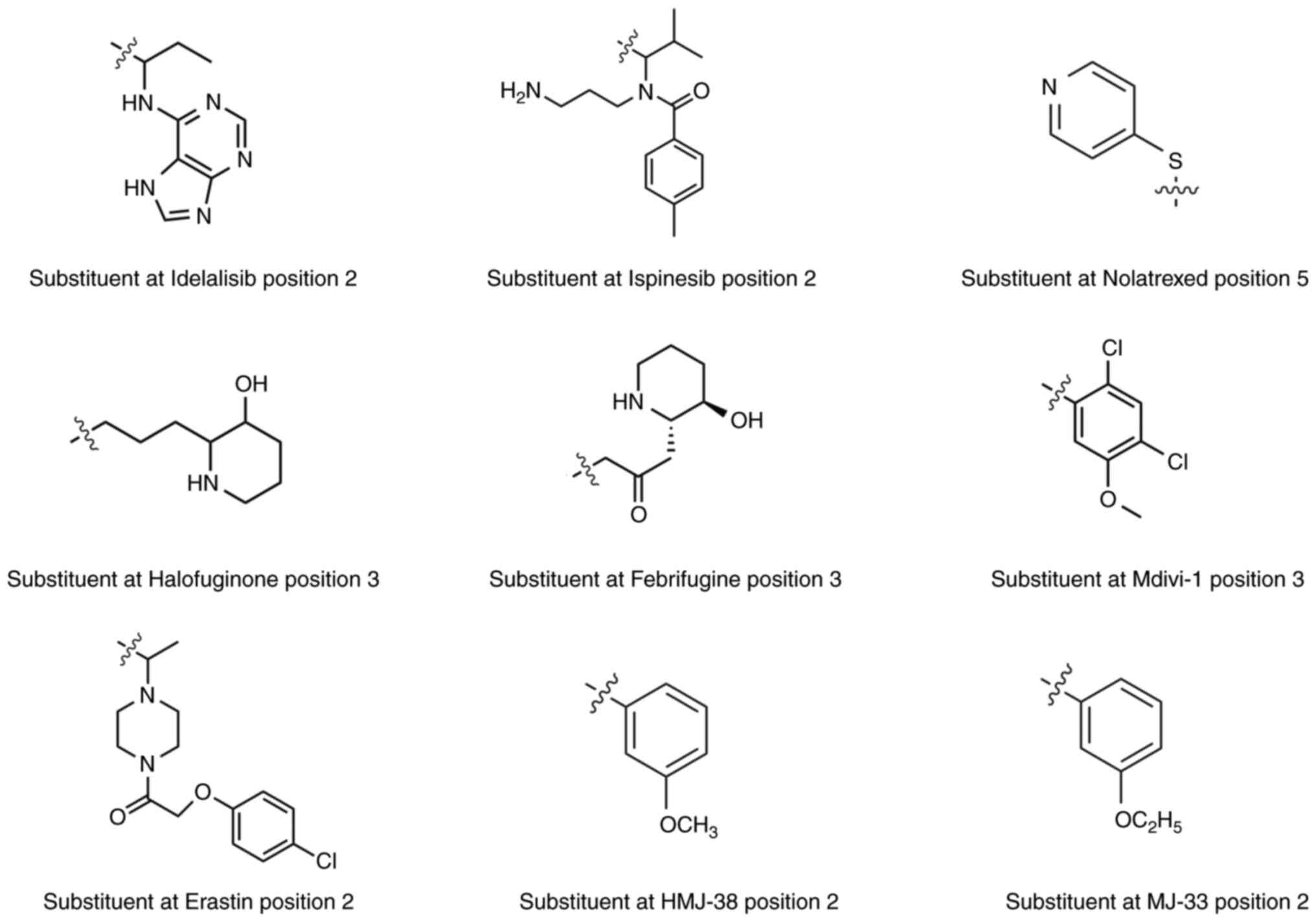

SAR of anticancer quinazolinone

compounds

SAR studies of quinazolinone derivatives reveal a

close association between molecular structure and biological

activity. Structural optimization and the introduction of various

substituents can effectively modulate anti-tumor activity,

pharmacokinetic stability and targeting specificity. The

substitution sites of quinazolinone are shown in Fig. 1.

The 2- and 3-positions are key sites for SAR

studies, as they directly influence selectivity, potency and

cellular activity. In anticancer compounds, substituents at

positions 2 and 3 are predominantly sulfur ethers and aryl ketones,

as seen in the investigational drug ispinesib. Electron-withdrawing

groups at the meta position, such as halogens and trifluoromethyl,

generally enhance inhibitory activity against EGFR, as exemplified

by the quinazoline-based drugs gefitinib and erlotinib, which

contain −Cl and −CF3 groups (174).

Substituents at the 6- and 7-positions typically

target the solvent-exposed regions or entry channels of the

ATP-binding pocket (175).

Modifications at these positions significantly affect solubility,

membrane permeability and pharmacokinetics. Halogen atoms are

frequently introduced at these positions to increase lipophilicity

and stability, thereby improving membrane penetration and

bioactivity, as observed with -Cl and -Br in halofuginone (176). However, methoxy groups

generally have the opposite effect, reducing the reactivity of the

ring toward various reactions (50). The 6,7-dimethoxyquinazolinone

derivative forms an additional hydrogen bond with Thr918 of VEGFR2

via the oxygen atom of the methoxy group. A molecular docking study

showed that it can strongly bind to the hydrophobic site of VEGFR2

kinase, making it a potent VEGFR2 inhibitor (174). Furthermore, Kurogi et al

(177) found from

structure-activity relationship studies that introducing methoxy

groups at the 6- and 7-positions of quinazolinone enhanced its

hypolipidemic activity. Therefore, the addition or removal of such

groups in vivo can serve as a tool for modulating the

toxicity of quinazoline derivatives.

Substitution at the 5-position is relatively

uncommon, as introducing substituents at this site may increase

steric hindrance. However, it shows specificity for cytotoxic

agents, such as the protein kinase inhibitor idelalisib and the

dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor nolatrexed (20). These positions can also serve as

linkers for synthesizing dual-target inhibitors. In the study on

RAF kinase inhibitors, Huestis et al (178) designed the 5-fluoro-substituted

quinazolinone compound GNE-0749. By masking the adjacent polar NH

group, they enhanced the molecule's interaction with RAF kinase and

significantly improved its solubility and permeability, thereby

endowing it with properties suitable for oral administration

(178). Table VI summarizes the SAR of several

common quinazolinone derivatives. Fig. 5 shows the specific structure of

these substituents.

| Table VISubstitution at different positions

of several common quinazolinone compounds. |

Table VI

Substitution at different positions

of several common quinazolinone compounds.

| Drug | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 |

|---|

| Idelalisib | H |

C8H10N5 | Benzene | H | F | H | H |

| Ispinesib | H |

C15H23N2O | Benzene | H | H | H | Cl |

| Nolatrexed | H | NH2 | H | H |

C5H4NS | H | H |

| Halofuginone | H | H |

C8H16NO | H | H | Cl | Br |

| Febrifugine | H | H |

C8H14NO2 | H | H | H | H |

| Mdivi-1 | H | S |

C7H5Cl2O | H | H | H | H |

| Erastin | H |

C14H18ClN2O2 | Ethoxybenzene | H | H | H | H |

| HMJ-38 | H |

C7H7O | H | H | H | Pyrrolidine | H |

| MJ-33 | H |

C8H9O | H | H | H | Pyrrolidine | H |

Discussion

This review examined the structure, applications

and mechanisms of cell death induced by quinazolinone and its

derivatives. Quinazolinone is a multifunctional heterocyclic

compound that has attracted considerable attention for its

promising biological activity (179). Quinazolinone derivatives act

through multiple cell death pathways, including classical

apoptosis, autophagy and ferroptosis associated with metabolic

stress and damage, as well as inflammatory responses triggered by

senescence, necrosis and pyroptosis. Importantly, quinazolinone and

its derivatives offer distinct advantages in overcoming tumor

resistance and immune evasion. Cancer cells often develop

resistance to chemotherapy through mechanisms such as drug efflux

and altered drug metabolism (180,181). Quinazolinone derivatives have

demonstrated the ability to counteract some of these mechanisms by

sensitizing cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Several

quinazolinone-based compounds have received FDA approval for cancer

treatment, while others have shown encouraging efficacy in

preclinical studies and in Phase I and II clinical trials (182). Despite these advances, further

rigorous clinical studies are needed to fully evaluate the safety,

efficacy and optimal dosing strategies of quinazolinone

derivatives.

Although quinazolinone and its derivatives show

considerable potential in cancer therapy, several challenges and

unresolved issues remain. First, the chemical synthesis of

quinazolinones still relies heavily on high temperatures and harsh

reaction conditions, and generates numerous by-products (183). A team from South China Normal

University developed a covalent organic framework, TAPP-Cu-An,

which enables efficient dehydrogenative cross-coupling reactions

under mild conditions (room temperature and light exposure),

facilitating the photochemical synthesis of 4-quinazolinone

(184). Furthermore, a team

from Guilin University of Technology developed a 4-DPAIPN catalyst,

using acetonitrile as the solvent and blue LED light irradiation,

achieving a metal-free synthesis of tetracyclic quinazolinones and

avoiding the use of precious metals (185). Second, although it is

established that these compounds act through multiple cell death

pathways, the interactions and regulatory mechanisms among these

pathways are not yet fully understood. Future research should

investigate the crosstalk between these pathways and determine how

quinazolinone modulates them in different cancer types to optimize

its anti-tumor effects. Most current studies have examined

combinations of quinazolinone derivatives with chemotherapy agents;

however, their synergistic potential with immunotherapy also

warrants exploration (4,186). Finally, most quinazolinone

derivatives suffer from poor water solubility, low oral

bioavailability and short half-life, which limit their therapeutic

efficacy in vivo (187).

Future research should consider the use of nanocarriers (such as

nanoparticles, liposomes and polymeric microparticles) to

encapsulate the drug, improve solubility in aqueous solutions and

enable targeted delivery, thereby maximizing therapeutic potential

(188). Additionally, prodrug

strategies can be employed, incorporating solubilizing moieties

such as phosphate esters or polyethylene glycol (PEG) groups, such

as PEG-400, to improve bioavailability (189).

Quinazolinone molecules can interact with

fluorescent dyes through covalent coupling, electrostatic

adsorption, or coordination bonding. These interactions allow

real-time tracking of drug delivery in vivo, enable

observation of drug absorption, transport and dynamic changes at

the cellular level, and can be applied in fluorescent imaging of

tumors (190). With advances in

synthetic chemistry and drug design, structural modifications of

quinazolinone compounds could further enhance specificity,

selectivity and therapeutic efficacy. Designing new quinazolinone

derivatives and investigating their roles in cancer treatment will

be critical for advancing this field. By optimizing molecular

structures to improve selectivity and cytotoxicity toward cancer

cells, significant progress in therapeutic outcomes may be

achieved.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JL and YuY wrote the manuscript. YuY conceived and

supervised the study. XK and YaY revised the manuscript. LW and QL

finalized the figures and checked the grammar of the text. All

authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted

version. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82374273), the Natural Science

Foundation of Henan (grant no. 252300420155), the Key Scientific

Research Project of Higher Education of Henan Province (grant no.

25CY031), the Innovation Project of Graduate Students at Xinxiang

Medical University (grant no. YJSCX202417Y) and the National

College Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program

(grant nos. 202310472034 and 202410472002).

References

|

1

|

Tiwary BK, Pradhan K, Nanda AK and

Chakraborty R: Implication of quinazoline-4(3H)-ones in medicinal

chemistry: A brief review. J Chem Biol Ther. 1:1042016.

|

|

2

|

Rakesh KP, Manukumar HM and Gowda DC:

Schiff's bases of quinazolinone derivatives: Synthesis and SAR

studies of a novel series of potential anti-inflammatory and

antioxidants. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 25:1072–1077. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sulthana MT, Chitra K, Alagarsamy V,

Saravanan G and Solomon VR: Anti-HIV and antibacterial activities

of novel 2-(3-Substituted-4-oxo-3, 4-dihydroquinazolin-2-yl)-2,

3-dihydrophthalazine-1,4-diones. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 47:112–121.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Salfi R, Hakim F, Bhikshapathi D and Khan

A: Anticancer evaluation of novel quinazolinone acetamides:

Synthesis and characterization. Anticancer Agents Med Chem.

22:926–932. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Gatadi S, Lakshmi TV and Nanduri S:

4(3H)-Quinazolinone derivatives: Promising antibacterial drug

leads. Eur J Med Chem. 170:157–172. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zayed MF: Medicinal Chemistry of

quinazolines as analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents.

ChemEngineering. 6:942022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mhetre UV, Haval NB, Bondle GM, Rathod SS,

Choudhari PB, Kumari J, Sriram D and Haval KP: Design, synthesis

and molecular docking study of novel triazole-quinazolinone hybrids

as antimalarial and antitubercular agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett.

108:1298002024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yaduwanshi PS, Singh S, Sahapuriya P,

Dubey P, Thakur J and Yadav S: Synthesis of some noval qunazolinone

derivatives for their anticonvulsant activity. Orient J Chem.

40:369–373. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Khalifa MM, Sakr HM, Ibrahim A, Mansour AM

and Ayyad RR: Design and synthesis of new benzylidene-quinazolinone

hybrids as potential anti-diabetic agents: In vitro α-glucosidase

inhibition, and docking studies. J Mol Struct. 1250:1317682022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Soliman AM, Karam HM, Mekkawy MH and

Ghorab MM: Antioxidant activity of novel quinazolinones bearing

sulfonamide: Potential radiomodulatory effects on liver tissues via

NF-κB/PON1 pathway. Eur J Med Chem. 197:1123332020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Osman EO, Emam SH, Sonousi A, Kandil MM,

Abdou AM and Hassan RA: Design, synthesis, anticancer, and

antibacterial evaluation of some quinazolinone-based derivatives as

DHFR inhibitors. Drug Dev Res. 84:888–906. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

El-Karim SS, Syam YM, El Kerdawy AM and

Abdel-Mohsen HT: Rational design and synthesis of novel

quinazolinone N-acetohydrazides as type II multi-kinase inhibitors

and potential anticancer agents. Bioorg Chem. 142:1069202024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|