Introduction

Bone metabolism is essential for maintaining the

integrity and function of the skeleton and ensuring a balanced

process of bone formation and resorption. Under inflammatory

conditions, bone metabolism is skewed with OC-mediated bone

resorption outpacing bone formation. This imbalance accelerates

bone loss and weakens the structural integrity of the skeleton

(1). Therefore, the development

of novel therapeutic strategies that simultaneously inhibit

osteoclastogenesis and regulate inflammatory responses is crucial

for alleviating inflammatory bone resorption and improving skeletal

health.

OCs are essential effector cells in bone metabolism

that are primarily responsible for local bone resorption and play a

crucial role in inflammatory bone degradation. Multiple signalling

pathways regulate OC differentiation and activity. Receptor

activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) activates the

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathway, which

subsequently stimulates the expression of NFATc1, driving OC

differentiation (2,3). The nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB)

pathway (4,5) and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase

(PI3K) pathway (6) also play

significant roles in osteoclastogenesis and the maintenance of OC

function. Inflammation is a crucial driver of bone degradation

(7). Chronic inflammation

induces oxidative stress, leading to increased production of

reactive oxygen species (ROS), activating OCs and exacerbating bone

resorption (8,9).

Current antiresorptive therapies, including

bisphosphonates (10,11), effectively target OC formation

but lack anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects and have limited

clinical utility (12,13). Therefore, an urgent need exists

to develop novel agents with anti-inflammatory properties that

inhibit abnormal OC production. Cynarin is a phenolic compound

isolated from artichokes (Cynara genus) with potent

antioxidant activity (14,15). In a mouse model of gouty

arthritis, cynarin has been shown to inhibit the NF-κB and JNK

pathways in macrophages, exerting anti-inflammatory and

anti-swelling effects (16). In

a mouse colitis model, it downregulated STAT3 and NF-κB (p65),

thereby suppressing M1 macrophage polarisation (17). However, the mechanism of action

of cynarin in inflammatory bone resorption remains unclear, and

further research is required to address these questions.

The present study has evaluated the potential of

cynarin as a dual-functional agent with anti-osteolytic and

anti-inflammatory properties. Specifically, its effects were

examined on RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, as well as on the

MAPK signalling pathway, ROS production and Nrf2 activation in

vitro. In addition, its efficacy in preventing inflammatory

bone loss was evaluated in vivo. Notably, cynarin was more

effective than alendronate in mitigating calvarial bone resorption.

These findings highlight the ability of cynarin to inhibit OC

formation and attenuate inflammation via a dual mechanism,

supporting its potential as a novel therapeutic agent for treating

inflammatory osteolysis.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Cynarin (Selleck Chemicals) was used at a purity of

99.97% (high-performance liquid chromatography peak purity test and

13C NMR test data are available upon request from the corresponding

author). Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and RANKL

were obtained from R&D Systems, Inc. Anisomycin and alendronate

were purchased from MedChemExpress, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

was sourced from MilliporeSigma. The tartrate-resistant acid

phosphatase (TRAP) staining kit was acquired from Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd. TRIzol reagent, PrimeScript™ RT reagent

kit and TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II Fast qPCR kit were

provided by Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The bicinchoninic acid

(BCA) protein assay kit, commercial nuclear and cytoplasmic protein

extraction kit and phenyl-methyl-sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) were

obtained from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. Primary

antibodies against histone H3 (cat. no. 9715), GAPDH (cat. no.

2118), phospho-(p)-JNK (cat. no. 4668), JNK (cat. no. 9252), p-ERK

(cat. no. 4370), ERK (cat. no. 4695), p-p38 (cat. no. 4511), p38

(cat. no. 9212) and RANK (cat. no. 4845), as well as secondary

antibodies (cat. nos. 7074 and 7076), were purchased from Cell

Signalling Technology, Inc. Primary antibodies specific to heme

oxygenase-1 (HO-1; cat. no. A1346) and RUNX2 (cat. no. A2851) were

acquired from ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd., while the DC-STAMP (cat.

no. MABF39-I) antibody was obtained from MilliporeSigma. Antibodies

targeting cathepsin K (CTSK; cat. no. ab19027), collagen I (COL1;

cat. no. ab270993) and osteopontin (OPN; cat. no. ab218237) were

purchased from Abcam. Antibodies against Nrf2 (cat. no.

16396-1-AP), Keap1 (cat. no. 10503-2-AP), osteocalcin (OCN; cat.

no. 16157-1-AP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα; cat. no.

17590-1-AP) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; cat. no.

22226-1-AP) were sourced from Proteintech Group, Inc.

Cell culture and treatment

RAW264.7 cells (cat. no. TIB-71; American Type

Culture Collection) were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle

Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100

U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Bone

marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were isolated and cultured

according to the protocol established by Rucci et al

(18). Primary BMMs were

incubated in α-Minimum Essential Medium containing 10% FBS, 100

U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 30 ng/ml M-CSF. Bone

marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were isolated from

the femurs and tibias of 4-week-old mice, as previously described

(19). BMSCs were cultured in

the same medium as BMMs, excluding M-CSF supplementation. All cells

were incubated under standard conditions in a humidified atmosphere

at 37°C with 5% CO2 to ensure optimal proliferation and

viability.

Cell viability assay

To evaluate the cytotoxic effects of cynarin,

RAW264.7 cells and BMMs were seeded in triplicate into 96-well

plates at a density of 8,000 cells per well. Cells were treated

with varying concentrations of cynarin (1, 10, 50, 100, 200 and 400

μM) and incubated for 24, 48 and 96 h to assess short-,

intermediate-, and long-term exposure effects. At each time point,

10 μl of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) solution was added to each well, and the plates were

incubated for an additional 2 h. Cell viability was subsequently

quantified by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate

reader.

OC formation and TRAP staining

analysis

BMMs were seeded in triplicate in 96-well plates to

ensure statistical robustness. After 24 h, osteoclastogenesis was

induced by adding RANKL (50 ng/ml) in the presence of cynarin at 0,

10, 50, 100, or 200 μM. Culture medium was replenished every

other day to maintain nutrient levels and compound stability. To

preserve cellular morphology during the differentiation period,

cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room

temperature. Following fixation, TRAP staining was performed

according to the manufacturer's protocol. TRAP-positive OCs were

identified, counted, and images were captured using an Olympus BX53

microscope equipped for brightfield microscopy at appropriate

magnification. Quantification of OC number and size was carried out

with ImageJ software, ensuring objective assessment of

differentiation across treatment groups.

Bone resorption assay

BMMs were cultured under the same conditions as

aforementioned. To initiate OC-mediated bone resorption, cells were

treated with RANKL (50 ng/ml) and cynarin (10, 50, 100, or 200

μM) until mature OC-like cells formed on bone slices. After

removing the cells, the bone slices were fixed in a 4%

paraformaldehyde + 2.5% glutaraldehyde mixed fixative for 24 h at

4°C. The samples after decalcification were dehydrated through a

graded ethanol series, subjected to critical point drying, and

sputter-coated with a 15 nm layer of gold/palladium. Images of

resorption pits were captured by scanning electron microscopy (SEM;

FEI Quanta 250).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) analysis

For RT-qPCR, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol

reagent, and its purity and concentration were assessed by

measuring the A260/A280 ratios on a NanoDrop

2000/2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.); only

samples with a ratio between 1.9-2.1 were used. A total of 1

μg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the

PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit according to the manufacturer's

instructions. qPCR was performed on a Light Cycler® 480

Instrument II (Roche) with TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II

FAST Kit using the following protocol: Initial denaturation at 95°C

for 30 sec; 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Gene

expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(20). Primer sequences are

listed in Table SI.

Western blotting (WB)

The treated cells were lysed on ice in RIPA buffer

(cat. no. P0013C; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), and the

lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min

at 4°C. A BCA kit was used to quantify protein concentrations.

Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated on 4-10%

SDS-polyacrylamide gels (cat. no. M00657; GenScript) and

transferred to PVDF membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk at 37°C for 1 h, then

incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (all at a

dilution of 1:1,000). After washing, secondary antibodies

(HRP-linked; 1:1,000) were administered and incubated at 37°C for 1

h to enable the detection of primary antibody-protein complexes.

Following the removal of unbound secondary antibodies, bands were

visualised using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and images were captured on an Odyssey 9120

system (LI-COR Biosciences). The grey value of each band was

analysed by ImageJ 24.0 software (National Institutes of

Health).

Immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of

podosome actin belt

OC differentiation was induced as aforementioned.

Upon the appearance of multinucleated OCs in RANKL-stimulated

control wells, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min

at room temperature to preserve cellular morphology. For

intracellular antibody staining, cells were permeabilised with 0.5%

Triton X-100 (MilliporeSigma) for 5 min, followed by washing to

remove any residual detergent. F-actin structures were stained with

FITC-conjugated phalloidin (MedChemExpress) for 30 min at room

temperature, while nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (cat. no.

C1006; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). All staining

procedures were conducted in the dark to prevent photobleaching.

After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), images of actin

ring borders were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted

fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation). The distribution of

podosome actin belts was quantified using ImageJ software.

Assessment of the generation of ROS

Intracellular ROS levels were assessed using the ROS

detection kit (cat. no. S0033; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Following thorough washing with PBS, cells were

incubated with 2 μM/l 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein

diacetate (DCFH-DA) for 20 min. The non-fluorescent DCFH-DA was

internalised by cells and hydrolysed by intracellular esterases to

form DCFH, which was subsequently oxidised by ROS to produce the

highly fluorescent compound DCF. Fluorescence intensity was

measured using a microplate reader, with excitation at 488 nm and

emission detection at 525 nm.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and

cytoplasmic extracts

RAW264.7 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and

then centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was

resuspended in cytoplasmic protein extraction reagent A (containing

PMSF) and vortexed vigorously for 5 sec. After incubating on ice

for 15 min, Reagent B was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 1

min before ultracentrifugation at 4°C. The cytoplasmic fraction was

extracted from the resulting supernatant. For nuclear protein

extraction, nuclear protein extraction reagent (containing PMSF)

was added to the pellet. The sample was vortexed at high speed for

30 min, followed by ultracentrifugation. The nuclear fraction was

collected from the supernatant. Protein concentrations were

quantified as aforementioned.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) followed by

bioinformatics evaluation

RAW264.7 cells were cultured under OC

differentiation conditions for 5 days, with or without cynarin.

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and stored at -80°C.

RNA quality and integrity were verified using a NanoDrop

spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to ensure

A260/A280 ratios between 1.9-2.1, and an

Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit (Agilent

Technologie, Inc.s) to confirm RNA Integrity Number values >9.0.

RNA sequencing was performed by Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co.,

Ltd. (http://www.biomarker.com.cn/)

following their standard Illumina sequencing protocols.

Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2

(version 1.20.0). Raw counts were normalised using the

median-of-ratios approach implemented in DESeq2, and differential

expression was defined as |Log2FC|≥0.58 (FC ≥1.5) with

unadjusted P<0.05. Volcano plots were generated to visualise

distribution of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), highlighting

the magnitude and statistical significance of expression changes.

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) pathway analyses were conducted using the BioMarker BioCloud

Platform (www.biocloud.org) (21).

LPS-induced skull osteolysis in vivo

mouse model

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with

the laboratory animal management guidelines. They were approved by

the Animal Ethics Committee of the Ninth People's Hospital,

affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine

(approval no. SH9H-2020-A1-1; Shanghai, China). Mice were housed

with a standard temperature (20-26°C) and humidity (50-60%), under

a 12-h light/dark cycle and fed standard rodent diet and water

ad libitum. Mice were monitored daily for weight loss and

general health and euthanized when humane endpoints (signs of

severe distress, unresponsiveness to treatment, and/or significant

weight loss) were reached. A calvarial osteolysis model was

established based on previously reported methodologies (22,23). A total of 48 male C57/BL6 mice

(6-8 weeks, 18-22 g) were randomly assigned to six groups: i) Sham

group (subcutaneous injection of 50 μl PBS); ii) LPS group

(subcutaneous injection of 10 mg/kg LPS in 50 μl); iii)

alendronate group (subcutaneous injection of 10 mg/kg LPS in 50

μl; intraperitoneal injection of 10 μg/kg alendronate

in 100 μl) (24,25); iv) cynarin low-dose group

(subcutaneous injection of 10 mg/kg LPS and 100 μM cynarin

in 50 μl); v) cynarin medium-dose group (subcutaneous

injection of 10 mg/kg LPS and 250 μM cynarin in 50

μl); and vi) cynarin high-dose group (subcutaneous injection

of 10 mg/kg LPS and 500 μM cynarin in 50 μl). During

the modelling process, anaesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal

injection of a 3% sodium pentobarbital solution at a dose of 50

mg/kg. Collagen sponges (4×4×2 mm), soaked in either PBS or LPS,

were implanted at the sagittal midline suture of the calvaria to

induce bone loss. All mice received subcutaneous or intraperitoneal

injections every other day for 10 days. No mice reached humane

endpoints. The mice were euthanised by filling with carbon dioxide

at the rate of 30% CO2 tank volume/min. Tissues were

collected after death confirmation: Absent pulse and breathing,

lost corneal reflexes, no response to deep toe stimulation and

mucosal greying. Blood was collected from anesthetised mice's

eyeballs and transferred into heparinised anticoagulant tubes.

After centrifugation, the plasma was separated and used to measure

biochemical indicators, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT),

aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), for

assessing liver and kidney function. The major organs (heart,

liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys) were dissected and fixed for

haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The calvarial bones were

isolated and preserved for further analysis.

Micro-computed tomography (CT)

scanning

Micro-CT scans were performed using a SkyScan 1076

system (Bruker Corporation) with a resolution of 9 μm. The

scan parameters were set to 29 kV, 175 μA, and a 300 msec

exposure time. Structural features of the bone were quantified

using SCANCO software (version 6.5-3; Scanco Medical AG).

Histological staining and analysis

After decalcifying in EDTA solution for 2 weeks, the

skull was paraffin-embedded, and 4-μm sections were

prepared. Serial sections were deparaffinized in xylene and

rehydrated through a graded ethanol series. H&E and TRAP

staining were performed to evaluate tissue morphology and OC

activity. For immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, endogenous

peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 3%

H2O2 in methanol for 15 min at room

temperature. Non-specific binding was blocked with 5% normal goat

serum (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) in PBS

for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with

primary antibodies (RANK, CTSK, OCN, RUNX2, TNFα, iNOS, p-P38,

p-ERK1/2 and p-JNK1/2, all at a dilution of 1:100) overnight at

4°C. After washing, sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibodies (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1

h at room temperature. Signal was developed using a DAB substrate

kit (cat. no. DA1016; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) and sections were counterstained with haematoxylin. For

IF staining, a similar protocol was followed. After blocking,

sections were incubated with primary antibodies against Nrf2

(1:100) and Keap1 (1:100) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation

with Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated secondary antibodies

(1:500; Cell Signalling Technology, Inc.) for 1 h at room

temperature in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

Stained sections (H&E, TRAP, IHC) were examined using a Leica

DM4000B light microscope. IF-stained sections were examined using

the same microscope equipped for epifluorescence. Positive staining

was quantified using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Group data are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation (SD) to indicate average values and variability. All

statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software

(version 10.3.1; Dotmatics). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons post hoc test was used for

comparisons of multiple groups. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

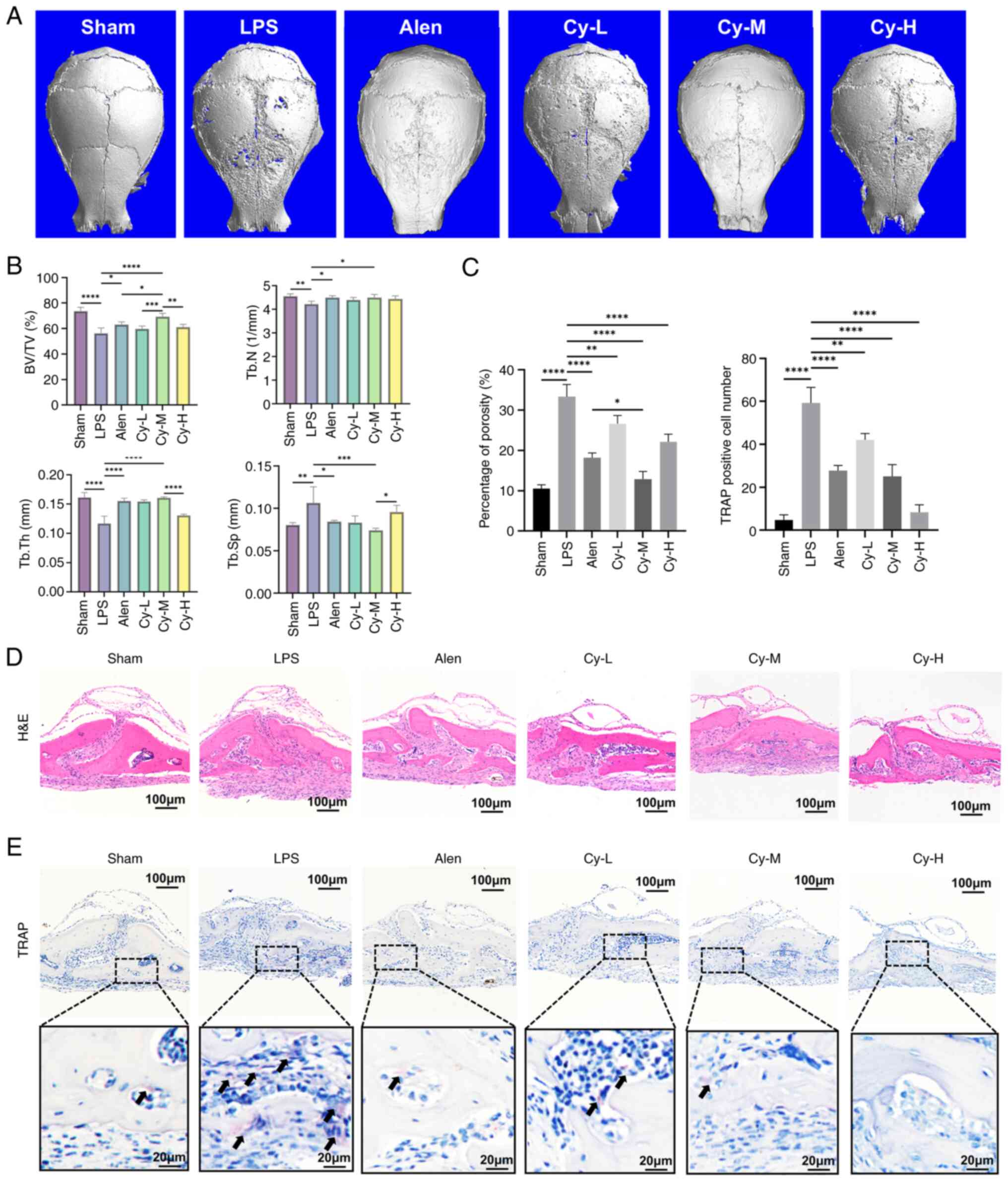

Cynarin attenuates LPS-induced calvarial

osteolysis in vivo

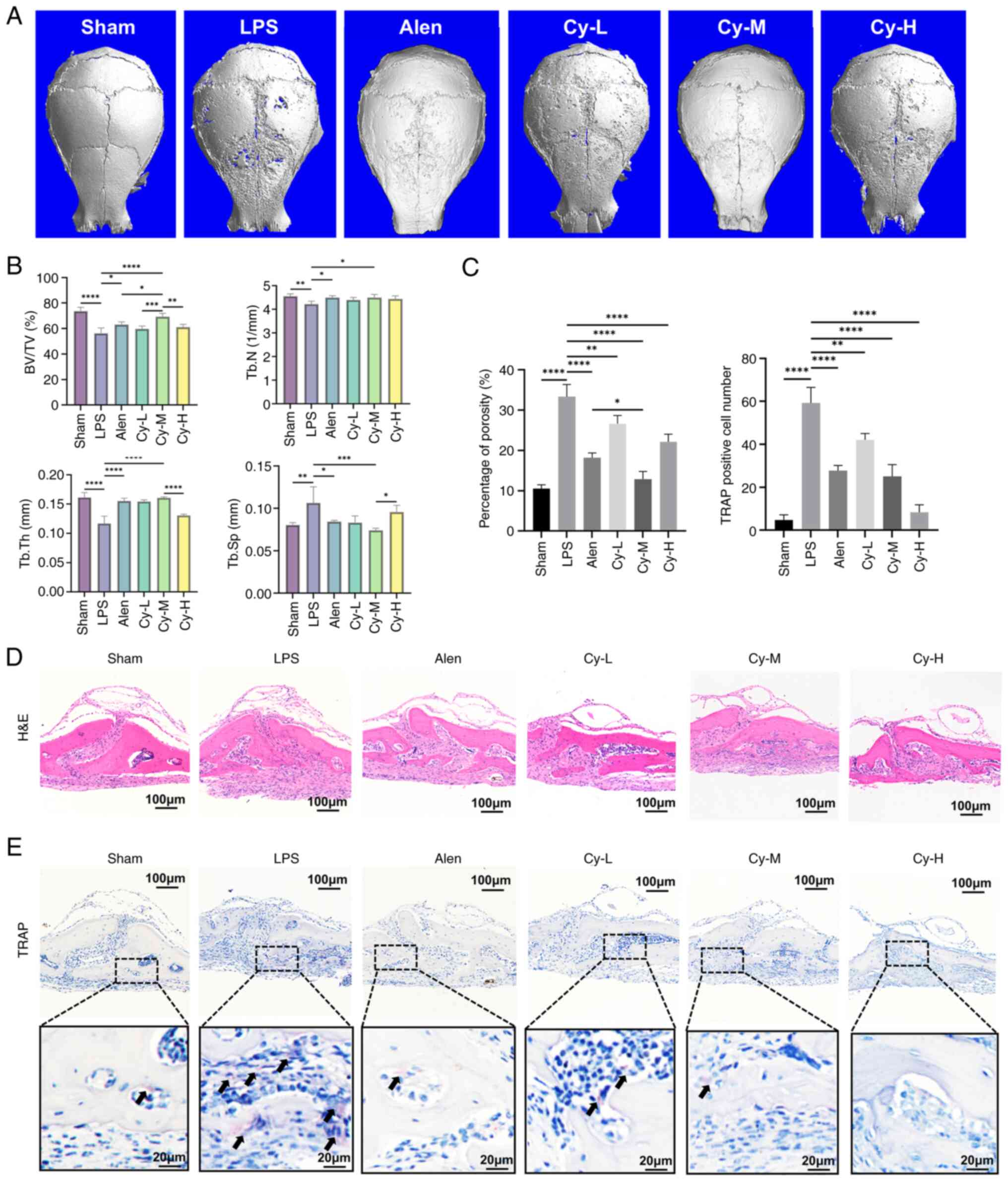

An LPS-induced osteolytic murine model was used to

assess the therapeutic effects of cynarin on inflammatory bone

loss. Throughout the experimental period, all the subjects

maintained stable conditions until a specified terminal time point.

Examination of histological sections from the vital organs of the

mice demonstrated no discernible damage, suggesting favourable

biocompatibility of the drug (Fig.

S1A). Serum biochemistry showed mild elevations in hepatic

indices (ALT, AST and total bilirubin) in the LPS group, which were

found to be significantly improved by alendronate and a medium-dose

of cynarin (P<0.05 vs. LPS for all). The renal indices (BUN,

creatinine and uric acid) remained unchanged among the groups

(Fig. S1B). Micro-CT

demonstrated that the medium-dose cynarin (Cy-M) group had

preserved bone microarchitecture, as evidenced by increased bone

volume, trabecular number, trabecular thickness and decreased

trabecular separation relative to LPS alone. These changes were

comparable to those observed with alendronate (Fig. 1A and B). H&E staining

confirmed reduced bone porosity in the Cy-M group (Fig. 1C and D), and TRAP staining

revealed a significant reduction in the number of TRAP-positive OCs

(Fig. 1C and E).

| Figure 1Cynarin shows therapeutic efficacy

comparable to alendronate in murine model of LPS-induced

osteolysis. (A) The micro-computed tomography reconstructions of

each group's murine calvaria. 6 weeks old C57/B6 mice were used to

establish model and were administrated by cynarin in indicated dose

for 10 days. (B) BV/TV, Tb.N, Tb.Th and Tb.Sp were evaluated by

quantitative analysis. (C) Quantitative analysis of porosity

percentage in H&E staining and TRAP positive cells number in

TRAP staining. (D) Representative images of calvarial histology

stained with H&E (magnification, ×100). (E) Representative

images of calvarial histology stained with TRAP (magnification,

×100). TRAP-positive cells are shown by black arrows. Animals were

randomly assigned to each group using a computer-generated

sequence. Histological scoring was conducted by an investigator who

was blinded to the treatment groups. All experiments were performed

with three independent biological replicates (n=3). The data are

presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 vs. Sham and LPS group separately. LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; BV/TV, bone volume to total volume ratio; Tb.N,

trabecular number; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp, trabecular

separation; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; Alen,

alendronate; Cy-M, medium-dose cynarin. |

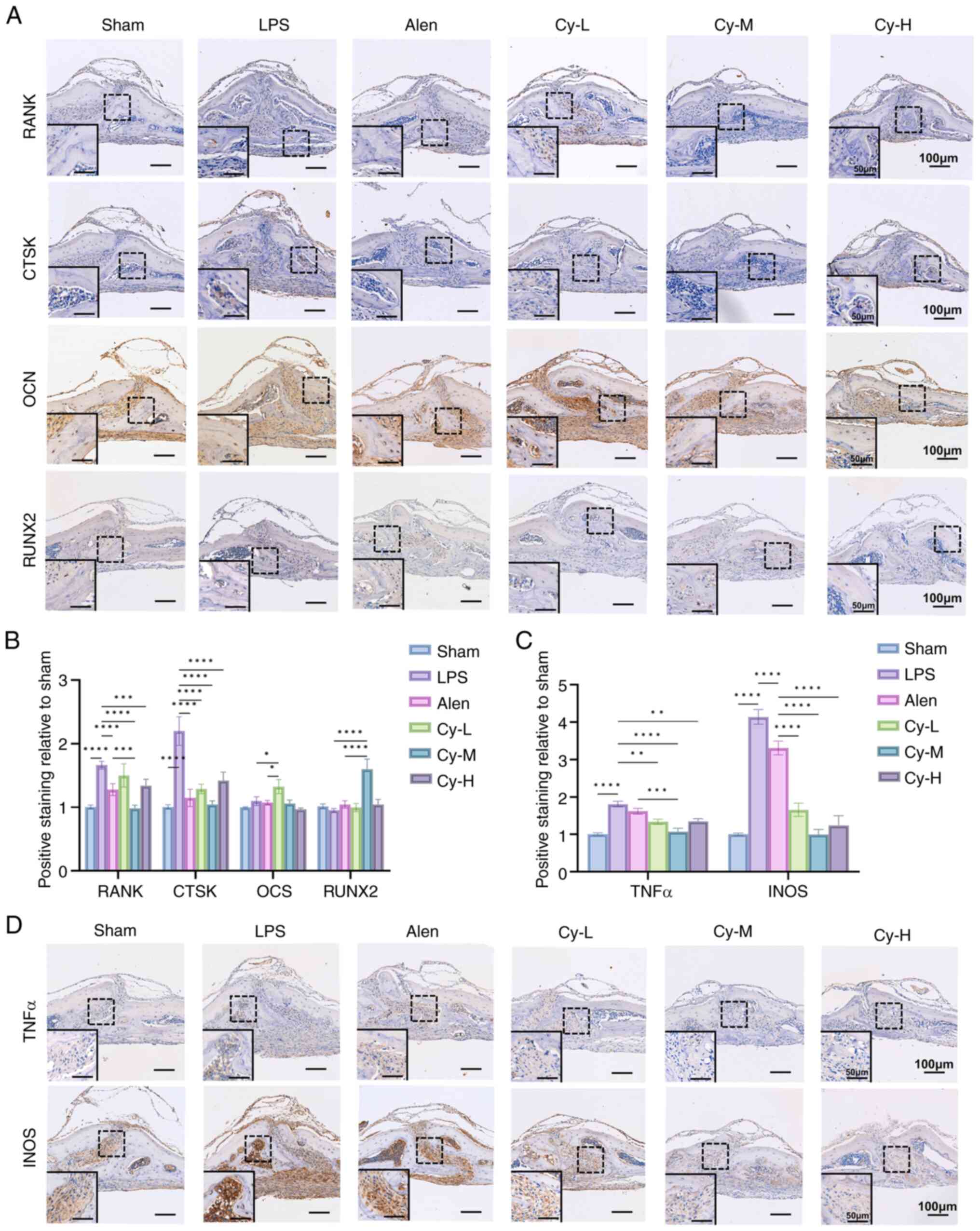

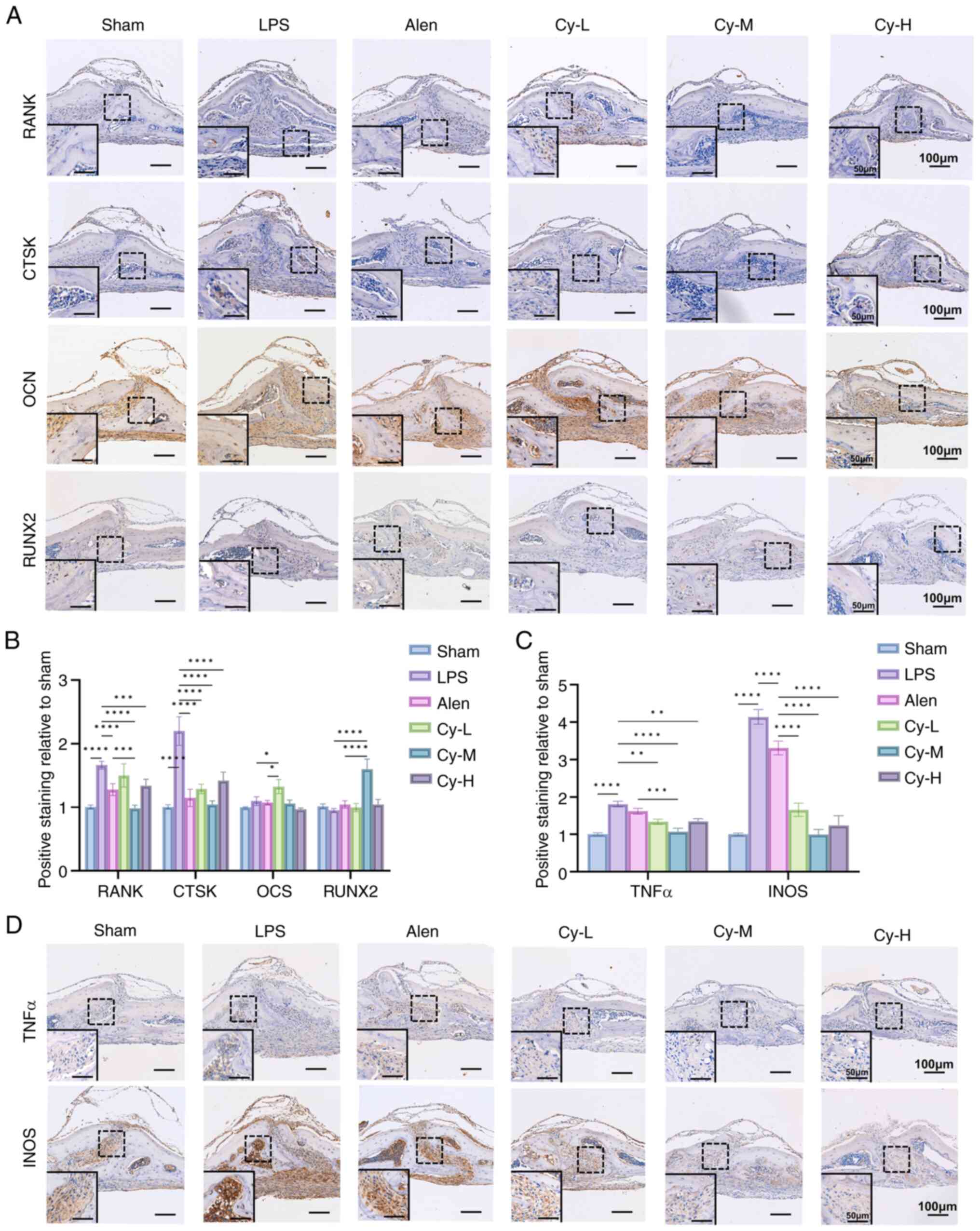

IHC further showed that cynarin reduced RANK and

CTSK expression while also increasing OCN and RUNX2 expression in

calvarial sections (Fig. 2A and

B), suggesting the inhibition of OC differentiation and the

support of osteoblast activity. Although cynarin modestly enhanced

osteoblast differentiation in vitro, the mechanism was not

investigated in the present study (Fig. S2). Moreover, cynarin

significantly decreased TNF-α and iNOS expression in calvarial

tissues (Fig. 2C and D),

indicating suppression of inflammatory signalling. Inflammatory

signals play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of osteolysis, and

inhibition of inflammation helps alleviate osteolysis. These

findings suggest that cynarin effectively preserves the bone

structure and mitigates bone resorption by inhibiting OC

differentiation and inflammation.

| Figure 2Cynarin exerts a more potent effect

in inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and reducing inflammation

in vivo. (A) Representative images of calvarial histology

stained with RANK, CTSK, OCN and RUNX2 (magnification, ×100). (B)

Quantitative analysis of the expression of RANK, CTSK, OCN and

RUNX2 in the IHC staining. (C) Quantitative analysis of the

expression of TNFα and iNOS in the IHC staining. (D) Representative

images of calvarial histology stained with TNFα and iNOS

(magnification, ×100). All experiments were performed with three

independent biological replicates (n=3). The data are presented as

the mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001 vs. Sham,

LPS and Alen group separately. RANK, receptor activator of nuclear

factor κB; CTSK, cathepsin K; OCN, osteocalcin; IHC,

immunohistochemical; iNOS; inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; Alen, alendronate; Cy-M, medium-dose

cynarin. |

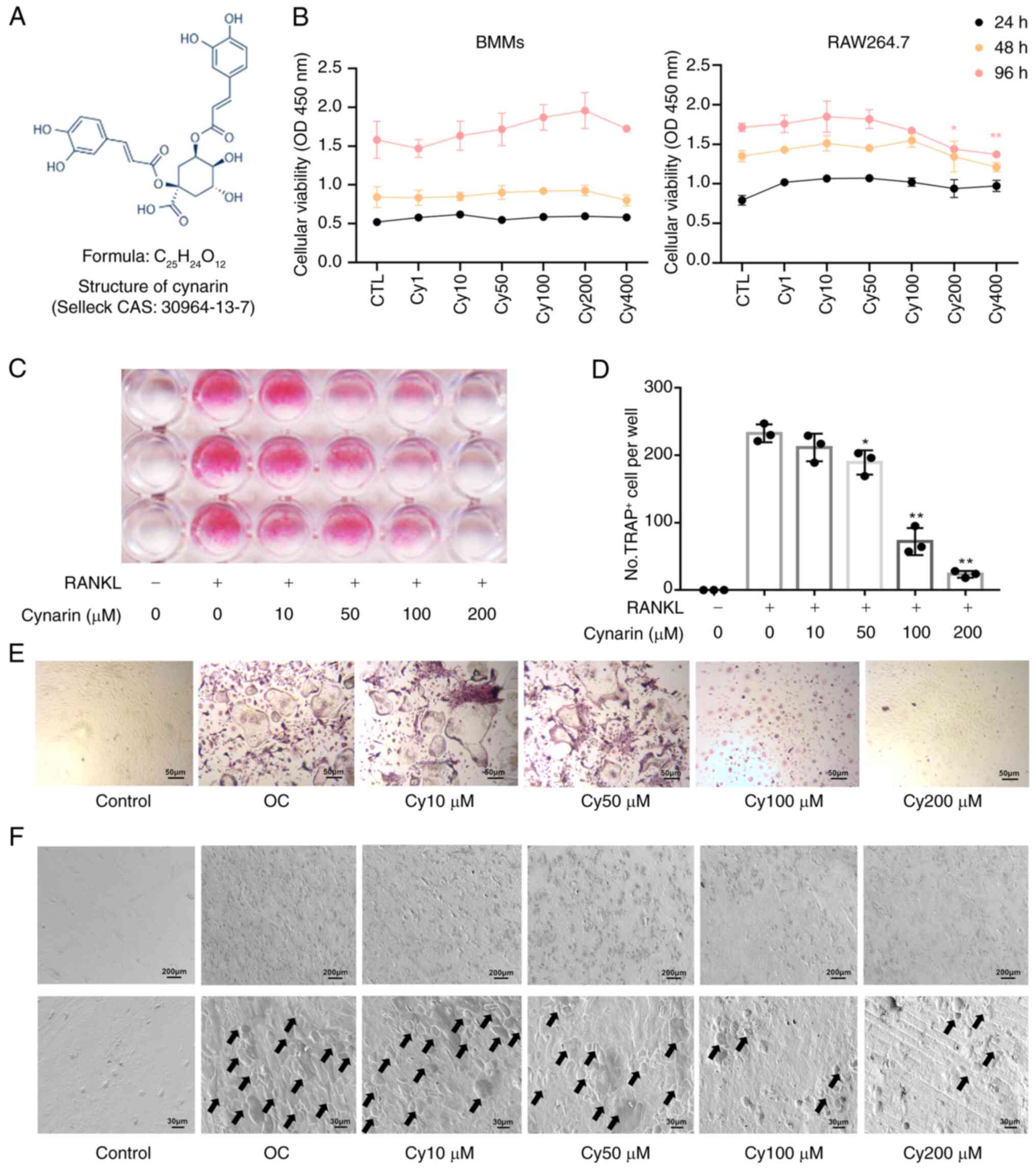

Cynarin inhibits OC differentiation and

bone resorption in vitro

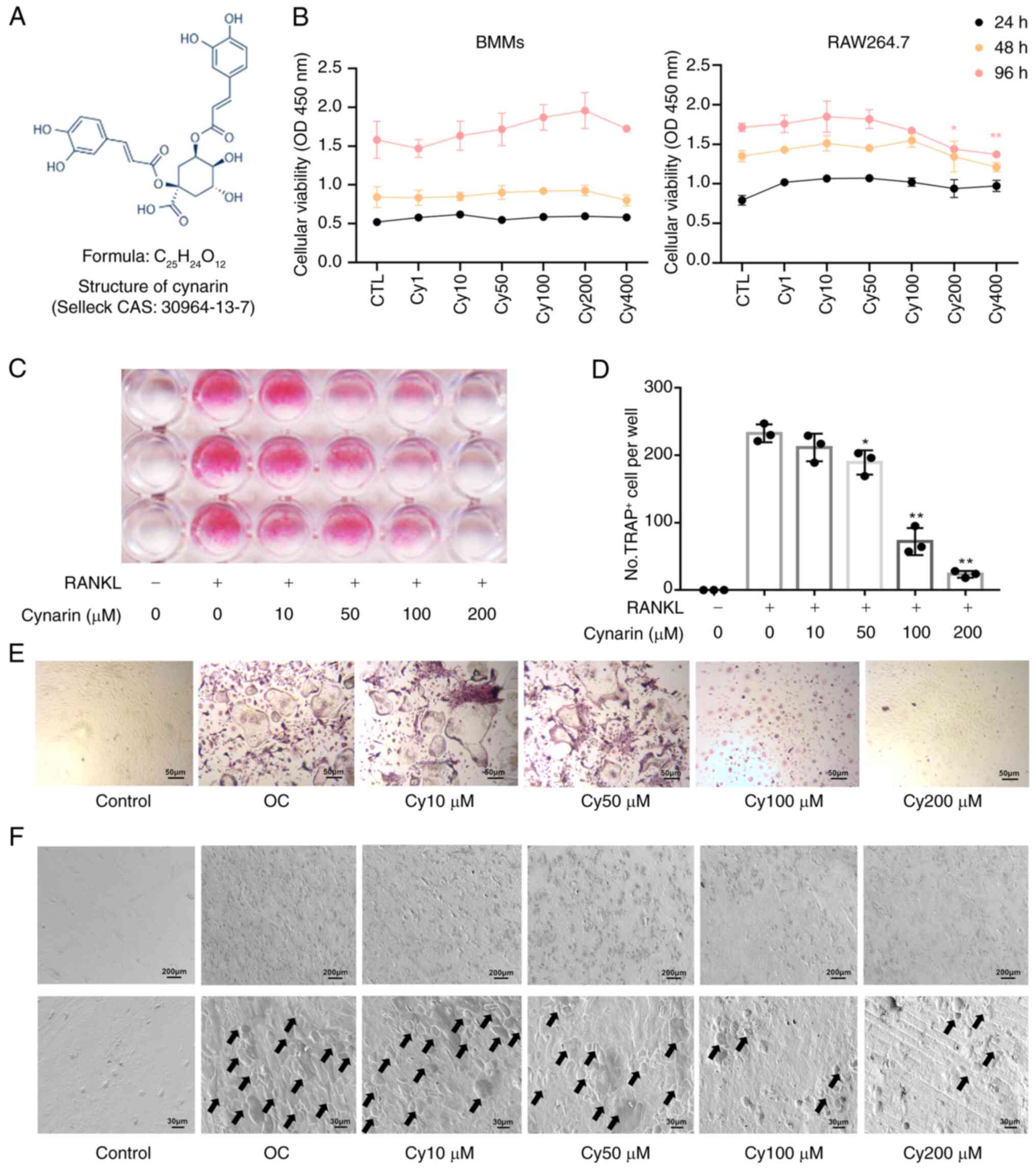

The chemical formula of cynarin is illustrated in

Fig. 3A. The performed cell

viability test revealed no cytotoxic effects of cynarin at

concentrations <200 μM (Fig. 3B). To explore the direct effects

of cynarin on OC differentiation, BMMs and RAW264.7 cells treated

with RANKL were used to induce osteoclastogenesis. TRAP staining

revealed a significant dose-dependent reduction in the number of

TRAP-positive OCs after cynarin treatment (Fig. 3C-E). The performed bone

resorption assay revealed that cynarin markedly reduced resorption

pits area at concentrations exceeding 50 μM after 9 days of

differentiation (Fig. 3F).

| Figure 3Cynarin restrains RANKL-induced OC

differentiation in vitro. (A) Chemical formula for cynarin.

(B) BMMs and RAW264.7 cells were treated with gradient

concentrations of cynarin for 24, 48 and 96 h, after which cells

proliferation and viability were detected by Cell Counting Kit-8

assay (n=3). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs.

CTL group. (C) BMMs were incubated with gradient concentrations of

cynarin for 5-7 days. Cells were stained for TRAP staining. Scan of

a 96-well plate after TRAP staining (n=3). (D) The count of

TRAP+ OCs per well was determined (n=3).

*P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. RANKL (+) and

Cynarin (-) group. (E) Representative images of TRAP staining

(magnification, ×200; (n=3). (F) BMMs were incubated with gradient

concentrations of cynarin for 9 days. The bone slides were

visualised under the scanning electron microscope (magnification,

×50, first row; ×300, second row). Black arrows indicate

osteoclastic absorption pits (n=3). The data are presented as the

mean ± SD. RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand;

OC, osteoclast; BMMs, bone marrow-derived macrophages; TRAP,

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase. |

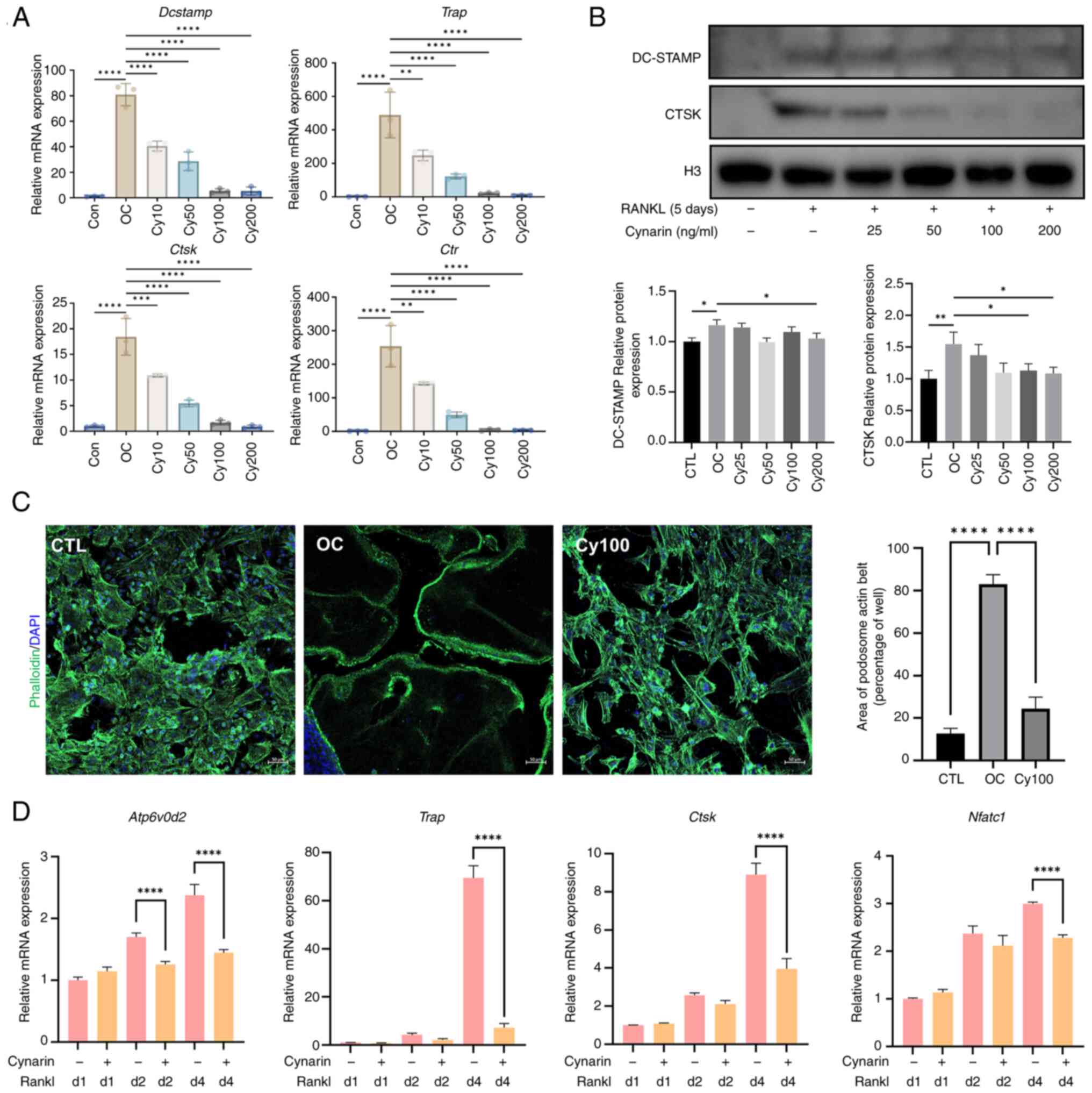

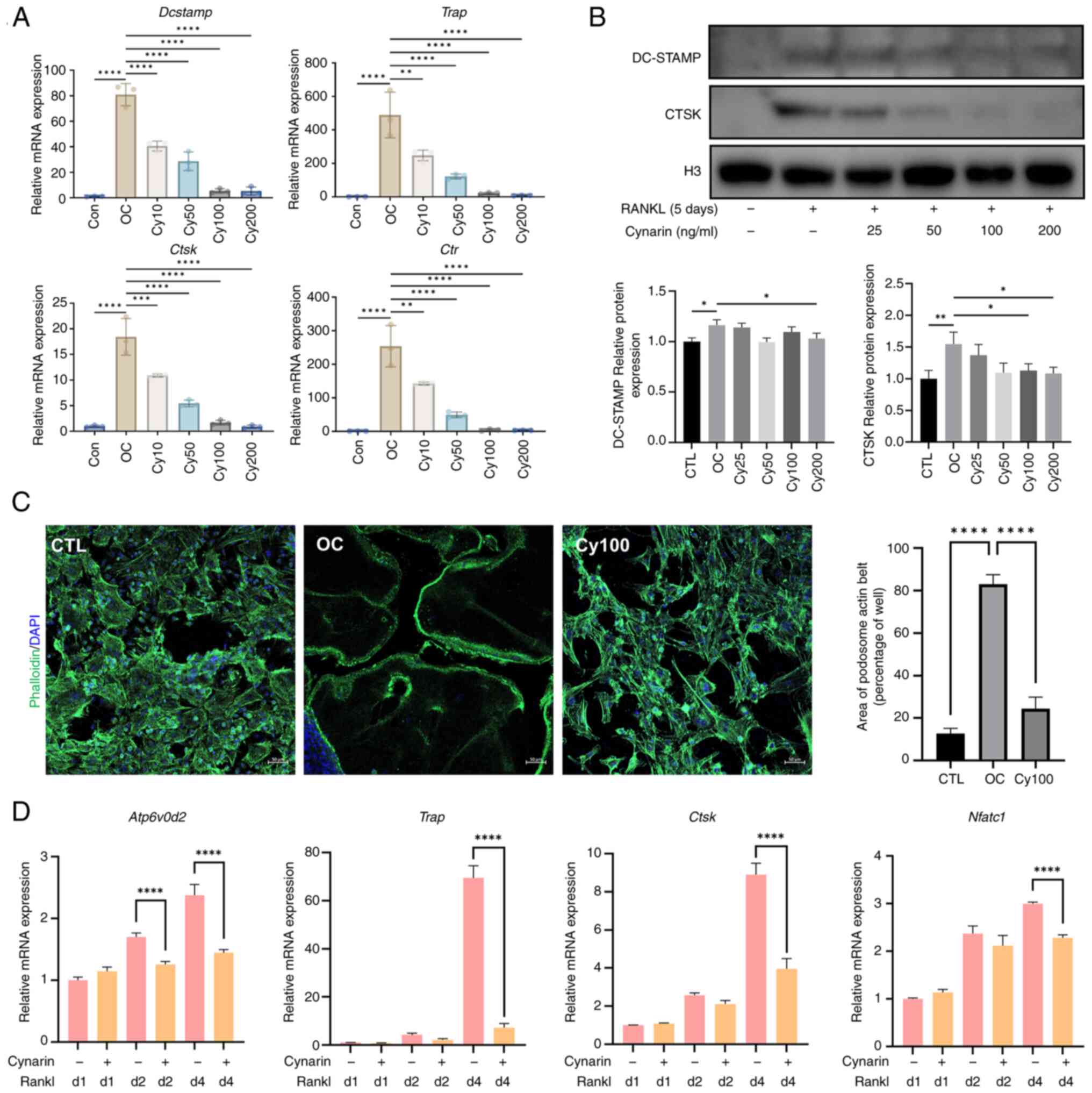

Further molecular analysis using RT-qPCR showed that

cynarin lowered the expression of Nfatc1, Dcstamp,

Trap, Atp6v0d2, Ctsk and Ctr (Fig. 4A and D). Notably, the suppressive

effect of cynarin on OC-related gene expression was most prominent

on day four (Fig. 4D). WB

revealed that cynarin reduced DC-STAMP and CTSK protein levels

during RANKL-induced differentiation (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, Actin staining

revealed that cynarin blocked the fusion of BMM precursor cells and

development of podosomal actin structures (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these results

suggested that cynarin inhibited OC differentiation and bone

resorption.

| Figure 4Cynarin downregulates

osteoclast-specific genes and proteins during osteoclastogenesis.

(A) RAW264.7 cells were treated with RANKL and gradient

concentrations of cynarin for 5 days. Dcstamp, Trap,

Ctsk and Ctr expression levels were normalised to

Gapdh expression by RT-qPCR (n=3). (B) RAW264.7 cells were

treated with RANKL and gradient concentrations of cynarin for 5

days. Expression levels of DC-STAMP and CTSK were detected by

western blotting. Quantitative densitometric analysis was performed

to normalize DC-STAMP and CTSK (n=3). (C) After 5 days of

macrophage colony-stimulating factor and RANKL induction, bone

marrow-derived macrophages were stained for immunofluorescence

analysis of podosome actin belt (magnification, ×200; (n=3). (D)

RAW264.7 cells were incubated with or without 100 μM cynarin

for 1, 2 and 4 days. Atp6v0d2, Trap, Ctsk, and

Nfatc1 expression levels were normalised to GAPDH

expression by RT-qPCR (n=3). The data are presented as the mean ±

SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. RANKL,

receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; CTSK, cathepsin K; TRAP,

tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; OC, osteoclast. |

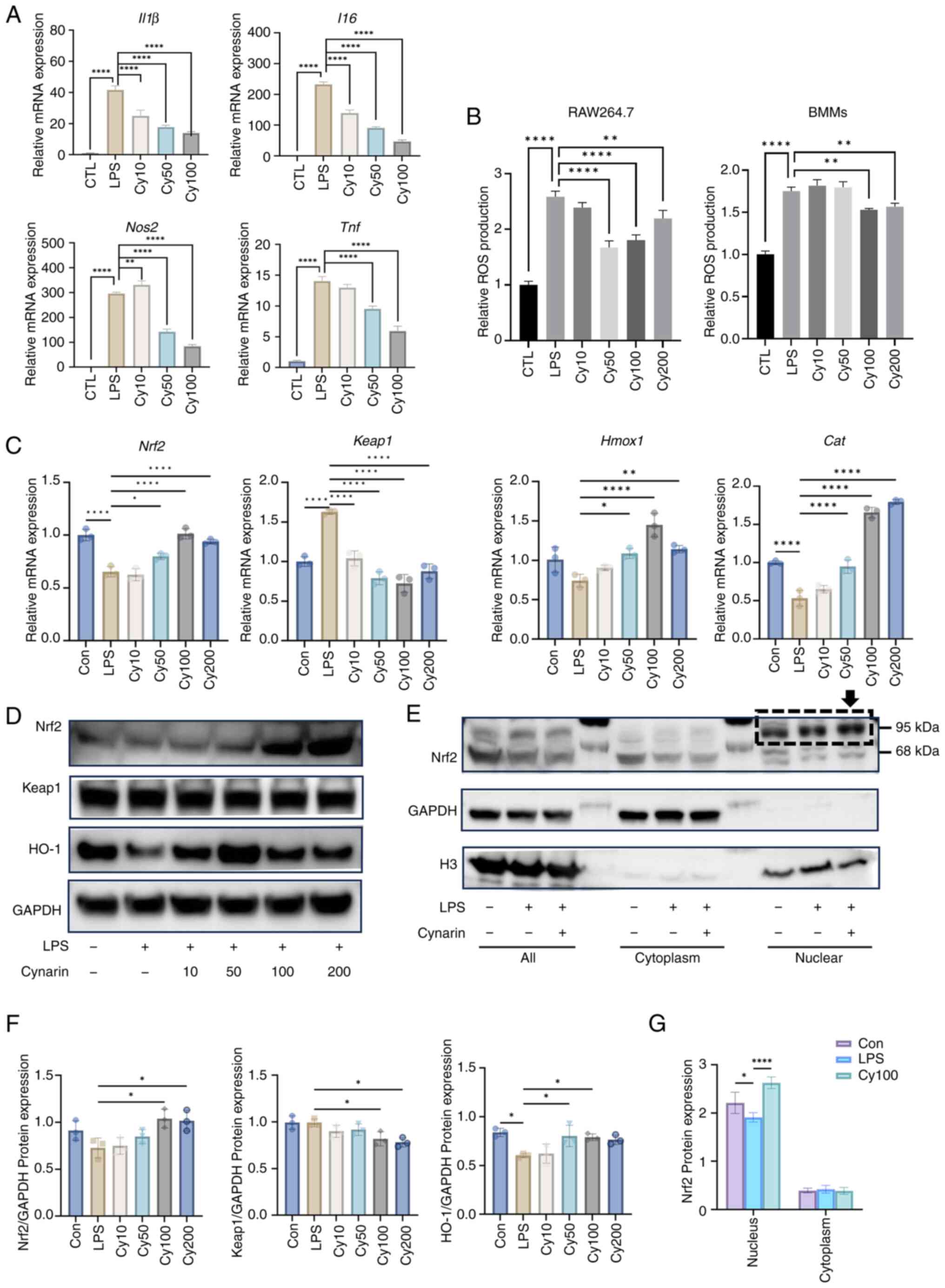

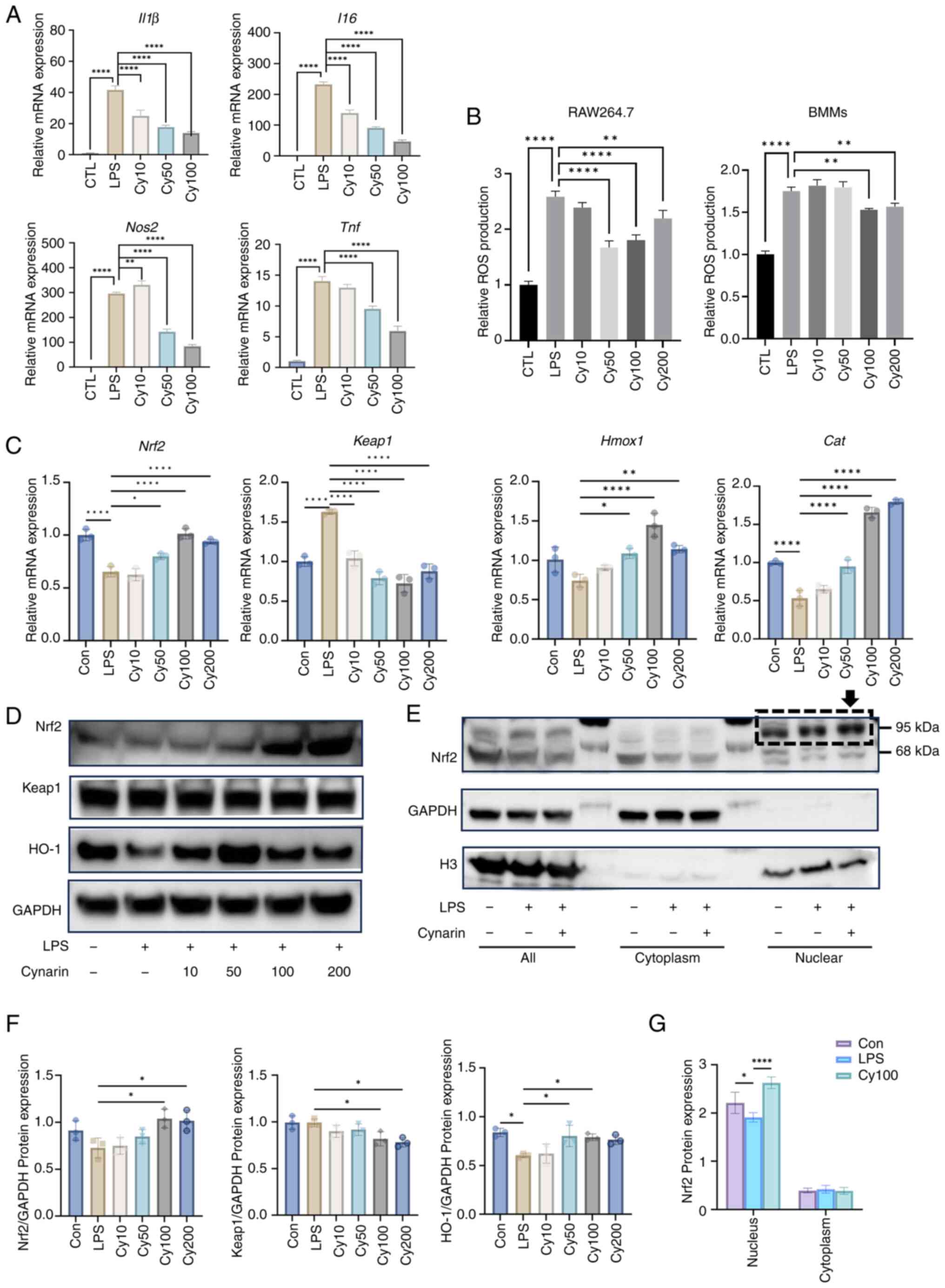

Cynarin activates Nrf2 to suppress

inflammation and oxidative stress in vitro

Since inflammation plays a critical role in

promoting osteoclastogenesis, the anti-inflammatory effects of

cynarin on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages were investigated.

Cynarin treatment significantly reduced the expression of

proinflammatory cytokines, including Tnf, IL1β,

IL6 and Nos2 at the mRNA level (Fig. 5A). Additionally, ROS levels were

significantly reduced in the cynarin-treated macrophages (Fig. 5B), indicating that cynarin

attenuated oxidative stress, which is a key contributor to

inflammation.

| Figure 5Cynarin suppresses

macrophage-mediated inflammation through activation of the

Nrf2-Keap1 signalling pathway. (A) RAW264.7 cells were exposed to

cynarin (10, 50 or 100 μM) for 24 h and then treated with

LPS (1 μg/ml) for 12 h. Expression levels of IL1β,

IL6, Nos2 and Tnf were detected by RT-qPCR

(n=3). (B) RAW264.7 cells and bone marrow-derived macrophages were

exposed to cynarin (10, 50, 100 or 200 μM) for 24 h and then

treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 12 h. Intracellular ROS

levels were measured with a ROS assay kit (n=3). (C) RAW264.7 cells

were exposed to cynarin (10, 50, 100 or 200 μM) for 6 h and

then treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 12 h. Expression levels

of Nrf2, Keap1, Hmox1 and Cat were

detected by RT-qPCR (n=3). (D) RAW264.7 cells were exposed to

cynarin (10, 50, 100 or 200 μM) for 24 h and then treated

with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. Expression levels of Nrf2,

Keap1 and HO-1 were detected by WB. (E) RAW264.7 cells were exposed

to 100 μM cynarin for 24 h and then treated with LPS (1

μg/ml) for 24 h. Nuclear extracts and cytoplasmic extracts

were used to test expression of Nrf2 by WB. (F) Quantitative

densitometric analysis was performed to normalize Nrf2, Keap1 and

HO-1 expression levels from D (n=3). (G) Quantitative densitometric

analysis was performed to normalize Nrf2 expression levels from E

(n=3). The data are presented as the mean ± SD.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

****P<0.0001 vs. CTL and LPS group separately. LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR; ROS, reactive oxygen species; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; WB,

western blotting. |

Mechanistically, cynarin treatment led to the

upregulation of Nrf2 expression and the downregulation of Keap1,

thus resulting in the induction of antioxidant enzymes, such as

HO-1 and catalase (Fig. 5C, D and

F). Moreover, nuclear fractionation assays confirmed that

cynarin promoted Nrf2 nuclear translocation, validating its role in

reducing oxidative stress and inflammation via Nrf2 activation

(Fig. 5E and G). These results

support the hypothesis that cynarin exerts its anti-inflammatory

effects by activating the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway activation.

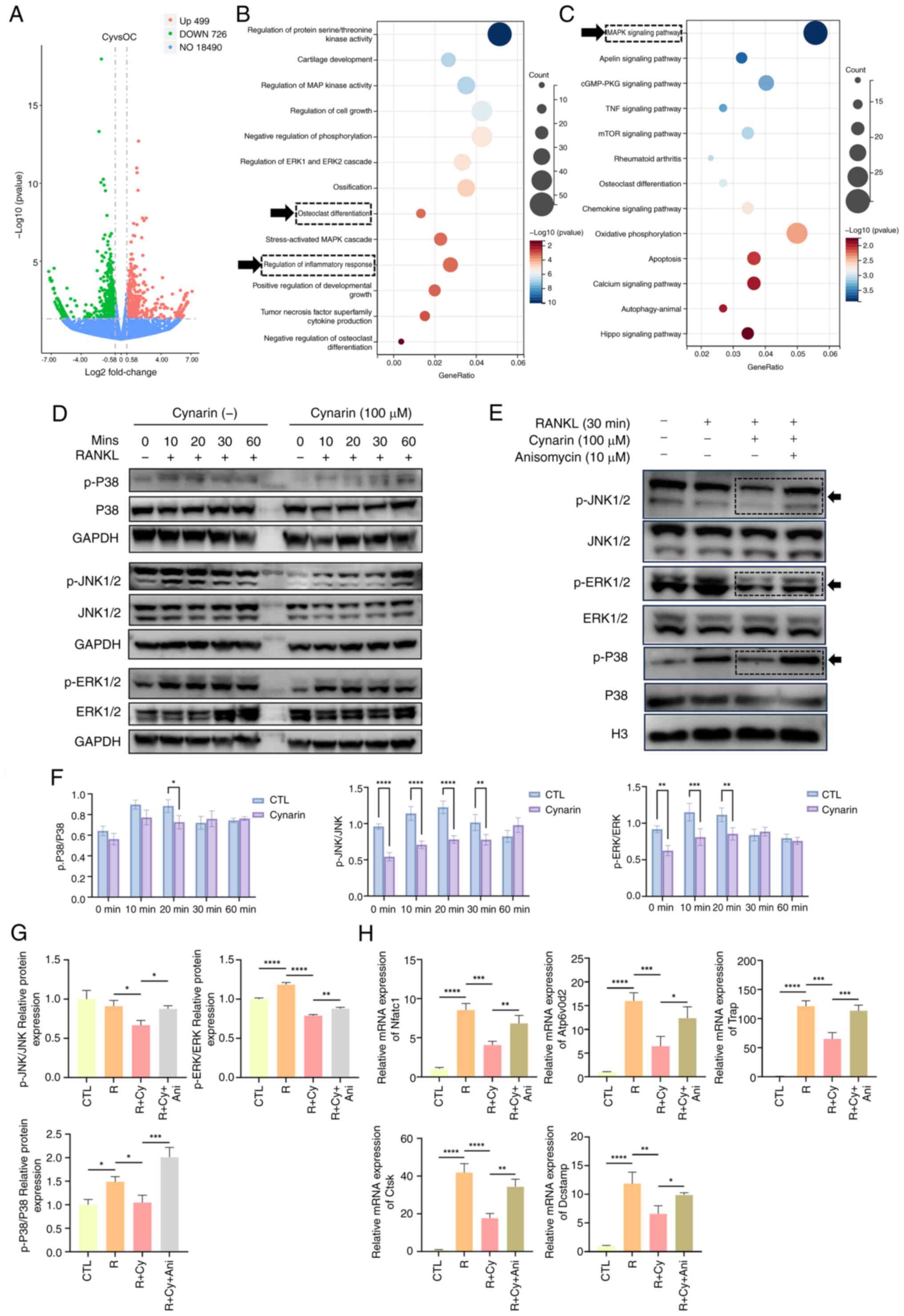

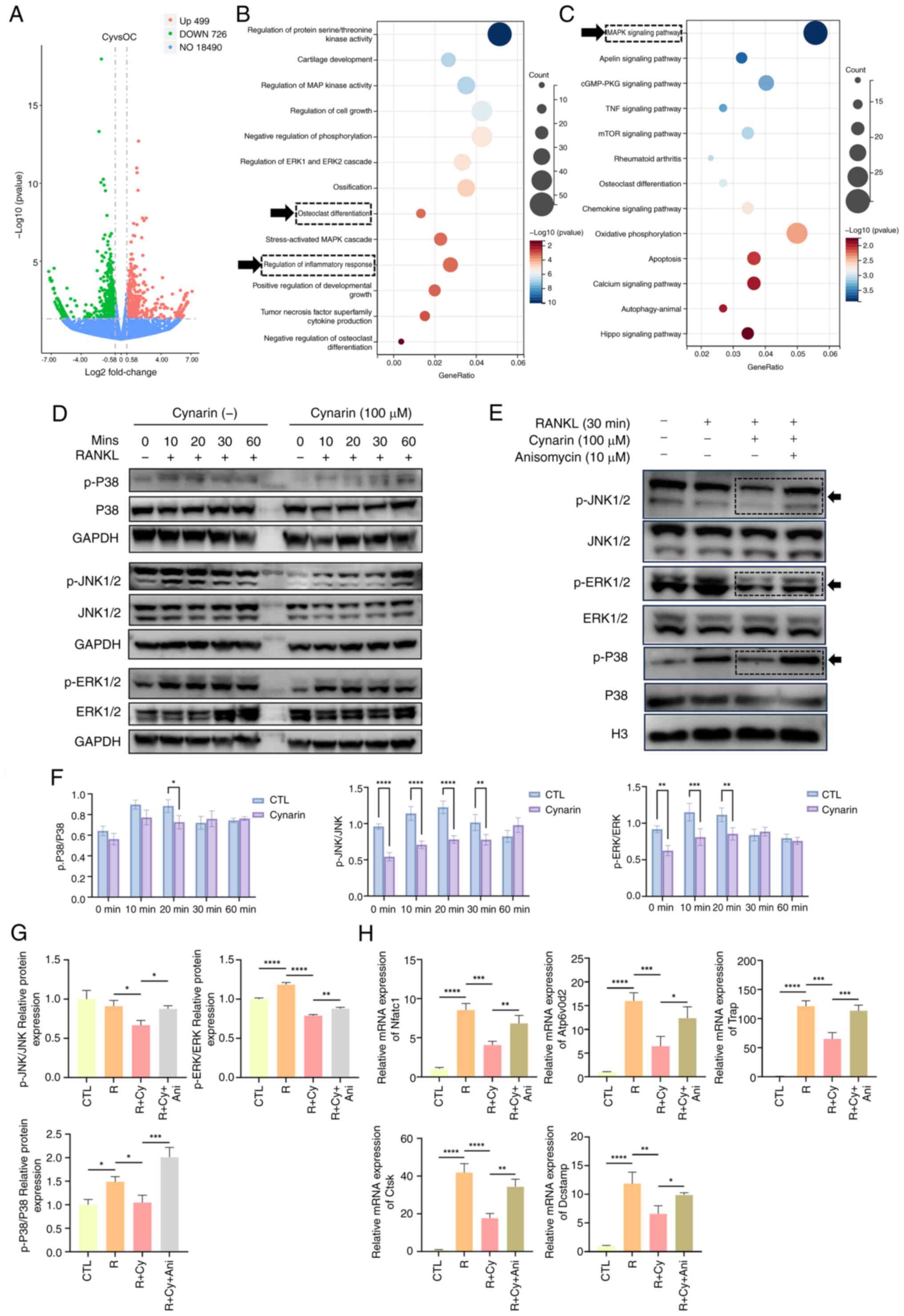

Cynarin suppresses MAPK signalling and

engages the Nrf2-Keap1 axis

To further elucidate the mechanism of cynarin

suppressing OC differentiation, cynarin was used for RNA-seq in

RANKL-induced RAW264.7 cells. A volcano plot illustrates that

cynarin treatment upregulated 499 genes and downregulated 726 genes

(Fig. 6A). To assess the

possible impact of cynarin on biological processes, GO enrichment

analysis was conducted. As depicted in Fig. 6B, the regulation of OC

differentiation and inflammatory response were prominently

associated with the therapeutic mechanisms of cynarin. KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis demonstrated profound modulation of the MAPK

signalling pathway following cynarin treatment (Fig. 6C).

| Figure 6Cynarin suppresses the MAPK

signalling pathway in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. (A) RANKL

induced RAW264.7 cells for 5 days with or without 100 μM

cynarin. Total RNA was extracted and sent for RNA sequencing. Genes

exhibiting |Log2FC|≥0.58 (FC ≥1.5) and unadjusted P≤0.05

were considered to be differentially expressed. Volcano plot of the

distinct upregulated and downregulated genes of Cy vs. OC (n=3).

(B) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of differential genes of Cy

vs. OC (n=3). (C) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway

analysis of differential genes of Cy vs. OC (n=3). (D) RAW264,7

cells were pretreated with 100 μM cynarin for 6 h and

stimulated with 50 ng/ml RANKL for 10 to 60 min. Expression levels

of total and phosphorylated forms of JNK, ERK, and P38 were

detected by WB. (E) RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μM

cynarin, 10 μM anisomycin for 30 min and stimulated with 50

ng/ml RANKL for 30 min. The ratio of phosphorylated JNK to JNK,

p-ERK to ERK and p-P38 to P38 were quantitatively determined by WB.

(F) Quantitative densitometric analysis was performed to normalize

p-JNK/JNK, p-ERK/ERK and p-P38/P38 expression levels from D (n=3).

(G) Quantitative densitometric analysis was performed to normalize

p-JNK/JNK, p-ERK/ERK and p-P38/P38 expression from E (n=3). (H)

RAW264,7 cells were treated with 100 μM cynarin, 10

μM anisomycin for 4 days in RANKL-induced

osteoclastogenesis. Expression levels of OC-specific genes were

detected by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (n=3). The data

are presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear

factor κB ligand; OC, osteoclast; p-, phosphorylated; WB, western

blotting; Ani, anisomycin. |

WB demonstrated that cynarin attenuated

RANKL-induced phosphorylation of JNK (10-30 min), ERK (10-20 min),

and p38 (20 min) (Fig. 6D and

F), indicating that cynarin suppressed osteoclastogenesis by

inhibiting MAPK signalling. To confirm this mechanism, anisomycin

(MAPK activator) was used. WB revealed that anisomycin counteracted

the inhibitory effects of cynarin on p-JNK, p-ERK and p-P38

(Fig. 6E and G). RT-qPCR

confirmed that anisomycin reversed the inhibitory effects of

cynarin on OC differentiation (Fig.

6H). These findings provide strong evidence that cynarin

inhibited osteoclastogenesis by suppressing MAPK signalling.

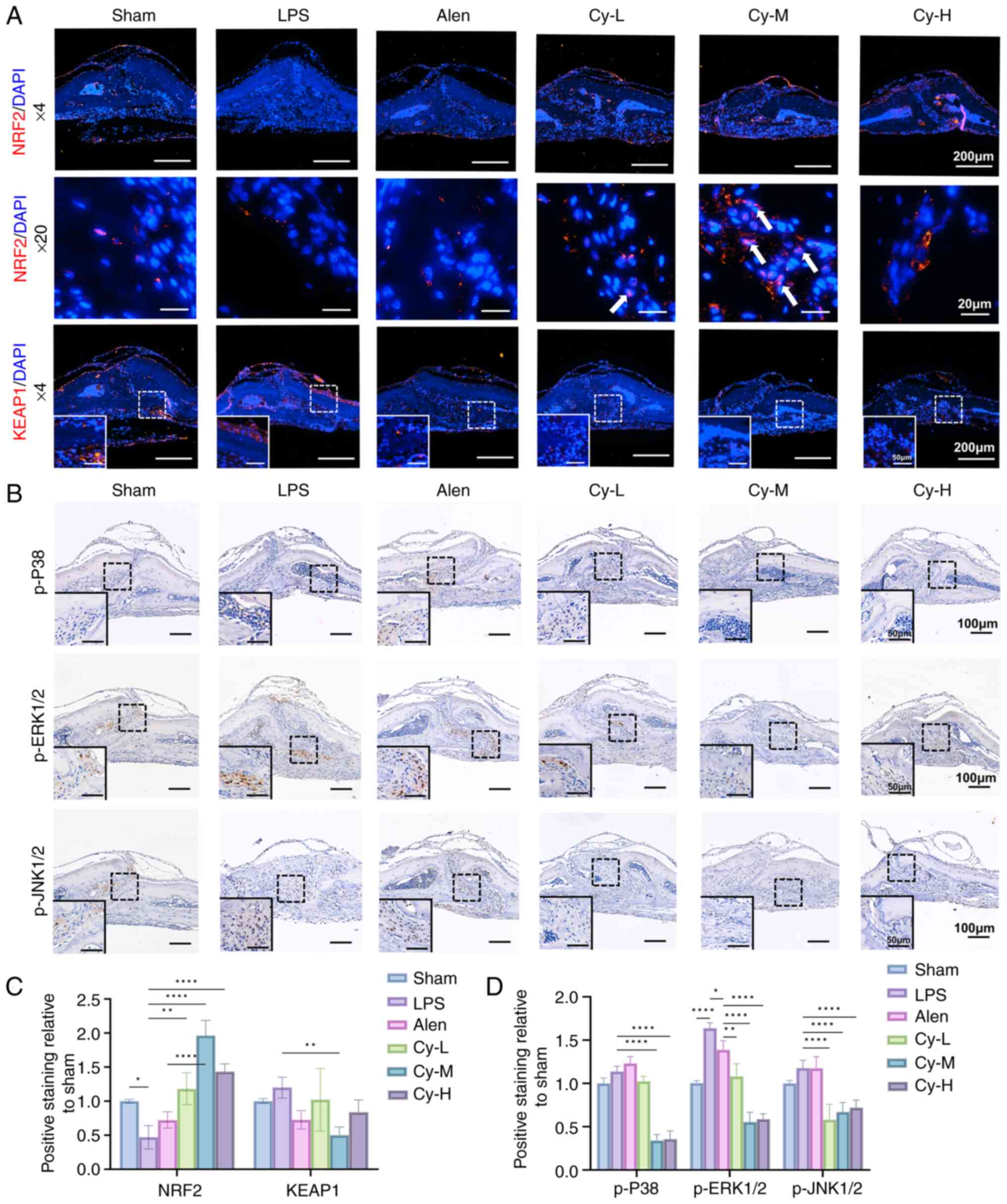

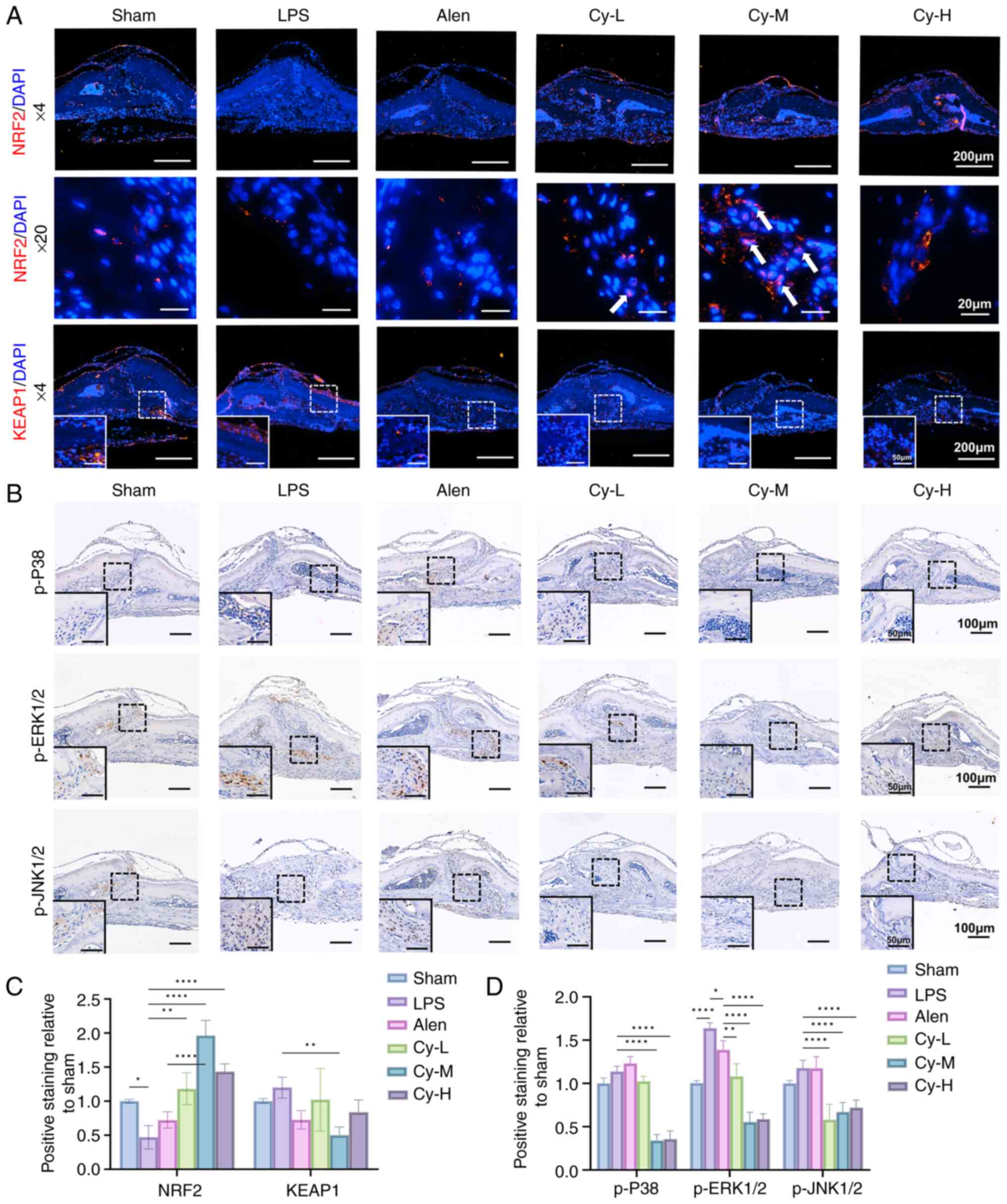

In vivo validation of the pathway regulation

showed that cynarin significantly increased Nrf2 expression,

decreased Keap1 expression, and promoted Nrf2 nuclear translocation

in calvarial tissues (Fig. 7A and

C). Furthermore, IHC staining showed that cynarin

administration significantly decreased p-P38, p-ERK1/2 and p-JNK1/2

levels compared with those in the LPS group (Fig. 7B and D). Collectively, cynarin

exerts dual regulatory effects in vivo by inhibiting OC

differentiation by suppressing the MAPK pathway and mitigating

inflammation and oxidative stress through activation of the

Nrf2-Keap1 axis. These combined actions therefore underscore the

potential of cynarin as a therapeutic candidate for the treatment

of inflammatory bone diseases.

| Figure 7Cynarin suppresses osteoclastogenesis

and inflammation via the MAPK and Nrf2-Keap1 pathways in

inflammatory bone resorption. (A) Representative images of

calvarial histology stained with Nrf2 and Keap1 (magnification,

×40, first row; ×200, second row; ×40, third row). (B)

Representative images of calvarial histology stained with p-ERK1/2,

p-JNK1/2 and p-P38 (magnification, ×100). (C) Quantitative analysis

of the expression of Nrf2 and Keap1 in the immunofluorescence

staining. (D) Quantitative analysis of the expression of p-ERK1/2,

p-JNK1/2 and p-P38 in the immunohistochemical staining. All

experiments were performed with three independent biological

replicates (n=3). The data are presented as the mean ± SD.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

****P<0.0001. p-, phosphorylated; Cy-M, medium-dose

cynarin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; Alen, alendronate. |

Discussion

The development of novel therapeutic strategies that

simultaneously suppress osteoclastogenesis and modulate

inflammation is critical for alleviating inflammatory bone

resorption and improving bone health. Naturally derived plant

compounds have garnered considerable attention because of their

favourable biological activities and safety profiles. Cynarin, a

bioactive compound extracted from artichoke (Cynara

scolymus), shows promise in this regard. The present study

aimed to evaluate the therapeutic potential of cynarin in the

prevention of bone resorption and inflammation-induced bone loss.

These findings demonstrate that cynarin significantly inhibits OC

differentiation and activity, suppresses inflammatory responses,

and modulates the key signalling pathways involved in

osteoclastogenesis and inflammation.

Our in vivo findings have shown that cynarin

effectively reduced LPS-induced osteolysis and preserved the bone

structure, with effects comparable to those of the widely used drug

alendronate sodium. Improvements in the liver and kidney function

indices following cynarin treatment provide a critical basis for

assessing its safety and therapeutic potential. However, further

clinical translation will require comprehensive pharmacokinetic

studies and the optimisation of the dosage forms to enhance

bioavailability and determine the appropriate dosage. Histological

evaluation showed decreased bone porosity and fewer TRAP-positive

OCs in the cynarin-treated mice. Additionally, cynarin

significantly reduced the expression of key OC differentiation

markers, suggesting that it inhibited OC differentiation and

activity. These findings align with those of previous studies that

emphasised the bone protective effects of various natural compounds

in inflammatory bone diseases. Well-known natural anti-inflammatory

agents such as resveratrol and curcumin show similar protective

effects by reducing OC activity (26). One limitation of the study is

that only male mice were used. Although this reduces confounding

variables such as the periodic fluctuations of female hormones

during the initial efficacy screening, it is necessary to be

cautious when applying our conclusions directly to female models or

patients. Future work will include both sexes to rigorously assess

the potential gender-specific effects of cynarin on cranial bone

repair. However, the present study offers a new perspective by

demonstrating that cynarin treatment significantly inhibits

inflammation and downregulates the levels of inflammatory factors

such as TNF-α and iNOS. Osteolysis is closely associated with

proinflammatory cytokine release and OC activation (27,28). In conclusion, cynarin may prevent

osteolysis and preserve the bone microstructure by regulating OC

production and inflammation, providing a dual mechanism of

action.

The inhibitory effect of cynarin on

osteoclastogenesis observed in our in vitro study was

consistent with the findings of our in vivo study. It was

next discovered that cynarin concentrations >50 μM

significantly suppressed OC formation as evidenced by TRAP staining

and SEM. To the best of our knowledge, this finding has not been

previously reported. The performed cell viability assays confirmed

that cynarin concentrations <200 μM exhibited no

significant cytotoxicity. It was demonstrated that varying

concentrations of cynarin suppressed Nfatc1, Dcstamp,

Trap, Ctsk and Atp6v0d2, and 100 μM was

identified as the optimal concentration. FITC-labelled phalloidin

staining indicated that 100 μM cynarin significantly

inhibited OC development. This effect was most evident after four

days of RANKL exposure.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that Nrf2 is a

key regulator of bone oxidative homeostasis. Transcriptome analysis

of Nrf2 or Keap1 knockout models revealed that Nrf2 deficiency

upregulates genes associated with mitochondrial oxidative

phosphorylation, including Car2, Calcr and

Mmp12, and increases OC production under oxidative stress

(29). Dong et al

(30) found that the Nrf2

activator bitopertin blocks Keap1-Nrf2 binding, reduces

intracellular iron levels, and inhibits OC formation. Nrf2

regulates the activation of genes that enhance antioxidant defence,

thereby reducing ROS accumulation (31). Under normal conditions, Nrf2 is

maintained at low levels because of its binding to Keap1. When

Keap1 is inhibited, Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus where it

activates genes involved in detoxification and antioxidant

responses. It was demonstrated that cynarin inhibits Keap1 during

inflammation, promotes Nrf2 nuclear translocation, and enhances the

expression of HO1 and Cat. In vivo experiments confirmed

that, compared with LPS and alendronate, medium-dose cynarin

treatment significantly increased Nrf2 expression, decreased Keap1

expression, and activated nuclear translocation. Inflammatory

conditions are commonly associated with elevated ROS, which are key

regulators of bone metabolism and function (32,33). In addition, it was demonstrated

that cynarin significantly reduces macrophages' inflammatory

response, inhibiting the production of IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS and TNF-α

while also reducing ROS production. The present results are

consistent with those of previous studies showing that Nrf2

activation is critical for controlling inflammation and preventing

cellular oxidative damage (34,35). The present study, to the best of

our knowledge, is the first to demonstrate that cynarin regulates

both oxidative stress and inflammation through the Nrf2-Keap1

signalling pathway. These results suggest that cynarin enhances the

antioxidant response by activating the Nrf2 pathway, thereby

inhibiting oxidative stress-driven OC differentiation. Compounds

such as curcumin, resveratrol and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)

have been demonstrated to inhibit OC differentiation and activity

(26,36). However, curcumin, resveratrol and

EGCG exerted their effects mainly through inhibition of NF-κB and

MAPK pathways, while the additional activation of Nrf2-Keap1 by

cynarin provided anti-inflammatory effects. These findings,

therefore, highlight the therapeutic potential of cynarin and

provide valuable insights into its use as a dual-target therapeutic

agent for inflammatory bone diseases.

The RNA-seq results indicated that cynarin inhibited

RANKL-induced OC differentiation via the MAPK pathway. MAPK are

well-known regulators of cell proliferation and differentiation

(37,38). The current findings indicated

that cynarin significantly inhibited P38, JNK and ERK

phosphorylation. This inhibition was reversed by treatment with

anisomycin (a MAPK agonist). Our in vivo experiments have

also confirmed that moderate-dose cynarin treatment significantly

reduced the expression of p-P38, p-ERK1/2 and p-JNK1/2 compared

with LPS treatment and alendronate sodium. In conclusion, cynarin

suppressed RANKL-induced OC differentiation by targeting the MAPK

pathway.

Increasing evidence suggests a crosstalk between

MAPK and Nrf2 signalling during osteoclastogenesis. Nrf2 activation

elevates the expression of detoxifying enzymes (for example, HO-1

and NQO1) that reduce intracellular ROS, thereby attenuating

ROS-dependent MAPK activation and downstream osteoclastogenic

transcription factors such as NFATc1. In osseous echinococcosis,

Echinococcus granulosus-driven inhibition of Nrf2 shifts the

balance toward unchecked MAPK activation and OC differentiation

(39). By contrast, carnosic

acid-induced Nrf2 restores antioxidant defences and suppresses MAPK

phosphorylation, forming a negative feedback loop that limits

RANKL-driven osteoclastogenesis (40). However, the interaction between

the Nrf2 pathway and MAPK signalling in the present study remains

to be elucidated. In future studies, the authors plan to use Nrf2

inhibitors such as ML385 and Nrf2-specific small interfering RNA to

transfect OC precursor cells. It was further elucidated whether

Nrf2 knockdown acts upstream of MAPK inhibition. The effects of

cynarin on osteoblast function were also investigated. The results

showed that cynarin promoted the expression of key osteogenic

markers, such as OCN and RUNX2, in both in vivo and in

vitro models. A potential role of cynarin in supporting bone

formation has also been demonstrated. However, further studies are

required to fully understand how cynarin affects osteoblast

activity at the molecular level.

Beyond transcriptional regulation, epigenetic

alterations such as DNA methylation, histone

acetylation/deacetylation and non-coding RNA expression are

increasingly being recognised as diagnostic biomarkers and

therapeutic entry points for OC-driven bone loss. Clinically

applicable assays, such as methylation-specific PCR or targeted

bisulphite sequencing panels, can quantify the promoter methylation

of osteoclastogenic genes or inflammatory mediators. Circulating

microRNAs (for example miR-21, miR-155 and miR-223) have been

proposed as minimally invasive biomarkers that mirror OC activity

and inflammatory status. Notably, the concept of leveraging

nucleotide-level variation to stratify patients has already been

demonstrated in other inflammatory conditions. For example,

Antonino et al (41)

systematically reviewed single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated

with chronic rhinosinusitis, underscoring the translational value

of molecular variation in diagnosis and management. Given that both

the MAPK and Nrf2-Keap1 axes are subject to epigenetic regulation,

integrating epigenetic testing could help identify patients who are

most likely to benefit from cynarin or combination regimens.

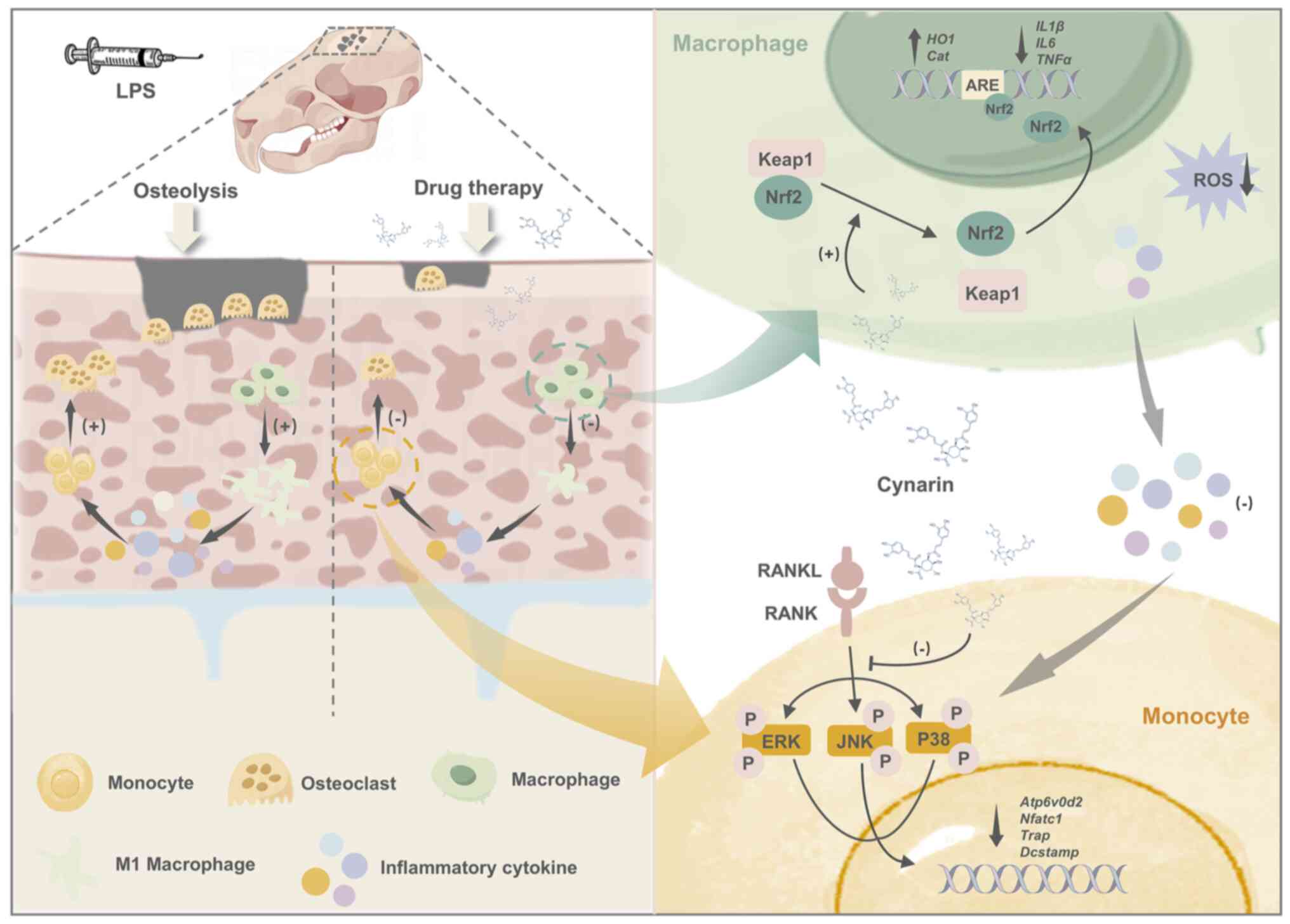

In conclusion, the present study has identified

cynarin as a potent anti-inflammatory and bone-preserving agent and

demonstrated its ability to inhibit OC differentiation and modulate

inflammatory processes via the MAPK and Nrf2-Keap1 pathways for the

first time (Fig. 8). This

dual-target therapeutic strategy effectively addresses OC-driven

bone resorption while mitigating the inflammatory processes

associated with diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and

osteoporosis. Given the ability of cynarin to modulate bone

resorption and inflammation, future clinical applications should

explore its potential to enhance bone healing in implant therapies

or in combination treatments for chronic inflammatory bone

diseases.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The data generated in the

present study may be found in the NCBI under accession number

PRJNA1301579 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1301579.

Authors' contributions

RC conceptualized the study, developed methodology

and wrote the original draft. YXW curated data and developed

methodology. ZL developed methodology and validated data. THW and

YM curated data. XRX and LS validated data. WFX and XZC

conceptualized the study. SYZ conceptualized and supervised the

study, and acquired funding. All authors contributed to writing,

reviewing and editing the manuscript. RC and SYZ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with

the laboratory animal management guidelines. They were approved

(approval no. SH9H-2020-A1-1) by the Animal Ethics Committee of the

Ninth People's Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of

Medicine (Shanghai, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82370979 and 82301108), Shanghai's

Top Priority Research Center (grant no. 2022ZZ01017), CAMS

Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (grant no. 2019-I2M-5-037),

Cross-disciplinary Research Fund of Shanghai Ninth People's

Hospital, Shanghai JiaoTong University School of Medicine (grant

no. JYJC202218) and the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology

Research Leader (grant no. 21XD1431500).

References

|

1

|

Nakano S, Inoue K, Xu C, Deng Z,

Syrovatkina V, Vitone G, Zhao L, Huang XY and Zhao B: G-protein

Gα13 functions as a cytoskeletal and mitochondrial

regulator to restrain osteoclast function. Sci Rep. 9:42362019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Udagawa N, Koide M, Nakamura M, Nakamichi

Y, Yamashita T, Uehara S, Kobayashi Y, Furuya Y, Yasuda H, Fukuda C

and Tsuda E: Osteoclast differentiation by RANKL and OPG signaling

pathways. J Bone Miner Metab. 39:19–26. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Park-Min KH, Lim E, Lee MJ, Park SH,

Giannopoulou E, Yarilina A, van der Meulen M, Zhao B, Smithers N,

Witherington J, et al: Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and

inflammatory bone resorption by targeting BET proteins and

epigenetic regulation. Nat Commun. 5:54182014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Boyce BF, Li J, Yao Z and Xing L: Nuclear

factor-kappa B regulation of osteoclastogenesis and

osteoblastogenesis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 38:504–521. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Guo Q, Jin Y, Chen X, Ye X, Shen X, Lin M,

Zeng C, Zhou T and Zhang J: NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy:

New insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 9:532024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Liu L, Geng H, Mei C and Chen L:

Zoledronic acid enhanced the antitumor effect of cisplatin on

orthotopic osteosarcoma by ROS-PI3K/AKT signaling and attenuated

osteolysis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:66615342021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Place DE, Malireddi RKS, Kim J, Vogel P,

Yamamoto M and Kanneganti TD: Osteoclast fusion and bone loss are

restricted by interferon inducible guanylate binding proteins. Nat

Commun. 12:4962021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cauley JA, Barbour KE, Harrison SL,

Cloonan YK, Danielson ME, Ensrud KE, Fink HA, Orwoll ES and

Boudreau R: Inflammatory markers and the risk of hip and vertebral

fractures in men: The osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS). J Bone

Miner Res. 31:2129–2138. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Domazetovic V, Marcucci G, Iantomasi T,

Brandi ML and Vincenzini MT: Oxidative stress in bone remodeling:

Role of antioxidants. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 14:209–216.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Moreau MF, Guillet C, Massin P, Chevalier

S, Gascan H, Baslé MF and Chappard D: Comparative effects of five

bisphosphonates on apoptosis of macrophage cells in vitro. Biochem

Pharmacol. 73:718–723. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kimachi K, Kajiya H, Nakayama S, Ikebe T

and Okabe K: Zoledronic acid inhibits RANK expression and migration

of osteoclast precursors during osteoclastogenesis. Naunyn

Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 383:297–308. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sakaguchi O, Kokuryo S, Tsurushima H,

Tanaka J, Habu M, Uehara M, Nishihara T and Tominaga K:

Lipopolysaccharide aggravates bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis

in rats. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 44:528–534. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cohen SB, Dore RK, Lane NE, Ory PA,

Peterfy CG, Sharp JT, van der Heijde D, Zhou L, Tsuji W and Newmark

R; Denosumab Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group: Denosumab treatment

effects on structural damage, bone mineral density, and bone

turnover in rheumatoid arthritis: A twelve-month, multicenter,

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical

trial. Arthritis Rheum. 58:1299–1309. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Adzet T, Camarasa J and Laguna JC:

Hepatoprotective activity of polyphenolic compounds from Cynara

scolymus against CCl4 toxicity in isolated rat hepatocytes. J Nat

Prod. 50:612–617. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Topal M, Gocer H, Topal F, Kalin P, Köse

LP, Gülçin İ, Çakmak KC, Küçük M, Durmaz L, Gören AC and Alwasel

SH: Antioxidant, antiradical, and anticholinergic properties of

cynarin purified from the Illyrian thistle (Onopordum illyricum

L.). J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 31:266–275. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wu C, Chen S, Liu Y, Kong B, Yan W, Jiang

T, Tian H, Liu Z, Shi Q, Wang Y, et al: Cynarin suppresses gouty

arthritis induced by monosodium urate crystals. Bioengineered.

13:11782–11793. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen S, Tang S, Zhang C and Li Y: Cynarin

ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute colitis in mice

through the STAT3/NF-κB pathway. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol.

46:107–116. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Rucci N, Zallone A and Teti A: Isolation

and generation of osteoclasts. Methods Mol Biol. 1914:3–19. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mao Y, Xie X, Sun G, Yu S, Ma M, Chao R,

Wan T, Xu W, Chen X, Sun L and Zhang S: Multifunctional prosthesis

surface: modification of titanium with cinnamaldehyde-loaded

hierarchical titanium dioxide nanotubes. Adv Healthc Mater.

13:e23033742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chen X, Li C, Cao X, Jia X, Chen X, Wang

Z, Xu W, Dai F and Zhang S: Mitochondria-targeted supramolecular

coordination container encapsulated with exogenous itaconate for

synergistic therapy of joint inflammation. Theranostics.

12:3251–3272. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen X, Chen X, Zhou Z, Mao Y, Wang Y, Ma

Z, Xu W, Qin A and Zhang S: Nirogacestat suppresses RANKL-Induced

osteoclast formation in vitro and attenuates LPS-Induced bone

resorption in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 382:1114702019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chen X, Chen X, Zhou Z, Qin A, Wang Y, Fan

B, Xu W and Zhang S: LY411575, a potent γ-secretase inhibitor,

suppresses osteoclastogenesis in vitro and LPS-induced calvarial

osteolysis in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 234:20944–20956. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Schwarz EM, Benz EB, Lu AP, Goater JJ,

Mollano AV, Rosier RN, Puzas JE and Okeefe RJ: Quantitative

small-animal surrogate to evaluate drug efficacy in preventing wear

debris-induced osteolysis. J Orthop Res. 18:849–855. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Tsutsumi R, Hock C, Bechtold CD, Proulx

ST, Bukata SV, Ito H, Awad HA, Nakamura T, O'Keefe RJ and Schwarz

EM: Differential effects of biologic versus bisphosphonate

inhibition of wear debris-induced osteolysis assessed by

longitudinal micro-CT. J Orthop Res. 26:1340–1346. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM, Malcangi G,

Avantario P, Azzollini D, Buongiorno S, Viapiano F, Campanelli M,

Ciocia AM, De Leonardis N, et al: Effects of resveratrol, curcumin

and quercetin supplementation on bone metabolism-a systematic

review. Nutrients. 14:35192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wu L, Guo Q, Yang J and Ni B: Tumor

necrosis factor alpha promotes osteoclast formation via PI3K/Akt

pathway-mediated blimp1 expression upregulation. J Cell Biochem.

118:1308–1315. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lin TH, Tamaki Y, Pajarinen J, Waters HA,

Woo DK, Yao Z and Goodman SB: Chronic inflammation in

biomaterial-induced periprosthetic osteolysis: NF-κB as a

therapeutic target. Acta Biomater. 10:1–10. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Sakai E and Tsukuba T: Transcriptomic

characterization reveals mitochondrial involvement in

Nrf2/Keap1-mediated osteoclastogenesis. Antioxidants (Basel).

13:15752024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Dong Y, Kang H, Peng R, Liu Z, Liao F, Hu

SA, Ding W, Wang P, Yang P, Zhu M, et al: A clinical-stage Nrf2

activator suppresses osteoclast differentiation via the

iron-ornithine axis. Cell Metab. 36:1679–1695.e6. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Baird L and Dinkova-Kostova AT: The

cytoprotective role of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Arch Toxicol.

85:241–272. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Tao H, Ge G, Liang X, Zhang W, Sun H, Li M

and Geng D: ROS signaling cascades: Dual regulations for osteoclast

and osteoblast. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 52:1055–1062.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Joo JH, Huh JE, Lee JH, Park DR, Lee Y,

Lee SG, Choi S, Lee HJ, Song SW, Jeong Y, et al: A novel pyrazole

derivative protects from ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis through

the inhibition of NADPH oxidase. Sci Rep. 6:223892016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li X, Chen Y, Mao Y, Dai P, Sun X, Zhang

X, Cheng H, Wang Y, Banda I, Wu G, et al: Curcumin protects

osteoblasts from oxidative stress-induced dysfunction via

GSK3β-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 8:6252020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Saha S, Buttari B, Panieri E, Profumo E

and Saso L: An overview of Nrf2 signaling pathway and its role in

inflammation. Molecules. 25:54742020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Xu H, Liu T, Jia Y, Li J, Jiang L, Hu C,

Wang X and Sheng J: (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits

osteoclastogenesis by blocking RANKL-RANK interaction and

suppressing NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol.

95:1074642021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Cargnello M and Roux PP: Activation and

function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated

protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 75:50–83. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Morrison DK: MAP kinase pathways. Cold

Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 4:a0112542012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liu Y, Li J, Zhang Z, Li Q, Tian Y, Wang

S, Shi C and Sun H: Echinococcus granulosus promotes MAPK

pathway-mediated osteoclast differentiation by inhibiting Nrf2 in

osseous echinococcosis. Vet Res. 56:812025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Thummuri D, Naidu VGM and Chaudhari P:

Carnosic acid attenuates RANKL-induced oxidative stress and

osteoclastogenesis via induction of Nrf2 and suppression of NF-κB

and MAPK signalling. J Mol Med (Berl). 95:1065–1076. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Antonino M, Nicolò M, Jerome Renee L,

Federico M, Chiara V, Stefano S, Maria S, Salvatore C, Antonio B,

Calvo-Henriquez C, et al: Single-nucleotide polymorphism in chronic

rhinosinusitis: A systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol. 47:14–23.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|