Programmed cell death (PCD) is a tightly regulated

biological process influenced by various external stimuli and

intracellular conditions. PCD encompasses several distinct forms of

cell death, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis,

ferroptosis and autophagy, each mediated through specific genetic

and molecular mechanisms (1).

These forms of cell death are essential for embryonic development,

the maintenance of tissue homeostasis and the clearance of

intracellular pathogens, and are regarded as fundamental processes

for preserving physiological stability (1,2).

PCD pathways can be categorized into lytic and non-lytic forms of

cell death. Lytic cell death, such as pyroptosis and necroptosis,

involves membrane potential loss and cellular swelling, resulted in

disrupted cell integrity and ultimately leading to cell rupture,

releasing a large amount of inflammatory mediators (2). Comparatively, non-lytic forms of

PCD, such as apoptosis, involve the coordinated breakdown of dying

cells into smaller fragments for the isolation of cellular

contents, which limits the release of cytokines and

damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), typically in a silent

manner without triggering a pronounced immune response (1).

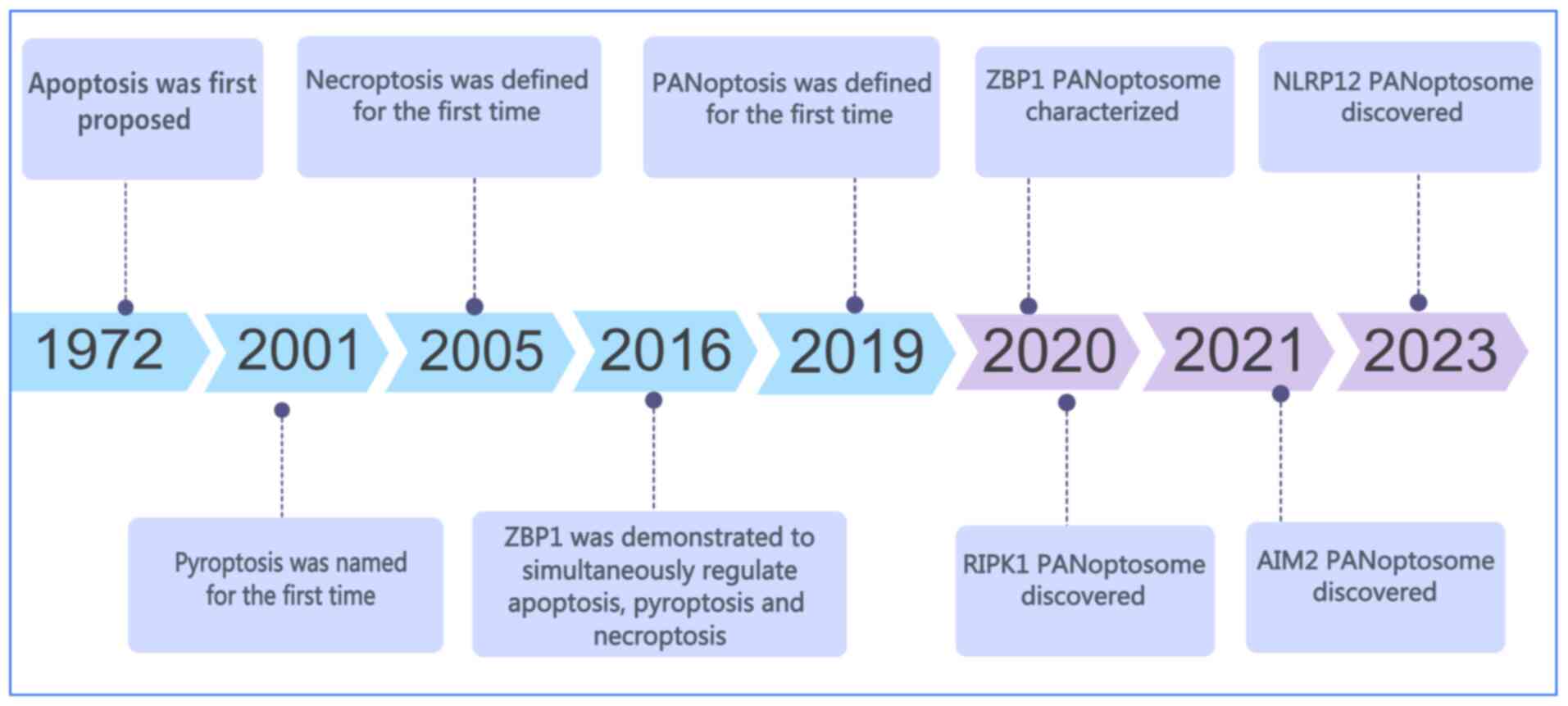

PANoptosis is a recently identified form of PCD that

is initiated by innate immune signaling, and integrates key

features of pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis. Notably, its

biological effects cannot be fully explained by any of these

pathways alone. The concept of PANoptosis was first introduced by

Malireddi et al in 2019 (3) (Fig.

1). Mechanistically, PANoptosis is mediated through the

assembly of a multiprotein complex known as the PANoptosome, which

incorporates essential components from the pyroptotic, apoptotic

and necroptotic pathways. This complex enables cross-talk and

coordinated activation among the three pathways, resulting in a

unified mode of cell death (4,5).

Due to the regulatory role of the PANoptosome, inhibition of a

single form of cell death is insufficient to prevent PANoptosis.

Instead, effective blockade requires targeting components within

the PANoptosome complex.

Emerging evidence has revealed that PANoptosis

contributes to the pathogenesis of several kidney diseases,

including both acute and chronic forms (6-12). Although the role of PANoptosis

has been extensively studied in cancer, infections and inflammatory

conditions, its function in renal pathology remains insufficiently

characterized. The present review summarizes the molecular

mechanisms underlying PANoptosis activation and explores its

potential involvement in acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic kidney

disease (CKD), diabetic kidney disease (DKD), renal cell carcinoma

(RCC) and drug-induced kidney injury, aiming to provide a

theoretical foundation for PANoptosis-targeted therapeutic

strategies in kidney disease.

A comprehensive search for studies published up to

May 2025 was performed on platforms including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Google Scholar

(https://scholar.google.com/), Web of

Science (https://webofscience.com/WOS),

ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com/) and CNKI (https://www.cnki.net/). The search adopted a

combination of subject terms and free terms, and was appropriately

adjusted according to the rules of the different databases. The key

terms included 'Kidney disease', 'Kidney failure', 'Renal

insufficiency', 'Renal failure', 'Nephropathy', 'Renal disease' and

'PANoptosome' or 'PANoptosis'. Notably, low-quality articles and

papers with incomplete information were excluded. The main

inclusion criteria for the literature were original research or

comprehensive reports. The research content clearly involved the

mechanism or therapeutic significance of PANoptosis in kidney

diseases, and the research subjects included humans and mammals.

The screening was independently conducted by two researchers, and

any disputes arising during the process were resolved through

mutual discussion or arbitration by a third-party senior

researcher.

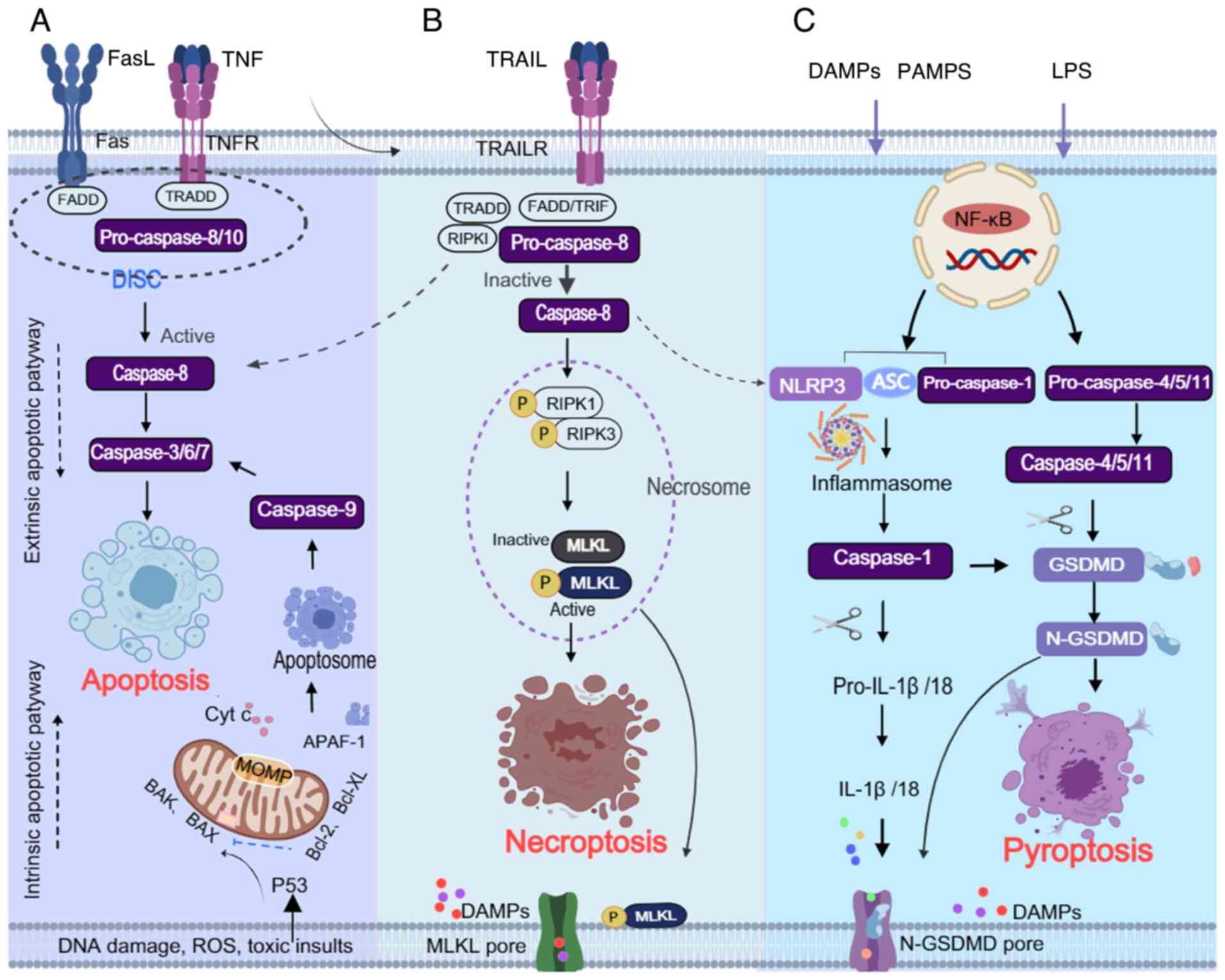

Apoptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis represent the

three primary forms of PCD, each characterized by distinct

initiators, signaling mediators and execution mechanisms. Among

them, apoptosis is the most extensively studied and was first

described by Kerr et al in 1972 (13) (Fig. 1). Apoptosis depends on the

involvement of caspases. Morphologically, apoptosis is defined by

characteristic features including cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic

condensation, membrane blebbing and nuclear chromatin condensation

(13,14). Apoptosis occurs through two main

pathways: The intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway and the extrinsic

(death receptor-mediated) pathway (Fig. 2A). The intrinsic pathway is

activated in response to intracellular stressors such as DNA

damage, oxidative stress or toxic insults. In this context, key

stress-sensing proteins, such as the tumor suppressor protein 53

(P53), serve a central regulatory role by transcriptionally

activating pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, such as BAK

and BAX, while concurrently suppressing anti-apoptotic proteins,

such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL (15-17). Activated BAK and BAX oligomerize

on the mitochondrial outer membrane, resulting in mitochondrial

outer membrane permeabilization and the release of cytochrome

c (Cyt c) into the cytosol (18). Cyt c subsequently binds to

apoptotic protease-activating factor 1, promoting the formation of

the apoptosome complex, which leads to the activation of caspase-9

(19,20). Caspase-9 then cleaves and

activates downstream effector caspases, including caspase-3 and

caspase-7, ultimately executing the apoptotic process (21). The extrinsic pathway is initiated

by the binding of death ligands to their corresponding receptors.

Fas and tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) recruit adaptor

proteins, such as TNFR-associated death domain protein (TRADD) and

Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD), forming the

death-inducing signaling complex, which activates caspase-8 and

caspase-10 (22-24). Active caspase-8/10 cleaves and

activates the effector caspases, including caspase-3, caspase-7 and

caspase-6, leading to apoptosis (25,26). Caspase-8 also cleaves BID, which

activates the intrinsic pathway and further promotes apoptosis

(27).

Pyroptosis is an inflammation-associated form of PCD

that occurs through the classical or non-classical pathways. While

this process shares some morphological features with apoptosis,

such as nuclear condensation and DNA fragmentation, its hallmark

characteristics include pore formation in the plasma membrane, cell

swelling, membrane rupture and the release of pro-inflammatory

intracellular contents; these events trigger a robust inflammatory

response (49-51). Upon exposure to toxic stimuli,

intracellular and extracellular danger signals induce the formation

of inflammasome complexes in the cytoplasm through the classical

caspase-1-dependent pathway or the non-classical

caspase-4/5/11-dependent pathway; these inflammasome complexes are

composed of Nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing

(NLRP)3/NLRP1, apoptosis-related speck-like protein (ASC) and

pro-caspase-1 (Fig. 2C).

Inflammasomes promote the production of caspase-1, and the

maturation and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, and induce cleavage of

the pyroptosis executioner protein gasdermin D (GSDMD). The

N-terminal fragment of GSDMD forms pores in the membrane,

initiating pyroptosis (51-54).

For a long time, different cell death modalities

were examined in isolation due to their regulation by distinct

molecular mechanisms. However, the identification of PANoptosis has

revealed that these pathways are interconnected at multiple levels

and can be activated simultaneously or sequentially within the same

cell. Rather than acting independently, these forms of cell death

can switch from one to another under specific conditions,

highlighting their close association and mutual regulation

(3,4).

Among the key mediators linking these pathways,

caspases have a central role. Caspase-8, classically recognized as

the initiator enzyme of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, promotes

the cleavage of BID to tBID, which subsequently activates BAX and

BAK, and initiates apoptotic signaling. However, increasing

evidence (22,55-60) has indicated that caspase-8 also

participates in necroptosis and pyroptosis (Fig. 2B and C); it can trigger

necroptosis mediated by RIPK3 and MLKL, and also contributes to

pyroptotic regulation (55-58). Caspase-8 forms an oligomeric

complex with RIPK1 and FADD, which facilitates the activation of

downstream effector caspases-3/7 and promotes apoptosis (59,60). Additionally, caspase-8 can

directly cleave RIPK1 and RIPK3, thereby suppressing necroptosis.

When caspase-8 activity is inhibited, this suppression is lifted,

allowing RIPK3 activation and promoting necroptotic cell death

(61,62). RIPK1 also contributes to

FADD/caspase-8-dependent apoptosis. Upon TNFR1 engagement, the

TNFR1 signaling complex recruits TRADD, which subsequently recruits

FADD. FADD then binds pro-caspase-8, facilitates its dimerization

and activation, and initiates apoptosis (63). Dillon et al (64) demonstrated through both in

vitro and in vivo studies that RIPK1 can regulate

FADD/caspase-8-mediated apoptosis as well as RIPK3/MLKL-induced

necroptosis, thereby preventing perinatal mortality in mice

(Fig. 2A and B). Caspase-8 also

has a regulatory role in pyroptosis by facilitating activation of

the NLRP3 inflammasome, promoting ASC complex formation and

caspase-1 activation, which in turn induces IL-1β secretion and

pyroptosis (55,62). In the context of Yersinia

infection, inhibition or deletion of transforming growth

factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) has been shown to enhance

caspase-8-mediated GSDMD cleavage, thereby favoring pyroptosis

while reducing apoptosis (65)

(Fig. 2A and C). Furthermore,

caspase-8 can act on other GSDM family members, such as GSDMC,

which is specifically cleaved under TNFα stimulation to generate

the N-terminal domain of GSDMC, leading to pore formation in the

plasma membrane and the induction of pyroptosis (66,67). During influenza virus infection,

caspase-8 activates caspase-3, which cleaves GSDMD into an inactive

form, thereby reducing IL-1β and IL-18 release, and suppressing

pyroptosis (68). These findings

collectively indicate that caspase-8 is a pivotal regulator linking

apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis.

Caspase-3, a key executioner of apoptosis, also

contributes to pyroptosis. Upon activation, it cleaves GSDME,

generating the GSDME-N fragment that induces pyroptotic membrane

disruption (69,70). Similarly, caspase-1, the terminal

effector of pyroptosis, has been shown to mediate apoptosis in the

absence of GSDMD by activating the BID/caspase-9/caspase-3 axis

(71,72).

In addition to caspases, multiple signaling

complexes and inflammasomes contribute to the cross-talk among

these cell death pathways. NLRP3, the most extensively studied

inflammasome, serves a critical role in pyroptosis by promoting

inflammatory responses. Potassium efflux, a known activator of

NLRP3, can result from MLKL-mediated membrane disruption during

necroptosis, which subsequently leads to caspase-1 activation and

IL-1β maturation (73-75) (Fig. 2B and C). Moreover, upregulation

of RIPK3 has been shown to trigger the RIPK3/MLKL/NLRP3/caspase-1

signaling cascade, further supporting the interconnected nature of

these pathways (76).

Collectively, these findings indicate that

apoptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis constitute an interconnected

network rather than three independent cell death pathways, with key

regulators, such as caspase-8, exerting multiple functions,

including promoting apoptosis through activation of caspase-3/7,

suppressing necroptosis by cleaving RIPK1 and RIPK3, and

participating in NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent pyroptosis.

Similarly, RIPK1 is involved in apoptosis and pyroptosis. These

pathways are not isolated but rather interdependent, with key

molecules functioning as receptors for initiating and recognizing

death signals, as adapters for recruiting downstream mediators, and

as effectors that execute the final cell death program.

The concept of PANoptosis emerged from studies

investigating the molecular overlap among pyroptosis, apoptosis and

necroptosis. Increasing evidence has suggested that these three

forms of PCD can occur simultaneously and are interconnected

through a complex molecular network, rather than acting as isolated

pathways (77-80), leading to the recognition of

PANoptosis as a distinct, coordinated form of cell death.

PANoptosis is a newly characterized PCD pathway regulated by innate

immune responses and mediated through the assembly of a

multiprotein complex known as the PANoptosome. It is initiated by

innate immune sensors and executed via caspases and RIPKs. The

PANoptosome integrates components from the pyroptotic, apoptotic

and necroptotic machinery, enabling their coordinated activation.

Regulation of the PANoptosome allows simultaneous control of all

three death pathways, while also providing a molecular scaffold

that facilitates interaction among key signaling molecules, thereby

driving PANoptosis (81,82).

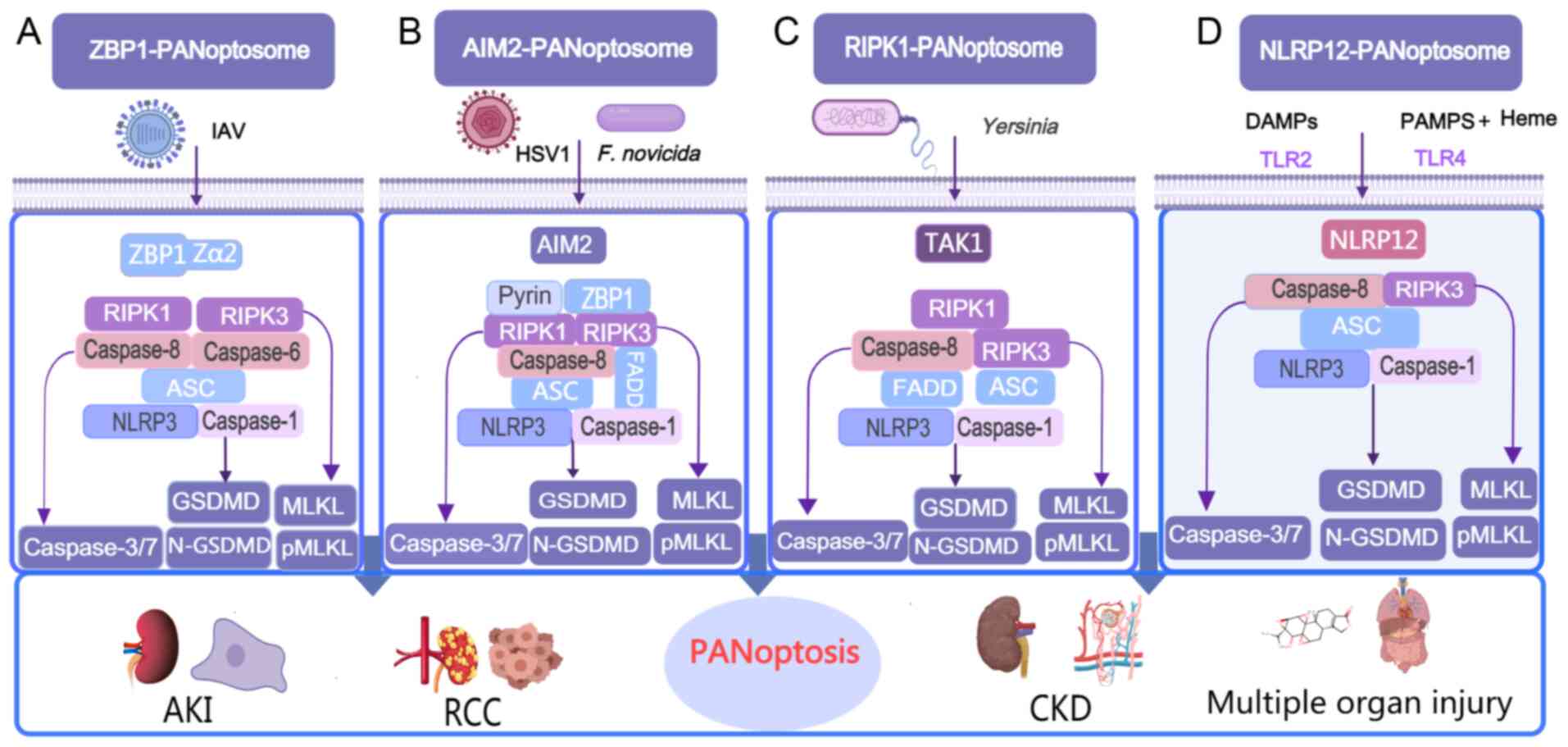

Activation of PANoptosis involves upstream receptors

and signaling cascades that lead to the formation of the

PANoptosome. These complexes serve as platforms for cross-talk

among the three PCD pathways and are essential for their

integration (83). The

PANoptosome typically comprises three categories of components

(5,8,11,80,83): i) Pattern recognition receptors

or sensors that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns

(PAMPs) and DAMPs, including Z-DNA binding protein 1 (ZBP1),

NLRP12, AIM2, RIPK1, pyrin and NLRP3; ii) adaptor proteins such as

ASC and FADD; and iii) catalytic effectors, including RIPK1, RIPK3,

caspase-1 and caspase-8. The composition of the PANoptosome is

context-dependent and varies according to the nature of the

stimulus or pathological condition. In general, the sensors

recognize PAMPs or DAMP,s and initiate PANoptosome assembly through

homotypic or heterotypic interactions among adaptor domains. This

assembly provides a structural platform for the convergence of

apoptotic, pyroptotic and necroptotic effectors. The resulting

complex enables the coordinated activation of caspases and RIPKs,

thereby inducing pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis in a

synchronized manner (80,83).

AIM2 is an inflammasome sensor belonging to the

PYHIN protein family that recognizes cytoplasmic double-stranded

DNA (dsDNA). Structurally, AIM2 contains an N-terminal pyrin domain

and a C-terminal HIN200 domain, and is primarily localized in the

cytoplasm (96-98). Upon detection of pathogen-derived

dsDNA, AIM2 initiates the formation of the AIM2-PANoptosome

complex. This assembly activates the inflammasome pathway, leading

to the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, and inducing pyroptosis

(99,100). In bone marrow-derived

macrophage models infected with herpes simplex virus 1 and

Francisella novicida, AIM2 has been shown to regulate other

innate immune sensors, including pyrin and ZBP1. Together with ASC,

caspase-1, caspase-8, RIPK3, RIPK1, NLRP3 and FADD, these

components assemble to form the AIM2-PANoptosome, driving

PANoptosis (82) (Fig. 3B). During infection, AIM2

deficiency markedly reduces inflammation and cell death, whereas

the absence of pyrin or ZBP1 produces a partial reduction in these

responses. These observations suggest that AIM2 functions as an

upstream regulator controlling the assembly and activation of the

AIM2-PANoptosome (82).

RIPK1 is another RHIM-containing protein that serves

a central role in inflammation, cell death and the regulation of

PANoptosis. It can activate necroptosis by promoting the

phosphorylation of RIPK3, which interacts with MLKL to induce cell

death through the RIPK3/MLKL axis (40,89,101). Dillon et al (64) reported that RIPK1 also

contributes to FADD/caspase-8-mediated apoptosis and

RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. TAK1 serves as a key upstream

regulator of RIPK1, controlling the formation and activation of

PANoptosomes (3,102,103). Under normal physiological

conditions, TAK1 inhibits TNF-mediated autocrine signaling by

suppressing TNF production and RIPK1 phosphorylation, thereby

preventing PANoptosis activation (28,79). In Yersinia-infected cells,

TAK1 inhibition or knockout promotes the assembly of the

RIPK1-PANoptosome, which includes RIPK1, caspase-8, caspase-1,

FADD, NLRP3, ASC and RIPK3 (Fig.

3C). This complex activates FADD-Caspase-8-mediated apoptosis,

RIPK3-MLKL-dependent necroptosis, and NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated

pyroptosis (79,87). Moreover, in the absence of TAK1,

microbial signals can activate PANoptosis through the RIPK3/MLKL

axis independent of RIPK1 kinase activity (3). Using models specifically lacking

TAK1, studies have demonstrated that inhibition of RIPK1 kinase

activity in TAK1-deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages can

suppress PANoptosis and inflammation, infection and myeloid

proliferation (77,79,104,105).

NLRP12 is a member of the NLR family and contains an

N-terminal pyrin domain, a central nucleotide-binding domain and a

C-terminal leucine-rich repeat region. It functions as an innate

immune sensor that modulates inflammatory signaling in response to

infection and cellular stress (106). It has been demonstrated that

heme, in conjunction with PAMPs, activates the Toll-like receptor

2/4 signaling axis, which induces the expression of NLRP12

(88). This induction promotes

the assembly of a PANoptosome complex composed of NLRP12, NLRP3,

ASC, caspase-1, caspase-8 and RIPK3, collectively referred to as

the NLRP12-PANoptosome (Fig.

3D). Activation of this complex leads to PANoptosis,

characterized by caspase-1, caspase-8 and caspase-3 activation,

MLKL phosphorylation, and cleavage of GSDMD or GSDME. A functional

study further revealed that NLRP12 deficiency confers protection

against heme-induced AKI and mortality in mice, underscoring its

critical role in disease pathogenesis (88). This finding suggests that NLRP12

and associated PANoptotic components may represent promising

therapeutic targets for hemolytic and inflammation-related

disorders (88).

AKI is a clinical syndrome characterized by a sudden

decline in renal function, and is associated with a high incidence

and poor clinical outcomes (107,108). The incidence of AKI affects

~20% of hospitalized patients and exceeds 50% among those in

intensive care units, making it a major contributor to in-hospital

mortality (109). Emerging

evidence (8,110-112) has indicated that PANoptosis

serves an important role in various AKI models, including those

induced by sepsis, ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and exposure

to nephrotoxic agents, such as chemicals and certain traditional

Chinese medicines.

Cell death and inflammation are central events in

the pathogenesis of AKI, with I/R injury being a primary cause.

Previous studies have demonstrated that apoptosis, pyroptosis and

necroptosis coexist in models of middle cerebral artery occlusion,

oxygen-glucose deprivation/recovery and retinal I/R injury

(113,114). Another study, by collecting

data from animal and cell experiments, reported that PANoptosis is

observed in ischemic brain injury (115). These findings suggest that

PANoptosis may represent a promising therapeutic target for

diseases associated with I/R injury. In I/R-induced AKI, renal

tubular epithelial cells experience endoplasmic reticulum stress,

oxidative stress and inflammation due to hypoxia, followed by

reperfusion, leading to acute tubular cell loss. Numerous animal

studies and analyses of kidney biopsies from transplant recipients

have demonstrated that I/R induces apoptosis in tubular epithelial

cells (116-118). Although apoptosis was initially

regarded as the principal mechanism of AKI, further studies have

shown that multiple cell death pathways are involved, and

inhibiting apoptosis alone is insufficient to prevent renal injury

(119). In I/R-induced AKI

models, NLRP3 activates caspase-1, leading to GSDMD cleavage and

the release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18,

thereby inducing pyroptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells

(120-122). Pyroptosis has also been

observed in AKI models caused by cisplatin and sepsis (123). Linkermann et al

(124,125) reported increased expression of

RIPK1 and RIPK3 in I/R-induced AKI, and demonstrated that treatment

with the necroptosis inhibitor necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) markedly

improved renal function. Similarly, the RIPK1 inhibitor Compound-71

has been shown to alleviate cisplatin-induced AKI by suppressing

necroptosis (126). In calcium

oxalate-induced AKI, ZBP1 activation of the RIPK3/MLKL axis

mediates necroptosis, whereas ZBP1 knockout can reduce necroptotic

activity and tubular injury (127). These findings underscore the

importance of simultaneously targeting apoptosis, pyroptosis and

necroptosis to protect against AKI-associated kidney damage.

While previous studies have often focused on

individual PCD pathways, the discovery of PANoptosis has shifted

attention to the integrated role of multiple death mechanisms in

AKI. In a mouse model of sepsis-induced AKI established by cecal

ligation and puncture, increased AIM2 expression in kidney tissue

has been shown to be associated with concurrent activation of

apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis and inflammasome signaling,

supporting the presence of PANoptosis (110). In vitro, PANoptosis has

been observed in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated human proximal

tubular epithelial HK-2 cells, and AIM2 silencing may reverse this

effect, suggesting that AIM2 mediates sepsis-induced renal injury

through regulation of PANoptosis (110). NLRP3, a key component of the

four types of PANoptosome, has also been shown to be involved in

I/R-induced AKI. The clinical agent 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nit

rostyrene has been report to reduce apoptosis, necroptosis and

pyroptosis in a renal I/R injury model by targeting NLRP3, thereby

alleviating tissue damage (8).

Furthermore, an aqueous extract of Achyranthes aspera can

ameliorate cisplatin-induced AKI by inhibiting DNA damage,

oxidative stress, inflammation and PANoptosis (111). In sepsis-induced AKI mouse

models, elevated levels of PANoptosis-related molecules, including

RIPK1, MLKL, caspase-3/7 and FADD, have been observed in renal

tissue, along with marked upregulation of ZBP1, particularly in the

renal interstitium, highlighting the essential role of PANoptosis

in the pathogenesis of sepsis-induced AKI (112) (Table I).

PANoptosis has been increasingly linked to

tumorigenesis and cancer progression (12). The boundaries between different

forms of PCD have become progressively less distinct, and

therapeutic strategies targeting a single form of cell death often

show limited efficacy (105).

The discovery of PANoptosis not only broadens the understanding of

cell death pathways but also offers novel approaches for cancer

therapy. RCC, characterized by the proliferation of malignant

epithelial cells, relies on strategies that effectively inhibit or

eliminate these cells. Inducing PANoptosis, which simultaneously

activates apoptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis, holds potential

therapeutic value for enhancing cancer cell clearance, and

suppressing tumor growth and metastasis. PANoptosis has been

investigated in several types of cancer, including colorectal

cancer, breast cancer and low-grade glioma (12,128,129).

Several studies have explored the association

between PANoptosis and cancer prognosis using data from The Cancer

Genome Atlas. One study reported that high expression of

PANoptosis-related genes, such as AIM2, caspase-3, caspase-4 and

TNFRSF10, was significantly associated with poor prognosis in KIRC

(132). Conversely, in skin

cutaneous melanoma, higher expression of genes including ZBP1,

NLRP1, caspase-8 and GSDMD was shown to be associated with better

survival outcomes (132).

Further analysis has identified PANoptosis-related prognostic

clusters, revealing underlying genetic mutations, distinct immune

cell populations and activated oncogenic pathways that may account

for differences in patient survival across tumor types (7). These findings highlight the

heterogeneous nature of PANoptosis gene expression and suggest it

may exert different roles depending on the cancer context.

Another study applied PANoptosis-related

differentially expressed genes to predict prognosis in patients

with KIRC. The high-risk PANoptosis group demonstrated an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, characterized by reduced

infiltration of antitumor CD4+ T cells and natural

killer cells, and elevated levels of immunosuppressive M2

macrophages and regulatory T cells. These findings suggest that

PANoptosis may contribute to KIRC progression and influence immune

regulation within the tumor microenvironment (9). In a separate study, Wang et

al (133) developed a ccRCC

prognostic risk model based on three specific PANoptosis-related

microRNAs, revealing that patients in the high-risk group exhibited

poorer outcomes and greater tumor malignancy. This group also

showed enrichment of immune-related pathways and heightened immune

activity, implying potential responsiveness to immunotherapy and

chemotherapy. By contrast, the low-risk group demonstrated

metabolic reprogramming, with increased fatty acid and amino acid

metabolism. Furthermore, PANoptosis-related long non-coding RNAs

have been associated with clinical outcomes, immune cell

infiltration, immunosuppressive states, oncogenic signaling

pathways and therapeutic responses in ccRCC. Single-cell sequencing

identified LINC00944 as a potential biomarker linked to T-cell

infiltration and PCD regulation, supporting its prognostic

relevance (134). A recent

study used bioinformatics analysis to characterize PANoptosis in

the three RCC subtypes (KIRC, KIRP and KICH) and proposed a novel

scoring system, the PANoptosis-Immunity Index (PANII). The PANII

effectively reflected the immune microenvironment status across RCC

subtypes and predicted response to immunotherapy. Functional

validation revealed that knockout of the PYCARD gene significantly

inhibited proliferation and invasion of KIRC cells in vitro,

confirming its role in promoting tumor progression (135) (Table I).

CKD has emerged as a growing global public health

concern, which markedly impairs patient quality of life. Over the

past three decades, the global mortality rate associated with CKD

has reached 41.5%, with ~1.2 million deaths reported in 2017. By

2040, CKD is projected to become the fifth leading cause of death

worldwide (136,137). CKD is a progressive and

long-term condition with diverse etiologies; however, renal

fibrosis represents the common pathological hallmark driving

progression to end-stage renal disease. The fibrotic process in CKD

typically begins with the gradual loss of epithelial cells,

including podocytes and tubular cells, as well as endothelial

cells, which is followed by progressive glomerular sclerosis,

collapse of peritubular capillaries and extensive

tubulointerstitial fibrosis. The development of renal fibrosis is

tightly associated with sustained inflammation and various forms of

cell death (138-140). Regardless of the initial cause

of kidney injury, nephrons are continuously lost, and fibrotic

lesions advance until end-stage renal disease becomes inevitable.

Therefore, targeting cell death pathways represents a potential

therapeutic strategy to prevent or slow CKD progression by limiting

the loss of functional kidney cells and suppressing inflammation.

Notably, apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis have been recognized

as central pathogenic events in CKD of different etiologies. A

large number of previous studies have confirmed that the

pathological mechanisms of CKD and DKD are related to renal cell

apoptosis (141-144), necroptosis (138,145-147) and pyroptosis (148,149).

Recent studies have revealed that three death modes

occur simultaneously in CKD and DKD, which is different from the

single death mode of PCD. Zhang et al (150) employed bioinformatics

approaches to investigate the relationship between PANoptosis and

CKD, identifying two central genes, FOS and PTGS2, as potential

mediators. These genes have previously been associated with tissue

inflammation, cell death and renal fibrosis, suggesting that

PANoptosis may contribute to the onset and progression of CKD

through their regulation (151-154). In a mouse model of post-burn

CKD, elevated levels of caspase-1, caspase-3 and IL-1β have been

observed in renal tissue, and apoptosis, pyroptosis and necroptosis

were demonstrated to be concurrently activated (155). Sustained inflammation following

burn injury led to caspase pathway activation, promoting

PANoptosis, and aggravating renal injury and CKD progression.

Treatment with the anti-inflammatory agent dexamethasone was able

to suppress multiple forms of cell death and alleviate renal damage

in this model (155) (Table I).

DKD, a major cause of end-stage kidney failure, is

marked by progressive podocyte loss. Using single-cell RNA

sequencing data, Lv et al (156) reported that TRAIL and death

receptor 5 (DR5) were highly expressed in the podocytes of patients

with DKD. These findings were further validated in renal biopsy

samples. In vitro and in vivo experiments

demonstrated that TRAIL induced the expression of

PANoptosis-related markers, including caspase-1, caspase-3,

phosphorylated (p)-MLKL and p-RIPK1, via DR5 in DKD podocytes. In

addition, the simultaneous activation of apoptosis, pyroptosis and

necroptosis exacerbated proteinuria and renal injury in mouse

models of DKD. These effects were mitigated by TRAIL inhibition or

gene knockout, indicating that the TRAIL/DR5 axis mediates podocyte

PANoptosis injury in DKD (156)

(Table I).

Collectively, these findings suggest that

PANoptosis may serve as a promising therapeutic target in CKD and

DKD. However, given the complex and heterogeneous nature of CKD

pathogenesis, current research on PANoptosis in this context

remains limited. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the

mechanistic roles and therapeutic implications of PANoptosis across

diverse CKD etiologies.

Recent studies have increasingly focused on the

role of PANoptosis in drug-induced renal injury (6,10,11,157,158). One investigation revealed that

the herbicide atrazine, known for its nephrotoxic effects, can

downregulate Sam50 expression in the kidney, resulting in

mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) instability and the release of mtDNA into

the cytoplasm. This mtDNA release activates the stimulator of IFN

genes (STING) pathway, which subsequently upregulates inflammatory

cytokines and key PANoptosis-associated molecules, including AIM2,

ZBP1 and pyrin. These molecular events drive STING-dependent

PANoptosis in renal tissue, ultimately leading to renal failure

(10).

Triptolide-induced multi-organ damage has also been

linked to a systemic inflammatory response and the activation of

various lytic cell death pathways. Notably, the cell death

triggered by triptolide cannot be mitigated by the inhibition of a

single pathway. It has been shown that triptolide simultaneously

activates markers of pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis in

macrophages. Immunofluorescence and immunoprecipitation assays have

confirmed the colocalization and aggregation of ASC, RIPK3 and

caspase-8, promoting the formation of the PANoptosome and inducing

PANoptosis, which contributes to both nephrotoxicity and

hepatotoxicity. Given that renal tubular epithelial cells and

podocytes possess the molecular machinery required for all three

forms of cell death, the authors of this previous study

hypothesized that PANoptosis likely occurs in these renal cell

types as well (157). In

aristolochic acid nephropathy (AAN), administration of aristolochic

acid I (AAI) has been shown to induce elevations in serum urea

nitrogen and creatinine levels, and to induce PANoptosis in renal

tubular epithelial cells. Both in vitro and in vivo

experiments have demonstrated that inhibition of PANoptosis may

alleviate AAI-induced renal injury, supporting its role in AAN

pathogenesis (158). The

anticancer agent CBL0137, either alone or in combination with LPS,

has been shown to activate systemic inflammation and PANoptosis

signaling. In mice, this treatment induced PANoptosis in

macrophages and resulted in multi-organ injury, including kidney

damage; mechanistically, CBL0137 promoted the formation of Z-DNA in

macrophage nuclei, thereby activating ZBP1. By contrast, knockout

of ZBP1 significantly reduced cell death induced by CBL0137

combined with LPS, highlighting the essential role of ZBP1 as a

core component of the PANoptosome in mediating PANoptosis (11). In a mouse model sensitized to

trichloroethylene, PANoptosis was observed in renal endothelial

cells, and the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IFNγ appeared to

act synergistically in driving this process. Inhibition of

peripheral TNFα and IFNγ attenuated PANoptosis, preserved

endothelial function and improved renal outcomes (6).

Beyond drug-induced renal injury, PANoptosis has

also been implicated in renal damage resulting from non-chemical

stressors. A recent study reported multi-organ injury, including

damage to the kidneys and liver, following heatstroke. It was shown

that ZBP1 mediates a PANoptosis-like cell death pathway during

heatstroke, characterized by concurrent activation of apoptosis,

pyroptosis and necroptosis. By contrast, deletion of ZBP1 abrogated

this cell death process, and reversed the renal and hepatic damage

induced by heatstroke (159)

(Table I).

Loss of parenchymal cells, together with

proliferation or recruitment of maladaptive cells, disrupts

cellular homeostasis and drives kidney injury and fibrosis

(160,161). Modulating cell death programs

may therefore represent an important approach to limiting renal

damage across kidney diseases. Since PANoptosis encompasses

multiple PCD patterns simultaneously, targeting and inhibiting

these pathways in parallel may enhance renal protection. Although

drugs directly targeting PANoptosis have not yet entered clinical

trials, a number of compounds that act on its key node molecules

are already in the clinical development stage for other indications

(162-166), which provides a unique

opportunity for the rapid initiation of clinical research on kidney

diseases.

Molecules that act as central hubs in PANoptosis,

such as ZBP1 and AIM2, can concurrently trigger pyroptosis,

apoptosis and necroptosis in response to microbial or endogenous

cues. Their inhibition or loss impairs activation of these effector

modules and reduces cell death (82,167,168). Notably, these hubs have been

implicated in AKI, RCC, drug-induced nephrotoxicity and other renal

pathologies, highlighting their broad relevance. At present,

specific inhibitors for ZBP1 and AIM2 are scarce, and traditional

treatment strategies mainly focus on the inhibition of their

downstream factors. However, some new technologies are attempting

to precisely degrade ZBP1. For example, a recent study on the

covalent recognition-based PROTAC molecule has confirmed that it

can cause upregulation of ZBP1 expression in H1N1 infection models,

inhibit the downstream necroptosis pathway, reduce the

phosphorylation levels of RIPK3 and MLKL, and simultaneously lower

the expression levels of IL-18, IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-β,

effectively alleviating inflammation (169). In tumor research, it has been

shown that the ZBP1 agonist CBL0137 can induce potent PANoptosis

and antitumor immunity in mouse models of ZBP1-deficient melanoma

(170). Conversely,

necrosulfonamide, a small molecule inhibitor targeting the ZBP1

RHIM domain, can be used to alleviate therapeutic side effects

(such as intestinal damage) (171). Recently, 4-sulfonic calixarenes

have been described as being able to block the binding of dsDNA to

the HIN200 domain of AIM2 and to inhibit AIM2 in vivo,

further blocking the release of the downstream factors caspase-1,

IL-1β and GSDMD (172). Further

work revealed that these compounds are structurally similar to the

clinically approved drug suramin, which can also inhibit AIM2

(172).

Therapeutic targeting of PANoptosome components is

also considered promising. For example, the NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950

has been shown to attenuate kidney injury in models of AKI

(173-175), CDK (176,177), DKD (178,179) and RCC (180). It has shown good safety and

efficacy both in vivo and in vitro. Another NLRP3

inhibitor, OLT1177 (dapansutrile), has been proven to effectively

reduce inflammatory indicators and has been shown to possess a good

safety profile in a phase II trial of acute gout attacks (181). This also indicates prospects

for the treatment of kidney diseases driven by metabolic stress,

such as DKD. Z-VAD-FMK, a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor widely

used to suppress apoptosis (182), and Nec-1, a necroptosis

inhibitor targeting RIPK1, have both demonstrated protective

effects in various kidney diseases (182,183), but have not yet entered

clinical trials. GSK2982772 is another RIPK1 inhibitor that has

been tested for safety and efficacy in phase II clinical trials for

psoriasis (165,166), rheumatoid arthritis (162) and ulcerative colitis (163). Given that RIPK1 is a key hub of

PANoptosis in multiple nephropathy models, reusing it for the

treatment of inflammatory nephropathy (such as lupus nephritis) is

an attractive clinically available strategy. Caspase-8 functions as

a key regulator across pathways, simultaneously influencing

apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis, thereby determining the cell

death mode following activation signals (62). A recent study reported that

inhibition of the caspase-8/caspase-3/NLRP3/GSDME-mediated pathway

alleviated pyroptosis and rescued renal tubular cell injury induced

by uric acid (184). Another

investigation revealed that TP53INP2, an autophagy-related protein,

can inhibit RCC progression by regulating the caspase-8 apoptotic

pathway (185). Another caspase

inhibitor (emricasan) has been shown in a clinical study on

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis to significantly reduce ALT levels

and the activation of caspase-3/7 in patients with non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease. Although the results of this study have not

been clinically translated, it provides a foundation for subsequent

research on specific caspase inhibitors (such as those targeting

caspase-8) (164). RIPK3 is

also another important component of PANoptosomes. A novel inhibitor

of RIPK3, Uh15-38, has been proven to effectively block necroptosis

of alveolar epithelial cells caused by IAV infection in mouse

models by inhibiting MLKL, and the levels of IL-1β and IL-18. In

addition, it can reduce lung inflammation and mortality without

affecting virus clearance or immune response (186). Its efficacy is consistent with

other pre-clinical type I kinase inhibitors and comparable to that

of currently Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs, such as

sorafenib and dasatinib (186).

In addition, sorafenib and edaravone have been shown to attenuate

renal fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction through

inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammation and the RIPK3/MLKL

pathway (187). Collectively,

these findings suggest that targeting hub molecules and components

of PANoptosis, including ZBP1, AIM2, RIPK1, NLRP3 and caspase

family members, represents a promising therapeutic option for

kidney diseases.

However, the interplay among apoptosis, pyroptosis

and necroptosis complicates therapeutic development. These pathways

often share molecular mediators and defense mechanisms, and they

may coexist within the same kidney disease, acting either

simultaneously or sequentially across different cell types.

Furthermore, inhibition of one pathway may be compensated for by

activation of others, resulting in limited therapeutic efficacy

with single-target approaches. Therefore, identifying strategies

that can simultaneously block multiple forms of cell death remains

a key focus for future research.

Current evidence has indicated that PANoptosis may

serve as a novel and promising therapeutic target in kidney

diseases. Unlike interventions aimed at suppressing a single form

of PCD, modulation of PANoptosis offers the potential to block

multiple cell death pathways concurrently, thereby providing

greater therapeutic benefit. This integrated approach represents a

new direction for the prevention of kidney injury and the

attenuation of disease progression; however, important challenges

remain. Although key molecules involved in PANoptosis and their

roles in distinct death pathways have been identified, the precise

mechanisms by which these factors cooperate within the PANoptosome,

and the hierarchy of control governing its assembly and signaling,

are not yet fully understood. The dynamic and context-dependent

composition of the PANoptosome, shaped by trigger signals, cell

type and microenvironment, further complicates efforts to define

universal assembly patterns. In vivo, notable technical

barriers also exist in capturing transient, large multiprotein

complexes and their intricate interaction networks. Additionally,

the essential components, recruitment rules, sequential assembly

mechanisms, and possible molecular switches or master regulators of

PANoptosomes remain to be established. Finally, reports of

PANoptosis in kidney diseases beyond AKI (8,110-112), CKD (150,155), DKD (156) and RCC (7,9,132-135) are limited (188). Its roles in hypertensive

nephropathy, nephrotic syndrome, IgA nephropathy, lupus nephritis

and polycystic kidney disease remain largely unexplored. These

knowledge gaps highlight urgent priorities for future

investigation.

Current research has revealed the mechanistic

complexity of PANoptosis, and its involvement in the onset,

progression and potential treatment of AKI, RCC, CKD, DKD and

drug-induced renal injury. The activation and composition of the

PANoptosome are highly variable, reflecting the context-dependent

nature of PANoptosis and offering deeper insight into its

regulatory role in cell death. As a result, PANoptosis has emerged

as a key process closely associated with the development of various

kidney diseases and presents a promising avenue for identifying

novel therapeutic targets. Nevertheless, the role of PANoptosis in

disease is not unidirectional; its effects on disease progression

and treatment can be dual in nature, which is particularly evident

in renal malignancies, where PANoptosis may exert both pro-tumor

and antitumor effects. Furthermore, the dominant cell death

pathways and the composition of PANoptotic complexes may vary

depending on disease etiology or pathological stage. In AKI and

CKD, greater attention should be directed toward cell death

occurring within the renal parenchyma, whereas in RCC, further

investigation is required to elucidate how the tumor immune

microenvironment shapes PANoptosis. These observations underscore

the need for continued in-depth research to elucidate its

regulatory mechanisms and disease-specific outcomes. Although

recent advances have expanded the understanding, the clinical

application of PANoptosis in kidney disease remains in its early

stages, and numerous questions remain unanswered. For example,

while it is known that the composition of the PANoptosome varies

with different stimuli or disease states, the mechanisms underlying

this variability remain unclear. Additionally, although specific

sensors are required to initiate PANoptosis in response to

pathogens or damage-associated signals, the precise identity and

disease-specific roles of these sensors remain to be fully defined.

Therefore, several future research directions merit attention.

First, it is essential to discover and validate reliable biomarkers

that can facilitate the precise selection of therapeutic strategies

targeting PANoptosis. Second, kidney cell-specific mechanisms

should be elucidated, as tubular epithelial cells, podocytes and

endothelial cells may assemble PANoptosomes with distinct

components and functional outputs, which is crucial for therapeutic

specificity. Third, a detailed characterization of the assembly and

regulatory mechanisms of renal PANoptosomes is needed to support

the identification of small-molecule targets. Fourth, across

diverse renal diseases, the validation of hub molecules and the

identification of regulators of PANoptosomes will provide a

foundation for the development of selective inhibitors.

Since its initial conceptualization in 2019, the

concept of PANoptosis has rapidly advanced as a field, offering a

transformative framework to understand the intricate interplay

between cell death and inflammation in kidney diseases. Unlike

strategies that focus on blocking a single cell death pathway,

targeting the integrated process of PANoptosis holds promise for

achieving more effective protection of kidney tissue, attenuation

of inflammation and improved clinical outcomes. Despite ongoing

challenges, continued investigation into kidney-specific mechanisms

of PANoptosis, together with the verification of therapeutic

targets, the development of efficient and safe pharmacological

agents, and the incorporation of precise biomarkers, is expected to

drive major advances. Thus, targeted modulation of PANoptosis may

emerge as a breakthrough approach in nephrology, providing novel

therapeutic opportunities for currently refractory kidney

diseases.

Not applicable.

LJ wrote the original manuscript. YL and LZ revised

the manuscript. ZF and MW searched the literature, and made

substantial contributions to conception and design. ZM edited the

manuscript. ML revised and supervised the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors contributed to the

article, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This work is funded by the National Nature Science Foundation of

China (grant no. 82274482).

|

1

|

Bedoui S, Herold MJ and Strasser A:

Emerging connectivity of programmed cell death pathways and its

physiological implications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:678–695.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Newton K, Strasser A, Kayagaki N and Dixit

VM: Cell death. Cell. 187:235–256. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Malireddi RKS, Kesavardhana S and

Kanneganti TD: ZBP1 and TAK1: Master regulators of NLRP3

inflammasome/pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PAN-optosis).

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 9:4062019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pandian N and Kanneganti TD: PANoptosis: A

unique innate immune inflammatory cell death modality. J Immunol.

209:1625–1633. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang Y, Pandian N, Han JH, Sundaram B, Lee

S, Karki R, Guy CS and Kanneganti TD: Single cell analysis of

PANoptosome cell death complexes through an expansion microscopy

method. Cell Mol Life Sci. 79:5312022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Xie H, Liang B, Zhu Q, Wang L, Li H, Qin

Z, Zhang J, Liu Z and Wu Y: The role of PANoptosis in renal

vascular endothelial cells: Implications for

trichloroethylene-induced kidney injury. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf.

278:1164332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mall R and Kanneganti TD: Comparative

analysis identifies genetic and molecular factors associated with

prognostic clusters of PANoptosis in glioma, kidney and melanoma

cancer. Sci Rep. 13:209622023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Uysal E, Dokur M, Kucukdurmaz F, Altınay

S, Polat S, Batcıoglu K, Sezgın E, Sapmaz Erçakallı T, Yaylalı A,

Yılmaztekin Y, et al: Targeting the PANoptosome with 3,4-meth

ylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene, reduces PANoptosis and protects the

kidney against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Invest Surg.

35:1824–1835. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jiang Z, Wang J, Dao C, Zhu M, Li Y, Liu

F, Zhao Y, Li J, Yang Y and Pan Z: Utilizing a novel model of

PANoptosis-related genes for enhanced prognosis and immune status

prediction in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Apoptosis.

29:681–692. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yi BJ, Wang CC, Li XW, Xu YR, Ma XY, Jian

PA, Talukder M, Li XN and Li JL: Lycopene protects against

atrazine-induced kidney STING-dependent panoptosis through

stabilizing mtDNA via interaction with Sam50/PHB1. J Agric Food

Chem. 72:14956–14966. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li YP, Zhou ZY, Yan L, You YP, Ke HY, Yuan

T, Yang HY, Xu R, Xu LH, Ouyang DY, et al: Inflammatory cell death

PANoptosis is induced by the anti-cancer curaxin CBL0137 via

eliciting the assembly of ZBP1-associated PANoptosome. Inflamm Res.

73:597–617. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Karki R, Sharma BR, Lee E, Banoth B,

Malireddi RKS, Samir P, Tuladhar S, Mummareddy H, Burton AR, Vogel

P and Kanneganti TD: Interferon regulatory factor 1 regulates

PANoptosis to prevent colorectal cancer. JCI Insight.

5:e1367202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kerr JF, Wyllie AH and Currie AR:

Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging

implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 26:239–257. 1972.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kroemer G: The pharmacology of T cell

apoptosis. Adv Immunol. 58:211–296. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tsujimoto Y: Role of Bcl-2 family proteins

in apoptosis: Apoptosomes or mitochondria? Genes Cells. 3:697–707.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Li PF, Dietz R and von Harsdorf R: p53

regulates mitochondrial membrane potential through reactive oxygen

species and induces cytochrome c-independent apoptosis blocked by

Bcl-2. EMBO J. 18:6027–6036. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Czabotar PE, Lessene G, Strasser A and

Adams JM: Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family:

Implications for physiology and therapy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

15:49–63. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kalkavan H and Green DR: MOMP, cell

suicide as a BCL-2 family business. Cell Death Differ. 25:46–55.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado

AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP and Wang X: Prevention of apoptosis by

Bcl-2: Release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science.

275:1129–1132. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Green DR and Reed JC: Mitochondria and

apoptosis. Science. 281:1309–1312. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hengartner MO and Horvitz HR: The ins and

outs of programmed cell death during C. elegans development. Philos

Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 345:243–246. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fox JL, Hughes MA, Meng X, Sarnowska NA,

Powley IR, Jukes-Jones R, Dinsdale D, Ragan TJ, Fairall L, Schwabe

JWR, et al: Cryo-EM structural analysis of FADD:Caspase-8 complexes

defines the catalytic dimer architecture for co-ordinated control

of cell fate. Nat Commun. 12:8192021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fu TM, Li Y, Lu A, Li Z, Vajjhala PR, Cruz

AC, Srivastava DB, DiMaio F, Penczek PA, Siegel RM, et al: Cryo-EM

structure of caspase-8 tandem DED filament reveals assembly and

regulation mechanisms of the death-inducing signaling complex. Mol

Cell. 64:236–250. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Kellert B,

Dimitrova DP, Langlais C, Hupe M, Cain K, MacFarlane M, Häcker G

and Leverkus M: cIAPs block Ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/caspase-8

containing intracellular cell death complex differentially

regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Mol Cell. 43:449–463. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Carneiro BA and El-Deiry WS: Targeting

apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 17:395–417. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Van Opdenbosch N and Lamkanfi M: Caspases

in cell death, inflammation, and disease. Immunity. 50:1352–1364.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Seol DW, Li J, Seol MH, Park SY, Talanian

RV and Billiar TR: Signaling events triggered by tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL): Caspase-8 is

required for TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 61:1138–1143.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap

P, Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA and Yuan J:

Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic

potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 1:112–119.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Khoury MK, Gupta K, Franco SR and Liu B:

Necroptosis in the pathophysiology of disease. Am J Pathol.

190:272–285. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Weinlich R, Oberst A, Beere HM and Green

DR: Necroptosis in development, inflammation and disease. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 18:127–136. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Murphy JM: The killer pseudokinase mixed

lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL). Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Biol. 12:a0363762020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Petrie EJ, Sandow JJ, Lehmann WIL, Liang

LY, Coursier D, Young SN, Kersten WJA, Fitzgibbon C, Samson AL,

Jacobsen AV, et al: Viral MLKL homologs subvert necroptotic cell

death by sequestering cellular RIPK3. Cell Rep. 28:3309–3319.e5.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, Thome M,

Attinger A, Valitutti S, Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Seed B and Tschopp

J: Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death

pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol.

1:489–495. 2000. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

He S, Liang Y, Shao F and Wang X:

Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages

through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 108:20054–20059. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kaiser WJ, Sridharan H, Huang C, Mandal P,

Upton JW, Gough PJ, Sehon CA, Marquis RW, Bertin J and Mocarski ES:

Toll-like receptor 3-mediated necrosis via TRIF, RIP3, and MLKL. J

Biol Chem. 288:31268–31279. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang T, Wang Y, Inuzuka H and Wei W:

Necroptosis pathways in tumorigenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:32–40.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray

TD, Guildford M and Chan FK: Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the

RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced

inflammation. Cell. 137:1112–1123. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vanden Berghe T, Kaiser WJ, Bertrand MJ

and Vandenabeele P: Molecular crosstalk between apoptosis,

necroptosis, and survival signaling. Mol Cell Oncol. 2:e9750932015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Wong WW, Gentle IE, Nachbur U, Anderton H,

Vaux DL and Silke J: RIPK1 is not essential for TNFR1-induced

activation of NF-kappaB. Cell Death Differ. 17:482–487. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang

LF, Wang FS and Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein

MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by

RIP3. Mol Cell. 54:133–146. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cai Z, Jitkaew S, Zhao J, Chiang HC,

Choksi S, Liu J, Ward Y, Wu LG and Liu ZG: Plasma membrane

translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for

TNF-induced necroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 16:55–65. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Robinson N, McComb S, Mulligan R, Dudani

R, Krishnan L and Sad S: Type I interferon induces necroptosis in

macrophages during infection with Salmonella enterica serovar

Typhimurium. Nat Immunol. 13:954–962. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

McComb S, Cessford E, Alturki NA, Joseph

J, Shutinoski B, Startek JB, Gamero AM, Mossman KL and Sad S:

Type-I interferon signaling through ISGF3 complex is required for

sustained Rip3 activation and necroptosis in macrophages. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 111:E3206–E3213. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xia B, Fang S, Chen X, Hu H, Chen P, Wang

H and Gao Z: MLKL forms cation channels. Cell Res. 26:517–528.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Negroni A, Colantoni E, Cucchiara S and

Stronati L: Necroptosis in intestinal inflammation and cancer: New

concepts and therapeutic perspectives. Biomolecules. 10:14312020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Woo Y, Lee HJ, Jung YM and Jung YJ:

Regulated necrotic cell death in alternative tumor therapeutic

strategies. Cells. 9:27092020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zychlinsky A, Prevost MC and Sansonetti

PJ: Shigella flexneri induces apoptosis in infected macrophages.

Nature. 358:167–169. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hilbi H, Moss JE, Hersh D, Chen Y, Arondel

J, Banerjee S, Flavell RA, Yuan J, Sansonetti PJ and Zychlinsky A:

Shigella-induced apoptosis is dependent on caspase-1 which binds to

IpaB. J Biol Chem. 273:32895–32900. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Cookson BT and Brennan MA:

Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol.

9:113–114. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wallach D, Kang TB, Dillon CP and Green

DR: Programmed necrosis in inflammation: Toward identification of

the effector molecules. Science. 352:aaf21542016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli

VG, Wu H and Lieberman J: Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes

pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature. 535:153–158. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Atabaki R, Khaleghzadeh-Ahangar H,

Esmaeili N and Mohseni-Moghaddam P: Role of pyroptosis, a

pro-inflammatory programmed cell death, in epilepsy. Cell Mol

Neurobiol. 43:1049–1059. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Bergsbaken T, Fink SL and Cookson BT:

Pyroptosis: Host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol.

7:99–109. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Rathinam VAK, Vanaja SK, Waggoner L,

Sokolovska A, Becker C, Stuart LM, Leong JM and Fitzgerald KA: TRIF

licenses caspase-11-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by

gram-negative bacteria. Cell. 150:606–619. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Fritsch M, Günther SD, Schwarzer R, Albert

MC, Schorn F, Werthenbach JP, Schiffmann LM, Stair N, Stocks H,

Seeger JM, et al: Caspase-8 is the molecular switch for apoptosis,

necroptosis and pyroptosis. Nature. 575:683–687. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Gurung P, Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Vande

Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Green DR,

Lamkanfi M and Kanneganti TD: FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming

and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3

inflammasomes. J Immunol. 192:1835–1846. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Man SM, Tourlomousis P, Hopkins L, Monie

TP, Fitzgerald KA and Bryant CE: Salmonella infection induces

recruitment of caspase-8 to the inflammasome to modulate IL-1β

production. J Immunol. 191:5239–5246. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Van Opdenbosch N, Van Gorp H, Verdonckt M,

Saavedra PHV, de Vasconcelos NM, Gonçalves A, Vande Walle L, Demon

D, Matusiak M, Van Hauwermeiren F, et al: Caspase-1 engagement and

TLR-induced c-FLIP expression suppress ASC/caspase-8-dependent

apoptosis by inflammasome sensors NLRP1b and NLRC4. Cell Rep.

21:3427–3444. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Park MY, Ha SE, Vetrivel P, Kim HH,

Bhosale PB, Abusaliya A and Kim GS: Differences of key proteins

between apoptosis and necroptosis. Biomed Res Int.

2021:34201682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Newton K, Wickliffe KE, Dugger DL,

Maltzman A, Roose-Girma M, Dohse M, Kőműves L, Webster JD and Dixit

VM: Cleavage of RIPK1 by caspase-8 is crucial for limiting

apoptosis and necroptosis. Nature. 574:428–431. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe

T and Kroemer G: Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: An ordered

cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11:700–714. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Schwarzer R, Laurien L and Pasparakis M:

New insights into the regulation of apoptosis, necroptosis, and

pyroptosis by receptor interacting protein kinase 1 and caspase-8.

Curr Opin Cell Biol. 63:186–193. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG and Goeddel DV:

TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF

receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 84:299–308. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Rodriguez DA,

Cripps JG, Quarato G, Gurung P, Verbist KC, Brewer TL, Llambi F,

Gong YN, et al: RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by

caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell. 157:1189–1202. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Orning P, Weng D, Starheim K, Ratner D,

Best Z, Lee B, Brooks A, Xia S, Wu H, Kelliher MA, et al: Pathogen

blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin

D and cell death. Science. 362:1064–1069. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Sarhan J, Liu BC, Muendlein HI, Li P,

Nilson R, Tang AY, Rongvaux A, Bunnell SC, Shao F, Green DR and

Poltorak A: Caspase-8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit

pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

115:E10888–E10897. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Hou J, Zhao R, Xia W, Chang CW, You Y, Hsu

JM, Nie L, Chen Y, Wang YC, Liu C, et al: PD-L1-mediated gasdermin

C expression switches apoptosis to pyroptosis in cancer cells and

facilitates tumour necrosis. Nat Cell Biol. 22:1264–1275. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Wang Y, Karki R, Zheng M, Kancharana B,

Lee S, Kesavardhana S, Hansen BS, Pruett-Miller SM and Kanneganti

TD: Cutting edge: Caspase-8 is a linchpin in caspase-3 and

gasdermin D activation to control cell death, cytokine release, and

host defense during influenza A virus infection. J Immunol.

207:2411–2416. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Rogers C, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Mayes L,

Alnemri D, Cingolani G and Alnemri ES: Cleavage of DFNA5 by

caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary

necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat Commun. 8:141282017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H,

Wang K and Shao F: Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through

caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature. 547:99–103. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Tsuchiya K, Nakajima S, Hosojima S, Thi

Nguyen D, Hattori T, Manh Le T, Hori O, Mahib MR, Yamaguchi Y,

Miura M, et al: Caspase-1 initiates apoptosis in the absence of

gasdermin D. Nat Commun. 10:20912019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD, Van Damme P,

Vanden Berghe T, Vanoverberghe I, Vandekerckhove J, Vandenabeele P,

Gevaert K and Núñez G: Targeted peptidecentric proteomics reveals

caspase-7 as a substrate of the caspase-1 inflammasomes. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 7:2350–2363. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Conos SA, Chen KW, De Nardo D, Hara H,

Whitehead L, Núñez G, Masters SL, Murphy JM, Schroder K, Vaux DL,

et al: Active MLKL triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome in a

cell-intrinsic manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E961–E969. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Gutierrez KD, Davis MA, Daniels BP, Olsen

TM, Ralli-Jain P, Tait SW, Gale M Jr and Oberst A: MLKL activation

triggers NLRP3-mediated processing and release of IL-1β

independently of gasdermin-D. J Immunol. 198:2156–2164. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón

G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM and Núñez G: K+ efflux is the

common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins

and particulate matter. Immunity. 38:1142–1153. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Lawlor KE, Khan N, Mildenhall A, Gerlic M,

Croker BA, D'Cruz AA, Hall C, Kaur Spall S, Anderton H, Masters SL,

et al: RIPK3 promotes cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation

in the absence of MLKL. Nat Commun. 6:62822015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Malireddi RKS, Gurung P, Mavuluri J,

Dasari TK, Klco JM, Chi H and Kanneganti TD: TAK1 restricts

spontaneous NLRP3 activation and cell death to control myeloid

proliferation. J Exp Med. 215:1023–1034. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Zheng M, Karki R, Vogel P and Kanneganti

TD: Caspase-6 is a key regulator of innate immunity, inflammasome

activation, and host defense. Cell. 181:674–687.e13. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Malireddi RKS, Gurung P, Kesavardhana S,

Samir P, Burton A, Mummareddy H, Vogel P, Pelletier S, Burgula S

and Kanneganti TD: Innate immune priming in the absence of TAK1

drives RIPK1 kinase activity-independent pyroptosis, apoptosis,

necroptosis, and inflammatory disease. J Exp Med.

217:jem.201916442020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Christgen S, Tweedell RE and Kanneganti

TD: Programming inflammatory cell death for therapy. Pharmacol

Ther. 232:1080102022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

81

|

Tweedell RE and Kanneganti TD: Advances in

inflammasome research: Recent breakthroughs and future hurdles.

Trends Mol Med. 26:969–971. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Lee S, Karki R, Wang Y, Nguyen LN,

Kalathur RC and Kanneganti TD: AIM2 forms a complex with pyrin and

ZBP1 to drive PANoptosis and host defence. Nature. 597:415–419.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Shi C, Cao P, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Zhang D,

Wang Y, Wang L and Gong Z: PANoptosis: A cell death characterized

by pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis. J Inflamm Res.

16:1523–1532. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Banoth B, Tuladhar S, Karki R, Sharma BR,

Briard B, Kesavardhana S, Burton A and Kanneganti TD: ZBP1 promotes

fungi-induced inflammasome activation and pyroptosis, apoptosis,

and necroptosis (PANoptosis). J Biol Chem. 295:18276–18283. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kesavardhana S, Malireddi RKS, Burton AR,

Porter SN, Vogel P, Pruett-Miller SM and Kanneganti TD: The Zα2

domain of ZBP1 is a molecular switch regulating influenza-induced

PANoptosis and perinatal lethality during development. J Biol Chem.

295:8325–8330. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Karki R, Lee S, Mall R, Pandian N, Wang Y,

Sharma BR, Malireddi RS, Yang D, Trifkovic S, Steele JA, et al:

ZBP1-dependent inflammatory cell death, PANoptosis, and cytokine

storm disrupt IFN therapeutic efficacy during coronavirus

infection. Sci Immunol. 7:eabo62942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Malireddi RKS, Kesavardhana S, Karki R,

Kancharana B, Burton AR and Kanneganti TD: RIPK1 distinctly

regulates Yersinia-induced inflammatory cell death, PANoptosis.

Immunohorizons. 4:789–796. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Sundaram B, Pandian N, Mall R, Wang Y,

Sarkar R, Kim HJ, Malireddi RKS, Karki R, Janke LJ, Vogel P and

Kanneganti TD: NLRP12-PANoptosome activates PANoptosis and

pathology in response to heme and PAMPs. Cell. 186:2783–2801.e20.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Kuriakose T, Man SM, Malireddi RK, Karki

R, Kesavardhana S, Place DE, Neale G, Vogel P and Kanneganti TD:

ZBP1/DAI is an innate sensor of influenza virus triggering the

NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death pathways. Sci Immunol.

1:aag20452016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Rebsamen M, Heinz LX, Meylan E, Michallet

MC, Schroder K, Hofmann K, Vazquez J, Benedict CA and Tschopp J:

DAI/ZBP1 recruits RIP1 and RIP3 through RIP homotypic interaction

motifs to activate NF-kappaB. EMBO Rep. 10:916–922. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Upton JW, Kaiser WJ and Mocarski ES:

DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced

programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus

vIRA. Cell Host Microbe. 11:290–297. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Kuriakose T and Kanneganti TD: ZBP1:

Innate sensor regulating cell death and inflammation. Trends

Immunol. 39:123–134. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

93

|

Thapa RJ, Ingram JP, Ragan KB, Nogusa S,

Boyd DF, Benitez AA, Sridharan H, Kosoff R, Shubina M, Landsteiner

VJ, et al: DAI senses influenza A virus genomic RNA and activates

RIPK3-dependent cell death. Cell Host Microbe. 20:674–681. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Zheng M and Kanneganti TD: Newly

identified function of caspase-6 in ZBP1-mediated innate immune

responses, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, PANoptosis, and host

defense. J Cell Immunol. 2:341–347. 2020.

|

|

95

|

Momota M, Lelliott P, Kubo A, Kusakabe T,

Kobiyama K, Kuroda E, Imai Y, Akira S, Coban C and Ishii KJ: ZBP1

governs the inflammasome-independent IL-1α and neutrophil

inflammation that play a dual role in anti-influenza virus

immunity. Int Immunol. 32:203–212. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Hornung V, Ablasser A, Charrel-Dennis M,

Bauernfeind F, Horvath G, Caffrey DR, Latz E and Fitzgerald KA:

AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating

inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 458:514–518. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Bürckstümmer T, Baumann C, Blüml S, Dixit

E, Dürnberger G, Jahn H, Planyavsky M, Bilban M, Colinge J, Bennett

KL and Superti-Furga G: An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen

identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome.

Nat Immunol. 10:266–272. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|