Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a distinct

BC subtype characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor,

progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

expression, along with unique molecular expression characteristics

(such as frequent mutations in TP53 and PIK3CA, and

dysregulation of MYC, EGFR and Wnt/β-catenin pathways), biological

behavior (such as early visceral metastasis and 'metastatic burst'

within 3 years post-diagnosis) and clinicopathological features

(such as higher histological grade, stromal tumor-infiltrating

lymphocytes and poorer 5-year survival) (1). TNBC exhibits a high rate of distant

metastasis (liver: 34.5%; brain: 9.8%; lung: 32.4%), high odds of

visceral and brain metastases, rapid progression (3-year distant

metastasis-free rate: 57.9% vs. 85.2% in luminal A; 1-year

recurrence rate after surgery: 18.4%), and limited treatment

options (2-6). Understanding the molecular basis of

TNBC occurrence and progression and identifying efficient

therapeutic targets are key issues in TNBC treatment that warrant

urgent attention.

BC stem cells (BCSCs) are tumor-initiating cells

that can self-renew and are highly tumorigenic. An increasing

amount of studies suggest that cancer stem cells promote

tumorigenesis, metastasis, recurrence and drug resistance as well

as are the major source for heterogeneity of cancer cells (7-9).

In 2003, Al-Hajj et al (10) purified BCSCs from BC patient

samples for the first time and showed that tumor stem cells, even

in limited quantities, induced tumorigenesis in immunodeficient

mice. At present, strategies for identifying BCSCs are primarily

based on two key biological characteristics of BCSCs, namely their

self-renewal ability and their differentiation ability, which

enable them to evade the effects of most cytotoxic chemotherapeutic

drugs (11). BCSCs also

frequently exhibit high levels of drug efflux and a superior

metabolic capacity. This makes them more likely to survive

chemotherapy than non-BCSCs, which leads to tumor recurrence and

metastasis (12,13). Therefore, combined treatment with

cancer stem cell antagonists and conventional cancer treatment

tools is a promising therapeutic approach for reducing BC

recurrence and metastasis.

The centromere protein U (CENPU) gene,

located on chromosome 4q35.1, participates in mitosis as an

important part of the centromere complex (14). In our previous study, it was

demonstrated that CENPU promoted angiogenesis in TNBC by

suppressing the ubiquitin-related degradation of cyclooxygenase-2

(15). In non-small cell lung

cancer, CENPU enhances the proliferative, migratory and invasive

potential of cells by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

(16). However, the mechanisms

underlying the effects of CENPU on BC formation are not

well-documented.

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is an important

neurotrophic factor involved in the regulation of cell

differentiation and target neuron survival. Both NGF and NGF

precursor protein (proNGF) are biologically active, but the two

proteins may have contrasting biological functions (17-20). The maturation of proNGF to NGF

requires cleavage by furin precursor protein-processing enzymes

(21,22).

Furin is the earliest discovered mammalian precursor

protein-processing enzyme and is primarily responsible for the

cleavage of functional proteins in an organism (23). Excessive or aberrant cleavage by

furin is associated with diseases, such as cancer (24). The shearing action of furin on

proNGF contributes to the paradoxical biological function of its

downstream receptors that activate different pathways depending on

the form of its ligand. Unprocessed proNGF exerts its

apoptosis-promoting effects by binding to low-affinity p75

neurotrophin receptor. By contrast, furin-processed NGF mediates

survival in tumor cells through high-affinity binding to the

tropomyosin receptor kinase A proto-oncogene receptor, which

interacts with and phosphorylates STAT3 to enhance gene

transcription and promote BCSC properties in TNBC and HER2-enriched

BC (20,25).

The study of BCSCs and their role in tumor

progression is crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies.

The objective of the present study was to investigate the

expression of CENPU in different types of breast lesions and its

potential role in BCSC self-renewal, tumorigenesis and the invasive

behavior of BC cells. Understanding the mechanisms underlying CENPU

function could provide insights into the molecular pathways that

drive BC aggression and metastasis. To achieve these aims, a

combination of immunohistochemistry, functional assays and

mechanistic studies was employed to explore the expression patterns

and functional significance of CENPU in BC cell lines.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Human MDA-MB-231 (TNBC) and T47D (BC) cells were

acquired from the American Type Culture Collection. Cal51 (TNBC)

cells were acquired from the German Collection of Microorganisms

and Cell Cultures GmbH. Cell culture was performed as previously

described (15). Specifically,

Cal51 was cultured in 15% DMEM/F12 medium, MDA-MB-231 in 10% DMEM

high-glucose medium, and T47D (luminal) in 10% RPMI-1640 medium

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All the media were

supplemented with 10% FBS (cat. no. 04-001-1ACS; Biological

Industries; Sartorius AG) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no.

P1400; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The

cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5%

CO2 and sub-cultured at 75-85% confluence. Cycloheximide

(CHX; cat. no. HY-12320) (20 μM) was purchased from

MedChemExpress. MG132 (cat. no. Y210207) (10 μM) and

chloroquine (CQ; cat. no. Y210184) (100 μM) were purchased

from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. Cell treatments were

performed at 37°C for 12 h. NGF-neutralizing antibody (cat. no.

ALM-006-250UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used at a final

concentration of 1 μg/ml in complete culture medium at 37°C

for 24 h before subsequent assays.

Immunoblotting

MDA-MB-231, T47D and Cal51 cells were lysed with

RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

supplemented with 1% PMSF. Cellular proteins were quantified using

a BCA Assay kit (MilliporeSigma). Equal volumes of total protein

(30 μg) were resolved using 10% SDS-PAGE and

electro-transferred onto PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma), and the

membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room

temperature. Next, the membranes were incubated with primary

antibodies overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used were as

follows: CENPU (1:1,000; cat. no. YN1585; Immunoway Biotechnology

Company), aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH; 0.5 μg/ml; cat. no.

ab131068; Abcam), CD44 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab243894; Abcam), NGF (1

μg/ml; cat. no. ab6199; Abcam), proNGF (1:500; cat. no.

ab221609; Abcam), furin (1:1,000; cat. no. 18413-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) and GAPDH (1:10,000; cat. no. 60004-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.). Subsequently, incubation with HRP-conjugated

secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature was performed. The

secondary antibodies used were anti-mouse HRP-conjugated IgG

(1:4,500; cat. no. AS003; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated IgG (1:4,500; cat. no. AS014; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.). Detection was performed using an ECL system

(PerkinElmer, Inc.). The target protein levels were normalized to

those of GAPDH. The band densities were analyzed using ImageJ

software (version 1.50i; National Institutes of Health).

Clinical specimen collection

BC and adjacent (>2 cm from the cancer tissue)

non-cancerous breast tissue specimens from 67 female patients

(median age, 45 years; range, 32-65 years) enrolled between January

2023 and June 2024 in Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute,

Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Academy of Medical

Sciences (Jinan, China) were used in immunoblotting and

immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiments. The study protocol was

approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shandong Cancer

Hospital and Institute, Shandong First Medical University and

Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (approval no.

SDTHEC2022009017; Jinan, China). The patient inclusion criteria

were as follows: i) First diagnosis of breast cancer; ii) patients

had not received any chemotherapy or hormone treatment; iii)

without breast surgery history; and iv) without motion artifact.

Breast cancer diagnosis was validated using ultrasound and MRI.

IHC

After being fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin

at room temperature for 24 h, the tissue was embedded in paraffin

and cut into 5-μm sections. Tissue sections were dewaxed by

treatment with xylene, followed by rehydration in an ethanol

gradient (5 min each). Subsequently, the sections were treated with

an antigen retrieval solution in a microwave oven for 10 min,

incubated in 3% H2O2 at 37°C for 15 min,

washed with PBS and blocked with 3% BSA (cat. no. A8020; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature

for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with anti-CENPU

(1:100; cat. no. 13186-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-proNGF

(1:200; cat. no. ANT-005; Alomone Labs), anti-NGF (1:300; cat. no.

ab216419; Abcam) and anti-furin (10 μg/ml; cat. no.

ab231573; Abcam) antibodies overnight at 4°C. Next, the sections

were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:1,000; cat. no. ab6721;

Abcam) at room temperature for 1 h. The signal was developed using

a 3,3'-diaminobenzidine color reagent, and the sections were

stained with hematoxylin at 37°C for 3 min, sealed and observed

under a light microscope (Nikon Corporation). Stained slides

scanned by Panoramic SCAN II (3DHISTECH, Ltd.) and images were

captured by CaseViewer software (version 2.9.0; 3dhistech.

com/news/caseviewer-becomes-slideviewer/). The H-score is

determined by the formula H-SCORE=∑(PI × I), where PI represents

the percentage of cells with a specific staining intensity and I

represents the corresponding staining intensity level.

Specifically, it is computed as (percentage of weakly-stained cells

x1) + (percentage of moderately-stained cells x2) + (percentage of

strongly-stained cells x3). The resulting H-score ranges from 0 to

300. The staining intensity and extent of positivity were evaluated

using the aforementioned scoring system to provide a

semi-quantitative estimation of overall staining patterns. The

composite scores were used to compare expression trends among

groups.

Transfection

A short hairpin RNA (sh/shRNA) against CENPU

(shCENPU) and a scrambled control shRNA (CON313) from

Syngentech Co., Ltd. were used. The target sequences of the shRNAs

were as follows: CON313, 5'-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3'; and

shCENPU, 5'-CAGGTATGAGCTATAATAA-3'. Cal51 and MDA-MB-231

cells were infected with shRNA-encoding lentiviruses to generate

stable cell lines. The lentiviral transfer vector pLKO.1-puro was

utilized within a third-generation system comprising packaging

plasmids pMD2.G and psPAX2. Transient transfection was performed in

293T cells (American Type Culture Collection) using Lipofectamine

3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 4 μg

total DNA at a 4:3:1 ratio (transfer vector:psPAX2:pMD2.G).

Transfected cells were maintained at 37°C for 72 h, and viral

supernatants were collected at 48/72 h, filtered (0.45 μm)

and concentrated by centrifugation (16 h at 6,800 rpm) at 4°C.

Target cells (MDA-MB-231/Cal51) were infected at MOI=10 with 8

μg/ml polybrene for 24 h. Post-transduction, cells underwent

puromycin selection (2 μg/ml for MDA-MB-231; 1 μg/ml

for Cal51) for 7 days, followed by maintenance at half-selection

dose. Functional assays were conducted ≥14 days post-selection to

ensure stable expression.

A CENPU overexpression plasmid and control

plasmid (CON220) from Syngentech Co., Ltd. were also used.

Transient transfection of MDA-MB-231 and Cal51 cells used

pcDNA3.1(+) with 2 μg plasmid DNA (A260/A280=1.85±0.05) per

35-mm well dish. Transfections employed Lipofectamine 3000 at a 1:2

DNA (μg):reagent (μl) ratio. Cells were incubated

with DNA-lipid complexes at 37°C for 6 h before medium replacement.

Further analyses were performed 24-48 h post-transfection.

ELISA

ELISA was performed using MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D

cell lysates. Cells were resuspended in PBS at a density of

1×106 cells/ml and subjected to ultrasonication on ice

using a Covaris E220 system (Covaris, LLC) under the following

parameters: 20 kHz frequency, 10-sec pulses per cycle (3 cycles in

total), with 10-sec intervals between pulses. After centrifugation

at 2,000-3,000 rpm at 2-8°C for 20 min, the supernatant was

collected and ELISA was performed using an NGF ELISA kit (cat. no.

LP-H017695; Shanghai Lanpai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Cell migration and invasion assays

A wound healing assay was performed to assess the

migratory potential of cells. MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D cells were

seeded in 6-well plates and cultured until the confluency was

>90%. After serum starvation, the cells were scratched with a

10-μl pipette tip to artificially create wounds on the cell

surface, and were imaged under a light microscope at 0 and 48 h.

ImageJ software (version 1.50i) was used for quantification of the

wound.

A Matrigel-precoated Transwell chamber (with

8-μm pores) was used for the invasion assay, while the

migration assay was performed using Transwell inserts without

Matrigel precoating, as previously described (15). A total of 150 μl Matrigel

diluent (Matrigel:DMEM=1:8; cat. no. 356234; Corning, Inc.) was

spread evenly on the cell inserts, which were placed in a 37°C and

5% CO2 incubator until the Matrigel solidified. A total

of 5×104 cells/ml were diluted in DMEM without FBS. A

total of 150 μl of the diluted cells were placed in the

upper layer of the Transwell chamber and 600 μl of DMEM

supplemented with 20% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Following

incubation (10-12 h for MDA-MB-231 and Cal51 cells and 24-36 h for

T47D cells), the cells in the upper chamber were gently wiped with

a cotton swab, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature

for 15 min, stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature

for 15 min and photographed under a light microscope. ImageJ

software (version 1.50i) was used for quantification.

Mammosphere formation assay

MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were collected, washed twice with serum-free DMEM/F12,

counted, and resuspended in DMEM/F12 without serum, supplemented

with B27, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor and 20 ng/ml basic

fibroblast growth factor (all from Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). A total of 2×103 cells/well were

seeded in an ultra-low adhesion culture plate (Corning, Inc.).

After 7 days of culture at 37°C, images were acquired under an

inverted light microscope and the mammospheres formed (defined as

cell clusters with a diameter ≥30 μm, with clear boundaries

and intact morphology) were counted. ImageJ software (version

1.50i) was used for quantification.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Lysates from MDA-MB-231 and Cal51 cells prepared in

RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were centrifuged at

12,000 × g, 4°C for 10 min to remove the debris. Per reaction, 500

μg total protein was incubated overnight with: Anti-CENPU

(1:2,000, cat. no. YN1585; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company),

anti-furin (1:1,000, cat. no. ab3467; Abcam), anti-proNGF (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab52918; Abcam) or rabbit IgG control (2

μg/reaction; cat. no. 2729; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.). Immune complexes were captured using the Pierce Co-IP kit

(cat. no. 88804; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions, employing Protein A/G magnetic beads

(cat. no. 88802; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The precipitated

proteins were analyzed by western blotting.

4D-data-independent acquisition (DIA)

quantitative proteomics

MDA-MB-231 cell lines transfected with the control

vector CON313, with knockdown of the CENPU gene (shCENPU),

and overexpression of CENPU were used, and the protein precipitates

obtained after acetone precipitation of the cell lysates were

collected as experimental samples. The samples were treated with

liquid nitrogen and grinded into powder, and were subsequently

incubated in lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% SDS, 40 mM

Tris-HCl; pH 8.5) containing 1 mM PMSF and 2 mM EDTA (final

concentration) at 4°C for 5 min. The samples were mixed thoroughly

and sonicated using an ultrasonic disruptor at 25% power for 10

min. Subsequently, they were centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for

10 min, and the supernatant was collected. Four times the volume of

cold acetone was added to the supernatant, and it was allowed to

precipitate overnight at −20°C, followed by centrifugation at

12,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. The precipitate was retained, washed

with cold acetone, and centrifuged again at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 5

min. The precipitate was again retained, and the washing step was

repeated three times. The protein pellets were air-dried and

resuspended in 8 M urea/100 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (pH

8.0). The BCA protein quantitation assay was used to measure the

total protein concentration. Subsequently, protein hydrolysis and

desalination are carried out. Liquid chromatography (LC) was

performed on a nanoElute UHPLC (Bruker Corporation). In total, ~200

ng peptides were separated within 40 min at a flow rate of 0.3

μl/min on a commercially available reverse-phase C18 column

with an integrated CaptiveSpray Emitter (25 cm × 75 μm; 1.6

μm particle size; Aurora Series with CSI; IonOpticks). The

separation temperature was kept by an integrated Toaster column

oven at 50°C. Mobile phases A and B were produced with 0.1% formic

acid in water and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Mobile phase B

was increased from 2 to 22% over the first 25 min, increased to 35%

over the next 5 min, further increased to 80% over the next 5 min,

and then held at 80% for 5 min. The LC process was coupled online

to a hybrid timsTOF Pro2 mass spectrometer via a CaptiveSpray

nano-electrospray ion source (Bruker Corporation). To establish the

applicable acquisition windows, timsTOF Pro2 was operated in

Data-Independent Parallel Accumulation-Serial Fragmentation (PASEF)

mode with four PASEF MS/MS frames in one complete frame. The

capillary voltage was set to 1,500 V, and the MS and MS/MS spectra

were acquired from 100 to 1,700 m/z. As for ion mobility range

(1/), 0.85 to 1.3 Vs/was used. The 'target value' of 10,000 was

applied to a repeated schedule, and the intensity threshold was set

at 2,500. The range of charge state was set from 0 to 5. The

collision energy was ramped linearly as a function of mobility from

45eV at 1/=1.3 Vs/to 27 eV at 1/=0.85 Vs/. The quadrupole isolation

width was set to 2 Thomson for m/z <700 and 3 Th for m/z

>800. Raw mass spectrometry data were analyzed with DIA-NN

software (v1.8.1) (https://github.com/vdemichev/DiaNN) using the

library-free method. The Homo sapiens SwissProt database

(https://www.uniprot.org/; 20,425 entries) was

used to create a spectral library with deep learning algorithms of

neural networks. Match Between Runs was applied to align precursor

retention times and m/z values across DIA runs, enabling cross-run

matching of peptide identifications; a spectral library from DIA

data was created and the data were reanalyzed using this library.

To comprehensively elucidate the functional characteristics of

various proteins, R software (clusterProfiler) version 3.10.1

(https://bioconductor.org/packages/clusterProfiler) was

employed to conduct functional annotation and enrichment analysis

on both the identified proteins and differentially expressed

proteins in each comparison group. This analysis encompassed Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Disease Ontology (DO)

(Fig. S1A and B), wherein all

differentially expressed proteins were mapped to the corresponding

terms in the KEGG (https://www.kegg.jp/) and DO (http://www.disease-ontology.org/) databases. The

number of proteins associated with each term was calculated,

followed by a hypergeometric test (equivalent to Fisher's exact

test; implemented in the R stats package version 4.3.2; https://www.r-project.org/) to identify significantly

enriched KEGG and DO terms among the differentially expressed

proteins. KEGG/DO terms were considered significantly enriched if

they met FDR-adjusted P<0.05 and fold change >2 (log2FC

>1).

Flow cytometry

MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D cells were used for the

experiment. After resuspending the cells with PBS, the proportion

of CD24−CD44+ cells was detected using a flow

cytometer. The cells were incubated with CD44 APC (1:40; cat. no.

559942; BD Biosciences) and CD24 PE (1:50; cat. no. 555428; BD

Biosciences) at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. Isotype controls, APC

IgG (1:100; cat. no. 555751; BD Biosciences) and PE IgG (1:100;

cat. no. 555749; BD Biosciences), were incubated under the same

conditions. A BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was

used for data acquisition, and the data were analyzed using FlowJo

v10.8.1 (Becton, Dickinson and Company).

Furin activity measurement

Furin activity in MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D cells

was measured by assessing the ability of the cells to digest

pERTKR-MCA. Briefly, each cell extract was incubated with

pERTKR-MCA (100 M) in a solution composed of 25 mM Tris, 25 mM

methyl-ethane-sulfonic acid and 2.5 mM CaCl2 (pH 7.4) at

37°C. Measurements were taken every 5 min for a total duration of

100 min. At a pH of 6.0 and a Ca2+ concentration of 1 mM, the

catalytic activity of furin was dynamically detected using a

fluorometer. The Km value was derived from the

Michaelis-Menten curve fitted to the enzymatic activity data

(velocity vs. substrate concentration). In the present study,

Km is indirectly reflected by the substrate

concentration at which the reaction velocity reaches half of

Vmax. A spectrofluorometer (FLUOstar OPTIMA; BMG

Labtech GmbH) was used for analysis. A furin inhibitor,

decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethyl ketone (DECRVKR-CMK) purchased from

Calbiochem (Merck KGaA), was used at a concentration of 10

μM. Cells were treated with this inhibitor at 37°C for 7

days.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

Total RNA from cells in each group was extracted

using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out

according to the manufacturer's instructions with a first-strand

cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Primer Express software (version 3.0; Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was utilized to design

gene-specific primers for each target gene. The primer sequences

were as follows: CENPU: 5'-GAAAAGAAAAGGCAGCGTATGA-3' (forward) and

5'-AATATGCTGCATTCCTAAGGGA-3' (reverse); GAPDH:

5'-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3' (forward) and

5'-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3' (reverse). The reaction conditions

included pre-denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, denaturation at 95°C

for 30 sec, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for

30 sec for a total of 40 cycles. CENPU mRNA expression was

calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (26).

Xenograft model

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal

Care Committee of Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute, Shandong

First Medical University and Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences

(approval no. SDTHEC2022009018; Jinan, China). To investigate the

tumorigenic potential of Cal51-shCENPU and Cal51-CON313

cells at varying concentrations, 1×106,

1×105, 1×104 and 1×103 cells

(resuspended in PBS) were injected into the mammary fat pads of NSG

mice (27,28). NSG mice were obtained from

Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University. A

total of 32 mice (4-6 weeks old; female; 18-20 g) were randomly

divided into 8 groups (n=4/group). Mice were maintained under

specific-pathogen-free (SPF) conditions (temperature, 25±1°C;

humidity, 55±5%; 12/12-h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum

access to irradiated food and autoclaved water. The tumor sizes

formed by the Cal51-shCENPU and Cal51-CON313 cell groups at

these different concentrations were measured and subjected to

statistical analysis to determine significant differences.

MDA-MB-231-shCENPU and MDA-MB-231-CON313 cells

(1×106 cells/specimen; resuspended in PBS) were injected

into the fat pads of 4-week-old female nude mice (Nanjing

Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University). A total of 15

female nude mice (age, 4 weeks; weight, 16-18 g) were randomly

divided into 3 groups (n=5/group). Mice were maintained under SPF

conditions (temperature: 25±2°C; humidity: 50±10%; 12/12-h

light/dark cycle) with free access to autoclaved food and acidified

water. The tumor dimensions were measured at 3-day intervals for 21

days. When the size of each tumor was ~100 mm3,

MDA-MB-231-CON313 mice were intraperitoneally injected with a furin

inhibitor (5 mg/kg DECRVKR-CMK) three times per week for 3 weeks.

The following humane endpoints were predefined in the present

study: i) Clear signs of pain or unremitting suffering; ii) rapid

weight loss; iii) persistent lack of appetite or abnormal behavior;

and iv) inability to stand or extreme weakness after excluding

anesthesia-related reasons (however, no anesthesia was administered

to the mice in the present study). However, during the experiment

no such signs were observed, indicating that the tumors did not

severely affect the health of the mice until the end of the study.

The tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula:

Volume=0.5 × (width2 × length). The maximum tumor volume

observed in the first experiment (Cal51 cells) was 936

mm3, and the maximum diameter was 1.3 cm. The maximum

tumor volume observed in the second experiment (MDA-MB-231 cells)

was 1,764 mm3, and the maximum diameter was 1.8 cm. At

study completion, the mice were euthanized using CO2

inhalation in accordance with the American Veterinary Medical

Association 2020 Guidelines (29). The procedure involved an initial

concentration of 30% CO2, a flow rate controlled at 50%

of the chamber volume per minute, and a gradual increase to 70% to

ensure rapid and humane loss of consciousness. Death was confirmed

by observing pupillary dilation and cessation of cardiac activity.

The tumors were then extracted, measured and used for subsequent

evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical processing was implemented with SPSS

software v18.0 (SPSS, Inc.). Intergroup comparisons were performed

using unpaired Student's t-test (two-group comparisons) or one-way

ANOVA (multi-group comparisons) followed by the Least Significant

Difference pos hoc test (for equal variances between groups). When

two types of treatment were used, a two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak

post hoc test was performed. All statistical differences were

established using two-tailed probability measures. Experimental

procedures were replicated in triplicate, and the data are

presented as the mean ± SD. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

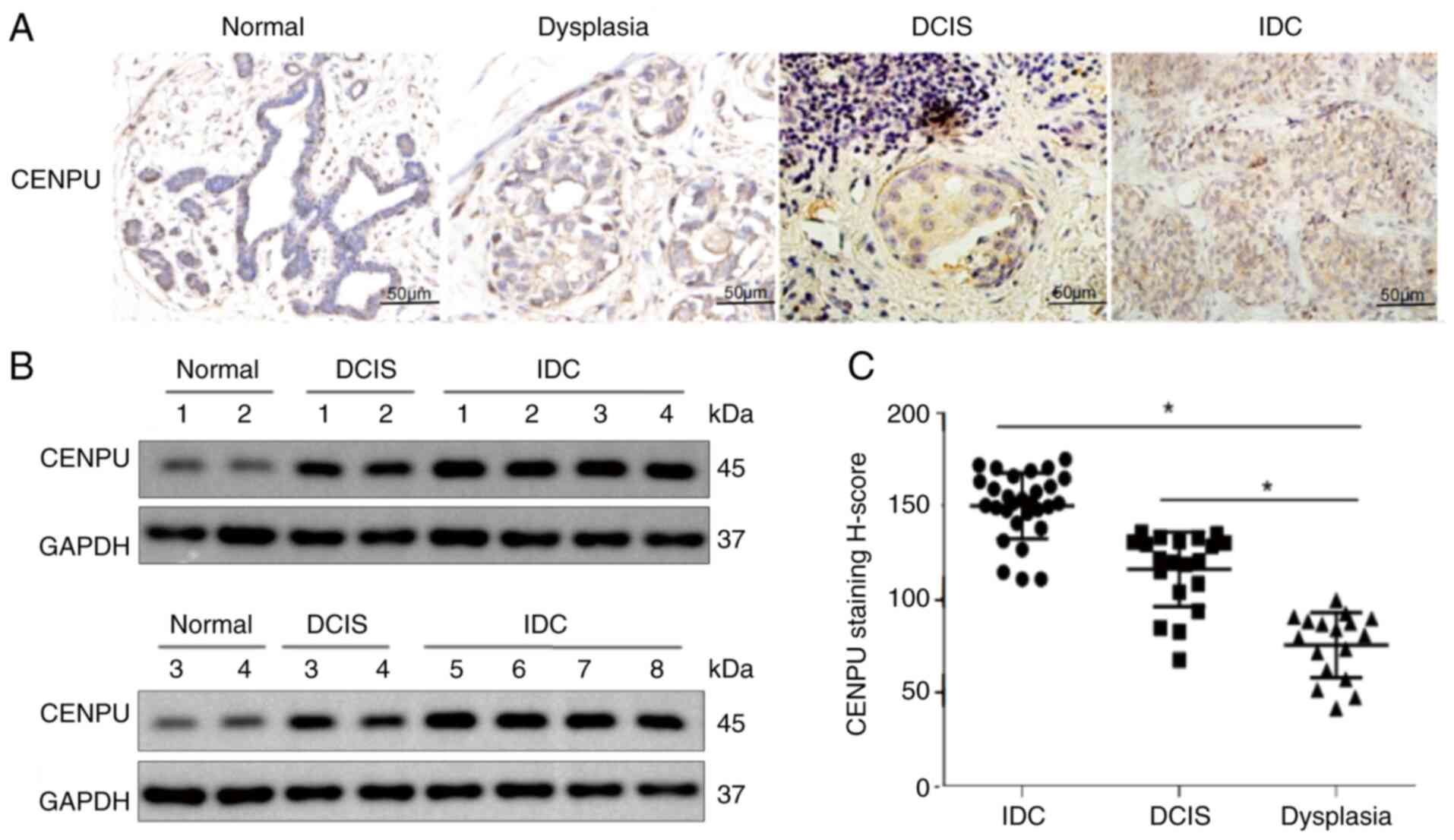

CENPU is expressed at high levels in

breast invasive ductal carcinoma

Our previous study showed that CENPU was markedly

upregulated in TNBC tissues compared with luminal breast cancer

tissues, and this upregulation was associated with a poor prognosis

(15). The present study

examined whether CENPU expression is associated with the degree of

invasiveness in BC. A total of 67 tissue samples were collected,

including 17 cases of breast dysplasia, 20 cases of ductal

carcinoma in situ and 30 cases of invasive ductal carcinoma.

IHC results confirmed that CENPU expression was positively

associated with the degree of invasiveness in BC (Fig. 1A and C). Next, four normal breast

tissue samples (adjacent tissues of the same patients with BC),

four ductal carcinoma in situ tissue samples and eight

breast invasive ductal carcinoma tissue samples were used to verify

the findings by western blotting. The results demonstrated that

compared with the normal breast and ductal carcinoma in situ

tissue samples, the invasive ductal carcinoma tissues exhibited

higher CENPU levels (Fig.

1B).

CENPU promotes the stem cell-like

properties of BCSCs

Cancer stem cells serve an important role in

tumorigenesis and recurrence. Given that our previous study showed

that high CENPU expression was associated with poor overall

survival (15), it was assessed

whether CENPU expression promotes the stem cell-like properties of

BCSCs. Firstly, the overexpression efficiency of CENPU in cells was

verified through PCR or western blotting (Fig. S2). Subsequently, a

CD24− CD44+ cell identification experiment

and a mammosphere formation assay were performed to determine the

association between CENPU expression and the stem cell-like

properties of BCSCs. Western blotting revealed that CD44 and ALDH

(30,31) were downregulated in

CENPU-knockdown MDA-MB-231 and Cal51 cells, where it had

been confirmed that CENPU was highly expressed in our previous

study (15) (Fig. 2A and B), and upregulated in

CENPU-overexpressing T47D cells, where it had been confirmed

that CENPU was expressed at a low level (15) (Fig. 2C).

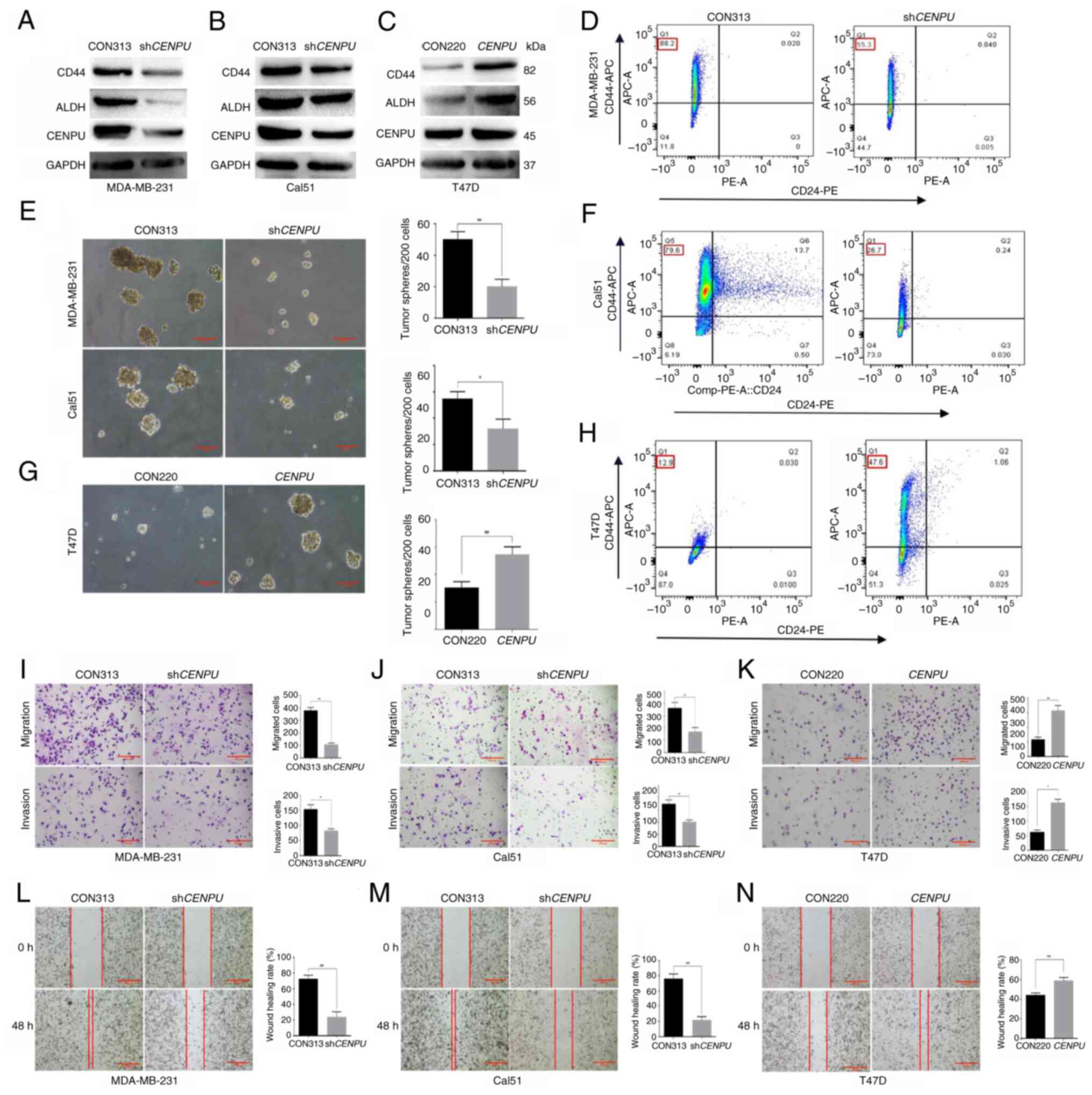

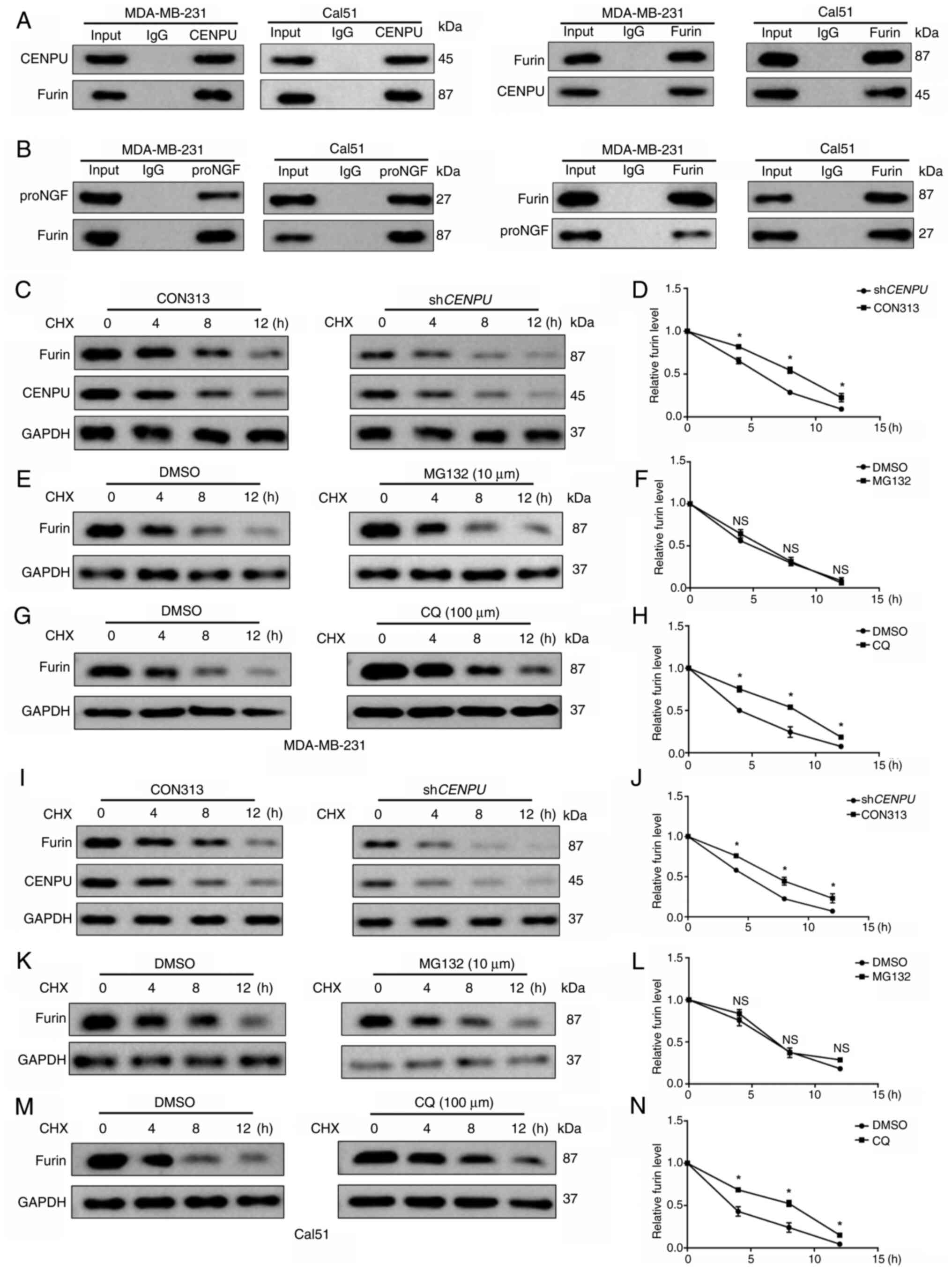

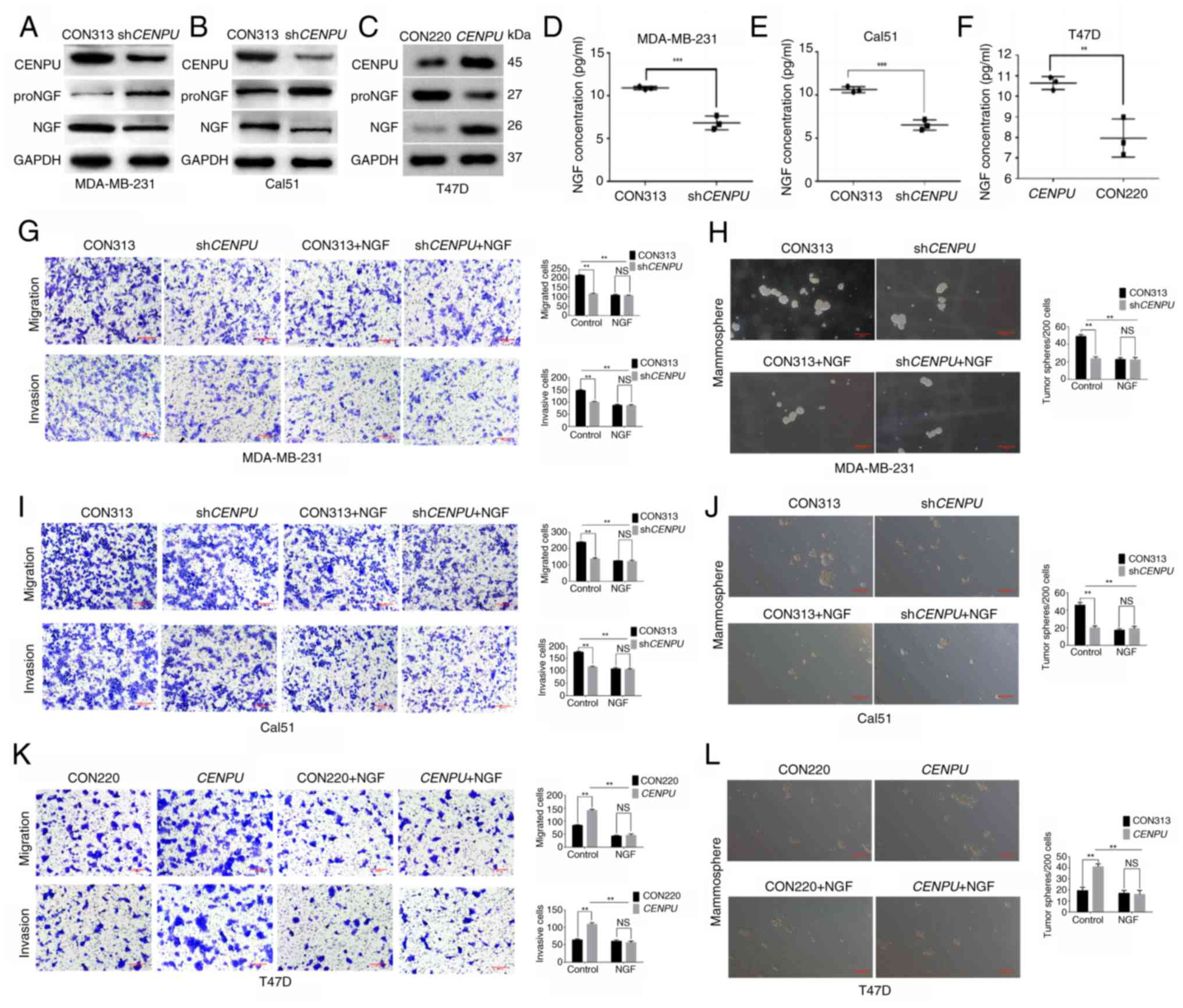

| Figure 2CENPU promotes tumorigenesis, stem

cell-like properties, migration and invasion in breast cancer

cells. Western blotting was performed to detect the expression

levels of CD44 and ALDH in (A) MDA-MB-231, (B) Cal51 and (C) T47D

cells with different CENPU expression levels. Association between

CENPU expression and the number of mammospheres per 200 cells in

(E) MDA-MB-231 and Cal51 cells and (G) T47D cells (scale bar, 100

μm). CD24− CD44+ flow cytometry

results showed that CENPU expression levels affected the percentage

of the CD24− CD44+ population among (D)

MDA-MB-231, (F) Cal51 and (H) T47D cells. Transwell assays were

performed to determine the effect of CENPU levels on the migration

and invasiveness of (I) MDA-MB-231, (J) Cal51 and (K) T47D cells

(scale bar, 200 μm). A wound healing assay was performed to

determine the effect of CENPU on the migration potential of (L)

MDA-MB-231, (M) Cal51 and (N) T47D cells (scale bar, 200

μm). *P<0.05; **P<0.01. CENPU,

centromere protein U; sh, short hairpin RNA; APC, allophycocyanin;

ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; PE, phycoerythrin. |

The mammosphere generation assay showed that

CENPU knockdown decreased the number and volume of

mammospheres (Fig. 2E).

Conversely, CENPU overexpression markedly enhanced the

number and volume of mammospheres (Fig. 2G). CENPU knockdown reduced

the rate of CD24− CD44+ cells (30,32,33) (Fig. 2D and F), whereas CENPU

overexpression exerted a contrasting effect (Fig. 2H). The aforementioned data

indicated that CENPU overexpression promoted the stem

cell-like properties of BCSCs.

The role of CENPU in BC progression was examined

using wound healing and Transwell assays, to determine the effect

of CENPU on cell migration and invasion. CENPU knockdown

inhibited the migratory and invasive potential of MDA-MB-231 and

Cal51 cells (Fig. 2I, J, L and

M), whereas CENPU overexpression enhanced the migratory

and invasive potential of T47D cells (Fig. 2K and N).

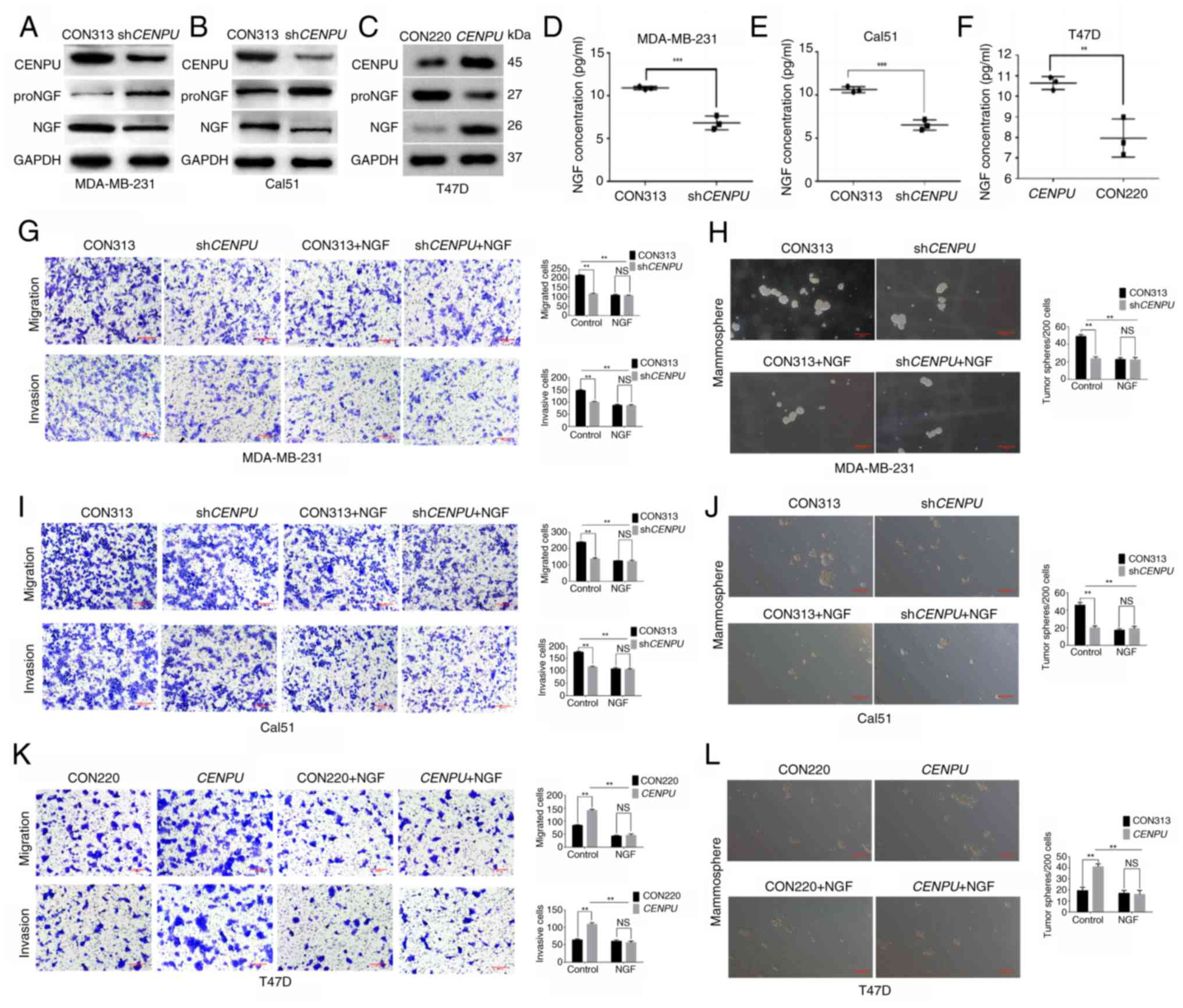

CENPU promotes the maturation conversion

of proNGF to NGF

Comparative DO and KEGG enrichment analyses of

MDA-MB-231 cell lines with CENPU knockdown (shCENPU) and

overexpression revealed that CENPU is significantly associated with

BC and related cancer signaling pathways. (Fig. S1A and B), while 4D-DIA

quantitative differential protein enrichment analysis showed that

the shCENPU group exhibited notably lower NGF expression

compared with the CON313 group (Fig. S1C). NGF is a critical

neurotrophic factor that controls differentiation and survival in

target neurons. NGF matures upon undergoing furin-mediated protease

cleavage of its proNGF form (34). Therefore, western blotting and an

ELISA were performed to examine whether CENPU knockdown and

overexpression affect the expression of NGF and proNGF. Western

blotting and ELISA results revealed that NGF expression was

markedly suppressed in MDA-MB-231 and Cal51 cells with CENPU

knockdown (Fig. 3A, B, D and E).

Conversely, NGF expression was markedly enhanced upon CENPU

upregulation in CENPU-overexpressing T47D cells (Fig. 3C and F). Furthermore, the changes

in CENPU expression affected proNGF and NGF expression in

contrasting manners. MDA-MB-231-shCENPU,

Cal51-shCENPU and T47D-CENPU cells, and their

corresponding controls, were treated with NGF-neutralizing

antibodies. The ability of CENPU to promote migration, invasion and

mammosphere formation was significantly suppressed when the cells

were treated with NGF-neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 3G-L). No significant differences

were observed between each overexpression or knockdown group and

the corresponding control treated with NGF. This indicated that NGF

may serve a critical role in the CENPU-induced promotion of BC

induction and progression.

| Figure 3CENPU promotes the conversion of

proNGF to NGF. Western blotting experiments were performed to

detect the expression of NGF and proNGF in (A)

MDA-MB-231-shCENPU, (B) Cal51-shCENPU and (C)

T47D-CENPU cells and their corresponding control groups. The

intracellular NGF levels in (D) MDA-MB-231, (E) Cal51 and (F) T47D

cells after 48 h of treatment were analyzed by ELISA using

ultrasonicated cell supernatants. After NGF-neutralizing antibodies

were added to (G) MDA-MB-231-shCENPU, (I)

Cal51-shCENPU and (K) T47D-CENPU cells, and their

corresponding control groups, Transwell migration and invasion

assays were conducted (scale bar, 200 μm). After

NGF-neutralizing antibodies were added to the (H)

MDA-MB-231-shCENPU, (J) Cal51-shCENPU and (L)

T47D-CENPU cells, and their corresponding control groups, a

mammosphere formation assay was performed to measure the number of

mammospheres per 200 cells that formed (scale bar, 100 μm).

*P<0.05; **P<0.01. CENPU, centromere

protein U; sh, short hairpin RNA; NGF, nerve growth factor; proNGF,

NGF precursor; NS, not significant. |

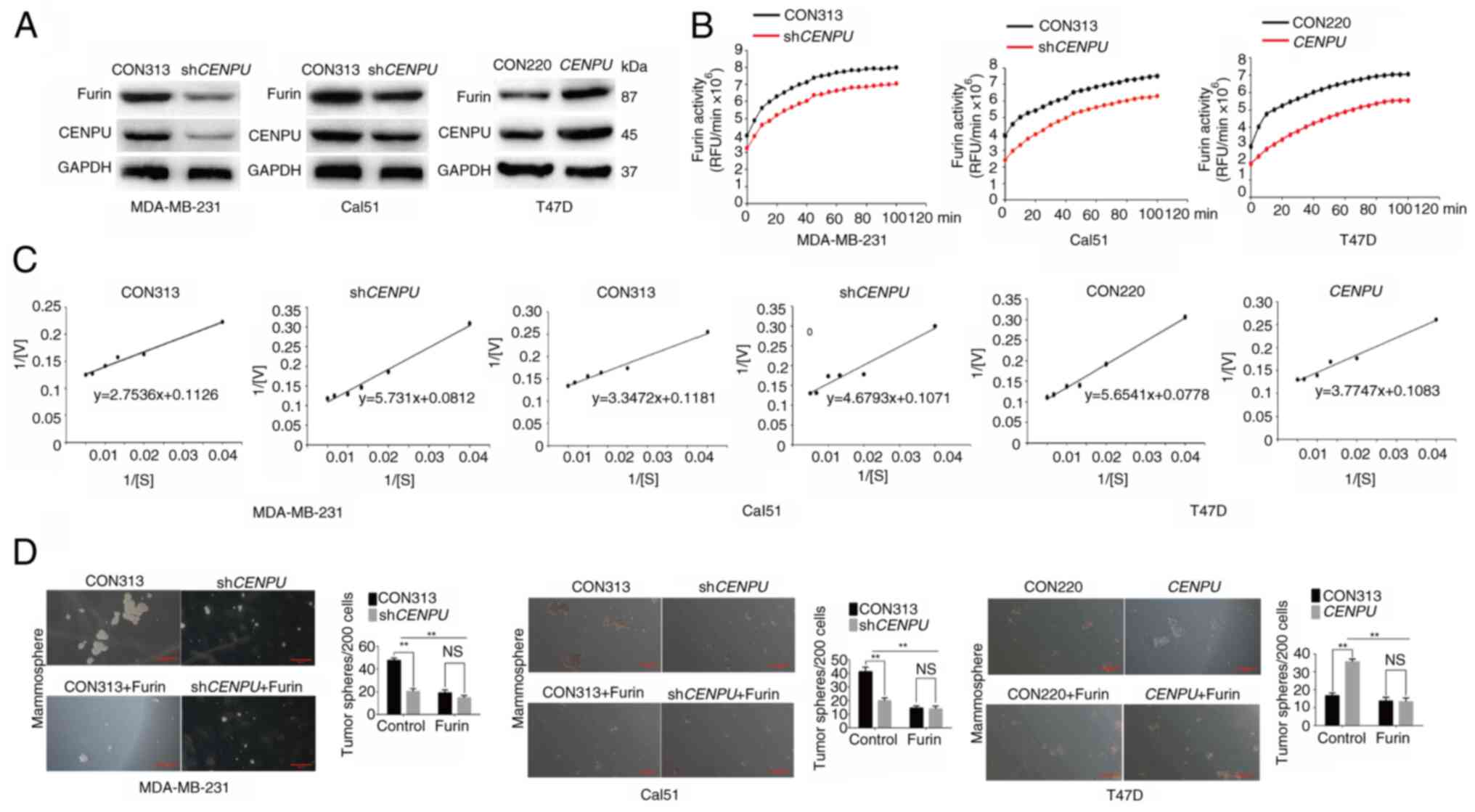

CENPU promotes NGF maturation by

enhancing the enzymatic activity of furin

The previous experiment demonstrated that CENPU

could affect the expression levels of proNGF and NGF. Furin is the

sole enzyme capable of cleaving proNGF, thereby facilitating its

conversion into NGF. Therefore, it was examined whether CENPU

regulates the expression of proNGF and NGF by affecting furin

activity. Western blotting revealed lower furin expression levels

in shCENPU-expressing MDA-MB-231 and Cal51 cells, and higher

furin expression levels in CENPU-overexpressing T47D cells

(Fig. 4A). Next, furin activity

was assayed by measuring the fluorescence intensity of the

furin-specific fluorescence substrate pERTKR-MCA. Furin activity

was suppressed in shCENPU-expressing MDA-MB-231 and Cal51

cells, and elevated in CENPU-overexpressing T47D cells

(Fig. 4B).

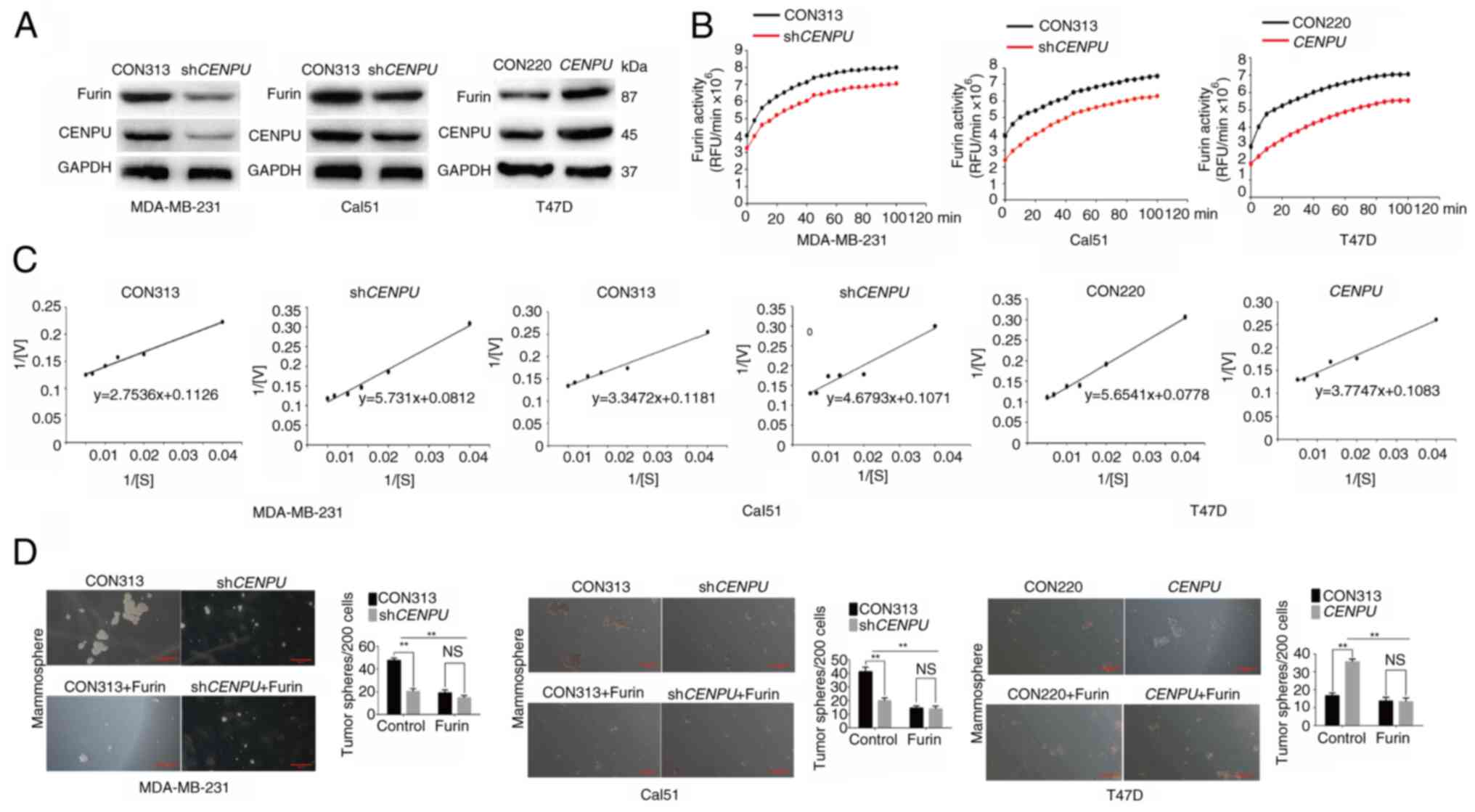

| Figure 4CENPU enhances the activity of furin.

(A) Western blotting was performed to determine the expression

levels of furin in MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D cells. (B) Furin

activity in MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D cells was measured based on

fluorescence intensity. (C) Michaelis constant values in the

experimental group and control group of MDA-MB-231, Cal51 and T47D

cells were obtained using double reciprocal plotting. (D)

Mammosphere formation assays were performed after treatment with a

furin inhibitor, and the number of tumor spheres per 200 cells was

quantified (scale bar, 100 μm). **P<0.01.

CENPU, centromere protein U; sh, short hairpin RNA; NS, not

significant; RFU, relative fluorescence units; V, reaction

velocity; S, substrate concentration. |

There are two methods to increase enzymatic

activity: i) Increasing the enzyme concentration; and ii)

increasing the affinity of the enzyme to the substrate, as

indicated by the Michaelis constant (Km). The

Km value is known as the meter constant, which

refers to the substrate concentration of the reaction that reaches

1/2Vmax, where Vmax is the

reaction velocity. Km is generally expressed in

mol/l, and this index is only determined by the intrinsic

characteristics of the enzyme but is independent of its

concentration. The larger the Km value, the

smaller the affinity of the enzyme to the substrate. Using the

double reciprocal plotting method, 1/V is plotted against 1/[S]

(where S is the substrate concentration) to generate a straight

line. The y-intercept of the line is 1/Vmax, and

the x-intercept is the absolute value of 1/Km

(35). At a pH of 6.0 and

Ca2+ concentration of 1 mM, the Km

value of pERTKR-MCA for furin in shCENPU-expressing

MDA-MB-231 cells was 68.63 μmol/l. The Km

in the control group was 24.45 μmol/l. The

Km values of pERTKR-MCA for furin were 43.70

μmol/l in shCENPU-expressing Cal51 cells and 24.45

μmol/l in the control group. The Km values

of pERTKR-MCA for furin were 34.86 and 72.67 μmol/l in the

CENPU-overexpressing T47D cells and the control group,

respectively (Fig. 4C). These

results showed that CENPU knockdown could reduce the

affinity of furin for its substrates, whereas CENPU

overexpression could increase this affinity.

MDA-MB-231-shCENPU, Cal51-shCENPU and

T47D-CENPU cells, and their corresponding controls, were

treated with a furin inhibitor. The results of the mammosphere

formation experiment indicated that the ability of CENPU to promote

mammosphere formation was inhibited when the cells were treated

with a furin inhibitor (Fig.

4D). No significant differences were observed between each

overexpression or knockdown group and the corresponding control

treated with furin.

CENPU enhances furin activity by

inhibiting its degradation in the lysosomal pathway

The previous experiment showed that CENPU could

influence both furin expression and activity. The presence of two

conserved LXXLL sequences and two superhelical zinc finger

structures at the C-terminal of CENPU suggest that CENPU may form a

dimer with other proteins and act as a receptor-binding protein in

signal transduction (36). CENPU

and furin co-immunoprecipitated with each other in MD-MB-231 and

Cal51 cells (Fig. 5A). Using

co-immunoprecipitation, it was also demonstrated that furin formed

protein complexes with proNGF (Fig.

5B).

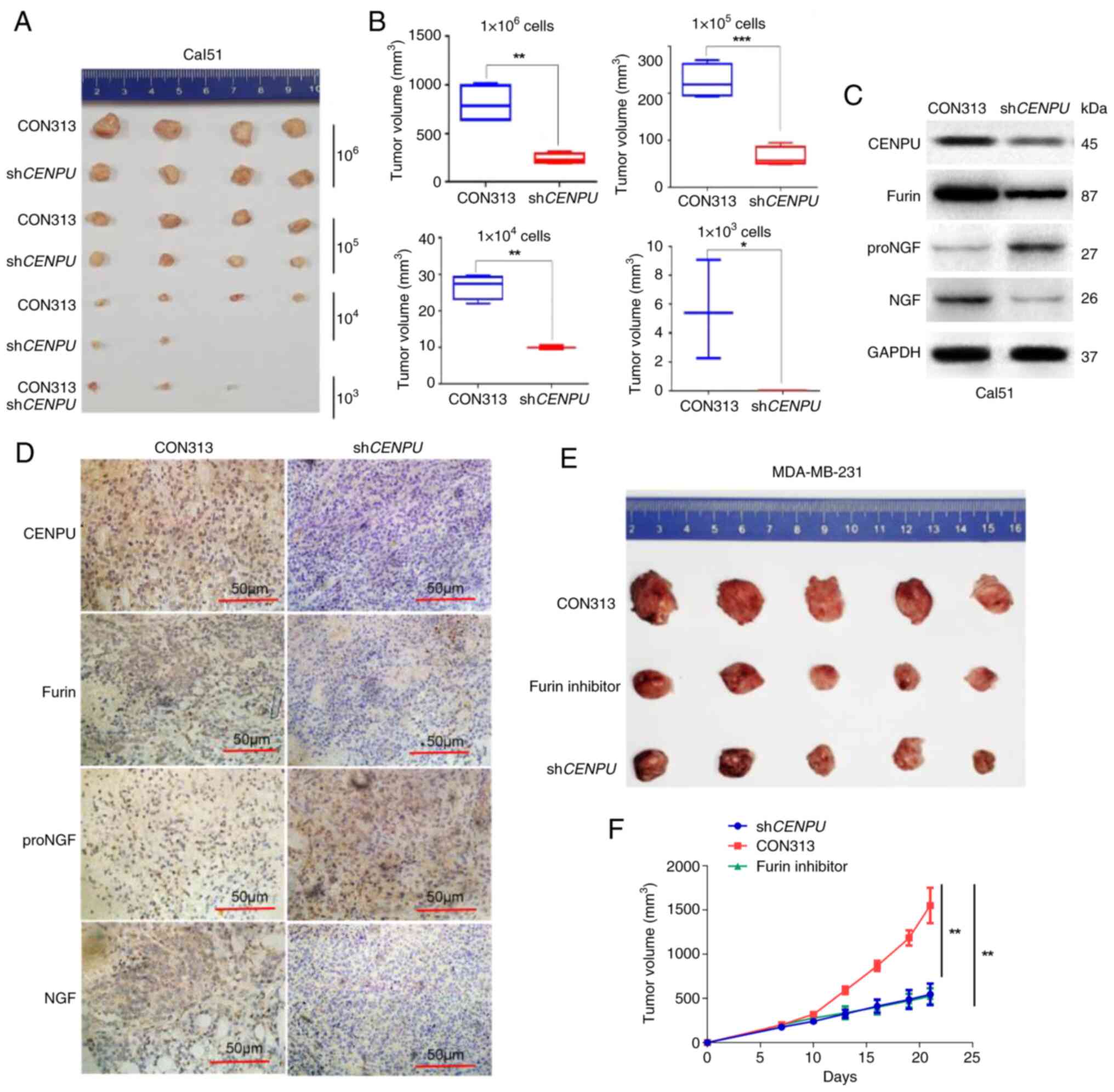

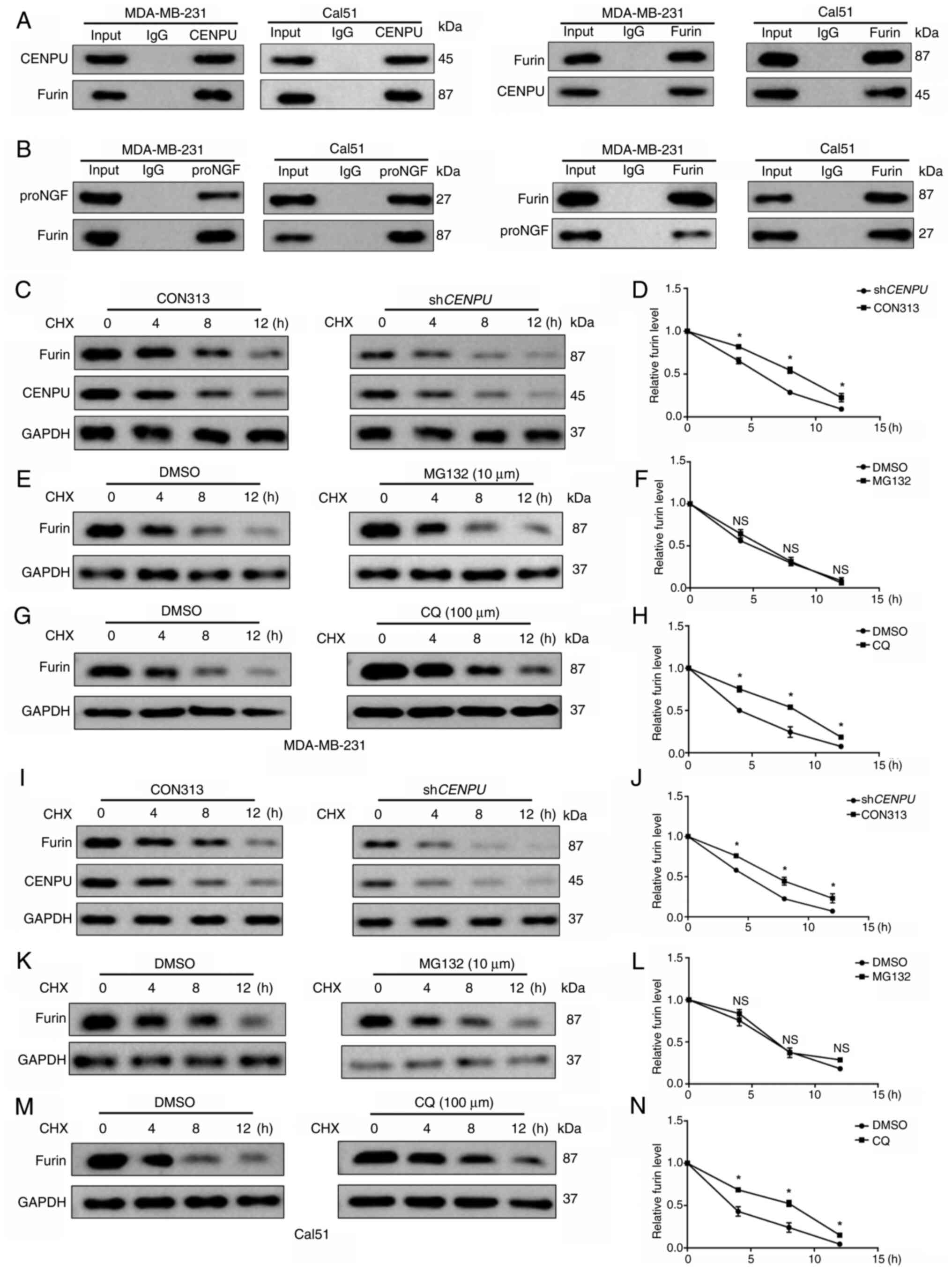

| Figure 5CENPU enhances furin activity by

inhibiting its degradation via the lysosomal pathway. (A) CENPU and

furin were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation. (B) Furin and

proNGF were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation. (C)

MDA-MB-231-shCENPU cells and their corresponding controls

were treated with CHX (20 μM) for the specified duration,

and protein levels were measured by western blotting. (D) Relative

expression of furin. (E) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with MG132

(10 μM) for 12 h, and then also treated with CHX (20

μM) for the indicated times. Protein levels were detected by

western blotting. (F) Relative expression of furin. (G) MDA-MB-231

cells were treated with CQ (100 μM) for 12 h, and then

treated with CHX (20 μM) for the indicated times. Protein

levels were detected by western blotting. (H) Relative expression

of furin. (I) Cal51-shCENPU cells and their corresponding

controls were treated with CHX (20 μM) for the specified

duration, and protein levels were measured by western blotting. (J)

Relative expression of furin. (K) Cal51 cells were treated with

MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h, and then treated with CHX (20

μM) for the indicated times. Protein levels were detected by

western blotting. (L) Relative expression of furin. (M) Cal51 cells

were treated with CQ (100 μM) for 12 h, and then treated

with CHX (20 μM) for the indicated times. Protein levels

were detected by western blotting. (N) Relative expression of

furin. *P<0.05 vs. DMSO or CON313 group. The

experimental and control groups in panels C-M were run on the same

gel/membrane and incubated with the corresponding primary

antibodies simultaneously. CENPU, centromere protein U; sh, short

hairpin RNA; NS, not significant; proNGF, nerve growth factor

precursor; CHX, cycloheximide; CQ, chloroquine. |

The precise mechanism by which CENPU upregulated

furin expression in BC cells was then explored. We hypothesized

that CENPU interacts with furin to inhibit its degradation.

CENPU knockdown promoted furin degradation in MDA-MB-231 and

Cal51 cells treated with cycloheximide, a protein biosynthesis

inhibitor, at indicated at 4, 8 and 12 h after treatment (Fig. 5C, D, I and J). The proteasomal

and lysosomal pathways are key pathways regulating protein

degradation in cells (37).

Therefore, the potential pathways involved in CENPU-regulated furin

degradation were investigated. Proteasome suppression by MG132 did

not affect furin degradation in cells with CENPU knockdown

compared with the control group (Fig. 5E, F, K and L). However, the

suppression of lysosomal activity by chloroquine further inhibited

furin degradation in MDA-MB-231-shCENPU and

Cal51-shCENPU cells (Fig. 5G,

H, M and N). The aforementioned findings indicated that CENPU

suppressed furin degradation via the lysosomal pathway.

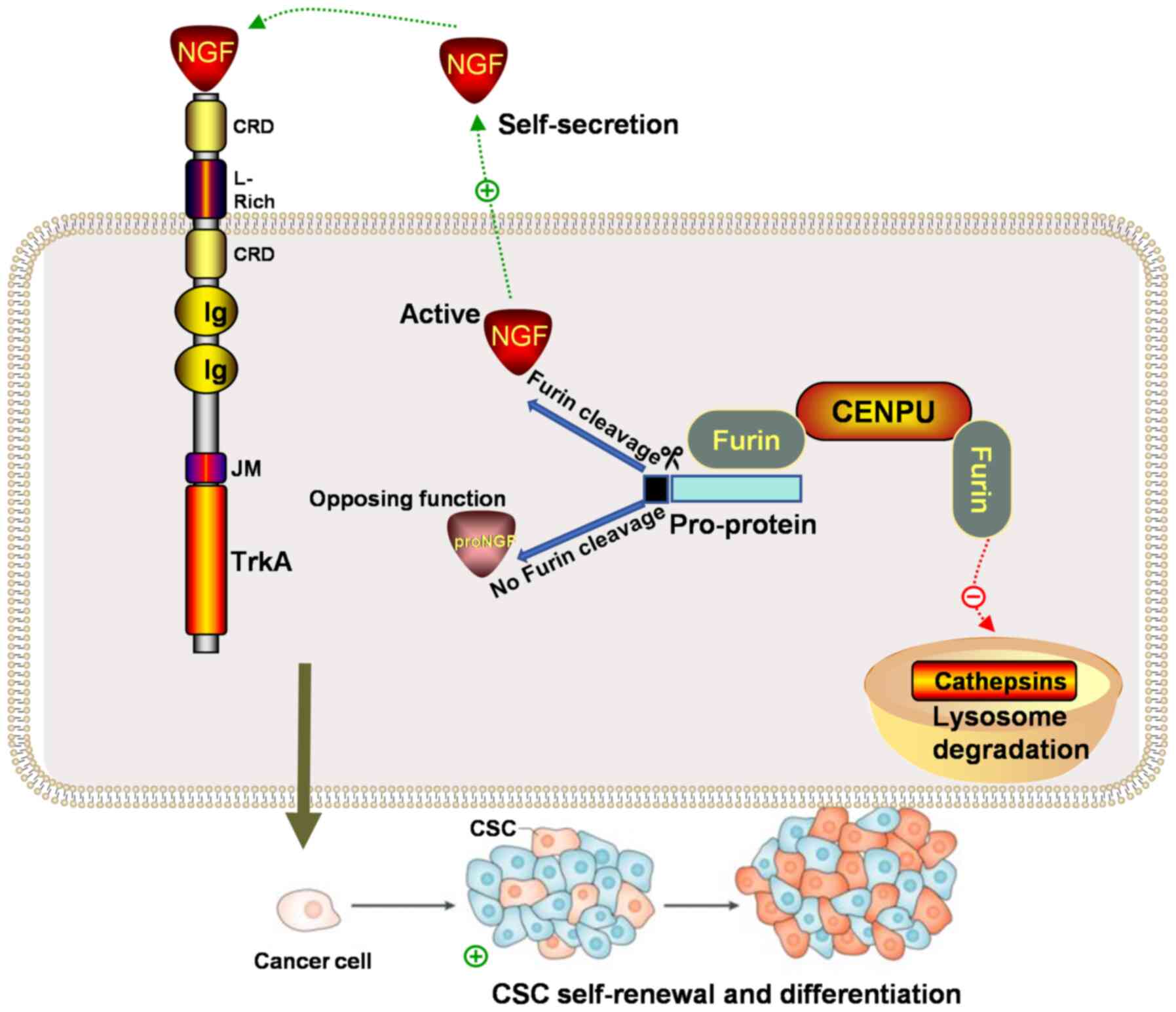

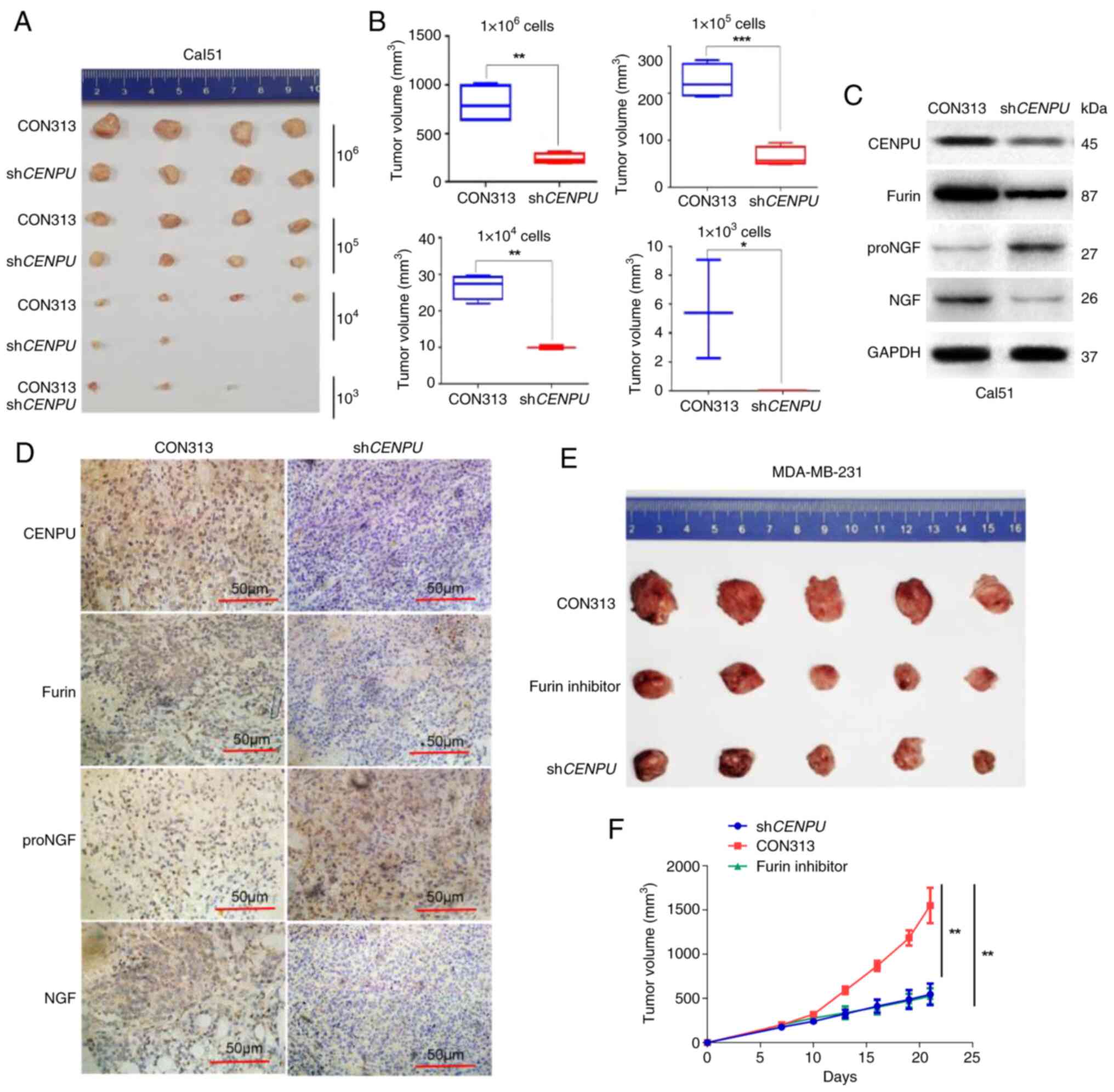

CENPU promotes tumorigenesis in TNBC in

vivo

Since an important function of CENPU in

tumorigenesis in the cultured cells was identified, the role of

CENPU in a mouse xenograft model was then examined. Female NSG mice

were injected with Cal51-shCENPU and Cal51-CON313 cells to

determine whether CENPU promotes tumorigenesis in vivo. The

mice injected with 1×104, 1×105 and

1×106 cells with stable CENPU knockdown exhibited

smaller xenograft tumors compared with that injected with CON313.

None of the mice injected with 1×103 cells with stable

CENPU knockdown exhibited formation of xenograft tumors.

This suggested that CENPU knockdown inhibited tumorigenesis

(Fig. 6A and B). IHC and western

blotting experiments showed that the furin and NGF protein levels

were considerably lower, and the proNGF protein level was higher in

shCENPU-Cal51 tumor samples compared with the control

samples (Fig. 6C and D).

| Figure 6CENPU knockdown can inhibit

tumorigenesis. (A) A total of 1×106, 1×105,

1×104 and 1×103 Cal51-shCENPU and

Cal51-CON313 cells were injected into the mammary fat pad of NSG

mice. (B) Sizes of the tumors formed in the Cal51-shCENPU

and Cal51-CON313 groups using different cell concentrations were

measured and statistically analyzed. The tumor tissues collected

from the Cal51-shCENPU and Cal51-CON313 groups were (C)

analyzed by western blotting and (D) subjected to

immunohistochemical staining (scale bar, 50 μm). (E) A total

of 1×106 MDA-MB-231-shCENPU and MDA-MB-231-CON313

cells were injected into the mammary fat pad of nude mice. When the

tumor size was ~100 mm3, the MDA-MB-231-CON313 mice were

administered a furin inhibitor (DECRVKR-CMK) by intraperitoneal

injection. (F) The volume of the final tumor was measured,

indicating that the furin inhibitor significantly inhibited tumor

growth in the MDA-MB-231-CON313 mice. Scale bar, 50 μm.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. CENPU, centromere protein U; sh, short

hairpin RNA; NS, not significant; NGF, nerve growth factor; proNGF,

NGF precursor. |

Furin inhibitor treatment can inhibit

CENPU-induced tumor growth

MDA-MB-231-shCENPU and MDA-MB-231-CON313

cells were injected into the mammary fat pads of nude mice. When

the tumor size was ~100 mm3, MDA-MB-231-CON313 mice were

intraperitoneally injected with the furin inhibitor DECRVKR-CMK.

The furin inhibitor could significantly inhibit CENPU-induced tumor

growth. This observation corroborated the aforementioned in

vitro findings (Fig. 6E and

F).

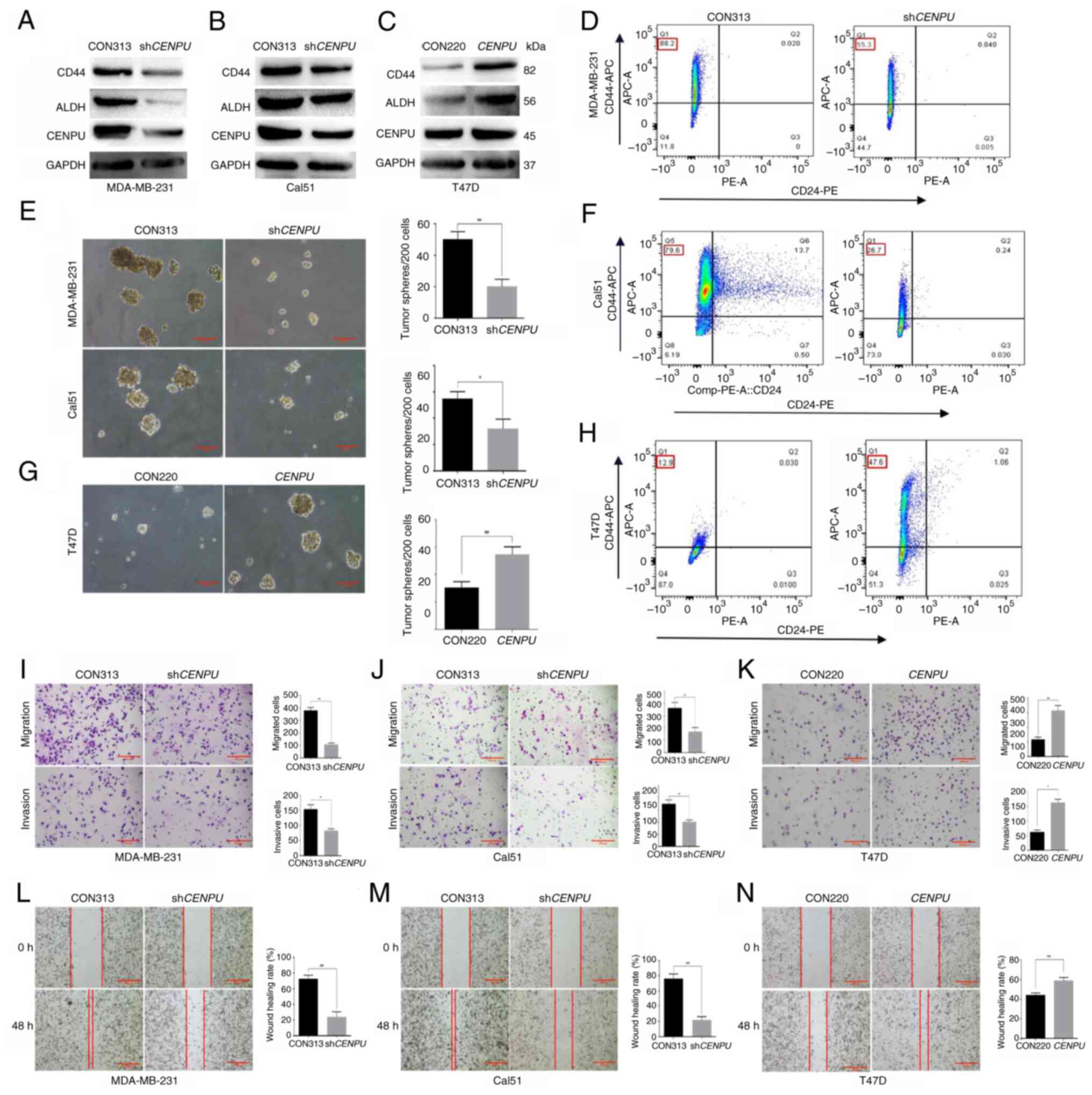

Discussion

The present study identified a potential role of

CENPU in TNBC tumorigenesis. Furthermore, the molecular mechanism

by which CENPU potentially promotes TNBC tumorigenesis and the stem

cell-like properties of BCSCs by enhancing NGF maturation was also

established. Specifically, the current study showed that CENPU

inhibited the lysosomal degradation of furin, and could bind to the

furin protein, increase its expression and enhance its enzymatic

activity. The enhancement of furin activity promoted the maturation

and transformation of proNGF into NGF. NGF promoted the BCSC-like

properties of TNBC cells (Fig.

7). Collectively, these data provided novel insights into how

CENPU may promote TNBC tumorigenesis and the stem cell-like

properties of TNBC cells.

Our previous study reported that CENPU was notably

upregulated in BC tissues compared with adjacent normal breast

tissues and expressed at higher levels in TNBC than in luminal BC

(15). The present showed that

CENPU expression was significantly associated with the degree of

invasiveness in BC. The effects of CENPU on TNBC tumorigenesis,

BCSC properties, migration and invasion were further investigated,

and the results demonstrated that CENPU promoted these

features.

CD44 is a multifunctional class I transmembrane

glycoprotein. In BCSCs, its expression is linked to self-renewal,

tumorigenesis, adhesion, invasion and metastasis. The

CD44+CD24−-low phenotype is widely used as a

marker for BCSC identification and isolation. ALDH1A1, as a stem

cell marker, has a high expression level in BCSCs and can promote

proliferation and spheroid formation (30-32). The present study demonstrated

that knockdown of CENPU reduced the proportion of CD44+

CD24− cells, while western blotting analysis revealed

downregulation of CD44 and ALDH expression. Conversely,

overexpression of CENPU exhibited the opposite effect. Therefore,

we hypothesize that overexpression of CENPU can promote the

stem-like characteristics of BCSCs.

NGF is a critical neurotrophic factor that

regulates the differentiation and survival of target neurons

(25). NGF is biosynthesized as

proNGF, and NGF maturation involves furin-associated protease

cleavage (38). Hayakawa et

al (39) reported that NGF

promoted gastric cancer development by altering cholinergic

signaling. Tomellini et al (40) demonstrated that NGF promoted

symmetric self-renewal, quiescence and epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition, thereby enlarging the BCSC compartment. In the present

study, NGF expression decreased with a decrease in the CENPU level,

whereas proNGF expression increased. Furthermore, after

NGF-neutralizing antibodies were added to the culture medium of BC

cells, the ability of CENPU to promote BC migration, invasion and

mammosphere formation was inhibited. Therefore, we hypothesize that

CENPU may promote NGF maturation.

Furin is a precursor protein-processing enzyme that

helps process multiple bioactive polypeptides or protein precursors

in the brain, glands and other peripheral tissues (41). There are large volumes of furin

present in tumor tissues, and studies have shown that furin

expression increases with the tumor proliferation rate (24,42,43). Furthermore, furin inhibition

suppresses the proliferation and infiltration of tumor cells

(44-46). The present results showed that

CENPU inhibited the lysosomal degradation of furin, bound to furin

and increased its expression, thereby enhancing its enzymatic

effect on proNGF. A furin inhibitor (DECRVKR-CMK), which was

administered in both in vivo and in vitro settings,

inhibited the ability of CENPU to promote tumorigenesis in

TNBC.

Collectively, the results of the present study

indicated that CENPU promoted TNBC invasion, tumorigenesis and BCSC

properties through the furin-proNGF-NGF signaling pathway. CENPU

enhanced the conversion of proNGF to NGF by inhibiting furin

degradation via the lysosomal pathway. However, there are certain

limitations to the present study that warrant discussion. Two

common strategies for enhancing enzyme activity were identified:

Increasing the enzymatic affinity for its substrates and raising

the enzymatic concentration. The present study demonstrated that

the overexpression of CENPU could elevate furin activity. Both the

substrate affinity of furin and its expression levels were

examined, and it was observed that CENPU enhanced the activity and

increased the expression of furin. However, while an increase in

furin activity and expression levels was observed, the underlying

molecular mechanisms that mediate these effects were not fully

elucidated. Furthermore, a previous study has suggested that the

activity of furin is regulated by its propeptide occupying the

active site in its proenzyme form, thus preventing substrate

binding (47). The present

findings, however, indicate that CENPU may modulate furin activity

through protein-protein interactions, which is not well-documented

in the existing literature. Therefore, further research should be

conducted to verify this hypothesis and explore the potential

mechanisms.

In summary, the current findings revealed a novel

mechanism underlying the tumor-promoting effect of CENPU,

specifically in TNBC. The inhibition of CENPU expression and its

downstream activated signaling pathway may be a novel strategy for

TNBC treatment.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The proteomics data generated in the present study

may be found in the ProteomeXchange (iProX) repository under

accession number PXD061628 or at the following URLs: https://www.iprox.cn/page/project.html?id=IPX0011300000

and http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD061628.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SS performed data collection, analysis and

interpretation. ZH and LQ conducted data collection and analysis.

DZ designed the study and supervised the data interpretation. SS

and DZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The human and animal experiments in the present

study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Cancer

Hospital and Institute, Shandong First Medical University and

Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences (approval nos.

SDTHEC2022009017 and SDTHEC2022009018, respectively; Jinan, China).

The human samples used in the present study were obtained with

written informed consent from patients or their families (due to

patient's physical reasons or low educational level) for use in

research.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Youth Natural Science

Foundation of Shandong Province (grant nos. ZR2023QH128,

ZR2023QH069 and ZR202211090247).

References

|

1

|

Derakhshan F and Reis-Filho JS:

Pathogenesis of triple-negative breast cancer. Annu Rev Pathol.

17:181–204. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mahtani R, Kittaneh M, Kalinsky K,

Mamounas E, Badve S, Vogel C, Lower E, Schwartzberg L and Pegram M;

Breast Cancer Therapy Expert Group (BCTEG): Advances in therapeutic

approaches for triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer.

21:383–390. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang M, Deng H, Hu R, Chen F, Dong S,

Zhang S, Guo W, Yang W and Chen W: Patterns and prognostic

implications of distant metastasis in breast cancer based on SEER

population data. Sci Rep. 15:267172025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhao S, Zuo WJ, Shao ZM and Jiang YZ:

Molecular subtypes and precision treatment of triple-negative

breast cancer. Ann Transl Med. 8:4992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li Y, Zhan Z, Yin X, Fu S and Deng X:

Targeted therapeutic strategies for triple-negative breast cancer.

Front Oncol. 11:7315352021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bou Zerdan M, Ghorayeb T, Saliba F, Allam

S, Bou Zerdan M, Yaghi M, Bilani N, Jaafar R and Nahleh Z: Triple

negative breast cancer: Updates on classification and treatment in

2021. Cancers (Basel). 14:12532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang R, Tu J and Liu S: Novel molecular

regulators of breast cancer stem cell plasticity and heterogeneity.

Semin Cancer Biol. 82:11–25. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu H, Song Y, Qiu H, Liu Y, Luo K, Yi Y,

Jiang G, Lu M, Zhang Z, Yin J, et al: Downregulation of FOXO3a by

DNMT1 promotes breast cancer stem cell properties and

tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 27:966–983. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

9

|

Zhu K, Xie V and Huang S: Epigenetic

regulation of cancer stem cell and tumorigenesis. Adv Cancer Res.

148:1–26. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A,

Morrison SJ and Clarke MF: Prospective identification of

tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

100:3983–3988. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Luo F, Zhang M, Sun B, Xu C, Yang Y, Zhang

Y, Li S, Chen G, Chen C, Li Y and Feng H: LINC00115 promotes

chemoresistant breast cancer stem-like cell stemness and metastasis

through SETDB1/PLK3/HIF1α signaling. Mol Cancer. 23:602024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lu H, Chen I, Shimoda LA, Park Y, Zhang C,

Tran L, Zhang H and Semenza GL: Chemotherapy-induced

Ca2+ release stimulates breast cancer stem cell

enrichment. Cell Rep. 18:1946–1957. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mannello F: Understanding breast cancer

stem cell heterogeneity: Time to move on to a new research

paradigm. BMC Med. 11:1692013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Singh P, Pesenti ME, Maffini S, Carmignani

S, Hedtfeld M, Petrovic A, Srinivasamani A, Bange T and Musacchio

A: BUB1 and CENP-U, primed by CDK1, are the main PLK1 kinetochore

receptors in mitosis. Mol Cell. 81:67–87.e9. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Pan T, Zhou D, Shi Z, Qiu Y, Zhou G, Liu

J, Yang Q, Cao L and Zhang J: Centromere protein U (CENPU) enhances

angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancer by inhibiting

ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of COX-2. Cancer Lett.

482:102–111. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Lou Y, Lu J, Zhang Y, Gu P, Wang H, Qian

F, Zhou W, Zhang W, Zhong H and Han B: The centromere-associated

protein CENPU promotes cell proliferation, migration, and

invasiveness in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 532:2155992022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bruno F, Arcuri D, Vozzo F, Malvaso A,

Montesanto A and Maletta R: Expression and signaling pathways of

nerve growth factor (NGF) and pro-NGF in breast cancer: A

systematic review. Curr Oncol. 29:8103–8120. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Marsland M, Dowdell A, Jiang CC, Wilmott

JS, Scolyer RA, Zhang XD, Hondermarck H and Faulkner S: Expression

of NGF/proNGF and their receptors TrkA, p75NTR and

sortilin in melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 23:42602022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Morisse M, Bourhis T, Lévêque R, Guilbert

M, Cicero J, Palma M, Chevalier D, le Bourhis X, Toillon RA and

Mouawad F: Influence of EGF and pro-NGF on EGFR/SORTILIN

interaction and clinical impact in head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma. Front Oncol. 13:6617752023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bradshaw RA, Pundavela J, Biarc J,

Chalkley RJ, Burlingame AL and Hondermarck H: NGF and ProNGF:

Regulation of neuronal and neoplastic responses through receptor

signaling. Adv Biol Regul. 58:16–27. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

21

|

Marcinkiewicz M, Marcinkiewicz J, Chen A,

Leclaire F, Chrétien M and Richardson P: Nerve growth factor and

proprotein convertases furin and PC7 in transected sciatic nerves

and in nerve segments cultured in conditioned media: Their presence

in Schwann cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells. J Comp

Neurol. 403:471–485. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yan R, Yalinca H, Paoletti F, Gobbo F,

Marchetti L, Kuzmanic A, Lamba D, Gervasio FL, Konarev PV, Cattaneo

A and Pastore A: The structure of the pro-domain of mouse proNGF in

contact with the NGF domain. Structure. 27:78–89.e3. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Thomas G: Furin at the cutting edge: From

protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 3:753–766. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

He Z, Khatib AM and Creemers JWM: The

proprotein convertase furin in cancer: More than an oncogene.

Oncogene. 41:1252–1262. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Regua AT, Aguayo NR, Jalboush SA, Doheny

DL, Manore SG, Zhu D, Wong GL, Arrigo A, Wagner CJ, Yu Y, et al:

TrkA interacts with and phosphorylates STAT3 to enhance gene

transcription and promote breast cancer stem cells in

triple-negative and HER2-enriched breast cancers. Cancers (Basel).

13:23402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Raninga PV, Zeng B, Moi D, Trethowan E,

Saletta F, Venkat P, Mayoh C, D'Souza RCJ, Day BW, Shai-Hee T, et

al: CBL0137 and NKG2A blockade: A novel immuno-oncology combination

therapy for Myc-overexpressing triple-negative breast cancers.

Oncogene. 44:893–908. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

28

|

Tang X, Cromwell CR, Liu R, Godbout R,

Hubbard BP, McMullen TPW and Brindley DN: Lipid phosphate

phosphatase-2 promotes tumor growth through increased c-Myc

expression. Theranostics. 12:5675–5690. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

American Veterinary Medical Association:

AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals. 2020 edition. AVMA;

Schaumburg, IL: 2020

|

|

30

|

Yan Y, Zuo X and Wei D: Concise review:

Emerging role of CD44 in cancer stem cells: A promising biomarker

and therapeutic target. Stem Cells Transl Med. 4:1033–1043. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Namekawa T, Ikeda K, Horie-Inoue K, Suzuki

T, Okamoto K, Ichikawa T, Yano A, Kawakami S and Inoue S: ALDH1A1

in patient-derived bladder cancer spheroids activates retinoic acid

signaling leading to TUBB3 overexpression and tumor progression.

Int J Cancer. 146:1099–1113. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Ghebeh H, Sleiman GM, Manogaran PS,

Al-Mazrou A, Barhoush E, Al-Mohanna FH, Tulbah A, Al-Faqeeh K and

Adra CN: Profiling of normal and malignant breast tissue show

CD44high/CD24low phenotype as a predominant stem/progenitor marker

when used in combination with Ep-CAM/CD49f markers. BMC Cancer.

13:2892013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

DA Cruz Paula A and Lopes C: Implications

of different cancer stem cell phenotypes in breast cancer.

Anticancer Res. 37:2173–2183. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Pareek S, Savaria

D, Hamelin J, Goulet B, Laliberte J, Lazure C, Chrétien M and

Murphy RA: Cellular processing of the nerve growth factor precursor

by the mammalian pro-protein convertases. Biochem J. 314:951–960.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Deichmann U, Schuster S, Mazat JP and

Cornish-Bowden A: Commemorating the 1913 michaelis-menten paper die

kinetik der invertinwirkung: Three perspectives. FEBS J.

281:435–463. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hanissian SH, Akbar U, Teng B, Janjetovic

Z, Hoffmann A, Hitzler JK, Iscove N, Hamre K, Du X, Tong Y, et al:

cDNA cloning and characterization of a novel gene encoding the

MLF1-interacting protein MLF1IP. Oncogene. 23:3700–3707. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Goldberg AL: Protein degradation and

protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature.

426:895–899. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lim KC, Tyler CM, Lim ST, Giuliano R and

Federoff HJ: Proteolytic processing of proNGF is necessary for

mature NGF regulated secretion from neurons. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 361:599–604. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hayakawa Y, Sakitani K, Konishi M, Asfaha

S, Niikura R, Tomita H, Renz BW, Tailor Y, Macchini M, Middelhoff

M, et al: Nerve growth factor promotes gastric tumorigenesis

through aberrant cholinergic signaling. Cancer Cell. 31:21–34.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

40

|

Tomellini E, Touil Y, Lagadec C, Julien S,

Ostyn P, Ziental-Gelus N, Meignan S, Lengrand J, Adriaenssens E,

Polakowska R and Le Bourhis X: Nerve growth factor and proNGF

simultaneously promote symmetric self-renewal, quiescence, and

epithelial to mesenchymal transition to enlarge the breast cancer

stem cell compartment. Stem Cells. 33:342–353. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Rockwell NC, Krysan DJ, Komiyama T and

Fuller RS: Precursor processing by kex2/furin proteases. Chem Rev.

102:4525–4548. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen C, Gupta P, Parashar D, Nair GG,

George J, Geethadevi A, Wang W, Tsaih SW, Bradley W, Ramchandran R,

et al: ERBB3-induced furin promotes the progression and metastasis

of ovarian cancer via the IGF1R/STAT3 signaling axis. Oncogene.

39:2921–2933. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhou B and Gao S: Pan-cancer analysis of

FURIN as a potential prognostic and immunological biomarker. Front

Mol Biosci. 8:6484022021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ji S, Li S, Gao H, Wang J, Wang K, Nan W,

Chen H and Hao Y: An AIEgen-based 'turn-on' probe for sensing

cancer cells and tiny tumors with high furin expression. Biomater

Sci. 11:2221–2229. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Chen M, Pan Y, Liu H, Ning F, Lu Q, Duan

Y, Gan X, Lu S, Hou H, Zhang M, et al: Ezrin accelerates breast

cancer liver metastasis through promoting furin-like

convertase-mediated cleavage of Notch1. Cell Oncol (Dordr).

46:571–587. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Liu Z, Gu X, Li Z, Shan S, Wu F and Ren T:

Heterogeneous expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and FURIN at single-cell

resolution in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res

Clin Oncol. 149:3563–3573. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Schaale D, Laspa Z, Balmes A, Sigle M,

Dicenta-Baunach V, Hochuli R, Fu X, Serafimov K, Castor T, Harm T,

et al: Hemin promotes platelet activation and plasma membrane

disintegration regulated by the subtilisin-like proprotein

convertase furin. FASEB J. 38:e701552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|