Introduction

Brain-heart crosstalk is now referred to as

neurocardiology, which addresses the effects of brain injury on the

heart or the effects of cardiac injury on the brain (1). There is increasing experimental and

clinical evidence not only suggesting a causal link from the heart

to the brain but also indicating the presence of a bidirectional

relationship, highlighting the powerful influence of the brain on

the heart (2).

Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation

plays a pivotal role in communication between the brain and heart,

leading to cardiac dysfunction (3). As the primary integrator of this

axis, the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus acts as

the primary integrator that modulates HPA axis activity, which can

increase blood pressure, alter heart rate and promote inflammation

in the cardiovascular system (4). The PVN is also a master controller

of the autonomic nervous system, which provides specialized

innervation to all autonomic relay centers (5), projecting to the rostral

ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) and spinal cord to regulate

sympathetic outflow (6).

Notably, a reduction in PVN activity promotes the improved recovery

of cardiac function after myocardial infarction (6).

Apelin, containing 77 amino acids, has been isolated

from bovine stomach extracts and its effects are mediated via

ligands for the orphan G-protein-coupled (APJ) receptor (7,8).

Apelin-13 is the main isoform that activates the APJ receptor. As a

novel regulator of activity, the apelin/APJ system is involved in

neurohumoral regulation of the HPA (9) and emerging evidence indicates that

apelin-13 and the APJ receptor are widely expressed in microglia

and neurons of the central nervous system (CNS) (10). Microinjection of apelin-13 into

the PVN increases c-Fos-like immunoreactivity in the PVN after 1.5

h (11), while chronic infusion

of apelin-13 in the PVN induces long-term hypertension and

sympathetic activation mediated by superoxide anions (12). Based on previous data, apelin-13

may affect the cardiovascular system via the vasopressinergic

system in the PVN and supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus

(13-15). A reduction in APJ mRNA expression

has been observed in the hypothalamus in postinfarct heart failure,

especially in presynaptic neurons of the PVN, which could attenuate

the pressor response to intracerebroventricularly infused apelin-13

(16).

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a well-known neuronal

transmitter that exerts inhibitory effects on the brain via the

GABAA receptor (GAR) and GABAB receptor

(GBR), which have been defined on the basis of pharmacological and

physiological research (17).

According to our previous study, the GABAergic system in the

medullary nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) contributes to the

central resetting of blood pressure and the development of

hypertension (18). NTS is

reciprocally connected with the pontine parabrachial and

Kölliker-Fuse nuclei to relay visceral afferent information to

other central autonomic network structures (19). Baroreceptor activation inhibits

vasopressin secretion, which might be regulated by the activation

of GABAergic projections to vasopressinergic neurons and the local

administration of a GAR antagonist inhibits vasopressinergic

neurons during the onset of hypertension (20). Thus, the apelin/APJ system,

vasopressinergic system and GABAergic system are vital pathways of

the CNS involved in the neural control of the cardiovascular system

in the hypothalamus, but they remain poorly understood in relation

to myocardial injury.

The parasympathetic endocrine system (PES) comprises

circulating peptides released from secretory cells that are

markedly modulated by vagal projections from the dorsal motor

nucleus of the vagus nerve (21). A total of four peptides present

in the circulatory system, isomatostatin (SST), cholecystokinin

(CCK), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and vasoactive intestinal

peptide (VIP), perform sympathetic antagonism to balance

sympathetic activation-induced pupillary dilation and increase the

rate and contractility of the heart (22).

The present study aimed to assess the effects of

apelin-13 in the PVN on the cardiac function of rats with

myocardial infarction (MI). The involved mechanisms, including

myocardial ischemia-related apoptotic and inflammatory pathway

markers in the heart and neuropeptides in the serum, were also

explored.

Materials and methods

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance

with the institutional guidelines of The First Hospital of Jilin

University and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and

Use Committee (approval no. 2020-0128). All studies were approved

locally and conformed to the guidelines from Directive 2010/63/EU

of the European Parliament on the protection of animals used for

scientific purposes. The male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased

from Charles River. A total of 246 male rats were used in the

present study (250-300 g; age, 8 weeks). The rats were maintained

under a 12-h light/dark cycle at a temperature of 20±2°C and a

relative humidity of 55±5%. Food and water were provided ad

libitum. The rat studies were performed under isoflurane

anesthesia (2.0-2.5% isoflurane, 100% oxygen at 2 l/min) in

spontaneous breathing. To perform histology studies and blood

tests, sodium pentobarbital (40-60 mg/kg) was intraperitoneally

injected to anesthetize the rats. The present study typically used

an initial dose of 40 mg/kg and occasionally administered

additional doses based on the condition of the rat. The rats were

then sacrificed by exsanguination while still under anesthesia.

Explanations of each reagent and buffer are presented in Appendix S1, Tables SI and SII.

Myocardial infarction (MI)

Male SD rats at 8 weeks of age were randomly

selected for MI modelling via left anterior descending (LAD) artery

ligation. Anesthesia was induced and maintained in the SD rats with

isoflurane (1-2% oxygen). Following anesthesia, the animals were

intubated and ventilated with a 16-gauge intravenous catheter and

placed in a supine position on a temperature control pad.

Left-sided thoracotomy was performed via a small incision between

the third and fourth intercostal spaces. The incision was expanded

by a blunt-ended retractor such that the lungs were not retracted.

The pericardial sac surrounding the heart was cut open to access

the heart. The heart was not exteriorized. Using a tapered

atraumatic needle, a 5-0 silk Prolene suture ligature was passed

underneath the LAD and tied with three knots. Visible blanching and

cyanosis of the anterior wall of the left ventricle and swelling of

the left atrium were indicative of successful ligation. Rats

subjected to cardiac exposure without coronary ligation served as

the sham-operated control group.

Western blot analysis

Micropunched NTS or PVN tissue from the brain

sections of the rats was treated with 1 ml lysis buffer,

homogenized for 15 sec, boiled for 3 min, ultrasonicated and

centrifuged. The supernatants were stored in a −80°C freezer.

Vasopressin 1a (V1a) receptor protein levels in

neuronal cultures were assessed using western blot analysis.

Cultures were washed with ice-cold PBS, scraped into lysis buffer

containing 8 μl/ml inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged at

10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was saved for the

protein assay.

Murine heart lysates were prepared by digesting

tissues in lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

and PMSF using a Qiagen Tissue Lyser (Qiagen GmbH; 50 rpm; 8 min;

4°C), followed by rocking for 1 h at 4°C, sonication on ice using

20 kHz in a pulse mode (3 sec on/5 sec off) for 10 cycles and

centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, with supernatants

stored at −80°C.

The protein concentration was determined with a BCA

protein concentration assay kit. For each sample, 20 μg

protein was separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to

nitrocellulose membranes (100 V, 2 h). Membranes were blocked in

PBS-T containing 10% milk and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 3

h, then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies

(anti-apelin polyclonal antibody, anti-GAR γ2 antibody,

anti-GABAB receptor1 antibody, anti-V1a receptor

antibody, anti-TGF-β1 antibody, anti-Smad2 antibody, anti-Bax

antibody and anti-Bcl-2 antibody; Table SI). After washing (15 min PBS-T

with 0.1% Tween followed by four 5-min PBS-T washes), the membranes

were incubated for 2 h at room temperature in horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies diluted

1:5,000. Immunoreactivity was detected by enhanced

chemiluminescence (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and the

protein bands were analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of

Health; v.1.53q).

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)

PCR

The present study used RT-qPCR to detect changes in

the expression of apelin-13, V1a receptor, GBR1 and GARγ2 in the

PVN and NTS of the rats and in the neuronal cultures. The isolation

of total RNA from PVN and NTS tissue and neuronal cultures was

performed with a RNeasy Mini Kit (cat. no. 74104; Qiagen GmbH) in

accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. RNA purity and

concentration were determined spectrophotometrically (Nanodrop

2000c; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For each RT-qPCR, 2

μg of total RNA was converted into cDNA with reverse

transcriptase. Genomic DNA was eliminated by DNase I. Real-time

PCRs were performed in a 10 μl total reaction volume using

96-well plates with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (cat. no.

208054; Qiagen GmbH) and the relative difference was expressed as

the fold change compared with control values, calculated using the

comparative cycle method (23).

The RT-qPCR system (ABI 7500; Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) with the following protocol: Initial denaturation

at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and

60°C for 34 sec. All steps adhered to the manufacturers' protocols

and each condition was assayed in three technical replicates. Data

were normalized to 18S rRNA. The sequences of the primers are

presented in Table SIII.

Brain nucleus microinjection

The rats were anaesthetized with a mixture of oxygen

and isoflurane (2-2.5%) via a nose cone. They were placed in a

stereotaxic frame (DW-2000, Chengdu Techman Co., Ltd.). The skin

overlying the midline of the skull was incised and a small hole was

drilled bilaterally on the dorsal surface of the cranium according

to the nucleus coordinates (24), including the PVN (bregma -1.92

mm, interaural 7.08 mm, midline 0.5, 5.8 mm ventral to the dura

mater) and NTS (bregma -13.68 mm, interaural -4.68 mm, midline 0.5,

8.0 mm ventral to the dura mater). A microsyringe was positioned in

the nucleus and controlled by a microsyringe pump controller.

Apelin gene transfer: The AAV2-apelin-13 virus or

AAV2-GFP (5×1012 GC/ml in 50 nl) was microinjected

unilaterally (right) into the PVN to induce endogenous apelin

expression.

Osmotic mini-pump implantation: A 28-gauge lower end

of a stainless-steel cannula (Alzet Brain Infusion Kit 2; Durect

Corporation) was implanted into the right NTS or PVN according to

the nucleus location aforementioned and then fixed on the skull

with dental cement. The upper end was connected to an osmotic

mini-pump for chronic continuous intranuclear infusion at 0.11

μl/h for 4 weeks. The pumps were filled with apelin-13 (100

μM; 100 μl) (25,13), a GAR agonist (muscimol; 100

μM, 100 μl) (18),

or a V1a receptor antagonist (SR49059; 200 μM, 100

μl) (26) and placed

subcutaneously on the backs of the rats.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed under inhaled

anesthesia with isoflurane (1-2% oxygen) using a 14-MHz transducer

at a depth of 1 cm for two-dimensional imaging. M-mode images were

taken at the mid-papillary muscle level and were used for

measurements.

Blood sample tests

Blood collected in a serum separation tube was

allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min before being

centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min. The serum from each subject

was either used immediately for analysis or divided into aliquots

and stored at −20°C for future use. The levels of somatostatin,

cholecystokinin, glucagon-like peptide-1 and vasoactive intestinal

peptide in the serum were quantified using enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits: Somatostatin (cat. no.

NBP2-80271; Novus Biologicals; Bio-Techne), cholecystokinin (cat.

no. EIAR-CCK-1; RayBiotech, Inc.), glucagon-like peptide-1 (cat.

no. E-EL-R3007-96T; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Wuhan

Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), and vasoactive intestinal

peptide (cat. no. NBP2-82466; Novus Biologicals; Bio-Techne). A

commercial arg8-Vasopressin ELISA kit (cat. no.

ADI-900-017A; Enzo Life Sciences) and a noradrenaline competitive

ELISA kit (cat. no. EEL010; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were

used for the quantitative measurement of plasma vasopressin and

noradrenaline levels.

Cardiac immunohistochemistry and

multiplex fluorescent immunohistochemistry staining

To assess the alterations in TGF-β1, Smad2, Bax and

Bcl-2 expression in cardiac tissues, the heart samples were fixed

in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h and embedded in paraffin.

Briefly, tissues were dehydrated in graded ethanol (70-100%),

cleared in xylene, infiltrated with paraffin wax at 60°C and

embedded in molds for solidification. All steps were performed with

agitation. To perform immunohistochemical staining, samples were

sectioned at 4-5 μm thickness. Following deparaffinization

and rehydration, antigen retrieval was conducted using citrate

buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 20 min. After blocking endogenous

peroxidase activity with 3% H2O2 and

nonspecific binding sites with normal serum (cat. no. abs933;

Absin), sections were incubated with primary antibodies (TGF-β1,

Smad2, Bax and Bcl-2) overnight at 4°C. HRP-conjugated secondary

antibodies were then applied, followed by DAB development (room

temperature; 10 min) and hematoxylin counterstaining (room

temperature; 5 min). Finally, sections were dehydrated, cleared in

xylene and mounted for microscopic examination. The multiplex

fluorescent immunohistochemistry staining was performed on

4-μm paraffin-embedded cardiac sections using sequential

tyramide signal amplification. Following deparaffinization and

initial antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0), sections were

blocked and incubated with the first primary antibody at 4°C 16 h,

followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and TSA570

development. Following microwave stripping in citrate buffer, the

cycle was repeated for Bax, SMAD2 and Bcl-2, with sodium azide

treatment between each round to inactivate residual HRP activity.

Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (room temperature; 5 min) and

slides were mounted with anti-fade medium. Multispectral imaging

was performed using a Vectra system (AKOYA Vectra Polaris; AKOYA

Inform 2.6; Akoya Biosciences, Inc.), with spectral unmixing to

separate fluorophore signals.

Rat apelin-13 gene adeno-associated virus

type 2 (AAV2) production

The rat apelin-13 gene was synthesized by Wuhan

Beisai Model Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The CMV promoter partial

sequence and the mCherry partial sequence were connected to both

ends of the gene (Appendix S1).

The virus concentration was 5×1012 GC/ml. The

information concerning the apelin-13 gene from NCBI is described in

Appendix S1.

Primary neuron culture

Primary neuron cultures were prepared from brain of

1-day-old neonatal rats. The neonatal rats were euthanized via an

intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 150

mg/kg and washed with 70% ethanol. Brain tissue (from 5-7 rats) was

mechanically dissociated in Solution D by pipetting 10 times. Cells

were further dissociated with 0.25% trypsin and DNase I (496 U/ml),

resuspended in DMEM containing 10% PDHS and plated onto

poly-L-lysine-precoated (for at least 4 h) Nunc plastic tissue

culture dishes. Prior to plating, the cell suspension was diluted

to the required number of cells/unit volume (3×106

cells/2 ml) of medium per 35-mm dish. The cells were grown in a

humidified atmosphere with 95% O2 and 5% CO2

for 3 days, after which the culture medium was replaced with fresh

DMEM containing cytosine arabinoside (ARC; 1 μM) and 10%

PDHS. After 3 days, the ARC was removed and replaced with normal

medium for an additional 5-9 days before use.

Immunocytochemistry of neuronal

cultures

Neuronal cultures from newborn Sprague-Dawley rats

were washed briefly with Dulbecco's PBS three times and then fixed

with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS/Tween) and 4% formaldehyde

solution for 15 min at 4°C. After three brief PBS-Tween washes,

cells were blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS-Tween at 37°C for 30

min. The blocking solution was completely removed without

additional washing. Primary antibodies (rabbit anti-rat APJ or V1a

antibody) diluted in 1 ml PBS-Tween were added and incubated at 4°C

overnight. Following three 3-min PBS-Tween washes, neurons were

incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h (Alexa

Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG; cat. no. 4412S; CST;

1:1,000) and washed three times (3 min each) with PBS-Tween. Nuclei

were stained with DAPI at room temperature for 5 min, washed four

times thoroughly, then mounted with anti-fade medium under glass

coverslips.

Masson's trichrome staining

To evaluate cardiac morphological changes and the

extent of cardiac fibrosis, heart tissues were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 24 h and embedded in paraffin. Cardiac

fibrosis was determined using Masson's trichrome staining of

4%-PFA-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 4-μm-thick heart

cross-sections. Briefly, dewaxed sections are treated with

potassium dichromate overnight, rinsed, then stained with Ponceau S

(5-10 min). After washing, slides are treated with phosphomolybdic

acid (1-3 min), directly stained with aniline blue (30 sec-2 min),

and differentiated in 1% acetic acid. Images were captured by light

microscopy for analysis. The fibrotic fraction was obtained by

calculating the ratio of blue (fibrotic) to total myocardial area

using ImageJ (v.1.53q; National Institutes of Health).

TUNEL staining

For apoptosis and α-actin co-staining,

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded heart sections were first

deparaffinized. Antigen retrieval was performed using the steamer

method in citric acid antigen repair buffer (pH 6.0), followed by

blocking with 3% goat serum at room temperature for 30 min. The

sections were incubated with terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl

transferase (TdT) mixed with deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP; 1:10)

at 4°C overnight. The following day, the sections were washed with

PBS three times and then nuclei were stained with DAPI for 10 min

at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, the sections were

mounted with an anti-fade mounting medium.

Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)

staining

After anaesthetizing the rats, heart tissue was

collected immediately and cold PBS was used to perfuse the left

ventricle within 5 min. The heart was then stored at −20°C for

20-30 min. Each heart was sectioned into five 2-mm transverse

slices, which were stained with preheated TTC solution for 15-30

min at 37°C. Next, the sections were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (room

temperature; 24 h) and images of the TTC-stained sections were

captured. The cardiac infarction area was pale and normal cardiac

tissue was red. The infarct size was quantified as the total

infarct area divided by the area at risk using ImageJ ((v.1.53q;

National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

The number of samples (n) used in each experiment is

indicated in the legends or shown in the figures and indicates

biological replicates. The results are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM). The

normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For

datasets with a normal distribution, statistical analyses were

performed via an unpaired two-tailed t test or one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple-comparisons test and

Dunnett's multiple-comparisons test. Two groups were statistically

compared via the unpaired Mann-Whitney U test if the datasets did

not pass the normality test. Statistical analyses were performed

using PRISM (GraphPad Software Inc.; Dotmatics; version 10).

Post-hoc power analysis was conducted for all key statistical

comparisons using the observed effect sizes and variances via the

WebPower platform (webpower.psychstat.org). P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Expression of apelin-13, the V1a receptor

and the GARγ2 receptor in MI model rats

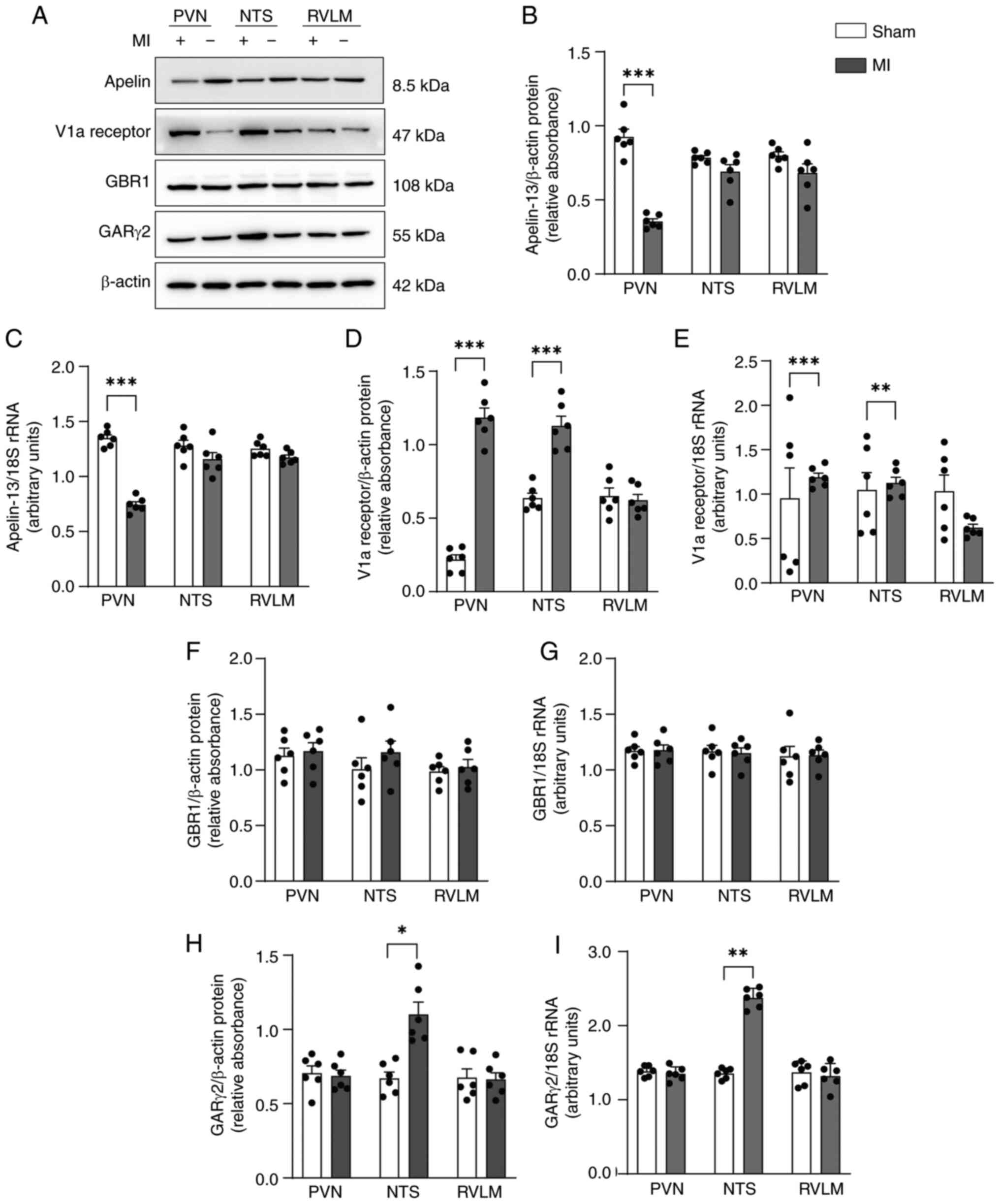

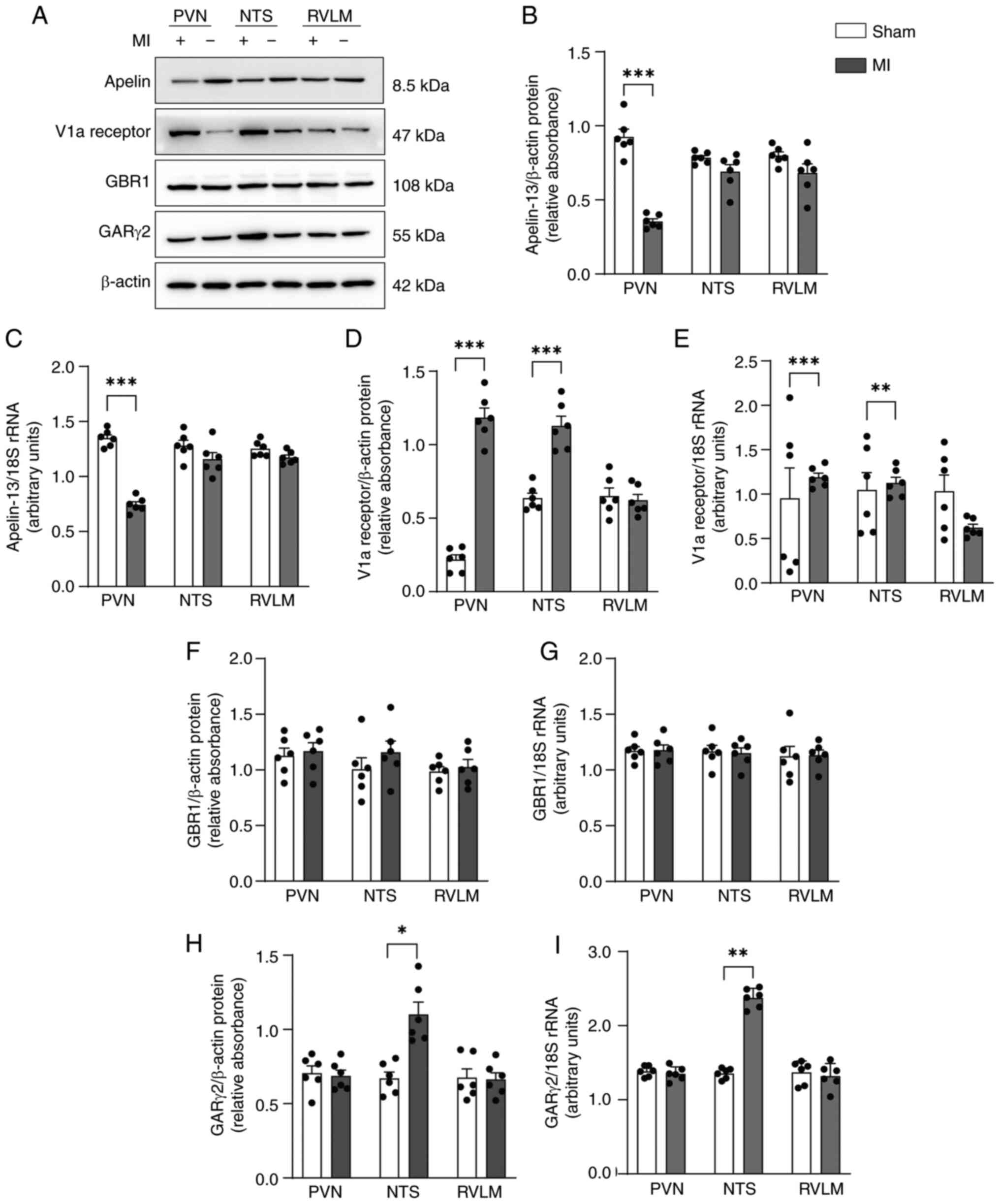

On day 28 following MI, apelin-13 expression was

markedly lower at both the protein and mRNA levels in the PVN but

not in the NTS or RVLM in MI model rats compared with sham rats

(Fig. 1A-C). V1a receptor

expression was increased in the PVN and NTS but not in the RVLM at

both the protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 1A, D and E). GARγ2 was higher in

the NTS but not in the PVN or RVLM in MI model rats compared with

sham control rats (Fig. 1A, H and

I). By contrast, GBR1 expression was not markedly affected

(Fig. 1A, F and G). These

findings indicated that apelin-13 expression was downregulated in

the PVN of MI rats and suggested that both V1a receptors and GARγ2

may play a role in central nervous system regulation of MI within

the PVN and nucleus NTS.

| Figure 1Expression of apelin-13, the V1a

receptor and the GARγ2 receptor in MI model rats. (A)

Representative western blots of apelin-13, the V1a receptor, the

GBR1 and the GARγ2 in the PVN, NTS and RVLM from MI model rats and

sham-operated control rats. (B) Quantification of apelin-13 protein

levels. (C) mRNA expression levels of apelin-13. (D) Quantification

of V1a receptor protein levels. (E) mRNA expression levels of the

V1a receptor. (F) Quantification of GBR1 protein levels. (G) mRNA

expression levels of GBR1. (H) Quantification of GARγ2 protein

levels. (I) mRNA expression levels of GARγ2. Normality was tested

using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data (n=6 rats per group; 3

technical replicates) in B-I are shown as mean ± SEM and were

analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t test.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. Post-hoc power exceeded 80% for all

comparisons. V1a, Vasopressin 1a; GAR, GABAA receptor;

MI, myocardial infarction; GBR1, GABAB receptor1; PVN,

paraventricular nucleus; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; RVLM,

rostral ventrolateral medulla. |

Effects of apelin-13 microinjection into

the PVN on cardiac function in MI model rats

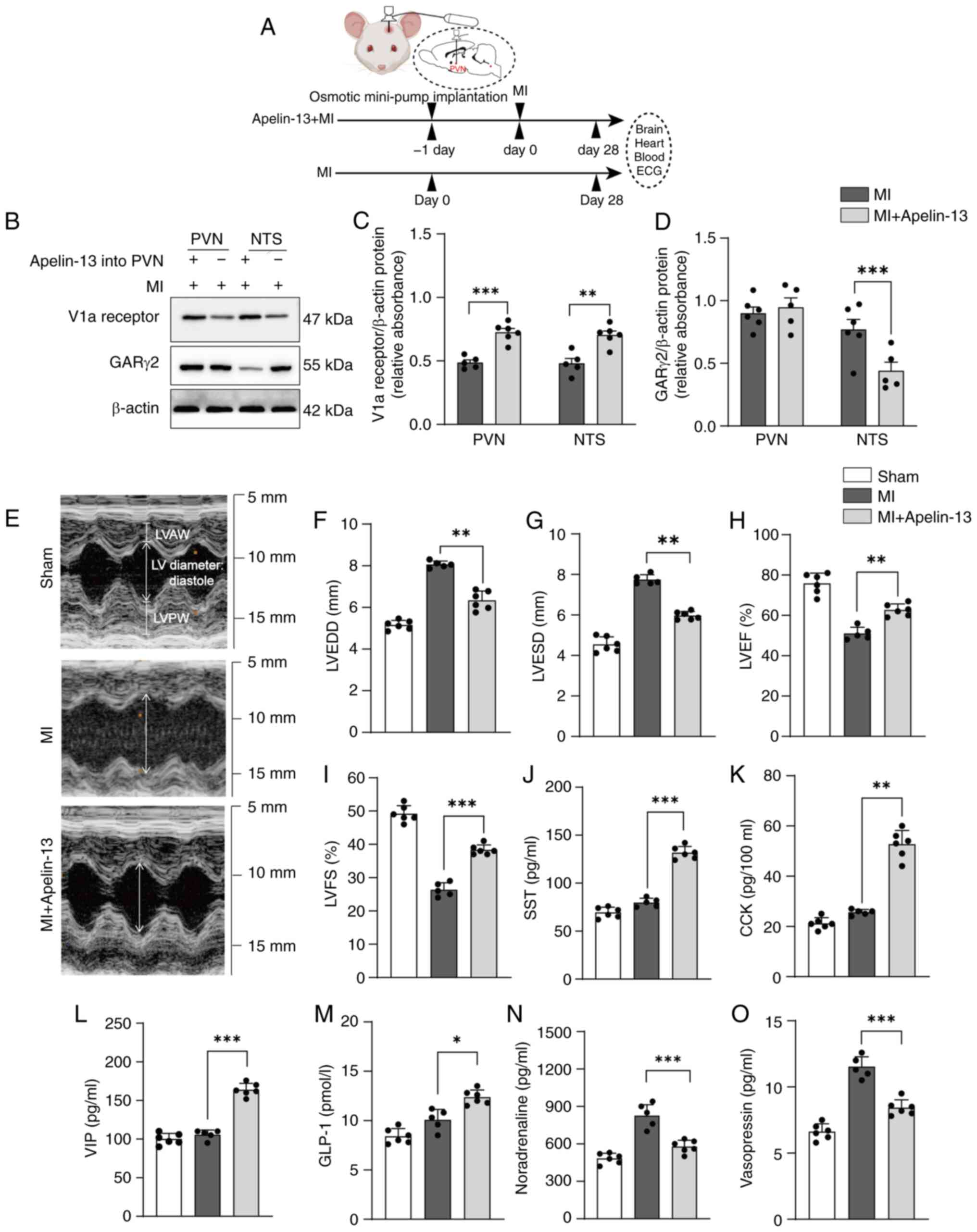

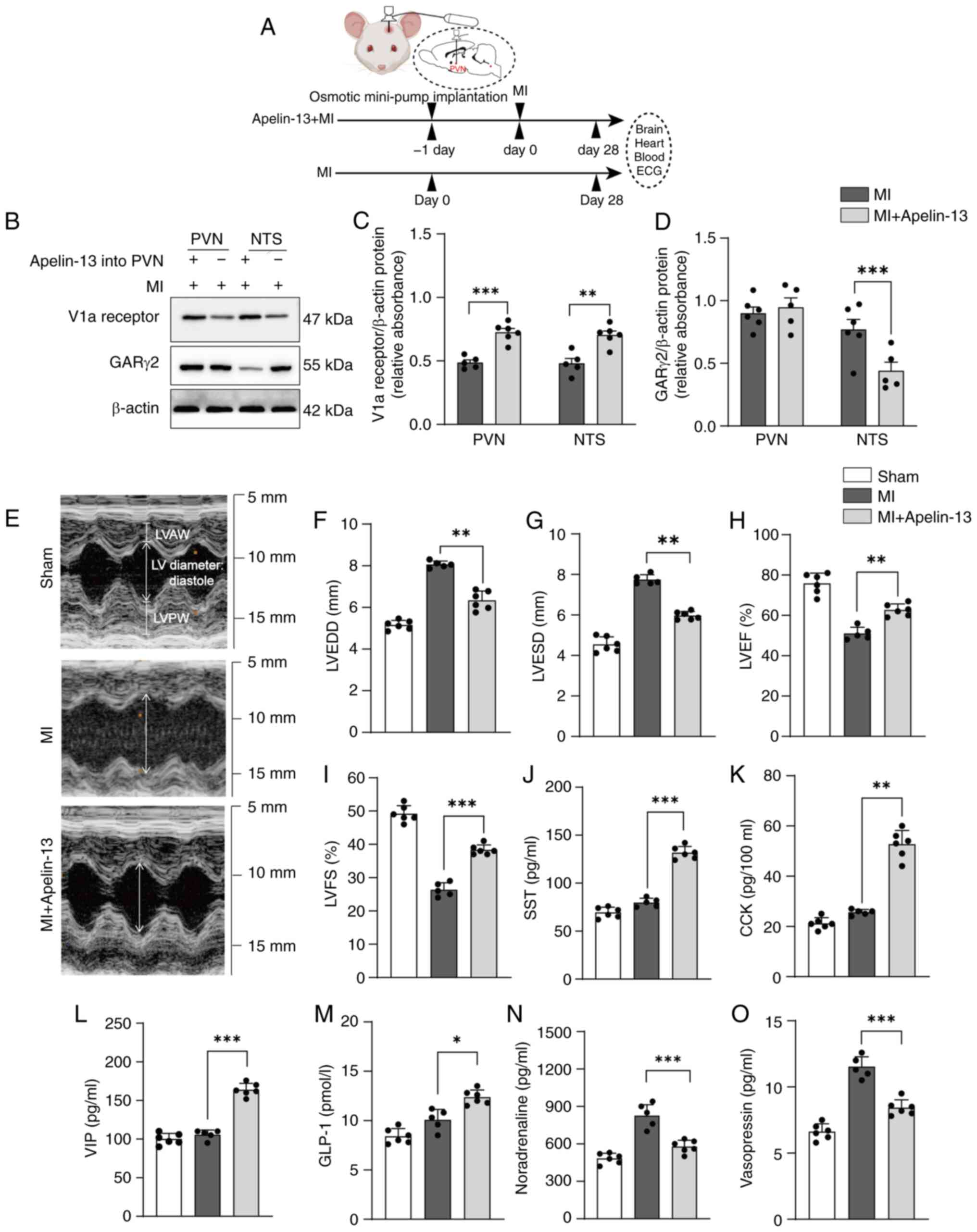

The present study investigated the effects of

continuous exogenous apelin-13 infusion into the PVN on MI rats

using osmotic minipump implantation. MI models were established one

day after implanting an osmotic mini-pump with apelin-13 into the

PVN (Fig. 2A). Continuous

apelin-13 infusion into the PVN of MI rats increased V1a receptor

expression in the PVN and NTS but decreased GARγ2 expression in the

NTS (Fig. 2B-D).

Echocardiography on day 28 after MI revealed improved cardiac

function in the rats that received continuous apelin-13 infusion

into the PVN (Fig. 2E).

Specifically, these rats presented a greater lower left ventricular

end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD; 6.34±0.45 vs. 8.06±0.16 mm,

P<0.01; Fig. 2F), lower left

ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD; 5.97±0.20 mm vs.

7.74±0.24 mm, P<0.001; Fig.

2G), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; 62.7±3.0% vs.

51.0±3.2%, P<0.01; Fig. 2H),

left ventricular fraction shortening (LVFS; 38.3±1.5% vs.

26.4±2.1%, P<0.001; Fig. 2I)

compared with the MI group. Compared with MI model rats, MI model

rats that received apelin-13 continuous infusion into the PVN

presented higher serum levels of SST (131.7±6.6 vs. 79.8±4.5 pg/ml;

P<0.001), CCK (52.7±5.6 vs. 25.6±1.1 pg/100 ml; P<0.001), VIP

(163.8±8.3 vs. 105.6±6.3 pg/ml; P<0.001) and GLP-1 (12.4±0.7 vs.

10.0±1.1 pg/ml; P<0.05; Fig.

2J-M), while showing markedly lower noradrenaline levels

(578.3±51.5 vs. 825.0±89.4 pg/ml, P<0.001; Fig. 2N) and vasopressin levels (8.4±0.6

vs. 11.5±0.8 pg/ml, P<0.001; Fig.

2O). These findings suggested apelin-13 in the PVN improved

post-MI cardiac function by activating both the vasopressinergic

signaling and parasympathetic neuroendocrine pathways.

| Figure 2Effects of apelin-13 microinjection

into the PVN on cardiac function in MI model rats. (A) MI models

were established one day after implanting an osmotic mini-pump

delivering apelin-13 into the PVN. Cardiac function was assessed

and tissue samples were collected 28 days after mini-pump

implantation. (B) Representative western blots for the V1a receptor

and GARγ2 in the PVN and NTS from MI model rats and MI model rats

continuously microinjected with apelin-13 into the PVN for 28 days.

(C) Quantification of V1a receptor protein levels. (D)

Quantification of GARγ2 receptor protein levels. (E) Representative

ultrasound images (M-mode) performed on days 28 after MI and

sham-operated control. Echocardiographic results for (F) LVEDD, (G)

LVESD, (H) LVEF and (I) LVFS (n=6 in the sham-operated control

group; n=5 in the MI group, one rat succumbed at 20 days; n=6 in

the MI + apelin group). Plasma levels of (J) SST, (K) CCK, (L) VIP,

(M) GLP-1, (N) noradrenaline and (O) vasopressin (n=6 in the

sham-operated control group; n=5 in the MI group, one rat succumbed

at 20 days; n=6 in the MI + apelin group). Normality was tested

using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data in C-D show mean ± SEM; F-O

show mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way

ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple-comparisons test.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. Post-hoc power exceeded 80% for all

comparisons. PVN, paraventricular nucleus; MI, myocardial

infarction; V1a, Vasopressin 1a; GAR, GABAA receptor;

NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; LVEDD, left ventricular

end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, lower left ventricular end-systolic

diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left

ventricular fraction shortening; SST, isomatostatin; CCK,

cholecystokinin; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide; GLP-1,

glucagon-like peptide 1. |

Effects of continuous apelin-13 infusion

into the PVN on myocardial ischemia-associated apoptotic and

inflammatory protein expression in MI rats

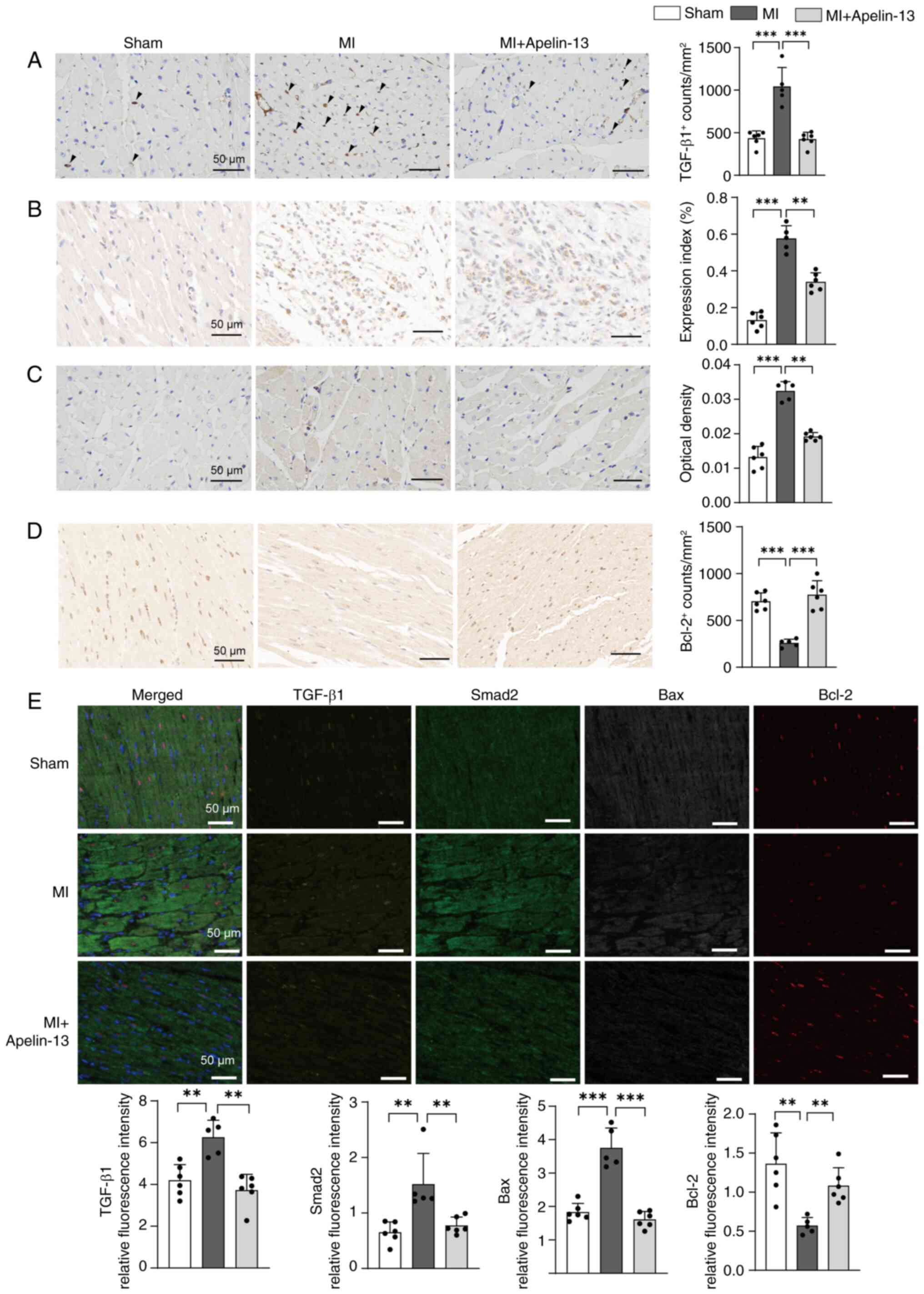

To investigate the cardioprotective mechanisms of

PVN apelin-13 infusion, myocardial expression of

ischemia-associated apoptotic and inflammatory proteins was

analyzed by immunohistochemistry and multiplex fluorescent

immunohistochemistry staining in heart tissues. Results from dual

staining consistently demonstrated the involvement of both

TGF-β/Smad and Bax/Bcl-2 signaling pathway in apelin-13-induced

cardioprotection within the PVN. Post-MI rats showed a significant

increase in TGF-β1 and Smad2 expression in heart tissue, which

contributed to ventricular remodeling. PVN infusion of apelin-13

effectively suppressed these increases compared to untreated MI

rats (Fig. 3A, B and E).

Compared to sham-operated controls, post-MI rats exhibited markedly

elevated Bax and reduced Bcl-2 expression in the myocardium.

Notably, PVN administration of apelin-13 effectively reversed these

alterations by downregulating Bax while upregulating Bcl-2

(Fig. 3C-E).

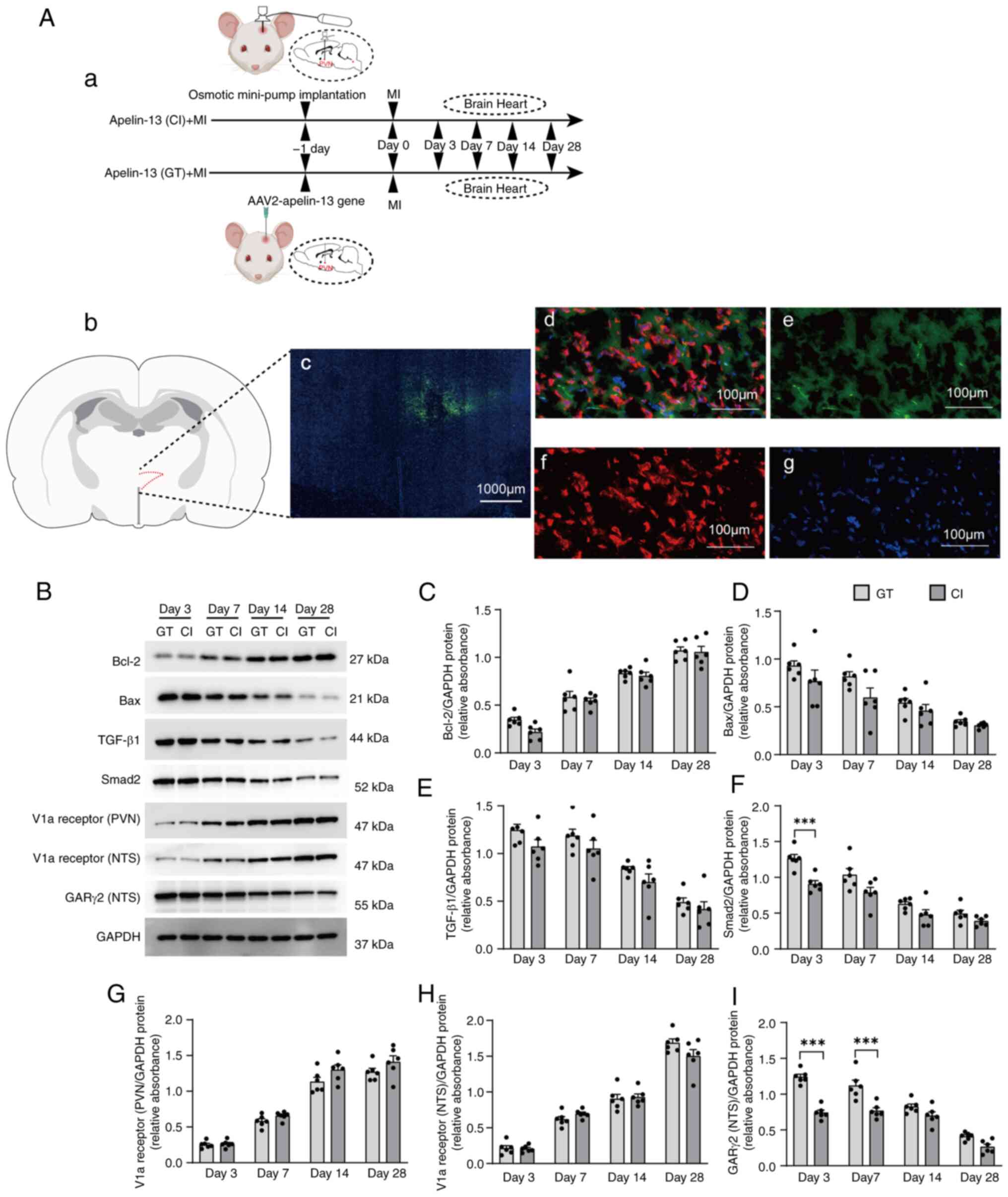

Comparison of AAV2-apelin-13 gene

transfer vs. apelin-13 infusion in PVN effects on myocardial

ischemia-related apoptotic and inflammatory proteins in MI model

rats

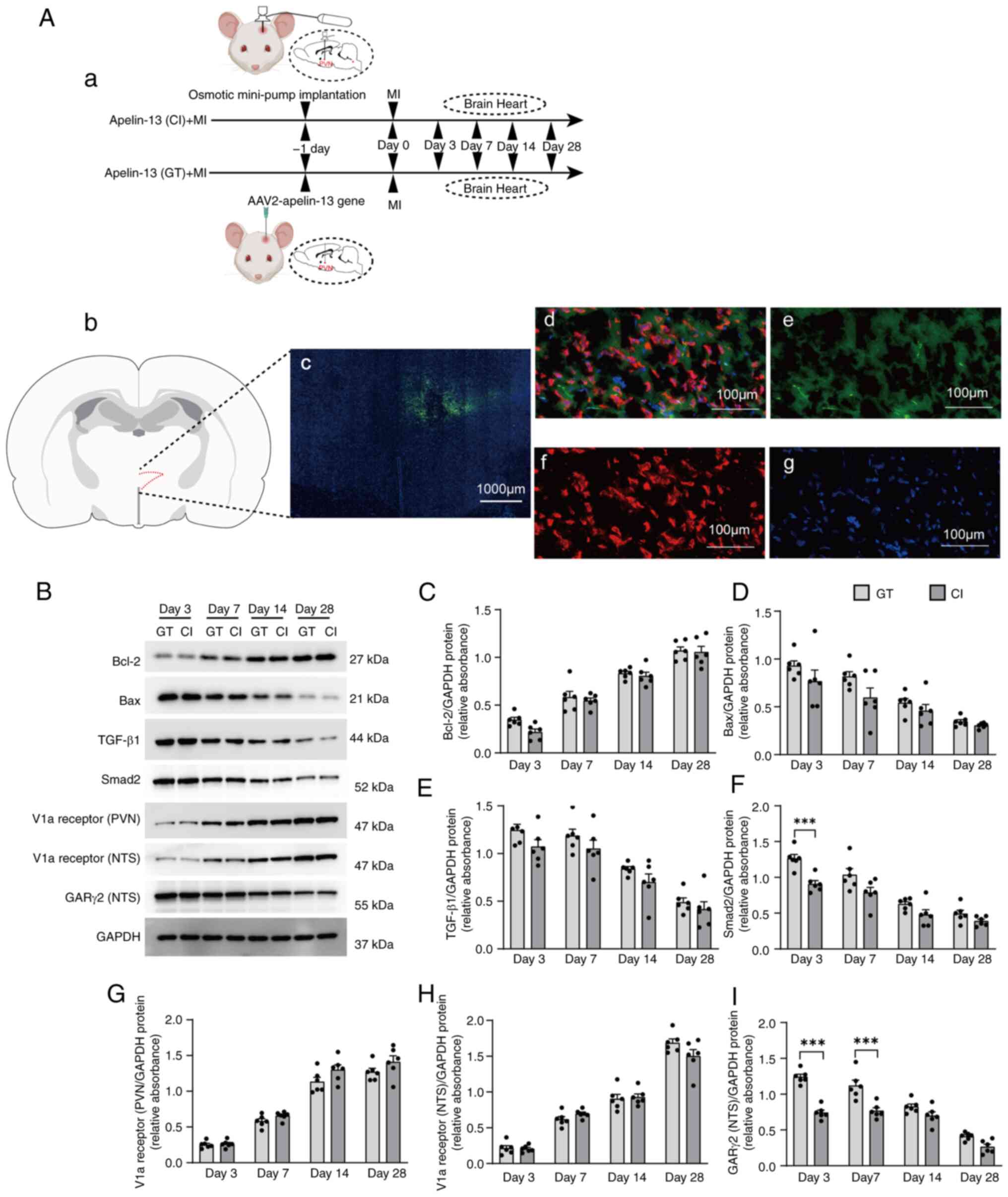

MI models were established one day after implanting

osmotic mini-pumps with apelin-13 or performing AAV2-apelin-13 gene

transfer into PVN. Heart and brain tissues were collected at 3-,

7-, 14- and 28-days post-MI (Fig.

4Aa). First, successful microinjection of AAV2-apelin-13 gene

into the PVN and its subsequent overexpression was confirmed

(Fig. 4Ab-g). Subsequently, the

effects of AAV2-apelin-13 gene transfer compared with continuous

apelin-13 infusion in the PVN were compared. AAV2-apelin-13 gene

transfer and continuous exogenous apelin-13 infusion into the PVN

of MI model rats both induced time-dependent upregulation of Bcl-2

and downregulation of Bax in cardiac tissue (Fig. 4B-D). Concurrently, the expression

of TGF-β1 and Smad2 progressively decreased over time (Fig. 4B, E and F). Correspondingly, V1a

receptor expression in the PVN and NTS were elevated, while GARγ2

expression in the NTS declined gradually (Fig. 4B and G-I). At the same selected

time points, there were no significant differences in the

aforementioned protein expression between AAV2-apelin-13 gene

transfer and continuous exogenous apelin-13 infusion. Therefore,

subsequent studies will employ a combined approach using

AAV2-mediated apelin-13 gene transfer specifically targeting the

PVN, coupled with concurrent implantation of osmotic mini-pumps to

deliver various antagonists to either the PVN or NTS for

comprehensive study.

| Figure 4Comparison of effects between

apelin-13 gene transfer and continuous infusion approaches. (Aa)

After implanting apelin-13 osmotic mini-pumps or delivering

AAV2-apelin-13 to the PVN, MI was induced and heart and brain

tissues collected at 3-, 7-, 14- and 28-days post-MI (n=6 in each

group). Location of the stained PVN brain sections shown in (b) and

(c), based on the rat brain atlas of C. Watson and G. Paxinos

(24). (c) Fluorescence

micrograph (magnification, ×10) demonstrating the localization of

apelin-13 within the PVN. 3v is the third ventricle. (d) Overlap of

(e), (f) and (g), showing that the green fluorescence is neuronally

located. (e) Fluorescence micrograph (magnification, ×40)

indicating the localization of apelin-13 in PVN cells immunostained

with an anti-apelin antibody (green). (f) Same field of cells as in

panel (e), immunostained with anti-NeuN antibodies (red). (g) DAPI

staining of the same field of cells in panel (e). (B) Molecular

pathways regulating apoptotic and inflammatory pathways were

assessed through western blotting of the expression of Bax, Bcl-2,

TGF-β1 and Smad2 over time in MI model rats and the expression of

the V1a receptor and GARγ2 induced by apelin-13 overexpression in

the PVN. (C and I) Quantification of the fold change in target gene

expression vs. GAPDH expression. The data (n=6 rats per group, 3

technical replicates) in (C-I) are shown as mean ± SEM and were

analyzed via an unpaired two-tailed t test. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Post-hoc power

exceeded 80% for all key comparisons. PVN, paraventricular nucleus;

MI, myocardial infarction; GT, gene transfer; CI, continuous

infusion. |

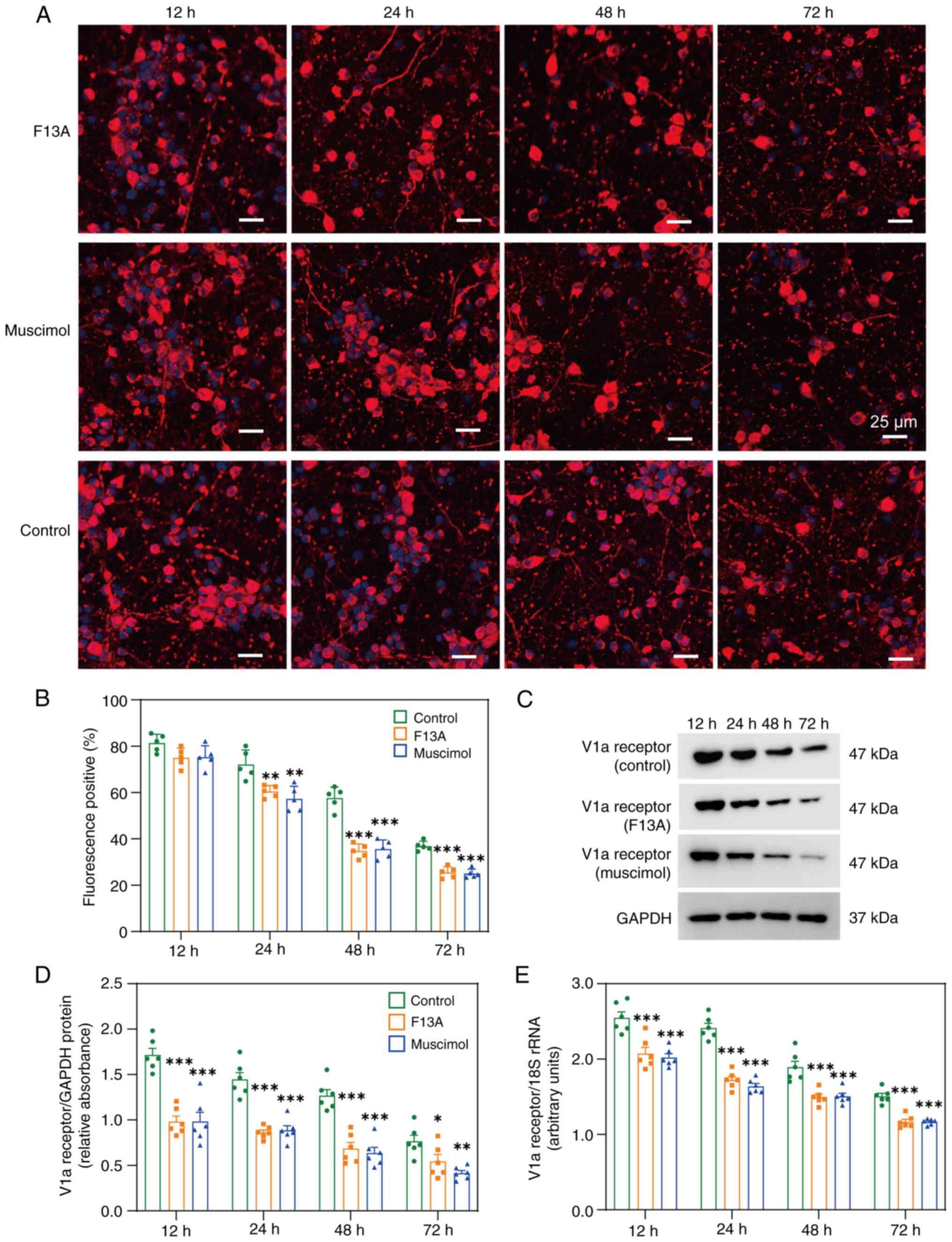

Effects of the APJ receptor and the GARγ2

receptor on the V1a receptor in primary cultured neurons

Prior to proceeding to further animal studies, it

was assessed whether the APJ receptor and GARγ2 modulated V1a

receptor expression in primary neuronal cultures.

Immunofluorescence staining of primary culture neurons (Fig. 5A and B) revealed a time-dependent

decrease in V1a receptor expression at both the protein (Fig. 5C and D) and mRNA levels (Fig. 5E) after treatment with either the

APJ receptor antagonist F13A or the GAR agonist muscimol.

Therefore, based on these observations, it was concluded that both

APJ receptor antagonist and GAR agonist muscimol markedly altered

V1a receptor expression, although the underlying mechanisms require

further investigation.

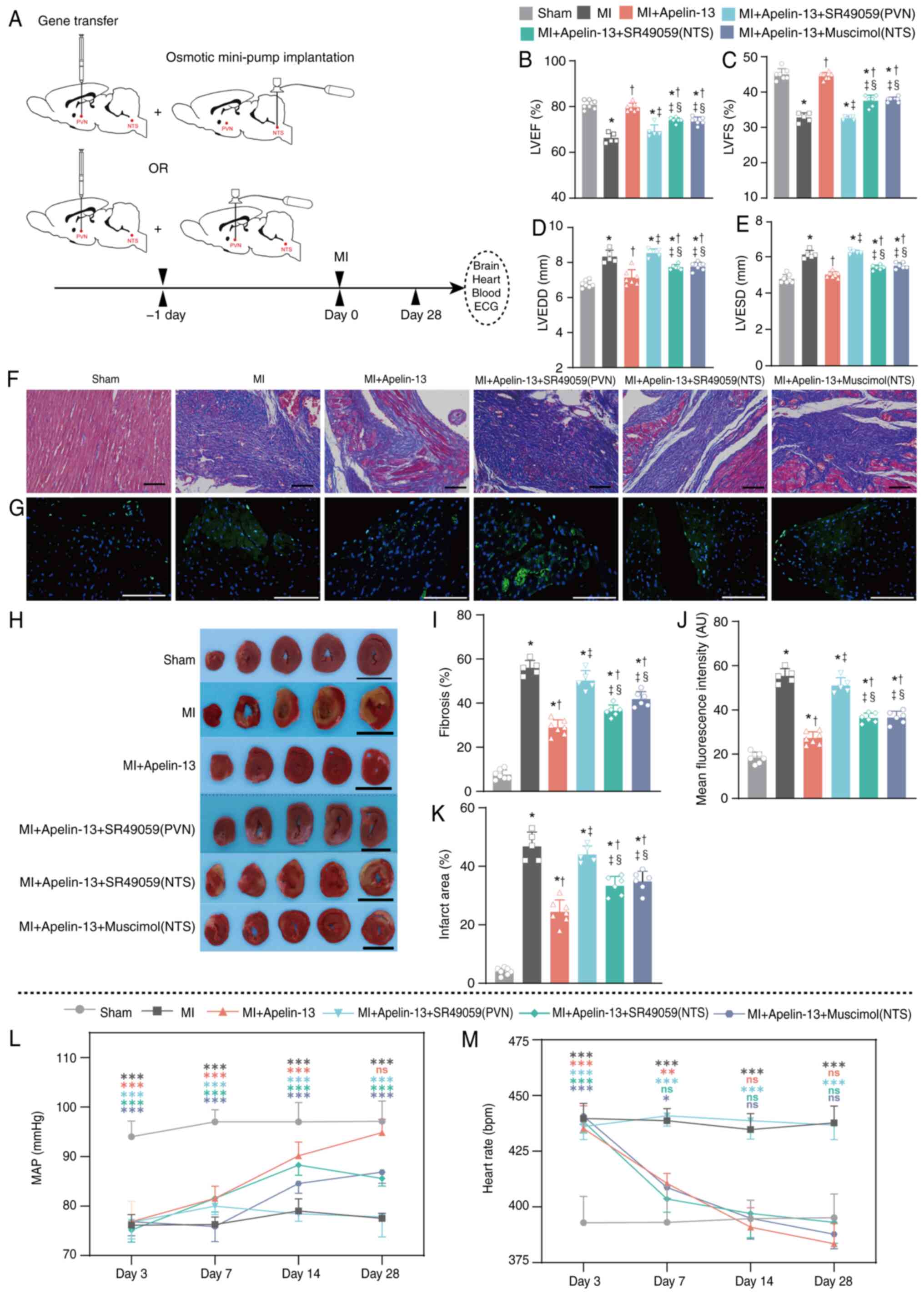

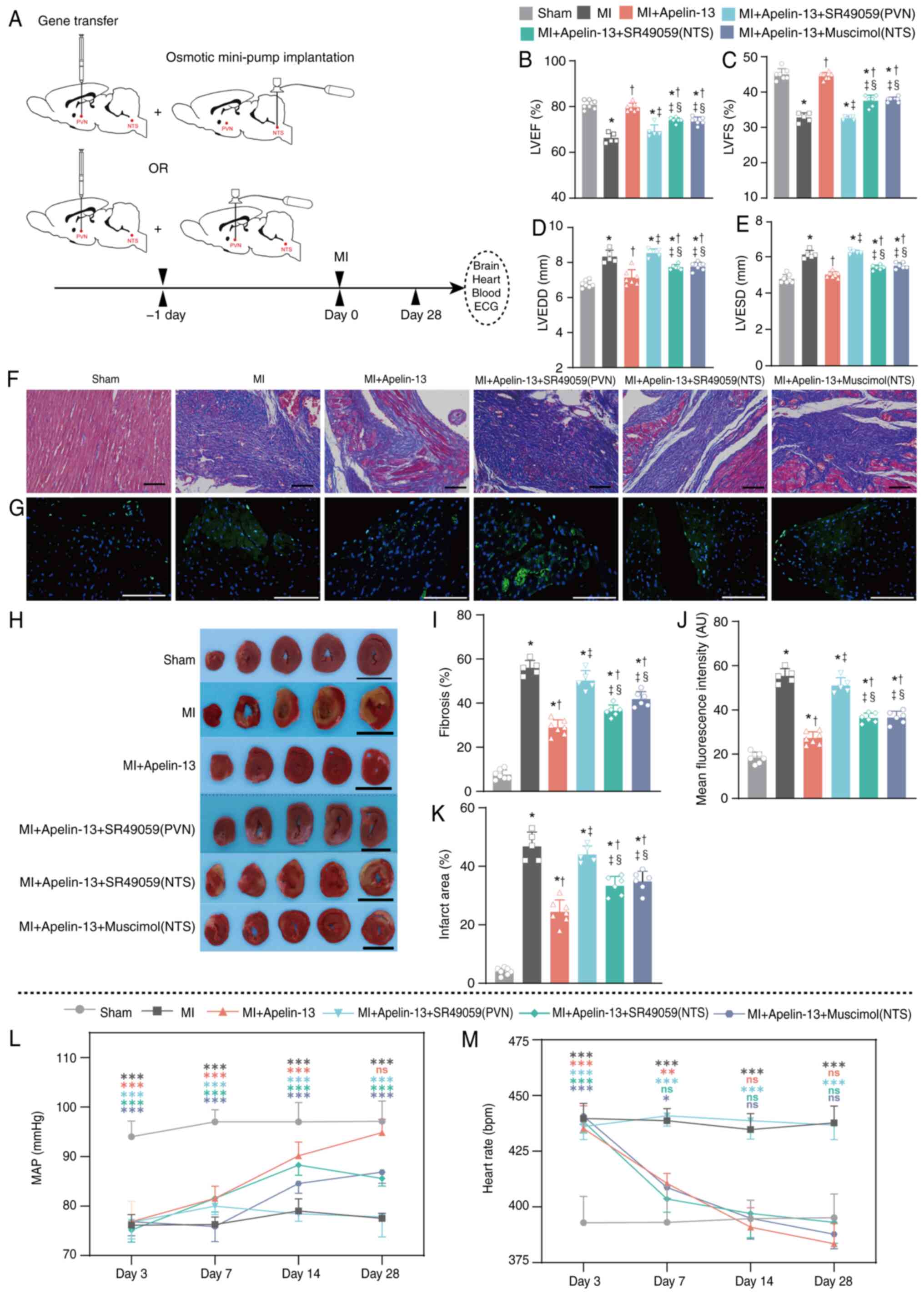

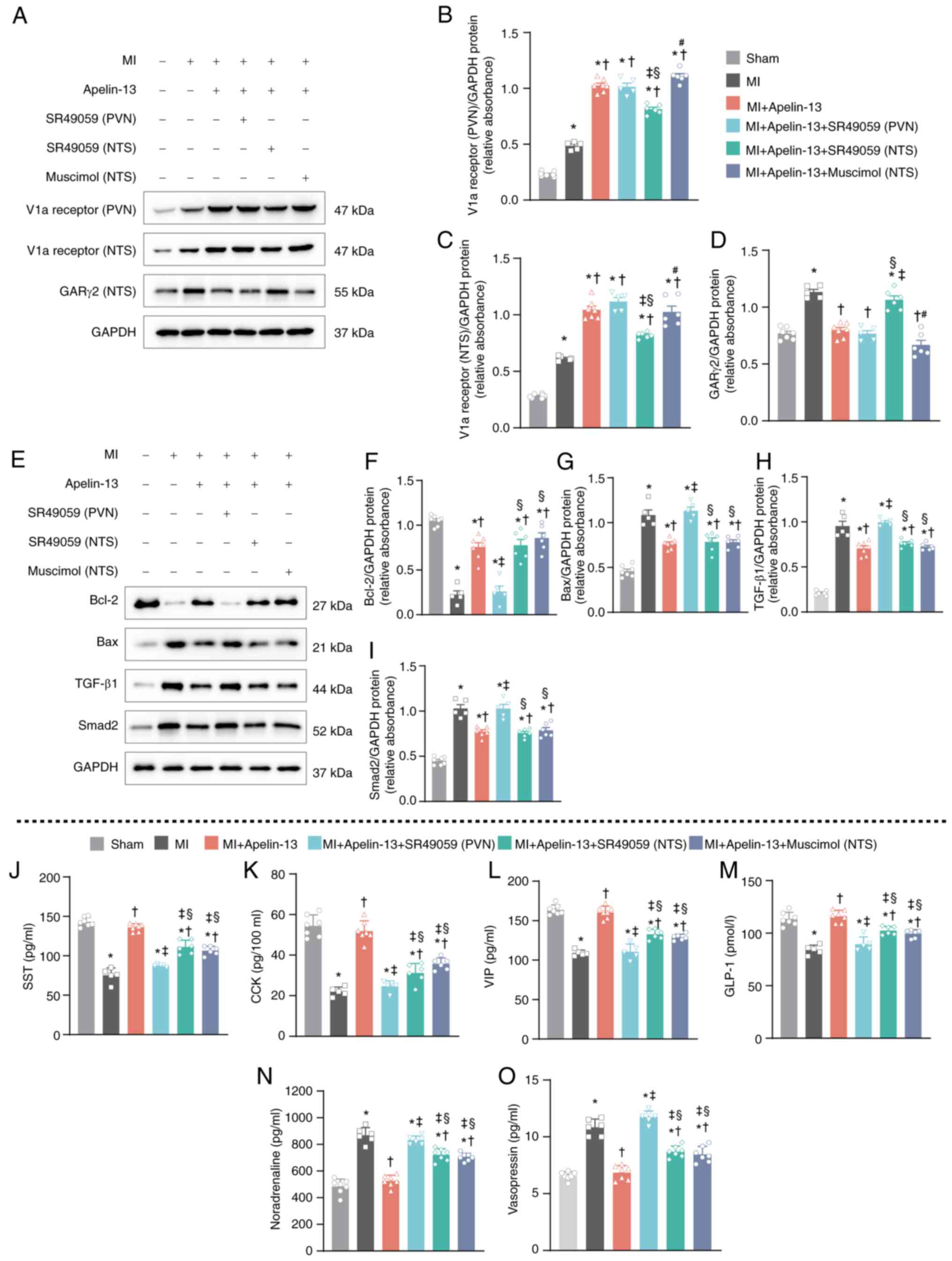

The effect of apelin-13 overexpression

(AAV2-apelin-13 gene transfer) in the PVN on V1a receptor-mediated

improvement in the cardiac function in MI model rats

To investigate PVN V1a receptor-mediated

cardioprotection, three interventions were employed: i) PVN

AAV2-apelin-13 with PVN osmotic minipump delivering V1a antagonist

SR49059; ii) PVN AAV2-apelin-13 with ipsilateral NTS minipump

(SR49059); and iii) PVN AAV2-apelin-13 with ipsilateral NTS

minipump containing the GAR agonist muscimol. The MI model was

constructed one day after the transfer of the apelin-13 gene into

PVN and the implantation of mini-pump (Fig. 6A). Prior to formal experiments,

the AAV2-GFP group was compared with the sham-operated group and no

significant difference was observed in relevant protein expression.

Therefore, in this experiment, only the sham-operated group was

used as controls (Fig. S1). The

overexpression of apelin-13 in the PVN of the MI model rats

markedly improved cardiac function, including the LVEF (79.1±1.8%

vs. 66.2±2.2%; P<0.05; Fig.

6B), LVFS (45.0±1.9% vs. 32.8±1.3%; P<0.05; Fig. 6C), LVEDD (7.14±0.45 vs. 8.34±0.36

mm; P<0.05; Fig. 6D) and

LVESD (5.01±0.17 vs. 6.12±0.23 mm; P<0.05) (Fig. 6E). These effects were attenuated

by continuous PVN/NTS microinjection of the V1a antagonist SR49059

and continuous NTS microinjection of the GAR agonist muscimol

(Fig. 6B-E). Compared with the

continuous microinjection of SR49059 into the PVN in MI model rats

overexpressing apelin-13, the continuous microinjection of SR49059

or muscimol into the NTS had fewer attenuating effects (Fig. 6B-E). The protective effects of

apelin-13 overexpression were evident in Masson staining (Fig. 6F), TUNEL assay (Fig. 6G) and TTC staining (Fig. 6H) following microinjection of

SR49059 into the PVN or NTS, or muscimol into the NTS. Bar graphs

of the Masson, TUNEL and TTC staining results indicated that

apelin-13 overexpression in the PVN markedly decreased fibrosis

(29.0±3.4% vs. 56.0±3.4%; P<0.05; Fig. 6I), the mean fluorescence

intensity (27.27±2.81 vs. 55.34±3.32 AU; P<0.05; Fig. 6J) and infarction area (24.4±4.1%

vs. 46.8±4.9%; P<0.05; Fig.

6K). Compared with the microinjection of SR49059 into the PVN,

the microinjection of SR49059 or muscimol into the NTS led to less

fibrosis, a lower mean fluorescence intensity and a reduced

infarction area (Fig. 6I-K).

Compared with the sham group, the MI rats with apelin-13

overexpression in the PVN had a similar MAP (94.9±2.7 vs. 97.1±4.1

mmHg; n=7; P>0.05) and HR (383.4±9.1 vs. 395.4±10.7 bpm; n=7;

P>0.05; Fig. 6L and M) at 28

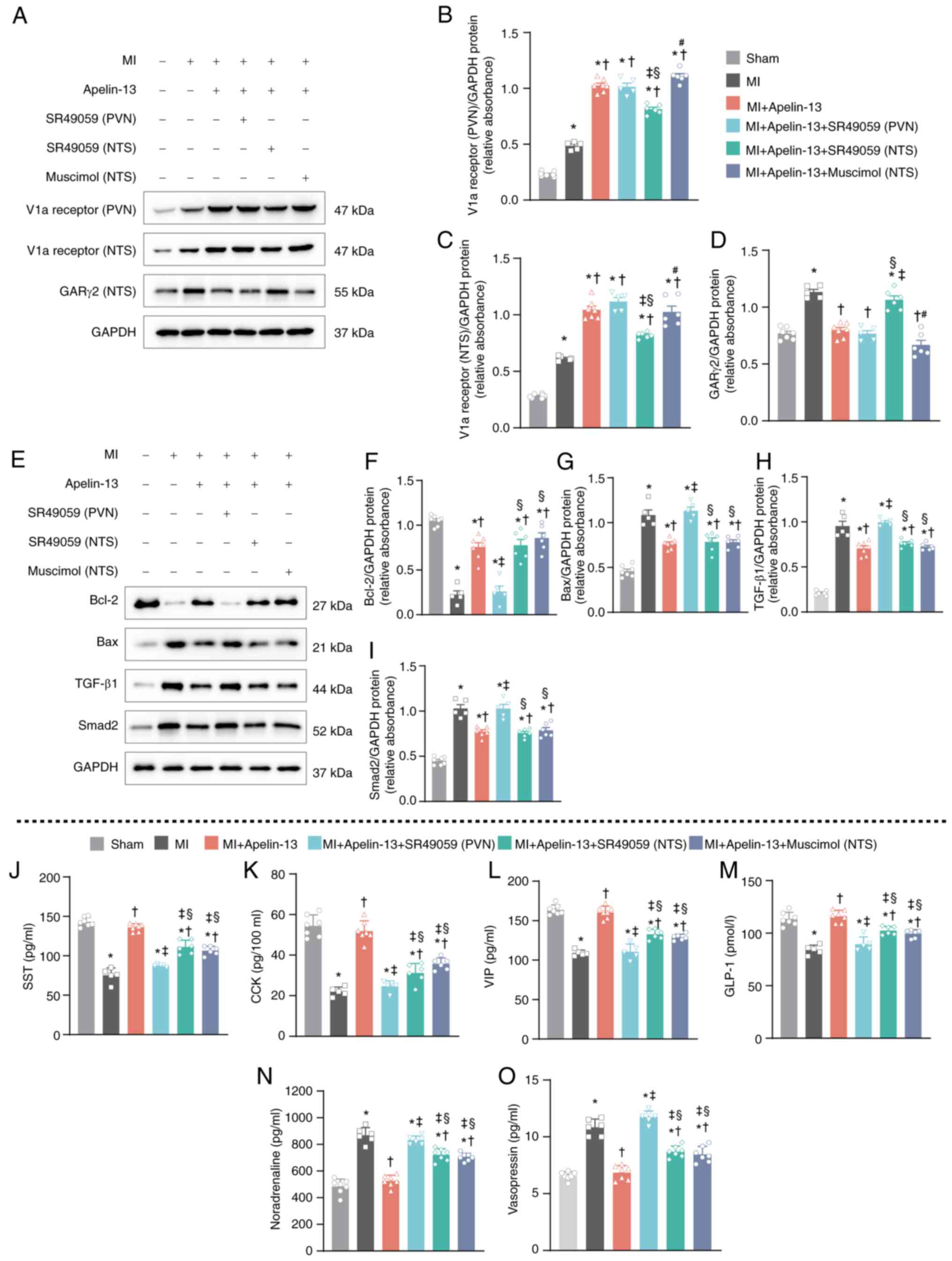

days after MI modelling. Continuous infusion of SR49059 into the

PVN/NTS and muscimol into the NTS differentially affected the

cardioprotective effects of apelin-13 in the PVN. The increase in

V1a receptor expression in the PVN caused by AAV2-apelin-13 gene

overexpression in the PVN was attenuated by the continuous

microinjection of the V1a receptor antagonist SR49059 into the NTS

but not into the PVN or the microinjection of the GAR antagonist

muscimol into the NTS (Fig. 7A and

B). In the NTS, increased V1a receptor expression caused by

AAV2-apelin-13 gene overexpression in the PVN was not attenuated by

the continuous microinjection of the V1a receptor antagonist

SR49059 into the PVN or NTS or by the GAR antagonist muscimol into

the NTS (Fig. 7A and C). The

decrease in GARγ2 expression in the NTS caused by AAV2-mediated

apelin-13 overexpression in the PVN was markedly attenuated by the

continuous microinjection of the V1a receptor antagonist SR49059 in

the NTS but not by the microinjection of SR49059 in the PVN or

muscimol in the NTS (Fig. 7A and

D). From the aforementioned results, it was found that the

expression of both V1a receptors and GAR2 in the NTS was regulated

by V1a receptors in the PVN. The apelin-13 gene

overexpression-induced increase in Bcl-2 (Fig. 7E and F) and decrease in Bax

(Fig. 7E and G), TGF-β1

(Fig. 7E and H) and Smad2

(Fig. 7E and I) were attenuated

by the microinjection of SR49059 into the PVN but not into the NTS

or by the microinjection of muscimol into the NTS. However, in the

serum, the increased levels of SST (Fig. 7J), CCK (Fig. 7K), VIP (Fig. 7L) and GLP-1 (Fig. 7M) induced by apelin-13

overexpression in the PVN of the MI model rats were attenuated by

the microinjection of SR49059 in the PVN or NTS and muscimol in the

NTS. In contrast, the decreased level of noradrenaline (Fig. 7N) and vasopressin (Fig. 7O) increased after the

microinjection of SR49059 in the PVN or NTS and muscimol in the

NTS. Together, these findings demonstrated that the V1a receptor in

the PVN/NTS and GARγ2 in NTS contribute to apelin-13-mediated

cardioprotection in MI models through vasopressinergic signaling

and PES.

| Figure 6Effect of apelin-13 overexpression

(AAV2-apelin-13 gene transfer) in the PVN on V1a receptor-mediated

improvements in cardiac function and cardiac morphology in MI model

rats. (A) The MI model was constructed one day following the

transfer of the apelin-13 gene into PVN and the implantation of

mini-pump (7 rats in each group). Echocardiographic results for (B)

LVEF, (C) LVSF, (D) LVEDD and (E) LVESD. (F) Representative

Masson's trichrome staining and (I) quantification. (G)

Representative TUNEL staining and (J) quantification of TUNEL

staining. (H) Representative TTC staining and (K) quantification.

The black scale bar in F is 100 μm; the white scale bar in G

is 50 μm; and the black scale bar in I is 1 cm. At 28 days

after MI modelling, the sham-operated control group had 7 rats, the

MI group had 5 rats (2 rats succumbed), the MI + apelin-13 group

had 7 rats, the MI + apelin-13 + SR49059 (PVN) group had 5 rats (2

rats succumbed), the MI + apelin-13 + SR49059 (NTS) group had 6

rats (1 rat succumbed) and the MI + apelin-13 + muscimol (NTS)

group had 6 rats (1 rat succumbed). Normality was tested using the

Shapiro-Wilk test. The data in B-E and H-M are shown as means ± SDs

and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's

multiple-comparisons test. In B-E and H-K, *P<0.05

vs. sham-operated control group; †P<0.05 vs. MI

group; ‡P<0.05 vs. MI + apelin-13 group;

§P<0.05 vs. MI + apelin-13 + SR49059(PVN);

#P<0.05 vs. MI + apelin-13 + SR49059 (NTS). The (L)

MAP and (M) heart rate were recorded in a conscious state at days

3, 7, 14 and 28 after MI modelling. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001; and ns, not

significant, vs. the sham-operated control group. Post-hoc power

exceeded 80% for all key comparisons. PVN, paraventricular nucleus;

V1a, Vasopressin 1a; MI, myocardial infarction; ECG,

Echocardiographic; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS,

left ventricular fraction shortening; LVEDD, left ventricular

end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, lower left ventricular end-systolic

diameter; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; MAP, mean arterial

pressure. |

| Figure 7Mechanisms of the effect of apelin-13

overexpression (AAV2-apelin-13 gene transfer) in the PVN on V1a

receptor-mediated improvement in cardiac function in MI model rats.

(A) Representative western blot image of V1a receptor expression in

the PVN or NTS and GARγ2 expression in the NTS. (B-D)

Quantification of V1a receptor expression. (E) Representative

western blotting to assess Bcl-2, Bax, TGF-β1 and Smad2 protein

levels in the heart and (F-I) quantification of the protein levels.

Plasma levels of (J) SST, (K) CCK, (L) VIP and (M) GLP-1 (n=7 in

the sham-operated control group; n=5 in the MI group, 2 rats

succumbed; n=7 in the MI + apelin-13 group; n=5 in the MI +

apelin-13 + SR49059 (PVN) group, 2 rats succumbed; n=6 in the MI +

apelin-13 + SR49059 (NTS) group, 1 rat succumbed; n=6 in the MI +

apelin-13 + muscimol (NTS) group, 1 rat succumbed). Representative

plasma levels of (N) noradrenaline and (O) vasopressin (n=7 in the

sham-operated control group; n=6 in the MI group, 1 rat succumbed;

n=7 in the MI + apelin-13 group; n=6 in the MI + apelin-13 +

SR49059 (PVN) group, 1 rat succumbed; n=6 in the MI + apelin-13 +

SR49059 (NTS) group, 1 rat succumbed; n=7 in the MI + apelin-13 +

muscimol (NTS) group). Normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk

test. The data in B-D and F-I show mean ± SEM; data in J-O are

shown as mean ± SD and were analyzed via one-way ANOVA, followed by

Tukey's multiple-comparisons test. In B-D and F-O,

*P<0.05 vs. sham-operated control group;

†P<0.05 vs. MI group; ‡P<0.05 vs. MI +

apelin-13 group; §P<0.05 vs. MI + apelin-13 + SR49059

(PVN); #P<0.05 vs. MI + apelin-13 + SR49059 (NTS).

Post-hoc power exceeded 80% for all key comparisons. PVN,

paraventricular nucleus; V1a, Vasopressin 1a; MI, myocardial

infarction; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; GAR, GABAA

receptor; SST, isomatostatin; CCK, cholecystokinin; VIP, vasoactive

intestinal peptide; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1. |

Discussion

The present study provided novel evidence of the

neural regulation of cardiac functions via apelin-13 in the PVN;

apelin-13 upregulated the expression of the V1a receptor in the PVN

and NTS and downregulated the expression of GARγ2 in the NTS.

Effects of a V1a receptor antagonist and GARγ2 agonist further

demonstrated that apelin-13 in the PVN is a novel factor involved

in the centrally mediated neural control of myocardial injury,

including in MI rat models. Furthermore, both myocardial TGF-β/Smad

signaling and the Bax/Bcl-2 apoptotic balance contribute to the

central-mediated cardioprotective effects of apelin-13 in PVN.

First, in MI model rats, apelin-13 expression was

decreased in the PVN but not in the NTS or RVLM. The PVN is a

critical central regulator of autonomic and humoral responses; it

receives afferent inputs from visceral receptors and circulating

hormones and then sends out projections to key cardiovascular

brainstem centers and spinal cord preganglionic neurons, thereby

modulating parasympathetic and sympathetic activity (27). The PVN is also involved in the

treatment of MI-induced heart failure via the inhibition of oxidant

signaling (6). Thus, it was

hypothesized that there were more pathways involved in the

mediation of cardiac function by apelin-13 in the PVN. Notably, V1a

receptor expression in the PVN and NTS increased following

apelin-13 microinjection into the PVN of MI model rats, whereas

GARγ2 expression in the NTS decreased after apelin-13

microinjection; these findings were further confirmed in MI models

with apelin-13 gene transmission. In the RVLM, the pressor effect

evoked by the bilateral microinjection of apelin-13 as a modulating

neurotransmitter in normotensive rats via the V1a receptor affects

vascular tone independent of GAR, whereas the presence of

presynaptic V1a receptors affects vasopressin release from the

PVN-RVLM projecting fibers (15). The observations in the present

study suggested that synaptic V1a receptors act as communicators

between the PVN and NTS for apelin-13-mediated nerve connections

and GARγ2 expression in the NTS.

These findings indicated that myocardial injury

induced the downregulation of apelin-13 expression in the PVN and

that upregulating apelin-13 expression in the PVN improved cardiac

function. Thus, it was hypothesized that the apelin/APJ system is

involved in the PVN-NTS axis for the regulation of cardiac

function, a novel concept of heart-brain interactions. The heart

and the brain are linked by multiple feedback signals and the

concept of cardio-cerebral syndrome in heart failure has been built

on the bidirectional interactions of failing heart and neuronal

signals (28). A previous review

indicated that the mechanisms of brain-heart interactions include

the physiological effects of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve

activities, central pathways regulating autonomic outflow, reflex

control of autonomic outflow and the integrative regulation of

autonomic outflow to the heart (29). More specifically, the sympathetic

and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system

directly control the heart and parasympathetic postganglionic

fibers innervate the atrial and ventricular myocardium by releasing

acetylcholine and VIP (30).

Consistently, in the present study, as a critical mediator of

synaptic inhibition in the brain (31), the expression of the γ2 subunit

of GAR in the NTS decreased after apelin-13 overexpression in the

PVN, which indirectly elevated parasympathetic efferent

excitability to activate the PES.

The V1a receptor is a transmembrane protein that

belongs to the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. The combined

activation of V1a receptors by vasopressin in the PVN has been

shown to increase renal sympathetic nerve activity (32). Subsequent to MI, within the PVN,

a notable elevation in the expression level of the V1a receptor was

observed. This augmented expression subsequently led to a

significant enhancement in the modulation of the autonomic

cardiovascular system, thereby playing a crucial role in the

intricate physiological adjustments that occur in response to the

myocardial damage. In NTS, V1a receptor can influence the

transmission and integration of baroreceptor reflex signals, which

play a crucial role in regulating blood pressure and heart rate.

Dysfunction of the V1a receptor-mediated modulation in the NTS may

contribute to abnormal blood pressure regulation and heart rate

variability after MI. The present study showed that apelin-13

overexpression in the PVN of MI model rats further elevated the

increased V1a receptor expression in the PVN and NTS, indicating

its involvement in apelin-13-mediated cardiac function.

The apelin/APJ system plays several important roles

in the neurohormonal regulation of heart function, including

vasodilatory effects, positive inotropic effects, fluid balance

regulation, antiapoptotic effects and interactions with other

neurohormonal systems (25,33). The present study revealed that

the improved cardiac function mediated by apelin/APJ in the PVN

involves PES activation by apelin-13 overexpression, including an

increase in the expression of four effectors, namely, SST, CCK,

GLP-1 and VIP. SST has been shown to exert a direct

cardiocytoprotective effect against simulated cardiomyocyte injury

via SST receptor 1 and SST receptor 2 in cardiomyocytes and

vascular endothelial cells (34). CCK, GLP-1 and VIP are involved in

cardiovascular regulation via different mechanisms in the

circulation (35-37). Thus, it was hypothesized that the

PES plays an important role in the heart-brain circuit. While the

pro-fibrotic and remodeling role of TGF-β/Smad signaling in the

heart has been well established (38), the histomorphometry and molecular

analyses of the present study demonstrated that apelin-13 in the

PVN mediates cardioprotection by modulating PES, ultimately

downregulating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, thereby

attenuating cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. Meanwhile, the

regulation of myocardial Bax/Bcl-2 expression was also involved in

the central cardioprotective effects mediated by apelin-13 in the

PVN.

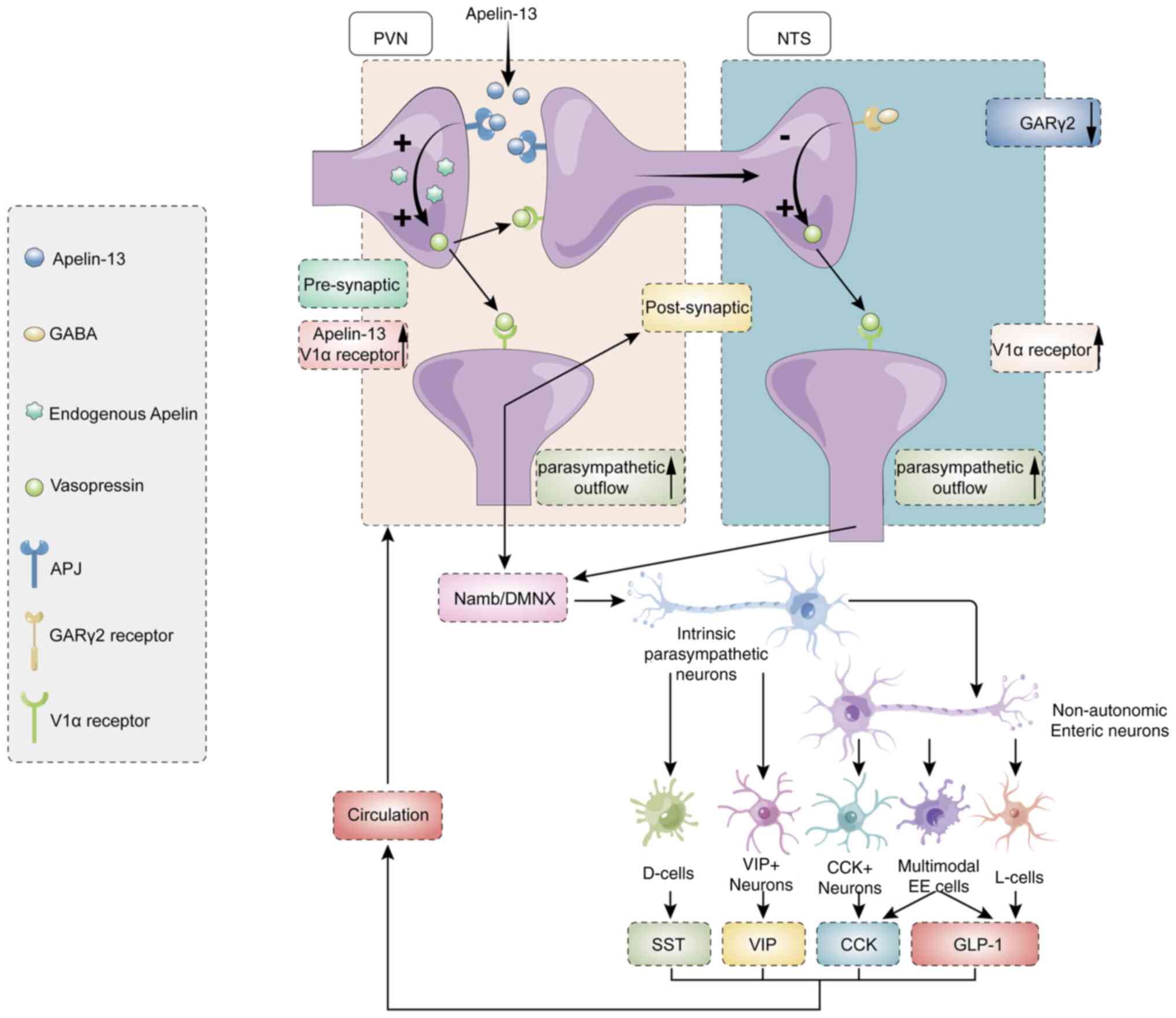

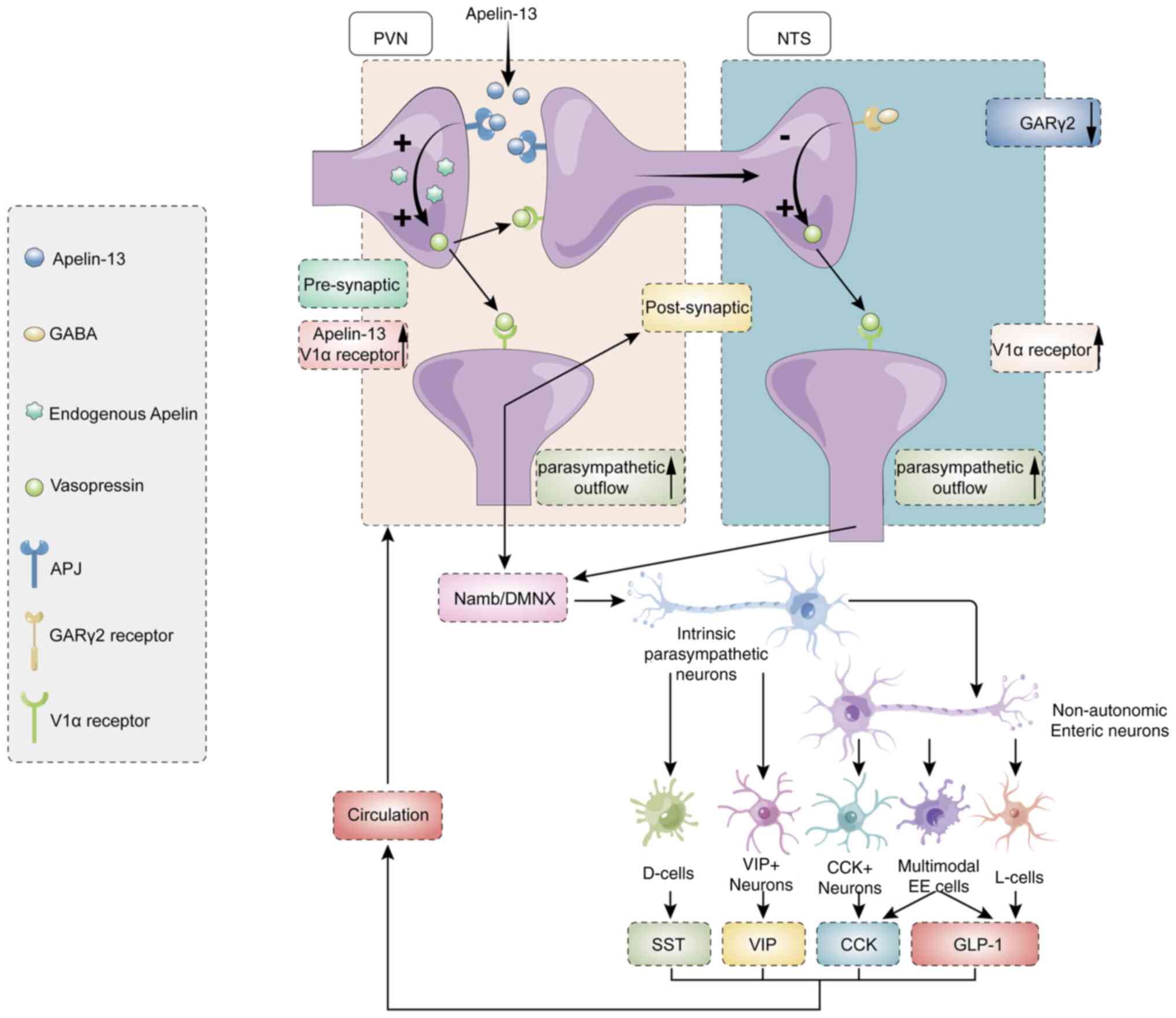

The present study provided novel evidence that

PVN-derived apelin-13 modulates cardiac function through dual

mechanisms: Upregulating V1a receptor expression in both PVN and

NTS nuclei and downregulating GARγ2 expression specifically in the

NTS. Mechanistically, PVN apelin-13 overexpression improved cardiac

performance via V1a receptors (PVN/NTS) and GARγ2 (NTS)-dependent

pathways. This regulation involves both parasympathetic signaling

and myocardial ischemia-associated pro-apoptotic/pro-inflammatory

cascades, establishing the first evidence for central neural

control of cardiovascular pathogenesis (Fig. 8).

| Figure 8Graphical model summarizing the

hypothesized pathway. Overexpression of apelin-13 in the PVN

promotes upregulation of V1a receptors in both the PVN and NTS,

while downregulating GARγ2 in the NTS. These neural modifications

collectively enhance parasympathetic outflow. Furthermore,

paraventricular endocrine system secretes circulating neurohumoral

factors that systemically mediate cardioprotection. PVN,

paraventricular nucleus; V1a, Vasopressin 1a; MI, myocardial

infarction; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; GAR, GABAA

receptor; SST, isomatostatin; CCK, cholecystokinin; GLP-1,

glucagon-like peptide 1; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide. |

Despite these meaningful findings, the present study

had certain limitations. Although it found novel evidence of neural

control of cardiomyocyte injury, the mechanism of interaction

between the PVN and NTS is not fully clear, except for direct

exposure to the neurotransmitter apelin-13 and vasopressin.

Importantly, the V1a receptor and GARγ2 in the NTS are indirectly

regulated by the apelin/APJ system in the NTS, but postsynaptic GAR

currents should be considered for modulating receptor expression.

Therefore, other unclear mechanisms are involved in receptor

interactions between the PVN and NTS. To address the limitation of

lacking electrophysiological evidence, future work will directly

record from PVN neurons that project to the NTS to determine how

their firing activity changes following apelin-13 administration.

Due to the technical challenges in precisely isolating the PVN and

NTS from neonatal rats, primary neuronal culture studies cannot

fully reflect the regulatory effects of APJ and GARγ2 on V1a

receptor expression in these nuclei. Moreover, the interaction

mechanisms between these receptors within specific nuclei require

further investigation. The mechanism by which GARγ2 regulates V1a

receptor expression remains unclear. Candidate transcription

factors potentially mediating this regulation include nuclear

factor-κB (NF-κB) (39,40), early growth response protein 1

(EGR1) (41,42) and cAMP response element-binding

protein (CREB) (43,44). Subsequent studies should further

investigate this mechanism through integrated approaches including

electrophysiology and single-cell RNA-sequencing. Since drugs may

diffuse from injection sites and transgene expression may spread

beyond target areas, other hypothalamic regions might unexpectedly

participate in cardiac regulation. Vasopressin present in the

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can interact with the HPA axis. This

interaction can enhance the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone

from the anterior pituitary gland to modulate cardiac function

(45). However, the levels of

vasopressin in CSF were unfortunately not assessed. Finally, four

peptides that act as neurotransmitters are released through a

complex network of gut sensing and vagal mechanisms. Other

neuropeptide levels could also be affected by apelin-13 in the PVN;

however, these levels were not detected or explored in the present

study. The present study selected male rats to minimize sex hormone

variability and ensure precision in stereotaxic brain nucleus

targeting during injections and minipump implantation.

Consequently, findings may not generalize to females; subsequent

studies will further validate results in ovariectomized and intact

female models.

In conclusion, apelin-13 in the PVN performs neural

control for cardiac function via the V1a receptor in the PVN and

NTS and GARγ2 in the NTS, offering novel evidence of brain-heart

interactions. The present study provided evidence for improving

cardiac function through the CNS in the future.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Sequence Read Archive under at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?cmd=Search&doptcmdl=EntrezGene&term=58812,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/2550, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/552

and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/2566.

Authors' contributions

WY, DW and XZ conducted the experiments. CX and WY

designed the experiments and analyzed the data. DW and CX drafted

the manuscript and all authors edited the manuscript. WY and DW

confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82070361).

References

|

1

|

Chen Z, Venkat P, Seyfried D, Chopp M, Yan

T and Chen J: Brain-heart interaction: Cardiac complications after

stroke. Circ Res. 121:451–468. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Simats A, Sager H and Liesz A: Heart brain

axis in health and disease: Role of innate and adaptive immunity.

Cardiovasc Res. 120:2325–2335. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zhao B, Li T, Fan Z, Yang Y, Shu J, Yang

X, Wang X, Luo T, Tang J, Xiong D, et al: Heart-brain connections:

Phenotypic and genetic insights from magnetic resonance images.

Science. 380:abn65982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Herman JP and Tasker JG: Paraventricular

hypothalamic mechanisms of chronic stress adaptation. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 7:1372016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Benarroch EE: The central autonomic

network: Functional organization, dysfunction, and perspective.

Mayo Clin Proc. 68:988–1001. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Infanger DW, Cao X, Butler SD, Burmeister

MA, Zhou Y, Stupinski JA, Sharma RV and Davisson RL: Silencing nox4

in the paraventricular nucleus improves myocardial

infarction-induced cardiac dysfunction by attenuating

sympathoexcitation and peri-infarct apoptosis. Circ Res.

106:1763–1774. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tatemoto K, Hosoya M, Habata Y, Fujii R,

Kakegawa T, Zou MX, Kawamata Y, Fukusumi S, Hinuma S, Kitada C, et

al: Isolation and characterization of a novel endogenous peptide

ligand for the human APJ receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

251:471–476. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lee DK, Cheng R, Nguyen T, Fan T,

Kariyawasam AP, Liu Y, Osmond DH, George SR and O'Dowd BF:

Characterization of apelin, the ligand for the APJ receptor. J

Neurochem. 74:34–41. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yang N, Li T, Cheng J, Tuo Q and Shen J:

Role of apelin/APJ system in hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Clin Chim

Acta. 499:149–153. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lv SY, Chen WD and Wang YD: The apelin/APJ

system in psychosis and neuropathy. Front Pharmacol. 11:3202020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Masaki T, Yasuda T and Yoshimatsu H:

Apelin-13 microinjection into the paraventricular nucleus increased

sympathetic nerve activity innervating brown adipose tissue in

rats. Brain Res Bull. 87:540–543. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ji M, Wang Q, Zhao Y, Shi L, Zhou Z and Li

Y: Targeting hypertension: superoxide anions are involved in apelin

induced long-term high blood pressure and sympathetic activity in

the paraventricular nucleus. Curr Neurovasc Res. 16:455–464. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang Q, Yao F, Raizada MK, O'Rourke ST

and Sun C: Apelin gene transfer into the rostral ventrolateral

medulla induces chronic blood pressure elevation in normotensive

rats. Circ Res. 104:1421–1428. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

De Mota N, Reaux-Le Goazigo A, El Messari

S, Chartrel N, Roesch D, Dujardin C, Kordon C, Vaudry H, Moos F and

Llorens-Cortes C: Apelin, a potent diuretic neuropeptide

counteracting vasopressin actions through inhibition of vasopressin

neuron activity and vasopressin release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

101:10464–10469. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Griffiths PR, Lolait SJ, Harris LE, Paton

JFR and O'Carroll AM: Vasopressin V1a receptors mediate the

hypertensive effects of [Pyr1]apelin-13 in the rat rostral

ventrolateral medulla. J Physiol. 595:3303–3318. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Czarzasta K, Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A,

Szczepanska-Sadowska, Fus L, Puchalska L, Gondek A, Dobruch J,

Gomolka R, Wrzesien R, Zera T, et al: The role of apelin in central

cardiovascular regulation in rats with post-infarct heart failure

maintained on a normal fat or high fat diet. Clin Exp Pharmacol

Physiol. 43:983–994. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kuriyama K, Hirouchi M and Kimura H:

Neurochemical and molecular pharmacological aspects of the GABA(B)

receptor. Neurochem Res. 25:1233–1239. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Li B, Liu Q, Xuan C, Guo L, Shi R, Zhang

Q, O'Rourke ST, Liu K and Sun C: GABAB receptor gene transfer into

the nucleus tractus solitarii induces chronic blood pressure

elevation in normotensive rats. Circ J. 77:2558–2566. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dampney RA: Functional organization of

central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev.

74:323–364. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Korpal AK, Han SY, Schwenke DO and Brown

CH: A switch from GABA inhibition to excitation of vasopressin

neurons exacerbates the development angiotensin II-dependent

hypertension. J Neuroendocrinol. Dec 9–2017.Epub ahead of print.

PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S and Drent ML: The

role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and

body weight in humans: A review. Obes Rev. 8:21–34. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gorky J and Schwaber J: Conceptualization

of a parasympathetic endocrine system. Front Neurosci. 13:10082019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Watson C and Paxinos G: The rat brain in

stereotaxic coordinates. 5th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004, pp.

51–57

|

|

25

|

Zhao Y, Li Y, Li Z, Xu B, Chen P and Yang

X: Superoxide anions modulate the performance of apelin in the

paraventricular nucleus on sympathetic activity and blood pressure

in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Peptides. 121:1700512019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kc P, Balan KV, Tjoe SS, Martin RJ,

Lamanna JC, Haxhiu MA and Dick TE: Increased vasopressin

transmission from the paraventricular nucleus to the rostral

medulla augments cardiorespiratory outflow in chronic intermittent

hypoxia-conditioned rats. J Physiol. 588:725–740. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Benarroch EE: Paraventricular nucleus,

stress response, and cardiovascular disease. Clin Auton Res.

15:254–263. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Havakuk O, King KS, Grazette L, Yoon AJ,

Fong M, Bregman N, Elkayam U and Kloner RA: Heart failure-induced

brain injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 69:1609–1616. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Silvani A, Calandra-Buonaura G, Dampney RA

and Cortelli P: Brain-heart interactions: Physiology and clinical

implications. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci.

374:201501812016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Coote JH: Myths and realities of the

cardiac vagus. J Physiol. 591:4073–4085. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kim JJ and Hibbs RE: Direct structural

insights into GABAA receptor pharmacology. Trends Biochem Sci.

46:502–517. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Komnenov D, Quaal H and Rossi NF: V1a and

V1b vasopressin receptors within the paraventricular nucleus

contribute to hypertension in male rats exposed to chronic mild

unpredictable stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol.

320:R213–R225. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Dalzell JR, Rocchiccioli JP, Weir RA,

Jackson CE, Padmanabhan N, Gardner RS, Petrie MC and McMurray JJ:

The emerging potential of the apelin-APJ system in heart failure. J

Card Fail. 21:489–498. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Vörös I, Sághy É, Pohóczky K, Makkos A,

Onódi Z, Brenner GB, Baranyai T, Ágg B, Váradi B, Kemény Á, et al:

Somatostatin and its receptors in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

injury and cardioprotection. Front Pharmacol. 12:6636552021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Han Z, Bi S, Xu Y, Dong X, Mei L, Lin H

and Li X: Cholecystokinin expression in the development of

myocardial hypertrophy. Scanning. 2021:82315592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Simms-Williams N, Treves N, Yin H, Lu S,

Yu O, Pradhan R, Renoux C, Suissa S and Azoulay L: Effect of

combination treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor

agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on incidence

of cardiovascular and serious renal events: Population based cohort

study. BMJ. 385:e0782422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Duggan KA, Hodge G, Chen J and Hunter T:

Vasoactive intestinal peptide infusion reverses existing myocardial

fibrosis in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 862:1726292019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Sarker M, Chowdhury N, Bristy AT, Emran T,

Karim R, Ahmed R, Shaki MM, Sharkar SM, Sayedur Rahman GM and Reza

HM: Astaxanthin protects fludrocortisone acetate-induced cardiac

injury by attenuating oxidative stress, fibrosis, and inflammation

through TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother.

181:1177032024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Liu H, Yu L, Yang L and Green MS:

Vasoplegic syndrome: An update on perioperative considerations. J

Clin Anesth. 40:63–71. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Fu Q, Yu Q, Luo H, Liu Z, Ma X, Wang H and

Cheng Z: Protective effects of wogonin in the treatment of central

nervous system and degenerative diseases. Brain Res Bull.

221:1112022025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Liu Y, Donovan M, Jia X and Wang Z: The

ventromedial hypothalamic circuitry and male alloparental behaviour

in a socially monogamous rodent species. Eur J Neurosci.

50:3689–3701. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Loveland JL and Fernald RD: Differential

activation of vasotocin neurons in contexts that elicit aggression

and courtship. Behav Brain Res. 317:188–203. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yan R, Liu Q, Zhang D, Li K, Li Y, Nie Y,

Zhang Y, Li P, Mao S and Li H: Inhibition of spreading

depolarizations by targeting GABAA receptors and voltage-gated

sodium channels improves neurological deficits in rats with

traumatic brain injury. Br J Pharmacol. Jun 24–2025.Epub ahead of

print. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Greenwood M, Gillard BT, Murphy D and

Greenwood MP: Dimerization of hub protein DYNLL1 and bZIP

transcription factor CREB3L1 enhances transcriptional activation of

CREB3L1 target genes like arginine vasopressin. Peptides.

179:1712692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Szczepanska-Sadowska E, Czarzasta K,

Bogacki-Rychlik W and Kowara M: The interaction of vasopressin with

hormones of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis: The

significance for therapeutic strategies in cardiovascular and

metabolic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 25:73942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|