Introduction

Heart failure (HF), one of the end-stage

manifestations of cardiovascular disease has an estimated

prevalence of ≥56 million individuals and a 5-year survival rate

following diagnosis remaining >50%. Consequently, it has been

recognized as an important issue in public health and a major cause

of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1,2).

HF not only considerably affects the quality of life of patients,

but may also lead to serious complications and can be

life-threatening (3). Despite

improvements in the guidelines for the treatment of HF, and the

development of new drugs and clinical studies, such as intravenous

recombinant human Neuregulin-1 and vericiguat (4,5),

the management of this condition remains challenging, especially in

terms of prognosis (6).

Previous studies have revealed that oxidative

stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium regulation and cell

death are associated with the onset and progression of HF (7-10). Notably, pyroptosis, a mode of

programmed cell death, has been shown to be associated with HF

(11). Pyroptosis is mainly

mediated by gasdermin D (GSDMD), which causes cell membrane rupture

through the generation of GSDMD N-terminal fragments (GSDMD-NT)

with pore-forming activity, resulting in the release of

inflammatory factors, and exacerbating cell death and tissue damage

(12). A recent study revealed

that GSDMD-NT perforates the mitochondrial membrane in pyroptosis,

leading to mitochondrial damage and inducing reactive oxygen

species (ROS) release. ROS further amplifies GSDMD binding and

mitochondrial damage in pyroptosis (13). Excessive release of ROS can

activate the NLR family pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3)

inflammasome in a positive cascade reaction with

thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), thereby mediating the

occurrence of pyroptosis (14).

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) is a key regulator

of the antioxidant response and can regulate oxidative stress by

eliminating ROS and inhibiting TXNIP expression (15,16).

Calycosin (CA) is a natural flavonoid compound that

has been demonstrated to exert various biological effects,

including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and pro-angiogenic

properties (17). CA has a broad

application prospect in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases,

and studies have revealed that CA can improve myocardial oxidative

stress (18), attenuate

myocardial fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction after myocardial

infarction, and inhibit HF after acute infarction (19,20). Previous studies have revealed

that CA inhibits pyroptosis and ameliorates myocardial injury by

inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (21,22). In addition, CA may upregulate

Nrf2 expression, and ameliorate myocardial oxidative stress and

mitochondrial damage, thereby protecting the myocardium (23). Therefore, the present study

further explored the therapeutic mechanism of CA based on the

Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway-mediated mitochondrial damage and pyroptosis

in HF.

Materials and methods

Reagents

CA was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology

Co., Ltd. Captopril (CAP; CAP purchase specification: 25 mg;

national drug approval number: H44021595) was used as the positive

control and was purchased from Guangdong Pidi Pharmaceutical Co.,

Ltd. Detection kit information was as follows: Rat N-terminal pro

B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) ELISA Kit (cat. no.

CSB-E08752r) was purchased from Cusabio Technology, LLC; lactate

dehydrogenase (LDH) ELISA kit (cat. no. SEB864Ra) was purchased

from CLOUD-CLONE CORP, CCC; malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kit (cat.

no. A003-1), superoxide dismutase (SOD) assay kit (cat. no.

A001-3-2) and microplate method total glutathione/glutathione

disulfide (T-GSH/GSSG) assay kit (cat. no. A061-1-1) were purchased

from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute. LDH cytotoxicity

colorimetric assay kit (cat. no. E-BC-K771-M) was purchased from

Elabscience. Antibody information was as follows: Nrf2 (cat. no.

80593-1-RR), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a

CARD (ASC; cat. no. 67494-1-Ig), IL-1β (cat. no. 29530-1-AP),

cytochrome c (cat. no. 66264-1-Ig) and β-actin (cat. no.

66009-1-Ig) antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc.;

TXNIP (cat. no. A9342), NLRP3 (cat. no. A5652), IL-18 (cat. no.

A23076) and GSDMD (full length and N terminal; cat. no. A24476)

antibodies were purchased from ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.;

Caspase-1 (pro- and cleaved-Caspase-1) (cat. no. ab286125), COX IV

(cat. no. ab16056), Goat Anti-rabbit IgG HRP (cat. no. ab150077)

and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG HRP (cat. no. ab205719) antibodies were

purchased from Abcam. Mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit

JC-1 (cat. no. C2006), ROS Assay kit (cat. no. S0033S) and MitoSOX

Red assay kit (cat. no. S0061S) were purchased from Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology. Masson Tricolor Staining kit (cat. no.

G1006) was purchased from Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.

Cell mitochondrial stress test kit (cat. no. 103015-100),

glycolytic stress test kit (cat. no. 103020-100) and Seahorse XF

base medium (cat. no. 102353-100) were purchased from Agilent

Technologies, Inc.

Establishment and treatment of rats

A total of 50 8-week-old male Wistar rats (weight,

180-220 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory

Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The rats were housed in the

Experimental Center of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong

University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Jinan, China) under

standard conditions (12-h light/dark cycle with free access to

water and food). The animal experimental procedures were approved

by the Experimental Animal Management Committee and the Ethics

Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of

Traditional Chinese Medicine. The animal experiments strictly

followed the guidelines of the Ethics Committee.

Rats were randomly divided into five groups: Sham,

HF, CA low-dose (CA-L), CA high-dose (CA-H) and CAP group

(n=10/group). In the present study, the HF model was constructed 4

weeks after ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery

in rats. Specifically, rats were anesthetized using 2-3% isoflurane

(3% induction and 2% maintenance) based on an isoflurane delivery

system. The left chest area of the rats was fully exposed under

aseptic conditions. The left chest area of the rats was shaved and

disinfected to ensure aseptic conditions. A minimally invasive open

thoracotomy was performed in the fourth intercostal space and the

LAD artery was permanently ligated using a 6-0 suture. After

ligation and squeezing out the gas from the chest cavity, the

muscle and skin were sutured at the surgical site layer by layer.

The Sham group underwent the same surgical procedures, but the

sutures were only passed through the LAD artery without ligation.

After 4 weeks, echocardiography was used to determine whether the

HF rat model was successfully constructed. CA was dissolved in DMSO

to prepare a 60 mg/ml stock solution, which was then diluted to the

appropriate working concentration using saline containing 20%

Sulfobutylether-β-Cyclodextrin (SBE-β-CD, Proteintech Group, Inc.)

according to experimental requirements. Subsequently, CA-L and CA-H

rats received intraperitoneal injections of 15 and 30 mg/kg CA,

respectively, daily for 4 weeks (24). The CAP group rats received 10

mg/kg CAP administered orally by gavage daily for 4 weeks. The Sham

and HF groups received intraperitoneal injections of 5 ml/kg saline

containing 20% SBE-β-CD daily for 4 weeks. Following

echocardiography and cardiac puncture for blood sampling, the rats

were euthanized through CO2 asphyxia (40% vol/min) for 5

min and death was confirmed by the absence of respiration and

heartbeat. Following euthanasia, rat hearts were immediately

collected. Due to limited tissue available from each rat, the

sample sizes used in each experiment varied. The following criteria

were established as humane endpoints: i) Weight loss >20% of the

initial body weight; ii) prolonged feeding impairment or mobility

deficits; iii) rats exhibited signs of depression accompanied by

hypothermia when not under anesthesia.

Echocardiography

At 4 weeks after surgery and treatment,

echocardiography was carried out on all rats to assess cardiac

function, in order to verify the construction of the HF model and

the therapeutic effect of CA. Specifically, after anesthetizing

rats with 2-3% isoflurane (3% induction and 2% maintenance) based

on an isoflurane delivery system, 2D long-axis images were recorded

using a portable Mindray M5 digital ultrasound scanner (Shenzhen

Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd.). During three cardiac

cycles, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and fractional

shortening (FS) were measured at the myocardial level using the

M-mode.

Histological analyses

A total of three fresh rat myocardial tissue samples

in each group were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (cat. no.

G1101-500ML, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at room

temperature for 24 h according to the instructions of the

manufacturer that supplied the paraformaldehyde, embedded in

paraffin and cut into 4-μm sections. Sections were stained

at room temperature with hematoxylin solution for 5 min, followed

by 15 sec in eosin solution for H&E staining. Sections were

stained at room temperature with Masson dye solution set at room

temperature according to the manufacturer's instructions for

Masson's trichrome staining. Images were obtained and

histopathological status was assessed using a digital section

scanner (WS-10; Zhiyue Medical Technology (Jiangsu) Co., Ltd.).

Masson's trichrome staining results were analyzed using ImageJ

1.52v software (National Institutes of Health).

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

Three left ventricular myocardial tissue samples in

each group were rinsed three times in pre-cooled PBS buffer, cut

into 1-2 mm3 pieces and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at

4°C for 24 h. The myocardial tissues were subsequently dehydrated

in a graded ethanol series, transitioned with propylene oxide and

embedded in Epon812 epoxy resin at 60°C for 48 h. Ultrathin

sections (70 nm) were cut using an ultramicrotome, collected on

200-mesh copper grids and dual-stained with 2% uranyl acetate and

lead citrate, both at room temperature for 15 min. Sections were

examined by TEM, focusing on mitochondrial morphology, cristae

integrity and myofibril arrangement.

Measurement of NT-proBNP, T-GSH/GSSG,

MDA, SOD and LDH

After anesthetizing the rats with isoflurane to

carry out echocardiography, 1 ml blood was collected through

cardiac puncture. Rat serum was isolated from blood by centrifuging

at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. NT-proBNP and LDH levels in the

serum samples were assessed at an absorbance of 450 nm according to

the standard procedure of the assay kits. Following cardiac

puncture for blood sampling, all rats were euthanized, and their

hearts were immediately collected. After isolation of five rat

myocardial tissue samples, the levels of T-GSH/GSSG, SOD and MDA in

myocardial tissues were detected using the assay kits, according to

the standard procedures of the test kits. Absorbance was measured

at 405, 450 and 532 nm using a microplate reader to detect

T-GSH/GSSG, SOD and MDA levels, respectively. Post-treatment, LDH

levels in cells were assessed at an absorbance of 450 nm according

to the standard procedure of the assay kits.

Immunohistochemistry staining

The paraffin-embedded myocardial tissue sections

were subjected for thermally repaired antigen using citrate buffer

(pH 6.0) at 95-100°C. Following natural cooling, they were washed

three times with PBS. Hydrogen peroxide (3%) solution was used to

inactivate endogenous enzymes. Subsequently, the sections were

incubated with Nrf2 antibody (1:500) at 4°C overnight, then

sections were incubated with the Goat Anti-rabbit IgG HRP secondary

antibody (1:1,000) for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were

immersed in diaminobenzidine, counterstained with hematoxylin and

finally imaged using a digital section scanner (WS-10; Zhiyue

Medical Technology (Jiangsu) Co., Ltd.). The results were analyzed

using ImageJ 1.52v software (National Institutes of Health).

Cell culture and treatments

Rat H9c2 cardiomyocytes were purchased from The Cell

Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences

and cultured in DMEM (Pricella Biotechnology) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. The present

study employed a hypoxia-reoxygenation (H/R) model to simulate

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. CA was dissolved in DMSO to

prepare a 0.1 M stock solution, which was then diluted to the

appropriate working concentration according to experimental

requirements. After model establishment, the experimental groups

were treated with CA solutions at different concentrations (10, 20

and 30 μM). Meanwhile, control and model groups were

established and treated with an equivalent concentration of DMSO

(0.03%) solution to eliminate solvent interference.

The method used to establish the H/R model for

cardiomyocytes was as follows: First, cultured cardiomyocytes were

placed in a hypoxia chamber with gas conditions adjusted to 1%

O2, 5% CO2 and 94% N2, and

incubated at 37°C for 12 h to simulate a hypoxic environment. After

the hypoxia period, the cells were transferred to a normoxic

incubator with gas conditions of 20% O2, 5%

CO2 and 75% N2, and incubated at 37°C for 24

h to simulate the reoxygenation process. Throughout the experiment,

the temperature, humidity and gas concentration within the

incubator were strictly controlled, and cell status was regularly

monitored to ensure the reproducibility and stability of the model

(25).

Cell transfection [small interfering RNA

(siRNA)-Nrf2]

Cell transfection was performed before H/R and/or CA

treatment. Pooled siRNAs targeting Nrf2 (#1, #2 and #3) were used

to effectively silence Nrf2 and eliminate off-target effects. The

siRNA sequences were as follows: Nrf2#1, forward

5'-GGAAGUCUUCAGCAUGUUATT-3' and reverse

5'-UAACAUGCUGAAGACUUCCTT-3'; Nrf2#2, forward

5'-CGAGAAGUGUUUGACUUUATT-3' and reverse

5'-UAAAGUCAAACACUUCUCGTT-3'; Nrf2#3, forward

5'-GGGUUCAGUGACUCGGAAATT-3' and reverse

5'-UUUCCGAGUCACUGAACCCTT-3'; non-targeting negative control (NC),

forward 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3' and reverse

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3' (Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd.).

H9c2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 1×105

cells/well and were treated at 37°C with 5% CO2 until

they reached 70-80% confluence. The 6-well plate for transfection

was prepared by discarding the medium, washing with PBS and adding

1.5 ml Opti-MEM (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) per

well. For each experimental group, 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes were

labeled and 250 μl Opti-MEM with 5 μl Lipofectamine™

3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was added, mixed

by pipetting and incubated at room temperature for 5 min.

Similarly, labeled tubes were prepared with 250 μl Opti-MEM

and 8 μl siRNA (concentration, 20 μM), mixed by

pipetting. The siRNA mixture was combined with the corresponding

Lipofectamine 3000 mixture, mixed thoroughly and incubated at room

temperature for 20 min. The mixture was then added to the 6-well

plate and the medium was replaced after 8 h at room temperature.

Cell functional assays were conducted 48 h later.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

A H9c2 cell suspension was seeded in a 96-well plate

at 100 μl/well and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2

for 24 h to allow cell attachment and proliferation. Different

concentrations of CA (0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 μM) were

added to each well, followed by an additional 24-h incubation. For

evaluating the protective effect of CA on H/R-induced cardiomyocyte

injury, cells were subjected to CA treatment following H/R

treatment; otherwise, this step was omitted for assessing the

direct impact of CA on cell viability. After incubation, 10

μl CCK-8 solution (Vazyme Biotech Co, Ltd.) was added to

each well, gently mixed and incubated for 2 h. The absorbance (OD

value) of each well was measured at 450 nm using a microplate

reader and cell viability was calculated to evaluate the effects of

different CA concentrations on H9c2 cell viability.

ROS detection

To evaluate intracellular ROS levels, a commercially

available ROS assay kit (cat. no. S0033S; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was employed. H9c2 cells were seeded in a 6-well

plate and cultured until they reached 70-80% confluence.

Post-treatment, the cell suspension was collected and transferred

to centrifuge tubes, followed by centrifugation at 200 × g at room

temperature for 5 min to pellet the cells, after which the

supernatant was carefully removed. The fluorescent probe

2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was diluted at

a ratio of 1:1,000 in serum-free medium to achieve a final

concentration of 10 μM and 1 ml of the diluted solution was

added to each tube. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 20

min to facilitate the uptake of DCFH-DA. After incubation, the

cells were washed twice with serum-free medium, with centrifugation

at 200 × g at room temperature for 5 min after each wash. Finally,

the cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl serum-free

culture medium and ROS levels were quantified using flow cytometry

(C6 Plus; Becton, Dickinson and Company) and observed under a

fluorescence microscope. The data were analyzed using FlowJo 10.6.2

(BD Biosciences).

Mitochondrial ROS staining

H9c2 cells inoculated in 6-well plates were

collected. Detection of mitochondrial ROS levels was performed

using the MitoSOX Red assay kit according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Cells were washed with PBS and were then examined

under a fluorescence microscope.

Immunofluorescence staining

H9c2 cells were seeded on coverslips in 24-well

plates and grown to 70% confluence before treatment.

Post-treatment, the plates were washed twice with PBS. Fixation was

carried out with 200 μl immunol staining fix solution

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) per well for 20 min at room

temperature, followed by two washes with PBS. Permeabilization was

carried out with 200 μl immunostaining permeabilization

buffer with Triton X-100 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for

10 min at room temperature, and the cells were washed twice with

PBS. Blocking was achieved with 200 μl 5% BSA for 1 h at

room temperature, followed by two washes with PBS. A Nrf2 primary

antibody (1:500) was then added (200 μl/well) and incubated

overnight at 4°C, followed by two washes with PBS. Subsequently, a

secondary antibody Goat Anti-rabbit IgG HRP (1:500) was added (200

μl/well) and incubated overnight at 4°C or for 90 min at

room temperature, followed by two washes with PBS. DAPI staining

was carried out (200 μl/well) for 10 min at room temperature

and the samples were then washed twice with PBS. Finally, cells

were mounted with antifade medium and images were captured under a

fluorescence microscope.

Annexin V-FITC/PI staining

Annexin V-FITC/PI detection kit (Vazyme Biotech Co,

Ltd.) was used to detect cell death. H9c2 cells were seeded in

6-well plates at 1×105 cells/well and were cultured at

37°C with 5% CO2 until they reached 70-80% confluence.

Post-treatment, the cells were collected and adherent cells were

digested using EDTA-free trypsin for 2 min. Cells were then stained

with 5 μl Annexin V-FITC and 5 μl PI staining

solution, incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min and

mixed with 400 μl 1× Binding Buffer. Stained cells were

analyzed by flow cytometry (C6 Plus, Becton, Dickinson and Company)

within 1 h and the data were analyzed using FlowJo 10.6.2 (BD

Biosciences).

Mitochondrial membrane potential assay

with JC-1

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured

until treatment was completed. The JC-1 working solution was

prepared according to the standard procedure of the JC-1 staining

kit. Cells were incubated with JC-1 working solution at 37°C for 20

min and analyzed using flow cytometry.

Cellular energy metabolism analysis

H9c2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at

1×105 cells/well and were cultured at 37°C with 5%

CO2 until they reached 70-80% confluence. Detection of

oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate

(ECAR) was performed using the cell mitochondrial stress test kit

and glycolytic stress test kit, following the manufacturer's

instructions. Post-treatment, cells were incubated with Seahorse XF

Base medium at 37°C, followed by the sequential addition of

oligomycin, FCCP [trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone,

Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone], rotenone

and antimycin A. The Seahorse analyzer [XF96; Agilent Technologies

(China) Co., Ltd.] was used to measure OCR and ECAR of the

cells.

Western blotting

Three rat myocardial tissue samples in each group

were used for Western blotting. Proteins were extracted from

cardiac tissues and cells using RIPA buffer (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) and PMSF (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). The extraction of mitochondrial proteins from cells

was carried out using the mitochondrial isolation and protein

extraction kit (Proteintech Group, Inc.). Protein concentrations

were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit and samples were

adjusted with loading buffer to ensure equal protein loading. A

total of 20 μg protein was then separated by SDS-PAGE on 10%

gels and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. To minimize non-specific

binding, the membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk at room

temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated at

the appropriate dilutions overnight at 4°C with the primary

antibodies: Nrf2 (1:1,000), TXNIP (1:1,000), NLRP3 (1:1,000), ASC

(1:5,000), Caspase-1 (1:500), GSDMD (1:1,000), IL-1β (1:1,000),

IL-18 (1:1,000), COX IV (1:2,000) and β-actin (1:50,000). Unbound

primary antibodies were removed by washing the membrane with PBS.

The membrane was then incubated with Goat Anti-rabbit IgG HRP and

Goat Anti-Mouse IgG HRP secondary antibodies (1:10,000) at room

temperature for 1 h to facilitate antibody-antigen complex

formation. Excess secondary antibody was removed by additional PBS

washes. For detection, the membrane was incubated with

electrochemiluminescence substrate solution (Vazyme Biotech Co,

Ltd.) for 3 min in the dark before imaging. β-actin and COX IV were

used as loading controls for total protein and mitochondrial

protein expression, respectively. Band intensities were

semi-quantified using ImageJ 1.52v software (National Institutes of

Health), with β-actin/COX IV serving as the internal control for

normalization. The relative expression levels of the target

proteins were calculated as the ratio of the target protein band

density to the β-actin/COX IV band density.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics

27.0 (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 10 software (Dotmatics). All

in vitro experimental data are presented from three

independent experiments. Continuous variables were presented as

mean ± SD. Group comparisons were conducted using one-way analysis

of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. Two-way analysis

of variance and post hoc tests were used to compare two variables

(siRNA and treatment). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

CA effectively improves cardiac function

and mitochondrial damage in HF-induced rats

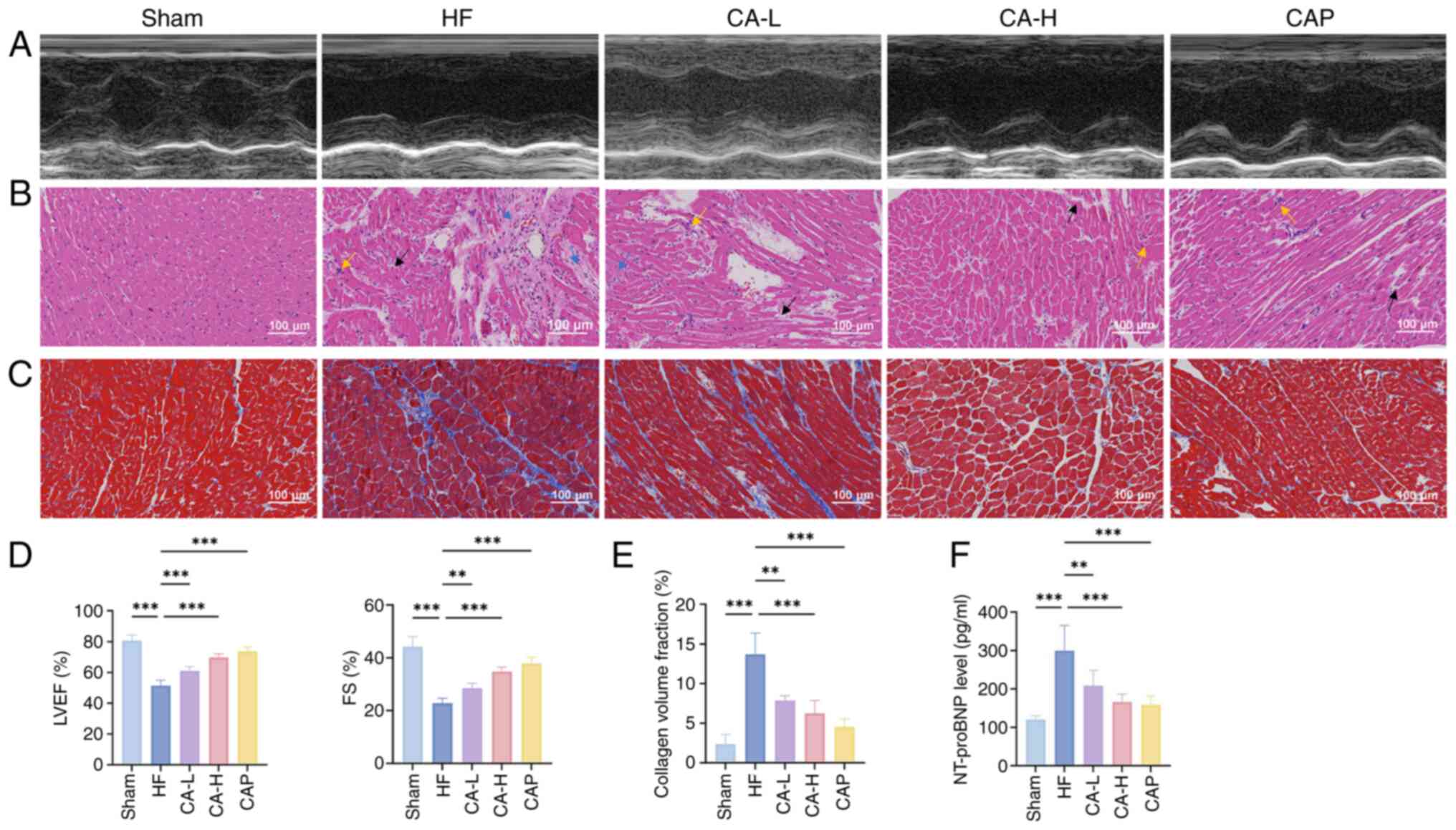

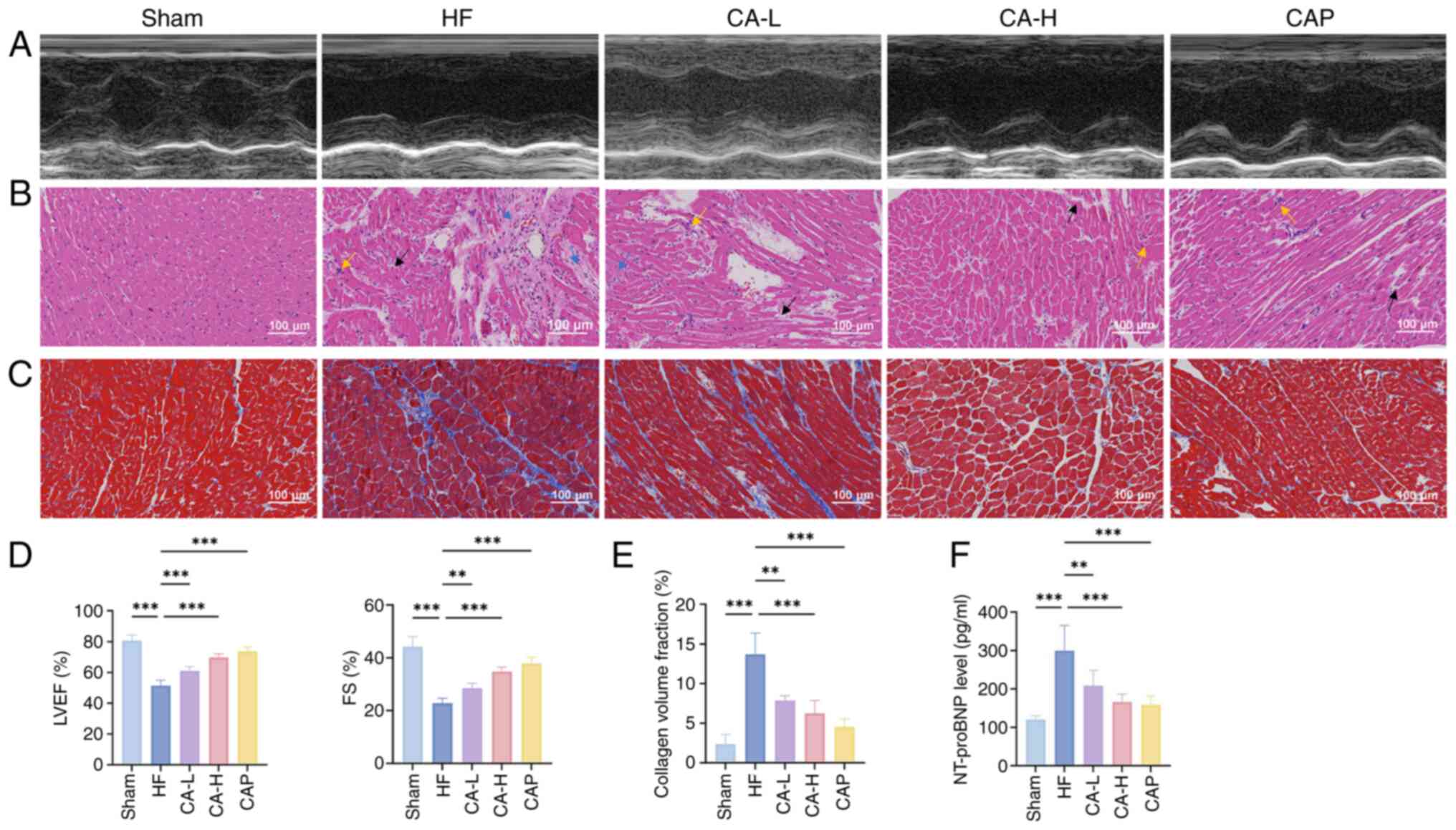

Echocardiography was used to assess cardiac function

in rats (Fig. 1A) and the

results revealed that LVEF and FS were significantly reduced in the

HF group compared with those in the Sham group. By contrast,

treatment with both doses of CA and with CAP exhibited improved

LVEF and FS (Fig. 1D). H&E

and Masson's trichrome staining further revealed that the

myocardial tissues of HF rats exhibited notable inflammatory

infiltration, cellular loss, disarrangement and interstitial

fibrosis, whereas CA and CAP treatment ameliorated the severity of

myocardial lesions (Fig. 1B, C and

E). In addition, CA and CAP treatment effectively reduced

levels of NT-pro BNP in HF-induced rats (Fig. 1F).

| Figure 1CA effectively improves cardiac

function in HF. (A) Representative echocardiography, (B) H&E

staining and (C) Masson's trichrome staining images of each group.

In H&E staining, the yellow arrows indicate inflammatory

infiltration, the black arrows indicate loss of myocardial cells

and the blue arrows indicate interstitial fibrosis. (D) Statistical

analysis of LVEF and FS of rats in each group, as determined by

echocardiography (n=5). (E) Quantitative analysis of Masson's

trichrome staining (n=3). (F) Serum NT-proBNP levels in rats of

each group (n=5). Data are presented as the mean ± SD,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CA, calycosin;

HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; FS,

fractional shortening; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic

peptide; CA-L, calycosin low-dose; CA-H, calycosin high-dose; CAP,

captopril. |

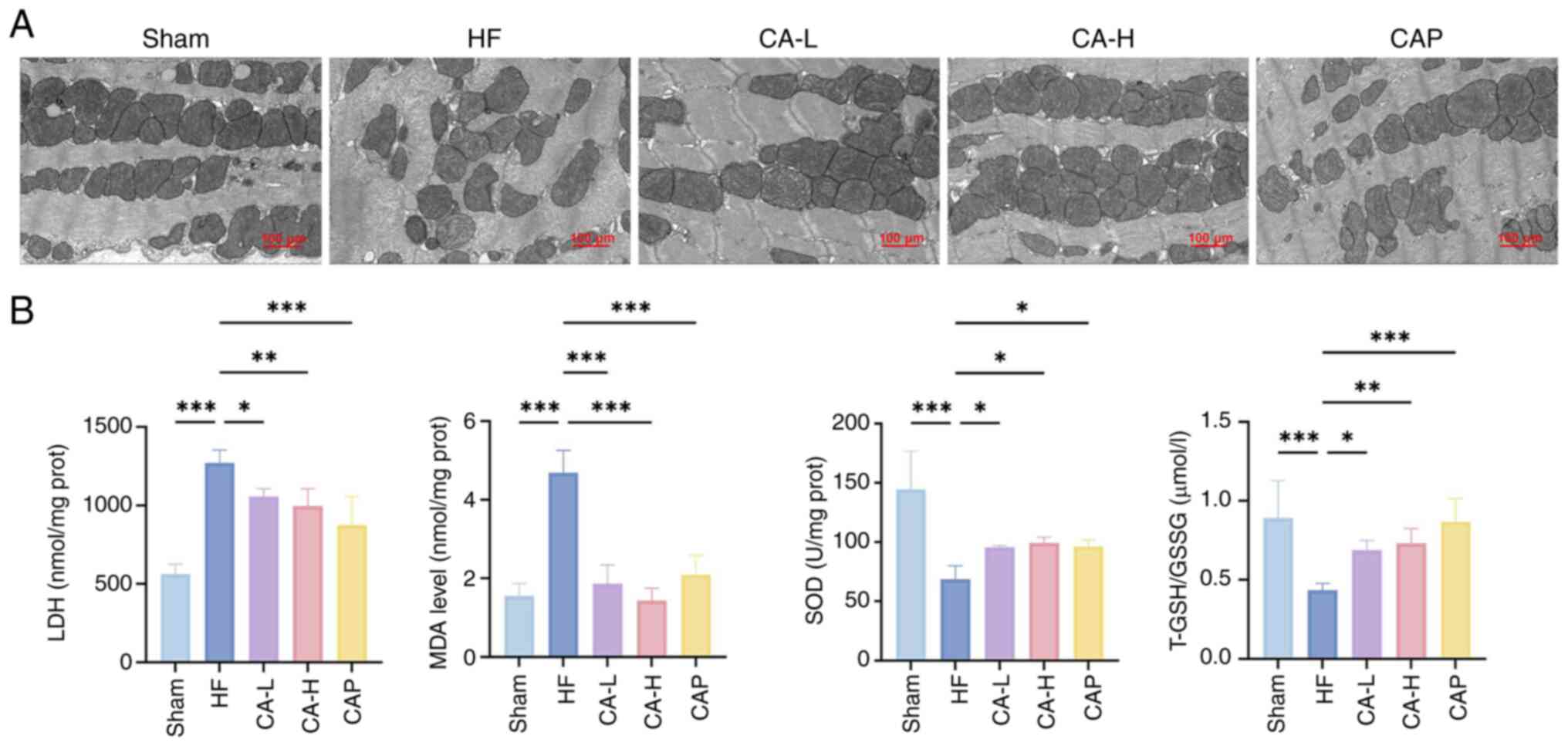

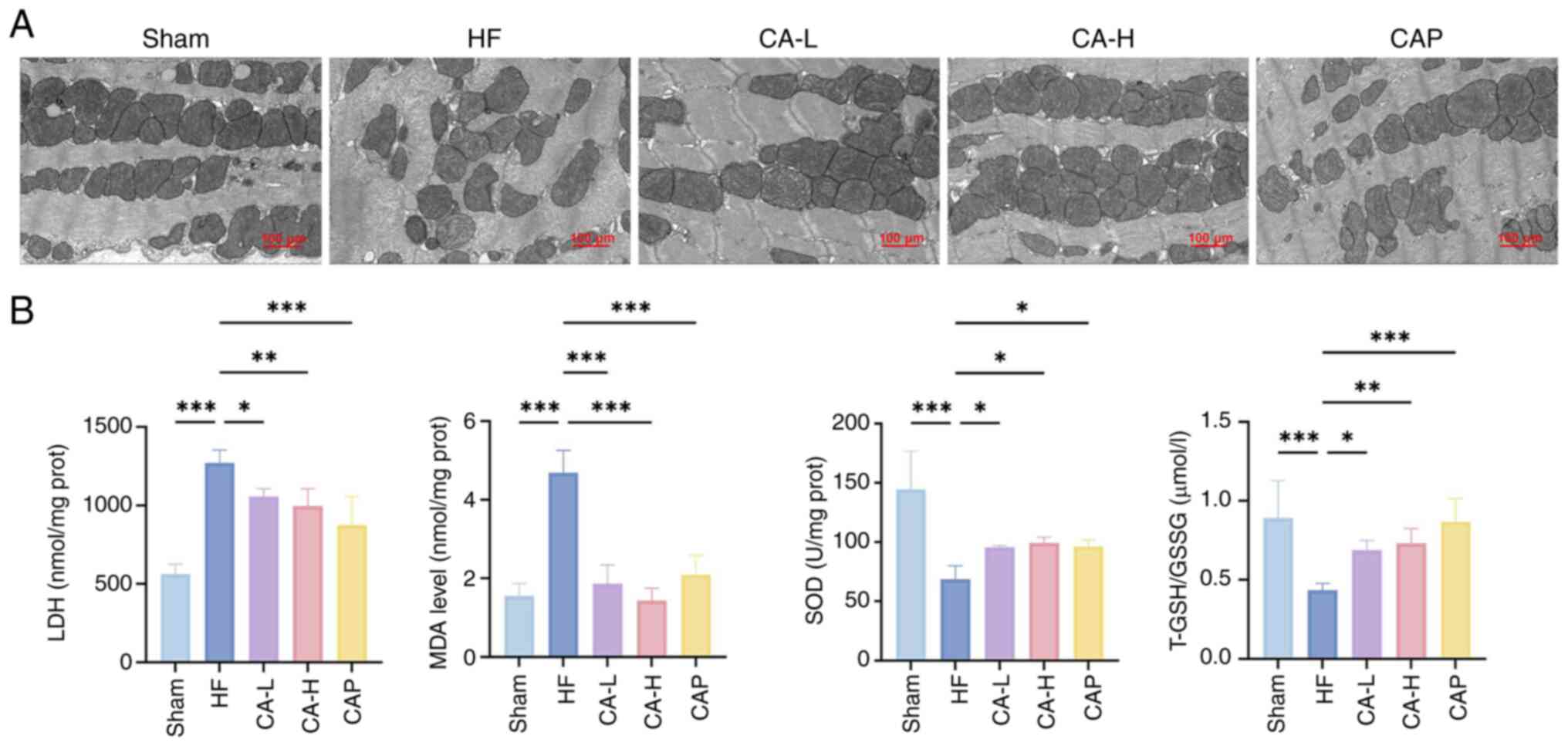

TEM was used to observe mitochondrial morphology in

the HF-induced rat myocardium. In addition, the oxidative

stress-related indicators LDH, MDA, SOD and T-GSH/GSSG were

measured to assess the levels of oxidative stress in the HF-induced

rat myocardium. TEM revealed that in the Sham group, the

mitochondria were neatly arranged, the membrane structure was

intact and the cristae were densely structured (Fig. 2A). In the HF group, mitochondrial

arrangement was disorganized, cristae were broken, mitochondria

were swollen and the membrane structure was damaged. By contrast,

CA and CAP treatment resulted in an improvement in mitochondrial

swelling, cristae breakage and relative membrane structural

integrity. In addition, rats with HF exhibited elevated levels of

LDH and MDA, and decreased levels of SOD and T-GSH/GSSG, indicating

significant oxidative stress in HF, which was significantly

prevented by CA and CAP treatment (Fig. 2B).

| Figure 2CA effectively improves mitochondrial

damage and cardiac oxidative stress in HF. (A) Representative

transmission electron microscopy images of rats in each group. (B)

Levels of oxidative stress-related indicators (n=5). Data are

presented as the mean ± SD, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CA, calycosin;

HF, heart failure; CA-L, calycosin low-dose; CA-H, calycosin

high-dose; CAP, captopril; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MDA,

malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; GSSG,

GSH disulfide. |

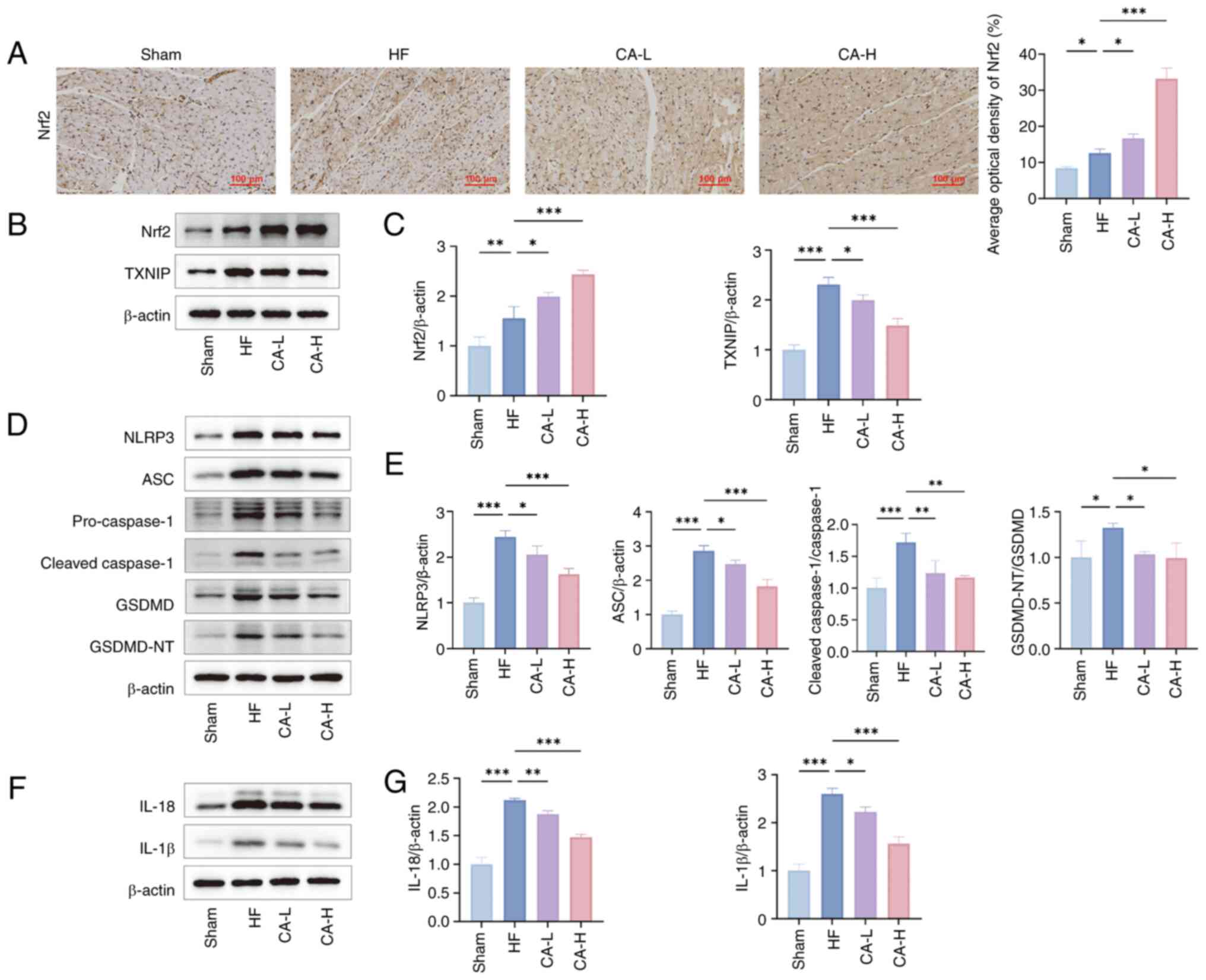

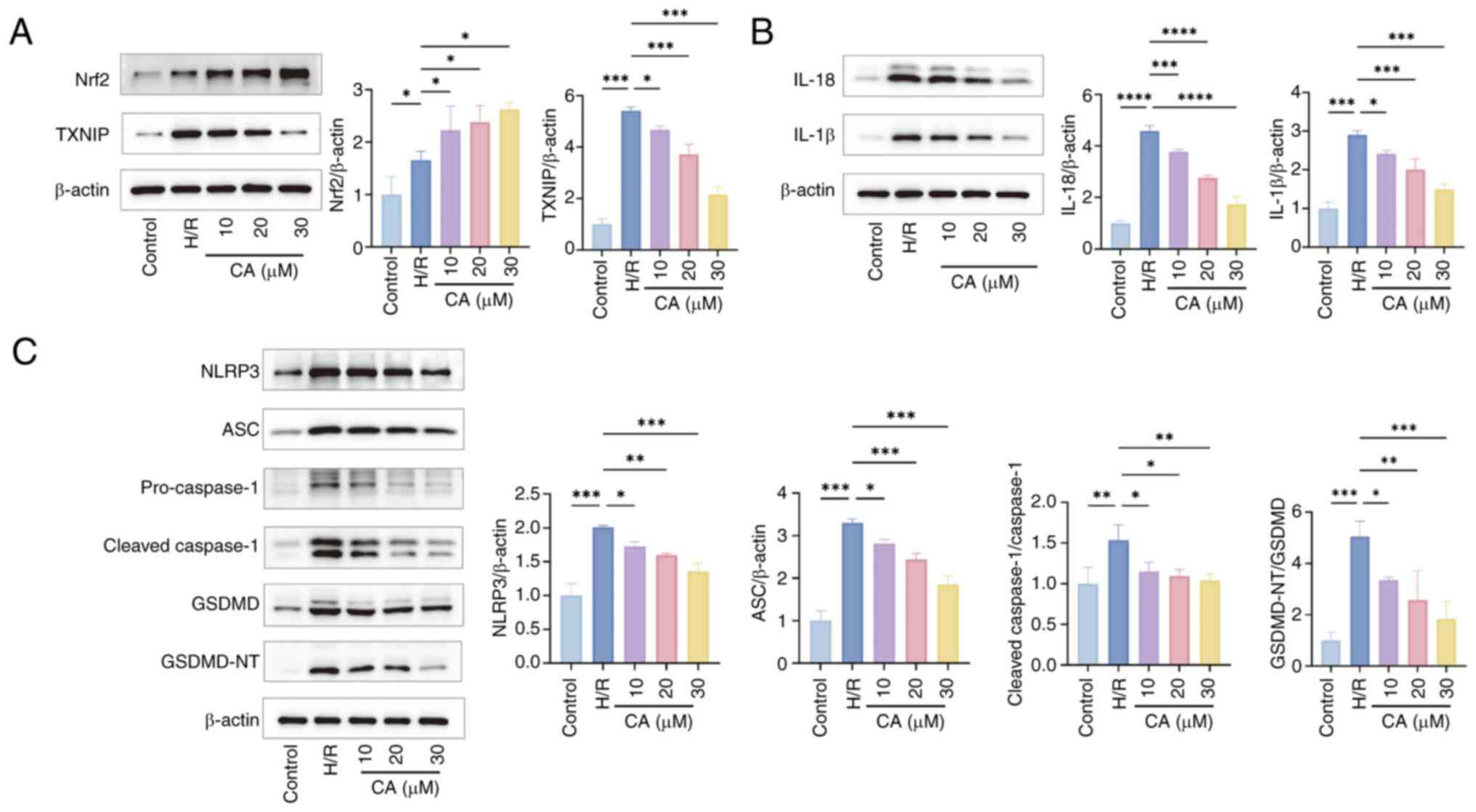

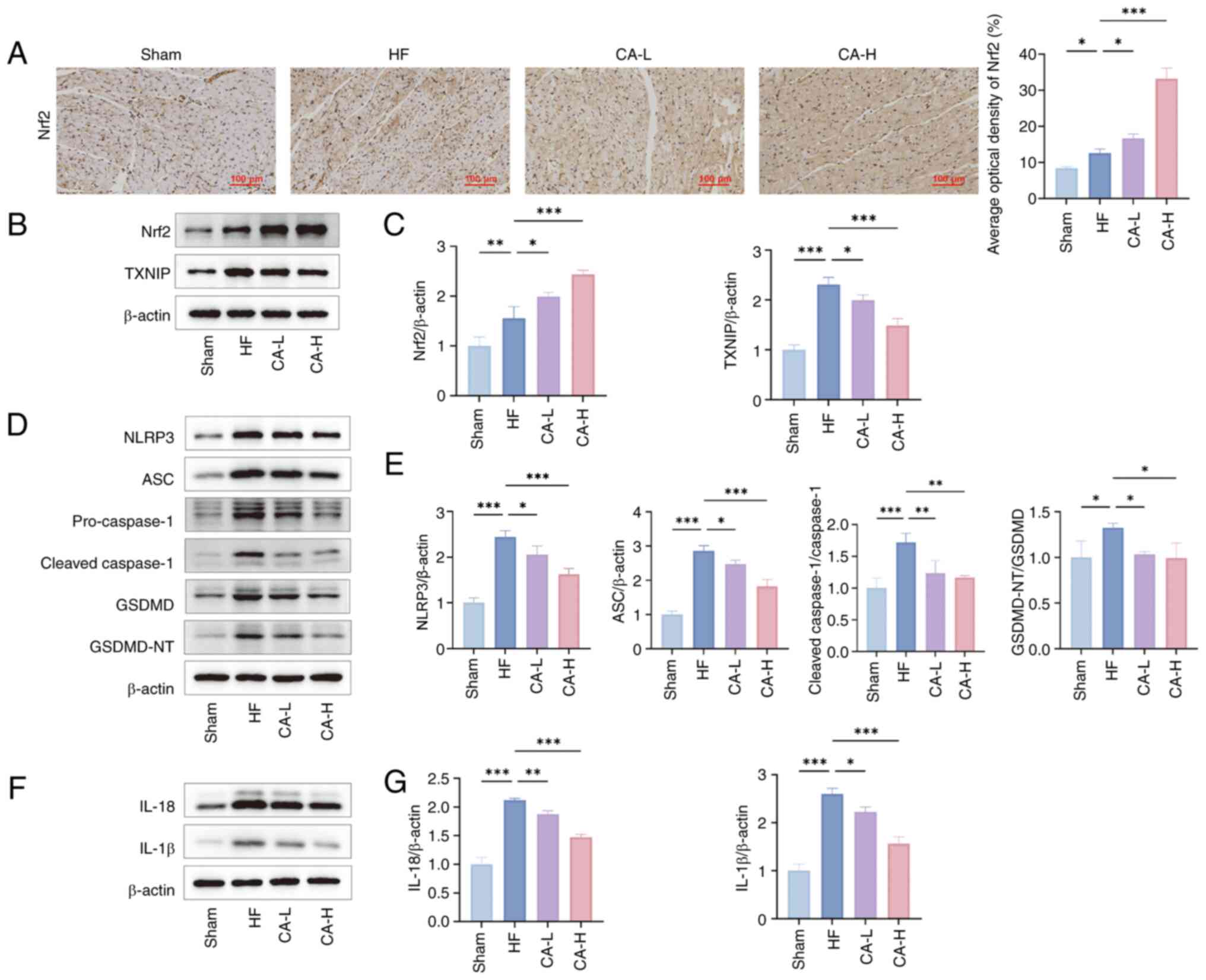

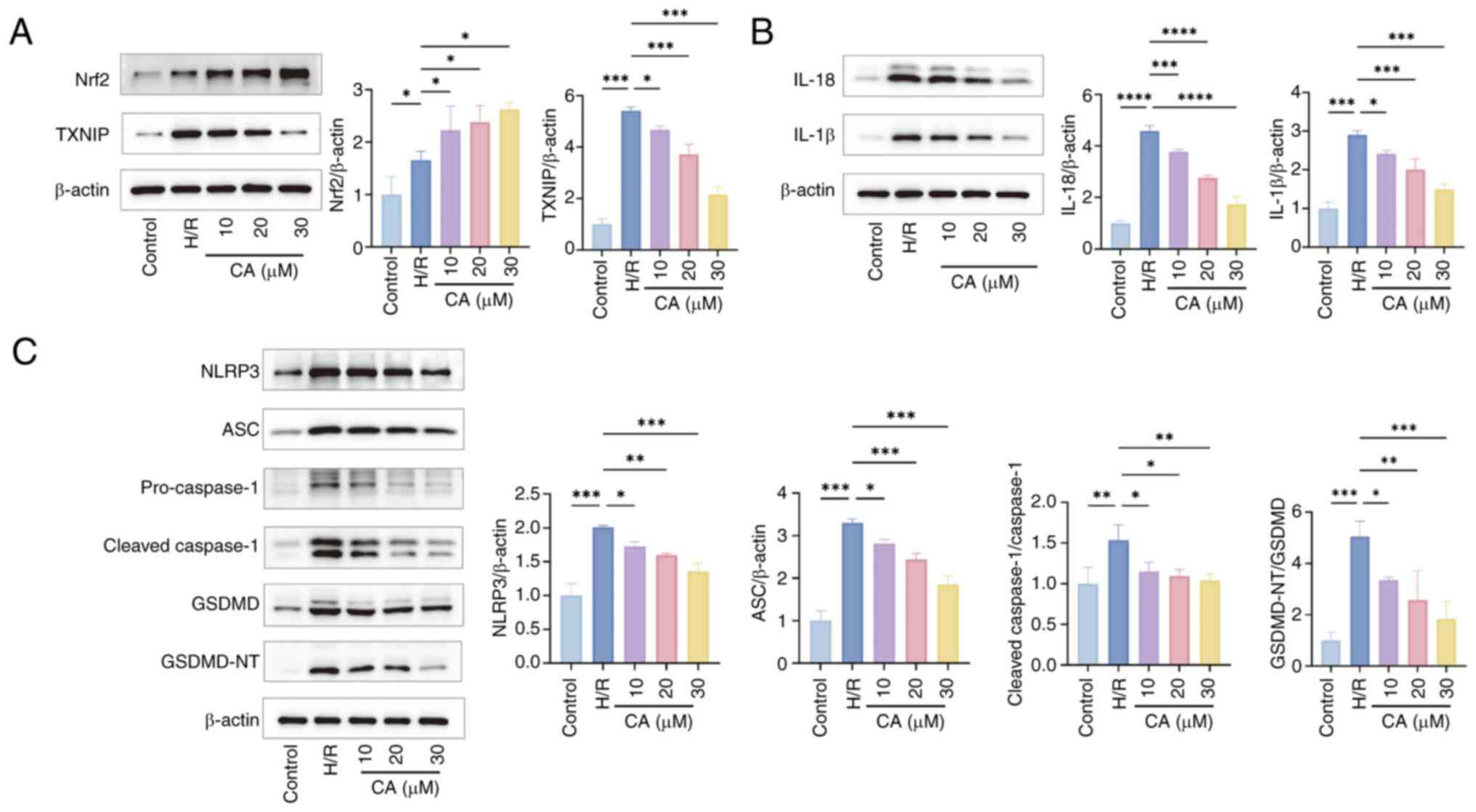

CA inhibits HF-induced pyroptosis via the

Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway

To further explore the mechanism of CA in the

treatment of HF, the present study measured the expression of

proteins in the Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway and related pyroptosis

proteins. Immunohistochemistry staining indicated that Nrf2

expression was upregulated in the HF group compared with the Sham

group, and was further increased following CA treatment (Fig. 3A). Western blotting results

further confirmed that compared with in the Sham group, Nrf2 and

TXNIP expression levels were upregulated in HF-induced rats. CA

treatment further upregulated the expression levels of Nrf2 and

inhibited the expression of TXNIP (Fig. 3B and C). In HF-induced rats, the

expression of related pyroptosis proteins and inflammatory

cytokines was upregulated, specifically, the NLRP3 inflammasome was

activated, and the expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, pro- and

cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT (Fig. 3D and E), IL-18 and IL-1β

(Fig. 3F and G) were elevated.

By contrast, CA treatment significantly downregulated the

expression of these pyroptosis-related proteins and inflammatory

cytokines.

| Figure 3CA improves pyroptosis in HF through

the Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway. (A) Representative Nrf2

immunohistochemistry images of each group and their quantitative

analysis (n=3). (B) Representative images of the expression levels

of Nrf2 and TXNIP in myocardial tissue of Wistar rats assessed by

western blotting. (C) Semi-quantitative analysis of Nrf2 and TXNIP

expressions (n=3). (D) Representative images of the expression

levels of NLRP3, ASC, pro- and cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT

in myocardial tissue of Wistar rats by western blotting. (E)

Semi-quantitative analysis of NLRP3, ASC, pro- and

cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT expressions (n=3). (F)

Representative images of the expression levels of IL-18 and IL-1β

in myocardial tissue of Wistar rats by western blotting. (G)

Semi-quantitative analysis of IL-18 and IL-1β expressions (n=3).

Data are presented as the mean ± SD, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CA, calycosin;

HF, heart failure; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; TXNIP, thioredoxin-interacting

protein; CA-L, calycosin low-dose; CA-H, calycosin high-dose; ASC,

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD; GSDMD,

gasdermin D; GSDMD-NT, GSDMD N-terminal fragments. |

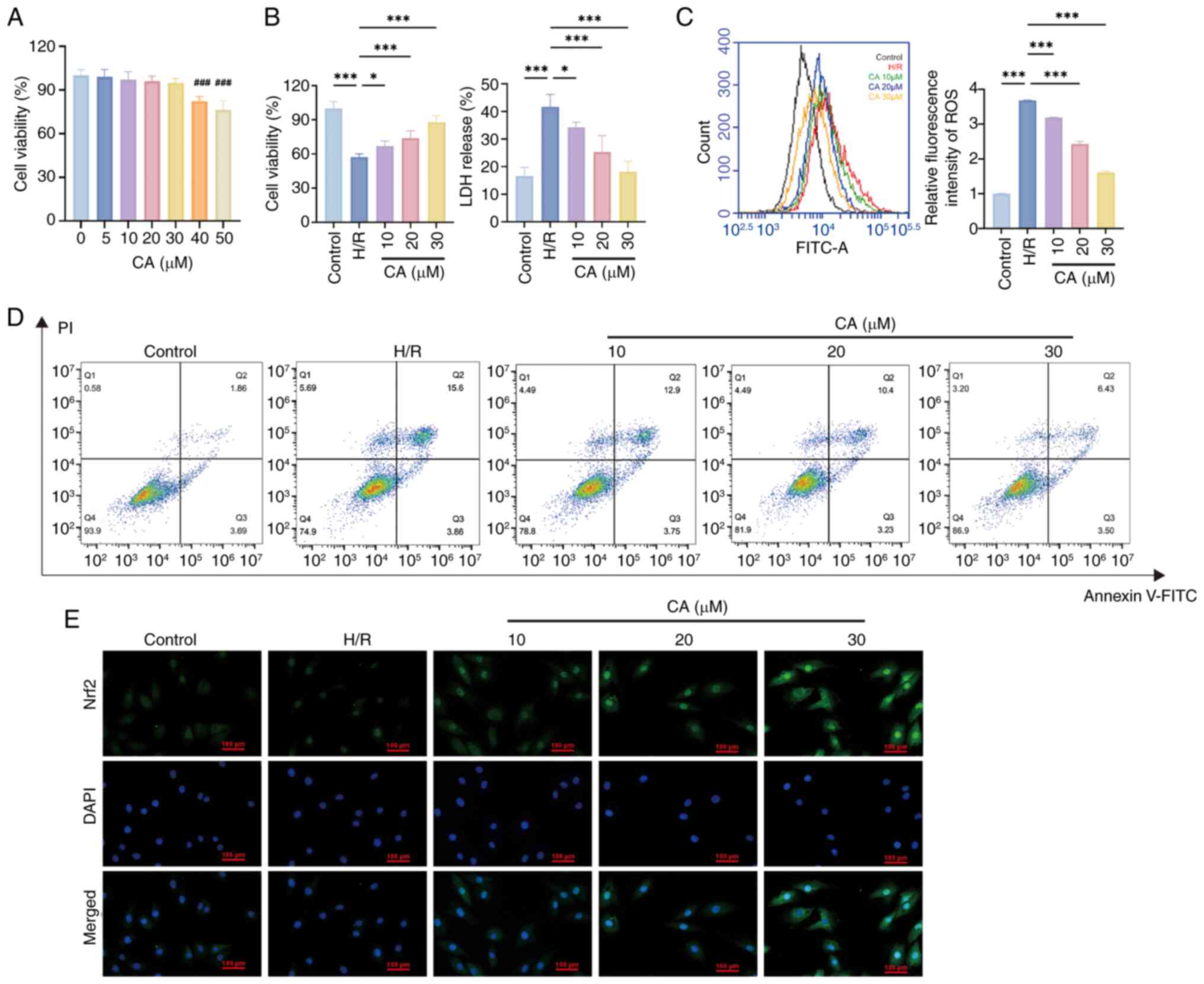

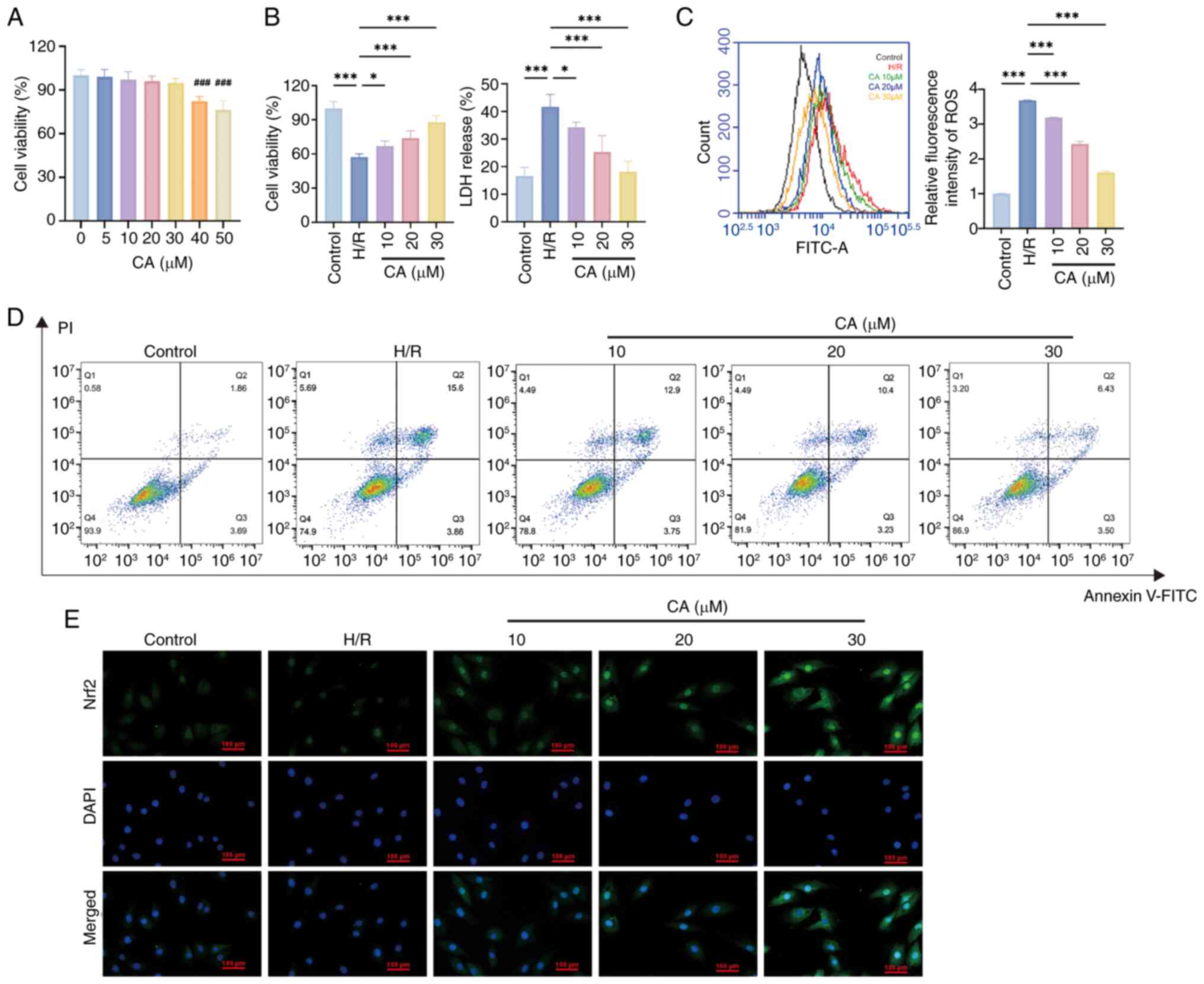

CA protects cardiomyocytes and inhibits

pyroptosis via the Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway

To further validate the potential cardioprotective

effects and therapeutic mechanisms of CA, further experiments were

conducted in H/R-treated H9c2 cells. The CCK-8 assay was used to

examine the biosafety of CA in H9c2 cells and the results showed

that CA was cytotoxic at concentrations ≥40 μM (Fig. 4A). Subsequently, the H/R model

was constructed and the cardioprotective effects of CA were

evaluated through the CCK-8 assay and by measuring LDH levels. The

results showed that H/R treatment significantly reduced cell

viability and promoted LDH release, whereas CA treatment

dose-dependently reversed this effect (Fig. 4B).

| Figure 4CA protects cardiomyocytes and

inhibits pyroptosis. (A) Detection of CA cytotoxicity using a Cell

Counting Kit-8 assay (n=3). ###P<0.001, compared with

0, 5, 10, 20, 30 μM groups. (B) Cardiomyocyte protective

effects of CA (n=3). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of cell death

with Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of

cardiomyocytes for Nrf2. (E) Detection of intracellular ROS levels

in cardiomyocytes (n=3). Data are presented as the mean ± SD,

*P<0.05, ***P<0.001. CA, calycosin;

Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor; ROS, reactive

oxygen species; H/R, hypoxia-reperfusion; LDH, lactate

dehydrogenase. |

During pyroptosis, GSDMD-NT can form membrane pores

in the plasma membrane and mitochondrial membrane, disrupting

membrane integrity and thereby leading to mitochondrial damage and

cell death, which was observed in the present study by Annexin V/PI

staining, with an increase in Annexin V+/PI+

cells detected in response to H/R, while CA treatment ameliorated

this increase in Annexin V+/PI+ cells (Fig. 4C). Immunofluorescence staining of

cardiomyocytes for Nrf2 revealed that Nrf2 levels were increased by

H/R treatment and further increased by CA treatment, and that CA

promoted Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, detection of

intracellular ROS levels revealed elevated ROS release in response

to H/R treatment, whereas CA treatment significantly reduced ROS

release (Fig. 4E). Western

blotting further indicated that H/R treatment upregulated the

expression levels of Nrf2, TXNIP, activated the NLRP3 inflammasome

and increased the expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, pro- and

cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT, IL-18 and IL-1β. CA treatment

further upregulated, the expression of Nrf2, inhibited the

expression of TXNIP (Fig. 5A)

and suppressed the expression and release of NLRP3, ASC, pro- and

cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT (Fig. 5C), IL-18 and IL-1β (Fig. 5B).

| Figure 5CA inhibits pyroptosis via the

Nrf2/reactive oxygen species/TXNIP pathway (n=3). (A)

Representative images of the expression levels and

semi-quantitative analysis of Nrf2 and TXNIP in cells by western

blotting (n=3). (B) and semi-quantitative analysis and

semi-quantitative analysis of IL-18 and IL-1β in cells by western

blotting and (n=3). (C) and semi-quantitative analysis and

semi-quantitative analysis of levels of NLRP3, ASC, pro- and

cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT in cells by western blotting

(n=3). Data are presented as the mean ± SD, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. CA, calycosin;

Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor; TXNIP,

thioredoxin-interacting protein; H/R, hypoxia-reperfusion, ASC,

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD; GSDMD,

gasdermin D; GSDMD-NT, GSDMD N-terminal fragments; NLRP3, NLR

family pyrin domain-containing protein 3. |

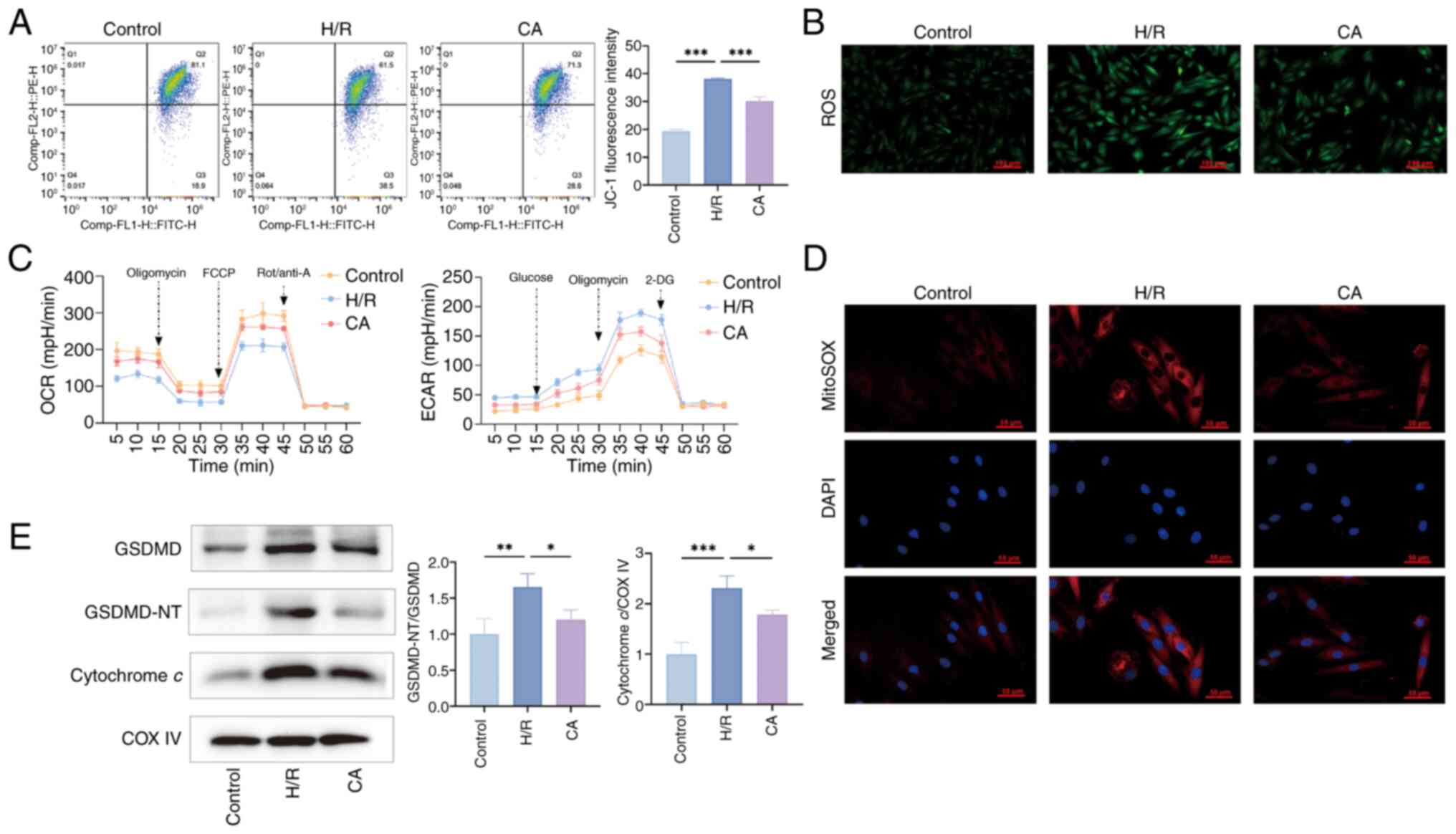

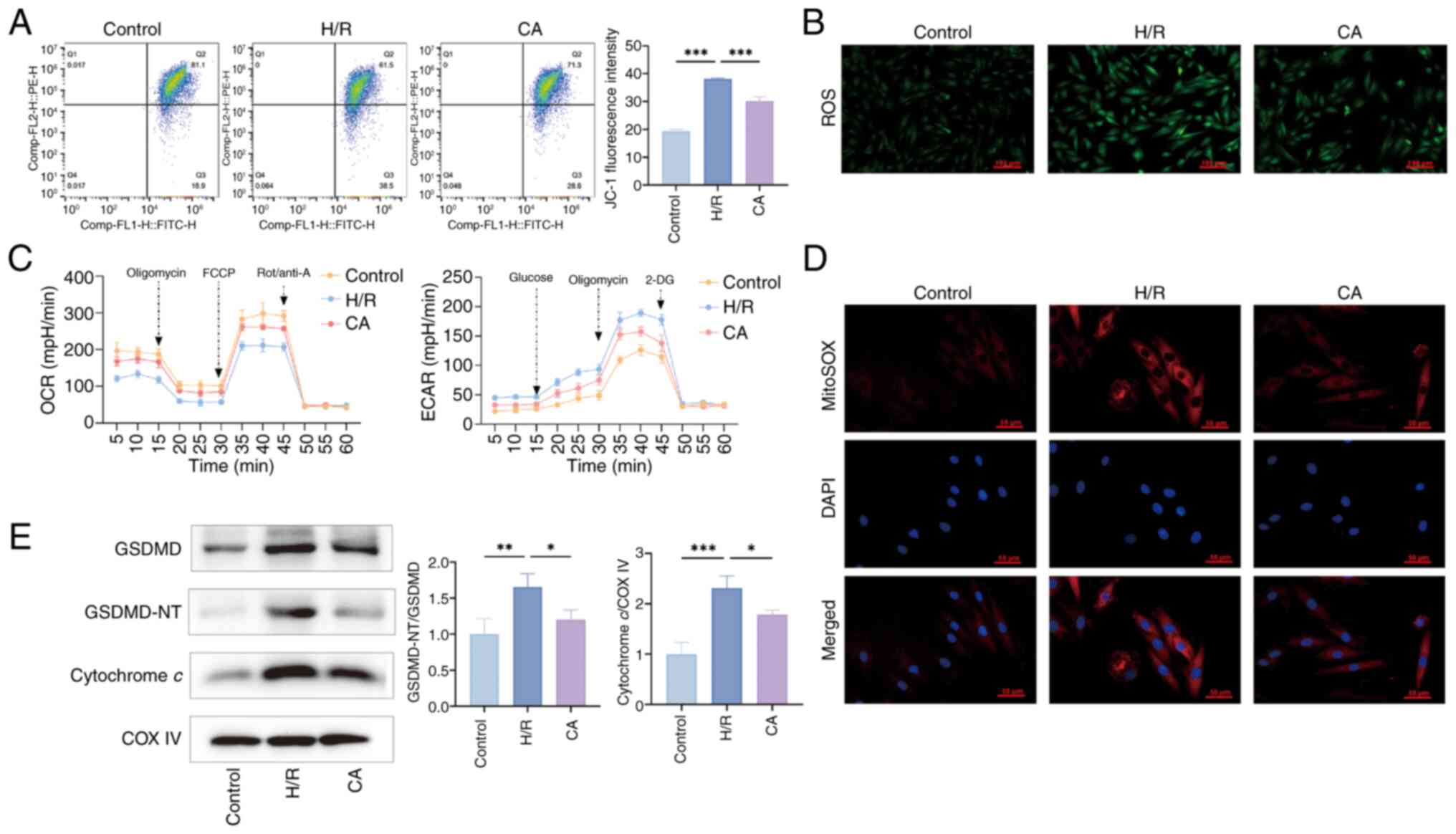

CA improves mitochondrial damage in

cardiomyocytes

Since CA protects cardiomyocytes in a dose-dependent

manner, CA 30 μM was used in the present study to further

investigate the improvement effect on mitochondrial damage. Flow

cytometry revealed that H/R treatment significantly decreased

mitochondrial membrane potential, while CA treatment prevented this

change (Fig. 6A). Furthermore,

ROS and mitochondrial ROS staining of the cells revealed an

increase in intracellular and mitochondrial ROS with H/R treatment,

which was improved by CA treatment (Fig. 6B and C). The ECAR and OCR were

used to assess mitochondrial glucose metabolism and oxidative

phosphorylation levels. As shown in Fig. 6D, H/R treatment promoted

glycolysis and inhibited mitochondrial respiration, while CA

treatment ameliorated this mitochondrial damage. In addition,

western blotting results indicated that H/R treatment upregulated

GSDMD expression levels, promoted GSDMD-NT activation and

upregulated cytochrome c expression levels in the

mitochondria; by contrast, CA treatment downregulated their

expression and activation (Fig.

6E).

| Figure 6CA improves mitochondrial damage in

cardiomyocytes. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of JC-1 staining was

used to detect changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (n=3).

(B) Representative intracellular ROS staining images of each group.

(C) Representative mitochondrial ROS staining images of each group.

(D) ECAR and OCR of cardiomyocytes were assessed (n=3). (E)

Expression levels of GSDMD, GSDMD-NT and cytochrome c

proteins were examined by western blotting (n=3). COX IV was used

as a loading control in mitochondria. Data are presented as the

mean ± SD, *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001. CA, calycosin; ROS, reactive oxygen

species; ECAR, extracellular acidification rate; OCR, oxygen

consumption rate; FCCP, Trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide

phenylhydrazone, Carbonyl cyanide

4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone; Rot/anti-A, rotenone/antimycin

A; GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-NT, GSDMD N-terminal fragments; H/R,

hypoxia-reperfusion. |

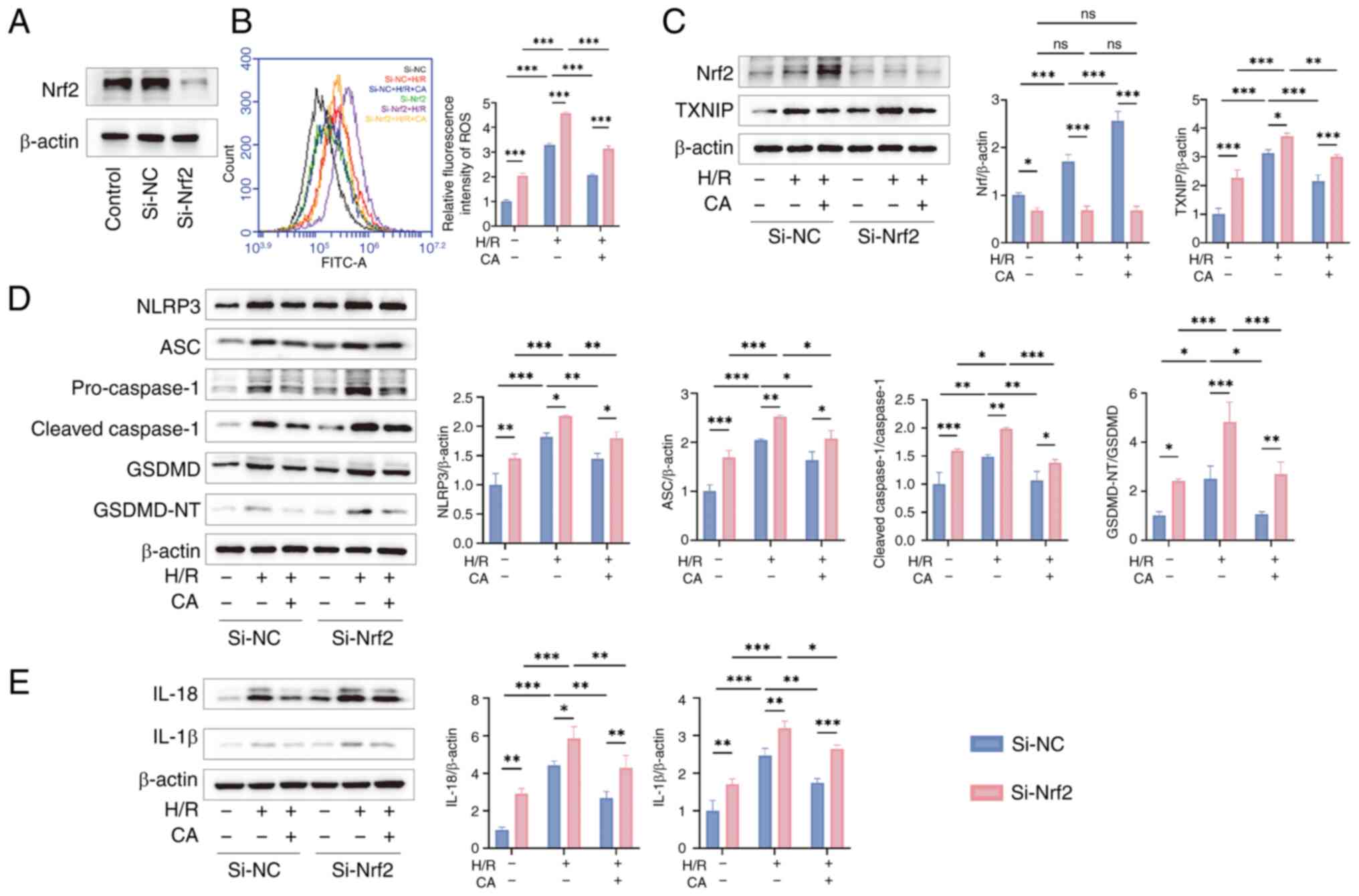

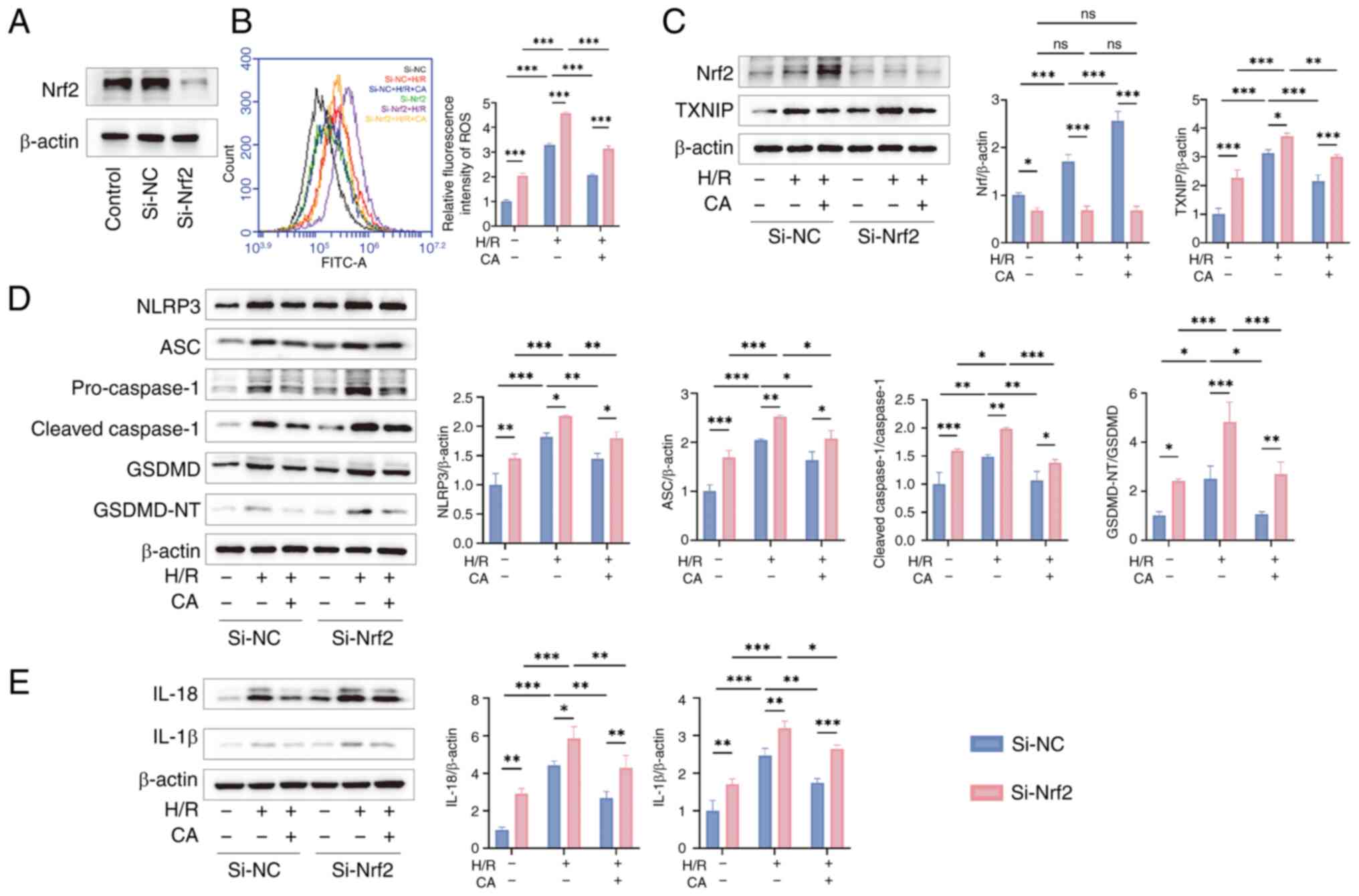

Silencing Nrf2 inhibits the therapeutic

effects of CA

To further validate the therapeutic mechanism of CA,

Nrf2 expression was knocked down using siRNA in H9c2 cells. After

verifying the efficiency of Nrf2 silencing (Fig. 7A), detection of intracellular ROS

levels confirmed that Nrf2 silencing significantly upregulated

intracellular ROS levels compared with Si-NC group, further

suggesting that CA exerts antioxidant effects through Nrf2

(Fig. 7B). Western blotting

results revealed that compared with the Si-NC group, Si-Nrf2

significantly reduced Nrf2 protein expression levels. Compared with

the Si-NC group, Nrf2 silencing in the Si-Nrf2 group significantly

upregulated the expression levels of TXNIP, activated NLRP3

inflammasome, and increased the expression levels of NLRP3, ASC,

pro- and cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT, IL-18 and IL-1β,

further confirming that Nrf2 silencing reversed the inhibitory

effect of CA on pyroptosis (Fig.

7C-E).

| Figure 7Silencing Nrf2 inhibits the

therapeutic effects of CA. (A) Transfection efficiency of si-Nrf2.

(B) Detection of intracellular ROS levels in each group (n=3). (C)

Representative images and semi-quantitative analysis of Nrf2 and

TXNIP in cells by western blotting (n=3). (D) Representative images

and semi-quantitative analysis of NLRP3, ASC, pro- and

cleaved-caspase-1, GSDMD, GSDMD-NT in cells by western blotting

(n=3). (E) Representative images and semi-quantitative analysis

levels of IL-18 and IL-1β in cells by western blotting (n=3). Data

are presented as the mean ± SD, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, no

significance. si, small interfering; CA, calycosin; Nrf2, nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

TXNIP, thioredoxin-interacting protein; ASC, apoptosis-associated

speck-like protein containing a CARD; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin

domain-containing protein 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D; GSDMD-NT, GSDMD

N-terminal fragments; H/R, hypoxia-reperfusion; NC, negative

control. |

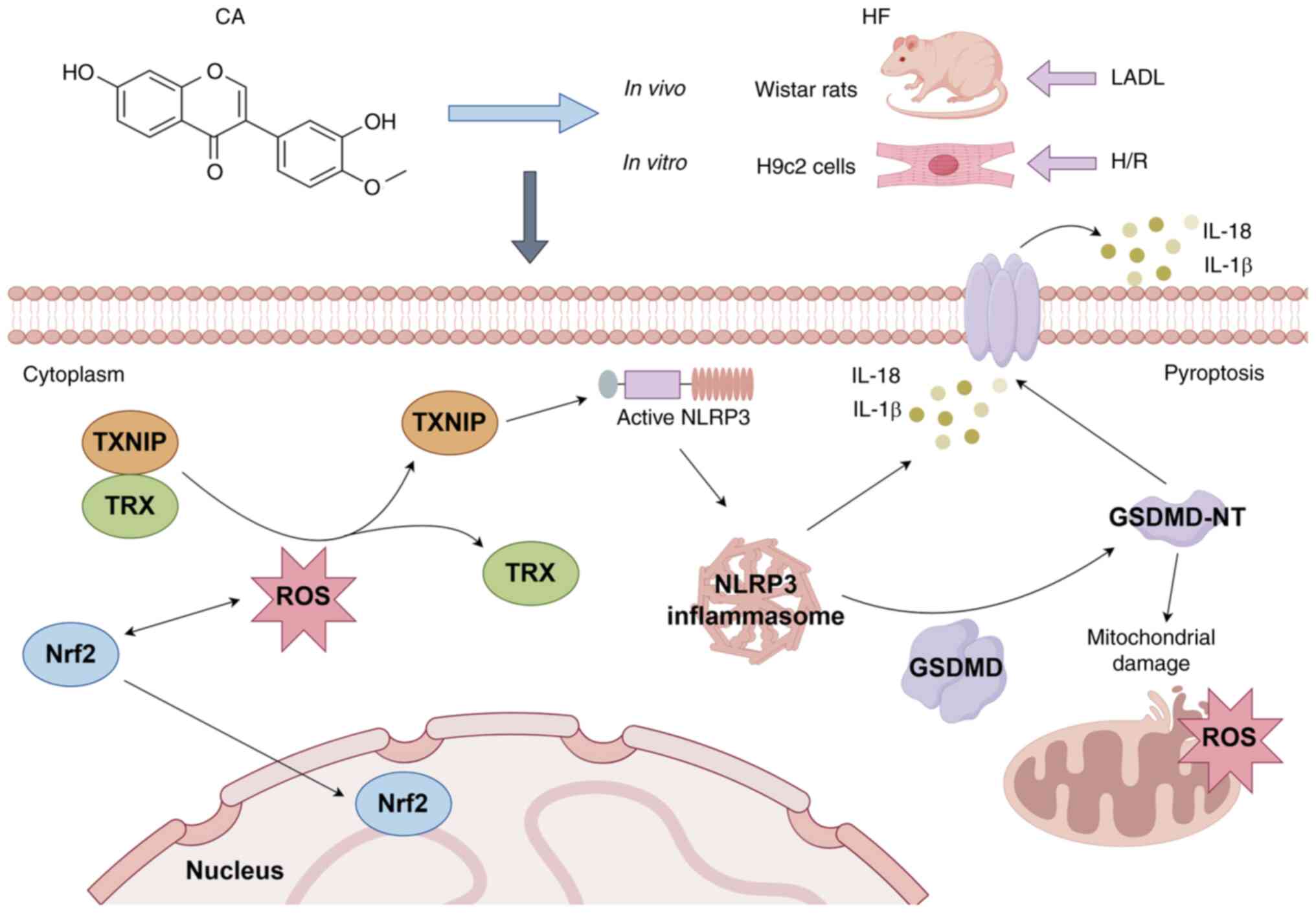

Discussion

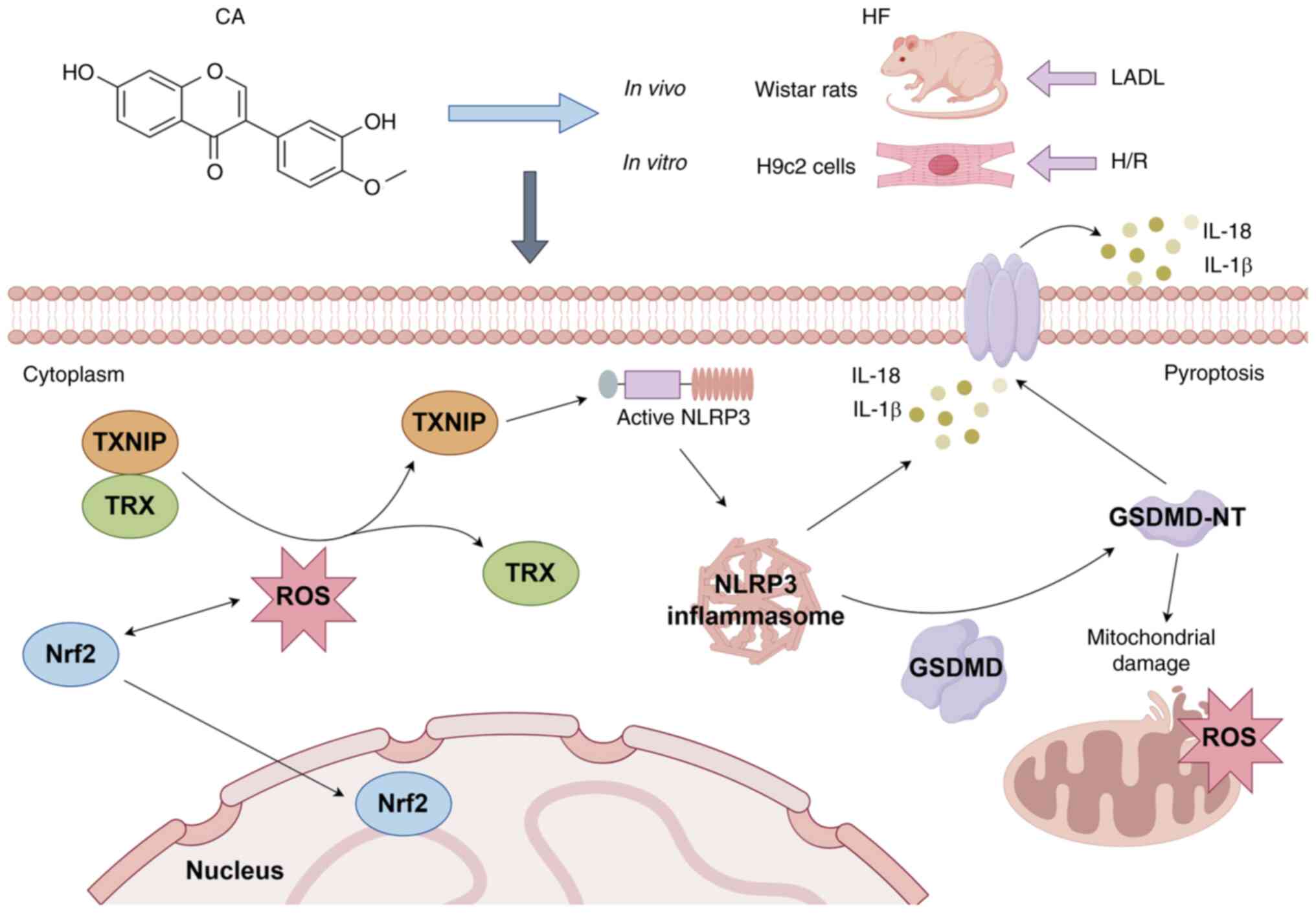

There is a consensus that inflammation, oxidative

stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death serve a central

role in the progression of HF (7,8,26). However, the specific mechanisms

of pyroptosis and effective interventions in HF remain unclear,

especially since previous studies have revealed that pyroptosis

also mediates mitochondrial damage in cells (13,27). To the best of our knowledge, the

present study is the first to systematically investigate the

therapeutic mechanism of CA to attenuate mitochondrial damage and

pyroptosis in HF via the Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway, which not only

demonstrated the cardioprotective effects of CA, but also confirmed

the complex interactions between oxidative stress, mitochondrial

damage and pyroptosis. Therefore, the present study proposes the

Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway as a potentially promising therapeutic

target for treating mitochondrial damage and pyroptosis in HF.

The natural flavonoid compound CA is the main

bioactive chemical in Radix Astragali, and has been shown to exert

anti-HF therapeutic effects (17-20). Previous studies have demonstrated

that CA regulates oxidative stress by modulating Nrf2 expression

(28,29), but the specific mechanism remains

to be investigated. Previous studies have demonstrated that CA

inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation-mediated pyroptosis and

ameliorates myocardial injury (21,22). However, these studies mainly

focused on phenotypes and downstream effector proteins, while the

effects on upstream signaling pathways were insufficiently studied,

resulting in an incomplete understanding of the mechanism of CA

treatment. Meanwhile, another study revealed that CA upregulates

Nrf2 expression levels, and alleviates myocardial oxidative stress

and mitochondrial damage, thereby protecting the myocardium

(21), warranting further

investigation of the effect of CA on Nrf2 regulation and pyroptosis

in the failing myocardium. The present study indicated that CA

improved cardiac function, attenuated cardiac oxidative stress, and

prevented myocardial fibrosis and inflammatory injury in HF via the

Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway, demonstrating the complex interactions

between oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and pyroptosis.

Nrf2 is a key regulator of cellular defense

mechanisms, particularly regulating cellular antioxidant responses

under oxidative stress conditions (15). During oxidative stress, Nrf2

dissociates from Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1),

translocates to the nucleus and activates the transcription of

antioxidant-responsive genes, enhancing ROS cellular scavenging

(30). TXNIP is a negative

regulator downstream of Nrf2/ROS. The activation of Nrf2 reduces

ROS levels, thereby inhibiting ROS-mediated dissociation of TXNIP

and TRX, and consequently attenuating TXNIP expression (31,32). Downregulation of TXNIP weakens

the interaction between TXNIP and NLRP3, thereby suppressing NLRP3

inflammasome activation and ultimately attenuating pyroptosis and

inflammatory responses (33,34). Therefore, Nrf2 is a key factor

linking oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Considerable oxidative stress is present in HF (8), resulting in elevated Nrf2 levels,

but this elevation is limited (35). Therefore, although Nrf2

expression is elevated, it is insufficient to completely counteract

the complex inflammatory response and oxidative stress, therefore

TXNIP expression remains high in HF (36-38). The present study has found that

both Nrf2 and TXNIP expression were upregulated in HF, consistent

with previous research findings. In the present study, CA treatment

was shown to improve oxidative stress indicators, such as LDH, MDA,

SOD and T-GSH/GSSG, in HF-induced rats. Western blotting and flow

cytometry results also confirmed that CA treatment upregulated Nrf2

expression, decreased ROS levels, and inhibited the expression of

TXNIP and corresponding pyroptosis proteins. Nrf2

immunofluorescence experiments revealed that CA treatment elevated

Nrf2 expression levels and confirmed its nuclear translocation.

These results highlight the role of Nrf2 in the treatment of HF

with CA.

To further confirm the central role of Nrf2 in the

anti-HF effects of CA, the present study used siRNA to silence

Nrf2. The results revealed that compared to the Si-NC group,

silencing Nrf2 markedly reduced the protective effects of CA,

including a significant increase in ROS levels and the expression

of downstream molecules. However, the natural compound CA has

multi-pathway, multi-target therapeutic advantages and its

therapeutic mechanism may involve the synergistic action of

multiple signaling pathways. Studies have revealed that CA can

improve myocardial fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction through the

TGFBR1 signaling pathway and can also inhibit inflammation and

fibrosis in HF-induced rats through the AKT-IKK/STAT3 axis

(19,20).

Pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death mediated

by GSDMD, has been reported to serve a key role in the pathological

process of HF, exacerbating inflammation and tissue damage

(11). Specifically, GSDMD is

activated by specific signals and undergoes a conformational change

into GSDMD-NT, which perforates the cell membrane, leading to

leakage of cellular contents and cellular swelling, ultimately

triggering cell rupture and death (12,39). The significant inflammatory

response and oxidative stress present in HF can activate multiple

pathways, such as the NF-κB signaling pathway that promotes GSDMD

and Caspase-1 transcription and synthesis. The in vivo and

in vitro results further confirmed that CA effectively

suppressed this synthesis. Furthermore, it inhibited NLRP3

inflammasome activation, thereby suppressing the further cleavage

and activation of GSDMD and Caspase-1, suggesting that CA inhibits

pyroptosis in failing cardiomyocytes. Mitochondrial dysfunction is

involved in a variety of pathological mechanisms such as disturbed

energy metabolism, dysregulation of calcium homeostasis,

inflammatory response and cell death, and has emerged as a key

target for HF (40). A recent

study confirmed that activation of GSDMD-NT during pyroptosis leads

not only to perforated rupture of cellular membranes, but also to

perforation of mitochondrial membranes, which in turn leads to

mitochondrial damage and release of ROS (13). Pyroptosis driven by GSDMD not

only leads to myocardial damage but also amplifies mitochondrial

damage and promotes the process toward HF. The crosstalk between

pyroptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction underscores the complexity

of HF pathophysiology. In the present study, CA treatment not only

attenuated pyroptosis but also ameliorated mitochondrial damage.

TEM examination of HF rats revealed that CA improved mitochondrial

ultrastructure and in vitro cellular experiments further

demonstrated that CA treatment downregulated the expression of

mitochondrial GSDMD-NT and improved mitochondrial membrane

potential, mitochondrial ROS levels and mitochondrial respiration,

which suggests that CA exerts its cardioprotective effects through

multiple pathways (Fig. 8).

| Figure 8Molecular mechanisms of CA treatment

for HF. CA promotes Nrf2 expression and its nuclear translocation,

thereby alleviating mitochondrial damage and pyroptosis in HF via

the Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway. This figure was generated by FigDraw.

CA, calycosin; HF, heart failure; LADL, left anterior descending

ligation; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; TRX, thioredoxin; TXNIP,

thioredoxin-interacting protein; H/R, hypoxia-reoxygenation; NLRP3,

NLR family pyrin domain-containing protein 3; GSDMD, gasdermin D;

GSDMD-NT, GSDMD N-terminal fragments. |

Natural compounds have demonstrated promising

potential in the treatment of HF due to their multi-targeting

properties, low side effects, and excellent anti-inflammatory and

antioxidant effects (41-43).

Compared with other similar natural compounds that modulate Nrf2,

such as sulforaphane and curcumin, CA has unique advantages and

preclinical therapeutic potential. Sulforaphane has antioxidant and

anti-inflammatory properties and has been shown to improve cardiac

function and prevent worsening of HF by regulating Nrf2 expression

levels (44). However, CA has a

unique advantage because of its ability to inhibit pyroptosis and

regulate the process of cell death in cardiomyocytes (21,22). Curcumin has antioxidant,

anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties, and has been shown

to improve HF by ameliorating ventricular hypertrophy and

inhibiting myocardial fibrosis (45,46). However, the low stability of

curcumin limits its further clinical translation (47). By contrast, CA has improved

stability and may be a more suitable choice for the clinical

treatment of HF.

The present study used LAD ligation to establish the

HF model and demonstrated that CA improved cardiac function and

myocardial damage, suppressed myocardial oxidative stress and

improved mitochondrial ultrastructure in HF-induced rats. However,

the LAD ligation model is widely used to study ischemic HF, as it

simulates the pathophysiological characteristics of human ischemic

HF by inducing local myocardial ischemia (48), which may not reflect the

pathological changes and cardiac remodeling specific to

non-ischemic HF. In H9c2 cells, the present study used the H/R

model to simulate HF and further confirmed the therapeutic

mechanism of CA against HF. However, the H/R model simulates

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, which captures the key

initiating mechanisms associated with ischemia-reperfusion stress

injury, but cannot fully reflect the complex, chronic adaptive and

maladaptive processes of chronic HF, whether of ischemic or

non-ischemic origin (49).

Notably, several limitations should be acknowledged.

Firstly, the LAD ligation model primarily simulates ischemic HF,

and the H/R model in H9c2 cells, although capable of capturing the

key mechanisms of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion stress injury,

may not fully reflect the pathophysiology of chronic HF. The

detection of ROS data at a single time point limits dynamic

understanding of oxidative stress in HF, therefore, this should be

further investigated using multiple time points. Furthermore, H9c2

cells are widely used in studies related to cardiovascular disease

(50-52), but they cannot fully represent

the physiological characteristics of primary cardiomyocytes. Future

studies should use primary cells to provide an improved simulation

of the pathophysiological progression of HF. Secondly, the present

study showed that CA inhibits pyroptosis in HF and improves

mitochondrial damage, possibly disrupting the crosstalk between

mitochondrial damage and pyroptosis. However, the exact mechanism

remains to be further validated through experiments such as

co-immunoprecipitation or proximity ligation assays to determine

the interaction between GSDMD-NT and mitochondria or using

cytosolic fractions to confirm mitochondrial outer membrane

permeabilization. Nrf2 silencing eliminated the protective effect

of CA; however, it remains unclear as to whether the effects of CA

are directly mediated by Nrf2 or through upstream/downstream

interactions. Therefore, additional validation is needed, including

experiments such as Nrf2 overexpression rescue after Nrf2

knockdown, or TXNIP knockout and Keap1-Nrf2 interaction after Nrf2

knockdown to confirm the specificity of Nrf2 and causality.

Finally, the present study is a preclinical basic study, which is a

preliminary exploration of the pharmacological efficacy of CA. The

clinical translational application of CA requires further

evaluation of aspects such as pharmacokinetics (bioavailability,

tissue distribution and metabolic stability) and safety. The sample

size of some experiments in the present study was also relatively

small; although consistent trends were observed in repeated

measurements, a larger sample size would enhance the accuracy and

scientific validity of the present study.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study

demonstrated, for the first time, that CA possibly disrupts the

crosstalk between pyroptosis-mitochondrial damage in HF via the

Nrf2/ROS/TXNIP pathway. CA may attenuate the activation of upstream

triggers of pyroptosis, ROS overproduction and downregulate the

downstream actuator protein, GSDMD-NT, thereby ameliorating cardiac

function and myocardial injury in HF. However, additional

validation is still required to further confirm the specificity of

Nrf2 in CA treatment.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HJY, YDY, YTX and YL conceived the study. HJY, QCH

and HY carried out the experiments. YDY and XJL analyzed the data.

HJY and QCH drafted the manuscript. YTX and YL reviewed and revised

the manuscript. YTX and YL confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experiment was reviewed and approved by

the Experimental Animal Management Committee and the Ethics

Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of

Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval no.

SDSZYYAWE20231031001).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

ASC

|

apoptosis-associated speck-like

protein containing a CARD

|

|

CA

|

calycosin

|

|

CA-L

|

CA low-dose

|

|

CA-H

|

CA high-dose

|

|

CAP

|

captopril

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

ECAR

|

extracellular acidification rate

|

|

FCCP

|

Trifluoromethoxy carbonylcyanide

phenylhydrazone, Carbonyl cyanide

4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone

|

|

FS

|

fractional shortening

|

|

GSDMD

|

gasdermin D

|

|

GSDMD-NT

|

GSDMD N-terminal fragments

|

|

HF

|

heart failure

|

|

H/R

|

hypoxia-reoxygenation

|

|

Keap1

|

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein

1

|

|

LAD

|

left anterior descending

|

|

LDH

|

lactate dehydrogenase

|

|

LVEF

|

left ventricular ejection fraction

|

|

MDA

|

malondialdehyde

|

|

NLRP3

|

NLR family pyrin domain-containing

protein 3

|

|

Nrf2

|

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor

|

|

NT-proBNP

|

N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic

peptide

|

|

OCR

|

oxygen consumption rate

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

|

TEM

|

transmission electron microscopy

|

|

T-GSH/GSSG

|

total glutathione/glutathione

disulfide

|

|

TRX

|

thioredoxin

|

|

TXNIP

|

thioredoxin-interacting protein

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of

Shandong Province (grant no. ZR2023MH053).

References

|

1

|

Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson

CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Beaton AZ, Boehme AK,

Buxton AE, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update:

A report from the American heart association. Circulation.

147:e93–e621. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Khan MS, Shahid I, Bennis A, Rakisheva A,

Metra M and Butler J: Global epidemiology of heart failure. Nat Rev

Cardiol. 21:717–734. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bozkurt B, Fonarow GC, Goldberg LR, Guglin

M, Josephson RA, Forman DE, Lin G, Lindenfeld J, O'Connor C,

Panjrath G, et al: Cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart

failure: JACC expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 77:1454–1469. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zannad F, O'Connor CM, Butler J, McMullan

CJ, Anstrom KJ, Barash I, Bonaca MP, Borentain M, Corda S, Gates D,

et al: Vericiguat for patients with heart failure and reduced

ejection fraction across the risk spectrum: An individual

participant data analysis of the VICTORIA and VICTOR trials.

Lancet. August 30–2025.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Cools JMT, Goovaerts BK, Feyen E, Van den

Bogaert S, Fu Y, Civati C, Van Fraeyenhove J, Tubeeckx MRL, Ott J,

Nguyen L, et al: Small-molecule-induced ERBB4 activation to treat

heart failure. Nat Commun. 16:5762025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rossignol P, Hernandez AF, Solomon SD and

Zannad F: Heart failure drug treatment. Lancet. 393:1034–1044.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Brown DA, Perry JB, Allen ME, Sabbah HN,

Stauffer BL, Shaikh SR, Cleland JG, Colucci WS, Butler J, Voors AA,

et al: Expert consensus document: Mitochondrial function as a

therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 14:238–250.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

van der Pol A, van Gilst WH, Voors AA and

van der Meer P: Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: Past,

present and future. Eur J Heart Fail. 21:425–435. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Dridi H, Kushnir A, Zalk R, Yuan Q,

Melville Z and Marks AR: Intracellular calcium leak in heart

failure and atrial fibrillation: A unifying mechanism and

therapeutic target. Nat Rev Cardiol. 17:732–747. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xiang Q, Yi X, Zhu XH, Wei X and Jiang DS:

Regulated cell death in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Trends Endocrinol Metab. 35:219–234. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhang Z, Yang Z, Wang S, Wang X and Mao J:

Overview of pyroptosis mechanism and in-depth analysis of

cardiomyocyte pyroptosis mediated by NF-κB pathway in heart

failure. Biomed Pharmacother. 179:1173672024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y,

Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F and Shao F: Cleavage of GSDMD by

inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature.

526:660–665. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Miao R, Jiang C, Chang WY, Zhang H, An J,

Ho F, Chen P, Zhang H, Junqueira C, Amgalan D, et al: Gasdermin D

permeabilization of mitochondrial inner and outer membranes

accelerates and enhances pyroptosis. Immunity. 56:2523–2541.e8.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I and

Tschopp J: Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress

to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 11:136–140. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Morgenstern C, Lastres-Becker I,

Demirdöğen BC, Costa VM, Daiber A, Foresti R, Motterlini R,

Kalyoncu S, Arioz BI, Genc S, et al: Biomarkers of NRF2 signalling:

Current status and future challenges. Redox Biol. 72:1031342024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sies H and Jones DP: Reactive oxygen

species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat

Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:363–383. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Deng M, Chen H, Long J, Song J, Xie L and

Li X: Calycosin: A review of its pharmacological effects and

application prospects. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 19:911–925.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ding WJ, Chen GH, Deng SH, Zeng KF, Lin

KL, Deng B, Zhang SW, Tan ZB, Xu YC, Chen S, et al: Calycosin

protects against oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis

by activating aldehyde dehydrogenase 2. Phytother Res. 37:35–49.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wang X, Li W, Zhang Y, Sun Q, Cao J, Tan

N, Yang S, Lu L, Zhang Q, Wei P, et al: Calycosin as a Novel PI3K

activator reduces inflammation and fibrosis in heart failure

through AKT-IKK/STAT3 axis. Front Pharmacol. 13:8280612022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen G, Xu H, Xu T, Ding W, Zhang G, Hua

Y, Wu Y, Han X, Xie L, Liu B and Zhou Y: Calycosin reduces

myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac function in

post-myocardial infarction mice by suppressing TGFBR1 signaling

pathways. Phytomedicine. 104:1542772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhang L, Fan C, Jiao HC, Zhang Q, Jiang

YH, Cui J, Liu Y, Jiang YH, Zhang J, Yang MQ, et al: Calycosin

alleviates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and pyroptosis by

inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2022:17338342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yuan HJ, Han QC, Yu H, Yu YD, Liu XJ, Xue

YT and Li Y: Calycosin treats acute myocardial infarction via NLRP3

inflammasome: Bioinformatics, network pharmacology and experimental

validation. Eur J Pharmacol. 997:1776212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Han Q, Shi J, Yu Y, Yuan H, Guo Y, Liu X,

Xue Y and Li Y: Calycosin alleviates ferroptosis and attenuates

doxorubicin-induced myocardial injury via the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4

signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 15:14977332024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xu S, Huang P, Yang J, Du H, Wan H and He

Y: Calycosin alleviates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by

repressing autophagy via STAT3/FOXO3a signaling pathway.

Phytomedicine. 115:1548452023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jiang Q, Chen X, Gong K, Xu Z, Chen L and

Zhang F: M6a demethylase FTO regulates the oxidative stress,

mitochondrial biogenesis of cardiomyocytes and PGC-1a stability in

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Redox Rep. 30:24548922025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Del Re DP, Amgalan D, Linkermann A, Liu Q

and Kitsis RN: Fundamental mechanisms of regulated cell death and

implications for heart disease. Physiol Rev. 99:1765–1817. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Evavold CL, Hafner-Bratkovič I, Devant P,

D'Andrea JM, Ngwa EM, Boršić E, Doench JG, LaFleur MW, Sharpe AH,

Thiagarajah JR and Kagan JC: Control of gasdermin D oligomerization

and pyroptosis by the ragulator-Rag-mTORC1 pathway. Cell.

184:4495–4511.e19. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Qi XM, Zhang WZ, Zuo YQ, Qiao YB, Zhang

YL, Ren JH and Li QS: Nrf2/NRF1 signaling activation and crosstalk

amplify mitochondrial biogenesis in the treatment of

triptolide-induced cardiotoxicity using calycosin. Cell Biol

Toxicol. 41:22024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lu CY, Day CH, Kuo CH, Wang TF, Ho TJ, Lai

PF, Chen RJ, Yao CH, Viswanadha VP, Kuo WW and Huang CY: Calycosin

alleviates H2 O2-induced astrocyte injury by

restricting oxidative stress through the Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling

pathway. Environ Toxicol. 37:858–867. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kobayashi EH, Suzuki T, Funayama R,

Nagashima T, Hayashi M, Sekine H, Tanaka N, Moriguchi T, Motohashi

H, Nakayama K and Yamamoto M: Nrf2 suppresses macrophage

inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine

transcription. Nat Commun. 7:116242016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang J, Li X, Han X, Liu R and Fang J:

Targeting the thioredoxin system for cancer therapy. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 38:794–808. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen Y, Cao X, Pan B, Du H, Li B, Yang X,

Chen X, Wang X, Zhou T, Qin A, et al: Verapamil attenuates

intervertebral disc degeneration by suppressing ROS overproduction

and pyroptosis via targeting the Nrf2/TXNIP/NLRP3 axis in four-week

puncture-induced rat models both in vivo and in vitro. Int

Immunopharmacol. 123:1107892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Choi EH and Park SJ: TXNIP: A key protein

in the cellular stress response pathway and a potential therapeutic

target. Exp Mol Med. 55:1348–1356. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Abderrazak A, Syrovets T, Couchie D, El

Hadri K, Friguet B, Simmet T and Rouis M: NLRP3 inflammasome: From

a danger signal sensor to a regulatory node of oxidative stress and

inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol. 4:296–307. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lu Y, An L, Taylor MRG and Chen QM: Nrf2

signaling in heart failure: Expression of Nrf2, Keap1, antioxidant,

and detoxification genes in dilated or ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Physiol Genomics. 54:115–127. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang B, Jin Y, Liu J, Liu Q, Shen Y, Zuo S

and Yu Y: EP1 activation inhibits doxorubicin-cardiomyocyte

ferroptosis via Nrf2. Redox Biol. 65:1028252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhou P, Yang L, Li R, Yin Y, Xie G, Liu X,

Shi L, Tao K and Zhang P: IRG1/itaconate alleviates acute liver

injury in septic mice by suppressing NLRP3 expression and its

mediated macrophage pyroptosis via regulation of the Nrf2 pathway.

Int Immunopharmacol. 135:1122772024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhan Y, Xu D, Tian Y, Qu X, Sheng M, Lin

Y, Ke M, Jiang L, Xia Q, Kaldas FM, et al: Novel role of macrophage

TXNIP-mediated CYLD-NRF2-OASL1 axis in stress-induced liver

inflammation and cell death. JHEP Rep. 4:1005322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Devant P and Kagan JC: Molecular

mechanisms of gasdermin D pore-forming activity. Nat Immunol.

24:1064–1075. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wu C, Zhang Z, Zhang W and Liu X:

Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial therapies in heart

failure. Pharmacol Res. 175:1060382022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Sunagawa Y, Iwashimizu S, Ono M, Mochizuki

S, Iwashita K, Sato R, Shimizu S, Funamoto M, Shimizu K,

Hamabe-Horiike T, et al: The citrus flavonoid nobiletin prevents

the development of doxorubicin-induced heart failure by inhibiting

apoptosis. J Pharmacol Sci. 158:84–94. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wu Y, Huang X, He Y, Chang J, Fang X, Kang

P, Feng N, Liu R, Xiao P, Shi D, et al: Mechanism of puerarin

alleviating myocardial remodeling through NSUN2-mediated m5C

methylation modification. Phytomedicine. 143:1568492025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sun SN, Liu X, Chen XL, Liang SL, Li J,

Liao HL, Fang HC, Ni SH, Li Y, Lu L, et al: Calycosin alleviates

myocardial fibrosis after myocardial infarction by restoring fatty

acid metabolism homeostasis through inhibiting FAP. Phytomedicine.

145:1570452025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bai Y, Chen Q, Sun YP, Wang X, Lv L, Zhang

LP, Liu JS, Zhao S and Wang XL: Sulforaphane protection against the

development of doxorubicin-induced chronic heart failure is

associated with Nrf2 upregulation. Cardiovasc Ther. 35:2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Jiang S, Han J, Li T, Xin Z, Ma Z, Di W,

Hu W, Gong B, Di S, Wang D and Yang Y: Curcumin as a potential

protective compound against cardiac diseases. Pharmacol Res.

119:373–383. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Saeidinia A, Keihanian F, Butler AE,

Bagheri RK, Atkin SL and Sahebkar A: Curcumin in heart failure: A

choice for complementary therapy? Pharmacol Res. 131:112–119. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Pan Y, Zhu G, Wang Y, Cai L, Cai Y, Hu J,

Li Y, Yan Y, Wang Z, Li X, et al: Attenuation of

high-glucose-induced inflammatory response by a novel curcumin

derivative B06 contributes to its protection from diabetic

pathogenic changes in rat kidney and heart. J Nutr Biochem.

24:146–155. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Grilo GA, Munoz J Jr, Lee DH, Hossain S,

Ma Y, Kain V, Lindsey ML and Halade GV: Macro- and microinjury

define the heart failure progression after permanent coronary

ligation or ischemia-reperfusion in young healthy mice. Am J

Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 329:H521–H533. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Heusch G: Molecular basis of

cardioprotection: Signal transduction in ischemic pre-, post-, and

remote conditioning. Circ Res. 116:674–699. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Laudette M, Lindbom M, Cinato M, Bergh PO,

Skålén K, Arif M, Miljanovic A, Czuba T, Perkins R, Smith JG, et

al: PCSK9 regulates cardiac mitochondrial cholesterol by promoting

TSPO degradation. Circ Res. 136:924–942. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Khodade VS, Liu Q, Zhang C, Keceli G,

Paolocci N and Toscano JP: Arylsulfonothioates: Thiol-activated

donors of hydropersulfides which are excreted to maintain cellular

redox homeostasis or retained to counter oxidative stress. J Am

Chem Soc. 147:7765–7776. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhao ST, Qiu ZC, Xu ZQ, Tao ED, Qiu RB,

Peng HZ, Zhou LF, Zeng RY, Lai SQ and Wan L: Curcumin attenuates

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion-induced autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis via Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a signaling. Int J Mol Med.

55:512025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|