Introduction

Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) engage

in intricate physical and biochemical interactions within

specialized subcellular domains, the mitochondria-associated

membranes (MAM), where their intermembrane distance is finely tuned

to 10-20 nm (1,2). ER-mitochondria juxtaposition at MAM

is mediated by tethering proteins including inositol trisphosphate

receptor (IP3R), voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), Mitofusin

2 (Mfn2), vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B

(VAPB) and protein tyrosine phosphatase-interacting protein-51

(PTPIP51) (3,4). IP3R-VDAC and VAPB-PTPIP51

complexes, as well as Mfn2 and Sigma-1R, regulate ER-mitochondria

Ca2+ flux (5-9). MAM are also enriched in lipid

biosynthesis enzymes, namely those involved in lipid droplets (LDs)

biogenesis (10,11). By regulating Ca2+ and

lipid exchange, MAM govern pivotal cellular events, including

mitochondrial bioenergetics and dynamics, redox balance, as well as

ER stress and innate immune responses, namely NOD-like receptor

family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation

(4,12-14). Dynamic and responsive to cellular

cues, MAM are vital platforms for intra-cellular homeostasis

(15) and their dysfunction is

implicated in various pathologies, including neurodegenerative

diseases, metabolic and cardiovascular disorders and cancer, some

of which are comorbidities of bipolar disorder (BD) (2,16-18).

BD is a chronic mental illness characterized by mood

swings between mania and depression, affecting 1-2% of the world's

population (19). Lifelong

treatment is required (20),

however, current drugs are limited and have notable side effects

(21). BD diagnosis is

complicated by the lack of specific biomarkers, emphasizing the

need for a deeper understanding of its pathophysiology (20,22). Despite its neurobiology remaining

unclear (20), anatomical and

neuropathological examinations of the brains of patients with BD

revealed abnormalities in the cellular resilience of neurons and

glial cells towards stress (23). Disruptions in mitochondrial

function and Ca2+ signaling, oxidative stress, apoptosis

and perturbation of ER stress and immune responses are consistently

reported in BD (23-27). Since these events are regulated

by MAM (18,25), which play a pivotal role in

coordinating cellular responses to stress, it was hypothesized that

MAM impairment may underlie the diminished cellular resilience

observed in BD. To test this, structural and functional changes

resulting from ER-mitochondria miscommunication were assessed in

dermal fibroblasts and monocytes from early-stage patients with BD

compared with matched healthy controls.

Given the challenges of live brain tissue sampling,

alternative in vitro models have emerged in BD research,

using both non-neuronal cells (such as fibroblasts) and neuronal

cells [such as olfactory neuronal epithelium and induced

pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) differentiated in a neuronal

phenotype]. Several studies emphasize the occurrence of peripheral

tissue alterations in various brain diseases (28-30). Moreover, patient-derived skin

fibroblasts are a relevant BD cellular model due to: i) Sharing

ontogenetic origin with the central nervous system (CNS) and

expressing similar receptors and signaling pathways as neurons

(31,32); ii) expressing genes implicated in

psychiatric disorders (33);

iii) easy accessibility through skin biopsies, with efficient

establishment and maintenance in culture (32); iv) external factors (such as

medication) disappearing after five passages (34); v) displaying molecular

similarities with CNS cells, reflecting findings observed in brain

tissue. Notably, the skin-brain axis is increasingly recognized as

a dynamic interaction where changes in the skin not only mirror

brain conditions but can also influence brain function. This

bidirectional communication is rooted in the shared ectodermal

origin of epidermal and neural tissues, with overlapping genetic,

environmental and molecular risk factors shaping both systems

(35). In the last decade, the

skin-brain axis has been presented as a new perspective for

understanding several diseases, including neurodevelopmental

diseases such as autism spectrum disorder (35), neurodegenerative diseases such as

Alzheimer's disease (AD) (36)

and, more recently, behavioral changes such as depression and

anxiety (37).

The present study, by investigating structural and

functional alterations of MAM in dermal fibroblasts from patients

with BD compared with matched healthy controls, identified

increased ER-mitochondria juxtaposition at MAM in BD cells, which

was associated with enhanced lipid transfer and formation of LDs,

decreased ER-mitochondria Ca2+ exchange, as well as

oxidative stress, ER stress-induced UPR and basal NLRP3

inflammasome activation. The present study revealed MAM as a

potential pathophysiological mechanism driving impaired cellular

resilience in BD and the skin-brain axis as a novel framework for

studying the molecular mechanisms underlying BD

pathophysiology.

Materials and methods

Culture of primary fibroblasts and

monocytes

Dermal fibroblasts and peripheral blood (monocytes)

were obtained from five male subjects diagnosed with early BD

[stage 2 (38)] during euthymia

and five age-(average age of 26±4.6) and gender-matched healthy

controls, aged between 18-35 years old (Table SI). Participants were assessed

regarding a DSM-5 BD criteria (39) through a validated diagnostic

interview (40). This study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centro Hospitalar e

Universitário de Coimbra (now ULS de Coimbra), reference 150/CES,

July 3, 2018, and the samples were taken following written informed

consent also approved by the same ethics committee (30). Dermal fibroblasts isolated from

skin biopsies were maintained in HAM's F10 medium (cat. no.

31550-023; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10%

(v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% (v/v)

antibiotic solution (10,000 U/ml penicillin, 10,000 μ/ml

streptomycin) and 1% (v/v) L-Glutamine and AmnioMAX™-II Complete

Medium (cat. no. 11269-016; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a

proportion of 1:5. Cells were cultured in 75 cm2 flasks

and maintained in a humidified 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere

at 37°C, with the medium changed every 3 days. Cultures were

passaged by trypsinization when cells reached 80-90% confluence.

Fibroblasts with 6-16 passages were used for assays (41). Primary monocytes were isolated

and cultured as previously described (42,43). Briefly, collected peripheral

blood was carefully layered onto Ficoll-Paque Plus, followed by

centrifugation to separate mononuclear cells. Monocytes

(CD14+ fraction) were then isolated using a magnetic

separation system with the Human Monocyte Isolation kit II

(Miltenyi Biotec), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Primary monocytes were cultured in glutamine-free RPMI 1640 Medium

(cat. no. 21870084 Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

supplemented with HEPES, 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml

penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamax, 1 mM

sodium pyruvate, and 0.1 mM non-essentials amino acids. Cells were

maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Live cell imaging of ER-tracker and

Mitotracker colocalization

Fibroblasts seeded for 48 h at a density of

0.1×105 cells/cm2 on 18 mm coverslips were

loaded for 30 min at 37°C with 0.1 μM Mitotracker Green

(cat. no. m7514; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

0.5 μM ER-tracker Red (cat. no. E34250 Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in Krebs medium (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM

Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 9.6 mM

glucose, 20 mM Hepes, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). Nuclei were

stained with 15 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 5 min at room

temperature (RT). Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 710

confocal microscope with plan-Apochromat 40×/1.4 objective (Zeiss

AG). Colocalization of Mitotracker with ER-tracker was measured by

using the Mander's coefficient of colocalization with the ImageJ

v2.14 (National Institutes of Health) JACoP plugin (44). Mitochondrial area was calculated

using the same plugin in Mitotracker Green images.

Confocal microscopy analysis of IP3R-VDAC

colocalization

Fibroblasts were cultured for 48 h at a density of

0.1×105 cells/cm2, at 37°C, in 12-well plates

with 18 mm coverslips. Immunocytochemistry was performed as

previously described (41).

Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, pH 7.4,

in PBS for 15 min. After permeabilization with 0.1% (v/v) Triton

X-100 for 5 min, fibroblasts were blocked for 1 h with 3% (w/v) BSA

prepared in 0.2% (v/v) Tween 20. Afterwards, cells were incubated

overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-VDAC1 (1:250; cat. no. ab14734;

Abcam) and rabbit anti-IP3R (1:1,000; cat. no. ab5804; Abcam)

primary antibodies. Cells were then incubated with the secondary

antibodies Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit (1:200; cat. no.

A11012; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and Alexa Fluor

488 goat anti-mouse (1:200; cat. no. A11001; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h, at RT. Proximity ligation assay

(PLA), using the Duolink reagents (cat. no. DUO92002/4-100RXN;

MilliporeSigma), was used following the manufacturer's

instructions. Cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, pH

7.4, in PBS for 15 min. Permeabilization was performed using 0.1%

(v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and blocking was done with 3%

(w/v) BSA prepared in 0.2% (v/v) Tween 20, for 1 h, at RT. After

permeabilization, fibroblasts were incubated overnight at 4°C with

the mouse anti-VDAC1 (1:250; cat. no. ab14734; Abcam) and rabbit

anti-IP3R (1:1,000; cat. no. ab5804; Abcam) primary antibodies,

prepared in blocking solution. Cells were then incubated with plus

and minus PLA probes (1:5) for 1 h at RT. The coverslips were

incubated with ligase (1:40) for 30 min at RT, followed by

incubation with polymerase (1:80) for 1 h and 20 min at RT. In both

techniques, nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (15

μg/ml) for 5 min at RT, and the coverslips were mounted

using Aqua-Poly/Mount mounting medium (cat. no. 18606 Polysciences

Inc.). Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal

microscope with plan-Apochromat 40×/1.4 objective (Zeiss AG).

Colocalization of VDAC1 with the IP3R was measured with Mander's

coefficient of colocalization through ImageJ v2.14 (National

Institutes of Health) JACoP plugin (44). The particle analysis function of

ImageJ was used to quantify the number of PLA red fluorescent spots

per cell.

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

Fibroblasts cultured for 48 h in a 100 mm cell

culture dish were fixed with 2.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M

sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 2 h, at RT. Post-fixation was

performed using 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide for 90 min. After rinsing

in buffer and distilled water, 1% (w/v) aqueous uranyl acetate was

added and incubated for 1 h, at RT, in the dark for contrast

enhancement. Samples were embedded in 2% (w/v) molten agar,

dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30-100%) and then

impregnated and embedded in Epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (70 nm)

were mounted on copper grids and stained with 0.2% (w/v) lead

citrate for 7 min. Observations were carried out on a FEI-Tecnai

G2 Spirit BioTwin electron microscope (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at 100 kV. ImageJ v2.14 (National Institutes of

Health) was used to measure the ER-mitochondria distance in

fibroblasts.

Western blot analysis of MAM components,

Ca2+ channels and ER stress markers

Skin fibroblasts were lysed on ice with an ice-cold

lysis RIPA buffer [250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris base, 1% (v/v) Nonidet

P-40, 0.5% (v/v) sodium deoxycholate (DOC), 0.1% (v/v) Sodium

Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), pH 8.0] freshly supplemented with 2 mM DTT,

1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. P2714;

MilliporeSigma), and PhosSTOP™ (cat. no. 4906837001;

MilliporeSigma). After 20 min on ice, nuclei and insoluble cell

debris were removed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min at

4°C, and the supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until

further use. The total protein amount of each sample was quantified

using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (cat. no.

23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Then, thirty micrograms of

protein from total cell lysates were separated by electrophoresis

in 10-12.5% SDS polyacrylamide gels (SDS/PAGE) and transferred to

PVDF membranes (cat. no. ipvh00010; MilliporeSigma). After blocking

with 5% (w/v) BSA during 1 h, at RT, membranes were incubated

overnight, at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: mouse

anti-VDAC (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-390996; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.), rabbit anti-MCU (1:1,000; cat. no. 14997S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), rabbit anti-STIM1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 11565-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), mouse anti-GRP78 (1:1,000; cat. no.

610978 BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-ATF4 (1:1,000; cat. no. 11815S;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), rabbit anti-ATF6 (1:1,000; cat.

no. ab37149; Abcam), mouse anti-Mfn2 (1:1,000; cat. no. sc-100560;

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), goat anti-Sigma-1R (1:1,000; cat.

no. sc-22948; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-VAPB

(1:1,000; cat. no. 14477-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), and rabbit

anti-PTPIP51 (1:1,000; cat. no. 20641-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.). Then membranes were incubated for 1 h, at RT, with

HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:20,000; cat. no. 31432;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:20,000;

cat. no. 31462; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) or rabbit anti-goat

IgG (1:20,000; cat. no. 31402; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

protein immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence

with the Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (cat. no. 32106;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in a Chemidoc Imaging System

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody

(1:10,000; cat. no. A5441; MilliporeSigma) was used for protein

loading control. The optical density of the bands was quantified

with the Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) (41). Stripping followed by reprobing

with another antibody to label proteins of different molecular

weight was performed in some membranes, as indicated in the figure

legends.

Fluorescence microscopy quantification of

lipid droplets and TOM-20

Fibroblasts cultured for 48 h at a density of

0.4×104 cells/cm2 in μ-slide 8 well

plates (cat. no. 80806 Ibidi) were fixed with 4% (w/v)

paraformaldehyde, pH 7.4 for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% (v/v)

Triton X-100 for 5 min and blocked with 3% (w/v) BSA prepared in

0.05% (w/v) saponin for 1 h, at RT. Cells were then incubated

overnight at 4°C with the rabbit anti-translocase of outer

mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOM20; 1:500; cat. no. sc-11415; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) primary antibody and then with Alexa

Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no.

A11008; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h, at RT.

After loading with the fluorescent probe LipidTOX red (1:200; cat.

no. H34476; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 2 h,

nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (15 μg/ml) for 5 min

at RT and confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 710

confocal microscope (Zeiss AG) with a plan-Apochromat 40×/1.4

objective. The number of red spots (LDs)/cell was quantified using

the Imaris Microscopy Image Analysis Software Spot function v10.2

(Oxford Instruments).

Single cell calcium imaging (SCCI)

Fibroblasts seeded for 48 h on 18 mm coverslips at a

density of 0.1×105 cells/cm2 were loaded for

30 min at 37°C with 4 μM Fluo-4/AM (cat. no. F14201;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) or 10 μM

Rhod-2/AM (cat. no. R1244; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), both prepared in solution A (135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM

MgCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 20 mM HEPES, 0.4 mM

KH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose and 1 mM

CaCl2, pH 7.4). After incubation, cells were kept in

solution B (135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM

MgSO4, 20 mM HEPES, 0.4 mM KH2PO4,

5.5 mM glucose and 0.5 mM EGTA, pH 7.4), at 37°C. Basal

fluorescence was recorded every 20 sec for 2 min and upon stimuli

with 100 μM histamine (cat. no. H7125; MilliporeSigma) the

fluorescence was recorded every 1 sec for at least 4 min. In a

Ca2+-free medium, store-operated Ca2+ entry

(SOCE) was analyzed upon induction of ER Ca2+ depletion

with 1 μM thapsigargin (cat. no. T9033; MilliporeSigma)

followed by the addition of 2 mM Ca2+ to promote the

uptake of Ca2+ from the extracellular medium (45). Images were acquired using a Zeiss

Cell Observer Spinning Disk microscope with plan-Apochromat 20×/0.8

objective (Zeiss AG).

Analysis of oxidative stress

Fibroblasts seeded for 48 h at a density of

0.4×104 cells/cm2 in μ-slide 8 well

ibidi plates (cat. no. 80806 Ibidi) were loaded with 5 μM

CellROX green (cat. no. C10444; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) in Krebs medium for 30 min, at 37°C. Live cell

imaging was performed during 3 min using a Zeiss Cell Observer Z1

microscope with a plan-Apochromat 20×/0.8 objective (Zeiss AG).

Fibroblasts cultured for 48 h at a density of 0.1×105

cells/cm2 were incubated with 10 μM MitoPY (cat.

no. SML0734; MilliporeSigma) in Krebs medium for 30 min at 37°C.

Basal fluorescence values were measured for 5 min in a fluorimeter

SpectraMax Gemini EM microplate reader set to 503 nm excitation and

540 nm emission wavelengths. Values were normalized to the protein

amount. An enzymatic superoxide dismutase (SOD) assay kit (cat. no.

19160-1KT-F; MilliporeSigma) was used to determine the activity of

the mitochondrial isoform of SOD, the superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2)

in primary fibroblasts derived from patients with BD and healthy

subjects, according to the manufacturer's instructions. For this

purpose and as previously described (42), fibroblasts were lysed on RIPA

buffer [250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris base, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.5%

(v/v) sodium deoxycholate (DOC), 0.1% (v/v) Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate

(SDS), pH 8.0], without supplements. The total activity of SOD and

particular the activity of SOD2 were differentiated by the

inclusion of 2 mM potassium cyanide (KCN), which selectively

inhibits cytosolic isoform of SOD antioxidant enzyme, the

superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1). The plate was then incubated at 37°C

for 20 min, and the absorbance was read in a spectrophotometer

Spectramax plus 384 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments) set to

450 nm. Values were normalized to the protein amount determined by

the BCA method.

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)

PCR quantification of pro-inflammatory mediators

Fibroblasts were plated at a density of

0.5×105 cells/cm2 and stabilized for 24 h.

RNA was extracted with the NZYol reagent (cat. no. MB18501;

Nzytech), and its concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 2000c

Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Samples were

stored at −80°C for subsequent use. Briefly, the total RNA (2

μg per sample) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the

NZY First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (cat. no. MB12502; Nzytech).

Then, RT-qPCR were performed, in triplicate for each sample, using

the NZYSpeedy qPCR Green Master Mix Kit (cat. no. MB22403;

Nzytech), in the CFX Connect RT-PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.), as previously described (46). Briefly, samples were denatured at

95°C for 3 min. 40 cycles were run for 10 sec at 95°C for

denaturation, 30 sec at 55°C for annealing and 30 sec at 72°C for

elongation. After amplification, a threshold was set for each gene,

and Cq values were calculated for all the samples (47). Gene expression changes were

analyzed using the CFX Maestro 1.1 system software (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The primer sequences were designed using the

Beacon Designer software version 7.7 (Premier Biosoft

International), and were thoroughly tested. The forward (F) and

reverse (R) primers used were indicated in Table SII (Eurofins Scientific). Hprt-1

was used as a house-keeping gene to normalize the results of the

genes of interest.

Colorimetric determination of caspase-1

activity

After 24 h of stabilization, the culture medium of

plated fibroblasts at a density of 0.5×105

cells/cm2 was replaced by FBS-free HAM's F10 medium and

cells were exposed to 5 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for

32 h or were kept in FBS-free HAM's F10 medium. Fibroblasts were

then lysed in lyses buffer (25 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM

MgCl2, pH 7.5) through consecutive series of

freezing/thawing in liquid N2. Proteins (100

μg/ml) were incubated with 4 mM caspase-1 substrate (cat.

no. SCP0066; MilliporeSigma) in buffer [25 mM HEPES, 10% (w/v)

sucrose, pH 7.5] freshly supplemented with 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS and 10

mM DTT. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, absorbance was measured at

405 nm in a standard Synergy HT Multi Detection Microplate

Reader.

ELISA measurement of secreted IL-1β

levels

Fibroblasts and monocytes were seeded at a density

of 0.5×105 cells/cm2 and 0.12×106

cells/well, respectively. Culture medium was then replaced by

FBS-free medium and cells were exposed to LPS at a concentration of

5 μg/ml (fibroblasts) or 1 μg/ml (monocytes) for 32 h

or kept in FBS-free medium. After concentrating fibroblast

supernatants with concentration columns (cat. no. VS0192; Sartorius

AG), IL-1β secretion was quantified by ELISA kit (cat. no. 437004;

BioLegend, Inc.) following manufacturer's instructions (42,43). Absorbance values were measured in

a standard Synergy HT Multi Detection Microplate Reader (BioTek

Instruments) set to 450 nm wavelength. IL-1β levels were expressed

as pg/ml in the case of fibroblasts and as values normalized to the

baseline values in the case of monocytes. For both cells, the

results were also presented as fold increase calculated by the

difference between the LPS-treated and baseline values.

Data analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of

the mean. Normality was assessed by the D'Agostino and Pearson and

Shapiro-Wilk tests. Statistical analysis was performed by using the

parametric unpaired Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney

non-parametric test. A two-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's or

Sidak's post-hoc test was used for multiple comparisons with two

factors. Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad

Prism software 9.0 (Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

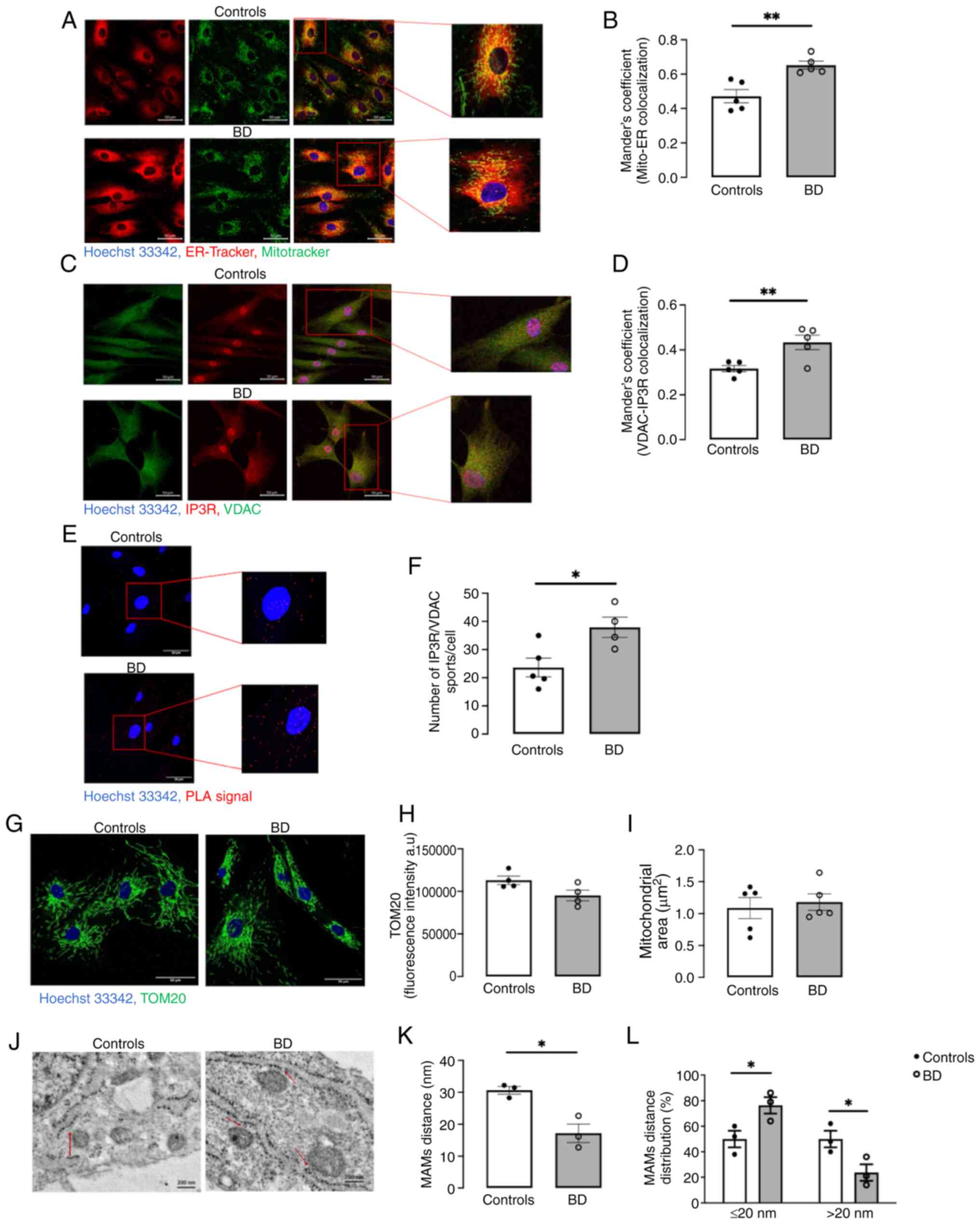

Tight ER-mitochondria juxtaposition in BD

fibroblasts

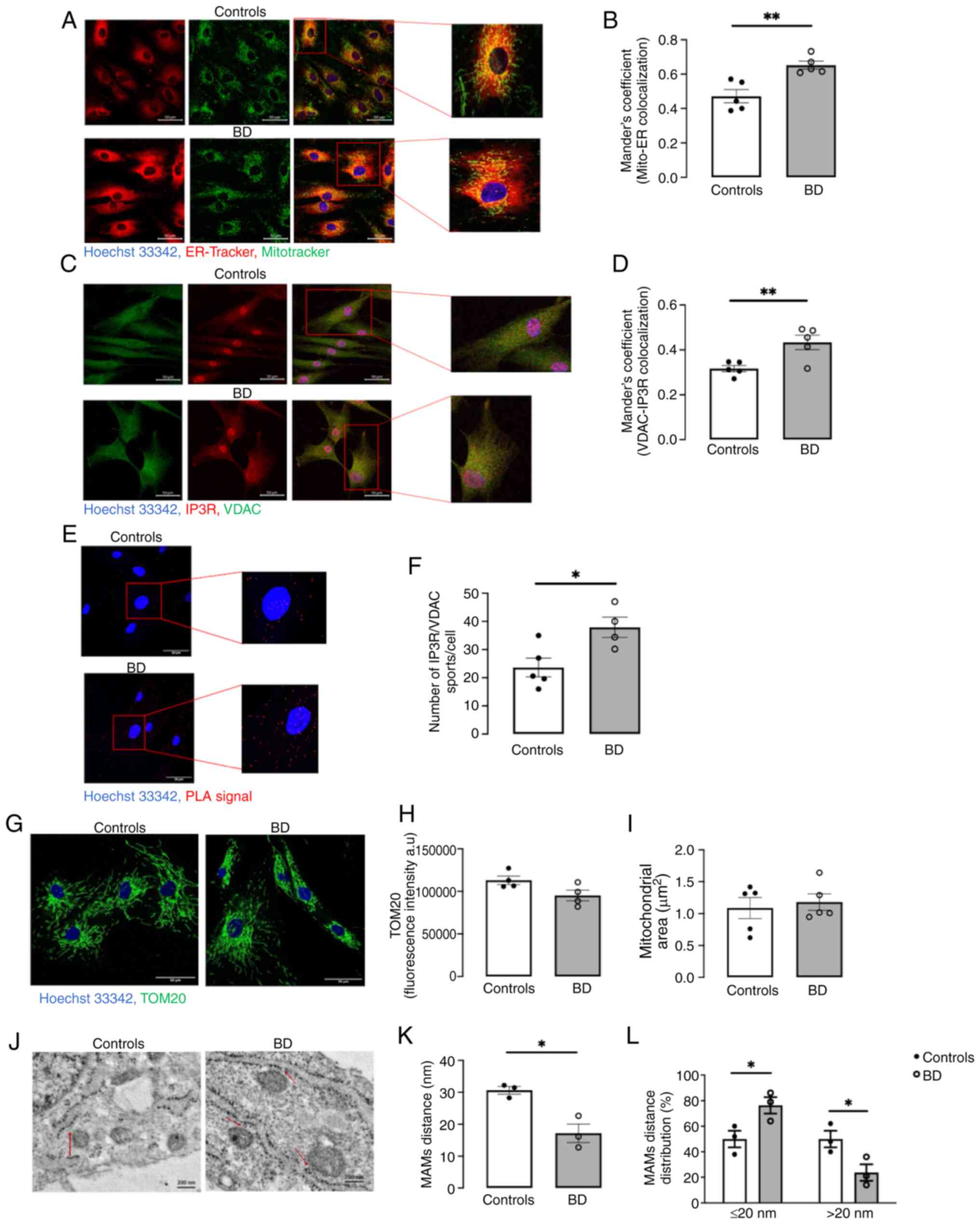

To investigate alterations in ER-mitochondria

apposition in fibroblasts derived from patients with BD and healthy

controls, the colocalization between the ER (ER-Tracker) and

mitochondria (Mitotracker) was assessed by confocal microscopy

(Fig. 1A). BD fibroblasts

exhibited increased ER-mitochondria colocalization compared with

controls (Fig. 1B). This

observation was corroborated by results demonstrating higher

proximity between IP3R (ER marker) and VDAC (mitochondria marker;

Fig. 1C and D), as well as by a

rise in the number of PLA dots, which results from enhanced

IP3R-VDAC contacts points, in BD fibroblasts compared with controls

(Fig. 1E and F), strongly

suggesting increased ER-mitochondria contacts in this BD cellular

model. Furthermore, the contact sites between the ER and

mitochondria (≤80 nm) were quantified by TEM (Fig. 1J). A significant reduction in the

physical distance between both organelles was identified in BD

fibroblasts compared with controls (Fig. 1K). The distribution of those

contacts clear demonstrate that BD fibroblasts exhibit a markedly

higher percentage of close contacts ≤20 nm (MAM) and a lower

percentage of long contacts >20 nm, in comparison with control

cells (Fig. 1L). Together, the

findings obtained using different microscopy approaches suggested

increased ER-mitochondria close contacts sites (MAM) in fibroblasts

derived from patients with BD. Notably, these alterations are

independent of changes in the number and area of mitochondria

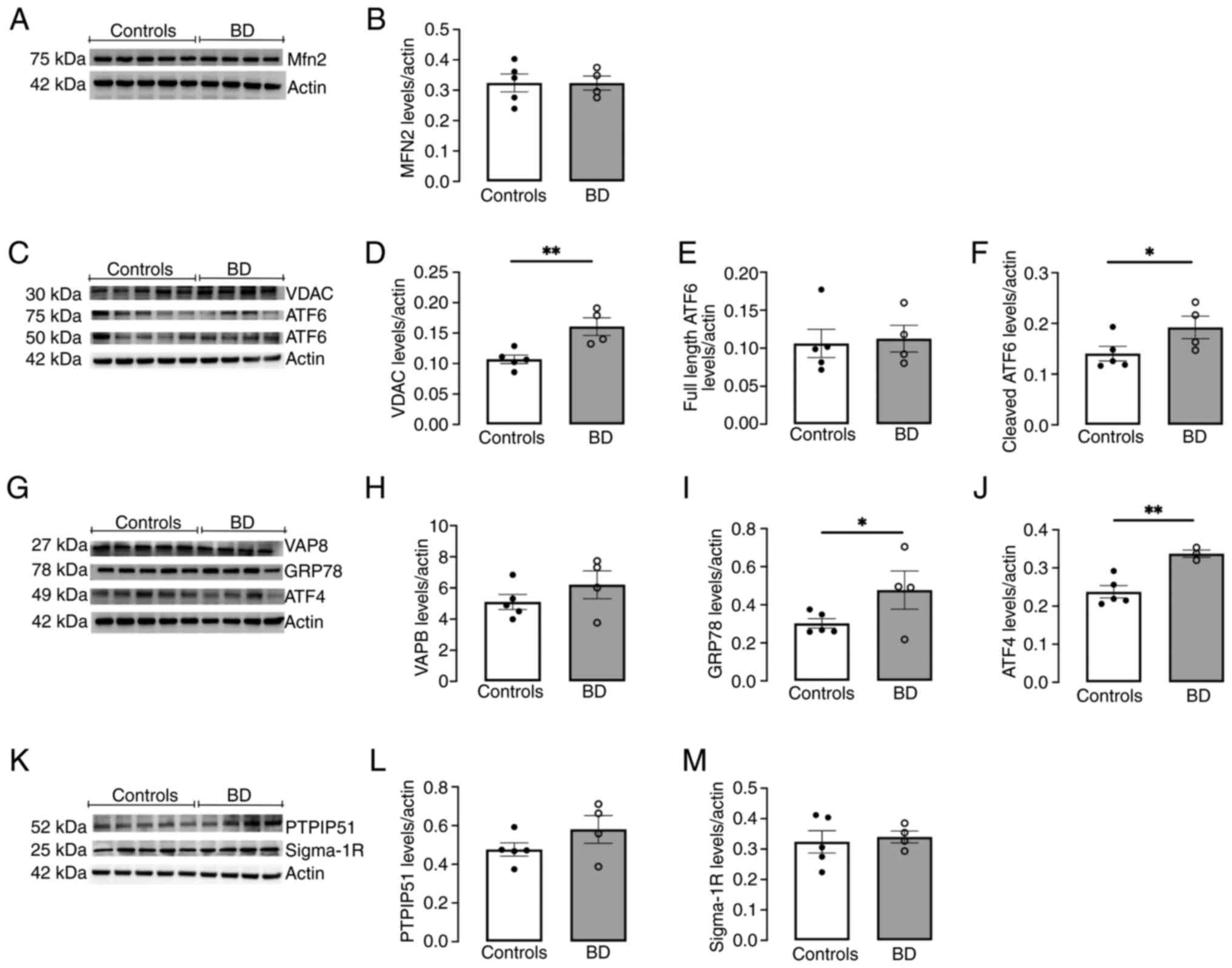

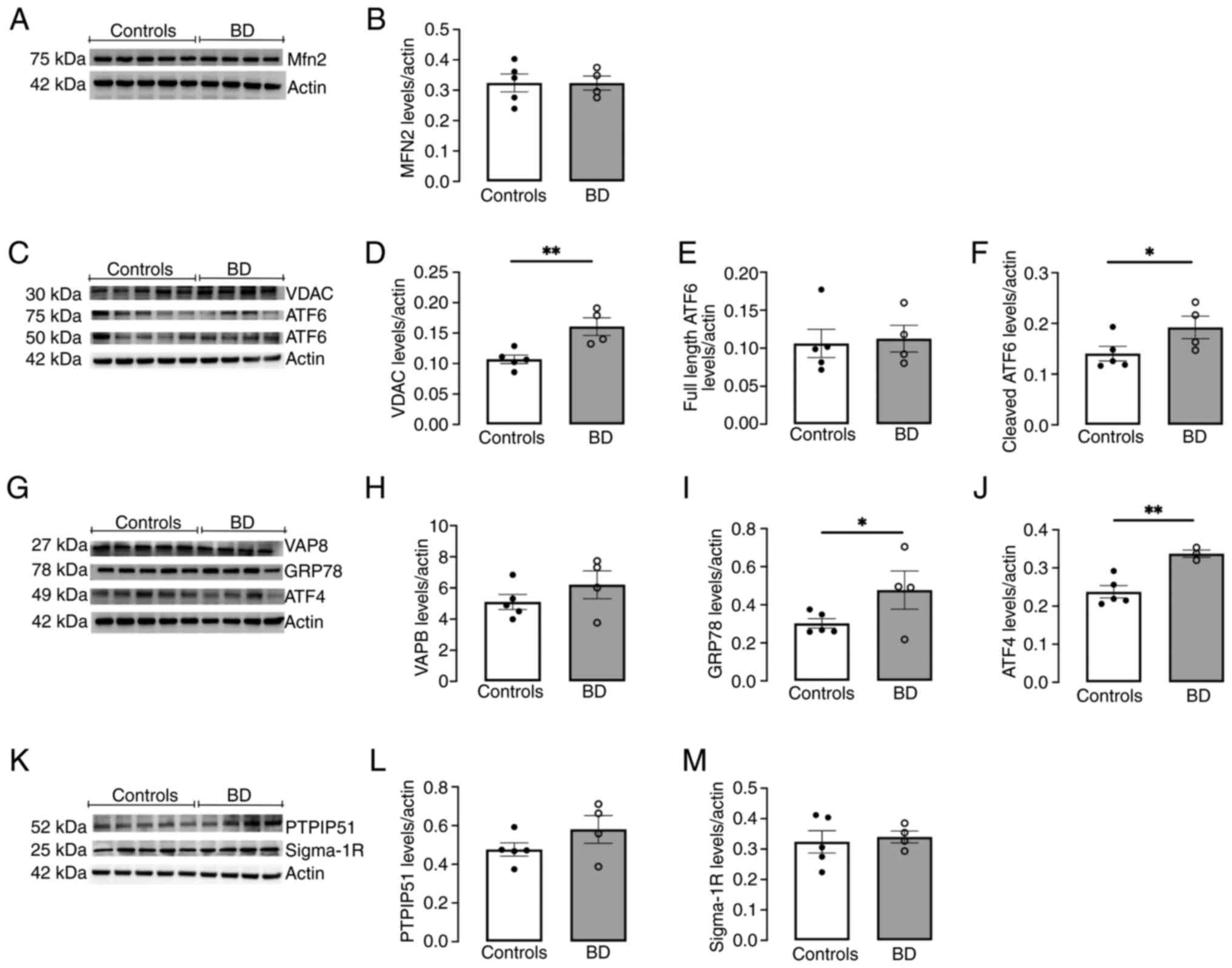

(Fig. 1G-I). To investigate

whether MAM upregulation in fibroblasts derived from patients with

BD is associated with changes in ER-mitochondria tethers, the

protein levels of key MAM tethering complexes, specifically Mfn2

(Fig. 2A and B), VDAC (Fig. 2C and D), VAPB (Fig. 2G and H) and PTPIP51 (Fig. 2K and L), were assessed by western

blotting. A significant rise in VDAC levels (Fig. 2C and D) and a qualitative, though

not statistically significant, increase in PTPIP51 content

(Fig. 2K and L) was observed in

BD fibroblasts compared with control cells.

| Figure 1ER-mitochondria contacts in primary

fibroblasts derived from patients with BD and healthy controls.

Colocalization of Mitotracker and ER-Tracker fluorescent probes was

evaluated by live cell imaging. (A) Representative confocal

microscopy images of Mitotracker (green) and ER-Tracker (red)

immunoreactivity and nuclei labelling with Hoechst 33342 (blue;

scale bar, 50 μm). (B) The mitochondrial fraction

(Mitotracker) that colocalizes with the ER (ER-Tracker) was

measured with the Mander's coefficient of colocalization using the

ImageJ software. Colocalization of the IP3R (ER marker) and the

VDAC (mitochondrial marker) was evaluated by immunocytochemistry.

(C) Representative confocal microscopy images of VDAC (green) and

IP3R (red) immunoreactivity and nuclei labelling with Hoechst 33342

(blue; scale bar, 50 μm). (D) The mitochondrial fraction

(VDAC) that colocalizes with the ER (IP3R) was measured with the

Mander's coefficient of colocalization (ImageJ software). Data

represent the means ± standard error of the mean of results

obtained by the analysis of five images from five participants per

group. The number of IP3R/VDAC dots per cell was determined by the

PLA. (E) Representative confocal microscopy images of PLA signal

IP3R/VDAC dots (red) and nuclei labelling with Hoechst 33342 (blue;

scale bar, 50 μm). (F) PLA fluorescent quantification was

performed using the Particle Analysis function of ImageJ software.

Data represent the means ± standard error of the mean of results

obtained by the analysis of five images from five controls and four

patients. The mitochondrial network was analyzed by

immunocytochemistry. (G) Representative confocal microscopy images

of TOM20 immunoreactivity (green) and Hoechst 33342-stained nuclei

(blue; scale bar, 50 μm). (H) TOM20 staining was analyzed

using the ImageJ software. Data represent the means ± standard

error of the mean of results obtained by the analysis of five

images collected from four participants per group. (I) The

mitochondrial area was quantified in the confocal images of

Mitotracker (Fig. 1A) using a

macro designed in the ImageJ software. Statistical significance of

differences between experimental groups was determined by unpaired

Student's t-test. The ER-mitochondria contacts were evaluated by

transmission electron microscopy. (J) Representative images of the

ER-mitochondria contacts (arrow; scale bar, 200 nm). (K)

ER-mitochondria distance was measured using the ImageJ software.

(L) Distribution of the ER-mitochondria contacts: close contacts

(≤20 nm; MAM) and large contacts (>20 nm). Data represent the

means ± standard error of the mean of results obtained by the

analysis of at least five images collected from three participants

per group. Statistical significance between groups was determined

using the unpaired Student's t-test *P<0.05,

**P<0.01; and the comparison of close (≤20 nm) and

large contacts (>20 nm) between the two groups was obtained

using the two-way ANOVA test, followed by the Sidak's post hoc

test: *P<0.05. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; BD, bipolar

disorder; IP3R, inositol trisphosphate receptor; VDAC,

voltage-dependent anion channel; PLA, proximity ligation assay;

TOM20, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20; MAM,

mitochondria-associated membranes. |

| Figure 2Levels of components of

ER-mitochondria contacts (Mfn2, VDAC, VAPB, PTPIP51 and Sigma-1R)

and ER stress-induced UPR markers (GRP78, ATF4 and ATF6) in primary

fibroblasts derived from patients with BD and healthy controls.

Protein levels of (A and B) Mfn2, (C and D) VDAC, (C, E and F)

ATF6, (G and H) VAPB, (G and I) GRP78, (G and J) ATF4, (K and L)

PTPIP51 and (K and M) Sigma-1R, were quantified by western blotting

in total cellular extracts obtained from primary fibroblasts

derived from patients with BD and healthy controls. β-actin was

used to control protein loading and to normalize the levels of the

proteins of interest. Data represent the means ± standard error of

the mean of results obtained in samples from five healthy controls

and four patients with BD. Statistical differences between

fibroblasts from patients with BD and healthy controls were

analyzed using the unpaired Student's t-test:

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. (A) The Mfn2

antibody was incubated in the first western blotting. VDAC and ATF6

antibodies were both incubated in the second western blotting. (C)

The ATF6 antibody, which recognizes both full-length (75 kDa) and

cleaved protein (50 kDa), was incubated on the VDAC western

blotting membrane, after a stripping procedure. (G) The VAPB, GRP78

and ATF4 antibodies were labelled on the third western blotting.

Upon incubation with the VAPB antibody, the western blotting

membrane was then incubated with ATF4 and GRP78, after a stripping.

(K) PTPIP51 and Sigma-1R antibodies were both incubated in the

fourth western blotting. The Sigma-1R antibody was incubated on the

PTPIP51 western blotting membrane, after a stripping. ER,

endoplasmic reticulum; UPR, unfolded protein response; BD, bipolar

disorder; MAM, mitochondria-associated membranes; Mfn2, Mitofusin

2; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion channel; VAPB, vesicle-associated

membrane protein associated protein B; PTPIP51, protein tyrosine

phosphatase-interacting protein-51; GRP78, glucose-regulated

protein 78; ATF4. activating transcription factor 4;

ATF6-activating transcription factor 6. |

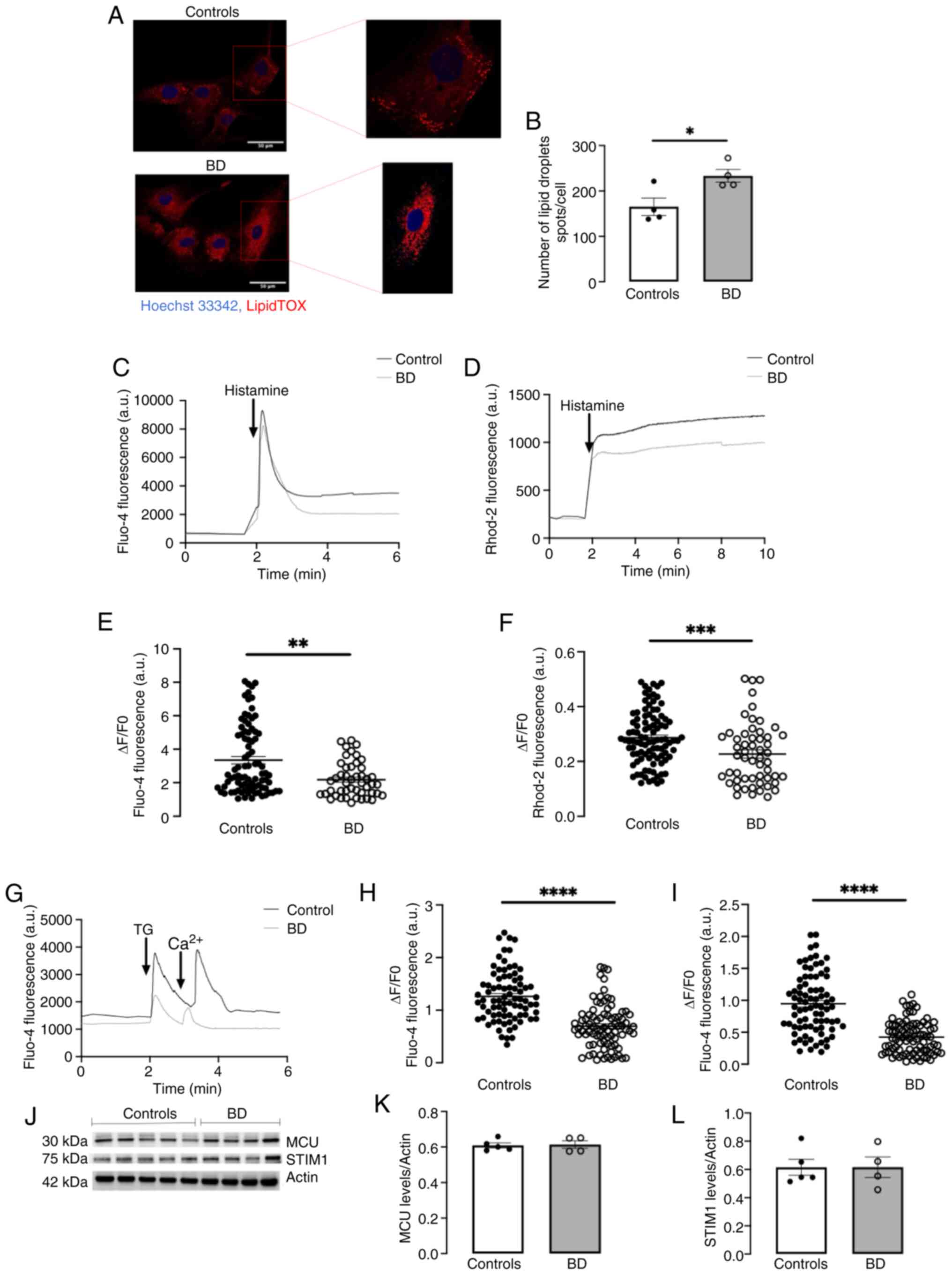

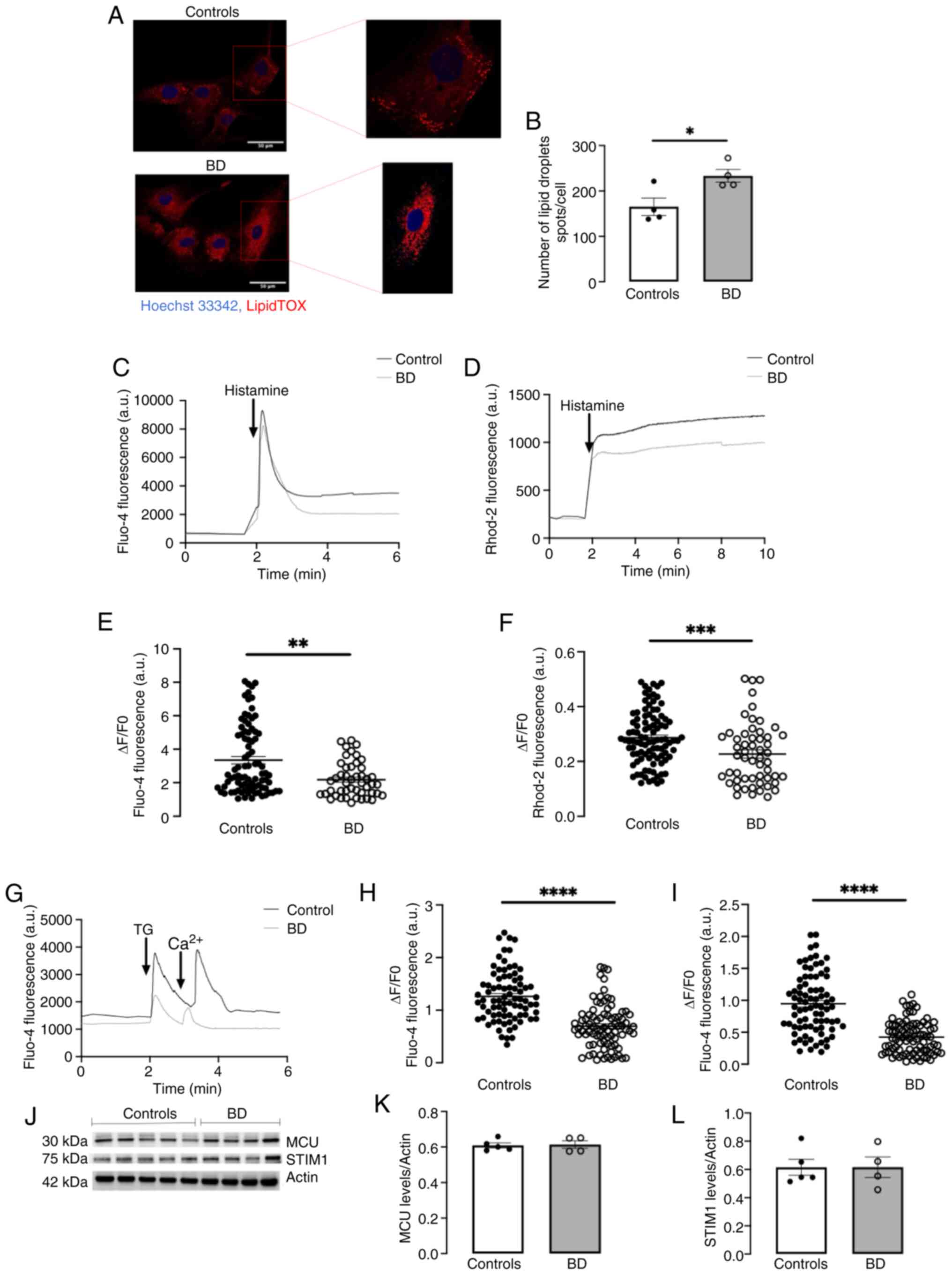

Altered lipid metabolism and calcium

homeostasis in BD fibroblasts

Given the pivotal role of MAM in the transfer of

Ca2+ and lipids between the ER and mitochondria, the

present study then evaluated MAM function in control and BD

fibroblasts, by examining lipid metabolism and Ca2+

fluxes (4,12-14).

The content of LDs was assessed as an indicator of

the efficacy of ER-mitochondria lipid transfer and, therefore, as a

measure of MAM function (10).

The quantity of LDs was evaluated by using lipidTOX, a fluorescent

probe with high affinity for LDs (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis

demonstrated a notable enhancement in the number of LDs per cell in

BD fibroblasts compared with control cells (Fig. 3B), suggesting a correlation

between upregulated MAM and enhanced lipid metabolism in BD.

| Figure 3Lipid droplets accumulation and

Ca2+ dynamics in primary fibroblasts derived from

patients with BD and healthy controls. The number of lipid droplets

per cell was determined using the LipidTOX fluorescent probe. (A)

Representative confocal microscopy images of lipid droplets spots

(red) and nuclei labelling with Hoechst 33342 (blue; scale bar, 50

μm). (B) Quantification of LipidTOX fluorescent was

performed using the Spot function of Imaris Microscopy Image

Analysis Software. Data represent the means ± standard error of the

mean of results obtained by the analysis of at least five images

collected from four participants per group. IP3R-mediated ER

Ca2+ efflux and its influx into mitochondria were

measured by SCCI with the fluorescent probes (C) Fluo-4 and (D)

Rhod-2, respectively, after treatment with histamine (100

μM). (E and F) The SCCI results were baseline-corrected and

normalized to calculate the normalized fluorescent calcium signals.

Data were expressed as ΔF/F0, where ΔF=F-F0. F represents the

highest post-stimulus value and F0 the mean baseline level. Data

represent the means ± standard error of the mean of results

obtained from 15-30 cells from each of the four participants per

group. (G) SOCE was evaluated by measuring Ca2+

oscillations with Fluo-4 after thapsigargin (1 μM,

TG)-induced ER Ca2+ depletion in Ca2+-free

medium and after addition of 2 mM CaCl2 to the

extracellular medium. (H and I) The SCCI results were

baseline-corrected and normalized to calculate the normalized

fluorescent calcium signals. Data were expressed as ΔF/F0, where

ΔF=F-F0. F represents the highest post-stimulus value and F0 the

mean baseline level. Data represent the means ± standard error of

the mean of results obtained from 15-30 cells from each of the four

participants per group. (J and K) MCU and (J and L) STIM1 protein

levels were evaluated in total cellular extracts obtained from

control and BD fibroblasts through western blotting. β-actin was

used to control protein loading and to normalize the levels of the

proteins of interest. Data represent the means ± standard error of

the mean of results obtained in samples from five healthy controls

and four patients with BD. The STIM1 antibody was incubated on the

Sigma-1R western blotting membrane, after a stripping. Statistical

difference between groups was evaluated with unpaired Student's

t-test (B, D, H, I and L) or with Mann-Whitney non-parametric test

(F and K): *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. BD, bipolar

disorder; IP3R, inositol trisphosphate receptor; ER, endoplasmic

reticulum; SCCI, single cell calcium imaging; STIM1, stromal

interaction molecule 1; MCU, mitochondrial Ca2+

uniporter protein. |

The IP3R-mediated ER-mitochondria Ca2+

transfer was determined by using Rhod-2AM, a mitochondrial

Ca2+ indicator. Notably, BD fibroblasts stimulated with

the IP3R agonist histamine exhibited a significant reduction in

mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake compared with controls

(Fig. 3D and F), despite the

decreased ER-mitochondria distance in BD cells. The data showed

that these differences were not due to downregulation of the

mitochondrial calcium uniport (MCU) at IMM, which aligns with the

ER IP3R and VDAC at outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) to

facilitate the transfer of Ca2+ into mitochondria

(48), since similar protein

levels were detected in both control and BD cells (Fig. 3J and K). Furthermore, they were

not associated with alterations in Sigma-1R, a modulator of

IP3R-mediated ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer, since its

protein levels were not affected in BD (Fig. 2K and M). The alterations in the

ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer observed between control

and BD cells might instead arise from compromised IP3R-mediated ER

Ca2+ release, since the cytosolic Ca2+ levels

measured with Fluo-4/AM in histamine-stimulated BD fibroblasts were

lower compared with those of control cells (Fig. 3C and E). This diminished release

observed in BD cells can result from a deficient replenishment of

Ca2+ in the ER lumen by SOCE-mediated extracellular

Ca2+ influx, which in turn can modulate mitochondrial

Ca2+ uptake (49,50). To evaluate SOCE, fibroblasts were

loaded with Fluo-4/AM in Ca2+-free medium and stimulated

with thapsigargin, an inhibitor of the Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum

Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pump, to assess ER Ca2+

release, followed by the addition of extracellular Ca2+

to investigate SOCE-mediated Ca2+ entry. The analysis of

ER Ca2+ content in thapsigargin-stimulated cells

revealed the depletion of ER Ca2+ and impaired

SOCE-dependent Ca2+ influx in BD fibroblasts compared

with controls (Fig. 3G-I). These

observations suggested that the reduced ER-mitochondria

Ca2+ transfer in BD cells resulted from the depletion of

ER Ca2+ stores caused by impaired Ca2+ influx

from the extracellular space through the SOCE pathway, which fails

to replenish the ER. Notably, the BD-associated SOCE impairment is

not due to alterations in the protein levels of stromal interaction

molecule 1 (STIM1), a key component of the SOCE machinery (Fig. 3J and L).

Overall, the results showed that the proximity

between the ER and mitochondria at MAM in BD cells was intimately

linked to increased lipid exchange and biogenesis of LDs, but not

with stimulation of the ER-mitochondria Ca2+

transfer.

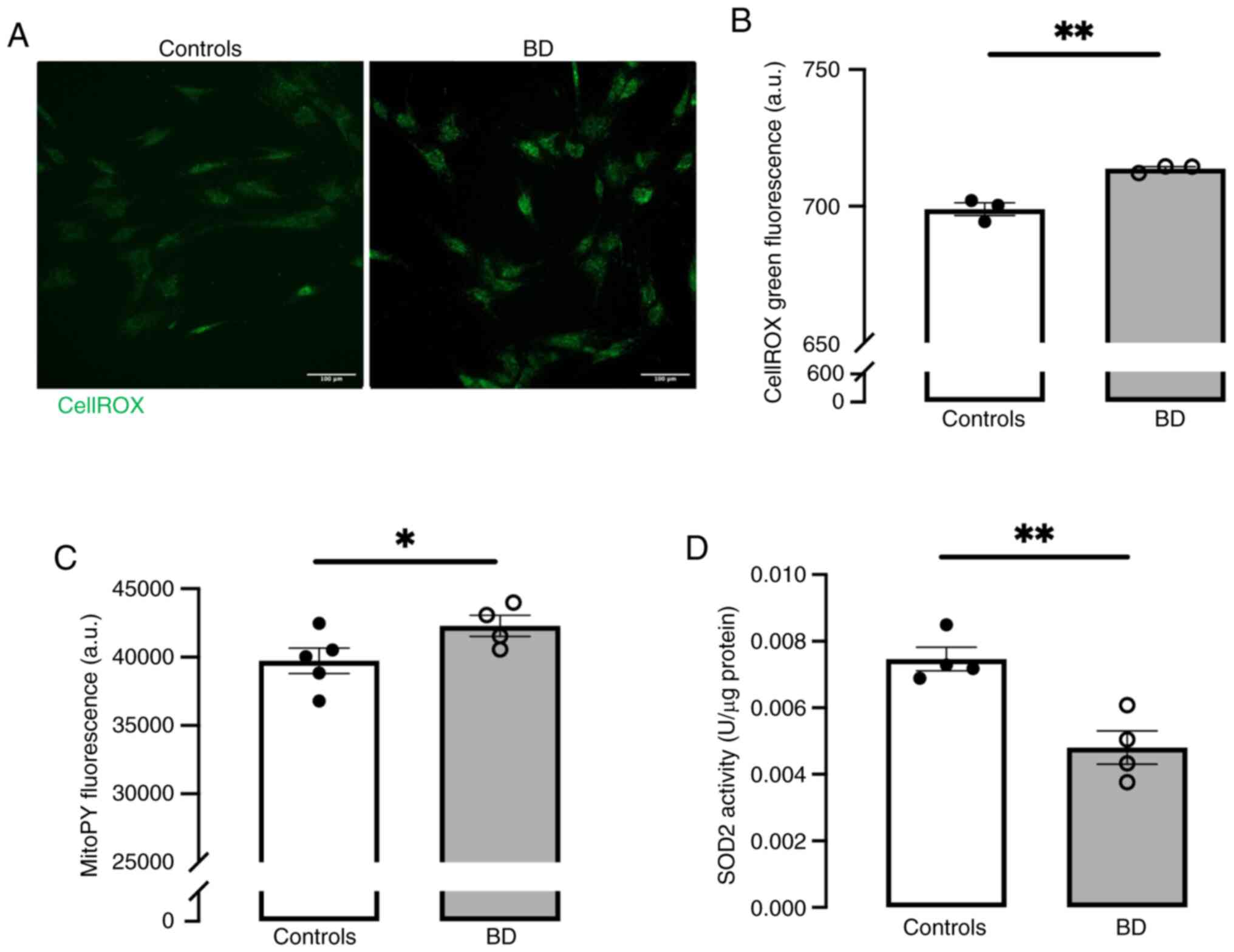

Impaired redox status in BD

fibroblasts

MAM play a crucial role in cellular redox status,

maintaining a dynamic equilibrium between reactive oxygen species

(ROS) production and antioxidant defenses (51). To assess oxidative stress in

fibroblasts derived from controls and patients with BD, ROS levels

were measured using CellROX and the mitochondrial-specific MitoPY

probes. A significant increase in ROS levels was observed (Fig. 4A and B) that are, at least in

part, generated in mitochondria (Fig. 4C), probably due to the inhibition

of SOD2 mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme (Fig. 4D).

ER stress-induced unfolded protein

response (UPR) markers in BD fibroblasts

The ER-mitochondria communication at MAM

coordinates cellular stress responses, particularly the UPR

(52). A notable upregulation in

the protein levels of several UPR markers, namely GPR78 (Fig. 2G and I), activating transcription

factor 4 (ATF4) (Fig. 2G and J)

and fragmented activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (Fig. 2C and F), was found in BD cells

compared with controls, indicating ER stress induction in these

patients.

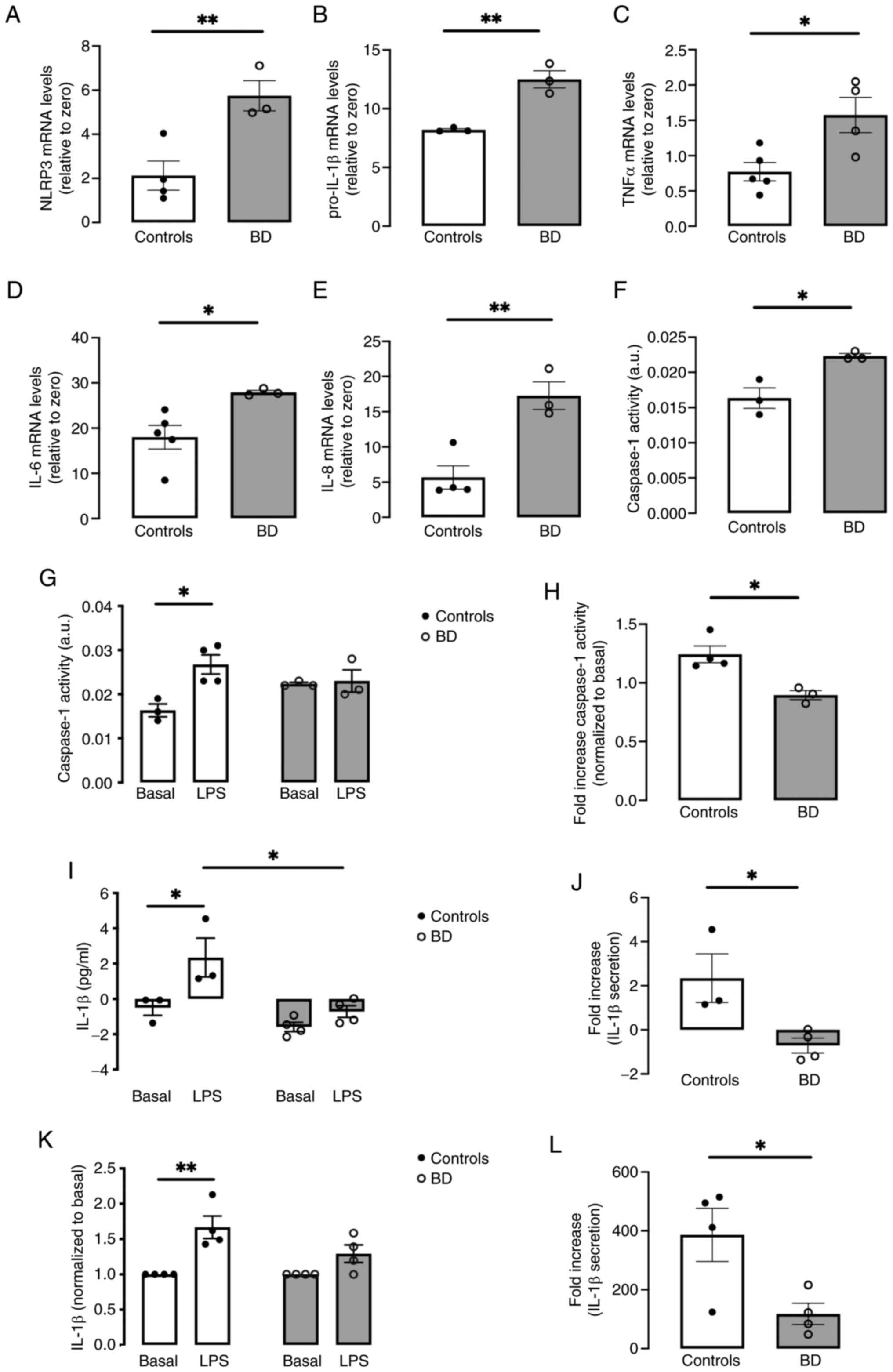

Sterile inflammation in fibroblasts and

monocytes derived from patients with BD

MAM provide a physical platform for NLRP3

inflammasome assembly by facilitating the communication among its

components: NLRP3, caspase-1 and ASC (53,54). Activation of the NLRP3

inflammasome induces a signaling cascade culminating in the release

of pro-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β)

(14,55). This cytosolic complex is

activated by MAM-derived signals, namely danger signals released by

dysfunctional mitochondria including ROS (13,14). Given the upregulation of MAM and

significant ROS accumulation in BD fibroblasts, it is hypothesized

that NLRP3 is activated in these cells playing a role in

maintaining a potent chronic inflammatory environment (56).

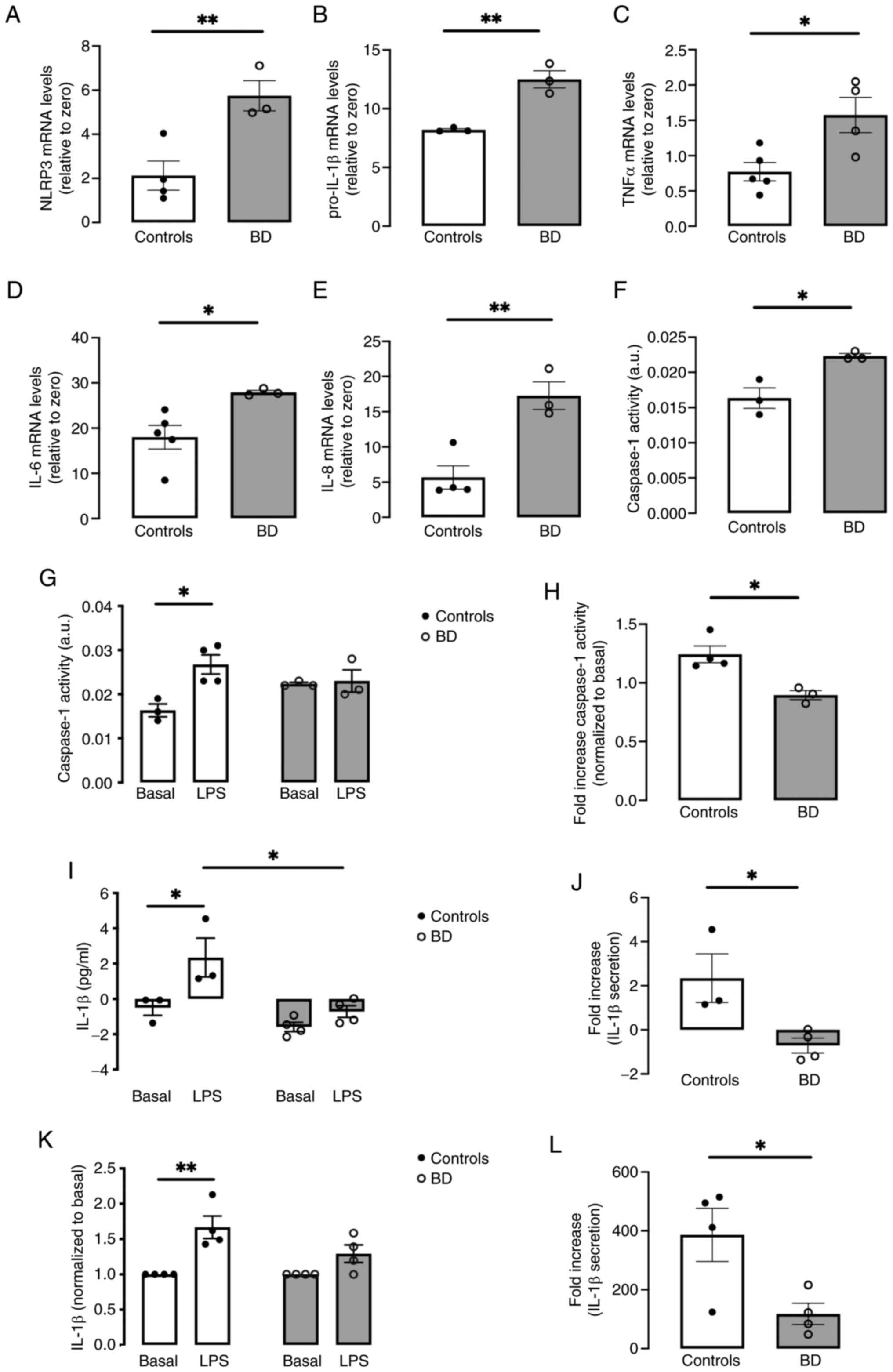

Increased mRNA levels of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β

assessed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 5A and

B), coupled with enhanced caspase-1 activity (Fig. 5F), in fibroblasts from patients

with BD compared with controls, suggested NLRP3 inflammasome

activation and sterile inflammation in BD. The upregulation of

other pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-6 and IL-8

detected in BD fibroblasts (Fig.

5C-E), provided strong evidence for a BD-associated

inflammatory state. Then, NLRP3 inflammasome activation was

evaluated under LPS-induced inflammation-prone conditions, by

quantifying secreted IL-1β levels, the classical readout of NLRP3

activation. A notable rise in IL-1β secretion was observed in

control fibroblasts treated with LPS for 32 h compared with

untreated control cells, which was not observed in BD cells

(Fig. 5I). This distinct pattern

of response to LPS was reinforced upon examining the stimulated

release of IL-1β, with a statistically significant decrease

observed in BD fibroblasts (Fig.

5J). Comparable outcomes were found in fibroblasts from

patients with BD and healthy subjects exposed to LPS for 12 h (data

not shown). Moreover, a marked increase in caspase-1 activity was

identified in LPS-exposed control fibroblasts, a response not

observed in treated BD fibroblasts (Fig. 5G). Comparing the fold increase of

caspase-1 in LPS-treated controls and BD fibroblasts reveals a

substantial reduction in the later (Fig. 5H). Lastly, IL-1β secretion was

quantified in primary monocytes isolated from the peripheral blood

of both patients with BD and healthy controls, exposed to LPS for

32 h. Similarly, these innate immune cells also exhibited a

deficient NLRP3 inflammasome activation when exposed to LPS

(Fig. 5K and L).

| Figure 5NLRP3 inflammasome activity and

inflammatory status in primary fibroblasts and monocytes derived

from patients with BD and healthy controls. Basal mRNA levels of

(A) NLRP3 and pro-inflammatory cytokines (B) pro-IL-1β, (C) TNFα,

(D) IL-6 and (E) IL-8 were evaluated by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR in fibroblasts from patients with BD

and healthy controls. (F) Baseline levels of caspase-1 activity in

control and BD fibroblasts. (G) Caspase-1 activity was analyzed in

total extracts from control and BD fibroblasts treated in the

absence or presence of 5 μg/ml LPS for 32 h. (H) Fold

increase of caspase-1 activity was calculated by normalizing the

levels of caspase-1 activity in control and BD fibroblasts treated

with LPS to the baseline values. Data represent the means ±

standard error of the mean of results obtained in cells from 3-5

participants per group. (I) IL-1β levels in supernatants from

control and BD fibroblasts incubated in the presence or absence of

5 μg/ml LPS for 32 h, were quantified using an ELISA kit an

expressed as pg/ml. (J) Fold increase of IL-1β secretion was

calculated by the difference between LPS-treated and basal values.

Data represent the means ± standard error of the mean of results

obtained in cells from three controls and four patients with BD.

(K) IL-1β levels in supernatants from primary monocytes derived

from healthy controls and patients with BD incubated in the

presence or absence of 1 μg/ml LPS for 32 h, were quantified

by ELISA. Results were normalized to the basal levels and represent

the means ± standard error of the mean of results obtained in cells

from four participants per group. (L) IL-1β secretion in monocytes

was also calculated as the fold increase observed upon LPS

treatment. Data represent means ± standard error of the mean of

results obtained in cells from four participants per group.

Statistical significance of differences between groups was

determined by the unpaired Student's t-test (A-F, H, J and L):

*P>0.05; **P>0.01; significance between

both basal and LPS-treated cells within each experimental group and

between the two groups were obtained using the two-way ANOVA test,

followed by the Tukey's post hoc test (G, I and K):

*P>0.05; **P>0.01. NLRP3, NOD-like

receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; BD, bipolar disorder;

LPS, lipopolysaccharide. |

Together, these findings illustrated that, under

basal conditions, patients with BD manifest a pro-inflammatory

state characterized by the upregulation of pro-inflammatory

cytokines. However, the response of the NLRP3 inflammasome to an

inflammatory stimulus is compromised in BD-derived cells,

indicating that these individuals are less responsive to

inflammation-prone conditions.

Discussion

The disruption of ER-mitochondria crosstalk at MAM

has been linked to the onset and progression of various human

pathologies, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and

metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (2,16-18), some of which are comorbidities of

BD. MAM play a crucial role in essential biological functions,

namely lipid metabolism, calcium homeostasis, mitochondrial

bioenergetics and dynamics, redox balance and control over ER

stress and inflammatory responses (15,52). These MAM-related cellular events

are disrupted in BD (25),

suggesting a link between MAM alterations and BD pathophysiology.

Hence, the present study addressed the role of MAM in BD by using

cell-based models derived from early-stage patients with BD and

matched healthy controls.

Results from several microscopy techniques

demonstrated increased ER-mitochondria colocalization and higher

percentage of close ER-mitochondria contacts (MAM) in BD

fibroblasts compared with controls, together with increased levels

of the OMM protein VDAC and a qualitative trend towards increased

PTPIP51 levels, suggesting alterations in ER-mitochondria tethering

in BD. These alterations could be further clarified if the

isolation of MAM was feasible in primary fibroblasts since

variations in MAM components are more accurately discerned in

isolated MAM fractions than total cell extracts (57). To the best of the authors'

knowledge, only one previous study has investigated MAM in BD.

Based on PLA findings, this study reported a reduction in these

contacts in iPSCs-derived neurons from patients with BD compared

with controls (58). In the

present study, data from PLA analysis were corroborated by other

fluorescence microscopy approaches and by TEM analysis, the gold

standard technique to measure the distance between these organelles

and, thus, to properly evaluate MAM. The discrepancies between the

present study and that of Kathuria et al (58) might arise from variability in

cohorts in terms of age, gender and disease stage, which are

determinant factors that can influence outcomes (59). Indeed, this study included only

early-stage male patients with BD (BD stage 2) aged between 18-35

years, whereas the previous study included both male and female

patients with BD aged between 18-65 years-old, meaning that

patients at different disease stages were probably enrolled in the

study.

The close ER-mitochondria juxtaposition at MAM

facilitates the efficient transfer of both Ca2+ and

lipids between these organelles. Notably, a decrease of

ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer was observed in BD cells

in conditions of MAM upregulation, which might arise from

compromised IP3R-mediated ER Ca2+ release. The present

study data strongly suggested that compromised ER-mitochondria

Ca2+ transfer in BD fibroblasts was likely to result

from the inability of SOCE-mediated extracellular Ca2+

influx to replenish ER Ca2+ stores, leading to

Ca2+ depletion that will affect the uptake of

Ca2+ by mitochondria (49,60). ROS generation in BD cells might

be the cause of SOCE impairment, as SOCE is modulated in a

redox-dependent manner (61). In

agreement, the downregulation of SOCE was recently reported in

iPSCs-derived neurons obtained from patients with BD (62). The hypothesis that BD

pathophysiology is at least partly caused by aberrant

Ca2+ homeostasis is supported by alterations in genes

encoding to Ca2+ channels such as calcium voltage-gated

channel subunit α1 C (CACNA1C), identified as greater risk for BD

(63).

The similar protein levels of the ER-resident

Sigma-1R suggested that the differences between BD and control

cells do not arise from alterations in this well-known modulator of

the IP3R-mediated ER Ca2+ release. However, Sigma-1R

activation leading to an antagonistic effect of IP3R in BD

fibroblasts cannot be ruled out. Previous reports indicate that

Sigma-1R can function in an agonist- or antagonist-sensitive

manner, by modulating the interaction between ankyrin B and IP3R3,

which in turn affects IP3R-VDAC coupling, thus directly interfering

with Ca2+ handling (64). Indeed, genetic variations in

SIGMAR1 have been identified in patients with BD (65). Another viable hypothesis is that

the deficient transfer of Ca2+ between the ER and

mitochondria reported in this study may be associated with the

mitochondrial dysfunction previously described by our research team

in BD fibroblasts (41).

Unchanged MCU protein levels ruled out that inhibition of

mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake at IMM contributes to

attenuate the ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in BD cells.

However, the hypothesis that MCU activity is inhibited in these

cells in the absence of changes in protein content cannot be

discarded.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, the present

study was pioneering in investigating LDs in BD. Its data showing

higher number of LDs in BD fibroblasts indicated disrupted lipid

metabolism in this pathology, which agrees with previous studies

highlighting significant changes in the lipidome of patients with

BD (66-69). The increase of LDs in BD cells is

expected to arise from heightened lipid transfer at MAM, a crucial

place for LDs biogenesis (70).

This positive correlation between upregulated MAM and increased LDs

content was previously documented in AD (10).

LDs have recently emerged as critical players in

cellular stress responses (71,72). Disruptions in LDs turnover can

instigate ER stress, which in turn can contribute to the

accumulation of LDs in several types of cells (73). Accordingly, LDs accumulation in

BD fibroblasts coincides with ER stress induction, as demonstrated

by increased protein levels of ER stress-induced UPR markers such

as ATF4 and ATF6, mediators of PERK and ATF6 UPR branches,

respectively, as well as glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), the

major ER-resident chaperone. The involvement of ER stress in BD

pathophysiology is supported by studies reporting higher GRP78

levels in peripheral blood cells from these patients, as well as by

the modulation of this ER stress marker by several mood stabilizers

(74,75).

The UPR activation under chronic ER stress

conditions markedly enhances the expression of pro-inflammatory

cytokines. Specifically, the PERK arm of UPR stimulates IL-6

production, while the ATF-6 branch upregulates IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα

cytokines (76). Notably, the

activation of both PERK and ATF6 UPR arms in the fibroblasts of

patients with BD occurs concomitantly with increased mRNA levels of

pro-IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6 and IL-8. The present study underscored that

BD fibroblasts display a baseline pro-inflammatory profile,

probably resulting from chronic ER stress. This observation agreed

with previous studies consistently reporting a rise of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in BD such as TNFα, IL-6 and IL-8 and

lower concentrations of anti-inflammatory cytokines, in both manic

and depressive BD states (77).

Moreover, higher IL-1β levels have been detected in the

cerebrospinal fluid of patients with BD, not only during periods of

remission following mania but also during euthymic states (78). BD-associated pro-inflammatory

status is also further supported by previous findings showing

altered numbers of circulating immune cells in peripheral blood

collected from those patients, including monocytes, leukocytes,

neutrophils and lymphocytes (42,79,80). Of note, the neuroanatomical white

matter brain changes described in patients with BD have been

closely linked to immune alterations (81). Additionally, the clinical

evidence that these patients exhibit a high prevalence of chronic

comorbidities, such as metabolic and autoimmune diseases further

strengthens the role of inflammation in BD pathophysiology

(82). Evidence from

meta-analysis reveals that the incidence of BD is markedly

increased in patients with autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis

(83). Similarly, psoriasis is

often accompanied by psychiatric comorbidities including anxiety

and depression, sleep disorders and suicidal behavior (37). This bidirectional interaction

highlights the intricate connection between skin diseases and

psychiatric conditions, reinforcing the hypothesis of the

skin-brain axis in BD. Recently, inflammation has been identified

as a key mediator underlying the interaction between psoriasis and

mental health commodities. T cells and their secreted inflammatory

cytokines play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of both psoriasis

and psychiatric disorders by interacting with the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, exacerbating immune

dysregulation and disease progression (37). Notably, a basal pro-inflammatory

status is evident in patients with BD, as shown by elevated levels

of pro-inflammatory cytokines in fibroblasts derived from them.

This inflammatory profile observed in fibroblasts from patients

with BD might suggest that dysregulated immune responses and

chronic inflammation are key players in disease development.

Moreover, these findings may reflect the neuroinflammatory

environment described in the brains of patients with BD (84), further supporting the skin-brain

axis as a critical route for understanding this complex

neuropsychiatric condition.

The activation of both IRE1a and PERK UPR pathways

induces the expression of pro-IL-1β and NLRP3 via NF-kB, promoting

the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and subsequent IL-1β release

(85). Notably, mitochondrial

ROS, which were found increased in BD fibroblasts, primarily due to

the inhibition of SOD2 mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme, have been

recognized as classical triggers for NLRP3 inflammasome activation

(14). In agreement, oxidative

stress has been implicated in BD pathophysiology (86). Furthermore, variations in genes

encoding antioxidant enzymes such as SOD2 and glutathione

peroxidase 3 have been reported in patients with BD (87). For instance, the polymorphism

rs4880 in SOD2, identified as a BD risk factor, results in reduced

activity of this enzyme (88).

Notably, NLRP3 inflammasome assembly takes place at

MAM platforms (13). Therefore,

the upregulation of MAM in fibroblasts from patients with BD can be

responsible for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, as evidenced by

increased mRNA levels of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, along with enhanced

caspase-1 activity, compared with controls. The pivotal role of

NLRP3 inflammasome in fostering the BD-associated pro-inflammatory

state has already been suggested by the upregulation of IL-1β,

NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1 in post-mortem frontal cortex of patients

with BD (26). The present study

disclosed that NLRP3 inflammasome activation under LPS-induced

inflammation-prone conditions was markedly lower in BD cells

compared with controls. Although fibroblasts possess the capability

to modulate inflammatory responses, their cytokines secretion is

relatively modest compared with immune cells (89,90), therefore, this study also

explored NLRP3 inflammasome activation in LPS-treated primary

monocytes isolated from both patients with BD and controls, and

similar results were obtained. Together, the present study

suggested a diminished responsiveness of cells from patients with

BD to inflammation-prone stressful conditions. The lower resilience

exhibited by BD cells can be attributed to the pre-activated state

of NLRP3 inflammasome under non-stimulated conditions. This

hypothesis is strengthened by our previous findings, showing that

NLRP3 inflammasome activation occurs in BD monocytes upon ER stress

induction, even in the absence of LPS priming (42). Accordingly, ATP treatment in

fibroblasts from patients with systemic sclerosis, which are in

pre-activated state, also induces IL-6 release in the absence of

LPS priming (91). Lastly, the

reduced cellular resilience due to compromised NLRP3 inflammasome

activity in BD may contribute to explain the high prevalence of

infectious diseases in these patients (92).

Fibroblasts and blood cells from individuals with

diagnosis of multiple brain diseases, including neuropsychiatric

conditions such as BD, have long been considered as valuable

patient-derived cell models, markedly contributing to increasing

our knowledge about the pathophysiology of brain disorders.

Although the findings of this study obtained in fibroblasts and

monocytes derived from patients with BD and control individuals

corroborate its conclusions, some limitations have been identified:

i) the sample size was relatively small; however, the statistically

significant differences observed between control and BD cells

support the present study as a pioneering proof-of-concept

demonstration of the role of MAM in BD; ii) the present study

focused exclusively on early-stage patients with BD and did not

include an assessment of later-stage cases, which should be

addressed in future studies; and iii) validation using neurons

differentiated from iPSCs could further strengthen the evidence of

MAM impairment in BD.

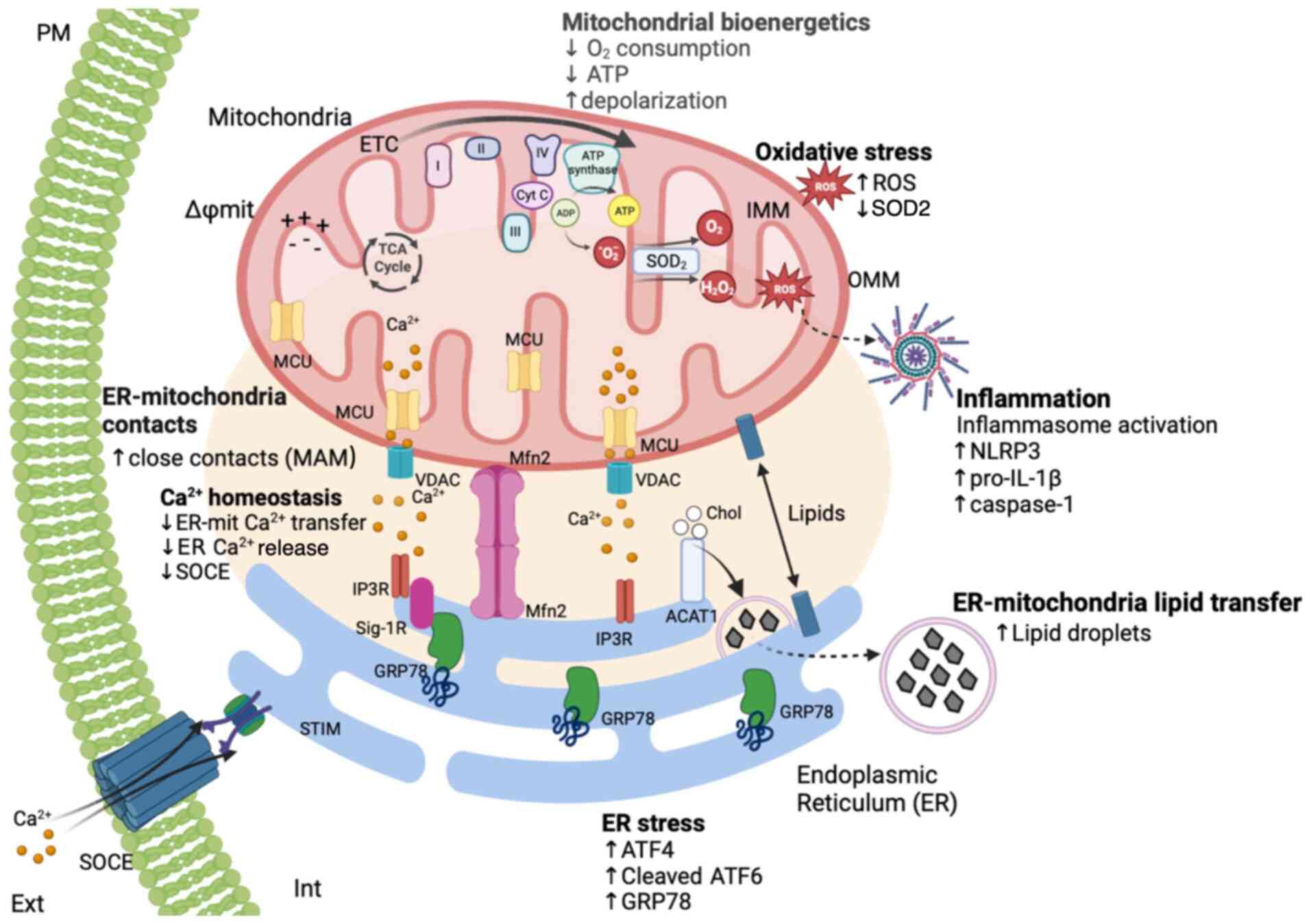

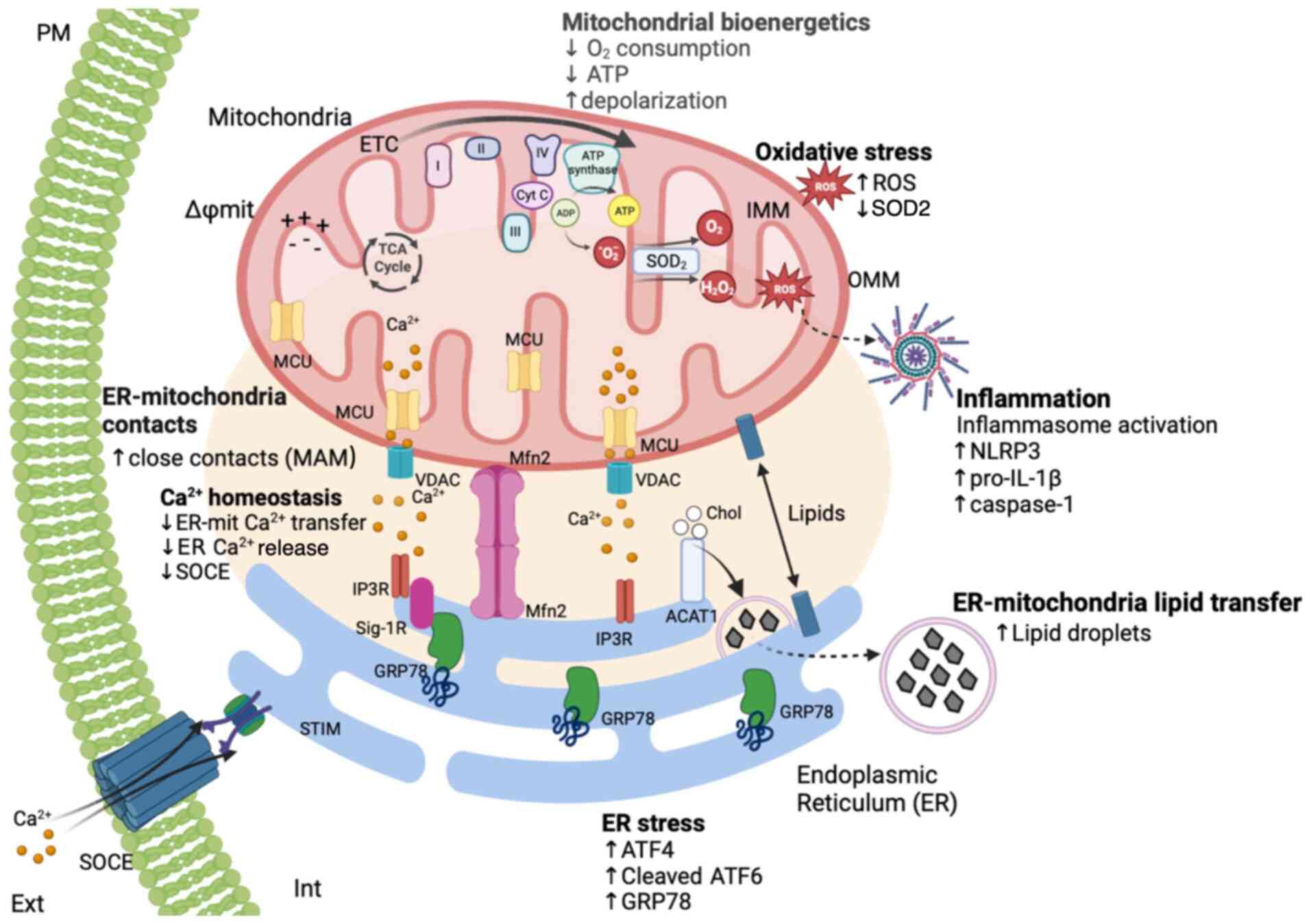

The comprehensive structural and functional

analysis conducted on cells obtained from early-stage patients with

BD and healthy controls markedly contributes to unravelling the

pivotal role of MAM in BD pathophysiology (Fig. 6). The increased ER-mitochondria

juxtaposition at MAM observed in BD cells correlated with enhanced

lipid transfer and formation of LDs, which occurs concomitantly

with decreased ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer that is

associated with impaired SOCE activity and a subsequent inability

to refill ER Ca2+ stores. The dysfunction of MAM may

underlie the previously reported mitochondrial respiratory

impairment and ATP depletion in BD cells (41), as well as the induction of

MAM-associated events identified in the present study, including

oxidative stress, ER stress-induced UPR and basal NLRP3

inflammasome activation.

| Figure 6The MAM hypothesis for BD.

Fibroblasts derived from patients diagnosed with BD exhibit

increased ER-mitochondria apposition and markedly higher percentage

of close ER-mitochondria contacts sites (MAM) in comparison with

healthy controls, in particular those <20 nm. This structural

alteration in the ER-mitochondria juxtaposition directly affects

the main functions of MAM, which are the inter-organelle transfer

of Ca2+ and lipids. As a consequence, ER-mitochondria

lipids transfer is enhanced increasing the formation of lipid

droplets while Ca2+ transfer is inhibited.

Concomitantly, BD fibroblasts exhibit lower SOCE and higher

oxidative stress levels due to the inhibition of SOD2 mitochondrial

antioxidant enzyme and accumulation of ROS in the cytosol and in

the mitochondria. In addition to these alterations in

Ca2+ and redox homeostasis as well as in lipid

metabolism, BD-specific changes in MAM are also associated with

induction of ER stress and sterile inflammation. A basal

pro-inflammatory status in BD is supported by the upregulation of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, which seems to be implicated in the

diminished susceptibility of both fibroblasts and monocytes derived

from patients with BD to inflammatory stimuli, as shown by the

lower activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in response to LPS. PM,

plasma membrane; MAM, mitochondria-associated membranes; BD,

bipolar disorder; MCU, mitochondrial calcium uniport; Cyt C,

cytochrome c; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle; ADP,

adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; O2,

superoxide anion; O2, oxygen;

H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; SOD2, superoxide

dismutase 2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; VDAC, voltage-dependent

anion channels; Mfn2, mitofusin 2; IP3R, inositol trisphosphate

receptor; Sig-1R, sigma-1 receptor; ACAT1, Acetyl-CoA

acetyltransferase 1; CE, cholesterol ester; SOCE, store-operated

calcium entry; STIM1, stromal interaction molecule 1; UPR, unfolded

protein response; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; NLRP3, NOD-like

receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; BD, bipolar disorder;

LPS, lipopolysaccharide. |

Although further research is needed, the present

study suggested that the skin-brain axis may provide a novel route

for understanding the pathophysiology of BD, with inflammation

potentially being a central mediator between these interconnected

systems.

In conclusion, MAM impairment was underscored as a

key pathophysiological mechanism in early BD stages suggesting that

these subcellular structures should be further exploring to search

novel therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are

included in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

ACP: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation,

writing-original draft. APM, RR, MC, TF, LSC: Data curation, formal

analysis, investigation. MB, JBDM, AM: Resources, methodology. NM:

Resources, methodology, funding acquisition. CC, MTC: Supervision,

writing-review and editing. CFP: Conceptualization, supervision,

project administration, funding acquisition, writing-review and

editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra (now ULS de

Coimbra), reference 150/CES, July 3, 2018 and both the skin

biopsies and the peripheral blood samples were taken following

informed consent also approved by the same ethics committee

(30).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

AD

|

Alzheimer's disease

|

|

ASC

|

apoptosis-associated speck-like

protein containing a C-terminal caspase-activation-and-recruitment

(CARD) domain

|

|

ATF4

|

activating transcription factor 4

|

|

ATF6

|

activating transcription factor 6

|

|

BD

|

bipolar disorder

|

|

Ca2+

|

calcium

|

|

CNS

|

central nervous system

|

|

ER

|

endoplasmic reticulum

|

|

GRP78

|

glucose-regulated protein 78

|

|

IMM

|

inner mitochondria membrane

|

|

iPSCs

|

induced pluripotent stem cells

|

|

IP3R

|

inositol trisphosphate receptor

|

|

LDs

|

Lipid droplets

|

|

LPS

|

lipopolysaccharide

|

|

MAM

|

mitochondria-associated membranes

|

|

MCU

|

mitochondrial Ca2+

uniporter protein

|

|

Mfn2

|

Mitofusin 2

|

|

SOD2

|

superoxide dismutase 2

|

|

NLRP3

|

NOD-like receptor family pyrin

domain-containing 3

|

|

OMM

|

outer mitochondrial membrane

|

|

PLA

|

proximity ligation assay

|

|

PTPIP51

|

protein tyrosine

phosphatase-interacting protein-51

|

|

RT-PCR

|

reverse transcriptase-polymerase

chain reactions

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

SCCI

|

single cell calcium imaging

|

|

SOCE

|

store-operated Ca2+

entry

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

|

STIM1

|

stromal interaction molecule 1

|

|

TEM

|

transmission electron microscopy

|

|

TOM-20

|

Translocase of Outer Mitochondrial

Membrane 20

|

|

ULS

|

Unidade Local de Saúde de Coimbra

|

|

UPR

|

unfolded protein response

|

|

VAPB

|

vesicle-associated membrane protein

associated protein B

|

|

VDAC

|

voltage-dependent anion channel

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the European Regional

Development Fund (ERDF), through the Centro 2020 Regional

Operational Programme under grant no. CENTRO-01-0145-FEDER-000012

(HealthyAging2020) and through the COMPETE 2020-Operational

Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalization and

Portuguese national funds via FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a

Tecnologia, under grant nos. PTDC/MED-NEU/28214/2017,

PTDC/MED-FAR/29369/2017 and UIDB/04539/2020, UIDP/04539/2020 and

LA/P/0058/2020. AP is a PhD fellow from FCT (grant no.

SFRH/BD/148653/2019). RR is Post-Doctoral Researcher (grant no. DL

57/2016/CP1448/CT0012).

References

|

1

|

Csordás G, Renken C, Várnai P, Walter L,

Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA and Hajnóczky G:

Structural and functional features and significance of the physical

linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 174:915–921.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Filadi R, Theurey P and Pizzo P: The

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling in health and disease:

Molecules, functions and significance. Cell Calcium. 62:1–15. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang X, Wen Y, Dong J, Cao C and Yuan S:

Systematic In-depth proteomic analysis of Mitochondria-associated

endoplasmic reticulum membranes in mouse and human testes.

Proteomics. 18:e17004782018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rowland AA and Voeltz GK: Endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondria contacts: Function of the junction. Nat Rev

Mol Cell Biol. 13:607–625. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

de Brito OM and Scorrano L: Mitofusin-2

regulates mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum morphology and

tethering: The role of Ras. Mitochondrion. 9:222–226. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Casellas-D Iaz S, Larramona-Arcas R, Riqu

E-Pujol G, Tena-Morraja P, Müller-Sánchez C, Segarra-Mondejar M,

Gavaldà-Navarro A, Villarroya F, Reina M, Martínez-Estrada OM and

Soriano FX: Mfn2 localization in the ER is necessary for its

bioenergetic function and neuritic development. EMBO Rep.

22:e519542021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yang S, Zhou R, Zhang C, He S and Su Z:

Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes in the

pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Cell Dev Biol.

8:5715542020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gómez-Suaga P, Pérez-Nievas BG, Glennon

EB, Lau DHW, Paillusson S, Mórotz GM, Calì T, Pizzo P, Noble W and

Miller CCJ: The VAPB-PTPIP51 endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria

tethering proteins are present in neuronal synapses and regulate

synaptic activity. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 7:352019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xu H, Guan N, Ren YL, Wei QJ, Tao YH, Yang

GS, Liu XY, Bu DF, Zhang Y and Zhu SN: IP3R-Grp75-VDAC1-MCU calcium

regulation axis antagonists protect podocytes from apoptosis and

decrease proteinuria in an Adriamycin nephropathy rat model. BMC

Nephrol. 19:1402018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

10

|

Area-Gomez E, Del Carmen Lara Castillo M,

Tambini MD, Guardia-Laguarta C, de Groof AJ, Madra M, Ikenouchi J,

Umeda M, Bird TD, Sturley SL and Schon EA: Upregulated function of

mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. EMBO J.

31:4106–4123. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Raturi A and Simmen T: Where the

endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondrion tie the knot: The

mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM). Biochimica et Biophysica

Acta (BBA)-Mol Cell Res. 1833:213–224. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

van Vliet AR, Verfaillie T and Agostinis

P: New functions of mitochondria associated membranes in cellular

signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1843:2253–2262. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P and Tschopp J: A

role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature.

469:221–225. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kelley N, Jeltema D, Duan Y and He Y: The

NLRP3 inflammasome: An overview of mechanisms of activation and

regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 20:33282019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Missiroli S, Patergnani S, Caroccia N,

Pedriali G, Perrone M, Previati M, Wieckowski MR and Giorgi C:

Mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) and inflammation. Cell

Death Dis. 9:3292018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Filadi R, Greotti E and Pizzo P:

Highlighting the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connection:

Focus on Mitofusin 2. Pharmacol Res. 128:42–51. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Area-Gomez E, de Groof A, Bonilla E,

Montesinos J, Tanji K, Boldogh I, Pon L and Schon EA: A key role

for MAM in mediating mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer

disease. Cell Death Dis. 9:3352018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Resende R, Fernandes T, Pereira AC,

Marques AP and Pereira CF: Endoplasmic Reticulum-mitochondria

contacts modulate reactive oxygen Species-mediated signaling and

oxidative stress in brain disorders: The key role of Sigma-1

receptor. Antioxid Redox Signal. 37:758–780. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Elsayed OH, Ercis M, Pahwa M and Singh B:

Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: Therapeutic trends,

challenges and future directions. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat.

18:2927–2943. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Huang Y, Zhang Z, Lin S, Zhou H and Xu G:

Cognitive impairment mechanism in patients with bipolar disorder.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 19:361–366. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sampogna G, Janiri D, Albert U, Caraci F,

Martinotti G, Serafini G, Tortorella A, Zuddas A, Sani G and

Fiorillo A: Why lithium should be used in patients with bipolar

disorder? A scoping review and an expert opinion paper. Expert Rev

Neurother. 22:923–934. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hu X, Yu C, Dong T, Yang Z, Fang Y and

Jiang Z: Biomarkers and detection methods of bipolar disorder.

Biosens Bioelectron. 220:1148422023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Pereira AC, Resende R, Morais S, Madeira N

and Fragão Pereira C: The ups and downs of cellular stress: The

'MAM hypothesis' for Bipolar disorder pathophysiology.

International J Clin Neurosciences Mental Health. S042017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Pereira AC, Oliveira J, Silva S, Madeira

N, Pereira CMF and Cruz MT: Inflammation in bipolar disorder (BD):

Identification of new therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Res.

163:1053252021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Resende R, Fernandes T, Pereira AC, De

Pascale J, Marques AP, Oliveira P, Morais S, Santos V, Madeira N,

Pereira CF and Moreira PI: Mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and

innate immune dysfunction in mood disorders: Do

Mitochondria-associated Membranes (MAMs) play a role? Biochim

Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1866:1657522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kim HK, Andreazza AC, Elmi N, Chen W and

Young LT: Nod-like receptor pyrin containing 3 (NLRP3) in the

post-mortem frontal cortex from patients with bipolar disorder: A

potential mediator between mitochondria and immune-activation. J

Psychiatr Res. 72:43–50. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Viswanath B, Jose SP, Squassina A,

Thirthalli J, Purushottam M, Mukherjee O, Vladimirov V, Patrinos

GP, Del Zompo M and Jain S: Cellular models to study bipolar

disorder: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 184:36–50. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Johnston JA, Cowburn RF, Norgren S,

Wiehager B, Venizelos N, Winblad B, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Schenk D,

Lannfelt L and O'Neill C: Increased β-amyloid release and levels of

amyloid precursor protein (APP) in fibroblast cell lines from

family members with the Swedish Alzheimer's disease APP670/671

mutation. FEBS Lett. 354:274–278. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Hoepken HH, Gispert S, Azizov M,

Klinkenberg M, Ricciardi F, Kurz A, Morales-Gordo B, Bonin M, Riess

O, Gasser T, et al: Parkinson patient fibroblasts show increased

alpha-synuclein expression. Exp Neurol. 212:307–313. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Onofre I, Mendonça N, Lopes S, Nobre R, de

Melo JB, Carreira IM, Januário C, Gonçalves AF and de Almeida LP:

Fibroblasts of machado joseph disease patients reveal autophagy

impairment. Sci Rep. 6:282202016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Oliveira NC, Russo FB and Beltrão-Braga

PCB: Differentiation of peripheral sensory neurons from iPSCs

derived from stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth

(SHED). Front Cell Dev Biol. 11:12035032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kálmán S, Garbett KA, Janka Z and Mirnics

K: Human dermal fibroblasts in psychiatry research. Neuroscience.

320:105–121. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Etemadikhah M, Niazi A, Wetterberg L and

Feuk L: Transcriptome analysis of fibroblasts from schizophrenia

patients reveals differential expression of schizophrenia-related

genes. Sci Rep. 10:6302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Akin D, Manier DH, Sanders-Bush E and

Shelton RC: Decreased serotonin 5-HT2A receptor-stimulated

phosphoinositide signalling in fibroblasts from melancholic

deppresed patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 29:2081–2087. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI