Cataracts, characterized by progressive

opacification of the ocular lens, are the leading cause of visual

impairment and blindness worldwide (1). Cataracts can be classified into

age-related cataracts (ARCs), congenital cataracts and secondary

cataracts caused by other reasons (2). ARCs, also known as senile

cataracts, constitute the most prevalent cataract subtype, with

typical onset after 50-60 years of age (3). Currently, no clinically proven

interventions exist to prevent ARC progression. Surgery remains the

gold-standard therapeutic approach, achieving rapid visual

rehabilitation in most cases (4). Despite surgical efficacy, ARCs

persist as a critical global health challenge due to high patient

volume, substantial surgical costs and potential postoperative

complications (5,6). Therefore, continuous and dedicated

efforts are required to develop improved therapeutic strategies for

ARC prevention and treatment.

ARCs develop through the long-term interplay of

multiple pathogenic factors, with complex and heterogeneous

underlying mechanisms. To date, multiple risk factors, including

aging, diabetes, genetic predisposition, oxidative stress and

ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure, have been implicated in ARC

pathogenesis (3). The current

understanding of ARC pathogenesis strongly implicates reactive

oxygen species (ROS) accumulation as a key driver, with numerous

studies demonstrating the pathogenic roles of superoxide anion

(O2−), hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH) generated

during aerobic metabolism (7-9).

Excessive ROS induce oxidative stress by chemically modifying and

damaging critical cellular components (10). Oxidative stress, in turn, causes

modifications in lens proteins (including enzymes, crystallins and

other chaperones), thereby reducing their solubility and stability,

and ultimately promoting crystallin aggregation (11). These alterations induce light

scattering within the lens, progressively leading to lens opacity

and subsequent visual acuity impairment (12). Oxidative stress also directly

damages lens epithelial cells (LECs), which are critical for

maintaining lens transparency and metabolic homeostasis, through

the peroxidation of proteins, lipids and DNA, while concurrently

activating signalling pathways and transcription factors (11,13-17). As the most metabolically active

components of the lens, LECs possess a sophisticated antioxidant

defence system to mitigate oxidative stress (18,19). However, when ROS levels exceed

the antioxidant capacity of LECs, oxidative damage to the LECs

triggers apoptosis, an early event in ARC pathogenesis (20,21).

Epigenetics refers to alterations in gene expression

without changes to the DNA sequence in response to environmental,

developmental and nutritional factors (22,23). These alterations are reversible

and subject to dynamic regulation, leading to heritable changes in

gene expression and cellular phenotypes (24). Extensive research has

demonstrated that epigenetic mechanisms function as pivotal

regulators of disease pathogenesis, influencing initiation,

progression, prevention and treatment (25,26). The emergence of aberrant

epigenetic changes is associated with the pathogenesis of various

diseases, including cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease and other

age-related disorders (27-30). Epigenetic modifications not only

underlie the molecular mechanisms driving disease development but

also serve as promising biomarkers for clinical diagnosis and

enable precision-targeted therapeutic interventions (31,32). Epigenetic modifications primarily

encompass DNA methylation, histone modifications, RNA

modifications, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and chromatin remodelling.

A substantial body of research has established the critical

involvement of epigenetic processes in gene expression regulation,

DNA damage repair, and cell cycle control and aging, highlighting

their fundamental importance in molecular biology and genetics

(33-35).

Breakthroughs in epigenetic research related to

ocular diseases have only emerged within the past decade.

Epigenetic modifications have grown into a leading frontier in

biomedical research, with accumulating studies revealing their

regulatory impact on several ocular diseases such as cataracts,

glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration

(36-39). Epigenetic research can deepen the

understanding of the molecular mechanisms of ocular diseases and

open novel avenues for the development of epigenome-targeted

treatments. The present review summarizes current advances in

epigenetic research on ARCs, discussing the implications of these

research advances for future investigations and the therapeutic

potential of epigenetic interventions in ARCs.

Epigenetic modifications represent heritable changes

in gene expression that occur independently of alterations in the

underlying DNA sequence (40).

Epigenetic modifications, including ncRNAs, DNA methylation,

histone modifications and N6-methyladenosine

(m6A) modification, are now widely acknowledged as key

molecular drivers in the development of ARCs (41-43). A deeper understanding of these

epigenetic mechanisms will elucidate disease pathogenesis and

enable targeted epigenetic therapies for ARCs. The subsequent

sections will first introduce key epigenetic alterations, including

ncRNAs, DNA methylation, histone modifications and m6A

modification, and then systematically examine their roles in ARC

pathogenesis.

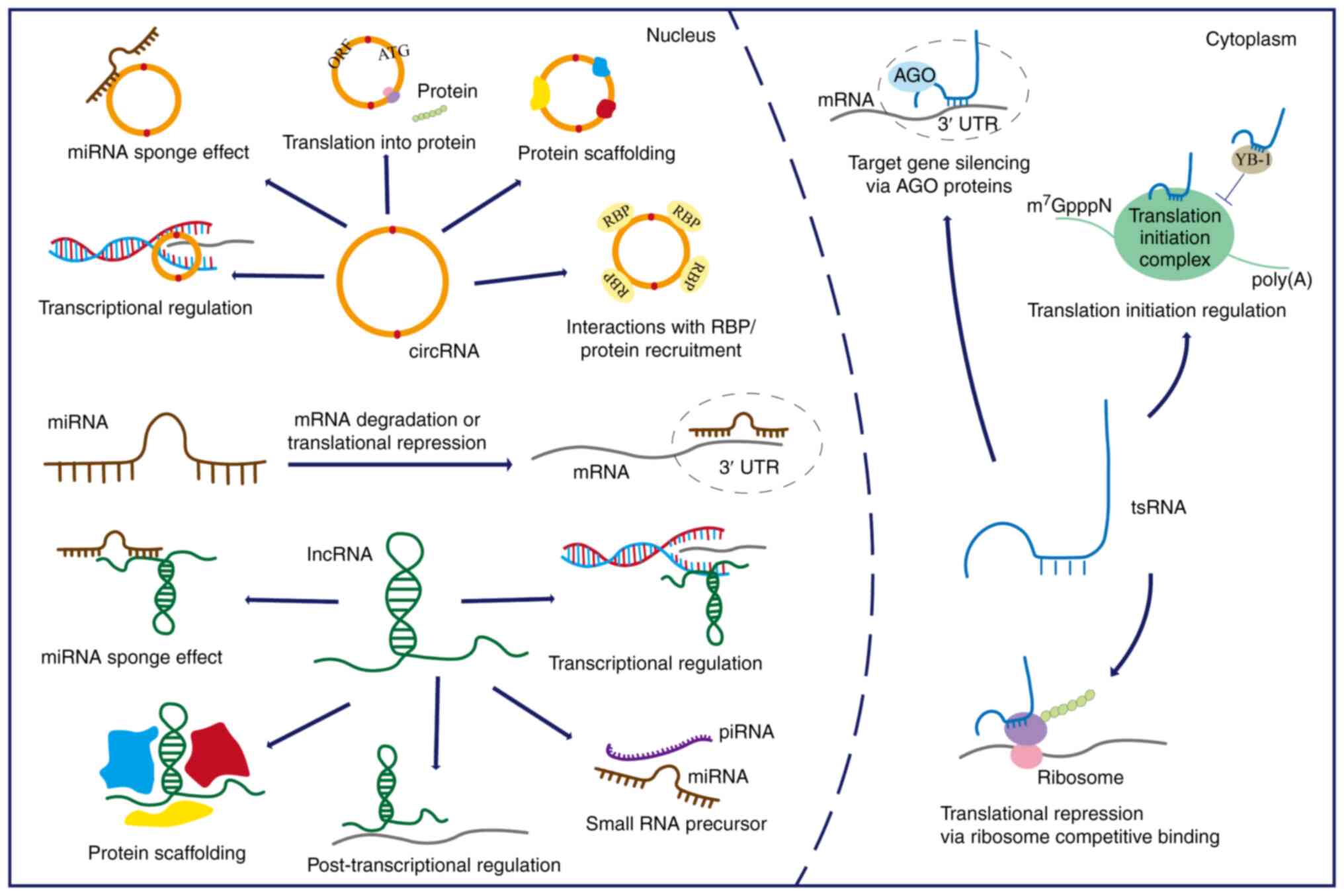

The central dogma of molecular biology describes the

flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein (44,45). For decades, research on cataract

pathogenesis has predominantly focused on protein-coding genes.

However, advances in sequencing technologies have enabled the

identification of numerous unique ncRNAs and confirmed their

cellular presence. ncRNAs represent a class of RNA molecules that

lack protein-coding sequences and are consequently not translated

into polypeptides or proteins. This category includes microRNAs

(miRNAs/miRs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs

(circRNAs), transfer RNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) and small

nuclear RNAs (46). Through

specific interactions with DNA, RNA and proteins, ncRNAs precisely

regulate nearly all biological pathways, including signal

transduction (47),

transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation (48,49), translational repression (50), and translation initiation

regulation (51) (Fig. 1). ncRNAs operate in both

physiological and pathological contexts, exhibiting strong

potential as novel molecular biomarkers and therapeutic targets

(52-54). Consequently, ncRNAs serve a

pivotal role in the pathogenesis and progression of ARCs, as

extensively documented in several studies (55-57). The present review primarily

focuses on reviewing advances in research on the four major ncRNAs

(miRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs and tsRNAs) and their regulatory

networks in ARCs.

miRNAs are the most extensively studied and best

characterized small ncRNAs to date. miRNAs are small ncRNA

molecules, typically 20-30 nucleotides in length, that serve

critical roles in structural, enzymatic and regulatory processes

across biological systems (58).

Precursor miRNAs undergo a tightly regulated series of nuclear and

cytoplasmic processing steps mediated by the endoribonucleases

DROSHA and DICER, respectively, ultimately yielding mature miRNAs.

The mature miRNAs are then incorporated into the RNA-induced

silencing complex and regulate gene expression by binding to the 3'

untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, leading to either mRNA

degradation or translational repression (58,59). miRNAs have also been reported to

interact with other regions, such as the 5' UTR, coding sequence

and gene promoters (60,61). Furthermore, accumulating evidence

has demonstrated that miRNAs can post-transcriptionally activate

gene expression in specific contexts, challenging the conventional

paradigm of miRNA-mediated silencing and highlighting their

functional versatility (62-64). Notably, miRNAs form intricate,

highly interconnected regulatory networks, wherein individual

miRNAs typically regulate multiple mRNA targets, and conversely,

most mRNAs are subject to combinatorial regulation by multiple

miRNAs (65). Diverse

physiological and pathological processes, including apoptosis

(66), autophagy (67), oxidative stress (68), senescence (69) and DNA repair (70), have been shown to influence the

biological characteristics of LECs in ARC, as evidenced by both

in vitro experiments and animal studies. miRNAs have been

demonstrated to serve important roles in these processes, making it

plausible that miRNAs are closely associated with cataract

formation (Table SI).

Studies have revealed alterations in miRNA

expression profiles between transparent and cataractous lenses

(71-73). For example, miRNA let-7b

expression exhibits a positive association with patient age, and

elevated miRNA let-7b expression is associated with higher nuclear

(N), cortical (C) and posterior subcapsular (P) cataract scores

according to the Lens Opacities Classification System III (74) in patients with ARCs (73). Similarly, miR-34a expression

levels vary among patients of different ages, with moderate

associations observed between high N, C and P cataract scores and

high miR-34a levels (75).

Elevated levels of miR-210-3p have been identified in the aqueous

humour of patients with ARCs, and the elevation demonstrated strong

diagnostic potential for ARCs while being associated with oxidative

stress marker levels (76).

miR-15a and miR16-1 are expressed at a higher level in the LECs of

patients with cataracts compared with normal controls (77). Notably, ARCs can be classified

into distinct subtypes based on the location of opacification,

including cortical cataracts, nuclear cataracts (NCs), and

posterior and anterior subcapsular cataracts (ASCs), while the

remainder is classified as mixed cataracts, and differential

expression of miRNAs has been observed among these subtypes

(72). The expression levels of

let-7a-5p, let-7d-5p, let-7g-5p and miR-23b-3p differ between

patients with NC and ASC, as measured in lens epithelium samples

(72). Thus, aberrant miRNA

expression levels may not only act as risk factors in the formation

and progression of ARC, but also serve as potential biomarkers for

ARCs based on their differential expression patterns in different

severity stages and subtypes of ARCs. However, no miRNAs are used

for clinical diagnosis currently, requiring further validation in

clinical practice.

miRNAs typically function by binding to target mRNAs

and inhibiting translation (58,59). Thus, specific miRNAs indirectly

contribute to cataract formation by regulating key factors involved

in cellular processes such as apoptosis, proliferation and

oxidative stress. For instance, miR-23b-3p promotes apoptosis and

inhibits autophagy in LECs under oxidative stress by directly

targeting and downregulating silent information regulator 1

(SIRT1), a critical mediator of oxidative stress resistance,

thereby contributing to ARC pathogenesis (78). Similarly, miR-211 induces

apoptosis and decreases cell viability by suppressing SIRT1

expression (79). E2F

transcription factor 3 (E2F3), a member of the E2F transcription

factor family, serves essential roles in regulating cell

proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation (80,81). As a key cell cycle regulator,

E2F3 promotes cell cycle re-entry in quiescent lens cells. However,

aberrant cell cycle re-entry may trigger programmed cell death

(82-84), and has been observed in LECs,

which is closely linked to ARC pathogenesis (85). Experimental evidence has

identified miR-34a (86),

miR-15a (87), miR-221 (88), miR-630 and miR-378a-5p (89), as direct post-transcriptional

suppressors of E2F3, collectively contributing to lens opacity

progression. miR-34a, the expression of which is increased in the

cataractous lens, triggers mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and

oxidative stress by suppressing Notch2 (90). In addition, the upregulation of

miR-34a together with the downregulation of hexokinase 1 (HK1)

inhibits the proliferation and induces the apoptosis of LECs, thus

accelerating the opacification of mouse lenses via the HK1/caspase

3 signalling pathway (91).

Furthermore, Cao et al (67) demonstrated that miRNA let-7c-5p

directly targeted excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair

deficiency, complementation group 6 (ERCC6), and thus, inhibited

its role in autophagy, a process necessary for maintaining lens

transparency through degradation of misfolded proteins and damaged

organelles. miR-378a is upregulated in human cataract tissues and

inhibits LEC proliferation while promoting apoptosis by modulating

the ROS/PI3K/AKT signalling pathway (92).

Emerging evidence has indicated that certain miRNAs

function as cataract suppressors by preventing lens opacification

(68,93,94). Given that ARC pathogenesis is

associated with apoptotic cell death in the lens, extensive

research has highlighted dysregulated apoptosis of LECs as a key

pathogenic mechanism in cataract development (95-97). Bcl-2 family proteins are

essential for the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (98). B-cell lymphoma-2-like-2 (BCL2L2),

a Bcl-2 family member, is an important regulator of apoptosis

(99). Zhang et al

(93) identified BCL2L2 as a

direct target of miR-133b, demonstrating that miR-133b-mediated

downregulation of BCL2L2 expression led to apoptosis inhibition.

While BCL2L2 promoted apoptosis, miR-133b functioned as an

anti-apoptotic regulator by suppressing BCL2L2 expression (93). Likewise, miR-182, which is

implicated in various ophthalmic disorders, including pterygium

(100), glaucoma (101) and age-related macular

degeneration (102), protects

LECs against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by regulating the

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase subunit 4

(NOX4) and p38 MAPK signalling pathway (68). Furthermore, miR-125b is

downregulated in ARC lens tissue, where it suppresses p53 mRNA

expression and exerts anti-apoptotic effects on LECs (94). Although numerous miRNAs have been

demonstrated to attenuate lens opacity progression, experimental

validation by in vivo studies conducted in animals, such as

rats or rabbits, remains limited. To the best of our knowledge,

only three in vivo studies have been reported at present.

Administration of antagomirs targeting miR-326 (103), miR-29a-3p (104) and miR-187 (105) independently inhibited cataract

formation in animal models of ARC, suggesting their potential as

non-surgical therapeutic candidates.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within miRNA

binding sites can affect the base pairing between miRNAs and their

target mRNAs, thereby altering miRNA-mediated gene regulation

(106). Oxidative DNA damage

and impaired DNA repair capacity in LECs are strongly involved in

ARC pathogenesis (107,108). Accumulating data have

demonstrated that SNPs within miRNA binding sites of oxidative DNA

damage repair genes may modulate ARC susceptibility (70,109,110). Zou et al (70) systematically analysed 10

miRNA-binding SNPs located in the 3' UTRs of seven oxidative

damage-related genes. Their findings demonstrated that the C allele

of XPC-rs2229090 increased susceptibility to the nuclear type of

ARC (ARNC). Mechanistically, the C allele exhibited stronger

binding affinity for hsa-miR-589-5p compared with the G allele,

resulting in reduced XPC expression and impaired DNA repair

capacity in LECs (70).

Furthermore, Kang et al (109) demonstrated that the protective

effect of Nei-like DNA glycosylase 2 (NEIL2)-rs4639T in ARCs may be

mediated through maintenance of normal NEIL2 expression levels,

potentially via disruption of the binding of rs4639T with

hsa-miR-3912-5p. Additionally, the rs78378222 polymorphism in the

p53 3' UTR contributes to ARC pathogenesis by regulating

miR-125b-mediated apoptosis in LECs (110). Taken together, these findings

suggest that SNP-mediated alterations in miRNA-dependent

post-transcriptional regulation constitute a novel pathogenic

mechanism in ARCs and reveal novel therapeutic targets.

In general, research on miRNA alterations in ARCs

has reached a relatively mature stage, with comprehensive studies

demonstrating the crucial roles of miRNAs in mediating LEC lesions

in vitro and cataract progression in vivo (103-105). Exosomal miRNAs have become a

research focus; however, their relationship with ARCs remains

poorly understood. At present, only two studies have demonstrated

the roles of exosomal miR-222-3p in ARC formation and miR-125a-3p

in disease progression (66,111). Exosomes are 50-200-nm

extracellular nanovesicles derived from multivesicular bodies in

the cytoplasm and serve as an important medium of intercellular

communication (112,113). Exosomes regulate receptor cells

and tissues by transmitting effectors, including proteins, mRNAs or

miRNAs (114). Various types of

cells can secret miRNAs via exosomes, a process that protects

miRNAs from degradation and ensures their function in target cells

(115). Exosomes transport

miRNAs to target cells without being degraded by RNAses, making

exosomal miRNAs more stable and reliable biomarkers than their

non-exosomal counterparts (116). Exosomal miRNAs are emerging as

promising biomarkers for aging and age-related diseases (117-119). Furthermore, exosomes represent

promising drug delivery vehicles due to their inherent advantages,

including high biocompatibility, high biological barrier

penetration and high circulatory stability (120). Therefore, investigating

exosomal miRNAs could help to elucidate the pathogenesis of ARCs,

facilitate biomarker identification and enable the development of

innovative intervention strategies.

Alongside short miRNAs, a wide array of longer

transcripts, referred to as lncRNAs, has been increasingly

characterized. lncRNAs are >200 bp long, and exhibit relatively

low expression levels, poor stability and limited evolutionary

conservation (121). Therefore,

lncRNA research presents considerable challenges due to these

inherent molecular characteristics, and is only recently undergoing

a surge. Notably, similar to miRNAs, most lncRNAs are associated

with human diseases; however, in contrast to their smaller

counterparts, lncRNAs exhibit cell type-specific expression

patterns and distinct subcellular localization (122). lncRNAs perform diverse

regulatory functions, including acting as miRNA sponges, signal

mediators, molecular decoys, chromatin modifiers, and regulators of

gene expression and pre-mRNA splicing (123,124). Among these functions, their

role as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) or miRNA sponges is

particularly significant. The ceRNA hypothesis, first proposed by

Salmena et al (125) in

2011, suggests that lncRNAs regulate gene expression

post-transcriptionally by competitively binding to miRNAs via

shared miRNA response elements, thereby preventing miRNA-mRNA

interactions. Through diverse molecular mechanisms, lncRNAs

regulate critical biological processes such as stem cell

maintenance, cellular differentiation and chromatin remodelling, as

well as transcription, splicing, translation, degradation and

transport of mRNA (126,127).

Previous studies have indicated that lncRNAs are highly active in

ARCs, where they may either promote or suppress disease initiation

and progression (Table SII)

(128-130).

Emerging evidence has established the pivotal role

of numerous lncRNAs as pathogenic drivers in ARC pathogenesis. As

aforementioned, lncRNAs can act as ceRNAs or endogenous miRNA

sponges, effectively sequestering miRNAs and attenuating their

post-transcriptional repression of target mRNAs (125). Building upon this theoretical

framework, Jin et al (133) experimentally validated miR-214

as a direct target of lncKCNQ1OT1. Their findings demonstrated that

lncKCNQ1OT1 knockdown upregulated miR-214 expression and

subsequently downregulated the expression of its downstream

effector caspase-1, indicating the pathogenic role of the

lncKCNQ1OT1/miR-214/caspase-1 axis in cataract formation (133). Furthermore, lncKCNQ1OT1

functions as a molecular sponge for miR-223-3p, which directly

targets BCL2L2. Through the lncKCNQ1OT1/miR-223-3p/BCL2L2 axis,

lncKCNQ1OT1 promotes apoptosis and pyroptosis, while exacerbating

oxidative damage in H2O2-treated LECs

(134). Another study

demonstrated that lncKCNQ1OT1 downregulation protected LECs from

oxidative stress-induced damage via the miR-124-3p/BCL-2-like 11

pathway (135). In addition to

lncKCNQ1OT1, TUG1 is another well-characterized lncRNA that

exacerbates the pathogenesis of ARC, and has been shown to promote

apoptosis in H2O2 or UV irradiation-treated

LECs through three distinct molecular pathways: TUG1/miR-196a-5p

(136), TUG1/miR-421/caspase-3

(20) and TUG1/miR-29b/second

mitochondria-derived activator of caspases (137). Furthermore, research has

identified multiple novel pathogenic lncRNAs, including NEAT1

(129,138), MEG3 (139,140) and OIP5-AS1 (141), with additional candidates

expected to emerge as research progresses.

By contrast, other studies have indicated that

certain lncRNAs exert protective effects to prevent ARC

progression. For example, lncRNA phospholipase C δ3 (PLCD3)-OT1 may

act as a ceRNA to promote PLCD3 expression by sponging miR-224-5p,

thus promoting cell proliferation and viability, and inhibiting

apoptosis, under oxidative stress conditions (142). Similarly, lncRNA

NONHSAT143692.2 modulates 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1)

expression in LECs by competitively binding to miR-4728-5p, thereby

protecting LECs from cell apoptosis and oxidative damage (130). Furthermore, Cheng et al

(143) revealed that lncRNA H19

suppressed apoptosis, mitigated oxidative damage, and promoted

proliferation and viability in UV irradiation-treated LECs through

the functional interplay of lncRNA H19, miR-29a and thymine DNA

glycosylase.

Although acting as miRNA sponges represents a

well-established function of lncRNAs (144-146), their other regulatory functions

are also implicated in cataract pathogenesis. lncRNAs are typically

classified into five major classes according to their relative

genomic locations: Antisense (AS), intergenic, overlapping,

intronic and full lapping (147). Within these lncRNA classes, AS

lncRNAs, which are reverse-strand complements of their endogenous

protein-coding counterparts, are generally non-protein-coding and

account for a substantial proportion of the entire long non-coding

transcriptome (148-150). Previous studies have

demonstrated that natural AS transcripts participate in diverse

biological processes by regulating sense gene expression at

multiple levels, including transcriptional regulation via gene

promoter activation, and post-transcriptional regulation through

mRNA stabilization and translational modulation (151,152). Glutathione peroxidase 3

(GPX3)-AS has been found to upregulate GPX3 expression at both the

mRNA and protein levels, enhancing the activity of this ROS

scavenger to inhibit LEC apoptosis, thereby revealing a potential

therapeutic target for ARCs (153). Furthermore, lncRNAs can also

serve as direct precursors for miRNA biogenesis (154). A representative example is

lncRNA H19, which serves as the precursor for miR-675, where H19

downregulation leads to reduced miR-675 expression. lncRNA H19

modulates LEC function via miR-675-mediated regulation of

crystallin αA (CRYAA) expression, offering novel insights into ARNC

pathogenesis (155).

Overall, lncRNAs participate in ARC pathogenesis

through multifaceted regulation of LEC biology, including oxidative

stress responses and apoptotic pathways. Given their functional

versatility and multi-target nature, the precise roles and

regulatory networks of several lncRNAs in ARC pathogenesis have yet

to be comprehensively characterized. Furthermore, although in

vitro experiments offer valuable mechanistic insights, their

translational relevance to whole organisms remains limited. To the

best of our knowledge, no in vivo models investigating

lncRNAs in ARCs have been reported at present. Animal models, which

better recapitulate the complexity of physiological systems, are

crucial for validating the observed in vitro effects.

circRNAs are single-stranded, covalently closed RNA

molecules without 5' caps and 3' poly-A tails, and are usually

produced through a back-splicing process (156,157). The absence of both 5' caps and

3' polyadenylated tails renders circRNAs resistant to

exonuclease-mediated degradation, thus ensuring their stability and

longevity in cellular processes (158). circRNAs possess distinctive

properties and diverse functions that continue to be elucidated.

Similar to lncRNAs, circRNAs can function as efficient miRNA

sponges, representing one of their most well-characterized

regulatory modes (159-161). Beyond their well-known role as

miRNA sponges, studies have revealed that circRNAs can also

interact with RNA-binding proteins (162), regulate RNA splicing and

transcription (163,164), and undergo translation into

functional peptides or proteins (165,166). circRNAs also participate in a

wide range of biological processes, including fibrosis, cell

apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation and angiogenesis

(167). In recent years, their

roles as vital regulators in multiple ocular diseases have

attracted increasing attention (168-170). Similar to linear ncRNAs,

circRNAs are implicated in cataract formation (Table SIII) (171-173). The circRNA/miRNA/mRNA

regulatory network has advanced the understanding of the molecular

basis of cataractogenesis.

Studies have characterized specific circRNAs that

contribute to ARC pathogenesis. For example, hsa_circ_0105558

promotes apoptosis and aggravates the oxidative damage of LECs

under H2O2 exposure through the

miR-182-5p/activating transcription factor 6 axis (174). hsa_circ_0007905 upregulates

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1

(EIF4EBP1) expression by competitively binding to miR-6749-3p,

consequently enhancing LEC apoptosis while inhibiting LEC

proliferation, resulting in ARC progression (175). Notably, hsa_circ_0007905

expression in LECs is upregulated through methyltransferase like 3

(METTL3)-mediated m6A modification (175). A comprehensive discussion of

m6A modifications of circRNAs is presented in the

m6A modification section. Notably, circMRE11A_013

(circMRE11A) acts primarily as a molecular scaffold that interacts

with UBX domain-containing protein 1 rather than functioning as a

miRNA sponge, and promotes excessive activation of

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM), ultimately inducing LEC

cell cycle arrest and senescence through the ATM/p53/p21 signalling

pathway (176). Furthermore,

recombinant adeno-associated virus vector virions of circMRE11A

have been injected into the mouse vitreous cavity, providing in

vivo evidence that circMRE11A drives lens aging and

opacification in mice (176).

In addition to circMRE11A, circSTRBP (hsa_circ_0088,427) exerts its

biological effects independently of miRNA sponging activity by

interacting with insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein

1 (IGF2BP1), and enhances the stability and expression of NOX4 mRNA

in LECs (171). circSTRBP

exacerbates H2O2-induced oxidative stress and

apoptosis in LECs by enhancing NOX4 mRNA stability through IGF2BP1

recruitment, providing novel perspectives for ARC intervention

(171).

Emerging evidence has identified multiple protective

circRNAs in ARC pathogenesis, with several candidates exhibiting

potent antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects in LECs. circRNA

homeodomain interacting protein kinase 3 (circHIPK3) promotes

viability and proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, and alleviates

oxidative damage in H2O2-treated LECs via

three distinct molecular pathways: circHIPK3/miR-221-3p/PI3K/AKT

(177),

circHIPK3/miR-193a/CRYAA (178)

and circHIPK3/miR-495-3p/histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) (179). circ_0060,144 regulates HIPK3

expression by sponging miR-23b-3p, thereby influencing LEC

homeostasis through regulation of proliferation, apoptosis and the

oxidative stress response (180). UV radiation downregulates

circRNA erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 expression, which

subsequently reduces 3'(2'), 5'-bisphosphate nucleotidase 1 levels

via miR-24-3p binding, thus inhibiting proliferation and promoting

apoptosis in LECs (181).

Furthermore, circRNA 06209 acts as a ceRNA by sequestering

miR-6848-5p to neutralize its suppressive effect on arachidonate

15-lipoxygenase, ultimately promoting proliferation and inhibiting

apoptosis in H2O2-treated LECs (182). Notably, injection of a

circRNA_06209-overexpressing plasmid into a

Na2SeO3-induced cataract model attenuated

lens opacity while reducing insoluble protein aggregation and

increasing soluble protein levels in the lens, demonstrating the

anti-cataract efficacy of circRNA_06209 in both in vitro and

in vivo settings (182).

Given that circRNAs exhibit high stability,

evolutionary conservation across species and tissue specificity

(183), investigating

ARC-related circRNAs as potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets

could open novel avenues for the diagnosis, prevention and

treatment of ARCs. However, only a limited number of circRNAs in

ARCs have well-characterized biological functions and mechanistic

pathways. While circRNAs employ diverse molecular mechanisms and

functions, current research on their roles in ARCs has largely

focused on their function as miRNA sponges and their interactions

with proteins (171,174,184-186), suggesting that novel functions

or mechanisms remain to be identified.

tsRNAs constitute a family of small ncRNAs produced

by the cleavage of precursor or mature transfer RNAs (tRNAs) via

specific endonucleases (187).

tsRNAs are mainly classified into two types: tRNA halves and

tRNA-derived fragments, based on the cleavage position of the

precursor or mature tRNAs (188). Advances in high-throughput

sequencing technologies have revealed that tsRNAs serve crucial

roles in the regulation of gene expression, post-transcriptional

modifications, apoptotic inhibition and protein translation

(189-191), while their dysregulation

contributes to various pathological processes in diseases such as

cancer, cardiovascular diseases and Alzheimer's disease (192-194). Investigations have begun to

reveal the crucial involvement of tsRNAs in ophthalmic diseases

(195-197). Through integrated

next-generation sequencing analysis, a study conducted in 2022

systematically established the first evidence of the changes in

tsRNA profiles in Emory mice, a well-characterized model for human

ARCs (198). A total of 422

differentially expressed tsRNAs were identified in 8-month-old mice

(156 upregulated and 266 downregulated), with Gene Ontology (GO)

analysis revealing that these target genes were predominantly

enriched in processes including but not limited to camera-type eye

development and sensory organ development (198). As tsRNA research remains in its

infancy, further investigations focusing on the association between

tsRNAs and ARCs, as well as their underlying molecular mechanisms,

are needed to provide novel insights into cataractogenic processes

and ARC disease management.

Understanding ncRNA functions in isolation becomes

increasingly difficult due to intricate regulatory networks among

ncRNAs. These networks involve multiple layers of interaction:

ncRNAs frequently share common protein-coding mRNA targets; miRNAs

functionally interact with other ncRNA species rather than

operating in isolation; and lncRNAs and circRNAs, in turn, regulate

the abundance of available miRNAs (199). ncRNA networks serve a pivotal

role in ARC pathogenesis by modulating gene expression, oxidative

stress responses and pathological processes in LECs, indicating

potential targets for early diagnosis and therapeutic intervention

(134,200).

In addition to the networks among different types

of ncRNAs, such as the aforementioned ceRNAs, interactions also

exist between the same type of ncRNAs. Emerging research across

various diseases, including cancers and cardiovascular diseases,

has revealed that certain miRNAs can be involved in the same

biological pathways either as effectors or regulators (201). Krek et al (202) demonstrated that myotrophin

(Mtpn) was a direct target of miR-124, let-7b and miR-375,

as evidenced by small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated

downregulation of Mtpn protein levels and suppression of

luciferase activity in dual-luciferase reporter assay.

Cotransfection of the luciferase reporter and a pool of siRNA

duplexes designed to mimic the function of miR-124, let-7b and

miR-375, resulted in normalized luciferase activity that was

substantially less than the activity in any of the groups

transfected with a single siRNA, revealing cooperative regulation

of Mtpn by these miRNAs (202). Similarly, lncRNAs could

interact with each other by co-regulating genes participating in

the same or similar biological functions (203). Multiple lncRNAs, such as

OIP5-AS1, TUG1 and NEAT1, have been implicated in the synergistic

regulation of genes and pathways in cancer (204). Current research on ncRNAs in

ARCs primarily focuses on their dysregulation in ARCs and the ceRNA

mechanism (104,140,174,205). The cooperative interactions

among ncRNAs remain poorly characterized and require further

analyses and validation to achieve a comprehensive understanding of

the cooperative behaviours of ncRNAs in ARC pathogenesis.

DNA methylation, a fundamental epigenetic

modification, stably modulates gene expression through heritable

regulatory mechanisms, influencing diverse physiological processes

and disease pathogenesis (206). In mammals and humans, DNA

methylation critically participates in numerous biological

processes, including genomic imprinting (207), X-chromosome inactivation

(208), transcriptional

regulation (209) and

tumorigenesis (210). DNA

methylation is a covalent chemical modification involving the

selective addition of methyl groups to DNA molecules, catalysed by

DNA methyltransferases (211).

Although DNA methylation occurs at various sites, including the C5

position of cytosine (212), N6

position of adenine (213) and

N7 position of guanine (214),

5-methylcytosine (m5C) remains the most prevalent and

extensively studied modification in humans, representing the

principal focus of DNA methylation research (215-217). The term 'DNA methylation' in

general primarily refers to the methylation of the 5th carbon atom

of cytosine within cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites, yielding

m5C (215,218).

CpG sites, consisting of cytosine-guanine

dinucleotides, are distributed throughout the genome (219). These sites frequently cluster

in CpG islands, genomic regions with a high density of CpG

dinucleotides, which are predominantly located near gene promoters

(220). CpG islands are

critical regulatory elements for gene expression, as promoter DNA

methylation can inhibit transcription factor binding or recruit

methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) proteins and HDACs, ultimately

inducing gene silencing (221,222). Hypermethylation of CpG islands

in promoter regions is strongly associated with transcriptional

silencing, whereas unmethylated states are typically associated

with active gene expression (108,223).

Previous studies in ophthalmology have indicated

that aberrant DNA methylation disrupts the expression of key genes,

such as RHO, OPN1LW and TUBA1A (227,228), contributing to the pathogenesis

of various ocular diseases, such as corneal and conjunctival

disorders, glaucoma (229),

cataracts (230), retinal

diseases (231), and ocular

tumours (232). As the leading

global cause of blindness, cataracts, particularly ARCs, serve as a

paradigm of ocular aging, wherein epigenetic dysregulation

synergizes with cumulative environmental stressors, including UV

radiation and chemical exposures (233,234). While congenital and traumatic

cataracts result from genetic mutations or physical injury, ARCs

stem from progressive lens opacification associated with multiple

factors, including oxidative stress, protein aggregation, and

critically, DNA methylation-mediated silencing of protective genes

in LECs (Table SIV) (108,235,236). For example, age-dependent

hypermethylation of the Klotho gene, a key anti-aging factor,

progressively silences its expression, leading to marked reduction

or even complete loss of Klotho expression at both mRNA and protein

levels, ultimately participating in ARC pathogenesis (237). Furthermore, both mRNA and

protein expression of DNA methylation-related genes (DNMT3B and

MBD3) are elevated in LECs of ARCs, further substantiating the

involvement of DNA methylation in ARC development (238).

To characterize the epigenetic landscape of ARCs,

several studies have examined genome-wide methylation patterns in

ARC samples. Chen et al (239) employed the MethylationEPIC

BeadChip (850K) to profile DNA methylation in anterior lens capsule

membranes from patients with ARCs and control subjects. By

integrating GO and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

pathway enrichment analyses with their previously published

transcriptome sequencing data, the authors identified

differentially methylated genes. Their analysis revealed 52,705

differentially methylated sites in the ARC group (13,858

hypermethylated and 38,847 hypomethylated) compared with the

control group, which consisted of non-ARC patients, with GO and

KEGG analyses highlighting functional associations with cell

membrane components, calcium signalling pathways and their

potential molecular mechanisms (239). Similarly, a study conducted in

2018 used DNA methylation microarrays, a high-throughput sequencing

approach, to identify methylated genes, and revealed that aberrant

methylation of collagen type IV α1 chain (COL4A1), gap junction

protein α3 and signal induced proliferation associated 1 like 3 was

associated with ARCs (240).

Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the role of these

DNA methylation changes in ARC pathogenesis.

Oxidative stress is a well-established driver of

LEC pathophysiology and a key contributor to ARC pathogenesis

(7-9). Emerging evidence has further linked

oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in LECs to cataract formation

(241,242). Therefore, DNA

methylation-mediated dysregulation of oxidative stress-related

genes and DNA damage repair genes has emerged as a primary research

focus, given its pivotal role in ARC development.

Methylation changes in oxidative stress-related

genes, as epigenetic modifications of the antioxidant defence

system, likely contribute to oxidative stress-induced lens damage

in ARC (223,235,243).

One of the main antioxidant defence mechanisms is

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activation. Nrf2

is a central nuclear transcriptional factor, which controls the

transcription of >200 protective genes, including 20 genes

encoding antioxidant enzymes (244). The activity of the Nrf2 pathway

is regulated through multiple mechanisms, both upstream and

downstream, as well as by other signalling pathways (245). Kelch-like ECH-associated

protein 1 (Keap1) is an oxidative stress sensor and a negative

regulator of Nrf2 (246). Under

basal conditions, Keap1 binds to Nrf2 in the cytoplasm, promoting

its ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation, and thus,

maintaining Nrf2 at basal levels (247). During oxidative stress,

elevated ROS disrupt the Keap1-Nrf2 interaction, enabling Nrf2

nuclear translocation. Within the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to

antioxidant response elements in target gene promoters, inducing

the expression of antioxidant enzymes that mediate ROS clearance

(248). The Nrf2/Keap1 pathway

serves as a master regulator of redox homeostasis, orchestrating

the expression of key antioxidant enzymes, including heme

oxygenase-1, GPX and superoxide dismutase (SOD), to mitigate

oxidative damage (249,250).

The Nrf2/Keap1 pathway is a critical regulator of

antioxidant defence in the lens, and its dysregulation may

contribute to ARC pathogenesis (246). Age-dependent demethylation of

the Keap1 promoter (223)

upregulates Keap1 expression, enhancing Nrf2 proteasomal

degradation and impairing Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defences. This

redox imbalance, driven by Keap1 promoter demethylation, gives rise

to ROS accumulation in LECs, ultimately promoting ARC development

(223). The methylation status

of the Keap1 promoter can be influenced by multiple exogenous and

endogenous compounds. Valproic acid (VPA), an antiepileptic drug,

alters the expression profiles of passive DNA demethylation pathway

enzymes such as Dnmt1, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, and the active DNA

demethylation pathway enzyme ten-eleven translocation 1 (TET1),

leading to DNA demethylation in the Keap1 promoter of LECs

(251). Similarly, sodium

selenite, a widely used experimental cataract-inducing agent,

suppresses Nrf2-dependent antioxidant protection while facilitating

lenticular protein oxidation and cataract formation (246). Furthermore, methylglyoxal

treatment in LECs results in loss of Keap1 promoter methylation and

impairment of the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant system (252). By contrast, ferulic acid, a

compound with well-documented antioxidant activity (253-255), protects LECs against

ultraviolet A-triggered oxidative stress via inhibition of Keap1

promoter demethylation (245).

Furthermore, co-treatment with exogenous acetyl-L-carnitine

effectively counteracts homocysteine (Hcy)-induced Keap1 gene

demethylation in LECs, while regulating Nrf2/Keap1 mRNA expression,

restoring antioxidant protein levels and mitigating Hcy-driven ROS

overproduction (256).

Under physiological conditions, the lens maintains

high endogenous glutathione (GSH) levels, which serve an essential

role in antioxidant defence by scavenging ROS and preserving

proteins in their reduced state (257). GSH-S-transferases (GSTs) are a

diverse group of phase II detoxification enzymes that catalyse the

conjugation of GSH to both endogenous oxidative stress products and

exogenous electrophilic compounds (258,259). All eukaryotic species possess

multiple cytosolic and membrane-bound GST isoenzymes, and the

cytosolic enzymes are encoded by at least five distantly related

gene families (α, μ, π, σ and θ classes) (260). Furthermore, several GST

isozymes modulate the MAPK signalling cascade, which mediates

cellular responses to oxidative stress (261,262).

NER is a highly conserved DNA repair pathway

responsible for processing helix-destabilizing and/or -distorting

DNA lesions, such as UV-induced photoproducts (269). During NER, Cockayne syndrome

complementation group B (CSB), encoded by the ERCC6 gene, recruits

NER repair factors to DNA damage sites and facilitates subsequent

repair (67). CSB protein

deficiency has been implicated in Cockayne syndrome (270). The expression of ERCC6 at both

mRNA and protein levels is reduced in LECs of ARNCs, and is

associated with methylation of a CpG site in the ERCC6 promoter,

suggesting epigenetic regulation of ERCC6 in LECs of ARNCs

(108). Furthermore,

ultraviolet-B (UVB) exposure contributes to ARNC development by

inducing DNA damage, which is typically repaired via the NER

mechanism (108). UVB-treated

human lens epithelium B3 (HLE-B3) and 239T cells exhibit

hypermethylation at the-441 CpG site (relative to the transcription

start site) within the Sp1 transcription factor binding region of

the ERCC6 promoter, along with increased recruitment of DNMT3B to

this site (108).

OGG1 is a key enzyme in the BER pathway that

specifically recognizes and excises the oxidatively damaged base

8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine, a mutagenic lesion that induces G:C→T:A

transversions (271). Loss of

functional OGG1 is associated with the pathogenesis of multiple

age-related diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, age-related

macular degeneration and ARCs (272-274). Hypermethylation of the

first-exon CpG island of the OGG1 gene has been observed in the

lens cortex of ARCs, and was associated with low OGG1 expression

and impaired DNA repair function, and eventually contributed to

lens opacity (275).

In addition, two other DNA repair genes exhibit

epigenetic silencing in ARC: The Werner syndrome gene (WRN) and

O6-methylguanine-methyltransferase (MGMT). WRN, which maintains

genomic stability by repairing DNA DSBs (276), is hypermethylated in the

promoter CpG island of ARC anterior lens capsules and its

expression is decreased compared with those in normal controls

(43). Similarly, MGMT, an

enzyme that removes mutagenic adducts from the O-6 position of

guanine, thereby protecting the genome against guanine-to-adenine

transitions (277), has been

observed to be hypermethylated and downregulated in ARCs (278). These deficiencies lead to the

accumulation of unrepaired DNA lesions, driving cell dysfunction

and genomic instability, which further promotes ARC progression

(108).

Numerous studies have established the indispensable

role of lens crystallins in maintaining lens clarity, optical

transparency and refractive function (279,280). CRYAA and αB-crystallin, the

subunits of oligomeric α-crystallin, constitute ~35% of total lens

proteins (281). In addition to

serving as a major structural protein component of the lens, CRYAA

exhibits molecular chaperone-like activity that protects other

crystallins from thermally induced inactivation or aggregation,

thereby being essential for maintaining lens transparency (280-282). Furthermore, CRYAA mediates

cytoprotective effects against both thermal and oxidative stress in

LECs (283), and a study has

demonstrated that CRYAA can delay cataract formation by trapping

denatured proteins prone to aggregation (279). CRYAA expression levels have

been reported to be reduced in ARC lenses, with hypermethylation of

the CRYAA gene promoter CpG islands representing a key mechanism

for CRYAA downregulation (230). Evidence indicates that

methylation of CpG sites in the CRYAA promoter directly reduces the

DNA-binding capacity of the transcription factor Sp1 (236). Treatment with the DNA

demethylating agent zebularine increases CRYAA expression in LECs,

suggesting a potential novel therapeutic strategy for ARCs

(230,236).

COL4A1 encodes the α1 chain of type IV collagen,

the major collagen component of basement membranes (284). Genome-wide methylation analysis

has revealed hypermethylation of the COL4A1 promoter region in

anterior lens capsule samples from patients with ARCs (240). In both HLE-B3 cells and

anterior lens capsules of rats, UVB irradiation induces DNA

hypermethylation of COL4A1 promoter CpG islands, and thus,

suppresses COL4A1 expression, indicating that epigenetic

alterations of the COL4A1 promoter might be involved in UVB-induced

lens damage in ARCs (285).

In summary, emerging evidence has highlighted the

role of DNA methylation in the pathogenesis of ARCs, linking

epigenetic dysregulation to oxidative stress, DNA damage and

cellular dysfunction of LECs. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns in

key genes may serve as potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

Further studies based on large-scale clinical research and model

systems are needed to identify and validate additional methylation

signatures, elucidate underlying mechanisms and explore targeted

epigenetic interventions.

As essential structural components, histone

proteins form the fundamental building blocks of chromatin.

Histones undergo posttranslational modifications (PTMs), which

modulate their affinity for DNA, and thus, influence chromatin

compaction states (286). These

modifications are highly dynamic and continuously changing in

response to histone-modifying enzyme activity, ultimately

generating specific PTM patterns linked to epigenetic diseases

(287). Posttranslational

histone modifications include acetylation, methylation,

phosphorylation, citrullination, ubiquitination and adenosine

diphosphate ribosylation (288,289). Of these, histone acetylation

and methylation have been most extensively studied, with

substantial evidence supporting their associations with ARCs

(Table SV) (43,108,235,243,290).

Histone acetylation is a reversible modification of

multiple lysine residues on histone tails, and dynamically

regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and HDACs (291). HATs are a class of enzymes that

catalyse the transfer of acetyl groups to lysine residues on

histone tails, promoting transcriptional activation by disrupting

the interaction between histone tails and nucleosomal DNA, thus

facilitating chromatin opening (292). By contrast, HDACs catalyse the

removal of acetyl groups from histone tails and suppress

transcriptional activity by producing a more condensed chromatin

state (293). To date, HDACs

have been classified into four major groups (classes I-IV)

(294). Among these, SIRT1, a

class III NAD+-dependent deacetylase and a member of the

sirtuin family, may be critical in protecting against oxidative

stress-induced ocular damage, including ARCs (295). Notably, SIRT1 expression is

upregulated in human ARCs, suggesting a compensatory mechanism in

response to stressors such as UV radiation and oxidative damage.

This upregulation may confer protection by modulating oxidative

stress responses and inhibiting apoptosis of LECs (296,297).

Histone methylation refers to the transfer of

methyl groups from SAM to specific lysine or arginine residues on

histone proteins (298). This

epigenetic modification is catalysed by histone methyltransferases,

while its removal is mediated by histone demethylases (299). Lysine residues can undergo

mono-, di- or tri-methylation, whereas arginine methylation is

limited to mono- or di-methylated states (299). The functional impact of histone

methylation on transcriptional regulation depends on both the

modified residue and the degree of methylation (298). For instance, methylation at

H3K4, H3K36 and H3K79 is associated with transcriptional

activation, whereas methylation at H3K9, H3K27 and H4K20 promotes

transcriptional repression (300). As histone methylation can

either activate or repress gene expression, it serves as a critical

regulator of transcriptional activity in LECs (235).

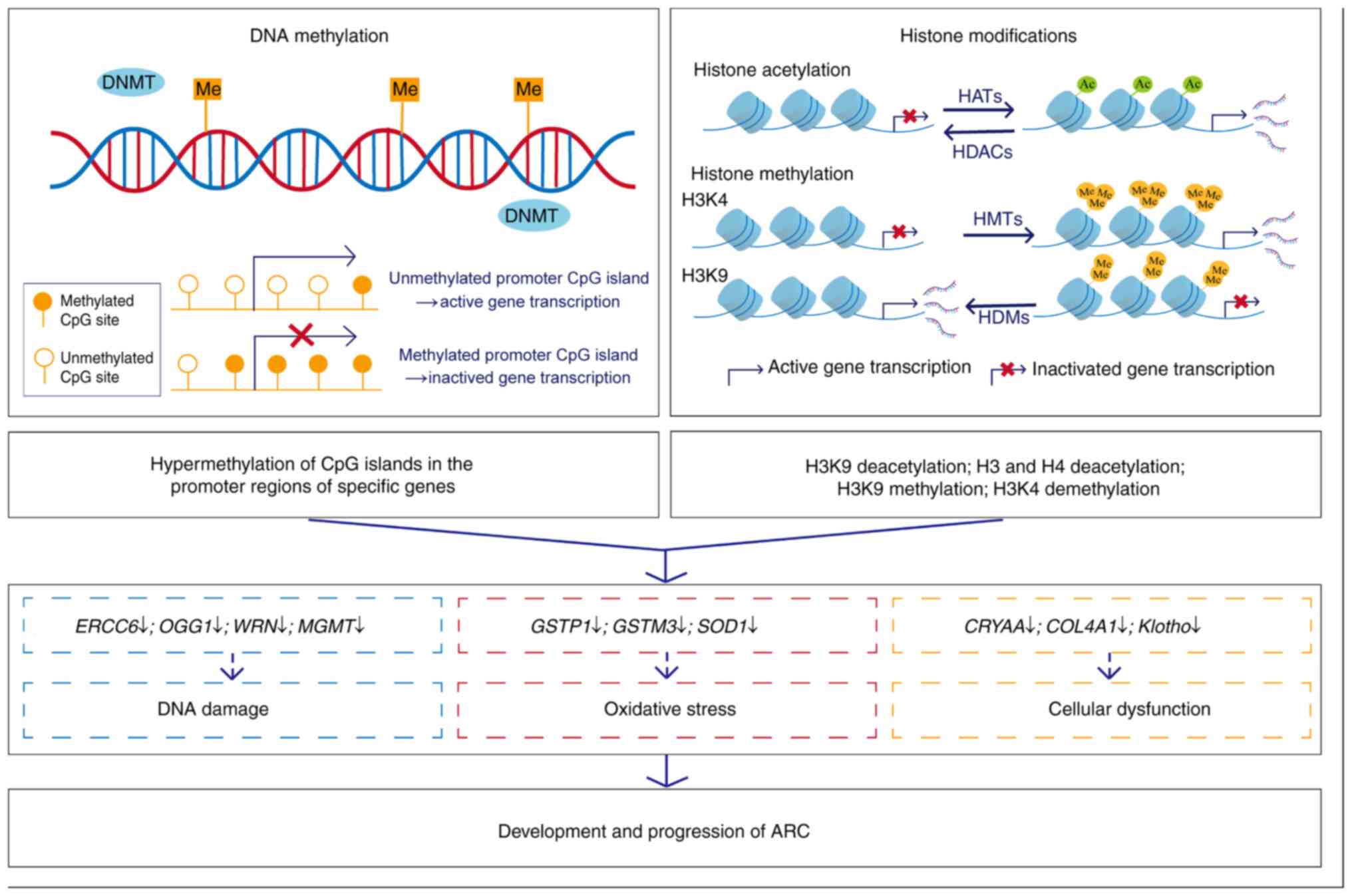

Histone modifications, along with DNA methylation,

influence the expression of certain genes in LECs. Dysregulation of

these genes exacerbates oxidative stress damage and DNA damage

while impairing normal cellular functions, thereby promoting the

development and progression of ARC (43,108,235-237,243,275,278,285,290) (Fig. 2). Notably, numerous genes

implicated in ARCs are dually regulated by both DNA methylation and

histone modifications (43,108,235,243). These epigenetic mechanisms do

not operate in isolation but instead engage in dynamic crosstalk,

wherein each modification reciprocally enhances or inhibits the

other to modulate gene expression (301). For instance, one study has

demonstrated that endogenous DNMT3A and DNMT3B are associated with

HDAC activity, where DNMT3A facilitates transcriptional repression

via specific molecular interactions between its ATRX-like PHD

domain and both HDAC1 and the co-repressor RP58 (302). Consequently, future research

examining the effects of DNA methylation and histone modifications

on target genes should systematically consider the crosstalk

between these two epigenetic mechanisms.

Similar to DNA modifications, RNA modifications are

dynamically regulated by specific enzymes that catalyse the

addition or removal of chemical groups on RNA nucleotides. These

modifications serve critical roles in molecular processes,

including pre-mRNA splicing, nuclear export, transcript stability

maintenance and translation initiation (303). Prevalent RNA modifications

include m6A, N1-methyladenosine, m5C and

7-methylguanosine (m7G) (304). Among these modifications,

m6A is the best-characterized modification, and is the

primary focus in this section.

Epigenetic regulation is implicated in oxidative

stress-related processes crucial in the initiation and development

of ARCs (223). ncRNA networks

regulate the expression of oxidative stress-related genes such as

NOX4, SIRT1 and GPX4, and aberrant levels of ncRNAs alter the

levels of pro-oxidant markers and antioxidant enzymes in LECs

(68,79,140). Clinically, associations have

been observed between abnormal ncRNA expression and changes in

oxidative stress markers in patients with ARCs (76). Wu et al (318) explored the relationship between

miRNAs and oxidative stress-related genes, and found that

cataract-regulated miRNAs could promote cataract formation not only

by targeting the 3' UTR, which is a classic regulatory pathway, but

also by binding to the TATA-box region of oxidative stress-related

genes, leading to the subsequent elevation of pro-oxidative genes

and inhibition of anti-oxidative genes. Furthermore, numerous

critical genes that serve protective roles in oxidative stress

processes, such as GSTP1, GSTM3 and SOD1, are regulated by DNA

methylation and histone modifications (235,243,290). Additional oxidative

stress-related genes implicated in ARC pathogenesis remain to be

fully characterized, particularly regarding their functional

contributions to disease progression and regulation through

epigenetic mechanisms.

Oxidative stress induced by exogenous stimuli can

also induce epigenetic alterations, since ROS can regulate the

activity of epigenetic enzymes involved in DNA, RNA and histone

modifications (319-321). For example, UVB exposure

induces the recruitment of DNMT3b and HDAC1 at the ERCC6 promoter,

thereby resulting in epigenetic alterations, including specific

hypermethylation of the CpG site and H3K9 deacetylation of ERCC6 in

LECs (108). At both cellular

and organismal levels, UVB exposure enhances the expression of

DNMTs, including DNMT1/2/3, and reduces the expression of TETs,

including TET1/2/3, leading to hypermethylation of COL4A1 promoter

CpG islands and subsequent inhibition of COL4A1 expression

(285). Furthermore, ROS can

directly induce the oxidation of m5C to

5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) (322). 5hmC may activate DNA

demethylation processes and serve as an intermediate of DNA

demethylation, thus causing DNA hypomethylation (322). Numerous studies have indicated

that dysregulation of 5hmC could be involved in multiple diseases,

including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases (323,324). However, the association between

5hmC and ARCs remains to be fully elucidated.

Epigenetic modulators, including DNA

methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTis) and histone deacetylase

inhibitors (HDACis), represent a novel class of therapeutic agents

capable of correcting aberrant epigenetic modifications, providing

innovative intervention strategies against molecular defects

underlying cancer and other diseases. These compounds offer unique

therapeutic advantages due to their reversible and targetable

nature, enabling precise gene regulation without modifying DNA

sequences (325-327). The DNMTis azacitidine and

decitabine are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes and acute

myeloid leukaemia, and exert their effects by inhibiting DNMTs and

reversing tumour-suppressor gene silencing through DNA

demethylation (328,329). Several other epigenetic drugs,

such as vorinostat, belinostat and romidepsin, are FDA-approved for

the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and peripheral T-cell

lymphomas (330-332). Although DNMTis and HDACis have

been extensively tested in clinical and preclinical trials for

human diseases (333-335), their effects in ARCs remain

poorly understood. The DNMTi 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (decitabine)

restores the transcriptional activities of GSTP1 in LECs (235), and trichostatin A (TSA; HDACi)

corrects the anacardic acid (HAT inhibitor)-induced imbalance

between HATs and HDACs, causing increased SOD1 expression by

reversing histone acetylation (290). These findings provide evidence

that DNMTis and HDACis could rescue LECs from dysregulated

expression of key genes induced by aberrant epigenetic alterations

during ARC development. Notably, HDACis also exhibit antioxidant

properties, as evidenced by multiple studies (336,337). Qiu et al (338) compared the protective effects

of four HDACis, β-hydroxybutyrate, TSA, suberoylanilide hydroxamic

acid (SAHA) and VPA, on HLECs following UVB exposure, and found

that low concentrations of HDACis (1 μmol/l SAHA) mildly

attenuated oxidative stress. Although these promising in

vitro findings support these drugs as possible candidates for

ARC intervention, further validation through well-controlled in

vivo studies is required for their clinical application.

Alterations in the expression patterns of various

ncRNAs have been reported in ARCs (41,72,131,198), suggesting that targeted

modulation of aberrant ncRNA activity may hold therapeutic

potential. Over the past decade, miRNA mimics and anti-miRNAs have

demonstrated therapeutic promise in clinical trials for various

diseases, such as advanced solid tumours, ulcerative colitis and

hepatitis C virus infection (339-341), whereas no lncRNA drug has

reached the clinical development stage (342). miRNA mimics replicate

endogenous miRNA functions to compensate for miRNA deficiency in

pathological conditions, while anti-miRNAs (antagomirs) are

engineered to suppress endogenous miRNAs that contribute to disease

progression (342). As

aforementioned, administration of anti-miRNAs targeting miR-326,

miR-29a-3p and miR-187 independently enhanced lens transparency and

ameliorated lens damage in ARC animal models, indicating their

potential as viable non-surgical alternatives for ARC intervention

(103-105). Furthermore, with increasing

recognition of the regulatory functions of circRNAs in disease

pathogenesis, circRNAs are increasingly being considered as targets

for therapeutic intervention (56,176,182). For instance, circRNA 06209

overexpression through plasmid injection in a rat model of ARCs

reduced lens opacity (182).

However, before ncRNA-based therapies advance to the preclinical

stage, several challenges must be addressed, including RNA

instability, immune activation and off-target effects (342).

Epigenetic modifiers hold potential for the

prevention and treatment of ARCs, but there is still a long way

ahead before these agents can be routinely implemented in clinical

practice. Future studies should focus on: i) Identifying novel

therapeutic targets and developing corresponding treatments; ii)

investigating and optimizing intraocular drug delivery systems with

high efficiency and biocompatibility; and iii) evaluating long-term

safety and efficacy in both animal models and clinical trials.

Technological breakthroughs and cutting-edge

research have sparked growing interest in the pivotal role of

epigenetics in ocular disease. Advances in omics and

high-throughput sequencing technologies have facilitated the

elucidation of the role of epigenetics in disease pathogenesis and

the identification of potential targets. This section highlights

two emerging technologies, single-cell multi-omics and spatial

transcriptomics, and discusses their transformative potential in

deciphering the epigenetic landscape of ARCs.

Single-cell multi-omics sequencing enables

simultaneous single-cell profiling of chromatin accessibility,

histone modifications, transcription factor binding, DNA

methylation and transcriptome analysis (343). This approach has revealed cell

type-specific epigenetic regulatory mechanisms in brain development

(344), cancer evolution

(345) and HIV-associated

immune exhaustion (346).

Tangeman et al (347)

described the first single-cell multiomic atlas of lens

development, depicting a comprehensive portrait of lens fibre cell

differentiation and exploring congenital cataract-linked regulatory

networks. However, to the best of our knowledge, single-cell

multi-omics has not yet been applied in research on ARCs. Current

research considers different omics levels individually, drawing

conclusions from each level separately, without data integration

for a cohesive understanding of the overall mechanisms. Single-cell

multi-omics could revolutionize ARC research by offering a

comprehensive understanding of the complex biological processes

involved in ARC pathogenesis.

Spatial transcriptomics allows high-resolution

profiling of gene expression in intact cell and tissue samples

(348), and has made

significant advances in recent years, exerting notable influence on

diverse fields, such as tissue architecture, developmental biology

and disease research, particularly in cancer and neurodegenerative

diseases (349). Given the

differential miRNA expression profiles among ARC subtypes defined

by the location of lens opacity (72), there may be differences in gene

expression profiles across different regions of the lens. To the

best of our knowledge, spatial transcriptomics remains unexplored

in epigenetic studies of ARCs. Spatial transcriptomics allows the

quantification and illustration of gene expression profiles within

the native spatial context (350), which could facilitate the

identification of epigenetic biomarkers and microenvironmental

interactions critical for understanding cataract pathogenesis.

The epigenetic clock, also known as DNA methylation

age (DNAmAge), is a biomarker for biological age prediction based

on DNA methylation patterns at specific CpG sites (351). By modelling linear correlations

between methylation levels and chronological aging, it serves as a

molecular 'timer' that can estimate cellular aging rates more

accurately than chronological age, with implications for disease

risk and lifespan prediction (352). Epigenetic age acceleration

(EAA) exhibits strong associations with age-related diseases by

reflecting discrepancies between DNAmAge and chronological age,

acting as a predictive biomarker for conditions such as

cardiovascular disorders, neurodegenerative diseases and type 2

diabetes (353).

To investigate the causal relationship between

epigenetic clocks and common age-related eye diseases or glaucoma

endophenotypes, Chen et al (354) conducted bidirectional

two-sample Mendelian randomization and found that ARCs were linked

to decreased HannumAge, a measure of extrinsic aging based on 71

age-related CpGs from whole blood samples of adults. Further

research is warranted to determine whether quantifying EAA can

effectively identify ARC susceptibility at early stages and whether

it may serve as a basis for developing targeted interventions to

delay lens opacification.

Breakthroughs in omics, bioinformatics and

high-throughput sequencing technologies have accelerated

discoveries regarding the role of epigenetics in ARCs, enabling a

deeper understanding of the initiation and progression mechanisms

of ARCs while potentially revolutionizing disease management

approaches. The present review comprehensively summarizes advances

in epigenetic research on ARCs, examining how ncRNAs, DNA

methylation, histone modifications and m6A modification

contribute to ARC pathogenesis, and exploring their clinical

potential for innovative therapeutic strategies. Epigenetics in

ARCs is an emerging field with immense potential for diagnosis,

treatment and prevention of lens opacities, as innovations over the

past decade have identified numerous epigenetic alterations as

potential biomarkers and intervention targets. Further studies are

required to identify therapeutic targets and biomarkers, elucidate

the precise mechanisms through which epigenetics influences disease

pathogenesis, evaluate the efficacy and safety of novel epigenetic

therapies, and translate these therapies into clinical

practice.

Not applicable.

WY collected the literature and drafted the

manuscript. YZ, SC, JG and ZP reviewed the manuscript and made

revisions to the manuscript. YY directed the work and revised the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82371036), and the Key Research and

Development Program of Zhejiang Province (grant no.

2025C02156).

|

1

|

Cicinelli MV, Buchan JC, Nicholson M,

Varadaraj V and Khanna RC: Cataracts. Lancet. 401:377–389. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Shiels A and Hejtmancik JF: Mutations and

mechanisms in congenital and age-related cataracts. Exp Eye Res.

156:95–102. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

3

|

Asbell PA, Dualan I, Mindel J, Brocks D,

Ahmad M and Epstein S: Age-related cataract. Lancet. 365:599–609.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Abdelkader H, Alany RG and Pierscionek B:

Age-related cataract and drug therapy: Opportunities and challenges

for topical antioxidant delivery to the lens. J Pharm Pharmacol.

67:537–550. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Meacock WR, Spalton DJ, Boyce J and

Marshall J: The effect of posterior capsule opacification on visual

function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 44:4665–4669. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang C, An Q, Zhou H and Ge H: Research

progress on the impact of cataract surgery on corneal endothelial

cells. Adv Ophthalmol Pract Res. 4:194–201. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Beebe DC, Holekamp NM and Shui YB:

Oxidative damage and the prevention of age-related cataracts.

Ophthalmic Res. 44:155–165. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kulbay M, Wu KY, Nirwal GK, Bélanger P and

Tran SD: Oxidative stress and cataract formation: Evaluating the

efficacy of antioxidant therapies. Biomolecules. 14:10552024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lou MF: Redox regulation in the lens. Prog

Retin Eye Res. 22:657–682. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rahman K: Studies on free radicals,

antioxidants, and co-factors. Clin Interv Aging. 2:219–236.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Berthoud VM and Beyer EC: Oxidative

stress, lens gap junctions, and cataracts. Antioxid Redox Signal.

11:339–353. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

12

|

Petrash JM: Aging and age-related diseases

of the ocular lens and vitreous body. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

54:ORSF54–ORSF59. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Babizhayev MA and Costa EB: Lipid peroxide

and reactive oxygen species generating systems of the crystalline

lens. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1225:326–337. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dische Z and Zil H: Studies on the

oxidation of cysteine to cystine in lens proteins during cataract

formation. Am J Ophthalmol. 34:104–113. 1951. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kleiman NJ and Spector A: DNA single

strand breaks in human lens epithelial cells from patients with

cataract. Curr Eye Res. 12:423–431. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kruk J, Kubasik-Kladna K and Aboul-Enein

HY: The role oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of eye diseases:

Current status and a dual role of physical activity. Mini Rev Med

Chem. 16:241–257. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kubota M, Shui YB, Liu M, Bai F, Huang AJ,

Ma N, Beebe DC and Siegfried CJ: Mitochondrial oxygen metabolism in

primary human lens epithelial cells: Association with age, diabetes

and glaucoma. Free Radic Biol Med. 97:513–519. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Brennan LA, McGreal RS and Kantorow M:

Oxidative stress defense and repair systems of the ocular lens.

Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 4:141–155. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cekić S, Zlatanović G, Cvetković T and

Petrović B: Oxidative stress in cataractogenesis. Bosn J Basic Med

Sci. 10:265–269. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Li G, Song H, Chen L, Yang W, Nan K and Lu

P: TUG1 promotes lens epithelial cell apoptosis by regulating

miR-421/caspase-3 axis in age-related cataract. Exp Cell Res.

356:20–27. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li WC, Kuszak JR, Dunn K, Wang RR, Ma W,

Wang GM, Spector A, Leib M, Cotliar AM, Weiss M, et al: Lens

epithelial cell apoptosis appears to be a common cellular basis for

non-congenital cataract development in humans and animals. J Cell

Biol. 130:169–181. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen X, Xu H, Shu X and Song CX: Mapping

epigenetic modifications by sequencing technologies. Cell Death

Differ. 32:56–65. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

23

|

Chen Y, Hong T, Wang S, Mo J, Tian T and

Zhou X: Epigenetic modification of nucleic acids: From basic

studies to medical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 46:2844–2872. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mazzio EA and Soliman KF: Basic concepts

of epigenetics: Impact of environmental signals on gene expression.

Epigenetics. 7:119–130. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Dawson MA and Kouzarides T: Cancer

epigenetics: From mechanism to therapy. Cell. 150:12–27. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Peixoto P, Cartron PF, Serandour AA and

Hervouet E: From 1957 to nowadays: A brief history of epigenetics.

Int J Mol Sci. 21:75712020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Gangisetty O, Cabrera MA and Murugan S:

Impact of epigenetics in aging and age related neurodegenerative

diseases. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 23:1445–1464. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Nikolac Perkovic M, Videtic Paska A,

Konjevod M, Kouter K, Svob Strac D, Nedic Erjavec G and Pivac N:

Epigenetics of Alzheimer's disease. Biomolecules. 11:1952021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Suárez R, Chapela SP, Álvarez-Córdova L,

Bautista-Valarezo E, Sarmiento-Andrade Y, Verde L, Frias-Toral E

and Sarno G: Epigenetics in obesity and diabetes mellitus: New

insights. Nutrients. 15:8112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sun L, Zhang H and Gao P: Metabolic

reprogramming and epigenetic modifications on the path to cancer.

Protein Cell. 13:877–919. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Okugawa Y, Grady WM and Goel A: Epigenetic

alterations in colorectal cancer: Emerging biomarkers.

Gastroenterology. 149:1204–1225.e12. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Trnkova L, Buocikova V, Mego M, Cumova A,

Burikova M, Bohac M, Miklikova S, Cihova M and Smolkova B:

Epigenetic deregulation in breast cancer microenvironment:

Implications for tumor progression and therapeutic strategies.

Biomed Pharmacother. 174:1165592024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Henikoff S and Greally JM: Epigenetics,

cellular memory and gene regulation. Curr Biol. 26:R644–R648. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Meng H, Cao Y, Qin J, Song X, Zhang Q, Shi

Y and Cao L: DNA methylation, its mediators and genome integrity.

Int J Biol Sci. 11:604–617. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wu Z, Zhang W, Qu J and Liu GH: Emerging

epigenetic insights into aging mechanisms and interventions. Trends

Pharmacol Sci. 45:157–172. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Desmettre TJ: Epigenetics in age-related

macular degeneration (AMD). J Fr Ophtalmol. 41:e407–e415. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kapuganti RS and Alone DP: Current

understanding of genetics and epigenetics in pseudoexfoliation

syndrome and glaucoma. Mol Aspects Med. 94:1012142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kowluru RA, Kowluru A, Mishra M and Kumar

B: Oxidative stress and epigenetic modifications in the