Introduction

Cancer cells cleverly evade T cell-mediated immune

responses by manipulating immune cells and leveraging immune

checkpoints to communicate with the host's defense mechanisms

within the tumor microenvironment (TME) (1). This process disrupts immune

surveillance, allowing tumors to escape detection and avoid

destruction. A critical component in this mechanism is programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1; also known as B7-H1 or CD274), a membrane

glycoprotein frequently overexpressed across various cancer types.

PD-L1 acts as a critical immune checkpoint molecule through its

interaction with programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1; also called

CD279), which is expressed on the surface of activated T

lymphocytes (2). This

interaction inhibits the activation of cytotoxic T cells, impairing

the immune system's ability to identify and eliminate cancer cells.

By hijacking this pathway, cancer cells can effectively evade

immune eradication, thereby promoting their survival and enabling

further progression (3).

Immunotherapies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 with

antibodies have shown significant and durable clinical responses in

treating various cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC), melanoma and renal cell carcinoma (4,5).

These therapies function by inhibiting the binding of PD-1 on

immune cells to PD-L1 on tumor cells, thereby enhancing the immune

system's ability to recognize and eradicate cancer cells. The

success of immune checkpoint blockade highlights its potential to

transform cancer treatment paradigms, providing new options for

patients who previously had limited alternatives (6). However, despite their notable

efficacy, these therapies do not benefit all patients and face

limitations such as poor tumor tissue penetration, adverse immune

reactions and lack of oral bioavailability (7). Additionally, targeting PD-L1 for

degradation, rather than merely blocking its interaction with PD-1,

might offer a more effective strategy by thoroughly disrupting the

PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis, potentially enhancing therapeutic

efficacy (8,9).

PD-L1 expression is regulated through multiple

mechanisms, including the activation of oncogenic transcription

factors such as c-Myc and NF-κB, which promote PD-L1 upregulation

at the gene transcription level. Additionally, post-translational

modifications, such as glycosylation and ubiquitination, are

essential for stabilizing PD-L1 and regulating its functional

protein levels (10). For

example, activating β-catenin during epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) induces the transcription and synthesis of the

STT3 gene (a catalytic subunit of the oligosaccharyltransferase

(OST) complex). This, in turn, promotes PD-L1 glycosylation,

thereby inhibiting its degradation in cancer stem cells (11). Furthermore, cyclin D-CDK4 and

glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) facilitate PD-L1

ubiquitination, marking it for proteasomal degradation (12,13). Notably, the oncogenic epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR) plays a key role in regulating PD-L1

expression. Inhibition of EGFR signaling destabilizes PD-L1 through

GSK3β activation, ultimately enhancing antitumor immunity (14). These findings suggested that

agents targeting EGFR may represent a promising approach to enhance

immune responses by promoting PD-L1 degradation.

GMI, a fungal immunomodulatory protein (FIP) from

Ganoderma microsporum, is a dietary supplement with both

nutritional and therapeutic benefits (15). Beyond its origin as an edible

mushroom, GMI has drawn significant attention for its diverse

biological properties, especially its potent anticancer activity.

GMI downregulates heat shock protein expression, which is

associated with apoptosis in lung cancer cells (16). In addition, it has shown

synergistic anticancer effects when combined with therapeutic

agents such as temozolomide and sotorasib in glioblastoma

multiforme (GBM) and KRASG12C mutant lung

cancers, respectively (17,18). GMI has been identified as an EGFR

degrader capable of disrupting EGFR-driven oncogenic signaling and

suppressing tumor growth in EGFR-positive cancers (19). However, whether GMI regulates

PD-L1 expression and enhances antitumor immune responses remains

unclear.

In the present study, the effects of GMI on PD-L1

expression were investigated and it was found that it promotes

GSK3β-mediated proteasomal degradation of PD-L1, leading to reduced

membrane PD-L1 levels. Furthermore, GMI enhances T cell-mediated

suppression of tumor cells. These findings collectively suggested

that GMI may serve as a functional food with potential therapeutic

benefits for enhancing antitumor immunity through modulating PD-L1

expression.

Materials and methods

Reagents

GMI was produced by MycoMagic Biotechnology. The

purification procedures and the detailed structural

characterization (Protein Data Bank ID: 3KCW) have been previously

documented (20). Bafilomycin A1

(Baf A1) and cycloheximide (CHX) were purchased from

MilliporeSigma. MG132 and lithium chloride (LiCl) were obtained

from ITW Reagents (PanReac AppliChem) and Enzo Life Sciences,

respectively. LY294002 and Osimertinib were purchased from

MedChemExpress and TargetMol, respectively. Anti-mouse PD-1

antibody (CD279; clone RMP1-14) was purchased from Bio X Cell.

Experimental cell lines and culture

conditions

Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC1), GBM8401 and Jurkat T

cells were obtained from the Bioresource Collection and Research

Center. A549 cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture

Collection. H1975 and T98G cells were obtained from Elabscience

Biotechnology, Inc. and the Japanese Cancer Research Resources

Bank, respectively. PC9 and CL1-5 cells were generously provided by

Dr Tsai of the National Yang Ming University and Dr P.C. Yang of

the National Taiwan University, respectively. U87, a human

glioblastoma cell line of unknown origin (21), was kindly provided by Dr T.H. Tu

of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. The LLC1-hPD-L1 cell line was

a gift from Dr K.L. Lan of the National Yang Ming Chiao Tung

University.

LLC1-hPD-L1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's

Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(VWR Life Science Seradigm), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% sodium

pyruvate, 1% L-glutamine (all from GIBCO; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and 200 μg/ml hygromycin B (MedChemExpress). Short

tandem repeat (STR) analysis was used for authentication in H1975,

A549 and GBM8401 cell lines. Detailed culture conditions for the

other cell lines have been previously described (18,19). All cell cultures were incubated

at 37°C in a humidified environment containing 5%

CO2.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) analysis

The extraction of membrane proteins used for

LC-MS/MS analysis has been previously described (22). Briefly, membrane proteins were

extracted from GMI-treated cells and subjected to proteomic

analysis. Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) regulated by GMI

were identified based on a fold change (GMI/CTL) of <0.75 or

>1.33. These DEPs were then analyzed for pathway enrichment

using ShinyGO V0.80 (23), and

the selected enriched pathway was visualized using KEGG diagrams,

with DEPs highlighted in red (24,25).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

(IP) assay

Western blot analysis was performed as previously

described (26). In brief,

treated cells were harvested and lysed in a cell lysis buffer

containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (MilliporeSigma).

The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,200 × g for 10 min

at 4°C, and protein concentrations in the supernatants were

quantified prior to analysis using the Bradford protein assay

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), with bovine serum albumin (BSA;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as the calibration standard.

Subsequently, 30 μg of total protein from each sample was

separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and

transferred onto PVDF membranes (0.45 μm; MilliporeSigma).

The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C

overnight, followed by incubation with species-specific secondary

antibodies at room temperature for 1 h prior to chemiluminescence

detection. For IP assay, cells were pretreated with a proteasome

inhibitor, followed by GMI treatment for the indicated time. Cell

lysates were prepared and centrifuged in IP lysis buffer containing

EDTA at 16,200 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Then, 400 μg of

supernatant was incubated overnight at 4°C with a PD-L1 antibody

(1:50) for immunoprecipitation. Ubiquitinated PD-L1 was

subsequently detected by western blotting. Antibodies for detecting

PD-L1 (rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no. 13684), phosphorylated (p-)GSK3β

(Ser 9; rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no. 5558), p-AKT (Ser473; rabbit;

1:1,000; cat. no. 4060), p-EGFR (Tyr1068; rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no.

3777) and ubiquitin (mouse; 1:1,000; cat. no. 3936) were acquired

through Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Antibodies specific to

GSK3β (rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no. GTX111192), caveolin (rabbit;

1:1,000; cat. no. GTX100205), EGFR (rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. no.

GTX121919), tubulin (rabbit; 1:10,000; cat. no. GTX112141), goat

anti-mouse IgG antibody (HRP; 1:10,000; cat. no. GTX213111-01) and

goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (HRP; 1:10,000; cat. no.

GTX213110-01) were obtained via GeneTex International Corporation.

AKT (rabbit; 1:1,000; cat. IR171-666) antibody was purchased from

iReal Biotechnology. Protein band intensities were quantified by

densitometric analysis using ImageJ software (version 1.53a;

National Institutes of Health), with values normalized to the

respective loading controls.

Extraction of plasma membrane PD-L1

The experimental procedures have been previously

documented (19). Briefly,

plasma membrane proteins were isolated using the Trident Membrane

Protein Extraction Kit (GeneTex International Corporation),

following the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted membrane

proteins were subsequently evaluated using western blot

analysis.

Immunofluorescence assay

H1975 and CL1-5 cells (2×104) were seeded

on coverslips and treated with GMI and/or LiCl for 3 h. Cells were

then subjected to fixation at room temperature for 15 min with 4%

paraformaldehyde (Bioman Scientific Company, Ltd.) and

permeabilized in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (MilliporeSigma)

for another 10 min. Blocking was performed with PBS containing 1%

BSA for 30 min. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C with

anti-PD-L1 primary antibodies (1:400; Abcam; cat. no. ab205921).

After washing with PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 20, the cells

were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with goat anti-rabbit

IgG antibody (DyLight488; 1:1,000; GeneTex International

Corporation; cat. no. GTX213110-04). Nuclei were visualized by

mounting cells with Fluoroshield containing DAPI (Millipore; cat.

no. F6057). Observations and imaging were performed using an

ImageXpress Pico digital microscope (Molecular Devices, LLC).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the Quick-RNA Miniprep

Kit (Zymo Research Corp.), following the manufacturer's

instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed from

500 ng of RNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (Takara Bio,

Inc.) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Amplification

of the cDNA was performed with TB Green® Premix Ex Taq

II (Takara Bio, Inc.) on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

thermocycling conditions were set as follows: initial denaturation

at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C

for 5 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 sec. The specific

primers for the genes of interest were as follows: PD-L1 forward,

5'-CAATGTGACCAGCACACTGAGAA-3' and reverse,

5'-GGCATAATAAGATGGCTCCCAGAA-3'; and GAPDH forward,

5'-TGGTATCGTGGAAGGACTCA-3' and reverse, 5'-AGTGGGTGTCGCTGTTGAAG-3'.

Relative PD-L1 mRNA levels were quantified by the comparative

2−ΔΔCq method (27),

using GAPDH as the endogenous control and normalized to the control

group.

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA)

transfection

Lentiviral shRNA transfection was conducted as

previously described (18).

Briefly, one CTL-shRNA (shCTL; TRCN0000208001; pLKO.1 empty-vector

negative control lacking an shRNA hairpin insert) and two

GSK3β-shRNA lentivirus constructs were obtained from the National

RNAi Core Facility (Taipei, Taiwan) and generated in 293T cells.

These lentiviruses were subsequently employed to transduce H1975

and CL1-5 cells, followed by selection with 5 μg/ml

puromycin (MilliporeSigma). The target sequences for GSK3β were

5'-AGCAAATCAGAGAAATGAAC-3' (shGSK3β#1; TRCN0000039565) and

5'-CCCAAACTACACAGAATTTAA-3' (shGSK3β#2; TRCN0000039999).

T cell-mediated tumor cell killing

assay

T cell cytotoxicity assay was conducted as

previously described (28,29). Primary T cells were isolated from

the spleens of LLC1-bearing mice using a magnetic cell separation

system with the mouse CD3ε MicroBead Kit (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH;

cat. no. 130-094-973), following the manufacturer's protocols.

Jurkat and isolated T cells were activated for 48 h by incubation

with Dynabeads™ Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 11161D) and Dynabeads™ Mouse

T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.;

cat. no. 11452D), respectively. Next, GMI-treated green fluorescent

protein (GFP)-expressing tumor cells were co-cultured with the

activated T cells for 72 h at the following effector-target ratios:

1:2 for LLC1-GFP cells, 1:1 for H1975-GFP cells, and 1:10 for

PC9-GFP cells. After removing the supernatant, the cells were

washed, trypsinized, centrifuged at 120 × g for 5 min at room

temperature, and resuspended in PBS. GFP fluorescence was measured

using a Varioskan LUX multimode microplate reader (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), with excitation set at 485 nm and emission at

520 nm.

Measurement of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and

granzyme B secreted by activated Jurkat T cells using a co-culture

assay and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Jurkat T cells were activated for 48 h using

Dynabeads™ Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.; cat. no. 11161D). H1975-GFP and PC9-GFP lung

cancer cells were pretreated with GMI for 24 h, detached with

trypsin, and then co-cultured with activated T cells at a 1:1 ratio

for both H1975-GFP and PC9-GFP cells. Supernatants were collected,

and levels of secreted IL-2 and granzyme B were measured using

Human IL-2 and Granzyme B ELISA Kit (BioLegend, Inc.; cat. no.

431804; and R&D Systems, Inc.; cat. no. DY2906-05,

respectively). The assay was conducted according to the

manufacturer's protocols, as previously described (20). In addition, to directly examine

the effect of GMI on T cell function, Jurkat T cells were treated

with GMI for 24 h. Culture supernatants were collected, and IL-2

secretion was measured by ELISA.

Syngeneic tumor model

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at National Yang Ming Chiao

Tung University (IACUC approval no. 1070805) and were conducted in

accordance with the established guidelines, following procedures as

described previously (17). A

total of 42 male C57BL/6 (National Laboratory Animal Center,

Taipei, Taiwan) mice were used in the present study. The animals

were 6-8 weeks of age and weighed 20-22 g at the start of the

experiments. They were housed under controlled conditions

(temperature 20-22°C; relative humidity 50±10%) with a 12/12-h

light/dark cycle and had free access to food and water. In

addition, group sizes were chosen in line with published LLC1

syngeneic practice and institutional guidance, where similar cohort

sizes have been sufficient to detect significant differences

(30-33). Briefly, mice were subcutaneously

injected with 1×105 LLC1 or LLC1-hPD-L1 cells, and then

treated intraperitoneally with GMI (5 mg/kg) or vehicle control

(PBS) every 3 days. In the tumor model involving GMI with or

without anti-PD-1 antibody treatment, mice were randomly divided

into four distinct treatment groups: control (CTL), anti-PD-1 mAb

(200 μg/mice), GMI (5 mg/kg), and GMI + anti-PD-1 mAb.

Treatments were administered every 2 days. Tumor volume was

calculated using the formula: length × width2 × 1/2. At

the study endpoint, the mice were humanely euthanized by carbon

dioxide (CO2) inhalation using a gradual fill rate of

30-70% of the chamber volume per min without pre-filling, and

tumors were excised and weighed.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were isolated

from GMI- and PBS-treated LLC1 tumors. Non-specific binding was

blocked using CD16/CD32 antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.;

cat. no. 14-0161-82), followed by staining on ice for 30 min with

anti-mouse CD3 (BioLegend, Inc.; cat. no. 100235), CD8 (BioLegend,

Inc.; cat. no. 100707) and CD4 (BioLegend, Inc.; cat. no. 100405)

antibodies, targeting immune markers. Samples were analyzed using a

CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and the

CD8+/CD4+ T cell ratio was determined. In a

separate assay, Jurkat T cells were treated with GMI for 24 h,

stained with PE anti-human CD69 antibody (BioLegend, Inc.; cat. no.

310905), and subsequently analyzed for surface CD69 expression

using flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All data were represented as the mean ± standard

deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. Comparisons

between two groups were performed using two-tailed unpaired

Student's t-tests. For comparisons among more than two groups,

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by

appropriate post hoc tests. Specifically, Dunnett's test was

applied when all groups were compared with the control group, while

Tukey's test was used for comparisons among all groups. Analyses

were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software (Dotmatics).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

GMI reduces relative membrane PD-L1

intensity in three lung cancer cell lines

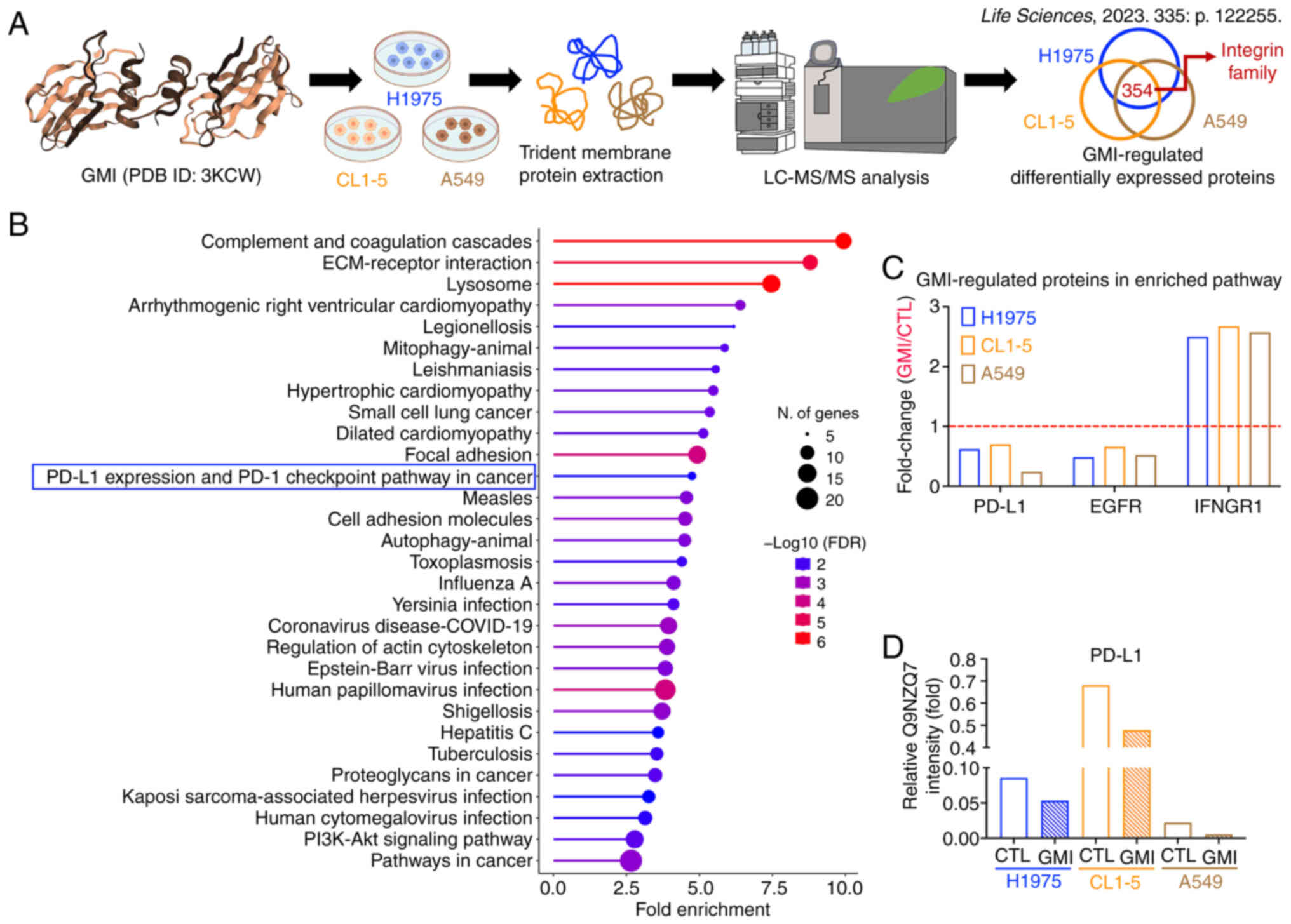

A previous proteomic analysis of membrane protein

extractions by the authors revealed that GMI downregulated members

of the integrin family in H1975, CL1-5 and A549 lung cancer cells

(Fig. 1A) (22). To further characterize the

functions of GMI-regulated DEPs, the KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis was performed. Among the enriched pathways, the 'PD-L1

expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer' was identified

(Fig. 1B and Table SI). Within this pathway, PD-L1

and EGFR were downregulated by GMI, while IFNGR1 was upregulated

(Figs. 1C and S1, and Table SII). Given that GMI is a

known EGFR degrader and that EGFR is closely associated with the

regulation of PD-L1 protein levels, the mechanism underlying

GMI-induced reduction of membrane PD-L1 intensity was investigated

in these three lung cancer cell lines (Fig. 1D).

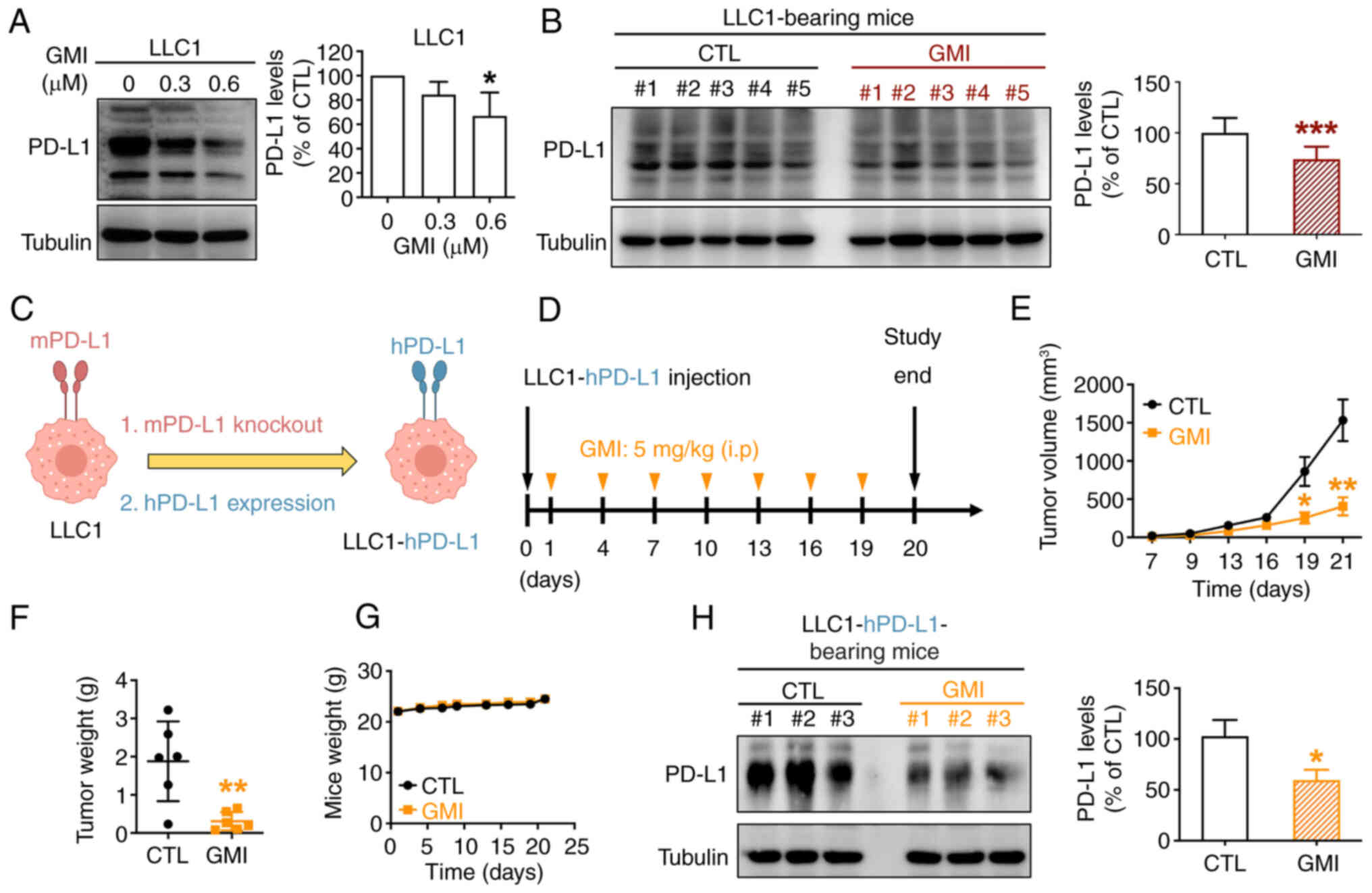

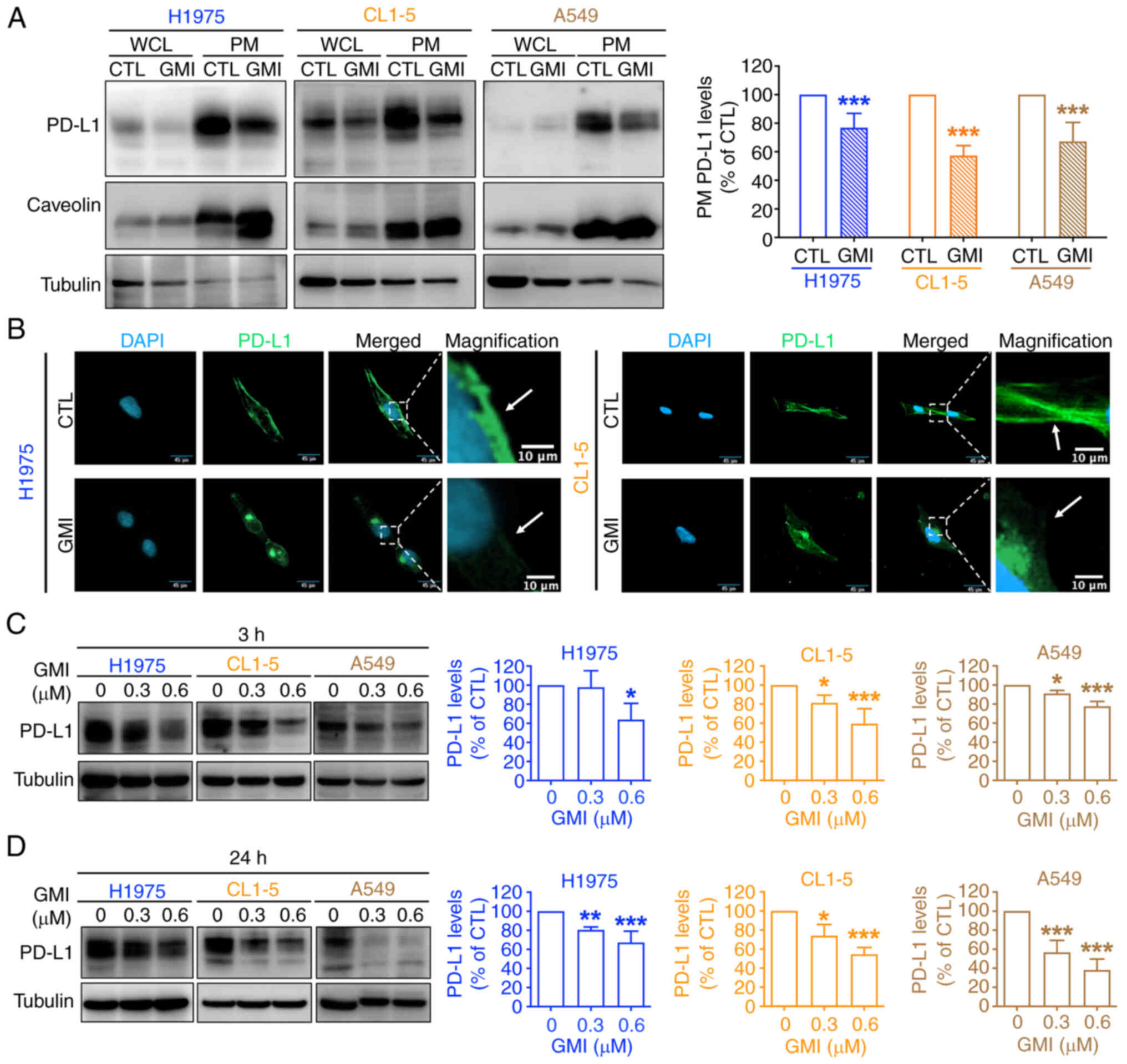

GMI decreases PD-L1 protein levels in

H1975, CL1-5 and A549 cells

A previous study by the authors showed that 0.6

μM GMI markedly modulated EGFR (19); therefore, this dose was selected

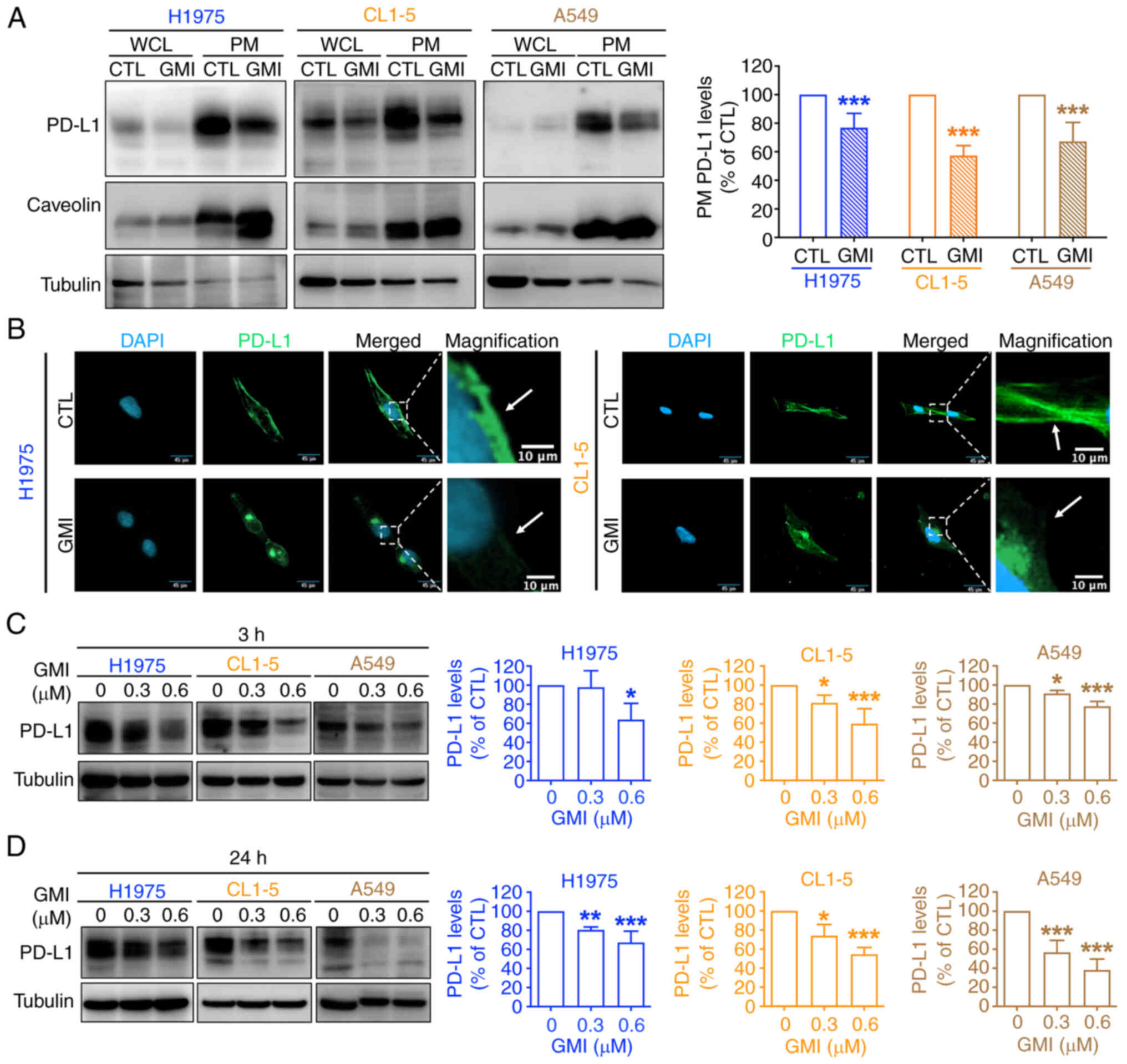

for subsequent assays. Membrane protein fractionation assays were

performed to evaluate the effects of GMI on plasma membrane PD-L1

levels. Consistent with our proteomic findings, a significant

decrease in membrane PD-L1 following GMI treatment was observed

(Fig. 2A). Immunofluorescence

analysis further confirmed that membrane PD-L1 accumulation was

significantly reduced in GMI-treated H1975 and CL1-5 cells

(Fig. 2B). Furthermore, PD-L1

protein expression was significantly reduced in all examined cell

lines after both short-term and long-term exposure to GMI (Fig. 2C and D). Basal PD-L1 levels were

assessed across a panel of lung cancer cell lines, revealing

relatively lower PD-L1 expression in A549 cells and higher

expression in H1975 cells (Fig.

S2A), echoing previous studies (34,35). Given that CL1-5 cells exhibited

intermediate PD-L1 levels, H1975 and CL1-5 cell lines were selected

for further investigation. In GBM cell lines, PD-L1 was highly

expressed in GBM8401 cells, minimally expressed in T98G cells, and

intermediate in U87 cells (Fig.

S2A). Notably, GMI reduced PD-L1 levels in both GBM8401 and U87

cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S2B and C). Collectively, these

findings suggested that GMI may play a role in modulating PD-L1

expression by effectively reducing membrane PD-L1 levels.

| Figure 2GMI reduces membrane PD-L1 protein

levels in lung cancer cells. (A) Left: Immunoblot analysis of PD-L1

in WCL and PM fractions isolated from H1975, CL1-5 and A549 cells

after 24 h treatment with 0.6 μM GMI. Caveolin and tubulin

were used as markers for PM and WCL fractions, respectively. Right:

quantification of PD-L1 levels in PM fractions normalized to

caveolin. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of PD-L1 (green) and

nuclei (DAPI, blue) in H1975 and CL1-5 cells treated with 0.6

μM GMI for 3 h. Scale bars, 45 μm (main images) and

10 μm (magnified insets). (C and D) Western blot analysis of

PD-L1 protein levels in H1975, CL1-5 and A549 cells treated with

indicated concentrations of GMI for 3 h (C) and 24 h (D). Tubulin

served as the loading control. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation from three independent experiments.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. GMI, Ganoderma microsporum

immunomodulatory protein; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; WCL,

whole-cell lysates; PM, plasma membrane. |

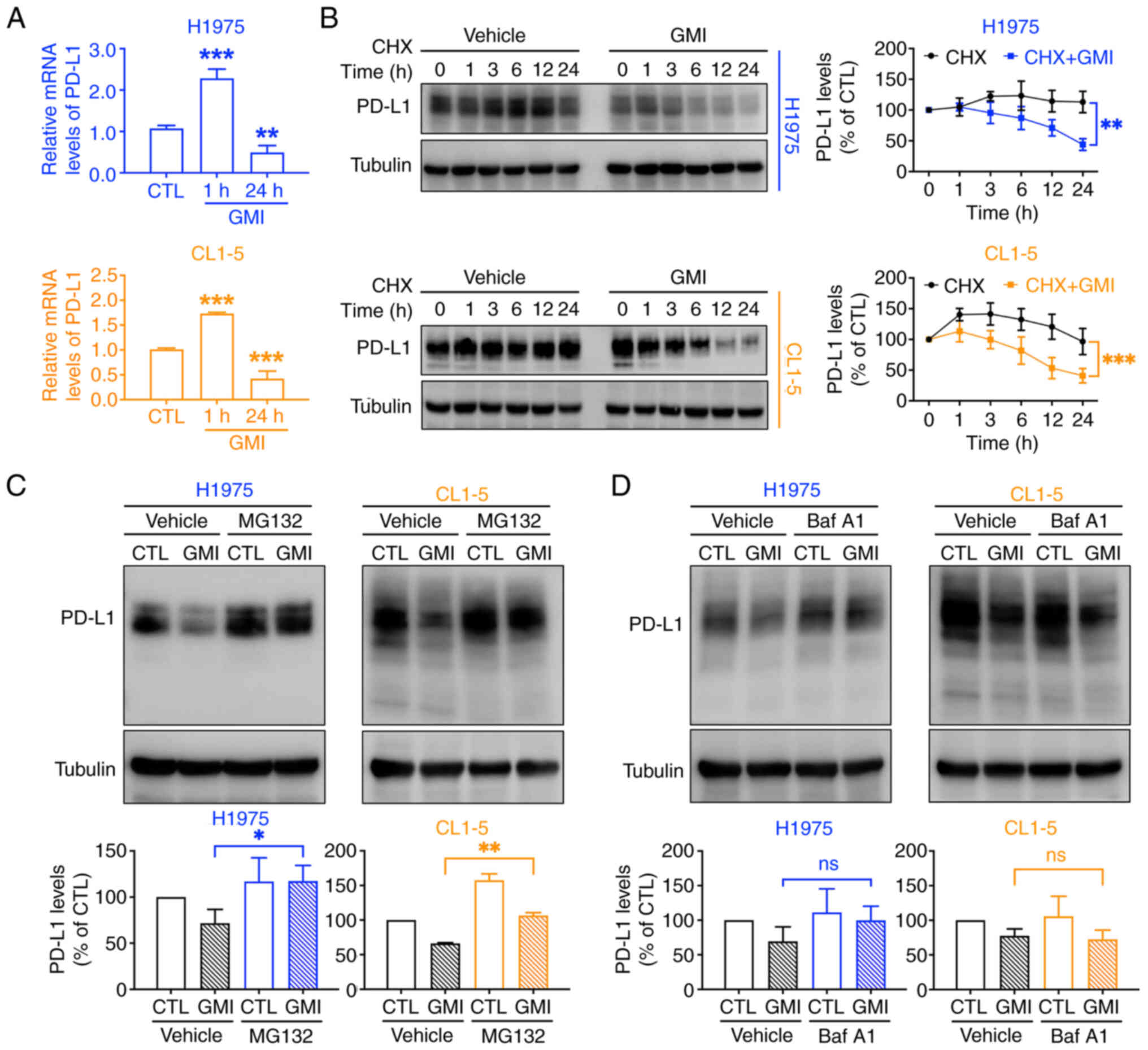

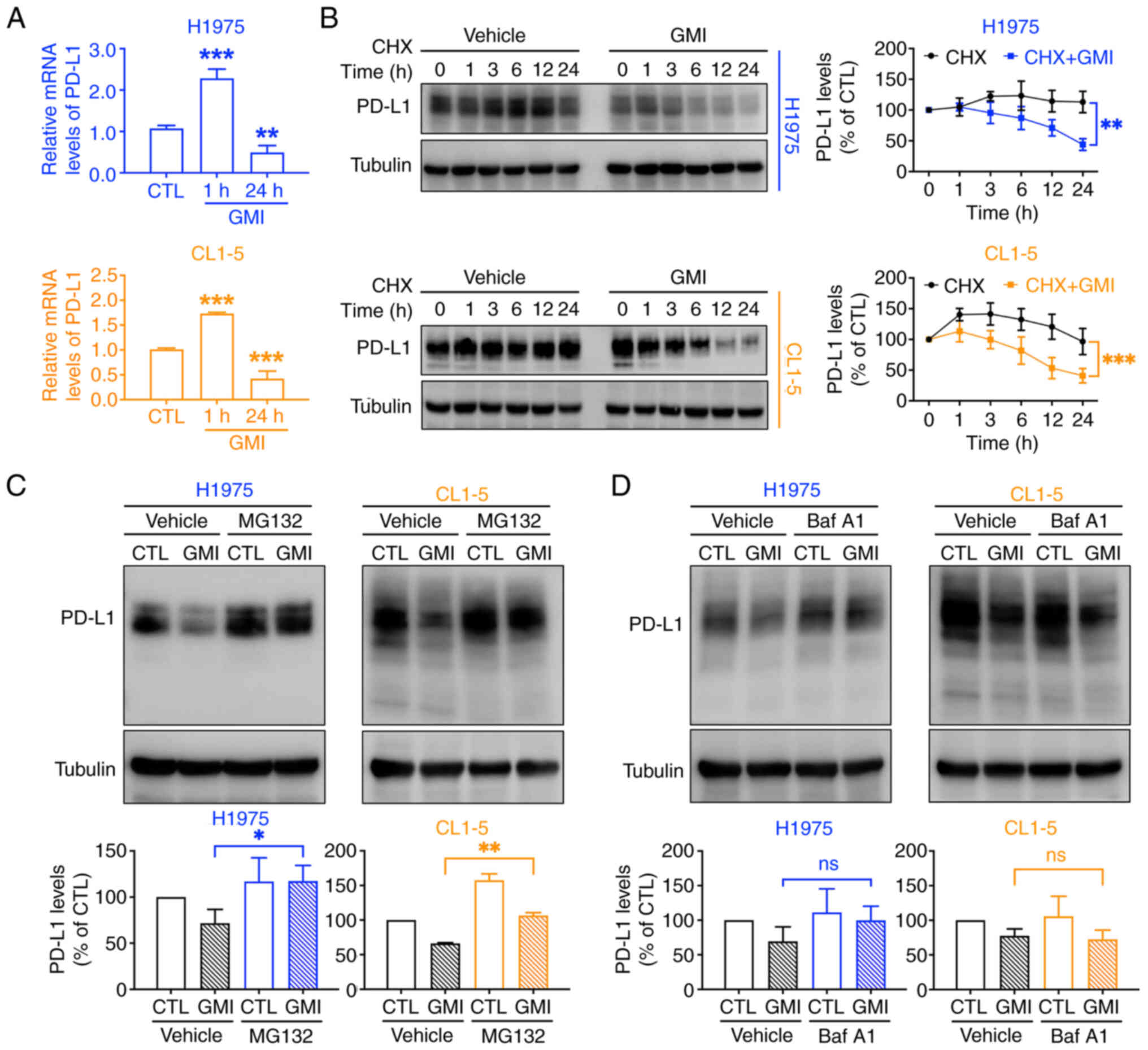

GMI suppresses PD-L1 mRNA levels and

promotes proteasomal PD-L1 degradation

It was next examined whether GMI influences

PD-L1 transcription. RT-qPCR assay revealed an initial

increase in PD-L1 mRNA levels at 1 h, followed by a

significant decrease at 24 h post-treatment (Fig. 3A). To assess the impact of GMI on

PD-L1 protein stability, CHX, the protein synthesis inhibitor, was

used. The findings of the present study revealed that PD-L1 protein

degradation was accelerated in cells exposed to GMI (Fig. 3B), indicating that GMI promotes

the post-translational regulation of PD-L1, leading to enhanced

protein degradation.

| Figure 3GMI induces proteasome-dependent

degradation of PD-L1. (A) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

analysis of PD-L1 mRNA expression in H1975 and CL1-5 cells

following treatment with 0.6 μM GMI for 1 and 24 h. (B) CHX

chase assay of H1975 and CL1-5 cells exposed to 200 μg/ml

CHX for 30 min, followed by incubation with or without 0.6

μM GMI for the indicated time points to assess PD-L1 protein

stability. (C and D) H1975 and CL1-5 cells were pretreated with 10

μM MG132 (C), a proteasome inhibitor, or 5 nM Baf A1 (D), a

lysosome inhibitor, and were then exposed to 0.6 μM GMI for

24 h. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from

three independent experiments. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. GMI,

Ganoderma microsporum immunomodulatory protein; PD-L1,

programmed death-ligand 1; CHX, cycloheximide; Baf A1, bafilomycin

A1; ns, not significant. |

PD-L1 can be degraded through either the proteasomal

or lysosomal pathway, both leading to reduced PD-L1 presence on the

cell membrane (36). To identify

the specific signaling pathway implicated in GMI-mediated PD-L1

reduction, cells were exposed to GMI combined with specific

inhibitors: MG132 for proteasomes and Baf A1 for lysosomes. The

findings revealed that GMI-triggered acceleration of PD-L1

breakdown was strongly mitigated in the presence of MG132 (Fig. 3C), implicating the proteasomal

pathway in this process. By contrast, Baf A1 did not inhibit the

degradation (Fig. 3D),

indicating that the lysosomal pathway is not significantly

involved. Furthermore, under endogenous (non-overexpression)

conditions, an in-cell ubiquitination assay showed a slight

increase in PD-L1 ubiquitination following GMI treatment, although

the effect was not pronounced (Fig.

S3A and B). These findings suggested that GMI reduces PD-L1

protein levels not only by suppressing its transcription but also

by enhancing the proteasome-dependent system and subsequent

degradation.

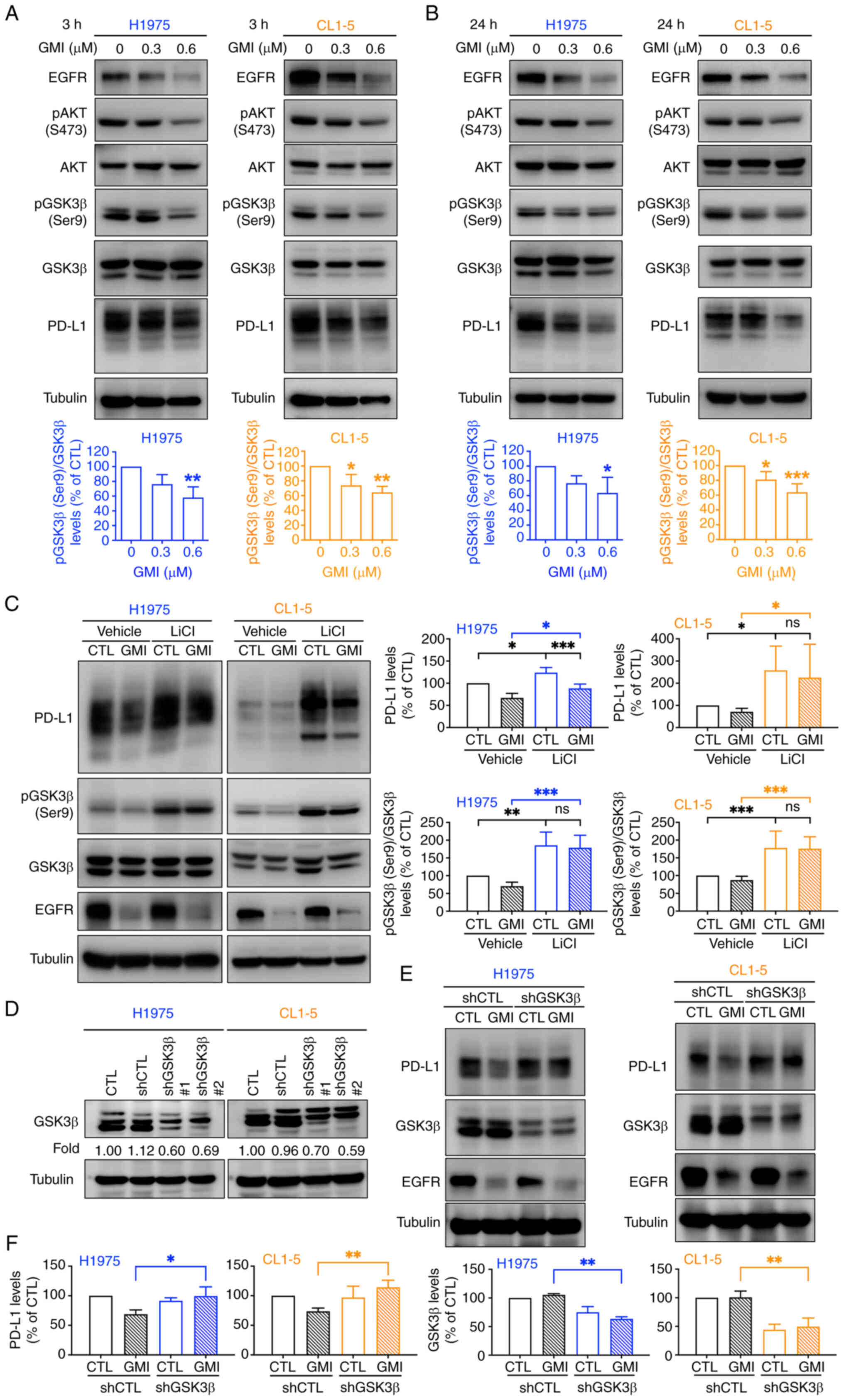

GMI destabilizes PD-L1 by promoting

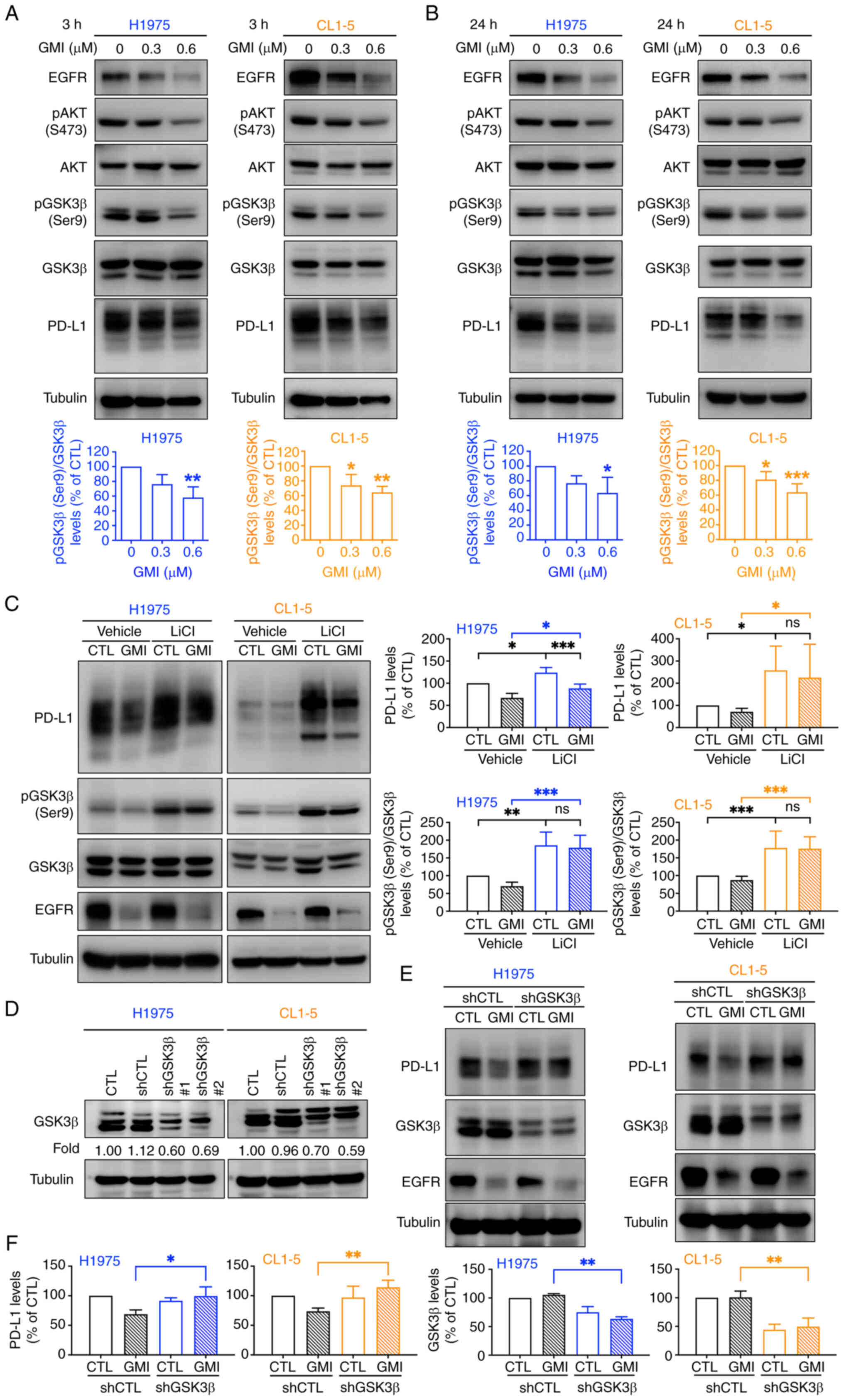

GSK3β-mediated proteasomal degradation

Activated EGFR induces AKT-mediated phosphorylation

of GSK3β at serine 9 (Ser9), rendering it inactive and thereby

stabilizing PD-L1 by preventing its proteasomal degradation

(37). It was hypothesized that

GSK3β signaling contributes to GMI-mediated PD-L1 degradation. The

present results demonstrated that GMI, as an EGFR degrader,

effectively suppressed EGFR expression and downstream AKT

activation (Fig. 4A and B;

Fig. S4A and B). Moreover,

treatment with GMI (0.6 μM) significantly reduced GSK3β Ser9

phosphorylation after both short-and long-term treatments,

indicating GSK3β activation concomitant with PD-L1 suppression

(Fig. 4A and B). Similar

reductions in PD-L1 expression were observed upon treatment with

osimertinib, an EGFR inhibitor, and LY294002, a PI3K/AKT inhibitor

(Fig. S4C). Conversely,

co-treatment with LiCl, a GSK3β inhibitor, significantly rescued

PD-L1 levels reduced by GMI (Fig.

4C), as confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. S5). To further validate GSK3β's

role, shRNA-mediated knockdown of GSK3β in both H1975 and CL1-5

cells attenuated GMI-induced PD-L1 degradation (Fig. 4D), resulting in elevated PD-L1

compared with GMI-treated parental cells (Fig. 4E and F). Collectively, these

findings demonstrated that GSK3β activation is crucial for

GMI-induced proteasomal degradation of PD-L1.

| Figure 4GMI facilitates PD-L1 degradation

through activation of GSK3β. (A and B) H1975 and CL1-5 cells were

treated with indicated concentrations of GMI for 3 h (A) and 24 h

(B). Protein expressions of EGFR, p-AKT (Ser473), p-GSK3β (Ser9)

and PD-L1 were analyzed by immunoblotting, with AKT, GSK3β and

tubulin as loading controls, and quantification of p-AKT and

p-GSK3β was performed relative to their corresponding total

proteins (AKT and GSK3β). (C) H1975 and CL1-5 cells were pretreated

with 25 mM LiCl, a GSK3β inhibitor, and were exposed to 0.6

μM GMI for 24 h. (D) Immunoblotting of GSK3β in H1975 and

CL1-5 cells expressing different GSK3β-targeting shRNAs. (E)

Immunoblotting analysis of PD-L1 and GSK3β in cancer cells

transduced with either GSK3β shRNA (shGSK3β#1) or control shRNA

(shCTL) lentiviruses and treated with or without 0.6 μM GMI

for 24 h. (F) Quantification of PD-L1 and GSK3β expression levels

shown in (E). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

from three independent experiments. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. GMI,

Ganoderma microsporum immunomodulatory protein; PD-L1,

programmed death-ligand 1; p-, phosphorylated; LiCl, lithium

chloride; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; p-, phosphorylated; ns, not

significant. |

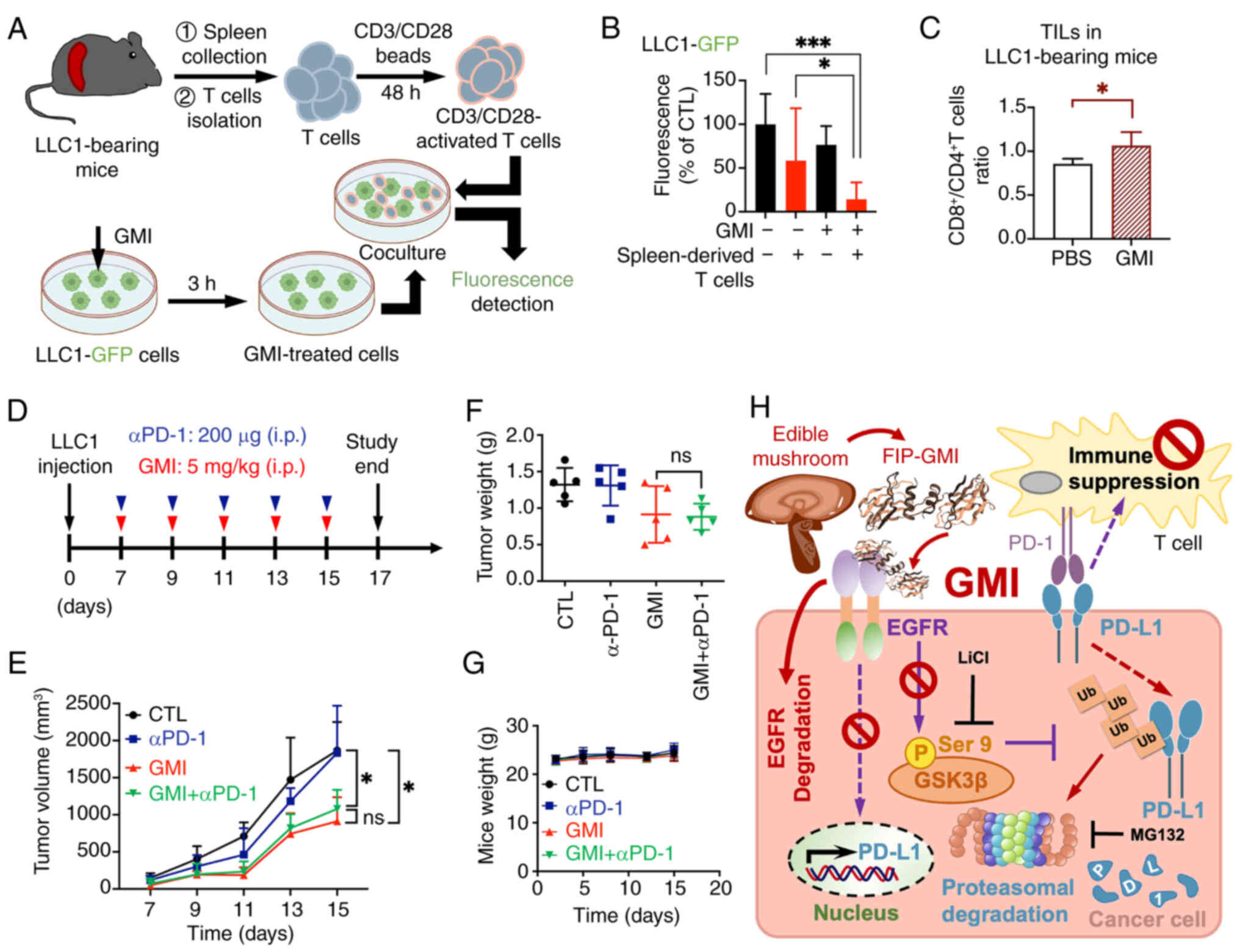

GMI suppresses tumor growth and reduces

PD-L1 expression in vivo

A previous study by the authors showed that GMI

effectively suppressed tumor growth in a LLC1-bearing mouse model

(19). In the present study, it

was further explored whether GMI can downregulate PD-L1 expression

in LLC1 cells both in vitro and in vivo. First, it

was observed that GMI treatment reduced PD-L1 levels in LLC1 cells

in vitro (Fig. 5A).

Subsequently, LLC1-bearing immune-competent C57BL/6 mice were

administered GMI or PBS (CTL) via intraperitoneal injection every 3

days (Fig. S6A). The results

demonstrated that GMI significantly suppressed tumor growth

(Fig. S6B), echoing our

previous findings, without affecting overall body weight, thus

revealing favorable tolerability of GMI (Fig. S6C). Western blot analysis of

harvested tumors revealed that GMI treatment significantly

decreased PD-L1 expression compared with the CTL group, indicating

that GMI induces PD-L1 degradation in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5B).

To further investigate whether GMI-induced

degradation of human PD-L1 (hPD-L1) in vivo, LLC1-hPD-L1

cells were utilized, where murine PD-L1 (mPD-L1) was replaced with

hPD-L1 (Figs. 5C and S2A). GMI suppressed PD-L1 levels in

LLC1-hPD-L1 cells in vitro (Fig. S7A) and promoted PD-L1

degradation through the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal pathway,

consistent with observations in H1975 and CL1-5 cells (Fig. S7B and C). LLC1-hPD-L1 cells were

subcutaneously inoculated into C57BL/6 mice to evaluate the in

vivo efficacy of GMI (Fig.

5D). Treatment with GMI significantly inhibited tumor growth

and reduced tumor weight without causing body weight loss (Figs. 5E-G and S7D). Tumor tissue analysis confirmed

GMI-mediated downregulation of PD-L1 expression (Fig. 5H). These findings indicated that

GMI suppresses PD-L1 expression and may enhance antitumor immunity

by facilitating PD-L1 degradation in tumor-bearing mice.

T cell suppresses the viability of

GMI-pretreated cancer cells

The binding of PD-L1 on cancer cell membranes to

PD-1 on T cells suppresses T cell activation, facilitating immune

evasion and tumor progression (38). Given the previous finding that

GMI promotes PD-L1 degradation on cancer cell surfaces, it was

hypothesized that this would enhance secretion of T cell cytokines,

such as IL-2 and granzyme B, thereby boosting the cytotoxic

response against tumor cells (29). To test this, co-culture

experiments were performed using T cells isolated from the spleens

of LLC1 tumor-bearing mice (Fig.

6A). Activated spleen-derived T cells significantly suppressed

the viability of GMI-treated LLC1 cells compared with untreated

controls (Fig. 6B). Next, lung

cancer cell lines H1975 and PC9, both harboring EGFR

mutations and stably expressing GFP, were pre-treated with GMI and

co-cultured with CD3/CD28-activated Jurkat T cells (29). This co-culture led to a

significant increase in IL-2 and granzyme B secretion compared with

co-cultures without GMI pretreatment (Fig. S8A and B). Furthermore,

tumor-eliminating activity assessed by relative fluorescence

intensity showed a significant decrease in viability of

GMI-pretreated lung cancer cells co-cultured with

CD3/CD28-stimulated Jurkat T cells (Figs. S8C-E). These results suggested

that GMI-mediated reduction of membrane PD-L1 may enhance

CD3/CD28-stimulated T cell suppression of cancer cell viability.

Interestingly, without tumor cells, GMI elevated CD69 expression

and enhanced IL-2 secretion in Jurkat T cells (Fig. S8F and G), indicating a direct

stimulatory effect on T cells. In addition, the presence of TILs,

including CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, in LLC1

tumor tissues was analyzed (Fig.

5B). Flow cytometry revealed a higher proportion of

CD8+ TILs in GMI-treated tumors (Figs. 6C and S9), indicating that GMI may promote

the infiltration of activated CD8+ cytotoxic T cells

into the TME through PD-L1 degradation. Collectively, the

aforementioned findings suggested that GMI-facilitated PD-L1

degradation may promote antitumor immunity.

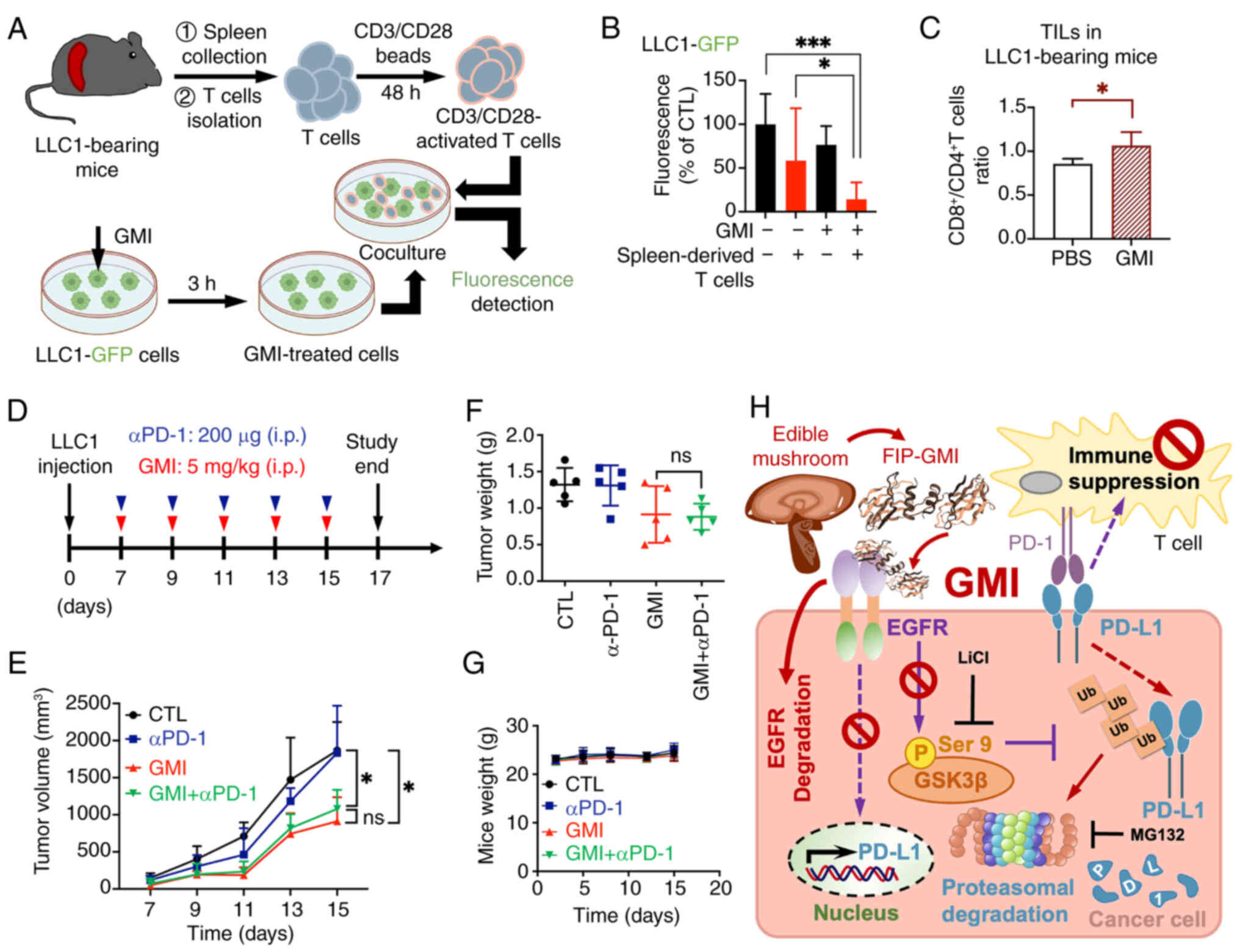

| Figure 6GMI regulates T cell-mediated

suppression of tumor cells ex vivo and promotes antitumor

immunity in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the

co-culture protocol. Activated spleen-derived T cells isolated from

LLC1-bearing mice were co-cultured with LLC1-GFP cells pretreated

with 0.6 μM GMI for 3 h. After 72 h of co-culture, GFP

fluorescence in LLC1-GFP cells was analyzed. (B) Quantification of

GFP fluorescence intensity in LLC1-GFP cells following co-culture

with activated T cells. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from LLC1-bearing mice treated with

control (PBS) or GMI (Fig. 5B).

The ratio of CD8+ to CD4+ T cells is shown.

(D) Treatment schedule for LLC1 syngeneic C57BL/6 mice receiving

intraperitoneal injections of GMI (5.0 mg/kg), anti-PD-1 antibody

(200 μg/mice), or their combination every 2 days. (E-G)

Tumor volume (E), tumor weight (F) and body weight (G) were

monitored at specified intervals throughout the experiment. Data

are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=5 mice per group). (H) Schematic

model illustrating how GMI enhances antitumor immunity by driving

PD-L1 breakdown. GMI, a FIP derived from an edible mushroom and

known as an EGFR degrader, reduces PD-L1 levels by downregulating

its mRNA expression and promoting GSK3β-mediated ubiquitination and

proteasomal degradation. This process further diminishes T cell

immune suppression and enhances antitumor immunity.

*P<0.05 and ***P<0.001. Ganoderma

microsporum immunomodulatory protein; GFP, green fluorescent

protein; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; FIPs, fungal

immunomodulatory proteins; LiCl, lithium chloride; ns, not

significant. |

Finally, analysis on whether combining GMI with PD-1

blockade (Fig. 6D) can further

enhance antitumor efficacy revealed that combination treatment (GMI

+ anti-PD-1 mAb) significantly suppressed tumor growth (Fig. 6E) and reduced tumor weight

(Figs. 6F and S10) compared with the control (PBS)

group. However, tumor suppression in the combined treatment group

was not significantly different from the GMI-only group.

Furthermore, in line with our earlier findings from the syngeneic

mouse model, body weights remained stable across all groups

(Fig. 6G), indicating that GMI

is safe for promoting PD-L1 degradation as a therapeutic

strategy.

Discussion

PD-L1 on tumor cells interacts with the PD-1

receptor on T lymphocytes, a key mechanism of immune evasion in

multiple cancer types. This interaction effectively suppresses the

immune system's ability to detect and eliminate malignant cells,

contributing to tumor progression. The development and approval of

multiple antibodies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway represent a

major advancement in cancer immunotherapy by disrupting this immune

checkpoint and restoring immune function in patients (39). Beyond inhibiting the PD-1/PD-L1

interaction between cancer cells and immune T cells, a more direct

strategy targeting PD-L degradation has gained attention. By

reducing PD-L1 expression on tumor cell surface, this approach may

diminish immune evasion and strengthen antitumor immunity,

positioning PD-L1 degradation as a promising therapeutic avenue

(40). Since EGFR activation

stabilizes PD-L1 by inhibiting its degradation, agents targeting

the EGFR pathway can modulate PD-L1 levels (12). Bioactive compounds derived from

medicinal mushrooms, including FIPs and polysaccharides, have

attracted considerable interest for their therapeutic potential,

particularly in cancer treatment (41). To the best of our knowledge, the

present study is the first to demonstrate that FIP-GMI, an approved

dietary ingredient and EGFR degrader, regulates antitumor immunity

by promoting PD-L1 degradation (Fig.

6H). Notably, previous studies by the authors revealed that GMI

can induce proteasomal degradation of key proteins, including EGFR

and Slug in lung and brain cancer cells (18,19), and ACE2 in SARS-CoV-2 infection

models (20). In the present

study, it was further demonstrated that GMI facilitates

GSK3β-mediated proteasomal degradation of PD-L1, suggesting that

GMI targets multiple substrates through this pathway across various

cell types. Moreover, proteomic analysis revealed that GMI

regulates a broad spectrum of membrane proteins (Fig. 1A), though the precise mechanisms

remain to be elucidated.

PD-L1 transcription is regulated by various

transcription factors. Notably, c-Myc binds directly to the PD-L1

gene promoter, with its inhibition reducing both PD-L1 mRNA and

protein levels, thereby boosting antitumor immunity (42). Similarly, Hippo pathway

effectors, such as the transcriptional activator yes-associated

protein and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

(STAT3), have been shown to regulate PD-L1 transcription in various

cancer types (43,44). EGFR inhibitors significantly

suppress PD-L1 mRNA in lung cancer cells with activating mutations

(14,45) and block EGF-induced PD-L1

upregulation, indicating that inhibiting EGFR activity regulates

PD-L1 mRNA expression. Previous research has shown that GMI reduces

STAT3 phosphorylation, hinting at transcriptional regulation of

PD-L1 (31). The current

findings confirmed that GMI significantly downregulates PD-L1 mRNA

expression in lung cancer cells within 24 h, likely by targeting

these critical transcriptional regulators. Additional

investigations could be carried out to examine how GMI influences

these transcription factors involved in regulating PD-L1 mRNA.

Moreover, other signaling pathways, including those involving

receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as anaplastic lymphoma kinase

(46) and neurotrophic RTK 1

(47), as well as the

PI3K-AKT-mTOR axis (48), also

upregulate both PD-L1 mRNA and protein expression.

Beyond transcriptional regulation, GMI promotes

PD-L1 degradation via GSK3β activity in lung cancer cells. Future

investigations could explore whether GMI exerts effects on broader

immune checkpoint regulatory pathways, extending beyond GSK3β, and

further evaluate its potential to disrupt both transcriptional and

post-translational processes governing PD-L1 expression.

GSK3β facilitates PD-L1 identification by the E3

ubiquitin ligase complex, which encompasses beta-transducing

repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), leading to ubiquitination and

proteasomal degradation. By contrast, EGFR activation inhibits

GSK3β via AKT-mediated phosphorylation, stabilizing PD-L1 and

promoting immune resistance (12). EGFR inhibitors, such as gefitinib

and osimertinib, counteract this stabilization effect by blocking

EGFR signaling, which can activate GSK3β (45). Consistently, the present study

demonstrated that GMI, the EGFR degrader, activates GSK3β, and

GSK3β inhibition or knockdown reverses GMI-induced PD-L1 reduction,

confirming its crucial role. Of note, short-term EGF exposure

partially rescued GMI-induced GSK3β activation (data not shown);

however, an EGFR overexpression rescue experiment was not

performed, suggesting that other RTKs may also regulate GSK3β

activity. Contrary to the previous study (12), the present findings revealed that

β-TrCP knockdown did not fully prevent PD-L1 degradation by GMI

(data not shown), suggesting involvement of alternative E3

ubiquitin ligases. Candidates include membrane-associated RING-CH 8

(MARCH8) and ariadne-1 homolog (ARIH1), which mediate PD-L1

degradation in EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells exposed to EGFR inhibitors

(14,49). Thus, GMI appears to regulate

PD-L1 via a β-TrCP-independent yet GSK3β-dependent mechanism,

warranting further exploration of novel E3 ubiquitin ligases

involved in GMI-mediated PD-L1 degradation.

Numerous PD-L1-targeting strategies, such as

proteolysis-targeting chimeras, lysosomal-targeted chimeras and

GlueBody chimeras, have shown considerable promise in promoting

PD-L1 degradation (50,51). However, these approaches often

face limitations associated with suboptimal drug delivery

efficiency, large molecular size and restricted tumor tissue

penetration (52). By contrast,

GMI is a naturally derived FIP with a favorable safety profile

(53). The findings of the

present study demonstrated that GMI effectively downregulates PD-L1

expression by repressing its transcription and enhancing

GSK3β-mediated proteasomal degradation. Unlike synthetic degraders

that frequently require intricate molecular design and chemical

modification, GMI offers potential advantages in terms of

biocompatibility, low toxicity and feasibility as a functional

dietary supplement. Overall, these characteristics underscore the

therapeutic significance of GMI and support its promise as a novel

and practical alternative to existing PD-L1-targeting

approaches.

Immune resistance and the immunosuppressive TME

remain major challenges in treating solid tumors (54). Elevated PD-L1 correlates with

tumor progression, reduced T-cell activity, and the development of

immune evasion. A promising therapeutic strategy that disrupts

PD-L1/PD-1 binding can re-engage T cell-mediated immunity.

Promoting PD-L1 degradation enhances immune responses and T cell

function, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes (55). The aqueous extract derived from

the medicinal herb Centipeda minima alleviates tumor burden

in mice harboring NSCLC cells by regulating PD-L1 expression and

enhancing CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity (56). Moreover, the natural marine

compound benzosceptrin C strongly promotes PD-L1 degradation and

exerts immune antitumor effects, effectively inhibiting tumor

growth in MC38 tumor-bearing mice (57). Collectively, these studies

indicate that using active compounds from natural products or

traditional Chinese medicine herbs may offer promising therapeutic

strategies for combating tumors and enhancing antitumor immunity.

Furthermore, FIPs, including FIP-vvo derived from Volvariella

volvacea, modulate immune responses and may support health by

boosting immune function (58).

The present study introduces fungal-derived GMI as a novel PD-L1

degrader. In vitro co-cultures showed that GMI effectively

reduces PD-L1 in cancer cells, significantly enhancing

CD3/CD28-stimulated T cell-mediated suppression of cancer cell

viability. Consistently, in vivo experiments demonstrated

significant tumor growth inhibition accompanied by increased

infiltration of CD8+ TILs, supporting enhanced antitumor

immunity within the TME. Notably, in the absence of tumor cells,

GMI upregulated Jurkat T-cell CD69 expression and increased IL-2

secretion (Fig. S8F and G),

indicating that, beyond downregulating PD-L1 on tumor cells, GMI

directly stimulates T cells and may thereby potentiate antitumor

immune responses. Future studies will further explore the molecular

mechanisms underlying this direct activation and its implications

for cancer immunotherapy.

No synergistic effect was observed when GMI was

administered in combination with anti-PD-1 in LLC1-bearing mice,

consistent with LLC tumors being relatively 'cold' and resistant to

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy (30).

This may explain the limited efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibodies in

our in vivo model. Prior studies indicate that checkpoint

inhibitors beyond PD-1/PD-L1, such as CTLA-4 blockade, which

modulates the CTLA-4/CD80 (CD86) axis or TIGIT blockade (targeting

the TIGIT/PVR axis), can elicit distinct immune responses that vary

with tumor type and microenvironment (59). Although CD80 and CD86 were not

detected in our proteomic analysis, PVR, an immune checkpoint

ligand involved in immune evasion (60), was unexpectedly identified,

suggesting that the TIGIT pathway may warrant further

investigation. Accordingly, investigating the combination of GMI

with blocking antibodies against other immune checkpoints, such as

CTLA-4 or TIGIT, presents an intriguing direction for future

research to better elucidate potential synergistic effects. It is

essential to highlight that no significant weight loss or visible

adverse effects were observed in our tumor-bearing model,

indicating that GMI is well-tolerated. In addition, recent research

by the authors demonstrated that GMI ameliorates SARS-CoV-2

envelope protein-induced inflammation and exerts anti-inflammatory

effects in mouse models of excessive immune activation (61). These results suggested that,

beyond its role in PD-L1 regulation, GMI may contribute to immune

homeostasis, potentially mitigating the risk of immune-related

adverse effects. Furthermore, a favorable safety profile for GMI

has been previously demonstrated, further supporting its potential

as a safe option in therapeutic applications (53). Collectively, the aforementioned

findings support GMI as a valuable supplement in cancer therapy by

targeting both tumor growth and immune evasion.

While PD-L1 has traditionally been studied for its

role as an immune checkpoint ligand, evidence highlights its tumor

cell-intrinsic functions, which may complicate its use as a

biomarker for immunotherapy. These intrinsic roles extend beyond

immune evasion and include promoting cancer cell survival,

invasion, EMT, stemness, metabolic reprogramming and therapy

resistance. Emerging studies have shown that PD-L1 can activate

intracellular signaling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT and MAPK, which

are crucial for cancer cell proliferation and survival (62,63). Moreover, intrinsic PD-L1 activity

in tumor cells drives NSCLC progression by facilitating EMT, and

elevated EMT levels in PD-L1-high NSCLC may serve as a predictor of

poor outcomes following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

(64). Additionally, PD-L1 has

been implicated in enhancing glycolysis, thereby supporting the

metabolic demands of rapidly growing tumors (65). Other intrinsic functions include

its involvement in the anti-apoptotic processes and chemotherapy

resistance, where PD-L1 helps protect cancer cells from these

therapeutic agents (66,67). Importantly, previous studies by

the authors showed that GMI suppresses lung and brain cancer cell

migration and metastasis by inhibiting Slug, a transcription factor

associated with EMT (18,22).

This mechanism may intersect with PD-L1's roles in promoting EMT

and metastasis, highlighting a potential link between GMI's effects

and the intrinsic functions of PD-L1. Future studies could clarify

whether GMI's suppression of EMT and metastasis is directly

mediated through its impact on PD-L1 signaling pathways. Such

investigations could provide deeper insights into the dual role of

GMI in targeting both the immune and non-immune functions of PD-L1,

further advancing its therapeutic potential.

A previous study (19) by the authors demonstrated that

GMI is a novel EGFR degrader capable of disrupting EGFR-driven

oncogenic signaling and inhibiting tumor progression in

EGFR-positive cancers. In xenograft models, GMI effectively

suppresses tumor growth in nude mice harboring tumors with both

EGFR wild-type and activating mutations, indicating a direct

cytotoxic effect (17,19). Notably, in immune-competent mouse

models, GMI inhibits tumor metastasis in a tail-vein injection

model and suppresses the growth of subcutaneous LLC1 tumors in

C57BL/6 mice (22). These

findings indicated that, beyond its direct cytotoxic effects, GMI

may also exert antitumor activity by enhancing endogenous immune

defense mechanisms. Building on this, the current study further

demonstrated that GMI suppresses tumor growth and induces PD-L1

downregulation in vivo, suggesting a dual mechanism of

action. One potential anticancer mechanism of GMI is its ability to

enhance antitumor immunity through PD-L1 degradation, thereby

alleviating immune suppression. While PD-L1 reduction contributes

to enhanced antitumor immunity, tumor suppression in nude mouse

models with defective T cell function suggests an additional direct

cytotoxic effect. This is consistent with the mechanisms of other

FDA-approved EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as osimertinib

and erlotinib, which not only disrupt EGFR signaling and induce

tumor cell apoptosis but also regulate immune responses by reducing

PD-L1 expression and modulating the TME (12,14). The observed reduction in PD-L1

levels and the concurrent increase in CD8+ T cell

infiltration in the TME indicated that GMI may exert its effects by

modulating the T cell landscape to combat tumors. This suggests

that GMI's effects extend beyond simply eliminating cancer cells,

potentially encompassing tumor suppression through PD-L1

downregulation on malignant cells.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly,

while the co-culture system employing Jurkat T cells and cancer

cells represents a well-established and widely adopted approach for

assessing the functional activation of Jurkat T cells (68), it fails to fully replicate

antigen-specific T cell-mediated antitumor responses or to provide

a reliable evaluation of T cell-mediated tumor cell cytotoxicity.

Alternative models, such as the co-culture of human peripheral

blood mononuclear cells with GMI-treated human cancer cells or the

co-culture of OVA-specific T cells with GMI-treated OVA-expressing

cancer cells (56), could better

elucidate the mechanisms underlying T cell-mediated antitumor

immunity in the context of GMI treatment. Secondly, while GMI

enhances antitumor immunity by promoting GSK3β-mediated PD-L1

degradation, without a T cell depletion assay, in vivo

antitumor effects in immune-competent mice remain unclear. In

addition, p-GSK3β (Ser9) was not quantified in the tumor samples;

therefore, while in vitro data support GSK3β-dependent PD-L1

degradation, GSK3β activation in vivo could not be directly

confirmed in this cohort. Lastly, proteomic analysis revealed that

GMI does not significantly alter surface MHC class I

(HLA-A/B/C/E/G/F) expression on several lung cancer cell lines

following GMI treatment (data not shown), suggesting no direct

effect on antigen presentation pathways. However, broader indirect

effects on immune modulation require further investigation.

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence

for the first time that the naturally derived FIP GMI, beyond its

cytotoxic effects as an EGFR degrader, promotes PD-L1 degradation

by decreasing its mRNA expression and inducing GSK3β-mediated

proteasomal degradation. This reduction of PD-L1 enhances

CD3/CD28-stimulated T cell-mediated suppression of cancer cell

viability and inhibits tumor growth with increased CD8+

T cell infiltration in vivo. Collectively, these results

highlight the promising potential of GMI as a therapeutic agent or

functional dietary supplement for cancer immunotherapy.

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgements

The authors are sincerely grateful to Ms Y-C Chen

of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University for providing technical

assistance.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the Ministry of

Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant no. Young Scholar

Fellowship Einstein Program; MOST 111-2636-B-A49-009) and the

National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (grant no. NSTC

112-2320-B-A49-010-MY3, NSTC 113-2320-B-A49-028-MY3, NSTC

113-2811-B-A49A-038 and NSTC 114-2811-B-A49A-015).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The data generated in the

present study may be found in the NYCU Dataverse under accession

number 10.57770/QNCRKI or at the following URL: https://doi.org/10.57770/QNCRKI.

Authors' contributions

LLL, WHH and TYL conceptualized the study. WJH

performed experiments, collected and analyzed data, interpreted the

results, and wrote the manuscript. WJH and LCH performed

bioinformatic analysis. LCH, ZHL, YRC and KFL performed in

vitro and in vivo experiments. TYL reviewed and edited

the manuscript. WJH and TYL confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures involving animals were conducted in

accordance with the guidelines established by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; approval no. 1070805) at

National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University (Taipei, Taiwan).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

GMI

|

Ganoderma microsporum

immunomodulatory protein

|

|

PD-L1

|

programmed death-ligand 1

|

|

EGFR

|

epidermal growth factor receptor

|

|

FIPs

|

fungal immunomodulatory proteins

|

|

PD-1

|

programmed cell death protein-1

|

|

GSK3β

|

glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

|

|

LiCl

|

lithium chloride

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

NSCLC

|

non-small cell lung cancer

|

|

DEPs

|

differentially expressed proteins

|

|

TILs

|

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

|

References

|

1

|

Zou W: Immunosuppressive networks in the

tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev Cancer.

5:263–274. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Han Y, Liu D and Li L: PD-1/PD-L1 pathway:

Current researches in cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 10:727–742.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sun C, Mezzadra R and Schumacher TN:

Regulation and function of the PD-L1 checkpoint. Immunity.

48:434–452. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Iwai Y, Hamanishi J, Chamoto K and Honjo

T: Cancer immunotherapies targeting the PD-1 signaling pathway. J

Biomed Sci. 24:262017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ,

Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al:

Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with

advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 366:2455–2465. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sharma P and Allison JP: Immune checkpoint

targeting in cancer therapy: Toward combination strategies with

curative potential. Cell. 161:205–214. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, Connell LC,

Schindler K, Lacouture ME, Postow MA and Wolchok JD: Toxicities of

the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann

Oncol. 26:2375–2391. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang N, Dou Y, Liu L, Zhang X, Liu X,

Zeng Q, Liu Y, Yin M, Liu X, Deng H and Song D: SA-49, a novel

aloperine derivative, induces MITF-dependent lysosomal degradation

of PD-L1. EBioMedicine. 40:151–162. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang T, Cai S, Cheng Y, Zhang W, Wang M,

Sun H, Guo B, Li Z, Xiao Y and Jiang S: Discovery of small-molecule

inhibitors of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis that promote PD-L1

internalization and degradation. J Med Chem. 65:3879–3893. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Cha JH, Chan LC, Li CW, Hsu JL and Hung

MC: Mechanisms controlling PD-L1 expression in cancer. Mol Cell.

76:359–370. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hsu JM, Xia W, Hsu YH, Chan LC, Yu WH, Cha

JH, Chen CT, Liao HW, Kuo CW, Khoo KH, et al: STT3-dependent PD-L1

accumulation on cancer stem cells promotes immune evasion. Nat

Commun. 9:19082018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li CW, Lim SO, Xia W, Lee HH, Chan LC, Kuo

CW, Khoo KH, Chang SS, Cha JH, Kim T, et al: Glycosylation and

stabilization of programmed death ligand-1 suppresses T-cell

activity. Nat Commun. 7:126322016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang J, Bu X, Wang H, Zhu Y, Geng Y,

Nihira NT, Tan Y, Ci Y, Wu F, Dai X, et al: Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase

destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune

surveillance. Nature. 553:91–95. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Qian G, Guo J, Vallega KA, Hu C, Chen Z,

Deng Y, Wang Q, Fan S, Ramalingam SS, Owonikoko TK, et al:

Membrane-associated RING-CH 8 functions as a novel PD-L1 E3 ligase

to mediate PD-L1 degradation induced by EGFR inhibitors. Mol Cancer

Res. 19:1622–1634. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Su YW, Huang WY, Lin SH and Yang PS:

Effects of reishimmune-S, a fungal immunomodulatory peptide

supplement, on the quality of life and circulating natural killer

cell profiles of patients with early breast cancer receiving

adjuvant endocrine therapy. Integr Cancer Ther.

23:153473542412421202024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lin TY, Hua WJ, Yeh H and Tseng AJ:

Functional proteomic analysis reveals that fungal immunomodulatory

protein reduced expressions of heat shock proteins correlates to

apoptosis in lung cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 80:1533842021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Hua WJ, Hwang WL, Yeh H, Lin ZH, Hsu WH

and Lin TY: Ganoderma microsporum immunomodulatory protein combined

with KRAS(G12C) inhibitor impedes intracellular AKT/ERK network to

suppress lung cancer cells with KRAS mutation. Int J Biol Macromol.

259:1292912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tseng AJ, Tu TH, Hua WJ, Yeh H, Chen CJ,

Lin ZH, Hsu WH, Chen YL, Hsu CC and Lin TY: GMI, Ganoderma

microsporum protein, suppresses cell mobility and increases

temozolomide sensitivity through induction of Slug degradation in

glioblastoma multiforme cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 219:940–948.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hua WJ, Yeh H, Lin ZH, Tseng AJ, Huang LC,

Qiu WL, Tu TH, Wang DH, Hsu WH, Hwang WL and Lin TY: Ganoderma

microsporum immunomodulatory protein as an extracellular epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR) degrader for suppressing

EGFR-positive lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 578:2164582023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yeh H, Vo DNK, Lin ZH, Ho HPT, Hua WJ, Qiu

WL, Tsai MH and Lin TY: GMI, a protein from Ganoderma microsporum,

induces ACE2 degradation to alleviate infection of SARS-CoV-2

Spike-pseudotyped virus. Phytomedicine. 103:1542152022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Allen M, Bjerke M, Edlund H, Nelander S

and Westermark B: Origin of the U87MG glioma cell line: Good news

and bad news. Sci Transl Med. 8:354re3532016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lo HC, Hua WJ, Yeh H, Lin ZH, Huang LC,

Ciou YR, Ruan R, Lin KF, Tseng AJ, Wu ATH, et al: GMI, a Ganoderma

microsporum protein, abolishes focal adhesion network to reduce

cell migration and metastasis of lung cancer. Life Sci.

335:1222552023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ge SX, Jung D and Yao R: ShinyGO: A

graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants.

Bioinformatics. 36:2628–2629. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Luo W and Brouwer C: Pathview: An

R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and

visualization. Bioinformatics. 29:1830–1831. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y,

Ishiguro-Watanabe M and Tanabe M: KEGG: Integrating viruses and

cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 49:D545–D551. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

26

|

Hsu WH, Hua WJ, Qiu WL, Tseng AJ, Cheng HC

and Lin TY: WSG, a glucose-enriched polysaccharide from Ganoderma

lucidum, suppresses tongue cancer cells via inhibition of

EGFR-mediated signaling and potentiates cisplatin-induced

apoptosis. Int J Biol Macromol. 193:1201–1208. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhang Y, Huang Y, Yu D, Xu M, Hu H, Zhang

Q, Cai M, Geng X, Zhang H, Xia J, et al: Demethylzeylasteral

induces PD-L1 ubiquitin-proteasome degradation and promotes

antitumor immunity via targeting USP22. Acta Pharm Sin B.

14:4312–4328. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lu CS, Lin CW, Chang YH, Chen HY, Chung

WC, Lai WY, Ho CC, Wang TH, Chen CY, Yeh CL, et al: Antimetabolite

pemetrexed primes a favorable tumor microenvironment for immune

checkpoint blockade therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 8:e0013922020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

He K, Barsoumian HB, Puebla-Osorio N, Hu

Y, Sezen D, Wasley MD, Bertolet G, Zhang J, Leuschner C, Yang L, et

al: Inhibition of STAT6 with antisense oligonucleotides enhances

the systemic antitumor effects of radiotherapy and Anti-PD-1 in

metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res.

11:486–500. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang TY, Yu CC, Hsieh PL, Liao YW, Yu CH

and Chou MY: GMI ablates cancer stemness and cisplatin resistance

in oral carcinomas stem cells through IL-6/Stat3 signaling

inhibition. Oncotarget. 8:70422–70430. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin TY, Hsu HY, Sun WH, Wu TH and Tsao SM:

Induction of Cbl-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor

degradation in Ling Zhi-8 suppressed lung cancer. Int J Cancer.

140:2596–2607. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Hsin IL, Chiu LY, Ou CC, Wu WJ, Sheu GT

and Ko JL: CD133 inhibition via autophagic degradation in

pemetrexed-resistant lung cancer cells by GMI, a fungal

immunomodulatory protein from Ganoderma microsporum. Br J Cancer.

123:449–458. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lin PL, Wu TC, Wu DW, Wang L, Chen CY and

Lee H: An increase in BAG-1 by PD-L1 confers resistance to tyrosine

kinase inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer via persistent

activation of ERK signalling. Eur J Cancer. 85:95–105. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu M, Wang X, Li W, Yu X,

Flores-Villanueva P, Xu-Monette ZY, Li L, Zhang M, Young KH, Ma X

and Li Y: Targeting PD-L1 in non-small cell lung cancer using CAR T

cells. Oncogenesis. 9:722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lemma EY, Letian A, Altorki NK and McGraw

TE: Regulation of PD-L1 trafficking from synthesis to degradation.

Cancer Immunol Res. 11:866–874. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Feng C, Zhang L, Chang X, Qin D and Zhang

T: Regulation of post-translational modification of PD-L1 and

advances in tumor immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 14:12301352023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zuazo M, Gato-Cañas M, Llorente N,

Ibañez-Vea M, Arasanz H, Kochan G and Escors D: Molecular

mechanisms of programmed cell death-1 dependent T cell suppression:

Relevance for immunotherapy. Ann Transl Med. 5:3852017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ghosh C, Luong G and Sun Y: A snapshot of

the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. J Cancer. 12:2735–2746. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Gou Q, Dong C, Xu H, Khan B, Jin J, Liu Q,

Shi J and Hou Y: PD-L1 degradation pathway and immunotherapy for

cancer. Cell Death Dis. 11:9552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Venturella G, Ferraro V, Cirlincione F and

Gargano ML: Medicinal Mushrooms: Bioactive Compounds, Use, and

Clinical Trials. Int J Mol Sci. 22:2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y, Do R, Walz S,

Fitzgerald KN, Gouw AM, Baylot V, Gütgemann I, Eilers M and Felsher

DW: MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and

PD-L1. Science. 352:227–231. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Miao J, Hsu PC, Yang YL, Xu Z, Dai Y, Wang

Y, Chan G, Huang Z, Hu B, Li H, et al: YAP regulates PD-L1

expression in human NSCLC cells. Oncotarget. 8:114576–114587. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Zhang N, Zeng Y, Du W, Zhu J, Shen D, Liu

Z and Huang JA: The EGFR pathway is involved in the regulation of

PD-L1 expression via the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway in

EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Oncol. 49:1360–1368.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Jiang XM, Xu YL, Huang MY, Zhang LL, Su

MX, Chen X and Lu JJ: Osimertinib (AZD9291) decreases programmed

death ligand-1 in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer cells.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 38:1512–1520. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ota K, Azuma K, Kawahara A, Hattori S,

Iwama E, Tanizaki J, Harada T, Matsumoto K, Takayama K, Takamori S,

et al: Induction of PD-L1 expression by the EML4-ALK oncoprotein

and downstream signaling pathways in non-small cell lung cancer.

Clin Cancer Res. 21:4014–4021. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Konen JM, Rodriguez BL, Fradette JJ,

Gibson L, Davis D, Minelli R, Peoples MD, Kovacs J, Carugo A,

Bristow C, et al: Ntrk1 promotes resistance to PD-1 checkpoint

blockade in mesenchymal Kras/p53 mutant lung cancer. Cancers

(Basel). 11:4622019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lastwika KJ, Wilson W III, Li QK, Norris

J, Xu H, Ghazarian SR, Kitagawa H, Kawabata S, Taube JM, Yao S, et

al: Control of PD-L1 expression by oncogenic activation of the

AKT-mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res.

76:227–238. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu X, He Z, Shan B, Zeng

Q, Zhao Q, Zhu H, Liao H, Cen X, et al: ARIH1 signaling promotes

antitumor immunity by targeting PD-L1 for proteasomal degradation.

Nat Commun. 12:23462021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Ren X, Wang L, Liu L and Liu J: PTMs of

PD-1/PD-L1 and PROTACs application for improving cancer

immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 15:13925462024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhang F, Jiang R, Sun S, Wu C, Yu Q,

Awadasseid A, Wang J and Zhang W: Recent advances and mechanisms of

action of PD-L1 degraders as potential therapeutic agents. Eur J

Med Chem. 268:1162672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gao H, Sun X and Rao Y: PROTAC technology:

Opportunities and challenges. ACS Med Chem Lett. 11:237–240. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Fu HY and Hseu RS: Safety assessment of

the fungal immunomodulatory protein from Ganoderma microsporum

(GMI) derived from engineered Pichia pastoris: Genetic toxicology,

a 13-week oral gavage toxicity study, and an embryo-fetal

developmental toxicity study in Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Rep.

9:1240–1254. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

54

|

Spitzer MH, Carmi Y, Reticker-Flynn NE,

Kwek SS, Madhireddy D, Martins MM, Gherardini PF, Prestwood TR,

Chabon J, Bendall SC, et al: systemic immunity is required for

effective cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 168:487–502. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yi M, Niu M, Xu L, Luo S and Wu K:

Regulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. J

Hematol Oncol. 14:102021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wang M, Guo H, Sun BB, Jie XL, Shi XY, Liu

YQ, Shi XL, Ding LQ, Xue PH, Qiu F, et al: Centipeda minima and

6-O-angeloylplenolin enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint

inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Phytomedicine.

132:1558252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Wang Q, Wang J, Yu D, Zhang Q, Hu H, Xu M,

Zhang H, Tian S, Zheng G, Lu D, et al: Benzosceptrin C induces

lysosomal degradation of PD-L1 and promotes antitumor immunity by

targeting DHHC3. Cell Rep Med. 5:1013572024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Li JP, Lee YP, Ma JC, Liu BR, Hsieh NT,

Chen DC, Chu CL and You RI: The enhancing effect of fungal

immunomodulatory protein-volvariella volvacea (FIP-vvo) on

maturation and function of mouse dendritic cells. Life (Basel).

11:4712021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sharma P, Goswami S, Raychaudhuri D,

Siddiqui BA, Singh P, Nagarajan A, Liu J, Subudhi SK, Poon C, Gant

KL, et al: Immune checkpoint therapy-current perspectives and

future directions. Cell. 186:1652–1669. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Freed-Pastor WA, Lambert LJ, Ely ZA,

Pattada NB, Bhutkar A, Eng G, Mercer KL, Garcia AP, Lin L, Rideout

WM III, et al: The CD155/TIGIT axis promotes and maintains immune

evasion in neoantigen-expressing pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell.

39:1342–1360. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Lin ZH, Yeh H, Lo HC, Hua WJ, Ni MY, Wang

LK, Chang TT, Yang MH and Lin TY: GMI, a fungal immunomodulatory

protein, ameliorates SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein-induced

inflammation in macrophages via inhibition of MAPK pathway. Int J

Biol Macromol. 241:1246482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Almozyan S, Colak D, Mansour F, Alaiya A,

Al-Harazi O, Qattan A, Al-Mohanna F, Al-Alwan M and Ghebeh H: PD-L1

promotes OCT4 and Nanog expression in breast cancer stem cells by

sustaining PI3K/AKT pathway activation. Int J Cancer.

141:1402–1412. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Gao L, Guo Q, Li X, Yang X, Ni H, Wang T,

Zhao Q, Liu H, Xing Y, Xi T and Zheng L: MiR-873/PD-L1 axis

regulates the stemness of breast cancer cells. EBioMedicine.

41:395–407. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Jeong H, Koh J, Kim S, Song SG, Lee SH,

Jeon Y, Lee CH, Keam B, Lee SH, Chung DH and Jeon YK:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by tumor cell-intrinsic

PD-L1 signaling predicts a poor response to immune checkpoint

inhibitors in PD-L1-high lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 131:23–36. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Chang CH, Qiu J, O'Sullivan D, Buck MD,

Noguchi T, Curtis JD, Chen Q, Gindin M, Gubin MM, van der Windt GJ,

et al: Metabolic competition in the tumor microenvironment is a

driver of cancer progression. Cell. 162:1229–1241. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ghebeh H, Lehe C, Barhoush E, Al-Romaih K,

Tulbah A, Al-Alwan M, Hendrayani SF, Manogaran P, Alaiya A,

Al-Tweigeri T, et al: Doxorubicin downregulates cell surface B7-H1

expression and upregulates its nuclear expression in breast cancer

cells: Role of B7-H1 as an anti-apoptotic molecule. Breast Cancer

Res. 12:R482010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Liu S, Chen S, Yuan W, Wang H, Chen K and

Li D and Li D: PD-1/PD-L1 interaction up-regulates MDR1/P-gp

expression in breast cancer cells via PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK

pathways. Oncotarget. 8:99901–99912. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zheng Y, Fang YC and Li J: PD-L1

expression levels on tumor cells affect their immunosuppressive

activity. Oncol Lett. 18:5399–5407. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|