Introduction

Myocardial fibrosis is a common end-pathologic

phenotype in a variety of cardiomyopathies that is characterized by

pathological dilatation of the myocardial interstitium and the

abnormal remodeling of extracellular matrix (ECM) components

(1). This ECM remodeling

involves not only an imbalance in the ratio of type I/III collagen,

but an abnormal cross-linking of fibronectin and disruption of the

laminin network, thereby leading to an increase in the elastic

modulus of myocardial tissue. In the context of acute myocardial

injury, fibrosis represents an evolutionarily conserved mechanism

of trauma repair. When the investigation of the repair response

moved beyond its spatial and temporal constraints, fibrosis

research shifted to pathological processes: A sustained activation

of the TGF-β/Smad pathway was shown to lead to a reduced

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity in abnormally

proliferating myofibroblasts. These cells were found to depend on

glycolysis to maintain a high state of collagen synthesis and an

excessive deposition of ECM was shown to result in a marked

increase in ventricular stiffness and chronic, deregulated or

excessively aggressive fibrotic responses in these tissues were

observed to disrupt the structural framework of the heart's

structural elements, thereby impeding tissue regeneration and

leading to dysfunction (2).

The primary mechanism responsible for cardiac

fibrosis is the process of overactivation and proliferation of

cardiac fibroblasts (CFs). Activated CFs, also known as

myofibroblasts, are the major contributors to ECM production, and

are the primary effector cells of cardiac fibrosis (3,4).

The abnormal activation and proliferation of CFs underlie the cell

biology of cardiac fibrosis. Under physiological conditions,

resident CFs exist in a relatively quiescent state and are

primarily responsible for maintaining ECM homeostasis, cardiac

structure and mediating electrophysiological conduction. However,

under conditions of cardiac injury, such as myocardial ischemic

injury and myocardial infarction, myofibroblasts secrete more ECM,

leading to cardiac fibrosis. The fibrotic process is further

exacerbated by sustained activation of the TGF-β/Smad signaling

pathway. In previous studies, the binding of TGF-β1 to the TβRII

receptor was shown to trigger the phosphorylation of Smad2/3,

leading to their subsequent nuclear translocation (5-7).

This process directly activates collagen synthesis genes,

ultimately leading to a cascade of amplified fibrotic signals. In

addition, previous studies have demonstrated that this pathological

remodeling inhibits the migration of endogenous cardiac stem cells

through the physical barrier effect of migration, ultimately

leading to diastolic dysfunction and arrhythmias (8,9).

The chronological application of therapeutic interventions, which

promote moderate ECM deposition in the acute phase and inhibit

pathological remodeling in the chronic phase, has provided novel

therapeutic paradigms. Therefore, in order to design further new

targets and therapeutic strategies, a deeper understanding of the

processes of normal and pathological tissue remodeling is

required.

Recent advances in fibrosis research have focused on

elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac

fibrogenesis, with particular emphasis on identifying potential

therapeutic targets. Among these, METTL3 has emerged as a key

regulatory enzyme in the fibrotic process (10). As was demonstrated in a

previously published study (11), METTL3, as the core catalytic

component of the methyltransferase complex, performs a crucial role

in mediating RNA modifications that influence fibrotic pathways.

Despite the advances that have been made in understanding the

processes of myocardial fibrosis, however, the therapeutic

landscape for myocardial fibrosis remains limited, highlighting the

urgent need for an even deeper understanding of its molecular

mechanisms. Currently, the most intensively studied RNA

modifications are N6-methyladenosine

(m6A) and 7-methylguanosine (m7G)

modifications, and their specific mechanisms of action in

myocardial fibrosis have been partly elucidated. Advancements in

this field of research will be crucial for the development of

effective therapeutic strategies against this debilitating

condition.

Types and functions of RNA

modifications

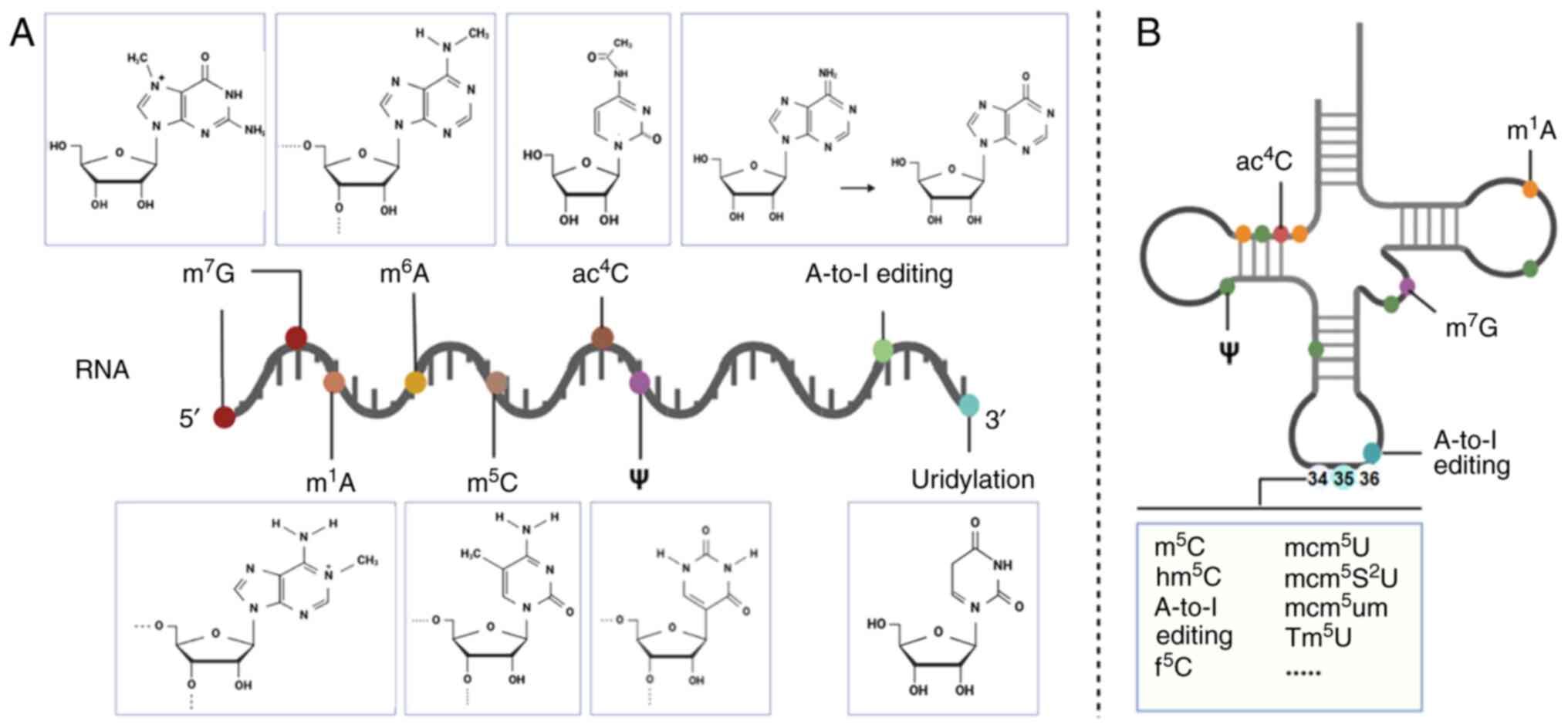

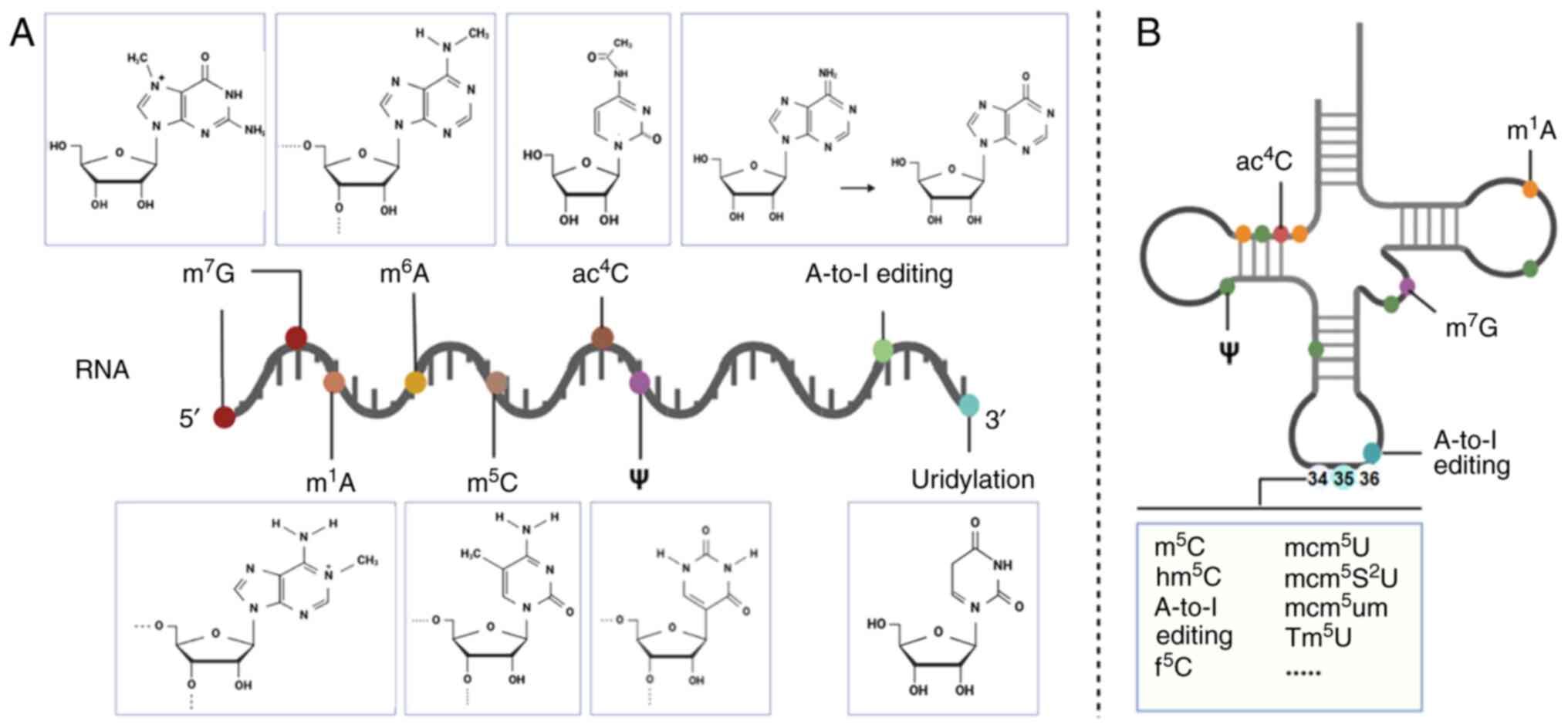

RNA modifications can be categorized into three main

groups, namely chemical motif modifications, nucleotide editing and

dynamic processing, and other regulatory modifications. The present

review focused on the types of RNA modifications in the first two

categories. Among the chemical motif modifications, methylation

modifications include m6A, methyladenosine

(m1A), 5-methylcytosine (m5C) and

m7G; acetylation modifications are mainly focused on

N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C); and

heterodimerization is mainly for pseudouridylation (Ψ), which

specifically modifies the U34 position of transfer RNA (tRNA)s.

Nucleotide editing and dynamic processing-type modifications

include adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) base substitutions and

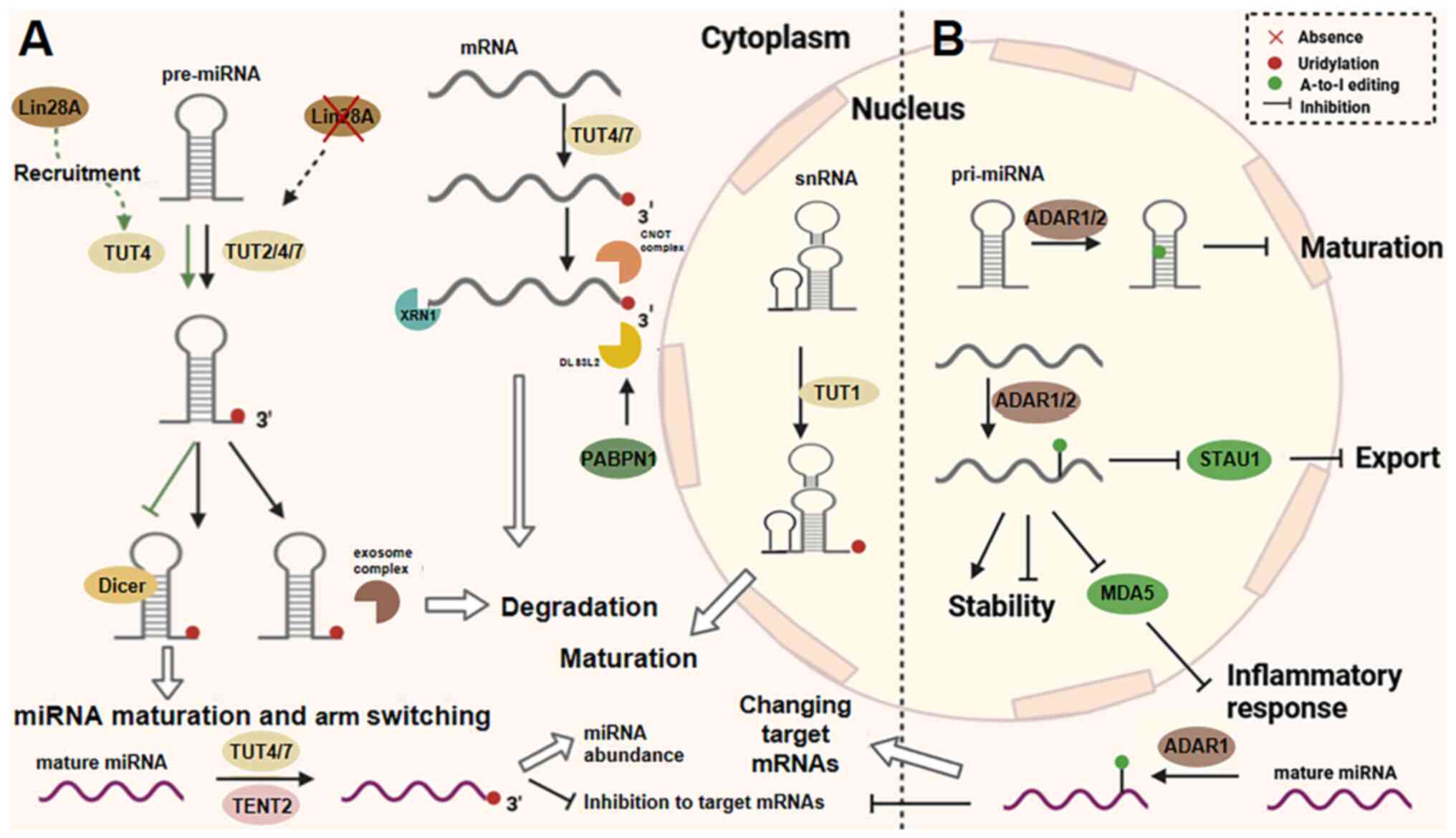

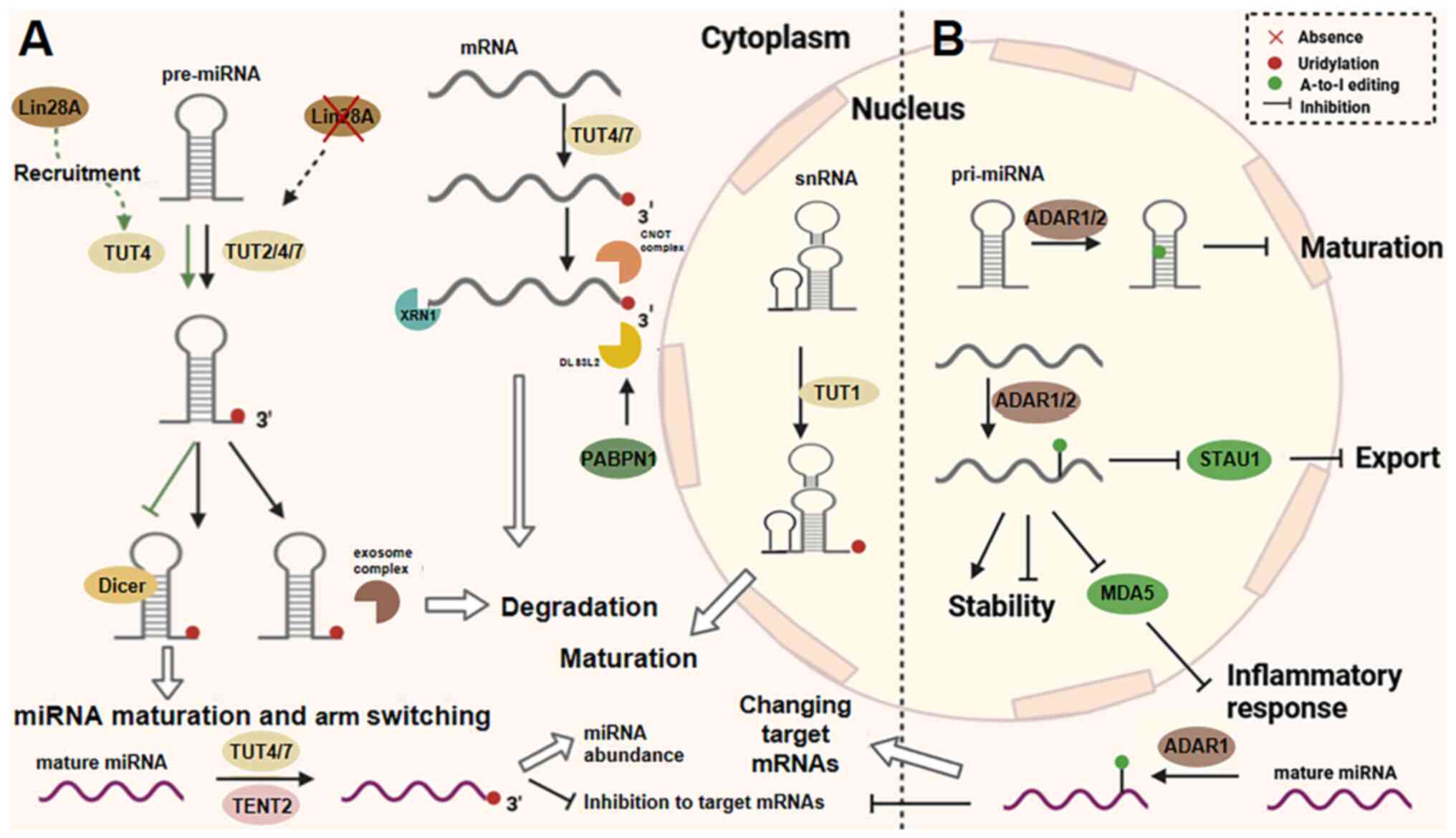

uridylation in nucleotide addition (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1A graphical depiction of the chemical

modifications occurring in RNA within mammalian cells is provided.

(A) The chemical structures of various RNA modifications, such as

involving mRNAs and microRNAs, as well as (B) Transfer RNAs, are

shown. Specifically, the modification at area 34 of the tRNA

regulates swing pairing, encompassing such as m5C, hm5C, and

others. A-to-I, adenine-to-inosine; m5C,

5-methylcytosine; m6A,

N6-methyladenosine; m1A,

1-methyladenosine, m7G, 7-methylguanosine;

ac4C, N4-acetylcytidine. |

m6A modifications

Since the discovery of nucleic acid methylation in

HeLa cells in the 1970s, m6A and m7G have

gradually entered the research landscape as important

epitranscriptome markers (12,13). After half a century of intensive

research, m6A has now been shown to be the most abundant

type of chemical modification in mammalian mRNAs, and its dynamic

and reversible modification properties have a key role in the

regulation of gene expression. In 2012, researchers achieved the

first systematic resolution of m6A modification at the

whole transcriptome level in human and mouse through developing

m6A-seq, a high-throughput sequencing technology

(14). This groundbreaking study

revealed that the m6A locus exhibits a remarkable

spatial distribution feature, namely, that it is mainly enriched in

two functional regions in the transcript: One is the long internal

exonic region of the coding region of the gene, whereas the other

is the 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR) close to the translation

termination codon. Notably, Meyer et al (15) further revealed, through a finer

localization analysis, that ~70% of the m6A sites in the

mammalian genome are densely distributed in the 3'-UTR interval

50-200 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the stop codon (16). This remarkable regiospecificity

suggests that m6A may be involved in regulating the

accessibility of microRNA (miRNA)-binding sites through either

spatial site-blocking effects or recruitment of specific reading

proteins. This discovery provides important clues towards

elucidating the precise molecular mechanism via which

m6A modification regulates post-transcriptional

processes through RNA-protein interaction networks.

The molecular architecture and functional regulatory

mechanisms of the m6A methyltransferase complex have

both been gradually elucidated. The complex comprises METTL3 and

METTL14 as the core catalytic subunits. Previous studies have shown

that METTL3 directly mediates S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent

methyl transfer reactions through its catalytic domain (17,18), whereas METTL14, though it was

previously shown not to be catalytically active (16), was responsible for substrate

recognition and spatial localization through its superior

RNA-binding ability (19-21).

The heterodimer formed by the two subunits not only constitutes the

catalytic core of the methylation reaction, but its structural

complementarity was shown to markedly enhance the thermodynamic

stability of the complex (22).

Wilms tumor 1-associated protein, which has been

identified as a key regulatory component of the complex, was found

to be not enzymatically active (23). Previous studies revealed that it

is able to regulate the methylation process through two key

mechanisms: First, it was shown to specifically interact with the

METTL3/METTL14 heterodimer, thereby promoting the aggregation of

the complex in nuclear speckles (19,23); and second, as a splicing factor,

it was shown to direct the complexes to target specific sites of

pre-mRNA through a phase separation mechanism (19,24). This dynamic regulatory network

ensures the spatiotemporal specific deposition of m6A

modifications on transcripts.

In addition to the core components, earlier studies

revealed that the m6A methylation system comprises

multiple classes of cofactors with distinct regulatory roles. For

example, Vir-like M6A methyltransferase associated/m6A

methyltransferase KIAA1429 was previously shown to mediate

co-localization of the complex with RNA polymerase II through

acting as a molecular scaffold (25). Similarly, the m6A

regulator, RNA binding motif protein 15/15B, has been shown to

enhance the complex's affinity for specific RNA motifs through its

RNA recognition motifs (26.) In addition, the E3 ubiquitin-protein

ligase Hakai and zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 were reported

to stabilize the subcellular localization of the complex via

deubiquitination modifications (27,28). These findings collectively

demonstrate that the modular assembly of these cofactors enables

the methyltransferase complexes to dynamically respond to cellular

signals, thereby facilitating the precise regulation of

m6A modifications (29).

In terms of substrate profile, the m6A

modification catalyzed by METTL3 has a broad RNA-type specificity,

covering classical RNA molecules such as mRNAs, tRNAs and ribosomal

RNA (rRNA)s, as well as regulatory RNAs, such as miRNA precursors

and long-stranded non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) (30). Notably, among mammalian mRNAs,

m6A modifications not only constitute the most abundant

post-transcriptional type of modification (31), but its dynamic and reversible

nature makes it a key regulatory node in the remodeling of gene

expression networks in pathological processes, including those of

cardiovascular diseases. This property has enabled METTL3 to

gradually become an important research target for the study both of

disease mechanisms and of the development of targeted

therapies.

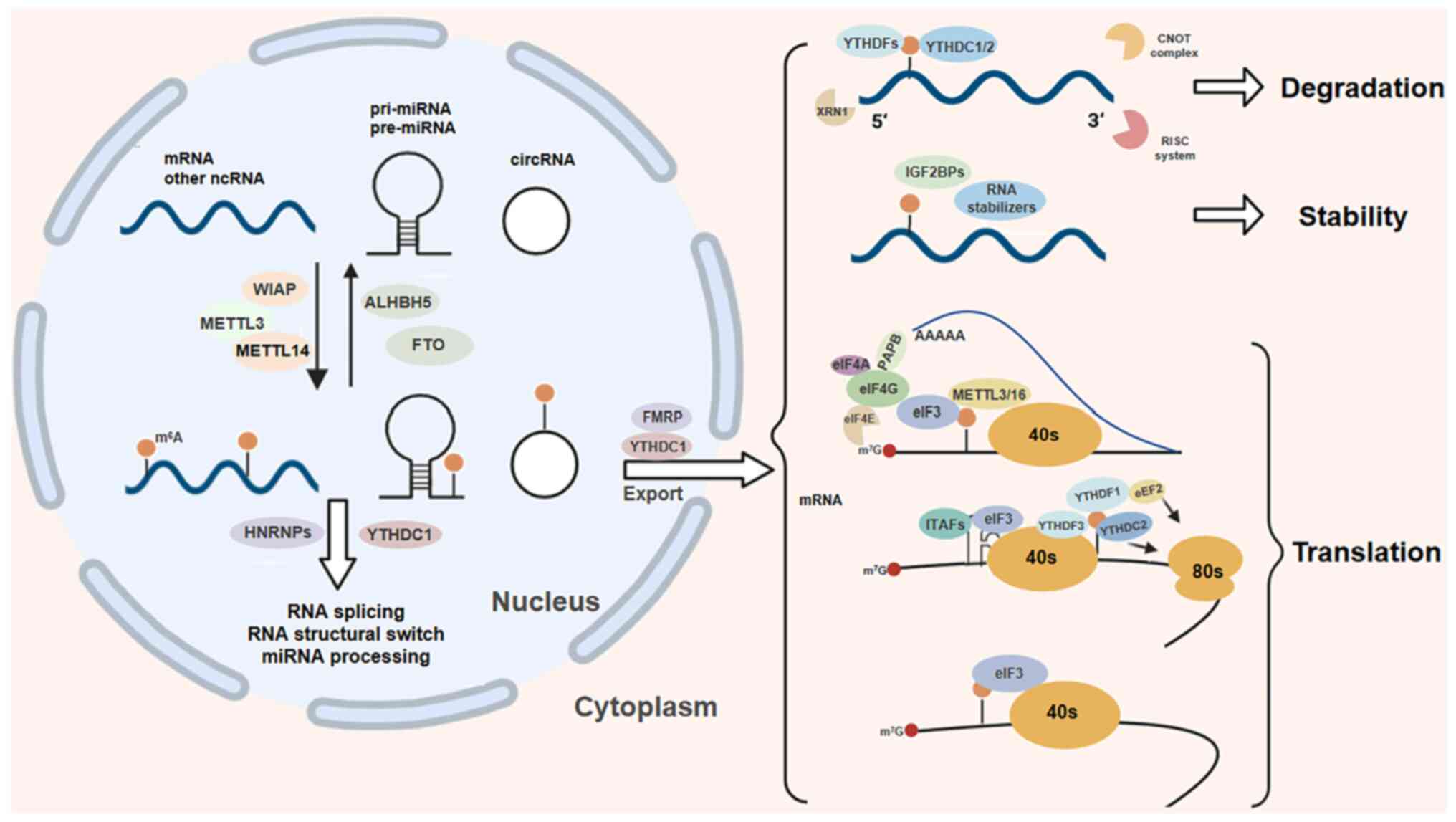

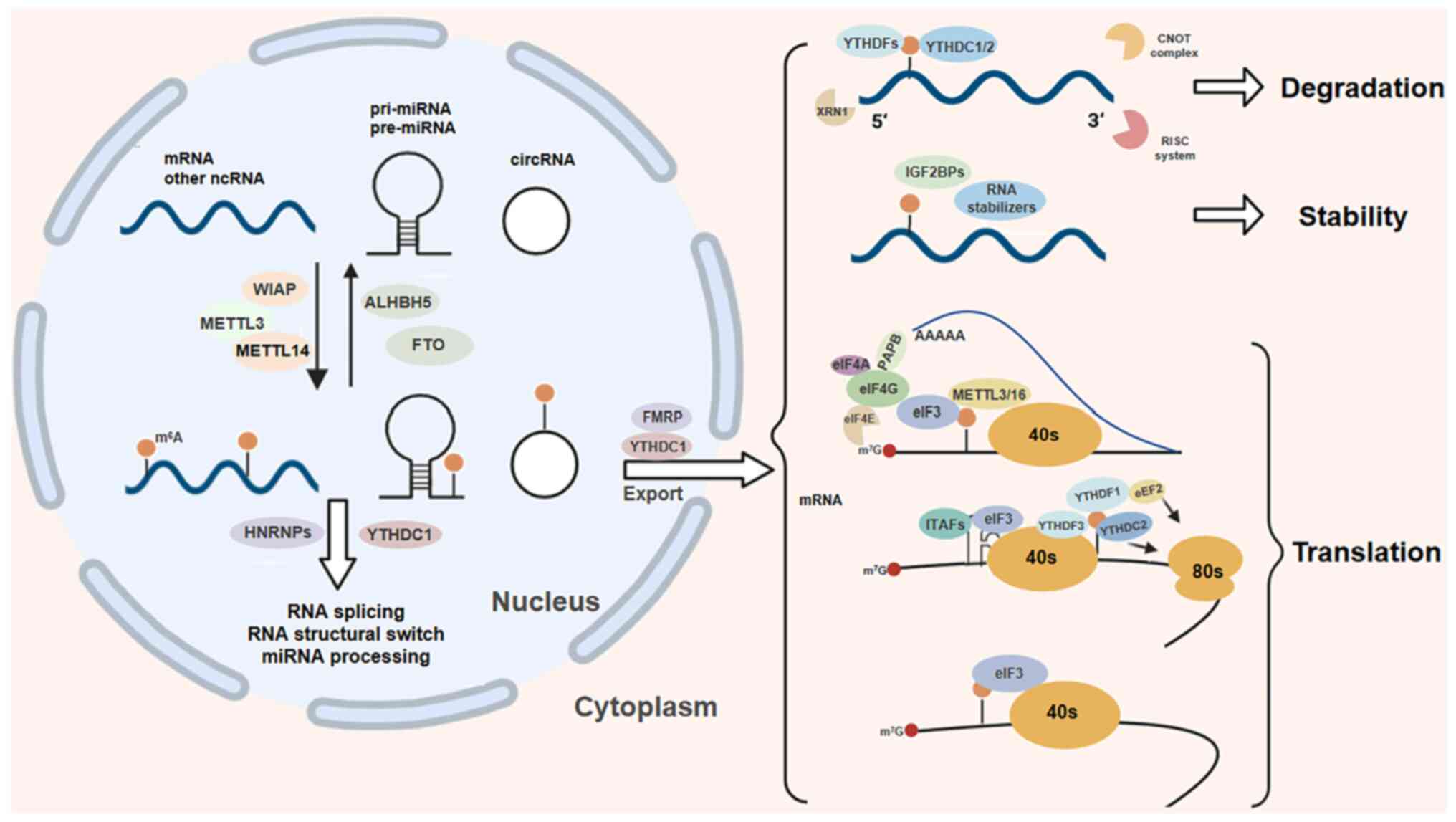

The functional realization of m6A

modifications relies on the dynamic recognition of their

methylation sites via specific reading proteins. Structural and

mechanistic analyses have classified m6A reading

proteins into three main categories. The first class comprises the

canonical YT521-B homology (YTH) domain family (YTHDF1-3 and

YTHDC1-2), where conserved aromatic residues within their

hydrophobic binding pockets were shown to mediate multiple aspects

of mRNA metabolism through the recognition of methylated adenosine

residues (32,33). The second category comprises a

family of non-classical RNA-binding proteins, including

insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins and

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins. Although these proteins

lack the YTH domain, structural studies have demonstrated that

their RNA recognition motifs, or K-homology domains, selectively

bind m6A-modified sites to regulate RNA stability and

subcellular localization. The third class of m6A reading proteins

is defined by translation-regulating factors, such as eukaryotic

initiation factor 3 (eIF3). Key studies have shown that eIF3 is

able to recognize m6A modifications within mRNA 5'-UTRs

through its hydrophobic binding pocket, thereby promoting ribosomal

preinitiation complex assembly to exert upstream translational

control, while concurrently influencing mRNA stability and

localization (32,33). Demethylases, including AlkB

homolog 5 (ALKBH5) and fat mass and obesity-associated protein

(FTO), were demonstrated to reverse m6A modifications

through enzymatic erasure mechanisms, as evidenced by biochemical

and structural studies (34)

(Fig. 2).

| Figure 2The biological functions of

m6A modification are diverse. This reversible process

involves 'writers' such as METTL3 and METTL14, and 'erasers' such

as FTO and ALKBH5 that remove the modification. The 'readers', such

as those with the YTH domain recognize and bind to

m6A-modified RNA, thereby influencing RNA processing and

its transport to the cytoplasm. Ultimately, m6A

modulation controls RNA translation, stability and degradation

within the cytoplasm. m6A,

N6-methyladenosine; METTL,

methyltransferase-like; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated;

ALKBH5, AlkB homolog 5; YTH, YT521-B homology. |

m1A modifications

The biological functions of m¹A, a key modification

in the epigenetic regulation of RNA, have been gradually unveiled

with the advance of research techniques. While earlier studies

focused on the distribution of m¹A in fungal tRNAs and rRNAs, a

breakthrough discovery based on the methylated RNA

immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq) technique showed that

m¹A modifications are also present in the coding region (CDS) and

the 5'-UTR region of mammalian mRNAs and that the degree of their

enrichment is markedly positively associated with the number of

variable translation initiation sites (35). However, Grozhik et al

(35), by performing chemometric

analysis, showed that the abundance of m¹A modifications in mRNAs

is markedly lower compared with other RNA types, suggesting that

they may exist as precise markers for specific functional sites,

rather than as global modifications.

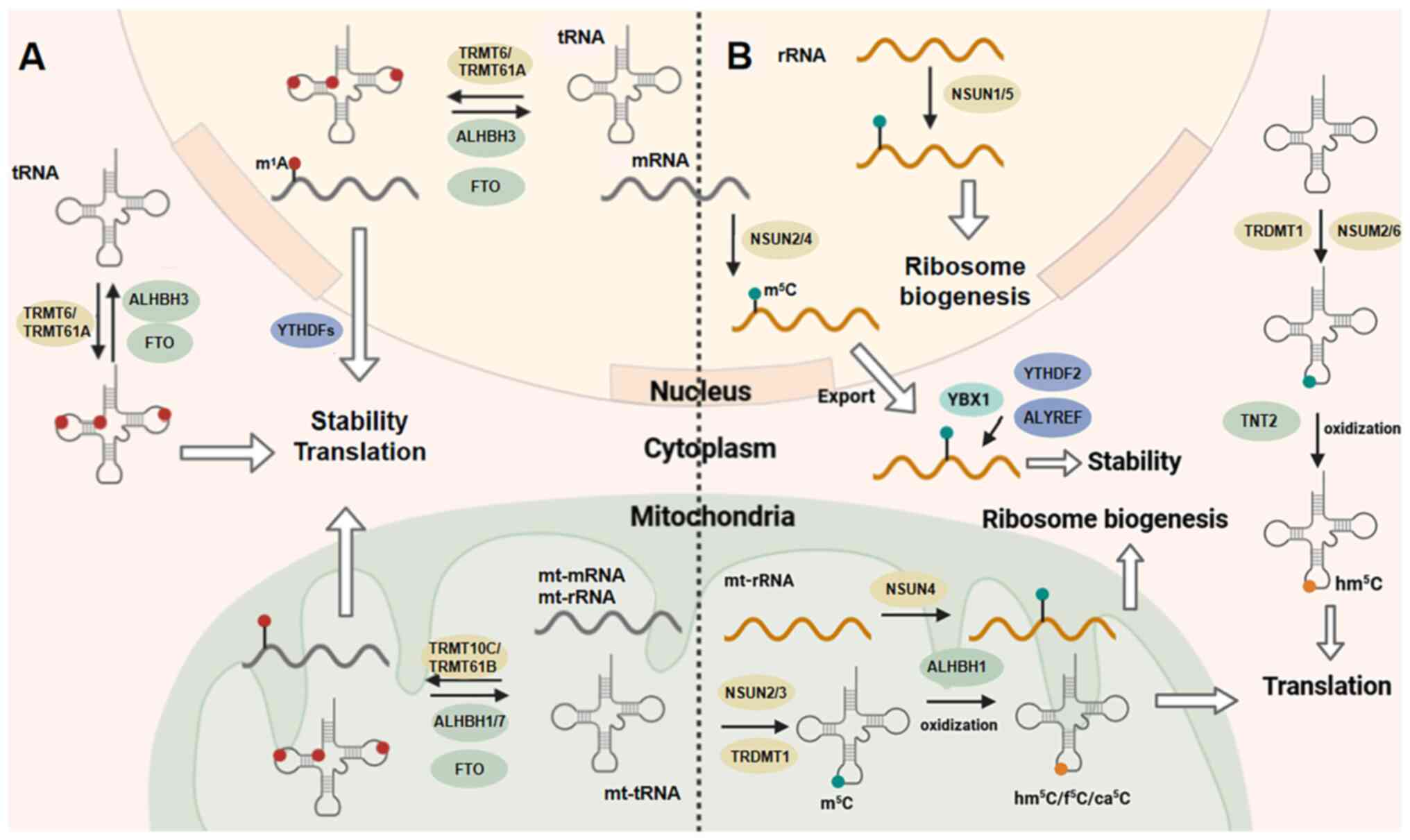

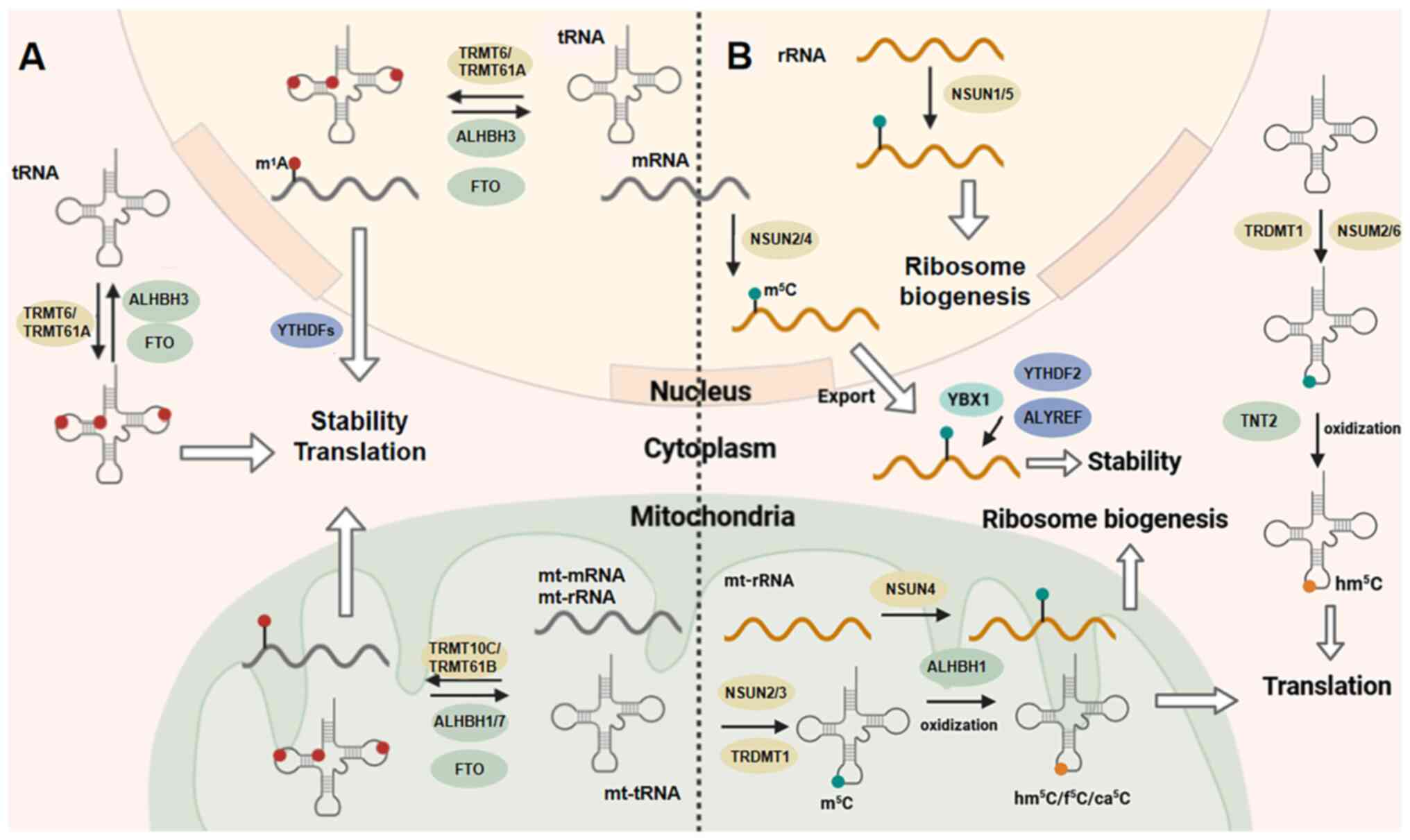

At the methylation regulatory level, members of the

tRNA methyltransferase (TRMT) family have been shown to exhibit a

subcellular functional division. TRMT61B, which was identified as

the first human m1A methyltransferase, primarily

catalyzes modifications of cytoplasmic tRNAs and rRNAs (36,37), whereas TRMT10C specifically

targets mitochondrial tRNAs and was further demonstrated to

maintain mitochondrial homeostasis through the regulation of energy

metabolism (38). Previous

studies have established that the AlkB homolog (ALKBH) family

enzymes precisely coordinate RNA demethylation dynamics; for

example, ALKBH3 promotes functional tRNA fragment generation via

erasing tRNA methylation, and actively mediates

m1A-dependent transcript degradation through its

demethylase activity (39,40). Another study (41) showed that ALKBH1 is able to

enhance the pool of translationally active tRNAs through

selectively removing m¹A modifications at position 58 of tRNAs,

thereby increasing their stability. Moreover, ALKBH7 was

characterized as a mitochondrial pre-tRNA-specific demethylase that

participates in cellular energy metabolism reprogramming (39). Furthermore, FTO not only

catalyzes m6A demethylation, but it also recognizes

stem-loop structures that enable it to demethylate tRNA m¹A

modifications, thereby markedly boosting nucleocytoplasmic protein

translation flux (42). In skin

scar research, staphylococcal nuclease and tudor domain containing

1 (SND1) was identified as an m¹A reader protein that both enhances

RNA stability and drives fibroblast proliferation and collagen

deposition in pathological scarring. However, its role in

cardiovascular diseases remains poorly understood (43). From the perspective of the

functions of SND1 and the existing mechanisms of cardiac fibrosis,

future studies should explore the role of SND1 in the progression

of cardiac fibrosis by investigating its effect on cardiac

fibrosis-associated signaling pathways (such as the TGF-β signaling

pathway), gene expression regulation and cellular metabolism.

Notably, m¹A modifications have been shown to

exhibit significant environmental stress sensitivity. Under serum

starvation or oxidative stress

(H2O2-stimulated) conditions, the abundance

of m¹A modification sites in mRNAs was found to be markedly

increased (39), whereas glucose

deprivation led to a decrease in m¹A tRNA levels through the

inhibition of TRMT enzyme activity, an effect that could be

reversed by knockdown of the ALKBH1 gene (41). This dynamic modification pattern

suggests that m¹A may act as a metabolic stress receptor that helps

cells to adapt to micro-environmental changes via modulating

translational reprogramming. For example, under energetic stress

conditions, dynamic changes in mitochondrial m¹A modification would

enable rapid regulation of oxidative phosphorylation activity by

influencing the translational efficiency of the respiratory chain

complex mRNA (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3m1A and m5C

modifications. (A) Within the cell nucleus, mRNAs and tRNAs undergo

methylation by enzymes including TRMT6 and TRMT61A. Specifically,

the methylation of m1A on mt-tRNA, rRNA and mRNA is

catalyzed by TRMT10C/TRMT61B. The enzymes FTO and ALKBH1/3/7 are

responsible for controlling the demethylation process.

Functionally, m1A employs various mechanisms to regulate

translation and RNA stability, with YTHDF serving as a potential

'reader' of m1A modifications. (B) Aspartic acid tRNA is a specific

target for methylation by the enzyme TRDMT1. The methyltransferases

NSUN1-6 function as 'writers' of m5C modifications in RNA,

influencing RNA nuclear export, metabolism, and function. Various

proteins, including ALYREF, YBX1 and YTHDF2, have been reported to

serve as 'readers' of m5C modifications. Additionally, TNT2, ALKBH1

are responsible for catalyzing the oxidation of m5C rather than its

elimination. m1A, 1-methyladenosine; m5C,

5-methylcytosine; Mt-mitochondrial; ALKBH1, AlkB homolog 1; YTH,

YT521-B homology; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated; ALKBH5,

AlkB homolog 5; YTH, YT521-B homology; rRNA, ribosomal RNA. |

m5C modifications

As a key contributor to RNA epigenetic modification,

the biological significance of m5C has undergone a

cognitive revolution from DNA-specific modification to widespread

regulation by RNA. during the early period of its investigation,

m5C was considered to exist only in DNA due to

limitations in the technologies available for detection, although

given the breakthroughs that have been made in high-throughput

sequencing and mass spectrometric techniques, researchers have

discovered that it is widely distributed in eukaryotic RNAs, and is

particularly enriched in high abundance in the anticodon loops of

tRNAs and in conserved regions of rRNAs (44). m5C deposition has been

shown to be mediated by the NOL1/NOP2/SUN structural domain (NSUN)

family, in concert with TRDMT1. In the tRNA modification system,

NSUN2 was identified to catalyze the methylation of both miRNA

precursors and mRNAs (45,46), whereas NSUN3, NSUN6 and TRDMT1

were shown to form a ternary system targeting tRNA-specific sites,

respectively (45,47-49); moreover, functional analyses

revealed that, in the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) modification system,

NSUN1 and NSUN5 regulate the structural maturation of rRNAs,

whereas NSUN4 participates in respiratory chain complex assembly

through mitochondrial rRNA/mRNA methylation (50-53).

A previous study also revealed diversified

m5C recognition mechanisms; namely, the YTH

domain-containing family protein 2 (YTHDF2)-mediated degradation of

m5C-methylated mRNAs through its YTH domain, the Y

box-binding protein 1 (YBX1)-mediated stabilization of

m5C-modified transcripts via cold shock domain binding,

and the functioning of Aly/REF export factor (ALYREF) as a nuclear

export factor that facilitates the cytoplasmic translocation of

m5C-marked mRNAs through specific RNA-protein

interactions (54). Notably, the

mechanism of dynamic regulation of m5C remains

controversial, given that its reversibility has not yet been

clarified (unlike that of m6A/m¹A) and this stability

implies that m5C modifications have a unique role in

long-term episodic memory regulation. Currently, the existing

experimental evidence has established that m5C

modifications are involved in organ growth, initiation of various

pathological conditions, and developmental processes (47,54-57). Taken together, these findings

have not only expanded the regulatory dimensions of RNA epigenetic

inheritance, but have also provided novel perspectives for the

continuing study of disease mechanisms and targeted therapies.

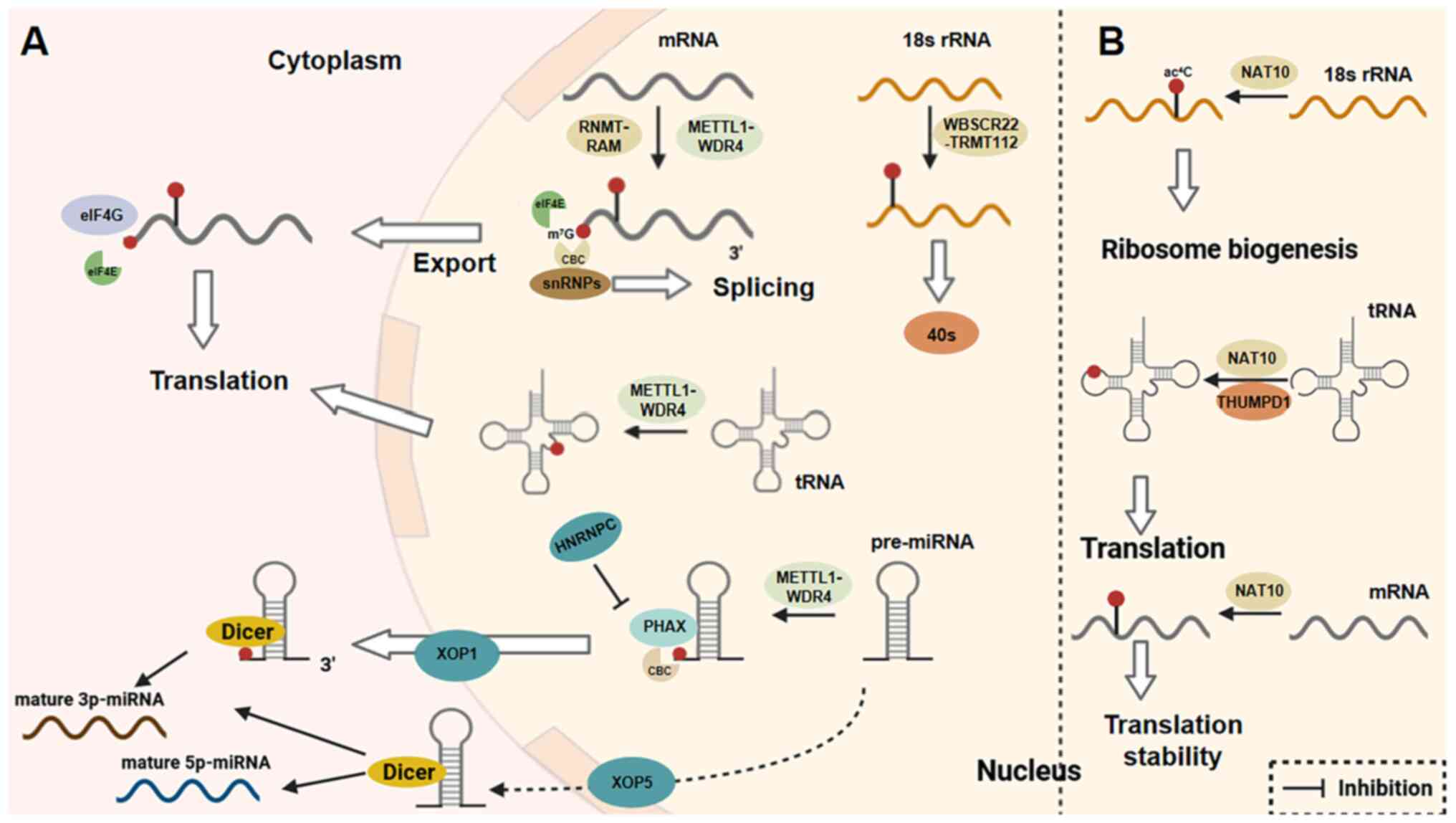

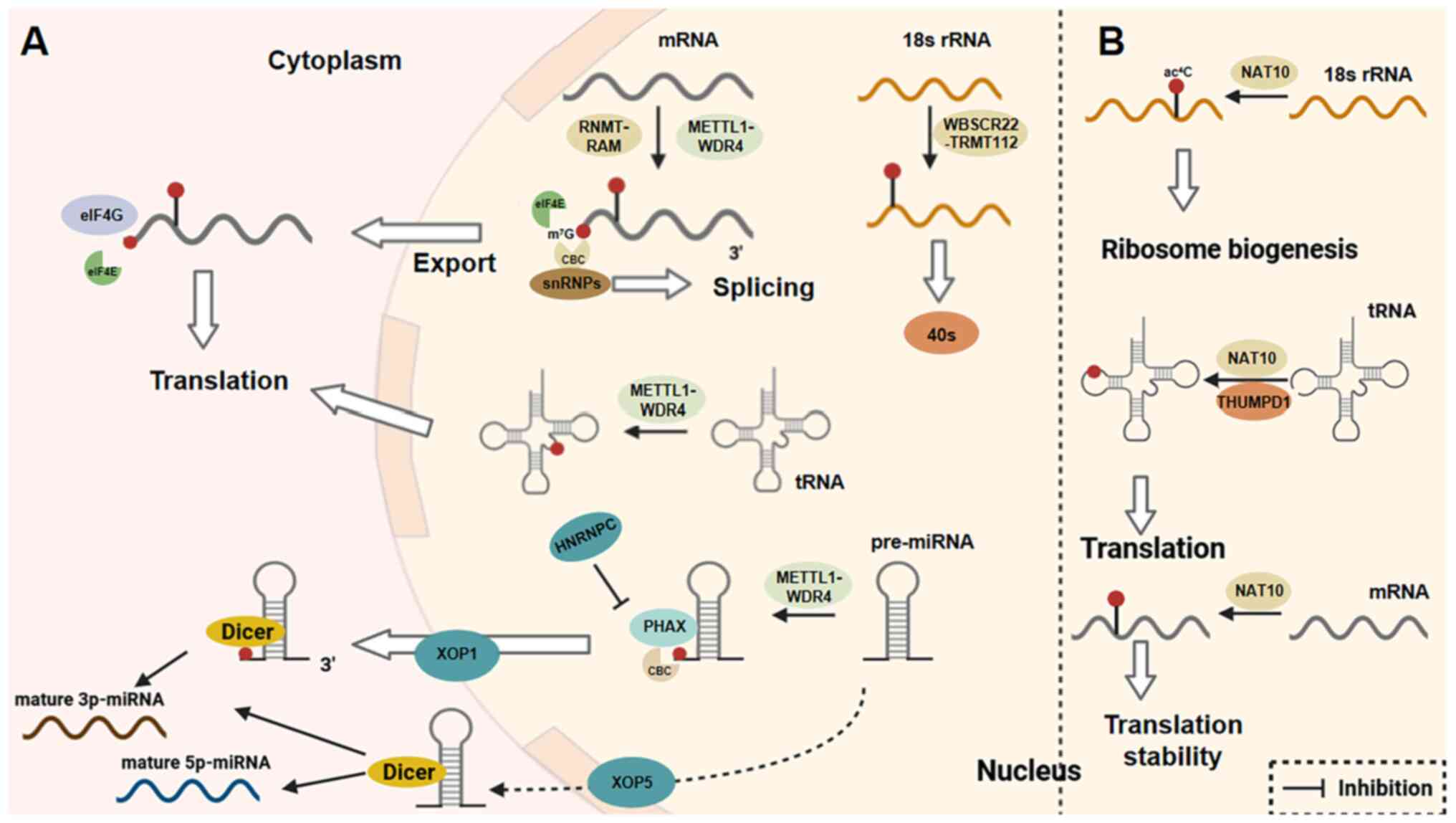

m7G modifications

Since the discovery of m7G modification

in the mammalian mRNA 5'-cap structure in the 1970s (58,59), its biological function is now

realized to extend from classical mRNA stability regulation to

multilevel gene expression networks. Genome-wide mapping has

further revealed that, beyond mRNA cap structures, m7G

is distributed across non-coding RNAs, including rRNAs, tRNAs and

miRNAs, and that this dynamic distribution pattern suggests

pervasive roles in post-transcriptional regulation (60).

Another previously published study (61) demonstrated that precise

m7G deposition relies on synergistic multi-enzyme

complexes; namely, that the mammalian mRNA cap methyltransferase

complex, RNMT-RAM, specifically catalyzes m7G

modifications in 5'-cap structures by spatially coupling

mRNA-capping enzymes into functional post-transcriptional

processing modules. In addition, the WBSCR22-TRMT112 complex

utilizes the SAM-binding structural domain to catalyze guanosine

methylation at position 1,639 of 18S rRNA, a modification that

served as a critical checkpoint for the maturation of the small

subunit of the ribosome (60)

and the METTL1-WDR4 complex has been shown to exhibit

multi-functional catalytic properties that are responsible for

mRNA, tRNA and miRNA-associated m7G modifications

(62-64).

At the level of functional regulation,

m7G coordinates RNA metabolism and translation through

multiple mechanisms, including prolongation of the mRNA half-life

of cap-structured m7G via the inhibition of 5'→3'

nucleic acid exonuclease activity (65-67), whereas internal m7G

modifications have been shown to promote RNA nucleocytoplasmic

translocation by binding to translocation factors. During

translation, METTL1-mediated modification of internal

m7G mRNA enhances the translation initiation efficiency

by reconfiguring the ribosome-binding interface, whereas the

m7G modification of tRNA led to an enhancement of the

decoding efficiency by optimizing the precision of codon-anti-codon

pairing (63,68). Non-coding RNA maturation is also

regulated by m7G; for example, the m7G

modification of 18S rRNA was identified to be a quality checkpoint

for ribosome biogenesis (60),

whereas m7G modification of miRNA precursors was shown

to regulate the abundance of mature miRNAs by altering the

accessibility of the cleavage site of Drosha, a ribonuclease III

enzyme that performs a crucial role in the biogenesis of

miRNAs.

A cryo-electron microscopy study revealed that the

METTL1-WDR4 complex achieves substrate-specific switching through

conformational changes: When the complex bound to tRNA, the WD40

structural domain of WDR4 was found to induce active-pocket

deformation, which led to a precise recognition of RAGGU motifs

(69). Abnormalities in this

dynamic catalytic mechanism are closely associated with

neurodevelopmental disorders and tumor metastasis; for example,

METTL1 deletion led to tRNA fragmentation, with the consequent

activation of the p53-dependent apoptotic pathway (63,68). In glioblastoma, METTL1

overexpression was shown to promote tumor cell invasion by

enhancing the methylation of oncogenic miRNA (for example, miR-21)

precursors (64). Taken

together, these findings have not only shed light on the molecular

regulatory network of m7G modification, but they also

may provide novel ideas for precision therapy targeting RNA

methylation.

ac4C modifications

As the only known RNA acetylation modification, the

biology of ac4C has undergone a cognitive leap from

prokaryotic to eukaryotic systems. Whereas early studies focused on

the ac4C modification of bacterial tRNA anticodon stem

loops and conserved regions of fungal rRNAs (70), the discovery of

N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) revealed the widespread

presence of this modification in mammalian RNAs. NAT10 catalyzes,

through ATP-dependent acetyltransferase activity, the formation of

ac4C in a conserved region of the 18S rRNA site (namely,

at position 1,842; ac4C1842). Further structural

analysis by cryo-electron microscopy revealed that

ac4C1842 serves as a molecular checkpoint for the

assembly of the small subunit of the ribosome through stabilizing

the helix 69 conformation of the 18S rRNA; its absence led to

aberrant processing of the rRNA precursor (70).

In the dynamic regulation of tRNAs, the deletion of

NAT10 was shown to lead to a decrease in the overall acetylation

level of tRNAs in human colon cancer cells, thereby markedly

affecting their structural stability (69). Of particular note,

ac4C modification close to the tRNA anticodon swing site

led to an increase in ribosome decoding efficiency via the

optimization of codon-anticodon geometry matching (71). Subsequent mRNA-level studies

identified that ac4C in the CDS region prolonged the

half-life of transcripts by resisting 3'→5' exonuclease activity,

whereas ac4C in the 5'-UTR region facilitated the

translation initiation of upstream open reading frames (ORFs)

through a 'leaky scanning' mechanism, via which the efficiency of

the main ORFs was enhanced (71,72). Furthermore, in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma, NAT10 was found to specifically catalyze

the acetylation modification of the lncRNA CTC-490G23.2, and this

modification drove tumor progression (73).

Physiologically, NAT10 promotes the osteogenic

differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by

stabilizing runt-related transcription factor 2 mRNA, which thereby

established its critical role in bone metabolic homeostasis

(74). At the pathomechanistic

level, NAT10 has been shown to be abnormally highly expressed in

malignant tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer

and its stability is enhanced by the acetylation of pro-oncogene

mRNAs (for example, Myc and Cyclin D1). Additionally, specific

alterations were observed in the serum exosomal ac4C

modification profiles of patients with esophageal carcinoma,

thereby suggesting that it has potential as a liquid biopsy marker

(73,75-79). For therapeutic applications,

ac4C-modified synthetic mRNAs have been demonstrated to

have unique advantages; specifically, repeated dosing was enabled

through reducing Toll-like receptor 7/8-mediated immunogenicity and

a 3-fold extension of the shelf-life of mRNA vaccines at ambient

temperature was achieved by enhancing their thermal stability

(80). These breakthroughs

provide new directions for RNA acetylation-based precision medicine

(Fig. 4).

| Figure 4m7G and ac4C

modifications. (A) In the nucleus, METTL1-WDR4 serves as the

'reader' for m7G modifications in mRNAs, pre-miRNAs and

tRNAs. WBSCR22-TRMT112 is responsible for reading 18S rRNA. The

mammalian mRNA cap methyltransferase complex, RNMT-RAM, on the

other hand, primarily targets mRNA for m7G modification.

m7G has various roles in enhancing translation rates, in

accelerating RNA export, in contributing to ribosome synthesis and

in facilitating the maturation of miRNAs. (B) Within the nucleus,

NAT10 and THUMPD1 primarily function as enzymes that catalyze

ac4C modifications on rRNAs, tRNAs and mRNAs. These

modifications are associated with translation efficiency, ribosome

biosynthesis, and mRNA stability, respectively. METTL,

methyltransferase-like; tRNAs m7G, 7-methylguanosine;

ac4C, N4-acetylcytidine; miRNA,

microRNA; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; NAT10, N-acetyltransferase

10; tRNA, transfer RNA. |

Uridylation modifications

Uridylation, a typical representative of RNA

3'-end-tail modification, causes predominantly an enrichment in

short poly(A)-tailed or U-tailed RNA molecules (81,82). Its catalytic system consists of

the terminal uridylyl transferase (TUT, or TUTase) and terminal

nucleotidyl transferase (TENT) families working in concert: TUT4/7

(ZCCHC11/6) was found to specifically recognize the 3'-overhanging

structure of mature miRNAs, mediating uridylation modifications of

precursor miRNAs, such as pre-let-7 (83,84). In addition, TENT2 was shown to

regulate the loading efficiency of Argonaute proteins through

selectively catalyzing the addition of uridine to the 3'-end of

mature miRNAs (83), and TENT5C

was shown to maintain mRNA stability via antagonizing the

de-adenylation enzyme CCR4-NOT complex (85).

At the level of dynamic metabolic regulation,

uridylation and de-adenylation form a precise balance: When poly(A)

binding protein cytoplasmic 1 (PABPC1) bound to long poly(A) tails,

it was found to inhibit TUTase activity through spatial

site-blocking effects, whereas, in the short poly(A) tail state,

PABPC1 was dissociated from the TUTase, thereby initiating the

process of uridylation (85-87). This antagonistic mode coexists

with a synergistic mode: The miRNA miR-1 was shown to promote

de-adenylation through recruiting CCR4, while enhancing

TUT4-mediated uridylation, thereby creating a positive feedback

loop of mRNA decay (82,85). Mammalian cells have been found to

clear uridylated RNA species through a dual pathway: 5'→3'

degradation is initiated by XRN1 exonuclease, which specifically

recognizes the TUT4/7-extended U-tail (88), whereas 3'→5' degradation is

mediated via DIS3-like exonuclease 2 (DIS3L2), which recognizes the

uridylation marker through the S1 structural domain. Exosomes

remove uridylated mRNAs through the polyadenylate-binding nuclear

protein 1 (PABPN1)-DIS3L2 axis, and the exosome also degrades

miRNAs (89-91). RNA-binding proteins, such as

human-antigen R, antagonize the degradative activity of DIS3L2 by

binding to uridine-enriched elements to form protective

ribonucleoprotein particles, and this dynamic equilibrium

determines the fate of uridylated RNAs (92-95).

In miRNA biosynthesis, uridylation also serves a

dual regulatory role: In terms of inhibitory modifications, the

RNA-binding protein Lin28 was shown to recruit TUT4 to the GGAG

motif of pre-let-7 and other pre-miRNAs, where the addition of an

oligo-uridine tail (+UUU) was found to block Dicer cleavage

(84). The operation of a

similar mechanism was observed in the inhibition of miR-191

processing (96). In terms of

mature miRNA functional modulation, uridylated miR-105 was shown to

reprogram its target profile by altering seed sequence

complementarity (97), whereas,

in another study (98),

TUT7-mediated pre-miRNA uridylation was found to promote the

differential loading of Argonaute-2 (Fig. 5).

| Figure 5Uridylation and A-to-I editing. (A)

In the cytoplasm, TUT2, TUT4 and TUT7 are responsible for the

addition of uridylates to pre-miRNAs, fully mature miRNAs and

mRNAs, whereas TUT1 is responsible for the uridylation of snRNAs in

the nucleus. The maturation of miRNAs is regulated by TENT2.

Uridylation is important in the maturation of miRNAs, snRNAs, the

activity of miRNAs, decay. (B) ADAR1 and ADAR2 function as the

'writer' of A-to-I editing for mRNAs, mature miRNAs and pri-miRNAs.

ADAR1/2 affects not only mRNA stability and production, but also

miRNA maturation and function. A-to-I, adenine-to-inosine; TUT,

terminal uridylyl transferase; miRNA, microRNA; snRNA, small

nuclear RNA; ADAR, adenosine deaminase acting on RNA. |

A-to-I RNA editing modifications

The adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) family

has been demonstrated to remodel RNA function through A-to-I

editing, and its sites of action are frequently co-localized with

Alu elements and long interspersed nuclear elements

retrotransposons in the genome (99,100). Although ADAR1 and ADAR2 share

catalytic structural domains, they display significant functional

heterogeneity: ADAR1 preferentially recognizes the

quasi-double-stranded regions formed by Alu elements through its

double-stranded RNA-binding domain (101), whereas ADAR2 targets

neuron-specific RNA substrates by virtue of its N-terminal nuclear

localization signal (102).

This difference in substrate selectivity establishes the functional

division of labor between the two ADAR family members in the

cell.

RNA editing regulates gene expression through a

mechanism that operates on multiple levels. At the level of

transcript remodeling, ADAR-mediated selective splicing has been

shown to alter protein heterodimer composition by retaining

specific exons; for example, A-to-I editing of miR-34a led to the

alteration of its seed sequence and a loss of inhibitory function

for target mRNAs (103),

whereas RNA secondary structure remodeling was found to block

Staufen double-stranded RNA binding protein 1-mediated RNA nuclear

export (101). At the level of

protein function regulation, the RNA editing of antizyme inhibitor

1 mRNA was shown to induce its nucleoplasmic shuttling function,

thereby regulating polyamine metabolic homeostasis, whereas

arginine codon (AGA) to termination codon (UGA) editing triggered

nonsense-mediated mRNA degradation (104-108).

During cancer progression, the ADAR family has been

shown to exhibit a 'double-edged sword' effect: ADAR1 inhibits

melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) from recognizing

endogenous double-stranded RNAs via editing Alu elements, thereby

enabling cells to evade immune surveillance (100,109-111), whereas its p150 isoform

promotes tumor metastasis through the editing of circular RNAs

(112-114). On the other hand, ADAR2 was

shown to restore oncogene expression, exerting a tumor-suppressive

role (112,113).

Subtype-specific regulation has been demonstrated to

further refine the functional network: For example, cytoplasmic

ADAR1-p110 regulates mature miRNA function, whereas nuclear

ADAR1-p150 maintains embryonic stem cell pluripotency. In cardiac

tissues, ADAR2 was shown to protect ADAR1 targets from over-editing

through competitive binding (114) and, moreover, a hierarchical

regulatory mechanism for editing activity was demonstrated in a

different study (115).

In inflammatory regulation, ADAR1 has been shown to

maintain immune homeostasis through three mechanisms: First,

through editing endogenous double-stranded RNA to block

MDA5-mediated intrinsic immune recognition; second, by moderately

activating the protein kinase R (PKR)-Z-DNA/RNA binding protein 1

axis to induce adaptive stress responses; and thirdly, by editing

viral RNA mimicry via its p150 isoform to prevent type I interferon

storms (100,109-111). Disruption of this dynamic

equilibrium makes an important contribution to autoimmune diseases

and viral infections, thereby providing novel targets for

immunomodulatory therapy.

Ψ modifications

Ψ, a very abundant post-transcriptional modification

in RNA, occurs via the action of pseudouridine synthetase (PUS),

catalyzing the isomerization of uridine. Its unique C-C glycosidic

bond (compared with the C-N bond of uridine) results in both a

higher thermodynamic stability of, and irreversible changes to, RNA

molecules, also serving as a consistent marker of the

epitranscriptome (116-118). The catalytic pathways may be

divided into two categories, first, the RNA-independent pathway, in

which PUS family members (for example, PUS1) directly recognize

RNA-specific structures (such as the T-arm deletion conformation of

tRNAs) to accomplish site-specific modifications through conserved

catalytic structural domains (119,120); and second, the RNA-dependent

pathway, which is mediated via the box H/ACA-type small nucleolar

ribonucleoprotein complexes, in which the protein Dyskerin acts as

the core catalytic subunit to direct the Ψ-modification of rRNA and

small nuclear RNA (snRNA) (121-123).

Mammalian PUS family members exhibit a fine

subcellular division of labor: In the cytoplasmic system, PUS10 has

been shown to specifically catalyze Ψ-modification at tRNA

positions 54/55 (124,125), whereas PUS1 regulates

transcript stability by recognizing mRNA stem-loop structures

(119,126). In the mitochondrion, TruB

pseudouridine synthase family member 1 (TRUB1) maintains the

Ψ-modification at tRNA position 55, and its absence was found to

lead to tRNA conformational disorder, which resulted in triggering

the defective assembly of the respiratory chain complex (127). In the nucleoplasmic system,

PUS3 targets tRNA modifications at positions 38/39 (128,129), and PUS7 was found to recognize

the UGUAR motif to regulate both small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA)

processing and pre-mRNA splicing (120,130). Ψ also has an important role in

the control of translation. Pseudouridylation of tRNAs has been

reported to regulate translation; in addition, the

pseudouridylation of rRNAs also affects mRNA translation. In 293T

cells, the presence of Ψ in mRNA codons was shown to increase

protein production and to accelerate the rate of recognition of

associated tRNAs (131).

The Ψ-modification has been shown to regulate the

translation process via a mechanism that operates on multiple

levels. Ψ in the mRNA CDS region forms a 'ribosomal speed bump'

that enhances the translation efficiency of rare codons through

prolonging the ribosomal retention time, whereas the Ψ-modification

of termination codons (namely, changing UGA to ΨGA) results in an

inhibition of the recognition of transcripts by the eukaryotic

release factor eRF1, resulting in an ≤15% prolongation of

readthrough translation (132,133). Under stress conditions,

Ψ-modification has also been shown to maintain the eIF2A

non-phosphorylated state by inhibiting PKR activation, resulting in

an increased efficiency of translation initiation (134). In addition, Ψ has been shown to

be involved in the global regulation of RNA metabolism: The RNA

pseudouridine synthase D4 (RPUSD4)/PUS1/PUS7-mediated

Ψ-modification of the pre-mRNA splice site was demonstrated to

alter the efficiency of splicing processing, and it was proposed

that this could be explained by its facilitation of RNA-binding

protein binding (135)

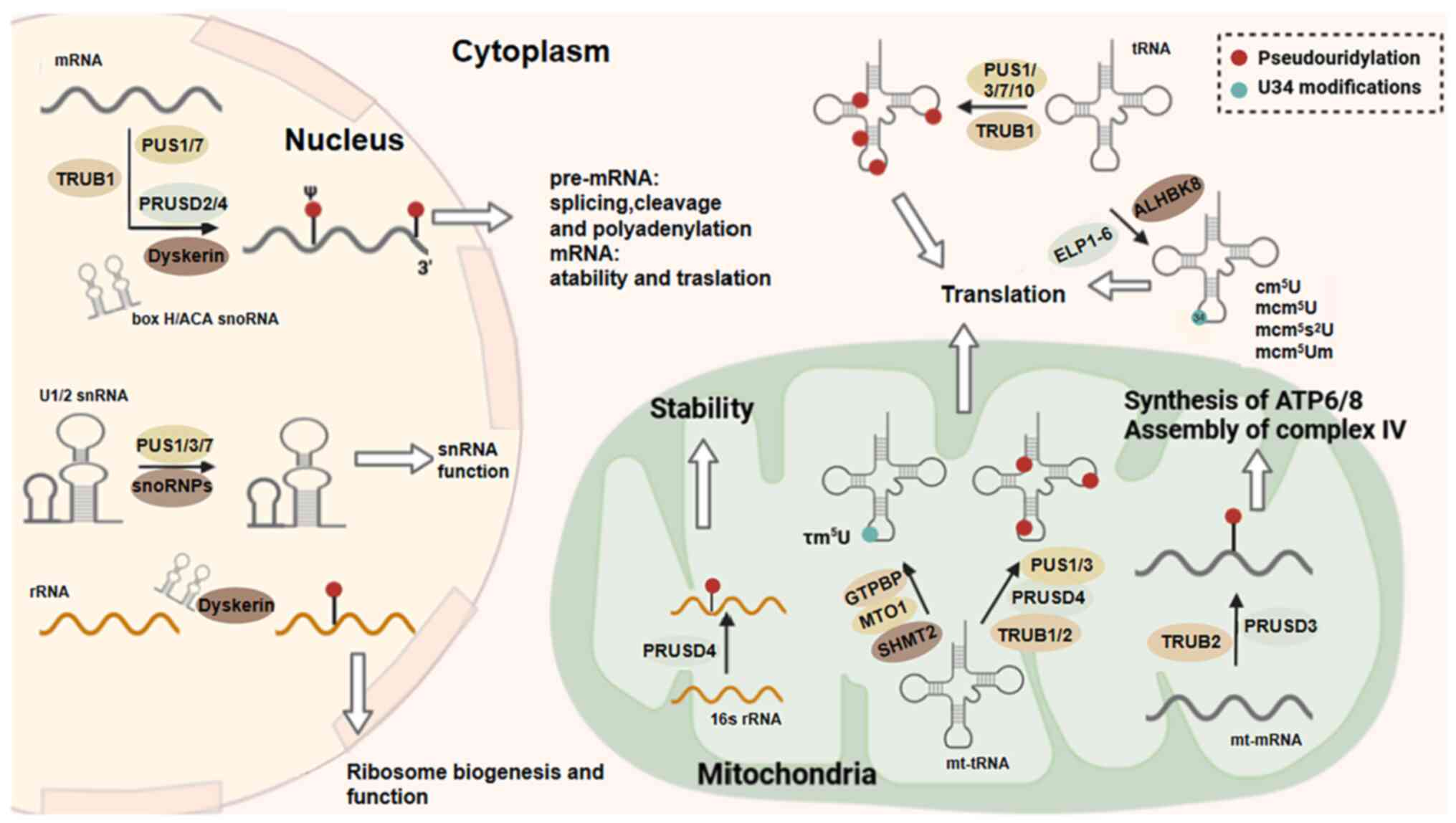

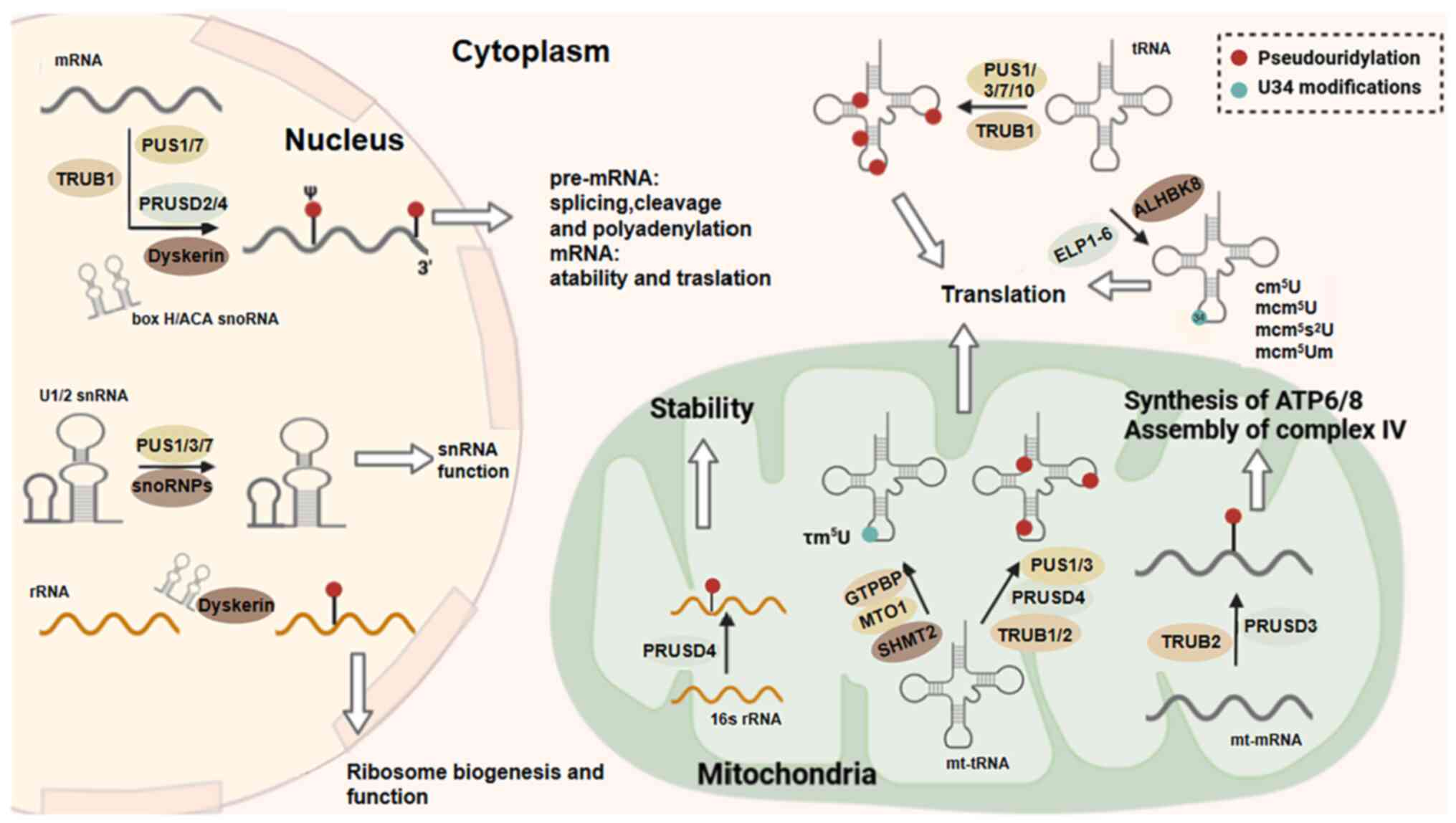

(Fig. 6).

| Figure 6Pseudouridylation and U34

modification. Pseudouridylation and U34 modification are important

processes that occur on tRNAs. In mammals, the RNA

pseudouridylation 'writers' primarily include PUS1/3/7/10,

PRUSD2-4, TRUB1/2 and Dyskerin. The catalysis of pseudouridylation

by Dyskerin relies on H/ACA snoRNA. From a functional standpoint,

pseudouridylation contributes to RNA processing, stability and

functionality. The translation of tRNA is markedly affected by

alterations at the U34 position, such as cm5U, τm5U, MCM5U, MCM5s2U

and MCM5Um. MCM5U and its derivatives are formed when ALKBH8

methylates cm5U, which is catalyzed by the ELP1-6 complex. The τm5U

modification in mt-tRNA is catalyzed by GTP binding protein 3 or

mitochondrial translation optimization 1 homolog, whereas SHMT2

provides the starting material for methyl synthesis. PUS,

pseudouridine synthetase; tRNA, transfer RNA; TRUB1/2, TruB

pseudouridine synthase family member 1/2; snoRNA, small nucleolar

RNA; SHMT2, serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2. |

At the pathological level, oxidative stress has

been shown to induce an increase in Ψ sites within the mRNA CDS

region of HeLa cells, a dynamic modification that assists tumor

cells in adapting to the microenvironment through stabilizing key

transcripts such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) (132). For example, the Ψ-modification

of HIF-1α mRNA promotes tumor cell survival under hypoxic

conditions via inhibiting nuclease degradation and enhancing the

glycolytic pathway activity mediated by HIF-1α. The discovery of

this epitranscriptomic buffering mechanism has provided novel ideas

for targeting RNA modifications in cancer therapy.

Modifications of U34 on tRNA

The chemical modification of U34 is a central

regulatory element for codon-decoding precision. In a couple of

previously published studies, U34 is able to extend the tRNA

recognition of synonymous codons through non-classical base pairing

(for example, the G-U wobble), a dynamic pairing mechanism that

fulfills a critical role in maintaining a balance between

translation rate and fidelity that is especially indispensable in

decoding NNN-AA-type codons, and an absence of U34 modifications

led to the accumulation of misfolded proteins, disruptions in

unfolded protein response processes and impaired translation

elongation (136,137) (Fig. 6).

Role of RNA modification in myocardial

fibrosis

Methylation in myocardial fibrosis

m6A in myocardial fibrosis

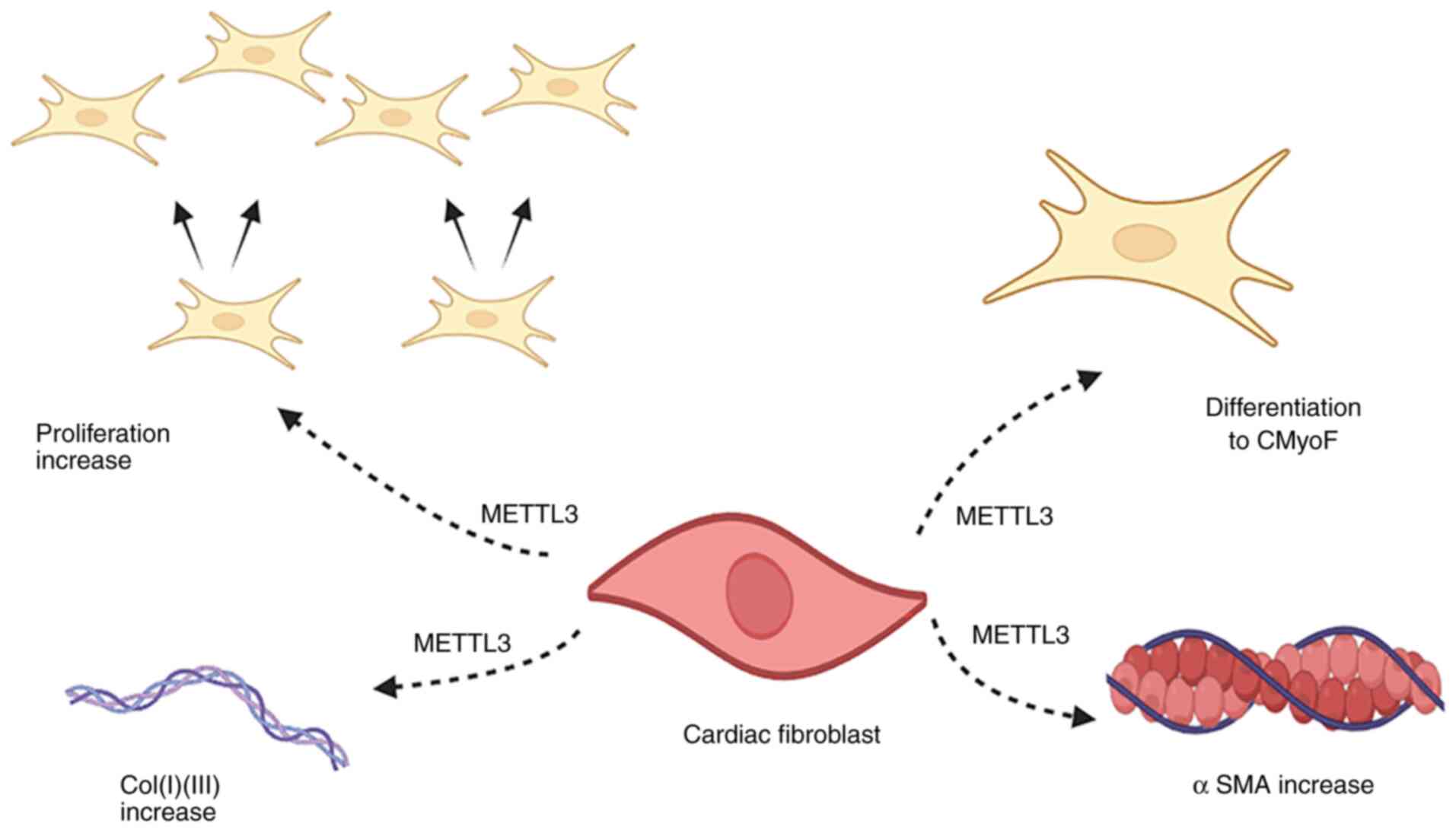

Research has shown that METTL3 is a key driver of

myocardial fibrosis, which regulates pro-fibrotic gene expression

through m6A modification to drive fibroblast activation and the

excessive deposition of ECM. Overexpression of METTL3 markedly

promotes the transdifferentiation of CFs into myofibroblasts, both

through upregulating the expression of type I/III collagen and

mesenchymal fibrosis markers and through activating the

TGF-β1-Mad2/3 signaling pathway (10) (Fig. 7). In addition, m6A modifications

weaken double-stranded RNA stability by triggering a significant

conformational shift of the RNA double strand to a hairpin

structure (for example, in the case of oligonucleotide 19/21),

which directly affects the ability to interact with recognition

proteins, such as FTO, ALKBH5 and YTHDF2. FTO and ALKBH5 were found

to be able to recognize the RNA double strand through m6A-induced

RNA conformational changes, thereby enabling them to distinguish

among substrates of highly similar sequences with dynamic

selectivity. Contrary to the currently held consensus view, the

GG(m6A)CU conserved motif was found not to be essential

for FTO/ALKBH5, whereas METTL3/YTHDF2 was strictly dependent on it.

This demonstrated that the m6A modification itself could

regulate demethylase substrate selectivity through dynamic changes

in RNA structure, challenging the traditional 'sequence motif

determinism' hypothesis, and providing a novel perspective for our

understanding of the functional complexity of the m6A

epitranscriptome (34).

The extracellular matrix glycoprotein tenascin C

(TNC) has been identified as a key downstream target of METTL3 in

recent years. A previous study showed that METTL3 is able to

enhance the mRNA stability of TNC by increasing its m6A

modification level (namely, through increasing the number of

methylated sites), leading to an elevated level of TNC protein

expression, which, in turn, exacerbates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and

fibrosis through the integrin αvβ3 signaling pathway (138). Overexpression of METTL3 has

also been shown to promote the m6A modification of

fibrogenic genes [for example, collagen, type I, α 1 (COL1A1) and

collagen, type III, α 1 (COL3A1)] through YTHDF2-dependent

mechanisms, which, in turn, promotes cardiomyocyte apoptosis and

fibrosis, leading to increased collagen deposition (139). In addition, it has been shown

that the RNA-methylated reading protein YTHDF2 inhibits excessive

mitochondrial autophagy via recognizing the m6A

modification site on BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting

protein 3 (BNIP3) mRNA and promoting its degradation. In myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury, due to an absence of YTHDF2 led

to an accumulation of BNIP3 protein, which resulted in the

induction of excessive mitochondrial autophagy and myocardial cell

death; on the other hand, overexpression of YTHDF2 was shown to

reduce the level of BNIP3, leading to a decrease in the area of

myocardial infarction (140).

In exploring pathway synergies, the mRNA stability of METTL3 was

found to be upregulated through m6A modification (with

the consequent prolongation of its half-life), leading to increased

insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 protein expression.

This molecule formed a synergy with TGF-β signaling to promote

α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression, thereby markedly

increasing the ability of CFs to migrate and to synthesize collagen

(141). By contrast with

previous findings on METTL3 overexpression, however, inhibition of

this protein was found to be associated with the downregulation of

fibrotic markers and decreased activity of CFs. In myocardial

fibrosis, m6A regulates programmed cell death, and

cardiomyocyte apoptosis is mediated via an upregulation of METTL3.

Elevated m6A levels could promote the transcriptional

degradation of autophagy-associated genes, which ultimately

exacerbate cardiac injury and fibrosis (142).

Although METTL3 has been shown to regulate

pre-METTL3 pre-fibrotic pathways through m6A

modifications, such as the TGF-β/HIF-1α/reactive oxygen species

(ROS) signaling pathway, identifying its therapeutic targets still

presents a major challenge: First, there is a need to clarify the

METTL3 pre-repair (early stage of injury) and pre-fibrotic

(chronic) processes, and second, there is the need to analyze the

synergistic reading proteins, such as those involved in the YTHDF2

and IGF2BP1 regulatory network. Small-molecule inhibitors targeting

METTL3 have entered preclinical studies and are able to markedly

reduce fibrotic areas by selectively inhibiting methyltransferase

activity. These advances will provide novel ideas for enabling us

to reverse pathological cardiac remodeling, although researchers

need to be wary of the risk of the genomic instability that may be

caused by overall m6A inhibition.

m7G in myocardial fibrosis

The dysregulation of m7G modification is

associated with a variety of diseases; however, the role of METTL1

in cardiac fibrosis remains poorly understood. One study (143) identified the critical

regulatory role of METTL1-mediated RNA m7G methylation

in myocardial fibrosis, and the underlying molecular mechanism.

Multidimensional experimental validation studies have shown that,

in fibrotic myocardial tissues from patients with myocardial

infarction and also on the basis of TGF-β1-induced in vitro

models, myocardial fibroblasts exhibit upregulated METTL1

expression levels (which are elevated compared with controls) and a

significant increase in the abundance of transcriptome-wide

m7G methylation (143). In a tamoxifen-induced,

fibroblast-specific METTL1-knockout mouse model (Col1a2-CreERT;

METTL1flox constructed using the Cre-loxP system), cardiac function

indices were found to be markedly improved following myocardial

infarction and histopathological analyses further revealed a

decreased interstitial collagen volume fraction and reduced

transformation rates of α-SMA-positive myofibroblasts. Moreover,

mechanistic studies demonstrated that METTL1, as a key component of

the m7G methylation system, could regulate the

TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway (including Smad7 and Smurf2) without

affecting fibroblast gene stability but by impacting mRNA

translation efficiency, thereby promoting an excessive deposition

of ECM proteins (namely, Col1a1, Col3a1 and fibronectin).

Single-cell sequencing analysis revealed that the deletion of

METTL1 specifically inhibited the differentiation of a fibroblast

subpopulation towards a pro-fibrotic phenotype, whereas no

significant effects were exerted on cardiomyocytes or on other

cardiac resident cells. This conclusion not only established for

the first time a direct link between RNA epigenetic modifications

and cardiac fibrosis, but it also provided a theoretical and

experimental basis for the development of novel anti-fibrotic

therapies targeting the METTL1-m7G axis.

Acetylation in myocardial

fibrosis

Recent studies (144,145) have shown that the RNA

acetyltransferase NAT10 dynamically regulates the cardiac fibrotic

process through ac4C modification. In neonatal CFs,

NAT10, through ac4C modification, increased the mRNA

stability and translational efficiency of angiomotin-like protein 1

(Amotl1), facilitating the interaction of the Amotl1 protein with

Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP), and driving YAP nuclear

translocation. This process led to a significant promotion of CF

proliferation (increased rate) and transdifferentiation of the CFs

into myofibroblasts (upregulation of α-SMA expression) through

activation of the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway. Consequently,

experiments wherein Amotl1 gene silencing was combined with the

YAP-selective inhibitor verticibufungin revealed an effective

blockade of the fibrotic phenotype induced by NAT10 overexpression,

which consequently led to reduced collagen deposition.

EGR3, an early growth response factor, promotes

myocardial fibrosis by activating the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling

pathway, which thereby promotes ECM remodeling and exacerbates

myocardial fibrosis (as denoted by an increased fibrotic area). The

lncRNA tsr007330 was shown to mediate ac4C modification

of EGR3 mRNA through recruiting NAT10, leading to an increased

expression of EGR3 protein, which, in turn, exacerbated the

condition. These findings confirmed the centrality of NAT10 in

post-myocardial infarction fibrosis, also revealing the

pathological significance of the non-coding

RNA-ac4C-EGR3 axis as a novel regulatory cascade

reaction (146).

ac4C modifications enhance fibrotic gene

expression through transcriptome reprogramming, additionally

fulfilling a key role in chromatin accessibility remodeling to

activate key signaling pathways (for example, the Hippo/YAP and

TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways). Small-molecule inhibitors targeting

NAT10 (for example, remodeling proteins) have been shown to have

preclinical potential, given their ability to markedly reduce

ac4C modification levels and to improve cardiac

function, although aspects of their tissue-specific delivery and

long-term safety have yet to be evaluated in depth.

Role of RNA modification in other

cardiovascular diseases

Hypertension

The pathogenesis of hypertension, as the leading

preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease worldwide,

involves a complex interaction of environmental and genetic factors

and is multiply regulated by the immune response, oxidative stress,

sympathetic nerves and the renin-angiotensin system. Studies have

revealed that RNA epigenetic modifications have a key role in blood

pressure homeostasis through regulating the function of vascular

smooth muscle cells (147,148).

ADAR2-mediated RNA editing presents an important

mechanism for maintaining vascular function. This enzyme regulates

the contractile properties of vascular smooth muscle cells by

specifically editing the fine filament protein A (FLNA) precursor

mRNA. When ADAR2 activity becomes aberrant, conformational changes

of the FLNA protein lead to an imbalance in the regulation of

vascular tone, which is closely associated with elevated diastolic

blood pressure. This finding revealed the precise regulatory role

of RNA editing in vascular dynamics (149).

Genetic polymorphisms in the FTO gene, an

m6A demethylase, have been found to be associated with

susceptibility to hypertension. Although the exact mechanism has

not yet been fully elucidated, this regulation at the epigenetic

level has provided novel perspectives to explain the genetic

predisposition to hypertension (150).

The RNA-binding protein HuR also acts as a

molecular hub of multiple modification sites, and participates in

the blood pressure regulatory network through binding

m6A, uridylated and A-to-I-modified transcripts. Reduced

levels of its expression in aortic tissues are associated with the

progression of hypertension and the creation of animal models has

confirmed that HuR deficiency triggers vasodilatory dysfunction and

compensatory myocardial hypertrophy. Mechanistic studies have shown

that HuR maintains the homeostasis of the NO/cGMP signaling pathway

by stabilizing soluble guanylate cyclase and foveolar protein 1

mRNA (151,152).

It should be noted that these regulatory mechanisms

do not exist in isolation. For example, HuR may indirectly affect

the editing efficiency of FLNA by regulating the mRNA stability of

ADAR2, whereas FTO-mediated m6A modification may

interfere with the ability of HuR to bind to target RNAs, forming a

multilevel epistatic regulatory network. This cross-talk property

highlights the systems biology significance of RNA modifications in

blood pressure regulation, and also provides a theoretical basis

for the development of novel antihypertensive strategies targeting

the epitranscriptome.

Atherosclerosis and coronary heart

disease

Atherosclerosis, as an inflammation-driven vascular

lesion, is characterized by lipid deposition and fibrous plaque

formation as its core pathology, which ultimately leads to coronary

artery stenosis and thrombotic events (153). Studies have shown that

m6A modification is heavily involved in the disease

process through regulating vascular inflammation and endothelial

function. In patients with coronary artery disease and in models of

atherosclerosis, the expression levels of the methyltransferases

METTL3 and METTL14 are markedly upregulated (154-156) and their mediated m6A

modifications promote plaque development through a dual mechanism:

First, by enhancing monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion and

activating the NF-κB/IL-6 signaling pathway, which drives the

inflammatory cascade; and second, by inhibiting the mRNA stability

of MyD88 in macrophages, which hinders M2-type polarization and

exacerbates the inflammatory microenvironment within the plaque.

Notably, knockdown of METTL14 leads to a marked reduction in the

macrophage inflammatory phenotype via inhibiting the NF-κB pathway

(156), whereas the

METTL3-m6A-YTHDF2 signaling axis further amplifies

monocyte/macrophage inflammatory responses by regulating the

metabolism of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (157). In addition, the synergistic

interaction of METTL3/14 with ADAR1 regulates vascular

calcification and neovascularization, suggesting their involvement

in a complex mechanism underlying plaque stability and ischemic

compensation (158,159).

In the progression of coronary heart disease, the

dynamic balance of RNA modifications exerts a key regulatory role

in cardiac function. A previous study specifically on

cardiomyocytes showed that the downregulation of FTO expression

under hypoxic conditions leads to an increase in m6A

levels and that FTO overexpression modulates both intracellular

calcium homeostasis and improved myocardial contractile function

through stabilizing ATP2A2 mRNA (encoding the SERCA2a protein)

(160). By contrast, ALKBH5

overexpression was found to inhibit cardiomyocyte proliferation and

to reduce cardiac function through the m6A-YTHDF1-YAP

signaling pathway, revealing a dual role for demethylases in

myocardial repair. In an acute myocardial infarction model,

endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles were shown to carry

the METTL3-m6A-HNRNPA2B1 complex, thereby exacerbating

cardiomyocyte apoptosis and dysfunction through the upregulation of

miR-503 (160).

The mechanism of I/R injury, a serious complication

of coronary heart disease, has been demonstrated to be closely

associated with the m6A modification network. In a

myocardial I/R model, METTL3 overexpression was found to promote

the binding of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D to

m6A-modified TFEB mRNA, to inhibit autophagy, and to

induce apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. TFEB inhibits METTL3 stability,

and activates ALKBH5 transcription through a negative feedback

loop, forming a dynamic regulatory balance (160). Gene intervention experiments

confirmed that the myocardium-specific knockdown of METTL14 led to

a reduction in the expression of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP),

a marker of heart failure, and also a significant improvement in

cardiac function following I/R injury (160). These findings not only revealed

the multilevel regulatory role of RNA modification in coronary

artery disease, but also provided a theoretical basis for

therapeutic strategies that are aimed at targeting the

m6A network (for example, METTL3 inhibitors or FTO

activators). Furthermore, m7G RNA modification exerts

dual roles through dynamic regulation via the methyltransferase

METTL1/WDR4 complex. A previous study (161) showed that, during the early

reperfusion phase (1-3 h), AKT-dependent phosphorylation activates

METTL1, thereby transiently enhancing the translation efficiency of

protective genes (for example, HIF-1α) to maintain metabolic energy

homeostasis. However, in the middle-to-late reperfusion phase

(>6 h), the sustained overexpression of METTL1 drives excessive

m7G modification. This serves to stabilize the mRNAs

encoding the pro-apoptotic factor caspase-3, and the pro-fibrotic

factor TGF-β1, thereby triggering oxidative stress bursts and

mitochondrial dysfunction. Mechanistic analyses have demonstrated

the core process involving the METTL1-mediated serine and arginine

rich splicing factor 9 (SRSF9)/nuclear factor of activated T-cells,

cytoplasmic 4 (NFATc4) signaling axis, where m7G

modification enhances the RNA stability of splicing factor SRSF9,

facilitating the alternative splicing of NFATc4 and nuclear

translocation, thereby activating the calcineurin pathway. This

cascade ultimately leads to pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy,

collagen deposition and cardiac functional deterioration. Targeting

METTL1 has also been shown to be a strategy to markedly mitigate

cardiac injury: Myocardial-specific knockout models exhibited a 40%

reduction in infarct size, with improved cardiac function (ejection

fraction and fractional shortening), whereas delivery strategies

(for example, ROS-responsive carriers) that block METTL1 activity

may offer novel translational avenues (162).

Cardiomyopathy

Primary cardiomyopathies encompass various types of

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and dilated cardiomyopathy, and

their pathogeneses are closely associated with genetic variation.

In HCM ~70% of cases were shown to be driven by mutations in the

genes of myosin-binding protein C and β-myosin heavy chain (MYH7)

(163), whereas mutations in

other key genes, such as α-myosin heavy chain, troponin T and

myosin ganglionic protein, may also lead to structural disorders of

the cardiac myocardium (164,165). Abnormal mitochondrial function,

specifically mitochondrial dysfunction in the myocardium, fulfills

an important role in the progression of cardiomyopathy, and

mutations in the GTP-binding protein 3 or mitochondrial translation

optimization 1 homolog genes were shown to elicit an impaired

assembly of respiratory chain complexes through impairing the

5-taurinomethyluridine (τm5U) modification of mitochondrial tRNAs,

ultimately leading to HCM (166). In a dilated cardiomyopathy

(DCM) model, specific knockdown of the pentatricopeptide repeat

domain 1 gene disrupted ribosomal large subunit assembly through

interfering with the Ψ-modification at position 2509 of 16S rRNA,

which had the effect of triggering defects in mitochondrial energy

metabolism with dysregulated mTOR signaling (167). In addition, conditional

knockdown experiments of YTHDC1 and ADAR1 confirmed that the

deletion of RNA-binding proteins could induce DCM through aberrant

m6A modification (168) and dysregulated RNA editing

(110), respectively.

Unlike genetic lesions, secondary cardiomyopathies

(for example, diabetic cardiomyopathy and chemotherapy

cardiotoxicity) are primarily driven by acquired factors. In

diabetic cardiomyopathy, METTL14-induced hypermethylation of the

lncRNA TINCR was found to enhance the degradation of TINCR via

YTHDF2, which consequently reduced the inhibitory effect of TINCR

on NLRP3 inflammasome targets. Furthermore, the lncRNA Airn was

shown to stabilize p53 mRNA through m6A modification, also

inhibiting the ubiquitin-mediated disruption of eIF2C, thereby

attenuating myocardial fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy

(169,170). In adriamycin-induced

cardiotoxicity, METTL14 was shown to exacerbate myocardial injury

by promoting iron death (specifically, through increasing the

levels of lipid peroxidation) through modulation of the

m6A modification of genes involved in glutathione

metabolism (171).

The aforementioned studies have revealed the

centrality of RNA epitope modification in cardiomyopathy: First,

METTL14 inhibitors may inhibit inflammatory vesicle activation

through restoring TINCR expression; subsequently, the

m6A-reading function, targeting YTHDC1, may correct

metabolic derangements in the cardiomyocytes; and lastly, ADAR1

activators may both repair RNA-editing aberrations and improve

myocardial electrophysiological stability. However, resolution of

the tissue-specific delivery systems with dynamic modification

profiles remains a key challenge for clinical translation.

Cardiac hypertrophy

Cardiac hypertrophy, as a compensatory response of

the myocardium to stress load, can be categorized into two types,

namely physiological and pathological, which exhibit significant

differences in their epitranscriptome regulatory mechanisms.

Physiological hypertrophy (for example, that induced by exercise)

was shown to be accompanied by a decrease in the overall

m6A levels of myocardial mRNA, and this was potentially

associated with the downregulation of METTL14 expression (160,172). By contrast, the molecular

mechanism of pathological hypertrophy (for example, that induced by

pressure overload), a major trigger of heart failure, involves a

complex dysregulation of the dynamic balance of m6A

modification. It is caused by a variety of cardiac diseases,

including both heart failure with maintained ejection fraction and

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. In the aortic arch

constriction model, the myocardium-specific knockdown of FTO was

shown to exacerbate ejection fraction-reduced heart failure

(173). On the other band, FTO

overexpression was demonstrated to inhibit the expression of

pathologic hypertrophy-associated genes, such as ANP and B-type

natriuretic peptide, through demethylation, resulting in a

reduction in the cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (174). This bidirectional regulatory

effect suggests that FTO fulfills a key role in maintaining the

fine balance between myocardial adaptation and pathological

remodeling.

METTL3 functions as an m6A

methyltransferase in an environment-dependent manner: Its

overexpression in the basal state enhances cardiac compensatory

function, although the myocardium-specific knockdown of METTL3 was

found to accelerate the progression of heart failure under pressure

overload conditions. Mechanistic studies have shown that the

Piwi-interacting RNA CHAPIR promotes pathological ventricular

hypertrophy by binding to and inhibiting METTL3 methylation

activity, thereby leading to hypomethylation of the mRNA of the

ADP-ribosyltransferase PARP10, and blocking the YTHDF2-mediated

degradation pathway (175,176). Notably, the

m6A-reading protein YTHDF2, whose expression is

upregulated in heart failure, was shown to promote the cardiac

hypertrophic phenotype through stabilizing myosin-7 (MYH7) mRNA

(namely, prolonging its half-life), thereby creating a vicious

circle (176).

Taken together, these findings have revealed a dual

role for the m6A modification network: Its first role is

to regulate myocardial compensation and dystrophic transition

through the balance of FTO-METTL3, and its second role is to drive

sustained progression of the hypertrophic phenotype through the

YTHDF2-MYH7 axis. Targeting this regulatory network (for example,

through the development of METTL3 mutagenic activators or YTHDF2

inhibitors) may provide possible novel strategies, although for

this to occur, technical challenges presented by matters such as

tissue-specific delivery and dynamic modification monitoring will

need to be addressed.

Summary and future outlook

The RNA epitranscriptional regulatory network of

myocardial fibrosis is associated with both breakthrough

therapeutic opportunities and complex biological challenges.

Methylation reactions (for example, m6A and

m7G) and ac4C serve as core modification

mechanisms that drive fibrotic progression through precisely

regulating fibroblast activation and extracellular matrix

deposition. METTL3 silencing markedly reduces the levels of

fibrosis markers such as collagen, revealing its potential as a

drug target; however, the potential toxicity of the molecule to

cardiomyocytes presents an obstacle to its clinical application: A

paradox that highlights the critical importance of cell-specific

effects. By way of contrast, the METTL1-m7G axis has

unique properties: In fibrotic tissues, from patients with

myocardial infarction and in TGF-β1-induced in vitro models,

METTL1 is specifically overexpressed in cardiac fibroblasts and is

accompanied by elevated levels of transcriptome-wide m7G

methylation; knockdown of METTL1 not only improves cardiac

function, but it also reduces collagen deposition and

α-SMA-positive myofibroblast transformation, more critically,

without affecting cardiomyocyte function. This selectivity stems

from the fact that METTL1 specifically promotes the excessive

deposition of ECM proteins by finely regulating mRNA translation

efficiency, rather than the stability of key genes of the TGF-β

pathway (or example, Smad7/Smurf2) through m7G

modification.

Acetylation modifications amplify fibrotic signals

through mechanisms at multiple levels in concert with methylation

networks. NAT10, as an RNA acetyltransferase, dynamically regulates

cardiac fibrosis through ac4C epigenetic modifications:

It enhances Amotl1 mRNA stability and translational efficiency,

promotes the binding of Amotl1 protein to YAP, and activates the

Hippo/YAP signaling pathway, ultimately accelerating fibroblast

proliferation and transdifferentiation. Notably, silencing of the

Amotl1 gene combined with YAP-specific inhibitors has been shown to

effectively block the fibrotic phenotype induced by NAT10

overexpression, and the synergistic effect of EGR3 with the

TGF-β/Smad3 pathway, and the multilayered regulation of fibrosis by

NAT10, further established its centrality to post-infarction

fibrosis. These findings reveal a hierarchical modification network

architecture: The METTL3-m6A modification initiates the

TGF-β transcriptional cascade, the NAT10-ac4C

modification stabilizes key effectors (for example, EGR3 mRNA), and

the METTL1-m7G modification enhances the translational

efficiency of downstream genes. Altogether, the three types of

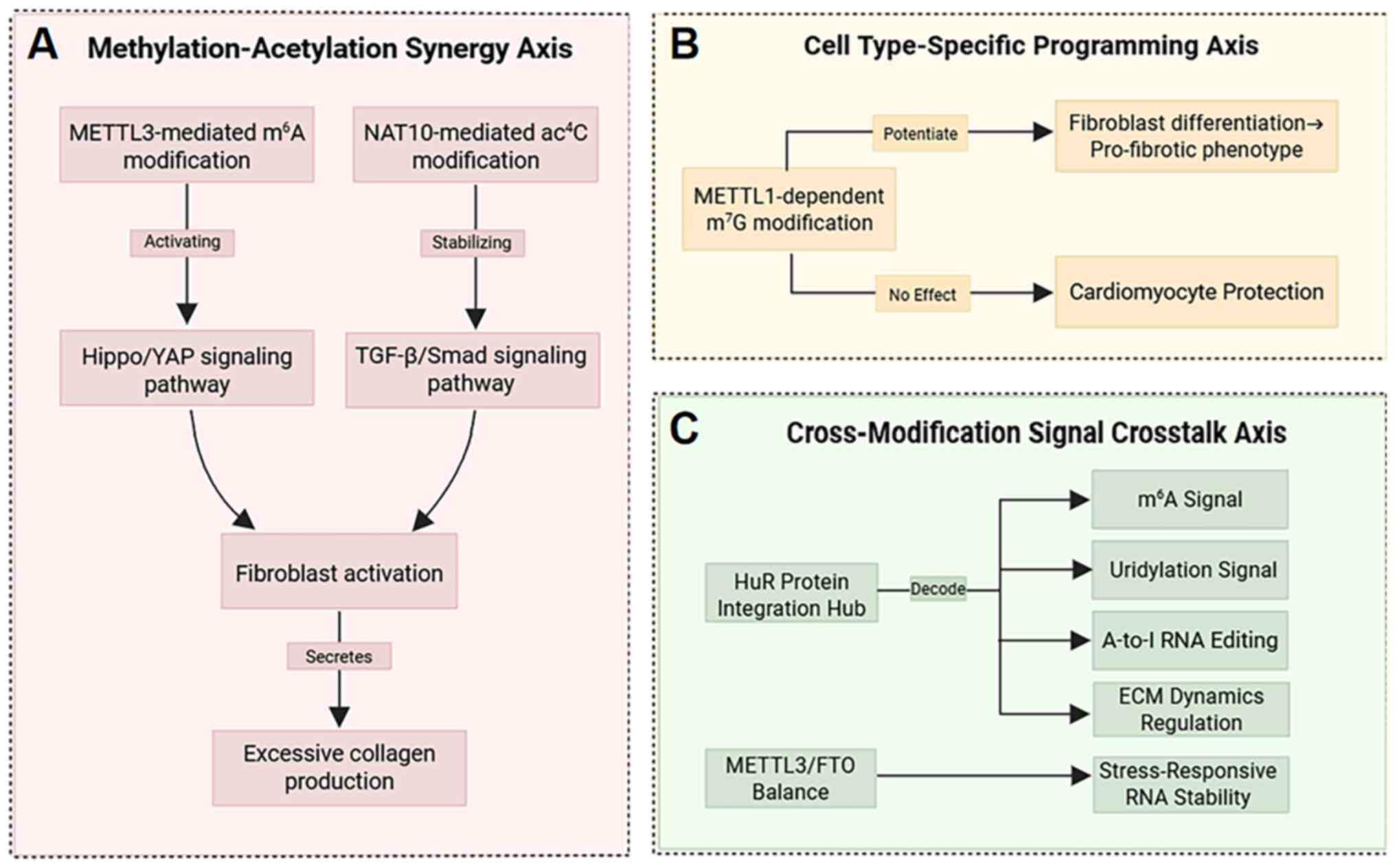

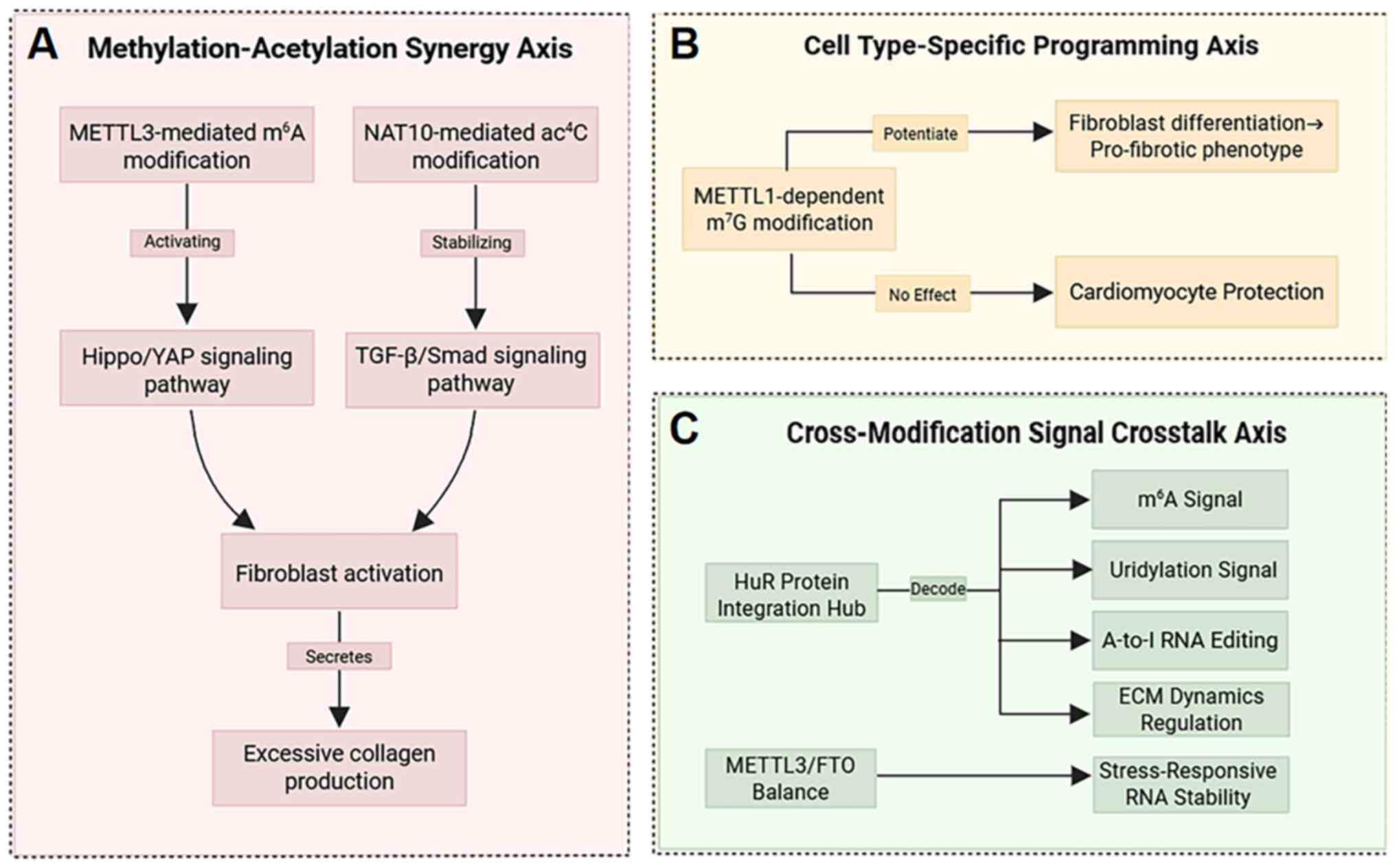

modification form a self-amplifying pathogenic cycle (Fig. 8).

| Figure 8The three-axis regulatory model is

shown: (A) Methylation-acetylation synergy, where METTL3-mediated

m6A modifications and NAT10-driven ac4C

modifications co-operatively target the Hippo/YAP and TGF-β/Smad

signaling pathways, exacerbating fibroblast activation and

excessive collagen production. (B) Cell-type-specific programming

revealed by single-cell analysis, as exemplified by

METTL1-catalyzed m7G modifications selectively promoting

fibroblast differentiation into pro-fibrotic phenotypes while

protecting cardiomyocytes. (C) Cross-modification crosstalk,

illustrated by the HuR protein integrating m6A,

uridylation, and A-to-I editing signals to regulate extracellular

matrix dynamics, while the METTL3/FTO balance influences

stress-responsive RNA stability. Collectively, these three axes

drive the pathological phenotype of myocardial fibrosis,

characterized by excessive collagen deposition, increased

ventricular stiffness and diastolic dysfunction. METTL1/3,

methyltransferase-like 1/3; m6A,

N6-methyladenosine; NAT10, N-acetyltransferase

10; YAP, Yes-associated protein; A-to-I, adenine-to-inosine; FTO,

fat mass and obesity-associated. |

These post-transcriptional modifications have been

demonstrated to affect cell function and RNA metabolism, to

regulate gene expression, and to influence both organ development

and cell differentiation, ultimately determining the cell's fate.

Through these chemical changes, cells have an improved ability to

adapt to internal and external stimuli (39,41,160). Innovative solutions are

required to circumvent the core bottlenecks faced by translational

medicine: The dual role of METTL3 in both the early repair of

injury and the chronic fibrosis stage requires the development of

spatiotemporal regulation strategies, such as ROS-responsive

nanocarriers for precise drug delivery of myocardial infarction.

The fibroblast specificity of METTL1 offers opportunities for

spatial targeting, which can be accomplished using the Col1a2

promoter-driven CRISPR-Cas9 system for cell-type specific

interventions. Future research should focus on three frontiers:

First, resolving the precise modification sites of METTL1 on

Smad7/Smurf2 mRNA and elucidating the underlying mechanism of

interaction with the translation machinery; second, exploring the

network interactions of m7G dynamic modifications with

other nodes of the TGF-β pathway; and third, developing

METTL1-specific small-molecule inhibitors and a serum exosome

modification fingerprinting diagnostic system. Current antifibrotic

treatments are still in the developmental stages; although RNA

modification networks have opened new therapeutic windows, existing

strategies are mostly limited to symptom control. Fundamental

breakthroughs are required for the integration of

epitranscriptomics, non-coding RNA and signaling pathway research;

for example, the development of CRISPR-Cas13d-mediated editing of

the Amotl1 mRNA ac4C locus, or patient stratification

(high m7G/ac4C ratio populations) to achieve

precision intervention. Ultimately, successful translation of

primary research results to the clinic will depend on our ability

to harness both cell-specific targeting (for example,

fibroblast-restricted METTL1 inhibition) and critical node

breakthroughs to move epitranscriptional regulation from the

mechanistic discovery mode to finding clinical solutions.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

KW conceived the present study and provided

suggestions for the revision of the manuscript. XW, RW and XC wrote

the manuscript and made the figures. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, a generative

AI/AI-assisted technology, namely DeepSeek, was used to improve the

readability and language of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Qingdao Science and

Technology Benefiting the People Demonstration Project (grant no.

24-1-8-smjk-7-nsh), Major Basic Research Projects in Shandong

Province (grant no. ZR2024ZD46) and Taishan Scholar Distinguished

Expert.

References

|

1

|

Liu M, López de Juan Abad B and Cheng K:

Cardiac fibrosis: Myofibroblast-mediated pathological regulation

and drug delivery strategies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 173:504–519.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Talman V and Ruskoaho H: Cardiac fibrosis

in myocardial infarction-from repair and remodeling to

regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 365:563–581. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ivey MJ and Tallquist MD: Defining the

cardiac fibroblast. Circ J. 80:2269–2276. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kendall RT and Feghali-Bostwick CA:

Fibroblasts in fibrosis: Novel roles and mediators. Front

Pharmacol. 5:1232014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tallquist MD and Molkentin JD: Redefining

the identity of cardiac fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cardiol. 14:484–491.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pellman J, Zhang J and Sheikh F:

Myocyte-fibroblast communication in cardiac fibrosis and

arrhythmias: Mechanisms and model systems. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

94:22–31. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hinz B: Myofibroblasts. Exp Eye Res.

142:56–70. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Thomas TP and Grisanti LA: The dynamic

interplay between cardiac inflammation and fibrosis. Front Physiol.

11:5290752020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hinderer S and Schenke-Layland K: Cardiac

fibrosis-A short review of causes and therapeutic strategies. Adv