Introduction

Membrane proteins (MPs) are proteins integrated into

biological membranes, where they interact with lipid domains to

execute a range of essential functions within living organisms

(1). These proteins are key for

maintaining the structural integrity and functional operation of

cells, engaging in numerous processes such as ion transport, signal

transduction and regulation of cellular homeostasis (2). MPs are central to the regulation of

ion gradients across membranes, modulation of cellular

communication and responsiveness to extracellular signals (3). In addition to their physiological

roles, MPs also carry out a pivotal role in the development of

multidrug resistance (MDR), rendering them central to mechanisms of

therapeutic resistance (2).

Research has expanded the understanding of MPs, revealing that

their functions extend beyond basic cellular roles to include key

involvement in complex physiological processes and disease states,

particularly in different types of cancer such as colorectal,

ovarian, lung breast (1-5).

In the majority of mammalian cells, MPs assist in

maintaining membrane structure, facilitate the transport of ions,

nutrients and waste products or facilitate intercellular

communication (3). They are

integral to the formation of cellular microenvironments that enable

efficient communication between cells, regulating processes such as

immune responses, tissue remodeling and apoptosis (6). MPs are also involved in the

establishment of the blood-brain barrier, the regulation of

neurotransmitter transport and cellular metabolic processes

(7). This array of functions

underscores their key roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and

regulating the essential biological processes necessary for

life.

Emerging research has emphasized the key role of MPs

in the pathogenesis of cancer, including breast cancer, colorectal

cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer and brain tumors (1,3-7).

For example, subfamilies of tyrosine kinase receptors, including

epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) and fibroblast growth

factor receptors (FGFRs), are key in signaling pathways that

regulate cell proliferation, survival and migration, all important

processes that drive tumorigenesis (8,9).

These receptors become activated upon binding of ligands to their

respective receptors, inducing conformational changes that initiate

signal transduction to the cytoplasm via processes such as

dimerization (10). Upon

activation, receptors trigger downstream signaling cascades that

regulate gene expression, cell cycle progression and metabolic

reprogramming (11). In cancer

cells, dysregulation of receptor signaling contributes to tumor

growth, metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy, highlighting MPs

as potential therapeutic targets for the management of cancer,

including breast cancer and pancreatic cancer (12,13). MPs carry out a key role not only

in maintaining normal cellular activities but also in cancer

development and chemotherapy resistance (3-5).

The tyrosine kinase receptor family, including EGFR and FGFR, has

garnered increasing attention for its role in regulating cancer

cell proliferation, survival and migration, particularly in the

context of chemotherapy resistance (3-5,8,9).

Cancer cells often exploit dysregulated membrane protein signaling

pathways to drive tumor growth and metastasis, with resistance

mechanisms frequently associated with alterations in membrane

protein function (13-15). For example, discoidin domain

receptor 2 interactions with collagen type I promote breast cancer

cell proliferation and enhance resistance to chemotherapy,

highlighting its potential role in chemoresistance in breast cancer

(13-15). Moreover, transmembrane proteins

(TPs) such as transmembrane (TMEM) 45A, TMEM158, TMEM88, TMEM205

and TMEM16A have been identified as key mediators of

chemoresistance in several types of cancer (4,5,13,14). These proteins regulate cell

proliferation, inhibit apoptosis or modulate the tumor

microenvironment (TME) to increase resistance of cancer cells to

chemotherapeutic agents (1,4-6,13,14). Therefore, MPs not only serve as

key targets in cancer therapy but can also help in understanding

and addressing chemotherapy resistance mechanisms.

The complexity of the nexus of signal transduction

mediated by MPs presents substantial challenges in elucidating

their precise roles in cellular processes and disease mechanisms

(16). One of the primary

challenges in research on MPs lies in establishing the

structure-function relationship that governs ligand activation and

enzyme activity specificity (17). Structural studies of MPs have

been hindered by their amphipathic nature, which complicates their

isolation and analysis in vitro (1,3-5,18). However, recent advances in

cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and other high-resolution

imaging techniques have enabled the structural elucidation of key

MPs, offering insights into their functional mechanisms at the

atomic level (19). These

technological advances have markedly improved the ability to study

MPs in their natural environments, thus facilitating the

development of targeted drugs with high specificity and efficacy

(19,20).

MPs are not only essential for cellular function but

also act as key therapeutic targets, making them central to drug

discovery efforts (21). They

are involved in a range of physiological processes, many of which

can be modulated by therapeutic agents targeting MPs to achieve

clinical effects. Drug discovery efforts have concentrated on

identifying small molecules, large molecules, peptides,

polysaccharides and antibodies, particularly those that can

specifically interact with MPs to regulate their activity (22). For example, monoclonal antibodies

targeting EGFR and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)

have been developed successfully and are now used in the treatment

of several types of cancer, including glioma and breast cancer

(22,23). Large molecule drugs, including

polysaccharides and peptides, are seen as promising alternatives to

traditional small molecule drugs, offering various therapeutic

benefits such as reduced toxicity and enhanced efficacy when used

in combination with conventional chemotherapy. For example,

polysaccharides derived from medicinal plants such as

Anemarrhena asphodeloides and Houttuynia cordata have

demonstrated notable bioactivities, including immune modulation and

anti-inflammatory effects, which can enhance the effectiveness of

cancer treatments, including lung cancer and liver cancer (24,25). Furthermore, recent studies have

highlighted the ability of peptides to target specific cancer cell

pathways, enhancing treatment outcomes in several types of cancer,

including pancreatic cancer (PC) (14,26). These findings underscore the

potential of utilizing large-molecule drugs in cancer therapies,

particularly in addressing the challenge of chemoresistance.

Furthermore, several PMPs, including ion channels, transporters and

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), are well-established

therapeutic targets for diseases ranging from cardiovascular

disorders to neurological conditions (27-29). Given the key role of MPs in the

pathophysiology of numerous diseases, understanding their

structural and functional properties is essential for the

development of novel drugs and therapies.

Biological processes, particularly those involving

MPs, constitute a complex, interconnected network within the cell.

Certain MPs can modulate interactions between various signaling

pathways that govern fundamental cellular processes, such as

metabolism, apoptosis and immune responses (30,31). The cyclic nature of these

networks is particularly key for understanding how drugs influence

cellular processes. The majority of therapeutic agents exert their

effects by binding to MPs, thereby modulating signaling pathways

essential for disease progression (32). Therefore, MPs serve as promising

targets for novel therapeutic strategies targeting specific disease

mechanisms at the molecular level. The expanding body of research

on MPs and their interactions with drugs continues to reveal novel

opportunities for drug development and personalized therapies

(21,33).

MPs are essential to cellular function and disease

pathogenesis (34). The study of

MPs is essential for advancing the understanding of both normal

physiology and disease mechanisms. Given their roles in signaling,

cellular maintenance and disease progression, MPs serve as key

targets for therapeutic intervention (7,12). Ongoing advancements in structural

biology, coupled with novel drug discovery technologies, highlight

novel opportunities for exploiting MPs as drug targets. Research on

MPs holds potential for developing innovative treatments for a

range of diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disorders and

neurological conditions (35-37).

Structure and function of the TMEM

proteins

MPs are classified according to their interactions

with membranes, which are categorized into peripheral MPs, integral

MPs and lipid-anchored MPs (38). Integral MPs contain ≥1

transmembrane segment, commonly referred to as a TP (4). TMEM proteins represent a subgroup

of integral MPs, defined by their ability to traverse the lipid

bilayer, thus establishing stable anchors within the membrane.

These proteins are essential in the transport of molecules across

the cellular membrane (5,39).

A protein is classified as a member of the TMEM family if it

contains at least one predicted transmembrane domain that spans the

biological membrane, either partially (in monomeric form) or fully

(in multimeric form) (4).

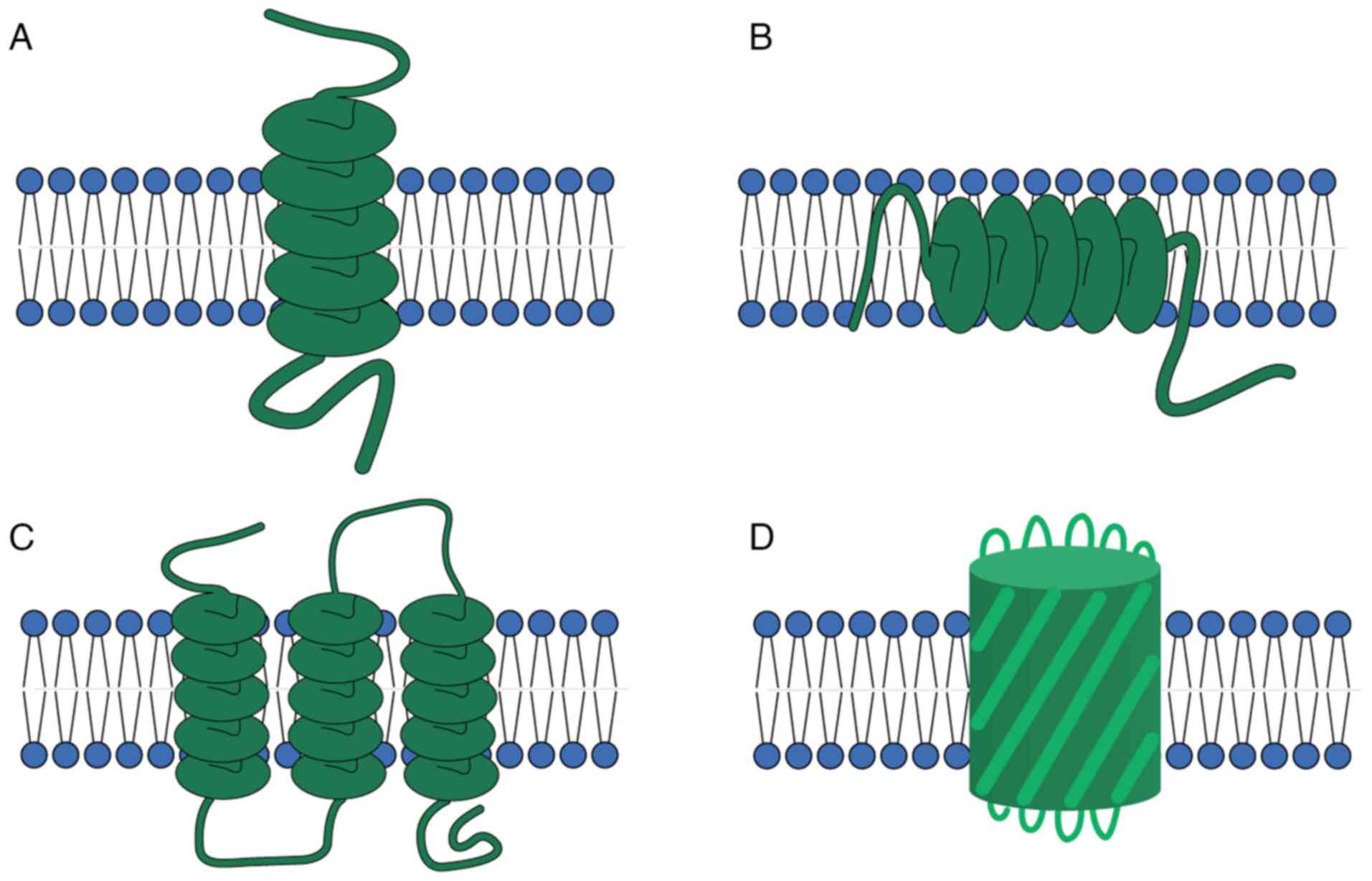

Due to their amphipathic nature, members of the TMEM

protein family adopt specific secondary structures when

incorporation into the membrane (40,41). Based on their different

structures, TMEMs can be divided into two categories: α-helical

proteins and β-barrel proteins (Fig.

1). These two structures are the dominant structures of all

transmembrane proteins, with α-helical proteins being mostly found

in the cytoplasm and subcellular septum (Fig. 1A-C), while β-barrel proteins are

mostly found in chloroplasts, bacteria and mitochondrial membranes

(Fig. 1D) (40,41). These structural features allow

TMEM proteins to modulate essential processes, including nutrient

transport, waste removal and signal transduction (40,41).

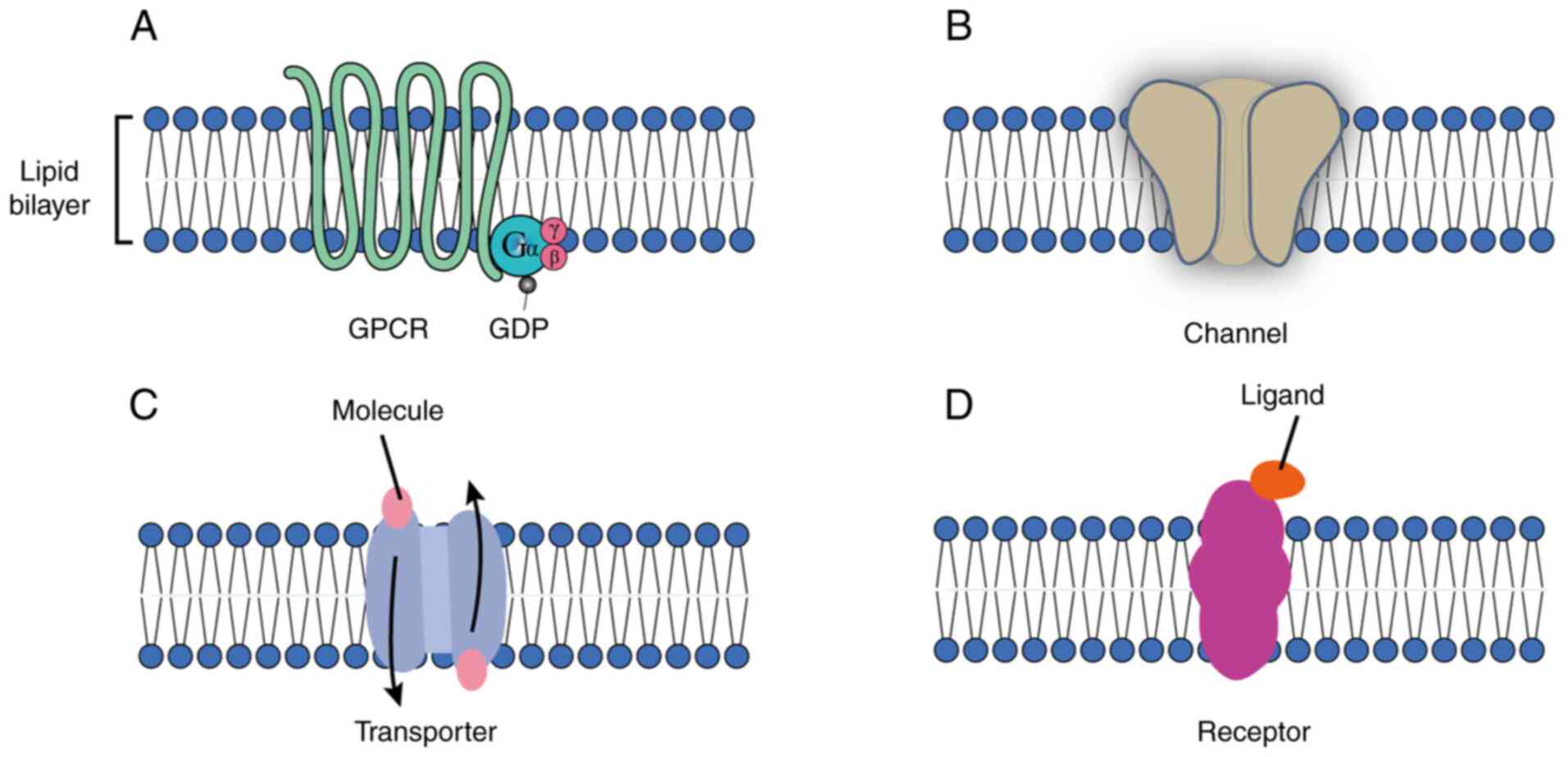

TMEM proteins exhibit considerable functional

diversity. These proteins are classified into distinct functional

groups, including GPCRs, ion channels, transporters, carriers and

other receptors (Fig. 2). GPCRs,

one of the largest and most versatile classes of TMEM proteins, are

involved in a range of signaling pathways that regulate essential

physiological processes, including sensory perception, immune

responses and cellular communication (42). Notably, TMEM proteins, including

GPCRs (Fig. 2A), carry out key

roles in cancer cell signaling, influencing tumor progression and

metastasis (43). Ion channels

(Fig. 2B) are TPs that form

pores, allowing ions (such as Na+, K+,

Ca2+ and Cl−) to passively flow across the

membrane. This movement is vital for processes such as nerve signal

transmission, muscle contraction and maintaining cellular ion

balance (44). Transporter

proteins (Fig. 2C) facilitate

the movement of molecules across the lipid bilayer, typically

against their concentration gradients. This process requires energy

and carries out a key role in nutrient uptake, waste removal and

the maintenance of cellular homeostasis (43,44). Dysfunction of these proteins is

implicated in a variety of diseases, including neurological and

cardiovascular disorders (43,44). TMEM proteins also function as

transmembrane receptors (Fig.

2D), such as the well-known EGFR, which is involved in

regulating cell growth, differentiation and survival. Dysregulation

of these transmembrane receptors is frequently associated with the

development and progression of various types of cancer, including

breast, lung, ovarian, cervical, bladder, esophageal, brain, and

head and neck cancer (45,46).

Previous studies have underscored the role of TMEM

proteins in various disease mechanisms, which highlights their

potential as therapeutic targets for drug development (47,48). For example, mutations in TMEM

proteins have been associated with several genetic disorders,

including cystic fibrosis, leading to defects in ion channels and

disruption of chloride transport (47,48). Moreover, TMEM proteins, such as

glucose transporters (GLUTs), carry out a pivotal role in cancer

metabolism by facilitating glucose uptake, therefore promoting

tumor growth, especially under nutrient-limited conditions

(49). This highlights the

potential of targeting TMEM proteins for therapeutic interventions

in a range of diseases.

The increasing understanding of the structural and

functional properties of TMEM proteins offers potential for drug

development. Their involvement in cellular signaling and molecular

transport makes them strong candidates for targeted therapies

(50). Advances in structural

biology, particularly the application of cryo-EM, have facilitated

the determination of the atomic structures of key TMEM proteins,

offering valuable insights into their functional mechanisms

(51-53). The TMEM family proteins are

essential components of the cellular membrane system, carrying out

key roles in cellular signaling and the transport of ions and small

molecules (39). Specific TMEM

proteins interact with hormone or neurotransmitter receptors,

inducing structural changes that initiate signaling cascades

important for cellular function. These proteins mediate the

selective transfer of ions or molecules across biological

membranes, thereby establishing concentration gradients essential

for cellular homeostasis and function (54). TMEM proteins are essential not

only to the plasma membrane but also to the membranes of various

intracellular organelles, including mitochondria, the endoplasmic

reticulum (ER), lysosomes and the Golgi apparatus, where they

participate in key biological processes (55). These processes carry out a key

role in an array of physiological functions and diseases, including

immune response regulation and tumorigenesis. Examples of key TMEM

proteins include TMEM45A in epidermal keratinization (56), TMEM16 in smooth muscle

contraction (57), TMEM165 in

protein glycosylation (58) and

TMEM9B in immune response modulation (59).

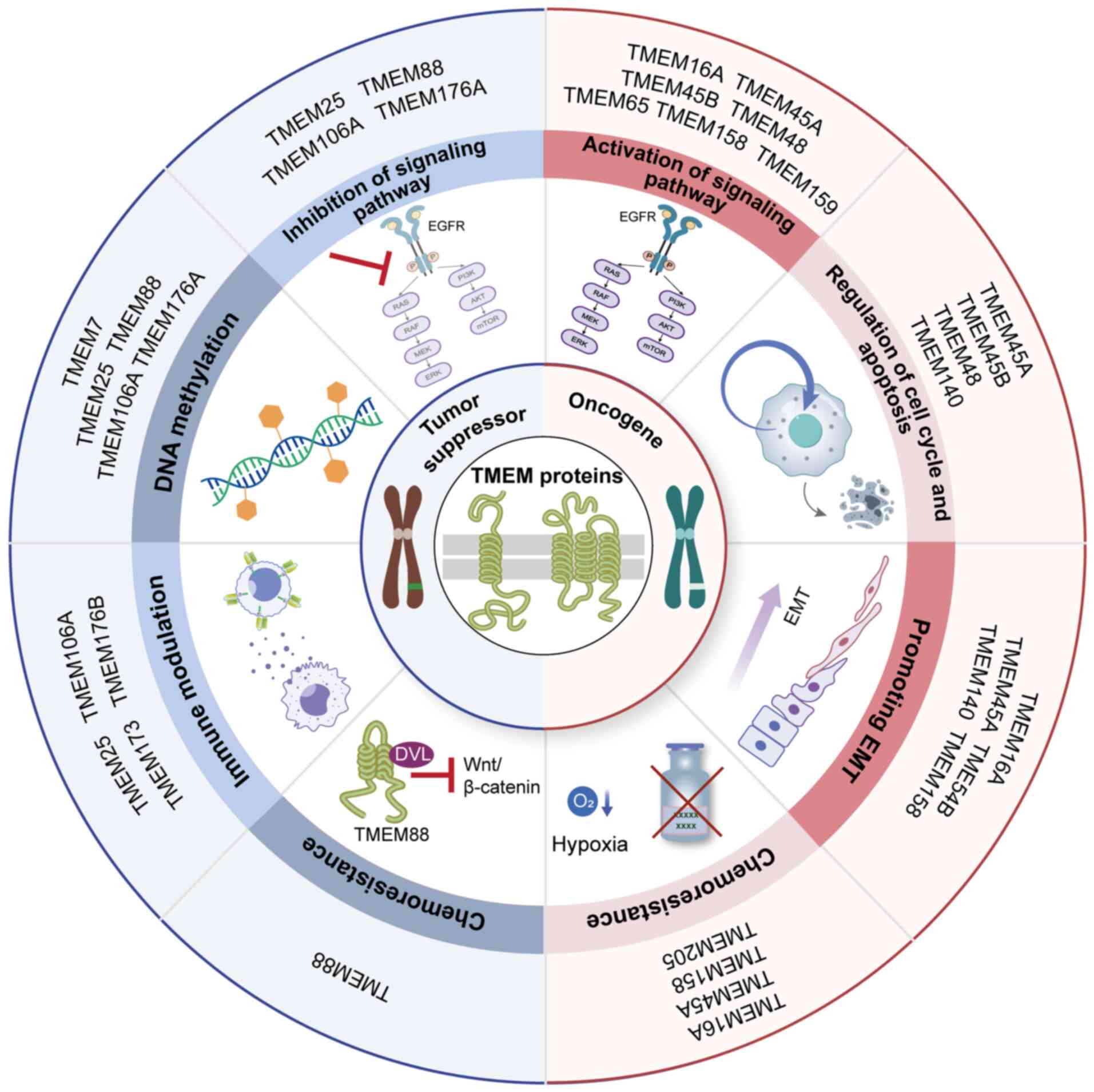

TMEM proteins are key contributors to cancer

biology, carrying out key roles in tumor initiation, progression

and metastasis. Their differential expression in various types of

cancer not only serves as biomarkers but also offers new targets

for therapeutic intervention (4,60). Furthermore, alterations in TMEM

protein expression levels or function are closely associated with

tumor progression, metastasis and drug resistance (60). Recent studies have emphasized the

vital role of TMEM proteins in cancer cell survival and

proliferation under harsh conditions, such as hypoxia or nutrient

deprivation, which are commonly associated with the TME (4,5,12-16,60,61). For example, TMEM16, an ion

channel, has been shown to regulate chloride and calcium ion flux,

thereby influencing cell proliferation and migration in cancer

cells (62). Likewise, TMEM65

has been implicated in regulating autophagy, an essential process

for maintaining cellular homeostasis and promoting cancer cell

survival (63). Given their

upregulated expression in various types of cancer, targeting

specific TMEM proteins presents a viable strategy for therapeutic

intervention. Therapeutic strategies may include the development of

small-molecule inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies that selectively

target these proteins, thereby inhibiting their function and

disrupting the signaling pathways they regulate (64). These approaches may address

certain limitations of conventional cancer therapies, such as drug

resistance and off-target effects, offering a more personalized and

effective treatment regimen (65).

The TMEM protein family is important for maintaining

cellular homeostasis and regulating various physiological

processes. Their involvement in the pathogenesis of cancer and

other diseases makes them potential candidates for targeted

therapies. Ongoing research into the molecular mechanisms of TMEM

proteins and their roles in disease progression is likely to lead

to novel therapeutic strategies, particularly for several types of

cancer and other disorders associated with abnormal TMEM protein

activity.

Research on the correlation between TMEM

proteins and cancer

TMEM family members as tumor suppressor

genes

TMEM7

Multiple regions on chromosome 3p are commonly

affected by loss of heterozygosity in several types of cancer

(66). TMEM7 is a candidate

tumor suppressor gene located at the 3p21.3 region of the human

genome. It is a 232-amino acid, single-pass membrane protein,

primarily expressed in the liver (67) and is integral to liver

carcinogenesis (Fig. 3). It

shares considerable sequence homology with the 28 kDa interferon-α

(IFN-α)-responsive protein, suggesting a potential role in immune

response modulation (67). TMEM7

has been implicated as a candidate tumor suppressor gene due to its

frequent downregulation or inactivation in several types of cancer.

Zhou et al (67) examined

primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues and HCC cell lines,

and found that TMEM7 mRNA expression was downregulated or silenced

in 85% of primary HCC samples and 33% of HCC cell lines. This

recurrent loss of function suggests that TMEM7 carries out a key

role in suppressing hepatocarcinogenesis (67). Mechanistically, the

downregulation of TMEM7 is primarily driven by epigenetic

modifications such as DNA methylation and histone deacetylation,

rather than by genomic deletions or mutations (67-69). To the best of our knowledge, no

homozygous deletions or mutations of TMEM7 have been identified in

HCC tissues or cell lines.

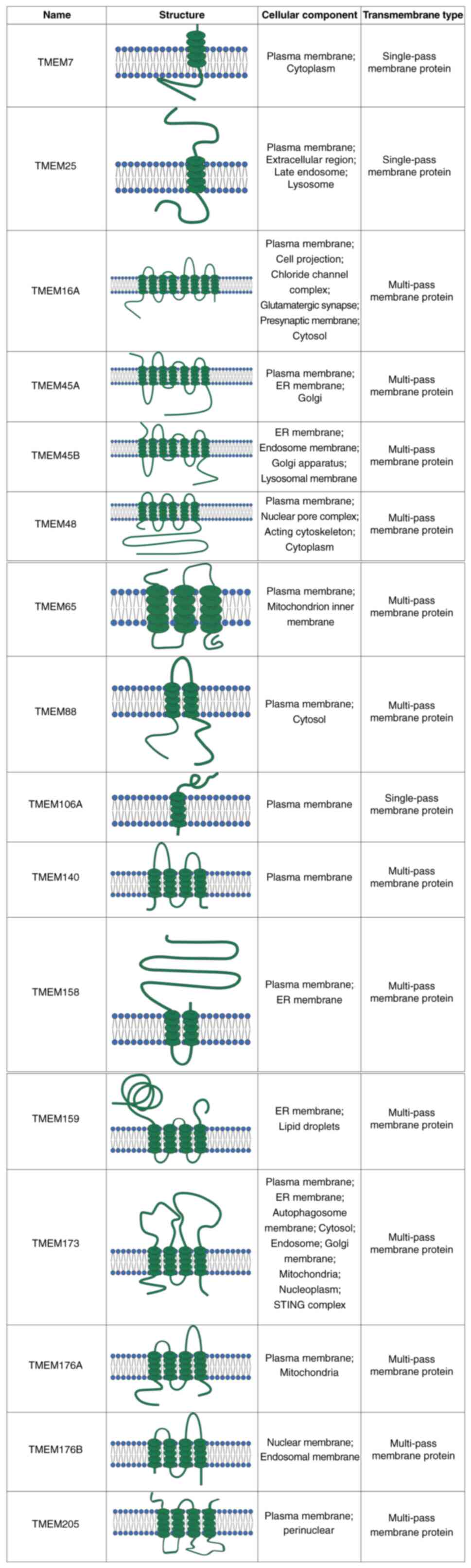

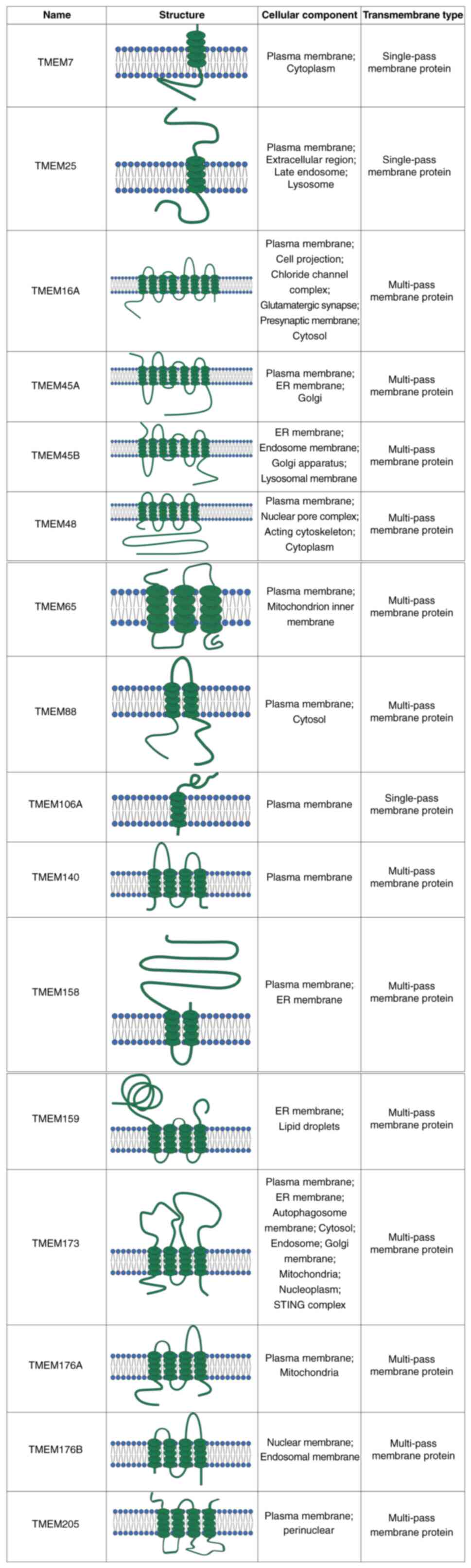

| Figure 3List of TMEM protein structures.

Representative schematic diagrams of 16 TMEM proteins, TMEM7,

TMEM25, TMEM16A, TMEM45A, TMEM45B, TMEM48, TMEM65, TMEM88,

TMEM106A, TMEM140, TMEM158, TMEM159, TMEM173, TMEM176A, TMEM176B

and TMEM205, illustrating their predicted transmembrane structures,

subcellular localization and classification as single-pass or

multi-pass membrane proteins. TMEM, transmembrane. |

Zhou et al (67) demonstrated that treatment with

DNA methylation inhibitors (such as 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine) and

histone deacetylase inhibitors (such as trichostatin A) can restore

TMEM7 expression in knockdown cell lines, confirming the role of

epigenetic alterations in its silencing. Through the ectopic

expression of TMEM7 in two HCC cell lines with TMEM7 knockdown,

cell proliferation, colony formation and cell migration were

inhibited, and tumor formation in nude mice was reduced. After 7

days of IFN-α treatment in two highly invasive HCC cell lines,

TMEM7 expression was markedly increased and cell migration was

inhibited, further establishing the role of TMEM7 in liver cancer

metastasis (67). These findings

also suggest that modulating TMEM7 expression via IFN-α may have

therapeutic potential for certain patients with HCC. While the role

of TMEM7 in HCC is well-documented, its interaction with other

genes on chromosome 3p further expands its roles. In a study by

Kholodnyuk et al (68)

involving human chromosome 3-mouse fibrosarcoma hybrids, the

transcription of TMEM7 and its neighboring genes (such as LTF and

SLC38A3) was found to be impaired in renal cell carcinoma (RCC)

cell lines, suggesting a broader tumor-suppressive role across

multiple cancer types (68).

The epigenetic silencing of TMEM7 during

hepatocarcinogenesis highlights the functional loss of TMEM7 as a

key factor in liver cancer development, while its restoration or

upregulation (by IFN-α, for example) offers potential therapeutic

benefits (67-69). Understanding the precise role of

TMEM7 in liver cancer progression may pave the way for targeted

therapies aimed at improving outcomes for patients with this

aggressive malignancy.

TMEM25

TMEM25, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily,

carries out a role in various cellular processes, including immune

responses, growth factor signaling and cell adhesion (70,71). Its expression is markedly altered

in several types of cancer, particularly in triple-negative breast

cancer (TNBC), colorectal cancer (CRC) and clear cell RCC (ccRCC),

making it a promising biomarker for diagnosis, prognosis and

therapeutic targeting. The functional importance of TMEM25 in

cancer is underscored by a study demonstrating its epigenetic

regulation, particularly through DNA methylation and histone

modifications, which affect its expression and role in

tumorigenesis (71).

In colon adenocarcinoma, Hrašovec et al

(70) observed a marked

downregulation of TMEM25 mRNA in 68% of tumor tissues from patients

with primary colon cancer. This downregulation was linked to

hypermethylation of a specific CpG site within the 5' untranslated

region of the TMEM25 gene, suggesting that epigenetic silencing

through DNA methylation is a key mechanism responsible for the

decreased expression of TMEM25 in colon adenocarcinoma. The inverse

relationship between TMEM25 hypermethylation and its expression

levels underscores the key role of epigenetic regulation in

modulating TMEM25 expression during colon carcinogenesis (70). In breast cancer, the expression

of TMEM25 is reduced in 50% of tumor samples compared with normal

tissues, as reported by Doolan et al (72). Increased TMEM25 expression levels

were associated with improved clinical outcomes, particularly in

patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy, where it was associated

with prolonged survival (72).

By contrast, TMEM25 expression was often undetectable in TNBC, a

subtype of breast cancer that is difficult to treat and associated

with poor prognosis (70-72).

In TNBC, TMEM25 acts as a suppressor of tumor progression by

inhibiting the activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway.

Specifically, TMEM25 physically interacts with the EGFR monomer,

preventing EGFR-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation. This interaction

sequesters unphosphorylated STAT3 in the cytoplasm, thereby

inhibiting its nuclear translocation and subsequent tumor-promoting

gene transcription (12,71,72). However, in TMEM25-deficient TNBC

cells, EGFR monomers can phosphorylate STAT3 independently of

ligand binding, leading to basal STAT3 activation and tumor

progression. Restoring TMEM25 expression through adeno-associated

virus delivery has been revealed to suppress STAT3 activation and

TNBC progression in preclinical models, highlighting its potential

as a therapeutic target (12,71,72). These findings indicate that

TMEM25 may act as a valuable prognostic marker in breast cancer,

particularly in predicting patient response to chemotherapy and

providing insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying

chemotherapy resistance. Growing evidence also indicates that

TMEM25 carries out a tumor-suppressive role in ccRCC, a subtype of

kidney cancer with limited therapeutic options (73). In ccRCC tissues, elevated DNA

methylation of TMEM25 has been observed, suggesting epigenetic

silencing in this type of cancer. Moreover, mutations in TMEM25

have been revealed to notably impact patient prognosis, with

reduced TMEM25 expression associating with a more aggressive

disease phenotype. Notably, the expression of TMEM25 in ccRCC is

strongly associated with several immune-related factors, including

immune checkpoint molecules, immune suppressive markers and major

histocompatibility complex molecules, implying that TMEM25 may be

involved in modulating the immune landscape of ccRCC (73). This interaction between TMEM25

and immune-related factors further underscores its role in immune

evasion within the TME.

TMEM25 has been identified as a promising prognostic

biomarker in colon cancer, breast cancer and ccRCC (70-72). Its expression is regulated

epigenetically, primarily through DNA methylation and histone

modifications, which suggests that reversing its epigenetic

silencing could offer a promising therapeutic approach.

Furthermore, the involvement of TMEM25 in immune modulation,

especially through its interactions with immune checkpoint

molecules, presents considerable promise for immunotherapeutic

interventions. This establishes TMEM25 as a key therapeutic target

in several types of cancer where its expression is reduced or

absent. Given its pivotal role in cancer progression and immune

regulation, TMEM25 may serve as a promising therapeutic target.

Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular pathways

through which TMEM25 influences tumor progression and immune

responses. Restoring or enhancing TMEM25 expression could

considerably improve treatment outcomes in colon cancer, breast

cancer, and ccRCC, thereby positioning it as a promising target in

future cancer therapies (70-72).

TMEM88

TMEM88 is a dual-transmembrane protein that

participates in several key biological processes, particularly the

regulation of human stem cell differentiation and embryonic

development (74,75). Previous studies have indicated

that TMEM88 carries out a key role in tumorigenesis, with its

expression being altered in several types of cancer (74,75). Notably, TMEM88 binds to

Dishevelled (DVL), preventing its interaction with LRP5/6 and

inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway. This leads to decreased

β-catenin activity and downregulation of Wnt target genes,

including c-Myc and cyclin D1 (75). While TMEM88 is widely expressed

in various types of tumors, it is typically downregulated in the

majority of tumor cells, suggesting its role as a potential tumor

suppressor (76).

The expression of TMEM88 is also markedly decreased

in thyroid cancer (TC) tissues and cell lines (75-77). Studies have revealed that TMEM88

inhibits the proliferation, colony formation and invasion of TC

cancer cells, primarily through binding to DVL (75-77). In both in vitro and in

vivo models, overexpression of TMEM88 has been shown to

suppress tumorigenic properties, further supporting the role of

TMEM88 as a tumor suppressor in TC. These findings suggest that

restoring TMEM88 expression or inhibiting its methylation may offer

a promising therapeutic strategy for treating TC. The involvement

of TMEM88 in bladder cancer has been further emphasized instudies

(78,79). Upregulation of TMEM88 in bladder

cancer leads to a marked reduction in cellular proliferation and

invasion (78,79). Bioinformatic analysis revealed

that TMEM88 expression was considerably reduced in bladder cancer

tissues compared with normal tissues (79). Zhao et al (79) provided evidence that loss of

TMEM88 expression in bladder cancer cells enhances invasive and

proliferative capacities, while re-expression of TMEM88 effectively

reverses these phenotypes (79).

Additionally, overexpression of TMEM88 in bladder cancer xenograft

models inhibited tumor growth (79), indicating that TMEM88 acts as a

tumor suppressor gene in bladder cancer as well.

The biological role of TMEM88 depends on its

subcellular localization. Membrane-localized TMEM88 inhibits Wnt

signaling, while cytosolic TMEM88 promotes tumor progression

through alternative pathways. Zhang et al (80) reported that cytosolic

localization of TMEM88 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is

associated with poor differentiation, a high TNM stage, lymph node

metastasis and worse overall survival (OS). TMEM88 was shown to

promote invasion and metastasis by activating the p38-GSK3 β-Snail

signaling pathway. Overexpression of TMEM88 in NSCLC cells

inhibited excessive cell proliferation, invasion and migration,

leading to the prevention of tumor growth in xenograft models

(80). Furthermore,

hypermethylation of the TMEM88 promoter has been observed in NSCLC

tissues, which is associated with a worse prognosis. Demethylation

of TMEM88 resulted in the inhibition of cell proliferation,

migration and invasion, suggesting that TMEM88 expression and its

epigenetic regulation carry out a key role in NSCLC progression

(81). In TNBC, TMEM88

overexpression in the cytosol stimulated invasion and metastasis by

interacting with DVL proteins and promoting Snail expression while

inhibiting tight junction proteins, such as zonula occludens-1 and

occluding (82). Thus, increased

TMEM88 expression was associated with improved prognosis in HCC and

bladder cancer, while its cytosolic localization was predictive of

a worse outcome in NSCLC and TNBC.

TMEM88 carries out a key role in regulating cell

proliferation, migration and invasion, and has demonstrated notable

potential as both a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target

across various types of cancer (79-82). Its expression is frequently

downregulated in tumors, and promoter hypermethylation of TMEM88 is

associated with a worse prognosis in NSCLC (80,81). These findings highlight TMEM88 as

a potential marker for disease progression and survival prediction.

The epigenetic regulation of TMEM88, particularly through DNA

methylation, offers a novel therapeutic avenue. Demethylating

agents can restore TMEM88 expression (81), thereby suppressing tumor cell

growth and metastasis. As a negative regulator of the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway, TMEM88 exhibits tumor-suppressive activity in

NSCLC, TC and bladder cancer. Therapeutic strategies aimed at

restoring or enhancing TMEM88 expression could thus represent a

viable approach for cancer treatment. Ongoing research into the

molecular mechanisms of TMEM88 is expected to further clarify its

value as both a therapeutic target and a prognostic biomarker in

clinical oncology.

TMEM106A

TMEM106A is located on chromosome 17 and consists of

262 amino acids. TMEM106A is a conserved type II TP that has been

implicated in suppressing tumorigenesis across multiple types of

cancer (83,84). TMEM106A is typically expressed in

normal gastric tissue and is often downregulated or silenced in

gastric cancer (GC), due to methylation of the promoter region, and

its methylation is associated with smoking and tumor metastasis

(83,84). Frequent methylation of TMEM106A

in GC tissues highlights its potential role as a tumor suppressor.

Xu et al (84)

demonstrated that overexpression of TMEM106A markedly inhibited GC

cell proliferation and induced apoptosis, while also delaying tumor

growth in xenograft models (84). Mechanistic studies suggested that

these effects were closely associated with the activation of

caspase-2, caspase-9 and caspase-3, as well as the inactivation of

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (84). Thus, TMEM106A has emerged as a

functional tumor suppressor in the pathogenesis of GC.

Methylation of TMEM106A is generally associated with

its reduced expression and the promoter region methylation serves

as a key regulatory mechanism in GC. The downregulation of TMEM106A

expression in patients with GC is associated with a worse

prognosis, emphasizing its clinical relevance as a prognostic

biomarker (85). In renal

cancer, TMEM106A expression is markedly reduced, and its

restoration in cancer cells leads to attenuated proliferation,

reduced migration and enhanced caspase-3-dependent apoptosis

(86). Similarly, the expression

of TMEM106A in HCC tissues is notably reduced compared with normal

liver tissue, accompanied by frequent promoter methylation in HCC

tissues, further reinforcing its potential as a tumor suppressor

(87). Treatment with

5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine in HCC cells with high methylation restored

TMEM106A expression and markedly suppressed the malignant behaviors

of these cells, including reduced cell migration, invasion and lung

metastasis (87). In vivo

experiments demonstrated that overexpression of TMEM106A in HCC

cells resulted in considerable tumor suppression, and this was

associated with the suppression of epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) and the inactivation of the ERK1/2/Slug signaling

pathway (87). Moreover, in

NSCLC, TMEM106A expression was revealed to be markedly decreased in

tumor tissues. Overexpression of TMEM106A in NSCLC cells reduced

proliferation, migration and invasion, while inducing apoptosis. It

also repressed EMT by modulating E-cadherin, N-cadherin and

vimentin expression, and inhibited the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling

pathway (88). In urothelial

carcinoma, TMEM106A was identified as a novel biomarker, with its

methylation levels in urine samples revealing high diagnostic

accuracy for early detection (89).

TMEM106A also exhibits antiviral activity,

specifically in the IFN-mediated antiviral immune response.

TMEM106A was revealed to interact with the receptor SCARB2 of

EV-A71 and CV-A16, thus disrupting viral binding to host cells and

preventing viral infection (90). This finding not only highlights a

novel mechanism of TMEM106A in antiviral immunity but also proposes

a potential therapeutic target for antiviral strategies. In

addition to its antiviral function, TMEM106A regulates macrophage

activation and immune responses, especially in bacterial

infection-induced inflammation. Its downregulation enhanced M1

macrophage polarization and exacerbated the LPS-induced

inflammatory response through the MAPK and NF-κB signaling

pathways, underscoring the key role of TMEM106A in immune

homeostasis (91).

TMEM106A carries out a key tumor-suppressive role in

various types of cancer, such as gastrointestinal tumors, liver

cancer and NSCLC, with its dysregulated expression, including

methylation, potentially serving as a valuable clinical prognostic

biomarker (84,86-91). Furthermore, the diverse functions

of TMEM106A in immune responses and antiviral defense establish it

as a potential target for future cancer treatments and immune

modulation strategies. Further research should prioritize

elucidating the specific mechanisms by which TMEM106A operates in

various types of cancer and exploring its clinical

applications.

TMEM173

TMEM173, also known as stimulator of interferon

genes (STING), is a key TP located on the outer membrane of the ER

and carries out a key role in cancer immunology and immunotherapy.

It is essential in innate immunity and is primarily expressed in

hematopoietic cells and immune organs such as the thymus and spleen

(92,93). Composed of four transmembrane

domains, TMEM173 forms dimers that allow ligand binding and

activation of immune responses, in addition to mediating reactions

to cytosolic DNA, which can result from infections, cellular stress

or genomic instability (94).

TMEM173 carries out a key role in host defense against pathogenic

infections by regulating type I IFN (IFN-I) signaling,

pro-inflammatory cytokines and innate immunity (95). In addition to its role in innate

immunity, TMEM173 also contributes to autoimmune inflammation,

oxidative stress and autophagy (96).

While TMEM173 has demonstrated tumor-suppressive

functions in various cancer types, including CRC, prostate cancer

and melanoma (92); it is

important to note that TMEM173 activation can act as a double-edged

sword in cancer. It promotes antitumor immunity by enhancing

dendritic cell (DC) maturation, T cell activation and macrophage

polarization toward an M1 phenotype, which supports tumor

elimination (97-99). T cell infiltration into tumors is

largely dependent on IFN-I signaling, and activation of TMEM173

enhances immune surveillance against tumors. For example, TMEM173

agonists have been revealed to amplify the cGAS-STING pathway,

leading to increased IFN-β secretion and T cell-mediated immune

responses in colorectal and breast cancer models (97). Additionally, TMEM173 activation

can reprogram tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) from an

immunosuppressive M2 phenotype to an immunostimulatory M1

phenotype, further enhancing antitumor immunity (97,100). TMEM173 expression is

downregulated in various types of cancer, including GC and HCC, and

this downregulation associates with tumor size, invasiveness and

lymph node metastasis. In vitro experiments have revealed

that knockout of TMEM173 promotes clonal formation, migration and

invasion of GC cells, whereas its activation induces apoptosis and

autophagy in malignant cells, inhibiting tumor growth (101). However, STING signaling can

also promote immune evasion and tumor progression. For example,

TMEM173 activation in tumor monocytes induces programmed death

(PD)-ligand 1 expression, which suppresses T cell activity and

contributes to resistance against TMEM173 agonist therapy (102). Similarly, TMEM173 signaling can

expand regulatory B cells that produce IL-35, which attenuates

natural killer (NK) cell function and compromises antitumor

immunity (103). TMEM173 may

carry out a key role in metastasis formation. Activation of TMEM173

promotes metastatic tumor formation and spread, partly through the

production of TNF-α and other cytokines (104). For example, Bu et al

(105) reported that, in

clinical samples from patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-induced

liver cancer, TMEM173 downregulation may contribute to immune

evasion and subsequently facilitate tumor progression.

TMEM173 is not only a key regulator of tumor

immunity but also holds substantial therapeutic potential within

cancer immunotherapy. Targeting TMEM173, either by modulating its

upstream or downstream signaling pathways, may provide novel

therapeutic strategies to enhance cancer treatment outcomes,

particularly when combined with immune checkpoint blockade

therapies (106). Therefore,

TMEM173 agonists are emerging as promising candidates for cancer

immunotherapy. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems have been

developed to enhance the spatiotemporal activation of TMEM173,

improving its therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target

effects (107). For example,

TME-responsive nanoparticles have been designed to simultaneously

activate TMEM173 and TLR4, leading to enhanced IFN-β production and

T cell responses in colorectal and metastatic breast cancer models

(97). Additionally, combining

TMEM173 agonists with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as

anti-PD-1 antibodies, has shown synergistic effects in preclinical

models (97,100). However, challenges remain in

translating TMEM173 agonists to clinical practice. Issues such as

poor drug stability, limited tumor targeting and immune-related

adverse events need to be addressed (103,108). Nanomedicine approaches,

including the use of radiosensitizers and targeted delivery

systems, are being explored to overcome these limitations.

TMEM173 is a central player in cancer immunology,

with its activation driving both antitumor immunity and immune

evasion. While TMEM173 agonists hold potential for cancer

immunotherapy, their clinical translation requires careful

consideration of the TME and potential off-target effects. Future

research should focus on developing targeted delivery systems and

combination therapies to maximize the therapeutic potential of

TMEM173 activation in cancer treatment.

TMEM176A/TMEM176B

TMEM176A and TMEM176B, both belonging to the

membrane-spanning 4-domains family, have emerged as key regulators

of immune responses and cancer progression. TMEM176A is localized

on chromosome 7q36.1 and has been identified as a potential tumor

suppressor in various types of cancer, including esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and CRC (109). In addition, TMEM176B, also

known as tolerance-related and induced, carries out a key role in

immune modulation and cancer progression (110).

TMEM176A has been revealed to suppress the growth

of ESCC cells both in vitro and in vivo (110-112), suggesting its potential as a

diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for ESCC. In ESCC, the loss of

TMEM176A expression is associated with promoter hypermethylation

(111). TMEM176A promoter

methylation occurs in ~66% of primary ESCC tumors, which associates

with its reduced expression, poor tumor differentiation, reduced

survival rates and aggressive cancer phenotypes (111). The restoration of TMEM176A

expression using demethylation agents, such as

5'-aza-2'-deoxycytidine, inhibits cell migration and invasion,

thereby promoting apoptosis in ESCC cells and suppressing cancer

progression. Additionally, in CRC, TMEM176A promoter methylation is

observed in nearly half of the primary tumors, with TMEM176A

overexpression resulting in suppressed cell proliferation,

migration, invasion and induced apoptosis (112). Notably, TMEM176A is also

involved in regulating glioma cell cycles through pathways such as

ERK1/2, further validating its role as a tumor suppressor (112). Collectively, these findings

establish TMEM176A as a potential tumor suppressor gene, with its

expression levels serving as valuable prognostic indicators across

multiple cancer types (113).

TMEM176B has been extensively studied in various

types of cancer, where it often promotes tumor progression. In CRC,

TMEM176B inhibits the NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing

protein 3 inflammasome, thereby suppressing NK cell activity and

promoting EMT, a key process in metastasis. Silencing TMEM176B

reduces tumor growth, metastasis and EMT while enhancing apoptosis

and immune activation (114).

In GC, TMEM176B overexpression drives tumor progression by

regulating the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway and amino acid

metabolism. Its knockdown inhibits cell proliferation, migration

and invasion, while promoting apoptosis. Clinically, TMEM176B

expression is associated with a worse prognosis, making it a

potential prognostic marker (115). TMEM176B also carries out a role

in ovarian cancer (OC), where it acts as a tumor suppressor. Its

downregulation is associated with increased EMT, proliferation and

metastasis, mediated through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Restoring TMEM176B expression inhibits these processes,

highlighting its therapeutic potential (116).

TMEM176B also carries out a key role in regulating

immune responses, especially in DCs (117). TMEM176B is recognized as a key

modulator of allograft tolerance and immune system function

(117). A study involving

autologous tolerogenic DCs (ATDCs) demonstrated that TMEM176B

expression in ATDCs was essential for inducing donor-specific

immune tolerance and prolonging graft survival (118). TMEM176B-deficient ATDCs failed

to cross-present antigens effectively, impairing their ability to

induce regulatory CD8+ T cells and hindering allograft

tolerance (118). TMEM176B

inhibits inflammasome activation, which dampens anti-tumor

immunity. Targeting TMEM176B unleashes inflammasome activity,

increasing CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor control and

enhancing the effects of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapies

(119). These findings

underscore the importance of TMEM176B in modulating immune

responses, particularly through its influence on antigen

cross-presentation and regulation of phagosomal pH, both of which

are important for immune tolerance (120). Additionally, TMEM176B has been

implicated in regulating immune checkpoint responses, particularly

in the context of PD-1 blockade therapy. Elevated TMEM176B

expression in tumor stromal cells is associated with a worse

prognosis, suggesting that it may act as a negative modulator of

anti-tumor immunity (121). Its

role in immune evasion has prompted investigations into its

potential as a biomarker for predicting patient response to immune

checkpoint inhibitors, including anti-PD-1 therapies. TMEM176B

negatively regulated the antitumor activity of CD146+

TAMs. Inhibition of TMEM176B enhanced TAM-mediated anti-tumor

immunity, highlighting a potential immunotherapeutic strategy

(122). Thus, as an

immune-regulating cation channel, TMEM176B modulates immune cell

trafficking and function, further highlighting its potential as a

therapeutic target (123).

TMEM176A and TMEM176B are known to physically

interact and co-localize at both the plasma membrane and vesicular

compartments within immune cells (124). In lymphoma, overexpression of

both proteins has been associated with immune evasion, enabling

cancer cells to evade immune surveillance and develop resistance to

chemotherapy (124,125). This interaction suggested that

the two proteins may function synergistically to regulate immune

responses and contribute to tumor progression. Both TMEM176A and

TMEM176B are downregulated during DC maturation, with their

overexpression inhibiting this process and suggesting a role in

maintaining an immature state that facilitates immune tolerance

(123).

TMEM176A and TMEM176B have emerged as key factors

in cancer biology, particularly in immune regulation and tumor

suppression. Their roles in immune modulation, especially through

the regulation of DC function and antigen cross-presentation,

position them as promising targets for novel therapeutic strategies

aimed at enhancing immune checkpoint blockade efficacy and

improving cancer immunotherapy outcomes. Future research should

focus on more comprehensively elucidating the precise molecular

mechanisms by which TMEM176A and TMEM176B regulate immune responses

and tumor progression. Clinical trials targeting these proteins,

either alone or in combination with existing immune checkpoint

inhibitors, may provide key insights into their therapeutic

potential.

TMEM family members as oncogenes

TMEM16A

TMEM16 proteins, also known as anoctamins, are a

family of ten MPs with various tissue expression and subcellular

localization. TMEM16A, also referred to as anoctamin 1 (ANO1), is a

calcium-activated chloride channel (CaCC) mapped to chromosome

11q13. It contains eight transmembrane domains and a highly

conserved, functionally undefined domain (DUF590), with its

expression predominantly observed in secretory epithelial cells,

smooth muscle tissue and sensory neurons (126). TMEM16A is acknowledged as a key

modulator of tumor progression. It is frequently amplified in a

variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, esophageal cancer

and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs), where its

expression is associated with a poor prognosis, increased tumor

size and advanced clinical stages (127).

TMEM16A carries out a key role in tumorigenesis by

activating key signaling pathways, including the EGFR and

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase pathways (128). Silencing of TMEM16A has been

revealed to inhibit the proliferation of esophageal and HNSCC cells

and induce apoptosis through the MAPK and AKT signaling pathways.

TMEM16A is involved in EMT, a key process in cancer metastasis, by

regulating the transition from an epithelial to a mesenchymal

state, thus enhancing cell migration and invasion (129). In CRC, TMEM16A carries out a

key role in disease progression by promoting cell migration and

invasion. It activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by

upregulating key components such as Frizzled protein 1 and

β-catenin, while downregulating GSK3β (129,130). The overexpression of TMEM16A is

notably elevated in HNSCC, esophageal and prostate cancer, where it

is associated with distant metastasis and a poor prognosis

(131).

The molecular mechanisms underlying these effects

include a role independent of its channel function in promoting

cell proliferation. Research suggests that TMEM16A regulates cancer

cell growth by interacting with other MPs rather than exclusively

through its chloride conductance (131). For example, TMEM16A has been

revealed to interact with EGFR, thereby potentiating EGFR signaling

in HNSCC cells (128). This

interaction not only stabilizes EGFR but also increases TMEM16A

protein expression, thereby establishing a feedback loop between

TMEM16A and EGFR signaling pathways, which likely contributes to

enhanced cancer cell proliferation and survival. Knockdown of

TMEM16A has been revealed to reduce myeloid cell leukemia 1

expression and promote the perinuclear redistribution of

p27Kip1, thereby inducing cell cycle arrest, suppressing

tumor proliferation and promoting apoptosis (132). However, Shiwarski et al

(133) reported that stable

reduction of TMEM16A expression enhanced the motility of HNSCC

cells and facilitated metastasis, independent of 11q13

amplification. Additionally, TMEM16A overexpression is associated

with increased Erk1/2 activity, reduced Bim expression and

decreased apoptotic activity, contributing to tumor progression and

cisplatin resistance (134).

These conflicting findings underscore the multifaceted role of

TMEM16A in HNSCC progression. Further studies revealed that TMEM16A

expression is associated with tumor subtype: In general, in HNSCC,

elevated TMEM16A levels associate with shorter survival and

increased risk of distant metastasis (135,136), whereas in human papilloma virus

(HPV)-positive HNSCC, its expression was not associated with

prognostic significance (136).

This suggests that TMEM16A-targeted therapies may be inappropriate

for HPV-positive patients. Collectively, these findings indicate

that the function of TMEM16A is context-dependent, shaped by the

TME and specific cellular subtypes. Continued clinical and

molecular investigations are required to clarify its precise role

in cancer progression.

TMEM16A has emerged as a potential biomarker for

several types of cancer, including esophageal and gastrointestinal

squamous cell carcinoma (127).

Its expression is associated with clinical staging and disease

progression, making it a valuable prognostic indicator. Moreover,

TMEM16A functions as a predictor of therapeutic response to

EGFR-targeted therapies, particularly in HNSCC, where TMEM16A

overexpression may mediate resistance to EGFR inhibitors (137). Given its key role in tumor

progression and interaction with EGFR signaling, TMEM16A represents

a compelling therapeutic target. Targeting TMEM16A in conjunction

with EGFR may offer a strategy to bypass resistance mechanisms and

enhance the efficacy of existing EGFR-targeted therapies in cancer

treatment (128).

Amplification of chromosome 11q13, where TMEM16A

(ANO1) is located, is associated with a poor prognosis in patients

with breast cancer. TMEM16A amplification and overexpression are

associated with a higher tumor grade and worse outcomes, primarily

through activation of EGFR and CaMKII signaling pathways to promote

cell proliferation (138).

TMEM16A expression also associates with immunohistochemical markers

such as β-catenin, cyclin D1 and E-cadherin, and has been

identified as an independent prognostic marker (139). Functional studies revealed that

TMEM16A inhibition induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and reduced the

invasiveness of breast cancer cells, underscoring its potential as

a therapeutic target (139,140). However, conflicting data

regarding its association with hormone receptors (HER2, ER and PR)

suggested that the role of TMEM16A may vary across molecular

subtypes and cellular contexts (140). Upregulation of TMEM16A is

notably associated with CRC progression and higher TNM staging

(141). Sui et al

(142) confirmed that TMEM16A

knockout inhibited the growth, migration and invasion of CRC cells

by suppressing the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. It has been reported

that endogenous TMEM16A knockout suppressed CRC cell proliferation

and induced apoptosis by inactivating the downstream Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway (142). Li

et al (143) proposed

that TMEM16A mRNA expression was associated with lymph node

metastasis in CRC and may thus serve as an independent predictive

marker for lymphatic involvement. These findings establish the key

role of TMEM16A in CRC progression and metastasis. Overexpression

of TMEM16A is associated with TNM staging and Gleason scoring in

prostate cancer, carrying out a key role in tumor growth,

progression and metastasis (144).

Silencing or inhibiting endogenous TMEM16A has been

revealed to suppress prostate cancer growth, induce apoptosis and

increase TNF-α expression levels (145). Notably, natural products such

as resveratrol and luteolin serve both as TMEM16A inhibitors and

antitumor agents, effectively reducing prostate cancer cell

proliferation and migration (146,147). These findings highlight the

therapeutic potential of targeting TMEM16A in prostate cancer

treatment. TMEM16A is considerably upregulated in epithelial OC

cells, and its upregulation is associated with increased staging

and lower differentiation (148). Downregulation of TMEM16A

suppressed OC cell growth by reducing PI3K/Akt phosphorylation and

disrupting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (148). These findings highlight the key

role of TMEM16A in OC progression, with its expression associated

with advanced disease and a poor prognosis. Given its role in

cancer progression, TMEM16A has emerged as a promising therapeutic

target. Inhibition of TMEM16A suppresses tumor growth, induces

apoptosis and enhances the efficacy of existing therapies (144-149). For example, allicin, a natural

compound from garlic, was shown to inhibit the chloride ion current

through the TMEM16A channel and exhibit synergistic anticancer

effects with cisplatin in lung cancer (149). Similarly, idebenone, a novel

TMEM16A inhibitor, can block chloride channel activity and was

shown to induce apoptosis in normal prostate and PC cells (150). Furthermore, TMEM16A inhibitors

such as T16Ainh-A01 and CaCCinh-A01 have demonstrated efficacy in

reducing tumor growth and invasiveness in prostate cancer (144).

TMEM16A, as a CaCC, carries out a key role in

calcium-activated chloride secretion, which is involved in the

pathogenesis of secretory diarrhea. Yin et al (151) revealed in rotavirus-induced

diarrhea that viral enterotoxin NSP4 enhanced intracellular calcium

levels, activating TMEM16A-mediated chloride secretion, which,

in-turn, contributed to fluid loss and diarrhea. Given that

chemotherapy-induced diarrhea in patients with cancer often

involves dysregulated epithelial ion transport, TMEM16A may

similarly contribute to this adverse effect. Thus, TMEM16A may

serve as a mechanistic link between increased chloride secretion

and diarrhea in both infectious and iatrogenic contexts.

TMEM16A, through its dual function as both a

chloride channel and a signaling modulator, carries out a pivotal

role in tumor biology. The regulation of cell proliferation,

migration and metastasis by TMEM16A, in addition to its association

with EGFR signaling, highlights its potential as both a prognostic

biomarker and a therapeutic target for various malignancies.

TMEM45A

TMEM45A consists of 275 amino acids, composed of

5-7 transmembrane domains and is primarily localized in the Golgi

apparatus (4). It is highly

expressed in the skin, where it carries out a key role in epidermal

differentiation and keratinization, processes essential for

preserving the structural integrity of the skin and barrier

function (152). Beyond its

role in normal cellular functions, TMEM45A is involved in the

pathogenesis of various types of cancer, including gliomas, breast

cancer, HCC, RCC and OC, where it is commonly upregulated (153).

TGF-β is a key factor regulating various cellular

processes such as proliferation, migration and invasion. In OC, the

expression of TMEM45A is closely associated with the activation of

the TGF-β signaling pathway. Silencing TMEM45A not only reduced

cell proliferation, adhesion and invasion, but also downregulated

cancer-promoting factors such as TGF-β1, TGF-β2, RhoA and ROCK2

(154). This association has

been revealed to contribute to tumor progression and metastasis and

a similar mechanism has been identified in glioma cell lines,

providing further evidence for the oncogenic potential of TMEM45A

in these cancer types (152,153). Notably, increased TMEM45A

expression in breast cancer and cervical cancer (CC) has been

associated with poor OS, indicating that TMEM45A could function as

an important prognostic biomarker for these malignancies (155).

TMEM45A short hairpin RNA inhibited the

proliferation of CC cells, arrested the cell cycle at the S phase

and promoted apoptosis. It also suppressed EMT by downregulating

Vimentin and N-cadherin, and upregulating E-cadherin, thereby

reducing the invasive and migratory ability of the cells. The

expression of TMEM45A in cisplatin-resistant cell lines SiHa/DDP

and HeLa/DDP was revealed to be increased compared with their

parental cells, and inhibiting TMEM45A markedly reduced the

IC50 of these resistant cells to cisplatin. Silencing

TMEM45A inhibited the proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT of

HPV-positive CC cells, regulated cell cycle distribution and

promoted apoptosis (156). Sun

et al (153) revealed

that TMEM45A was overexpressed in glioma tissues compared with

non-tumorous brain tissues. TMEM45A mRNA levels progressively

increased with higher histological grades of glioma and were

associated with shorter survival times of patients. Knockout of

TMEM45A in glioma cell lines markedly inhibited cell proliferation

and induced G1 phase arrest, and reduced the migratory and invasive

abilities of glioma cells. Notably, treatment with TMEM45A small

interfering (si)RNA downregulated key proteins involved in cell

cycle progression (Cyclin D1, CDK4 and proliferating cell nuclear

antigen) as well as invasion-related proteins (MMP-2 and MMP-9),

providing a potential mechanistic explanation for its role in

glioma.

TMEM45A is closely associated with intratumoral

heterogeneity, a major challenge in cancer treatment. In lung

adenocarcinoma, TMEM45A was revealed to be overexpressed in tumor

tissues compared with healthy tissues, and its expression was

associated with markers such as GLUT1, MCT4 and CA9, which are

associated with a hypoxic microenvironment and altered metabolism

(157). Similarly, in ccRCC,

TMEM45A upregulation associated with poor OS, disease-free survival

and advanced clinicopathological features such as higher

histological grade and TNM stage (158).

TMEM45A is a multifunctional protein associated

with tumorigenesis, chemotherapy resistance and fibrosis. Its

ability to modulate key signaling pathways, including TGF-β and

Notch, positions it as a promising candidate for therapeutic

targeting. In GC, increased TMEM45A expression was associated with

poor prognosis and immune cell infiltration, making it a potential

independent prognostic marker (159). In breast cancer, TMEM45A

expression is associated with poor survival and resistance to

CDK4/6 inhibitors such as palbociclib, further underscoring its

prognostic value (160).

Furthermore, the association of TMEM45A with a poor prognosis in

various types of cancer and its involvement in MDR highlights its

potential as a biomarker for cancer progression and therapeutic

resistance (155,161,162). In breast cancer, engineered

exosomes loaded with siRNA targeting TMEM45A restored sensitivity

to palbociclib and suppressed tumor growth (160). Similarly, in CC, TMEM45A

knockdown reversed cisplatin resistance and inhibited

proliferation, migration and EMT in HPV-positive cell lines

(156). Future research

focusing on the molecular mechanisms underlying the functions of

TMEM45A in these contexts are essential for the development of

targeted therapies aimed at overcoming resistance and improving

patient outcomes.

TMEM45B

TMEM45B has attracted considerable attention due to

its involvement in various types of cancer, including lung cancer,

PC and GC (163). Okada et

al (163) have highlighted

that TMEM45B as an oncogene that plays a pivotal role in cancer

pathogenesis by regulating essential cellular processes, including

proliferation, invasion, migration, and apoptosis.

In lung cancer, TMEM45B overexpression is

associated with poor patient survival. Knockdown of TMEM45B reduced

cell proliferation, induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and

inhibited cell migration and invasion. These effects were mediated

through the regulation of cell cycle-related proteins (CDK2 and

CDC25A), apoptosis-related proteins (Bcl2 and Bax) and

metastasis-related proteins (MMP-9, Twist and Snail). TMEM45B may

thus serve as a potential prognostic marker and therapeutic target

in lung cancer (164). TMEM45B

is highly expressed in PC tissues and cell lines. Its knockdown

inhibited cell proliferation, invasion and migration while inducing

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Conversely, TMEM45B overexpression

promoted these processes and inhibited apoptosis. Gene set

enrichment analysis revealed that TMEM45B regulated genes that are

involved in the cell cycle and metastasis pathways, further

supporting its oncogenic role in PC (165). Shen et al (166) also demonstrated that in GC,

TMEM45B was overexpressed in both tissues and cell lines. Silencing

TMEM45B inhibited cell proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT.

This suppression was mediated through the inhibition of the

JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway, as evidenced by reduced levels of

phosphorylated JAK2 and STAT3 upon TMEM45B knockdown (166).

Moreover, in osteosarcoma, Li et al

(167) verified the

upregulation of TMEM45B expression and revealed that its knockdown

in U2OS cells effectively suppressed proliferation, migration and

invasion in vitro, and inhibited tumor growth in xenograft

models. This effect was associated with the downregulation of key

proteins such as β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc, which are

important for cancer cell proliferation and metastasis (167). These findings collectively

indicate that TMEM45B is a potent regulator of tumorigenesis across

various cancer types. Its dysregulated expression may act as a

potential prognostic biomarker for cancer progression and it holds

promise as a therapeutic target. Furthermore, previous studies have

demonstrated that the regulatory effects of TMEM45B extend to

modulating the TME, influencing immune responses and potentially

modulating the response to chemotherapeutic agents (167,168). Similarly, TMEM45B has been

identified as a novel predictive biomarker for prostate cancer

progression and metastasis. Its expression is notably increased in

tumor cell lines with high metastatic potential and is associated

with biochemical recurrence, distant metastasis and a poor OS.

Multivariate analysis confirmed that TMEM45B was an independent

risk factor for metastasis, making it a promising prognostic marker

for patients with prostate cancer (169).

TMEM45B exerts its oncogenic effects through

multiple signaling pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin, JAK2/STAT3

and TGF-β. It regulates key cellular processes such as

proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion by modulating the

expression of downstream target genes and proteins. Additionally,

the involvement of TMEM45B in EMT and chemotherapy resistance

further underscores its role in cancer progression. Given its

central role in regulating key pathways involved in cancer

progression, TMEM45B may be developed as a targeted therapy,

thereby improving patient outcomes.

TMEM48

TMEM48 is a member of the nuclear pore complex

(NPC) family of proteins and is essential for maintaining nuclear

membrane integrity and enabling nuclear transport (170). The protein consists of six

transmembrane domains and is vital for NPC assembly, which is

important for regulating several cellular processes, including

chromosome segregation, gene transcription, DNA replication, DNA

damage repair and apoptosis (170,171). Alterations in the expression of

NPC proteins, including TMEM48, have been associated with the onset

and progression of various malignancies, such as breast, melanoma,

pancreatic, colon, gastric, prostate, esophageal, lung cancer and

lymphoma (170-172).

Previous studies have highlighted the involvement

of TMEM48 in NSCLC (170-173). Qiao et al (173) demonstrated that TMEM48

expression was markedly increased in NSCLC tissues compared with

adjacent normal tissues. This overexpression was associated with a

poor prognosis, including reduced survival times, increased tumor

size and lymph node metastasis. TMEM48 regulates essential cellular

processes, such as proliferation, migration and invasion, by

regulating genes involved in the cell cycle and DNA replication.

Knockdown of TMEM48 in NSCLC cell lines led to reduced cell

proliferation, induction of G1 phase cell cycle arrest and

inhibition of migration and invasion. Furthermore, silencing of

TMEM48 triggered apoptosis in NSCLC cells. In an in vivo

study, silencing TMEM48 led to a notable reduction in tumor weight

in xenograft models (173).

Moreover, the study by Akkafa et al

(6) suggests that microRNA

(miR)-421, an miR targeting TMEM48, potentiates apoptotic signaling

pathways in NSCLC. Suppression of TMEM48 by miR-421 upregulated the

expression of apoptosis-related proteins, such as caspase-3, PTEN

and p53, which collectively promote cell death. This indicated that

targeting TMEM48 may serve as a therapeutic strategy for improving

the efficacy of treatments in NSCLC. TMEM48 has been identified in

other types of cancer, such as CC (174). In CC, TMEM48 is overexpressed

and its knockdown inhibited cell proliferation, migration and

invasion both in vitro and in vivo (174). Jiang et al (174) indicated that TMEM48 promotes CC

progression by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, as

evidenced by the reduced expression of β-catenin, TCF1 and AXIN2

following TMEM48 knockdown. This suggested that TMEM48 is important

in tumorigenesis by modulating key signaling pathways involved in

cancer progression.

TMEM48 is a promising prognostic marker and

therapeutic target. Given its central role in regulating cellular

functions key for tumor progression, TMEM48 represents a valuable

target for future therapeutic strategies focused on inhibiting

cancer growth and metastasis. Further research is needed to explore

the therapeutic potential of TMEM48 in various malignancies,

including its modulation by miRNAs.

TMEM65

TMEM65 is a mitochondrial inner membrane protein

whose deficiency has been implicated in a mitochondrial disorder

characterized by a complex encephalomyopathic phenotype (175,176). Clinical manifestations include

microcephaly, craniofacial dysmorphism, psychomotor regression,

generalized hypotonia, growth retardation, lactic acidosis,

intractable seizures and dyskinetic movements, notably in the

absence of cardiomyopathy (175). Previously, TMEM65 has emerged

as a pivotal factor in cancer biology, with its involvement

reported across various malignancies, including CRC, TNBC, GC and

HCC (175-180). TMEM65 carries out a

multifaceted role in tumorigenesis by modulating mitochondrial

dynamics, driving metabolic reprogramming and regulating signaling

pathways associated with cancer progression and therapeutic

resistance. This contrast between its role in congenital

mitochondrial disease and acquired malignancies underscores its

biological value and potential as a therapeutic target.

In CRC, TMEM65 is transcriptionally regulated by

the CHD6-TCF4 axis, which is activated by both EGF and Wnt

signaling pathways. CHD6, a chromatin remodeler, binds to Wnt

signaling transcription factor TCF4 to facilitate TMEM65

expression. This axis promotes mitochondrial dynamics and ATP

production, essential for cancer cell proliferation, migration and

invasion. Targeting the CHD6-TMEM65 axis with Wnt inhibitors and

anti-EGFR therapies showed promise in restricting CRC growth

(176). TMEM65 acts as an

oncogene in TNBC, where it was revealed to be upregulated by the

transcription factor MYC and DNA demethylase TET3. TMEM65 enhanced

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and reactive oxygen species

production, which, in turn, activates hypoxia inducible factor

(HIF)-1α and SERPINB3 and promotes cancer stemness, progression,

and cisplatin resistance. Inhibition of MYC and TET3 attenuated

TMEM65-driven TNBC progression, highlighting its potential as a

therapeutic target (177).

TMEM65 amplification and overexpression are common in GC and are

associated with a poor prognosis. TMEM65 promoted tumorigenesis by

activating the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway through its

interaction with YWHAZ, a protein that inhibits ubiquitin-mediated

degradation. Silencing TMEM65 suppresses tumor growth and

metastasis, making it a promising therapeutic target in GC

(163). In HBV-related HCC,

TMEM65 amplification was driven by HBV integration-induced genomic

rearrangements. TMEM65 contributes to tumorigenesis by promoting

mitochondrial function and metabolic reprogramming, which are key

for cancer cell survival and proliferation (178).

TMEM65 expression is associated with tumor immune

infiltration, particularly CD8+ T effector cells and

immune checkpoint markers. Its role in modulating the TME and

immune response makes it a potential biomarker for predicting

prognosis and the efficacy of immunotherapy (179). TMEM65 may serve as a target for

chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies and antibody-drug

conjugates. Its overexpression in cancer tissues and low expression

in normal tissues make it an attractive candidate for immune-based

interventions (180). TMEM65 is

a pivotal oncogene that drives cancer progression through its roles

in mitochondrial dynamics, metabolic reprogramming and signaling

pathway activation. Its overexpression is associated with poor

prognosis across multiple cancer types, making it a promising

biomarker and therapeutic target. Future research should focus on

developing targeted therapies that exploit the oncogenic function

of TMEM65 while minimizing off-target effects.

TMEM140

TMEM140, also known as FLJ11000, is a TP encoded by

a gene located on chromosome 7q33, consisting of 185 amino acids

(181). Although initially

identified for its role in supporting hematopoietic stem cells

in vitro (181-183), TMEM140 has since been

associated with various biological processes, including

tumorigenesis and viral infection (182). Guan et al (183) have highlighted the dual

functions of TMEM140 as both a prognostic biomarker and a potential

therapeutic target in cancer and its role in inhibiting herpes

simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) replication. TMEM140 has emerged as a key

player in various types of cancer, including gliomas and GC.

Gliomas are among the most common and aggressive primary brain

tumors, characterized by a poor prognosis and limited treatment

options. TMEM140 is overexpressed in gliomas compared with normal

brain tissues and its high expression is associated with a larger

tumor size, higher histologic grade and shorter OS (181). An In vitro study using

glioma cell lines have revealed that silencing TMEM140 inhibited

cell proliferation, migration and invasion, with concurrent arrest

in the G1 phase of the cell cycle and activation of apoptotic

pathways (181). It regulates

cell cycle progression by shortening the cell cycle and reducing

apoptosis, thereby promoting tumor cell proliferation.

Additionally, TMEM140 enhanced tumor cell adhesion and survival by

modulating the expression of adhesion and anti-apoptotic proteins

(181-183). In vivo silencing of

TMEM140 led to a marked reduction in tumor volume and weight

(183), highlighting its

pivotal role in tumor growth. These findings identify TMEM140 as a

novel prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for gliomas,

underscoring its potential for clinical application in glioma

treatment. Beyond gliomas, TMEM140 has been implicated in other

cancer types through its co-expression with long-chain

acyl-coenzyme A synthetase 5 and this was predictive of improved

prognosis in breast, ovarian and lung cancer (184). This suggests that TMEM140 may

carry out a context-dependent role in cancer progression,

potentially acting as a tumor suppressor in certain malignancies

(184). Furthermore, TMEM140

has been identified as a candidate gene in HTLV-1-infected cancer

cells, indicating its broader relevance in cancer biology (185).

TMEM140 is a multifunctional protein that is

involved in several processes in cancer biology, autoimmune

diseases and viral infections. In systemic sclerosis, the

involvement of TMEM140 in DNA methylation changes indicates a

potential key role in disease pathogenesis, particularly in

fibroblast function (186).

Additionally, its role in inhibiting HSV-1 replication highlights

its promise as an antiviral target. Given its diverse functions,

TMEM140 may serve as a compelling candidate for further

investigation, with implications for therapeutic strategies across

a variety of diseases.

TMEM158

TMEM158, located on chromosome 3p21.3, also known

as BBP, Ras-induced senescence 1 protein, p40BBP and HBB, was

initially recognized as an upregulated potential tumor suppressor

gene in the context of Ras V12 lentiviral infection-induced

senescence in fibroblasts (187). Li et al (188) have highlighted its key role in

the development of various types of cancer. Importantly, TMEM158 is

overexpressed in Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma), with somatic