The global cancer burden has reached alarming

proportions, with the International Agency for Research on Cancer

(IARC) reporting >20 million new cases and 9.7 million

fatalities in 2022, a figure projected to surge to 35 million by

2050, creating an urgent need for innovative therapies that balance

efficacy with safety (1). This

escalating crisis has renewed interest in Traditional Chinese

Medicine (TCM) as a source of complementary agents to counter the

limitations of conventional treatments, such as toxicity and

resistance (2,3), with Schisandra chinensis (Wu

Wei Zi) emerging as a pivotal candidate. Its berries, called 'five

flavors' (sour, sweet, bitter, pungent, and salty), are classified

in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020) as warm and sour-sweet

(5), targeting lung/heart/kidney

meridians for chronic cough and liver disorders (4-6).

Critically, modern research has validated its systemic

bioactivities: organ protection via Nrf2/NF-κB modulation to

alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation (7,8),

neuro-hepatic shielding through antifibrotic repair (9-11), and immune reprogramming via

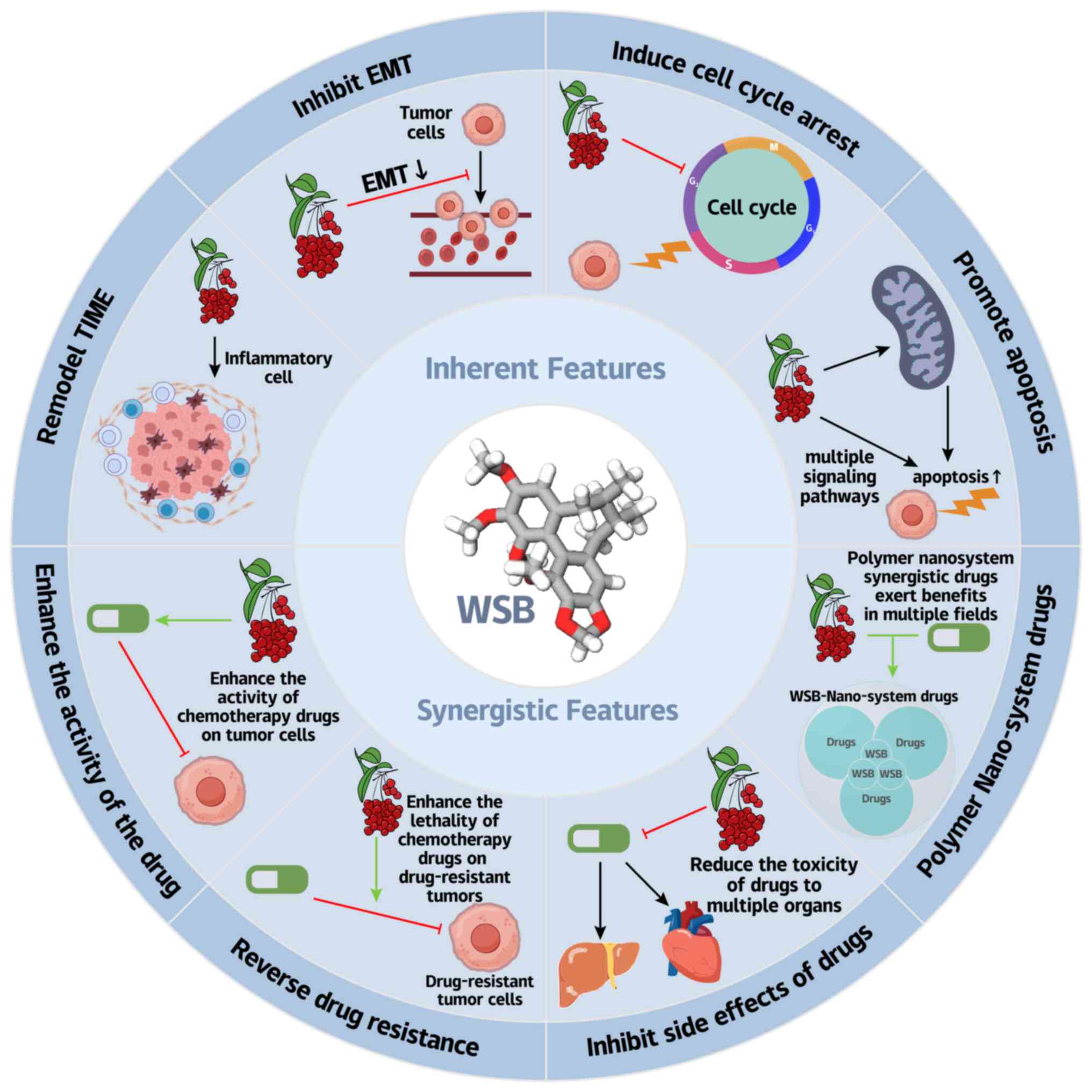

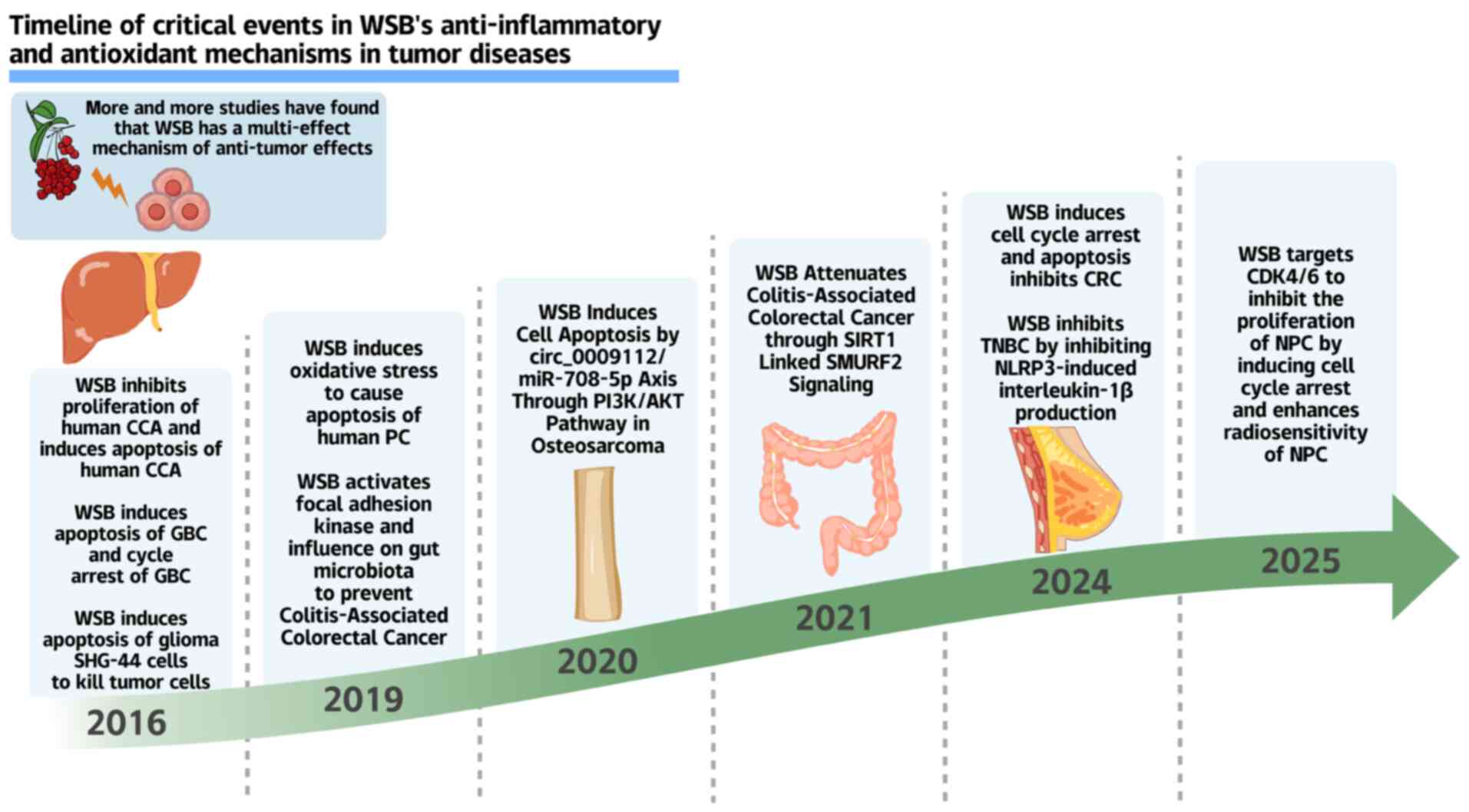

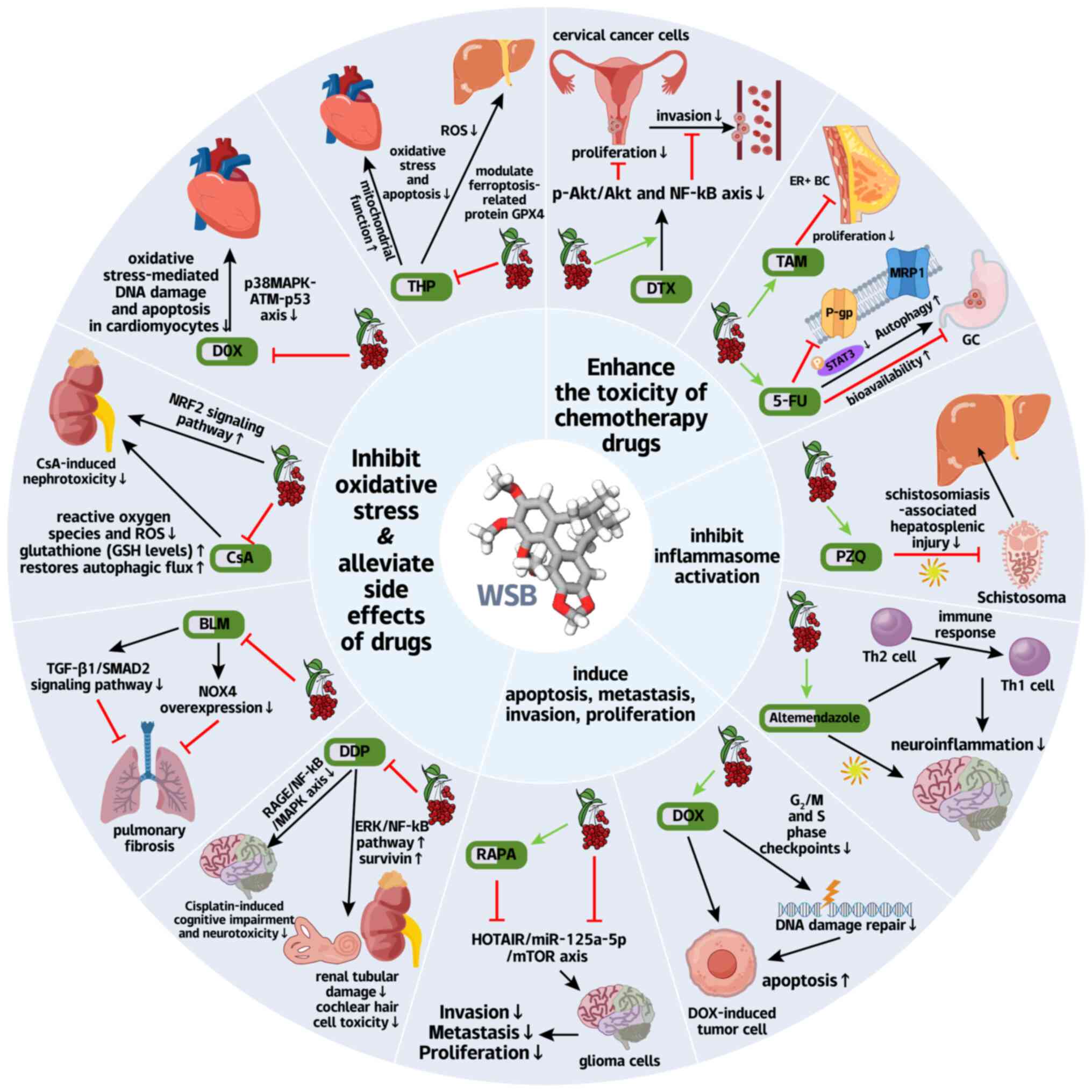

macrophage/Th1-Th2 regulation (12,13) (Fig. 1).

Among its bioactive lignans, Wuweizisu B

(Schisandrin B, WSB) stands out as the premier anticancer agent

(6,14-17) (Fig. 2), boasting exceptional

bioavailability and tissue distribution (14,18) to orchestrate pleiotropic effects

from hepatoprotection to proliferation control (19-22). Its structural analogs (such as

schisandrin A/C and gomisins) synergistically combat cancer through

direct tumor suppression (apoptosis/cell cycle arrest), metastasis

blockade, microenvironment remodeling (immune activation), and

chemosensitization (MDR reversal via STAT3/P-gp/survivin

modulation) (4,17,23-27). Notably, WSB's ability to reverse

MDR, a major driver of chemotherapy failure, positions it as a key

ally against refractory cancers (28-30).

The present review therefore deciphered WSB's

anticancer potential through molecular mechanisms, organ-specific

efficacy, and clinical translation strategies as a dual

chemosensitizer-cytoprotective agent, bridging traditional wisdom

with contemporary pharmacology to chart a roadmap for integrated

oncology (Figs. 3-6).

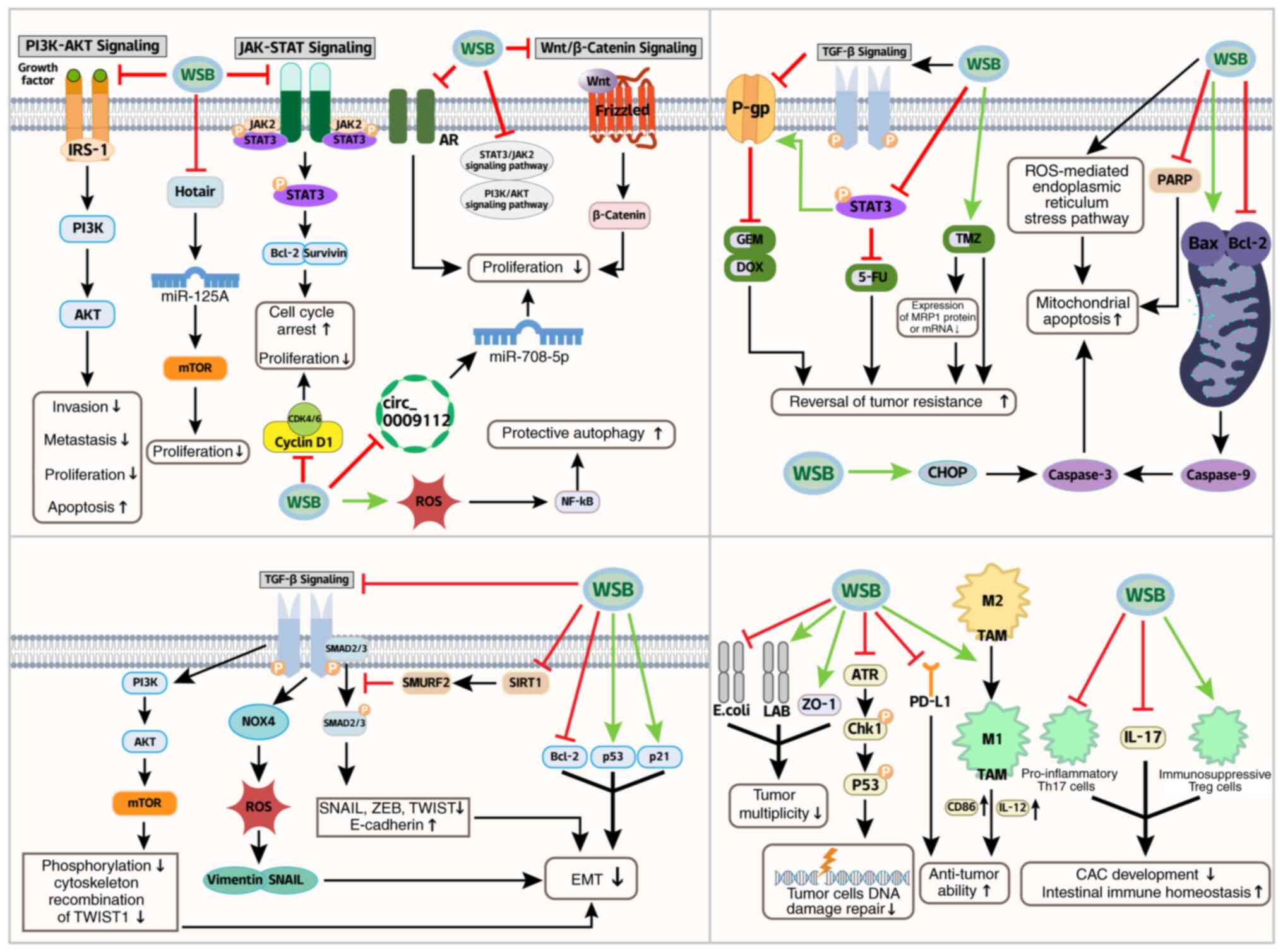

As a prototypical multitarget natural compound, WSB

exhibits remarkable therapeutic potential across a spectrum of

gastrointestinal malignancies through its unique ability to

simultaneously modulate oncogenic signaling networks, metabolic

reprogramming, and tumor microenvironment remodeling. This section

systematically elucidates the organ-specific anticancer mechanisms

of WSB along the digestive tract, supported by compelling

preclinical evidence highlighting it as a promising candidate for

integrative oncology approaches (Fig. 3).

GC remains a significant global health burden, with

the IARC reporting ~968,000 new cases and 660,000 deaths worldwide

in 2022, ranking fifth in incidence and mortality among all cancers

(1,31). Chemotherapy and immunotherapy,

have spurred interest in TCM as a complementary approach for GC

treatment (32). WSB exhibits

potent antitumor effects in GC. WSB exerts its antitumor effects

through a coordinated molecular cascade: by effectively inhibiting

STAT3 phosphorylation, WSB inactivates this oncogenic transcription

factor, thereby blocking downstream survival genes (Bcl-2 and

Survivin) and metastatic drivers (33) (Fig. 3; Table I). Crucially, suppression of

STAT3 expression directly represses Cyclin D1 transcription

(34) (Fig. 3), leading to significant

downregulation of the expression of Cyclin D1 mRNA, the core

regulator of the G1/S transition, which induces cell

cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase in SGC-7901

cells. Notably, the optimal inhibitory effect was observed at a

concentration of 50 mg/l after 48 h of treatment (35) (Fig. 3; Table I). However, this therapeutic

cascade is concentration dependent: while 50 mg/l optimally

balanced these effects, higher doses (100 mg/l) paradoxically

activated protective autophagy via reactive oxygen species

(ROS)/NF-κB feedback, potentially compromising treatment efficacy

(36) (Fig. 3).

Despite these advances, the precise molecular

mechanisms underlying the anti-GC effects of WSB remain unclear.

Furthermore, studies indicate that the effective in vitro

concentration of WSB (50 mg/l) far exceeds the achievable peak

plasma concentration in humans (2.1 μM) (37). Existing research is based solely

on cell and mouse experiments and lacks tumor microenvironment

simulation, which may lead to overestimation of clinical efficacy.

Future studies should focus on elucidating these pathways to

facilitate the clinical translation of WSB-based therapies.

CRC ranks as the third most prevalent malignancy

globally, with GLOBOCAN 2022 reporting 1.9 million new cases and

930,000 mortalities annually (38). Projections indicate that this

burden will increase to 3.2 million cases by 2040, underscoring the

urgent need for safer therapies. While current regimens combining

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy with surgery/radiotherapy

remain standard, ≥50% of patients experience grade 3-4 toxicity,

including myelosuppression, gastrointestinal injury, and

neurotoxicity (39,40). These limitations highlight the

imperative for novel agents such as WSB that synergize with

conventional therapies while mitigating adverse effects.

Critically, TGF-β drives metastatic plasticity by

dynamically regulating both EMT and its reverse process,

mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET). TGF-β induces EMT through

the activation of the suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic

(SMAD) and non-SMAD pathways, leading to the suppression of

epithelial genes (such as CDH1) and the upregulation of mesenchymal

markers (such as VIM and FN1), thereby enabling cancer cell

migration and invasion (45,48) (Fig. 3). Conversely, at metastatic

sites, reduced TGF-β signaling promotes MET through SMAD7-mediated

suppression of the EMT transcription factors SNAIL/ZEB and

reactivation of the miR-200 family, which collectively restore

epithelial phenotypes to facilitate metastatic colonization

(49,50) (Fig. 3). This bidirectional regulation

of cellular plasticity highlights the central role of TGF-β in

coordinating both the dissemination and secondary outgrowth of

metastatic cancer cells.

Similar to its mechanism in colorectal cancer, WSB

also exhibits inhibitory effects on TGF-β-induced EMT in lung

cancer (LC) and breast cancer (BC). In LC, the WSB downregulates

the expression of proteins such as TGF-β1 and Bcl-2 while

upregulating p53 and p21 expression (51) (Fig. 3; Table I). These regulatory effects

reduce the suppression of epithelial genes and the upregulation of

mesenchymal markers. In BC, WSB blocks TGF-β-promoted ROS

production and increases cell motility by inhibiting NADPH oxidase

4, thereby reducing the metastasis of BC cells (52) (Fig. 3). Collectively, these findings

underscore WSB's conserved capacity to target the TGF-β-mediated

EMT across diverse malignancies, with context-dependent molecular

nuances tailored to tissue-specific pathways. Such cross-organ

inhibitory activity reinforces the WSB as a promising candidate for

developing broad-spectrum antimetastatic therapeutics, in cancers

characterized by dysregulated TGF-β-EMT signaling axes.

In colitis-associated cancer models, WSB

demonstrates dual chemopreventive effects: FAK-dependent tight

junction stabilization (increased ZO-1 expression) and microbiota

remodeling (increased Lactobacillus abundance with reduced

Escherichia coli colonization), reducing tumor multiplicity

by 75% (53) (Fig. 3; Table I). Additionally, compared with

that in the general population, the incidence of colitis-associated

cancer (CAC) induced by ulcerative colitis (UC) is markedly greater

(54,55). Moreover, the pathogenesis of UC

is closely associated with environmental factors, genetic

predisposition, the gut microbiota, and immune dysregulation

(56,57). WSB markedly inhibits the

differentiation of the proinflammatory Th17 cells and IL-17

secretion while promoting the generation of immunosuppressive Treg

cells, thereby preventing CAC development and maintaining

intestinal immune homeostasis (21) (Fig. 3).

Building upon the multitarget mechanism of WSB in

coordinately regulating the microbiota-barrier-immunity axis,

through the FAK-dependent tight junction restoration and the

microbiota remodeling to suppress the carcinogenic microenvironment

coupled with immune reprogramming to block the inflammation-cancer

transition from UC to CRC, its integrated preventive and

therapeutic potential offers novel strategies for high-risk UC

patients. Although preclinical data are promising, clinical

translation of WSB still faces challenges in terms of

pharmacokinetic optimization and validation of target biomarkers

such as SIRT1/SMURF2. Current exploratory trials are focusing on

combination therapies of WSB with immune checkpoint inhibitors (TCM

+ immunotherapy), which may overcome chemoresistance through

synergistic effects and unlock new therapeutic dimensions for

high-risk CAC patients. Furthermore, integration with targeted

delivery systems could enhance its translational value, enabling

the transition from the multi-mechanism intervention to precision

medicine (58).

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has emerged

as a significant global health challenge, affecting 25-30% of

adults worldwide; the progressive of NAFLD, nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis, occurs in 10-20% of cases and often progresses to

cirrhosis and HCC (59-61). In the absence of FDA-approved

therapies for NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, WSB, a bioactive

lignan derived from Schisandra chinensis, has shown promise

as a multi-target therapeutic agent capable of modulating metabolic

homeostasis, inflammatory responses, and fibrotic processes.

Mechanistically, WSB ameliorates hepatic steatosis by activating

the AMPK/mechanistic target of mTOR pathway, which enhances

autophagic flux, promotes fatty acid oxidation, and suppresses de

novo lipogenesis (62-64) (Fig. 4).

Notably, hepatic steatosis is often the initial step

in NAFLD progression, and unresolved steatosis can drive the

development of liver fibrosis, a critical pathological feature that

accelerates disease severity. Liver fibrosis is primarily driven by

the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), and WSB targets

these activated HSCs through multiple coordinated pathways to exert

anti-fibrotic effects. It induces mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis

in HSCs by modulating the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and activating caspase-3,

while simultaneously inhibiting TGF-β1-induced HSC activation

(65) (Fig. 4). WSB promotes ferroptosis in

HSCs via NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy, suggesting a novel approach

for fibrosis treatment (66)

(Fig. 4). Cannabinoid receptor 2

has been identified as a key target in liver fibrosis, and WSB

alleviates CCl4-induced fibrosis by inhibiting the NF-κB

and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways

in Kupffer cells, thereby reducing inflammatory cytokine release

(67-69) (Fig. 4). Further studies revealed that

WSB directly targets miR-101-5p, downregulating the activity of the

TGF-β signaling pathway to inhibit fibrosis (70-72) (Fig. 4).

As well as targeting HSCs and Kupffer cells, WSB

modulates macrophage polarization to further alleviate liver

inflammation and fibrosis, although this regulation is context- and

dose-dependent, reflecting its adaptability to diverse

microenvironments. WSB inhibits peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor γ (PPARγ)-mediated NF-κB activation to suppress M1

macrophage markers (CD86/TNF-α) in liver fibrosis models (73) (Fig. 4), under oxidative stress, it

promotes M2 polarization via the Nrf2 pathway (74) (Fig. 4), while in tumor

microenvironments, high-dose WSB may increase immunosuppression

through STAT3 (75) (Fig. 4). These seemingly contradictory

results probably reflect the WSB's multitarget regulatory effects

on macrophage plasticity rather than genuine mechanistic

conflicts.

Moreover, the therapeutic potential of WSB in liver

disease extends to regenerative strategies: It enhances the

differentiation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells into

functional hepatocyte-like cells by activating the JAK2/STAT3

pathway, which could complement its antifibrotic effects by

promoting liver repair (76)

(Fig. 4). However, compared with

those of other differentiation methods, the efficiency and

functional maturity of WSB-induced HLCs require thorough

assessment. More importantly, the direct application of WSB in

vivo to modulate the fate of the endogenous or the transplanted

MSCs requires a careful evaluation of pharmacokinetics, targeted

delivery, potential off-target effects on other cell types, and

long-term safety.

As NAFLD progresses to advanced stages, cirrhosis

can predispose patients to HCC, a leading cause of cancer-related

mortality globally, with limited therapeutic options for

advanced-stage patients (77).

WSB demonstrates significant anti-HCC activity through mechanisms

that align with its earlier roles in metabolic regulation and

inflammation while also targeting tumor-specific pathways. It

synergizes with NK cells to induce pyroptosis in HepG2 cells via

perforin-granzyme B-caspase 3-GSDME, highlighting its role in

immune microenvironment modulation (24) (Fig. 4; Table I). The Ras homolog family member

α/ρ-associated protein kinase 1 (RhoA/ROCK1) pathway, which is

involved in HCC cell proliferation and metastasis, is effectively

suppressed by WSB, leading to inhibited migration and invasion of

Huh-7 cells both in vitro and in vivo (78-80) (Fig. 4; Table I). These findings underscore the

potential of WSB as a multifaceted therapeutic agent for treating

HCC that targets both tumor cells and the immune system. However,

the narrow therapeutic window (IC50 ~266.4 μM in

HepG2 cells vs. significant toxicity in normal cells at >200

μM) poses a major translational challenge (81). In addition, achieving effective

antitumor concentrations in vivo without unacceptable

toxicity may require advanced delivery strategies or synergistic

combinations with standard therapies.

In summary, while WSB shows preclinical promise for

NAFLD, fibrosis, and HCC via multiple target mechanisms, its

translational challenges are significant. The narrow therapeutic

window and context-dependent immune modulation complicate clinical

application. Key gaps include defining the in vivo

therapeutic window, developing toxicity mitigation strategies (such

as targeted delivery), and obtaining human pharmacokinetic/safety

data, necessitating rigorous clinical trials.

CCA, a highly aggressive malignancy originating from

the biliary epithelium with frequent extension to the ampulla of

Vater (82), represents the

second most common primary liver cancer and remains notoriously

resistant to conventional chemotherapy, contributing to its dismal

5-year survival rate, which is <20% for advanced cases (83). Preclinical studies have

demonstrated that WSB exerts multimodal anti-CCA activity through

i) potent induction of mitochondrial apoptosis, as evidenced by an

increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and significant activation of caspase-3/9

and PARP cleavage and ii) effective G0/G1

cell cycle arrest via downregulation of Cyclin D1 and CDK4/6

inhibition at clinically achievable concentrations (84) (Fig. 3; Table I). These findings demonstrate the

potential of WSB as a promising therapeutic candidate, particularly

given its dual-targeting ability against both proliferative

signaling and apoptotic resistance pathways, two hallmark features

of CCA pathogenesis that contribute to clinical

chemoresistance.

GBC, one of the most aggressive malignancies of the

biliary system, is associated with a dismal clinical prognosis.

Studies by Pehlivanoglu et al (85) have indicated that only 5% of

invasive GBC patients are diagnosed at the early T1b stage, with a

5-year survival rate of up to 92%; however, most patients are

diagnosed at the locally advanced or metastatic stage, resulting in

an overall 5-year survival rate of <10%. Furthermore, Brindley

et al (86) reported that

the objective response rate to current chemotherapy regimens (such

as gemcitabine plus cisplatin) for biliary tract cancers, including

GBC, is only ~20%, highlighting the urgency to explore novel

therapeutic agents (86)

(Table I). As an active

component derived from the traditional Chinese herb, WSB has

recently demonstrated multitargeted antitumor potential in GBC

treatment, with its mechanisms of action supported by multiple

studies (84,87,88). In terms of apoptosis induction,

Yang et al (84) reported

that WSB can upregulate the proapoptotic protein Bax and

downregulate the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, disrupt mitochondrial

membrane potential, promote the release of cytochrome c,

activate the caspase-9/3 cascade, and cleave PARP, thereby inducing

apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells (Fig. 3; Table I). Similarly, studies on BC have

confirmed that WSB can enhance mitochondrial apoptotic signaling

through a ROS-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway (such

as upregulating CHOP and GPR78), suggesting a common mechanism of

apoptotic regulation across different tumor types (52) (Fig. 3). With respect to cell cycle

regulation, Hui et al (87) reported that the overexpression of

Cyclin D1 in GBC is closely associated with poor prognosis. WSB can

markedly inhibit the activity of the Cyclin D1/CDK4/6 complex while

upregulating the expression of the CDK inhibitor p21, thereby

blocking the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and

causing cell arrest in the G0/G1 phase

(Fig. 3; Table I). This mechanism is highly

consistent with the action pathway of CDK4/6 inhibitors observed in

BC, further validating its rationality (88) (Table I).

Notably, the antitumor potential of WSB is not

limited to GBC. Studies on its mechanisms in various other tumors,

such as BC, have shown commonalities in regulating apoptosis, the

cell cycle, and metastasis, providing a basis for its potential as

a broad-spectrum antitumor candidate. In terms of clinical

translation, combined with the current application of targeted

drugs such as FGFR and IDH1 inhibitors in biliary tract cancers

(89), WSB is expected to be

used in combination with existing targeted immunotherapies, further

enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of GBC through synergistic

effects on multiple pathways (90,91).

NPC represents a distinct epithelial malignancy with

a unique geographical distribution and strong etiological

association with EBV infection (92). While radiotherapy demonstrates

excellent efficacy in early-stage disease (achieving 90% cure

rates), the majority of patients present with locally advanced or

metastatic disease at diagnosis because of the tumor's insidious

growth pattern and early metastatic propensity (93). This clinical reality highlights

the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies that can overcome

the limitations of current treatments, which are often associated

with significant toxicity and suboptimal outcomes in advanced cases

(94).

The mechanism of action of WSB in NPC is reflected

mainly in two aspects: First, WSB inhibits cell proliferation by

targeting CDK4/6. It can directly bind to CDK4/6 and downregulate

the expression of CDK4/6 in NPC cells (such as HONE-1 and CNE-1

cells) and although it upregulates Cyclin D1, it inhibits the

formation of complexes between Cyclin D1 and CDK4/6, thereby

hindering Rb phosphorylation and inducing cell cycle arrest at the

G1 phase. Notably, it has no significant effect on

normal nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Second, it enhances

radiosensitivity by promoting radiotherapy-induced DNA

double-strand breaks [at 4 h after radiotherapy, the number of

phosphorylated histone H2A variant X (γ-H2AX) foci in the

combination group was markedly greater than that in the

radiotherapy alone group: for example, 21.4 vs. 13.2 foci/nucleus

in HONE-1 cells] and delaying damage repair (at 12 h after

radiotherapy, the number of γ-H2AX foci was still greater: For

example, 7.6 vs. 3.9 foci/nucleus in HONE-1 cells) (95) (Fig. 3; Table I). In addition, WSB can induce

NPC cells to arrest at the G1 phase, which is more

sensitive to radiotherapy, and prevent them from entering the S

phase (radiation-resistant phase), thereby enhancing the killing

effect of radiotherapy on tumor cells.

Notably, this mechanism of action of WSB is highly

consistent with its performance in other malignant tumors. For

instance, in LC studies, WSB also blocks the cell cycle at the

G0/G1 phase by downregulating the expression

of CDK4/6 and Cyclin D1 (96)

(Fig. 3; Table I). Similarly, in gallbladder

cancer (GBC), a correlation between CDK4 downregulation and

G1 phase arrest has been observed, suggesting that its

conservation of cell cycle regulation may make it a potential

therapeutic agent across tumor types (97). More importantly, compared with

clinically used CDK4/6 inhibitors such as palbociclib, WSB is

safer. Although palbociclib can enhance the radiosensitivity of NPC

by inhibiting DNA damage repair, it is often accompanied by adverse

reactions such as neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy (98). By contrast, WSB at a

concentration of 40 μM exerts no significant effect on the

proliferation or cell cycle of normal nasopharyngeal epithelial

cells (NP69) and has even been confirmed to exert protective

effects on tissues such as the liver and myocardium in animal

models, which supports its low toxicity advantage in clinical

applications (65,99,100).

From the perspective of the molecular mechanisms of

radioresistance, the radioresistance of NPC cells is often

associated with efficient DNA double-strand break repair capacity

(101) (Table I). The repair-inhibiting effect

of WSB, as reflected by the delay in γ-H2AX foci, may be related to

the regulation of the ATM and ATR kinases pathway (102) (Table I). Existing studies have shown

that WSB can inhibit ATR protein kinase activity to interfere with

the DNA damage response, and this mechanism may further explain its

radiosensitizing effect in NPC. In addition, the synergistic effect

of WSB and radiotherapy in 3D organoid models (markedly reduced

activity of HONE-1 organoids) is more consistent with the in

vivo tumor microenvironment, verifying its effectiveness under

complex physiological conditions and providing key evidence for

translation from basic research to clinical practice. These

characteristics make WSB not only promising for improving the

radiotherapy effect of locally advanced NPC, but also potentially

applicable in combination with existing targeted drugs (such as

EBV-related signaling inhibitors) to construct multitarget

therapeutic regimens, thereby offering new ideas for overcoming the

therapeutic bottlenecks of NPC.

LC is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy

globally, with recent epidemiological data revealing ~2.5 million

new cases each year, 12.4% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide and

1.8 million annual fatalities, accounting for 18.7% of total cancer

mortality (1). While the advent

of molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapies has

revolutionized treatment paradigms, the prognosis for advanced

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients remains poor, with

5-year survival rates persistently <20% (103). This therapeutic impasse stems

primarily from two key challenges: The development of drug

resistance mechanisms and dose-limiting treatment toxicity.

At the molecular level, the WSB strongly inhibits

the ATR protein kinase activity, effectively compromising the

G2/M checkpoint integrity following DNA damage through

the suppression of critical phosphorylation events in p53 and

checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) (102) (Fig. 3; Table I). This distinctive mechanism of

action potentiates the efficacy of conventional DNA-damaging

anticancer therapies, presenting a novel strategic approach for

targeting ATR-dependent DNA repair mechanisms in LC treatment.

In the A549 non-small cell LC cell line, WSB

demonstrates dual cell cycle regulatory effects, inducing

G0/G1 phase arrest while simultaneously

promoting caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death. Notably, it

suppresses TGF-β1-induced EMT in A549 cells through epigenetic

silencing of ZEB1 and restoration of E-cadherin expression

(104), a key mechanism given

that EMT drives LC metastasis by disrupting epithelial adhesion via

downregulated the E-cadherin and upregulated mesenchymal markers

(Fig. 3), enabling invasive

potential, thereby equipping WSB with the capacity to inhibit

metastatic progression through suppression of the EMT pathway.

These findings collectively position WSB as a

multifaceted therapeutic candidate capable of targeting both

primary tumor growth and metastatic dissemination. The anti-cancer

mechanisms of WSB require further elucidation, particularly

regarding its dose-response relationship/optimal therapeutic

window. Systematic pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies are

needed to establish clinically effective and safe dosing

regimens.

WSB demonstrates significant antitumor activity in

PC through a multipronged mechanism that addresses both disease

progression and therapeutic resistance (15,105,106). In the context of standard

androgen deprivation therapies, which aim to block AR signaling,

which is crucial for PC cell growth (107), WSB effectively suppresses AR

signaling (108) (Fig. 3; Table I). This not only complements the

action of existing therapies but also enhances sensitivity to them,

potentially overcoming the resistance that often develops over

time. For instance, drugs such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone

agonists/antagonists and anti-androgen drugs target AR signaling,

and the modulation of this pathway by WSB could enhance the

efficacy of these drugs.

Of particular clinical relevance, WSB maintains its

efficacy against chemotherapy-resistant phenotypes. In

radiotherapy, which aims to kill cancer cells by damaging their

DNA, the ability of WSB to modulate cellular processes may enhance

the radiosensitivity of cancer cells (95) (Table I). Overall, these findings

underscore the promise of WSB as a multitarget therapeutic agent

for PC management, with potential applications in combination with

existing endocrine, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy approaches.

Gliomas, which originate from brain glial cells,

represent the most prevalent primary intracranial tumors in adults

(40-60% of central nervous system tumors) (112). WSB exerts potent antitumor

effects on glioblastoma through the induction of mitochondrial

apoptosis (via Bax/Bcl-2 modulation and caspase-3 cleavage) and

G0/G1 cell cycle arrest (through

CDK4/6-Cyclin D1 suppression) in SHG-44 and U87MG cells (113,114) (Fig. 3; Table I). RNA sequencing analyses

reveals that WSB inhibits the HOTAIR/miR-125a/mTOR pathway,

reducing glioma cell migration by 55-70% (115) (Fig. 3).

Synergy with standard therapies enhances efficacy:

Temozolomide combination therapy overcomes resistance by

suppressing O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity and

blocking the repair of O6-methylguanine lesions. This leads to

unrepaired DNA damage, persistent double-strand breaks, and

enhanced apoptotic signaling through DNA damage response pathway

activation (116,117) (Fig. 3; Table I). Similarly, rapamycin

synergizes with WSB through dual epigenetic and mTOR-targeted

inhibition, WSB indirectly suppresses mTOR expression via

downregulation of HOTAIR expression and upregulation of miR-125a-5p

expression, whereas rapamycin directly inhibits mTOR activity.

Preclinically, WSB monotherapy achieves 68% tumor growth

inhibition, which increases to 85% when WSB is combined with

rapamycin (115,118) (Figs. 3 and 5; Table

I).

These findings position WSB as a multifaceted

therapeutic agent against glioblastoma, leveraging intrinsic

pro-apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory properties while

synergizing with conventional and targeted (rapamycin) therapies to

overcome key resistance mechanisms. Future clinical translation

should prioritize optimizing delivery strategies to penetrate the

blood-brain barrier and validating predictive biomarkers (such as

HOTAIR/MGMT expression) for patient stratification in combination

regimens.

In BC, WSB overcomes chemoresistance through

multimodal targeting: i) Chemosensitization: STAT3 is often

overactivated, which contributes to the upregulation of P-gp, a

major efflux pump responsible for pumping chemotherapeutic drugs

out of cancer cells, leading to drug resistance (119,120). WSB acts by inhibiting STAT3

signaling. As reported in studies on other cancer types, such as

neuroblastoma, the activation of STAT3 can protect cells from

apoptosis and is associated with drug resistance (121) (Fig. 3). By blocking the STAT3

phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, WSB effectively

downregulates the expression of P-gp in MCF-7/ADR cells. This

downregulation reverses the efflux of doxorubicin (DOX), thereby

increasing the intracellular concentration of DOX. As a result, the

IC50 of DOX in MCF-7/ADR cells is markedly reduced from

12.3 to 2.8 μM, enhancing the sensitivity of cancer cells to

chemotherapeutic agents (122)

(Fig. 3; Table I); ii) by blocking the

TGF-β/NOX4/ROS signaling, WSB inhibits vimentin and Snail

expression, reducing metastatic potential in 4T1-Luc models (lung

nodules ↓65%) (52,104,123) (Fig. 3); and iii) WSB polarizes

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) toward the antitumor M1

phenotype, increasing the expression of the M1 marker CD86 and

upregulating M1-characteristic IL-12. In triple-negative breast

cancer (TNBC) cells, WSB suppresses programmed cell death ligand 1

(PD-L1) and high levels of PD-L1 bind to T-cell PD-1, inhibiting

T-cell activation and cytotoxicity. By reducing PD-L1 expression,

WSB enhances T-cell recognition and the killing of cancer cells,

strengthening antitumor immune responses in the BC microenvironment

(23,124) (Fig. 3; Table I). Preclinical studies have

demonstrated that WSB monotherapy achieves 58% tumor growth

inhibition in estrogen receptor (ER) + BC xenografts, synergizing

with tamoxifen to achieve 82% suppression (Fig. 5).

Building on its dual anti-inflammatory and

chemosensitizing actions, WSB warrants clinical prioritization in

endometritis and TNBC, conditions with unmet therapeutic needs.

Synergistic strategies (such as PD-1 inhibition) could amplify

STAT3/PD-L1 blockade, while nanotechnology may overcome

bioavailability barriers. The mechanistic exploration of

AR-mitochondrial crosstalk in orchitis could redefine the

management of male infertility. Cross-disciplinary innovation will

catalyze WSB's transition to transformative therapies.

Osteosarcoma, the most prevalent malignant bone

tumor in adolescents, has a poor prognosis, especially in

metastatic cases (125-127) (Fig. 3). WSB inhibits osteosarcoma

progression by targeting circ_0009112/miR-708-5p and by suppressing

migration and invasion via the PI3K/AKT pathway while inducing

apoptosis (128,129) (Fig. 3; Table I). It also blocks Wnt/β-catenin

and PI3K/AKT signaling, arresting the cell cycle at the

G1 phase, inhibiting proliferation, and reducing lung

metastasis in preclinical models without significant toxicity

(63). These findings highlight

WSB's potential as a therapeutic candidate for osteosarcoma.

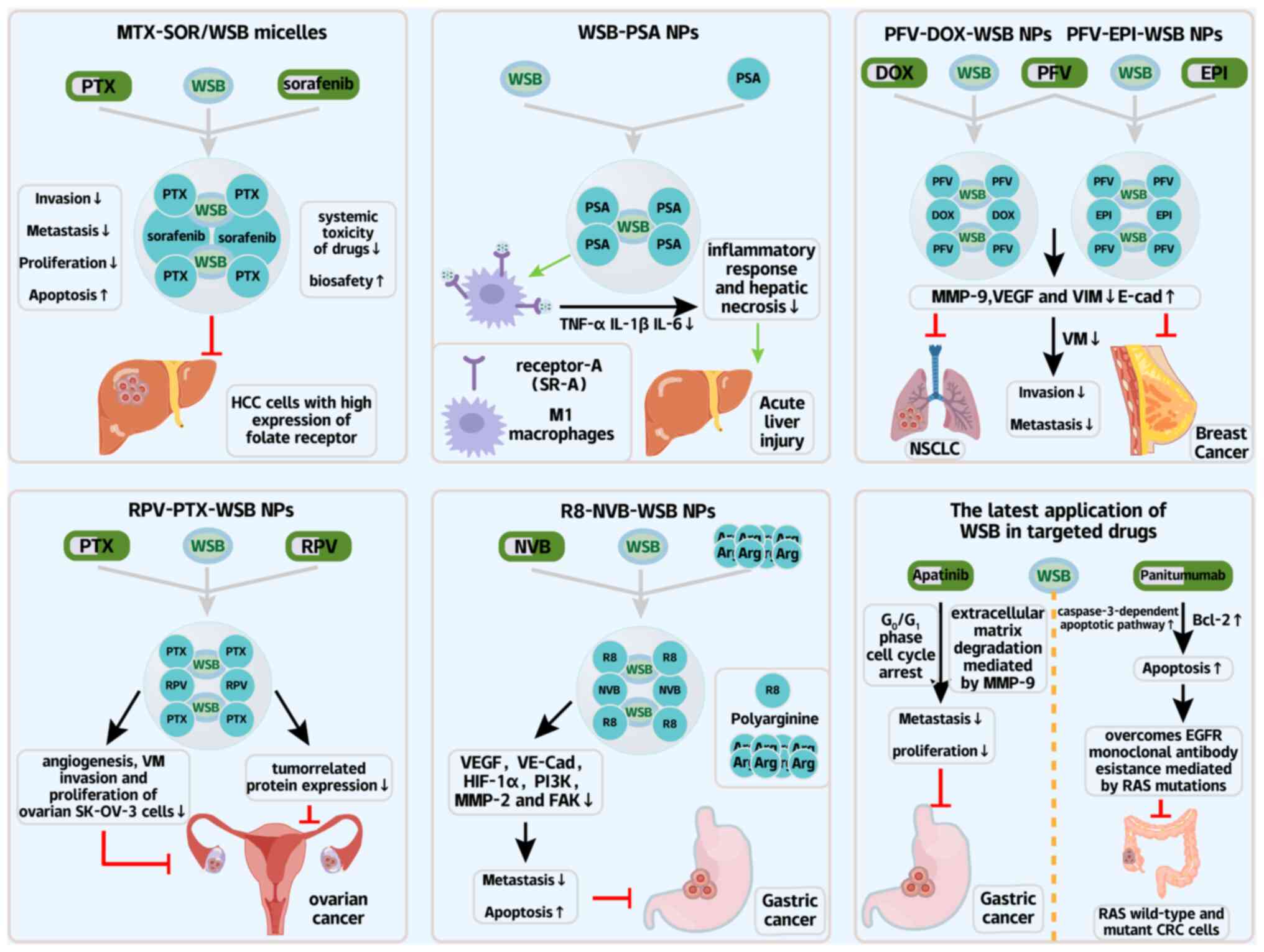

As a pleiotropic bioactive compound, WSB enhances

chemotherapy efficacy while mitigating adverse effects through

multitarget modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell

death pathways. Its integration with advanced drug delivery systems

further improves pharmacokinetics, offering a paradigm for

low-toxicity precision oncology (Fig. 5).

Notably, the capacity of WSB to modulate MDR,

enhance chemosensitivity, particularly well-characterized in BC,

extends to a coordinated protective role against

chemotherapy-induced organ damage, creating a synergistic

therapeutic profile. In BC, WSB reverses DOX resistance by

downregulating the P-gp via STAT3 inhibition (122) (Fig. 5; Table II), while simultaneously

counteracting DOX-induced cardiotoxicity through p38MAPK-ATM-p53

axis regulation (130,131) (Fig. 5; Table II), thus amplifying anti-tumor

efficacy while mitigating cardiac injury. This dual action aligns

with its ability to sensitize ER+ BC to tamoxifen (achieving 82%

tumor suppression in combination) (132) (Fig. 5), demonstrating that WSB's

MDR-reversing effects are paired with tissue-specific toxicity

attenuation.

Furthermore, in cisplatin-based regimens, where

drug resistance and systemic toxicity often limit efficacy, WSB not

only enhances chemosensitivity by overcoming efflux mechanisms but

also protects normal tissues: it upregulates survivin via ERK/NF-κB

to shield renal tubules and cochlear hair cells (133,134) (Table II) and inhibits the

RAGE/NF-κB/MAPK pathways to prevent neurotoxicity (135) (Fig. 5; Table II). Similarly, for thiotepa, the

pro-oxidant activity of WSB in tumor cells (driving apoptosis) is

balanced by its suppression of excessive ROS in normal tissues,

preserving hepatic and cardiac function via GPX4-mediated

ferroptosis inhibition (136-138) (Fig. 5; Table II).

Beyond specific chemotherapeutics, WSB synergizes

with supportive agents to mitigate broader complications: In

combination with glycyrrhizic acid, it suppresses TGF-β1/SMAD2

signaling and NOX4 overexpression in bleomycin-induced pulmonary

fibrosis (139) (Fig. 5), a common side effect of

alkylating agents; in cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxicity, it

activates Nrf2 to reduce ROS, elevate glutathione, and restore

autophagy (140) (Fig. 5), thus protecting renal function

during immunosuppressive chemotherapy regimens; and in

schistosomiasis, it enhances praziquantel efficacy while

alleviating hepatosplenic injury (141,142) (Fig. 5), a model for reducing parasitic

coinfection complications during chemotherapy.

Collectively, these findings underscore the unique

therapeutic duality of WSB in cancer chemotherapy: It not only

enhances antitumor efficacy by reversing MDR and sensitizing

malignancies (as exemplified in BC) but also safeguards normal

tissues through targeted mechanisms, mitigating the systemic

toxicity that often limits treatment tolerance. This multifaceted

profile positions WSB as a promising adjuvant in chemotherapeutic

regimens, addressing the longstanding challenge of balancing

efficacy and safety across diverse cancer types and treatment

modalities.

WSB potentiates chemotherapy through synergistic

pathway inhibition: When combined with docetaxel (DTX), WSB

downregulates phosphorylated (p-)AKT/AKT and NF-κB expression,

ultimately inhibiting cervical cancer proliferation and invasion

(143) (Fig. 5; Table II). In GC, WSB and apatinib

induce G0/G1 arrest and suppress

MMP-9-mediated metastasis (144,145) (Fig. 5; Table II). With the DOX, WSB disrupts

DNA repair by abrogating G2/M checkpoints and amplifying

apoptosis (146,147) (Table II). Moreover, Additional studies

have demonstrated that WSB can also increase the sensitivity of

glioblastoma cells (GBM U87 and A172) to the antitumor drug

temozolomide by downregulating the expression of MRP1 protein or

mRNA (116,148) (Fig. 3; Table II).

However, when WSB is co-administered with P-gp

substrate chemotherapeutic agents such as paclitaxel and

doxorubicin, it promotes the drug efflux, thereby reducing

intracellular drug accumulation in tumor cells (81,149) (Figs. 3 and 5; Table

II). Additionally, WSB downregulates organic anion transporting

polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) expression, which may impair the hepatic

uptake and subsequent activation metabolism of OATP-dependent drugs

such as irinotecan (150).

Furthermore, WSB exhibits complex pharmacokinetic interactions with

FK506; by competing for CYP3A-mediated metabolism, WSB accelerates

its own clearance while simultaneously inhibiting FK506 metabolism

(149) (Table II). These findings necessitate

the preclinical-to-clinical translation via the pharmacogenomic

screening: tumors with low P-gp/MRP1 and high OATP1B1 could

prioritize WSB combinations (such as DTX/WSB in cervical cancer)

while avoiding coadministration with P-gp substrates in

ABCB1-overexpressing tumors.

In summary, WSB acts as a double-edged sword in

combination chemotherapy: On one hand, it enhances the antitumor

efficacy of drugs such as docetaxel and apatinib by inhibiting key

signaling pathways (p-AKT/NF-κB) and disrupting DNA repair

mechanisms. On the other hand, the WSB-induced upregulation of

P-gp/MRP efflux pumps and suppression of OATP1B1 may antagonize the

therapeutic effects of paclitaxel, doxorubicin, and irinotecan.

Additionally, it engages in complex pharmacokinetic competition

with CYP3A substrate drugs (such as tacrolimus). Therefore,

clinical combination strategies must be precisely designed on the

basis of drug transport and metabolic profiles to mitigate

interaction risks and maximize synergistic benefits.

MDR, driven by drug efflux, cancer stem cells and

the tumor microenvironment (TME), remains a critical clinical

hurdle (151).

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that WSB

effectively overcomes RAS-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in

colorectal cancer (152)

(Fig. 6; Tables I and II). Resistance to EGFR-targeted

therapy in colorectal cancer primarily arises from tumor-intrinsic

and microenvironment-driven adaptive mechanisms: RAS/RAF mutations

(such as KRAS in 40% and BRAF V600E in 8-10% of cases) lead to

constitutive activation of downstream signaling, while bypass

pathways such as the ERBB2/MET/IGF-1R amplification or

overexpression maintain survival signals through feedback loops

(153-156). Additionally, metabolic

reprogramming (enhanced glycolysis and dysregulated lipid

synthesis) and tumor microenvironment factors (such as HGF/TGF-β

secretion by cancer-associated fibroblasts) further contribute to

drug resistance (157-159). To counteract these resistance

mechanisms, WSB synergizes with panitumumab by activating

caspase-3-dependent apoptosis and suppressing Bcl-2 expression,

thereby reversing drug resistance. This mechanism could translate

to clinical trials testing WSB + panitumumab in RAS-mutant CRC,

with Bcl-2 as a predictive biomarker (Fig. 6).

In combination with 5-FU, WSB downregulates P-gp

and MRP1, reverses MDR, and triggers autophagic death via STAT3

inhibition (33,160) (Figs. 3 and 5; Table

II). This mechanism is supported by extensive evidence that ABC

transporters (such as P-gp/ABCB1 and MRP1/ABCC1) mediate drug

efflux in CRC (161-164), and TCM compounds (such as

evodiamine and neferine) restore chemosensitivity by suppressing

these transporters (165,166). Such data support the potential

of WSB as a chemosensitizer in neoadjuvant settings, where reducing

the ABC transporter activity could increase 5-FU response

rates.

These findings confirm the potential of WSB as an

ideal chemosensitizer and provide a new strategy for the

comprehensive treatment of colorectal cancer.

WSB has been established as a promising and

clinically feasible anticancer agent (167). The core advantages of these

systems include the following: i) Passive tumor targeting

leveraging the enhanced permeability and retention effect (168); ii) enhanced active targeting

via ligand modification (169);

and iii) precise drug release enabled by the design of

pH/enzyme-sensitive carriers (170). Clinically, this is evidenced by

successful nanoscale antitumor formulations, such as the polymeric

micelle Genexol®-PM (loaded with paclitaxel), approved

in South Korea for the treatment of metastatic BC and NSCLC.

Compared with conventional paclitaxel, Genexol®-PM

markedly improved the objective response rate (ORR: 56 vs. 27%) and

reduced the incidence of neutropenia (171) (Fig. 6). Similarly, the liposomal

formulation Lipusu® (paclitaxel for injection) is

approved in China for the treatment of ovarian cancer and BC. Its

combination regimen with cisplatin effectively treats inoperable

NSCLC patients (172) (Fig. 6).

Stimulus-responsive nanotechnology have yielded the

pH-sensitive formulations in which methotrexate-modified

sorafenib/WSB micelles (methotrexate-SOR/WSB) demonstrate

remarkable tumor specificity, dissociating in the acidic tumor

microenvironment to simultaneously inhibit HCC progression and

reduce systemic toxicity (173)

(Fig. 6; Table II). With the respect to

inflammatory modulation, albumin-based nanocarriers engineered with

palmitic acid modifications (PSA systems) achieve targeted WSB

delivery to M1 macrophages, effectively suppressing NF-κB-mediated

inflammation in liver injury models while improving survival by 50%

(75 vs. 25% in controls) (174)

(Fig. 6; Table II).

Combinatorial approaches use polymeric nanosystems

that coencapsulate the WSB with doxorubicin. These factors leverage

the pH-dependent release kinetics to enhance mitochondrial

targeting in BC stem cells, demonstrating the dual benefits of

overcoming chemoresistance while preserving cardiac function

(175,176) (Fig. 6; Table II). The field has further

advanced through peptide-directed delivery platforms, including the

PFV-modified liposomes that exploit tumor-specific integrin αvβ3

overexpression to disrupt metastatic vasculogenic mimicry networks

(177) (Fig. 6; Table II), and RPV-conjugated systems

that the achieve tumor penetration while suppressing the

angiogenesis through VE-cadherin/MMP-9 regulation (178,179) (Fig. 6). Particularly innovative are

charge-mediated R8-modified vinorelbine/WSB liposomes that

concurrently inhibit EMT and prevent the treatment-limiting

myelosuppression (180,181) (Fig. 6; Table II).

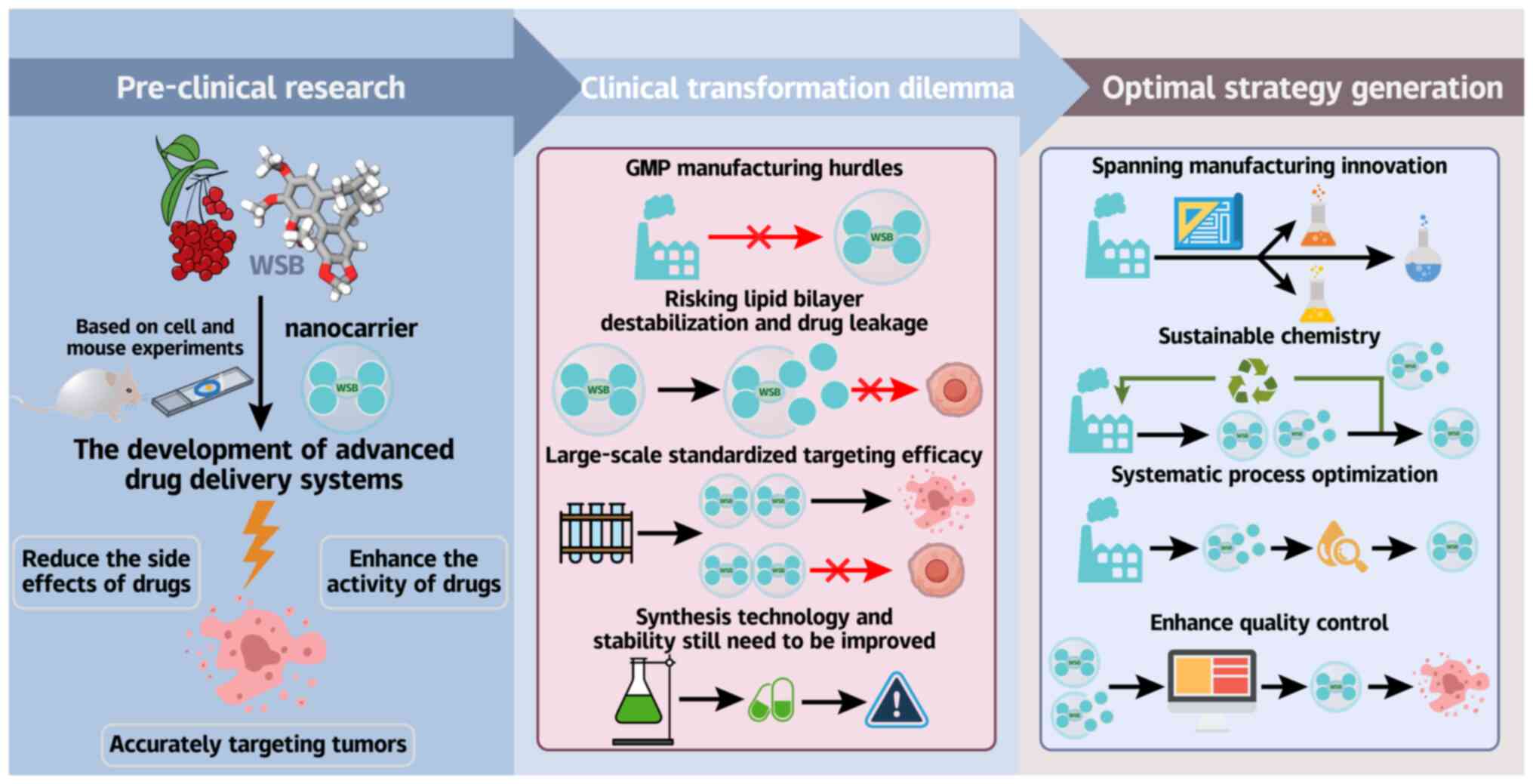

Despite these compelling preclinical results,

clinical translation faces the significant hurdles associated with

Good Manufacturing Practice manufacturing. For PFV-liposomes,

extrusion-based preparation results in shear sensitivity during

scale-up, risking lipid bilayer destabilization and drug leakage

(177). The PSA platform

requires strict control of palmitic acid conjugation stoichiometry

to maintain targeting efficacy, a critical quality attribute that

is challenging to standardize in large batches (182,183). Organic solvent residues

necessitate complex purification (174), increasing production costs.

Analytical complexity is heightened in codelivery systems, where

simultaneous quantification of hydrophilic/hydrophobic drugs

requires specialized methods (177).

To bridge this translational gap, integrated

solutions are essential. These include the adoption of continuous

manufacturing approaches such as microfluidic mixing to replace

batchwise liposome extrusion (184,185), coupled with the greener

synthesis methods such as supercritical CO2-based

nanoparticle production to eliminate toxic chlorinated solvents

(186,187). The implementation of QbD

principles is essential for optimizing critical conjugation

parameters (such as reaction time and pH control) in PSA

nanoparticle fabrication, whereas advanced process analytical

technology (PAT) systems should be employed for real-time

monitoring of critical quality attributes throughout production

(188). These synergistic

advancements, spanning manufacturing innovation, sustainable

chemistry, systematic process optimization and enhanced quality

control, collectively address the key technical and regulatory

hurdles impeding clinical translation (Fig. 7).

While WSB nanocarriers exemplify the TCM-modern

oncology integration, industrial viability hinges on resolving the

material, process, and regulatory gaps, a challenge demanding

cross-disciplinary collaboration.

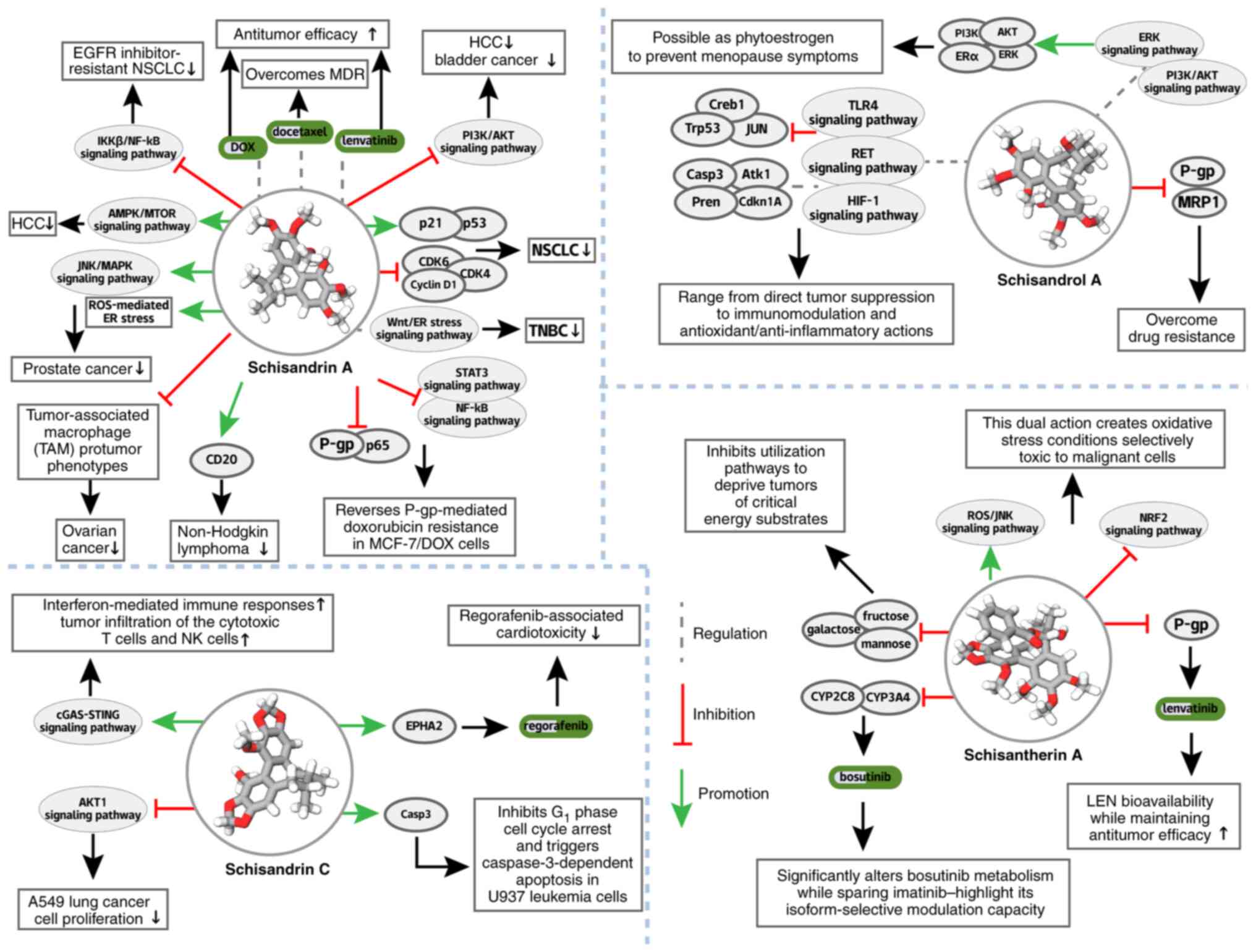

Further studies have demonstrated the efficacy of

Sch A in bladder cancer through inhibition of the ALOX5-mediated

activity of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (206) (Fig. 8; Table III). In HCC, Sch A acts via

AMPK/mTOR-dependent mitochondrial ferroptosis (207) (Fig. 8; Table III) and in PC, it activates

ROS-mediated ER stress and the JNK/MAPK signaling pathway (208) (Fig. 8; Table III). Emerging evidence also

suggests its activity against non-Hodgkin lymphoma through CD20

inhibition (209) (Fig. 8; Table III).

In addition, Sch A reverses P-gp-mediated

doxorubicin resistance via the P-gp/NF-κB/STAT3 inhibition

(210) (Fig. 8), complementing the WSB's

STAT3-dependent P-gp downregulation by disrupting

transporter-substrate interactions. It restores gefitinib

sensitivity in EGFR-resistant NSCLC (211) (Fig. 8), synergizing with Lenvatinib

(LEN) (212) (Fig. 8), expanding WSB's

chemosensitization scope to the EGFR-TKI resistance.

Innovative drug delivery platforms have augmented

the therapeutic potential of Sch A. Ultrasound-targeted microbubble

destruction with Span-PEG carriers enhances Sch A uptake in

Walker-256 hepatoma cells, inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

(213) (Fig. 8). A microemulsion system loaded

with docetaxel and Sch A overcomes esophageal cancer MDR (211) (Fig. 8), whereas long-circulating

liposomes loaded with Sch A/doxorubicin (SchA-DOX-Lip) enhance

apoptosis induction and tumor targeting in HCC (214) (Fig. 8). These advancement strategies

are directly applicable to WSB, leveraging structural similarity

for formulation optimization. Together, their complementary

mechanisms and shared delivery solutions support lignan-based

combination therapies, maximizing clinical utility.

In toxicity mitigation, SC counteracts

regorafenib-induced hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicity via EphA2

Ser897 phosphorylation and EPHA2 restoration (217,218), complementing WSB's DOX

cardioprotection (p38MAPK-ATM-p53 axis) (130,131) (Fig. 8), with structural similarity

enabling tissue-specific cytoprotection (liver/heart vs. WSB's

cardiac focus).

SC's dual capacity supports combination strategies:

Coadministration with regorafenib to reduce toxicity while

enhancing efficacy. Formulation advances (such as targeted

delivery), adaptable from WSB's nanotechnology research, could

optimize tissue-specific distribution, maximizing its integrative

potential.

Pharmacokinetically, the STA modulates drug

metabolism to enhance efficacy: it increases the cyclophosphamide

exposure (227), selectively

inhibits CYP3A4/CYP2C8 (altering bosutinib but not imatinib

metabolism) (228) (Fig. 8) and, most notably, increases LEN

bioavailability in patients with HCC via intestinal P-gp

suppression (229,230) (Fig. 8).

SAL, a dibenzocyclooctadiene lignan that shares

structural homology with WSB, exhibits multitargeted activity

across liver diseases, from NAFLD to HCC, complementing the hepatic

effects of WSB through overlapping yet distinct mechanisms

(231,232).

In HCC, SAL targets STAT3 to inhibit proliferation

and downregulate PD-L1, enhancing CTL activity (235) (Fig. 9) and complementing anti-HCC

mechanisms of WSB [such as RhoA/ROCK1 inhibition (78-80) (Fig. 9)] by increasing the degree of

immunomodulation and WSB minimally affects liver cancer. This

convergence of metabolic, fibrotic, and immunologic regulation

positions SAL as a bridge between WSB's hepatic protection and

novel immunotherapeutic strategies in HCC.

Clinically, the ability of SAL to span

NAFLD-fibrosis-HCC progression, paired with the broader anticancer

spectrum of WSB, supports the use of combination strategies.

Formulation advances, which are adaptable to WSB research, could

optimize the pharmacokinetics of both compounds, maximizing their

synergistic potential in liver disease management.

Translational efforts should focus on optimizing

bioavailability (exploiting WSB's formulation advances),

identifying biomarkers and developing combinations, capitalizing on

the structural overlap of GA with WSB to design coordinated

regimens that maximize pathway coverage across NSCLC, osteosarcoma,

CRC and melanoma.

In hepatic fibrosis, GD selectively disrupts the

PDGF-BB/PDGFRβ cascade to suppress HSC activation and induce

apoptosis in activated HSCs (241) (Fig. 9), complementing the anti-fibrotic

effects of WSB (such as TGF-β/SMAD inhibition) by targeting PDGFRβ,

a pathway that WSB does not directly engage in, thereby broadening

lignan-mediated control of fibrosis in CCl4-induced

models. Beyond the liver, GD protects against UV-induced

keratinocyte damage via the ROS scavenging and the apoptotic

pathway inhibition while suppressing melanogenesis through the

PKA/CREB/MITF axis inhibition (242) (Fig. 9), extending the ROS-modulating

properties (shared with WSB) of the lignan class to dermatological

contexts, with structural similarity enabling both to regulate

oxidative stress, but in tissue-specific ways (hepatic vs.

cutaneous).

Translational efforts should focus on optimizing

targeted delivery systems (adaptable from formulation research on

WSB), exploring synergies with existing

antifibrotics/dermatological agents and investigating preventive

potential in high-risk populations, leveraging the structural

overlap of GD with WSB to design combination strategies that

maximize dual efficacy in hepatic and dermatological

pathologies.

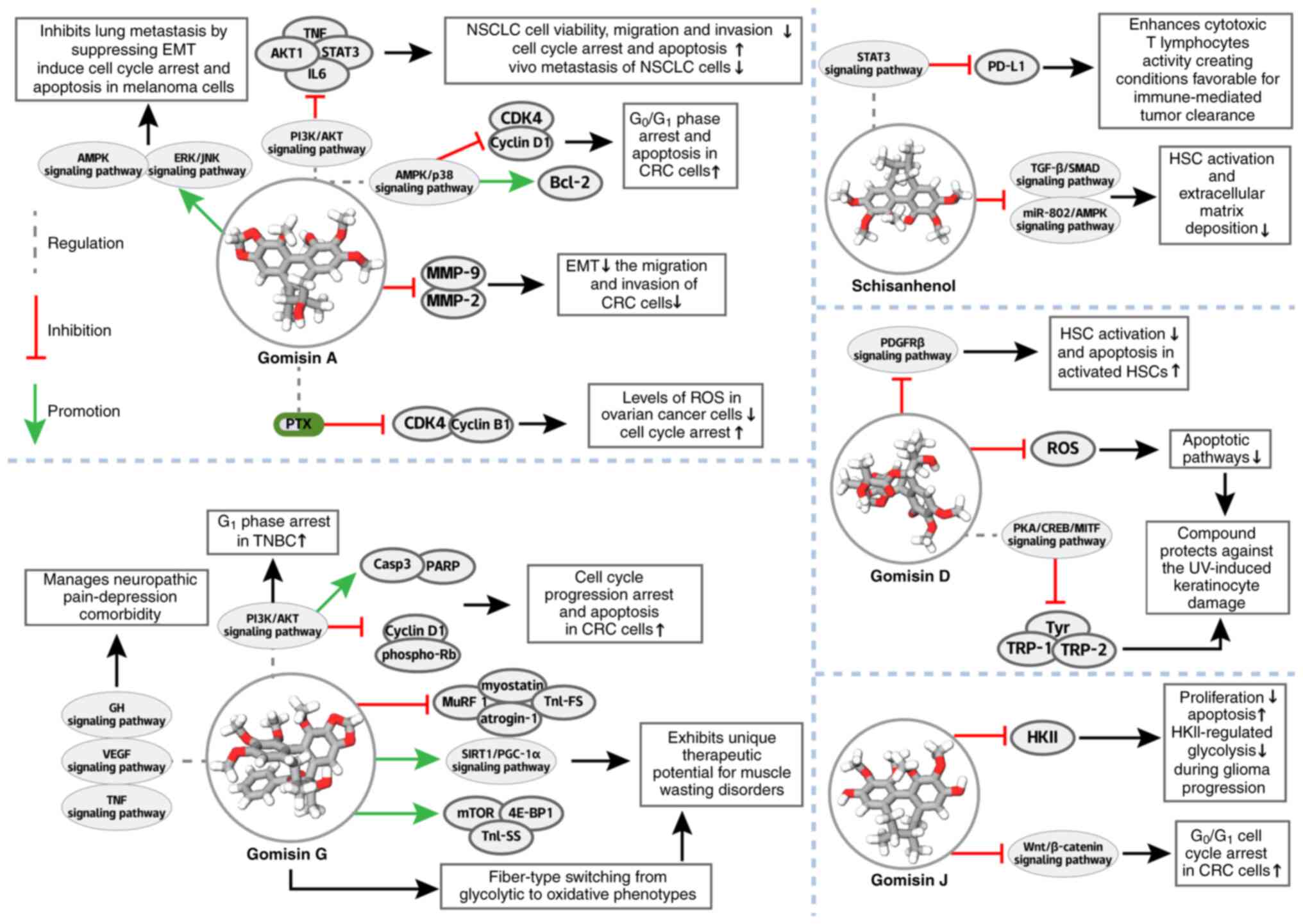

In oncology, GG inhibits PI3K-AKT signaling to

induce apoptosis (via PARP/caspase-3 cleavage) and suppresses the

cell cycle (Cyclin D1/phospho-Rb downregulation) in colorectal

cancer and triggers G1 arrest in TNBC through inhibition

of the AKT activity (243,244) (Fig. 9; Table III), mirroring the ability of

WSB to target PI3K/AKT in various types of cancer but with enhanced

specificity for inhibition of the activity of PI3K, creating a

complementary strategy with respect to the broader inhibition of

WSB. As well as tumors, GG counteracts muscle wasting via myostatin

modulation and the SIRT1/PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial

biogenesis (245) (Fig. 9) and alleviates neuropathic

pain-depression comorbidity through TNF/VEGF/GH regulation

(246) (Fig. 9), extending the multitarget

potential (shared with WSB) of the lignan class to nononcologic

contexts, leveraging structural similarity to drive pleiotropic

effects.

Translational efforts should focus on WSB progress:

Optimizing structure-activity relationships (to increase target

specificity), improving pharmacokinetics via advances in

formulation (adaptable from WSB delivery research) and identifying

biomarkers for stratification. The ability of GG to complement WSB

in oncology while expanding into other therapeutic areas

underscores the versatility of the lignan class, rooted in their

conserved dibenzocyclooctadiene scaffold.

GJ demonstrates significant potential as an

anticancer agent, exhibiting efficacy across multiple cancer types

through simultaneous targeting of diverse oncogenic pathways. In BC

models, GJ uniquely induces both classical apoptosis and

necroptosis, showing particular efficacy against

apoptosis-resistant populations that drive treatment failure and

recurrence (247). This dual

cell death mechanism addresses a critical clinical challenge in

managing aggressive BC subtypes.

The anticancer activity of GJ extends to CRC, where

it suppresses the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (a key driver of colorectal

carcinogenesis) and induces G0/G1 cell cycle

arrest (248) (Fig. 9; Table III). These coordinated actions

on oncogenic signaling and cell cycle regulation underlie its

potent antitumor effects in CRC. In glioma models, GJ adopts a

multifaceted approach: triggering mitochondrial apoptosis while

disrupting tumor metabolism via the HKII-mediated glycolysis

inhibition (249) (Fig. 9; Table III), simultaneously targeting

cell survival and energy production pathways essential for tumor

growth.

The multi-target activity of GJ its and capacity to

overcome treatment resistance position it as a promising

therapeutic candidate, necessitating further development of

optimized formulations, predictive biomarkers, and rational

combination strategies for clinical translation.

Not applicable.

LZ, YL, CL, and YT conceived and supervised this

work. LZ, YL, ZC, JM, ZH, and XS organized the literature, wrote

the manuscript and created charts. LZ and YL provided funding. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was financially supported by the Social

Science and Technology Research Major Project of Zhongshan (grant

no. 2021B3011) and the Guangdong Medical University Undergraduate

Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (grant nos.

GDMUCX2024017, GDMU2023355 and 202510571017).

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liu Y, Fang C, Luo J, Gong C, Wang L and

Zhu S: Traditional Chinese medicine for cancer treatment. Am J Chin

Med. 52:583–604. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Li Y, Miao J, Liu C, Tao J, Zhou S, Song

X, Zou Y, Huang Y and Zhong L: Kushenol O Regulates GALNT7/NF-κB

axis-Mediated Macrophage M2 Polarization and Efferocytosis in

papillary thyroid carcinoma. Phytomedicine. 138:1563732025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Szopa A, Ekiert R and Ekiert H: Current

knowledge of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. (Chinese

magnolia vine) as a medicinal plant species: A review on the

bioactive components, pharmacological properties, analytical and

biotechnological studies. Phytochem Rev. 16:195–218. 2017.

|

|

5

|

Yang K, Qiu J, Huang Z, Yu Z, Wang W, Hu H

and You Y: A comprehensive review of ethnopharmacology,

phytochemistry, pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics of Schisandra

chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. and Schisandra sphenanthera Rehd. et

Wils. J Ethnopharmacol. 284:1147592022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Olas B: Cardioprotective potential of

berries of Schisandra chinensis Turcz. (Baill.), their components

and food products. Nutrients. 15:5922023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Shan Y, Jiang B, Yu J, Wang J, Wang X, Li

H, Wang C, Chen J and Sun J: Protective Effect of Schisandra

chinensis polysaccharides against the immunological liver injury in

mice based on Nrf2/ARE and TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. J Med

Food. 22:885–895. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yan T, Mao Q, Zhang X, Wu B, Bi K, He B

and Jia Y: Schisandra chinensis protects against dopaminergic

neuronal oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and apoptosis via the

BDNF/Nrf2/NF-κB pathway in 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson's disease mice.

Food Funct. 12:4079–4091. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xu G, Lv X, Feng Y, Li H, Chen C, Lin H,

Li H, Wang C, Chen J and Sun J: Study on the effect of active

components of Schisandra chinensis on liver injury and its

mechanisms in mice based on network pharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol.

910:1744422021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yuan R, Tao X, Liang S, Pan Y, He L, Sun

J, Wenbo J, Li X, Chen J and Wang C: Protective effect of acidic

polysaccharide from Schisandra chinensis on acute ethanol-induced

liver injury through reducing CYP2E1-dependent oxidative stress.

Biomed Pharmacother. 99:537–542. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zhang M, Xu L and Yang H: Schisandra

chinensis Fructus and its active ingredients as promising resources

for the treatment of neurological diseases. Int J Mol Sci.

19:19702018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Qiu Q, Zhang W, Liu K, Huang F, Su J, Deng

L, He J, Lin Q and Luo L: Schisandrin A ameliorates airway

inflammation in model of asthma by attenuating Th2 response. Eur J

Pharmacol. 953:1758502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lee K, Ahn JH, Lee KT, Jang DS and Choi

JH: Deoxyschizandrin, Isolated from Schisandra berries, induces

cell cycle arrest in ovarian cancer cells and inhibits the

protumoural activation of tumour-associated macrophages. Nutrients.

10:912018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lee PK, Co VA, Yang Y, Wan MLY, El-Nezami

H and Zhao D: Bioavailability and interactions of schisandrin B

with 5-fluorouracil in a xenograft mouse model of colorectal

cancer. Food Chem. 463:1413712025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nasser MI, Han T, Adlat S, Tian Y and

Jiang N: Inhibitory effects of Schisandrin B on human prostate

cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 41:677–685. 2019.

|

|

16

|

Sowndhararajan K, Deepa P, Kim M, Park SJ

and Kim S: An overview of neuroprotective and cognitive enhancement

properties of lignans from Schisandra chinensis. Biomed

Pharmacother. 97:958–968. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Tan S, Zheng Z, Liu T, Yao X, Yu M and Ji

Y: Schisandrin B induced ROS-mediated autophagy and Th1/Th2

imbalance via selenoproteins in Hepa1-6 cells. Front Immunol.

13:8570692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhan SY, Shao Q, Fan XH, Li Z and Cheng

YY: Tissue distribution and excretion of herbal components after

intravenous administration of a Chinese medicine (Shengmai

injection) in rat. Arch Pharm Res. Apr 19–2014.Epub ahead of print.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

Guo J, Shen Y, Lin X, Chen H and Liu J:

Schisandrin B promotes T(H)1 cell differentiation by targeting

STAT1. Int Immunopharmacol. 101:1082132021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nasser MI, Zhu S, Chen C, Zhao M, Huang H

and Zhu P: A comprehensive review on Schisandrin B and its

biological properties. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020:21727402020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen Z, Guo M, Song G, Gao J, Zhang Y,

Jing Z, Liu T and Dong C: Schisandrin B inhibits Th1/Th17

differentiation and promotes regulatory T cell expansion in mouse

lymphocytes. Int Immunopharmacol. 35:257–264. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kortesoja M, Karhu E, Olafsdottir ES,

Freysdottir J and Hanski L: Impact of dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans

from Schisandra chinensis on the redox status and activation of

human innate immune system cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 131:309–317.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chang CM, Liang TR and Lam HYP: The use of

Schisandrin B to combat Triple-negative breast cancers by

inhibiting NLRP3-Induced interleukin-1β production. Biomolecules.

14:742024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Song A, Ding T, Wei N, Yang J, Ma M, Zheng

S and Jin H: Schisandrin B induces HepG2 cells pyroptosis by

activating NK cells mediated anti-tumor immunity. Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 472:1165742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Xie Z, Yang T, Zhou C, Xue Z, Wang J and

Lu F: Integrative bioinformatics analysis and experimental study of

NLRP12 reveal its prognostic value and potential functions in

ovarian cancer. Mol Carcinog. 64:383–398. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Chen X, Liu C, Deng J, Xia T, Zhang X, Xue

S, Song MK and Olatunji OJ: Schisandrin B ameliorates

adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats via modulation of inflammatory

mediators, oxidative stress, and HIF-1α/VEGF pathway. J Pharm

Pharmacol. 76:681–690. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang L, Chen H, Tian J and Chen S:

Antioxidant and anti-proliferative activities of five compounds

from Schisandra chinensis fruit. Industrial Crops Products.

50:690–693. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chen T, Xiao Z, Liu X, Wang T, Wang Y, Ye

F, Su J, Yao X, Xiong L and Yang DH: Natural products for combating

multidrug resistance in cancer. Pharmacol Res. 202:1070992024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Krishnan SR and Bebawy M: Circulating

biosignatures in multiple myeloma and their role in multidrug

resistance. Mol Cancer. 22:792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li Z and Yin P: Tumor microenvironment

diversity and plasticity in cancer multidrug resistance. Biochim

Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1878:1889972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chen YC, Malfertheiner P, Yu HT, Kuo CL,

Chang YY, Meng FT, Wu YX, Hsiao JL, Chen MJ, Lin KP, et al: Global

prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection and incidence of

gastric cancer between 1980 and 2022. Gastroenterology.

166:605–619. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yuan J, Khan SU, Yan J, Lu J, Yang C and

Tong Q: Baicalin enhances the efficacy of 5-Fluorouracil in gastric

cancer by promoting ROS-mediated ferroptosis. Biomed Pharmacother.

164:1149862023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

He L, Chen H, Qi Q, Wu N, Wang Y, Chen M,

Feng Q, Dong B, Jin R and Jiang L: Schisandrin B suppresses gastric

cancer cell growth and enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy drug

5-FU in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 920:1748232022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Zhang F, Wang Z, Yuan J, Wei X, Tian R and

Niu R: RNAi-mediated silencing of Anxa2 inhibits breast cancer cell

proliferation by downregulating cyclin D1 in STAT3-dependent

pathway. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 153:263–275. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu XN, Zhang CY, Jin XD, Li YZ, Zheng XZ

and Li L: Inhibitory effect of schisandrin B on gastric cancer

cells in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 13:6506–6511. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Li M, Tang Q, Li S, Yang X, Zhang Y, Tang

X, Huang P and Yin D: Inhibition of autophagy enhances the

anticancer effect of Schisandrin B on head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 38:e235852024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhang F, Zhai J, Weng N, Gao J, Yin J and

Chen W: A comprehensive review of the main lignan components of

Schisandra chinensis (North Wu Wei Zi) and Schisandra

sphenanthera (South Wu Wei Zi) and the Lignan-induced drug-drug

interactions based on the inhibition of cytochrome P450 and

P-glycoprotein activities. Front Pharmacol. 13:8160362022.

|

|

37

|

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V,

Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N and Bray F:

Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and

mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 72:338–344. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vodenkova S, Buchler T, Cervena K,

Veskrnova V, Vodicka P and Vymetalkova V: 5-fluorouracil and other

fluoropyrimidines in colorectal cancer: Past, present and future.

Pharmacol Ther. 206:1074472020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yoshino T, Cervantes A, Bando H,

Martinelli E, Oki E, Xu RH, Mulansari NA, Govind Babu K, Lee MA and

Tan CK: Pan-Asian adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the

diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with metastatic

colorectal cancer. ESMO Open. 8:1015582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Co VA, El-Nezami H, Liu Y, Twum B, Dey P,

Cox PA, Joseph S, Agbodjan-Dossou R, Sabzichi M, Draheim R and Wan

MLY: Schisandrin B suppresses colon cancer growth by inducing cell

cycle arrest and apoptosis: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic

potential. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 7:863–877. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Pu Z, Zhang W, Wang M, Xu M, Xie H and

Zhao J: Schisandrin B attenuates Colitis-associated colorectal

cancer through SIRT1 linked SMURF2 signaling. Am J Chin Med.

49:1773–1789. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cheifetz S, Hernandez H, Laiho M, ten

Dijke P, Iwata KK and Massagué J: Distinct transforming growth

factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor subsets as determinants of cellular

responsiveness to three TGF-beta isoforms. J Biol Chem.

265:20533–20538. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dong X, Zhao B, Iacob RE, Zhu J, Koksal

AC, Lu C, Engen JR and Springer TA: Force interacts with

macromolecular structure in activation of TGF-β. Nature. 542:55–59.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lamouille S, Xu J and Derynck R: Molecular

mechanisms of Epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 15:178–196. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Vincent T, Neve EP, Johnson JR, Kukalev A,

Rojo F, Albanell J, Pietras K, Virtanen I, Philipson L, Leopold PL,

et al: A SNAIL1-SMAD3/4 transcriptional repressor complex promotes

TGF-beta mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol.

11:943–950. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Xue G, Restuccia DF, Lan Q, Hynx D,

Dirnhofer S, Hess D, Rüegg C and Hemmings BA: Akt/PKB-mediated

phosphorylation of Twist1 promotes tumor metastasis via mediating

cross-talk between PI3K/Akt and TGF-β signaling axes. Cancer

Discov. 2:248–259. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lin T, Zeng L, Liu Y, DeFea K, Schwartz

MA, Chien S and Shyy JY: Rho-ROCK-LIMK-cofilin pathway regulates

shear stress activation of sterol regulatory element binding

proteins. Circ Res. 92:1296–1304. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yu J, Lei R, Zhuang X, Li X, Li G, Lev S,

Segura MF, Zhang X and Hu G: MicroRNA-182 targets SMAD7 to

potentiate TGFβ-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

metastasis of cancer cells. Nat Commun. 7:138842016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Tian XJ, Zhang H and Xing J: Coupled

reversible and irreversible bistable switches underlying

TGFβ-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Biophys J.

105:1079–1089. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Liu Z, Zhang B, Liu K, Ding Z and Hu X:

Schisandrin B attenuates cancer invasion and metastasis via

inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS One.

7:e404802012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Zhang B, Liu Z and Hu X: Inhibiting cancer

metastasis via targeting NAPDH oxidase 4. Biochem Pharmacol.

86:253–266. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Li J, Lu Y, Wang D, Quan F, Chen X, Sun R,

Zhao S, Yang Z, Tao W, Ding D, et al: Schisandrin B prevents

ulcerative colitis and colitis-associated-cancer by activating

focal adhesion kinase and influence on gut microbiota in an in vivo

and in vitro model. Eur J Pharmacol. 854:9–21. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sun R, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Tang T, Cao Y,

Yang L, Tian Y, Zhang Z, Zhang P and Xu F: Temporal and spatial

metabolic shifts revealing the transition from ulcerative colitis

to colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh).

12:e24125512025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang J, Mengli Y, Zhang T, Song X, Ying

S, Shen Z and Yu C: Deficiency in epithelium RAD50 aggravates UC

via IL-6-Mediated JAK1/2-STAT3 signaling and promotes development

of Colitis-associated cancer in mice. J Crohns Colitis.

19:jjae1342025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Porter RJ, Kalla R and Ho GT: Ulcerative

colitis: Recent advances in the understanding of disease

pathogenesis. F1000Res. 9:F1000Faculty Rev-294. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Tatiya-Aphiradee N, Chatuphonprasert W and

Jarukamjorn K: Immune response and inflammatory pathway of

ulcerative colitis. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 30:1–10. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Guo G, Tan Z, Liu Y, Shi F and She J: The

therapeutic potential of stem Cell-derived exosomes in the

ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. Stem Cell Res Ther.

13:1382022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Guo X, Yin X, Liu Z and Wang J:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) pathogenesis and natural

products for prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 23:154892022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Asaoka Y, Terai S, Sakaida I and Nishina

H: The expanding role of fish models in understanding non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease. Dis Model Mech. 6:905–914. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Sheka AC, Adeyi O, Thompson J, Hameed B,

Crawford PA and Ikramuddin S: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A

review. JAMA. 323:1175–1183. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Leong PK and Ko KM: Schisandrin B: A

Double-edged sword in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Oxid Med

Cell Longev. 2016:61716582016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yan LS, Zhang SF, Luo G, Cheng BC, Zhang

C, Wang YW, Qiu XY, Zhou XH, Wang QG, Song XL, et al: Schisandrin B

mitigates hepatic steatosis and promotes fatty acid oxidation by

inducing autophagy through AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. Metabolism.

131:1552002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ma R, Zhan Y, Zhang Y, Wu L, Wang X and

Guo M: Schisandrin B ameliorates non-alcoholic liver disease

through anti-inflammation activation in diabetic mice. Drug Dev

Res. 83:735–744. 2022.

|

|

64

|

Li Z, Zhao L, Xia Y, Chen J, Hua M and Sun

Y: Schisandrin B attenuates hepatic stellate cell activation and

promotes apoptosis to protect against liver fibrosis. Molecules.

26:68822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Ma M, Wei N, Yang J, Ding T, Song A, Chen

L, Zheng S and Jin H: Schisandrin B promotes senescence of

activated hepatic stellate cell via NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy.

Pharm Biol. 61:621–629. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Trojnar E, Erdelyi K, Matyas C, Zhao S,

Paloczi J, Mukhopadhyay P, Varga ZV, Hasko G and Pacher P:

Cannabinoid-2 receptor activation ameliorates hepatorenal syndrome.

Free Radic Biol Med. 152:540–550. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Wang HQ, Wan Z, Zhang Q, Su T, Yu D, Wang

F, Zhang C, Li W, Xu D and Zhang H: Schisandrin B targets

cannabinoid 2 receptor in Kupffer cell to ameliorate CCl4-induced

liver fibrosis by suppressing NF-κB and p38 MAPK pathway.

Phytomedicine. 98:1539602022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Yang YY, Hsieh SL, Lee PC, Yeh YC, Lee KC,

Hsieh YC, Wang YW, Lee TY, Huang YH, Chan CC and Lin HC: Long-term

cannabinoid type 2 receptor agonist therapy decreases bacterial

translocation in rats with cirrhosis and ascites. J Hepatol.

61:1004–1013. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Lei Y, Wang QL, Shen L, Tao YY and Liu CH:

MicroRNA-101 suppresses liver fibrosis by downregulating

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol.

43:575–584. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Cuiqiong W, Chao X, Xinling F and Yinyan

J: Schisandrin B suppresses liver fibrosis in rats by targeting

miR-101-5p through the TGF-β signaling pathway. Artif Cells Nanomed

Biotechnol. 48:473–478. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Meroni M, Longo M, Erconi V, Valenti L,

Gatti S, Fracanzani AL and Dongiovanni P: mir-101-3p downregulation

promotes fibrogenesis by facilitating hepatic stellate cell

transdifferentiation during insulin resistance. Nutrients.

11:25972019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Chen Q, Bao L, Lv L, Xie F, Zhou X, Zhang

H and Zhang G: Schisandrin B regulates macrophage polarization and

alleviates liver fibrosis via activation of PPARγ. Ann Transl Med.