Introduction

Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ

dysfunction resulting from a dysregulated host response to

infection (1). Each year, an

estimated 48.9 million people worldwide develop sepsis, leading to

approximately 11 million deaths and accounting for nearly one-fifth

of all global mortality (2,3).

Sepsis is a challenging health problem worldwide with lingering

sequelae (4-6). Sepsis is considered a pathway to

death initiated by the host immune defense system failing to

restore homeostasis in response to an invading pathogen (7-12). Understanding the potential

molecular and cellular features involved in complex immune

pathological mechanisms is key for sepsis management. Neutrophils,

as the most abundant type of white blood cell, are essential

frontline responders to infection (13). In different stages of sepsis,

neutrophils exhibit different transcriptomic profiles and

biological functions (14),

providing phenotypical diversity. Neutrophil subpopulations have

been classified with different subsets causing various

pathophysiological changes in the complex environment of sepsis,

such as immune dysregulation, coagulation dysfunction and organ

damage (15).

Neutrophil heterogeneity in sepsis has been

extensively investigated (16-21). In disagreement with the previous

consensus of neutrophil homogeneity, studies have indicated that

neutrophils may remain in the circulation long enough to interpret

environmental signals and execute specific molecular programs,

providing a rationale for neutrophil diversity in vivo and

promoting neutrophil heterogeneity research (16-21). Researchers have identified

different subsets of neutrophils via surface proteins, such as CD

molecules (22-25). However, there are no uniform

standards for different neutrophil subpopulations distinguished by

phenotypes (26), resulting in

confusing neutrophil nomenclature and disagreements regarding

neutrophil function. It remains unclear whether neutrophil subsets

present in sepsis result from bone marrow mobilization or are

specific subsets formed under the influence of sepsis. Moreover,

whether the neutrophil response to sepsis represents a transient

and reversible activation, or profound gene reprogramming with

long-lasting consequences for host immunity remains unknown. Ng

et al (21) proposed that

the integration of protein and transcript composition, functional

properties, tissue distribution, and genomic organization provides

a more definitive framework for classifying immune cells, thereby

offering a more precise approach to defining true neutrophil

heterogeneity (21). To define

these features, multi-omics analyses provide a more comprehensive

understanding of cellular heterogeneity.

Omics analyses evaluate the complete set of

molecular data, comprising genome, transcriptome, proteome and

metabolome (27). Single omics

studies, predominantly single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), have

revealed notable heterogeneity of neutrophils (28-30). High-throughput analysis based on

scRNA-seq enables broad screening of neutrophil heterogeneity,

allowing precise identification of neutrophil subsets combined with

more practical methods, such as flow cytometry (28). As a combination of single omics

approaches, multi-omics unveils the information of a single

regulatory layer and the association between different layers

(31,32). Sepsis is heterogeneous and has a

complicated immunological mechanism, resulting in modulation of

neutrophil diversity (7,33). Multi-omics analyses can help to

elucidate underlying differences of neutrophils in sepsis that have

not been identified by previous classification methods.

The present review summarizes the phenotypical and

functional heterogeneity of neutrophils, as well as advances in the

discovery of neutrophil subsets in sepsis using single omics

approaches and the complex biological mechanisms of neutrophils in

sepsis using multi-omics analysis. The holistic perspective of

multi-omics clarifies the dynamic interplay between neutrophils and

the host immune response, and provides a foundation for the

identification of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Neutrophil heterogeneity in sepsis

In sepsis, exposure to local or systemic extrinsic

factors may modify neutrophil properties, resulting in the

diversity of neutrophils (21).

Neutrophil phenotypes and functions reflect key features of

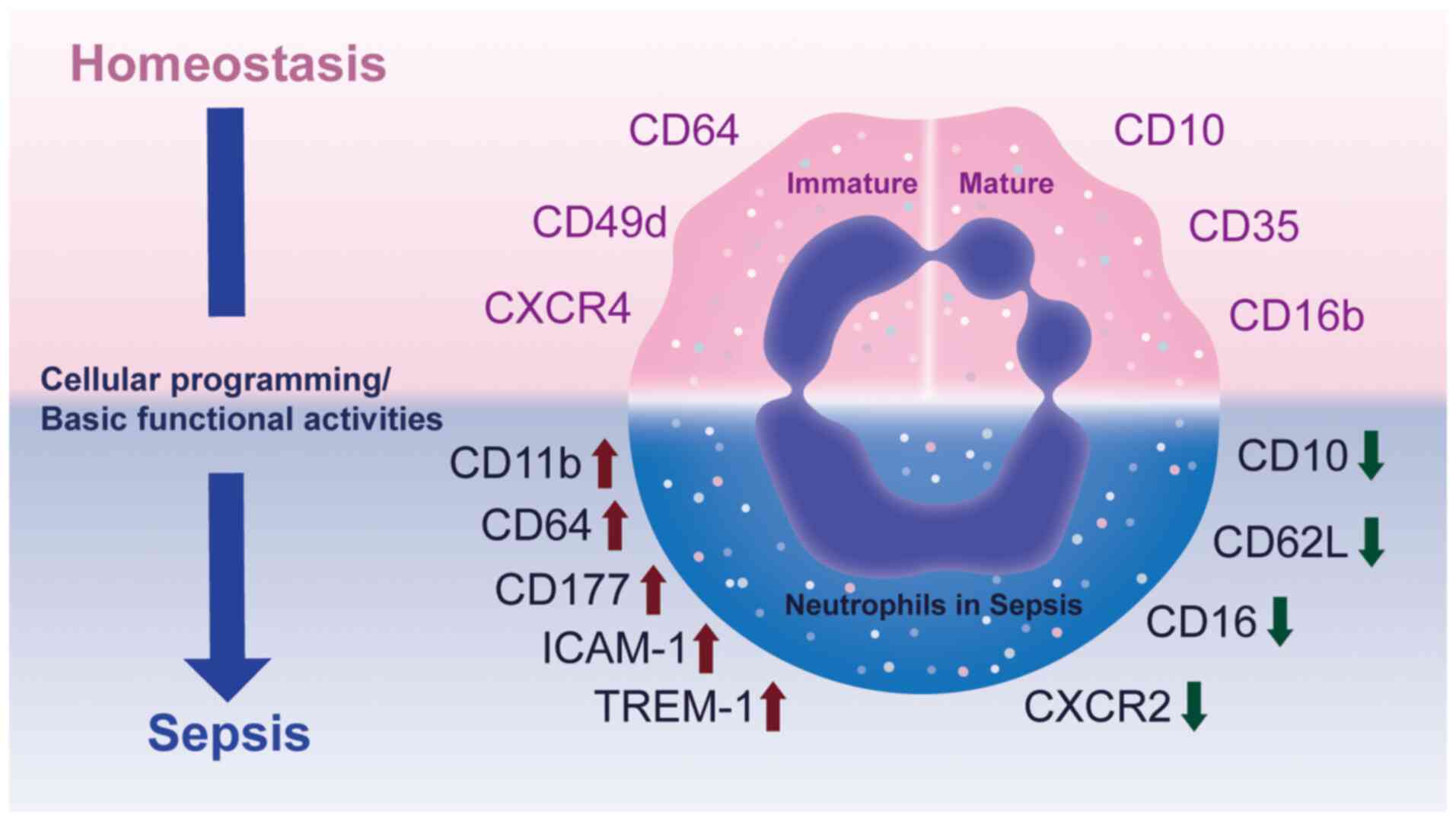

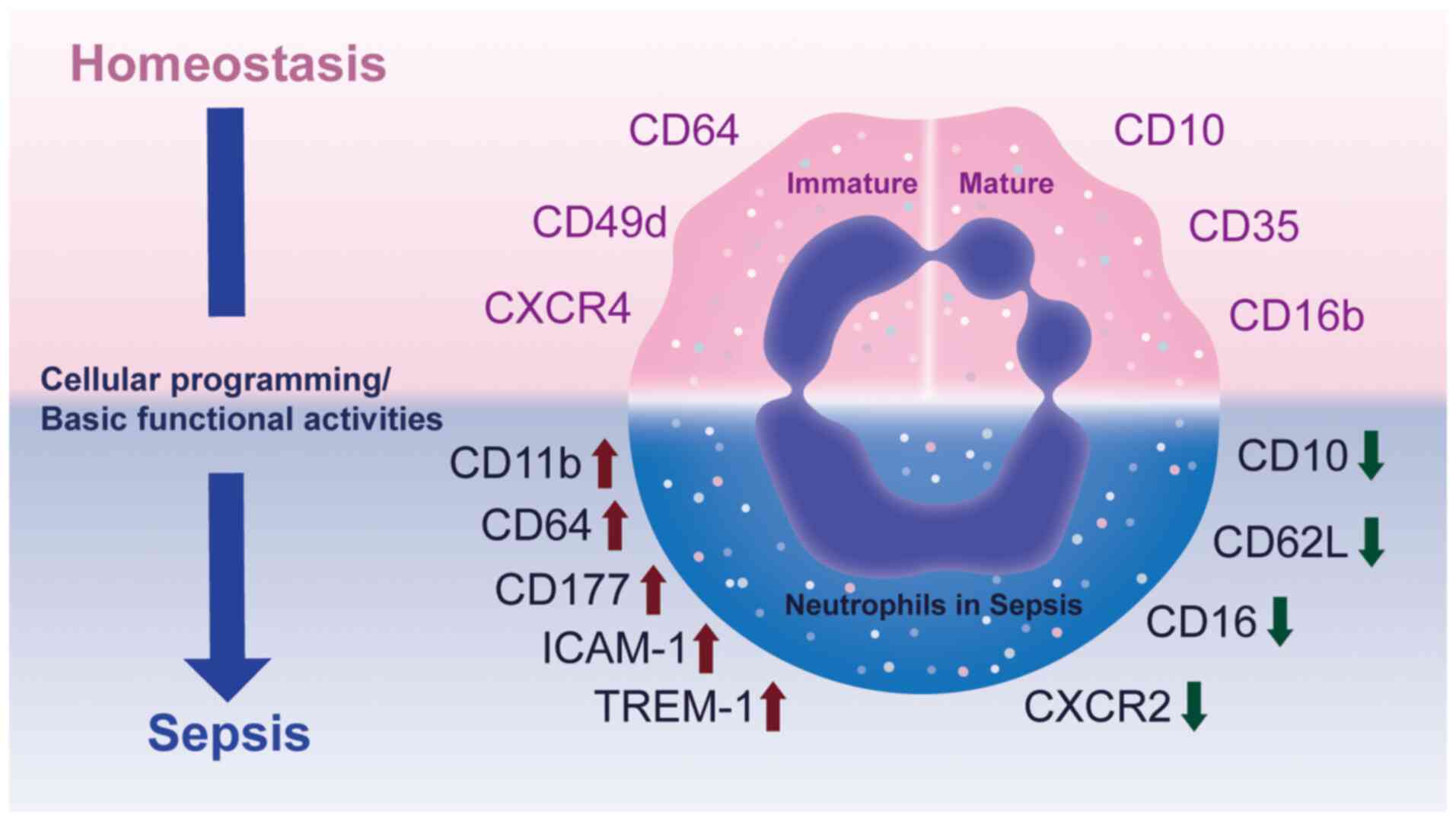

neutrophil heterogeneity (Fig.

1).

| Figure 1Phenotypical heterogeneity of

neutrophils in homeostasis and sepsis. Under homeostatic

conditions, immature neutrophils are characterized by expression of

CD64, CD49d and CXCR4, whereas mature neutrophils typically express

CD10, CD16b and CD35. During sepsis, both immature and mature

neutrophils are exposed to inflammatory cues that reprogram

cellular activities and functional states, leading to marked

phenotypical shifts. Specifically, surface molecules such as CD11b,

CD64, CD177, ICAM-1 and TREM-1 are upregulated, while CD10, CD62L,

CD16 and CXCR2 are downregulated. These alterations reflect changes

in neutrophil activation, adhesion and migration, however, the

precise functional consequences and regulatory mechanisms

underlying these transitions remain incompletely understood. CXCR,

C-X-C chemokine receptor; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion

molecule-1; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid

cells-1. |

Phenotypical diversity of neutrophils in

sepsis

Morphologically, the stages of neutrophil

development include promyelocytes, myelocytes, metamyelocytes, band

cells and segmented neutrophils, among which the segmented

neutrophil is considered the mature form (34). Because of their characteristic

multilobed nuclei at the mature stage, neutrophils are often

referred to as polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs).

CD11b+ CD66b+ CD15+

CD14- are commonly used phenotypical markers for human

neutrophils (22). In

homeostasis, as neutrophils mature, neutrophil surface markers

changed to facilitate altered function. Immature neutrophils

express more C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) than mature

neutrophils, which may promote its retention in bone marrow

(23). CD16b, CD35 and CD10

appear after neutrophil maturation, whereas CD49d and CD64

disappear (24).

During sepsis, neutrophils present with phenotypical

alterations. Seree-Aphinan et al (25) found that a decrease in CXCR2

surface levels is associated with sepsis due to internalization of

the CXCR2 receptor induced by circulating chemokines (35,36). Other studies also support

decreased expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 on the surface

of neutrophils in patients with septic shock (37,38). In addition, CD11b is decreased,

but CXCR1 expression does not change significantly (37,38). Demaret et al demonstrated

that CD10dim CD16dim neutrophils have an

increased frequency in patients with septic shock (39). Neutrophils exhibit increased

CD11b expression and decreased CD62L expression following

stimulation with IL-8 or N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-pheny lalanine

(39). Similarly, suppressor

cells mobilized during acute inflammation are characterized by

normal expression of CD16, low expression of CD62L and high

expression of CD11b and CD11c (40). Geng et al identified a

third immune regulatory neutrophil in different inflammation

conditions (41). This hybrid

neutrophil subset extravasates at sites of inflammation or

infection and expresses dendritic cell markers CD11c, major

histocompatibility complex class II and costimulatory molecules.

Ode et al (42), using a

mouse model of sepsis, found that the frequency and number of

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 positive neutrophils are

increased. CD64, a high-affinity immunoglobulin Fcγ receptor I,

mediates phagocytosis of bacteria. Under homeostatic conditions,

the expression of CD64 on neutrophils is comparatively low

(42). By contrast, during

infection, proinflammatory cytokines induce a 10-fold increase in

CD64 expression (43,44). In addition, CD64 expression on

neutrophils is specific for bacterial infection (45,46). Triggering receptor expressed on

myeloid cells-1, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is

upregulated when PMNs are exposed to bacteria (47). Demaret et al (48) revealed that the expression of

CD177 mRNA and protein is increased in circulating neutrophils in

sepsis.

When differentiating solely by markers, however, it

remains unclear whether certain neutrophil subsets are true

lineages or simply represent differentiation and maturation states

induced by the tissue environment.

Functional heterogeneity of neutrophils

in sepsis

As first-line immune cells, neutrophils are required

to adapt to diverse environments and respond promptly. To address

this challenge, neutrophils have multiple capabilities. Typical

functions of neutrophils encompass granule generation and

degranulation, secretion of antimicrobial proteins, production of

reactive oxygen species (ROS), phagocytosis, and formation of

neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (49). NETs are DNA scaffolds containing

granule-derived proteins, such as enzymatically active proteases

and anti-microbial peptides, formed to immobilize invading

microorganisms or in response to sterile stimuli (50). Table I summarizes the functional

diversity of neutrophils in sepsis (39,40,51-65).

| Table IHeterogeneity of neutrophil functions

in sepsis. |

Table I

Heterogeneity of neutrophil functions

in sepsis.

| Functional

aspect | Observations in

sepsis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| NET formation

(NETosis) | Decreased NETosis

observed in septic patients; associated antimicrobial defense | (51) |

| Apoptosis

regulation | Increased

neutrophil production and decreased apoptosis in bone marrow;

delayed apoptosis in circulating neutrophils | (39,51,64) |

| Phagocytosis | Enhanced phagocytic

function in septic shock; immature neutrophils show decreased

phagocytosis | (39,52,64-66) |

| Oxidative burst/ROS

production | Upregulated ROS

generation early in sepsis; decreased oxidative burst in late

sepsis; excessive ROS may drive tissue injury | (39,40,56,58-61) |

|

Chemotaxis/migration | Strongly inhibited

chemotaxis; defective migration in septic patients; mediated by GRK

activation via LPS and cytokines | (39,52-57,64,65) |

| Proinflammatory

cytokine release | High production of

TNF-α, IL-1β, chemokines, leukotrienes, adhesion molecules, ROS and

nitric oxide; immature neutrophils show high TNF-α/IL-10 ratio | (62,64) |

| Immunosuppressive

features | Neutrophil

subpopulation suppresses T cell proliferation via hydrogen peroxide

release | (40) |

| Mature vs. immature

neutrophils | Immature

neutrophils exhibit prolonged lifespan, decreased

phagocytosis/migration and proinflammatory profile; mature

neutrophils exhibit stronger innate immune functions | (64,65) |

| Aged

neutrophils | Decreased return to

bone marrow; preferential migration to inflammation sites; enhanced

phagocytic activity compared with non-aged neutrophils | (66) |

A UK cohort study identified neutrophil dysfunction

in sepsis, including a notable and sustained reduction in NETosis

(active NET release accompanied by cell death), along with

defective neutrophil migration and delayed apoptosis (51). In addition, Demaret et al

(39) found increased neutrophil

production and decreased apoptosis in the bone marrow in sepsis.

The oxidative burst and phagocytic function of neutrophils in

patients with septic shock are increased, but their chemotactic

function is strongly inhibited (39,52). Several studies have shown that

the migration ability of neutrophils in sepsis patients is reduced

(53-56). The underlying mechanism may be

that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and cytokines in sepsis activate G

protein-coupled receptor kinase on circulating neutrophils, thereby

inducing neutrophils to become desensitized to chemoattractant

(57). Martins et al

(58) also demonstrated that ROS

production is upregulated in neutrophils during sepsis. Notably,

neutrophil oxidative burst is decreased in the late stages of

sepsis (39). These opposing

findings suggested that septic shock may involve a transition from

immune activation to immune suppression, during which neutrophils

may exhibit immunosuppressive features that compromise the host

antimicrobial defense (40,59). For example, Pillay et al

(40) identified a neutrophil

subpopulation that mediates the suppression of T cell proliferation

by releasing neutrophils via local hydrogen peroxide.

The recruitment of bone marrow neutrophils increases

and their apoptosis decreases during sepsis. Functional

characteristics of neutrophils in patients with septic shock

included enhanced respiratory burst and phagocytosis, as well as

inhibited chemotaxis. High production of ROS and proinflammatory

cytokines by neutrophils at sites far from the initial infection

may be part of the pathophysiology of sepsis (56,60,61). Proinflammatory factors, including

tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β, chemokines, leukotrienes,

adhesion molecules, ROS, and nitric oxide, serve an important role

in amplifying inflammation, recruiting immune cells and inducing

tissue injury during sepsis (62). Decreased motility associated with

acute neutrophil activation is hypothesized to play a role in the

development of multiorgan failure following sepsis (63).

The functions of mature and immature neutrophils in

sepsis are heterogenous. Drifte et al reported that immature

circulating neutrophils of patients with septic shock support

innate immune defenses to a lesser extent than mature neutrophils

(64). Moreover, immature

neutrophils possess a longer lifespan and a stronger capacity to

resist spontaneous apoptosis (64). Compared with mature granulocytes,

the phagocytosis and migration abilities of immature neutrophils

are lower (64,65). The high TNF-α/IL-10 ratio in

immature neutrophils suggests these cells adopt a proinflammatory

profile, characterized by predominant production of inflammatory

cytokines (64). Aged

neutrophils also have different characteristics. Using a mouse

model, Uhl et al (66)

reported that the number of aged neutrophils returning to the bone

marrow is decreased during an acute inflammatory response to

endotoxemia, owing to rapid migration to sites of inflammation.

Upon reaching inflamed tissues, aged neutrophils exhibit higher

phagocytic activity than subsequently recruited non-aged

neutrophils (66).

The abundant phenotypical and functional

heterogeneity of neutrophils has been extensively studied, but the

underlying mechanisms of diversity remain unclear (21,67). Neutrophils exhibit plasticity,

allowing them to respond and adapt to various stimuli. Such

context-dependent and reversible changes may resemble stable

subsets, thereby confounding the interpretation of true

heterogeneity. Because the methodologies used to study neutrophil

heterogeneity need improvement and investigations of neutrophil

heterogeneity are in an exploratory stage, additional studies are

needed to understand whether neutrophil heterogeneity is the result

of cell programming or the basic functional activity of cells.

Neutrophil heterogeneity in sepsis by

omics

The intricate nature of sepsis and its impact on

neutrophil function has prompted researchers to investigate the

molecular underpinnings of neutrophil heterogeneity using omics

technologies (68-76). Each omics layer sheds light on

neutrophil behavior in sepsis, providing insight into their roles

in both host defense and immune dysregulation. Table II provides a brief summary of

omics techniques (68-76).

| Table IIOmics levels, research scope and

technology. |

Table II

Omics levels, research scope and

technology.

| Omics level | Definition | Research scope |

Technology/platform | Explanation | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Genomics | Comprehensive

analysis of the genome, including DNA sequence, structural variants

and mutations | WGS; WES | Short-read seq

(Illumina, Inc.); long-read seq (PacBio, ONT) | WGS covers the

entire genome to detect variants; WES focuses on protein-coding

regions; long-read seq resolves structural variants and repetitive

elements | (68-70) |

| Epigenomics | Study of

genome-wide epigenetic modifications regulating gene expression

without altering DNA sequence | DNA methylation

profiling; chromatin accessibility mapping; protein-DNA interaction

profiling | Bisulfite seq;

ATAC-seq; ChIP-seq | DNA methylation

profiling reveals CpG methylation; ATAC-seq measures chromatin

accessibility; ChIP-seq identifies histone modifications or TF

binding | (71) |

|

Transcriptomics | Profiling of RNA

expression levels to capture gene activity | Bulk RNA-seq;

scRNA-seq; spatial transcriptomics | Short-read

sequencing (Illumina, Inc.); in situ capture platforms (10x

Genomics, Slide-seq) | Bulk RNA-seq

quantifies average transcript abundance; scRNA-seq resolves

cell-to-cell heterogeneity; spatial transcriptomics retains tissue

architecture while measuring gene expression | (72) |

| Proteomics | Global profiling of

protein abundance, modification and interactions | Protein

identification and quantification | MS-based proteomics

(LC-MS/MS, DIA, TMT); antibody-based proteomics (RPPA, CyTOF) | MS-based methods

enable high-throughput protein identification and quantification;

antibody-based methods provide sensitive detection of specific

proteins | (73,74) |

| Metabolomics | Systematic

identification and quantification of metabolites reflecting cell

metabolic state | Targeted and

untargeted metabolomics | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR

platforms | Targeted

metabolomics measures predefined metabolites with high sensitivity;

untargeted metabolomics broadly surveys metabolites to capture

global metabolic changes | (75,76) |

Genome

Genomic studies have revealed polymorphisms and

mutations within genes associated with neutrophil functions that

may predispose individuals to sepsis or influence disease severity

(77-80). Andiappan et al (77) investigated the expression

quantitative trait loci (eQTL) of neutrophils and identified 21,210

eQTLs on 832 unique genes. The aforementioned study used Ingenuity

Pathway Analysis to reveal an enrichment of neutrophil eQTLs in

inflammatory disease, consistent with the established role of

neutrophils in host defense against pathogens (77). Utilizing a genome-wide

association study, Wang et al (78) investigated NET biomarkers to

explore the causal association between NET and sepsis.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO)-DNA complex is a biomarker of NET (79). With every standard deviation

increase in the levels of the MPO-DNA complex, there is an ~18%

increase in the risk of sepsis, a 51% increase in the risk of

28-day death from sepsis, ~38% rise in the risk of requiring

intensive care due to sepsis and ~125% higher risk of 28-day death

from sepsis requiring intensive care (80). Elevated NET levels may elevate

the risk of sepsis onset, progression and mortality (80).

Beyond the genome, the epigenome provides an

additional layer of regulation that shapes neutrophil

heterogeneity. Epigenetic mechanisms such as histone modification,

DNA methylation and chromatin accessibility dynamically modulate

transcriptional programs, enabling neutrophils to adopt diverse

functional states in response to microenvironmental cues. Using

chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing of histone H3K4me3, Piatek

et al (80) characterized

the epigenetic regulation of human neutrophil plasticity and

heterogeneity following stimulation with LPS, TNF-α or IL-10. The

aforementioned study revealed that changes in H3K4me3-marked

transcriptional start sites are associated with diverse functional

programs, including neutrophil activation, cytokine production,

apoptosis, histone remodeling and NF-κB signaling pathways

(80). IL-10 induces a distinct

subset of apoptotic yet transcriptionally active neutrophils, which

display a non-canonical NF-κB driven cytokine profile while

simultaneously suppressing the canonical NF-κB pathway (80). These findings highlight that

epigenomic profiling uncovers previously unrecognized heterogeneity

in neutrophil functional states, and that H3K4me3-associated DNA

binding sites may serve as potential therapeutic targets for

immunomodulation.

Transcriptome

Building on the genomic foundation, transcriptomic

studies have advanced understanding of neutrophil heterogeneity

(81-88).

Bulk transcriptomic profiling in patients with

sepsis has identified 37 differentially expressed genes, with

functional enrichment and protein-protein interaction analyses

highlighting immune and inflammatory signaling pathways, including

the PI3K/AKT axis, as key regulators of neutrophil specialization

(81). Validation in whole-blood

neutrophil samples from patients with sepsis patients further

confirmed these transcriptional alterations (81). These findings demonstrate

sepsis-associated transcriptional alterations, but the limited

resolution of bulk transcriptomics obscures cellular heterogeneity

and prevents the identification of distinct neutrophil subsets.

scRNA-seq provides a deeper resolution. Xie et al (28) identified eight transcriptional

neutrophil clusters in mice, with G0-G4 representing bone marrow

developmental stages and G5a-c representing three transcriptionally

distinct mature neutrophil subsets in peripheral blood. Bacterial

infection accelerates the transition from immature to mature states

without altering overall heterogeneity but induces stage-specific

transcriptional reprogramming: Early progenitors upregulate genes

regulating immune effector functions and ROS metabolism, while

mature subsets exhibit increased cytokine production (28). Infection also reshapes

transcription factor networks, with defense-associated factors such

as interferon regulatory factor 7 activated in immature cells and

metabolic regulators such as forkhead box protein P1 (Foxp1) and

CCCTC-binding factor (Ctcf) downregulated in mature subsets,

suggesting a redistribution of cell resources toward host defense

(28). However, a murine model

raises questions about their direct applicability to human sepsis,

where immune and inflammatory contexts may differ (28). In human sepsis, Xu et al

(82) identified novel

neutrophil subtypes enriched in late differentiation stages,

characterized by upregulation of alkaline phosphatase,

liver/bone/kidney (ALPL), CD177 molecule (CD177), S100

calcium-binding protein A8 (S100A8), S100A9), and syntaxin

binding protein 2 (STXBP2), providing potential biomarkers for

therapy. Hong et al (83)

further categorized neutrophils into four subsets (Neu1-Neu4) by

single-cell transcriptomic profiling, with Neu1 expansion

associated with septic shock and higher Sequential Organ Failure

Assessment (SOFA) scores. A Neu1-specific gene module, including

NFKBIA (NFKB inhibitor alpha, an inhibitor of NF-κB signaling),

CXCL8 (C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8, encoding interleukin-8),

G0S2 (G0/G1 switch gene 2, a regulator of cell cycle and

apoptosis), and FTH1 (ferritin heavy chain 1, involved in iron

storage and oxidative stress response), demonstrates strong

predictive value for shock. Consistently, Neu1 expresses cell

surface markers such as CD123, CD38 and CD69, which have been

linked to poor prognosis (84-87). However, whether these subsets

represent stable cell states or transient activation phenotypes

remains unresolved.

Beyond proinflammatory subtypes, immunosuppressive

phenotypes have also been reported: Qi et al (88) identified a PD-L1high

neutrophil subset induced via the p38α pathway, involving mitogen-

and stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) and MAPK-activated protein

kinase 2 (MK2),, capable of suppressing T cell activation and

promoting apoptosis or trans-differentiation (88).

Collectively, transcriptomics reveals that

neutrophil heterogeneity in sepsis arises from dynamic

transcriptional reprogramming, encompassing both proinflammatory

and immunosuppressive subsets with distinct clinical relevance.

Proteome

Transcriptomic profiling has advanced understanding

of neutrophil gene expression patterns in sepsis, but does not

directly link transcriptional changes to protein function.

Proteomics fills this gap by quantifying protein abundance and

activity, thereby capturing more immediate functional adaptations

of neutrophils.

Tak et al (89) identified CD62Ldim

neutrophils as a distinct subset that typically resides outside

circulation but is recruited during acute inflammation. Their

proteomic signature, enriched in proteins associated with adhesion,

activation and immune regulation, underscores functional

specialization beyond conventional morphological classification

(89). However, whether these

proteomic differences translate into stable functional phenotypes

or reflect transient activation states remains uncertain,

especially since CD62L shedding can occur in multiple inflammatory

contexts (89). This raises the

question of whether CD62Ldim neutrophils represent a

subset or activation-driven state detectable by proteomics but less

evident in physiological conditions. In parallel, hypoxia, a

hallmark of sepsis pathophysiology, triggers notable proteome

remodeling (90). Watts et

al demonstrated that hypoxic neutrophils upregulate

inflammatory receptors, including formyl peptide receptor (FPR) and

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor beta

chain (GM-CSF receptor β), enhance lysosomal protein scavenging and

sustain biosynthesis of granule and cytoskeletal proteins through

de novo synthesis (91).

These findings highlight the metabolic adaptability of neutrophils

under stress (91). The reliance

on murine models and controlled hypoxic exposure limits direct

extrapolation to human sepsis, where hypoxia is heterogeneous,

dynamic and often accompanied by additional insults such as

acidosis or oxidative stress (90,91). Furthermore, whether such

proteomic adaptations enhance host defense or contribute to

maladaptive inflammation remains unresolved.

Taken together, proteomic profiling demonstrates

that neutrophils are not passive effectors but metabolically

flexible cells capable of remodeling the proteome in response to

inflammatory and metabolic stressors. Nevertheless, studies are

largely descriptive and rely on either ex vivo stimulation

or animal models, which may not capture the temporal and spatial

complexity of sepsis in patients (89-91).

Metabolome

Proteomics reveals alterations in signaling

molecules, surface receptors and effector proteins that directly

regulate neutrophil behavior but does not capture the intricate

biochemical pathways that govern these changes in cell function and

energy metabolism. Metabolic reprogramming refers to the dynamic

reshaping of cell metabolic pathways in response to environmental

and functional demands (92). In

neutrophils, metabolomics has revealed that this process extends

beyond glycolysis to include oxidative phosphorylation and the

pentose phosphate pathway, enabling distinct effector functions

such as chemotaxis, ROS generation and NET formation (93). This metabolic adaptability

constitutes a fundamental basis of neutrophil heterogeneity,

particularly in sepsis.

In a recent study, Li et al (94) observed significant alterations in

neutrophil metabolism as severe corona virus disease 2019

(COVID-19) progresses, particularly in amino acid, redox and

central carbon metabolism. Metabolic changes in neutrophils are

associated with decreased activity of the glycolytic enzyme GAPDH

(94). When GAPDH is inhibited,

glycolysis is suppressed, leading to an increase in pentose

phosphate pathway activity, but this also diminishes the neutrophil

respiratory burst (94).

Furthermore, inhibiting GAPDH triggers the formation of NETs, which

depends on the activity of neutrophil elastase (94). This inhibition results in an

increase in neutrophil pH and blocking this pH rise prevents both

cell death and NET formation (94). These findings indicated that

neutrophils in severe COVID-19 exhibit a heterogeneous and

dysfunctional metabolic profile, which contributes to their

impaired function.

Multi-omics to explore neutrophil

heterogeneity in sepsis

Each layer of omics offers insight into genomic

variants, transcriptional changes, protein modification or

metabolic shift. However, they often present a limited view of the

complex interplay between these biological layers. For example,

genomics identifies genetic predispositions that shape neutrophil

responses, but does not capture the dynamic processes that occur

during gene expression and protein translation. Similarly,

transcriptomics reveals altered gene expression profiles associated

with sepsis but may overlook the functional implications of changes

at the protein level. Transitioning from single to multi-omics

allows for a more holistic perspective by integrating data across

different layers of biological information. Multi-omics approaches

not only facilitate the identification of distinct neutrophil

subsets and their functional states in real time but also enhance

understanding of how metabolic changes influence neutrophil

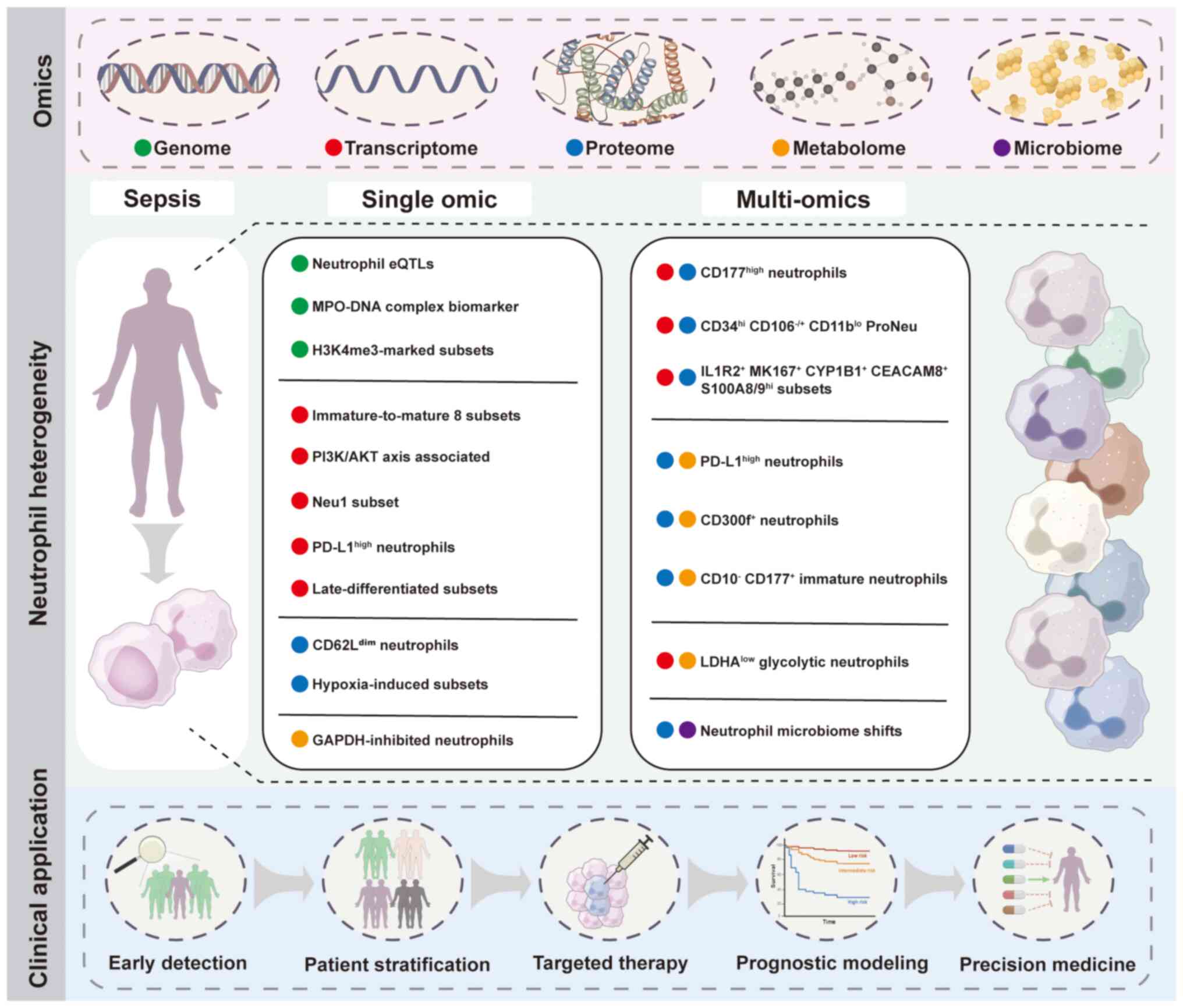

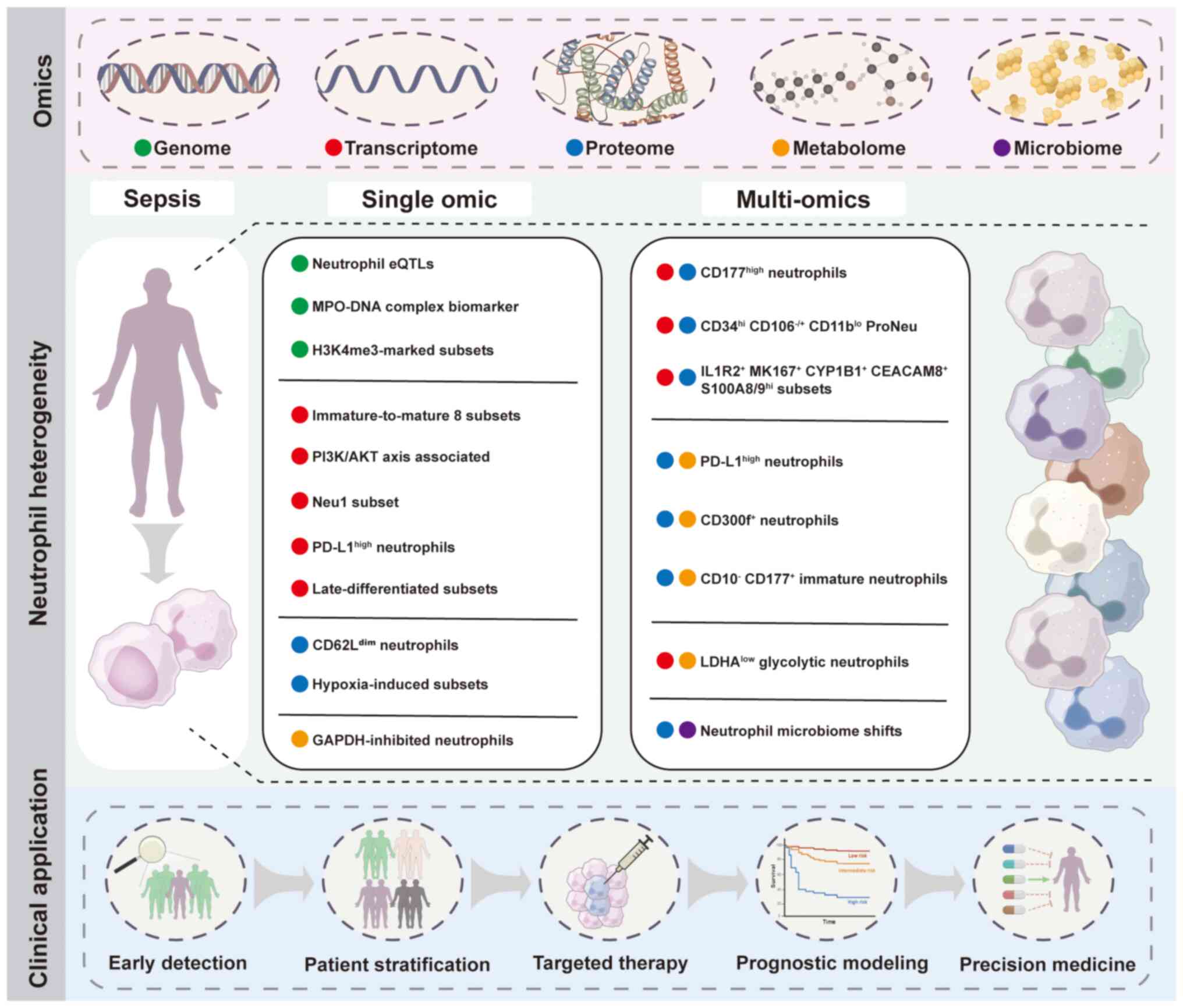

activity during sepsis (Fig.

2).

| Figure 2Multi-omics approaches reveal

neutrophil heterogeneity and clinical implications in sepsis. Omics

layers include genome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome and

microbiome. Neutrophil subsets and characteristics are identified

through single-omics studies and multi-omics integration in sepsis.

Potential clinical applications of neutrophil heterogeneity

profiling include early detection, patient stratification, targeted

therapy, prognostic modeling and precision medicine. eQTL,

expression quantitative trait loci; MPO, myeloperoxidase; H3K4me3,

histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation; PI3K/AKT, phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase/protein kinase B; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; MKI67,

marker of proliferation Ki-67; CYP1B1, cytochrome P450 family 1

subfamily B member 1; CEACAM8, carcinoembryonic antigen-related

cell adhesion molecule 8; S100A8/9, S100 calcium-binding protein

A8/9; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; Neu1, neutrophil subtype

1. |

Transcriptome and proteome

Integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data has

advanced understanding of neutrophil heterogeneity and its

functional consequences during sepsis. By linking gene expression

with protein abundance and post-translational modification, these

approaches not only delineate the molecular programs of neutrophils

but also capture how these programs are dynamically reconfigured

under septic conditions.

The source of neutrophil heterogeneity remains

debated. On one hand, studies have suggested that circulating

neutrophils follow a predefined differentiation trajectory derived

from hematopoietic progenitor cells (95,96). On the other hand, in vitro

experiments have shown that stimulation of mature neutrophils with

inflammation-associated molecules can also reshape their

transcriptome, indicating that microenvironmental cues serve a

crucial role in driving functional diversity (88,97). Thus, both developmental origin

and peripheral reprogramming may contribute to heterogeneity.

Kaiser et al (98) used

transcriptomics and proteomics to reveal mechanisms associated with

functional reprogramming of peripheral neutrophils during acute

infection. Transcriptome analysis revealed increased expression of

classical neutrophil markers such as CXCL8, SOD2, S100A8/A9, CSF3

receptor and myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen (MNDA)

(98). Activation markers and

antimicrobial genes are upregulated, including cystatin F (CST7),

S100 calcium binding protein A12 (S100A12), interleukin 1 receptor

type 2 (IL1R2) and annexin A1 (ANXA1) (98). The aforementioned study used mass

spectrometry to assess whether post-infection transcriptomic

alterations are reflected in the proteome of human neutrophils

(98). Corresponding

upregulation at both transcriptional and protein levels included

interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 and alkaline phosphatase

(98). In addition, patients

with acute bacterial infections show enrichment of

CD177high neutrophils (98). Both transcription and protein

expression of CD177 are positively associated with disease severity

(98). These results suggest

that the transcriptome response of neutrophils is effectively

translated into the proteome during bacterial inflammation.

However, the aforementioned study did not resolve how

transcriptomic shifts intersect with upstream regulatory mechanisms

such as chromatin accessibility and transcription factor activity

(95), leaving the drivers of

neutrophil reprogramming incompletely understood. Moreover,

although CD177 expression is associated with disease severity, its

biological role remains unclear, especially since up to 10% of

individuals lack CD177 without apparent immune defects (99-101). This raises the possibility that

CD177 serves as a context-dependent marker rather than a direct

effector. Finally, the cohort size and baseline heterogeneity may

limit generalizability, and larger longitudinal studies are

required to clarify the stability and functional relevance of

CD177+ neutrophils in bacterial infection (99-101).

In parallel, Kwok et al (102) identified a programmed

neutrophil lineage within granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs)

and analyzed the heterogeneous neutrophil subsets at different

stages of this lineage in sepsis. During the differentiation of

GMPs into preNeus, the aforementioned study described two

phenotypically distinct types of neutrophil progenitors, termed

proNeus (102). These include

the CD34hi CD106- CD11blo proNeu1

and the CD34lo CD106+ CD11bhi

proNeu2 subset (102).

Proteomics shows progressive upregulation of CD11b and

downregulation of CD34 expression during the differentiation of GMP

into preNeus (102). Other

differentially expressed cell surface markers include CD81, CD49a,

CD106 and CD63, which may serve as positive or exclusive markers

(102). Transcriptomics

confirms the downregulated expression of lineage-associated genes

and upregulated expression of granule protein genes in the GMP

differentiation trajectory during sepsis, suggesting that sepsis

promotes ProNeu1 differentiation (102). ProNeu1 and proNeu2 are both

early neutrophil progenitor cell populations, but their functions

are not identical (102).

ProNeu1 exhibits a stronger capacity for proliferation than proNeu2

(102). During the early stages

of sepsis inflammation, proNeu1 expands specifically and

extensively, which decreases monocyte differentiation (102). However, proNeu2 remains largely

unchanged during infection (102).

A recent multi-omics study by Kwok et al

demonstrated that septic neutrophils acquire immunosuppressive

properties and are enriched in patients with the sepsis response

signature group 1 (SRS1) (103). Single-cell transcriptomics and

cell surface protein profiling reveal the expansion of immature and

functionally distinct neutrophil subsets, including

CEACAM8+ degranulating cells, S100A8/9hi

cells, IL1R2+, peptidyl arginine deiminase type

4+, MPO+ and proliferative MK167+

CYP1B1+ neutrophils, many of which are specific to

sepsis rather than sterile inflammation (103). Coculture assays further

demonstrate that these septic subsets inhibit CD4+ T

cell activation (103).

Epigenomic profiling of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

revealed CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (CEBPA)- and β

(CEBPB)-driven regulatory programs consistent with the activation

of both steady-state and emergency granulopoiesis, linking

neutrophil reprogramming to systemic alteration in hematopoiesis

(103). Importantly, within the

SRS1 subtype, neutrophil subsets such as IL1R2+ and

MK167+ CYP1B1+ cells are significantly

enriched and exhibit STAT3- and CEBPB-dependent gene expression

programs, indicating that neutrophil heterogeneity is not only a

reflection of sepsis pathology but also a driver of

immunosuppressive disease endotypes (103). However, the single-cell cohorts

analyzed may not represent the spectrum of sepsis, and causal

involvement of transcription factors such as CEBPB and STAT3

requires direct experimental validation.

Transcriptome and metabolome

Integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic

approaches provides insights into how metabolic reprogramming

shapes neutrophil heterogeneity during sepsis.

Neutrophils are reliant on glycolysis to fuel key

antimicrobial functions, including chemotaxis, phagocytosis,

oxidative burst and NET formation (104-106), yet their metabolic flexibility

is altered in the septic milieu. Pan et al (107) demonstrated that sepsis-tolerant

neutrophils exhibit reduced glycolytic activity associated with

downregulation of LDHA via the PI3K/Akt/hypoxia-inducible factor

(HIF)-1α pathway, leading to impaired chemotactic and phagocytic

capacity. Metabolomic profiling further revealed that lactate

levels are diminished in septic neutrophils compared with

non-septic infected controls, highlighting a distinct metabolic

state of glycolytic suppression (107).

Lactate, long regarded as a metabolic byproduct, is

a immunomodulatory metabolite capable of exerting feedback control

over immune cell metabolism (108,109). While evidence in monocytes and

macrophages has demonstrated lactate-driven immunosuppression

(110,111), its role in neutrophil biology

remains less well understood. Pan et al (107) suggested that reduced lactate

production in sepsis may represent a unique metabolic signature of

neutrophil dysfunction, warranting further exploration of

lactate-mediated feedback in neutrophil plasticity. At the

molecular level, transcriptomic changes in key glycolytic enzymes,

including LDHA, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1, glucose

transporter 1 (GLUT1) and pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) converge with

metabolomic alterations, reinforcing the key role of glycolysis in

neutrophil effector responses (107). Stabilization of HIF-1α restores

LDHA expression and glycolytic activity, thereby rescuing

neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis, underscoring the

PI3K/Akt/HIF-1α axis as a central regulator of neutrophil function

in sepsis (107).

Collectively, combined transcriptomic and

metabolomic analyses uncover a metabolically defined neutrophil

subpopulation in sepsis characterized by glycolytic suppression and

functional impairment (107).

This multi-omics perspective not only advances understanding of

neutrophil heterogeneity but also highlights metabolic checkpoints

such as glycolysis and HIF-1α signaling as potential therapeutic

targets to restore neutrophil immunity in sepsis (107).

Proteome and metabolome

Exploring the association between protein

expression profiles and metabolic signatures reveals key regulatory

hubs and pathways that influence neutrophil activation, survival

and effector functions.

Using a proteomic approach, Parthasarathy et

al (112) examined the

differential expression of neutrophil subsets in patients with

sepsis. The expression of CD10, CD16 and CD86 is downregulated,

while human leukocyte antigen- DR isotype (HLA-DR), CD11b, CD80,

CD184, CD63 and CD66b are upregulated in sepsis (39,112,113). The aforementioned study

identified a specific mature neutrophil subset with high expression

of CD274 (PD-L1) and CD300f. Previous studies have shown that

blocking of PD-L1 improves survival in patients with sepsis

(114-116), and CD300f deletion stimulates

neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection and decreases

septic death in mice (117).

According to the expression of CD177, immature neutrophil subsets

are divided into two subgroups: CD10- CD177+

and CD10- CD177- (113). CD177 rapidly mobilizes specific

particles to the cell surface following cell activation (112). Differential expression of CD184

(CXCR4) and HLA-DR in CD10- CD177+ immature

neutrophil subsets is observed in patients with sepsis (118). Aged neutrophils expressing

CD184 exhibit a higher migratory activity and phagocytic capacity

than the subsequently recruited non-aged neutrophils (65). HLA-DR expression was increased in

CD10- CD177+ septic neutrophils (112). The expression and role of

HLA-DR on neutrophils remains unclear (119,120). Soluble factors pentraxin 3

(PTX3), angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), endothelial cell-specific

molecule-1 (Endocan), growth arrest-specific 6 (Gas6) and the

inflammatory marker procalcitonin are upregulated in sepsis

(112). These factors are

elevated in patients with sepsis and contribute to vascular leak

and endothelial dysfunction (121,122). Correlation analysis shows that

CD10 is inversely correlated with these factors (112). Notably, immature neutrophils

store and release PTX3 during inflammation, and this factor

predicts disease severity and mortality in sepsis (123-126). Immature neutrophils may be a

driver of vascular inflammation or leak in sepsis.

While these observations provide insights into the

functional diversity of neutrophil subsets and their potential

links to soluble mediators and vascular pathology, limitations

remain. Distinguishing sepsis from other infections or organ

failure remains clinically challenging. Integrated multi-omics

approaches have revealed associations between neutrophil

phenotypes, soluble mediators and metabolic alterations. However,

these findings are largely observational and derived from limited

patient cohorts (112).

Therefore, further mechanistic studies are needed to validate

whether specific neutrophil subsets and their products directly

drive vascular leakage and immune dysregulation in sepsis.

Proteome and microbiome

The combined investigation of proteome and

microbiome has revealed the functional dynamics of neutrophils in

the context of sepsis.

Wang et al (127) isolated neutrophils from

patients with sepsis after surgery and characterized intracellular

bacterial communities, also termed as the neutrophil-specific

microbiome. The aforementioned study showed that the proportion of

actinobacteria decreased, while the levels of proteobacteria

increased (127). Compared with

healthy controls, the abundance of Escherichia/Shigella,

Klebsiella and Bradyrhizobium is higher in patients with

sepsis (127). The

neutrophil-specific microbiome of patients with sepsis exhibits

heterogeneity (127).

Dysregulation of the circulating microbiota may increase the risk

of postoperative infectious events (128). In addition, quantitative

proteomic analysis of neutrophils derived from patients with

demonstrates proteins involved in bactericidal activities of

neutrophils are downregulated, especially in patients with septic

shock (127). Significant

downregulation of some immunomodulatory-associated proteins is also

observed in sepsis patients, including integrin α-M, IgA Fc

receptor and lactotransferrin (127). MMP9 is significantly

downregulated in patients with septic shock, indicating that the

migratory activity of neutrophils is impaired (128). Proteomic analysis reveals a

decrease in neutrophil function in sepsis (127).

Beyond elucidating the molecular heterogeneity of

neutrophils, multi-omics suggests potential biomarkers and

therapeutic targets with translational relevance. Table III summarizes representative

neutrophil-associated biomarkers identified from multi-omics, along

with their potential diagnostic or prognostic value in sepsis

(28,77,78,80-83,88,89,91, 94,98,102,103,107,112,115,117,127).

| Table IIIClinical translation and biomarker

potential of neutrophil signatures identified by multi-omics in

sepsis. |

Table III

Clinical translation and biomarker

potential of neutrophil signatures identified by multi-omics in

sepsis.

|

Biomarker/subtype | Omics source | Clinical

relevance | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Neutrophil

eQTL | Genomics | Identification of

21,210 neutrophil eQTLs (832 genes) underscores the role of

neutrophils in host defense and inflammation | (77) |

| MPO-DNA

complex | Genomics | Elevated MPO-DNA

associated with increased risk of sepsis (18%), 28-day mortality

(51%) and ICU requirement (38%) and mortality (125%) | (78) |

| H3K4me3-marked

subsets | Epigenome | IL-10 induces

transcriptionally active neutrophils, contributing to inflammation

resolution; H3K4me3 positioning suggests potential

immunotherapeutic targets | (80) |

| Transcriptional

neutrophil clusters | Transcriptome

(scRNA-seq) | Infection

accelerates immature-to-mature transition; developmental

stage-dependent neutrophil responses to infection | (28) |

| DEGs | Transcriptome (bulk

RNA-seq) | DEGs enriched in

immune/inflammatory signaling and PI3K/AKT pathway; AKT1 validated

as a potential therapeutic target in sepsis | (81) |

| Neutrophil subtypes

enriched at late differentiation stage | Transcriptome

(scRNA-seq) | A total of two

novel subsets enriched in human sepsis; five hub genes validated in

mice; candidate biomarkers and therapeutic targets (ALPL, CD177,

S100A8/A9, STXBP2) | (82) |

| Neu1 | Transcriptome

(scRNA-seq) | Neu1 associated

with septic shock and SOFA score; Neu1_C module predictive for

shock (AUC=0.81); expresses poor prognosis markers (CD123, CD38,

CD69) | (83) |

|

PD-L1high neutrophils | Transcriptome

(scRNA-seq) | Immunosuppressive

subset in sepsis (p38α/MSK1/MK2 dependent); directly inhibits T

cell response; associated with immune suppression and poor host

defense; potential therapeutic target via PD-L1 blockade | (88) |

| CD62Ldim

neutrophils | Proteome | Distinct subset

recruited during acute inflammation; proteomic profile enriched in

adhesion/activation pathways; potential biomarker of systemic

inflammation | (89) |

| Hypoxia-induced

neutrophil proteomic remodeling | Proteome | Inflammatory

receptor upregulation (FPR, GM-CSFRβ) and lysosomal protein

scavenging sustain neutrophil metabolism under stress; metabolic

pathways as potential therapeutic targets in hypoxic inflamed

tissue | (91) |

| GAPDH-inhibited

neutrophils in severe COVID-19 | Metabolome | Dysregulated amino

acid, redox and carbon metabolism; suppressed glycolysis with PPP

shift; GAPDH inhibition triggers pathogenic NET formation; links

neutrophil metabolic dysfunction to tissue damage and highlights

GAPDH as a potential therapeutic target | (94) |

|

CD177high neutrophils | Transcriptome and

proteome | Expanded during

acute bacterial infection; TLR4/NF-κB driven transcriptional

plasticity enhances antibacterial programs; CD177 upregulation is

associated with inflammation severity and may serve as a marker of

acute infectious states | (98) |

CD34hi

CD106-

CD11blo ProNeu1 | Transcriptome and

proteome | Early committed

progenitor; expands in early sepsis with high proliferative

capacity, suppressing monocyte output; potential biomarker of

emergency granulopoiesis | (102) |

CD34lo

CD106+

CD11bhi ProNeu2 | Transcriptome and

proteome | Intermediate

progenitor; stable during sepsis; reference subset for maturation

trajectory | (102) |

IL1R2+,

MK167+

CYP1B1+, CEACAM8+, S100A8/9hi | Transcriptome

(scRNA-seq) and proteome | Sepsis-specific;

inhibit CD4+ T cells; enriched in SRS1 endotype;

associated with STAT3/CEBPB-driven immunosuppression | (103) |

| LDHAlow

glycolytic neutrophils | Transcriptome and

metabolome | Exhibit suppressed

glycolysis with impaired chemotaxis and phagocytosis; dysfunction

mediated by PI3K-Akt-HIF-1α-LDHA axis; reversible by HIF-1α

activation, suggesting therapeutic potential for restoring immune

competence in sepsis | (107) |

| CD10-

CD177+ immature neutrophils | Proteome and

metabolome | Associated with

SOFA score and endothelial dysfunction (PTX3, Ang-2, endocan); PTX3

release associated with severity and mortality; associated with

metabolic dysregulation and identified as a feature for patient

stratification | (112) |

|

PD-L1high neutrophils | Proteome and

metabolome | PD-L1 blockade

improves survival in murine CLP sepsis model | (115) |

| CD300f+

neutrophils | Proteome and

metabolome | Disruption or

deletion of CD300f decreases septic mortality in murine CLP model

of sepsis | (117) |

| Neutrophil

microbiome shifts | Proteome and

microbiome | Associated with

impaired bactericidal activity and migration; downregulation of

ITGAM, LTF and MMP9; associated with septic shock | (127) |

Challenges and limitations

Despite the advances in understanding neutrophil

heterogeneity in sepsis through multi-omics, key challenges hinder

the full potential of these approaches.

Patient heterogeneity is a key obstacle to

characterizing neutrophil heterogeneity in sepsis through

multi-omics approaches. Variations in demographic and physiological

backgrounds (age, sex, genetic factors) shape neutrophil

development and lifespan, potentially masking sepsis-specific

changes (129-132). Underlying comorbid conditions

may introduce baseline alterations in neutrophil function, thereby

contributing to heterogeneity and complicating the attribution of

omics signatures solely to sepsis (133). In addition, pathogen type,

primary infection site and therapeutic intervention may induce

distinct neutrophil activation programs, while clinical

trajectories range from hyperinflammation to immunosuppression,

generating variable molecular patterns (33,134-136). These sources of variability

make datasets harder to compare, decrease reproducibility and blur

the true sepsis-associated neutrophil signatures. To overcome this

challenge, future studies should incorporate strategies such as

stratified analyses, matched cohort designs and standardized

metadata collection to distinguish patient-level variability from

the intrinsic biological diversity of neutrophils in sepsis.

Sample preparation is a key step in multi-omics

studies, but introduces inherent biases, particularly during cell

isolation and processing. For example, methods based on density

gradient centrifugation may inadvertently exclude low-density

neutrophils (LDNs), which are typically found in the peripheral

blood mononuclear cell fraction (137). By contrast, commonly used

methods obtain samples from peripheral blood or tissue, followed by

red blood cell lysis or enzymatic digestion (138). The cells are centrifuged,

resuspended, washed and filtered to ensure high-quality viable

cells. Neutrophils are purified by either positive or negative

selection using magnetic beads or fluorescence-activated cell

sorting and subjected to scRNA-seq for downstream analysis

(28). Other improvements

include initial selection of total neutrophils using magnetic beads

followed by density gradient separation of LDNs (139,140). In addition, density

gradient-based approaches to neutrophil isolation may result in

preparations containing small numbers of contaminating leukocytes,

primarily eosinophils, a potential source of bias despite the small

contribution of these leukocytes to the overall gene expression

profile (141). These technical

variations can lead to discrepancies between in vitro or

ex vivo findings and the actual in vivo behavior of

neutrophils, particularly within the complex microenvironment of

sepsis.

The temporal dynamics of neutrophil changes during

sepsis are not well understood. The heterogeneity of neutrophils in

sepsis results from a complex interaction between intrinsic factors

and disease-associated changes over time. Sepsis is a dynamic

condition, marked by rapid shifts in immune response, from

excessive inflammation in the early stage to immunosuppression in

the later stages (33). However,

most current multi-omics studies focus on single time-point

analyses, providing a static snapshot of neutrophil phenotypes,

which may overlook the ongoing changes in neutrophils during the

immune transition in sepsis (83,112). Therefore, longitudinal

multi-omics studies are necessary to capture the immune switching

of neutrophils over time and improve understanding of this dynamic

process.

Each omics layer provides a unique resolution and

focus for capturing biological heterogeneity, yet these differences

also impose analytical limitations. The integration of multi-omics

data from high-throughput platforms inherently faces challenges due

to their diverse characteristics (142). Picard et al (143) highlighted that the

heterogeneity of data complicates the integration process. For

example, transcriptomic data is often subjected to RNA-seq

normalization, while proteomic data typically rely on mass

spectrometry-specific scaling methods, leading to differing data

ranges and distribution patterns. These disparities necessitate

alignment procedures before integration. Data quality also poses a

concern. Issues such as noise, missing values and batch effects

notably impact the outcomes of the analysis (144). In addition, there are kinetic

differences between RNA and protein expression. For example,

Hoogendijk et al (145)

reported that nearly 30% of the transcriptome -proteome pairs

showed inconsistent dynamics during neutrophil differentiation.

This discrepancy may contribute to the inconsistency between the

transcriptome data from scRNA-seq and the protein-based surface

marker data from mass cytometry. These mismatches complicate the

classification of cell populations and the annotation of functional

roles.

Conclusion

Sepsis is a life-threatening syndrome characterized

by a systemic inflammatory response to infection, leading to

multiorgan dysfunction and potential mortality. The pathophysiology

of sepsis involves complex interactions between pathogens, the

immune system and various host factors. Advancements in research

have demonstrated the key role of immune cells in sepsis,

particularly neutrophils, which are frontline responders in the

immune system. The functional and phenotypical heterogeneity of

these immune cells during sepsis can influence outcomes.

In terms of phenotypical diversity, neutrophils in

sepsis exhibit various surface markers and morphologies that

reflect their activation state, origin and roles in the

inflammatory response. Functionally, neutrophils exhibit

heterogeneity in their ability to degranulate, phagocytose, release

ROS, form NETs, migrate, undergo apoptosis and mediate

immunosuppression. Understanding these functional differences is

key for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at

modulating neutrophil activity during sepsis.

The study of neutrophil heterogeneity in sepsis

through multi-omics approaches has provided insights into the

complex and adaptive nature of these immune cells. Multi-omics

studies have revealed that the differentially expressed genes,

proteins and metabolites underlying neutrophil heterogeneity are

not independent events but reflect interconnected layers of

regulation. Transcriptomic analyses have identified altered

expression of transcription factors and signaling molecules that

reprogram neutrophil activation, survival and differentiation,

while proteomic profiling has identified changes in effector

functions, including degranulation, phagocytosis and cytokine

release (81,88). Metabolomic data have further

indicated shifts in glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation and amino

acid metabolism that provide energetic and biosynthetic support for

these functions. In addition, epigenomic profiling has elucidated

associations between chromatin accessibility and histone

modifications with NF-κB signaling, apoptosis and cytokine

regulation, thereby uncovering previously unrecognized neutrophil

subsets (80,107). Multi-omics integration has

identified transcription factor-driven programs, such as

CEBPA/CEBPB- and STAT3-dependent networks, which connect emergency

granulopoiesis with the emergence of sepsis-specific neutrophil

subsets (103). Collectively,

these interconnected regulatory networks provide a mechanistic

basis by which neutrophils acquire distinct functional states,

thereby contributing to the phenotypical and functional

heterogeneity observed in sepsis.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZT designed the study. DC, PZ, JL, SC, SG, YC, YS,

TT, LD and TC performed the literature review. ZL wrote the

manuscript. CZ edited the manuscript. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

scRNA-seq

|

single-cell RNA sequencing

|

|

PMN

|

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

NET

|

neutrophil extracellular trap

|

|

LPS

|

lipopolysaccharide

|

|

TNF-α

|

tumor necrosis factor-α

|

|

eQTL

|

expression quantitative trait

loci

|

|

IPA

|

ingenuity pathway analysis

|

|

MPO

|

myeloperoxidase

|

|

COVID-19

|

coronavirus disease 2019

|

|

GMP

|

granulocyte-monocyte progenitor

|

|

SRS1

|

sepsis response signature group 1

|

|

CEBPB

|

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β

|

|

LDN

|

low-density neutrophil

|

|

AI

|

artificial intelligence

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Hubei Province health and

family planning scientific research project (grant no.

WJ2023M015).

References

|

1

|

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW,

Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche

JD, Coopersmith CM, et al: The third international consensus

definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA.

315:801–810. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford

KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer

S, et al: Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and

mortality, 1990-2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease

Study. Lancet. 395:200–211. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK,

Hartog CS, Tsaganos T, Schlattmann P, Angus DC and Reinhart K;

International Forum of Acute Care Trialists: Assessment of global

incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current

estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 193:259–272.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Prescott HC and Angus DC: Enhancing

recovery from sepsis: A review. JAMA. 319:62–75. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Prescott HC, Langa KM and Iwashyna TJ:

Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and

other acute medical conditions. JAMA. 313:1055–1057. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shankar-Hari M, Saha R, Wilson J, Prescott

HC, Harrison D, Rowan K, Rubenfeld GD and Adhikari NKJ: Rate and

risk factors for rehospitalisation in sepsis survivors: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 46:619–636. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

van der Poll T, van de Veerdonk FL,

Scicluna BP and Netea MG: The immunopathology of sepsis and

potential therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Immunol. 17:407–420. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen S, Zhang C, Luo J, Lin Z, Chang T,

Dong L, Chen D and Tang ZH: Macrophage activation syndrome in

Sepsis: from pathogenesis to clinical management. Inflamm Res.

73:2179–2197. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chang TD, Chen D, Luo JL, Wang YM, Zhang

C, Chen SY, Lin ZQ, Zhang PD, Tang TX, Li H, et al: The different

paradigms of NK cell death in patients with severe trauma. Cell

Death Dis. 15:6062024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chen S, Zhang C, Chen D, Dong L, Chang T

and Tang ZH: Advances in attractive therapeutic approach for

macrophage activation syndrome in COVID-19. Front Immunol.

14:12002892023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen D, Zhang C, Luo J, Deng H, Yang J,

Chen S, Zhang P, Dong L, Chang T and Tang ZH: Activated autophagy

of innate immune cells during the early stages of major trauma.

Front Immunol. 13:10903582023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yang J, Chang T, Tang L, Deng H, Chen D,

Luo J, Wu H, Tang T, Zhang C, Li Z, et al: Increased expression of

Tim-3 is associated with depletion of NKT Cells In SARS-CoV-2

infection. Front Immunol. 13:7966822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fine N, Tasevski N, McCulloch CA,

Tenenbaum HC and Glogauer M: The Neutrophil: Constant defender and

first responder. Front Immunol. 11:5710852020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kangelaris KN, Clemens R, Fang X, Jauregui

A, Liu T, Vessel K, Deiss T, Sinha P, Leligdowicz A, Liu KD, et al:

A neutrophil subset defined by intracellular olfactomedin 4 is

associated with mortality in sepsis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol

Physiol. 320:L892–L902. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Shen XF, Cao K, Jiang JP, Guan WX and Du

JF: Neutrophil dysregulation during sepsis: an overview and update.

J Cell Mol Med. 21:1687–1697. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Silvestre-Roig C, Hidalgo A and Soehnlein

O: Neutrophil heterogeneity: Implications for homeostasis and

pathogenesis. Blood. 127:2173–2181. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Naranbhai V, Fairfax BP, Makino S, Humburg

P, Wong D, Ng E, Hill AV and Knight JC: Genomic modulators of gene

expression in human neutrophils. Nat Commun. 6:75452015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Coit P, Yalavarthi S, Ognenovski M, Zhao

W, Hasni S, Wren JD, Kaplan MJ and Sawalha AH: Epigenome profiling

reveals significant DNA demethylation of interferon signature genes

in lupus neutrophils. J Autoimmun. 58:59–66. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pillay J, den Braber I, Vrisekoop N, Kwast

LM, de Boer RJ, Borghans JA, Tesselaar K and Koenderman L: In vivo

labeling with 2H2O reveals a human neutrophil lifespan of 5.4 days.

Blood. 116:625–627. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ericson JA, Duffau P, Yasuda K,

Ortiz-Lopez A, Rothamel K, Rifkin IR and Monach PA; ImmGen

Consortium: Gene expression during the generation and activation of

mouse neutrophils: Implication of novel functional and regulatory

pathways. PLoS One. 9:e1085532014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ng LG, Ostuni R and Hidalgo A:

Heterogeneity of neutrophils. Nat Rev Immunol. 19:255–265. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Grecian R, Whyte MKB and Walmsley SR: The

role of neutrophils in cancer. Br Med Bull. 128:5–14. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Day RB and Link DC: Regulation of

neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow. Cell Mol Life Sci.

69:1415–1423. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Elghetany MT: Surface antigen changes

during normal neutrophilic development: A critical review. Blood

Cells Mol Dis. 28:260–274. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Seree-Aphinan C, Vichitkunakorn P,

Navakanitworakul R and Khwannimit B: Distinguishing sepsis from

infection by neutrophil dysfunction: A promising role of CXCR2

surface level. Front Immunol. 11:6086962020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Silvestre-Roig C, Fridlender ZG, Glogauer

M and Scapini P: Neutrophil diversity in health and disease. Trends

Immunol. 40:565–583. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang X, Fan D, Yang Y, Gimple RC and Zhou

S: Integrative multi-omics approaches to explore immune cell

functions: Challenges and opportunities. iScience. 26:1063592023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xie X, Shi Q, Wu P, Zhang X, Kambara H, Su

J, Yu H, Park SY, Guo R, Ren Q, et al: Single-cell transcriptome

profiling reveals neutrophil heterogeneity in homeostasis and

infection. Nat Immunol. 21:1119–1133. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shaath H, Vishnubalaji R, Elkord E and

Alajez NM: Single-cell transcriptome analysis highlights a role for

neutrophils and inflammatory macrophages in the pathogenesis of

severe COVID-19. Cells. 9:23742020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Deerhake ME, Reyes EY, Xu-Vanpala S and

Shinohara ML: Single-Cell transcriptional heterogeneity of

neutrophils during acute pulmonary cryptococcus neoformans

infection. Front Immunol. 12:6705742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Civelek M and Lusis AJ: Systems genetics

approaches to understand complex traits. Nat Rev Genet. 15:34–48.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

32

|

Johnson Chavarria EC: A primer of human

genetics. Yale J Biol Med. 89:6032016.

|

|

33

|

van der Poll T, Shankar-Hari M and

Wiersinga WJ: The immunology of sepsis. Immunity. 54:2450–2464.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Borregaard N: Neutrophils, from marrow to

microbes. Immunity. 33:657–670. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Stadtmann A and Zarbock A: CXCR2: From

bench to bedside. Front Immunol. 3:2632012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Phillipson M and Kubes P: The neutrophil

in vascular inflammation. Nat Med. 17:1381–1390. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chishti AD, Shenton BK, Kirby JA and

Baudouin SV: Neutrophil chemotaxis and receptor expression in

clinical septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 30:605–611. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Rios-Santos F, Alves-Filho JC, Souto FO,

Spiller F, Freitas A, Lotufo CM, Soares MB, Dos Santos RR, Teixeira

MM and Cunha FQ: Down-regulation of CXCR2 on neutrophils in severe

sepsis is mediated by inducible nitric oxide synthase-derived

nitric oxide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 175:490–497. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Demaret J, Venet F, Friggeri A, Cazalis

MA, Plassais J, Jallades L, Malcus C, Poitevin-Later F, Textoris J,

Lepape A and Monneret G: Marked alterations of neutrophil functions

during sepsis-induced immunosuppression. J Leukoc Biol.

98:1081–1090. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pillay J, Kamp VM, van Hoffen E, Visser T,

Tak T, Lammers JW, Ulfman LH, Leenen LP, Pickkers P and Koenderman

L: A subset of neutrophils in human systemic inflammation inhibits

T cell responses through Mac-1. J Clin Invest. 122:327–336. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

41

|

Geng S, Matsushima H, Okamoto T, Yao Y, Lu

R, Page K, Blumenthal RM, Ward NL, Miyazaki T and Takashima A:

Emergence, origin, and function of neutrophil-dendritic cell

hybrids in experimentally induced inflammatory lesions in mice.

Blood. 121:1690–1700. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ode Y, Aziz M and Wang P: CIRP increases

ICAM-1(+) phenotype of neutrophils exhibiting elevated iNOS and

NETs in sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 103:693–707. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hoffmann JJ: Neutrophil CD64: A diagnostic

marker for infection and sepsis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 47:903–916.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hoffmann JJ: Neutrophil CD64 as a sepsis

biomarker. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 21:282–290. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Cid J, Aguinaco R, Sánchez R, García-Pardo

G and Llorente A: Neutrophil CD64 expression as marker of bacterial

infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect.

60:313–319. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Li S, Huang X, Chen Z, Zhong H, Peng Q,

Deng Y, Qin X and Zhao J: Neutrophil CD64 expression as a biomarker

in the early diagnosis of bacterial infection: A meta-analysis. Int

J Infect Dis. 17:e12–e23. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Bouchon A, Facchetti F, Weigand MA and

Colonna M: TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator

of septic shock. Nature. 410:1103–1107. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Demaret J, Venet F, Plassais J, Cazalis

MA, Vallin H, Friggeri A, Lepape A, Rimmelé T, Textoris J and

Monneret G: Identification of CD177 as the most dysregulated

parameter in a microarray study of purified neutrophils from septic

shock patients. Immunol Lett. 178:122–130. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes GL, Metzler KD

and Zychlinsky A: Neutrophil function: From mechanisms to disease.

Annu Rev Immunol. 30:459–489. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Boeltz S, Amini P, Anders HJ, Andrade F,

Bilyy R, Chatfield S, Cichon I, Clancy DM, Desai J, Dumych T, et

al: To NET or not to NET: Current opinions and state of the science

regarding the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell

Death Differ. 26:395–408. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Patel JM, Sapey E, Parekh D, Scott A,

Dosanjh D, Gao F and Thickett DR: Sepsis Induces a Dysregulated

Neutrophil Phenotype That Is Associated with Increased Mortality.

Mediators Inflamm. 2018:40653622018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Martins PS, Kallas EG, Neto MC, Dalboni

MA, Blecher S and Salomão R: Upregulation of reactive oxygen

species generation and phagocytosis, and increased apoptosis in

human neutrophils during severe sepsis and septic shock. Shock.

20:208–212. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Alves-Filho JC, Spiller F and Cunha FQ:

Neutrophil paralysis in sepsis. Shock. 34(Suppl 1): S15–S21. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Reddy RC and Standiford TJ: Effects of

sepsis on neutrophil chemotaxis. Curr Opin Hematol. 17:18–24. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Tavares-Murta BM, Zaparoli M, Ferreira RB,

Silva-Vergara ML, Oliveira CH, Murta EF, Ferreira SH and Cunha FQ:

Failure of neutrophil chemotactic function in septic patients. Crit

Care Med. 30:1056–1061. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Brown KA, Brain SD, Pearson JD, Edgeworth

JD, Lewis SM and Treacher DF: Neutrophils in development of

multiple organ failure in sepsis. Lancet. 368:157–169. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Arraes SM, Freitas MS, da Silva SV, de

Paula Neto HA, Alves-Filho JC, Auxiliadora Martins M, Basile-Filho

A, Tavares-Murta BM, Barja-Fidalgo C and Cunha FQ: Impaired

neutrophil chemotaxis in sepsis associates with GRK expression and

inhibition of actin assembly and tyrosine phosphorylation. Blood.

108:2906–2913. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Martins PS, Brunialti MK, Martos LS,

Machado FR, Assunçao MS, Blecher S and Salomao R: Expression of

cell surface receptors and oxidative metabolism modulation in the

clinical continuum of sepsis. Crit Care. 12:R252008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59