Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), one of the most

devastating microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus,

manifests initially as microalbuminuria and progressively evolves

into end-stage renal disease through characteristic glomerulopathic

changes (1). This trajectory

underscores the critical need to elucidate its molecular

pathogenesis and develop targeted interventions for early renal

preservation. Previous evidence implicates glomerular podocytes as

primary targets in diabetic renal injury, where their structural

and functional integrity governs glomerular filtration barrier

competence (2). Notably, the

high mitochondrial density in these specialized epithelial cells,

which rely predominantly on oxidative phosphorylation for energy

homeostasis, renders them particularly vulnerable to metabolic

disturbances. Consequently, podocyte mitochondrial dysfunction is

increasingly recognized as a pivotal driver of DN progression,

involving disrupted energy metabolism, exacerbated oxidative

stress, and impaired organelle quality control mechanisms (3).

Emerging evidence indicates that complement system

activation, particularly through the C3a/C3aR axis, is involved in

progressive DN (4,5). Substantial studies demonstrate that

C3aR blockade reduces podocyte mitochondrial dysfunction and

oxidative stress while alleviating renal damage in DN rodent models

(6-8). Mitophagy, a selective autophagic

process essential for cellular homeostasis, eliminates damaged

mitochondria via lysosomal degradation (9). In early diabetes, renal cells

exhibit enhanced clearance of glucose-damaged mitochondria.

However, disease progression coincides with increased mitochondrial

fission, heightened oxidative stress and defective mitophagy. This

failure to eliminate compromised mitochondria permits damaging

factor release (reactive oxygen species), thus driving DN

advancement (10). In both

high-glucose environments and DN models, a decrease in the

expression of key proteins involved in mitophagy, such as PINK1,

parkin and microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3B

(LC3B), has been observed in podocytes. Conversely, the expression

of P62, an indicator of impaired autophagy, significantly increases

(11-13). These findings suggest that

dysfunction in podocyte mitophagy may play a crucial role in the

pathogenesis of DN.

Despite evidence linking C3a/C3aR to DN, the

mechanisms underlying its role in podocyte mitophagy remain

unclear. While our prior clinical and animal data demonstrated

local complement C3 activation and reduced mitophagy in DN, the

direct regulatory involvement of C3a/C3aR in mitophagy

downregulation remains undefined. The current study aimed to

evaluate C3a/C3aR effects on glomerular podocytes utilizing both

human podocyte cultures and db/db murine models. Markedly increased

renal C3 and C3aR expression was observed in diabetic mice and high

glucose (HG)-exposed podocytes. Importantly, a novel regulatory

role for C3a/C3aR was identify in maintaining podocyte

mitochondrial homeostasis through PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 signaling-mediated

mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy. These findings suggest that

targeting C3aR to preserve mitochondrial function and cellular

bioenergetics upstream of cellular damage represents a promising

therapeutic strategy for DN.

Materials and methods

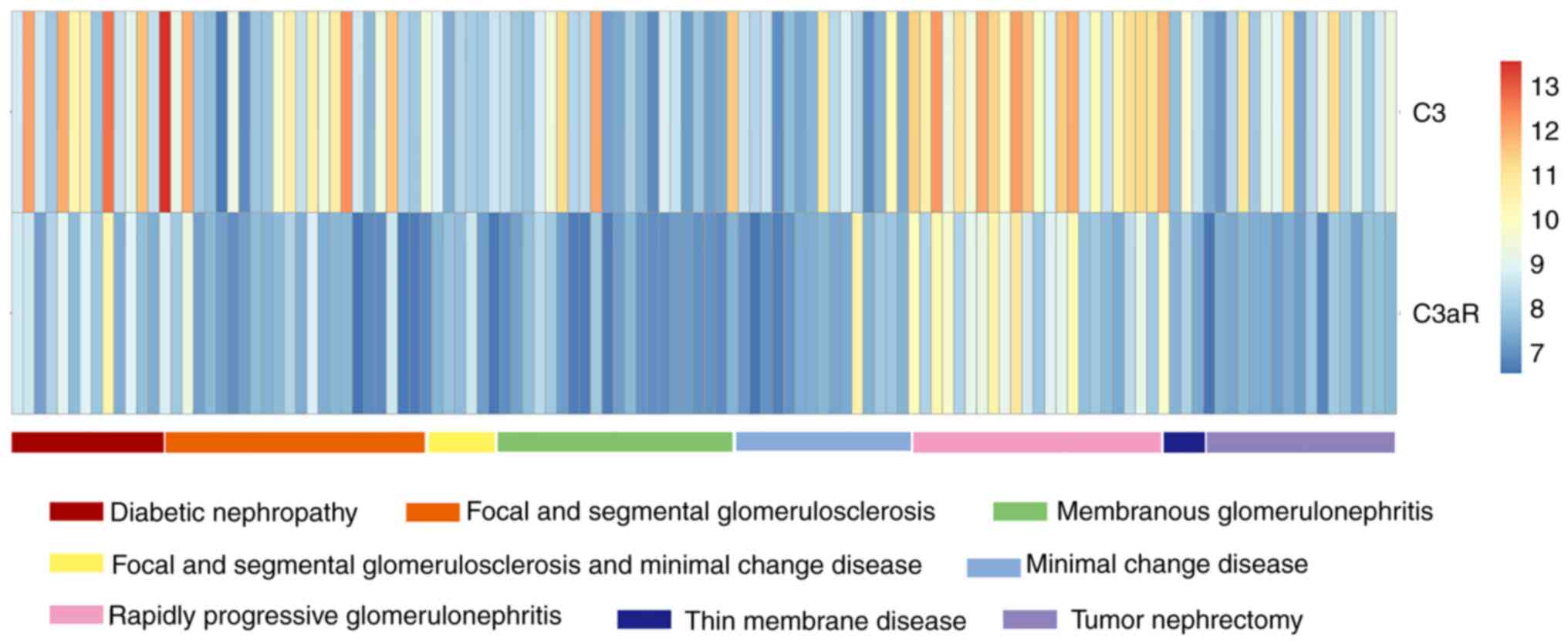

Gene expression profiling data and

preprocessing

Transcriptomic profiles of human kidney podocytes

were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession no.

GSE47183), comprising 122 samples across eight pathological

categories, including DN (n=14), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

(FSGS, n=23), FSGS with minimal change disease (MCD, n=6),

membranous glomerulonephritis (n=21), MCD (n=15), rapidly

progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN, n=23), thin membrane disease

(TMD, n=3), and tumor nephrectomy controls (n=17) (14,15), The dataset was normalized using

Robust Multichip Average standardization with the affy package

(v1.78.0; Bioconductor Release 3.18, https://bioconductor.org). After normalization, the

platform file was used to map each probe to Entrenz Gene ID. If a

probe maps to multiple genes or does not map to any genes, the

expression value of the probe is deleted. If multiple probes map to

the same gene, the average value of these probes is taken as the

expression value of the gene. The normalized data was visualized

using pheatmap (Bioconductor pheatmap package).

Animals and reagents

Male C57BLKS/JGpt wild-type (wt/wt, 8-week-old,

20-25 g, n=10) and db/db mice (8-week-old, 45-55 g, n=20) were

procured from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. All procedures were conducted

in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals (16) and approved by

the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fujian Medical

University (approval no. IACUC FJMU 2023-Y-1033; Fuzhou, China).

Animals were maintained under standardized conditions (12/12-h

light/dark cycle, 22±2°C, 60% humidity) with ad libitum access to

food and water. Following a 7-day acclimatization period, wt/wt

mice served as non-diabetic controls (NC, n=6). Diabetic db/db mice

were randomly allocated into two experimental groups (n=6/group):

i) A C3aR antagonist (C3aRA)-treated group, which received

intraperitoneal injections of SB290157 (10 mg/kg; cat. no.

HY-101502A/CS-6852; MedChemExpress) every 48 h (17); and ii) a vehicle group, which

received equivalent volumes of 5% DMSO in sterile saline. SB290157

was freshly reconstituted in vehicle solution (5% DMSO in 0.9%

NaCl) under aseptic conditions. All solutions were filtered through

0.22-μm membranes prior to administration. After 8 weeks of

intervention, 24-h urine was collected from all mice using a

metabolic cage (Fig. S1).

Euthanasia was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 2% sodium

pentobarbital at a dose of 100 mg/kg. Next, bilateral kidneys were

excised, the renal capsule was removed, and the kidneys were

sectioned by sagittal. Kidney tissue was either fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h or rapidly frozen in liquid

nitrogen.

Measurement of serum creatinine, urinary

albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR), 24-h urinary total protein (UTP)

and cell-culture medium C3a level

Metabolic cages were used to collect 24 h urine

samples. The contents of serum creatinine, 24-h UTP and UACR were

measured using an automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman Coulter,

Inc.). Cell-culture medium C3a levels were measured by using ELISA

kits (Human Complement C3a; cat. no. USEA387Hu; Wuhan Cloud-Clone

Corp.), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Histological analysis

Kidney sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated

and were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and

Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS).

Cell culture

An immortalized human podocyte cell line was donated

by Professor Moin A. Saleem (Bristol University, UK) and was

retained and donated by the Nephrology Laboratory of Wuhan

University. Cells were cultured in low-glucose Roswell Park

Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The human immortalized podocytes used in

the present study were of passages 16-23. The podocytes were

propagated at 33°C and treated with interferon

[insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS)-G; 10 U/ml; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.]. Next, cells were differentiated without

ITS-G at 37°C for 7 days. For further evaluation, the podocytes

were stimulated with HG (30 mM glucose) and mannitol (24.5 mM

mannitol + 5.5 mM glucose) containing 1% FBS with or without

incubation with C3a or C3aRA (SB290157) for 24 h.

Application of small interfering RNA

(siRNA)

A duplex siRNA was designed to target human C3aR

(NCBI: NM 004054.4; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=NM+004054.4).

The target sequence is GCUUCAAACAACCUCUAAU (1746-1764 bp) and the

siRNA nucleotide sequences for C3aR were r(GCCUCAAACAACCUCUAAU)

dTdT (Sense) and r(AUUAGAGGUUGUUUGAGGC) dGdG (Antisense). A duplex

siRNA was designed to target human PINK1 (NCBI: NM 032409.3;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=NM+032409.3).

The target sequence is GCTGGAGGAGTATCTGATA (1,449-1,467 bp) and the

siRNA nucleotide sequences for PINK1 were r(GCUGGAGGAGUAUCUGAUA)

dTdT (Sense) and r(UAUCAGAUACUCCUCCAGC) dGdG (Antisense).

Meanwhile, Negative control (NC) siRNA with no homology to

mammalian genomes served as negative control, which nucleotide

sequences were r (UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU) dTdT (Sense) and r

(ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA) dTdT (Antisense). All siRNAs were synthesized

by Shanghai Hanheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. For transfection, cells

were seeded at 60% confluency in antibiotic-free medium and

transfected with 50 nM siRNA using RNAFit™ Transfection Reagent

(cat. no. HB-RF-1000; Shanghai Hanheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection for downstream

analysis, with protein expression verification performed by western

blotting (Fig. S2).

TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

(TUNEL) assay

Paraffin-embedded kidney sections and cell slides

were processed with a TUNEL assay kit (Dalian Meilun Biology

Technology Co., Ltd.) to detect apoptosis. Paraffin-embedded renal

sections were deparaffinized using xylene and rehydrated with

ethanol. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 37°C for 10

min. The deparaffinized sections and fixed cell slides were

incubated first with 20 μg/ml DNase-free proteinase K for 30

min at room temperature and then with TdT reaction mix for 60 min

at 37°C in the dark. Next, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI

(0.001 mg/ml). Images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope.

The apoptotic cells were identified and quantified by counting the

number of positive cells in three fields per group.

Immunohistochemistry

Xylene and ethanol were used to deparaffinize and

dehydrate renal sections, respectively, and citrate buffer was used

for antigen retrieval. The sections were incubated with antibodies

against C3 (1:5,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), C3aR

(1:5,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), Mnf2 (1:1,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) or PINK1 (1:1,000; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h. Next, the sections were stained

with an enhanced polymer detection system (Beijing Zhongshan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Diaminobenzidine was used as an HRP-specific

substrate.

Immunofluorescence

Renal tissue sections and cell slides were washed

with PBS, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and

blocked with 5% BSA (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C

for 30 min. Next, samples were incubated with a primary antibody

overnight at 4°C. The following antibodies were employed: Mouse

anti-TOMM20 (1:100; cat. no. 11802-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

rabbit anti-synaptopodin (1:200; cat. no. ab224491; Abcam) and

guinea pig anti-nephrin (1:200; cat. no. GP-N2; ProGen). After PBS

washing, sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with

goat anti-guinea pig, goat anti-mouse, or goat anti-rabbit

secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 488 or 594,

followed by treatment with DAPI (0.001 mg/ml) for 10 min at room

temperature. Quantification of the TOMM20/nephrin toward staining

was performed in 10-15 glomeruli per section using ImageJ 1.40g

(National Institutes of Health), and data were expressed as a

percentage of the TOMM20/nephrin co-staining area (yellow) on the

total glomerular TOMM20 area (red). Samples were examined under a

confocal inverted laser microscope (LSM 510 Meta; Carl Zeiss

AG).

Preparation of C3a solution

Human complement C3a (cat. no. 204881; 50 μg;

Merck KGaA) was diluted to a concentration of 5-10 M using sterile

PBS at a pH of 7.2. The resulting solution was aliquoted into 50

μl portions and stored at −80°C. This solution was utilized

for extrinsic interventions on podocytes at different time points

and concentrations.

Cytoskeleton visualization

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 37°C

for 15 min, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100,

blocked with 5% BSA for 30 min and stained with 500 nM Alexa Fluor™

488 phalloidin (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30

min and DAPI (0.001 mg/ml) for 15 min. The cytoskeleton was

visualized in the composite image of the F-actin (phalloidin,

green). The average intensity of F-actin was measured using ImageJ

1.40g software.

Double labeling GFP/LC3B-DsRed/Mito

adenovirus mitophagy assay

A mixture of 20 μl DsRed-Mito (red)

adenovirus stock solution (1x1010 PFU/ml) + 20 μl

GFP-LC3B (green) adenovirus stock solution (1x1010

PFU/ml) + 160 μl RPMI-1640 medium was prepared to make a

final volume of 200 μl adenovirus mix (1x109

PFU/ml). Podocytes were washed with PBS three times for 3 min each,

and 250 μl RPMI-1640 medium was added to each well. Next, 15

μl of the adenovirus mix (optimal MOI=100, Fig. S3) was added to each well, and

after 4 h of infection, an additional 250 μl RPMI-1640

medium was added. Next, the virus-containing medium was aspirated,

and complete medium was added for 12-h incubation. Subsequently,

cells were fixed, their nuclei were stained, and images were

captured. By utilizing the dual fluorescence adenovirus system

(GFP/LC3B-DsRed/Mito), the dynamic process of mitophagy could be

precisely tracked in real-time tracked. Quantification of

GFP-LC3B (green)-associated Mito-DsRed (red) staining was

performed using ImageJ 1.40g software. Analysis included

determining the total number of LC3-positive points and the

percentage of Mito-LC3B overlap among LC3-positive points. Each

experiment involved analyzing at least ≥5 cells.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from kidney tissues and

podocytes using RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) containing a protease inhibitor

cocktail (cat. no. P1005; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and

a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. P1082; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Tissue homogenates were centrifuged at

12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the protein concentrations of

supernatants were determined by using a BCA protein assay kit (cat.

no. P0009; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and stored at

−80°C. Equal amounts of proteins (40 μg) were loaded per

lane on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to polyvinylidene

difluoride (PVDF) membranes (MilliporeSigma), which were blocked

with 5% non-fat milk for 2 h at room temperature. Next, the

membranes were incubated with primary antibody against β actin

(1:2,000; cat. no. A1978; MilliporeSigma), C3 (1:500; cat. no.

sc-28294; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), C3aR (1:500; cat. no.

sc-53738; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), parkin (1:1,000; cat.

no. 14060-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), PINK1 (1:500; cat. no.

23274-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), TOMM20 (1:500; cat. no.

11802-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), LC3B (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab192890; Abcam), ZO 1 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab96587; Abcam),

synaptopodin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab224491; Abcam), podocin (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab50339; Abcam), PI3K [p85α (54 + 85 kDa); 1:1,000; cat.

no. MA5-14942; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

phosphorylated (p)-AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. MA5-14952;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and FoxO1 (1:1,000;

cat. no. MA5-17151; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at

4°C overnight. Blots were incubated with Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L)

HRP conjugate (cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) or Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)

HRP conjugate (cat. no. ab6789; Abcam) at 1:10,000 dilution in 5%

non-fat milk/TBST for 1 h at 25°C. Images were analyzed in ImageJ

(v1.54f; National Institutes of Health) using the Gel Analyzer

tool. Rolling ball radius (50 pixels) was applied for background

subtraction.

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

Mouse kidneys were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and

0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (Ph 7.2) overnight at 4°C. Samples

were embedded in epoxy resin after being washed with 0.1 M

cacodylate buffer and saline, followed by a gradual series of

ethanol dehydration. Sections (60-90 nm thickness) were then

incubated on copper grids, contrasted with aqueous uranyl acetate

and lead citrate, and analyzed. Images were recorded with a TEM

(H7500; Hitachi, Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error

of the mean. Comparisons between two groups were performed using a

paired Student's t test. For multiple groups, the data were

analyzed by one- or two way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc

tests, where appropriate. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. All statistical analyses were

performed using GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 software (GraphPad;

Dotmatics).

Results

Expression of C3 and C3aR in different

kidney-related diseases

The results of the present study were analyzed by

comparing the expression levels of the same gene in different

kidney-related diseases. As shown in Fig. 1, the expression levels of C3 and

C3aR were relatively high in RPGN and DN, compared with the other

kidney-related diseases, indicating that the activation of

complement C3 may be closely related to the occurrence and

development of DN.

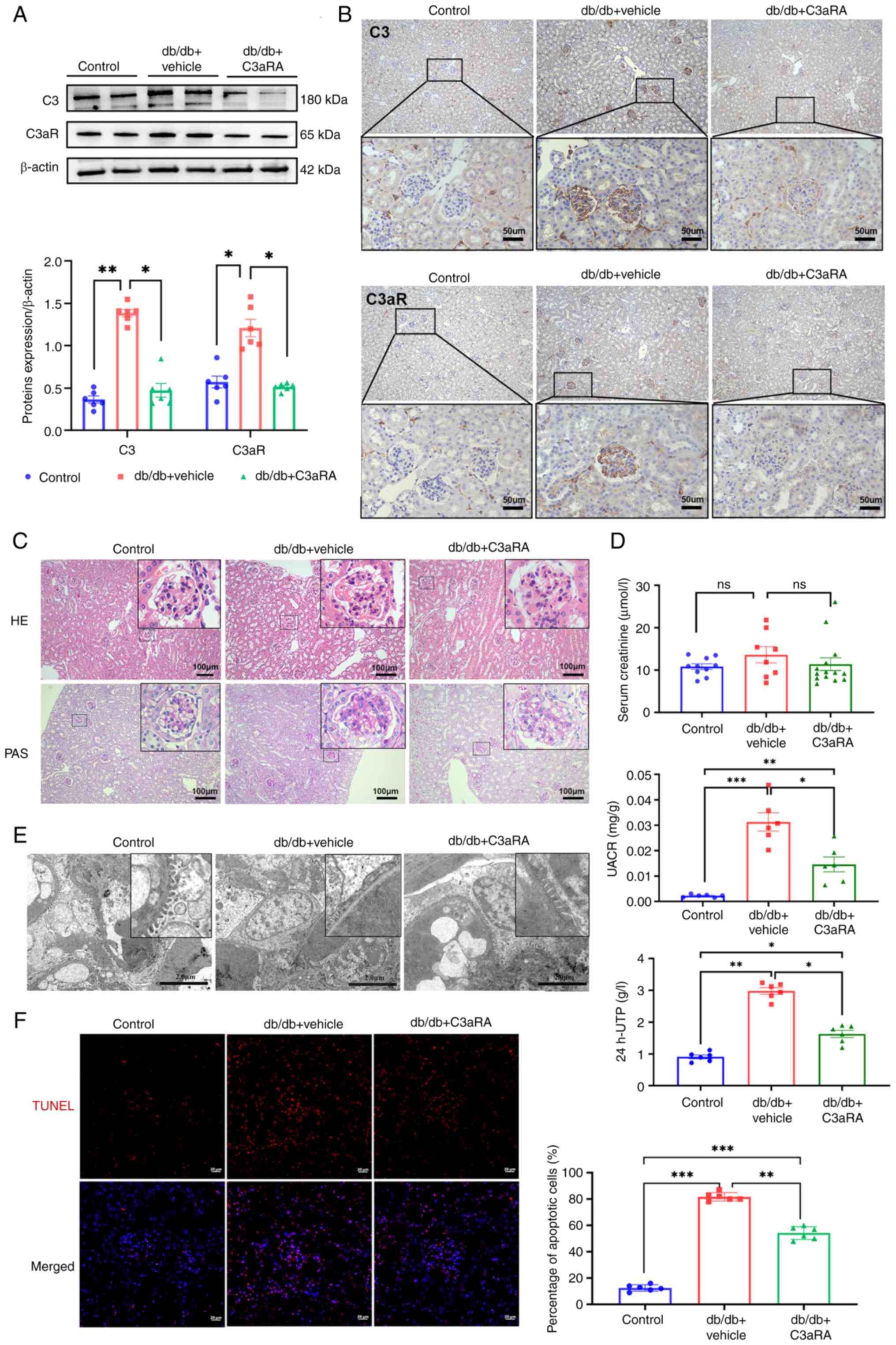

Inhibiting C3aR shows promise in

ameliorating renal damage in DN mice

Further validation was conducted in vivo in a

DN model (db/db mice). Although serum C3a levels showed no

significant difference (Fig.

S4), renal C3 and C3aR protein expression was significantly

increased in DN mice versus non-diabetic controls (Fig. 2A). Glomerular-localized

C3/C3aR proteins levels (Fig.

2B) were substantially reduced following SB290157 treatment.

Histological analysis revealed that db/db mice exhibited glomerular

hypertrophy, mesangial hyperplasia, increased cellularity and

matrix expansion (H&E and PAS staining; Fig. 2C). C3aRA intervention attenuated

mesangial matrix deposition without exacerbating cellular

proliferation. Biochemical assessments demonstrated significantly

elevated UACR, 24 h-UTP, blood glucose levels, total cholesterol,

or triglyceride levels and kidney/body weight ratios (Table SI) in db/db mice versus

controls, despite non-significant differences in serum creatinine.

Electron microscopy confirmed diffuse podocyte foot process

effacement with increased renal apoptosis. C3aRA treatment

significantly reduced body weight (Fig. S5), UACR and 24 h-UTP, restored

organized foot process architecture, and diminished apoptosis

(Fig. 2D-F). Collectively, these

data indicated that C3aR antagonism ameliorates proteinuria

and histopathological damage in experimental DN.

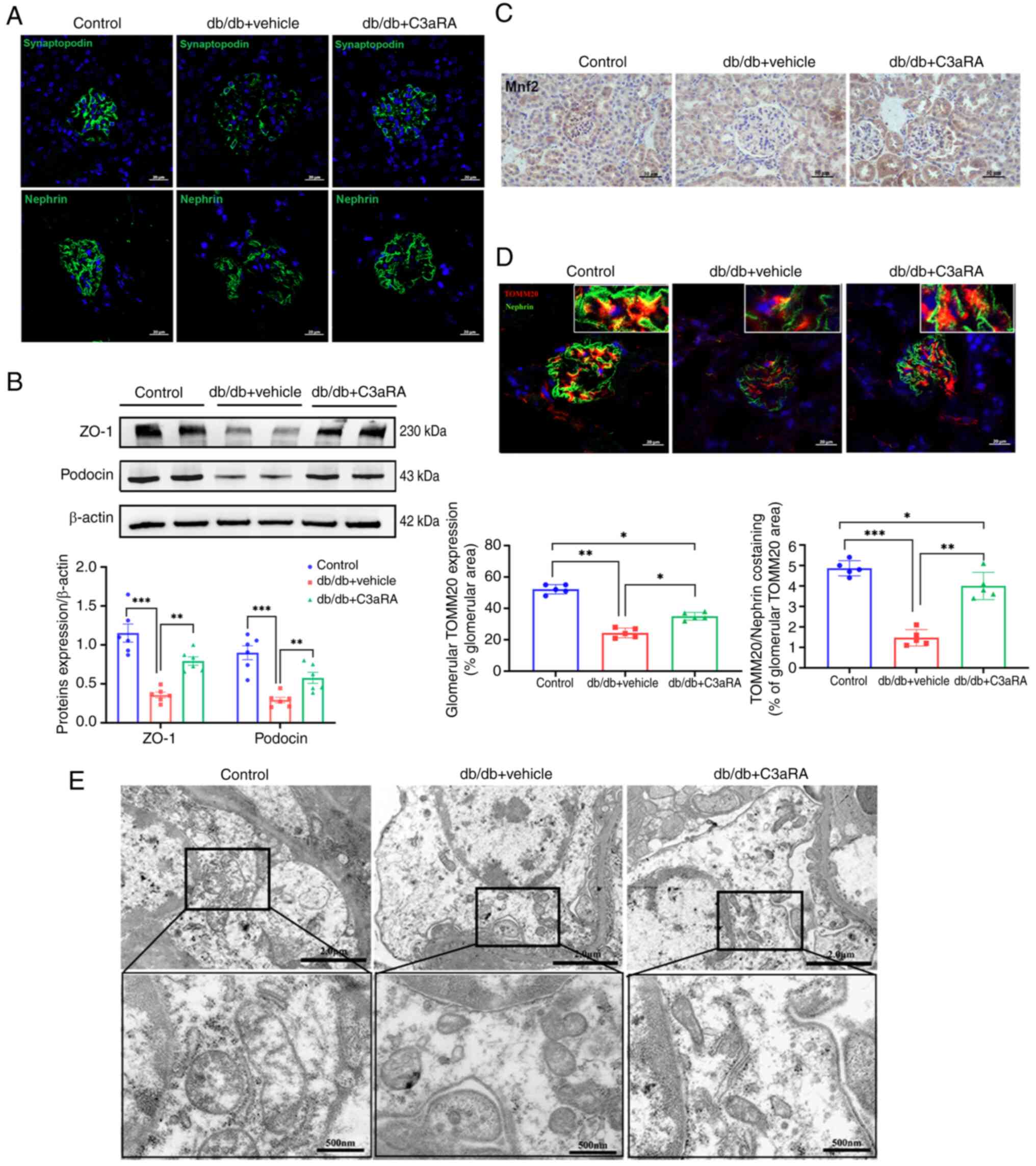

C3aR inhibition ameliorates podocyte

dysfunction and mitochondrial injury in diabetic mice

Accumulating evidence has identified podocyte injury

as a critical pathogenic mechanism in DN progression (11,18). Immunofluorescence analysis

demonstrated significantly diminished fluorescence intensity and

disrupted cytoskeletal architecture in db/db podocytes. C3aRA

intervention upregulated synaptopodin and nephrin expression in DN

models (Fig. 3A). Protein

quantification revealed marked downregulation of the glomerular

filtration barrier components ZO-1 and podocin in db/db renal

tissues versus controls, and these effects were reversed by C3aR

blockade (Fig. 3B).

The mitochondrial integrity regulators Mfn2 (fusion

protein) and TOMM20 (a translocase of the outer mitochondrial

membrane) exhibited significantly reduced glomerular deposition in

db/db mice (Fig. 3C and D).

Ultrastructural analysis confirmed mitochondrial swelling, matrix

disorganization and cristae fragmentation (Fig. 3E). C3aRA treatment normalized

Mfn2 and TOMM20 expression (Fig. 3C

and D) and restored mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 3E), indicating significant

attenuation of podocyte mitochondrial damage.

Comparative analysis of mitophagy and

signaling pathway alterations in DN

Western blot analysis of renal tissue homogenates

revealed significantly reduced expression of the mitophagy markers

LC3B-II/LC3B-I, PINK1 and parkin in DN model mice versus controls

(Fig. 4B). Immunohistochemistry

demonstrated diminished PINK1 deposition in both glomerular and

tubular compartments of db/db mice, with pronounced reduction in

glomeruli (Fig. 4A). Notably,

intraperitoneal administration of SB290157 partially reversed these

alterations, significantly elevating LC3B-II/LC3B-I, PINK1 and

parkin protein levels (Fig. 4B)

while enhancing glomerular PINK1 deposition (Fig. 4A). These findings indicated that

C3aRA mitigates impaired autophagic flux and enhances

PINK1-mediated mitophagy in diabetic kidneys.

It was observed in previous experiments by the

authors that p-AKT was activated in renal tissues of db/db mice,

while t-AKT expression levels remained stable (Fig. S6A). Further immunoblotting

demonstrated PI3K/AKT pathway activation in diabetic renal tissue,

characterized by increased PI3K expression and p-AKT, concomitant

with FoxO1 suppression (Fig.

4C). C3aR antagonism significantly attenuated PI3K/p-AKT

upregulation while restoring FoxO1 expression (Fig. 4C), indicating that modulation of

this signaling axis contributes to the therapeutic effect.

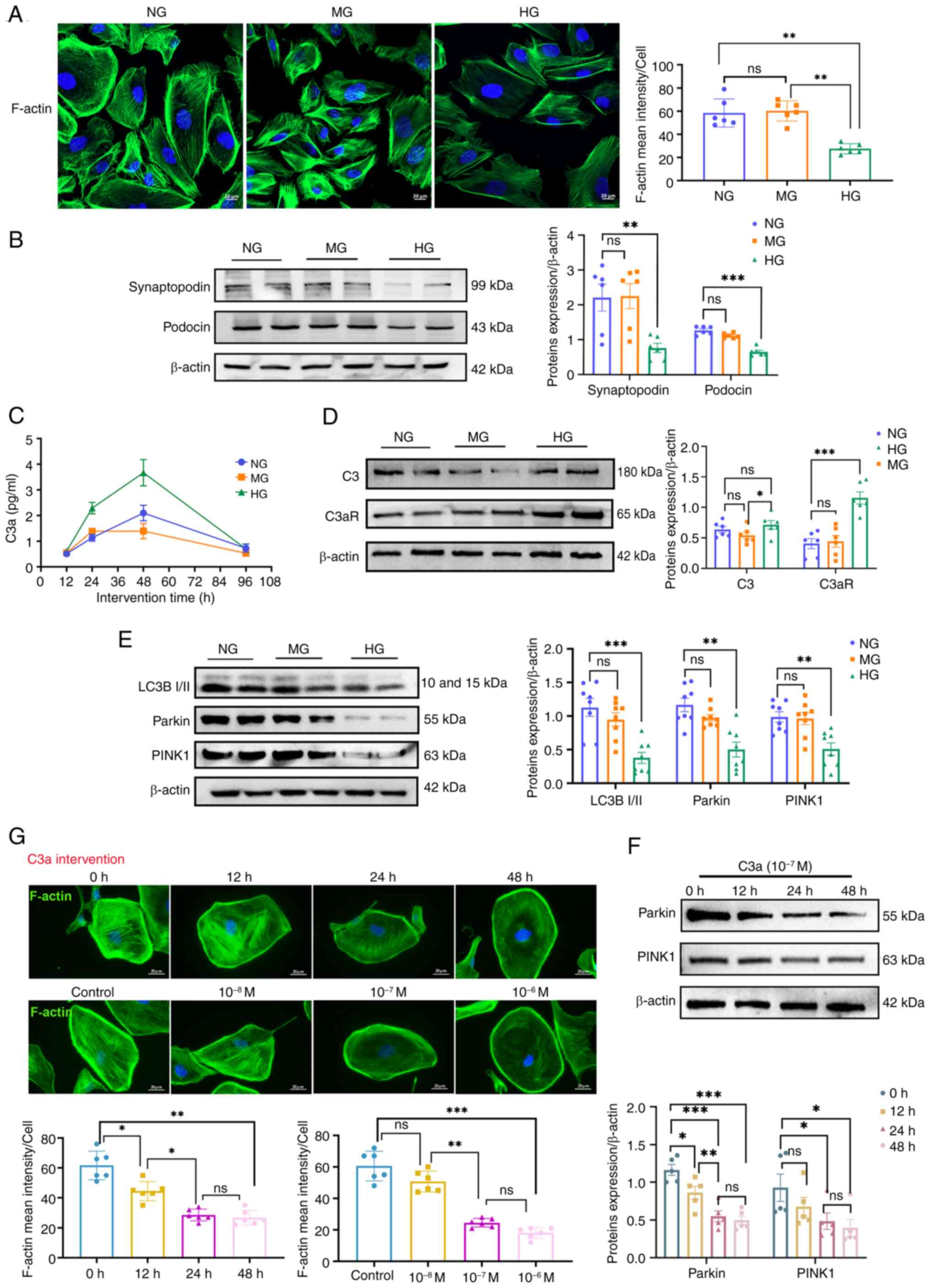

HG and C3a induce podocyte injury and

suppress mitophagy in vitro

The C3/C3aR axis is implicated in impaired podocyte

mitophagy in DN. To investigate this mechanistically, hyperglycemic

injury was modeled in vitro by using conditionally

immortalized podocytes. Podocytes were cultured for 24 h under

normal glucose (NG, 5.5 mM glucose), HG (30 mM glucose) or mannitol

high osmotic control (MG, 24.5 mM mannitol + 5.5 mM glucose)

conditions. HG-exposed podocytes exhibited F-actin disassembly with

reduced fluorescence intensity versus NG/MG controls (Fig. 5A), which was accompanied by

significant downregulation of synaptopodin and podocin (Fig. 5B). C3aR expression significantly

increased under HG conditions (Fig.

5D). ELISA revealed time-dependent C3a accumulation in

supernatants, with HG cultures showing accelerated generation (≤96

h) despite comparable cellular C3 expression across groups

(Fig. 5C). Mitophagy markers

(LC3B-II/LC3B-I, PINK1 and parkin) were significantly suppressed in

HG-treated podocytes (Fig. 5E),

confirming complement axis activation and mitophagy impairment.

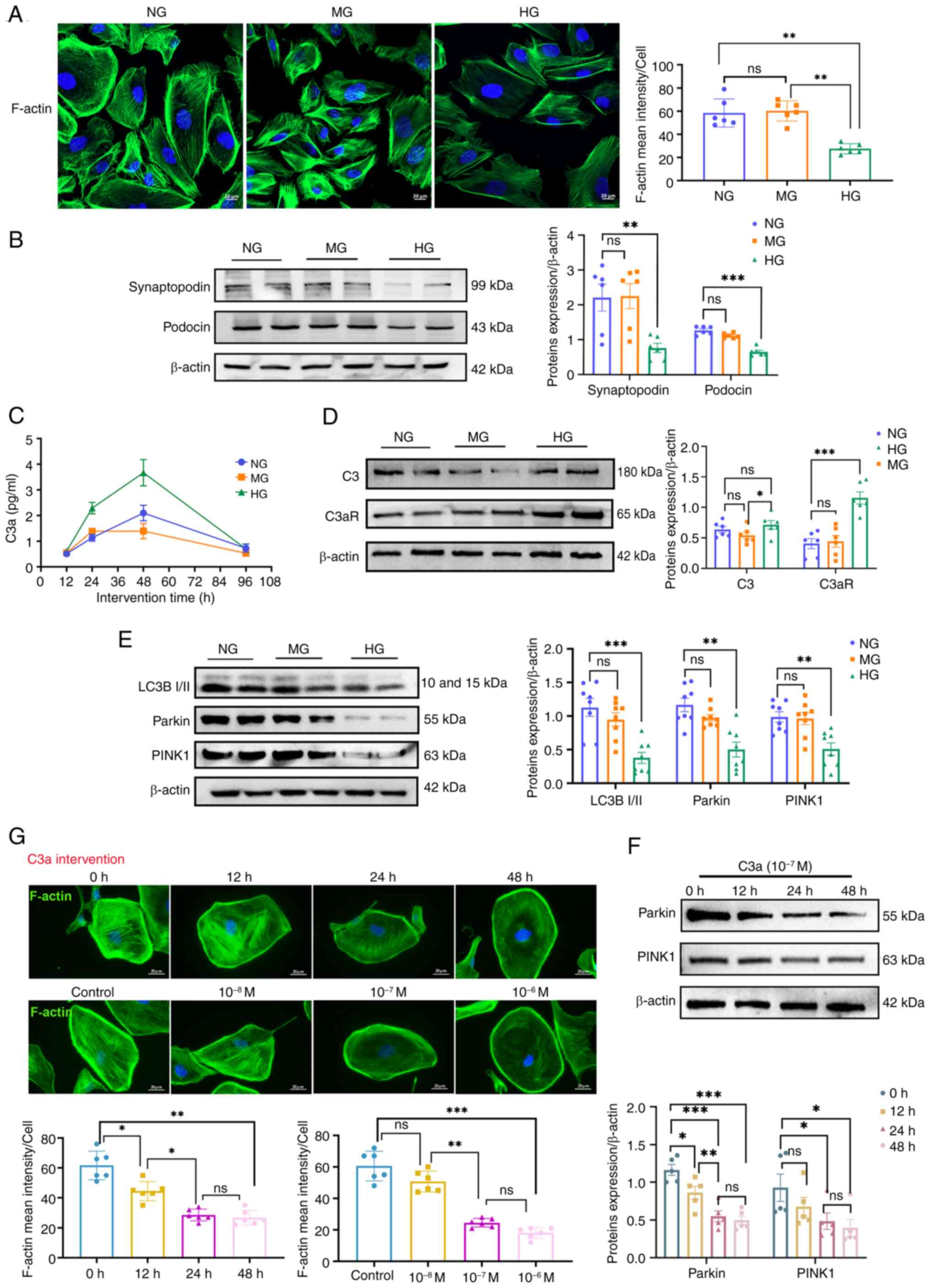

| Figure 5Effects of HG and C3a on podocyte

damage and mitophagy. Normal glucose refers to 5.5 mM glucose,

while the mannitol high osmotic control group was subjected to 24.5

mM mannitol + 5.5 mM glucose, and HG represents the intervention

group (30 mM glucose). (A) Representative images (left) and

quantification (right) of podocyte cytoskeleton, with F-actin

(green) stained using phalloidin (n=6). Scale bar, 20 μm.

(B) Protein levels of synaptopodin and podocin in podocytes (n=6).

Corresponding histograms are shown on the bottom panel of

representative protein bands. (C) ELISA detection of C3a levels in

podocytes at different time points (n=6). (D) Protein levels of C3

and C3aR in podocytes (n=6). Corresponding histograms are shown on

the right panel of representative protein bands. (E) Protein levels

of LC3B I/II, parkin and PINK1 in podocytes (n=8). Corresponding

histograms are shown on the bottom panel of representative protein

bands. (F) Protein levels of parkin and PINK1 in podocytes (n=5).

Corresponding histograms are shown on the right panel of

representative protein bands. (G) Representative images and

quantification (bottom) of podocyte cytoskeleton induced by

different times and concentrations of C3a (10−7 M for

12, 24 and 48 h; or 10−8, 10−7 and

10−6 M for 24 h) (n=6). Scale bar, 20 μm.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. ns, no statistically significant

difference; HG, high glucose. |

Complementing these findings, direct C3a exposure

(10−7 M) induced dose- and time-dependent cytoskeletal

disorganization, which was most pronounced at 24 h (Fig. 5G). Concomitant reductions in

PINK1 and parkin expression demonstrated C3a's causal role in

mitophagy suppression (Fig. 5F),

establishing its direct contribution to podocyte injury.

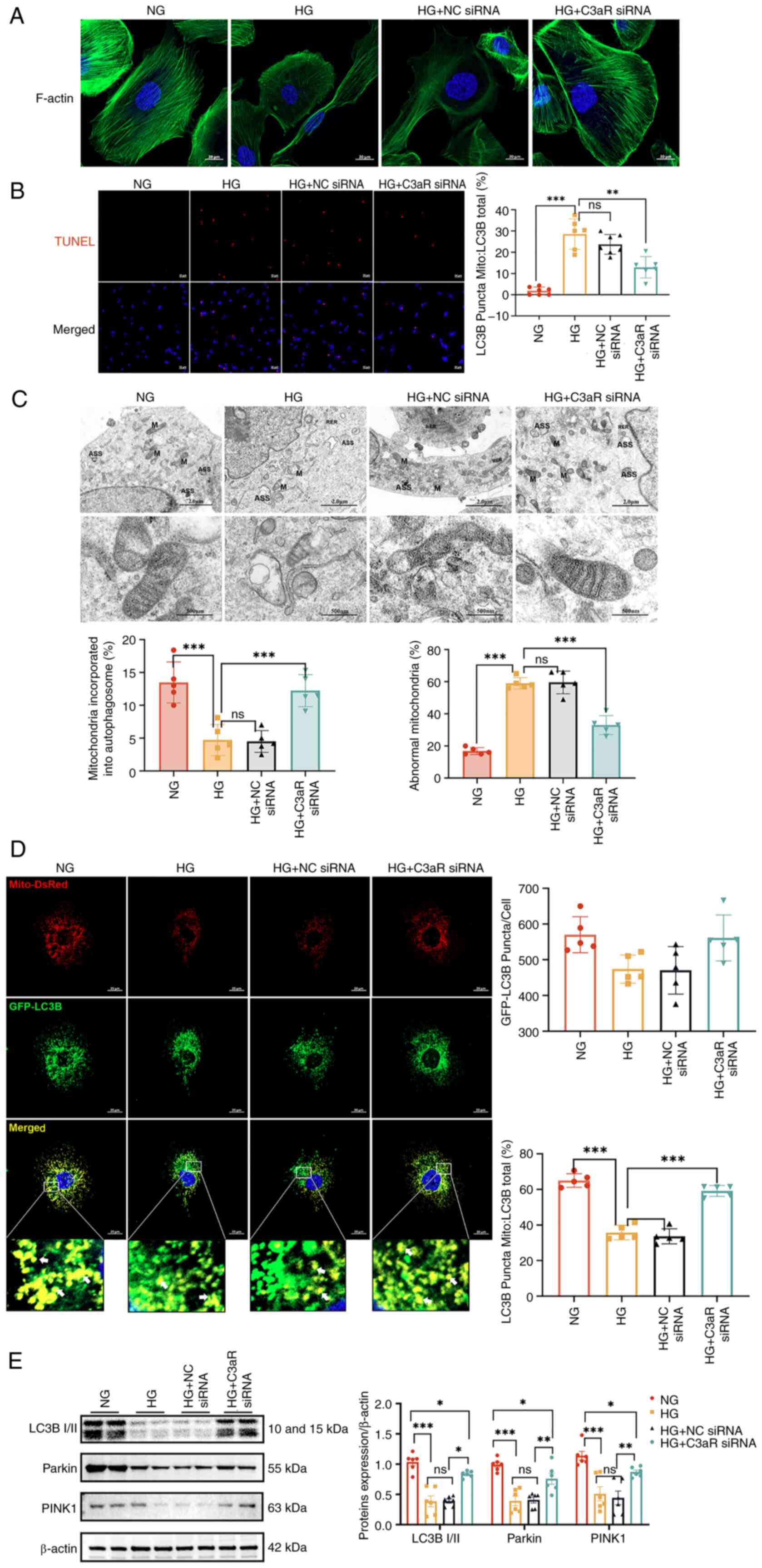

C3aR knockdown ameliorates HG-induced

podocyte injury and mitophagy suppression

To mechanistically validate the involvement of the

C3a/C3aR axis in podocyte injury and mitophagy impairment under

hyperglycemic conditions, siRNA-mediated C3aR downregulation was

employed in cultured podocytes. Comparative analysis revealed that

both HG-exposed and HG + NC siRNA groups exhibited fragmented

F-actin microfilaments with cytoskeletal disorganization, elevated

apoptotic indices, mitochondrial swelling with cristae

fragmentation, and minimal autolysosome formation, which

collectively indicate profound mitochondrial damage and suppressed

autophagic flux (Fig. 6A-C). By

contrast, C3aR-knockdown podocytes under HG conditions demonstrated

restored F-actin bundling with increased filament density, reduced

apoptosis, preserved mitochondrial ultrastructure (characterized by

mild swelling and intact cristae), decreased proportions of damaged

mitochondria and a significant increase in autophagosome-engulfed

mitochondria.

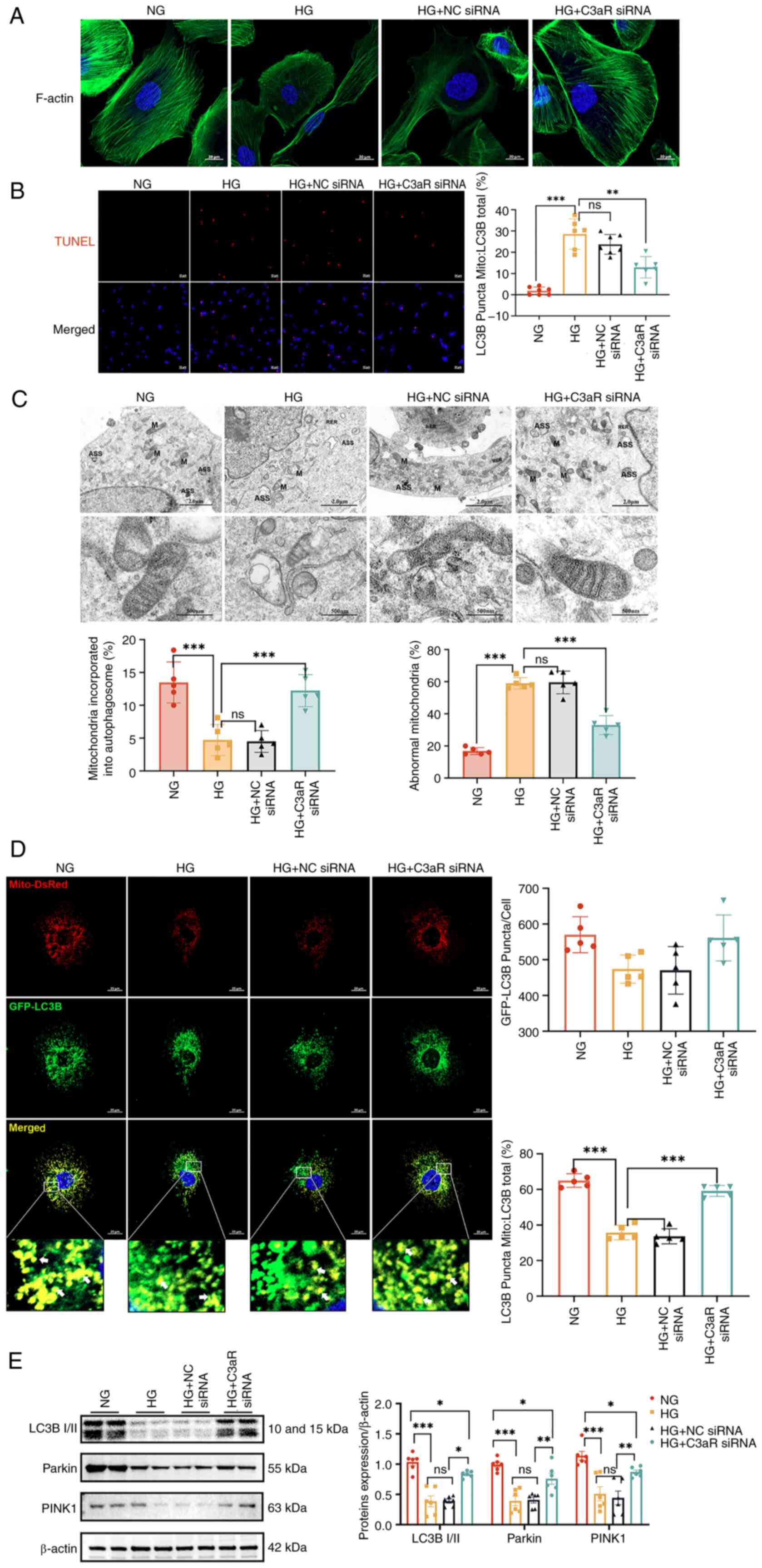

| Figure 6Inhibition of C3aR improves

HG-induced podocyte and mitochondrial autophagic damage. (A)

Changes in cell cytoskeleton after blocking C3aR in a HG

environment. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence images

of podocytes in each group using a TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end

labeling assay. Scale bar, 50 μm. The lower panel presents

the statistical analysis of apoptosis ratios in podocytes for each

group (n=6). (C) Transmission electron microscopy examination of

mitochondrial morphology. Scale bar, 2.0 μm and 500 nm. The

statistical charts on the right side of the electron microscopy

images represent the percentages of damaged mitochondria and

mitochondria enveloped by autophagosomes (n=5). (D) Transfection of

immortalized human podocytes with adenovirus GFP-LC3B (green) and

DsRed-Mito (red). Scale bar, 20 μm. The statistical charts

on the right side represent the number of GFP-LC3B-positive puncta

per cell and the proportion of LC3B spots on mitochondria (Mito) to

total LC3B. Quantification of GFP-LC3B (green)-associated

Mito-DsRed (red) staining intensity normalized by GFP-LC3B area

(n=5). (E) Protein levels of LC3B I/II, parkin and PINK1 in

podocytes (n=6). Corresponding histograms are shown on the right

panel of representative protein bands. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. ns, no

statistically significant difference; HG, high glucose; NG, normal

glucose; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative control. |

For dynamic quantification of mitophagic flux,

adenoviral transduction of GFP-LC3B/DsRed-Mito reporters revealed

significantly fewer mitochondrial LC3+ puncta in the HG

and HG + NC siRNA groups versus normoglycemic controls (P<0.01),

indicative of impaired mitophagosome biogenesis. This deficit was

reversed by C3aR knockdown, which increased mitochondrial

LC3+ puncta by 2.1-fold (Fig. 6D). Immunoblot analysis further

confirmed that C3aR silencing significantly upregulated the

LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio (1.8-fold, P<0.001), as well as PINK1

(1.5-fold, P<0.01), and parkin (1.7-fold, P<0.001) expression

levels in HG-treated podocytes (Fig.

6E), establishing that C3aR blockade restores mitophagic

activity in DN.

C3a/C3aR axis suppresses mitophagy via

PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 signaling in hyperglycemia-induced podocyte

injury

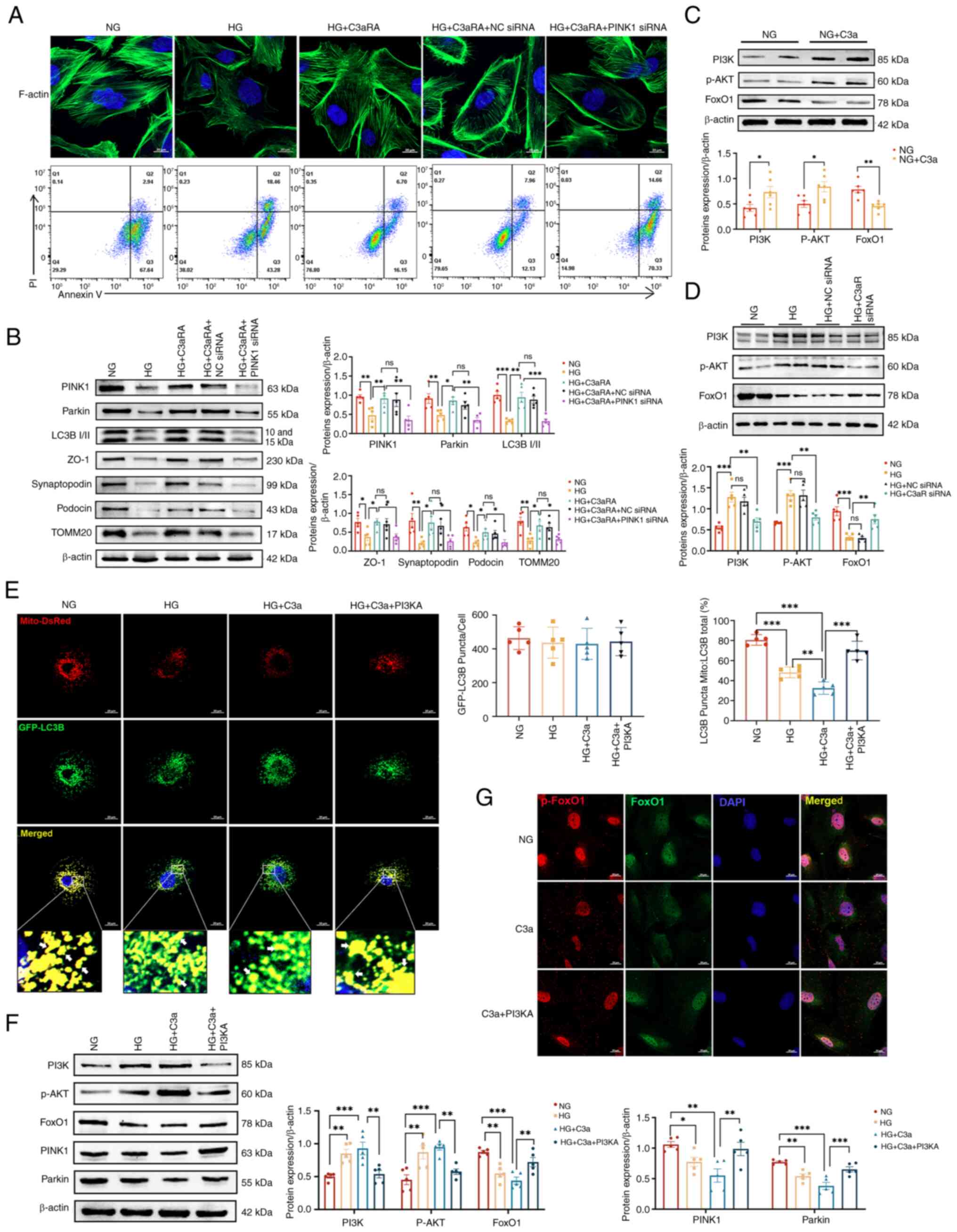

To delineate the role of C3a/C3aR in diabetic

podocyte dysfunction, PINK1 knockdown was combined with C3aRA.

HG-exposed podocytes exhibited cytoskeletal disorganization and

elevated apoptosis, and these phenotypes partially ameliorated by

C3aRA. Crucially, PINK1-silenced podocytes (HG + C3aRA + PINK1

siRNA) displayed exacerbated F-actin fragmentation with reduced

fluorescence intensity and increased apoptosis compared with HG +

C3aRA and HG + C3aRA + NC siRNA controls (Fig. 7A). Immunoblot analysis confirmed

that PINK1 knockdown significantly reduced mitophagy markers

(PINK1, parkin and LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio) and diminished the levels

of key podocyte integrity proteins (ZO-1, synaptopodin and podocin)

and of the mitochondrial translocase TOMM20 (P<0.05).

Importantly, PINK1 silencing attenuated C3aRA-mediated protection

against HG-induced injury, indicating that C3a/C3aR induces

podocyte damage through PINK1-mediated mitophagy impairment

(Fig. 7B). Following

pretreatment of podocytes with HG and HG + C3a, activation of p-AKT

was observed (Fig. S6B).

Mechanistically, C3a stimulation significantly enhanced PI3K/AKT

phosphorylation while suppressing FoxO1 expression versus

normoglycemic controls (Fig.

7C). Both HG exposure and C3aR knockdown similarly activated

PI3K/AKT signaling and reduced FoxO1, while C3aR inhibition

reversed these effects (Fig.

7D), consistent with the aforementioned in vivo data.

Under HG conditions with C3a overexpression, treatment with

LY294002 (a PI3K inhibitor; cat. no. HY-10108; MedChemExpress),

which was dissolved in DMSO and applied to podocytes at a final

concentration of 20 μM for 24 h prior to protein extraction,

reduced PI3K/AKT phosphorylation, restored FoxO1 expression and

increased the number of mitochondrial LC3+ puncta (by

2.3-fold, P<0.001) with elevated mitophagic flux (Fig. 7E and F). C3a induced FoxO1

nuclear export through enhanced phosphorylation, a process that was

significantly attenuated by LY294002 (Fig. 7G). These results indicated that

C3a/C3aR mediates hyperglycemia-induced podocytopathy by

suppressing mitophagy through PI3K/AKT-dependent inhibition of

FoxO1-PINK1 signaling.

Discussion

Increasing evidence suggests that the complement

system and its downstream components contribute to the development

of DN (19). The kidneys, in a

diabetic state, are continuously exposed to metabolic and

hemodynamic stress, leading to cellular damage and activation of

innate immune responses, including the complement system (20), with complement C3 serving as the

central hub in the complement cascade (21). Previous studies have indicated

that patients and animals with DN exhibit renal glomerular C3

deposition (4,22). In the present study, a markedly

higher expression of C3 and C3aR was observed in podocytes of

patients with DN compared with those of patients with other

kidney-related diseases. This suggests that complement system

activation, particularly the C3a/C3aR axis, is closely associated

with HG-induced kidney damage and proteinuria. Based on clinical

problems, db/db mice were employed to simulate the process of renal

damage in clinical DN, which is a spontaneous diabetic mouse model

with leptin receptor gene deficiency. Compared with the STZ-induced

type 2 diabetes mouse model, db/db mice showed obesity and more

obvious renal damage. In addition, the occurrence of diabetes in

db/db mice is more similar to that in clinical patients with type 2

diabetes because there is no artificial interference (23,24).

In the current study, db/db mice exhibited C3

deposition and elevated C3aR levels, accompanied with podocyte

loss, increased levels of proteinuria and renal tissue damage.

Podocyte apoptosis can result in podocyte loss and damage,

exacerbating the severity of proteinuria in patients with DN

(25,26). Previous literature has reported

that the C3a/C3aR axis in podocytes can initiate autocrine

IL-1β/IL-1R1 signaling, downregulating nephrin expression and

leading to rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton (27). Similarly, in the present study,

blocking C3aR increased the expression of the podocyte functional

proteins nephrin and synaptopodin in DN mice glomeruli, and

improved podocyte cytoskeleton alignmen in HG. This suggests the

involvement of the C3a/C3aR axis in podocyte damage in DN, which is

primarily manifested in cytoskeleton disruption and downregulation

of nephrin expression, with C3aRAs potentially contributing to the

maintenance of podocyte homeostasis.

Podocytes exhibit high dynamism, thus necessitating

substantial energy to maintain the normal organization of the

cytoskeleton and podocyte foot process remodeling (28). Impaired mitophagy is considered a

hallmark of human DN and rodent models of DN (29). Currently, the PINK1/parkin

pathway is considered one of the most crucial mediators in the

process of mitophagy (30). The

present study confirmed a decrease in PINK1/parkin-mediated

mitophagy levels in the db/db mice and in podocytes under HG

conditions in vitro. Similarly, reduced PINK1/parkin

mitophagy has been reported in HK-2 cells under HG conditions,

STZ-induced DN models (12,31), proximal tubular cells (32), glomerular mesangial cells

(33), podocytes, and db/db

mouse models of DN (34),

aligning with the current findings. By contrast, certain previous

studies have reported abnormal activation of PINK1/parkin-mediated

mitophagy in db/db mice (35,36). The db/db mice model effectively

recapitulates early-stage DN manifestations, including

characteristic glomerular pathology, podocyte injury and the

albuminuric phase, but fails to develop progressive renal fibrosis

or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) features typically observed in

advanced human DN, primarily due to its constrained 24-week

observation window, species-specific attenuation of fibrotic

pathways, and absence of sustained glomerulosclerosis that would

culminate in functional renal failure, thereby limiting its

translational relevance for late-stage DN therapeutic interventions

requiring fibrosis or ESRD endpoints. The db/db mice model remains

the gold standard for initiating events in DN but necessitates

complementary approaches for disease culmination studies. In

subsequent studies, therapeutic strategies targeting fibrosis/ESRD

reversal must be validated using complementary models (for example,

uninephrectomized db/db mice or DBA/2J-STZ mice). These seemingly

disparate results may be attributed to different stages of DN. In

the early stages of DN, the number of damaged mitochondria

increases, and compensatory mitophagy is enhanced to eliminate

these mitochondria. As DN progresses to a certain stage,

compensatory mitophagy becomes insufficient to clear an adequate

number of damaged mitochondria, resulting in a decompensated state

and a decrease in mitophagy levels (37). Since there were no genetic

background differences in the animals used in these studies,

further research is needed to explain these conflicting results

observed in the activation pattern of PINK1/parkin-mediated

mitophagy.

Numerous previous studies, including one conducted

by our group, have reported the key role of C3a/C3aR in

accelerating apoptosis. CRP interacts with the C3a/C3aR axis to

promote the process of DN through podocyte autophagy (38), and the treatment of DN mice with

a C3aRA enhanced podocyte density and preserved their phenotype,

limiting proteinuria and glomerular injury (8). Overall, this suggests that the

C3a/C3aR axis plays an important role in diabetic podocyte injury,

which may involve podocyte autophagy. The current study also found

that C3aR blockade protected podocytes and mitochondria from damage

in DN, as evidence by the corresponding changes in mitophagy levels

during the process. The majority of previous studies have shown

significant changes in the expression of mitophagy-related genes in

the entire lysates of kidney tissues or cells, with little

localization within mitochondria. Although the C3a/C3aR axis has

been demonstrated to affect mitochondrial biogenesis, including

impairing PPARα/CPT-1α-mediated renal tubular mitochondrial fatty

acid oxidation (39), there is

currently no relevant research on the involvement of the C3a/C3aR

axis in podocyte mitophagy. In the present study, Mito-LC3B

adenovirus was utilized for exogenous transfection of immortalized

human podocytes, and the co-localization assessment of mitochondria

and lysosomes helped further elucidate the role of

PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy in C3a-induced podocyte damage

under HG conditions. The results revealed a significant decrease in

mitophagy flux in podocytes cultured in a HG environment compared

with the NG control group. Inhibition of C3aR improved the reduced

mitophagy induced by HG, confirming that the C3a/C3aR axis

downregulates mitophagy levels in podocytes, participating in the

process of podocyte damage. While initially characterized as a C3aR

antagonist, subsequent studies have demonstrated that SB290157

inhibits C5aR1 (Ki≈1 μM) at higher concentrations, and C5aR1

similarly mediates inflammation and podocyte injury in DN.

Moreover, SB290157 exhibits concentration-dependent (>μM)

activation of PAR1 and PAR2, both expressed in renal cells. To

mitigate these potential off-target effects, our experimental

design rigorously maintained concentrations ≤0.5 μM.

Furthermore, complementary C3aR siRNA experiments in cellular

models confirmed that the pharmacological profile of SB290157

persisted under these constrained conditions.

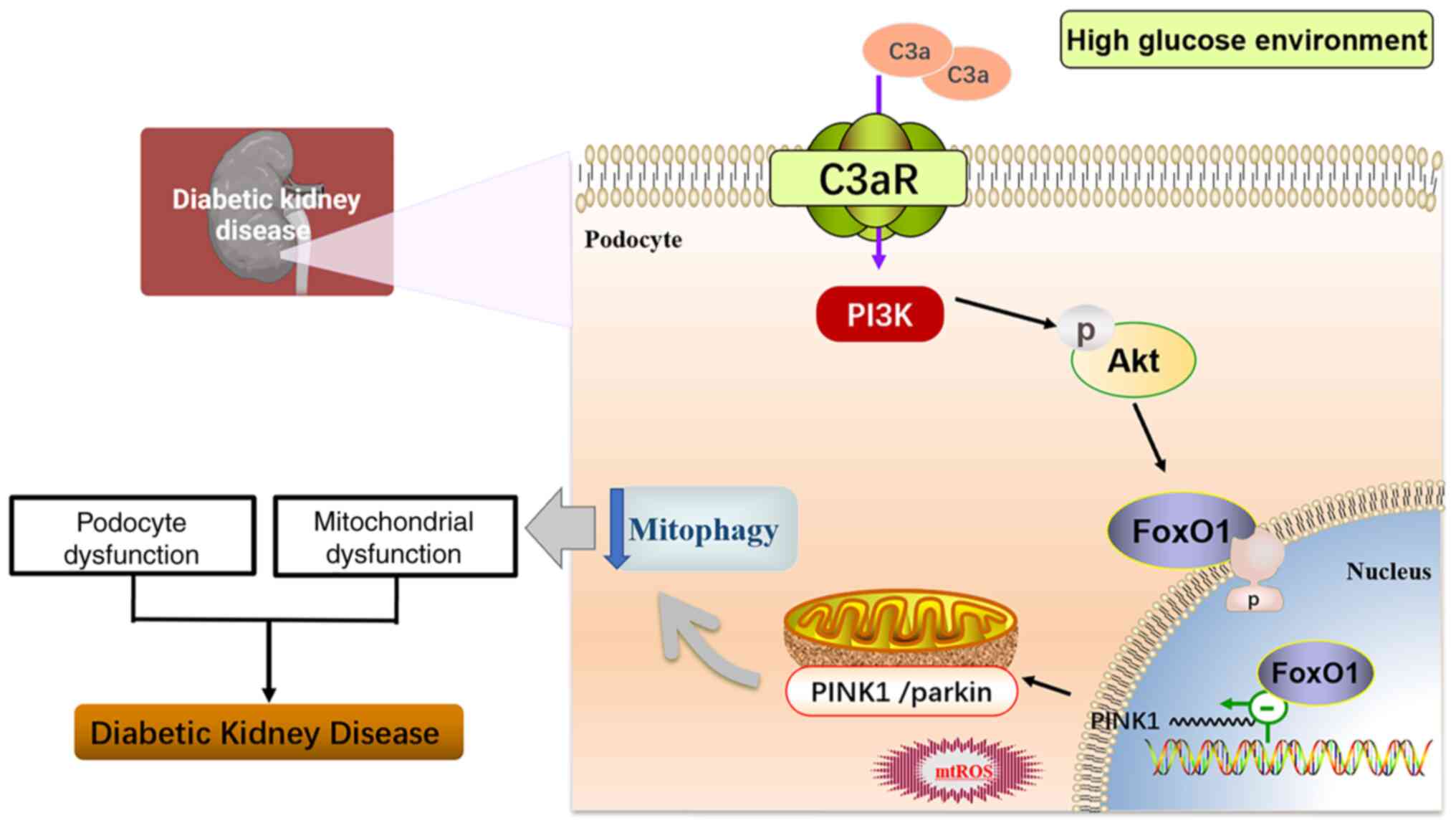

The present study delineates a novel mechanistic

link between the C3a/C3aR axis and podocyte mitophagy dysregulation

in DN, centrally orchestrated by the PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 signaling

pathway. Numerous previous studies have reported the activation of

the PI3K/AKT pathway in DN animal models (40-43), and that inhibiting the PI3K/AKT

pathway could enhance podocyte autophagy levels and reduce

proteinuria (44,45). In the present study, increased

expression of PI3K/AKT signaling molecules was observed in the

renal tissues of db/db mice and in podocytes cultured in a HG

environment in vitro. Blocking C3aR expression inhibited the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT signaling

prevents phosphorylation of FoxO1, enabling its nuclear

translocation, thereby regulating gene expression associated with

cell death, proliferation, differentiation, cellular metabolism,

and oxidative stress (46,47). Previous studies have established

that PI3K/AKT signaling exacerbates insulin resistance in diabetes

by inhibiting FOXO-driven metabolic adaptations (48,49). FoxO1 overexpression prevents

podocyte damage and improves the progression of DN (50). The current study uncovers that

C3a, a complement effector, acts as an upstream trigger of PI3K/AKT

in podocytes. In diabetic environments, C3aR binding activates

PI3K/AKT, which subsequently phosphorylates and inactivates FoxO1.

This redirects FoxO1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, repressing

the transcription of mitophagy genes (such as PINK1 and parkin).

The current findings support the observations that C3aR blockade

restores mitochondrial integrity, mechanistically linking

complement to FoxO1-driven redox and metabolic homeostasis.

However, in the present study, only PI3K inhibitors were used, and

the expression changes of the downstream signal molecules AKT and

FoxO1 were indirectly detected. Their direct role and existence in

the nucleus or cytoplasm are not yet clear; thus, further studies

are required in the future.

Additionally, a limitation of the present study is

that the exclusive focus on complement C3 and C3aR, lacking the

assessment of complement fragment C3a levels. Although a

significant increase in C3a under HG conditions was detected in

vitro in cultured podocytes, no noticeable differences in

circulating C3a expression were observed in the mouse experiments.

Considering the possibility of localized activation of complement

C3a in the kidney, future studies should construct models to

measure C3a levels in urine or locally collected blood from the

kidneys.

In summary (Fig.

8), the present study demonstrated for the first time that the

C3a/C3aR axis regulates the PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 signaling pathway, and

then leads to diabetic renal injury by inhibiting podocyte

mitophagy, suggesting that blocking C3aR may be an innovative

therapeutic strategy for treating patients with DN.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MW and JW conceived and designed the study. MW, XW,

SR, TZ and JZ performed the experiments. JC, XW, SR, EL, DY and KN

analyzed the data. MW was a major contributor in writing the

manuscript. JW and MW assume overall responsibility for the

manuscript. JW and JC confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

JW and JC was responsible for supervision, funding acquisition and

interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the

NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved

by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fujian

Medical University (approval no. IACUC FJMU 2023-Y-1033; Fuzhou,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Professor Liangdi Xie from

the Fujian Hypertension Research Institute, The First Affiliated

Hospital of Fujian Medical University for his providing the

experimental site and instruments. Additionally, the authors would

like to thank Mr Changshen Xu and Ms Guili Lian from the Fujian

Hypertension Research Institute, The First Affiliated Hospital of

Fujian Medical University for their technical assistance and

research resources. The authors also thank the Public Technology

Platform, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical

University for its technical support.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Fujian Provincial Health

Technology Project (grant no. 2021CXA018), the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82470733 and 82401848).

References

|

1

|

Ma J, Yiu WH and Tang SCW: Complement

anaphylatoxins: Potential therapeutic target for diabetic kidney

disease. Diabet Med. 42:e154272025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

2

|

Li X, Zhao S, Xie J, Li M, Tong S, Ma J,

Yang R, Zhao Q, Zhang J and Xu A: Targeting the NF-κB p65-MMP28

axis: Wogonoside as a novel therapeutic agent for attenuating

podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy. Phytomedicine.

138:1564062025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wang T, Chen Y, Liu Z, Zhou J, Li N, Shan

Y and He Y: Long noncoding RNA Glis2 regulates podocyte

mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy via

sponging miR-328-5p. J Cell Mol Med. 28:e182042024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Woroniecka KI, Park ASD, Mohtat D, Thomas

DB, Pullman JM and Susztak K: Transcriptome analysis of human

diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 60:2354–2369. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wehner H, Höhn D, Faix-Schade U, Huber H

and Walzer P: Glomerular changes in mice with spontaneous

hereditary diabetes. Lab Invest. 27:331–340. 1972.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li L, Chen L, Zang J, Tang X, Liu Y, Zhang

J, Bai L, Yin Q, Lu Y, Cheng J, et al: C3a and C5a receptor

antagonists ameliorate endothelial-myofibroblast transition via the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in diabetic kidney disease.

Metabolism. 64:597–610. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li L, Yin Q, Tang X, Bai L, Zhang J, Gou

S, Zhu H, Cheng J, Fu P and Liu F: C3a receptor antagonist

ameliorates inflammatory and fibrotic signals in type 2 diabetic

nephropathy by suppressing the activation of TGF-β/smad3 and IKBα

pathway. PLoS One. 9:e1136392014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Morigi M, Perico L, Corna D, Locatelli M,

Cassis P, Carminati CE, Bolognini S, Zoja C, Remuzzi G, Benigni A

and Buelli S: C3a receptor blockade protects podocytes from injury

in diabetic nephropathy. JCI Insight. 5:e1318492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ma K, Chen G, Li W, Kepp O, Zhu Y and Chen

Q: Mitophagy, mitochondrial homeostasis, and cell fate. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 8:4672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Stanigut AM, Tuta L, Pana C, Alexandrescu

L, Suceveanu A, Blebea NM and Vacaroiu IA: Autophagy and mitophagy

in diabetic kidney disease-a literature review. Int J Mol Sci.

26:8062025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tagawa A, Yasuda M, Kume S, Yamahara K,

Nakazawa J, Chin-Kanasaki M, Araki H, Araki S, Koya D, Asanuma K,

et al: Impaired podocyte autophagy exacerbates proteinuria in

diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 65:755–767. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhou D, Zhou M, Wang Z, Fu Y, Jia M, Wang

X, Liu M, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Zhou Y, et al: Progranulin alleviates

podocyte injury via regulating CAMKK/AMPK-mediated autophagy under

diabetic conditions. J Mol Med (Berl). 97:1507–1520. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhou D, Zhou M, Wang Z, Fu Y, Jia M, Wang

X, Liu M, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Lu Y, et al: PGRN acts as a novel

regulator of mitochondrial homeostasis by facilitating mitophagy

and mitochondrial biogenesis to prevent podocyte injury in diabetic

nephropathy. Cell Death Dis. 10:5242019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Martini S, Nair V, Keller BJ, Eichinger F,

Hawkins JJ, Randolph A, Böger CA, Gadegbeku CA, Fox CS, Cohen CD,

et al: Integrative biology identifies shared transcriptional

networks in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 25:2559–2572. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ju W, Greene CS, Eichinger F, Nair V,

Hodgin JB, Bitzer M, Lee YS, Zhu Q, Kehata M, Li M, et al: Defining

cell-type specificity at the transcriptional level in human

disease. Genome Res. 23:1862–1873. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

National Research Council Committee for

the Update of the Guide for the C. and A. Use of Laboratory. The

National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National

Institutes of Health, in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals. National Academies Press. Copyright© 2011. National

Academy of Sciences; Washington, DC: 2011

|

|

17

|

Ames RS, Lee D, Foley JJ, Jurewicz AJ,

Tornetta MA, Bautsch W, Settmacher B, Klos A, Erhard KF, Cousins

RD, et al: Identification of a selective nonpeptide antagonist of

the anaphylatoxin C3a receptor that demonstrates antiinflammatory

activity in animal models. J Immunol. 166:6341–6348. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yasuda-Yamahara M, Kume S, Tagawa A,

Maegawa H and Uzu T: Emerging role of podocyte autophagy in the

progression of diabetic nephropathy. Autophagy. 11:2385–2386. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Flyvbjerg A: The role of the complement

system in diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 13:311–318. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tesch GH: Diabetic nephropathy-is this an

immune disorder? Clin Sci (Lond). 131:2183–2199. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sahu A and Lambris JD: Structure and

biology of complement protein C3, a connecting link between innate

and acquired immunity. Immunol Rev. 180:35–48. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kelly KJ, Liu Y, Zhang J and Dominguez JH:

Renal C3 complement component: Feed forward to diabetic kidney

disease. Am J Nephrol. 41:48–56. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Racine KC, Iglesias-Carres L, Herring JA,

Wieland KL, Ellsworth PN, Tessem JS, Ferruzzi MG, Kay CD and

Neilson AP: The high-fat diet and low-dose streptozotocin type-2

diabetes model induces hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in

male but not female C57BL/6J mice. Nutr Res. 131:135–146. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang L, Zhou R, Li G, Zhang X, Li Y, Shen

Y and Fang J: Multi-omics characterization of diabetic nephropathy

in the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Comput Struct

Biotechnol J. 27:3399–3409. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jin J, Shi Y, Gong J, Zhao L, Li Y, He Q

and Huang H: Exosome secreted from adipose-derived stem cells

attenuates diabetic nephropathy by promoting autophagy flux and

inhibiting apoptosis in podocyte. Stem Cell Res Ther. 10:952019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yuen DA, Stead BE, Zhang Y, White KE,

Kabir MG, Thai K, Advani SL, Connelly KA, Takano T, Zhu L, et al:

eNOS deficiency predisposes podocytes to injury in diabetes. J Am

Soc Nephrol. 23:1810–1823. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Angeletti A, Cantarelli C, Petrosyan A,

Andrighetto S, Budge K, D'Agati VD, Hartzell S, Malvi D, Donadei C,

Thurman JM, et al: Loss of decay-accelerating factor triggers

podocyte injury and glomerulosclerosis. J Exp Med.

217:e201916992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Galvan DL, Green NH and Danesh FR: The

hallmarks of mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease.

Kidney Int. 92:1051–1057. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen K, Dai H, Yuan J, Chen J, Lin L,

Zhang W, Wang L, Zhang J, Li K and He Y: Optineurin-mediated

mitophagy protects renal tubular epithelial cells against

accelerated senescence in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Death Dis.

9:1052018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nguyen TN, Padman BS and Lazarou M:

Deciphering the molecular signals of PINK1/parkin mitophagy. Trends

Cell Biol. 26:733–744. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li W, Du M, Wang Q, Ma X, Wu L, Guo F, Ji

H, Huang F and Qin G: FoxO1 promotes mitophagy in the podocytes of

diabetic male mice via the PINK1/parkin pathway. Endocrinology.

158:2155–2167. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhao Y and Sun M: Metformin rescues Parkin

protein expression and mitophagy in high glucose-challenged human

renal epithelial cells by inhibiting NF-κB via PP2A activation.

Life Sci. 246:1173822020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yi X, Yan W, Guo T, Liu N, Wang Z, Shang

J, Wei X, Cui X, Sun Y, Ren S and Chen L: Erythropoietin mitigates

diabetic nephropathy by restoring PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy.

Front Pharmacol. 13:8830572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sun J, Zhu H, Wang X, Gao Q, Li Z and

Huang H: CoQ10 ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic

nephropathy through mitophagy. J Endocrinol. 240:445–465. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu X, Wang W, Song G, Wei X, Zeng Y, Han

P, Wang D, Shao M, Wu J, Sun H, et al: Astragaloside IV ameliorates

diabetic nephropathy by modulating the mitochondrial quality

control network. PLoS One. 12:e01825582017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Liu X, Lu J, Liu S, Huang D, Chen M, Xiong

G and Li S: Huangqi-Danshen decoction alleviates diabetic

nephropathy in db/db mice by inhibiting PINK1/Parkin-mediated

mitophagy. Am J Transl Res. 12:989–998. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yang M, Li C, Yang S, Xiao Y, Chen W, Gao

P, Jiang N, Xiong S, Wei L, Zhang Q, et al: Mitophagy: A novel

therapeutic target for treating DN. Curr Med Chem. 28:2717–2728.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zhang L, Li W, Gong M, Zhang Z, Xue X, Mao

J, Zhang H, Li S, Liu X, Wu F, et al: C-reactive protein inhibits

C3a/C3aR-dependent podocyte autophagy in favor of diabetic kidney

disease. FASEB J. 36:e223322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Wang C, Wang Z, Xu J, Ma H, Jin K, Xu T,

Pan X, Feng X and Zhang W: C3aR antagonist alleviates C3a induced

tubular profibrotic phenotype transition via restoring PPARα/CPT-1α

mediated mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in renin-dependent

hypertension. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 28:2382023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Chen Y, Zheng YF, Lin XH, Zhang JP, Lin F

and Shi H: Dendrobium mixture attenuates renal damage in rats with

diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Mol

Med Rep. 24:5902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ma Z, Liu Y, Li C, Zhang Y and Lin N:

Repurposing a clinically approved prescription Colquhounia root

tablet to treat diabetic kidney disease via suppressing

PI3K/AKT/NF-kB activation. Chin Med. 17:22022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Dong R, Zhang X, Liu Y, Zhao T, Sun Z, Liu

P, Xiang Q, Xiong J, Du X, Yang X, et al: Rutin alleviates EndMT by

restoring autophagy through inhibiting HDAC1 via PI3K/AKT/mTOR

pathway in diabetic kidney disease. Phytomedicine. 112:1547002023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhang Y, Yang S, Cui X, Yang J, Zheng M,

Jia J, Han F, Yang X, Wang J, Guo Z, et al: Hyperinsulinemia can

cause kidney disease in the IGT stage of OLETF rats via the

INS/IRS-1/PI3-K/Akt signaling pathway. J Diabetes Res.

2019:47097152019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zheng D, Tao M, Liang X, Li Y, Jin J and

He Q: p66Shc regulates podocyte autophagy in high glucose

environment through the Notch-PTEN-PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Histol

Histopathol. 35:405–415. 2020.

|

|

45

|

Wang X, Jiang L, Liu XQ, Huang YB, Wang

AL, Zeng HX, Gao L, Zhu QJ, Xia LL and Wu YG: Paeoniflorin binds to

VEGFR2 to restore autophagy and inhibit apoptosis for podocyte

protection in diabetic kidney disease through PI3K-AKT signaling

pathway. Phytomedicine. 106:1544002022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen Y, Li Z, Li H, Su W, Xie Y, Pan Y,

Chen X and Liang D: Apremilast regulates the Teff/Treg balance to

ameliorate uveitis via PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 signaling pathway. Front

Immunol. 11:5816732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Miao Z, Liu Y, Xu Y, Bu J and Yang Q:

Oxaloacetate promotes the transition from glycolysis to

gluconeogenesis through the Akt-FoxO1 and JNK/c-Jun-FoxO1 axes and

inhibits the survival of liver cancer cells. Int Immunopharmacol.

161:1150512025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Xu Z, Liu K, Zhang G, Yang F, He Y, Nan W,

Li Y and Lin J: Transcriptome analysis reveals that the injection

of mesenchymal stem cells remodels extracellular matrix and

complement components of the brain through PI3K/AKT/FOXO1 signaling

pathway in a neuroinflammation mouse model. Genomics.

117:1110332025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Deng A, Wang Y, Huang K, Xie P, Mo P, Liu

F, Chen J, Chen K, Wang Y and Xiao B: Artichoke (Cynara scolymus

L.) water extract alleviates palmitate-induced insulin resistance

in HepG2 hepatocytes via the activation of IRS1/PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 and

GSK-3β signaling pathway. BMC Complement Med Ther. 23:4602023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Cosenso-Martin LN, Takaoka LY and

Vilela-Martin JF: Randomized study comparing vildagliptin vs

glibenclamide on glucose variability and endothelial function in

patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Diabetes

Metab Syndr Obes. 13:3221–3229. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

![Expression levels of mitophagy and

related pathway proteins in mouse renal tissues. (A)

Immunohistochemical analysis of the mitophagy-specific protein

PINK1. Magnification, x100. (B) Protein levels of LC3B I/II, parkin

and PINK1 in kidney tissues (n=6). Corresponding histograms are

shown on the right panel of representative protein bands. (C)

Protein levels of PI3K [PI3-kinase p85α (54 + 85 kDa)],

phosphorylated-AKT and FoxO1 in kidney tissues (n=6). Corresponding

histograms are shown on the right panel of representative protein

bands. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001. p-, phosphorylated.](/article_images/ijmm/56/6/ijmm-56-06-05664-g03.jpg)