Introduction

Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening systemic

inflammatory response syndrome caused by a dysregulated host

response to infection, contributing to a considerable global

mortality rate (as of 2017, ~48.9 million cases of sepsis were

recorded globally, with 11 million reported sepsis-related

mortalities, accounting for 19.7% of all global mortalities)

(1). The initial event of sepsis

is the recognition of microbe-derived pathogen-associated molecular

patterns or endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns by host

pattern recognition receptors (2). This recognition triggers

intracellular signal transduction pathways. Under physiological

conditions, immune cells interact via this signaling network,

inducing an innate immune response to eliminate pathogens and

maintain cellular stability. However, certain host signaling

pathways in sepsis become abnormally activated, leading to an

explosive release of cytokines and alarmins (3). These inflammatory mediators

markedly upregulate the expression of inflammation-related genes

and act as key effector molecules in driving excessive systemic

inflammatory responses and subsequent immunosuppression. This

process further promotes the massive release of inflammatory

mediators such as cytokines and chemokines, ultimately culminating

in a cytokine storm (4,5).

The liver carries out a key role as a defensive

barrier that protects the body against potential threats (6). It can be activated by microbes or

alarm signals, resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory

cytokines and the recruitment of immune cells to assist in

microbial clearance. Additionally, the intricate immune

surveillance mechanisms of the liver, supported by its strategic

anatomical positioning, enable it to collaborate with both

parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells to eliminate bacteria from

the bloodstream and regulate the inflammatory and immune responses.

This collaboration mitigates the risk of bacteremia and serves as a

notable barrier against microbial invasion (7). However, the liver is frequently

targeted by dysregulation of inflammation. Immune cells are

susceptible to various substances. These substances include

antigens, endotoxins, danger signals and microorganisms circulating

in the bloodstream. Excessive stimulation may cause these cells to

become abnormally activated and may also make them undergo

apoptosis which disrupts immune function and contributes to

inflammation dysregulation (8,9).

Therefore, prompt intervention targeting liver injury during sepsis

management is key to effectively mitigating inflammatory responses

and cytokine storms, thereby protecting against further organ

damage and improving patient outcomes.

Radioprotective 105 (RP105), also known as CD180, is

a type I transmembrane protein characterized by an extracellular

domain rich in leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and a short cytoplasmic

tail (10). Analogous to the

Toll protein in Drosophila, RP105 was the first mammalian molecule

to exhibit similarity to Toll through its extracellular LRRs.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the primary component of the cell wall

of gram-negative bacteria. It is also a key virulence factor. It

causes infections such as sepsis and septic shock. During sepsis

progression, LPS binds directly to pattern recognition receptors on

immune cell surfaces. This binding activates the Toll-like Receptor

4 (TLR4) inflammatory signaling pathway. This activation triggers a

release of inflammatory cytokines, resulting in an 'inflammatory

cytokine storm' that can damage tissues and organs. As a key

negative regulator of the TLR4 signaling pathway and an essential

modulator of the immune system (11,12), RP105 prevents the excessive

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting TLR4

mediated pro-inflammatory signals, serving as a protective strategy

against exaggerated inflammatory responses. Consequently, RP105

carries out a key role in regulating immune response and

controlling inflammation during sepsis.

Although numerous studies have reported the

anti-inflammatory effects of RP105 in various disease models

(13-16), its effect on sepsis-induced liver

injury remains poorly documented. Moreover, the molecular

mechanisms underlying the protective role of RP105, particularly

whether it modulates intracellular cytokine signaling pathways,

have not been elucidated. Therefore, the present study aimed to

investigate the function of RP105 in sepsis-induced hepatic injury

using a CLP mouse model.

Materials and methods

Mice and treatments

Wild-type (WT) mice and RP105 knockout (KO) mice

[total number, 24 (WT, 12; KO, 12); male C57BL/6 mice; 8-12 weeks

old; weighing 20-25 g] were purchased from GemPharmatech Co. Ltd.

After purchase, the mice were raised at the Animal Experiment

Center of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (Wuhan, China).

Mice were kept in a breeding environment with a room temperature of

20-25°C, humidity 50-70% and a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. All mice

had free access to standard animal food and water. All experimental

procedures were conducted in accordance with the National

Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals (17). Every effort was

made to minimize the suffering of the mice used. Before the

official experiment begins, the mice undergo an adaptive feeding

period and are provided with sterilized clean drinking water.

Genotypes of the knockout mice were confirmed using PCR. WT and KO

mice were randomly assigned to different treatment groups (n=6 for

single-variable animal experiments following previous studies that

also used six animals per group to ensure reproducibility and

statistical reliability) (18,19), data collection and analysis was

carried out under blinded conditions.

Anesthesia protocol

C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized by inhalation of 5%

isoflurane for induction, followed by maintenance with 2-2.5%

isoflurane. The animals were positioned in a prone position on a

37°C thermoregulated heating pad (Harvard Apparatus) with

continuous monitoring of rectal temperature maintained at

36.5±0.5°C.

Animal procedures

In this experiment, the duration of the laparotomy

procedure for cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) is 10 min; the

modeling cycle of the CLP model (the time from the completion of

the modeling procedure to the end of the experiment) is 24 h.

Following anesthesia, a 1 cm midline laparotomy was carried out on

the left side of the xiphoid to expose the cecum. The cecum was

then ligated at 75% of the distance between the distal pole and the

base using 4-0 silk suture, followed by two through-and-through

punctures with a 25-gauge needle near the distal end. The cecum was

subsequently repositioned and the abdominal cavity was closed in

two layers with 5-0 sutures. Postoperatively, mice received 1 ml of

pre-warmed sterile saline via subcutaneous injection for fluid

resuscitation and were maintained at 37°C for thermal support.

Control mice underwent identical surgical

procedures, including cecal exteriorization, but without ligation

or puncture. The monitored parameters included body temperature,

mobility, food/water intake and pain-related behaviors, with

assessments conducted hourly. Terminal blood samples (1 ml) were

collected from the inferior vena cava, and liver tissues were

harvested. All procedures were performed under deep anesthesia

immediately prior to euthanasia. The serum obtained by

centrifugation (3,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and liver tissues were

stored at −80°C for future experimental use.

Euthanasia procedure

Mice were euthanized by 5% isoflurane overdose until

respiratory arrest (~5 min), with mortality confirmed via cardiac

cessation, absent corneal reflex and fixed pupil dilation (per AVMA

Guidelines 2020) (20).

Cell culture and LPS-induced model

Both Raw264.7 cells (cat. no. YC-C020) and the RP105

(alias, CD180) knockout cell line (cat. no. YKO-M041) were

commercially obtained from Ubigene). In the present study,

CRISPR/Cas9 technology was used for gene KO, with the negative

control (NC) group consisting of untransfected WT cells. The RP015

KO cell line was generated by precisely deleting a 382-base pair

fragment (completely removing exon 3) in clone C7 (the KO cell line

was produced by Ubigene). All cells were cultured in a humidified

incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) maintained at 37°C and

5% CO2 in high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

(cat. no. G4511; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (cat. no.

A5256701; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) For the

experiment, the cultures were placed in the aforementioned medium

overnight (at 37°C with 5% CO2) and 1 μg/ml LPS

(InvivoGen) was administered when the cells reached 80-90%

confluence, with treatment for 24 h.

H&E

After washing the excised liver tissues, which were

stored at −80°C, with sterile normal saline, they were fixed in 4%

buffered paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 24 h, then

embedded in paraffin for subsequent processing. All

paraffin-embedded sections were cut to 4-μm thickness,

stained with H&E at room temperature. After dewaxing and

rehydration (Sections were sequentially dehydrated through a graded

ethanol series (100, 95, 80, 70%) and finally immersed in distilled

water for 5 min to achieve rehydration), stain the sections were

incubated with hematoxylin for 5 min, then eosin for 15 min, both

at room temperature, followed by observation and imaging using a

light microscope. Two pathologists, blinded to the experimental

groups, randomly selected three different fields of view to

evaluate the liver injury of each animal. The liver injury score

was used to assess the characteristics of sepsis-induced liver

injury, and the pathological scoring was carried out according to

previous studies (21,22). The degrees of inflammatory

infiltration, thrombosis and necrosis were graded separately (0 was

defined as absent and four as severe). The total score of liver

histological scoring was expressed as the sum of the scores of each

parameter, with a maximum of 12 points.

Biochemical analysis

Serum samples stored at −80°C were thawed at room

temperature for 30 min. After complete thawing, they were

centrifuged at low speed (750 × g for 30 sec at 4°C), gently mixed

by vortexing and air bubbles in the tubes were thoroughly aspirated

to prevent interference with the experimental results.

Subsequently, standardized processing and streamlined detection

were conducted by professional medical technicians using a fully

automated biochemical analyzer. Serum levels of alanine

aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were

measured using the BS-2000 automatic biochemical analyzer (Shenzhen

Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd.). All detection

procedures were carried out at the Experimental Center of Zhongnan

Hospital, Wuhan University (Wuhan, China).

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissues of the

mice using the Trizol kit (cat. no. R0016; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), followed by reverse transcription of the RNA into

cDNA using the Hifair® V one-step RT-gDNA digestion

SuperMix kit (cat. no. 11142ES10; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.). A total of 1 μg RNA was used for cDNA

conversion. The reverse transcription procedure was carried out as

follows: Initial primer annealing at 30°C for 5 min, followed by

cDNA synthesis at 55°C for 30 min and final enzyme inactivation at

85°C for 5 min. qPCR was carried out using SYBR Green dye (Biosharp

Life Sciences). The qPCR amplification protocol consisted of an

initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles

of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C

for 30 sec with fluorescence signal acquisition. Relative gene

expression levels were determined using the 2-ΔΔCq

(23) method and normalized to

the β-actin reference gene. The primers for the target genes are

listed in Table I.

| Table IPrimer sequences of the target

genes. |

Table I

Primer sequences of the target

genes.

| Gene | Forward primer

sequence (5'-3') | Reverse primer

sequence (5'-3') |

|---|

| IL-1β C |

ACCTCACAAGCAGAGCACAAG |

GAAACAGTCCAGCCCATACTTTAGG |

| IL-6 |

CTTCTTGGGACTGATGCTGGTGAC |

TCTGTTGGGAGTGGTATCCTCTGTG |

| TNF-α |

AAGACACCATGAGCACAGAAAGC |

GCCACAAGCAGGAATGAGAAGAG |

| RP105 G |

ACCAACTCACTTCAGACA |

TGACTAAGAGCCTCAATGC |

| β-Actin |

CAGCAAGCAGGAGTACGATGAGTC |

CAGTAACAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCAC |

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Liver tissue was first fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h (at room temperature), embedded in paraffin and sliced

into sections of 4-μm thickness. These sections were

dewaxed, rehydrated for 30 min at room temperature, blocked with 3%

BSA for 30 min at 37°C, and finally incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies: anti-RP105 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab184956; Abcam)

and anti-Caspase3 (1:200; cat. no. 19677-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.). The slides were then incubated with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG

H&L (1:1,000; cat. no. ab205718; Abcam) at 37°C for 1 h.

Immunoreactivity was visualized using 3,3-diaminobenzidine

tetrahydrochloride, which produces a brown precipitate at the

antigen site. Subsequently, the cell nuclei were re-counterstained

with Mayer's Hematoxylin Stain Solution (cat. no. G1080; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature

for 1 min, the slides were dehydrated and cells were observed and

imaged under a light microscope.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

IF followed a protocol similar to that reported

previously (24). The sections

were prepared following the same protocol as used for IHC; they

were then incubated (overnight at 4°C) with anti-myeloperoxidase

(MPO; 1:100; cat. no. 22225-1-AP; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology),

anti-F4/80 (1:5,000; cat. no. ab300421; Abcam) and anti-suppressor

of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2; 1:1,000; cat. no. A9190; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.). After washing to remove the unbound antibody,

the slides were incubated with a secondary antibody (1:1,000; cat.

no. ab205718; Abcam) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (cat. no.

ab150080; Abcam) or XFD488 tyramide reagent (100 μl was

applied to each sample and they were incubated for 5-10 min at room

temperature; cat. no. 11070; AAT Bioquest, Inc.). Next, nuclei were

stained with DAPI. Finally, the slides were observed and imaged

under a fluorescence microscope.

Western blotting (WB)

Precooled RIPA lysis buffer (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to a sterile centrifuge tube, along

with grinding beads. Frozen liver tissue (30-50 mg) was added to a

centrifuge tube, followed by grinding to obtain a homogenate (the

entire operation was carried out on ice). After grinding, the

centrifuge tube was transferred to a refrigerated centrifuge and

centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. After centrifugation,

the supernatant was carefully aspirated, which served as the

protein extract. The total protein concentration was determined

using the BCA method. For electrophoresis, 30 μg of protein

per lane was loaded for animal tissue samples, and 50 μg of

protein per lane was loaded for cell samples. After separating

proteins with different molecular weights using SDS-PAGE (10 and

12%), the proteins were electrically transferred onto a PVDF

membrane. Following a 2-h blocking treatment of the membrane with

5% BSA solution, the membrane was incubated overnight with a

specific primary antibody at 4°C. Subsequently, followed by

labeling with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (1:5,000, cat. no.

AS014; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.). Finally, the protein bands on

the membrane were visualized using ECL (Biosharp Life Sciences).

Briefly, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the

following corresponding primary antibodies: Anti-RP105 (1:1,000,

cat. no. ab184956; Abcam), anti-SOCS2 (1:1,000; cat. no. A9190;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), anti-JAK2 (1:1,000, cat. no A11497;

ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), BCL-2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 26593-1-AP;

Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology), anti-BAX (1:1,000; cat. no. T40051;

Abmart Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.), anti-p53 upregulated

modulator of apoptosis (PUMA; 1:1,000, cat. no. A3752; ABclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.), anti-Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-inducible α

(GADD45A; 1:500, cat. no. A13487; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.),

anti-phosphorylated-JAK2 (p-JAK2; 1:2,000; cat. no. 4406; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-STAT3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 30835;

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-phosphorylated (p-STAT3)

(1:2,000, cat. no. 9145; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and

anti-β-actin (1:50,000, cat. no. AC026; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.)

antibodies.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

RNA was extracted from the animal tissues of the

four groups, using Trizol which was the same as in RT-qPCR

experiment. RNA integrity was evaluated by using the RNA Nano 6000

assay kit from Bioanalyzer After confirming RNA quality, mRNA was

enriched from total RNA using poly-T oligonucleotide-attached

magnetic beads (cat. no. N401-01/02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The

purified mRNA was then fragmented and used for cDNA synthesis.

First-strand cDNA was generated with random hexamer primers and

M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H-) (Fast RNA-seq

Lib Prep Kit V2; cat. no. RK20306; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.),

followed by second-strand synthesis using the same kit. Adapter

sequences were ligated to construct the sequencing library.

High-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq

platform using the NovaSeq X Plus 25B Reagent Kit (300 cycles; cat.

no. 20104706; Illumina Inc.) to generate 150 bp paired-end reads.

The final library was loaded at a concentration of 80-120 pM.

Following construction, libraries were quantified (Qubit 2.0

Fluorometer; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), diluted to 1.5

ng/μl, assessed for insert size (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and finally quantified for effective

concentration (>1.5 nM) by quantitative PCR. After obtaining the

RNA-seq gene expression matrix, differential expression analysis

was carried out using the DESeq2 R package (1.20.0; https://github.com/mikelove/DESeq2). The

CLP-treated WT group (CLP group) and CLP-treated RP105 knockout

group (RP105 KO + CLP group) were selected for differential gene

comparison analysis, aiming to explore the molecular mechanism by

which RP105 exerts its effects on mice in the CLP model.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened by two

simultaneous criteria: Absolute log2 fold change (log2FC)≥1

(ensuring biologically significant expression changes) and adjusted

P-value (Padj) <0.05 (controlling false positives and ensuring

statistical reliability). Raw sequencing data generated in the

present study are available in the GEO database (dataset no.

GSE298411; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term=GSE298411).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

After thorough grinding, the mouse liver tissue

(30-50 mg) was lysed with 200 μl immunoprecipitation lysis

buffer on ice for 30 min using immunoprecipitation lysis buffer

(cat. no. BK0004-02; Boyi Bio ACE.). The lysate was then subjected

to centrifugation at 4 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting

supernatant, which contained the protein sample, was mixed with

SOCS2 antibody (1:1,000; A9190; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

incubated overnight at 4°C. Next, 20 μl of Protein A/G

agarose beads were added to the antibody-protein mixture and

incubated for an additional 1 h at room temperature. The complexes

were then separated using magnetic bead-based isolation, followed

by elution and denaturation procedures according to the

manufacturer's instructions (cat. no. BK0004-02; Boyi Bio ACE) and

analyzed by WB.

Flow cytometry

Fresh Raw246.7 cells were washed with 1 ml

pre-cooled PBS at 4°C by pipetting, followed by centrifugation at

1,000-1,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C to collect the cells. The washing

step was repeated twice. A volume of 100 μl 1X binding

buffer (cat. no. G1511-50T; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

working solution was added to the cell pellet to resuspend the

cells. Cells were then mixed thoroughly with 5 μl of Annexin

V-FITC and 5 μl of Propidium Iodide. The mixture was

incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 min. After

staining and incubation, 400 μl 1X Binding Buffer working

solution was added to each tube, mixed well and samples were

analyzed using a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX; Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (V10.8; BD

Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad

Prism 8.0 software (Dotmatics). All data are presented as the mean

± standard deviation. Differences between groups were analyzed

using two-way ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant.

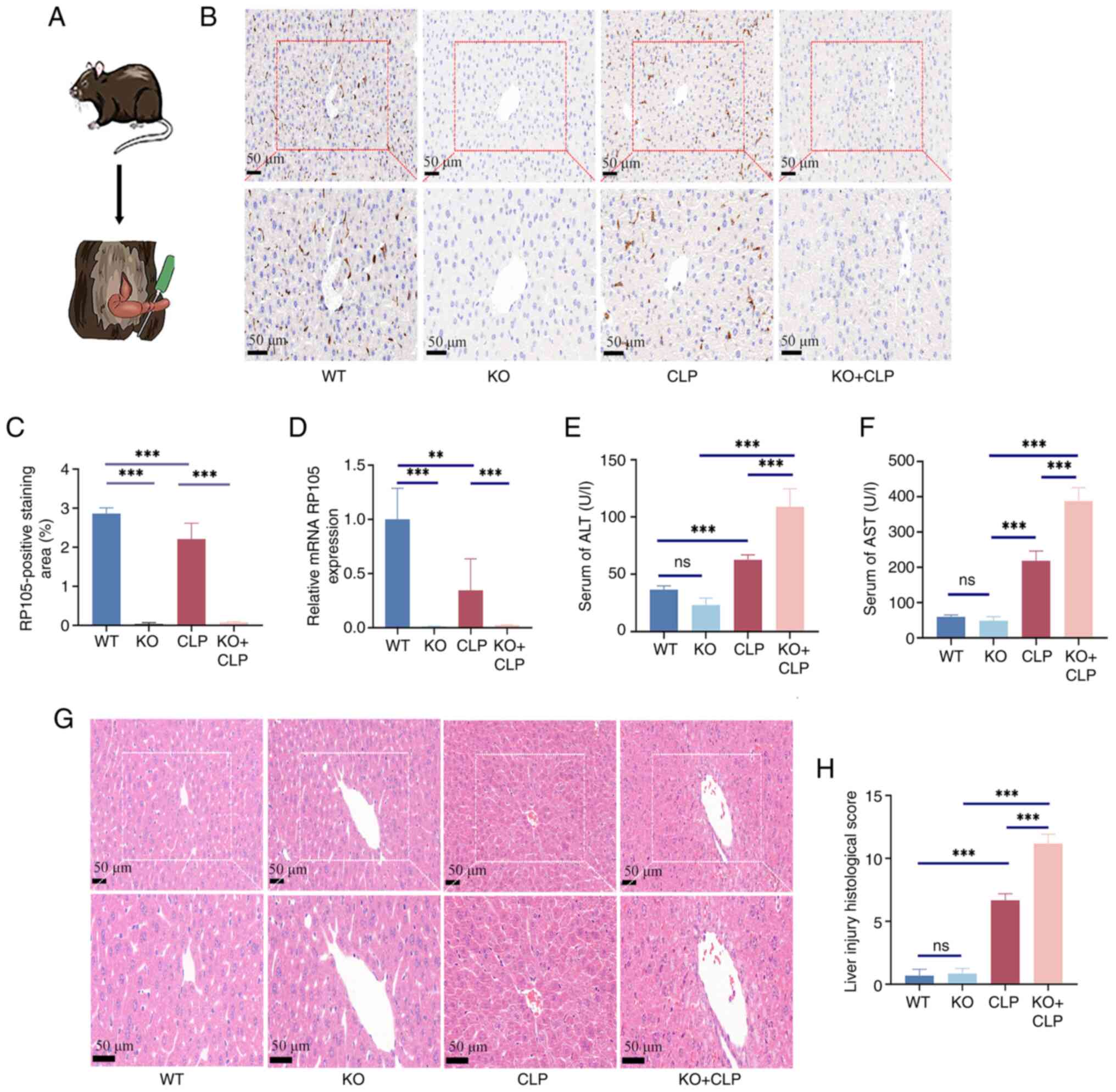

Results

Knockout of RP105 exacerbates hepatic

inflammation and injury in the CLP model

To clarify the specific effect of RP105 on the liver

during sepsis, a septic mouse model was induced using CLP and was

used to evaluate the functional status of hepatocytes in the liver.

A schematic diagram of the animal experiment is shown in Fig. 1A. The knockout efficiency was

verified in the liver of RP105 KO mice using IHC and qPCR (Fig. 1B-D). Examination of serum ALT and

AST levels, indicators of liver function damage, revealed that ALT

and AST levels were significantly increased in RP105 KO + CLP mice

(ALT, 109.0±15.66; AST, 387.7±37.92) compared with the CLP group

(ALT, 62.7±4.20; AST, 218.1±27.96; Fig. 1E and F). Moreover, the

observations revealed significant pathological changes in the liver

of RP105 KO + CLP mice, including severe edema, sinusoidal

congestion and pronounced hepatocellular necrosis. By contrast,

mice in the CLP group exhibited only mild to moderate edema and

sinusoidal congestion (Fig. 1G and

H). These findings suggest that RP105 carries out a key role in

maintaining normal liver structure and function during sepsis.

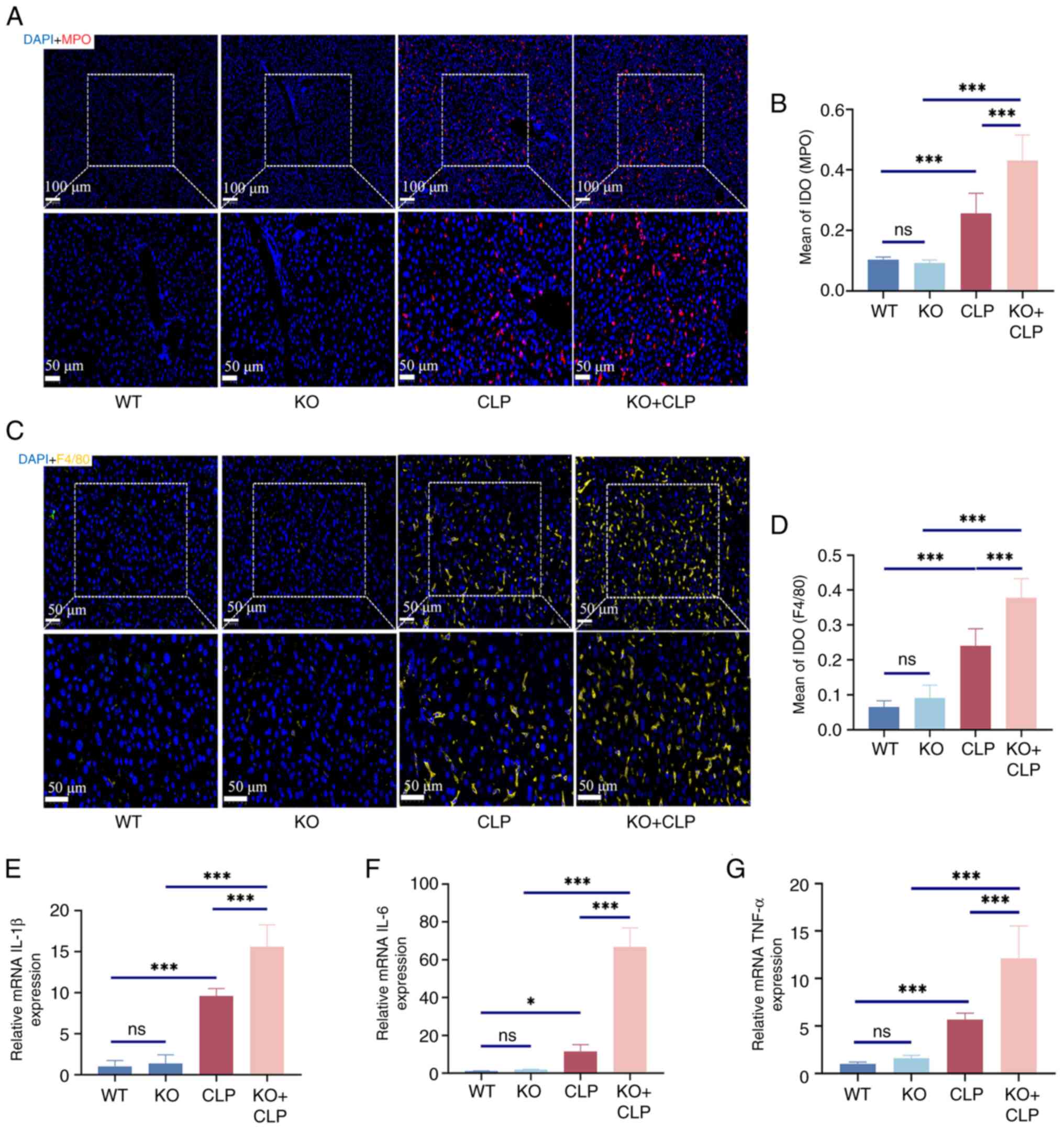

To further demonstrate the role of RP105 in septic

liver injury, additional analysis of inflammatory cell infiltration

was conducted by measuring classic markers of inflammation, MPO and

F4/80. Compared with the CLP group (MPO, 0.2562±0.0663; F4/80,

0.2408±0.0487), a significant increase in the expression levels of

these markers was observed in the liver tissues of RP105 KO mice

(MPO, 0.4306±0.0847; F4/80, 0.3776±0.0552), confirming the

intensified infiltration of inflammatory cells in the liver

(Fig. 2A-D). Furthermore, qPCR

technology was used to assess the expression levels of key

pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. The

results indicated that, compared with the CLP group (IL-1β,

9.59±0.92; IL-6, 11.51±3.54; TNF-α, 5.70±0.66), RP105 KO + CLP mice

(IL-1β, 15.61±2.66; IL-6, 66.84±9.99; TNF-α, 12.12±3.42) exhibited

significantly elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines

(Fig. 2E-G). These finding

highlights the key role of RP105 in regulating the balance between

inflammatory responses.

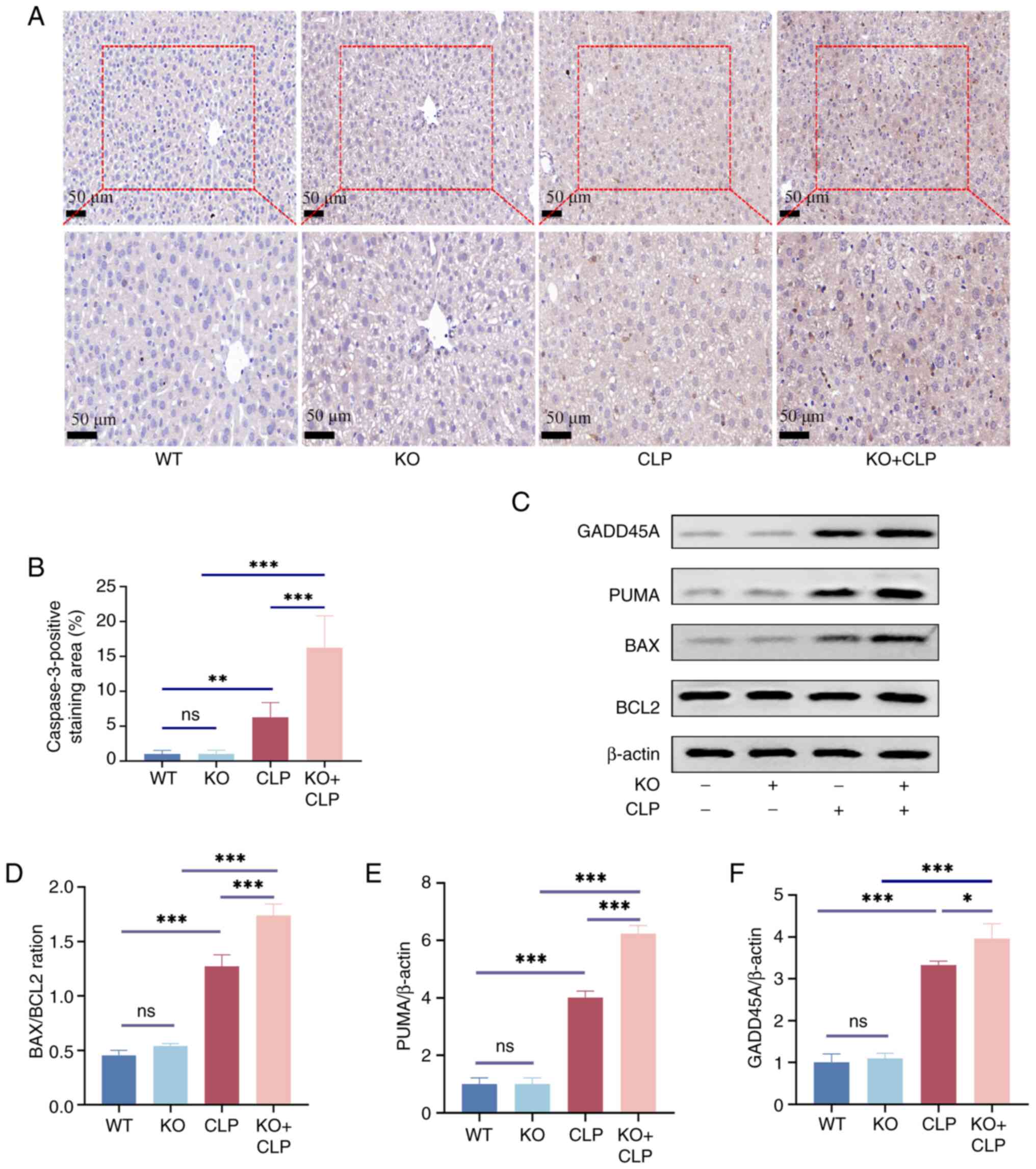

Knockout of RP105 aggravates hepatocyte

apoptosis in the CLP model

Accordingly, the level of apoptosis in the mouse

liver was measured. Analysis of the IHC experiment revealed that,

compared with the CLP group, there was enhanced expression of

Caspase3 in the RP105 KO + CLP group (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, compared to

the CLP group, the ratios of the apoptosis-related proteins

GADD45A, PUMA and BAX to BCL2 were significantly upregulated in the

RP105 KO + CLP group (Fig.

3C-F), further confirming the activation of the apoptotic

signaling pathway. These findings emphasize that, in the context of

sepsis, the absence of RP105 exacerbates apoptosis in the mouse

liver, highlighting the protective role of RP105 against hepatic

damage in an inflammatory condition.

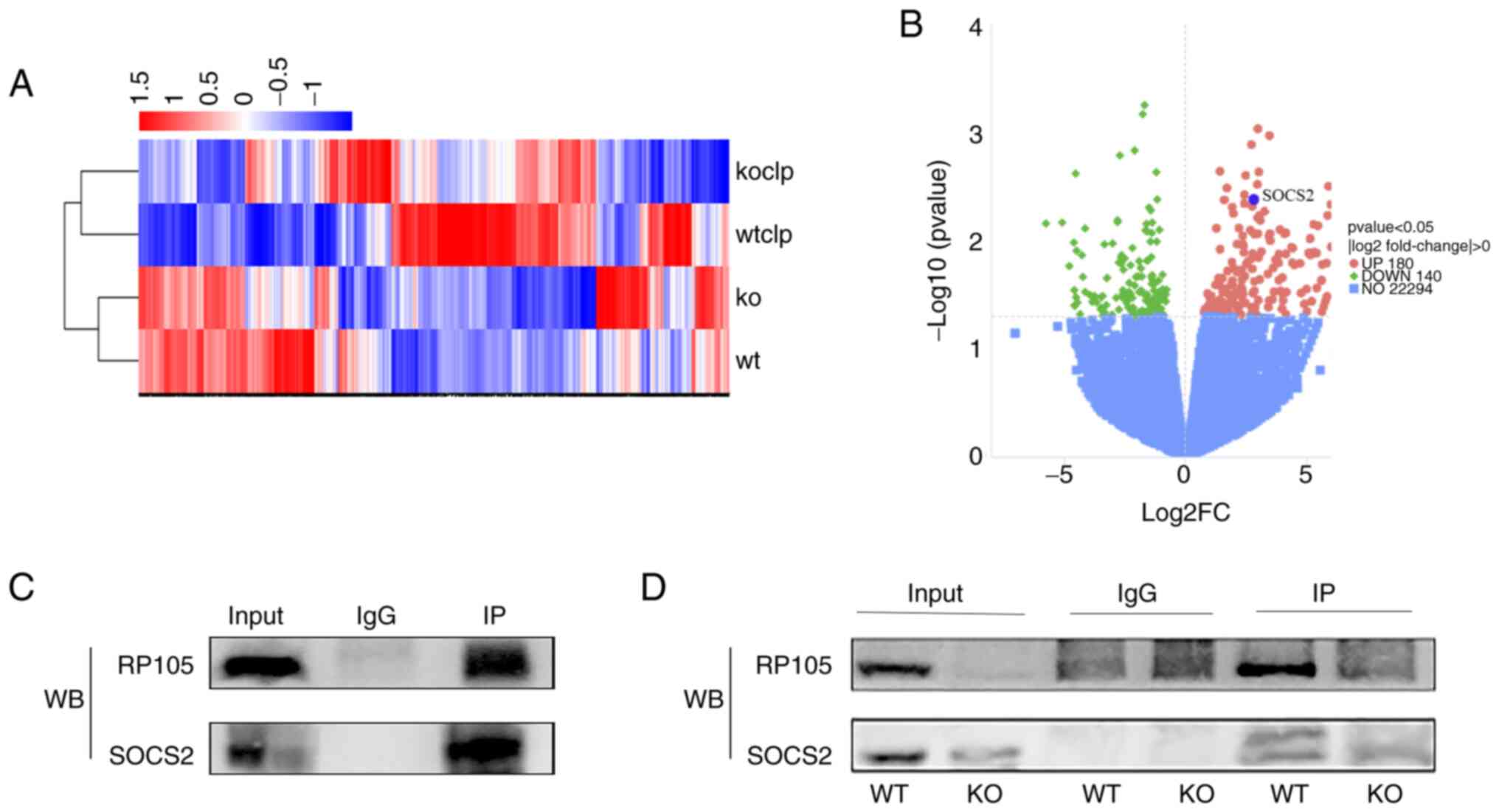

RP105 exhibits the ability to interact

with SOCS2

Following RP105 knockout, the liver function

impairment, inflammatory response and apoptosis observed in the

mouse CLP model were exacerbated. To explore the potential

mechanisms of RP105 in this model, three samples from each of the

two groups (CLP and RP105 KO + CLP groups) were randomly selected

and RNA-seq analysis was carried out. To visually represent these

DEGs, heatmaps were created for clustering analysis (Fig. 4A). The volcano plot revealed 320

DEGs between the CLP and RP105 KO + CLP groups, with 180

upregulated and 140 downregulated genes (Fig. 4B). Notably, significant

upregulation of SOCS2 gene expression was observed within the

upregulated gene set in CLP model mice compared with the RP105 KO +

CLP group (Fig. 4A and B), which

warrants further investigation. Current evidence indicates that

SOCS2 carried out a key anti-inflammatory regulatory role. For

instance, SOCS2 suppresses inflammation and apoptosis during

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis progression by restricting NF-κB

activation in macrophages (25).

More importantly, studies have identified SOCS2 as a feedback

inhibitor of TLR-induced activation, capable of specifically

suppressing TLR signaling pathway activation (26,27), a mechanism associated with the

immune function of RP105 (15,28,29). Although RNA-seq analysis

identified multiple DEGs, pathway enrichment analysis and

literature review revealed that other upregulated DEGs revealed

weaker direct associations with inflammatory regulation. Therefore,

SOCS2 was ultimately selected as the core target for subsequent

mechanistic investigations.

To further explore the interplay between RP105 and

SOCS2, Co-IP was carried out. This experiment revealed that SOCS2

specifically binds to RP105 in mouse tissue samples, providing

preliminary evidence for a direct interaction between the two

proteins (Fig. 4C). To

strengthen this conclusion, a comparative Co-IP experiment was

carried out using liver samples from RP105 KO and WT mice. This

approach enabled the direct assessment of the effect of RP105

deficiency on the binding capacity of SOCS2. The experimental

results revealed that the specific binding between SOCS2 and RP105,

observed in the WT mouse liver, completely disappeared following

RP105 knockout (Fig. 4D). This

finding not only corroborates the initial results but also suggests

the existence of an interaction between RP105 and SOCS2.

Reduction of SOCS2 expression in sepsis

liver by knockdown of RP105

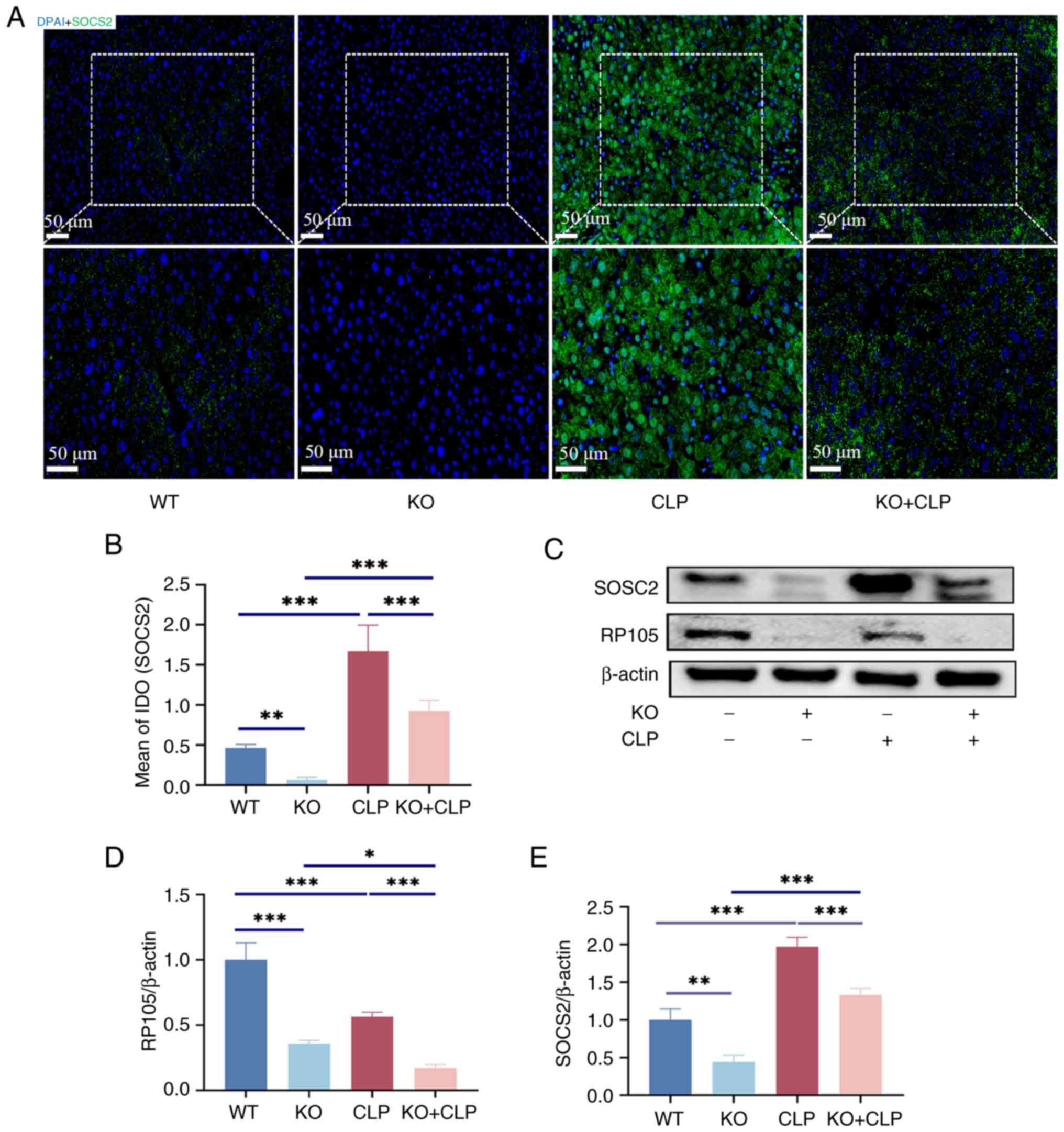

To validate the RNA-seq analysis, SOCS2 protein

expression levels across four groups: WT, RP105 KO, CLP and RP105

KO + CLP groups as assessed. IHC and WB was employed to provide

direct evidence of the differential expression of SOCS2 under

various treatment conditions (Fig.

5A-E), not only to gain a deeper understanding of the

subcellular localization of the SOCS2 protein, but also to observe

potential alterations in its intracellular distribution pattern

under conditions of sepsis and RP105 knockout. After CLP surgery,

SOCS2 expression was significantly increased in the liver of mice.

Although RP105 expression was reduced in the CLP group when

compared with the WT group, SOCS2 expression was still markedly

elevated, likely due to the activation of SOCS2 expression by

CLP-induced inflammation. However, in the RP105 KO + CLP group,

SOCS2 expression was significantly suppressed. Despite this, SOCS2

expression in the RP105 KO + CLP group was still increased compared

with that in the knockout group (Fig. 5A-E), suggesting that in the

inflammatory environment, SOCS2 expression is not only regulated by

RP105 but may also be influenced by other complex signaling

pathways.

RP105 mediates SOCS2 expression to

hepatic inflammation and injury in the CLP model through the

JAK2/STAT3 pathway

In a murine model of sepsis, RNA-seq analysis

revealed significant differential expression of SOCS2 between RP105

knockout mice and wild-type controls (Fig. 4A and B). SOCS2 serves as a

negative feedback regulator within the complex regulatory network

of cytokine signaling. The classic negative feedback regulatory

signaling pathway involves the activation of the JAK2/STAT3

pathway. Building upon this finding, in-depth functional validation

of the canonical SOCS2-mediated JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway was

conducted.

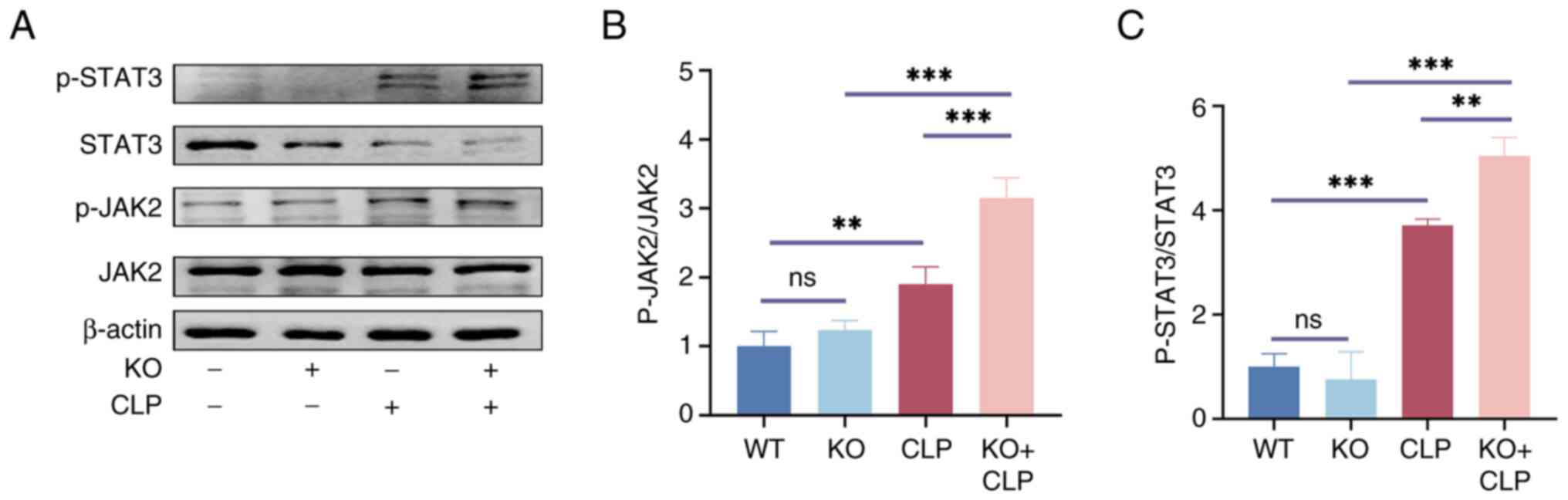

To confirm the function of RP105 and its role in

sepsis-induced liver injury through inactivation of the JAK2/STAT3

pathway via the upregulation of SOCS2, WB experiments were

conducted on liver tissues from the four groups to accurately

assess the expression levels of JAK2, p-JAK2, STAT3 and p-STAT3. WB

indicated that, in the absence of CLP treatment, there were no

significant differences in the basal expression levels of JAK2 and

STAT3 among the groups. However, a remarkable change was observed

following CLP surgery: In the RP105 KO + CLP group, the

phosphorylation levels of JAK2 and STAT3 were significantly

elevated compared with the CLP group (Fig. 6A-C).

RP105 regulates the inf lammatory

response of LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages by modulating the

SOCS2/JAK2/STAT3 pathway

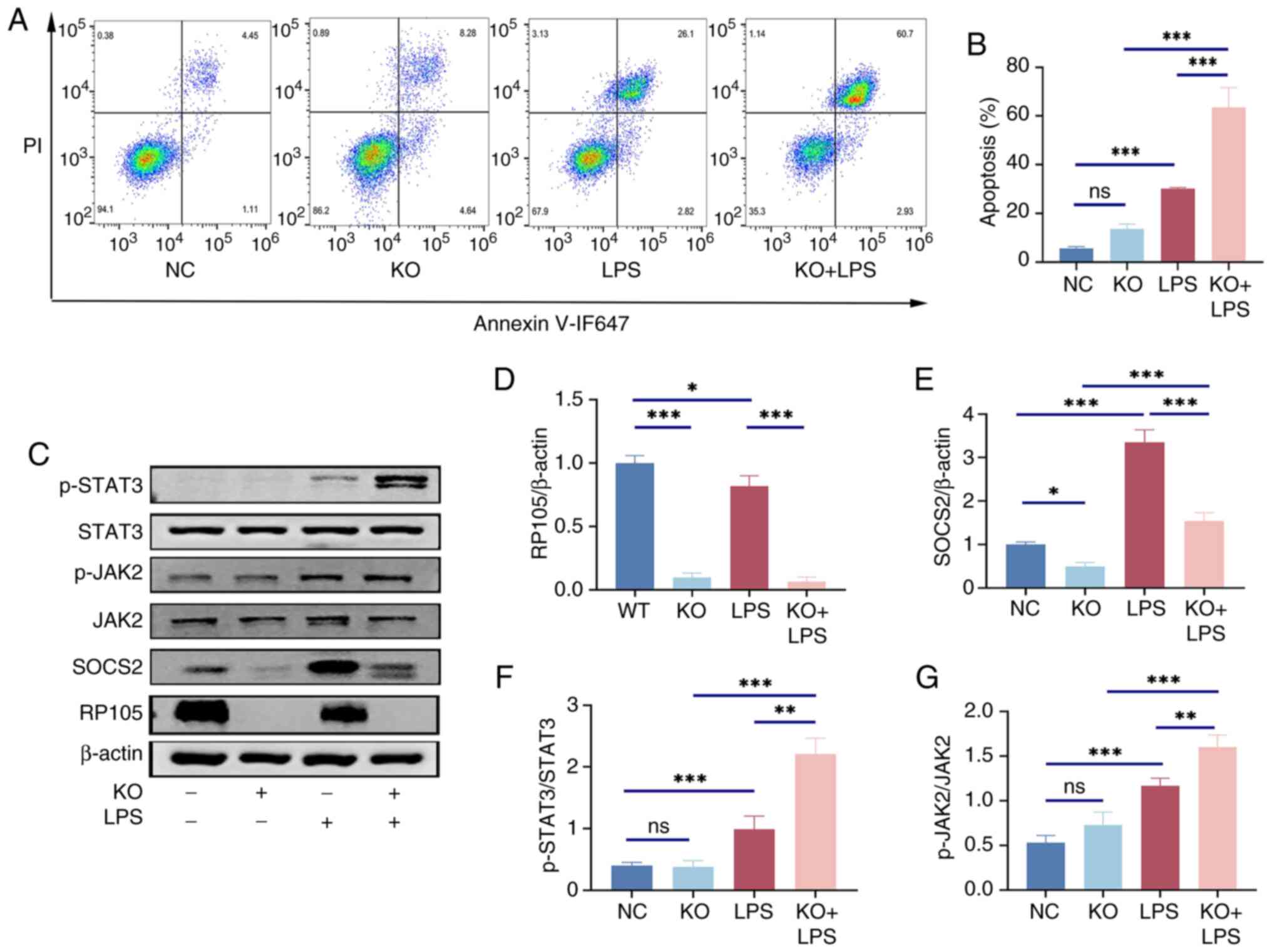

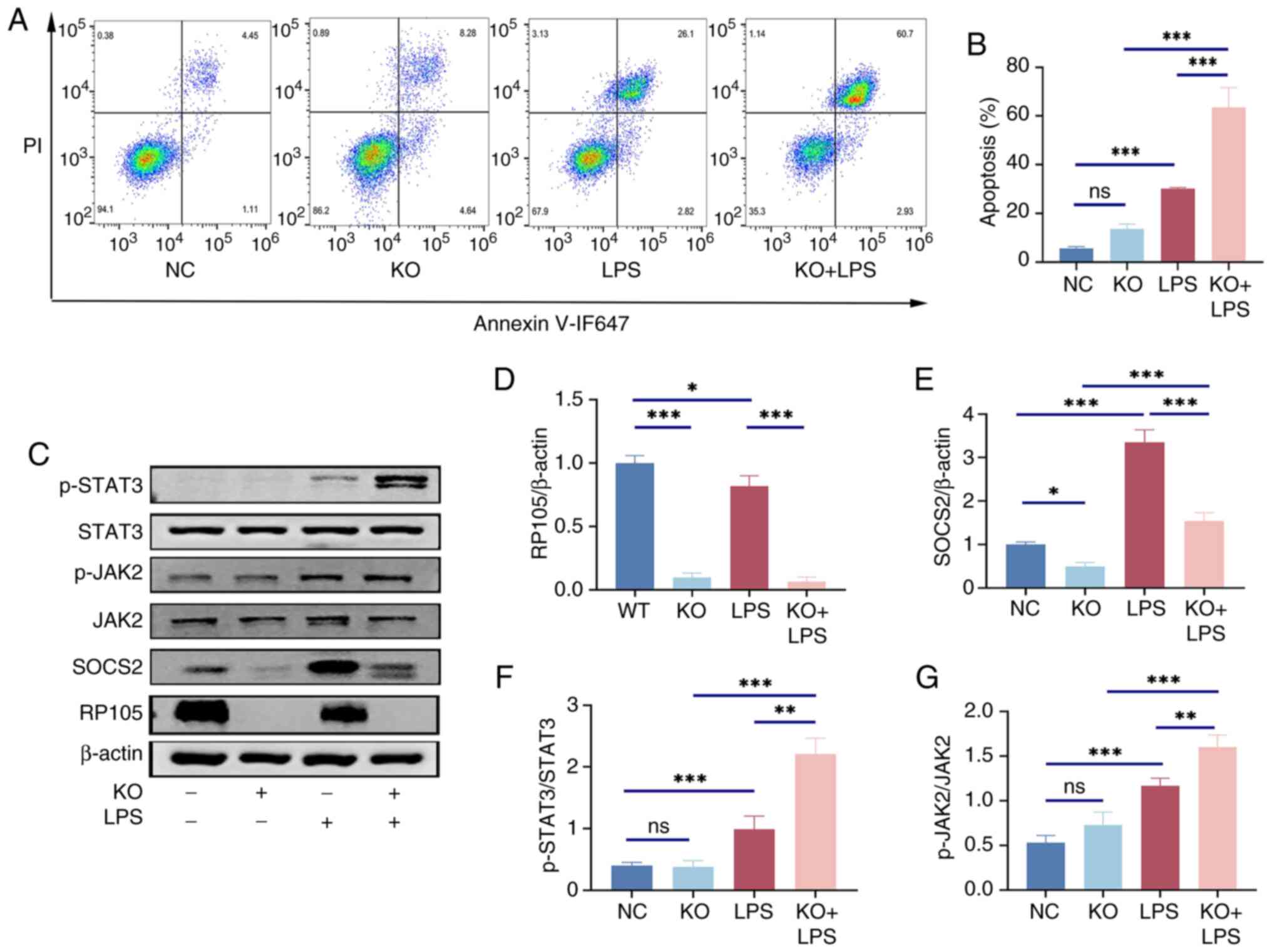

To verify in vitro whether RP105 can

ameliorate the inflammatory response in sepsis by regulating the

SOCS2/JAK2/STAT3 pathway, the expression of relevant proteins in

RAW264.7 cells after LPS stimulation were assessed. Flow cytometry

analysis of the cellular model revealed that, compared with normal

cells, RAW264.7 macrophages with RP105 knocked out exhibited a

significant increase in apoptosis rate after LPS stimulation

(Fig. 7A and B). WB revealed

that the changes in protein expression within this pathway were

similar to those observed at the animal level (Fig. 7C-G).

| Figure 7RAW264.7 cells with KO of RP105 gene

expression exhibits exacerbated damage from LPS under the influence

of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. (A) Representative flow

cytometric images and (B) analysis of apoptosis after LPS treatment

in RAW264.7 cells. (C) Representative western blotting images and

analysis of (D) RP105/β-actin, (E) SOCS2/β-actin, (F) p-JAK2/JAK2

and (G) p-STAT3/STAT3. ns, P>0.05, *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; NC, negative control; KO, knockout; RP105,

radioprotective 105; SOCS2, suppressor of cytokine signaling 2. |

Discussion

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response syndrome

triggered by pathogenic microorganisms, such as bacteria (30). When these pathogens invade the

body, they release toxins that activate the immune system of the

host. Excessive release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines

leads to a systemic inflammatory response, which can result in

multiple organ dysfunction (31). Impaired liver function is closely

associated with the prognosis of sepsis and serves as a robust

independent predictor of mortality (32). Understanding the changes in liver

function during sepsis is key to improving the survival rates of

patients with sepsis. The present study selected CLP as an animal

model for sepsis to simulate the septic environment in vivo,

as it is widely regarded as the gold standard for sepsis research

(33-35).

RP105 was initially identified as a surface marker

of B cells in mice and humans (36). It belongs to a class of type I

transmembrane receptors and exhibits substantial structural

similarity to TLRs. Similar to TLR4, RP105 contains abundant LRRs

(10), which are common

structural domains found in several proteins. The LRR domain

carries out a key role in protein-protein interactions through its

specific three-dimensional structure (37), facilitating the recognition and

activation of various immune responses and interactions with

exogenous pathogens (38). By

sensing extracellular stimuli, RP105 acts as a bridge to transmit

signals to the intracellular effectors. As a TLR homolog, RP105

carries out a key role in the negative regulation of inflammation.

Although the beneficial effects of RP105 have been well established

in TLR4-dependent contexts, recent data have also highlighted its

roles in TLR4-independent pathways (19,39,40). RP105 possesses pathways

independent of TLR4 signal transduction and can physically interact

with the PI3K pathway, carrying out a significant role in improving

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through the PI3K/AKT pathway

(41).

Building on the established role of RP105 in the

anti-inflammatory process (14),

the potential of RP105 as a therapeutic target for modulating

septic liver injury was investigated. The study revealed that RP105

is key for protecting liver function. Compared with the control

group, RP105 knockout mice exhibited aggravated liver dysfunction

after CLP treatment, accompanied by relevant histopathological

changes and a more intense inflammatory response. This is

consistent with previous studies that have emphasized the role of

RP105 as a negative regulator of inflammation (13,42-44). Further RNA-Seq results revealed

that among the DEGs, SOCS2 was downregulated in RP105 KO mice.

Co-IP experiments demonstrated that SOCS2 specifically binds to

RP105 in mouse tissues. This was confirmed by comparative Co-IP

using liver samples from RP105 KO and WT mice: The SOCS2-RP105

binding observed in WT liver disappeared after RP105 knockout,

suggesting an interaction.

To validate the results of RNA-seq analysis, an

in-depth assessment of SOCS2 protein expression levels across four

experimental groups was conducted: WT, RP105 KO, CLP and RP105 KO +

CLP. Analysis revealed an apparent paradox in SOCS2 expression:

While CLP surgery alone induced a significant upregulation of SOCS2

in the liver, its expression was markedly reduced in RP105 KO + CLP

mice. This finding suggests that the induction of SOCS2 during

sepsis may require the presence of RP105. One possible explanation

is that under inflammatory stress, RP105 facilitates SOCS2

expression, possibly through a direct interaction, as supported by

the Co-IP results demonstrating specific binding between RP105 and

SOCS2. In the absence of RP105, this regulatory axis may be

disrupted, leading to an insufficient upregulation of SOCS2 in

response to the strong inflammatory stimulus induced by CLP.

Consequently, as shown by the increased phosphorylation of JAK2 and

STAT3 in RP105 KO + CLP mice, the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway

becomes hyperactivated, further aggravating liver inflammation and

injury. Together, these data suggest that RP105 is important not

only for maintaining hepatic homeostasis during sepsis but also for

ensuring appropriate SOCS2 induction to restrain cytokine-mediated

damage. Notably, despite the suppression of SOCS2 expression in the

CLP group with RP105 knockout, SOCS2 expression was still increased

in the RP105 KO + CLP group. This finding suggests that in an

inflammatory environment, SOCS2 expression is not only regulated by

RP105 but also is influenced by other complex pathways. For

instance, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β may induce SOCS2

expression through alternative signaling pathways (45).

Additionally, in the CLP group, despite a decrease

in RP105 expression compared with the WT group, SOCS2 expression

significantly increased. This may be due to the inflammatory

environment triggered by CLP surgery activating SOCS2 expression,

which may override the regulatory effect of RP105 on SOCS2.

However, this also raises the possibility that RP105 is not the

sole upstream regulator of SOCS2 and inflammatory cues such as

IL-1β or IL-6 may independently enhance SOCS2 expression through

STAT-dependent transcription. Such a compensatory induction, though

present, appears insufficient to suppress downstream signaling in

the absence of RP105. In summary, the present study not only

validates the results of RNA-seq analysis but also uncovers the

complex regulatory mechanisms of SOCS2 in inflammatory responses

and the pivotal role of RP105 in this process. These observations

suggest that the RP105-SOCS2 interaction may serve as a regulatory

checkpoint that constrains excessive activation of the JAK2/STAT3

axis during septic liver injury. The disruption of this checkpoint

in RP105-deficient conditions may contribute to signal

amplification, cytokine storm and hepatocyte apoptosis. These

findings provide new insights into the understanding of the

inflammatory responses and the search for potential therapeutic

targets.

SOCS2, operates within classic feedback loops by

targeting the degradation of signaling intermediates, thereby

blocking further signal transduction (46). Imbalances in these proteins can

lead to a wide range of pathological changes, highlighting the

essential role of SOCS2 in regulating cell fate and inflammatory

processes (47). As a pivotal

signaling protein, SOCS2 exhibits diverse functions across various

cell types (48,49), underscoring its importance.

Notably, SOCS2 carries out a key role in modulating immune

responses and inflammatory pathways, which are vital for

maintaining organismal health (50). Previous research (25) has reported that SOCS2 in

macrophages exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects by

modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway, while also attenuating

inflammation through the inhibition of the inflammasome signaling

pathway. Additionally, SOCS2 has been revealed to be vital in

balancing immune responses and protecting against oxidative stress

during acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury, acting as a key

regulatory factor in liver immune responses following acetaminophen

therapy (51).

SOCS2 serves as a negative feedback regulator within

the complex regulatory network of cytokine signaling. By

interacting precisely with core molecules in the signaling complex,

it effectively blocks further extension of the signaling chain,

achieving negative feedback regulation of the cytokine signaling

pathway. A classic example of this regulatory mechanism is the

activation of the JAK/STAT pathway. During inflammation, SOCS2

forms complexes with key proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway, thereby

effectively inhibiting the amplification and transmission of

inflammatory signals. This ensures timely termination and precise

regulation of cellular responses to inflammatory factors, thus

inhibiting inflammatory reactions. We hypothesize that the

JAK2/STAT3 pathway carries out a key role in protecting against

liver injury due to sepsis mediated by RP105 through SOCS2. In the

present study, we found that the phosphorylation levels of

JAK2/STAT3 in the liver tissues of RP105 KO mice subjected to the

CLP model and in RAW264.7 macrophages treated with LPS were both

increased compared with those in the control groups. This

consistent activation across in vivo and in vitro

systems suggests that SOCS2 carries out a non-redundant role in

restraining this pathway, and its suppression in the absence of

RP105 may permit uncontrolled signaling propagation. These findings

suggest that RP105 mitigates the progression of sepsis-induced

liver injury through the inactivation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway

mediated by SOCS2.

Based on the aforementioned research findings, we

hypothesize that intervention methods targeting the enhancement of

the RP105-SOCS2 interaction can be designed to evaluate their

intervention effects in the early stage of septic liver injury.

Additionally, through prospective cohort studies, the levels of

RP105 and SOCS2 in patients with sepsis at the time of admission

can be detected, the associations between these levels and liver

injury grading as well as treatment efficacy can be analyzed, and a

combined prediction model based on their expression levels can be

established, which will provide reference indicators for early

clinical intervention.

While the present study provides insights into the

role of RP105 in sepsis pathogenesis using murine models, it is

essential to recognize the inherent limitations in translating

these findings to human diseases due to fundamental differences in

immune regulation and pathophysiology between species. Although

murine models are indispensable for mechanistic investigations,

they cannot fully replicate the complexity of human sepsis, as

evidenced by significant interspecies variations in TLR signaling

pathways, cytokine networks and cellular immune responses.

RP105 protects against septic liver injury by

binding SOCS2 to inhibit JAK2/STAT3 signaling, thereby attenuating

inflammation and apoptosis. The study is the first to demonstrate

the RP105-SOCS2 interaction in septic liver injury, revealing the

RP105/SOCS2 axis as a potential therapeutic target.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the GEO database under accession number GSE298411 or at the

following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term=GSE298411.

Authors' contributions

QD designed cell and animal experiments, curated

data, developed methodology, conducted formal analysis and wrote

the original draft. HD and QY curated data, conducted formal and

software analysis and developed methodology. RC, ZF and JX

collected the information and revised, conducted analyses using

software tools and finalized the manuscript. HP and QX proposed the

preliminary idea and design for the present study and reviewed and

revised the manuscript. QD and QX confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee for Laboratory Animal Welfare of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Nanchang University (approval no.

CDYFY-IACUC-202407QR198).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82460131 and 82060122) and Natural

Science Foundation of JiangXi province (grant no.

20224ACB206027).

References

|

1

|

Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford

KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer

S, et al: Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and

mortality, 1990-2017: Analysis for the global burden of disease

study. Lancet. 395:200–211. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Takeuchi O and Akira S: Pattern

recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 140:805–820. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Raymond SL, Holden DC, Mira JC, Stortz JA,

Loftus TJ, Mohr AM, Moldawer LL, Moore FA, Larson SD and Efron PA:

Microbial recognition and danger signals in sepsis and trauma.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1863:2564–2573. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fajgenbaum DC and June CH: Cytokine storm.

N Engl J Med. 383:2255–2273. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chousterman BG, Swirski FK and Weber GF:

Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol.

39:517–528. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Protzer U, Maini MK and Knolle PA: Living

in the liver: Hepatic infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 12:201–213.

2012. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Heymann F and Tacke F: Immunology in the

liver-from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

13:88–110. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yan J and Li S and Li S: The role of the

liver in sepsis. Int Rev Immunol. 33:498–510. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Elmi AN and Kwo PY: The liver in sepsis.

Clin Liver Dis. 29:453–467. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Miyake K, Yamashita Y, Ogata M, Sudo T and

Kimoto M: RP105, a novel B cell surface molecule implicated in B

cell activation, is a member of the leucine-rich repeat protein

family. J Immunol. 154:3333–3340. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Divanovic S, Trompette A, Atabani SF,

Madan R, Golenbock DT, Visintin A, Finberg RW, Tarakhovsky A, Vogel

SN, Belkaid Y, et al: Negative regulation of Toll-like receptor 4

signaling by the Toll-like receptor homolog RP105. Nat Immunol.

6:571–578. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Schultz TE and Blumenthal A: The

RP105/MD-1 complex: Molecular signaling mechanisms and

pathophysiological implications. J Leukoc Biol. 101:183–192. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Yang J, Yang C, Yang J, Ding J, Li X, Yu

Q, Guo X, Fan Z and Wang H: RP105 alleviates myocardial ischemia

reperfusion injury via inhibiting TLR4/TRIF signaling pathways. Int

J Mol Med. 41:3287–3295. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fan Z, Pathak JL and Ge L: The potential

role of RP105 in regulation of inflammation and osteoclastogenesis

during inflammatory diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7132542021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhu J, Zhang Y, Shi L, Xia Y, Zha H, Li H

and Song Z: RP105 protects against ischemic and septic acute kidney

injury via suppressing TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathways. Int

Immunopharmacol. 109:1089042022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wezel A, de Vries MR, Maassen JM, Kip P,

Peters EA, Karper JC, Kuiper J, Bot I and Quax PHA: Deficiency of

the TLR4 analogue RP105 aggravates vein graft disease by inducing a

pro-inflammatory response. Sci Rep. 6:242482016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen F, Xu W, Tang M, Tian Y, Shu Y, He X,

Zhou L, Liu Q, Zhu Q, Lu X, et al: hnRNPA2B1 deacetylation by SIRT6

restrains local transcription and safeguards genome stability. Cell

Death Differ. 32:382–396. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Li T, Sun H, Li Y, Su L, Jiang J, Liu Y,

Jiang N, Huang R, Zhang J and Peng Z: Downregulation of macrophage

migration inhibitory factor attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome mediated

pyroptosis in sepsis-induced AKI. Cell Death Discov. 8:612022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Duo H, Yang Y, Luo J, Cao Y, Liu Q, Zhang

J, Du S, You J, Zhang G, Ye Q and Pan H: Modulatory role of

radioprotective 105 in mitigating oxidative stress and ferroptosis

via the HO-1/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis in sepsis-mediated renal injury.

Cell Death Discov. 11:2902025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kollias NS, Hess WJ, Johnson CL, Murphy M

and Golab G: A literature review on current practices, knowledge,

and viewpoints on pentobarbital euthanasia performed by

veterinarians and animal remains disposal in the United States. J

Am Vet Med Assoc. 261:733–738. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gong S, Yan Z, Liu Z, Niu M, Fang H, Li N,

Huang C, Li L, Chen G, Luo H, et al: Intestinal microbiota mediates

the susceptibility to polymicrobial sepsis-induced liver injury by

granisetron generation in mice. Hepatology. 69:1751–1767. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Liang H, Song H, Zhang X, Song G, Wang Y,

Ding X, Duan X, Li L, Sun T and Kan Q: Metformin attenuated

sepsis-related liver injury by modulating gut microbiota. Emerg

Microbes Infect. 11:815–828. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Zhong X, Xiao Q, Liu Z, Wang W, Lai CH,

Yang W, Yue P, Ye Q and Xiao J: TAK242 suppresses the TLR4

signaling pathway and ameliorates DCD liver IRI in rats. Mol Med

Rep. 20:2101–2110. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li S, Han S, Jin K, Yu T, Chen H, Zhou X,

Tan Z and Zhang G: SOCS2 suppresses inflammation and apoptosis

during NASH progression through limiting NF-κB activation in

macrophages. Int J Biol Sci. 17:4165–4175. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

26

|

Posselt G, Schwarz H, Duschl A and

Horejs-Hoeck J: Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 is a feedback

inhibitor of TLR-induced activation in human monocyte-derived

dendritic cells. J Immunol. 187:2875–2884. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Baetz A, Frey M, Heeg K and Dalpke AH:

Suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins indirectly

regulate toll-like receptor signaling in innate immune cells. J

Biol Chem. 279:54708–54715. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang J, Zeng P, Yang J and Fan ZX: The

role of RP105 in cardiovascular disease through regulating TLR4 and

PI3K signaling pathways. Curr Med Sci. 39:185–189. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Divanovic S, Trompette A, Petiniot LK,

Allen JL, Flick LM, Belkaid Y, Madan R, Haky JJ and Karp CL:

Regulation of TLR4 signaling and the host interface with pathogens

and danger: The role of RP105. J Leukoc Biol. 82:265–271. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW,

Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche

JD, Coopersmith CM, et al: The third international consensus

definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA.

315:801–810. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M and Rhodes A:

Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet. 392:75–87. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Recknagel P, Gonnert FA, Westermann M,

Lambeck S, Lupp A, Rudiger A, Dyson A, Carré JE, Kortgen A, Krafft

C, et al: Liver dysfunction and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

signalling in early sepsis: Experimental studies in rodent models

of peritonitis. PLoS Med. 9:e10013382012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bastarache JA and Matthay MA: Cecal

ligation model of sepsis in mice: New insights. Crit Care Med.

41:356–357. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

34

|

Dejager L, Pinheiro I, Dejonckheere E and

Libert C: Cecal ligation and puncture: The gold standard model for

polymicrobial sepsis? Trends Microbiol. 19:198–208. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA and

Ward PA: Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and

puncture. Nat Protoc. 4:31–36. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Miyake K, Yamashita Y, Hitoshi Y, Takatsu

K and Kimoto M: Murine B cell proliferation and protection from

apoptosis with an antibody against a 105-kD molecule:

Unresponsiveness of X-linked immunodeficient B cells. J Exp Med.

180:1217–1224. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Miura Y, Shimazu R, Miyake K, Akashi S,

Ogata H, Yamashita Y, Narisawa Y and Kimoto M: RP105 is associated

with MD-1 and transmits an activation signal in human B cells.

Blood. 92:2815–2822. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Ishii A, Matsuo A, Sawa H, Tsujita T,

Shida K, Matsumoto M and Seya T: Lamprey TLRs with properties

distinct from those of the variable lymphocyte receptors. J

Immunol. 178:397–406. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yang J, Zhai Y, Huang C, Xiang Z, Liu H,

Wu J, Huang Y, Liu L, Li W, Wang W, et al: RP105 attenuates

ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative stress in the myocardium via

activation of the Lyn/Syk/STAT3 signaling pathway. Inflammation.

47:1371–1385. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Guo X, Hu S, Liu JJ, Huang L, Zhong P, Fan

ZX, Ye P and Chen MH: Piperine protects against pyroptosis in

myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury by regulating the

miR-383/RP105/AKT signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 25:244–258.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Guo X, Jiang H and Chen J: RP105-PI3K-Akt

axis: A potential therapeutic approach for ameliorating myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int J Cardiol. 206:95–96. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Liu B, Zhang N, Liu Z, Fu Y, Feng S, Wang

S, Cao Y, Li D, Liang D, Li F, et al: RP105 involved in activation

of mouse macrophages via TLR2 and TLR4 signaling. Mol Cell Biochem.

378:183–193. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Huang W and Yang J, He C and Yang J: RP105

plays a cardioprotective role in myocardial ischemia reperfusion

injury by regulating the Toll-like receptor 2/4 signaling pathways.

Mol Med Rep. 22:1373–1381. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Sun Y, Liu L, Yuan J, Sun Q, Wang N and

Wang Y: RP105 protects PC12 cells from oxygen-glucose

deprivation/reoxygenation injury via activation of the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 41:3081–3089. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sarajlic M, Neuper T, Föhrenbach Quiroz

KT, Michelini S, Vetter J, Schaller S and Horejs-Hoeck J: IL-1β

induces SOCS2 expression in human dendritic cells. Int J Mol Sci.

20:59312019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Krebs DL and Hilton DJ: SOCS proteins:

Negative regulators of cytokine signaling. Stem Cells. 19:378–387.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Elliott J and Johnston JA: SOCS: Role in

inflammation, allergy and homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 25:434–440.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Keating N and Nicholson SE: SOCS-mediated

immunomodulation of natural killer cells. Cytokine. 118:64–70.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Hu J, Winqvist O, Flores-Morales A,

Wikström AC and Norstedt G: SOCS2 influences LPS induced human

monocyte-derived dendritic cell maturation. PLoS One. 4:e71782009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang D, Pan A, Gu J, Liao R, Chen X and

Xu Z: Upregulation of miR-144-3p alleviates Doxorubicin-induced

heart failure and cardiomyocytes apoptosis via SOCS2/PI3K/AKT axis.

Chem Biol Drug Des. 101:24–39. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Monti-Rocha R, Cramer A, Gaio Leite P,

Antunes MM, Pereira RVS, Barroso A, Queiroz-Junior CM, David BA,

Teixeira MM, Menezes GB and Machado FS: SOCS2 is critical for the

balancing of immune response and oxidate stress protecting against

acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Front Immunol.

9:31342018. View Article : Google Scholar

|