Cholesterol is an essential component of mammalian

cell membranes and is indispensable for maintaining normal cellular

functions (1). The synthesis of

cholesterol is maintained through a dynamic homeostatic process,

with intracellular cholesterol levels being precisely regulated by

a sophisticated feedback system involving synthesis, uptake,

efflux, transport, esterification and enzymatic conversion

(2). Cancer cells frequently

exhibit an elevated demand for cholesterol to facilitate their

growth (3). Specifically, they

augment the uptake of exogenous cholesterol and lipoproteins and

reprogram cholesterol metabolism by regulating genes related to

cholesterol synthesis, efflux and intake to increase cholesterol

influx and decrease efflux (4,5).

Additionally, tumors can elevate cholesterol levels within the

tumor microenvironment (TME) by stimulating cholesterol efflux from

monocytes and macrophages via intercellular signaling (6). Furthermore, cholesterol serves as a

precursor for biologically active metabolites, such as oxysterols

(7), steroid hormones (8) and lipid rafts (LRs) (9), which collectively promote cancer

cell proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis and other

pro-tumorigenic processes (10).

A previous study has shown that the crosstalk

between cholesterol metabolism and the TME contributes to

tumorigenesis and progression (11). Moreover, oncogenic signaling

pathways (12), ferroptosis

(13), autophagy (14), epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT) (15) and the immune

response (16) are modulated

through cholesterol metabolism. Current evidence indicates that

targeting cholesterol metabolism, either alone or in combination

with other strategies, to enhance cancer treatment efficacy has

proven to be a viable antitumor approach. Notably, interventions

targeting cholesterol metabolism enzymes [such as HMG-CoA reductase

(HMGCR) (17), sterol regulatory

element binding proteins (SREBPs) (18), squalene epoxidase (SQLE)

(19) and acetyl-CoA

acetyltransferase 1 (ACAT1) (20)] or transporters [ATP-binding

cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) (21), ATP-binding cassette transporter

G1 (ABCG1) (22) and low-density

lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) (23)] have shown considerable anticancer

potential.

However, the association between cholesterol and

cancer progression is currently controversial. Several

epidemiological studies have shown that hypercholesterolemia and

high cholesterol diets are associated with an increased risk of

developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (24), colorectal cancer (CRC) (25), prostate cancer (PC) (26) and other cancer types (27). Consistently, statins and

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors,

which effectively lower serum cholesterol levels by targeting

cholesterol metabolism genes, have been found to suppress cancer

progression in certain settings (28). By contrast, other large cohort

studies report that serum total cholesterol (TC) levels are either

inversely correlated with cancer risk or show no significant

association (29,30). For instance, a large-scale

prospective Korean cohort study demonstrated that higher TC levels

were negatively associated with mortality rates in HCC and gastric

cancer (GC) (31). The role of

dietary cholesterol in carcinogenesis is similarly debated. While

high-cholesterol diets have been shown to accelerate HCC and CRC

development (32), a recent

study showed a significant positive association between higher

daily dietary cholesterol intake and ovarian cancer (OV) risk,

whereas abnormal lipid levels were not associated with the risk of

OV (33). These conflicting

epidemiological data underscore the complexity of the role of

cholesterol in cancer and highlight the need for further

mechanistic and population-level studies to clarify the

relationship between serum cholesterol levels and cancer risk.

In the present review, the latest progress in the

interaction between cholesterol and cancer progression is

summarized, focusing on the functional roles of cholesterol and its

derivatives within cancer cells and their reciprocal regulation

within the TME. The current therapeutic strategies targeting

molecules such as HMGCR, SREBPs and SQLE are also discussed,

offering new perspectives for anticancer drug development.

Cholesterol is an essential lipid molecule and a

critical component for maintaining normal functions in the human

body (1,34). Cholesterol fulfills multiple

vital roles, including maintaining membrane integrity, facilitating

cell signaling cell membrane structure, mediating cell

communication, enhancing immunity and serving as a precursor for

synthesizing steroids, sex hormones, vitamin D, bile salts and

oxysterols (35-37). Cholesterol metabolites also hold

significant value. In the liver, cholesterol is converted into bile

acids, which are essential for the emulsification and absorption of

dietary lipids and represent the primary route for eliminating

excess cholesterol from the body (38,39). Moreover, cholesterol serves as

the precursor for all steroid hormones (such as cortisol,

aldosterone, estrogen and testosterone). In the skin, under

ultraviolet radiation, cholesterol is transformed into a vitamin D

precursor, which is subsequently activated to regulate calcium and

phosphate homeostasis (40-42). Thus, in healthy individuals, the

homeostasis of cholesterol metabolism is indispensable for cellular

activity, digestion function, endocrine regulation and skeletal

health.

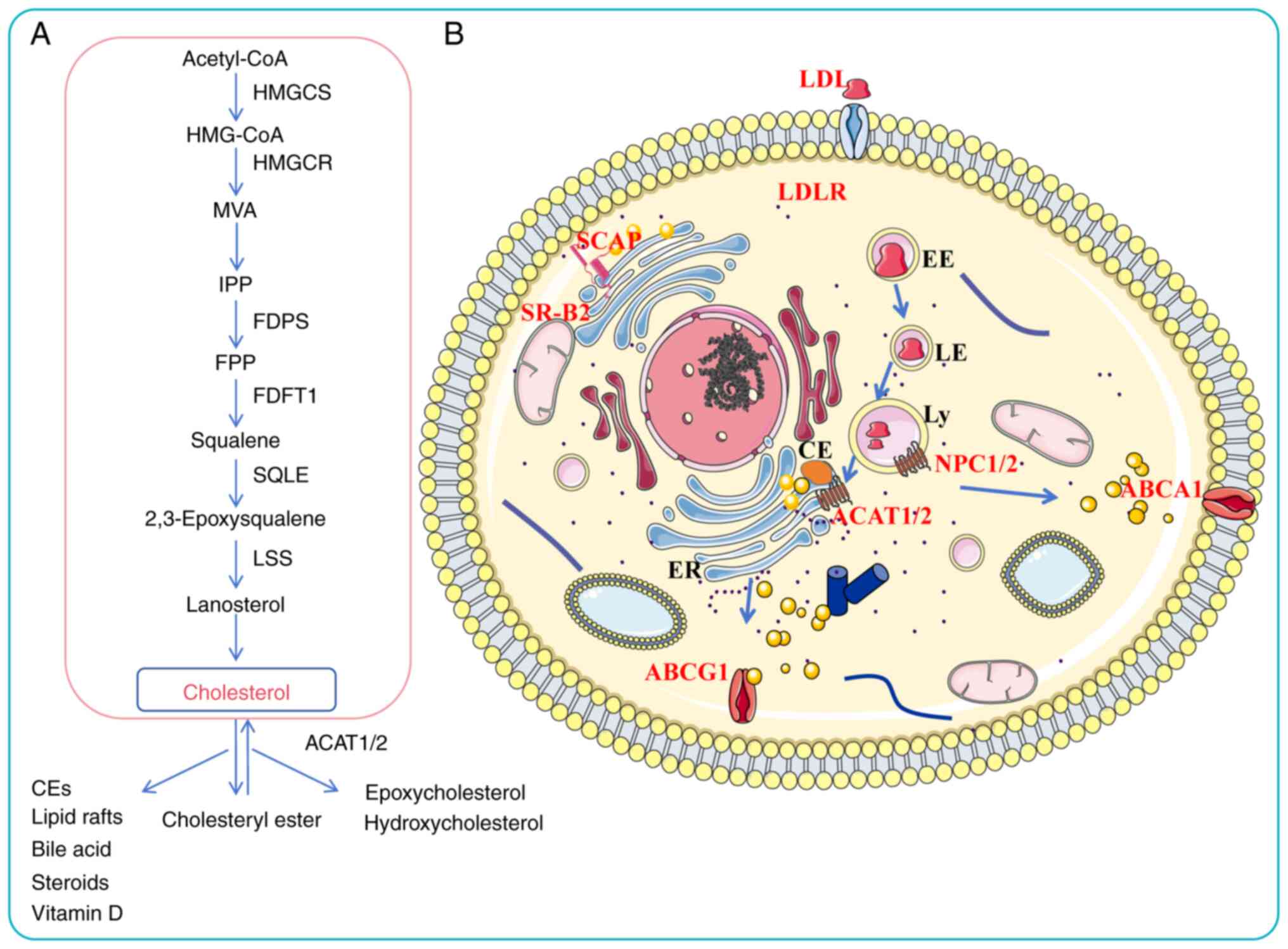

The body acquires cholesterol through two primary

pathways: Endogenous synthesis (70-80%) and exogenous dietary

intake (20-30%) (43). Dietary

cholesterol is absorbed by Niemann-Pick-C1 like-1 protein (NPC1L1)

on the intestinal epithelial cell membrane and subsequently

esterified by ACAT1/2, enabling its uptake by the liver in the form

of chylomicrons (44). The liver

esterifies cholesterol synthesized internally and absorbed from

food, assembling it with apolipoproteins and other components into

very low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs), which are subsequently

secreted into the bloodstream. These VLDLs are metabolized into

low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), which are taken up by peripheral

tissues via LDLRs. Excess cholesterol in peripheral tissues is

delivered back to the liver via high-density lipoprotein

cholesterol (HDL-C)-mediated reverse cholesterol transport, where

it can be recycled or converted to bile acids for excretion

(1,45). Intracellular cholesterol levels

are regulated through receptor-mediated endocytosis of LDL-C and

HDL-C, as well as through de novo synthesis in the

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) via the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, which

includes squalene biosynthesis and modification procedures

(34). Key regulatory enzymes in

this pathway are HMGCR and SQLE, which catalyze the conversion of

HMG-CoA to MVA and squalene to 2,3-epoxysqualene, respectively.

Subsequent steps involve enzymes such as farnesyl diphosphate

synthase (FDPS) and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPs),

which are crucial for the biosynthesis of farnesyl pyrophosphate

(FPP) and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP). Under the action of

squalene synthase and squalene epoxidase, FPP is converted to

squalene and eventually to cholesterol (46).

Cholesterol homeostasis is transcriptionally

regulated by SREBPs. When intracellular cholesterol levels are

high, SREBPs are retained in the ER through interaction with the

SREBP cleavage-activating protein/insulin-induced gene-1 (INSIG-1)

complex. When the cholesterol level of the endoplasmic membrane

decreases, SREBPs are transported to the Golgi apparatus. Following

proteolytic processing, their transcriptionally active N-terminal

domains are released (47).

Excess intracellular cholesterol is either esterified by ACAT1 and

stored in lipid droplets or refluxed from cells via transporters

such as ABCA1 and ABCG1 (48).

The dysregulation of cholesterol metabolic enzymes is implicated in

various pathologies, including familial hypercholesterolemia

(49), atherosclerosis (35) and Alzheimer's disease (50). In summary, cholesterol levels in

normal cells are tightly controlled through a balance of synthesis,

uptake, efflux, transport and esterification. A thorough

understanding of these regulatory mechanisms is essential for

elucidating the pathophysiology of cholesterol-related disorders

(Fig. 1).

During growth and invasion, cancer cells require a

continuous supply of cholesterol to sustain biosynthetic processes

and cellular functions. Consequently, abnormal activation of

cholesterol metabolism genes is commonly observed across multiple

types of cancer (51).

Cholesterol metabolism-related genes are upregulated, cholesterol

influx is increased and cholesterol efflux is decreased. HMGCR is

the primary rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis, and

its high expression in malignant tumors promotes tumor progression.

For instance, HMGCR induces immunosuppression in OV by activating

X-box binding protein 1 and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1),

correlating with poor prognosis (52). In PC, stromal HMGCR upregulation

induced by coculture with malignant cells promotes tumor growth

(53). HCC is an aggressive

human cancer with increasing incidence worldwide (54). Research has revealed that HMGCR

promotes tumor growth in a mouse model of primary liver cancer by

enhancing cholesterol synthesis and activating the PDZ-binding

motif/TEA domain transcription factors 2/anillin/kinesin family

member 23 pathway (55).

Additionally, HMGCR overexpression augments the growth and

migration of GC cells (56),

breast cancer (BC) cells (57)

and glioblastoma (GBM) cells (58).

SQLE, as the second rate-limiting enzyme downstream

of HMGCR, is considered an oncogene that promotes carcinogenic

signaling (68). It has been

reported that SQLE could enhance the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to

promote distant metastasis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

(69). In CRC, SQLE induces EMT

by triggering the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thereby promoting tumor

metastasis (70). Moreover,

SQLE, which is abnormally expressed in liver cancer models, induces

immune suppression by promoting cholesterol accumulation in the TME

and inhibiting CD8+ T cell function (71). Research has also shown that SQLE

contributes to the resistance of BC cells to apoptosis by enhancing

glycolysis (72). SQLE

expression is specifically elevated in HCC and is strongly

associated with poor clinical outcomes (73). SQLE significantly augments HCC

growth in both in vitro and in vivo models, linked to

the activation of serine-threonine kinase receptor associated

protein-dependent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/SMAD

signaling pathways (74).

Farnesyl-diphosphate farnesyltransferase (FDFT1),

another key enzyme in the cholesterol pathway, is dysregulated in

various tumor types and represents a potential biomarker and

therapeutic target (75). FDFT1

is highly expressed in HCC tissues and is correlated with poor

patient prognosis (76,77). In HCC, FDFT1 suppressed

fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase B expression, thereby releasing

its inhibitory control over the AKT signaling pathway and

activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, ultimately promoting tumor growth

and metastasis (76). Prognosis

analysis showed that FDFT1, as a potential prognostic marker, was

associated with shorter survival in patients with CRC and may

partially contribute to the formation of a suppressive immune

microenvironment (78). This

indicates that the tumor-promoting effect of FDFT1 is dependent on

the TME (79). Notably, another

study has revealed a unique role of FDFT1 in CRC. This study found

that under fasting conditions, SREBP2 upregulates FDFT1 expression,

while elevated FDFT1 expression negatively regulates the

AKT/mTOR/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) signaling pathway,

thereby inhibiting glycolysis and proliferation in CRC cells

(80). This suggests that FDFT1

may exert tumor-suppressive effects under specific metabolic

conditions, such as fasting, indicating the complexity of its

functional role.

ACAT1 is a multifunctional metabolic enzyme that

plays a complex and sometimes seemingly contradictory role in

various cancer types; it can suppress tumors under specific

conditions while simultaneously promoting tumor progression through

different mechanisms (81). In

HCC, ACAT1-mediated acetylation of glycerophosphate

O-acyltransferase (GNPAT) can stabilize GNPAT protein levels

by antagonizing tripartite motif containing 21-catalyzed

ubiquitination, ultimately promoting xenograft tumor growth

(82). In bladder cancer (BLCA),

ACAT1 promotes BLCA cell proliferation and invasion by activating

the AKT/GSK3β/c-Myc signaling pathway (83). Additionally, a recent study has

identified ACAT1 as a key factor in reducing the sensitivity of GBM

to ferroptosis, with its mechanism of action dependent on the

regulation of the iron efflux protein, solute carrier family 40

member 1 (84). However, under

the influence of exogenous proinflammatory factors interleukin

(IL)-12 and IL-18 proteins, ACAT1 is phosphorylated at the S60 site

and translocates from mitochondria to the nucleus. Within the

nucleus, it exerts its acetyltransferase activity, specifically

acetylated the K146 site of the NF-κB family protein p50, thereby

releasing its transcriptional repression on multiple immunochemical

genes and natural killer (NK) cell activation ligands, thereby

powerfully recruiting and activating NK cells. This enhances their

tumor-killing capacity and inhibits tumor growth (85).

NPC1L1 is the primary protein responsible for the

absorption of exogenous cholesterol. NPC1L1 is highly expressed in

CRC and serves as an independent prognostic factor that is

significantly correlated with pathological staging (86,87). An in vitro study revealed

that targeting NPC1L1 with ezetimibe blocks the AKT/mTOR signaling

pathway in HCC and suppresses cancer cell activity (88).

Collectively, these findings underscore that

cholesterol metabolism is notably reprogrammed in cancer cells,

with multiple enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway actively

contributing to tumor development and progression.

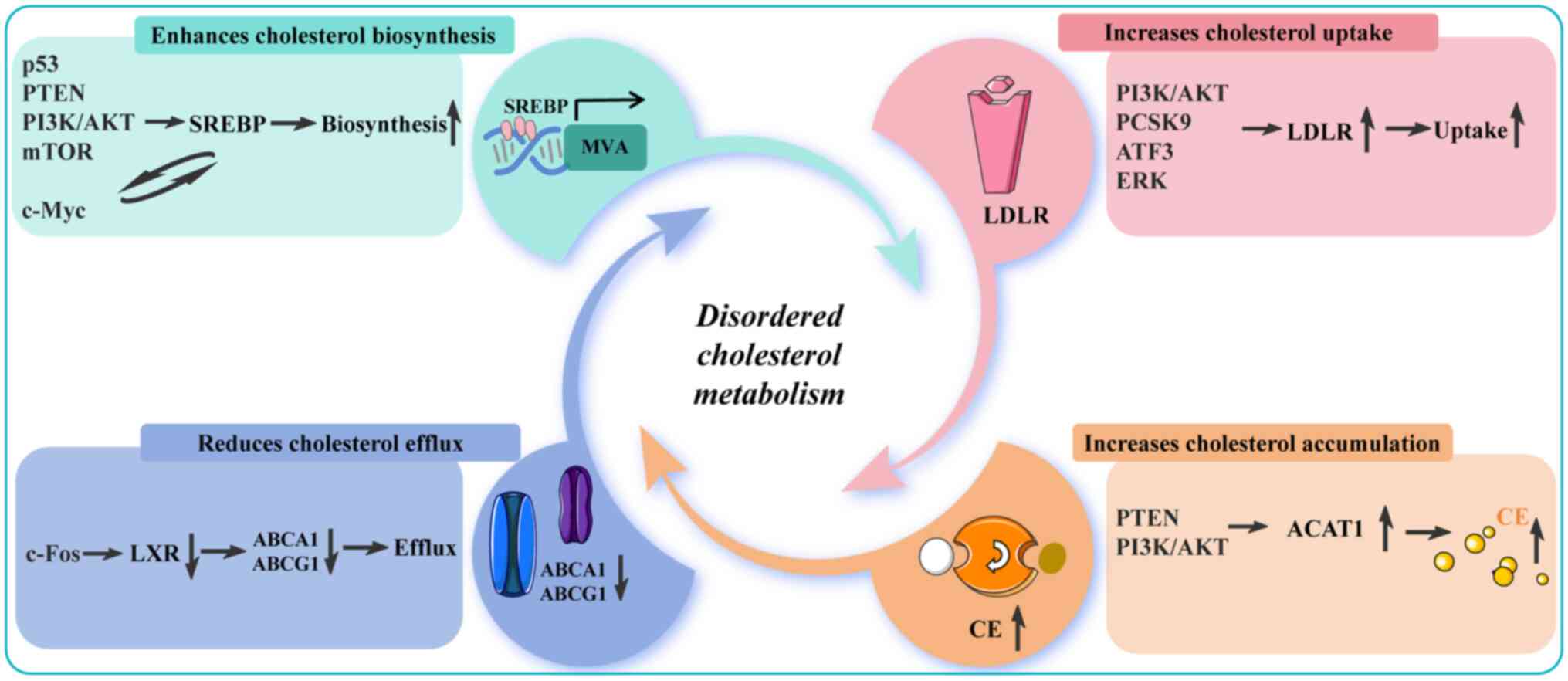

Numerous studies have demonstrated that aberrantly

activated genes or signaling pathways can promote cancer cell

proliferation and suppress apoptosis through the regulation of

cholesterol metabolism-related genes (89-93). For instance, the tumor suppressor

p53 can inhibit the MVA pathway, and its deficiency or mutation

releases multiple constraints on tumor growth (94). The p53 protein directly

suppresses the transcription of SQLE and SREBP genes by binding to

their promoters, thereby downregulating the MVA pathway in CRC,

HCC, OV and BC (95). By

contrast, upregulated or unmutated p53 transcriptionally induces

ABCA1 gene expression to block SREBP2 activation and inhibit the

MVA pathway (96,97). In recent years, the function of

the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog protein (PTEN)

in metabolic regulation has attracted significant attention

(98). As a phosphatase, PTEN

dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, thereby

directly inhibiting the oncogenic PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

(99). PTEN suppression in

endocrine therapy-resistant BC cells leads to increased SQLE

expression and a corresponding sensitization to the inhibition of

cholesterol synthesis (100).

In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), PTEN deficiency

enhances the protein stability of SQLE by activating the

PI3K/AKT/GSK3β-mediated proteasome pathway (101). Activated AKT phosphorylates the

cytoplasmic phosphorylating rate-limiting enzyme

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxy kinase 1, which is translocated to the

ER and acts as a protein kinase that phosphorylates the INSIG

protein and disrupts the interaction between the INSIG protein and

the SREBP shear-activating proteins, which in turn activates the

transcription of SREBPs as well as downstream genes related to

lipid synthesis and uptake and promotes the progression of HCC

(102). AKT regulates SREBP

activation by activating mTOR1; it promotes the protein expression

of nuclear SREBP2 through a dual mechanism: First, by

phosphorylating and inhibiting its nuclear translocation inhibitor,

lipin1; second, by regulating cholesterol transport from lysosomes

to the ER (103). Furthermore,

suppression of ciliary function activates the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway, which synergistically promotes transcription of MVA

pathway genes by directly interacting with SREBP2 (104).

Liver X receptors (LXRs) are nuclear receptors and

members of the nuclear receptor family that regulate intracellular

lipid homeostasis. Activated by high intracellular cholesterol,

LXRs function as cholesterol sensors (105). c-Fos promotes alterations in

cholesterol metabolism by suppressing the transcriptional activity

of LXRα, leading to the accumulation of toxic sterols and bile

acids, thereby promoting hepatocellular carcinogenesis (106). High expression of anoctamin-1

contributes to in vivo metastasis of primary esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting LXR signaling, leading to

cholesterol accumulation and decreased cholesterol hydroxylation

via downregulation of the expression of the cholesterol hydroxylase

cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily A member 1 (107).

LDLR is the key molecule that maintains cholesterol

balance in the body, releasing cholesterol into cells for

utilization while simultaneously lowering cholesterol levels in the

blood (108). LDLR-mediated

cholesterol uptake plays a contributory role in cancer (109). A recent study has demonstrated

that leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B1 directly binds to

the LDLR protein to form a complex, thereby enhancing LDLR-mediated

cholesterol uptake and conferring resistance to ferroptosis in

multiple myeloma (MM) cells (110).

Apolipoprotein B (APOB) is an essential structural

component of VLDL and LDL; its C-terminal region contains an

LDLR-binding domain that specifically recognizes LDLRs on

hepatocyte surfaces, mediating LDL uptake and clearance to maintain

plasma cholesterol homeostasis (111). APOB is classified into two

primary subtypes: i) ApoB-100, which is synthesized in the liver

and serves as the major structural protein of VLDL,

intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), and LDL; and ii) ApoB-48,

which is synthesized in the small intestine, constitutes the core

component of chylomicrons and is primarily responsible for

transporting dietary lipids (112). APOB is closely associated with

metastasis in CRC and liver cancer. Compared with the control

group, silencing of APOB in HCC cells has been shown to increase

the relative rate of cell proliferation (113). A recent nested case-control

study revealed that genetically predicted APOB levels are

associated with a 31% reduction in HCC risk [95% confidence

interval (CI), 19-42%] and each 0.1 g/l increase in circulating

APOB levels was linked to an 11% decrease in HCC risk (95% CI,

8-14%) (114). Another

prospective cohort study from Sweden also found that elevated

circulating levels of APOB increased the risk of developing CRC

(115).

PCSK9 is a key regulator of LDLR protein levels,

binding to LDLRs on the cell surface and directing them to

lysosomes for degradation (116). In the TME, tumor cell-derived

PCSK9 disrupts T-cell receptor signaling by binding to LDLR on the

membrane of CD8+ T cells and directing LDLR to lysosomal

degradation. This impaired CD8+ T cell activation,

proliferation and effector function, ultimately leads to lymphoma

metastasis in mice (117). In

lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), the long non-coding RNA EMX2OS

competitively binds to microRNA-1185-5p to regulate the LDLR,

thereby promoting lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion

(118). In addition, MEK/ERK

signaling increases intracellular cholesterol uptake by

upregulating LDLR expression, leading to HCC metastasis (119).

Similarly, dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism

can activate gene expression. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

(PARP1) is a multifunctional human ADP-ribosyl transferase

(120). In addition to

maintaining genomic integrity, PARP1 participates in

transcriptional regulation (121). A recent study revealed that

long-term high cholesterol promotes OV progression by activating

focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/collagen type V alpha 1 chain (COL5A1)

signaling through the upregulation of PARP1 expression (122). Several cholesterol derivatives

and metabolites, including 7-ketocholesterol (123), 15α-hydroxycholesterol (124), 25-hydroxycholesterol (25-HC)

(125), 17-β-estradiol

(126) and vitamin D (127), have been shown to induce PARP1

expression.

Cholesterol is a key structural component of LRs. In

PC cells, elevated serum cholesterol levels can increase

cholesterol content within tumor cell liposomes, thereby activating

the LR-mediated Src/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (128,129). Mitochondrial cholesterol also

exhibits physiological activity and promotes tumor cell

proliferation and metastasis. For instance, a recent study revealed

that the interaction between cytotoxin-associated protein A and

cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) promotes mitochondrial cholesterol

accumulation. This accumulated cholesterol then activates

autophagy, thereby enhancing GC cell proliferation and suppressing

apoptosis (130). The c-Myc

proto-oncogene encodes a family of transcription factors and is one

of the most commonly activated oncogenes in human tumors (131). Yang et al (132) found that c-Myc protein directly

promotes SQLE transcription, thereby increasing cholesterol

production and promoting tumor cell growth. Similarly, activated

c-Myc protein has also been observed to enhance HMGCR

transcriptional expression in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

(133). Notably, upregulated

SREBP1 protein directly interacts with SREBP1 binding elements in

the c-Myc promoter region in PC to induce c-Myc activation to drive

tumor stemness and metastasis (134). These studies illustrate a

reciprocal regulatory relationship between cholesterol metabolism

and genes, highlighting their critical roles in tumor cell

proliferation and invasion (Fig.

2).

A large body of preclinical evidence has underscored

the critical and multifaceted roles of cholesterol metabolism in

cancer progression (135-138). Targeting key nodes of this

pathway, such as inhibition of the MVA pathway, has emerged as a

promising antitumor strategy (1,139). At present, statins, which act

as inhibitors of HMGCR, and PCSK9 inhibitors have emerged as the

predominant agents targeting cholesterol metabolism, extensively

employed in both basic and clinical research (140,141). The anticancer function of

statins has attracted significant attention. Existing evidence

indicates that statins can promote tumor cell proliferation,

differentiation and apoptosis (76,142,143). A clinical study demonstrated

that initiating statin therapy within 1 year of diagnosis results

in a 58% relative improvement in BC-specific survival and a 30%

relative improvement in OS (144). Similarly, simvastatin (SIM)

blocks the isoprenylation of Rab5 GTPase and its mediated endosomal

maturation in antigen-presenting cells by depleting GGPP through

inhibition of the MVA pathway, ultimately enhancing antitumor

immunity by boosting antigen presentation and T cell activation

(145). Bisphosphonates (BPs)

are another widely studied inhibitor of the MVA pathway, which

inhibits FDPS activity and prevents the conversion of isopentenyl

pyrophosphate (IPP) to FPP (47,146,147). Bisphosphonate therapy has been

reported to improve the prognosis of patients with bona fide MM, PC

and BC (148). Moreover, BPs

can reduce bone and visceral metastases in women with BC (149,150). Previous studies suggest that

SQLE upregulation is closely associated with tumor progression. For

instance, upregulated SQLE promotes HCC cell invasion by activating

ERK (151) or AKT/mTOR

signaling (152). However,

targeting SQLE with terbinafine can delay tumor progression in

endometrial cancer (ECa) (153), PC (154), CRC (155), HCC (156) and BC (157). Ezetimibe is an FDA-approved

drug that acts on NPC1L1 to inhibit the progression of CRC

(86), BC (158) and PC (159) by inhibiting intestinal

cholesterol absorption. Intracellular cholesterol accumulation

triggers LXRs and excess cholesterol is excreted via ABCA1 or ABCG1

(160). The LXR agonists

RGX-104 (161), LXR 623

(162) and T0901317 (163) increase ABCA1 expression in a

variety of tumor cells, decrease intracellular cholesterol levels

and effectively inhibit the growth of mouse xenograft tumors.

Additionally, T0901317 can reduce myeloid-derived suppressor cell

infiltration through the LXR/APOE pathway, thereby lifting immune

suppression, enhancing T cell function and ultimately improving

overall immune therapy response (164).

The NPC1 protein, which regulates endolysosomal

cholesterol transport, has recently emerged as a therapeutic

target. NPC1 represents a convergence point for cholesterol derived

from LDL, HDL and VLDL, allowing simultaneous targeting of multiple

cholesterol sources (170). A

previous study has shown that targeted inhibition of NPC1

downregulates mTORC1 signaling and reduces autophagy and tumor

growth (171). Moreover,

lowering NPC1 expression enhances the therapeutic efficacy of

cisplatin or trastuzumab in NSCLC (172), GC (173) and PC (174), leading to improved patient

prognosis. These findings highlight the clinical potential of

combining cholesterol metabolism inhibitors with existing

anticancer agents to overcome therapy resistance. Cancer therapies

targeting cholesterol metabolism are summarized in Table I.

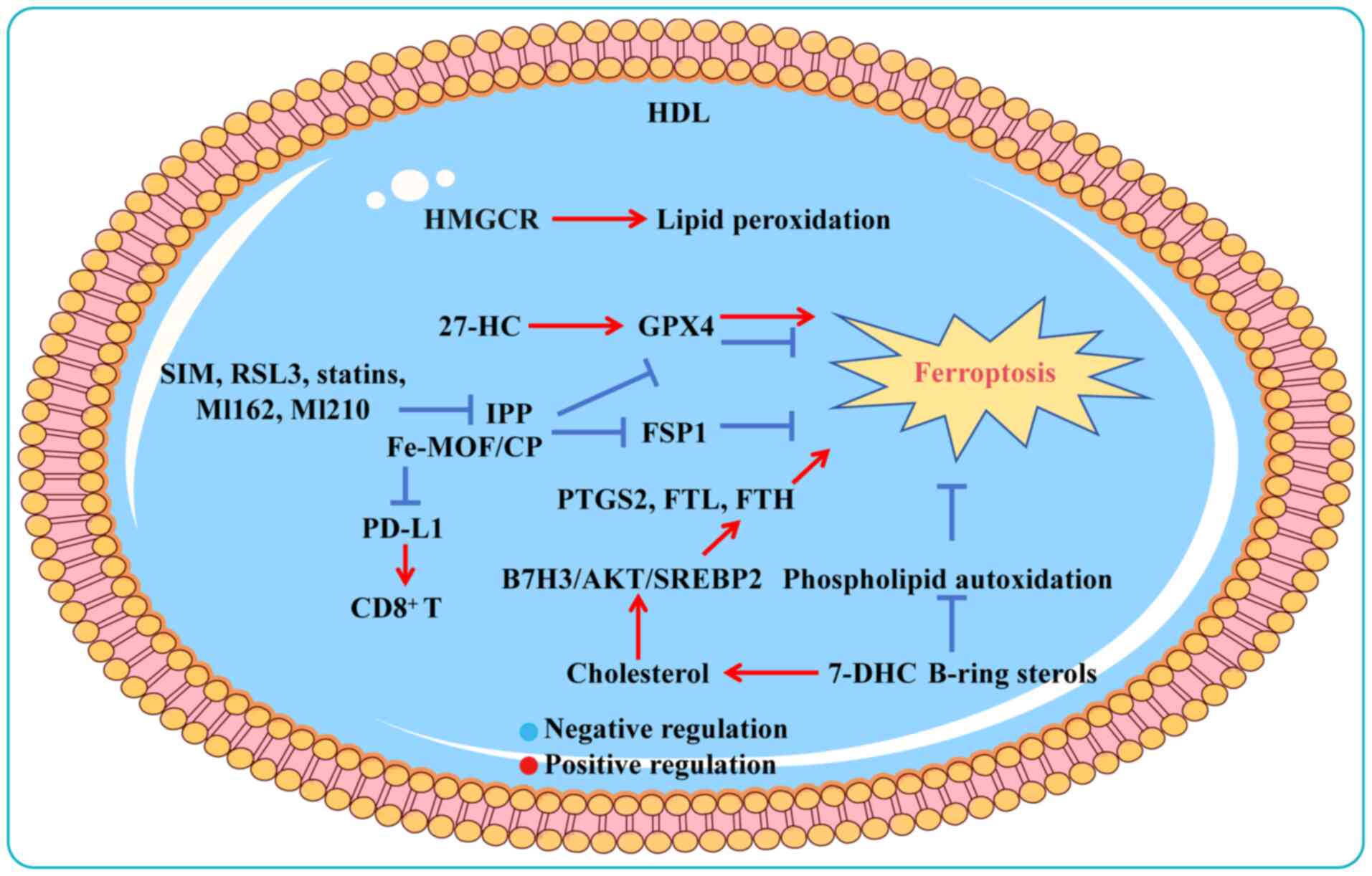

Ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death driven

by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, represents a promising

therapeutic avenue in oncology due to its involvement in tumor

progression and treatment resistance (175). Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)

and solute carrier family 7 member 11 are central to regulating

ferroptosis (176). Elevated

cholesterol levels in cancer cells have been shown to suppress

ferroptosis and impair immune responses (177). Recent studies have shown that

7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) and B-ring sterols act as

free-radical-trapping antioxidants to protect mitochondrial

membranes from phospholipid autoxidation, thereby resisting

ferroptosis (178,179). While most cancer cells succumb

under stress, surviving populations often accumulate high

cholesterol levels to evade ferroptosis death (84,180,181). Chronic exposure to

27-hydroxycholesterol (27-HC), an abundant metabolite of

circulating cholesterol, causes sustained expression of GPX4 and

significantly increases the tumorigenic and metastatic capacity of

BC cells (13). These findings

highlight that aberrant cholesterol metabolism can influence cancer

pathogenesis by activating ferroptosis. In cancer cells, increased

uptake via the upregulation of lipoprotein receptors and increased

synthesis rates through the hyperactive MVA pathway results in

cholesterol accumulation, fostering cellular proliferation, tumor

metastasis and immune suppression (182-184). Studies have revealed that GPX4

relies on the output of the MVA pathway to hinder lipid

peroxidation production and ferroptosis sensitivity in HCC cells

(185,186). Exogenous cholesterol

supplementation activates the B7H3-mediated AKT/SREBP2 signaling

pathway to promote ferroptosis resistance in CRC cells as well as

xenograft tumor formation in mice (187).

Elevated cholesterol levels reduce membrane fluidity

and promote LR formation, thereby inhibiting the diffusion of lipid

peroxidation substrates and suppressing ferroptosis (188-190). A novel nanozyme composed of an

iron metal-organic framework (Fe-MOF) and nanoparticles loaded with

cholesterol oxidase and PEGylation (CP) for integrated ferroptosis

and immunotherapy, depletes cholesterol and disrupts LR integrity,

downregulates GPX4 and ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and

further promotes ferroptosis. Concurrently, Fe-MOF/CP augments

immunogenic cell death, reduces programmed death-ligand 1

expression and revitalizes exhausted CD8+ T cells

(191). Similarly, in

cholesterol-addicted lymphoma cells, targeting SCARB1 via HDL

nanoparticles to reduce cholesterol uptake not only eliminates GPX4

expression but also triggers a compensatory response that enhances

cholesterol biosynthesis, ultimately leading to ferroptosis

(189). GPX4, a core regulator

of ferroptosis, is modulated by IPP, a product of the MVA pathway

and an intermediate in cholesterol synthesis. Thus, regulating the

upstream synthesis pathways of IPP using inhibitors (such as FIN56,

RSL3, statins, ML162 and ML210) induces ferroptosis by suppressing

GPX4 (a protein responsible for preventing lipid peroxide

formation); whereas FIN56 and withaferin can trigger GPX4

degradation (192). Squalene

and HMGCR are thought to exert anti-ferroptosis effects on cancer

cells (180,193). For example, SIM can inhibit the

expression of HMGCR to downregulate the MVA pathway, GPX4 and FSP1,

thereby inducing triple-negative BC cell ferroptosis (194,195). Conversely, SQLE exerts

anti-ferroptosis effects, whereas exogenous cholesterol

hydroperoxide induces dose-dependent cell death (196,197). These findings highlight the

therapeutic potential of targeting cholesterol biosynthesis to

sensitize cancer cells to ferroptosis (Fig. 3).

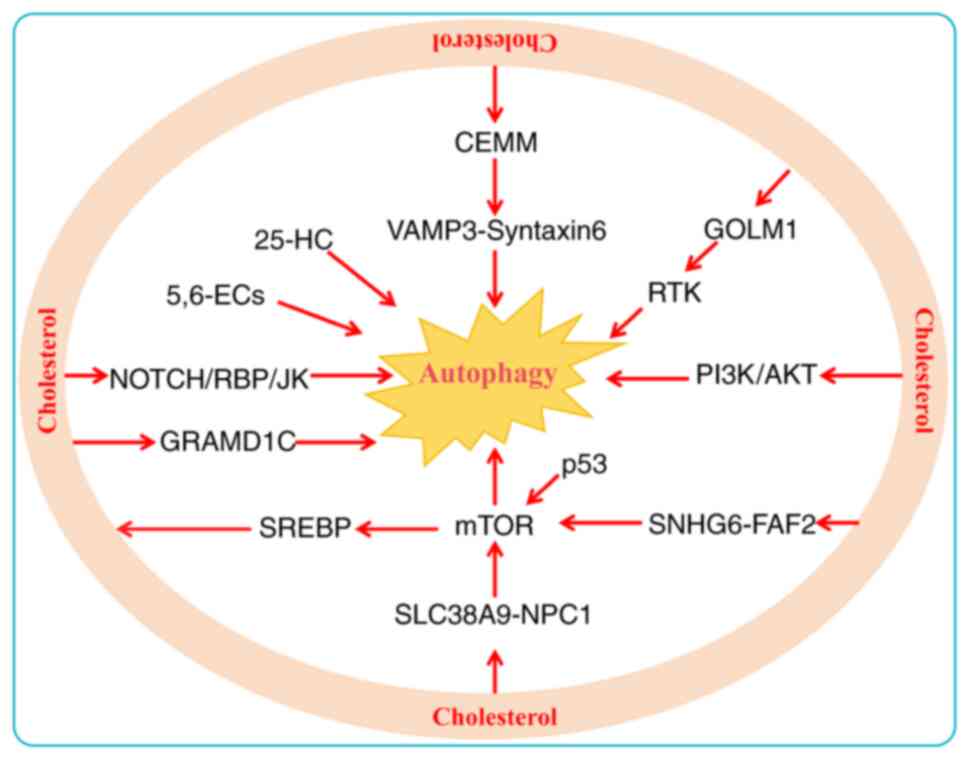

In cancer, autophagy exhibits a context-dependent

dual role, capable of both suppressing and promoting tumorigenesis

(198). During the early

stages, autophagy prevents tumor initiation by eliminating

oncogenic proteins, toxic misfolded aggregates and damaged

organelles (199). However, in

the later stages of tumorigenesis, autophagy functions as a dynamic

degradation and recycling system that can enhance cancer

invasiveness by promoting metastasis, thereby sustaining tumor

survival and growth (200).

Autophagy involves a variety of signaling pathways, such as the

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), mTOR, AKT, HIF-1α and p53

pathways (201). Lysosomal

cholesterol activates mTORC1 through the SLC38A9/NPC1 signaling

axis, inducing autophagy that promotes tumor metastasis and

invasion (202). Similarly,

another study revealed that cholesterol also induces autophagy in

HCC cells by activating mTORC1 via the SNHG6/FAF2/mTOR axis,

increasing the incidence of HCC driven by a high cholesterol diet

(203). In MM, researchers have

reported that cholesterol accumulation mediates autophagy

activation via the PI3K/AKT pathway (204). Conversely, phosphorylated AKT

levels as well as rapamycin signaling are markedly suppressed after

the use of statins by lowering intracellular cholesterol levels

(205). The mTOR, AKT and p53

pathways also modulate SREBP activity, which in turn regulates

cholesterol synthesis (96,206). Among these, the AKT and mTOR

pathways are the most frequently studied de novo cholesterol

synthesis pathways in cancer cells (207). mTOR serves as the core molecule

mediating the regulatory function of AKT over SREBPs. mTOR operates

through a dual mechanism: on the one hand, it is activated by AKT

(206); on the other, it drives

cholesterol biosynthesis by enhancing SREBP2 activity and

inhibiting its degradation (208). Whether cholesterol-induced

autophagy initiates positive feedback regulation of these pathways

warrants further investigation.

Emerging evidence indicates that cholesterol

enrichment within organelles facilitates the recruitment of

autophagy-initiation proteins and enhances autophagosome formation,

contributing to chemoresistance (209,210). The cholesterol transporter

protein GRAM domain containing 1B can coordinate cellular processes

by mediating cholesterol distribution between organelles, thereby

inhibiting autophagosome formation and reducing mitochondrial

bioenergetic metabolism (211).

Furthermore, cholesterol-rich membrane microstructure domain

(CEMM)-mediated sequestration of the vesicle-associated membrane

protein 3/syntaxin-6 complex inhibits autophagosome fusion.

Conversely, CEMM deficiency promotes autophagosome formation and

confers doxorubicin resistance in BC (212). Similarly, cholesterol inhibits

the autophagic degradation of receptor tyrosine kinase in a Golgi

membrane protein 1-dependent manner to promote HCC metastasis

(213). Cholesterol

accumulation in lysosomes induces autophagy initiation and enhances

carboplatin resistance in OV cells by activating the

NOTCH/DNA-binding protein recombination signal binding protein-Jκ

signaling pathway (214). These

results emphasize that cholesterol is an important regulator of

signaling pathways in cancer.

Cholesterol metabolites also play a key role in

activating autophagy. High 25-HC levels promote Kras-driven PDAC

progression. Mechanistically, 25-HC promotes autophagy, leading to

the downregulation of MHC-I and a reduction in CD8+

T-cell infiltration into tumors (215). BC is one of the most common

female cancer types in the world, with estrogen receptor-positive

BC being the most common subtype (216). The accumulation of

cholesterol-5,6-epoxide (5,6-EC) metabolites enhances resistance to

tamoxifen through the activation of autophagy to potentiate

antiestrogen binding site activity (217,218). Unraveling the molecular

interactions within the regulatory networks of cholesterol

metabolism and autophagy provides core guidance for identifying

novel anti-cancer targets and formulating targeted strategies

(Fig. 4).

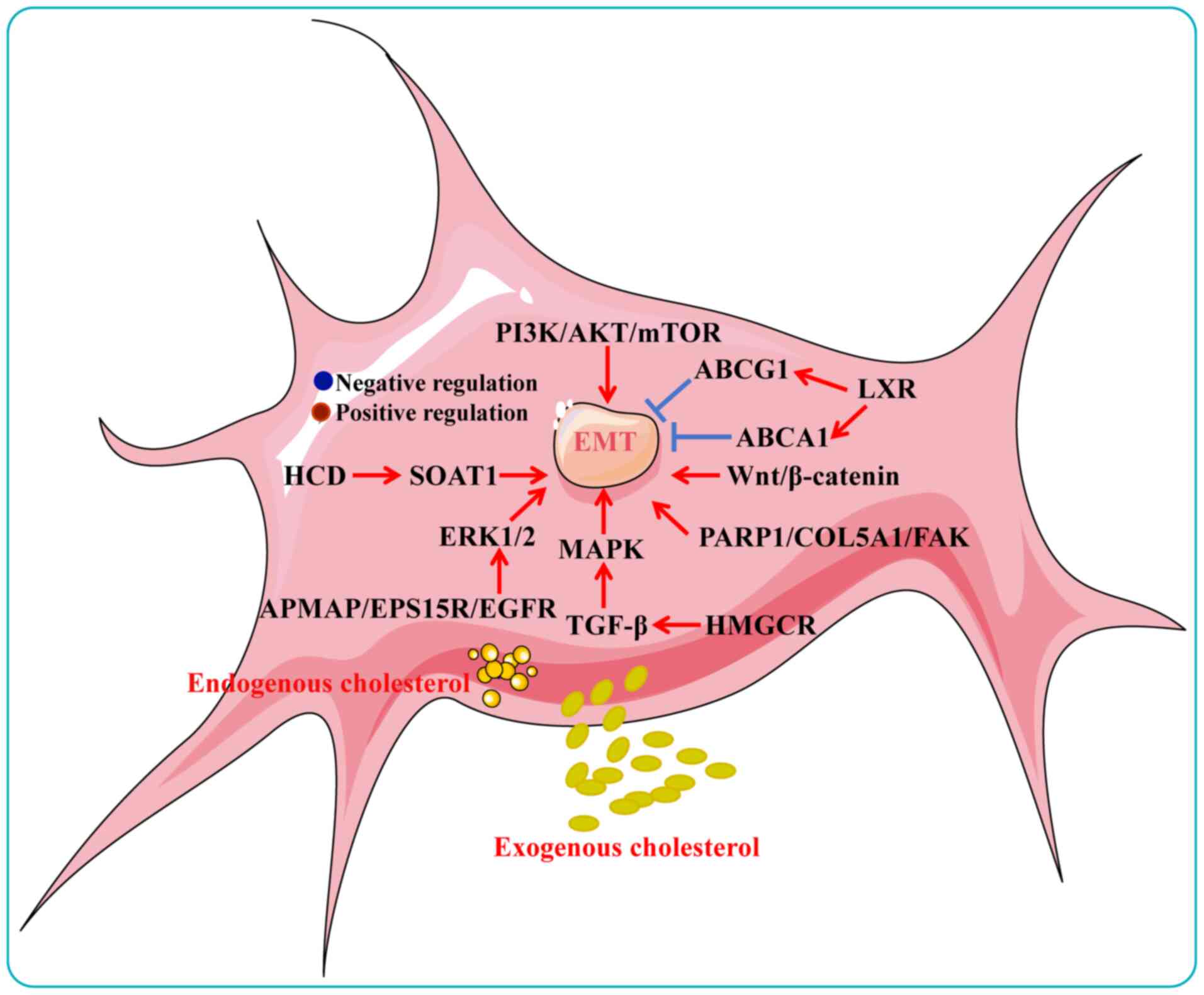

EMT is a key driver of tumor growth and metastasis,

promoting a malignant phenotype by conferring enhanced metastatic

capacity and resistance to therapeutic interventions. Tumor EMT

states have also been found to exhibit high plasticity during

transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes (219). The progression of EMT is

governed by the precise coordination of a core set of transcription

factors, such as Snail1/2, zinc finger enhancer-binding protein 1

and Twist1, whose expression levels directly determine the degree

of EMT activation and the transformation of cellular phenotypes

(220). Cholesterol increases

the risk of EMT in cancer. A high-cholesterol diet promotes lung

metastasis of HCC in mice by activating sterol

O-acyltransferase 1 (SOAT1)-mediated EMT. Mechanistically,

SOAT1 increases cholesterol accumulation and esterification,

thereby driving EMT and HCC progression (93). Treatment with 20 μmol/l

cholesterol was found to promote in vivo graft tumor growth

and distal metastasis in CRC by inducing EMT (19). Cholesterol has been demonstrated

to regulate several classical signaling pathways that activate EMT.

Cholesterol (10 μmol/l) induces adipocyte

membrane-associated protein binding to EGFR substrate 15-associated

protein, activates ERK1/2 and facilitates the EMT process in PC

cells (221). The integrity of

LRs is essential for the formation of the TGF-β receptor (TβR)

I/TβRII/TGF-β1 complex, and LR disruption impedes canonical TGF-β

signaling. Cholesterol within LRs promotes EMT, migration and

invasion in BC cells via TGF-β-mediated MAPK activation (222). High cholesterol also promotes

proliferation and migration in BC and PDAC cells through activation

of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (223,224), and similarly induces EMT in

melanoma via the MAPK pathway (225). Notably, our latest study

revealed that long-term treatment of OV cells with high cholesterol

concentrations (>20 μmol/l) significantly induces the

expression of cellular EMT transcription factors and mesenchymal

cell marker proteins. Mechanistically, cholesterol promotes

invasion of orthotopic ovarian tumors into the liver and kidney in

mice through activation of the PARP1/COL5A1/FAK/EMT axis (122). These studies collectively

indicated that cholesterol plays a key role in promoting EMT.

Cholesterol-related genes also have key roles in

EMT-induced metastasis and drug resistance. Upregulation of ABCA1

in CRC facilitates EMT induction and enhances the migratory and

invasive abilities by modulating caveolin-1 stability (226). High ABCG1 expression enhances

cisplatin resistance in LUAD by activating Slug-mediated EMT

(227). Dysregulation of

cholesterol metabolism not only promotes the development of HCC but

also drives tumors to exhibit highly invasive characteristics,

including intrahepatic spread and early extrahepatic metastasis

(76,228,229). A recent study has shown that

high expression of 7-DHC reductase is correlated with poor

prognosis in patients with BLCA and promotes metastasis in mice via

PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mediated EMT activation (230). 27-HC, the most abundant

oxysterol, increases the risk of BC progression by promoting EMT

and oncogenic transformation of BC stem cells through LXR

activation (15). Accumulation

of apolipoprotein E leads to cholesterol enrichment in HCC cells,

stimulating PI3K/AKT signaling, inducing EMT and increasing

sorafenib resistance and invasiveness (231). Aberrant HMGCR expression

enhances statin resistance in therapy-resistant PC cells and

augments TGF-β-induced EMT in lung and ovarian epithelial

carcinomas (232-234). Additionally, HMGCR augments

TGF/β-induced EMT progression in epithelial cell carcinomas (lung

and ovarian) (235).

Collectively, this scientific evidence highlights the important

role played by cholesterol in promoting EMT, providing a new means

of targeting cholesterol metabolism to combat tumor progression

(Fig. 5). Cholesterol-activated

EMT markers and transcription factors in different cancer types are

summarized in Table II.

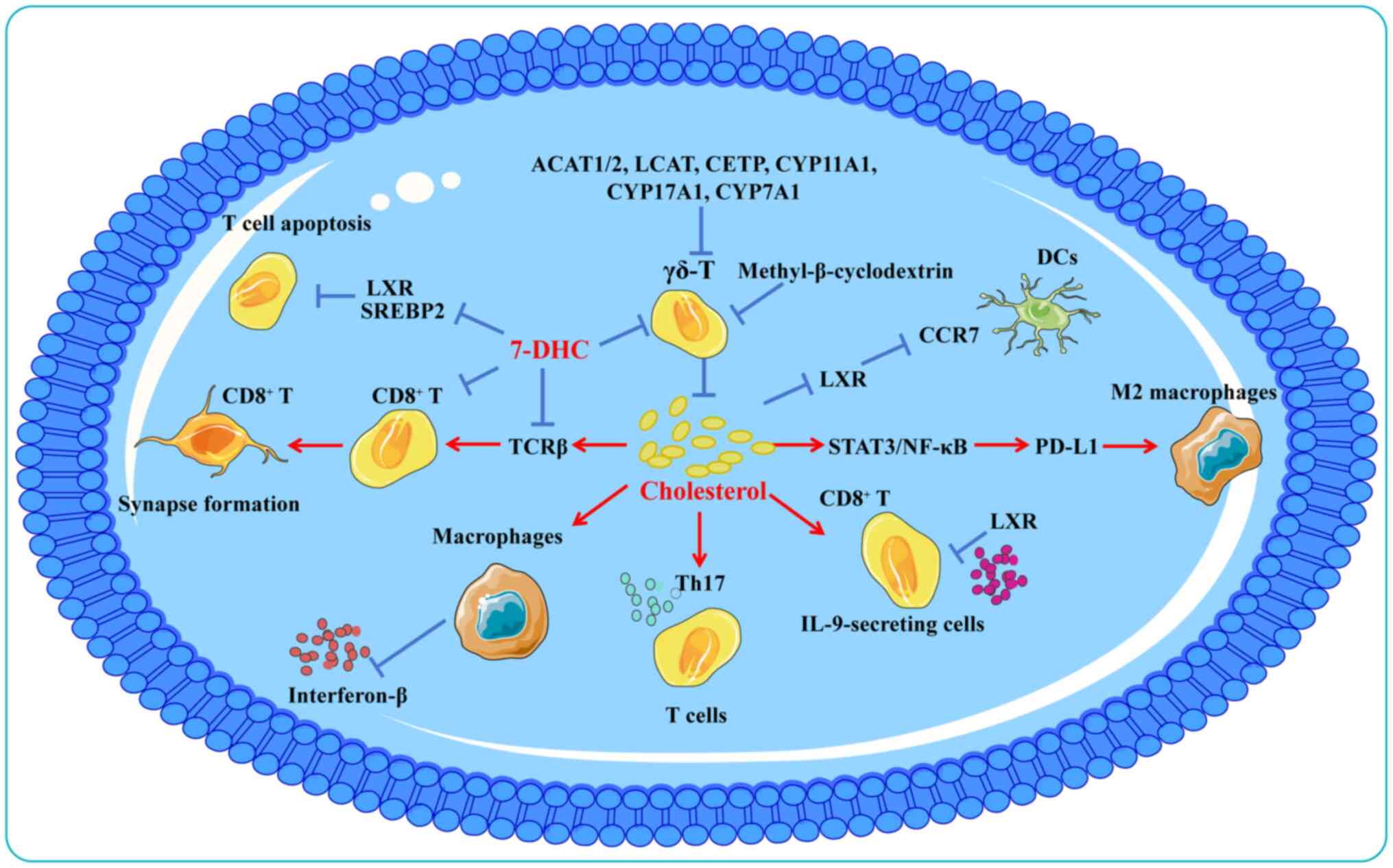

Recent studies have demonstrated that modulation of

systemic cholesterol metabolism could improve responses to

immunotherapy (16,136,236). Cholesterol depletion is a key

metabolic basis for tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) acquiring

an immunosuppressive phenotype (6). In patients with CRC, cholesterol

metabolism promotes macrophage polarization towards a pro-tumor

phenotype and is associated with poorer prognosis (237). Notably, replenishing

cholesterol or adding 7-DHC to mouse macrophages was shown to

inhibit interferon-β production (238). In a murine melanoma model,

cholesterol accumulation in the TME induced functional exhaustion

of CD8+ T cells (239). Cholesterol metabolism exhibits

different effects on different T cell subsets. Cholesterol enhances

receptor signaling and immune synapse formation in CD8+

T cells by binding to T cell receptor β (240). Another in vivo study

demonstrated that inhibition of ACAT1 by knockdown or

pharmacological inhibition can inhibit intracellular cholesterol

esterification in T cells and enhance the proliferative and

effector capacity of CD8+ T cells, whereas

CD4+ T cells are unaffected (241). In C57BL/6J mice, genes involved

in cholesterol esterification (ACAT1/2, lecithin cholesterol

acyltransferase and cholesterol ester transfer protein) and

utilization (CYP11A1, CYP17A1 and CYP7A1) are upregulated in γδ T

cells compared with αβ T cells (242). Moreover, cholesterol depletion

using methyl-β-cyclodextrin reduces the activation phenotype of γδ

T cells (243). However, the

impact of hypercholesterolemia or lipid-lowering treatments on T

cell signaling in human patients remains unclear.

Cholesterol has also been identified as a key

immunomodulatory factor, whose accumulation promotes tumor immune

escape. In the TME, cholesterol attenuates the efficacy of PD-L1

blockade by activating the signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3/nuclear factor κB pathway, driving macrophages

toward an M2-like phenotype that accelerates CRC progression

(244). Additionally,

cholesterol upregulates PD-L1 expression on cancer cells,

facilitating immune evasion (245,246). Hyaluronic acid oligomers

secreted by tumor cells increase cholesterol efflux from TAMs,

promoting M2 polarization and tumor progression (6). Although IL-9-secreting

CD8+ T cells (Tc9 cells) exhibit potent antitumor

activity, cholesterol suppresses IL-9 expression and impairs Tc9

cell function through LXR activation (247). In microsatellite-stable CRC,

tumor cells secrete distal cholesterol precursors that polarize T

cells into Th17 cells, promoting tumor growth (248).

Cholesterol derivatives similarly modulate immune

responses. 27-HC promotes the development of the BC pre-metastatic

microenvironment by attracting polymorphonuclear neutrophils and

γδ-T cells at metastatic sites and depleting CD8+ T

cells (249). Furthermore,

27-HC induces T cell cholesterol deficiency by inhibiting SREBP2

and activating LXR, leading to autophagy-mediated T cell apoptosis

(14). In HCC, oxidized sterols

activate LXRα in dendritic cells (DCs), downregulating CC chemokine

receptor 7 expression and impairing DC migration to lymphoid

organs, thereby suppressing antitumor immunity (250).

In summary, the conflicting results of cholesterol

in modulating immunotherapy suggest that a deeper understanding of

the regulatory mechanisms of cholesterol metabolism in the

interactions between tumor cells and immune cells in the TME will

contribute to the development of new cancer immunotherapy

strategies (Fig. 6). Targeting

cholesterol metabolism in the tumor immune microenvironment

represents a promising approach to enhance antitumor immunity.

Although extensive basic and preclinical studies

have demonstrated the involvement of cholesterol in cancer

development and the potential of targeting its metabolism, the

relationship between serum cholesterol levels and tumor risk

remains controversial, with epidemiological studies reporting

conflicting findings (3).

Several large-scale studies have indicated a positive association

between elevated serum cholesterol and cancer risk. For example,

two prospective cohort studies provided evidence that higher

cholesterol levels were positively associated with the risk of

high-grade PC (251,252). Another study revealed an

association between the use of statins to lower serum cholesterol

levels and the risk of developing or dying from 13 tumor types,

including HCC, MM, BC, ECa and CRC (253). A 10 mg/dl increase in

cholesterol was correlated with a 9% increase in PC recurrence

(128). In OV, elevated

preoperative LDL-C was significantly associated with a poorer OS,

whereas high HDL-C was correlated with improved progression-free

survival (254). Patients with

advanced-stage OV are typically accompanied by the presence of

malignant ascites (MAs) and high cholesterol levels in these MAs

(255). Moreover, high

cholesterol levels promote drug resistance in OV cells by

increasing the expression of multidrug resistance protein 1

(256). Dietary cholesterol and

tumor risk also deserve attention. According to population-based

cohort studies, tumorigenesis is closely related to dietary

structure (257), and changes

in dietary structure effectively prevent tumorigenesis and

progression (258,259). Increased dietary cholesterol

intake is positively associated with the risk of BC (260). Dietary cholesterol is a risk

factor for the development of ECa, with a 35% increased risk of

tumor development for every 150 mg/kcal of cholesterol consumed

(261). Esophageal cancer (EC)

ranks as the ninth most common cancer worldwide, with genetic

factors, dietary factors and environmental risk factors potentially

influencing its progression (262). A meta-analysis that

investigated the association between high-cholesterol diets and EC

revealed that dietary cholesterol intake may increase the risk of

EC (summarized odds ratio, 1.424; 95% CI, 1.191-1.704) (263). Pancreatic cancer (PCa) risk is

associated with elevated serum cholesterol levels, which are

partially influenced by diet (264). A study involving 258 patients

with PCa and 551 controls demonstrated that a plant-based

cholesterol-lowering diet is associated with a reduced risk of PCa

(265). In addition, higher

cumulative dietary cholesterol intake is positively associated with

the risk of GC (266), HCC

(267) and OV (267). The incidence of OV is

significantly lower by 40% in individuals consuming a

low-cholesterol diet than those on a conventional diet (268). However, studies on dietary

cholesterol and lung cancer risk have consistently shown no

correlation (115,269,270).

Conversely, other epidemiological studies reported

no clear association or even an inverse relationship between

cholesterol and cancer. For instance, a large prospective cohort

study from South Korea found that the association between serum TC

levels and cancer was dependent on the cancer type (251). Further comparison across cancer

types revealed that elevated serum TC levels showed a significant

positive association with the risk of PC and CRC in men, as well as

BC in women. Conversely, there was a significant negative

association with the overall risk of HCC and GC in the general

population. Moreover, a population-based cohort study has suggested

that serum TC levels may be negatively associated with the risk of

OV and that circulating lipid levels are not strongly correlated

with the risk of OV (271).

These studies showed that the positive correlation and negative

correlation coexisted, indicating that the association was cancer

type specific. Similarly, our latest study showed that higher daily

dietary cholesterol intake was significantly positively associated

with the risk of OV, whereas abnormal lipid levels were not

associated with the risk of OV (33).

These conflicting epidemiological results suggest

that the role of cholesterol in cancer development remains

uncertain, warranting further investigation into its underlying

mechanisms. Key issues include the reliability of dietary study

data, the limitations of animal models in simulating human disease

states and the potentially opposing effects of serum cholesterol

across different tumor stages. The current epidemiological evidence

regarding cholesterol and cancer risk is indeed contradictory,

stemming from multiple confounding factors and methodological

challenges. The primary concern is reverse causality: Actively

growing tumors consume large amounts of cholesterol to build

membrane structures and synthesize signaling molecules, potentially

leading to reduced serum cholesterol levels. Thus, observed low

cholesterol levels may result from undetected tumors rather than

cause them. This is particularly notable in studies of malignancies

such as liver and stomach cancer, potentially completely reversing

the apparent 'protective association' (272,273). Cancer type specificity further

complicates this relationship as metabolic dependencies vary

significantly across tumor types: Hormone-sensitive cancers such as

PC and OV may rely more heavily on cholesterol as a steroid hormone

precursor, showing positive correlations; whereas other tumor types

may exhibit no clear association or even negative correlations

(274,275). Methodological limitations also

warrant attention: Dietary cholesterol studies rely on

self-reporting, introducing recall bias; single serum cholesterol

measurements may fail to reflect long-term exposure levels; and

statin use confounds the association between serum cholesterol and

cancer risk. Most critically, correlation does not imply causation.

Observational studies reveal statistical associations but cannot

establish biological mechanisms. These conflicting findings suggest

systemic cholesterol levels may be unreliable cancer risk

indicators, while targeted interventions affecting intracellular

cholesterol metabolism may hold greater therapeutic promise than

systemic cholesterol reduction. Recently, we suggested that low

levels of cholesterol promote tumor progression, that high

cholesterol may inhibit tumor cell growth and that chronically high

levels of cholesterol ultimately screen for more proliferative and

invasive tumor cells (122).

Evidence from these studies suggests that the dysregulation of

cholesterol homeostasis is an important factor in cancer

development, but its true link to tumor progression remains

unclear. Studies are needed to link population epidemiological

data, molecular mechanisms and clinical data more broadly to more

effectively unravel the processes by which cholesterol affects

cancer. The associations of serum cholesterol and dietary

cholesterol with the risk of cancer development are summarized in

Table III.

The present review describes the role of

cholesterol in cancer progression from a multidimensional

perspective. First, how cholesterol activates oncogenes and

oncogenic signals was discussed. Then, the molecular mechanisms

regulated by cholesterol in cancer were summarized. Finally, the

ongoing controversies regarding cholesterol levels and cancer risk

within epidemiological studies were addressed. Although substantial

evidence supports a definitive role for cholesterol metabolism in

tumorigenesis and progression, several critical questions remain

unresolved. For example, whether the specific roles of cholesterol

metabolites or derivatives are consistent, what the causal

relationship is between abnormal cholesterol metabolism and

tumorigenesis and how cholesterol metabolism influences other

metabolic processes such as glucose metabolism. Notably, studies on

the heterogeneity of cholesterol metabolism (such single-cell

metabolomics) and comparative analyses across cancer types (such as

BC vs. liver cancer) are fewer and deserve focused attention. This

complexity suggests that not only do we need to modulate from a

single cholesterol metabolic pathway but also interfere with the

activation of oncogenes or oncogenic signals and that a combination

of different drugs or inhibitors may be a more effective antitumor

regimen.

In conclusion, dysregulation of cholesterol

metabolism is increasingly recognized as a critical facilitator of

cancer development. While population-based epidemiological findings

have been inconsistent, both basic and clinical studies indicate

that targeting cholesterol metabolism can significantly inhibit

tumor progression. These insights provide a robust foundation for

the development of cholesterol-focused therapeutics and offer

promising new strategies for cancer prevention and treatment.

Not applicable.

ZH was responsible for conceptualization, writing

the original draft and visualization. LZ and SG helped to revise

the manuscript and collect literature. GX and XY were responsible

for supervision, writing, reviewing and editing. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

This review was funded by the Research Fund of Sichuan Academy

of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital (grant

no. 24QNPY025), in part by the Natural Science Foundation of

Sichuan Province (grant no. 2025YFHZ0308).

|

1

|

Luo J, Yang H and Song BL: Mechanisms and

regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

21:225–245. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ouimet M, Barrett TJ and Fisher EA: HDL

and reverse cholesterol transport. Circ Res. 124:1505–1518. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kuzu OF, Noory MA and Robertson GP: The

role of cholesterol in cancer. Cancer Res. 76:2063–2070. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cao D and Liu H: Dysregulated cholesterol

regulatory genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Med Res.

28:5802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Geng F and Guo D: SREBF1/SREBP-1

concurrently regulates lipid synthesis and lipophagy to maintain

lipid homeostasis and tumor growth. Autophagy. 20:1183–1185. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Goossens P, Rodriguez-Vita J, Etzerodt A,

Masse M, Rastoin O, Gouirand V, Ulas T, Papantonopoulou O, Van Eck

M, Auphan-Anezin N, et al: Membrane cholesterol efflux drives

tumor-associated macrophage reprogramming and tumor progression.

Cell Metab. 29:1376–1389.e4. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Spann NJ and Glass CK: Sterols and

oxysterols in immune cell function. Nat Immunol. 14:893–900. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Miller WL and Auchus RJ: The molecular

biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and

its disorders. Endocr Rev. 32:81–151. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Simons K and Toomre D: Lipid rafts and

signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 1:31–39. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Riscal R, Skuli N and Simon MC: Even

cancer cells watch their cholesterol! Mol Cell. 76:220–231. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ma X, Xiao L, Liu L, Ye L, Su P, Bi E,

Wang Q, Yang M, Qian J and Yi Q: CD36-mediated ferroptosis dampens

intratumoral CD8+ T cell effector function and impairs

their antitumor ability. Cell Metab. 33:1001–1012.e5. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gabitova-Cornell L, Surumbayeva A, Peri S,

Franco-Barraza J, Restifo D, Weitz N, Ogier C, Goldman AR, Hartman

TR, Francescone R, et al: Cholesterol pathway inhibition induces

TGF-β signaling to promote basal differentiation in pancreatic

cancer. Cancer Cell. 38:567–583.e11. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Liu W, Chakraborty B, Safi R, Kazmin D,

Chang CY and McDonnell DP: Dysregulated cholesterol homeostasis

results in resistance to ferroptosis increasing tumorigenicity and

metastasis in cancer. Nat Commun. 12:51032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yan C, Zheng L, Jiang S, Yang H, Guo J,

Jiang LY, Li T, Zhang H, Bai Y, Lou Y, et al: Exhaustion-associated

cholesterol deficiency dampens the cytotoxic arm of antitumor

immunity. Cancer Cell. 41:1276–1293.e11. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Luo M, Bao L, Chen Y, Xue Y, Wang Y, Zhang

B, Wang C, Corley CD, McDonald JG, Kumar A, et al: ZMYND8 is a

master regulator of 27-hydroxycholesterol that promotes

tumorigenicity of breast cancer stem cells. Sci Adv.

8:eabn52952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hu C, Qiao W, Li X, Ning ZK, Liu J,

Dalangood S, Li H, Yu X, Zong Z, Wen Z and Gui J: Tumor-secreted

FGF21 acts as an immune suppressor by rewiring cholesterol

metabolism of CD8+T cells. Cell Metab. 36:630–647.e8.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yarmolinsky J, Bull CJ, Vincent EE,

Robinson J, Walther A, Smith GD, Lewis SJ, Relton CL and Martin RM:

Association between genetically proxied inhibition of HMG-CoA

reductase and epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA. 323:646–655. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kawamura S, Matsushita Y, Kurosaki S,

Tange M, Fujiwara N, Hayata Y, Hayakawa Y, Suzuki N, Hata M, Tsuboi

M, et al: Inhibiting SCAP/SREBP exacerbates liver injury and

carcinogenesis in murine nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin

Invest. 132:e1518952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li C, Wang Y, Liu D, Wong CC, Coker OO,

Zhang X, Liu C, Zhou Y, Liu Y, Kang W, et al: Squalene epoxidase

drives cancer cell proliferation and promotes gut dysbiosis to

accelerate colorectal carcinogenesis. Gut. 71:2253–2265. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fan J, Lin R, Xia S, Chen D, Elf SE, Liu

S, Pan Y, Xu H, Qian Z, Wang M, et al: Tetrameric Acetyl-CoA

acetyltransferase 1 is important for tumor growth. Mol Cell.

64:859–874. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Viaud M, Abdel-Wahab O, Gall J, Ivanov S,

Guinamard R, Sore S, Merlin J, Ayrault M, Guilbaud E, Jacquel A, et

al: ABCA1 exerts tumor-suppressor function in myeloproliferative

neoplasms. Cell Rep. 30:3397–3410.e5. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Roundhill EA, Jabri S and Burchill SA:

ABCG1 and Pgp identify drug resistant, self-renewing osteosarcoma

cells. Cancer Lett. 453:142–157. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kong W, Wei J, Abidi P, Lin M, Inaba S, Li

C, Wang Y, Wang Z, Si S, Pan H, et al: Berberine is a novel

cholesterol-lowering drug working through a unique mechanism

distinct from statins. Nat Med. 10:1344–1351. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ioannou GN, Morrow OB, Connole ML and Lee

SP: Association between dietary nutrient composition and the

incidence of cirrhosis or liver cancer in the United States

population. Hepatology. 50:175–184. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Xu R, Shen J, Song Y, Lu J, Liu Y, Cao Y,

Wang Z and Zhang J: Exploration of the application potential of

serum multi-biomarker model in colorectal cancer screening. Sci

Rep. 14:101272024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jamnagerwalla J, Howard LE, Allott EH,

Vidal AC, Moreira DM, Castro-Santamaria R, Andriole GL, Freeman MR

and Freedland SJ: Serum cholesterol and risk of high-grade prostate

cancer: Results from the REDUCE study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic

Dis. 21:252–259. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Zhao B, Gan L, Graubard BI, Männistö S,

Albanes D and Huang J: Associations of dietary cholesterol, serum

cholesterol, and egg consumption with overall and cause-specific

mortality: Systematic review and updated meta-analysis.

Circulation. 145:1506–1520. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Demierre MF, Higgins PD, Gruber SB, Hawk E

and Lippman SM: Statins and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer.

5:930–942. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Siemianowicz K, Gminski J, Stajszczyk M,

Wojakowski W, Goss M, Machalski M, Telega A, Brulinski K and

Magiera-Molendowska H: Serum total cholesterol and triglycerides

levels in patients with lung cancer. Int J Mol Med. 5:201–205.

2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhou P, Li B, Liu B, Chen T and Xiao J:

Prognostic role of serum total cholesterol and high-density

lipoprotein cholesterol in cancer survivors: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 477:94–104. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Oh MJ, Han K, Kim B, Lim JH, Kim B, Kim SG

and Cho SJ: Risk of gastric cancer in relation with serum

cholesterol profiles: A nationwide population-based cohort study.

Medicine (Baltimore). 102:e362602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Zhang X, Coker OO, Chu ES, Fu K, Lau HCH,

Wang YX, Chan AWH, Wei H, Yang X, Sung JJY and Yu J: Dietary

cholesterol drives fatty liver-associated liver cancer by

modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gut. 70:761–774. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zhang X, Ding HM, Deng LF, Chen GC, Li J,

He ZY, Fu L, Li JF, Jiang F, Zhang ZL and Li BY: Dietary fats and

serum lipids in relation to the risk of ovarian cancer: A

meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Nutr. 10:11539862023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ikonen E and Olkkonen VM: Intracellular

cholesterol trafficking. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

15:a0414042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

von Eckardstein A, Nordestgaard BG,

Remaley AT and Catapano AL: High-density lipoprotein revisited:

Biological functions and clinical relevance. Eur Heart J.

44:1394–1407. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

36

|

Dang EV and Reboldi A: Cholesterol sensing

and metabolic adaptation in tissue immunity. Trends Immunol.

45:861–870. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Griffiths WJ and Wang Y: Cholesterol

metabolism: From lipidomics to immunology. J Lipid Res.

63:1001652022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

38

|

Long T, Debler EW and Li X: Structural

enzymology of cholesterol biosynthesis and storage. Curr Opin

Struct Biol. 74:1023692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Schade DS, Shey L and Eaton RP:

Cholesterol review: A metabolically important molecule. Endocr

Pract. 26:1514–1523. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Halimi H and Farjadian S: Cholesterol: An

important actor on the cancer immune scene. Front Immunol.

13:10575462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Goicoechea L, Conde de la Rosa L, Torres

S, García-Ruiz C and Fernández-Checa JC: Mitochondrial cholesterol:

Metabolism and impact on redox biology and disease. Redox Biol.

61:1026432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Meng Y, Heybrock S, Neculai D and Saftig

P: Cholesterol handling in lysosomes and beyond. Trends Cell Biol.

30:452–466. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Feingold KR: Lipid and lipoprotein

metabolism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 51:437–458. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chandel NS: Lipid metabolism. Cold Spring

Harb Perspect Biol. 13:a0405762021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Xiao X, Kennelly JP, Ferrari A, Clifford

BL, Whang E, Gao Y, Qian K, Sandhu J, Jarrett KE, Brearley-Sholto

MC, et al: Hepatic nonvesicular cholesterol transport is critical

for systemic lipid homeostasis. Nat Metab. 5:165–181. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kennelly JP and Tontonoz P: Cholesterol

transport to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb Perspect

Biol. 15:a0412632023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Faulkner RA, Yang Y, Tsien J, Qin T and

DeBose-Boyd RA: Direct binding to sterols accelerates endoplasmic

reticulum-associated degradation of HMG CoA reductase. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 121:e23188221212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Chen L, Zhao ZW, Zeng PH, Zhou YJ and Yin

WJ: Molecular mechanisms for ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux.

Cell Cycle. 21:1121–1139. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hu X, Chen F, Jia L, Long A, Peng Y, Li X,

Huang J, Wei X, Fang X, Gao Z, et al: A gut-derived hormone

regulates cholesterol metabolism. Cell. 187:1685–1700.e18. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Saher G: Cholesterol metabolism in aging

and age-related disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 46:59–78. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Xu H, Zhou S, Tang Q, Xia H and Bi F:

Cholesterol metabolism: New functions and therapeutic approaches in

cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1874:1883942020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Mittal S, Nenwani M, Pulikkal Kadamberi I,

Kumar S, Animasahun O, George J, Tsaih SW, Gupta P, Singh M,

Geethadevi A, et al: eIF4E enriched extracellular vesicles induce

immunosuppressive macrophages through HMGCR-mediated metabolic

rewiring. Adv Sci (Weinh). e063072025.Epub ahead of print.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ashida S, Kawada C and Inoue K: Stromal

regulation of prostate cancer cell growth by mevalonate pathway

enzymes HMGCS1 and HMGCR. Oncol Lett. 14:6533–6542. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Martin OP, Wallace MS, Oetheimer C, Patel

HB, Butler MD, Wong LP, Huang P, Elbaz J, Costentin C, Salloum S,

et al: Single-cell atlas of human liver and blood immune cells

across fatty liver disease stages reveals distinct signatures

linked to liver dysfunction and fibrogenesis. Nat Immunol.

26:1596–1611. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Saito Y, Yin D, Kubota N, Wang X, Filliol

A, Remotti H, Nair A, Fazlollahi L, Hoshida Y, Tabas I, et al: A

therapeutically targetable TAZ-TEAD2 pathway drives the growth of

hepatocellular carcinoma via ANLN and KIF23. Gastroenterology.

164:1279–1292. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Li Z, Liu C, Wang M, Wei R, Li R, Huang K,

Liang H, Li G and Zhao L: Cholesterol confers resistance to

Apatinib-mediated ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Cell Biosci.

15:952025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Li MX, Hu S, Lei HH, Yuan M, Li X, Hou WK,

Huang XJ, Xiao BW, Yu TX, Zhang XH, et al: Tumor-derived

miR-9-5p-loaded EVs regulate cholesterol homeostasis to promote

breast cancer liver metastasis in mice. Nat Commun. 15:105392024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Xue X, He Z, Liu F, Wang Q, Chen Z, Lin L,

Chen D, Yuan Y, Huang Z and Wang Y: Taurochenodeoxycholic acid

suppresses the progression of glioblastoma via HMGCS1/HMGCR/GPX4

signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell Int.

25:1602025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Nakagawa H: Lipogenesis and MASLD:

Re-thinking the role of SREBPs. Arch Toxicol. 99:2299–2312. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Li Y, Wu S, Zhao X, Hao S, Li F, Wang Y,

Liu B, Zhang D, Wang Y and Zhou H: Key events in cancer:

Dysregulation of SREBPs. Front Pharmacol. 14:11307472023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Geng F, Zhong Y, Su H, Lefai E, Magaki S,

Cloughesy TF, Yong WH, Chakravarti A and Guo D: SREBP-1 upregulates

lipophagy to maintain cholesterol homeostasis in brain tumor cells.

Cell Rep. 42:1127902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Chen Y, Deng X, Li Y, Han Y, Peng Y, Wu W,

Wang X, Ma J, Hu E, Zhou X, et al: Comprehensive molecular

classification predicted microenvironment profiles and therapy

response for HCC. Hepatology. 80:536–551. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhou J, Qu G, Zhang G, Wu Z, Liu J, Yang

D, Li J, Chang M, Zeng H, Hu J, et al: Glycerol kinase 5 confers

gefitinib resistance through SREBP1/SCD1 signaling pathway. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 38:962019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Su F and Koeberle A: Regulation and

targeting of SREBP-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Metastasis

Rev. 43:673–708. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

65

|

Chen F, Li H, Wang Y, Tang X, Lin K, Li Q,

Meng C, Shi W, Leo J, Liang X, et al: CHD1 loss reprograms

SREBP2-driven cholesterol synthesis to fuel androgen-responsive

growth and castration resistance in SPOP-mutated prostate tumors.

Nat Cancer. 6:854–873. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Gao W, Guo X, Sun L, Gai J, Cao Y and

Zhang S: PKMYT1 knockdown inhibits cholesterol biosynthesis and

promotes the drug sensitivity of triple-negative breast cancer

cells to atorvastatin. PeerJ. 12:e177492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Wu R, Li N, Huang W, Yang Y, Zang R, Song

H, Shi J, Zhu S and Liu Q: Melittin suppresses ovarian cancer

growth by regulating SREBP1-mediated lipid metabolism.

Phytomedicine. 137:1563672025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Wen J, Zhang X, Wong CC, Zhang Y, Pan Y,

Zhou Y, Cheung AH, Liu Y, Ji F, Kang X, et al: Targeting squalene

epoxidase restores anti-PD-1 efficacy in metabolic

dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis-induced hepatocellular

carcinoma. Gut. 73:2023–2036. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Li J, Yang T, Wang Q, Li Y, Wu H, Zhang M,

Qi H, Zhang H and Li J: Upregulation of SQLE contributes to poor

survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci.

18:3576–3591. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Liu Q, Zhang Y, Li H, Gao H, Zhou Y, Luo

D, Shan Z, Yang Y, Weng J, Li Q, et al: Squalene epoxidase promotes

the chemoresistance of colorectal cancer via

(S)-2,3-epoxysqualene-activated NF-κB. Cell Commun Signal.

22:2782024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Wu J, Hu W, Yang W, Long Y, Chen K, Li F,

Ma X and Li X: Knockdown of SQLE promotes CD8+ T cell infiltration

in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Signal. 114:1109832024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Xu M, Pan G, Zhang Q, Huang J, Wu Y and

Ashan Y: FOXM1 boosts glycolysis by upregulating SQLE to inhibit

anoikis in breast cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

151:1622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Shen T, Lu Y and Zhang Q: High squalene

epoxidase in tumors predicts worse survival in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma: Integrated bioinformatic analysis on

NAFLD and HCC. Cancer Control. 27:10732748209146632020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Zhang Z, Wu W, Jiao H, Chen Y, Ji X, Cao

J, Yin F and Yin W: Squalene epoxidase promotes hepatocellular

carcinoma development by activating STRAP transcription and

TGF-β/SMAD signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 180:1562–1581. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Kanmalar M, Abdul Sani SF, Kamri NINB,

Said NABM, Jamil AHBA, Kuppusamy S, Mun KS and Bradley DA: Raman

spectroscopy biochemical characterisation of bladder cancer

cisplatin resistance regulated by FDFT1: A review. Cell Mol Biol

Lett. 27:92022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Cai D, Zhong GC, Dai X, Zhao Z, Chen M, Hu

J, Wu Z, Cheng L, Li S and Gong J: Targeting FDFT1 reduces

cholesterol and bile acid production and delays hepatocellular

carcinoma progression through the HNF4A/ALDOB/AKT1 axis. Adv Sci

(Weinh). 12:e24117192025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Wu Z, Duan W, Xiong Y, Liu J, Wen X, Zhao

F, Xiang D, Wang J, Kasim V and Wu S: NeuroD1 drives a KAT2A-FDFT1

signaling axis to promote cholesterol biosynthesis and

hepatocellular carcinoma progression via histone H3K27 acetylation.

Oncogene. Sep 1–2025.Epub ahead of print.

|

|

78

|

Yang C, Huang S, Cao F and Zheng Y: A

lipid metabolism-related genes prognosis biomarker associated with

the tumor immune microenvironment in colorectal carcinoma. BMC

Cancer. 21:11822021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Zhang HL, Zhao R, Wang D, Mohd Sapudin SN,

Yahaya BH, Harun MSR, Zhang ZW, Song ZJ, Liu YT, Doblin S and Lu P:

Candida albicans and colorectal cancer: A paradoxical role revealed

through metabolite profiling and prognostic modeling. World J Clin

Oncol. 16:1041822025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Weng ML, Chen WK, Chen XY, Lu H, Sun ZR,

Yu Q, Sun PF, Xu YJ, Zhu MM, Jiang N, et al: Fasting inhibits

aerobic glycolysis and proliferation in colorectal cancer via the

Fdft1-mediated AKT/mTOR/HIF1α pathway suppression. Nat Commun.

11:18692020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Goudarzi A: The recent insights into the

function of ACAT1: A possible anti-cancer therapeutic target. Life

Sci. 232:1165922019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Gu L, Zhu Y, Lin X, Tan X, Lu B and Li Y:

Stabilization of FASN by ACAT1-mediated GNPAT acetylation promotes

lipid metabolism and hepatocarcinogenesis. Oncogene. 39:2437–2449.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Wang T, Wang G, Shan D, Fang Y, Zhou F, Yu

M, Ju L, Li G, Xiang W, Qian K, et al: ACAT1 promotes proliferation

and metastasis of bladder cancer via AKT/GSK3β/c-Myc signaling

pathway. J Cancer. 15:3297–3312. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

84

|

Sun S, Qi G, Chen H, He D, Ma D, Bie Y, Xu

L, Feng B, Pang Q, Guo H and Zhang R: Ferroptosis sensitization in

glioma: Exploring the regulatory mechanism of SOAT1 and its