Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was

proposed by Ludwig in 1986. It refers to a fatty liver disease

characterized by excessive fat deposition in hepatocytes (with a

fat content of ≥5%), excluding alcohol and other factors related to

chronic liver diseases (1-4).

In 2020, the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver

proposed the term 'metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver

disease (MAFLD)', emphasizing the role of metabolic disorders in

the progression of fatty liver disease (5). In 2023, an international panel of

experts reached a consensus and the European Association for the

Study of the Liver, from an etiological perspective, renamed it as

'metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)'

(6,7). This change highlights the critical

role of metabolic abnormalities in the occurrence and development

of the disease (8). While

avoiding 'stigmatization', this concept also provides explanations

for the coexistence of MASLD and alcoholic-associated liver disease

(9,10).

The etiology of MASLD is complex, with its core

being the interplay between metabolic dysfunction (such as insulin

resistance and dyslipidemia) and multifactorial elements (including

genetics, environment and lifestyle), rather than being attributed

to a single factor. Researchers have established various animal

models of MASLD using diverse methodologies to investigate its

pathophysiological characteristics. Currently, common

interventional drugs mainly include: Farnesoid X receptor agonists,

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α/γ/δ agonists,

GLP-1 agonists and fibroblast growth factor 19/21 analogs (11). For individuals with a body mass

index >35, bariatric surgery is primarily recommended. In the

treatment of MASLD, although chemical drugs have advanced rapidly,

their efficacy remains limited with notable adverse effects. By

contrast, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) not only enables

comprehensive regulation targeting the multifactorial pathogenesis

of MASLD, but also strives to improve the quality of life of

patients, thereby opening up new possibilities for the management

of MASLD (12).

In recent years, influenced by unhealthy lifestyles

and dietary habits, the prevalence of MASLD has been increasing

annually. The global incidence rate has reached 25-35%, with a

prevalence of 29.2% in China (13). It is projected that the number of

MASLD patients in China will reach 315 million by 2030, imposing a

heavy economic burden on society (14). Even mild fatty liver disease

increases the risk of death by 71% and this risk is positively

associated with the severity of the disease (14). Currently, while the incidence of

viral liver diseases is on the decline, the incidence of MASLD is

rising, making early intervention for MASLD an urgent priority. The

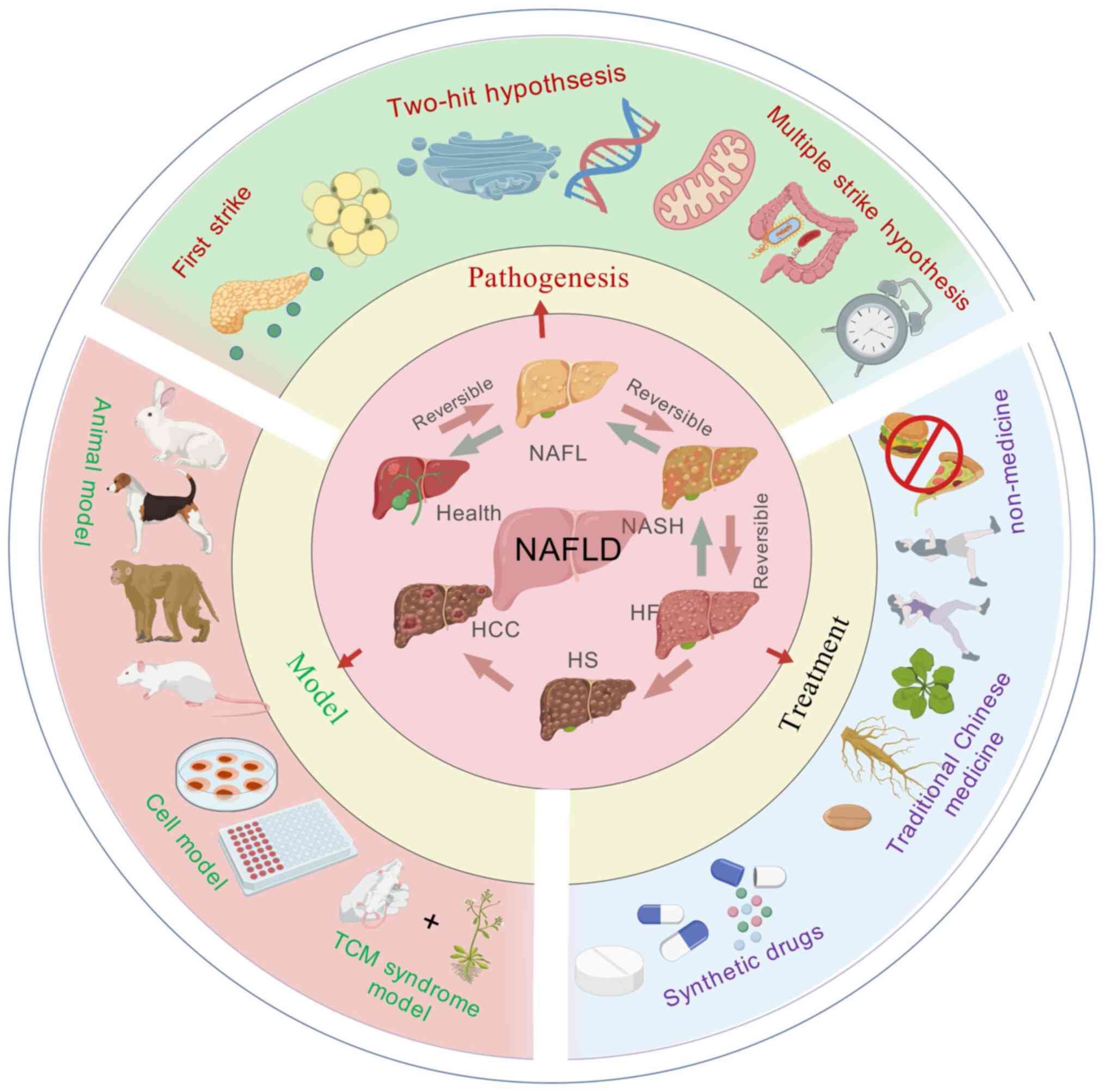

present study analyzed the pathogenesis, experimental models and

therapeutic approaches of MASLD, aiming to provide novel scientific

insights and strategies for future research, clinical treatment and

drug development.

To compile the research progress on the

pathogenesis, model and treatment of MASLD as comprehensively as

possible, the present study searched for 'pathogenesis', 'model',

'treatment' and 'traditional Chinese medicine' in existing

scientific databases. The references related to MASLD were obtained

from both online and offline databases, spanning the period from

1980-2025 with a total of 385 references. Online databases included

PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com/), Elsevier

(https://www.elsever.com/), Sci-Hub (https://sci-hub.st/), Wiley (https://www.wiley.com/), SpringerLink (https://link.springer.com/), Google Scholar

(https://scholar.google.com/), EMBASE

(https://www.embase.com/), Cochrane Library and

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (https://www.cnki.net/). Other references were obtained

from ancient Chinese books, pharmacopoeias and other articles. The

present authors used BioGDP (https://biogdp.com/) as well as Adobe Illustrator

(Adobe Systems, Inc.) for graphing.

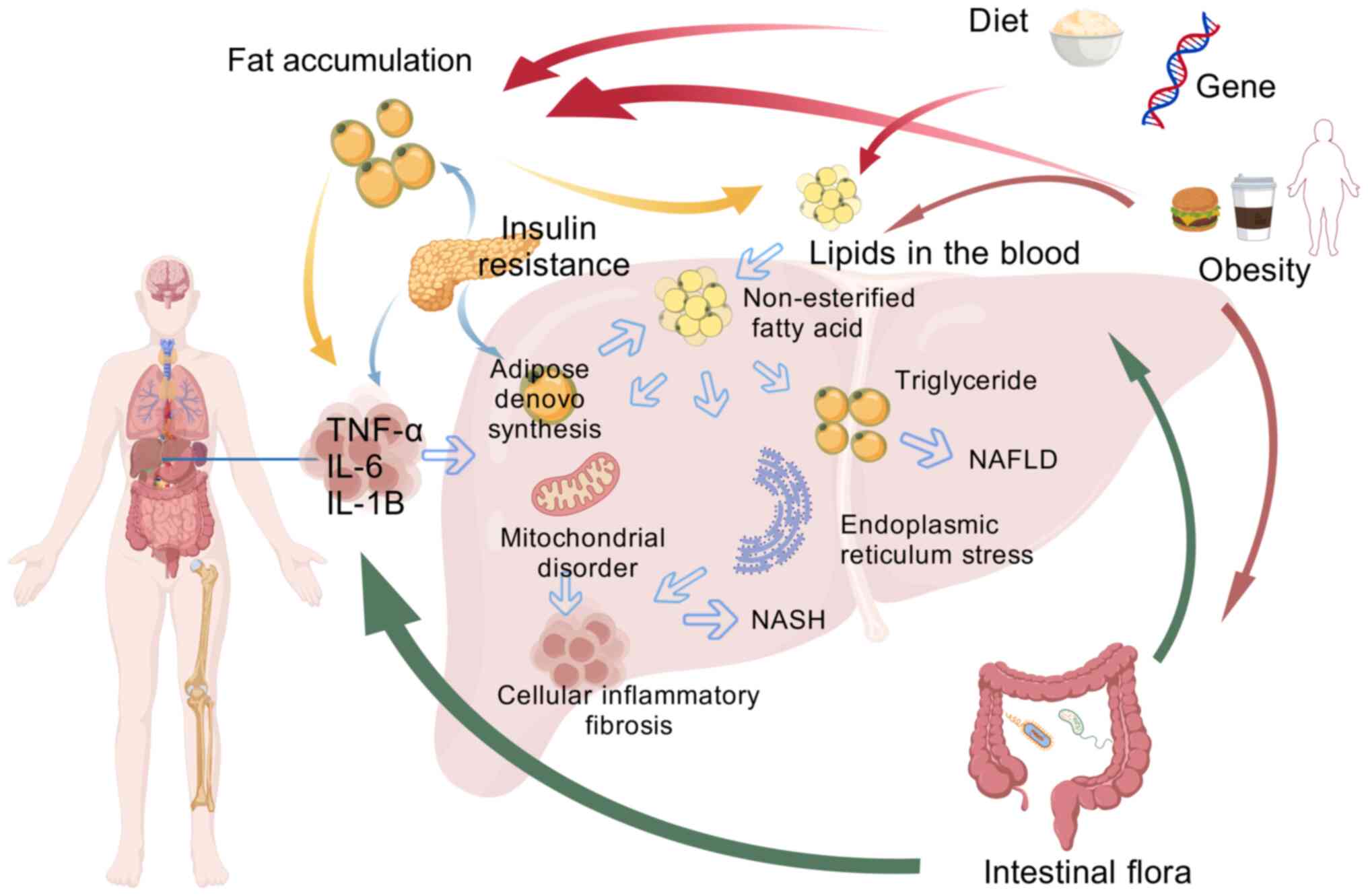

The pathogenesis of MASLD remains unclear due to its

complexity and diversity. As the main metabolic organ, the liver's

metabolism is closely connected with multiple organs and systems in

the human body. There are intricate links between these organs and

systems. Some consider that the hypothesis of 'multiple parallel

strikes' could be an improved explanation of the causes of MASLD

development and these strikes included oxidative stress,

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, lipid metabolism disorders,

abnormal adipokines and cytokines production and mitochondrial

dysfunction (15). One study

found that mitochondrial dysfunction might be a central factor in

the development of MASLD and other factors that cause disease

progression also involve mitochondrial dysfunction (16). The pathogenesis of MASLD is now

being investigated by combining different pathogenic pathways for

an improved understanding of metabolic diseases.

The 'first strike' mainly refers to insulin

resistance (IR) caused by obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus

(T2DM) and hepatic steatosis caused by excessive accumulation of

triglyceride (TG) and cholesterol in the liver parenchymal cells in

the form of lipid droplets. The 'Two-hit' hypothesis includes

inflammatory cytokines, lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial

dysfunction and oxidative stress (17), of which oxidative stress is the

primary driver (18). This

hypothesis posits that with steatosis, the liver undergoes ER

stress, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to

an increase in oxidative metabolites, hepatocellular damage and

secretion of a large number of inflammatory factors, which

ultimately leads to further deterioration into liver disease, liver

fibrosis, cirrhosis, inflammatory necrosis and other reactions

(19,20). In the early stages of MASLD,

classical activation of macrophage M1 in the liver can promote

further inflammation and IR, as well as steatosis (21). Among them, inflammatory cytokines

such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α),

IL-1β and cyclooxygenase-2 contribute to the development of chronic

inflammatory diseases (22).

IL-6 has been shown to have both anti-inflammatory and

pro-inflammatory effects, but its role in MASLD is controversial.

IL-10, produced primarily by monocytes and B cells, is an

anti-inflammatory factor with immunomodulatory properties (22). Other inflammatory cells of the

innate immune system, such as natural killer T cell and natural

killer cells, also play the important roles in the pathogenesis of

MASLD and MASH (21). However,

the factors that induce MASLD in clinical practice are diverse and

as research has deepened, the two-hit hypothesis has already shown

certain limitations and cannot fully explain the pathogenesis of

MASLD. Recently, the 'three-strike' and 'multiple-strike'

hypotheses have been proposed, which include gut microbiota toxins,

IR, cytokines and inflammation, oxidative stress due to

mitochondrial dysfunction, lipid peroxidation, ER stress, intrinsic

immune regulation, circadian rhythm disruption and immune system

development. Imbalances, circadian patterns and genetics are all

parallel and mutually reinforcing factors that contribute to the

onset and development of MASLD (23,24) (Fig. 1).

The role of liver sinusoidal endothelial cell (LSEC)

in the development and progression of MASLD is being gradually

recognized. LSEC is the most predominant liver nonparenchymal cell

(NPC), accounting for 15-20% of the total number of hepatocytes but

only 3% of the total volume of the liver (25). The biggest difference between

LSECs and other vascular endothelial cells is the presence of

window pores and the lack of a basement membrane. LSECs are

considered the most permeable endothelial cells in mammals

(25). Window pores are small

pores with diameters ranging from 50-200 nm, accounting for 2-20%

of the endothelial surface area (26). MASLD manifests as NAFL in the

early stage, which is not accompanied, or only accompanied by mild,

inflammation. LSEC acts as the first line of defense in the

initiation of MASLD (27),

exerting anti-inflammatory effects, preventing the over-activation

of the hepatic immune system and maintaining the microenvironmental

homeostasis of hepatic sinusoids. It has been shown that the unique

window pore structure of LSECs in a physiological state serves an

important role in maintaining the stability of the liver, which

manifests pro-vasodilatory, strong endocytosis, anti-inflammatory

and anti-fibrotic effects (28).

This window pore regulates the act in the endothelial cell skeleton

of LSECs through the form of calcium-calmodulin-actin complex to

adjust and control the size of the window pore on the endothelial

cells of LSEC; if the size, number, and permeability of window

pores in LSECs could not be effectively improved, they would

disappear in the course of time. From the initial manifestation of

fat accumulation to inflammatory symptoms, as well as hepatic

fibrosis and in severe cases, cirrhosis, LSEC regulates blood flow

through the secretion of two substances, nitric oxide (NO) and

endothelin-1 (ET-1) (27). NO

promotes vasodilatation and ET-1 induces vasoconstriction. Reduced

NO bioavailability induces LSEC capillarization characterized by

loss of the LSEC window pore and basement membrane formation and

leads to an imbalance in its secretion of vasoactive substances,

which contributes to MASLD progression. With the progression of

MASLD, LSEC undergoes capillarization and hepatic sinusoidal

endothelial dysfunction, which gradually shifts from an

anti-inflammatory to a pro-inflammatory phenotype and promotes the

progression of inflammation, fibrosis and angiogenesis. Hepatic

sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction precedes the development of

hepatic inflammation or fibrosis. It is a major feature and early

event in MASLD pathogenesis (29).

IR refers to the phenomenon of reduced sensitivity

of tissues and organs to insulin, which is the initiation and

central link in the progression of MASLD (30). It has been found that the degree

of IR in MASLD patients is positively associated with the severity

of the disease (31). IR acts on

target organs mainly the liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue;

the body's sensitivity to insulin is reduced, so that the

biological effect of insulin on target organs is reduced and

glucose uptake and utilization are reduced, thus failing to

maintain blood glucose stability. Compensatory overproduction of

pancreatic islets and eventual development of hyperinsulinemia,

result in elevated hepatic synthesis and accumulation of total

cholesterol (TC) and elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels,

leading to inactivation of the enzyme LDL lipase, which is critical

for cholesterol clearance. Large amounts of TG cannot be cleared

and IR-induced hyperinsulinemia inhibits apolipoprotein B100

synthesis and reduces very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) related

lipid output from hepatocytes (32). In addition, IR leads to

decreasing lipid metabolism, increasing lipolysis and hepatic

uptake of large amounts of free fatty acid (FFA). By contrast,

fatty acid β-oxidation is inhibited by hyperinsulinemia and large

amounts of FFA are deposited in the liver, exacerbating

hepatocellular steatosis (33).

Excessive deposition of lipids further exacerbates IR and they are

mutually influencing and reinforcing processes (34). MASLD also leads to lower levels

of adiponectin (ADPN), a protein released from adipocytes. ADPN

aggravates steatosis in hepatocytes (35) and plays a role in regulating

glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as exhibiting

anti-inflammatory and anti-insulin resistance effects (36). In addition, Shah and Fonseca

(37) found that iron overload

could reduce insulin sensitivity and IR, which are closely related

to the occurrence of MASLD. The main reason is that iron can

activate the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway.

Activation of this pathway causes hepatocytes to produce an

inflammatory response, which accelerates the formation of MASLD.

Although iron is an essential trace element in the human body, a

study found that iron overload is closely related to the occurrence

of MASLD (37). Iron overload

can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cause oxidative

stress. Iron overload can also affect lipid metabolism and insulin

signaling, which can accelerate the progression of MASLD (38). Using hepatic puncture biopsy,

Nelson et al (39)

discovered that 34.5% of 849 patients with MASLD had intrahepatic

iron deposition, which suggested that iron deposition was a risk

factor for the progression of MASLD patients to advanced liver

diseases.

Adipokines are small-molecule proteins secreted by

tissues to regulate adipocytes, mainly including leptin (LP) and

ADPN. A study (40) found that

IR is closely related to the secretion of LP, resistin and ADPN.

ADPN is an adipokine that affects hepatic fat and glucose

metabolism, which interacts with adiponectin receptor1 and

adiponectin receptor 2. Adiponectin receptor 2 is mainly expressed

in liver tissues. Clinical studies have shown that the serum level

of ADPN in patients with MASLD is low and negatively is associated

with the severity of fatty liver (40). In addition, serum lipocalin

levels are reduced in MASLD patients and are associated with the

degree of hepatic necroinflammation, leading to the suggestion that

hypo-lipocalinemia will lead to the progression of MASLD, which may

be related to the fact that ADPN acts on the sterol regulatory

element-binding protein-1C to inhibit lipolysis of fats (41). Studies have shown a close

relationship between LP and the development of MASLD and that LP

can lead to the activation of hepatic LP and can lead to the

activation of hepatic stellate cells in MASLD and promote the

development of MASLD to liver fibrosis (41). Moreover, LP is also associated

with IR; when the feedback regulation mechanism between pancreatic

islets-adipocytes is damaged, the sensitivity of insulin to LP

decreases. It makes the fatty acid content of hepatocytes rise,

which promotes the increase in the synthesis of TGs in the

hepatocytes, leading to the formation of MASLD (42). Wang et al (43) found that the amount of ADPN

expression can be used to predict the occurrence of MASLD to a

certain extent. Resistin is a prepeptide adipocytokine containing a

108-amino-acid segment, named after its anti-insulin effect. In

another study, RES was found to be highly expressed in adipose

tissue and serum of both high-fat diet-induced obese rats and

transgenic obese rats (44).

Activation of resistin can induce the release of inflammatory

factors and promote the development of liver fibrosis (45).

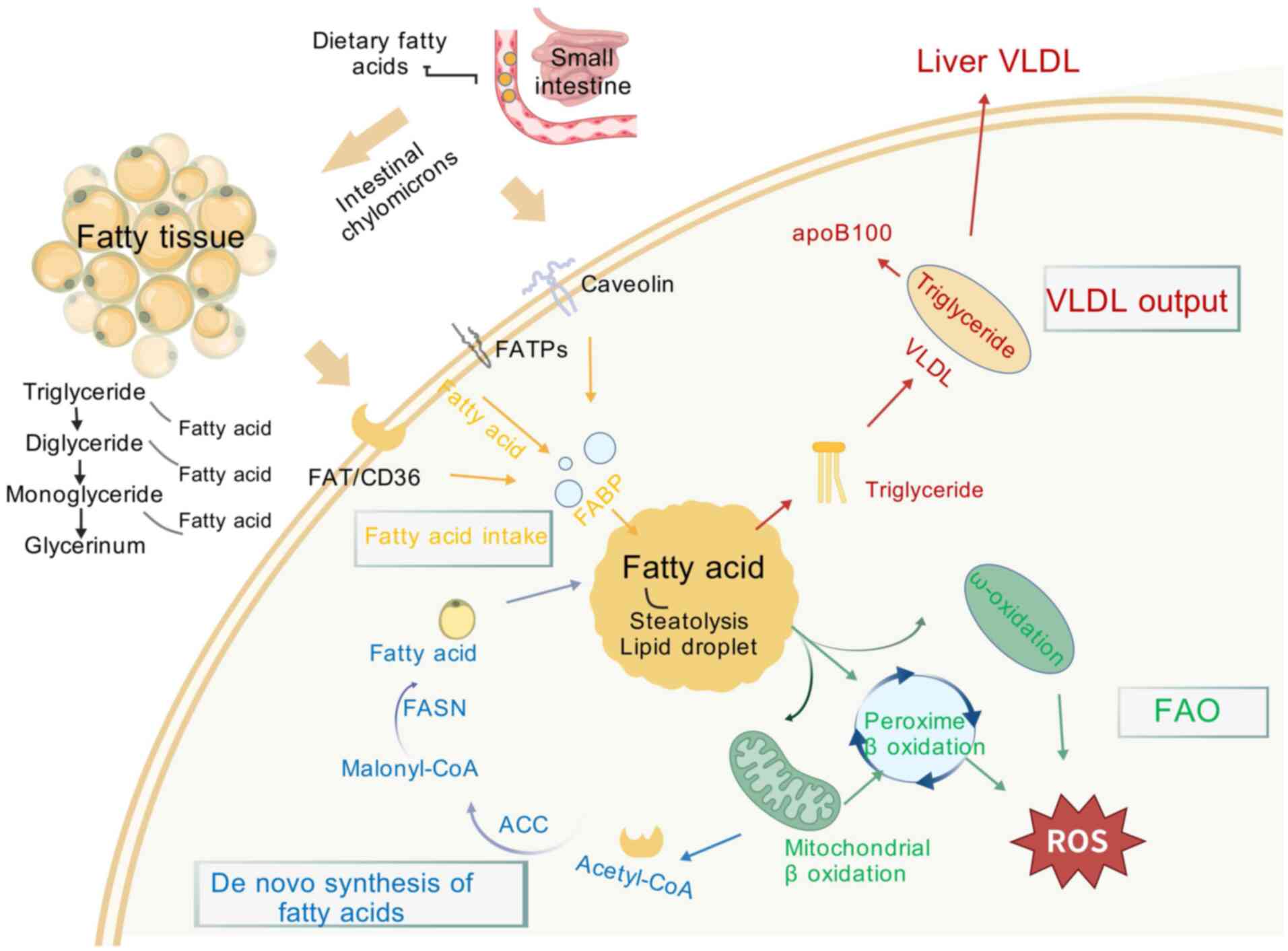

Lipotoxicity refers to lipid metabolism disorders

leading to an increase in FFA, excessive FFA makes pancreatic islet

β-cells dysfunctional, inducing them to produce a large amount of

NO, causing a series of cytotoxic injuries. Markedly increased

plasma FFA level in MASLD patients is the main reason for increased

IR in the body. In addition, increasing plasma FFA content leads to

fatty acid oxidation overload in hepatocytes, induces mitochondrial

damage and generates large amounts of ROS, causing oxidative

stress, ER stress and inflammatory response, which advances the

process of disease progression. The mechanisms of hepatic fatty

acid metabolism on MASLD are shown in Fig. 2.

The normal number of hepatocytes is controlled by

hepatocyte apoptosis, which maintains the liver at a normal size

and plays an important role in the development of the liver and the

maintenance of internal homeostasis, it is the defender of

hepatocytes against infections, tumors and autoimmune reactions;

under pathological conditions apoptosis of hepatocytes is the

central link in the basis of injury and other liver diseases.

Lipotoxicity induces apoptosis in hepatocytes, called

lipoapoptosis. It has been demonstrated that FFA-treated

hepatocytes show an increase in the expression of pro-apoptotic

proteins and apoptosis regulators upregulated by tumor suppressor

genes, a process that is accompanied by a decrease in the

expression of the anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma-2. The

aforementioned process initiates the mitochondria-induced apoptosis

pathway, which activates caspase-3,6,7 leading to apoptosis

(46). Hepatocyte apoptosis is

closely related to the pathogenesis of MASLD (47).

Mitochondria are an important site for hepatic FFA

oxidation. When FFA and related metabolites in the liver increase

in excess, it causes mitochondrial microstructure swelling and

mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in impaired β-oxidation,

altering the permeability of the ER membrane, inducing the

production of a large number of ROS. ATP generation is reduced,

causing oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage (48). In the meantime, ROS generated by

oxidative stress in the mitochondrial membrane react with

unsaturated fatty acids of mitochondrial membrane phospholipids,

nucleic acids and other macromolecules to cause lipid peroxidation

and the products of lipid peroxidation produce endogenous ROS and

O2−, which can damage mitochondrial DNA structure and

further diminish the anti-oxidant effect of mitochondria (49). In addition, ROS generated by

oxidative stress in hepatocytes can trigger an inflammatory

response. This response induces neutrophil infiltration and

activates Kupffer cells (KCs) to secrete ROS and TNF-α. These

events create a vicious cycle of oxidative stress, leading to VLDL

deposition in the liver and the development of MASLD. Further

hepatocyte necrosis may occur due to other cytokines, such as

transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IL-6 and C-reactive protein

(49,50).

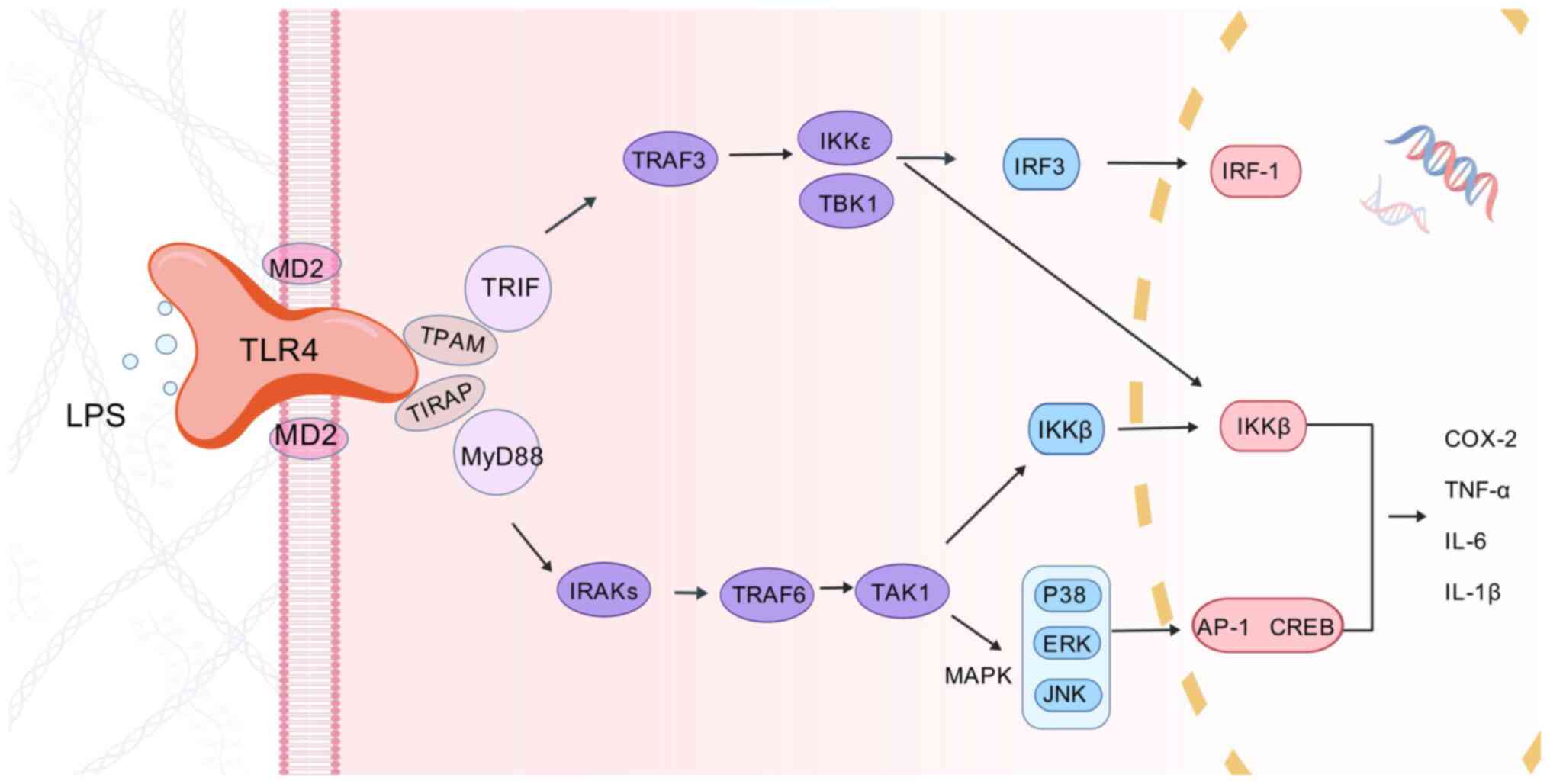

Persistent inflammation is the main driver of MASLD

progression to MASH and fibrosis and activation of toll-like

receptors (TLRs) is thought to be a key factor in triggering

hepatic steatotic inflammation. The liver, as a central immune

organ, possesses the largest number of resident macrophages, known

as KCs. KCs account for 35% of the liver's NPC and 80-90% of all

tissue macrophages in the body. KCs are considered to be the first

immune cells to come into contact with intestinal or hepatic

autoimmune reactive substances and are rich in the expression of

TLRs (51). Accumulation of

lipids in hepatocytes will result in lipotoxicity, which will lead

to hepatocyte damage or death. Damaged or dead hepatocytes release

damage-associated pattern molecules, including mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA) and high mobility group protein-1 (HMGB1) (52). Among them, mtDNA can directly

activate recombinant TLR9 in KCs, triggering an inflammatory

cascade (53). Recombinant

toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (Fig.

3) is another TLR family member upregulated in MASLD and

lipopolysaccharide (LPS), ROS, HMGB1 and various damage-associated

molecular patterns can bind to TLR4 in KCs to promote TNF-α, IL-1β,

IL-6 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production of various

pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby contributing to hepatic

inflammation and the progression of MASLD (54). In addition to triggering the

inflammatory response through lipotoxicity that causes hepatocyte

injury or death, excess FFA in the liver can also exacerbate the

inflammatory response through direct or indirect activation of

TLR4. Circulating FFA, especially saturated fatty acid (SFA), acts

as non-microbial TLR4 agonists and triggers inflammatory responses.

SFA is thought to have a similar recognition pathway to LPS, a

natural ligand of TLR4, in order to activate the TLR4 signaling

pathway, thereby triggering downstream inflammatory pathways

(55). Furthermore, to activate

TLR4, SFA is also thought to activate recombinant TLR2 to promote

the development of inflammatory responses (56). It has been shown that SFA can

activate TLR by interacting with TLR co-receptors, such as cluster

of differentiation36 (CD36) or LDL receptors, to promote

inflammation (57). In addition,

FFA can interact with various other cytokines, such as hepatocyte

nuclear factor 4-α (HNF-4α), leading to overall changes in

signaling pathways that regulate metabolism and stress (58). Lipotoxicity can also further

induce ER stress, impair autophagy and promote aseptic inflammatory

responses, thereby exacerbating hepatocyte injury and death

(59,60). Cholesterol synthesis is markedly

increased in patients with MASLD, suggesting that cholesterol may

also be one of the important driving forces in its development

(61). Cholesterol not only

promotes de novo lipid synthesis but also induces lipid

peroxidation (62). Moreover, it

has been found that increased dietary cholesterol intake leads to

hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress in mice, suggesting that

cholesterol probably plays a contributory role in the disease

progression of MASLD (63).

Lipid accumulation in hepatocytes can affect

mitochondrial function, ER membrane fluidity and calcium ion

homeostasis. It has been found that thioesterase superfamily member

2 (THEM2) promotes the uptake of saturated fatty acids by ER

phospholipid membranes, reduces ER membrane fluidity and affects

the activity of ER Ca2+associated ATPase. The

dysregulation of Ca2+ signaling can cause protein

misfolding and secretion (64).

Non-esterified fatty acids can expand the membrane structure of the

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria association. Changes in the

membrane structure of the ER allow Ca2+ to flow into the

cytoplasm or mitochondria, which in turn alters the open channels

of the mitochondria and cytochrome c is released into the

cytoplasm. Ca2+ entering the cytoplasm can activate the

Ca2+ dependent protein kinase, which together with

cytochrome c induces the onset of apoptosis (65). ROS generated by mitochondria can

enter the ER and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR), which

can activate three types of ER transmembrane protein receptors:

Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK),

activating transcription factor-6α (ATF-6α) and inosital-requiring

enzyme-1α (IRE1α), which mediate three signaling pathways. The

three transmembrane proteins mediate three signaling pathways,

which can maintain the stability of ER protein synthesis to a

certain extent in the early stage of steatosis, but under the

continuous stimulation of lipids and ROS, the three transmembrane

proteins mediate the signaling pathways that can activate cellular

inflammation and apoptosis, accelerating the progression of hepatic

steatosis (66).

In the process of hepatocellular steatosis, one of

the hallmarks of MASLD is the appearance of the UPR in hepatocytes,

which can inhibit mitochondrial lipid oxidation through the

UPR-induced ATF-6α pathway and promote fatty acid synthesis via the

PERK, ATF-6α and IRE1α signaling pathways, which together promote

intracellular lipid accumulation (67,68). Hepatocyte lipid accumulation and

ER stress form a positive feedback loop that continuously

exacerbates hepatocyte steatosis. The occurrence of chronic

inflammation in hepatocytes is also one of the main features of

metabolic disorders. The inflammatory response can activate the UPR

through three major signaling pathways (PERK, ATF-6α and IRE1α).

The UPR can also interact with NF-κB and N-terminal

kinase/activator protein 1-regulated pro-inflammatory pathways to

accelerate disease progression (66,69).

The intestinal flora is a symbiotic group of

microorganisms that act synergistically with the host. Under normal

circumstances, the intestinal flora of the human body is in a state

of equilibrium. Imbalances in the intestinal flora can be caused by

environmental factors, immune levels, bile secretion, changes in

gastric acidity and alkalinity and impaired intestinal peristalsis.

In recent years, it has been found that dysbiosis is one of the

causative factors of MASLD (70). The intestinal flora mainly

influences the liver through the 'gut-liver axis'. Normally, there

is a balance between the barrier function of the intestine and the

detoxification capacity of the liver and trace amounts of

intestinal bacteria cross the mucosa and enter the venous

bloodstream and are cleared by the liver (71). When intestinal flora dysbiosis

occurs, metabolic disorders will occur, the permeability of the

intestinal tract will increase and a large amount of intestinal

bacterial metabolites, bacterial components and other harmful

substances will enter the liver through the portal vein via the

intestinal-hepatic axis and through the enterohepatic circulation

reach the liver and bind to the TLR4 of hepatocytes and exacerbate

the hepatic inflammatory response, oxidative stress and lipid

accumulation, which further stimulate the inflammatory response.

Intestinal microorganisms change their phenotype and virulence by

sensing the various adverse signals generated during intestinal

stress, shifting from a commensal to a pathogenic mode and causing

damage to the organism (72).

Ley et al (73) found

that changes in the composition of the gut microbial community

associated with obesity as well as IR were observed after the

adoption of two different dietary patterns. IR, an important

feature of MASLD, can be improved after antibiotic treatment

(74). A study conducted by Le

et al (75) demonstrated

that when gut microbes from successfully modeled MASLD mice were

transplanted into normal control mice, the normal control mice

developed MASLD and this study strongly confirmed that the

development of MASLD is associated with the development of MASLD

and its effects on the gut microbial community. This study also

confirms the correlation between the development of MASLD and gut

microbes. A Chinese cohort study reported that

high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae (HiAlc-Kpn), which

produces large amounts of alcohol, was detected in 61% of MASLD

patients. In order to investigate the relationship between HiAlc

bacteria and fatty liver disease, they fed specific pathogen free

(SPF) mice with HiAlc-Kpn. It is noteworthy that HiAlc-Kpn feeding

induced chronic hepatic steatosis. They investigated the

relationship between intestinal flora imbalance and severe MASLD

lesions (MASH and fibrosis) and showed that an increase in the

number of Ruminococcus was positively associated with an

aggravation of the degree of fibrosis (76). In addition, LPS is an important

component of the cell wall of Gram-negative bacilli. It is

recognized by pattern receptors and mediates the LPS-CD14-TLR4

signaling pathway, which activates intrahepatic KCs. These KCs

release large amounts of cytokines, such as IL-6, CD68 and TNF-α.

LPS also causes inflammation and metabolic disorders in

vivo, including increased fat burning, elevated circulating

free FFA and TG and deposition of FFA in the liver. This process

may contribute to inflammation and trigger IR, which can ultimately

lead to MASLD. The deposition of FFA in the liver may also promote

inflammation, leading to IR, which in turn triggers the development

of MASLD (77). Dysbiosis may

also contribute to MASH through other mechanisms, such as ethanol

production and interference with choline metabolism (22). Overall, intestinal flora and its

harmful metabolites (including EtOH, SFA, polyamines and

H2S) may be drivers of liver injury (76).

BA is synthesized in the liver and the main raw

material for synthesis is cholesterol. BA regulates glucose and

lipid metabolism. BA, along with its downstream receptors farnesoid

X receptor (FXR) and Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5),

plays an important role in lipid metabolism in the liver (78). BA also regulates the cholesterol

metabolic pathway, allowing cholesterol to be eliminated as a

water-soluble product and impaired regulation can lead to an

inflammatory response that can exacerbate the development of MASLD

(79). In a MASLD mouse model,

Jiang et al (80) found

that the administration of antibiotics to mice on a high-fat diet

reduced triacylglycerol accumulation in the liver. Activation of

TGR5 by BA in brown adipose tissue and muscle increases energy

expenditure and reduces diet-induced obesity (81). Activated TGR5 can downregulate

the expression level of inflammatory factors, promote energy

expenditure in adipose and muscle tissues and regulate the body's

immunity, which has a positive effect on improving MASLD (82). Watanabe et al (83) found in an animal experiment that

cholesterol and TG levels were markedly elevated in mice lacking

FXR in vivo. FXR has a positive effect on lipid regulation

and also reduces the generation of inflammatory responses; FXR

plays a key role in the regulation of BA and regulates lipid

metabolism. In addition, BA can affect the growth of bacteria and

is a bacteriostatic substance. Conversely, intestinal flora can

also regulate BA, intestinal flora and BA metabolism affect each

other. However, the effects of different flora are inconsistent.

For example, Aspergillus and Anaplastic bacilli in

the intestine will reduce the synthesis of BA and aggravate

inflammatory reactions, while Actinobacteria will increase

the synthesis of BA, reduce the inflammatory response and reduce

the damage of hepatocytes (84).

The normal metabolism of BA plays a crucial role in maintaining the

balance of intestinal flora. Gut microorganisms can also accelerate

the metabolism of primary BA and produce secondary BA, increasing

BA types (85). LPS produced by

intestinal flora can stimulate NF-κB to recruit inflammatory

factors and increase the level of inflammation in the body. These

studies suggest that influencing the gut flora by modulating the

signaling pathways between BA and their controlled receptors is a

promising new therapeutic approach for the treatment of MASLD

(86).

Phenotypic changes in LSEC are one of the key events

in the progression of MASLD in humans, suggesting that the

progression of MASLD inflammation, hepatic fibrosis and impaired

hepatic lipid metabolism may affect the expression of Fc γ receptor

IIb (FcγR IIb) and macrophage function in LSEC (87). Autophagy is an intracellular

process that maintains homeostasis in vivo by forming

double-membrane autophagosomes that encapsulate to-be-degraded

material and bind to lysosomes to self-digest excessive or

defective organelles. Autophagy can be categorized into three

types: Macroautophagy, microautophagy and molecular

chaperone-mediated autophagy, of which the most common is

macroautophagy. Autophagy is related to MASLD and macroautophagy is

the main type of autophagy that regulates MASLD. Liver autophagy is

defective and autophagy level is reduced in MASLD patients and

autophagy shows different functions at different stages of MASLD

(87). In the early stage of

MASLD, autophagy inhibits apoptosis (87), while in the late stage, autophagy

is pro-apoptotic, which also indicates that autophagy is involved

in the whole stage of MASLD development (87). Recombinant autophagy-related

protein 7 (Atg7), a core member of the anti-thymocyte globulin

(ATG) gene family, is responsible for driving the classical

degradation and the major stages of autophagy, which is a key

component of the autophagy-associated gene family. Abnormal

expression of Atg7, a core member of the ATG gene family, can drive

the main stage of classical degradation of autophagy, resulting in

defective autophagy in cells. In Atg7 knockout mice, hepatic

autophagy activity was markedly reduced and intracellular lipid

accumulation was increased, leading to the formation of MASLD

(88). Phosphatidylinositol-3

kinase (PI3K) is a key regulator of the activation of the mammalian

target of rapamycin (mTOR), which is considered an important

regulator upstream of the ATG gene. The PI3K inhibitor

3-methyladenine blocked the formation of autophagosomes, increased

the lipid content of hepatocytes and promoted the formation of

MASLD (89).

Inflammatory response induced by immune system

dysfunction has been found to be one of the hallmarks of MASH and a

progressive form of MASLD (90).

Under normal conditions, the liver has immune defense and

immunoregulatory functions and when the intensity of the immune

system's response to autoantigens exceeds the limits of immune

regulation and affects its physiological functions, it will cause

inflammatory damage to its tissues or organs, leading to the

occurrence of autoimmune diseases. The liver has a large number of

immune cells involved in the immune response and it has been found

that macrophages are the largest proportion of immune cells

(80-90%) in the human liver and they are closely related to the

development and severity of MASLD (91). In patients with MASLD, macrophage

infiltration occurs around the portal vein and is observed at an

early stage before evidence of inflammation appears. In addition,

macrophages are capable of producing a variety of inflammatory

factors, such as NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6 and IL-8 and activating

nuclear transcription factors like NF-κB, which also play an

important role in the progression of MASLD (92). NF-κB, as a nuclear

transcriptional regulator of inflammatory genes, which is

activated, enters the nucleus and promotes the transcription and

expression of inflammatory factors, releasing a large number of

inflammatory factors. After entering the liver, NF-κB leads to

oxidative stress in hepatocytes, activates the expression of

pro-apoptotic proteins in mitochondria, promotes hepatocyte

apoptosis and exacerbates the progression of MASLD (93). TNF-α is one of the important

regulators mediating hepatocyte injury and is also a bridge between

inflammation and metabolism that plays a key role in the

development of MASLD. TNF-α regulates the inflammatory signaling

pathway and exacerbates the inflammatory response in MASLD through

pathways such as NF-κB and p38 mitogen-activated kinase (94). IL-2 can promote the proliferation

of activated B cells and is also a growth factor for all T cell

subpopulations and can positively feedback regulate the production

of cytokines such as TNF-α, leading to a further increase in IL-2

in MASLD livers (95). IL-6 can

inhibit the activity of lipoprotein esterase, which can reduce the

ability to catabolize lipids and promote the formation of hepatic

lipids. IL-8 can cause inflammatory cells to accumulate in the

liver and cause inflammation and lipid accumulation in hepatocytes

can also stimulate the inflammation of MASLD hepatocytes. The

accumulation of lipids in hepatocytes can also stimulate KCs to

release TNF-α, which further promotes the production of IL-8 and

participates in the inflammatory response of hepatocytes, leading

to the aggravation of hepatocyte injury (96).

Genetic biomarkers for MASLD include DNA sequence

variants, such as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and the most

studied SNPs in MASLD are rs738409 and rs58542926, which are

located in patatin-like phospholipase domain containing protein 3

(PNPLA3) and transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2),

respectively. The risk of developing MASLD has been found to be

influenced by single nucleotide gene polymorphisms. For example,

SNPs in the PNPLA3 gene and mutations in the PNPLA3 gene are

associated with MASLD. PAPLA3 is one of the members of the

patatin-like phospholipase family that have been identified as

being closely associated with the development of MASLD (97,98), PNPLA3 was found to be expressed

mainly in the liver and adipocytes, with non-specific TG lipase and

acylglycerol transacylase activities involved in TG hydrolysis in

hepatocytes. Mutations in PNPLA3 antagonize normal proteasomal

degradation and increase the risk of MASLD and its severity. TM6SF2

is a multiple transmembrane protein that is involved in lipid

transfer, VLDL secretion and TC synthesis. For the rs58542926

variant of the TM6SF2 gene (E167K), a mutation in the TM6SF2 allele

results in decreased VLDL secretion and fatty acid retention in the

liver, leading to hepatic steatosis and progression of MASLD

(99). Hydroxysteroid (17-β)

dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13) is a gene encoding the hepatic lipid

droplet protein 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 13 and it has

been found that HSD17B13 expression is markedly upregulated in

patients and mice with MASLD, suggesting that HSD17B13 usually

produces a product that promotes hepatocyte injury (100). Other SNP genes associated with

MASLD include neuromucin and glucokinase regulatory protein. In

addition, the level of immunity and metabolic rate of an individual

are genetically related.

MicroRNAs are a class of RNA regulators, ~22

nucleotides in length and a growing number of studies on

diet-induced and genetic (ob/ob) models of obese rodents and

patients with severe MASLD suggest a potential role for miRNAs in

MASLD pathogenesis and IR (101). A number of miRNAs have been

identified, including miR-122 and miR-21 and their expression

levels in both peripheral blood and liver have been associated with

the development of MASLD (102). One study found that serum

miR-122 was upregulated 7.2-fold in patients with MASH compared

with healthy subjects and 3.1-fold compared with patients with

simple steatosis. This suggests that serum miR-122 is an

extra-hepatic feature of MASH. Moreover, in a mouse model without

elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), the elevated serum miR-122

levels were positively associated with the severity of MASLD

(103). It has been observed

that the expression level of miR-21 in the liver of diet-induced

MASH mice progressively decreased with disease progression,

compared with the control group (103). It has been found that miR-27a

attenuates neoplastic liver lipogenesis and obesity-induced MASLD

by inhibiting the fatty acid synthase (FAS) gene and stearoyl

coenzyme A desaturase-1 in the liver. Histological analyses also

showed reduced lipid accumulation in the livers of mice with

hepatic miR-27a overexpression, suggesting reduced hepatic

steatosis; furthermore, trichrome staining of miR-27a overexpressed

livers showed markedly reduced fibrosis and lower MASLD activity

scores, reflecting improved development of MASLD (104). miR-155 is one of the miRNAs

that can regulate KCs, which are involved in inflammatory processes

that control innate and adaptive immunity in alcoholic and MASLD

diseases (103). Szabo and Csak

(105) proposed that miR-155

was a major regulator of inflammation and mice lacking miR-155 on

methionine choline deficiency (MCD) with attenuated steatosis but

no change in serum ALT or inflammation indicative of liver damage

after diet-induced steatohepatitis. In another MASH model, however,

miR-155 deficiency resulted in enhanced hepatic steatosis (105). A study has found miR-16 to be

elevated in MASLD patients with simple steatosis and others have

found that serum miR-16 is elevated in MASH patients and is

associated with the stage of fibrosis (106). It has been observed that the

expression of miR-197, miR-146b, miR-181d and miR-99a is markedly

decreased in MASLD patients. Additionally, the hepatic levels of

miR-301a-3p and miR-34a-5p increase monotonically from simple

steatosis to MASH to cirrhosis. Conversely, miR-375 levels decrease

monotonically during this progression (107). Some MASLD-related miRNAs, such

as miR-149, had elevated expression levels in both FA-treated human

hepatocellular carcinomas cells and MASLD animal models (102).

Some studies have found a large number of circadian

rhythmically expressed genes in the liver, which are involved in

maintaining the metabolic balance of the body. MASLD is closely

related to daily lifestyle. Irregular lifestyle may cause liver

overload, including lack of sleep and little exercise. In addition,

long-term intake of high-fat and high-protein foods, omitting

breakfast, adding meals before bedtime and other bad dietary habits

are also risk factors for MASLD (110). Sleep deprivation leads to an

increased risk of morbidity and mortality (111). Epidemiologic studies have shown

that sleep deprivation leads to altered glucose homeostasis, IR,

weight gain, obesity, metabolic syndrome and DM, all of which are

associated with MASLD. In experimental studies, it has been found

that sleep disorders may induce MASLD through pro-inflammatory

markers such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6. In addition, sleep

deprivation increases growth hormone-releasing peptide levels and

decreases LEP levels, which increases appetite and further

contributes to obesity and chronic insomnia activates the

hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis, which increases stress

hormones, exacerbates IR and promotes the development of MASLD

(112,113). Another study found that

increased mRNA expression in hepatic biological clock genes, a

decrease in levels of key metabolism-regulating enzymes, hepatic

inflammation and steatosis can occur, which is associated with

glucose and fatty acid metabolism (111). In the case of liver-specific

knockout of BMAL1, which results in the loss of key metabolic gene

oscillations in the liver and subsequently exacerbates oxidative

damage to hepatocytes and induces IR. The glucocorticoid rhythm

plays a key role in coordinating glucose, lipid and protein

metabolism and it is an entrainment signal for the systemic

circadian rhythm through the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus,

the peripheral clock in the liver and adipose tissue. The kidney is

regulated by the autonomic nervous system and rhythmic entrainment

signals. It has been noted that the oscillation of the cellular

redox state, independently of the biological clock transcriptional

feedback loop and in the metabolic process, may control the

circadian rhythm (114).

Circadian rhythm disruption will lead to cellular dysfunction,

which in turn affects the metabolic function of the liver (115). It induces metabolic dysfunction

and the occurrence of obesity, fatty liver, metabolic syndrome and

other conditions.

Social stress is closely related to emotional and

physical health and one of the factors that can trigger the

development of MASLD is excessive stress (116). Some studies suggest that

emotional problems such as anxiety and depression may have an

effect on the progression of chronic liver diseases, including

MASLD (117). A study by

Youssef et al (118)

confirmed the association of depression and anxiety with the

severity of histologic features of MASLD by examining 567 patients,

demonstrating that depression was markedly dose-dependent with more

severe hepatocellular ballooning and that patients with subclinical

depression were 2.1 times more likely to develop more severe

hepatocellular ballooning than patients without depressive

symptoms.

Studies have shown that hyperinsulinemia, lipid and

lipoprotein metabolism changes caused by high-fat diet (HFD),

high-carbohydrate diet, or high-fat and high-carbohydrate diets may

promote the occurrence and development of MASLD (119). Yu et al (120) explored the relationship between

dietary choline and MASLD, choline deficiency stimulated hepatic

fat accumulation and increased dietary choline intake in

normal-weight Chinese women associated with a reduced risk of

MASLD. Soft drinks and meat intake were markedly associated with

the increased risks of MASLD (121,122). High salt intake may affect

MASLD by increasing plasma levels of triglyceride (TG) and it

intake also stimulates endogenous fructose production. Lanaspa

et al (123) found that

a high salt diet activated the aldose reductase pathway in the

liver, leading to endogenous fructose production, which induced LEP

resistance with the development of the metabolic syndrome and

MASLD. In a study based on a northern Chinese population, the

correlation between salt intake and MASLD in DM patients was

analyzed by Spearman analysis, which showed a positive correlation

between salt intake and the incidence of MASLD, suggesting that the

likelihood of MASLD in DM patients increases with increasing salt

intake (124). A variety of

mechanisms, including the anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and

anti-fibrotic effects of coffee, may be related to the protective

effects of coffee against MASLD (125). Studies have shown that caffeine

may stimulate the hepatic autophagy-lysosomal pathway and induce

fatty acid oxidation (126).

However, how caffeine activates autophagic flux is still unclear

(125). Active smoking has also

been associated with a high risk of MASLD and a study has

demonstrated the association of smoking history with advanced liver

fibrosis in patients with MASLD (127). A cross-sectional study of 2,691

Chinese men found that ex-smokers and heavy smokers (≥40

cigarettes/day) had a higher prevalence of MASLD than never-smokers

and some studies have reported that smoking is an independent risk

factor for MASLD, which may exacerbate MASLD (128,129).

Commonly used laboratory animals include rats, mice

and rabbits. Among them, rats and mice are the most widely used.

Rats are represented by Wistar and Sprague Dawley (SD). There are

more diverse mouse strains, with C57BL/6J being the most common.

The present study summarized rat, mouse, rabbit, monkey, chicken,

hamster and guinea pig models. The models summarized include

diet-induced models, drug-induced models, special models and

spontaneous models. Diet-induced models include HFD, MCD,

choline-deficient amino acid-defined (CDAA) and atherogenic diet.

It has the advantages of simple operation, low cost, repeatability

and low mortality, but the disadvantage is that it is

time-consuming. Drug-induced models usually use drugs such as

streptozotocin (STZ), carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), LPS

and tetracycline. Their advantages are short modeling time and

economy, while its disadvantages are that the drugs have high

toxicity. Special models mainly use gene knockout methods to make

model animals prone to fatty liver. Compared with other models, the

modeling time of spontaneous formation of fatty liver in special

models is short, but it has requirements for the variety of animals

and high cost. Spontaneous models mainly include monkeys. Monkeys

are similar to humans in genes and can develop MASLD in old age

without the need for a high-fat diet or drug induction. The

modeling method of the nutritional model is to feed laboratory

animals with high-sugar, high-fat and high-calorie diets or to

create an MCD. The drug-induced model aims to build the model by

administering drugs such as CCl4, tetracycline,

polychlorinated biphenyl 118, so that the drugs exert their effects

or even cause poisoning. The special strain model is to select

certain diseases that can spontaneously form fatty liver,

hyperlipidemia and other diseases closely related to MASLD or can

spontaneously present symptoms relates to MASLD. The aforementioned

modeling methods can be used independently and the pathological

characteristics or disease phenotypes of the model can be

reasonably selected according to different experimental

requirements, they can also be used in combination to reduce the

modeling time and improve the success rate of the model. The

pathogenesis of MASLD is complex and a single animal model cannot

fully mimic human MASLD. The ideal animal experimental model is a

composite model formed by combining gene mutation or specific

target gene modification with diet and drug/toxin induction. The

phenotype of such a MASLD animal model is closer to that of human

MASLD and the experimental results are more applicable to

humans.

Rats are of moderate size and have strong fertility

and blood collection abilities. Currently, commonly used rat models

for constructing MASLD diseases in laboratories include Wistar

rats, SD rats and Zucker rats (Table

I).

It is found that 93% of genomic regions of mice are

arranged in an order similar to that of human beings and they are

characterized by inexpensive feeding, rapid reproduction, easy

modeling and small inter-individual differences that facilitate the

observation of parallel experiments. MASLD mouse models can

simulate different pathogenic factors and the development of MASLD

at each stage of the disease, guide the search for the pathogenesis

of MASLD and its potential therapeutic targets and also be used for

the screening and evaluation of MASLD drugs, which are closely

related to the research of MASLD. Mouse models have been induced by

high-fat and high-sugar diets, subcutaneous injections of

CCl4 and gastrointestinal nutritional solutions, with

high-fat diets being the main modality. Mice commonly used in

current experimental studies include C57BL/6J mice, Kunming mice

and gene-deficient mice (Table

II).

In addition to rodents, other animals are commonly

used to establish MASLD models, including rabbits, monkeys and

chickens (Table III). These

models are helpful for studying the disease progression and

providing crucial evidence for exploring the pathogenesis of MASLD

and evaluating the efficacy of drugs (Table IV).

At present, animal models are the most commonly

used in the research of MASLD. However, animal models have some

unfavorable factors, such as large individual differences, long

model-building cycles, difficult control of experimental conditions

and differences between animals and humans. By contrast, cell

models are superior in overcoming the aforementioned factors.

According to experimental requirements, cell viability can be

maintained all the time, which is close to the process of human

diseases and the cellular mechanisms of diseases can be studied in

a targeted manner. Therefore, establishing a cell model of MASLD

in vitro has important theoretical significance and broad

application value for studying its pathogenesis and disease

development and further preventing and treating MASLD.

Existing model cells can be classified into human

primary hepatocytes, animal primary hepatocytes, human hepatocytes,

hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs), induced pluripotent stem cells

(iPSCs) and liver slices. The culture forms can be divided into

monoculture, co-culture and three-dimensional culture. Advantages

and disadvantages of different cell lines and different culture

methods were shown in Fig.

4.

Monoculture refers to the adherent culture of one

type of cell, which is the most basic culture method. Compared with

co-culture, monoculture has the advantages of simple operation,

unlimited subculture and short model-building time, which is

conducive to high-throughput drug screening experiments. Therefore,

it is widely used in the research of fatty liver. Human hepatocyte

cell lines, primary human hepatocytes (PHH), animal primary

hepatocytes and HLC can be used for induction culture. The

excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) leads to the

occurrence of fibrosis (194),

which is a major cause of liver function impairment. The limitation

of monoculture is that it cannot explore the cell-ECM interaction

and cannot well mimic the phenotype of liver fibrosis. The

three-dimensional liver fibrosis cell model mentioned below can

solve this problem and can also well simulate the human ECM

structure in vitro (195).

PHH is generally extracted from surgically resected

tissues and separated from the tissues by two-step collagenase

perfusion or magnetic cell separation techniques (196), which can well mimic the

physiological situation of the human liver. However, due to its

rapid dedifferentiation in vitro and the need to obtain

ethical permission for specimen acquisition, these reasons limit

the use of primary hepatocytes. The improved medium supplemented

with various chemicals solves the problem of limited traditional

primary hepatocyte culture time. The PHH cultured with this medium

can be comparable to PHH spheroids for at least 4 weeks and has the

potential to simulate steatosis disease models (197).

Due to individual differences among different

donors and the influence of various factors in the cell separation

process, the experimental results may be unstable and have poor

reproducibility. In addition, the culture conditions of human

primary hepatocytes are relatively harsh, they can only be cultured

in the short term and cannot be subcultured indefinitely, which is

not conducive to the progress of the experiment. The scarcity of

human liver samples and ethical issues also hinder the wide

application of human primary hepatocytes.

Animal primary hepatocytes are often derived from

the livers of rodents and the hepatocytes are isolated and

extracted by perfusion or non-perfusion methods. The non-perfusion

method mechanically separates and digests with collagenase or

trypsin on small pieces of liver tissue. The non-perfusion method

is simple to operate but often has the problem of incomplete

digestion, while the perfusion method can greatly improve the

viability of the isolated hepatocytes, with a survival rate as high

as 80% (198). The two-step

collagenase perfusion method is the standard procedure for

isolating primary hepatocytes. The improved standard procedure can

show higher cell viability (85-95%) through multi-parameter

perfusion control (199).

Animal primary cells solve the ethical and quantitative restriction

problems of human primary hepatocytes. However, they are affected

by different animal sources and batches, have poor reproducibility,

are relatively sensitive and have harsh cultural conditions.

HLC can be derived from embryonic stem cells,

induced pluripotent stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells, endodermal

cells and hepatic progenitor cells. Hepatocyte nuclear and

epidermal growth factors are often used to promote cell-directed

differentiation. Oncostatin M (OSM) helps to promote the maturation

of fetal hepatocytes and OSM is often added during the maturation

stage to promote complete cell differentiation. Although the

subsequent culture time of HLC is longer than that of traditional

PHH, its induction time is long (2-4 weeks) and the cost is high

(200). There is also no

unified standard for the types and ratios of cytokines and

nutrients during the differentiation process and these factors

limit the application prospects of HLC.

Induced pluripotent stem cells can differentiate

into various somatic cells without causing immune rejection and

ethical issues. The HLCs differentiated from human iPSCs can be

comparable to primary hepatocytes in terms of morphological and

functional characteristics and have the advantages of wide sources,

large cultivation quantities and stable phenotypes, making up for

the deficiencies of primary hepatocytes (204). However, the induced pluripotent

hepatocyte technology still has problems, such as low efficiency of

inducing cell transformation, possible gene mutations during the

induction process and tumorigenic risks, which limit its wide

application.

The co-culture model can make up for the defects of

the monoculture model. Introducing a second type of cell into the

model increases the interaction between cells and can offer an

improved simulation of the physiological functions of the liver.

The advantages of the co-culture model are that it compensates for

the shortcomings of the monoculture model, has simple culture

conditions and enables high-throughput experiments. However, there

are not a great number of existing co-culture model types and there

is great potential for future development. Chen and Ma (205) established a co-culture model of

HepG2 cells and THP-1 macrophages. Firstly, the macrophages adhered

to a sterile glass slide and then the slide was placed into a

6-well plate inoculated with HepG2 cells. A mixed fatty acid with a

concentration of 1 mmol/l (the ratio of PA:OA was 1:2) was added

and an MASLD model was established after 24-h induction. Giraudi

et al (206) co-cultured

HuH7 and human hepatic stellate cells. After 24-h induction with

fatty acids, the intracellular lipid accumulation increased and the

expression of α-smooth muscle actin increased, indicating that the

hepatic stellate cells were activated and the cells showed the

characteristics of steatosis and fibrosis. In another study, human

primary hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells and KCs were

co-cultured. The cells were stimulated with fatty acids, glucose,

insulin and inflammatory cytokines to simulate MASH. In this model,

the de novo lipogenesis in the cells was enhanced and the

cells showed symptoms of oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis

and activation of hepatic stellate cells (207). The co-culture of human primary

hepatocytes and endothelial cells can support hepatocytes to

maintain their phenotypic morphology, improve their specific

functions and form capillary-like structures, which is more

conducive to simulate the in vivo environment and studying

the pathological mechanisms of fatty liver disease (208).

In the living liver tissue, there is substance

transport and signal transduction between hepatocytes and the ECM

and the ECM also plays a role in supporting the three-dimensional

structure (209). When human

primary hepatocytes are cultured in the traditional two-dimensional

system for a long time, morphological changes occur due to

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, resulting in the loss of

hepatocyte polarity and related liver functions (210). The construction of a

three-dimensional model is more complicated. For the

three-dimensional model of PHH, KCs and hepatic stellate cells

co-cultured with the help of a three-dimensional microphysiological

system, at least two weeks of induction with FFA is required

(211). The co-culture mode

with multiple hepatocytes can more accurately simulate the liver

microenvironment, but it requires more stringent culture

conditions. In the case of few or no precedents, researchers are

required to preliminarily explore the culture medium suitable for

the survival and proliferation of multiple cells, at least

considering the effects of pH value, osmotic pressure and gas

environment. Three-dimensional culture is divided into

three-dimensional monoculture and three-dimensional co-culture.

The three-dimensional co-culture model can be used

to study more complex fatty liver phenotypes, such as inflammation

and liver fibrosis. In the three-dimensional co-culture model,

human hepatocytes are cultured together with non-parenchymal cells,

which can simulate the interactions between various types of cells

in the liver in three-dimensional space. The advantage of the

three-dimensional co-culture model is that it can maintain

important metabolic functions for a long time and induce fatty

liver pathological phenotypes under relevant conditions.

Hepatic spheroids are spheres formed by the

self-aggregation of hepatocytes cultured in suspension without a

substrate-promoting cell attachment. The size of the spheroids can

be controlled by changing the number of starting cells and this

controllability provides convenience for standardized measurement.

The cell sources for hepatic spheroid culture can be primary

hepatocytes, hepatocyte cell lines and induced pluripotent stem

cells. Single-cell and multi-cell cultures can both form hepatic

spheroids. Compared with the planar culture of cells, the

three-dimensional structure presents superior characteristics of

the liver. HepG2 cell spheroids are more sensitive to hepatotoxic

substances. Compared with HepG2 cells cultured in a monolayer, the

half-maximal effective concentration values of a number of drugs

are markedly reduced (213).

Hepatic spheroids cultured from PHH can survive up to 7 weeks

(214) and can achieve 100%

specificity and 69% sensitivity in distinguishing hepatotoxic

substances (215). Compared

with hepatic spheroids derived from single-cell culture, multi-cell

co-culture spheroids may have more development potential. Hepatic

spheroids constructed by co-culturing PHH and NPC perform

outstandingly in glycogen storage (216) and albumin synthesis, indicating

that co-culture hepatic spheroids can offer an improved imitation

of the structure and function of the human liver (217).

Organoids have a self-renewing stem cell population

and can exhibit some organ characteristics, which contain single or

multiple cell types. It has been reported that organoids from adult

hepatocytes can be cultured for up to 2.5 months (218). PHH and pluripotent stem cells

can both simulate the adult liver. For the induction of pluripotent

stem cells, a three-dimensional model can be constructed after

monolayer culture induction to maturity or directly cultured in

three dimensions at the undifferentiated stage (219). The induction of MASLD requires

the addition of FFA to the culture medium. Liver organoids in this

hepatotoxic environment for a long time show lipid droplet

formation and TG accumulation and the upregulation of the

expressions of genes related to lipid metabolism, inflammatory

cytokines and fibrosis markers, showing the typical biochemical

characteristics of MASLD progression (220). In addition, liver organoids can

also be derived from liver cancer cells to simulate the cancer

microenvironment, playing an important role in the field of

anti-cancer research.

Liver-on-a-chip technology is used to simulate the

minimum functional unit of liver tissue, mainly constructed with

the assistance of computer aided design software. When designing a

microfluidic chip, factors such as flow rate, design size and

aspect ratio need to be considered. In a three-dimensional culture

system, microfluidic devices can reproduce the characteristics of

the multi-cell microenvironment by controlling various parameters

(221) and conducting cell

culture and sample secretions. Although liver-on-a-chip technology

is costly and the chip manufacturing process is complex, it can

mimic the complex in vivo liver microenvironment, precisely

control chemical gradients and manipulate parameters such as time,

so it has broad development prospects in the research field of

cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions.

3D-bioprinting technology polymerizes various

biological materials through inkjet, extrusion, laser

polymerization, or digital light processing. In the field of liver

model construction, a vascularized hepatic lobule model containing

hepatocytes and endothelial cells has been developed through

extrusion technology. Compared with a simple mixture of hepatocytes

and endothelial cells, this model has increased albumin and urea

secretion and a superior imitation of liver functions (222). With the development of

3D-bioprinting technology, the optimization of 'ink' has also been

put on the agenda. Type I collagen is the main component of the

ECM. When collagen I is mixed with thiolated hyaluronic acid in

different ratios, it was found that the ratio of 3:1 can offer an

improved maintenance of biological activity (223). The bioprinting method for MASLD

needs to be further explored. One possible idea is to culture

monolayers of steatotic hepatocytes as 'ink' to print

three-dimensional structures or to induce lipotoxic substances

after printing a liver model (224,225).

The chronic stress method uses one or several

stress factors to change the emotional state of experimental

animals (226). Although this

method has a good effect, it takes a long time and only one

emotional stimulus is applied to the rats for a long time, which is

likely to cause the rats to adapt to the stimulus, resulting in

insignificant emotional changes. To improve the errors caused by

this method, unpredictable stress is now mostly used in the

experiment, which can minimize errors and prevent rats from

adapting to the stimulus. Sun et al (227) used fixed-time foot electroshock

combined with noise stimulation to increase the diversity of

chronic stress methods.

The chronic restraint method is a way to restrict

the activities of experimental animals by placing them in restraint

devices, thus triggering emotional changes in the experimental

animals. Some scholars have established the MASLD model by using

long-term chronic restraint stress. They mainly applied restraint

stress to rats by using plastic restrainers. To prevent the rats

from breaking free, they also carried out punctures multiple times

to make the restrainers fit closely with the rats. The rats were

restrained for 6 h every day and this lasted for 9 weeks (228-231).

Since MASLD is a chronic disease, according to the

theory that chronic diseases often lead to deficiency and blood

stasis, patients with this disease usually present with various

syndromes of deficiency and blood stasis, among which the syndrome

of blood stasis is the most common. Patients with this syndrome

show symptoms such as masses in the right hypochondrium, loss of

appetite, abdominal distension, weakness, loose stools, dull

complexion and a pale and dark tongue. Liu et al (232) prepared the MASLD model of blood

stasis syndrome by feeding rats with a high-fat and HFFD and

intraperitoneally injecting 30 mg/kg STZ. The results showed that

the rats' body weight firstly increased then decreased. Their fur

was yellowish, dull, wilting and lacking luster. Their mental state

was poor, they were inactive and easily startled and their claws

were dull and had a low temperature. Moreover, the levels of ALT,

AST, TC, TG and LDL-C in rats were increased and there was

inflammatory infiltration in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes.

Researchers have prepared the MASLD model of blood stasis type by

using high-fat feed combined with leg-binding stimulation and

reagent intervention methods. After 8 weeks, the rats showed

manifestations such as dull hair and irritability, an increased

liver index, diffuse fatty hepatocytes, varying degrees of

macrovesicular and microvesicular steatosis and occasionally

inflammatory cell infiltration. Meanwhile, they also had

pathological manifestations consistent with MASLD (233).

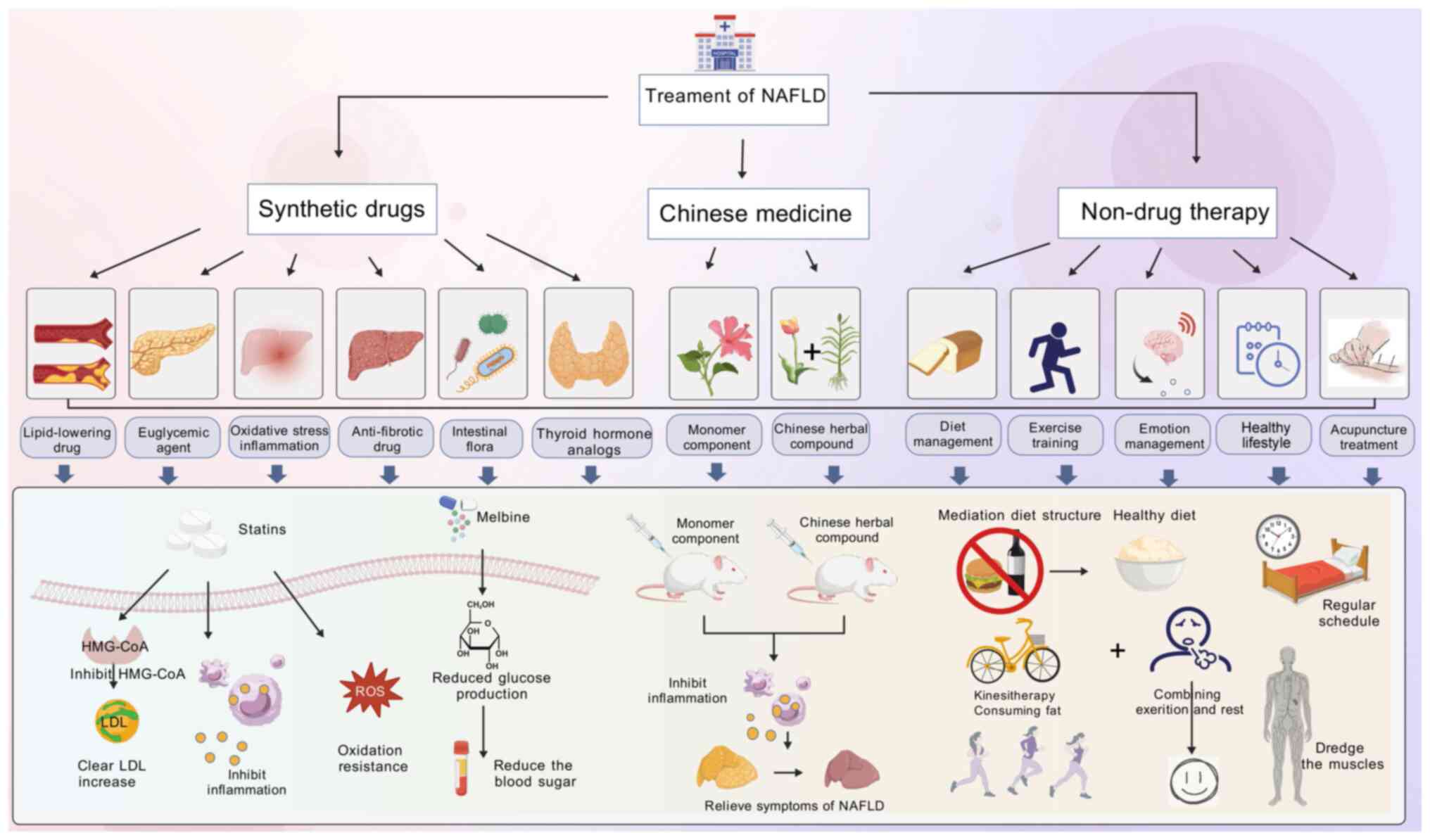

In the process of treating MASLD, since the changes

in liver tissue of most patients are at the stage of simple

steatosis, the priority of treatment should be to solve the problem

of overweight and improve the patient's IR. The secondary aim is to

avoid 'additional blows' leading to MASH and acute liver failure

and to reduce hepatic fat deposition in patients (234). Currently, the main clinical

drugs for MASLD are lipid-lowering drugs, insulin sensitizers,

anti-fibrotic and thyroid hormone drugs. Moreover, inhibition or

reduction of microRNA activity by targeted drugs can alleviate the

condition, which provides a new idea for the proposal of MASH

typing and the development of individualized treatment modalities

(235,236). The precise treatment of

different subtypes of MASH patients with targeted drugs is also the

development trend of future drug research (Fig. 5). The drugs for the targets in

the treatment of MASLD disease are shown in Table V.

Lipid metabolism disorder is the main clinical

characteristic of MASLD patients and it is an important factor in

the development of MASLD to hepatitis and cirrhosis, so

lipid-lowering has become an important method of treatment for

MASLD patients. At present, the best lipid-lowering effect of drugs

is from statins, their mechanisms are mainly through the inhibition

of hydroxy methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA), thereby blocking

the synthesis of hepatic cholesterol and causing hepatic

compensatory LDL receptor synthesis, so that the plasma LDL and LDL

clearance increases. At the same time, statins can also exert

anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects (237). However, there are more problems

in the use of statins, such as producing hepatotoxicity and muscle

toxicity (238). In recent

years, it has been found that inhibition of proprotein

convertase-subtilisin-kexin type 9 (PCSK9) can markedly reduce LDL

levels. Another experimental study found that the combination of

statins with PCSK9 inhibitors was more effective than statins alone

(239). In addition, ezetimibe

and PCSK9 inhibitors (IIb, C) can be used in combination in

statin-intolerant patients (240).

IR is a key link in the pathogenesis of MASLD,

insulin sensitizers can effectively target the 'one strike' and

increase insulin sensitivity to improve IR. Thus, enhancing the

sensitivity of effector organs to insulin has become an important

way to treat MASLD. Metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1),

thiazolidinediones and other drugs are currently more popular.

Metformin contains two guanidinium groups in its

structure and is a common oral metformin hypoglycemic drug in

clinical practice. It lowers blood glucose by decreasing glucose

production in the liver, increasing glucose metabolism and thus

improving IR and has a certain effect on weight loss and regulation

of lipid metabolism (241).

However, metformin is generally not used alone in the treatment of

MASLD (242). Some studies have

shown that metformin can markedly reduce the levels of ghrelin,

insulin and C-peptide in MASLD patients, but the improvement of

liver fibrosis and liver inflammation is not significant (243,244). Although metformin is not the

first choice for the treatment of MASLD, it is effective in

improving body weight, lipids and glucose metabolism in patients

with MASLD or MASLD combined with T2DM (245).

GLP-1 is a well-established target in the field of

diabetes. Liraglutide is a GLP-1 agonist used for the treatment of

type 2 diabetes (1.2 to 1.8 mg/day) and obesity (3 mg/day). In

addition to acting on the pancreas, GLP-1 can improve peripheral

insulin sensitivity, participate in the physiological regulation of

blood glucose, increase hepatic glucose uptake and glycogen

synthesis, delay gastric emptying and reduce appetite and reduce

the occurrence of atherosclerosis (246). Several GLP-1 drugs have been

studied in clinical trials for their ability to promote insulin

secretion, induce β-cell proliferation, inhibit postprandial

glycogen release and delay gastric emptying. It has been shown that

GLP-1 receptor agonists can enhance insulin sensitivity in effector

organs, promote fatty acid oxidation, reduce lipogenesis and

improve glucose metabolism after binding to the receptor (247).

Polyene phosphatidylcholine has anti-oxidant,

anti-inflammatory properties, reduces hepatocyte damage and

apoptosis and can effectively target the pathological symptoms

caused by MASLD and its combination with metformin drugs for the

treatment of patients with MASLD as well as MASH is markedly more

effective than monotherapy (248). Obeticholic acid (OCA), as a

nuclear transcription factor FXR agonist, has good application in

the treatment of MASLD by affecting the gene expression of various

metabolic and cellular damage pathways, such as lipid metabolism,

IR and oxidative stress (249).

Pioglitazones are first-generation insulin

sensitizers, which can specifically bind and activate PPAR-γ,

improve IR, participate in glucose and lipid metabolism and inhibit

the expression of LP and the expression of TNF-α, so as to reduce

the hepatic lipid deposition and inhibit liver inflammation and

fibrosis formation (250).

Sumida and Yoneda (251) found

that pioglitazone not only improved IR but also improved hepatic

glucose-lipid metabolism, steatosis and inflammatory necrosis in

patients with MASLD by activating PPAR-γ. The American Academy of

Liver Diseases recommended pioglitazone in 2017 guidelines for the

diagnosis and treatment of MASLD (252). Pioglitazone is not widely

available because of safety concerns, including congestive heart

failure, bone fractures in women and the possibility that

pioglitazone may lead to an increased risk of bladder cancer

(253). The second-generation

insulin sensitizer MSDC-0602K did not show the side effects

associated with the first-generation insulin sensitizers. According

to the report of the latest phase IIb 52-week double-blind study

(254), MSDC-0602K markedly

reduced fasting glucose, insulin, glycosylated hemoglobin and

markers of liver injury without dose-limiting side effects.

However, it did not show a significant effect on the liver

histology of the biopsy technique used. The information gained from

this trial may provide a pre-basis for future study.

In the disease process of MASLD, increased

oxidative stress and defective anti-oxidant defense mechanisms

promote liver injury as well as disease progression to MASH

(255). Therefore, drugs with

anti-oxidant activity can be used in the treatment of MASLD.

Vitamin E is present in the phospholipid bilayer of cell membranes

and helps to prevent oxidative damage caused by free radicals

(256). The randomized

controlled trial of PIVENS selected non-diabetic and non-cirrhotic

MASH patients, conducted a 2-year trial of vitamin E (800 IU/d),

pioglitazone and placebo and showed that vitamin E had significant

histological improvements and that 36% of patients treated with

vitamin E had improved steatosis, inflammation and remission of

MASH (257). This suggested

that vitamin E is favorable for the treatment of MASLD and MASH

(258). However, long-term use

of vitamin E may increase the risk of prostate cancer and

hemorrhagic shock, so vitamin E should not be used for long-term