Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is an aggressive malignancy,

ranking third and second globally in terms of morbidity and

mortality rates, respectively (1). The incidence of CRC in China is

also rising steadily (2). The

primary treatment approach for CRC combines surgery with

chemotherapy and radiotherapy; however, not all patients respond to

these standard therapies (3).

Despite ongoing advancements in combined treatment strategies,

including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and

immunotherapy, the survival rate of CRC remains suboptimal, with a

high recurrence rate (3,4).

Oxaliplatin, a third-generation cisplatin analog, is

widely used in CRC treatment (5). While the 5-fluorouracil, folinic

acid and oxaliplatin regimen is initially effective, ~50% of

patients with stage II and III CRC develop resistance to

oxaliplatin-based adjuvant therapy (6). Previous studies have identified

several mechanisms of oxaliplatin resistance, including

anti-apoptotic signaling, ferroptosis, DNA repair, autophagy and

altered drug transport (7,8).

However, the precise mechanisms underlying oxaliplatin resistance

remain unclear.

KPT-330, a selective exportin 1 (XPO1) inhibitor,

has shown marked efficacy in tumor treatment (9,10). Ferreiro-Neira et al

(11) demonstrated that KPT-330

enhances the sensitivity of CRC to radiotherapy, suggesting a

potential novel therapeutic model, the combination therapy with

KPT-330 and radiotherapy. A separate report has indicated that

sequential administration of XPO1 and an ataxia telangiectasia and

Rad3-related protein inhibitor (AZD-6738) improved therapeutic

outcomes in TP53-mutated CRC (12). Additionally, KPT-330 has been

found to enhance the efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy in

lung and ovarian cancer (13,14). However, to the best of our

knowledge, no studies have explored the relationship between

KPT-330 and oxaliplatin resistance in CRC. Thus, the combination of

oxaliplatin and KPT-330 warrants investigation as a potential

strategy for overcoming resistance in CRC, with further exploration

of its underlying mechanisms.

We hypothesized that KPT-330 could restore

oxaliplatin sensitivity in resistant CRC cells. To test this

hypothesis, the present study aimed to systematically evaluate the

therapeutic potential of KPT-330 in combination with oxaliplatin in

oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells. The present investigation focused

on the underlying mechanisms of this combination regimen. Changes

in the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) were monitored to

assess mitochondrial function, and the effects on cell death

pathways, including apoptosis and ferroptosis, were investigated.

Furthermore, the present study examined the role of key molecular

players by analyzing p53 nuclear translocation, p21 expression and

the expression of the ferroptosis-related gene solute carrier

family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11). Finally, a subcutaneous xenograft

model was established to evaluate the in vivo efficacy of

this combination regimen.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

HCT116 (cat. no. CCL-247), HCT8 (cat. no. CCL-244)

and FHC (cat. no. CRL-1831) cell lines were obtained from American

Type Culture Collection. The β-actin (cat. no. 4967S), GAPDH (cat.

no. 2118), p21 (cat. no. 2947), cleaved poly (ADP-ribose)

polymerase (PARP) (cat. no. 5625T), cleaved caspase-3 (cat. no.

9664L), Bax (cat. no. 5023T), PARP (cat. no. 9532S), caspase-3

(cat. no. 9668S) and Bcl-2 (cat. no. 15071T) antibodies were

sourced from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. CDK1 (cat. no.

A11420), cyclin B1 (CCNB1; cat. no. A19037), XPO1 (cat. no. A0299),

glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4; cat. no. A11243) and SLC7A11 (cat.

no. A2413) antibodies were obtained from ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.

The Lamin B1 (cat. no. AF5161) antibody was obtained from Affinity

Biosciences, Ltd. The p53 (cat. no. sc-126) and Ki67 (cat. no.

sc-23900) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat. nos. ZB-2306 and

ZB-2305) were obtained from Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.

Cell culture

All cells were cultured in a 37°C incubator with 5%

CO2. The oxaliplatin-resistant HCT116 and HCT8 cell

lines (HCT8/L-OHP and HCT116/L-OHP) were developed by progressively

increasing oxaliplatin concentrations, starting at 2 μM and

reaching a final concentration of 14 μM, over a period of ≥9

months. HCT8, HCT8/L-OHP and HCT116/L-OHP cells were cultured in

RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no. CR-31800; Cienry Co., Ltd.) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (cat. no. BC-SE-FBS01C; Bio-Channel

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and 10,000 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin

(cat. no. ant-pm-05; InvivoGen). The HCT116 cell line was cultured

in McCoy's 5A medium (cat. no. CR-16600; Cienry Co., Ltd.) with 10%

fetal bovine serum and 10,000 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, while

FHC cells were cultured in DMEM (cat. no. CR-12800; Cienry Co.,

Ltd.) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 10,000 U/ml

penicillin-streptomycin.

Cell viability test

For cell viability assays, 5×103 cells

per well were plated on 96-well plates and treated with different

drugs at 37°C for 48 h. For single-agent dose-response curves,

cells were treated with oxaliplatin (0.33, 1, 3.3, 10, 33 and 100

μM; cat. no. HY-17371; MedChemExpress) or KPT-330 (0.001,

0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1 and 3 μM; cat. no. S7252;

Selleck Chemicals). For two-agent dose-response curves, cells were

treated with a combination of oxaliplatin (0.33, 1, 3.3, 10, 33 and

100 μM) and KPT-330 (10 and 33 nM). After silencing of XPO1,

cells were treated with oxaliplatin (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32

μM). For experiments involving combination therapy and

specific inhibitors, the following treatments were performed on

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells: Cells were treated with single

agents, including oxaliplatin (10 μM) and KPT-330 (33 nM),

as well as their combination. For inhibitor assays, a combination

of oxaliplatin (10 μM) and KPT-330 (33 nM) was used along

with either Z-VAD-FMK (10 μM; cat. no. HY-16658B;

MedChemExpress) or Fer-1 (1 μM; cat. no. HY-100579;

MedChemExpress). Separately, oxaliplatin (2, 10 and 40 μM)

was used to treat CRC (HCT8, HCT116, HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells) and normal cells (FHC cells). Cell viability was then

assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (cat. no. MA0218; Dalian

Meilun Biology Technology Co., Ltd.). Cells were incubated with

Cell Counting Kit-8 solution at 37°C for 2 h according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Annexin V and PI staining

Apoptosis was detected using the Annexin V-FITC/PI

kit [cat. no. AT101C; MultiSciences (Lianke) Biotech Co., Ltd.].

Following treatment with different drugs (oxaliplatin, 10

μM; KPT-330, 33 nM; Z-VAD-FMK, 10 μM) at 37°C for 48

h, cells were harvested and stained with annexin V and PI for 15

min, and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fortessa; BD Biosciences).

Apoptotic cells were quantified as the sum of early apoptotic cells

(annexin V+/PI-) in the lower-right quadrant

and late apoptotic cells (annexin V+/PI+) in

the upper-right quadrant. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software

(version 10.8; BD Biosciences).

Cell cycle assay

For cell cycle analysis, 2×105 cells per

well were seeded on 6-well plates and cultured for 24 h in

serum-free medium until they reached 30-40% confluence. Cells were

then treated with drugs (oxaliplatin, 10 μM; KPT-330, 33 nM;

or the combination) for 48 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator.

In a separate experiment, HCT116 and HCT116/L-OHP cells were

treated with oxaliplatin (2 μM) for 48 h at 37°C. After

treatment, cells were harvested, stained using the Cell Cycle

Staining Kit [cat. no. CCS012; MultiSciences (Lianke) Biotech Co.,

Ltd.] for 15 min at room temperature in the dark, and analyzed by

flow cytometry (Fortessa; BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using

FlowJo software (version 10.8; BD Biosciences).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay

Cells (2×105 per well) were seeded on

6-well plates and cultured until they reached 30-40% confluence.

The cells were then treated with drugs (oxaliplatin, 10 μM;

KPT-330, 33 nM; or the combination) for 48 h at 37°C in a

CO2 incubator. In a separate experiment, HCT116 and

HCT116/L-OHP cells were treated with oxaliplatin (2 μM) for

48 h at 37°C. After treatment, the cells were incubated in

serum-free medium containing 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein

diacetate (cat. no. S0033; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology),

MitoSOX Red (cat. no. HY-D1055; MedChemExpress), a fluorescent

probe specifically designed for the detection of mitochondrial

superoxide, or the C11-BODIPY probe (cat. no. D3861; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), a fluorescent probe for the

detection of lipid peroxidation in cells, at 37°C for 20 min.

Following incubation, the fluorescence intensity was measured by

flow cytometry (CytoFLEX; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Data were

analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.8; BD Biosciences).

Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA)

levels

Cells (2×105 per well) were seeded into

6-cm dishes and cultured overnight. After 48 h of drug treatment

(oxaliplatin, 10 μM; KPT-330, 33 nM; or the combination) at

37°C, cells were harvested and lysed. The BCA Protein Assay Kit

(cat. no. P0012; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was used to

quantify the protein concentration. Following protein

quantification, MDA (cat. no. S0131S; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) working solution was added to the lysate, and the

mixture was heated at 100°C for 15 min. After centrifugation at

1,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature, the supernatant was

collected and its absorbance was measured at 532 nm using a

microplate reader.

Measurement of glutathione (GSH)

levels

Cells (2×105 per well) were seeded into

6-cm dishes and cultured overnight. After 48 h of drug treatment

(oxaliplatin, 10 μM; KPT-330, 33 nM; or the combination) at

37°C, cells were harvested, processed according to the GSH and GSSG

Assay Kit instructions (cat. no. S0053; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), and the absorbance was finally measured

spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 412 nm.

Measurement of the MMP

Cells (2×105 per well) were seeded on

6-well plates and cultured overnight. After 48 h of drug treatment

(oxaliplatin, 10 μM; KPT-330, 33 nM; or their combination)

at 37°C in a CO2 incubator, the treated cells were

incubated with 1 ml JC-1 staining buffer (cat. no. C2006; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 20 min at 37°C in the dark. In a

separate experiment, HCT116 and HCT116/L-OHP cells were also

treated with oxaliplatin (2 μM) for 48 h at 37°C and then

stained with 1 ml JC-1 staining buffer for 20 min at 37°C in the

dark. After incubation, the supernatant was removed, and cells were

centrifuged at 600 × g for 4 min at 4°C. The cells were then washed

twice with JC-1 washing buffer (1X) and resuspended in the washing

buffer. JC-1 fluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry (Fortessa;

BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version

10.8; BD Biosciences).

Xenograft tumor model

All animal procedures were approved by the Ethical

Review Committee and Laboratory Animal Welfare Committee of the Sir

Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine

(approval no. SRRSH2025-0023; Hangzhou, China). The experimental

mice were purchased from Hangzhou Ziyuan Laboratory Animal

Technology Co., Ltd. A total of 20 female BALB/c nude mice (16-18

g; 6 weeks old) were used in the present study. The mice were

housed in a standard specific-pathogen-free environment for 1 week

before the experiment for acclimation. Housing conditions were

maintained at 22±2°C and 55±10% humidity, with a 12/12 h light/dark

cycle (7:00-19:00), with free access to food and sterile water.

For tumor implantation, 2×106

HCT116/L-OHP cells suspended in 100 μl PBS were

subcutaneously injected into the right flank of each mouse. After 1

week, the mice were randomly assigned to four treatment groups (5

mice per group): Vehicle control (5% DMSO, 40% PEG300, 5% Tween 80

and 50% ddH2O; once per week), oxaliplatin (cat. no.

HY-17371; MedChemExpress) alone (10 mg/kg; once per week), KPT-330

(cat. no. S7252; Selleck Chemicals) alone (10 mg/kg; once per

week), or a combination of oxaliplatin and KPT-330.

Tumor size was measured with Vernier calipers on the

indicated days following the start of treatment: Days 1, 3, 5, 8,

10, 12, 15, 17, 20, 22, 24, 27 and 29. The total time interval from

injection to final tumor measurement was 35 days. Euthanasia was

performed at the end of the pre-defined 4-week treatment period. At

that time, the maximum tumor diameter was 16.8 mm, and the maximum

tumor volume was 1,209.6 mm3. Euthanasia was performed

by gradually filling a chamber with CO2 at a

displacement rate of 35% of the chamber volume per min, with

exposure for ≥5 min after visible cessation of respiration. Death

was confirmed by the loss of respiration, loss of muscle tone and

subsequent cervical dislocation after CO2 inhalation.

Tumors were dissected and embedded in paraffin on day 29 after the

start of treatment. The tumor volume was calculated using the

following formula: Tumor volume (mm3)=tumor length ×

tumor width2/2.

Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM)

Before being fixed for TEM, HCT116/L-OHP cells were

treated with oxaliplatin (10 μM), KPT-330 (33 nM) or a

combination of both. In a separate experiment, HCT116 and

HCT116/L-OHP cells were treated with oxaliplatin (2 μM). All

treatments were performed for 48 h at 37°C. Experimental cells were

fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer

(pH 7.4) for 2 h at 25°C, and then stored at 4°C in the same

fixative overnight. After three washes with PBS, the samples were

incubated in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at room temperature,

followed by three washes with water. The samples were then

incubated in 2% uranyl acetate for 30 min at room temperature.

After dehydration through a series of ethanol steps (15 min each in

50, 70, 90 and 100% ethanol) and two 20-min washes in 100% acetone,

the samples were embedded in epoxy resin for 24 h at 60°C and

sectioned into ultrathin slices (90 nm). The sections were imaged

using a Tecnai G2 Spirit 120kV transmission electron microscope

(FEI; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay

The tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde

overnight at 4°C, followed by dehydration, clearing and paraffin

embedding. The paraffin sections (5 μm) were then baked at

60°C for 2 h, deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a

descending series of graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was carried

out using sodium citrate buffer for 10 min at 100°C. Endogenous

peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2

for 10 min at room temperature. Non-specific binding was blocked

with 10% goat serum (cat. no. SL038; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at room temperature. The sections

were then incubated with primary antibodies against Ki67 (1:1,000;

cat. no. sc-23900; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or p53 (1:1,000;

cat. no. sc-126; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C.

After washing, the sections were incubated with an HRP-conjugated

goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; ZB-2305; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) secondary antibody for 1 h at 37°C. Color

was developed with a DAB kit (cat. no. ZLI-9017; Beijing Zhongshan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 30 sec at room temperature,

and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min at

room temperature before being mounted and observed under a light

microscope (Whole Slide Scanning System; Olympus VS200; Olympus

Corporation). To evaluate the percentage of Ki67-positive nuclei,

five fields per group were randomly selected and a total of 1,000

cells were counted. The Ki67 proliferation index was calculated as

the percentage of Ki67-positive nuclei out of the total number of

cells counted.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) analysis of mRNA expression

Total RNA from treated cells was extracted using the

AG RNAex Pro Reagent (cat. no. AG21101; Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical

Technology Co., Ltd.) and the SteadyPure RNA Extraction Kit (cat.

no. AG21024; Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd.).

Prior to RNA extraction, cells were treated with oxaliplatin (10

μM), KPT-330 (33 nM) or a combination of both for 48 h at

37°C. RNA (~1.0 μg) was reverse-transcribed to generate the

first strand of cDNA using the Evo M-MLV RT Mix Kit with gDNA Clean

for qPCR Ver.2 (cat. no. AG11728; Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical

Technology Co., Ltd.). The reverse transcription reaction was

performed at 37°C for 15 min, followed by heating at 85°C for 5

sec. qPCR was performed using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix

(cat. no. Q711-02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The thermocycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30

sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec (denaturation) and

60°C for 30 sec (annealing/extension). GAPDH was used as the

internal reference gene. The relative gene expression levels were

quantified using the 2-ΔΔCq method (15). The primer pairs used for qPCR

were as follows: GAPDH forward, 5'-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3' and

reverse, 5'-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3'; CDK1 forward,

5'-AAACTACAGGTCAAGTGGTAGCC-3' and reverse,

5'-TCCTGCATAAGCACATCCTGA-3'; CCNB1 forward,

5'-AATAAGGCGAAGATCAACATGGC-3' and reverse,

5'-TTTGTTACCAATGTCCCCAAGAG-3'; SLC7A11 forward,

5'-TCTCCAAAGGAGGTTACCTGC-3' and reverse,

5'-AGACTCCCCTCAGTAAAGTGAC-3'; and GPX4 forward,

5'-ACAAGAACGGCTGCGTGGTGAA-3' and reverse,

5'-GCCACACACTTGTGGAGCTAGA-3'.

Western blot analysis

Treated cells and tissues were washed 2-3 times with

PBS, then lysed using RIPA buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Prior to protein analysis, HCT8,

HCT116, HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells were treated with a range

of oxaliplatin concentrations (1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 μM).

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells were also treated with a series

of KPT-330 concentrations (10, 33, 100, 333 and 1,000 nM).

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells were treated with oxaliplatin (10

μM), KPT-330 (33 nM) or a combination of both. Additionally,

after silencing of p53, HCT116/L-OHP cells were treated with

oxaliplatin (10 μM), KPT-330 (33 nM) or a combination of

both. All cell treatments were conducted for 48 h at 37°C. The

lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to collect

the protein. Protein concentrations were quantified using a BCA

assay (cat. no. MA0082-2; Dalian Meilun Biology Technology Co.,

Ltd.). Proteins (20 μg/lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE

and transferred onto PVDF membranes (cat. no. ISEQ00010;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA

(cat. no. 9048-46-8; Dalian Meilun Biology Technology Co., Ltd.)

for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with the specified

primary antibodies specific to the target proteins β-ACTIN (cat.

no. 4967S), GAPDH (cat. no. 2118), p21 (cat. no. 2947), cleaved

PARP (cat. no. 5625T), cleaved caspase-3 (cat. no. 9664L), Bax

(cat. no. 5023T), PARP (cat. no. 9532S), caspase-3 (cat. no.

9668S), Bcl-2 (cat. no. 15071T), CDK1 (cat. no. A11420), CCNB1

(cat. no. A19037), XPO1 (cat. no. A0299), GPX4 (cat. no. A11243),

SLC7A11 (cat. no. A2413), Lamin B1 (cat. no. AF5161) and p53 (cat.

no. sc-126), all at a dilution of 1:1,000, overnight at 4°C.

Afterwards, the membranes were washed three times with PBS and

incubated with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

(cat. nos. ZB-2306 and ZB-2305; 1:10,000) for 1 h at room

temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an FDbio-Dura ECL

kit (cat. no. FD8020; Hangzhou Fude Biological Technology Co.,

Ltd.), and semi-quantified using ImageJ analysis software (version

8; National Institutes of Health).

A fractionation assay [HCT8/L-OHP and HCT116/L-OHP

cells were treated with oxaliplatin (10 μM), KPT-330 (33 nM)

or a combination of both for 48 h at 37°C] was performed to obtain

nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions using the Nuclear and

Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (cat. no. P0028B; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The separated fractions were then subjected to

western blotting as aforementioned.

Immunofluorescence analysis

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells (5×104

per well) were seeded in confocal culture dishes (cat. no. 801001;

Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and cultured overnight. The

cells were then treated with oxaliplatin (10 μM), KPT-330

(33 nM) or a combination of both for 48 h at 37°C. Following

treatment, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight

at 4°C, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature

for 15 min and blocked with 10% goat serum (cat. no. MB4508-1;

Dalian Meilun Biology Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for

1 h. After blocking, cells were incubated with a mouse anti-p53

antibody (cat. no. sc-126; 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.)

at 4°C overnight. The cells were then incubated with a goat

anti-mouse secondary antibody (cat. no. A-11001; Alexa Fluor 488;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature.

Finally, the cells were stained with DAPI (1 mg/ml; cat. no. D3571;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 5 min at room temperature to

visualize the nuclei, and images were captured using a laser

scanning confocal fluorescence microscope. The fractional area of

p53 in the nucleus was quantified by analyzing 10 cells from each

treatment group, and was analyzed using ImageJ analysis software

(version 8; National Institutes of Health).

Cell transfection

The target sequences of small interfering RNAs

(siRNAs; Table SI) were

synthesized by Suzhou GenePharma Co., Ltd. For transient

transfection, Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (cat. no. 13778030; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used according to the manufacturer's

protocol. A total of 5 μl of si-RNA (20 μM), 100

μl Opti-MEM (cat. no. CR22600; Cienry Co., Ltd.) and 6

μl Lipofectamine RNAiMAX were mixed at room temperature for

20 min. This complex was then added to 0.9 ml RPMI-1640 medium

(resulting in a final siRNA concentration of 100 nM), and the cells

were transfected for 8 h at 37°C. After transfection, cells were

allowed to recover for 24 h at 37°C before being used in subsequent

experiments. The transfection efficiency was determined by western

blot analysis.

Ethynyldeoxyuridine (EdU) assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using an EdU assay

kit (cat. no. C10310; Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.). Cells

(1×105 per well) were seeded on 12-well plates and

cultured overnight. After 48 h of drug treatment (oxaliplatin, 10

μM; KPT-330, 33 nM; or the combination) at 37°C, cells were

incubated with EdU at a final concentration of 50 μM for 2 h

at 37°C. The cells were then fixed, permeabilized and stained

according to the manufacturer's instructions of the EdU assay kit.

Finally, the images were captured using a laser scanning confocal

fluorescence microscope.

Crystal violet assay

Cells (1×105 per well) were seeded on

12-well plates. When the cells reached 30-40% confluence, they were

treated with oxaliplatin (5 or 10 μM), KPT-330 (10 or 33 nM)

or a combination of the two (KPT-330 at 10 or 33 nM with

oxaliplatin at 5 or 10 μM) for 48 h at 37°C in a

CO2 incubator. The cells were then washed three times

with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for

15 min. Afterwards, the cells were washed twice with PBS and

stained with crystal violet at room temperature for 20 min. The

cells were washed three times with water, and images were

captured.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD of at least

three independent biological replicates (n≥3). All statistical

analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics).

Differences among multiple groups were compared using one-way

ANOVA. If the data met the assumption of homogeneity of variances,

Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference post hoc test was used. If

the assumption was violated, Welch's ANOVA with Dunnett's T3 post

hoc test was performed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

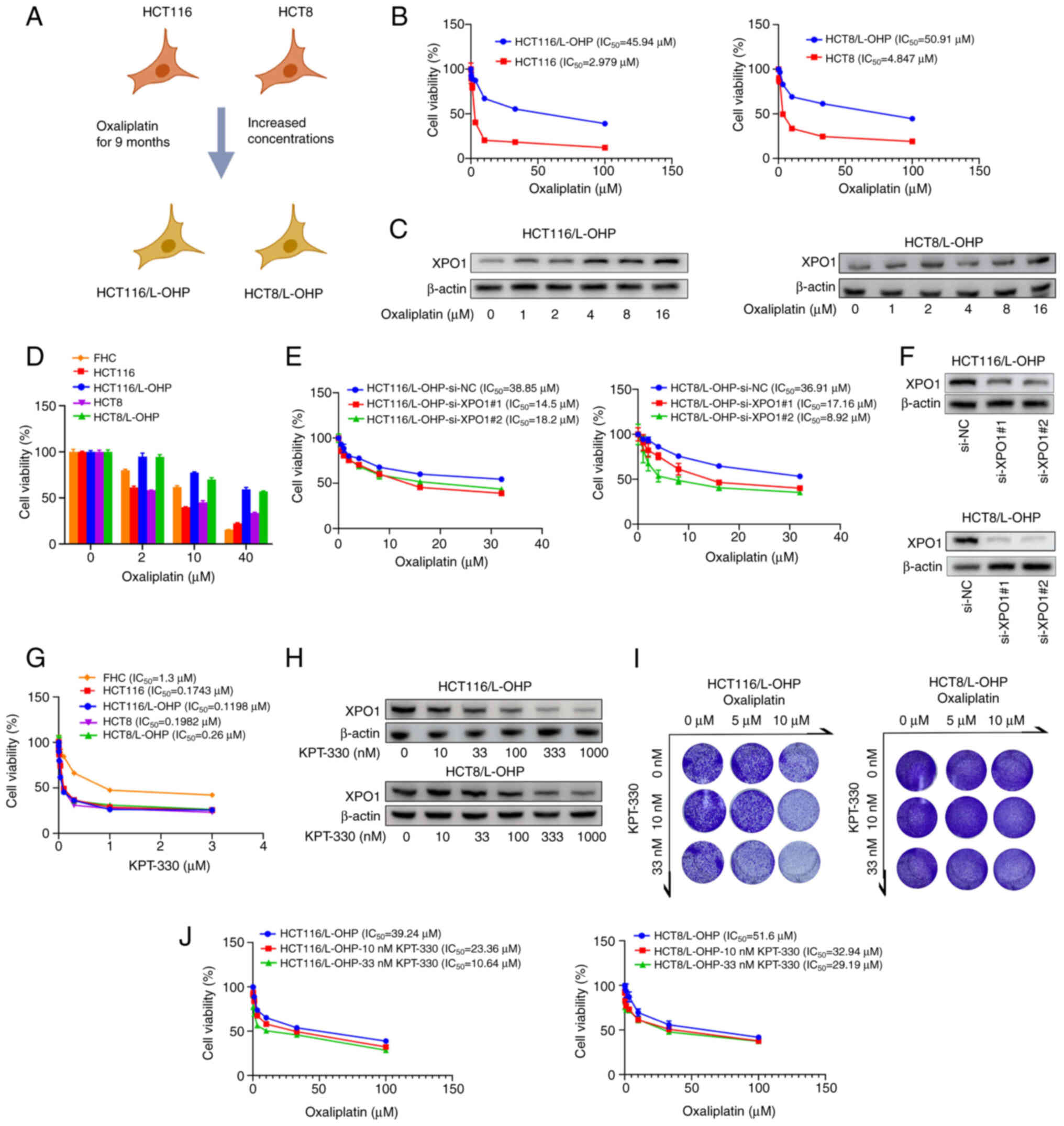

KPT-330 and oxaliplatin combined inhibit

the proliferation of oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells

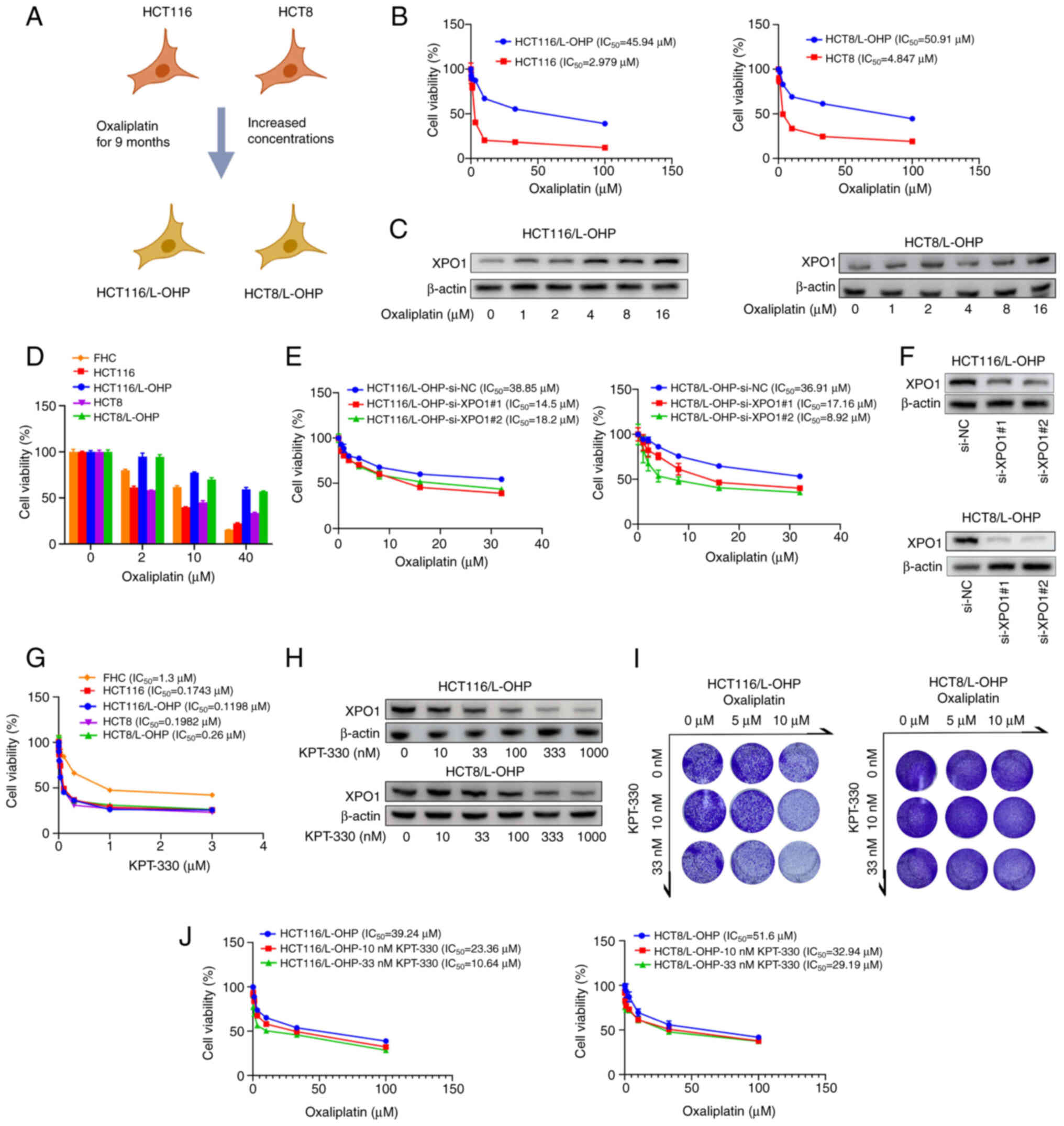

Oxaliplatin-resistant cell lines were established

using oxaliplatin-sensitive CRC cell lines (HCT116 and HCT8)

(Fig. 1A). Notably, HCT116/L-OHP

and HCT8/L-OHP cells exhibited higher IC50 values (45.94

μM for HCT116/L-OHP cells and 50.91 μM for HCT8/L-OHP

cells) compared with their parental counterparts HCT116 (2.979

μM) and HCT8 (4.847 μM) cells (Fig. 1B). Previous research has

suggested that XPO1 expression is negatively associated with the

prognosis of patients with CRC, positioning XPO1 as a potential

therapeutic target for CRC (16). Furthermore, KPT-185, a selective

XPO1 inhibitor, synergistically induces apoptosis in human

pancreatic and colon cancer cell lines when combined with

oxaliplatin (17). In line with

these findings, XPO1 expression was higher in the newly established

oxaliplatin-resistant cell lines compared with their parental

counterparts (Fig. S1A).

Oxaliplatin treatment induced a concentration-dependent increase in

XPO1 expression in both HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells (Fig. 1C). Additionally, a similar

induction of XPO1 expression was observed in both HCT116 and HCT8

cells following oxaliplatin treatment (Fig. S1B).

| Figure 1Combination of KPT-330 and

oxaliplatin synergistically inhibits the viability of

oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells. (A) Schematic illustrating the

process of constructing oxaliplatin-resistant HCT116/L-OHP and

HCT8/L-OHP cell lines. (B) Dose-response curves for oxaliplatin in

the four CRC cell lines, with cell viability measured using the

CCK-8 assay after 48 h of treatment. (C) Immunoblot analysis of

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells treated with oxaliplatin for 48

h. (D) Viability of four CRC cell lines and FHC cells treated with

oxaliplatin for 48 h, measured using a CCK-8 assay. (E) Viability

of indicated cancer cell lines after silencing of XPO1 or

transfection with si-NC, followed by 48 h of oxaliplatin treatment.

(F) Immunoblot analysis of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells after

silencing of XPO1 or transfection with si-NC. (G) Dose-response

curves for KPT-330 in the four CRC cell lines and FHC cells, with

cell viability assessed using a CCK-8 assay after 48 h of

treatment. (H) Immunoblot analysis of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells treated with KPT-330 for 48 h. (I) Crystal violet assay for

indicated cancer cell lines treated with different dosages of

oxaliplatin and KPT-330. (J) Dose-response curves for oxaliplatin

in the two CRC cell lines with a fixed dose of KPT-330, with cell

viability measured using a CCK-8 assay after 48 h of treatment.

CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; CRC, colorectal cancer; NC, negative

control; si, small interfering RNA; XPO1, exportin 1. |

The cytotoxic effects of oxaliplatin and KPT-330

were subsequently assessed in vitro using four CRC cell

lines (HCT8, HCT8/L-OHP, HCT116 and HCT116/L-OHP) and the

non-cancerous FHC cells. Low concentrations of oxaliplatin

decreased the viability of sensitive CRC cells, whereas high

concentrations of oxaliplatin decreased the viability of FHC cells.

The inhibitory effect on resistant CRC cells was less pronounced

than that on sensitive CRC cells and FHC cells (Fig. 1D). The IC50 values for

KPT-330 ranged between 0.1 and 0.3 μM in CRC cells, while

1.3 μM KPT-330 suppressed the viability of non-cancerous FHC

cells (Fig. 1G). Silencing of

XPO1 using two distinct siRNAs in HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells, which are resistant to oxaliplatin, enhanced their

sensitivity to oxaliplatin (Fig. 1E

and F). The inhibition of XPO1 expression by KPT-330 was found

to be dose-dependent, and KPT-330 could enhance the sensitivity of

oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells to oxaliplatin by downregulating

XPO1 expression (Fig. 1H-J).

These results collectively demonstrated a synergistic effect of

KPT-330 and oxaliplatin in overcoming resistance in CRC cells.

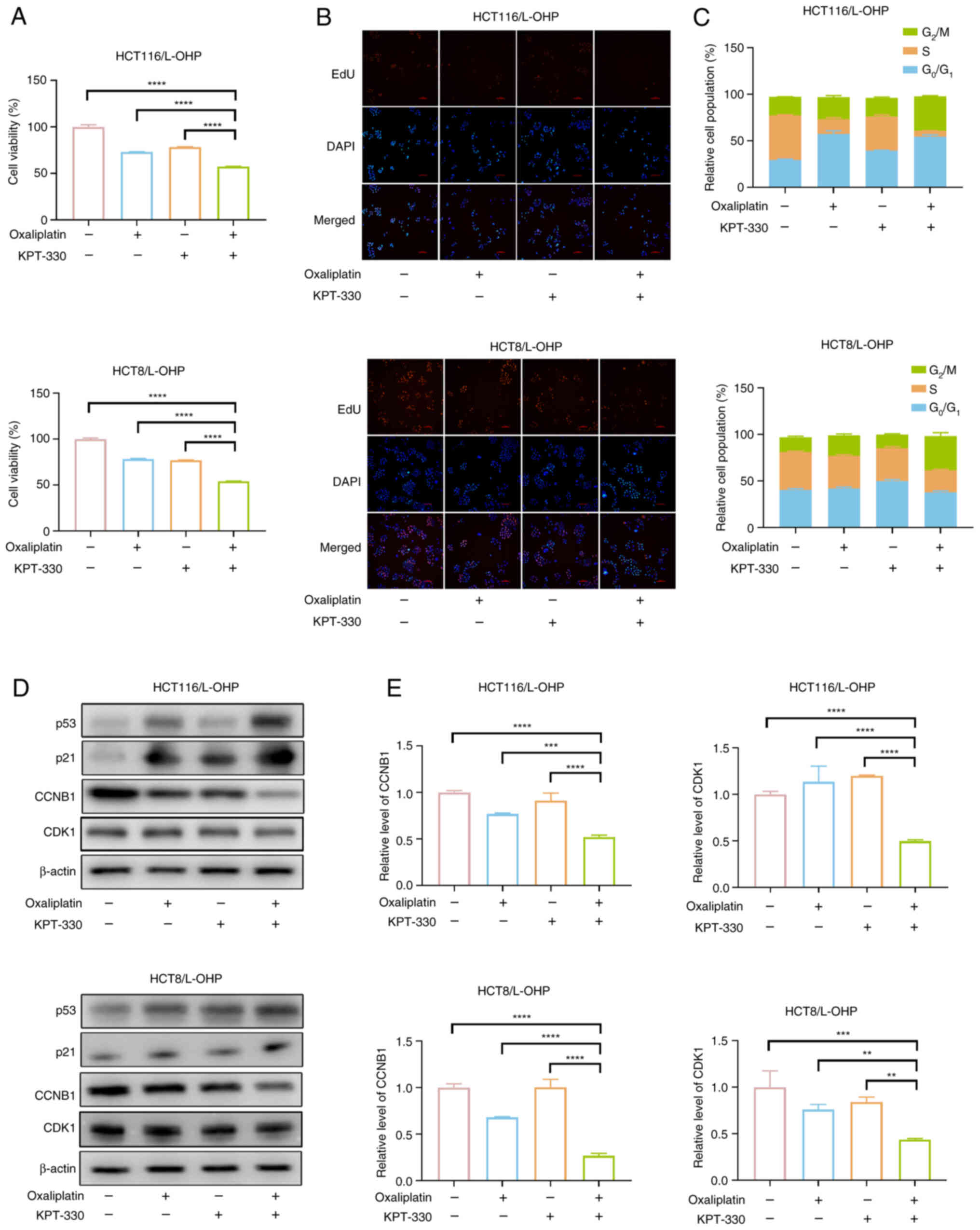

Combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin

induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in oxaliplatin-resistant

CRC cells

In subsequent experiments, the combination treatment

for 48 h resulted in a more significant reduction in the viability

of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells compared with oxaliplatin

alone (Fig. 2A). EdU staining

was employed to assess the impact of the KPT-330 and oxaliplatin

combination on cell proliferation, revealing a pronounced

inhibition of proliferation in both HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells following combined treatment (Fig. 2B). Oxaliplatin primarily induces

G2/M cell cycle arrest and a transient delay in the S

phase (18). When comparing the

cell cycle distribution of HCT116 and HCT116/L-OHP cells after 48 h

of oxaliplatin (2 μM) treatment, a clear accumulation in the

G2/M phase was observed in HCT116 cells, accompanied by

a reduction in cells in the S and G0/G1

phases (Fig. S2A). In

HCT116/L-OHP cells, the combination treatment further reduced the

proportion of cells in the S phase and notably increased the

proportion of cells in the G2/M phase compared with

oxaliplatin (10 μM) alone (Fig. S2B and C). In HCT8/L-OHP cells,

where oxaliplatin as a single agent had minimal effects, the

combination therapy increased the proportion of cells in the

G2/M phase compared with oxaliplatin (10 μM)

alone (Fig. S2B and C). These

results suggested that KPT-330 and oxaliplatin influenced proteins

associated with the G2/M phase, as evidenced by the

increase in the G2/M cell population following

combination treatment. To explore the underlying mechanism of the

cell cycle arrest induced by the combination, the expression of key

G2/M arrest markers was analyzed by western blotting.

The protein and mRNA levels of CCNB1 and CDK1, which are critical

regulators of the G2/M phase, were reduced following

combined treatment (Fig. 2D and

E). Given the known role of p53 and p21 in modulating the

CDK1-CCNB1 complex (19), the

present results demonstrated that the combination treatment

upregulated p53 and p21 protein expression, as evidenced by a

subsequent downregulation of CDK1 and CCNB1 protein levels

(Fig. 2D). These results

collectively indicated that the KPT-330 and oxaliplatin combination

induced G2/M cell cycle arrest in oxaliplatin-resistant

CRC cells.

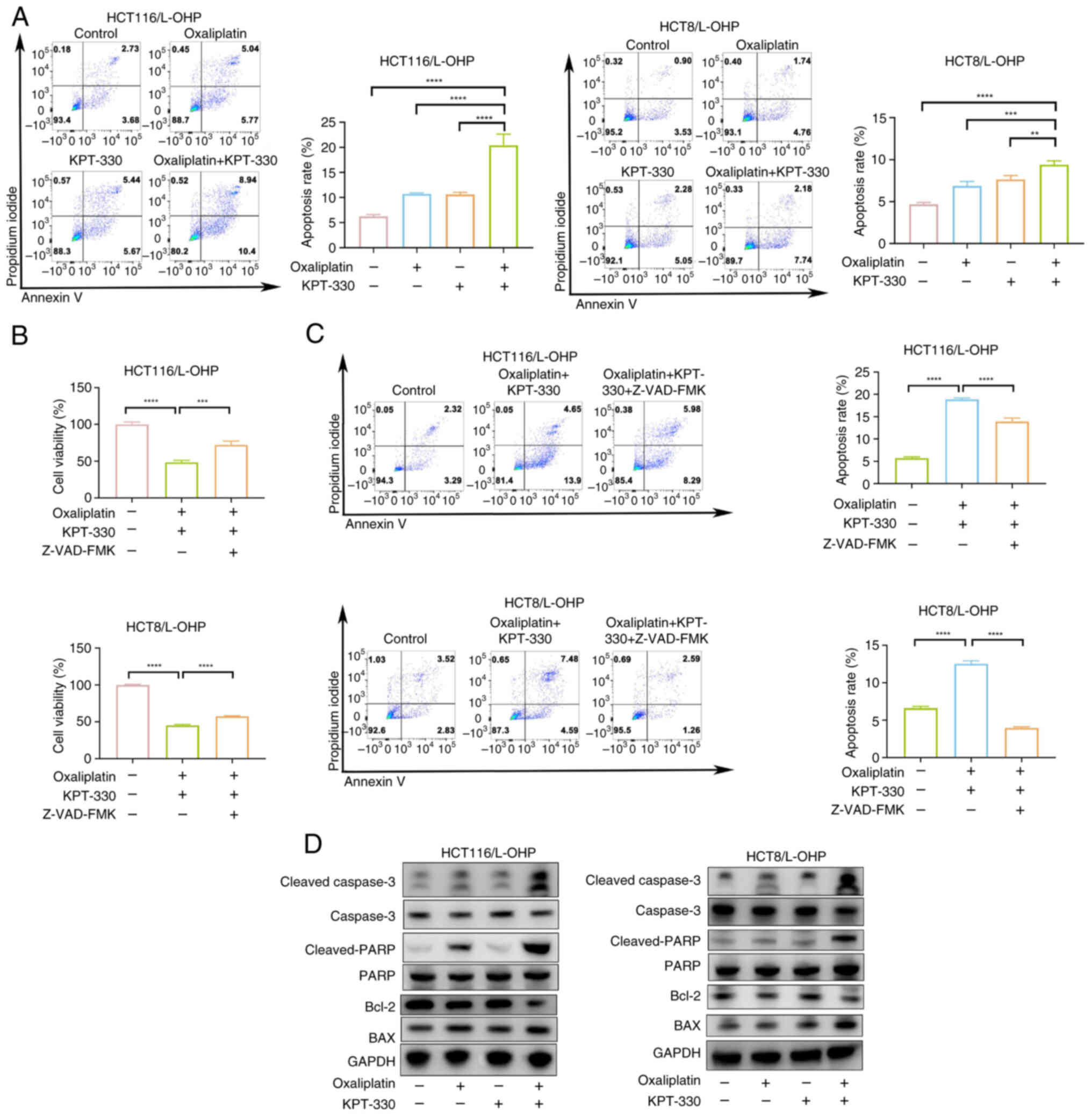

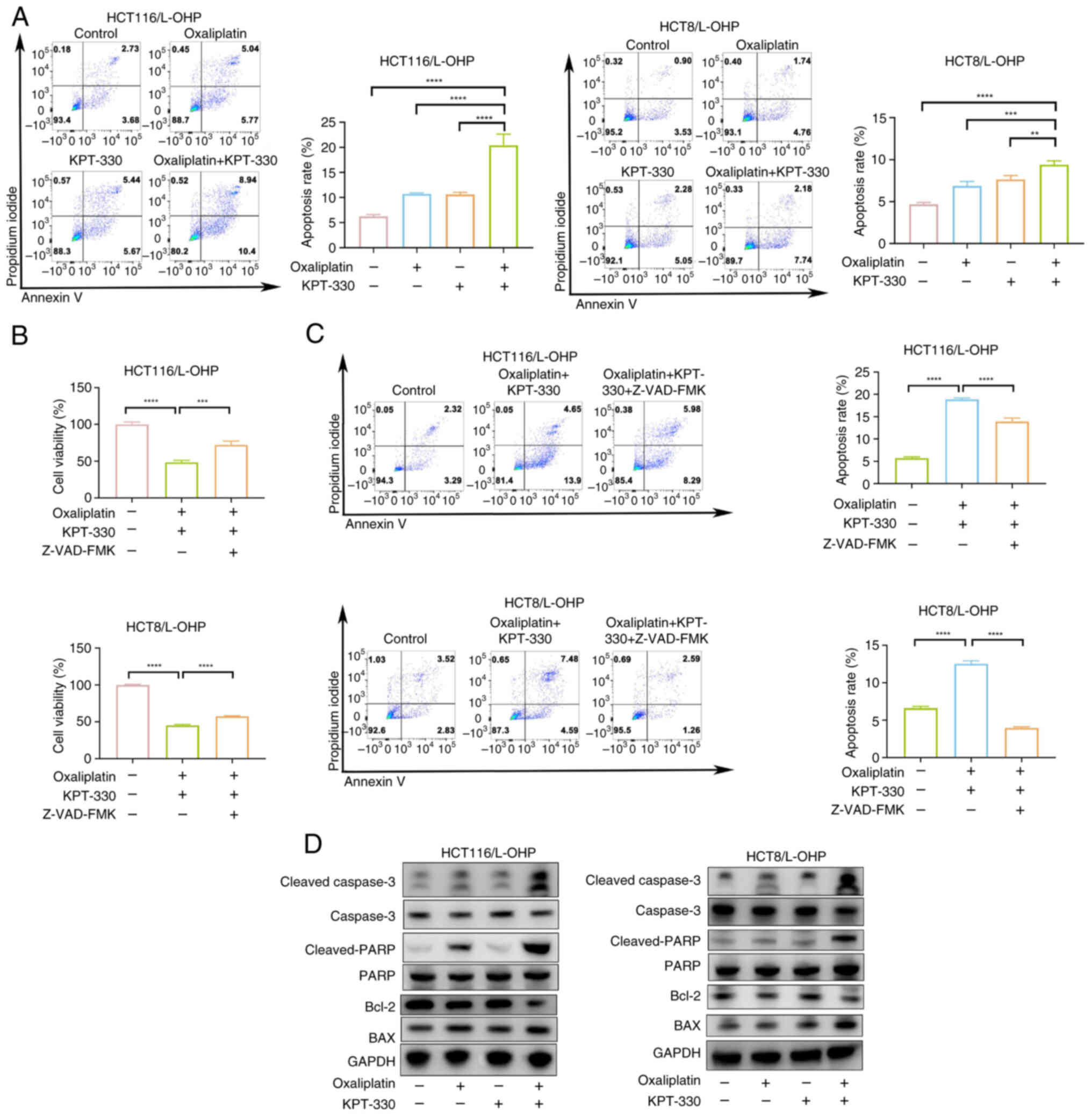

Combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin

induces apoptosis in oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells

Compared with HCT116/L-OHP cells, oxaliplatin

induced a significant increase in apoptosis in HCT116 cells

(Fig. S3A), indicating that

resistance to oxaliplatin in CRC is associated with anti-apoptotic

mechanisms (20). To further

explore whether the combination of oxaliplatin and KPT-330

synergistically induces apoptosis in oxaliplatin-resistant CRC

cells, apoptosis levels were quantitatively assessed. While

treatment with either oxaliplatin or KPT-330 alone did not

significantly induce apoptosis in HCT116/L-OHP or HCT8/L-OHP cells,

the combination therapy markedly enhanced apoptosis (Fig. 3A). To investigate whether the

observed apoptosis was caspase-dependent, Z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase

inhibitor, was employed (21,22). The results revealed that

Z-VAD-FMK effectively blocked apoptosis induced by the combination

therapy (Fig. 3B and C). Western

blotting further demonstrated that oxaliplatin combined with

KPT-330 increased cleaved PARP levels (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these results

suggested that KPT-330 potentiated oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis in

CRC cells.

| Figure 3Combination of KPT-330 and

oxaliplatin induces apoptosis in oxaliplatin-resistant colorectal

cancer cells. (A) Apoptosis rate of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells treated with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination for 48

h, assessed by flow cytometry. The sum of early apoptotic cells

(annexin V+/PI-) in the lower-right quadrant

and late apoptotic cells (annexin V+/PI+) in

the upper-right quadrant indicates apoptotic cells, and was used

for quantification. (B) Viability of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells treated with oxaliplatin and KPT-330 or the combination with

Z-VAD-FMK for 48 h, analyzed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. (C)

Apoptosis rate of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells treated with

oxaliplatin and KPT-330 or the combination with Z-VAD-FMK for 48 h,

analyzed by flow cytometry. The sum of early apoptotic cells

(annexin V+/PI-) in the lower-right quadrant

and late apoptotic cells (annexin V+/PI+) in

the upper-right quadrant indicates apoptotic cells, and was used

for quantification. (D) Immunoblot analysis of HCT116/L-OHP and

HCT8/L-OHP cells treated with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the

combination for 48 h. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. PARP, poly

(ADP-ribose) polymerase. |

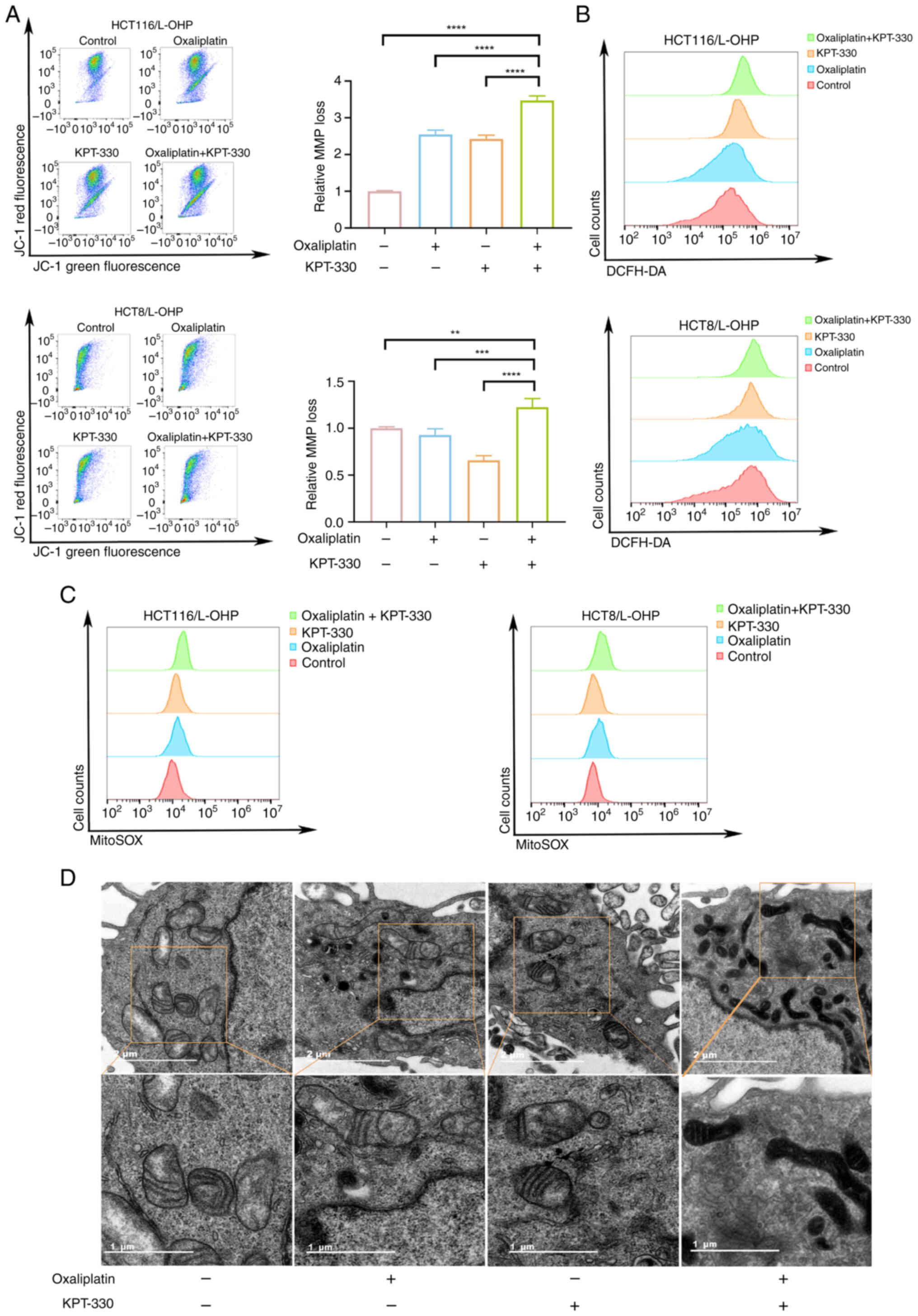

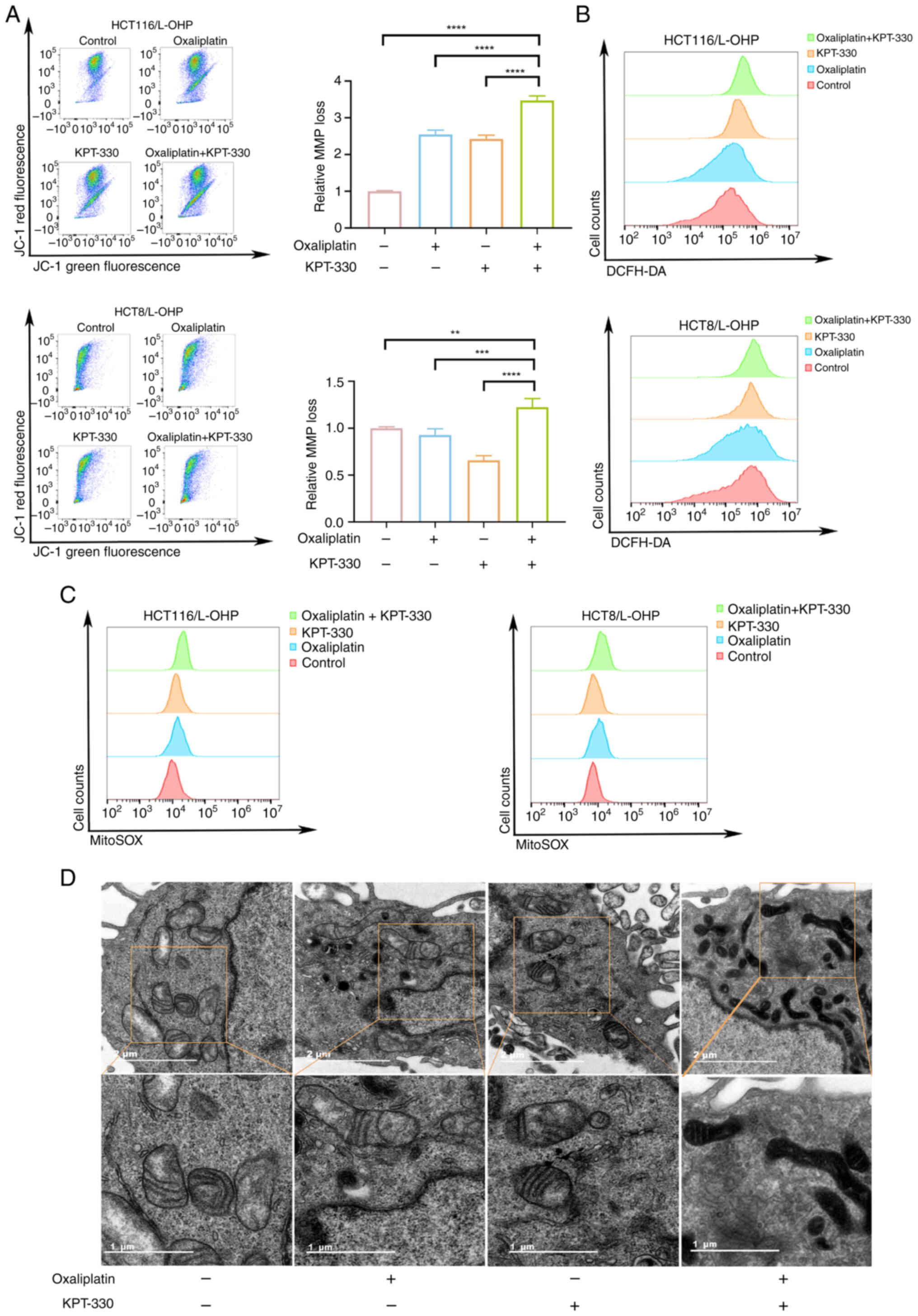

Combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin

increases the levels of ROS and induces mitochondrial

dysfunction

Apoptosis is a multifaceted process involving

caspase activation, MMP changes, the balance between pro-apoptotic

and anti-apoptotic proteins, and other signaling pathways (23). Compared with HCT116/L-OHP cells,

HCT116 cells exhibited greater sensitivity to oxaliplatin-induced

changes in the MMP (Fig. S3B).

To investigate whether the combination treatment induced apoptosis

by affecting the MMP, JC-1, a fluorescent indicator of the MMP, was

used. In both HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells, combination

treatment with oxaliplatin and KPT-330 induced greater

mitochondrial depolarization than monotherapy (Fig. 4A). However, in HCT8/L-OHP cells,

low-dose KPT-330 treatment did not affect mitochondrial

depolarization (Fig. 4A).

Notably, the MMP loss in both KPT-330 and oxaliplatin monotherapy

groups was lower than that of the control group. This finding

suggests that while the single agents induced apoptosis, they might

be triggering a different or less direct mitochondrial pathway in

these resistant cells. Alternatively, the observed decrease in MMP

loss could be a result of the adaptive mechanisms of the cells,

which enables them to maintain mitochondrial function and viability

under single-agent stress, thereby contributing to drug resistance.

These results suggested that combination therapy may induce

mitochondrial dysfunction. To further determine if this dysfunction

is linked to increased ROS production, ROS levels were measured in

the cells. Oxaliplatin treatment had a negligible effect on ROS

induction in HCT116/L-OHP cells, in contrast to its marked effect

on sensitive HCT116 cells (Fig.

S3C), combination therapy increased ROS levels in both

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells (Fig. 4B). Given that most intracellular

ROS are generated within mitochondria, the MitoSOX Red reagent, a

mitochondria-targeted form of dihydroethidium, was used to examine

mitochondrial ROS levels. The combination of oxaliplatin and

KPT-330 further elevated mitochondrial ROS levels in both

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells compared with either monotherapy

treatment (Fig. 4C). TEM images

revealed morphological changes in the mitochondria following

treatment with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination. Notably,

the combination therapy resulted in increased membrane density and

a shrunken mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 4D). Additionally, compared with

those in HCT116/L-OHP cells, mitochondria in HCT116 cells displayed

impaired morphology following oxaliplatin treatment (Fig. S3D). These results suggested that

the combination of oxaliplatin and KPT-330 induced mitochondrial

dysfunction through the elevation of ROS levels.

| Figure 4Combination of KPT-330 and

oxaliplatin increases the levels of reactive oxygen species and

induces mitochondrial dysfunction. (A) HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells were treated with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination for

48 h, stained with JC-1, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The bar

chart shows the relative MMP loss in the four treatment groups. (B)

HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells were treated with oxaliplatin,

KPT-330 or the combination for 48 h, stained with DCFH-DA, and

analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells

were treated with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination for 48 h,

stained with MitoSOX, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D)

Representative transmission electron microscopy images of

mitochondrial morphology in HCT116/L-OHP cells treated with

oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination for 48 h. Scale bars, 2

μm (upper panel) or 1 μm (lower panel).

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. DCFH-DA,

2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; MMP, mitochondrial

membrane potential. |

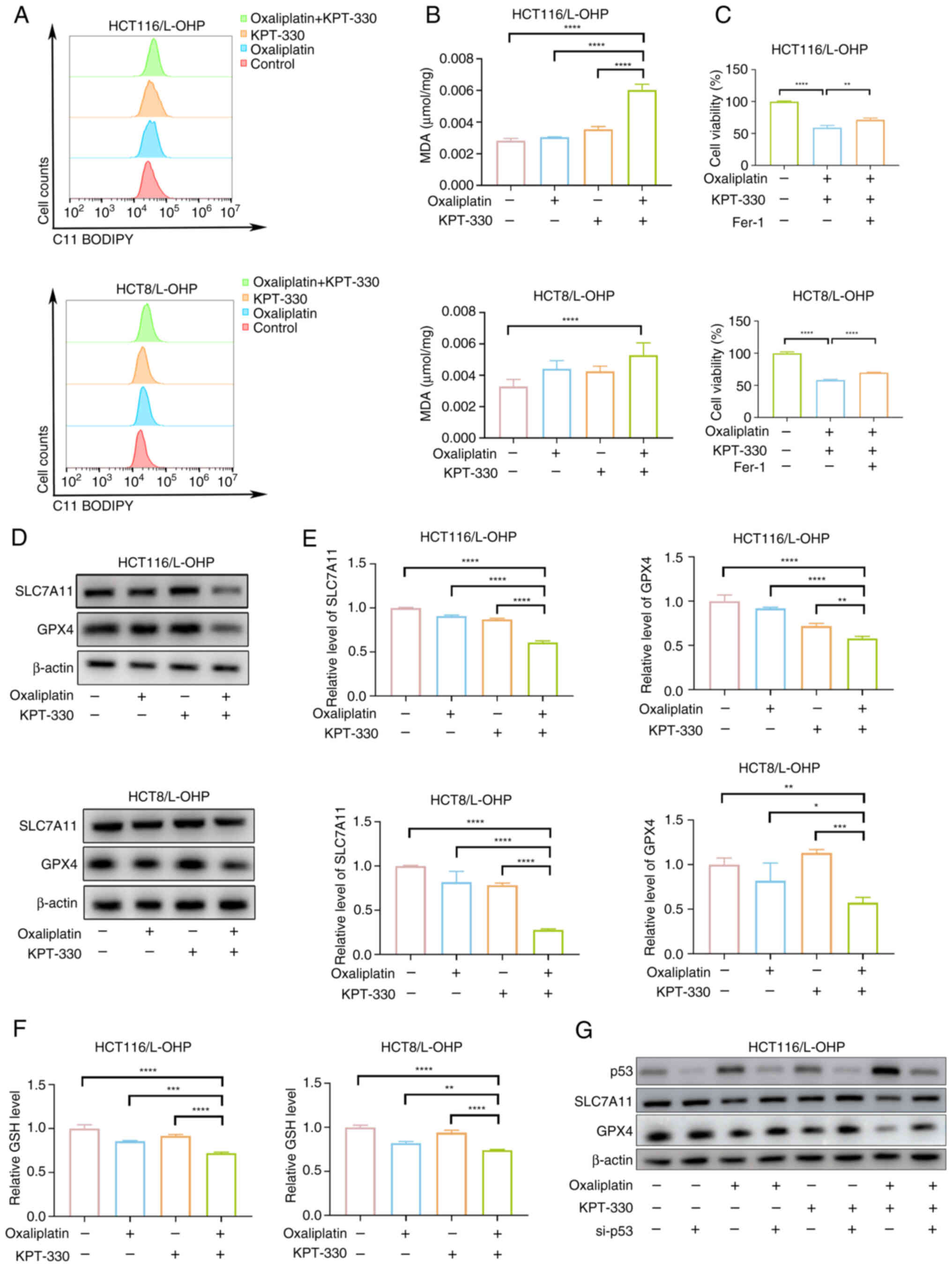

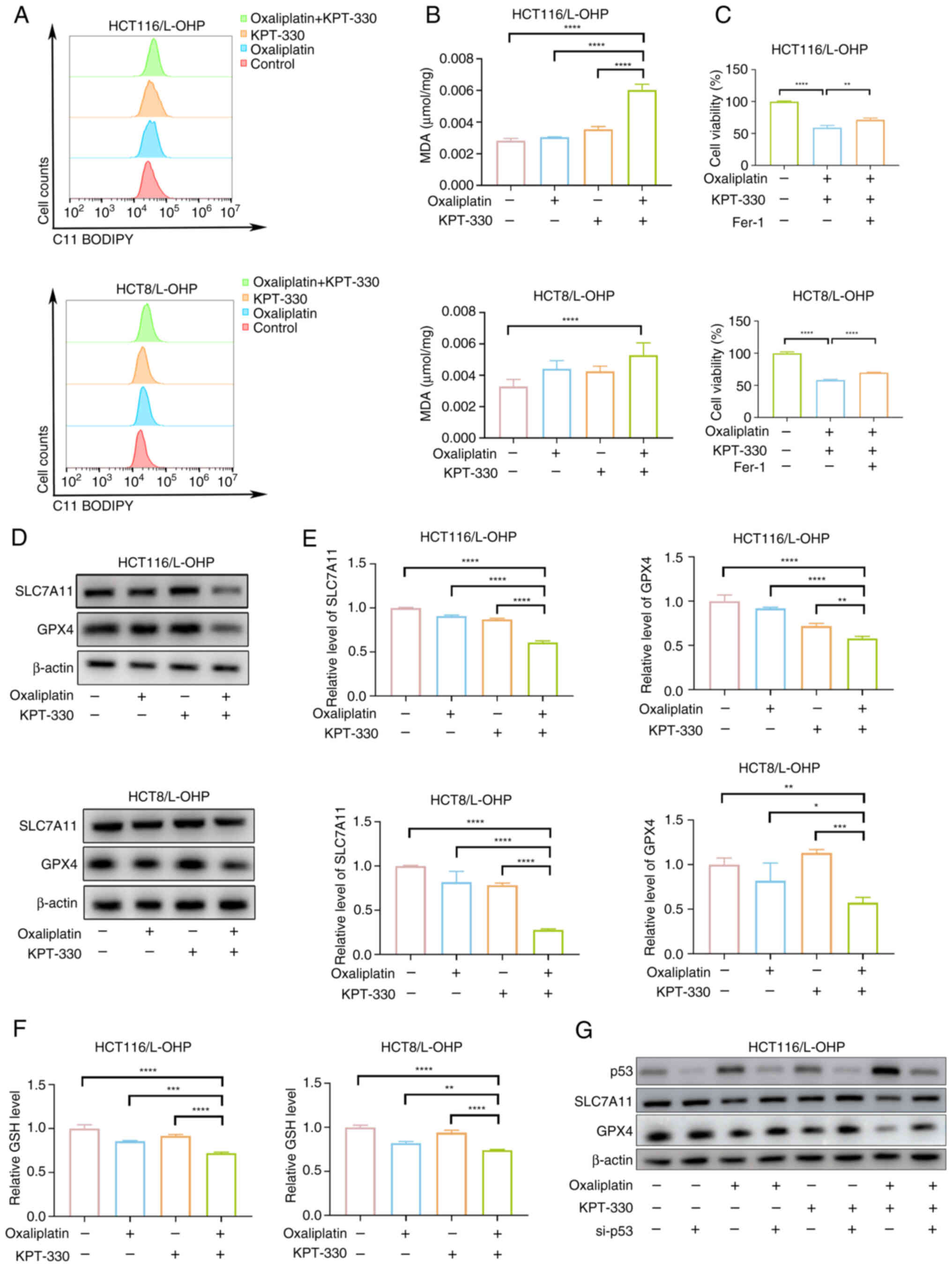

Combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin

inhibits SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression to induce ferroptosis

The present TEM results (Fig. 4D) revealed that HCT116/L-OHP

cells treated with combination therapy exhibited distinct

morphological features characteristic of ferroptosis, an

iron-dependent, non-apoptotic form of cell death marked by the

accumulation of cytotoxic lipid ROS, leading to lipid membrane

damage and perforation (24).

Inducing ferroptosis can overcome oxaliplatin resistance in CRC

cells (25,26). To further explore whether

combination therapy sensitizes oxaliplatin-resistant cells to

oxaliplatin by triggering ferroptosis, several experiments were

conducted. Both lipid peroxidation and MDA levels were increased

following combination treatment with oxaliplatin and KPT-330

(Fig. 5A and B). Inhibition of

cell viability by the combination therapy was partially reversed

using the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fig. 5C). The present results

demonstrated that combination therapy enhanced p53 expression. As a

key regulator in tumorigenesis and development, p53 serves a

critical role in both oxaliplatin resistance and ferroptosis

(27). Based on this, it was

hypothesized that combination therapy promotes p53 expression to

activate ferroptosis-related signaling. Combination treatment

reduced the mRNA and protein levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4 (Fig. 5D and E), and similarly decreased

GSH levels (Fig. 5F). Knockdown

of p53 partially counteracted the reduction in SLC7A11 and GPX4

expression induced by the combination therapy (Figs. S4 and 5G). These results indicated that the

combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin induced ferroptosis by

promoting p53 expression, which in turn suppressed SLC7A11 and GPX4

expression.

| Figure 5Combination of KPT-330 and

oxaliplatin inhibits SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression to induce

ferroptosis. (A) HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells were treated

with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination for 48 h, stained with

C11-BODIPY, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) MDA levels after

treatment of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells with oxaliplatin,

KPT-330 or the combination for 48 h. (C) Viability of HCT116/L-OHP

and HCT8/L-OHP cells treated with KPT-330 and oxaliplatin or the

combination with Fer-1 for 48 h, analyzed using a Cell Counting

Kit-8 assay. (D) Immunoblot analysis of HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP

cells treated with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination for 48

h. (E) mRNA expression levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4 in HCT116/L-OHP

and HCT8/L-OHP cells treated with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the

combination for 48 h. (F) Relative GSH levels assessed after

treating HCT116/L-OHP and HCT8/L-OHP cells with oxaliplatin,

KPT-330 or the combination for 48 h. (G) Immunoblot analysis of

HCT116/L-OHP cells after knockdown of p53, and treatment with

oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination for 48 h.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Fer-1,

ferrostatin-1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, glutathione;

MDA, malondialdehyde; si, small interfering RNA; SLC7A11, solute

carrier family 7 member 11. |

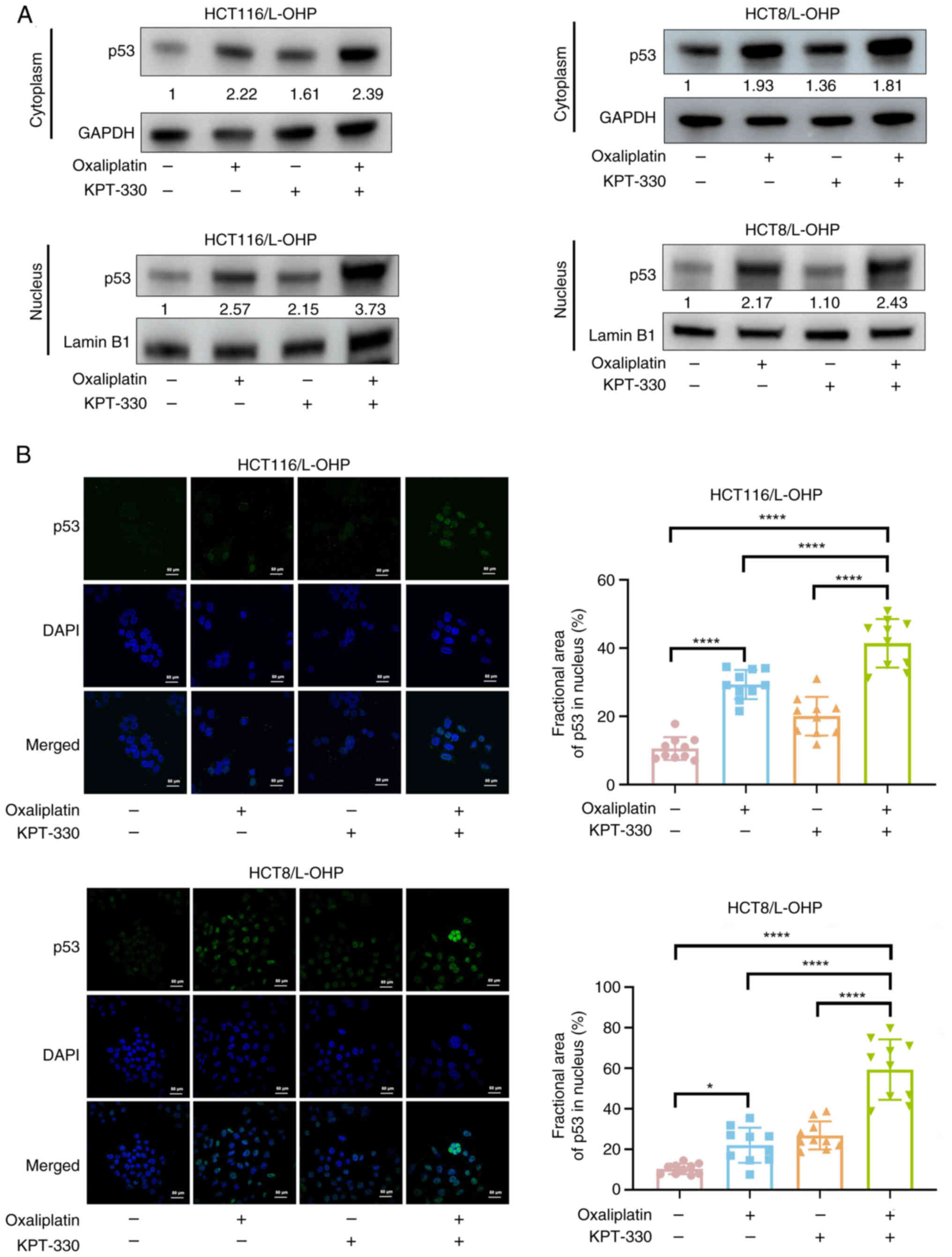

Combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin

induces p53 nuclear retention

Combination treatment enhanced p53 expression. Given

that XPO1 mediates the nuclear export of p53, the balance between

its nuclear and cytoplasmic localization is a key mechanism that

influences oxaliplatin sensitivity (28). Additionally, increased

cytoplasmic p53 levels diminish cellular sensitivity to oxaliplatin

(28,29). Cell fractionation experiments

revealed that oxaliplatin monotherapy resulted in elevated p53

levels in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions (Fig. 6A). Immunofluorescence analysis

further demonstrated that oxaliplatin treatment alone notably

promoted nuclear accumulation of p53 (Fig. 6A and B). In HCT116/L-OHP cells,

combination therapy further enhanced nuclear p53 accumulation

(Fig. 6A and B). In HCT8/L-OHP

cells, the combination therapy not only reduced p53 nuclear export

(Fig. 6A) but also increased

nuclear p53 expression (Fig. 6A and

B). In conclusion, these results indicated that the combination

of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin induced p53 nuclear retention.

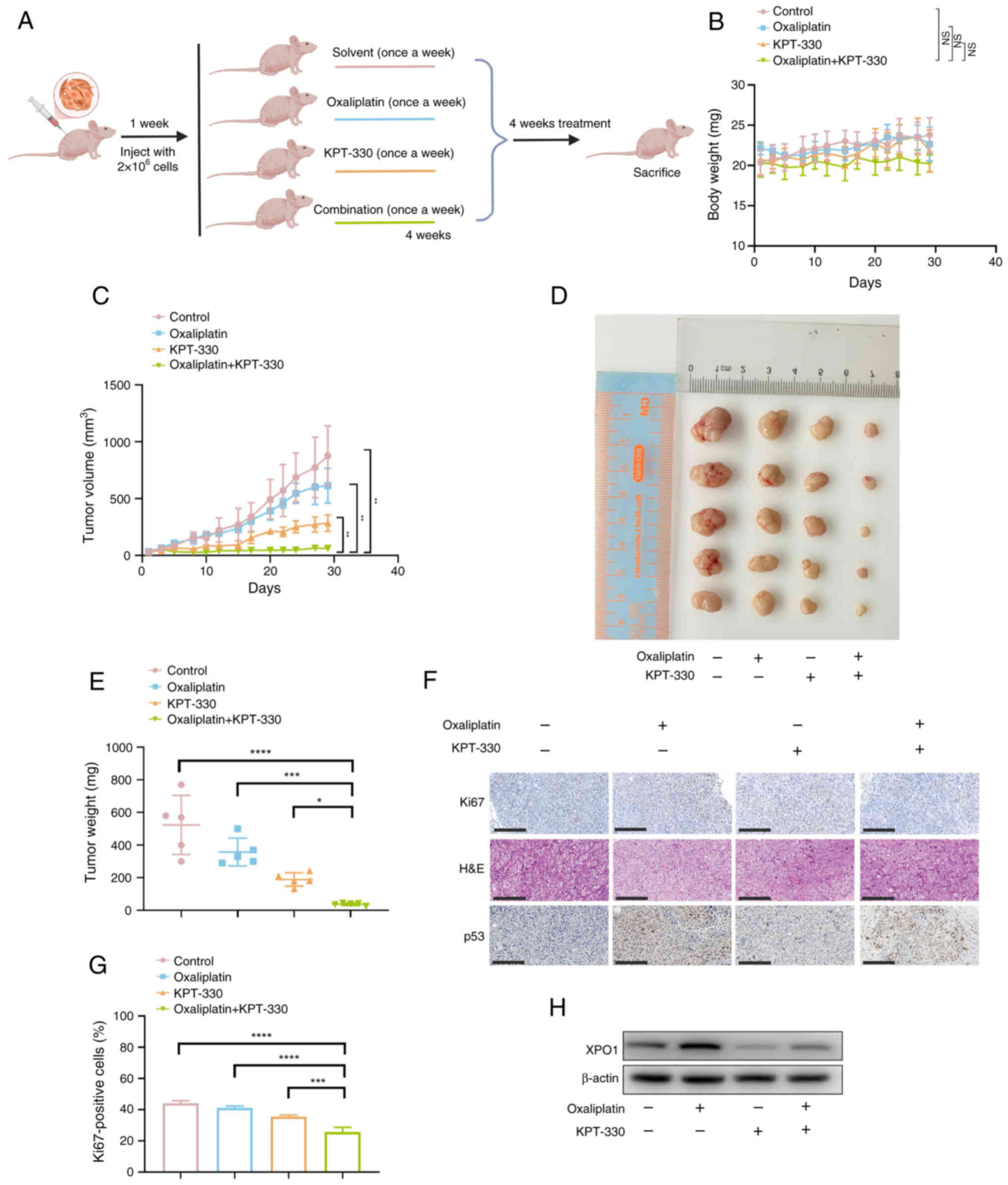

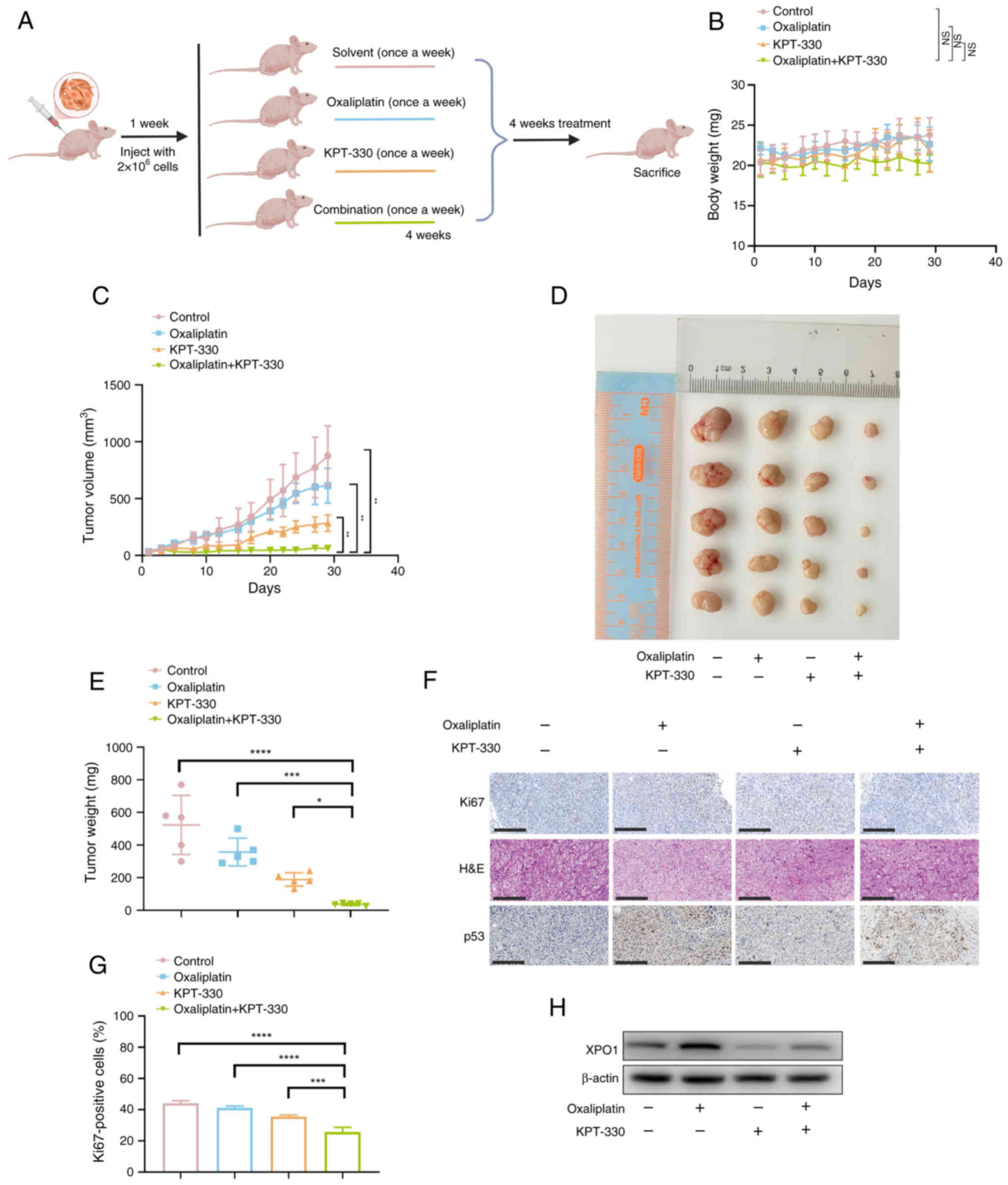

Combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin

effectively suppresses tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model

Assessing the effectiveness of synergistic

inhibition in animal models is crucial. A subcutaneous xenograft

model was established by injecting HCT116/L-OHP cells

subcutaneously. At 1 week after tumor implantation, four treatment

groups were formed: Vehicle (once a week), oxaliplatin (10 mg/kg;

once a week), KPT-330 (10 mg/kg; once a week) and combination

treatment (Fig. 7A). After 4

weeks of treatment, the body weight of mice in the combination

therapy group was not significantly different from those of the

single-drug (oxaliplatin or KPT-330) and vehicle control groups

(Fig. 7B). Additionally, after 4

weeks of treatment, the combination therapy group showed a

significant reduction in both tumor volume and mass compared with

the monotherapy (oxaliplatin or KPT-330) and control groups

(Fig. 7C-E), supporting the

present in vitro findings. Further IHC staining revealed

that the combination treatment reduced the proliferation index, as

indicated by decreased Ki67 expression (Fig. 7F and G). Combination therapy with

KPT-330 significantly enhanced the nuclear accumulation of p53, an

effect that was only partially achieved with oxaliplatin treatment

alone (Fig. 6A and B). IHC

analysis of xenograft tumors revealed a similar trend, with the

combination treatment promoting p53 accumulation, particularly in

the nucleus (Fig. 7F).

Additionally, western blot analysis revealed that oxaliplatin

treatment increased XPO1 expression (Fig. 7H). These data demonstrated the

effectiveness of the combination of oxaliplatin and KPT-330 in

overcoming oxaliplatin resistance in CRC.

| Figure 7Combination of KPT-330 and

oxaliplatin effectively suppresses tumor growth in a mouse

xenograft model. (A) A subcutaneous tumor xenograft model was

established by injecting HCT116/L-OHP cells into the subcutaneous

tissue of nude mice. At 1 week after tumor establishment, four

treatment groups were formed: Vehicle control, oxaliplatin, KPT-330

and combination. (B) Body weight curves of mice during the in

vivo efficacy assessment of oxaliplatin and KPT-330 in

HCT116/L-OHP xenografts. The NS symbol indicates that the weight in

the combination therapy group was not significantly different from

those in the single-drug (oxaliplatin or KPT-330) and vehicle

control groups at the final timepoint. (C) Growth curve of tumor

volume in the in vivo efficacy assessment of oxaliplatin and

KPT-330 in HCT116/L-OHP xenografts. (D) Representative images of

tumors from all groups (n=5). (E) Tumor weights in each group

(n=5). (F) Representative staining images of Ki67, H&E and p53

in HCT116/L-OHP xenograft tumors. Scale bar, 50 μm. (G)

Quantification of Ki67 in HCT116/L-OHP xenograft tumors treated

with oxaliplatin, KPT-330 or the combination. (H) Immunoblot

analysis of HCT116/L-OHP xenograft tumors treated with oxaliplatin,

KPT-330 or the combination. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001,

****P<0.0001. NS, not significant; XPO1, exportin

1. |

Discussion

Oxaliplatin is a widely used chemotherapeutic agent

in the treatment of CRC (7).

However, the development of resistance to oxaliplatin limits its

clinical efficacy (30). This

resistance is often associated with the adaptive tolerance of tumor

cells to cell death mechanisms (31). Therefore, strategies aimed at

enhancing tumor cell sensitivity to oxaliplatin are critical for

developing effective approaches to overcome chemoresistance. In the

present study, a mechanism was proposed to explain how KPT-330

overcomes oxaliplatin resistance. First, it was observed that

oxaliplatin treatment alone increased the expression levels of

XPO1, which in turn, enhanced the nuclear and cytoplasmic levels of

p53. This mislocalization of p53 prevented it from performing its

tumor-suppressing function in the nucleus, thereby reducing the

sensitivity of the CRC cells to oxaliplatin. KPT-330 combined with

oxaliplatin restored oxaliplatin sensitivity by promoting the

nuclear localization of p53. As shown in our model, KPT-330 blocked

the XPO1-mediated nuclear export of p53 by inhibiting XPO1, leading

to its accumulation in the nucleus. The nuclear p53 then acts as a

transcription factor, leading to the downregulation of SLC7A11 and

the upregulation of p21. This, along with a decrease in MMP,

collectively promotes both apoptosis and ferroptosis in the CRC

cells, effectively overcoming oxaliplatin resistance (Fig. S5).

Several tumor suppressor proteins (TSPs), such as

p53 and p21, are crucial for maintaining cellular integrity by

regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis and DNA damage repair

(32). Consequently,

mislocalization of TSPs to the cytoplasm can contribute to tumor

progression (33). One approach

to prevent such mislocalization is to inhibit the nuclear export of

these proteins (34). XPO1

serves as the sole nuclear export receptor for multiple TSPs

(35). Upregulation of XPO1

expression has been linked to poor prognosis and chemoresistance in

various cancer types, including breast cancer, CRC and leukemia

(34-36). The XPO1 inhibitor KPT-330 induces

nuclear accumulation of TSPs and restores their tumor-suppressive

activity (14). In the present

study, oxaliplatin not only increased XPO1 expression but also

upregulated p53 expression in both the cytoplasm and nucleus in

oxaliplatin-resistant cells. This suggests that targeting XPO1

could be a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

In the cytoplasm, p53 is rapidly degraded via the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, making it barely detectable (37). Maintaining p53 activity is a

hallmark of sensitivity to oxaliplatin (38). p53 remains in the cytoplasm of

platinum-resistant cells in lung and ovarian cancer (39,40). The mislocalization of p53 results

in its inactivation, which is a critical factor in chemoresistance

(41,42). In the present study, the

combination of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin treatment increased p53

nuclear localization, downregulated SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression,

and promoted ferroptosis compared with either oxaliplatin or

KPT-330 monotherapy. Conversely, inhibition of p53 accumulation by

transfection with si-p53 partially restored SLC7A11 and GPX4

expression. These results suggested that the detection of p53

nucleocytoplasmic localization could serve as a potential biomarker

for predicting CRC response to oxaliplatin.

While the present study demonstrated the

synergistic efficacy of KPT-330 and oxaliplatin in overcoming

oxaliplatin resistance in CRC, several limitations remain. Direct

validation of these findings in clinical samples from patients with

CRC is essential. Additionally, the present study did not predict

responsiveness based on p53 nucleocytoplasmic localization in

relevant clinical samples. Future research will focus on analyzing

XPO1 expression and p53 localization in patient tissues,

particularly those from patients with CRC exhibiting oxaliplatin

resistance, to confirm these results and further explore the

translational potential of this combination therapy.

While the present in vivo experiments

indicated no significant changes in body weight, suggesting a lack

of acute severe toxicity during the treatment period, a thorough

evaluation of the long-term safety and potential systemic side

effects of combination therapy is crucial. Future research will

focus on rigorous toxicology studies and comprehensive assessments

of organ-specific toxicities, which are essential for its eventual

clinical translation.

Furthermore, while the present study

comprehensively outlined the role of the p53-XPO1 axis in the

ability of KPT-330 to restore oxaliplatin sensitivity in CRC, the

full range of the mechanistic actions of KPT-330 may extend beyond

p53. Other factors contributing to increased cytoplasmic p53

levels, such as the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and nuclear

transport mechanisms, were not fully explored. For instance,

impaired p53 nuclear import could contribute to its cytoplasmic

retention (42). As a selective

XPO1 inhibitor, KPT-330 may also affect the nuclear-cytoplasmic

transport of other critical proteins, including additional tumor

suppressors or factors (such as ERK5, DEAD-box helicase 17 and

FOXO1) involved in drug resistance (33,43). Future investigations should

explore these potential targets and alternative signaling pathways

to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted role

of KPT-330 in overcoming oxaliplatin resistance.

In conclusion, KPT-330 promoted p53 nuclear

accumulation and enhanced the sensitivity of oxaliplatin-resistant

CRC to oxaliplatin. These findings suggest a promising strategy for

overcoming oxaliplatin resistance in CRC and highlight the

potential of KPT-330 as a novel sensitizing agent for this

chemotherapy.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CL, XJ, YC, KC, FW, QZ, XX, ZSC, LX and SD

contributed to the conception and design of the study. CL, XJ, YC,

KC, FW, QZ and XX contributed to data acquisition. CL, LX and SD

contributed to data analysis and interpretation. CL and LX

contributed to the writing of the original draft. SD and ZSC

contributed to mentoring, writing, review and editing. CL, XJ and

LX confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Animal welfare and experimental procedures were

carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Ethical Review

Committee and Laboratory Animal Welfare Committee of the Sir Run

Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (approval

no. SRRSH2025-0023, Hangzhou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82072628 and 32200593), the Key

Research and Development Program of Zhejiang (grant no.

2022C03032), and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang

Province, China (grant no. LQ23H160040).

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N and Chen WQ:

Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: A

secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J

(Engl). 134:783–791. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bullock AJ, Schlechter BL, Fakih MG,

Tsimberidou AM, Grossman JE, Gordon MS, Wilky BA, Pimentel A,

Mahadevan D, Balmanoukian AS, et al: Botensilimab plus balstilimab

in relapsed/refractory microsatellite stable metastatic colorectal

cancer: A phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 30:2558–2567. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tripathi PK, Mittal KR, Jain N, Sharma N

and Jain CK: KRAS pathways: A potential gateway for cancer

therapeutics and diagnostics. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov.

19:268–279. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Capdevila J, Elez E, Peralta S, Macarulla

T, Ramos FJ and Tabernero J: Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in the

management of colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther.

8:1223–1236. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sargent D, Sobrero A, Grothey A, O'Connell

MJ, Buyse M, Andre T, Zheng Y, Green E, Labianca R, O'Callaghan C,

et al: Evidence for cure by adjuvant therapy in colon cancer:

Observations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients

on 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 27:872–877. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zeng K, Li W, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang L,

Zhang W, Xing Y and Zhou C: Inhibition of CDK1 overcomes

oxaliplatin resistance by regulating ACSL4-mediated ferroptosis in

colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e23010882023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Li Y, Gan Y, Liu J, Li J, Zhou Z, Tian R,

Sun R, Liu J, Xiao Q, Li Y, et al: Downregulation of MEIS1 mediated

by ELFN1-AS1/EZH2/DNMT3a axis promotes tumorigenesis and

oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 7:872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Abdul Razak AR, Mau-Soerensen M, Gabrail

NY, Gerecitano JF, Shields AF, Unger TJ, Saint-Martin JR, Carlson

R, Landesman Y, McCauley D, et al: First-in-class, first-in-human

phase I study of selinexor, a selective inhibitor of nuclear

export, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol.

34:4142–4150. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ben-Barouch S and Kuruvilla J: Selinexor

(KTP-330)-a selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE):

Anti-tumor activity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 29:15–21. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ferreiro-Neira I, Torres NE, Liesenfeld

LF, Chan CH, Penson T, Landesman Y, Senapedis W, Shacham S, Hong TS

and Cusack JC: XPO1 inhibition enhances radiation response in

preclinical models of rectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 22:1663–1673.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Inoue A, Robinson FS, Minelli R, Tomihara

H, Rizi BS, Rose JL, Kodama T, Srinivasan S, Harris AL, Zuniga AM,

et al: Sequential administration of XPO1 and ATR inhibitors

enhances therapeutic response in TP53-mutated colorectal cancer.

Gastroenterology. 161:196–210. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Quintanal-Villalonga A, Taniguchi H, Hao

Y, Chow A, Zhan YA, Chavan SS, Uddin F, Allaj V, Manoj P, Shah NS,

et al: Inhibition of XPO1 sensitizes small cell lung cancer to

first- and second-line chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 82:472–483. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

14

|

Chen Y, Camacho SC, Silvers TR, Razak AR,

Gabrail NY, Gerecitano JF, Kalir E, Pereira E, Evans BR, Ramus SJ,

et al: Inhibition of the nuclear export receptor XPO1 as a

therapeutic target for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Clinical

Cancer Research. 23:1552–1563. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhou J, Lei Z, Chen J, Liao S, Chen Y, Liu

C, Huang S, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang P, et al: Nuclear export of BATF2

enhances colorectal cancer proliferation through binding to CRM1.

Clin Transl Med. 13:e12602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Azmi AS, Kauffman M, McCauley D, Shacham S

and Mohammad RM: Novel small-molecule CRM-1 inhibitor for GI cancer

therapy. J Clin Oncol. 30(suppl 4): abstr 245. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Chiu SJ, Lee YJ, Hsu TS and Chen WS:

Oxaliplatin-induced gamma-H2AX activation via both p53-dependent

and -independent pathways but is not associated with cell cycle

arrest in human colorectal cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact.

182:173–182. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Schmidt AK, Pudelko K, Boekenkamp JE,

Berger K, Kschischo M and Bastians H: The p53/p73-p21(CIP1) tumor

suppressor axis guards against chromosomal instability by

restraining CDK1 in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 40:436–451. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Martinez-Balibrea E, Martinez-Cardus A,

Gines A, Ruiz de Porras V, Moutinho C, Layos L, Manzano JL, Bugés

C, Bystrup S, Esteller M and Abad A: Tumor-related molecular

mechanisms of oxaliplatin resistance. Mol Cancer Ther.

14:1767–1776. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yapasert R, Khaw-On P and Banjerdpongchai

R: Coronavirus Infection-associated cell death signaling and

potential therapeutic targets. Molecules. 26:74592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Arango D, Wilson AJ, Shi Q, Corner GA,

Arañes MJ, Nicholas C, Lesser M, Mariadason JM and Augenlicht LH:

Molecular mechanisms of action and prediction of response to

oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 91:1931–1946.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xu X, Lai Y and Hua ZC: Apoptosis and

apoptotic body: Disease message and therapeutic target potentials.

Biosci Rep. 39:BSR201809922019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir

H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK,

Kagan VE, et al: Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking

metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171:273–285. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yang C, Zhang Y, Lin S, Liu Y and Li W:

Suppressing the KIF20A/NUAK1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway induces

ferroptosis and enhances the sensitivity of colorectal cancer to

oxaliplatin. Aging (Albany NY). 13:13515–13534. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lin JF, Hu PS, Wang YY, Tan YT, Yu K, Liao

K, Wu QN, Li T, Meng Q, Lin JZ, et al: Phosphorylated NFS1 weakens

oxaliplatin-based chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer by

preventing PANoptosis. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:542022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Di Y, Zhang X, Wen X, Qin J, Ye L, Wang Y,

Song M, Wang Z and He W: MAPK Signaling-mediated RFNG

phosphorylation and nuclear translocation restrain

oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis and ferroptosis. Adv Sci (Weinh).

11:e24027952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang Z, Zhan Y, Xu J, Wang Y, Sun M, Chen

J, Liang T, Wu L and Xu K: β-Sitosterol reverses multidrug

resistance via BCRP suppression by inhibiting the p53-MDM2

interaction in colorectal cancer. J Agric Food Chem. 68:3850–3858.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

O'Brate A and Giannakakou P: The

importance of p53 location: Nuclear or cytoplasmic zip code? Drug

Resist Updat. 6:313–322. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kanemitsu Y, Shimizu Y, Mizusawa J, Inaba

Y, Hamaguchi T, Shida D, Ohue M, Komori K, Shiomi A, Shiozawa M, et

al: Hepatectomy followed by mFOLFOX6 versus hepatectomy alone for

liver-only metastatic colorectal cancer (JCOG0603): A phase II or

III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 39:3789–3799. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Luo S, Yue M, Wang D, Lu Y, Wu Q and Jiang

J: Breaking the barrier: Epigenetic strategies to combat platinum

resistance in colorectal cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 77:1011522024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kau TR, Way JC and Silver PA: Nuclear

transport and cancer: From mechanism to intervention. Nat Rev

Cancer. 4:106–117. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lai C, Xu L and Dai S: The nuclear export

protein exportin-1 in solid malignant tumours: From biology to

clinical trials. Clin Transl Med. 14:e16842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Turner JG, Dawson JL, Grant S, Shain KH,

Dalton WS, Dai Y, Meads M, Baz R, Kauffman M, Shacham S and

Sullivan DM: Treatment of acquired drug resistance in multiple

myeloma by combination therapy with XPO1 and topoisomerase II

inhibitors. J Hematol Oncol. 9:732016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Saenz-Ponce N, Pillay R, de Long LM,

Kashyap T, Argueta C, Landesman Y, Hazar-Rethinam M, Boros S,

Panizza B, Jacquemyn M, et al: Targeting the XPO1-dependent nuclear

export of E2F7 reverses anthracycline resistance in head and neck

squamous cell carcinomas. Sci Transl Med. 10:eaar72232018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kim J, McMillan E, Kim HS, Venkateswaran

N, Makkar G, Rodriguez-Canales J, Villalobos P, Neggers JE,

Mendiratta S, Wei S, et al: XPO1-dependent nuclear export is a

druggable vulnerability in-mutant lung cancer. Nature. 538:114–117.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Oren M and Rotter V: Mutant p53

gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

2:a0011072010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Toscano F, Parmentier B, Fajoui ZE,

Estornes Y, Chayvialle JA, Saurin JC and Abello J: p53 dependent

and independent sensitivity to oxaliplatin of colon cancer cells.

Biochem Pharmacol. 74:392–406. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Nishitsuji K, Mito R, Ikezaki M, Yano H,

Fujiwara Y, Matsubara E, Nishikawa T, Ihara Y, Uchimura K, Iwahashi

N, et al: Impacts of cytoplasmic p53 aggregates on the prognosis

and the transcriptome in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci.

115:2947–2960. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Komlodi-Pasztor E, Trostel S, Sackett D,

Poruchynsky M and Fojo T: Impaired p53 binding to importin: A novel

mechanism of cytoplasmic sequestration identified in

oxaliplatin-resistant cells. Oncogene. 28:3111–3120. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Prokocimer M and Peller S: Cytoplasmic

sequestration of wild-type p53 in a patient with therapy-related

resistant AML: First report. Med Oncol. 29:1148–1150. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Fang J, Zou M, Yang M, Cui Y, Pu R and

Yang Y: TAF15 inhibits p53 nucleus translocation and promotes HCC

cell 5-FU resistance via post-transcriptional regulation of UBE2N.

J Physiol Biochem. 80:919–933. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wang Z, Pan B, Yao Y, Qiu J, Zhang X, Wu X

and Tang N: XPO1 intensifies sorafenib resistance by stabilizing

acetylation of NPM1 and enhancing epithelial-mesenchymal transition

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 160:1144022023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|