Proteins, glucose and lipids are universally

recognized as the three nutrients essential for sustaining human

life. Amino acids (AAs), the basic structural units of proteins,

serve not only as building blocks but also as critical substrates

for synthesizing key biological regulators, such as thyroid

hormones, underscoring their profound physiological significance

(1-3). Every human protein is composed of a

combination of 20 AAs, including nine essential AAs (EAAs) and 11

non-essential AAs (NEAAs). EAAs are defined as those AAs whose

carbon skeletons cannot be synthesized de novo or whose

endogenous production is insufficient to meet metabolic demands

(4,5). The fundamental nutritional roles of

AAs have long been well-established. However, recent studies have

highlighted their emerging functions as signaling molecules in the

regulation of energy balance and metabolic homeostasis. Beyond

their involvement in protein metabolism, AAs also serve as critical

molecular regulators of glucose and lipid metabolism (6,7).

Generally, AAs regulate cellular life activities

through two primary mechanisms: Metabolism and sensing. In the

context of AA sensing, the direct binding of AAs to specific

sensors represents a more evolutionarily streamlined and efficient

regulatory mechanism (8). The

human body's detection of elevated concentrations of specific AAs

can trigger the binding of these molecules to cell membranes or

intracellular sensors, thereby initiating transport processes or

signal transduction pathways (9). The human body's sensing of AA

concentrations can also occur indirectly through the detection of

surrogate molecules, such as metabolites, which reflect their

abundance (10). At the organism

level, distinct pathways for sensing intracellular and

extracellular AA concentrations are integrated and coordinated to

maintain systemic metabolic homeostasis. This adaptive response to

fluctuations in AA availability is orchestrated by a sophisticated

regulatory network (11). This

network comprises a variety of dynamic components, which play a

pivotal role in activating downstream effectors at both cellular

and molecular levels.

In cancer, these processes are reprogrammed to

fulfill the heightened metabolic demands of rapidly proliferating

cells, allowing tumors to sustain survival under nutrient-limited

conditions and to thrive across diverse microenvironments (12). Cancer cells exhibit reprogrammed

AAs metabolism, marked by enhanced uptake and utilization of

specific AAs, including glutamine, serine and glycine (13-16). This metabolic reprogramming

supports cancer cells in sustaining anabolic processes,

facilitating energy production and maintaining redox homeostasis

(15). Notably, the capacity to

sense AA levels in both extracellular and intracellular

compartments is intricately linked to these metabolic adaptations

(17). The AA sensing pathway

acts as a pivotal regulatory mechanism in determining cancer cell

fate, integrating nutrient availability with growth signaling and

stress response pathways (18,19). Key molecular sensors and

signaling pathways involved in AAs detection include the

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), general control

nonderepressible 2 (GCN2), activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)

and the Sestrin (SESN) family of proteins (20-23). These pathways play a pivotal role

in orchestrating cellular responses to AA levels fluctuations,

modulating protein synthesis, autophagy and metabolic

reprogramming. Furthermore, their dysregulation in cancer has

profound implications for tumor progression, metastasis and

therapeutic resistance.

Investigating the mechanisms of AA sensing and

identifying key AA sensors are crucial for deciphering the

regulatory networks that govern cellular life activities and

disease progression. These insights not only advance the

understanding of tumor biology but also unveil novel therapeutic

opportunities. By targeting AA sensing pathways or exploiting

metabolic vulnerabilities, it is possible to disrupt the metabolic

adaptability of cancer cells and suppress tumor growth. The present

review aimed to summarize current knowledge on AA sensing in

cancer, with a focus on its molecular mechanisms, implications for

tumor biology and potential therapeutic applications.

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a

central regulator of cell growth, orchestrating cellular

homeostasis in response to nutrients, growth factors (GFs) and

environmental cues (24). mTOR,

composed of 2,549 AAs, is a member of the phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase-related kinase superfamily, and assembles into two

functionally distinct complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and

mTORC2, through interactions with various accessory proteins

(24,25). mTORC1 serves as a central hub in

AA sensing (26) and it is

assembled from core components that form its functional

architecture (27,28). Among these, Raptor is a key

regulatory protein that binds to the TOR signaling motif,

facilitating the recruitment of mTORC1 substrates and stabilizing

the complex. In this complex, mTOR provides catalytic activity,

while the mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8 enhances the

stability of the mTOR kinase domain, making these components

indispensable for the assembly and functionality of mTORC1

(29,30). Non-core components, such as DEP

domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein and 40 kDa proline-rich

Akt substrate (PRAS40), act as negative regulators by binding to

mTOR and modulating its activity (31,32). FK506-binding protein 12 and

rapamycin form a ternary complex with the FRB domain of mTOR,

partially blocking substrate access to its kinase active site and

thereby mediating rapamycin's inhibitory effect on mTORC1 (33). mTORC1, together with its

downstream effector components, forms a comprehensive sensing

pathway. Moreover, mTORC1 is ubiquitously expressed across diverse

tissues and organs, playing a pivotal role, particularly in

metabolically active and rapidly proliferating tissues (34).

mTORC1 integrates diverse environmental signals,

including ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein 1, DNA

damage, ATP, GFs, AAs, glucose, cholesterol and oxygen. These

upstream signals enable mTORC1 to orchestrate distinct

physiological functions, thereby maintaining cellular and

organismal homeostasis (35-38). The upstream signals of mTORC1 can

be classified into two distinct categories based on their

dependency: GFs-dependent signals and AAs-dependent signals

(39). The specific mechanisms

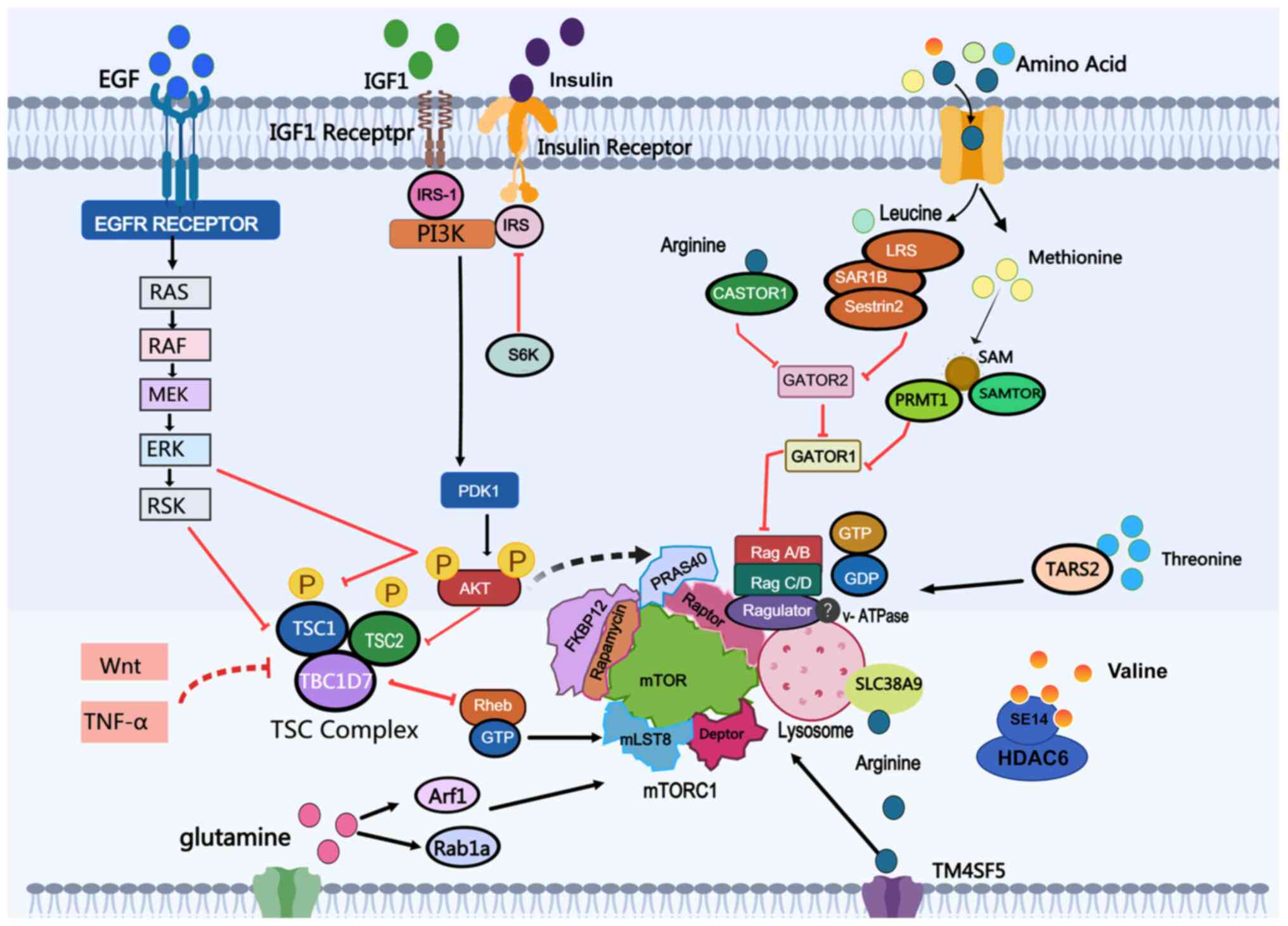

are presented in this section as shown in Fig. 1.

Nearly all GF-dependent signals are transduced

through the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)-Ras homolog enriched

in brain (Rheb) cascade. Rheb, a GTPase, directly binds to and

activates mTORC1, inducing a conformational change in the complex

(40). The biological activity

of Rheb is regulated by the TSC complex, which integrates multiple

upstream signals and modulates mTORC1. TSC functions as a

Rheb-specific GTPase-activating protein (GAP) and is composed of

TSC1, TSC2 and TBC1 Domain Family Member 7 (41). Receptor tyrosine kinase-dependent

RAS signaling activates mTORC1 via ERK and its downstream effector

p90 Ribosomal S6 Kinase, leading to the phosphorylation of TSC2

(42,43). Additionally, the EGF signal can

activate mTORC1 through AKT-Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 4-mediated

Rheb deubiquitination, resulting in the release of Rheb from the

TSC (44).

Unlike other signals, AAs regulate mTORC1 through

distinct pathways. The mechanisms underlying AAs' signal

transmission upstream of mTORC1 have been progressively elucidated

and specific sensors or signaling pathways for individual AAs have

also been identified (20). AA

sensing primarily operates through two pathways: The Rag

GTPase-mediated lysosomal sensing and the Rag-independent pathways,

along with the regulatory networks that fine-tune these processes

(38).

Rag GTPases, which form heterodimers (RagA or RagB

with RagC or RagD), play a critical role in lysosomal AA sensing

(47-49). Their nucleotide-binding states

dictate the recruitment of mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface

(50,51). When AAs are abundant, RagA/B are

GTP-bound, while RagC/D are GDP-bound. This configuration allows

the Rag GTPase heterodimer to bind Raptor and recruit mTORC1 to the

lysosomal surface for activation by Rheb. Under AA deprivation, the

Rag GTPase heterodimer switches to an inactive state (RagA/B

GDP-bound and RagC/D GTP-bound), causing mTORC1 to dissociate from

the lysosomal surface and preventing its activation. The activity

of Rag GTPase is tightly regulated by a network of complexes that

modulate its nucleotide-binding state, creating a robust mechanism

to couple nutrient availability with cell growth (52). Rag GTPase is anchored to the

lysosomal surface through its interaction with the Ragulator

complex, which consists of Late Endosomal/Lysosomal Adaptor, MAPK

and MTOR Activator (LAMTOR)1 (p18), LAMTOR2 (p14), LAMTOR3 (MP1),

LAMTOR4 (C1ORF59) and LAMTOR5 (HBXIP) (53). Myristoylation and palmitoylation

at the N-terminus of LAMTOR1 are critical for the lysosomal

localization of the Ragulator-Rag GTPase complex (53,54). AAs can induce conformational

changes in vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) and weaken its interaction

with the Ragulator complex, suggesting that lysosomal lumen AAs may

signal to Rag GTPases through V-ATPase and Ragulator. However, the

precise mechanism by which V-ATPase senses AAs remains to be

elucidated (55).

Although Rag GTPases are central in sensing

extracellular AAs and glucose levels, the regulatory network of

mTORC1 is more complex, encompassing pathways independent of Rag

GTPases. Certain alternative mechanisms can activate mTORC1

independently of Rag GTPases. For instance, the small GTPase Arf1

can substitute for Rag proteins to activate mTORC1 in response to

glutamine. Research has found that the downregulation of Arf1

expression in pancreatic cancer (PC) can promote tumor

proliferation, migration and invasion and is considered to be

associated with the glutamine-sensing role of Arf1 in PC (56). Additionally, glutamine stimulates

Rab1a, facilitating the interaction between mTORC1 and Rheb at the

Golgi apparatus, thereby bypassing lysosomal recruitment (57,58). It is noteworthy that the role of

Rab1a varies across different tumors. Overexpression of Rab1a is

markedly associated with short-term survival and metastasis in

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with elevated Rab1a levels

correlating with sensitivity to Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) inhibitors.

Conversely, Rab1a overexpression renders cancer cells vulnerable to

JAK1-targeted therapies (59).

However, in breast cancer, downregulation of Rab1a inhibits cell

growth, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(60). These pathways underscore

the adaptability of mTORC1 in responding to diverse cellular

conditions.

The identification of AA sensors marks a

breakthrough in the field of AA sensing, as these are pivotal in

regulating mTORC1 activity (62). As key molecular detectors of

intracellular and lysosomal AA levels, these sensors are localized

in the cytosol and lysosomal compartments, where they recognize

specific AAs and transduce signals to mTORC1 through diverse

molecular mechanisms (63).

The leucine sensor was the first to be discovered.

Initially identified for their roles in oxidative stress responses,

SESN1 and SESN2 did not garner significant attention from

researchers. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that SESN1

and SESN2 inhibit the mTORC1 pathway through the AMPK-TSC signaling

axis (64,65). The absence of SESN1 and SESN2

abolishes mTORC1 inhibition under leucine deprivation.

Additionally, SAR1 homolog B (SAR1B) and leucyl-transfer (t)RNA

synthetase were proposed as alternative leucine sensors by some

researchers (66,67). While multiple mechanistic

hypotheses were proposed, the precise mechanisms remain unclear.

Cytosolic Arginine Sensor For MTORC1 Subunit 1 (CASTOR1) inhibits

GAP Activity Towards Rags (GATOR)2 under arginine-deprived

conditions, thereby suppressing mTORC1 activation. In the presence

of arginine, however, arginine binds to CASTOR1, disrupting its

interaction with GATOR2 and activating mTORC1 signaling (68,69). Transmembrane 4 L six family

member 5 (TM4SF5) is a transmembrane protein that acts as an

arginine sensor by binding arginine via its extracellular loop

(70). In contrast to CASTOR1,

TM4SF5 translocates to the lysosome under arginine-replete

conditions and directly promotes mTORC1 activation (71). Methionine, a key nutritional

regulator of mTORC1 activation, is sensed indirectly through its

metabolite S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), unlike other AAs (72). Under methionine-deprived

conditions, SAM Sensor Upstream Of mTORC1 (SAMTOR) binds to GATOR1,

enhancing its GAP activity and inhibiting mTORC1. By contrast,

under methionine-replete conditions, SAMTOR dissociates from

GATOR1, while Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1)

methylates NPR2 Like, GATOR1 Complex Subunit to suppress GATOR1

activity, thereby activating mTORC1. Additionally, mitochondrial

threonyl-tRNA synthetase 2 (TARS2) was identified as a sensor for

threonine. In the presence of threonine, TARS2 interacts with

inactive Rag GTPase, promoting GTP loading on RagA and facilitating

mTORC1 activation (73). Solute

carrier family 38 member 9 serves as an intrinsic lysosomal AA

sensor, specifically detecting arginine. Moreover, it mediates the

efflux of other AAs, such as leucine, from lysosomes, thereby

promoting mTORC1 activation under nutrient-deprived conditions

(74-76).

mTORC1 is critical in regulating cellular

homeostasis and growth, and its dysregulation is strongly linked to

the pathogenesis of various diseases, including cancer. Genetic

mutations and environmental factors can both drive tumorigenesis by

disrupting mTORC1 activity. Recent studies highlighted the critical

role of the AA-mTORC1 signaling axis in cancer biology.

Under nutrient-replete conditions, including ample

AAs and GFs, mTORC1 phosphorylates downstream substrates, activates

anabolic processes such as protein synthesis and promotes cell

growth (77). mTORC1 inhibits

eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), causing

its dissociation from eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E

and enhancing mRNA translation efficiency. This mechanism allows

tumor cells to rapidly synthesize cell cycle-related proteins and

growth-promoting factors (78).

The phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 by mTORC1 is critically involved in

breast cancer (BC) and plays a similarly critical role in the

progression of colorectal cancer (CRC) and head and neck squamous

cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (79,80). Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1

(S6K1) regulates cell growth, ribosome biogenesis, glucose

homeostasis, and lipogenesis, with the critical role of mTORC1 in

these processes being well-established (81). mTORC1 activates S6K1, which

phosphorylates the S6 protein and other targets, enhancing ribosome

biogenesis and translation efficiency, thereby driving cellular

growth and proliferation (82)

In NSCLC, the activation of ATF4-induced Developmental and DNA

Damage Response 1 inhibits mTORC1/S6K1 signaling, complicating

therapeutic interventions (83).

Metabolic reprogramming in tumors has been widely

recognized in recent years as a hallmark of tumorigenesis and

cancer progression (84). To

support their sustained growth, tumor cells undergo extensive

adaptations in energy metabolism (85). mTORC1 plays a pivotal role in the

metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells. By modulating the uptake

and utilization of AAs, tumor cells obtain essential substrates for

growth and proliferation, thereby sustaining their rapid expansion

and survival (86). mTORC1 also

drives de novo lipid synthesis by activating sterol

regulatory element-binding proteins and enhances nucleotide

biosynthesis via S6K1-dependent activation of Carbamoyl Phosphate

Synthetase 2-Aspartate Transcarbamylase-Dihydroorotase, the

rate-limiting enzyme in pyrimidine synthesis (87). CRC development is associated with

mTORC1 dysregulation, where aberrant AA sensing drives tumor growth

and metabolic reprogramming (88).

In addition to promoting anabolic metabolism, mTORC1

also suppresses catabolic autophagy, thereby preventing the

degradation of newly synthesized cellular components (89). Furthermore, AA

deprivation-induced autophagy is predominantly mediated by the

mTORC1 signaling pathway, enabling the recycling of intracellular

components and ensuring that cancer cells sustain high metabolic

activity (89,90). Under nutrient-replete conditions,

mTORC1 promotes cell growth and suppresses autophagy. By contrast,

under nutrient-deprived conditions, mTORC1 inhibition induces

autophagy to sustain cellular metabolism (89). Autophagy activation and increased

glutamine synthesis are critical for maintaining AA homeostasis

during starvation. Glutamine metabolism is sufficient to restore

mTORC1 activity during prolonged AA deprivation in an

autophagy-dependent manner (91).

AA sensors drive cancer development and progression

by promoting mTORC1 hyperactivation in tumor. The role of SESN2 in

cancer is complex, with its effects potentially varying across

tumor types. In CRC, SESN2 promotes tumor cell growth while

modulating p53 in the context of mTORC1 signaling (92). However, in NSCLC, SESN2

differentially regulates mTORC1 and mTORC2, reprogramming lipid

metabolism and enabling the survival of glutamine-deprived cancer

cells by maintaining energy and redox homeostasis (93). SAR1B is frequently deleted in

lung cancer (LC). A study showed that inhibiting SAR1A and SAR1B

promotes mTORC1-dependent tumor growth in mouse xenograft models

(66). PRMT1 upregulation is

critical in the development and progression of multiple solid

tumors and leukemias (94,95).

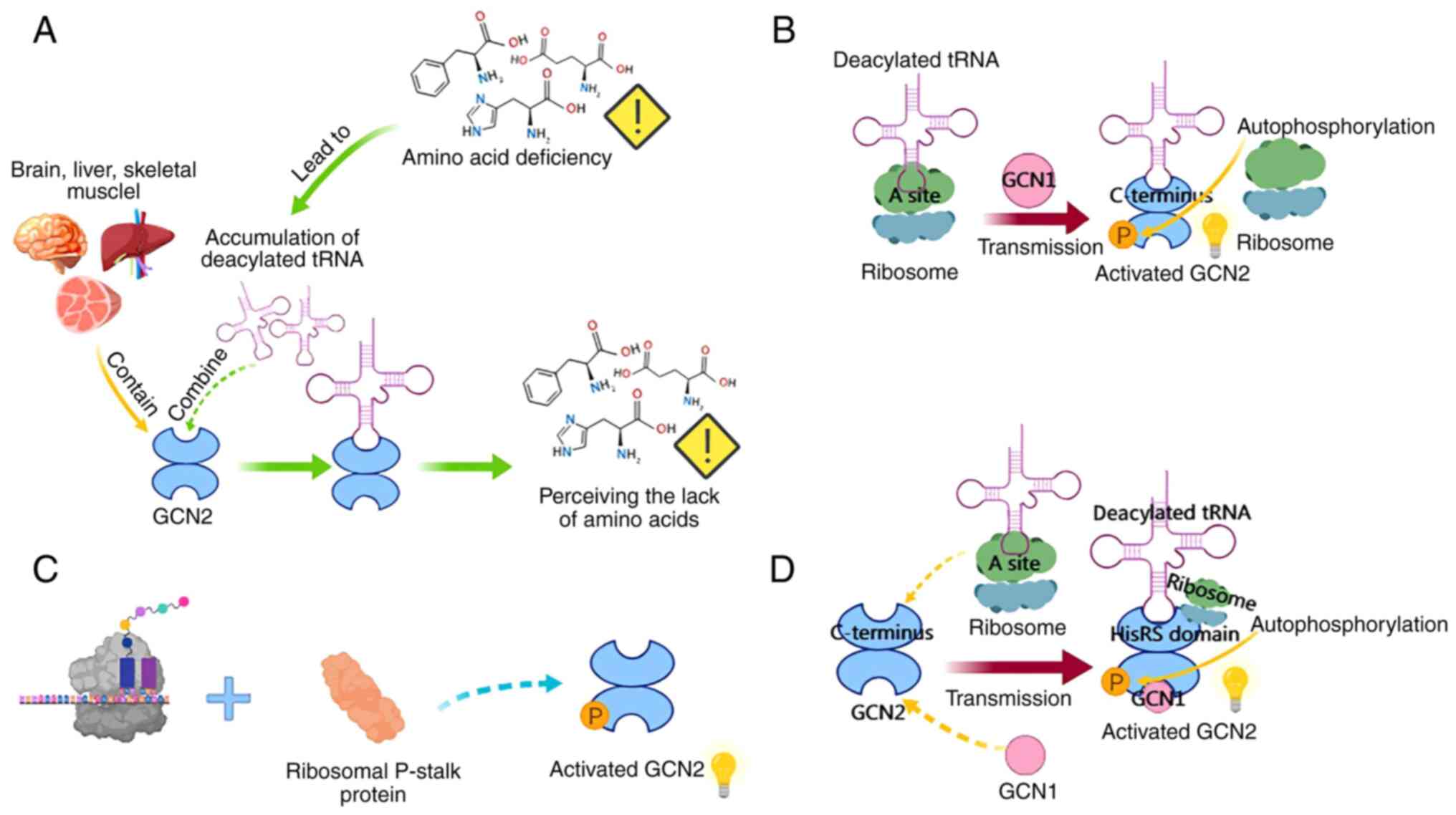

General control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2), a member

of the conserved serine/threonine kinase family, primarily senses

AA deficiency by binding to deacylated tRNA. It serves as a key

kinase in the cellular response to AA starvation or ribosomal

stress (96-98). GCN2 consists of five conserved

domains and forms an inactive homodimer. Its autoinhibitory

molecular interactions prevent aberrant activation of the kinase

domain under basal conditions (99). In mammals, GCN2 is ubiquitously

expressed, with particularly high levels in the brain, liver and

skeletal muscle (100-102). The GCN2 signaling pathway

comprises core components, including GCN2, deacylated tRNA and

GCN1, as well as downstream regulators such as eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), ATF4 and fibroblast

growth factor 21. Together, they sense AAs deficiency and regulate

cellular and organismal metabolic homeostasis (103-105).

GCN2 interacts with GCN1 via its RWD domain and

associates with the ribosome to promote activation (105). GCN1 transfers deacylated tRNA

from the ribosomal A site to GCN2, thereby activating GCN2

(106). Notably, this

deacylated tRNA accumulates in cells under AA deprivation (97). Deacylated tRNA acts as an

intracellular sensor of AA deficiency, interacting with the

C-terminal region of GCN2, particularly the HisRS-like domain,

which also participates in the autoinhibition of the kinase domain

(96,107). The HisRS-like domain of GCN2 is

a pseudoenzyme capable of directly binding deacylated tRNA

(96). Beyond deacylated

tRNA-related mechanisms, GCN2 can also be activated through

ribosomal translation stalling and the ribosomal P-stalk (108,109). The relationship between these

two mechanisms has long been a puzzle. Recent studies showed that

deacylated tRNA binds to the HisRS domain to activate GCN2, while

the ribosomal P-stalk protein serves as an alternative activating

ligand on stalled ribosomes (107). GCN2 undergoes

autophosphorylation upon activation, which, together with eIF2α

phosphorylation, can serve as a useful biomarker for determining

the activation status of GCN2 in cancer samples (103). The specific mechanism is shown

in Fig. 2.

GCN2 has been strongly linked to various cancers and

hematological malignancies (110,111). Compared with healthy tissues,

the total levels of GCN2 and phosphorylated GCN2 are markedly

elevated in tissue samples from CRC, NSCLC, BC and hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) (21). As a

central sensor of AA availability, GCN2 orchestrates the cellular

response to nutrient deprivation, a common challenge for rapidly

proliferating tumor cells. GCN2 maintains intracellular homeostasis

by modulating protein synthesis (112), upregulating AA transporters

(98), promoting autophagy

(113,114) and enhancing the utilization of

scarce AAs for protein synthesis (115). These functions highlight the

pivotal role of GCN2 in sustaining tumor cell stability and driving

tumorigenesis.

Under severe AA deprivation, GCN2 enhances ATF4

expression, directly inducing the stress-response protein SESN2

(116). SESN2 plays a critical

role in maintaining mTORC1 inhibition by preventing its lysosomal

localization, ultimately resulting in a significant reduction in

overall protein synthesis in cancer cells (117). Additionally, under leucine or

arginine deprivation, GCN2 can suppress mTORC1 activity through an

ATF4-independent mechanism (102,118). Under AA deprivation, GCN2

activation and mTORC1 inhibition coordinately maintain organismal

metabolic homeostasis (105).

These mechanisms directly influence cancer cell survival by

maintaining AA homeostasis. The integrated stress response (ISR) is

a critical cellular mechanism that protects against environmental

stress. A key feature of GCN2 in the ISR is its function as an AA

depletion sensor (119).

Combining tumor asparagine synthesis restriction with dietary

asparagine limitation effectively suppresses tumor growth in

multiple murine cancer models, a process mediated by the GCN2-ATF4

pathway (120). Proline

deprivation in melanoma cells also activates GCN2, leading to

reduced protein synthesis (121). In CRC, arginine deprivation

activates the GCN2 pathway, suppressing protein synthesis through

mTOR signaling inhibition (122). Arginine can mitigate interferon

(IFN)-γ-induced malignant transformation of mammary epithelial

cells, including the suppression of cell proliferation, migration

and colony formation, potentially via the NF-κB-GCN2/eIF2α pathway

(123). Additionally, arginine

deprivation induces a comprehensive stress response, promoting cell

cycle arrest and quiescence in HCC cells, a process also dependent

on GCN2. Preclinical studies demonstrated that combining dietary

arginine restriction, GCN2 inhibition and pharmacological treatment

enhances apoptosis in HCC cells and induces tumor regression,

closely linked to reduced mRNA and protein levels (102).

GCN2 regulates the expression of >60 solute

carrier (SLC) genes, reducing AA levels. Following GCN2 deletion,

supplementation with essential AAs partially restored the

proliferation of GCN2-deficient prostate cancer (PCa) cells,

highlighting the critical role of GCN2-mediated SLC transporter

regulation in maintaining AA homeostasis for PCa growth (124). GCN2 plays a pivotal role in

redirecting scarce AAs from diverse metabolic pathways to protein

synthesis, particularly under AA deprivation (125). Tryptophan, an essential AA, is

among the rarest encoded by the genetic code, with roles extending

beyond its function as a fundamental protein building block

(126). Tryptophan-degrading

enzymes, such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) and

tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, are frequently upregulated in various

cancers, as their metabolites are critical in tumor immune evasion

(127,128). When tumors experience

insufficient blood supply, their demand for oxygen and essential

nutrients (glucose and AAs) increases. A key adaptive strategy

employed by tumors is to restore blood supply through the

angiogenic switch (129).

Limiting sulfur-containing AAs triggers angiogenesis by

upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor expression in

endothelial cells in vitro, enhancing their migration and

sprouting. This process also increases capillary density via the

GCN2/ATF4 AA starvation response pathway (130). In specific cancers, such as CRC

and gastric cancer, mitochondrial signaling activates GCN2, driving

a metabolic shift toward glycolysis. This shift represents a

strategic adaptation in energy production to support cell

proliferation and survival (131,132). Tumors employ alternative

bioenergetic pathways to offset the energy and catabolic demands of

rapid, uncontrolled proliferation under glucose deprivation. These

pathways include glutamine metabolism, where glutamine is utilized

for mitochondrial ATP production and serves as a carbon and

nitrogen source for synthesizing AAs, nucleotides and lipids

(133). As a precursor for AA

synthesis, glutamine deprivation disrupts this AA supplementation

pattern in tumors, resulting in starvation, deacylated tRNA

accumulation and activation of the GCN2–ATF4 pathway (134,135). Under NEAA deficiency, the

GCN2-ATF4 pathway is essential for the long-term survival of

several solid tumors and mitigates the resulting stress (136,137). The GCN2 pathway may also drive

cancer progression within the tumor microenvironment by modulating

immune responses, as GCN2 acts as a key regulator of macrophage

functional polarization and CD4+ T cell subset

differentiation (138). The

mechanisms by which GCN2 regulates macrophages and T cells are

relatively complex. Depleting the single AA arginine from the

culture medium can strongly activate the GCN2 pathway in T cells,

and the deprivation of arginine in activated CD8+ T

cells leads to the activation of the GCN2-ATF4 stress response

pathway (113). Under prolonged

stimulation with IFN-γ, melanoma cells undergo IDO1-mediated

tryptophan depletion, leading to frameshift mutations during mRNA

translation and the production of mutated peptides. These mutated

peptides can be recognized by T cells, thereby activating them

(139). The absence of GCN2 in

T cells is associated with proliferation defects during the

activation process. In a murine glioma model, CD8+ T

cells lacking GCN2 exhibit impaired antitumor immunity. However, in

the B16 melanoma model, the specific deletion of GCN2 did not

affect antitumor immunity; however, the underlying mechanisms

warrant further investigation (113). A related study on melanoma

found that the deletion of GCN2 in myeloid-derived suppressor cells

promotes the phenotypic transformation of tumor-associated

macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, thereby enhancing

the antitumor immune response. This phenomenon is attributed to

alterations in the tumor microenvironment, characterized by an

increase in pro-inflammatory activation of macrophages and

myeloid-derived suppressor cells, as well as elevated expression of

IFN-γ in intratumoral CD8+ T cells. Mechanistically,

cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-2/ATF4 is essential

for the maturation and polarization of macrophages and

myeloid-derived suppressor cells in both mice and humans. GCN2

modifies the function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by

promoting the enhanced translation of the transcription factor

CREB-2/ATF4 (140).

GCN2 activation may enhance tumor cell resistance to

chemotherapy and radiotherapy by regulating stress responses and

metabolic adaptations, promoting survival under therapeutic stress.

In hematological malignancies, multiple myeloma (MM) is notoriously

challenging to treat and highly prone to drug resistance. GCN2

inhibition was shown to exhibit synergistic effects with proteasome

inhibitors, offering potential new therapeutic strategies for MM

(141,142). Moreover, treating certain MM

cells with ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, induces AA

depletion, GCN2 activation and subsequent suppression of protein

synthesis. This suggests that GCN2 regulates tumor survival by

responding to diverse metabolic stresses (143). The role of GCN2 in reactive

oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis may contribute to its ability to

promote chemotherapy resistance. Inhibiting GCN2 with the inhibitor

GCN2iB prevents the recovery of certain MM cells (144). Following stress, GCN2

inhibition not only alters AA levels, consistent with its classical

function, but also modulates glutathione, N-acetylcysteine and

cysteine levels, suggesting that GCN2 also aids cells in recovering

from chemotherapy-induced ROS stress.

mTORC1 and GCN2 are central in the metabolism of

cancer cells, which often encounter extreme nutritional conditions,

such as AA deprivation. These cells must rely on effective

signaling networks to adapt to these changes (145). The regulatory network between

mTORC1 and GCN2 represents a classic dynamic equilibrium and

coordinated response system. By sensing the availability of AAs,

these two entities interact and coordinate with each other to

jointly regulate cellular metabolic activities, thereby influencing

cancer growth, survival, metastasis and drug resistance (146).

Arginine is a conditionally EAA, whose metabolic

processes play a critical role in cancer biology and immunotherapy,

being associated with the onset, progression and immune evasion of

cancer (146). When

intracellular levels of arginine are sufficient, mTORC1 is

activated, promoting protein synthesis and cell growth (147). In the context of arginine

deficiency, GCN2 is activated as an AA stress sensor, inhibiting

translation to conserve AA resources and facilitating cellular

adaptation to an environment deficient in AAs (148). HCC continuously suppresses the

expression of urea cycle genes, thereby exhibiting a

nutrient-dependent relationship with exogenous arginine. Arginine

can be interconverted with proline and glutamate and it promotes

cell growth by activating mTORC1 (149). Under the influence of the GCN2

kinase, arginine deficiency promotes cell cycle arrest and

quiescence in HCC cells (102).

Arginine deficiency can lead to the inhibition of mTORC1 and the

activation of GCN2, thereby maintaining the survival strategies of

cells. This mechanism assists HCC cells in continuing to

proliferate in adverse microenvironments, playing a crucial role,

particularly in the drug resistance and metastasis of HCC. LC also

exhibits an absolute deficiency of arginine; however, there is a

lack of further research findings in this direction (150).

Glutamine is a critically important AA in the

metabolism of cancer cells. It not only participates in protein

synthesis but also serves as a nitrogen source for metabolic

processes within the cell (151). In the absence of glutamine,

activated GCN2 upregulates ATF4 to induce the expression of the

stress response protein SESN2, which is crucial for maintaining the

inhibition of mTORC1. Furthermore, the induction of SESN2 during

glutamine deprivation is essential for cell survival, indicating

that SESN2 serves as a significant effector molecule in the GCN2

signaling pathway, regulating AA homeostasis through the inhibition

of mTORC1. PC is characterized by an increased dependency on

glutamine metabolism (152).

Increased glutamine uptake can promote the progression of PC via

the mTORC1 pathway (153). In

PC characterized by glutamine depletion, the activation of GCN2 can

inhibit translation initiation, thereby enabling adaptation to this

environment (112).

The role of the AA sensing mechanisms in cancer

therapy has attracted growing attention, primarily involving the

two key pathways, mTORC1 and GCN2. By detecting and responding to

intracellular and extracellular AA levels, these pathways regulate

cellular growth, metabolism and survival, playing a crucial role in

cancer cell adaptation to nutrient stress and hostile

microenvironments. Overall, targeted therapies leveraging AA

sensing mechanisms not only offer novel perspectives for cancer

treatment but may also synergize with existing therapies to enhance

efficacy and overcome resistance, holding substantial clinical

potential. In the subsequent sections, the present review

summarizes therapeutic agents targeting AA sensing mechanisms in

cancer, their respective targets and recent advancements in this

field.

In cancer, hyperactivation of the mTORC1 signaling

pathway is frequently observed, with mTOR mutations identified in

multiple malignancies (154,155). Traditional mTOR inhibitors,

such as rapamycin and its analogs, exhibit moderate clinical

anticancer activity, primarily through mTORC1 inhibition (154). Although rapamycin analogs

demonstrated clinical efficacy in cancer, they have not fully

unlocked the antitumor potential of mTOR targeting. Given the

pivotal role of the mTOR kinase domain in mediating both

rapamycin-sensitive and rapamycin-insensitive functions, mTOR

catalytic inhibitors were developed as second-generation anti-mTOR

agents. Notably, these inhibitors demonstrate potent antitumor

activity in vitro and in vivo (156). Vistusertib, also known as

AZD2014, is a newly developed mTORC1/2 kinase inhibitor that

demonstrated superior efficacy compared with rapamycin. A clinical

trial involving refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma revealed

that AZD2014 markedly delays the time to cancer regrowth when

compared with everolimus (157). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small RNA

molecules that regulate gene expression and play roles in diverse

biological processes, including cancer progression. Studies

demonstrated that targeting the mTOR pathway with miRNAs offers

potential for improving the efficacy of radiotherapy (RT) (158).

The PI3K/protein kinase B (PKB)/mTOR signaling

pathway plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of

various cancers by suppressing apoptosis and promoting cancer cell

proliferation. Generally, multi-target inhibitors within this

pathway are more effective than single-target inhibitors. PI3Kα

inhibitors demonstrate clinical efficacy in patients with estrogen

receptor-positive BC harboring PIK3CA mutations, providing insights

into mTOR signaling reactivation as a mechanism of resistance to

PI3Kα inhibition (159).

Alpelisib is recognized as the only approved PI3Kα inhibitor for BC

treatment (160). However, a

recent study on the allosteric, mutant-selective PI3Kα inhibitor

STX-478 demonstrated its ability to suppress tumor growth in mice

with PIK3CA mutations without inducing hyperglycemia or other

metabolic dysfunctions. Upon approval, it may emerge as a

next-generation therapeutic candidate (161). Beyond solid tumors, PI3Kα

inhibitors are also employed in treating hematological

malignancies, particularly lymphomas (162).

However, treatment with the GCN2 inhibitor GCN2ib

alleviates adipocyte-mediated translational repression, rescuing

ALL cell quiescence. This intervention markedly diminishes the

protective effects of adipocytes against chemotherapy and other

external stressors, offering a novel therapeutic opportunity for

ALL (163). Pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is characterized by a highly inflammatory

tumor microenvironment, marked by significant heterogeneity,

metastatic potential and extreme hypoxia, making it a highly

aggressive malignancy (164).

Combining GCN2 inhibitors with redox factor-1 inhibitors markedly

enhances the therapeutic efficacy of targeted therapies against

PDAC (165). Additionally,

research confirmed that the rapid activation of GCN2 following

treatment with the WEE1 kinase inhibitor AZD1775 in small cell lung

cancer (SCLC) triggers a stress response in SCLC cells, thereby

enhancing the efficacy of WEE1 inhibitors in this context (166). Combined targeting

strategies AA transporter inhibitors directly modulate AA

sensing pathways, including mTORC1 and GCN2, by restricting

nutrient uptake in tumors, thereby reshaping the immune

microenvironment. Their synergy with stress pathways, immunotherapy

and metabolic interventions provides novel avenues for cancer

treatment.

L-type AA transporter 1 (LAT1) is involved in AA

transport and metabolism, with JPH203 serving as a potent inhibitor

of this target (167). JPH203

markedly sensitizes cancer cells to radiation at minimally toxic

concentrations and is expected to enhance the efficacy of RT when

used in combination (168).

Furthermore, JPH203 inhibits the proliferation of human thyroid

cancer cell lines and mTORC1 signaling by blocking LAT1. In a fully

immunocompetent mouse model of thyroid cancer, treatment with

JPH203 resulted in the in vivo growth arrest of thyroid

tumors (169). The first Phase

I trial of JPH203 in a cohort of patients with advanced solid

tumors revealed that, among 17 patients, after excluding two who

withdrew from the study due to grade 3 hepatic impairment, the

disease control rate in the remaining patients with

cholangiocarcinoma was 60% (170). V-9302, a small-molecule

antagonist of the glutamine transporter ASCT2, was shown to

effectively suppress intracellular glutamine levels and disrupt

downstream glutamine metabolism. Mechanistically, V-9302 induces

apoptosis and autophagy, enhances oxidative stress and inhibits the

mTORC1 signaling pathway (171). This compound exhibited potent

antitumor activity by attenuating the growth and proliferation of

HNSCC. A new alternative to V-9302, Yuanhuacine, was also

demonstrated to serve as a potential therapeutic agent for HNSCC by

modulating ASCT2-mediated glutamine metabolism (172).

AA sensing serves as a fundamental regulatory

mechanism for cellular metabolic homeostasis and is critically

implicated in tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Its emerging

role in cancer metabolism has positioned it as a promising

therapeutic target. Classical AA sensing pathways, including the

mTORC1 and GCN2 axes, have been extensively characterized for their

roles in cancer metabolic reprogramming. Specifically, mTORC1

promotes anabolic processes to fuel cell growth under AAs-dependent

conditions, whereas GCN2 activates the ISR via detection of

uncharged tRNAs during nutrient scarcity, thereby suppressing

global protein synthesis while facilitating stress-adaptive gene

expression. Recent advances unveiled novel perceptual mechanisms,

such as the discovery in 2025 that HDAC6 can function as a sensor

for valine, participating in a tumor-specific AA sensing network

(173). This finding enhances

the understanding of the complexity and context-dependence of these

regulatory systems. Within the tumor microenvironment, malignant

cells exploit AA sensing pathways to overcome metabolic

constraints, thereby enhancing proliferation, evading apoptosis and

developing therapeutic resistance. Clinically, dysregulated AA

sensing correlates with aggressive tumor phenotypes, metastatic

dissemination and chemoresistance. These insights have spurred

therapeutic innovations, including targeted pathway inhibitors and

AA-restricted dietary regimens, which demonstrate preclinical

efficacy in modulating tumor metabolism.

Despite progress in understanding AA sensing in

tumorigenesis and metastasis, several challenges remain. Tumor

subtype-specific AA dependencies complicate precision therapies,

while functional redundancy among sensing pathways may trigger

compensatory mechanisms. Additionally, the crosstalk between AA

sensing and broader metabolic networks, including glycolysis and

lipid metabolism, remains unclear. Future research should focus on

developing dual-target inhibitors, identifying novel AA sensors and

mapping tumor-specific AA dependencies across cancers. At the

single-cell level, exploring pathway heterogeneity could provide

insights into differential tumor cell responses. Moreover,

combining nutritional interventions with drug therapies may offer

new strategies to target cancer metabolism. However, challenges

such as tissue specificity and model differences must be addressed

to improve the translation of these findings into clinical

practice.

Not applicable.

CWZ conceived the study, developed methods,

performed analyses and drafted the manuscript. YXH contributed to

methodology, data analysis and manuscript editing. WYY provided

conceptual guidance, resources, and supervised the project. QH

assisted with experimental validation and manuscript revision. NC

led the study design, secured funding and oversaw all research

phases. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Professor Na Chen ORCID: 0009-0006-6119-9211. Dr

Chaowei Zhang ORCID: 0000-0001-7017-1954.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China under (grant no. 62372276).

|

1

|

Gao S, Qian X, Huang S, Deng W, Li Z and

Hu Y: Association between macronutrients intake distribution and

bone mineral density. Clin Nutr. 41:1689–1696. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Golshan M, Dortaj H, Rajabi M, Omidi Z,

Golshan M, Pourentezari M and Rajabi A: Animal origins free

products in cell culture media: A new frontier. Cytotechnology.

77:122025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Hellmann A, Turyn J, Zwara A, Korczynska

J, Taciak A and Mika A: Alterations in the amino acid profile in

patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma with and without

Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14:11992912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Thompson R and Pickard BS: The amino acid

composition of a protein influences its expression. PLoS One.

19:e02842342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li B, Roden DM and Capra JA: The 3D

mutational constraint on amino acid sites in the human proteome.

Nat Commun. 13:32732022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang Y, Fan C, Zhang Y, Kang T and Jiang

J: Untargeted metabolomics reveals the role of lipocalin-2 in the

pathological changes of lens and retina in diabetic mice. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 65:192024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhu ZG, Ma JW, Ji DD, Li QQ, Diao XY and

Bao J: Mendelian randomization analysis identifies causal

associations between serum lipidomic profile, amino acid biomarkers

and sepsis. Heliyon. 10:e327792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jin J, Meng T, Yu Y, Wu S, Jiao CC, Song

S, Li YX, Zhang Y, Zhao YY, Li X, et al: Human HDAC6 senses valine

abundancy to regulate DNA damage. Nature. 637:215–223. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Scalise M, Console L, Rovella F, Galluccio

M, Pochini L and Indiveri C: Membrane transporters for amino acids

as players of cancer metabolic rewiring. Cells. 9:20282020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ma Y, Han X, Fang J and Jiang H: Role of

dietary amino acids and microbial metabolites in the regulation of

pig intestinal health. Anim Nutr. 9:1–6. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Van Winkle LJ: Amino acid transport and

metabolism regulate early embryo development: Species differences,

clinical significance, and evolutionary implications. Cells.

10:31542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Grobben Y: Targeting amino

Acid-metabolizing enzymes for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol.

15:14402692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu N, Shi F, Yang L, Liao W and Cao Y:

Oncogenic viral infection and amino acid metabolism in cancer

progression: Molecular insights and clinical implications. Biochim

Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1877:1887242022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fan Y, Xue H, Li Z, Huo M, Gao H and Guan

X: Exploiting the Achilles' heel of cancer: Disrupting glutamine

metabolism for effective cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol.

15:13455222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wu D, Zhang K, Khan FA, Pandupuspitasari

NS, Guan K, Sun F and Huang C: A comprehensive review on signaling

attributes of serine and serine metabolism in health and disease.

Int J Biol Macromol. 260:1296072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kadivar D, Eslami Moghadam M and Notash B:

Effect of geometric isomerism on the anticancer property of new

platinum complexes with glycine derivatives as asymmetric N, O

donate ligands against human cancer. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol

Spectrosc. 322:1248092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kelly B and Pearce EL: Amino Assets: How

Amino Acids Support Immunity. Cell Metab. 32:154–175. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hushmandi K, Einollahi B, Saadat SH, Lee

EHC, Farani MR, Okina E, Huh YS, Nabavi N, Salimimoghadam S and

Kumar AP: Amino acid transporters within the solute carrier

superfamily: Underappreciated proteins and novel opportunities for

cancer therapy. Mol Metab. 84:1019522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jakobsen S and Nielsen CU: Exploring amino

acid transporters as therapeutic targets for cancer: An examination

of inhibitor structures, selectivity issues, and discovery

approaches. Pharmaceutics. 16:1972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhang S, Lin X, Hou Q, Hu Z, Wang Y and

Wang Z: Regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids in mammalian cells: A

general picture of recent advances. Anim Nutr. 7:1009–1023. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gold LT and Masson GR: GCN2: Roles in

tumour development and progression. Biochem Soc Trans. 50:737–745.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Tang H, Kang R, Liu J and Tang D: ATF4 in

cellular stress, ferroptosis, and cancer. Archi Toxicol.

98:1025–1041. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jiang C, Dai X, He S, Zhou H, Fang L, Guo

J, Liu S, Zhang T, Pan W and Yu H: Ring domains are essential for

GATOR2-dependent mTORC1 activation. Mol Cell. 83:74–89.e9. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Berdenis van Berlekom A, Kübler R,

Hoogeboom JW, Vonk D, Sluijs JA, Pasterkamp RJ, Middeldorp J,

Kraneveld AD, Garssen J, Kahn RS, et al: Exposure to the amino

acids histidine, lysine, and threonine reduces mTOR activity and

affects neurodevelopment in a human cerebral organoid model.

Nutrients. 14:21752022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kumar M, Sahoo SS, Jamaluddin MFB and

Tanwar PS: Loss of liver kinase B1 in human seminoma. Front Oncol.

13:10811102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yue S, Li G, He S and Li T: The central

role of mTORC1 in amino acid sensing. Cancer Res. 82:2964–2974.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kaizuka T, Hara T, Oshiro N, Kikkawa U,

Yonezawa K, Takehana K, Iemura S, Natsume T and Mizushima N: Tti1

and Tel2 are critical factors in mammalian target of rapamycin

complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 285:20109–20116. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xu C, Pan X, Wang D, Guan Y, Yang W, Chen

X and Liu Y: O-GlcNAcylation of Raptor transduces glucose signals

to mTORC1. Mol Cell. 83:3027–3040.e11. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jie H, Wei J, Li Z, Yi M, Qian X, Li Y,

Liu C, Li C, Wang L, Deng P, et al: Serine starvation suppresses

the progression of esophageal cancer by regulating the synthesis of

purine nucleotides and NADPH. Cancer Metab. 13:102025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fu Y, Fu Z, Su Z, Li L, Yang Y, Tan Y,

Xiang Y, Shi Y, Xie S, Sun L and Peng G: mLST8 is essential for

coronavirus replication and regulates its replication through the

mTORC1 pathway. mBio. 14:e00899232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ma K, Xian W, Liu H, Shu R, Ge J, Luo ZQ,

Liu X and Qiu J: Bacterial ubiquitin ligases hijack the host

deubiquitinase OTUB1 to inhibit MTORC1 signaling and promote

autophagy. Autophagy. 20:1968–1983. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang C and Jiang D: Exogenous PRAS40

reduces KLF4 expression and alleviates hypertrophic scar fibrosis

and collagen deposition through inhibiting mTORC1. Burns.

50:936–946. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ye Q, Zhou W, Xu S, Que Q, Zhan Q, Zhang

L, Zheng S, Ling S and Xu X: Ubiquitin-specific protease 22

promotes tumorigenesis and progression by an

FKBP12/mTORC1/autophagy positive feedback loop in hepatocellular

carcinoma. MedComm (2020). 4:e4392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Fernandes SA, Angelidaki DD, Nüchel J, Pan

J, Gollwitzer P, Elkis Y, Artoni F, Wilhelm S, Kovacevic-Sarmiento

M and Demetriades C: Spatial and functional separation of mTORC1

signalling in response to different amino acid sources. Nat Cell

Biol. 26:1918–1933. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Meng D, Yang Q, Melick CH, Park BC, Hsieh

TS, Curukovic A, Jeong MH, Zhang J, James NG and Jewell JL: ArfGAP1

inhibits mTORC1 lysosomal localization and activation. EMBO J.

40:e1064122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Daigh LH, Saha D, Rosenthal DL, Ferrick KR

and Meyer T: Uncoupling of mTORC1 from E2F activity maintains DNA

damage and senescence. Nat Commun. 15:91812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Condon KJ, Orozco JM, Adelmann CH,

Spinelli JB, van der Helm PW, Roberts JM, Kunchok T and Sabatini

DM: Genome-wide CRISPR screens reveal multitiered mechanisms

through which mTORC1 senses mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 118:e20221201182021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Jiang C, Tan X, Liu N, Yan P, Hou T and

Wei W: Nutrient sensing of mTORC1 signaling in cancer and aging.

Semin Cancer Biol. 106-107:1–12. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhu M, Teng F, Li N, Zhang L, Zhang S, Xu

F, Shao J, Sun H and Zhu H: Monomethyl branched-chain fatty acid

mediates amino acid sensing upstream of mTORC1. Dev Cell.

56:31712021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yao Y, Hong S, Yoshida S, Swaroop V,

Curtin B and Inoki K: The Cullin3-Rbx1-KLHL9 E3 ubiquitin ligase

complex ubiquitinates Rheb and supports amino Acid-induced mTORC1

activation. Cell Rep. 44:1151012025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

41

|

Hartung J, Müller C and Calkhoven CF: The

dual role of the TSC complex in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 31:452–465.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wan ZY, Tian JS, Tan HW, Chow AL, Sim AY,

Ban KH and Long YC: Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 is an

essential mediator of metabolic and mitogenic effects of fibroblast

growth factor 19 in hepatoma cells. Hepatology. 64:1289–1301. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Feng Y, Li T, Li Y, Lin Z, Han X, Pei X,

Zhang Y, Li F, Yang J, Shao D and Li C: Glutaredoxin-1 promotes

lymphangioleiomyomatosis progression through inhibiting

Bim-mediated apoptosis via COX2/PGE2/ERK pathway. Clin Transl Med.

13:e13332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Deng L, Chen L, Zhao L, Xu Y, Peng X, Wang

X, Ding L, Jin J, Teng H, Wang Y, et al: Ubiquitination of Rheb

governs growth factor-induced mTORC1 activation. Cell Res.

29:136–150. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

45

|

Crosby P, Hamnett R, Putker M, Hoyle NP,

Reed M, Karam CJ, Maywood ES, Stangherlin A, Chesham JE, Hayter EA,

et al: Insulin/IGF-1 drives PERIOD synthesis to entrain circadian

rhythms with feeding time. Cell. 177:896–909.e20. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Liu L, Xiao B, Hirukawa A, Smith HW, Zuo

D, Sanguin-Gendreau V, McCaffrey L, Nam AJ and Muller WJ: Ezh2

promotes mammary tumor initiation through epigenetic regulation of

the Wnt and mTORC1 signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120:e23030101202023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Shi H, Chapman NM, Wen J, Guy C, Long L,

Dhungana Y, Rankin S, Pelletier S, Vogel P, Wang H, et al: Amino

acids license kinase mTORC1 activity and treg cell function via

small G proteins rag and rheb. Immunity. 51:1012–1027.e7. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist

RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L and Sabatini DM: The Rag GTPases bind

raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science.

320:1496–1501. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP

and Guan KL: Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient

response. Nat Cell Biol. 10:935–945. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Rogala KB, Gu X, Kedir JF, Abu-Remaileh M,

Bianchi LF, Bottino AMS, Dueholm R, Niehaus A, Overwijn D, Fils AP,

et al: Structural basis for the docking of mTORC1 on the lysosomal

surface. Science. 366:468–475. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Anandapadamanaban M, Masson GR, Perisic O,

Berndt A, Kaufman J, Johnson CM, Santhanam B, Rogala KB, Sabatini

DM and Williams RL: Architecture of human Rag GTPase heterodimers

and their complex with mTORC1. Science. 366:203–210. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Doxsey DD, Tettoni SD, Egri SB and Shen K:

Redundant electrostatic interactions between GATOR1 and the Rag

GTPase heterodimer drive efficient amino acid sensing in human

cells. J Biol Chem. 299:1048802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Egri SB, Ouch C, Chou HT, Yu Z, Song K, Xu

C and Shen K: Cryo-EM structures of the human GATOR1-Rag-Ragulator

complex reveal a spatial-constraint regulated GAP mechanism. Mol

Cell. 82:1836–1849.e5. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Sanders SS, De Simone FI and Thomas GM:

mTORC1 signaling is Palmitoylation-dependent in hippocampal neurons

and Non-neuronal cells and involves dynamic palmitoylation of

LAMTOR1 and mTOR. Front Cell Neurosci. 13:1152019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Laufenberg LJ, Crowell KT and Lang CH:

Alcohol acutely antagonizes Refeeding-induced alterations in the

Rag GTPase-ragulator complex in skeletal muscle. Nutrients.

13:12362021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Cheng J, Lou Y and Jiang K: Downregulation

of long non-coding RNA LINC00460 inhibits the proliferation,

migration and invasion, and promotes apoptosis of pancreatic cancer

cells via modulation of the miR-320b/ARF1 axis. Bioengineered.

12:96–107. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Li FL and Guan KL: The Arf family GTPases:

Regulation of vesicle biogenesis and beyond. BioEssays: News and

reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental Biology.

45:e22002142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Fan SJ, Snell C, Turley H, Li JL,

McCormick R, Perera SM, Heublein S, Kazi S, Azad A, Wilson C, et

al: PAT4 levels control amino-acid sensitivity of

rapamycin-resistant mTORC1 from the Golgi and affect clinical

outcome in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 35:3004–3015. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

59

|

Huang T, Chen B, Wang F, Cai W, Wang X,

Huang B, Liu F, Jiang B and Zhang Y: Rab1A promotes

IL-4R/JAK1/STAT6-dependent metastasis and determines JAK1 inhibitor

sensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett.

523:182–194. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Xu H, Qian M, Zhao B, Wu C, Maskey N, Song

H, Li D, Song J, Hua K and Fang L: Inhibition of RAB1A suppresses

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and proliferation of

triple-negative breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 37:1619–1626. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhao T, Fan J, Abu-Zaid A, Burley SK and

Zheng XFS: Nuclear mTOR signaling orchestrates transcriptional

programs underlying cellular growth and metabolism. Cells.

13:7812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wolfson RL and Sabatini DM: The dawn of

the age of amino acid sensors for the mTORC1 pathway. Cell.

26:301–309. 2017.

|

|

63

|

Talaia G, Bentley-DeSousa A and Ferguson

SM: Lysosomal TBK1 responds to amino acid availability to relieve

Rab7-dependent mTORC1 inhibition. EMBO J. 43:3948–3967. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Chen F, Peng S, Li C, Yang F, Yi Y, Chen

X, Xu H, Cheng B, Xu Y and Xie X: Nitidine chloride inhibits mTORC1

signaling through ATF4-mediated Sestrin2 induction and targets

IGF2R for lysosomal degradation. Life Sci. 353:1229182024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Oricchio E, Katanayeva N, Donaldson MC,

Sungalee S, Pasion JP, Béguelin W, Battistello E, Sanghvi VR, Jiang

M, Jiang Y, et al: Genetic and epigenetic inactivation of SESTRIN1

controls mTORC1 and response to EZH2 inhibition in follicular

lymphoma. Sci Transl Med. 9:eaak99692017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Chen J, Ou Y, Luo R, Wang J, Wang D, Guan

J, Li Y, Xia P, Chen PR and Liu Y: SAR1B senses leucine levels to

regulate mTORC1 signalling. Nature. 596:281–284. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Kim JH, Jung K, Lee C, Song D, Kim K, Yoo

HC, Park SJ, Kang JS, Lee KR, Kim S, et al: Structure-based

modification of pyrazolone derivatives to inhibit mTORC1 by

targeting the leucyl-tRNA synthetase-RagD interaction. Bioorg Chem.

112:1049072021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Gai Z, Hu S, He Y, Yan S, Wang R, Gong G

and Zhao J: L-arginine alleviates heat stress-induced mammary gland

injury through modulating CASTOR1-mTORC1 axis mediated

mitochondrial homeostasis. Sci Total Environ. 926:1720172024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Wang J, Shen C, Zhao G, Hanigan MD and Li

M: Dietary protein re-alimentation following restriction improves

protein deposition via changing amino acid metabolism and

transcriptional profiling of muscle tissue in growing beef bulls.

Anim Nutr. 19:117–130. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Jung JW, Kim JE, Kim E and Lee JW: Amino

acid transporters as tetraspanin TM4SF5 binding partners. Exp Mol

Med. 52:7–14. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jung JW, Macalino SJY, Cui M, Kim JE, Kim

HJ, Song DG, Nam SH, Kim S, Choi S and Lee JW: Transmembrane 4 L

six family member 5 senses arginine for mTORC1 signaling. Cell

Metab. 29:1306–1319.e7. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Gu X, Orozco JM, Saxton RA, Condon KJ, Liu

GY, Krawczyk PA, Scaria SM, Harper JW, Gygi SP and Sabatini DM:

SAMTOR is an S-adenosylmethionine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway.

Science. 358:813–818. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Kim SH, Choi JH, Wang P, Go CD, Hesketh

GG, Gingras AC, Jafarnejad SM and Sonenberg N: Mitochondrial

Threonyl-tRNA synthetase TARS2 is required for Threonine-sensitive

mTORC1 activation. Mol Cell. 81:398–407.e4. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Wang D, Wan X, Du X, Zhong Z, Peng J,

Xiong Q, Chai J and Jiang S: Insights into the Interaction of

lysosomal amino acid transporters SLC38A9 and SLC36A1 involved in

mTORC1 signaling in C2C12 Cells. Biomolecules. 11:13142021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wang S, Tsun ZY, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant

GA, Plovanich ME, Yuan ED, Jones TD, Chantranupong L, Comb W, et

al: Metabolism. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals

arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 347:188–194. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Wang X, Zhang T, Li W, Wang H, Yan L,

Zhang X, Zhao L, Wang N and Zhang B: Arginine alleviates

Clostridium perfringens α toxin-induced intestinal injury in vivo

and in vitro via the SLC38A9/mTORC1 pathway. Front Immunol.

15:13570722024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Dev G, Chawla AS, Gupta S, Bal V, George

A, Rath S and Arimbasseri GA: Differential Regulation of two arms

of mTORC1 pathway Fine-tunes global protein synthesis in resting B

lymphocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 23:160172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Knight JRP, Alexandrou C, Skalka GL,

Vlahov N, Pennel K, Officer L, Teodosio A, Kanellos G, Gay DM,

May-Wilson S, et al: MNK inhibition sensitizes KRAS-mutant

colorectal cancer to mTORC1 inhibition by reducing eIF4E

phosphorylation and c-MYC expression. Cancer Discov. 11:1228–1247.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

79

|

Savukaitytė A, Gudoitytė G, Bartnykaitė A,

Ugenskienė R and Juozaitytė E: siRNA knockdown of REDD1 facilitates

Aspirin-mediated dephosphorylation of mTORC1 target 4E-BP1 in

MDA-MB-468 human breast cancer cell line. Cancer Manag Res.

13:1123–1133. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Llanos S and García-Pedrero JM: A new

mechanism of regulation of p21 by the mTORC1/4E-BP1 pathway

predicts clinical outcome of head and neck cancer. Mol Cell Oncol.

3:e11592752016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Amar-Schwartz A, Ben Hur V, Jbara A, Cohen

Y, Barnabas GD, Arbib E, Siegfried Z, Mashahreh B, Hassouna F,

Shilo A, et al: S6K1 phosphorylates Cdk1 and MSH6 to regulate DNA

repair. ELife. 11:e791282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Yang L, Miao L, Liang F, Huang H, Teng X,

Li S, Nuriddinov J, Selzer ME and Hu Y: The mTORC1 effectors S6K1

and 4E-BP play different roles in CNS axon regeneration. Nat

Commun. 5:54162014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Jang SK, Kim G, Ahn SH, Hong J, Jin HO and

Park IC: Duloxetine enhances the sensitivity of non-small cell lung

cancer cells to EGFR inhibitors by REDD1-induced mTORC1/S6K1

suppression. Am J Cancer Res. 14:1087–1100. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zhang X, Song W, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Zhao Y,

Hao S and Ni T: The role of tumor metabolic reprogramming in tumor

immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 24:174222023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

He L, Cho S and Blenis J: mTORC1, the

maestro of cell metabolism and growth. Genes Dev. 39:109–131.

2025.

|

|

87

|

Vaidyanathan S, Salmi TM, Sathiqu RM,

McConville MJ, Cox AG and Brown KK: YAP regulates an

SGK1/mTORC1/SREBP-dependent lipogenic program to support

proliferation and tissue growth. Dev Cell. 57:719–731.e8. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Solanki S, Sanchez K, Ponnusamy V, Kota V,

Bell HN, Cho CS, Kowalsky AH, Green M, Lee JH and Shah YM:

Dysregulated amino acid sensing drives colorectal cancer growth and

metabolic reprogramming leading to chemoresistance.

Gastroenterology. 164:376–391.e13. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Jin C, Zhu M, Ye J, Song Z, Zheng C and

Chen W: Autophagy: Are amino acid signals dependent on the mTORC1

pathway or independent? Curr Issues Mol Biol. 46:8780–8793. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhao Z, Liu J, Gao X, Chen Z, Hu Y, Chen

J, Zang W and Xue W: SCYL1-mediated regulation of the mTORC1

signaling pathway inhibits autophagy and promotes gastric cancer

metastasis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 150:4562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Tan HWS, Sim AYL and Long YC: Glutamine

metabolism regulates autophagy-dependent mTORC1 reactivation during

amino acid starvation. Nat Commun. 8:3382017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Ro SH, Xue X, Ramakrishnan SK, Cho CS,

Namkoong S, Jang I, Semple IA, Ho A, Park HW, Shah YM and Lee JH:

Tumor suppressive role of sestrin2 during colitis and colon

carcinogenesis. ELife. 5:e122042016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Byun JK, Choi YK, Kim JH, Jeong JY, Jeon

HJ, Kim MK, Hwang I, Lee SY, Lee YM, Lee IK and Park KG: A positive

feedback loop between sestrin2 and mTORC2 is required for the

survival of Glutamine-depleted lung cancer cells. Cell Rep.

20:586–599. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Shen S, Zhou H, Xiao Z, Zhan S, Tuo Y,

Chen D, Pang X, Wang Y and Wang J: PRMT1 in human neoplasm: Cancer

biology and potential therapeutic target. Cell Commun Signal.

22:1022024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Zhou M, Huang Y, Xu P, Li S, Duan C, Lin

X, Bao S, Zou W, Pan J, Liu C and Jin Y: PRMT1 promotes the

Self-renewal of leukemia stem cells by regulating protein

synthesis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 12:e23085862025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Yin JZ, Keszei AFA, Houliston S, Filandr

F, Beenstock J, Daou S, Kitaygorodsky J, Schriemer DC,

Mazhab-Jafari MT, Gingras AC and Sicheri F: The HisRS-like domain

of GCN2 is a pseudoenzyme that can bind uncharged tRNA. Structure.

32:795–811.e6. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Kim Y, Sundrud MS, Zhou C, Edenius M,

Zocco D, Powers K, Zhang M, Mazitschek R, Rao A, Yeo CY, et al:

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibition activates a pathway that

branches from the canonical amino acid response in mammalian cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:8900–8911. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Brüggenthies JB, Fiore A, Russier M,

Bitsina C, Brötzmann J, Kordes S, Menninger S, Wolf A, Conti E,

Eickhoff JE and Murray PJ: A cell-based chemical-genetic screen for

amino acid stress response inhibitors reveals torins reverse stress

kinase GCN2 signaling. J Biol Chem. 298:1026292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Sannino S, Yates ME, Schurdak ME,

Oesterreich S, Lee AV, Wipf P and Brodsky JL: Unique integrated

stress response sensors regulate cancer cell susceptibility when

Hsp70 activity is compromised. ELife. 10:e649772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Nelson AT, Cicardi ME, Markandaiah SS, Han

JY, Philp NJ, Welebob E, Haeusler AR, Pasinelli P, Manfredi G,

Kawamata H and Trotti D: Glucose hypometabolism prompts RAN

translation and exacerbates C9orf72-related ALS/FTD phenotypes.

EMBO Rep. 25:2479–2510. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Yuan J, Yu Z, Gao J, Luo K, Shen X, Cui B

and Lu Z: Inhibition of GCN2 alleviates hepatic steatosis and

oxidative stress in obese mice: Involvement of NRF2 regulation.

Redox Biol. 49:1022242022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

102

|

Missiaen R, Anderson NM, Kim LC, Nance B,

Burrows M, Skuli N, Carens M, Riscal R, Steensels A, Li F and Simon

MC: GCN2 inhibition sensitizes arginine-deprived hepatocellular

carcinoma cells to senolytic treatment. Cell Metab.

34:1151–1167.e7. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Stonyte V, Mastrangelopoulou M, Timmer R,

Lindbergsengen L, Vietri M, Campsteijn C and Grallert B: The

GCN2/eIF2αK stress kinase regulates PP1 to ensure mitotic fidelity.

EMBO Rep. 24:e561002023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Weber SL, Hustedt K, Schnepel N, Visscher

C and Muscher-Banse AS: Modulation of GCN2/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway in

the liver and induction of FGF21 in young goats fed a Protein-

and/or Phosphorus-reduced diet. Int J Mol Sci. 24:71532023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Ge MK, Zhang C, Zhang N, He P, Cai HY, Li

S, Wu S, Chu XL, Zhang YX, Ma HM, et al: The

tRNA-GCN2-FBXO22-axis-mediated mTOR ubiquitination senses amino

acid insufficiency. Cell Metab. 35:2216–2230.e8. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Müller MBD, Kasturi P, Jayaraj GG and

Hartl FU: Mechanisms of readthrough mitigation reveal principles of

GCN1-mediated translational quality control. Cell.

186:3227–3244.e20. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Bou-Nader C, Gaikwad S, Bahmanjah S, Zhang

F, Hinnebusch AG and Zhang J: Gcn2 structurally mimics and

functionally repurposes the HisRS enzyme for the integrated stress

response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 121:e24096281212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Ishimura R, Nagy G, Dotu I, Chuang JH and

Ackerman SL: Activation of GCN2 kinase by ribosome stalling links

translation elongation with translation initiation. ELife.

5:e142952016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Inglis AJ, Masson GR, Shao S, Perisic O,

McLaughlin SH, Hegde RS and Williams RL: Activation of GCN2 by the

ribosomal P-stalk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:4946–4954. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Piecyk M, Ferraro-Peyret C, Laville D,

Perros F and Chaveroux C: Novel insights into the GCN2 pathway and

its targeting. Therapeutic value in cancer and lessons from lung

fibrosis development. FEBS J. 291:4867–4889. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Chen C, Xie Y and Qian S: Multifaceted

role of GCN2 in tumor adaptation and therapeutic targeting. Transl

Oncol. 49:1020962024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Nofal M, Wang T, Yang L, Jankowski CSR,

Hsin-Jung Li S, Han S, Parsons L, Frese AN, Gitai Z, Anthony TG, et

al: GCN2 adapts protein synthesis to scavenging-dependent growth.

Cell Syst. 13:158–172.e9. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

113

|

St Paul M, Saibil SD, Kates M, Han S, Lien

SC, Laister RC, Hezaveh K, Kloetgen A, Penny S, Guo T, et al: Ex

vivo activation of the GCN2 pathway metabolically reprograms T

cells, leading to enhanced adoptive cell therapy. Cell Rep Med.

5:1014652024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Zhao L, Deng L, Zhang Q, Jing X, Ma M, Yi

B, Wen J, Ma C, Tu J, Fu T and Shen J: Autophagy contributes to

sulfonylurea herbicide tolerance via GCN2-independent regulation of

amino acid homeostasis. Autophagy. 14:702–714. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Nakamura A, Nambu T, Ebara S, Hasegawa Y,

Toyoshima K, Tsuchiya Y, Tomita D, Fujimoto J, Kurasawa O, Takahara

C, et al: Inhibition of GCN2 sensitizes ASNS-low cancer cells to

asparaginase by disrupting the amino acid response. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 115:e7776–e7785. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Blagojevic B, Almouhanna F, Poschet G and

Wölfl S: Cell Type-specific metabolic response to amino acid

starvation dictates the role of Sestrin2 in regulation of mTORC1.

Cells. 11:38632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Ye J, Palm W, Peng M, King B, Lindsten T,