Introduction

Cognitive impairment encompasses a continuum of

conditions characterized by deficits in memory, attention,

executive function, language and visuospatial abilities, ranging

from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to more severe forms such as

dementia, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), vascular dementia and

other neurodegenerative disorders (1). These cognitive deficits

significantly compromise individual autonomy, reduce quality of

life and impose growing burdens on caregivers and healthcare

systems (2). As the global

population ages, the prevalence of cognitive disorders is projected

to rise dramatically, amplifying their public health and

socio-economic impact. Despite advances in pharmacological and

behavioral interventions, current treatment options remain limited

in efficacy, particularly for dementia, underscoring the urgent

need to identify modifiable risk factors and implement preventive

strategies at earlier stages of disease progression.

One such modifiable factor that has gained

increasing attention is diet-particularly the role of high-fat

diets (HFDs) in the development and progression of cognitive

dysfunction. An HFD is typically defined as one in which total

energy intake from fats exceeds 35-40%, with a disproportionate

enrichment in saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and trans fats, often

coupled with insufficient intake of carbohydrates, essential amino

acids, dietary fiber and micronutrients (3). Over the past several decades, the

global spread of Western dietary patterns-marked by increased

consumption of processed foods, sugary beverages and high-fat fast

food-has contributed to the widespread adoption of HFDs across both

developed and developing nations (4). As a result, the incidence of

metabolic disorders linked to high-fat consumption, such as

obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and non-alcoholic fatty

liver disease, has escalated to epidemic proportions (5-7).

Emerging research suggests that chronic exposure to

HFDs may not only impair systemic metabolic homeostasis but also

exert deleterious effects on brain health (3,8,9).

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that individuals with

high dietary fat intake, particularly SFAs, have a significantly

increased risk of developing MCI and dementia (10,11). For instance, longitudinal cohort

studies have revealed that older adults adhering to diets rich in

saturated fats experience accelerated cognitive decline and exhibit

higher incidences of AD compared to those following diets high in

polyunsaturated or monounsaturated fats (12). Conversely, adherence to dietary

patterns rich in unsaturated fatty acids-such as the Mediterranean

or Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diets-has been

associated with reduced cognitive decline and improved neurological

outcomes, supporting the notion that the type and quality of

dietary fat play a critical role in modulating cognitive health

(13,14).

HFD-induced cognitive impairment is driven by a

multifactorial network of neuropathological processes, including

neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction,

insulin resistance and gut microbiota dysbiosis (15). These mechanisms collectively

disrupt synaptic plasticity, impair neurogenesis and compromise

neuronal survival, particularly in hippocampal regions critical for

learning and memory. Individual susceptibility-such as advanced

age, female sex and genetic predispositions like the apolipoprotein

E ε4 (APOE-ε4) allele-can amplify these deleterious effects.

Given the rising global prevalence of both HFD

consumption and dementia-related disorders, elucidating the

mechanistic links between diet and neurodegeneration has become a

pressing public health priority. Importantly, the modifiable nature

of diet offers a compelling avenue for early intervention. Emerging

strategies-including adherence to Mediterranean or DASH dietary

patterns, regular physical exercise, insulin-sensitizing or

anti-inflammatory pharmacotherapy, and microbiota-targeted

interventions such as probiotics-show promise in mitigating

HFD-associated cognitive decline. A more comprehensive

understanding of how dietary fats interact with neuroimmune,

metabolic and microbial pathways may pave the way for personalized,

mechanism-based prevention and treatment strategies aimed at

preserving cognitive function across the lifespan.

Association between HFD and cognitive

function

Epidemiological and experimental evidence

of cognitive impairment induced by HFDs

A substantial body of epidemiological research has

identified a significant association between chronic HFD

consumption and increased risk of cognitive decline, MCI and

dementia (Table I) (8,16-21). Prospective cohort studies in

diverse populations have consistently shown that long-term

adherence to HFD-particularly those rich in SFAs-is linked to

poorer cognitive outcomes and a higher incidence of AD (10,11). For instance, a longitudinal study

involving ~6,000 older adults reported that individuals in the

highest quartile of SFA intake experienced markedly faster

cognitive decline and a >2-fold increased risk of developing AD

compared to those in the lowest quartile (22,23). Similar trends of accelerated

cognitive deterioration have been observed in other

population-based studies, further supporting the link between high

SFA intake and impaired cognitive outcomes (8,24). Complementary findings from animal

studies further substantiate this association: Rodents exposed to

chronic SFA-enriched diets exhibit impairments in spatial learning

and memory, along with pathological features characteristic of AD,

such as enhanced β-amyloid deposition and tau hyperphosphorylation

(25). Early manifestations of

cognitive impairment in HFD models include disrupted circadian

rhythms and diminished semantic fluency, with clinical symptoms

predominantly affecting memory, executive function, learning

ability and other early cognitive domains associated with

neurodegeneration. Experimental evidence indicates that HFD impairs

spatial memory, as reflected by increased escape latency in the

Morris water maze, indicative of hippocampal dysfunction (26). In humans, elevated serum free

fatty acids (FFAs) are associated with impaired delayed recall,

particularly in individuals with reduced hippocampal volume

(27,28). High intake of SFAs has been

consistently linked to memory decline in older adults. A

longitudinal study involving >2,500 elderly participants found

that those with the highest SFA intake had more than double the

risk of developing AD compared to those with the lowest intake

(24). A meta-analysis of four

independent cohorts revealed that individuals in the highest SFA

quartile had a 39% higher risk of AD and a 105% higher risk of

all-cause dementia compared to the lowest quartile (29). Dose-response analysis indicated

that each additional 4 grams per day of SFA intake were associated

with a 15% increased risk of AD. Furthermore, excessive SFA intake

has been linked to accelerated episodic and prospective memory

loss, particularly in older women, who exhibited a 40% slower

recall rate and prolonged task completion times in

neuropsychological assessments such as the Trail Making Test

(30).

| Table IEffects of HFD on cognitive function:

Evidence from animal and human studies. |

Table I

Effects of HFD on cognitive function:

Evidence from animal and human studies.

| Subjects | Study design | Diet used | Main findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 6-month-old male

C57BL/6 mice (aged model) | 1, 2 and 4-month

randomized controlled feeding (HFD vs. normal diet) | HFD: 60 kcal% fat;

normal diet: 10 kcal% fat | ↓ Object place

recognition; ↑ Tau hyperphosphorylation, microglial activation,

IL-6 in hippocampus | (16) |

| Transgenic AD mice

(tauopathy model) | 30-week HFD feeding

starting at 2 months of age | HFD: 23.5% fat;

Control diet: 4.8% fat | ↑ Depression-like

behavior; ↓ cognition; ↑ Tau pathology and metabolic disorders | (17) |

| Juvenile/adolescent

rodents (mice and rats) | Various durations

(short to long term) HFD feeding | High-fat/high-sugar

diets (varied fat content) | ↓ Spatial and

relational memory; altered neurotransmission; ↓ neurogenesis; ↑

hippocampal inflammation | (18) |

| Control and triple

transgenic Alzheimer's (3xTg-AD; triple-transgenic) mice | Long-term HFD vs.

normal diet, with chronic intranasal insulin intervention | HFD vs. normal diet

(exact fat % not specified) | ↓ Cognition; ↑

brain insulin resistance; ↓ brain mass and dentate gyrus size;

intranasal insulin improved outcomes | (19) |

| Humans (review of

multiple studies) and rodents | Review of acute and

chronic exposure studies | High-energy diets

high in fat and/or sugar (varied fat types) | ↑ Memory impairment

before weight gain; ↑ inflammation; ↓ BDNF; potential benefits from

omega-3 and curcumin supplementation | (20) |

| Healthy male adults

(22±1 years) (n=16) | Randomized

crossover design; 5 days of high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet vs.

standard diet, 2-week washout; cardiac and cognitive

assessments | High-fat (75% of

calories), low-carbohydrate diet for 5 days | ↑ Plasma free fatty

acids; ↓ cardiac PCr/ATP; ↓ attention, speed and mood | (21) |

Beyond memory, executive dysfunction is another

hallmark of HFD-induced impairment. Clinically, this manifests as

reduced cognitive flexibility and impaired decision-making, while

in rodent models, this has been demonstrated by increased error

rates in reversal learning tasks, attributed to disrupted synaptic

plasticity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Impulse control deficits

are also evident, as shown by decreased inhibition performance in

Go/No-Go tasks, potentially linked to downregulation of striatal

dopamine D2 receptors (31).

Learning processes are likewise compromised: Mice on

an HFD exhibit reduced exploration of novel objects, suggesting

deficits in novelty recognition, and extinction of conditioned fear

memory is delayed, likely due to amygdala-PFC circuit disruptions

that contribute to anxiety-related cognitive rigidity. These

impairments are associated with altered expression of synaptic

proteins such as synaptophysin and postsynaptic density protein 95

(PSD-95), as well as reduced levels of bone-derived neurotrophic

factor (BDNF), all of which are critical for synaptic plasticity

(32). Chronic HFD has been

shown to downregulate these proteins in the hippocampus and cortex,

impairing neuronal communication and long-term potentiation (LTP)

(33).

Taken together, current epidemiological and

experimental evidence suggest that long-term HFD, particularly

SFA-rich diets, exert a detrimental effect on multiple cognitive

domains, including memory, executive function and learning.

However, it is important to acknowledge the inherent limitations of

observational studies, including potential residual confounding and

lack of causal inference. Therefore, further well-designed

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are necessary to validate these

associations and inform evidence-based dietary guidelines for

cognitive health promotion.

Modifiers of HFD-induced cognitive

impairment

The adverse cognitive effects of HFDs do not occur

in isolation but are significantly modulated by individual-level

factors such as age, sex, and genetic predisposition.

Age is a well-established modifier of HFD-induced

cognitive outcomes. Numerous studies have shown that older

individuals are more susceptible to the detrimental neurological

effects of chronic HFD exposure compared to younger populations.

Aging is associated with increased vulnerability to HFD-induced

neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and insulin resistance-key

mechanisms contributing to accelerated cognitive decline and

heightened dementia risk (34,35). Animal studies corroborate these

findings, demonstrating that aged rodents exhibit more severe

cognitive impairments and neuropathological changes in response to

prolonged HFD intake than younger counterparts (36-38). Epidemiological data in humans

further support these age-related interactions, indicating more

pronounced cognitive deficits among older adults consuming an

SFA-rich diet (8,39).

Sex differences also influence HFD-related cognitive

vulnerability. Both clinical and preclinical evidence suggests that

females may be more sensitive to cognitive impairments associated

with high dietary fat intake. Population-based studies report

stronger associations between HFD and cognitive decline in women

than in men (40). Similarly,

animal models show enhanced diet-induced insulin resistance,

neuroinflammation and hippocampal dysfunction in female subjects,

potentially due to hormonal fluctuations and the loss of

estrogen-mediated neuroprotection with ageing (26,41,42).

Genetic predisposition further modulates the impact

of HFD on cognitive function. The APOE-ε4 allele-an established

genetic risk factor for AD-has been shown to amplify the

neurocognitive consequences of chronic HFD exposure. Carriers of

the APOE-ε4 allele demonstrate faster cognitive decline and greater

vulnerability to HFD-related neurodegeneration than non-carriers

(43,44). Additionally, polymorphisms in

genes involved in inflammatory and metabolic pathways may

exacerbate HFD-induced disruptions in lipid metabolism, neuroimmune

responses and cerebral insulin signaling, thereby potentiating

cognitive dysfunction (45,46).

In summary, the cognitive impact of HFDs is strongly

modulated by host-specific factors such as age, sex and genetic

background. These interactions underscore the multifaceted nature

of HFD-induced cognitive impairment. A comprehensive understanding

of how HFD synergizes with individual risk factors is essential for

developing effective strategies to mitigate cognitive decline.

Potential mechanisms

HFDs, particularly those rich in SFAs, have

consistently been associated with adverse cognitive outcomes.

Evidence from both preclinical models and clinical studies

indicates that excessive SFA intake induces a cascade of

deleterious pathophysiological processes, including

microglia-mediated neuroinflammation, increased oxidative stress,

impaired insulin signaling, gut microbiota dysbiosis and disruption

of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity. These interrelated

mechanisms converge to impair neuronal function and accelerate

cognitive decline (47-50).

Neuroinflammation

Neuroinflammation is recognized as a central

mechanism through which HFDs contribute to cognitive impairment.

Chronic HFD consumption activates microglia-the principal immune

effector cells in the central nervous system (CNS)-prompting a

shift from a homeostatic surveillance state toward a

pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype (46,51). Under physiological conditions,

microglia play key roles in maintaining synaptic plasticity,

clearing cellular debris, and supporting adult neurogenesis.

However, diets rich in SFAs-such as palmitic acid, lauric acid and

stearic acid-trigger aberrant microglial activation. SFAs bind to

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on microglial surfaces, activating

MyD88-dependent signaling pathways and serving as potent inducers

of nuclear factor κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling

cascades. These pathways, together with endoplasmic reticulum

stress responses, initiate and amplify pro-inflammatory signaling

(52). Consequently, activated

microglia release large quantities of inflammatory cytokines

(TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2) and reactive

oxygen species (ROS), leading to synaptic loss, neuronal injury,

and impaired hippocampal function (53,54). Furthermore, SFAs may act

synergistically with advanced glycation end products derived from

processed lipids to exacerbate neuroinflammation. These cytokines

amplify local neuroinflammatory cascades and directly disrupt

neuronal integrity by impairing synaptic transmission, reducing

synaptic plasticity, and promoting neuronal apoptosis.

Notably, HFD-induced neuroinflammation can occur

within days of dietary exposure, preceding systemic metabolic

disturbances. This inflammatory response often begins in the

mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH)-a region highly sensitive to

circulating lipid signals due to its specialized median eminence

BBB and tanycyte-mediated transport. HFDs also promote the

recruitment of bone marrow-derived myeloid cells to the MBH and

hippocampus, where they differentiate into microglia-like

pro-inflammatory cells, reinforcing the inflammatory milieu and

enhancing M1 polarization (55).

Importantly, this neuroinflammatory response occurs independently

of body weight gain, suggesting a direct impact of dietary fat on

central immune activation. Prolonged HFD exposure further

propagates glial activation to other brain regions, including the

hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, contributing to spatial memory

deficits and depression-like behaviors (16).

Prolonged HFD exposure further propagates glial

activation to other brain regions, including the hippocampus and

prefrontal cortex, contributing to spatial memory deficits and

depression-like behaviors (56-58). For instance, Sobesky et al

(59) demonstrated that mice

maintained on an HFD exhibited marked microglial activation in the

hippocampus, elevated IL-1β expression and significant spatial

memory deficits in the Morris water maze. Similarly, Spencer et

al (60) reported that

prolonged consumption of SFAs in rodents increased microglial

activation and TNF-α expression, resulting in decreased synaptic

density and impaired hippocampal-dependent learning tasks. Notably,

pharmacological inhibition of microglial activation attenuated

these cognitive impairments, highlighting a causal role for

neuroinflammation (16,51,61).

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative

stress

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a pivotal mechanism by

which HFD consumption contributes to cognitive impairment, often

accompanied by energy dysregulation and enhanced oxidative stress

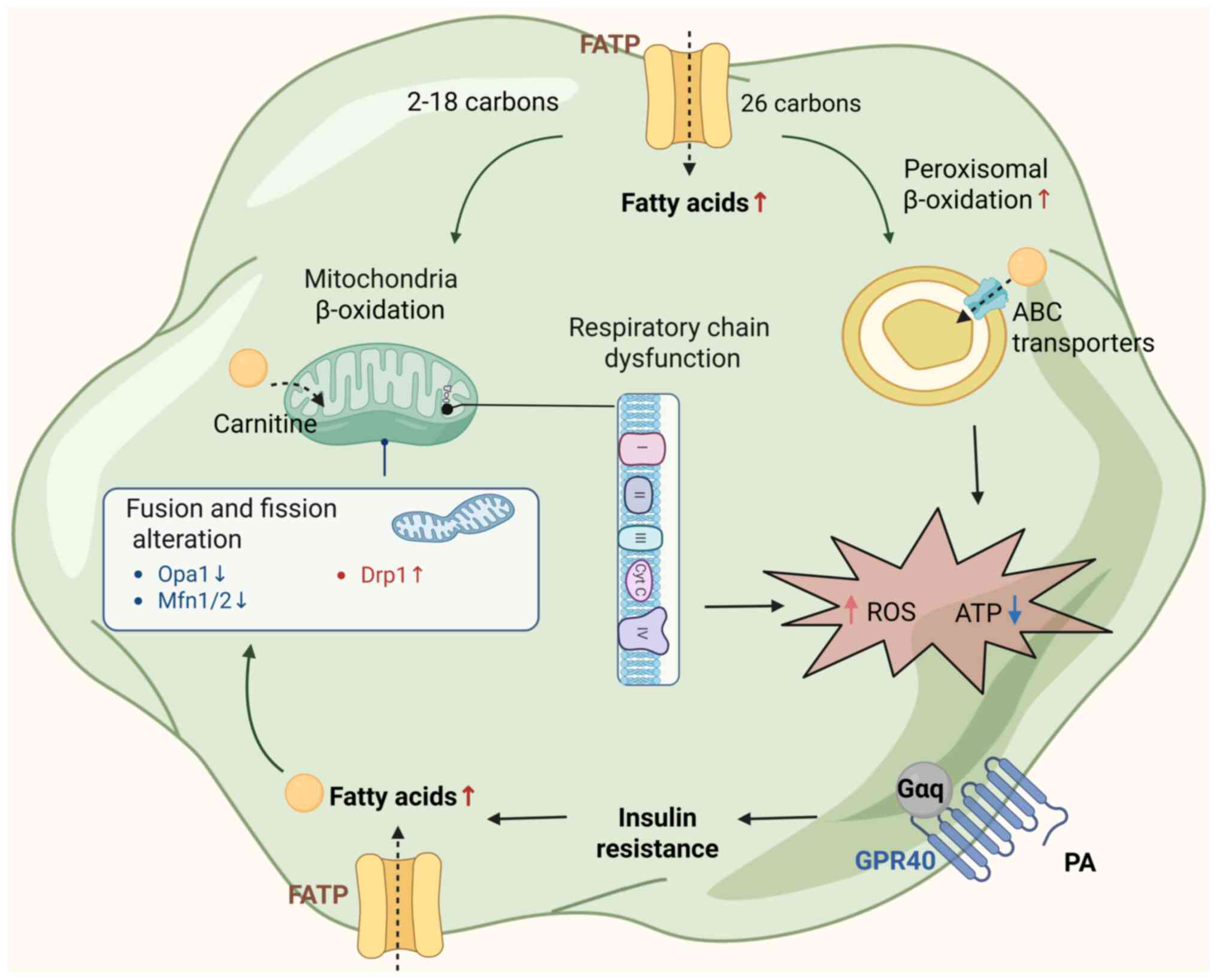

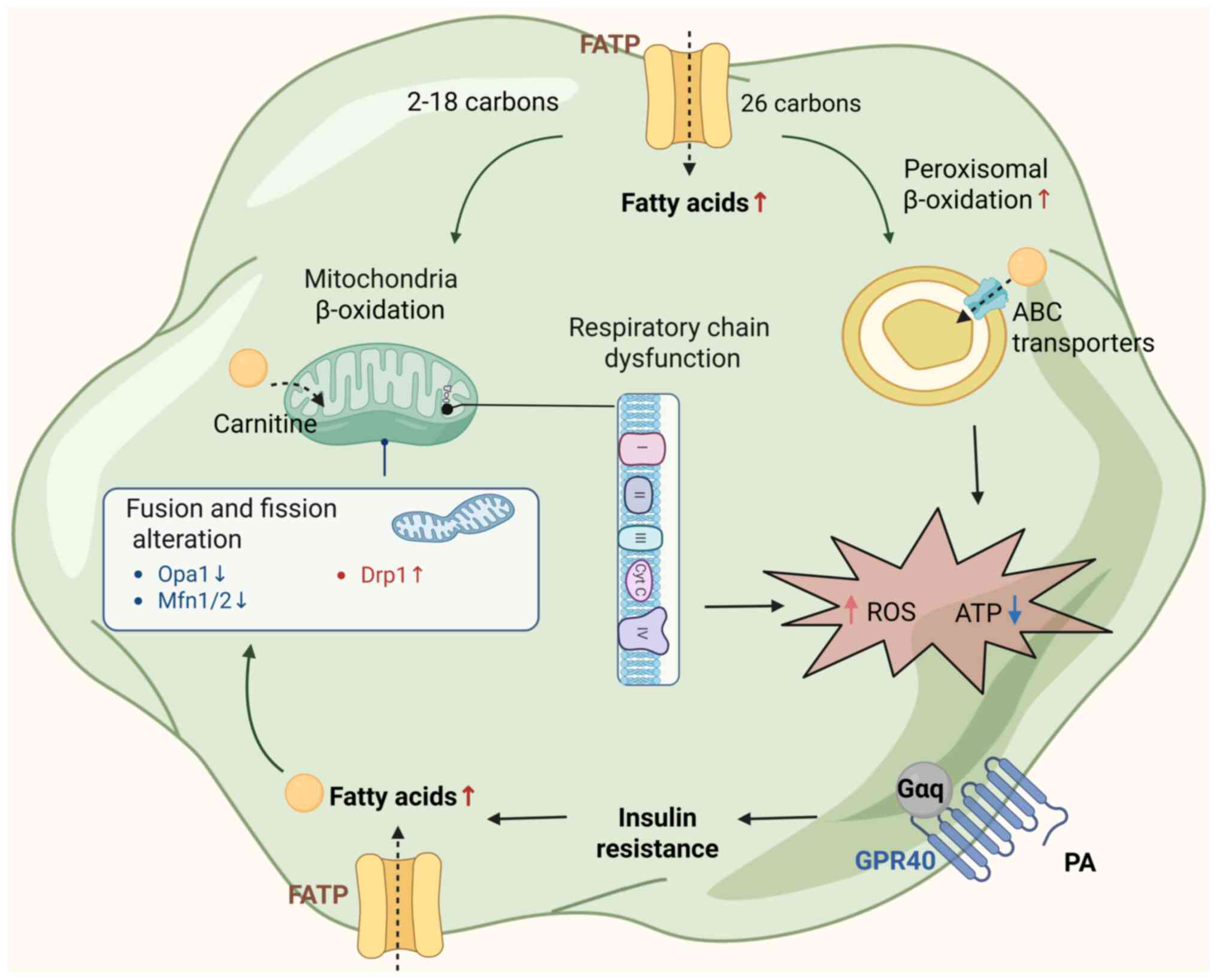

(Fig. 1). HFD induces a

disruption of mitochondrial dynamics, favoring pathological

fragmentation. Fatty acids enter cells via fatty acid transport

proteins and are directed toward either mitochondrial β-oxidation

(for 2-18 carbon chains) or peroxisomal metabolism (for ≥26 carbon

chains via ATP binding cassette transporters). In mitochondria,

fatty acid oxidation is carnitine-dependent and contributes to ATP

production. However, chronic exposure to high levels of saturated

SFAs impairs mitochondrial dynamics. Specifically, SFA-rich diets

markedly upregulate dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), particularly

its phosphorylation at Ser616, promoting Drp1 translocation from

the cytosol to the outer mitochondrial membrane, where it

oligomerizes to drive mitochondrial fission. Concurrently, the

expression of fusion-related proteins-including mitofusins 1/2 and

optic atrophy 1-is significantly reduced, impairing mitochondrial

fusion capacity. This imbalance leads to mitochondrial network

fragmentation, structural disruption and functional decline.

Notably, such metabolic impairment extends beyond the central

nervous system. Bone marrow-derived monocytes exposed to an HFD

exhibit similar mitochondrial fragmentation, lactate accumulation

and bioenergetic inefficiency, suggesting a systemic mitochondrial

reprogramming that may amplify the neuroenergetic imbalance through

peripheral-to-central metabolic cross-talk (62,63).

| Figure 1Mechanism of mitochondrial

dysfunction induced by HFD. HFD increases circulating FFAs, which

are taken up via FATPs and directed to mitochondrial and

peroxisomal β-oxidation. Insulin resistance promotes excessive FFA

influx, overwhelming mitochondrial capacity. Impaired mitochondrial

dynamics (↓Opa1, ↓Mfn1/2, ↑Drp1) and respiratory chain dysfunction

lead to reduced ATP production and elevated ROS levels. These

alterations contribute to cellular energy failure and oxidative

stress, exacerbating cognitive decline. ABC, ATP binding cassette;

HFD, high-fat diet; FATPs, fatty acid transport proteins; FFAs,

free fatty acids; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ATP, adenosine

triphosphate; OPA1, optic atrophy protein 1; Mfn1/2, mitofusin 1/2;

Drp1, dynamin-related protein 1; Cyt c, cytochrome c; PA,

phosphatidic acid; GPR, G protein-coupled receptor; Gαq, guanine

nucleotide-binding protein α q subunit. |

Furthermore, excessive SFAs stimulate mitochondrial

fatty acid β-oxidation, enhancing electron flux through complexes I

and III of the electron transport chain. Additionally, peroxisomal

β-oxidation does not generate ATP directly. Instead, it transfers

electrons directly to molecular oxygen. This process increases

electron leakage, leading to overproduction of ROS, including

superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (·OH) (9,64-67). These ROS species damage

mitochondrial DNA, respiratory enzymes and phospholipid membranes,

further exacerbating mitochondrial dysfunction (68-70). Excess ROS accumulation causes

oxidative damage via lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA

fragmentation. Lipid peroxidation products, such as malondialdehyde

(MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), are particularly toxic to

neurons. Elevated levels of MDA and 4-HNE have been detected in the

hippocampus and cortex of HFD-fed animals and are closely

associated with impairments in spatial memory, working memory and

executive function (71,72). For instance, Liu et al

(73) demonstrated that

long-term HFD exposure in mice led to significantly increased

hippocampal MDA levels, reduced antioxidant enzyme activities

[e.g., superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase], and

worsened spatial learning in the Morris water maze.

Insulin resistance

Insulin signaling is essential for maintaining

neuronal glucose metabolism, mitochondrial bioenergetics, synaptic

plasticity and neuronal survival-all of which are fundamental to

cognitive function. In the CNS, insulin binds to its receptor,

triggering the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates

(IRS), which in turn activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase

(PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway (45,74,75). This cascade not only promotes

neuronal glucose uptake via glucose transporters (GLUT), i.e.,

GLUT3 and GLUT4, and supports mitochondrial function, but also

plays key roles in neurogenesis, synaptic remodeling and cell

viability.

HFD exposure impairs both peripheral and central

insulin signaling, contributing to systemic insulin resistance.

Peripherally, an HFD may diminish insulin's anti-lipolytic

function, resulting in excessive FFA release from adipose tissue.

These circulating FFAs accumulate in metabolic organs-including

liver, skeletal muscle, brain and astrocytes-overloading oxidative

pathways and increasing mitochondrial and peroxisomal β-oxidation

(Fig. 1). Notably, palmitic acid

(a major SFA in HFDs) reduces GLUT1 expression at the BBB, thereby

limiting glucose delivery to the brain, diminished glucose uptake

and compromised neuronal energy homeostasis (76-78).

In the CNS, insulin resistance particularly affects

the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex-regions crucial for memory

encoding and executive function (36,45,79). Dysfunctional insulin signaling

reduces Akt activation and downregulates BDNF, contributing to

synaptic degeneration, reduced dendritic spine density and impaired

LTP, which are key substrates of cognitive performance (80,81). For instance, Arnold et al

(48) reported that HFD-fed mice

showed reduced insulin receptor activity, lower Akt phosphorylation

and impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity, as well as spatial

learning and memory deficits. Similarly, Kothari et al

(36) demonstrated that chronic

HFD exposure suppressed BDNF expression and reduced dendritic

complexity in the hippocampus, correlating with cognitive decline.

Furthermore, HFD-induced insulin resistance may promote AD-like

neuropathology via multiple mechanisms. It activates downstream

kinases such as glycogen synthase kinase-3β, inducing pathological

tau hyperphosphorylation at Ser396/404 and facilitating

neurofibrillary tangle formation. It also suppresses

insulin-degrading enzyme, reducing Aβ clearance and accelerating

amyloid plaque accumulation. Additionally, impaired insulin

signaling inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of neural

progenitor cells, thereby limiting adult hippocampal neurogenesis

and reducing cognitive flexibility and plasticity (82).

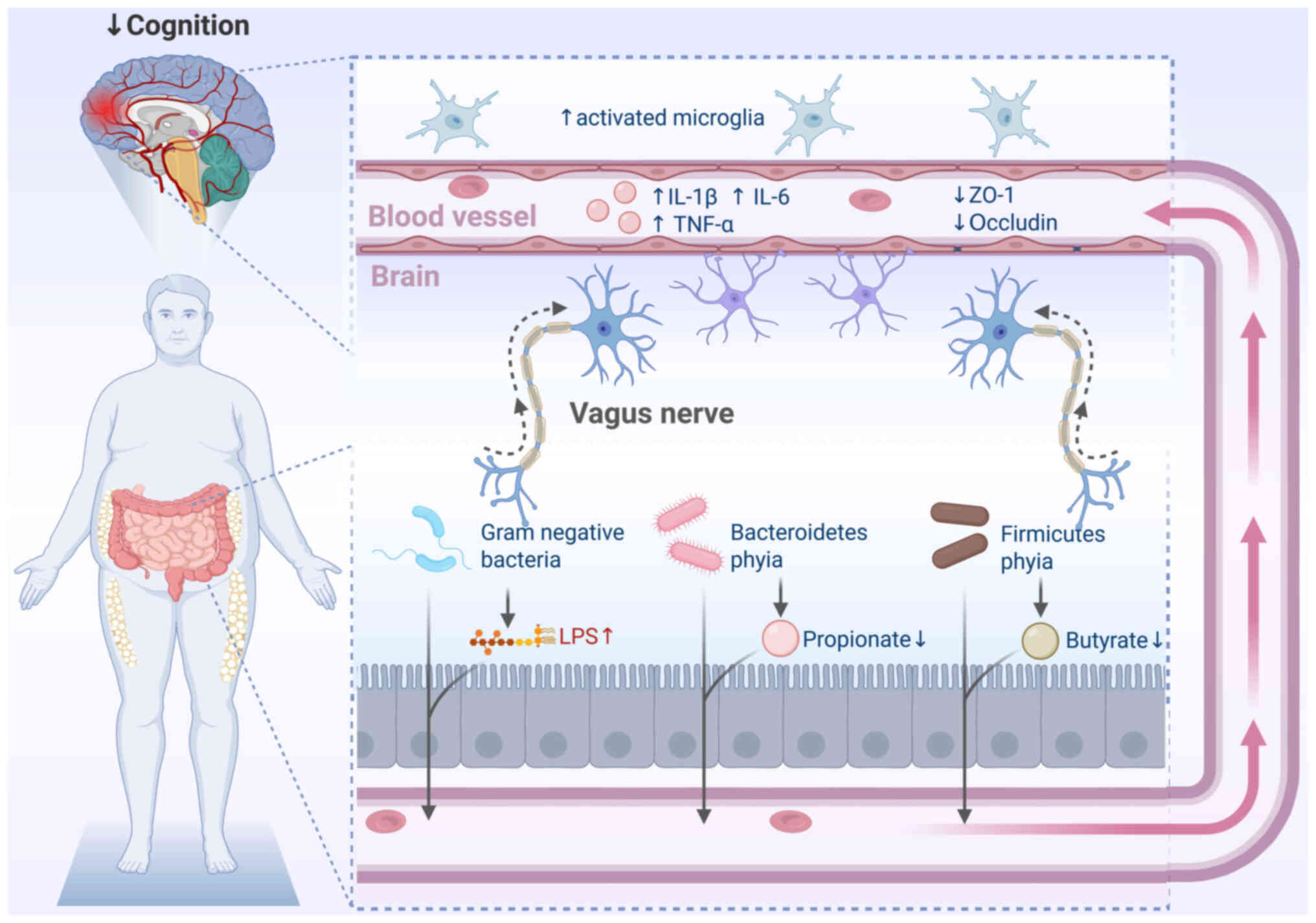

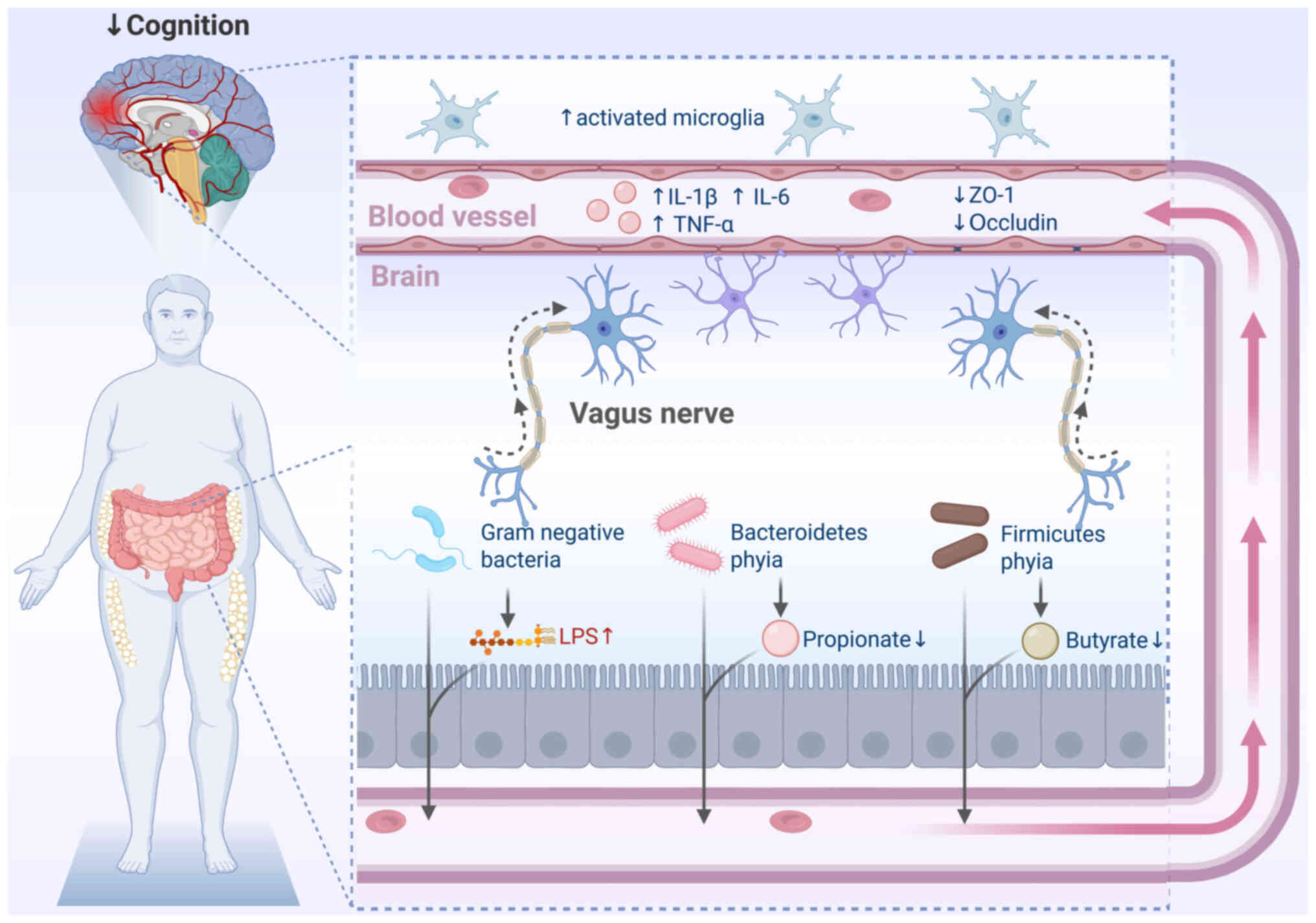

Gut microbiota dysbiosis

The gut microbiota-comprising trillions of bacteria,

archaea, viruses and fungi-plays a pivotal role in regulating host

metabolism, immune responses and CNS function via the gut-brain

axis (83-85) (Fig. 2). Human studies have shown that

individuals consuming Western-style high-fat diets HFDs exhibit

distinct gut microbial profiles associated with impaired memory and

executive function (86). These

profiles are typically characterized by a reduction in beneficial

genera such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, and

an overrepresentation of pro-inflammatory taxa including members of

the Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and

Desulfobacterota phyla (87-90).

| Figure 2Gut-brain axis disruption in

HFD-induced cognitive impairment. HFD induces gut microbiota

dysbiosis, characterized by an increased

Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio and elevated levels of

Gram-negative Proteobacteria. This leads to elevated LPS and

reduced SCFAs, such as propionate and butyrate. These changes

compromise intestinal barrier integrity, allowing microbial

products to enter circulation and activate neuroinflammatory

pathways via the vagus nerve or systemic cytokines. Consequent

microglial activation, elevated IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, and reduced

tight junction proteins (ZO-1, occludin), contribute to blood-brain

barrier disruption and cognitive decline. HFD, high-fat diet; LPS,

lipopolysaccharides; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; IL,

interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; ZO-1, zonula

occludens-1. |

Animal models have validated these associations:

Fecal microbiota transplantation from HFD-fed mice into germ-free

recipients reproduces spatial learning deficits and

neuroinflammation (91). By

contrast, microbiota-targeted interventions-including probiotics

(Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus), prebiotics (e.g.,

inulin, fructooligosaccharides) and polyphenol-rich diets-have

demonstrated the ability to restore gut microbial homeostasis,

enhance short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, suppress systemic

inflammation and improve cognitive outcomes in HFD-fed animal

(92,93).

HFD-induced dysbiosis alters gut-brain axis

communication through multiple pathways, including neural (e.g.,

vagus nerve), humoral, and immune mechanisms (94). One of the most significant

consequences is the dysregulation of microbial metabolite

production. HFD significantly reduces SCFAs such as acetate,

propionate, and butyrate-metabolites essential for maintaining gut

barrier integrity, regulating immune responses, and exerting

anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective functions. Concurrently, HFD

increases the production of harmful metabolites such as

lipopolysaccharide (LPS), trimethylamine-N-oxide and secondary bile

acids (86,95,96). Depletion of SCFAs impairs the

expression of antimicrobial peptides, particularly regenerating

islet-derived protein 3γ, further weakening the gut epithelial

barrier and increasing intestinal permeability. This allows

microbial products like LPS to enter systemic circulation, where

they activate TLR4 and trigger inflammatory cascades that elevate

circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and

IL-6 (97,98). These cytokines subsequently

exacerbate BBB permeability, promote microglial activation and

initiate CNS neuroinflammation (99).

Other potential mechanisms

In addition to inflammation, oxidative stress,

insulin resistance, and gut dysbiosis, HFD consumption contributes

to cognitive deterioration through several additional mechanisms,

including BBB disruption, epigenetic modifications, and

neurotransmitter imbalance.

One critical pathway involves the breakdown of BBB

integrity. Chronic HFD exposure significantly increases BBB

permeability, as evidenced by enhanced Evans blue dye extravasation

and increased infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the

brain parenchyma-findings closely correlated with impaired spatial

memory performance (100). This

compromised barrier allows peripheral inflammatory mediators, ROS

and LPS to enter the CNS, thereby promoting microglial activation,

neuroinflammation and cerebral Aβ deposition. Studies have shown

that saturated fat-enriched diets exacerbate BBB disruption and

facilitate plasma-derived Aβ accumulation in the brain, aggravating

AD-like neuropathology (101).

Additionally, oxidized cholesterol produced during high-temperature

cooking, along with excess SFAs, directly damages cerebrovascular

endothelial cells, reduces cerebral perfusion and promotes the

development of white matter hyperintensities-radiological markers

strongly linked to executive dysfunction and cognitive decline

(102).

Epigenetic dysregulation is another significant

contributor. Chronic HFD intake has been shown to reduce histone

acetylation and increase DNA methylation at the promoter region of

BDNF, leading to reduced BDNF expression. This downregulation

impairs synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis-both essential for

learning and memory (103). HFD

also disrupts the expression of core circadian clock genes such as

Bmal1 and Clock, causing neuronal metabolic

desynchronization and cognitive dysfunction. These epigenetic

changes further perpetuate neuroinflammation and oxidative stress,

creating a maladaptive neurochemical environment that exacerbates

cognitive decline (104).

HFD also induces widespread alterations in

neurotransmitter homeostasis. Animal studies have reported elevated

dopamine release alongside disruptions in multiple neurotransmitter

systems, including glutamate, acetylcholine, γ-aminobutyric acid,

serotonin and dopamine. Impaired glutamate reuptake results in

extracellular glutamate accumulation, contributing to

excitotoxicity, neuronal injury and impaired synaptic plasticity

(105). Cholinergic

dysfunction, characterized by reduced synthesis and release of

acetylcholine, impairs attention and learning capabilities

(106). Furthermore, an HFD

decreases the expression of neurotensin, a neuropeptide involved in

dopaminergic reward regulation, further disrupting reward pathways

and contributing to compulsive overeating, metabolic dysregulation

and cognitive deficits.

Intervention strategies

Given the multifactorial mechanisms underlying

HFD-induced cognitive impairment, a variety of intervention

strategies have been explored to improve cognitive function by

targeting different pathological pathways (Table II) (22,88,93,107-120).

| Table IINutritional and therapeutic

strategies to combat cognitive decline. |

Table II

Nutritional and therapeutic

strategies to combat cognitive decline.

| Intervention

type | Main

intake/substances or strains | Key components and

mechanisms | Cognitive

improvement and research findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| MIND diet | Leafy greens (e.g.,

spinach, kale)

Berries (e.g., blueberries, strawberries)

Nuts

Fish

Whole grains

Poultry

Legumes

Olive oil | ↑ Antioxidants

(vitamins E, C, polyphenols, lavonoids)

↑ Omega-3 fatty acids

↑ Dietary fiber

↓ Inflammation

Promotes antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protection of brain

cells | ↓ Alzheimer's

disease risk (up to 53%)

↓ Cognitive decline rate (equivalent to being cognitively '7.5

years younger')

↑ Memory, executive function and language abilities | (22,107,108) |

| Mediterranean

diet | Fresh fruits and

vegetables

Whole grains

Fish and seafood

Olive oil (main fat source)

Nuts

Moderate red wine

Legumes | ↑ Monounsaturated

fatty acids (olive oil)

↑ Omega-3 fatty acids

↑ Antioxidants (vitamins E, C, polyphenols)

↓ Inflammation and oxidative stress

Improves cerebrovascular health | ↓ Mild cognitive

impairment and dementia risk

↑ Memory and language function

↑ Brain vascular health

↓ Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress | (109,110) |

| Antidiabetic

drugs | Metformin | Metformin: ↑ AMPK

activity, improves energy metabolism, modulates gut microbiota, ↓

inflammation and oxidative stress | ↓ Cognitive decline

rate and significantly reduced dementia risk

↑ Memory and language functions | (111,112) |

| Intranasal

insulin | Intranasal insulin:

↑ Brain insulin receptor activation, improves neuronal glucose

uptake and synaptic plasticity | | (113,114) |

| Anti-inflammatory

drugs | Various

anti-inflammatory agents (research ongoing) | ↓ Release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain

↓ Oxidative stress and neuronal damage

↓ Neuroinflammation | ↓ Rate of cognitive

decline, especially in inflammation-related cognitive

impairment

Still under clinical research | (115,116) |

| Probiotics | Lactobacillus

rhamnosus | Modulates gut

microbiota balance

↓ Pro-inflammatory cytokines,

↓ neuroinflammation

Influences neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin) and brain

signaling | ↓ Beta-amyloid

deposition

↑ Spatial memory

↑ Attention and language learning abilities (clinical trials) | (93,117,118) |

| Bifidobacterium

longum | ↑ Gut barrier

function

↑ Short-chain fatty acid production, anti-inflammatory

effects

Regulates neuroendocrine and immune responses | ↑ Cognitive

function (especially combined with omega-3

supplementation)

-↑ Mood and sleep quality, indirectly promoting cognitive

health | (88,119,120) |

Dietary interventions

Dietary modification is among the most accessible

and effective strategies for mitigating cognitive impairment

associated with chronic HFD exposure. Nutritional patterns

emphasizing balanced macronutrient intake-such as the Mediterranean

diet and DASH diet-have been consistently linked to reduced risks

of cognitive decline and dementia (121).

The Mediterranean diet is characterized by high

consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, fish,

nuts and olive oil, with moderate intake of dairy products and red

wine. Epidemiological and interventional studies have demonstrated

significant cognitive benefits associated with this dietary pattern

(122). For instance, the

large-scale PREDIMED RCT reported that older adults adhering to a

Mediterranean diet supplemented with either extra-virgin olive oil

or mixed nuts exhibited substantial improvements in memory and

executive function compared to those following a low-fat control

diet (123). Similarly, the

DASH diet-emphasizing fruits, vegetables, lean protein sources such

as skinless poultry, fish and legumes, and low-fat dairy products

while limiting saturated fat intake-has been shown to benefit

cognitive function (108,124,125). Older adults adhering to the

DASH diet demonstrate superior performance on executive function

and memory tasks relative to control groups (108).

These neuroprotective effects are largely attributed

to high intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly

eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which

enhance neuronal membrane fluidity, reduce neuroinflammation,

promote neurogenesis and support synaptic plasticity (109,126-128). Observational studies have

consistently linked greater omega-3 PUFA consumption, particularly

from fatty fish and nuts, with improved cognitive outcomes and a

reduced risk of dementia. These findings are corroborated by

clinical trials demonstrating that omega-3 supplementation improves

memory and executive performance in older adults (129-131). Likewise, monounsaturated fatty

acids, such as oleic acid-abundant in olive oil-have shown

cognitive benefits by reducing oxidative stress, improving brain

insulin sensitivity and enhancing cerebrovascular function

(123).

Meal timing also plays a pivotal role in metabolic

regulation and cognitive health. Time-restricted eating, which

confines caloric intake to defined daily windows, has been shown to

restore circadian rhythmicity by normalizing clock gene expression

[e.g., brain and muscle ARNT-like 1 (Bmal1)] and reducing

hippocampal oxidative stress in HFD-fed models (132,133). Additionally, dietary

supplementation with antioxidants-including vitamins E and C, and

polyphenols, such as resveratrol, quercetin and curcumin-has

demonstrated efficacy in attenuating oxidative stress, preserving

mitochondrial function and improving cognitive outcomes.

Resveratrol, in particular, enhances mitochondrial biogenesis,

lowers oxidative burden and maintains synaptic integrity in

HFD-exposed rodents, ultimately improving learning and memory

performance (134). Similarly,

curcumin has been shown to reduce lipid peroxidation, normalize

antioxidant enzyme activity and mitigate memory deficits in

diet-induced obesity models (135).

Importantly, dietary interventions achieve greater

efficacy when combined with structured physical exercise. Evidence

from both preclinical and clinical studies suggests that

synergistic effects arise from this integration: While diet

optimizes nutrient intake, reduces oxidative stress and restores

metabolic balance, exercise further enhances neurotrophic support,

insulin sensitivity and cerebral blood flow (136,137). For instance, overweight

individuals adhering to Mediterranean or DASH dietary patterns

alongside regular aerobic training exhibited more pronounced

improvements in executive function and memory performance compared

to those receiving either intervention alone (138).

Exercise interventions

Regular physical exercise represents a potent

intervention to counteract cognitive decline associated with

chronic HFD exposure, particularly in the context of HFD-induced

insulin resistance (139,140).

In preclinical studies, voluntary aerobic exercise

markedly increases BDNF expression and promotes hippocampal

neurogenesis, thereby reversing HFD-induced deficits in memory

performance (141). Exercise

also upregulates other neurotrophic mediators, including nerve

growth factor and insulin-like growth factor-1, which collectively

enhance neuronal survival, dendritic branching and synaptogenesis

(142). For instance, rats

undergoing aerobic training after chronic HFD exposure exhibited

increased expression of synaptic proteins, such as synaptophysin

and PSD-95, correlating with improved spatial learning and memory

performance (143).

These animal findings are mirrored in clinical

studies. In older adults, aerobic exercise has been shown to

increase hippocampal volume, elevate serum BDNF levels and enhance

spatial memory, supporting the translational relevance of animal

data (139). Furthermore,

overweight or obese individuals engaging in structured aerobic

training-particularly when combined with dietary

modifications-exhibited significant improvements in executive

function, processing speed and attentional control when compared to

sedentary controls (144).

From a metabolic perspective, aerobic exercise

improves systemic and cerebral glucose homeostasis by upregulating

GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle and brain tissues (145). In HFD-fed rodents, treadmill

exercise restored hippocampal insulin signaling pathways, including

IRS-1 phosphorylation and PI3K/Akt activity, thereby reversing

HFD-induced cognitive decline (146). Exercise also exerts potent

anti-inflammatory effects in the CNS. It reduces the expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, and attenuates

microglial activation within the hippocampus and cortex. For

instance, in AD models, treadmill training ameliorated memory

deficits by downregulating IL-1β and phosphodiesterase-5 expression

and restoring phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein

signaling (140,147). Similarly, voluntary wheel

running reversed HFD-induced microglial activation and rescued

memory consolidation processes (148). In addition, regular physical

activity combats oxidative stress by enhancing the activity of

endogenous antioxidant enzymes-including SOD, catalase and

glutathione peroxidase-while preserving mitochondrial integrity and

reducing ROS accumulation in brain tissue (149).

Microbiota-targeted interventions

Microbiota-targeted therapies-including probiotics,

prebiotics and next-generation bacterial strains-have emerged as

promising strategies to modulate the gut-brain axis and ameliorate

cognitive impairment associated with HFD exposure.

Probiotics, defined as live beneficial

microorganisms (e.g., Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium species), and prebiotics, which are

non-digestible fibers such as inulin and fructooligosaccharides

(FOS) that selectively promote the growth of commensal microbes,

have demonstrated consistent neuroprotective effects in preclinical

models. For example, oral administration of Lactobacillus

plantarum in HFD-fed mice restored gut microbial diversity,

reduced systemic and hippocampal inflammation, upregulated synaptic

proteins such as synaptophysin and PSD-95, and reversed deficits in

learning and memory (117).

Similarly, supplementation with Bifidobacterium-containing

probiotic formulations normalized microbial composition, enhanced

hippocampal BDNF expression and alleviated HFD-induced spatial

memory deficits and anxiety-like behaviors (150).

Clinical trials further support the cognitive

benefits of microbiota modulation. In an RCT, elderly individuals

with MCI receiving a multispecies probiotic mixture (L.

acidophilus, L. casei, B. bifidum) exhibited significant

improvements in cognitive performance, reduced circulating

proinflammatory cytokines and enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity

compared to placebo (151).

Similarly, prebiotic interventions with inulin or FOS have been

shown to increase the abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria,

strengthen intestinal barrier integrity, suppress systemic

inflammation and subsequently improve cognitive outcomes in

populations with metabolic syndrome or cognitive decline.

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological interventions targeting HFD-induced

cognitive impairment primarily aim to modulate neuroinflammation,

oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and disrupted neuroplasticity

signaling. A range of agents-including anti-inflammatory drugs,

insulin sensitizers, and neurotrophic modulators-have demonstrated

cognitive benefits in both preclinical and clinical studies.

Anti-inflammatory agents such as nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs and selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors

have shown promise in preclinical models. For instance, celecoxib

effectively attenuates microglial activation, reduces

pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and TNF-α, and improves

hippocampal-dependent memory performance in HFD-fed rodents

(102,152). Minocycline, a tetracycline

derivative with central anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective

properties, similarly reduces hippocampal inflammation, preserves

synaptic architecture, and enhances spatial learning and memory

(153,154).

Insulin sensitizers, including metformin and

thiazolidinediones (e.g., rosiglitazone, pioglitazone), exert

neuroprotective effects by restoring central insulin signaling,

reducing neuroinflammation and mitigating oxidative stress

(155). Metformin improves

hippocampal IRS phosphorylation and downstream PI3K/Akt signaling,

enhancing synaptic plasticity and memory function in metabolic

dysfunction models (156,157). Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists further promote adult

neurogenesis and synaptic remodeling, contributing to cognitive

improvements in HFD-fed animals (158). In addition, glucagon-like

peptide-1 receptor agonists (e.g., liraglutide, exenatide)

represent a novel class of therapeutics with dual metabolic and

neuroprotective actions (159).

These agents enhance insulin signaling in the brain, reduce

hippocampal inflammation and oxidative stress, stimulate

neurogenesis, and improve learning and memory performance in

HFD-exposed rodents. Clinical trials in obese and diabetic patients

have also demonstrated cognitive benefits, suggesting translational

potential for diet-associated neurocognitive disorders (160,161). Neuroplasticity-targeted

therapies offer additional avenues. Pharmacological agents that

enhance BDNF signaling-such as selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors (SSRIs), PDE inhibitors and histone deacetylase

inhibitors-have been shown to restore synaptic plasticity and

cognitive function. For instance, fluoxetine, a commonly used SSRI,

upregulates hippocampal BDNF expression and reverses cognitive

deficits in HFD-fed rodents (162,163).

Limitations and future perspectives

Limitations

Despite substantial evidence linking chronic HFD

intake to cognitive impairment, several limitations remain in

current research, which hinder the establishment of definitive

causal relationships (26,55).

A major limitation lies in the predominant reliance

on observational epidemiological studies and preclinical animal

models. While these approaches have elucidated critical mechanistic

insights, their applicability to human physiology remains limited

due to species-specific metabolic, neuroimmune and behavioral

differences (164). Notably,

numerous rodent studies utilize acute or supra-physiological doses

of dietary fat, which fail to recapitulate the chronic, moderate

exposures and complex eating patterns typical of human dietary

habits-including meal timing, social eating behaviors and food

processing. Furthermore, substantial heterogeneity across

studies-including variations in dietary fat composition (e.g.,

saturated vs. unsaturated), intervention durations, cognitive

assessment tools and demographic characteristics complicates

cross-study comparisons and undermines the generalizability of

findings (165).

The bidirectional relationship between metabolic

dysfunction and gut microbiota dysbiosis poses another unresolved

challenge. It remains elusive whether microbial alterations serve

as a causal antecedent or secondary consequence of HFD-induced

metabolic changes (16).

Similarly, while microglial activation is frequently implicated in

cognitive decline, conflicting data persist. For instance,

inhibition of microglial activation via Triggering Receptor

Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 (TREM2) deletion has been shown to

mitigate cognitive deficits in HFD-fed mice, suggesting a

pathogenic role (166).

Conversely, other models of neuroinflammation do not consistently

produce cognitive impairments, indicating that additional

mechanisms-such as BBB disruption, mitochondrial dysfunction and

oxidative stress-likely contribute to cognitive decline in a

context-dependent manner (167).

Genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity in human

populations adds further complexity. Polymorphisms in genes such as

TLR4, or variations in neuroimmune and metabolic regulatory

pathways, may modulate individual vulnerability to HFD-related

cognitive impairment and influence response to microbiota-targeted

interventions (168).

Furthermore, neuromodulatory strategies-such as vagus nerve

stimulation-while efficacious in preclinical settings, have shown

inconsistent cognitive benefits in human trials, underscoring the

challenges of translational fidelity (169).

Future perspectives

Given the multifaceted and interconnected mechanisms

by which chronic HFD contributes to cognitive decline, future

research must adopt a more integrative and mechanistically grounded

approach to uncover effective preventive and therapeutic

strategies. While preclinical studies have yielded extensive

insights, their translational relevance remains limited (121,170,171). Robust clinical validation

through well-powered, longitudinal RCTs is urgently needed to

establish causal links between dietary fat subtypes and cognitive

outcomes, particularly across genetically and metabolically diverse

populations. Such trials should incorporate long-term exposure

assessments and harmonized cognitive endpoints to improve

comparability and external validity (172).

At the mechanistic level, the field is poised to

benefit from emerging tools such as single-cell multi-omics,

spatial transcriptomics and metabolic flux analysis. These

approaches allow for high-resolution dissection of how HFD alters

brain homeostasis at cellular and molecular levels-uncovering how

neuronal, glial, immune and vascular cell types interact in

spatially distinct and temporally dynamic ways (173). Integrating these datasets may

clarify unresolved questions, such as whether microbiota dysbiosis

precedes metabolic dysfunction or merely reflects it, and how the

gut-brain axis mediates diet-induced neuroinflammation and synaptic

degeneration.

Importantly, the pronounced heterogeneity in

individual responses to HFD highlights the necessity of

personalized interventions. Moving beyond 'one-size-fits-all'

recommendations, future strategies should be tailored to individual

characteristics such as APOE genotype, insulin sensitivity,

microbiome enterotype and sex-specific vulnerabilities. Precision

nutrition-guided by validated biomarkers such as plasma ceramides

or microbial metabolites-holds particular promise for early risk

stratification and targeted intervention (174). Furthermore, there is growing

recognition that single-modality interventions are unlikely to

fully reverse or prevent HFD-induced cognitive dysfunction. Future

studies should prioritize multimodal strategies that combine

dietary modification, structured physical activity, pharmacologic

agents targeting neuroinflammation or insulin resistance,

microbiota-targeted therapies (e.g., Akkermansia muciniphila

supplementation) and neuromodulation techniques (e.g., transcranial

direct current stimulation). Such integrative approaches are better

positioned to tackle the complex neurobiological cascades

underlying metabolic-cognitive deterioration.

Conclusions

HFD consumption accelerates cognitive decline

through converging mechanisms such as neuroinflammation, oxidative

stress, insulin resistance, gut dysbiosis and synaptic dysfunction.

These effects are further modulated by genetic and demographic

factors, including APOE genotype, age and sex. Current evidence

supports the efficacy of integrative interventions-such as

Mediterranean-style diets, physical exercise, metabolic modulators

and microbiota-targeted therapies-in mitigating HFD-induced

neurodegeneration. Future research should focus on validating these

strategies in diverse populations via large-scale trials and

leveraging multi-omics technologies to guide precision

prevention.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MY was involved in the conceptualization of the

study, drafted the manuscript, writing-review & editing and

visualization. FW contributed to the conceptualization of the study

and writing-review & editing. FX, XH and HW were responsible

for writing-review & editing. MY and FW performed the

literature search and selection. LZ and HZ contributed to

writing-review & editing acquired funding and supervised the

study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82505742 and 82274663); the Hubei

Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Research

Fund (grant no. ZY2025M053); the Joint Foundation Project of Hubei

Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2025AFD527) and

Jianghan University Fundamental Research Program (grant no.

2024JCYJ13).

References

|

1

|

Roberts R and Knopman DS: Classification

and epidemiology of MCI. Clin Geriatr Med. 29:753–772. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu YT, Prina

AM, Winblad B, Jönsson L, Liu Z and Prince M: The worldwide costs

of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimers Dement.

13:1–7. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yi W, Chen F, Yuan M, Wang C, Wang S, Wen

J, Zou Q, Pu Y and Cai Z: High-fat diet induces cognitive

impairment through repression of SIRT1/AMPK-mediated autophagy. Exp

Neurol. 371:1145912024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting

Collaborators: Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in

2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the global

burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 7:e105–e125.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Frazier K, Kambal A, Zale EA, Pierre JF,

Hubert N, Miyoshi S, Miyoshi J, Ringus DL, Harris D, Yang K, et al:

High-fat diet disrupts REG3γ and gut microbial rhythms promoting

metabolic dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe. 30:809–823. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wang X, Song R, Clinchamps M and Dutheil

F: New insights into high-fat diet with chronic diseases.

Nutrients. 15:40312023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jones-Muhammad M and Warrington JP: When

high-fat diet plus hypertension does not equal vascular

dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 321:H128–H130. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cao GY, Li M, Han L, Tayie F, Yao SS,

Huang Z, Ai P, Liu YZ, Hu YH and Xu B: Dietary fat intake and

cognitive function among older populations: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 6:204–211. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Song M, Bai Y and Song F: High-fat diet

and neuroinflammation: The role of mitochondria. Pharmacol Res.

212:1076152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Roberts RO, Roberts LA, Geda YE, Cha RH,

Pankratz VS, O'Connor HM, Knopman DS and Petersen RC: Relative

intake of macronutrients impacts risk of mild cognitive impairment

or dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 32:329–339. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Valentin-Escalera J, Leclerc M and Calon

F: High-Fat diets in animal models of Alzheimer's disease: How can

eating too much fat increase Alzheimer's disease Risk? J Alzheimers

Dis. 97:977–1005. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Hoscheidt S, Sanderlin AH, Baker LD, Jung

Y, Lockhart S, Kellar D, Whitlow CT, Hanson AJ, Friedman S,

Register T, et al: Mediterranean and western diet effects on

Alzheimer's disease biomarkers, cerebral perfusion, and cognition

in mid-life: A randomized trial. Alzheimers Dement. 18:457–468.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Yanai H: Effects of N-3 polyunsaturated

fatty acids on dementia. J Clin Med Res. 9:1–9. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Román GC, Jackson RE, Gadhia R, Román AN

and Reis J: Mediterranean diet: The role of long-chain ω-3 fatty

acids in fish; polyphenols in fruits, vegetables, cereals, coffee,

tea, cacao and wine; probiotics and vitamins in prevention of

stroke, age-related cognitive decline, and Alzheimer disease. Rev

Neurol (Paris). 175:724–741. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Di Meco A and Praticò D: Early-life

exposure to high-fat diet influences brain health in aging mice.

Aging Cell. 18:e130402019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

de Paula GC, Brunetta HS, Engel DF, Gaspar

JM, Velloso LA, Engblom D, de Oliveira J and de Bem AF: Hippocampal

function is impaired by a short-term high-fat diet in mice:

Increased blood-brain barrier permeability and neuroinflammation as

triggering events. Front Neurosci. 15:7341582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Xiong J, Deng I, Kelliny S, Lin L,

Bobrovskaya L and Zhou X: Long term high fat diet induces metabolic

disorders and aggravates behavioral disorders and cognitive

deficits in MAPT P301L transgenic mice. Metab Brain Dis.

37:1941–1957. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Boitard C, Cavaroc A, Sauvant J, Aubert A,

Castanon N, Layé S and Ferreira G: Impairment of

hippocampal-dependent memory induced by juvenile high-fat diet

intake is associated with enhanced hippocampal inflammation in

rats. Brain Behav Immun. 40:9–17. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sanguinetti E, Guzzardi MA, Panetta D,

Tripodi M, De Sena V, Quaglierini M, Burchielli S, Salvadori PA and

Iozzo P: Combined effect of fatty diet and cognitive decline on

brain metabolism, food intake, body weight, and counteraction by

intranasal insulin therapy in 3xTg mice. Front Cell Neurosci.

13:1882019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Attuquayefio T, Stevenson RJ, Boakes RA,

Oaten MJ, Yeomans MR, Mahmut M and Francis HM: A high-fat

high-sugar diet predicts poorer hippocampal-related memory and a

reduced ability to suppress wanting under satiety. J Exp Psychol

Anim Learn Cogn. 42:415–428. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Holloway CJ, Cochlin LE, Emmanuel Y,

Murray A, Codreanu I, Edwards LM, Szmigielski C, Tyler DJ, Knight

NS, Saxby BK, et al: A high-fat diet impairs cardiac high-energy

phosphate metabolism and cognitive function in healthy human

subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 93:748–755. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM,

Barnes LL, Bennett DA and Aggarwal NT: MIND diet slows cognitive

decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement. 11:1015–1022. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney

CC, Bennett DA, Aggarwal N, Schneider J and Wilson RS: Dietary fats

and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol.

60:194–200. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, Tangney

CC and Wilson RS: Dietary fat intake and 6-year cognitive change in

an older biracial community population. Neurology. 62:1573–1579.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Galloway S, Takechi R, Nesbit M,

Pallebage-Gamarallage MM, Lam V and Mamo JCL: The differential

effects of fatty acids on enterocytic abundance of amyloid-beta.

Lipids Health Dis. 18:2092019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Evans AK, Saw NL, Woods CE, Vidano LM,

Blumenfeld SE, Lam RK, Chu EK, Reading C and Shamloo M: Impact of

high-fat diet on cognitive behavior and central and systemic

inflammation with aging and sex differences in mice. Brain Behav

Immun. 118:334–354. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Boraxbekk CJ, Stomby A, Ryberg M, Lindahl

B, Larsson C, Nyberg L and Olsson T: diet-induced weight loss

alters functional brain responses during an episodic memory task.

Obes Facts. 8:261–272. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yao X, Yang C, Jia X, Yu Z, Wang C, Zhao

J, Chen Y, Xie B, Zhuang H, Sun C, et al: High-fat diet consumption

promotes adolescent neurobehavioral abnormalities and hippocampal

structural alterations via microglial overactivation accompanied by

an elevated serum free fatty acid concentration. Brain Behav Immun.

119:236–250. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Ruan Y, Tang J, Guo X, Li K and Li D:

Dietary fat intake and risk of Alzheimer's disease and dementia: A

meta-analysis of cohort studies. Curr Alzheimer Res. 15:869–876.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

You SC, Geschwind MD, Sha SJ, Apple A,

Satris G, Wood KA, Johnson ET, Gooblar J, Feuerstein JS, Finkbeiner

S, et al: Executive functions in premanifest Huntington's disease.

Mov Disord. 29:405–409. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Klaus K, Vaht M, Pennington K and Harro J:

Interactive effects of DRD2 rs6277 polymorphism, environment and

sex on impulsivity in a population-representative study. Behav

Brain Res. 403:1131312021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Nieto-Estévez V, Defterali Ç and Vicario

C: Distinct effects of BDNF and NT-3 on the dendrites and

presynaptic boutons of developing olfactory bulb GABAergic

interneurons in vitro. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 42:1399–1417. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

McLean FH, Grant C, Morris AC, Horgan GW,

Polanski AJ, Allan K, Campbell FM, Langston RF and Williams LM:

Rapid and reversible impairment of episodic memory by a high-fat

diet in mice. Sci Rep. 8:119762018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhang Y, Peng Y, Deng W, Xiang Q, Zhang W

and Liu M: Association between dietary inflammatory index and

cognitive impairment among American elderly: A cross-sectional

study. Front Aging Neurosci. 16:13718732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Valcarcel-Ares MN, Tucsek Z, Kiss T, Giles

CB, Tarantini S, Yabluchanskiy A, Balasubramanian P, Gautam T,

Galvan V, Ballabh P, et al: Obesity in aging exacerbates

neuroinflammation, dysregulating synaptic function-related genes

and altering eicosanoid synthesis in the mouse hippocampus:

Potential role in impaired synaptic plasticity and cognitive

decline. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 74:290–298. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

36

|

Kothari V, Luo Y, Tornabene T, O'Neill AM,

Greene MW, Geetha T and Babu JR: High fat diet induces brain

insulin resistance and cognitive impairment in mice. Biochim

Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1863:499–508. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Julien C, Tremblay C, Phivilay A,

Berthiaume L, Emond V, Julien P and Calon F: High-fat diet

aggravates amyloid-beta and tau pathologies in the 3xTg-AD mouse

model. Neurobiol Aging. 31:1516–1531. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Henn RE, Elzinga SE, Glass E, Parent R,

Guo K, Allouch AM, Mendelson FE, Hayes J, Webber-Davis I, Murphy

GG, et al: Obesity-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive

impairment in young adult versus middle-aged mice. Immun Ageing.

19:672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Morris MC, Evans DA, Tangney CC, Bienias

JL, Schneider JA, Wilson RS and Scherr PA: Dietary copper and high

saturated and trans fat intakes associated with cognitive decline.

Arch Neurol. 63:1085–1088. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chatterjee S, Peters SA, Woodward M,

Arango SM, Batty GD, Beckett N, Beiser A, Borenstein AR, Crane PK,

Haan M, et al: Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for dementia in

women compared with men: A pooled analysis of 2.3 million people

comprising more than 100,000 cases of dementia. Diabetes Care.

39:300–307. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

41

|

Sanz-Martos AB, Roca M, Plaza A, Merino B,

Ruiz-Gayo M and Olmo ND: Long-term saturated fat-enriched diets

impair hippocampal learning and memory processes in a sex-dependent

manner. Neuropharmacology. 259:1101082024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Muscat SM, Butler MJ, Mackey-Alfonso SE

and Barrientos RM: Young adult and aged female rats are vulnerable

to amygdala-dependent, but not hippocampus-dependent, memory

impairment following short-term high-fat diet. Brain Res Bull.

195:145–156. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Armstrong NM, An Y, Beason-Held L, Doshi

J, Erus G, Ferrucci L, Davatzikos C and Resnick SM: Predictors of

neurodegeneration differ between cognitively normal and

subsequently impaired older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 75:178–186.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

44

|

Laitinen MH, Ngandu T, Rovio S, Helkala

EL, Uusitalo U, Viitanen M, Nissinen A, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H

and Kivipelto M: Fat intake at midlife and risk of dementia and

Alzheimer's disease: A population-based study. Dement Geriatr Cogn

Disord. 22:2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kleinridders A, Ferris HA, Cai W and Kahn

CR: Insulin action in brain regulates systemic metabolism and brain

function. Diabetes. 63:2232–2243. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Martiskainen H, Helisalmi S, Viswanathan

J, Kurki M, Hall A, Herukka SK, Sarajärvi T, Natunen T, Kurkinen

KM, Huovinen J, et al: Effects of Alzheimer's disease-associated

risk loci on cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and disease

progression: A polygenic risk score approach. J Alzheimers Dis.

43:565–573. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Fan L, Borenstein AR, Wang S, Nho K, Zhu

X, Wen W, Huang X, Mortimer JA, Shrubsole MJ and Dai Q; Alzheimer's

Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: Associations of circulating

saturated long-chain fatty acids with risk of mild cognitive

impairment and Alzheimer's disease in the Alzheimer's disease

neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) cohort. EBioMedicine. 97:1048182023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Arnold SE, Lucki I, Brookshire BR, Carlson

GC, Browne CA, Kazi H, Bang S, Choi BR, Chen Y, McMullen MF and Kim

SF: High fat diet produces brain insulin resistance,

synaptodendritic abnormalities and altered behavior in mice.

Neurobiol Dis. 67:79–87. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Li C, Shi L, Wang Y, Peng C, Wu L, Zhang Y

and Du Z: High-fat diet exacerbates lead-induced blood-brain

barrier disruption by disrupting tight junction integrity. Environ

Toxicol. 36:1412–1421. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Meza-Miranda ER, Camargo A, Rangel-Zuñiga

OA, Delgado-Lista J, Garcia-Rios A, Perez-Martinez P, Tasset-Cuevas

I, Tunez I, Tinahones FJ, Perez-Jimenez F and Lopez-Miranda J:

Postprandial oxidative stress is modulated by dietary fat in

adipose tissue from elderly people. Age (Dordr). 36:507–517. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Valdearcos M, Douglass JD, Robblee MM,

Dorfman MD, Stifler DR, Bennett ML, Gerritse I, Fasnacht R, Barres

BA, Thaler JP and Koliwad SK: Microglial inflammatory signaling

orchestrates the hypothalamic immune response to dietary excess and

mediates obesity susceptibility. Cell Metab. 26:185–197. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yanguas-Casás N, Crespo-Castrillo A, de

Ceballos ML, Chowen JA, Azcoitia I, Arevalo MA and Garcia-Segura

LM: Sex differences in the phagocytic and migratory activity of

microglia and their impairment by palmitic acid. Glia. 66:522–537.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Block ML, Zecca L and Hong JS:

Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: Uncovering the molecular

mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 8:57–69. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Ransohoff RM: How neuroinflammation

contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. 353:777–783. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Liang Z, Gong X, Ye R, Zhao Y, Yu J, Zhao

Y and Bao J: Long-Term high-fat diet consumption induces cognitive

decline accompanied by tau hyper-phosphorylation and microglial

activation in aging. Nutrients. 15:2502023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kipnis J, Cohen H, Cardon M, Ziv Y and

Schwartz M: T cell deficiency leads to cognitive dysfunction:

Implications for therapeutic vaccination for schizophrenia and

other psychiatric conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

101:8180–8185. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Yirmiya R and Goshen I: Immune modulation

of learning, memory, neural plasticity and neurogenesis. Brain

Behav Immun. 25:181–213. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Toyama K, Koibuchi N, Hasegawa Y, Uekawa

K, Yasuda O, Sueta D, Nakagawa T, Ma M, Kusaka H, Lin B, et al:

ASK1 is involved in cognitive impairment caused by long-term

high-fat diet feeding in mice. Sci Rep. 5:108442015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sobesky JL, Barrientos RM, De May HS,

Thompson BM, Weber MD, Watkins LR and Maier SF: High-fat diet

consumption disrupts memory and primes elevations in hippocampal

IL-1β, an effect that can be prevented with dietary reversal or

IL-1 receptor antagonism. Brain Behav Immun. 42:22–32. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Spencer SJ, Korosi A, Layé S, Shukitt-Hale

B and Barrientos RM: Food for thought: how nutrition impacts

cognition and emotion. NPJ Sci Food. 1:72017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Crupi R, Marino A and Cuzzocrea S: n-3

fatty acids: Role in neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. Curr Med

Chem. 20:2953–2963. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Butler MJ, Mackey-Alfonso SE, Massa N,

Baskin KK and Barrientos RM: Dietary fatty acids differentially

impact phagocytosis, inflammatory gene expression, and

mitochondrial respiration in microglial and neuronal cell models.

Front Cell Neurosci. 17:12272412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Alkan I, Altunkaynak BZ, Gültekin Gİ and

Bayçu C: Hippocampal neural cell loss in high-fat diet-induced

obese rats-exploring the protein networks, ultrastructure,

biochemical and bioinformatical markers. J Chem Neuroanat.

114:1019472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Lin MT and Beal MF: Mitochondrial

dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases.

Nature. 443:787–795. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kelty TJ, Taylor CL, Wieschhaus NE, Thorne

PK, Amin AR, Mueller CM, Olver TD, Tharp DL, Emter CA, Caulk AW and

Rector RS: Western diet-induced obesity results in brain

mitochondrial dysfunction in female Ossabaw swine. Front Mol

Neurosci. 16:13208792023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

66

|

Grel H, Woznica D, Ratajczak K, Kalwarczyk

E, Anchimowicz J, Switlik W, Olejnik P, Zielonka P, Stobiecka M and

Jakiela S: Mitochondrial dynamics in neurodegenerative diseases:

Unraveling the role of fusion and fission processes. Int J Mol Sci.

24:130332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Madreiter-Sokolowski CT, Hiden U, Krstic

J, Panzitt K, Wagner M, Enzinger C, Khalil M, Abdellatif M, Malle

E, Madl T, et al: Targeting organ-specific mitochondrial

dysfunction to improve biological aging. Pharmacol Ther.

262:1087102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Haack F, Lemcke H, Ewald R, Rharass T and

Uhrmacher AM: Spatio-temporal model of endogenous ROS and

raft-dependent WNT/beta-catenin signaling driving cell fate

commitment in human neural progenitor cells. PLoS Comput Biol.

11:e10041062015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ghosh P, Fontanella RA, Scisciola L,

Pesapane A, Taktaz F, Franzese M, Puocci A, Ceriello A,

Prattichizzo F, Rizzo MR, et al: Targeting redox imbalance in

neurodegeneration: Characterizing the role of GLP-1 receptor

agonists. Theranostics. 13:4872–4884. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Bórquez DA, Urrutia PJ, Wilson C, van

Zundert B, Núñez MT and González-Billault C: Dissecting the role of