Introduction

Epigenetics constitutes an important part of the

immunoregulatory mechanisms within the human body. The

posttranslational modification of histones represents a notable

epigenetic mechanism that influences DNA structure and function,

primarily encompassing mechanisms such as methylation, acetylation,

phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Among them, histone acetylation

is a commonly and extensively studied epigenetic regulatory

mechanism. It carries out a pivotal role in modulating chromatin

activity and subsequent gene transcription (1). The process of histone acetylation

is reversible and is meticulously regulated by a series of enzymes.

For instance, histones undergo acetylation under the catalytic

influence of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) families. However,

this acetylation can be reversed and removed by histone

deacetylases (HDACs), leading to the inhibition of gene

transcription. As their name implies, HDACs are responsible for

removing acetyl groups from histones, thereby influencing the

expression of DNA-encoded genes that are associated with these

histone molecules (2). Moreover,

an abundance of evidence suggests that HDACs can also deacetylate

non-histone proteins, which consequently exerts influence on

cellular physiological processes (3). Given their effects on the cellular

functions, HDACs carry out a pivotal role in regulating both innate

and adaptive immune pathways. Consequently, HDACs are widely

recognized as key inflammatory and immune regulators. Numerous HDAC

inhibitors (HDACis) have been developed as therapeutic agents, with

cancer currently being their main clinical indication. Promising

clinical progress is being made regarding their therapeutic effects

on inflammatory diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, HIV infection

and other conditions (4,5). As aforementioned, HDAC-mediated

deacetylation holds great importance for gene transcriptional

activity and can serve as an effective target for regulating the

immune response of the body.

The gut microbiota constitutes a highly intricate

community of microorganisms that colonize in the human intestinal

tract. It facilitates the digestion and metabolism of nutrients, as

well as promoting the maintenance of host immune homeostasis. This

beneficial effect can be largely attributed to the key molecular

signals delivered by a 'healthy' microbiome. These signals can stem

from microbial surface antigens or active metabolites, and they

hold importance for the proper development and function of the

immune system (6,7). A previous study revealed that

microbial signals are capable of calibrating the transcriptional

programs of host cells through epigenetic modifications, which in

turn regulate both innate and adaptive immune responses. Notably,

metabolites originating from the microbiota, acting as key

epigenetic substrates and enzyme regulators, have the potential to

promote crosstalk between the microbiota and the host by inducing

histone modifications (8).

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are metabolic products generated by

gut microbes and are recognized as pivotal mediators in the

interplay between the microbiota and the immune system.

Importantly, SCFAs can exert immunomodulatory effects at both local

intestinal and systemic levels, primarily relying on evolutionarily

conserved processes involving the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)

signaling and the HDAC inhibition (9). Specifically, SCFAs can function as

the HDACi, targeting the epigenome by inducing chromatin remodeling

that subsequently influences cellular processes and functions.

Typically, the HDAC inhibition targeted by SCFAs fosters a

tolerogenic or anti-inflammatory cellular phenotype, which carries

out a key role in maintaining immune homeostasis. It is

well-established that the anti-inflammatory effects of SCFAs,

grounded in HDAC inhibition, encompass not only epithelial cells

but also a diverse range of immune cells, including peripheral

blood monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages

and T cells (6,10,11). Collectively, these findings

substantiate the key notion that SCFA metabolites can act as

epigenetic regulators, thereby enabling the gut microbiota to

modulate host immune responses.

In recent years, the multifaceted HDAC inhibition

exhibited by SCFAs has been increasingly elucidated. SCFAs not only

increase the epithelial barrier function in the gut but also shape

the host immune system, thereby promoting both intestinal and

systemic immune homeostasis. Given these findings, the present

systematic review discusses, at both cellular and systemic levels,

the regulatory effects of SCFAs on host immunity mediated by HDAC

inhibition. The present review was conducted in accordance with the

PRISMA guidelines (12).

Comprehensive searches were carried out across Medline (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medline/), PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/),

Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/), Web of Science (URL:

https://www.webofscience.com/) and other

databases (https://www.sciencedirect.com/) from inception until

September 30, 2025. The search strategy utilized the full terms

'short-chain fatty acids' (abbreviated as 'SCFAs') and 'histone

deacetylases' (abbreviated as 'HDAC'), along with other core terms

such as 'acetate', 'propionate', 'butyrate' and 'acetylation'.

These were combined with modifiers, including 'gut microbiota',

'immune cells', 'T/B cells', 'immune diseases' and

'anti-bacterial/anti-inflammatory effects', using Boolean operators

('AND', 'OR') to refine the search. Examples of search strings are

as follows: ('Short-chain fatty acids' OR 'SCFAs') AND 'gut

microbiota', ('short-chain fatty acids' OR 'SCFAs') AND 'histone

deacetylases' OR 'HDAC' OR 'acetylation') AND ('anti-bacterial

effects' OR 'anti-inflammatory effects') and ('acetate' OR

'propionate' OR 'butyrate') AND ('histone deacetylases' OR 'HDAC'

OR 'acetylation') AND ('immune cells' OR 'T/B cells' OR 'immune

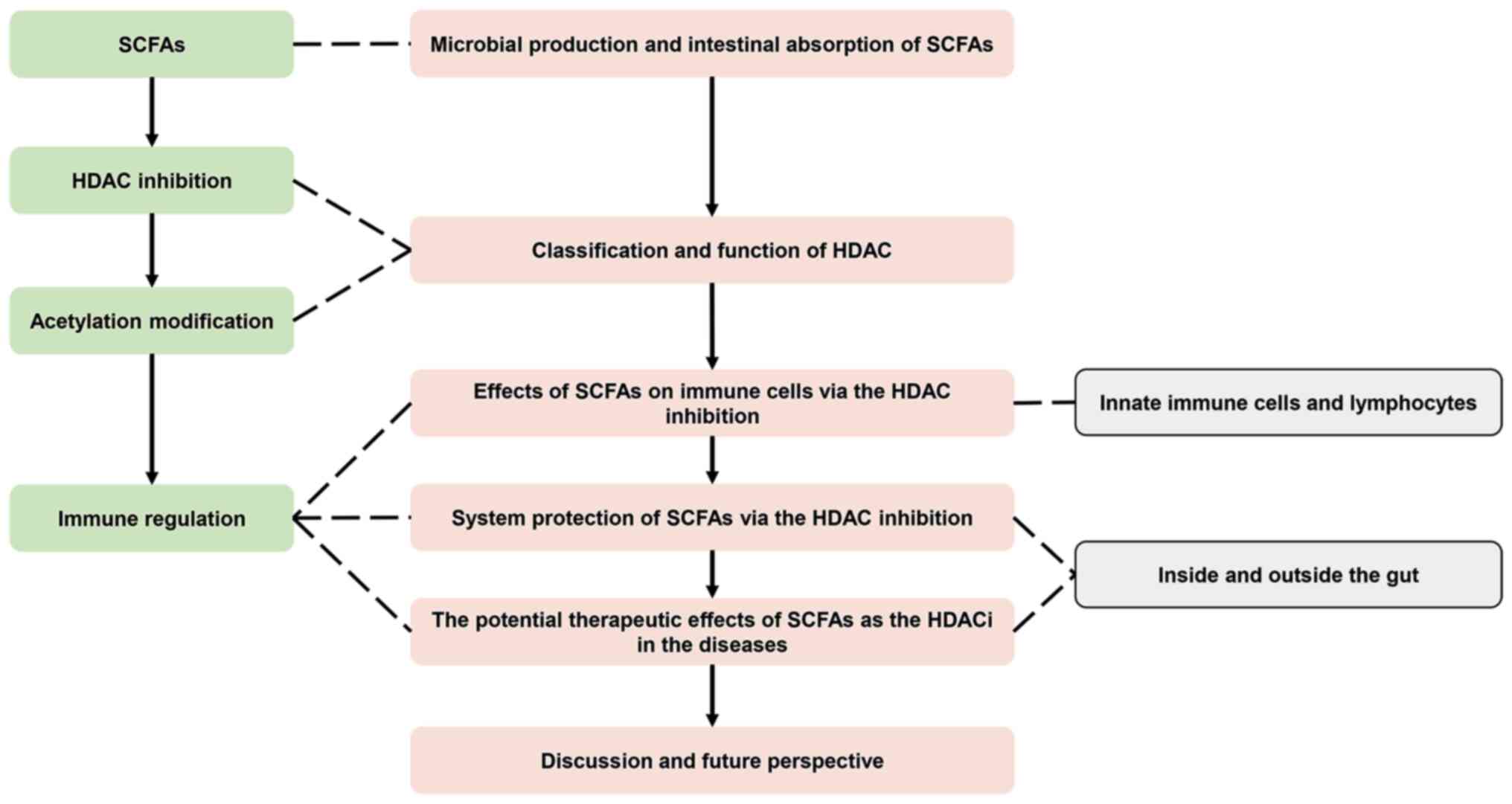

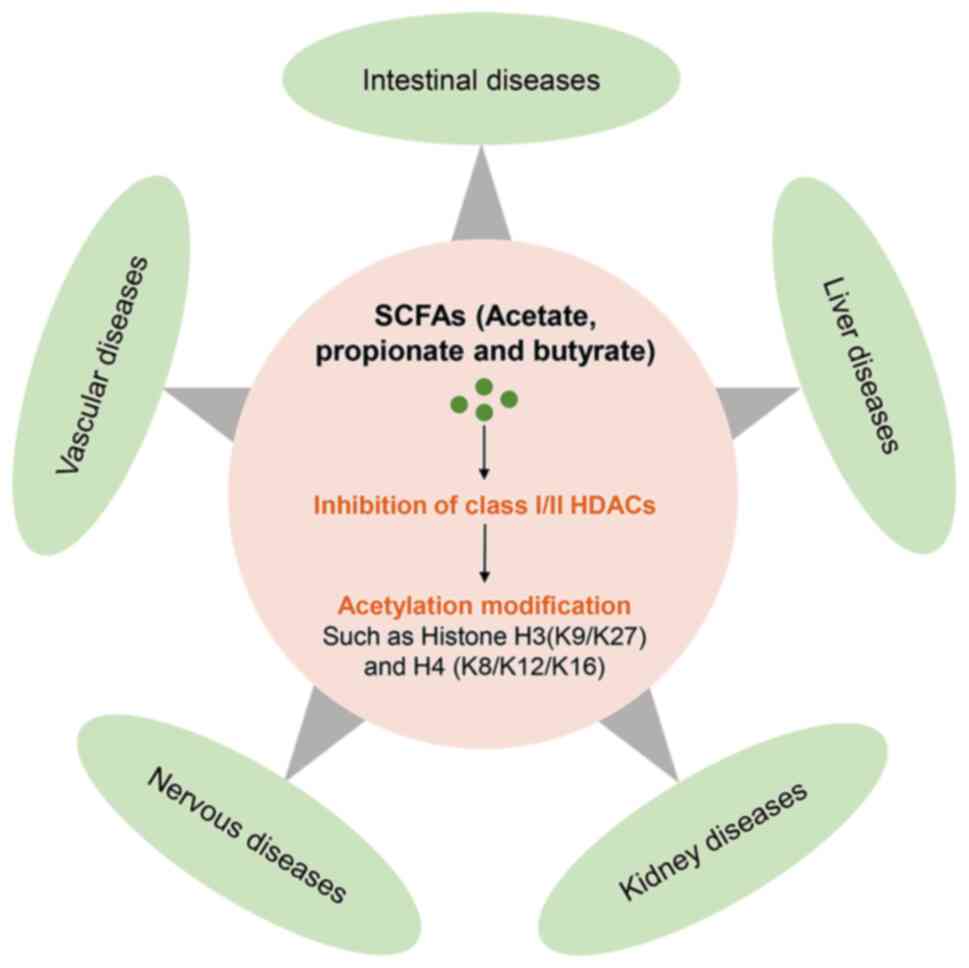

diseases'). According to these, the present review begins by

providing an overview of the microbial production and intestinal

absorption of SCFAs, accompanied by a detailed description of the

classification and function of HDACs. Furthermore, it offers a

comprehensive summary of the direct effects exerted by SCFAs on

immune cells (innate immune cells and lymphocytes) through HDAC

inhibition, as well as the systemic protective roles they carry out

both within and outside the gut. Finally, the present review delves

into the therapeutic potential of SCFAs as HDACi in ameliorating

various immune-related diseases and discusses the research

prospects. The outline of the present review is depicted in

Fig. 1.

Microbial synthesis and intestinal

absorption of SCFAs

Indigestible carbohydrates, such as dietary fibers,

serve as the key sources of SCFAs (13). Given that the human gut lacks

specific metabolic enzymes, carbohydrates require fermentation by

intestinal microorganisms to be hydrolyzed and subsequently

converted into SCFAs. The gut microbial population, which ranges

from 1013 to 1014 in number, encodes the vast

majority of carbohydrate-active enzymes that complete the metabolic

conversion of carbohydrates into SCFAs (13). SCFAs encompass acetate (C2),

propionate (C3), butyrate (C4), valerate (C5), caproate (C6), as

well as other branched SCFAs such as iso-valeric acid and

iso-butyric acid. Notably, acetate, propionate and butyrate

constitute the majority (90-95%) of intestinal SCFAs (14). The synthesis of these SCFAs

occurs through distinct pathways, yet all can trace their origins

back to the common precursor, pyruvate. Pyruvate is generated

through the glycolytic pathway of (deoxy-) hexoses and the pentose

phosphate pathway, following the microbial hydrolysis of

carbohydrates. Gut microbiota can produce acetate by metabolizing

pyruvate through either the acetyl-CoA pathway or the

Wood-Ljungdahl pathway. The biosynthesis of propionate proceeds via

three pathways: The acrylate pathway, the succinate pathway and the

propanediol pathway. Butyrate synthesis is facilitated by the key

enzymes such as butyrate kinase or butyryl-CoA: Acetate CoA

transferase (15,16) (Fig. 2). Acetate serves as the primary

net product of the majority of intestinal bacteria, while the

synthesis of propionate and butyrate demonstrates distinct,

species-specific characteristics. For example, bacteria that

generate propionate through the succinate pathway predominantly

belong to the phyla Bacteroidetes and Negativicutes

(within the Firmicutes phylum) (15). The propanediol pathway, which is

responsible for metabolizing deoxy-hexoses such as fucose and

rhamnose, is notably more prevalent among members of the

Lachnospiraceae family. Furthermore, Coprococcus

catus, a genus within Lachnospiraceae, has the ability

to increase propionate production via the acrylate pathway

(17). Numerous microbes

originating from the Firmicutes phylum, including

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Eubacterium biforme and

Eubacterium rectale, are capable of generating butyrate

through the butyryl-CoA: Acetate CoA-transferase pathway. By

contrast, a limited species of Firmicutes, such as

Coprococcus eutactus and Subdoligranulum variabile,

employ butyrate kinase for butyrate synthesis (18).

The types and quantities of SCFAs are determined by

the factors such as the type of digested substrate and the

composition of the microbiota. The uncontroversial finding is that

the relative molar ratio of the three main SCFAs-acetate,

propionate and butyrate-in the intestine and feces is ~60:20:20%

(19). SCFAs generated by

microbes can be absorbed by the colonic epithelium and subsequently

enter the bloodstream. The main transmembrane transport mechanisms

involved in this process include passive diffusion, GPCRs and

carrier transportation. Carrier proteins responsible for mediating

the epithelial transport of SCFAs comprise H+-coupled

monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) and Na+-coupled sodium-coupled

MCTs (SMCTs). The expression of these transporters is modulated by

physiological conditions as well as disease states. MCT1 is

expressed on the apical membrane, while both MCT1 and MCT4 are

expressed on the basolateral membrane of colonic epithelium. These

transporters facilitate the influx of SCFAs from the lumen and

their efflux into the bloodstream. Additionally, SMCT1 and 2 are

exclusively expressed on the apical membrane of colonic epithelial

cells, where they mediate the influx of SCFAs from the lumen

(20,21). After being absorbed, different

SCFAs exhibit distinct distribution patterns within the body. For

example, the majority of butyrate serves as the primary energy

source for the intestinal mucosal epithelium. Propionate can cross

the intestinal epithelium and once absorbed, it undergoes

metabolism in the liver and participates in gluconeogenesis.

Conversely, acetate can enter the blood to exert its effects in the

peripheral circulation and finally be metabolized by peripheral

tissues (22).

SCFAs carry out a key role in maintaining host

health and influencing disease progression. On the one hand, SCFAs

can regulate the expression of relevant genes to protect intestinal

epithelial cells (IECs), as well as promote energy homeostasis and

host metabolism. SCFAs can also affect the activity and function of

innate immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils and DCs,

along with T and B cells. Through these actions, they effectively

regulate the immune system and inflammatory responses (23). SCFAs are able to modulate immune

and inflammatory responses through two main mechanisms: Activating

GPCRs (specifically GPR41, GPR43 and GPR109A) and inhibiting HDACs.

However, it is important to emphasize that SCFAs display both

pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects. These dual effects

are likely associated with their local concentration and the

activity of the receptors they bind to (23,24).

Therefore, SCFAs constitute a vital class of

metabolites that are efficiently synthesized by the gut microbiota

and subsequently absorbed and utilized by the intestinal tract. The

absorbed SCFAs can regulate energy metabolism, as well as immune

and inflammatory responses, thus carrying out a pivotal role in

maintaining both intestinal and host homeostasis (23,24).

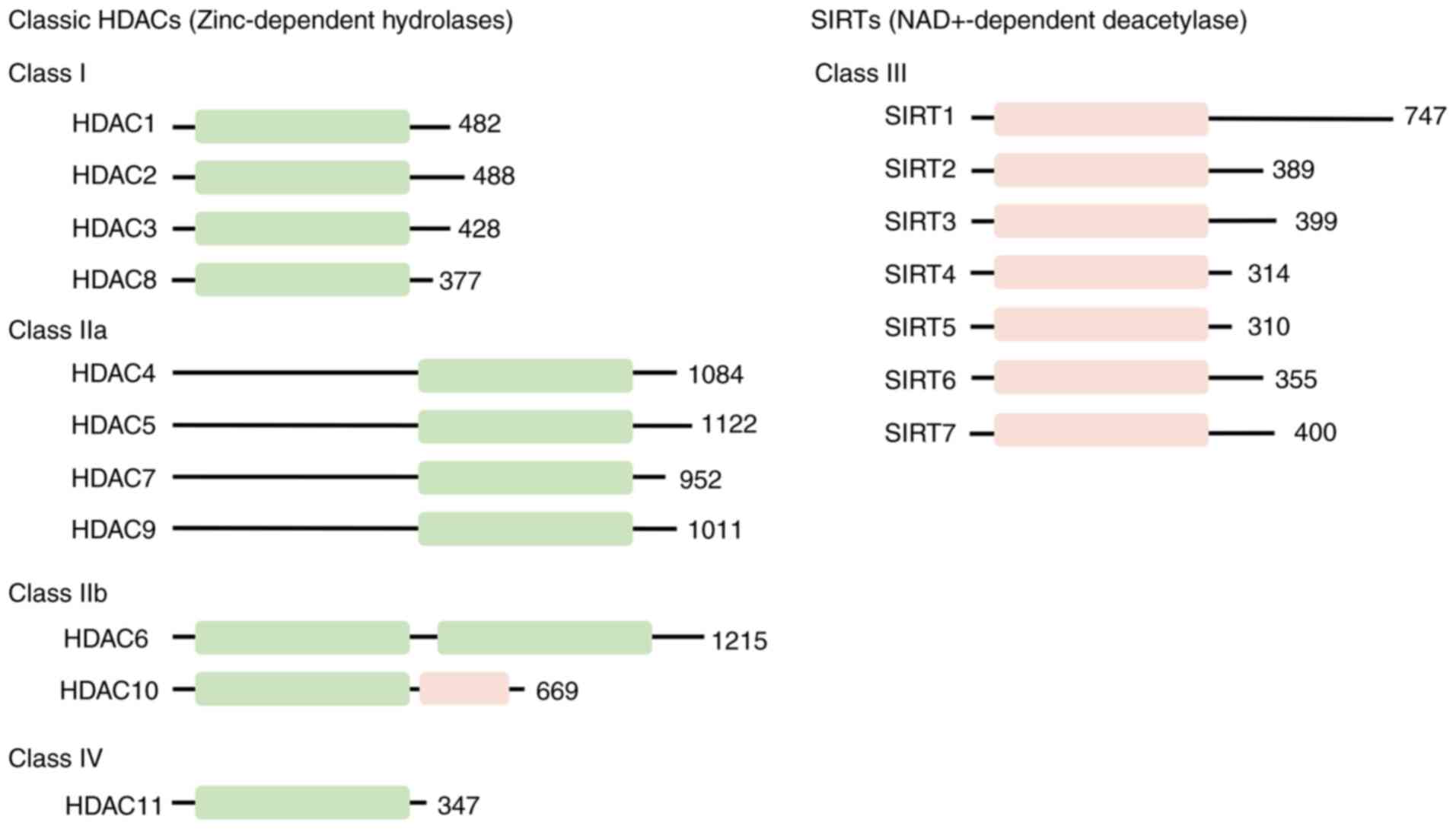

Classification and function of HDACs

HDACs exhibit evolutionary conservation in

organisms. Based on differences in sequence similarity and

enzymatic mechanisms, HDACs can be categorized into four distinct

classes: Class I Rpd3-like proteins, including HDAC1, 2, 3 and 8;

class II Hda1-like proteins, including HDAC4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10;

class III Sir2-like proteins, namely sirtuins (SIRTs)1-7, which are

structurally distinct from class I or II HDACs; and the unique

class IV protein, HDAC11 (Fig.

3) (25,26). Class I HDACs are detectable

within the nucleus and demonstrate ubiquitous expression and share

sequence similarity with the yeast Rpd3 protein. Conversely, class

II HDACs display sequence similarity to the yeast Hda1 protein and

carry out tissue-specific roles. Class II HDACs can be further

subdivided into class IIa (HDAC4, 5, 7 and 9) and class IIb (HDAC6

and 10). Class IIa HDACs possess relatively low activity and are

capable of shuttling between the cytosol and nucleus, whereas class

IIb HDACs prefer to act on non-histone proteins and are primarily

located in the cytosol (25,26). The class IV protein HDAC11 shares

sequence similarity with both class I and II proteins. Furthermore,

class I, II and IV all belong to the family of zinc-dependent

hydrolases and are collectively known as classical HDACs. By

contrast, class III HDACs mainly comprise NAD+-dependent SIRTs1-7,

which share sequence similarity with the Sir2 protein (27,28). Except for HDAC11, the

physiological roles of other HDACs have been extensively

investigated. For example, class I and II HDACs can modulate a

variety of cellular functions, including cell proliferation,

differentiation and development. They are also implicated in

cellular inflammation, immune responses and even cancer progression

(29-31). SRITs are associated with a wide

range of cellular processes, such as cell survival, cell cycle

progression, apoptosis, DNA repair and cellular metabolism.

Dysregulation of their enzymatic activity is associated with the

pathogenesis of tumors, metabolic disorders, infectious diseases

and neurodegenerative conditions (28).

Epigenetic alterations that cause human diseases are

emerging as ideal candidates for therapeutic interventions. The

deacetylation activity of HDACs, which is intricately associated

with various cellular processes, positions them as potentially

effective targets for treating human diseases (32). At present, HDACis constitute a

category of natural or synthetic compounds that exhibit potent

epigenetic regulatory capabilities. These inhibitors can disrupt

HDAC function and induce histone acetylation to modulate the

expression of genes. Importantly, HDACis exhibit pleiotropic

effects at both the cellular and systemic levels and are widely

acknowledged for their extensive therapeutic potential in

inflammatory diseases and cancer (32). Notably, microbial SCFAs

themselves act as the representative HDACis. The extensive HDAC

inhibitory activity of SCFAs across various cell types, as well as

their crucial roles in immunoregulation, are being systematically

investigated. Consequently, the present review focused on and

summarized the immunomodulatory effects of SCFAs as HDACis,

encompassing their effects from immune cells to the systemic

level.

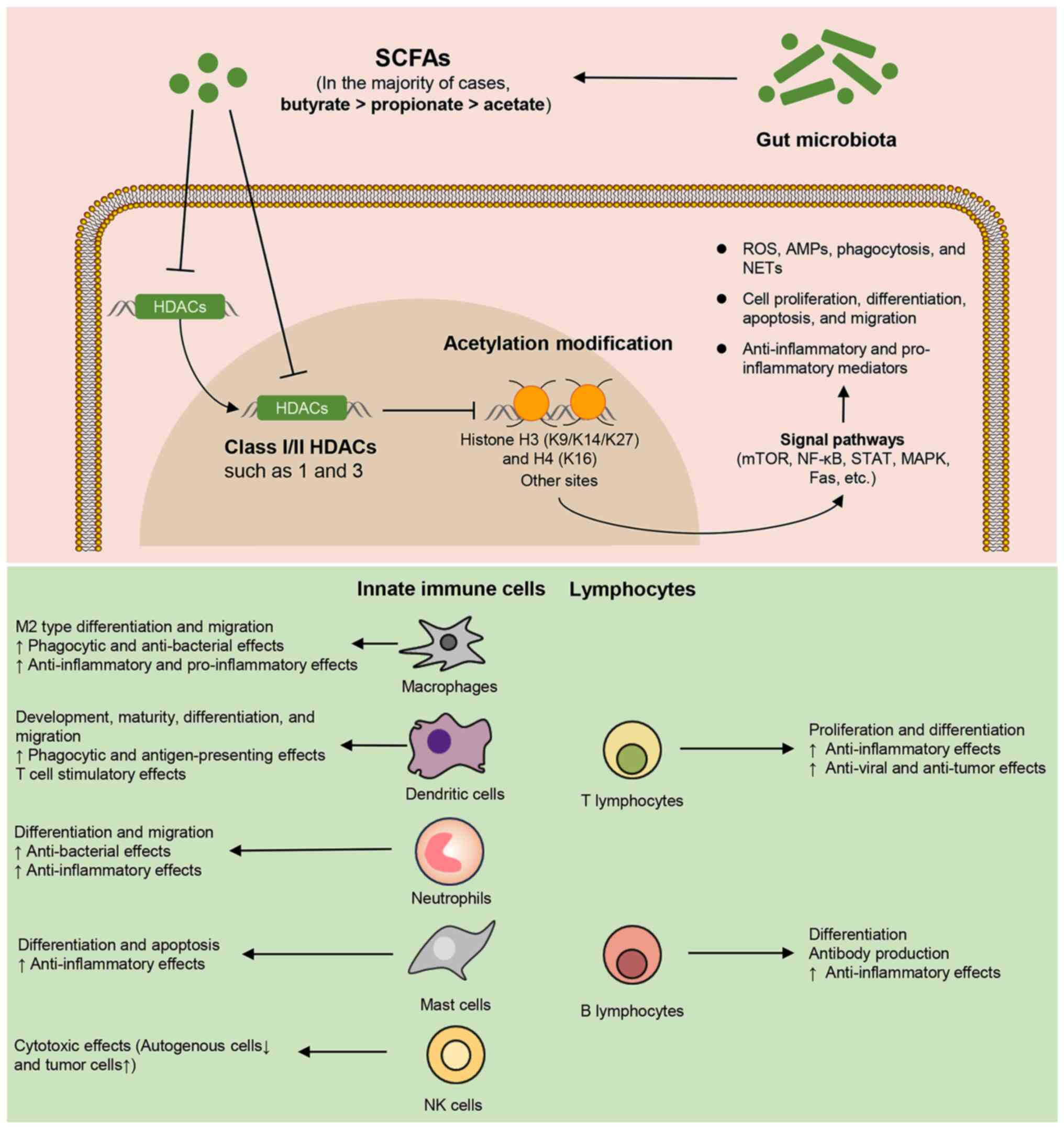

Effects of SCFAs on immune cells via HDAC

inhibition

SCFAs are vital microbial metabolites that notably

influence the intricate interplay between microbes and the host

immune system. HDAC inhibition stands as the principal mechanism by

which SCFAs regulate gene acetylation modifications in numerous

immune cells. Importantly, SCFAs can serve as potent inhibitors of

class I/II HDACs (33). In this

section, a comprehensive review of the regulatory effects of SCFAs

on immune cell activities and functions via HDAC inhibition was

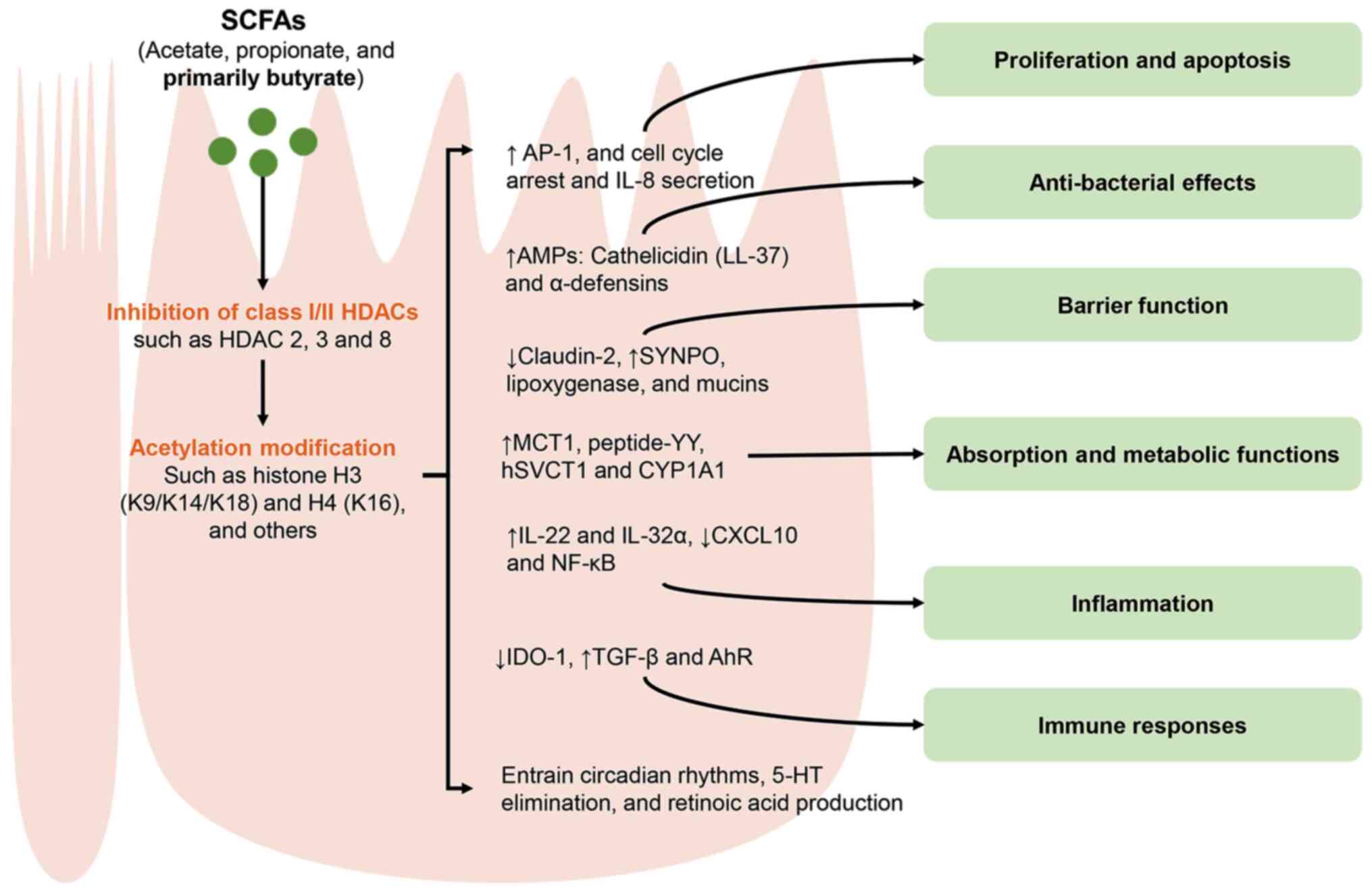

conducted (Fig. 4). The present

review focuses on the inhibitory effects of microbial SCFAs on

class I and II HDACs in innate immune cells, as well as their

effects on the associated acetylation modifications (such as

histones H3 and H4). These immune cells mainly include macrophages,

DCs, neutrophils, mast cells (MCs) and natural killer (NK) cells,

along with T/B lymphocytes (Fig.

4). This highlights the pivotal regulatory role of SCFAs, which

is mediated through HDAC inhibition, at the immune cell level.

Thus, this allows for a deeper understanding of the direct

contribution of microbial SCFAs to the host immune system from the

perspective of epigenetic regulation.

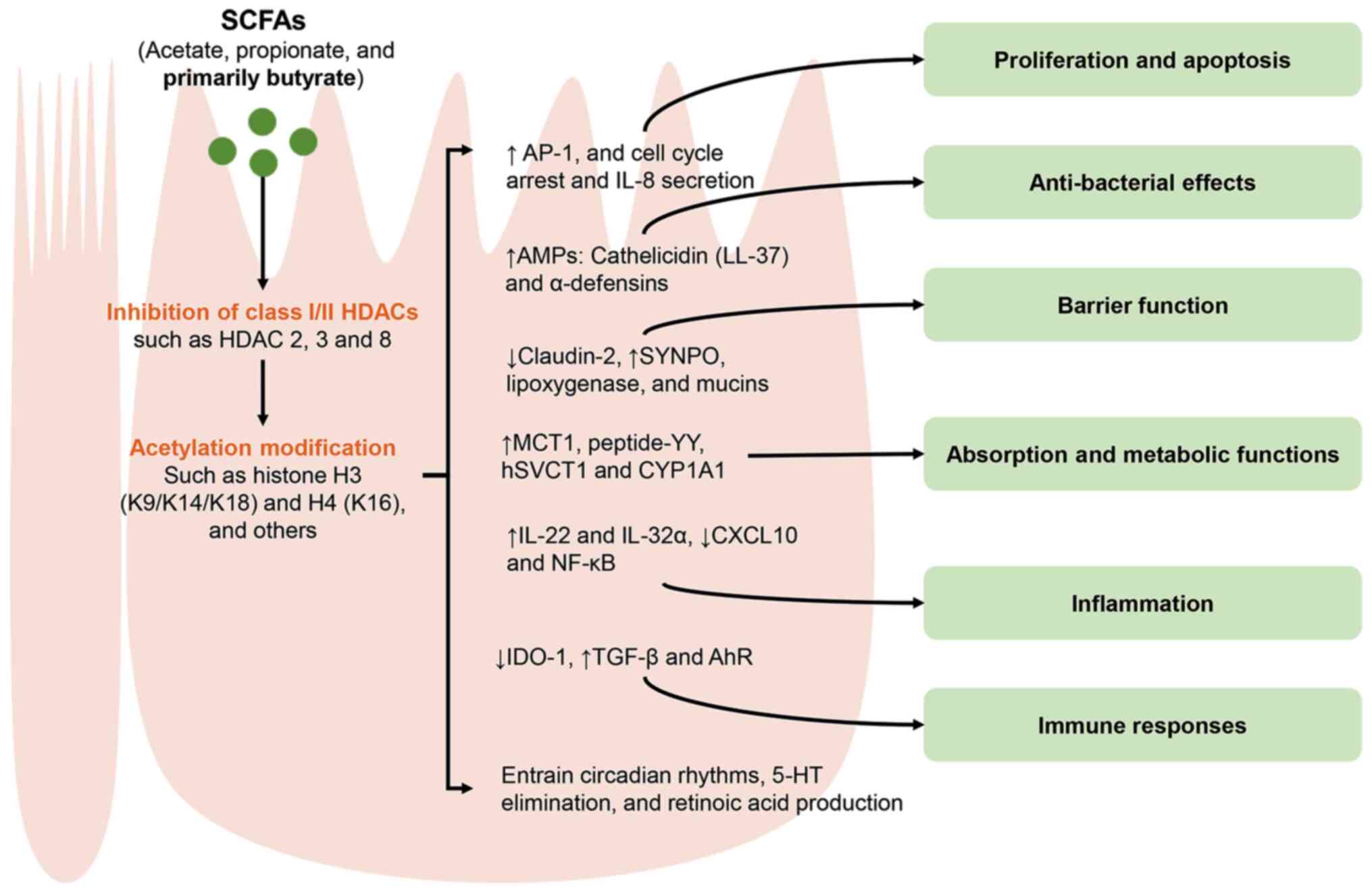

| Figure 4Regulatory effects of microbial SCFAs

on immune cell activities and function via HDAC inhibition. SCFAs,

primarily consisting of acetate, propionate and butyrate, are

capable of promoting acetylation modifications at histones H3

(K9/K14/K27), H4 (K16) and other sites by inhibiting class I/II

HDACs. In the majority of cases, the intensity of HDAC inhibition

by SCFAs is in the order of butyrate > propionate > acetate.

The HDACi effect of SCFAs enables them to modulate the expression

of various genes and signaling pathways, ultimately influencing the

activities and functions of immune cells. SCFAs, short chain fatty

acids; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HDACi, histone deacetylase

inhibitor; ROS, reactive oxygen species; AMPs, antimicrobial

peptides; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; M2, macrophage

subset 2. |

Innate immune cells

Macrophages

Macrophages are extensively distributed throughout

the body and carry out a pivotal role in innate immunity, primarily

by eliminating bacteria, regulating inflammation and promoting

tissue repair (34). In

particular, the tissue-resident macrophages exhibit direct

activities aimed at eliminating invading bacteria and increasing

the defenses of the body. Butyrate emerges as a representative SCFA

that modulates the anti-bacterial functions of macrophages. Its

underlying mechanism is considered to be associated with HDAC

inhibition rather than GPCR activities. For example, SCFAs can

enhance the anti-bacterial activity of macrophages differentiated

in vitro. Notably, 1 mM butyrate exhibits a stronger effect

compared with 1 mM propionate, while acetate at the same dosage

fails to demonstrate such an activity. The potent anti-bacterial

function induced by butyrate stems from glycolysis and mTOR

inhibition, which does not require GPCRs but instead depends on

HDAC3 inhibition (34). Butyrate

(given orally at 150 mM for 21 days or used in vitro at 1 mM

for 24 h) can enhance the anti-bacterial activity of macrophages by

promoting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) after

infection, markedly improving leptospirosis in hamsters (35). However, acetate and propionate do

not have this effect. Mechanistically, butyrate promotes ROS

production through MCT-mediated HDAC3 inhibition (35). In addition to phagocytosis and

anti-bacterial actions, butyrate at 2 mM for 48 h can also restrict

the alternative activation of macrophages induced by IL-4,

including inhibiting the activity of regulatory T (Treg) cells and

reducing their production of IL-17A. The effects of butyrate can be

replicated by HDACis such as trichostatin A (TSA) and valproic acid

(VPA) and this replication occurs independently of GPCR signaling

(36). Furthermore, the

hydroxylated derivative of butyrate, 4-hydroxybutyrate, can also

promote the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in mouse

bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) in an HDAC

inhibition-dependent manner, thereby enhancing the endogenous

anti-bacterial activity of the immune system. Specifically,

butyrate within the concentration range of 0.5-12 mM, when treated

for 24 h, can markedly increase the expression levels of

cathelicidin LL-37 (37).

The response of activated macrophages to

inflammation is determined by distinct cellular subsets: The

pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and the anti-inflammatory M2

phenotype. M1 macrophages are induced by inflammatory stimuli such

as IFN-γ and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and they participate in

inflammatory and immune responses by secreting pro-inflammatory

cytokines and presenting antigens. M2 macrophages, on the other

hand, can be activated by cytokines such as IL4 and IL13, and

mainly secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β,

carrying out a key role in inflammation resolution and immune

modulation (38). In the

majority of cases, SCFAs, primarily butyrate, can attenuate the

release of pro-inflammatory mediators from activated macrophages

through inhibition of HDAC, thus exerting anti-inflammatory

effects. For instance, when compared with acetate and propionate,

butyrate at 1 mM for 24 h demonstrates a more potent reduction in

the levels of pro-inflammatory mediators including NO, IL-6 and

IL-12p40 released by LPS-induced BMDMs. It also inhibits the

transcription of IL-6, Nos2, IL-12a and IL-12b in colonic lamina

propria (LP) macrophages both in vitro and in vivo,

thereby producing anti-inflammatory effects. The anti-inflammatory

effects of butyrate are independent of GPCRs, and instead increase

the acetylation levels of histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9) at the promoter

regions of IL-6, Nos2 and IL-12b in cells via HDAC inhibition

(39). In staphylococcal

lipoprotein (Sa.LPP)-induced macrophage inflammation, butyrate and

propionate (but not acetate) at 3 mM for 21 h can markedly suppress

the NF-κB, IFN-β/STAT1 and HDAC pathways, leading to a reduction in

cellular NO release. Similarly, butyrate exerts a stronger effect

when compared with propionate in inducing H3K9 acetylation.

Additionally, the HDAC inhibitor TSA also decreases NO production

induced by Sa.LPP. These findings imply that HDAC inhibition,

rather than GPCR signaling, serves as the key molecular mechanism

by which butyrate and propionate inhibit NO release from

macrophages induced by Sa.LPP (40). Furthermore, butyrate can also

inhibit inflammatory responses by regulating other macrophage

activities, with its underlying mechanisms being associated with

HDAC inhibition (41,42). For instance, macrophage migration

is associated with tissue inflammation and immune responses.

Treatment with 2 mM butyrate for 1 h can inhibit the migratory

activity of RAW264.7 cells and rat peritoneal macrophages triggered

by LPS. This effect is mediated by inhibiting the activities of

iNOS, steroid receptor coactivator and focal adhesion kinase,

similar to the effects of the HDACi TSA (41). In addition to restricting

inflammatory macrophages, butyrate exerts anti-inflammatory effects

by promoting the polarization of M2 macrophages, both in

vitro at a concentration of 50 μg/ml for 24 h and in

vivo at 150 mM for 11 days. Furthermore, it enhances the

migratory and wound-healing capabilities of M2-BMDMs. Butyrate

primarily enhances the STAT6 signaling pathway through its HDAC

inhibitory activity, which involves HDAC1 inhibition and H3K9

acetylation. This action facilitates polarization of BMDMs toward

the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, thereby alleviating

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (42). Collectively, the evidence

underscores the anti-inflammatory activities of SCFAs, especially

butyrate, in macrophages through HDAC inhibition. These activities

include inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators,

regulating cell migration and promoting M2-type cell polarization.

Such mechanisms hold therapeutic potential for treating

inflammatory diseases.

SCFAs exhibit anti-inflammatory properties under

homeostatic conditions, whereas they can trigger pro-inflammatory

programs in the presence of pathogen- and danger-associated

molecular patterns. For example, butyrate and propionate has been

have been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and subsequent

IL-1β release in LPS-induced macrophages through HDAC inhibition.

Butyrate, at a concentration of 1 mM, can notably promote IL-1β

release and at 4 mM, it can induce the maximal release of IL-1β

starting from 6 h of stimulation. Mechanistically, the inhibitory

effect of butyrate on HDAC promotes the acetylation of H3K27,

blocks the transcription of FLICE-like inhibitory protein and

IL-10, thereby activating the NLRP3 inflammasome without inducing

pyroptosis (43). Park et

al (44) demonstrated that

sodium butyrate is capable of upregulating the gene expression of

COX-2 in RAW264.7 macrophages that are stimulated by LPS. This

upregulation occurs via MAPK-dependent increases in the

phosphorylation and acetylation of histone H3 at the COX-2 promoter

region. COX-2 is a pivotal enzyme implicated in inflammatory

responses and is rapidly activated in macrophages induced by LPS.

When 5 mM butyrate is co-administered with 10 ng/ml LPS, it elicits

the most notable induction of COX-2 promoter activity. By contrast,

butyrate at this concentration alone exerts no discernible effect

on the promoter activity of COX-2. These research findings

collectively imply that SCFAs do not invariably exert

anti-inflammatory effects.

DCs

DCs serve as professional phagocytes and

antigen-presenting cells, carrying out a pivotal role in initiating

T-cell activation and adaptive immune responses. DCs mainly

comprise two major types, namely immature DCs (iDCs) and mature DCs

(mDCs). iDCs can capture antigens and, upon immune stimulation,

transform into mDCs, thereby activating their antigen-presentation

and T-cell stimulation functions (45). SCFAs are involved in regulating

the development, maturation, differentiation, migration and

antigen-presentation functions of DCs. Research suggests that some

of these regulatory mechanisms are associated with HDAC inhibition.

For example, the SCFAs butyrate and propionate both at 0.5 mM for 6

days can inhibit the development of DCs from bone marrow precursor

cells induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

(GM-CSF), while having no impact on granulocyte development.

Mechanistically, these SCFAs are transported into cells via the

transporter (Slc5a8) and inhibit the expression of PU.1 and RelB

through their ability to inhibit HDAC (histone H4 acetylation).

Acetate is also a substrate for Slc5a8, but it is not an HDACi and

does not influence DC development. This suggests that HDAC

inhibition carries out a vital role in DC development (46).

The SCFA butyrate can induce DCs to remain in an

immature state and impede their maturation. Research has revealed

that butyrate at 1 mM for 24 h can markedly downregulate the

expression of surface markers on mDCs. Additionally, it enhances

the intracellular endocytic capacity of these cells, diminishes

their T-cell stimulatory ability, promotes the production of IL-10

and inhibits the production of IL-12 and IFN-γ. These findings

collectively underscore the specific immunosuppressive

characteristics of butyrate (47). However, the regulatory effect of

butyrate on the phenotypic differentiation of certain DCs may not

always be associated with HDAC inhibition. For instance, butyrate,

when applied at a concentration of 200 μM for 5 d, does not

hinder DC differentiation induced by IL-4 and GM-CSF, whereas it

suppresses the acquisition of CD1a that is triggered by cytokine

and TLR2 agonist stimulation. Nevertheless, this regulatory effect

on CD1a acquisition is not closely associated with the HDAC

inhibitory activity of butyrate (48). Upon activation, iDCs transform

into mDCs, which can migrate to secondary lymphoid organs and

initiate cellular immunity. However, butyrate (200 nM; 24 h) and

other HDACi, including TSA and scriptaid, demonstrate effective

inhibitory effects on the migration of iDCs stimulated by

macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, as well as on the chemotaxis of

mDCs. The actions of these HDACi involve a reduction in the surface

expression of C-C chemokine receptor type 1 on iDCs and C-X-C

chemokine receptor type 4 on mDCs. Additionally, they inhibit the

phosphorylation of MAPKs, specifically p38, ERK1/2 and JNK

(49,50). The uptake of foreign antigens by

DCs and their subsequent presentation to T cells can be affected by

their dendritic activity. A study has revealed that SCFAs, such as

butyric acid (1 mM) and valeric acid (10 mM) applied for 24 h, can

promote dendritic elongation by inhibiting HDACs rather than

relying on GPCRs, activating the SFK/PI3K/Rho signaling pathway and

inducing actin polymerization. These effects ultimately lead to an

enhanced capacity for antigen uptake and presentation in DCs.

Notably, the HDACi TSA also replicates the dendrite-promoting

effects of SCFAs (51).

DCs carry out a pivotal role in activating T-cell

immune responses due to their remarkable capacity for antigen

uptake. Among the SCFAs, butyrate stands out as a representative

HDACi that can influence the regulation of DC functions in T-cell

proliferation and differentiation (52-54). In the majority of cases, butyrate

exhibits immunosuppressive properties in T-cell responses

stimulated by DCs. For example, butyrate can alter the

developmental trajectory of conventional DCs (cDCs). When

administered at 0.5 mM for 4 days, butyrate selectively inhibits

the cDC2 lineage and their ability to drive CD4+ T cell

proliferation. However, it promotes an increase in the

differentiation of Foxp3+ Treg cells, thereby contributing to the

intestinal tissue homeostasis. These effects of butyrate are

independent of GPCR activity and are instead attributed to the

inhibition of HDAC3 (52).

Butyrate at 2 mM for 48 h has the ability to induce the production

of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (RALDH1), an enzyme that is

responsible for retinoic acid synthesis in DCs. Consequently, it

inhibits the maturation and metabolic reprogramming of LPS-induced

human monocyte-derived DCs and promotes their polarization towards

IL-10-producing type 1 Treg cells. The effects of butyrate rely on

RALDH activity, which is driven by the combined action of HDAC

inhibition and GPR109A signaling, thereby inducing a tolerogenic DC

phenotype (53). Additionally,

butyrate promotes the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine

IL-17 by T cells, an effect that is associated with the release of

cytokine IL-23 by activated DCs. Berndt et al (54) by using LPS to induce mouse bone

marrow-derived DCs, discovered that 1 mM butyrate for 18 h could

considerably inhibit LPS-induced DC maturation and downregulate

IL-12 production, while concurrently increasing IL-23 production.

The upregulation of the mRNA subunit IL-23p19 at the

pre-translational level is consistent with the effect of HDACi on

epigenetic modifications of gene expression. The researchers

observed that butyrate treatment increased the production of IL-17

and IL-10 by T cells co-cultured with activated DCs, but had no

such effect on IFN-γ, IL-4 or IL-13. The in vivo therapeutic

efficacy of butyrate is dependent on the route of administration.

Specifically, oral administration exacerbates colitis, whereas

systemic administration improves it. These findings collectively

suggest that butyrate induces the production of DC IL-23 and the

T-cell pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17, thereby modulating

chemically induced colitis (54).

Neutrophils

Neutrophils represent a key type of immune cell that

defends against various pathogens, with their anti-bacterial

mechanism of releasing neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).

Research has revealed that SCFAs at physiological concentrations

can regulate NET formation in neutrophils. For instance, SCFAs

(acetate, propionate and butyrate) at the colonic concentrations

are capable of inducing NET formation in neutrophils in

vitro. When tested at concentrations of SCFAs present in human

peripheral blood, only acetate at concentrations of 100 μM

(fasting) and 700 μM (postprandial) can considerably induce

NET formation. This effect of SCFAs is partially mediated by

FFA2R/GPR43 (55). Furthermore,

the mechanism by which acetate acting as a HDACi to regulate NET

release has also been revealed (56). For example, acetate (at a

concentration of 10 mM for 24 h) can considerably enhance the

acetylation of histone Ace-H3, H3K9ace and H3K14ace, thereby

promoting NETosis in neutrophil-like HL-60 cells, which is a

specific form of cell death in which neutrophils release NETs

(56).

The accumulation and activation of neutrophils at

inflamed sites are associated with the mechanisms of tissue

inflammation. The SCFAs, primarily butyrate, exert notable

anti-inflammatory effects on activated neutrophils, and this

mechanism is associated with HDAC inhibition (57-60). For instance, 1.6 mM butyrate can

markedly reduce the production of pro-inflammatory mediators,

namely TNF-α, CINC-2αβ and NO, in both in vitro and

ex-vivo neutrophils stimulated by LPS. Notably, propionate

exhibits a relatively weaker effect compared with butyrate. It can

exert notable inhibitory effects on the release of pro-inflammatory

mediators from neutrophils when its concentration reaches 12 mM.

Their anti-inflammatory properties are associated with the

inhibition of HDAC activity and NF-κB activation (57). Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory

effects of butyrate on peripheral neutrophils have been

well-validated in both intestinal inflammation models and patients

with enteritis. For example, oral administration of 200 mM butyrate

can markedly alleviate dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis

in mice by inhibiting the neutrophil-derived production of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, calprotectins and NET

formation. In addition, 0.5 mM butyrate can suppress the migration

and NET formation of neutrophils isolated from patients with IBD,

which encompasses Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

Mechanistically, the influence of butyrate on the production of

pro-inflammatory mediators is mediated in an HDACi-dependent manner

rather than through GPCR signaling (58). In general, a reduction in

neutrophil apoptosis is associated with persistent inflammation and

may trigger local and systemic inflammatory responses.

Consequently, regulating neutrophil apoptosis is a key event for

resolving inflammation. Additionally, the HDACi SCFAs may be

important microbial metabolites for regulating neutrophil

apoptosis. For example, butyrate and propionate, each at 4 mM for

20 h, can notably induce apoptosis in both inactivated and

TNF-α/LPS-activated neutrophils. Their mechanisms are independent

of GPCRs and MAPKs. Their mechanisms may be related to their HDAC

inhibitory activity, which promotes the acetylation of histone H3

and controls the mRNA expression of associated apoptotic protein a1

(59). Butyrate can induce a

reduction in the proliferation and an elevation in the apoptosis of

CD34+ progenitor cells, and quantitatively and qualitatively impair

terminal neutrophil differentiation. This effect of butyrate is

accompanied by the increased acetylation of histones 3 and 4,

specifically at the H3K9 and H4K16 sites. This observation is

consistent with the action exhibited by the HDACi, VPA (60). Taken together, all the findings

suggest that butyrate can act as a potent HDACi to suppress

neutrophil function and promote its apoptosis, ultimately leading

to an effective suppression of tissue inflammation caused by

neutrophils.

MCs

Activation of MCs carries out a pivotal role in

inflammation and allergic reactions. SCFAs, owing to their HDACi

activity, can effectively suppress the activity and function of

MCs. Among SCFAs, butyrate and propionate, rather than acetate,

inhibit the activation of primary human or mouse MCs via both IgE-

and non-IgE-mediated degranulation in a concentration-dependent

manner. These effects are associated with HDAC inhibition and are

independent of the stimulation of SCFA receptors GPR41, GPR43 or

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. Epigenomic analysis

reveals that 5 mM butyrate not only triggers a redistribution of

global H3K27 acetylation levels, but also induces a notable

reduction in acetylation at the promoter regions of genes including

the tyrosine kinases BTK, SYK and LAT. These kinases are key

transducers in the FcεRI signaling pathway that mediates MC

activation (61). Additionally,

the HDACi butyrate can inhibit the proliferation and induce

apoptosis in P815 mastocytoma cells. It also suppresses

FcεRI-dependent cytokine production in murine primary bone

marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs). Mechanistically, butyrate at 2

mM for 12 h notably enhances H3K9 acetylation in both P815 and

BMMCs, while reducing the FcεRI-dependent mRNA expression of TNF-α

and IL-6 in BMMCs. This effect is similarly observed with TSA, a

well-known HDACi (62). A study

conducted by Gudneppanavar et al (62) found that butyrate (5 mM, 24 h)

can act as an HDACi to downregulate the growth factor stem cell

factor (SCF) receptor KIT and its associated phosphorylation,

thereby notably attenuating SCF-mediated proliferation and

pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion in BMMCs. Mechanistically,

butyrate primarily affects MC function through the inhibition of

HDAC1/3. These findings suggest that butyrate can weaken MC

function and its inflammatory response by epigenetically modifying

histones and downregulating the SCF/KIT/p38/Erk signaling axis

(63). Similarly, the

proliferative activities of three transformed human MC

lines-HMC-1.1, HMC-1.2 and LAD2-are also sensitive to the

inhibitory effects of the HDACi butyrate. Butyrate (0-1,000

μM) considerably reduces the expression of c-KIT mRNA and

KIT protein in these three cell lines in a dose-dependent manner.

The effects of butyrate are associated with cell cycle arrest and a

moderate increase in histamine content, tryptase expression and

granularity (64).

NK cells

NK cells are of importance in anti-viral defense,

anti-tumor responses and immune regulation. They are capable of

directly eliminating virus-infected cells and cancer cells, as well

as regulating the activities of other immune cells through cytokine

secretion. The SCFA butyrate (250 μM, 24 h) can inhibit HDAC

activity on human NK cells and influence the epigenetic landscape,

phenotype and regulatory functions of NK cells. Specifically,

butyrate induces the generation of CD69+ NK cells while

simultaneously reducing the proportion of CD56bright NK

cells. The inhibition of CD56bright NK cells by butyrate

can weaken the attack of NK cells on autologous CD4+ T cells

(65). In addition, similar to

other HDACi, butyrate (5 mM) can enhance the sensitivity of DAOY

and PC3 tumor cells to the cytotoxic effects of IL-2-activated

peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). NK cells serve as the

primary effector cells involved in the lysis of tumor cells.

Butyrate also increases the tumor surface expression of ligands for

activating NK receptors, namely NKG2D and DNAM-1. As a result, it

enhances the susceptibility of tumor cells to the cytotoxic effects

of NK cells (66).

Lymphocytes

T lymphocytes

T lymphocytes are the primary effector cells in

cellular immunity, mediating inflammatory and immune responses

through the production of various cytokines. There is a wide

variety of T cells, including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, γδ T

cells and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). CD4+ T cells are further

subdivided into subsets such as Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg (67). Under physiological conditions,

SCFAs have a regulatory role in inhibiting T cell activation,

thereby mitigating tissue inflammatory responses. For instance,

within intestinal tissues, butyrate (0.0625-0.5 mM) for 4 days is

more effective than other SCFAs in reducing the activity of in

vitro human LP CD4+ T cells and the production of inflammatory

cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-17. The anti-inflammatory effects of

butyrate are mediated by both histone acetylation and GPR43

signaling (68). Additionally,

butyrate (used in vivo at 200 mM or in vitro at 0.5

mM) has a broad stimulatory effect on IL-22 production by CD4+ T

cells and ILCs in mouse spleens, mesenteric lymph nodes, LP and

human peripheral blood. The anti-inflammatory effect of butyrate

resulting from this is associated with GPR41 and HDAC inhibition

(69). Similar to other HDACi,

butyrate (1.1 mM) can induce T cell anergy, a state of

antigen-specific proliferative unresponsiveness in CD4+ T cells

exposed to antigen. The effect of butyrate in inducing

proliferative unresponsiveness in Th1 cells does not rely on

general histone hyperacetylation but rather on the secondary effect

of histone acetylation, namely the upregulation of p21(Cip1)

(70). Furthermore, the

anti-inflammatory effects of butyrate include inhibiting

IFN-γ-mediated inflammation in colonic epithelial cells and

inducing T cell apoptosis to eliminate inflammatory sources.

Mechanistic analysis indicated that high concentrations of butyrate

(>3 mM) inhibit the activation and proliferation of murine

splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro and suppresses

IFN-γ-induced STAT1 activation and iNOS upregulation in human

colonic epithelial cells. Importantly, butyrate can induce

hyperacetylation of the Fas promoter and upregulation of Fas by

inhibiting HDAC1 activity, thereby inducing apoptosis in CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells. This leads to the inhibition of T cell activation and

the elimination of the inflammatory source in the colon (71).

However, SCFAs also possess a regulatory role in

enhancing the T cell immune activity, particularly in cellular

immunity against tumors and viruses. Research has revealed that a

relatively high concentration of butyrate (1 mM) can maintain or

even increase the ability of T cell receptor (TCR)-transduced CD4+

and CD8+ T cells to release cytokines in response to antigens.

Mechanistically, HDAC inhibition by butyrate can enhance the

transgenic expression of T cells in vitro and their

anti-tumor function. This indicates that the HDACi butyrate can

augment the tumor-responsive effect of functionally TCR-transduced

T cells (72). SCFAs,

specifically butyrate and pentanoate, can enhance the anti-tumor

activity of two CD8+ T cell subsets, cytotoxic T lymphocytes and

chimeric antigen receptor T cells, through metabolic and epigenetic

reprogramming. In particular, they can promote the function of mTOR

as a central cellular metabolic sensor and inhibit class I HDAC

activity. Consequently, these CD8+ T cells exhibit increased

production of effector molecules such as CD25, IFN-γ and TNF-α

(73). In addition, 1 mM

butyrate can also promote the production of granzyme B and IFN-γ in

Tc17 cells, a subset of CD8+ T cells. The increased IFN-γ

expression induced by butyrate is mediated through its HDAC

inhibitory activity rather than through GPR41 and GPR43 signaling

pathways. Moreover, a relatively high concentration of acetate (25

mM) can also increase the production of IFN-γ in CD8+ T

lymphocytes, but its underlying mechanism relies on cellular

metabolism and mTOR activity (74). Acetate also has a regulatory role

in increasing the susceptibility of T cells to HIV-1. Alterations

in the fecal microbiota and intestinal epithelial damage associated

with HIV-1 infection are likely to causing microbial translocation,

thereby exacerbating disease progression and virus-related

comorbidities. Notably, the physiological concentration of acetate,

that is 20 mM, is capable of enhancing viral production in primary

human CD4+ T cells. It also promotes the integration of HIV-1 DNA

into the host genome by impairing class I/II HDAC activity. This

suggests that acetate can increase the susceptibility of CD4+ T

cells to productive HIV-1 infection and may influence the

progression of HIV-1-mediated diseases (75). These findings indicate that SCFAs

acting as HDACi may hold importance for adoptive immunotherapy

against cancer and anti-viral immunity.

Depending on distinct cytokine environments, SCFAs

can regulate the differentiation process of naïve T cells into

effector cells and Treg cells. For instance, acetate (10 mM),

propionate (1 mM) and butyrate (0.5 mM) can induce the

differentiation of naïve T cells into Th1 and Th17 cells under

polarizing conditions: Th17 (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, TGF-β1,

anti-IL-4 and anti-IFN-γ) or Th1 (IL-12, IL-2 and anti-IL-4). They

can also induce the generation of Treg cells such as IL-10+ T cells

and Foxp3+ T cells. This effect of SCFAs on T cell differentiation

is independent of GPCR receptor signals (GPR41 or GPR43) but

depends on HDAC inhibitory activity. Specifically, the inhibition

of HDAC by SCFAs increases the acetylation of p70 S6 kinase

(P70S6K) and the phosphorylation of rS6, which subsequently drives

T cell differentiation through the mTOR pathway to promote either

immunity or immune tolerance (76). However, SCFAs are also capable of

exerting distinct regulatory effects on T cell differentiation. A

study conducted by Chen et al (77) revealed that 0.5 mM butyrate can

promote the expression of IFN-γ and T-bet to facilitate Th1 cell

differentiation while inhibiting the expression of IL-17, Rorα and

Rorγt to suppress Th17 cell differentiation. Notably, under both

Th1 and Th17 conditions, butyrate can promote the production of

IL-10. This, in consequence, diminishes the capacity of T cells to

induce colitis, and this effect partially depends on the role of

Blimp1. Mechanistically, butyrate promotes Th1 differentiation (but

not Th17) by inhibiting HDACs, and this effect is independent of

GPR43 signaling. Kespohl et al (78) discovered that butyrate at low

concentrations (0.1-0.5 mM) can promote the differentiation of

Foxp3+ Tregs under TGF-β1 conditions. By contrast, when the

concentration reaches 1 mM, butyrate induces the expression of

Th1-associated genes, namely T-bet and IFN-γ, in T cells. These

dual effects are mediated by the SCFA-induced HDAC inhibition (H3

acetylation) and are independent of the FFA2/GPR43 and FFA3/GPR41

receptors, as well as the Slc5a8 transporter of SCFAs.

Additionally, butyrate elevates the expression levels of T-bet and

IFN-γ in the colon, exacerbating acute colitis in germ-free (GF)

mice. These findings suggest that butyrate requires TGF-β1 to

mediate the differentiation of anti-inflammatory Foxp3+ Tregs and

can promote inflammatory Th1-related factors at high

concentrations, with both effects being associated with HDAC

inhibition (78).

Among these T cell subsets, the balance between Th17

and Treg cells is a key factor in determining tissue immune

homeostasis and can be regulated by SCFAs (79). Studies (80,81) have revealed that butyrate

produced by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, rather than other

metabolites, can ameliorate colitis in a DSS-induced mouse model.

Mechanistically, butyrate (used in vitro at 0.62 mM or in

vivo at 100 mg/kg) inhibits HDAC3 and c-Myc-related metabolism

in T cells, reducing Th17 differentiation. It also promotes the

expression of Foxp3 by inhibiting HDAC1 and blocks the

IL-6/STAT3/IL-17 downstream pathway. Through these mechanisms,

butyrate helps maintain Th17/Treg balance in the gut and exerts

potent anti-inflammatory effect (80,81). Butyrate at 1 mM for 5 days is

also capable of mediating the K16 acetylation of histone H4, thus

upregulating RorγT expression in differentiated Th17 cells while

downregulating it in CD4+ T cells under Th17 differentiation

conditions. This indicates that butyrate can primarily participate

in the epigenetic regulation of RorγT in Th17 cells through HDAC

inhibition and is related to specific stages of T cell

differentiation (82). More

importantly, microbiota-derived butyrate can also promote the gene

expression and protein acetylation of Foxp3 to facilitate the

differentiation of peripheral Treg cells. Butyrate (500 μM)

exerts additional regulatory effects by reducing the expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in DCs. It achieves this through the

acetylation of histone H3, which indirectly promotes the induction

of Treg cells. Similarly, propionate exerts HDAC inhibitory

activity, enabling it to promote the differentiation of peripheral

Treg cells. By contrast, acetate does not possess this activity

(83). The aforementioned

findings demonstrate that SCFAs can regulate the differentiation

and function of T cell subsets based on their HDAC inhibitory

activity.

B lymphocytes

SCFAs have the capacity to modulate B cell

differentiation, antibody responses and antibody-driven

autoimmunity. Notably, propionate and butyrate, primarily at low

doses (30 and 20 mM, respectively), can affect B cell function by

moderately enhancing class-switch DNA recombination (CSR). However,

at higher doses (propionate, 150 mM and butyrate, 140 mM), they

lead to a reduction in the expression of activation-induced

cytidine deaminase (AID) and Blimp1, as well as a decrease in CSR,

somatic hypermutation and plasma cell (PC) differentiation. These

effects stem from the direct regulatory role of SCFAs as the HDACi

on the intrinsic epigenetic of B cells (84). For instance, by exerting HDAC

inhibitory activity, SCFAs upregulate microRNAs that specifically

target Aicda and Prdm1 mRNAs. As a result, the expression levels of

Aicda and Prdm1 (which respectively encode AID and Blimp1) within B

cells are diminished (84).

Furthermore, as a potent immunosuppressive agent,

butyrate can drive the differentiation of regulatory B cells

(Bregs) and enhance their anti-inflammatory functions. B10 cells

represent a subset of Bregs that can produce the anti-inflammatory

cytokine IL-10. SCFAs (0.5 mM) for 48 h can promote the generation

of mouse and human B10 cells in vitro. Additionally, an

increase of B10 cells by 150 mM butyrate has been observed in both

healthy mice and mice with DSS-induced colitis. The effects of

SCFAs are dependent on HDAC inhibitory activity and are independent

of GPCRs. Butyrate, similar to other HDACi, can activate the p38

MAPK signaling pathway to facilitate B10 cell generation (85). Moreover, butyrate at 0.5 mM for

24 h possesses the ability to regulate the differentiation and

anti-inflammatory functions of IL-10+IgM+ PCs. Mechanistically, the

inhibition of HDAC3 represents a potential pathway through which

butyrate induces the differentiation of IL-10+IgM+ PCs and the

expression of IL-10 (86).

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that SCFAs exhibit

regulatory activity on B cell differentiation and function based on

HDAC inhibition.

System protection of SCFAs via HDAC

inhibition

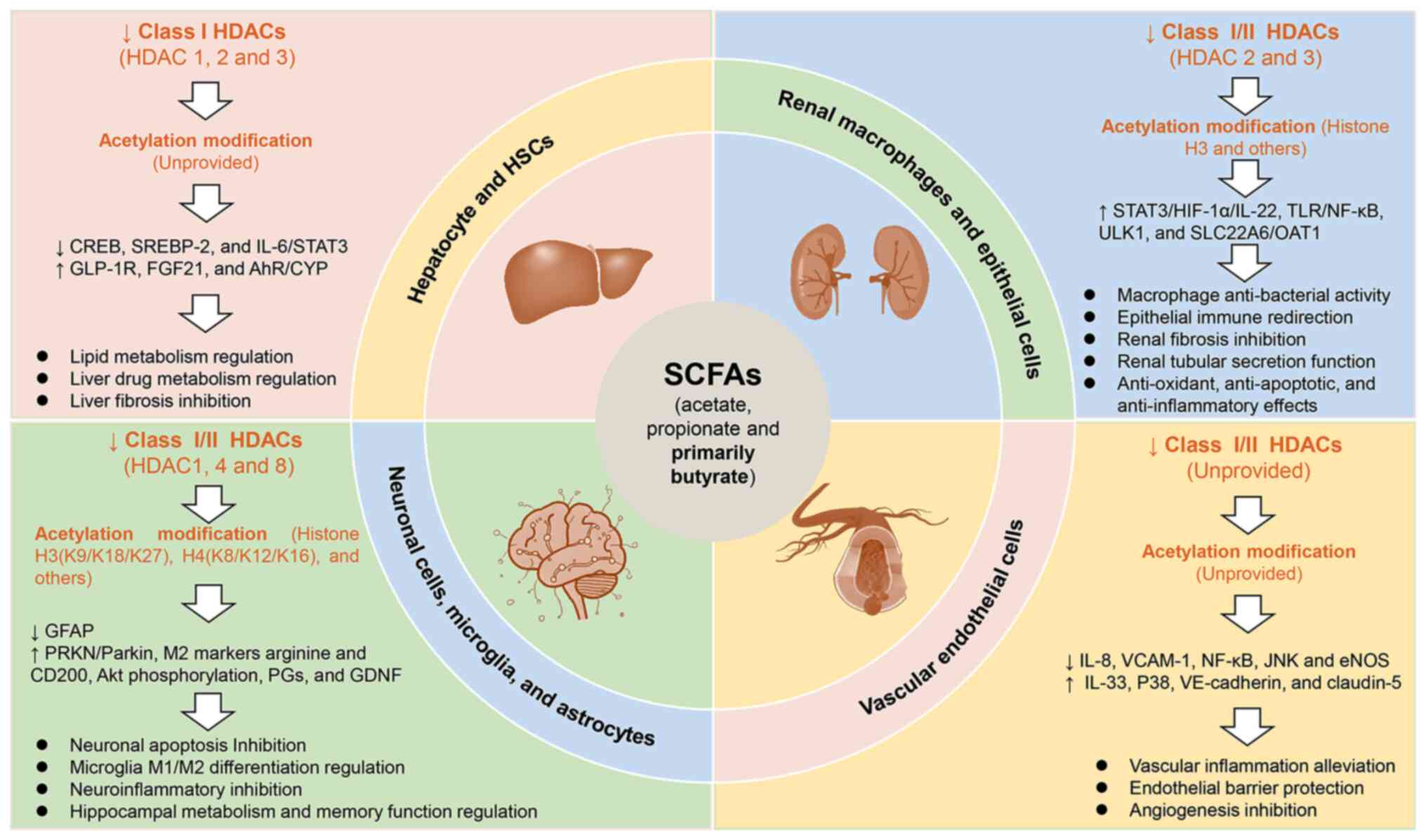

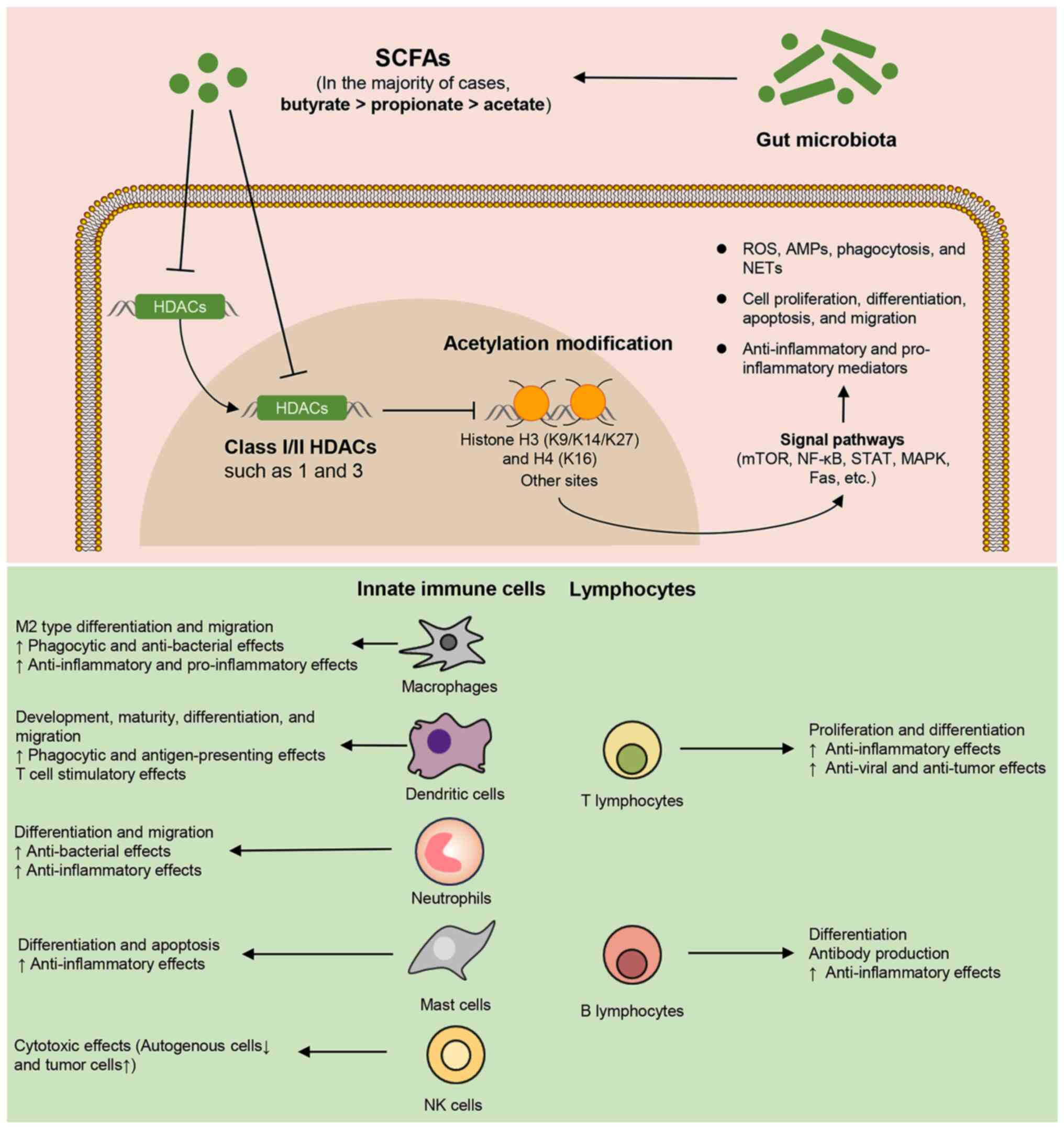

In addition to immune cells, SCFAs also contribute

to the regulation of tissue-resident cells, thereby influencing the

host's immune equilibrium. Histone acetylation modifications are

widely recognized as being associated with key cellular processes

under both physiological and pathological conditions. In this

section, the relevant findings regarding the host-protective

effects (categorized into intestinal and extra-intestinal effects)

of microbial SCFAs based on HDAC inhibition are summarized. These

highlight that SCFAs regulate the activity and function of

intestinal immune cells and IECs through their HDAC inhibitory

activity, thereby modulating the local gut immune homeostasis. In

particular, SCFAs, mainly acetate, propionate and butyrate, exert

intestinal epithelial protective effects by inhibiting class I and

class II HDACs (2, 3 and 8) and promoting acetylation modifications

of histones H3/H4 and other sites. These protective effects

encompass, but are not limited to, the proliferation and apoptosis,

anti-bacterial effect, barrier function, absorption and metabolic

function, inflammation and immune responses of IECs (Fig. 5). Similarly, the HDAC inhibitory

activity and acetylation-modified effects of these SCFAs contribute

to tissue protection in extra-intestinal organs such as the liver,

kidney, nerves and blood vessels. Mechanistically, SCFAs can

inhibit class I and II HDACs (1, 2, 3, 4 and 8) and promote

acetylation modifications of histone H3/H4 and other sites. This

influences a wide range of activities and functions of various cell

types, including hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) in

the liver, renal macrophages and epithelial cells in the kidney,

neuronal cells, microglia and astrocytes in the nervous system, and

vascular endothelial cells (Fig.

6). The aforementioned findings underscore the systemic

protection of SCFAs based on HDAC inhibition, which are associated

with the functional regulation of multiple tissue-resident cells

both inside and outside the gut.

| Figure 5Regulatory effects of SCFAs on the

activities and function of IECs through HDAC inhibition. SCFAs,

such as acetate, propionate and primarily butyrate, can extensively

modulate various cellular signaling pathways by inhibiting class

I/II HDACs (2, 3 and 8) and promoting acetylation modifications of

histones H3 (K9/K14/K18), H4 (K16) and other sites. Consequently,

these actions have a notable impact on the activities and function

of IECs. IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; SCFAs, short chain

fatty acids; HDACs, histone deacetylases; AP-1, activator

protein-1; AMPs, antimicrobial peptides; MCT, monocarboxylate

transporters; SYNPO, synaptopodin; hSVCT, human sodium-dependent

vitamin C transporters; CYP1A1, cytochrome P450 1A1; CXCL10, C-X-C

motif chemokine ligand 10; IDO-1, indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1;

AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; 5-HT,

5-hydroxytryptamine/serotonin. |

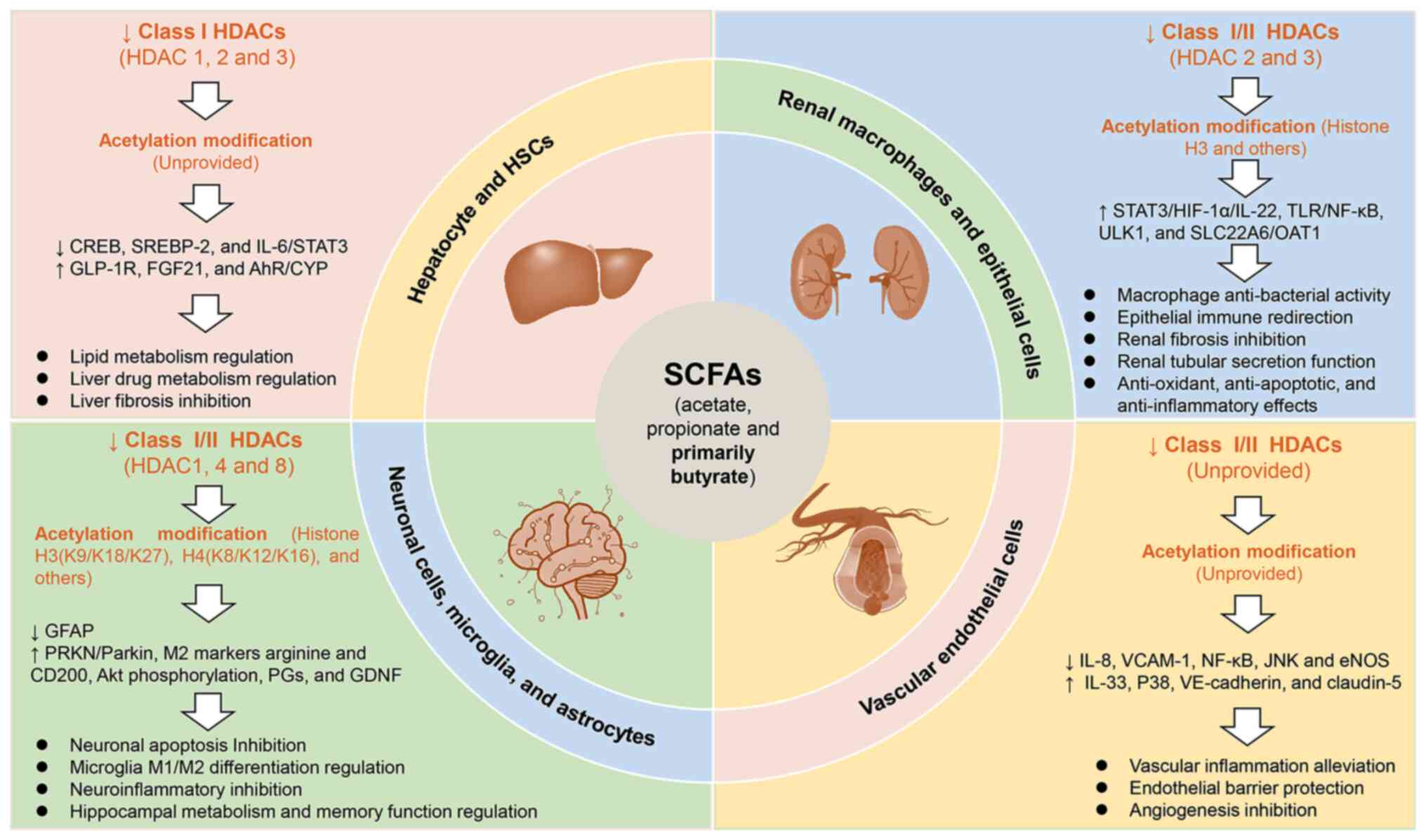

| Figure 6The extraintestinal protective

effects of SCFAs based on HDAC inhibition. The SCFAs, namely

acetate, propionate and primarily butyrate, exert immunoprotective

effects on extra-intestinal organs, including the liver, kidney,

nerves and blood vessels. These effects are achieved through the

mechanism of HDAC inhibition. Mechanistically, SCFAs are capable of

inhibiting the activities of class I and II HDACs (1, 2, 3, 4 and

8), while simultaneously regulating acetylation modifications at

histone H3 (K9/K18/K27), H4 (K8/K12/K16) and other sites. These

actions modulate the activities and functions of different

tissue-resident cells, ultimately contributing to the systemic

protection of SCFAs. SCFAs, short chain fatty acids; HDAC, histone

deacetylase; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element

binding protein; SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding

transcription factor; GLP-1R, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor;

FGF21, fibroblast growth factor 21; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor;

CYP, cytochromes P450; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; PRKN,

parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase; M1, macrophage subset 1;

M2, macrophage subset 2; PGs, prostaglandins; GDNF, glial cell line

derived neurotrophic factor; HSCs, hepatic stellate cellsHIF-1α,

hypoxia inducible factor-1α; TLR, toll-like receptor; ULK1, unc-51

like autophagy activating kinase 1; SLC22A6, solute carrier family

22 member 6; OAT1, organic anion transporter-1; VCAM-1, vascular

cell adhesion molecule-1; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide

synthase. |

Inside the gut

Immune cells

SCFAs can alleviate intestinal immune cell

inflammation through HDAC inhibition and acetylation modification.

For instance, research has revealed that butyrate is more effective

than acetate and propionate in markedly reducing LPS-induced

expression of pro-inflammatory mediators in both BMDMs and colonic

LP macrophages in vitro and in vivo. This

anti-inflammatory effect of butyrate is independent of GPCRs and

instead occurs through HDAC inhibition, which increases H3K9

acetylation at the promoter regions of cellular inflammatory genes

(39). In addition, under

colitis conditions, butyrate can improve anemia and reduce TNF-α

production by colonic macrophages. It does so by promoting

ferroportin (FPN)-dependent iron export from macrophages, thus

regulating iron homeostasis. The FPN-inducing effect of butyrate (1

mM in vitro) relies on its inhibitory activity against HDAC

at the Slc40a1 promoter (87).

Compared with other SCFAs, butyrate (0.0625-0.5 mM) administered

for 4 days more effectively reduces the activation, proliferation

and production of inflammatory cytokines (such as IFN-γ and IL-17)

in human intestinal LP CD4+ T cells in vitro. The effects of

butyrate can be attributed to its promotion of histone acetylation

in both unstimulated and TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells, as well as

through GPR43 signaling (68).

Butyrate (used in vivo at 200 mM or in vitro at 0.5

mM) can also promote IL-22 production by intestinal and circulating

CD4+ T cells and ILCs via GPR41 and HDAC inhibition, thereby

suppressing intestinal infection and inflammation. Mechanistically,

butyrate upregulates the expression of AhR and HIF-1α, which are

differentially regulated by mTOR and STAT3, leading to increased

IL-22 levels in CD4+ T cells under Th1 conditions. Importantly,

butyrate also increases the accessibility of HIF-1α binding sites

at the IL-22 promoter in CD4+ T cells through histone modification

(69). γδT cells are

tissue-resident T cells that carry out innate immune functions and

can produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17, participating in

host defense and the regulation of tissue inflammation. A previous

study has revealed that the SCFA propionate (200 mM in vivo

or 1 mM in vitro) can directly act on intestinal γδT cell

populations and inhibit IL-17 production, with its mechanism of

action being associated with HDAC inhibition. Therefore, the impact

of propionate on γδT cell activity may provide a potential pathway

to prevent chronic intestinal inflammation and cancer progression

(88).

IECs

The regulatory roles of microbial SCFAs in the

activities and function of IECs through HDAC inhibition are

currently under extensive investigation (89-119). These effects of SCFAs are

multifaceted, encompassing but not limited to cellular activities

such as proliferation, differentiation and anti-bacterial action,

as well as cellular functions including absorption, metabolism,

inflammation and immunity.

First and foremost, SCFAs can regulate the

proliferative activity of IECs via HDAC inhibition or histone

acetylation. For instance, 2 mM butyrate can activate the AP-1

response in colonic epithelial cells by inhibiting HDACs. AP-1 is a

transcription factor that carries out a key role in determining

cell proliferation, differentiation, transformation, cell migration

and apoptosis (89). A recent

study has demonstrated that butyrate at 150 mM in vivo or 1

mM in vitro can also restrict the differentiation and

proliferation of intestinal tuft cells by inhibiting HDAC3, serving

as an important product of the microbiota in calibrating intestinal

type 2 immunity (90). Another

SCFA, propionate, can promote the spreading and polarization of

epithelial cells by inhibiting HDACs and activating GPR43 and

STAT3, thereby enhancing the renewal rate and persistence of the

intestinal epithelium (91). It

is important to emphasize that, by contrast, butyrate exerts an

inhibitory effect on the cellular activity of cancerous IECs or can

induce apoptosis. For example, Mariadason et al (92) revealed that 2 mM butyrate

markedly triggers activities such as cell cycle arrest, apoptosis,

IL-8 secretion, in undifferentiated colon Caco-2 cells, and

consistently, while consistently and selectively inducing high

levels of histone hyperacetylation. Previously, it was reported

that butyrate could have contradictory effects on the activity of

normal colonic epithelial cells and cancer cells. For instance,

when exposed to the HDACi butyrate at a concentration of 1-2 mM,

colon cancer cell lines exhibit a notable increase in alkaline

phosphatase activities, urokinase receptor expression and IL-8

secretion. By contrast, butyrate inhibits alkaline phosphatase

activities in the primary normal cells but markedly suppresses

urokinase receptor and IL-8 secretion (93). Another example is that 5 mM

butyrate can inhibit cell proliferation and stimulate cell

differentiation in the colon cancer cell line HT-29. The effects of

butyrate in this cell line stem from the induction of cyclin D3 and

p21, as well as its role as an HDACi in promoting histone H4

hyperacetylation (94).

AMPs are potent defensive molecules released by IECs

that participate in innate immunity, carrying out a key role in

maintaining mucosal homeostasis (95). Current research has yielded

substantial evidence indicating that HDACs affect the expression of

relevant defense genes. In particular, the regulatory function of

microbial SCFAs as HDACi in modulating the anti-bacterial activity

of IECs, mediated by AMPs, is being gradually elucidated. For

example, Fischer et al (95) has indicated that inhibiting HDAC

activity can enhance AMP production from IECs upon bacterial

challenge, without increasing the expression of inflammatory

cytokines. Cathelicidin (LL-37) is a major AMP within the

intestinal non-specific innate immune system. The SCFA butyrate

(2-4 mM) can induce the expression of LL-37 in a time-dependent

manner in gastrointestinal cancer cells that lack LL-37. The

induction of LL-37 by butyrate is due to the parallel acetylation

of histone H4 and non-histone HMGN2, and is associated with the

suppression of MEK-ERK signaling pathway (96). α-defensins, also known as

cryptdins, are the primary bactericidal AMP molecules produced by

intestinal Paneth cells and their activation requires MMP7. SCFAs,

including butyrate, propionate and acetate, induce the expression

of α-defensins and MMP7 in Paneth cells in vitro. Histone

deacetylation (specifically HDAC8 inhibition) and STAT3 might be

involved in the butyrate (1-2 mM)-mediated induction of α-defensin,

contributing to the restoration of the intestinal anti-microbial

barrier function (97). However,

not all regulation of AMP genes by SCFAs is determined by

inhibiting HDAC activity. For instance, the induction of host

defense peptides, namely pBD3 and pEP2C, by butyrate in porcine

IECs (IPEC J2) is associated with the expression of TLR2 and EGFR,

rather than HDAC inhibition (98).

HDAC inhibition carries out a key role in how SCFAs

maintain the barrier function of IECs. Representative SCFAs, namely

butyrate, propionate and acetate, reduce the activation of

epithelial Caco-2 cells induced by inflammatory cytokines such as

TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-1β. In particular, butyrate (0-8 mM) exerts a

pronounced dose-dependent preventive effect on inflammation and

inflammation-induced barrier disruption in both

inflammation-induced Caco-2 cells and co-culture models of

PBMCs/Caco-2 cells. Additionally, butyrate can regulate the release

of inflammatory cytokines from activated PBMCs and immune cell

phenotypes. Meanwhile, the HDACi can replicate the epithelial

barrier-protective effect of butyrate (99). Notably, the mechanisms by which

SCFAs, mainly butyrate, enhance IEC barrier function by inhibiting

HDAC expression are currently being elucidated (100-103). For example, one study showed

that butyrate (5 or 10 mM) can suppress the expression of

claudin-2, a permeability-promoting tight-junction protein, in IECs

in an IL-10RA-dependent manner. This suppression is achieved

through the combined actions of HDAC inhibition (H3K9 acetylation)

and STAT3 activation (100).

The actin-binding protein synaptopodin (SYNPO) is localized within

intestinal epithelial tight junctions (TJs) and F-actin stress

fibers, carrying out a key role in maintaining barrier integrity

and cell motility. The mechanism underlying the relationship

between butyrate (5 mM) and epithelial barrier restoration likely

involves the induction of SYNPO expression through HDAC inhibition

in both epithelial cell lines and murine colonic enteroids

(101). Furthermore, 1 mM

butyrate can reduce TJ permeability in intestinal monolayers by

activating lipoxygenase and the HDACi TSA mimics this effect of

butyrate (102). When butyrate

(2 mM for 24 h) serves as an energy source for the human polarized

colonic goblet cell line HT29-Cl.16E, it promotes the expression of

mucin (MUC) genes that protect the epithelial barrier. It is

noteworthy that the HDAC inhibitory action of butyrate can

participate in regulating the expression of MUC3 gene, yet it does

not affect the expression of the MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC5B genes

(103).

SCFAs can regulate the absorption and metabolic

function of IECs through HDAC inhibition. Indeed, the

representative SCFA, butyrate, serves as the primary energy source

for colonic cells. However, the absorption of butyrate is not

actually secondary to its inhibition of HDACs. A study has

demonstrated that butyrate at 5 mM for 24 h activates the MCT1

promoter via the NF-κB pathway rather than through HDAC, leading to

an enhanced absorption of SCFAs in Caco-2 cells (104). Consequently, as the effective

HDACi, SCFAs carry out a more notable role in regulating the

absorption and metabolic behaviors of nutrients or other exogenous

substances in the IECs. For instance, when propionate and butyrate

are each administered at 2 mM for 24 h, they considerably increase

the expression of peptide-YY (PYY) in both human intestinal cell

lines and mouse primary cells. PYY is an important hormone secreted

by heterogeneous enteroendocrine cells that is involved in food

intake and insulin secretion. This effect is primarily attributed

to the HDAC-inhibitory activity of SCFAs and the partial role of

FFA2, also known as GPR43 (105). Butyrate can also mediate

epigenetic regulation of the sodium-dependent vitamin C

transporters (such as hSVCT1) by inhibiting HDAC isoforms 2 and 3,

thereby regulating the absorption of vitamin C in the intestinal

epithelium (106).

Nevertheless, butyrate also has the ability to regulate the

metabolism of cytotoxic substances in epithelial cells. Sodium

butyrate (0.5 mM) can induce the acetylation of histone H3 (at

Lys14) and histone H4 (at Lys16) in colonic epithelial cells. This

action triggers the expression of cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1), a

metabolic enzyme for dietary carcinogens such as benzo[a]pyrene

(BaP) (107).

The regulatory role of SCFAs in epithelial

inflammation can also be partially attributed to the inhibition of

HDAC. Specifically, SCFAs can directly modulate the cytokine

releasing of IECs through inhibiting HDAC activity. For instance,

butyrate at 3 mM for 16 h can markedly enhance the signaling of the

protective cytokine IL-22 in human epithelial Caco-2 and DLD1

cells. Independently of IL-22R1 regulation, butyrate can increase

the accessibility of STAT3 at affected gene loci, and this

mechanism is associated with HDAC inhibition (108). When administered at the same

concentration of 10 mM for 12 h, butyrate, rather than acetate and

propionate, can stimulate the expression of the cytotoxic

pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-32α in IEC lines, namely HT-29, SW480

and T84. Additionally, butyrate can enhance IL-1β-induced

expression of IL-32α mRNA. This effect is not associated with the

activity of PI3K, a mechanism involved in IL-32α expression.

Instead, it predominantly depends more heavily on the inhibition of

HDACs (109). When compared

with acetate and propionate, 2 mM butyrate emerges as the most

potent inhibitor in preventing the release of CXCL10 from the IEC

HT-29 cells activated by IFN-γ and IFN-γ+TNF-α. This action

contributes to reducing epithelial inflammation, maintaining immune

homeostasis and upholding the integrity of the gut barrier.

Butyrate also inhibits the protein expression of IRF9 and

phosphorylated JAK2, along with the mRNA expression of CXCL10,

SOCS1, JAK2 and IRF9 in cells. By inhibiting HDAC activity,

butyrate prevents the epithelial release of CXCL10, with an effect

comparable with that of the well-known HDACi such as TSA (110). The impact of butyrate on the

colonic inflammatory response is partly due to its regulation on

NF-κB activation based on HDAC inhibition. Exposure of HT-29 cells

to 4 mM butyrate for 18 h eliminates their constitutive NF-κB p50

dimer activity. Another notable finding is that butyrate

selectively regulates NF-κB activation. It can markedly suppress

the activation of NF-κB triggered by TNF-α and phorbol ester, while

enhancing the NF-κB activation induced by IL-1β. The regulatory

effect of butyrate on NF-κB may be partially attributed to its

ability to inhibit HDACs, as the HDACi TSA exerts a similar effect

(111).

SCFAs, primarily butyrate, also possess regulatory

effects on the immune activity of IECs, which can be influenced by

the HDAC inhibitory activity. For instance, butyrate (0.5-8 mM; 24

h) can modulate the expression of the immune effector indolamine

2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO-1) in both human primary IECs and IEC cell

lines. Independent of the transcriptional mechanisms involving

GPCRs (GPR41, GPR43 and GPR109a), butyrate downregulates IDO-1

expression through a dual mechanism: A reduction in STAT1 levels

and its HDAC inhibitory property (112). The SCFA butyrate also regulates

host T-cell responses by interacting with IECs to improve the

intestinal mucosal immune system. One notable effect is the

enhancement of the accumulation of anti-inflammatory Treg cells in

the gut. In vitro studies have demonstrated that butyrate

can induce the TGF-β production in primary IEC cells or cell lines,

promoting the expression of Foxp3 and the anti-inflammatory

cytokine IL-10 under Treg conditions. This inductive effect of

butyrate is independent of GPCRs and their associated signaling

pathways but relies on HDAC inhibition mediated by SP1 (113,114). A study has shown that SCFAs

(acetate, propionate and butyrate) and AhR play similar protective

roles in intestinal inflammation and Treg cell induction. In

particular, 5 mM butyrate markedly increases the expression of

AhR-responsive genes (such as Cyp1a1/CYP1A1) in mouse colon cells

YAMC and human colon cells Caco-2. The HDACi, including

panobinostat and vorinostat, exhibit effects similar to those of

SCFAs. They enhance AhR ligand-mediated induction and subsequent

histone acetylation (115).

Modoux et al (116) have

uncovered that butyrate is not an AhR ligand but acts as an HDACi

to remodel chromatin. By synergizing with known ligands, butyrate

increases the recruitment of AhR to the promoters of target genes,

thereby enhancing AhR activation.

Moreover, when SCFAs act as HDACi, they can also

influence intestinal epithelial homeostasis through alternative

pathways (117-119). For instance, previous research

has disclosed that SCFAs (primarily 1 mM butyrate) produced by gut

microbiota can entrain intestinal epithelial circadian rhythms via

an HDACi-dependent mechanism. This finding deepens the

comprehension of how the microbial and circadian rhythm networks

jointly regulate intestinal epithelial homeostasis (117). Both treatment with the HDACi

butyrate (5 mM) and TSA (1 μM) for 24 h can reduce the

expression of the serotonin (5-HT) transporter (SERT) in Caco-2

cells. Consequently, this reduction promotes the clearance of

extracellular 5-HT. Reduced SERT expression and the subsequent high

levels of 5-HT are associated with various intestinal diseases,

such as inflammation or intestinal infections. The mechanism by

which butyrate and TSA downregulate intestinal SERT involves the

inhibition of HDAC2 and an increased binding of acetylated histone

H3 or H4 to the human SERT (hSERT) promoter 1 (hSERTp1) (118). Moreover, the SCFA butyrate at 2

mM for 24 h has the ability to stimulate the production of retinoic

acid in the IEC cell line through HDAC3 inhibition (resulting in

H3K18 acetylation), thereby promoting mucosal homeostasis. This is

attributed to the fact that IECs play a key role in upholding

mucosal immune homeostasis, through the production of retinoic acid

(119).

Outside the gut

Hepatic protection

Current evidence indicates that among SCFAs,

butyrate primarily exerts regulatory effects on the activity and

function of hepatocytes through HDAC inhibition. The HDACi action

of butyrate is mainly associated with the metabolic functions of

the liver, with a particular emphasis on lipid metabolism. For

instance, Zheng et al (120) discovered that butyrate (at 2 mM

in vitro and 5% butyrate by weight in vivo) can

suppress lipogenic genes and activate genes related to lipid

oxidation in hepatocytes. As a result, it ameliorates hepatic

steatosis and abnormal lipid metabolism in mice fed with high-fat

and fiber-deficient diets. The underlying molecular mechanism of

butyrate has been elucidated as the activation of the liver

GPR41/43-mediated CaMKII-CREB signaling pathway and the inhibition

of the HDAC1-CREB signaling pathway. Glucagon-like peptide-1

(GLP-1) is a protein involved in regulating metabolic processes and

has a beneficial effect on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and

steatohepatitis. The study has shown that butyrate can reverse the

decline in hepatic GLP-1 caused by a high-fat diet and alleviate

hepatic steatosis. From a mechanistic perspective, butyrate (5 mM)

for 24 h enhances the expression of GLP-1R in liver HepG2 cells by

inhibiting HDAC2, rather than through the activity of GPR43/GPR109a