Introduction

Sepsis is a prevalent inflammatory response induced

by microbial infection, with severe manifestations potentially

leading to multiorgan dysfunction (1). The current literature indicates

that the incidence of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury (SAKI)

among patients with sepsis in intensive care units is ~51%, with a

mortality rate of 41%. Despite these statistics, effective

therapeutic interventions remain limited (2). Studies have revealed that the

pathogenesis of SAKI involves multiple mechanisms, particularly

inflammation, which activates innate immune components such as

monocytes-macrophages, natural killer T cells and neutrophils, all

of which are integral to the injury response in SAKI (3,4).

Positive outcomes correlate with reduced levels of inflammatory

factors, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α

(TNF-α), indicating that early inflammatory response suppression

benefits patients with high-risk SAKI (5).

As essential components of the innate immune system,

macrophages play a critical role in regulating inflammatory

responses when activated. Studies have reported that renal

macrophages are involved in regulating kidney infections,

ischemia-reperfusion injury, drug toxicity, and diabetic

nephropathy (6-8). In SAKI, infiltration of glomerular

and interstitial macrophages is observed, with proinflammatory

macrophages predominating in the early stages; these macrophages

stimulate leukocyte infiltration and proinflammatory cytokine

secretion and produce cytotoxic substances. However, the transition

from the M1 phenotype to the M2 phenotype signifies a shift from

the injury phase to the repair phase in the ischemically damaged

kidney and is essential for tubular cell proliferation and

functional recovery (9). In

addition, this phenotypic conversion can lead to the secretion of

anti-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs),

which mediate the cleavage of chemokines and chemotactic agents,

inhibit inflammatory cell activity and aid in kidney injury repair

(10). Moreover, dysregulation

of the macrophage phenotypic transition causes prolonged

inflammation and impairs tissue healing (11). Thus, in-depth research on the

mechanisms of macrophages in sepsis is crucial for the development

of new therapeutic strategies to mitigate SAKI.

The remarkable plasticity of macrophages to modify

their phenotypes and functions in response to environmental stimuli

is crucial for maintaining health and combating disease. However,

the molecular mechanisms underlying this remarkable plasticity

remain only partially understood. Advances in the field of

epigenetics have illuminated the complex regulatory networks that

govern macrophage behavior by affecting mRNA stability, folding,

degradation, splicing, translation, and export (12). Epigenetics involves the

differential expression of genes resulting from modifications in

noncoding sequences, which can influence gene expression patterns

in response to environmental stimuli, thereby affecting cellular

function and organ homeostasis and contributing to processes such

as inflammation, tissue repair and immune regulation (13). N6-methyladenosine

(m6A) is a predominant posttranscriptional modification

in eukaryotic RNAs (14,15).

m6A methylation is catalyzed primarily by

m6A 'writer' enzymes [such as [Wilms' tumor

1-associating protein (WTAP), methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3),

vir like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA),

methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) and RNA binding motif protein

15 (RBM15), which catalyze methylation reactions), 'eraser' enzymes

[such as fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO)] and ALKBH5,

which remove m6A modifications and regulate RNA

stability) and 'reader' enzymes [such as YTH domain family proteins

1-3 (YTHDF1-3), YTH domain-containing proteins 1-2 (YTHDC1-2), and

Insulin-like growth factor-2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs), which

recognize m6A-modified RNA] (16). Dysregulation of these enzymes can

markedly affect macrophage behavior. For example, the upregulation

of IGF2BP1 in SAKI is linked to renal dysfunction and damage

through the enhancement of macrophage migration inhibitory

factor-related pyroptosis via the activation of the NLR family

pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome (17). Similarly, FTO downregulates

acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member in an

m6A-dependent manner to inhibit ferroptosis and

alleviate macrophage inflammation (18). In acute lung injury (ALI),

elevated METTL14 and increased m6A levels are detected

in circulating monocyte-derived macrophages, which are recruited to

and infiltrate the lungs, suggesting that METTL14-induced NLRP3

inflammasome activation exacerbates ALI (19). These findings underscore the

potential of m6A methylation as a critical mediator of

cellular injury and disease pathogenesis. An analysis of the

datasets GSE32707 (20) and

GSE69063 (21) revealed that FTO

was the only gene among the m6A-associated proteins that

exhibited simultaneous and significant downregulation in the

transcriptome of peripheral blood samples from patients with

sepsis. Nevertheless, few studies have explored the precise role of

FTO in regulating macrophage reprogramming in SAKI.

Thus, in the present study, the regulatory

mechanisms of m6A methylation in macrophages during SAKI

were investigated. The overexpression of FTO in SAKI mitigated

renal damage and reduced the expression and production of

proinflammatory cytokines by modulating the m6A

modification of MMP-9 mRNA. Conversely, knocking down MMP-9

exacerbated renal dysfunction and renal damage and promoted the

production of proinflammatory factors both in vivo and in

vitro. Therefore, it was hypothesized that targeting FTO could

be a promising alternative therapeutic strategy for the treatment

of SAKI in the future.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic methods

The sepsis-related single-cell RNA sequencing

(scRNA-seq) dataset GSE32707 and sepsis-related RNA sequencing

dataset GSE69063, pertaining to peripheral blood mononuclear cells

from patients, were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)

database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The 'limma'

package in R (https://bioconductor.org/packages/limma/;

version3.58.1) was used to identify differentially expressed genes

(DEGs) linked to sepsis. Genes were identified based on an adjusted

P-value <0.05 and an absolute log2-fold change (FC)

>1.

Mice

A total of 125 male C57BL/6 mice (~25g; aged 6-8

weeks) were supplied by SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and

used for all the experimental procedures. Each mouse was kept in a

ventilated cage in a pathogen-free environment (temperature,

20-26°C; humidity, 40-70%; under a 12-h light/dark cycle) and was

provided with a standard rodent diet. All experimental procedures

involving the care and use of mice were approved by the Ethics

Committee of Dongguan People's Hospital (approval no.

IACUC-AWEC-202406500R1). The mice underwent moderate cecal ligation

and puncture (CLP) surgery and their survival rates were

subsequently monitored. Blood and tissue samples were collected at

12 or 24 h after surgery.

CRISPR/Cas9-regulated knockout of

MMP-9

A total of 6 male Mmp9−/− mice

(6-8 weeks old) were used in the present study. Mice were housed in

a facility with 12-h light/dark cycle at 23±3°C and 40-70%

humidity. To generate the MMP-9 knockout mice used in the present

study, the one-step CRISPR-Cas9 zygote-injection protocol that has

been extensively validated in the literature was followed (22). Briefly, the single-guide (sg)RNA

sequences used to target the MMP-9 gene (gRNA-A1,

5'-CCATGACGATCTCACAGCTCGGG-3'; gRNA-A2,

5'-CAGGCTCTCTACTGGGCGTTAGG-3'; gRNA-B1,

5'-GTTCACGAGACCTCAGTTGATGG-3'; and gRNA-B2,

5'-ATTCAGTTGCCCCTACTGGAAGG-3') were designed and synthesized by

Cyagen Biosciences, Inc. Fertilized eggs (n=100) were generated by

in vitro fertilization: oocytes were harvested from 5 female

C57BL/6JCya and sperm obtained from 2 male C57BL/6JCya (all mice

supplied from Cyagen Biosciences, Inc.). Then mixed sgRNA/Cas9

protein complexes were subsequently assembled immediately before

injection by combining Cas9 protein and the four sgRNAs and

co-injected into fertilized eggs. The injected embryos were

cultured in KSOM medium overnight and those developed to the

two-cell stage were transferred into the oviduct of pseudopregnant

ICR female mice. The F0 founder mice were identified by PCR, which

were bred to wild type C57BL/6JCya mice to test germ line

transmission and F1 animal generation. The F1 mice were screened by

PCR amplification by using the following wild-type (WT) primers:

F1, 5'-CCAGTGAGAAGCATCTAAGAGAAG-3'; R1,

5'-GACTCCTTGGGGAAGGAAAGATG-3'; Mmp9−/− primers:

F2, 5'-CCAGTGAGAAGCATCTAAGAGAAG-3'; R2,

5'-GACACAGTCTGACCTGAACCATAA-3'. Homozygous

MMP9−/− mice were obtained by inter-crossing

heterozygotes and were verified by PCR and western blotting. All

animal studies were performed in accordance with the guidelines

approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Cyagen

Biosciences, Inc. (approval no. GACU23-MS004-788).

Cell culture

The RAW264.7 cell line (cat. no. CL-0190; Procell

Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was cultured in Dulbecco's

modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; cat. no. C11995500BT; Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; cat. no. FND500; Shanghai ExCell Biology, Inc.). Mycoplasma

testing was performed on the cell lines with a MycoBlue Mycoplasma

Detector kit (cat. no. D101; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). After

stimulation with 1 μg/ml LPS (cat. no. L2630;

MilliporeSigma), at various time points, the supernatant, mRNA, and

proteins were collected for subsequent analysis.

Lentiviral constructs

For RNA interference (RNAi) mediated by

lentiviruses, short hairpin (sh)RNA targeting MMP-9 was generated

by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. All lentiviral particles were

generated with a 2nd packaging system. 293T cells (cat. no. GNHu44;

Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences) were seeded at

5×106 cells per 10-cm dish 24 h before transfection. For

one dish, a total of 45 μg plasmid DNA [transfer

(GV):packaging (pHelper 1.0):envelope (pHelper 2.0)=4:3:2] was

transfected with transfection kit (cat. no. GRCT105; Shanghai

GeneChem Co., Ltd.). Medium was replaced 8-12 h post-transfection;

viral supernatants were harvested at 48 h, filtered (0.45

μm, cat. no. SLHP033R; Millipore) and centrifuged at 75,000

× g for 2 h at 4°C. The pelleted virions were gently resuspended in

ice-cold PBS, vortexed briefly, and centrifuged again at 10,000 × g

for 5 min at 4°C to remove debris. The final concentrated

lentivirus was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use. The

sequences of the shRNAs used were as follows:

5'-CACTTACTATGGAAACTCAAA-3' and 5'-GACCATCATAACATCACATAC-3'. A

lentivirus that overexpresses mouse FTO and insulin-like growth

factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3) was also created by

Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with

these recombinant lentiviral plasmids to establish the

FTO-overexpressing (oe-FTO) RAW264.7 cell line and the

MMP-9-knockdown (shMMP-9) RAW264.7 cell line at the appropriate

multiplicity of infection (MOI=30); an empty lentiviral vector was

used as a control for transfection. At 72 h post-transduction cells

were selected with puromycin (5 μg/ml; cat. no. A1113803;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 7 days, then maintained

in 2 μg/ml puromycin until assays were performed. All

experiments were carried out between passage 3 and 6 after

selection.

CLP

The CLP surgery was performed according to the

established protocol by Rittirsch et al (23) and Liu et al (24), with minor adaptations. Briefly,

mice were anesthetized by induction started with 4% sevoflurane in

an acrylic chamber and the concentration was adjusted accordingly

by the absence of pedal withdrawal reflex. Maintenance anesthesia

was administered at 2-2.5% sevoflurane via a nose cone, with

continuous monitoring of anesthetic depth throughout the procedure.

Following abdominal shaving and aseptic preparation, a 1.5-2 cm

midline laparotomy was performed to exteriorize the cecum. The

cecum was ligated at ~50% between the cecal tip and the ileo-cecal

valve with 5-0 silk suture and punctured with a 21-gauge needle. A

small droplet of feces was extruded to ensure patency before the

cecum was returned to the abdominal cavity. The incision was closed

in two layers with 5-0 silk. Postoperatively, mice received 1 ml

pre-warmed (37°C) sterile saline subcutaneously, along with

buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, s.c.) administered every 8 h. Food and

water were provided ad libitum.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)

The eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice received tail

vein injections of Ctrl-AAV or FTO-AAV (Shanghai GeneChem Co.,

Ltd.), with each mouse receiving 1011 viral particles.

The enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene was carried by

the AAV. Gene overexpression was verified in mice injected with

AAVs by western blotting and immunofluorescence (IF) one month

later.

Isolation of peritoneal macrophages

(PMs)

Peritoneal lavage fluid was collected and

centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at 4°C, after which the red blood

cells were lysed by Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (cat. no. R1010;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). F4/80+ PMs

were subsequently isolated using a kit (cat. no. 100-0659; Stemcell

Technologies, Inc.) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS

and 100 IU/ml penicillin-streptomycin before use.

Dot blot assay

Total RNA (2 μg/μl) was heated to 95°C

for 5 min, and 2 μl of mRNA was spotted onto an Amersham

Hybond-N+ membrane (cat. no. RPN303B; Cytiva). The membrane was

crosslinked, blocked for 1 h at room temperature (RT) with 5%

non-fat dry milk (cat. no. 36120ES76; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.), incubated with an anti-m6A antibody (cat.

no. ab284130; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. The following day, after

incubation with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, Goat

Anti-Rabbit IgG(H+L) (peroxidase/HRP conjugated; 1:8,000; cat. no.

E-AB-1003; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), for 1 h at

RT, the membrane were detected with ECL A/B reagents (cat. no.

1705061; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and visualized on a ChemiDoc

system (G:B0XChemiXX9; Syngene).

In vitro phagocytosis assay

The RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with pHrodo Green

E. coli BioParticles (cat. no. P35366; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C for 1 h and then fixed and stained

with rhodamine phalloidin (PHDR1; Cytoskeleton, Inc.) at 4°C for 30

min. The phagocytosis efficiency was evaluated as the MFI of the

internalized pHrodo Green bioparticles per macrophage.

Pretreatment with recombinant MMP-9

(rMMP9)

Cells were pretreated with recombinant MMP-9 protein

(cat. no. 50560-MNAH1; Sino Biological) at a concentration of 100

ng/ml for 2 h at 37°C. The cells were subsequently stimulated with

LPS (1 μg/ml) for an additional 6 h.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

For sectioning, the samples were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde (cat. no. BL539A; Biosharp Life Sciences) for 24 h

at RT, washed three times (5 min each) with phosphate-buffered

saline (PBS; cat. no. C0221A; Beyotime Biotechnology), dehydrated

through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene (cat. no.

X821391; Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd.), and embedded in

paraffin. The cells were permeabilized with a 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100

solution and blocked with 5% normal goat serum (cat. no. C0265;

Beyotime Biotechnology) in PBS for 1 h at 4°C. Following

permeabilization, the sections or cells were incubated with the

corresponding antibodies (1;100) overnight at 4°C and a secondary

antibody (1:500; cat. no. A0423; Beyotime Biotechnology) for 1 h at

RT. Following DAPI staining (1-2 drops; cat. no. P0131; Beyotime

Biotechnology) for 5 min at RT, fluorescence images were acquired

using a confocal fluorescence microscope at multiple

magnifications: ×10, ×20, or ×63. For cells, the IF staining steps

were the same as aforementioned.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and

histological analysis

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (cat. no.

BL539A; Biosharp Life Sciences) for 24 h at RT, followed by

dehydration with various ethanol concentrations and, finally, the

samples were embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Using a

microtome, the samples were sliced into 5 μm sections and

then deparaffinized and hydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed

by heating slides in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (cat. no. BL604A,

Biosharp Life Sciences) for 10-15 min at 95°C, followed by cooling

to RT. Then an appropriate volume (1-2 drops) of endogenous

peroxidase blocking reagent (cat. no. PV-6000D; Beijing Zhongshan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was applied, and the sections were

incubated for 10 min at RT. Primary antibodies diluted in antibody

diluent (cat. no. ZLI-9029, Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) were applied overnight at 4°C. The following antibodies

were used: anti-MMP-9 (1:100; cat. no. ab228402; Abcam), anti-FTO

(1:200; cat. no. ab126605; Abcam), anti-CD86 (1:100; cat. no.

19589; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-CD163 (1:100; cat.

no. GB113751; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) and anti-F4/80

(1:200; cat. no. GB12027; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.).

After three PBS washes, sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit or anti-rat secondary antibody (1-2 drops; cat.

no. PV-6000D; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

for 30 min at 37°C. Immunoreactivity was developed with DAB

substrate kit (100 μl; cat. no. PV-6000D; Beijing Zhongshan

Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Nuclei were counterstained with

hematoxylin (cat. no. C0107; Beyotime Biotechnology) for 3-5 min at

RT, followed by blueing in distilled water. Slides were dehydrated,

cleared and mounted with neutral balsam. After staining, the

samples were analyzed using a light microscope, and the images were

independently evaluated by two pathologists. The semiquantitative

immunoreactivity score was calculated in a blinded manner.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining

H&E staining was performed to observe tissue

morphological changes, and the histological scores for kidney

injury were assessed (25). The

severity of kidney tissue damage was evaluated based on luminal

cell swelling, renal interstitial congestion, cell death, edema and

protein casts. Kidney injury was scored on a 5-point scale: 0 for

normal structure, 1 for ≤10% damage, 2 for 11-25% damage, 3 for

26-45% damage, 4 for 46-75% damage, and 5 for ≥76% damage (26).

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)

PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the tissues or cells

using TRIzol® reagent (cat. no. 15596026; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol and then 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed

into cDNA with a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (cat. no. 11141ES60;

Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was subsequently performed using cDNA

templates, primers and SYBR Green Mix (cat. no. 11184ES08; Shanghai

Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Thermocycling conditions: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. A melting-curve

analysis (65-95°C, 0.5°C increments) was included to confirm

product specificity. GAPDH or β-actin served as internal controls

for coding genes. The calculations were based on the

2−∆∆Cq method (27)

and the sequences of the primers used are listed in Table I.

| Table IPrimers for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (murine). |

Table I

Primers for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (murine).

| Gene | Forward primer

(5'-3') | Reverse primer

(5'-3') |

|---|

| FTO |

TTCATGCTGGATGACCTCAATG |

GCCAACTGACAGCGTTCTAAG |

| ALKBH5 |

GCATACGGCCTCAGGACATTA |

TTCCAATCGCGGTGCATCTAA |

| METTL3 |

CCCAACCTTCCGTAGTGATAG |

TGGCGTAGAGATGGCAAGAC |

| METTL14 |

GGTCGGAGTGTGAACCTGAT |

GGTCCTCTTCCACGCTGTAT |

| WTAP |

TAATGGCGAAGTGTCGAATG |

CTGCTGTCGTGTCTCCTTCA |

|

MMP-9 |

GCAGAGGCATACTTGTACCG |

TGATGTTATGATGGTCCCACTTG |

|

IL-6 |

TAGTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCC |

TTGGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTC |

|

TNF-α |

CAGGCGGTGCCTATGTCTC |

CGATCACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAG |

| GAPDH |

AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA |

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer

(cat. no. WB3100; Suzhou NCM Biotech Co., Ltd.) with a protease

inhibitor cocktail (cat. no. HY-K0010; MedChemExpress). Protein

concentration was determined with the BCA protein assay kit (cat.

no. P0009; Beyotime Biotechnology). Protein (~30 μg per

lane) was separated on 8-12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels according to

the molecular weight of the target proteins and electro-transferred

onto 0.22 μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes

(cat. no. ISEQ00010; MilliporeSigma). Then membranes were blocked

for 1 h at RT with 5% non-fat dry milk (cat. no. 36120ES76;

Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Primary antibodies were

diluted in primary antibody dilution buffer (cat. no. P0023A;

Beyotime Biotechnology) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The

following antibodies were used: anti-β-tubulin (cat. no. 30302ES60;

Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), anti-β-actin (cat. no.

3700; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-GAPDH (cat. no.

30201ES60; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), anti-MMP-9

(cat. no. ab228402; Abcam), anti-FTO (cat. no. ab126605; Abcam),

anti-CD206 (cat. no. 24595; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

anti-CD86 (cat. no. 19589; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

anti-NF-κB (cat. no. 8242; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

anti-IGF2BP3 (cat. no. 14642-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

anti-phosphorylated NF-κB (cat. no. 3033; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.). The following day, after incubation with an

HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:8,000; cat. no. E-AB-1003 and

cat. no. E-AB-1001; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for

1 h at RT, the proteins in the membrane were detected with ECL A/B

reagents (cat. no. 1705061; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and imaged

on a ChemiDoc system (G:B0XChemiXX9; Syngene).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

RAW264.7 cells (5×106 per 10-cm dish)

were collected and lysed in 1 ml IP lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013;

Beyotime Biotechnology) with protease inhibitors (cat. no.

HY-K0010; MedChemExpress) for 30 min. Lysates were centrifuged at

4°C and 12,000 × g for 10 min. Then they were divided into input,

anti-IgG and anti-IGF2BP3 groups. Protein A/G magnetic beads (cat.

no. HY-K0202; MedChemExpress; 25 μl per reaction) were

preincubated with anti-IGF2BP3 (cat. no. 14642-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) or anti-IgG (cat. no. 2729S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) antibodies at 4°C for 2 h, which then were added

to 400 μl lysates and incubated at 4°C overnight. The tubes

were placed on the DynaMag™-2 magnet (cat. no. 12321D;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 min on ice and

the magnetic-bead washing was performed. Following three washes

with buffer consisting of 1X PBS containing 0.5% Tween-20 (cat. no.

ST1727; Beyotime Biotechnology), the coprecipitated proteins were

eluted by boiling in 1X SDS sample buffer (95°C; 10 min) and

subjected to analysis through western blot.

Puromycin labeling

The cells at 70% confluence were treated with 50

μg/ml puromycin for 10 min at 37°C. The cells were lysed and

processed for western blot analysis. The lysates were incubated

with a puromycin-specific antibody (cat. no. PMY-2A4; 0.5

μg/ml; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), followed by

incubation with a secondary antibody. Finally, the protein bands

were visualized to assess puromycin incorporation.

RNA stability

To assess MMP-9 mRNA stability, cells were treated

with actinomycin D (5 μg/ml; cat. no. M4881Abmole

Bioscience, Inc.) to inhibit transcription. Samples were collected

at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h posttreatment. Total RNA was subsequently

extracted, and the expression of MMP-9 mRNA was assessed through

RT-qPCR.

Protein decay assay

After pretreatment with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 12

h, the macrophages were exposed to medium supplemented with

cycloheximide (CHX; 50 μg/ml) for various durations before

western blot analysis was performed.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

The release of IL-6 and TNF-α was measured using

specific ELISA kits (cat. nos. M6000B and MTA00B; R&D Systems).

Serum levels of creatinine (Cr; cat. no. C013-2-1; Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN;

cat. no. C011-2-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) were

evaluated according to the kit manufacturers' instructions.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and lactate

dehydrogenase (LDH) assays

Cell viability was assessed using a CCK-8 assay

(cat. no. CA1210; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.), and LDH levels in the cell culture supernatant were measured

using an LDH assay kit (cat. no. C20300; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation

sequencing (MeRIP-seq) and MeRIP-qPCR

Poly(A) RNA was initially isolated, and 3 μg

of RNA was retained as an input group. PGM beads were incubated

with 2 μl of anti-m6A or anti-rabbit

immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, which were subsequently combined

with RNA. The methylated mRNAs were subsequently purified and

further quantified through qPCR, with m6A enrichment in

each sample normalized to the input.

MeRIP-seq and RNA-seq data

deposition

MeRIP-seq and RNA-seq raw reads and processed count

matrices have been uploaded to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO) under accession numbers: GSE297677 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE297677)

and GSE297679 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE297679).

Quantitative analysis of western and dot

blots

After ECL exposure, chemiluminescent signals were

captured. Non-saturated 8-bit TIFF files were analyzed with ImageJ

v. 1.51j8 (National Institutes of Health) (28). For western blots, each lane was

outlined with the rectangular selection tool, background subtracted

with the 'rolling-ball' radius set to 50 pixels, and band

intensities calculated as the area under the peak. Values were

normalized to the corresponding β-actin or GAPDH signal and

expressed as fold-change relative to the sham/control lane loaded

on the same gel. Dot-blot arrays were processed similarly: Global

m6A levels were calculated as the ratio of

m6A dot intensity to total RNA (methylene-blue) signal.

All data were exported to perform statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

The results are shown as the mean±standard deviation

and statistical tests were performed with GraphPad Prism software

(Dotmatics, version 8.0.1). Survival curves were compared between

experimental and control groups using the log-rank test; due to the

limited sample size, hazard ratios were not computed. The data were

analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test for comparing

multiple groups or an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test for

comparing two groups. For the time-course data, observations at

different time points are independent rather than repeated

measures, and a one-way ANOVA was therefore used instead of

repeated-measures ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

SAKI is accompanied by increased

m6A methylation and reduced FTO expression

Studies have demonstrated a close association

between epigenetic mechanisms and sepsis; however, the specific

relationship between m6A methylation levels and sepsis

remains inadequately understood (29,30). The screening process is

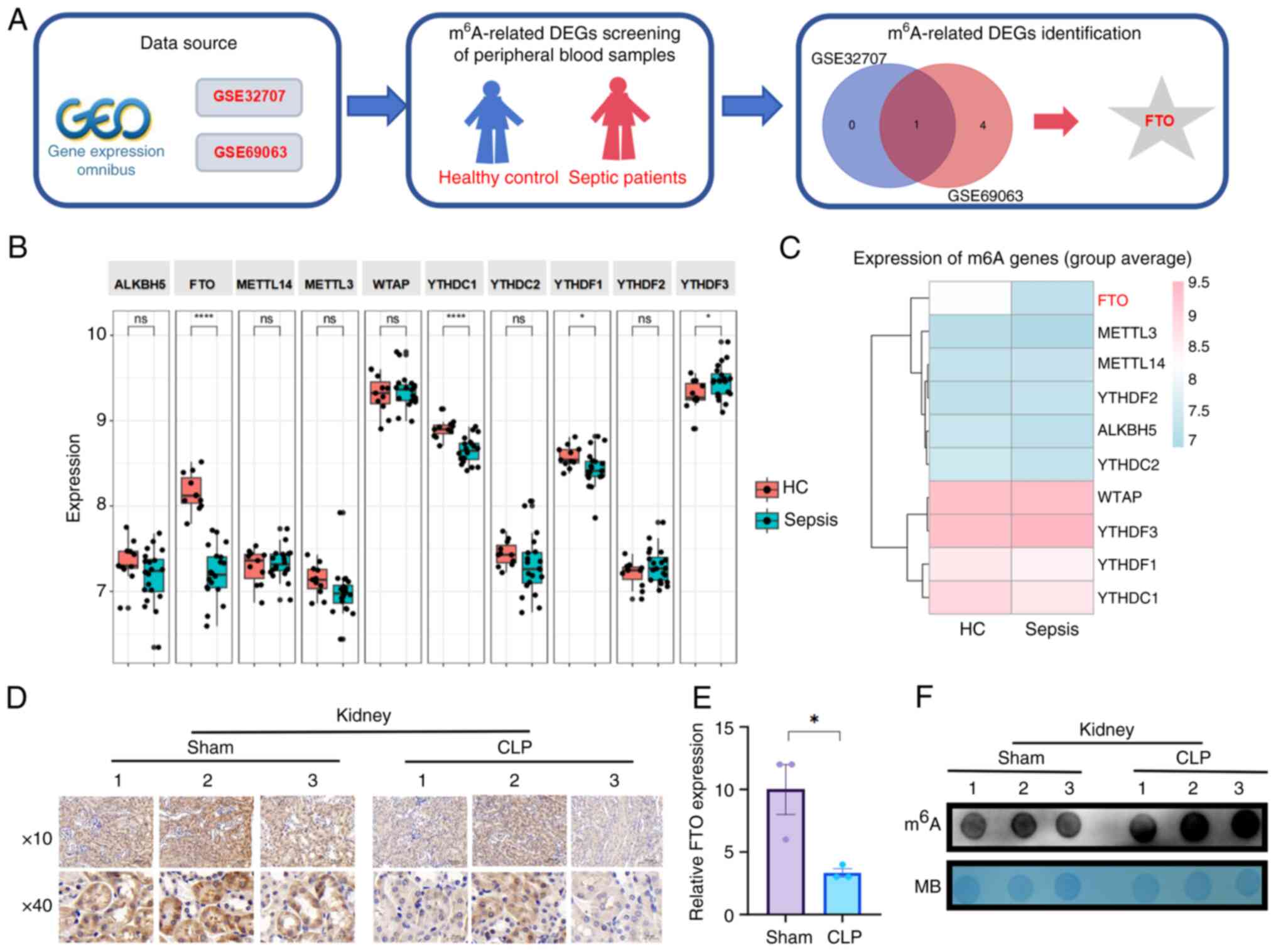

illustrated in Fig. 1A. As

depicted, differential expression analyses were conducted utilizing

the limma package, resulting in the identification of 13 genes

associated with m6A modification, which are represented

in a scatter plot (Fig. 1B). In

particular, FTO was identified as the only gene whose expression

was markedly downregulated, as shown by analysis of the GSE32707

dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. To explore this

finding further, the present study analyzed the GSE69063 dataset

and demonstrated a decrease in the expression of FTO among

m6A-related proteins within the transcriptome of

peripheral blood samples from patients with sepsis (Fig. 1C).

Furthermore, a septic mouse model was established by

performing CLP surgery to simulate clinical polymicrobial sepsis.

Histological analysis revealed that the CLP-treated mice exhibited

inflammatory infiltration across various organs (Fig. S1A). IL-6 secretion rapidly

increased within 12 h following CLP (Fig. S1B). IHC and Western blot

analyses revealed that FTO expression was lower in the kidney

tissues of CLP-induced septic mice than in the kidney tissues of

sham-operated mice (Figs. 1D and

E and S1C and D).

Consistent with the decrease in FTO expression, the results of the

dot blot array revealed a notable increase in m6A

modification levels in the kidney tissues of septic mice (Figs. 1F and S1E). Taken together, these findings

suggested the potential involvement of FTO in SAKI.

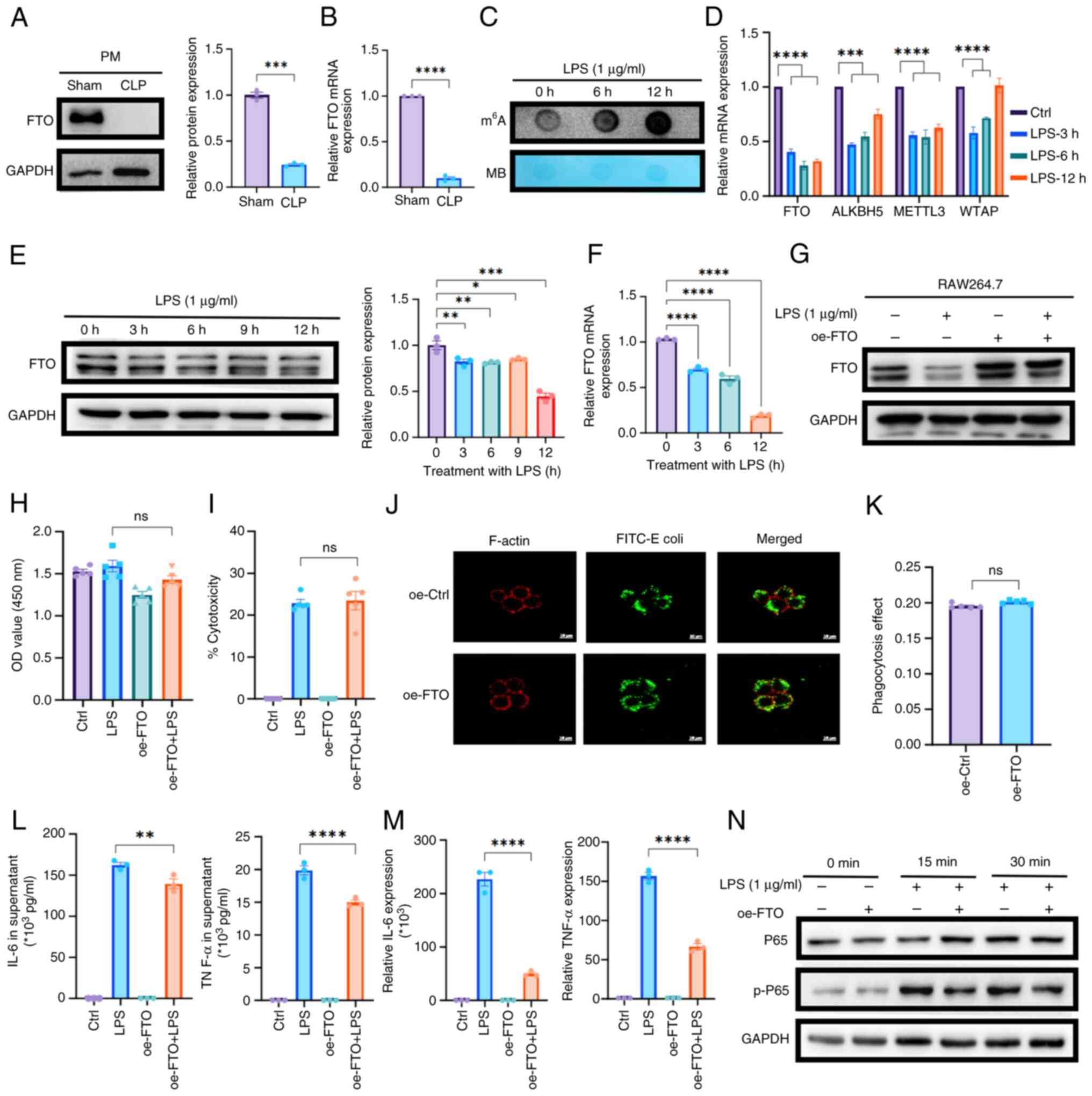

Overexpression of FTO inhibits the

proinflammatory response of macrophages

As previously reported, macrophage polarization

represents a promising novel therapeutic approach for facilitating

repair in AKI (31). To

investigate the alterations in FTO expression in macrophages from

septic mice, PMs were isolated from these mice. Western blot and

qPCR analyses revealed a decrease in FTO expression in the PMs of

septic mice compared with those of sham-operated mice (Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, blotting

assays revealed a concomitant increase in m6A

methylation levels in macrophages treated with 1 μg/ml LPS

for 0, 6 and 12 h (Figs. 2C and

S1F). LPS-treated macrophages

were then collected for qPCR analysis to assess the mRNA expression

levels of enzymes related to m6A modification. The

findings indicated that among the key m6A-related

enzymes, both ALKBH5 and FTO were downregulated, which is

consistent with the observed m6A modification trends;

FTO demonstrated the most pronounced decrease in expression

(Figs. 2D and S1G and H). Western blotting and qPCR

revealed significant, time-dependent downregulation of FTO

expression in LPS-treated macrophages (Fig. 2E and F). These results suggested

that FTO is a crucial protease involved in m6A

modification and plays a pivotal role in the reprogramming of

macrophages during sepsis.

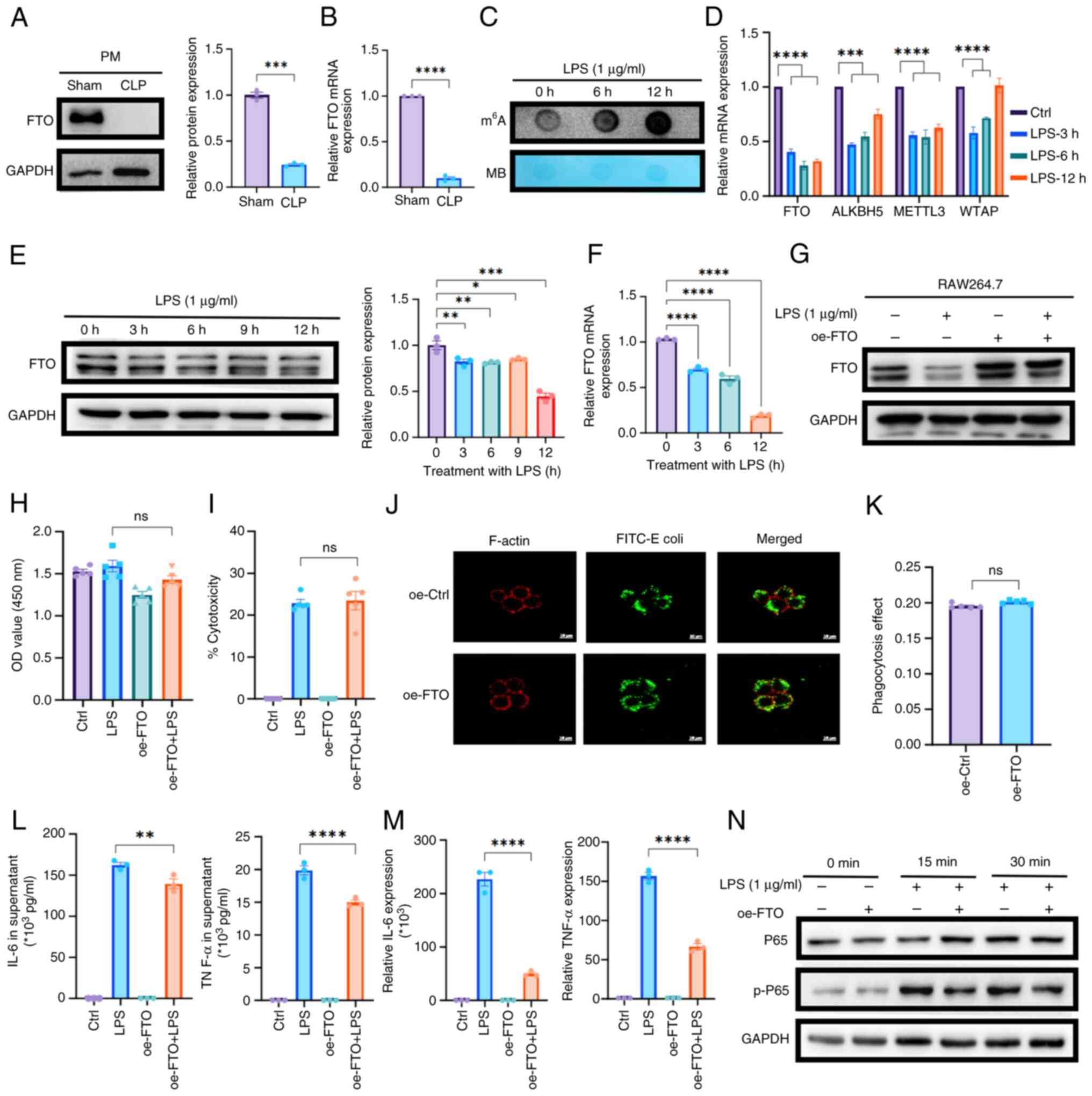

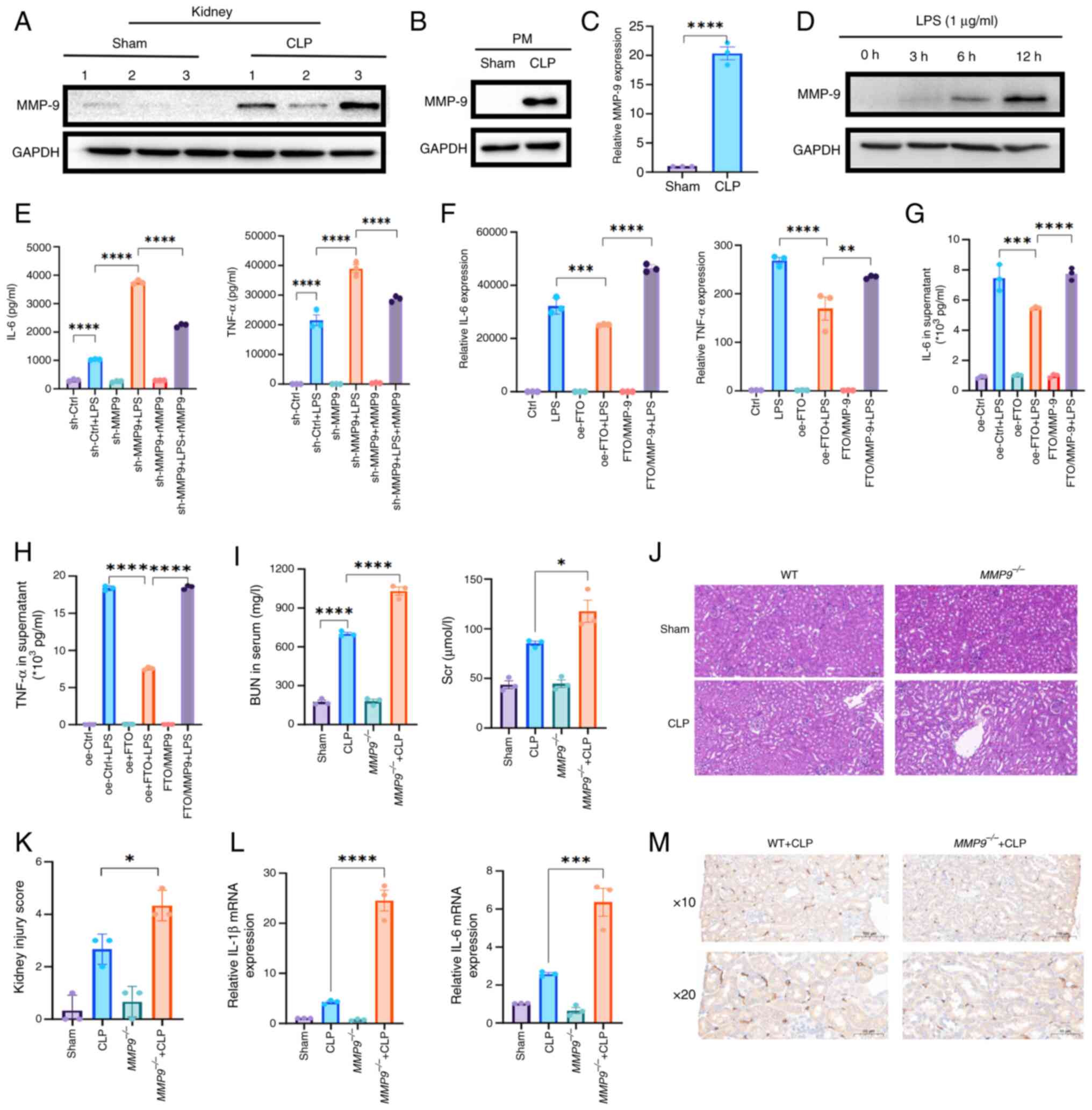

| Figure 2FTO modulates macrophage function and

inflammatory responses in SAKI. (A) Western blotting and (B) qPCR

revealed the downregulation of FTO expression in PMs isolated from

septic mice compared with those from sham-operated controls (n=3).

(C) Dot blot analysis revealed a time-dependent increase in

m6A methylation levels in RAW264.7 cells treated with

LPS (1 μg/ml) for 0, 6 and 12 h. (D) qPCR analysis of

m6A-related enzymes in LPS-treated macrophages. (E)

Western blotting and (F) qPCR demonstrated a time-dependent

reduction in FTO protein expression in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells.

(G) Western blotting confirmed FTO overexpression in oe-FTO

macrophages with or without treatment with LPS for 12 h. (H) CCK-8

and (I) LDH assays revealed that FTO overexpression does not induce

cytotoxicity or affect macrophage proliferation. (J and K)

Phagocytosis assays demonstrated that compared with control

treatment, upregulation of FTO expression did not alter the

phagocytic capacity of macrophages (original magnification, ×63).

(L) ELISA revealed that overexpression of FTO expression markedly

inhibited the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α. (M) qPCR experiments

confirmed the suppressive effect of FTO on the mRNA expression

levels of IL-6 and TNF-α. (N) Western blot analysis revealed that

FTO attenuated the activation of inflammatory pathways by

inhibiting NF-κB signaling. *P<0.05;

**P<0.01; ***P<0.001;

****P<0.0001; ns, not significant. FTO, fat mass and

obesity-associated protein; SAKI, sepsis-induced acute kidney

injury; qPCR, quantitative PCR; PMs, peritoneal macrophages; LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; m6A, N6-methyladenosine; oe, over

expression; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ELISA, enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay. |

To investigate the regulatory function of FTO in

macrophages, macrophages overexpressing FTO were generated by

transfecting them with lentiviral vectors encoding mouse FTO

inserts according to the endogenous expression of FTO. The efficacy

of the transfection was confirmed by western blotting (Figs. 2G and S1I). Next, CCK-8 and LDH assays were

performed and it was found that the overexpression of FTO in

macrophages neither induced cytotoxic effects nor influenced

macrophage proliferation (Fig. 2H

and I). Given that phagocytosis is the principal mechanism

through which macrophages eradicate pathogens, phagocytosis assays

were performed. The results demonstrated that FTO upregulation did

not alter the phagocytic capacity of macrophages compared with that

of the control group (Fig. 2J and

K). Macrophages secrete proinflammatory cytokines that

exacerbate SAKI by promoting renal tubular epithelial cell injury

and impairing mitochondrial function (32). Surprisingly, ELISAs revealed that

the secretion of the inflammatory factors IL-6 and TNF-α in the

supernatant of LPS-stimulated macrophages was markedly inhibited by

FTO upregulation (Fig. 2L).

These observations were corroborated by qPCR experiments (Fig. 2M). Moreover, examination of

classic pathways associated with inflammatory factors indicated

that FTO attenuated the activation of inflammatory pathways by

inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB pathway (Figs. 2N and S1J). Next, western blot analysis of

macrophage polarization markers, specifically CD86 and CD206,

revealed that the upregulation of FTO led to a reduction in CD86

expression and an increase in CD206 expression (Fig. S1K and L). These findings

suggested that M1 macrophage polarization is decreased by FTO,

potentially representing a mechanism through which FTO attenuates

the secretion of inflammatory factors. Overall, the overexpression

of FTO reduced the LPS-induced inflammatory response.

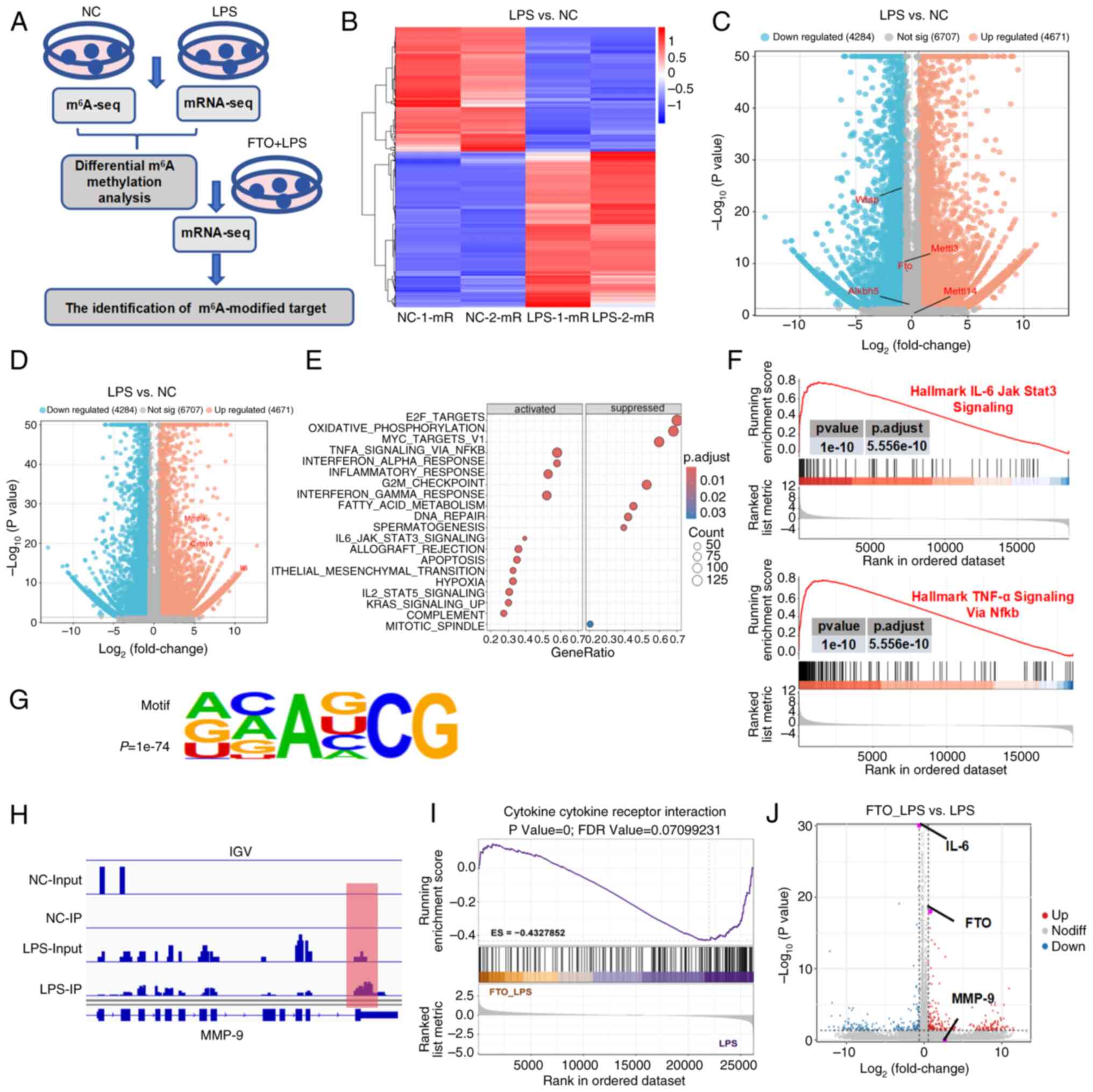

Identification of MMP-9 as the key target

of m6A modification

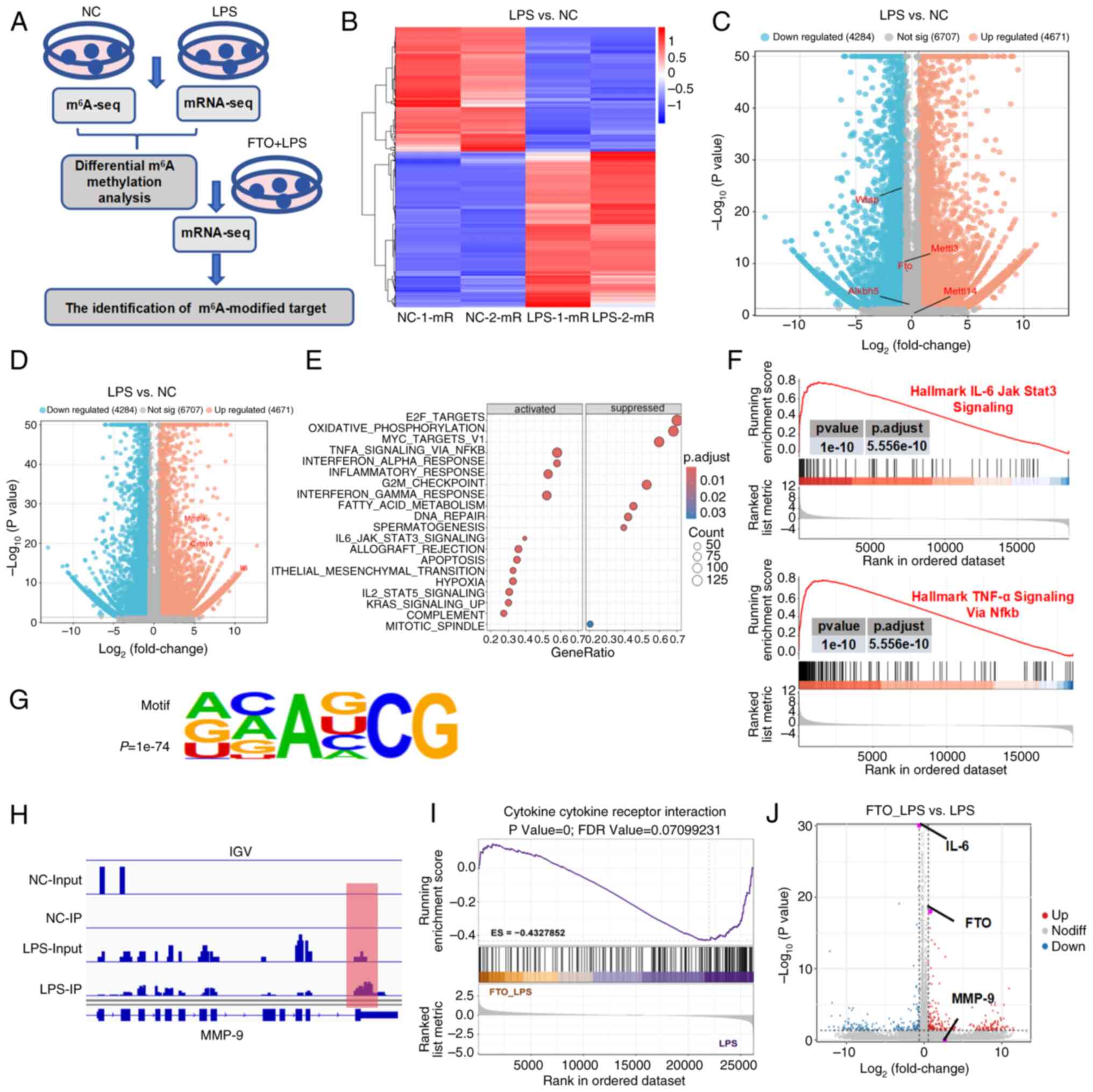

To elucidate the underlying mechanism through which

FTO exerts anti-inflammatory effects in SAKI, transcriptome

sequencing (RNA-seq) and MeRIP-seq were utilized to investigate

transcriptional alterations in macrophages stimulated with LPS

(Fig. 3A). First, hierarchical

clustering revealed 2169 upregulated genes and 1738 downregulated

genes after LPS treatment (Fig.

3B). An earlier study demonstrated that FTO modulated the

TNF-α-induced inflammatory response in cementoblasts through

m6A modification of MMP-9 (33). Specifically, consistent with the

results of the analysis of patients with sepsis, FTO expression was

decreased, whereas the expression levels of MMP-9, CXCL10 and IL-6

were upregulated in LPS-induced macrophages compared with control

macrophages (Fig. 3C and D).

Moreover, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the DEGs revealed

significant enrichment of several key GO terms associated with the

immune response (Fig. 3E),

including the TNF-α signaling pathway and the IL-6/JAK/STAT3

pathway (P<0.05; Fig. 3F).

When the m6A methylomes of macrophages were mapped, the

m6A consensus sequence GGAC (RRACH) motif was highly

enriched within m6A sites in the immunopurified RNA

(Fig. 3G). MMP-9 was identified

as a candidate gene that markedly overlapped between the mRNA-seq

data; it demonstrated a greater than 60-fold change (P<0.05)

between the WT and LPS-stimulated macrophages, and the

m6A level on this gene was more than 16 times greater

than that in the input (P<0.05). Different m6A peaks

were detected around the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of MMP-9 mRNA

in macrophages (Fig. 3H).

Additionally, transcriptomic sequencing was conducted to compare

the gene expression profiles of macrophages with FTO overexpression

after 6 h of LPS stimulation. mRNA-seq analysis revealed that the

DEGs were markedly enriched in pathways related to the inflammatory

response, such as cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions,

highlighting their role in regulating proinflammatory signaling

pathways (P<0.05; Fig. 3I).

Specifically, elevated FTO levels are associated with increased

MMP-9 expression, whereas increased FTO levels lead to markedly

reduced IL-6 expression (Fig.

3J).

| Figure 3MMP-9 is the key target of

FTO-mediated m6A modification. (A) Flowchart of the

multiomics analysis of macrophages. (B) Hierarchical clustering of

differentially expressed genes in macrophages following LPS

treatment. Volcano plot showing (C) downregulated FTO expression

and (D) upregulated MMP-9 expression in LPS-induced macrophages

compared with NC. (E) GO analysis of the DEGs revealed that the

DEGs were enriched in immune response-related terms. (F) GSEA

revealed that key pathways, including the TNF-α signaling and

IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathways, were markedly associated with the

inflammatory response in LPS-treated macrophages. (G) Motif

analysis of m6A methylomes in macrophages. (H)

Integrative Genomics Viewer image showing that the m6A

peaks of MMP-9 mRNA were near the 3'UTR. (I) mRNA-seq revealed that

DEGs associated with FTO overexpression in LPS-stimulated

macrophages were enriched in cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction

pathways. (J) Volcano plot showing that elevated FTO levels were

associated with increased MMP-9 expression. MMP-9, matrix

metalloproteinase 9; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein;

m6A, N6-methyladenosine; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NC,

negative control; GO, gene ontology; DEGs, differentially expressed

genes; gene set enrichment analysis; TNF-α, tumor necrosis

factor-α; IL-6, interleukin-6. |

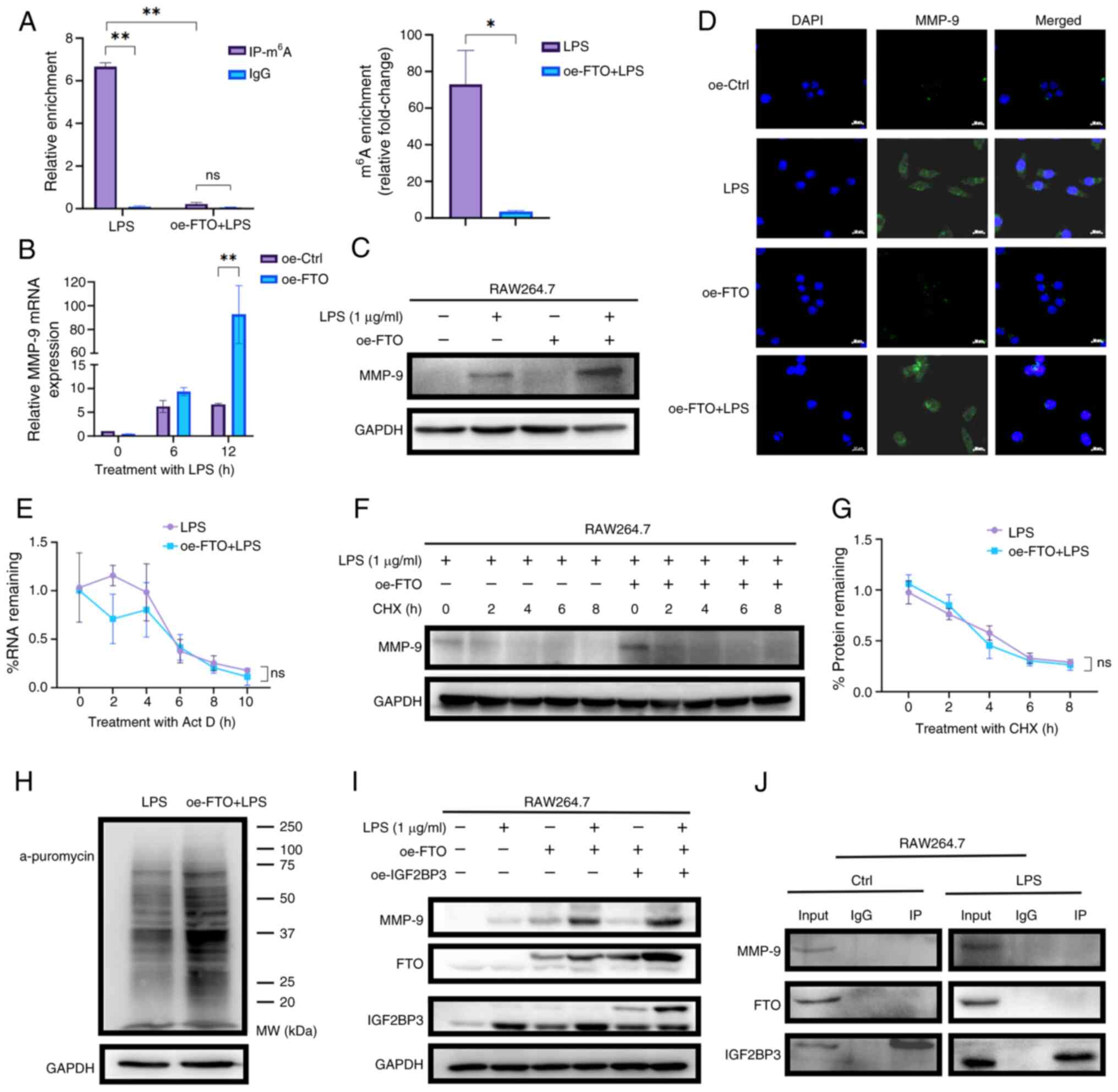

FTO increases MMP-9 levels through

m6A modification

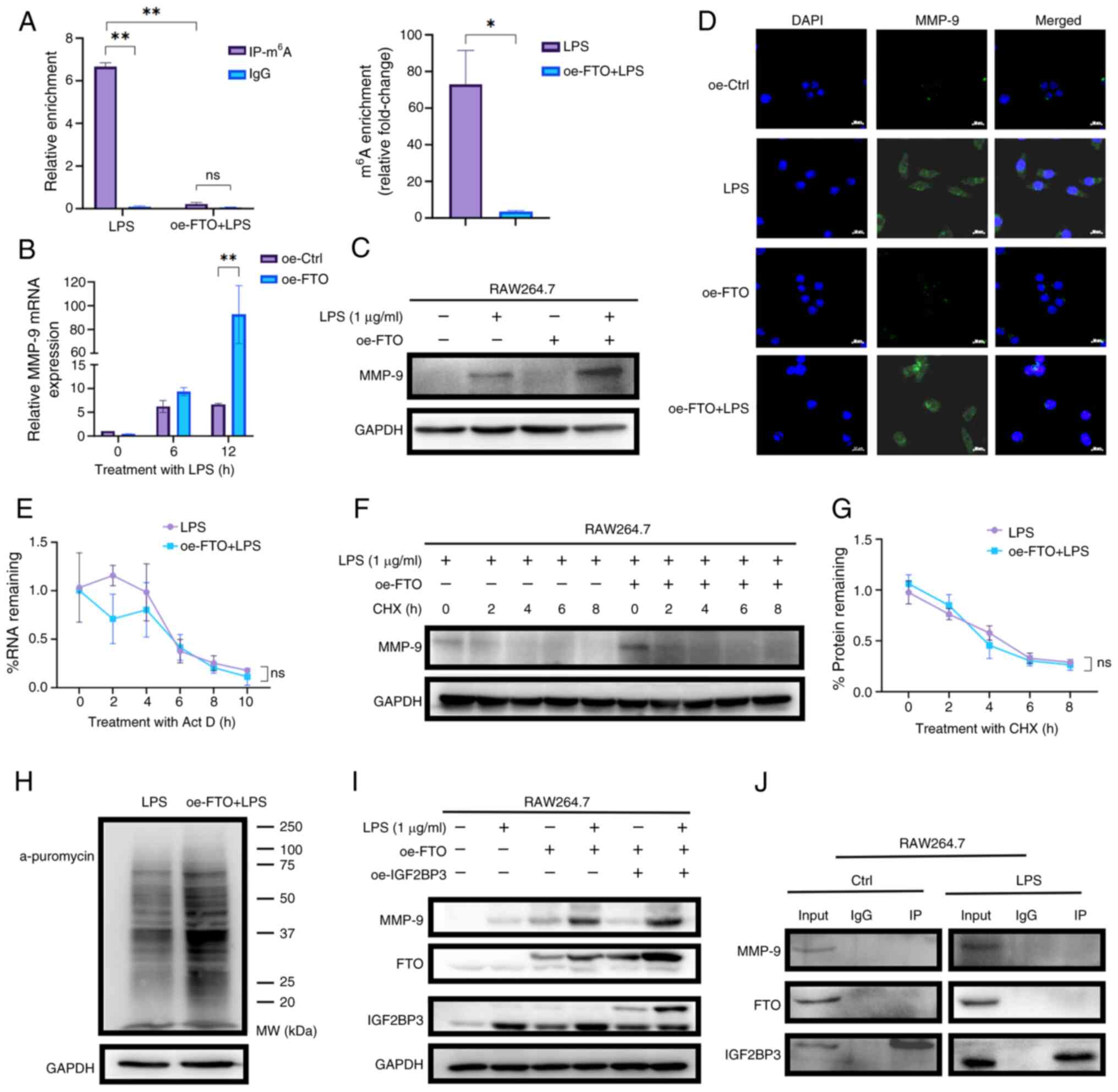

MMP-9 is the most extensively investigated MMP and

is known for its critical involvement in numerous biological

processes (34). To determine

whether MMP-9 functions as a downstream target of FTO in

macrophages, MeRIP-qPCR was conducted, which confirmed that

m6A-enriched MMP-9 mRNA levels were reduced by ~20-fold

in oe-FTO macrophages treated with LPS (oe-FTO+LPS; Fig. 4A). Notably, compared with that in

the respective LPS-treated group (LPS group), the MMP-9 expression

levels in both bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. S1M and N) and RAW264.7

macrophages (Figs. 4B and C and

S2A) markedly increased in

response to overexpression with FTO. These findings were further

corroborated by IF assays, which confirmed that elevated FTO levels

led to the upregulation of MMP-9 in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 4D). The present study further

explored the potential mechanisms involved in the

m6A-regulated expression of MMP-9. The LPS and

oe-FTO+LPS groups were treated with Act-D to block transcription

and the results suggested that FTO-mediated m6A did not

markedly affect the mRNA stability of MMP-9 in macrophages

(Fig. 4E). Furthermore, the LPS

and oe-FTO+LPS groups were treated with CHX to block protein

translation and the data revealed that treatment with CHX

attenuated FTO-induced MMP-9 upregulation, suggesting that FTO did

not affect the protein stability of MMP-9 (Fig. 4F and G). A puromycin labeling

assay revealed that FTO overexpression increased mRNA translation

and drove an increase in nascent MMP-9 polypeptide synthesis

following LPS treatment (Figs.

4H and S2B). Given that

FTO-mediated m6A demethylation enhances MMP-9

translation and considering the role of m6A readers in

modulating translational output, it was investigated whether the

m6A reader IGF2BP3 serves as a downstream amplifier.

FTO-overexpressing (oe-FTO) RAW264.7 macrophages were transduced

with a lentiviral vector encoding IGF2BP3 (oe-IGF2BP3) or an empty

control vector. The results revealed that FTO overexpression

elevated both IGF2BP3 and MMP-9 levels and additional IGF2BP3

overexpression in FTO-overexpressing macrophages further amplified

MMP-9 expression (Figs. 4I and

S2C). To assess whether these

proteins interact directly, Co-IP assays were performed in

macrophages; however, IGF2BP3 did not co-precipitate either with

FTO or MMP-9 (Fig. 4J). These

results indicated that IGF2BP3 facilitated the upregulation of

MMP-9 induced by FTO without directly binding with those two

proteins. Thus, FTO-mediated m6A demethylation enhances

MMP-9 expression by promoting mRNA translation efficiency rather

than increasing the stability of MMP-9 mRNA in macrophages in

response to LPS.

| Figure 4FTO upregulates MMP-9 expression in

an m6A-dependent manner in macrophages. (A) MeRIP-qPCR

confirmed the decreased level of m6A modification of

MMP-9 mRNA in LPS-treated macrophages overexpressing FTO. (B) qPCR

and (C) western blot analyses demonstrated that compared with

control macrophage treatment, LPS stimulation increased MMP-9

expression in FTO-overexpressing macrophages. (D)

Immunofluorescence assays confirmed that elevated FTO levels

upregulated MMP-9 protein expression in macrophages following LPS

treatment. (E) Actinomycin D treatment revealed that FTO-mediated

m6A modification did not markedly affect the mRNA

stability of MMP-9 in macrophages treated with LPS for 12 h. (F)

CHX treatment and (G) quantification demonstrated that FTO did not

markedly affect MMP-9 protein stability following LPS treatment.

(H) Puromycin labeling of nascent polypeptides revealed that FTO

enhanced protein synthesis in macrophages treated with LPS for 12

h. (I) overexpression of IGF2BP3 in FTO-overexpressing macrophages

led to the further upregulation of MMP-9. (J) Co-IP experiment

identified the IGF2BP3 did not co-precipitate either with FTO or

MMP9 in macrophages. *P<0.05; **P<0.01;

ns, not significant. FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein;

MMP-9, matrix metalloprot einase 9; m6A,

N6-methyladenosine; MeRIP-seq, methylated RNA immunoprecipitation

sequencing; qPCR, quantitative PCR; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; oe,

over expression; IGF2BP3, insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding

protein 3. |

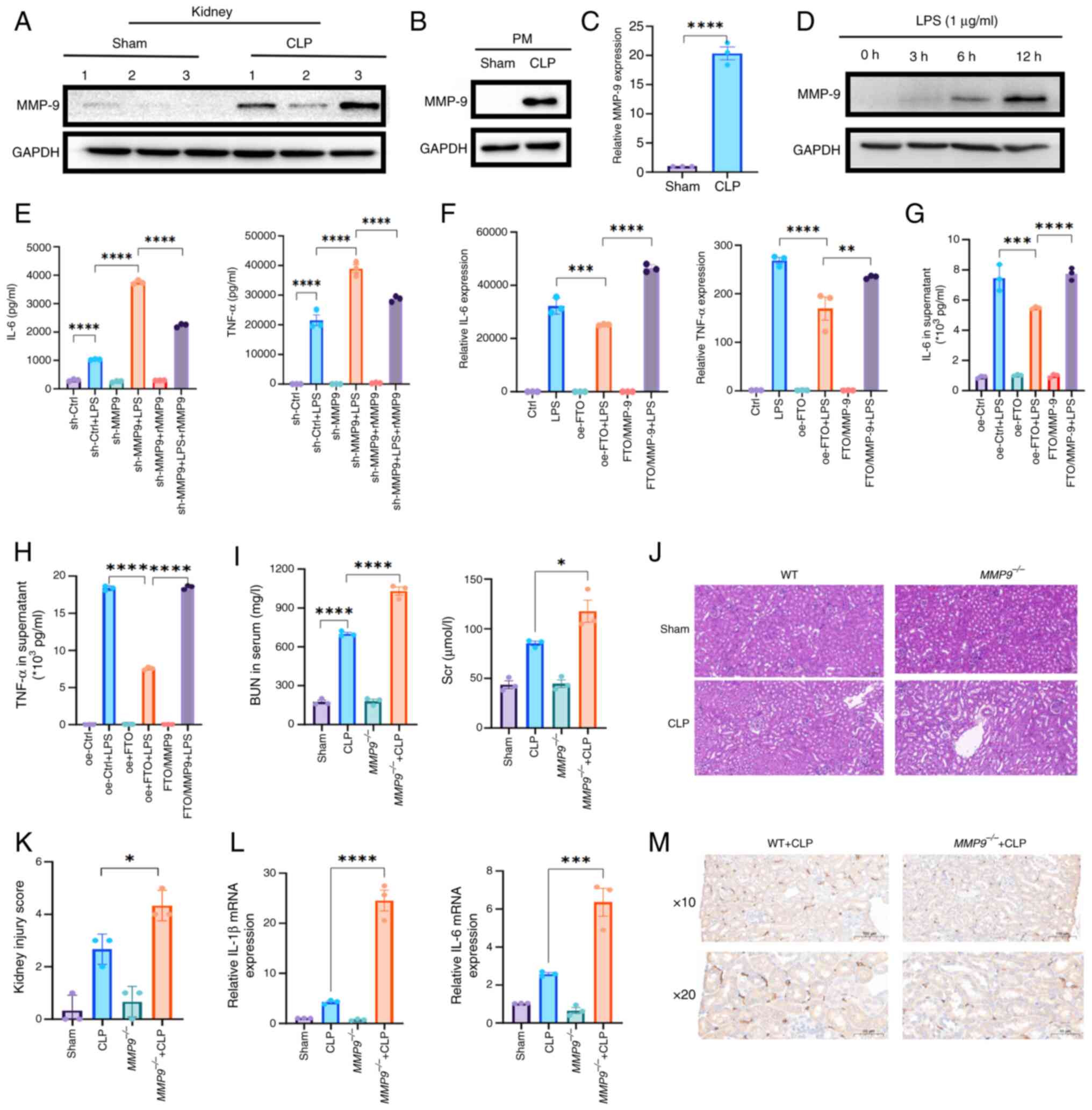

MMP-9 deficiency exacerbates inflammatory

responses in vitro and in vivo

In mice with SAKI, increased levels of MMP-9 were

observed in the kidney (Figs. 5A

and S2D), which aligns with the

results obtained from CLP-derived PMs (Figs. 5B and C and S2F). Furthermore, the abundance of the

MMP-9 protein substantially increased in a time-dependent manner in

LPS-stimulated macrophages (Figs.

5D and S2G). Therefore, to

investigate the functional role of MMP-9 in sepsis, MMP-9-knockdown

macrophages (sh-MMP9) were established by transfecting them with

lentiviral vectors encoding mouse MMP-9 shRNAs and their knockdown

verified by western blotting (Fig.

S2H). A CCK-8 assay was performed and it was found that MMP-9

knockdown did not affect macrophage proliferation (Fig. S2I). qPCR revealed that the

knockdown of MMP-9 resulted in significant increases in the

expression levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, whereas pretreatment with

rMMP9 effectively reversed these effects (Fig. S2J). These findings were

corroborated by the results of the ELISAs, which revealed that the

depletion of MMP-9 strongly promoted the production of TNF-α and

IL-6; however, pretreatment with recombinant MMP-9 effectively

attenuated the increased release of TNF-α and IL-6 caused by MMP-9

knockdown (Fig. 5E).

Additionally, MMP-9 was knocked down in FTO-overexpressing

macrophages (FTO/MMP-9; Fig.

S2K). Consistent with these findings, FTO upregulation impaired

the proinflammatory effect on macrophages, whereas decreased MMP-9

reversed this effect, as demonstrated by qPCR and ELISAs (Fig. 5F-H). Moreover, western blot

analysis revealed that MMP-9 depletion contributed to CD86

upregulation (Fig. S3A and

B).

| Figure 5Depletion of MMP-9 increases the

release of proinflammatory factors and exacerbated renal injury in

SAKI model mice. (A) Western blot analysis revealed an increased

abundance of MMP-9 in the kidneys of mice with SAKI (n=3). (B)

Western blot and (C) qPCR analyses revealed an increased abundance

of MMP-9 in CLP-derived PMs (n=3). (D) Western blot analysis

revealed a time-dependent increase in the abundance of the MMP-9

protein in LPS-stimulated macrophages. (E) ELISA confirmed that

MMP-9 depletion markedly increased the production of IL-6 and

TNF-α. (F) qPCR analysis revealed markedly increased expression

levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in MMP-9-depleted oe-FTO macrophages

following LPS treatment. (G and H) ELISA confirmed that MMP-9

depletion markedly increased the production of TNF-α and IL-6 in

MMP-9-depleted oe-FTO macrophages following LPS treatment. (I) The

detection of BUN and Cr in the serum of MMP9−/−

mice revealed that kidney dysfunction was exacerbated 24 h post-CLP

(n=3). (J and K) H&E staining revealed more severe renal injury

in MMP9−/− mice than in wild-type controls

following CLP surgery (n=3, original magnification, ×10). (L) qPCR

analysis revealed that MMP-9 deletion increased the expression

levels of IL-1β and IL-6 in the kidneys of CLP-treated mice (n=3).

(M) IHC staining results showing the expression of F4/80 and

reduced infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages in the kidneys of

MMP9−/− mice after CLP surgery (n=3).

*P<0.05; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. MMP-9, matrix

metalloproteinase 9; SAKI, sepsis-induced acute kidney injury;

qPCR, quantitative PCR; CLP, cecal ligation and puncture; PMs,

peritoneal macrophages; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ELISA,

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; oe, over expression; BUN, blood

urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; CLP, cecal ligation and puncture;

H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; WT, wild-type. |

To further elucidate the role of MMP-9 in SAKI,

MMP9−/− mice were subjected to CLP. The loss of

MMP-9 through CRISPR-Cas editing consistently exacerbated kidney

dysfunction 24 h post-CLP, as indicated by the elevated

concentrations of BUN and Cr in the MMP-9−/− mice

subjected to CLP (Fig. 5I).

Furthermore, H&E staining revealed that the depletion of MMP-9

resulted in increased cytoplasmic vacuoles in the proximal tubule

cells of the cortex and outer stripe of the outer medulla (OSOM) 24

h post-CLP compared with vacuoles in the WT group following CLP

surgery (Fig. 5J and K).

Moreover, qPCR analysis revealed that the deletion of MMP-9

increased the expression levels of IL-1β and IL-6 in the kidney

(Fig. 5L). Since F4/80hi

macrophages play a protective role in SAKI (35), an IHC assay was performed and it

revealed that MMP-9 deficiency decreased the infiltration of F4/80+

macrophages in the kidney (Fig.

5M). Moreover, the IHC result revealed a slight increase in the

expression of CD86 in MMP9−/− mice compared with

that in WT controls after CLP surgery, which suggest that the

proportion of CD86-positive macrophages is greater in

MMP9−/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. S3C). These results indicated that

the absence of MMP-9 exacerbated kidney damage and increased the

levels of proinflammatory cytokines in CLP-treated mice.

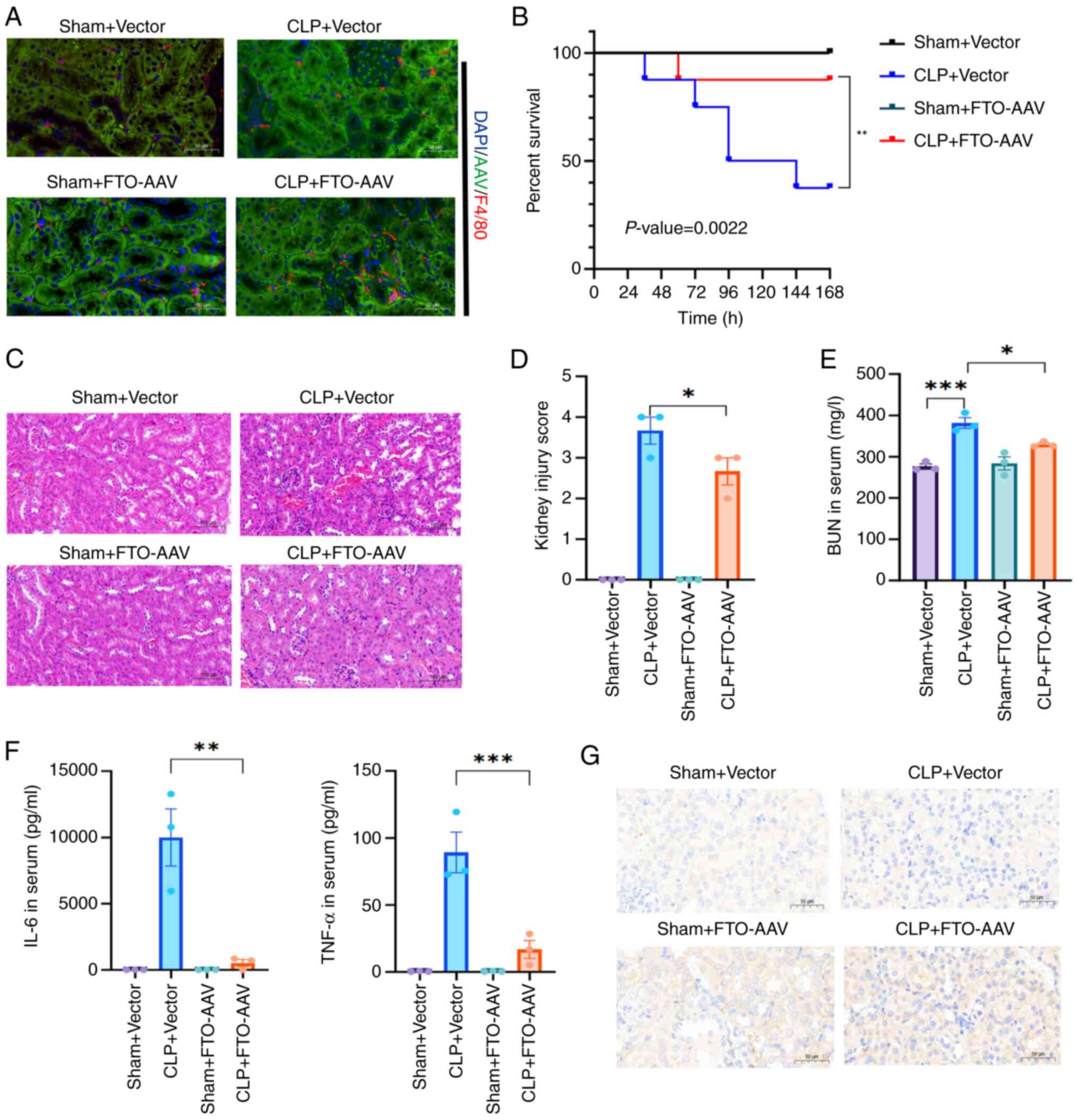

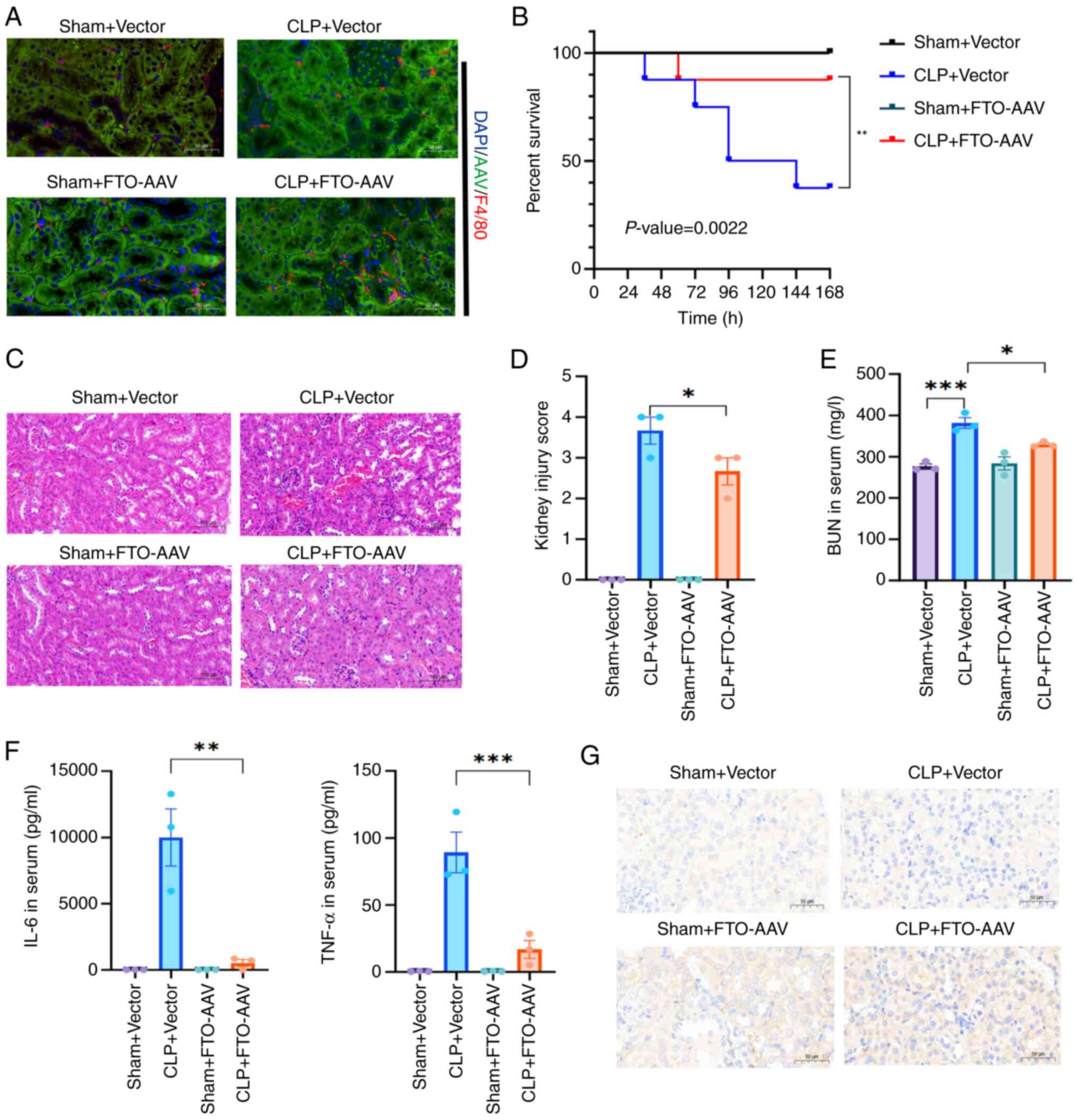

FTO overexpression protects mice from

CLP-induced SAKI

To elucidate the in vivo function of FTO,

AAVs were used to induce the overexpression of FTO in murine

models. The successful overexpression of FTO in the kidney was

subsequently confirmed via IF and western blot analyses (Figs. 6A and Fig. S3D). Subsequent observations

revealed a reduction in the sepsis mortality rate among the

FTO-overexpressing mice subjected to CLP surgery (n=8; survival at

7 days: CLP+vector, 37.5%, vs. CLP+FTO-AAV, 87.5%; P<0.01;

Fig. 6B). Moreover, H&E

staining of pathological sections confirmed that FTO overexpression

mitigated CLP-induced SAKI (Fig. 6C

and D). FTO overexpression consistently alleviated kidney

dysfunction 24 h post-CLP, as evidenced by low BUN levels in the

CLP+FTO-AAV group (Fig. 6E).

Moreover, ELISA revealed that the upregulation of FTO diminished

the release of IL-6 and TNF-α (Fig.

6F). Furthermore, an IHC assay demonstrated that the abundance

of MMP-9 increased in the kidneys of mice with SAKI and further

increased with FTO overexpression (Fig. 6G). IF revealed that FTO

overexpression also increased the infiltration of F4/80+

macrophages (Fig. 6A). Overall,

these findings indicated that FTO-mediated MMP-9 upregulation

modulates renal inflammation and increases the survival of

CLP-treated mice.

| Figure 6FTO overexpression ameliorated SAKI

and improved survival in CLP mice. (A) Representative IF images

showing successful overexpression of FTO in a murine model and the

expression of F4/80 (n=3). (B) Survival curve using the log-rank

test revealed a significant reduction in sepsis mortality in

FTO-overexpressing mice compared with vector control mice (n=8;

P=0.0022 <0.01). (C and D) H&E staining of kidney sections

revealed that FTO overexpression mitigated CLP-induced renal injury

(n=3). (E) Overexpression of FTO reduced the CLP-induced increase

in serum BUN levels (n=3). (F) ELISAs revealed that FTO

overexpression reduced serum IL-6 and TNF-α production (n=3). (G)

An IHC assay revealed increased MMP-9 abundance in the kidneys of

FTO-overexpressing mice after CLP surgery (n=3, original

magnification, ×20). *P<0.05 was considered to

indicate statistical significance; **P<0.01;

***P<0.001. FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated

protein; SAKI, sepsis-induced acute kidney injury; CLP, cecal

ligation and puncture; IF, immunofluorescence; H&E, hematoxylin

and eosin staining; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; ELISA, enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay; IHC, immunohistochemistry. |

Discussion

m6A is a widespread posttranscriptional

modification that induces epigenetic modifications in RNA. Mounting

evidence has shown that m6A modification profoundly

affects the progression of various diseases, including metabolic

syndrome, cancer and infectious diseases (36). However, the role of

m6A modification in kidney diseases, particularly SAKI

remains relatively unexplored. FTO expression is closely involved

in septic patients, showing a positive correlation with monocytes

and exhibiting the highest diagnostic value among target genes,

which gives it potential as a vital diagnostic biomarker for the

treatment of SAKI (37). In the

present study, consistent with analyses conducted on septic

patients, in vivo experiments demonstrated that FTO

expression is universally downregulated in key tissues and PMs when

they are exposed to inflammatory stimuli. Furthermore, increased

levels of the FTO protein were strongly associated with decreased

m6A modification and moderate inflammatory responses.

Although both FTO and ALKBH5 were modestly downregulated in

LPS-stimulated macrophages, FTO was prioritized for three

converging reasons: (i) According to bioinformatics analysis and

overall m6A levels, the expression of FTO, which acts as

a key eraser to induce m6A demethylation, was markedly

downregulated; (ii) the magnitude of FTO downregulation (mean 70%)

upon LPS was more pronounced than that of ALKH5 and consistent with

the peak release of proinflammatory cytokines; (iii) This

observation is corroborated by clinical data showing a significant

reduction (~45%) of FTO expression in septic patients compared with

healthy controls (38).

Furthermore, a genome-wide association study reinforces the

clinical relevance of the present study, reporting an association

between lower FTO expression and an increased risk of AKI (39). While ALKBH5 may also contribute,

these observations provided a stronger, multi-level rationale for

prioritizing FTO in the present study. The therapeutic potential of

FTO was further underscored by the intervention study, wherein

AAV-mediated FTO upregulation markedly prolonged the survival of

CLP-treated mice, mitigated CLP-induced inflammation.

FTO is a member of the Fe(II) and

2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase family of proteins (40,41) and is associated with several

other diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, neuropsychiatric

disorders and various types of cancer (42,43). However, its role in inflammation

appears to be context-dependent. For instance, FTO knockdown was

reported to upregulate proinflammatory cytokines in rat

cardiomyocytes (44), whereas

ablation of FTO could inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome and ameliorate the

inflammatory response in LPS-induced sepsis models (45). The present study found a distinct

anti-inflammatory effect of FTO in sepsis-associated organ injury

that may be attributed to its role in modulating MMP-9 expression

and macrophage polarization towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype,

which is distinct from the pro-inflammatory mechanisms observed in

LPS-induced sepsis.

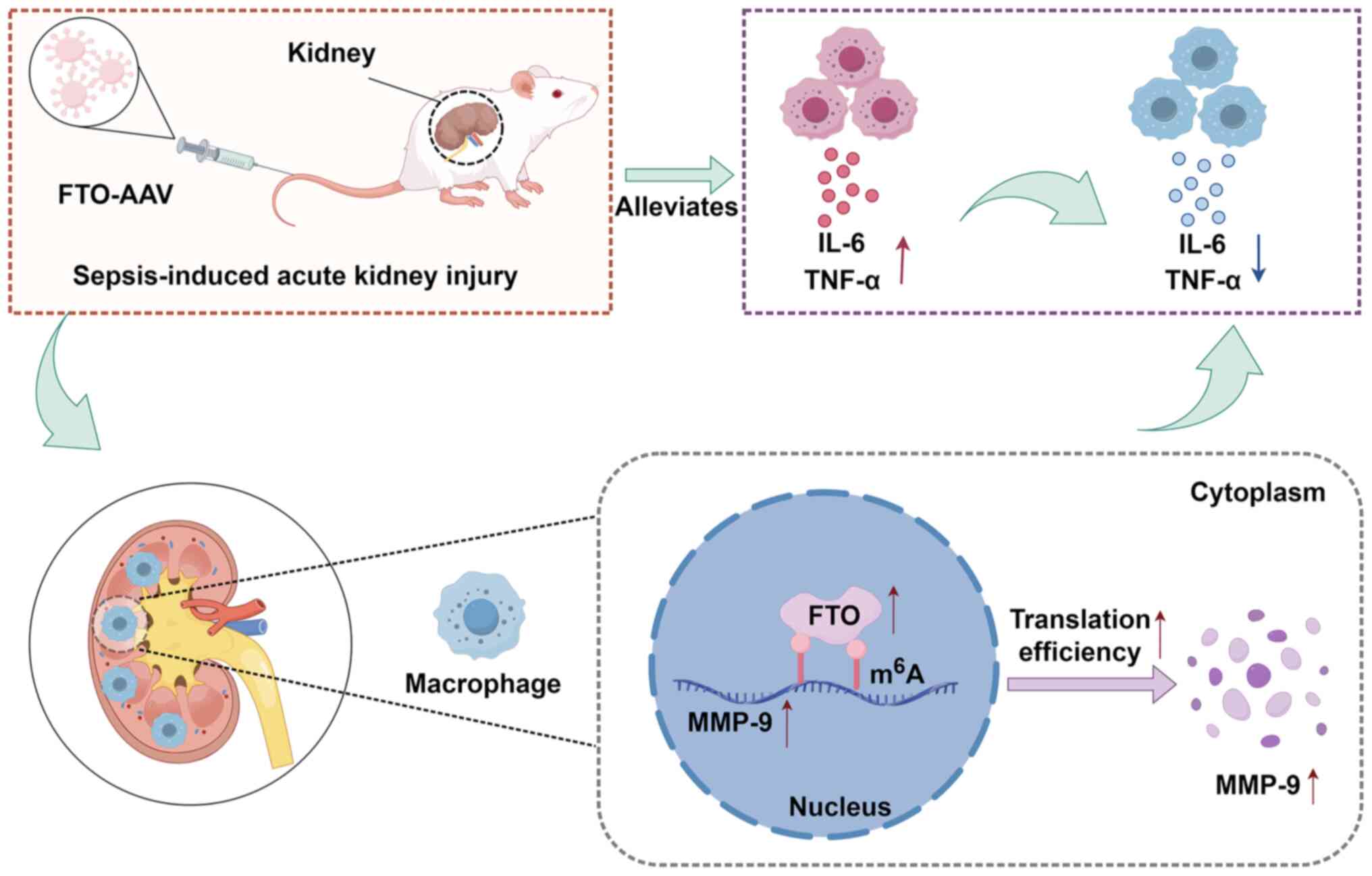

MMP-9 exhibits context-dependent functions across

various cell types and disease etiologies of kidney injury,

contributing to both physiological and pathological processes. For

instance, MMP-9 deficiency increased the apoptosis of tubular

epithelial cells and delay the recovery of renal function in folic

acid induced AKI (46). MMP-9

also protected from glomerular tubule damage in cisplatin induced

AKI (47). While in the model of

ischemic AKI, MMP-9 deficiency mitigated microvascular loss which

associated with renal hypoxia (48). The present study found that MMP-9

deficiency in macrophages increased IL-6 and TNF-α release and

renal damage during SAKI, consisted with clinical observation that

correlate low MMP-9 expression with worse survival (49). Mechanistically, MMP-9 was

identified as a critical target of FTO-mediated m6A

modification in LPS-stimulated macrophages, with its expression

being upregulated in response to FTO overexpression. Notably,

elevated FTO primarily affects MMP-9 translation efficacy rather

than mRNA stability, leading to increased MMP-9 levels in

macrophages. However, the need for further investigation into the

specific mechanisms by which FTO enhances MMP-9 mRNA translation

efficiency remains a critical area for future research. The

FTO/m6A/MMP-9 protected against SAKI by suppressing

inflammatory responses, which offers novel insights into

therapeutic targets for SAKI (Fig.

7). Moreover, the clinical translatability of this axis is

supported by studies reporting that decreased plasma MMP-9 and

increased TIMP-1 in SAKI patients, with the MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio

being a superior prognostic indicator for disease severity and

survival (50,51). Thus, it was hypothesized that the

FTO/MMP-9 axis represents a promising biomarker candidate, worthy

of future clinical validation to determine its prognostic and

therapeutic utility.

Although recent studies have demonstrated certain

therapeutic effects in animal models, the clinical application of

FTO-AAV may encounter safety challenges, including potential

immunogenicity and off-target effects. FTO is ubiquitously

expressed and involved in critical physiological processes such as

energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity (52,53). While the present study

established a critical role of FTO in macrophage of SAKI,

contributory or synergistic effects from FTO activity in other cell

types cannot be excluded. Its overexpression in renal tubular

epithelial cells, for example, has been shown to protect against

ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting autophagy (54). The current reliance on

computational analyses and preclinical models thus represents

another limitation for direct clinical translation.

The present study delineated a novel

FTO/m6A/MMP-9 signaling axis in macrophages that

conferred protection against SAKI by modulating inflammatory

responses. These findings provided new insights into the epigenetic

mechanisms underlying SAKI and highlighted the therapeutic

potential of targeting this pathway. In conclusion, a comprehensive

understanding of the cell-specific actions of FTO and rigorous

safety assessments are imperative before any therapeutic strategies

can be advanced to the clinic.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ZC and QL provided scientific expertise, supervised

the experiments and provided reagents. XC and ZC conceived and

designed the study. XC, ZS and JZ performed the experiments,

analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JC and ZL

collaboratively performed the animal experiments. ZY provided the

scientific expertise and data for the animal experiments. ZC and QL

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics

Committee of Dongguan People's Hospital (approval no. IAC

UC-AWEC-202406500R1).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

m6A

|

N6-methyladenosine

|

|

SAKI

|

sepsis-induced acute kidney

injury

|

|

CLP

|

cecal ligation and puncture

|

|

FTO

|

fat mass and obesity-associated

protein

|

|

LPS

|

lipopolysaccharide

|

|

IL-6

|

interleukin-6

|

|

TNF-α

|

tumor necrosis factor-α

|

|

MMP-9

|

matrix metalloproteinase 9

|

|

ALI

|

acute lung injury

|

|

GEO

|

gene expression omnibus

|

|

DEGs

|

differentially expressed genes

|

|

FC

|

fold change

|

|

qPCR

|

quantitative PCR

|

|

DMEM

|

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's

medium

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

IHC

|

immunohistochemistry

|

|

H&E

|

hematoxylin and eosin staining

|

|

AAV

|

adeno-associated virus

|

|

RNA-seq

|

transcriptome sequencing

|

|

MeRIP-seq

|

methylated RNA immunoprecipitation

sequencing

|

|

GO

|

gene ontology

|

|

CHX

|

cycloheximide

|

|

Co-IP

|

Co-immunoprecipitation

|

|

RT

|

Room temperature

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by projects from the Guangdong

Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant no.

2025A1515011341), by the National Cancer Center/National Clinical

Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital & Shenzhen Hospital,

the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical

College, Shenzhen (grant nos. E010224010, SZ2020ZD012 and

E010224009) and the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (grant

no. SZSM202311003).

References

|

1

|

Gao Q, Zheng Y, Wang H, Hou L and Hu X:

circSTRN3 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by

regulating miR-578/toll like receptor 4 axis. Bioengineered.

13:11388–11401. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Peerapornratana S, Manrique-Caballero CL,

Gómez H and Kellum JA: Acute kidney injury from sepsis: Current

concepts, epidemiology, pathophysiology, prevention and treatment.

Kidney Int. 96:1083–1099. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

He J, Zheng F, Qiu L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Ye

H and Zhang Q: Plasma neutrophil extracellular traps in patients

with sepsis-induced acute kidney injury serve as a new biomarker to

predict 28-day survival outcomes of disease. Front Med (Lausanne).

11:14969662024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Peng Y, Fang Y, Li Z, Liu C and Zhang W:

Saa3 promotes pro-inflammatory macrophage differentiation and

contributes to sepsis-induced AKI. Int Immunopharmacol.

127:1114172024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Han HI, Skvarca LB, Espiritu EB, Davidson

AJ and Hukriede NA: The role of macrophages during acute kidney

injury: Destruction and repair. Pediatr Nephrol. 34:561–569. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

He J, Zhao S and Duan M: The response of

macrophages in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. J Clin Med.

12:11012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Karuppagounder V, Arumugam S,

Thandavarayan RA, Sreedhar R, Giridharan VV, Afrin R, Harima M,

Miyashita S, Hara M, Suzuki K, et al: Curcumin alleviates renal

dysfunction and suppresses inflammation by shifting from M1 to M2

macrophage polarization in daunorubicin induced nephrotoxicity in

rats. Cytokine. 84:1–9. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Huen SC and Cantley LG:

Macrophage-mediated injury and repair after ischemic kidney injury.

Pediatr Nephrol. 30:199–209. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lee S, Huen S, Nishio H, Nishio S, Lee HK,

Choi BS, Ruhrberg C and Cantley LG: Distinct macrophage phenotypes

contribute to kidney injury and repair. J Am Soc Nephrol.

22:317–326. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pérez S and Rius-Pérez S: Macrophage

polarization and reprogramming in acute inflammation: A redox

perspective. Antioxidants (Basel). 11:13942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hu D, Wang Y, You Z, Lu Y and Liang C:

lnc-MRGPRF-6:1 promotes M1 polarization of macrophage and

inflammatory response through the TLR4-MyD88-MAPK pathway.

Mediators Inflamm. 2022:69791172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhu X, Tang H, Yang M and Yin K:

N6-methyladenosine in macrophage function: A novel target for

metabolic diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 34:66–84. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hari Gopal S, Alenghat T and Pammi M:

Early life epigenetics and childhood outcomes: A scoping review.

Pediatr Res. 97:1305–1314. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Harvey ZH, Chen Y and Jarosz DF:

Protein-based inheritance: Epigenetics beyond the chromosome. Mol

Cell. 69:195–202. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhang L, Lu Q and Chang C: Epigenetics in

health and disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1253:3–55. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Liu Y, Yang D, Liu T, Chen J, Yu J and Yi

P: N6-methyladenosine-mediated gene regulation and therapeutic

implications. Trends Mol Med. 29:454–467. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Mao Y, Jiang F, Xu XJ, Zhou LB, Jin R,

Zhuang LL, Juan CX and Zhou GP: Inhibition of IGF2BP1 attenuates

renal injury and inflammation by alleviating m6A modifications and

E2F1/MIF pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 19:593–609. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhao Y, Ding W, Cai Y, Li Q, Zhang W, Bai

Y, Zhang Y, Xu Q and Feng Z: The m6A eraser FTO

suppresses ferroptosis via mediating ACSL4 in LPS-induced

macrophage inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1870:1673542024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cao F, Chen G, Xu Y, Wang X, Tang X, Zhang

W, Song X, Yang X, Zeng W and Xie J: METTL14 contributes to acute

lung injury by stabilizing NLRP3 expression in an IGF2BP2-dependent

manner. Cell Death Dis. 15:432024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dolinay T, Kim YS, Howrylak J, Hunninghake

GM, An CH, Fredenburgh L, Massaro AF, Rogers A, Gazourian L,

Nakahira K, et al: Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical

mediators of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

185:1225–1234. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

McGrath FM, Francis A, Fatovich DM,

Macdonald SP, Arendts G, Woo AJ and Bosio E: Genes involved in

platelet aggregation and activation are downregulated during acute

anaphylaxis in humans. Clin Transl Immunology. 11:e14352022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang H, Wang H, Shivalila CS, Cheng AW,

Shi L and Jaenisch R: One-step generation of mice carrying reporter

and conditional alleles by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering.

CELL. 154:1370–1379. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA and

Ward PA: Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and

puncture. Nat Protoc. 4:31–36. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu Y, Song R, Zhao L, Lu Z, Li Y, Zhan X,

Lu F, Yang J, Niu Y and Cao X: m6A demethylase ALKBH5 is

required for antibacterial innate defense by intrinsic motivation

of neutrophil migration. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:1942022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Aronoff GR, Sloan RS, Dinwiddie CJ Jr,

Glant MD, Fineberg NS and Luft FC: Effects of vancomycin on renal

function in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 19:306–308. 1981.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen Y, Wei W, Fu J, Zhang T, Zhao J and

Ma T: Forsythiaside A ameliorates sepsis-induced acute kidney

injury via anti-inflammation and antiapoptotic effects by

regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. BMC Complement Med Ther.

23:352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Gallo-Oller G, Ordoñez R and Dotor J: A

new background subtraction method for western blot densitometry

band quantification through image analysis software. J Immunol

Methods. 457:1–5. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Carson WF, Cavassani KA, Dou Y and Kunkel

SL: Epigenetic regulation of immune cell functions during

post-septic immunosuppression. Epigenetics. 6:273–283. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Córneo EDS, Michels M and Dal-Pizzol F:

Sepsis, immunosuppression and the role of epigenetic mechanisms.

Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 17:169–176. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mu YF, Mao ZH, Pan SK, Liu DW, Liu ZS, Wu

P and Gao ZX: Macrophage-driven inflammation in acute kidney

injury: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Transl Res.

278:1–9. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li T, Qu J, Hu C, Pang J, Qian Y, Li Y and

Peng Z: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) suppresses

mitophagy through disturbing the protein interaction of

PINK1-Parkin in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Cell Death

Dis. 15:4732024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li B, Du M, Sun Q, Cao Z and He H:

m6 A demethylase Fto regulates the TNF-α-induced

inflammatory response in cementoblasts. Oral Dis. 29:2806–2815.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Huang H: Matrix metalloproteinase-9

(MMP-9) as a cancer biomarker and MMP-9 biosensors: Recent

advances. Sensors (Basel). 18:32492018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Privratsky JR, Ide S, Chen Y, Kitai H, Ren

J, Fradin H, Lu X, Souma T and Crowley SD: A macrophage-endothelial

immunoregulatory axis ameliorates septic acute kidney injury.

Kidney Int. 103:514–528. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

36

|

Wiener D and Schwartz S: The

epitranscriptome beyond m6A. Nat Rev Genet. 22:119–131.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zhang Q, Bao X, Cui M, Wang C, Ji J, Jing

J, Zhou X, Chen K and Tang L: Identification and validation of key

biomarkers based on RNA methylation genes in sepsis. Front Immunol.

14:12318982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zeng H, Xu J, Wu R, Wang X, Jiang Y, Wang

Q, Guo J and Xiao F: FTO alleviated ferroptosis in septic

cardiomyopathy via mediating the m6A modification of BACH1. Biochim

Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1870:1673072024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Siew ED, Hellwege JN, Hung AM, Birkelo BC,

Vincz AJ, Parr SK, Denton J, Greevy RA, Robinson-Cohen C, Liu H, et

al: Genome-wide association study of hospitalized patients and

acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 106:291–301. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Flamand MN, Tegowski M and Meyer KD: The

proteins of mRNA modification: Writers, readers, and erasers. Annu

Rev Biochem. 92:145–173. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Fedeles BI, Singh V, Delaney JC, Li D and

Essigmann JM: The AlkB family of Fe(II)/α-Ketoglutarate-dependent

dioxygenases: Repairing nucleic acid alkylation damage and beyond.

J Biol Chem. 290:20734–20742. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li Y, Su R, Deng X, Chen Y and Chen J: FTO

in cancer: Functions, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic

implications. Trends Cancer. 8:598–614. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Reitz C, Tosto G, Mayeux R and Luchsinger

JA; NIA-LOAD/NCRAD Family Study Group; Alzheimer's Disease

Neuroimaging Initiative: Genetic variants in the fat and obesity

associated (FTO) gene and risk of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One.

7:e503542012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Dubey PK, Patil M, Singh S, Dubey S, Ahuja

P, Verma SK and Krishnamurthy P: Increased m6A-RNA methylation and

FTO suppression is associated with myocardial inflammation and

dysfunction during endotoxemia in mice. Mol Cell Biochem.

477:129–141. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

45

|

Luo J, Wang F, Sun F, Yue T, Zhou Q, Yang

C, Rong S, Yang P, Xiong F, Yu Q, et al: Targeted inhibition of FTO

demethylase protects mice against LPS-induced septic shock by

suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome. Front Immunol. 12:6632952021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bengatta S, Arnould C, Letavernier E,

Monge M, de Préneuf HM, Werb Z, Ronco P and Lelongt B: MMP9 and SCF

protect from apoptosis in acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol.

20:787–797. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu J, Li Z, Lao Y, Jin X, Wang Y, Jiang

B, He R and Yang S: Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and

experimental verification reveal the mechanism of San-Huang

decoction in treating acute kidney injury. Front Pharmacol.

14:10604642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lee SY, Hörbelt M, Mang HE, Knipe NL,

Bacallao RL, Sado Y and Sutton TA: MMP-9 gene deletion mitigates

microvascular loss in a model of ischemic acute kidney injury. Am J

Physiol Renal Physiol. 301:F101–F109. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Fiotti N, Mearelli F, Di Girolamo FG,

Castello LM, Nunnari A, Di Somma S, Lupia E, Colonetti E, Muiesan

ML, Montrucchio G, et al: Genetic variants of matrix

metalloproteinase and sepsis: The need speed study. Biomolecules.

12:2792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Maitra SR, Jacob A, Zhou M and Wang P:

Modulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of

matrix metalloproteinase-1 in sepsis. Int J Clin Exp Med.

3:180–185. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Niño ME, Serrano SE, Niño DC, McCosham DM,

Cardenas ME, Villareal VP, Lopez M, Pazin-Filho A, Jaimes FA, Cunha

F, et al: TIMP1 and MMP9 are predictors of mortality in septic

patients in the emergency department and intensive care unit unlike

MMP9/TIMP1 ratio: Multivariate model. PLoS One. 12:e1711912017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|