Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a small

double-stranded DNA virus, for which >200 genotypes have thus

far been identified (1). HPV

infection can alter the host cellular immune response, including

suppression of interferon (IFN) production, which impairs viral

clearance and leads to persistent infection, thereby contributing

to the development of various associated diseases (2,3).

Currently, HPV is classified into low- and high-risk types based on

the degree of pathogenicity. High-risk HPV is closely associated

with various malignancies, including cervical and anal cancer,

whereas low-risk HPV infections are mainly associated with

verrucous hyperplasia of the skin and mucous membranes, such as

condyloma acuminatum (4,5). The HPV genome contains eight open

reading frames and is organized into three functional regions: The

early region, the late region and the long control region. The

early region encodes six non-structural proteins: E1, E2, E4, E5,

E6 and E7 (6); among these, E1,

E2, E4 and E5 are involved in viral DNA replication, whereas E6 and

E7 are recognized as the primary oncoproteins responsible for

cellular transformation (7). The

E7 protein is an acidic polypeptide consisting of 98-105 amino

acids (aa) (8). E7 exhibits

multiple biological functions and has been shown to interact with

key regulatory proteins, including pRB, p107, p130, MPP2 and DNA

methyltransferase 1, thereby modulating their activities. These

interactions contribute to the dysregulation of critical cellular

processes, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, migration,

survival and apoptosis (9-12). With the growing progression of

attitudes towards sexual relationships, the infection rate of HPV

is increasing annually (13-15). In recent years, a large-scale

multicenter study in China has demonstrated that the overall

prevalence of HPV among women is 17.70%, representing an upward

trend compared with the prevalence rate reported in the same

population group in 2008 (16.1%) (16). Furthermore, the age of onset of

HPV-related diseases is decreasing and the locations of onset are

variable, thus making HPV more difficult to treatment (17). Notably, the current therapeutic

options for HPV-related diseases remain relatively limited

(18). For example, for cervical

cancer resulting from high-risk HPV, surgical removal of the lesion

is frequently performed in clinical practice (19,20). By contrast, condyloma acuminatum

caused by low-risk HPV can be alleviated by physical methods, such

as microwave treatment and cryotherapy for wart removal (21,22). However, as there has been no

breakthrough yet in research on the specific mechanism underlying

persistent HPV infection, effective means to completely eliminate

HPV are still lacking in the clinical setting. Therefore, a radical

cure has not yet been achieved in clinical practice Recurrent

disease not only exerts a profound impact on the physical and

mental health of patients, but also imposes considerable economic

burdens on their families and society at large. Thus, studying the

mechanism underlying persistent HPV infection is a current focus of

research. Subsequently, exploring drugs and methods for specific

viral clearance after HPV infection may be of important medical

relevance and social value, with the aim of preventing and treating

diseases associated with HPV infection.

The immune system, functioning as a pivotal system

responsible for immune responses and functions, encompasses diverse

cell types, tissues and organs that operate together to shield the

entire organism from the invasion of various pathogens (23,24). Notably, the role of energy

metabolism in immune regulation has garnered increasing attention

in previous years (25,26). Mitophagy, constituting a specific

type of autophagy that selectively eliminates dysfunctional

mitochondria, has garnered increasing attention regarding its

association with the immune functions of the body (27). Mitophagy can influence the immune

functions of host cells through multiple modalities, including

inhibiting the activation of inflammasomes, interfering with the

expression of type I IFNs and suppressing the initiation of

apoptosis in host cells (28,29).

Previous studies have demonstrated that mitophagy

can impact the innate immune state of cells by suppressing

activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and can serve a crucial role

in cellular immune responses by regulating proteins, including

mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein, retinoic acid-inducible

gene I, melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 and

stimulator of IFN genes (STING), to inhibit the expression of type

I IFNs (30-34). Knocking out the expression of

mitophagy-related genes can release a considerable quantity of

cytochrome c into the cytoplasm, thereby impeding the

activation of caspase-3/-7 and suppressing apoptosis (35). Thus, mitophagy is closely

associated with the immune functions of cells. According to the

variance in autophagosome recognition pathways, mitophagy is

classified into two types: i) Ubiquitin-related mitophagy, mediated

by the PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin (a RING-between-RING E3

ubiquitin protein ligase) pathway (36,37); and ii) ubiquitin-independent

mitophagy, mediated by the Bcl-2 and adenovirus E1B 19

kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3)/BNIP3-like (BNIP3L) pathway

(38).

Currently, a considerable number of studies

(28,39,40) have focused on the impact of

viruses on the mitophagy of host cells. Viruses such as hepatitis B

virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), herpes simplex virus (HSV)

and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can induce the mitophagy of

host cells to suppress innate immunity and maintain a persistent

infection. Notably, viruses can directly recognize mitophagy

pathway proteins to influence mitophagy in host cells or can

indirectly affect the level of mitophagy by influencing the

metabolic status of host cells. For example, HBV can promote

mitophagy by activating the PINK1/Parkin pathway, thereby

facilitating viral replication (41). The viral IFN regulatory factor 1

encoded by human herpesvirus type 8 can directly bind to BNIP3L,

activating mitophagy to enhance its replication within the host

(42). Simultaneously, the

non-structural protein 5A of HCV can activate mitophagy by

increasing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

(43). In the early stage after

HIV infection, the single-stranded RNA of HIV type 1 activates

mitophagy by increasing the generation of ROS and causing

mitochondrial membrane depolarization (44). Emerging evidence has indicated

that HPV is implicated in the regulation of mitophagy (45,46). These aforementioned research

findings suggest that viruses can affect the immune response of

host cells by influencing the intracellular level of mitophagy,

thereby perpetuating the infection of host cells.

The present study aimed to investigate the impact of

the early protein E7 of HPV on mitophagy pathway activity and to

further assess the mechanism underlying persistent HPV

infection.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Primary normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs)

were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc. and were

cultured in Epilife medium, without any antibiotics, supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Human Keratinocyte Growth

Supplement (all from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Siha and 293T cells

(The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of

Sciences) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

μg/ml streptomycin. All cells were cultured at 37°C in the

presence of 5% CO2.

Construction of HPV11/16 E7-expressing

and HTRA1-expressing NHEKs

The HPV11 E7 gene was amplified from the pBR322

vector [cat. no. 45151D; American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)]

and HPV16 E7 gene was amplified from the pBluescript SK-vector

(cat. no. 45113; ATCC). These two vectors contain the full-length

genomes of HPV11 and HPV16, respectively. The amplified E7 genes

were then cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (cat. no. V79020;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently, HPV11/16

E7 were cloned from the pcDNA3.1 vector into the

pHAGE-fEF1a-IRES-ZsGreen lentiviral expression vector (provided by

Professor Xiaojian Wang, Institute of Immunology, Zhejiang

University, Hangzhou, China). In addition, the gene encoding

Flag-HTRA1 was synthesized via full-gene synthesis and subsequently

cloned into pHAGE-fEF1a-IRES-ZsGreen lentiviral expression vector.

The empty pHAGE-fEF1a-IRES-ZsGreen lentiviral expression vector was

used as a negative control. Lentiviral packaging used the 2nd

generation system. For transfection, 293T cells cultured to 90%

confluence were used; lentiviral, packaging (psPAX2; provided by

Professor Xiaojian Wang) and envelope (pMD2.G; provided by

Professor Xiaojian Wang) plasmids were co-transfected at a 4:3:1

molar ratio (total DNA: 12 μg) using PolyJet™ In

Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (cat. no. SL100688; SignaGen

Laboratories) at 37°C for 8 h, and viral supernatants were

collected at 72 h post-transfection. NHEKs were then infected with

lentiviruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20, with

medium replaced 24 h post-infection. Stable cell lines were

selected using puromycin; 72 h post-infection, fluorescent protein

expression was assessed under a fluorescence microscope (IX83;

Olympus Corporation), and when fluorescent cells reached ~30%, they

were cultured for another 48 h before selection with 2 μg/ml

puromycin. The medium was changed every 24 h during selection, and

the same puromycin concentration was maintained for subsequent

cultures. Stable cell pools were ready for downstream experiments 1

week after selection initiation. Western blotting verified the

successful expression of HPV11/16 E7 and HTRA1 in NHEKs.

Knockdown of HPV16 E7 and HTRA1

The HPV16 E7 short hairpin (sh)RNA sequence was

cloned into the hU6-MCS-Ubiquitin-EGFP-IRES-puromycin vector (cat.

no. GV248; Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.). shRNA lentivirus packaging

used the 2nd generation system. For transfection, 293T cells

cultured to 80% confluence were used; lentiviral, packaging

(pHelper 1.0; Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.) and envelope (pHelper

2.0; Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.) plasmids were co-transfected at a

4:3:2 molar ratio (total DNA: 45 μg) using GeneChem

Transfection Reagent (Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.) at 37°C for 6 h,

and viral supernatants were collected at 72 h post-transfection.

Siha cells were infected at a MOI of 20, with medium replaced 12 h

post-infection. Stable cell lines were then obtained by puromycin

screening; 72 h post-infection, fluorescent protein expression was

assessed under a fluorescence microscope, and when fluorescent

cells reached ~30%, they were cultured for another 48 h before

screening with 2 μg/ml puromycin. The medium was changed

every 24 h during screening, and the same puromycin concentration

was maintained for subsequent cultures. Stable cell pools were

ready for downstream experiments 1 week after screening initiation.

The knockdown efficiency of shRNAs was evaluated by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), demonstrating significant

downregulation of both HPV16 E7 and HTRA1 expression (Fig. S1A and B).

The sequences of the shRNAs, which are presented in

the 5'-3' direction, were as follows: HPV16 E7 shRNA,

TGCGTACAAAGCACACACGTA; HTRA1 shRNA, GGGTCTGGGTTTATTGTGT; shRNA

negative control, TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT.

Transmission electron microscopy

NHEKs (6×106) were harvested without

rinsing and immediately suspended in electron microscope fixative

(cat. no. BP006; BIOSSCI). After 5 min, cells were scraped

unidirectionally, centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min, resuspended

in 1 ml fresh fixative at room temperature, and stored at 4°C. For

agar pre-embedding, the pellet was centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 5

min, washed three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), then

mixed with warm 1% agarose and embedded using forceps before

solidification. Post-fixation, the samples were incubated with 1%

osmium tetroxide (cat. no. 02602-AB; Ted Pella, Inc.) in 0.1 M

phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h in the dark at room temperature,

followed by three 15-min buffer washes. Dehydration was performed

using a graded series of ethanol (30, 50, 70, 80 95 and 100%; 10

min each), followed by two 10-min acetone changes, all at room

temperature. Subsequently, infiltration and embedding were

performed. A mixture of acetone and 812 (cat. no. 02660-AB; SPI

Supplies) embedding agent in a 1:1 ratio was used to treat the

samples at 37°C for 3h, followed by a 1:2 mixture at 37°C

overnight. Finally, pure 812 embedding agent was used to treat the

samples at 37°C for 6 h. The pure 812 embedding agent was poured

into the embedding plate, the sample was inserted and the plate was

incubated at 37°C overnight. The next step was polymerization,

where the embedding plate was placed in a 60°C oven for 48 h, and

the resin blocks were removed for later use. Ultra-thin sectioning

was then performed, with the resin blocks being cut into 70-nm

sections on an ultrathin sectioning machine and collected on 200

mesh copper grids. Finally, staining was carried out by placing the

copper grids in 2% uranyl acetate (cat. no. 02624-AB; Ted Pella,

Inc.) saturated alcohol solution for 10 min at room temperature in

the dark, followed by three washes with ultrapure water. The grids

were then stained with 2% lead citrate solution for 10 min at room

temperature in the absence of CO2, washed three times

with ultrapure water, and slightly dried with filter paper. The

copper grid sections were placed in a copper grid box and dried at

room temperature overnight, and were then observed under a

transmission electron microscope (HT7700; Hitachi, Ltd.).

Generation and identification of

HTRA1(−/−) mice

HTRA1 gene knockout mice (cat. no. S-KO-10732;

strain no. KOCMP-56213-Htra1-B6N-VA) and wild-type (WT) mice (cat.

no. C001072; strain no. C57BL/6NCya) were procured from Cyagen

Biosciences Inc. The genotype verification process for HTRA1(−/−)

mice was performed as follows: The toe tissue of 7-day-old WT and

HTRA1(−/−) mice (n=20 mice/group) was cut without anesthesia. These

mice were housed together with their respective dams and separately

from other adult animals to prevent interference and ensure

individual monitoring. Mouse toe tissue was collected in a labeled

microcentrifuge tube for DNA extraction, followed by the addition

of 100 μl 0.05 mol/l NaOH, incubation at 95°C for 45 min,

neutralization with 30 μl 0.1 mol/l Tris-HCl (pH 8.0),

centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, and

transfer of the supernatant to a new tube for PCR. PCR was

performed using Taq Plus Master Mix II (cat. no. P213-01; Vazyme

Biotech Co., Ltd.) under the following conditions: 94°C for 3 min

(1 cycle), followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 35

sec and 72°C for 35 sec, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5

min (1 cycle). For electrophoresis, a 1.5% agarose gel was prepared

in 1X TAE buffer containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml);

subsequently, PCR products and a DNA marker were loaded, the gel

was run at 100-20 V for 25-30 min, and finally the bands were

visualized under UV light, images were captured and band patterns

were analyzed for genotyping (Fig.

S1D). The specific verification primer sequences (presented in

a 5'-3 'direction) were as follows: WT, forward (F)

CTAGGTGATAGCGGTGGAAGTC, reverse (R) ACAAGTGTATCTGGGCTTCCTG, target

band size, 504 bp; HTRA1(−/−), F CAATGGACGAGCCCTGTATCAATC, R

CACTGACTGCTTTTCCAGAGGTCC, target band size, 349 bp.

For subsequent experiments, 8-week-old mice WT and

HTRA1(−/−) mice were used (previously genotyped at 7 days of age).

Each experimental group consisted of 10 male (weight, 26.1±1.2 g)

and 10 female (weight, 20.5±1.2 g) mice. All mice, including

neonates, were housed under the following controlled environmental

conditions: Temperature, 20-26°C; relative humidity, 40-70%; 12-h

light/dark cycle (lights on from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM). The bedding

consisted of dust-free and absorbent wood shavings. Ventilation was

maintained to ensure adequate air exchange and removal of harmful

gases, while minimizing direct airflow and noise exposure. Standard

laboratory chow and water were provided ad libitum. Animals

were monitored daily for general health and behavior, and

observations were systematically recorded.

WT and HTRA1(−/−) C57BL/6NCya mice at 8 weeks of age

were humanely euthanized in accordance with institutional animal

care guidelines, and tissue RNA was isolated and submitted for

RNA-seq analysis.

Methods of mouse anesthesia and

euthanasia

To comply with animal welfare guidelines and reduce

unnecessary suffering, predefined humane endpoints were applied to

HTRA1(−/−) and WT mice during tissue collection: Mice were

immediately euthanized before severe distress occurred if they

showed pre-sampling signs such as involuntary vocalization, an

inability to maintain a normal posture, severe dehydration (sunken

eye sockets, loss of skin elasticity), refusal to eat/drink for

>24 h or unexpected skin pathologies (ulceration, bleeding,

unrelated inflammation); if anesthesia was inadequate (purposeful

movement, vocalization during sampling); or re-anesthesia failed.

In the present study, no mice met the criteria for humane endpoints

and therefore none were euthanized before the end of the

experiment. For anesthesia, the dosage of 5% chloral hydrate was

used based on the individual body weight of each mouse, and

administered at a standardized concentration of 300 mg/kg.

Following physical restraint, the anesthetic was injected into the

lower abdominal region via a lateral abdominal approach. Following

anesthesia, mouse ears were surgically excised using sterile

scissors for subsequent IHC analysis, and euthanasia was performed

by cervical dislocation immediately after tissue collection. All

procedures adhered to the 3Rs principle and AVMA Guidelines for the

Euthanasia of Animals (47,48).

Total RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

analysis

Transcriptomics analysis was conducted on Siha cells

with HPV16 E7 gene knockdown, and also on the skin of HTRA1(−/−)

mice. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from the samples with

TRIzol® reagent (cat. no. 15596026CN; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Only high-quality samples (OD260/280,

1.8-2.2; OD260/230, ≥2.0; RNA quality number, ≥6.5; 28S:18S, ≥1.0;

>1 μg) were chosen following quality checks on a 5300

Bioanalyzer (Agilent Biotechnologies, Inc.) and quantification on

an ND-2000 (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For library

construction, 1 μg total RNA was used to isolate and

fragment mRNA via oligo(dT) beads, after which, double-stranded

cDNA was synthesized (SuperScript Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), and processed for end repair, phosphorylation to enable

efficient ligation with sequencing adapters (catalyzed by T4

polynucleotide kinase to add 5'-phosphate groups using ATP) and

3'-end 'A' addition to cDNA fragments. Subsequently, 300-bp cDNA

fragments were selected, amplified by PCR (15 cycles; Phusion

Polymerase; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), quantified (Qubit 4.0;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and sequenced. Paired-end

sequencing with a read length of 150 bp (2×150 bp) was performed on

the NovaSeq X Plus platform (Illumina, Inc.) using the NovaSeq X

Plus Reagent Kit (300 cycles; cat. no. 20104705; Illumina, Inc.),

consistent with the reagents typically used by Meiji Biomedical

Technology Co., Ltd. for NovaSeq X Plus-based sequencing services.

The final library was loaded at a concentration of 15 pM. Molar

concentration was determined using the KAPA Library Quantification

Kit (cat. no. 07960140001; Roche Diagnostics) via qPCR, ensuring

accurate loading for the NovaSeq X Plus platform. Raw reads were

trimmed/quality-controlled using fastp (v0.19.5; https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp) (49) to obtain clean reads, which were

aligned to the reference genome with HISAT2 (v2.1.0; https://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/)

(50) and assembled by StringTie

(v2.1.2; https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/) (51). Transcript expression (transcripts

per million) and gene abundance (RSEM) were calculated, and

differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified via DESeq2

(v1.24.0; https://bioconductor.org/packages/stats/bioc/DESeq2/)

(52) (|log2FC|≥1, FDR≤0.05) or

DEGseq (v1.38.0; https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/DEGseq/versions/1.26.0)

(53) (|log2FC|≥1, FDR≤0.001).

Gene Ontology (GO) (Goatools; v0.6.5; https://github.com/tanghaibao/goatools) (54) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes (KEGG) (KOBAS; v2.1.1; http://bioinfo.org/kobas/download/) (55) enrichment analyses were performed

for DEGs (Bonferroni-corrected P≤0.05) using Goatools and KOBAS,

respectively. Heatmaps were generated using the Weighted Gene

Co-expression Network Analysis (v1.63; https://cran.r-project.org/package=WGCNA) (56). Finally, alternative splicing

events were identified via rMATS (v4.0.2; http://rnaseq-mats.sourceforge.net/) (57) (focusing on reference-similar

isoforms or novel junctions, detecting exon inclusion/exclusion,

alternative 5'/3' ends and intron retention). The RNA-seq analysis

was performed by Meiji Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.

Isobaric tags for relative and absolute

quantitation (iTRAQ) analysis

iTRAQ analysis was performed on Siha cells with

stable HPV16 E7 knockdown. At ~70% confluence, cells were washed

2-3 times with ice-cold PBS, detached with 0.25% trypsin (cat. no.

V5117; Promega Corporation), centrifuged at 800-1,000 × g for 5 min

at 4°C, and washed once more with PBS. Cell pellets were then

resuspended in SDT lysis buffer (4% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6;

100-200 μl per 1×106 cells), vortexed, sonicated

on ice (200-300 W, 3 sec pulse/5 sec interval, 10-15 cycles), and

boiled at 95°C for 15 min. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for

15 min at 4°C, the supernatants were quantified using a

bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (cat. no. P0012; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) and stored at −20°C. For SDS-PAGE validation, 20

μg protein was mixed with 6X loading buffer, denatured at

95°C for 5 min, separated on a 12% gel (250 V, 40 min), and stained

with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. For iTRAQ processing, 150 μg

protein was reduced with 100 mM DTT (cat. no. 43819-5G;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at 95°C for 5 min, transferred to a 30

kDa filter, washed with UA buffer (8 M urea, 150 mM Tris-HCl, pH

8.5), alkylated with 50 mM IAA (cat. no. I1149-5G; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) in the dark for 30 min, and washed with 25 mM

NH4HCO3 (cat. no. A6141-25G; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA). Digestion was performed overnight at 37°C with 4

μg trypsin (substrate:enzyme 37.5:1) in

NH4HCO3. Peptides were collected, desalted,

lyophilized, reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid (cat. no. A117;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and quantified by measuring the

absorbance at a wavelength of 280 nm. The peptides were separated

using a nanoflow liquid chromatography system (Easy nLC; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on an Acclaim™ PepMap™ RSLC analytical

column (50 μm × 15 cm, NanoViper; cat. no. 164943; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 0.1% formic acid/water-acetonitrile

gradients (elution times of 1/2/3 h; flow rate, 300 nl/min). The

peptides were analyzed on a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) operated in positive mode with a

resolution of 70,000 for mass spectrometry scans and higher-energy

collisional dissociation for fragmentation. This experiment adopted

a non-targeted proteomics analysis strategy with full scan combined

with MS2 fragmentation. The nitrogen gas parameters used were: A

temperature of 300°C, a nebulizer pressure of 40 psi and a flow

rate of 7 l/min, which were fully compatible with the experimental

process. Raw data were processed with Proteome Discoverer 2.1

(https://thermo.flexnetoperations.com/control/thmo/login?nextURL=%2Fcontrol%2Fthmo%2Fhome)

(58) to generate.mgf files,

searched against the UniProt human database (https://www.uniprot.org/) (59) via MASCOT 2.6 (https://www.matrixscience.com//server.html) (45), and filtered for FDR<0.01 to

obtain results.

GFP-LC3 and Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos

colocalization

A GFP-LC3 plasmid (1 μg/ml; cat. no.

17-10193; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was transfected into HPV11/16

E7-overexpressing cells at 37°C for 6 h using liposome transfection

reagent (Lipofectamine® 3000; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After

the 6-h transfection, the culture medium was replaced with fresh

medium, and the cells were continuously cultured under the same

conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). At 36 h post-transfection,

the cells were stained with 100 nM Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos (cat.

no. C1035; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 20 min at room

temperature followed by instant observation. The number of all

punctate granules and yellow punctate granules within the cells was

quantified using a fluorescence microscope. For each sample, 100

cells were observed. After computing the ratio of yellow punctate

granules to all punctate granules, the mean value of the data was

obtained, and intergroup comparisons were carried out. A higher

proportion of yellow punctate granules indicated enhanced

mitophagy.

Western blot analysis

Cells were collected and lysed in

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (containing 1%

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; Fdbio Science) for 30 min on ice.

The lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and

the supernatants were collected. The supernatants were then

harvested and the protein concentrations were quantified using a

BCA kit. Since HTRA1 is an exosomal protein, when determining the

expression levels of HTRA1, intracellular and extracellular

proteins need to be assessed simultaneously (60,61). Firstly, for extracellular lysate

extraction, the cell culture medium was collected, and an

equivalent volume of methanol was added and mixed thoroughly, after

which, 1/3 volume of chloroform was added and the sample was

vortexed. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g

for 10 min at 4°C and liquid stratification could be observed. Upon

carefully removing the uppermost layer of liquid (being cautious to

avoid disturbing the thinner protein middle layer), 500 μl

methanol was added. After thorough vortexing, the mixture was

centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the

upper layer of liquid was removed (being careful to avoid

disturbing the extracellular lysate protein at the bottom layer)

and the protein was incubated at 55°C for 5 min. The volume of the

intracellular and extracellular lysates was kept consistent.

After protein extraction, the protein samples (10

μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 12% gels and were

subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes

(0.2 μm; cat. no. 1620177; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) using

a wet transblotting apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Upon

blocking with 10% nonfat milk (Difco; BD Biosciences) for 1 h at

room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight with the

following primary antibodies diluted to 1:1,000 in primary antibody

diluent (cat. no. FD0040; Hangzhou Fude Biological Technology Co.,

Ltd.): Mitophagy Antibody Sampler kit (cat. no. 43110; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), polyclonal rabbit anti-HTRA1 (cat. no.

SAB1300009; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), polyclonal rabbit anti-LC3B

(cat. no. L8918; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), monoclonal mouse

anti-GAPDH (cat. no. G8795; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), monoclonal

rabbit anti-p62 (cat. no. ab109012; Abcam), anti-Flag (cat. no.

M1403-2; HUABIO), polyclonal rabbit anti-HPV11/16 E7 (prepared in

our laboratory) (62-65) and monoclonal rabbit anti-pRB

(cat. no. ab181616; Abcam). After washing the membranes three times

with PBS (10 min each), they were incubated for 2 h at room

temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (H+L; cat. no. A0208; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L; cat. no.

A0216; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) secondary antibodies

diluted to 1:500 in 5% skimmed milk. The specific protein bands

were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (cat. no.

FD8020; Hangzhou Fude Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) using a blot

scanner (v2.3; ChemiDoc Touch; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). ImageJ

(version 1.54f; National Institutes of Health) was used for image

processing and semi-quantitative analysis.

RT-qPCR

The relative gene expression levels were measured by

RT-qPCR. Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ High

Fidelity RT-PCR Kit (cat. no. R022A; Takara Bio, Inc.) according to

the manufacturer's protocol. The relative gene expression levels

were measured by qPCR in a total volume of 10 μl including 1

μl cDNA, 5 μl 2X SYBR Premix Ex Taq I (cat. no.

RR390A; Takara Bio, Inc.), 0.4 μl forward primer, 0.4

μl reverse primer, 0.2 μl carboxy-X-rhodamine and 3

μl double-distilled H2O run on an ABI 7500 system

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). qPCR was

carried out in 96-well plates at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40

cycles at 95°C for 10 sec and 58°C for 30 sec. Relative gene

expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq

method, with GAPDH as the reference gene to normalize the

expression of target genes (66). The primer sequences (presented in

the 5'-3' direction) were as follows: HTRA1, F

TCCCAACAGTTTGCGCCATAA,R CCGGCACCTCTCGTTTAGAAA; IFN-β, F

AACTGCAACCTTTCGAAGCCTTT, RAGAGCAATTTGGAGGAGACACTT; HPV16 E7, F

CCGGACAGAGCCCATTACAA, R TTTGTACGCACAACCGAAGC; HPV11 E7, F

GATGTGACAGCAACGTCCGA, R GTGTGCCCAGCAAAAGGTCT; PODXL, F

CTCCCTGCTAGACCTCCTG, R TGCAGAATCCGAGACTCTTCAT; CEBPD, F

CTGTCGGCTGAGAACGAGAA, R TCTTTGCGCTCCTATGTCCC; S10A6, F

CTCCCTACCGCTCCAAGC, R CACCTCCTGGTCCTTGTTCC; ANXA8, F

ATGGCCTGGTGGAAATCCTG, R TCATGCTGCTGAGGGTCTTG; GAPDH, F

CTCACCGGATGCACCAATGTT, R CGCGTTGCTCACAATGTTCAT.

Clinical samples

The inclusion criteria for patients with condyloma

acuminatum were as follows: Male participants, aged 18-45 years

(mean ± SD, 30.9±4.8 years; median, 30 years); clinically confirmed

condyloma acuminatum with HPV11 PCR positivity; absence of

comorbidities; and no prior HPV vaccination. The exclusion criteria

in the patient group were as follows: Other HPV types except for

HPV11 detected by PCR; those with any history of HPV vaccination;

individuals with mental illness, cognitive impairments or critical

illnesses; or minors. The inclusion criteria for the participants

in the healthy control group were: Male participants, aged 18-45

years (mean ± SD, 29.8±4.5 years; median, 30 years); normal

foreskin tissue, with no evidence of HPV infection; and no prior

HPV vaccination. The exclusion criteria in the control group were

as follows: Detection of HPV via PCR; prior HPV vaccination; and

individuals with mental illness, cognitive impairments or critical

illnesses; or minors. Condyloma acuminatum and normal foreskin

tissue samples were utilized for immunohistochemical analysis, with

15 cases enrolled in each group.

The inclusion criteria for patients with cervical

cancer were as follows: Female participants, aged 18-45 years (mean

± SD, 31.6±4.9 years; median, 31 years); clinically confirmed

cervical cancer with HPV16 PCR positivity; absence of

comorbidities; and no prior HPV vaccination. The exclusion criteria

in the patient group were as follows: Other HPV types except for

HPV16 detected by PCR; those with any history of HPV vaccination;

pregnant women; individuals with mental illness, cognitive

impairments or critical illnesses; or minors. The inclusion

criteria for the participants in the control group were: Female

participants, aged 18-45 years (mean ± SD, 30.9±4.8 years; median,

31 years); clinically confirmed cervical cancer but a negative HPV

test; and no prior HPV vaccination. The exclusion criteria for the

control group were as follows: Detection of HPV via PCR; prior HPV

vaccination; pregnant women; individuals with mental illness,

cognitive impairments or critical illnesses; or minors. Cervical

cancer tissues positive for HPV16 (HPV16+) or negative

for HPV (HPV−) were used for immunohistochemical

analysis, with 15 cases in each group.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tissue samples (condyloma acuminatum and normal

foreskin tissues, HPV− and HPV16+ cervical

cancer tissues, and mouse ear tissues) were collected and fixed in

4% formaldehyde (cat. no. BL539A; Biosharp Life Sciences) at room

temperature for 48 h. Subsequently, the samples were

paraffin-embedded and sectioned (3-4 μm). The sections were

then incubated in an oven at 60°C for 2 h, and subsequently

underwent dewaxing and hydration processes. To inhibit endogenous

peroxidase activity, 1% hydrogen peroxide dissolved in methanol was

added to the slides, followed by antigen retrieval through

high-pressure heat repair. Subsequently, 10% goat serum (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was added to block non-specific

antigens, followed by incubation at room temperature (~25°C) for 30

min. The goat serum was removed from the sections, and the

corresponding primary antibodies [anti-HPV11/16 E7, 1:500, prepared

in our laboratory (62-65); or anti-HTRA1, 1:1,000, cat. no.

55011-1-AP, Proteintech Group, Inc.] were added, followed by

incubation at room temperature for 1 h. After cleaning, a polymer

enhancer was applied and incubated at room temperature for 15 min,

and a HRP-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG; 1:500;

cat. no. A0208; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was added and

incubated at room temperature for 30 min prior to DAB color

development. The color developing solution was prepared by mixing 1

ml diluent with 40 μl DAB stock solution. The durations for

color development were ~1 min for HPV11/16 E7 and ~30 sec for

HTRA1. The reaction was promptly terminated with tap water to

prevent excessive color development. Subsequently, hematoxylin

counterstaining, ethanol dehydration, xylene dewaxing and neutral

gum sealing were carried out, and images were captured using an

inverted light microscope (IX83; Olympus Corporation). The IHC

results in the present study were assessed using a

semi-quantitative scoring system. Briefly, scores were assigned

independently based on staining intensity and the percentage of

positive cells, with the final score calculated as the product of

these two values. Staining intensity was scored as follows: 0, no

detectable staining; 1, light yellow staining, 2, yellow staining;

and 3, brown staining. The percentage of positive cells was scored

as follows: 1, ≤25%; 2, 26-50%; 3, 51-75%; and 4, >75%.

Construction of truncated plasmids

Based on the functional domain architecture of the

HTRA1 protein, three truncated mutants were designed, namely IB

[deletion (del) 35-111 aa], KAZAK (del 115-155 aa) and PDZ (del

382-480 aa). Each target gene fragment was synthesized via

full-gene synthesis and subsequently cloned into Flag-tagged

expression vectors (cat. no. GV657: Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.).

The control group was transfected with the CMV enhancer-MCS-polyA-E

F1A-zsGreen-sv40-puromycin plasmid vector (cat. no. GV658; Shanghai

GeneChem Co., Ltd.). Briefly, 5 μl recombinant plasmids were

mixed with 50 μl chemically competent DH5α cells (cat. no.

9057; Takara Bio, Inc.) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The

mixture was heat-shocked at 42°C for 90 sec, followed by immediate

cooling on ice for 2 min. Subsequently, 500 μl pre-warmed

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (cat. no. L8291; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) without antibiotics was added, and the

cells were shaken at 37°C for 1 h to allow recovery and expression

of the antibiotic resistance gene. An aliquot of the transformation

mixture was plated onto LB agar plates containing ampicillin, which

were then incubated inverted at 37°C for 12-16 h. Subsequently,

5-10 single colonies were selected and inoculated into 50 μl

liquid LB medium supplemented with ampicillin. Cultures were

incubated at 37°C with shaking for 2-3 h and 2 μl of each

culture was used directly as a template in colony PCR

amplification. A single bacterial colony was aseptically picked

using a sterile pipette tip and transferred into a 20-μl

identification reaction mixture. The mixture was gently homogenized

by pipetting and immediately subjected to PCR amplification. The 20

μl reaction system consisted of 9 μl

ddH2O, 10 μl 2X Taq Plus Master Mix, 0.5

μl forward primer (10 μM), 0.5 μl reverse

primer (10 μM) and the single colony as the template.

Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95°C for 5 min, followed by 22 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for

30 sec, annealing at 56°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 1

min per kb, with a final extension step at 72°C for 8 min. PCR

products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and

clones exhibiting the expected band size [(IB (del 231 bp), KAZAK

(del 123 bp) and PDZ (del 87 bp)] were considered positive.

Plasmids from positive clones were extracted and subjected to

Sanger sequencing. The obtained sequences were aligned with the

reference target gene sequence to confirm the correct insertion and

absence of mutations, deletions, or insertions, thereby completing

the validation of the recombinant plasmid. Following sequence

confirmation [IB (del 35-111 aa), KAZAK (del 115-155 aa) and PDZ

(del 382-480 aa)], the verified clones were cultured for plasmid

amplification, and high-purity plasmid DNA was extracted. The

extracted plasmids (1 μg/well for 6-well plates) were then

transfected into HPV11/16 E7-overexpressing 293T cells, which were

seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/well in 6-well plates

(70-80% confluence), using Lipofectamine 3000 according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The transfection was performed at 37°C for

6 h in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. After the 6-h

transfection, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium,

and the cells were continuously cultured under the same conditions

(37°C, 5% CO2). The cells were harvested for subsequent

co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP) assays at 48 h

post-transfection.

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells (30% confluence) were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) for 15 min at room

temperature. For immunofluorescence assays, the cells were then

permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10 min. Next, the fixed

permeabilized cells were blocked with 10% goat serum containing 1%

bovine serum albumin (cat. no. 15260037; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 60 min at room temperature, and incubated

overnight at 4°C with polyclonal rabbit anti-HTRA1 IgG (1:100; cat.

no. 55011-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). The cells were

subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated donkey

anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; cat. no. 711-565-152; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) for 2 h in the dark. Finally, the cell nuclei were

stained with DAPI (1:1,000; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

for 10 min at room temperature, and images were obtained under a

Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss AG).

CO-IP

HPV11/16 E7-overexpressing NHEKs were cultured under

optimal conditions prior to subsequent CO-IP. In addition, 293T

cells were cultured to 60-80% confluence and then infected with

lentiviruses expressing HPV11/16 E7 protein. Subsequently, the

HPV11/16 E7-overexpressing 293T cells were further cultured to

60-80% confluence, and then transfected with truncated HTRA1

plasmids (IB, KAZAK and PDZ, respectively) as aforementioned. The

cells were then incubated at 37°C. After 48 h of culture, the cells

were harvested for subsequent experiments. Cells were harvested and

lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing 1%

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Fdbio Science) for 30 min. Following

centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, the supernatants

were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using a

BCA protein assay kit. Protein A/G magnetic beads (50 μl;

cat. no. 36417ES03; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were

first transferred to a 1.5-ml tube, placed on a magnetic separation

rack (cat. no. FMS012; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 30

sec, and the storage buffer was then carefully removed. The beads

were washed three times with 500 μl ice-cold weak RIPA lysis

buffer (cat. no. P0013D; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Antibody coupling was performed by adding 2 μg of either

Flag antibody, E7 antibody or control IgG antibody to the beads,

bringing the total volume to 300 μl with weak RIPA buffer,

and incubating the suspensions at 4°C with end-over-end rotation

for 2 h to allow formation of the antibody-bead complexes.

Subsequently, 500 μl cell lysate, which was pre-adjusted to

2 mg/ml total protein, was added to each antibody-conjugated bead

preparation, and the mixtures were rotated overnight at 4°C to

capture the target proteins. The next day, the tubes were placed on

the magnetic rack, the supernatants were discarded and the beads

were subjected to five stringent washes with 1 ml ice-cold weak

RIPA buffer per wash. After the final wash, 50 μl 1X SDS

loading buffer was added to each bead pellet, the suspensions were

vortexed thoroughly, heated at 100°C in a metal block for 10 min to

elute the immunocomplexes, and then chilled on ice for 2 min. The

tubes were briefly centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 sec, returned

to the magnetic rack and the clarified supernatants were carefully

transferred to fresh tubes for subsequent western blot analysis.

The IgG control antibodies used in this process included Normal

Rabbit IgG (cat. no. 30000-0-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

Normal Mouse IgG (cat. no. B900620; Proteintech Group, Inc.),

polyclonal mouse anti-Flag (tag for truncated plasmids, cat. no.

M1403-2; HUABIO) and polyclonal rabbit anti-HPV11/16 E7 (prepared

in our laboratory). Given that both high-risk and low-risk HPV E7

proteins are well established to interact with pRB (9,10), the specificity of HPV11/16 E7

antibodies in NHEKs overexpressing HPV11/16 E7 were validated using

a CO-IP assay followed by detection of pRB; the results

demonstrated that HPV11/16 E7 antibodies effectively captured and

co-precipitated pRB, confirming their functional utility (Fig. S1E).

ELISA

To evaluate the levels of IFN-β secreted by NHEKs

with overexpression of HPV11/16 E7 and knockdown of HTRA1, the

IFN-β ELISA kit (cat. no. E-EL-H0085; Elabscience; Elabscience

Bionovation Inc.) was used. Cell supernatants were collected by

centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and stored at −20°C

until analysis. The assay was conducted according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Optical density (OD) values were

measured within 5 min using a microplate reader set at a reference

wavelength of 630 nm and a detection wavelength of 450 nm. The OD

value of the blank well was subtracted from all other well readings

(duplicate wells were averaged). A standard curve was generated by

plotting the mean OD values against the known standard

concentrations, and a four-parameter logistic regression model was

applied for curve fitting. The concentrations of IFN-β in the

samples were interpolated from the standard curve and multiplied by

the respective dilution factors to obtain the final

concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Data, with the exception of IHC results, are

presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences

between groups were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's

honestly significant difference post hoc test. IHC data are

presented as median values with interquartile range, and

statistical analysis of IHC data was performed using the

Mann-Whitney U test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

HPV E7 promotes mitophagy in

keratinocytes

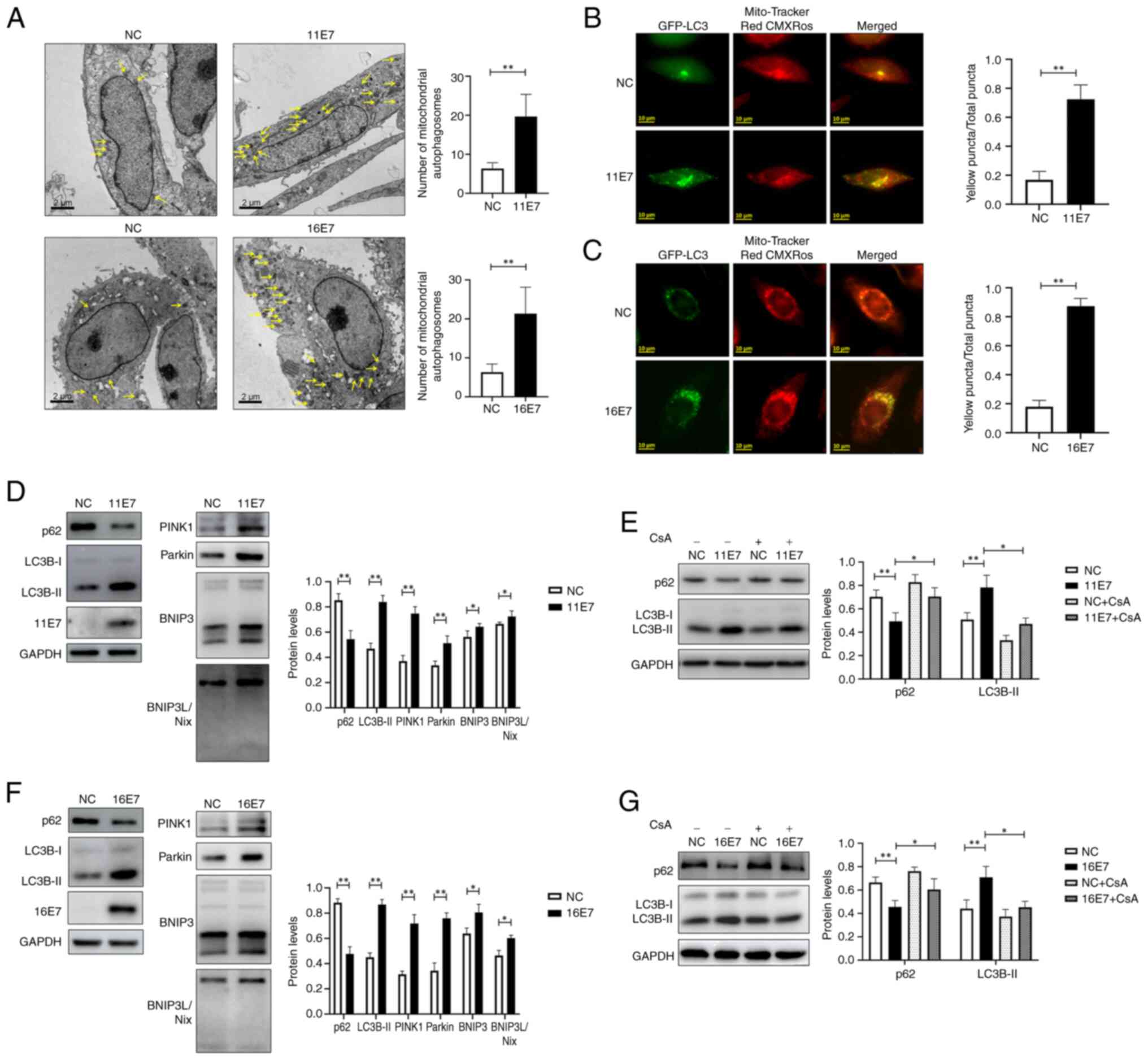

Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe

the number of mitochondrial autophagosomes in the control group and

in NHEKs overexpressing HPV11/16 E7 (Fig. 1A). The results demonstrated that

there were more mitochondrial autophagosomes in NHEKs

overexpressing HPV11/16 E7 than in control cells. In addition,

intracellular mitophagy was monitored via co-localization of

GFP-LC3 and Mito-Tracker Red CMXRos (Fig. 1B and C), and it was observed

that, compared with that in the control groups, the proportion of

yellow puncta was higher in the HPV11/16 E7 overexpression groups,

suggesting a higher level of mitophagy in these groups. The

expression levels of the mitophagy-related proteins LC3 and p62, as

well as the status of the mitophagy-related pathways PINK1/Parkin

and BNIP3/BNIP3L were examined by western blotting (Fig. 1D and F). The experimental results

indicated that HPV11/16 E7 may activate the PINK1/Parkin and

BNIP3/BNIP3L pathways, enhance LC3 expression, suppress p62

expression and consequently promote mitophagy in keratinocytes;

however, this phenomenon was inhibited by the mitophagy inhibitor

cyclosporine A (cat. no. HY-B0579; MedChemExpress; 5 μmol/l,

12 h, 37°C) (Fig. 1E and G).

HPV E7 enhances the expression of the

HTRA1 gene in keratinocytes

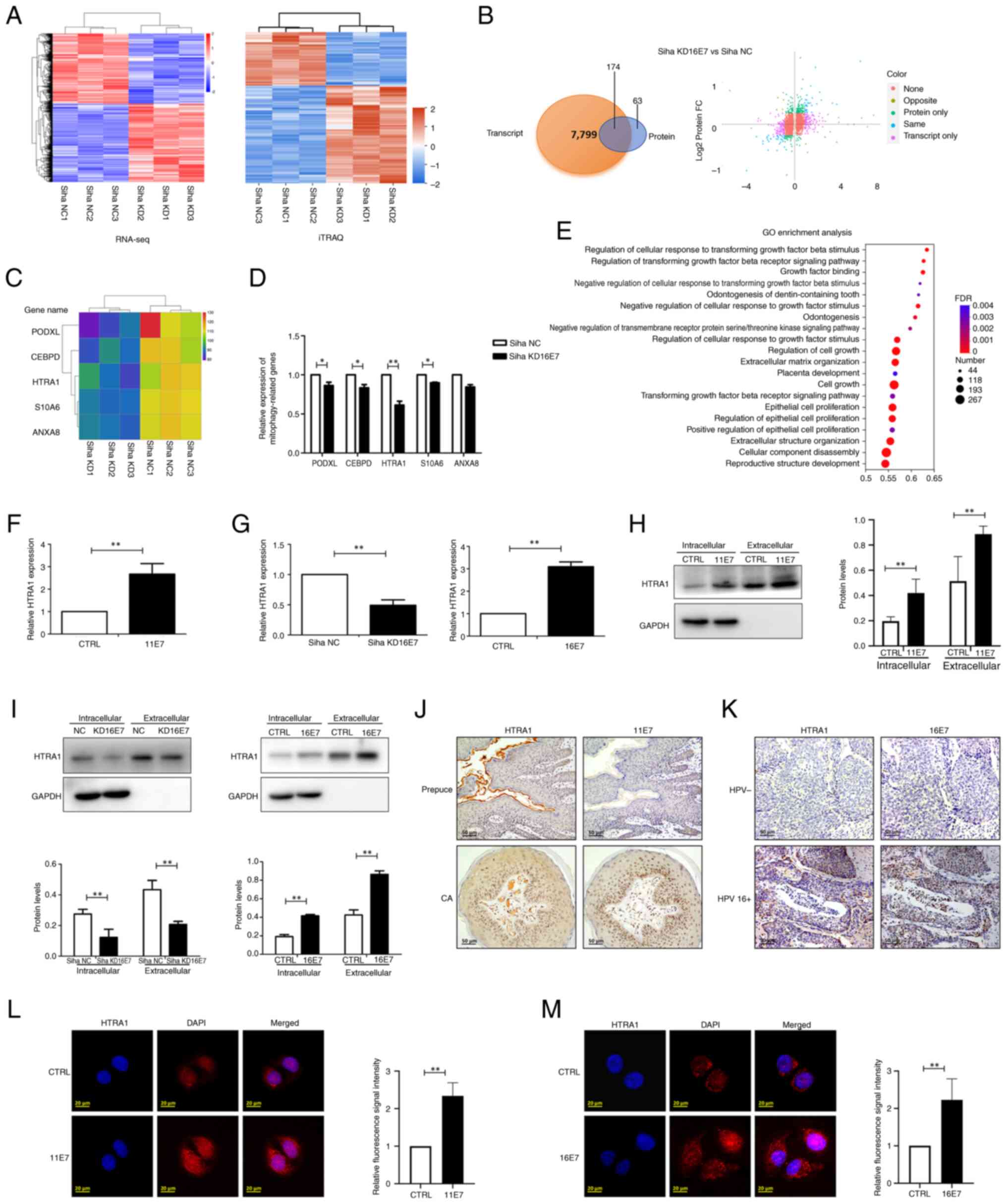

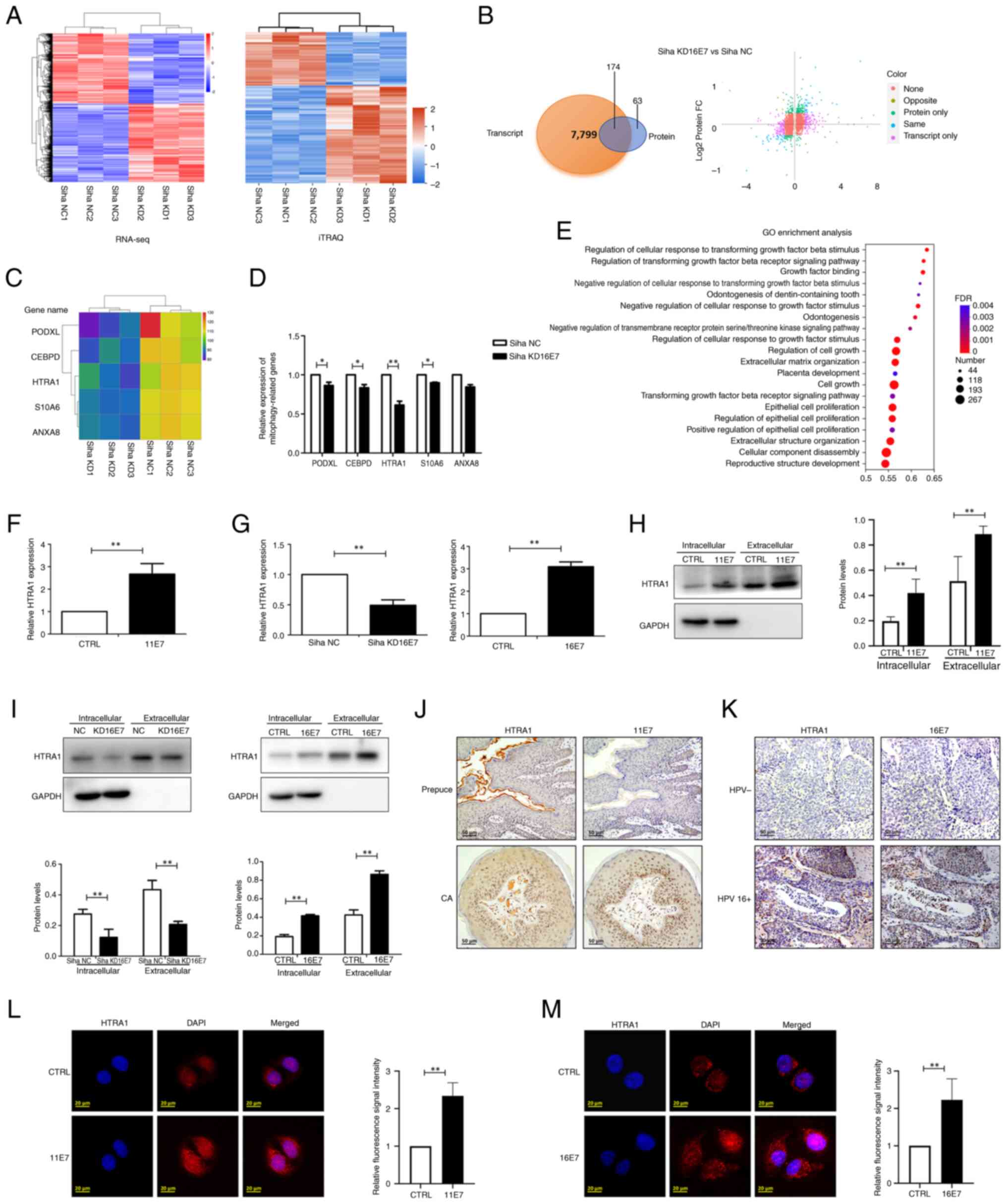

Siha cells with stable knockdown of HPV16 E7 were

employed to perform RNA-seq analysis at the transcriptional level

and iTRAQ analysis at the protein level. The heatmaps showed

significant differences between the control and the knockdown

groups (Fig. 2A), and a total of

174 genes exhibiting consistent expression trends and statistically

significant alterations in both transcriptomic and proteomic

profiles were identified (Fig.

2B). Among these, five potential mitophagy-related genes were

selected for further validation based on a comprehensive review of

the literature: PODXL (67,68), CEBPD (69,70), HTRA1 (71,72), S10A6 (73,74) and ANXA8 (75,76) (Fig. 2C). RT-qPCR was subsequently

performed to assess the expression levels of these genes in the

control and knockdown groups. The results demonstrated that PODXL,

CEBPD, HTRA1 and S10A6 were significantly downregulated in the

knockdown group; notably, HTRA1 exhibited the most pronounced

differential expression between the two groups (Fig. 2D). In addition, GO analysis of

the RNA-seq data revealed that among the statistically significant

GO terms, HTRA1 was involved in multiple GO terms associated with

mitophagy (Fig. 2E). For

example, GO:0090288 'negative regulation of cellular response to

growth factor stimulus (77,78), GO:0090101 'negative regulation of

transmembrane receptor protein serine/threonine kinase signaling

pathway (79) and GO:0090287

'regulation of cellular response to growth factor stimulus

(80) are biological processes

closely related to mitophagy.

| Figure 2HPV E7 facilitates the expression of

HTRA1 within keratinocytes. (A) Heatmap of RNA-seq and iTRAQ

analyses. (B) Examination of differentially expressed genes via

RNA-seq and iTRAQ analyses. 'None' indicates that there was no

difference in the expression of these genes between groups;

'opposite' indicates that the expression trend of the gene was

opposite in RNA-seq and iTRAQ analyses; 'same' indicates that the

expression trend of the gene was consistent in RNA-seq and iTRAQ

analyses; 'transcript only' indicates that these alterations were

observed exclusively in the RNA-seq data; 'protein only' indicates

that these alterations were observed exclusively in the iTRAQ data.

(C) Heatmap presenting the potential genes related to mitophagy

derived from the analysis (PODXL, CEBPD, HTRA1, S10A6 and ANXA8).

(D) qPCR was used to verify the expression of potential

mitophagy-related genes in the HPV16 E7 KD group. (E) GO analysis

of RNA-seq data indicated that HTRA1 was significantly enriched in

GO terms associated with mitophagy. (F) qPCR was used to detect the

expression of HTRA1 in HPV11 E7-overexpressing NHEKs. (G) qPCR was

used to detect the expression of HTRA1 in HPV16 E7-overexpressing

NHEKs and in stable Siha cells with knockdown of HPV16 E7. (H)

Western blotting was used to confirm the expression of

intracellular and extracellular HTRA1 in HPV11 E7-overexpressing

NHEKs. (I) Western blotting was used to determine the expression of

intracellular and extracellular HTRA1 in HPV16 E7-overexpressing

NHEK cells and HPV16 E7 KD Siha cells. (J) Examination of the

expression of HTRA1 and HPV11 E7 in CA and normal foreskin samples

by IHC. (K) Examination of the expression of HTRA1 and HPV16 E7 in

HPV-negative cervical cancer and HPV 16-positive cervical cancer

tissues by IHC. Intracellular expression levels of HTRA1 protein

were assessed and compared between the CTRL group and the (L) HPV11

E7 and (M) HPV16 E7 overexpression groups using immunofluorescence

analysis. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. CA,

condyloma acuminatum; HPV, human papillomavirus; HTRA1,

high-temperature requirement A serine peptidase 1; GO, Gene

Ontology; IHC, immunohistochemistry; iTRAQ, isobaric tags for

relative and absolute quantitation; NC, negative control; KD,

knockdown; NHEK, normal human epidermal keratinocyte; qPCR,

quantitative PCR; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing. |

In addition, compared with in the control group, the

expression of HTRA1 was significantly downregulated both

intracellularly and extracellular in the 16E7 knockdown group

(Fig. 2G and I). Furthermore, a

lentivirus was used to stably express HPV11 E7 in NHEKs, and the

expression of HTRA1 was subsequently assessed. It was noticed that

low-risk HPV11 E7 was capable of facilitating the mRNA and protein

expression levels of HTRA1 (Fig. 2F

and H). Concurrently, elevated intracellular and extracellular

expression of HTRA1 was observed in both HPV11+

condyloma acuminatum tissue specimens and HPV16+

cervical cancer tissue, with normal foreskin tissue and

HPV− cervical cancer tissue samples serving as

respective controls.(Fig. 2J and

K). Although HTRA1 is primarily recognized as a secreted

protein, previous evidence has suggested that it also exhibits

intracellular expression (81,82). Immunofluorescence staining

revealed detectable levels of HTRA1 within NHEKs (Fig. 2L and M). Furthermore, the group

overexpressing HPV11 and HPV16 E7 exhibited a higher expression of

HTRA1 compared with that in the control group.

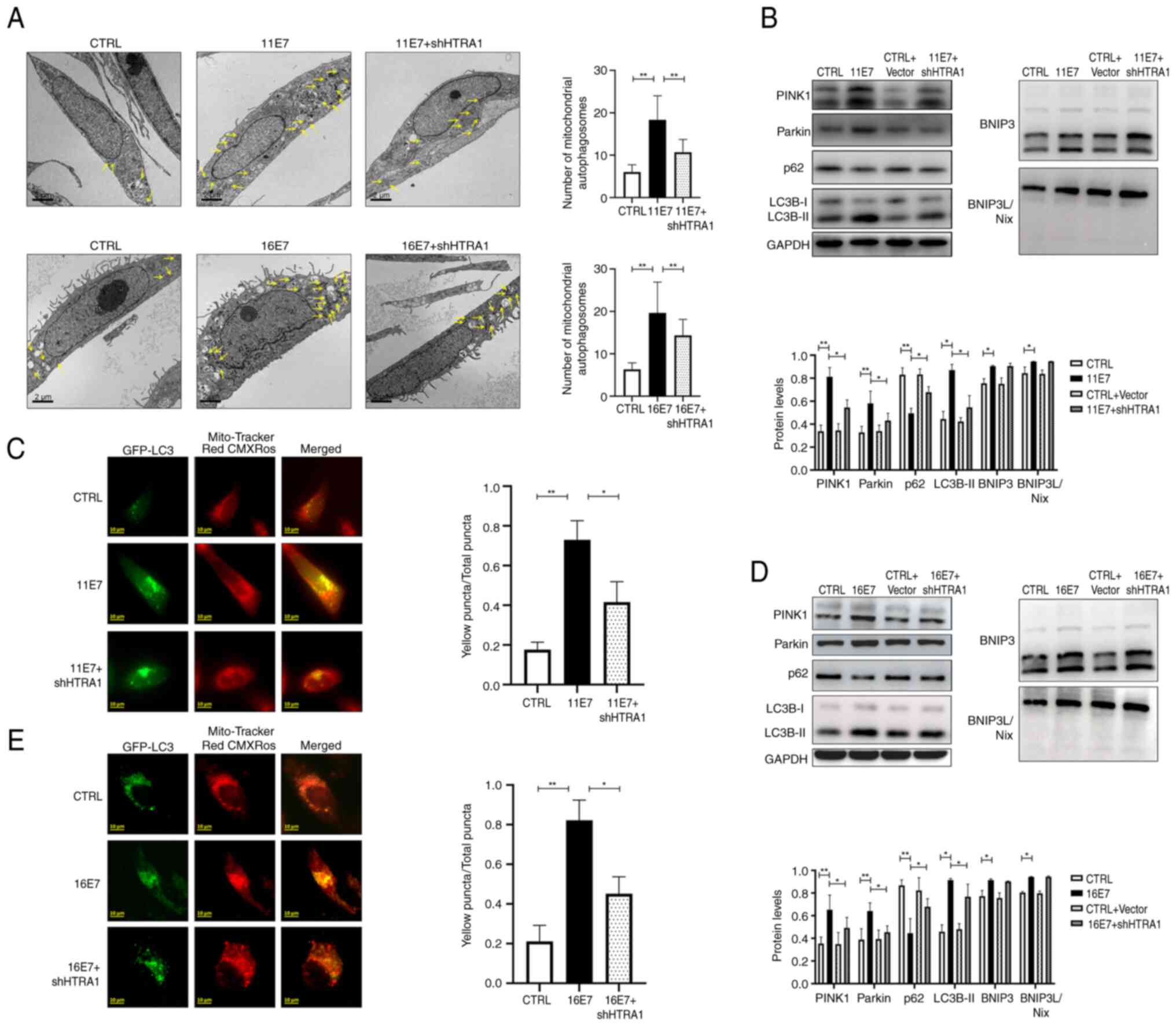

HPV E7 induces mitophagy in keratinocytes

through the modulation of HTRA1 gene expression

A lentivirus was used to stably express HPV11/16 E7

in NHEKs and HTRA1 knockdown was subsequently performed.

Intracellular mitophagy vesicles were observed by transmission

electron microscopy (Fig. 3A).

Compared with in the HPV11/16 E7 overexpression group, the number

of intracellular mitophagy puncta decreased after knocking down the

expression of HTRA1. Intracellular mitophagy was further examined

by observing the co-localization of GFP-LC3 and Mito-Tracker Red

CMXRos (Fig. 3C and E). It was

revealed that the proportion of yellow punctate granules decreased

following HTRA1 knockdown in HPV11/16 E7-overexpressing NHEKs,

indicating reduced mitophagy activity in the HTRA1 knockdown group.

Western blotting was employed to detect the expression levels of

the mitophagy-related proteins LC3 and p62, as well as proteins

associated with mitophagy pathways (Fig. 3B and D).The results confirmed

that following HTRA1 knockdown, the differences in p62 and LC3B

expression levels between the control group and the HPV E7

overexpression group were significantly diminished. Furthermore,

the role of HTRA1 in mediating HPV E7-induced activation of the

PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway was investigated. The results

demonstrated that overexpression of HPV E7 activated this pathway;

however, upon HTRA1 knockdown, the difference in PINK1/Parkin

pathway activity between the control group and the HPV E7

overexpression group was markedly attenuated; however, changes in

BNIP3/BNIP3L were not statistically significant.

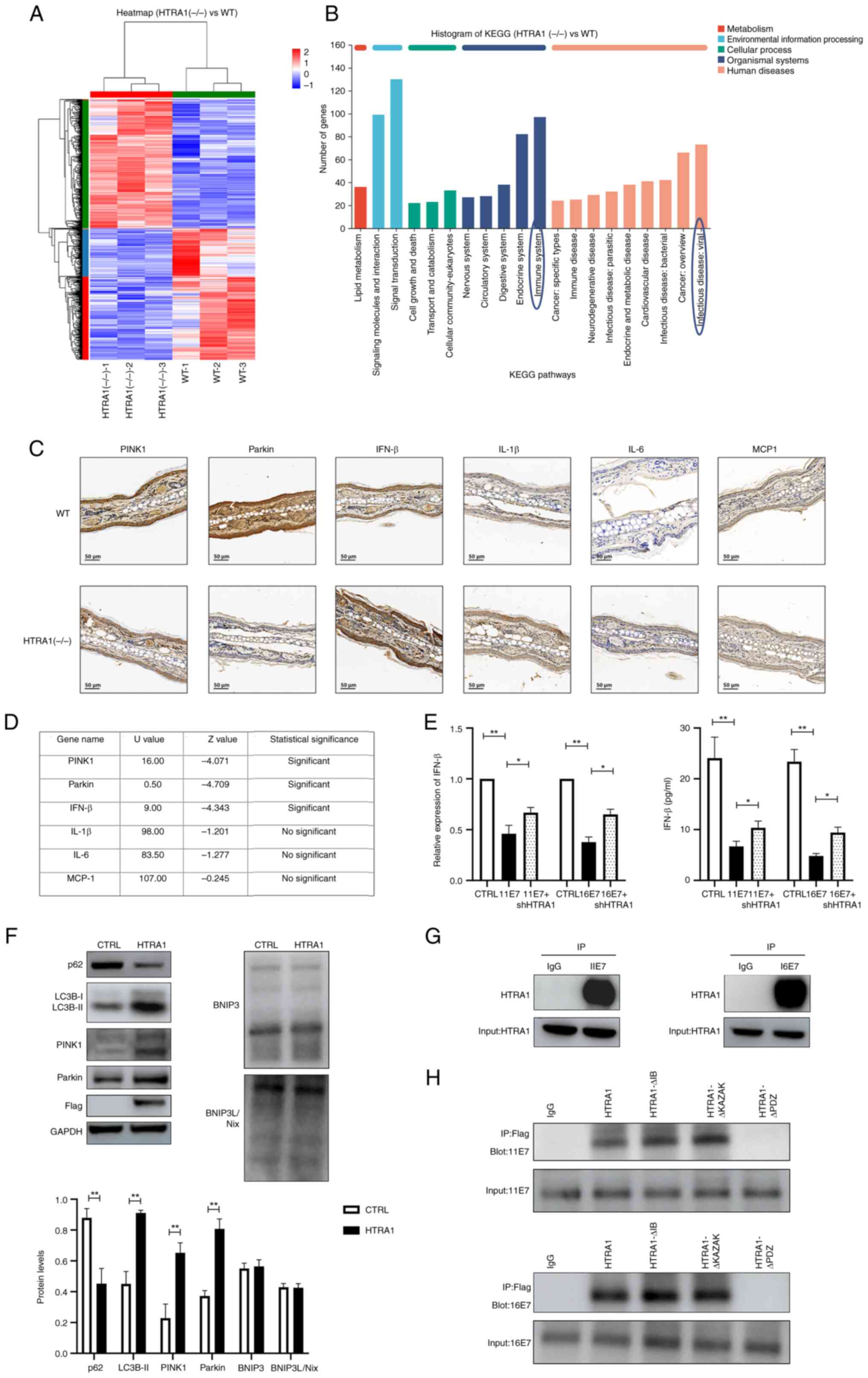

Knocking out HTRA1 attenuates

mitophagy

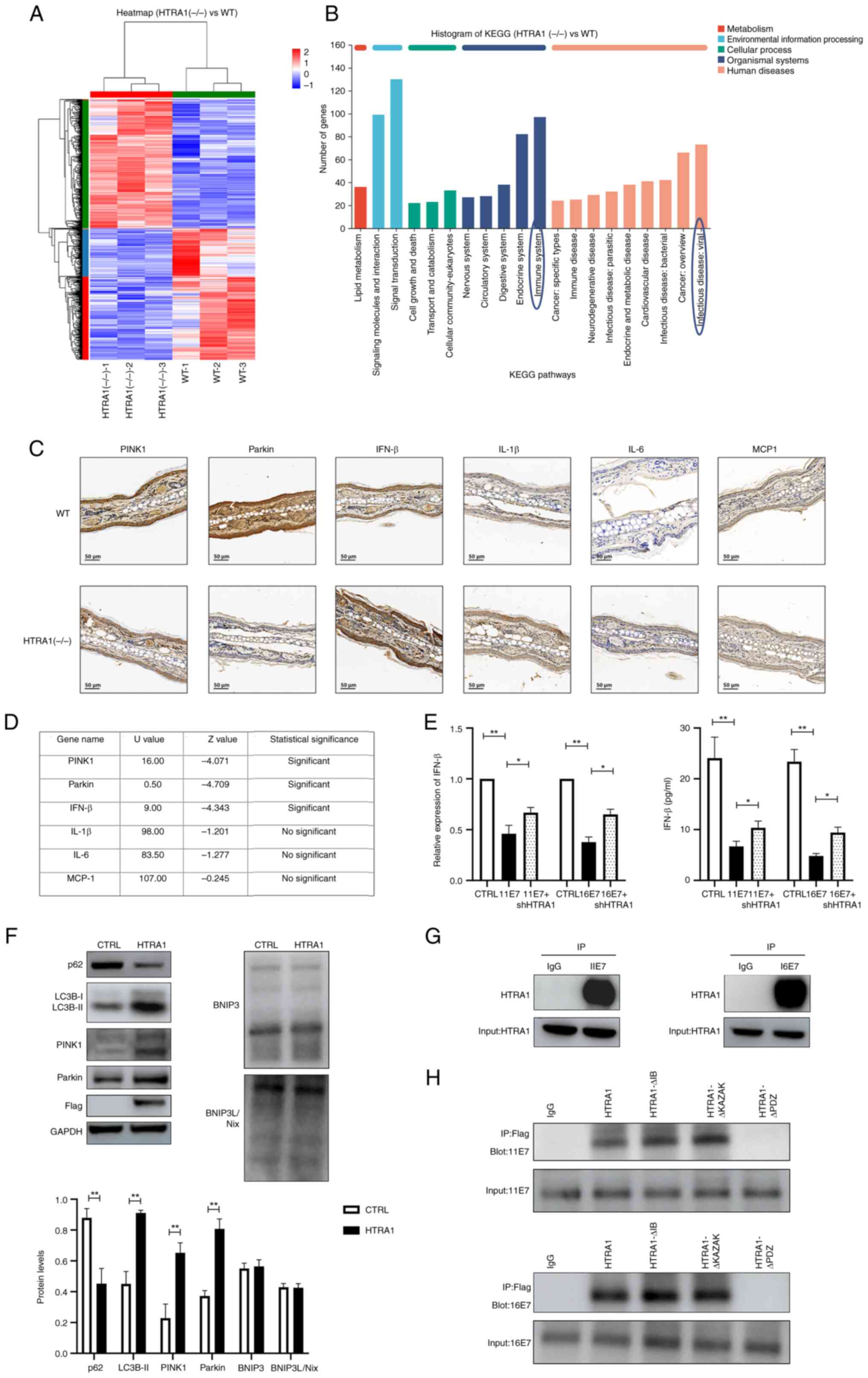

HTRA1(−/−) mice were acquired from Cyagen

Biosciences Inc. The genotype was detected and verified by agarose

gel electrophoresis (Fig. S1D).

Subsequently, skin tissue was harvested from 8-week-old WT and

HTRA1(−/−) mice, and total RNA was extracted for RNA-seq. The

resulting sequences were subjected to heatmap visualization and

KEGG signaling pathway analysis (Fig. 4A and B). The findings indicated

that HTRA1 was closely associated with the 'Immune system' and

'Infectious disease: viral'. Furthermore, HTRA1 was shown to be

closely related with 'Lipid metabolism', 'Signal transduction' and

'Cellular community-eukaryotes'. Subsequently, IHC was applied to

evaluate PINK1, Parkin, IFN-β, IL-1β and IL-6 expression in the ear

tissues of WT and HTRA1(−/−) mice. The results were statistically

analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test and demonstrated

downregulation of PINK1 and Parkin expression in the HTRA1(−/−)

group, alongside an upregulation of IFN-β expression; however,

changes in inflammatory factors such as IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1 were

not statistically significant (Fig.

4C and D). These results indicated that knockdown of HTRA1

could inhibit the expression of PINK1 and Parkin, while promoting

type I IFN production. Subsequently, qPCR and ELISA were employed

to assess the expression levels of type I IFNs in HPV11/16

E7-overexpressing NHEKs following HTRA1 gene knockdown. The results

demonstrated that the reduced IFN expression levels, induced by HPV

E7 overexpression, exhibited partial recovery after HTRA1 knockdown

(Fig. 4E). To investigate the

functional role of HTRA1, HTRA1 was overexpressed in NHEKs and the

expression levels of autophagy-related proteins were assessed using

western blot analysis. Western blot analysis indicated that

overexpression of HTRA1 alone may promote mitophagy by affecting

the expression levels of proteins in the PINK1/Parkin pathway,

whereas the expression levels of proteins in the other classic

mitophagy-related pathway, BNIP3/BNIP3L, remained unchanged

(Fig. 4F). To investigate the

regulatory effect of HPV E7 on HTRA1, an IP assay was performed,

which confirmed the physical interaction between the two proteins

(Fig. 4G). To precisely map the

binding site, three truncated HTRA1 mutant plasmids were generated

based on its known protein domain structure, and these constructs

were transfected into 293T cells stably overexpressing HPV E7

(Fig. S1C). Subsequent CO-IP

analysis demonstrated that truncation of the PDZ domain in HTRA1

abolished the interaction between HPV E7 and HTRA1 (Fig. 4H). These findings confirm that

HPV E7 specifically binds to the PDZ domain of HTRA1, suggesting

that this domain is critical for molecular interaction.

| Figure 4Knockout of HTRA1 can suppress

mitophagy. (A) Heatmap illustrating the differential gene

expression RNA-seq analysis of the skin of HTRA1(−/−) mice. For

each sample, 1 μg total RNA was utilized to assess RNA

integrity and construct libraries. A poly(A) mRNA selection system

was employed to eliminate ribosomal RNA contamination. The purified

RNA underwent reverse transcription, end-repairing, adapter

ligation and PCR amplification prior to sequencing on the Illumina

HiSeq 2500 platform. (B) KEGG pathway analysis of differentially

expressed genes from the RNA-seq results of HTRA1(−/−) mouse skin.

(C) Immunohistochemical assessment of PINK1, Parkin, IFN-β, IL-1β,

IL-6 and MCP-1 expression in the ear tissues of WT and HTRA1(−/−)

mice. (D) Mann-Whitney U test was employed to perform statistical

analysis of the immunohistochemistry results. (E) Quantitative PCR

and ELISA was employed to assess the levels of IFN-β in HPV11/16

E7-overexpressing NHEKs following HTRA1 gene knockdown. (F) Western

blotting was performed to evaluate the expression levels of

mitophagy-related markers and their associated signaling pathways

in NHEK cells with HTRA1 overexpression (Flag tag). All protein

expression levels were normalized to the loading control GAPDH. (G)

IP was utilized to investigate the interaction between HPV E7 and

HTRA1 in NHEKs. (H) Truncated HTRA1 plasmids were constructed and

transfected into 293 cells overexpressing HPV E7. Next, IP was

applied to identify the specific binding sites between HPV E7 and

HTRA1. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. BNIP3, Bcl-2

and adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3; BNIP3L,

BNIP3-like; CTRL, control; HPV, human papillomavirus; HTRA1,

high-temperature requirement A serine peptidase 1; IFN, interferon;

IP, immunoprecipitation; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes; NHEK, normal human epidermal keratinocyte; PINK1,

PTEN-induced kinase 1; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; sh, short hairpin;

WT, wild-type. |

Discussion

During the process of viral infection of epithelial

cells, the early proteins of HPV exert a crucial role in the

pathogenic process (6). The

functions of the early proteins of HPV are both synergistic and

notably distinct. Thus, exploring their individual functions holds

great importance.

Previous studies have revealed that the HPV E7

protein can dampen the immune response of epithelial cells through

multiple mechanisms, such as limiting the secretion of IFNs

(83), suppressing the

expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, restraining the activity

of antigen-presenting cells (65) and downregulating the activity of

T cells (84,85), thus leading to persistent viral

infection. Among these mechanisms, there are more studies on the

inhibition of the secretion of type I IFNs. For example, HPV16/18

E7 affects the cGAS-STING pathway by interacting with NLRX1 and

upregulating the expression of SUV39H1, thereby suppressing the

production of type I IFNs. HPV18 E7 can also physically interact

with interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF1) and recruit histone

deacetylases to the IFN-β promoter, thereby inhibiting the

IRF1-mediated activation of the IFN-β promoter and blocking its

transcription (87,88). Although previous studies have

affirmed that HPV E7 can impact the immune response of epithelial

cells, clinically, it is still not possible to eliminate persistent

viral infections and patients continue to be affected by persistent

HPV infection. Additionally, recent studies (89,90) have predominantly focused on

high-risk HPV, while there are relatively fewer studies (91,92) on low-risk HPV. However, diseases

related to low-risk HPV, such as condyloma acuminatum, have a high

recurrence rate; therefore, it is of considerable importance to

concurrently explore how high- and low-risk HPV E7 affect the local

immune microenvironment. In the present study, both high- and

low-risk HPV E7 were examined. Transmission electron microscopy,

fluorescence co-localization and western blotting were applied to

assess mitophagy levels in NHEKs overexpressing HPV11/16 E7,

revealing that HPV E7 significantly enhanced mitophagy in these

cells. The association between mitophagy and immune response

requires further investigation.

In recent years, the role of energy metabolism in

immune regulation has garnered increasing attention (93,94). Notably, certain organelles in

eukaryotic cells have been implicated in the regulation of energy

metabolism (23). Mitophagy, as

a specific autophagic phenomenon for the selective elimination of

damaged mitochondria, can impact the immune function of host cells

through multiple pathways, including inhibiting the activation of

inflammasomes (95,96), interfering with the expression of

type I IFNs (97,98) and preventing the initiation of

apoptosis in host cells (99,100), thereby affecting the cellular

immune state. Numerous studies have focused on the influence of

viruses on mitophagy in host cells. Viruses such as HBV, HCV, HSV

and HIV can induce mitophagy in host cells to suppress innate

immunity and sustain their persistent infection (101-103). However, at present, relatively

few studies (48,104) have focused on the association

between HPV and mitophagy. Several studies have investigated the

relationship between HPV E7 and autophagy. For example, it has been

confirmed that the expression of HPV16 E7 reduces the level of

dual-specificity phosphatase 5, leading to activation of the

MAPK/ERK signal, and the induction of classical autophagy through

the mTOR and AMPK pathways (65). However, research investigating

the association between HPV E7 and mitophagy remains limited.

Notably, a previous study reported that high-risk HPV E7 could

affect the mitophagy status of host cells (46); nevertheless, the specific

mechanism remains unexplained, and to the best of our knowledge, no

studies to date have focused on the association between low-risk

HPV E7 and mitophagy. In the present study, two classical mitophagy

pathways were assessed using western blotting. The results

demonstrated that HPV E7 promoted mitophagy through the modulation

of PINK1/Parkin and BNIP3/BNIP3L pathways Upon HTRA1 silencing, the

expression of the PINK1/Parkin pathway was markedly reduced,

whereas the BNIP3/BNIP3L pathway exhibited minimal downregulation,

with no statistically significant changes observed. By contrast,

HTRA1 overexpression alone significantly enhanced the activation of

the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Collectively, these findings indicated

that HPV E7 may regulate two distinct mitophagy pathways, while

HTRA1 predominantly influences mitophagy via its effects on the

PINK1/Parkin signaling axis.

HTRA1 is a non-glycosylated serine protease, which

encompasses a C-terminal PDZ domain and an N-terminal insulin-like

growth factor binding protein-like domain (105). Previous studies have

demonstrated that HTRA1 is associated with various biological

processes (106), regulates the

occurrence and development of tumors (107), and interacts with TGF-β family

proteins to regulate retinal angiogenesis as well as the survival

and maturation of neurons during development (108). HTRA1 serves a role in diseases

such as osteoarthritis (109,110), cartilage degeneration (111,112), coronary artery disease

(113), cerebral small vessel

disease (114) and macular

degeneration (115). However,

despite the identification of numerous functions at present, there

are relatively limited studies (116,117) on the exploration in-depth of

the function of HTRA1 protein. To date, to the best of our

knowledge, no study has focused on the association between HPV and

HTRA1, nor has the association between HTRA1 and mitophagy been

explored. In the present study, Siha cells with stable knockdown of

HPV16 E7 expression were employed for combined RNA-seq

(transcriptional level) and iTRAQ (protein level) analyses. The

results revealed that the expression of HTRA1 was decreased in the

knockdown group. GO analysis suggested that HTRA1 was closely

related to mitophagy. Furthermore, NHEKs overexpressing HPV11/16 E7

were utilized to verify that HPV E7 enhanced the expression of

HTRA1 at the transcriptional and translational levels.

Additionally, HTRA1 knockdown in HPV11/16

E7-overexpressing NHEKs was achieved using shRNA. The results

indicated that knockdown of HTRA1 significantly inhibited mitophagy

in keratinocytes and restored the suppression of type I IFNs.

Collectively, these findings suggested that HPV E7 may enhance

HTRA1 expression to activate the PINK1/Parkin pathway, thereby

promoting mitophagy in host cells and influencing type I IFN

expression, which ultimately affects the immune response of

keratinocytes and facilitates persistent viral infection.

In the present study, IP was employed to ascertain

whether HPV E7 and HTRA1 bind to each other to regulate their

expression. The outcomes demonstrated that HPV E7 could directly

bind to HTRA1 to impact its expression, which is in accordance with

the literature (118). To

further elucidate the direct interaction between HPV E7 and HTRA1,

truncated mutant plasmids were constructed, and it was identified

that HPV E7 specifically bound to the PDZ domain of HTRA1 to exert

its biological function. In subsequent studies, we aim to further

elucidate the exact binding motif of HPV E7 and the underlying

molecular mechanisms by which this interaction upregulates HTRA1

expression, leading to modulation of the PINK1/Parkin signaling

pathway and the regulation of mitophagy. Although HTRA1 is

predominantly recognized as a secreted protein, accumulating

evidence has demonstrated its functional role within intracellular

compartments (61,119-121). The current study revealed that

HTRA1 exhibited a detectable level of intracellular expression.

Considering that HPV E7, as a viral oncoprotein, primarily executes

its biological functions inside the cell, the present experimental

data confirmed a direct interaction between HPV E7 and HTRA1. Based

on these findings, it may be hypothesized that HPV E7 could

modulate the expression and biological activities of HTRA1 through

binding to its intracellularly localized form. The present findings

suggested that HTRA1 serves a role in regulating the

ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy pathway PINK1/Parkin, thereby

promoting mitophagy. Further exploration is warranted regarding how

HTRA1 affects this ubiquitin-related pathway. Furthermore, the

current study revealed that HPV E7 could also influence the

non-ubiquitinated mitophagy pathway BNIP3/BNIP3L; however, this

effect did not occur through modulation of HTRA1. This mechanism is

under further exploration. Our laboratory team is actively

investigating the underlying molecular mechanisms to further

elucidate the role of HTRA1 in the regulation of mitophagy. Future

investigations should aim to elucidate the specific mechanisms by

which HPV E7 impacts the BNIP3/BNIP3L pathway and further examine

how HPV influences mitophagy.

At present, research on the relationship between

HPV and mitophagy remains relatively limited. The current study has

partially addressed this knowledge gap; however, several aspects of

this research require further refinement. For example, the present

study primarily focused on the regulatory role of the single HPV E7

gene in mitophagy, without examining the effects of complete HPV

viral particles on host cell mitophagy. In future studies, we aim

to simulate the natural infection process of HPV using pseudovirus

infection models to further elucidate the underlying mechanisms by

which the virus influences mitophagy, thereby enhancing the

understanding of its association with persistent HPV infection.

Furthermore, additional investigation into the key

gene HTRA1 is recommended to better understand its biological

function and potential regulatory mechanisms. The present findings

indicated that HTRA1 can independently induce mitophagy and that

its expression is closely associated with this process. However,

its impact on downstream immune signaling pathways remains unclear.

In the next phase of our research, RNA-seq data from HTRA1(−/−)

mice will be analyzed to identify and validate alterations in

relevant immune-related genes and signaling pathways. This approach

will allow for a systematic evaluation of the role of HTRA1 in

immune regulation. Regarding clinical samples and translational

applications, the preliminary observations of the current study

suggested that HTRA1 expression may be elevated in tissues from

patients positive for HPV11 and HPV16; however, the current sample

size is limited. Our future study aims to expand the sample

collection to include additional HPV16+ cervical cancer

tissues and HPV11+ condyloma acuminatum specimens. All

cervical cancer samples will be included in the analysis following

pathological classification. Subsequently, we aim to employ

immunohistochemical techniques to assess HTRA1 expression across

samples and perform comparative analyses. Based on these results,

stratified statistical and systematic analyses will be conducted to

explore the potential associations between HTRA1 expression and

clinical features. Ultimately, the aim for these findings is to

provide a scientific foundation for the development of

HTRA1-targeted therapeutics aimed at treating diseases associated

with persistent HPV infection.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that HPV

E7 could promote the expression of HTRA1 to activate the

PINK1/Parkin pathway in keratinocytes, leading to enhanced

mitophagy and reduced expression of type I IFN in host cells. The

findings are expected to offer novel concepts and targets for the

treatment of HPV persistent infection-related disorders.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. The RNA-seq data generated

in the present study may be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus

database under accession numbers GSE307971 and GSE308049, or at the

following URLs:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE307971

and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE308049,

respectively.

Authors' contributions

HC and XS confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. HC, XS and BZ designed the research. XS, BZ, SC and DK

performed the research. BZ, SC and DK analyzed the data and all

authors interpreted the data. BZ drafted the manuscript. HC and XS

revised the manuscript content. HC takes responsibility for the

integrity of the data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experimental procedures involving mice were

approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw

Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (approval no.

202402156; Hangzhou, China). All human samples were collected

following the collection of written informed consent from the

research participants. All experimental procedures involving human

tissues were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sir Run

Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (approval

nos. 20210923-39 and 2021072 9-263). The NHEKs used in the present

study purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc. The

Medical Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang

University School of Medicine has confirmed that ethics approval is

not required for the use of these cells.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all

patients prior to their participation in the current study,

including consent for publication of the present study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82103740 and 82471846) and the

Science and Technology Projects of Zhejiang Province (grant no.

2022RC198).

References

|

1

|

Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, Bravo IG,

Stoler M, Broker TR and Stanley MA: The biology and life-cycle of

human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. 30(Suppl 5): F55–F70. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Woodworth CD: HPV innate immunity. Front

Biosci. 7:d2058–d2071. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chen L, Hu H, Pan Y, Lu Y, Zhao M, Zhao Y,

Wang L, Liu K and Yu Z: The role of HPV11 E7 in modulating

STING-dependent interferon β response in recurrent respiratory

papillomatosis. J Virol. 98:e01925232024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C

and Murakami I: Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease

association. Rev Med Virol. 25(Suppl 1): S2–S23. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Crosbie EJ, Einstein MH, Franceschi S and

Kitchener HC: Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet.

382:889–899. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

McBride AA: Oncogenic human

papillomaviruses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci.

372:201602732017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Duensing S and Münger K: The human

papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins independently induce

numerical and structural chromosome instability. Cancer Res.

62:7075–7082. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Klingelhutz AJ and Roman A: Cellular

transformation by human papillomaviruses: lessons learned by

comparing high- and low-risk viruses. Virology. 424:77–98. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang B, Chen W and Roman A: The E7

proteins of low- and high-risk human papillomaviruses share the

ability to target the pRB family member p130 for degradation. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:437–442. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

10

|

Münger K, Werness BA, Dyson N, Phelps WC,