Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a common chronic metabolic

disorder with multifactorial etiology (1). It is characterized by elevated

blood glucose levels or hyperglycemia, which results from either

insufficient insulin production due to β-cell dysfunction or

impaired insulin action secondary to insulin resistance (2). In recent years, the incidence and

prevalence of DM have risen sharply due to changes in lifestyle,

including prolonged physical inactivity, sedentary behavior and

excessive intake of high-fat and high-sugar (HFHS) diets. According

to the latest epidemiological data from the International Diabetes

Federation, >425 million people world-wide are currently

affected by DM, a figure expected to rise to 629 million by 2045

(3), underscoring the growing

threat of DM to global health.

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the most common

complications of DM, affecting ~40% of patients with DM throughout

disease progression (4). DN is

primarily attributed to chronic hyperglycemia-induced microvascular

damage in the kidneys, which leads to impaired renal perfusion and

subsequently triggers inflammation, oxidative stress,

glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, ultimately

resulting in progressive and irreversible renal dysfunction. As DN

progresses, patients may develop symptoms such as edema,

hypertension and proteinuria; in advanced stages, some individuals

require dialysis to maintain internal homeostasis, which severely

compromises both life expectancy and quality of life (5). Diabetic osteoporosis (DOP) is

another common complication of DM, with a complex pathogenesis

involving multiple pathophysiological mechanisms, including

diminished insulin-mediated inhibition of bone resorption, enhanced

bone destruction due to chronic inflammation and local accumulation

of advanced glycation end-products in bone tissue (6). The principal complication

associated with DOP is fragility fractures. Clinical investigations

have shown that individuals with DM are 1.38-1.7 times more likely

to sustain proximal femoral fractures and 2.03 times more likely to

experience vertebral fractures than healthy individuals (7-9).

Although fractures associated with DOP are not directly fatal, they

markedly impair the self-care ability of patients with DM, imposing

a substantial burden on both patients and their families. More

importantly, there appears to be a potential link between DN and

DOP, two major complications of DM. A study by Xia et al

(10) demonstrated that patients

with DN are at markedly higher risk of developing DOP compared with

those with DM without DN. Conversely, a case-control study by Yan

et al (11) identified

osteoporosis (OS) as an independent risk factor for DN among

patients with DM. These findings indicate that treatment strategies

for DM must consider both kidney and bone status to prevent the

reciprocal exacerbation between DN and DOP, a key step toward

improving clinical outcomes and extending patient lifespan.

Akebia saponin D (ASD), a natural small-molecule

bioactive compound isolated from Dipsacus asper, exhibits

multiple pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory,

antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects (12). Previous cellular and animal

studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of ASD in

diseases such as bronchial asthma, cerebral hemorrhage and hepatic

steatosis (13-15). However, the efficacy of ASD in

treating DM complications remains largely unexplored.

Semaglutide, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1

(GLP-1) receptor agonist, has been widely used in clinical practice

for the management of type 2 DM (T2DM) (16). Specifically, Semaglutide

facilitates glycemic control and weight reduction in patients with

T2DM by enhancing insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon release,

delaying gastric emptying and improving insulin sensitivity

(17). However, the therapeutic

potential and underlying mechanisms of Semaglutide in DN and DOP

remain inadequately elucidated.

Accordingly, the present study intended to construct

a dual-complication DM rat model characterized by both DN and DOP

using high-fat feeding and repeated low-dose streptozotocin (STZ)

injections. ASD, selected for its documented anti-inflammatory,

antioxidant and anti-apoptotic properties and its potential

benefits in metabolic disorders and Semaglutide were then

administered to the animals to comprehensively assess their

combined efficacy in improving DN and DOP, as well as to explore

the potential mechanisms involved. It was hypothesized that ASD and

Semaglutide may exert synergistic protective effects against DN and

DOP by modulating the Klotho-p53 signaling axis. The outcomes of

this research may provide a theoretical basis for the combined use

of ASD and Semaglutide and contribute novel perspectives on the

management of DM complications.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

A total of 42 male Sprague-Dawley rats (SPF grade;

180-220 g; 8 weeks old) were provided by Guangdong Medical

Laboratory Animal Center [Production License No. SCXK (Yue)

2022-0002]. Only male rats were used in order to avoid the

potential variability associated with the estrous cycle in females,

which could influence glucose metabolism, bone turnover and renal

function (18,19). This approach was chosen to

minimize hormonal fluctuations and ensure experimental consistency.

Rats were housed under controlled conditions (20-26°C; 30-70%

humidity; 12 h light/dark cycle) with free access to food and

water. Ethical approval for the present study was obtained from the

Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Guangdong Medical Laboratory

Animal Center (approval no. D202505-13).

Reagents, virus construction and animal

grouping

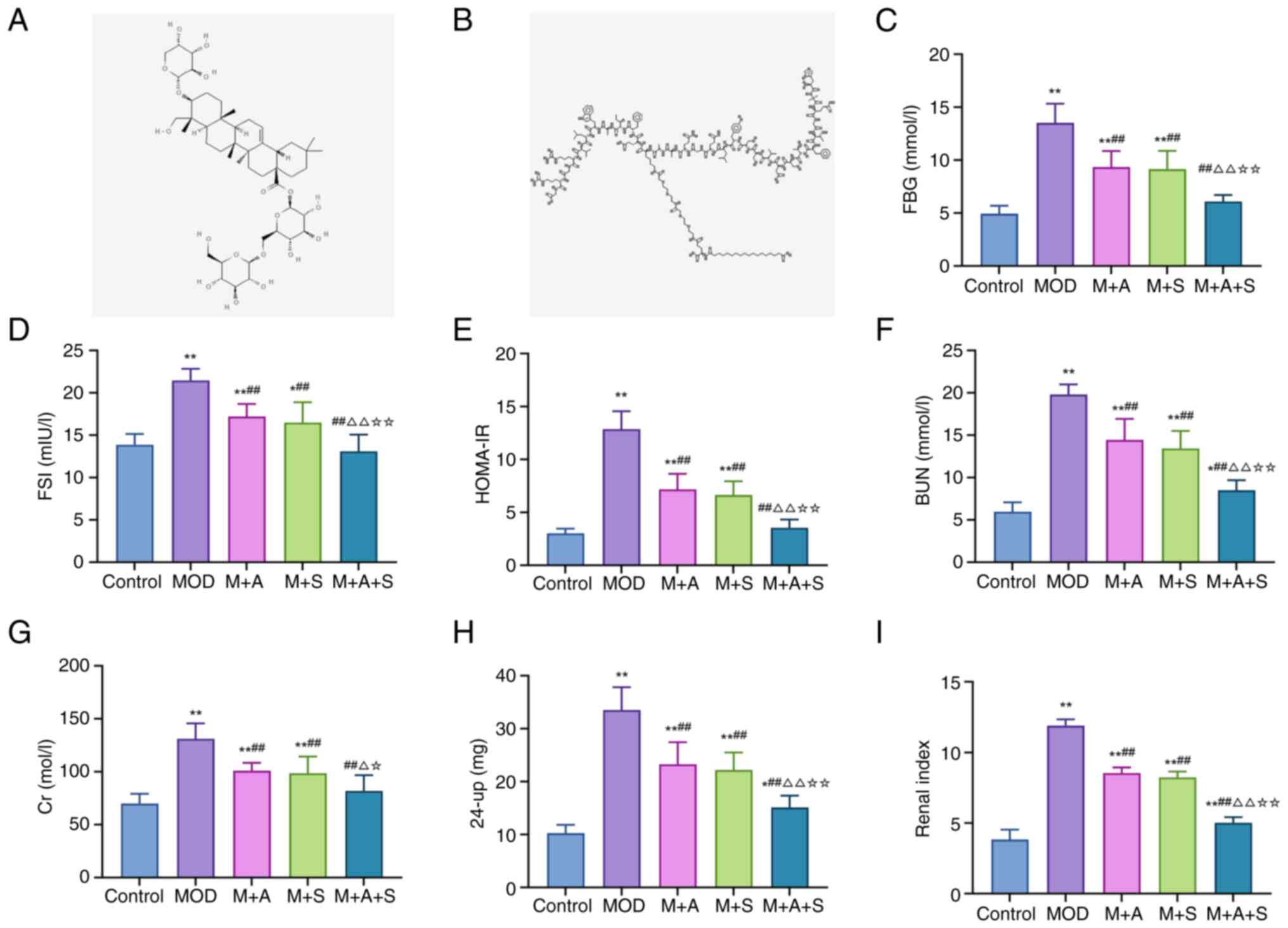

STZ, ASD and Semaglutide were obtained from

MedChemExpress and the chemical structures of ASD and Semaglutide

are shown in Fig. 1A and B. STZ

(30 mg/kg) was freshly prepared in 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH

4.5) and administered intraperitoneally once daily for two

consecutive days. ASD (90 mg/kg/day) was dissolved in DMSO (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and diluted with PBS

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; pH 7.4) for

oral gavage, with a final volume of 10 ml/kg. Semaglutide (120

μg/kg/day, subcutaneous injection, 12 weeks) was dissolved

in PBS(pH 7.4) and administered subcutaneously at a dose volume of

1 ml/kg (20). The dosage was

selected based on previous clinical and preclinical studies

demonstrating safe and effective exposure (21,22). A formal dose-response trial was

not conducted in the present study. All doses were adjusted

according to body surface area to ensure pharmacological

equivalence (23). To silence

Klotho expression, a recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV)

encoding either Klotho-specific short hairpin (sh)RNA (sh-Klotho)

or non-targeting control shRNA (shNC) was synthesized by Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd. Viral particles were prepared using standard

protocols and purified by polyethylene glycol precipitation and

ultracentrifugation and administered via tail vein injection (200

μl/injection) every three days.

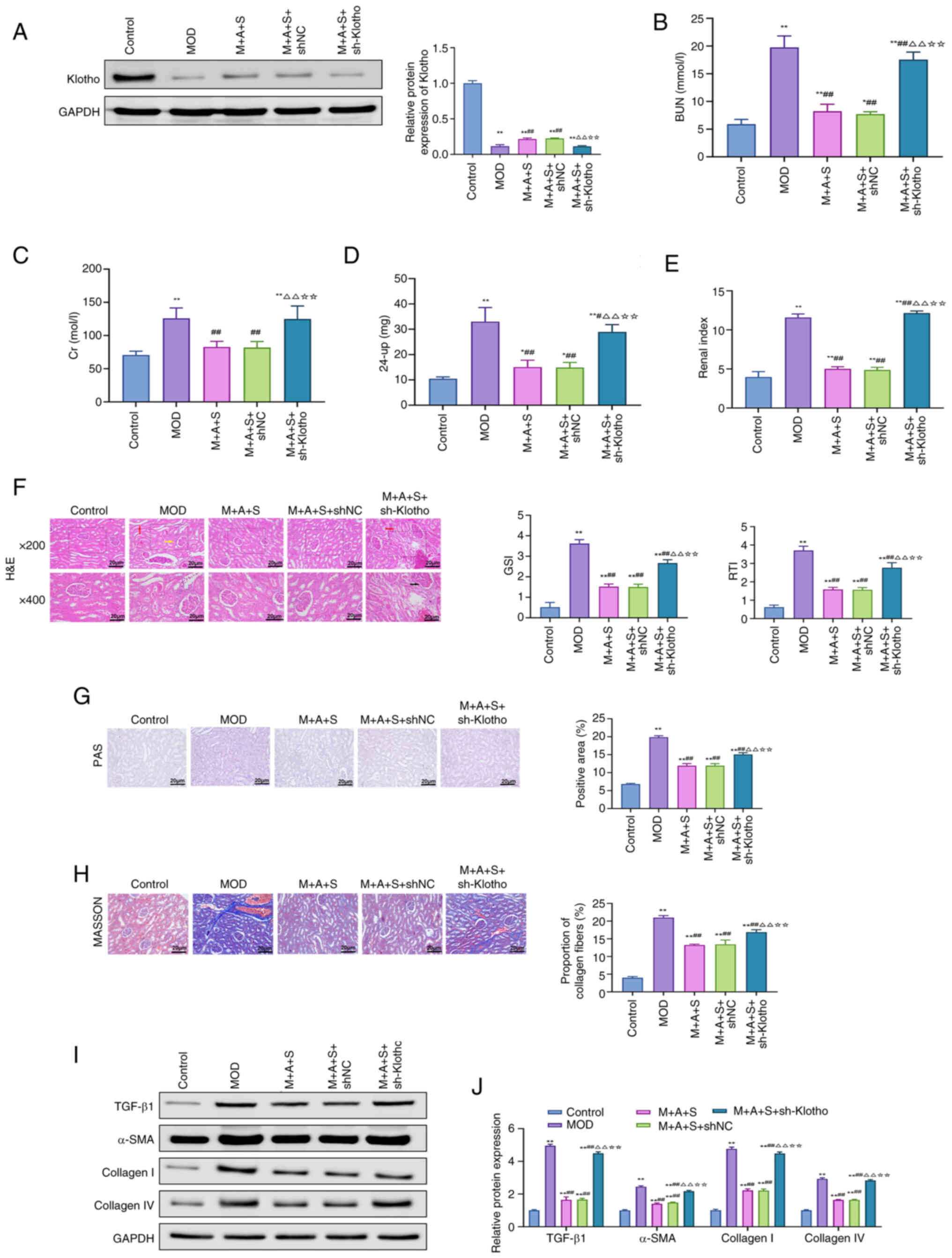

| Figure 1Chemical structures of ASD and

Semaglutide and their effects on glucose metabolism and renal

function in diabetic rats. Two-dimensional structures of (A) ASD

and (B) Semaglutide were retrieved from PubChem. Enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay analysis of (C) FBG, (D) FSI and (E) HOMA-IR.

(F-I) Biochemical analysis of BUN, Cr, 24-up and renal index.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control;

##P<0.01 vs. MOD; ΔP<0.05,

ΔΔP<0.01 vs. M + A; ☆P<0.05,

☆☆P<0.01 vs. M + S. ASD, akebia saponin D; FBG,

fasting blood glucose; FSI, fasting serum insulin; HOMA-IR,

homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; BUN, blood urea

nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; 24-up, 24-h urinary protein. |

Following one week of acclimatization, the rats were

randomly assigned into seven groups (n=6 per group). During the

modeling process, two rats in the MOD group and one rat in the M +

S group died and one rat in the MOD group did not meet the diabetic

criteria (fasting blood glucose <7.8 mmol/l). Thus, the final

numbers of rats analyzed were: Control (n=6), MOD (n=3), M + A

(n=6), M + S (n=5), M + A + S (n=6), M + A + S + shNC (n=6) and M +

A + S + sh-Klotho (n=6). A T2DM model was established based on

previously validated methods (24-26), involving high-fat high-sucrose

(HFHS) feeding for 8 weeks followed by two consecutive low-dose

intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ; 30 mg/kg). This

combination is widely recognized as a reliable method to induce

T2DM-like phenotypes, as it produces insulin resistance with

partial β-cell dysfunction rather than complete β-cell destruction

typical of type 1 diabetes (T1DM). Rats with fasting blood glucose

(FBG) >7.8 mmol/l and reduced insulin sensitivity were

considered successfully modeled. The experimental groups were as

follows: i) Control: Standard diet + vehicle (sodium citrate

buffer, i.p.) + saline via oral gavage for 12 weeks. ii) Model

(MOD): HFHS diet + STZ + saline via oral gavage for 12 weeks. iii)

MOD + ASD (M + A): MOD model + ASD via oral gavage for 12 weeks.

iv) MOD + Semaglutide (M + S): MOD model + Semaglutide via

subcutaneous injection for 12 weeks. v) MOD + ASD + Semaglutide (M

+ A + S): Combined ASD (oral gavage) and Semaglutide (subcutaneous)

for 12 weeks. vi) M + A + S + shNC: Same as group 5, plus tail vein

injection of AAV-shNC every three days. vii) M + A + S + sh-Klotho:

Same as group 5, plus tail vein injection of AAV-shKlotho every

three days. The ASD dose used in the present study was referenced

from the research by Yu et al (27), while the Semaglutide dose was

based on the clinically recommended safe and effective dosage

(21,22).

Sample collection and processing

After the final treatment, rats were placed in

PhenoMaster metabolic cages (TSE Systeme GmbH) for 24 h, with free

access to water but no food. Urine was collected, centrifuged

(1,000 × g; 5 min; 4°C) and supernatant was analyzed for protein

concentration using a BCA kit (Shanghai Lianshui Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.). Results were recorded as 24-h urinary protein (24 up)

levels. The following morning, rats were anesthetized and

sacrificed by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at

a dose of 150 mg/kg. Body and kidney weights were measured to

calculate the renal index (kidney weight/body weight). Blood

samples were collected via abdominal aorta, centrifuged (1,500 × g;

5 min; 4°C) and serum stored at −80°C. Both kidneys and femurs were

harvested under sterile conditions, cleared of soft tissues and

stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Biochemical analysis

The femoral tissues were defatted, crushed and

acid-digested. Serum, urine and femur extracts were analyzed for

blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), calcium

(Ca2+) and phosphate (PO43−)

levels using a HITACHI-7170S automatic biochemical analyzer

(Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation). Serum levels of

glycometabolic and bone turnover markers were measured using

commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits.

Glycometabolic indicators included fasting blood glucose (FBG; cat.

no. E02G0462; Shanghai BlueGene Biotech), fasting serum insulin

(FSI; cat. no. mlE2721; Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.). The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

(HOMA-IR), which was calculated using the formula: HOMA-IR=(FBG ×

FSI)/22.5. This calculation was used to indirectly evaluate insulin

sensitivity in the diabetic rat model. Bone turnover markers were

quantified using rat ELISA kits from Shanghai Enzyme-linked

Biotechnology Co., Ltd: alkaline phosphatase (ALP; cat. no.

ml107021), procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (PINP; cat. no.

ml038224-1), C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX-I; cat.

no. ml003410) and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP; cat.

no. ml059485). Each assay was performed in triplicate.

Histological analysis of kidney and femur

tissues

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for

24 h at 4°C, kidney and femur tissues were embedded in paraffin and

sectioned into 4-μm slices using a microtome (Leica

Biosystems). Kidney sections were made in the coronal plane and

femur sections along the longitudinal axis. Sections were

deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol

solutions (28). Hematoxylin and

eosin (H&E) staining was performed to assess renal and femoral

structural integrity. The glomerulosclerosis index (GSI) and renal

tubular interstitial injury index (RTI) were calculated according

to previous studies (29). In

femoral sections, osteoblasts and osteocytes were quantified.

Additional staining included periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) for

glomerular basement membrane injury: 0.5% periodic acid for 10 min

at room temperature (RT), Schiff reagent 15 min, two sulfite washes

(5 min each), and hematoxylin counterstain 2 min, followed by

dehydration, clearing, and mounting. Masson's trichrome was

performed for renal fibrosis evaluation: Bouin's solution 56°C, 30

min, Weigert's iron hematoxylin 10 min, Biebrich scarlet-acid

fuchsin 10 min, phosphomolybdic/phosphotungstic acid 10 min,

aniline blue 10 min, and 1% acetic acid 2 min, followed by

dehydration, clearing and mounting. Images were acquired an Olympus

BX53 microscope (Olympus Corporation) and quantified using ImageJ

v1.53 (NIH) based on three randomly selected fields per

section.

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)

analysis

Femoral microarchitecture was assessed by SkyScan

1276 micro-CT (Bruker Corporation). Scanning parameters included

300 μA tube current, 75 kV tube voltage, 75 msec exposure

time, 0.7° rotation step and 12 μm voxel resolution,

averaging 2 frames per step. Images were reconstructed with NRecon

(version 1.7.4.6; Bruker Corporation) software and the region of

interest was defined as a 2.4 mm volume of trabecular bone starting

1 mm proximal to the distal growth plate. Quantitative analysis

using CTAn (version 1.20.3.0; ROI) software included measurements

of bone mineral density (BMD), bone mineral content (BMC), bone

volume/tissue volume (BV/TV), bone surface/bone volume (BS/BV),

trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th),

trabecular number (Tb.N) and structure model index (SMI).

Three-point bending test

Femoral biomechanical properties were evaluated

using an RGWF4005 electronic universal testing machine (Shenzhen

Reger Instrument Co. Ltd.) after micro-CT scanning. During testing,

the distal and proximal ends of the femur were fixed on two support

points spaced 10 mm apart and a vertical downward force was applied

to the midshaft of the femur until fracture occurred. The ultimate

load, bending strength and Young's modulus were recorded to

evaluate mechanical integrity.

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraffin-embedded kidney and femur sections (4

μm; prepared as aforementioned) were baked at 60°C for 30-60

min before staining. Paraffin sections were subjected to

heat-induced antigen retrieval in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH

6.0) at 95°C, followed by blocking with 3% BSA (MilliporeSigma) for

1 h. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary

antibodies anti-Klotho (1:200; cat. no. PA5-21078), anti-p53

(1:200; cat. no. MA5-12453) and anti-γ-H2AX (1:200; cat. no.

MA5-33062), all from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

After primary incubation, slides were washed in PBST (3×5 min),

incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h

at RT, and washed again in PBST (3×5 min). Nuclei were

counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml, 5 min, RT; protected from

light), rinsed in PBS, and mounted with anti-fade medium. Images

were captured from three random fields on an Olympus fluorescence

microscope (Olympus Corporation) using 10×, 20×, and 40× objectives

(identical acquisition settings across groups), and fluorescence

intensities were quantified using ImageJ v1.53 (NIH).

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from bilateral residual

kidney and femur tissues using RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) supplemented with protease and phosphatase

inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA

protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology) and 30 μg protein

per lane was loaded. Equal amounts of protein were separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), transferred to

polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) and blocked in 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at

room temperature. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C

with the following primary antibodies (all from Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.): TGF-β1 (cat. no. MA5-16949; 1:1,000),

α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; cat. no. 14-9760-82; 1:1,000),

Collagen I (cat. no. PA1-26204; 1:1,000), Collagen IV (cat. no.

PA5-104508; 1:1,000), osteoprotegerin (OPG; cat. no. MA5-15715;

1:1,000), osteocalcin (OCN; cat. no. MA1-20786; 1:1,000), receptor

activator of nuclear factor κ-b ligand (RANKL; cat. no. MA1-41161;

1:1,000), Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2; cat. no.

PA5-82787; 1:1,000), Klotho (cat. no. MA5-32784, 1:1,000),

γ-Histone H2AX (γ-H2AX; cat. no. MA5-33062, 1:1,000),

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated protein (ATM; cat. no. MA1-23152;

1:1,000), phosphorylated (p-)ATM (cat. no. MA1-2020; 1:1,000), p53

(vMA5-12557; 1:1,000), p21 (cat. no. MA5-14949, 1:1,000) and GAPDH

(vMA5-15738; 1:5,000). After TBST washes, HRP-conjugated secondary

antibodies (cat. nos. 32460 and 62-6520; 1:10,000; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) were applied for 1 h at room temperature. Bands

were visualized using an ECL chemiluminescent substrate

(SuperSignal West Pico PLUS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

imaged on a Tanon 5200 system (Tanon Science and Technology Co.,

Ltd.). Densitometry was performed using ImageJ v1.53 (NIH), and

target signals were normalized to GAPDH. Each sample was analyzed

in triplicate.

Bioinformatics analysis

Transcriptomic datasets related to DN and OS were

obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (GSE30528 and

GSE35958). Data were downloaded using GEOquery (v2.70.0;

Bioconductor; https://bioconductor.org/packages/GEOquery) in R

(v4.3.2; The R Foundation; https://www.r-project.org/), normalized and

batch-corrected with limma (v3.58.1; Bioconductor; https://bioconductor.org/packages/limma)

and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using

DESeq2. Targets of ASD and Semaglutide were retrieved from ChEMBL

(https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl),

intersected with DEGs related to DN and OS. Gene Ontology (GO) and

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses

were conducted via ClusterProfiler to explore biological functions

and pathways. Protein structures were downloaded from the Protein

Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) and compound

structures from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Docking was

performed in AutoDock Vina (The Scripps Research Institute) and

visualized using PyMOL v2.5.4 (https://www.pymol.org/).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0

(IBM Corp.). The Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene's test were applied

to assess normality and homogeneity of variances. If the data met

these assumptions, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test

was conducted. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation

(SD). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

ASD and Semaglutide improve glucose

metabolism and renal function in diabetic rats

Abnormal glucose metabolism and impaired renal

filtration and barrier functions are key features of DM and DN. To

evaluate the pharmacological effects of ASD and Semaglutide, the

present study first assessed metabolic and renal indicators.

ELISA results showed that the levels of FBG, FSI and

HOMA-IR in the MOD group were markedly higher than those in the

Control group. However, treatment with ASD or Semaglutide alone (M

+ A/M + S group) reduced these markers and the combined therapy (M

+ A + S group) led to the most significant improvement (Fig. 1C-E). Similarly, biochemical

analysis revealed that the levels of BUN, Cr, 24-up and renal index

were markedly increased in the MOD group. All parameters were

markedly decreased following treatment, with the M + A + S group

showing superior renoprotection (Fig. 1F-I). These findings suggested

that ASD and Semaglutide together improve glucose homeostasis and

attenuate renal dysfunction in diabetic rats, with combination

therapy outperforming monotherapy. Although body weight after 6

weeks of HFHS feeding was not recorded in the present study,

previous reports using the same modeling protocol have consistently

shown an initial increase in body weight during HFHS feeding

followed by a moderate decline after STZ injection, reflecting

typical T2DM progression rather than T1DM (25).

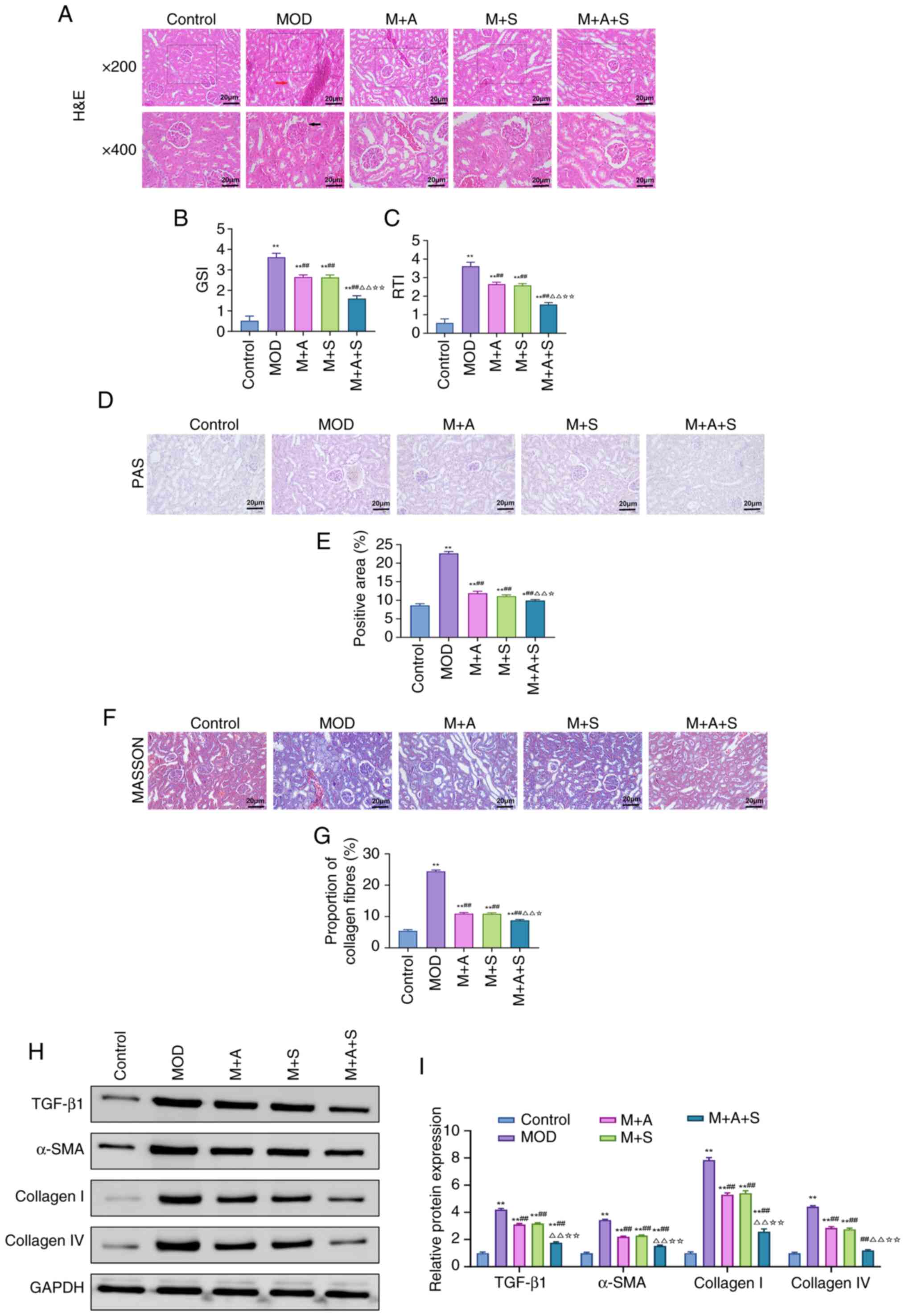

ASD and Semaglutide alleviate renal

pathological damage in diabetic rats

Kidney injury in DN involves both functional

impairment and structural abnormalities. To assess the

histopathological improvements following treatment, H&E, PAS

and Masson staining were performed.

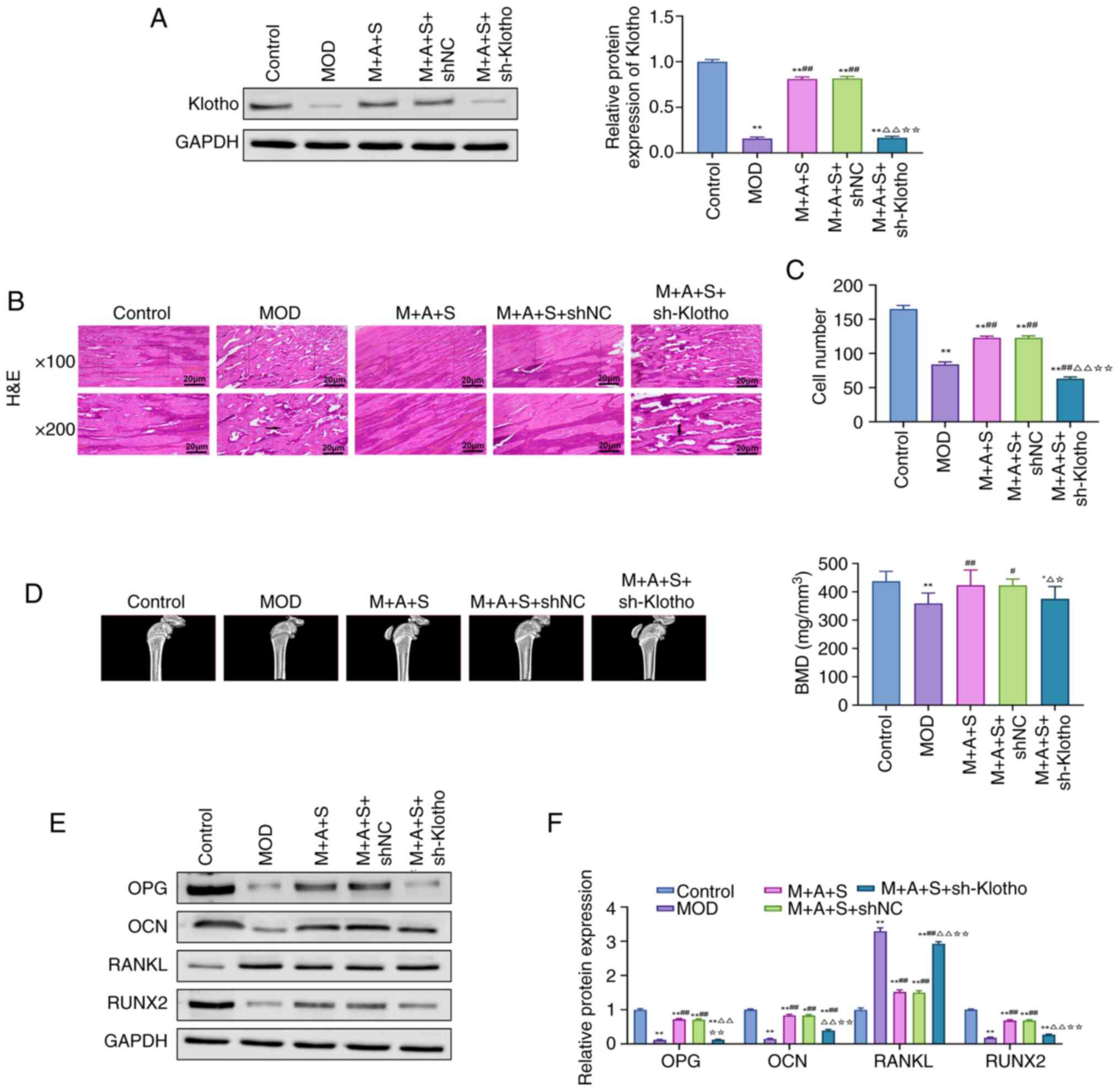

H&E staining (Fig. 2A) revealed pronounced glomerular

hypertrophy, basement membrane thickening, mesangial expansion and

inflammatory infiltration in the MOD group. The two monotherapies

partly alleviated these lesions, while the M + A + S group

demonstrated the most comprehensive improvement, as reflected by

markedly reduced GSI and RTI scores (Fig. 2B and C). PAS staining (Fig. 2D and E) showed marked glomerular

and tubular basement membrane thickening in the MOD group, along

with prominent PAS-positive deposits. Treatment reversed these

changes, with the M + A + S group achieving the greatest reduction

in PAS-positive area. Masson staining (Fig. 2F and G) showed extensive collagen

deposition in MOD rats, which was markedly reduced after treatment.

The collagen area percentage was lowest in the M + A + S group,

indicating superior antifibrotic efficacy. At the molecular level,

western blot analysis (Fig. 2H and

I) confirmed significant upregulation of TGF-β1, α-SMA,

Collagen I and Collagen IV in the MOD group. These profibrotic

markers were markedly downregulated by combination therapy, with

levels approaching those of the Control group.

| Figure 2ASD and Semaglutide alleviate renal

pathological damage in diabetic rats. (A-C) H&E staining was

used to observe kidney structure (magnification, ×200 and ×400) and

perform GSI and RTI scoring. (D) PAS staining and (E)

quantification of PAS-positive area. (F) Masson staining and (G)

quantification of collagen deposition. (H) Western blot analysis of

TGF-β1, α-SMA, Collagen I and Collagen IV. (I) Quantification of

protein expression normalized to GAPDH. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 vs. Control; ##P<0.01 vs. MOD;

ΔP<0.05, ΔΔP<0.01 vs. M + A;

☆P<0.05, ☆☆P<0.01 vs. M + S. ASD,

akebia saponin D; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; GSI,

glomerulosclerosis index; RTI, renal tubular interstitial injury

index; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin. |

Collectively, these findings demonstrated that ASD

and Semaglutide synergistically attenuate renal injury, reduce

basement membrane thickening and suppress renal fibrosis, with the

combination therapy yielding superior outcomes compared with

monotherapy.

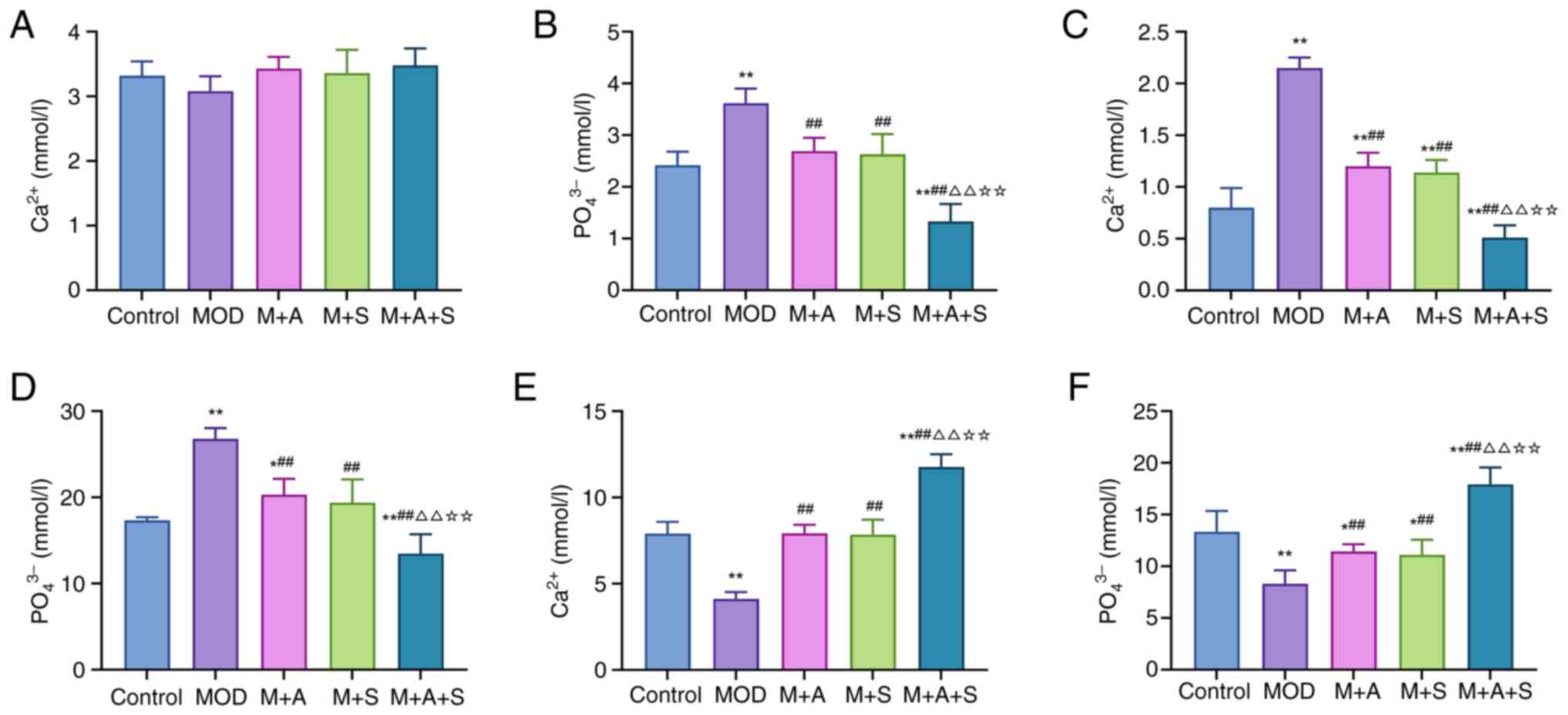

ASD and Semaglutide improve calcium and

phosphate metabolism in diabetic rats

Disrupted calcium and phosphate metabolism is a

common feature of internal environment disturbance in patients with

DM and may play an important role in DM-related renal injury and OS

(30). Therefore, the levels of

Ca2+ and PO43− in serum, urine and

femur were measured in the present study to evaluate the

therapeutic effects of ASD and Semaglutide. As shown in Fig. 3A-F, the MOD group exhibited

markedly elevated serum PO43− (Fig. 3B), increased urinary excretion of

Ca2+ and PO43− (Fig. 3C and D) and reduced femoral

Ca2+ and PO43− content (Fig. 3E and F), indicating systemic

calcium-phosphate imbalance. Treatment with either ASD or

Semaglutide partly restored these parameters, while the combined

treatment (M + A + S) achieved the most substantial correction,

including normalization of serum phosphate, reduction in renal loss

and restoration of bone mineral content. In summary, these findings

suggested that ASD and Semaglutide synergistically restore mineral

homeostasis in diabetic rats, with combination therapy

demonstrating superior efficacy.

ASD and Semaglutide alleviate diabetic

osteoporosis-related femoral damage

DOP is characterized by reduced trabecular bone,

decreased bone density and disrupted bone structure (31). To evaluate structural changes,

H&E staining and micro-CT were performed.

H&E staining (Fig. 4A) revealed sparse, thinned and

disorganized trabeculae in MOD rats. Treatment with ASD or

Semaglutide partially improved trabecular integrity, while the

combined group (M + A + S) showed the most substantial recovery, as

confirmed by markedly higher osteocyte counts (Fig. 4B). Micro-CT analysis (Fig. 4C and D) demonstrated that MOD

rats had markedly lower BMD, BMC, BV/TV, Tb.Th and Tb.N,

accompanied by elevated BS/BV, Tb.Sp and SMI. These changes reflect

weakened and porous bone architecture. All parameters improved

following treatment and the M + A + S group exhibited the most

pronounced normalization, indicating a synergistic effect of ASD

and Semaglutide in preventing DOP-related skeletal

deterioration.

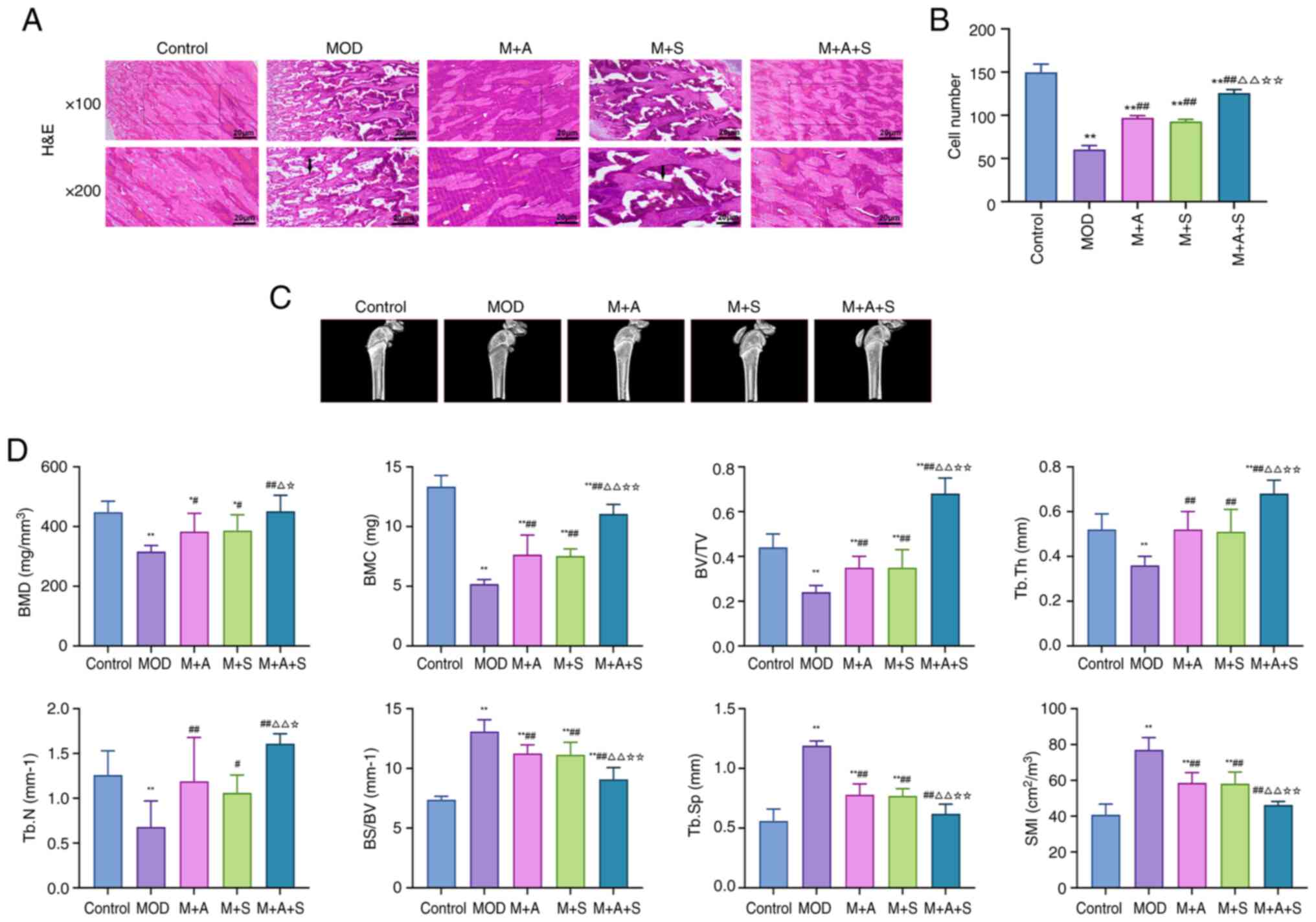

ASD and Semaglutide improve bone strength

and restore osteogenic-resorptive balance in diabetic rats

DOP is associated with both reduced bone mechanical

strength and dysregulated bone metabolism, increasing fracture risk

in patients with DM (32,33).

In the present study, the effects of ASD and Semaglutide on femoral

bone strength, metabolism and remodeling were comprehensively

evaluated.

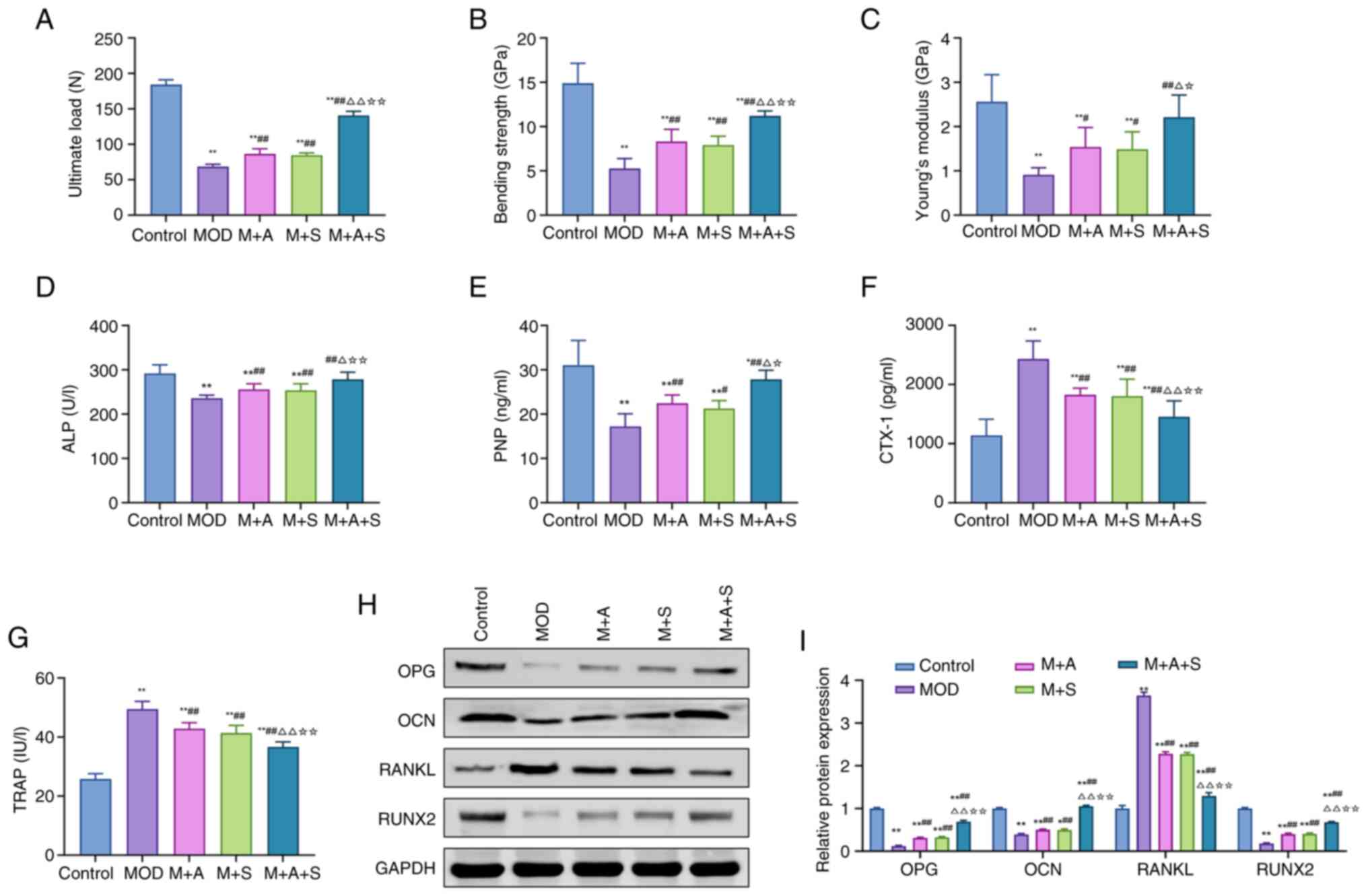

Three-point bending tests revealed that MOD rats

exhibited markedly reduced ultimate load, bending strength and

elastic modulus, indicating biomechanical fragility. ASD and

Semaglutide both improved these parameters, while the combination

therapy (M + A + S) led to the most substantial enhancements,

suggesting superior restorative effects (Fig. 5A-C).

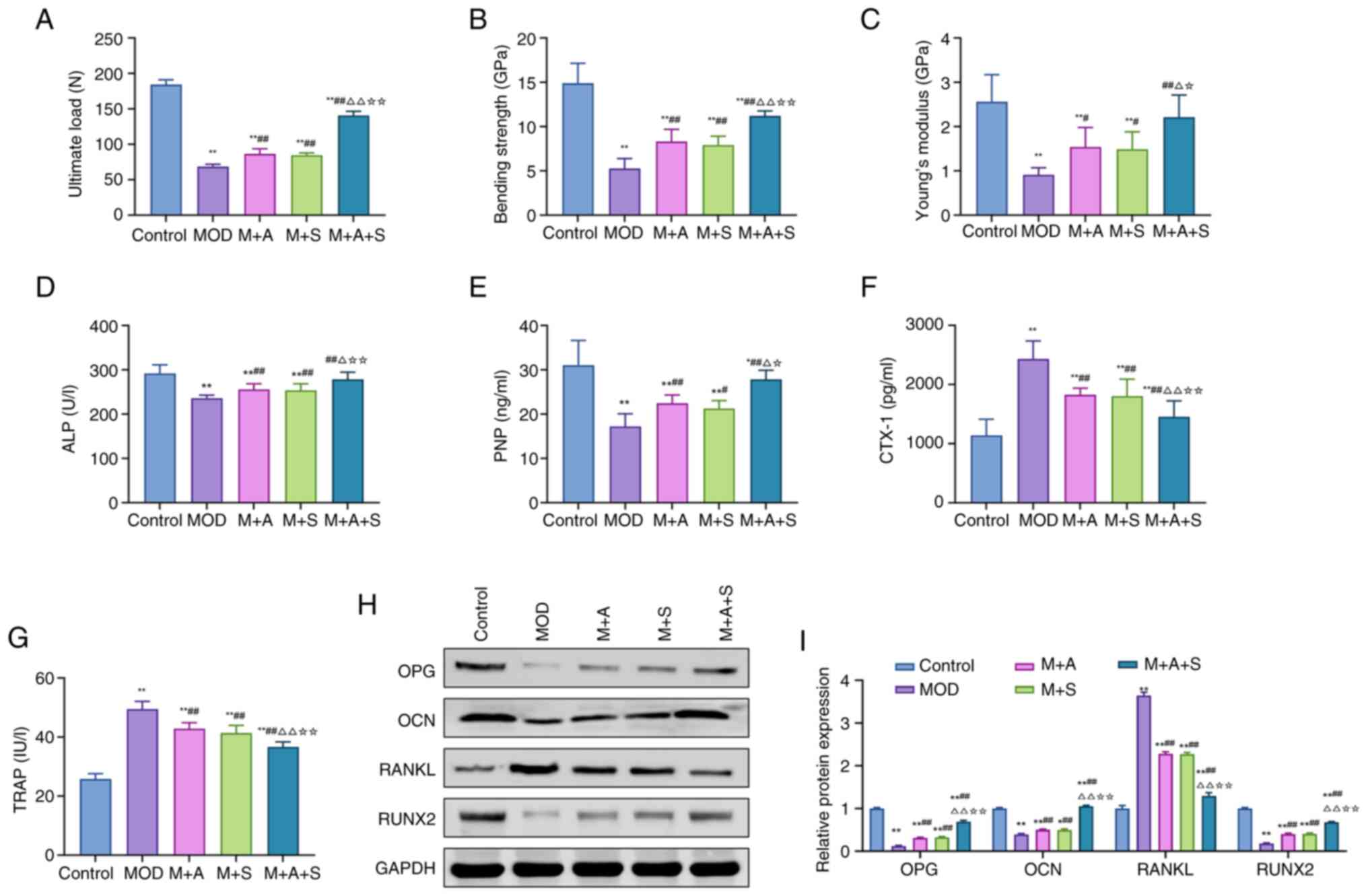

| Figure 5Effects of ASD and Semaglutide on

bone metabolism and remodeling in diabetic rats. (A-C) Three-point

bending tests measuring ultimate load, bending strength and Young's

modulus of the femur. The serum levels of (D) ALP, (E) PINP, (F)

CTX-1 and (G) TRAP were measured using ELISA. (H) Western blot and

(I) quantification of femoral protein expression (OPG, OCN, RANKL

and RUNX2). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs.

Control; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. MOD;

ΔP<0.05, ΔΔP<0.01 vs. M + A;

☆P<0.05, ☆☆P<0.01 vs. M + S. ASD,

akebia saponin D; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PINP, procollagen type

I N-terminal propeptide; CTX-1, C-terminal telopeptide of type I

collagen; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; OPG,

osteoprotegerin; OCN, osteocalcin; RANKL, receptor activator of

nuclear factor κ-b ligand; RUNX2, Runt-related transcription factor

2. |

To further explore underlying mechanisms, serum and

tissue markers related to bone formation and resorption were

assessed. As shown in Fig. 5D-G,

MOD rats displayed decreased levels of ALP and PINP and increased

levels of CTX-I and TRAP. These changes indicate suppressed

osteogenesis and enhanced bone resorption. Treatment with ASD or

Semaglutide partially reversed these abnormalities, with M + A + S

showing the most marked correction. At the protein level (Fig. 5H and I), MOD rats exhibited

reduced expression of OPG, OCN and RUNX2, along with upregulation

of RANKL, a key stimulator of osteoclastogenesis. ASD and

Semaglutide effectively normalized these markers, with combination

therapy demonstrating the most pronounced modulation.

Together, these results indicated that the combined

administration of ASD and Semaglutide enhances both bone mechanical

integrity and metabolic homeostasis in DOP, probably by promoting

osteogenesis and inhibiting bone resorption and achieves greater

therapeutic efficacy than either agent alone.

Network pharmacology analysis of ASD and

Semaglutide

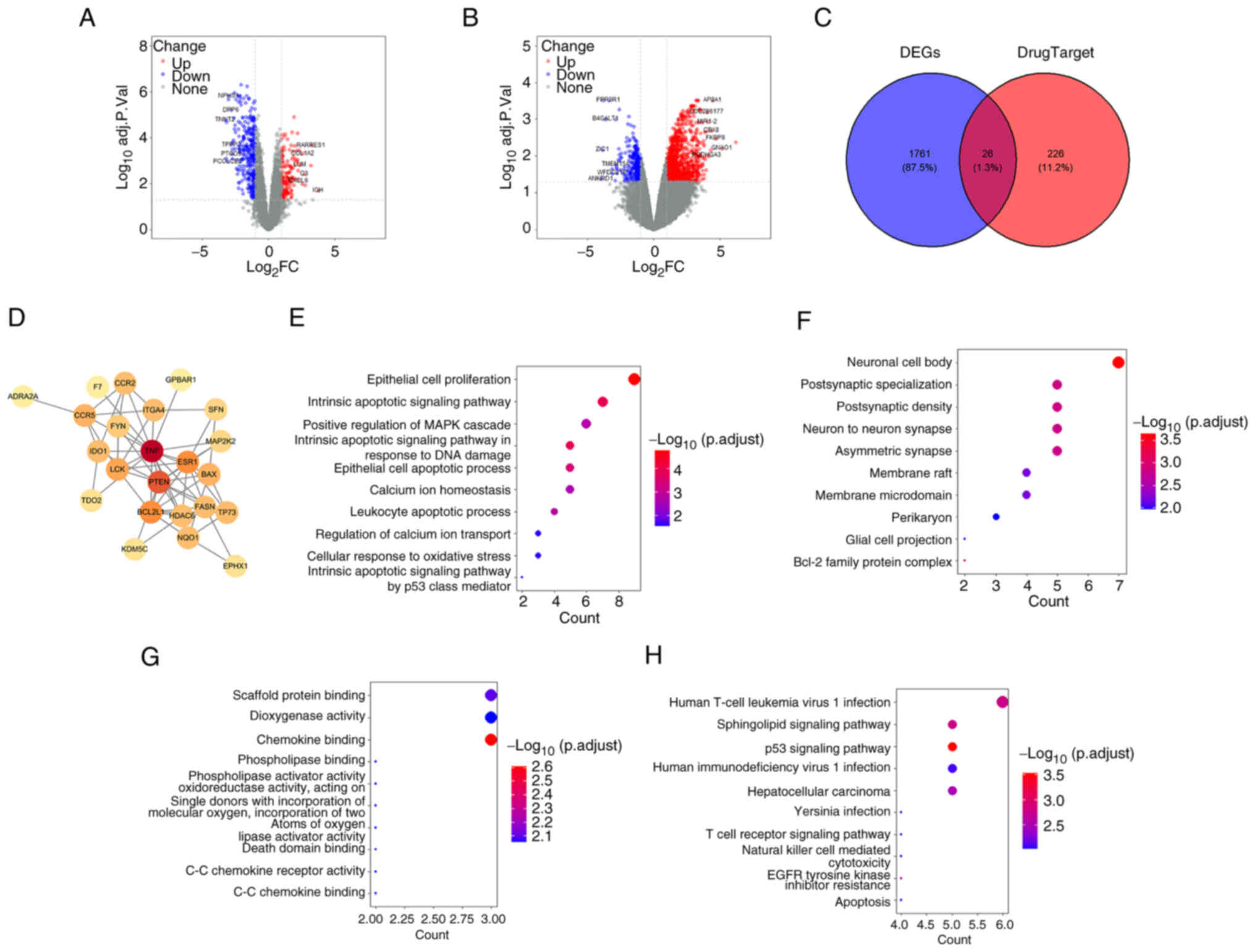

After demonstrating the effectiveness of ASD and

Semaglutide in treating DN and DOP, the present study used network

pharmacology methods to further investigate their potential

molecular targets and mechanisms. Through transcriptomic data

analysis and KEGG enrichment analysis, the key molecules and

signaling pathways were identified.

The transcriptomic datasets for DN (GSE30528) and OS

(GSE35958) were both obtained from the GEO database. As shown in

Fig. 6A and B, after

differential expression analysis (adj. P<0.05;

|log2FC| >1), 1,787 disease-related genes were

identified. Drug-related targets of ASD and Semaglutide (n=252)

were obtained from ChEMBL. Their intersection yielded 26

overlapping genes (Fig. 6C),

which were used to construct a protein-protein interaction network

(Fig. 6D), with TNF, PTEN and

ESR1 emerging as central hub genes. GO enrichment analysis showed

that these targets were involved in apoptotic signaling, oxidative

stress response, MAPK cascade and calcium ion homeostasis (Fig. 6E-G). Cellular localization

included neuronal compartments and membrane microdomains, while

molecular functions encompassed chemokine binding, oxidoreductase

and death domain activity. KEGG pathway analysis (Fig. 6H) revealed enrichment in p53

signaling, sphingolipid metabolism, T-cell receptor and

apoptosis-related pathways, suggesting potential involvement of

these signaling cascades in the pharmacological actions of ASD and

Semaglutide.

These findings implied that ASD and Semaglutide may

exert therapeutic effects via shared molecular targets involved in

inflammation, apoptosis and cellular stress responses, with the p53

pathway emerging as a potential mechanistic link.

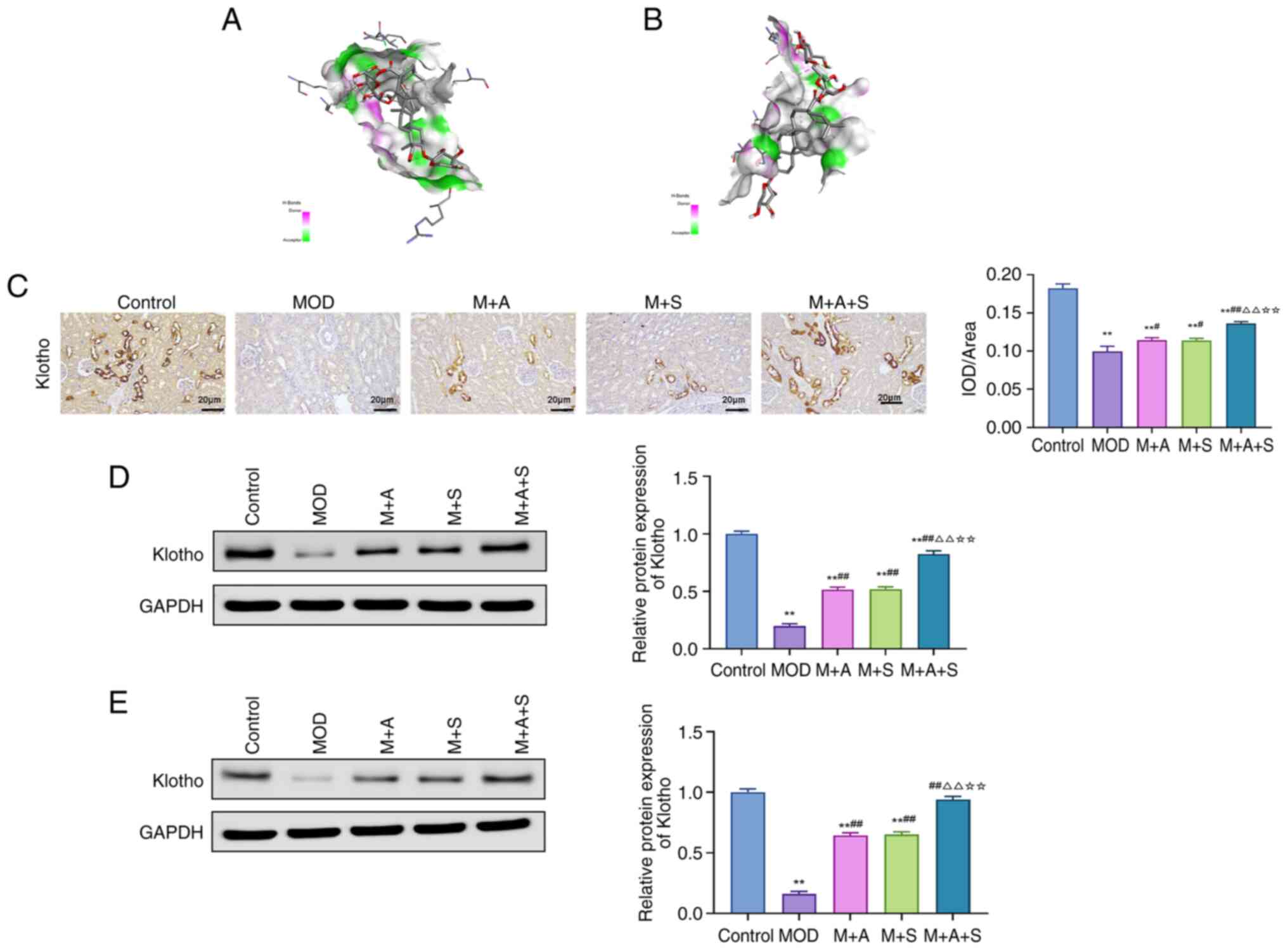

Molecular docking and expression analysis

of Klotho in diabetic rats

Given the emerging role of Klotho in diabetic

complications and its potential interaction with the p53 pathway

(34), the present study

explored whether ASD could directly bind to Klotho or p53 proteins

using molecular docking. The binding energy of ASD with Klotho

was-9.5 kcal/mol, while that with p53 was-7.6 kcal/mol, indicating

a stronger affinity for Klotho (Fig.

7A and B).

Immunofluorescence and western blotting results

showed that the Klotho protein level was markedly reduced in the

kidney and femur tissues of rats in the MOD group, while treatment

with ASD or Semaglutide markedly increased its expression, with the

most pronounced effect observed in the M + A + S group (Fig. 7C-E).

These results implied that ASD may modulate the p53

pathway by targeting Klotho protein, thereby playing a role in the

prevention of DN and DOP.

ASD and Semaglutide inhibit the p53

pathway and DNA damage in the kidney and femur tissues of diabetic

rats

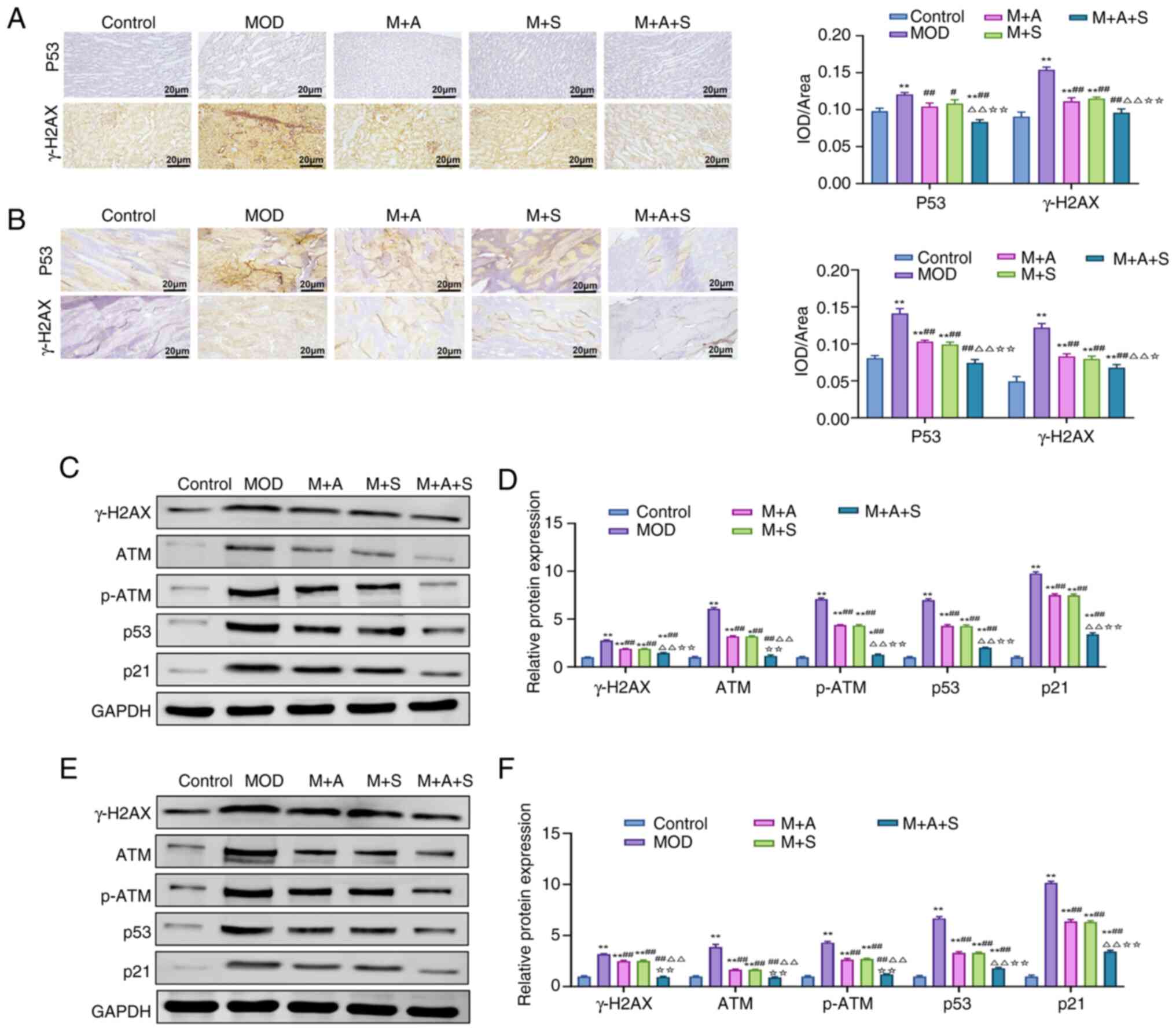

Abnormal activation of the p53 signaling pathway can

lead to DNA damage, thereby exacerbating tissue injury (35). Therefore, the present study

further investigated whether ASD and Semaglutide alleviated

DN-related renal damage and DOP-related bone damage by inhibiting

the p53 signaling pathway.

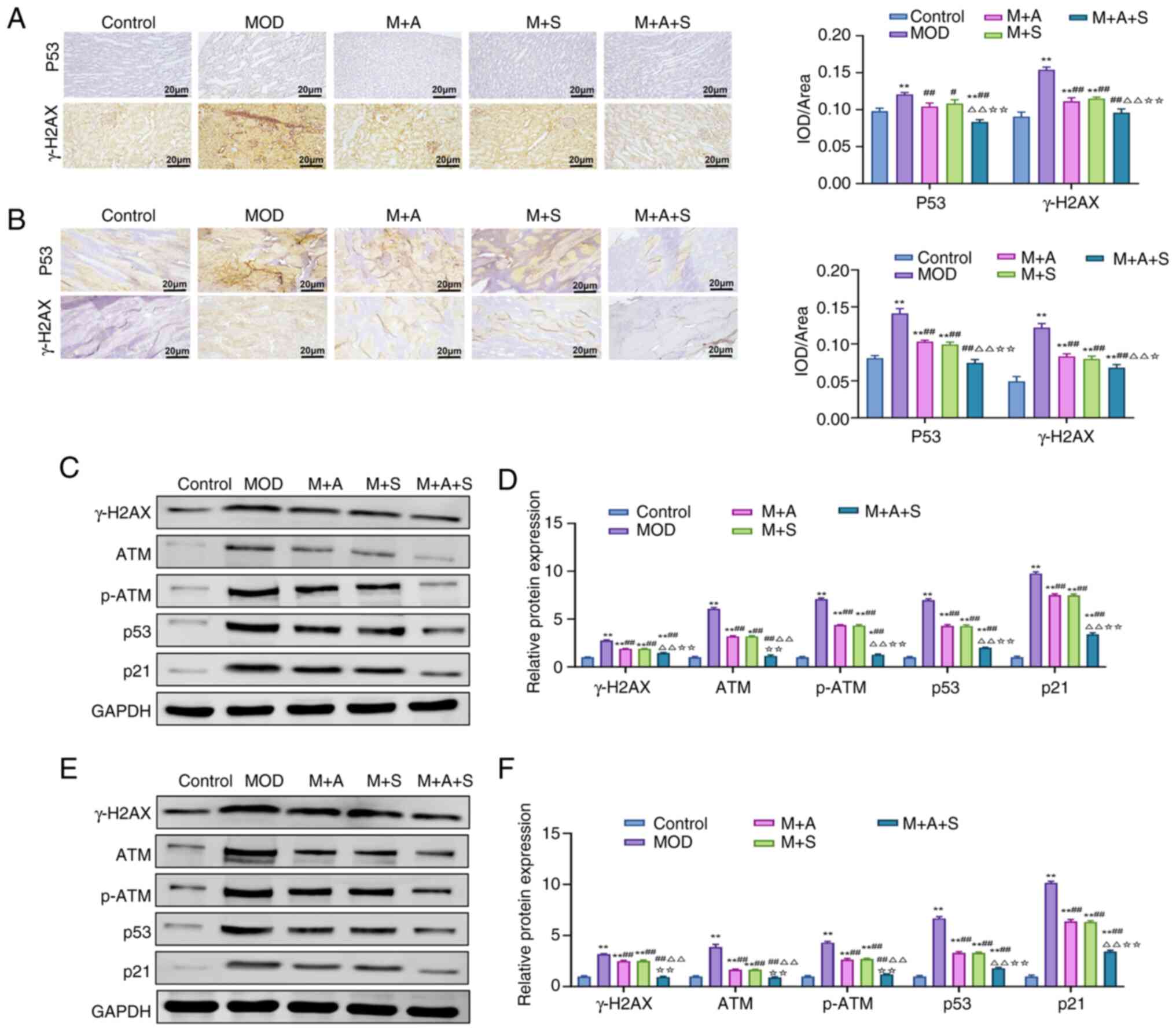

Immunofluorescence results (Fig. 8A and B) revealed markedly

elevated levels of p53 and the DNA damage marker γ-H2AX in MOD

rats. Treatment with ASD or Semaglutide reduced their expression,

with the most pronounced suppression observed in the M + A + S

group. Consistently, western blot analysis (Fig. 8C-F) showed upregulation of key

proteins involved in DNA damage signaling, including ATM, p-ATM,

p53, p21 and γ-H2AX, in MOD rats. All these markers were

downregulated following ASD or Semaglutide treatment and

combination therapy yielded the strongest inhibitory effect. These

results suggested that combined treatment with ASD and Semaglutide

could suppress the excessive activation of the p53 signaling

pathway to reduce DNA damage, thereby exerting a protective effect

in DN and DOP.

| Figure 8ASD and Semaglutide inhibit the p53

pathway and DNA damage in the kidney and femur tissues of diabetic

rats. Immunohistochemical staining of p53 and γ-H2AX in (A) kidney

and (B) femur tissues, respectively. (C-F) Western blotting and

quantification analysis of DNA damage-related proteins, including

γ-H2AX, ATM, p-ATM, p53 and p21, in (C and D) kidney and (E and F)

femur tissues. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs.

Control; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. MOD;

ΔΔP<0.01 vs. M + A; ☆P<0.05,

☆☆P<0.01 vs. M + S. ASD, akebia saponin D; p-,

phosphorylated; ATM, ATM, ataxia-telangiectasia mutated

protein. |

Knockdown of Klotho reverses the

therapeutic effects of ASD and Semaglutide in diabetic nephropathy

and diabetic osteoporosis

To further confirm whether Klotho served as a key

target for the protective effects of ASD and Semaglutide, the

present study applied AAV to knock down Klotho and observed its

effect on the therapeutic outcomes.

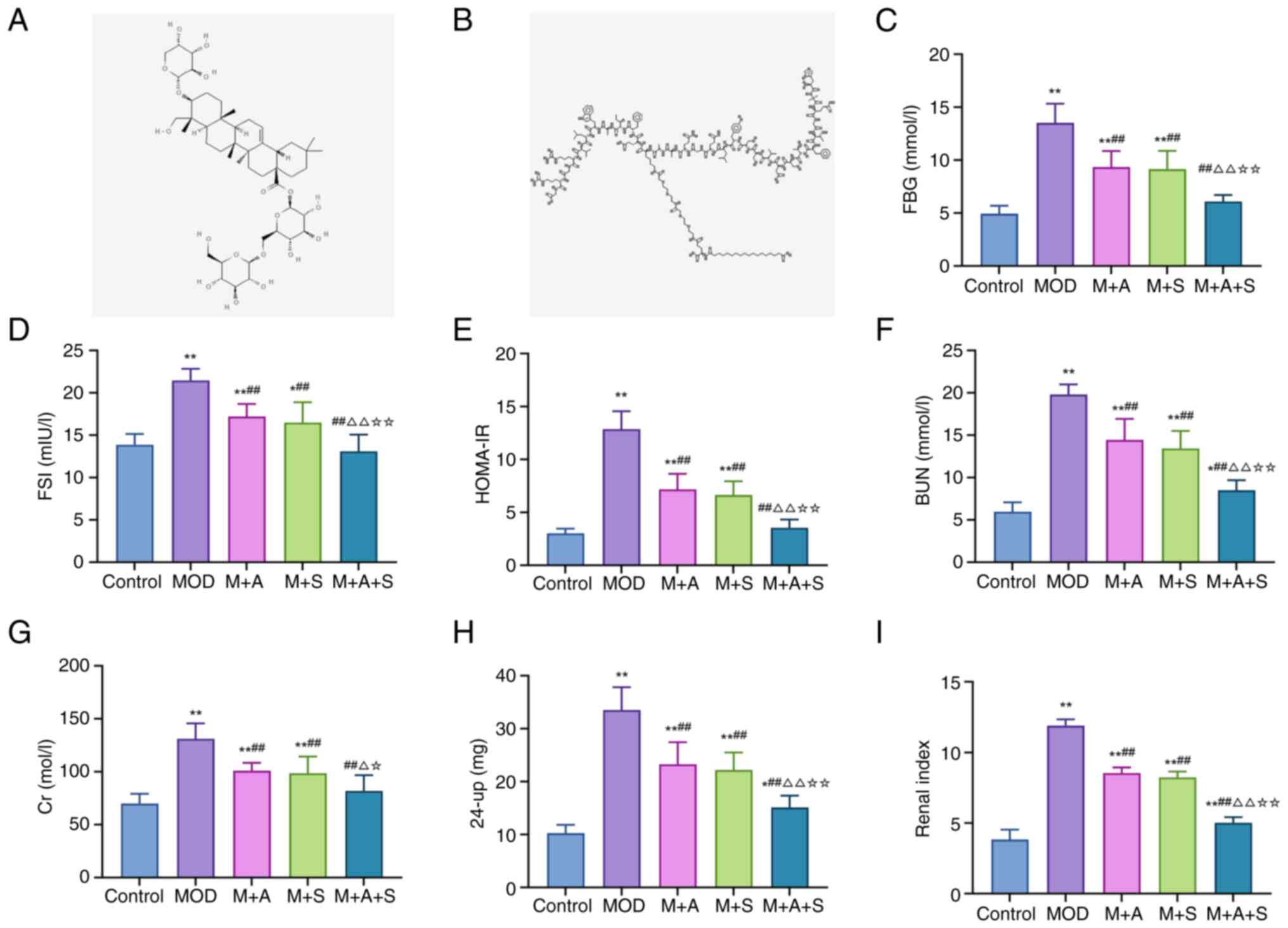

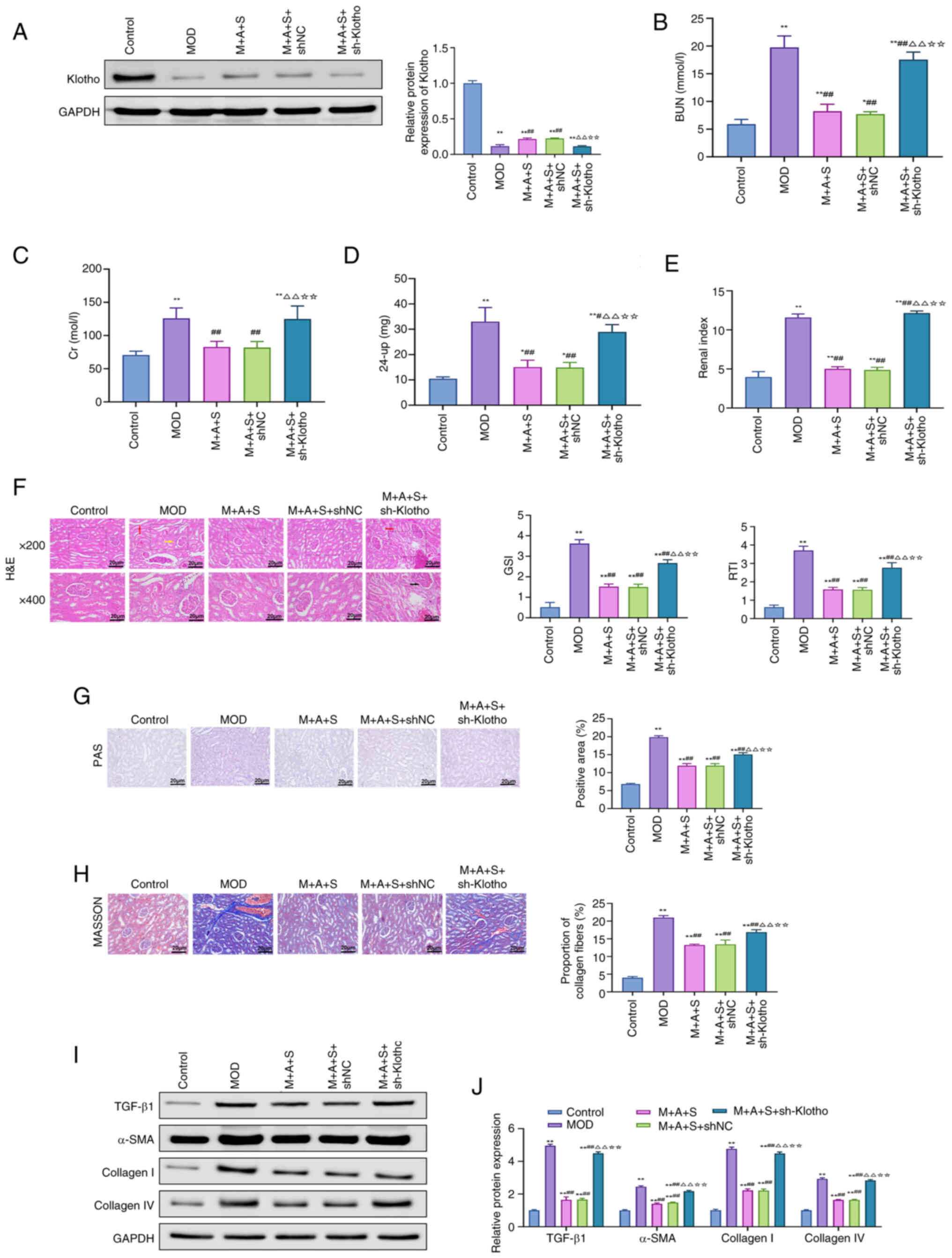

Western blotting results confirmed successful Klotho

knockdown in both kidney and femur tissues in M + A + S + sh-Klotho

group (Figs. 9A and 10A). Functionally, renal injury

indicators, including BUN, Cr, 24-up and renal index, were markedly

elevated in the MOD group and attenuated by M + A + S treatment.

However, these improvements were partially or fully reversed upon

Klotho knockdown (Fig. 9B-E).

Histopathological analysis (Fig.

9F-H) demonstrated that glomerular damage, basement membrane

thickening and fibrosis, improved in the M + A + S group, were

exacerbated again in the M + A + S + sh-Klotho group.

Correspondingly, TGF-β1, α-SMA, Collagen I and IV expression levels

were re-elevated (Fig. 9I and

J), confirming that the anti-fibrotic effects of the therapy

depended on Klotho expression.

| Figure 9Klotho knockdown abrogates the

renoprotective effects of ASD and Semaglutide. (A) Western blot

analysis of Klotho protein levels in rat kidney tissues. (B-E)

Serum levels of (B) BUN, (C) Cr, (D) 24-up and (E) kidney index.

(F) H&E, (G) PAS and (H) Masson staining of renal tissue, with

corresponding quantification of GSI, RTI, PAS-positive area and

fibrosis index. (I) Western blotting and (J) quantification of

renal TGF-β1, α-SMA, Collagen I and Collagen IV protein levels.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control;

##P<0.01 vs. MOD; ΔΔP<0.01 vs. M + A +

S; ☆☆P<0.01 vs. M + A + S + shNC. ASD, akebia saponin

D; BUN Cr, creatinine; 24-up, 24-h urinary protein; H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; GSI,

glomerulosclerosis index; RTI, renal tubular interstitial injury

index; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; sh, short hairpin. |

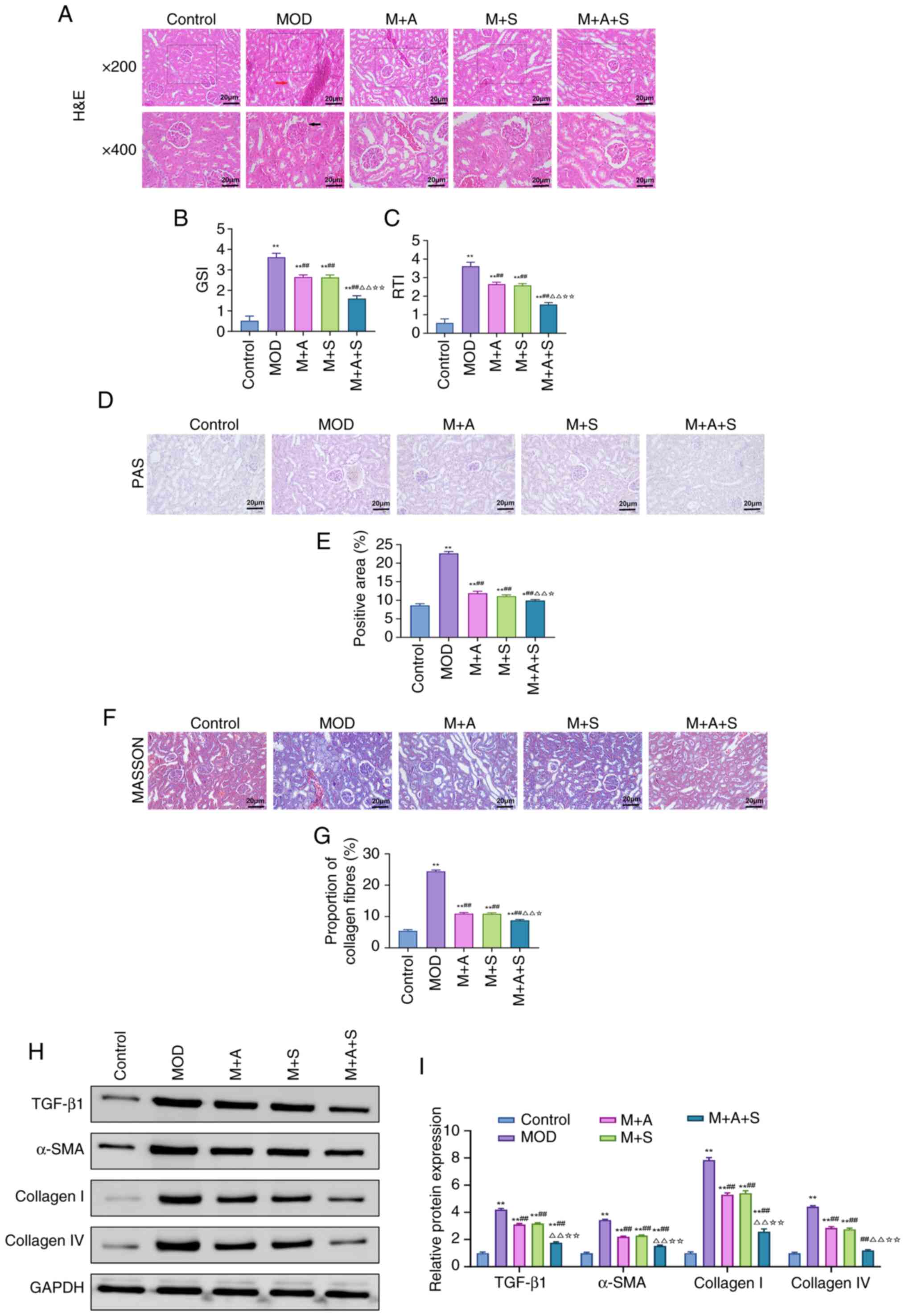

| Figure 10Knockdown of Klotho reverses the

therapeutic effects of ASD and Semaglutide in the treatment of

diabetic osteoporosis. (A) Western blot analysis of Klotho protein

levels in rat femur tissue. (B and C) H&E staining to assess

histological changes in rat femur tissues and cell counting of

osteocytes and osteoblasts. (D) Micro-CT measurement of BMD in rat

femur. (E and F) Western blot and quantification analysis of bone

metabolic markers (OPG, OCN, RANKL and RUNX2).

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Control;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. MOD;

ΔP<0.05, ΔΔP<0.01 vs. M + A + S;

☆P<0.05, ☆☆P<0.01 vs. M + A + S + shNC.

ASD, akebia saponin D; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; Micro-CT,

micro-computed tomography; OPG, osteoprotegerin; OCN, osteocalcin;

RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-b ligand; RUNX2,

Runt-related transcription factor 2. |

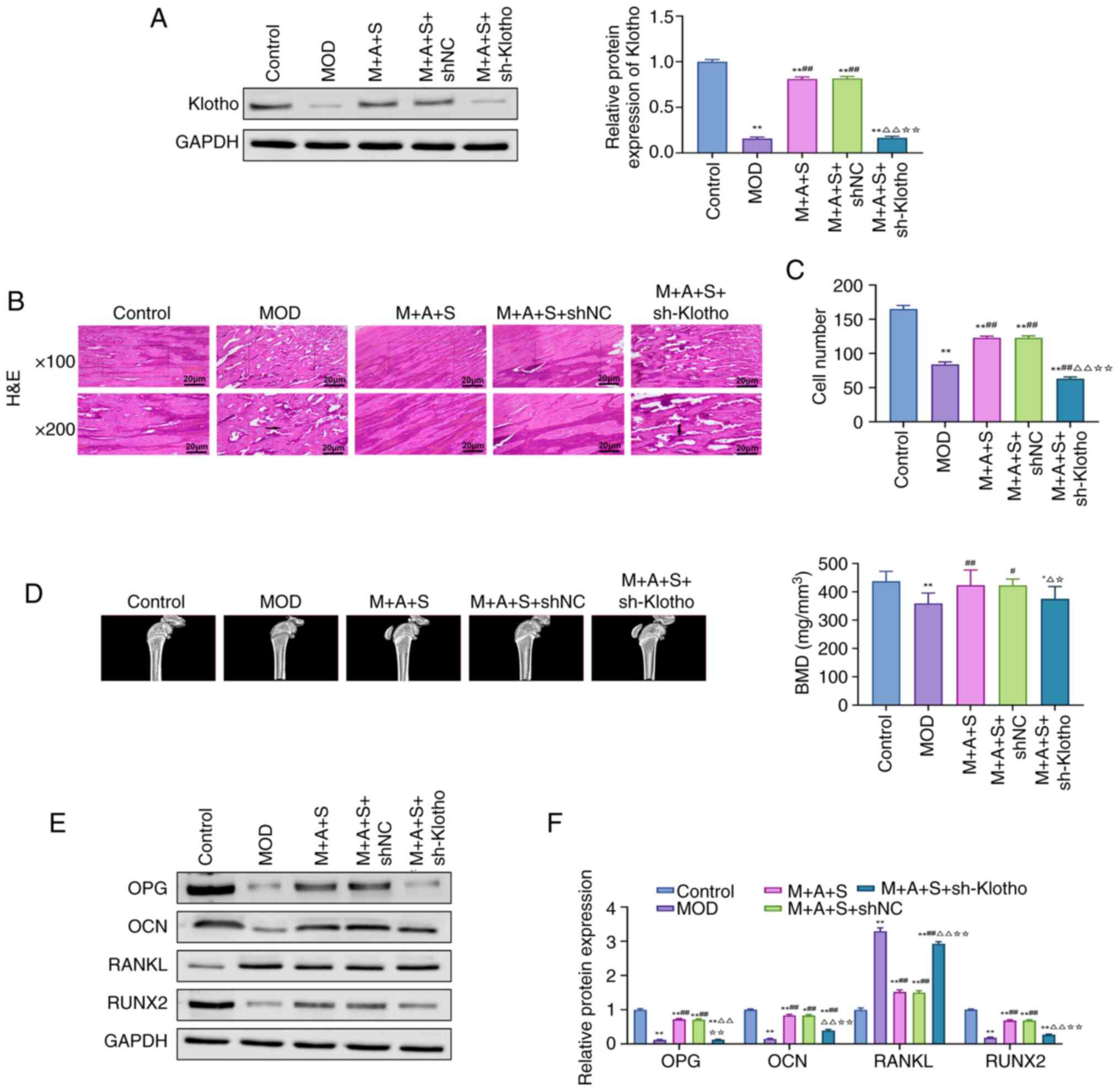

In terms of the femur, trabecular structure

improvements observed in the M + A + S group were abolished in

sh-Klotho rats, with reduced osteoblast/osteocyte numbers and

increased marrow cavity (Fig. 10B

and C). Micro-CT analysis revealed that BMD improvements were

also lost following Klotho knockdown (Fig. 10D). Moreover, the osteoanabolic

proteins OPG, OCN and RUNX2 decreased again, while RANKL increased,

indicating a shift back toward osteoclastic activation (Fig. 10 E and F).

Collectively, these results demonstrated that the

therapeutic effects of ASD and Semaglutide on DN and DOP are

Klotho-dependent, confirming Klotho as a critical mechanistic

target.

Discussion

The present study indicated that co-administration

of ASD and Semaglutide exerted significant therapeutic effects on

both DN and DOP, potentially through modulation of the Klotho-p53

signaling axis. To the to the best of the authors' knowledge, the

present study was the first to confirm the effect of ASD and

Semaglutide combination therapy in DM complications and to

elucidate the specific signaling pathways involved. Clinically, the

present study provides a novel dual-target strategy for the

comprehensive prevention and management of DM-associated

complications. Since patients with DM often face both renal damage

and osteoporosis, the combined therapy of ASD and Semaglutide may

represent a highly valuable therapeutic strategy, potentially

reducing damage to the kidney and skeletal systems while

controlling blood glucose, which is of great importance for

improving patient quality of life and prolonging lifespan.

The first challenge of the present study lies in how

to establish an animal model that accurately reflects the

characteristics of patients with T2DM with both DN and DOP in the

real world. Although a high-fat, high-sugar diet combined with STZ

injection is widely recognized as the primary method for

constructing a DM animal model, the optimal STZ protocol remains a

subject of debate (36). A

single high-dose injection is generally regarded as mimicking T1DM,

whereas multiple low-dose injections, when combined with dietary

manipulation, are more often employed to simulate the progressive

insulin resistance and partial β-cell dysfunction characteristic of

T2DM (33). The present study

therefore adopted the latter approach, seeking to more closely

approximate the clinical features of T2DM and its associated

complications. Specifically, both single high-dose STZ injection

and multiple low-dose STZ injections have been used in different

studies. However, the mainstream view is that a single high-dose

STZ injection (typically 50-75 mg/kg) directly destroys pancreatic

β-cells, leading to absolute insulin deficiency and rapidly

inducing hyperglycemia, simulating T1DM. By contrast, multiple

low-dose STZ injections (typically 20-40 mg/kg per injection,

sustained for more than 4 weeks) gradually destroy pancreatic

β-cells and simulate the chronic process of insulin resistance and

β-cell dysfunction, improved mimicking the pathological features of

T2DM (37). Therefore, the

present study adopted a high-fat, high-sugar diet combined with

repeated low-dose STZ injections to attempt to establish a T2DM rat

model. Comparing the MOD group rats with the Control group rats, it

was found that the MOD group rats exhibited increased fasting blood

glucose, elevated HOMA-IR, abnormal renal function indicators,

destruction of kidney tissue structure, damage to femoral

trabecular microstructure and reduced femoral biomechanical

properties, thereby confirming that the MOD group rats exhibited

both the kidney damage characteristics of DN and the bone damage

characteristics of DOP. This provides a solid foundation for

subsequent research.

The present study systematically evaluated the

therapeutic synergy of ASD and Semaglutide from multiple

perspectives. When examining the effects of the combined treatment

of ASD and Semaglutide in alleviating DN kidney injury, the present

study addressed three aspects: Serum and urine markers, kidney

tissue structure and the degree of kidney fibrosis. First, it was

found that after receiving ASD and Semaglutide combination therapy,

the serum metabolic waste products BUN and Cr levels were markedly

reduced in T2DM rats, indicating a recovery in kidney filtration

function; 24-up levels decreased, suggesting an improvement in

glomerular barrier function; and the kidney index decreased,

indicating alleviated kidney enlargement and congestion. Secondly,

H&E staining visually showed reduced damage to the glomeruli

and renal tubules; PAS staining showed decreased local deposition

of glycation end products that directly damage the kidneys; and

Masson staining reflected the inhibition of the kidney fibrosis

process. Furthermore, combination therapy markedly downregulated

TGF-β1, a key pro-fibrotic cytokine, as well as the major fibrotic

matrix components α-SMA, Collagen I and Collagen IV (38), further confirming a significant

improvement in kidney fibrosis. Lu et al (39) found that ASD slows DN progression

by activating the NRF2/HO-1 pathway and inhibiting the NF-κB

pathway and multiple studies have confirmed the anti-DN effects of

Semaglutide (40,41), which are consistent with the

findings of the present study.

When elucidating the effects of ASD combined with

Semaglutide in alleviating DOP bone tissue damage, the present

study also provided evidence from multiple perspectives. First,

H&E staining clearly showed that the trabecular structure was

markedly restored in T2DM rats following combined treatment.

Second, micro-CT results indicated that the combined therapy

markedly increased the trabecular health indicators BMD, BMC,

BV/TV, Tb.Th and Tb.N, while markedly decreasing the trabecular

rarity indicators BS/BV, Tb.Sp and SMI, suggesting an improvement

in trabecular structure. Furthermore, three-point bending tests

demonstrated that the combined treatment markedly enhanced the

mechanical strength and stability of T2DM rat bones. Last,

following combined treatment, osteogenesis-related biomarkers such

as ALP, PINP, OPG, OCN and RUNX2 were markedly elevated, while bone

resorption-related markers, including CTX-1, TRAP and RANKL, were

markedly decreased (42),

further confirming the osteogenic and anti-osteoporotic effects of

ASD and Semaglutide. Previous studies have shown that Semaglutide

improves bone metabolism in patients with DM (43,44), which is consistent with our

findings. However, limited research has explored whether ASD can

improve bone quality, making this one of the significant

innovations of our study.

Importantly, to clarify the interdependency of renal

and skeletal protection, the present study investigated whether ASD

and Semaglutide synergistically attenuated the progression of both

DM-related complications and further examined calcium and

phosphorus metabolism in T2DM rats. Previous studies have shown

that dysregulation of calcium-phosphorus metabolism is a key factor

in the mutual aggravation of DN and DOP. Specifically, during DN

progression, tubular damage often leads to phosphate retention and

hyperphosphatemia, which suppresses osteoblast activity and calcium

absorption, ultimately exacerbating osteoporosis. Conversely, as

bone tissue serves as a reservoir for calcium and phosphate,

disturbances in bone metabolism can result in excessive phosphate

release, increasing the burden on renal excretion and accelerating

renal dysfunction and DN progression (45,46). The present study showed that

combined ASD and Semaglutide treatment markedly reduced serum

phosphate levels, decreased urinary calcium and phosphate excretion

and enhanced bone mineralization, thereby alleviating

calcium-phosphorus metabolic disorders and playing a critical role

in the simultaneous protection of kidney and bone health.

Upon confirming the dual efficacy of ASD and

Semaglutide in ameliorating DN and DOP, the present study further

investigated the potential molecular mechanisms, with a focus on

the Klotho-p53 signaling axis. Klotho was initially identified as

an anti-aging protein highly expressed in renal distal tubules and

the choroid plexus of the brain (47). Subsequent studies revealed that

soluble Klotho is widely present in urine, blood and cerebrospinal

fluid and participates in multiple physiological processes by

regulating various intracellular signaling pathways, including

insulin/IGF-1, p53 and Wnt (48,49). Aberrant Klotho expression is now

recognized as a hallmark of DM (50,51). Nie et al (52) reported markedly lower serum

Klotho levels in patients with DM compared with healthy controls,

with levels declining further as disease duration increased.

Similarly, Kim et al (53) found that serum Klotho may serve

as an early predictor of DN risk. Among the proteins regulated by

Klotho, p53 is particularly relevant to DM. While p53 normally

maintains oxidative balance by upregulating antioxidant genes, its

role in DM is largely deleterious, contributing to disease

progression (54). p53 can

induce β-cell DNA damage, promote β-cell apoptosis, inhibit glucose

transport and glycolysis, promote gluconeogenesis and downregulate

insulin receptor expression, all contributing to insulin resistance

and DM progression (55). Based

on this, it was hypothesized that upregulation of Klotho to

suppress p53 signaling may represent a key mechanism underlying the

therapeutic effects of ASD and Semaglutide. To test this, the

present study first conducted a bioinformatics analysis. Among

1,787 DN/DOP-related targets and 246 ASD/Semaglutide-related

targets, multiple Klotho-p53 axis-associated molecules were

enriched, with KEGG pathway analysis highlighting the p53 pathway.

Furthermore, molecular docking showed strong interactions between

ASD and both Klotho and p53, with low binding energies. In

vivo, combined ASD and Semaglutide therapy markedly increased

Klotho protein levels and reduced p53 expression in renal and

femoral tissues, while Klotho knockdown attenuated their protective

effects, supporting the hypothesis that the Klotho-p53 axis

mediates their therapeutic action.

Nevertheless, the optimal dosing strategy and

long-term safety of this combination therapy require further

evaluation. Specifically, the present study did not investigate

dose-response relationships or potential adverse effects associated

with prolonged administration of ASD and Semaglutide. This

limitation restricts the immediate clinical application of the

therapy and future studies should therefore focus on optimizing

dosing regimens, monitoring toxicity profiles and conducting

long-term safety assessments in both preclinical and clinical

settings. In addition, several limitations of the present study

should be acknowledged. First, the research was conducted in a rat

model of T2DM, which may not fully replicate the complexity of

human diabetic nephropathy and osteoporosis and therefore the

translational relevance should be interpreted with caution. Second,

the sample size was relatively modest, which may limit the

statistical power to detect subtle effects. Third, although the

present study focused on the Klotho-p53 signaling axis, other

molecular pathways could also contribute to the observed

therapeutic benefits and further mechanistic exploration is

warranted. Finally, the present study did not include long-term

follow-up or clinical validation and thus the efficacy and safety

of ASD combined with Semaglutide need to be confirmed in larger

preclinical studies and clinical trials.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that the

natural small-molecule compound ASD and the long-acting GLP-1

receptor agonist Semaglutide exert a significant synergistic effect

in the treatment of DN and DOP, with superior efficacy compared

with either agent alone. Mechanistically, their combined action in

mitigating DM-related complications is likely mediated through

modulation of the Klotho-p53 signaling axis. These findings offer

new insights into the prevention and treatment of DM-associated

complications.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QZ was responsible for conceptualization,

investigation, formal analysis and writing the original draft. DW

was responsible for methodology, data curation, validation and

visualization. HXJ was responsible for investigation, resources and

data curation. DW and HXJ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. ZJZ was responsible for investigation, software and formal

analysis. LYL was responsible for methodology, histological

analysis and western blotting. LNL was responsible for

investigation, immunofluorescence and micro-CT analysis. LW was

responsible for software, bioinformatics analysis, molecular

docking, writing, reviewing and editing. YMX was responsible for

conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing the

original draft, writing, reviewing and editing. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval for the present study was obtained

from the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Guangdong Medical

Laboratory Animal Center (approval no. D202505-13).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

Dr Yaoming Xue ORCID: 0000-0003-1356-4780

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82270862) and the Guangdong Basic

and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant no.

2024A1515220024).

References

|

1

|

Yang T, Qi F, Guo F, Shao M, Song Y, Ren

G, Linlin Z, Qin G and Zhao Y: An update on chronic complications

of diabetes mellitus: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic

strategies with a focus on metabolic memory. Mol Med. 30:712024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lovic D, Piperidou A, Zografou I, Grassos

H, Pittaras A and Manolis A: The growing epidemic of diabetes

mellitus. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 18:104–109. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda

B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA,

Ogurtsova K, et al: Global and regional diabetes prevalence

estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from

the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 157:1078432019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Magee C, Grieve DJ, Watson CJ and Brazil

DP: Diabetic nephropathy: A tangled web to unweave. Cardiovasc

Drugs Ther. 31:579–592. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Thipsawat S: Early detection of diabetic

nephropathy in patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review of

the literature. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 18:147916412110588562021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bao K, Jiao Y, Xing L, Zhang F and Tian F:

The role of wnt signaling in diabetes-induced osteoporosis.

Diabetol Metab Syndr. 15:842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Vestergaard P: Discrepancies in bone

mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type

2 diabetes-a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 18:427–444. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Janghorbani M, Van Dam RM, Willett WC and

Hu FB: Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and

risk of fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 166:495–505. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wang J, You W, Jing Z, Wang R, Fu Z and

Wang Y: Increased risk of vertebral fracture in patients with

diabetes: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int Orthop.

40:1299–1307. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Xia J, Zhong Y, Huang G, Chen Y, Shi H and

Zhang Z: The relationship between insulin resistance and

osteoporosis in elderly male type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic

nephropathy. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 73:546–551. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yan P, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Miao Y, Gao C

and Wan Q: Association of circulating Omentin-1 with Osteoporosis

in a Chinese Type 2 diabetic population. Mediators Inflamm.

2020:93897202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yang S, Hu T, Liu H, Lv YL, Zhang W, Li H,

Xuan L, Gong LL and Liu LH: Akebia saponin D ameliorates metabolic

syndrome (MetS) via remodeling gut microbiota and attenuating

intestinal barrier injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 138:1114412021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xuan L, Yang S, Ren L, Liu H, Zhang W, Sun

Y, Xu B, Gong L and Liu L: Akebia saponin D attenuates allergic

airway inflammation through AMPK activation. J Nat Med. 78:393–402.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gu L, Ye L, Chen Y, Deng C, Zhang X, Chang

J, Feng M, Wei J, Bao X and Wang R: Integrating network

pharmacology and transcriptomic omics reveals that akebia saponin D

attenuates neutrophil extracellular Traps-induced neuroinflammation

via NTSR1/PKAc/PAD4 pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage. FASEB

J. 38:e233942024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Gong LL, Yang S, Zhang W, Han FF, Lv YL,

Wan ZR, Liu H, Jia YJ, Xuan LL and Liu LH: Akebia saponin D

alleviates hepatic steatosis through BNip3 induced mitophagy. J

Pharmacol Sci. 136:189–195. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kristensen SL, Rorth R, Jhund PS, Docherty

KF, Sattar N, Preiss D, Køber L, Petrie MC and McMurray JJV:

Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor

agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes

Endocrinol. 7:776–785. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yao H, Zhang A, Li D, Wu Y, Wang CZ, Wan

JY and Yuan CS: Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor

agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for

type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ.

384:e0764102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Beery AK and Zucker I: Sex bias in

neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev.

35:565–572. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mauvais-Jarvis F: Sex differences in

metabolic homeostasis, diabetes, and obesity. Biol Sex Differ.

6:142015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Du J, Zhu M, Li H, Liang G, Li Y and Feng

S: Metformin attenuates cardiac remodeling in mice through the

Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 20:838–845. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

O'Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B,

Mosenzon O, Pedersen SD, Wharton S, Carson CG, Jepsen CH, Kabisch M

and Wilding JPH: Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with

liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: A

randomised, Double-blind, placebo and active controlled,

dose-ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 392:637–649. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Davies M, Faerch L, Jeppesen OK,

Pakseresht A, Pedersen SD, Perreault L, Rosenstock J, Shimomura I,

Viljoen A, Wadden TA, et al: Semaglutide 2.4 mg once a week in

adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): A

randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, phase 3

trial. Lancet. 397:971–984. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nair AB and Jacob S: A simple practice

guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin

Pharm. 7:27–31. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Huang KC, Chuang PY, Yang TY, Tsai YH, Li

YY and Chang SF: Diabetic rats induced using a High-fat diet and

Low-dose streptozotocin treatment exhibit gut microbiota dysbiosis

and osteoporotic bone pathologies. Nutrients. 16:12202024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Srinivasan K, Viswanad B, Asrat L, Kaul CL

and Ramarao P: Combination of high-fat diet-fed and low-dose

streptozotocin-treated rat: A model for type 2 diabetes and

pharmacological screening. Pharmacol Res. 52:313–320. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liu MM, Dong R, Hua Z, Lv NN, Ma Y, Huang

GC, Cheng J and Xu HY: Therapeutic potential of liuwei dihuang pill

against KDM7A and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in diabetic

nephropathy-related osteoporosis. Biosci Rep. 40:BSR202017782020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yu X, Wang LN, Du QM, Ma L, Chen L, You R,

Liu L, Ling JJ, Yang ZL and Ji H: Akebia Saponin D attenuates

amyloid β-induced cognitive deficits and inflammatory response in

rats: Involvement of Akt/NF-κB pathway. Behav Brain Res.

235:200–209. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cardiff RD, Miller CH and Munn RJ: Manual

hematoxylin and eosin staining of mouse tissue sections. Cold

Spring Harb Protoc. 2014:655–658. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gu LY, Yun S, Tang HT and Xu ZX: Huangkui

capsule in combination with metformin ameliorates diabetic

nephropathy via the Klotho/TGF-beta1/p38MAPK signaling pathway. J

Ethnopharmacol. 281:1135482021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yaroslavceva MV, Bondarenko ON, El-Taravi

YA, Magerramova ST, Pigarova EA, Ulyanova IN and Galstyan GR:

Etiopathogenetic features of bone metabolism in patients with

diabetes mellitus and Charcot foot. Probl Endokrinol (Mosk).

70:57–64. 2024.In Russian. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ma R, Zhu R, Wang L, Guo Y, Liu C, Liu H,

Liu F, Li H, Li Y, Fu M and Zhang D: Diabetic osteoporosis: A

review of its traditional Chinese medicinal use and clinical and

preclinical research. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2016:32183132016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen F, Wang P, Dai F, Zhang Q, Ying R, Ai

L and Chen Y: Correlation between blood glucose fluctuations and

osteoporosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Endocrinol.

2025:88894202025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ishtaya GA, Anabtawi YM, Zyoud SH and

Sweileh WM: Osteoporosis knowledge and beliefs in diabetic

patients: A cross sectional study from Palestine. BMC Musculoskelet

Disord. 19:432018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Prud'homme GJ and Wang Q:

Anti-Inflammatory role of the klotho protein and relevance to

aging. Cells. 13:14132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Marei HE, Althani A, Afifi N, Hasan A,

Caceci T, Pozzoli G, Morrione A, Giordano A and Cenciarelli C: p53

signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Cancer Cell Int.

21:7032021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Goyal SN, Reddy NM, Patil KR, Nakhate KT,

Ojha S, Patil CR and Agrawal YO: Challenges and issues with

streptozotocin-induced diabetes-A clinically relevant animal model

to understand the diabetes pathogenesis and evaluate therapeutics.

Chem Biol Interact. 244:49–63. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Rais N, Ved A, Ahmad R, Parveen K, Gautam

GK, Bari DG, Shukla KS, Gaur R and Singh AP: Model of

Streptozotocin-nicotinamide induced type 2 diabetes: A comparative

review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 18:e1711211980012022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Klinkhammer BM and Boor P: Kidney

fibrosis: Emerging diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Mol

Aspects Med. 93:1012062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Lu C, Fan G and Wang D: Akebia Saponin D

ameliorated kidney injury and exerted anti-inflammatory and

anti-apoptotic effects in diabetic nephropathy by activation of

NRF2/HO-1 and inhibition of NF-KB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol.

84:1064672020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Moellmann J, Klinkhammer BM, Onstein J,

Stöhr R, Jankowski V, Jankowski J, Lebherz C, Tacke F, Marx N, Boor

P and Lehrke M: Glucagon-Like peptide 1 and its cleavage products

are renoprotective in murine diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes.

67:2410–2419. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Veneti S and Tziomalos K: Is there a role

for glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in the management of

diabetic nephropathy? World J Diabetes. 11:370–373. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Fernandez-Villabrille S, Martin-Carro B,

Martin-Virgala J, Rodríguez-Santamaria MDM, Baena-Huerta F,

Muñoz-Castañeda JR, Fernández-Martín JL, Alonso-Montes C,

Naves-Díaz M, Carrillo-López N and Panizo S: Novel biomarkers of

bone metabolism. Nutrients. 16:6052024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Onoviran OF, Li D, Toombs Smith S and Raji

MA: Effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists on

comorbidities in older patients with diabetes mellitus. Ther Adv

Chronic Dis. 10:20406223198626912019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Herrou J, Mabilleau G, Lecerf JM, Thomas

T, Biver E and Paccou J: Narrative review of effects of

Glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor agonists on bone health in people

living with obesity. Calcif Tissue Int. 114:86–97. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Sun M, Wu X, Yu Y, Wang L, Xie D, Zhang Z,

Chen L, Lu A, Zhang G and Li F: Disorders of calcium and phosphorus

metabolism and the Proteomics/Metabolomics-Based research. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 8:5761102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Winiarska A, Filipska I, Knysak M and

Stompor T: Dietary phosphorus as a marker of mineral metabolism and

progression of diabetic kidney disease. Nutrients. 13:7892021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Buchanan S, Combet E, Stenvinkel P and

Shiels PG: Klotho, Aging, and the failing kidney. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 11:5602020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hosseini L, Babaie S, Shahabi P, Fekri K,

Shafiee-Kandjani AR, Mafikandi V, Maghsoumi-Norouzabad L and

Abolhasanpour N: Klotho: Molecular mechanisms and emerging

therapeutics in central nervous system diseases. Mol Biol Rep.

51:9132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kanbay M, Copur S, Ozbek L, Mutlu A, Cejka

D, Ciceri P, Cozzolino M and Haarhaus ML: Klotho: A potential

therapeutic target in aging and neurodegeneration beyond chronic

kidney disease-a comprehensive review from the ERA CKD-MBD working

group. Clin Kidney J. 17:sfad2762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Tang A, Zhang Y, Wu L, Lin Y, Lv L, Zhao

L, Xu B, Huang Y and Li M: Klotho's impact on diabetic nephropathy

and its emerging connection to diabetic retinopathy. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14:11801692023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Hejrati A, Zabihi T, Riazi S and Sarv F:

Klotho: A possible diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target in

diabetes complications. Int J Diabetes Developing Countries. 1–16.

2025.

|

|

52

|

Nie F, Wu D, Du H, Yang X, Yang M, Pang X

and Xu Y: Serum klotho protein levels and their correlations with

the progression of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes

Complications. 31:94–98. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kim SS, Song SH, Kim IJ, Lee EY, Lee SM,

Chung CH, Kwak IS, Lee EK and Kim YK: Decreased plasma alpha-Klotho

predict progression of nephropathy with type 2 diabetic patients. J

Diabetes Complications. 30:887–892. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lahalle A, Lacroix M, De Blasio C, Cisse

MY, Linares LK and Le Cam L: The p53 Pathway and Metabolism: The

tree that hides the forest. Cancers (Basel). 13:1332021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kung CP and Murphy ME: The role of the p53

tumor suppressor in metabolism and diabetes. J Endocrinol.

231:R61–R75. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|