Introduction

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), also known

as fetal growth restriction, is defined as a condition in which a

fetus is small for gestational age (SGA) and falls below the 10th

percentile for gestational age and sex. (1). In 2020, one in five newborns

worldwide (23.4 million) were SGA, a condition linked to ~20% of

term stillbirths (2). Maternal

nutrition and stress during pregnancy, such as high-altitude

pregnancy, smoking and preeclampsia, can lead to adverse effects

(3,4). Among these, antenatal

hypoxia-induced placental insufficiency has been identified as a

primary risk factor for stillbirths, neonatal deaths and perinatal

morbidity associated with IUGR (5-7).

Antioxidant supplementation has been attempted to treat IUGR, but

has not achieved success (8,9).

Therefore, it remains crucial to discover new and efficacious

treatments for IUGR.

The 16-amino acid mitochondria-derived peptide,

MOTS-c, is synthesized by encoding a compact open reading frame

located within the genomic sequence of the mitochondrial 12S

ribosomal RNA gene (10). It has

been reported that MOTS-c induces transcription of antioxidant

genes and enhances cellular resistance to oxidative stress injury

(11). Low plasma levels of

MOTS-c are associated with endothelial mitochondrial dysfunction in

patients with obesity and coronary artery disease (12,13). MOTS-c serves key roles in the

onset and development of cardiovascular diseases, aging and

age-related diseases (14,15). In addition, supplementation with

MOTS-c inhibits oxidative stress in rotenone-induced neuron

degeneration (13), diabetic

cardiomyopathy (16) and

diabetic nephropathy (17).

However, the role of MOTS-c in hypoxia-induced IUGR remains

unclear.

The placenta possesses a diverse range of

antioxidant defense systems that effectively mitigate the

accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Among these systems,

the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway

serves a pivotal role in governing oxidative stress-associated

disorders (18). Nrf2 is

typically bound to Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) in

the cytoplasm, but dissociates upon exposure to ROS and moves into

the nucleus where it activates genes associated with antioxidant

defense mechanisms (19).

Furthermore, the KEAP1-Nrf2 pathway is also activated by aerobic

exercise or MOTS-c (20). We

previously demonstrated that MOTS-c could directly increase

synthesis of Nrf2 independent of protein degradation and promote

Nrf2 nucleus translocation (21,22). During pregnancy, Nrf2 protects

the fetus from adverse oxidative stress conditions by ensuring

proper placental function (23).

Evidence suggests that Nrf2 deficiency leads to reduced fetal

weight and placental volume (24). However, it remains unclear

whether MOTS-c regulates oxidative stress in IUGR via activation of

the Nrf2-mediated anti-oxidative pathway. The present study aimed

to investigate whether MOTS-c alleviates hypoxia-induced placental

restriction and IUGR by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 69 C57BL/6 wild-type mice (46 female and

23 male), aged 6-8 weeks, and weighing 18-20 g, were sourced from

the Jiangnan University Laboratory Animal Center (Wuxi, China).

Nrf2 knockout (KO) mice were obtained from the Model Animal

Research Institute of Nanjing (Nanjing, China). These mice were

housed in a specific pathogen-free facility environment, which

maintained an ambient humidity of 50% and a temperature range of

22-25°C. The mice had free access to food and water and were

subjected to a 12-h light-dark cycle managed by an automated light

control system. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal

Experimentation Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University [approval

nos. 2 0220930m1080501(383) and 20231115m1080530(555)]. All animal

experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines

established by the International Association for the Assessment and

Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (25) and the relevant laws of the

National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals.

IUGR mouse model establishment and sample

collection

Females were paired with males (with a total of 23

pairs) overnight for mating purposes, and the day of observation of

a vaginal plug was designated as gestational day (GD) 0. The IUGR

mouse model was established as previously reported (26,27) and as similarly described in our

previous studies (28,29). Briefly, 17 pregnant mice were

housed under hypoxic conditions (FiO2=0.105) from GD 11

to GD 17.5, which refers to IUGR group. The control group of

pregnant mice were housed under normoxic conditions

(FiO2=0.21) throughout pregnancy. To determine the

protective effects of MOTS-c, randomly selected control and IUGR

pregnant mice received intraperitoneal injections of 5 mg/kg MOTS-c

once a day from GD 11 to 17.5 (10,30,31), which refers to the MOTS-c (n=6)

and IUGR + MOTS-c groups (n=5), respectively. Meanwhile, control

and IUGR mice were injected with an equivalent volume of

physiological saline from GD 11 to 17.5, which refers to the normal

group (n=6) and IUGR group (n=6) respectively. No suitable drug is

presently available for use as a positive control in the treatment

of hypoxia-induced IUGR (8,9),

therefore, no positive control group was included.

To explore the protective mechanisms of MOTS-c,

pregnant C57BL/6 mice and Nrf2 knockout (KO) mice were randomly

divided into six groups: Normal (n=6), Nrf2−/− (n=4),

IUGR (n=6), IUGR + MOTS-c (n=5), Nrf2−/− + IUGR (n=4),

and Nrf2−/− + IUGR + MOTS-c (n=5). MOTS-c (5 mg/kg) was

intraperitoneally injected daily from GD 11 to 17.5, with an

equivalent volume of physiological saline injected as the loading

control. On GD 17.5, each pregnant mouse was terminally

anesthetized using pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg,

intraperitoneally) as previously reported (32,33). The maternal blood was collected

according to our previous study (34). Briefly, the mice were fixed in a

supine position. After making a sternal incision, blood was

collected by inserting a 26-G needle vertically through the second

intercostal space into the heart, using a vacuum tube system. The

blood was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, centrifuged at

105.45 × g for 10 min at 4°C and then the separated serum was used

for the study. Finally, the mice were then euthanized via cervical

dislocation, and death was confirmed by the absence of a heartbeat

and cessation of breathing. After euthanizing the dams, caesarean

section surgery was performed via hysterectomy as according to a

previous study (35). Briefly,

the abdomen was sterilized with 70% ethanol and an abdominal

incision was made to retrieve the uterus, which was transferred

onto a sterile gauze over a heating pad. Finally, the pups were

extracted by incising the uterine wall and applying gentle

pressure. Fetuses and placentas were then collected. The total

number of fetuses were counted, and the weight of the fetuses and

placentas were measured. The placental efficiency was calculated as

follows: Placental efficiency (%)=(fetal weight/placental weight) ×

100 (36). Fetal pups were

anesthetized by inhalation of 2% isoflurane and sacrificed via

cervical dislocation. Euthanasia was confirmed by the absence of

heartbeat under the dissecting microscope, with the tissue appears

pale. Placental tissues were collected for subsequent experiments;

all collected samples were stored at −80°C until use.

Synthesis of MOTS-c peptides

The human MOTS-c peptide was synthesized by the

Mimotopes Pty Ltd., using 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl solid-phase

chemistry in accordance with standard peptide synthesis protocols

(37). The synthesized peptide

had purity >95%, as determined through high-performance liquid

chromatography by Mimotopes Pty Ltd. The amino acid sequence of

MOTS-c was as follows: Met-Arg-Tr

p-Gln-Glu-Met-Gly-Tyr-Ile-Phe-Tyr-Pro-Arg-Lys-Leu-Arg. The MOTS-c

peptide was dissolved in distilled deionized water at a

concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored at −20°C.

Histopathological staining

Placental tissues were fixed in a 4%

paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature for 48 h, and embed

in paraffin and sectioned (4-μm thick). The sections were

stained with hematoxylin and eosin (cat. no. D006-1, Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). Briefly, the sections were

stained with Harris's hematoxylin (0.1%) for 6 min, differentiated

with 1% acid ethanol, rinsed and blued with tap water, following

counterstaining with eosin Y (0.5-1%) for 1 min at room

temperature. Images of placenta sections were captured using a

Panoramic MIDI scanner (3DHISTECH Ltd.; magnification, ×20) and for

each sample, ~10 images were acquired. Imaging and quantification

were performed blinded. The area of the segmented blood sinusoid

regions was quantified using the area measurement tool of the

ImageJ software version 1.53k (National Institutes of Health). Data

on the areas of blood sinusoids were statistically analyzed to

calculate the means and standard deviation. The assessment of

placental angiogenesis was performed by quantifying the sinusoidal

areas.

Immunohistochemical staining

To detect intracellular antigens, the placental

sections (4-μm thick) were deparaffinized at 65°C for 60 min

and rehydrated using gradient alcohol. Antigen retrieval was

performed using tris-EDTA buffer at 98°C for 25 min, followed by

permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room

temperature. To minimize non-specific binding, sections were

blocked with 5% normal goat serum (cat. no. A7906; MilliporeSigma)

for 2 h at room temperature. For HRP-based assays, endogenous

peroxidases were quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for

15 min before blocking. The placental sections were then incubated

with the primary antibodies against CD31 (1:100; cat. no. #77699s;

Cell Signaling Technology) and MOTS-c (1:100; cat. no.

#MOTSC-101AP; FabGennix International Inc.) overnight at 4°C. At

room temperature, the samples were co-incubated with the

corresponding fluorescence labeled secondary antibody (1:100; cat.

no. 33106ES60; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 60 min,

and freshly prepared DAB (cat. no. #CW20695; CWBIO) staining was

then performed. Finally, sections were counterstained with

hematoxylin (cat. no. I030-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute), dehydrated and cleared. Images were captured using

Panoramic MIDI (3D HISTECH Ltd.) and analyzed using the Panoramic

Viewer software version 2.1 (3DHISTECH Ltd.).

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

MOTS-c content in the serum and placental tissues of

the pregnant mice was quantified using an ELISA kit (cat. no

#MM-46300M1; Jiangsu Meimian Industrial Co., Ltd.) following the

manufacturer's guidelines.

Cell culture and treatments

The immortalized human umbilical vein endothelial

cells (HUVECs) and human placental trophoblast cell (HTR-8/SVneo)

were obtained from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The

Chinese Academy of Sciences. These cells were cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; cat. no. 319-005-CL;

Wisent, Inc.) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no.

40130ES76; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin mixture (cat. no. C0222; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology). Incubation conditions were set to a humidified

atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2.

In investigating the effects of MOTS-c on

hypoxia-induced HUVECs and HTR-8/SVneo cells, the cells were

pre-treated with 10 μM MOTS-c under normoxic conditions (21%

O2) or an equivalent volume of phosphate buffer saline

(PBS), followed by modeling under hypoxic conditions for 48 h; the

use of 1% O2 is a well-established model in the in

vitro study of hypoxia-related diseases, and has been

demonstrated to cause dysregulation of angiogenesis and

proliferation in HUVECs as previously described (38). To mimic the abnormal angiogenesis

under hypoxia exposure, HUVECs were exposed to an oxygen

concentration of FiO2=0.01 for 48 h. The procedure for

each experimental approach was standardized to ensure consistent

operational steps and treatment conditions across three replicates.

HUVECs and HTR-8/SVneo cells used were confined to those within the

3rd to 5th passages for experimental consistency and reliability.

The experiment was independently repeated for three times.

To determine the role of Nrf2 in hypoxia-stimulated

HUVECs, ML385 (cat. no. HY-100523; MedChemExpress), a specific Nrf2

inhibitor was used as previously reported (39). Briefly, HUVECs were stimulated

with ML358 (5 μM) for 1 h, followed by administration with

MOTS-c (10 μM) for 2 h and exposed to hypoxia (1%

O2) for an additional 48 h.

Optical Microscopy

For morphological assessment, HUVECs were examined

under a phase-contrast microscope equipped with a digital camera

(DP11, Olympus), and images were documented.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated by the Cell Counting

Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (cat. no. C0037; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Cells were seeded at a density of 1×104

cells/well in 96-well plates. After rinsing with PBS, the cells

were exposed to CCK-8 solution (1:10 dilution). The cells were

incubated at 37°C for 2 h, and then the absorbance were measured at

450 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.).

Nrf2 overexpression in HUVECs

The Nrf2 overexpression plasmid was constructed and

obtained from OBiO Technology (Shanghai) Corp., Ltd. Briefly, after

reaching 80% confluence, the cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1

plasmid or Nrf2 overexpression plasmids (1 μg/ml) using a

transfection reagent (cat. no. C10511-05; Guangzhou RiboBio Co.,

Ltd.) and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, the

medium was changed and exposed to normoxic (21% O2) or

hypoxic (1% O2) conditions for 48 h. Cells were then

harvested for downstream analysis, with Nrf2 overexpression

verification performed by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR).

Nrf2 siRNA transfection in HUVECs

Nrf2 siRNA was obtained from KeyGEN BioTECH.

Briefly, after reaching 80% confluence, HUVECs cells were

transfected with control siRNA (20 μM) or Nrf2 siRNA (20

μM) using a transfection reagent (cat. no. C10511-05;

Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. After 12 h, the medium was changed and the cells were

cultured for 36 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then

harvested for downstream analysis, with Nrf2 knockdown verification

performed by RT-qPCR. The siRNA sequences used were as follows:

Nrf2 sense (S), 5'-GCAGCAAACAAGAGAUGGCAAdTdT-3' and anti-sense

(AS), 5'-UUGCCAUCUCUUGUUUGCUGCdTdT-3'; and negative control siRNA

(vector-siRNA) S, 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT-3' and AS,

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAdTdT-3'.

ROS measurements

The ROS production in HUVECs and HTR-8/SVneo cells

were assessed using 2',7'-dichlorodihydro fluorescein diacetate

(DCFH-DA) diacetyldichlorofluorescein staining solution (1:1,000;

cat. no. E004-1-1; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) in

the dark at 37°C for 15 min, and analyzed with a Zeiss fluorescence

microscope (Zeiss AG). The mitochondrial ROS levels were assessed

using MitoSOX (cat. no. #40778ES50; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.). The cells were treated with a MitoSOX working solution

(5 mM) at 37°C for 20 min. Then, the ROS fluorescence intensity was

visualized using a confocal microscope (Zeiss AG).

Immunofluorescence staining

For Nrf2 immunofluorescence staining in HUVECs,

cells were fixed with 100% methanol for 15 min at −20°C, followed

by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min and blocked

with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (cat. no. HY-D0842;

MedChemExpress) for 60 min at room temperature. The cells were then

incubated with Nrf2 antibody (cat. no. #ab62352; Abcam) at 1/100

dilution overnight at 4°C followed by a further incubation with

Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. 33103ES60;

Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 1

h. The Nrf2 antibody specificity was validated by Nrf2 siRNA

knockdown (Fig. S1). The nuclei

were labelled with DAPI solution (1 mg/ml; cat. no. #P0131;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 10 min at room

temperature. Images were captured using a confocal microscope.

For Ki-67 and Nrf2 immunofluorescence staining in

placental tissues, the sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton

X-100 for 10 min and blocked with 5% BSA (cat. no. HY-D0842;

MedChemExpress) for 2 h at room temperature. The samples were

incubated with primary antibodies anti-Ki-67 (1:100; cat. no.

#9129; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-Nrf2 (1:100; cat.

no. #62352; Abcam) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with

secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (cat. no.

#33103ES60; 1:200; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) or

Alexa Fluor 594 (cat. no. #33112ES60; 1:200; Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, the nuclei were stained

with DAPI (1 μg/ml; cat. no. HY-D1738; MedChemExpress) for 5

min at room temperature. Images were acquired using a Zeiss Axio

Imager 2 fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss AG). The number of

immunoreactivity positive cells was quantified as the percentage of

total cells. All samples were blinded during imaging and

quantification.

Tube formation assay

Matrigel (50 μl; cat. no. #082704; Shanghai

Nova Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd) was added to each well of

96-well plates and allowed to solidify in a cell incubator at 37°C

with 5% CO2 for 60 min. Next, 3×104 HUVECs in

100 μl of DMEM containing 5% fetal bovine serum (cat. no.

40130ES76; Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (cat. no. C0222; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). were added to each well. After 6 h of incubation,

tubular structures were examined and visualized using a Zeiss Axio

Imager 2 fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss AG), and the tube

lengths were quantified using ImageJ software version 1.53k

(National Institutes of Health). The angiogenic capability was

quantified by measuring the number of tubes and the mean mesh size

per field from three randomly selected fields per well.

L-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), superoxide

dismutase activity (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) content

LDH concentration, SOD activity and the MDA content

were quantified in the serum of pregnant mice and HUVECs using kits

from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (LDH kit, cat. no.

A020-2; SOD kit, cat. no. A001-3-2: MDA kit, cat. no. A003-1-2)

following the manufacturer's protocols.

Determination of mitochondrial membrane

potential (MMP)

The MMP was assessed using JC-1 dye (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). Briefly, JC-1 dye added to the cell

suspension to achieve a final dye concentration of 10 μM.

The cells were incubated with the JC-1 dye mixture at 37°C for 15

min to allow the dye to enter the cells and accumulate in the

mitochondria. JC monomers (488 nm) and JC aggregates (570 nm) were

visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation),

and images were acquired from a random selection of 3-4 fields per

well.

Western blotting

Placentas and HUVEC cells were lysed using RIPA

buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

containing with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (cat. no.

P1045; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Nuclear and

cytoplasmic extracts from placental tissues were prepared using a

Nuclear Extraction Kit (cat. no. W037-1-1; Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The protein concentrations were determined according

to the manufacturer instructions using a BCA Protein Assay kit

(cat. no. P0009; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Subsequently, the lysates were separated on 8 and 10% SDS-PAGE gels

and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (cat. no.

P2938; MilliporeSigma; Merck KGaA). Following a 2 h blocking step

at room temperature with 5% BSA (cat. no. HY-D0842; MedChemExpress)

in Tris-buffered saline, the membranes were incubated overnight at

4°C with primary antibodies targeting CD31 (1:1,000; cat. no.

77699s; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), vascular endothelial

growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2; 1:1,000; cat. no. 26415-1-AP;

Proteintech), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA; 1:1,000;

cat. no. 66828-1-Ig; Proteintech), Nrf2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 62352;

Abcam) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH;

1:5,000; cat. no. 263962; Abcam). After washing, the membranes were

incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature

(Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, 1:5,000; cat. no. CW0102S; Goat Anti-Rabbit

IgG, 1:5,000; cat. no. CW0103S; Jiangsu CoWin Biotech Co., Ltd.)

corresponding to the primary antibody source. Protein bands were

visualized using a ChemiDocTM XRS Plus luminescence image analyzer

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) with an ECL system (MilliporeSigma;

Merck KGaA), and quantified using ImageJ software version 1.53k

(National Institutes of Health).

Reverse transcription

quantitative-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from the placental tissue was extracted

using TRIzol Reagent (cat. no. R401; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) and

then reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA using a PrimeScript

RT Reagent Kit (cat. no. R323; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) according

to the manufacturer's protocol. Target mRNA amplification was

measured using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (cat. no. 11201ES08; Shanghai

Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) with a LightCycler® 480

detection PCR system (Roche Diagnostics). The PCR amplification

protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5

min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec,

annealing at 55°C for 20 sec and extension at 72°C for 20 sec.

Quantification was performed employing the 2−ΔΔCq method

(40), with GAPDH serving as the

reference gene. The primer sequences are provided in Table I.

| Table IPrimers for reverse-transcription

quantitative PCR analysis. |

Table I

Primers for reverse-transcription

quantitative PCR analysis.

A, Mouse primers

|

|---|

| Gene | Sequence

(5'-3') |

|---|

| Pgf | F:

AGTGGAAGTGGTGCCTTTCAA |

| R:

GTGAGACACCTCATCAGGGTA |

| Fatp4 | F:

ACTGTTCTCCAAGCTAGTGCT |

| R:

GATGAAGACCCGGATGAAACG |

| Glut1 | F:

TCAAACATGGAACCACCGCTA |

| R:

AAGAGGCCGACAGAGAAGGAA |

| Snat2 | F:

GGGACATAAGGCGTATGGTCT |

| R:

GGTAGCTTGACATAGCCCCAA |

| Igf2 | F:

CGTGGCATCGTGGAAGAGT |

| R:

ACGTCCCTCTCGGACTTGG |

| Nrf2 | F:

TCTTGGAGTAAGTCGAGAAGTGT |

| R:

GTTGAAACTGAGCGAAAAAGGC |

| Gapdh | F:

AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| R:

GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA |

|

| B, Human

primers |

|

| Gene | Sequence

(5'-3') |

|

| VEGFA | F:

AGGGCAGAATCATCACGAAGT |

| R:

AGGGTCTCGATTGGATGGCA |

| VEGFR2 | F:

GGCCCAATAATCAGAGTGGCA |

| R:

CCAGTGTCATTTCCGATCACTTT |

| CD31 | F:

CCAAGGTGGGATCGTGAGG |

| R:

TCGGAAGGATAAAACGCGGTC |

| GAPDH | F:

GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT |

| R:

GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

Statistical analyses

Statistical data are depicted as means ± standard

deviation. The D'Agostino-Pearson test and Shapiro-Wilk test were

used for normality tests. For quantitative data obeying normal

distribution, comparisons between two groups were performed using

Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test. To compare among ≥3 groups,

the Brown-Forsythe analysis was used to test for homogeneity of

variance, if the variance was homogeneous, the Tukey's test of

one-way analysis of variance was used. If variances were not

homogeneous, Dunnett's T3 test was used to test for differences

between multiple groups. The association between different targets

was analyzed using Pearson's correlation test. Analyses were

performed using the GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0.2;

Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Decreased levels of MOTS-c in the serum

and placenta of pregnant mice is associated with reduced fetal

weight and lower placental vascular density

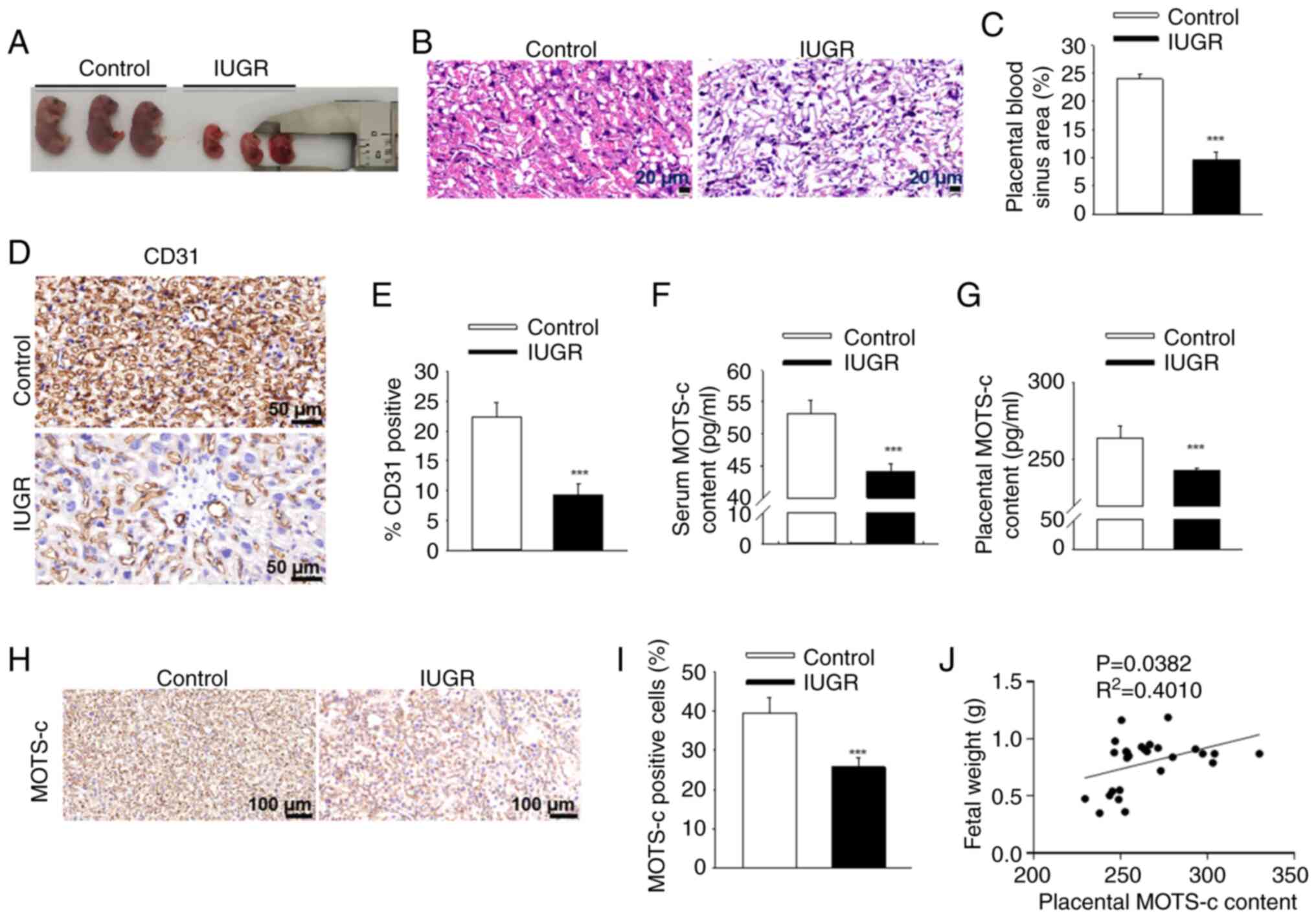

Exposure to hypoxia during pregnancy led to

significant fetal growth restriction (Fig. 1A), evidenced by reduced fetal

body weight and diminished placental efficiency (the

fetal-to-placental weight ratio; Table II). Additionally, the blood

sinus areas within the placenta were significantly reduced in IUGR

mice (Fig. 1B and C). The

expression levels of CD31, a vascular marker, were significantly

lower in the placenta of IUGR mice compared with that of the

Controlgroup (Fig. 1D and E).

These findings suggested a reduction in placental vascular density

following antenatal maternal hypoxia exposure. MOTS-c content was

significantly reduced in both maternal serum and placenta after

hypoxic exposure (Fig. 1F and

G), further validated by immunohistochemistry of placental

tissues, with 34.8% reduction of MOTS-c positive cells in IUGR mice

when compared with the control group (Fig. 1H and I). Furthermore, placental

MOTS-c levels exhibited a positive correlation with fetal mouse

weight (R2=0.4010; P=0.0382; Fig. 1J). These data suggested that the

decreased fetal weight and placental vascular density resulting

from antenatal maternal hypoxia may be associated with reduced

MOTS-c content.

| Table IIDescriptive statistics of dams and

fetuses exposed to hypoxia. |

Table II

Descriptive statistics of dams and

fetuses exposed to hypoxia.

| Characteristic | Normal | IUGR | P-value |

|---|

| Maternal body

weight, g | 31.9±1.1 | 29.6±1.3a | 0.0087 |

| Litter size | 7.6±1.4 | 7.4±1.6 | 0.8626 |

| Litter parameters,

n | 53 | 52 | |

| Fetal weight

(g) | 0.90±0.085 | 0.49±0.075b | <0.0001 |

| Crown-rump length

(mm) | 8.6±0.4 | 8.0±0.4 | 0.0333 |

| Placenta, n | 53 | 52 | |

| Placenta weight

(g) | 0.0772±0.0102 | 0.0836±0.00790 | 0.2954 |

| Fetal/weight

ratio | 11.8±2.0 | 6.0±1.2b | 0.0001 |

MOTS-c promotes placental angiogenesis

and increased fetal weight in IUGR mice

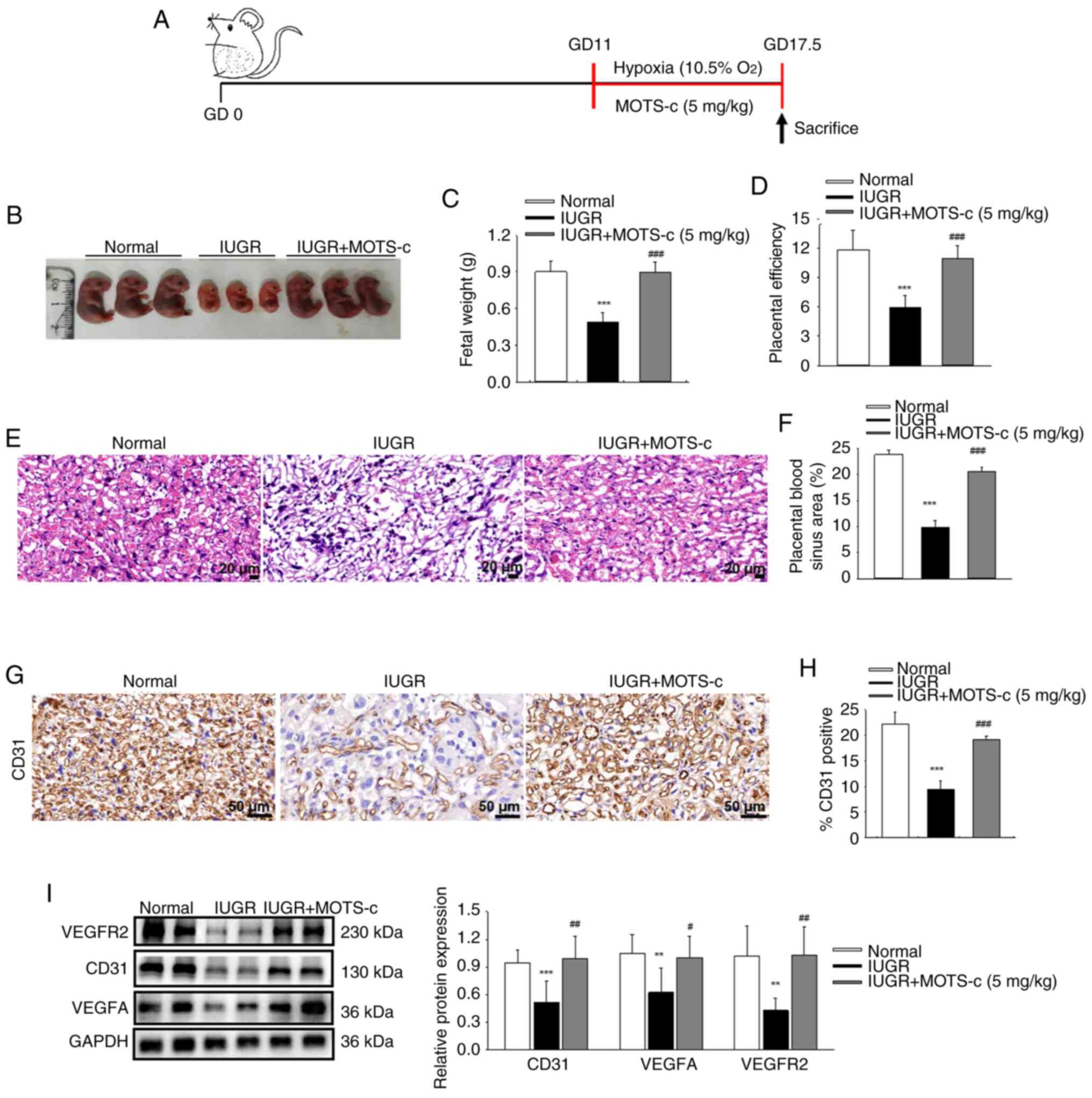

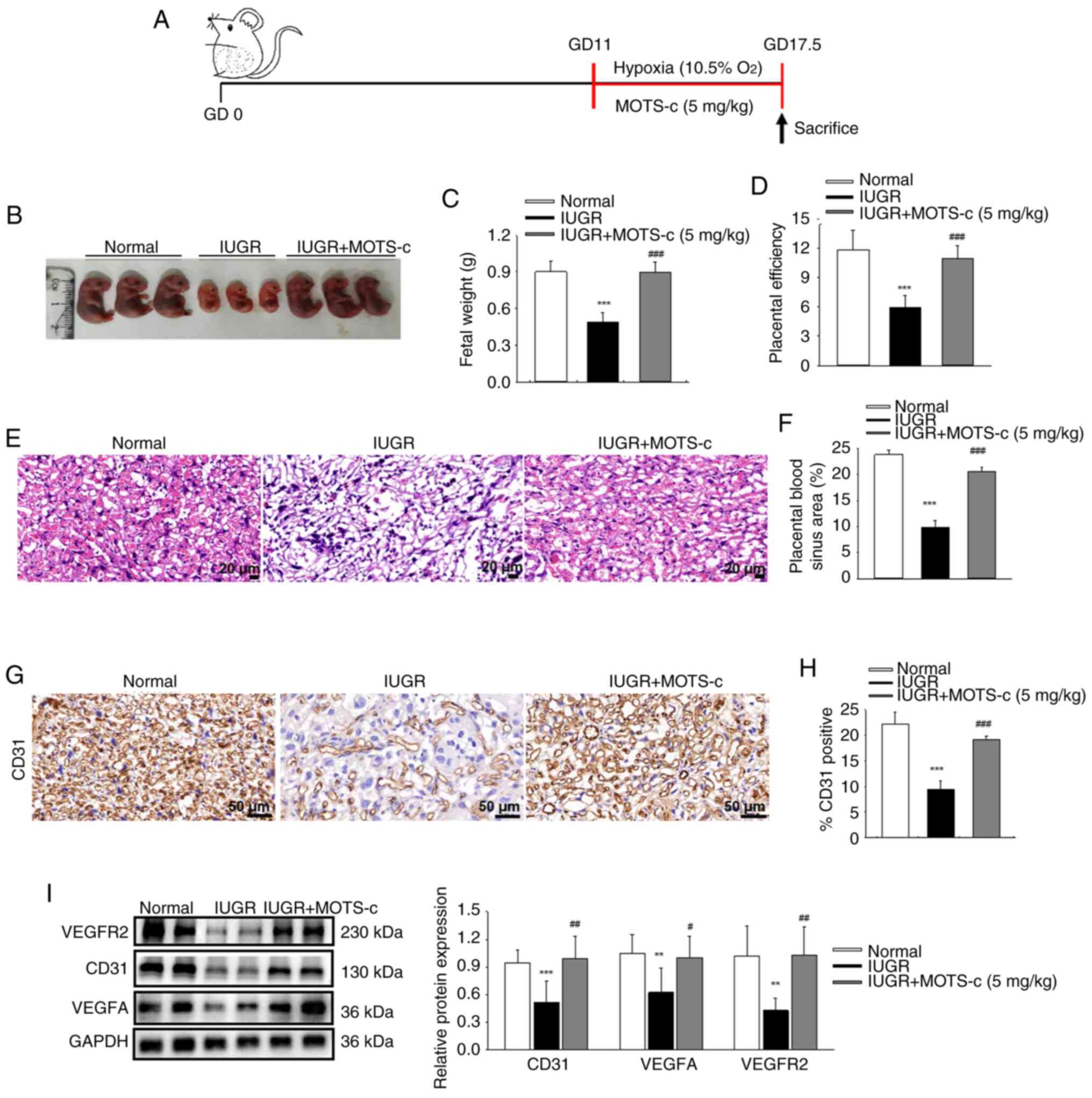

To assess the potential benefits of MOTS-c

supplementation on fetal growth, synthetic MOTS-c peptide was

administered intraperitoneally. The timeline of this experimental

study is schematically presented in Fig. 2A. This intervention resulted in a

significant increase in maternal serum and placental MOTS-c

content, as showed in Fig. S2A-D. When compared with that of the

normal group, the MOTS-c group mice showed no significant

differences in fetal growth, as indicated by normal size,

morphology and fetal weight (Fig.

S3A and B), fetal weight of the MOTS-c group remained normal

for up to 4 weeks after birth (Fig.

S3C). Therefore, subsequent investigations focused solely on

the effects of MOTS-c on IUGR mice. MOTS-c administration

significantly improved fetal development, with increased fetal size

and fetal weight compared with that of the IUGR group (Fig. 2B and C). Furthermore, the ratio

of fetal to placental weight was significantly increased following

MOTS-c administration in the IUGR mice compared with the untreated

IUGR mice (Fig. 2D). In

addition, MOTS-c administration significantly improved blood sinus

areas (Fig. 2E and F) and

upregulated CD31 expression in the placenta in the IUGR + MOTS-c

group compared with that of the IUGR group (Fig. 2G and H). These findings suggested

beneficial effects of MOTS-c treatment against hypoxia-induced poor

placental vascular density and subsequent fetal development. As the

VEGF pathway is recognized as a major regulatory mechanism

governing developmental angiogenesis (41), the expression levels of VEGFA and

VEGFR2 were investigated. The protein expressions levels of VEGFA

and VEGFR2 were decreased in placental tissues following hypoxic

exposure in the IUGR group, while in comparison, MOTS-c treatment

significantly upregulated the VEGF pathway in the IUGR + MOTS-c

group (Fig. 2I). These results

suggested that MOTS-c improved hypoxia-induced IUGR by promoting

placental angiogenesis.

| Figure 2MOTS-c administration protects

against hypoxia-induced fetal growth restriction. (A) Schematic

timeline of the experimental setup. (B) Morphology of fetal mice on

GD17.5. (C) Mean fetal weights within each litter. (D) Placental

efficiency, which represents the ratio of fetal to placenta weight.

(E) Representative images of H&E staining of placental tissues.

Scale bar, 20 μm. (F) Quantification of placental blood

sinus area. (G) Representative IHC images CD31. Scale bar, 50

μm. (H) Quantification of CD31 positive area. (I) Western

blotting analysis of CD31, VEGFA and VEGFR2 protein expression in

placenta. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Normal, n=6; IUGR,

n=6; IUGR + MOTS-c, n=5. **P<0.01 vs. normal,

***P<0.001 vs. normal; #P<0.05 vs.

IUGR; ##P<0.01 vs. IUGR; ###P<0.001 vs.

IUGR. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; GD, gestational day;

VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A; VEGFR2, VEGF receptor

2. |

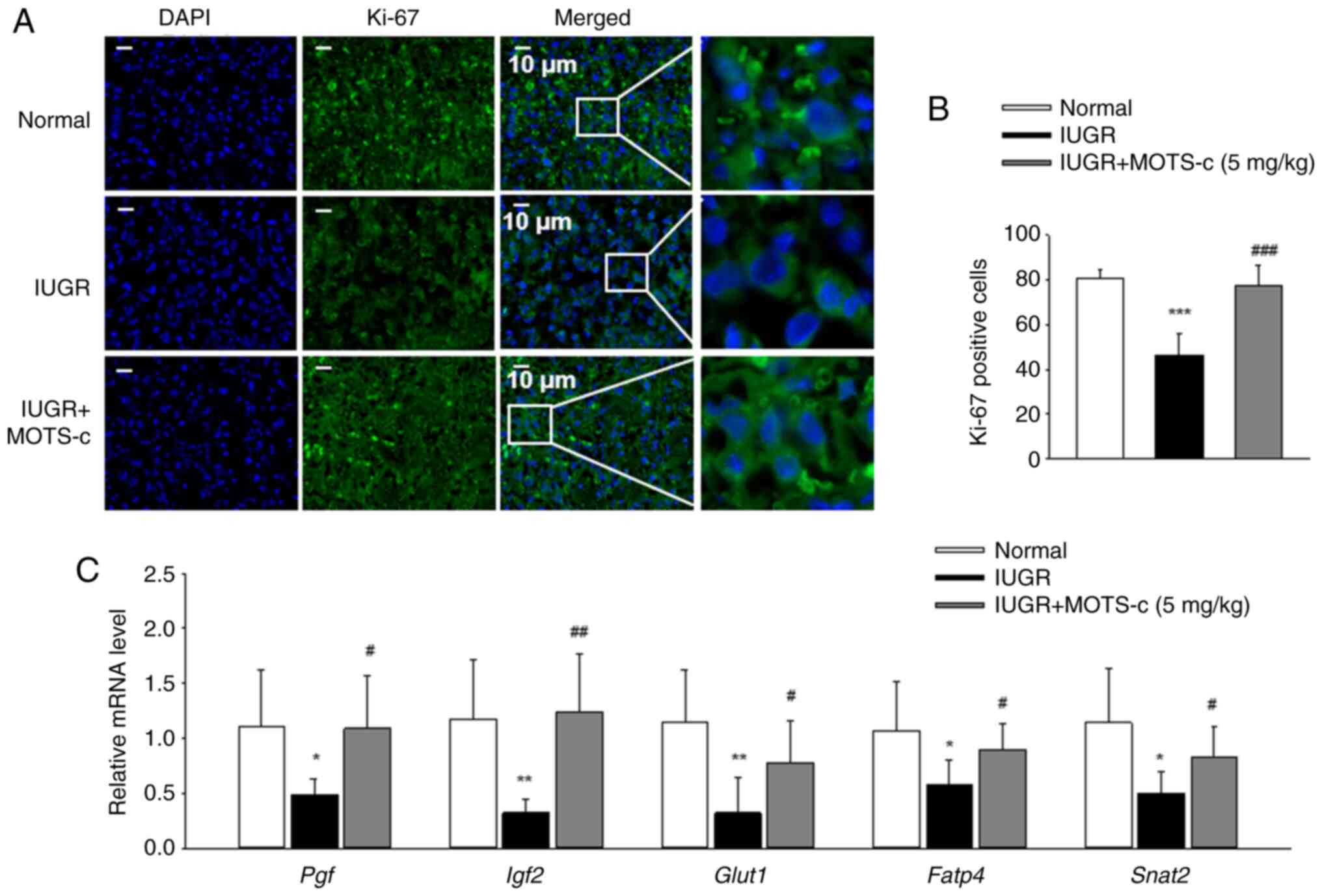

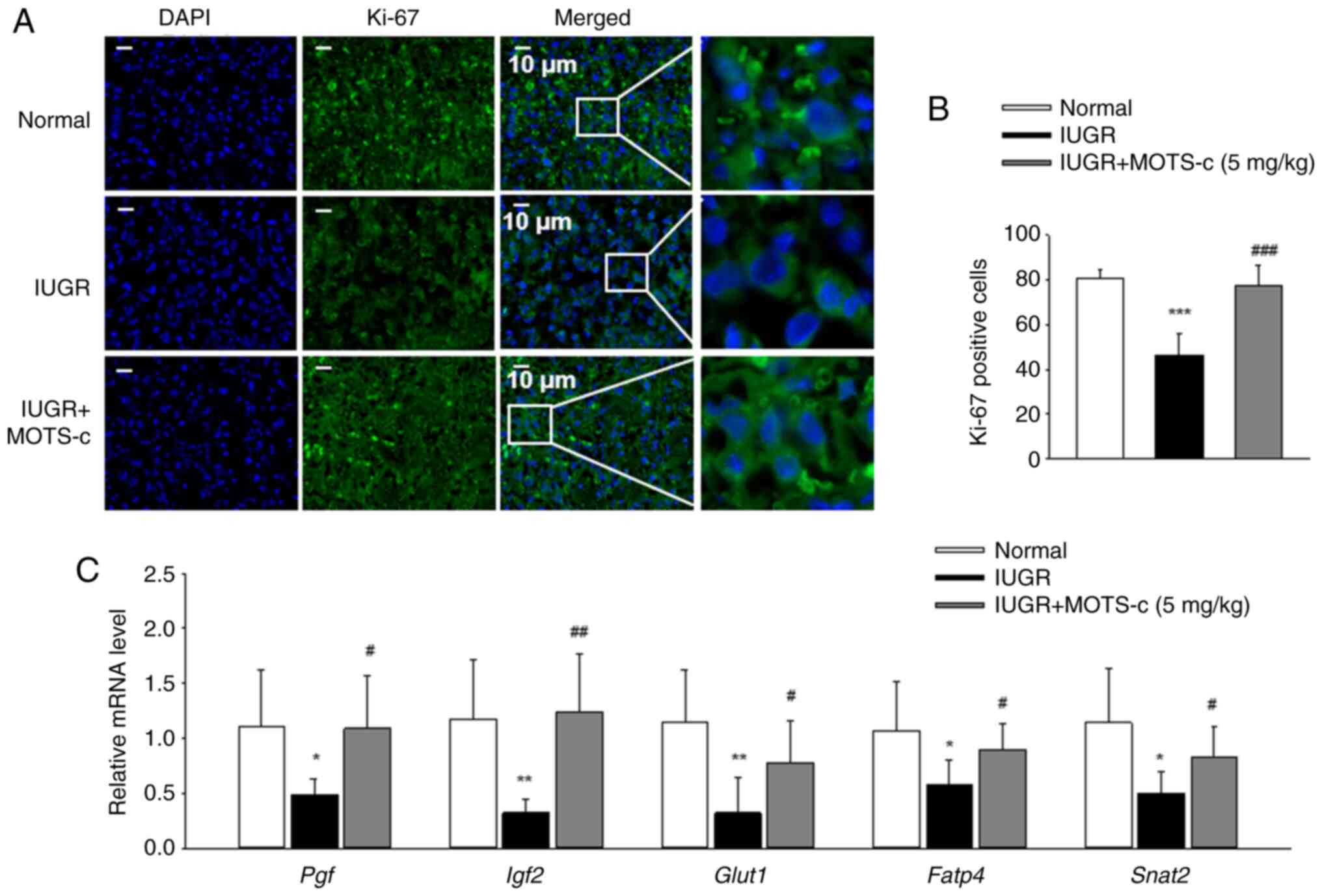

Increased cell proliferation and

upregulation of mRNA expression of nutrient transporter genes in

placental tissues are associated with MOTS-c treatment

To investigate the role of MOTS-c on cell

proliferation in placenta subjected to IUGR, placental tissues of

the normal, IUGR and IUGR + MOTS-c group mice were stained with

Ki-67, a marker for cell proliferation, and the number of positive

cells was quantified. The concentration of Ki-67-positive cells

were significantly decreased in hypoxia-exposed placental tissues

compared with that in the normal group, which was subsequently

reversed by MOTS-c administration (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, the mRNA

expression levels of placental growth factor (Pgf),

sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter-2 (Snat2),

glucose transporter type 1 (Glut1), insulin-like growth

factor 2 (Igf2) and fatty acid transporter 4 (Fatp4)

in placental tissues were assessed. Hypoxia exposure resulted in

the downregulation of placental growth factors (Pgf and

Igf2), as well as placental nutrient transport-related genes

(Glut1, Fatp4 and Snat2) in the IUGR group;

MOTS-c treatment in the IUGR + MOTS-c group significantly increased

the mRNA expression levels when compared with that in the IUGR

group (Fig. 3C). These findings

suggested that MOTS-c treatment exerted a beneficial effect on

placental proliferation defects in hypoxic environments.

| Figure 3Administration of MOTS-c improves

placental injury. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of

Ki-67 in placental tissues. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B)

Qualification of Ki-67 positive cells. (C) Relative mRNA expression

levels of Pgf, Igf2, Glut1, Fatp4 and

Snat2 in placenta. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Normal, n=6; IUGR, n=6; IUGR + MOTS-c, n=5. *P<0.05

vs. normal, **P<0.01 vs. normal,

***P<0.001 vs. normal; #P<0.05 vs.

IUGR; ##P<0.01 vs. IUGR; ###P<0.001 vs.

IUGR. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; Pgf, placental growth

factor; Igf2, insulin-like growth factor 2; Glut1, glucose

transporter type 1; Fatp4, fatty acid transporter 4; Snat2,

sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter-2. |

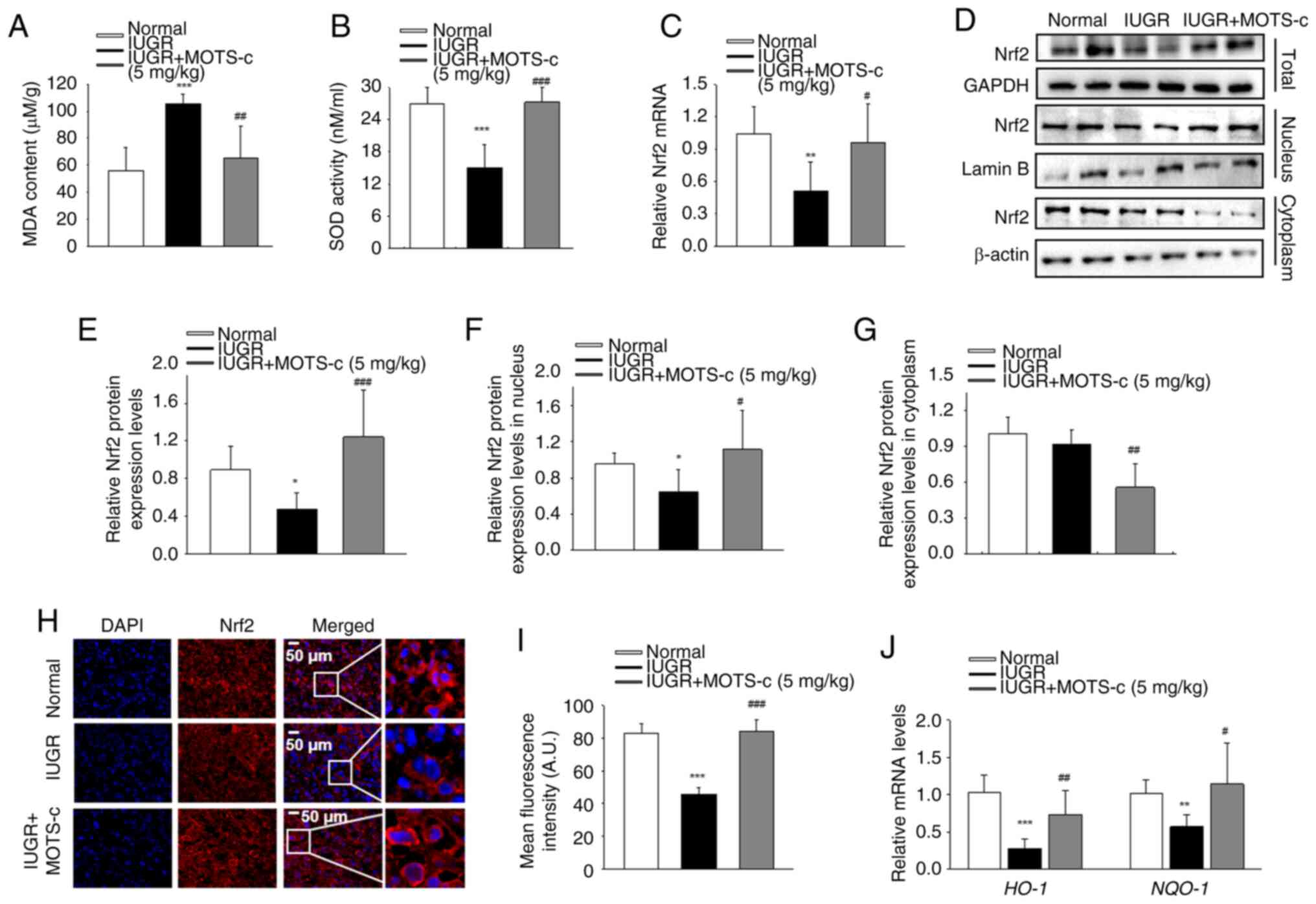

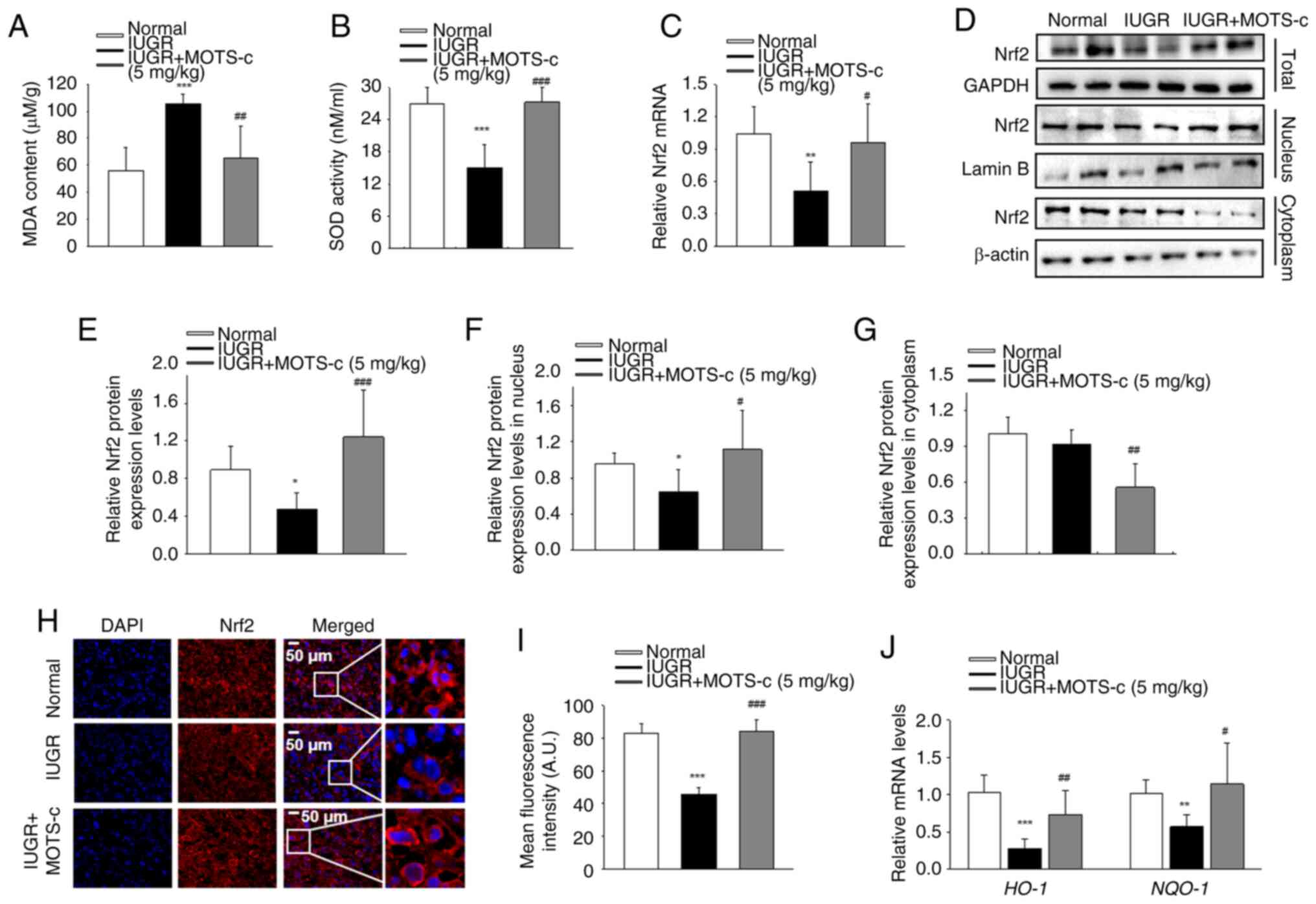

MOTS-c mitigates hypoxia-mediated

oxidative stress in the placenta tissue

MOTS-c administration effectively mitigated

oxidative stress-induced damage in placental tissues, as evidenced

by a significant reduction in MDA levels and an increased SOD

activity in the IUGR + MOTS-c group compared with that of the IUGR

group (Fig. 4A and B). Nrf2,

which upregulates the expressions of numerous antioxidant genes,

serves a key role in inhibiting oxidative stress in the placenta

(42). Maternal hypoxia exposure

resulted in significantly decreased Nrf2 mRNA expression levels in

the placenta of the IUGR group, while MOTS-c treatment restored

Nrf2 mRNA expression levels in the IUGR + MOTS-c group (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, total, nuclear

and cytoplasmic Nrf2 protein expression levels were also examined.

Hypoxia restricted Nrf2 nuclear translocation, while MOTS-c

significantly increased nuclear Nrf2 expression in placental

tissues (Fig. 4D-G). The

accumulation and nuclear translocation of Nrf2 was also detected by

immunofluorescence, which demonstrated that in the IUGR + MOTS-c

group, MOTS-c treatment promoted Nrf2 nuclear translocation

compared with that in the IUGR group (Fig. 4H and I). In addition, MOTS-c

treatment was associated with increased mRNA expression levels of

heme oxygenase 1 and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1, which are

known Nrf2 downstream targeted anti-oxidative genes (Fig. 4J). These results suggest that

MOTS-c activate Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway.

| Figure 4MOTS-c mitigates hypoxia-mediated

oxidative stress in placenta. (A) MDA content in placenta. (B) SOD

activity in placenta. (C) Nrf2 mRNA expression levels in placenta.

(D) Representative western blotting images. (E) Total Nrf2

expression in placental tissues. (F) Nuclear Nrf2 expression in

placental tissues. (G) Nrf2 expression in cytoplasm of placental

tissues. (H) Representative immunofluorescence images and (I)

quantification of Nrf2 in placenta. Scale bar, 50 μm. (J)

Relative mRNA expression levels of HO-1 and NQO-1. Data are

expressed as the mean ± SD. Normal, n=6; IUGR, n=6; IUGR + MOTS-c,

n=5. *P<0.05 vs. normal, **P<0.01 vs.

normal, ***P<0.001 vs. normal; #P<0.05

vs. IUGR; ##P<0.01 vs. IUGR; ###P<0.001

vs. IUGR. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; SOD, superoxide

dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; NQO-1, NAD(P)H quinone

dehydrogenase 1. |

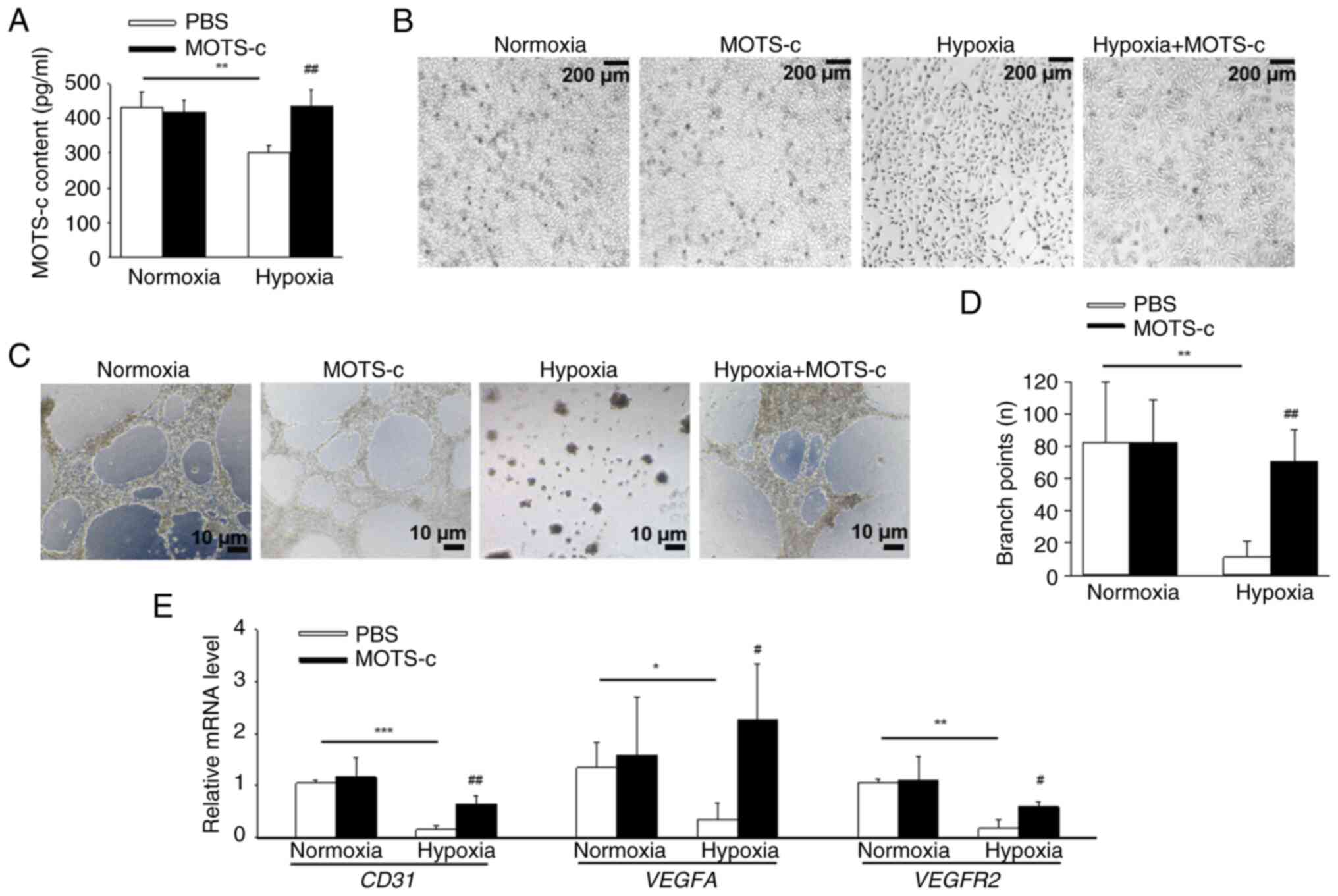

MOTS-c treatment attenuates

hypoxia-induced injury in HUVEC cells

To elucidate the effects of MOTS-c on HUVECs, MOTS-c

(10 μM) was used for subsequent in vitro assays,

according to the CCK-8 results (Fig. S4A), since MOTS-c (20 and 40

μM) resulted in significantly decreased cell viability. It

was demonstrated that MOTS-c content significantly decreased after

hypoxic stimuli compared with HUVECs in normoxic conditions, which

was consistent with the in vivo results. Exogenous MOTS-c

(10 μM) significantly increased the MOTS-c content in

hypoxia-induced HUVECs compared with that in the hypoxia group.

(Fig. 5A). MOTS-c administration

restored hypoxia-induced abnormal morphology in HUVECs (Fig. 5B) and significantly increased

tube formation of HUVECs (Fig. 5C

and D) compared with that in the hypoxia group. Furthermore,

MOTS-c treatment increased mRNA expression levels of CD31,

VEGFA and VEGFR2 under hypoxic conditions in HUVECs

compared with that in the hypoxia group (Fig. 5E). In addition, MOTS-c treatment

promoted proliferation in hypoxia-exposed HUVECs, as evidenced by

the significantly increased levels of Ki-67 positive cells under

MOTS-c treatment compared with the control group (Fig. S4B and C). These results

suggested that MOTS-c mitigated hypoxia-induced injury and promoted

angiogenesis and proliferation in HUVECs.

It was further investigated whether MOTS-c functions

in other cell types in the placenta; placental trophoblast cells

are critically important for pregnancy and embryonic development

(43). Thus, human placental

trophoblast cells (HTR-8/SVneo) was also examined. MOTS-c treatment

significantly increased cell viability reduced cell injury and

enhanced the mRNA levels of nutrient transporter genes, including

Pgf, Igf2, Glut1, Fatp4 and

Snat2 (Fig. S5A-C).

Furthermore, MOTS-c treatment significantly reduced ROS production

in hypoxia-stimulated HTR-8/SVneo cells compared with that of the

PBS treated HTR-8/SVneo cells under hypoxic conditions (Fig. S5D and E). These results

indicated that the beneficial effects of MOTS-c against hypoxia was

not limited to HUVECs.

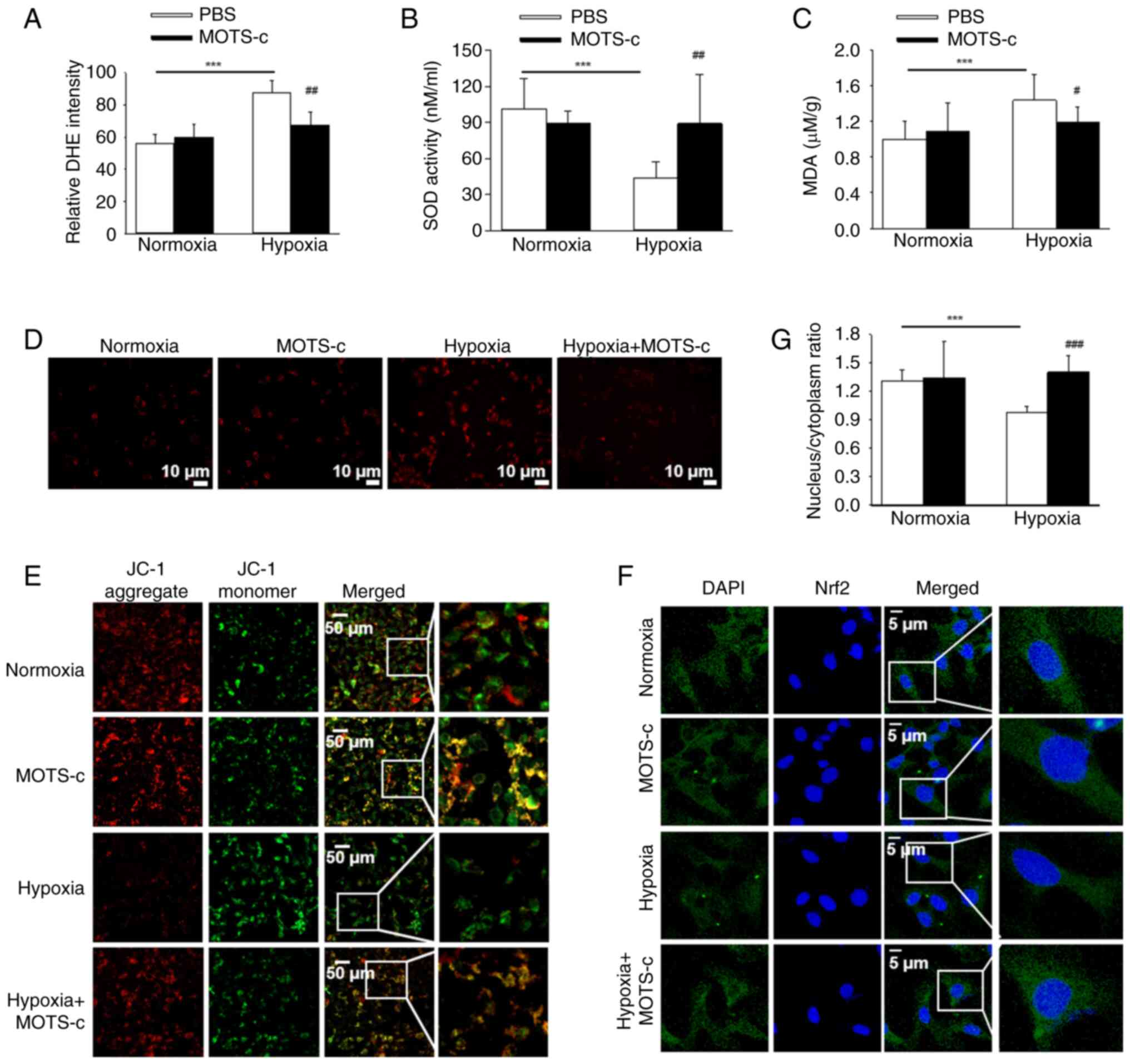

MOTS-c treatment increased Nrf2 nuclear

translocation and attenuated mitochondrial injury in HUVECs

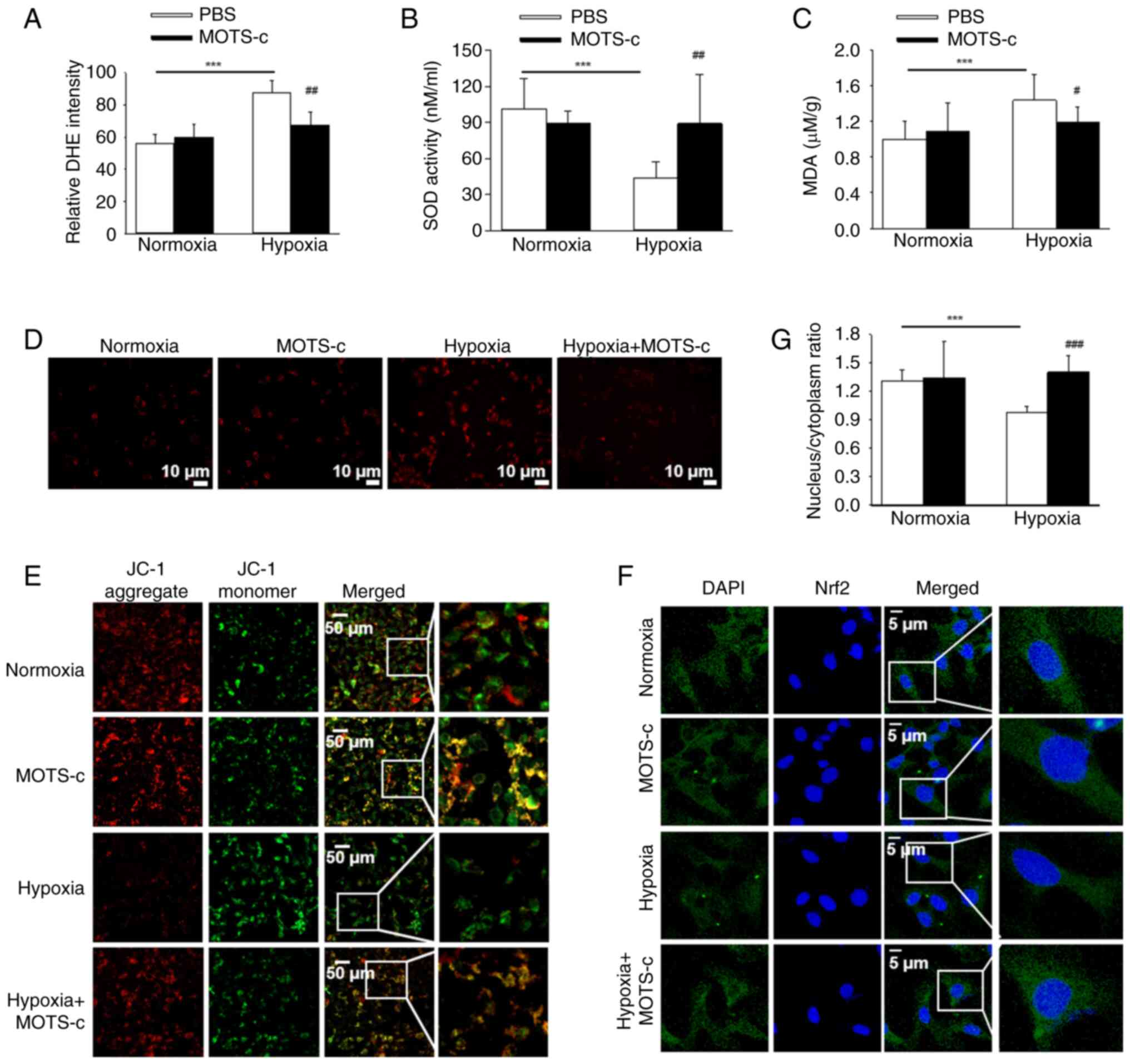

The antioxidant effect of MOTS-c treatment was also

examined in HUVECs. Intracellular ROS production was assessed using

DCFH-DA staining, which demonstrated that MOTS-c treatment

significantly suppressed the hypoxia-induced ROS generation

compared with that of PBS-treated hypoxic cells (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, MOTS-c treatment

under hypoxic conditions resulted in significantly reduced MDA

content and restored SOD activity in HUVECs compared with that of

PBS-treated hypoxic cells (Fig. 6B

and C). Additionally, mitochondrial ROS levels were evaluated

using MitoSOX staining, which similarly demonstrated that MOTS-c

treatment significantly inhibited hypoxia-induced mitochondrial ROS

generation compared with that of PBS-treated hypoxic cells

(Fig. 6D). Concurrently, MMP

levels was assessed using JC-1 staining, which demonstrated that

MOTS-c significantly reduced MMP levels in hypoxic HUVECs compared

with untreated cells (Fig. 6E).

Consistent with the present in vivo findings, MOTS-c

treatment promoted Nrf2 nuclear translocation in hypoxia-induced

HUVECs (Fig. 6F and G). These

findings suggested that MOTS-c exerted its protective effects, at

least in part, through enhanced Nrf2 activity and by mitigating

mitochondrial injury in hypoxia-induced HUVECs.

| Figure 6MOTS-c exposure attenuates oxidative

stress in HUVECs. (A) Relative intensity of DCFH-DA staining. (B)

Cellular SOD activity. (C) Cellular MDA content. (D) Representative

images of MitoSOX staining. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E)

Representative images of JC-1 staining. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(F) Representative immunofluorescence images of Nrf2 in HUVECs.

Scale bar, 5 μm. (G) Relative nuclear to cytoplasm

fluorescence ratio. Results are representative of three independent

experiments. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, n=4.

***P<0.001, #P<0.05 vs. PBS under

hypoxic conditions, ##P<0.01 vs. PBS under hypoxic

conditions; ###P<0.001 vs. PBS under hypoxic

conditions. SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde;

DCFH-DA,2'7'-dichlorodihydro fluorescein diacetate ; Nrf2, nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. |

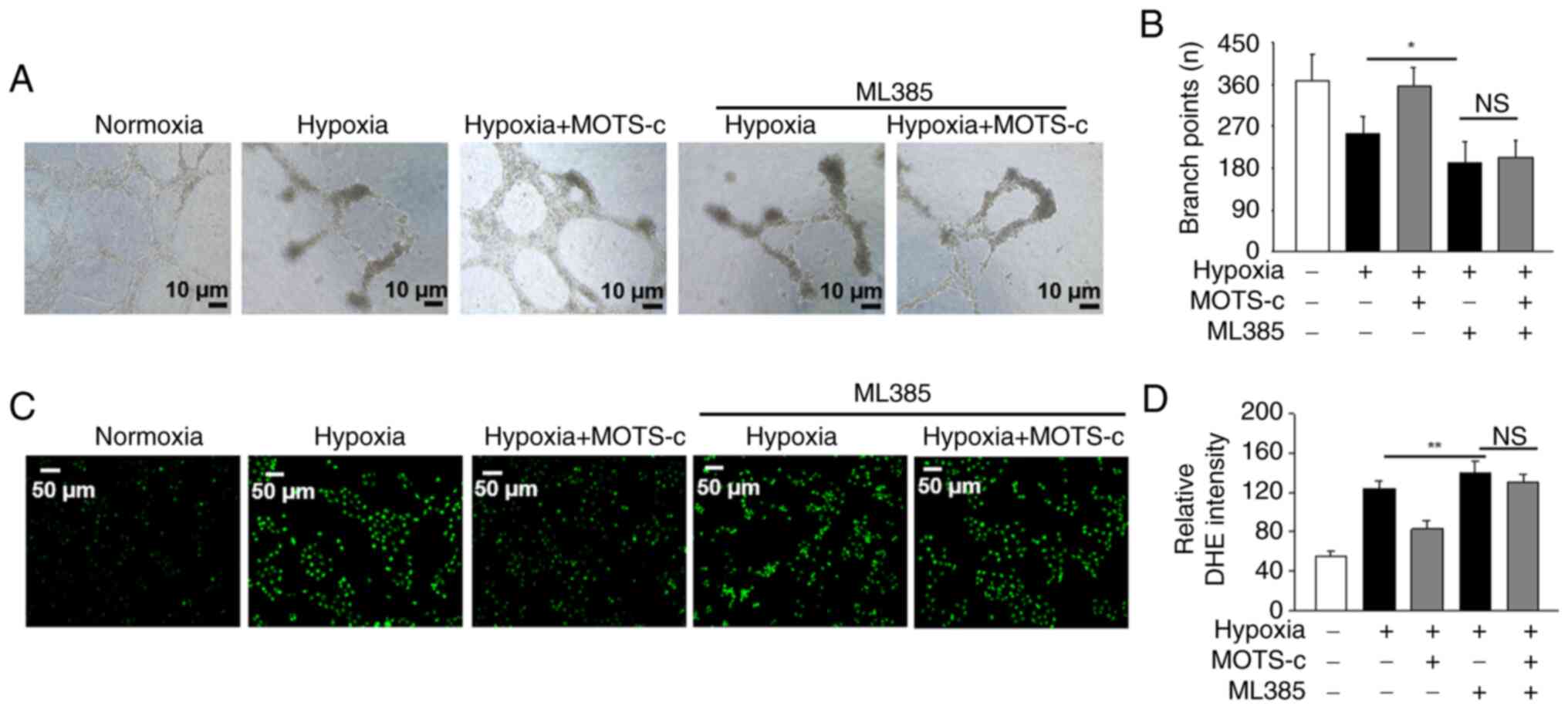

Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 offsets the

protective effect of MOTS-c against hypoxia in HUVECs

To investigate whether Nrf2 serves a role in the

protective effects of MOTS-c against hypoxia in HUVECs, ML385, a

specific Nrf2 inhibitor was used (39). It was demonstrated that

pretreatment with ML385 under hypoxic conditions inhibited tube

formation compared with the hypoxia group, implying the

significance of Nrf2. MOTS-c treatment, upon co-administration of

ML385 in hypoxia-induced HUVECs, failed to promote tube formation

(Fig. 7A and B). Additionally,

pretreatment with ML385 under hypoxic conditions increased ROS

production compared with the hypoxia group, and MOTS-c did not

reduce the generation of ROS in ML385-pretreated HUVECs under

hypoxic stimuli (Fig. 7C and D).

These findings suggested that the protective effect of MOTS-c

against hypoxia-induced HUVECs injury in HUVECs may partially rely

on Nrf2 activation.

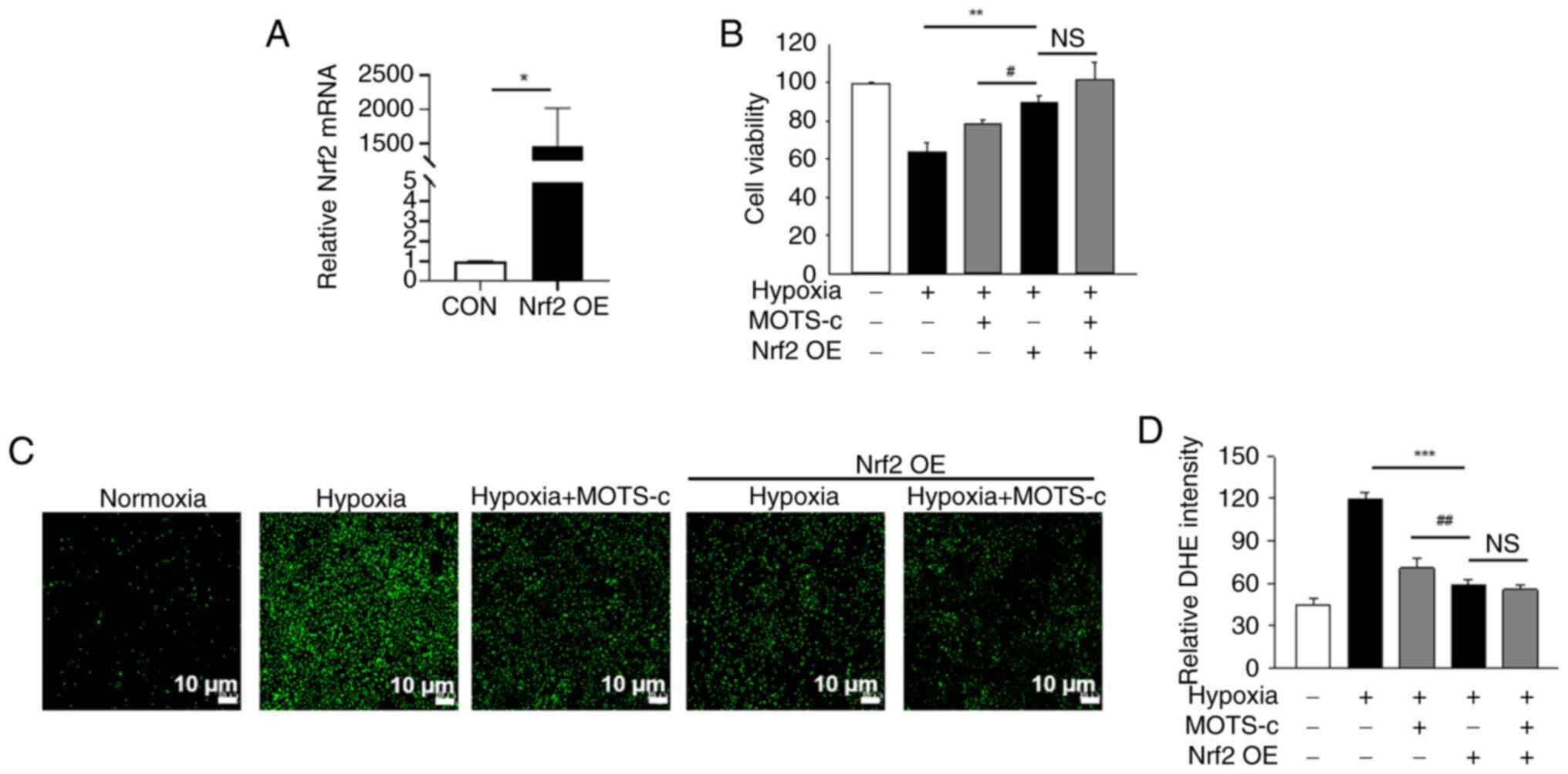

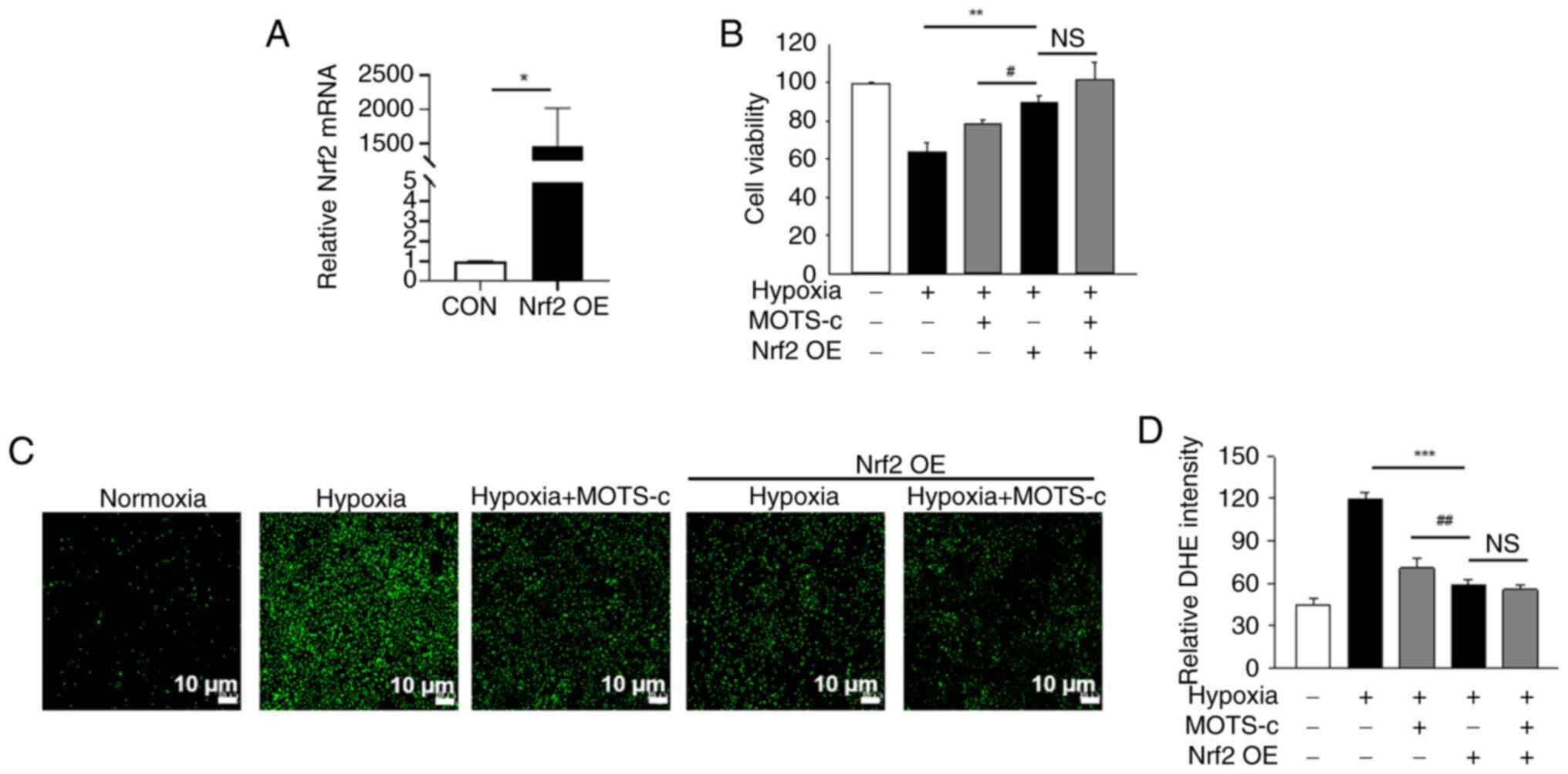

Nrf2 overexpression fails to enhance the

beneficial effect of MOTS-c on hypoxia-stimulated HUVECs

In addition to Nrf2 inhibition, the effects of Nrf2

overexpression on hypoxia-exposed HUVECs was also determined. Under

hypoxic conditions, Nrf2 overexpression significantly increased

Nrf2 mRNA expression levels in HUVECs compared with control cells,

which indicated the efficiency of the Nrf2 transfection (Fig. 8A). Nrf2 overexpression

significantly enhanced cell viability under hypoxic conditions.

However, there was no significant difference between the Nrf OE and

MOTS-c + Nrf2 OE groups under hypoxic stimuli (Fig. 8B). In addition, Nrf2

overexpression markedly reduced ROS production under hypoxic

conditions, and Nrf2 overexpression failed to further inhibit ROS

generation in MOTS-c treated HUVECs under hypoxic conditions

(Fig. 8C and D).

| Figure 8Nrf2 overexpression does not enhance

the beneficial effects of MOTS-c on hypoxia-stimulated HUVECs. (A)

Relative Nrf2 mRNA expression levels. (B) Cell viability. (C).

Representative images of DCFH-DA staining and (D) quantification of

cellular ROS. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are expressed as the

mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,

***P<0.001, #P<0.05,

##P<0.01. NS, not significant; Nrf2, nuclear factor

erythroid 2-related factor 2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; OE,

overexpression; DCFH-DA, 2',7'-dichlorodihydro fluorescein

diacetate. |

MOTS-c protects against hypoxia-induced

placental insufficiency in an Nrf2-dependent manner

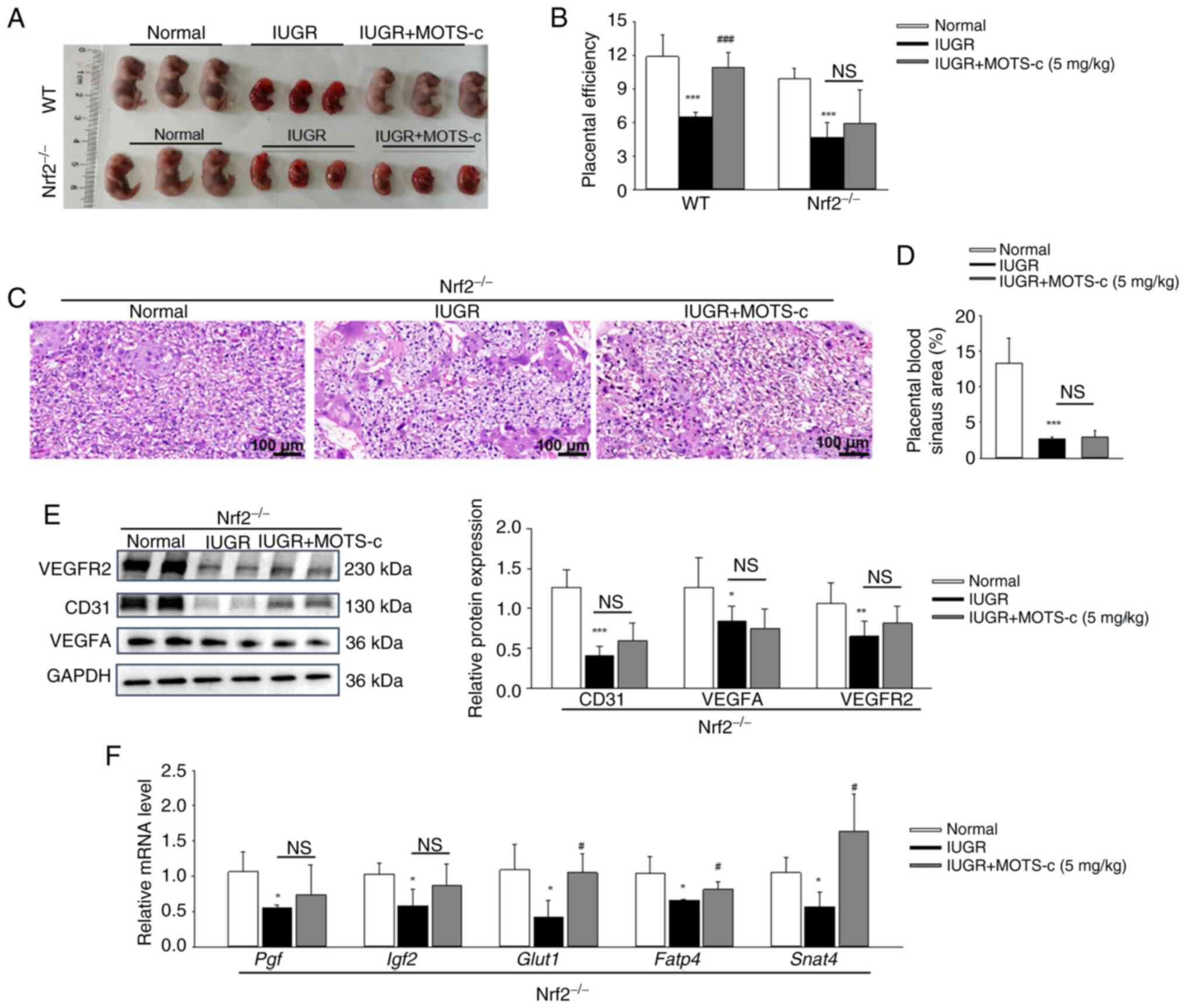

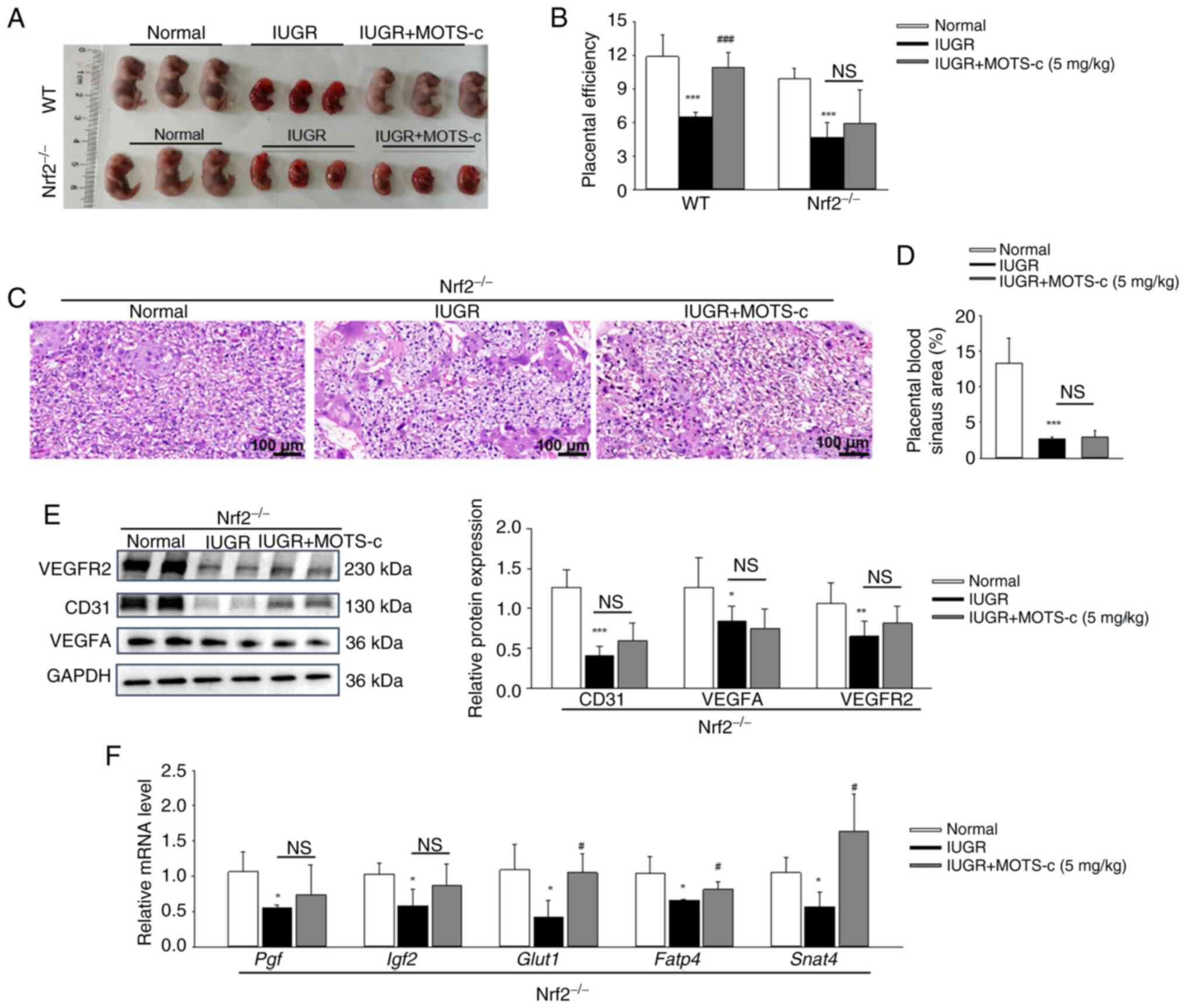

To further investigate the role of Nrf2 in the

protective effects of MOTS-c against hypoxia-induced IUGR and

placental insufficiency, Nrf2−/− pregnant mice were

exposed to hypoxic conditions for further investigation. Placental

tissues from Nrf2−/− mice exhibited no Nrf2 protein

expression (Fig. S6A and B).

MOTS-c treatment did not affect fetal growth restriction in Nrf2

deficiency mice, as evidenced by unchanged fetal size, morphology

and the fetal to placenta weight ratio in Nrf2−/−

pregnant mice when compared with the hypoxia-treated

Nrf2−/− pregnant mice (Fig. 9A and B). Notably, MOTS-c

administration failed to enhance the blood sinus areas (Fig. 9C and D) and did not upregulate

the protein expressions of CD31, VEGFA and VEGFR2 in

Nrf2−/− mice (Fig.

9E). Additionally, MOTS-c supplementation did not impact the

mRNA expressions of placental growth factors, including Pgf

and Igf2 in Nrf2−/− mice. However, MOTS-c

upregulated the expression levels of placental nutrient

transport-related genes, such as Glut1, Fatp4 and

Snat2, in Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 9F). This suggested that the

beneficial effects of MOTS-c on placental nutrient

transport-related genes might be independent of Nrf2.

| Figure 9MOTS-c protects against

hypoxia-induced placental insufficiency in an Nrf2-dependent

manner. (A) Morphology of fetal mice on GD17.5 in WT and Nrf2 KO

mice. (B) Placental efficiency, which represents the ratio of fetal

to placenta weight. (C) Representative images of H&E staining

of placental tissues. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Quantification

of the placental blood sinus area. (E) Western blotting analysis of

CD31, VEGFA and VEGFR2 protein expression levels in placenta. (F)

Relative mRNA expression levels of Pgf, Igf2,

Glut1, Fatp4 and Snat2 in placenta. Data are

expressed as mean ± SD. n=4-6. *P<0.05 vs. normal,

**P<0.01 vs. normal, ***P<0.001 vs.

normal, #P<0.05 vs. IUGR, ###P<0.001

vs. IUGR.. NS, not significant; IUGR, intrauterine growth

restriction; GD, gestational day; Pgf, placental growth factor;

Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; Igf2,

insulin-like growth factor 2; Glut1, glucose transporter type 1;

Fatp4, fatty acid transporter 4; Snat2, sodium-dependent neutral

amino acid transporter-2; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor

A; VEGFR2, VEGF receptor 2. |

Discussion

IUGR is characterized by a fetus that is small for

gestational age. A study of 600,000 stillbirths (≥22 weeks) from 12

countries reported that being small for gestational age contributed

to ~20% of term stillbirths (2).

However, there is currently no effective treatment for IUGR. The

present study investigated the effects of MOTS-c peptides on

hypoxia-induced IUGR, and demonstrated that MOTS-c administration

significantly mitigated hypoxia-induced IUGR, promoted placental

angiogenesis, suppressed oxidative stress and ameliorated placental

injury both in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, the

protective effects of MOTS-c were shown to be Nrf2-dependent, as

the protective effect of MOTS-c were abolished not only in Nrf2

inhibitor treated HUVECs, but also in Nrf2 KO mice. To the best of

our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate that

MOTS-c treatment could attenuate hypoxia-induced IUGR, and thus

suggest a new strategy for treating hypoxia-related neonatal

disease.

Prenatal hypoxia, a common consequence of

complicated pregnancies, serves a key role in triggering IUGR

(44,45). In such cases, the placenta fails

to adequately supply oxygen and nutrients to the developing fetus,

resulting in low birth weight (LBW) (7). Normal development of the placental

vascular tree is essential for both proper placental growth and

nutrient delivery from mother to fetus. Studies have reported

impaired angiogenesis in placental tissues of infants with LBW

(46,47), which has been identified as an

important pathophysiologic contributor to IUGR. VEGFA and its

receptor VEGFR2 are vital for blood vessel development and their

reduction has been observed in LBW placentas (48). Higher expression of the NADPH

oxidase 2 and lower vessel density were found in LBW placentas, as

NADPH oxidase 2 inhibited VEGFA-mediated placental angiogenesis

(49). Dietary supplementation

with adenosine has been shown to enhance placental angiogenesis and

reduce the incidence of IUGR in piglets (50). Therefore, improving placental

angiogenesis appears crucial for alleviating IUGR. Consistent with

this notion, the present study demonstrated that MOTS-c treatment

accelerated the formation of placental blood vessels in IUGR by

increasing blood sinus areas and upregulating angiogenesis-related

markers CD31 and VEGF. In addition, increased Ki-67 positive cells

in both placental tissues and hypoxia-exposed HUVECs were observed.

Ki-67 is widely considered a marker of proliferation, which is

mainly expressed during the active phases of the cell cycle:

G1, S, G2 and mitosis (51). However, low amounts of Ki-67 may

also be detected in quiescent cells (52). The present study found positive

Ki-67 signals peripheral to DAPI staining in placental tissues,

while the Ki-67 signal was totally located in the nucleus of

HUVECs. The observed extra-nuclear Ki-67 immunofluorescence signal

in tissues is a well-documented phenomenon as reported in previous

studies (53,54). It was considered that the

apparent peripheral signal potentially reflected different cell

type and cell cycle stages. Furthermore, MOTS-c was injected

intraperitoneally from GD 11 to 17.5, and beneficial effects of

MOTS-c administration on maintaining placenta angiogenesis and

proliferation, attenuating placental insufficiency, and

subsequently alleviating IUGR were observed. The timing of the

experiment was aligned with prior work, in which MOTS-c was

administered concurrently with the induction of the disease model

(10,30,31,55).

The placenta is highly susceptible to oxidative

stress, which in turn triggers placental vascular dysfunction and

insufficiency (56). Oxidative

stress in the placenta is a major contributor to the development of

IUGR. Elevated levels of MDA and decreased catalase activity have

been observed in plasma and placental tissues of pregnancies with

IUGR (57). Therefore, restoring

redox homeostasis through antioxidant therapy would be an effective

treatment for these pregnancy complications (58). However, a previous clinical trial

showed limited success in using antioxidant therapy for hypoxic

pregnancy (59,60). Therefore, further investigation

into alternative treatment options for IUGR is warranted. The

present study found that that administration of MOTS-c reduced MDA

content and increased SOD activity in placental tissues. The in

vitro experiments demonstrated a decrease in ROS generation

after MOTS-c treatment in hypoxia-induced HUVECs, which indicated

the anti-oxidative stress effects of MOTS-c. Dysfunctional

mitochondria are another source of ROS overproduction in

individuals with IUGR (61). The

present study demonstrated that MOTS-c treatment reduced MMP levels

and inhibited mitochondria ROS generation, which suggested a

protective role of MOTS-c on mitochondrial function. These results

indicated that MOTS-c ameliorated mitochondrial dysfunction and

restored antioxidant enzymes, thereby reducing ROS generation and

alleviated placental insufficiency in IUGR.

The transcription factor Nrf2 serves a crucial role

in coordinating the cellular antioxidant defense system, regulating

the expression of >100 genes involved in oxidative stress

responses and detoxification processes (62,63). The activation of Nrf2 is

suggested to be a compensatory mechanism that safeguards the fetus

against oxidative damage. A previous study reported that in both

human and rat IUGR groups, placentas had lower Nrf2 expression

levels compared with that of the control group placentas (64). Similarly, the downregulation of

Nrf2 was found in placental tissues from patients with eclampsia

(65). The present study

similarly demonstrated downregulated expression of Nrf2, especially

the reduced nuclear Nrf2 expression in hypoxia-induced maternal

placenta compared with the normal group of mice, and that MOTS-c

administration increased Nrf2 nuclear accumulation compared with

the IUGR group. Cytoplasmic and nuclear Nrf2 protein expressions

were verified through immunoblotting, and Nrf2 immunofluorescence

was performed. However, there remains a limitation regarding the

quantitative analyses of Nrf2 distribution (nuclear/cytoplasmic

ratio) in placenta tissue in the present study. The detection of

Nrf2 subcellular localization is important as nuclear translocation

of Nrf2 directly reflect its activation status (19), thus further research regarding

Nrf2 subcellular localization, particularly precise quantification

is warranted. Additionally, increased transcriptional activity of

Nrf2 under MOTS-c administration was demonstrated in the present

study. However, it was assessed at only one time point, and the

relevant pharmacokinetics of Nrf2 activation over time following

MOTS-c administration is important to optimize dosing regimen to

maintain efficacy of MOTS-c. For example, to investigate the

optimal Nrf2 activity time after MOTS-c treatment, future work

could establish the Nrf2 signaling pathway activation reporting

system using secreted Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) as the reporter

gene, thus the activity of Gluc could be monitored constantly in

MOTS-c-treated cells. Furthermore, a reporter protein

complementation imaging assay could be established to screen and

observe Nrf2 nuclear translocation in MOTS-c-treated cells and

living animals in the future.

The protective effects of MOTS-c were abolished

when the Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 and Nrf2 KO mice were used in the

present study. By contrast, Nrf2 overexpression failed to enhance

the beneficial effects of MOTS-c on cell viability and ROS

generation in hypoxia-stimulated HUVECs, in which there was no

difference between the Hypoxia + Nrf2 OE and Hypoxia + MOTS-c +

Nrf2 OE groups. Notably, under hypoxic conditions, Nrf2

overexpression (Hypoxia + Nrf2 OE group) demonstrated more

pronounced cytoprotective effects (increased cell viability and

decreased ROS production) compared with that of MOTS-c-treated

cells (Hypoxia + MOTS-c group). This result further highlighted the

central regulatory role of Nrf2 against oxidative stress damage,

which overall suggested that the protective role of MOTS-c against

hypoxia-induced abnormal placental injury and fetal growth is at

least partially dependent on Nrf2. However, the specific mechanism

how MOTS-c regulates Nrf2 has not been fully elucidated until now.

Previous studies from the present research group have demonstrated

that MOTS-c could directly increase synthesis of Nrf2 independent

of protein degradation and promote Nrf2 nuclear translocation

(21,22), and demonstrated nuclear

accumulation of Nrf2 under MOTS-c administration in the IUGR model.

Future research should focus on elucidating the regulatory

mechanism of MOTS-c on Nrf2 and investigating the impact of MOTS-c

presence or absence on the interaction between Nrf2 and KEAP1 in

response to hypoxia or other stress conditions. Notably, the mRNA

expression levels of nutrient transporters (Glut1,

Fatp4 and Snat4) were still upregulated under MOTS-c

administration in Nrf2 KO mice in the present study. It has been

reported that MOTS-c induces glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation

in mitochondrial fusion dependent way, and that MOTS-c functionally

prevents nutrient metabolism disorders, including insulin

resistance, obesity and bone metabolism (66). These studies suggest that MOTS-c

can function on nutrient transporters in other non-Nrf2-dependent

pathways, such as targeting the mitochondrion. Our previous study

found altered glucose and lipid metabolic levels in IUGR offspring

in vivo (28); whether

MOTS-c treatment alters actual amino acid, glucose or fatty acid

levels in fetal serum and functions in regulating glucose or fatty

acid in the offspring could be investigated in future research.

The present study has several clinical

implications. First, significantly decreased maternal serum MOTS-c

content following hypoxic exposure was observed, which suggested

that plasma MOTS content could potentially serve as a novel marker

for diagnosing IUGR. Second, the in vivo and in vitro

experiments demonstrated that administration of MOTS-c effectively

attenuated hypoxia-induced IUGR, which suggested that MOTS-c

peptides may offer a novel therapeutic approach for treating

hypoxia-related neonatal disease, including IUGR.

Several limitations of the present study should be

acknowledged. First, a single dose of MOTS-c (5 mg/kg) was used in

the present study from GD11 to GD17.5; however, future work should

include a dose-response experiment from GD11 to GD17.5 or at later

stages in pregnancy to determine the optimal therapeutic

concentration, administration time and potential toxicity of

MOTS-c. Second, further randomized clinical trials are needed to

confirm the endogenous levels of MOTS-c in human placentas or

maternal serum from IUGR pregnancies to further the clinical

understanding of MOTS-c in IUGR. Currently, the MOTS-c ELISA kit is

most commonly used to determine MOTS-c content in body fluids, such

as serum. However, this detection system present challenges and can

potentially lead to strongly differing results (67). The previous study has established

an LC/MS-based method for MOTS-c quantification; therefore, serum

or amniotic fluid MOTS-c content may be measured in human IUGR

pregnancies using LC/MS in future (67). Furthermore, future studies should

focus on the long-term development of main organs such as lungs,

heart and brain in offspring mice following MOTS-c administration

in an IUGR mouse model.

In conclusion, MOTS-c treatment effectively

improved placental insufficiency in hypoxia-induced IUGR by

activating the Nrf2-mediated anti-oxidant pathway. The present

provided insights for developing MOTS-c as a therapeutic strategy

for fetal diseases associated with hypoxic pregnancy, including

IUGR.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DC, HMZ and QFP performed study conceptualization.

HMZ and XLS managed project administration and data collection.

SPL, SCL and ZXX conducted investigation, provided resources,

developed software and performed validation. YXW and JFH curated

data. DC, XLS, YXW, JFH and QFP acquired funding. DC, QFP and JFH

contributed to writing. DC and HMZ confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The experimental procedures were approved by the

Experimental Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiangnan University

[approval nos. 20220930m1080501(383) and 20231115m1080530(555)] and

conducted according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animal published by the US National Institutes of Health (8th

edition).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

GD

|

gestational day

|

|

HUVEC

|

human umbilic vein endothelial

cells

|

|

IUGR

|

intrauterine growth restriction

|

|

MDA

|

malondialdehyde

|

|

Nrf2

|

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

|

VEGFA

|

vascular endothelial growth factor

A

|

|

VEGFR2

|

VEGF receptor 2

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82171704 and 82100018), Natural

Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BE2023684),

Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no.

ZR2021MH333), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central

Universities (grant no. JUSRP121062), Translational medicine

Project of Wuxi Commission of Health (grant no. ZH202101), Wuxi

Taihu Talent Training Project (Double hundred Medical Youth

Professionals Program; grant no. HB2020054) and the Clinical

research and translational medicine program of the Affiliated

Hospital of Jiangnan University (grant no. LCYJ202239).

References

|

1

|

Ahmadzadeh E, Polglase GR, Stojanovska V,

Herlenius E, Walker DW, Miller SL and Allison BJ: Does fetal growth

restriction induce neuropathology within the developing brainstem?

J Physiol. 601:4667–4689. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lawn JE, Ohuma EO, Bradley E, Idueta LS,

Hazel E, Okwaraji YB, Erchick DJ, Yargawa J, Katz J, Lee ACC, et

al: Small babies, big risks: Global estimates of prevalence and

mortality for vulnerable newborns to accelerate change and improve

counting. Lancet. 401:1707–1719. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jardine J, Walker K, Gurol-Urganci I,

Webster K, Muller P, Hawdon J, Khalil A, Harris T and van der

Meulen J; National Maternity Perinatal Audit Project Team: Adverse

pregnancy outcomes attributable to socioeconomic and ethnic

inequalities in England: A national cohort study. Lancet.

398:1905–1912. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Reynolds LP, Borowicz PP, Caton JS, Crouse

MS, Dahlen CR and Ward AK: Developmental programming of fetal

growth and development. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract.

35:229–247. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hendrix MLE, Bons JA, Alers NO,

Severens-Rijvers CAH, Spaanderman MEA and Al-Nasiry S: Maternal

vascular malformation in the placenta is an indicator for fetal

growth restriction irrespective of neonatal birthweight. Placenta.

87:8–15. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zur RL, Kingdom JC, Parks WT and Hobson

SR: The placental basis of fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol

Clin North Am. 47:81–98. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

D'Agostin M, Di Sipio Morgia C, Vento G

and Nobile S: Long-term implications of fetal growth restriction.

World J Clin Cases. 11:2855–2863. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Perez M, Robbins ME, Revhaug C and

Saugstad OD: Oxygen radical disease in the newborn, revisited:

Oxidative stress and disease in the newborn period. Free Radic Biol

Med. 142:61–72. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Joo EH, Kim YR, Kim N, Jung JE, Han SH and

Cho HY: Effect of endogenic and exogenic oxidative stress triggers

on adverse pregnancy outcomes: Preeclampsia, fetal growth

restriction, gestational diabetes mellitus and preterm birth. Int J

Mol Sci. 22:101222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Lee C, Zeng J, Drew BG, Sallam T,

Martin-Montalvo A, Wan J, Kim SJ, Mehta H, Hevener AL, de Cabo R

and Cohen P: The mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c promotes

metabolic homeostasis and reduces obesity and insulin resistance.

Cell Metab. 21:443–454. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim KH, Son JM, Benayoun BA and Lee C: The

mitochondrial-encoded peptide MOTS-c translocates to the nucleus to

regulate nuclear gene expression in response to metabolic stress.

Cell Metab. 28:516–524.e7. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shen C, Wang J, Feng M, Peng J, Du X, Chu

H and Chen X: The mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c attenuates

oxidative stress injury and the inflammatory response of H9c2 cells

through the Nrf2/ARE and NF-κB pathways. Cardiovasc Eng Technol.

13:651–661. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Xiao J, Zhang Q, Shan Y, Ye F, Zhang X,

Cheng J, Wang X, Zhao Y, Dan G, Chen M and Sai Y: The

mitochondrial-derived peptide (MOTS-c) interacted with Nrf2 to

defend the antioxidant system to protect dopaminergic neurons

against rotenone exposure. Mol Neurobiol. 60:5915–5930. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kim SJ, Miller B, Kumagai H, Silverstein

AR, Flores M and Yen K: Mitochondrial-derived peptides in aging and

age-related diseases. Geroscience. 43:1113–1121. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Li Y, Li Z, Ren Y, Lei Y, Yang S, Shi Y,

Peng H, Yang W, Guo T, Yu Y and Xiong Y: Mitochondrial-derived

peptides in cardiovascular disease: Novel insights and therapeutic

opportunities. J Adv Res. 64:99–115. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Wu N, Shen C, Wang J, Chen X and Zhong P:

MOTS-c peptide attenuated diabetic cardiomyopathy in STZ-induced

type 1 diabetic mouse model. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 39:491–498.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yang M, Chen W, He L, Wang X, Liu D, Xiao

L and Sun L: The role of mitokines in diabetic nephropathy. Curr

Med Chem. 32:1276–1287. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T,

Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K and Hatayama I: An

Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II

detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 236:313–322. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ulasov AV, Rosenkranz AA, Georgiev GP and

Sobolev AS: Nrf2/Keap1/ARE signaling: Towards specific regulation.

Life Sci. 291:1201112022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Fasipe B, Li S and Laher I: Exercise and

vascular function in sedentary lifestyles in humans. Pflugers Arch.

475:845–856. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wang DD, Xu B, Sun JJ, Sui M, Li SP, Chen

YJ, Zhang YL, Wu JB, Teng SY, Pang QF and Hu CX: MOTS-c mimics

remote ischemic preconditioning in protecting against lung

ischemia-reperfusion injury by alleviating endothelial barrier

dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 229:127–138. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang Y, Huang J, Zhang Y, Jiang F, Li S,

He S, Sun J, Chen D, Tong Y, Pang Q and Wu Y: The

mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c alleviates radiation

pneumonitis via an Nrf2-dependent mechanism. Antioxidants (Basel).

13:6132024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lamberto F, Peral-Sanchez I, Muenthaisong

S, Zana M, Willaime-Morawek S and Dinnyés A: Environmental

alterations during embryonic development: Studying the impact of

stressors on pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Genes

(Basel). 12:15642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kweider N, Huppertz B, Rath W, Lambertz J,

Caspers R, ElMoursi M, Pecks U, Kadyrov M, Fragoulis A, Pufe T and

Wruck CJ: The effects of Nrf2 deletion on placental morphology and

exchange capacity in the mouse. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.

30:2068–2073. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

The American Association for:

Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. JAMA. 207:17071969.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang KCW, Larcombe AN, Berry LJ, Morton

JS, Davidge ST, James AL and Noble PB: Foetal growth restriction in

mice modifies postnatal airway responsiveness in an age and

sex-dependent manner. Clin Sci (Lond). 132:273–284. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Kalotas JO, Wang CJ, Noble PB and Wang

KCW: Intrauterine growth restriction promotes postnatal airway

hyperresponsiveness independent of allergic disease. Front Med

(Lausanne). 8:6743242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen D, Wang YY, Li SP, Zhao HM, Jiang FJ,

Wu YX, Tong Y and Pang QF: Maternal propionate supplementation

ameliorates glucose and lipid metabolic disturbance in

hypoxia-induced fetal growth restriction. Food Funct.

13:10724–10736. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen D, Man LY, Wang YY, Zhu WY, Zhao HM,

Li SP, Zhang YL, Li SC, Wu YX, Ling-Ai and Pang QF: Nrf2 deficiency

exacerbated pulmonary pyroptosis in maternal hypoxia-induced

intrauterine growth restriction offspring mice. Reprod Toxicol.

129:1086712024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lu H, Tang S, Xue C, Liu Y, Wang J, Zhang

W, Luo W and Chen J: Mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c increases

adipose thermogenic activation to promote cold adaptation. Int J

Mol Sci. 20:24562019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tang M, Su Q, Duan Y, Fu Y, Liang M, Pan

Y, Yuan J, Wang M, Pang X, Ma J, et al: The role of MOTS-c-mediated

antioxidant defense in aerobic exercise alleviating diabetic

myocardial injury. Sci Rep. 13:197812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Li Z, LoBue A, Heuser SK, Li J, Engelhardt

E, Papapetropoulos A, Patel HH, Lilley E, Ferdinandy P, Schulz R

and Cortese-Krott MM: Best practices for blood collection and

anaesthesia in mice: Selection, application and reporting. Br J

Pharmacol. 182:2337–2353. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mohamed AS, Hosney M, Bassiony H,

Hassanein SS, Soliman AM, Fahmy SR and Gaafar K: Sodium

pentobarbital dosages for exsanguination affect biochemical,

molecular and histological measurements in rats. Sci Rep.

10:3782020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chen D, Qiu YB, Gao ZQ, Wu YX, Wan BB, Liu

G, Chen JL, Zhou Q, Yu RQ and Pang QF: Sodium propionate attenuates

the lipopolysaccharide-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition

via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem.

68:6554–6563. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xia Y, Liu C, Li R, Zheng M, Feng B, Gao

J, Long X, Li L, Li S, Zuo X and Li Y: Lactobacillus-derived

indole-3-lactic acid ameliorates colitis in cesarean-born offspring

via activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. iScience.

26:1082792023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen Y, Wu Q, Wei J, Hu J and Zheng S:

Effects of aspirin, vitamin D3, and progesterone on pregnancy

outcomes in an autoimmune recurrent spontaneous abortion model.

Braz J Med Biol Res. 54:e95702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Coin I, Beyermann M and Bienert M:

Solid-phase peptide synthesis: From standard procedures to the

synthesis of difficult sequences. Nat Protoc. 2:3247–3256. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Jia Y, Wang Q, Liang M and Huang K: KPNA2

promotes angiogenesis by regulating STAT3 phosphorylation. J Transl

Med. 20:6272022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen D, Gao ZQ, Wang YY, Wan BB, Liu G,

Chen JL, Wu YX, Zhou Q, Jiang SY, Yu RQ, et al: Sodium propionate

enhances Nrf2-mediated protective defense against oxidative stress

and inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced neonatal mice. J

Inflamm Res. 14:803–816. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Pérez-Gutiérrez L and Ferrara N: Biology

and therapeutic targeting of vascular endothelial growth factor A.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24:816–834. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Vornic I, Buciu V, Furau CG, Gaje PN,

Ceausu RA, Dumitru CS, Barb AC, Novacescu D, Cumpanas AA, Latcu SC,

et al: Oxidative stress and placental pathogenesis: A contemporary

overview of potential biomarkers and emerging therapeutics. Int J

Mol Sci. 25:121952024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Knöfler M, Haider S, Saleh L, Pollheimer

J, Gamage TKJB and James J: Human placenta and trophoblast

development: Key molecular mechanisms and model systems. Cell Mol

Life Sci. 76:3479–3496. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Murray AJ: Oxygen delivery and

fetal-placental growth: Beyond a question of supply and demand?

Placenta. 33(Suppl 2): e16–e22. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ducsay CA, Goyal R, Pearce WJ, Wilson S,

Hu XQ and Zhang L: Gestational hypoxia and developmental

plasticity. Physiol Rev. 98:1241–1334. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Su EJ, Xin H, Yin P, Dyson M, Coon J,

Farrow KN, Mestan KK and Ernst LM: Impaired fetoplacental

angiogenesis in growth-restricted fetuses with abnormal umbilical

artery doppler velocimetry is mediated by aryl hydrocarbon receptor

nuclear translocator (ARNT). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 100:E30–E40.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

47

|

Carr DJ, David AL, Aitken RP, Milne JS,

Borowicz PP, Wallace JM and Redmer DA: Placental vascularity and

markers of angiogenesis in relation to prenatal growth status in

overnourished adolescent ewes. Placenta. 46:79–86. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Hu C, Yang Y, Deng M, Yang L, Shu G, Jiang

Q, Zhang S, Li X, Yin Y, Tan C and Wu G: Placentae for low birth

weight piglets are vulnerable to oxidative stress, mitochondrial

dysfunction, and impaired angiogenesis. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2020:87154122020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hu C, Wu Z, Huang Z, Hao X, Wang S, Deng

J, Yin Y and Tan C: Nox2 impairs VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis in

placenta via mitochondrial ROS-STAT3 pathway. Redox Biol.

45:1020512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wu Z, Nie J, Wu D, Huang S, Chen J, Liang

H, Hao X, Feng L, Luo H and Tan C: Dietary adenosine

supplementation improves placental angiogenesis in IUGR piglets by

up-regulating adenosine A2a receptor. Anim Nutr. 13:282–288. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lanng MB, Møller CB, Andersen ASH,

Pálsdóttir AA, Røge R, Østergaard LR and Jørgensen AS: Quality

assessment of Ki67 staining using cell line proliferation index and

stain intensity features. Cytometry A. 95:381–388. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Bullwinkel J, Baron-Lühr B, Lüdemann A,

Wohlenberg C, Gerdes J and Scholzen T: Ki-67 protein is associated

with ribosomal RNA transcription in quiescent and proliferating

cells. J Cell Physiol. 206:624–635. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Li C, Xiao N, Song W, Lam AHC, Liu F, Cui

X, Ye Z, Chen Y, Ren P, Cai J, et al: Chronic lung inflammation and

CK14+ basal cell proliferation induce persistent

alveolar-bronchiolization in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters.

EBioMedicine. 108:1053632024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Devi K, Tomar MS, Barsain M, Shrivastava A

and Moharana B: Regeneration capability of neonatal lung-derived

decellularized extracellular matrix in an emphysema model. J

Control Release. 372:234–250. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Xinqiang Y, Quan C, Yuanyuan J and Hanmei