Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a metabolic disease that can be

categorized as primary or secondary (1). With the annual increase in the

incidence of OP, related research has intensified in recent years

(2). However, the specific

pathogenic mechanisms underlying OP remain unclear (3). Current evidence suggests that

excessive apoptosis of osteoblasts is one of the causes of OP

(4,5). Osteoblast apoptosis occurs as a

result of hyperglycemia (6,7),

estrogen deficiency (8,9), long-term metabolic disorders

(10) and glucocorticoid

abnormalities (11).

Apoptosis refers to the process of programmed cell

death in multicellular organisms (12). Previous studies have revealed

that inhibition of osteoblast apoptosis may improve OP prognosis

(13,14). However, effective strategies for

maintaining osteoblast viability and preventing cell death under

hyperglycemic conditions remain uncertain (6,7).

Methylated RNA nucleotides are present in all

kingdoms of life and numerous biological processes rely on dynamic

and reversible methylation of coding and non-coding RNAs (15). N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA

methylation is the most common reversible RNA modification that

regulates several important RNA processes after transcription

(16). Appropriate RNA

methylation is crucial for cell development and tissue homeostasis

(17). As a reversible

post-translational modification, RNA methylation also affects RNA

stability (18). Among

eukaryotes, m6A is the predominant type of RNA modification,

accounting for 60% of all RNA modifications (19).

Microarrays are high-throughput platforms used to

analyze gene expression and to examine a broad range of signaling

pathways with considerable reliability (20,21). In the present study, focus was

addressed on the expression of miR-4765. Forkhead box protein K2

(FOXK2), secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SFRP1) and LINC00312

were predicted using publicly available online databases. Finally,

the methylation site of LINC00312 was predicted using SRAMP.

The results of the present study revealed that

miR-4765 inhibits apoptosis by targeting FOXK2 and SFRP1, whereas

LINC00312 promotes apoptosis by binding to miR-4765. Moreover,

METTL3 increases the methylation of LINC00312 in a YTHDF2-dependent

manner, thereby reducing LINC00312 expression.

Materials and methods

Database usage

The gene expression profile dataset GSE74209 was

selected from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). GSE74209 was

generated using the Agilent GPL20999 platform titled miRCURY LNA

microRNA Array, 7th generation (hsa, miRBase 20; https://www.mirbase.org/) and was submitted by

De-Ugarte et al (22).

The GSE74209 dataset contained 12 samples, of which six were from

patients with OP and the other six were bone tissues from healthy

controls. Thereafter, the GSE74209 dataset was analyzed using the

GEO2R method (Fig. S1A-H).

After obtaining differentially expressed microRNAs (miRNAs or

miRs), enrichment analysis was performed on the upregulated and

downregulated miRNAs (Fig.

S2A-E). miR-4765 expression levels were detected in GSE74209

cells (Fig. S2F and Table SI).

miR-4765 was selected as the target miRNA because its differential

expression was the most significant. The target genes of miR-4765

were predicted by identifying overlapping genes across different

databases [TargetScan, http://www.targetscan.org/; microRNA database (miRDB,

http://mirdb.org/); and DNA Intelligent Analysis

(DIANA; http://diana.imis.athena-innovation.gr/)]. It was

observed that miR-4765 has two overlapping genes, FOXK2 and SFRP1.

Bioinformatic analysis was performed on the union set of all

possible target genes (Fig. S3A-D,

Tables SII and SIII). Using sequence alignment (BLAST),

LINC00312 was found to closely correlate with miR-4765 expression

(Fig. S4A and B). Finally,

using the SRAMP database (http://www.cuilab.cn/sramp), the possible methylation

sites on LINC00312 were predicted.

Cell culture

hFOB 1.19, a well-characterized human osteoblastic

cell line, is widely used in OP research because of its stable

osteoblastic phenotype (for example, expression of osteocalcin and

collagen I) and responsiveness to osteogenic stimuli. Human-derived

hFOB 1.19 cells (Chinese Academy of Sciences) are commonly used as

in vitro models of osteogenic apoptosis. hFOB 1.19 cells

were propagated in DMEM/F12 (Hyclone; Cytiva) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (Hyclone; Cytiva) and 1% streptomycin and

penicillin (Hyclone; Cytiva), after which they were incubated at

maximum humidity in a 35°C incubator containing 5% CO2

and 95% air. The culture medium was replaced daily. The cells were

incubated in serum-free medium for 24 h before treatment and then

cultured for 5 days in the presence of varying concentrations (1,

2.5, 3.5 and 4.5 g/l) of glucose at 35°C.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

Processed cells were inoculated into a 96-well plate

at a concentration of 5×103 cells/well. After allowing

the cells to adhere to the well surface, reagents were added to

each well using a reagent kit of 10 μl (Dojindo Molecular

Technologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions

followed by incubation in a CO2 incubator (35°C, 5%

CO2 and 95% air) for 1 h. Finally, enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed (ELx808; BioTek, Inc.),

and the absorbance (wavelength set at 450 nm) in each well was

measured using optical density (OD) values to represent the

relative number of cells.

Cell transfection

MicroRNA-4765 (miRNA-4765) mimics, miRNA-4765

inhibitors, and a nonsense sequence as the miRNA negative control

(NC) were obtained from Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. The LINC00312

overexpression (OE) plasmid, sh-LINC00312, and a nonsense sequence

of the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) NC were obtained from Shanghai

GeneChem Co., Ltd. The METTL3 OE plasmid, YTHDF2 OE plasmid,

sh-METTL3, sh-YTHDF2, and a nonsense sequence similar to NC were

obtained from Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. hFOB 1.19 cells were

transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 containing 2 μg plasmid

or 5 μl miRNA oligo (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) for 6 h at 35°C following the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA was extracted 24 h after transfection and proteins were

extracted 48 h after transfection.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the

TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen

Sciences, Inc.). Reverse transcription PCR of miRNAs, lncRNAs and

mRNAs was performed using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. RT-qPCR was performed using the QuantiTect SYBR Green

PCR Kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), and the results were

analyzed using a Roche Light Cycler® 480 II system

(Roche Diagnostics). First, an initial denaturation step was

performed at 95°C for 2 min. This was followed by 40 cycles of

amplification, each consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec,

annealing at 55°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 30 sec. The

relative miRNA expression of each gene was normalized to that of U6

RNA, whereas the relative mRNA and lncRNA expression of each gene

was normalized to that of GAPDH RNA. Relative quantification of

gene expression was performed using the 2−ΔΔCq method.

The following primer sequences were used: miR-4765 forward,

5'-CCGCGTGAGTGATTGATAGCTATGTTC-3' and reverse,

5'-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3'; U6 forward, 5'-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3' and

reverse, 5'-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3'; LINC00312 forward,

5'-AGGGCAGGGTACTCTGATTGGC-3' and reverse,

5'-TGGCTTCTCTCCTGGCTCTGC-3'; FOXK2 forward,

5'-AAGAACGGGGTATTCGTGGAC-3' and reverse, 5'-CTCGGGAACCTGAATGTGC-3';

SFRP1 forward, 5'-ACGTGGGCTACAAGAAGATGG-3' and reverse,

5'-CAGCGACACGGGTAGATGG-3'; METTL3 forward,

5'-TTGTCTCCAACCTTCCGTAGT-3' and reverse,

5'-CCAGATCAGAGAGGTGGTGTAG-3'; YTHDF2 forward,

5'-AGCCCCACTTCCTACCAGATG-3' and reverse,

5'-TGAGAACTGTTATTTCCCCATGC-3'; and GAPDH forward,

5'-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3' and reverse,

5'-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3'. The following short hairpin (shRNA)

target sequences (excluding plasmid backbone sequences) were

employed in the present study: Mimics, sense

5'-UGAUUGAUAGCUAUGUUCAA-3' and antisense

5'-UUGAACAUAGCUAUCAAUCA-3'; Mimics-NC sense,

5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3' and antisense,

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3'; Inhibitor, 5'-UUGAACAUAGCUAUCAAUCA-3'

and Inhibitor-NC, 5'-CAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAA-3'. Additionally, the

following shRNA constructs were used: Sh-FOXK2,

CCGAGTGATGCCATCTGACCTCAAT; Sh-SFRP1, GAGTACGACTACGTGAGCTTCCAGT;

Sh-LINC00312, CCGCTTGCTGATGGACTCCAAGTAT; Sh-METTL3,

GGAGGAGTGCATGAAAGCCAGTGAT; Sh-YTHDF2, AGTCCCTCCATTGGCTTCTCCTATT;

and Sh-NC, 5'-CCUAAGGUUAAGUCGCCCUCG-3'.

Western blotting

hFOB 1.19 cells were lysed in

radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) containing the protease inhibitor

phenyl-methyl-sulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), followed by centrifugation of the lysates (12,000 ×

g) at 4°C for 30 min. Protein concentration was determined using a

Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) at a concentration of 3 μg/μl in RIPA

and loading buffer. Cell lysates were separated using 10% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at 150 V with

protein ladders (cat. no. 26616; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

after which the 30 μl proteins were transferred to

polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes at 350 mA for 90 min.

Membranes were incubated in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) solution for 2 h at

room temperature (20-25°C) and then with the following primary

antibodies at 4°C overnight (concentrations were considered

according to the manufacturer's instructions): Anti-cleaved

caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 9661; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), anti-FOXK2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 12008; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), anti-SFRP1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 4690; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-METTL3 antibody (1:1,000; cat.

no. ab195352; Abcam), anti-YTHDF2 antibody (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab220163; Abcam) and anti-GAPDH (1:10,000; cat. no. 10494-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.). The membranes were then incubated with a

secondary antibody (1:10,000; cat. no. SA00001-2; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) for 2 h at room temperature (20-25°C) and visualized

using an Ultrasensitive Enhanced Chemiluminescence Detection kit

(cat. no. PK10002; Proteintech Group, Inc.). ImageJ software

(v1.52; National Institutes of Health) was used for densitometric

analysis.

Flow cytometry assay for apoptosis

Apoptosis was quantified using an Annexin V-FITC/PI

Apoptosis Detection Kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) following the

manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, hFOB1.19 cells were seeded

into a 6-well plate at a density of 5×105 cells per well

and then treated according to the experimental requirements for

each group. After treatment, cells were collected, washed twice

with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 1X

Annexin V binding buffer to achieve a concentration of

~1×106 cells/ml. Subsequently, 100 μl of the cell

suspension was mixed with 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC and 5

μl of PI and then incubated at room temperature (20-25°C) in

the dark for 15 min. After incubation, 400 μl of 1X Annexin

V binding buffer was added to each sample. Flow cytometry was

performed using a Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman

Coulter Inc.). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using

the FlowJo version 10.8.1 software (BD Biosciences). The cells were

classified as follows: Annexin V-FITC-negative/PI-negative (viable

cells), Annexin V-FITC-positive/PI-negative (early apoptotic

cells), Annexin V-FITC-positive/PI-positive (late

apoptotic/necrotic cells), and Annexin V-FITC-negative/PI-positive

(necrotic cells). The total percentage of apoptotic cells was

calculated as the sum of early apoptotic (Annexin

V+/PI−) cells and late apoptotic (Annexin

V+/PI+) cells.

Dual-luciferase reporter experiment

293T cells (Chinese Academy of Sciences) were seeded

onto 24-well plates and cultured overnight, followed by

transfection with wild- and mutant-type FOXK2 and SFRP1 plasmids

(0.1 μg pMIR-REPORT-wild-type-FOXK2 and

pMIR-REPORT-wild-type-SFRP1 or pMIR-REPORT-mutant-type-FOXK2 and

pMIR-REPORT-mutant-type-SFRP1 plasmids per well) (Shanghai GeneChem

Co., Ltd.) using Roche X-tremeGENE HP (cat. no. 06366236001; Roche

Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

cells were then co-transfected with either 0.4 μg miR-4765

mimics or 0.4 μg miR-4765 NCs (Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd.). Luciferase activity was quantified 48 h after transfection

using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System according to the

manufacturer's instructions (Promega Corporation). Firefly

luciferase activity was normalized to the Renilla luciferase

activity.

293T cells (Chinese Academy of Sciences) were seeded

into 24-well plates and cultured overnight, followed by

transfection with wild- and mutant-type LINC00312 plasmids (0.1

μg pMIR-REPORT-wild-type-LINC00312 or pMIR-RE

PORT-mutant-type-LINC00312 plasmids per well) (Shanghai GeneChem

Co., Ltd.) using Roche X-tremeGENE HP (cat. no. 06366236001; Roche

Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

cells were then co-transfected with either 0.4 μg miR-4765

mimics or 0.4 μg miR-4765 NCs (Shanghai GenePharma Co.,

Ltd.). Luciferase activity was quantified 48 h after transfection

using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System according to the

manufacturer's instructions (Promega Corporation). Firefly

luciferase activity was normalized to the Renilla luciferase

activity.

293T cells (Chinese Academy of Sciences) were seeded

onto 24-well plates and cultured overnight, following which they

were transfected with wild- and mutant-type LINC00312 plasmids (0.1

μg pMIR-REPORT-wild-type-LINC00312 or

pMIR-REPORT-mutant-type-LINC00312 plasmids per well) (Shanghai

GeneChem Co., Ltd.) using Roche X-tremeGENE HP (cat. no.

06366236001; Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The cells were then co-transfected with either 0.4

μg METTL3/YTHDF2 OE plasmids or 0.4 μg METTL3/YTHDF2

NCs (Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.). Luciferase activity was

quantified 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase

Reporter Assay System according to the manufacturer's instructions

(Promega Corporation). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized

to the Renilla luciferase activity.

m6A quantification

EpiQuik™ m6A RNA Methylation Quantification Kit

(Colorimetric, P-9005) (Epigentek Group Inc.) was used to detect

m6A levels from extracted RNA according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Each well contained 200 ng of RNA. Finally, an ELISA

was performed (ELx808; BioTek, Inc.), and the absorbance

(wavelength set at 450 nm) in each well was measured using OD

values to represent the relative methylation level.

RNA immunoprecipitation-qPCR

(RIP-qPCR)

RIP experiments were conducted using a Magna RIP kit

(cat. no. 17-700; MilliporeSigma) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. For these experiments, anti-m6A (cat. no. ab151230),

anti-METTL3 (EPR18810; cat. no. ab195352), anti-YTHDF2 (EPR20318;

cat. no. ab220163), and IgG were used as NCs. Finally, RNA was

isolated and purified from the binding proteins using proteases,

and qPCR experiments were conducted using a previously described

method.

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the

Institutional Review Board of the General Hospital of the Northern

Theater Command (approval no. 2025-26; Shenyang, China) and

performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. A total of 50

8-week-old C57BL/6J male specific-pathogen-free mice weighing 22±2

g from China Medical University were provided free access to water

and food and bred under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle with the

temperature set at 22.5±2.5°C. The mice were randomly divided into

the following groups: The control group (5 non-diabetic mice fed a

normal diet) and the diabetic model group (45 mice fed a high-fat

diet containing 60% fat, 20% protein, and 20% carbohydrates). Among

the diabetic group, 20 received METTL3-related treatment, 20

received LINC00312-related treatment, and 5 remained untreated

diabetic controls. The mice were intraperitoneally injected with

either vehicle or streptozotocin (STZ) diluted in 0.1 M citrate

buffer at a dose of 100 mg/kg. One week after STZ injection, a

diabetic mouse model was considered to have been successfully

established when fasting blood glucose levels reached 7.8 mmol/l

and insulin sensitivity was reduced.

The experimental duration lasted 8 weeks from STZ

injection to the endpoint. Humane endpoints for euthanasia included

weight loss exceeding 20% of the baseline, severe lethargy,

inability to eat or drink, or signs of distress (for example,

hunched posture or labored breathing). Animal health and behavior

were monitored daily by visual inspection and weekly body weight

measurements. At study completion, all animals were euthanized

under isoflurane anesthesia (5% induction, 2% maintenance),

followed by cervical dislocation. Death was confirmed by the

absence of a heartbeat, respiratory arrest, and fixed dilated

pupils. No unexpected deaths occurred during the experiments.

Plasma measurements

Venous blood (tail vein) was collected to measure

fasting blood glucose using a OneTouch glucometer analyzer (Roach

Blood Glucose Instrument) and fasting plasma insulin (FINS) using a

mouse insulin kit (Merck KGaA). The insulin sensitivity index was

calculated as ln (FINS • FPG).

Adenovirus injection

METTL3- and LINC00312-carrying adenoviruses for OE

(OE-METTL3 and OE-LINC00312), small hairpin adenoviruses (sh-METTL3

and sh-LINC00312), and the corresponding empty vector-carrying

adenoviruses (OE-NC or sh-NC) were constructed by Shanghai GeneChem

Co., Ltd. Thereafter, 40 successfully established diabetes mouse

models were randomly selected to receive adenovirus treatment (20

received METTL3-related treatment and the remaining 20 received

LINC00312-related treatment). Adenovirus-packaged OE-METTL3 and

OE-LINC00312, sh-METTL3 and sh-LINC00312, or the corresponding NC

was consecutively injected into the tail vein of the mice (100

μg/kg body weight) twice a week for 4 weeks. Thereafter,

mouse femurs were dissected for subsequent experimental

studies.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The femurs of the experimental mice were separated

and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature

(20-25°C). After fixation, the samples were decalcified in 10%

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 2 weeks, dehydrated, and

embedded in paraffin. Finally, 3 μm-thick tissue sections

were created and deparaffinized in xylene. After rehydration,

sections were exposed to an antigen epitope. Peroxidase activity

was quenched for 10 min with 3% H2O2. After

washing with PBS, the sections were incubated for 30 min in 5% BSA

at room temperature (20-25°C) and then incubated overnight in

primary rabbit polyclonal anti-FOXK2 (cat. no. 30660-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and anti-SFRP1 antibody (cat. no.

26460-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at 4°C overnight. Next,

secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody was added for 90 min at room

temperature (20-25°C). Finally, sections were processed with an ABC

working solution (OriGene Technologies, Inc.) for 20 min at room

temperature (20-25°C) and developed with 3,3-diaminobenzidine

(OriGene Technologies, Inc.). Brown particles were presented as

positively expressed. The results were analyzed using a light

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT)

scan

To measure the bone microstructure, the femurs and

tibias of the experimental mice were separated, after which the

soft tissue was removed and incubated in sterile PBS. Finally, the

prepared bone tissue was placed into the micro-CT system (NEMO

Micro-CT, NMC-200; Heping Medical Technology) operated according to

the manufacturer's instructions (tube voltage, 80 KV; tube current,

0.06 mA; source to detector distance, 410 mm; distance from source

to scanned object, 90 mm; frames per second, 20/sec; frames in all,

4,000; reconstruction type, FDK; horizontal FOV, 50 mm; axis FOV,

16 mm; pixel size 0.05×0.05×0.05 mm; scanning accuracy, 35

μm; dimensions, 1,000×1,000×608; CT threshold,

1,497.95).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics

(version 23.0; IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad

Software Inc.; Dotmatics). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Each assay was repeated

independently three times, and measurement data were expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation. All pairwise comparisons were

reanalyzed using Tukey's honest significant difference test.

Specifically, after performing one-way ANOVA for comparisons

between three or more groups, Tukey's HSD test was used to

determine significant differences.

Results

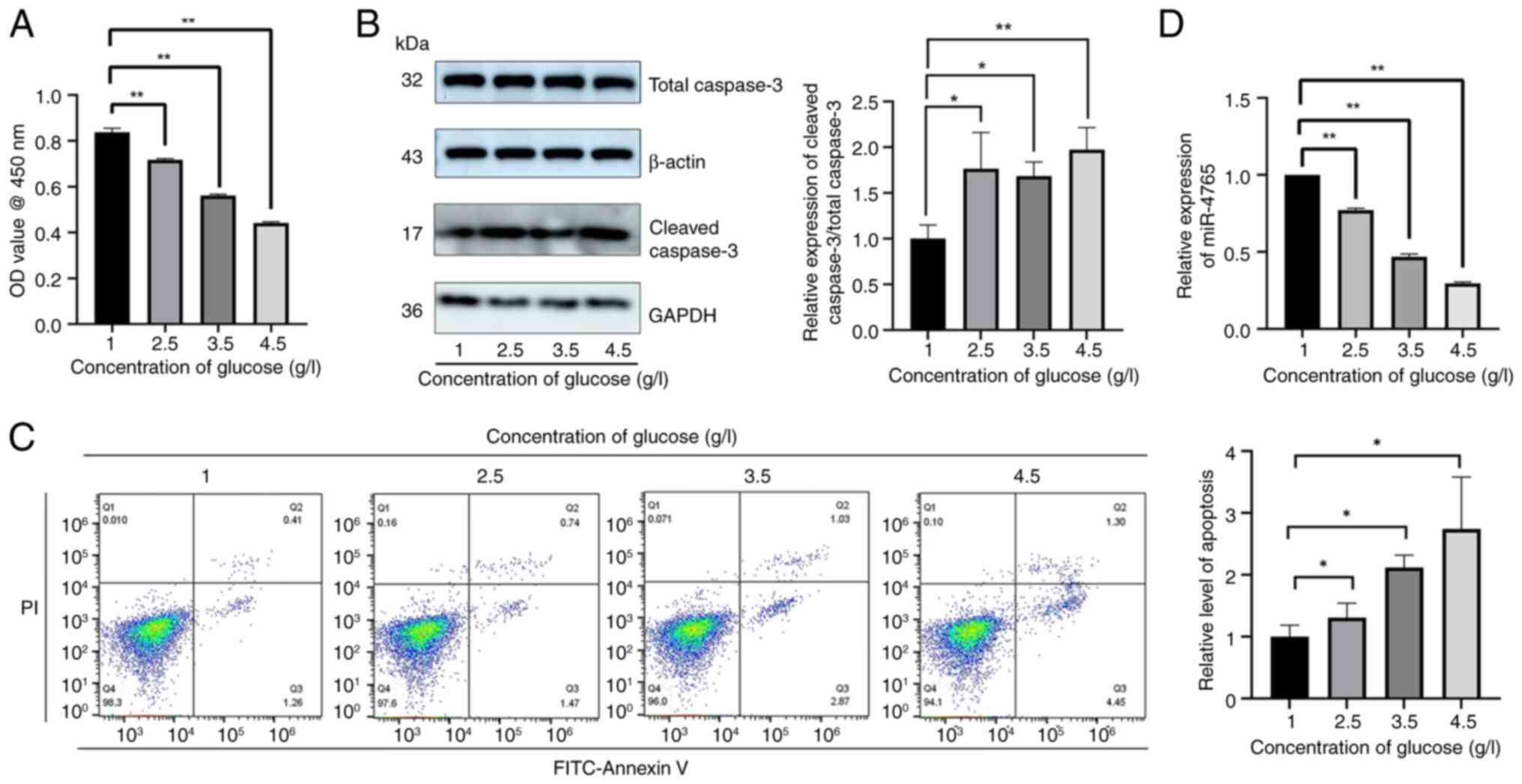

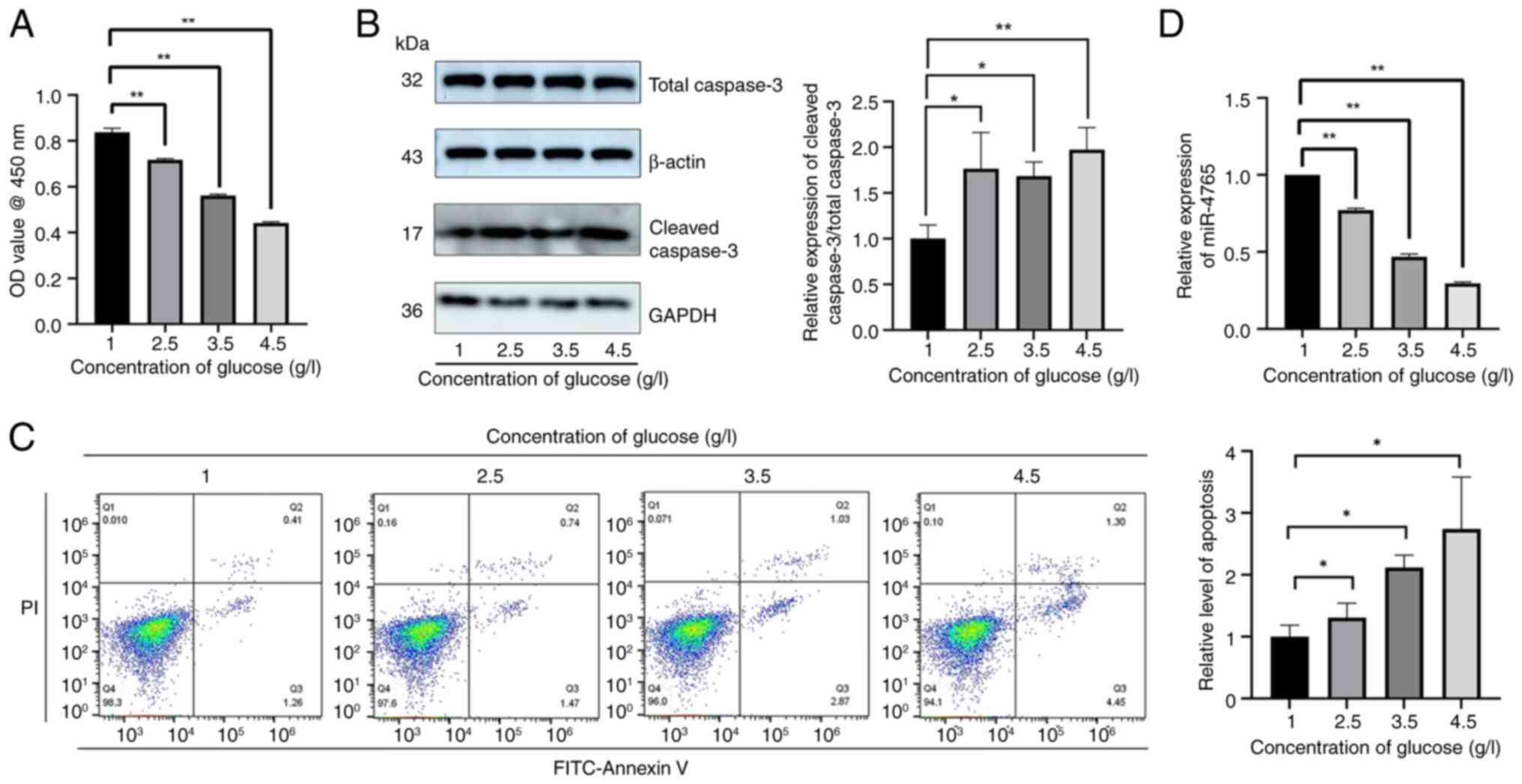

Hyperglycemia induces hFOB 1.19 cell

apoptosis and inhibits miR-4765 expression

To determine whether a hyperglycemic environment can

cause OP, induce hFOB 1.19 cell apoptosis, and inhibit miR-4765

expression, hFOB 1.19 cells were cultured in media with various

glucose concentrations (1, 2.5, 3.5, and 4.5 g/l). The results of

the CCK-8 assay indicated that the number of cells decreased as the

glucose concentration increased (Fig. 1A). Thereafter, western blotting

was used to determine the expression level of cleaved caspase-3

(Fig. 1B); Annexin V staining

was used to determine the apoptosis level (Fig. 1C); and RT-qPCR was used to

determine the expression level of miR-4765 (Fig. 1D). The apoptotic level of hFOB

1.19 cells was significantly increased, whereas the expression

level of miR-4765 was the lowest at a glucose concentration of 4.5

g/l. Therefore, a medium with a glucose concentration of 4.5 g/l

was selected to simulate OP in the subsequent experiments.

| Figure 1Hyperglycemia can induce hFOB 1.19

cell apoptosis and inhibit miR-4765 expression. (A) Viability of

hFOB 1.19 cells under various glucose concentrations (1, 2.5, 3.5

or 4.5 g/l). Cell viability was expressed as OD values. (B) Cleaved

caspase-3 protein expression in hFOB 1.19 cells under various

glucose concentrations (1, 2.5, 3.5 or 4.5 g/l). (C) Apoptosis

levels detected using Annexin V staining in hFOB 1.19 cells under

various glucose concentrations (1, 2.5, 3.5 or 4.5 g/l). (D)

miR-4765 expression in hFOB 1.19 cells under various glucose

concentrations (1, 2.5, 3.5 or 4.5 g/l). Data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. OD, optical density; miR, microRNA. |

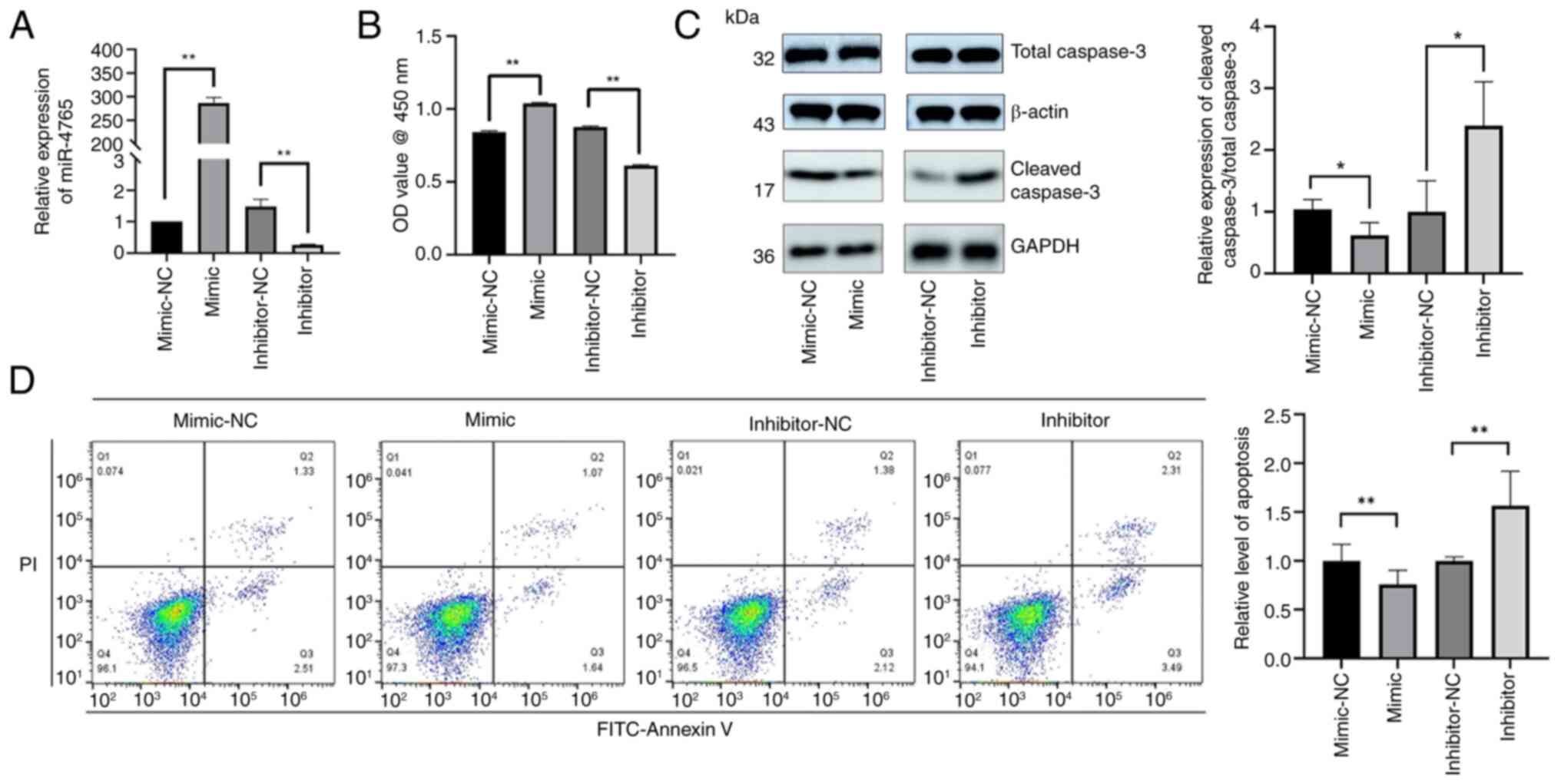

miR-4765 inhibits hFOB 1.19 cell

apoptosis

To examine the effects of miR-4765 on hFOB 1.19

cells, cells were transfected with miR-4765 mimics and miR-4765

mimic NC and subsequent experiments were conducted (Fig. 2A). The results of the CCK-8 assay

showed that miR-4765 OE promoted an increase in cell count

(Fig. 2B). Western blotting and

Annexin V staining showed that transient transfection of miR-4765

mimics into hFOB 1.19 cells inhibited apoptosis (Fig. 2C and D). Transfection with

miR-4765 inhibitors increased apoptosis (Fig. 2B-D).

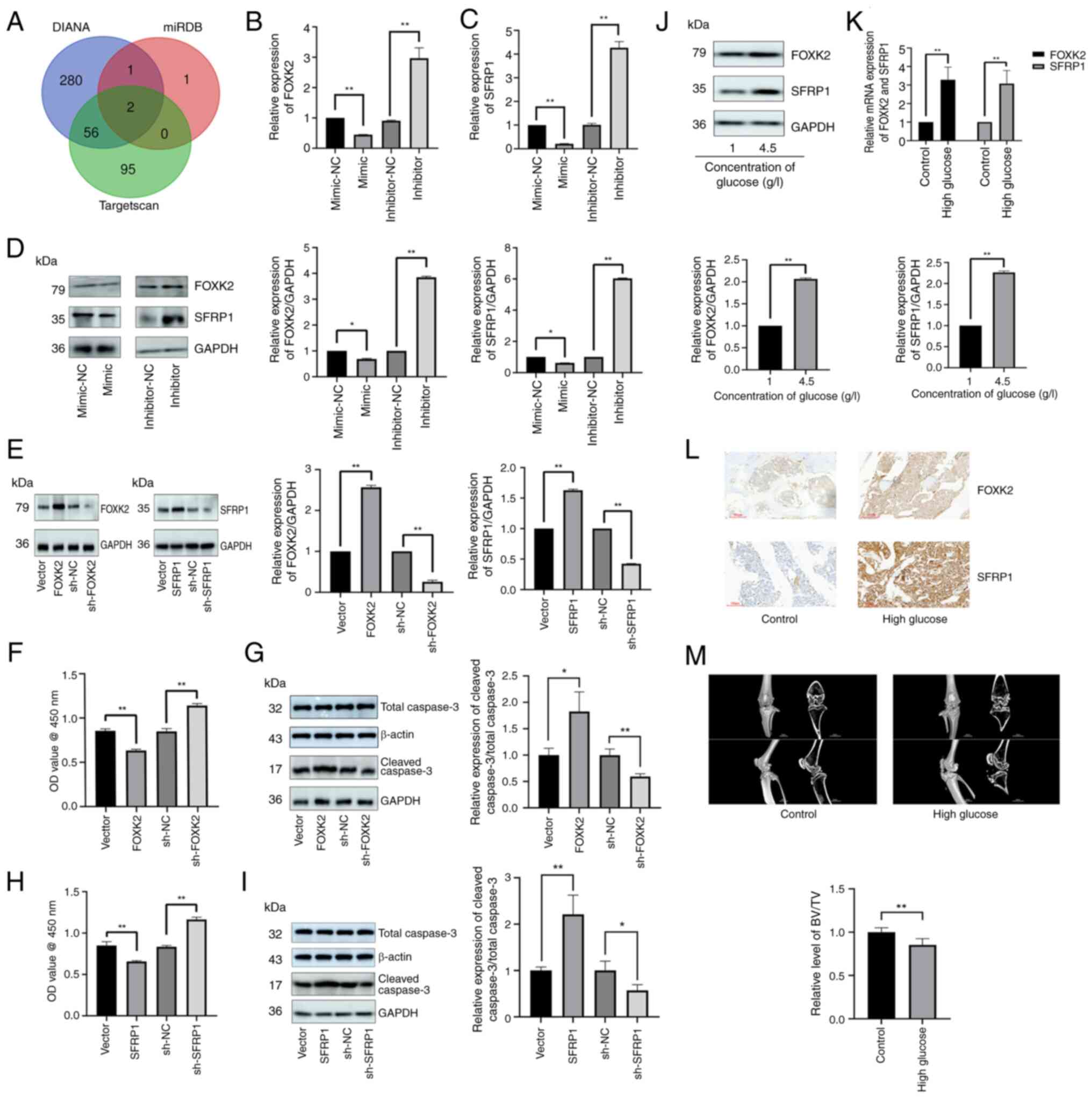

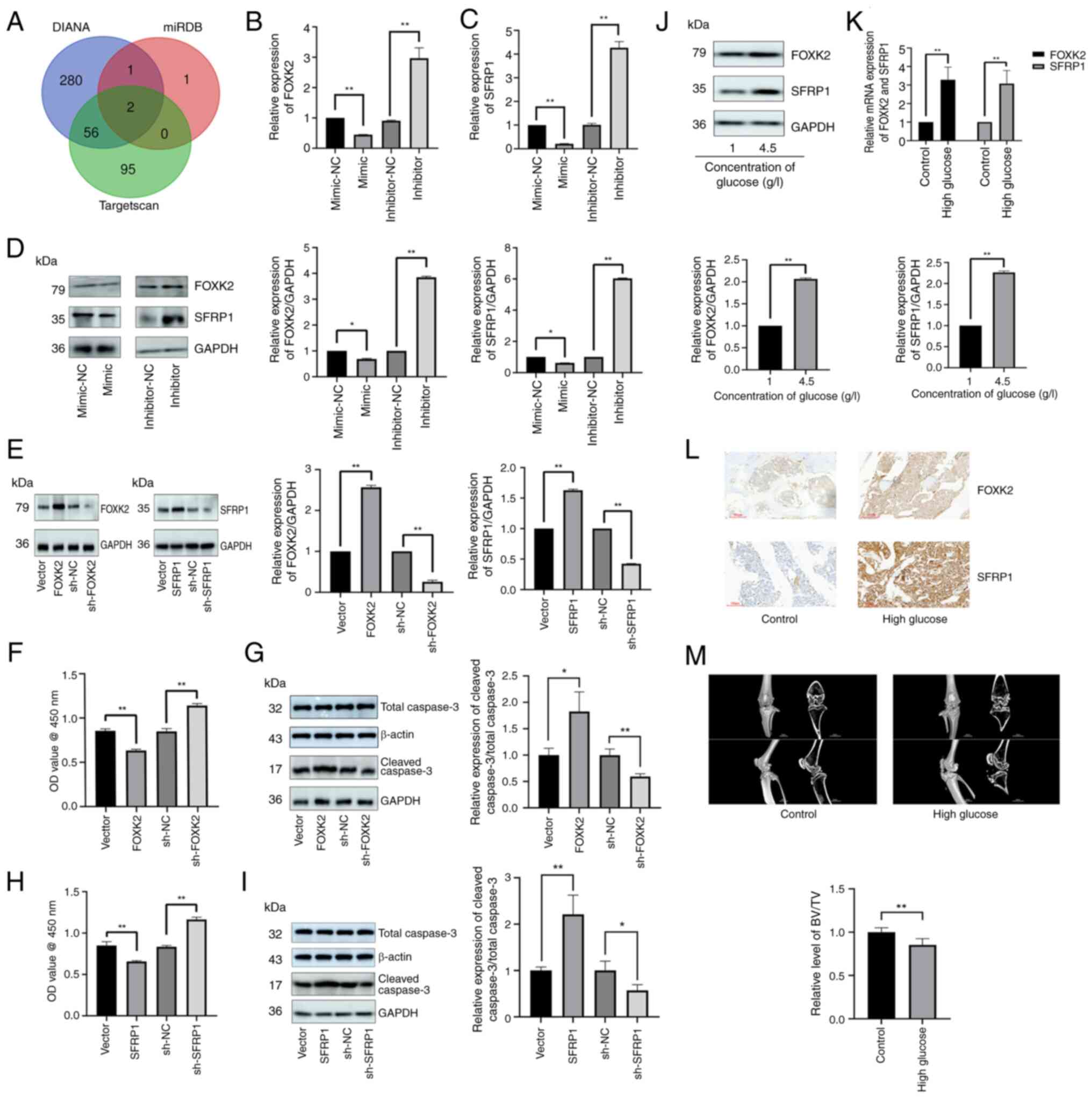

FOXK2 and SFRP1 are potential target

genes of miR-4765 predicted using the miRDB

To further investigate the molecular mechanisms

through which miR-4765 affects apoptosis, several online

target-prediction tools were used, including miRDB, DIANA and

TargetScan, based on which two candidate target genes were

identified (Fig. 3A). To assess

the effects of miR-4765 on FOXK2 and SFRP1 expression, hFOB 1.19

cells were transfected with miR-4765 mimics and inhibitors.

Accordingly, miR-4765 mimics lowered FOXK2 and SFRP1 levels,

whereas miR-4765 inhibitors elevated them (Fig. 3B-D). To examine the effects of

FOXK2 and SFRP1 on hFOB 1.19 cells, the cells were transfected with

sh-FOXK2, sh-SFRP1, sh-FOXK2 NC, or sh-SFRP1 NC (Fig. 3E). The results of the CCK-8 assay

and analysis of cleaved caspase-3 protein expression showed that

FOXK2 and SFRP1 knockouts increased the number of cells (Fig. 3F-I). Moreover, transfection with

FOXK2 and SFRP1 OE plasmid promoted apoptosis (Fig. 3E-I).

| Figure 3FOXK2 and SFRP1 are potential target

genes of miR-4765 predicted using databases. (A) Venn diagram of

target genes overlapping with miR-4765 from three different

databases (TargetScan, miRDB and DIANA). (B) FOXK2 mRNA expression

after transfection with miR-4765 mimics, inhibitors, and the

corresponding NCs. (C) SFRP1 mRNA expression after transfection

with miR-4765 mimics, inhibitors, and the corresponding NCs. (D)

FOXK2 and SFRP1 protein expression after transfection with miR-4765

mimics, inhibitors, and corresponding NCs. (E) Transfection

efficiency of FOXK2 and SFRP1 OE plasmids, sh-FOXK2 and sh-SFRP1,

and the corresponding NCs. (F) Viability of hFOB 1.19 cells after

transfection with FOXK2 OE plasmid, sh-FOXK2, and the corresponding

NCs. Cell viability was expressed as OD values. (G) Cleaved

caspase-3 protein expression after transfection with FOXK2 OE

plasmid, sh-FOXK2, and the corresponding NCs. (H) Viability of hFOB

1.19 cells after transfection with SFRP1 OE plasmid, sh-SFRP1, and

the corresponding NCs. Cell viability was expressed as OD values.

(I) Cleaved caspase-3 protein expression after transfection with

SFRP1 OE plasmid, sh-SFRP1, and the corresponding NCs. (J) FOXK2

and SFRP1 expression in hFOB 1.19 cells under various glucose

concentrations (1 or 4.5 g/l). (K) FOXK2 and SFRP1 mRNA expression

in the bone tissues of control and diabetic mice. (L) FOXK2 and

SFRP1 protein expression determined via immunohistochemical

staining in the bone tissues of control and diabetic mice with OP.

(M) Micro-computed tomography of the knee joint in control and

diabetic mice with OP. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=3).

*P<0.05 and **P<0.01. miR, microRNA;

NC, negative control; sh-, short hairpin; OD, optical density; OE,

overexpression; OP, osteoporosis. |

A hyperglycemic environment promoted the expression

of FOXK2 and SFRP1 both in vitro and in vivo

(Fig. 3J-L). Finally, the bone

microstructure indices were assessed using micro-CT (Fig. 3M). The bone microstructure showed

more features of OP in diabetic mice than in control mice.

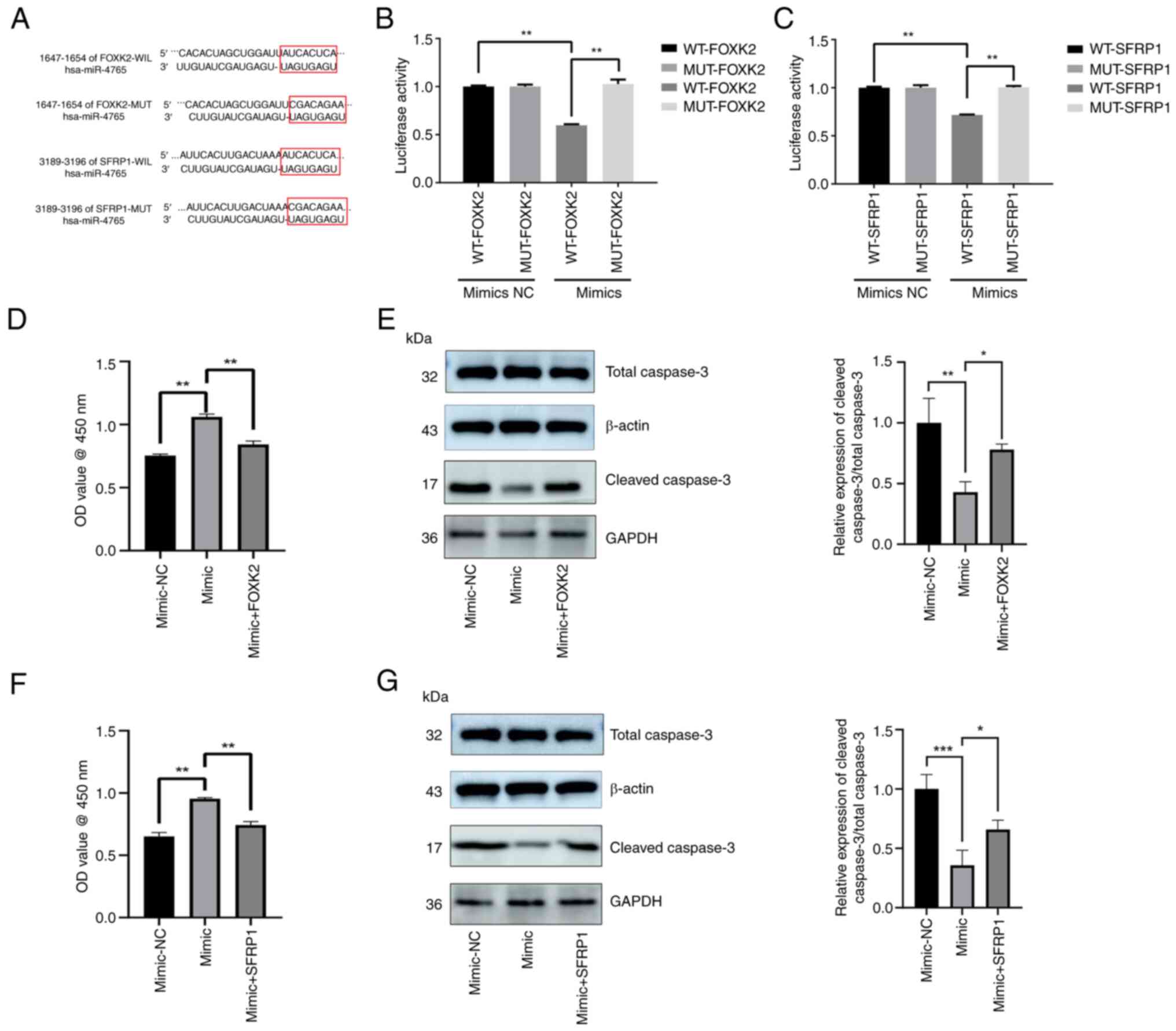

miR-4765 directly targets the

3'-untranslated region (UTR) of FOXK2 and SFRP1

The wild-type 3'-UTR of FOXK2 and SFRP1 mRNA was

cloned with the predicted miR-4765 binding sites, along with the

mutant-type 3'-UTR located upstream of the luciferase-coding

sequence (Fig. 4A). Luciferase

activity was lower in cells co-transfected with miR-4765 mimics and

FOXK2/SFRP1 mRNA wild-type 3'-UTR fragments than in those

co-transfected with miR-4765 mimics NC and FOXK2/SFRP1 mRNA

wild-type 3'-UTR fragments. Conversely, luciferase activity was

greater in cells co-transfected with miR-4765 mimics and

FOXK2/SFRP1 mRNA mutant-type 3'-UTR fragments than in those

co-transfected with miR-4765 mimics and FOXK2/SFRP1 mRNA wild-type

3'-UTR fragments (Fig. 4B and

C). Finally, FOXK2/SFRP1 OE plasmids and miR-4765 mimics were

co-transfected into hFOB 1.19 cells, and the extent of apoptosis

was determined using the CCK-8 assay and cleaved caspase-3 protein

expression. The results revealed that FOXK2 and SFRP1 partially

reversed the anti-apoptotic effects of miR-4765 (Fig. 4D-G). These results indicated that

FOXK2 and SFRP1 may be direct targets of miR-4765, suggesting that

miR-4765 influences apoptosis by targeting FOXK2 and SFRP1.

LINC00312 may act as a miR-4765 sponge to

regulate FOXK2 and SFRP1, as predicted using database analysis

To examine whether LINC00312 interacts with

miR-4765, hFOB 1.19 cells were transfected with LINC00312 OE

plasmid, sh-LINC00312, or LINC00312 NC. After confirming successful

transfection (Fig. 5A), it was

found that LINC00312 OE plasmids reduced miR-4765 expression,

whereas sh-LINC00312 increased it (Fig. 5B).

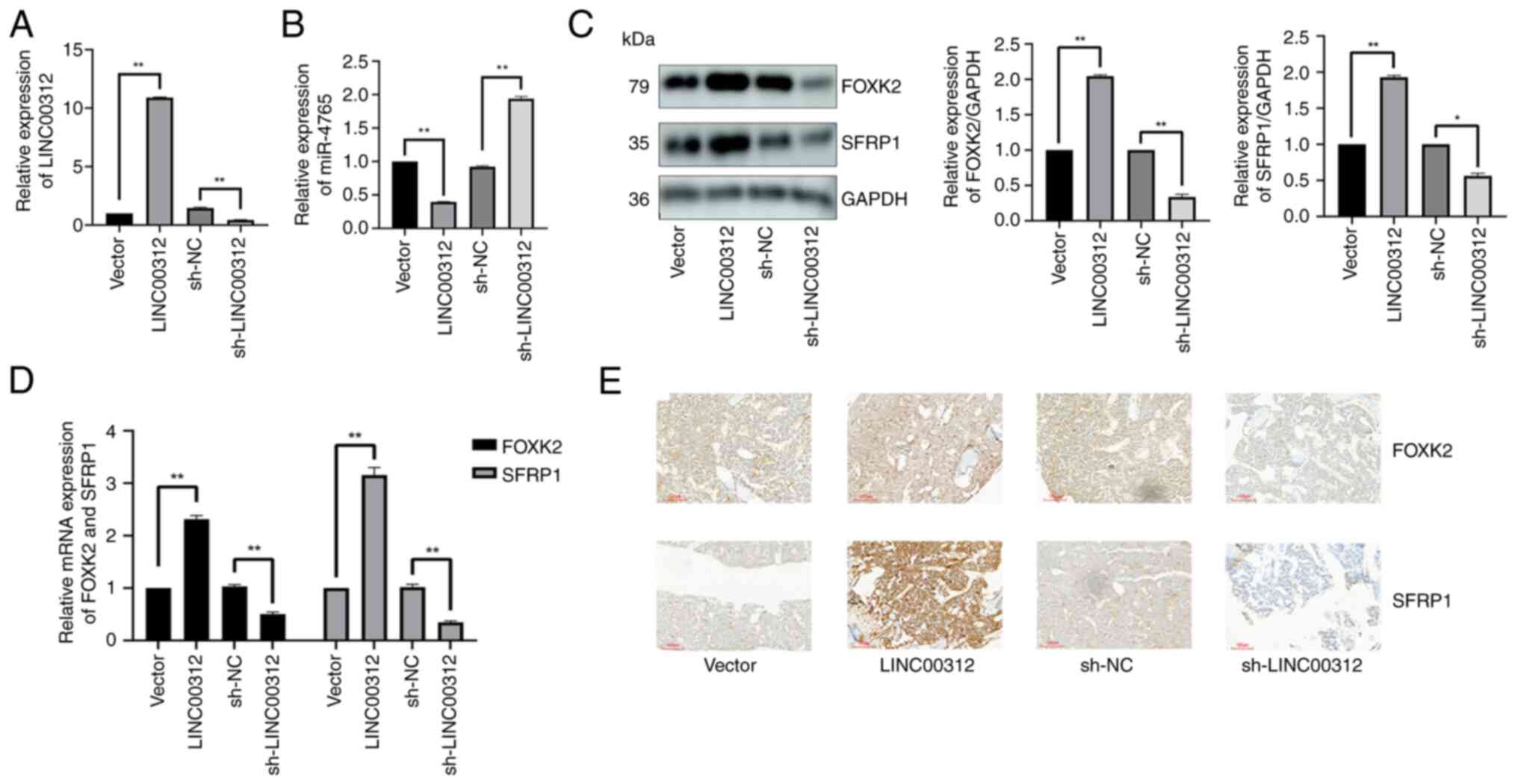

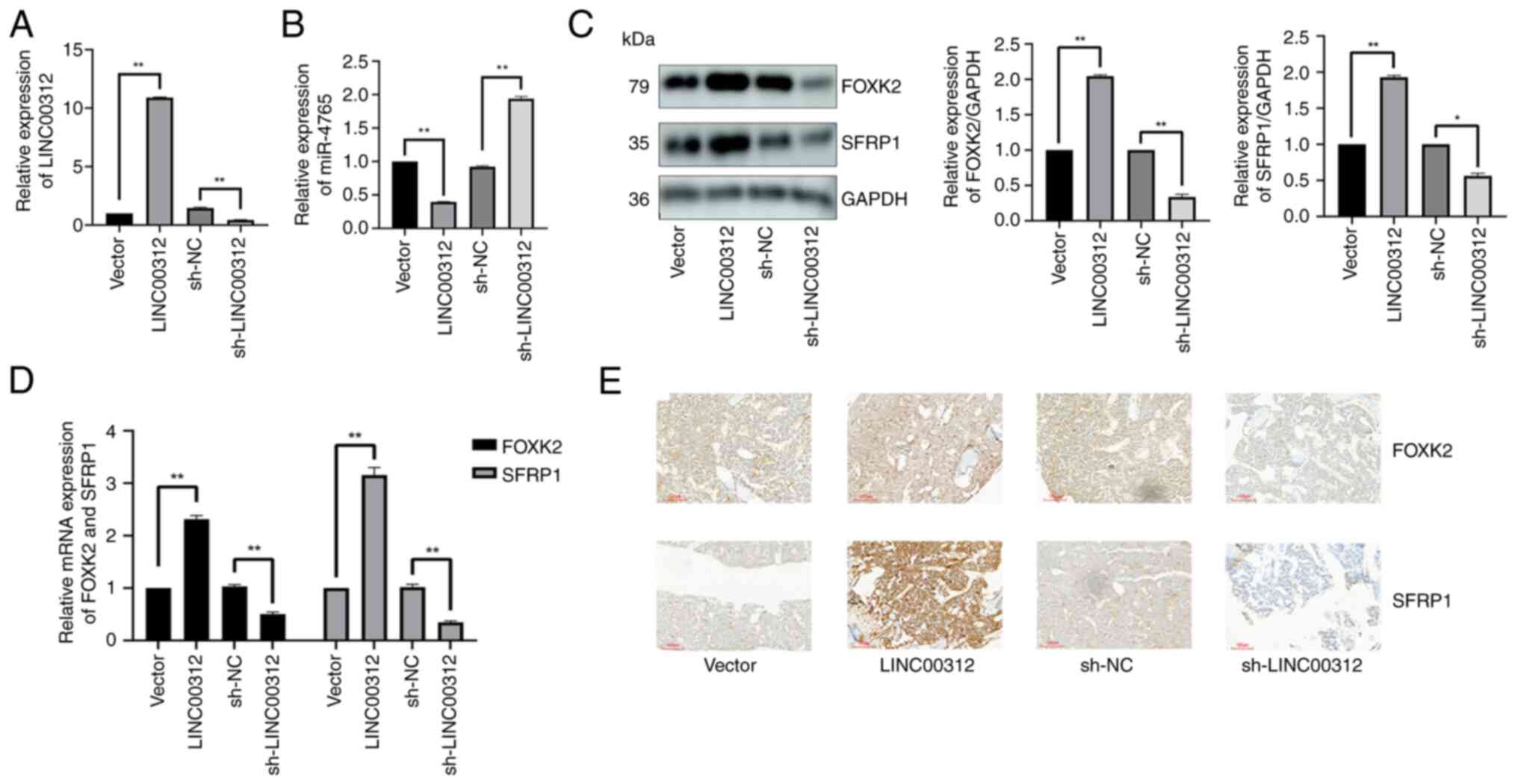

| Figure 5LINC00312 may act as an miR-4765

sponge to regulate FOXK2 and SFRP1 as predicted using the database.

(A) Transfection efficiency of LINC00312 OE plasmids and

sh-LINC00312. (B) miR-4765 expression after transfection with

LINC00312 OE plasmids, sh-LINC00312, and the corresponding NCs. (C)

FOXK2 and SFRP1 protein expression after transfection with

LINC00312 OE plasmids, sh-LINC00312, and the corresponding NCs. (D)

FOXK2 and SFRP1 mRNA expression in the bone tissues of diabetic

mice with OP after adenovirus transfection with LINC00312 OE

plasmids, sh-LINC00312, and the corresponding NCs. (E) FOXK2 and

SFRP1 protein expression determined using immunohistochemical

staining in the bone tissues of diabetic mice with OP after

adenovirus transfection with LINC00312 OE plasmids, sh-LINC00312,

and the corresponding NCs. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. miR, microRNA; NC, negative control; OE,

overexpression; sh-, short hairpin; OP, osteoporosis. |

To assess the effects of LINC00312 on FOXK2 and

SFRP1, hFOB 1.19 cells were transfected with LINC00312 OE plasmid,

sh-LINC00312, or LINC00312 NC. The LINC00312 OE plasmid increased

FOXK2 and SFRP1 levels, whereas sh-LINC00312 decreased these levels

(Fig. 5C).

To assess the effects of LINC00312 on FOXK2 and

SFRP1 in vivo, diabetic OP mice were injected with

LINC00312-carrying adenoviruses for OE-LINC00312, sh-LINC00312, or

the corresponding NC. OE-LINC00312 increased the FOXK2 and SFRP1

mRNA (Fig. 5D) and protein

(Fig. 5E) levels in vivo,

whereas sh-LINC00312 decreased these levels.

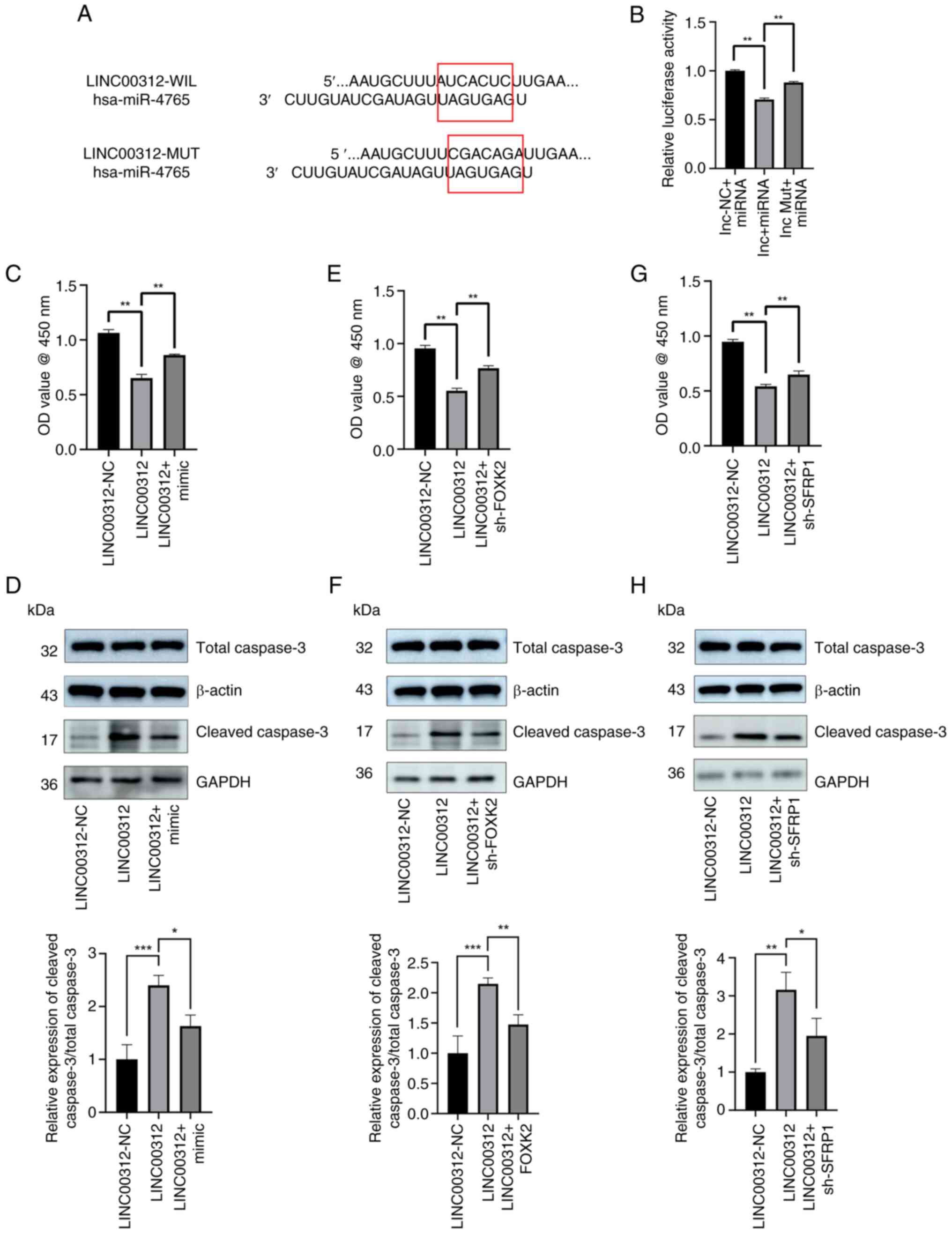

LINC00312 can be directly combined with

miR-4765

The wild-type 3'-region of LINC00312 was cloned with

the presumed miR-4765-binding sites, along with the mutant

3'-region located upstream of the luciferase-coding sequence

(Fig. 6A). Luciferase activity

was lower in cells co-transfected with miR-4765 mimics and

LINC00312 wild-type 3'-region fragments than in cells

co-transfected with miR-4765 mimics NC and LINC00312 wild-type

3'-region fragments. Conversely, luciferase activity was greater in

cells co-transfected with miR-4765 mimics and LINC00312 mutant-type

3'-region fragments than in cells co-transfected with miR-4765

mimics and LINC00312 wild-type 3'-region fragments (Fig. 6B). Finally, hFOB 1.19 cells were

co-transfected with the LINC00152 OE plasmid and miR-4765 mimics,

after which the extent of cell apoptosis was determined using the

CCK-8 assay and cleaved caspase-3 protein expression. The results

demonstrated that miR-4765 partially reversed the apoptotic effects

of LINC00312 (Fig. 6C and D).

Concurrently, hFOB 1.19 cells were co-transfected with the

LINC00152 OE plasmid and sh-FOXK2 and sh-SFRP1, after which the

extent of cell apoptosis was determined using the CCK-8 assay and

cleaved caspase-3 protein expression. Notably, it was found that

sh-FOXK2 and sh-SFRP1 partially reversed the apoptotic effects of

LINC00312 on hFOB 1.19 cells (Fig.

6E-H). These results indicated that LINC00312 can directly bind

to miR-4765 as an RNA sponge and exert its ceRNA function.

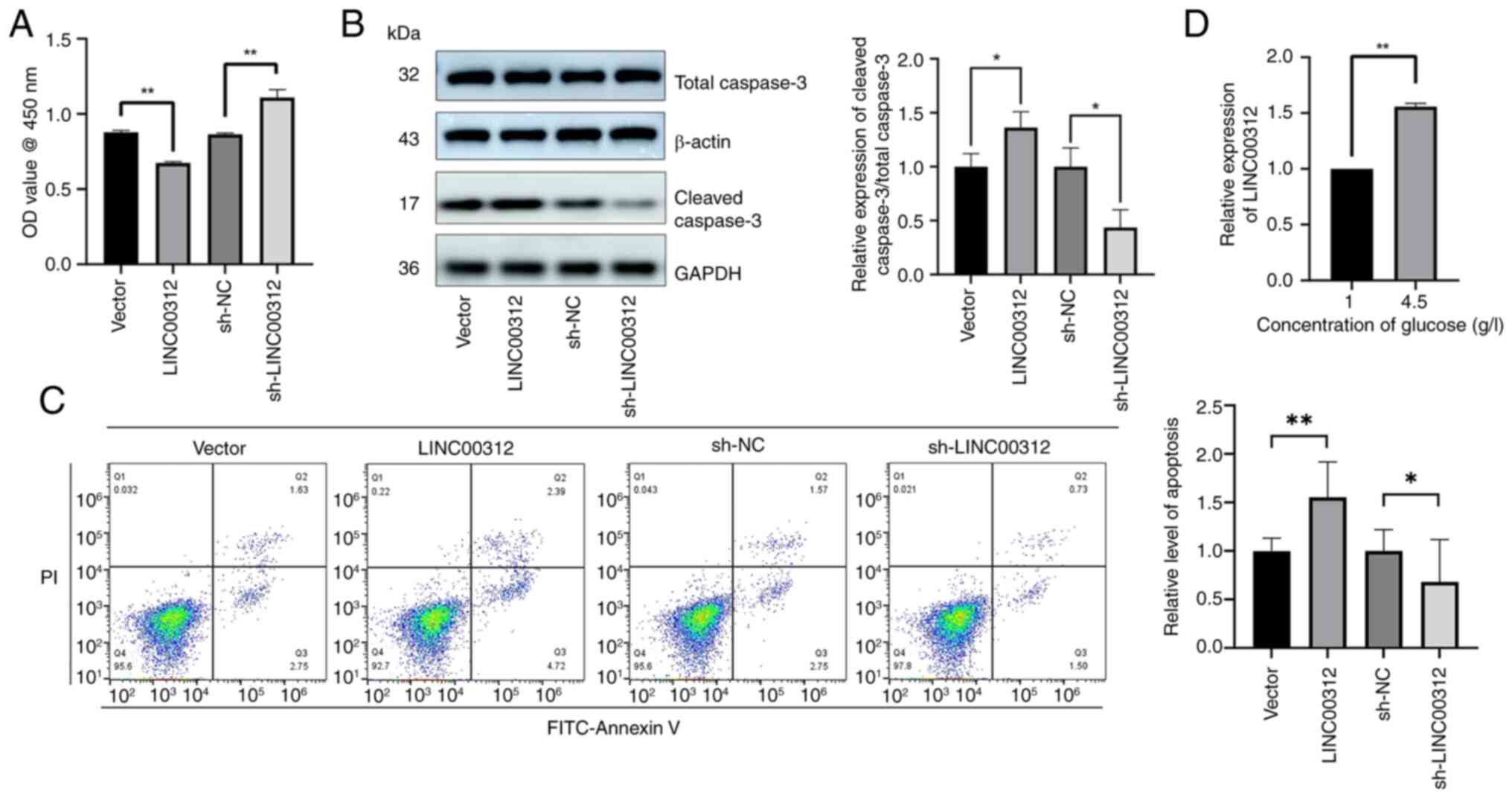

LINC00312 promotes hFOB 1.19 cell

apoptosis

To examine the apoptotic effects of LINC00312 on

hFOB 1.19 cells, cells were transfected with sh-LINC00312 or

LINC00312 NC. The results of the CCK-8 assay demonstrated that

after LINC00312 knockout increased the number of cells (Fig. 7A). Western blotting and Annexin V

staining showed that transfection with sh-LINC00312 inhibited hFOB

1.19 cell apoptosis (Fig. 7B and

C), whereas transfection with the LINC00312 OE plasmid

increased apoptosis (Fig. 7A and

B). The hyperglycemic environment promoted the expression of

LINC00312 (Fig. 7D).

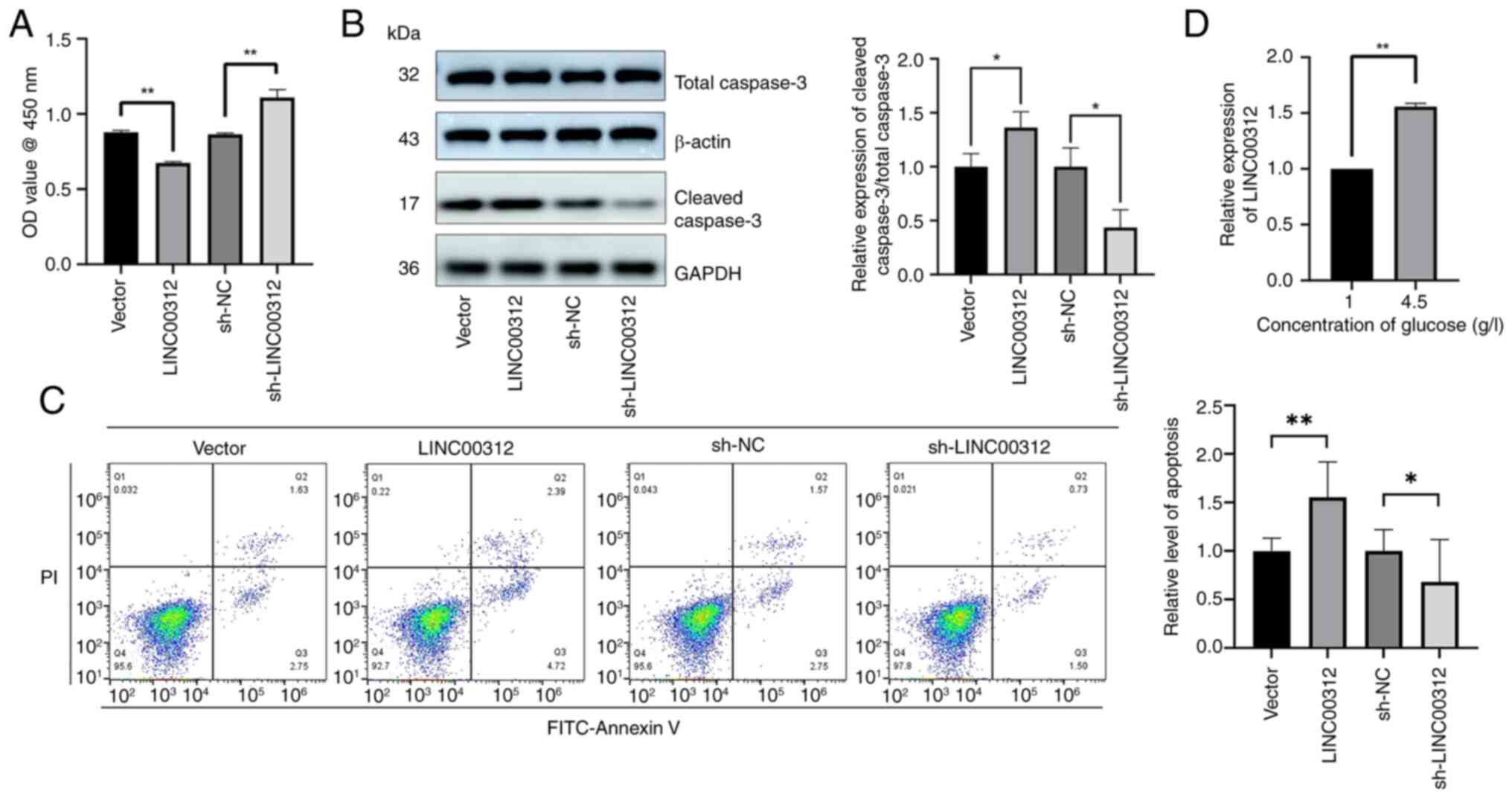

| Figure 7LINC00312 can promote hFOB 1.19 cells

apoptosis. (A) Viability of hFOB 1.19 cells after transfection with

LINC00312 OE plasmids, sh-LINC00312, and the corresponding NCs.

Cell viability was expressed as OD values. (B) Cleaved caspase-3

protein expression after transfection with LINC00312 OE plasmids,

sh-LINC00312, and the corresponding NCs. (C) Apoptosis levels

determined via Annexin V staining after transfection with LINC00312

OE plasmids, sh-LINC00312, and the corresponding NCs. (D) LINC00312

expression in hFOB 1.19 cells under various glucose concentrations

(1 or 4.5 g/l). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation

(n=3). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. OD,

optical density; NC, negative control; OE, overexpression; sh-,

short hairpin. |

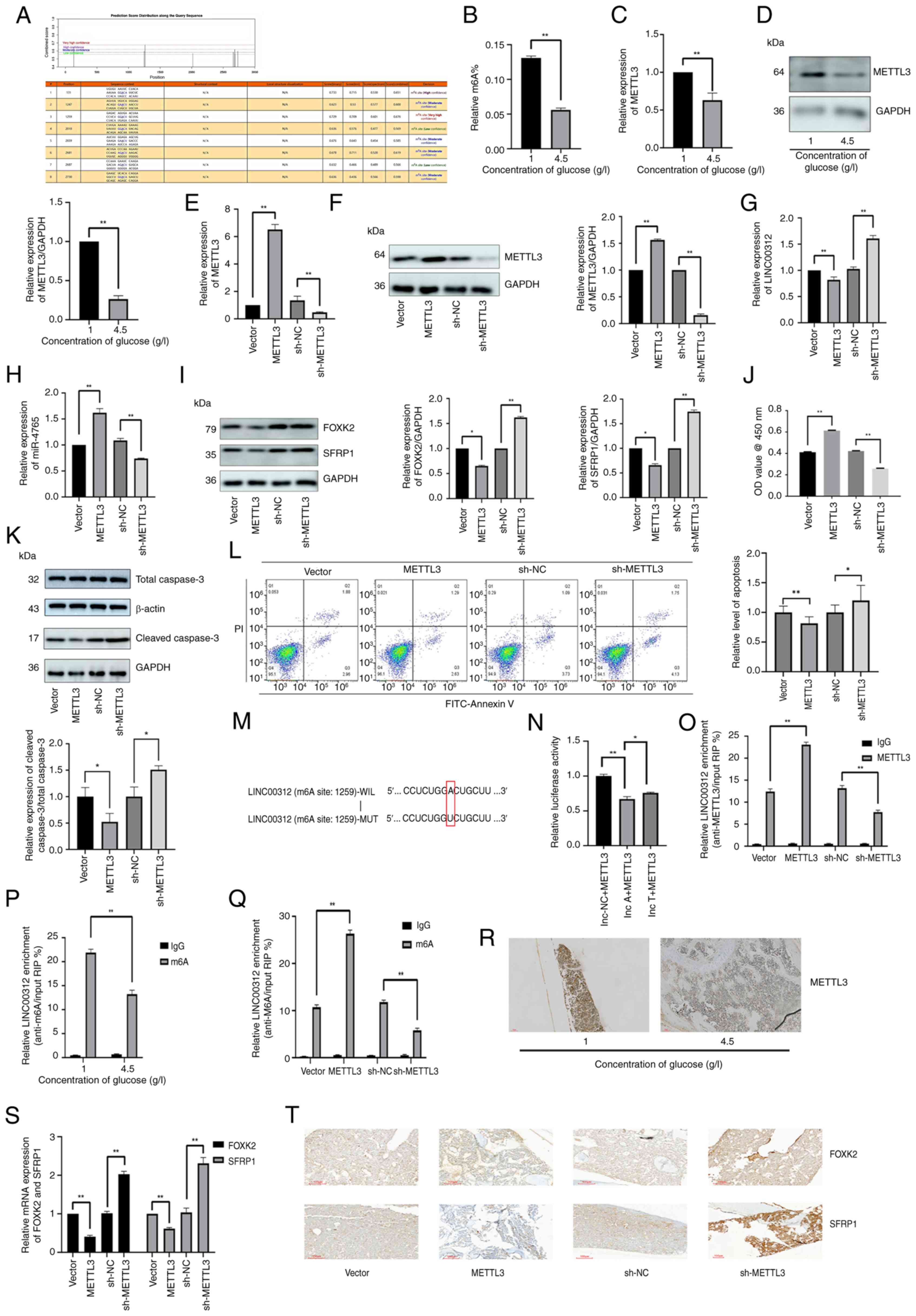

METTL3 reduces LINC00312 expression by

increasing its methylation level

Previous studies have shown that methylation can

occur in OP and that lncRNAs may undergo methylation changes.

Therefore, it was proposed that changes in LINC00312 levels in OP

are associated with changes in its methylation status. First, it

was predicted that LINC00312 contains an m6A modification site

(score=0.676) based on the SRAMP website (Fig. 8A). ELISA was used to detect

differences in m6A modification levels between high glucose

(HG)-induced and low glucose (LG)-cultured osteoblasts. A

hyperglycemic environment inhibited methylation levels (Fig. 8B). Next, RT-qPCR and western

blotting were used to detect the RNA and protein expression levels

of METTL3 in osteoblasts cultured under high- and low-glucose

conditions, respectively. Notably, the mRNA and protein expression

levels of METTL3 decreased in the hyperglycemic environment

(Fig. 8C and D).

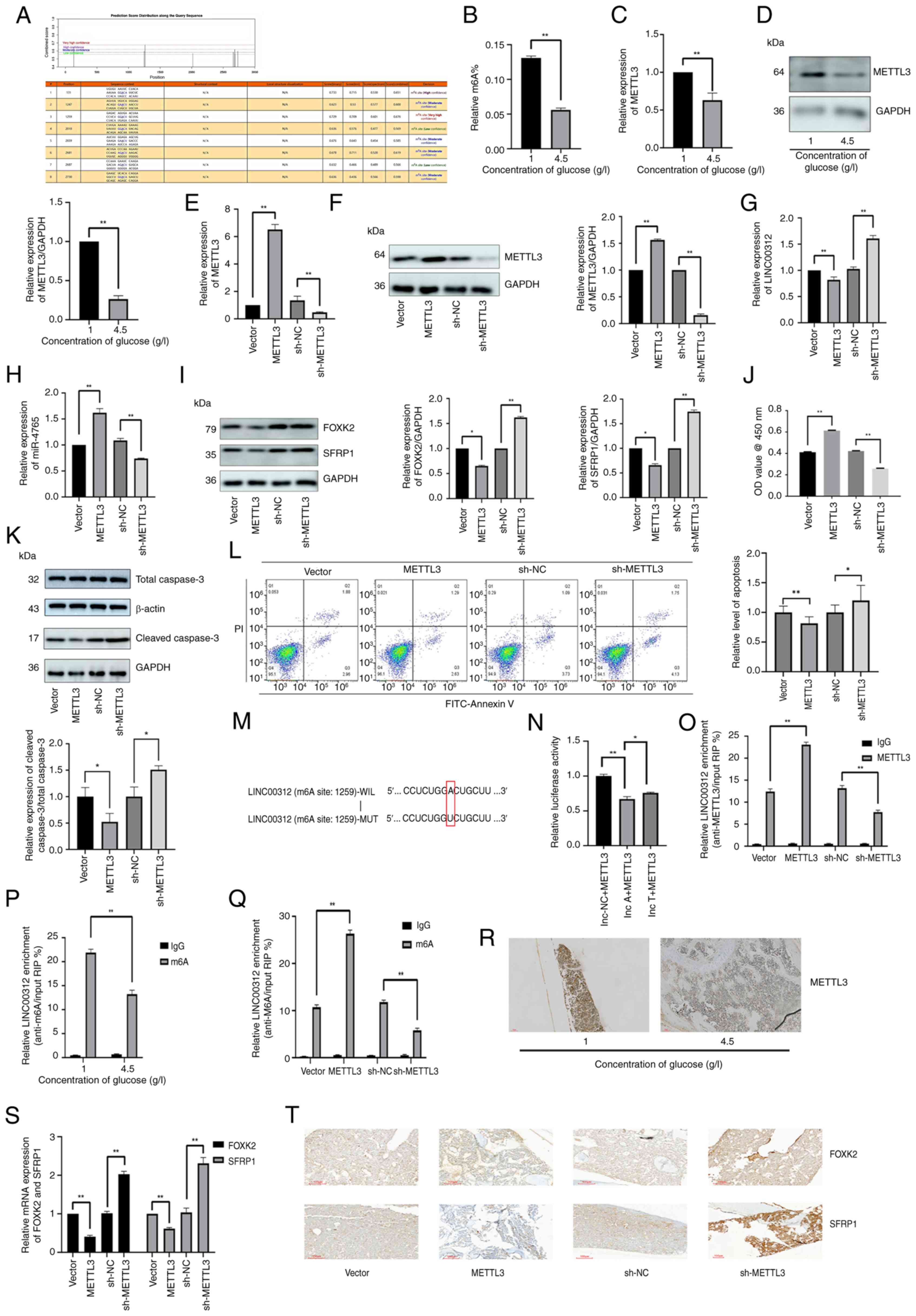

| Figure 8METTL3 reduces the expression level

of LINC00312 by increasing its methylation level. (A) SRAMP was

used to predict the possible m6A modification locations of

LINC00312. (B) Relative m6A level of hFOB 1.19 cells under various

glucose concentrations (1 or 4.5 g/l) determined via m6A

colorimetric analysis. (C) METTL3 mRNA expression in hFOB 1.19

cells under various glucose concentrations (1 or 4.5 g/l). (D)

METTL3 protein expression in hFOB 1.19 cells under various glucose

concentrations (1 or 4.5 g/l). (E) Transfection efficiency of

METTL3 OE plasmids and sh-METTL3. METTL3 mRNA expression after

transfection with METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the

corresponding NCs. (F) Transfection efficiency of METTL3 OE

plasmids and sh-METTL3; METTL3 protein expression after

transfection with METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the

corresponding NCs. (G) LINC00312 expression after transfection with

METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the corresponding NCs. (H)

miR-4765 expression after transfection with METTL3 OE plasmids,

sh-METTL3, and the corresponding NCs. (I) FOXK2 and SFRP1 protein

expression after transfection with METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3,

and the corresponding NCs. (J) Viability of hFOB 1.19 cells after

transfection with METTL3 OE plasmid, sh-METTL3, and the

corresponding NCs. Cell viability was expressed as OD values. (K)

Cleaved caspase-3 protein expression after transfection with METTL3

OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the corresponding NCs. (L) Apoptosis

levels determined via Annexin V staining after transfection with

METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the corresponding NCs. (M) m6A

modification locations of LINC00312. (N) Luciferase activity in

293T cells co-transfected with METTL3 OE plasmids and LINC00312 WT

or MUT 3'-region. (O) Relative enrichment of METTL3 in LINC00312

after transfection with METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the

corresponding NCs. (P) Relative enrichment of m6A in LINC00312

under various glucose concentrations (1 or 4.5 g/l) determined via

methylated RNA immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR assays. (Q)

Relative enrichment of m6A in LINC00312 after transfection with

METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the corresponding NCs. (R)

METTL3 protein expression determined via IHC staining in the bone

tissues of diabetic mice with OP and non-diabetic mice. (S) FOXK2

and SFRP1 mRNA expression in the bone tissues of diabetic mice with

OP after adenovirus transfection with METTL3 OE plasmids,

sh-METTL3, and the corresponding NCs. (T) FOXK2 and SFRP1 protein

expression determined via IHC staining in the bone tissues of

diabetic mice with OP after adenovirus transfection with METTL3 OE

plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the corresponding NCs. Data are presented

as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. OE, overexpression; sh-, short hairpin; WT,

wild type; MUT, mutant; NC, negative control; OD, optical density;

miR, microRNA; OP, osteoporosis; IHC, immunohistochemical. |

To further investigate the biological function of

METTL3, hFOB 1.19 cells were transfected with a METTL3 OE plasmid

and sh-METTL3. After successful transfection (Fig. 8E and F), expression levels of the

downstream LINC00312-miR-4765-FOXK2/SFRP1 axis were determined. OE

of METTL3 lowered LINC00312, FOXK2, and SFRP1 expression levels,

but increased miR-4765 expression levels, whereas sh-METTL3 induced

the opposite effect (Fig. 8G-I).

The results of the CCK-8 assay, cleaved caspase-3 protein

expression, and Annexin V staining showed that METTL3 OE increased

the number of cells, whereas sh-METTL3 decreased the cell number

and promoted apoptosis (Fig.

8J-L). Finally, to further investigate how METTL3 inhibits

LINC00312 expression, dual-luciferase reporter assay and RIP-qPCR

were performed. Accordingly, it was revealed that METTL3 binds

directly to LINC00312 (Fig.

8M-O). Using methylated RIP-qPCR, it was found that the m6A

modification level of LINC00312 was lower in HG-induced osteoblasts

than that in LG-cultured osteoblasts (Fig. 8P). Moreover, the METTL3 knockout

reduced the relative enrichment of m6A in LINC00312 cells, whereas

METTL3 OE had the opposite effect (Fig. 8Q).

Next, IHC was used to detect the protein expression

levels of METTL3 in diabetic mice with OP and in non-diabetic mice.

Notably, diabetic mice with OP exhibited decreased protein

expression of METTL3 (Fig.

8R).

To assess the effects of METTL3 on FOXK2 and SFRP1

in vivo, diabetic mice with OP were injected with

METTL3-carrying adenoviruses OE-METTL3, sh-METTL3, or the

corresponding NC. Accordingly, it was found that OE-METTL3

decreased the FOXK2 and SFRP1 mRNA (Fig. 8S) and protein (Fig. 8T) expression levels in

vivo, whereas sh-METTL3 increased them.

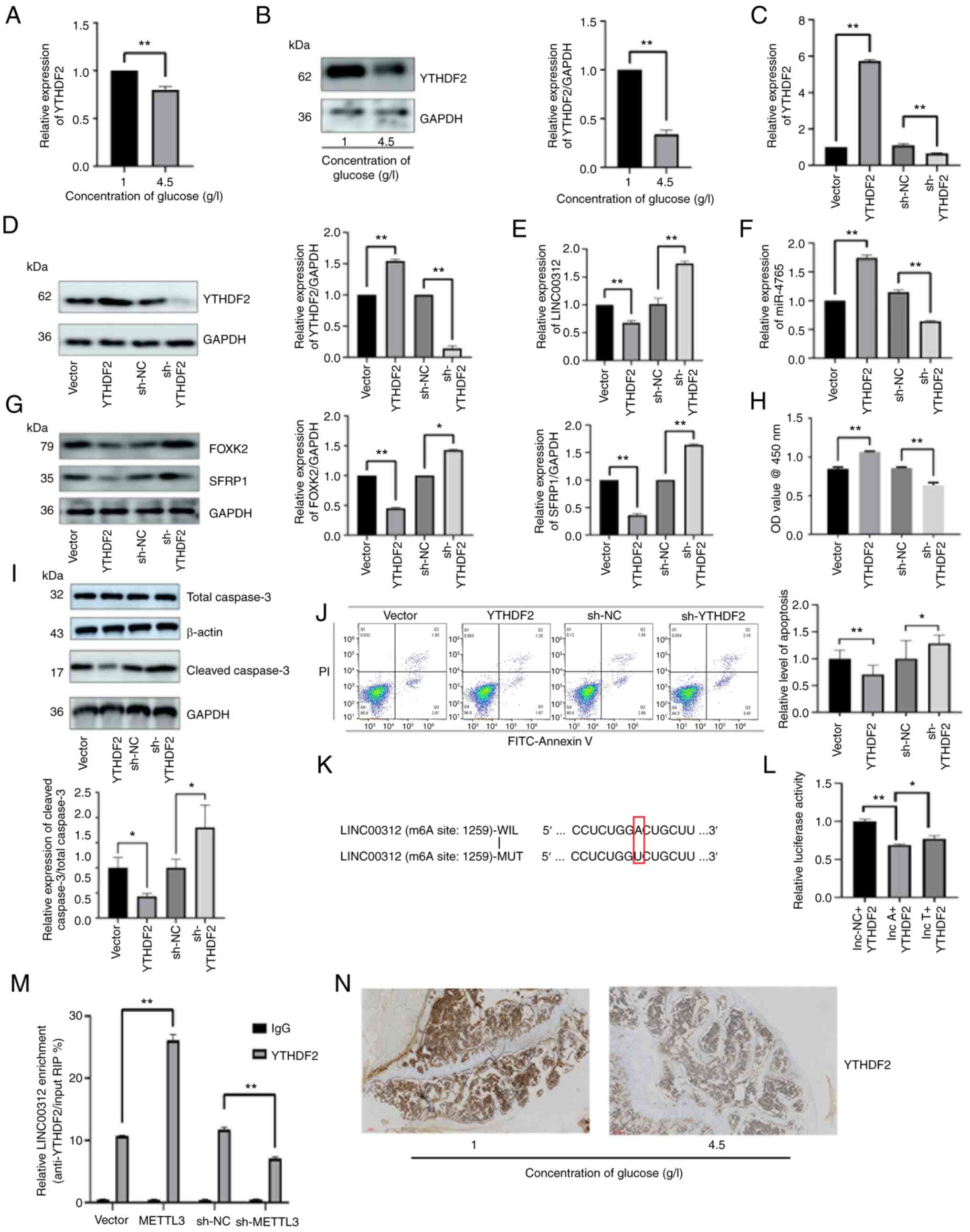

YTHDF2 contributes to increased LINC00312

methylation

METTL3-mediated m6A modifications typically occur in

a reader-dependent manner. First, RT-qPCR and western blotting were

used to detect the mRNA and protein expression levels of YTHDF2 in

HG-induced and LG-cultured osteoblasts, respectively. Notably, the

expression of YTHDF2 decreased in HG environments (Fig. 9A and B). To further investigate

the biological function of YTHDF2, hFOB 1.19 cells were transfected

with the YTHDF2 OE plasmid and sh-YTHDF2. After successful

transfection (Fig. 9C and D),

the expression levels of the downstream

LINC00312-miR-4765-FOXK2/SFRP1 axis were determined. Notably, the

YTHDF2 OE plasmid lowered LINC00312, FOXK2 and SFRP1 expression

levels but increased miR-4765 expression levels, whereas sh-YTHDF2

produced the opposite effect (Fig.

9E-G). The results of the CCK-8 assay, cleaved caspase-3

protein expression, and Annexin V staining showed that YTHDF2 OE

increased the number of cells, whereas sh-YTHDF2 produced the

opposite effect (Fig. 9H-J). To

further investigate how YTHDF2 inhibited LINC00312 expression, a

dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed. Notably, it was found

that YTHDF2 directly binds to LINC00312 (Fig. 9K and L). It was investigated

whether METTL3 regulates m6A methylation of LINC00312 in hFOB 1.19

cells in an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. RIP-qPCR was used to

examine the interaction between YTHDF2 and LINC00312 after

transfecting hFOB 1.19 cells with the METTL3 OE plasmid and

sh-METTL3. METTL3 inhibition in hFOB 1.19 cells reduced the

interaction between YTHDF2 and LINC00312 compared with that in the

sh-NC group, whereas its OE had the opposite effect (Fig. 9M).

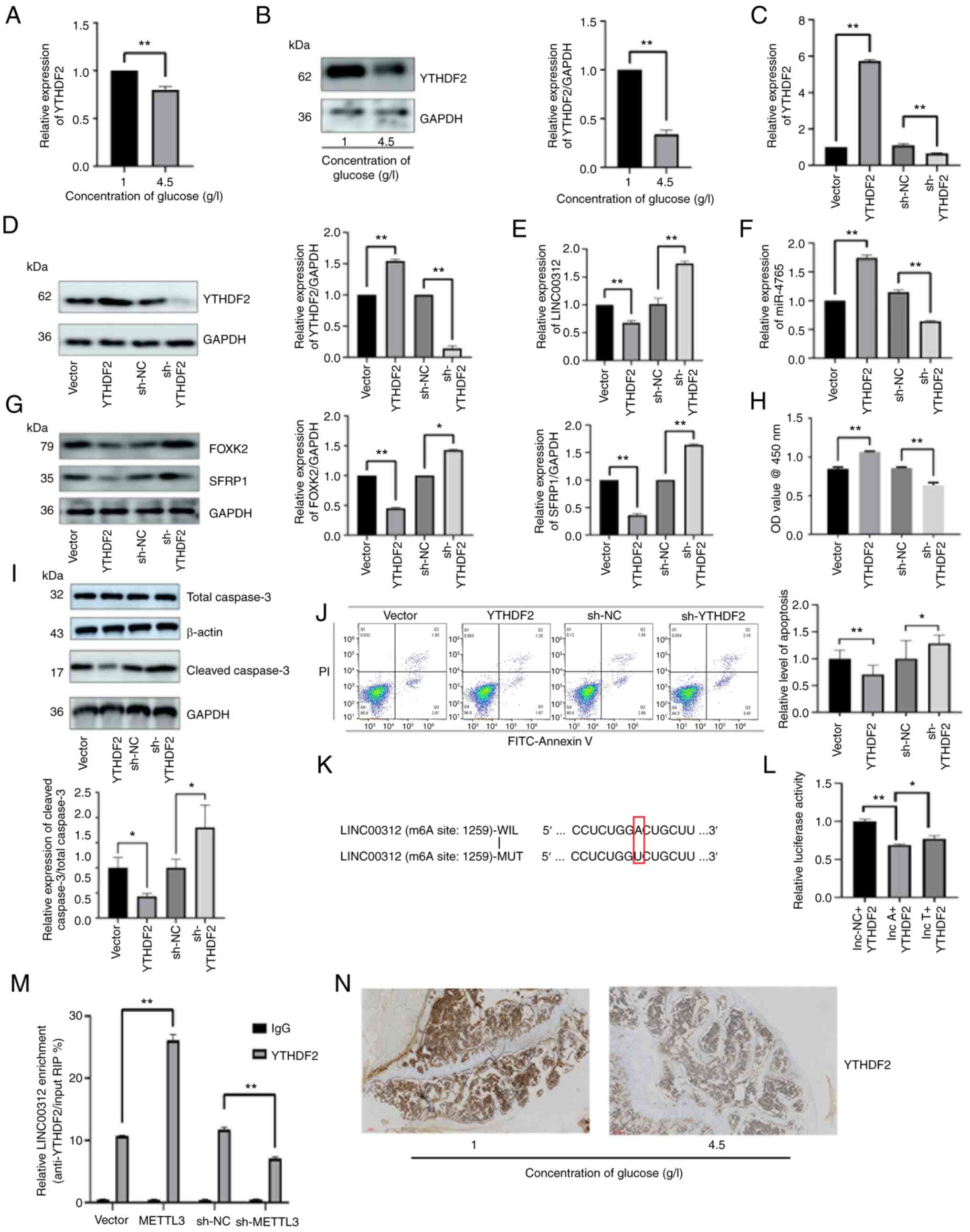

| Figure 9YTHDF2 participates in increasing the

methylation level of LINC00312. (A) YTHDF2 mRNA expression in hFOB

1.19 cells under various glucose concentrations (1 or 4.5 g/l). (B)

YTHDF2 protein expression in hFOB 1.19 cells under various glucose

concentrations (1 or 4.5 g/l). (C) Transfection efficiency of

YTHDF2 OE plasmids and sh-YTHDF2. YTHDF2 mRNA expression after

transfection with YTHDF2 OE plasmids, sh-YTHDF2, and the

corresponding NCs. (D) Transfection efficiency of YTHDF2 OE

plasmids and sh-YTHDF2. YTHDF2 protein expression after

transfection with YTHDF2 OE plasmids, sh-YTHDF2, and the

corresponding NCs. (E) LINC00312 expression after transfection with

YTHDF2 OE plasmids, sh-YTHDF2 and the corresponding NCs. (F)

miR-4765 expression after transfection with YTHDF2 OE plasmids,

sh-YTHDF2, and the corresponding NCs. (G) FOXK2 and SFRP1 protein

expression after transfection with YTHDF2 OE plasmids, sh-YTHDF2,

and the corresponding NCs. (H) Viability of hFOB 1.19 cells after

transfection with YTHDF2 OE plasmids, sh-YTHDF2, and the

corresponding NCs. Cell viability was expressed as OD values. (I)

Cleaved caspase-3 protein expression after transfection with YTHDF2

OE plasmids, sh-YTHDF2, and the corresponding NCs. (J) Apoptosis

level determined via Annexin V staining after transfection with

YTHDF2 OE plasmids, sh-YTHDF2, and the corresponding NCs. (K) m6A

modification locations of LINC00312. (L) Luciferase activity in

293T cells co-transfected with YTHDF2 OE plasmids and LINC00312 WT

or MUT 3'-region. (M) Relative enrichment of YTHDF2 in LINC00312

after transfection with METTL3 OE plasmids, sh-METTL3, and the

corresponding NCs. (N) YTHDF2 protein expression determined via

immunohistochemical staining in the bone tissues of diabetic mice

with osteoporosis and non-diabetic mice. Data are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01. WT, wild type; MUT, mutant; NC, negative

control; OD, optical density; OE, overexpression; sh-, short

hairpin; miR, microRNA. |

Finally, IHC was used to detect the protein

expression levels of YTHDF2 in diabetic mice with OP and

non-diabetic mice. Notably, the protein expression levels of YTHDF2

decreased in diabetic mice with OP (Fig. 9N).

Discussion

Based on the GSE74209 database, miR-4765 expression

was increased in healthy individuals and decreased in patients with

OP. Thereafter, upstream lncRNAs and downstream target genes were

predicted using the databases (TargetScan, miRDB and DIANA), and

LINC00312 and FOXK2/SFRP1 were identified. The m6A modification

site within LINC00312 was predicted using an online database

(SRAMP). Finally, cell experiments were conducted to verify the

accuracy of the predictions.

FOXK2, a member of the Foxk family of forkhead

transcription factors, is widely involved in various cellular

activities, such as regulating aerobic glycolysis (23), suppressing the hypoxic response

(24), and inhibiting atrophy

and autophagy programs (25), as

well as in various cell cycle regulation processes. Some studies

have suggested that FOXK2 promotes apoptosis, which is consistent

with the results of the present study. FOXK2 OE induces apoptosis

in clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells in vivo (26). Moreover, another study found that

FOXK2 promotes apoptosis in a human osteosarcoma cell line (U2OS)

based on caspase-3 activity (27). However, other studies have

suggested that FOXK2 also inhibits apoptosis. In fact, a previous

study found that FOXK2 promotes granulosa cell proliferation via

the PI3K/AKT/mTOR regulatory pathway (28).

SFRP1, which modulates Wnt signaling by directly

interacting with Wnt, has been widely involved in various diseases,

such as Alzheimer's disease (29), retinal neurogenesis (30,31) and leukemia (32), as well as in the pathogenesis of

OP. Some studies have indicated that SFRP1 promotes OP, which is

consistent with the results presented herein. For instance, a

previous study found that increasing the expression level of SFRP1

reduced bone formation and mass (33). Another study showed that SFRP1

suppressed the proliferation of bone marrow stromal/mesenchymal

stem/stromal cells (BMSCs) and decreased calcium nodule formation

and alkaline phosphatase activity (34). Evidence further suggests that

SFRP1, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, is

significantly upregulated in OP (35). Therefore, the inhibition of SFRP1

expression plays an important role in bone formation by inducing

osteoblast differentiation (36). Nonetheless, other studies have

suggested that increasing SFRP1 expression promotes bone formation

and that SFRP1 can be used to treat OP (37).

LINC00312, an lncRNA, produces an intron-less

transcript that is considered to function as a tumor suppressor.

LINC00312 is involved in various cytological processes, such as DNA

damage repair (38), invasion

and migration (39-41). Moreover, LINC00312 promotes

apoptosis, which is consistent with the results presented herein.

For example, a previous study found that LINC00312 enhances the

sensitivity of the cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer subline

SKOV3/DDP to cisplatin by promoting apoptosis via the

Bcl-2/Caspase-3 signaling pathway (42). Another study showed that forced

expression of LINC00312 using a lentiviral vector inhibited

proliferation and induced apoptosis in human hepatoblastoma and

primary human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (43). LINC00312, which is regulated by

HOXA5, has also been found to inhibit tumor proliferation and

promote apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer (44). Additionally, LINC00312 inhibits

the proliferation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and induces

apoptosis (45).

Previous studies have demonstrated that METTL3

inhibits OP. METTL3 expression is upregulated during osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs (46).

A previous study using osteoporotic models showed that METTL3

expression levels were reduced and that METTL3 silencing inhibited

the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs (47) and adipose-derived stem cells

(48), ultimately leading to OP

in mice (49). METTL3 has also

been reported to alleviate OP by promoting osteogenic

differentiation through the Wnt signaling pathway (50), LINC00657/miR-144-3p/BMPR1B axis

(51), and MIR99AHG/miR-4660

axis (52). Moreover, Chinese

Ecliptae herba has been found to possess therapeutic effects

against OP by increasing METTL3 expression (53). One study indicated that METTL3

can trigger the development of OP. Another study using mouse

calvaria-derived 3T3-like established 1 cells demonstrated that a

METTL3 knockout could treat OP by reducing ferroptosis levels

(54). Other studies have shown

that METTL3 facilitates OP by promoting osteoclast differentiation

(55).

Interestingly, three potential conflict points can

be established: First, the different cell types involved, with

osteogenesis acting on mesenchymal stem cells or osteoblasts, while

osteoclastogenesis targets monocyte precursors; second, different

molecular levels of action, with osteogenesis regulating mRNA

stability (for example, embryonic lethal, abnormal vision,

Drosophila-like 1 target) and miRNA processing (56,57), whereas osteoclastogenesis

operates through the ceRNA mechanism (58); and the third and most critical

point, the complete independence of downstream pathways, with

osteogenesis following the Wnt/β-catenin or BMP pathways, and

osteoclastogenesis relying on RANK/RANKL signaling. This

tissue-specific regulation is akin to the same key (METTL3), which

allows different locks (cell environments) to access different

doors (pathways). Given that bone homeostasis relies on the balance

between osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis, the dual role of

METTL3 may represent a natural mechanism for maintaining

equilibrium, similar to controlling the accelerator and brake.

However, under pathological conditions (for example, diabetes or

postmenopausal estrogen deficiency), changes in the

microenvironment induce an imbalance.

As a therapeutic target, METTL3 regulates the

maturation of miR-324-5p and miR-4526, activates the osteogenic

pathway (56,57), and blocks the methylation of

circ_0008542, thereby inhibiting the bidirectional effects of the

osteoclastic pathway on bone metabolism (58); however, its use requires cell

type-specific regulation to avoid conflicting bidirectional

effects. Although METTL3 expression is directly associated with

bone metabolic activity, clinically validated data are still

lacking (59). Regarding the

synergistic effect, METTL3 agonists could theoretically promote

osteogenesis while bisphosphonates inhibit bone resorption, leading

to complementary therapeutic benefits. Animal experiments have

shown that miR-324-5p promotes significant bone regeneration,

suggesting synergistic enhancement (56). However, the current findings

remain at the mechanistic and theoretical levels, and direct

evidence from clinical research is yet to be obtained.

YTHDF2 targets ncRNAs to release their osteogenic

potential. For example, YTHDF2 has been shown to promote bone

formation by degrading the inhibitory lncRNA LINC01013, thereby

relieving the suppression of osteogenic genes (for example,

osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein) (60). This mechanism is similar to our

hypothesis in the current study, in which the degradation of

LINC00312 promotes bone formation. Both mechanisms suggest the

enhancement of osteogenesis through the clearance of inhibitory

factors, with differences in their biological outcomes. A previous

study emphasized the promotion of osteogenic differentiation,

whereas the current study highlighted the inhibition of osteogenic

apoptosis. Although existing literature has only reported LINC01013

as a target of YTHDF2, the current study, to the best of the

authors' knowledge, is the first to reveal the inhibitory effects

of LINC00312, thereby expanding the target spectrum of YTHDF2. The

differences from previous findings are mainly attributable to the

type of target gene, which ultimately determines the functional

direction. First, targeting promoting factors inhibits bone

formation; that is, YTHDF2 significantly inhibits osteoblast

differentiation and mineralization by degrading runt-related

transcription factor 2 mRNA (61). Similarly, YTHDF2 binds to

fibroblast growth factor 21 mRNA (a factor that promotes bone

formation), which may indirectly inhibit osteogenic differentiation

under hyperglycemic conditions by mediating its degradation

(62). Second, the present study

focused on the regulation of cell fate rather than on direct

osteogenesis. In this context, YTHDF2 inhibits bone resorption by

degrading osteoclast-related genes (for example, Traf6 and Map4k4)

and suppressing the NF-κB/MAPK pathway (63,64).

The present study has some notable limitations.

Although the role of LINC00312 and FOXK2/SFRP1 in hFOB 1.19 cells

was directly investigated, their levels in healthy individuals and

patients with OP remain unclear. However, further studies are

required to explore the clinical relevance of LINC00312 and

FOXK2/SFRP1 expression. The present study primarily examined

osteoblast apoptosis in OP; however, it did not provide a

systematic analysis of osteogenic differentiation, such as the

expression of specific differentiation markers or mineralization

dynamics. Future studies could include the time-course detection of

key markers, such as Runx2 and ALP, as well as the assessment of

mineralized nodule formation. Additionally, in vivo

double-fluorescence labeling can be used to quantify the dynamic

mineral deposition rates. These approaches would help clarify the

overall impact of the intervention on osteogenic function, thereby

offering a more comprehensive understanding of bone formation

mechanisms and supporting the development of optimized targeted

therapies.

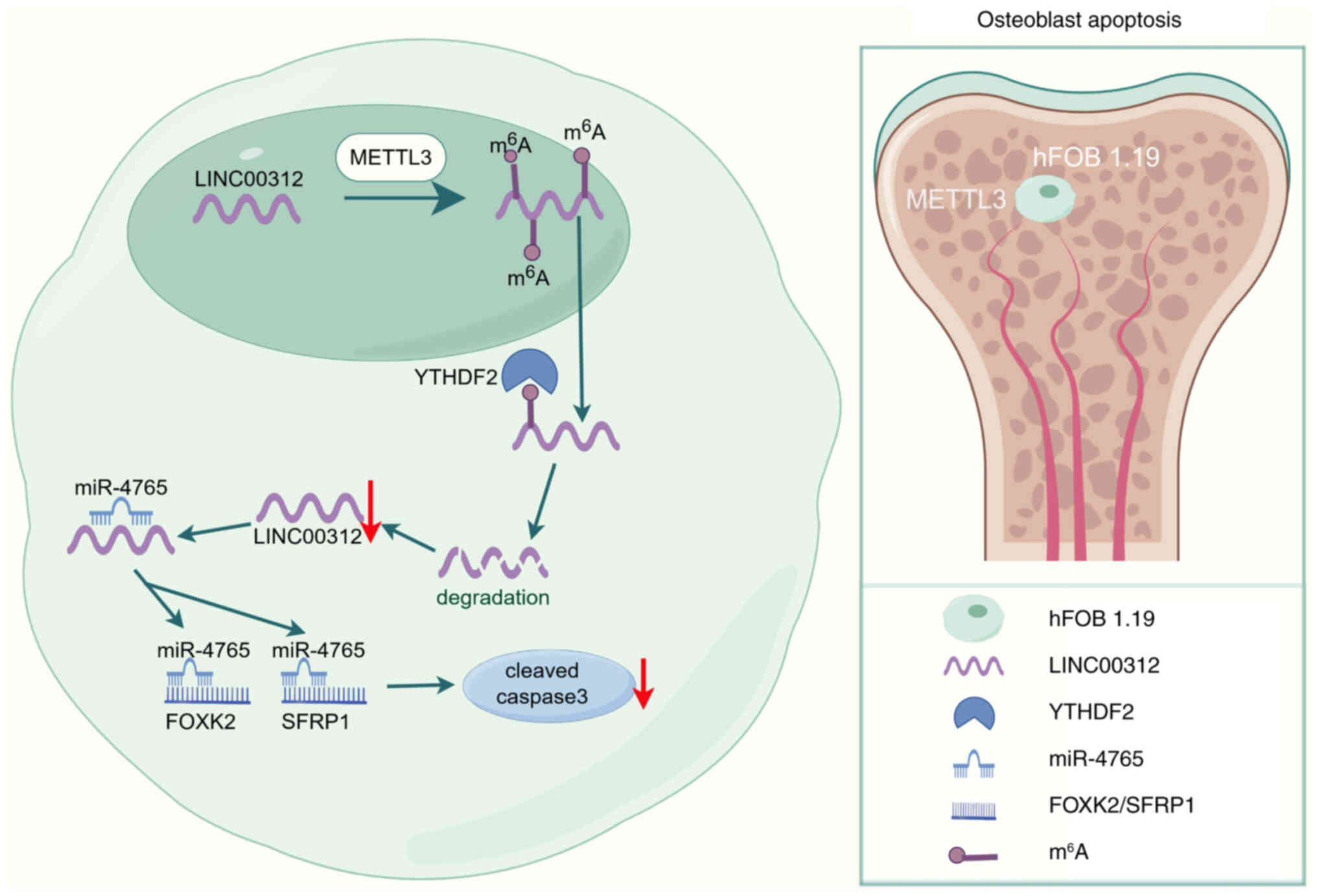

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

demonstrated that LINC00312 promotes the apoptosis of hFOB 1.19

cells by targeting the miR-4765-FOXK2/SFRP1 axis. Moreover,

miR-4765 OE downregulated FOXK2/SFRP1 expression and decreased

apoptosis of hFOB 1.19 cells. Collectively, these findings

indicated that the LINC00312/miR-4765/FOXK2/SFRP1 axis, which is

m6A modified by METTL3 in a YTHDF2-dependent manner, may be a novel

biomarker and therapeutic target for OP (Fig. 10).

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YW conceived and designed the present study. YT

performed the language editing, arrangement of data and drawing of

figures. GY performed bioinformatics analysis. All authors read and

approved the final version of this manuscript. YW, YT and GY

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments were performed in accordance

with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use

of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Review

Board of the General Hospital of the Northern Theater Command

(approval no. 2025-26; Shenyang, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

OP

|

osteoporosis

|

|

lncRNA

|

long non-coding RNA

|

|

ceRNA

|

competing endogenous RNA

|

|

micro-CT

|

micro-computed tomography

|

|

IHC

|

immunohistochemistry

|

|

m6A

|

N6-methyladenosine

|

|

miRNAs

|

microRNAs

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

NC

|

negative control

|

|

OD

|

optical density

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

RIPA

|

radioimmunoprecipitation assay

|

|

PVDF

|

polyvinylidene difluoride

|

|

RIP-qPCR

|

RNA immunoprecipitation-qPCR

|

|

STZ

|

streptozotocin

|

|

FINS

|

fasting plasma insulin

|

|

OE

|

overexpression

|

|

PBS

|

phosphate-buffered saline

|

|

UTR

|

untranslated region

|

|

miRDB

|

microRNA database

|

|

DIANA

|

DNA intelligent analysis

|

|

U2OS

|

human osteosarcoma cell line

|

|

BMSCs

|

bone marrow stromal/mesenchymal

stem/stromal cells

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

|

1

|

Hendrickx G, Boudin E and Van Hul W: A

look behind the scenes: The risk and pathogenesis of primary

osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 11:462–474. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

US Preventive Services Task Force;

Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW,

Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, et al: Vitamin D, calcium, or

combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in

community-dwelling adults: US preventive services task force

recommendation statement. JAMA. 319:1592–1599. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kern LM, Powe NR, Levine MA, Fitzpatrick

AL, Harris TB, Robbins J and Fried LP: Association between

screening for osteoporosis and the incidence of hip fracture. Ann

Intern Med. 142:173–181. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chotiyarnwong P and McCloskey EV:

Pathogenesis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and options for

treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 16:437–447. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ambrogini E, Almeida M, Martin-Millan M,

Paik JH, Depinho RA, Han L, Goellner J, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL,

O'Brien CA and Manolagas SC: FoxO-mediated defense against

oxidative stress in osteoblasts is indispensable for skeletal

homeostasis in mice. Cell Metab. 11:136–146. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wu M, Ai W, Chen L, Zhao S and Liu E:

Bradykinin receptors and EphB2/EphrinB2 pathway in response to high

glucose-induced osteoblast dysfunction and hyperglycemia-induced

bone deterioration in mice. Int J Mol Med. 37:565–574. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wongdee K and Charoenphandhu N: Update on

type 2 diabetes-related osteoporosis. World J Diabetes. 6:673–678.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kushwaha P, Ahmad N, Dhar YV, Verma A,

Haldar S, Mulani FA, Trivedi PK, Mishra PR, Thulasiram HV and

Trivedi R: Estrogen receptor activation in response to Azadirachtin

A stimulates osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in mice.

J Cell Physiol. 234:23719–23735. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tyagi AM, Mansoori MN, Srivastava K, Khan

MP, Kureel J, Dixit M, Shukla P, Trivedi R, Chattopadhyay N and

Singh D: Enhanced immunoprotective effects by anti-IL-17 antibody

translates to improved skeletal parameters under estrogen

deficiency compared with anti-RANKL and anti-TNF-α antibodies. J

Bone Miner Res. 29:1981–1992. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tamura Y, Kawao N, Yano M, Okada K,

Okumoto K, Chiba Y, Matsuo O and Kaji H: Role of plasminogen

activator inhibitor-1 in glucocorticoid-induced diabetes and

osteopenia in mice. Diabetes. 64:2194–2206. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rojas E, Carlini RG, Clesca P, Arminio A,

Suniaga O, De Elguezabal K, Weisinger JR, Hruska KA and

Bellorin-Font E: The pathogenesis of osteodystrophy after renal

transplantation as detected by early alterations in bone

remodeling. Kidney Int. 63:1915–1923. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhang H, Wang Y and He Z:

Glycine-histidine-lysine (GHK) alleviates neuronal apoptosis due to

intracerebral hemorrhage via the miR-339-5p/VEGFA pathway. Front

Neurosci. 12:6442018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xu X, Yang J, Ye Y, Chen G, Zhang Y, Wu H,

Song Y, Feng M, Feng X, Chen X, et al: SPTBN1 prevents primary

osteoporosis by modulating osteoblasts proliferation and

differentiation and blood vessels formation in bone. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:6537242021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang Y, Cao X, Li P, Fan Y, Zhang L, Li W

and Liu Y: PSMC6 promotes osteoblast apoptosis through inhibiting

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway activation in ovariectomy-induced

osteoporosis mouse model. J Cell Physiol. 235:5511–5524. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Glasner H, Riml C, Micura R and Breuker K:

Label-free, direct localization and relative quantitation of the

RNA nucleobase methylations m6A, m5C, m3U, and m5U by top-down mass

spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:8014–8025. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kang HJ, Cheon NY, Park H, Jeong GW, Ye

BJ, Yoo EJ, Lee JH, Hur JH, Lee EA, Kim H, et al: TonEBP recognizes

R-loops and initiates m6A RNA methylation for R-loop resolution.

Nucleic Acids Res. 49:269–284. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

17

|

Blanco S, Bandiera R, Popis M, Hussain S,

Lombard P, Aleksic J, Sajini A, Tanna H, Cortés-Garrido R, Gkatza

N, et al: Stem cell function and stress response are controlled by

protein synthesis. Nature. 534:335–340. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shen W, Gao C, Cueto R, Liu L, Fu H, Shao

Y, Yang WY, Fang P, Choi ET, Wu Q, et al: Homocysteine-methionine

cycle is a metabolic sensor system controlling

methylation-regulated pathological signaling. Redox Biol.

28:1013222020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Qin Y, Li L, Luo E, Hou J, Yan G, Wang D,

Qiao Y and Tang C: Role of m6A RNA methylation in cardiovascular

disease (Review). Int J Mol Med. 46:1958–1972. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Abelson S: Eureka-DMA: An easy-to-operate

graphical user interface for fast comprehensive investigation and

analysis of DNA microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 15:532014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zhou X, Su Z, Sammons RD, Peng Y, Tranel

PJ, Stewart CN Jr and Yuan JS: Novel software package for

cross-platform transcriptome analysis (CPTRA). BMC Bioinformatics.

10(Suppl 11): S162009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

De-Ugarte L, Yoskovitz G, Balcells S,

Güerri-Fernández R, Martinez-Diaz S, Mellibovsky L, Urreizti R,

Nogués X, Grinberg D, García-Giralt N and Díez-Pérez A: MiRNA

profiling of whole trabecular bone: Identification of

osteoporosis-related changes in MiRNAs in human hip bones. BMC Med

Genomics. 8:752015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sukonina V, Ma H, Zhang W, Bartesaghi S,

Subhash S, Heglind M, Foyn H, Betz MJ, Nilsson D, Lidell ME, et al:

FOXK1 and FOXK2 regulate aerobic glycolysis. Nature. 566:279–283.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Shan L, Zhou X, Liu X, Wang Y, Su D, Hou

Y, Yu N, Yang C, Liu B, Gao J, et al: FOXK2 elicits massive

transcription repression and suppresses the hypoxic response and

breast cancer carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 30:708–722. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bowman CJ, Ayer DE and Dynlacht BD: Foxk

proteins repress the initiation of starvation-induced atrophy and

autophagy programs. Nat Cell Biol. 16:1202–1214. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang F, Ma X, Li H, Zhang Y, Li X, Chen

L, Guo G, Gao Y, Gu L, Xie Y, et al: FOXK2 suppresses the malignant

phenotype and induces apoptosis through inhibition of EGFR in

clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 142:2543–2557. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Marais A, Ji Z, Child ES, Krause E, Mann

DJ and Sharrocks AD: Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the

forkhead transcription factor FOXK2 by CDK•cyclin complexes. J Biol

Chem. 285:35728–35739. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cui Z, Liu L, Kwame Amevor F, Zhu Q, Wang

Y, Li D, Shu G, Tian Y and Zhao X: High expression of miR-204 in

chicken atrophic ovaries promotes granulosa cell apoptosis and

inhibits autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:5800722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Esteve P, Rueda-Carrasco J, Inés Mateo M,

Martin-Bermejo MJ, Draffin J, Pereyra G, Sandonís Á, Crespo I,

Moreno I, Aso E, et al: Elevated levels of

secreted-frizzled-related-protein 1 contribute to Alzheimer's

disease pathogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 22:1258–1268. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Esteve P, Sandonìs A, Cardozo M, Malapeira

J, Ibañez C, Crespo I, Marcos S, Gonzalez-Garcia S, Toribio ML,

Arribas J, et al: SFRPs act as negative modulators of ADAM10 to

regulate retinal neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 14:562–569. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Rodriguez J, Esteve P, Weinl C, Ruiz JM,

Fermin Y, Trousse F, Dwivedy A, Holt C and Bovolenta P: SFRP1

regulates the growth of retinal ganglion cell axons through the Fz2

receptor. Nat Neurosci. 8:1301–1309. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Renström J, Istvanffy R, Gauthier K,

Shimono A, Mages J, Jardon-Alvarez A, Kröger M, Schiemann M, Busch

DH, Esposito I, et al: Secreted frizzled-related protein 1

extrinsically regulates cycling activity and maintenance of

hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 5:157–167. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Gu H, Shi S, Xiao F, Huang Z, Xu J, Chen

G, Zhou K, Lu L and Yin X: MiR-1-3p regulates the differentiation

of mesenchymal stem cells to prevent osteoporosis by targeting

secreted frizzled-related protein 1. Bone. 137:1154442020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tang L, Lu W, Huang J, Tang X, Zhang H and

Liu S: miR-144 promotes the proliferation and differentiation of

bone mesenchymal stem cells by downregulating the expression of

SFRP1. Mol Med Rep. 20:270–280. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gu H, Wu L, Chen H, Huang Z, Xu J, Zhou K,

Zhang Y, Chen J, Xia J and Yin X: Identification of differentially

expressed microRNAs in the bone marrow of osteoporosis patients. Am

J Transl Res. 11:2940–2954. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhang X, Zhu Y, Zhang C, Liu J, Sun T, Li

D, Na Q, Xian CJ, Wang L and Teng Z: miR-542-3p prevents

ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis in rats via targeting SFRP1. J

Cell Physiol. 233:6798–6806. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Liu HP, Hao DJ, Wang XD, Hu HM, Li YB and

Dong XH: MiR-30a-3p promotes ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis in

rats via targeting SFRP1. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 23:9754–9760.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Guo Z, Wang YH, Xu H, Yuan CS, Zhou HH,

Huang WH, Wang H and Zhang W: LncRNA linc00312 suppresses

radiotherapy resistance by targeting DNA-PKcs and impairing DNA

damage repair in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis.

12:692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

No authors listed. Expression of concern:

Overexpression of long intergenic noncoding RNA LINC00312 inhibits

the invasion and migration of thyroid cancer cells by

down-regulating microRNA-197-3p. Biosci Rep. 40:BSR–20170109_EOC.

2020.

|

|

40

|

Peng Z, Wang J, Shan B, Li B, Peng W, Dong

Y, Shi W, Zhao W, He D, Duan M, et al: The long noncoding RNA

LINC00312 induces lung adenocarcinoma migration and vasculogenic

mimicry through directly binding YBX1. Mol Cancer. 17:1672018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

No authors listed. Retraction:

Overexpression of long intergenic noncoding RNA LINC00312 inhibits

the invasion and migration of thyroid cancer cells by

down-regulating microRNA-197-3p. Biosci Rep. 41:BSR–20170109_RET.

2021.

|

|

42

|

Zhang C, Wang M, Shi C, Shi F and Pei C:

Long non-coding RNA Linc00312 modulates the sensitivity of ovarian

cancer to cisplatin via the Bcl-2/Caspase-3 signaling pathway.

Biosci Trends. 12:309–316. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wu J, Zhou X, Fan Y, Cheng X, Lu B and

Chen Z: Long non-coding RNA 00312 downregulates cyclin B1 and

inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation in vitro and

in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 497:173–180. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhu Q, Lv T, Wu Y, Shi X, Liu H and Song

Y: Long non-coding RNA 00312 regulated by HOXA5 inhibits tumour

proliferation and promotes apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer.

J Cell Mol Med. 21:2184–2198. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhang W, Huang C, Gong Z, Zhao Y, Tang K,

Li X, Fan S, Shi L, Li X, Zhang P, et al: Expression of LINC00312,

a long intergenic non-coding RNA, is negatively correlated with

tumor size but positively correlated with lymph node metastasis in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Mol Histol. 44:545–554. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Liu J, Chen M, Ma L, Dang X and Du G:

piRNA-36741 regulates BMP2-mediated osteoblast differentiation via

METTL3 controlled m6A modification. Aging (Albany NY).

13:23361–23375. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Yan G, Yuan Y, He M, Gong R, Lei H, Zhou

H, Wang W, Du W, Ma T, Liu S, et al: m6A methylation of

precursor-miR-320/RUNX2 controls osteogenic potential of bone

marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids.

19:421–436. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Luo D, Peng S, Li Q, Rao P, Tao G, Wang L

and Xiao J: Methyltransferase-like 3 modulates osteogenic

differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells in osteoporotic rats.

J Gene Med. 25:e34812023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Wu Y, Xie L, Wang M, Xiong Q, Guo Y, Liang

Y, Li J, Sheng R, Deng P, Wang Y, et al: Mettl3-mediated

m6A RNA methylation regulates the fate of bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells and osteoporosis. Nat Commun. 9:47722018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Wu T, Tang H, Yang J, Yao Z, Bai L, Xie Y,

Li Q and Xiao J: METTL3-m6 A methylase regulates the

osteogenic potential of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in

osteoporotic rats via the Wnt signalling pathway. Cell Prolif.

55:e132342022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Peng J, Zhan Y and Zong Y: METTL3-mediated

LINC00657 promotes osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem

cells via miR-144-3p/BMPR1B axis. Cell Tissue Res. 388:301–312.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Li L, Wang B, Zhou X, Ding H, Sun C, Wang

Y, Zhang F and Zhao J: METTL3-mediated long non-coding RNA MIR99AHG

methylation targets miR-4660 to promote bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cell osteogenic differentiation. Cell Cycle. 22:476–493. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

53

|

Tian S, Li YL, Wang J, Dong RC, Wei J, Ma

Y and Liu YQ: Chinese ecliptae herba [Eclipta prostrata (L.) L.]

extract and its component wedelolactone enhances osteoblastogenesis

of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via targeting METTL3-mediated

m6A RNA methylation. J Ethnopharmacol. 312:1164332023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Lin Y, Shen X, Ke Y, Lan C, Chen X, Liang

B, Zhang Y and Yan S: Activation of osteoblast ferroptosis via the

METTL3/ASK1-p38 signaling pathway in high glucose and high fat

(HGHF)-induced diabetic bone loss. FASEB J. 36:e221472022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Wang C, Zhang X, Chen R, Zhu X and Lian N:

EGR1 mediates METTL3/m6A/CHI3L1 to promote

osteoclastogenesis in osteoporosis. Genomics. 115:1106962023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Xiao J, Xu Z, Deng Z, Xie J and Qiu Y:

METTL3 facilitates osteoblast differentiation and bone regeneration

via m6A-dependent maturation of pri-miR-324-5p. Cell Immunol.

413:1049742025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Song Y, Gao H, Pan Y, Gu Y, Sun W and Liu

J: METTL3 promotes osteogenesis by regulating

N6-methyladenosine-dependent primary processing of hsa-miR-4526.

Stem Cells. 43:sxae0892025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wang W, Qiao SC, Wu XB, Sun B, Yang JG, Li

X, Zhang X, Qian SJ, Gu YX and Lai HC: Circ_0008542 in osteoblast

exosomes promotes osteoclast-induced bone resorption through m6A

methylation. Cell Death Dis. 12:6282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Liu J, Chen X and Yu X: Unraveling the

role of N6-methylation modification: From bone biology to

osteoporosis. Int J Med Sci. 22:2545–2559. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Song J, Wang Y, Zhu Z, Wang W, Yang H and

Shan Z: Negative regulation of LINC01013 by METTL3 and YTHDF2

enhances the osteogenic differentiation of senescent pre-osteoblast

cells induced by hydrogen peroxide. Adv Biol (Weinh).

8:e23006422024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Sun Q, Zhao T, Li B, Li M, Luo P, Zhang C,

Chen G, Cao Z, Li Y, Du M and He H: FTO/RUNX2 signaling axis

promotes cementoblast differentiation under normal and inflammatory

condition. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1869:1193582022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wang Z, Tang Y, Liu Y, Zeng Y and Zhang M: