Glioblastoma (GBM) stands as the most common

malignant primary brain tumor type affecting the adult central

nervous system (CNS), comprising 48% of all malignant CNS tumors

and 57% of gliomas. The isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) wild-type

subtype of GBM is designated as grade IV by the World Health

Organization due to its aggressive behavior (1-3).

Current GBM treatment typically involves a multifaceted approach,

including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, supported by

innovative physical therapies and targeted drugs. During surgical

procedures, gross total resection (GTR) employs advanced techniques

such as 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) fluorescence guidance and

intraoperative desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

to precisely locate tumor boundaries (4-6).

Notably, the biological traits of GBM profoundly impact surgical

outcomes, with IDH-mutant tumors being more responsive to GTR due

to their reduced aggressiveness (7). In radiotherapy, the addition of

temozolomide (TMZ) to conventional radiation therapy notably

increases patient survival compared with single-modality treatment

(8). For elderly patients

(>70 years old), hypofractionated radiotherapy is used to

minimize toxicity (9).

Chemotherapy, predominantly with TMZ, operates by inducing

O6-guanine methylation, thereby causing DNA damage. A

phase III clinical trial combining TMZ with lomustine has shown

potential for extending patient lifespan (10,11). Innovative physical therapies such

as tumor-treating fields exhibit antitumor activity by causing

neuronal depolarization and disrupting microtubule formation during

cell division, specifically targeting rapidly proliferating tumor

cells (12,13). Although their combination with

TMZ can increase the median overall survival (mOS), these therapies

are associated with a higher rate of systemic side effects

(14). Targeted therapies,

including bevacizumab (BEV), enhance progression-free survival

(PFS), but do not improve OS and may increase adverse reactions

(15,16).

The pathological hallmarks of GBM are manifested in

three distinct aspects. Firstly, there is the widespread

infiltrative growth of tumor cells, which spread along nerve fiber

bundles and vascular spaces. Secondly, radially arranged

pseudopalisading structures develop around necrotic cores. Lastly,

a triad of vascular abnormalities is observed, including

pathological angiogenesis, abnormal endothelial cell proliferation

and intravascular thrombosis (17,18). Clinical studies have shown that

patients with GBM often exhibit a hypercoagulable state, which is

strongly linked to the aggressiveness of the tumor (19-22). The matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)

family plays a key role in this process (23). MMPs are zinc-dependent

endopeptidases classified into subfamilies based on their substrate

specificity and structural features, including collagenases (MMP-1,

-8 and -13), gelatinases (MMP-2 and -9), stromelysins (MMP-3 and

-10), and membrane-bound MMPs (MMP-14, -16 and -17) (24,25). These enzymes critically regulate

tumor invasion and metastasis by mediating epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT), degrading extracellular matrix (ECM) components

and promoting tumor angiogenesis (26-28). In GBM, the expression of several

MMPs, particularly MMP-2 and MMP-9, is significantly increased, and

their enhanced activity correlates with invasive tumor growth and

blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, highlighting the crucial role

of MMPs in disease progression (29,30).

In recent years, notable advancements have occurred

in mechanistic studies on MMPs during the invasion process of GBM

(31-33). However, two major obstacles must

be addressed before their effective clinical targeting. Firstly,

the BBB, with its complex interplay of active transport systems

(including uptake and efflux proteins) and metabolic enzymes, poses

a formidable biological barrier. This barrier effectively hinders

small molecules from reaching the brain, thus considerably

diminishing drug accumulation efficiency (34). Emerging drug delivery approaches,

utilizing nano-drug delivery systems such as liposomes (35), nanoparticles (NPs) (36) and hydrogel carriers (37), offer promise for enhancing the

targeted accumulation of antitumor agents in the brain.

Additionally, the multifactorial mechanisms underlying TMZ

resistance involve not only DNA damage repair mediated by

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT)

overexpression and drug efflux transporter activation (38,39), but also mismatch repair defects

(40), glioma stem cell (GSC)

self-renewal (41) and aberrant

cell signaling pathways (42).

Breakthroughs in synthesizing natural medicines and novel compounds

have presented innovative strategies to tackle drug resistance

(43,44), thereby expanding GBM treatment

options and paving the way for targeted therapies.

The present review comprehensively examines the

regulatory mechanisms of the MMP family in GBM invasion, focusing

on recent developments. It further explores recent progress in

therapeutic approaches, including natural bioactive compounds,

small molecules and nanotechnology-driven combinations. The aim of

the present study is to establish a theoretical foundation and

guide treatment innovations for GBM.

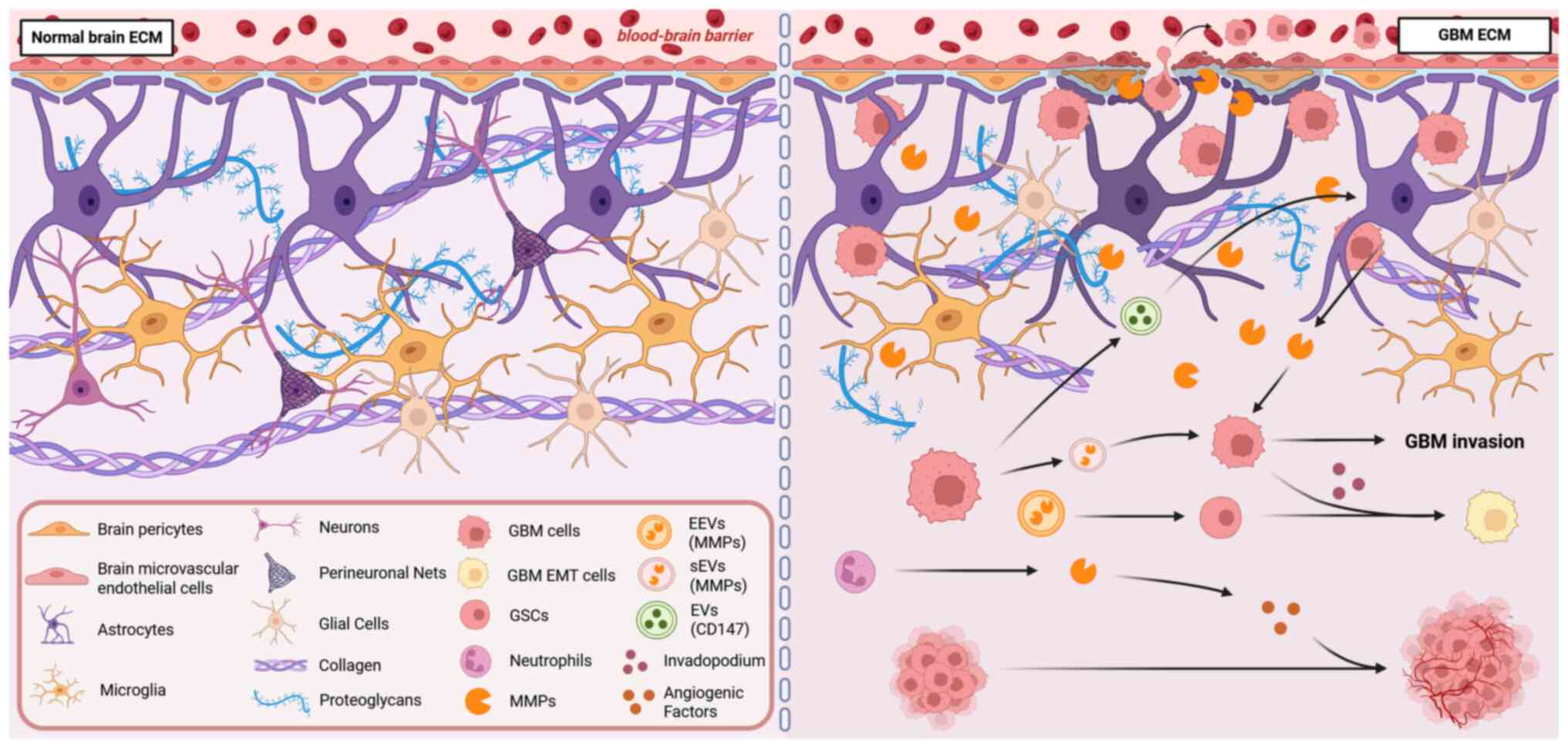

The ECM is crucial in GBM malignant invasion, a

process mediated by MMPs. In the brain, the ECM preserves the

homeostasis of the neural microenvironment via specific structures

and functions of the basilar membrane, interstitial matrix and

perineuronal nets (PNNs) (45).

However, GBM disrupts this balance by degrading the ECM and

triggering pro-invasive signals such as EMT. This occurs through

the abnormal overexpression of MMPs, including MMP-2, MMP-9 and

MMP-14, which stimulate the development of invasive pseudopodia in

tumor cells and aid in the spread of intercellular vesicles

(46-49) (Fig. 1).

The ECM in the brain plays a dual role in GBM

invasion. On one hand, GBM directly degrades ECM components by

upregulating MMPs. On the other hand, it creates a microenvironment

that promotes invasion by forming invasive pseudopodia and

releasing extracellular vesicles carrying MMPs. Specifically, the

ECM can be classified into three types based on location: i) The

basement membrane, which is located around blood vessels

(neurovascular unit), and consists of components such as collagen

and laminin, which help maintain the stability of the blood

vessel-neural interface; ii) the interstitial matrix, which is

distributed in the interstitial space between neurons and glial

cells, and forms a loose network with hyaluronic acid and

proteoglycans to support intercellular material exchange; and iii)

the PNN, which directly surrounds neuronal cell bodies and

dendrites, and is composed of a hyaluronic acid scaffold and

chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (such as aggrecan), forming a

dense structure whose formation relies on neuronal activity

(45). In GBM, contrary to the

widespread notion that most models involve membrane-type (MT)-MMPs

activating progelatinase A, previous research has revealed that

MT-MMPs are predominantly produced by GBM cells and play a direct

role in their migration (46).

Notably, MMP-17 and MMP-25 exhibit particularly pronounced effects

in this process (46). During

GBM invasion, a marked elevation in MMP-9 levels leads to the

breakdown of the ECM. This degradation is accompanied by increased

prolidase activity, which releases metabolites such as proline.

Simultaneously, the production of proline within GBM cells serves

to further augment their invasive capabilities (47). Additional research has shown

that, from a cellular structural perspective, GBM cells have the

ability to form invasive pseudopodia equipped with matrix-degrading

functions. These cells also secrete small extracellular vesicles

(sEVs) enriched in MMP-2. These sEVs not only exhibit a close

association with pseudopod activity but can also be internalized by

adjacent GBM cells. This internalization significantly enhances the

invasive potential of the recipient cells by transferring highly

invasive pseudopod activity (48). Furthermore, vesicles released by

GBM cells can stimulate astrocytes to secrete MMP-9, thereby

further facilitating the invasion of GBM (49).

In addition, the ECM modulates tumor angiogenesis

via a dual mechanism. Firstly, it interacts with cell receptors,

activating signaling pathways such as MAPK, and thereby enhancing

endothelial cell proliferation, migration and survival (50,51). Secondly, ECM remodeling,

facilitated by proteases such as MMPs and fibrinolytic enzymes,

releases angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth

factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and fibroblast

growth factor-2, further influencing angiogenesis (52,53). In GBM, a distinctive pathological

trait emerges where MMPs degrade the ECM, paving the way for new

tumor angiogenesis, while potentially altering the function and

structure of preexisting blood vessels (23). Notably, tumor-infiltrating

neutrophils elevate the expression of VEGFA through the secretion

of MMP-9, introducing an additional layer of angiogenesis

regulation (54). Furthermore,

previous bioinformatics analysis has uncovered a significant

association between elevated MMP-14 expression and several

angiogenesis-related signaling pathways, such as Visfatin, VEGF and

TGF-β, as well as the endothelial-mesenchymal transition process

(55). Previous research has

indicated that MMP-14 can stimulate angiogenesis in GBM (56).

EMT modulates the tumor microenvironment (TME)

through multiple mechanisms, thereby enhancing the invasiveness of

GBM. EMT augments the aggressiveness of tumor cells by inducing the

formation of actin-rich invadopodia, which are dynamic adhesive

structures capable of locally releasing MMP-mediated proteolytic

enzymes at cell-ECM contact zones, thus facilitating cellular

invasion (57). Within the TME,

endothelial cell-derived vesicles activate the NF-κB signaling

pathway within GBM stem cells (GSCs) by delivering MMPs, inducing

the transformation of pro-neural cells into a mesenchymal phenotype

and promoting the shift towards an invasive phenotype (58). Previous research has revealed an

interaction between MMP-14 and TGF-β receptor signaling in GBM.

These two factors induce the programmed activation of EMT through

the stimulation of Snail transcription factors. This synergistic

action of proteases and growth factors ultimately leads to a highly

invasive tumor phenotype (59).

MMPs are not only key molecules mediating ECM

degradation and driving tumor invasion in GBM, but their expression

and activity levels constitute critical biomarkers reflecting the

invasive potential of GBM. In GBM tissues, particularly at the

tumor invasion front and in neovascularization areas, MMP

expression is significantly higher than in normal brain tissue.

Concurrently, MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression levels have been found to

be further elevated in recurrent GBM tissues, closely correlating

with malignant biological behaviors such as tumor invasion,

dissemination and recurrence (60). Furthermore, MMPs are important in

bodily fluid tests. A prospective study showed that serum MMP-9

concentrations were significantly elevated in patients with GBM

(n=66) and correlated with tumor activity status. Serum MMP-9

levels in patients without radiological lesions were significantly

lower than in those with active disease (P=0.0002), suggesting its

potential as a serum marker for disease monitoring, although MMP-9

showed no significant correlation with OS (61). However, a subsequent larger

prospective study (n=192) challenged this view. That study, through

systematic analysis of serum samples, found that, although MMP-9 is

highly expressed in GBM tissue, its serum level did not correlate

significantly with radiological disease status (P=0.33), indicating

that circulating MMP-9 cannot reliably reflect local GBM

progression. While a longitudinal increase in serum MMP-9 showed a

weak correlation with shorter survival [hazard ratio (HR)=1.1 per

doubling; P=0.04], multivariate analysis revealed that it was not

an independent prognostic factor (P=0.11). These results further

suggest the limited clinical value of serum MMP-9 as a dynamic

monitoring or independent prognostic biomarker for GBM (62). Notably, compared with serum,

continuous monitoring in patients with recurrent GBM (n=4)

undergoing a specific biochemotherapy regimen (irinotecan,

thalidomide and doxycycline) revealed that MMP-9 levels in the

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) significantly and continuously increased

over the treatment period (P=0.001), and this elevation preceded

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detection of tumor progression

signs, suggesting that CSF-derived MMP-9 could serve as an early

biomarker for GBM recurrence or progression (63).

MMPs as biomarkers can also assess treatment

response to GBM drugs. A previous prospective-retrospective

dual-cohort analysis found that, in patients with recurrent GBM,

the group with high baseline plasma MMP-2 levels, when subjected to

the anti-angiogenic drug BEV, exhibited a significantly improved

objective response rate (80 vs. 17.6%), median PFS (7.1 vs. 4.2

months) and mOS (12.8 vs. 5.9 months) compared with the low-level

group. Crucially, this predictive value was only evident in the BEV

treatment group and disappeared in the cytotoxic drug-only

treatment group, suggesting MMP-2 is a predictive biomarker

specific to BEV efficacy (64).

In addition, a retrospective analysis of the large phase III

AVAglio trial (NCT00943826) confirmed that baseline plasma MMP-9

levels could predict survival benefit from BEV in patients with

newly diagnosed GBM. Patients in the low MMP-9 group had a

significantly prolonged OS by 5.2 months (HR=0.51; P=0.0009),

whereas the high MMP-9 group showed no significant benefit

(54). Additionally,

multi-cohort transcriptome analysis revealed that low tumor tissue

MMP-9 mRNA expression was not only associated with longer OS

(P=0.0012) and PFS (P=0.0066), but also significantly predicted the

degree of survival benefit that patients received from standard TMZ

chemoradiotherapy, whereas the high MMP-9 group had limited

benefit, suggesting that tissue MMP-9 expression is a potential

predictive biomarker of TMZ efficacy (65).

In summary, the localized expression of MMPs in

tissues, their dynamic changes in bodily fluids and their value as

predictors of treatment response provide crucial molecular basis

for assessing GBM invasiveness, predicting patient prognosis,

real-time monitoring of disease status and guiding individualized

treatment strategies. Although the value of serum MMP-9 as an

independent monitoring and prognostic biomarker has been questioned

by large-sample studies, highlighting the need for careful

consideration of source specificity in its clinical application,

the overall central role of MMPs as core biomarkers in disease

progression and treatment prediction remains solid. Given the core

driving role of MMPs in the pathological process of GBM and their

biomarker value, untangling their complex regulatory networks is an

indispensable foundation for developing novel and effective

targeted intervention strategies.

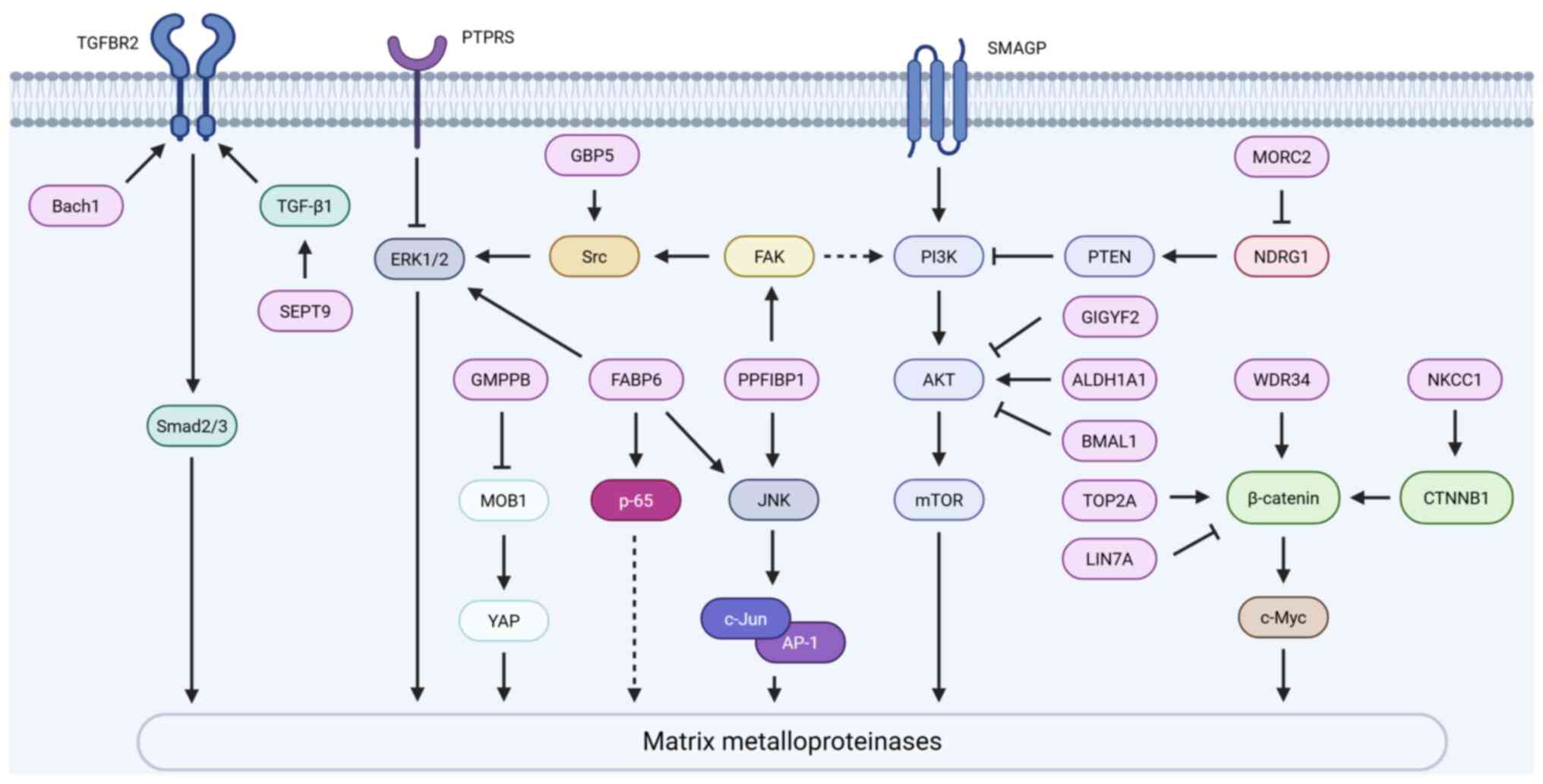

Multiple signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT,

MAPK, TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin, play a crucial role in regulating

the expression and activity of MMP-2, MMP-9 and other MMPs

(66-69). Non-coding RNAs also participate

in the regulation of MMP expression (70,71). Additionally, epigenetic

mechanisms contribute to the modulation of MMP expression (72). At the same time, metabolic

reprogramming and alterations in the TME collectively form multiple

factors influencing MMP function (33,73-75). This diverse range of mechanisms

lays a theoretical groundwork for deciphering the invasive

processes of GBM, and pinpoints prospective targets for therapeutic

intervention (Table SI).

Aberrant expression of MMPs in GBM is controlled by

several signaling pathways that considerably interact (Fig. 2). First, the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway is permanently activated and plays a critical role in GBM

(76), significantly driving the

upregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression. Aldehyde dehydrogenase

(ALDH)1A1 activates this pathway by specifically enhancing the

phosphorylation of the AKT protein at the Ser473 and Thr308

residues, thereby promoting the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9, and

driving the invasiveness of GBM cells (77). This effect can be synergistically

amplified by small transmembrane glycoprotein (78). Notably, the micro-orchidism

family CW-type zinc finger protein 2 (MORC2), which exhibits high

expression in GBM cells, binds to and inhibits the transcription of

N-Myc downstream regulated gene 1 (NDRG1), leading to the

downregulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression.

This subsequently relieves the inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway, ultimately inducing the upregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9,

and enhancing tumor invasion and migration. Conversely, knocking

down MORC2 or overexpressing NDRG1 can reverse this signaling

pathway and inhibit tumor progression (66). It is noteworthy that GRB10

interacting GYF protein 2 and brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1

inhibit AKT phosphorylation, thereby downregulating MMP-9

expression and impairing the invasive capacity of GBM cells,

untangling the complexity of PI3K/AKT pathway regulation of MMPs

(79,80). WD repeat domain 34 in GBM

inhibits PTEN while activating both the PI3K/AKT and Wnt/β-catenin

pathways, thus significantly increasing the levels of

phosphorylated (p)-AKT, nuclear β-catenin and c-Myc, and

consequently upregulating MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression and promoting

cell invasion (81).

Regarding the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, DNA

topoisomerase IIα directly binds to the β-catenin promoter to

enhance its transcription, thus promoting β-catenin protein

expression and its nuclear accumulation, alongside a significant

increase in MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA levels and enzymatic activity

(67,82). By contrast, Lin-7 homolog A

inhibits the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, thereby

suppressing the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 as well as their

pro-invasive functions (83).

The activation of this pathway is also associated with the

sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC1). High expression

of NKCC1 in GBM (its expression level significantly correlates with

tumor grade, P<0.05), when knocked down, leads to reduced

protein levels of the key Wnt/β-catenin pathway effector β-catenin,

which is accompanied by downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9, thus

significantly impairing tumor cell invasion. This indicates that

NKCC1 regulates MMP expression via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway, thereby affecting cell invasion (84).

The TGF-β signaling pathway is also an important

mechanism for regulating MMPs. Overexpression of broad-complex,

tramtrack, and Bric-à-brac domain and cap 'N' collar homolog 1

significantly upregulates TGF-β receptor 2 (TGFBR2) and its

downstream mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (Smad)2/3

protein levels, and enhances MMP-2 protein expression and secretion

activity (68). Further research

revealed that Septin 9 (SEPT9) was highly expressed in GBM tissues,

and positively correlated with TGF-β1. Knocking down SEPT9 led to a

significant reduction in MMP-9 protein expression, thereby

inhibiting GBM cell invasion. Previous in vivo experiments

further confirmed that targeted inhibition of SEPT9 effectively

reduced lung metastasis in GBM, thus highlighting the crucial role

of SEPT9 in promoting GBM distant metastasis by upregulating MMP-9

(85).

In addition to the aforementioned key pathways, the

MAPK (including the ERK and JNK branches) and NF-κB signaling

pathways are also involved in the regulation of MMPs (69,86). Receptor-type tyrosine-protein

phosphatase S expression is downregulated in GBM tissues, and its

loss leads to increased phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2,

subsequently upregulating the transcription and protein expression

of MMP-2 and MMP-3, thus promoting cell invasion (87). Fatty acid-binding protein 6

(FABP6) was shown to be highly expressed in GBM tissues; its

knockdown not only led to significant downregulation of MMP-2, but

also reduced the activation levels of p-ERK, p-JNK and p-p65

(NF-κB), ultimately inhibiting tumor cell invasion. This suggests

that FABP6 may influence MMP-2 and consequently GBM invasion by

regulating the ERK/JNK/NF-κB signaling axis (69). PPFIA binding protein 1 expression

was revealed to be positively associated with GBM progression. It

enhanced the phosphorylation levels of FAK (Y397), Src (Y416), JNK

and c-Jun, significantly upregulated MMP-2 expression, and enhanced

tumor infiltration within the brain parenchyma (86,88-90). Human guanylate-binding protein 5

was demonstrated to enhance MMP-3 expression activity by promoting

the phosphorylation of Src and ERK1/2 (91). Furthermore, GDP-mannose

pyrophosphorylase B was shown to be highly expressed in GBM, and

its knockdown activated the Hippo signaling pathway, and promoted

the phosphorylation of Mps one binder kinase activator-like 1 and

Yes-associated protein, thereby inhibiting MMP-3 expression and

impairing cell invasion ability (32).

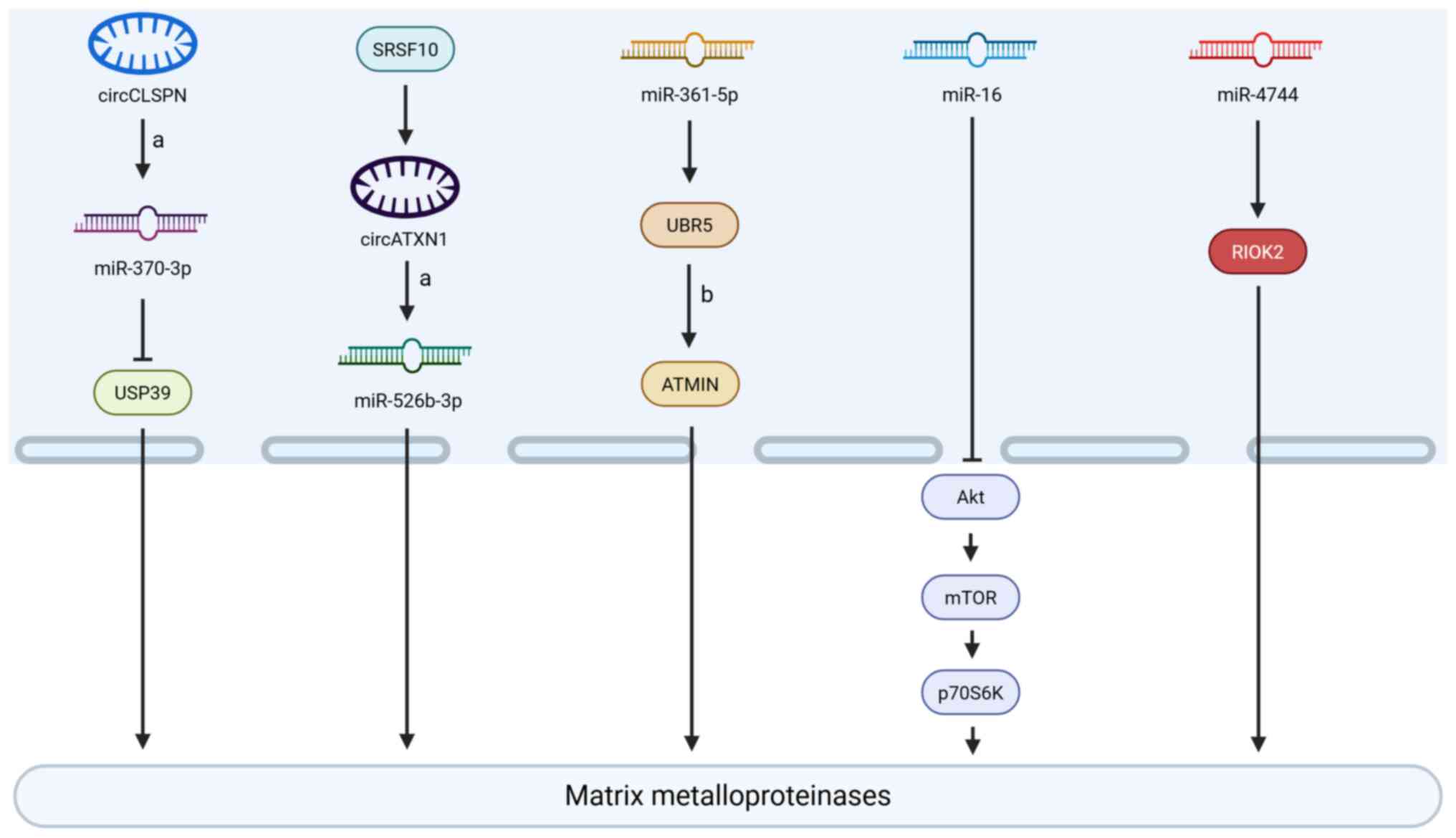

Non-coding RNAs modulate the invasive capacity of

GBM cells by interactively regulating the expression levels of

MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Fig. 3). Among

them, an endogenous circular (circ) RNA derived from exons 11 to 14

of the CLSPN gene (Homo sapiens_circ_0011591, circCLSPN) was

shown to function as a competitive endogenous RNA by sequestering

microRNA (miRNA or miR)-370-3p, thus releasing ubiquitin-specific

peptidase 39 from miRNA-mediated repression, and resulting in

marked upregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression (70,92). Concurrently, circATXN1, mediated

by serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 10, promoted MMP-2

expression, and enhanced the invasive potential of GBM cells by

binding to miR-526b-3p and blocking its inhibitory effect on

downstream target genes (93).

Both miR-361-5p and miR-16, which are significantly downregulated

in GBM, have been demonstrated to possess tumor

invasion-suppressive potential. Overexpression of miR-361-5p was

shown to directly target the ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component

N-recognin 5 (UBR5), thus inhibiting the UBR5-mediated

ubiquitination and degradation of ATM-interacting protein (ATMIN),

thereby stabilizing ATMIN protein and downregulating MMP-2

expression, ultimately blocking GBM cell migration and invasion

(71). In addition, miR-16

overexpression was demonstrated to suppress the phosphorylation of

key nodes in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [namely, AKT

(Ser473), mTOR (Ser2448) and p70S6K (Thr389)], leading to

downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression, and thereby

inhibiting GBM cell migration and invasion (94). Additionally, right open reading

frame kinase 2 (RIOK2), a member of the RIO kinase family that is

highly expressed in GBM, was shown to enhance cell migration and

invasion by upregulating MMP-2 and MMP-9. By contrast, miR-4744

could directly target and suppress RIOK2 expression, effectively

reversing its pro-invasive effects (95).

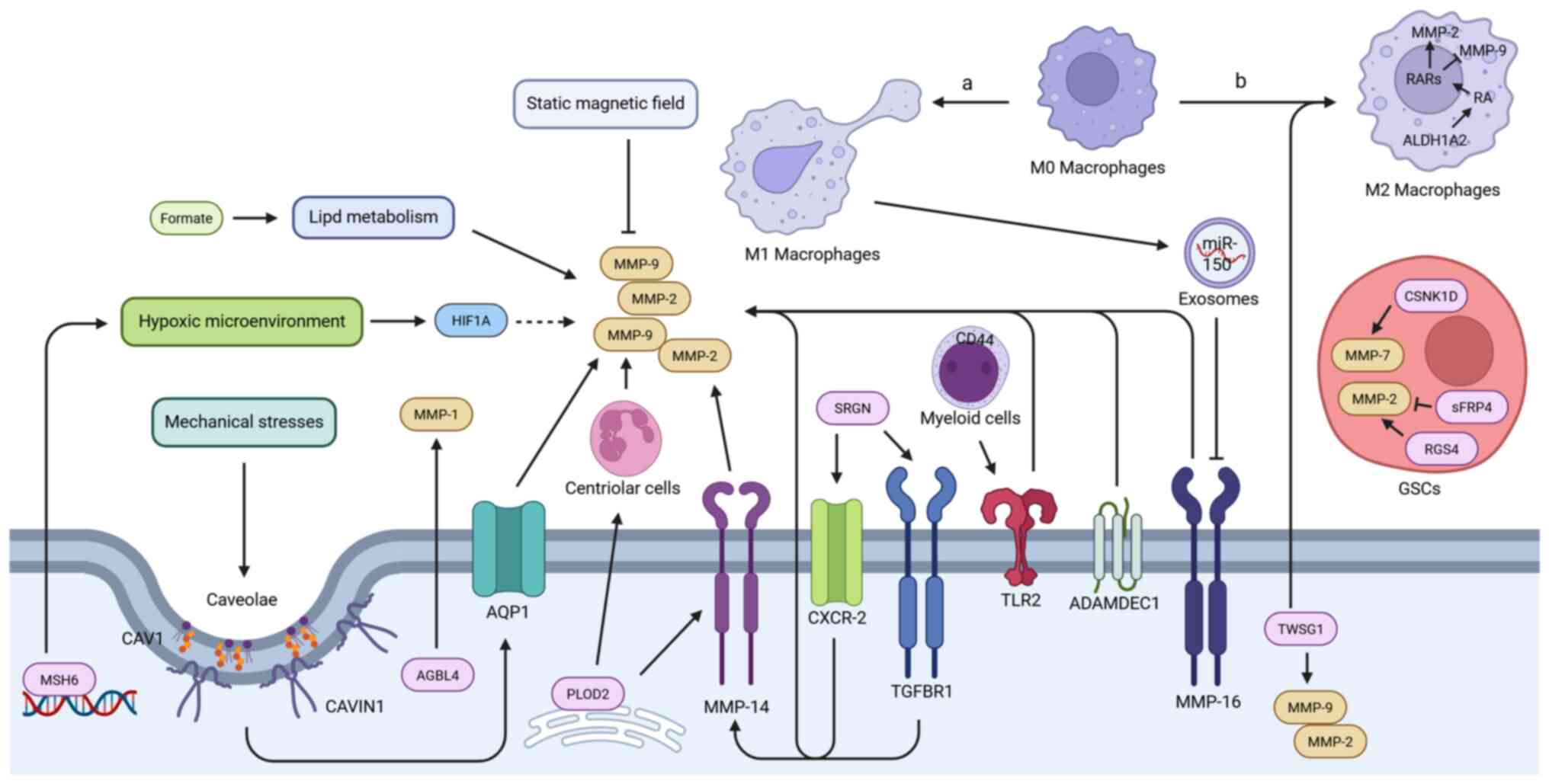

GBM invasion involves complex interactions within

the TME that modulate the expression and activity of MMPs. This

occurs through metabolic reprogramming, physical stimuli and immune

modulation (Fig. 4).

Metabolically, formate treatment was shown to significantly

activate the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in GBM cells, and

enhanced their invasive capacity by reprogramming lipid metabolism.

(U-13C)glucose/glutamine stable isotope tracing and

lipidomics analysis confirmed that formate drives fatty acid

synthesis and cytosolic lipid accumulation. Fatty acid synthase

inhibitor could block this metabolic reprogramming process, and

effectively suppress formate-induced MMP-2 expression and invasion

(73,96). Concurrently, serglycin enhanced

the expression of MMP-9 and MMP-14 by activating the TGFBR1 and

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR-2) signaling axes,

contributing to the pro-invasive effect in GBM (97).

Physical environmental factors are also crucial.

Mechanical stress stimuli such as high osmotic pressure (440

mOsmol/kg) or hydrostatic pressure (30 mmHg) can significantly

upregulate the mRNA expression and secretion levels of MMP-2 and

MMP-9 in GBM cells, as well as enhance their invasive ability

(74). Previous research

indicated that such pressure stimuli upregulated the expression of

caveolin-1 (CAV1) and caveolae-associated protein 1 (CAVIN1),

promote caveolae formation, and thereby induce MMP-2 and MMP-9

expression and invasion. This process may be related to

CAV1/CAVIN1-mediated induction of aquaporin-1 (AQP1). The Cancer

Genome Atlas analysis shows that co-high expression of CAV1/AQP1

predicts poor prognosis (98,99). Notably, AQP1 has been

demonstrated to directly mediate pro-MMP-9 activation (100). Conversely, static magnetic

field (1,000±100 Gs) treatment was shown to significantly

downregulate MMP-2 protein expression in GBM cells. When combined

with TGF-β1, the inhibitory effect on MMP-2 and the accompanying

reduction in invasive capacity were more pronounced (101). A hypoxic microenvironment,

which is a hallmark feature of GBM, influences MMP regulation. The

high expression of MutS protein homolog 6 in GBM exacerbated the

accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (HIF1α) protein

induced by hypoxia, thereby significantly enhancing the invasive

capacity mediated by MMP-2 and MMP-9 (102). Furthermore, twisted

gastrulation BMP signaling modulator 1 was revealed to be highly

expressed in GBM. Its knockdown not only significantly inhibited

tumor cell migration and invasion, and downregulated MMP-2 and

MMP-9, but also remodeled the phenotype of tumor-associated

macrophages, reducing M2-type markers [such as CD206, arginase 1,

interleukin (IL)-10 and TGF-β] and upregulating M1-type markers

(such as inducible nitic oxide synthase and IL-1β) in co-cultured

THP-1 cells (103-106).

Intrinsic factors within tumor cells are also

important for regulating MMPs in the microenvironment. ATP/GTP

binding protein like 4 (AGBL4), which is highly expressed in

recurrent GBM tissues, has been shown to drive tumor migration by

specifically upregulating MMP-1 expression; in vivo

experiments further revealed that inhibiting AGBL4 delays

intracranial tumor progression and prolongs the survival of

tumor-bearing animals, an effect that can be partially reversed by

high MMP-1 expression (31).

ADAM-like Decysin 1 expression level in GBM was shown to be

significantly associated with tumor malignancy and poor prognosis,

and it promoted tumor cell invasion by upregulating MMP-2

expression (107).

Notably, the stemness and invasiveness of GSCs in

the microenvironment are regulated by specific proteins and MMPs.

Elevated expression of casein kinase 1D (CSNK1D) in GBM tissues was

demonstrated to promote the upregulation of GSC stemness markers

[CD133 and SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2)] as well as MMP2

and MMP-7 expression upon its overexpression, enhancing cell

invasion. By contrast, knockdown of CSNK1D inhibited stemness and

invasion, and prolonged survival in model mice (75). Similarly, regulator of G protein

signaling 4 knock out also significantly downregulated MMP2

expression in GSCs and inhibited invasion (108). Conversely, secreted frizzled

related protein 4 utilized its N-terminal cysteine-rich domain and

C-terminal cysteine-rich domain to effectively inhibit MMP-2

activity in GSCs, suggesting a potential negative regulatory

mechanism (109).

The regulation of MMP expression by myeloid cells in

the microenvironment also affects tumor invasion, with macrophages

of different polarization states exhibiting distinct functions. M1

macrophages were shown to directly inhibit MMP-16 expression in

tumor cells by releasing exosome-encapsulated miR-150 (33). Given that MMP-16 could upregulate

MMP-2, this inhibition indirectly reduced MMP-2 expression levels

(110). By contrast, M2

macrophages rely on retinoic acid (RA) produced by ALDH1A2

catalysis to selectively upregulate MMP-2 while downregulating

MMP-9 expression, but this regulation does not directly affect the

protease activity of the tumor cells themselves (111). It is noteworthy that the

regulation of MMPs by myeloid cells is influenced by tumor cells.

On one hand, lysyl hydroxylase 2 expressed by GBM cells not only

promoted the release of active MMP-2 by tumor cells via

upregulating MMP-14, but also regulated secreted factors to

activate neutrophils to release MMP-9, thereby synergistically

increasing microenvironmental MMP levels and enhancing invasion

(112). On the other hand, GBM

cells could induce wild-type myeloid cells to significantly

upregulate MMP-9 mRNA expression upon Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)

agonist stimulation. This response was shown to be markedly

attenuated in CD44-deficient myeloid cells, which also lost their

ability to promote GBM cell invasion in Boyden chamber co-culture

models, confirming that CD44 is a key molecule mediating the

pro-invasive function of myeloid cells, partly through MMP-9

(113).

From natural products to small-molecule compounds,

both can effectively regulate the expression and activity of MMP-2,

MMP-9, MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-14 (114-118). Concurrently, the development of

combination therapy strategies and nanomaterial-based drug delivery

systems has provided new approaches for precise and controllable

drug release, thereby further enhancing therapeutic efficacy

(119-121). These diverse and multi-target

intervention techniques collectively present expansive

opportunities for halting the progression of GBM.

Natural active products modulate MMPs through

multi-target mechanisms, presenting potential avenues for cancer

treatment. Curcumin and its derivatives, as well as the

structurally related natural sesquiterpene Zerumbone, have been

demonstrated to effectively inhibit the invasion and migration of

GBM cells by targeting and suppressing the expression and activity

of MMP-2 and MMP-9. In an ex vivo stress model induced by

norepinephrine (NE), curcumin significantly downregulated the

expression and secretion of CD147 and its downstream effector

molecules MMP-2 and MMP-9 by inhibiting ERK1/2 phosphorylation,

thereby blocking NE-mediated GBM cell invasion (114). Concurrently,

bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC) was shown to act synergistically on the

PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways. After treating GBM

cells with BDMC for 48 h, the protein levels of key molecules,

including PI3K, p-AKT, MEK, p-ERK1/2, NF-κB, and the downstream

MMP-2 and MMP-9, were significantly downregulated, which was

accompanied by the inhibition of GBM cell migration and invasion

(122). Notably, the natural

compound Zerumbone also exhibited significant anti-invasive

effects, inhibiting the migration and invasion of GBM cells in a

concentration- and time-dependent manner. It downregulated the

total protein levels of ERK1/2 and AKT, thereby cooperatively

inhibiting the mRNA expression, protein content and enzymatic

activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9, consequently blocking GBM cell

invasion (123). Similarly, the

turmeric extract Curzerene significantly reduced MMP-9 levels in

glioma cells by inhibiting glutathione S-transferase A4 expression

and the phosphorylation of molecules of the mTOR/p70S6K signaling

axis, thus effectively suppressing GBM migration and invasion both

ex vivo and in a nude mouse xenograft model (124). Furthermore, the photodynamic

effect of curcumin provides a novel approach for inhibiting tumor

invasion. Upon activation by 430-nm blue light irradiation for 5-10

min, curcumin induced a significant increase in intracellular

reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in GBM cells. Flow cytometry

and immunofluorescence results confirmed that elevated ROS was

accompanied by downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression,

indicating that blue light-activated curcumin could inhibit MMP-2

and MMP-9 via the ROS pathway, thereby attenuating the invasive

potential of GBM cells (125).

Concurrently, various natural compounds effectively

inhibit GBM invasion by influencing MMP expression or activity.

Isocucurbitacin B inhibited GBM cell proliferation, migration and

invasion in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. It reduced

the mRNA and protein expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 by

downregulating the total protein levels and phosphorylation of

PI3K, AKT and MAPK1/3, thereby blocking GBM invasiveness (126). Also acting on the MAPK

signaling pathway, Coriolus versicolor and its active

molecule, the methyl ester of 9-KODE (AM), significantly inhibited

tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation, and

dose-dependently reduced MMP-3 mRNA and protein levels. Invasion

assays further confirmed that AM directly impaired the invasive

capacity of GBM cells (115).

The myrrh resin extract Guggulsterone (GS) significantly reduced

the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in GBM cells by activating dual

degradation pathways involving the proteasome and lysosome, thereby

inhibiting their migration and invasion. This mechanism was

experimentally verified. Both the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and

the lysosome inhibitor NH4Cl effectively reversed the

GS-induced downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 and the associated

inhibition of invasion. An orthotopic xenograft model further

demonstrated that GS reduced intratumoral MMP-2 levels and

prolonged the survival of tumor-bearing mice (127). The natural sesquiterpene

lactone compound Alantolactone, extracted from the roots of

Inula helenium, specifically inhibited the activity of

Lin-11, Isl-1, and Mec-3 kinase (LIMK), inducing the

dephosphorylation and activation of its key substrate, cofilin.

This subsequently increased the ratio of monomeric actin (G-actin)

to filamentous actin (F-actin), ultimately leading to significant

downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression, thereby effectively

inhibiting the migration and invasion of GBM cells (128). Targeting the secretion process

of MMPs, the compound erythrose from rhubarb root extract inhibited

the extracellular secretion of neuroleukin by blocking its binding

to the gp78 receptor, thereby significantly downregulating the

expression levels of MMP-1 and MMP-9 in GSCs and ultimately

inhibiting their ex vivo invasive capacity (116). Furthermore, kaempferol extract

and its biotransformation product (KPF-ABR) also exhibited

significant anti-invasive effects. Both significantly downregulated

MMP-9 expression and inhibited the tumor promoter

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced activation of

cell migration. Notably, KPF-ABR, enriched with kaempferol

aglycone, was particularly effective, notably blocking the

TPA-stimulated upregulation of MMP-9 and inhibiting neurosphere

formation by GSCs (129). Other

natural products have also been shown to exert anti-invasive

effects by inhibiting MMPs, including Bacoside A and Diosgenin,

which effectively inhibited the invasive ability of GBM cells by

downregulating MMP-2 and MMP-9 (130,131).

Beyond plant-derived components, fungi, animals and

metabolites also demonstrate potential for targeting MMPs to

inhibit GBM invasion. The fungus-derived compound

10,11-dehydrocurvularin significantly downregulated MMP-2 levels by

inhibiting PI3K-p85 expression and blocking AKT phosphorylation,

thereby suppressing GBM invasion (43). Antrodia camphorate, also a

fungus, and the quinone derivative coenzyme Q (CoQ)0 from its

fermentation broth, inhibited the invasive ability of GBM cells by

downregulating the expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (132). By contrast, the structurally

similar CoQ10 exerted its anti-invasive effect by directly

inhibiting the enzymatic activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (133). Additionally, the animal-derived

component bee venom and the metabolite Urolithin B have been

reported to inhibit the enzymatic activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9,

thereby reducing GBM invasiveness (134,135). Notably, melatonin, an important

endogenous hormone, has also been confirmed to effectively inhibit

the invasive capacity of GBM tumor spheroids by suppressing the

mRNA and protein expression levels of MMP-9 (136).

In summary, this section systematically described

how natural active ingredients, including curcuminoids, fungal and

animal metabolites, significantly inhibit the invasive ability of

GBM by targeting key signaling pathways and proteins such as

PI3K/AKT, MAPK and NF-κB (Table

SII), thereby regulating MMP gene expression, protein secretion

and enzymatic activity. This provides a solid theoretical

foundation and candidate strategies for developing innovative

therapies against GBM metastasis.

Various small molecule compounds regulate the

expression and activity of MMPs through different molecular

mechanisms, thus inhibiting the invasive behavior of GBM. Core

signaling pathways serve as key regulatory points. For instance,

Chrysomycin A downregulated the expression of β-catenin and its

downstream target proteins c-Myc and cyclin D1 by inhibiting the

phosphorylation levels of AKT and GSK-3β, thereby regulating and

reducing MMP-2 protein expression, ultimately suppressing the

migration and invasion capabilities of GBM cells (137). The cell-penetrating peptide

trans-activator of transcription (Tat)-nuclear translocation signal

(NTS) inhibited NF-κB phosphorylation by specifically blocking the

nuclear translocation of annexin-A1, consequently downregulating

the expression and activity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (117). The farnesoid X receptor agonist

GW4064 downregulated MMP-2 activity by inhibiting protein kinase C

alpha (PKCα) phosphorylation, an effect reversible by the PKCα

agonist phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (138). Concurrently, the specific

p53-Snail binding inhibitor GN25 also affected the invasion process

by reducing MMP-2 expression (139). Furthermore, metabolism

regulation is involved; PPARγ agonists (such as pioglitazone and

rosiglitazone) and the PPARα agonist WY-14643 were shown to inhibit

MMP2 by upregulating the regulatory factor X1, effectively

suppressing tumor invasion in in vivo models (140). Notably, ion channel function

has also been demonstrated to be associated with MMP regulation;

for example, the hERG channel agonist NS1643 reduced MMP-9 protein

levels (141). In terms of

epigenetic regulation, the histone deacetylase inhibitor

suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) significantly inhibited

MMP14 transcription in GBM cells by reducing histone H3 lysine 27

acetylation levels, and this downregulation has been demonstrated

as a key mechanism for SAHA-mediated radiosensitization (118). Non-coding RNA networks are also

crucial. The sevoflurane derivative Sev downregulated MMP-2 and

MMP-9 through the circRELN/miR-1290/RORA and miR-27b/VEGF signaling

pathways and by direct targeting by miR-34a-5p, with its

anti-invasive effects confirmed in both cellular experiments and

tumor-bearing mice (142-144). Similarly, propofol was shown to

inhibit MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity via the

circNCAPG/miR-200a-3p/RAB5A pathway (145). Viral vectors, such as the

third-generation oncolytic adenovirus TS-2021 (with E1A regulated

by Ki67/TGF-β2 UTR and carrying IL-15), was revealed to

significantly downregulate MMP3 expression by inhibiting

p-MKK4/p-JNK signaling, thereby effectively suppressing the

invasive ability of GBM cells (146).

Notably, certain compounds demonstrate significant

clinical translational potential. The novel compound NP16

(structural feature, 3,4,5-trimethoxymethyl on the N-phenyl ring)

significantly downregulates MMP-9 levels by inhibiting COX-2

expression and blocking STAT3 phosphorylation and nuclear

translocation. In a C6 orthotopic model, its tumor inhibition rate

(66.01%) surpassed that of TMZ (54.83%). It also exhibited

favorable BBB penetration capability (brain/blood concentration

ratio, 0.38) and significantly prolonged the survival of

tumor-bearing rats (147). A

class of Pt(IV) complexes, designed to overcome challenges in GBM

treatment, are based on a cisplatin core with axial ligands

comprising the anthraquinone drug Rhein and a hydrophilic acetic

acid ligand, achieving dual-drug synergistic effects via linkers of

different lengths. These complexes exhibit superior synergistic

effects compared with single agents in inhibiting MMP-2 and MMP-9

expression and cell migration, and remain active under hypoxic

conditions. Computational simulations predict enhanced BBB

penetration capability, offering a novel direction for combination

therapy (148).

In summary, this section not only untangled the

diverse molecular mechanisms by which small molecules target the

regulation of MMPs to inhibit GBM invasion (involving key signaling

pathways, metabolism, non-coding RNAs and ion channels), but also

highlighted the considerable clinical translational potential of

certain compounds [such as NP16 and novel Pt(IV) complexes] with

excellent BBB penetration and in vitro/in vivo activity in

overcoming GBM invasiveness (Table

SIII).

In recent years, various design strategies for

nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems targeting MMPs have

emerged in the field of GBM therapy. Researchers have developed

intelligent delivery platforms that specifically respond to

different MMP subtypes. For instance, dual-sensitive NPs rapidly

dissociate in the TME with high MMP-9 expression, releasing the

loaded doxorubicin while simultaneously forming nanogels. This

process significantly enhanced drug penetration and retention

within the tumor core, effectively inhibited GBM spheroids and

tumor volume, and substantially prolonged the survival time of mice

(119). Similarly, leveraging

MMP subtype responsiveness, D@MLL nanocarriers can be transported

across the BBB by monocytes driven by low-dose radiotherapy-induced

high C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 expression. Subsequently,

doxorubicin is rapidly released in areas of high MMP-2 activity,

triggering immunogenic cell death, as evidenced by significantly

upregulated calreticulin expression and high mobility group box 1

release. Concurrently, this promotes the polarization of

tumor-associated macrophages towards the M1 phenotype and activates

CD8+ T cells, thereby synergistically inhibiting GBM

progression and extending survival (149). Furthermore, nano-delivery

systems can synergize with radiotherapy to enhance efficacy. For

example, Au@DTDTPA(Gd) NPs combined with X-ray radiotherapy

significantly inhibit the invasive capacity of escape cells from

GBM spheroids, and attenuate their invasiveness and stem cell-like

characteristics (such as SOX2 downregulation) by reducing MMP-2

secretion and activity and inducing mitotic catastrophe (150). Additionally, fMbat NPs achieve

BBB-crossing capability via transferrin receptor-mediated

transport, effectively delivering batimastat to the GBM TME and

potently inhibiting MMP-2 activity in GBM cells (151). Dual-targeting liposomes

(co-loaded with daunorubicin and rofecoxib) and

carboxymethyl-stevioside-modified magnetic NPs can simultaneously

inhibit the expression and function of MMP-2 and MMP-9, effectively

suppressing GBM invasion (35,152). Notably, CuO NPs not only

significantly downregulate the expression of proteins such as

MMP-9, EphA2 and YKL-40 in the hippocampus and cells of GBM model

rats to restrict tumor invasion, but also demonstrate the potential

to improve spatial recognition and memory abilities in model rats

(36).

In summary, the aforementioned nanodrug delivery

systems, by achieving specific responses to MMP-rich

microenvironmental stimuli, controlled drug release and multiple

mechanisms of action (such as enhancing the permeability and

retention effect, triggering immune responses, synergizing with

radiotherapy, inhibiting invasion and crossing the BBB), provide

powerful novel strategies for precisely targeting and modulating

MMP-related key pathological processes in GBM (Table SIV).

In pharmacological interventions targeting MMPs,

combination therapy strategies have significantly enhanced

antitumor efficacy through multi-target synergistic effects. Among

these, the combination of chemotherapeutic agents with other

treatment modalities has demonstrated substantial potential. TMZ,

as a foundational chemotherapeutic drug, was shown to synergize

with photodynamic therapy in downregulating the expression of

MMP-2, HIF-1α and glucose transporter 1, thereby inhibiting glucose

uptake and ATP production. This effectively blocked tumor invasion

and energy supply, significantly suppressed tumor growth, and

prolonged the survival of tumor-bearing mice, with effects superior

to monotherapy (120). Natural

products and their derivatives can also synergize with TMZ. The

combination of TMZ and Chuanxiong essential oil (CEO) was

demonstrated to reverse drug resistance and inhibit GBM cell

invasion ex vivo by suppressing MMP-9 expression.

Furthermore, the combination of ligustilide, a key component of

CEO, with TMZ enhanced tumor suppression effects and TMZ

sensitivity in animal models (153). The combination of TMZ with

4-methylumbelliferone was revealed to inhibit invasion by reducing

MMP-2 activity and enhanced the drug sensitivity of cells resistant

to TMZ and vincristine (154).

The combined application of cordycepin and doxorubicin has also

been confirmed to inhibit MMP-9-mediated invasion at the cellular

level (155).

miRNA replacement therapy combined with

chemotherapeutic drugs has also demonstrated significant

synergistic potential. A previous study found that the combined

application of overexpressed miR-181a and carmustine effectively

curbs the invasive capacity of GBM cells by targeting and

inhibiting MMP-2 expression (121). It is noteworthy that the

proteasome inhibitor bortezomib alone can significantly

downregulate MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression and inhibit invasion. When

combined with the polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) inhibitor CFI-400945,

it synergistically enhanced the downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9

as well as the inhibition of invasion. Conversely, overexpression

of PLK4 reversed this effect and attenuated the efficacy of

bortezomib. The core mechanism involves the synergistic activation

of PTEN expression and the inhibition of the phosphorylation and

expression of proteins of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, ultimately

leading to the downregulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression

(156). Combined therapy with

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand and celastrol inhibited GBM

cell invasion by upregulating GSK-3β, reducing the transcription

and protein levels of β-catenin and its downstream targets c-Myc,

cyclin D1 and MMP-2 (157).

Similarly, ex vivo experiments with aprepitant combined with

5-ALA demonstrated effective restriction of GBM cell invasion

through inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity (158).

In summary, the above section has systematically

elaborated on strategies involving chemotherapy combined with

physical/natural therapies, miRNA replacement therapy, targeted

drug combinations and signaling pathway inhibitors (Table SV) to synergistically regulate

MMPs and their associated signaling networks (such as the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin pathways). These strategies not

only significantly inhibit tumor invasion and overcome drug

resistance, but also effectively suppress tumor growth and prolong

survival, thereby establishing a solid mechanistic foundation and

providing direction for the development of more efficient,

multi-targeted anti-GBM treatment plans.

Although intervention strategies targeting MMPs have

demonstrated therapeutic potential in preclinical studies, their

clinical translation faces important challenges. These challenges

primarily stem from the inability of existing model systems to

adequately recapitulate the complex pathobiology of GBM, resulting

in a gap between preclinical data and outcomes from human

trials.

The limitations of tumor models represent the

primary obstacle. Long-term cultured GBM cell lines (such as

U-251MG) undergo significant genomic drift. Characteristic

chromosomal abnormalities (including deletions in 18q11-23 and

amplifications in 4q12) emerge in subclones, leading to aberrant

activation of key tyrosine kinase receptors such as PDGFRα. These

genetic alterations drive cells to acquire enhanced proliferative,

clonogenic and invasive capacities, causing their biological

characteristics to deviate markedly from the original tumor

features (159). More

importantly, GBM exhibits heterogeneity at both histological and

molecular levels. The TME harbors diverse cell populations

(including GSCs, differentiated tumor cells, necrotic areas and

aberrant vasculature), which display significant differences in

proliferation kinetics, invasive properties and therapeutic

sensitivity (160).

Concurrently, complex genomic variations (including mutations, copy

number alterations and epigenetic modifications) and distinct

molecular subtypes (such as proneural, classical and mesenchymal)

collectively result in differential signaling pathway activation

states and varied responses to MMP-targeted therapies (161,162). Existing models struggle to

replicate this complexity, introducing systematic bias into

efficacy evaluations. The results may not encompass all tumor cell

subpopulations, and predictions of potential adverse effects are

often inadequate. This has been corroborated by a phase II clinical

trial, where the combination of TMZ with the broad-spectrum MMP

inhibitor marimastat improved the 6-month PFS rate in patients with

recurrent GBM; however, 47% of patients experienced dose-limiting

joint toxicity (163), further

underscoring the fundamental limitations of preclinical models in

assessing toxicity risks.

The complex pathological structure of the BBB

constitutes the second major obstacle. In the GBM microenvironment,

aberrantly upregulated MMP activity and an imbalance with their

natural inhibitor, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1, lead

to degradation and loss of agrin, a key component of the

perivascular basal lamina. This subsequently disrupts the

structural integrity of astrocytic end-feet, causing BBB leakage in

the tumor core (164). However,

at the invasive front, the BBB structure remains relatively intact

and harbors active efflux pump systems, such as P-glycoprotein and

breast cancer resistance protein, creating a spatially

heterogeneous drug delivery barrier (165,166). This unique pathological

structure results in highly uneven intratumoral distribution of

therapeutic agents, making it difficult for targeted drugs to reach

effective concentrations in the invasive regions (167,168). Furthermore, the physicochemical

properties of the drugs themselves (such as lipophilicity) are

directly related to their ability to penetrate the intact BBB and

resist efflux pumps. Highly lipophilic compounds tend to accumulate

in peripheral tissues, potentially causing systemic toxicity, while

polar molecules often fail to effectively reach central targets

(169). However, existing in

vitro BBB models cannot mimic these dynamic pathological

changes and spatial heterogeneity, leading to fundamental

limitations in predicting drug permeability and the therapeutic

window.

MMPs occupy a central position in the invasion

process of GBM, primarily through three mechanisms: i) Facilitating

EMT via ECM degradation; ii) remodeling the vascular niche; and

iii) thereby fueling tumor malignancy. The expression of MMPs is

modulated by a network of signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT,

MAPK and TGF-β, as well as transcription factors such as Snail and

activator protein 1, and non-coding RNAs. Notably, physicochemical

factors within the tumor niche also exert a marked influence on the

enzymatic activity of MMPs.

Therapeutic strategies targeting MMPs show

considerable promise. Several reported small-molecule compounds

exhibit excellent BBB penetration capability and superior ex

vivo inhibitory efficacy compared with TMZ. Nanodelivery

systems can synergistically address the dual challenges of BBB

penetration and targeted delivery. By enabling drug release

specifically in response to MMPs, these systems hold potential for

circumventing the joint toxicity associated with the broad-spectrum

inhibitor marimastat, which arises from the non-selective

inhibition of MMPs involved in joint formation (170,171). Concurrently, in cell therapy,

chlorotoxin-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells

(NCT04214392), administered via intracavitary tumor injection in

patients with recurrent GBM, have shown promising preliminary

clinical data. These cells demonstrated persistence within the

tumor cavity and a favorable safety profile (absence of systemic

inflammation or anti-CAR antibody responses, and no dose-limiting

toxicities), and achieved transient disease stabilization in 3 out

of 4 patients (172), providing

initial evidence for MMP-targeted therapies.

Previous research on the side effects of MMP-related

drug interventions have revealed that TMZ can upregulate MMP-9,

enhancing tumor invasiveness (173). Although the combination of

radiotherapy and TMZ reduces GBM cell viability, it enhances the

invasive capacity of GBM cells by inducing the secretion of sEVs

carrying MMP-2 and upregulating thrombospondin-1 in invasive

pseudopodia (48,174). It is noteworthy that excessive

fluoride accumulation can significantly enhance GBM invasiveness by

activating the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (175). Furthermore, physical therapies

carry potential risks; surgical thermal injury markedly increases

MMP-9 activity by activating astrocytes, thereby exacerbating the

malignant progression of GBM (176). These phenomena reveal that

single interventions may trigger compensatory invasive mechanisms,

highlighting the complexity of precisely regulating the MMP

network.

Due to the intricate MMP regulatory network and

bottlenecks in clinical translation, interdisciplinary

technological collaboration is essential. To mitigate issues of

genetic drift in GBM cell lines, prioritizing the use of

low-passage cells is crucial for ensuring experimental

reproducibility. Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly

becoming a key driver for overcoming clinical translation hurdles.

AI algorithms, such as convolutional neural networks and vision

transformers, can efficiently capture disease features from MRI

images, significantly improving GBM classification accuracy and

reducing scan times. Integrated with high-throughput omics data

(genomics and transcriptomics), AI can more precisely delineate GBM

molecular subtypes, laying the groundwork for targeted drug

therapies (177-180). The application of AI has

further expanded to surgical planning [including predicting

interstitial thermal therapy ablation areas to optimize prognosis

(181)], drug development [such

as predicting drug responses and mechanisms (182)] and precision medicine

[including developing personalized treatment plans or predicting

therapeutic efficacy (183)].

Simultaneously, developing physiologically relevant ex vivo

BBB models is a core component for translating preclinical research

to the clinic. Microfluidic technology has successfully established

three-dimensional co-culture BBB models incorporating human brain

vascular pericytes, astrocytes and endothelial cells. These models

exhibit physiologically relevant structure, selective permeability,

reversibility, and effectively simulate GBM-induced vascular

remodeling and drug delivery barriers (184). Three-dimensional (3D) printing

technologies, such as two-photon lithography, have also been

employed to construct controllable brain TME models, achieving

tri-culture of endothelial cells, astrocytes and glioma spheroids

to form a functional BBB (185). Notably, 3D gradient hydrogel

models, by mimicking the dynamic changes in matrix stiffness within

the GBM microenvironment, have revealed a dose-dependent

association between mechanical stress stimulation and the

regulation of MMP activity (186,187), offering novel perspectives for

understanding the mechanical mechanisms of BBB disruption.

In summary, although interventions targeting MMPs

show potential in GBM treatment, their complex biological

functions, potential pro-invasive effects and challenges in

clinical translation remain core issues to be resolved. Future

research, through multidisciplinary integration and the close

combination of basic mechanistic exploration, innovative technology

application and clinical translation studies, may transform

strategies such as targeting MMPs into clinical regimens that

improve survival outcomes for patients with GBM.

Not applicable.

BZ conceived and designed the review, as well as

wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. YH performed data

extraction and synthesis, provided original insights and

interpretations, and critically revised the manuscript. HZ acquired

funding, supervised the project, designed the review scope, and

conducted expert analysis. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

We express sincere gratitude to Dr Jinpeng Hu

(Department of Neurosurgery, The First Hospital of China Medical

University, Shenyang, P.R. China) for his expert guidance in

manuscript revision, figure preparation, and table design.

The present research was supported by the Chen Xiao-Ping

Foundation for the Development of Science and Technology of Hubei

Province (grant no. CXPJJH123003-058) and the General Program of

Joint Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Provincial Science and

Technology Plan (grant no. 2025-MSLH-480).

|

1

|

Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, Cioffi G,

Waite KA, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS statistical

report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors

diagnosed in the United States in 2016-2020. Neuro Oncol. 25(12

Suppl 2): iv1–iv99. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Xiao D, Yan C, Li D, Xi T, Liu X, Zhu D,

Huang G, Xu J, He Z, Wu A, et al: National brain tumour registry of

China (NBTRC) statistical report of primary brain tumours diagnosed

in china in years 2019-2020. Lancet Reg Health West Pac.

34:1007152023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ,

Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, Hawkins C, Ng HK, Pfister SM,

Reifenberger G, et al: The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the

central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23:1231–1251. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Barone DG, Lawrie TA and Hart MG: Image

guided surgery for the resection of brain tumours. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD0096852014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pirro V, Alfaro CM, Jarmusch AK, Hattab

EM, Cohen-Gadol AA and Cooks RG: Intraoperative assessment of tumor

margins during glioma resection by desorption electrospray

ionization-mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

114:6700–6705. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

De Boer E, Harlaar NJ, Taruttis A,

Nagengast WB, Rosenthal EL, Ntziachristos V and Van Dam GM: Optical

innovations in surgery. Br J Surg. 102:e56–e72. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hervey-Jumper SL and Berger MS: Maximizing

safe resection of low- and high-grade glioma. J Neuro-Oncol.

130:269–282. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller

M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn

U, et al: Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide

for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 352:987–996. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Perry JR, Laperriere N, O'Callaghan CJ,

Brandes AA, Menten J, Phillips C, Fay M, Nishikawa R, Cairncross

JG, Roa W, et al: Short-course radiation plus temozolomide in

elderly patients with glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 376:1027–1037.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rodríguez-Camacho A, Flores-Vázquez JG,

Moscardini-Martelli J, Torres-Ríos JA, Olmos-Guzmán A, Ortiz-Arce

CS, Cid-Sánchez DR, Pérez SR, Macías-González MDS,

Hernández-Sánchez LC, et al: Glioblastoma treatment:

State-of-the-art and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci.

23:72072022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Weller M and Le Rhun E: How did lomustine

become standard of care in recurrent glioblastoma? Cancer Treat

Rev. 87:1020292020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kirson ED, Dbalý V, Tovaryš F, Vymazal J,

Soustiel JF, Itzhaki A, Mordechovich D, Steinberg-Shapira S,

Gurvich Z, Schneiderman R, et al: Alternating electric fields

arrest cell proliferation in animal tumor models and human brain

tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:10152–10157. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Giladi M, Schneiderman RS, Voloshin T,

Porat Y, Munster M, Blat R, Sherbo S, Bomzon Z, Urman N, Itzhaki A,

et al: Mitotic spindle disruption by alternating electric fields

leads to improper chromosome segregation and mitotic catastrophe in

cancer cells. Sci Rep. 5:180462015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, Read W,

Steinberg D, Lhermitte B, Toms S, Idbaih A, Ahluwalia MS, Fink K,

et al: Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance

temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in

patients with glioblastoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

318:2306–2316. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, Henriksson R,

Saran F, Nishikawa R, Carpentier AF, Hoang-Xuan K, Kavan P, Cernea

D, et al: Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly

diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 370:709–722. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Le Rhun E, Preusser M, Roth P, Reardon DA,

van den Bent M, Wen P, Reifenberger G and Weller M: Molecular

targeted therapy of glioblastoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 80:1018962019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Navone SE, Guarnaccia L, Locatelli M,

Rampini P, Caroli M, La Verde N, Gaudino C, Bettinardi N, Riboni L,

Marfia G and Campanella R: Significance and prognostic value of the

coagulation profile in patients with glioblastoma: Implications for

personalized therapy. World Neurosurg. 121:e621–e629. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cuddapah VA, Robel S, Watkins S and

Sontheimer H: A neurocentric perspective on glioma invasion. Nat

Rev Neurosci. 15:455–465. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Streiff MB, Ye X, Kickler TS, Desideri S,

Jani J, Fisher J and Grossman SA: A prospective multicenter study

of venous thromboembolism in patients with newly-diagnosed

high-grade glioma: Hazard rate and risk factors. J Neurooncol.

124:299–305. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen Y, Fei W, Shi Y, Ma W, Jiao W, Tao F,

Zhu J, Wang Y and Feng X: Venous thromboembolism risk factors in

pediatric patients with high-grade glioma: A multicenter

retrospective study. Front Pediatr. 13:15952232025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Marras LC, Geerts WH and Perry JR: The

risk of venous thromboembolism is increased throughout the course

of malignant glioma: An evidence-based review. Cancer. 89:640–646.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Semrad TJ, O'Donnell R, Wun T, Chew H,

Harvey D, Zhou H and White RH: Epidemiology of venous

thromboembolism in 9489 patients with malignant glioma. J

Neurosurg. 106:601–608. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Brat DJ, Castellano-Sanchez AA, Hunter SB,

Pecot M, Cohen C, Hammond EH, Devi SN, Kaur B and Van Meir EG:

Pseudopalisades in glioblastoma are hypoxic, express extracellular

matrix proteases, and are formed by an actively migrating cell

population. Cancer Res. 64:920–927. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gross J and Lapiere CM: Collagenolytic

activity in amphibian tissues: A tissue culture assay. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 48:1014–1022. 1962. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Visse R and Nagase H: Matrix

metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases:

Structure, function, and biochemistry. Circ Res. 92:827–839. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Quintero-Fabián S, Arreola R,

Becerril-Villanueva E, Torres-Romero JC, Arana-Argáez V,

Lara-Riegos J, Ramírez-Camacho MA and Alvarez-Sánchez ME: Role of

matrix metalloproteinases in angiogenesis and cancer. Front Oncol.

9:13702019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Gialeli C, Theocharis AD and Karamanos NK:

Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their

pharmacological targeting. FEBS J. 278:16–27. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Niland S, Riscanevo AX and Eble JA: Matrix

metalloproteinases shape the tumor microenvironment in cancer

progression. Int J Mol Sci. 23:1462021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Dibdiakova K, Majercikova Z, Galanda T,

Richterova R, Kolarovszki B, Racay P and Hatok J: Relationship

between the expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their

tissue inhibitors in patients with brain tumors. Int J Mol Sci.

25:28582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wolburg H, Noell S, Fallier-Becker P, Mack

AF and Wolburg-Buchholz K: The disturbed blood-brain barrier in

human glioblastoma. Mol Aspects Med. 33:579–589. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Zhang S, Cheng L, Su Y, Qian Z, Wang Z,

Chen C, Li R, Zhang A, He J, Mao J, et al: AGBL4 promotes malignant

progression of glioblastoma via modulation of MMP-1 and

inflammatory pathways. Front Immunol. 15:14201822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang ZL, Abdallah AS, Shen GX, Suarez M,

Feng P, Yu YJ, Wang Y, Zheng SH, Hu YJ, Xiao X, et al: Silencing

GMPPB inhibits the proliferation and invasion of GBM via hippo/MMP3

pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 24:147072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yan P, Wang J, Liu H, Liu X, Fu R and Feng

J: M1 macrophage-derived exosomes containing miR-150 inhibit glioma

progression by targeting MMP16. Cell Signal. 108:1107312023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hitchcock SA: Blood-brain barrier

permeability considerations for CNS-targeted compound library

design. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 12:318–323. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xie HJ, Zhan-Dui N, Zhao J, Er-Bu AGA,

Zhen P, ZhuoMa D and Sang T: Evaluation of nanoscaled dual

targeting drug-loaded liposomes on inhibiting vasculogenic mimicry

channels of brain glioma. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol.

49:595–604. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Tian S, Xu J, Qiao X, Zhang X, Zhang S,

Zhang Y, Xu C, Wang H and Fang C: CuO nanoparticles for glioma

treatment in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 14:232292024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Castro-Ribeiro ML, Castro VIB, Vieira De

Castro J, Pires RA, Reis RL, Costa BM, Ferreira H and Neves NM: The

potential of the fibronectin inhibitor arg-gly-asp-ser in the

development of therapies for glioblastoma. Int J Mol Sci.

25:49102024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang WB, Chuang JY, Ko CY, Chang WC and

Hsu TI: Dehydroepiandrosterone induces temozolomide resistance

through modulating phosphorylation and acetylation of Sp1 in

glioblastoma. Mol Neurobiol. 56:2301–2313. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Munoz JL, Bliss SA, Greco SJ, Ramkissoon

SH, Ligon KL and Rameshwar P: Delivery of functional anti-miR-9 by

mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes to glioblastoma multiforme

cells conferred chemosensitivity. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids.

2:e1262013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

McFaline-Figueroa JL, Braun CJ, Stanciu M,

Nagel ZD, Mazzucato P, Sangaraju D, Cerniauskas E, Barford K,

Vargas A, Chen Y, et al: Minor changes in expression of the

mismatch repair protein MSH2 exert a major impact on glioblastoma

response to temozolomide. Cancer Res. 75:3127–3138. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Song H and Park KH: Regulation and

function of SOX9 during cartilage development and regeneration.

Semin Cancer Biol. 67(Pt 1): 12–23. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Guo XR, Wu MY, Dai LJ, Huang Y, Shan MY,

Ma SN, Wang J, Peng H, Ding Y, Zhang QF, et al: Nuclear

FAM289-galectin-1 interaction controls FAM289-mediated tumor

promotion in malignant glioma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 38:3942019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yan H, Fu Z, Lin P, Gu Y, Cao J and Li Y:

Inhibition of human glioblastoma multiforme cells by

10,11-dehydrocurvularin through the MMP-2 and PI3K/AKT signaling

pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 936:1753482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yuan Z, Yang Z, Li W, Wu A, Su Z, Jiang B

and Ganesan S: Triphlorethol-a attenuates U251 human glioma cancer

cell proliferation and ameliorates apoptosis through JAK2/STAT3 and

p38 MAPK/ERK signaling pathways. J Biochem Mol Toxicol.

36:e231382022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

De Jong JM, Broekaart DWM, Bongaarts A,

Mühlebner A, Mills JD, Van Vliet EA and Aronica E: Altered

extracellular matrix as an alternative risk factor for

epileptogenicity in brain tumors. Biomedicines. 10:24752022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Thome I, Lacle R, Voß A, Bortolussi G,

Pantazis G, Schmidt A, Conrad C, Jacob R, Timmesfeld N, Bartsch JW

and Pagenstecher A: Neoplastic cells are the major source of

MT-MMPs in IDH1-mutant glioma, thus enhancing tumor-cell intrinsic

brain infiltration. Cancers (Basel). 12:24562020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Sawicka MM, Sawicki K, Jadeszko M,

Bielawska K, Supruniuk E, Reszeć J, Prokop-Bielenia I, Polityńska

B, Jadeszko M, Rybaczek M, et al: Proline metabolism in WHO G4

gliomas is altered as compared to unaffected brain tissue. Cancers

(Basel). 16:4562024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Whitehead CA, Fang H, Su H, Morokoff AP,

Kaye AH, Hanssen E, Nowell CJ, Drummond KJ, Greening DW, Vella LJ,

et al: Small extracellular vesicles promote invadopodia activity in

glioblastoma cells in a therapy-dependent manner. Cell Oncol

(Dordr). 46:909–931. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Colangelo NW and Azzam EI: Extracellular

vesicles originating from glioblastoma cells increase

metalloproteinase release by astrocytes: The role of CD147

(EMMPRIN) and ionizing radiation. Cell Commun Signaling. 18:212020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Perruzzi CA, De Fougerolles AR,

Koteliansky VE, Whelan MC, Westlin WF and Senger DR: Functional

overlap and cooperativity among αv and β1 integrin subfamilies

during skin angiogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 120:1100–1109. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Whelan MC and Senger DR: Collagen I

initiates endothelial cell morphogenesis by inducing actin

polymerization through suppression of cyclic AMP and protein kinase

A. J Biol Chem. 278:327–334. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Davis S, Aldrich TH, Jones PF, Acheson A,

Compton DL, Jain V, Ryan TE, Bruno J, Radziejewski C, Maisonpierre

PC and Yancopoulos GD: Isolation of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for

the TIE2 receptor, by secretion-trap expression cloning. Cell.

87:1161–1169. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Winer A, Adams S and Mignatti P: Matrix

metalloproteinase inhibitors in cancer therapy: Turning past