Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) continue to be the

primary cause of death worldwide, with myocardial infarction

contributing markedly to global morbidity and mortality (1). The timely restoration of coronary

blood flow through thrombolytic therapy or percutaneous coronary

intervention (PCI) has been proven to effectively reduce infarct

size (2). However,

ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury induces secondary myocardial

damage, mainly affecting cardiomyocytes and cardiac microvascular

endothelial cells (CMECs). This secondary injury is characterized

by myocardial stunning, microvascular dysfunction, reperfusion

arrhythmias and lethal reperfusion injury (3). Microvascular I/R injury involves

CMEC apoptosis, microvascular spasm and impaired perfusion, all of

which exacerbate myocardial damage after reperfusion (4). Beyond conventional clinical risk

scores and left ventricular ejection fraction, microvascular

obstruction due to I/R injury has been identified as an independent

predictor of infarct size and poor prognosis (5-7).

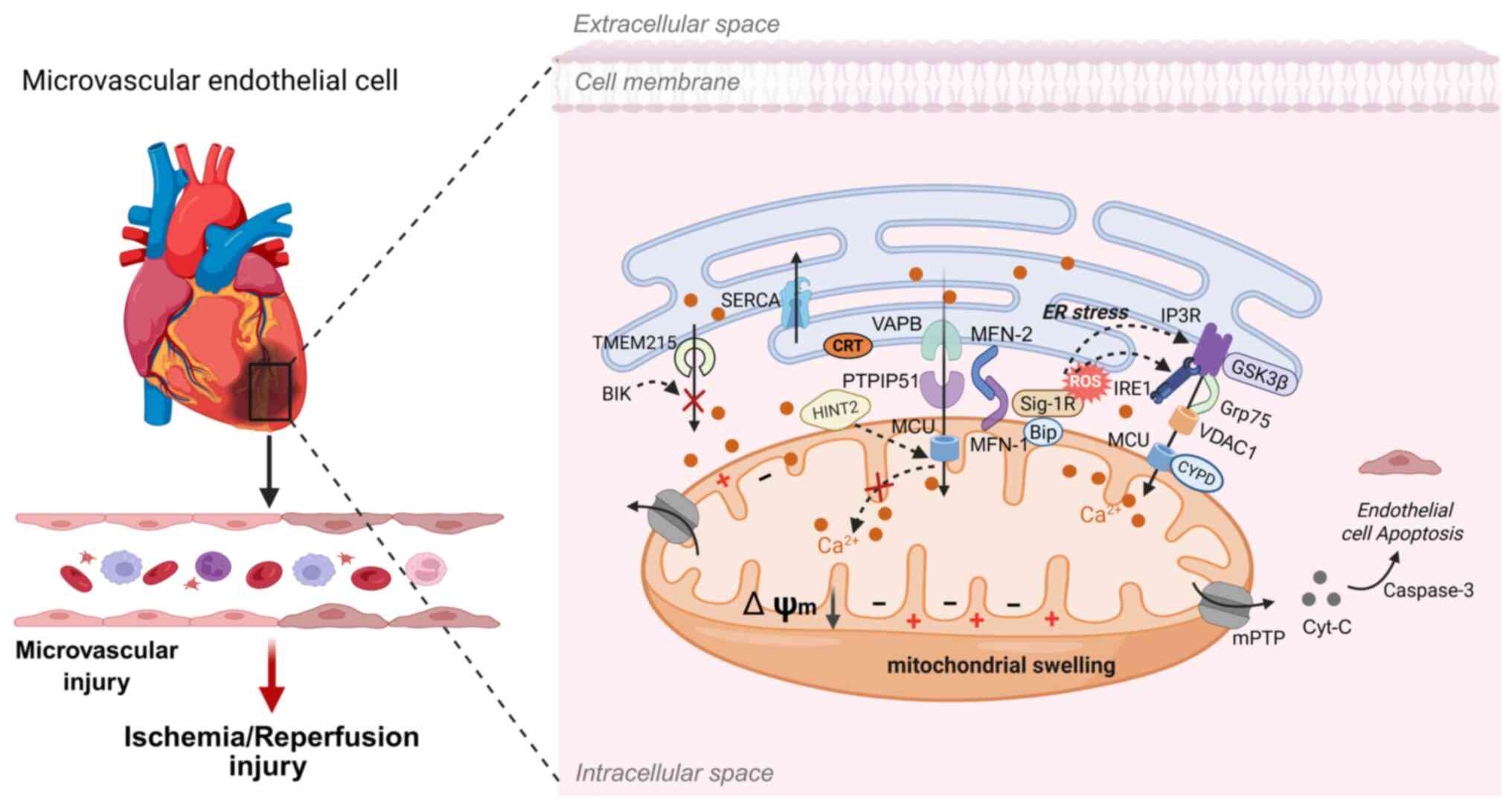

Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum

membranes (MAMs) serve as key signaling hubs involved in

fundamental cellular processes, including calcium (Ca2+)

and lipid homeostasis, mitochondrial dynamics and energy production

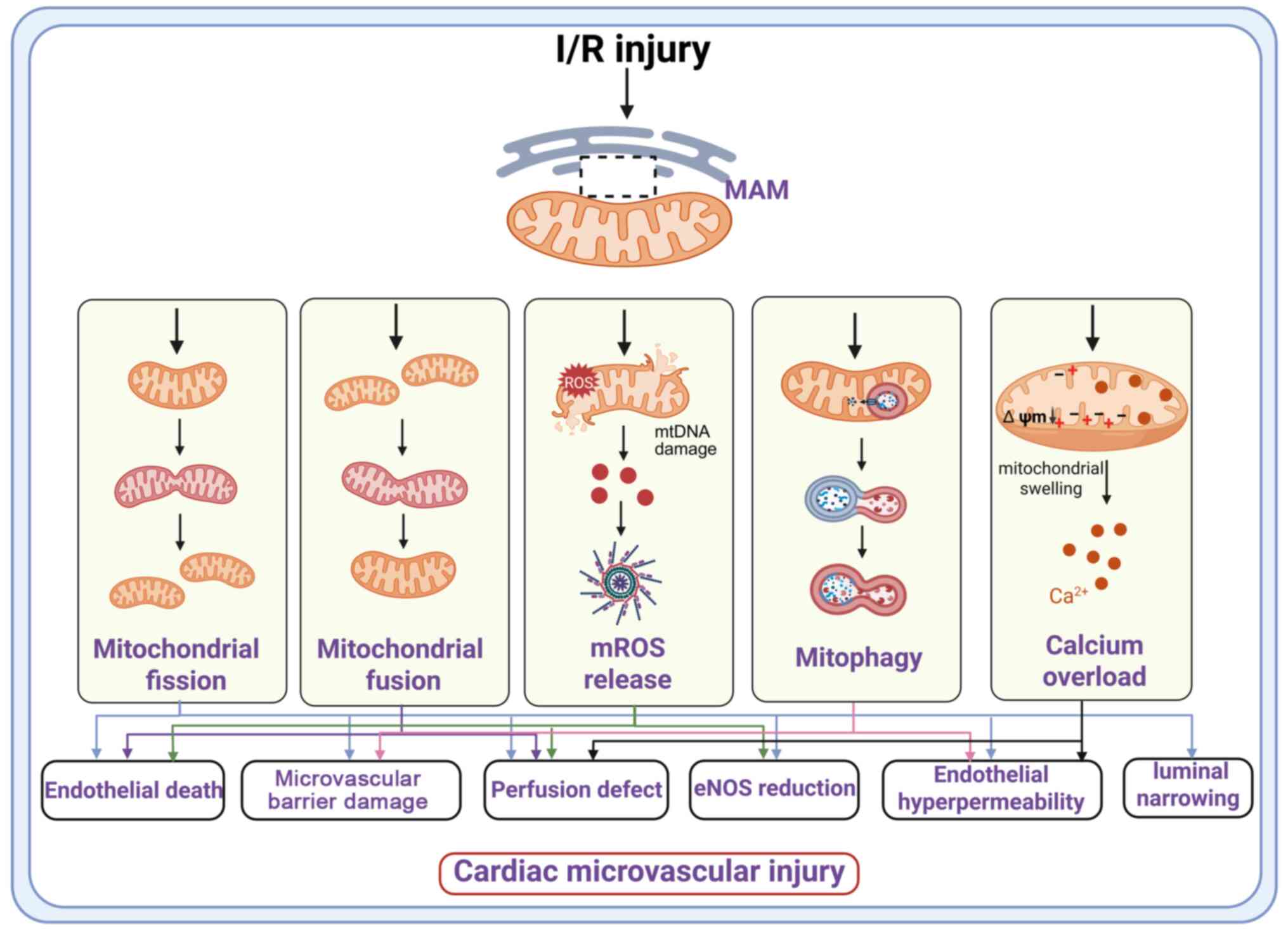

(8). During cardiac

microvascular I/R injury, abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and

impaired mitophagy (2,9) further exacerbate microvascular

dysfunction by compromising vascular patency, altering vascular

tone and amplifying inflammatory responses (10). Further, excessive mitochondrial

Ca2+ uptake leads to overactivation of the electron

transport chain (ETC) and excessive generation of reactive oxygen

species (ROS) (11). This

pathological cascade leads to the collapse of the mitochondrial

membrane potential and promotes the opening of the mitochondrial

permeability transition pore (mPTP) (12). Thus, mitochondrial dysfunction

represents a central mechanism in microvascular I/R injury

(13,14) (Fig. 1).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the largest cellular

organelle composed of a continuous network of tubules and sheets,

plays a fundamental role in protein folding, lipid synthesis and

Ca2+ storage (15,16). Maintenance of ER proteostasis is

vital for secretory function, whereas prolonged ER stress drives

cellular dysfunction and contributes to the pathogenesis of CVD

(17). Research highlights

dynamic crosstalk between the ER and mitochondria as a critical

regulator of cellular homeostasis (18). First described by Wilhelm

Bernhard in 1956 as the connection between the ER and mitochondria

(19), MAMs were later isolated

as unique subcellular structures using subcellular isolation

techniques and density-gradient centrifugation (20). Disruption of MAM integrity

impairs ER-mitochondria communication, leading to homeostatic

imbalance and contributing to various diseases, including cancer,

neurological disorders and CVDs (21). The present review summarized

recent advances in MAM-mediated regulation of mitochondrial quality

control and Ca2+ signaling, offering valuable insights

for future investigations into the molecular mechanisms with

particular emphasis on potential therapeutic strategies.

Mitochondria are central to cellular bioenergetics

and are traditionally described as the powerhouse of the cell,

producing ATP through oxidative phosphorylation driven by the ETC

and oxygen reduction (22). As

well as ATP generation, mitochondria regulate apoptosis,

Ca2+ homeostasis, inflammation and immune responses

(23). In microvascular

endothelial cells, which primarily depend on glycolysis for energy,

mitochondria exhibit a punctate distribution pattern (24). Mitochondria consist of a double

membrane defining four compartments: the outer mitochondrial

membrane (OMM), the intermembrane space (IMS), the inner

mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and the matrix. The OMM contains

porins that mediate exchange with other organelles (25), the IMS stores key apoptotic

factors (26) and the IMM, with

its highly invaginated cristae, harbors the ETC and ATP synthase,

enabling efficient ATP synthesis (27). The IMM is characterized by its

low permeability and high cardiolipin content (28).

MAMs are dynamic contact sites where the OMM and ER

membranes are closely apposed but remain distinct (29). The distance between the two

membranes ranges from ~10 nm up to 80-100 nm (29), as identified by electron

microscopy, with smooth ER-mitochondria contacts typically closer

(10-15 nm) than rough ER contacts (20-30 nm) (30), suggesting that gap width

influences the degree of functional coupling (31). Based on the extent of

ER-mitochondria membrane contact, MAMs are categorized into three

forms: Type I (partial wrapping, ~10% OMM coverage), Type II

(extensive contact, ≤50% of the mitochondrial surface) and Type III

(complete encapsulation) (32).

Type I predominates in most cells, encompassing 10-15% of the OMM

(31).

Studies underscore the therapeutic potential of

targeting MAMs to mitigate hypoxia-induced endothelial injury

(33). Hypoxia directly damages

endothelial mitochondria, characterized by elevated mitochondrial

ROS (mROS), impaired mitophagy, reduced mitochondrial biogenesis

and mitochondrial cristae disruption (34-36). Regulatory proteins and non-coding

(nc)RNAs play key roles in this context. MARCH5, a key regulator of

mitochondrial dynamics, apoptosis and mitophagy, protects

endothelial cells against hypoxia-induced injury via Akt/eNOS

signaling (37), whereas RIPK3

exacerbates damage by upregulating 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors

(IP3R) expression, leading to Ca2+ overload

and oxidative damage (38). The

long (l)ncRNA Malat1 preserves microvascular function after

myocardial infarction by regulating mitochondrial dynamics through

the miR-26b-5p/mitofusin-1 (MFN1) axis (39). Similarly, the compound FL3

promotes MFN1-dependent mitochondrial fusion, stabilizes

Ca2+ homeostasis and alleviates myocardial injury

(40). These findings

demonstrate that endothelial dysfunction and mitochondrial stress

are closely associated with the pathogenesis of microvascular I/R

injury. Targeted modulation of MAMs, therefore, represents a

promising therapeutic strategy for protecting endothelial integrity

and preserving cardiac function (41-43).

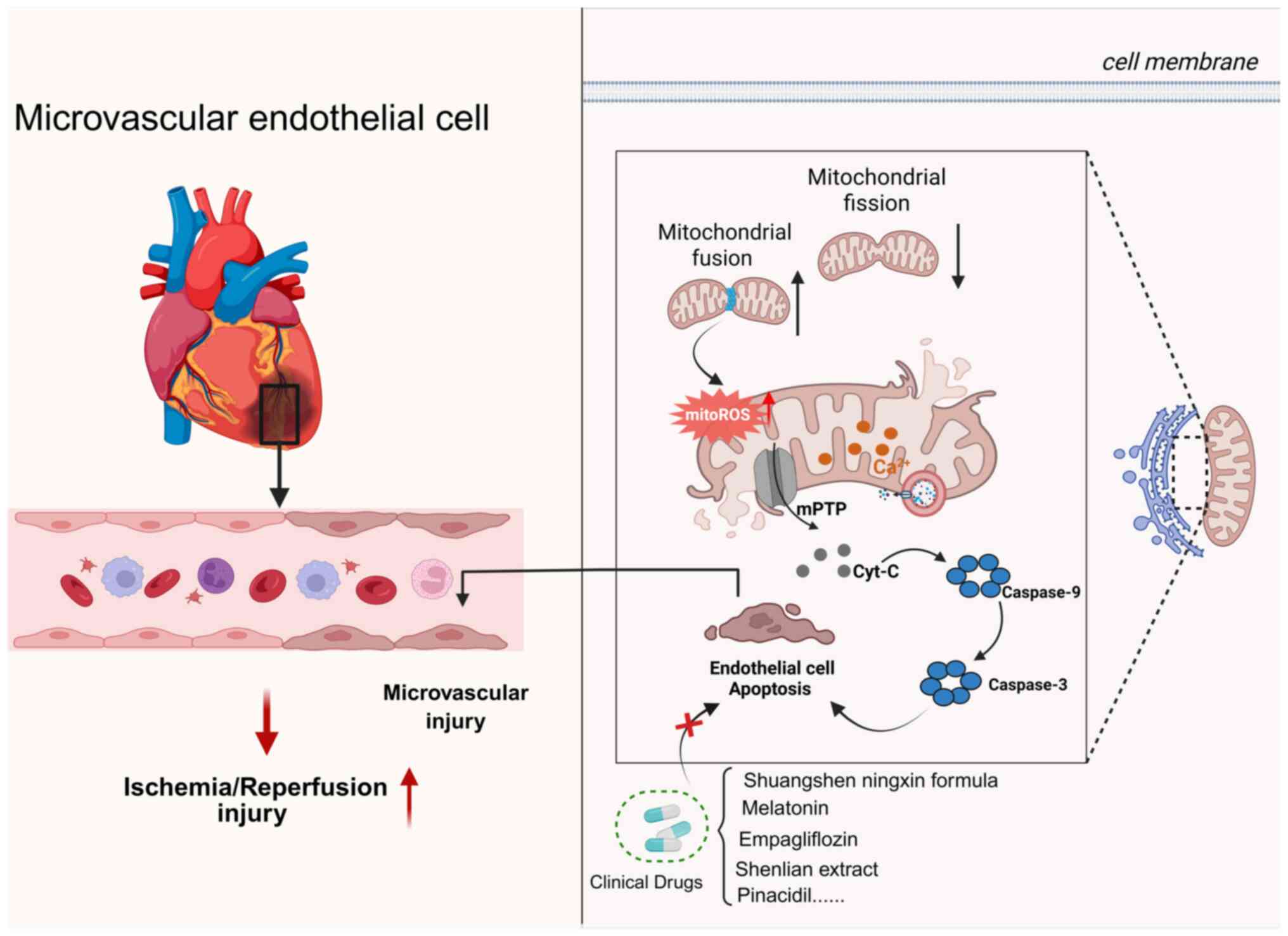

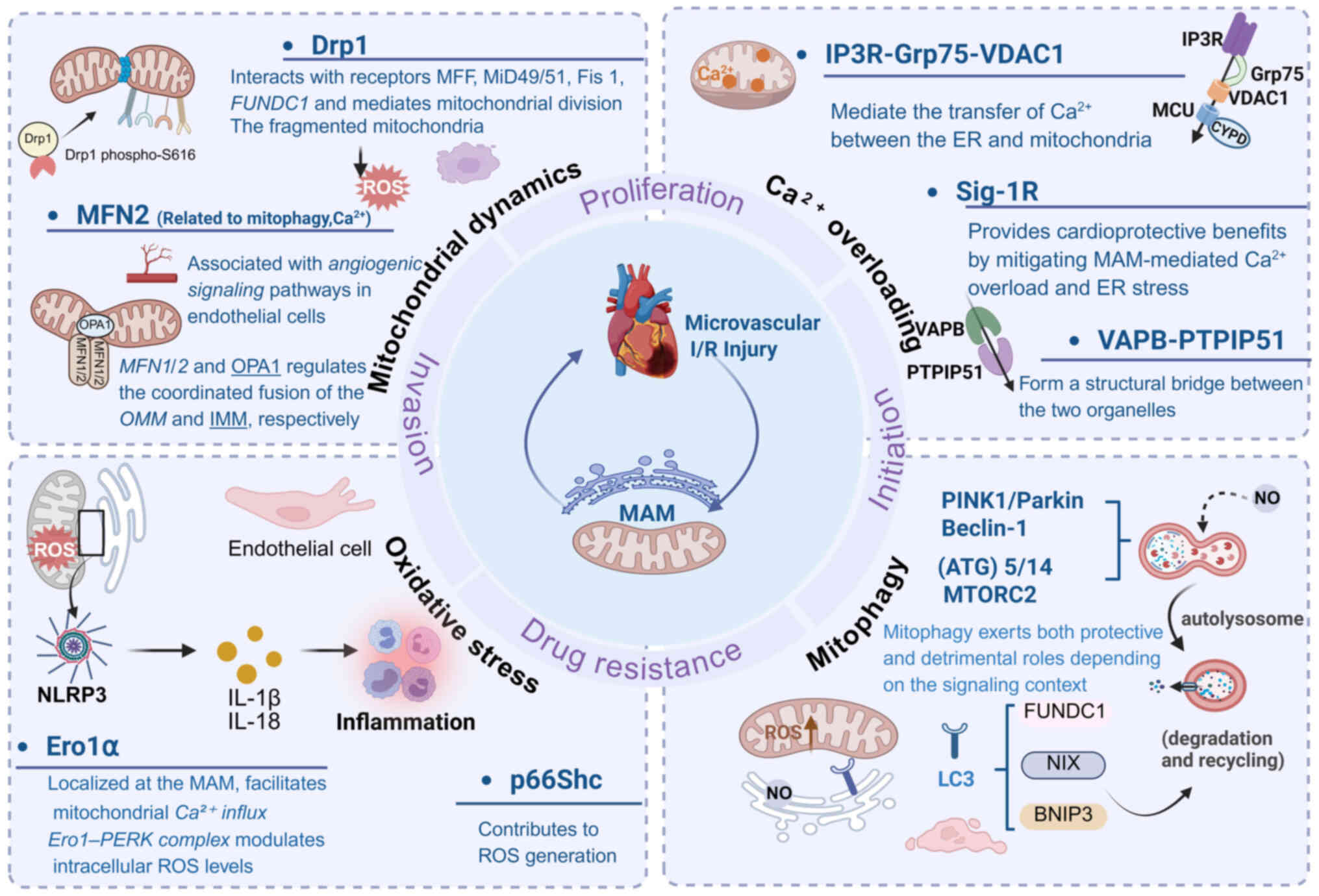

As a crucial component of the mitochondrial quality

control (MQC) system, mitochondrial dynamics facilitates the

selective removal of damaged organelles and renewal of functional

ones (44). Mitochondria

continuously undergo fission, fusion and degradation to preserve

endothelial homeostasis in response to various cellular cues

(45,46). The balance between these fusion

and fission processes determines mitochondrial morphology and

functionality (47-49). Enhanced fusion or reduced fission

promotes the formation of an elongated mitochondrial network,

whereas excessive fission or impaired fusion leads to mitochondrial

fragmentation (50-52).

MAMs serve as a vital regulatory hub that

coordinates mitochondrial by recruiting specific signaling

molecules and effector proteins, ensuring precise spatiotemporal

regulation of mitochondrial fission and fusion (53,54). Quantitative analyses indicates

that >80% of fission and ~60% of fusion events occur at MAMs

(55). These findings underscore

their role as central hubs that coordinate mitochondrial dynamics

and preserve endothelial homeostasis, particularly under stress

conditions.

Mitochondrial fission in cardiac microvascular

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Mitochondrial fission is markedly

upregulated during myocardial I/R injury (56). This process is primarily

initiated at MAMs, where the ER outlines the future division site

even before dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) recruitment (57). Drp1 subsequently accumulates at

ER-mitochondria contact sites, where its fission activity is

regulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as

phosphorylation, ubiquitination and acetylation. These PTMs are

mediated by various enzymes, including cyclin-dependent kinases

(CDKs) and protein kinase A (PKA) (58-60). For example, phosphorylation of

Drp1 at Ser616 promotes its oligomerization and assembly into

constrictive rings on the OMM (61), whereas phosphorylation at Ser637

prevents Drp1 translocation to mitochondria (62). Experimental studies have shown

that inhibiting Drp1 improves microvascular endothelial function,

reduces mROS and attenuates mitochondrial fission (61).

Special attention should be given to the role of

mitochondrial fission proteins within the MAM-associated signaling

network. During the fission process, Drp1 is actively recruited to

the OMM (63). Drp1 then binds

to receptors mitochondrial dynamics protein of 49 kDa (MiD49),

mitochondrial dynamics protein of 51 kDa (MiD51), mitochondrial

fission factor (MFF) and mitochondrial fission protein 1 (Fis1),

constricting the mitochondrial membrane in a GTP-dependent manner,

thereby dividing a single mitochondrion into two separate

organelles (64,65). Immunofluorescence analysis of

Drp1 has shown that Fis1 and MFF are key determinants of both the

number and size of Drp1 puncta on mitochondria. Either MiD49 or

MiD51 can independently mediate Drp1 recruitment and promote

mitochondrial fission even in the absence of Fis1 and MFF (66). Modulation of mitochondrial

fission protein expression markedly influences mitochondrial

morphology: Suppression of MFF disrupts Drp1 foci from the OMM,

leading to elongation of the mitochondrial network, whereas MFF

overexpression facilitates Drp1 recruitment and promotes

mitochondrial fission (67). MFF

and Drp1 interact both in vitro and in vivo and

MFF-dependent mitochondrial fission occurs independently of Fis1.

In endothelial cells, MFF serves as the primary principal adaptor

for Drp1 recruitment (67).

FUN14 domain-containing protein 1 (FUNDC1), a

recently identified mitochondrial outer membrane protein, localizes

to mitochondria-ER contact sites by interacting with the ER

membrane protein calnexin under hypoxic conditions (68). During hypoxia, sustained

mitophagy disrupts the FUNDC1-calnexin interaction, exposing the

cytoplasmic loop of FUNDC1, which subsequently binds to Drp1 and

initiates mitochondrial fission (68). Furthermore, at mitochondria-ER

contact sites, inverted formin-2 (INF2) becomes activated and

promotes actin polymerization (69). Actin filament formation between

the ER and mitochondria likely generates mechanical force that

facilitates mitochondrial constriction and enhance Drp1 assembly

(70). Following fission, the

severing and depolymerizing activity of INF2 enables the rapid

clearance of actin filaments.

MFF-driven excessive fission promotes apoptosis

through a number of mechanisms. Pathological fission contributes to

mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and the

subsequent release of cytochrome c into the cytosol

(74,75), although whether fission precedes

or follows MOMP remains unresolved. Studies suggest three major

apoptotic pathways triggered by excessive mitochondrial fission.

First, fission induces double-strand breaks in mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA), impairing transcription and replication. mtDNA damage

disrupts ETC activity, increases proton leakage and elevates ROS

generation (76,77). Second, mROS oxidize cardiolipin,

decreasing its binding affinity for cytochrome c and

facilitating its release into the cytosol, thereby activating

apoptotic signaling (78).

Third, mitochondrial fragmentation promotes the polymerization of

voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) and displaces hexokinase

2 (HK2) from VDAC1 (79). These

changes open the mPTP. The combined effects of oxidative stress,

MOMP and mPTP activation exacerbate cardiac microvascular I/R

injury, leading to impaired endothelial nitric oxide synthase

(eNOS) synthesis, endothelial barrier breakdown, loss of vascular

integrity, capillary obstruction and abnormal vascular permeability

(80,81). Thus, MFF-mediated mitochondrial

fission represents a key pathological mechanism in microvascular

I/R injury and represents a potential therapeutic target (78).

In summary, excessive fission serves as a key

pathological driver of I/R injury (82). Therapeutic intervention of

MAM-associated molecular pathways, therefore, represents a

promising strategy for attenuating cardiac microvascular I/R injury

by suppressing pathological mitochondrial fission. Several agents

have been shown to act through this axis. Shuangshen Ningxin

formula, a traditional Chinese medicine compound, alleviates

cardiac microvascular I/R injury by improving mitochondrial

function through the regulation of the NR4A1/MFF/Drp1 pathway

(83). Melatonin exerts

protective effects against cardiac microvascular I/R injury by

activating AMPKα and promoting inhibitory phosphorylation of Drp1

at Ser637, suppressing fission and enhancing ATP synthase activity.

It also attenuates cardiac microvascular injury by targeting the

mitochondrial fission-VDAC1-HK2-mPTP-mitophagy cascade (79). Similarly, Bax inhibitor-1 (BI1)

preserves mitochondrial integrity under I/R conditions by reducing

F-actin-mediated fission, suppressing xanthine oxidase (XO)

activity and limiting ROS production, ultimately maintaining

endothelial viability and barrier function (84). Furthermore, BI1 is also

associated with microvascular protection in I/R injury via

repressing Syk-Nox2-Drp1-mitochondrial fission pathways (85). The ROS-JNK-Drp1 pathway has been

identified as a primary mechanism driving endothelial cell injury

and mitochondrial fission during hypoxia-reoxygenation injury; its

inhibition may provide a novel therapeutic strategy to prevent

coronary no-reflow injury (86).

Empagliflozin protects against microvascular I/R injury by

suppressing mitochondrial fission via inactivation of the

DNA-PKcs/Fis1 pathway (87). By

contrast, pretreatment with 2'-hydroxycinnamaldehyde (HCA) reduces

Drp1 expression and improves microvascular function during

reperfusion (88).

MAMs exert multifaceted control over mitochondrial

fission. Resident proteins and signaling cascades at MAMs

facilitate mitochondrial constriction and Drp1 recruitment,

promoting fragmentation. Protective mechanisms suppress pro-fission

proteins or inhibit associated signaling pathways. These mechanisms

collectively reduce mROS, prevent mPTP opening and preserve

endothelial cell viability. The MAM-mitochondrial fission axis

represents a promising therapeutic target for ameliorating cardiac

microvascular I/R injury.

Mitochondrial fusion in cardiac microvascular

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Compared with mitochondrial fission,

mitochondrial fusion in endothelial cells during myocardial

infarction has been less extensively studied. However,

mitochondrial fusion is essential for mitochondrial repair and

functional recovery, as it facilitates the exchange of matrix and

membrane components, preserving mitochondrial integrity and

maintaining bioenergetic homeostasis. Mitochondrial fusion involves

the coordinated fusion of the OMM and IMM, which is regulated

primarily by MFN1/2 and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), respectively

(56,89) (Table I). Mitofusin-2 (MFN2) is

particularly important because it not only mediates OMM fusion but

also regulates mitochondria-ER tethering at MAMs (90,91). MFN2 plays a crucial role in

maintaining normal mitochondrial functions, including fusion,

axonal transport, inter-organelle communication and mitosis

(92). Unlike MFN1, which is

confined to the mitochondrial membrane, MFN2 is distributed across

the ER, OMM and MAMs. Homotypic interactions between MFN2 molecules

on adjacent membranes, or heterotypic interactions between

ER-localized MFN2 and mitochondrial MFN1, form dimeric or

multimeric complexes that maintain an optimal distance of 10-30 nm

between the two organelles (91,93). Loss or downregulation of MFN2

enhances both structural and functional coupling between the ER and

mitochondria. Thus, MFN2 acts as a negative regulator of excessive

ER-mitochondria tethering and its reduced expression disrupts this

control, promoting aberrant and potentially harmful ER-mitochondria

crosstalk (94). OPA1 then

remodels the IMM, restoring membrane continuity and structural

integrity. This step requires the cardiolipin-binding domain of

OPA1.

Fusion of the inner and outer mitochondrial

membranes is further regulated by proteolytic processing and

ubiquitination (95). At the

IMM, long OPA1 (L-OPA1) is cleaved at sites S1 and S2 to form short

OPA1 (S-OPA1) (96,97). The AAA+ protease YME1L mediates

S2 cleavage under basal conditions, whereas the stress-responsive

metalloprotease OMA1 cleaves at S1, thereby disrupting the OPA1

isoform balance (98-100). Under physiological conditions,

a near-equivalent ratio of L-OPA1 to S-OPA1 preserves membrane

fusion activity (101,102). Pathological stimuli,

particularly loss of membrane potential, activate OMA1 (103), shifting the ratio and impairing

fusion, leading to fragmentation (104).

MFN1 and MFN2 are not only central to mitochondrial

structure but are also closely associated with angiogenic signaling

pathways in vascular endothelial cells (105). Loss of MFN1/2 disrupts fusion

and mitochondrial networks, leading to reduced membrane potential,

impaired endothelial cell survival and reduced responsiveness to

VEGF signaling, which then suppresses angiogenesis. Fusion is also

essential for maintaining protein synthesis and energy metabolism,

as well as preventing mitochondrial DNA loss (106). Despite these protective roles,

MFN2 exerts context-dependent regulatory effects on cellular

physiological and pathological processes. In cardiomyocytes, MFN2

depletion limits mPTP opening and increases tolerance to

Ca2+-induced injury, improving resistance to ischemia

during I/R (107). In other

cell types or under pathological stress, silencing or deletion of

MFN2 enhances mitochondria-ER interactions, promotes

Ca2+ transport into mitochondria and increases

susceptibility to Ca2+-induced cell death (93). These findings suggest that the

function of MFN2 varies according to cell type and disease state.

Moreover, MFN2 and OPA1 transcriptional levels are markedly reduced

during I/R injury, consistent with functional inhibition of

mitochondrial fusion. Regulation of mitochondrial function can

mitigate hypoxic-stress-induced apoptosis (108). Overexpression of the

sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump sarco/endoplasmic

reticulum Ca2+ATPase (SERCA) in CMECs reverses MFN2/OPA1

downregulation, increases mitochondrial fusion, reduces

fragmentation and improves microvascular integrity by restoring

Ca2+ homeostasis (109).

ER stress and impaired intercellular connections are

closely associated with mitochondrial fusion-related disorders.

This pathogenic cascade is characterized by the loss of

cardiac-specific Lon peptidase 1 (LonP1), disruption of the MAM

structure, defective mitochondrial fusion and activation of the ER

unfolded protein response (UPRER) (110). These interrelated changes

contribute to metabolic reprogramming and cardiac structural

remodeling. Fusion dysfunction also activates the

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-, leucine-rich repeat-

and pyrin domain-containing receptor 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome,

triggering vascular inflammatory responses (111). During the early stages of I/R,

impaired fusion leads to interstitial edema and endothelial cell

swelling, further reducing microcirculatory perfusion (112). In female mouse models, I/R

injury disrupts endothelial connections, decreases connexin 43

expression and alters the balance of MMP-3 and TIMP-1 (113,114). Restoration of MFN2 expression

reverses these changes and increases endothelial progenitor cell

marker expression, including platelet endothelial cell adhesion

molecule 1 (CD31), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

(VEGFR2), Fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 (FLT4) and Kinase Insert

Domain Receptor (KDR) (114).

Loss of cell junctions compromises endothelial barrier function,

increasing susceptibility to platelet and coagulation system

activation and exacerbating microvascular thrombosis (115). This mechanism impairs

myocardial perfusion during reperfusion by promoting microvascular

obstruction. Downregulation of MFN2 reduces mitochondrial

Ca2+ overload by decreasing CypD-VDAC1-IP3R1

interactions. However, MFN2 broadly supports endothelial integrity,

microvascular structure and maintenance of fusion (116). These results suggest that MFN2

exerts a dual role in cardiac microvascular I/R injury by

regulating endothelial cell metabolism, apoptosis and inflammatory

responses while preserving MAM homeostasis.

Most of these findings are derived from

loss-of-function studies using RNA interference to inhibit MFN1/2

or OPA1 expression in endothelial cells in vitro (51,117). However, the protective effects

of MFN1/2- or OPA1-mediated fusion have not been conclusively

validated in rescue experiments using transgenic mouse models or

virus-mediated overexpression. Moreover, interactions between

mitochondrial fission and fusion in cardiac microvascular I/R

injury remain poorly defined. For example, whether active induction

of fusion can directly inhibit fission is unclear. Research

suggests that the MFN2/Drp1 expression ratio may reflect the

dynamic balance between fusion and fission (118), providing a potential avenue for

further investigation; however, its clinical applicability has yet

to be established.

Oxygen is transported from the bloodstream through

endothelial cells to the surrounding perivascular tissues. Research

indicates that endothelial dysfunction can impair this process by

reducing the rate of oxygen diffusion across the arteriolar wall

(119). Under hypoxic

conditions, impaired respiration promotes excessive production of

mROS (120). The mROS are

primarily generated within the ETC of the IMM during oxidative

phosphorylation (121,122). While moderate ROS levels act as

second messengers in physiological signaling, excessive ROS induces

oxidative stress, causing endothelial senescence and cell death.

Ischemia- or inflammation-induced oxidative stress activates

mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways, leading to further cell

death (123,124). I/R injury is particularly

associated with ROS accumulation. Activation of XO during

reperfusion markedly increases ROS, reduces nitric oxide (NO)

bioavailability and triggers microvascular spasm and impaired

perfusion (125). Furthermore,

mitochondrial superoxide oxidizes tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) to

dihydrobiopterin (BH2), preventing BH4 binding to eNOS. This

uncoupling of eNOS decreases NO production and exacerbates vascular

dysfunction (126).

Protective mechanisms also regulate oxidative

stress. MAMs are implicated in multiple cardiovascular disorders,

mainly by promoting oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiac

tissue (127). They represent

the only known binding platform for the NLRP3 inflammasome complex,

contributing markedly to ROS-mediated oxidative injury (128). The NLRP3 inflammasome is

composed of NLRP3, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC)

and caspase-1 (129). NLRP3 is

localized to the ER, whereas ASC is anchored on the OMM. MAMs serve

as scaffolds that facilitate NLRP3 inflammasome assembly by

enabling the interaction between NLRP3 and ASC (130). mROS are essential regulators of

NLRP3 activation. They promote dissociation of

thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) from thioredoxin (TRX),

after which TXNIP binds to NLRP3, initiating caspase-1 activation

and cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 (131). This cascade drives robust

inflammatory responses. In CMECs, TXNIP-dependent NLRP3 activation

has been identified as a novel mechanism of injury during

myocardial I/R (129). The

extent of myocardial infarction and subsequent functional recovery

is strongly affected by the intensity of this inflammatory response

(132). Thus, NLRP3 activation

serves as a critical mechanistic link between mitochondrial

dysfunction and inflammation, playing a key role in microvascular

dysfunction following I/R injury (128). Experimental studies demonstrate

that early inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activity during

reperfusion improves cardiac function and reduces infarct size,

highlighting it as a promising therapeutic target (133).

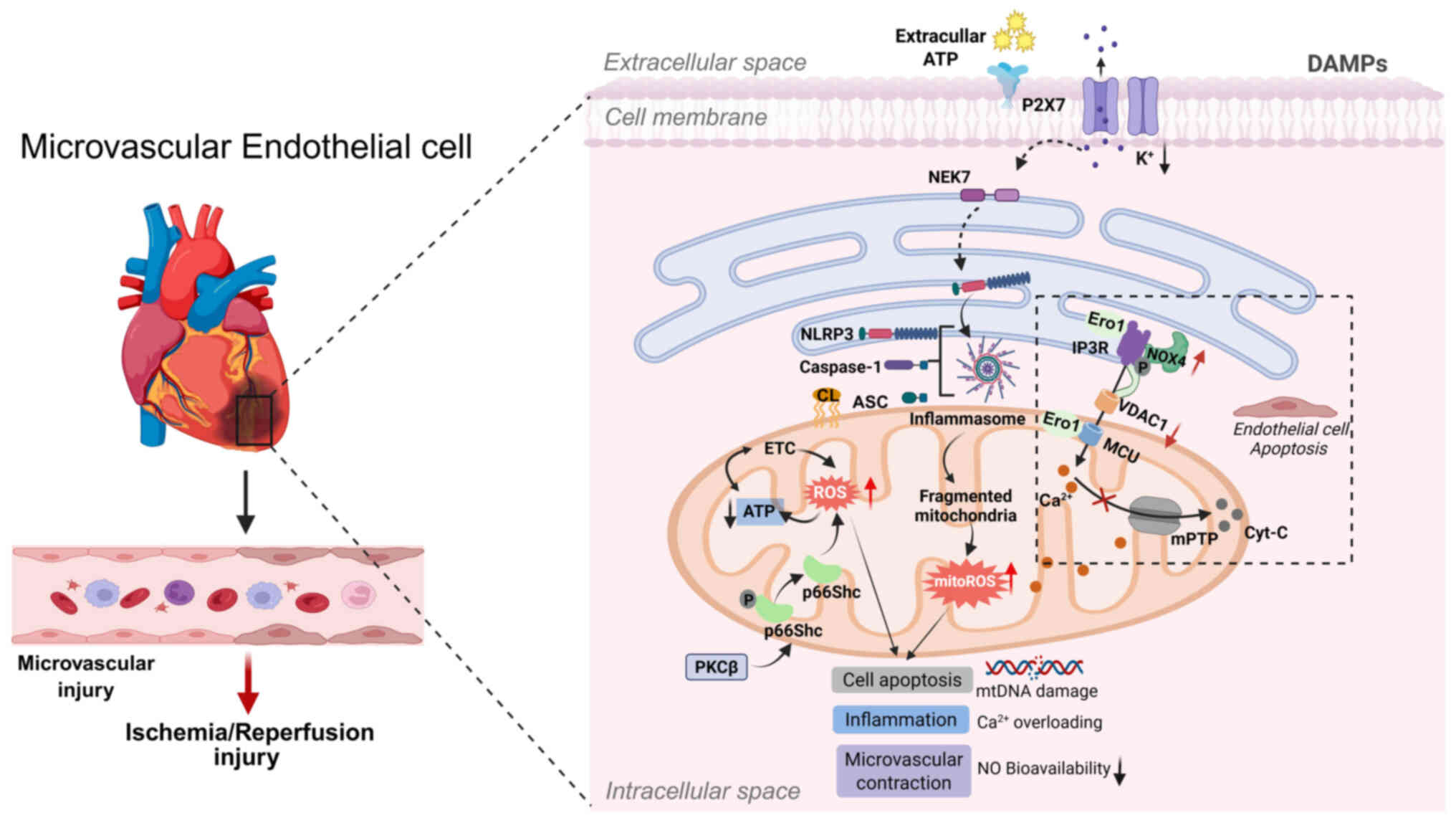

Elevated ROS levels at MAMs can trigger the release

of mtDNA and the opening of the mPTP. Within MAMs, mtDNA functions

as a damage-associated molecular pattern, initiating NLRP3

inflammasome activation and downstream inflammatory signaling

(134). During cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion, necrotic cardiomyocytes release ATP, which

binds to P2X7 receptors on neighboring non-ischemic cardiomyocytes.

This interaction induces potassium ion (K+) efflux,

lowering cytoplasmic K+ concentration. The resulting

hypokalemic state activates NIMA-related kinase 7 (NEK7), promoting

inflammasome assembly and NLRP3 activation (135). Moreover, decreased

extracellular H+ concentration increases

Na+/H+ and Na+/Ca2+

exchange, aggravating intracellular Ca2+ overload

(135). This increases

mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation within MAMs and further

stimulates ROS production. Excess ROS induces cardiolipin release

from the IMM, enabling cardiolipin to bind NLRP3 and promote

inflammasome formation. Inhibition of two voltage-dependent anion

channel (VDAC1 and VDAC2) isoforms in the OMM markedly reduces

NLRP3 inflammasome activation, caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β

production (127). These

findings suggest potential therapeutic targets for reducing

inflammation and improving heart function following myocardial

infarction.

The MAM serves as an important site for ROS

generation. Structural proteins located at the MAM, such as

endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1 (Ero1) (136) and 66-kDa isoform of the growth

factor adaptor Shc (p66Shc) (137), play pivotal roles in redox

signaling between mitochondria and the ER, thereby regulating ROS

production (Table I). Ero1α,

localized at the MAM (138),

facilitates Ca2+ influx by activating the mitochondrial

calcium uniporter (MCU) (139).

During early stages of ER stress, Ero1α interacts with PKR-like

endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), a PKR-like ER kinase, forming

the Ero1-PERK complex that coordinates mitochondrial fusion,

enhances ER-mitochondria interactions, restores mitochondrial

bioenergetics and modulates intracellular ROS levels (140). PERK functions as a

MAM-anchoring protein, promoting the formation of MAMs through

oligomerization (141) and

transmitting ROS signals to mitochondria (142). Furthermore, the Ero1-PERK

complex reduces ER Ca2+ levels and promotes

ER-to-mitochondria Ca2+ flux (143). Conversely, the absence of PERK

impairs Ero1α-mediated IP3R oxidation, thereby

disturbing mitochondrial redox homeostasis (144). Similarly, under oxidative

stress, activated protein kinase C β (PKCβ) phosphorylates p66Shc

at Ser36, triggering its translocation to mitochondria or the MAMs,

where it contributes to ROS generation (137,145). Although ROS derived from p66Shc

may support short-term cellular repair responses (146), persistent activation can lead

to the onset and progression of various cardiovascular diseases

(147). NADPH oxidase (Nox),

particularly the Nox1, Nox2 and Nox4 isoforms (148), is a major contributor to ROS

production in myocardial I/R injury. Nox4 localizes to MAMs, where

its expression increases under stress conditions. It functions as

an endoplasmic reticulum-localized source of ROS, maintaining basal

IP3R oxidation necessary for OXPHOS and regulating redox

signaling within the ER under stress conditions (149). At these sites, Nox4 facilitates

Akt-mediated phosphorylation of IP3R, which inhibits

Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria and prevents

mPTP-dependent cell death. This localized redox signaling underlies

the protective role of Nox4 in reducing necrosis in both

cardiomyocytes and intact hearts following I/R injury (149) (Fig. 2).

A number of therapeutic strategies have been

reported to alleviate oxidative stress and protect cardiac

function. ENPP2 regulates redox balance and mitochondrial activity,

reducing hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in CMECs (150). Liproxstatin-1, a ferroptosis

inhibitor, protects the myocardium by downregulating VDAC1 and

restoring GPX4 (151). In a

pressure-overload mouse model, ginkgolide A (GA) reduced oxidative

stress and increased NO bioavailability in the heart (152). Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)

analogs, such as liraglutide, have demonstrated cardioprotective

effects in clinical trials by lowering oxidative stress and

vascular inflammation, preventing eNOS uncoupling and preserving

endothelial function (153).

Histone deacetylase 7-derived peptides promote angiogenesis and

limit oxidative stress in hind limb ischemia, preserving

endothelial integrity (154).

Naringin (Nar) improves cardiac microvascular function, potentially

by facilitating NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S1

(NDUFS1) translocation to mitochondria, reducing ROS and protecting

endothelial cells (155).

Furthermore, PSS-carrying nanoparticles minimize oxidative stress

and reverse coronary microcirculatory dysfunction (156).

Regulation of ROS production and mitigation of

oxidative damage constitute the primary mechanisms by which MAMs

modulate cellular functions during oxidative stress responses

(157). Importantly,

MAM-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress does not occur in

isolation; elevated ROS levels drive a shift in mitochondrial

dynamics from fusion toward fission. These fragmented mitochondria

become major sources of apoptotic signals and excessive mROS

generation (158). Excessive

ROS stimulation further amplifies mitochondrial dysfunction,

leading to swelling, loss of cristae structure and rupture of the

outer membrane, ultimately releasing apoptosis-related proteins

into the cytoplasm and activating the apoptotic cascade (159). Further research on how

MAM-inflammasome crosstalk contributes to oxidative stress is

essential for elucidating the mechanisms underlying cardiac

microvascular I/R injury and developing effective therapeutic

strategies.

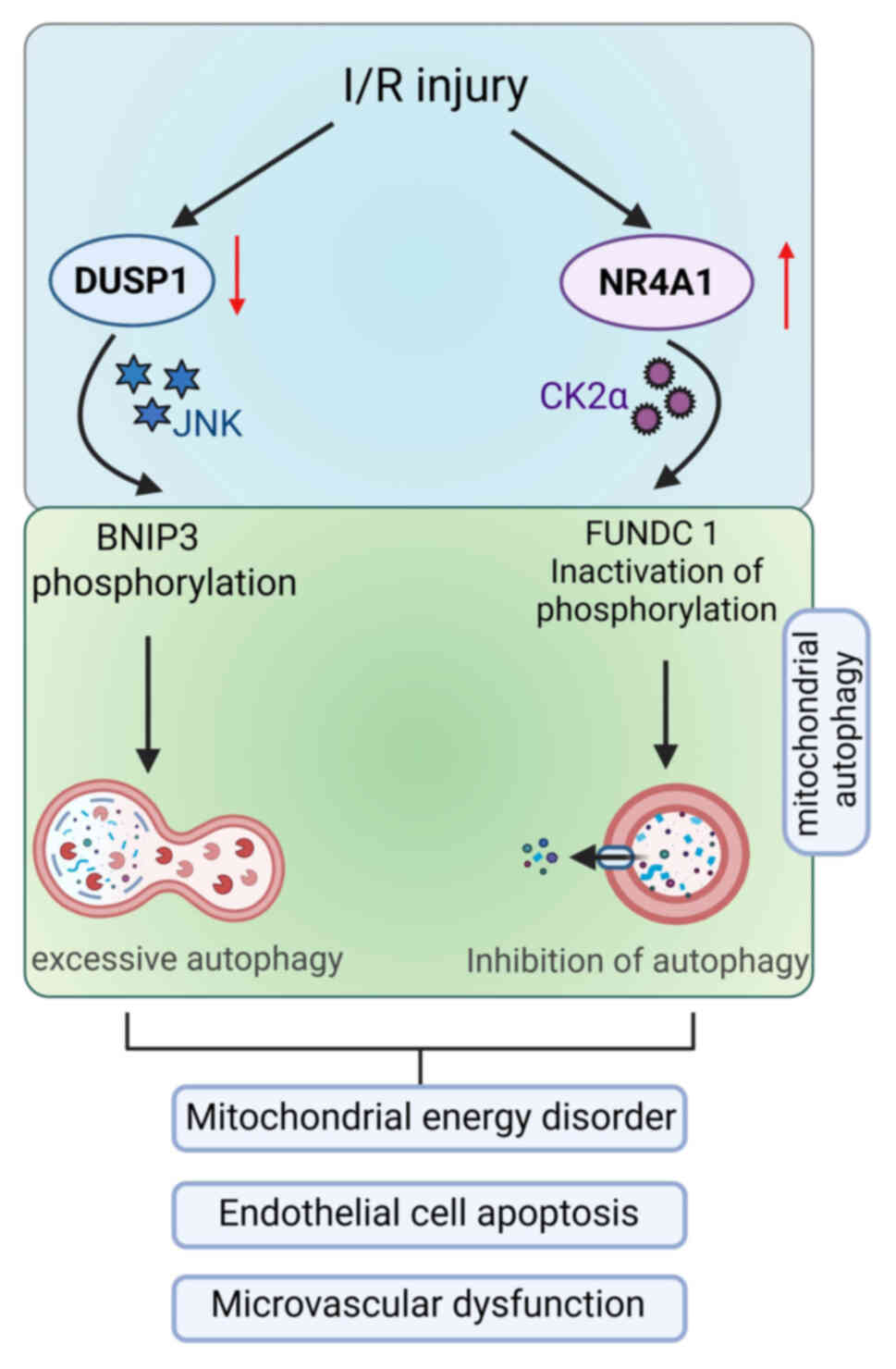

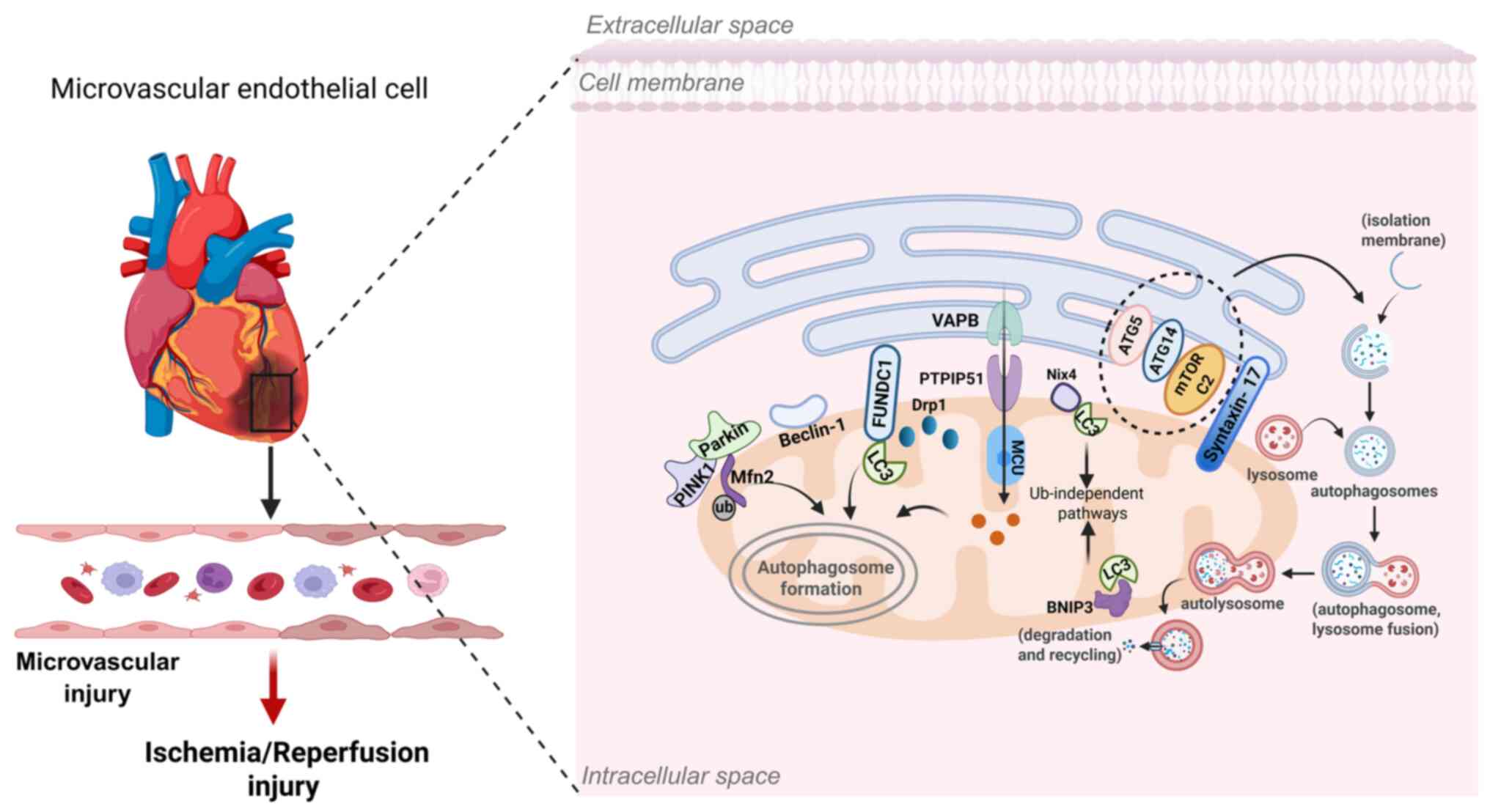

Mitophagy, the selective autophagic degradation of

damaged mitochondria, is essential for maintaining cellular

homeostasis and regulating energy metabolism. It has emerged as a

potential therapeutic target for limiting I/R injury (160) and protecting the

microvasculature (48). MAMs

play a central role in this process by functioning as specialized

subdomains where both initiation and progression of mitophagy

occur. The pathway proceeds through different stages: initiation,

phagophore elongation, autophagosome closure, lysosomal fusion and

degradation and is regulated by a set of autophagy-related genes

and proteins (161). Mitophagy

signaling depends on receptor proteins at the OMM, including

FUNDC1, BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3),

Nip3-like protein X (Nix) and mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin protein

ligase 1 (Mul1), as well as the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin

(162). Upstream regulation is

closely associated with mitochondrial dynamics. Mitochondrial

fission, often a prerequisite for mitophagy, is regulated by

proteins such as MFF, whose activity is influenced by DUSP1

(72) and NR4A1 (73). In CMECs, NR4A1 inhibits mitophagy

by suppressing FUNDC1 (73),

whereas DUSP1 promotes it through BNIP3 phosphorylation (Fig. 3).

Beclin1, which is also enriched at MAMs, enhances

autophagic flux and regulates ER-mitochondria interactions,

functioning as a protective factor against I/R injury (171). The serine residue at position

15 of Beclin1 can be phosphorylated by Unc-51-like

autophagy-activating kinase 1 (ULK1) (172), a kinase involved in mitophagy

(173) and this modification is

essential for Beclin1's association with MAMs during the mitophagic

process. Localization of Beclin1 at MAMs ensures that autophagosome

formation occurs in proximity to damaged mitochondria, facilitating

their efficient sequestration and degradation (171). Furthermore, studies have shown

that Beclin1-driven autophagy suppresses caspase-4-mediated

apoptosis, thereby protecting microvascular endothelial cells from

I/R-induced injury (174).

Crosstalk among various mitophagy adaptors

ultimately determines the net effect of mitophagy. Fission of

damaged mitochondria into smaller fragments facilitates their

elimination through mitophagy (186). Autophagy and fission occur

simultaneously, forming a coordinated response (187). Moderate mitophagy limits

excessive fragmentation induced by pathological fission (175,188,189). Thus, fission is both a

prerequisite for mitophagy activation and, when excessive, a

process that can be counterbalanced by appropriately regulated

mitophagy. Taken together, these findings underscore that mitophagy

exerts both protective and detrimental roles depending on the

signaling context. The precise contribution of specific adaptors in

endothelial cells and their interactions with fission machinery

remain unclear. Therefore, the controlled regulation of mitophagy

represents a key area of investigation for mitigating microvascular

I/R injury.

Several molecular regulators modulate this process.

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and the Sigma-1 receptor

(Sig-1R) are key MAM-associated proteins that alleviate ER stress

and reduce Ca2+ uptake, conferring cardioprotection

during I/R (206,207). GSK-3β, an enzyme responsible

for phosphorylating and inactivating glycogen synthase (208,209), can be recruited to the MAM,

where it regulates IP3R1-mediated calcium release. This

regulation promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation and

induces the opening of the mPTP. As a result, inhibition of GSK-3β

has been suggested to exert cardioprotective effects during I/R

injury (206). The Sig-1R is a

specific chaperone localized at MAMs (207). Overexpression of Sig-1R

enhances ER-to-mitochondria Ca2+ flux and through its

interactions with ankyrin and the ER chaperone BiP. Under

physiological conditions, Sig-1R remains bound to BiP; however,

under ER stress or following ER Ca2+depletion, Sig-1R

dissociates from BiP and binds to IP3R instead. This

interaction stabilizes IP3R, preventing its degradation

and restoring efficient Ca2+ transfer from the ER to

mitochondria (207). Moreover,

Sig-1R stabilizes MAM structure through its interactions with VDAC1

and IP3R and provides cardioprotective benefits by

mitigating MAM-mediated Ca2+ overload and ER stress

(207). Under conditions of

elevated ROS, Sig-1R also interacts with reactive oxygen species,

thereby activating and stabilizing IRE1 (210).

Cyclophilin D (CypD), a key regulator of the mPTP

located in the matrix. During H/R, increased interactions within

the CypD-VDAC1-GRP75-IP3R1 super-complex drive

mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and cardiomyocyte death

(126). Genetic ablation of

CypD protects against I/R-induced necrosis by limiting this

aberrant Ca2+ transfer (211,212). Similarly, deletion of the

PPIF gene (encoding CypD), or knockdown of IP3R1

or GRP75, reduces H/R-induced Ca2+ overload and cell

death (211). Pharmacological

interventions also provide protection; melatonin attenuates

oxidative stress and reduces CMEC mortality by inhibiting

IP3R-VDAC-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ influx,

increasing endothelial resistance to oxidative damage (77).

MAM tethering is also regulated by the OMM protein

PTPIP51 and the ER protein vesicle-associated membrane

protein-associated protein-B (VAPB), which form a structural bridge

between the two organelles (213). Overexpression of PTPIP51

strengthens this physical connection, enhances ER-mitochondria

coupling and increases mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake through

MCU activation (214,215). However, pharmacological or

genetic inhibition of MCU abolishes this effect and protects

cardiomyocytes from apoptosis (211). The ER chaperone calreticulin

(CRT), with its high Ca2+-binding capacity, also plays a

key role in buffering and storage. Upregulation of CRT restores

Ca2+ homeostasis by improving ER Ca2+

reserves (216) (Fig. 5). Collectively, MAM-associated

proteins regulate calcium transport through distinct and highly

coordinated mechanisms (Table

II).

Therapeutically, pinacidil has been shown to

preserve CRT expression, reduce endothelial Ca2+

overload and prevent mitochondrial apoptosis in CMECs, ultimately

improving microvascular density, increasing blood flow, reducing

infarct size and attenuating the no-reflow phenomenon following I/R

injury (217). Other protective

mechanisms involve ER-transmembrane proteins such as transmembrane

protein 215 (TMEM215), which protect endothelial cells by

inhibiting BCL-2-interacting killer (BIK). Since BIK promotes

ER-to-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer, its suppression by

TMEM215 reduces pathological Ca2+ flux and supports cell

survival during reperfusion (218).

Damage to this microvascular network during I/R can

result in interstitial hemorrhage and edema (220). The MAM functions as a pivotal

signaling hub that orchestrates mitochondrial dynamics, oxidative

stress responses, mitophagy and calcium homeostasis. Importantly,

these mitochondrial alterations do not occur in isolation but are

intricately interconnected (Fig.

6). Core MAM-associated proteins such as Drp1, MFN2, FUNDC1,

Ero1α, IP3R, VDAC1 and Sig-1R play essential roles in

maintaining normal microvascular physiology. By integrating these

key MAM components, molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways,

advances in understanding cardiac microvascular I/R injury have

provided new perspectives for addressing clinical conditions such

as the no-reflow phenomenon and microvascular angina (Fig. 7).

Moreover, several pharmacological agents, including

empagliflozin, Shuangshen Ningxin Pill and melatonin, have been

shown to exert protective effects against microvascular I/R injury

through MAM-related mechanisms (Table IV). However, most of the current

evidence remains confined to cellular and animal models. Future

research, focusing on the safety, controllability and efficacy of

MAM-targeted interventions at the human microvascular level may

enable the development of more effective therapeutic

strategies.

Despite these advances, the inherent complexity and

dynamic nature of MAMs present major challenges to further

investigation. Our current understanding of MAMs remains limited,

particularly regarding how their morphology, inter-organelle

distance, membrane thickness and number of contact sites influence

cellular energy metabolism and contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Beyond serving as a structural bridge between mitochondria and the

ER, the bidirectional regulatory mechanisms by which MAMs

coordinate organelle function remain incompletely understood, for

instance, the role of MAM-localized MFN2. It also remains unclear

whether MAMs show conserved structural and functional features

across different cardiovascular cell types, how their formation can

be selectively modulated for therapeutic benefit and whether they

might serve as early biomarkers of microvascular injury.

Furthermore, the temporal dynamics, spatial organization and

hierarchical signaling networks that govern MAM remodeling in

endothelial cells under stress conditions are still poorly

characterized.

Future research should aim to develop multiscale

integrative models of MAMs to elucidate the causal relationships

between their dynamic remodeling and microvascular pathological

responses. Employing advanced in vivo multi-omics and

imaging technologies, such as the Split-GFP contact sensor

(221,222) and serial block-face scanning

electron microscopy (223), may

provide deeper insights into their structural and functional

characteristics. Given the involvement of MAMs in key cellular

processes, including energy metabolism, inflammation and cell

death, their dysregulation likely contributes to the pathogenesis

of cardiovascular, metabolic and neurological disorders. Therefore,

clarifying the molecular mechanisms underlying MAM function could

not only enhance our understanding of cardiovascular

microcirculatory pathology but also reveal broadly applicable

therapeutic targets for multiple diseases. However, pharmacological

strategies targeting MAMs alone may be limited by individual

metabolic variations and comorbid conditions; thus, future

investigations should emphasize combinatorial regulatory

approaches, such as dual-target therapies that modulate both MAMs

and mitochondrial metabolism.

Not applicable.

YW and B F conceived the idea for the present

review and drafted the manuscript. YtW and ZS created the figures

and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. HY, WC and CZ

reviewed and modified the manuscript and screened literature. ZL

provided valuable guidance and analysis during the present review.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the Jilin Provincial Natural

Science Foundation (grant no. YDZJ202401052ZYTS).

|

1

|

Marin W, Marin D, Ao X and Liu Y:

Mitochondria as a therapeutic target for cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion injury (Review). Int J Mol Med. 47:485–499.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yang M, Linn BS, Zhang Y and Ren J:

Mitophagy and mitochondrial integrity in cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1865:2293–2302. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhao BH, Ruze A, Zhao L, Li QL, Tang J,

Xiefukaiti N, Gai MT, Deng AX, Shan XF and Gao XM: The role and

mechanisms of microvascular damage in the ischemic myocardium. Cell

Mol Life Sci. 80:3412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Abbate A, Kontos MC and Biondi-Zoccai GGL:

No-reflow: The next challenge in treatment of ST-elevation acute

myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 29:1795–1797. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Davidson SM, Arjun S, Basalay MV, Bell RM,

Bromage DI, Bøtker HE, Carr RD, Cunningham J, Ghosh AK, Heusch G,

et al: The 10th biennial hatter cardiovascular institute workshop:

Cellular protection-evaluating new directions in the setting of

myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, and cardio-oncology. Basic

Res Cardiol. 113:432018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

de Waha S, Patel MR, Granger CB, Ohman EM,

Maehara A, Eitel I, Ben-Yehuda O, Jenkins P, Thiele H and Stone GW:

Relationship between microvascular obstruction and adverse events

following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction: An individual patient data pooled

analysis from seven randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 38:3502–3510.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Eitel I, de Waha S, Wöhrle J, Fuernau G,

Lurz P, Pauschinger M, Desch S, Schuler G and Thiele H:

Comprehensive prognosis assessment by CMR imaging after ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 64:1217–1226.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gao P, Yan Z and Zhu Z:

Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes in

cardiovascular diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:6042402020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kuznetsov AV, Javadov S, Margreiter R,

Grimm M, Hagenbuchner J and Ausserlechner MJ: The role of

mitochondria in the mechanisms of cardiac ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Antioxidants (Basel). 8:4542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kluge MA, Fetterman JL and Vita JA:

Mitochondria and endothelial function. Circ Res. 112:1171–1188.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bertero E, Popoiu TA and Maack C:

Mitochondrial calcium in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury and

cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 119:569–585. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wong R, Steenbergen C and Murphy E:

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore and calcium handling.

Methods Mol Biol. 810:235–242. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

13

|

Pang B, Dong G, Pang T, Sun X, Liu X, Nie

Y and Chang X: Emerging insights into the pathogenesis and

therapeutic strategies for vascular endothelial injury-associated

diseases: Focus on mitochondrial dysfunction. Angiogenesis.

27:623–639. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Luo Z, Yao J, Wang Z and Xu J:

Mitochondria in endothelial cells angiogenesis and function:

Current understanding and future perspectives. J Transl Med.

21:4412023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Parkkinen I, Their A, Asghar MY, Sree S,

Jokitalo E and Airavaara M: Pharmacological regulation of

endoplasmic reticulum structure and calcium dynamics: Importance

for neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Rev. 75:959–978. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhou X, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Fan L, Zhu Y,

Chen Y, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Wang H, Pan Z, et al: Endothelial FIS1

DeSUMOylation protects against hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circ

Res. 133:508–531. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ren J, Bi Y, Sowers JR, Hetz C and Zhang

Y: Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in

cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 18:499–521. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lackner LL: The expanding and unexpected

functions of mitochondria contact sites. Trends Cell Biol.

29:580–590. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Copeland DE and Dalton AJ: An association

between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum in cells of the

pseudobranch gland of a teleost. J Biophys Biochem Cytol.

5:393–396. 1959. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Vance JE: Phospholipid synthesis in a

membrane fraction associated with mitochondria. J Biol Chem.

265:7248–7256. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ronayne CT and Latorre-Muro P: Navigating

the landscape of mitochondrial-ER communication in health and

disease. Front Mol Biosci. 11:13565002024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Anderson AJ, Jackson TD, Stroud DA and

Stojanovski D: Mitochondria-hubs for regulating cellular

biochemistry: Emerging concepts and networks. Open Biol.

9:1901262019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mishra SR, Mahapatra KK, Behera BP, Patra

S, Bhol CS, Panigrahi DP, Praharaj PP, Singh A, Patil S, Dhiman R

and Bhutia SK: Mitochondrial dysfunction as a driver of NLRP3

inflammasome activation and its modulation through mitophagy for

potential therapeutics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 136:1060132021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Leung SWS and Shi Y: The glycolytic

process in endothelial cells and its implications. Acta Pharmacol

Sin. 43:251–259. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

25

|

Kühlbrandt W: Structure and function of

mitochondrial membrane protein complexes. BMC Biol. 13:892015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Vázquez-Meza H, Vilchis-Landeros MM,

Vázquez-Carrada M, Uribe-Ramírez D and Matuz-Mares D: Cellular

compartmentalization, glutathione transport and its relevance in

some pathologies. Antioxidants (Basel). 12:8342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Jagtap YA, Kumar P, Kinger S, Dubey AR,

Choudhary A, Gutti RK, Gutti RK, Singh S, Jha HC, Poluri KM and

Mishra A: Disturb mitochondrial associated proteostasis:

Neurodegeneration and imperfect ageing. Front Cell Dev Biol.

11:11465642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Schiaffarino O, Valdivieso González D,

García-Pérez IM, Peñalva DA, Almendro-Vedia VG, Natale P and

López-Montero I: Mitochondrial membrane models built from native

lipid extracts: Interfacial and transport properties. Front Mol

Biosci. 9:9109362022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Giacomello M and Pellegrini L: The coming

of age of the mitochondria-ER contact: A matter of thickness. Cell

Death Differ. 23:1417–1427. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Csordás G, Renken C, Várnai P, Walter L,

Weaver D, Buttle KF, Balla T, Mannella CA and Hajnóczky G:

Structural and functional features and significance of the physical

linkage between ER and mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 174:915–921.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Filadi R, Theurey P and Pizzo P: The

endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling in health and disease:

Molecules, functions and significance. Cell Calcium. 62:1–15. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang N, Wang C, Zhao H, He Y, Lan B, Sun L

and Gao Y: The MAMs structure and its role in cell death. Cells.

10:6572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Mohan AA and Talwar P: MAM kinases:

Physiological roles, related diseases, and therapeutic

perspectives-a systematic review. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 30:352025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Adesina SE, Kang BY, Bijli KM, Ma J, Cheng

J, Murphy TC, Michael Hart C and Sutliff RL: Targeting

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species to modulate hypoxia-induced

pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 87:36–47. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Haslip M, Dostanic I, Huang Y, Zhang Y,

Russell KS, Jurczak MJ, Mannam P, Giordano F, Erzurum SC and Lee

PJ: Endothelial uncoupling protein 2 regulates mitophagy and

pulmonary hypertension during intermittent hypoxia. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 35:1166–1178. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ye JX, Wang SS, Ge M and Wang DJ:

Suppression of endothelial PGC-1α is associated with

hypoxia-induced endothelial dysfunction and provides a new

therapeutic target in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol

Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 310:L1233–L1242. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lei W, Li J, Li C, Chen L, Huang F, Xiao

D, Zhang J, Zhao J, Li G, Qu T, et al: MARCH5 restores endothelial

cell function against ischaemic/hypoxia injury via Akt/eNOS

pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 25:3182–3193. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhou H, Wang J, Zhu P, Hu S and Ren J:

Ripk3 regulates cardiac microvascular reperfusion injury: The role

of IP3R-dependent calcium overload, XO-mediated oxidative stress

and F-action/filopodia-based cellular migration. Cell Signal.

45:12–22. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chen Y, Li S, Zhang Y, Wang M, Li X, Liu

S, Xu D, Bao Y, Jia P, Wu N, et al: The lncRNA Malat1 regulates

microvascular function after myocardial infarction in mice via

miR-26b-5p/Mfn1 axis-mediated mitochondrial dynamics. Redox Biol.

41:1019102021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhong Z, Hou Y, Zhou C, Wang J, Gao L, Wu

X, Zhou G, Liu S, Xu Y and Yang W: FL3 mitigates cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting mitochondrial fusion to

restore calcium homeostasis. Cell Death Discov. 11:3042025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Groschner LN, Waldeck-Weiermair M, Malli R

and Graier WF: Endothelial mitochondria-less respiration, more

integration. Pflugers Arch. 464:63–76. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wang J, Toan S and Zhou H: New insights

into the role of mitochondria in cardiac microvascular

ischemia/reperfusion injury. Angiogenesis. 23:299–314. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Pang B, Dong G, Pang T, Sun X, Liu X, Nie

Y and Chang X: Advances in pathogenesis and treatment of vascular

endothelial injury-related diseases mediated by mitochondrial

abnormality. Front Pharmacol. 15:14226862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Dorn GW II: Evolving concepts of

mitochondrial dynamics. Annu Rev Physiol. 81:1–17. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Murphy E and Steenbergen C: Mechanisms

underlying acute protection from cardiac ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Physiol Rev. 88:581–609. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang HH, Wu YJ, Tseng YM, Su CH, Hsieh CL

and Yeh HI: Mitochondrial fission protein 1 up-regulation

ameliorates senescence-related endothelial dysfunction of human

endothelial progenitor cells. Angiogenesis. 22:569–582. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Liu Y, Huo JL, Ren K, Pan S, Liu H, Zheng

Y, Chen J, Qiao Y, Yang Y and Feng Q: Mitochondria-associated

endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM): A dark horse for diabetic

cardiomyopathy treatment. Cell Death Discov. 10:1482024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tagaya M and Arasaki K: Regulation of

mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy by the mitochondria-associated

membrane. Adv Exp Med Biol. 997:33–47. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Bernal AF, Mota N, Pamplona R, Area-Gomez

E and Portero-Otin M: Hakuna MAM-Tata: Investigating the role of

mitochondrial-associated membranes in ALS. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol

Basis Dis. 1869:1667162023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Chan DC: Fusion and fission: Interlinked

processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu Rev Genet.

46:265–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chen W, Zhao H and Li Y: Mitochondrial

dynamics in health and disease: Mechanisms and potential targets.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ferrier V: Mitochondrial fission in life

and death. Nat Cell Biol. 3:E2692001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Gatti P, Schiavon C, Cicero J, Manor U and

Germain M: Mitochondria- and ER-associated actin are required for

mitochondrial fusion. Nat Commun. 16:4512025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Hemel IMGM, Sarantidou R and Gerards M: It

takes two to tango: The essential role of ER-mitochondrial contact

sites in mitochondrial dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol.

141:1061012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Guo Y, Li D, Zhang S, Yang Y, Liu JJ, Wang

X, Liu C, Milkie DE, Moore RP, Tulu US, et al: Visualizing

intracellular organelle and cytoskeletal interactions at nanoscale

resolution on millisecond timescales. Cell. 175:1430–1442.e17.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Al Ojaimi M, Salah A and El-Hattab AW:

Mitochondrial fission and fusion: Molecular mechanisms, biological

functions, and related disorders. Membranes (Basel). 12:8932022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Friedman JR, Lackner LL, West M,

DiBenedetto JR, Nunnari J and Voeltz GK: ER tubules mark sites of

mitochondrial division. Science. 334:358–362. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Hyun HW, Min SJ and Kim JE: CDK5

inhibitors prevent astroglial apoptosis and reactive astrogliosis

by regulating PKA and DRP1 phosphorylations in the rat hippocampus.

Neurosci Res. 119:24–37. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Ganesan V, Willis SD, Chang KT, Beluch S,

Cooper KF and Strich R: Cyclin C directly stimulates Drp1 GTP

affinity to mediate stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfission. Mol

Biol Cell. 30:302–311. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

60

|

Bravo-Sagua R, Parra V, Ortiz-Sandoval C,

Navarro-Marquez M, Rodríguez AE, Diaz-Valdivia N, Sanhueza C,

Lopez-Crisosto C, Tahbaz N, Rothermel BA, et al: Author correction:

Caveolin-1 impairs PKA-DRP1-mediated remodelling of ER-mitochondria

communication during the early phase of ER stress. Cell Death

Differ. 26:24942019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Giedt RJ, Yang C, Zweier JL, Matzavinos A

and Alevriadou BR: Mitochondrial fission in endothelial cells after

simulated ischemia/reperfusion: Role of nitric oxide and reactive

oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 52:348–356. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Ko AR, Hyun HW, Min SJ and Kim JE: The

differential DRP1 phosphorylation and mitochondrial dynamics in the

regional specific astroglial death induced by status epilepticus.

Front Cell Neurosci. 10:1242016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Otera H, Ishihara N and Mihara K: New

insights into the function and regulation of mitochondrial fission.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1833:1256–1268. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ding Y, Liu N, Zhang D, Guo L, Shang Q,

Liu Y, Ren G and Ma X: Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic

reticulum membranes as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular

diseases. Front Pharmacol. 15:13983812024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Ilamathi HS and Germain M: ER-mitochondria

contact sites in mitochondrial DNA dynamics, maintenance, and

distribution. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 166:1064922024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Losón OC, Song Z, Chen H and Chan DC:

Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in

mitochondrial fission. Mol Biol Cell. 24:659–667. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Otera H, Wang C, Cleland MM, Setoguchi K,

Yokota S, Youle RJ and Mihara K: Mff is an essential factor for

mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in

mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 191:1141–1158. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Wu W, Lin C, Wu K, Jiang L, Wang X, Li W,

Zhuang H, Zhang X, Chen H, Li S, et al: FUNDC1 regulates

mitochondrial dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial contact site under

hypoxic conditions. EMBO J. 35:1368–1384. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Korobova F, Ramabhadran V and Higgs HN: An

actin-dependent step in mitochondrial fission mediated by the

ER-associated formin INF2. Science. 339:464–467. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Ji WK, Chakrabarti R, Fan X, Schoenfeld L,

Strack S and Higgs HN: Receptor-mediated Drp1 oligomerization on

endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 216:4123–4139. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Li S, Li J, Li Y, Ye Q, Wang R, Liu X, Li

H, Peng D and Duan X: Regulation of NR4A1 by Taohong Siwu decoction

inhibits endothelial cell apoptosis in cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 353:1202852025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Jin Q, Li R, Hu N, Xin T, Zhu P, Hu S, Ma

S, Zhu H, Ren J and Zhou H: DUSP1 alleviates cardiac

ischemia/reperfusion injury by suppressing the Mff-required

mitochondrial fission and Bnip3-related mitophagy via the JNK

pathways. Redox Biol. 14:576–587. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Zhou H, Wang J, Zhu P, Zhu H, Toan S, Hu

S, Ren J and Chen Y: NR4A1 aggravates the cardiac microvascular

ischemia reperfusion injury through suppressing FUNDC1-mediated

mitophagy and promoting Mff-required mitochondrial fission by CK2α.

Basic Res Cardiol. 113:232018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Landes T and Martinou JC: Mitochondrial

outer membrane permeabilization during apoptosis: The role of

mitochondrial fission. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1813:540–545. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Adebayo M, Singh S, Singh AP and Dasgupta

S: Mitochondrial fusion and fission: The fine-tune balance for

cellular homeostasis. FASEB J. 35:e216202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Hu SY, Zhang Y, Zhu PJ, Zhou H and Chen

YD: Liraglutide directly protects cardiomyocytes against

reperfusion injury possibly via modulation of intracellular calcium

homeostasis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 14:57–66. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Zhu H, Jin Q, Li Y, Ma Q, Wang J, Li D,

Zhou H and Chen Y: Melatonin protected cardiac microvascular

endothelial cells against oxidative stress injury via suppression

of IP3R-[Ca2+] c/VDAC-[Ca2+]m axis by

activation of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Cell Stress Chaperones.

23:101–113. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Zhou H, Hu S, Jin Q, Shi C, Zhang Y, Zhu

P, Ma Q, Tian F and Chen Y: Mff-dependent mitochondrial fission

contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiac microvasculature

ischemia/reperfusion injury via induction of mROS-mediated

cardiolipin oxidation and HK2/VDAC1 disassociation-involved mPTP

opening. J Am Heart Assoc. 6:e0053282017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Zhou H, Zhang Y, Hu S, Shi C, Zhu P, Ma Q,

Jin Q, Cao F, Tian F and Chen Y: Melatonin protects cardiac

microvasculature against ischemia/reperfusion injury via

suppression of mitochondrial fission-VDAC1-HK2-mPTP-mitophagy axis.

J Pineal Res. 63:e124132017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Shenouda SM, Widlansky ME, Chen K, Xu G,

Holbrook M, Tabit CE, Hamburg NM, Frame AA, Caiano TL, Kluge MA, et

al: Altered mitochondrial dynamics contributes to endothelial

dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 124:444–453. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Qu K, Yan F, Qin X, Zhang K, He W, Dong M

and Wu G: Mitochondrial dysfunction in vascular endothelial cells

and its role in atherosclerosis. Front Physiol. 13:10846042022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, Yellon DM,

Davidson SM and Hausenloy DJ: Inhibiting mitochondrial fission

protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Circulation. 121:2012–2022. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Liu Z, Han X, You Y, Xin G, Li L, Gao J,

Meng H, Cao C, Liu J, Zhang Y, et al: Shuangshen ningxin formula

attenuates cardiac microvascular ischemia/reperfusion injury

through improving mitochondrial function. J Ethnopharmacol.

323:1176902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Zhou H, Wang J, Hu S, Zhu H, Toanc S and

Ren J: BI1 alleviates cardiac microvascular ischemia-reperfusion

injury via modifying mitochondrial fission and inhibiting

XO/ROS/F-actin pathways. J Cell Physiol. 234:5056–5069. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Zhou H, Shi C, Hu S, Zhu H, Ren J and Chen

Y: BI1 is associated with microvascular protection in cardiac

ischemia reperfusion injury via repressing

Syk-Nox2-Drp1-mitochondrial fission pathways. Angiogenesis.

21:599–615. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Chen Y, Liu C, Zhou P, Li J, Zhao X, Wang

Y, Chen R, Song L, Zhao H and Yan H: Coronary endothelium no-reflow

injury is associated with ROS-modified mitochondrial fission

through the JNK-Drp1 signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2021:66995162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Zou R, Shi W, Qiu J, Zhou N, Du N, Zhou H,

Chen X and Ma L: Empagliflozin attenuates cardiac microvascular

ischemia/reperfusion injury through improving mitochondrial

homeostasis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 21:1062022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Cheng YH, Chiang CY, Wu CH and Chien CT:

2'-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde, a natural product from cinnamon,

alleviates ischemia/reperfusion-induced microvascular dysfunction

and oxidative damage in rats by upregulating cytosolic BAG3 and

Nrf2/HO-1. Int J Mol Sci. 25:129622024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Mishra P, Carelli V, Manfredi G and Chan

DC: Proteolytic cleavage of Opa1 stimulates mitochondrial inner

membrane fusion and couples fusion to oxidative phosphorylation.

Cell Metab. 19:630–641. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Zhao L, Zhuang J, Wang Y, Zhou D, Zhao D,

Zhu S, Pu J, Zhang H, Yin M, Zhao W, et al: Propofol ameliorates

H9c2 cells apoptosis induced by oxygen glucose deprivation and

reperfusion injury via inhibiting high levels of mitochondrial

fusion and fission. Front Pharmacol. 10:612019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

de Brito OM and Scorrano L: Mitofusin 2

tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 456:605–610.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Stuppia G, Rizzo F, Riboldi G, Del Bo R,

Nizzardo M, Simone C, Comi GP, Bresolin N and Corti S: MFN2-related

neuropathies: Clinical features, molecular pathogenesis and

therapeutic perspectives. J Neurol Sci. 356:7–18. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Filadi R, Greotti E, Turacchio G, Luini A,

Pozzan T and Pizzo P: Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic

reticulum-mitochondria coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

112:E2174–E2181. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Prinz WA: Bridging the gap: Membrane

contact sites in signaling, metabolism, and organelle dynamics. J

Cell Biol. 205:759–769. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Yang F, Wu R, Jiang Z, Chen J, Nan J, Su

S, Zhang N, Wang C, Zhao J, Ni C, et al: Leptin increases

mitochondrial OPA1 via GSK3-mediated OMA1 ubiquitination to enhance

therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Cell

Death Dis. 9:5562018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Sprenger HG and Langer T: The good and the

bad of mitochondrial breakups. Trends Cell Biol. 29:888–900. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Romanello V, Scalabrin M, Albiero M,

Blaauw B, Scorrano L and Sandri M: Inhibition of the fission

machinery mitigates OPA1 impairment in adult skeletal muscles.

Cells. 9:5972019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Yin W, Li R, Feng X and James Kang Y: The

involvement of cytochrome c oxidase in mitochondrial fusion in

primary cultures of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc

Toxicol. 19:365–373. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Anderson CJ, Kahl A, Fruitman H, Qian L,

Zhou P, Manfredi G and Iadecola C: Prohibitin levels regulate OMA1

activity and turnover in neurons. Cell Death Differ. 27:1896–1906.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

100

|

Schulman JJ, Szczesniak LM, Bunker EN,

Nelson HA, Roe MW, Wagner LE II, Yule DI and Wojcikiewicz RJH: Bok

regulates mitochondrial fusion and morphology. Cell Death Differ.

26:2682–2694. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Ding M, Liu C, Shi R, Yu M, Zeng K, Kang

J, Fu F and Mi M: Mitochondrial fusion promoter restores

mitochondrial dynamics balance and ameliorates diabetic

cardiomyopathy in an optic atrophy 1-dependent way. Acta Physiol

(Oxf). 229:e134282020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Hong Y, Tak H, Kim C, Kang H, Ji E, Ahn S,

Jung M, Kim HL, Lee JH, Kim W and Lee EK: RNA binding protein HuD

contributes to β-cell dysfunction by impairing mitochondria

dynamics. Cell Death Differ. 27:1633–1643. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Meyer JN, Leuthner TC and Luz AL:

Mitochondrial fusion, fission, and mitochondrial toxicity.

Toxicology. 391:42–53. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Wu W, Zhao D, Shah SZA, Zhang X, Lai M,

Yang D, Wu X, Guan Z, Li J, Zhao H, et al: OPA1 overexpression

ameliorates mitochondrial cristae remodeling, mitochondrial

dysfunction, and neuronal apoptosis in prion diseases. Cell Death

Dis. 10:7102019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Lugus JJ, Ngoh GA, Bachschmid MM and Walsh

K: Mitofusins are required for angiogenic function and modulate

different signaling pathways in cultured endothelial cells. J Mol

Cell Cardiol. 51:885–893. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Sabouny R and Shutt TE: The role of

mitochondrial dynamics in mtDNA maintenance. J Cell Sci.

134:jcs2589442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Papanicolaou KN, Khairallah RJ, Ngoh GA,

Chikando A, Luptak I, O'Shea KM, Riley DD, Lugus JJ, Colucci WS,

Lederer WJ, et al: Mitofusin-2 maintains mitochondrial structure

and contributes to stress-induced permeability transition in

cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 31:1309–1328. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Peng C, Rao W, Zhang L, Wang K, Hui H,

Wang L, Su N, Luo P, Hao YL, Tu Y, et al: Corrigendum to 'Mitofusin

2 ameliorates hypoxia-induced apoptosis via mitochondrial function

and signaling pathways title of article' [International Journal of

Biochemistry and Cell Biology 69 (2015) 29-40]. Int J Biochem Cell

Biol. 73:1372016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Tan Y, Mui D, Toan S, Zhu P, Li R and Zhou

H: SERCA overexpression improves mitochondrial quality control and

attenuates cardiac microvascular ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol

Ther Nucleic Acids. 22:696–707. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Li Y, Huang D, Jia L, Shangguan F, Gong S,

Lan L, Song Z, Xu J, Yan C, Chen T, et al: LonP1 links

mitochondria-er interaction to regulate heart function. Research

(Wash D C). 6:01752023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Liu P, Xie Q, Wei T, Chen Y, Chen H and

Shen W: Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome induces vascular

dysfunction in obese OLETF rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

468:319–325. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Jung M, Dodsworth M and Thum T:

Inflammatory cells and their non-coding RNAs as targets for

treating myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 114:42018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Xue J, Yan X, Yang Y, Chen M, Wu L, Gou Z,

Sun Z, Talabieke S, Zheng Y and Luo D: Connexin 43

dephosphorylation contributes to arrhythmias and cardiomyocyte

apoptosis in ischemia/reperfusion hearts. Basic Res Cardiol.

114:402019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Veeranki S and Tyagi SC: Mdivi-1 induced

acute changes in the angiogenic profile after ischemia-reperfusion

injury in female mice. Physiol Rep. 5:e132982017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Rouault P, Guimbal S, Cornuault L,

Bourguignon C, Foussard N, Alzieu P, Choveau F, Benoist D, Chapouly

C, Gadeau AP, et al: Thrombosis in the coronary microvasculature

impairs cardiac relaxation and induces diastolic dysfunction.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 44:e1–e18. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Paillard M, Tubbs E, Thiebaut PA, Gomez L,

Fauconnier J, Da Silva CC, Teixeira G, Mewton N, Belaidi E, Durand

A, et al: Depressing mitochondria-reticulum interactions protects