Osteoporosis, a prevalent metabolic bone disease

with notable medical and socioeconomic implications, is

characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural

deterioration, leading to weakened bone strength and an increased

risk of fragility fractures (1).

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

in the United States, ~20% of postmenopausal women have been

diagnosed with osteoporosis (2).

As the global population ages, this prevalence is expected to

increase in the coming years (3). For individuals with osteoporosis,

the lifetime risk of fractures can reach up to 40%; from the

perspective of patients, fractures, along with the subsequent loss

of mobility and independence, often result in a substantial decline

in quality of life. Moreover, osteoporotic fractures, particularly

of the hip and spine, are associated with a 12-month excess

mortality rate of up to 20%, primarily due to hospitalization,

which increases the risk of complications such as pneumonia or

thromboembolic events from prolonged immobility, further

compounding the public health burden (4). The pathophysiology of osteoporosis

is marked by an imbalance between bone resorption and formation,

which is influenced by factors such as aging, hormonal changes,

nutritional deficiencies and genetics (5,6).

Notably, the interaction between osteoblasts and osteoclasts is

crucial for maintaining bone homeostasis. Osteoblasts express and

secrete receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL), which promotes

the differentiation of osteoclast precursors into mature

osteoclasts. Conversely, when bone resorption disrupts the bone

structure, osteoclasts release insulin-like growth factors (IGFs),

which stimulate osteogenic differentiation (7). However, dysregulated bone

remodeling negatively affects bone mass. A reduction in osteoblast

activity, responsible for producing the calcified organic

extracellular matrix, leads to increased bone resorption.

Simultaneously, osteoclasts degrade the extracellular matrix and

the cumulative effect of these processes can result in bone loss

(8). Understanding the

underlying mechanisms of bone remodeling and the factors

influencing bone mass is critical for developing effective

strategies to prevent and treat osteoporosis.

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), including

leucine, isoleucine and valine, are essential amino acids primarily

known for their role in muscle protein synthesis (9). In addition to their function in

skeletal muscle, BCAAs have been linked to the regulation of

metabolic disorders such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and

cancer (10). They may also

influence aging and longevity in animal models (11). Recent research has identified a

range of molecules involved in maintaining bone homeostasis, with

BCAAs emerging as potential modulators within this regulatory

network (12).

The present review summarizes the interactions

between bone metabolism and BCAA metabolism, focusing on the causes

and consequences of metabolic abnormalities. It also explores the

relationship between bone metabolism and osteoporosis, highlighting

how dysregulated BCAA metabolism may contribute to osteoporosis.

Finally, the potential of BCAAs as a treatment for osteoporosis is

discussed, offering novel insights into their role in bone health.

In conclusion, the current review may enhance understanding of the

mechanisms by which BCAAs contribute to the pathogenesis of

osteoporosis. It not only provides dietary recommendations but also

emphasizes the potential for BCAA-based interventions in the

management of osteoporosis, paving the way for novel therapeutic

approaches to combat this disease.

Bone is a dynamic, metabolically active tissue and

an essential organ system in higher vertebrates, serving as the

primary structural component of the skeleton. It is a specialized

connective tissue composed of osteocytes, osteoblasts, bone-lining

cells and osteoclasts. The bone matrix consists of ~60% inorganic

mineral phase (primarily semi-crystalline, carbonated

hydroxyapatite), 30% organic phase, which includes type I collagen

fibrils and non-collagenous proteins, and 10% water (13). Additionally, small leucine-rich

proteoglycans, a key component of non-collagenous proteins, are

present in the bone matrix (14).

Bone performs four critical functions: i) Providing

structural support and anchorage for muscles, ii) protecting vital

organs such as the brain and bone marrow, iii) supporting

hematopoiesis (15-17), and iv) serving as a metabolic

reservoir for calcium and phosphate. These physiological functions

rely on the tightly regulated processes of bone modeling and

remodeling to maintain skeletal homeostasis (18).

Bone remodeling involves the resorption of old or

damaged bone by osteoclasts, followed by the formation of new bone

by osteoblasts (19). In

contrast to bone modeling, remodeling is a coupled, spatially and

temporally coordinated process that does not alter bone shape

(20). It is a tightly regulated

physiological process and dysfunction in any component of this

system can disrupt bone metabolism, contributing to conditions such

as osteoporosis (21).

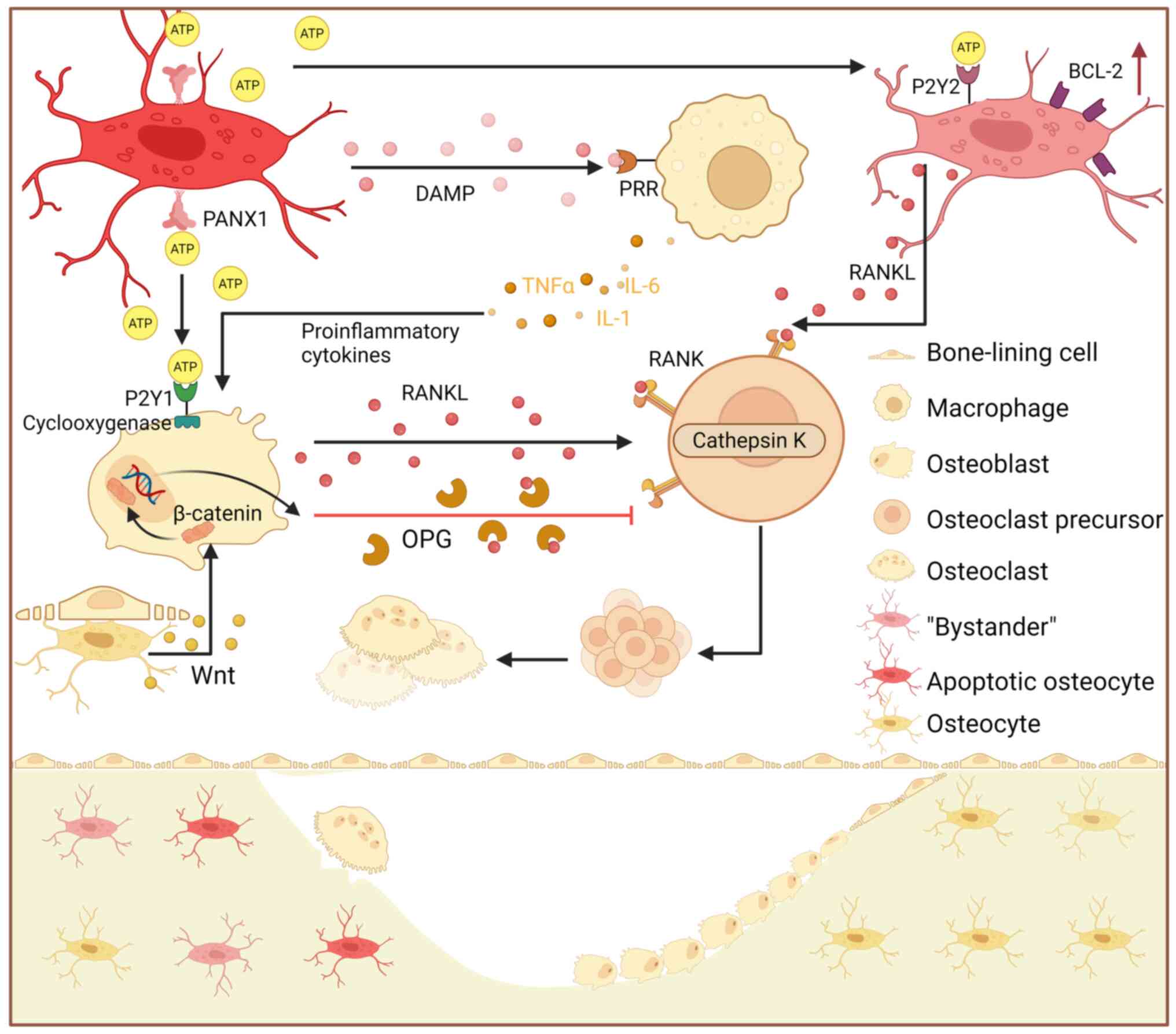

Bone metabolism is a complex process precisely

coordinated by osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes. Osteoclasts

originate from mononuclear precursors of the monocyte/macrophage

lineage, and their differentiation and activation depend on two

critical signals: Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (22) and RANKL (23,24), as substantiated by Nakahama et

al (25). The binding of

RANKL to receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) on osteoclast

precursors initiates osteoclastogenesis (26). Mature, functional osteoclasts

form a ruffled border mediated by Src kinase (27,28) and secrete cathepsin K to degrade

the bone matrix, accomplishing bone resorption (29,30). Gelb et al (29) demonstrated that osteoclasts from

human patients with cathepsin K gene mutations fail to efficiently

degrade the bone organic matrix, providing direct clinical evidence

linking cathepsin K to osteoclastic resorption.

Osteoblasts are derived from various sources,

including bone marrow stromal cells and bone-lining cells (31). During bone resorption, factors

released from the bone matrix, such as transforming growth factor-β

(TGF-β) and IGF-1, recruit osteoblast precursors to the bone

surface (32). Osteoblast

differentiation is primarily regulated by the canonical

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Upon activation of this pathway,

β-catenin is stabilized and translocates into the nucleus, where it

binds to LEF/TCF transcription factors. This interaction activates

the expression of osteogenic genes such as Runx2, promoting the

differentiation of osteoblasts from progenitor cells into mature

cells (33). Mature osteoblasts

then secrete type I collagen and other components, forming osteoid

and facilitating its mineralization to build new bone. After

completing their task, most osteoblasts undergo apoptosis, while

some differentiate into osteocytes or revert to quiescent

bone-lining cells (34,35).

Osteocytes, embedded within the mineralized matrix,

serve as key regulators of bone homeostasis (36). By contrast, necrotic osteocytes

release damage-associated molecular patterns (37), which bind to pattern recognition

receptors (38), initiating the

production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-1 and

IL-6 (39). These cytokines

indirectly amplify RANKL signaling (40) by increasing RANKL expression in

osteoblasts (41). Osteocyte

apoptosis is a critical trigger for bone remodeling (37), as these cells recruit osteoclasts

to microcracks, initiating targeted bone resorption and maintaining

dynamic bone tissue homeostasis (42). Kringelbach et al (41) demonstrated that apoptosis in the

MLO-Y4 osteocyte cell line induces the release of adenosine

triphosphate (ATP) via the activation of Pannexin 1 (PANX1)

channels. A similar phenomenon has been observed in mice treated

with a P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) inhibitor, highlighting the role of

P2X7R as a coactivator of PANX1 (43). The released ATP subsequently

stimulates RANKL expression through a signaling cascade involving

the purinergic receptor P2Y (P2Y)1 receptor and cyclooxygenase

activity (44-46). ATP released from apoptotic

osteocytes likely binds to P2Y2 receptors on osteocytes in the

penumbra regions, known as 'bystander' osteocytes (47); this binding may also trigger

RANKL production and release (43).

The termination of bone remodeling involves multiple

steps, including the secretion of osteoprotegerin (OPG) by mature

osteoblasts and/or osteocytes, which may serve as a key inhibitory

signal (48). Additionally,

upregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 in 'bystander'

osteocytes near the damage site helps protect viable osteocytes

from osteoclastogenic stimuli originating from adjacent apoptotic

cells (Fig. 1) (49,50).

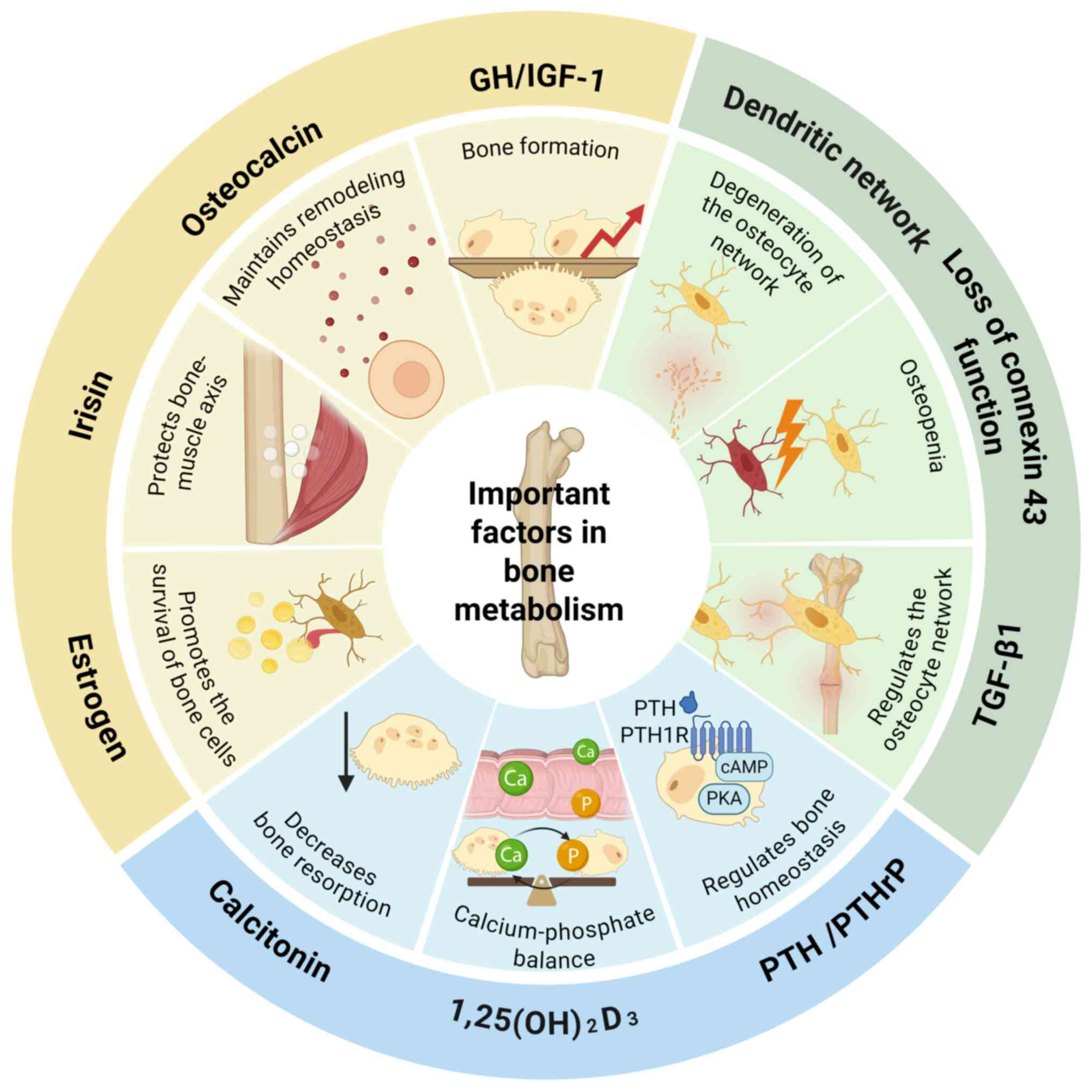

Bone metabolism is regulated by both local

intercellular signaling among bone cells and a range of systemic

factors. Calcium and phosphate regulators maintain mineral

homeostasis, which is crucial for bone mineralization.

1,25(OH)2D3 enhances intestinal calcium and

phosphate absorption directly (51), while also modulating osteoblast

and osteoclast activity (52-54). Concurrently, parathyroid hormone

(PTH) and PTH-related peptide regulate calcium-phosphate

homeostasis in bone and the kidneys by activating the cyclic

adenosine monophosphate-protein kinase A pathway through the PTH1

receptor (55,56). Elevated phosphate levels, in

turn, stimulate the secretion of fibroblast growth factor 23, which

suppresses 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis and promotes

renal phosphate excretion, creating a critical feedback loop

(57,58). Calcitonin acts antagonistically

by directly inhibiting bone resorption to lower blood calcium

levels (59,60), thereby ensuring precise

regulation of calcium homeostasis.

Osteocyte communication and the integrity of the

network are central to the mechanosensing and signaling system of

bone. Connexin 43 (Cx43) underpins intercellular communication

among osteocytes, and its loss of function directly impairs bone

mass acquisition and maintenance (61-63). Similarly, the integrity of the

osteocyte dendritic network is essential, with age-related declines

in network function directly associated with cortical bone

deterioration (64).

Additionally, TGF-β1 signaling is a key intrinsic regulator of this

network, preserving bone mechanical integrity by modulating

dendritic length and the expression of genes such as sclerostin and

MMPs (65). These factors,

particularly in aging and metabolic diseases (including diabetes

and obesity), interact with the broader bone metabolism regulatory

network (66).

The balance between bone formation and resorption

directly determines the net outcome of bone remodeling. For

example, growth hormone, by stimulating IGF-1 expression, increases

bone turnover with a net anabolic effect, leading to modest bone

mass gain (67,68). Estrogen promotes osteocyte

survival via semaphorin 3A (69), fluid flow shear stress (70), Wnt/β-catenin signaling (71) and Cx43 expression (72), helping to counteract age-related

bone loss. The myokine irisin also serves a protective role in the

bone-muscle axis by reducing osteocyte apoptosis (73). Additionally, vitamin K-dependent

osteocalcin, secreted by osteoblasts, connects bone metabolism to

systemic energy metabolism, broadening the regulation of bone

homeostasis (Fig. 2) (74).

Bone metabolic imbalance is a complex condition

arising from a variety of physiological and pathological factors. A

primary underlying mechanism is the disruption of the dynamic

balance between osteoclastic bone resorption and osteoblastic bone

formation. This dysregulation can lead to skeletal disorders such

as osteoporosis, which is characterized by reduced bone mass and

increased susceptibility to fractures. Contributing factors include

hormonal imbalances, inadequate nutrition and genetic

predispositions (75).

Hormonal changes, particularly those involving

estrogen and PTH, serve a central role in bone metabolism. Estrogen

deficiency, commonly observed in postmenopausal women, accelerates

bone resorption, thereby promoting osteoporosis (76). Similarly, parathyroid gland

disorders disrupt calcium and phosphate metabolism, further

exacerbating bone loss (77).

The skeleton also functions as an endocrine organ; hormones such as

osteocalcin regulate both energy metabolism and bone homeostasis,

highlighting the close link between skeletal and metabolic health

(78).

Nutritional factors markedly influence bone health.

Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake is essential for maintaining

bone density, with deficiencies in these nutrients leading to

impaired bone mineralization and an increased fracture risk

(79). Additionally, while high

protein intake exerts a bone-anabolic effect, this benefit can be

counteracted by a high dietary acid load, ultimately promoting bone

loss (80). The role of vitamin

K, particularly in relation to osteocalcin, is also important;

vitamin K is involved in the carboxylation of osteocalcin, a

process essential for bone mineralization and metabolic regulation

(74).

Genetic factors and metabolic disorders predispose

individuals to bone metabolism disorders. Conditions such as

hypophosphatasia and lysosomal storage disease result in skeletal

abnormalities and heightened osteoporosis risk. These genetic

disorders often cause imbalances in calcium and phosphate

metabolism, which are critical for bone health (81). Additionally, abnormalities in

purine metabolism have been identified as a notable factor in bone

remodeling, contributing to osteoporosis in various high-risk

populations (82).

Environmental and lifestyle factors, such as

physical inactivity, smoking and excessive alcohol consumption, are

well-established negative influences on bone health. These factors

increase oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are

detrimental to bone remodeling (83-85). The accumulation of advanced

oxidation protein products has been shown to contribute to bone-fat

imbalance during skeletal aging, highlighting the impact of

oxidative stress on bone metabolism (Table I) (86-88).

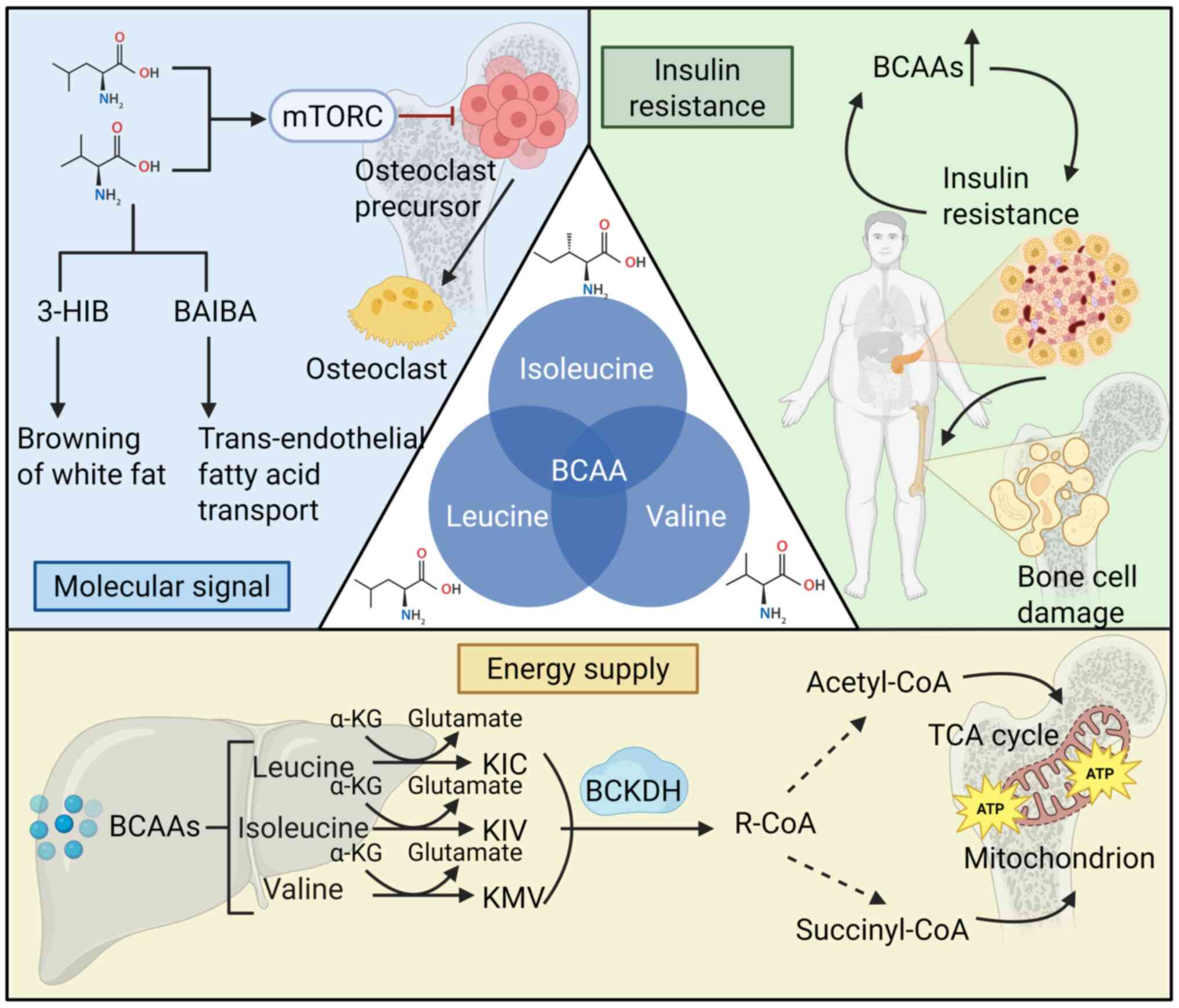

BCAAs, comprising leucine, isoleucine and valine,

are essential amino acids that must be sourced from the diet, as

they cannot be synthesized endogenously in animals (89). Despite being classified together

as BCAAs, leucine, isoleucine and valine exhibit distinct

structural, metabolic and functional characteristics, which

underlie their intricate regulation of bone metabolism (90). Leucine, with its highly

hydrophobic isobutyl side chain, is the most hydrophobic of the

three, a property essential for its function as a signaling

molecule. This hydrophobicity facilitates the role of leucine in

activating downstream targets, establishing its dominant role in

signal transduction (91).

Beyond serving as fundamental components for protein

synthesis, BCAAs are key regulators of cellular metabolism, energy

production and signal transduction (92). After ingestion, BCAAs undergo

enzymatic transformation across various tissues, with the highest

concentrations observed in skeletal muscle, brown adipose tissue,

liver, kidney and heart (93).

Enzymes such as BCAA transaminase (BCAT) and branched-chain

α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) catalyze the production of

important metabolites, including branched-chain α-ketoacids

(BCKAs), acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA, which contribute to processes

such as the tricarboxylic acid cycle and fatty acid metabolism

(Fig. 3) (94). The distinct metabolic pathways of

the three BCAAs suggest that they may exert differential effects on

bone metabolism by regulating cellular energy status, metabolite

pools and signal transduction pathways.

As critical nutrient signals, BCAAs modulate

cellular metabolism and energy production. They activate anabolic

pathways, particularly the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)

signaling pathway, which promotes protein synthesis in skeletal

muscle and enhances immune cell proliferation and function,

including T cells and natural killer cells (95). Additionally, emerging evidence

has highlighted a 'muscle-bone axis', where skeletal muscle and

bone tissue interact bidirectionally (96). Immune cells, including osteoclast

precursors and macrophages, also serve pivotal roles in bone

resorption and remodeling (97).

By influencing both the musculoskeletal and immune systems, BCAAs

likely exert indirect yet notable effects on bone metabolism and

homeostasis. Further research is needed to elucidate the direct

regulatory roles of BCAAs in bone metabolism, particularly through

pathways involving cellular metabolism and energy balance.

BCAAs and their metabolic derivatives function as

molecular signals in bone metabolism. Both leucine (98) and valine (99) activate the mTOR complex 1

(mTORC1) pathway. The biochemical pathways of BCAA metabolism are

well-characterized, and preclinical studies have indicated that

inhibition of mTOR suppresses osteoclast differentiation and

survival, potentially impairing bone resorption (100-103). These findings are further

supported by the BOLERO-2 trial, where everolimus, a clinically

used mTOR inhibitor, demonstrated beneficial effects on bone in

patients with advanced breast cancer (104). Metabolic derivatives of valine,

such as β-aminoisobutyric acid (BAIBA) and 3-hydroxyisobutyric acid

(3-HIB), act as myo-osseous metabolic messengers, regulating bone

homeostasis through distinct signaling pathways. BAIBA, regulated

by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ

coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), activates the PPARα pathway, inducing

white adipose tissue browning, improving insulin sensitivity and

potentially enhancing osteogenesis while inhibiting

osteoclastogenesis (105).

Conversely, 3-HIB promotes trans-endothelial fatty acid transport

via FATP3/4, leading to lipotoxicity and insulin resistance, which

may disrupt bone homeostasis (106). Further research is needed to

better define the direct roles of BCAAs in bone metabolism through

these signal transduction pathways, supported by additional

well-designed clinical studies.

Metabolomic analyses from large randomized

controlled trials have established circulating BCAA levels as key

indicators of metabolic health. These levels, beyond body mass

index, predict the risk of insulin resistance, cardiovascular

diseases and diabetes, and reveal ethnic differences in

obesity-associated metabolic disturbances (107,108). A Mendelian randomization study

further indicated that elevated BCAA levels are linked to an

increased risk of type 2 diabetes (109). Collectively, these findings

suggest that dysregulated BCAA metabolism contributes to the

pathogenesis of insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes (110,111). Moreover, insulin resistance may

promote BCAA accumulation (112,113), creating a self-perpetuating

cycle. Insulin resistance, frequently accompanied by altered BCAA

metabolism, adversely affects bone health by impairing osteoblast

function and inhibiting bone formation (Fig. 3) (114).

Disorders in BCAA metabolism contribute to a complex

pathological network that impacts bone metabolism. This network

involves both direct regulation of bone cells (osteoblasts and

osteoclasts) (115), and

indirect effects mediated by systemic metabolic disturbances,

ultimately disrupting bone homeostasis (114,116).

A key mechanism through which BCAA metabolism

directly influences bone metabolism is its role in osteoclast

maturation. Studies have shown that inhibition of BCAT1, a key

enzyme in BCAA metabolism, effectively reduces osteoclast

maturation (12,117). BCAT1 catalyzes the conversion

of BCAAs to their metabolites (BCKAs), which fuel cellular energy

production (90) and sustain the

expression of essential osteoclastogenic factors (such as NFATc1

and ATP6v0d2) (118), as well

as the regulation of fusion-related genes (including DCSTAMP and

CD9) (119,120). These processes collectively

underlie its critical role in the later stages of osteoclast

differentiation. In vivo animal experiments have further

confirmed that BCAT1 is central to the osteoclast multinucleation

regulatory network. Its deletion markedly inhibits osteoclast

activity, increases bone mass and improves bone strength. These

results establish a strong link between abnormal BCAA metabolism

and bone metabolic disorders mediated by osteoclasts (117).

In contrast to osteoclasts, the impact of BCAA

metabolism on osteoblasts is more complex, highlighting the adverse

effects of abnormal BCAA metabolism on bone health. Singha et

al (121) demonstrated that

rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, can effectively suppress osteoblast

proliferation and differentiation by reducing RUNX2 protein

expression, decreasing alkaline phosphatase activity and inhibiting

matrix mineralization, supporting the pro-osteogenic role of mTORC1

in osteogenesis. However, dysregulated BCAA metabolism, such as

chronic overaccumulation or insufficient breakdown products, may

disrupt the mTORC1 pathway (122). Prolonged activation of mTORC1

can induce 'metabolic stress' in osteoblasts, characterized by

G1 phase cell cycle arrest and reduced proliferative

capacity, ultimately impairing bone metabolism (123). These findings suggest that

BCAAs regulate osteoblast differentiation to a certain extent via

the mTOR signaling pathway; however, its translational

applicability in humans remains to be confirmed through rigorously

designed clinical investigations.

High glutamine levels further inhibit the

mTORC2/Akt-S473/RUNX2 axis by activating mTORC1, which leads to the

ubiquitin-mediated degradation of RUNX2, thereby suppressing

osteogenic differentiation (124). These findings indicate that the

regulatory role of mTORC1 signaling in osteoblast differentiation

may be context-dependent, necessitating additional in vitro

experiments or clinical studies to confirm these results.

As aforementioned, dysregulated BCAA metabolism is

linked to various metabolic disorders, including obesity and type 2

diabetes, both of which are well-established risk factors for

osteoporosis and other bone-related conditions (125). In patients with obesity and

type 2 diabetes, elevated BCAA levels are strongly associated with

insulin resistance. BCAAs activate the mTORC1 signaling pathway,

which decouples insulin signal transduction, thereby exacerbating

insulin resistance (114,126). Furthermore, intermediate

products of BCAA metabolism, such as BCKAs, inhibit insulin signal

transduction, further aggravating metabolic disorders (127). These metabolic disruptions not

only affect systemic metabolism but also impair bone homeostasis by

disrupting energy metabolism and signal transduction in osteocytes

(115,128).

Additionally, BCAAs influence lipid metabolism, and

disruptions in this pathway can lead to altered lipid profiles that

may negatively affect bone density and strength. Impaired BCAA

catabolism has been linked to lipid accumulation, which can

adversely impact bone tissue (129,130). BCAA metabolic disorders may

worsen the complex pathological network of bone metabolism by

modulating oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Elevated

BCAA and fatty acid levels induce mitochondrial dysfunction,

increase oxidative stress, and activate inflammatory signaling

pathways, all of which can contribute to bone metabolic diseases,

such as osteoporosis, by impairing osteocyte function and

disrupting the bone microenvironment (131,132). Furthermore, BCAA metabolic

disorders may indirectly influence bone metabolism by interfering

with lipid metabolism (133).

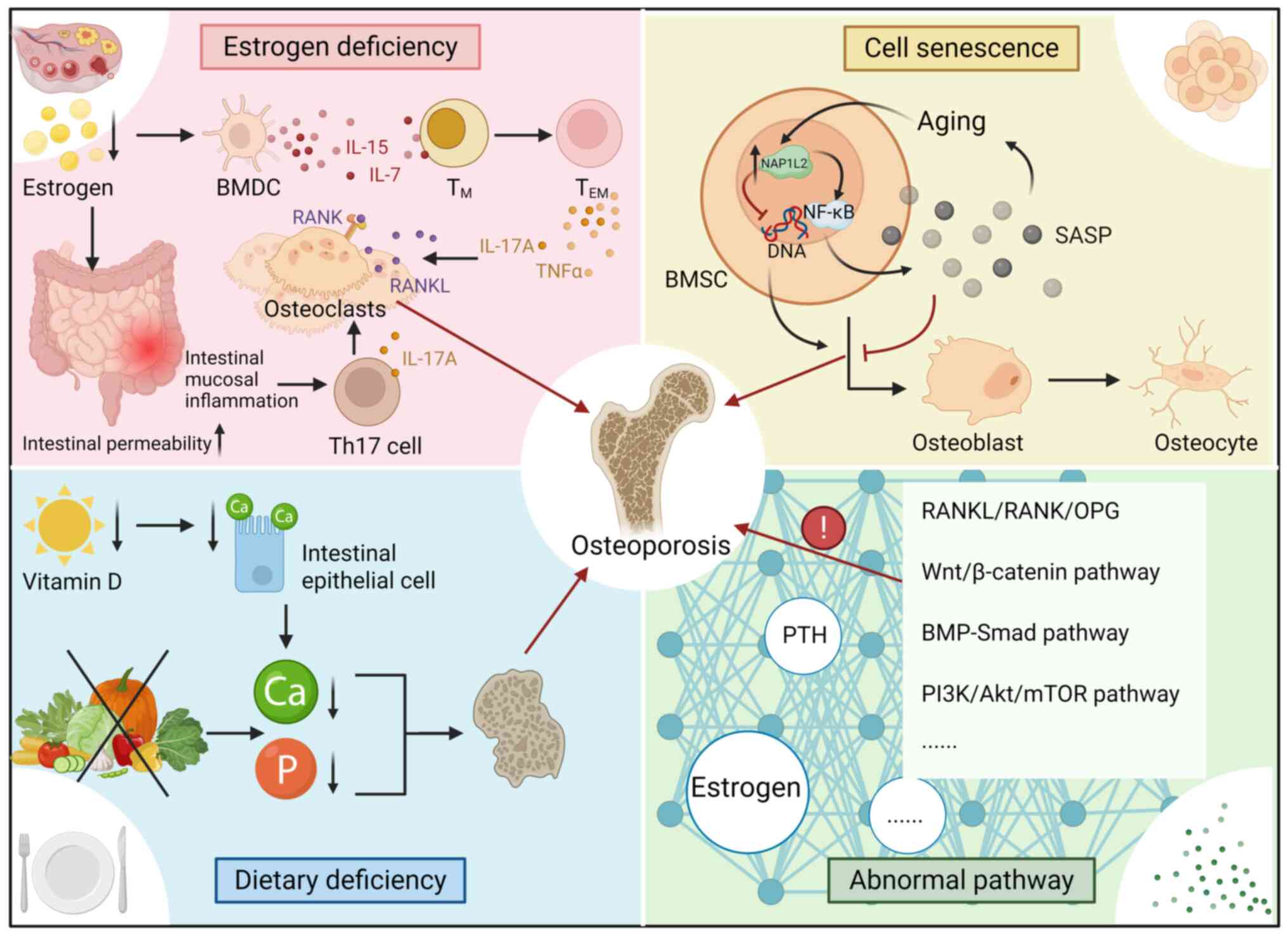

Osteoporosis is a prevalent metabolic bone disorder

characterized by generalized bone mass loss and deterioration of

bone microarchitecture, which increases bone fragility and the risk

of fragility fractures (135).

Notably, osteoporosis also elevates the likelihood of secondary

complications, such as pneumonia or thromboembolic events,

particularly due to immobilization following a fracture (4). Rather than a singular condition,

osteoporosis encompasses a spectrum of distinct pathological

states, typically classified as primary or secondary. Primary

osteoporosis includes two main subtypes: Type I, or postmenopausal

osteoporosis, which predominantly affects women after menopause due

to estrogen deficiency, and type II, also known as age-related or

senile osteoporosis, which is associated with aging in both sexes.

By contrast, secondary osteoporosis arises from various underlying

medical conditions, reduced physical activity or the adverse

effects of medical treatments (136).

The primary pathological features of osteoporosis

include decreased bone mass, disrupted bone microarchitecture and

an imbalance in bone remodeling, where bone resorption outpaces

bone formation, leading to a net loss of bone tissue (135).

Type I osteoporosis primarily results from estrogen

deficiency, which accelerates bone resorption by increasing the

RANKL/OPG ratio and enhancing osteoclast activity (137). Several bone metabolism pathways

are implicated in this process: i) Estrogen deficiency prolongs the

lifespan of bone marrow dendritic cells and increases the secretion

of IL-7 and IL-15, which promote the conversion of memory T

(TM) cells into effector TM cells. The

subsequent release of TNFα and IL-17A acts synergistically with

RANKL to stimulate osteoclastogenesis and enhance osteoclast

activity. ii) Estrogen deficiency also increases intestinal

permeability and triggers inflammation in the intestinal mucosa,

resulting in elevated production of T helper 17 (Th17) cells.

IL-17A produced by Th17 cells further enhances osteoclast

differentiation and bone resorption. Additionally, metabolites from

gut microbiota, such as butyric acid, polyamines and other

short-chain fatty acids, may indirectly promote osteoclast

activity; however, the exact mechanisms remain to be fully

elucidated (138).

Vitamin D deficiency impairs calcium absorption, a

condition further exacerbated by inadequate dietary calcium intake.

This disruption in calcium homeostasis leads to increased bone

resorption and heightened bone remodeling. In a large European

cohort study of 8,532 postmenopausal women with insufficient

vitamin D levels, 97% were found to have osteoporosis (139). Another study revealed that 82%

of individuals with osteoporosis had calcium intakes below the

recommended daily amount of 1,000 mg (140). Moreover, phosphorus deficiency,

a common marker of poor nutritional status in elderly patients, is

associated with an elevated risk of fractures (141). Thus, deficiencies in vitamin D,

calcium and phosphorus further increase fracture risk in elderly

women with osteoporosis.

During the progression of osteoporosis in the

elderly, both cellular senescence and epigenetic regulatory

pathways serve key roles in modulating bone metabolism. As aging

progresses, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) undergo

senescence, accompanied by an upregulation of nucleosome assembly

protein 1 like 2 (NAP1L2) expression. NAP1L2 contributes to bone

loss through two primary mechanisms. First, it activates the NF-κB

signaling pathway, leading to increased secretion of

senescence-associated factors, such as IL-6 and IL-8. These factors

exacerbate cellular senescence and impair the osteogenic

differentiation of BMSCs, thus negatively impacting bone formation.

Second, as a histone chaperone, NAP1L2 recruits sirtuin 1 to

deacetylate H3K14ac at the promoters of key osteogenic genes,

including Runx2, Sp7 and Bglap, causing their transcriptional

repression. This epigenetic modification further inhibits

osteogenic differentiation, reduces bone formation, and accelerates

the development of osteoporosis (142).

Abnormal cellular functions also contribute to

osteoporosis pathogenesis: i) Inhibition of osteoblast

differentiation and function, which is associated with

downregulation of the BMP/Smad (143) and Wnt/β-catenin (144) pathways, thus preventing MSCs

from differentiating into osteoblasts; ii) overactivation of

osteoclasts, bone matrix degradation is accelerated due to

lysosomal acidification abnormalities, such as increased V-ATPase

activity (145) and elevated

cathepsin K activity (146);

and iii) dysfunction in the osteocyte network, where osteocyte

apoptosis and the accumulation of microdamage impair mechanosignal

perception, inhibiting bone repair (147). Furthermore, senescence or

mechanical stimulation reduces the upregulation of sclerostin,

which antagonizes the Wnt pathway and inhibits bone formation

(148).

Dysregulated molecular signaling pathways also

contribute to osteoporosis, particularly those involved in the

RANKL/RANK/OPG system, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, the BMP-Smad

pathway and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Additionally, hormonal and

cytokine networks, particularly those involving PTH and estrogen,

are disrupted, with well-established roles in bone metabolism

(Table II; Fig. 4).

BCAA catabolism primarily occurs in skeletal muscle,

where they are broken down into their respective ketoacids and

further metabolized. This process is essential for maintaining

muscle function and overall metabolic balance. Impaired BCAA

catabolism can lead to elevated circulating levels of BCAAs and

their ketoacids, which are associated with metabolic disturbances

that may contribute to the development of osteoporosis. For

example, increased BCAA levels can disrupt insulin signaling

pathways, potentially resulting in insulin resistance, a recognized

risk factor for osteoporosis (149).

Moreover, the regulation of key enzymes in BCAA

metabolism, such as BCAT and BCKDH, is crucial for maintaining

metabolic homeostasis. Inhibition of BCAT1 has been shown to impair

osteoclast differentiation, suggesting its potential as a

therapeutic target to halt the progression of osteoporosis

(12). Emerging evidence has

indicated that the expression of these metabolic enzymes is

influenced by factors such as physical activity and transcriptional

coactivators, including PGC-1α. In skeletal muscle, PGC-1α enhances

the expression of BCAA-metabolizing enzymes, facilitating BCAA

degradation and potentially alleviating the detrimental effects of

their accumulation (150).

As the incidence of osteoporotic events continues to

increase, the management of osteoporosis has increasingly focused

on long-term strategies. Consequently, identifying safe, accessible

and effective nutritional interventions to maintain skeletal health

has become a key area of clinical research. BCAAs, due to their

widespread presence in daily diets and ease of adherence, have

attracted growing interest for their potential effects on bone

metabolism, suggesting translational and clinical intervention

value.

Cellular and animal studies have shown that

exogenous BCAAs can modulate bone metabolism through the activation

of signaling pathways, such as mTOR. This regulation occurs through

two concurrent effects: Promoting osteogenic differentiation and

inhibiting excessive osteoclast activation (151-154). Additionally, clinical

observational studies have identified a positive association

between higher BCAA levels and the preservation of bone mineral

density (BMD) (151). These

findings suggest that BCAA supplementation may offer therapeutic

potential in delaying osteoporosis progression. Similarly, Carbone

et al (155) and Urano

et al (156) have

indicated that higher BCAA levels are associated with better BMD.

Together, these studies imply that elevated BCAA levels may be

associated with improved bone health and a reduced risk of

osteoporosis.

However, these findings do not establish a causal

relationship. Residual confounding factors, such as total dietary

protein intake, combination with other substances or physical

activity, may influence both BCAA levels and bone health.

Additionally, the relationship between BCAAs and bone health has

been reported to vary across different disease stages or metabolic

conditions (116). Therefore,

well-designed clinical studies are critical, and further research

involving additional human data is necessary.

Among the BCAAs, leucine is recognized as a critical

amino acid for muscle function (157-159). BCAAs can effectively prevent

and improve sarcopenia, as well as reduce fat infiltration in

skeletal muscles, thus preserving muscle mass and function

(160). A clinical intervention

study conducted by Wang et al (161) demonstrated that leucine

supplementation enhances muscle performance by improving

cytoskeletal dynamics.

In elderly individuals and post-surgical

rehabilitation populations, the combination of BCAA supplementation

and exercise has proven effective in enhancing muscle strength,

which is critical for restoring mobility and providing mechanical

stimulation to the skeleton (167,168). Although the direct efficacy of

BCAA supplementation in treating osteoporosis in humans requires

further validation, it remains a promising approach and warrants

targeted clinical research.

BCAT1 catalyzes the transfer of the amine group from

BCAAs to α-ketoglutarate, generating glutamate and α-ketoacids,

which are subsequently oxidized to provide cellular energy.

Therefore, BCAT1 is crucial for preserving BCAA homeostasis and

ensuring their continued availability for energy production. In a

mouse model, Go et al (12) observed that a 400 μM BCAA

solution effectively promoted osteoclast differentiation, whereas a

higher concentration (800 μM) inhibited it, suggesting a

negative feedback mechanism for BCAAs. Additionally, Huynh et

al reported (169) that

mTORC1, a key nutrient sensor known to be activated by BCAAs

(98), inhibits osteoclast

differentiation through calcineurin and NFATc1 signaling. BCAA

levels are regulated not only by BCATs but also by their primary

transporter, LAT1. Ozaki et al demonstrated that deleting

the gene encoding LAT1 (Slc7a5) specifically in osteoclasts

resulted in osteoclast activation and bone loss (170). Furthermore, Pereira et

al (117) validated the

functional role of the macrophage multinucleation network (MMnet),

a trans-regulated gene co-expression network enriched for

osteoclast-related genes, in regulating osteoclast multinucleation,

resorption, bone mass and strength. These findings suggest that

factors such as BCAT1, mTORC1, Slc7a5 and MMnet may serve as

potential therapeutic targets to inhibit osteoclast formation,

offering a strategy for osteoporosis treatment.

A recent study indicated that elevated BCAA levels

are associated with insulin resistance and an increased risk of

metabolic syndrome (171). In

addition, a longitudinal study conducted between 2016 and 2022 with

3,090 Brazilian participants revealed a positive association

between total BCAA intake (specifically >16 g) and the risk of

obesity (172). These findings,

along with the results from other experiments, are summarized in

Table III. Additionally, in

populations with BCAA metabolism disorders, such as patients with

diabetes mellitus and liver cirrhosis, abnormal BCAA levels may

impact bone metabolism (173).

Therefore, the potential benefits of regulating BCAAs must be

evaluated in conjunction with the metabolic health status of the

individual.

The accumulation of adipose tissue within the bone

marrow space can induce an inflammatory state (176), which in turn promotes bone

resorption and impairs the differentiation of MSCs and

hematopoietic stem cells (177). Furthermore, plant-based foods,

rich in dietary fiber and polyphenols, can enhance energy

expenditure through thermogenesis and regulation of lipid

metabolism, thereby helping reduce fat accumulation (178). Increasing the proportion of

healthy plant-based foods in the diet, which may reduce bone marrow

adipose tissue or modulate the function of bone marrow adipocytes,

could serve as a potential target for improving bone quality and

has important implications for the development of novel therapeutic

strategies (179).

BCAA has attracted increasing attention due to its

diverse biological activities and therapeutic potential. The

present review focused on its effects in bone metabolism and

osteoporosis. Notably, BCAA regulates the muscular and immune

systems by activating the mTOR pathway, thereby influencing bone

function. It also acts as a molecular signal to exert direct or

indirect effects on bone metabolism and bone homeostasis. BCAA

metabolic disorders contribute to a complex pathological network

that involves not only the direct regulation of osteoblasts and

osteoclasts, but also indirect effects mediated by systemic

metabolic abnormalities. Collectively, these factors disrupt bone

homeostasis and may ultimately lead to osteoporosis.

Evidence from animal and human studies have

suggested that BCAA intake may be associated with increased BMD,

supporting its potential as a nutritional target for maintaining

bone health and preventing osteoporosis; however, most current

evidence is derived from in vitro and animal experiments,

which are limited by interspecies metabolic differences and dose

conversion issues, restricting clinical translation (180,181). Moreover, high-quality

population-based studies and prospective intervention trials remain

scarce. Existing studies often suffer from poor reproducibility due

to small sample sizes and inconsistent intervention methods

(182,183). The specific mechanisms of BCAA

action within the bone microenvironment have not been fully

elucidated, and the effects of individual metabolic differences and

disease states on BCAA metabolism require further investigation.

Future work should explore the molecular mechanisms of BCAA in

greater depth. Multicenter, large-sample, long-term randomized

controlled trials are needed to determine the long-term effects of

different BCAA doses and ratios on BMD and bone turnover markers

(155). Integration of advanced

technologies, such as metabolomics, may promote the development of

precise nutritional intervention strategies.

As research on the modulation of bone metabolism by

BCAAs and their role in osteoporosis treatment continues to grow,

these studies will further enhance the understanding and improve

strategies targeting BCAA metabolic processes in disease therapy.

The current review not only provides a reference for further

development and investigation of the impact of BCAA metabolism on

osteoporosis progression, but also serves as a guide for regulating

BCAA metabolism to achieve precision treatment of osteoporosis.

Furthermore, these targeted therapeutic strategies may offer

innovative treatment options for bone metabolism-related

diseases.

Not applicable.

QX, HZ and RY drafted and revised the manuscript.

YZ and FL contributed to the literature search, evidence

extraction, thematic organization, critical interpretation of the

reviewed studies, and the preparation and refinement of the

figures. BC contributed to the literature search, screening,

evidence evaluation, and assisted in organizing and interpreting

the included studies. XC conceived the review, supervised the

overall academic direction and critically revised the manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present review was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China Incubation Project (grant no. Institute-level:

2023YNFY12009); the National College Students' Innovative

Entrepreneurial Training Plan Program (grant no. 202410403067); the

Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College

Students in Jiangxi Province (grant no. S202410403035); the

Doctoral Start-up Fund (grant no. B3477); and the Nanchang

University Second Affiliated Hospital In-Hospital Project (grant

no. 2023efy002).

|

1

|

Li H, Xiao Z, Quarles LD and Li W:

Osteoporosis: Mechanism, molecular target and current status on

drug development. Curr Med Chem. 28:1489–1507. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhang X, Wang Z, Zhang D, Ye D, Zhou Y,

Qin J and Zhang Y: The prevalence and treatment rate trends of

osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. PLoS One. 18:e02902892023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wang L, Yu W, Yin X, Cui L, Tang S, Jiang

N, Cui L, Zhao N, Lin Q, Chen L, et al: Prevalence of osteoporosis

and fracture in China: The China osteoporosis prevalence study.

JAMA Netw Open. 4:e21211062021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D,

Sambrook PN and Eisman JA: Mortality after all major types of

osteoporotic fracture in men and women: An observational study.

Lancet. 353:878–882. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Harada S and Rodan GA: Control of

osteoblast function and regulation of bone mass. Nature.

423:349–355. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Raisz LG: Pathogenesis of osteoporosis:

Concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest. 115:3318–3325.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gao M, Gao W, Papadimitriou JM, Zhang C,

Gao J and Zheng M: Exosomes-the enigmatic regulators of bone

homeostasis. Bone Res. 6:362018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang Y, Li Q, Peng X, Ji P, Zhang Y, Jin

J, Yuan Z, Jiang J, Tian G, Cai M, et al: Targeting

chaperone-mediated autophagy to regulate osteoclast activity as a

therapeutic strategy for osteoporosis. Mater Today Bio.

35:1023112025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Harper AE, Miller RH and Block KP:

Branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 4:409–454.

1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mansoori S, Ho MY, Ng KK and Cheng KK:

Branched-chain amino acid metabolism: Pathophysiological mechanism

and therapeutic intervention in metabolic diseases. Obes Rev.

26:e138562025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Trautman ME, Richardson NE and Lamming DW:

Protein restriction and branched-chain amino acid restriction

promote geroprotective shifts in metabolism. Aging Cell.

21:e136262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Go M, Shin E, Jang SY, Nam M, Hwang GS and

Lee SY: BCAT1 promotes osteoclast maturation by regulating

branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Exp Mol Med. 54:825–833.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Weiner S and Traub W: Bone structure: From

angstroms to microns. FASEB J. 6:879–885. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hua R, Han Y, Ni Q, Fajardo RJ, Iozzo RV,

Ahmed R, Nyman JS, Wang X and Jiang JX: Pivotal roles of biglycan

and decorin in regulating bone mass, water retention, and bone

toughness. Bone Res. 13:22025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber

JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P,

Bringhurst FR, et al: Osteoblastic cells regulate the

haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 425:841–846. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, Huang H, He X, Tong

WG, Ross J, Haug J, Johnson T, Feng JQ, et al: Identification of

the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size.

Nature. 425:836–841. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Taichman RS and Emerson SG: Human

osteoblasts support hematopoiesis through the production of

granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 179:1677–1682.

1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bolamperti S, Villa I and Rubinacci A:

Bone remodeling: an operational process ensuring survival and bone

mechanical competence. Bone Res. 10:482022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hattner R, Epker BN and Frost HM:

Suggested sequential mode of control of changes in cell behaviour

in adult bone remodelling. Nature. 206:489–490. 1965. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Barak MM: Bone modeling or bone

remodeling: That is the question. Am J Phys Anthropol. 172:153–155.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yan C, Zhang P, Qin Q, Jiang K, Luo Y,

Xiang C, He J, Chen L, Jiang D, Cui W and Li Y: 3D-printed bone

regeneration scaffolds modulate bone metabolic homeostasis through

vascularization for osteoporotic bone defects. Biomaterials.

311:1226992024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Akatsu T, Tanaka

H, Sasaki T, Nishihara T, Koga T, Martin TJ and Suda T: Origin of

osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of

differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment

prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 87:7260–7264. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Boyle WJ, Simonet WS and Lacey DL:

Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 423:337–342.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Teitelbaum SL: Bone resorption by

osteoclasts. Science. 289:1504–1508. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Nakahama KI, Hidaka S, Goto K, Tada M, Doi

T, Nakamura H, Akiyama M and Shinohara M: Visualization and

quantification of RANK-RANKL binding for application to disease

investigations and drug discovery. Bone. 195:1174732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Holliday LS, Patel SS and Rody WJ Jr:

RANKL and RANK in extracellular vesicles: Surprising new players in

bone remodeling. Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucl Acids. 2:18–28.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Soriano P, Montgomery C, Geske R and

Bradley A: Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to

osteopetrosis in mice. Cell. 64:693–702. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Boyce BF, Yoneda T, Lowe C, Soriano P and

Mundy GR: Requirement of pp60c-src expression for osteoclasts to

form ruffled borders and resorb bone in mice. J Clin Invest.

90:1622–1627. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gelb BD, Shi GP, Chapman HA and Desnick

RJ: Pycnodysostosis, a lysosomal disease caused by cathepsin K

deficiency. Science. 273:1236–1238. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Saftig P, Hunziker E, Everts V, Jones S,

Boyde A, Wehmeyer O, Suter A and von Figura K: Functions of

cathepsin K in bone resorption. Lessons from cathepsin K deficient

mice. Adv Exp Med Biol. 477:293–303. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mizoguchi T and Ono N: The diverse origin

of bone-forming osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 36:1432–1447. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Tang Y, Wu X, Lei W, Pang L, Wan C, Shi Z,

Zhao L, Nagy TR, Peng X, Hu J, et al: TGF-beta1-induced migration

of bone mesenchymal stem cells couples bone resorption with

formation. Nat Med. 15:757–765. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bodine PV and Komm BS: Wnt signaling and

osteoblastogenesis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 7:33–39. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Eriksen EF: Cellular mechanisms of bone

remodeling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 11:219–227. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Hong AR, Kim K, Lee JY, Yang JY, Kim JH,

Shin CS and Kim SW: Transformation of mature osteoblasts into bone

lining cells and RNA sequencing-based transcriptome profiling of

mouse bone during mechanical unloading. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul).

35:456–469. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wang JS and Wein MN: Pathways controlling

formation and maintenance of the osteocyte dendrite network. Curr

Osteoporos Rep. 20:493–504. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Komori T: Cell death in chondrocytes,

osteoblasts, and osteocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 17:20452016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Takeuchi O and Akira S: Pattern

recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 140:805–820. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Messmer D, Yang H, Telusma G, Knoll F, Li

J, Messmer B, Tracey KJ and Chiorazzi N: High mobility group box

protein 1: An endogenous signal for dendritic cell maturation and

Th1 polarization. J Immunol. 173:307–313. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Giannoni P, Marini C, Cutrona G, Matis S,

Capra MC, Puglisi F, Luzzi P, Pigozzi S, Gaggero G, Neri A, et al:

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells impair osteoblastogenesis and

promote osteoclastogenesis: Role of TNFα, IL-6 and IL-11 cytokines.

Haematologica. 106:2598–2612. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kringelbach TM, Aslan D, Novak I, Schwarz

P and Jørgensen NR: UTP-induced ATP release is a fine-tuned

signalling pathway in osteocytes. Purinergic Signal. 10:337–347.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Verborgt O, Gibson GJ and Schaffler MB:

Loss of osteocyte integrity in association with microdamage and

bone remodeling after fatigue in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 15:60–67.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cheung WY, Fritton JC, Morgan SA,

Seref-Ferlengez Z, Basta-Pljakic J, Thi MM, Suadicani SO, Spray DC,

Majeska RJ and Schaffler MB: Pannexin-1 and P2X7-receptor are

required for apoptotic osteocytes in fatigued bone to trigger RANKL

production in neighboring bystander osteocytes. J Bone Miner Res.

31:890–899. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Luckprom P, Wongkhantee S, Yongchaitrakul

T and Pavasant P: Adenosine triphosphate stimulates RANKL

expression through P2Y1 receptor-cyclo-oxygenase-dependent pathway

in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontal Res. 45:404–411.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Buckley KA, Hipskind RA, Gartland A,

Bowler WB and Gallagher JA: Adenosine triphosphate stimulates human

osteoclast activity via upregulation of osteoblast-expressed

receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand. Bone.

31:582–590. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gallagher JA: ATP P2 receptors and

regulation of bone effector cells. J Musculoskelet Neuronal

Interact. 4:125–127. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cusato K, Bosco A, Rozental R, Guimarães

CA, Reese BE, Linden R and Spray DC: Gap junctions mediate

bystander cell death in developing retina. J Neurosci.

23:6413–6422. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Cawley KM, Bustamante-Gomez NC, Guha AG,

MacLeod RS, Xiong J, Gubrij I, Liu Y, Mulkey R, Palmieri M,

Thostenson JD, et al: Local production of osteoprotegerin by

osteoblasts suppresses bone resorption. Cell Rep. 32:1080522020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Kennedy OD, Laudier DM, Majeska RJ, Sun HB

and Schaffler MB: Osteocyte apoptosis is required for production of

osteoclastogenic signals following bone fatigue in vivo. Bone.

64:132–137. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Verborgt O, Tatton NA, Majeska RJ and

Schaffler MB: Spatial distribution of Bax and Bcl-2 in osteocytes

after bone fatigue: complementary roles in bone remodeling

regulation? J Bone Miner Res. 17:907–914. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lieben L, Carmeliet G and Masuyama R:

Calcemic actions of vitamin D: Effects on the intestine, kidney and

bone. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 25:561–572. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zarei A, Morovat A, Javaid K and Brown CP:

Vitamin D receptor expression in human bone tissue and

dose-dependent activation in resorbing osteoclasts. Bone Res.

4:160302016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lips P and van Schoor NM: The effect of

vitamin D on bone and osteoporosis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 25:585–591. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Bikle DD: Vitamin D and bone. Curr

Osteoporos Rep. 10:151–159. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Arnaud CD Jr, Tenenhouse AM and Rasmussen

H: Parathyroid hormone. Annu Rev Physiol. 29:349–372. 1967.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Martin TJ, Sims NA and Seeman E:

Physiological and pharmacological roles of PTH and PTHrP in bone

using their shared receptor, PTH1R. Endocr Rev. 42:383–406. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Quarles LD: Skeletal secretion of FGF-23

regulates phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

8:276–286. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Jüppner H: Phosphate and FGF-23. Kidney

Int. 79121:S24–S27. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Naot D, Musson DS and Cornish J: The

activity of peptides of the calcitonin family in bone. Physiol Rev.

99:781–805. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Xu J, Wang J, Chen X, Li Y, Mi J and Qin

L: The effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide on bone

homeostasis and regeneration. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 18:621–632.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Lecanda F, Warlow PM, Sheikh S, Furlan F,

Steinberg TH and Civitelli R: Connexin43 deficiency causes delayed

ossification, craniofacial abnormalities, and osteoblast

dysfunction. J Cell Biol. 151:931–944. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Chung DJ, Castro CH, Watkins M, Stains JP,

Chung MY, Szejnfeld VL, Willecke K, Theis M and Civitelli R: Low

peak bone mass and attenuated anabolic response to parathyroid

hormone in mice with an osteoblast-specific deletion of connexin43.

J Cell Sci. 119(Pt 20): 4187–4198. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Zhang Y, Paul EM, Sathyendra V, Davison A,

Sharkey N, Bronson S, Srinivasan S, Gross TS and Donahue HJ:

Enhanced osteoclastic resorption and responsiveness to mechanical

load in gap junction deficient bone. PLoS One. 6:e235162011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Tiede-Lewis LM, Xie Y, Hulbert MA, Campos

R, Dallas MR, Dusevich V, Bonewald LF and Dallas SL: Degeneration

of the osteocyte network in the C57BL/6 mouse model of aging. Aging

(Albany NY). 9:2190–2208. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Dole NS, Mazur CM, Acevedo C, Lopez JP,

Monteiro DA, Fowler TW, Gludovatz B, Walsh F, Regan JN, Messina S,

et al: Osteocyte-Intrinsic TGF-β signaling regulates bone quality

through perilacunar/canalicular remodeling. Cell Rep. 21:2585–2596.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Kreis NN, Friemel A, Ritter A, Hentrich

AE, Siebelitz E, Louwen F and Yuan J: In-depth analysis of

obesity-associated changes in adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal

stromal/stem cells and primary cilia function. Commun Biol.

8:14622025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Olney RC: Regulation of bone mass by

growth hormone. Med Pediatr Oncol. 41:228–234. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Iglesias L, Yeh JK, Castro-Magana M and

Aloia JF: Effects of growth hormone on bone modeling and remodeling

in hypophysectomized young female rats: A bone histomorphometric

study. J Bone Miner Metab. 29:159–167. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Hayashi M, Nakashima T, Yoshimura N,

Okamoto K, Tanaka S and Takayanagi H: Autoregulation of osteocyte

Sema3A orchestrates estrogen action and counteracts bone aging.

Cell Metab. 29:627–637.e5. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Sharma D, Larriera AI, Palacio-Mancheno

PE, Gatti V, Fritton JC, Bromage TG, Cardoso L, Doty SB and Fritton

SP: The effects of estrogen deficiency on cortical bone

microporosity and mineralization. Bone. 110:1–10. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Jackson E, Lara-Castillo N, Akhter MP,

Dallas M, Scott JM, Ganesh T and Johnson ML: Osteocyte

Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation upon mechanical loading is altered

in ovariectomized mice. Bone Rep. 15:1011292021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Ma L, Hua R, Tian Y, Cheng H, Fajardo RJ,

Pearson JJ, Guda T, Shropshire DB, Gu S and Jiang JX: Connexin 43

hemichannels protect bone loss during estrogen deficiency. Bone

Res. 7:112019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

He Z, Li H, Han X, Zhou F, Du J, Yang Y,

Xu Q, Zhang S, Zhang S, Zhao N, et al: Irisin inhibits osteocyte

apoptosis by activating the Erk signaling pathway in vitro and

attenuates ALCT-induced osteoarthritis in mice. Bone.

141:1155732020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Al-Suhaimi EA and Al-Jafary MA: Endocrine

roles of vitamin K-dependent-osteocalcin in the relation between

bone metabolism and metabolic disorders. Rev Endocr Metab Disord.

21:117–125. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Yang D, Gong G, Song J, Chen J, Wang S, Li

J and Wang G: Ferroptosis-mediated osteoclast-osteoblast crosstalk:

Signaling pathways governing bone remodeling in osteoporosis. J

Orthop Surg Res. 20:8882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Baek KH, Chung YS, Koh JM, Kim IJ, Kim KM,

Min YK, Park KD, Dinavahi R, Maddox J, Yang W, et al: Romosozumab

in postmenopausal Korean women with osteoporosis: A Randomized,

double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study.

Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 36:60–69. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Kasiske BL, Kumar R, Kimmel PL, Pesavento

TE, Kalil RS, Kraus ES, Rabb H, Posselt AM, Anderson-Haag TL,

Steffes MW, et al: Abnormalities in biomarkers of mineral and bone

metabolism in kidney donors. Kidney Int. 90:861–868. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Schwetz V, Pieber T and Obermayer-Pietsch

B: The endocrine role of the skeleton: Background and clinical

evidence. Eur J Endocrinol. 166:959–967. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Kärkkäinen M, Tuppurainen M, Salovaara K,

Sandini L, Rikkonen T, Sirola J, Honkanen R, Jurvelin J, Alhava E

and Kröger H: Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on

bone mineral density in women aged 65-71 years: A 3-year randomized

population-based trial (OSTPRE-FPS). Osteoporos Int. 21:2047–2055.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Remer T, Krupp D and Shi L: Dietary

protein's and dietary acid load's influence on bone health. Crit

Rev Food Sci Nutr. 54:1140–1150. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Langeveld M and Hollak CEM: Bone health in

patients with inborn errors of metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord.

19:81–92. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Yang K, Li J and Tao L: Purine metabolism

in the development of osteoporosis. Biomed Pharmacother.

155:1137842022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Iantomasi T, Romagnoli C, Palmini G,

Donati S, Falsetti I, Miglietta F, Aurilia C, Marini F, Giusti F

and Brandi ML: Oxidative stress and inflammation in osteoporosis:

Molecular mechanisms involved and the relationship with microRNAs.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:37722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Johnson JT, Hussain MA, Cherian KE, Kapoor

N and Paul TV: Chronic alcohol consumption and its impact on bone

and metabolic health - A narrative review. Indian J Endocrinol

Metab. 26:206–212. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Ehnert S, Aspera-Werz RH, Ihle C, Trost M,

Zirn B, Flesch I, Schröter S, Relja B and Nussler AK: Smoking

dependent alterations in bone formation and inflammation represent

major risk factors for complications following total joint

arthroplasty. J Clin Med. 8:4062019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Huang YS, Gao JW, Ao RF, Liu XY, Wu DZ,

Huang JL, Tu C, Zhuang JS, Zhu SY and Zhong ZM: Accumulation of

advanced oxidation protein products aggravates bone-fat imbalance

during skeletal aging. J Orthop Translat. 51:24–36. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Schröder K: NADPH oxidases in bone

homeostasis and osteoporosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 132:67–72. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Jiang N, Liu J, Guan C, Ma C, An J and

Tang X: Thioredoxin-interacting protein: A new therapeutic target

in bone metabolism disorders? Front Immunol. 13:9551282022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Le Couteur DG, Solon-Biet SM, Cogger VC,

Ribeiro R, de Cabo R, Raubenheimer D, Cooney GJ and Simpson SJ:

Branched chain amino acids, aging and age-related health. Ageing

Res Rev. 64:1011982020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Brosnan JT and Brosnan ME: Branched-chain

amino acids: Enzyme and substrate regulation. J Nutr. 136(1 Suppl):

207S–211S. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Han JM, Jeong SJ, Park MC, Kim G, Kwon NH,

Kim HK, Ha SH, Ryu SH and Kim S: Leucyl-tRNA synthetase is an

intracellular leucine sensor for the mTORC1-signaling pathway.

Cell. 149:410–424. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Zhang S, Zeng X, Ren M, Mao X and Qiao S:

Novel metabolic and physiological functions of branched chain amino

acids: A review. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 8:102017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Neinast MD, Jang C, Hui S, Murashige DS,

Chu Q, Morscher RJ, Li X, Zhan L, White E, Anthony TG, et al:

Quantitative analysis of the whole-body metabolic fate of

branched-chain amino acids. Cell Metab. 29:417–429.e4. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Wang W, Liu Z, Liu L, Han T, Yang X and

Sun C: Genetic predisposition to impaired metabolism of the

branched chain amino acids, dietary intakes, and risk of type 2

diabetes. Genes Nutr. 16:202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Bonvini A, Coqueiro AY, Tirapegui J,

Calder PC and Rogero MM: Immunomodulatory role of branched-chain

amino acids. Nutr Rev. 76:840–856. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Deng AF, Wang FX, Wang SC, Zhang YZ, Bai L

and Su JC: Bone-organ axes: Bidirectional crosstalk. Mil Med Res.

11:372024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Hasegawa T, Kikuta J, Sudo T, Matsuura Y,

Matsui T, Simmons S, Ebina K, Hirao M, Okuzaki D, Yoshida Y, et al:

Identification of a novel arthritis-associated osteoclast precursor

macrophage regulated by FoxM1. Nat Immunol. 20:1631–1643. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Anthony JC, Yoshizawa F, Anthony TG, Vary

TC, Jefferson LS and Kimball SR: Leucine stimulates translation

initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a

rapamycin-sensitive pathway. J Nutr. 130:2413–2419. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Yang M, Zhang X, Ding Y, Yang L, Ren W,

Gao Y, Yao K, Zhou Y and Shao W: The effect of valine on the

synthesis of α-Casein in MAC-T cells and the expression and

phosphorylation of genes related to the mTOR signaling pathway. Int

J Mol Sci. 26:31792025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Glantschnig H, Fisher JE, Wesolowski G,

Rodan GA and Reszka AA: M-CSF, TNFalpha and RANK ligand promote

osteoclast survival by signaling through mTOR/S6 kinase. Cell Death

Differ. 10:1165–1177. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Kneissel M, Luong-Nguyen NH, Baptist M,

Cortesi R, Zumstein-Mecker S, Kossida S, O'Reilly T, Lane H and

Susa M: Everolimus suppresses cancellous bone loss, bone

resorption, and cathepsin K expression by osteoclasts. Bone.

35:1144–1156. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Ory B, Moriceau G, Redini F and Heymann D:

mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and its derivatives) and nitrogen

containing bisphosphonates: Bi-functional compounds for the

treatment of bone tumours. Curr Med Chem. 14:1381–1387. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Benslimane-Ahmim Z, Heymann D, Dizier B,

Lokajczyk A, Brion R, Laurendeau I, Bièche I, Smadja DM,

Galy-Fauroux I, Colliec-Jouault S, et al: Osteoprotegerin, a new

actor in vasculogenesis, stimulates endothelial colony-forming

cells properties. J Thromb Haemost. 9:834–843. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Gnant M, Baselga J, Rugo HS, Noguchi S,

Burris HA, Piccart M, Hortobagyi GN, Eakle J, Mukai H, Iwata H, et

al: Effect of everolimus on bone marker levels and progressive

disease in bone in BOLERO-2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 105:654–663. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Roberts LD, Boström P, O'Sullivan JF,

Schinzel RT, Lewis GD, Dejam A, Lee YK, Palma MJ, Calhoun S,

Georgiadi A, et al: β-Aminoisobutyric acid induces browning of

white fat and hepatic β-oxidation and is inversely correlated with

cardiometabolic risk factors. Cell Metab. 19:96–108. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Jang C, Oh SF, Wada S, Rowe GC, Liu L,

Chan MC, Rhee J, Hoshino A, Kim B, Ibrahim A, et al: A

branched-chain amino acid metabolite drives vascular fatty acid

transport and causes insulin resistance. Nat Med. 22:421–426. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Batch BC, Shah SH, Newgard CB, Turer CB,

Haynes C, Bain JR, Muehlbauer M, Patel MJ, Stevens RD, Appel LJ, et

al: Branched chain amino acids are novel biomarkers for

discrimination of metabolic wellness. Metabolism. 62:961–969. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Connelly MA, Wolak-Dinsmore J and Dullaart

RPF: Branched chain amino acids are associated with insulin

resistance independent of leptin and adiponectin in subjects with

varying degrees of glucose tolerance. Metab Syndr Relat Disord.

15:183–186. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Lotta LA, Scott RA, Sharp SJ, Burgess S,

Luan J, Tillin T, Schmidt AF, Imamura F, Stewart ID, Perry JR, et

al: Genetic predisposition to an impaired metabolism of the

branched-chain amino acids and risk of type 2 diabetes: A mendelian

randomisation analysis. PLoS Med. 13:e10021792016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Felig P, Marliss E and Cahill GF Jr:

Plasma amino acid levels and insulin secretion in obesity. N Engl J

Med. 281:811–816. 1969. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ,

Stevens RD, Lien LF, Haqq AM, Shah SH, Arlotto M, Slentz CA, et al:

A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that

differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin

resistance. Cell Metab. 9:311–326. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Wang Q, Holmes MV, Davey Smith G and

Ala-Korpela M: Genetic support for a causal role of insulin

resistance on circulating branched-chain amino acids and

inflammation. Diabetes Care. 40:1779–1786. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Mahendran Y, Jonsson A, Have CT, Allin KH,

Witte DR, Jørgensen ME, Grarup N, Pedersen O, Kilpeläinen TO and

Hansen T: Genetic evidence of a causal effect of insulin resistance

on branched-chain amino acid levels. Diabetologia. 60:873–878.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Lynch CJ and Adams SH: Branched-chain

amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 10:723–736. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Liang Z, Su Z, Yang H, Zheng J, Wu X,

Huang M, Duan L, Chen S, Wei B, Fan X and Lin S: Branched-chain

amino acids in bone health: From molecular mechanisms to

therapeutic potential. Biomed Pharmacother. 192:1186452025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

116

|

Zhao H, Zhang F, Sun D, Wang X, Zhang X,

Zhang J, Yan F, Huang C, Xie H, Lin C, et al: Branched-Chain amino

acids exacerbate obesity-related hepatic glucose and lipid

metabolic disorders via attenuating Akt2 signaling. Diabetes.

69:1164–1177. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Pereira M, Ko JH, Logan J, Protheroe H,

Kim KB, Tan ALM, Croucher PI, Park KS, Rotival M, Petretto E, et

al: A trans-eQTL network regulates osteoclast multinucleation and

bone mass. Elife. 9:e555492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Kim JH and Kim N: Regulation of NFATc1 in

osteoclast differentiation. J Bone Metab. 21:233–241. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Yagi M, Miyamoto T, Sawatani Y, Iwamoto K,

Hosogane N, Fujita N, Morita K, Ninomiya K, Suzuki T, Miyamoto K,

et al: DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts

and foreign body giant cells. J Exp Med. 2005. 202:345–351. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Ishii M, Iwai K, Koike M, Ohshima S,

Kudo-Tanaka E, Ishii T, Mima T, Katada Y, Miyatake K, Uchiyama Y

and Saeki Y: RANKL-induced expression of tetraspanin CD9 in lipid

raft membrane microdomain is essential for cell fusion during

osteoclastogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 21:965–976. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Singha UK, Jiang Y, Yu S, Luo M, Lu Y,

Zhang J and Xiao G: Rapamycin inhibits osteoblast proliferation and

differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells and primary mouse bone marrow

stromal cells. J Cell Biochem. 103:434–446. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Han HS, Ahn E, Park ES, Huh T, Choi S,

Kwon Y, Choi BH, Lee J, Choi YH, Jeong YL, et al: Impaired BCAA

catabolism in adipose tissues promotes age-associated metabolic

derangement. Nat Aging. 3:982–1000. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Chen A, Jin J, Cheng S, Liu Z, Yang C,

Chen Q, Liang W, Li K, Kang D, Ouyang Z, et al: mTORC1 induces

plasma membrane depolarization and promotes preosteoblast

senescence by regulating the sodium channel Scn1a. Bone Res.

10:252022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Gayatri MB, Gajula NN, Chava S and Reddy

ABM: High glutamine suppresses osteogenesis through mTORC1-mediated

inhibition of the mTORC2/AKT-473/RUNX2 axis. Cell Death Discov.

8:2772022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|