Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth leading

cause of cancer death worldwide, and despite the wide application

of surgical resection, radiation therapy and molecular targeted

therapy for HCC treatment, its prognosis remains poor, seriously

threatening people's life and health (1,2).

The 5-year survival rate of patients with HCC is 5-30%, and

extrahepatic metastasis is the main cause of death. Therefore, it

is urgently necessary to elucidate in detail the pathological

mechanisms of HCC and explore novel treatments.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is composed of

various elements, such as macrophages, fibroblasts and

extracellular stroma, which are closely associated with tumor

progression and metastasis (3,4).

Macrophages play a key role in tumor progression, and numerous

studies reported that various changes in the TME result in the

transformation of M2-type macrophages, namely tumor-associated

macrophages (TAMs) (5). A large

number of TAMs infiltrating the TME often indicates poor prognosis

in patients with cancer (6,7).

However, the exact mechanisms that change macrophage phenotypes

remain unclear. Although tumor cells regulate macrophage function

via direct cellular contact with cell membrane ligands and integrin

signaling, there is evidence that paracrine factors released by

tumor cells are major contributors to immune microenvironment

remodeling. HCC-derived cytokines and growth factors such as C-C

motif chemokine ligand 2, transforming growth factor beta,

macrophage migration inhibitory factor and hepatocyte growth factor

are essential for macrophage recruitment and differentiation

(8). High-mobility group box 1

protein derived from HCC cells induces M2 macrophage polarization

(9). Thus, exploring the

molecular crosstalk between tumor cells and macrophages in HCC may

provide clues for a novel treatment strategy.

As an important part of the Skp1-Cullin1-F-box (SCF)

E3 ubiquitination complex, F-box affects numerous biological

processes in cells, such as cell cycle, immune regulation and

signal transduction (10,11).

Ubiquitination induces the degradation of the proteasome, thus

promoting or inhibiting the occurrence and metastasis of tumors.

F-box only protein 22 is an F-box protein encoded by the

FBXO22 gene located on human chromosome 15q24.2. FBXO22

binds to histone lysine demethylase 4A (KDM4A) and regulating its

homeostasis, whereas KDMA4 affects genome replication and

stability, that is, parameters that may be associated with

tumorigenesis (12). In

addition, FBXO22 mediates the degradation of Kruppel-like factor 4

and thereby promotes HCC progression (13). However, the effects of FBXO22 on

macrophages in HCC remain unclear. Thus, in the present study, it

was investigated whether FBXO22 facilitates HCC progression by

regulating macrophages via the modulation of the release of

paracrine factors by tumor cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

MHCC97-H (97H) cells, obtained from Shanghai Yaji

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (cat. no. YS-C258), were cultured in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (cat. no. G4511; Wuhan

Servicebio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C in the atmosphere of

95% air and 5% CO2. Trypsin (0.25%) was used for

digestion when the cells reached 70-80% confluence. THP-1 cells

(cat. no. YS-C361; Shanghai Yaji Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were

cultured in the RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no. G4538; Wuhan Servicebio

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C in the atmosphere of 95% air and

5% CO2. Both cell lines were collected for subsequent

experiments in the logarithmic growth phase after three passages.

97H and THP-1 cells were examined for short tandem repeats, and

both were found not to be contaminated with other cells. In

addition, both 97H and THP-1 cells tested negative for

mycoplasma.

Cell transfection and treatment

97H cells were firstly transfected with the

overexpression (oe)-FBXO22 or oe-NC lentivirus (MOI=10; OligoBio)

for 72 h at 37°C to establish 97H-NC or 97H-FBXO22 cells, and then

97H-NC or 97H-FBXO22 cells were transfected with small interfering

(si)-IMPA1 or si-NC mRNAs (20 μM; OligoBio) for 48 h at

37°C, respectively. Also, 97H-NC or 97H-FBXO22 cells were treated

with cycloheximide (CHX; 200 μg/ml; cat. no. HY-12320;

MedChemExpress) for different periods (2, 4 and 8 h) or MG132 (10

μM; cat. no. HY-13259; MedChemExpress) for 12 h. The THP-1

cells were transfected with the si-NC or si-SLC5A3 mRNAs (20

μM; OligoBio) for 48 h at 37°C. All the transfections were

performed via Lipofectamine 2000 (cat. no. 11668027; Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A total of 24 h later, the

transfected cells were harvested for the following experiments. The

siRNA sequences were as follows: si-IMPA1:

5'-GAAUGUUAUGCUGAAAAGUUC-3'; si-SLC5A3-1:

5'-GCACUUACACUUAUGAUUAUU-3'; si-SLC5A3-2:

5'-GCAAGUUAAAGUAAUACUAAA-3'; si-SLC5A3-3:

5'-GUGACUUAGACUCUAUCUUUA-3'; and si-NC:

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3'.

Co-culture of 97H and THP-1 cells

97H cells were transfected with oe-FBXO22

lentivirus or si-IMPA1 and added to the upper compartment of

Transwell chambers after 24 h. Then, the THP-1 cells were added to

the lower compartment and co-cultured with the 97H cells

transfected with oe-FBXO22 or si-IMPA1 and cultured

in the upper compartment for 24 h; the ratio of 97H/THP-1 cells was

1:2, whereupon the cells were collected for flow cytometric

analysis.

Flow cytometry

THP-1 cells (1×106 cells/100 μl)

were stained with a FITC-labelled anti-human CD86 antibody (cat.

no. 374203; 1:20; BioLegend, Inc.) or a PE-labelled anti-human

CD206 antibody (cat. no. 321105; 1:20; BioLegend, Inc.) for 30 min

at room temperature and analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur flow

cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software version 10.8.1

(FlowJo LLC).

Cell viability

THP-1 cells (2×103 cells/100 μl)

were seeded into a 96-well plate, Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent (10

μl; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was added to each

well, and the cells were incubated for 3 h at 37°C in the dark. The

optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm using a

microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x; Molecular Devices, LLC).

Dual luciferase reporter assay

The IMPA1 3'-untranslated region (UTR)

containing wild or mutant binding sites was cloned into the

psiCHECKTM-2 vector, and 293T cells (cat. no. CL-0005; Life Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) were co-transfected with oe-NRF2

and IMPA1 3'-UTR psiCHECKTM-2 plasmid for 48 h via

Lipofectamine 2000 (cat. no. 11668027; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The cells were then harvested and washed with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and luciferase activity was

measured using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (cat. no.

E1910; Promega Corporation). For statistical analysis,

Renilla fluorescence value, firefly fluorescence value, and

the background fluorescence value were read, respectively. Firefly

was the internal control. The relative luciferase activity was

calculated as follows:

(Renilla-background)/(firefly-background).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using an RNA Extraction Kit

(cat. no. R1200; Yuduobio), and reverse transcribed into

complementary DNA using a reverse transcription kit (Aidlab

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer's instructions.

RT-qPCR was performed using an ABI-7500 Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with genes

primers and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.).

PCR amplification conditions were as follows: 94°C for 10 min,

(94°C for 20 sec, 55°C for 20 sec, 72°C for 20 sec) for 40 cycles.

The data were analyzed using the 2−∆∆Cq method as

previously described (14), and

β-actin (ACTB) mRNA level was used for the normalization of

expression data. The following primers were used: SLC5A3

forward, 5'-AGCACCGTGAGTGGATACTTC-3' and reverse,

5'-CCCTGACCGGATGTAAATTGG-3'; IMPA1 forward,

5'-TAACTCTAGCAAGACAAGCTGGA-3' and reverse,

5'-TCAACTTTTTGGTCCGTAGCAG-3'; and ACTB forward,

5'-AGCGAGCATCCCCCAAAGTT-3' and reverse,

5'-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATT-3'.

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed via RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no.

G2008; Wuhan Servicebio Biotechnology Co., Ltd), and the protein

content was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein

assay kit (cat. no. E112; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.). The equal

amount (40 μg per lane) of protein was separated using 10%

SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and then the protein was transferred onto

a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was maintained with 5%

non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with the

primary antibodies against the following proteins: PI3K (1:10,000;

cat. no. 67071-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), phosphorylated (p-)

PI3K (1:1,000; cat. no. AF3242; Affinity Biosciences), AKT1

(1:10,000; cat. no. 80457-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.), p-AKT1

(1:5,000; cat. no. 80462-1-RR, Proteintech Group, Inc.), FBXO22

(1:2,000; cat. no. 13606-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), IMPA1

(1:300; cat. no. 16593-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), SLC5A3

(1:1,000; cat. no. DF4521; Affinity Biosciences), PTEN (1:5,000;

cat. no. 60300-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.), and NRF2 (1:2,000;

cat. no. 16396-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). β-actin protein

level was the internal control. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

goat anti-mouse IgG (1:3,000; cat. no. SA00001-1-A; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) served as the secondary antibody. Finally, an enhanced

chemiluminescence kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) was utilized to

determine the protein bands, and the optical density was analyzed

using the Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics,

Inc.).

Bioinformatics analysis

Based on the TIMER database (https://compbio.cn/timer3/), the correlation between

FBXO22 and macrophages in HCC was predicted.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Co-IP assays were performed using an IP kit (cat.

no. P2179S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). 97H cells were

lysed in RIPA lysis buffer including phenyl-methane-sulfonyl

fluoride, followed by the incubation with an anti-NRF2 (1:2,000) or

anti-PTEN antibody (1:5,000) at 4°C overnight, and IgG served as

negative control. Then the mixture of the lysis buffer (500

μl), the antibodies (1 μg), and protein A+G magnetic

beads (30 μl) was incubated at 4°C for 4 h, and was

separated using a magnetic rack. Then the obtained magnetic beads

were washed using PBS for 5 times, and 40 μl of 1X loading

buffer was added. The magnetic beads were boiled for 10 min in a

98°C metal bath, and then were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 3 min,

and beads with bound protein were removed, and the targeted protein

was tested using western blotting.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

The ChIP assay was performed to analyze the

interaction between NRF2 and IMPA1 using a Pierce Agarose ChIP kit

(cat. no. 26156; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Briefly,

homogenates of 97H cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-FBXO22

were sonicated to generate short fragments of genomic DNA, and

equal amounts of treated chromatin were added to microwells

containing an anti-NRF2 antibody. Then, cross-linked DNA was

released from the antibody-captured protein-DNA complex, and

purified DNA was used for PCR analysis.

Liquid chromatography tandem-mass

spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

97H cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-FBXO22

were used for non-targeted metabolomic analysis by Bioprofile

(www.bioprofile.cn/bxdx/list.aspx). Briefly,

metabolomics profiling was analyzed using a UPLC-ESI-Q-Orbitrap-MS

system (UHPLC; Shimadzu Nexera X2 LC-30AD; Shimadzu) coupled with

Q-Exactive Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The electrospray

ionization (ESI) with positive-mode and negative mode were applied

for MS data acquisition separately. The ESI source conditions were

set as follows: Spray Voltage: 3.8 kv (positive) and 3.2 kv

(negative); Capillary Temperature: 320°C; Sheath Gas (nitrogen)

flow: 30 arb (arbitrary units); Aux Gas flow: 5 arb; Probe Heater

Temp: 350°C; S-Lens RF Level: 50. The instrument was set to acquire

over the m/z range 70-1050 Da for full MS. The full MS scans were

acquired at a resolution of 70,000 at m/z 200, and 17,500 at m/z

200 for MS/MS scan. The maximum injection time was set to for 100

ms for MS and 50 ms for MS/MS. The isolation window for MS2 was set

to 2 m/z and the normalized collision energy (stepped) was set as

20, 30 and 40 for fragmentation. For statistical analysis, variable

importance in projection (VIP) value >1 was the initial

screening criterion to identify metabolites differentially

expressed between 97H cells transfected with oe-NC or

oe-FBXO22, and univariate statistical analysis (P<0.05)

was further employed to determine whether the levels of metabolites

were significantly different.

Establishment of a xeno-transplanted

tumor model and experimental groups

97H cells were resuspended in PBS to prepare cell

suspension (5×107 cells/ml), and then HCC was induced by

a subcutaneous injection of 97H cell suspension (100

μl/mouse) into the thigh of 3-5-week old male BALB/C nude

mice (Cavens Laboratory Animal). Before the experiments, mice were

acclimated for 1 week. All mice (n=30; 11-15 g) were provided free

and unlimited access to normal chow and water, housed under

suitable temperature (22±2°C) and humidity (65±5%) with a 12/12-h

light/dark cycle. The model mice were randomly divided into six

groups (n=4): control, myo-inositol (this group received 200 mg/ml

myo-inositol intra-gastrically) (15,16), 97H-NC + si-NC (this group

received a subcutaneous injection of 97H-NC cells followed by

intratumoral injections of si-NC once weekly for 2 weeks),

97H-FBXO22 + si-NC group (this group received a subcutaneous

injection of 97H-FBXO22 cells followed by intratumoral injections

of si-NC once weekly for 2 weeks), 97H-NC + si-IMPA1 (this group

received a subcutaneous injection of 97H-NC cells followed by

intratumoral injections of si-IMPA1 once weekly for 2 weeks),

97H-FBXO22 + si-IMPA1 (this group received a subcutaneous injection

of 97H-FBXO22 cells followed by intratumoral injections of si-IMPA1

once weekly for 2 weeks). Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days

for ~3 weeks. A total of 21 days later, the mice were euthanized

using the cervical dislocation under the inhalation anesthesia of

isoflurane. Briefly, mice were put in the desiccator with

isoflurane (3.0%), and shook the desiccator after 3 min, if the

mouse turned to a lateral position and did not attempt to return to

its lying position, indicating that the mouse has been fully

anesthetized. Then isoflurane (1.5%) was used for maintaining

anesthesia, and the mouse did not respond when its tail, toes, or

the cornea was touched, then a laboratory professional quickly

performed cervical dislocation, and which should be as fast as

possible to reduce mouse pain. The present study adhered to the

recommendations outlined in the ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0 and was

approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the

First Affiliated Hospital, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang

University (approval no. CDYFY-IACUC-202501GR136; Nanchang,

China).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining

After the fixation with 4% polyformaldehyde liquid

for 24 h at 4°C, dehydration and transparency, the tumor tissues

were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm sections. The

sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature for 8 min and blocked with

10% goat serum (cat. no. 16210064; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) at room temperature for 30 min. Then the sections were

incubated with anti-CD86 (1:100; cat. no. 19589S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) or anti-CD206 (1:200; cat. no. 24595S; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) antibodies at 4°C overnight and

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; cat.

no. S0002; Affinity Biosciences) at room temperature for 30 min.

Then the sections were stained with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine and

hematoxylin at room temperature for 10 min. Finally, images of the

sections were captured using an inverted fluorescence microscope

(Olympus Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed by the

unpaired Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software; Dotmatics), followed

by Tukey's post hoc test. The Brown-Forsythe test was used to

assess variance homogeneity in ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

FBXO22-induced myo-inositol release by

97H cells promotes M2 polarization of THP-1 cells

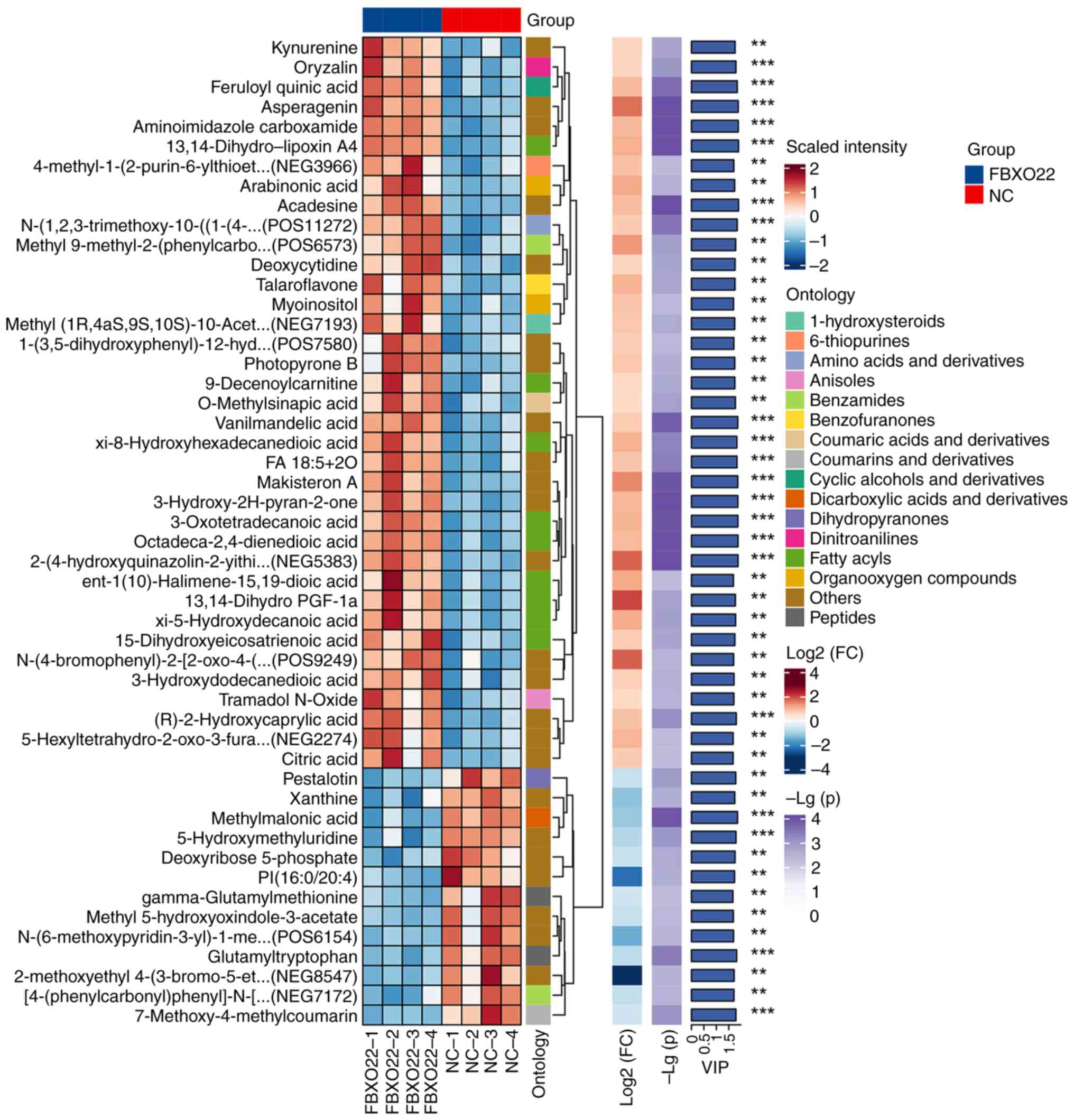

Results of non-targeted metabolomic analysis of 97H

cells transfected with oe-NC or oe-FBXO22 and hierarchical

clustering of the top 50 differential metabolites (VIP >1) are

illustrated in Fig. 1. Based on

human metabolome database HMDB-HU, out of the top six metabolites

(P<0.01; Fig. 1; Table I), myo-inositol and

R-3-hydroxydodecanoic acid were selected for further validation,

owing to their commercial availability. Both RT-qPCR and western

blot analyses revealed that, compared with R-3-hydroxydodecanoic

acid, myo-inositol exhibited the best promoting effect on Arg1

expression and inhibitory effect on inducible nitric oxide synthase

expression in THP-1 cells (Fig. S1A

and B); thus, myo-inositol was selected for the following

experiments. Then, the effects of myo-inositol on macrophages were

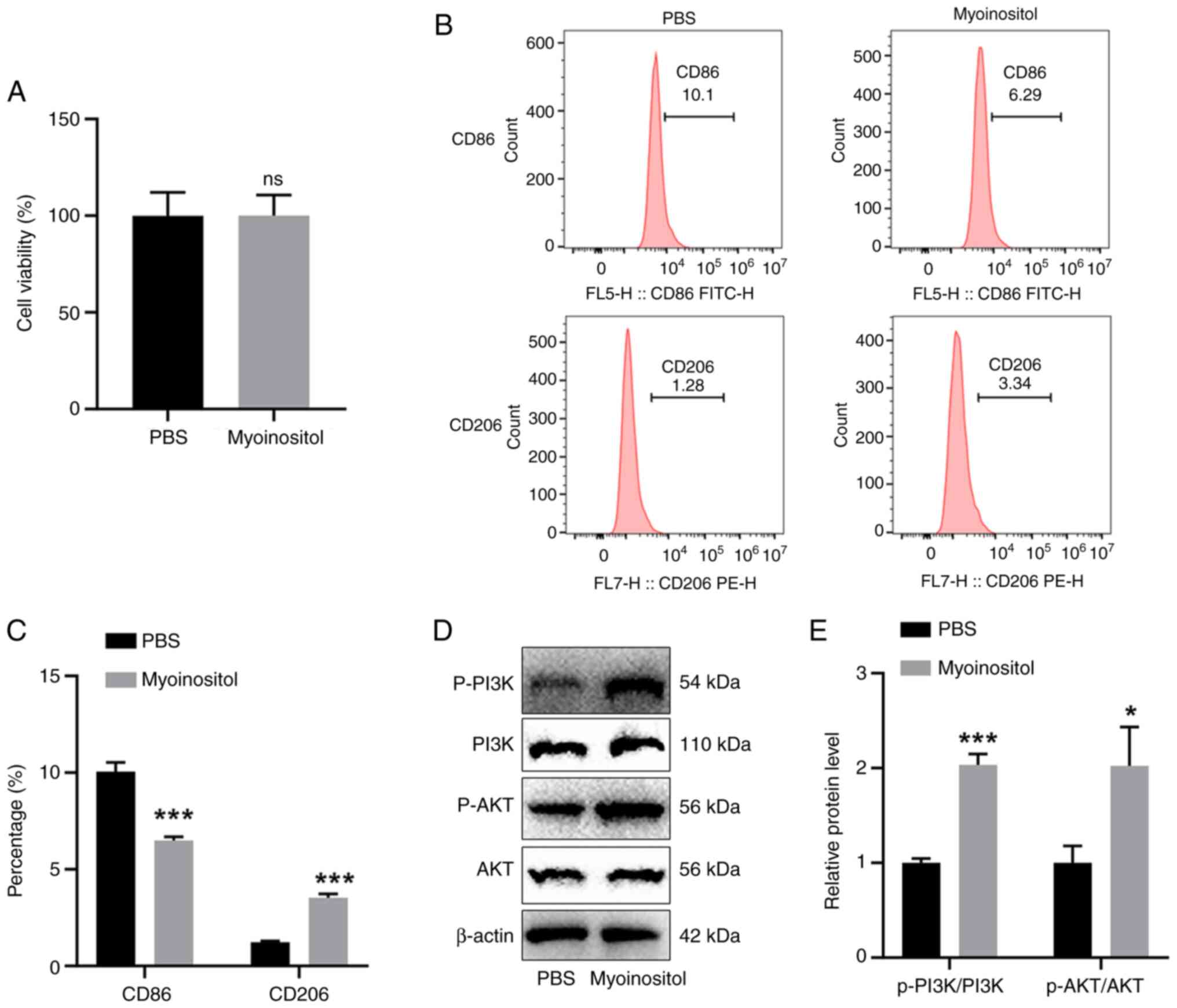

investigated. Myo-inositol did not significantly affect cell

viability (Fig. 2A). Flow

cytometry revealed that myo-inositol significantly reduced the

number of CD86-positive THP-1 cells and increased the number of

CD206-positive THP-1 cells (Fig. 2B

and C). In addition, myo-inositol significantly increased

p-PI3K and p-AKT levels in THP-1 cells (Fig. 2D and E). Based on the results

illustrated in Figs. 1, 2 and S1, it was concluded that

FBXO22 overexpression induces the release of myo-inositol in

97H cells and further promotes M2 polarization of macrophages.

| Table IMetabolites in Fig. 1 that were annotated to the human

metabolome database HMDB-HU. |

Table I

Metabolites in Fig. 1 that were annotated to the human

metabolome database HMDB-HU.

| Alignment ID | Metabolite

name | BLOCKID | P-value | FC |

|---|

| NEG5475 | 13,14-Dihydro-

lipoxin A4 |

HMDB-HU-SE-N207 | 3.60E-05 | 2.093572 |

| POS6421 |

9-Decenoylcarnitine | HMDB-HU-SE-P86 | 0.002324526 | 1.522776 |

| NEG1282 | Arabinonic

acid |

HMDB-HU-UR-N167 | 0.002978637 | 2.182012 |

| NEG1549 | Myo-inositol |

HMDB-HU-SE-N114 | 0.004211906 | 1.812636 |

| NEG5087 | ent-1(10)-Halimene-15,19-dioic acid |

HMDB-HU-SE-N494 | 0.004829203 | 2.215659 |

| NEG2332 |

(R)-3-Hydroxydodecanoic acid |

HMDB-HU-SE-N152 | 0.007715954 | 3.134245 |

| NEG4975 |

5,8,12-Trihydroxy-9-octadecenoic acid |

HMDB-HU-SE-N261 | 0.011872046 | 2.293262 |

| NEG5058 |

Bicyclo-Prostaglandin E2 |

HMDB-HU-SE-N901 | 0.01287796 | 1.65443 |

| POS7620 |

Tetradeca-5,7,9-trienoylcarnitine |

HMDB-HU-UR-P525 | 0.014604632 | 1.581081 |

| NEG332 | Citraconic

anhydride | HMDB-HU-UR-N65 | 0.023404697 | 1.500645 |

| NEG4602 | Octadecenedioic

acid |

HMDB-HU-SE-N1015 | 0.039284274 | 1.509278 |

| POS5061 | Creatine

riboside |

HMDB-HU-UR-P452 | 0.046645468 | 1.579277 |

| POS4124 |

Butenylcarnitine | HMDB-HU-SE-P75 | 0.062279284 | 1.838155 |

| POS434 |

1-Pyrrolidinecarboxaldehyde |

HMDB-HU-SE-P259 | 0.062433302 | 1.738346 |

| POS2353 | Homoarecoline |

HMDB-HU-SE-P283 | 0.100541459 | 2.153713 |

| NEG8112 |

Taurohyocholate | HMDB-HU-SE-N52 | 0.112350153 | 1.548636 |

| POS2183 |

Dimethylamphetamine |

HMDB-HU-SE-P297 | 0.191678682 | 1.517535 |

Myo-inositol promotes M2 polarization of

THP-1 cells via SLC5A3

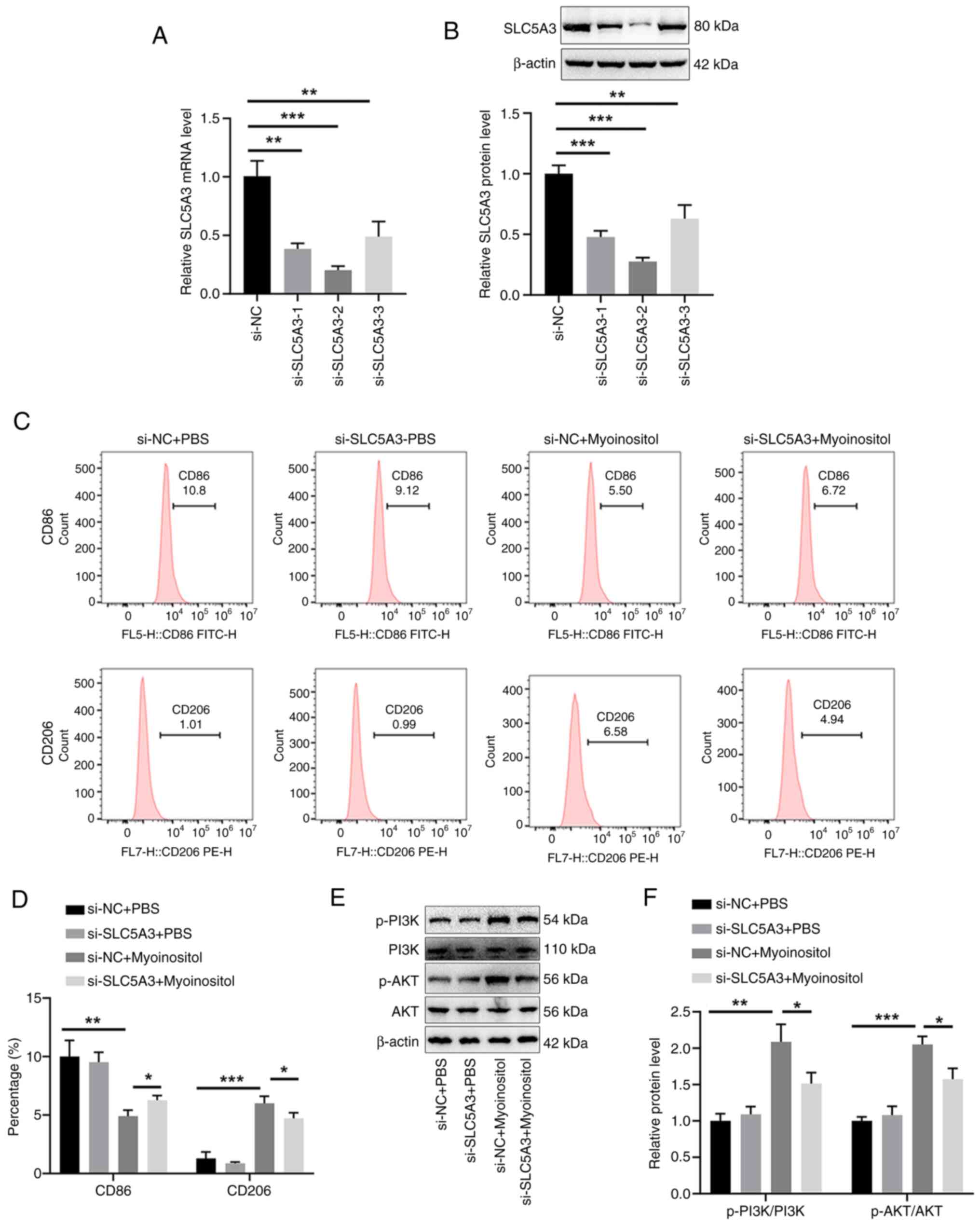

SLC5A3 transports myo-inositol from the outside to

the inside of the cells; thus, the role of SLC5A3 in the

stimulatory effect of myo-inositol on M2 polarization of THP-1

cells was explored. First, three si-SLC5A3 siRNAs were used

to silence SLC5A3 expression in THP-1 cells, and

si-SLC5A3-2 was selected because of its high knockdown

efficiency (Fig. 3A and B). Flow

cytometric analysis revealed that the marked reduction in

CD86-positive cells and increase in CD206-positive cells induced by

myo-inositol were reversed by si-SLC5A3 in THP-1 cells

(Fig. 3C and D). Western blot

analysis revealed that increased p-PI3K and p-AKT levels induced by

myo-inositol in THP-1 cells were significantly reversed by the

incubation with si-SLC5A3 (Fig. 3E and F). These results suggested

that SLC5A3 promotes the effect of myo-inositol on M2 polarization

of THP-1 cells.

FBXO22-induced myo-inositol release

promotes M2 polarization of THP-1 cells via the PTEN/NRF2/IMPA1

axis

Actually, in our preliminary experiments, the TIMER

database revealed that FBXO22 is positively correlated with M2

macrophages in HCC (Fig. S2).

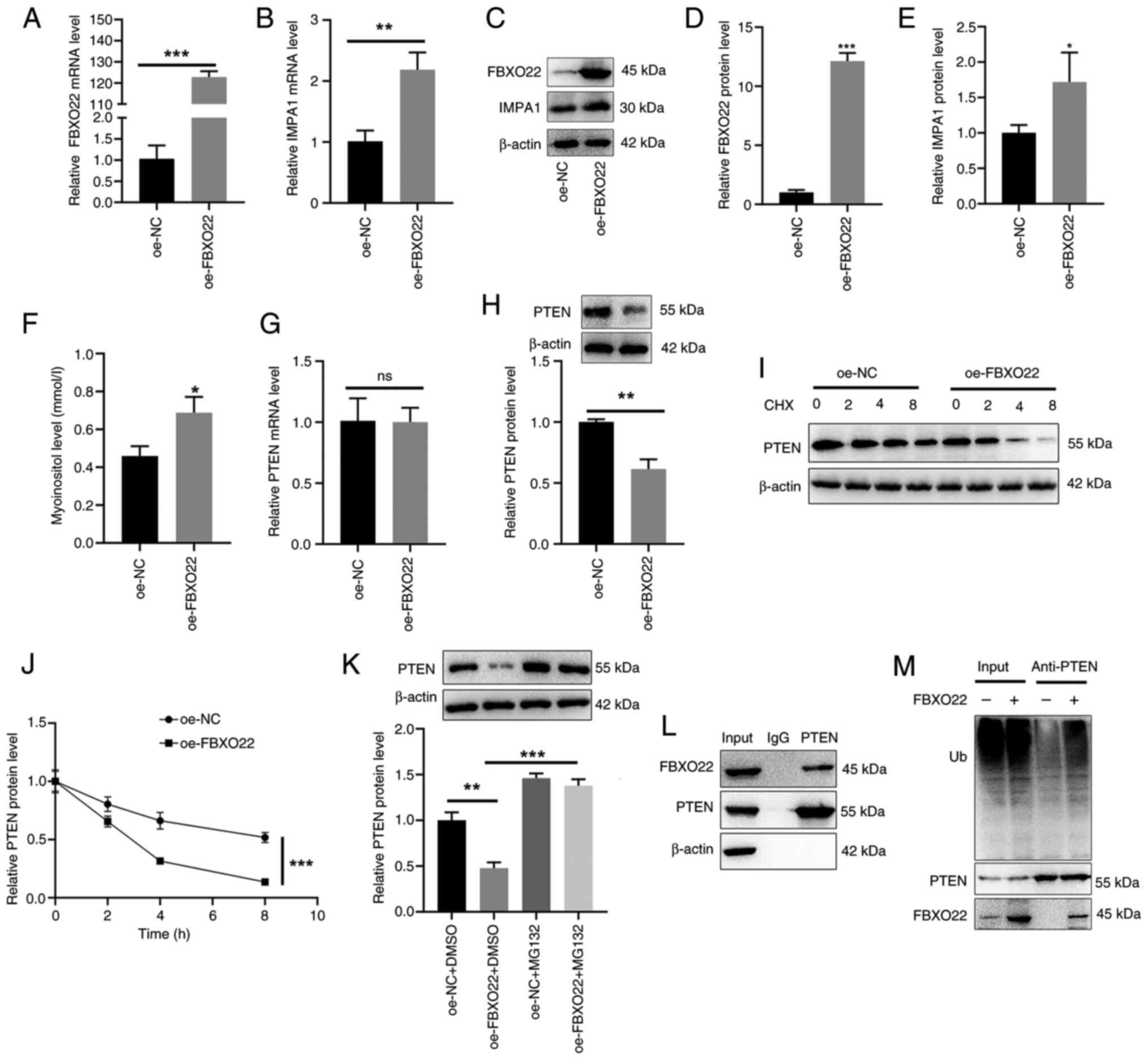

Thus, the mechanisms by which FBXO22-induced myo-inositol release

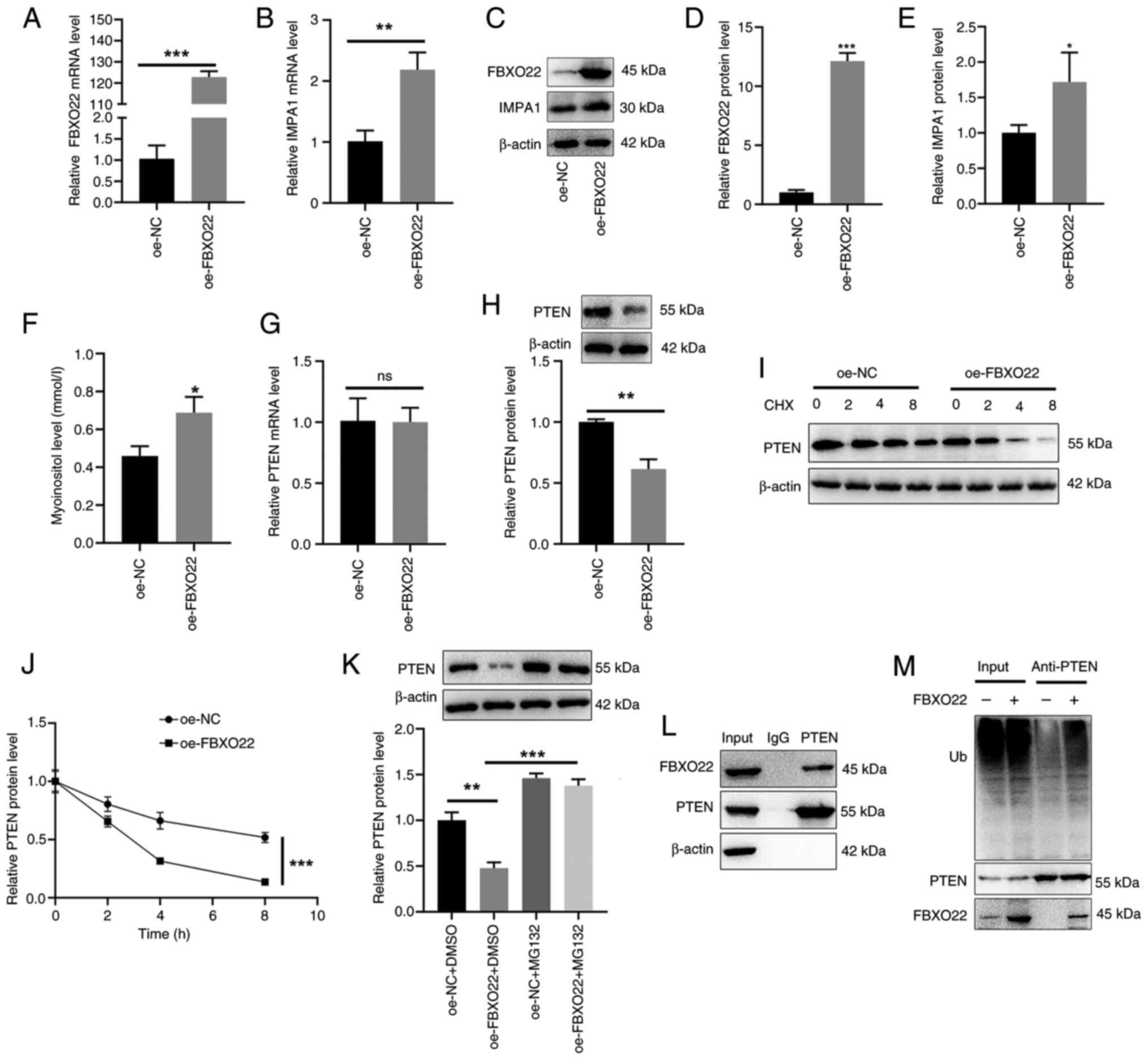

promoted M2 polarization were explored. It was found that

transfection with oe-FBXO22 significantly upregulated

FBXO22 mRNA expression and protein level (Fig. 4A, C and D), IMPA1 mRNA

expression and protein level (Fig.

4B, C and E), and myo-inositol release (Fig. 4F) in 97H cells. In addition,

transfection with oe-FBXO22 did not affect PTEN mRNA

expression (Fig. 4G) but

significantly reduced PTEN protein level (Fig. 4H) in 97H cells. The use of CHX

and proteasome inhibitor MG132 further confirmed that FBXO22

degraded PTEN, reducing PTEN protein level (Fig. 4I-K). Furthermore, co-IP analysis

revealed an interaction between FBXO22 and PTEN (Fig. 4L) and the promoting effect of

FBXO22 on PTEN ubiquitination (Fig.

4M) in 97H cells.

| Figure 4FBXO22 induces PTEN ubiquitination

and subsequent degradation in THP-1 cells. 97H cells were

transfected with oe-FBXO22. Reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and western blotting were performed

to detect mRNA expression levels and protein levels of (A, C and D)

FBXO22, (B, C and E) IMPA1 and (G and H) PTEN.

(F) A myo-inositol detection kit was used to detect myo-inositol in

cell supernatants. (I and J) 97H cells were transfected with

oe-FBXO22, followed by the treatment with CHX (200

μg/ml) for different periods (2, 4 and 8 h). Western

blotting was performed to detect PTEN protein levels. (K) 97H cells

were transfected with oe-FBXO22 followed by the treatment

with MG132 (10 μM) for 12 h. Western blotting was performed

to detect PTEN protein levels. (L) 97H cells were incubated with an

anti-PTEN antibody, and western blotting was performed to detect

FBXO22 protein levels. (M) 97H cells were incubated with an

anti-PTEN antibody, followed by the transfection with

oe-FBXO22. Western blotting was performed to detect PTEN

ubiquitination levels. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. CHX,

cycloheximide; oe-, overexpression; NC, negative control. |

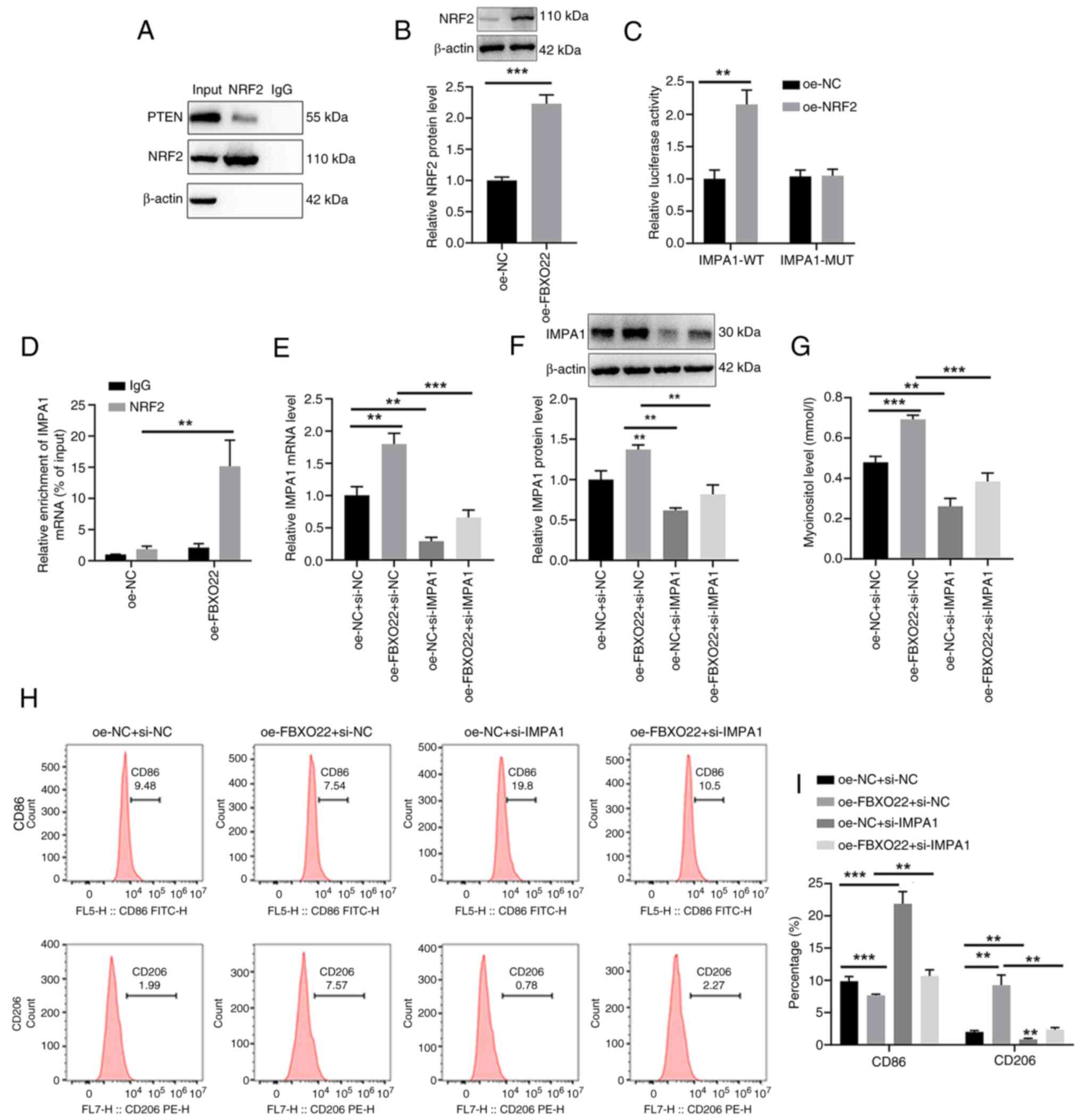

In addition, co-IP analysis demonstrated a direct

interaction between PTEN and NRF2 in 97H cells (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis showed

that treatment with oe-FBXO22 significantly upregulated NRF2

protein levels in 97H cells (Fig.

5B). The luciferase assay revealed that NRF2 bound to the

promoter region of IMPA1 mRNA to promote IMPA1

transcription in 293T cells (Fig.

5C). The ChIP assay further showed the direct transcriptional

regulation of IMPA1 by NRF2 in 97H cells (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, transfection with

oe-FBXO22 significantly increased IMPA1 mRNA

expression and protein level (Fig.

5E and F) and myo-inositol release (Fig. 5G) in 97H cells, the changes that

were markedly reversed by the treatment with si-IMPA1. Flow

cytometric analysis also demonstrated that co-transfection with

si-IMPA1 significantly reversed the decrease in

CD86-positive cells and increase in CD206-positive cells induced in

97H cells by transfection with oe-FBXO22 (Fig. 5H and I). These results suggested

that FBXO22 degrades PTEN by promoting PTEN ubiquitination, which

upregulates NRF2 protein levels and stimulates IMPA1 to induce

myo-inositol release by 97H cells, thus promoting M2 polarization

of THP-1 cells.

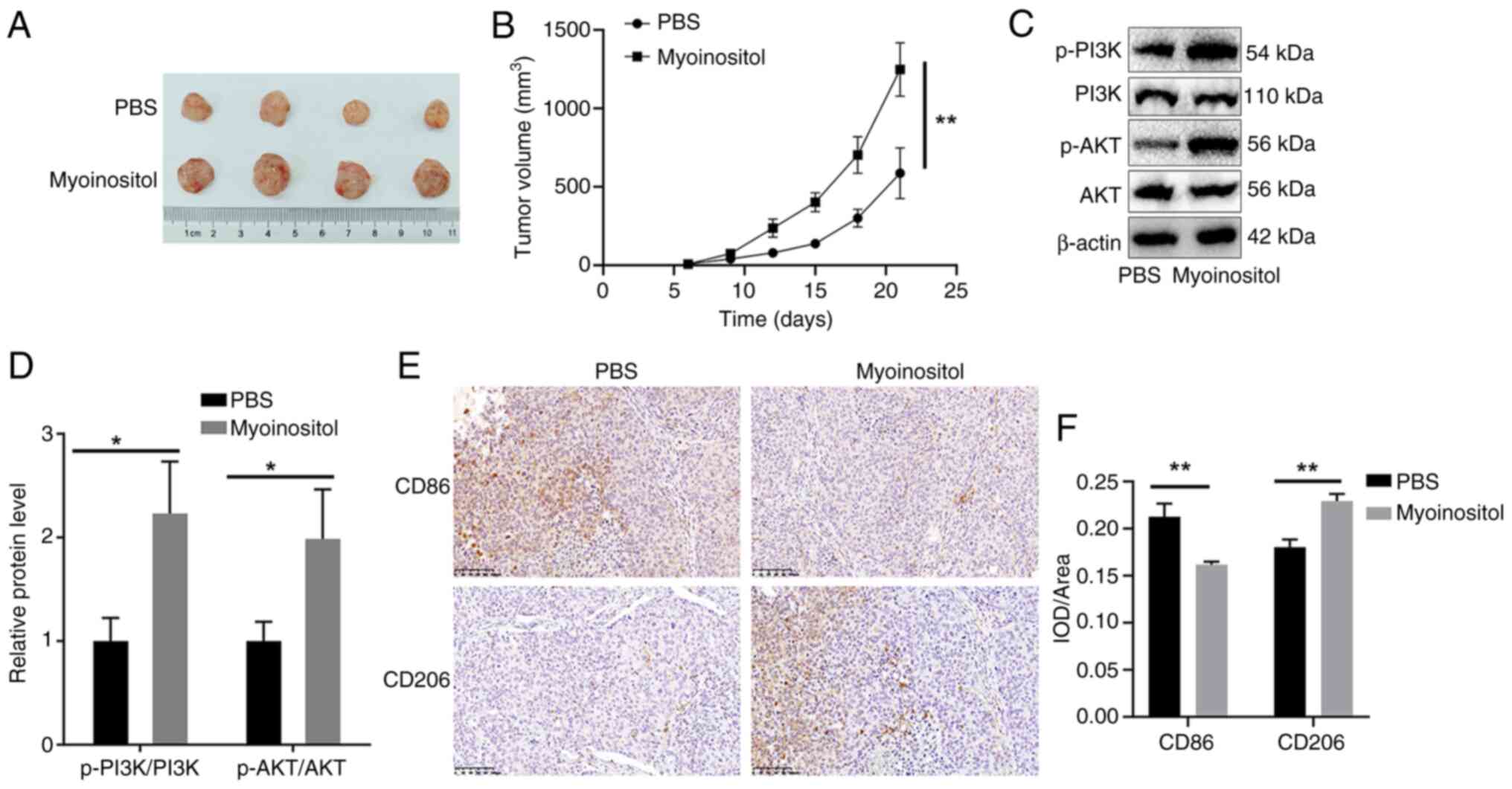

Myo-inositol promotes tumor growth and

induces M2 polarization in HCC mice

Finally, the effect of myo-inositol was assessed

in vivo. The tumor volume in the myo-inositol group was

significantly larger compared with that in the PBS group (Fig. 6A and B). In addition, treatment

with myo-inositol significantly increased p-PI3K and p-AKT levels

(Fig. 6C and D), reduced the

number of CD86-positive cells, and increased the number of

CD206-positive cells in HCC tumor tissues (Fig. 6E and F). These results suggested

that myo-inositol promotes HCC progression in vivo.

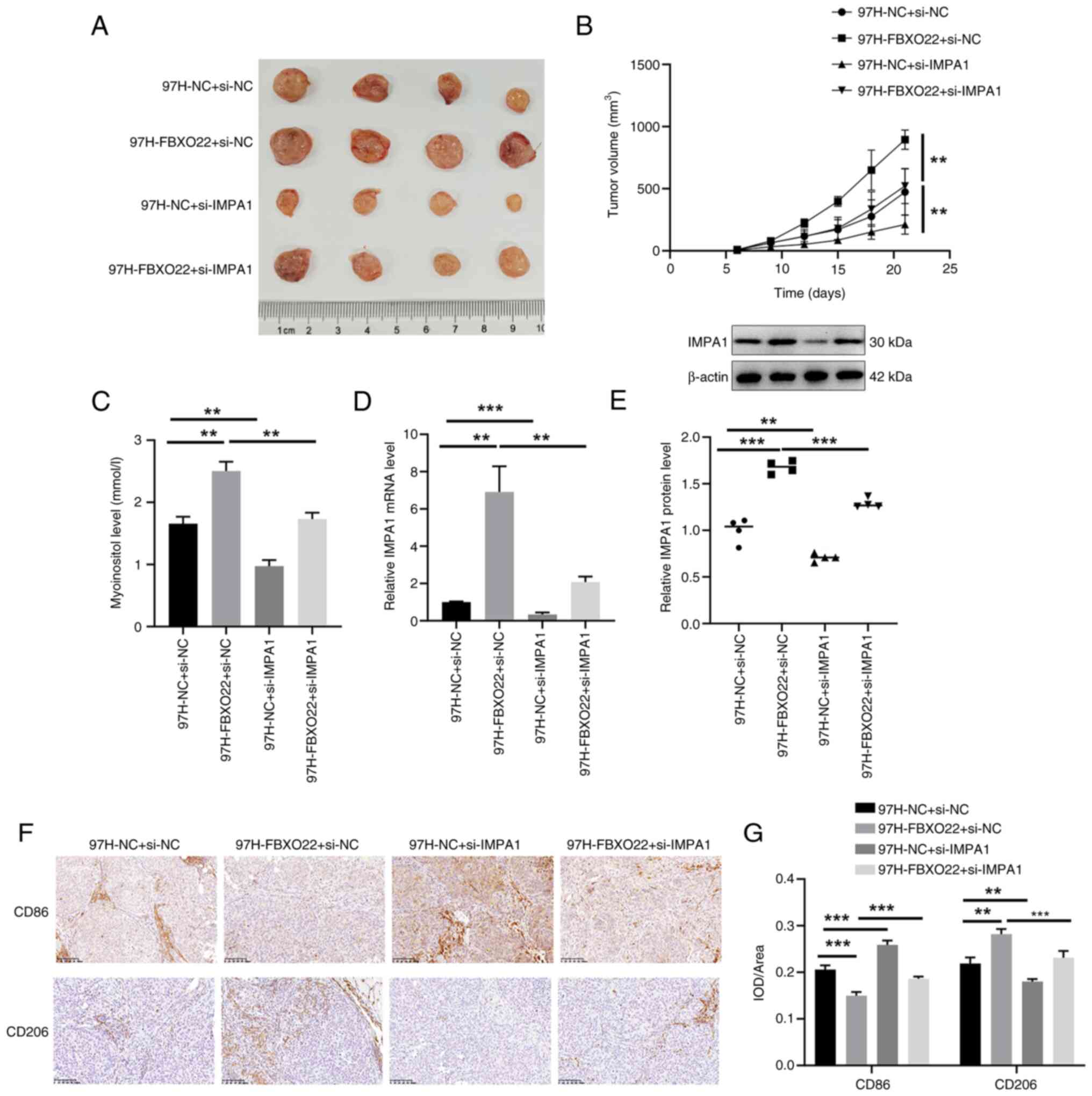

FBXO22 promotes tumor growth and induces

M2 polarization via IMPA1 in HCC mice

Furthermore, FBXO22 overexpression

significantly increased tumor volume (Fig. 7A and B), myo-inositol levels

(Fig. 7C), IMPA1 mRNA

expression and protein level (Fig.

7D and E), reduced the number of CD86-positive cells, and

increased the number of CD206-positive cells (Fig. 7F and G) in mouse HCC tumors.

Notably, these changes were all significantly reversed by

si-IMPA1. These results suggested that FBXO22 upregulates

myo-inositol levels, thus promoting tumor growth and inducing M2

polarization via IMPA1 in HCC tumors.

Discussion

Post-translational modifications of proteins,

including glycosylation, acetylation, methylation and

ubiquitination, play a key role in various cellular processes, such

as signal transduction, cell proliferation, apoptosis and immune

responses (17). Ubiquitination

is one of the most common post-translational modifications, during

which ubiquitin molecules are linked to specific target proteins by

E3 ligases, initiating a cascade reaction that degrades or

dysregulates target proteins. Multiple E3 ligases are closely

related to tumorigenesis, and the identification of E3 ligases that

target oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins has become a hot

topic in cancer research (18,19).

In previous years, an increasing number of E3

ligases have been associated with HCC occurrence and development

(20,21). FBXO22 is the F-box receptor

subunit of the SCF E3 ligase that belongs to the F-box protein

family (22). FBXO22 forms a

complex with lysine demethylase to target p53 and thus plays a role

in regulating body aging (23).

Recently, increasing attention has been paid to the role of FBXO22

in malignant tumors. Tian et al (13) reported that FBXO22 promotes HCC

progression by regulating the degradation of Kruppel-like factor 4.

In addition, Zhang et al (24) reported that FBXO22 regulates the

ubiquitination and degradation of p21 to promote HCC development.

Zheng et al (25) found

that FBXO22 regulates HIF-1 and VEGF impacting angiogenesis in

melanoma, whereas the deletion of FBXO22 significantly inhibited

migration, invasion and angiogenesis in melanoma. Lin et al

(26) reported that FBXO22

promotes the progression of cervical cancer by targeting p57Kip2

via ubiquitination and degradation. These studies demonstrated that

FBXO22 plays an important role in the occurrence and development of

various tumors by regulating multiple substrate proteins.

Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) is

a known tumor suppressor expressed in various tumors, including HCC

(27). Liu et al

(28) reported that E3 ubiquitin

ligase HRD1 promotes PTEN degradation by inducing its

ubiquitination, thereby facilitating HCC progression. Xu et

al (29) reported that E3

ubiquitin ligase MARCH8 promotes the malignant progression of HCC

by inducing the ubiquitination and degradation of PTEN. In

addition, Ge et al (30)

reported that FBXO22 degrades nuclear PTEN to promote

tumorigenesis. As expected, in the present study, FBXO22

significantly reduced PTEN protein level in HCC cells, but did not

affect PTEN mRNA expression. Experiments with CHX and MG132

further showed that FBXO22 degraded PTEN and reduced its levels.

Co-IP analysis revealed an interaction between FBXO22 and PTEN and

the stimulatory effect of FBXO22 on PTEN ubiquitination in 97H

cells. Increased activity of NRF2 was closely associated with PTEN

loss in human carcinogenesis (31). Furthermore, there was the

evidence that Nrf2 activation is influenced by PTEN/PI3K-mediated

degradation (32). In the

present study, co-IP analysis demonstrated a direct interaction

between PTEN and NRF2 in 97H cells, and that transfection with

oe-FBXO22 upregulated NRF2 protein levels in 97H cells.

Thus, it was hypothesized that FBXO22 degrades PTEN by inducing

PTEN ubiquitination, which upregulated NRF2 protein levels in HCC

cells. In addition, in vivo experiments revealed the

promoting effect of FBXO22 on tumor growth and M2-type macrophages

in HCC mice, although the mechanisms underlying these effects are

unclear. Actually, the increased FBXO22 level also correlated

strongly with a poor prognosis in patients with HCC (24,33). However, in the present study, the

clinical analysis of FBXO22 was not conducted.

In addition to classical stimuli, macrophage

differentiation is determined by redundant factors in parenchymal

cells. HGF induces M2 polarization of macrophages, promoting tumor

progression by participating in the anti-inflammatory response in

various tissues (34). Zhao

et al (35) reported that

miR-144/miR-451a overexpression stimulated M1 polarization of

macrophages by reducing the secretion of HGF and MIF by HCC cells,

thus activating cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Thus, it was wondered

whether FBXO22 induces M2 polarization of macrophages to promote

HCC progression via paracrine factors. Thus, in the present study,

non-targeted metabolomic analysis of 97H cells transfected with

oe-FBXO22 was performed, and myo-inositol was selected for

subsequent experiments. Myo-inositol is a ubiquitous compound found

in all living organisms and reduction in myo-inositol was shown to

affect PI3K-dependent inhibition of programmed cell death (36). Antony et al (37) reported that myo-inositol

stimulated adipocyte differentiation via increasing PPAR-γ

expression and enhanced insulin receptor signaling via the

PI3K/p-Akt pathway in adipose tissues. Jiang et al (38) reported that supplementation with

dietary myo-inositol increased white blood cell counts and improved

phagocytosis of leucocytes in fish. Ghosh et al (39) reported that myo-inositol in

fermented sugar matrix improves macrophage function for host

defense against invading pathogens. An in vivo experiment on

lung cancer revealed that the combination of myo-inositol and

chemo-preventive agents increases the infiltration of lung tumors

by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (40). Additionally, a clinical study

revealed that the higher myo-inositol in the temporal lobes of

patients with temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with a higher

frequency of CD4+T-cell and CD19+B-cell

subsets (41). However,

myo-inositol was neurotoxic to Schwann cells (42). In the present study, myo-inositol

was found to be non-toxic to 97H cells. The PI3K/AKT pathway is

involved in the inflammatory response and affects macrophage

polarization, proliferation and migration. AKT is activated via the

phosphorylation by PI3K, which induces M2-type macrophages to

attenuate inflammatory response (43,44). As expected, myo-inositol

activated the PI3K/AKT pathway and induced M2-type polarization of

THP-1 cells. Given that both these effects were markedly reversed

by transfection with si-SLC5A3, it can be concluded that

SLC5A3 participates in the promoting effect of myo-inositol on M2

polarization.

IMPA1 catalysis is the rate-limiting step in

myo-inositol synthesis. In the present study, considering the

higher transfection efficiency of 293T cells, the luciferase assay

was performed in 293T cells to reveal that NRF2 directly bound to

IMPA1 mRNA. Furthermore, to better understand the

interaction between NRF2 and IMPA1 in HCC, 97H cells were employed

for ChIP assay, and the direct transcriptional regulation of

IMPA1 by NRF2 was observed in 97H cells. Transfection with

oe-FBXO22 elevated NRF2 protein levels in 97H cells. In

addition, the increased IMPA1 expression and myo-inositol release

induced by the treatment with oe-FBXO22 were reversed by

si-IMPA1 in 97H cells, suggesting that FBXO22 induced

myo-inositol release in HCC cells via the NRF2/IMPA1 axis.

Furthermore, the increase in the number of M2-type macrophages

induced by 97H cells transfected with oe-FBXO22 was reversed

by the co-transfection with si-IMPA1. In vivo

experiments further confirmed that the stimulatory effect of

myo-inositol on tumor growth and M2-type macrophages in HCC was

associated with the FBXO22/IMPA1 axis.

In summary, the results of the present study

demonstrated that FBXO22 degraded PTEN by inducing its

ubiquitination, which upregulated NRF2 protein expression. This, in

turn, stimulated IMPA1 to induce myo-inositol release by HCC cells.

The resulting induction of M2-type polarization in macrophages via

SLC5A3 promoted HCC tumor growth. However, the therapeutic targets

of the FBXO22/myo-inositol relationship in vivo remained

unexplored and require further investigation.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LLB, JX and SHC contributed to the conception and

main experiments of the present study and wrote the draft of the

manuscript. JHH performed the in vitro experiments. MXZ, BML

and JH contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. MYH

contributed to acquisition of data, revised the article and

provided software and resources. LLB and MYH confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital,

Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University (approval no.

CDYFY-IACUC-202501GR136; Nanchang, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Training Program for

Academic and Technical Leaders in Major Disciplines-Young Talents

(grant no. 20232BCJ23039), the National Natural Science Foundation

of China (grant nos. 82260514, 82160095 and 82003121), the Natural

Science Foundation of Jiangxi (grant nos. 20224ACB206001 and

20242BAB20409), the Key Laboratory Project of Digestive Diseases in

Jiangxi (grant no. 2024SSY06101) and the Jiangxi Clinical Research

Center for Gastroenterology (grant no. 20223BCG74011).

References

|

1

|

Ferenci P, Fried M, Labrecque D, et al:

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): A global perspective. Arab Journal

of Gastroenterology. 11:174–179. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Brown ZJ, Tsilimigras DI, Ruff SM, Mohseni

A, Kamel IR, Cloyd JM and Pawlik TM: Management of hepatocellular

carcinoma A review. JAMA Surg. 158:410–420. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Vitale I, Manic G, Coussens LM, Kroemer G

and Galluzzi L: Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor

microenvironment. Cell Metab. 30:36–50. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hinshaw DC and Shevde LA: The tumor

microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res.

79:4557–4566. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li Z, Wu T, Zheng B and Chen L:

Individualized precision treatment: Targeting TAM in HCC. Cancer

Lett. 458:86–91. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Du M, Sun L, Guo J and Lv H: Macrophages

and tumor-associated macrophages in the senescent microenvironment:

From immunosuppressive TME to targeted tumor therapy. Pharmacol

Res. 204:1071982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Christofides A, Strauss L, Yeo AT, Cao C,

Charest A and Boussiotis V: The complex role of tumor-infiltrating

macrophages. Nat Immunol. 23:1148–1156. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yang T, Wang Y, Dai W, Zheng X, Wang J,

Song S, Fang L, Zhou J, Wu W and Gu J: Increased B3GALNT2 in

hepatocellular carcinoma promotes macrophage recruitment via

reducing acetoacetate secretion and elevating MIF activity. J

Hematol Oncol. 11:502018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shiau DJ, Kuo WT, Davuluri GVN, Shieh CC,

Tsai PJ, Chen CC, Lin YS, Wu YZ, Hsiao YP and Chang CP:

Hepatocellular carcinoma-derived high mobility group box 1 triggers

M2 macrophage polarization via a TLR2/NOX2/autophagy axis. Sci Rep.

10:135822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nguyen KM and Busino L: The biology of

F-box proteins: The SCF family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 1217:111–122. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ho MS, Tsai PI and Chien CT: F-box

proteins: The key to protein degradation. J Biomed Sci. 13:181–191.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tan MKM, Lim HJ and Harper JW: SCFFBXO22

regulates histone H3 lysine 9 and 36 methylation levels by

targeting histone demethylase KDM4A for ubiquitin-mediated

proteasomal degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 31:3687–3699. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Tian X, Dai S, Sun J, Jin G and Jiang Y,

Meng F, Li Y, Wu D and Jiang Y: F-box protein FBXO22 mediates

polyubiquitination and degradation of KLF4 to promote

hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Oncotarget. 6:22767–22775.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Croze ML, Vella RE, Pillon NJ, Soula HA,

Hadji L, Guichardant M and Soulage CO: Chronic treatment with

myo-inositol reduces white adipose tissue accretion and improves

insulin sensitivity in female mice. J Nutr Biochem. 24:457–466.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical

Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers. FDA;

Rockville, MD: 2005

|

|

17

|

Toit AD: Post-translational modification:

Sweetening protein quality control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

15:2952014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wang S, Osgood AO and Chatterjee A:

Uncovering post-translational modification-associated

protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 74:1023522022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Park J, Cho J and Song EJ:

Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as a target for anticancer

treatment. Arch Pharm Res. 43:1144–1161. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Brauckhoff A, Ehemann V, Schirmacher P and

Breuhahn K: Reduced expression of the E3-ubiquitin ligase seven in

absentia homologue (SIAH)-1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Verh

Dtsch Ges Pathol. 91:269–277. 2007.In German.

|

|

21

|

Lin XT, Zhang J, Liu ZY, Wu D, Fang L, Li

CM, Yu HQ and Xie CM: Elevated FBXW10 drives hepatocellular

carcinoma tumorigenesis via AR-VRK2 phosphorylation-dependent GAPDH

ubiquitination in male transgenic mice. Cell Rep. 42:1128122023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kipreos ET and Pagano M: The F-box protein

family. Genome Biol. 1:1–7. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Johmura Y, Sun J, Kitagawa K, Nakanishi K,

Kuno T, Naiki-Ito A, Sawada Y, Miyamoto T, Okabe A, Aburatani H, et

al: SCFFbxo22-KDM4A targets methylated p53 for degradation and

regulates senescence. Nat Commun. 7:105742016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Zhang L, Chen J, Ning D, Liu Q, Wang C,

Zhang Z, Chu L, Yu C, Liang HF, Zhang B and Chen X: FBXO22 promotes

the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating the

ubiquitination and degradation of p21. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

38:1012019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zheng Y, Chen H, Zhao Y, Zhang X, Liu J,

Pan Y, Bai J and Zhang H: Knockdown of FBXO22 inhibits melanoma

cell migration, invasion and angiogenesis via the HIF-1α/VEGF

pathway. Invest New Drugs. 38:20–28. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Lin M, Zhang J, Bouamar H, Wang Z, Sun LZ

and Zhu X: Fbxo22 promotes cervical cancer progression via

targeting p57Kip2 for ubiquitination and degradation. Cell Death

Dis. 13:8052022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Dahia PL: PTEN, a unique tumor suppressor

gene. Endocr Relat Cancer. 7:115–129. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu L, Long H, Wu Y, Li H, Dong L, Zhong

JL, Liu Z, Yang X, Dai X, Shi L, et al: HRD1-mediated PTEN

degradation promotes cell proliferation and hepatocellular

carcinoma progression. Cell Signal. 50:90–99. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xu Y, Zhang D, Ji J and Zhang L: Ubiquitin

ligase MARCH8 promotes the malignant progression of hepatocellular

carcinoma through PTEN ubiquitination and degradation. Mol

Carcinog. 62:1062–1072. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ge MK, Zhang N, Xia L, Zhang C, Dong SS,

Li ZM, Ji Y, Zheng MH, Sun J, Chen GQ and Shen SM: FBXO22 degrades

nuclear PTEN to promote tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 11:17202020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Rojo AI, Rada P, Mendiola M, Ortega-Molina

A, Wojdyla K, Rogowska-Wrzesinska A, Hardisson D, Serrano M and

Cuadrado A: The PTEN/NRF2 axis promotes human carcinogenesis.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 21:2498–2514. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Ding C, Zou Q, Wu Y, Lu J, Qian C, Li H

and Huang B: EGF released from human placental mesenchymal stem

cells improves premature ovarian insufficiency via NRF2/HO-1

activation. Aging (Albany NY). 12:2992–3009. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Lei Z, Luo Y, Lu J, Fu Q, Wang C, Chen Q,

Zhang Z and Zhang L: FBXO22 promotes HCC angiogenesis and

metastasis via RPS5/AKT/HIF-1α/VEGF-A signaling axis. Cancer Gene

Ther. 32:198–213. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Choi W, Lee J, Lee J, Lee SH and Kim S:

Hepatocyte growth factor regulates macrophage transition to the M2

Phenotype and promotes murine skeletal muscle regeneration. Front

Physiol. 10:9142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhao J, Li H, Zhao S, Wang E, Zhu J, Feng

D, Zhu Y, Dou W, Fan Q, Hu J, et al: Epigenetic silencing of

miR-144/451a cluster contributes to HCC progression via paracrine

HGF/MIF-mediated TAM remodeling. Mol Cancer. 20:462021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Meng PH, Raynaud C, Tcherkez G, Blanchet

S, Massoud K, Domenichini S, Henry Y, Soubigou-Taconnat L,

Lelarge-Trouverie C, Saindrenan P, et al: Crosstalks between

Myo-Inositol metabolism, programmed cell death and basal immunity

in arabidopsis. PLoS One. 4:e73642009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Antony PJ, Gandhi GR, Stalin A,

Balakrishna K, Toppo E, Sivasankaran K, Ignacimuthu S and Al-Dhabi

NA: Myoinositol ameliorates high-fat diet and

streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats through promoting insulin

receptor signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 88:1098–1113. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Jiang WD, Feng L, Liu Y, et al: Effects of

graded levels of dietary myo-inositol on non-specific immune and

specific immune parameters in juvenile Jian carp (Cyprinus carpio

var. Jian). Aquaculture Research. 41:1413–1420. 2010.

|

|

39

|

Ghosh N, Das A, Biswas N, Mahajan SP,

Madeshiya AK, Khanna S, Sen CK and Roy S: Myo-inositol in fermented

sugar matrix improves human macrophage function. Mol Nutr Food Res.

66:e21008522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kassie F, Bagherpoor AJ, Kovacs K and

Seelig D: Combinatory lung tumor inhibition by myo-inositol and

iloprost/rapamycin: Association with immunomodulation.

Carcinogenesis. 43:547–556. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Mueller C, Hong H, Sharma AA, Qin H,

Benveniste EN and Szaflarski JP: Brain temperature, brain

metabolites, and immune system phenotypes in temporal lobe

epilepsy. Epilepsia Open. 9:2454–2466. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Niwa T, Sobue G, Maeda K and Mitsuma T:

Myoinositol inhibits proliferation of cultured Schwann cells:

Evidence for neurotoxicity of myoinositol. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

4:662–666. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hofmann BT and Jücker M: Activation of

PI3K/Akt signaling by n-terminal SH2 domain mutants of the p85α

regulatory subunit of PI3K is enhanced by deletion of its

c-terminal SH2 domain. Cell Signal. 24:1950–1954. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Baitsch D, Bock HH, Engel T, Telgmann R,

Müller-Tidow C, Varga G, Bot M, Herz J, Robenek H, von Eckardstein

A and Nofer JR: Apolipoprotein E induces antiinflammatory phenotype

in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 31:1160–1168. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|