Introduction

With the widespread use of nuclear energy technology

across various fields, the likelihood of humans being exposed to

low-dose ionizing radiation has significantly increased, and the

resulting health issues have garnered attention. Different tissues

in the human body exhibit varying levels of tolerance to radiation,

with the eye lens being particularly sensitive. A study by Neriishi

et al (1) on

postoperative cataract cases among atomic bomb survivors revealed a

significant dose-response relationship between radiation exposure

and the incidence of postoperative cataracts. For each 1 Gy

increase in radiation dose, the ratio of postoperative cataract

incidence (OR) rose by 1.39, with an estimated dose threshold of

0.1 Gy (1). In a nearly 20-year

prospective cohort study of radiation technicians in the United

States, the risk of cataract was also elevated in the group with

the highest occupational exposure to ionizing radiation (average

dose 60 mGy) compared with the lowest group (average dose 5 mGy)

(2). Radiation-induced cataract

is no longer regarded as a typical tissue response with a clearly

defined threshold for relatively high doses.

Epidemiological studies have found that chronic

occupational radiation exposure significantly increases the risk of

posterior subcapsular, cortical and nuclear cataracts, especially

posterior subcapsular cataracts, with a higher risk observed in

women than in men (3). Following

exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation, the lens fails to develop

normally, leading to slow DNA damage and repair within lens

epithelial cells (LECs) (4), as

well as abnormal proliferation and differentiation (5), abnormal degradation of cell

organelles (6), and proteomic

and liposomal changes (7),

ultimately resulting in lens opacity and cataract formation. A

previous study demonstrated that low-dose ionizing radiation can

enhance the proliferation and migration of HLE-B3 cells, and

upregulates the protein levels of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc,

which is linked to the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway (8). Vigneux et

al (9) irradiated HLE-B3

cells with X-rays, which also revealed a clear radiation damage

response. The proliferation and migration of HLE-B3 cells

significantly decreased after 0.2 Gy irradiation, with

proliferation peaking at 7 days post-irradiation (9). By contrast, the specific reaction

of SRA01/04 cells to radiation damage has not been reported in

detail. SRA01/04 cells and HLE B3 cells are both Human lens

epithelial cell lines. The SRA01/04 cell line is widely used in

studying pathogenesis of cataracts, such as the oxidative stress

model, autophagy regulation and lens fibrosis. According to the

literature, whole-genome expression analysis of HLE-B3 and SRA01/04

cells were performed by Illumina Human HT12 Expression Bead Chip

microarray. The results showed that both cell lines significantly

expressed several genes related to lens biology or cataract,

including PAX6, ZEB2, PVRL3, SPARC, COL4A1 and SLC16A12 (10). As another human lens epithelial

cell line, SRA01/04 cells may exhibit different biological

characteristics under the same experimental conditions.

Importantly, based on prior studies, the detailed molecular

mechanism by which the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway induces lens

opacity in response to low-dose ionizing radiation urgently

requires further investigation.

A preliminary gene chip analysis results showed that

the expression of the HMGB1 gene underwent significant changes in

SRA01/04 cells after 0.2 Gy of γ-radiation (11). The expression of HMGB1 is closely

related to cell survival, proliferation and migration (12). Shu et al (13) found that increased expression of

HMGB1 in chondrocytes induces phosphorylation of GSK-3β and

upregulates β-catenin expression, thereby promoting chondrocyte

apoptosis and cartilage matrix degradation. Wang et al

(14) found that elevated

expression of HMGB1 promotes the proliferation and migration of

lung cancer cells, and this oncogenic behavior is mediated through

the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Chen et

al (15) also reported that

elevated expression of HMGB1 in human bronchial epithelial cells

leads to the phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β through the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which results in the accumulation of

β-catenin in the cytoplasm and its subsequent translocation to the

nucleus for expression, thereby inducing the occurrence of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Therefore, it was

hypothesized that the increase of HMGB1 expression in LECs induced

by low-dose ionizing radiation can activate the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway, thus promoting the proliferation and migration

of LECs and inducing lens opacification.

To address the knowledge gaps in understanding the

damaging effects of SRA01/04 cells under low-dose ionizing

radiation and the molecular mechanisms regulated by the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, SRA01/04 cells were infected with

lentivirus to inhibit HMGB1 expression, and the regulatory

relationship between HMGB1 expression and the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway in these cells following low-dose ionizing

radiation exposure. The present study was specifically designed to

address two fundamental objectives: First, to delineate the

mechanistic relationship between low-dose ionizing

radiation-induced alterations in proliferative and migratory

capacities of SRA01/04 cells and concurrent Wnt/β-catenin signaling

activation. Second, to systematically characterize the molecular

circuitry governing radiation-triggered Wnt/β-catenin pathway

activation in human LECs, with particular emphasis on identifying

key regulatory nodes within this pathological cascade.

Materials and methods

SRA01/04 cell line

SRA01/04 cells are adherent cells obtained from the

American Type Culture Collection and are derived from normal LECs

of infants with retinopathy of prematurity. The cell line was

established by transfecting these cells with a plasmid vector

carrying the Simian Virus 40 large T antigen (TagSV40) (16). Cells were authenticated by STR

profiling and verified to be mycoplasma-free.

Cell irradiation

In the present study, low doses were set at 0.05,

0.075, 0.1 and 0.2 Gy, while high doses were at 0.5 and 2 Gy,

serving as controls. The irradiation methods were as follows: The

SRA01/04 cells were irradiated with 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5

Gy gamma rays using a 137Cs radiation source at a dose

rate of 9.73 mGy/min, conducted at the National Secondary Standard

Dosimetry Laboratory of the Radiation Safety Institute of the

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. A ferrous

sulfate dosimeter was utilized for radiation source calibration to

ensure accurate dosing. SRA01/04 cells were also irradiated with 2

Gy γ-rays from a 60Co radioactive source at a dose rate

of 1 Gy/min at the Beijing Irradiation Center. The distance from

the sample to the cobalt source was 68 cm, and the dose was

calibrated by physical measurement using an ionization chamber,

with a dose calibration uncertainty of 0.1%.

Cell proliferation assay

For this assay, SRA01/04 cells (6,000 cells/well)

were seeded in 100 μl of medium in 96-well plates, with six

wells seeded for each group. On the second day after adherent

growth, the cells were randomly assigned to the 0-2 Gy irradiation

groups. A total of 10 μl of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

reagent (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) were added to each well at

various times post-irradiation, and the plates were incubated for 1

h at 37°C. Absorbance values were measured at 450 nm using a

microplate reader once color development was adequate. This

experiment was independently repeated three times. Cell viability

was determined using the following formula: Cell

viability=(irradiated group optical density (OD) value-blank group

OD value)/(0 Gy group OD value-blank group OD value).

Gap closure assay

SRA01/04 cells in favorable growth condition were

harvested, and 50 μl of the cell suspension at a density of

2×105 cells/ml was seeded into each well of an Ibidi

culture insert, placed within a culture dish. A total of 1 ml of

medium with 10% FBS was added to the dish surrounding each insert,

with three replicate wells for each group (17). The following day, after the cells

had adhered, they were irradiated with γ-rays at doses of 0, 0.05,

0.075, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 and 2 Gy. Immediately after irradiation, the

inserts were gently removed using sterile tweezers to create

uniform cell-free wounds (scratches). The dishes were then returned

to the incubator.

Cell migration into the gap area was monitored at 8,

24, 48 and 72 h using an inverted microscope, and images were

captured. Closure of the gap at each time point was measured using

ImageJ 1.54 software (National Institutes of Health). The gap

closure rate was calculated as follows: The Gap Closure Rate

(%)=[(Initial Gap Width-Gap Width at Time t)/Initial Gap Width]

×100%. In total, 3 fields of view were analyzed for each dosage and

time point, and an average gap closure rate was calculated.

Transwell migration assay

The healthy SRA01/04 cells were inoculated into T-25

culture flasks and subjected to γ-ray irradiation at various doses:

0, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 and 2 Gy. At 8 h, 48 h and 7 days

post-irradiation, the cells were resuspended at a density of

4×104 cells/ml. A total of 200 μl of the

suspension was added to the upper chamber of Transwell inserts

(5-μm pore size). The lower chamber received 600 μl

of medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) as a chemoattractant. After the cells adhered to

the chamber surface, the medium with 10% FBS in the chambers was

replaced with serum-free medium. The cells were allowed to migrate

in a 37°C incubator for 8 h. The medium was discarded, and the

Transwell inserts were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS). Non-migratory cells on the upper surface were wiped off,

while migratory cells on the underside of the filter were fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10-30 min,

immersed in anhydrous methanol for 20 min, and stained with Giemsa.

All migratory cells on the entire membrane surface were counted

under a light microscope. This experiment was independently

repeated three times.

Clone formation experiment

Following the Transwell migration assay, SRA01/04

cells that had migrated to the lower chamber after γ-ray

irradiation at various doses were harvested. These cells were

trypsinized, resuspended, and seeded into 6-well plates at a

density of 1,000 cells per well (three replicate wells per group).

Cells were cultured for 7-10 days, with medium changes every 3

days, to allow clonogenic colony formation. Upon observation of

clearly defined colonies (cell clusters larger than 50 μm in

diameter), cultures were terminated. Cells were gently washed once

with 1X PBS, fixed with anhydrous methanol for 30 min, and stained

with Giemsa for 30 min. After air-drying at room temperature, cell

clones were manually counted and images were captured.

Mouse irradiation and Giemsa staining of

posterior lens capsule

Six-week-old Specific pathogen free (SPF) C57BL/6J

mice (15 males weighing 20±2 g and 15 females weighing 18±2 g) were

ordered from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co.,

Ltd. [License no.: (SCXK (Beijing) 2021-0006], raised in the animal

room of the Institute of Occupational Health and Poisoning Control,

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Each cage

contained 6 mice housed under 12/12-h light-dark cycle. The

temperature was kept at ~22°C and humidity at 40-60%. Sterile

distilled water and SPF-grade feed were provided ad libitum.

The mice were checked daily for weight, health and behavior.

C57BL/6J mice (three males and three females per

group) were subjected to whole-body γ-ray irradiation at doses of

0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 2 Gy. For the 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 Gy

irradiations, a 137Cs radiation source was used with a

dose rate of 9.73 mGy/min. For the 2 Gy irradiation, a

60Co radiation source was employed with a dose rate of 1

Gy/min.

Six months after irradiation at different doses,

mice were euthanized by an intraperitoneal injection of an overdose

of 1% pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg), death was confirmed by the

absence of a heartbeat and respiratory arrest, and their eyeballs

were enucleated. The lenses were dissected out, with the lens

capsules separated. The posterior lens capsules of the mice were

spread flat on glass slides with the inner side facing up, and

Giemsa staining solution was directly applied, allowing it to stain

for 20-30 min. The stained posterior capsules were then examined

under an inverted microscope for the presence of stained cells.

All animal experimental procedures were approved by

the Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the

National Institute for Radiological Protection, Chinese Center for

Disease Control and Prevention [approval no. (2022)005; Beijing

China].

Western blot assay

To analyze protein expression in SRA01/04 cells,

cell lysates were first prepared and mixed with 5X loading buffer,

followed by boiling at 100°C for 10 min to denature the proteins.

The BCA method was used for protein quantification. The denatured

protein samples (30 μg per lane) were then subjected to

electrophoresis on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels

to separate the proteins based on their molecular weights. After

electrophoresis, the separated proteins were transferred onto

nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5%

skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20

(TBST) for 1 h at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding

of antibodies. A variety of primary antibodies, including rabbit

anti-β-catenin (1:1,000; cat. no. 8480; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.), rabbit anti-cyclin D1 (1:200; cat. no. ab16663; Abcam),

rabbit anti-c-Myc (1:1,000; cat. no. 18583; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), rabbit anti-HMGB1 (1:10,000; cat. no. ab79823;

Abcam), rabbit anti-Phospho-β-catenin (1:1,000; cat. no. 9561; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), and mouse anti-GAPDH (1:1,000; cat.

no. TA-08; ZSGB-BIO), were added and incubated overnight at 4°C to

allow specific binding to their target proteins. After incubation,

the membranes were washed three times with TBST and then incubated

with anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:4,000; cat. no. ZB-5305;

ZSGB-BIO) or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:3,000; cat. no.

ZB-5301; ZSGB-BIO) for 1 h. Immunoreactive bands were detected

using the SuperSignal West Pico PLUS chemiluminescent substrate

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The membranes were developed and

imaged on the ChemiDoc XRC+ chemiluminescence imaging system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The gray value of the bands was

measured using Image Lab (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). All protein

expression experiments were independently repeated three times.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

analyses

A cell suspension of 2×105 cells/ml was

inoculated onto sterile coverslips in a 24-well plate. The

following day, after the cells had adhered and proliferated, they

were exposed to 0, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 and 2 Gy of

γ-radiation. After irradiation, the cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. The coverslips

were then carefully oriented with the cell-containing side up, and

PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 was added to permeabilize the

cells for 10 min at room temperature. Next, to block non-specific

antibody binding, the coverslips were treated with PBS containing

3% BSA (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and

incubated on a slow shaker at room temperature for 1 h. The primary

antibody rabbit anti-β-catenin (1:80; cat. no. 8480; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) was added to the samples. After incubation, the

coverslips were washed three times with PBS and then incubated with

the secondary antibodies: Anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), F(ab')2

Fragment (Alexa Fluor® 594 Conjugate) (1:600; cat. no.

8890; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 1 h.

VECTASHIELD® Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector

Laboratories, Inc.) was added to stain the nuclei for 10 min in the

dark at room temperature. After washing with 1X PBS, the coverslips

were mounted. The cellular localization of β-catenin was observed

and photographed using a laser confocal microscope (LSM700; Zeiss

GmbH).

shRNA lentivirus vector construction

The construction of the shRNA lentiviral vector was

completed by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. The lentiviral vector

skeleton was GV493 (hU6-MCS-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin). A total of

three candidate interference sequences were designed for the

knockdown of the HMGB1 gene in cells, as detailed in Table I. Negative control (NC) cell

lines were constructed from lentiviral vectors with a control

sequence (TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT) inserted at the same site.

| Table IInterference sequence. |

Table I

Interference sequence.

| Sequence name | Interference

sequence (5'-3') |

|---|

| sh1-HMGB1 |

GATGCAGCTTATACGAAATAA |

| sh2-HMGB1 |

TCGGGAGGAGCATAAGAAGAA |

| sh3-HMGB1 |

TTCCTCTTCTGCTCTGAGTAT |

The shRNA expression vector was co-transfected with

two packaging plasmids, pHelper 1.0 and pHelper 2.0, into 293T

cells using the transfection reagent. Lentiviral particles were

harvested from the culture supernatant of 293T packaging cells at

48 h post-transfection. The collected supernatant was pooled and

clarified by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C,

followed by filtration through a 0.45-μm membrane. The viral

particles were concentrated via ultracentrifugation at 25,000 rpm

for 2 h at 4°C. The resulting viral pellet was resuspended in a

sterile PBS solution, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Well-grown SRA01/04 cells were seeded into 6-well

plates. The following day, after cell attachment, they were

transduced with lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of

10. The viral supernatant was replaced with fresh complete medium

after 16-24 h of incubation, and the cells were cultured for an

additional 48 h. Transduction efficiency was confirmed to exceed

80% by assessing the intensity of green fluorescent protein (GFP)

expression under a fluorescence microscope. At 72 h

post-transduction, the medium was replaced with a selection medium

containing 2 μg/ml puromycin to select for stably transduced

cells. After 1 week of selection, stable knock-down cell lines were

established. Subsequently, the cells were expanded in medium with a

reduced puromycin concentration of 0.67 μg/ml. All

experiments were conducted following one week of this expansion

phase.

Statistical analyses

SPSS 27.0 software (IBM Corp.) was used for

statistical analysis of data. GraphPad Prism 9 software (Dotmatics)

was used for plotting. Experimental data were expressed as the mean

± standard deviation (SD). Independent sample t-tests were used for

comparisons between two groups, while one-way ANOVA followed by

Fisher's LSD post hoc test or the Kruskal-Wallis H test followed by

Dunn's post hoc test was applied for comparisons among multiple

groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Effects of ionizing radiation on cell

proliferation and migration

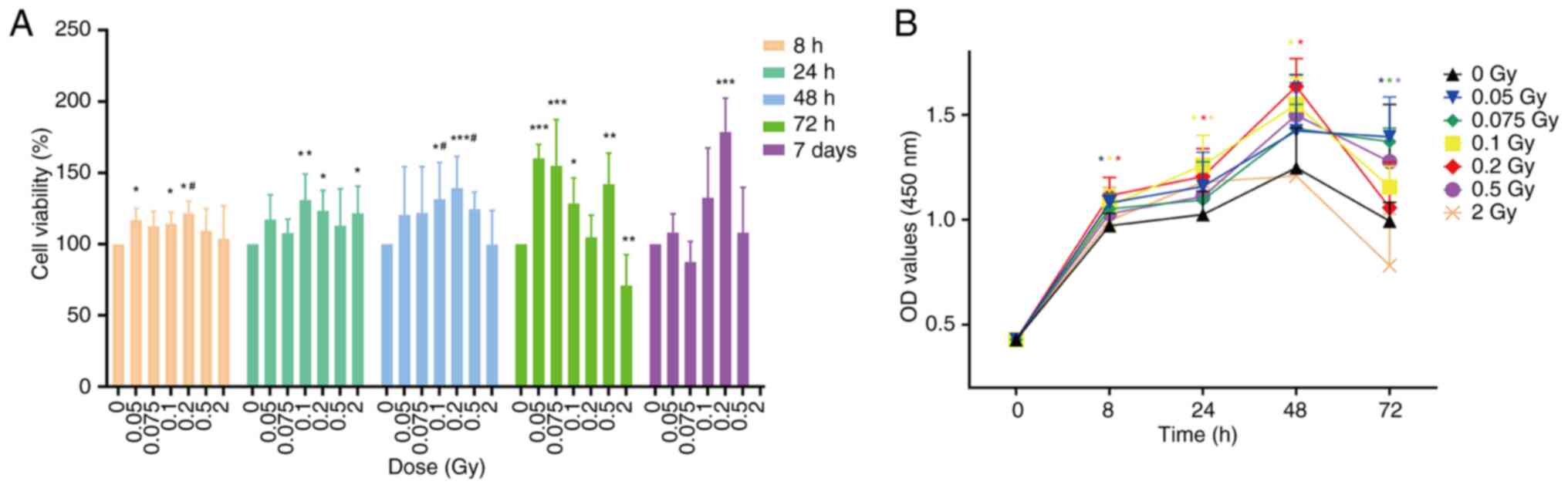

Cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay. At 8 h

after irradiation with 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 Gy, cell viability was

significantly enhanced compared with the non-irradiated group

(P<0.05). By 24 h post-irradiation, significant enhancement in

viability was observed in cells treated with 0.1, 0.2, and 2 Gy,

with statistical significance at P<0.05 or P<0.01. At 48 h

post-irradiation, cell viability in the low-dose groups and the 0.5

Gy group was enhanced compared with the non-irradiated group, with

the most significant increase observed after 0.2 Gy irradiation

(P<0.001). However, cell viability began to decline in the 2 Gy

group, showing no significant difference when compared with the

non-irradiated group (P>0.05). At 72 h post-irradiation, cell

viability in the low-dose groups and the 0.5 Gy group remained

higher than that of the non-irradiated group, while cell viability

in the 2 Gy group was significantly reduced compared with the

non-irradiated group (P<0.01) (Fig. 1A). Additionally, in Fig. 1B it is also illustrated that the

OD values of all groups gradually increased from 0 to 48 h

post-irradiation. At 72 h, although the OD values of the low-dose

and 0.5 Gy groups showed a slight decrease, they remained higher

than the non-irradiated group. Overall, from 0 to 72 h

post-irradiation, the OD values of the low-dose and 0.5 Gy groups

were higher than those of the non-irradiated group, indicating

increased cell proliferation. By contrast, the OD value of the 2 Gy

group was lower than the non-irradiated group at 72 h

post-irradiation, indicating reduced proliferative capacity. These

changes suggest that low-dose ionizing radiation (0.05-0.2 Gy)

promotes the proliferation of SRA01/04 cells, particularly after

irradiation with 0.1 or 0.2 Gy, where significant enhancements in

proliferation capacity were observed between 8 and 48 h

(P<0.05). Conversely, 2 Gy irradiation weakened cell

proliferation capacity.

To exclude the potential stimulation effect of

low-dose ionizing radiation on early-stage cell proliferation, the

CCK-8 method was utilized to evaluate cell viability 7 days

post-irradiation with various doses. As depicted in Fig. 1, the cell viability of the 0.2 Gy

group was significantly increased compared with the non-irradiated

group (P<0.001), while the 0.1 Gy group showed a non-significant

increase (P>0.05).

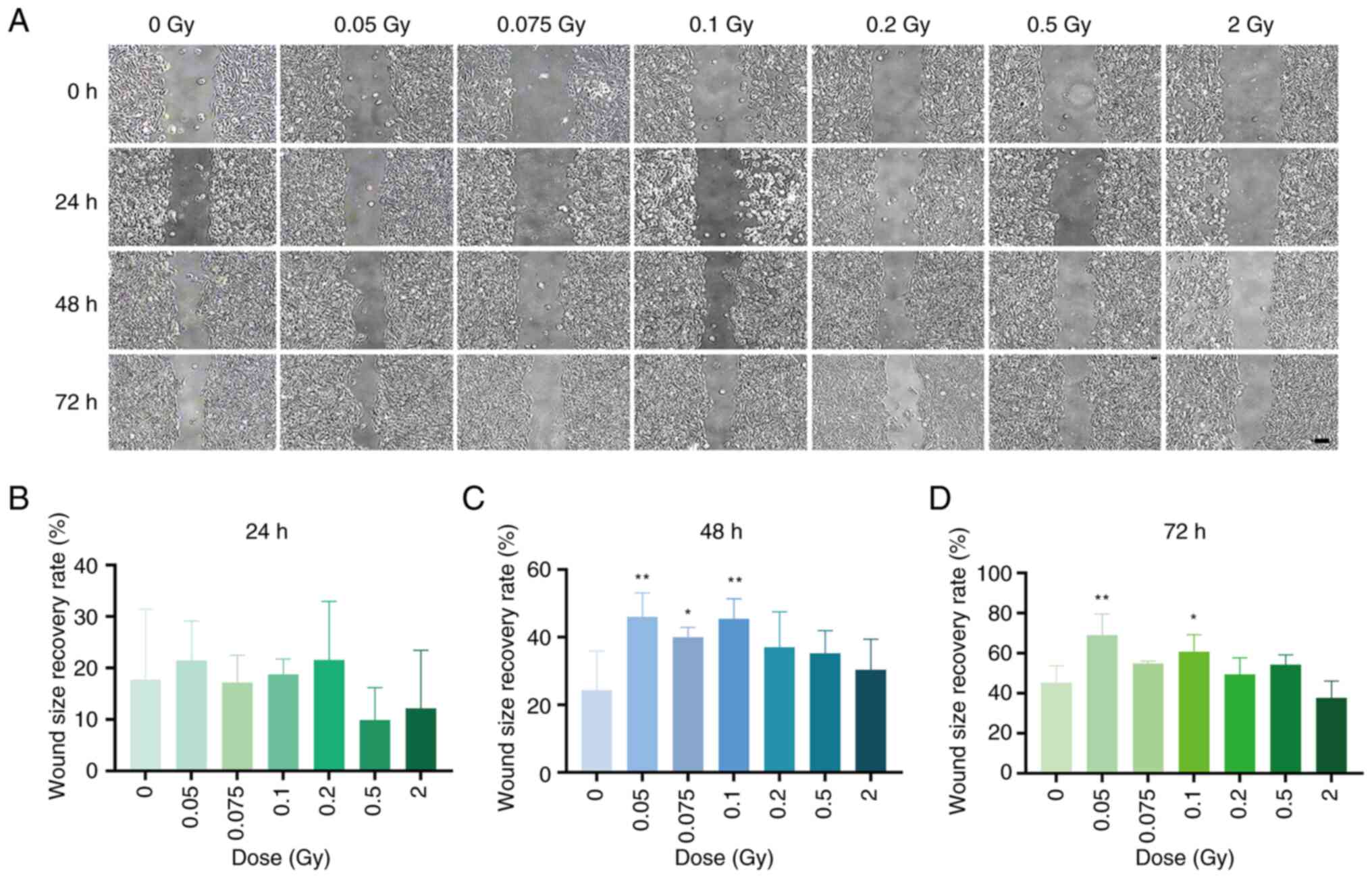

The effects of various doses of γ-ray irradiation on

SRA01/04 cell migration were evaluated using the gap closure and

Transwell migration assay. The gap closure assay indicated that at

48 h post-irradiation with different doses of γ-rays, the gap

closure ability of the 0.05, 0.075 and 0.1 Gy groups was

significantly enhanced compared with the non-irradiated group

(P<0.05 or 0.01). At 72 h post-irradiation, the gap closure

ability of the 0.05 and 0.1 Gy groups continued to show

significantly increased(P<0.05 or P<0.01), whereas the 2 Gy

group displayed a non-significant decrease in gap closure ability

(P>0.05) (Fig. 2A and B). The

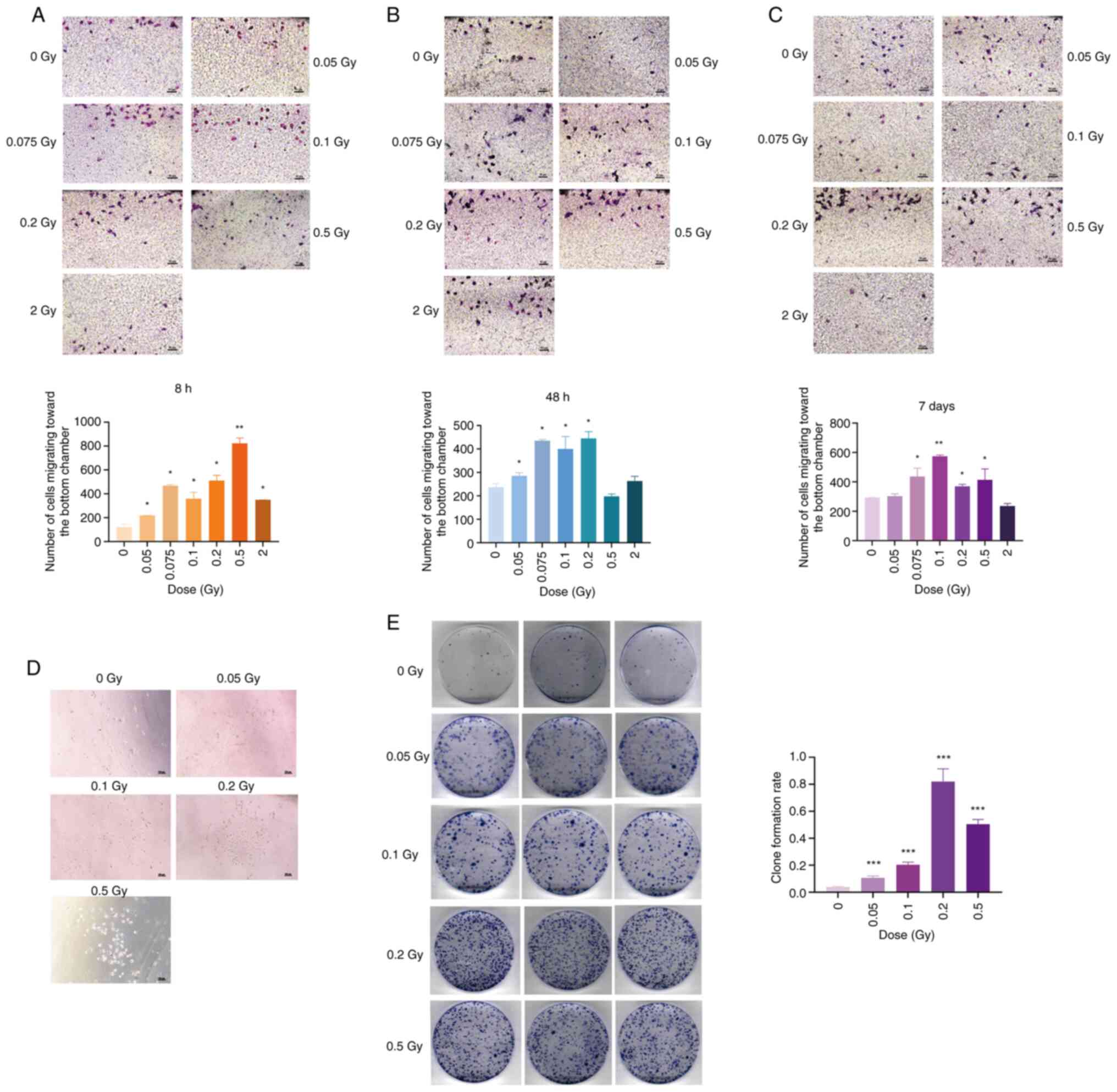

Transwell migration assay revealed that at 8 h after irradiation,

all irradiated groups demonstrated a significantly higher number of

migratory cells than the unirradiated group (P<0.05 or

P<0.01) (Fig. 3A). At 48 h

post-irradiation, low-dose irradiated cells exhibited significantly

increased migration compared with the non-irradiated group

(P<0.05), while no significant difference was observed in the

0.5 and 2 Gy groups (P>0.05) (Fig. 3B). After 7 days of irradiation

with 0.075, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5 Gy, the number of migratory cells

remained significantly higher than in the non-irradiated group

(P<0.05 or P<0.01), whereas 2 Gy irradiation resulted in a

non-significant decrease in migration ability (P>0.05) (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these findings

suggest that low-dose ionizing radiation (0.05-0.2 Gy) promotes

SRA01/04 cell migration.

Furthermore, in the Transwell migration assay

conducted 7 days after irradiation, it was observed that some

SRA01/04 cells not only migrated to the bottom of the chamber but

also took up residence within the lower pores, continuing to

proliferate along the walls (Fig.

3D). It has been reported that cultured SRA01/04 cells are not

sensitive to serum and can survive in a medium containing 1% serum.

When serum concentration is restored, these cells can revert to

normal proliferation patterns (18). The adherent cells at each dose

point were collected, and the proliferation ability of the cells

that had migrated into the wells 7 days after irradiation was

assessed using a colony formation assay. Results presented in

Fig. 3E indicated that 7 days

after SRA01/04 cells were irradiated with 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5

Gy, the number of clone colonies formed by the migratory cells was

significantly higher than in the non-irradiated group (P<0.001).

This suggests that low-dose ionizing radiation can promote the

proliferation of migratory SRA01/04 cells.

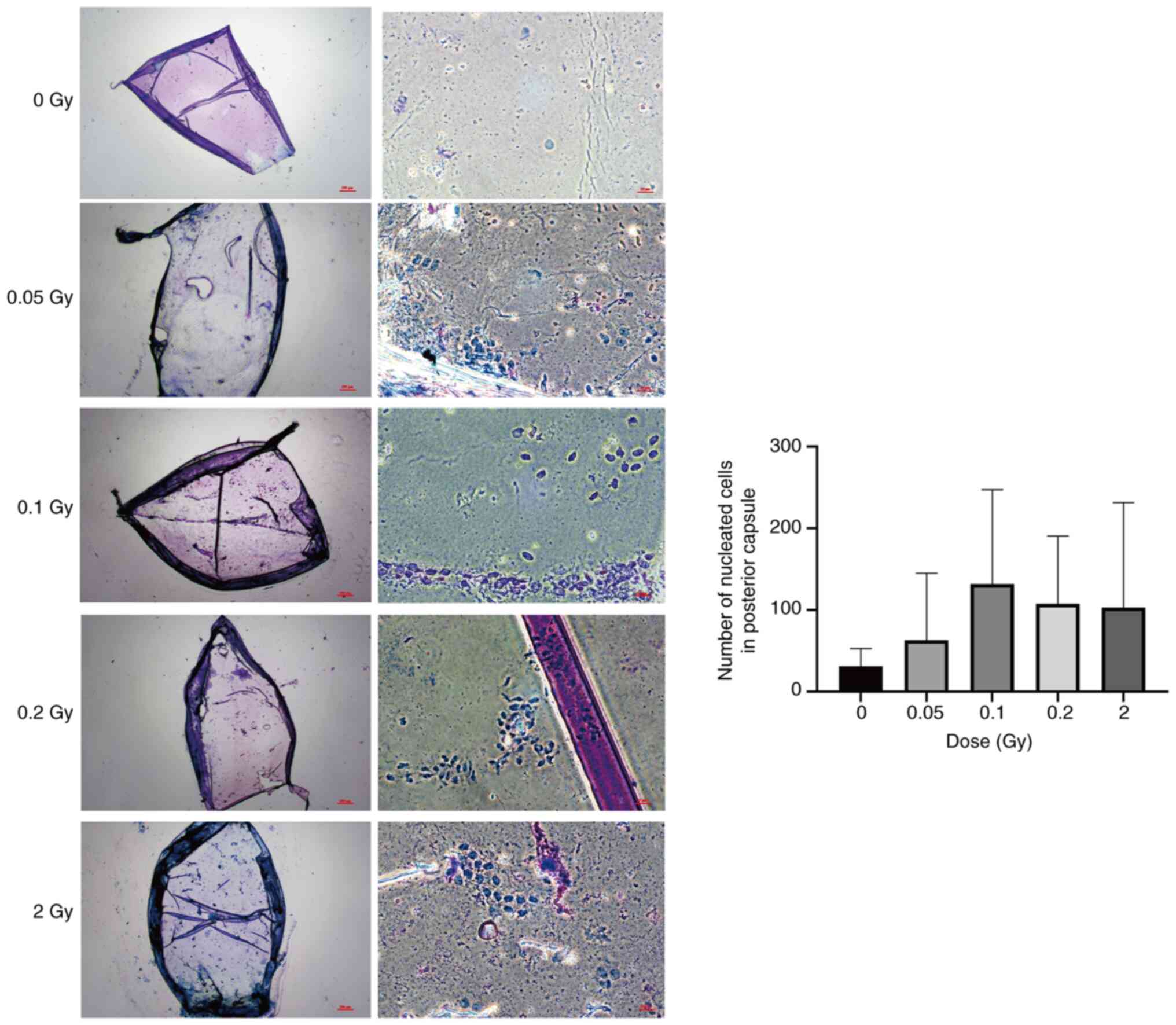

Effect of ionizing radiation on the

migration of mouse LECs

In a previous study by the authors, it was reported

that in the third month following exposure to low dose ionizing

radiation, scattered and randomly distributed migrating cells with

regular nuclei were observed within the posterior lens capsule of

mice (8). In the current study,

both the radiation dose and observation time were escalated. At 6

months after irradiation with low doses (0.05-0.2 Gy) and 2 Gy,

scattered nucleated cells with regular nuclear morphology were

still observed in the posterior capsule of all irradiated groups

(Fig. 4). After 0.1 Gy

irradiation, the highest number of nucleated cells in the posterior

capsule was observed, consistent with our previous findings.

However, at six months post-irradiation, the lens aspect ratio

distortion described by Markiewicz et al (19) was not observed in either the

low-dose or 2 Gy groups. Additionally, no lens opacity was

detected.

Effect of low-dose ionizing radiation on

β-catenin and its related protein expression in SRA01/04 cells

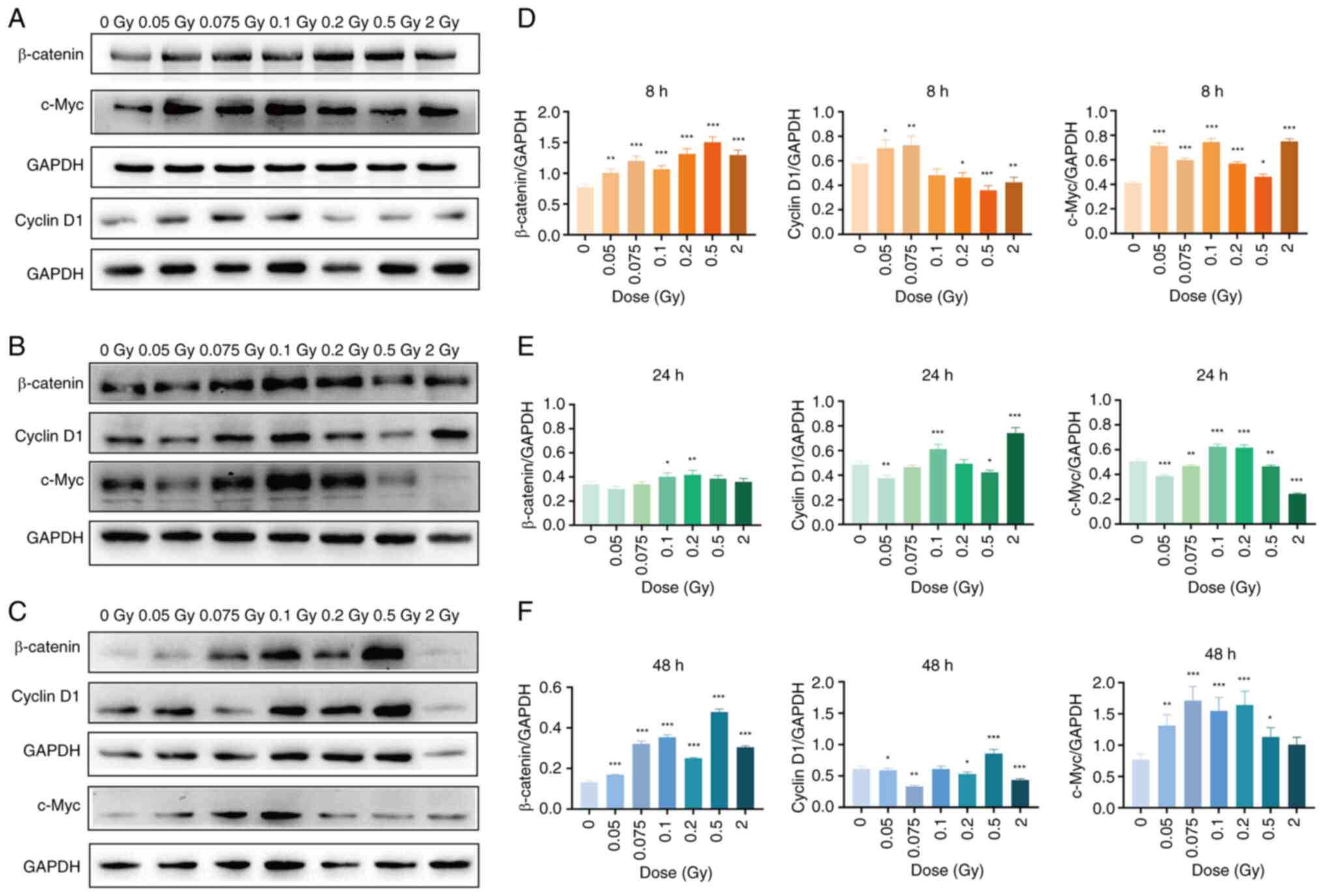

As shown in Fig.

5, the expression levels of β-catenin and c-Myc in the

irradiated group were significantly higher than those in the

non-irradiated group at 8 h after exposure to different doses of

γ-rays (P<0.05, P<0.01 or P<0.001). Meanwhile, cyclin D1

expression was also significantly elevated in the 0.05 and 0.075 Gy

groups relative to the non-irradiated group (P<0.05 or

P<0.01) (Fig. 5A). At 24 h

post-irradiation, β-catenin and c-Myc expression remained

significantly higher in the 0.1 and 0.2 Gy groups (P<0.05,

P<0.01 or P<0.001), while c-Myc expression in the 2 Gy group

significantly decreased (P<0.001) compared with the

non-irradiated group. Moreover, the cyclin D1 expression level was

significantly higher in the 0.1 and 2 Gy groups (P<0.001)

compared with the non-irradiated group (Fig. 5B). At 48 h, low-dose (0.05-0.2

Gy) and 0.5 Gy irradiation continued to induce significant

upregulation of β-catenin and c-Myc compared with the

non-irradiated group (P<0.05, P<0.01 or P<0.001). Cyclin

D1 expression increased significantly compared with the

non-irradiated group 48 h after 0.5 Gy irradiation (P<0.001) but

was significantly lower after 2 Gy irradiation compared with the

non-irradiated group (P<0.001) (Fig. 5C). These results indicated that

low-dose ionizing radiation can differentially upregulate the

protein expressions of β-catenin, cyclin D1 and c-Myc in SRA01/04

cells.

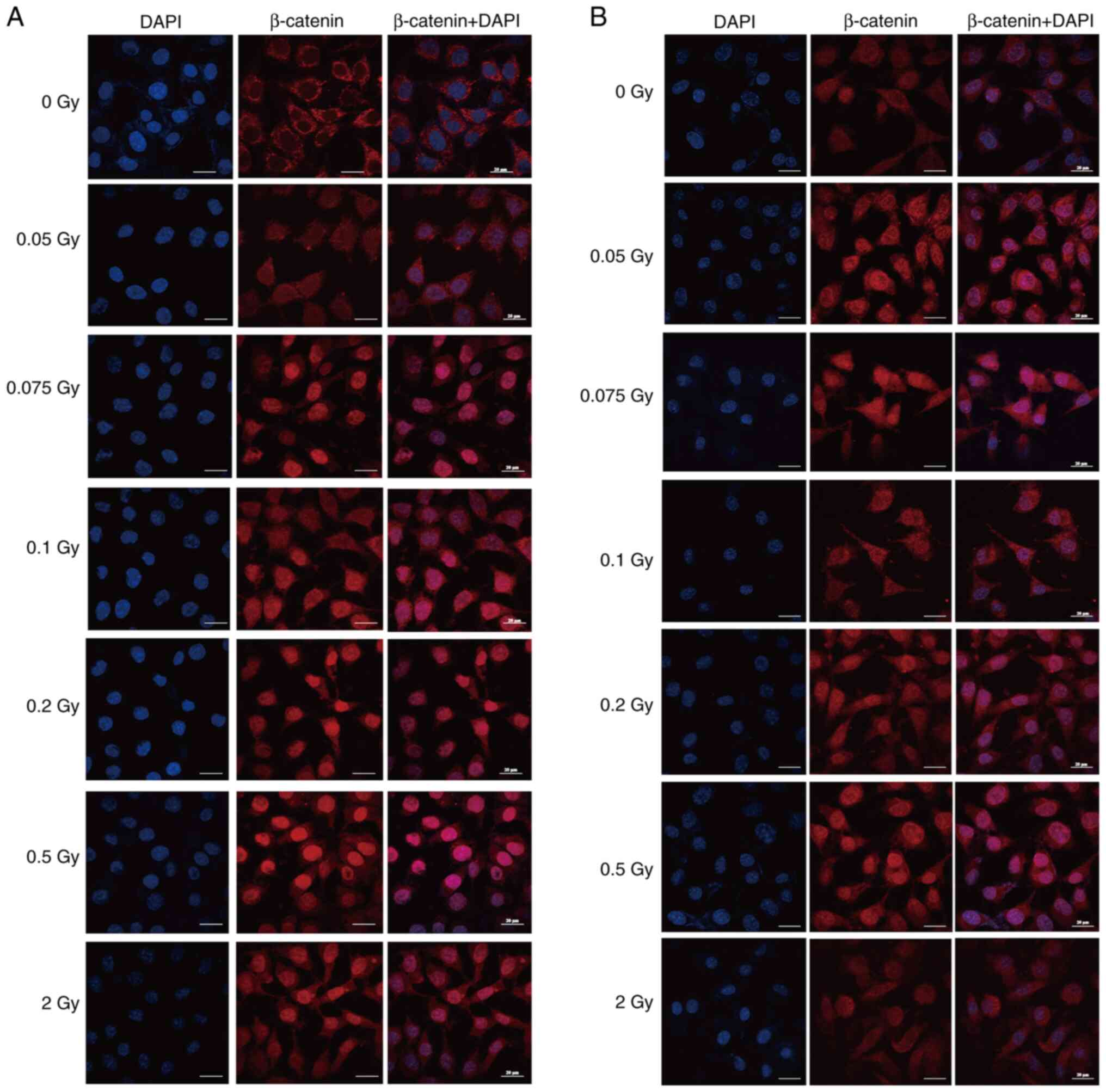

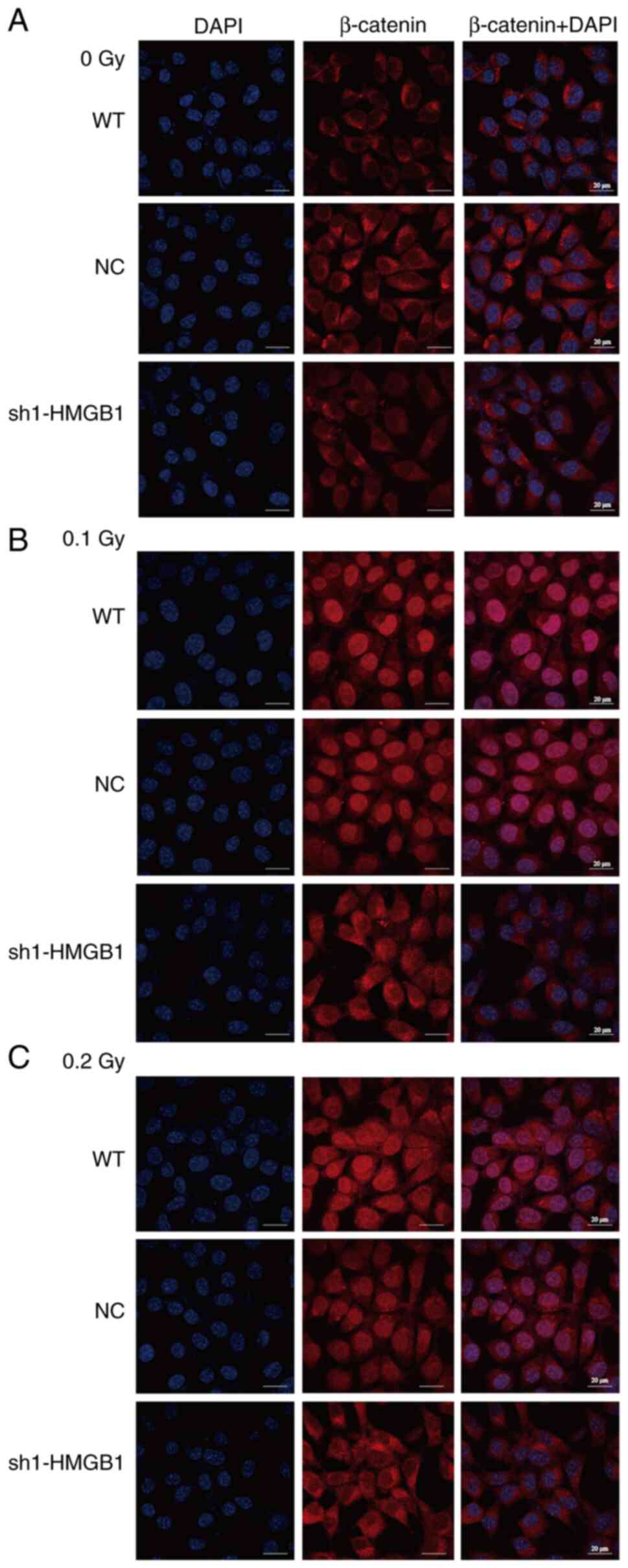

To elucidate the impact of γ-ray irradiation on the

expression and localization of β-catenin in SRA01/04 cells,

immunofluorescence assays were conducted with cells exposed to a

spectrum of γ-ray doses. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, β-catenin was mainly

localized in the cell membrane and cytoplasm or uniformly expressed

on the cell membrane in the non-irradiated group. At 24 and 48 h

after low-dose (0.05-0.2 Gy) and 0.5 Gy irradiation, a distinct

translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus was observed with

notable accumulation within the nucleus. After 2 Gy irradiation,

β-catenin was also significantly expressed in the nucleus at 24 h,

while the localization of β-catenin did not significantly change

compared with the non-irradiated group at 48 h. These results

suggested that low-dose ionizing radiation may activate the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in SRA01/04 cells, which is

associated with abnormal cell proliferation and migration.

Effect of HMGB1 on the expression and

localization of β-catenin after low-dose γ-irradiation

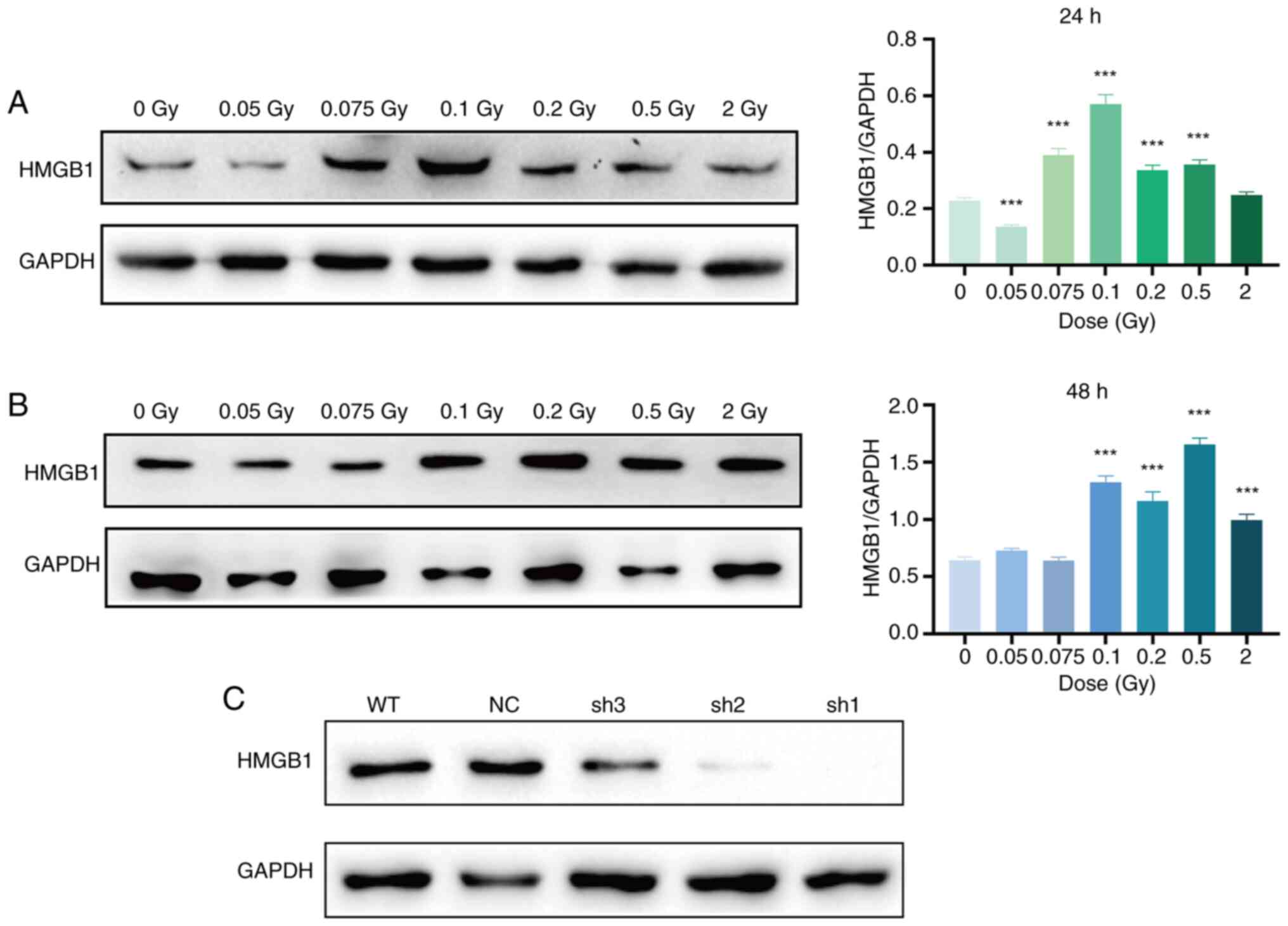

In SRA01/04 cells, HMGB1 expression significantly

increased at 24 h after 0.075, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5 Gy irradiation and

at 48 h after 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 and 2 Gy irradiation compared with the

non-irradiated group (P<0.001) (Fig. 7A and B). Subsequently, the cells

were infected with lentivirus, and the knockout effects of three

different interfering sequences targeting HMGB1 were evaluated by

western blot analysis. Both sh1 and sh2 interfering sequences

markedly reduced HMGB1 protein expression, with the sh1 sequence

emerging as the most effective in HMGB1 suppression. The sh1

sequence was selected for subsequent experiments (Fig. 7C). Leveraging this foundation,

the intricate relationship between HMGB1 expression in LECs after

exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation and the activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway were explored.

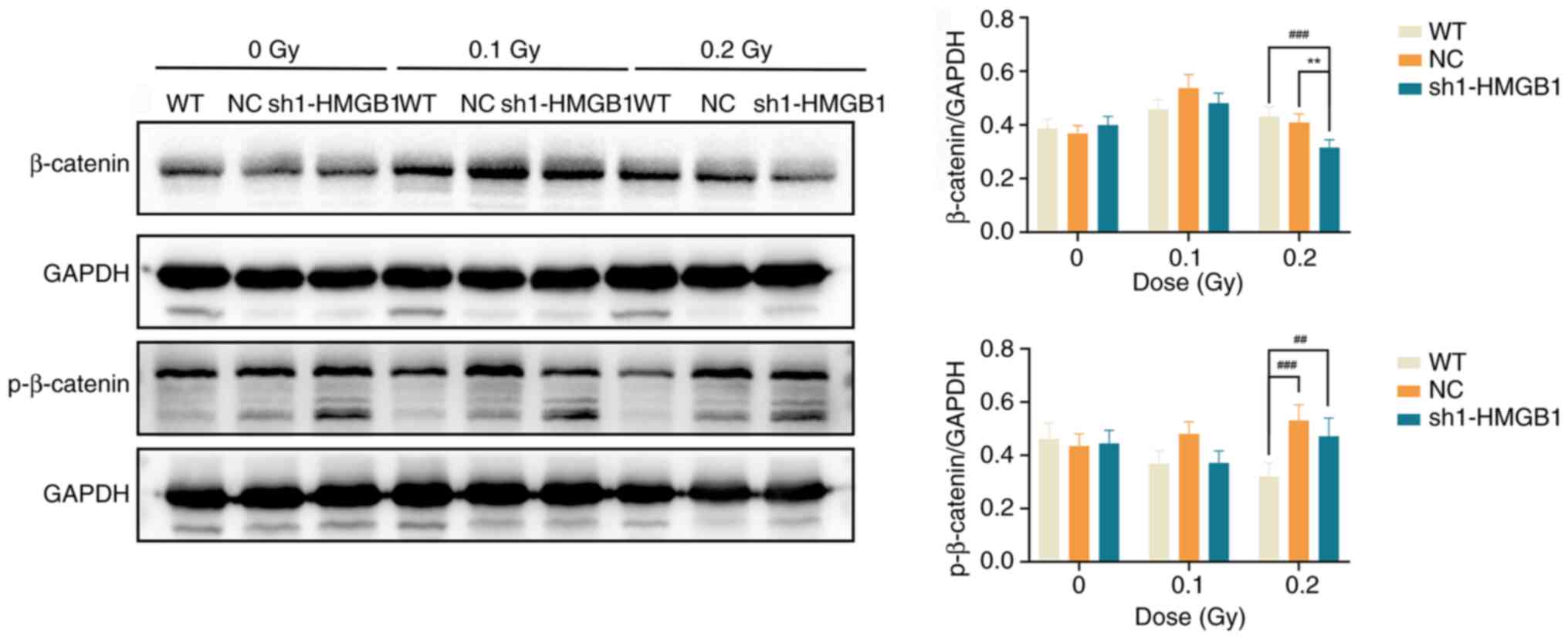

Previous studies have established that nuclear

translocation of β-catenin is a key step in Wnt signaling, while

its phosphorylation is the primary mechanism controlling the

pathway's 'on' and 'off' states, phosphorylation of β-catenin at

Ser33, Ser37 and Thr41 can prevent its nuclear translocation and

the activation of target gene transcription (20,21). Western blot analysis was used to

assess the expression of total and phosphorylated β-catenin

(p-β-catenin) in HMGB1-knockout cells. The results showed that in

the non-irradiated groups, there were no significant differences in

total β-catenin or p-β-catenin among the different cell groups

(P>0.05). However, at 48 h following exposure to low-dose

radiation (particularly at 0.2 Gy), the knockdown group exhibited a

significantly lower level of total β-catenin compared with the

wild-type (WT) and NC groups (P<0.01 or P<0.001); conversely,

the level of p-β-catenin was significantly higher in the knockdown

group than in the WT group (P<0.01), suggesting an inhibition of

the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway after HMGB1-knockdown (Fig. 8). Using confocal laser scanning

microscopy, the localization of β-catenin was examined in

HMGB1-knockdown cells exposed to various low doses of γ-radiation.

The findings of the present study indicated that in unirradiated

cells, β-catenin expression was predominantly confined to the cell

membrane and cytoplasm in the WT, NC and HMGB1-knockdown groups,

suggesting that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway remained in

inactivated state (Fig. 9A).

Nevertheless, at 48 h post-exposure to 0.1 and 0.2 Gy radiation,

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway significantly activated, marked by

the expression of β-catenin translocated into the nucleus in the WT

and NC groups (Fig. 9B and C).

By contrast, in the HMGB1-knockdown group, β-catenin remained

predominantly expressed in the cell membrane and cytoplasm,

exhibiting minimal nuclear expression and no detectable nuclear

translocation (Fig. 9B and C).

This observation suggests that low-dose ionizing radiation cannot

fully activate the intracellular Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in

HMGB1-knockdown cells.

Impact of HMGB1 on cell proliferation and

migration after low-dose γ-ray irradiation

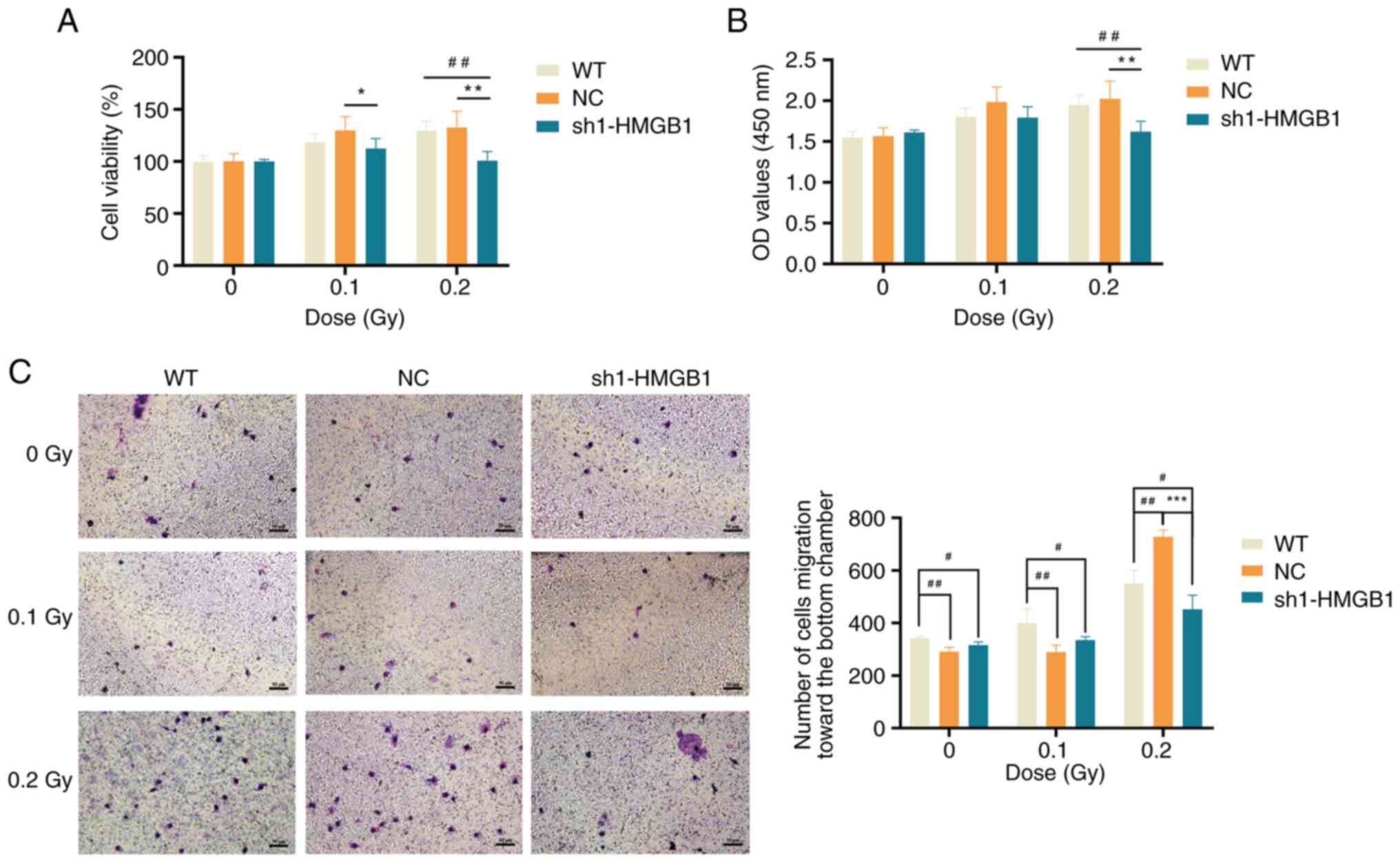

To investigate the role of HMGB1 in abnormal

proliferation and migration of LECs induced by low-dose ionizing

radiation, CCK-8 and Transwell migration assays were conducted to

assess the proliferation and migration abilities of HMGB1-knockdown

cells at 48 h after 0.1 and 0.2 Gy irradiation. The results of

CCK-8 assay indicated that, without radiation, there was no

significant difference in OD values between the knockdown group and

the NC or WT groups (P>0.05) (Fig. 10A and B), suggesting that cell

proliferation was not significantly influenced by HMGB1 knockdown.

However, at 48 h after 0.1 Gy irradiation, the cell viability of

the knockdown group was significantly diminished compared with the

NC group (P<0.05) and also demonstrated a reduction compared

with the WT group, with lower OD values than both NC and WT groups

(Fig. 10A and B). Similarly, at

48 h after 0.2 Gy irradiation, both cell viability and OD values of

the knockdown group were significantly lower than those of the NC

and WT groups (P<0.01) (Fig. 10A

and B). These findings indicated that the proliferative ability

of the knockdown group is weakened compared with the WT and NC

groups after the same low-dose γ-ray exposure.

The results of the Transwell migration assays showed

that at 48 h whether the cells were unirradiated or exposed to 0.1

Gy irradiation, the WT group exhibited a significantly stronger

cell migration ability compared with both the NC group and the

knockdown group (P<0.05 or P<0.01) (Fig. 10C). This suggested that HMGB1

knockdown diminishes cell migration ability, although it is also

possible that the lentivirus itself exerts an influence on the

migration of SRA01/04 cells. At 48 h after 0.2 Gy irradiation, the

cell migration ability of the knockdown group was significantly

weaker than the NC group and the WT group (P<0.05 or P<0.001)

(Fig. 10C). These findings

indicated that the migration ability of the knockdown group is

weakened compared with the WT groups after the same low-dose γ-ray

exposure.

Discussion

The induction of cataracts by ionizing radiation is

a complex process likely associated with multiple factors such as

DNA damage, oxidative stress and telomere abnormalities (22). Although significant strides have

been made in research, the mechanism of opacification in the lens

posterior capsule due to low-dose ionizing radiation remains far

from fully elucidated.

The present study investigated the potential

mechanism by which low-dose ionizing radiation induces abnormal

proliferation and migration of LECs, leading to lens opacity. It

was initially identified that low-dose ionizing radiation enhanced

HMGB1 expression in SRA01/04 cells. Furthermore, the impact of

HMGB1 expression on the proliferation and migration of LECs

following exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation may be associated

with the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

It has been previously reported that low-dose

ionizing radiation can promote abnormal proliferation and migration

of HLE-B3 cells. The HLE-B3 cell line is an immortalized human lens

epithelial cell line that maintains proliferation ability, stable

epithelial morphology in long-term culture and stable

differentiation ability (23).

However, a single cell line may not fully replicate the

physiological and pathological properties of normal LECs, as these

cells may exhibit genetic and phenotypic variations compared with

the actual cells. Genetic background plays an important role in

low-dose ionizing radiation-induced lens opacity. For instance, Gao

et al (24) found in a

case-control study of individuals from the Yangjiang

high-background radiation area that those carrying the allele of

ATM rs189037 and the C allele of TP53 rs1042522 have an increased

risk of radiation-induced lens opacity. To improve the

comprehensiveness of the study, another common human lens

epithelial cell line, SRA01/04, was selected. During continuous

culture, SRA01/04 cells maintain their characteristics as

epithelial cells and do not differentiate into lens fiber cells.

The cell proliferation experiment showed that both cell viability

and the number of live cells increased after irradiating SRA01/04

cells with 0.05-0.5 Gy γ-rays at 8-72 h. Cell viability remained

elevated at 7 days after low-dose irradiation, indicating a lack of

significant dose-response relationship. This further supports the

idea that low-dose ionizing radiation can promote proliferation in

LECs. However, exposure to a higher dose of 2 Gy resulted in a

temporary increase in cell proliferative capacity at 24 h

post-irradiation. At 72 h and beyond after 2 Gy irradiation, the

cell proliferative capacity diminished or showed no significant

difference compared with the unirradiated group. In a study by Chen

et al (25) on the

effects of neutron radiation on rat lenses, high-dose ionizing

radiation significantly induced apoptosis in LECs, while the

low-dose radiation group exhibited less apoptosis. The heightened

sensitivity of lens cells to radiation is not necessarily linked to

ionizing radiation-induced cell death.

Additionally, results from the migration assay

revealed an increase in the number of cells migrating to the bottom

of the Transwell chamber at different time points after low-dose

ionizing radiation. This was accompanied by an expansion of the gap

closure area, indicating that low-dose ionizing radiation enhances

the migratory ability of SRA01/04 cells. A colony formation assay

demonstrated that low-dose ionizing radiation significantly

promoted the proliferation of migratory SRA01/04 cells. It was

observed that SRA01/04 cells continued to grow well and maintained

their proliferation ability after migrating from serum-free medium

to a medium containing 10% FBS following low-dose radiation

exposure. The irradiated group exhibited a significantly higher

number of colony-forming units compared with the non-irradiated

group. Low-dose ionizing radiation also markedly enhanced the

proliferation of migratory cells. Meanwhile, the effects of 0.05,

0.1, 0.2 and 2 Gy on the proliferation and density of mouse lens

cells over an extended period were assessed, discovering scattered

nucleated cells in the posterior capsule of the lens after

irradiation. Nucleated cells were also detected in the posterior

lens capsule of unirradiated mice, potentially related to a

heightened risk of spontaneous cataract development in middle-aged

mice. It was hypothesized that extended exposure to low-dose

radiation may lead to changes in lens shape and visual impairment

over time, which necessitates confirmation through population

epidemiological studies.

Precise spatiotemporal regulation of canonical Wnt

signaling is crucial for eye development. In a lens injury model

simulating cataract surgery, researchers detected Wnt signaling

activation in residual LECs within 12 h post-surgery, indicating an

upregulation during the development of posterior capsular

opacification (26). Numerous

studies have implicated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the

proliferation, migration and EMT of HLE-B3 cells (8,27). It was found that the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway also plays an important role in the

proliferation and migration of SRA01/04 cells induced by low-dose

ionizing radiation. The protein expressions of β-catenin, cyclin D1

and c-Myc in SRA01/04 cells were increased to varying degrees after

different doses of irradiation at various times. At certain time

points, the expression of these three proteins exhibited a

double-phase reaction; that is, the expression level increased with

the dose after low-dose irradiation, usually peaking at 0.1 Gy, and

could increase again after higher doses. Similar observations were

reported by Chauhan et al (28). Whole-genome sequencing was

performed on HLE cells 20 h post-exposure to X-ray irradiation at

doses of 0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.25, 0.5, 2 and 5 Gy. Some genes

demonstrated a nonlinear biphasic response in terms of fold change

at low doses (<0.5 Gy), reaching a peak at 0.25 Gy. At doses

greater than 0.5 Gy, the fold change of these genes gradually

increased. Low-dose ionizing radiation significantly reduced the

expression of β-catenin protein on the cell membrane and increased

the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, suggesting that the

proliferation and migration of SRA01/04 cells promoted by low-dose

ionizing radiation were related to the activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The molecular mechanism by which

low-dose ionizing radiation activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway inducing lens opacity will be explored.

HMGB1, one of the most abundant non-histone nuclear

proteins, is normally located in the nucleus and plays a role in

regulating gene transcription, DNA damage repair and chromosome

structure stability (29). It

can also be released passively by dead or damaged cells or actively

secreted by activated immune cells into the extracellular

environment, triggering an inflammatory response (30). Increased expression and secretion

of HMGB1 are associated with tumor proliferation, invasion and

migration in various cancers, and HMGB1 can serve as a potential

biomarker to identify tumors (31). In the present study, HMGB1

expression in SRA01/04 cells was inhibited using lentiviral

infection technology. Following 0.2 Gy γ-ray irradiation, total

β-catenin expression decreased in the knockdown cells compared with

WT cells, while phosphorylated β-catenin expression increased.

Immunofluorescence analysis further revealed that after low-dose

γ-ray irradiation, β-catenin no longer translocated to the nucleus

in HMGB1-knockdown cells. Genetic ablation of HMGB1 abolished

radiation-induced β-catenin nuclear translocation, suggesting that

HMGB1 may be involved in regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway activated by low-dose ionizing radiation. Previous studies

also have reported that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is

regulated by HMGB1. Wang et al (32) found that miR-665 deactivates the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in retinoblastoma by directly

targeting HMGB1, thereby inhibiting tumor development. Zhou et

al (33) showed that

administering exogenous HMGB1 to rats with myocardial infarction

improved cardiac function via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

activation. In the cell proliferation and migration experiments of

the present study, HMGB1-knockdown cells subjected to 0.1 or 0.2 Gy

γ-ray irradiation exhibited significantly reduced proliferation and

migration capabilities compared with the WT group irradiated with

the same dose, resulting in 77% reduction in proliferation rate and

82% suppression of migratory activity. In addition, the

proliferation and migration abilities of knockdown cells after

low-dose irradiation were still enhanced compared with those of

unirradiated knockdown cells, indicating that low-dose ionizing

radiation can promote the proliferation and migration of HMGB1

knockdown cells, but the promoting effect was weaker than that of

WT cells. Based on in vitro research results, future study

by the authors will use lens-specific HMGB1-conditional knockout

mice to clarify the role of the HMGB1/Wnt-β-catenin signaling axis

in mediating low-dose ionizing radiation-induced ocular lens

opacity.

In summary, the preliminary findings of the present

study indicated that low-dose γ-ray irradiation upregulates HMGB1

expression in SRA01/04 cells, which may promote cell proliferation

and migration by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

The activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway appears to be

partially dependent on HMGB1 expression. Future investigations are

needed to further explore the interactions and molecular mechanisms

between the two in regulating the functional abnormalities of LECs

induced by low-dose ionizing radiation. The present study unravels

a novel molecular target for lens opacity induced by low-dose

ionizing radiation, aiding in early intervention and treatment of

radiation-induced cataracts.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PW and MT conceived and designed the study. PW and

CP conducted experimental research and acquired data. PW, CP and LF

performed data analysis, interpretation and visualization. DY, YH

and YL prepared the experimental animal model and examined tissue

staining. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript or

revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript and confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved [approval no.

(2022)005] by the Experimental Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee

of the National Institute for Radiological Protection, Chinese

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Beijing, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

References

|

1

|

Neriishi K, Nakashima E, Minamoto A,

Fujiwara S, Akahoshi M, Mishima HK, Kitaoka T and Shore RE:

Postoperative cataract cases among atomic bomb survivors: Radiation

dose response and threshold. Radiat Res. 168:404–408. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chodick G, Bekiroglu N, Hauptmann M,

Alexander BH, Freedman DM, Doody MM, Cheung LC, Simon SL, Weinstock

RM, Bouville A and Sigurdson AJ: Risk of cataract after exposure to

low doses of ionizing radiation: A 20-year prospective cohort study

among US radiologic technologists. Am J Epidemiol. 168:620–631.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Azizova TV, Hamada N, Grigoryeva ES and

Bragin EV: Risk of various types of cataracts in a cohort of Mayak

workers following chronic occupational exposure to ionizing

radiation. Eur J Epidemiol. 33:1193–1204. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ahmadi M, Barnard S, Ainsbury E and Kadhim

M: Early responses to low-dose ionizing radiation in cellular lens

epithelial models. Radiat Res. 197:78–91. 2022.

|

|

5

|

Barnard S, Uwineza A, Kalligeraki A,

McCarron R, Kruse F, Ainsbury EA and Quinlan RA: Lens epithelial

cell proliferation in response to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res.

197:92–99. 2022.

|

|

6

|

Siddam AD, Gautier-Courteille C,

Perez-Campos L, Anand D, Kakrana A, Dang CA, Legagneux V, Méreau A,

Viet J, Gross JM, et al: The RNA-binding protein Celf1

post-transcriptionally regulates p27Kip1 and Dnase2b to control

fiber cell nuclear degradation in lens development. PLoS Genet.

14:e10072782018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kumar B and Reilly MA: The development,

growth, and regeneration of the crystalline lens: A review. Curr

Eye Res. 45:313–326. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang P, Li YW, Lu X, Liu Y, Tian XL, Gao

L, Liu QJ, Fan L and Tian M: Low-dose ionizing radiation: Effects

on the proliferation and migration of lens epithelial cells via

activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol

Environ Mutagen. 888:5036372023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Vigneux G, Pirkkanen J, Laframboise T,

Prescott H, Tharmalingam S and Thome C: Radiation-induced

alterations in proliferation, migration, and adhesion in lens

epithelial cells and implications for cataract development.

Bioengineering (Basel). 9:292022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Terrell AM, Anand D and Lachke SA:

Molecular characterization of human lens epithelial cell lines

HLE-B3 and SRA01/04 and their utility to model lens biology. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 56:40112015.

|

|

11

|

Wang P, Fan L, Lu X, Gao L, Liu Q and Tian

M: Identification of differential mRNA expression profiles in lens

epithelial cells induced by low-dose ionizing radiation. Radiat

Prot. 43:175–185. 2023.In Chinese.

|

|

12

|

Li PF, Borgia F, Custurone P, Vaccaro M,

Pioggia G and Gangemi S: Role of HMGB1 in cutaneous melanoma: State

of the art. Int J Mol Sci. 23:39272022.

|

|

13

|

Shu Z, Miao X, Tang T, Zhan P, Zeng L and

Jiang Y: The GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in

HMGB1-induced chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage matrix

degradation. Int J Mol Med. 45:769–778. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wang XH, Zhang SY, Shi M and Xu XP: HMGB1

promotes the proliferation and metastasis of lung cancer by

activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

19:15330338209480542020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chen YC, Statt S, Wu R, Chang HT, Liao JW,

Wang CN, Shyu WC and Lee CC: High mobility group box 1-induced

epithelial mesenchymal transition in human airway epithelial cells.

Sci Rep. 6:188152016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Weatherbee B, Barton JR, Siddam AD, Anand

D and Lachke SA: Molecular characterization of the human lens

epithelium-derived cell line SRA01/04. Exp Eye Res. 188:1077872019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jin M, Gao D, Wang R, Sik A and Liu K:

Possible involvement of TGF-β-SMAD-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal

transition in pro-metastatic property of PAX6. Oncol Rep.

44:555–564. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Oharazawa H, Ibaraki N, Lin LR and Reddy

VN: The effects of extracellular matrix on cell attachment,

proliferation and migration in a human lens epithelial cell line.

Exp Eye Res. 69:603–610. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Markiewicz E, Barnard S, Haines J, Coster

M, van Geel O, Wu W, Richards S, Ainsbury E, Rothkamm K, Bouffler S

and Quinlan RA: Nonlinear ionizing radiation-induced changes in eye

lens cell proliferation, cyclin D1 expression and lens shape. Open

Biol. 5:1500112015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kim W, Kim M and Jho EH: Wnt/β-catenin

signalling: From plasma membrane to nucleus. Biochem J. 450:9–21.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shah K and Kazi JU:

Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of WNT/beta-catenin signaling.

Front Oncol. 12:8587822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hamada N: Ionizing radiation sensitivity

of the ocular lens and its dose rate dependence. Int J Radiat Biol.

93:1024–1034. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Andley UP, Rhim JS, Chylack LJ Jr and

Fleming TP: Propagation and immortalization of human lens

epithelial cells in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

35:3094–3102. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Gao Y, Su YP, Li XL, Lei SJ, Chen HF, Cui

SY, Zhang SF, Zou JM, Liu QJ and Sun QF: ATM and TP53 polymorphisms

modified susceptibility to radiation-induced lens opacity in

natural high background radiation area, China. Int J Radiat Biol.

98:1235–1242. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen Y, Feng J, Liu J, Zhou H, Luo H, Xue

C and Gao W: Effects of neutron radiation on Nrf2-regulated

antioxidant defense systems in rat lens. Exp Ther Med. 21:3342021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang Y, Mahesh P, Wang Y, Novo SG, Shihan

MH, Hayward-Piatkovskyi B and Duncan MK: Spatiotemporal dynamics of

canonical Wnt signaling during embryonic eye development and

posterior capsular opacification (PCO). Exp Eye Res. 175:148–158.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bao XL, Song H, Chen Z and Tang X: Wnt3a

promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and

proliferation of lens epithelial cells. Mol Vis. 18:1983–1990.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chauhan V, Rowan-Carroll A, Gagné R, Kuo

B, Williams A and Yauk CL: The use of in vitro transcriptional data

to identify thresholds of effects in a human lens epithelial

cell-line exposed to ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Biol.

95:156–169. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kianian F, Kadkhodaee M, Sadeghipour HR,

Karimian SM and Seifi B: An overview of high-mobility group box 1,

a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine in asthma. J Basic Clin Physiol

Pharmacol. 31:2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ulloa L and Messmer D: High-mobility group

box 1 (HMGB1) protein: Friend and foe. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.

17:189–201. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wang Y, Jiang Z, Yan J and Ying S: HMGB1

as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for malignant

mesothelioma. Dis Markers. 2019:41831572019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang S, Du S, Lv Y, Zhang F and Wang W:

MicroRNA-665 inhibits the oncogenicity of retinoblastoma by

directly targeting high-mobility group box 1 and inactivating the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cancer Manag Res. 11:3111–3123. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

33

|

Zhou X, Hu X, Xie J, Xu C, Xu W and Jiang

H: Exogenous high-mobility group box 1 protein injection improves

cardiac function after myocardial infarction: Involvement of Wnt

signaling activation. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012:7438792012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|