Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most common type

of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-associated

mortalities worldwide (1) with a

10-year survival rate of 8.2% (2). Although notable advances have been

made in cancer research over recent decades, major challenges

persist in the treatment of cancer. Malignant invasion, recurrent

metastases and chemoresistance remain the primary contributors to

disease relapse (3).

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is typically diagnosed at an

advanced stage, making curative surgical intervention difficult.

Currently, the clinical efficacy of molecular targeted therapies

and immunotherapies for HCC is limited by factors such as drug

resistance and tumor recurrence (4). This limitation underscores the need

to elucidate the molecular mechanisms driving HCC progression and

to identify novel therapeutic targets, thereby laying a strong

scientific foundation for the development of more effective

treatment strategies (5).

Stomatin-like protein 2 (STOML2, also known as

SLP-2) is a unique member of the stomatin family, encoded by a gene

located on chromosome 9p13 (6).

A defining structural feature of STOML2 is the absence of the

N-terminal hydrophobic domain found in other homologous proteins

(7). STOML2 is predominantly

localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it faces the

intermembrane space, and participates in the regulation of

mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism through interactions

with inner membrane components (8,9).

Notably, a previous study demonstrated that upregulation of STOML2

is closely associated with the development of various tumors

(10,11), highlighting its potential

functional importance.

Currently, a growing body of research has suggested

that STOML2 exhibits dysregulated expression in various malignant

tumors. STOML2 has been reported to be upregulated in ovarian

cancer (10,12), gastric cancer (13), papillary thyroid carcinoma

(14), colorectal cancer

(15), gallbladder cancer

(11), HCC (16), and squamous cell carcinoma of the

head and neck (17). While

STOML2 upregulation has been observed in HCC, its precise molecular

mechanisms, particularly its role in metastasis, signaling pathways

and interaction with prohibitin (PHB), remain largely

uncharacterized. Malignancy is increasingly recognized as a

progressive and chronic disease (18). For example, HCC is typically

secondary to persistent liver injury, and its characteristic

pathological changes include excessive release of various

cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, and aberrant vascularization

(19). These pathological

features not only markedly increase the complexity of clinical

treatment but also critically influence long-term prognosis.

Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor

progression, identifying novel biomarkers for HCC and its

prognosis, and establishing new therapeutic targets hold scientific

and clinical importance. The present study aimed to investigate the

pro-tumorigenic role of STOML2 in HCC. The study aimed to determine

whether its effects are mediated through an interaction with PHB

and the subsequent activation of the MAPK signaling pathway.

Furthermore, the therapeutic potential of targeting this axis, in

combination with sorafenib, was explored for STOML2-upregulated

HCC.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

The present study is a retrospective analysis that

enrolled a cohort of 72 patients with histologically confirmed HCC

who underwent surgical resection at the North China University of

Science and Technology Affiliated Hospital (Tangshan, China).

Patient recruitment and sample collection took place between

January 2015 and December 2023. The cohort had a mean age of 65

years (median: 63.5 years; range: 42-82 years) with a

male-to-female ratio of 2.5:1. Fresh tumor tissues and matched

adjacent non-tumor liver tissues (obtained >2 cm from the tumor

margin) were collected, fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formalin at

room temperature for 24 h and processed into paraffin-embedded

blocks for subsequent analysis. The inclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Pathologically confirmed primary HCC; ii) no prior

chemotherapy or radiotherapy; iii) availability of complete

clinicopathological data. Key exclusion criteria included: i) A

history of other malignancies; ii) any anticancer treatment before

surgery; iii) inadequate tissue sample quality. The study protocol

was approved by the Ethics Committee of the North China University

of Science and Technology Affiliated Hospital (approval no.

20250403024), and written informed consent was obtained from all

participants.

Cell culture

The liver cancer cell lines HCCLM3, HepG2, Hep3B,

MHCC97L and Huh7, the non-tumorigenic human hepatocyte cell line

THLE-2 and 293T cells were purchased from Xiamen Yimo Biotechnology

Co., Ltd. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle

medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with

10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.), 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All cell lines

were authenticated using short tandem repeat profiling.

Establishment of overexpression and

knockdown cell lines

STOML2 knockdown was achieved using a short hairpin

RNA (shRNA; shSTOML2) cloned into the psi-LVRH1P-Puromycin

lentiviral vector (MailGene Scientific). For overexpression, the

STOML2-coding sequence was cloned into the

pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-T2A-Puromycin vector (MailGene Scientific). PHB

knockdown (shPHB) was similarly achieved using a shRNA cloned into

the psi-LVRH1P-Puromycin vector (MailGene Scientific). The shRNA

sequences (5'-3') were as follows: shSTOML2-1,

GCTCAAACAACCATGAGATCA; shSTOML2-2, GGAAATTGTCATCAACGTGCC; shPHB,

GAAATCACTGTGAAATTT. A non-targeting scrambled shRNA (Scr) was used

as a negative control for knockdown experiments, with the following

sequence: 5'-GCTTCGCGCCGTAGTCTTA-3'; this was cloned into the same

psi-LVRH1P-Puromycin vector. For overexpression experiments, the

'Mock' condition refers to cells transduced with the empty

pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-T2A-Puromycin vector. The Huh7-STOML2 cell line

refers to Huh7 cells stably infected with the STOML2 overexpression

plasmid.

Lentiviral particles were produced using a

second-generation packaging system. Briefly, 293T cells were

co-transfected with 2.0 μg target plasmid, 1.5 μg

packaging plasmid psPAX2 (cat. no. V010353; NovoPro Bioscience Co.,

Ltd.) and 0.5 μg envelope plasmid pMD2.G (cat. no. V010404;

NovoPro Bioscience Co., Ltd.) in a 4:3:1 ratio using

Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 48 h at 37°C. Viral supernatants were

collected 48 h post-transfection, filtered and used to transduce

target cells (HCCLM3 and Huh7) in the presence of 8 μg/ml

polybrene (Biosharp Life Sciences). The multiplicity of infection

was optimized to 10 for each cell line. Transduction was carried

out for 24 h, after which the virus-containing medium was replaced

with fresh complete medium. A total of 48 h post-transduction,

cells were selected with 1.5 μg/ml puromycin (cat. no.

BL528A; Biosharp Life Sciences) (for 1 week to establish stable

polyclonal populations). The puromycin concentration for

maintenance was reduced to 0.75 μg/ml. Infection efficiency

was confirmed using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and western blotting.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from HCC cells and frozen

tissue samples (stored at −80°C) using TRIzol® reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). cDNA was synthesized

from 1 μg total RNA using the PrimeScript™ RT Kit (Takara

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) in accordance with the manufacturer's

protocol. Briefly, the RT reaction was carried out at 37°C for 15

min, followed by inactivation at 85°C for 5 sec. qPCR was performed

using the QuantStudio® 3 Real-Time PCR system (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with SYBR Green Premix

Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co.,

Ltd.). The qPCR thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial

denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec; followed by 40 cycles of

denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for

30 sec. Gene expression was quantified using the 2−ΔDCq

method (20), with GAPDH as the

endogenous control. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The

primers used were as follows: STOML2, forward

5'-GCAGAAGGGAAGAAACAGGC-3' and reverse 5'-GAGAACGCGCTGACATACTG-3';

PHB, forward 5'-AGAGAGAGCTGGTCTCTCCAGG-3' and reverse

5'-TCCACCGCTTCTGTGAACTC-3'; and GAPDH, forward

5'-CCAGCAAGAGCACAAGAGGA-3' and reverse

5'-GGGGAGATTCAGTGTGGTGG-3'.

Western blotting and

co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Total proteins were extracted from frozen HCC

tissues and cultured cells using RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no.

WB3100; Suzhou NCM Biotech Co., Ltd.) supplemented with protease

and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined

using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. WB6501; Suzhou NCM

Biotech Co., Ltd.). A total of 20 μg protein lysate/lane was

separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and transferred onto PVDF

membranes (MilliporeSigma). The membranes were blocked with 1%

bovine serum albumin (BSA; cat. no. A8010; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature.

Subsequently, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies (1:500) specific to the target proteins STOML2

(cat. no. 10348-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), PHB (cat. no.

GB113098-100; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), p62 (cat. no.

18420-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.), Beclin1 (cat. no. 11306-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), RAF1 (cat. no. 26863-1-AP; Proteintech

Group, Inc.), phosphorylated (p)-RAF1 (cat. no. 9427; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), MEK1/2 (cat. no. 11049-1-AP;

Proteintech Group, Inc.), p-MEK1/2 (cat. no. 9154; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), ERK1/2 (cat. no. 11257-1-AP; Proteintech Group,

Inc.), p-ERK1/2 (cat. no. 80031-1-RR; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

GAPDH (cat. no. 60004-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.). After washing

with TBS-0.1% Tween-20 to remove unbound primary antibodies, the

membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies

(cat. no. ZB-2301; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the protein

bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescent kit (cat.

no. WP20005; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Images of the blots were captured and

the band intensity was semi-quantified using Image Lab software

(version 6.1; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

For the co-IP assay, STOML2 was expressed as a

Flag-tagged fusion protein and PHB was expressed as a Myc-tagged

fusion protein. The coding sequences were cloned into the

pCDH-CMV-Flag (cat. no. HSE067321; MailGene Scientific) and

pCDH-CMV-Myc (cat. no. HSH067460; MailGene Scientific) vectors,

respectively. For transfection, 293T cells were seeded at a density

of 5×105 cells/well in a 6-well plate and grown to

70-80% confluence. They were co-transfected simultaneously with a

total of 2 μg plasmid DNA (Flag-STOML2 and Myc-PHB

constructs at a 1:1 ratio) using Lipofectamine 3000 according to

the manufacturer's instructions. The transfection complex mixture

was incubated with the cells for 24 h at 37°C. The cells were

harvested 48 h post-transfection and lysed with IP Lysis Buffer

(cat. no. 87787; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on ice for 30 min.

Cell debris was removed using centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15

min at 4°C. The supernatant was then collected and the protein

concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit. A

total of 400 μg protein lysate was used for each IP

reaction. Lysates were pre-cleared by incubation with 20 μl

Protein A/G agarose beads (cat. no. sc-2003; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h at 4°C with gentle agitation. The

pre-cleared supernatants were then incubated overnight at 4°C with

the appropriate antibodies: Anti-Flag antibody (1:500 dilution;

cat. no. 66008-4-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) for

immunoprecipitating Flag-STOML2 or normal rabbit IgG (1:500

dilution; cat. no. 30000-0-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) was used as

a negative control. Anti-Myc antibody (1:500 dilution; cat. no.

60003-2-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) was used to for

immunoprecipitating Myc-PHB or normal rabbit IgG was used as a

negative control. The following day, 30 μl Protein A/G

agarose beads were added to each sample, and each sample was

incubated for an additional 4 h at 4°C to capture the

antibody-antigen complexes. The beads were then collected using

centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C and washed three times

with the same IP Lysis Buffer. After the final wash, the bound

proteins were eluted from the beads by boiling in 2X SDS-PAGE

loading buffer at 95°C for 10 min. The eluted proteins were then

separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed using western blotting as

aforementioned.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

Each of the three HCC cell lines (HCCLM3, HepG2 and

Huh7) were seeded on a coverslip placed in a 6-well plate at a

density of 2×104 cells/well. After overnight incubation

at 37°C, the cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100

for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were blocked in 5% BSA for

1 h at room temperature and then incubated with the following

primary antibodies at 4°C overnight: STOML2 rabbit antibody (1:200

dilution; cat. no. 10348-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and PHB

mouse antibody (1:200 dilution; cat. no. 60092-1-Ig; Proteintech

Group, Inc.). The next day, the cells were incubated with the

corresponding secondary antibody [Goat Anti Rabbit IgG (H+L)

conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500;cat. no. A32731TR); Goat

Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500 dilution;

cat. no. A32742); both Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.]

for 1 h at room temperature in the dark and then counterstained

with 1 μg/ml DAPI for 10 min at room temperature. Finally,

the stained cells were observed and images were captured under a

fluorescence microscope (400857; Nikon Corporation). For each

experimental group, at least five random fields of view were

captured and analyzed.

Cell proliferation assay

For the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay, 3,000

cells were seeded in each well of 96-well plates, and were

incubated for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h at 37°C. Prior to each

measurement, the culture medium was removed and replaced with fresh

medium containing CCK-8 reagent (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.). After 1 h of incubation in a cell culture

incubator, absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate

reader (Tecan Group, Ltd.) at the indicated time points.

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was also assessed using a wound

healing assay. HCC cells were seeded in 6-well plates and grown to

100% confluence. To eliminate the influence of cell proliferation,

the cells were serum-starved by replacing the growth medium with

serum-free medium for 12 h prior to wounding and throughout the

duration of the assay. A linear wound was then created using a

200-μl pipette tip, the wound area was marked and the plates

were incubated under standard culture conditions for 24 h.

Subsequently, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15

min at room temperature, stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20

min at room temperature and images were captured under an inverted

light microscope (Nikon Corporation). The results were

semi-quantified by measuring the wound width at 0 and 24 h using

ImageJ software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of Health). The

percentage of wound closure was calculated as follows: [(Wound

width at 0 h-Wound width at 24 h)/Wound width at 0 h] ×100.

Cell invasion assay

Cell invasion was quantified using the

Matrigel-coated Transwell assay. Transwell inserts (pore size, 8

μm; Corning, Inc.) were pre-coated with 100 μl

Matrigel matrix (1 mg/ml; cat. no. 356234; Corning, Inc.) and

incubated at 37°C for 6 h to form a gel. A total of

1×105 cells in 500 μl serum-free DMEM were seeded

into the upper chamber of coated inserts. The inserts were placed

in 24-well plates containing 500 μl DMEM supplemented with

10% FBS in the lower chamber. After 24 h, the cells that had

migrated to the lower chamber were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 15 min at room temperature, stained with 0.1% crystal violet

for 20 min at room temperature and images were captured under an

inverted light microscope for quantification. All experiments were

performed in triplicate.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tissue sections fixed in 4% neutral-buffered

formalin at room temperature for 24 h were embedded in paraffin (4

μm) and were sequentially deparaffinized in xylene and

rehydrated in a graded ethanol series (50, 70, 85, 95 and 100%).

For antigen retrieval, slides were heated in 10 mM sodium citrate

buffer (pH 6.0) using a microwave at 100°C for 20 min. After

cooling, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating

the sections with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, the sections were blocked with 5% normal

goat serum (cat. no. C0625; Beyotime Biotechnology) for 1 h at room

temperature. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with

primary antibodies against STOML2 (1:300 dilution; cat. no.

10348-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or Ki-67 (1:300 dilution; cat.

no. 27309-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) diluted in blocking

buffer. After washing, the sections were incubated for 1 h at room

temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bound

antibodies were visualized using a DAB substrate kit (cat. no.

k346889-2; Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. STOML2 expression was assessed via IHC

staining by two independent pathologists who were blinded to all

clinical data. Staining intensity was graded on a scale of 0

(negative) to 3 (strong). The percentage of positive tumor cells

was scored as 0 (0%), 1 (1-25%), 2 (26-50%), 3 (51-75%) or 4

(76-100%). A final IHC score was derived by multiplying the

intensity and proportion scores, yielding a value between 0 and 12.

Any discrepant assessments were resolved through a joint

re-evaluation to reach a consensus. Stained sections were observed

and images were captured under a light microscope (Nikon

Corporation).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were

sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm. Sections were

deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol

series and stained with hematoxylin at room temperature (cat. no.

C0107-100; Beyotime Biotechnology) for 5 min. After washing, the

sections were differentiated in 1% acid ethanol, blued in Scott's

tap water (cat. no. S5134; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and

counterstained with 1% eosin Y (cat. no. 318906; Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA) solution for 2 min. Finally, the sections were

dehydrated, cleared in xylene and mounted with a synthetic mounting

medium for light microscopy (Eclipse E100; Nikon Corporation).

MAPK pathway inhibition using

sorafenib

For MAPK pathway inhibition, Huh7 cells

overexpressing STOML2 were pre-treated with sorafenib (20

μM; cat. no. HY10201; MedChemExpress) for 24 h at 37°C prior

to subsequent assays, including western blotting, flow cytometry

and functional assays. An equal volume of DMSO (cat. no. HY-Y0320;

MedChemExpress) was used as the vehicle control in all experiments.

The final concentration of DMSO in the culture medium did not

exceed 0.1%.

Flow cytometry

For cell cycle analysis, ~1×106 cells

were washed with PBS and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol at −20°C for

≥2 h. Fixed cells were then pelleted, washed with PBS and treated

with 100 μg/ml RNase A at 37°C for 30 min from the Cell

Cycle Detection Kit (cat. no. C1052; Beyotime Biotechnology) to

remove RNA. Cellular DNA was then stained with 50 μg/ml PI

in the dark at room temperature for 30 min according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The stained cells were incubated in

the dark at room temperature for 30 min and analyzed using a flow

cytometer (BD Accuri C6; BD Biosciences). The percentages of cells

in the G0/G1, S and G2/M phases of

the cell cycle were determined from the DNA histograms using

software FlowJo (version 10.8.1; BD Biosciences).

Cell apoptosis was assessed using an Annexin

V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (cat. no. 556547; BD

Biosciences). Cells were harvested, washed twice with cold PBS and

resuspended in 1X Binding Buffer at a density of 1×106

cells/ml. Subsequently, a 100-μl aliquot of the cell

suspension was incubated with 5 μl Annexin V-FITC and 5

μl PI for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Following

incubation, 400 μl 1X Binding Buffer was added to each tube,

and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6; BD

Biosciences) within 1 h. Data were analyzed using the software

FlowJo (version 10.8.1; BD Biosciences).

Animal experiments

The animal experiments performed in the present

study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of North China

University of Science and Technology (Tangshan, China; approval no.

2025SY3011).A total of 35 BALB/c male nude mice (age, 4-5 weeks;

weight, 18-22 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory

Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Mice were housed under specific

pathogen-free conditions at a controlled temperature of 24°C and

humidity of 50%, under a 12-h light/dark cycle. To establish a

subcutaneous HCC model, mice were randomly divided into seven

groups (n=5/group), as follows: Group 1, injected with HCCLM3-Scr

cells; Group 2, injected with HCCLM3-shSTOML2-1 cells; Group 3,

injected with HCCLM3-shSTOML2-2 cells; Group 4, injected with

Huh7-mock cells; Group 5, injected with Huh7-STOML2 cells; Group 6,

injected with Huh7-STOML2-Scr cells; Group 7, injected with

Huh7-STOML2-shPHB cells. A total of 3×106 cells

suspended in 200 μl PBS were injected subcutaneously into

the dorsal neck region of each mouse. The experiments conducted on

these mice included: Monitoring of tumor growth kinetics, final

tumor weight measurement upon resection and IHC. After 25 days,

mice were euthanized by gradual displacement of chamber air with

CO2 at a flow rate of 35% of the chamber volume/min,

after which death was confirmed by the absence of a heartbeat and

fixed, dilated pupils. Tumor width (W) and length (L) were measured

weekly using vernier calipers, and tumor volume (mm3)

was calculated as follows: (W2 × L)/2. The humane endpoint criteria

for euthanasia were as follows: i) If a mouse lost 15-20% of its

initial body weight, or exhibited noticeable emaciation and muscle

atrophy; ii) if the mouse completely lost its appetite for 24 h, or

was unable to eat or drink independently; iii) if signs of distress

or discomfort were observed, such as excessive scratching of a

tumor leading to skin bleeding; and iv) if the tumor became

ulcerated and infected, grew rapidly or impaired the normal feeding

and behavior of the animal. After any of the criteria was met, mice

were euthanized and tumors were isolated. The largest tumor volume

in nude mice was 0.843 cm3 and the largest diameter was

0.85 cm. None of the pre-defined humane endpoints were reached

prior to the scheduled endpoint of the study.

Bioinformatics analysis

The online tool Gene Expression Profiling

Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) was employed to generate

the Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve. For this analysis, The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (LIHC)

cohort was used, which includes data from 371 patients with primary

LIHC. Patients with STOML2 expression levels above the median were

classified as the 'High-expression' group, whereas those with

expression levels below the median constituted the 'Low-expression'

group. The corresponding clinical information for the LIHC cohort

was downloaded from TCGA (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/projects/TCGA-LIHC).

For independent validation of STOML2 expression, two

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets were analyzed: GSE40367

(21,22) and GSE14520 (23). The GSE40367 dataset (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE40367)

includes profiles from 6 healthy control patient tissues, 10

primary HCC tumors and 18 metastatic HCC lesions. The GSE14520

dataset (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE14520)

comprises 22 paired normal liver tissues and 22 HCC tissues.

Differential expression analysis of STOML2 between HCC and normal

tissues was performed using the data from these cohorts. All

analyses were conducted utilizing R version 4.0.3 (https://www.r-project.org/). The following R packages

were used for data processing, analysis and visualization: 'limma'

package (24) (version 3.46.0)

and 'ggplot2' package (25)

(version 3.3.5).

In silico protein interaction

prediction

Potential interacting partners of STOML2 were

predicted using the STRING database (version 11.0; https://string-db.org/). The search was performed

using the full-length human STOML2 protein, with the minimum

required interaction score set to the highest confidence

(0.945).

Statistical analysis

Data from at least three independent experiments are

presented as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range.

Statistical significance was assessed using unpaired Student's

t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons between groups. For

paired comparisons such as between tumor and adjacent normal

tissues from the same patients, the paired Student's t-test was

used for normally distributed continuous data and the Wilcoxon

signed-rank test was used for non-parametric or ordinal data (such

as IHC scores). For comparisons among three or more groups, one- or

two-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey's post hoc test for

multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. GraphPad Prism 9.0 software

(Dotmatics) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

STOML2 expression is upregulated in HCC

tissues

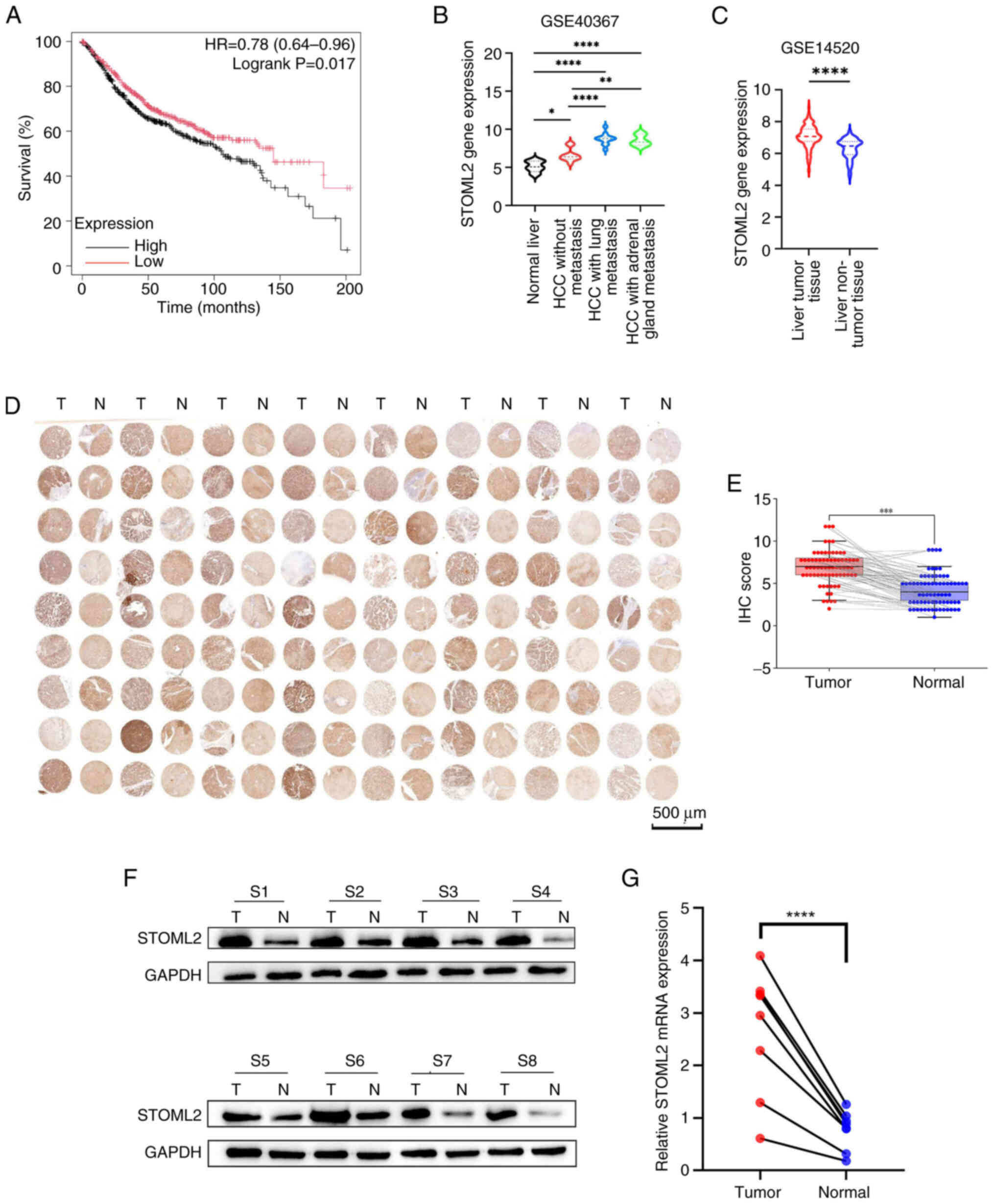

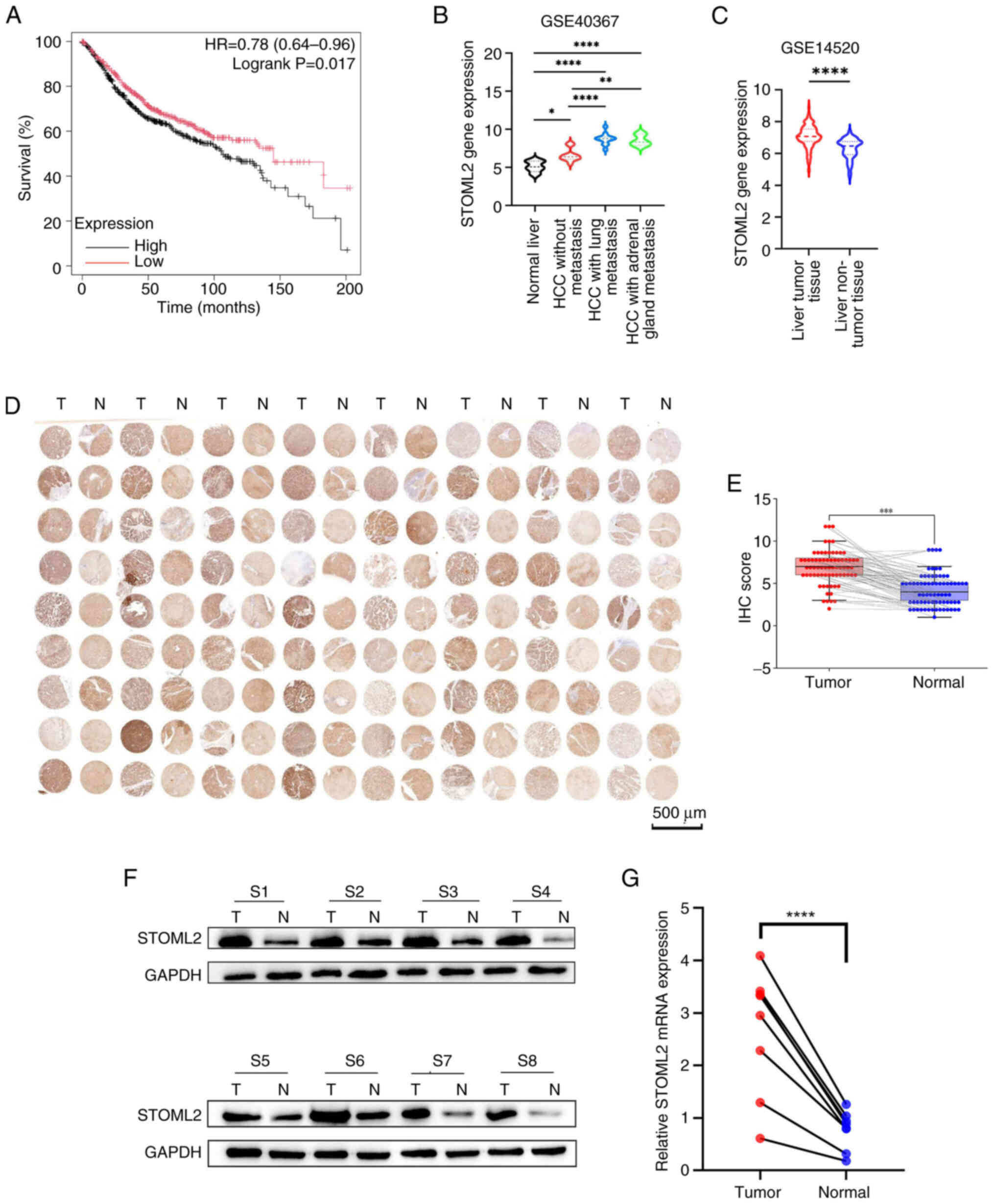

To explore the clinical relevance of STOML2 in HCC,

patient survival was first analyzed using TCGA dataset via the

GEPIA platform. The results indicated a significant association

between high STOML2 expression and poor prognosis (Fig. 1A). Further analysis of two public

datasets from the GEO confirmed that STOML2 expression was

significantly upregulated in HCC tissues compared with that in

paired normal liver tissues (Fig.

1C). In addition, STOML2 exhibited higher expression in the

lung and adrenal metastatic lesions of patients with HCC compared

with in healthy control patients (Fig. 1B). To further validate the

expression of STOML2 in HCC tissues, immunohistochemical staining

was performed on 72 paired HCC and adjacent non-tumor liver

tissues. Notably, STOML2 protein levels were significantly higher

in tumor tissues compared with those in control tissues (Fig. 1D and E). Additionally, the

results of RT-qPCR and western blotting of samples from eight

randomly selected patients with HCC further confirmed that the mRNA

and protein levels of STOML2 were significantly higher in tumor

tissues than in normal liver tissues (Fig. 1F and G). These findings indicated

that STOML2 is consistently upregulated in HCC tissues and that it

may serve a role in disease progression.

| Figure 1STOML2 expression is upregulated in

HCC tissues. (A) Overall survival analysis using The Cancer Genome

Atlas dataset showed that patients with HCC exhibiting high STOML2

expression had a significantly worse prognosis. P=0.017, log-rank

test. (B and C) STOML2 expression levels across various cancer

types determined using public datasets from the Gene Expression

Omnibus. (B) GSE40367 dataset comparing normal liver tissue,

non-metastatic HCC, HCC with lung metastasis and HCC with adrenal

metastasis (*P<0.05, **P<0.01,

****P<0.0001, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post

hoc test, n=6, 10, 12 and 6, respectively). Data are presented as

median with interquartile range. (C) GSE14520 dataset comparing HCC

tissues and normal liver tissues (****P<0.0001,

unpaired Student's t-test, n=65 and 50, respectively). Data are

presented as median with interquartile range. (D) STOML2 protein

expression in 72 paired HCC tissues (denoted as T) and adjacent

normal tissues (denoted as N) was evaluated using IHC with tissue

microarrays. (E) Semi-quantitative comparison of IHC staining (IHC

score) for tumor tissues vs. adjacent normal tissues (n=72 pairs).

Individual paired data points are shown as scatter plots, with

lines connecting each tumor tissue to its matched adjacent normal

tissue. The bars represent the median IHC score for each group,

with error bars indicating the interquartile range.

***P<0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test. STOML2

expression was assessed in eight randomly selected paired HCC and

normal tissues using (F) western blotting and (G) reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (n=8 pairs).

(F) Representative images from three independent experiments are

shown and (G) data were obtained from three independent

experiments. ****P<0.0001, paired Student's t-test.

Labels S1-S8 represent eight randomly selected paired HCC and

adjacent normal tissue samples from individual patients. HCC,

hepatocellular carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; STOML2,

stomatin-like protein 2. |

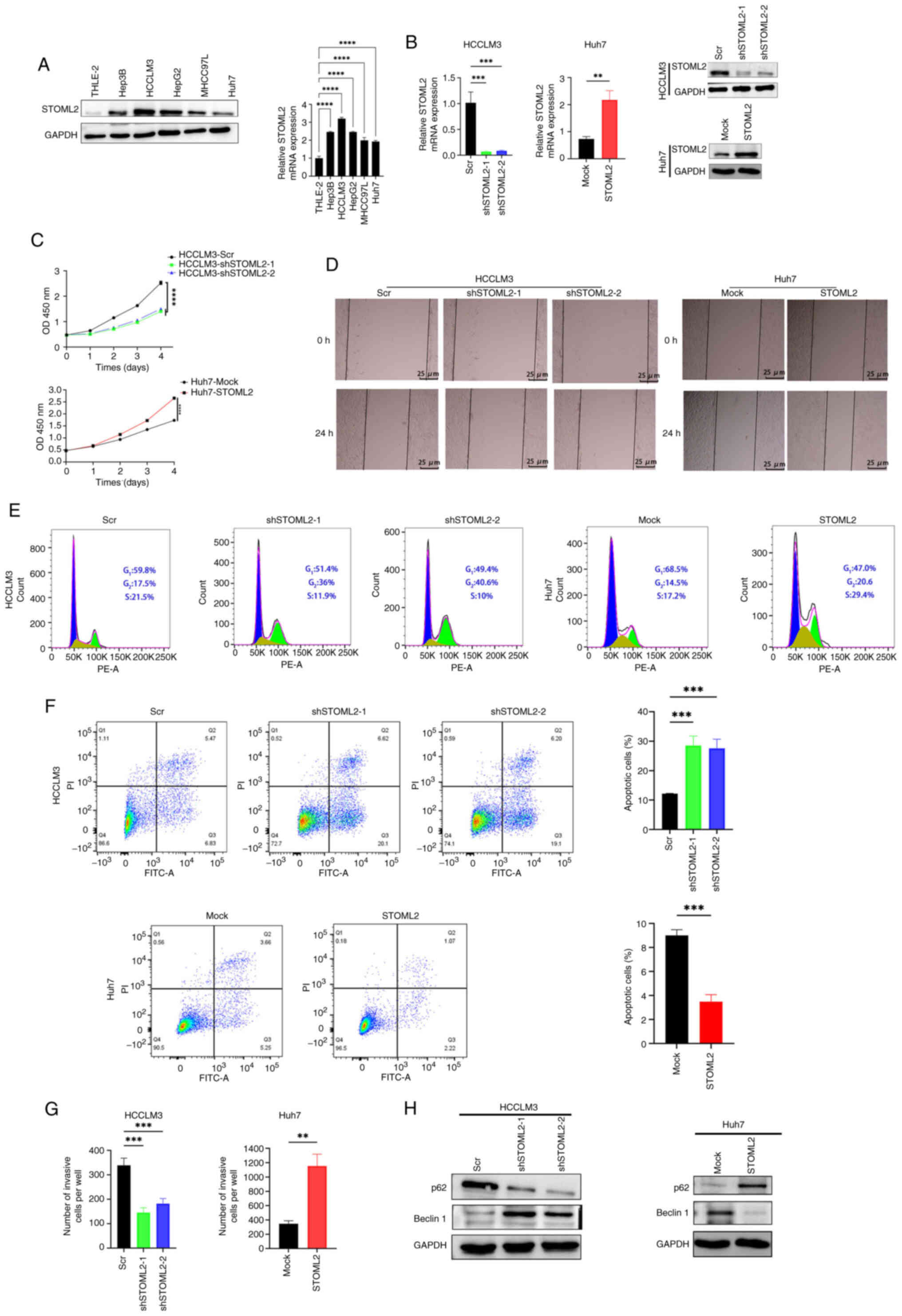

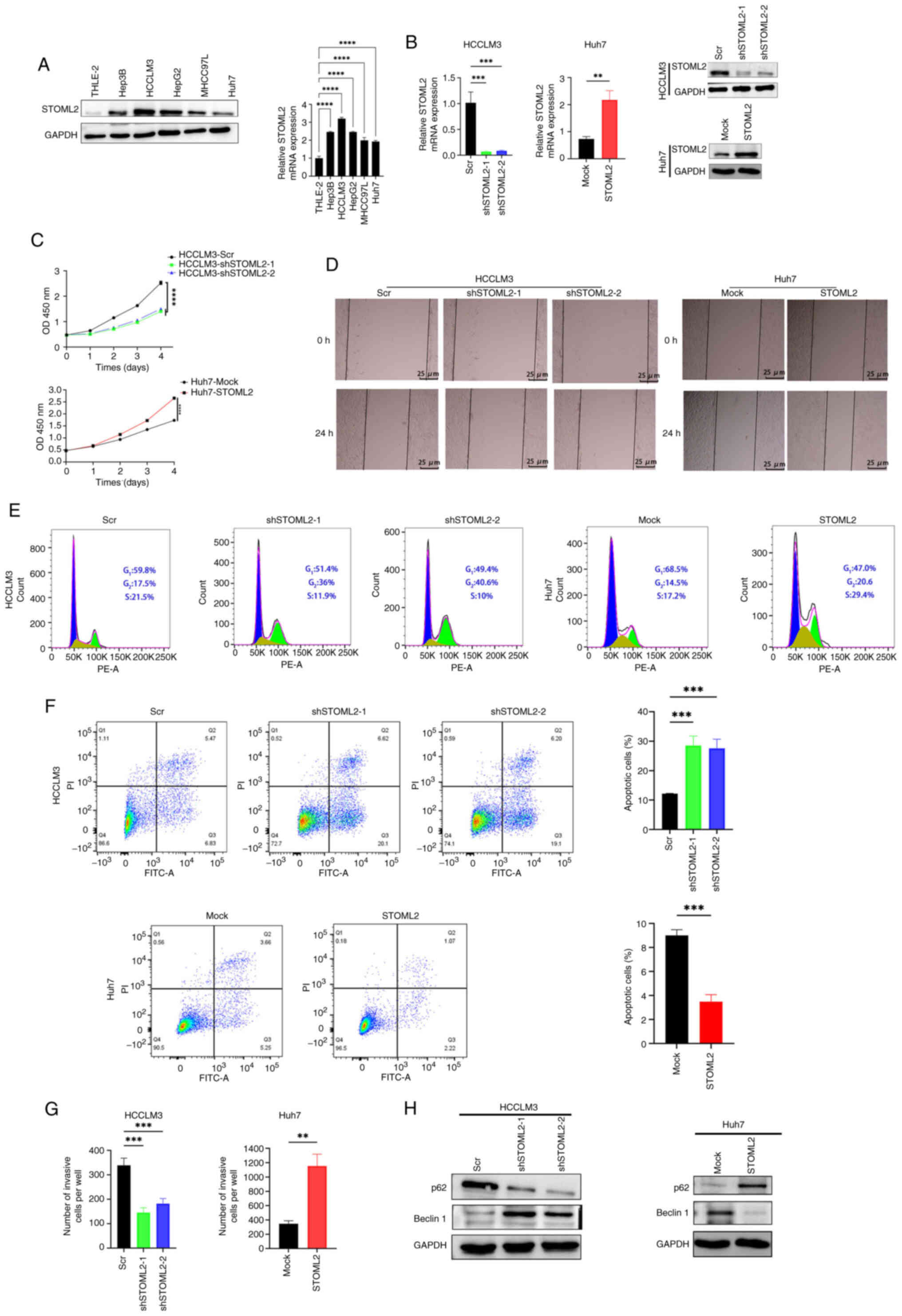

STOML2 promotes HCC cell proliferation,

migration and invasion, induces autophagy and inhibits

apoptosis

To investigate the role of STOML2 in HCC

progression, the current study first examined its expression in

liver cancer cell lines with varying metastatic potential, as well

as in non-tumorigenic human hepatocyte cells, using western

blotting and RT-qPCR (Fig. 2A).

The results revealed that STOML2 was highly expressed in HCC cell

lines compared with that in the non-tumorigenic human hepatocyte

cell line THLE-2. Based on previous reports (26,27), the highly metastatic HCCLM3 cell

line exhibits high endogenous STOML2 expression, making it suitable

for knockdown experiments; conversely, the low metastatic Huh7 cell

line displays relatively low STOML2 levels, rendering it

appropriate for overexpression studies. Accordingly, the Huh7 cell

line was infected with the STOML2-overexpression vector

(Huh7-STOML2), whereas the HCCLM3 cell line was infected with

shSTOML2 (HCCLM3-shSTOML2). Transduction efficiency was verified by

western blotting and RT-qPCR (Fig.

2B). The CCK-8 (Fig. 2C),

wound healing (Figs. 2D,

S2D and S2E) and Transwell

(Figs. 2G and S2A) assays showed that STOML2

overexpression promoted the proliferation, migration and invasion

of Huh7 cells, whereas STOML2 knockdown reduced these malignant

behaviors in HCCLM3 cells. The flow cytometric analysis revealed

that STOML2 knockdown markedly inhibited cell cycle progression and

decreased the proportion of S-phase HCCLM3 cells, whereas STOML2

overexpression had the opposite effect (Fig. 2E). In addition, flow cytometry

showed that STOML2 overexpression inhibited late apoptosis in Huh7

cells, whereas STOML2 knockdown induced apoptosis in HCCLM3 cells

(Fig. 2F). As available evidence

links autophagy to enhanced cancer cell proliferation and invasion

(28,29), the current study next examined

the effect of STOML2 on autophagy-associated proteins (Fig. 2H). The results indicated that

STOML2 overexpression promoted the proliferation and invasion of

HCC cells and the level of autophagy-related proteins. By contrast,

STOML2 knockdown suppressed the malignant phenotype and these

autophagy-related markers.

| Figure 2STOML2 promotes proliferation,

migration, invasion and autophagy, and inhibits apoptosis in HCC

cells. (A) STOML2 expression levels in five HCC cell lines and

normal hepatocytes were determined using western blotting and

RT-qPCR. Representative western blot images and quantitative

RT-qPCR data (mean ± SD) from three independent experiments are

shown (****P<0.0001, one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey's post-hoc tests). (B) Knockdown efficiency in HCCLM3 cells

and overexpression efficiency in Huh7 cells were evaluated using

western blotting and RT-qPCR. Representative western blot images

and quantitative RT-qPCR data (mean ± SD) from three independent

experiments are shown (***P<0.001,

**P<0.01, comparisons between two groups were

analyzed by unpaired Student's t-test, whereas comparisons among

three groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post-hoc test). (C) Cell Counting Kit-8 assay showing the

proliferation of STOML2-knockdown HCCLM3 cells,

STOML2-overexpressing Huh7 cells and their respective controls.

Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments

(****P<0.0001, comparisons between two groups were

analyzed by unpaired Student's t-test, whereas comparisons among

three groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's

post-hoc test). (D) Wound healing assay assessing the migratory

ability of STOML2-overexpressing or -knockdown HCC cells.

Representative images from three independent experiments are shown.

(E) Cell cycle distribution analysis of STOML2-knockdown HCCLM3

cells, STOML2-overexpressing Huh7 cells and their respective

controls. Representative images from three independent experiments

are shown. (F) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis rates of

STOML2-overexpressing or -knockdown HCC cells along with their

respective controls (***P<0.001, comparisons between

two groups were analyzed by unpaired Student's t-test, whereas

comparisons among three groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA

followed by Tukey's post-hoc test). Representative flow cytometry

plots and quantitative data (mean ± SD) from three independent

experiments are shown. (G) Transwell assay measuring the invasive

capacity of HCC cells following STOML2 overexpression or knockdown

(***P<0.001, **P<0.01, comparisons

between two groups were analyzed by unpaired Student's t-test,

whereas comparisons among three groups were analyzed by one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test). Data are presented as

mean ± SD. (H) Western blotting of autophagy markers p62 and

Beclin1 in STOML2-overexpressing or -knockdown HCC cells.

Representative western blot images from three independent

experiments are shown. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; RT-qPCR,

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; Scr,

scramble; sh, short hairpin; STOML2, stomatin-like protein 2. |

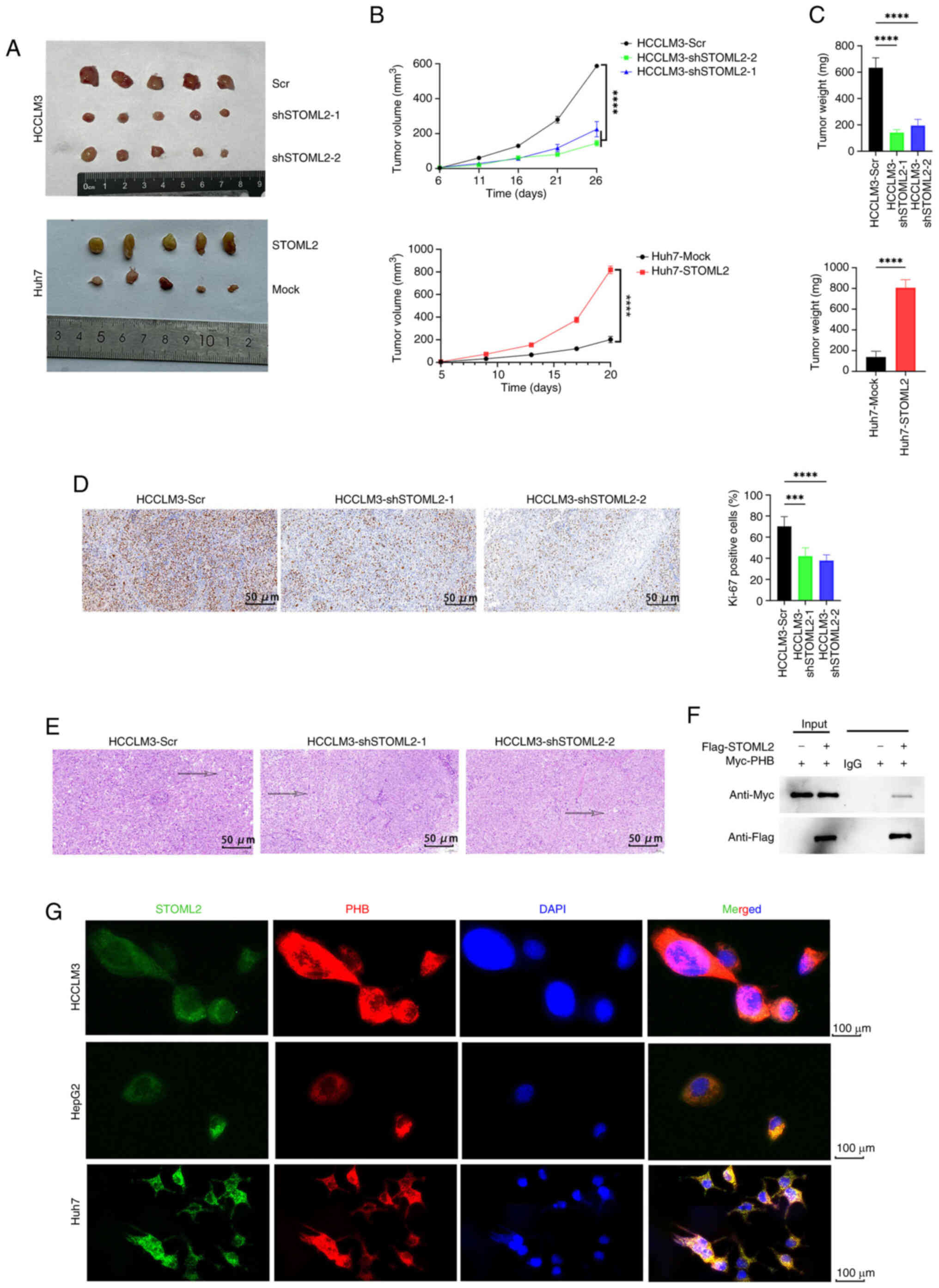

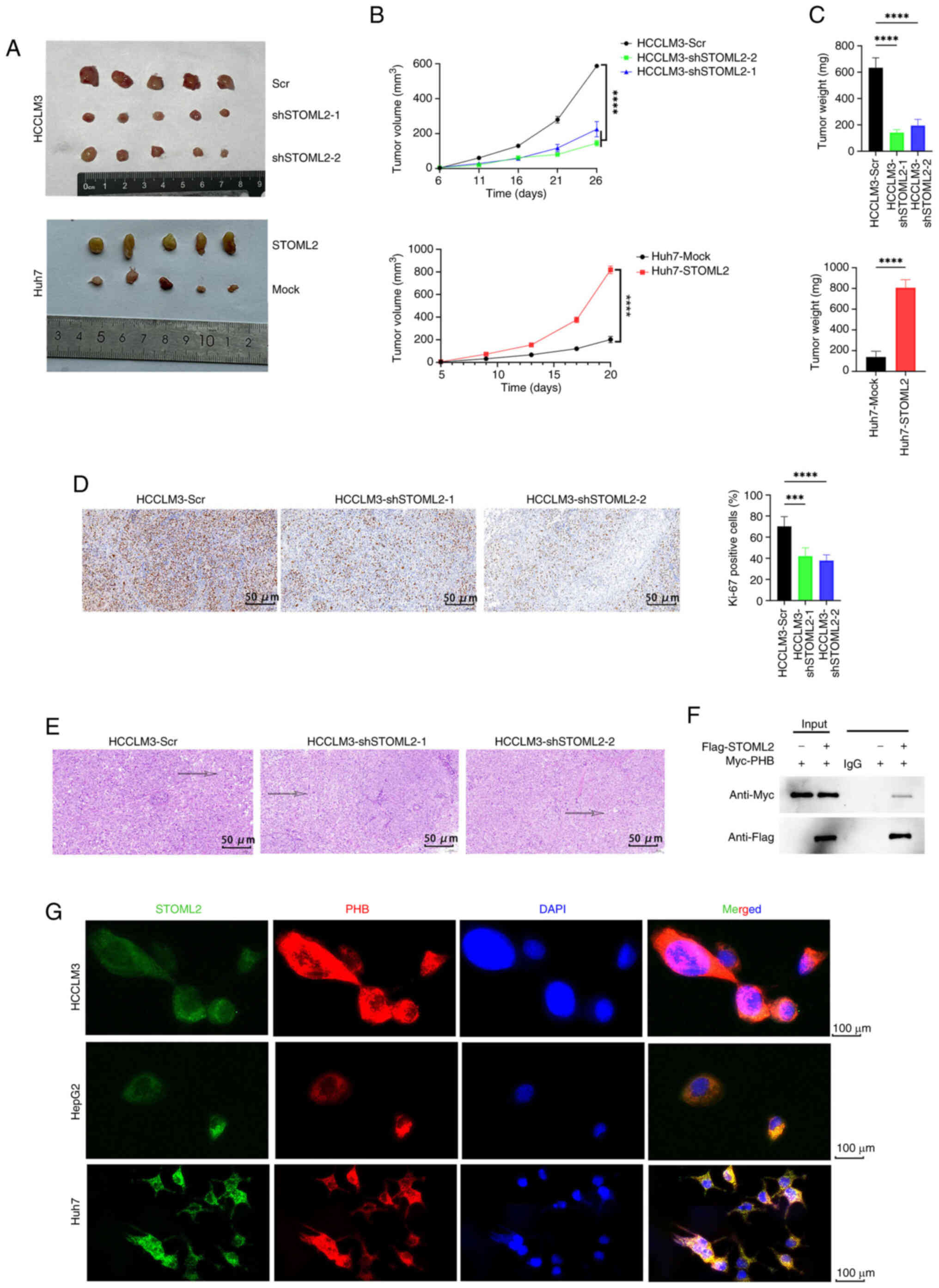

STOML2 promotes HCC growth and

progression in vivo

To investigate the oncogenic role of STOML2 in

vivo, a subcutaneous tumor model was established in BALB/c nude

mice. Tumor mass and growth curve analyses revealed that

overexpression of STOML2 in Huh7 cells significantly promoted tumor

growth (Fig. 3A-C). By contrast,

knockdown of STOML2 in HCCLM3 cells markedly inhibited tumor

growth. H&E staining showed notable changes in intercellular

spacing within tumor tissues, but no marked differences in cellular

morphology between the groups (Fig.

3E). The immunohistochemical analysis of Ki-67 showed that

STOML2 knockdown significantly inhibited HCC proliferation in

vivo, as indicated by lower Ki-67 expression (Fig. 3D). In summary, these in

vivo findings provide direct evidence that STOML2 functions as

a critical driver of HCC tumor growth.

| Figure 3STOML2 promotes hepatocellular

carcinoma growth and progression in vivo. (A-E) Subcutaneous

implantation of STOML2-overexpressing Huh7 cells and

STOML2-knockdown HCCLM3 cells along with their control cells in

BALB/c nude mice. (A) Each mouse received 3×106 cells as

a subcutaneous injection at the dorsal region of their neck. Tumors

were harvested 25 days post-injection. (B) Tumor growth curves

obtained at the indicated time points (****P<0.0001,

comparisons between two groups were analyzed by unpaired Student's

t-test, whereas comparisons among three or more groups were

analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test). Data

are presented as mean ± SD. (C) Final tumor mass measured upon

removal (****P<0.0001, unpaired Student's t-test or

one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons).

Data are presented as mean ± SD. (D) Representative

immunohistochemistry images showing a positive association between

STOML2 and Ki-67 expression in tumor tissues. Quantitative data are

presented as mean ± SD from multiple fields of view

(****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons).

(E) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of tumor

sections. Images are representative of tumors from each group. (F)

Co-immunoprecipitation assay demonstrating interaction between

STOML2 and PHB in vitro. Representative western blot images

from three independent experiments are shown. (G)

Immunofluorescence staining showing colocalization of STOML2

(green), PHB (red) and DAPI (blue) in HCCLM3, HepG2 and Huh7 cells.

Representative images from three independent experiments are shown.

PHB, prohibitin; Scr, scramble; sh, short hairpin; STOML2,

stomatin-like protein 2. |

STOML2 interacts with PHB and activates

the RAF/MEK/ERK MAPK pathway

To elucidate the regulatory mechanism of STOML2 in

HCC, the STRING database was used to predict potential

STOML2-interacting proteins (Fig.

S1B). PHB, a known chaperone of STOML2 (30), showed the highest binding score

of 0.945 (Table SI). To further

validate this interaction, co-IP was performed, which confirmed

that STOML2 binds to PHB in vitro (Fig. 3F). IF staining of HCCLM3, HepG2

and Huh7 cells further revealed cytoplasmic co-localization of

STOML2 and PHB (Fig. 3G). As PHB

is known to serve an important role in the RAS-activated

RAF/MEK/ERK signaling cascade, the current study assessed the

phosphorylation status of key proteins in the MAPK pathway, p-RAF1,

p-MEK1/2 and p-ERK1/2. The levels of these phosphorylated proteins

were significantly elevated in STOML2-overexpressing Huh7 cells

compared with in the control cells, and were significantly reduced

in STOML2-knockdown HCCLM3 cells compared with in the knockdown

control cells (Fig. 4A),

indicating an opposing regulatory effect. Collectively, these

results suggested that STOML2 interacts with PHB to activate the

RAF/MEK/ERK MAPK signaling pathway, thereby promoting HCC

progression.

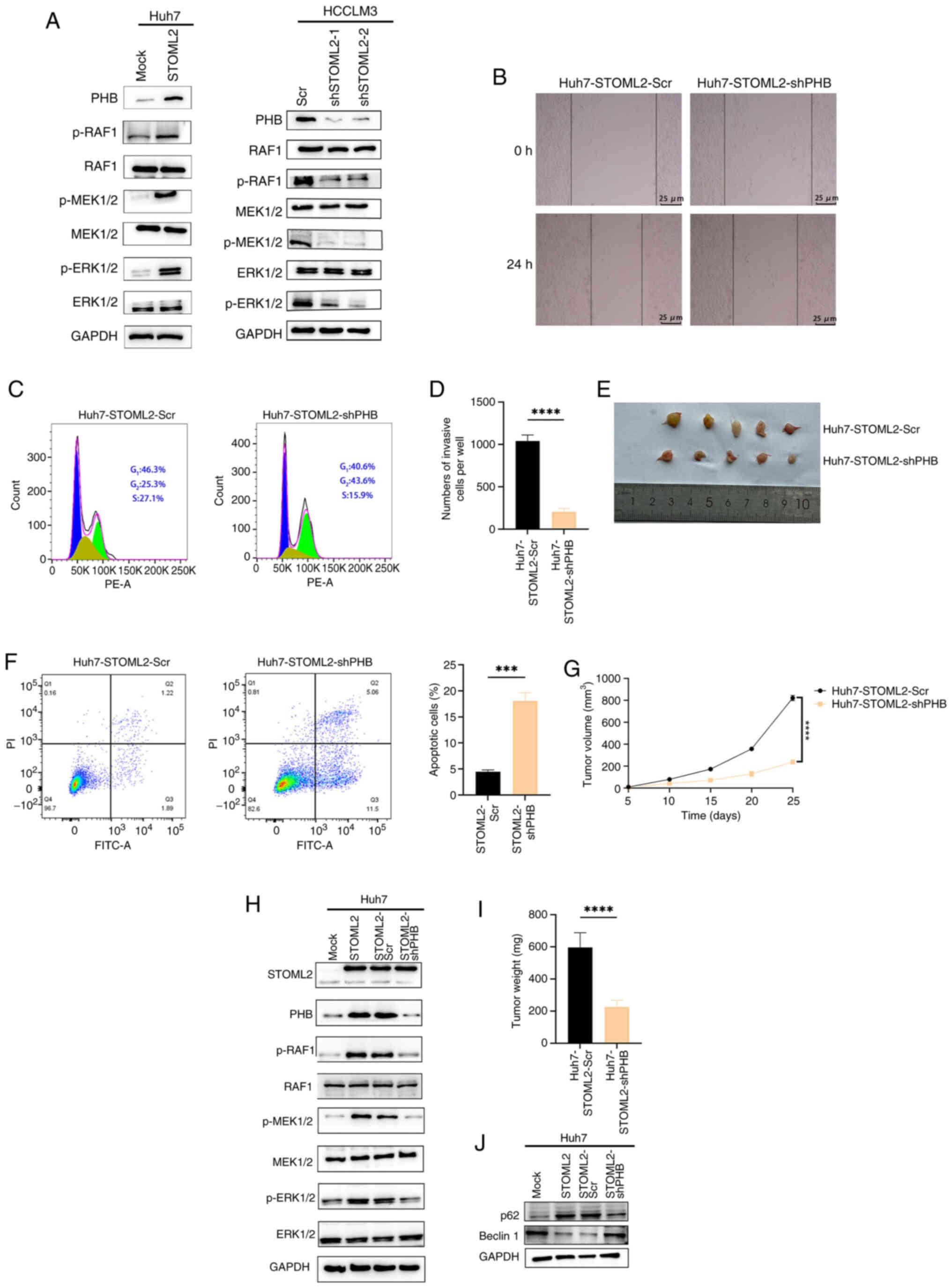

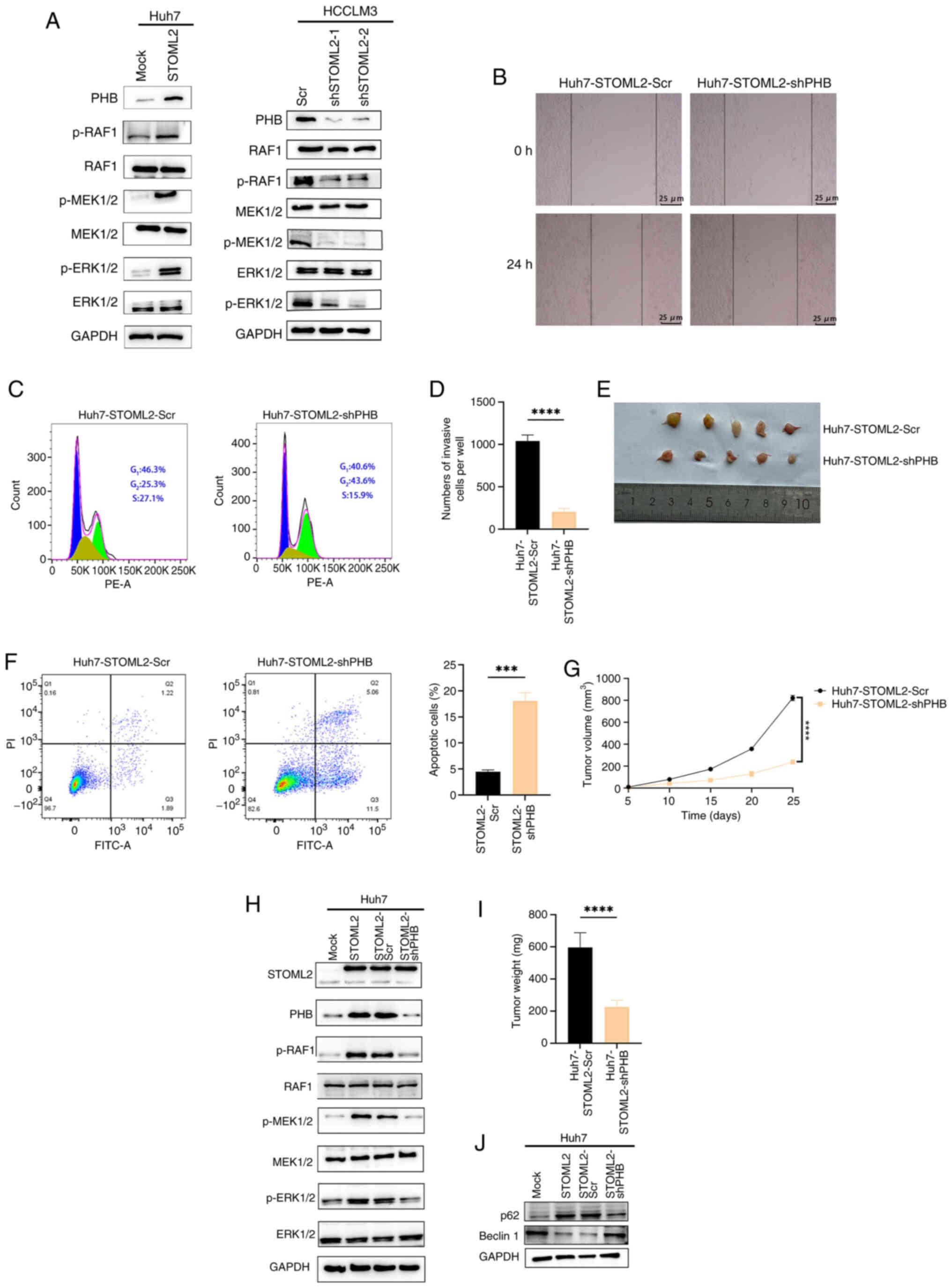

| Figure 4PHB knockdown inhibits STOML2-induced

proliferation and invasion while promoting pro-apoptotic autophagy

in HCC cells. (A) Western blot analysis of STOML2, PHB and key

proteins of the MAPK signaling pathway in Huh7-STOML2,

HCCLM3-shSTOML2 and their respective control cells. Representative

western blot images from three independent experiments are shown.

(B) Wound healing assay (scale bar, 25 μm), (C) cell cycle

analysis and (D) Transwell assay (****P<0.0001,

unpaired Student's t-test) demonstrating that PHB knockdown

attenuated the cell cycle progression, migration and invasion of

STOML2-overexpressing Huh7 cells. Representative images and

quantitative analysis (mean ± SD) from three independent

experiments are shown. (E) Huh7-STOML2-Scr control and

Huh7-STOML2-shPHB cells were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c

nude mice. Each mouse was injected with 3×106 cells in

the dorsal region of their neck. (F) Flow cytometric analysis

showing that PHB knockdown promoted apoptosis in

STOML2-overexpressing Huh7 cells. Representative flow cytometry

plots and quantitative data (mean ± SD) from three independent

experiments are shown. (unpaired Student's t-test,

***P<0.001). (G) Tumor growth curves obtained at the

indicated time points. Data are presented as mean ± SD

(****P<0.0001, unpaired Student's t-test). (H)

Western blotting of STOML2, PHB and MAPK signaling pathway proteins

in Huh7-STOML2 cells with or without PHB knockdown. Representative

western blot images from three independent experiments are shown.

(I) Tumor mass measured at removal. ****P<0.0001,

unpaired Student's t-test. Data are presented as mean ± SD. (J)

Western blotting of p62 and Beclin1 in Huh7-STOML2 cells with or

without PHB knockdown. Representative western blot images from

three independent experiments are shown. p-, phosphorylated; PHB,

prohibitin; Scr, scramble; sh, short hairpin; STOML2, stomatin-like

protein 2. |

PHB knockdown inhibits STOML2-induced

migration, tumor growth, and autophagy and promotes apoptosis in

HCC cells

To further investigate the role of PHB in

STOML2-driven HCC progression, the current study first confirmed

the knockdown efficiency of shPHB in parental Huh7 cells, which

significantly reduced both PHB mRNA and protein levels compared

with Scr (Fig. S1A).

Subsequently, shPHB was introduced into Huh7 cells overexpressing

STOML2. STOML2 overexpression upregulated PHB expression, and

enhanced RAF, MEK and ERK phosphorylation; by contrast, PHB

knockdown markedly reduced the phosphorylation of these MAPK

pathway proteins (Fig. 4H). To

evaluate the functional effect of PHB knockdown on Huh7-STOML2

cells, wound healing (Figs. 4B

and S2F) and Transwell assays

(Figs. 4D and S2B), and a cell cycle analysis

(Fig. 4C) were performed. These

assays demonstrated that PHB knockdown markedly attenuated

STOML2-induced cell migratory and invasive capacity. Furthermore,

flow cytometric analysis showed that the level of apoptosis was

significantly increased in the PHB-knockdown group compared with

that in the Scr group (Fig. 4F).

In vivo, the subcutaneous implantation of Huh7-STOML2-shPHB

cells into nude mice resulted in significantly slower tumor growth

and smaller tumor volume than implantation of control cells

(Fig. 4E, G and I). Western

blotting further confirmed that PHB knockdown reduced

autophagy-related protein levels in these cells compared with those

in control cells (Fig. 4J).

These in vitro and in vivo study findings indicated

that PHB gene knockdown may significantly attenuate STOML2-induced

migration and autophagy in HCC cells.

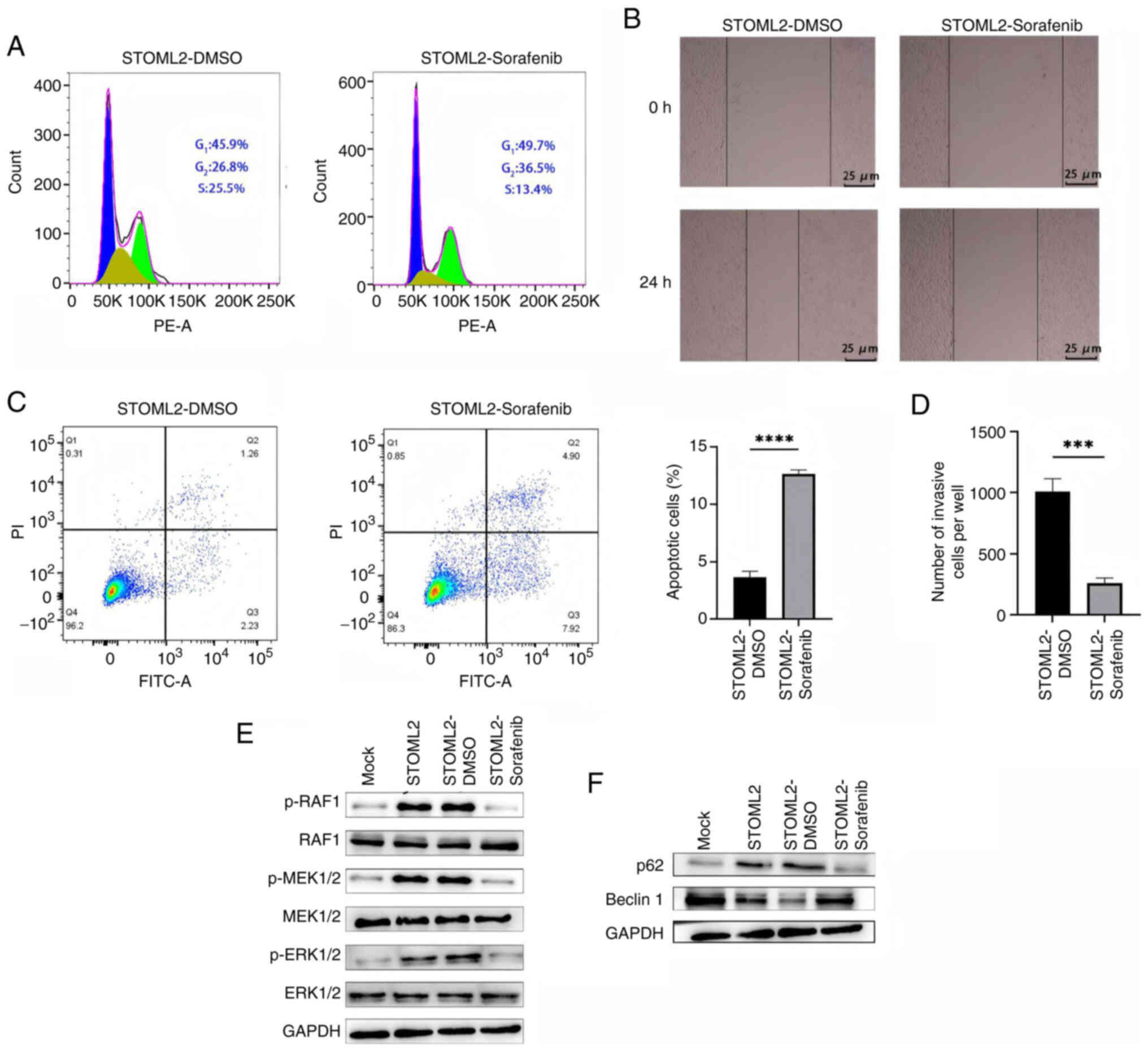

Sorafenib attenuates STOML2-induced

migration and autophagy while promoting apoptosis in HCC cells

To elucidate the mechanism by which STOML2 regulates

the progression of HCC via the RAF/MEK/ERK MAPK signaling pathway,

STOML2-overexpressing Huh7 cells were treated with the RAF1

inhibitor sorafenib. Sorafenib markedly inhibited the

STOML2-induced phosphorylation of RAF, MEK and ERK, confirming

inhibition of MAPK pathway activation (Fig. 5E). Sorafenib treatment also

markedly attenuated the cell cycle progression, migration and

invasion of Huh7 cells induced by STOML2 overexpression, as

determined using cell cycle analyses (Fig. 5A), and wound healing (Figs. 5B and S2G) and Transwell (Figs. 5D and S2C) assays. Notably, although

sorafenib further increased the levels of autophagy-related

proteins (Fig. 5F), the flow

cytometric analysis results showed a significant elevation in the

level of apoptosis (Fig. 5C),

suggesting that sorafenib may convert STOML2-driven 'protective

autophagy' into pro-apoptotic signaling by blocking MAPK pathway

activation. This observation is consistent with the results

obtained for PHB-knockdown cells and reinforces the central role of

the STOML2-PHB-MAPK axis in driving the malignant phenotype of HCC.

Overall, these findings suggested that sorafenib may reverse the

migration, invasion and autophagy-dependent survival advantage in

HCC cells conferred by STOML2, while simultaneously inducing

apoptosis by targeting and blocking STOML2-mediated activation of

the MAPK pathway. These results provide mechanistic evidence

supporting the use of sorafenib in patients with HCC and high

STOML2 expression.

Discussion

The stomatin family of proteins is characterized by

a conserved stomatin domain (30), which enables these proteins to

carry out diverse cellular functions in various cell types,

including membrane scaffolding and regulation of ion channel

activity (31). As a member of

this family, STOML2 (also known as SLP-2) is an inner mitochondrial

membrane protein that has been implicated in protecting

mitochondria from stress-induced hyperfusion (32). Increasing evidence has suggested

that STOML2 expression is upregulated across multiple cancer types

and is associated with poor prognosis (33,34). However, the mechanism of action

of STOML2 in HCC cells remains unclear. The present study

demonstrated that STOML2 was significantly upregulated in both HCC

tissues and cell lines. Functional assays using STOML2

overexpression and knockdown models revealed STOML2 promoted HCC

cell proliferation and invasion, underscoring its potential role as

a pro-tumorigenic factor in HCC.

The stomatin proteins have been implicated in the

regulation of transcription, energy metabolism, apoptosis and

mitochondrial autophagy in tumor cells. Zheng et al

(27) reported that STOML2 can

promote HCC metastasis and drug resistance by directly binding to

PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), stabilizing its half-life, and

activating the PINK1-Parkin-dependent mitochondrial autophagy

pathway. Under hypoxic conditions or following treatment with the

antiangiogenic drug lenvatinib, HIF-1α-mediated upregulation of

STOML2 triggers protective mitochondrial autophagy, thereby

reducing drug efficacy. By contrast, inhibiting STOML2 activity or

mitochondrial autophagy has been shown to significantly enhance the

antitumor effects of lenvatinib (35). Notably, autophagy serves a

crucial role in cancer progression (36). In pancreatic cancer, Qin et

al (35) demonstrated that

STOML2 may inhibit mitochondrial autophagy and enhance

chemosensitivity by stabilizing presenilin-associated rhomboid-like

proteins and accelerating PINK1 degradation. Although the mechanism

contrasts with that of the STOML2-PINK1 axis in HCC, both studies

underscore the central role of STOML2 in mitochondrial quality

control. These tissue-specific differences may be influenced by

variations in tumor microenvironment or genetic background,

suggesting that the regulatory network of STOML2 should be

investigated further. In the current study, STOML2 overexpression

was revealed to inhibit apoptosis and induce the expression of

autophagy-associated proteins in HCC cells. Emerging evidence has

suggested that autophagy serves as a critical regulator of cell

survival and death (37). This

contrasts with the findings of Guo et al (38) in glioma, where the

FoxM1-ubiquitin conjugating enzyme 2C axis was reported to promote

tumor survival by suppressing autophagic cell death. These findings

suggest that autophagy serves a dual role in cancer, with its net

effect dependent on upstream regulatory pathways and stress

conditions. Consequently, therapeutic targeting of STOML2 should be

combined with the specific signaling landscape of the tumor to

optimize its efficacy.

PHBs, mitochondrial proteins belonging to the same

SPFH protein family as STOML2, participate in diverse cellular

processes including proliferation, senescence, energy metabolism

and assembly of the mitochondrial respiratory complexes (39). Notably, the protein levels of

PHB-1 and PHB-2 have been shown to be markedly reduced in

STOML2-depleted cells, suggesting that STOML2 may regulate PHB

stability through direct or indirect interactions (40). Christie et al (41) demonstrated that STOML2 binds

directly to PHB and that PHB-driven mitophagy partly explains how

STOML2 regulates cell proliferation. In colorectal cancer, Ma et

al (3) reported that STOML2

can promote tumor cell proliferation by activating the RAF/MEK/ERK

pathway via binding to PHB, an effect reversed by PHB knockdown or

RAF1 inhibition. The RAS proteins regulate key signaling pathways

involved in both normal cellular growth and malignant

transformation, mediating a broad spectrum of biological function

(43,44). It has been well-documented that

PHBs, which are ubiquitously expressed and evolutionarily

conserved, are essential for RAS-mediated activation of the

RAF/MEK/ERK pathway (44). In

addition, PHBs are necessary for the membrane localization and

activation of RAS to C-RAF in vivo (45). Consistent with these findings,

the current study verified that STOML2 may directly interact with

PHB in HCC using IF staining and co-IP assays in three HCC cell

lines. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that PHB knockdown in

STOML2-overexpressing HCC cells restored the effects of STOML2,

promoting apoptosis, and suppressing both proliferation and the

expression of autophagy-associated proteins. Together with previous

evidence, the present study supports the hypothesis that STOML2

promotes cancer cell proliferation through the STOML2-PHB-MAPK

signaling axis, which warrants further evaluation. Increasing

evidence (46,47) has highlighted that the oncogenic

role of STOML2 is characterized by synergistic activation of

multiple pathways, establishing it as a critical tumor-promoting

gene in HCC.

Sorafenib, a small-molecule multi-target kinase

inhibitor, serves diverse roles in cancer therapy. It inhibits the

MAPK pathway to suppress cell proliferation, blocks receptor

tyrosine kinases such as platelet-derived growth factor receptor

and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor to reduce tumor

angiogenesis, and promotes apoptosis (48). Sorafenib is currently approved by

the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of

renal cell carcinoma, advanced HCC and differentiated thyroid

cancer (49). In the present

study, sorafenib attenuated STOML2-induced migration and cell cycle

progression in HCC, and enhanced apoptosis while inhibiting MAPK

signaling. However, the inhibitory effects of sorafenib are broad

and not specific to the MAPK pathway; therefore, its use in HCC

treatment needs to be further evaluated. Despite the success of

targeted therapies for cancer, the widespread emergence of drug

resistance remains a major clinical challenge (50).

Notably, previous studies (51,52) on mitochondria-related genes

further support the pivotal role of STOML2 in HCC. For example, the

downregulation of ferredoxin 1 (FDX1), a mitochondrial iron-sulfur

cluster synthase, has been shown to activate mitochondrial

autophagy and promote HCC progression via reactive oxygen species

accumulation (53). Similar to

that of STOML2, dysregulation of FDX1 leads to metabolic

reprogramming and enhances tumor cell adaptability. This suggests

that mitochondrial homeostatic regulatory genes such as STOML2 and

FDX1 may form a synergistic network contributing to HCC

development. Future studies should investigate potential

interactions between STOML2 and genes such as FDX1 to elucidate

more complex mitochondrial regulatory mechanisms in liver

cancer.

In summary, the present study systematically

elucidated the mechanism by which STOML2 regulates autophagy to

promote HCC progression via the PHB-MAPK axis. Combined with the

existing literature, the current findings further highlight the

multifaceted role of STOML2 as a mitochondrial hub protein. Future

studies are recommended to expand upon this work in several

important directions. First, it is necessary to investigate whether

STOML2 synergizes with other mitochondrial proteins, such as FDX1,

in driving HCC metabolic reprogramming, particularly at the

intersection between mitochondrial energy metabolism and oxidative

stress. Second, the mechanisms regulating STOML2 expression remain

unclear. Potential regulatory factors such as the microRNA-200

family or epigenetic modifications (such as DNA methylation)

warrant exploration and may offer new strategies for targeted

intervention. Third, combination therapies targeting the

STOML2-PHB-MAPK axis, such as co-administering sorafenib with

autophagy inhibitors, could exhibit enhanced efficacy by

synergistically blocking pro-oncogenic signaling; these should be

evaluated in preclinical models. Finally, for STOML2 to transition

from a molecular target to a clinically applicable biomarker,

systematic validation of its utility in patient stratification,

prognosis prediction and therapeutic response monitoring is needed.

Advancing these areas of research will provide a more comprehensive

understanding of the pathological importance of STOML2 and may

offer innovative strategies to improve the prognosis of patients

with HCC.

The present study demonstrated that STOML2 was

significantly upregulated in HCC, and indicated that it may promote

cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth by interacting with PHB

and activating the MAPK signaling pathway to mediate autophagy.

These findings suggest that STOML2 may serve as a novel biomarker

and potential therapeutic target in HCC.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HH and HZ were involved in the conception and design

of the study. HH and SH performed the experiments and collected the

data. HH, YX and JC were responsible for data analysis,

interpretation and validation, and confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. HH wrote the original draft. HZ, SH, YX and JC

reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study involving human participants was approved

by the Ethics Committee of the North China University of Science

and Technology Affiliated Hospital (approval no. 20250403024). All

procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards

of the responsible committees on human experimentation at our

institution and with the national bioethical regulations of the

People's Republic of China. Furthermore, the study was performed in

compliance with the tenets of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All

patients provided written informed consent. The animal experiments

performed in the present study were approved by the Animal Ethics

Committee of North China University of Science and Technology,

(approval no. 2025SY3011).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

co-IP

|

co-immunoprecipitation

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

IF

|

immunofluorescence

|

|

PHB

|

prohibitin

|

|

STOML2

|

stomatin-like protein 2

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Health Commission of

Hebei Province (grant no. 3101030211003).

References

|

1

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

De Toni EN, Schlesinger-Raab A, Fuchs M,

Schepp W, Ehmer U, Geisler F, Ricke J, Paprottka P, Friess H,

Werner J, et al: Age independent survival benefit for patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) without metastases at diagnosis: A

population-based study. Gut. 69:168–176. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ma W, Chen Y, Xiong W, Li W, Xu Z, Wang Y,

Wei Z, Mou T, Wu Z, Cheng M, et al: STOML2 interacts with PHB

through activating MAPK signaling pathway to promote colorectal

cancer proliferation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:3592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Keum N and Giovannucci E: Global burden of

colorectal cancer: Emerging trends, risk factors and prevention

strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:713–732. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pinter M, Scheiner B and Pinato DJ: Immune

checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma: Emerging

challenges in clinical practice. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

8:760–770. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Owczarek CM, Treutlein HR, Portbury KJ,

Gulluyan LM, Kola I and Hertzog PJ: A novel member of the

STOMATIN/EPB72/mec-2 family, stomatin-like 2 (STOML2), is

ubiquitously expressed and localizes to HSA chromosome 9p13.1.

Cytogenet Cell Genet. 92:196–203. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang Y and Morrow JS: Identification and

characterization of human SLP-2, a novel homologue of stomatin

(band 7.2b) present in erythrocytes and other tissues. J Biol Chem.

275:8062–8071. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mitsopoulos P, Chang Y, Wai T, König T,

Dunn SD, Langer T and Madrenas J: Stomatin-like protein 2 is

required for in vivo mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplex

formation and optimal cell function. Mol Cell Biol. 35:1838–1847.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mitsopoulos P, Lapohos O, Weraarpachai W,

Antonicka H, Chang Y and Madrenas J: Stomatin-like protein 2

deficiency results in impaired mitochondrial translation. PLoS One.

12:e01799672017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Guo X and Guo H and Guo H: Clinical

significance of SLP-2 in epithelial ovarian cancer and its

regulatory effect on the Notch signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med

Pharmacol Sci. 24:1666–1671. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang WX, Lin QF, Shen D, Liu SP, Mao WD,

Ma G and Qi WD: Clinicopathological significance of SLP-2

overexpression in human gallbladder cancer. Tumour Biol.

35:419–423. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhang J, Song X, Li C and Tian Y:

Expression and clinical significance of SLP-2 in ovarian tumors.

Oncol Lett. 17:4626–4632. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu D, Zhang L, Shen Z, Tan F, Hu Y, Yu J

and Li G: Increased levels of SLP-2 correlate with poor prognosis

in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 16:498–504. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Attia AS, Hussein S, Sameh H, Khalil A,

Waley AB, Matar I and Sameh R: Diagnostic and prognostic utility of

TROP-2, SLP-2, and CXCL12 expression in papillary thyroid

carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 39:211–221. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

Zhou C, Li Y, Wang G, Niu W, Zhang J, Wang

G, Zhao Q and Fan L: Enhanced SLP-2 promotes invasion and

metastasis by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signal pathway in colorectal

cancer and predicts poor prognosis. Pathol Res Pract. 215:57–67.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Yin R, Tao Y, Han J, Zhang J, Yu K, Zheng

Y, Li X and Huang C: STOML2 inhibits sorafenib-induced ferroptosis

in hepatocellular carcinoma via p-AKT signaling pathway. Am J

Cancer Res. 15:1614–1628. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Qu H, Jiang W, Wang Y and Chen P: STOML2

as a novel prognostic biomarker modulates cell proliferation,

motility and chemo-sensitivity via IL6-Stat3 pathway in head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 11:683–695.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shao YY, Shau WY, Chan SY, Lu LC, Hsu CH

and Cheng AL: Treatment efficacy differences of sorafenib for

advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis of randomized

clinical trials. Oncology. 88:345–352. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kitano K, Murayama T, Sakamoto M, Nagayama

K, Ueno K, Murakawa T and Nakajima J: Outcome and survival analysis

of pulmonary metastasectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J

Cardiothorac Surg. 41:376–382. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-delta delta c(t)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Shi Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, Niu K, Mao X, Feng

K and Zhang Y: N6-methyladenosine with immune infiltration and

PD-L1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Novel perspective to

personalized diagnosis and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14:11538022023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Roessler S, Lin G, Forgues M, Budhu A,

Hoover S, Simpson RM, Wu X, He P, Qin L, Tang Z, et al: Integrative

genomic and transcriptomic characterization of matched primary and

metastatic liver and colorectal carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci.

11:88–98. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Ji F, Zhang J, Mao L, Tan Y, Ye M, He X,

Zhao Y, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhang N, et al: Liver-specific gene PGRMC1

blocks c-Myc-induced hepatocarcinogenesis through ER

stress-independent PERK activation. Nat Commun. 16:502025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: Limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Cao T, Li Q, Huang Y and Li A:

plotnineSeqSuite: A Python package for visualizing sequence data

using ggplot2 style. BMC Genomics. 24:5852023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li X, Zheng Y, Yu K, Hou S, Cui H, Yin R,

Zhou Y, Sun Q, Zhang J and Huang C: Stomatin-like protein 2

promotes cell proliferation and survival under 5-fluorouracil

stress in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Biol Rep. 51:2282024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zheng Y, Huang C, Lu L, Yu K, Zhao J, Chen

M, Liu L, Sun Q, Lin Z, Zheng J, et al: STOML2 potentiates

metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by promoting PINK1-mediated

mitophagy and regulates sensitivity to lenvatinib. J Hematol Oncol.

14:162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu P, Li L, Wang W, He C and Xu C: MST4

promotes proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of gastric cancer

by enhancing autophagy. Heliyon. 9:e167352023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

He R, Liu Y, Fu W, He X, Liu S, Xiao D and

Tao Y: Mechanisms and cross-talk of regulated cell death and their

epigenetic modifications in tumor progression. Mol Cancer.

23:2672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Genin EC, Bannwarth S, Ropert B,

Lespinasse F, Mauri-Crouzet A, Augé G, Fragaki K, Cochaud C,

Donnarumma E, Lacas-Gervais S, et al: CHCHD10 and SLP2 control the

stability of the PHB complex: A key factor for motor neuron

viability. Brain. 145:3415–3430. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lapatsina L, Brand J, Poole K, Daumke O

and Lewin GR: Stomatin-domain proteins. Eur J Cell Biol.

91:240–245. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Tondera D, Grandemange S, Jourdain A,

Karbowski M, Mattenberger Y, Herzig S, Da Cruz S, Clerc P, Raschke

I, Merkwirth C, et al: SLP-2 is required for stress-induced

mitochondrial hyperfusion. EMBO J. 28:1589–1600. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Cui Z, Zhang L, Hua Z, Cao W, Feng W and

Liu Z: Stomatin-like protein 2 is overexpressed and related to cell

growth in human endometrial adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 17:829–833.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang Y, Cao W, Yu Z and Liu Z:

Downregulation of a mitochondria associated protein SLP-2 inhibits

tumor cell motility, proliferation and enhances cell sensitivity to

chemotherapeutic reagents. Cancer Biol Ther. 8:1651–1658. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Qin C, Wang Y, Zhao B, Li Z, Li T, Yang X,

Zhao Y and Wang W: STOML2 restricts mitophagy and increases

chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer through stabilizing

PARL-induced PINK1 degradation. Cell Death Dis. 14:1912023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Niu X, You Q, Hou K, Tian Y, Wei P, Zhu Y,

Gao B, Ashrafizadeh M, Aref AR, Kalbasi A, et al: Autophagy in

cancer development, immune evasion, and drug resistance. Drug

Resist Updat. 78:1011702025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Klionsky DJ, Petroni G, Amaravadi RK,

Baehrecke EH, Ballabio A, Boya P, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Cadwell K,

Cecconi F, Choi AMK, et al: Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO

J. 40:e1088632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Guo L, Ding Z, Huang N, Huang Z, Zhang N

and Xia Z: Forkhead Box M1 positively regulates UBE2C and protects

glioma cells from autophagic death. Cell Cycle. 16:1705–1718. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mcclung JK, Jupe ER, Liu XT and Dell'Orco

RT: Prohibitin: Potential role in senescence, development, and

tumor suppression. Exp Gerontol. 30:99–124. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Da Cruz S, Parone PA, Gonzalo P, Bienvenut

WV, Tondera D, Jourdain A, Quadroni M and Martinou JC: SLP-2

interacts with prohibitins in the mitochondrial inner membrane and

contributes to their stability. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1783:904–911.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Christie DA, Lemke CD, Elias IM, Chau LA,

Kirchhof MG, Li B, Ball EH, Dunn SD, Hatch GM and Madrenas J:

Stomatin-like protein 2 binds cardiolipin and regulates

mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Mol Cell Biol. 31:3845–3856.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Downward J: Targeting RAS signalling

pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:11–22. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Wellbrock C, Karasarides M and Marais R:

The RAF proteins take centre stage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

5:875–885. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Xu L, Meng L, Xiang W, Wang X, Yang J, Shu

C, Zhao XH, Rong Z and Ye Y: Prohibitin 2 confers NADPH oxidase

1-mediated cytosolic oxidative signaling to promote gastric cancer

progression by ERK activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 224:130–143.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Sharma A and Qadri A: Vi polysaccharide of

salmonella typhi targets the prohibitin family of molecules in

intestinal epithelial cells and suppresses early inflammatory

responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:17492–17497. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ma W, Xu Z, Wang Y, Li W, Wei Z, Chen T,

Mou T, Cheng M, Luo J, Luo T, et al: A positive feedback loop of

SLP2 activates MAPK signaling pathway to promote gastric cancer

progression. Theranostics. 8:5744–5757. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wai T, Saita S, Nolte H, Müller S, König

T, Richter-Dennerlein R, Sprenger HG, Madrenas J, Mühlmeister M,

Brandt U, et al: The membrane scaffold SLP2 anchors a proteolytic

hub in mitochondria containing PARL and the i-AAA protease YME1L.

EMBO Rep. 17:1844–1856. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lierman E, Lahortiga I, Van Miegroet H,

Mentens N, Marynen P and Cools J: The ability of sorafenib to

inhibit oncogenic PDGFRbeta and FLT3 mutants and overcome

resistance to other small molecule inhibitors. Haematologica.

92:27–34. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Abdelgalil AA, Alkahtani HM and Al-Jenoobi

FI: Sorafenib. Profiles Drug Subst Excip Relat Methodol.

44:239–266. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Fischer PM: Approved and experimental

small-molecule oncology kinase inhibitor drugs: A mid-2016

overview. Med Res Rev. 37:314–367. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Tsvetkov P, Detappe A, Cai K, Keys HR,

Brune Z, Ying W, Thiru P, Reidy M, Kugener G, Rossen J, et al:

Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress.

Nat Chem Biol. 15:681–689. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Lin X, Zheng J, Li Y, Liu L, Liu Q, Lin J

and Sun Y: Mitochondria-related genes as prognostic signature of

endometrial cancer and the effect of MACC1 on tumor cells. PLoS

One. 20:e03230022025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Sun B, Ding P, Song Y, Zhou J, Chen X,

Peng C and Liu S: FDX1 downregulation activates mitophagy and the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to promote hepatocellular carcinoma

progression by inducing ROS production. Redox Biol. 75:1033022024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|