Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic and progressive metabolic

disorder, with an incidence rate increasing year by year (1). Diabetes can cause systemic changes,

which increase the mortality and disability rates of patients with

diabetes and it has attracted widespread attention from clinicians

and patients (2). However, once

diabetes occurs, the symptoms are generally severe and progress

rapidly, which seriously threatens the survival of patients with

diabetes (3). Diabetes

complications have always been a research hotspot and focus in the

diagnosis and treatment for researchers, including neurological

complications, microvascular complications and macrovascular

complications. Macrovascular complications mainly include

cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications caused by

involvement of the coronary arteries, cerebrovascular vessels and

peripheral arteries, as well as diabetic foot. Microvascular

complications mainly include diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy

(4).

At present, numerous studies focus on

diabetes-related lung diseases, especially diabetes-induced lung

injury. Due to the abundant reserve of the pulmonary capillary

network, the respiratory symptoms of diabetes are not obvious in

the early stages of the disease and are easily confused with the

manifestations of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications,

making them easily overlooked by clinicians and patients. However,

once diabetes-related lung injury occurs, the symptoms are

generally severe and progress rapidly, posing a serious threat to

the survival of patients with diabetes (5). Diabetes-related lung injury is

mainly manifested as interstitial lung disease, including

inflammatory cell infiltration, increased collagen content,

oxidative stress, widened alveolar septa and tissue fibrosis

(6). Research shows that

significant abnormalities in lung function have been found in

patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, as well as in

children and adults with diabetes (7). Studies have found that the reduced

pulmonary diffusion function in patients with diabetes is mainly

due to thickening of the alveolar basement membrane and alveolar

microvascular disease. Although pulmonary dysfunction is widely

observed in patients with diabetes, its specific mechanisms and

clinical implications require further exploration (8,9).

Diabetes-related pulmonary complications encompass heightened

susceptibility to respiratory infections and chronic conditions,

including pneumonia, asthma, pulmonary fibrosis and tuberculosis,

along with sleep-disordered breathing. A study indicates that

>50% of mortality cases among Japanese patients with diabetes

stem from these respiratory disorders (9). Another study shows that the

fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family is closely related to the

biological function of the lungs (10). Other members of the FGF family

play important roles in lung development and disease. For example,

FGF9 and FGF18 also exhibit important biological effects in

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (10). Endocrine members of the FGF

family, such as FGF19 and FGF21, play an anti-fibrotic role in

various organs. Research has shown that FGF19 can markedly reduce

pulmonary fibrosis in mouse models and may affect the fibrosis

process in the lungs by regulating the function of fibroblasts

(11). In addition, the FGF

signaling pathway also plays an important role in the repair and

regeneration of the lungs. Recent studies have shown that FGF4 has

an important biological role in the lungs (12,13). FGF4 belongs to the paracrine

subfamily of fibroblast growth factors (which also includes FGF5

and FGF6). It has a molecular weight of 22 kDa and is encoded by a

gene located on human chromosome 11 (11q13.3). FGF4 primarily binds

to and activates specific fibroblast growth factor receptors

(FGFRs), including FGFR1c, FGFR2c and FGFR3c. In vivo, FGF4

can be secreted by multiple organs under specific physiological

conditions, such as the liver, heart and testes. It has been

reported that FGF4 can alleviate diabetes and hyperglycemia

(14,15). However, up to now, the effect of

FGF4 on diabetic lung injury has not been elucidated.

The present study evaluated the effect of FGF4 on

high glucose-induced lung injury. In vitro, MLE-12 (a murine

alveolar epithelial cell line) and BEAS-2B (a human bronchial

epithelial cell line) were used to evaluate FGF4's protective

effect against lung cell damage induced by high glucose. It was

found that FGF4 markedly alleviated the damage caused by high

glucose to lung cells. The current study has laid a solid

foundation for further research on the effect of FGF4 on

high-glucose lung injury.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Streptozotocin (STZ) was purchased from

MilliporeSigma. PVDF membrane, Immobilon, BCA Kit (protein

concentration determination) and hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)

staining kit were from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd. and Masson trichrome staining solution were from Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. Antibodies for TNF-α,

IL-6, superoxide dismutase (SOD)1, 4-Hydroxynonenal and

NFE2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) were from Abcam. Goat anti-rabbit IgG

labeled with horseradish peroxidase, goat anti-mouse IgG labeled

with horseradish peroxidase and electrochemiluminescence (ECL) were

from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. TGF-β1 and

4-hydroxynonenal (4HNE) were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

Cell culture plates, FBS, BSA and TBST buffer were from Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology. CyclinD1, proliferating cell nuclear

antigen (PCNA), phosphorylated (p-)IκB, p-P65 and p-STAT3 were from

Proteintech Group, Inc. malondialdehyde (MDA; cat. no. A003-1-2),

SOD (cat. no. A001-3-2) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX; cat. no.

H545-1-1) were from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute.

Cell culture

MLE12 cells and BEAS-2B were cultured using

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were cultured in a 5%

CO2 incubator at 37°C for 24-48 h.

CCK-8 detection assay

Cells in the logarithmic growth phase (8,000 per

well) were inoculated into 96-well plates. When the cells reached

~70% confluence, they were treated with high glucose (30 mmol/l) at

different time points. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the

absorbance was detected using a microplate reader (OD:450 nm).

ELISA assay

The cell culture supernatant was collected,

subjected to centrifugation (2,000 × g) for 20 min at 4°C then the

supernatant was collected for subsequent detection. The reagent kit

was taken out of the refrigerator and allowed to reach room

temperature. The standard curve was prepared according to the kit's

operating instructions (TNF-α, cat. no. SEKM-0034; IL6, cat. no.

SEKM-0007; IL-1β, cat. no. SEKM-0002) and the expression levels of

inflammatory factors were finally calculated based on the results

of the microplate reader.

Cellular immunofluorescence assay

Lung cells were seeded onto 12-well cell culture

plates containing coverslips (5×104). After seeding, the

plates were transferred to a cell incubator until the cells reached

60% confluence. After FGF4 administration, the seeded cell culture

plates were removed from the incubator and the culture supernatant

was gently aspirated from each well to remove metabolites and

unabsorbed nutrients. Each well was washed to ensure removal of

non-cellular components. Fixative (4% paraformaldehyde solution)

was slowly and evenly added to ensure coverage of all cells for 20

min at 37°C. After fixation, the fixative was carefully discarded

to avoid damaging the cells. Each well was washed four times to

remove excess fixative. For cell permeabilization, Triton X-100 was

appropriately diluted with PBS to 0.5%. This permeabilization

solution was added at 200 μl per well to cover the cells and

incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After washing with PBS,

10% goat serum solution (cat. no. S9070; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) was added at 200 μl per well and

incubated at room temperature for 1 h to block non-specific sites

in the wells and reduce non-specific binding of subsequent primary

antibodies to non-target proteins. After blocking, the

corresponding primary antibodies (LC3, 1:50 dilution; LAMP1, 1:60

dilution; TOM20, 1:100 dilution) were added and incubated overnight

at 4°C. After incubation, 1 ml of PBS was added to each well and

unbound primary antibodies were removed by washing to reduce

background signal. Diluted secondary antibody solution (1:500

dilution) was added for 60 min to promote the formation of

complexes between the secondary antibody and the primary

antibody-bound protein. After secondary antibody incubation, the

wells were washed four times with PBS. DAPI was used to

counterstain the cell nuclei. After secondary antibody incubation

and washing, 200 μl of DAPI solution was added to label the

cell nuclei through the binding of DAPI (0.5 μg/ml) to DNA

for 24 h at 37°C. After DAPI incubation, the cells were washed with

PBS in the dark at low speed. After mounting, the cell samples were

observed using a confocal microscope (Fv3000; Olympus

Corporation).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane

potential (MMP)

MMP was assessed using the fluorescent dye TMRE.

Cells were seeded onto confocal dishes and incubated with 2

μg/ml TMRE at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 30

min. After washing, the cells were examined under a confocal

microscope (Fv3000; Olympus Corporation).

JC-1 staining

After treatment with FGF4, the cells were washed

three times with PBS. JC-1 staining working solution was added to

the cells and incubated in a culture incubator for 30 min at 4°C.

Upon completion of the incubation, the cells were washed three

times with PBS and the cell samples were then examined using a

(Fv3000; Olympus Corporation).

Determination of oxidative stress

indicators

The determination of MDA (cat. no. A003-1-2), SOD

(cat. no. A001-3-2) and GPX (cat. no. H545-1-1) was performed using

commercial kits according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

cell supernatant was collected and the absorbance of the sample was

measured at a 450 nm wavelength.

Knockdown of adenosine monophosphate

(AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by siRNA

The AMPK-targeting siRNA was designed and

synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Corporation with the following

sequences: Sense strand 5'-CAGGCAUCCUCAUAAUUTT-3' and Anti-sense

strand 5'-AAUUAUAUGAGGAUGCCUGTT-3'. A scrambled control siRNA

(Sense: 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT-3'; Anti-sense:

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAdTdT-3') was used as negative control. For

transfection, 15 pmol of siRNA was pre-mixed with 1.5 μl

Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 5 min before being added to cells. After 8 h

of incubation at 37°C, the medium was replaced with fresh complete

medium, followed by 24-48 h of culture before assessing

transfection efficiency (Fig.

S1).

Establishment of diabetic mouse

models

Male C57BL/6J mice (n=20; weight: 20-22g; 6-8 weeks

old) were purchased from Guangdong Yaokang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

and housed at an indoor temperature of 21±2°C with a humidity of

30-70% (12-h light/dark cycle). The animals had ad libitum

access to food and water. After one week of adaptive feeding, all

experimental mice were subjected to body weight and fasting blood

glucose measurements. A type 1 diabetic model was established using

a low-dose STZ intraperitoneal injection method as reported in the

literature. A certain amount of STZ powder was dissolved in 0.1 M

sodium citrate solution (pH 4.5) to prepare a 1% STZ solution.

Prior to administration, mice in all groups were fasted for 3 h

with free access to water. Mice in the diabetes mellitus (DM)

groups received intraperitoneal injections of STZ at a dose of 50

mg/kg body weight once daily for five consecutive days, while mice

in the Ctrl groups received intraperitoneal injections of an equal

volume of 0.1 M sodium citrate solution once daily for five

consecutive days. One week after the last STZ injection, blood

glucose levels were measured from tail vein blood samples. Mice

with blood glucose levels ≥16.7 mmol/l on three separate days were

considered to have successfully developed diabetes. Mice that did

not meet this criterion received supplementary injections until

their blood glucose levels reached the required threshold. After

successfully establishing the DM model, the mice were randomly

divided into four groups (n=5 per group): The control group, DM

group, DM + FGF4 treatment group (0.5 mg/kg) and DM + FGF4

treatment group (1 mg/kg). FGF4 was administered via

intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 0.5-1 mg/kg twice a week for

a total experimental period of 15 days. At the end of the

experiment, all mice were sacrificed by anesthesia (the mice were

sacrificed before the end of the experiment due to reaching humane

endpoint criteria) to ensure no additional suffering. The criteria

(humane endpoints) established in this study also included

emergency situations that might occur during the experimental

process, including: 20% body weight loss from baseline, severe

mobility impairment, overt signs of distress and end-stage disease.

The entire experimental period was 45 days. Animal health and

behavior were monitored twice daily (morning and evening)

throughout the study (physical condition, behavioral signs).

Sacrifice was performed by cervical dislocation, under anesthesia

(sodium pentobarbital; 50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection).

Mortality was confirmed by sustained absence of vital signs

(respiration, heartbeat, reflexes) for 1 min. The present study was

performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of

Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care

and Use Committee (IACUC) of Guangdong University Affiliated

Hospital (202410-235) (https://www.gdmuah.com/kxyj/llsc.htm).

H&E staining

After fixation with 4% formaldehyde for 24 h at

25°C, tissue samples were dehydrated using alcohol of different

concentrations. The tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned

at 4 μm. The tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin

staining solution at room temperature for 5 min. After rinsing with

running water, the sections were treated with differentiation

solution for 30 sec. After washing, eosin staining solution was

added to stain the sections for 30 sec. The sections were immersed

in tap water for 5 min. After clearing with xylene, the sections

were mounted using neutral balsam. The tissue sections were then

observed using a light microscope.

Masson staining

Lung tissue sections (4 μm) were incubated

with Weigert iron hematoxylin staining solution for ~10 min at

25°C. The sections were then treated with alcohol differentiation

solution for 5-15 sec. After rinsing with tap water, the sections

were immersed in Masson bluing solution for 3 min to restore blue

coloration. After rinsing with tap water, the tissue sections were

stained with Ponceau fuchsin staining solution for 5-10 min.

Subsequently, the sections were rinsed with weak acid working

solution for 1 min. They were then washed with phosphomolybdic acid

solution for 1-2 min, followed by another rinse with weak acid

working solution for 1 min. The tissue sections were directly

transferred to aniline blue staining solution for 1-2 min and then

rinsed with weak acid working solution for 1 min. After dehydration

with ethanol, the sections were observed using a light microscope

(magnification, ×10-20). A total of five non-overlapping fields

were randomly selected.

Western blot analysis

Lung tissue was placed in a 2 ml EP tube, pre-cooled

tissue RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. R0020, Solarbio) was added and

the tissue was homogenized using a tissue homogenizer. The sample

was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant

was collected. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA kit.

The proteins (30 μg/lane) were separated by 4-10% SDS-PAGE.

After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a PVDF

membrane, which was washed three times with TBST (0.05% Tween)

solution for 10 min each. The PVDF membrane with target proteins

was blocked in 5% skimmed milk powder at room temperature for 1 h.

The membrane was then washed three times with TBST solution for 10

min each. Primary antibodies (PGC-1α, 1:3,000 dilution; TFAM,

1:2,000 dilution; β-actin, 1:4,000 dilution) diluted in 5% BSA were

added and the membrane was incubated on a shaker at 4°C overnight.

After washing three times with TBST (10 min each), secondary

antibodies (HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody at a

1:5,000 dilution) were added and incubated for 2 h. ECL luminescent

solution was prepared according to the instructions. The PVDF

membrane with target proteins was evenly coated with the

luminescent solution and placed in a fully automated

chemiluminescence imaging system for exposure. Blots were

quantified using ImageJ 1.52a software (National Institutes of

Health).

Immunohistochemistry

The tissue sections were permeabilized with 0.1%

Triton X-100 for 15 min. The sections (4 μm) were blocked

with 10% goat serum (as antigen blocking solution) for 2 h at 25°C.

Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the

sections with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min at room

temperature. The corresponding primary antibodies solution (IL6,

cat. no. 1:EPR23819-103, 1:150 dilution; IL-1β, cat. no. EPR19147,

1:200 dilution) was then added and the slides were incubated at 4°C

for 12 h. After incubation, the sections were thoroughly washed

with PBS. Fluor594-labeled secondary antibody (cat. no. K1034G,

1:500 dilution) was added and incubated for 60 min at 37°C. After

washing, the sample was observed using a laser confocal microscope

(Fv3000; Olympus Corporation).

Statistical analysis

All experimental results are presented as mean ± SD,

SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp.) was used for statistical analysis. All data

were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk method and data

that met normal distribution were analyzed using One-way ANOVA

variance analysis. Tukey's post hoc test was used to assess the

associations among different groups. Data that did not meet normal

distribution were analyzed using the rank sum test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

The effect of FGF4 on high

glucose-induced lung cell injury

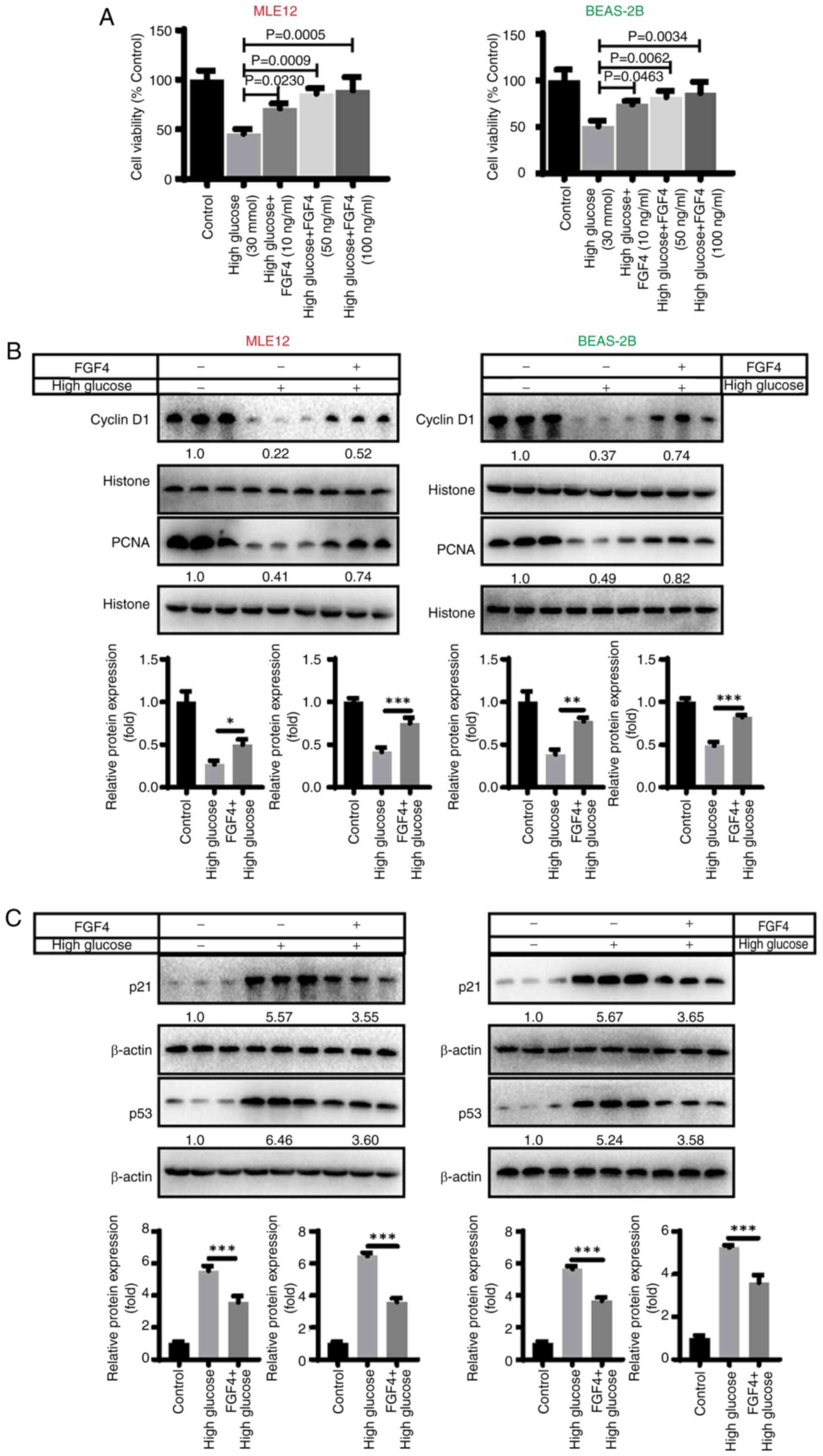

CCK8 assays were used to detect the effect of FGF4

on high-glucose-induced lung cells. High glucose treatment [30

mmol/l; this selection of glucose concentrations is based on

reference (15)] induced a

decrease in the proliferative capacity of lung cells, indicating

that high glucose has a significant inhibitory effect on lung cell

proliferation. By contrast, when cells were treated with FGF4 (10,

50 and 100 ng/ml; the selection of these concentrations was based

on preliminary experiments), the proliferative capacity of cells

was markedly increased (Fig.

1A). In addition, the present study evaluated the effect of

FGF4 on the expression of cell cycle-related proteins. The results

illustrated that the expression of CyclinD1 and PCNA was markedly

downregulated in the high glucose group, while in the FGF4

treatment group, the expression level of CyclinD1 was markedly

upregulated (Fig. 1B).

Similarly, the expression of p21 and p53 (cell cycle inhibitors)

was markedly reduced after FGF4 treatment, implying that FGF4 can

promote cell proliferation (Fig.

1C).

The effect of FGF4 on high

glucose-induced lung cell inflammation and oxidative stress

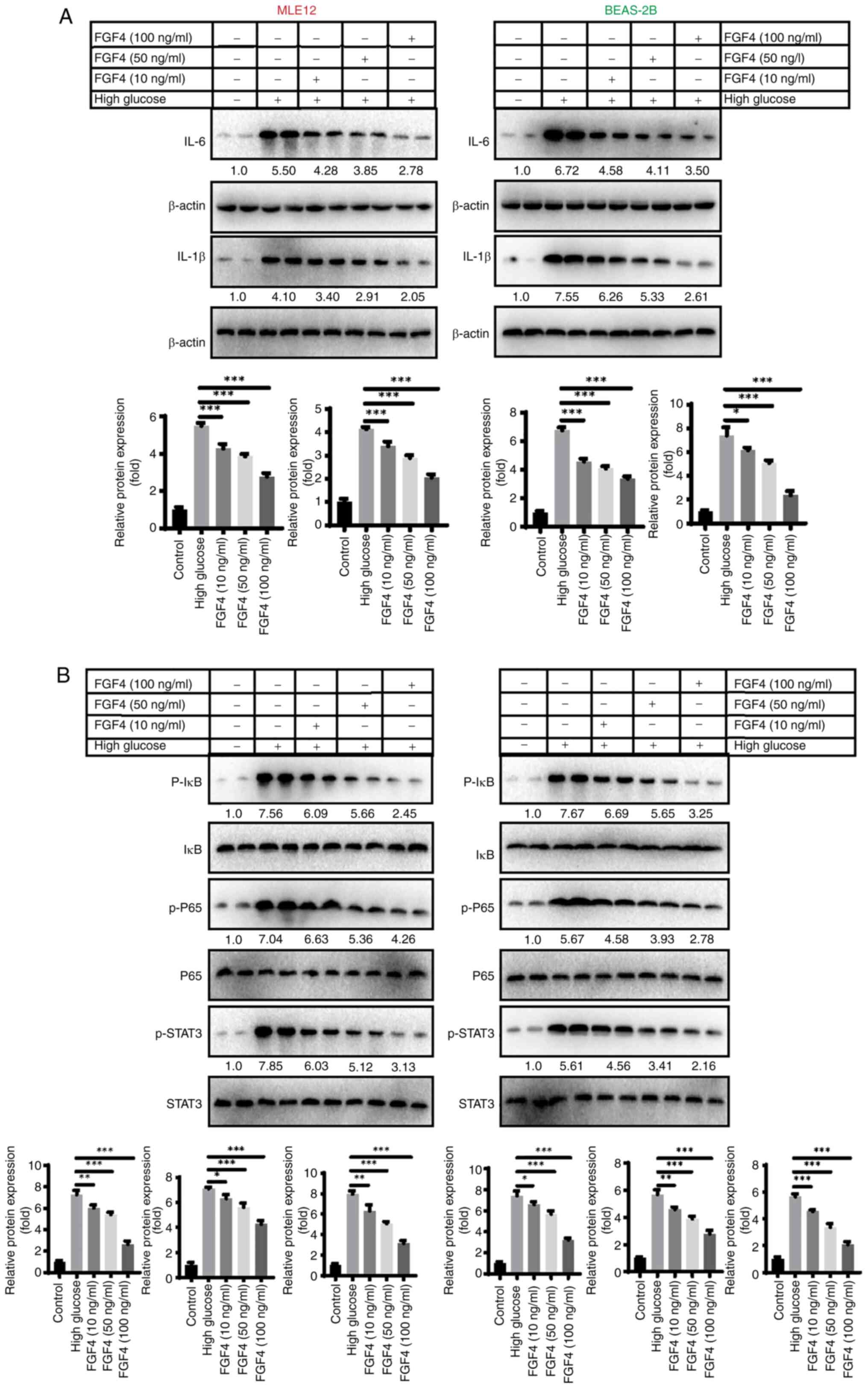

The present study first evaluated the effect of FGF4

on the expression of inflammatory factors in high glucose-induced

lung cells. As shown in Fig. 2A,

western blot analysis revealed that treatment with FGF4 at

concentrations of 10, 50 and 100 ng/ml led to decreased expression

levels of IL-6 and IL-1β. Additionally, the protein expression

levels of p-IκB, p-P65 and p-STAT3 were all reduced following FGF4

treatment (Fig. 2B). The present

study also assessed the effect of FGF4 on oxidative stress and the

results demonstrated that FGF4 could reduce the levels of reactive

oxygen species (ROS) and MDA, while increasing the level of SOD

(Fig. S2).

Effect of FGF4 on high glucose-induced

lung tissue fibrosis

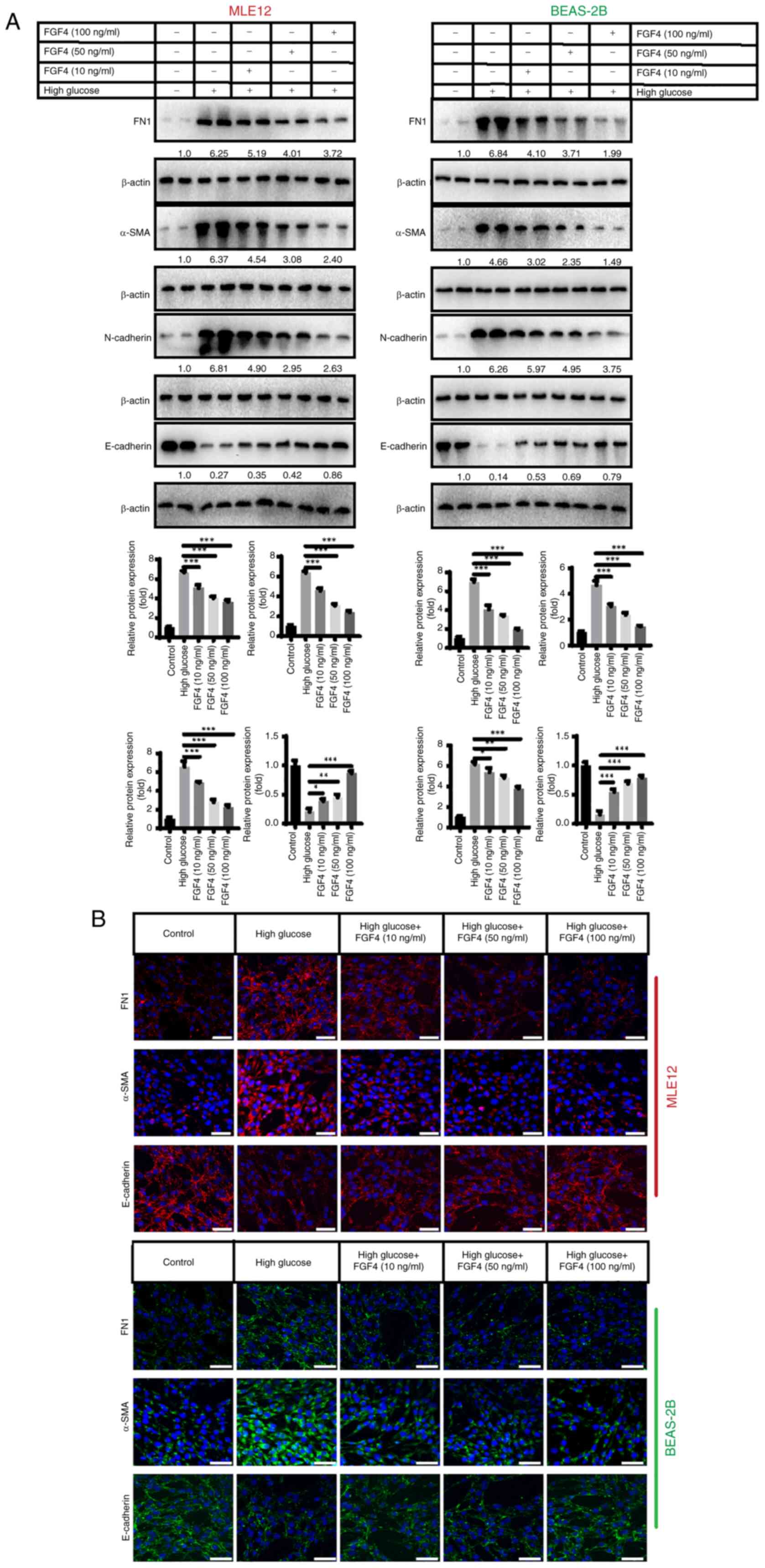

Fig. 3 shows that

high glucose stimulation promotes lung tissue fibrosis. The present

study investigated the expression of fibronectin 1 (FN1), α-smooth

muscle actin (α-SMA) and epithelial cell markers (E-cadherin and

N-cadherin). The results revealed that in the high-glucose group,

the protein expression of FN1, α-SMA and N-cadherin was

upregulated, while E-cadherin protein expression was downregulated.

It was observed that after FGF4 treatment, the expression levels of

FN1, α-SMA and N-cadherin were also markedly decreased, while

E-cadherin expression was increased (Fig. 3A). In addition, indirect

immunofluorescence assays yielded similar results (Fig. 3B).

FGF4 alleviates high glucose-induced

inhibition of mitochondrial autophagy

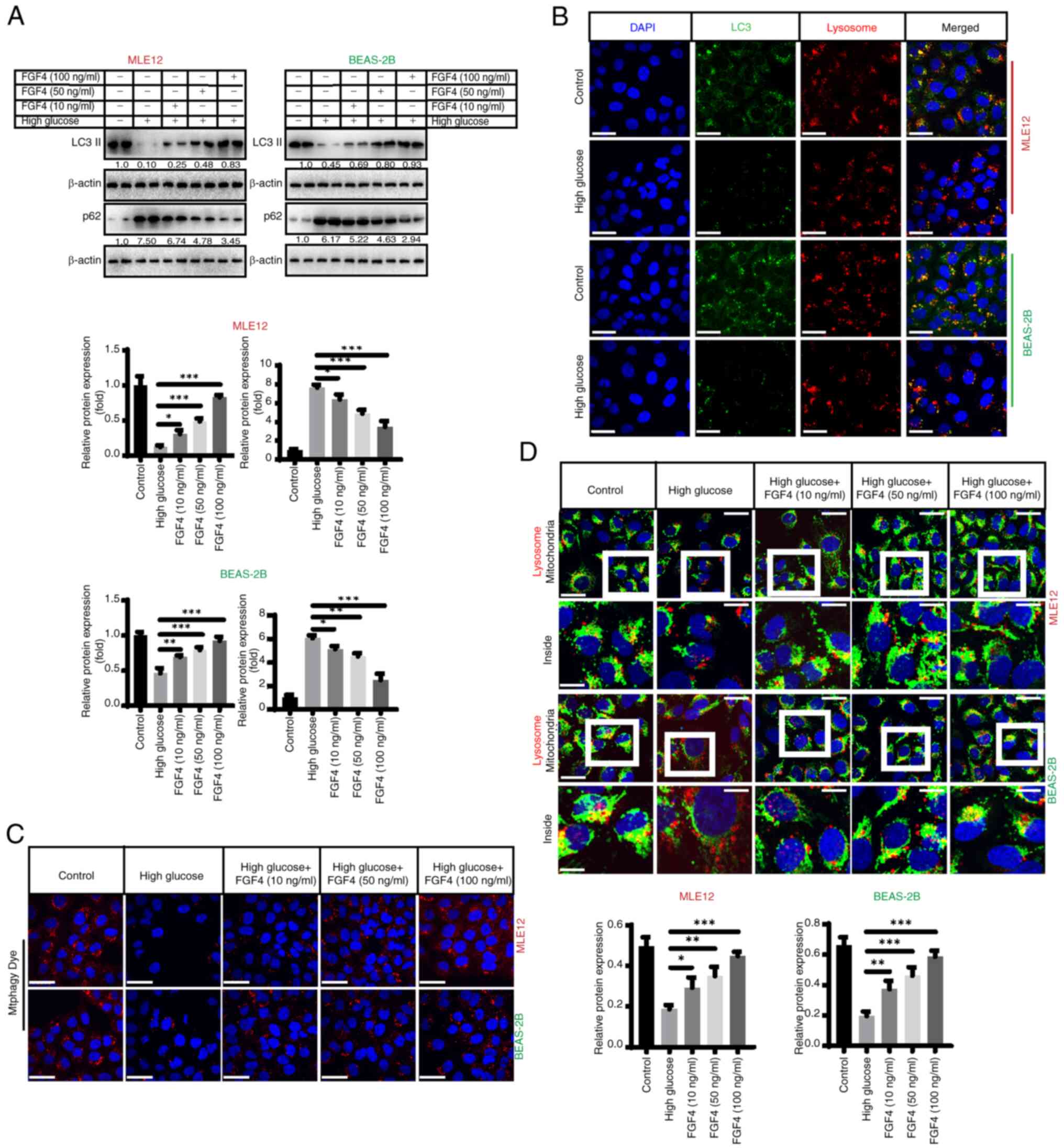

The present study assessed the impact of high

glucose on mitochondrial autophagy. It first evaluated the effect

of high glucose on autophagy and found that the expression of

LC3-II decreased, while the expression level of p62 markedly

increased (Fig. 4A). Indirect

immunofluorescence also demonstrated that high glucose inhibited

autophagy, as the co-localization (yellow fluorescence) of LC3

(green fluorescence) and lysosomes (red fluorescence) was markedly

reduced (Fig. 4B). Furthermore,

we found that mitophagy (red fluorescence) was markedly inhibited

by high glucose treatment and FGF4 promoted autophagy when assessed

using specific fluorescent probes (Fig. 4C). Additionally, fluorescence

co-localization (yellow fluorescence) showed that mitochondrial

autophagy (lysosomes: red fluorescence; mitochondria: green

fluorescence) was partially restored following FGF4 treatment

(Fig. 4D). In addition, the

expression level of TOM20 increased in the high-glucose treatment

group, while its level markedly decreased after FGF4 treatment,

indicating enhanced mitophagy (Fig.

S4A). MMP staining with JC-1 revealed that mitochondrial

membrane potential had undergone depolarization and its level

increased after FGF4 treatment (Fig. S4B).

In general, PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin

mediates autophagy of mitochondria with impaired membrane

potential. However, PINK1/Parkin decreased under high-glucose

treatment. After FGF4 treatment, the level of mitochondrial

autophagy was partially restored (Fig. S4C). This suggested that FGF4 may

regulate mitochondrial activity by modulating mitochondrial

biosynthesis and autophagy pathways.

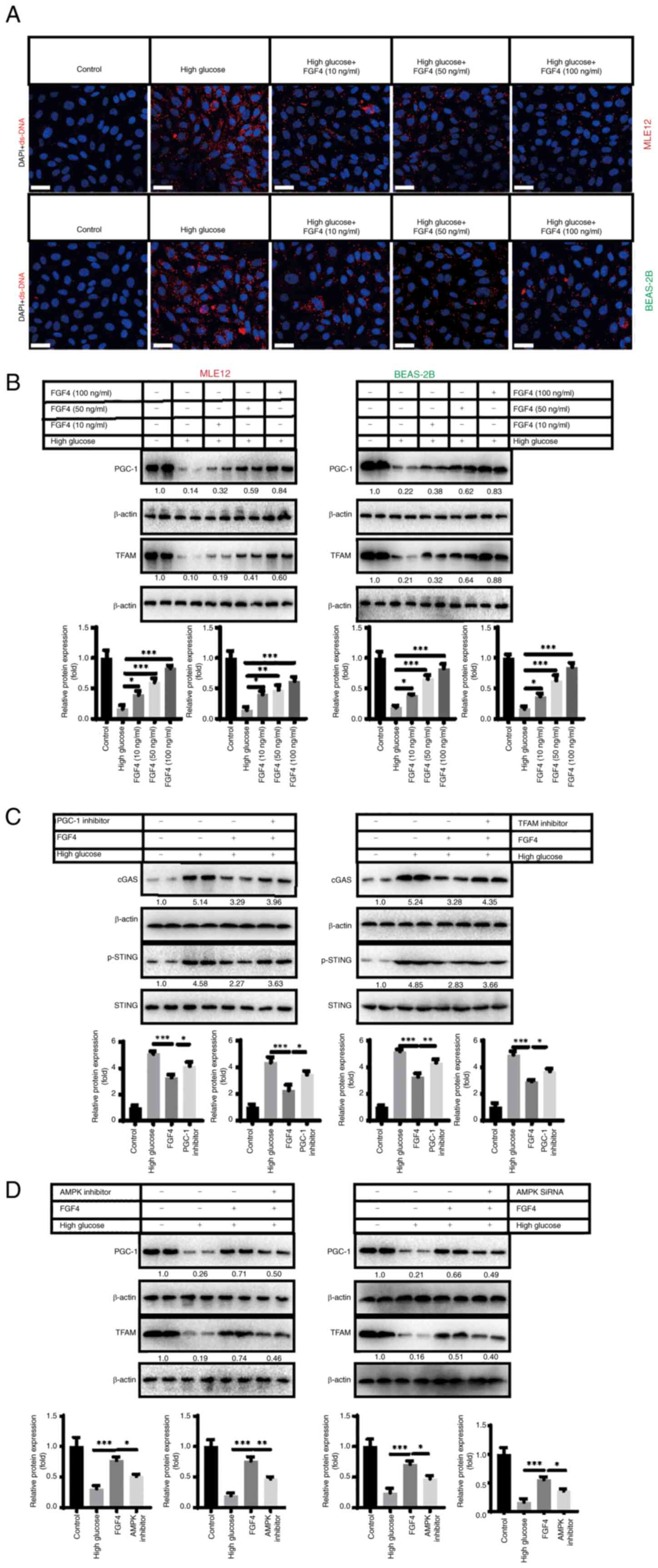

High glucose induces release of mtDNA

from lung mitochondria and activates cGAS-STING signaling

High glucose-induced injury can lead to

mitochondrial damage (16).

Therefore, the present study further focused on mitochondria as a

target and explored the potential molecular mechanisms by which

FGF4 combats high glucose-induced lung cell damage. It was

hypothesized that dysfunctional mitochondria may release

damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) into the cytoplasm.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), as an important DAMP, further activates

the inflammatory response in lung cells. This may be one of the

potential molecular mechanisms underlying the current study. To

this end, the present study conducted relevant experiments to

verify this hypothesis. Using indirect immunofluorescence, it was

found that the level of mitochondrial DNA (red fluorescence) in the

cytoplasm markedly increased under high-glucose treatment, while

mtDNA levels markedly decreased following FGF4 treatment (Fig. 5A). The present study continued to

explore how FGF4 repaired mitochondria and reduced mtDNA leakage. A

previous study showed that the PGC-1-mitochondrial transcription

factor A (TFAM) signaling pathway regulates mitochondrial

biosynthesis and maintains mitochondrial function (17). The present study demonstrated

that high glucose severely inhibited the expression of PGC-1 and

TFAM, while FGF4 treatment partially restored the expression of

these molecules (Fig. 5B). When

the expression of PGC-1/TFAM was inhibited, it was found that the

alleviating effect of FGF4 on cGAS-STING signaling was partly

offset (Fig. 5C). Further

experiments showed that FGF4 activated the PGC-1/TFAM signaling

axis through AMPK: when AMPK was inhibited, the activity of the

PGC-1/TFAM signaling pathway was markedly reduced (Figs. 5D and S3). These data suggested that FGF4

regulates cGAS-STING signaling through the AMPK-PGC-1-TFAM

signaling axis.

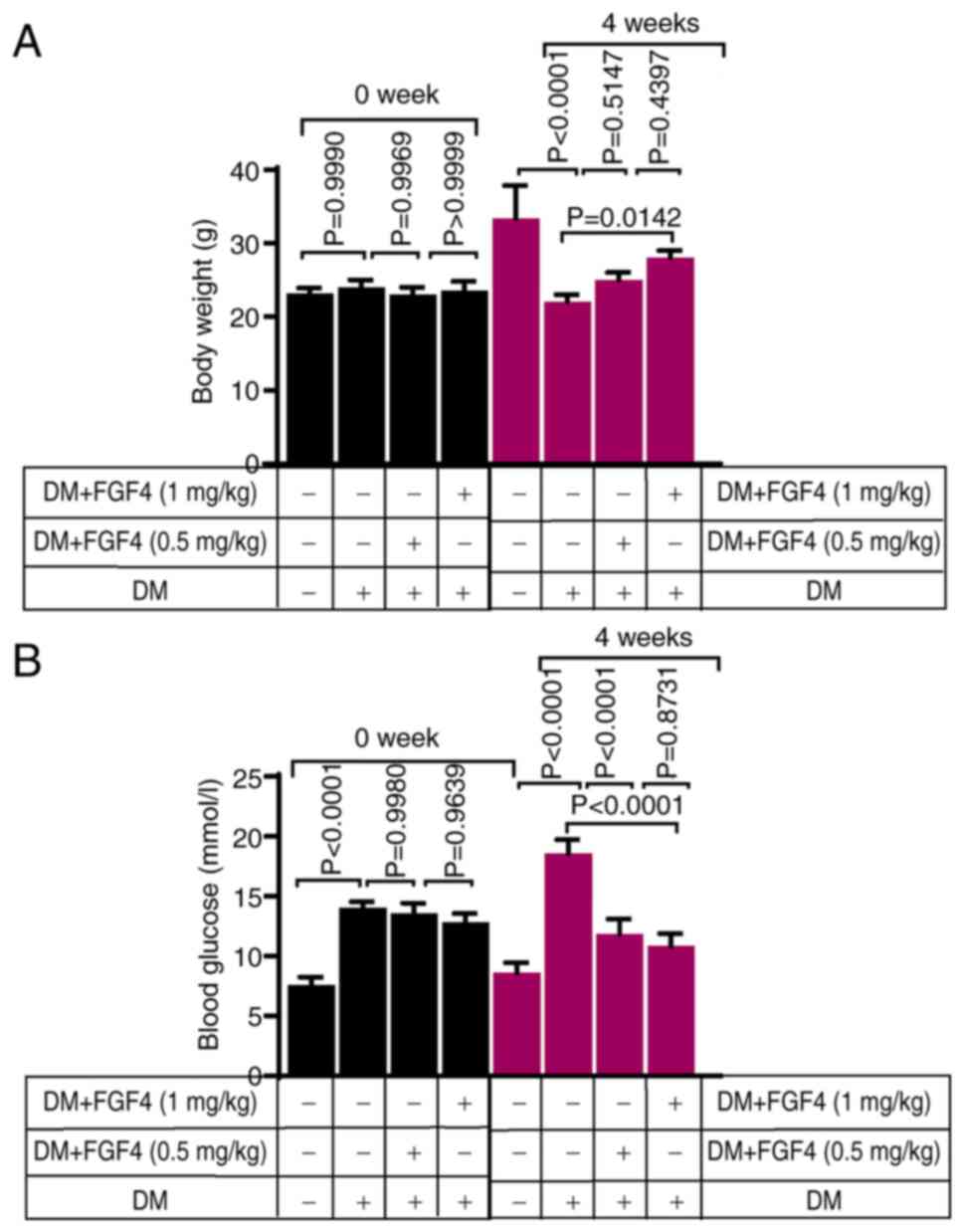

The effect of FGF4 on body weight and

blood glucose in diabetic mice

Changes in body weight of mice in each group before

and after the experiment are shown in Fig. 6A. As expected, at week 0, there

were no significant differences in body weight among the groups.

Compared with the diabetic group, the body weight of mice in the

FGF4 treatment group increased slightly, suggesting that FGF4 can

alleviate diabetes-induced weight loss. In addition, changes in

blood glucose levels in mice across all groups before and after the

experiment were evaluated. Blood glucose levels of mice in each

group before and after the experiment are shown in Fig. 6B. Prior to the experiment (week

0), blood glucose levels in the diabetic and diabetic + FGF4 groups

were markedly higher than those in the control group, indicating

successful establishment of the diabetic mouse model. At the end of

the fourth week, blood glucose levels in the FGF4 treatment group

were markedly lower than those in the diabetic group, suggesting

that FGF4 has a significant hypoglycemic effect in diabetic mice,

which is consistent with previous findings.

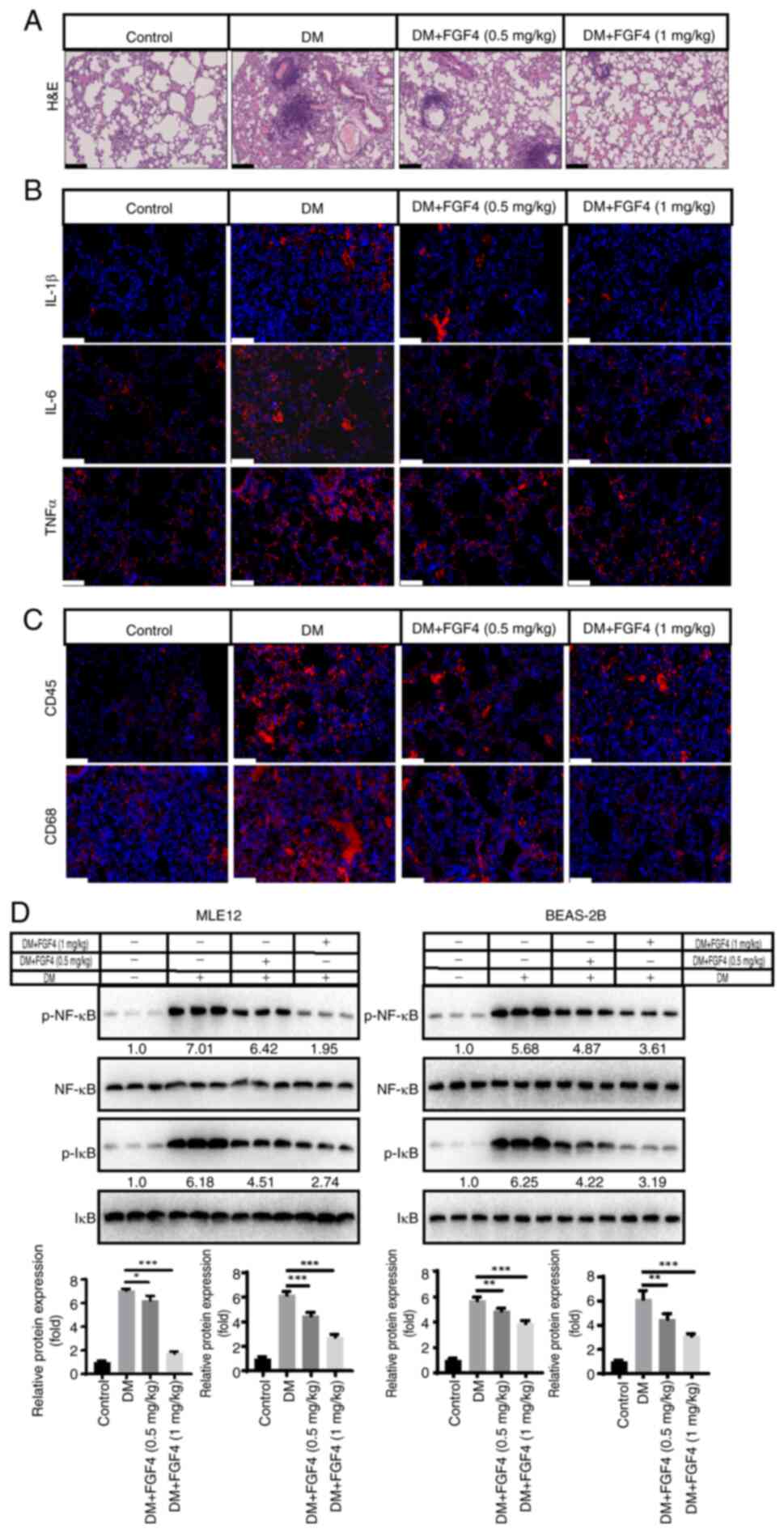

Effect of FGF4 on lung tissue

inflammation in diabetic mice

The present study evaluated the effect of FGF4 on

pathological changes in lung tissue of diabetic mice. From H&E

staining results, compared with the diabetic model group, the

alveolar structure in the control group was clear and intact, with

no obvious exudation in the alveolar cavity and no significant

widening of alveolar septa. However, in diabetic mice, the alveolar

structure was destroyed and inflammatory cell infiltration was

observed. In the FGF4 treatment group, pathological changes were

markedly alleviated compared with the DM group (Fig. 7A). To further evaluate pulmonary

inflammation in diabetic mice, we used immunohistochemistry to

detect the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6. As shown in Fig. 7B, compared with the control

group, the expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in lung

tissues of diabetic mice were markedly higher, while their

expression levels in the FGF4 treatment group were markedly lower

than those in the diabetic group (DM). These results suggested that

FGF4 can downregulate the expression of inflammatory factors.

Furthermore, immunofluorescence showed that the infiltration of

inflammatory cells (CD45+ and CD68+ cells)

was markedly reduced (Fig. 7C).

In addition, the expression level of the inflammatory factor NF-κB

was also markedly decreased (Fig.

7D).

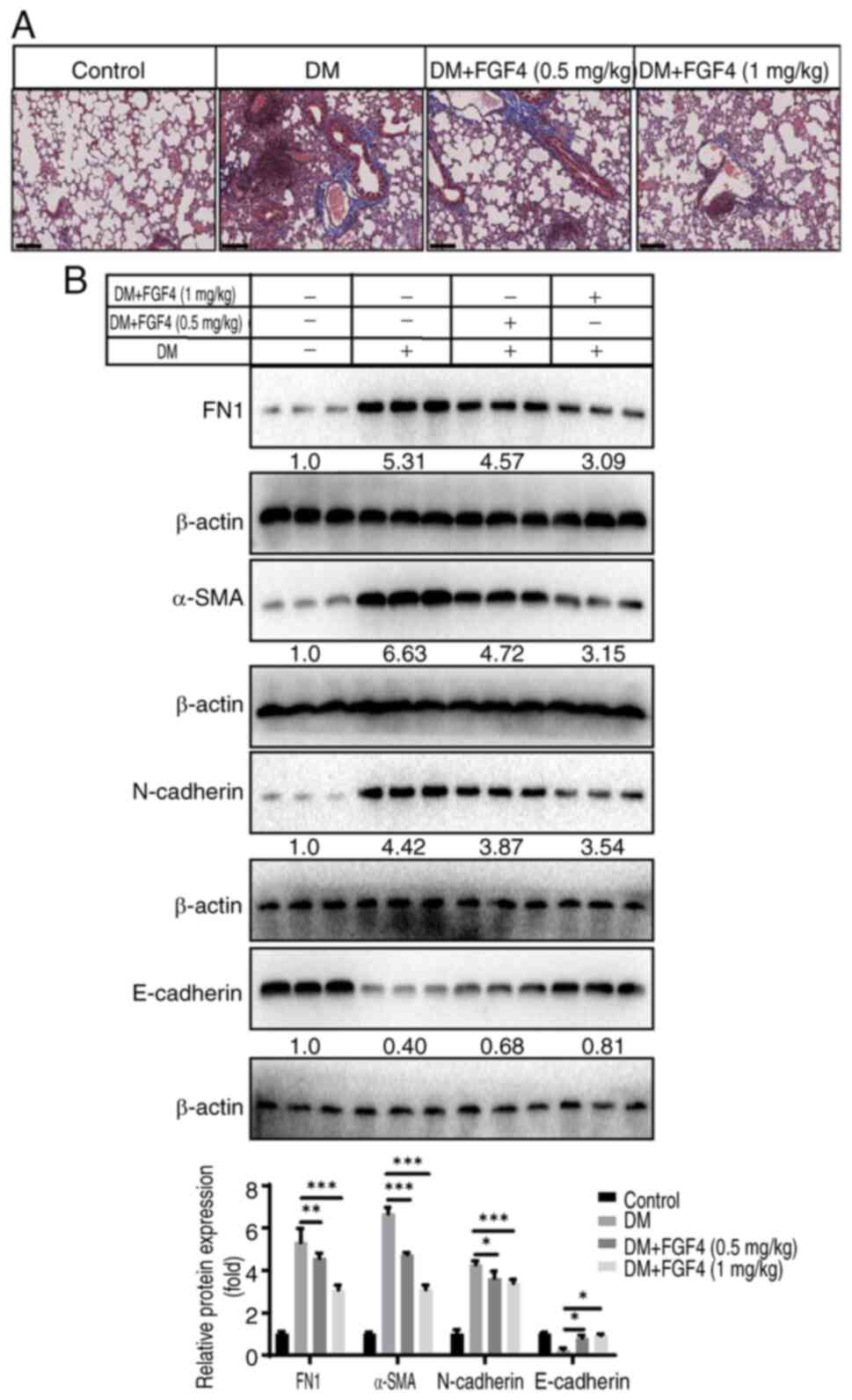

Effect of FGF4 on the degree of pulmonary

fibrosis in diabetic mice

The present study continued to evaluate the effect

of FGF4 on the fibrosis level in mouse lung tissues and performed

Masson staining: As shown in Fig.

8A, there was no significant collagen deposition in lung

tissues of the control group, while more blue-stained collagen

fibers were observed in lung tissues of the DM group. By contrast,

only a small amount of collagen fibers were observed in lung

tissues of the FGF4 treatment group. The present study also

examined the expression of FN1, α-SMA, E-cadherin and N-cadherin

proteins. The results showed that after FGF4 treatment, the

expression of FN1, α-SMA and N-cadherin was downregulated, while

the expression of E-cadherin was upregulated (Fig. 8B).

Effect of FGF4 on the

oxidative-antioxidant balance in lung tissue of diabetic mice

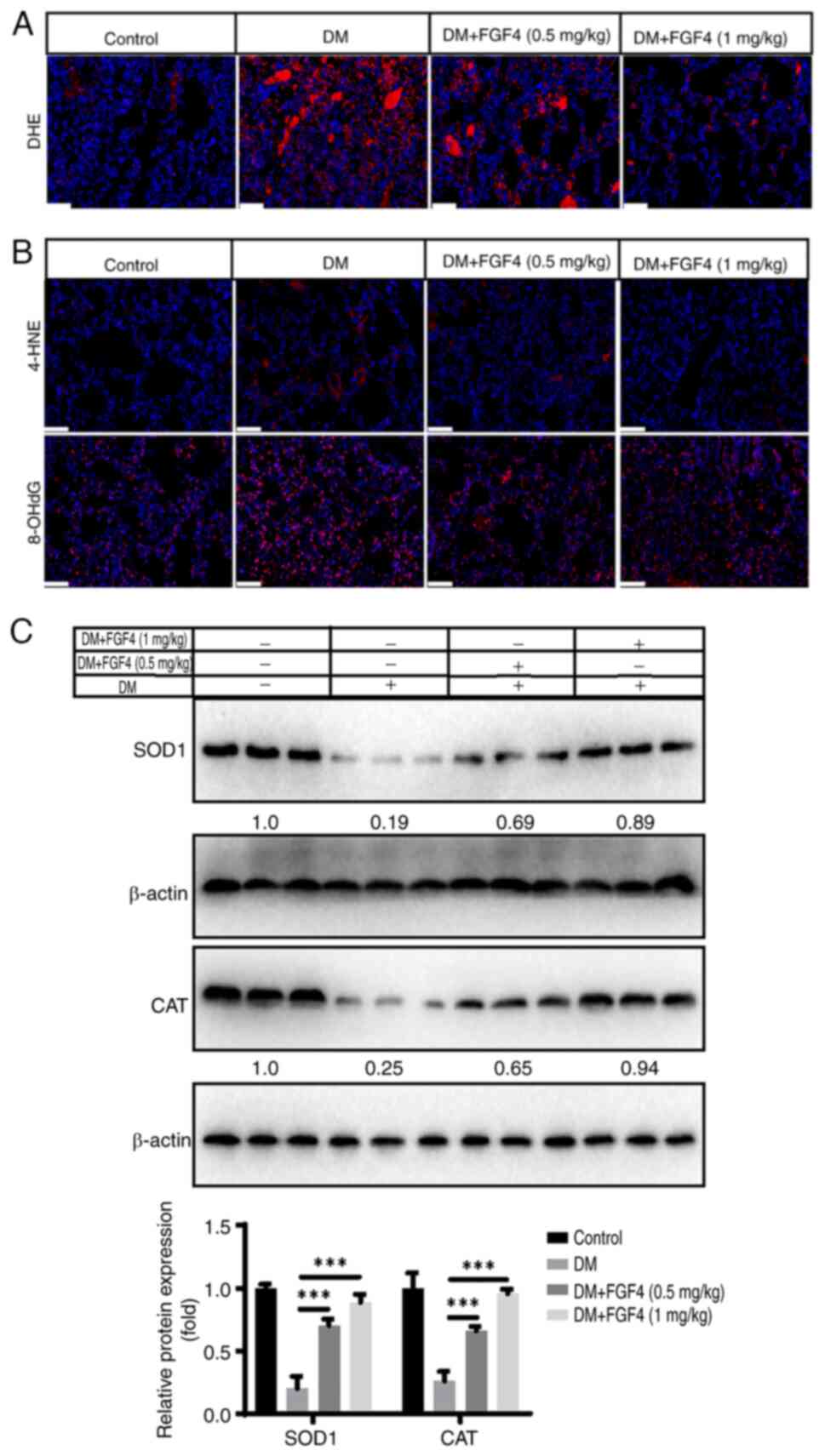

Given that oxidative stress is involved in the

pathogenesis of diabetes-related lung injury (1), the present study first analyzed the

effect of FGF4 on oxidative stress. DHE staining showed that ROS

levels in lung tissue markedly decreased under FGF4 treatment

(Fig. 9A). In addition, the

present study evaluated the levels of 4-HNE and 8-OHdG. Compared

with the control group, the expression level of 4-NHE and 8-OHdG in

the diabetic group was markedly increased, while the expression

levels of 4-HNE and 8-OHdG in the FGF4 group were markedly lower

than those in the DM group. These results suggested that oxidative

stress damage occurs in the lung tissues of diabetic mice and FGF4

administration can alleviate this oxidative stress response

(Fig. 9B). Antioxidant proteins,

including SOD1 and catalase (CAT) were also evaluated. The results

showed that the expression of SOD1 and CAT in the diabetic group

was markedly reduced, whereas their expression levels were markedly

increased after FGF4 treatment (Fig.

9C).

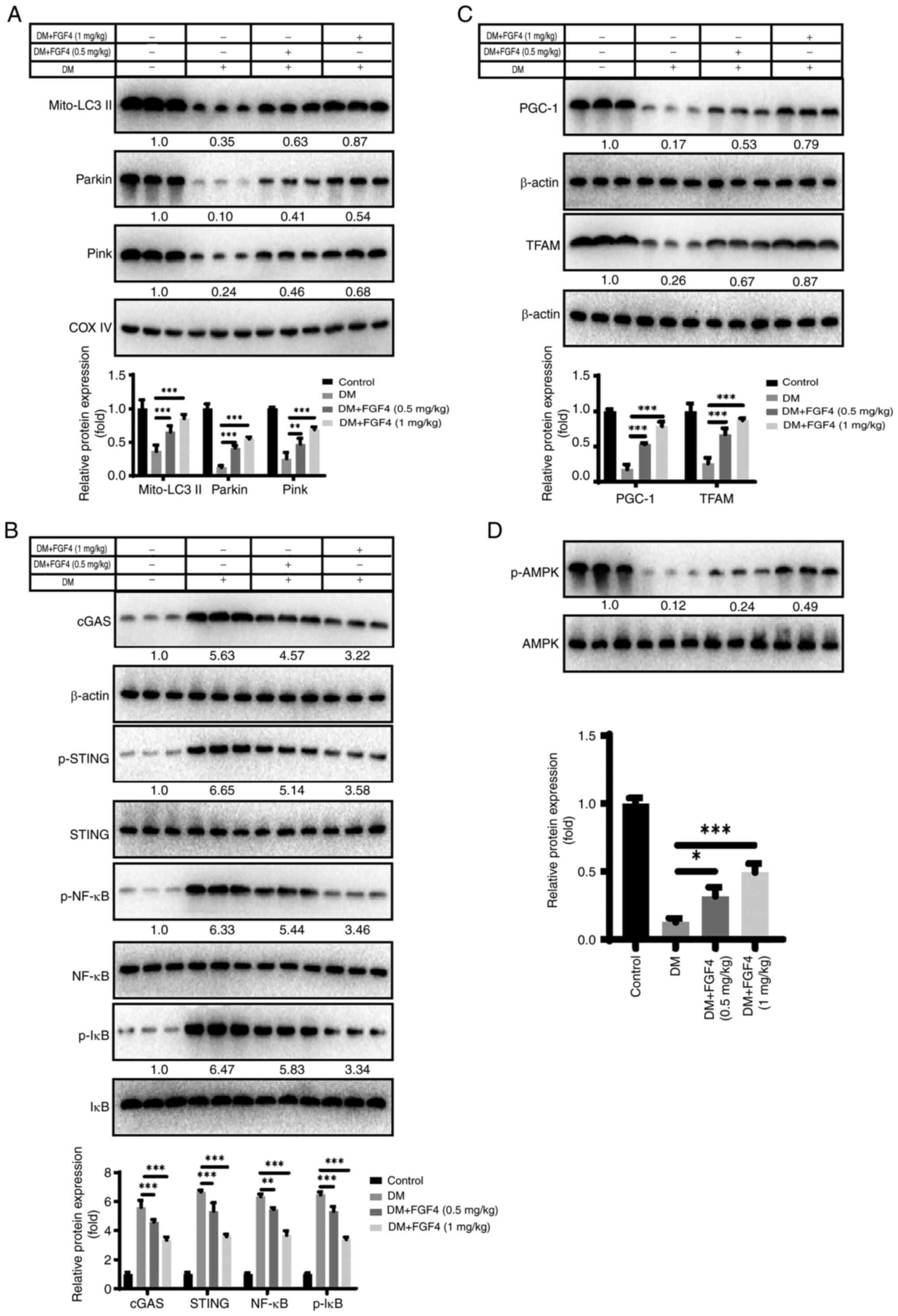

Effect of FGF4 on mitochondrial autophagy

and cGAS-STING signaling in vivo

The present study also evaluated explored the

potential molecular mechanism by which FGF4 ameliorates lung cell

injury in vivo. First, it analyzed the effect of diabetes

mellitus (DM) on mitochondrial autophagy. Western blot analysis

showed that FGF4 alleviated the inhibition of mitochondrial

autophagy induced by DM (Fig.

10A). The present study further analyzed the effect of FGF4 on

the cGAS-STING signaling pathway and the results revealed that the

activity levels of the cGAS/STING/NF-κB signaling pathway were

markedly reduced (Fig. 10B).

Similarly, FGF4 increased the expression of PGC-1 and TFAM, which

is consistent with the findings from in vitro cell models

(Fig. 10C). Additionally, FGF4

treatment increased AMPK phosphorylation in vivo (Fig. 10D).

Discussion

Diabetes can lead to lung injury and abnormal lung

function, a condition known as diabetic lung disease. Chronic and

persistent hyperglycemia stimulates the production of inflammatory

proteins, which accumulate in small blood vessels and connective

tissues. Glycation modifications of collagen and elastin in lung

tissue can induce interstitial fibrotic changes (18). In addition, diabetes-induced

systemic inflammation is another major cause of lung injury.

Dysregulation of inflammatory regulatory mechanisms can trigger

excessive inflammatory responses in the lungs, resulting in

impaired lung function (19). In

the present study, a type 1 diabetes model was established via

intraperitoneal injection of low-dose STZ. After successful

modeling, FGF4 intervention was administered to further investigate

the role and potential mechanism of FGF4 in diabetes-related lung

injury. Results showed that blood glucose levels in experimental

mice decreased and their body weight rebounded. These findings

indicated that FGF4 exhibits a protective effect against

diabetes-related lung injury in both in vitro and in

vivo models. First, to the best of the authors' knowledge, this

is the first study to reveal that FGF4 can alleviate

high-glucose-induced lung injury; Second, it identified a new

molecular mechanism by which FGF4 promotes mitophagy to mitigate

high glucose-mediated lung damage; Third, it was found that FGF4

can ameliorate lung injury, particularly pulmonary fibrosis

(another original observation).

In vitro experiments showed that FGF4 could

mitigate high glucose-induced lung cell damage and promote cell

proliferation. For instance, FGF4 increased Ki67 expression while

suppressing p21 and p53 expression.

Inflammatory responses and oxidative stress play

important roles in the pathogenesis of diabetes-related lung injury

(20). The present study first

evaluated the effect of FGF4 on lung tissue in both in vitro

and in vivo models of diabetic mice. H&E staining showed

that the alveolar structure was destroyed, the alveolar septa were

markedly widened and inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in

the widened alveolar septa, small bronchi and around blood vessels,

suggesting that diabetic mice had developed pulmonary

complications. Furthermore, the levels of the inflammatory factors

TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were assessed and the results showed that

FGF4 treatment reduced the inflammatory response. The present study

also evaluated NF-κB levels and found that its expression was

markedly decreased.

Clinical and laboratory evidence supports that

oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathophysiology of

diabetes and its complications. Continuous high-glucose stimulation

can lead to the accumulation of large amounts of ROS in the lungs,

inducing oxidative stress injury and further aggravating pulmonary

inflammatory responses (21).

The coexistence of oxidative stress and inflammation is a common

cause and high-risk factor for diabetes. The present study found

that FGF4 alleviated oxidative stress levels in both in

vitro and in vivo models. Previous studies have also

shown that multiple members of the FGF family exhibit antioxidant

stress effects; for example, FGF1, FGF2 and FGF21 play important

roles in antioxidant stress and aging (10,22).

In addition, pulmonary fibrosis is another important

pathological change in diabetes-induced lung injury (23). A key mechanism promoting tissue

fibrosis is epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and animal

experiments have confirmed that inhibiting EMT can reduce the

progression of tissue fibrosis. Continuous high-glucose stimulation

can induce EMT, mainly mediated by the upregulation of

fibroblast-specific TGF-β1. The present study showed that FGF4

relieved pulmonary fibrosis in diabetic mice by inhibiting the

production of pulmonary fibrosis, as evaluated by the expression of

relevant markers.

Autophagy is a cellular degradation program involved

in responses to various stimuli (24). Thus, autophagy dysfunction may

lead to a number of pathological changes, including cancer and

immune abnormalities (25). It

is ubiquitous across organisms, involving the formation of

autophagosomes that recognize damaged or dysfunctional organelles

and macromolecules. Autophagy can be divided into different types,

such as chaperone-mediated autophagy, microautophagy and

macroautophagy. By analyzing its nature, mitochondrial autophagy

(mitophagy) is recognized as a specialized type of autophagy and

studies have found that it is closely associated with cellular

homeostasis. Based on differences in phagocytic and recognition

mechanisms, these processes can be roughly categorized into two

pathways: Ubiquitin-dependent and receptor-dependent. In the first

pathway, PINK1/Parkin is most critical; its mechanism primarily

involves the binding of damaged mitochondria to ubiquitinated outer

membrane proteins, which recruits p62. p62 then binds to LC3 on the

autophagosome membrane, promoting the encapsulation of damaged

mitochondria within autophagosomes to complete mitochondrial

degradation (26). The second

pathway relies on interactions between γ-aminobutyric acid

receptor-related proteins and LC3 on autophagosomal membranes, such

as NIX, FUNDC1 and BNIP3 located on the outer membrane of damaged

mitochondria. FUNDC1 and BNIP3 directly interact with LC3 before

being recognized by phagocytic vesicles (26).

The present study showed that under high-glucose

conditions, FGF4 markedly enhanced mitophagy levels. Specifically,

LC3 protein expression was markedly increased, while p62 protein

levels were markedly reduced. Additionally, under high-glucose

conditions, the mitochondrial membrane potential in the FGF4

treatment group was higher than that in both the empty vector group

and the high-glucose group. This finding further confirmed the

increased mitophagy levels in the FGF4-treated group.

The cGAS-STING signaling pathway and mitochondrial

autophagy play important roles in inhibiting mtDNA leakage

(27). Mitophagy is a cellular

process that maintains mitochondrial health by eliminating damaged

mitochondria. When mitochondria are damaged, mitophagy prevents the

accumulation of mtDNA in the cytoplasm, thereby avoiding the

triggering of inflammatory responses mediated by the cGAS-STING

pathway (28). In this process,

mitophagy not only optimizes mitochondrial function but also

maintains cellular homeostasis by inhibiting the cGAS-STING

signaling. By contrast, the cGAS-STING pathway triggers an immune

response upon detecting mtDNA leakage, further affecting cellular

function and survival. The present study found that FGF4 can

inhibit the activation of cGAS-STING by regulating the PGC-1α-TFAM

signaling pathway.

It is important to mention that most other FGF

family members (such as FGF21 and FGF23) have been widely reported

for their association with hyperglycemia, whereas research on FGF4

remains relatively limited. In terms of practical application

potential, the experimental results demonstrated that FGF4 holds

significant promise, as its biological activity may be stronger

compared with other FGF members. Therefore, FGF4 may be a promising

drug for treating lung damage caused by diabetes.

The current study has several limitations. First,

toxicological studies of FGF4 need to be conducted in future work.

Second, the targeting specificity of FGF4 requires improvement, as

it can distribute to various tissues and organs after entering the

bloodstream. Third, the short half-life of FGF4 needs to be

addressed in future studies, to overcome this limitation, it is

planned to employ the nano-sustained release materials as a

strategic solution to markedly prolong FGF4's therapeutic window

and enhance its bioavailability. Fourth, while the current study

employed a type 1 diabetes model, future research will use a type 2

diabetes model to evaluate the effects of FGF4. Fifth, the lack of

an insulin control group in vivo also represents one of the

limitations in the current study. Future research will focus on

developing strategies to enhance the specific targeting of FGF4 to

lung tissue, such as using lung-targeted nanomaterials.

FGF4 holds important significance in alleviating

diabetic lung injury. Patients with diabetes often develop

pulmonary complications and FGF4, as a novel long-acting

glucose-regulating factor, can not only effectively regulate blood

glucose but also alleviate pulmonary inflammation and injury

through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. This

discovery provides a new strategy for the treatment of

diabetes-related lung injury, which is expected to improve the lung

health of patients with diabetes, enhance their quality of life and

holds important clinical and scientific value.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

QF and JX participated in study design and data

collection. QW, FL, ZL, YO and KH carried out the initial analysis.

QF and JX drafted the article. JG and TW confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Zhanjiang Science and

Technology Plan Projects (grant nos. 2024B01314, 2025B01228 and

2022A01192), the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program

for College Students of Guangdong Province (grant no.

S202510571085); and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training

Program for College Students of Guangdong Medical University (grant

nos. GDMUCX2024081 and GDMUCX2024304).

References

|

1

|

Banday MZ, Sameer AS and Nissar S:

Pathophysiology of diabetes: An overview. Avicenna J Med.

10:174–188. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cole JB and Florez JC: Genetics of

diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat Rev Nephrol.

16:377–390. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Klein S, Gastaldelli A, Yki-Järvinen H and

Scherer PE: Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 34:11–20.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chan JCN, Lim LL, Wareham NJ, Shaw JE,

Orchard TJ, Zhang P, Lau ESH, Eliasson B, Kong APS, Ezzati M, et

al: The lancet commission on diabetes: Using data to transform

diabetes care and patient lives. Lancet. 396:2019–2082. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Goldman MD: Lung dysfunction in diabetes.

Diabetes Care. 26:1915–1918. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hsia CCW and Raskin P: Lung function

changes related to diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther.

9(Suppl 1): S73–S82. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mameli C, Ghezzi M, Mari A, Cammi G,

Macedoni M, Redaelli FC, Calcaterra V, Zuccotti G and D'Auria E:

The diabetic lung: Insights into pulmonary changes in children and

adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Metabolites. 11:692021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

van Gent R, Brackel HJ, de Vroede M and

van der Ent CK: Lung function abnormalities in children with type 1

diabetes. Respir Med. 96:976–978. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zheng H, Wu J, Jin Z and Yan LJ: Potential

biochemical mechanisms of lung injury in diabetes. Aging Dis.

8:7–16. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yang L, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang D, Li X,

Zhao C and Huang X: FGF/FGFR signaling: From lung development to

respiratory diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 62:94–104. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ghanem M, Archer G, Crestani B and

Mailleux AA: The endocrine FGFs axis: A systemic anti-fibrotic

response that could prevent pulmonary fibrogenesis? Pharmacol Ther.

259:1086692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wang X, Zhou L, Ye S, Liu S, Chen L, Cheng

Z, Huang Y, Wang B, Pan M, Wang D, et al: rFGF4 alleviates

lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting the

TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 117:1099232023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Liu Y, Ji J, Zheng S, Wei A, Li D, Shi B,

Han X and Chen X: Senescent lung-resident mesenchymal stem cells

drive pulmonary fibrogenesis through FGF-4/FOXM1 axis. Stem Cell

Res Ther. 15:3092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sundaram SM, Lenin RR and Janardhanan R:

FGF4 alleviates hyperglycemia in diabetes and obesity conditions.

Trends Endocrinol Metab. 34:583–585. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Baumgartner-Parzer SM, Wagner L,

Pettermann M, Grillari J, Gessl A and Waldhäusl W:

High-glucose-triggered apoptosis in cultured endothelial cells.

Diabetes. 44:1323–1327. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Blake R and Trounce IA: Mitochondrial

dysfunction and complications associated with diabetes. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1840:1404–1412. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yao K, Zhang WW, Yao L, Yang S, Nie W and

Huang F: Carvedilol promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by regulating

the PGC-1/TFAM pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

(HUVECs). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 470:961–966. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Khateeb J, Fuchs E and Khamaisi M:

Diabetes and lung disease: An underestimated relationship. Rev

Diabet Stud. 15:1–15. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

19

|

Xiong XQ, Wang WT, Wang LR, Jin LD and Lin

LN: Diabetes increases inflammation and lung injury associated with

protective ventilation strategy in mice. Int Immunopharmacol.

13:280–283. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lontchi-Yimagou E, Sobngwi E, Matsha TE

and Kengne AP: Diabetes mellitus and inflammation. Curr Diab Rep.

13:435–444. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Forgiarini LA Jr, Kretzmann NA, Porawski

M, Dias AS and Marroni NA: Experimental diabetes mellitus:

Oxidative stress and changes in lung structure. J Bras Pneumol.

35:788–791. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Shimizu M and Sato R: Endocrine fibroblast

growth factors in relation to stress signaling. Cells. 11:5052022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Yang J, Xue Q, Miao L and Cai L: Pulmonary

fibrosis: A possible diabetic complication. Diabetes Metab Res Rev.

27:311–317. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Klionsky DJ and Emr SD: Autophagy as a

regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science. 290:1717–1721.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Levine B and Kroemer G: Autophagy in the

pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 132:27–42. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mizushima N: Autophagy: Process and

function. Genes Dev. 21:2861–2873. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kim J, Kim HS and Chung JH: Molecular

mechanisms of mitochondrial DNA release and activation of the

cGAS-STING pathway. Exp Mol Med. 55:510–519. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Villarejo-Zori B,

Viedma-Poyatos Á, Zapata-Muñoz J, Benítez-Fernández R, Frutos-Lisón

MD, Tomás-Barberán FA, Espín JC, Area-Gómez E, Gomez-Duran A and

Boya P: Mitophagy curtails cytosolic mtDNA-dependent activation of

cGAS/STING inflammation during aging. Nat Commun. 15:8302024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|